A PUBLICATION OF THE HERB SOCIETY OF AMERICA ISSUE 83 ~ 2018

Herbarist

HSA Board of Directors

Rie Sluder President

Amy Schiavone Vice President

Maryann Readal Secretary

Linda Lange Treasurer

Karen O’Brien Botany & Horticulture Chair

Jen Munson Education Chair Open Development Chair

Gloria Hunter Membership Chair

Rae McKimm Nominating and Awards Chair/ Past President

Kim Labash

Bill Varney

Central District Membership Delegate

Open Southeast District Membership Delegate

Joan Keif West District Membership Delegate

Susan Belsinger Honorary President Administrative Staff

Gretchen Faro Interim Office Manager

Karen Kennedy Education Coordinator

Chris Wilkinson Librarian/Archivist

Holly Gielink Membership/Administrative Assistant

Paula Byrne Accountant

The Herbarist

Debbi Paterno Publication Design, Debbi Paterno Graphic Design

SP Mount Printing Printer

The Herbarist Committee

Maryann Readal Secretary

Lois Sutton, Ph.D. Chair

Jean Berry

Henry Flowers

Shirley Hercules

Gayle Southerland

Barbara Williams

The opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of The

Sponsors

It

of

Herb

of America not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment.

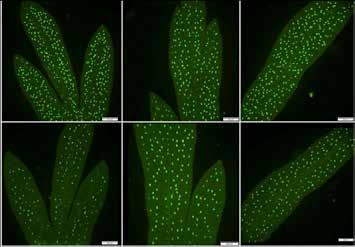

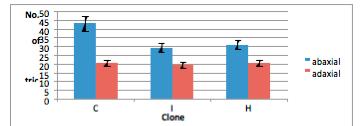

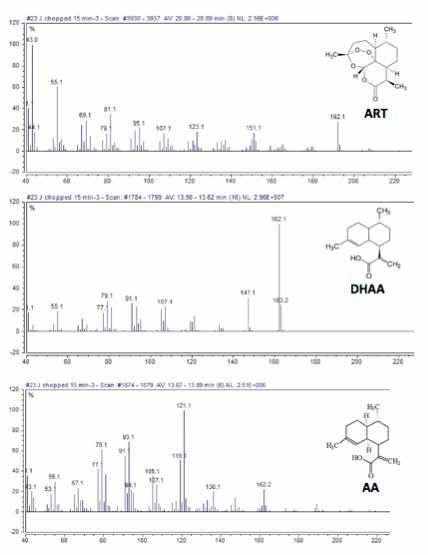

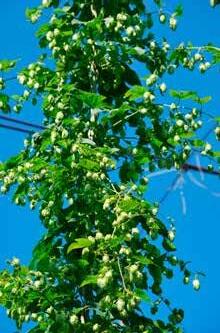

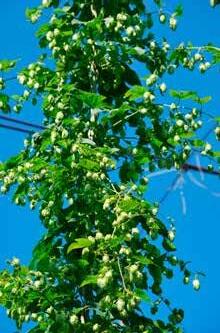

Medicinal Comments on Bay and Old Bay® 3 By James A. “Jim” Duke, Ph.D. Designing Garden Rooms with Fun and Focus in Mind 7 By P. Allen Smith Herbs in the Extreme 11 By Lois Sutton, Ph.D. Chocolate: Improving Upon “Perfection” 15 By Christine Moore Herbs in British Folk Songs 21 By Mary Bellis Williams, Ph.D. Herbs Play Historic and Modern Role in Beer 30 By Paris Wolfe Fruit of the Bine 33 By Jacqui Highton Annual Research Grant Report (2015/2016) 39 By Delini K. Samarasinghe

the cover: illustration of Salvia greggii by Lotus McElfish

On

for this issue of The Herbarist include William Donley, Andy MacPhillimy, Maryann Readal, and Lois Sutton

policy

is the

The

Society

Membership Delegate

District Porterfield Membership Delegate

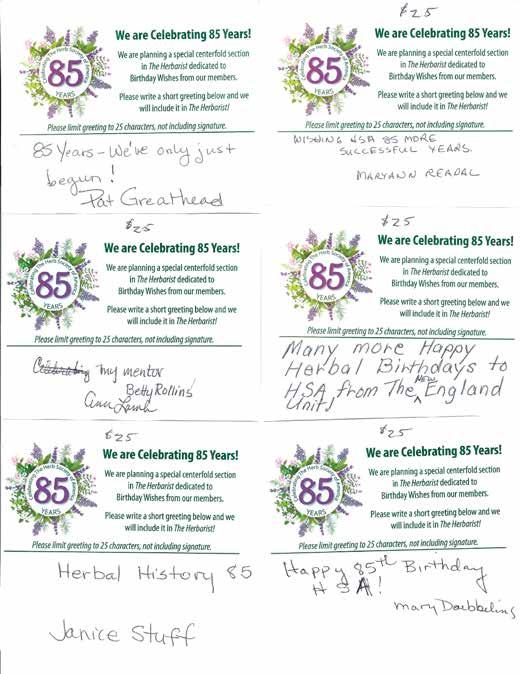

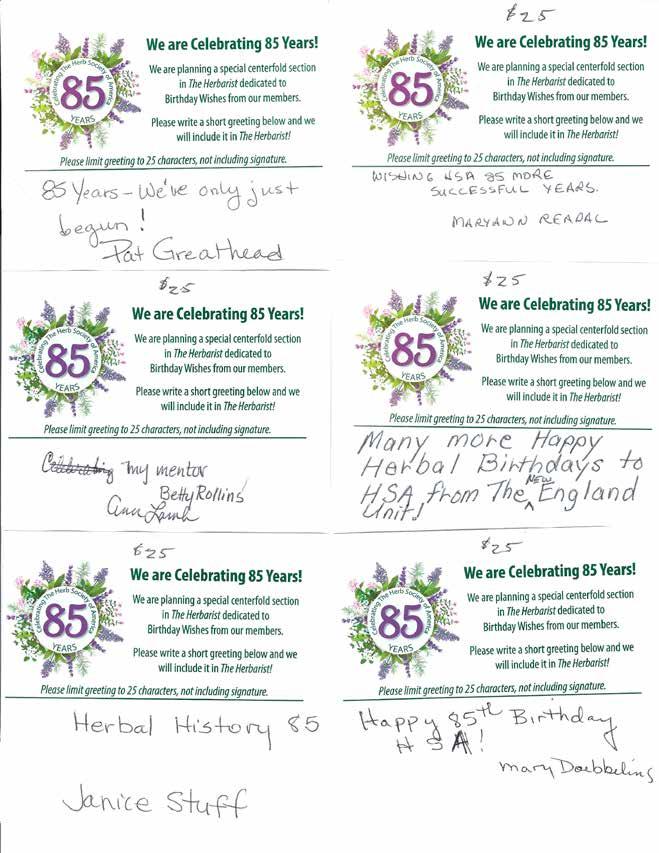

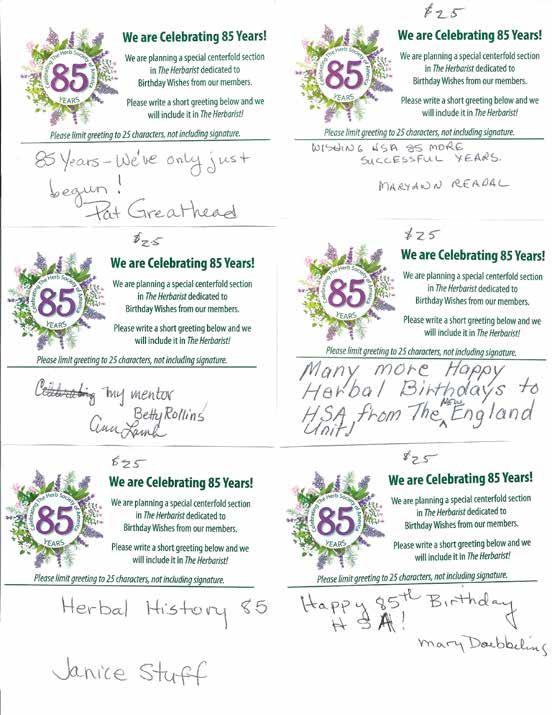

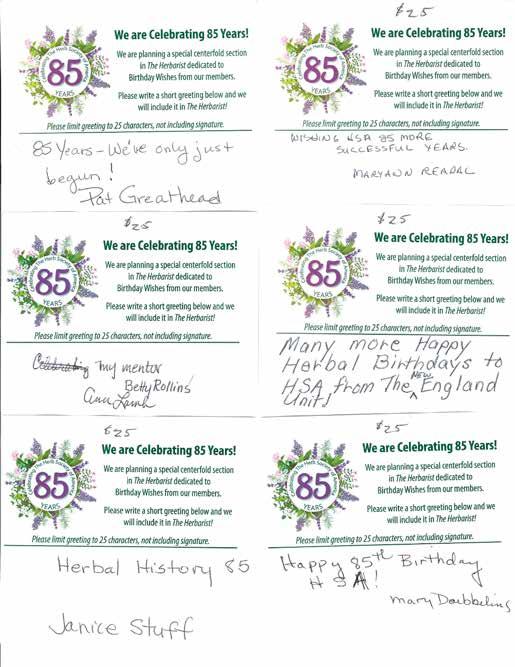

Pat Greathead Central District

Bonnie Great Lakes

District Membership Delegate Open Northeast District Membership Delegate

Mid-Atlantic

South

Society. Manuscripts, advertisements, comments and letters to the editor may be sent to: The Herbarist, The Herb Society of America 9019 Kirtland-Chardon Rd. Kirtland, Ohio 44094 440.256.0514 www.herbsociety.org editor@herbsociety.org The Herbarist, No. 83 Contents 3 Issue 83 2018 BAY An Herb Society of America Guide THE HERB SOCIETY OF AMERICA 9019 Kirtland Chardon Road, Kirtland, Ohio 44094 © 2009 The Herb Society of America 1 2 3 4 5 7 8 6 9 10 11 Medicinal Comments on Bay and Old Bay ® James A. “Jim” Duke, Ph.D. Editor’s Note: The following first appeared in The Herb Society of America’s Essential Guide to Bay, 2009. We have chosen to reprint it in The Herbarist in Dr. Duke’s memory, hoping to bring smiles and memories to those who knew him and, perhaps, to introduce his broad knowledge and irascible teaching style to those who did not meet him during his life.

