Chia! More Than a Pet

Herbal Trees

Bamboo: Nature’s Gift to Re-green the Earth

Want to Make Your Own “Signature” Fragrance? We Show You How!

A Publication of The Herb Society of America Issue 77 2011 LOVING LOVAGE

Cover lcR.4.indd 2 11/2/11 10:57 AM

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Linda Lain, President

Debbie Boutelier, Vice President

Sue Edmundson, Secretary/Communications Chair

Linda Lange, Treasurer/Finance & Operations

Open Position, Central District Membership Delegate

Linda Wells, Great Lakes District Membership Delegate

Katherine Schlosser, Mid-Atlantic District Membership Delegate

Claudia Van Nes, Northeast District Membership Delegate

Mary Doebbeling, South Central District Membership Delegate

Rae McKimm, Southeast District Membership Delegate

Karen Mahshi, West District Membership Delegate

Carol Czechowski, Education Chair

Elizabeth Kennel, Botany & Horticulture Chair

Diane Poston, Membership Chair

Karen O’Brien, Development Chair

Lois Sutton, PhD, Nominating Chair

Jim Adams, Honorary President

ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF

Katrinka Morgan — Executive Director

Laurie Alexander Membership

Karen Frandanisa — Accountant

Helen Tramte — Librarian/Horticulturist

Janeen Wright—Educator/Editor/Horticulturist

THE HERBARIST

Janeen Wright/Robin Siktberg — Editors

Libby Armstrong —Designer

XPress Printing —Printer

THE HERBARIST COMMITTEE

Elizabeth Kennel (Chair), Anne Abbott, Caroline Amidon, Joyce Brobst, Carol Czechowski, Linda Lain, Stefan Lura, Sara Moore, Ellen Scannell, Lois Sutton, PhD

The opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of The Society.

Manuscripts, advertisements, comments, and letters to the editor may be sent to:

The Herbarist, The Herb Society of America

9019 Kirtland-Chardon Rd.

Kirtland, Ohio 44094

Phone: (440) 256-0514 • Fax: (440) 256-0541

e-mail: editor@herbsociety.org

website: www.herbsociety.org

The Herbarist, No. 77

By Laura McNerney

1 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011 Lovage: An Herb to Love ............................................................ 2 By

Cha-Cha-Cha-Chia: An Ancient American Herb ...................... 5 By Margaret Conover, PhD Up Close and Personal: A Look at the Mediterranean Herbs and Their Native Habitat ......................12

Belsinger Popular Chamomile .................................................................20

Nature’s Medicine Chest ...........................................................24 By Jane Knaapen Cole Dock: A Useful Weed ................................................................31 By

Raising Cane in Bamboo Valley ...............................................35

What is Essential These Days? ..................................................42 By

Winderweedle Herbal Trees That Have Changed the World ............................48

Cover: The blooms and foliage of Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa), a plant native to the midwestern and eastern parts of the United States and Canada. Photo by Robin Siktberg

Front Cover: The skyline of Austin, Texas, along with the Driskill Hotel (bottom right) and an egret feeding at Lady Bird Lake (bottom left). Photos from Wikimedia Commons THE

It is the policy of The Herb Society of

not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health

publication

educational

endorsement

Carol Ann Harlos

By Susan

By Jesse Vernon Trail

Katherine Montgomery

Sue

By Christine Moore Front

Inside

Disclaimer:

America

use. The information in this

is intended for

purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an

of any particular medical or health treatment. Please consult a health care provider before pursuing any herbal treatments.

An Herb to Love

Lovage

Iby Carol Ann Harlos

Iby Carol Ann Harlos

so love the smell of lovage soup. The aroma evokes memories of both multi-course dinners and simple meals of lovage soup and homemade bread for two. Once, I displayed lovage along with other herbs at a dozynki (Polish harvest festival), which celebrates the end of the growing season. I encouraged visitors to touch and taste the fresh herbs I had displayed on a table. I still laugh when I recall a lady visiting the United States from Warsaw, Poland, who said to me, “This is a very important herb.” I naively asked, “Why?” I only knew this herb as delicious.

2 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

She replied, “You feed it to your husband. It’s good for you. You know what I mean?” Now I understood the reason that lovage is called lubczyk in Poland, coming from the Polish word lubiec, meaning “to love.” In English it is known variously as bladder seed, Cornish lovage, old English lovage, and Italian lovage. The name lovage apparently refers to the plant’s common use as a love charm or aphrodisiac.

While currently named Levisticum officinale, the architect of the binomial system of nomenclature, Carolus Linnaeus, originally called it Ligusticum levisticum. (Lovage once grew profusely in Liguria, Italy, from which this name probably derived.) Lovage is closely related to Cnidium monnieri, in Vietnam (used in place of parsley), Ligusticum porteri in Mexico, and L. scoticum, which grows in Scotland. Levisticum officinale is native to Europe, but it has naturalized widely.

My husband and I have enjoyed this perennial herb in the garden for years. It is a truly beautiful plant, both ornamental and tasty. Lovage grows in Zones 5 to 8 but seems to grow best when the summers heat up gradually. The plants have a tendency to yellow in prolonged hot weather even when supplied with adequate amounts of water. When lovage comes up in the spring it has a beautiful green color, and because it grows rapidly, it is six feet tall before you know it. I cut mine back in mid-summer to encourage new growth. Lovage is tolerant of any well-drained soil, but thrives in a deep, rich soil with plenty of humus added. A pH range of 5.0-7.6 is recommended for the best growth. Exposure to full sun is best, but partial shade will do. Like its cousins, angelica and fennel, lovage

uses a lot of nutrients from the soil, so regular fertilization is beneficial. I put compost on ours every spring.

Lovage is in the Apiaceae family, which includes carrots, dill, and many other useful plants. Celery is a member of this family and lovage looks much like this better-known relative. The leaves are alternate and ternately (in threes) compound. They are deeply divided, dark green on top and a lighter green on the underside. The leaf petioles sheath the stem at the nodes where the leaves join the plant stem. Stems are hollow and were sometimes used as straws—even now they are used in Bloody Marys early in the season. The stems emerge from the base of the ever-expanding crown. Flowers of lovage are yellow, and like the leaves, have a sharp celerylike, lemony fragrance. Individual flowers are small, each on its own stalk, together they form compound umbels looking much like a flattened umbrella, which is borne on top of a tall stalk. Each tiny flower makes two seeds.

Our lovage has not suffered from any diseases or insect damage. However, my research on this topic led me to the Missouri Botanical Garden, where the tarnished plant bug, celeryworm, and leaf miner were listed as possible insect problems. Early blight and leaf blight (fungal diseases) also were listed as potential problems.

Propagating lovage is easily accomplished by simple division of the parent plant or by digging up part of the plant along its outer edge. I have used both of these methods when sharing my plants with other gardeners. These methods work best in the spring before the plant begins its spring growth, but if the plant pieces are given enough water, lovage

Lovage Soup

1 large can chicken broth

2 leeks washed and cut into slices (I think leeks give a more subtle taste to the soup.)

OR 1 large onion, peeled and chopped

4 tablespoons butter

3 medium potatoes, peeled and chopped

1 cup lovage leaves (removed from stalks, washed and patted dry)

½ to 1 cup milk or cream Melt butter, being careful not to brown it. Add onions or leeks. Cover kettle and turn stove to lowest setting. Gradually sweat the onions to release flavor. Add the prepared potatoes, lovage, and chicken broth. Gradually bring to a boil and then let simmer until potatoes are fork tender. Turn off stove and let mixture cool to room temperature. Add mixture to a blender or food processor. Blend. Return soup to kettle.

Do not boil. Add about half a cup heavy cream or milk to taste. Season to taste or do so at the table. To serve, pour soup into individual bowls. Garnish with fresh lovage leaves. Enjoy!

can be propagated successfully during the summer and early autumn. It easily grows from seed as well.

I have used all parts of this incredible herb except the roots. The leaves, stems, roots, and seeds can be eaten raw or cooked. Leaves are used in soups and tossed into salads. Stems can be chopped and used in stews, or with the leaves, can even be candied and used to decorate pastries. The stems can also be blanched and eaten

3 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

like those of celery. I harvest the seeds for use in the kitchen. The seeds taste a bit sweeter than the leaves and are delicious sprinkled on salads or used in breads, rice, cheese, and potatoes. Ancient Greeks often chewed the seeds to aid digestion.

When visiting Poland, I learned that some people in southern Poland call lovage “maggi.” Maggi is a condiment, which tastes similar to soy sauce but is made from lovage instead of soybeans. It is common to find it on the table along with salt and pepper.

