HSA Board of Directors

Linda Lange President

Betsy Smith Vice President

Maryann Readal Secretary/Communications

Laura A. Mullen Treasurer/Finance

Gayle Engels Botany & Horticulture Chair

Open Education Chair

Open Development Chair

Casey King Membership Chair

Rosemary Lovall-Sale Honorary President

Membership Delegates

Open Central District

Krystal Maxwell Great Lakes District

Kim Labash Mid-Atlantic District

Roxanne Varian Northeast District

William "Bill" Varney South Central District

Sharon Hosch Southeast District

Lisa-Marie Maryott West District

Administrative Staff

Laura Lee Martin Executive Director

Karen Kennedy Educator

Lisa Murphy Development and Membership

Becky Geissinger Financial Services

Kateri Kramer Digital Media and Marketing

Cindy Gill Accountant

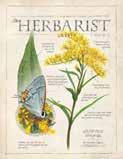

The Herbarist

Debbi Paterno Publication Design, Debbi Paterno Graphic Design

SP Mount Printing Printer

The Herbarist Committee

Lois Sutton, PhD Chair

Maryann Readal HSA Secretary

Jean Berry

Shirley Hercules

Gayle Southerland

Barbara J. Williams

The opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of The Society. Manuscripts, advertisements, comments, and letters to the editor may be sent to:

The Herbarist, The Herb Society of America 9019 Kirtland-Chardon Rd., Kirtland, Ohio 44094 440.256.0514 www.herbsociety.org editorherbarist@gmail.com

The Herbarist, No. 87

© The Herb Society of America

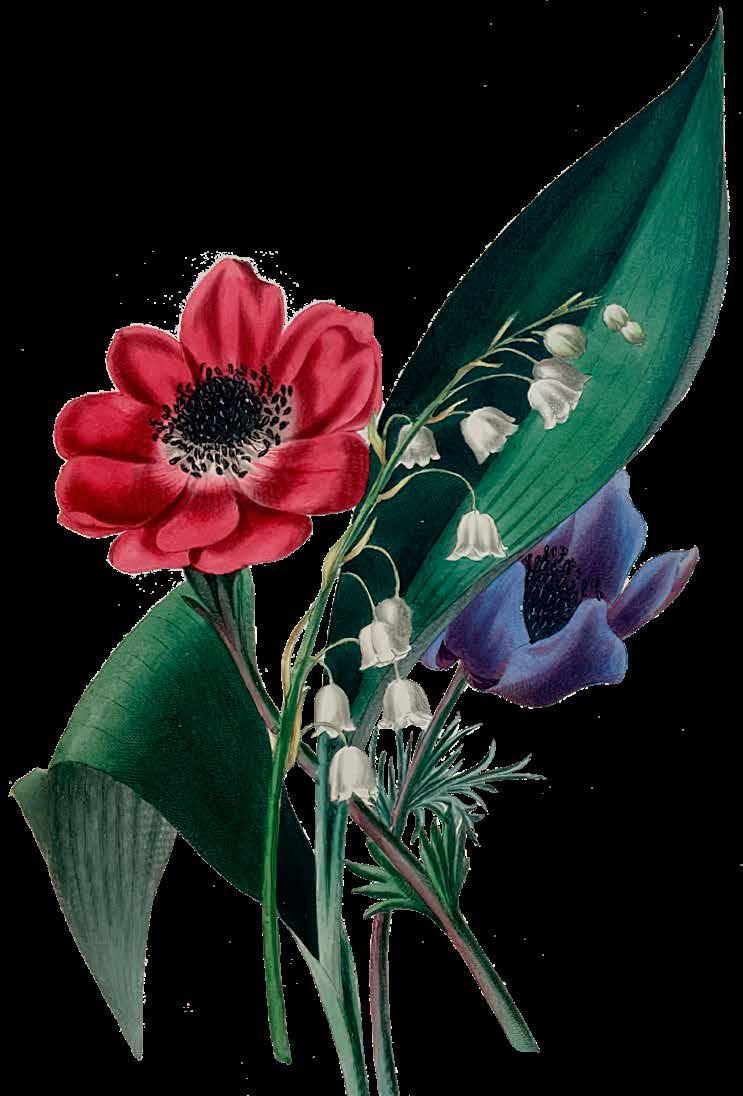

A complete list of sponsors and underwriters may be found on page 56. Cover art from The Romance of Nature, or, the flower-seasons illustrated Louise A. Talmey, 1836.

Front cover sponsored by Maryann and Tom Readal

2 Dandelions... more than a Weed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 By Carol Ann Harlos (Sponsored by Mary Remmel Wohlleb) Every Herb is a Native Somewhere 7 By Barbara J. Williams (Sponsored by Texas Thyme Unit) Herbs in the American Economy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 By Brian Varian, PhD (Sponsored by Christine (Chrissy) Moore) The Lighter Side of Nightshades . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 By Erin Holden (Sponsored by Central District) They Give Their All . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29 By Lois Sutton, PhD (Sponsored by Big Sue Arnold) The Richness of Rare Books . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 By Amy Dawson (Sponsored by Maryann Readal) A Walk with a Royal Herb 42 By Rose Loveall (Sponsored by Andy MacPhillimy and Lois Sutton, PhD) Chimney Swifts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46 By Judy Semroc (Sponsored by Janice Stuff, PhD) Growing Herbs Indoors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 Susan Betz (Sponsored by Wisconsin Unit) The Herbarist Author Biographies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

As if no artifice of fashion, business, politics, had ever been,

Forth from its sunny nook of shelter’d grass- innocent, golden, calm as the dawn, The spring’s first dandelion shows its trustful face.

Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, 1891 - 1892

o one has ever chosen dandelion as Perennial of the Year or Herb of the Year. I doubt they ever will! Dandelion is a highly adaptive diverse species. It can colonize widely differing habitats, from a fertilized dense lawn to bare soil between plants in a tilled field. Most people consider dandelions “weeds.”

Taraxacum officinale (L.) Weber ex.F.H.Wigg, dandelion, is not native to the New World. Europeans brought them to the west for use as a potherb. This member of the Asteraceae family is an invasive species that has naturalized in North America quite easily (Baumgradt, 1982). Botanists have identified several distinct dandelion biotypes (plants of one species that are different genetically). To some degree these biotypes specialize in their

choice of habitats. A dandelion that is in an environment that complements its biotype produces more seed heads than it would in a less complementary environment. This is because of differences in the root hairs, which absorb water and soil nutrients (Michigan State University, 2015).

The leaves of dandelion are pinnately lobed and deeply serrated forming a “lion’s tooth” in outline. This is supposedly the origin of the “dent-de-lion.”

Carolus Linnaeus, the father of the Sandra Cunningham | Dreamstime.com

Issue 87 2022

Carol Ann Harlos

Simple and fresh and fair from winter’s close emerging,

binomial system of nomenclature, gave the dandelion the name Leontodon taraxacum. Dandelion’s scientific name has changed several times. It has been called Taraxacum leontodon, T. taraxacum, and T. vulgare, the last name because it is “common” (Porter, 1967).

Dandelion use has a rich history. It was among the original bitter herbs of the Passover. The Israelites were commanded to eat the Paschal lamb “with unleavened bread and with bitter herbs” (Exodus 12:8). Bitter herbs consisted of chicory, bitter cress, dandelion, hawk weed, sow thistles, and wild lettuce. Today these plants still grow on the peninsula of Sinai, in Palestine, and in Egypt (Hourdajian, 2006).

The genus name Taraxacum may come from the Greek word “tatassein” meaning “to disturb” or from the Persian word “tarkhashqún” meaning “bitter potherb” or “bitter endive” (Engels and Brickman, 2016). The species name officinale, of course, refers to the dandelion root’s use in medicine.

It has been used through history to treat disorders of the kidney and stomach. People believed that dandelions acted as a bladder and kidney stimulant, i.e., a diuretic. The French gave it the name “pissenlit” and the English called it “pissabed.” It is also believed to stimulate the liver and to increase blood circulation (Engels and Brinckmann, 2016).

A front-page article in the April 2021 issue of SNJ Today newspaper declared the “Dandelion Capital of the World” to be Vineland, New Jersey. Well-tended dandelions go from Vineland to markets in Baltimore, New York City, and Philadelphia. At the

yearly festival celebrating dandelions, attendees can sample a variety of dandelion dishes.

Because of their aggressive colonization in disturbed soils, farmers have questioned whether they should manage dandelions in their pastures. The plants don’t seem to affect the quality of pasture forage. In fact, livestock can eat dandelions (Bergen, Mayer, and Kozub, 1990).

Dandelion juice is a milk-like latex. This is true of dandelion’s nearest relatives as well... lettuce, chicory, hawksbeard, and hawk weed.

4

The leaves are delicious when young and are high in vitamins A and C, as well as the minerals iron, copper, and phosphorus. Their use is unlimited in a salad, steamed, or in a stir fry, or as an addition to soup (Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials, n.d.). They are good with onions, eggs, and bacon. They can be incorporated into fritters. If you think spinach, instead think dandelion greens.

You may have noticed dandelions in full sun, but they can grow in shade. They don’t seem to mind drought; their highly developed tap root stores food and water used by the plant to overwinter and in drought. The roots usually grow from about six to eighteen inches deep but can grow to ten feet giving dandelion the name “earth nail” by the Chinese (Duke Gardens, n.d.). (Imagine digging that one out!) The roots are contractile, so the growing point of the dandelion plant is kept near the surface of the soil. The roots contract while the leaves grow in the form of a circle or rosette of leaves close to the ground. The rosette makes it difficult for the seeds of other plants to compete. Look under the snow, and you may see dandelion rosettes. In areas where soil is compacted, dandelion roots do some good as they “dig” into the soil, aerating it. If they are dug out, other plant species have an easier time getting established.