Recently I published Duke’s Handbook of Medicinal Plants of the Bible. Many Biblical species have what I call level two evidence, with clinical proof (much more important, and usually from recent research) or historical approval by Commission E (A German commission that assessed the safety and efficacy of herbs) for certain indications I have scored over 3,000 medicinal herbs on a four-level classification for efficacy

f = folkloric evidence only

1 = animal, chemical (isolated phytochemical, in vitro, or in vivo) or epidemiological evidence

2 = clinical proof for a plant’s extracts (or historical approval by Germany’s Commission E, or by the Caribbean TRAMIL Commission)

3 = clinical proof for the plant itself (for example, bilberry, garlic, ginger, turmeric, etc ) (or historical approval by Germany’s Commission E, or by the Caribbean TRAMIL Commission)

DIABETES

In the case of bay, the Herb of the Year™, I still have no level 2 evidence for any indication But bay leaf was one of four spices (bay, cinnamon, cloves, turmeric) studied by USDA’s Dr Richard Anderson He suggested that less than a spoonful of any could improve insulin

metabolism dramatically So, in my The Green Pharmacy (1997) I created the formula “dia-beanie soup” food pharmacy for diabetes

An outstanding USDA scientist, Dr Richard Anderson demonstrated bay leaves experimentally help improve insulin utility

The leaves do lower blood sugar levels in experimental animals I add bay leaves to my Dia-Beanie Soup (yes, a soup with medicinal intent, something the FDA is trying to curb, and I am trying to stimulate)

Most beans contain slow release carbohydrates and the beans themselves are hypoglycemic So is the bay, as proven experimentally by Dr Anderson Let’s add some other compatible spices, especially garlic and onion, and hot pepper, each of which offers other substances against the diabetes Dashes of rosemary, sage, and tarragon also add their anti-diabetic potential, such that the soup contains more than a dozen anti-diabetic phytochemicals

I enjoy the bay-bean Dia-Beanie soup with the bay “insulinade” that I proposed in The Green Pharmacy. Start out with Anderson’s mix: bay leaf, cinnamon, cloves, and turmeric Add a pinch or two of each of them to a teapot and steep for ten minutes I’d also add fenugreek that is well proven and a pinch of coriander and cumin (evidence not so strong) In animal studies, both have been shown to lower blood sugar somewhat, and the rosemary, sage, and tarragon go as well with the insulinade Don’t use sugar with the tea Instead add stevia, a non-nutritive sweetener that has its own hypoglycemic phytochemicals

These days, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is getting worse and worse, especially that acquired in hospitals Hospitals may discharge patients with MRSA infections if they can be safely treated at home There are now a number of antibiotics used to effectively treat methicillin resistant staphylococcal infections Bay is just one of several spices that contain anti-MRSA phytochemicals

One serving

½ cup dry lentils, wash and strain off any stones, soak 1 hour

1 heaping teaspoon fenugreek

½ cup chopped onions

Chives

Leeks

Ramps

Scallions

Mix and match the Allium as available.

Dash of curry or powdered turmeric

Oregano or Biblical hyssop

1 whole bay leaf

½ clove garlic

Simmer for two hours or until tender; salt, pepper, and paprika to taste.

After my November tasting, I’m cutting back on the fenugreek, too bitter for my occidental palate, although my sample soup was much better the day after, losing most of the bitterness. Matter of fact, it was great with diced raw onion.

Note: More importantly parthenolide, and hence bay, can be added to an immune boosting lentil soup.

In 2008, Japanese scientists identified two chemicals in bay leaf extracts (probably bay leaf tea) that were active, not only against MRSA but also another bacterium, Enterococcus (which is developing resistance to vancomycin, but is fortunately sensitive to newer antibiotics)

But this scores only a one in my evidence base These two compounds are just two, in dilute concentrations, among thousands of other biologically active compounds in bay They would need to be concentrated to have any effect against the serious MSRA infection Even if these were used pure, just one or two compounds, the MRSA would quickly become resistant to them You’d need a cocktail of several natural anti-MRSA phytochemicals to reinforce the pure synthetic antibiotics Other herbs with anti-MRSA activity include the Biblical garlic, leek and onion, also green tea and turmeric

ARTHRITIS

The bay contains half a dozen natural COX-2-Inhibitors that your genes may have known for thousands or millions of years, depending on whether you are faith-based (bay does occur in the Holy Land) or evolutionist (Natural COX-2-Inhibitors, like the synthetic Celebrex or Vioxx, can relieve inflammation )

Here are six compounds that are COX-2-Inhibitors in bay

(+) catechin kaempferol caffeic acid parthenolide eugenol quercetin

You can find dozens of other activities of these and dozens of other useful phytochemicals on my public domain USDA database: http://phytochem nal usda gov

OLD BAY® SEASONINGS COX-2-INHIBITORS AND ARTHRITIS

Arthritis away with OLD BAY®? Wow – OLD BAY® Seasoning has many other COX-2 inhibiting spices in its formulation too I suppose our Herb of the Year™, bay, like Chesapeake Bay, contributed to the name of the familiar Old Bay® Both the black and red pepper are important, the red pepper’s very potent capsaicin and the black pepper’s piperine that facilitates the uptake of the curcumin

Old Bay® contains several spices that contain collectively more than 13 COX-2-Inhibitors: apigenin, caffeic acid, capsaicin (more potent than Vioxx), (+) catechin, cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, 10-gingerol, kaempferol, oleanolic acid, 8-paradol, parthenolide, quercetin, salicylates, and shogaol

HEADACHE

I am perhaps still alone in suggesting that bay leaf might work like the very bitter feverfew in preventing migraines But bay contains some of the same compounds, parthenolides, suggested by some scientists of underlying the antimigraine activity of feverfew I’d mix the feverfew and bay if I targeted for migraine Here are some phytochemicals from bay that might contribute to the relief of migraine in addition to those natural COX-2-Is

BAY PHYTOCHEMICALS AND MIGRAINE

(http://www phytochem nal usda gov)

• 5 HT Inhibitor Parthenolide; rutin

• Analgesic Borneol; caffeic acid; camphor; caryophyllene; eugenol; linalool; mannitol; myrcene; p-cymene; quercetin; reticuline; terpineol; thymol

• Anti-inflammatory (+) catchin; (-) epicatechin; 1, 8 cineole; alpha pinene; alpha terpineol; artecanin; beta pinene; boldine; borneol; caffeic acid; carvacrol; caryophyllene; caryophyllene oxide; cinnamic acid; delta 3 carene; eugenol; eugenyl acetate; isoquercitrin; kaempferol; limonene; linalool; mannitol; parthenolide; quercetin; quercitrin; rutin; salicylates; santamarin; santamarine; thymol

• Anti-migraine

Parthenolide

• Anti-neuralgic Camphor; parthenolide

• Anti-nociceptive (+) gallocatechin; 1,8 cineole; isoquercitrin; myrcene; quercetin; rutin

• Antispasmodic

1,8 cineole; alpha pinene; alpha terpinene; benzaldehyde; beta pinene; borneol; bornyl acetate; caffeic acid; camphor; carvacrol; caryophyllene; cinnamic acid; eugenol; eugenyl acetate; geraniol; kaempferol; limonene; linalool; mannitol; myrcene; neral; p coumaric acid; parthenolide; quercetin; quercitrin; reticuline; rutin; santamarin; santamarine; terpinen 4 ol; terpineol; thymol; valerianic acid

• COX-2 Inhibitor

(+) catechin; caffeic acid; eugenol; kaempferol; limonene; parthenolide; quercetin

• Counter-irritant

1,8 cineole; camphor; formic acid; thymol

• Cyclooxygenase Inhibitor

(+) catechin; carvacrol; kaempferol; parthenolide; quercetin; thymol

• Myorelaxant

1,8 cineole; boldine; borneol; bornyl acetate; eugenol methyl ether; limonene; methyl eugenol; myrcene; rutin; thymol

• Sedative

1,8 cineole; alpha pinene; alpha terpineol; benzaldehyde; beta eudesmol; borneol; bornyl acetate; caffeic acid; carvone; caryophyllne; citral; eugenol; geraniol; geranyl acetate; limonene; linalool; methyl eugenol; nerol; p-cymene; thymol

• Tranquilizer

Alpha pinene; borneol

• Vasodilator

(-) epicatechin; eugenol; kaempferol; proanthocyanidins; quercetin; rutin

Back in the days of the anthrax scare at Brentwood outside Washington, I figured that garlic and bay might boost the immune system to ward off an anthrax infection The authorities always tell us that we are more liable to get infection if we have a depressed

Dr. Jim Duke’s Lentil Soup

5 Issue 83 2018 MEDICINAL COMMENTS ON BAY AND OLD BAY® MEDICINAL COMMENTS ON BAY AND OLD BAY®

immune system I’ve never heard them tell us that boosting the immune systems can help prevent the infection from getting the upper hand

Garlic will keep the neighbors away but not their germs When it comes to stray anthrax or bubonic plague, it might help to at least complement the several antibiotics used to treat these serious infections There are no clinical trials comparing these antibiotics with lentil soup or garlic or bay leaf Perhaps this will never happen However, I’d bet more on garlic or bay leaf than the lentil soup, that dilutes garlic and bay leaf Lentil soup, if pleasing, can boost the immune system (if you’ll take your mind off anthraciphobia), while providing hundreds of gentle antiseptic phytochemicals

BAYLEAF AND BUBONIC BUZZWORDS

Saturday, I dressed down my sister-in-law for leaving big pieces of bay leaf in that great stew she whipped up I told her that there have been a few deaths due to pieces of bay leaf lodging in the gullet or esophagus So, you should steep it in your stews and remove, as in a muslin tea bag, or you should completely pulverize it Little could I have predicted then that two days later, I’d be suggesting that bay leaf be added to my pox-busting lentil soup