Harvesting lovage leaves and stems is simple. Cut the stem being harvested back to the ground to stimulate new growth and to improve the appearance of the plant. Keep the cuttings moist until you are ready to prepare the leaves for use. Remove individual leaves by hand or simply cut them off. Rinse and pat dry on paper towels. Now the leaves are ready for use. The leaves of lovage can be dried for use

later, but I prefer to place washed and towel-dried leaves on aluminum foil, roll them up into a packet, and place it in the freezer. This preserves the green color and more importantly, the oils that give lovage its taste.

Don’t believe those who say that lovage is merely a celery substitute—it has its own unique taste. Both celery and lovage contain a chemical called cedanolid, but lovage contains more so it has a stronger flavor. The taste of lovage leaves reminds me a bit more of fennel rather than of celery.

I have experimented with collecting seeds from my lovage plants, saving seeds from both early in the season and at the end. I cut off the seed heads and gently shake them over sheets of white paper. I have found that those collected later had a much higher germination rate. The more mature seeds are darker in color and fall easily from the spent flowers.

Lovage seeds seem moist even at the end of the growing season. Viewed under a microscope, the seeds look flat and ridged. I store the dried seeds in closed glass bottles and freeze them until the next spring. I have found that their viability drops drastically after one year. Companies that sell seeds suggest sowing lovage seeds outdoors at the site where the plants are to grow. My seeds are started indoors, and I set the plants on the porch to harden off before planting in the ground.

Don’t ignore the beauty of lovage as a cut plant. Combine cuttings from your lovage plants in arrangements with other herbs. Since lovage is easy to grow and so versatile in the kitchen, try some next year in your garden. Experiment with it in your cooking or make the lovage soup recipe found in the sidebar. Make this flavorful plant part of your garden and your cuisine.

Bibliography

Bremness, Lesley. The Complete Book of Herbs. London: Dorling Kindersley, 1988.

Missouri Botanical Garden. http:// www.mobot.org/gardeninghelp/ plantfinder /alpha.asp. (accessed March 24, 2011).

Peter, K.V. (ed). Handbook of Herbs and Spices, vol. 2. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing, Ltd., 2004.

Peter, K.V. (ed.). Handbook of Herbs and Spices, vol. 3. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing, Ltd., 2006.

Phillips, Roger. The Random House Book of Perennials, vol. 2. New York: Random House, 1991.

Porter, C.L. Taxonomy of Flowering Plants. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1967.

Raghavan, Susheela. Handbook of Spices, Seasonings, and Flavorings. New York: CRC Press, 2007.

Tucker, Arthur O. and Thomas DeBaggio. The Encyclopedia of Herbs. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2009.

Carol Ann Harlos is a garden columnist for Forever Young magazine. An HSA member at large from Amherst, NY, she is president of Herb Gardeners of the Niagara Frontier and writes a monthly newsletter on herbs. Carol Ann is a member of the American Horticulture Society, Niagara Frontier Botanical Society, and the Garden Writers Association. She is a lecturer at Buffalo State College where she teaches mathematics.

4 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Lovage (Levisticum officinale) Lovage leaves have a sharp, celerylike lemony fragrance. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

An Ancient American Herb

by Margaret Conover, PhD

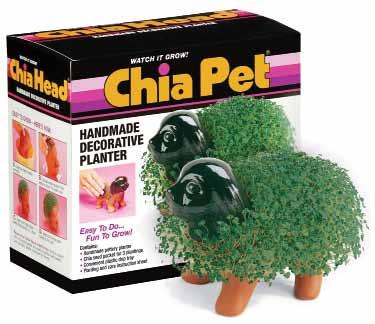

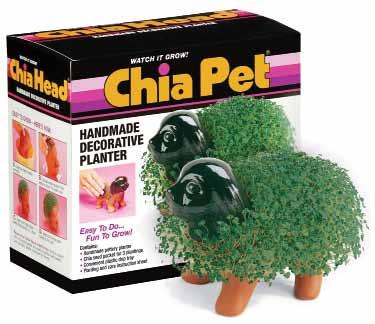

Ch-ch-ch-chia! It’s the pottery that grows! This jingle from daytime television ads is stuck in our heads, and the Chia Pet™ has become an American cultural icon. Chia seeds, spread on the surface of a clever terra cotta figurine, receive water through the porous clay and sprout into an amusing display of green “hair.” Chia Pets™ appeal to the gardener in each of us, young and old, especially to shut-ins and apartment dwellers. They make an excellent gift for the person who has everything. Millions of Chia Pets™ have been sold world wide since their introduction more than 25 years ago. What you may not know is that these seeds, which seem to be grown primarily for entertainment, have become the fastest growing product in the health food market. Where did this idea come from? What are chia seeds and how did they emerge from mere tabletop entertainment to the fastestgrowing (no pun intended) product in the health food market?

Botany

The seeds planted on a Chia Pet™ (Fig. 1) come from Salvia hispanica (chia, Mexican chia), an annual plant native to the arid highlands of Mexico and Central America. Chia is a member of the mint family, Lamiaceae, and has the square stem, opposite leaf

arrangement, and fragrant foliage typical of that family. At maturity, S. hispanica can be more than 10 feet tall. The flowers, which appear late in the fall, are blue or sometimes white. They are arranged in terminal spikes (Fig. 2).

Salvia hispanica is sometimes confused with several other plants also known as chia: Salvia columbariae (golden chia or California chia), S. tiliifolia (Tarahumara chia, lindenleaf sage), S. polystachia (chia sage), S. carduacea (thistle sage) and Hyptis suaveolens (chia grande, chan, or Colima chia). These plants range in distribution from Northern California to Central America. They vary in size and are often weeds of roadsides and impoverished soils. Although the seeds of these plants are similar, when the plants flower they may easily be distinguished by inflorescence structure and leaf shape.

Chia Pet™ History

The first television commercials for Chia Pets™ appeared in 1983, so we assume that they are a recent invention. Yet, in Europe there is a long tradition of sprouting seeds on the exterior of clay figurines. The Danish “karse-grise,” or cress pig, is a collector’s item still in use in many homes, and novelty “grass-growing

heads” were a fad in Europe during the last century. According to a 1912 article in Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, “The droll effect of a clay-colored gentleman with vividly green hair and a beard will amuse the most fractious of small convalescents and affords interest for many a weary hour.” In the United States, clay heads were popular well into the 1950s (Fig.3). However, since these figurines were sold with cress or timothy seed, none could be called a “chia pet.”

Growing up in the 1930s, Walter “Bud” Houston, of Rushville, Illinois, encountered one of these grassgrowing heads in his local barbershop. Later, while travelling internationally as owner of a lawn and garden products business, Mr. Houston discovered a cottage industry near Oaxaca, Mexico, where effigy figures of bulls and rams were produced (Fig. 4). Chia seeds were sprouted on these figures, which were displayed, as they are today, on street-side altars during the Easter season. In 1976, Mr. Houston commissioned the production of these figures, which he packaged together with chia seeds and distributed to drug store chains. He marketed them as “Chia Pets™. ”

Rights to the Chia Pet™ name and business were purchased in 1983

6 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Figure 1 (left)- Chia seeds are about the size of a poppy seed. Photo by Margaret Conover

Figure 2 (right)- Salvia hispanica in flower. Photo by Margaret Conover

by a young marketing genius from San Francisco, Joseph Pedott, who redesigned the packaging, improved the manufacturing standards, created the “ch-ch-ch-chia” jingle, and produced one of television’s most memorable commercial advertisements.

Initially, Chia Pets™ were sold with seeds of Salvia columbariae, collected from wild Californian plants. Seeds from cultivated Salvia hispanica were substituted after they became readily available. Company literature once stated that chia was “a form of cress,” an error suggesting the historic connection to cress pigs and grass-growing heads.

Now produced in China, Chia Pets™ come in dozens of shapes, including animals, cartoon characters, and political figures. Millions have been sold, and Mr. Pedott, still active in the business at age 80, has donated his records to the Smithsonian Institution (7).

Pre-Columbian Uses of Chia

Before 3400 BCE, many crops were domesticated in the fertile valleys surrounding present day Mexico City. Corn, beans, squash, avocados, chile, agave, amaranths, pumpkins, and chocolate still are grown today and

are considered essential to traditional Mexican cuisine.

Chia was also among these early Mesoamerican crops. When Cortez arrived in Mexico, he found the population of 11 million Aztecs using chia seed in nearly every aspect of their lives. According to some interpreters of Codex Mendoza and other sixteenth-century records, chia was one of the most important Aztec crops, second only to corn (2). Chia seed was eaten daily. It was toasted, ground, and incorporated, along with corn meal, into breads and porridges (4). There is no evidence that sprouts or vegetative plant parts had any culinary value to the Aztecs.