The flower buds of dandelions grow from the top of the root. There are no true stems. If you cut off the plant top, the plant will simply regenerate. (This explains why mowing the lawn does not rid you of dandelions!) Chopping up the soil is no help either, as pieces of the taproot grow into new plants. The roots are edible though, and can be boiled, fried, or dried. Dried roots can be used as a coffee substitute similar to chicory, a close relative (Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials, n.d.). A gardening tip: Be careful when purchasing dandelion seed to grow in your garden for the leaves. “Italian dandelion” seeds, for example, are actually chicory. Pay attention to the genus and species name. The leaves simply don’t taste the same as true dandelion. Keep in mind that some cities and states prohibit growing dandelions (Mahr, n.d.).

The flower stalks are hollow pseudostems (false stems) ranging from about six inches to two feet. The flower heads are compound inflorescences growing to one to two inches in diameter. The pseudostem branches over and over. Each flower head is not a single flower with many petals but one hundred to three hundred identical ray flowers. Take a flower apart and count them. “He loves me. He loves me not.” Each ray flower has a yellow petal with five notches at the top which you can see with a magnifying glass.

The flowering peaks in early summer but can recur in September and October. Take the time to observe the behavior of dandelion flower heads. You will see that the heads open up through much of the day in the early spring, but close up, sometimes quite tightly, by the middle of the day from about June through August. The flower heads also remain closed on overcast days. Do you remember picking bouquets of

dandelions as a child (or perhaps later)? The flower heads close shortly after picking. I remember thinking that my bouquets needed water, so I put them in a glass of water. Nothing changed! The flower heads also close when the seeds are maturing. Then they reopen for their release. Voila!

I keep honeybees. All pollinators are welcome including the native mason bees, the native digger bees. I love watching bees, some fly species, and occasional wasps probing dandelion flower heads. Dandelions are unique. We have been taught that nectar attracts insects to plants. In the process of gathering nectar, insects pollinate the flowers, a good exchange. BUT dandelions don’t need insects to pollinate them, as the fruit (the holders of the seeds) develop asexually, the process termed parthenogenesis. Each individual flower produces seed whether or not an insect visits. This is called apomixis. It occurs in hundreds of plant species. Examples include citrus plants, wild beets, strawberries, and some forage grasses. This means that the seeds that are produced from these plants are all identical (Schader, 2021).

The seed heads of dandelions have interesting names. Two are “blowball,” an obvious reference to a childhood activity, and “monkshead,” what the flower head looks like after the seeds blow off (a tonsure). The fruits of dandelions are achenes—simple, dry fruits with one seed inside each fruit, about an eighth of an inch long. I looked at them under my binocular microscope. The seeds looked ribbed. The achenes don’t split open. They float away in the parachute structure. They germinate on top or near the top of the soil. They don’t need a dormancy period, so they germinate soon after landing.

5 DANDELIONS... MORE THAN A WEED Issue 87 2022

You can dig dandelions in the wild, cut fresh leaves, or cut the flowers for making wine. (I can tell you from experience that picking one gallon of dandelion flower heads is quite an undertaking.) Wash the flower heads. You then must remove the many thousands of individual flowers. Before harvesting the flower heads, please take care to ensure that they haven’t been sprayed with pesticides or sprayed upon by a passing creature. Or let the flowers be... for insects and for children.

If you wish to grow your own dandelions especially for greens, you can collect wild dandelion seeds. You may also purchase dandelion seeds from vendors such as Johnny’s Selected Seeds or Richter’s Herbs. Most people who intentionally grow dandelions do so for the leaves. For good tasting dandelion leaves, cast the seeds in rich well-draining soil. If you want neat rows in your garden, space the seeds about nine inches apart. Otherwise, plant

spacing is not critical. Cut the leaves when young to reduce the possibility of a bitter taste. If you aren’t interested in the flowers, cut them off so the plant’s energy goes back into leaf production. Fresh leaves can be harvested all season long.

The first time you choose to use dandelions in food, do so cautiously. Some people react to the milky sap. The greens may disagree with your digestive system (Carter, 2020). Don’t forget... there will be more dandelions for you to harvest later.

The lore of dandelions is, of course, fun. We have all held a dandelion flower head filled with seeds and blown them away. What remains are said to tell the number of remaining years of your life, or whether or not you will meet someone to love. If you catch one of the seed heads, you are lucky and may make a wish (Plant-lore, 2021). I did not know the lore of dandelions as a child. I blew the dandelion parachutes away because it was simply fun!

Literature Cited

Baumgardt, John Philip. 1982. How to identify flowering plant families. Portland, OR: Timber Press. Bergen, P., James R. Mayer, and Gerald C. Kozub. 1990. Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) use by cattle grazing on irrigated pasture. Weed Technology. 4(2): 258-263. Accessed March 13, 2022. Available from jstor.org/stable/3987070

Carter, Gary. 2020. Rethinking the dandelion. Horticulture. 117(4): 15-17.

Cleveland Clinic Health Essentials. n.d. Can you eat dandelions? Accessed January 29, 2022. Available from health.clevelandclinic.org/dandelion-health-benefits/ Duke Gardens. n.d. Meet a Plant: Dandelion. Accessed January 31, 2022. Available from https://gardens.duke.edu/sites/default/files/Duke%20Gardens%20-%20Meet%20 a%20Plant%20Dandelion.pdf

Engels, Gayle and Josef Binckmann. 2016. Dandelion. Herbalgram. 109:8-15. Accessed January 29, 2022. Available from https://www.herbalgram.org/resources/herbalgram / Issues/109/table-of-contents/hg109-herbpro-dandelion/ Hourdajian, Dara. 2006. Taraxacum officinale. Introduced Species Project, Columbia University. Accessed January 29, 2022. Available from columbia.edu/itc/cerc/danoff-burg/ invasion_bio/inv_spp_summ/Taraxacum_officinale.htm

Mahr, Susan. n.d. Dandelion, Taraxacum officinale. Extension Service, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Accessed January 29, 2022. Available from https://hort.extension.wisc. edu/articles/dandelion-taraxacum-officinale/ Michigan State University. 2015. Dandelion. Accessed January 29, 2022. Available from canr.msu.edu/resources/dandelion-taraxacum-officinale

Plant-Lore. 2021. Dandelion. Accessed January 31, 2022. Available from https://www.plant-lore.com/dandelion/ Porter, C. L. 1967. Taxonomy of flowering plants, 2nd edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Schader, Meg. 2021. How does a dandelion reproduce? Accessed January 29, 2022. Available from sciencing.com/how-does-a-dandelion-reproduce-12003581.html

DANDELIONS... MORE THAN A WEED

Barbara J. Williams

he Herb Society of America urges members to grow native plants. Take a step back and look at your garden. It is likely that you, in fact, have plants that are native in various areas around the world! Our “native” plants may be recent arrivals in geological time. We grow them because we desire them for their use and delight.

WHERE IN THE WORLD DID PLANTS FIRST DEVELOP?

All living things originally evolved from a single common ancestor. Only those species best suited to the environment of that time, and of every time since, have survived until today.

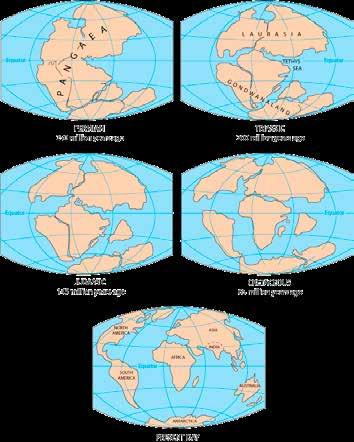

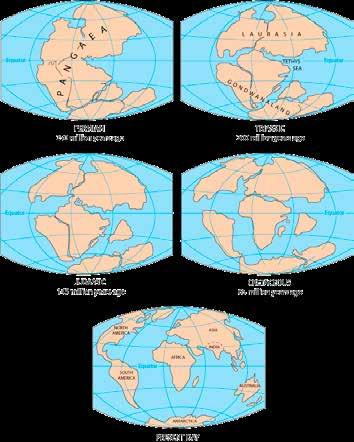

The oldest known fossil of a vascular plant dates from 433-427 million years ago (Mya), when the location of the land masses of our planet were quite different from their locations today. Continents have drifted apart and coalesced multiple times. (Dahl and Arens, 2020).

The Gymnosperms (seed plants) (370 Mya) and Angiosperms

(conifers) (325 Mya) began to evolve during the Late Devonian (Dahl and Arens, 2020). None of those plants exist today. As newer plants evolve, they displace others. Seed plants displaced many, but not all conifers.

Flowering plants made their first appearance 130 Mya. Bees and other flying insects evolved at about the same time. Flowers needed bees to spread pollen and help them reproduce and bees needed flowers to provide food (Lloyd, 2008).

The last great extinction event, which killed the dinosaurs, also killed about 50% of all plant species. It occurred 66-65 Mya, with massive disruption of plant communities. This had a huge effect on plant distribution worldwide.