If the anthraciphobia led you to drink too much booze, Japanese scientists identified half a dozen ethanol-absorption-inhibitors from bay leaf Through a bioassay-guided separation using inhibitory activity on blood ethanol elevation in oral ethanolloaded rats, various sesquiterpenes [costunolide, dehydrocostus lactone, zaluzanin-D, reynosis, santamarine, 3alphaacetoxyeudesma-1,4(15),11(13)-trien-12, 6alpha-+ ++olide (6), and 3-oxoeudesma-1,4,11(13)-triuen-12, 6alpha-olide] were identified as the active principles from the leaves Some of the sesquiterpenes seem to selectively inhibit ethanol absorption

BAY LEAF FOR INFECTION

• Analgesic

Borneol; caffeic acid; camphor; eugenol; myrcene; p-cymene; quercetin; reticuline

• Anesthetic

1,8 cineole; benzaldehyde; camphor; carvacrol; cinnamic acid; eugenol; linalool; methyl eugenol; thymol

• Antibacterial (-) epicatechin; (-) epigallocatechin; 1,8 cineole; acetic acid; alpha pinene; alpha terpineol; benzaldehyde; bornyl acetate; caffeic acid; carvacrol; caryophyllene; cinnamic acid; citral; delta 3 carene; delta cadinene; eugenol; geraniol; isoquercitrin; kaempferol; limonene; linalool; methyl eugenol; myrcene; neral; nerol; p coumaric acid; parthenolide; perillyl alcohol; quercetin; quercitrin; reticuline; rutin; terpinen 4 ol; terpineol; terpinyl acetate; thymol

• Anti-nocioceptive Myrcene

• Antiseptic

1,8 cineole; actinodaphnine; alpha terpineol; benzaldehyde; beta pinene; caffeic acid; camphor; carvacrol; carvone; citral; eugenol; formic acid; geraniol; guaijaverin; hexanal; hexanol; kaempferol; limonene; linalool; methyl eugenol; nerol; parthenolide; proanthocyanidins; terpinen 4 ol; terpineol; thymol

• Antiviral

(-) epicatechin; alpha pinene; beta bisabolene; bornyl acetate; caffeic acid; kaempferol; limonene; linalool; neryl acetate; p-cymene; proanthocyanidins; quercetin; quercitrin; rutin

• Fungicide

1,8 cineole; acetic acid; caffeic acid; camphor; caprylic acid; carvacrol; cinnamic acid; citral; elemicin; eugenol; geraniol; linalool; methyl eugenol; myrcene; p coumaric acid; p-cymene; parthenolide; perillyl alcohol; propionic acid; reticuline; terpinen 4 ol; terpinolene; thymol

• Fungistatic

Formic acid; limonene; methyl eugenol

• Immunostimulant

(+) catechin; (-) epicatchin; astragalin; benzyldehyde; caffeic acid

or many of us, design of any kind is a daunting subject; it frightens us because we are afraid of making a mistake. In Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird , the author’s brother, who has put off completing a school report on birds until the last minute, is paralyzed by fear as he stares at the blank sheet of paper before him. Feeling frustrated and overwhelmed, he is uncertain how to begin. The solution comes in some simple advice offered by his father. “Bird-by-bird, Buddy. Just take it birdby-bird.”

In that same spirit, my 12 principles of design are a “bird-by-bird” method of designing a garden. These universal principles have become the set of tools I use to create gardens that can embody the key elements of the world’s greatest landscapes but are scaled to each individual’s site, taste, and budget. When woven into the plan of the garden, they are unifying components that magically transform the space into a place of enchantment and beauty.

I used these principles when creating the garden rooms at Moss Mountain Farm, my home in Arkansas. The principles are divided naturally into two main categories. The first six focus on building the framework or bones of the garden. The second six principles add decorative or finishing touches to your garden, as well as personality, charm, and, last but not least, fun!

1. Enclosure

Enclosures anchor a garden to its location, giving both the house and the garden a sense of permanence and lasting beauty Establishing clearly defined enclosures made from a wide selection of materials, including plants, fences, and walls, is a vital element in the design of a garden home This framework allows you to rearrange the “furniture” (in this case the perennials, small shrubs, and annuals) as often as you’d like without remodeling the entire “house ” Enclosures also add a sense of security and comfort and establish order by creating manageably sized spaces

2. Shape and form

We generally notice a plant’s flowers, color, or foliage before considering its shape Different plant shapes convey “personality ” While a columnar plant creates an air of formality, a climbing plant adds a casual and

I chose a circular layout for this room of the Terrace Garden. The vase-shaped chaste trees (Vitex) give this room a regal feel.

P. Allen Smith

I chose a circular layout for this room of the Terrace Garden. The vase-shaped chaste trees (Vitex) give this room a regal feel.

P. Allen Smith

6 7 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018 MEDICINAL COMMENTS ON BAY AND OLD BAY®

Photo credits from left to right: Theresa Mieseler, Pat Crocker, Susan Belsinger, Henry Oakeley

sometimes wild effect to the garden room Consider how to combine plants of different shapes to create the borders of your garden rooms

The overall shape of a garden room can have symbolic associations Circles, for example, can represent infinity because they lack a beginning and an end Planning the shape and form of your garden room is important, as it determines the feeling of the spaces within it

3. Framing the view

The goal of framing a view is to draw attention to an object or scene You can accomplish this by opening a sight line to the desired object and screening and blocking surrounding distractions Views inside or outside the garden room may be framed

to something that holds our interest When a single object dominates a space, it has a way of radiating its own energy— almost a center of gravity that anchors and organizes a space With attention focused toward something of interest, the stage is set for the opportunity of surprise

For instance, upon entering a garden room you may see a sculpture in the distance that draws you in Wanting to have a closer look, you walk toward the sculpture but are surprised to discover there are other garden rooms to the left and right Your curiosity is piqued, encouraging you to explore more of the garden

6. Structures

There is something exhilarating about embellishing an ordinary outbuilding to make it more attractive and then integrating it into the framework of a garden Out of practical and sometimes mundane objects, we can create beauty

Structures add to the sense of enclosure, screen views, and provide a center of visual interest They also represent an anchoring element, a firm point from which we can begin to absorb the richness and diversity of the entire space

reds and oranges stir warmth and excitement

Limit your selections in each garden room to the range of a single-color family, with perhaps a bit of its complement for contrast

Each enclosure should have its own color theme, just like each room of your home A garden room can be simple and monochromatic, or it can have a well-coordinated range of colors with just a splash of contrast to invigorate the feeling of space

Broad sweeps of color are more effective than dabs and patches

8. Texture, pattern, and rhythm

The cadence created when three or more objects are equally spaced in an obvious pattern implies rhythm, order, and dependability Repeated objects placed closely together tend to quicken the rhythm and the same objects spaced farther apart slow it down

9. Abundance

Gardens are about making a bold statement

The credit for this idea goes to Mother Nature

As you look around natural settings, you will find that plants often grow in large colonies If you follow this lead, growing plants in a large drift or colonies, then your garden will appear more spontaneous and natural

4. Entry

An entry to a garden is often a visitor’s first impression It represents your personal invitation to everything that lies beyond and should be part of each garden room Symbolically, entrances are signs of welcome They also serve as directional guides and transition points from one area to the next

Just as we accent the entrance to our homes with “welcome” mats and pots bursting with seasonal blooms, we are compelled to embellish significant thresholds in the garden

5. Focal point

A focal point serves as a visual “hook,” drawing the eye

7. Color

Create a green framework that holds the garden together

Shades of green serve as a frame, just as wall color in an interior room provides a unifying element for the other colors in the room’s furniture, draperies, and accessories I find it useful to match the mood of the garden room with colors that evoke that feeling Blues and lavenders soothe, helping us to feel restful and calm, while hot colors such as

Use surface characteristics, recognizable motifs, and the cadence created by the spacing of objects as elements of design These elements add layers of richness and interest to a garden Contrasting surface characteristics of plants and materials heighten the visual impact in garden rooms Repeating motifs create a feeling of continuum within a garden room and give harmony to the design

The yellow hues of the coleus foliage complement the purple flowers of the Mexican sage.

10. Whimsy

To gain its full effect, abundance must be contained to the point where it is not a distraction A few “workhorse plants” used generously establish abundance without excess Generous plantings allow selective cuttings without diminishing the overall visual impact Staggered bloom times extend the impact of the display while maximizing the use of the bed space

I love using whimsical touches to personalize the garden These elements add harmony, wit, and surprise Silly sculptures, gnomes,

My favorite reason for applying the principle of abundance to the garden - ample plantings provide enough to share!

My favorite reason for applying the principle of abundance to the garden - ample plantings provide enough to share!