Medicinally, chia seeds were included in herbal infusions made to treat a variety of ailments, presumably because chia aided in the uptake and absorption of active ingredients. Ground seeds were applied as a poultice to aid in wound healing. Oil, pressed from the seeds, was used externally as an ointment or emollient to protect the skin of those exposed to water during their work. There is also some evidence that chia roots were used in herbal infusions to treat respiratory ailments.

Chia seed oil is a “drying oil” similar to the oil of flax seed (linseed oil); when

exposed to air it hardens into a clear, shiny impermeable layer. Like linseed oil in Europe, chia seed oil was used by the Aztecs to make paints with which to decorate objects made from gourds, wood, and clay. Chia oil also was used for making body paints.

The importance of chia in traditional Mesoamerican society is reflected in linguistics; the word chia means “powerful” in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs. Pictograms or glyphs for some place names include images of chia seeds.

More than 500 years ago, chia cultivation was at its peak. Once a staple crop of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, chia disappeared from cultivation after European contact and is now virtually unknown, even in the most traditional Mexican cuisine.

Modern Indigenous Uses of Chia

A few remnant populations of Salvia hispanica can be found growing wild in remote parts of Mexico and Guatemala, and ethnobotanical field research has been conducted with the people living nearby (4). Researchers found that very few of the preColumbian uses of chia still exist, but some new uses were identified.

7 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Figure 3 (left)- Prior to 1960, grass-growing heads like this one were produced in Europe and America and sold by garden centers and florists. Photo by Margaret Conover

Figure 4 (right)- Chia bulls as they were originally manufactured near Oaxaca, Mexico, 1982. Photo courtesy of Chia Pet Company

seed is toasted and ground together with corn to make a flour pinole, which is added to water to make a ceremonial beverage that is consumed on special occasions.

As a medical ingredient for infusions, chia seeds still are used in some villages as they were in ancient times. Several native informants also reported the practice of inserting a chia seed under the eyelid to remove foreign objects, a use unknown to the Aztecs, which may have been patterned after a similar traditional European use of clary sage (Salvia sclarea).

Traditional artisans of Michoacan use chia seed oil, as did their ancestors, to produce lacquered folk art known as macque. The process involves mixing natural earth pigments and chia oil with aje, the fatty exudate from a type of scale insect. Similar to the complicated technique for making Chinese lacquerware, this process is considered by some to be evidence of pre-Columbian contact between China and Mesoamerican civilizations (12).

Consumption of chia seed is infrequent among indigenous populations of Mexico and Central America. In some of these villages chia

Several native informants described culinary uses of chia seed that, although presumably unknown to the Aztecs, were described more than a century ago by botanist Edward Palmer (13). He says, of a dessert made from ground raw chia seeds, sugar, and a little water, “One readily acquires a liking for it and learns to eat it rather as a luxury than on account of its exceedingly nutritious properties.” Palmer also described a beverage made from infusing chia seeds in water to which is added some lemon and sweetener. The beverage was popular throughout Mexico as early as 1850, and was sold from large gourds by street vendors. This beverage is still served in parts of Mexico under the name chia fresca or agua de chia.

A similar chia seed beverage, iskiate, is consumed by the Tarahumara people, who famously run 100-mile races through the rugged mountains of the Sierra Madre in their homemade sandals (11). The chia seed used by the Tarahumara, perhaps wildharvested Salvia tiliifolia or Hyptis suaveolens, is considered by them to be the secret of their endurance.

For the Chumash and other coastal and inland tribes of California, the native species of chia, Salvia columbariae, is both prominent in creation mythology and has been found in burial sites (8). Culinary and medicinal uses for this species are similar to the uses reported for S. hispanica in Mexico.

Rediscovery of Chia

At the beginning of the health food movement in the 1960s, chia began to attract attention. Calling it “Indian

Running Food,” some claimed that Native American warriors could run long distances eating nothing but one teaspoon of chia seed a day (3). In California, Harrison Doyle promoted the use of S. columbariae (6) calling it “the seed that’s worth its weight in gold!” He recounts the legend of a prospector who, stranded and dying beside a watering hole, was offered a cup full of chia seed mush by a passing Indian and was miraculously cured overnight. In The Magic of Chia, author James F. Scheer retells these stories, claiming that chia seeds can cure prostate cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, pre-menstrual syndrome, and more (14). Some modern health food experts have repeated these claims.

Is Chia a “Superfood?”

Chia seed (Salvia hispanica) now is available at health food stores throughout the United States. The seed is sold whole, ground, or as an ingredient in chips and energy bars, and some brands claim “superfood” status for their product. But just how realistic is this claim?

Chia seed has a mild nutty taste and is quite palatable. It is non-allergenic and approved by the FDA as a food. According to the USDA Nutrition Database, just one ounce of chia seed provides 137 calories, 4 grams of protein, 11 grams of fiber, 9 grams of fat, and high levels of calcium (18% DV), phosphorous (27%DV), and manganese (30%DV).

Chia seed is an especially good source of both fiber and omega-3-fatty acids. One ounce of chia seed can provide nearly half the average daily requirement for fiber, much of which is soluble fiber contained in the seed coat. When then seeds are mixed with water, the seed coat absorbs sufficient liquid to increase substantially in volume (Fig. 5) to form “chia gel.” In

8 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Figure 5 - Comparison of hydration of alfalfa seeds (1) with chia seeds (2). 10 grams of seed were added to 100 ml of water and stirred for 15 minutes. Photo by Margaret Conover

one study, diabetics who consumed one ounce of chia seed daily for three months experienced reduced aftermeal blood sugar and plasma insulin levels (10), as well as lower blood pressure and improvement in other heart health factors. However, there is as yet, no evidence for the claim that chia gel can aid in weight loss and the control of acid reflux.

Chia seed has the highest levels of any plant-based source of omega-3-fatty acids: one ounce provides 5 grams of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). Omega3-fatty acid deficiencies are implicated in many human health problems, including heart disease, eczema, and ADHD (1), suggesting perhaps that there is some truth behind the claims for chia’s “superfood” status. We must wait for the results of more studies.

Chia seed often is recommended as a substitute for flaxseed, which is also high in fiber and omega-3 fatty acids. Chia is superior to flaxseed, however, because it can be digested whole, and does not require refrigeration, as does flaxseed. Chia seed oil is available in capsule form, and has been added to some cosmetics and skin lotions, as an emollient.

Chia seed has become a popular amendment to some animal feeds. Early research shows that omega-3 fatty acid content of eggs will increase when chickens are given chia seed (2). Some horse owners claim that horses fed chia seed exhibit relief from colic and skin conditions.

Sprouts of chia seeds are quite edible and probably high in vitamins. However, levels of the two main beneficial nutrients found in the seed, fiber, and fat are much reduced in the sprouts. The manufacturer of the Chia Pet™ expressly warns against eating sprouts grown on their product.

Two Easy Chia Recipes

Chia Gel

Note: Chia gel is the basis for both recipes. Make chia gel by stirring together 1 tablespoon of chia seed and ½ cup of water. Let sit for 10 minutes, stirring a few times to break up any lumps. Refrigerate for up to 2 weeks.

Chia-mayo (Fig. 6)

Add ½ cup of chia gel to ½ cup of real mayonnaise. Mix well. Refrigerate and use as a mayonnaise substitute, for up to 2 weeks.

Iskiate (Chia Fresca)

Add ½ cup of chia gel to 1 quart of water. Add the juice of 1 lemon and ½ cup of sugar. Stir, then refrigerate ½ hour to allow the flavors to blend. Serve over ice.

9 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Figure 6 - Tomatoes dressed with “Chia-Mayo,” a mixture of mayonnaise and chia gel. Photo by Margaret Conover

What Can You Do With Chia?

• Add chia gel to your morning orange juice.

• Experiment with the fragrance of chia leaves and invent “pot-pourria de chia.”

• Grow chia plants: participate in field trials to test Salvia hispanica as a cover crop and bee plant. http://www.ars. usda.gov/pandp/docs. htm?docid=19317

• Grow a Chia PetTM with your children or grandchildren.

• Plant some of the other “chia sages” mentioned in this article and try to harvest the seeds.

Foliage of Salvia hispanica promises to hold beneficial properties, but at present, these are largely undetermined and untested. The leaves are pleasantly fragrant and so must contain some essential oils, as do other members of the Lamiaceae. Australian herbalist, Isabell Shipard (15), recommends tea made from chia leaves for a “blood cleanser and tonic, also for fevers, pain relief, arthritis, respiratory problems, mouth ulcers, diabetes, diarrhea, gargle for inflamed throats, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and triglyceride levels, and to strengthen the nervous system.” One recent study identified antimicrobial substances in the leaves of a chia sage, Salvia polystachia (5). Research on the therapeutic value of S. hispanica leaves has not been conducted.