During the time between 5.33 Mya to 2.59 Mya, the continents continued to drift and move toward their present locations. The land bridge between North America and Asia formed. Much later South America became connected to North America (Tallis, 1991). Africa drifted toward Europe creating the Mediterranean

7

Issue 87 2022

Image by anncapictures from Pixabay

Sea and the Alps. India crashed into Asia. All these movements had effects on plant distribution (Knoll, 2012; Lloyd, 2008).

The last Glacial Period began approximately 115,000 years ago and ended about 11,700 years ago. Since then, factors other than continental location have influenced plant distribution. In many cases human intervention has had an influence as well (Knoll, 2012; Lloyd, 2008).

About 10,000 years ago, humans in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East began to develop agriculture. Plant domestication began with cultivation. Agriculture began in specific locations, but as people moved across the earth, they took plants with them. Today we don’t always know where the plants we grow originated (Lloyd, 2008).

CONTINENTAL DRIFT INFLUENCED WHERE HERBAL PLANTS EVOLVED

You can see from the abbreviated timeline above, combined with the illustration showing the drift of continents across the globe (Figure 1), that 250 million years ago the entire landmass of the world was combined into what is now called the supercontinent Pangaea. Any foundational plant that evolved at that time might have successor plants scattered worldwide.

become North America next to what would become Eurasia, ancestral South America next to what would become Africa, and eventual Australia and Antarctica next to each other. At that period, what would become India was a drifting island.

C ontinental drift since that time has connected North and South America, formed the widening Atlantic Ocean between North/South America and Europe/Africa, and seen Antarctica drift south to the pole while Australia moved north. India collided with Asia, pushing up the Himalaya Mountains. The resulting ocean currents of today help to drive both climate and weather, and thus drive the ecology of plants (Raven, 1972).

HOW DOES THIS RELATE TO WHERE HERB PLANTS ARE NATIVE?

Over the last 25-50 years, scientists have explained the evolutionary theory of plants, and indeed of all living things (Brockman, 2016; Gould, 2002; Tallis, 1991). I have related that theory to the specific plants we call herbs.

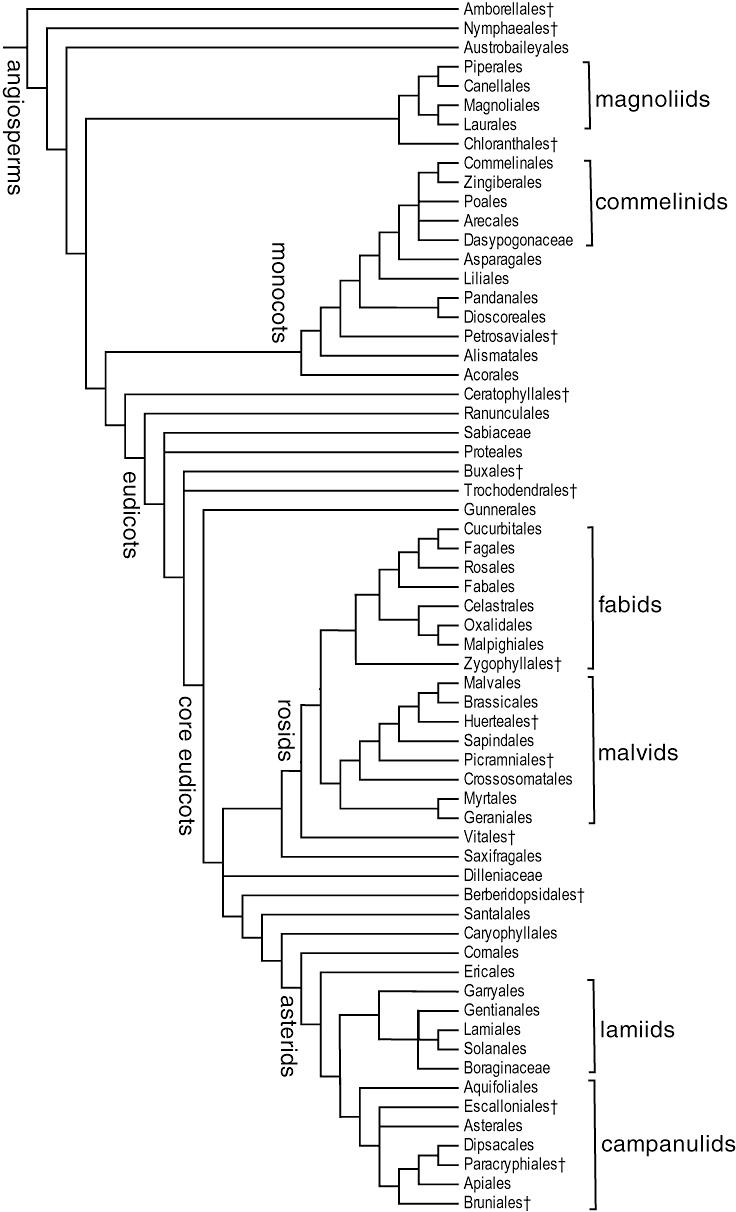

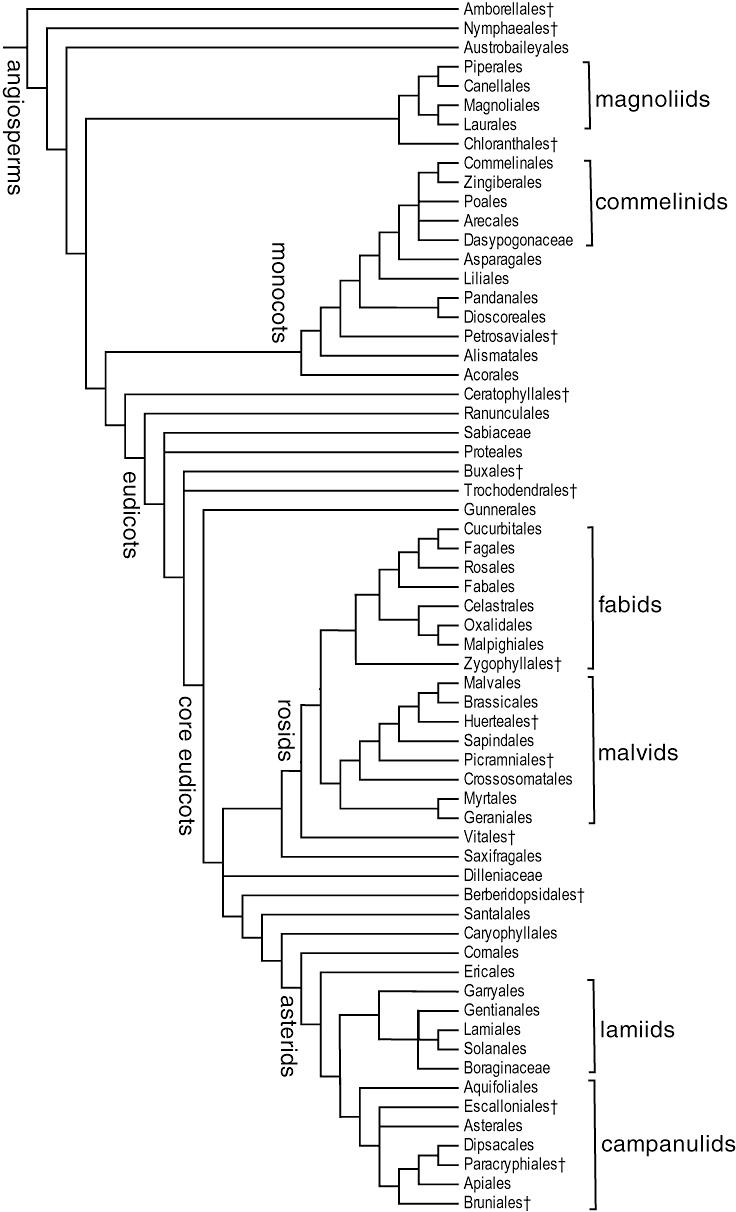

Every plant today evolved from an earlier plant, which may or may not still exist. The Angiosperm Phylogeny diagram (Figure 2)shows sequential evolution of parent plants over time. The parent plants are at the level of order as indicated by the ‘ales’ ending to each name. This is the grouping above family in the hierarchy of plant taxonomy: order, family, genus, species. This means one hypothetical ancestor plant might have resulted in many of today’s herbs. You can see that the monocots evolved earlier than the dicots (Eudicots). For example, one monocot herb, garlic, is included in the order Asperagales, family Amararyllidaceae, genus Allium. A dicot herb, English lavender, is included in order Lamiales, family Lamiaceae, genus Lavandula.

One hypothetical plant may have evolved into members of multiple families. A member of Order Gentianales might have resulted in Rubia and Coffea in the family Rubiacaea and Asclepias and Catharanthus in the family Apocynaceae.

This visualization of evolution implies that plants that evolved earlier in time evolved when continents were together and those that evolved later did so when continents had drifted apart.

The categories below do not represent discrete areas on earth with hard margins. There are overlaps and plants might fit more than one category. I have listed only a few examples in each category. Readers will find more extensive, but not exhaustive, lists in the tables at the end of the article. A section preceding the literature citations delineates the sources consulted.

COSMOPOLITAN HERB PLANTS

By 200 Mya, Pangaea began to break up into a northern continent, today called Laurasia, and a southern continent, Gondwana (Raven, 1972). About 145 Mya, the earth consisted of a continent that would

The foundational plant of all herbs likely evolved when all future land masses were together in one continent, Pangaea. Cosmopolitan plants are in a genus which contains plants native to all continents. Currently scientists cannot identify on which continent these cosmopolitan plants originally evolved, so we say they are native on all, excluding Antarctica. Fossil evidence might be available in the future, and in most cases, would exclude

8 EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE The HERBARIST

Australia which separated from Antarctica relatively recently. Antarctica had a climate conducive to plant growth in extreme ancient times. Each cosmopolitan plant genus had eons to evolve into many species with possible worldwide distribution.