8 9 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018 DESIGNING GARDEN ROOMS WITH FUNCTION AND FUN IN MIND DESIGNING GARDEN ROOMS WITH FUNCTION AND FUN IN MIND

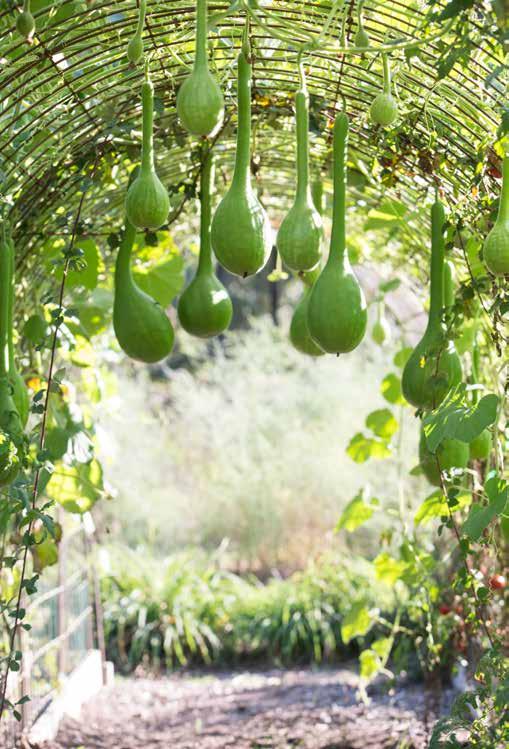

A tunnel leading from the Terrace Gardens into the East Garden at Moss Mountain Farm frames the view of Miss Big Fig.

or a favorite quote engraved into stepping stones are fun additions to the garden

Houses, pens, and coops for our animals can also add a touch of whimsy, serving both function and fantasy My honeybees reside in a hive altered to look like an Italian villa —a Bee Palace —fit for a queen and her court

Certain plants, because of nostalgia or their strange appearance,

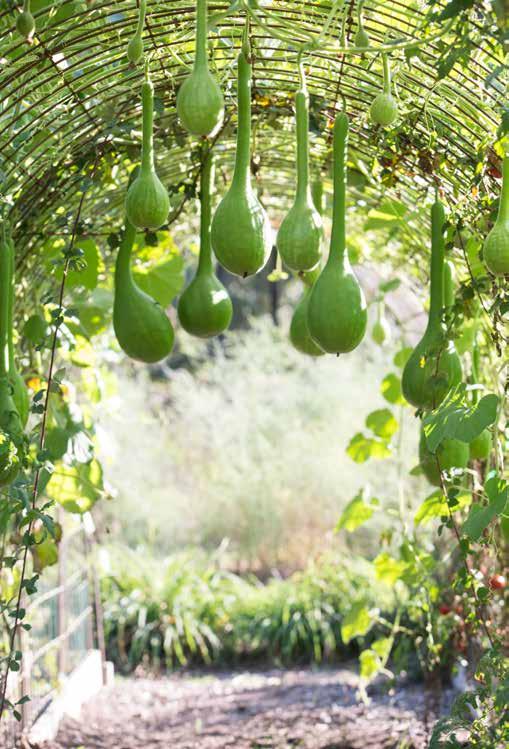

offer their own form of delight Gourds, pumpkins, Japanese lanterns, elephant ears, and banana trees are jolly in an almost defiant way, flying in the face of modern efficiency and pragmatism

The garden is a place that reminds us to not take things too seriously When you relax and let things happen, all kinds of wonderful surprises develop

11. Mystery

Using the unknown, the unseen, and the imagination, mystery piques a sense of curiosity, excitement, and occasional apprehension through the garden’s design Simple effects such as moving water will inspire curiosity and beckon visitors toward its sound A partially obscured view of a spectacular rambling rose in full bloom can also lure people down a path to get a closer look A gate, door, or portal that suggests something beyond in a garden will play to our subconscious since we long to see through to the other side

Paths are one of the best ways to embrace mystery A curve in a path, positioned in a way to hide the next vantage point in the garden, will always encourage the curious visitor to follow its course

12. Time

As you design your garden, try to assemble plants and materials that are appropriate to the age of the property or architectural style of your house Gardens have certain “spirits of age” that should be met to feel authentic Understanding a sense of place is about recognizing its history and connecting the design of your garden with that time

Editor’s note: These principles are covered in more detail in P Allen Smith’s Garden Home: Creating a Garden for Everyday Living For more views of Moss Mountain Farm and gardens designed by P. Allen Smith visit www.pallensmith.com or www. pallensmith.com/garden-home

Herbs in the

When I study herbs, generally I’m reading about plants in cultivated gardens Fortunately, there are Herb Society of America members who take us out of the usual garden settings For example, Patricia Kenny and Katherine Schlosser have taught us about sea herbs, and Rhonda Fleming Hayes described her move to a wetland herbal garden (Kenny 2017; Schlosser 2017; Hayes 2009) Recent hikes in the Big Bend National Park (Texas) vividly reminded me that herbs, intriguing plants that they are, successfully grow in another extreme, one with scant water

There are four major deserts in the United States: the Chihuahuan, the Sonoran, the Mojave, and the Great Basin (a simplified map of these desert regions may be found at http://www mbgnet net/sets/desert/ofworld htm) The Chihuahuan Desert is the largest, covering 175,000 square

miles It may be the most accessible as there are two Texas parks, the Big Bend Ranch State Park and the Big Bend National Park, within its boundaries Combined, these two parks comprise more than one million acres of desert, much of it accessible by driving, paddling, or hiking

Shrubs and low growing cacti dominate the botanical landscape of Big Bend Jay Sharp, a writer for the e-newsletter DesertUSA, notes that these shrubs exhibit the survival strategies of small leaves, protective thorns, multiple branches, disagreeable smells and tastes, and extensive root systems He further describes a group of shrubs as “drought avoiders” with the additional characteristic of shedding their leaves and twigs when little water is available The North American creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens Engelm.) are two shrubs

10 11 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018 DESIGNING GARDEN ROOMS WITH FUNCTION AND FUN IN MIND HERBS IN THE EXTREME

Visitors to the farm are always enchanted by the tunnel of dipper gourds in the vegetable garden. I grow them for amusement and use them as decorations.

A scattering of creosote bush and ocotillo in Big Bend State Park, Texas

Creosote bush in bloom

Lois Sutton, Ph.D.

frequently seen in the Big Bend parks

For a remarkable desert plant with a host of anecdotal stories, the creosote bush offers a relatively unattractive appearance There are five species of Larrea, four occurring in South America and one in North America (Mabry, Hunziker and Difeo, Jr 1977) The bush grows three to nine feet high Creosote bush branches, stems, and small bifurcated leaves are olive-green throughout most of the year Only after spring rains do the leaves change in color to dark-green, and yellow flowers appear A sticky resinous substance covers the entire creosote bush, producing an old-fashioned medicinal odor When the flowers and fruits mature, they contain less resin

The shrubs tend to grow in an evenlyspaced arrangement This may be because of creosote’s root system growing such that it does not compete spatially with other nearby plants, root secretions of tannins or phenols that prohibit nearby growth of competing plants, or soil saturation by water-soluble phytochemicals in the leaves and stems (Mabry, Hunziker and Difeo, Jr 1977; Bown 2001) This characteristic is so well known that it is mentioned in the memoirs of Mary King Rodge, a woman

who grew up in El Paso, Texas, in the 20s and 30s She relates this exchange between her mother and their gardener

“After Mr. Stone finished the trench, he pointed to a clump of creosote bushes in the far corner of the yard … ‘I can get rid of that there creosote for you, Mrs. King, so it won’t bother you no more.’ ‘Why would I want to kill it?’ she asked. ‘Creosote, that’s why. Don’t nothing grow under creosote … Drops some kind of poison on the ground, killing its own young. Wherever you got creosote, you ain’t got nothing else.’… ‘No don’t chop it down. I sort of like it.’” (Rodge 1999, 77).

Matt Turner states in his book, The Remarkable Plants of Texas, that creosote has no culinary uses for humans or other mammals (Turner 2009) However, buried

in the history of the Big Bend are experiments assessing camels as useful pack animals in this desert environment In 1859 Lt Edward Hartz and Lt William Echols set out across a section of the Chihuahuan Desert with both mules and camels They brought no feed for the camels but reported that the camels ate such desert plants as creosote, ocotillo, prickly pear, and catclaw (Maxwell 1971; Texas Highways 2014)

B N Timmerman, citing studies at the New Mexico Agriculture Experimental Station, notes the leaf residue (after processing to remove most of the resins) provides as much protein as alfalfa for cattle (Mabry, Hunziker and Difeo, Jr 1977, 255) Alma Hutchens offers a testimonial from Ralph W Davis, a longtime cattle rancher in North Dakota, to its nutritive value: “In springtime if an old cow can pull through until the creosote bush puts out tender shoots, she will get fat, shed her old rough winter coat, and be glossy and pretty in four weeks, and she will bring her calf and be able to nurse it into a fine animal This drama of life I have witnessed year after year for the past 50 or more ” (Hutchens 1992, 78)

The shrub, because of its numbers, provides habitat for many insects (thirty species in five orders) as well as providing nectar for hummingbirds on their northern migration (Mabry, Hunziker and Difeo, Jr 1977, 176, 184-185) The plants are a water and nutrient source despite the plants’ natural defenses of resinous leaf coating and fine hairs on mature fruits (Mabry, Hunziker and Difeo, Jr 1977, 177) Additionally, the shrubs may provide a place to hide from other predatory insects and birds and offer a protected place to deposit eggs

As late as the 1960s the food and textile industries used an antioxidant found in creosote, NDGA, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, to prevent rancidity in fats and oils (Bown 2001) and to serve as a preservative for natural fibers (Arteaga, Andrade-Cetto and Cárdenas 2005) Reports of renal and kidney toxicity led the US Food and Drug Administration to ban its use as a food additive by 1981 (Arteaga, Andrade-Cetto

find an old livestock enclosure fenced by ocotillo branches (Turner 2009, 129) Turner describes ocotillo buildings ranging from simple houses (perhaps with adobe used to reinforce the walls) to temporary hunting or storage sheds (Turner 2009, 131-132; Native American Ethnobotany Database 1972) An interesting added benefit of an ocotillo structure is that even after the branches have been cut from the trunk, they retain the ability to generate ephemeral leaves when it rains If the branches are stuck in the ground, they may eventually root and create a living fence (Maxwell 1971)

There is little wonder with this vibrant response to water that native peoples living in the desert looked for ocotillo uses beyond that of a construction material

Perhaps hummingbirds on their spring northern migration suggested the usefulness of ocotillo blossoms as a nectar, i e sugar, source to these peoples The Cahuilla Indians used the blossoms to flavor water (Native American Ethnobotany Database 1972) Sucking on the end of a flower gives one a burst of sweetness (Native American Ethnobotany Database 1936) The Papago Indians, who lived in similar areas, pressed the nectar out of the flowers, allowed it to harden, and then chewed it like candy (Native American Ethnobotany Database 1935)

and Cárdenas 2005)