Cooking with Chia

Because it is so high in fiber, chia seed generally is added to the diet in small quantities and is rarely the center of attention in any dish. A few tablespoons of chia gel (see sidebar) can be added to many dishes, and chia seed can easily be substituted for flax seed in any recipe. In general, chia recipes fall into the following categories:

• Baked goods, breads, cookies, and desserts, fortified with ground or whole seeds.

• Main dishes, especially stews, casseroles, and egg dishes, enhanced with ground seeds or chia gel.

• Cereals and snacks, in which chia is cooked together with oatmeal for a hot breakfast or added to a granola or energy bar recipe.

• Beverages, which includes fruit juices and smoothies, with chia gel added in order to thicken the texture and to absorb and concentrate the flavors.

• Raw vegan recipes that have no animal or cooked ingredients included. Faux tapioca pudding is a raw recipe worth trying: combine chia seeds with sweetened nut-milk and allow the mixture to gel to a pudding consistency.

The few chia recipe books that have been written are limited in distribution. A collection of online recipes is compiled at www.chiativity.org.

Growing Chia

It should be no surprise to readers that Chia Pet™ sprouts will not survive beyond a few weeks. However, under normal gardening conditions seeds of S. hispanica will sprout and grow to six or more feet with very little effort. Plants prefer full sun, and poor, fairly dry soil. Volatile oils in the leaves deter predation by insects, and there are no diseases of concern.

The main disappointment for those who wish to grow and harvest their own chia seed in North America is that the plants are day length sensitive. The short day length that triggers blooming does not occur until late October, not leaving time to set seed before the first frost of fall. Researchers in Kentucky recently created some mutant strains of S. hispanica which will flower at daylengths of about 15 hours (9), but these are not yet available to consumers. Would-be chia growers may wish to experiment with some of the other chia species. Salvia tiliifolia, in particular, is very well adapted to flower and set seed at temperate latitudes, to the point where it self-seeds and becomes weedy.

Growth Outlook

In the last few years, interest in consuming chia seeds has skyrocketed. Chia seeds have been featured in national publications like the Vegetarian Times and discussed

10 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

by television personalities including Dr. Oz on Oprah. Tons of chia seed, grown in Australia and in Central and South America, have been shipped to distributors all over the world, and certified organic seed has come into production. Even the Chia Pet™ company is about to release its own brand of edible chia seed.

There is a great deal more to be learned about chia. Scientific and medical research has just begun to show results. Long distance runners are still testing their improved endurance, cooks and gardeners haven’t had much chance to experiment with cooking and growing methods, and distributors haven’t fully assessed consumer demand.

As more information about chia becomes available, I hope to play a role in the revival of this ancient American herb by informing and educating the public. I provide useful and reliable information about chia, and post new developments on my website: www.chiativity.org. I created educational materials for the middle school classroom, “Beyond the Chia Pet,” with support from The Herb Society of America, which is ready for distribution, as are some pamphlets and activity kits (16). Please contact me for more information and please try chia.

References

1. Allport, Susan. 2008. The queen of fats: why omega-3s were removed from the western diet and what we can do to replace them. Berkeley: University of California Press.

2. Ayerza, Ricardo and Wayne Coates. 2005. Chia: rediscovering a forgotten crop of the Aztecs. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

3. Balls, Edward K. 1965. Early uses of California plants. California natural history guide No. 10.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

4. Cahill, Joseph. 2003. Ethnobotany of chia, Salvia hispanica L. (Lamiaceae). Economic Botany 57(4): 604-618.

5. Calzada, Fernando, Lilian YepezMulia, Amparo Tapia-Contreras, Elihú Bautista, Emma Maldonado and Alfredo Ortega. 2010. Evaluation of the antiprotozoal activity of neo-clerodane type diterpenes from Salvia polystachya against Entamoeba histolytica and Giardia lamblia. Phytotherapy research 24(5): 662-665.

6. Doyle, Harrison. 1973. Golden chia: ancient indian energy food. Vista, California: Hillside Press.

7. Edwards, Owen. 2007. Growth industry: for 26 years, marketing whiz Joe Pedott’s green-pelted figures have been holiday-season hits. Smithsonian 38(9): 32-33.

8. Immel, Diana. 2003. Chia: Salvia columbariae Benth. USDA, NRCS, National Plant Data Center. http://plants.usda.gov/ plantguide/pdf/cs_saco6.pdf (accessed August 17, 2011).

9. Jamboonsri, Watchareewan, Timothy D. Phillips, Robert L. Geneve, Joseph P. Cahill, and David F. Hildebrandt. 2011. Extending the range of an ancient crop; a new ω3 source. Gen. Res. Crop Evol. (in press). DOI: 10.1007/s10722-011-9673-x.

10. Kreiter, Ted. 2009. The whole grain promise. Saturday evening post. 281(2): 70-71.

11. McDougall, Christopher. 2009. Born to run. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

12. Menzies, Gavin. 2008. 1421: The year China discovered America. New York: Harper.

13. Palmer, Edward. 1891. Notes on chia. Zoe 2(2): 140-142.

14. Scheer, James. 2000. The magic of chia: revival of an ancient wonder food. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

15. Shipard, Isabell. 2009. Chia: crop potential and uses. Permaculture Research Institute of the USA. http://www.permacultureusa. org/2009/04/05/chia-croppotential-and-uses/ (accessed August 17, 2011).

16. Conover, Margret. 2011. Ch-chchi-chia seeds for inquiry. Science Scope 34(8): 20-24.

Dr. Margaret Conover is a botany lecturer and author who teaches at the New York Botanical Garden and the New York Center for Teacher Development. As a Fulbright Fellow to Australia, she completed dissertation research on the leaf venation patterns of the lily family. She is co-founder of the Long Island Botanical Society and currently serves as newsletter editor. As a recipient of an Education Grant from The Herb Society of America, Dr. Conover created an interdisciplinary curriculum for middle school students entitled “Beyond the Chia Pet.” She owns and operates a small business: Chia Power, which is dedicated to the promotion of the use of chia for fun and food. She is a Master Gardener and a member of the Long Island Unit of The Herb Society of America.

11 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

and

Up-Close Personal

A Look at the Mediterranean Herbs and Their Native Habitat

by Susan Belsinger

by Susan Belsinger

The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011 12

During the summers of 2008 and 2010, I had the great pleasure of teaching a Holistic Herbal Mediterranean Cooking Class on the isle of Syros in the Aegean Sea. The American College of Healthcare Sciences offered this study-abroad class; Dorene Petersen is president of the college and was my co-teacher. Our classroom base was in the kitchen and on the outdoor patios of the Villa Abela, with a view overlooking Abela Bay. We spent as much time outside the villa as in the kitchen—walking the picturesque country roads, hiking across the hills, swimming in the aquamarine sea, visiting the outdoor marketplace and quite a few tavernas, and sightseeing when we had the opportunity. Come with me now on a tour across the Greek island of Syros, where I will help you envision the native terrain and habitat for the indigenous herbs of the Mediterranean region. By looking closely at how these plants tenaciously cling onto the parched, rockstrewn earth, in scorching heat, with little rain, you will be able to better understand how these herbs grow and what they need in order to prosper in our home gardens.

Riding the ferry from the port of Pireaus, Greece, south to the isle of Syros in the Cyclades was one of those “Aha!” moments for me. On the rocky cliffs that hang over the sea, the native Mediterranean herbs hold on for dear life. Without much soil or rain, in relentless sun and wind, these herbal plants, which we pamper in our own gardens, lead a hardscrabble existence. The reality of their place of origin has caused me to rethink what these herbs really need to grow.

I am enchanted with the herbs that live in this area. From our familiar thyme and sage, to the closely-related Coridothymus capitatus (syn. Thymus

capitatus or Thymbra capitata) and Salvia fruticosa, these plants have adapted in order to survive this rugged existence. They send out deep roots to find moisture and hold on to the rocky slopes; most have thicker leaves to retain moisture and a few even develop barbs or thorns in order to survive grazing animals. Their essential oils are so concentrated they are practically overwhelming.