Herbal genera native on all major continents include Artemisia, Berberis, Chenopodium, Eleocharis, Geranium, Heliotropium, Hypericum, Ilex, Mentha, Prunella, Salvia, Solanum, and Stachys.

CIRCUMBOREAL HERB PLANTS

Circumboreal plants are native in the north temperate area on all continents around the world and in a few cases in both the north and south temperate zones. What conditions in earth’s past would have made this possible? When you look at the map of the continents at 200 Mya as they began to break up, you can see the area of Laurasia, which later broke apart to form North America and Eurasia, is apparent. Gondwana would eventually, and much

later, form South America and Africa, as well as Australia and Antarctica. The plants that evolved into the genera that we now call herbs evolved that many years ago. Some genera in this category include the so-called alpine plants.

Circumboreal herb plants include such well known genera as Aconitum, Achillea, Allium, Angelica, Genista, Iris, Juniperus, Lilium, Paeonia, Pulmonaria, Ranunculus, Rosa, Salix, Taxus, Valeriana. (See Table 1 on page 14 for a more extensive list.)

EASTERN HEMISPHERE HERB PLANTS

Mediterranean Native Herbs

These plants are native in areas surrounding the Mediterranean Sea: the southern tier of European countries, western Asia, and northern Africa. This section contains many of the plants we think of as culinary mainstays.

Climate and weather are influential factors in the plant populations circling the Mediterranean. About 65 Mya, Africa and Europe began to drift closer together and the Mediterranean Sea began to form. This drift pushed up the Alps, a great influence on weather. Mediterranean climate is characterized by dry summers and mild, wet winters.

Human influence also became a factor. People who traveled around the perimeter of the Mediterranean Sea, particularly after agriculture was developed around 8,000 BCE, could have established the plants in the areas they settled. This means we can’t tell today exactly where in this area a genus first originated.

Some of the plants listed below reflect these assumptions of native origins. Some are placed in more restricted Mediterranean regions such as in western Asia and north Africa, or from Italy to Greece, or from southern Europe to Iran.

Plants in this category include some of the most studied groups. Just a few of them include Anethum, Borago, Brassica, Coriandrum, Digitalis, Foeniculum, Laurus, Melissa, Origanum, Papaver, Petroselinum, Rosmarinus, Satureja, Thymus. (Refer to Table 2 on page 14 for a broader listing.)

9 EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE Issue 87 2022

Figure 2. 2003 update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants

Source: APG IV by K. Bremer, M. Chase, J.L. Reveal, D. Soltis, P. Soltis, and P. Stevens.

Northern European Native Herbs

These plants evolved first in northern Europe and thus have a more specific area of origin than those included with Mediterranean plants listed above. This implies fairly recent evolution. Genera include Aesculus, Arnica, Atropa, Filipendula, Gentiana, Humulus, Lavandula, Oenothera, Pimpinella, Taracum, Urginea, Urtica, Vinca.

Sub-Saharan African Native Herbs

The Sahara Desert extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. It separates herbs native along the Mediterranean from southern plants, which have had extended periods to evolve in separate ways. Nearly the entire area, except for southern Africa, lies in the Tropics. Much of this area is relatively flat, apart from the northeastern portion and the Rift Valley.

A few of the herbal genera of the area include Aloe, Aspalathus, Boswellia, Catharanthus, Cynara, Euphorbia, Hoodia, Pelargonium, Rauvolfia, Ricinus (Mahomoodally, 2013).

Asian Native Herbs

Plants described here are native over a wide area including Central Asia, China, Korea, Japan, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This encompasses the gamut of climates and a wide range of native herbal plants. The following partial list demonstrates some of this vast number of native Asian genera: Astragalus, Camellia, Cinnamomum, Cymbopogon, Ephedra, Ginkgo, Glycyrrhiza, Indigofera, Jasminum, Ocimum, Patchouli, Perilla, Piper, Ramie, Zingiber. (See Table 3 on page 14.)

Australasian Native Herbs

From 56-34 Mya, Australia, Antarctica, and South America were still joined. The Australian portion had a wet, warm climate. By 16.3 Mya, the climate had begun to get drier, and by 30,000 –40,000 years ago, it was substantially drier. This has restricted the numbers of original genera that still exist today (Australian Museum, 2021).

A few herbal genera of Australia include Acacia, Alpinia, Backhousia, Callistris, Capparis, Colocassia, Duboisia, Eucalyptus, Grevillea, Melaleuca, Nymphaea, Prosthanthera, Santalum, Solanum, Tasmannia (Brayshaw, 2016).

10 The HERBARIST

Aloe, an African native Photo credit: Barbara J. Williams

WESTERN HEMISPHERE HERB PLANTS

By 65 Mya, North America and Eurasia were drifting apart, and North American species began to evolve. South America also moved away from Africa. This resulted in some genera that are exclusively American and others containing species that are European, African, and/or American. They diverged after the original parent evolved in Laurasia or in Gondwana. Much more recently, about 2.8 Mya, North and South America became connected and plant distributions spread between them. Some genera appear on more than one list because the original plant evolved when land masses were still together.

North American Native Herbs

The bioregion of North America is considered to extend through northern Mexico. This includes habitats from arctic to semitropical and a vast area where plants of great diversity evolved before the northern and southern continents were joined at the Isthmus of Panama (O’Dea, et al., 2016). Some plants migrated from Asia to North America when the land bridge formed. Thuja is a genus that evolved in North America and migrated to Asia. Some other North American herbal plants are Agave, Baptisia, Coreopsis, Echinacea, Eupatorium, Hamamelis, Lobelia, Monarda, Rhus, Salix, Solidago, Tagetes, Viola, Yucca, Zinnia (See Table 4 on page 15).

South American Native Herbs

South America’s climate is dominated by the effects of the Andes Mountains which run nearly the entire length of the continent and by the huge tropical Amazon River basin. You might expect to see more duplication of genera in Africa and South America because of their shared origins as part of the ancient landmass of Gondwana. Environmental differences since the separation, especially the development of the Sahara Desert in Africa, have not favored survival of foundational plants that evolved before the separation. Some exceptions to this are the genera Annona, Ceiba, Drimys, and Manilkara. A few other South American herbal genera are Aloysia, Amaranthus, Asclepias, Capsicum, Datura, Glycyrrhiza, Hevea, Ipomoea, Lobelia, Nicotiana, Stevia, Tagetes, Theobroma, Tropaeolum, Vanilla (Table 5 on page 15 contains a more extensive list).

HERBS WITH DISJUNCT POPULATIONS

Disjunct plant populations result when plants are separated geographically from others of their kind for various reasons. Recently, researchers have determined that global events as far

back as 145 Mya have influenced some of these plant separations. Populations may have been isolated when their particular habitat was disconnected or fragmented such as occurred when the Americas drifted away from Europe and Africa, or where India joined with Asia. Disjunction might also have been the result of climate change, glaciation, or mountain (Raven, 1972).

Further disjunctions might also stem from long range dispersal (by wind or animals, including humans) or even parallel evolution. Human-introduced species may have outcompeted native plants. Fragmentation of native herb populations results when movement between one suitable habitat to the next is disrupted. This could have led to either the expansion or contraction of a species’ original range (Pimm, 2014; Tallis, 1991).

These distinct plant populations may have first evolved under many differing circumstances and original distribution does not necessarily relate to any specific time in the past or any specific location on the planet. It is not possible today to identify where these plants originated. Herbs with demonstrated disjunct native populations include Acer, Asarum, Amaranthus, Buxus, Hamamelis, Hypericum, Magnolia, Panax, Sambucus, Teucrium.

THE HUMAN ROLE IN PLANT DISTRIBUTION

Aside from the occasional earthquake or volcanic eruption to indicate that the continents continue to move across the surface of the earth, little has happened to change where plants have evolved in the last 10,000 years. The planet has slowly (until recently) warmed following the end of the last ice age.

Ancient hominids appeared on earth 2.5 Mya. Homo sapiens evolved between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago, began moving out of Africa, and then around the globe. By 45,000 years ago, humans had reached Australia and by 16,000 years ago they had traveled the land bridge and settled the Americas (Harari, 2015). During all those years they depended on the plants and animals

11 EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE Issue 87 2022

in their environment, and they discovered many uses for wild plants through trial and error.

There are cave paintings depicting herbs in France that date between 25,000 BCE and 13,000 BCE. People began making healing ointments by combining fragrant plants with sesame oil and olive oil as early as 7,000 BCE (Robbelen, 1988).

Prehistory is defined as the time before writing was developed, between 3,400 BCE and 3,100 BCE in Egypt and Samaria. Egyptians were writing about herbs by 2,800 BCE and Sumerians produced a written herbal record around the 25th century BCE. Greek merchants traded in sage, thyme, and marjoram and kept written records of their activities in the markets of Athens by 700 BCE (Pan, 2014). Hippocrates wrote about as many as four hundred plants that he used to treat disease (Herbal Academy, 2021).