Traditional medicinal uses of creosote abound by native peoples, ranchers, and cowboys In 1848 a U S – Mexican boundary survey commission recommended creosote as a treatment for rheumatism (Hutchens 1992) An antiseptic solution made by soaking leaves and twigs in boiling water has been used for ailments ranging from saddle sores to cuts, bruises, and bites A salve made by boiling the leaves in lard has been used for fungal infections such as ringworm and athlete’s foot (Turner 2009, 142)

A second desert shrub, Fouquieria splendens Engelm or ocotillo, reminds us of the ingenuity and observational skills of peoples living in stressful environments

Ocotillo’s desert profile is a clump of slender, leafless branches, ranging from three to twenty feet in height The minimal trunk makes it appear that the branches are dead, stuck upright in the ground Within 24 – 48 hours of rain short-shoot leaves grow between the main stem and the spine; these leaves last only a few weeks More continuous spring rains stimulate the growth of long-shoot leaves and tubular reddish-orange flowers on the ends of the stems Part of the leaf will harden later into a sharp, stiff, persistent spine that contributes to the knobby appearance of the dry-weather leafless branches Considered a characteristic species of the Chihuahuan Desert, ocotillo provides hikers with a vision of history when they

The Cahuilla also ground the dried seeds into flour that they then used to make porridge or cakes, like hotcakes or flat cornmeal cakes (Native American Ethnobotany Database 1972)

There have been a variety of medicinal uses for the flowers, stems, and roots Immersing oneself, or simply one’s feet, in a root decoction will fight fatigue (Turner 2009, 132) Michael Moore writes in his book Los Remedios that the primary use of teas from the stems and flowers has been for coughs and sore throat (Moore 1990) While his book provides a tea recipe, he also notes the addition of whiskey to the tea!

In a treeless environment ocotillo stems, especially with their resins, provide fuel for campfires or rustic stoves (Native American Ethnobotany Database 1972;

12 13 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018 HERBS IN THE EXTREME

Residual spines along stem of ocotillo

Ocotillo in bloom with short lived green leaves

HERBS IN THE EXTREME

Use of ocotillo stems as shade cover

Maxwell 1971) The stems burn for a long time, a value outweighing ocotillo’s oily smoke Among the common names for ocotillo is candlewood, which Turner associates with this use as fuel He also

notes that ocotillo translates from Spanish as “little torch” (Turner 2009, 133)

to make note of them as we pass by and to appreciate what they historically, and still, add to the complexity of our natural surroundings

Literature Cited

Arteaga, Silvia, Adolfo Andrade-Cetto, René Cárdenas. Larrea tridentata (creosote bush), an abundant plant of Mexican and US-American deserts and its metabolite nordihydroguaiaretic acid. 2005. J of Ethnopharmacology. 98: 231-39.

Bown, Deni. The Herb Society of America’s new encyclopedia of herbs & their uses. 2001. New York & London: Dorling Kindersley Limited.

Hayes, Rhonda Fleming. Herb gardening at the water’s edge. The Herbarist. 2009. 75: 36-40.

Hutchens, Alma R. A handbook of Native American herbs. 1992. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Kenny, Pat. Sea vegetables and ocean herbs. July 2017. Available from www.herbsociety.org, members-only section, past webinars.

Mabry, T.J., J.H. Hunziker and D.R. Difeo, Jr., eds. Creosote bush: biology and chemistry of Larrea in New World deserts. 1977.

Stroudsburg, PA: Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross, Inc.

Maxwell, Ross. The Big Bend of the Rio Grande. 1971. Austin, TX: The University of Texas Press.

Moore, Michael. Los remedios.1990. Santa Fe, NM: Red Crane Books.

Native American Ethnobotany Database. Fouquieriaceae Fouquieria splendens Engm. Ocotillo Accessed November 15, 2017. Available from http://naeb.brit.org

-Castetter, Edward F. and Ruth M. Underhill. 1935. Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest II. The ethnobiology of the Papago Indians.

-Gifford, E.W. 1936. Northeastern and Western Yavapai.

-Bean, Lowell John and Katherine Siva Saubel. 1972. Temalpakh (From the earth): Cahuilla Indian knowledge and usage of plants. Rodge, Mary King. Where the creosote blooms. A memoir by Mary King Rodge. 1999. Ft. Worth TX: Texas Christian University Press (Number Nineteen in the Chisholm Trail Series).

Schlosser, Katherine. Herbs by the sea. Fall 2017. Available www.herbsociety.org, members only section, Green Bridges Notes. Sharp, Jay. How desert plants survive: the desert food chain part 3. Available from http://www.desertusa.com/food_chain_k12/ kids_3.html Accessed October 17, 2016.

Texas Highways. The great camel experiment. 2014. Accessed October 2, 2017. Available from http://www.texashighwas.com/history/ item/7475-the-great-camel-experiment-texas-camel-corps

Turner, Matt W. Remarkable plants of Texas: uncommon accounts of our common natives. 2009. Austin TX: University of Texas Press. All photographs by Andy MacPhillimy

ew things in life are “perfect” but chocolate might be one of them. While a decadent chocolate dessert is always welcome, sometimes a little foil-wrapped candy can hit the spot when the need for something sweet suddenly grips us. Appearing in everything from Easter confections to exquisite sculptures, chocolate has become even trendier of late with companies blending in novel ingredients, such as chili peppers and sea salt or touting their fair trade status. Some even list the chocolate’s specific origins, a characteristic that contributes to different flavor nuances in the final product.

timeout.com

Christine Moore

14 15 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018 HERBS IN THE EXTREME

Amazing chocolate shop interior Source:

Certainly, creosote bush and ocotillo remind us that herbs, useful plants, may appear in surprising places It is our charge CHOCOLATE: IMPROVING UPON “PERFECTION”

Regardless of its social or culinary status, all chocolate goes through a series of proprietary steps during which chocolatiers manipulate the beans to create custom blends to their liking (Coe & Coe 1996; Food & Agriculture Organization 2011) As important as that process is, it’s the genetics of the cacao tree that plays the most significant role in the beans’ character and quality Therefore, it’s no surprise that scientists have now turned to the tree’s genes for improving its overall growth, performance, and flavor

Chocolate Legacy

have been known for almost 4,000 years! Later evidence of the cultural uses of cacao beans and chocolate in religious ceremonies, as the base for a bitter drink, and for currency and trade comes from the Mayans who left written records (Coe and Coe 2007) In fact, cacao was so prized that taxes were paid and goods purchased with its seeds even into the 18th century (Food & Agriculture Organization 2011; Ghirardelli Chocolate Company 2007; ICE Futures U S 2012)

Addictive Behavior

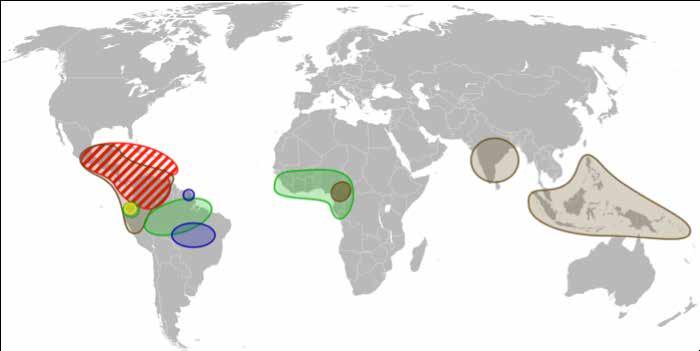

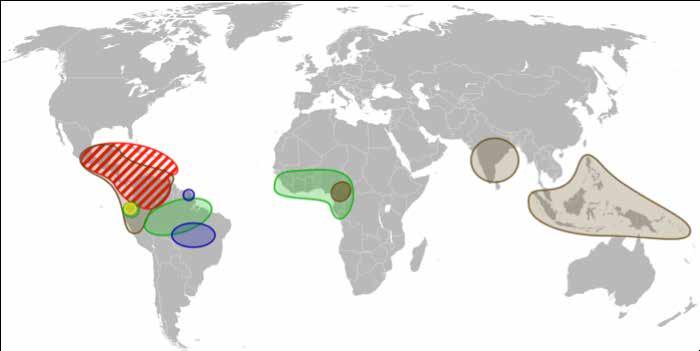

Image 2 World map showing distribution of four major varieties of cacao

Credit: Semhur

Image 2 World map showing distribution of four major varieties of cacao

Credit: Semhur

The migration of Theobroma cacao (cacao) through the Americas and beyond is well-documented Historically, cacao’s native range runs through the South American rainforests of Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, and Brazil Indigenous peoples moved the plant as far north as Central America (Guatemala and southern Mexico) Archaeological evidence identifies theobromine, a major component of cacao, in the lining of vessels dating around 1800 B C E suggesting that the steps of converting cacao seeds to chocolate

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cacao species - World distribution map -blank.svg

When Christopher Columbus first encountered cacao in the New World in the early 16th century, he and his fellow travelers thought it was worthless and never gave it further consideration (Coe and Coe 1996) By the end of the 16th century, however, Spaniards in Europe were consuming cacao as a specialty drink In the 17th and 18th centuries, cacao made its way through the rest of Europe, with sugar added for sweetness and milk products for smoothness From that point forward, chocolate’s place in global history was sealed (Coe and Coe 1996) (See also The Chocolate Tree: A Natural History of Cacao by Allen M Young for another comprehensive history of Theobroma cacao.)