A group of students, along with Dorene and me, set out from the little port town of Finikis on a walking trail that slowly climbed and crossed a hillside covered in native plants and descended back down to a lovely

private little bay. Hiking across the herb-blanketed rise, then looking straight down—a sheer drop-off to the sea—and outward at the azure waters of the Aegean was thrilling. Being immersed in these wild herbs was a sensory experience that I shall never forget. As we hiked in the hot sun, passing through different groups of vegetation, their various aromas would drift up to meet our noses. This was not a fast hike—it was more like moseying along—since we examined every type of flora, their growing habits, individual characteristics, and their fragrance and flavor as we walked. I brought up the rear since I was taking photos and lingering.

A volunteer caper bush (Capparis spinosa) growing atop a whitewashed wall. Opposite page: An arrangement of freshly picked Mediterranean herbs. Photos by Susan Belsinger

A volunteer caper bush (Capparis spinosa) growing atop a whitewashed wall. Opposite page: An arrangement of freshly picked Mediterranean herbs. Photos by Susan Belsinger

Plants like sage, St. John’s-wort, and thyme were easily recognized, although they were different varieties than I grow at home in Maryland in my Zone 7 garden. I was delighted to see rock rose (Cistus ladanifer) and mastic (Pistacia lentiscus) for the first time. I smelled immortelle (Helichrysum italicum) with its mouthwatering scent before I saw it. Being there in the moment, sharing the exhilaration of discovery with likeminded individuals was awesome. Tears of joy ran down my cheeks. I followed the group on the path across this hillside of magical herbs.

We stood at the end of the trail feeling like we were in paradise, surrounded by fragrant immortelle, overlooking a turquoise, crystal-clear bay with a white sandy beach. What better way to end a long hot hike? I set down my camera, emptied my pockets full of native Mediterranean herbal potpourri, and jumped in the Aegean Sea with the rest of the group.

Some Mediterranean Herbs Along the Way…

Capparis spinosa ~ Caper ~ Cappari Capers—the classic food of Greece— with their uniquely pungent, slightly bitter taste. Oddly, this hardy shrub has bright green, oval leaves in the hot weather and loses them in the rainy season, the opposite of how Mediterranean plants usually adapt. In the summer, one will find the plants almost anywhere a bird might drop a seed—draped from rock walls and ledges or clinging to cracks in old buildings or in the pavement. I saw more than a few growing out of the ruins at the Parthenon! During caper season, the perennial shrubs produce flower buds which are harvested and pickled to make a popular Mediterranean condiment. If the buds aren’t picked everyday, they bloom, producing a beautiful white flower with a fuchsia stamen that lasts only a day before the fruit begins to form. One can look out in the morning and

see locals gathering the immature buds in small buckets and coffee cans. In the market, there are five gallon buckets full of capers for sale by the kilo. Immature buds, small leaves, and the larger fruit pods are all pickled in brine and eaten; they are purported to stimulate the appetite. I find this to be one of the most fascinating plants of the Mediterranean region.

Cistus spp., Cistus landanifer, ~ Rock Rose ~ Ladania, Xistari

I was so excited to find rock rose— and lots of it—on our hike. I’ve taken Rescue Remedy ™ for years and always wondered what the first herbal ingredient listed on the label looked and smelled like. Apparently there are four species of this perennial in Greece, some growing in the mountains and some on the coast. The one I saw was Cistus ladanifer. Thick ovate leaves cover the shrubs and the five-petaled, rose-pink blooms last just one day. The seed pods, which resemble a flower, are a deep, rust brown. I almost thought it was a different species entirely until I saw both bloom and pod on the same plant. Ladanum, or labdanum, is the resin which is gathered from the flowers and is sticky and gum-like. This fragrant and antiseptic substance is used in medicine, ointments and balms, and in incense.

Foeniculum vulgare ~ Fennel~ Marathos, Maratho

Fennel grows wild all over the Mediterranean region. Looking out the car window en route to Villa Abela, I strained to see what the odd white pods were hanging from the fennel along the dry dirt road. I was sure it was Foeniculum, yet couldn’t imagine it bearing a pod. Well the laugh was on me—when I got out to inspect the plants I found them covered with large-shelled snails. The snails were devouring the foliage;

14 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Caper flowers last just one day. A close-up of a just-opened caper blossom is on the left and a one-day old spent bloom is on the right. Photo by Susan Belsinger

Left: Close up of Wild fennel (Foeniculum vulgare)

Below: Immortelle (Helichrysum italicum)

Photos by Susan Belsinger

The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Above: Rock rose (Cistus landanifer) with just opened pink petals and russet-colored spent blooms.

15 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

when they got to the upper part of the stems their weight made the stems bend and splay out. The plants looked sort of comical, as if they were decorated with ornaments. Many of the four-foot tall plants were just long green stems with yellow flower umbels on top, with occasional leafy sprigs near the flowers still left intact. Fennel is a perennial along the coast and in the hills. Its leaves, roots, and seeds are used for medicine and food. Because of the intense heat, the plants had a very strong flavor, less foliage than usual was needed to flavor a dish, which was good since the snails had defoliated much of the fennel, leaving less available. Fennel is used mostly with seafood, namely fish and octopus, and fresh vegetables, such as beans and other legumes.

Helichrysum italicum ~ Everlasting Flower, Curry Plant~ Immortelle

To me, this plant contains the essence of the Greek isles. I was not very familiar or particularly fond of everlastings until I was introduced to immortelle on the dirt road on the way to the villa on Syros. It is a pretty enough plant with small golden flowers, but it was the fragrance that captivated me. When I picked the first branch, I inhaled the scent over and over, trying to decide what it smelled like. At first, it has the aroma of curry—mild, though not overwhelming. I have grown what is known as curry plant at home; however, it did not have the smell of this sun-baked evergreen shrub. I placed the branch on my bedside table and as it dried it seduced me further with its olfactory allure. I decided its bouquet is a combination of curry, toast, and caramel (not the chewy confection, but rather the goldenbrown syrup that one cooks on the top of the stove—the base of a good flan). I fell asleep at night salivating

from this sweet, sensual aroma and awoke hungry. This aromatic herb is ornamental and culinary and is used in rice and vegetable dishes as well as with eggs and other savories. Its essential oil is extraordinary.

Hypericum spp. ~ St. John’s-wort~ Spathohorto

The bright yellow and orange flowers of St. John’s-wort, a plant that first pops into my mind when I think of the herbs from this region, dotted the hills of Syros. Greece has 26 species of Hypericum—some of them looked like the ones in my garden—although the ones abroad are much more compact and covered with more flowers. In summer there are as many fresh bright yellow blooms as there are russetorange dried blooms on every plant. They are dazzling in the sunlight, and their pleasant, slightly spicy aroma floats up as one brushes past. The dried flowers of this perennial plant are collected in summer and infused in olive oil for about 40 days. I saw bottles filled with bright red, macerated St. John’s-wort at the market and purchased one to bring home.

Lavandula dentata ~ Fringed Lavender ~ Levanta, Lavandis

The lavender that I saw, primarily on the mainland of Greece, was growing on the roads and hillsides along with rosemary. Most of the plants I saw up close were Lavandula dentata, which is often called toothed or fringed lavender, and L. stoechas (French or Spanish lavender). There were some on the island of Syros, but unless they were in a garden where they were being watered, they were burned on top with brown and dried sections.

Malva sylvestris ~ Common Mallow Malakhē

This lovely plant survives in poor soil along roadsides and in fields and

waste places. There are more than 16 species of Malva in the Mediterranean region. The purplish-pink flowers of this annual are abundant from summer to fall. Mallow has been used throughout history but seems to be neglected today. The small leaves, shoots, and sometimes the immature seed capsules taste slightly sour and are used in salads, while the flowers are made into tea, often combined with chamomile.

Origanum vulgare ~ Greek oregano ~ Righani

In Mediterranean marketplaces, you will often see oregano dried with the blooms left on and tied in bundles. Truly, it is the herbal sine qua non of both Greek and Italian cuisine.

Origanum vulgare ssp. hirtum is spicy and somewhat hot to the tongue; it is used in everything from soup to salad dressings, meat, poultry, vegetables, pasta, and pizza. It grows wild, perennially in sunny gardens, fields, and hillsides.