Trade always has included trade in plants. The Silk Road refers to a network of routes used by traders for more than 1,500 years, from when the Han dynasty of China opened trade in 130 BCE until 1453 CE, when the Ottoman Empire closed trade with the West (National Geographic, 2019). The period of European history extending from about 400 to 1400 CE is traditionally known as the Middle Ages. Far from being the Dark Ages, the period was marked by economic and trade expansion and demographic and urban growth. The Crusades between 1096 – 1204 CE took people from Europe to the Middle East and back (Britannica/Crusades). The great cultures of Native Peoples in the Americas involved travel and trade over long distances and included the sharing of plants as well as obsidian, quartz, and copper (American Indian History Timeline, n.d.).

Colonists from Europe who settled in North America in the 1600s and 1700s brought seeds of their most useful plants to the New World. The fact that they did this when they had little room on shipboard shows how important herbs were to them. People

transported plants from their native habitats to a new continent, where they became introduced genera. Some of them include Plantago (plantain), Mentha (mint), Lavandula (lavender), Petroselinum (parsley), Calendula (pot marigold), Rosa (roses), Taraxacum (dandelion), Matricaria (chamomile), Thymus (thyme), and Achillea (yarrow) (Peak House Heritage Center, 2021).

THE PLANTS IN YOUR GARDEN

Even if you grow North American native herb plants, intermingled with them may be introduced plants brought here by early settlers, plus many more plants native to other parts of the world. Those plants may have even longer evolutionary histories then North American natives. Look around your garden. You may well be growing herbs from some of the cosmopolitan genera, dating all the way back to Pangaea.

Barbara J. Williams 1937 – 2022

I read of a man who stood to speak at the funeral of a friend... He said what mattered most of all was the dash between the years... The Dash Poem, Linda Ellis

Barbara filled that dash for all of her fellow HSA members and friends by sharing her extensive horticultural knowledge and copy editing skills. Celebrate her life each time you open The Herbarist to one of her articles.

EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE

Pot marigold (Calendula officinalis), a garden herb introduced to the New World Photo credit: Fanghong

Sources of information about area of plant origin: Bown, Deni. 2001. The Herb Society of America new encyclopedia of herbs and their uses. New York: DK Publishing. https://britannica.com/ https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/ https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org

https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/ https://www.fs.fed.us/wildflowers/ https://www.kew.org/plants/ https://www.livescience.com/ https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info

https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/plantfinder/plantfindersearch.aspx https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ https://www.wildflower.org/plants/ http://www.worldfloraonline.org/

Literature cited

American Indian History Timeline. Accessed February 13, 2022. Available from: https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/indianed/tribalsovereignty/training/ AncientCivilization-WorldHistory%20STI.pdf

Australian Museum. 2021. Accessed December 30, 2021. Available from: https://australian.museum/learn/australia-over-time/evolving-landscape/

Brayshaw, Helen. 2016. Traditional aboriginal cuisine in the Herbert/Burdekin district of north Queensland. Journal of James Cook University. Accessed December 17, 2021. Available from: https://journals.jcu.edu.au/linq/article/view/475/303

Brockman, John ed. 2016. Life: the leading edge of evolutionary biology, genetics, anthropology, and environmental science. New York: Harper Perennial.

Dahl, Tais and Susanne Arens. 2020. The impacts of land plant evolution on Earth’s climate and oxygenation rate – an interdisciplinary review. Chemical Geology 547:119665. Accessed November 14, 2021. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009254120302047

Gould, Stephen Jay. 2002. The structure of evolutionary theory. Cambridge, MA: Belnap Press of Harvard University.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2015. Sapiens: a brief history of humankind. New York: Harper Perennial.

Herbal Academy. 2021. Accessed December 19, 2021. Available from: https://theherbalacademy.com/herbal-history/

Knoll, Andrew H. 2012. A Brief History of Earth. New York: Harper Collins.

Lloyd, Christopher. 2008. What on earth happened? New York: Bloomsbury USA.

McCormick Science Institute. 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. Available from: https://www.mccormickscienceinstitute.com/resources/history-of-spices

Mahomoodally, M. Fawzi. 2013. Traditional medicines in Africa: an appraisal of ten potent African medicinal plants. Accessed January 12, 2022. Available from: https://www. hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2013/617459/

National Geographic. Jul. 26, 2019. Accessed February 13, 2022. Available from: https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/silk-road/#:~:text=The%20Silk%20 Road%20is%20neither,off%20trade%20with%20the%20West

O’Dea, Aaron, Harilaos A. Lessios, Anthony G. Coates, Ron I. Eyten, and Sergio A. Restreppo-Moreno, et al. 2016. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Science Advances 2(8). Accessed December 18, 2021. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1600883#

Pan, Si-Yuan, Gerhard Litscher, Si-Hua Gao, Shu-Feng Zhou, Zhi-Ling Yu et al. 2014. Historical perspective of traditional indigenous medical practices: the current renaissance and conservation of herbal resources. Accessed December 20, 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4020364/

Peak House Heritage Center. 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. Available from: https://peakhouseheritagecenter.org/about-the-plants-3/

Pimm, S.L., C.N. Jenkins, R. Abell, T.M. Brooks, J.L. Gittleman, et al. 2014. The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science, 344:987– 997. Accessed November 16, 2021. Available from: https://senate.ucsd.edu/media/206192/science-2014-pimm-extinction-review.pdf

Raven, Peter H. 1972. Plant species disjunctions. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 235-239. Accessed December 22, 2021. Available from: https://doi. org/10.2307/2394756

Robbelen, Gerhard, R. Keith Downey, Amram Ashri, and Paulden Ford Knowles. 1989. Oil crops of the world: their breeding and utilization. New York: McGraw Hill. Seed Leaves. 2021. Accessed December 20, 2021. Available from: https://www.seedleaves.com/herbs

Tallis, J. H. 1991. Plant Community History. London: Chapman and Hall.