World grindings of cocoa beans for the food industry reached a staggering 3 6 million tons in 2010 (Food and Agriculture Organization 2010) We have become “hooked” on chocolate in the centuries since Columbus In the 1990s, a more insidious kind of addiction was ushered in, one more lethal than just an overactive sweet tooth Illegal drug abuse was advancing through segments of the United States population with great speed The Federal Government initiated a “war on drugs” hoping to stem the tide of illicit material coming across the borders This “war” presented an interesting dilemma for government officials The United States Department of State realized that, in theory, removing undesirable plants from certain countries might be a worthwhile cause, but, if something more profitable did not replace them, the ensuing void would likely send farmers back to drug plant cultivation

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cacao species - World distribution map -blank.svg

Theobroma cacao (Trinitarios)

Theobroma cacao (Criollos)

cultivated in South America For example, it requires many of the same growing conditions as coca (Erythroxylum coca), the source of cocaine, and is a more stable crop overall ” But, when researchers first embarked on this new venture, cacao’s yields were not as high as coca’s, so SPCL needed to make a convincing case that cacao was a viable alternative for farmers Ironically, these farmers soon learned that chocolate is very profitable as global demand for chocolate is significantly greater than it is for drugs, said Meinhardt But, dampening the impact of drug cultivation in foreign countries wasn’t the only concern for SPCL Ultimately, to be a viable alternative, cacao also had to live up to hefty expectations: perfection

Narrowing the Playing Field

Scientists believe that in the early days of cacao cultivation and consumption, the people of Central and South America favored some trees more than others based on which tree’s fruit had superior flavor According to The Ghirardelli Chocolate Cookbook, the three most common varieties of cacao are Forastero, Criollo, and Trinitario Of these, Forastero is the most frequently used as it produces the greatest yields and is the most disease resistant However, it lacks superior flavor (Forastero makes up roughly 80% of global

cacao production [Ghirardelli Chocolate Company 2007]) Criollo has excellent flavor and is, by far, the highest quality of the three varieties, but it is also more susceptible to disease making it a very expensive form of cacao Trinitario is a naturally-occurring hybrid of the two that combines the higher yields and greater disease resistance of Forastero with the better quality and flavor of Criollo (Coe and Coe 1996) Despite its superiority, Trinitario production still trails far behind the cheaper, easier-to-grow Forastero

Theobroma cacao (Trinitarios)

Theobroma cacao (Trinitarios)

Theobroma cacao (Forasteros)

Theobroma cacao (Forasteros)

Theobroma cacao (Nacional)

Theobroma cacao (Nacional)

Theobroma cacao (Criollos)

Theobroma cacao (Criollos)

World map showing distribution of four major varieties of cacao

Theobroma cacao (Forasteros)

credit: Semhur

Theobroma cacao (Nacional)

State Department representatives met with United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) researchers to determine if there was a suitable crop that would act as a good replacement for the illicit crops and that would also help stabilize local governments This collaboration initiated the establishment of the Sustainable Perennial Crops Laboratory (SPCL), aka “the chocolate lab,” at the Agricultural Research Service in Beltsville, MD I happened to stumble upon the SPCL during a 2010 USDA poster session in Washington, D C Their display, which highlighted their research on Theobroma cacao, was the most popular exhibit at the program SPCL has three primary research goals: germplasm evaluation, preservation and conservation, and technology improvement I was immediately intrigued, so I contacted Dr Lyndel Meinhardt, research leader of SPCL, to discover more about the work that he and his colleagues were performing with this prized herbal tree

“As it turns out,” Dr Meinhardt explained, “ Theobroma is a very good substitute for the illicit plant material

A January 12, 2011 The New York Times article by Florence Fabricant, “A Eureka Moment for Chocolate”, described a rare Forestero variation, Nacional, that has a mutation for white seeds as well as the common purple seeds This tree had been widely grown in Ecuador but died out due to disease Two men bringing supplies to miners in a Peruvian mountain valley rediscovered some of these trees and sent plant materials to the Agricultural Research Service for study Dr Meinhardt found that these trees were pure Nacional and described them as “very rare ” He further explained that the white-seeded type produces fruit (and seeds) with a milder flavor than the purple

variety Franz Zeigler, a Swiss chocolate expert also quoted in the article, labeled the resultant chocolate as having an “intense, floral aroma and a persistent mellow richness Its lack of bitterness is remarkable ” Because of its rarity (most of the trees in cultivation had succumbed to disease by the 20th century), Nacional is extremely expensive; only four chocolatiers in Europe and North America are using this delicate form of cacao

Even though early 20th century seed collecting trips resulted in millions of tons of wonderful chocolate over the years, a question remains: Could there be even tastier chocolate awaiting us? This is a major reason the SPCL is earnestly seeking out new, wild-collected plant material in the species’ native range Like other domesticated crops, cacao’s wild relatives possess diverse, genetically-controlled

Three varieties of Theobroma cacao – Criollo, Trinitario, Forestero credit: Tamorlan

16 17 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018

Fruit of Nacional variety credit: Luchoastudillo

CHOCOLATE: IMPROVING UPON “PERFECTION”

CHOCOLATE: IMPROVING UPON “PERFECTION”

traits not found in cultivated plants These serve as a valuable resource for breeders looking for genetic solutions to modern cacao production challenges New genetic material could vastly improve cacao breeding lines and may result in superior flavor in the final products More important than improved flavor, however, is the overall health of cacao crops grown around the world, for a dead tree is undoubtedly a poor producer!

Even though early 20th century seed collecting trips resulted in millions of tons of wonderful chocolate over the years, a question remains:

Could there be even tastier chocolate awaiting us?

Challenges and Importance of Cacao Genetic Diversity

The need for new genetic diversity in cacao may be at the forefront of chocolate science today, but it has been a recognized need for much longer: “Since the early part of the 20th century, numerous missions have been undertaken to collect and conserve cacao ex situ in gene banks The catastrophic impact of cacao diseases led expeditions to collect disease-resistant germplasm from the Upper Amazon region in the 1930s” (CacaoNet 2012) Unfortunately, those early botanists could only access the rainforest by watercraft, which limited their seed collecting to trees found along Amazonian waterways

Because cacao seeds are highly perishable, “losing their viability quickly after being harvested” (Durham 2011), traveling greater distances inland to collect from a broader selection of trees wasn’t feasible without proper seed storage equipment Nevertheless, the collected seeds were sent to germplasm banks in the Americas Dr Meinhardt states, “There are more than 5,000 different varieties of cacao currently in [germplasm] collections around the world While this sounds like a large amount, most are breeding lines derived from a small number of [original] types, so it actually represents a small fraction of the genetic diversity that still exists in the wild” (Durham 2011) Today, most of the cacao tree stock used in production lines around the world is descended from those same seeds collected in the early 1900s “In recent years more emphasis has been placed on systematic collections to capture genetic diversity” (CacaoNet 2012) This genetic diversity may ultimately change the face of chocolate production in the modern era As our love for chocolate continues to grow (Food and Agriculture Organization 2001; Food and Agriculture Organization 2010; International Cocoa Organization 2010; Pay 2009), issues of sustainability loom ever closer Among the greatest challenges of low genetic diversity in agricultural crops are pest and disease pressure In a species monoculture, the incidence of disease increases exponentially “Cacao has always been plagued by serious losses from pests and diseases, with estimates of losses as high as 30% to 40% of global production” or onetwo billion in US dollars (LMC International 2011) Fungal infections are particularly devastating and “can cause yield losses of 75% in susceptible varieties” (Case 2011; Durham 2011) The biggest offenders are fungal witches’ broom disease (Crinipellis perniciosa), frosty pod rot (Moniliophthora roreri), black pod (Phytophthora spp ) and vascular streak dieback (Oncobasidium theobroma) (LMC International, 2011) If trees become infected with any of these fungal pathogens, farmers risk losing significant

portions of their harvest, with the potential for large swings in overall cacao production and farm income Production variations also affect the global market price index resulting in significantly higher prices for finished chocolate products (International Cocoa Organization 2010; ICE Futures U S 2012) Loss of crops and income are particularly devastating for small farmers who are the primary growers in many cacao producing countries The International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) estimates that 90% of world cacao production comes from farms of only two to five hectares (five to twelve acres) (Food and Agriculture Organization 2001; International Cocoa Organization 2011[2]) According to the World Cocoa Foundation the number of people who depend upon cacao for their livelihood is 40-50 million (CacaoNet 2012)

Dr Meinhardt’s group, along with scientists from Peru’s Instituto de Cultivos Tropicales, is working diligently to identify and preserve new and distinctive cacao strains not already in germplasm collections and to identify any wild trees that show increased resistance to witches’ broom disease or frosty pod rot pathogens As of 2009, they had acquired more than 300 cacao specimens collected during Peruvian expeditions, which represents a significant increase in cacao germplasm diversity

With increased diversity comes the opportunity for valuable discoveries Among those 300+ specimens collected, the group found a new type that differs in flavor from previous types—a potentially great find for the chocolate industry The group also introduces new cultivars for production: “… in 2011, they released nine new, high-yielding selections of Theobroma cacao. The new selections could offset some disease losses because they yield more beans than current varieties” (Case 2011)

Other scientists from around the world are also contributing to the knowledge base Claire Lanaud of CIRAD, France, and Mark Guiltinan of Pennsylvania State University, along with their international team of scientists have mapped the Criollo

variety’s genome to better identify the traits that lead to disease resistance, as well as better flavor For example, Siela Maximova, Associate Professor of Horticulture at Pennsylvania State University stated, “Our analysis of the Criollo genome has uncovered the genetic basis of pathways leading to the most important quality traits of chocolate… It has also led to the discovery of hundreds of genes potentially involved in pathogen resistance, all of which can be used to accelerate the development of elite varieties of cacao in the future” (Messer 2010)

Ancient Plant, Modern Farming

Since the early 1990s, scientists have been developing ways to make chocolate production more sustainable for thousands of cacao farmers in producing countries In 2000, a key stakeholder, the World Cocoa Foundation (WCF), began working with cacao scientists and companies worldwide to promote better industry practices Its core commitments are ensuring a sustainable supply of quality cocoa that benefits both growers and users; empowering farmers to make choices that help develop strong, prosperous cocoa communities; and promoting sustainable production practices that maintain and increase biodiversity and crop diversification (LMC International 2011; World Cocoa Foundation 2012)

Theobroma needs 50% shade in equatorial regions This requirement alone encourages better agroforestry and farming practices By necessity, farmers need to maintain significant forest cover to provide that essential shade (LMC International 2011; Messer 2010) This discourages cutting down rainforest for timber or ranching

Better sampling and testing of Theobroma germplasm also aids identification of disease-resistant traits, which when incorporated into current breeding lines, may decrease the likelihood of crop failure from witches’ broom disease, frosty pod rot or other diseases Additionally, if researchers working alongside farmers can identify plants that

yield greater harvests per tree, then fewer tracts of land are necessary for cultivation to produce the same amount of product