Pistacia lentiscus~ Mastic ~ Masticha, Mastika

Mastic is a little-known herb in the United States, but it is used in everything from breads, baked goods, puddings, ice cream and other desserts, to toothpaste, chewing gum, cosmetics, and incense. The gum resin from the mastic tree, which is related to the pistachio tree, is harvested from slits made in the bark. The island of Chios in the Aegean Sea is the center of mastic production; this island has been fought over for centuries since mastic is a valuable commodity. The process of making mastic and seeing the cooperative of medieval villages where the people who grow and harvest mastic live intrigues me; I plan to visit there someday. We found a patch of this or a similar Pistacia species on our hike; they were covered with red fruit, dark evergreen

16 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

When I pick or crush in my hand a twig of bay, or brush against a bush of rosemary, or tread upon a tuft of thyme, or pass through incense-laden Cistus, I feel that here is all that is best and purest and most refined, and nearest to poetry in the range of faculty of the sense of smell. ~Gertrude Jekyll

The hillsides are covered with indigenous herbs on the southern side of the isle of Syros. The herbs end abruptly where rocky cliffs meet the Aegean Sea. Photo by Susan Belsinger

The hillsides are covered with indigenous herbs on the southern side of the isle of Syros. The herbs end abruptly where rocky cliffs meet the Aegean Sea. Photo by Susan Belsinger

foliage, and thorns. The flavor of mastic is resinous and slightly piney, and the shrubs we found had this aroma. I bought mastic tears and powder, chewing gum, toothpaste, and lotion while in Greece and I have enjoyed all of them.

Portulaca oleracea ~ Purslane ~ Andrákla, Glistrída

Although I saw some purslane growing in the wild, it was abundant in the more cultivated areas and sold by the kilo in the marketplace. The succulent leaves and stems were tied in bundles and sold as a fresh green, as well as pickled in jars. The slightly tart, crunchy leaves, which are rich in iron, vitamin C, and omega-3 fatty acids, are used fresh in salads, combine well with yogurt, and are also wilted like a cooked green. Purslane is usually harvested before it flowers.

Rosmarinus officinalis ~ Rosemary ~ Dendrolivano

When riding from the airport into Athens, I saw rosemary bushes, lavender, and chaste trees (Vitex agnuscastus) interspersed with large masses of blooming oleander growing all along the roadsides and the medians. During my stroll through the city, I noticed rosemary growing wild on the hillsides as I neared the Acropolis. The rosemary plants there, as well as on the islands, are tough and compact. The upright plants are dense and the leaves are thicker and shorter; prostrate plants naturally cascade down rock walls and ruins. Sometimes they show burn from the sun and lack of precipitation. The oil and flavor is resinous and piney, though slightly bitter; it is used especially with lamb, pork, poultry, breads, and potatoes.

Greek sage (Salvia fruticosa) has thick,downy leaves and seems to be growing right out of the rock. Photo by Susan Belsinger

Salvia fruticosa ~ Greek Sage~ Phaskomilo, Faskomilo, Faskomilia Greek sage grows wild on the hillsides in dense groupings; it has thick leaves and has a more pungent flavor than the commonly used Salvia officinalis. Greek sage seems to tolerate hot climates, and it is hardy to Zone 8. The strong, pungent, slightly resinous and bitter flavor of sage is used most often with fatty foods such as sausage, meat, game, cheese, and some fish. It is used with beans and legumes, and the leaves are sometimes fried and used as a garnish for other dishes.

Coridothymus capitatus (syn. Thymus capitatus)~ Cretan Thyme, Conehead Thyme ~ Thimos, Thimari This ancient herb is a close relative to Thymus, but it has its own genus and is sometimes called conehead thyme. Due to its high carvacrol and thymol content, it has a strong flavor similar to oregano or savory. Coridothymus capitatus is a compact, woody subshrub covered with small needle-like foliage and lovely pinkish-purple flowers. It is this herb that gives the flavor and fame to Mount Hymettus honey. When Satureja thymbra is not available, Cretan thyme is sometimes used as a substitute in meat, poultry, and game recipes.

Vitex agnus-castus ~ Vitex, Chaste Tree ~ Ligariá

This handsome deciduous shrub grows wild in southern Europe; its leaves are palmate and the flower spikes range from deep purple through lavender blue, to lovely pink, and white. When I first saw it growing — literally abuzz with pollinators on a hillside with rosemary, I had to climb in the thicket to see if it really was Vitex. Although it is not used for culinary purposes, Vitex agnus-castus has been used for centuries for symptoms of both menstruation and menopause, as well as to promote lactation.

Concluding Thoughts about How Mediterranean Herbs Grow

Herbs need sun, water, and good drainage to grow. In my home garden, I provide my herb plants with adequate drainage (considering I have dense clay soil), and water often if there is not enough precipitation. I amend my garden loam with humus, along with mineral mulch. Of course, I have no control over the weather. In the Mediterranean on the rocky slopes, I noted first and foremost that these plants have unbelievable drainage because of the lay of the land. Truly, they are hanging on to rock— limestone, sandstone, and granite— and their roots penetrate the dry, compacted, mineral-rich soil. Summer sun beats down relentlessly and there is very little rain. It does rain in fall, winter, and spring, so they must store this water somehow in order to get through the heat of summer. There is generally a constant sea breeze, so the plants may gain some moisture from the sea air and spray.

As we walked, we noticed that different herbs appeared in groups and patches—or even stripes of certain species running down the hillside. There were patches of Greek sage (Salvia fruticosa), and then big clusters of rock rose, or Thymbra capitata. Then there was a huge group of mastic plants, and then no more, and we’d be back among the rock rose or immortelle. The herbs of the Mediterranean region are well adapted to rocky soil, good drainage, excellent air circulation, and hot sun. Give your grey-and-green Mediterranean herbs these essential elements and they will grow for you.

Bibliography

Belsinger, Susan and Tina Marie Wilcox. “A Gray-and-Green Garden of Mediterranean Herbs.” In Designing an Herb Garden. New York: Brooklyn Botanic Garden, 2004.

Bown, Deni. The Herb Society of America Encyclopedia of Herbs. and their Uses. London: Dorling Kindersley, 1995.

Chisholm, Hugh. The Encyclopedia Britannica 21: 734. http://tinyurl. com/3gnt2gm (Accessed August 1, 2011)

Lambraki, Myrsini. Herbs, Greens, Fruit: The Key to the Mediterranean Diet. Crete: translated by George Trialonis, 2001.

_____. Honey, Wild flowers and Healing plants of Crete. Crete: translated by George Trialonis, 2003. Musselman, Lytton John. Figs, Dates, Laurel, and Myrrh: Plants of the Bible and Quran. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 2007.

Petersen, Dorene. Essential Oil of Cistus. American College of Healthcare Sciences, 2006.

Herb Companion. Mediterranean Companions. http://www. herbcompanion.com/Gardening/ Mediterranean-Companions.aspx. (Accessed August 1, 2011)

Susan is an active member of the Potomac Unit of HSA and a recipient of the 2006 Joanna McQuail Reed Award for the Artistic Use of Herbs. She is a well-known culinary herbalist and educator, food writer, and photographer. Susan is a contributing blogger for Taunton Press (www. vegetablegardener.com). Check out her weekly articles, photos and recipes on herbs, gardening, and related subjects.

19 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

One of the 26 species of St. John’s wort (Hypericum spp.) which grows in Greece. Photo by Susan Belsinger

PopularChamomile

by Jesse Vernon Trail

Chamomile is a popular herb for good reason. It is possible to relax with a cup of flavorful chamomile tea after having bathed in a chamomile rinse and soothed your chapped hands with chamomile hand cream. The dainty, daisy-like flowers add bright cheer to the garden and the plants have the added benefit of being easy to grow. Some gardens even include a chamomile lawn! However, there is much confusion regarding chamomile, especially among gardeners. The plant has been known by many names, both common and scientific, and chamomile is often confused with daisies or even asters.

Numerous Names

Two delightful plants are often associated with the common name chamomile, Chamaemelum nobile and Matricaria chamomilla. Both of these chamomiles have their own distinctive traits, and yet they also have many similar characteristics, such as their appearance, fragrance, and how they are used. The botanical names of both species have changed several times, and many references still use the older synonyms. The many common names are often specific to certain geographical regions.

The word chamomile is from the Greek kamai (on the ground, referring to the short growth habit) and the Greek melon (apple, suggesting the apple-like fragrance of both species); translated directly, the name would be “ground apple.” Both chamomile and camomile are accepted common name spellings, though chamomile appears to be more frequently used.

Chamaemelum nobile is often referred to as Roman or English chamomile, though on occasion it may also be referred to as corn chamomile, Russian chamomile, sweet chamomile, and

garden chamomile. In older references, it may be listed as Anthemis nobilis or more rarely as Ormensis nobilis; both are names that predate the current one of C. nobile (3).

Matricaria chamomilla is often referred to as German or wild chamomile, though it may also be called Hungarian chamomile, scented chamomile, common chamomile, blue chamomile, sweet false chamomile, scented mayweed, or the fanciful name of pin heads. It is often listed as Matricaria recutita and less frequently as Chamomilla recutita. No wonder there is confusion!