13 Issue 87 2022 EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE

Table 1. Circumboreal Herb Genera

Aconitum

Achillea

Allium

Alnus

Anemone

Angelica

Aquilegia

Arctostaphylos

Artemisia

Asarum

Astragalus

Astrantia

Asarum

Astrantia

Betula

Castilleja

Cerastium

Chrysosplenium

Colchicum

Convallaria

Corydalis

Daphne

Delphinium

Dianthus

Echinops

Epimedium

Equisetum

Eranthis

Table 2. Mediterranean Herb Genera

Alchemilla

Althaea

Amoracia

Anchusa

Anethum

Anthriscus

Armoracia

Borago

Brassica

Calendula

Carum

Chamaemelum

Coriandrum

Crocus

Cynara

Digitalis

Foeniculum

Galium

Table 3. Asian Herb Genera

Aconitum

Alpinia

Andrographis

Angelica

Aquilaria

Areca

Astragalus

Atractylodes

Bambusa

Berberis

Broussonetia

Callicarpa

Camellia

Cananga

Caryota

Centelia

Chrysanthmum

Erodium

Euphorbia

Galium

Genista

Gypsophila

Hedysarium

Hypericum

Inula

Iris

Juniperus

Lathyrus

Lilium

Limaria

Linum

Narcissus

Ornithogalum

Osmanthus

Paeonia

Paris

Picea

Pimus

Poa

Pulmonaria

Prunus

Ranunculus

Rhamnus

Pheum

Rhodiola

Rhododendron

Rosa

Salix

Sambucus

Saussurea

Saxifraga

Scrophulara

Silene

Stellaria

Taxus

Tilia

Trifolium

Vaccinium

Veronica

Vicia

Genista Iris

Jasminum

Laurus

Lawsonia

Levisticum

Linum

Marrubium

Matricaria

Melissa

Nepeta

Nigella

Origanum

Papaver

Petroselinum

Poterium

Pulmonaria

Reseda

Rosmarinus

Rubia

Ruta

Sanguisorba

Santolina

Saponaria

Satureja

Silybum

Sinapis

Symphytum

Tanacetum

Teucrium

Thymus

Trigonella

Valeriana

Verbascum

Verbena

Cinnamomum

Cocinium

Commiphora

Coptis

Copyis

Curcuma

Cymbopogon

Dioscorea

Eletteria

Eleutherococcus

Elsholtzia

Epimedium

Fargesia

Ephedra

Garcinia

Ginkgo

Glorisa

Glycyrrhiza

Hydnocarpus

Indigofera

Isatis

Jasminum

Kadsura

Lawsonia

Litchi

Lonicera

Lycoris

Malus

Melaleuca

Mentha

Myristica

Nelumbo

Nordostachys

Ocimum

Oenanthe

Paeonia

Panax

Patchouli

Perilla

Phyllanthus

Phyllostachys

Picrorhiza

Piper

Plantago

Podophyllum

Prunus

Ramie

Rauvolfia

Rehmannia

Reynoutria

Rheum

Rosa

Rubus

Saccharum

Santolum

Sesbania

Styrax

Suzygium

Swertia

Tabernaemontana

Terminalia

Trachelospermum

Vitex

Withonia

Woodfordia

Zingiber

Ziziphus

14 The HERBARIST

EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE

Table 4. North American Herb Genera

Achillea

Actaea

Adiantum

Agastache

Agave

Aloysia

Amelanchier

Anaphalis

Andorpogon

Anemone

Antennaria

Aralia

Arctostaphylos

Arisaema

Aristolochia

Arnica

Aronia

Asclepias

Asimina

Baptisia

Callicarpa

Calycanthus

Campanula

Campsis

Carpinus

Ceanothus

Cephalanthus

Claytonia

Clinopodium

Comptonia

Coreopsis

Cunila

Desmodium

Echinacea

Elymus

Ephedra

Epilobium

Erigeron

Eriogonum

Erythronium

Eschscholzia

Eupatorium

Fagus

Fallugia

Filipendula

Fouquieria

Fragaria

Gaillardia

Gaultheria

Gillenia

Glandularia

Gleditsia

Gutierrezia

Hamamelis

Helianthus

Hepatica

Table 5. South American Herb Genera

Abutilon

Aloysia

Amaranthus

Anacardium

Ananas

Annona

Aristolochia

Asclepias

Bertholletia

Brugmansia

Capsicum

Carica

Ceiba

Chrysobalanus

Chusquea

Cucurbita

Datura

Drimys

Fragaria

Furcraea

Gevuina

Glycyrrhiza

Heuchera

Hydrastis

Hypericum

Hyptis

Ilex

Iris

Juniperus

Larix

Ledum

Lepidium

Liatris

Lindera

Linum

Lippia

Lobelia

Lonicera

Lycium

Mahonia

Maianthemum

Malpighia

Mirabilis

Mitchella

Monarda

Morella

Muhlenbergia

Oenothera

Opuntia

Osmorhiza

Ostrya

Parthenocissus

Passiflora

Pectis

Penstemon

Persea

Phlox

Physalis

Physocarpus

Phytolocca

Pinus

Podophyllum

Poliomintha

Prosopis

Prunella

Prunus

Pulsatilla

Pycnanthemum

Quercus

Ratibida

Rhus

Ribes

Rubus

Rudbeckia

Salix

Sambucus

Sanguinaria

Sanguisorba

Scutellaria

Senecio

Simmondsia

Solidago

Stellaria, Stylophorum

Symphyotrichum

Tagetes

Thuja

Tiarella

Tilia

Tsuga

Typha

Ulmus

Urtica

Vaccinium

Veratrum

Verbena

Viburnum

Viola

Vitis

Xanthorrhiza

Yucca

Zanthoxylum

Zinnia

Zizia

Gomphrena, Hevea

Hippeastrum

Iochroma

Ipomoea

Jubaea

Lantana

Lapageria

Lobelia

Lupinus

Manihot

Manilkara

Maytenus

Nicotiana

Ocotea

Onothera

Papaya

Passiflora

Plumeria

Psidium

Puya

Roystonea

Schinus

Solanum

Stevia

Tagetes

Theobroma

Tropaeolum

Vanilla

Verbena

Zea

Zinnia

15 Issue 87 2022

EVERY HERB IS A NATIVE SOMEWHERE

n economic analysis of the production of herbs in the United States can be challenging. Services and goods produced for personal consumption, such as herbs grown in a backyard garden, escape the notice of government statisticians—unless, of course, the gardener is also a government statistician! Those herbs which do not enter into a commercial transaction do not, therefore, contribute to a nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). This statistical shortcoming of GDP was, rather famously, conveyed by the British economist, Arthur Cecil Pigou, who wrote that ‘if a man marries his housekeeper or his cook, [GDP] is diminished’ (Pigou, 1932).1

Inevitably, official statistics will understate the actual production of herbs since a portion of the production will be consumed within the household of the producer. The extent of this understatement may be quite large, given the minimal barriers to the smallscale production of herbs, for which the capital requirements can be as simplistic as a shovel and several pots.

While recognizing that official statistics exclude a perhaps considerable portion of herb production, this article nevertheless attempts an economic assessment of herb production, i.e., commercial herb production, in the United States over the past two decades. The earliest source of official data on herb production in the United States is the 1998 Census of Horticultural Specialties (CHS), and the year 1998 therefore serves as the starting point of the analysis. We can appreciate that the agricultural production data available for the United States, unlike for many other developed countries, are so crop specific that data are actually reported for herbs. This herbal data renders the United States an opportune country for

Brian D. Varian, PhD

1

Brian D. Varian, PhD

1

Daphnusia | Dreamstime.com

In The Economics of Welfare, Pigou used the now antiquated term ‘national dividend,’ of which a modern equivalent would be GDP.

evaluating the place of herbs in a national economy. Therefore, the scope for cross-country comparisons is limited indeed.

The subject of herbs in the American economy has not exactly enjoyed a surfeit of scholarship, and this should not come as a surprise. In 2019, the value of American herb production amounted to a meager $0.41 per capita (population data from Bureau of the Census; herb production data from National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2019 Census of Horticultural Specialties; n.b. Unless otherwise stated, all statistics in this article have been at least partly derived from the Censuses of Horticultural Specialties). While the American herb ‘industry’ may be described as small, its economic dimension deserves examination, not least because such an examination will find— the author hopes—a receptive and interested audience among readers of The Herbarist.

Census of Horticultural Specialties

The first Census of Horticultural Specialties was conducted in 1889, and censuses have been conducted at irregular intervals ever since. During its first century, the census was administered by the Bureau of the Census. However, beginning with the 1998 census, the National Agricultural Statistics Service of the Department of Agriculture took over responsibility for its administration. This transfer of responsibility coincided with a more detailed reporting of horticultural data, including data for herbs, which continued to be reported in the 2009, 2014, and 2019 censuses. The CHS divides herbs into two categories: 1) cut fresh herbs and 2) annual bedding/garden plants (hereafter ‘garden herbs’). Garden herbs are further broken into three sub-categories: flats, pots, and hanging baskets. And within the sub-category of pots, a distinction is made between pots that are less than five inches and pots that are more than five inches. It is important to observe that the Census of Horticultural Specialties only extends to fresh herbs, not to dried and crushed herbs; thus, the scope of this study is confined to fresh herbs. For each category and sub-category of

herbs covered in the census, data are reported at the national and state levels, subject to certain exceptions described shortly. The reported data include the value of production and the number of ‘operations.’

What constitutes an operation? For the Census of Horticultural Specialties, an operation is defined as an entity that produces $10,000 or more of horticultural specialty products within the census year. Thus, a farm producing $1 of herbs is an operation, provided its production and sales exceed the $10,000 threshold on account of non-herb horticultural specialty products, e.g., broccoli. Yet, a farm producing $9,000 of herbs but no non-herb horticultural specialty products would not be considered an operation; $10,000 is the magic number. To account for the production of horticultural specialty products by (commercial) non-operations, the National Agricultural Statistics Service follows a complex statistical reweighting procedure not particularly worth explaining here. 2 Still, the definition of an operation is important. We must note that respondents to the CHS are legally entitled to confidentiality. While the mere existence of an operation is not considered confidential data, the value of its production is considered confidential data. Thus, any data that might permit the public to infer the dollar value of a firm’s production is not included in the CHS. The CHS will often suppress data at the state level, especially for those states with a small number of operations. 3 Uniquely, in the 2009 census, the entire national value had to be suppressed for the category of cut fresh herbs; for that year, the value of herb production is only available for the category of garden herbs.

National Trends

The value of herb production has not followed a consistent course since 1998. As indicated in Table 1, the value of herb production increased from 1998-2014, but thereafter declined between the census years of 2014 and 2019. In terms of current (i.e., non-price-adjusted) values, the decline in production between 2014 and 2019 was 20 percent. However, herbs, like so many other commodities, tend to have increasing prices. Since the CHS reports only current values, it is necessary to price-adjust these current values to determine the real decline in herb production between 2014 and 2019. For this study, we can convert current values to real values using the average prices of small potted herbs. The CHS consistently reports the values and quantities of (small and large) potted herbs produced, thus enabling the calculation of

2 To put it briefly, the National Agricultural Statistics Service samples one-third of those entities with horticultural production falling beneath the $10,000 threshold and then reweights the reported data. There is a further reweighting to account for operations that do not respond to the census.

3 Consider, for example, a state with two operations: one very large and one very small. Since the value of herb production for the very large producer would closely approximate the value of production for the state, the public would be easily able to surmise the former. Hence, the confidentiality of the respondent would be undermined.

17 HERBS IN THE AMERICAN ECONOMY, 1998-2019

Fresh cut herbs

Photo credit: Arnaud25

Issue 87 2022

United States, Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States (2011). Available from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2010/compendia/statab/130ed.html

United States, Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Available from https://www.bea.gov/data

United States, Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available from https://www.bls.gov/data/tools.htm

United States, International Trade Commission, Dataweb database. Available from https://dataweb.usitc.gov/(account required to access)

the average prices of potted herbs.4 Here, the assumption is that the price fluctuations of small potted herbs are representative of the price fluctuations of herbs more generally. In terms of real (i.e., price-adjusted) values, the decline in production between 2014 and 2019 was 23 percent, although the real value remains above its 1998 level.

Table 1. Value of herb production in the United States, 1998-2019 ($ million)

accounts for such a small share of the United States’ GDP that it is convenient to express the share on a dollars-per-million basis, rather than as percentages. The share of the herb industry in GDP rose from $5.67 per million in 1998 to $9.56 per million in 2014, before declining to $6.30 per million in 2019—not very much greater than the initial share in 1998 (GDP data from Bureau of Economic Analysis).

Sources: National Agricultural Statistics Service, 1998-2019 Censuses of Horticultural Specialties.

Notes: Current values are converted to real values using the average price of a small potted herb, which is calculable from the Census of Horticultural Specialties. The values of cut fresh herb and total herb production are unavailable for 2009 because the production value of cut fresh herbs was suppressed for this year, in the interest of reporter confidentiality.