Fair Trade Chocolate

“Fair trade” chocolate—one of the newer angles in chocolate production—has become a topic of much discussion Fair trade is “a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect, that seeks greater equity in international trade It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, disadvantaged producers and workers” (World Fair Trade Organization 2009) Groups like the WCF and other non-governmental organizations are helping direct the cocoa industry toward more ethical and sustainable practices The WCF states that two of its primary goals are “to build partnerships with the cocoa farmers, origin governments and environmental organizations… and to support training and education that improve the well-being of cocoa farming families” (World Cocoa Foundation 2012; Pay 2009) Because most cocoa is grown by impoverished farmers, many large chocolate companies are joining the effort to “promote a sustainable cocoa economy through economic and social development and environmental stewardship in cocoagrowing communities” (World Cocoa Foundation, 2012) (See http:// worldcocoafoundation org/about-wcf/ members/ for a list of WCF members )

Between five and six million farmers grow cacao world-wide, most of whom are small producers in small communities These same small farms produce 90% of the world’s cocoa (Food and Agriculture Organization 2001; International Cocoa Organization 2011[2]) Since cacao harvesting does not lend itself to automation (the fruit needs to be harvested by hand), ethical labor and fair trade laws are always going to be industry-wide concerns

Big Business

To focus on the cocoa industry as a stand-alone entity, however, gives an incomplete picture From the inception of

chocolate confectionery, thousands of other businesses have relied on chocolate production for their survival, including those involved with marketing, sales, and distribution of finished products The success of agricultural products associated with the chocolate industry rises and falls with the success of cacao production itself “The U S chocolate industry is comprised of approximately 450 companies that manufacture more than 90% of the chocolate and confectionery products; another 250 companies supply those manufacturers” (World Cocoa Foundation 2009)

The International Cocoa Organization, which promotes a sustainable world cocoa economy, notes that within that economy resides a host of other internationallytraded commodities “For every dollar of cocoa imported, between one and two dollars of domestic agricultural products are used in the making of chocolate” (World Cocoa Foundation 2009) Common products include milk, milk products, nuts, sugar, and other sweeteners With so much riding on chocolate’s success, both economically and socially, some of the most prestigious institutions in the world, including the USDA Agricultural Research Service have now joined the effort to improve cacao’s performance (Food and Agriculture Organization 2001)

Oftentimes, progress brings with it a host of other challenges Chocolate’s progress is no exception Despite such challenges as germplasm diversity, disease, and price swings, many cultures have embraced cacao with remarkable enthusiasm and creativity, thus securing its place not only in the human heart, but also on the global market Chocolate lovers may think chocolate is perfect the way it is, but improvement is always possible With a commitment to collaborative research, germplasm evaluation and conservation, as well as improved agricultural practices, groups like the Sustainable Perennial Crops Laboratory and their counterparts around the world are making great strides toward a more prosperous—and flavorful! —cacao industry

19 Issue 83 2018 18 The HERBARIST

IMPROVING UPON

IMPROVING

“PERFECTION”

CHOCOLATE:

“PERFECTION” CHOCOLATE:

UPON

Literature Cited

CacaoNet. 2012. Global strategy: where we are now on cacao germplasm conservation and use. Accessed September 18, 2012. Available from: www.cacaonet.org

Case, Christine L. The microbiology of chocolate. Accessed October 12, 2011. Available from: http://skylinecollege.net/case/chocolate.html

Coe, Sophie D. and Michael D. Coe. 1996. The true history of chocolate. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

-2007 (revised edition). The true history of chocolate. New York, NY: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

Durham, Sharon. September 2011. Peruvian cacao collection trip yields treasures. Agricultural Research Accessed October 12, 2011. Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/AR/archive/sep11/cacao0911.htm

Food and Agriculture Organization. 2001. Infosheet cocoa. Accessed October 12, 2011. Available from: www.fao.org/docs/eims/upload/216251/infosheet_cocoa

Food and Agriculture Organization, Economic and Social Development Department. 2010. Medium-term prospects for agricultural commodities, 3. Sugar, tropical beverage crops and fruit. FAO Corporate Document Repository. Accessed October 12, 2011. Available from: www.fao.org/docrep/006/y5143e/y5143e0x.htm

Ghirardelli Chocolate Company. 2007. The Ghirardelli chocolate cookbook. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press.

ICE Futures U.S. 2012. Cocoa. Accessed January 8, 2013. Available from: https://www.theice.com/publicdocs/ICE_cocoa_Brochure

International Cocoa Organization. July 30, 2010. The world cocoa economy: past and present. Accessed September 7, 2011. Available from: www.icco.org/about-us/international-cocoa-agreements/cat_view/30-related-documents/45-statistics-otherstatistics.html

International Cocoa Organization. July 25, 2011[1]. The chocolate industry. Accessed December 17, 2012. Available from: http://www.icco.org/about-cocoa/ chocolate-industry.html

International Cocoa Organization. July 25, 2011[2]. Production. Accessed December 17, 2012. Available from: http://www.icco.org/economy/production.html

LMC International. 2011. Cocoa sustainability. Accessed September 7, 2011. Available from: www.canacacao.org/uploads/smartsection/19_LMC_WCF_cocoa_ sustainability_report_2010_11

Messer, Andrea. December 2010. Food of the gods’ genome sequence could make finest chocolate better. Accessed January 9, 2013. Available from: http://live.psu.edu/printstory/50523

Pay, Ellen. 2009. The market for organic and fair-trade cocoa: increasing incomes and food security of small farmers in West and Central Africa through exports of organic and fair-trade tropical products. Accessed October 12, 2011. Available from: www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/organicexports/docs/Market_Organic_FT_Cocoa.pdf

World Cocoa Foundation. 2009. Economic profile of the US chocolate industry. Accessed September 7, 2011. Available from: www.worldcocoafoundation.org

World Cocoa Foundation. 2012. Our work: our approach. Accessed December 17, 2012. Available from: www. worldcocoafoundation.org

World Fair Trade Organization. 2009. Fair trade glossary. Accessed November 13, 2017. Available from: https://www. fairtrade.net/fileadmin/user_upload/content/2009/about_ fairtrade/ 2011-06-28-fair-trade-glossary_WFTO-FLOFLOCERT.pdf

Bibliography

Grivet, Louis and Howard-Yana Shapiro. Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 2009.

Young, Allen M. The Chocolate Tree: A Natural History of Cacao. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. 2007. (Originally published by Smithsonian Nature Books, 1994.)

The HERBARIST 20

Mary Bellis Williams, Ph.D.

IMPROVING

Fields

of lavender credit: Brice CHOCOLATE:

UPON “PERFECTION”

Then there’s “Are you going to Scarborough Fair, parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme, remember me to one who lives there. She once was a true love of mine.” (Sharp 1916, 167) This very old song was popularized in the mid-20th century by Simon and Garfunkel

Most people no longer remember the meaning of the herbs in the song It’s about a man trying to attain his true love The herbs tell what he is looking for Parsley is comfort but is also associated with sexual performance; sage is strength, healing, and prosperity; rosemary is remembrance and love (and keeps ghosts away!); and thyme is courage and strength (Baker 1996)

Folk songs from the British Isles abound with references to herbs, flowers, and trees, integral to the tale told An old Welsh song goes like this: “Upon the shore red roses blowing. Upon the shore, white lilies growing. Upon the shore, my love, my only; are his nights long, are his days lonely? Upon the shore, through wind and weather, a stone, where we once talked together, has now white lilies showing, and shoots of fragrant rosemary growing.” (Hywel 1987, 14) Lilies, roses, and rosemary have meaning in the story Roses speak of love and fertility, lilies for purity, and rosemary for remembrance

Usually these plants have sweet connotations, but some plants have pricklier meanings In the ancient song Barbara Allen (Solomon 1967, 20) a haughty girl rejected her suitor, but when he died of love, she regretted her cruelty and died too Here’s what has been sung about them for at least 400 years: “Barb’ry Allen was buried in the old church-yard; Sweet William was buried beside her. Out of Sweet Williams’s heart there grew a rose; out of Barb’ry Allen’s, a briar. They grew and grew in the old church-yard, ‘til they could grow no higher; at the end they formed a true lovers’ knot, and

the rose grew round the briar.” The rose has always symbolized love, and in this story, love wins, with the rose embracing the briar

Many British songs use the rose to speak of love in all its aspects

The Scottish My Love is Like the Red Red Rose compares the loved one to the beauty of the rose in completely favorable terms, but Ye Banks and Braes (Farmer 1901, 128) tells a story that includes the painful thorn as well:

Oft ha’e I roved by bonnie Doon, to see the rose and woodbine twine;

And ilka bird sang o’ its love, and fondly sae did I o’ mine. Wi’ lightsome heart I pu’d (pulled) a rose, fu’ sweet upon its thorny tree;

But my fause (false) lover stole my rose, and ah! He left the thorn wi’ me.

The gorgeous medieval song, The Seeds of Love (Baring-Gould and Sharp 1890), entwines herbs, flowers, passion, and disappointment together The gardening metaphor is so wellsuited to speak of love, and here’s the rose AND thorn again:

I sowed the seeds of love, I sowed them in the spring;

I gathered them up in the morning so soon, while small birds did sweetly sing.

My garden was planted well with flowers everywhere,

But I had not the liberty then for to choose the flower that I loved dear.

The gardener standing by, I asked to choose for me;

He chose me the Violet, the Lily and the Pink, but these I refused all three.

The Violet I did not like because it fades so soon;

The Lily and the Pink I then did overthink, and vowed I’d stay till June.

In June is a red, red Rose, and that is the flower for me, I’ll pluck it and think that no Lily nor Pink can match with the bud on that tree.

The maiden rejects the violet (faithfulness), the lily (purity), and the pink (perfection and protection) plucks the red rose of passion and fertility, only to be wounded by its thorn After she is wounded by love, she chooses hyssop, which stands for protection and purification then, she needed it!

In O Gin My Love Were Yon Red Rose (Armes 1917, 1) the Scottish lover sings his devotion:

O gin my love were yon red rose, that grows upon the castle wa’ (wall), and I mysel’ a drap of dew, down on that red rose I would fa’ (fall).