Roman or English ChamomileChamaemelum nobile

C. nobile is a fast growing perennial, becoming branched and spreading or forming a dense mat 9 to 12 inches high when it is in flower. It is an excellent groundcover with finely divided leaves that are somewhat coarser than those of M. chamomilla. Daisy-like flowers have a solid deep yellow central disc, ½ to ¾ inch in diameter, which is surrounded by creamy white ray flowers.

Roman chamomile is hardy to Zone 4 and grows well in a moist (but not wet), well-drained soil with added organic matter and full sun to partial shade. Seed can be sown in spring or fall, though a more reliable propagation method is by spring division of the runners or roots, or by layering. Moreover, to a lesser degree, cultivars can be propagated from cuttings.

Roman Chamomile Cultivars of Note

Chamaemelum nobile ‘Treneague’ is the best cultivar for a lawn, as it does not flower and forms a mossy carpet only one to two inches high with a spread of about 18 inches. Although

Other Chamomiles

A number of other plants are known by the common name of chamomile; all of them are members of the genus Anthemis.

Anthemis arvensis (scentless chamomile, corn chamomile, or field chamomile) is an annual, biennial, or short-lived perennial. Flowering from May to October, it grows 6-20 inches in height and is considered a weed in commercial crop production because it forms dense, permanent patches in the fields, reducing yield. www. agdepartment.com/noxiousweeds/pdf/ Scentlesschamomile.pdf

Anthemis cotula (stinking chamomile, dog fennel, or stinking mayweed) The common names give away this plant’s primary attribute—its strong and unpleasant scent. It is an annual and grows to a height of 6-18 inches. Handling it may cause skin blisters on sensitive persons.

Anthemis marschalliana (Marshall chamomile) A mat-forming perennial that grows up to 12 inches in the summer. This chamomile has finely cut silvery leaves and golden yellow flowers, with woolly, white bracts that have black margins.

Anthemis sancti-johannis is known as St. John’s chamomile.

Many cultivars have been developed from crosses between Anthemis tinctoria and Anthemis sancti-johannis.

Left: The bright yellow, conicalshaped, central discs of chamomile are a prominent feature of the flowers. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

21 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

‘Treneague’ can be difficult to establish, it is less invasive and requires less mowing than other species. Chamamelum nobile ‘Flore Pleno’ has double flowers and ranges from four to six inches tall, also with an approximately 18-inch spread. This is the chamomile most commonly used in commercial production (5).

A Chamomile Lawn

Because of its low, mat-forming habit, Roman chamomile is the best species to use for a wonderfully-scented lawn. It can be walked on, releasing a delightful fragrance, though it is best to subject it only to light foot traffic. Keep in mind that chamomile lawns can be maintenance intensive. Compared with grass lawns, chamomile lawns are less hardy and they require diligent weeding. A chamomile lawn will shrivel in a hot, dry area; a layer of mulch will help to keep the roots cooler and the soil evenly moist, though be careful not to bury smaller plants. Planting is best done in spring, placing each plant about six inches on center. Water regularly and deeply, especially at first, to ensure a strong root system. Eventually, the chamomile lawn will need to be mowed, but wait until the root system is firmly established. Until that time, trim the plants lightly with hand shears if needed. Mowing with a lawn mower should be done on a regular basis with the blades set fairly high—about three inches.

German ChamomileMatricaria chamomilla –

This is an annual species with an erect or ascending habit that grows to a variable height of about two feet or taller. Depending on the geographic location and other factors, German chamomile may behave as a biennial or short-lived perennial, but for the most part it is an annual. It is a much-

“In the Victorian language of flowers, chamomile represents adversity. Perhaps this symbolism comes from the ability of the plant to rise again after being stepped on.”

branched (or stemmed) plant, with finely divided foliage and a single terminal flower at the end of each of its many stems. The daisy-like flowers, which appear in abundance from early summer to autumn, are smaller and less strongly scented than Roman chamomile, though they still have a strong, sweet fragrance. Each flower has a raised, central hollow disc receptacle with yellow tubular florets. This is surrounded by a single row of white petals that are often recurved or bent backward. As a matter of fact, the best way to tell the two chamomiles apart is to split the flower receptacle with a fingernail. The receptacle of German chamomile is hollow; that of Roman chamomile is solid throughout.

German chamomile prefers full sun and a moist-to-dry, well-drained soil that is neutral or slightly acidic. It is a good container plant. Seed propagation is quite easy and plants will also self-sow readily (sometimes too readily). The tiny seeds are best mixed with a fine sand (to make sowing more even) and spread lightly where they are to grow. This is usually done in early spring, though sowing in mid-summer is also reported to work well. German chamomile seeds have unstable viability and they need

light in order to germinate. Once they sprout, thin the seedlings to six inches apart.

Similarities and Shared Uses

Both M. chamomilla and C. nobile have daisy-like blossoms, feathery or deeply divided foliage, and a fragrance and flavor somewhat similar to that of apples. Both species will escape cultivation to naturalize widely. Handling these plants can cause dermatitis or similar allergic reactions, though this is rare (4).

Culinary Uses

Chamomile has very few culinary uses. Finely chopped leaves may be mixed with either sour cream or butter for baked potato toppings. Fresh flowers can be used as a garnish or tossed in a salad. In Spain, where chamomiles are called manzanilla (meaning “little apple”), the flowers are used to flavor the finest dry sherries (2).

Chamomile Tea

Chamomile is probably best known as the key ingredient in an aromatic, delicately flavored, slightly bitter tea that is soothing and pleasant to drink. As a testament to its wide popularity, the tea is available for purchase in many places, such as grocery stores and select restaurants. It is easily made from either dried (two teaspoons) or fresh flowers (one teaspoon) per cup. Steep for two to four minutes— not longer unless a really

Right: Early morning dew on the flowerhead of Roman chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile). Next page: Chamomile flowers in various stages of bloom.

Photos by H. Zell

22 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

strong flavor is desired—then strain. The flowers can be placed in a tea ball so that straining is not necessary. Honey, lemon, ginger, or peppermint can be added to provide a twist from the original flavor.

Medicinal Uses

Chamomile has been used since antiquity to treat a variety of ailments, including skin disorders, diarrhea and stomach upset, colds, insomnia, anxiety, and gum inflammation. Its most popular use is as a sleep aid. The few scientific studies that have been done show that there is some merit to a few of these treatments. One study found that chamomile had a modest benefit for people with mild to moderate generalized anxiety disorder (1). Another found that chamomile aided in healing mouth sores associated with radiation and chemotherapy treatments (6). It has anti-spasmodic (which is probably why it has historically been used to treat stomach and intestinal cramps), anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, antifungal, and anti-viral properties (6). Additional research needs to be done, however, to determine chamomile’s true value in treating many of these disorders.

Cosmetic Uses

to chemical means. I have found that using chamomile tea is a simple and safe, yet very effective means of control. The recipe I use in order to ensure a strong brew is to place one chamomile tea bag in four cups of boiling water and allow this to sit for 24 hours or more. Pour the tea into a plant mister and spray the seedlings as soon as they appear. Continue misting each day until the seedlings have developed their second set of leaves. You can also use this tea to water the seedlings from beneath the seed trays. Spray this mixture onto your vegetables, greenhouse plants, and garden plants to help control other fungal diseases such as mildew.

Clinical Psychopharmacology (29)4:378-82.

2. Hylton,William H., ed. 1974. The Rodale herb book. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press.

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS).

http://www.itis.gov/index.html (accessed August 19, 2011).

Mills, Simon and Kerry Bone. 2005. Essential guide to herbal safety. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, Inc. Tucker, Arthur O. and Thomas DeBaggio. 2009. The encyclopedia of herbs. Portland, OR: Timber Press.

6. University of Maryland Medical Center. German chamomile. http://www.umm. edu/altmed/articles/german chamomile-000232.htm. (accessed September 1, 2011).

Bibliography

Boxer, Arabella and Phillippa Boxer. The Herb Book. London: Octopus, 1980.

Hylton, William H., ed. The Rodale Herb Book. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Press, 1974.

Reader’s Digest. The Complete Illustrated Book of Herbs. New York: Readers Digest, 2009.

Chamomile is a common ingredient in many skin and hair products. Both chamomiles are used in rinses for blonde hair. Chamomile is found in skin washes, lotions, bath oils, and hand creams. People who are allergic to ragweed and other members of the Asteraceae family may have an allergic reaction if they use products containing chamomile (4,6).

Pest and Disease Control

Chamomile tea is an old method used to control the deadly killer of seedlings, “damping-off disease,”

Chamomile tea is anti-fungal and antibacterial, so a strong brew can be used with a sponge or cloth to wipe surfaces around the kitchen. Both chamomiles are also reputed to be excellent insect repellents.