Of course, the population of the United States has grown since 1998, and therefore we might question whether growth in herb production has kept pace with growth in the population. From 1998-2014, real herb production per capita, expressed in constant 2019 prices, increased from $0.33 to $0.55, before falling to $0.41 in 2019 (population data from Bureau of the Census, including 2011 Statistical Abstract). As with the real value of production, the per capita real value of production peaked with the 2014 census. Another way to evaluate the development of the herb industry is in relation to total economic output, or GDP. The herb industry

W hile the herb industry comprises a very small share of the United States’ total economic output, it comprises a greater, though still very modest, share of the United States’ farm output.5 Indeed, the share of the herb industry in farm output may be a more relevant statistic to consider, since it is ultimately the farmer/gardener who decides upon the composition of agricultural production and whether or not to substitute toward (or away from) herbs. In other words, the share of the herb industry in farm output will be more suggestive of the decisions that producers and potential producers make. This share has increased from $650.13 per million in 1998 to $1,010.40 per million in 2014, followed by an even further increase to $1,094.69 per million in 2019 (farm output data from Bureau of Economic Analysis). Unlike the herbal share of GDP, the herbal share of farm output did not peak in 2014 but has continued to increase. In the most recent intercensal interval of 2014-19, the herb industry has been a better-than-average performing industry within a worse-than-average performing sector, i.e., the farm sector.

A s already discussed, the consistent reporting of data on the values and quantities of potted herbs permits the calculation of the average prices of potted herbs. Figure 1 depicts the average prices of small potted herbs and the consumer price index (CPI), which is the conventional index used to measure inflation. In the figure, both series reference a value of 100 for 1998. From 19982019, the average price of a small potted herb has increased at a rate of 2.7 percent per annum, which was greater than rate of inflation of 2.2 percent per annum (CPI data from Bureau of Labor Statistics). The rate was greater than the inflation rate for the 19982009 and 2009-14 intercensal intervals but not for the most recent intercensal interval. From 2014-19, the average price of a small potted herb increased at a rate of 0.8 percent per annum, compared to an inflation rate of 1.6 percent per annum (CPI data from Bureau of Labor Statistics). This beneath-inflation price increase, alongside declining real production of herbs, would ordinarily suggest a slackening of demand for herbs. However, it would be

4 It is preferable to rely upon the average price of a most disaggregated category of herbs, such as small potted herbs, rather than rely upon the average price of a more highly aggregated category of herbs, such as (all) potted herbs. The more general the grouping, the more likely that movements in the average price will be influenced by compositional changes within the category. The average price of small potted herbs is used, instead of the price of large potted herbs, because small potted herbs comprise most of the value of potted herb production.

5 Farm output consists of agricultural output less the output of forestry, fishing, and related activities.

HERBS IN THE AMERICAN ECONOMY, 1998-2019

12

1998 2009 2014 2019 Current value Garden herbs 20.4 62.1 96.8 69.5 Cut fresh herbs 31.0 -- 70.9 65.1 Total 51.4 167.7 134.6 Real value (in constant 2019 prices) Garden herbs 35.8 72.2 100.9 69.5 Cut fresh herbs 54.4 -- 73.9 65.1 Total 90.2 174.8 134.6

Potted herbs for sale

Photo credit: Lois Sutton

imprudent to draw such a conclusion in this instance, since not only domestic but also foreign producers supply the American market for fresh herbs, and herb imports will partly determine price movements in the American market.

diversification toward herb production would have the effect of reducing the per-operation average.

19982000200220042006200820102012201420162018

Small potted herb Consumer price index

Sources: National Agricultural Statistics Service, 1998-2019 Censuses of Horticultural Specialties for the average price of a small potted herb; Bureau of Labor Statistics for the consumer price index.

Notes: A small potted herb refers to the category of ‘pots less than five inches,’ which are separately distinguished in the Census of Horticultural Specialties.

Table 2 shows the numbers of operations producing garden herbs and cut fresh herbs. The trends are quite different, with the number of operations declining for garden herbs and rising for cut fresh herbs. While the number of firms producing cut fresh herbs is ever increasing, the average real value of cut fresh herb production per operation has diminished, by more than twothirds, since 1998. This development should not alarm proponents of the herb industry, since, as already mentioned, the real value of cut fresh herbs is higher in 2019 than in 1998. Additionally, it is worth remembering that the operations producing cut fresh herbs may also be involved in other branches of horticultural production. If an operation traditionally engaged in non-herbal horticulture commences a small-scale cultivation of herbs, such a

I n determining the number of operations involved in herb production, we have a limited opportunity for international comparison. Dumville’s (1988, p. 84) study of the herb industry in the United Kingdom estimated that, in 1986, there were between 90 and 120 producers of containerized herb plants, which would be closest to the American category of garden herbs. Standardizing by population, these figures equate to 1 producer of garden herbs for every 470-630 thousand of the UK population in 1986 (UK population data from Office for National Statistics).6 Considering the number of operations producing garden herbs in the United States in 2009, the first year for which this figure is reported, there was 1 producer of garden herbs for every 130 thousand of the American population (American population data from Bureau of the Census, 2011 Statistical Abstract). While cross-country differences between the definition of an ‘operation’ and a ‘grower,’ as well as the two-decade difference between the data, make for a rather rough-and-ready comparison, the ratios nevertheless suggest that the incidence of commercial herb production in the United States is not low, at least in relation to another advanced economy.

State Variation

In 2019, the states with the largest number of operations producing garden herbs were Michigan (162), Pennsylvania (147), Ohio (128), New York (122), and Wisconsin (113). The only state lacking a single such operation was Nevada! The leading states, in terms of the number of operations producing cut fresh herbs, were Michigan (50), Florida (47), Pennsylvania (43), Ohio (34), and Oregon (32). Of course, the average value of herb production per operation will vary across states, and the number of operations alone does not reveal very much about the significance of herb production to each state’s economy or to its farm sector. Regrettably, given the smaller number of operations producing cut fresh herbs, the CHS often must suppress state-level data on the value of cut fresh herb production to maintain the confidentiality of the small number of respondents— occasionally just a single respondent. Thus, the ensuing analysis in this section will pertain to just garden herbs.

Sources: National Agricultural Statistics Service, 1998-2019 Censuses of Horticultural Specialties.

Notes: Data are not available for garden herbs in 1998 because the Census of Horticultural Specialties did not report aggregate data for this category. Rather, data are only reported for the individual sub-categories of flats, pots, and hanging baskets. Since some operations would have produced garden herbs across multiple sub-categories, the total number of operations producing garden herbs cannot be calculated as the sum of the operations in each sub-category, lest some operations be double (or triple) counted. The average real value of cut fresh herbs per operation is unavailable for 2009 because the production value of cut fresh herbs was suppressed for this year, in the interest of reporter confidentiality.

As for the value of garden herbs produced in 2019, the five leading states were Connecticut (14.3 percent of national production), Alabama (13.1 percent), California (8.7 percent), Texas (7.4 percent), and Michigan (6.2 percent).7 Collectively, these five states accounted for 49.8

6 It is not possible to standardize by the value of herb production because the United Kingdom does not collect data on herb production specifically (author’s personal correspondence with United Kingdom Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs, 16 December 2021).

19 HERBS IN THE AMERICAN ECONOMY, 1998-2019

14

Figure 1. Herb prices and the consumer price index, 1998-2019

80 100 120 140 160 180 200

1998 level = 100 Year

1998 2009 2014 2019 Number of operations Garden herbs 2,285 2,161 1,822 Cut fresh herbs 192 323 524 700 Average real value per operation (in constant 2019 prices) Garden herbs $31,605 $46,695 $38,138 Cut fresh herbs $283,245 -- $141,110 $93,076

Table 2. Herb operations in the United States, 1998-2019

Issue 87 2022

percent of national garden herb production, by value, in 2019. Their combined share has changed little since previous censuses, with these five states accounting for 45.8 percent in 2014 and 50.5 percent in 2009. 8 The tremendous variation in the sizes (economic and geographic) of the fifty states makes it important to standardize the state-level values of garden herbs in terms of state-level GDP or farm output. Due to data suppression, we cannot determine the states with the highest shares of garden herb production in their GDPs with absolute certainty. Still, in 2019, the shares for Alabama ($39.43 per million) and Connecticut ($34.60 per million) were extremely high, compared to a national figure of $3.25 per million for garden herbs (GDP data from Bureau of Economic Analysis).

As for the share of garden herbs in farm production, the very highest shares are claimed by the New England states: Connecticut ($35,148.10 per million, or 3.5 percent), New Hampshire ($8,036.93 per million), and Massachusetts ($7,721.24 per million), compared to a national figure of $564.97 per million for garden herbs (farm output data from Bureau of Economic Analysis). Alabama and Alaska also performed well according to this measure. In terms of the share of garden herbs in farm production, we can question whether those states with lower shares have been ‘catching up’ or, to borrow an economist’s term, converging upon those states with the highest shares, principally in New England.9 In other words, have those states with initially lower shares of garden herbs in farm output experienced faster rates of

7 While some of the state-level data for garden herbs was suppressed, it is impossible for any of the ‘suppressed’ states to be among the top five, since only 5.7 percent of the national total was suppressed, i.e., unattributed to individual states.

