HSA Board of Directors

Susan Liechty President

Rae McKimm Vice President

R ie Sluder Secretary

Linda Lange Treasurer/Finance

Pat Greathead Central District Membership Delegate

B onnie Great Lakes District Porterfield Membership Delegate

Cindy Meier Mid-Atlantic District Membership Delegate

J en Munson Northeast District Membership Delegate

S ara Holland South Central District Membership Delegate

P.J. Stamps- Southeast District

K itchen Membership Delegate

J ody Lacey West District Membership Delegate

Jackie Johnson Publications Chair

K aren O’Brien B otany & Horticulture Chair

C arol Schmidt D evelopment Chair

Dava Stravinsky Education Chair

Pat Sweetman M embership Chair

D ebbie Boutelier Nominating Chair/Past President

D ebra Knapke Ho norary President

K atrinka Morgan E xecutive Director

Administrative Staff

K atrinka Morgan E xecutive Director

L aurie Alexander M embership Coordinator

Christina Wilkinson Librarian/Archivist

K aren Kennedy Ed ucation Coordinator

Amy Rogers O ffice Administrator

K aren Frandanisa Accountant

Brent DeWitt Editor/Designer

The Herbarist

Brent DeWitt Editor/Designer

SP Mount Printing Printer

The Herbarist Committee

Jackie Johnson Publications Chair

Lois Sutton, Ph.D. Chair

Jean Berry

Shirley Hercules

Pat Larson

G ayle Southerland

B arbara Williams

The opinions expressed by contributors are not

This issue of The Herbarist celebrates The Society’s gardens, gardeners, educational programs, and especially, The National Herb Garden. Herbs enrich and enhance our lives. An herb garden intertwines the worlds of cooking, gardening, healing, and history. The lives of The Society’s members have all been touched in one way or another by herbs.

We celebrate the 35th anniversary of the National Herb Garden with the history, a photographic tour of the seasons, and an interview with three past curators. Learn about the living collections policy and how it affects the National Arboretum’s past, present and future of plant materials.

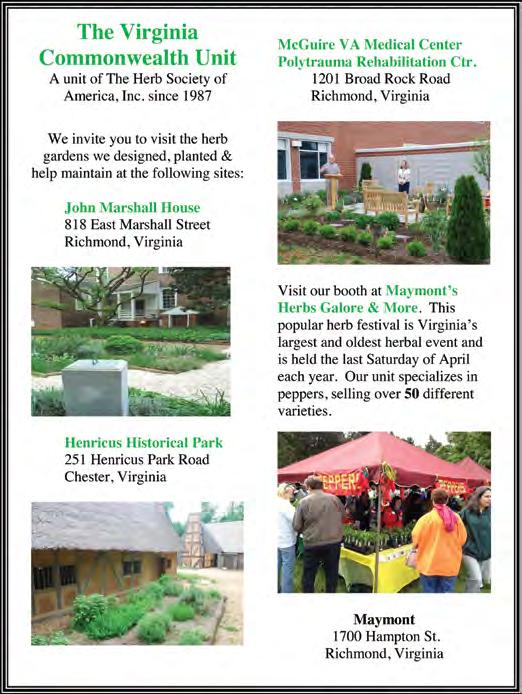

Gardens hold the power to captivate our attention no matter the size. The Gardens of The Herb Society of America is a recent signature program to emphasize the value we place on one of our most important community outreach efforts, HSA’s unit herb gardens. The many gardens featured in this issue will take you on a journey across the country.

If you are looking for ways to make your own garden more earthfriendly, read about the native herb conservation program, GreenBridges. This program brings awareness to native plants and demonstrates how to create spaces for pollinators to live and thrive.

There is something reassuring about herbs. They are predictable, reliable and timeless. Anne Abbott shares her many years of experience with the plant collections held by HSA members around the country. See why we are so proud of our collections, and how you can continue to help support these wonderful botanical gems.

A garden can be a state of mind as well as a place to be — those of us who love the garden somehow manage never to forget that. Beth Haebel shares her experience of visiting an herb garden early in her life. We find such wonderful people and experiences in a garden.

If you think your treasured herbs can educate only in their garden settings, read “Get Ready, Get Set and Show” Elizabeth Kennel covers all the aspects of flower and herb judging, giving you tips for winning that blue ribbon.

The Herbarist 2015 demonstrates to all of us, especially the next generation of gardeners, how one’s actions today can positively affect the future. Who would have thought over 35 years ago that an idea planted in the minds of several dedicated and passionate Society members would become the National Herb Garden that we know and love. The Herb Society of America will remain a leader in the herb world as long as we keep our roots firmly planted and continue the time-honored tradition of herb gardening.