The Irish song Red Is the Rose (Soodlum 1982), also compares a beloved to roses, but this time with the girl fairer than the rose:

The gardener standing by, he bid me take great care;

For that under the blossom and under the leaves is a thorn that will wound and tear.

Of Hyssop I’ll take a spray, no other flowers I’ll touch; That all in the world may both see and may say, that I loved one flower too much.

Red is the rose by yonder garden grows And fair is the lily of the valley.

Clear is the water that flows from the Boyne, But my love is fairer than any.

The Loyal Lover (Baring-Gould and Sharp 1890), a girl makes a gift for her lover of highly symbolic herbs: roses for love, lilies for purity and chastity, pinks for protection, and thyme for virtue and

I’ll weave my love a garland, it shall be dressed so fine; I’ll set it round with roses, with lilies, pinks, and thyme. And I’ll present it to my love when he comes back from sea,

For I love my love, and I love my love, because my love loves me.

Then there is thyme For such a small plant, it has an outsize importance with ancient, traditional, and magical meanings attributed to it Greek maidens wore it in their hair, trusting that it made them irresistible to men It is also believed to increase clairvoyance Sleeping on a pillow of thyme dispels melancholy, cures nightmares, and inspires courage But thyme also signifies virtue A Bunch of Thyme (Soodlum 1982) is about loss of innocence and virginity The betrayed girl sings:

Come all ye maidens, young and fair, all you that are blooming in your prime.

Always beware and keep your garden fair. Let no man steal away your thyme.

22 23 The HERBARIST Issue 83 2018 HERBS IN BRITISH FOLK SONGS HERBS IN BRITISH FOLK SONGS

For thyme it is a precious thing. And thyme brings all things to my mind.

Thyme with all its flavours, along with all its joys, Thyme brings all things to my mind.

For once I had a bunch of thyme. I swore it never would decay.

There came a lusty sailor, who chanced to pass the way, and stole my bunch of thyme away.

Thyme doesn’t always lead to disappointment or abandonment

The lovely Scottish tune Wild Mountain Thyme (Luboff 1965, 62) invites us to a thyme-picking excursion: Oh, the summer time is coming, and the trees are sweetly blooming, and the wild mountain thyme grows around the blooming heather. Will ye go, lassie, go? And we’ll all go together, to pluck wild mountain thyme, all around the blooming heather, will ye go, lassie, go?

Which made her repent and so often lament, still wishing again in the north for to be.

“Oh! The oak, and the ash, and the bonny ivy tree, They flourish at home in my own country.”

These three trees were all sacred to the druids and important symbolically in culture Oaks symbolize strength, longevity, fertility, protection, and steadfastness The ash means protection and features in the Norse story of the Great Tree that connects all creation The “ivy tree” is ivy climbing a tree, and it figures in many stories and myths It symbolizes wedded love The northcountry lass was longing for home, but also for the benefits these trees promised

The willow is traditionally associated with love, protection, and healing But it also symbolizes melancholy and mourning In Hamlet, Ophelia sings “O willow, willow” before drowning herself An old English folk song, The Sprig of Thyme (Sharp 1916, 79), is a sad story telling of seduction and abandonment with herbs for each phase: rose, willow, thyme, and rue Thyme stands for virtue and innocence, rose, passionate love Willow is for betrayal Rue, the bitter herb of grace, signifies regret and repentance:

And what about the little primrose? It is delicate and sunny, but think of the expression, “he led her down the primrose path ” Now you have a good idea what the primrose means: easy pleasure without thought of consequences In several folk songs, such as Sweet Nightingale (Baring-Gould and Sharp 1890, 62) and As I Walked Through the Meadow (Sharp 1916, 122), a persistent suitor entices a maiden to recline on a bank of primroses In one song, he takes her next morning to the church to marry, but in the other, he seduces her and leaves her

Some trees are rightly considered herbs In Oh! The Oak and the Ash (Farmer 1901, 154), a homesick girl wishes herself back home in the north of England by remembering the trees that grew there:

A north-country lass up to London did pass, although with her nature it did not agree;

O once I had thyme of my own, and in my own garden it grew;

I used to know the place where my thyme it did grow, but now it is covered with rue, With rue, but now it is cover’d with rue.

The rue it is a flourishing thing, it flourishes by night and by day;

So beware of a young man’s flattering tongue, he will steal your thyme away, away, He will steal your thyme away.

I sowed my garden full of seeds, but the small birds they carried them away

In April, May, and in June likewise, when the small birds sing all day, all day, English oak, Quercus robur credit: Jean-Pol Grandmont

When the small birds sing all day.

In June there was a red, a rosy bud, and that seem’d the flower for me;

And oftentimes I snatched at the red, a rosy bud, till I gained the willow, willow tree,

Till I gained the willow tree.

O the willow, willow tree it will twist, and the willow, willow tree it will twine,

And so it was that young and false-hearted man when he gained this heart of mine, of mine, when he gained this heart of mine.

O thyme it is a precious, precious thing on the road that the sun shines upon;

But thyme it is a thing that will bring you to an end,

And that’s how my time has gone, has gone, and that’s how my time has gone.

Willow, as melancholy or mourning, can be found in the 1975 Steeleye Span recording of a very old song, All Around My Hat. [Note: Steeleye Span is a British folk-rock group ] The song in all its versions is always about separation from a loved one, sometimes by death, sometimes by the woman’s marriage to another man, sometimes by one lover being transported to Australia The rousing chorus is:

All ‘round my hat I will wear a green willow

All ‘round my hat for a twelve month and a day

If anybody asks me the reason why I wear it

It’s all because my true love is far, far away.

In the old Irish song, Down by the Sally Gardens (Soodlum 1982), willows are referred to as Sally, from Salix, part of the botanical name for willow The willows along rivers were called Sally Gardens, and this song again is a lament for lost love:

‘Twas down by the Sally Gardens my love and I did meet.

She passed the Sally Gardens with little snow-white feet.

She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow upon the tree,

But I being young and foolish with her did not agree.

In a field down by the river my love and I did stand,

And on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand.

She bid me take life easy as the grow grown on the weirs, But I was young and foolish and now I am full of tears.

The English folk song Strawberry Fair (Baring-Gould and Sharp 1890, 56) tells of a young man on his way to the Strawberry Fair who falls in love at first sight with a beautiful girl selling cherries, roses, and strawberries She offers her produce to him, but he replies:

Your cherries soon will be wasted away, singing, singing, buttercups and daisies,

Your roses wither and never stay, Fol-de-dee!

‘tis not to seek such perishing ware, that I am tramping to Strawberry Fair.

I want to purchase a generous heart, singing, singing, buttercups and daisies,

A tongue that is neither nimble nor tart, Fol-de-dee!

An honest mind, but such trifles are rare, I doubt they’re found at Strawberry Fair.

The price I offer, my sweet pretty maid, singing, singing, buttercups and daisies,

A ring of gold on your finger displayed, Fol-de-dee!

So come, make over to me your ware, in church to-day at Strawberry Fair.

Ri-fol, Ri-fol, Tol-de-riddle-li-do,

Ri-fol, Ri-fol, Tol-de-riddle-dee.

Regarding the strawberry, Dr William Butler, an English writer in the 1600s, said: “Doubtless God could have made a better berry, but doubtless God never did ” The strawberry has many customs around it, like Desdemona’s fateful handkerchief embroidered with strawberries in Othello. The heart-shaped berry stands for purity, passion, and healing It is a symbol of Venus Medieval stone carvers put strawberry designs on altars to indicate righteousness and perfection Such good attributes for this delicious berry!

Heart-shaped strawberry credit: Grendelkhan

Another plant that appears in folk song is broom, a woody shrub with bright yellow flowers that grows wild on mountains, moors, and shores in Britain The plant has dense branches, making it

25

24 HERBS IN BRITISH FOLK SONGS

Issue 83 2018 HERBS IN BRITISH FOLK SONGS

Wild Mountain Thyme credit: Richard Webb

very useful as a broom It was cut for this purpose and bound around a stick to make a broom for sweeping the house The flower symbolizes devotion and ardor (Conway 1973, 73) Leaping over a flowering branch of broom on their wedding day is supposed to make a couple fertile Butterflies love the flower and it is considered one of the nine fairy herbs

Two folk songs that feature broom are The Broom of the Cowdenknowes (Boyle and Boyle 2002) and Green Broom (Sharp 1916, 110) They are quite different in their outcomes, but both involve a young person who attracts a spouse from a higher station In both, ardor is paramount

In Broom of the Cowdenknowes a shepherdess meets a stranger who rides by her pasture each morning He plays a pipe (presumably a bagpipe) They fall in love and have an affair She becomes pregnant and is banished by her family She then seeks out her lover, finds he is a lord, and they marry They live in his country, but she is homesick and wants to return to “the bonnie bonnie broom ” Cowdenknowes is about 30 miles from Edinburgh The chorus, sung by the shepherdess, says:

O, the broom, the bonnie, bonnie broom, the broom o’ the Cowdenknowes.

Fain would I be with my ain true love, wi’ his pipy and my ewes.

The “pipy” is his pipe played very well, because the last verse says:

He tuned his pipe and reed sae sweet the birds stood list’ning by,

Even the dull cattle stood and gaz’d, charm’d with his melody.

The song Green Broom handsome and lazy son of an old man whose trade is cutting broom for sale father tries to get his son out of bed before noon to get to work to help the family business, threatening to set the lad’s room on fire if he doesn’t We join the story there:

Then Jack he did rise and did sharpen his knives, and he went to the woods cutting broom, green broom,

To market and fair, crying ev’rywhere: O fair maids, do you want any broom, green broom? O fair maids, do you want any broom?

A lady sat up in her window so high, and she heard Johnny crying green broom, green broom; She rung for her maid and unto her she said: O go fetch me the lad that cries broom, green groom. O go fetch

me the lad that cries broom.

Then John he came back, and upstairs he did go, and he enter’d that fair lady’s room, her room.