8 Although, the composition of the five largest states has changed somewhat over time.

growth in their shares, so that their shares converge upon the shares in the leading states? In Figure 2, the horizontal axis measures the share of garden herbs in farm output in 2009, while the vertical axis measures the annual growth rate of the share of garden herbs in farm output from 2009-19. Due to data suppression, we can only plot points for a sample of thirty-nine states—the thirty-nine states for which the production value of garden herbs was available in both 2009 and 2019. For the 39-state sample, there is a statistically significant positive correlation (p=0.065) between the initial share in 2009 and the growth rate of the share from 2009-19, which would be evidence against the presence of convergence. However, removing the ‘Connecticut outlier’ from the sample renders the correlation statistically insignificant (p=0.344), although the correlation remains positive. Regardless, this statistical analysis yields no evidence in favor of convergence.

Foreign Trade

The Census of Horticultural Specialties (CHS) is not compatible with the United States’ foreign trade statistics; the commodities are classified according to different systems. The United States’ foreign trade statistics record herbs under various commodity classifications, sometimes within the same commodity classification as non-herbs. Thus, our attempt to identify herbs within the foreign trade statistics is imperfect.

Three common herbs (basil, mint, and sage) carry assigned Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) codes. Their unique numbers clearly identify them within the foreign trade statistics. However, these commodity classifications include both fresh and dried varieties of the herbs, whereas only fresh herbs

9 To be more precise, what is being considered here is the existence of an unconditional β-convergence in the shares of garden herbs in farm output.

20 The HERBARIST

Commercial mint farm

Photo credit: Lois Sutton

15

Figure 2. State shares of garden herb production in farm output (and growth thereof), 2009-19

AL AK AR CA CO CT GA HI ID IL IN KS KY LA ME MD MA MI MN MS MT NH NJ NY NC OH OK OR PA RI SD TN TX UT VT WA WV PERCENT WY -0.2 -0.15 -0.1 -0.05 0 0.05 0.1 0.15 0.2 020004000600080001000012000 Growth rate of share of garden herbs in farm output, 200919 (percent per annum)

Sources: National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2009 and 2019 Censuses of Horticultural Specialties for values of garden herb production; Bureau of Economic Analysis for values of farm output.

Share of garden herbs in farm output, 2009 ($ per million)

are included in the CHS. For each of these three herbs, data are available for the quantities imported, and therefore no price adjustment is necessary. Figure 3 presents the quantities imported, which reference a value of 100 for 2004. Over the period from 2004-2019, imports of basil increased by 149 percent, mint by 626 percent, and sage by 44 percent (International Trade Commission, Dataweb database).

cut fresh herbs produced in the United States. While the data do not permit exact comparisons between imports and domestic production of fresh herbs, it can nevertheless be concluded that the importation of herbs is a big business, with imports constituting a substantial, if not dominant, share of the United States’ consumption of fresh herbs. Undoubtedly, the United States’ tariff-free treatment of these imports enhances the value each year (International Trade Commission, Dataweb database).

Conclusion

This article has identified several trends that have emerged within the American herb industry. First, herbs comprise an increasing share of the United States’ farm output. Second, there has been a pronounced and sustained increase in the number of operations producing cut fresh herbs, coinciding with a decline in the peroperation average real value of cut fresh herbs produced. Third, in the American market, domestic production of herbs is supplemented, to an increasing extent, by the importation of herbs. As might be expected, there is considerable variation among the states, with respect to the number of herbal operations and the significance of the herb industry to GDP and farm output.

The United States imports these three herbs from an array of countries; again, bear in mind that a portion of these imports are of the dried variety. In 2019, the leading sources were Mexico for basil (35.9 percent of basil imports), Colombia for mint (56.8 percent of imports), and Albania for sage (63.9 percent of imports) (International Trade Commission, Dataweb database). In that year, imports of just these three herbs alone amounted to a combined $61.7 million, or nearly as much as the entire value of

Literature Cited

Dumville, Caroline. 1988. The herb industry. Professional Horticulture. 2:82-85. Pigou, A. C. 1932. The economics of welfare. London: Macmillan.

T his brief study has focused on the output of the American herb industry. Yet, there remains much to explore regarding the inputs of the industry: the labor, land, raw materials, capital, and human capital, which combine to produce commercial herbs. The availability of data is an obstacle, but not an insuperable one; data collected directly from firms would make such a study feasible. The effects of government policies on the herb industry are another area deserving of scholarly pursuit. Although very much a start, I hope that this article has piqued your interest in the economic dimension of herbs.

United Kingdom, Office for National Statistics. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates

United States, Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Census of Horticultural Specialties (1998, 2009, 2014, 2019). Available from https://www. nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Census_of_Horticultural_Specialties/index.php

United States, Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. Available from https://www.census.gov/data.html

United States, Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States (2011). Available from https://www.census.gov/library/ publications/2010/compendia/statab/130ed.html

United States, Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Available from https://www.bea.gov/data

United States, Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available from https://www.bls.gov/data/tools.htm

United States, International Trade Commission, Dataweb database. Available from https://dataweb.usitc.gov/ (account required to access)

2121 Issue 87 2022 HERBS IN THE AMERICAN ECONOMY, 1998-2019

16

Figure 3. Import quantities of basil, mint, and sage, 2004-2019

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 Basil Mint Sage 2004 level = 100 2004 2009 2014 2019

Source: International Trade Commission, Dataweb database. Notes: All quantities have been expressed relative to their 2004 levels, which were 5,521,520 kilograms for basil, 176,374 kilograms for mint, and 2,709,464 kilograms for sage.

These Plants (Probably) Won’t Kill You

Erin Holden

The nightshade (Solanaceae) family has fascinated me for a long time. Just the word “nightshade” conjures up images of witches dancing around a bubbling cauldron in the dark of night, brewing up nefarious concoctions, and making pacts with the devil. Indeed, the flying ointments made by witches of the Middle Ages relied on deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna L.), mandrake (Mandragora officinarum L.), and henbane (Hyoscyamus niger L.).These are all nightshades that can cause hallucinations, delirium, and (in the case of deadly nightshade), a sensation of flying (Lee, 2007). They could also kill you in the right (or in this case, wrong) dosage. I later learned that when used correctly, even plants as dangerous as deadly nightshade can be medicinally beneficial.

Image by S. Hermann & F. Richter from Pixabay

Image by S. Hermann & F. Richter from Pixabay

Imagine my surprise when I discovered my beloved potato belonged in this family, as well as other garden favorites, like tomatoes and eggplants. The more I investigated the Solanaceae, the more I saw that humanity’s relationship with this family is long and complex. Throughout history people have employed plants in this family not only for food, but as medicine and poison; for magic, ritual/spiritual use, and recreation; and ornamentation in our gardens—even petunias are nightshades!

Often there is no definitive line between these uses. What we might consider as “magical” use today in the West, was, and in some cultures still is, tied to medicine. Medicine and ritual use are likewise closely linked. So, what makes Solanaceae so special?

Many solanaceous plants contain a unique set of alkaloids, naturally occurring compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom and often taste bitter. Nightshades’ main alkaloids are hyoscyamine, scopolamine, and solanine, as well as the familiar nicotine. Some members of this family, like deadly nightshade and jimsonweed (Datura stramonium L.), contain dangerous levels of alkaloids, while others, like potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), contain lower, safer levels. The important thing to understand about these alkaloids is they can pass the blood-brain barrier and cause dose-dependent hallucinations and psychoactive effects—the higher the dose, the greater the effect. This accounts for many of the uses for which people have employed non-food nightshades for thousands of years.

The Solanaceae family comprises about one hundred genera containing around 2,400 species (Davenport, 2004; Olmstead et al., 2008). The plants are herbaceous, with some vines and a few shrubs and small trees. Leaves are alternate and usually simple, but they can be pinnate. The flowers have five sepals and five petals, which are partially or fully fused into a tubular corolla, five stamens, and a superior ovary with two fused carpels. The fruits can be either a berry (like the tomato) or a capsule (like jimsonweed). They’re found worldwide, with about forty genera endemic to tropical Latin America but only fifty species native in the United States and Canada (Morris and Taylor, 2017; The Plant List Database, 2013).

Botanical literature often refers to nightshades as Old World (those native to Europe, Asia, and Africa) and New World (those native to the Americas). Europeans tended to fear Old World plants like deadly nightshade, henbane, and mandrake, as many of them could be deadly if used incorrectly. On the other hand, people in the New World revered and respected their nightshades as many of them were staple foods, such as chili peppers, tomatoes, and potatoes, or were considered sacred, like

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha)

Ashwagandha is an Old World nightshade that seems to have escaped the veil of superstition and suspicion that surrounds its more notorious cousins. Its native range extends from the Mediterranean to South and East Africa, over to the Middle East, and into India and Sri Lanka. It’s a small branching shrub, growing two to three feet tall, and producing small red fruits surrounded by a lantern-like calyx (like a tiny Chinese lantern or tomatillo). The common name translates from Sanskrit to mean “smells like a horse,” referring to the strong odor of the root. It could also suggest the effects of taking ashwagandha, which may give one “the power of a horse” (Singh, Bhalla, de Jager, and Gilca, 2011). The specific epithet, somnifera, alludes to the herb’s sleep-promoting properties. This plant has a long history of use in Ayurvedic medicine, going back 6,000 years. There is evidence dating to at least 1000 BCE of the scholar Punarvasu Atreya teaching medical students how to use it (Singh and Kuma, 1998). A plant that scholars commonly accept as ashwagandha appears in the oldest surviving copy of Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica from the 6th century, and then again

23

THE LIGHTER SIDE OF NIGHTSHADES

Potato flowers showing fused petals

Photo credit: Ezhuttukari

Withania somnifera, ashwagandha, fruit

Photo credit: Wowbobwow12