References

1. Amsterdam, J.D., Y. Li, I. Soeller, K. Rockwell, J.J. Mao and J. Shults. 2009. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral Matricaria recutita (chamomile) extract therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of

Jesse Vernon Trail is a horticulturist, amateur botanist, and author of several magazine articles. He is an instructor and curriculum developer for topics such as gardening, (including herbs), environmental concerns and awareness, and sustainability issues.

23 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

by Jane Knaapen Cole

by Jane Knaapen Cole

The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011 24

When most people think of herbs they picture neat garden beds of parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme. However, many herbs are not what we would traditionally think of as herbs at all; they are wildflowers or desert plants, trees or vines. They grow in the woods and fields, providing healing, flavor, and fiber to cultures living off the land. Before European settlement, the natives who inhabited North America had intimate knowledge of the plants around them, using them in all parts of their lives. This article covers some of the primary herbal plants used by the Native Americans who lived near the Great Lakes and who were part of the Woodland Culture.

The Woodlands included the forested eastern section of North America which stretched east of the Mississippi River and north of Cape Hatteras, and extended north of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence Seaway into the Canadian Maritimes. Traditionally, Woodland Indians were farming, hunting, and fishing people. Tribes in the Great Lakes region include the Ojibwe (Chippewa), Ottawa, Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Cree, Sauk, Fox, Kickapoo, Miami, Peoria, Illinois, Shawnee, and Mascouten. Most of these were of the Algonkian family. Some of these tribes have stories of migrating from other areas. For example, the Ojibwe tell of coming from the eastern ocean in the 1400s. The Dakota Sioux were driven into the Great Lakes area by EuropeanAmerican expansion. In the 1800s the Oneida were moved to the area by treaty (4).

In coastal areas, native people generally lived near the shore in agricultural villages and moved inland for fall and winter hunting. Those inland might have lived in permanent, settled villages or

moved between two or three central settlements within their territory throughout the year, sending hunting parties onto the prairies for buffalo or into the deep woods for other animals.

Woodland Indians lived in domeshaped wigwams and longhouses of saplings covered with bark or woven mats, which were furnished with sleeping mats and furs, pottery cooking vessels, wooden spoons and bowls, baskets, bags, and other tools or equipment. Their leather and fur clothing was painted or decorated with designs symbolizing plants and animals (4).

Woodland tribes had a network of trade routes and rather sophisticated agriculture practices. They developed and carried with them frost-resistant corn and chose edible nut trees and apple trees to plant near their villages for easy harvest. They semicultivated the raspberry, two kinds of strawberries, grapes, juneberries, mayapple and milkweeds, and they encouraged the growth of plants used for food, medicine, and fiber. Those in the Woodland culture sprouted pumpkin seeds in their houses to have seedlings ready to be planted out when danger of frost passed. They burned the forest to make clearings to plant corn, which had been soaked in a decoction of plants before sowing to protect the seed from insects and birds. They obtained oil from nuts and sunflower seeds and knew which roots were good to eat and how to prepare them. Where sugar maples grew, they established sugar-making camps in early spring and made sugar from maple syrup.

Indian medicine women and men spent years learning which parts of a plant to use and how to prepare them in the proper dosage. Some plants were smoked for medicine, for their

narcotic effect, or to please the spirits upon whose goodwill their existence depended (2).

The native herbs I grow are tolerant of drought and frost, provide a habitat for birds and butterflies, add color to my garden, and connect me to those who lived here and used them in the past. With so many native plants to choose from, I decided to write about the ones in and around my garden.

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium): This is not a native plant, but has been naturalized here so long it is mentioned in the ethnobotany of many native people. It was known as the “life medicine” to the Navaho, who used it for impaired vitality, as an astringent, salve, and pain killer for toothaches. The Ojibwe steamed the leaves and inhaled the smoke to treat headaches and used the flower heads in the kinnikinnick mixture smoked in medicine lodge ceremonies. They and the Meskwaki also used the plant to treat colds, fevers, hemorrhages, cramps, wounds, and children’s diseases. The Winnebago used it in smudges or infusions to treat earaches (1,5) and used the plant to stop bleeding. The Potawatomi placed seed heads on a pan of live coals to produce smoke to keep the witches away (5).

Meadow Anemone (Anemone canadensis): The Ojibwe ate the root to clear the throat for singing, for lumbar pain, and to treat wounds and sores. The Iroquois used it to get rid of worms and counteract witch medicine.

Pasque Flower

(Anemone patens): Native Americans used a poultice of the crushed leaves to treat rheumatism and headaches (2,5). The crushed sepals were placed in the nose to stop

25 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

the preservative properties of wild ginger and that it could be used to keep meat from spoiling too quickly (2). They used wild ginger to fight nausea and infection. The flavor of the root has a lemony tang rather than the “bite” of true ginger and was used to season meat and fish. Wild ginger was applied in poultices used to treat burns and bruises and in combination with Acorus calamus (sweet flag) as an infusion for coughs, colds, and bronchial trouble. Native Americans also used wild ginger to treat heart palpitations, to promote sweating, and as a tonic. They also added it to their food for protection from witchcraft. Women used it to induce a normal menstrual cycle and as a contraceptive (2). The root was chewed and the spittle put on bait to enable Meskwaki fisherman to catch catfish (1).

New England Aster (Symphotrichum novaeangliae, syn. Aster novaeangliae), Bigleaf Aster (Eurybia macrophylla, syn. Aster macrophyllus): A poultice of New England aster roots was used for pain, infusions for diarrhea and fever, and a smudge for respiratory problems. The Meskwaki and Potawatomi used it in smudges to revive unconscious patients. The Chippewa smoked New England aster during hunting trips to attract animals. The smoke seemed to resemble the natural scent of deer (2). The smoke was also believed to keep evil spirits away (2). Ojibwe also smoked the young leaves of the aster to attract deer when hunting (1) and used it for food.

bleeding (5). The plant is considered dangerous to use internally—too much of it is poisonous—but the medicine men and women had much skill with using poisonous plants (1).

Columbine

(Aquilegia canadensis): The chewed root was used to treat stomach and bowel troubles. Many tribes used an infusion of columbine to relieve itching caused by poison ivy and other skin rashes (2). The Meskwaki also used the seeds to scent tobacco smoked in ceremonies. The fragrance was believed to hold strong powers of persuasion (2). Seeds were useful to lovers. They were “chewed into a paste and applied to just the right areas” (2).

Wild Ginger

(Asarum canadense): The Ojibwe word for this plant, paabwan, means “seasoner.” Not only did they find it flavorful, they also knew about

Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca, A. incarnata): These plants have provided fiber, food, and medicine for native people all over the United States and southern Canada. Milkweed species have been used in salves, as diarrhea medicine, as a contraceptive, to relieve sore throats, expel tapeworms, treat colic, and to cure snakebites. The chewed root was applied to swelling and rashes. The Winnebago used the spring greens in soup. Chippewa made an infusion from the root to add to a strengthening bath for children (1). Milkweed fiber was also enormously useful and was made into fishnets, wampum belts, and other types of rope (1).

).

26 The Herbarist i Issue 77 2011

Native Americans believed that the fragrance of columbine held strong powers of persuasion. Photo by Robin Siktberg

The blooms of milkweed (Asclepias syriaca

Photo by Robert Vidéki, Doronicum Kft., Bugwood.org

Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera): An immensely important plant to Native Americans, the paper birch was used for medicine, decorations, canoes, shelter, and much more. The root was used to flavor Ojibwe medicine in order to disguise unpleasant tastes (1). It was cooked with maple syrup to alleviate cramps (1). The Potawatomi used birch twigs in a similar manner and also chewed the twigs to relieve the pain from many types of ailments (2). (Little did they know that the twigs contain methyl salicylate, one of the components of aspirin). An infusion made from the leaves and twigs provided relief from skin sores and other ailments (2). Menominee tribes valued birch as a tonic and as a treatment for dysentery and pain. The inner bark yielded a red dye. Snowshoes, sunglasses, wigwams, torches, and of course, canoes were made from the outer bark (2). Broken limbs were wrapped in soaking wet birch bark; when it dried, it shrank around the limb and held it securely in place (2).

Black Cohosh (Actaea racemosa, syn. Cimicifuga racemosa): Native Americans boiled black cohosh root in water and drank it for rheumatism, sore throats, rattlesnake bites, gynecological problems, and childbirth. In the nineteenth century, black cohosh root was often combined with alcohol to produce Pinkham’s Compound; a home remedy for female ailments which later became a patented medicine.