Susan Liechty HSA President, 2014–2016

3 Issue 81 2015

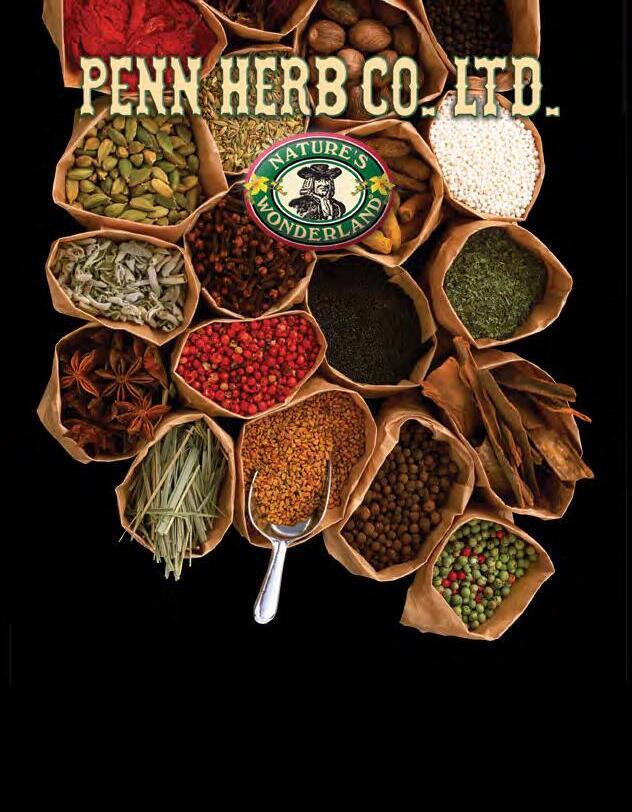

necessarily those of The Society. Manuscripts, advertisements, comments and letters to the editor may be sent to: T he Herbarist, The Herb Society of America 9019 Kirtland-Chardon Rd. Kirtland, Ohio 44094 440.256.0514 www.herbsociety.org T he Herbarist, No. 81 History of NHG . . . . . . . . 4 By Sandy Salkeld de Holl Value in the Genes . . . . . . . . 8 By Scott Aker NHG Photo Gallery . . . . . . . . 13 By Pat Kenny Integrity and Outreach: Building a Strong Foundation for the National Herb Garden . . . . 18 By Chrissy Moore A Conversation With Past NHG Curators . . . . 26 By Holly Shimizu, Jim Adams, Janet Walker Under the Arbor: An NHG Educational Series . . . 30 By Billi Parus, Chrissy Moore Plant Collections of The Herb Society of America –2015 . . 33 By Anne Abbott GreenBridges: A Way of Life . . . . . . 40 By Lorraine Grochowski-Kiefer Promising Plants –Where Are They Now? . . . . 44 By Karen Kennedy Learn, Explore, Grow –Visit the Units’ Gardens! . . . 47 By Lois Sutton Ph.D. Pharmacy Garden . . . . . . . . 54 By Henry Flowers Herb Gardening in Large Public Venues . . . . 58 By The Herbarist Committee A Lesson in Taxonomy in a Public Herb Garden . . . 64 By Barbara J. Williams Get Ready, Get Set, Show! Going For The Blue At A Flower Show . 71 By Elizabeth Kennel On the cover: Back to the Garden by Brent DeWitt, Editor Digital Illustration Welcome toThe Herbarist! It is the policy of The Herb Society of America not to advise or recommend herbs for medicinal or health use. This information is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered as a recommendation or an endorsement of any particular medical or health treatment.

very special seed was sown in 1957, when Mrs. Foster Stearns, then editor of The Herbarist, wrote “My dream for the future is that some day we can have a national demonstration of some sort, in some central spot, and

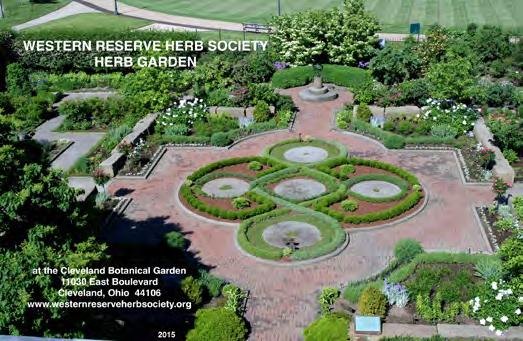

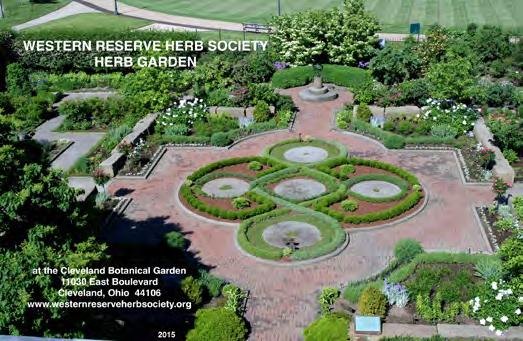

garden. She had chaired the Western Reserve Unit while they were establishing a garden at the Garden Center of Greater Cleveland, now the Cleveland Botanical Garden. This experience served her well as she held many consultations with lawyers

The National Herb Garden–Years and Still Growing!

Sandy Salkeld de Holl

It is the largest designed herb garden in North America . It has been called a jewel in the crown of the United States National Arboretum in Washington, D .C . It is a true national treasure

It is the National Herb Garden, and it was given by The Herb Society of America to our nation to celebrate the Bicentennial

As we celebrate its 35th Anniversary, we should reflect on how it all began .

bring our many varied gifts of specialized knowledge and talent to bear. With everyone contributing we may really surprise t he world.” Many did contribute in countless ways, but the seed lay dormant for almost ten years.

In 1966, HSA president Edna Cashmore said, “It has long been a dream of mine to establish an herb garden at the United Nations.” She continued to pursue this as chairman of a specially formed HSA garden committee. Later that year the committee learned that there were plans to develop demonstration gardens at the U.S. National Arboretum. The arboretum director, Dr. Henry Skinner, informed the garden committee that they could proceed with plans and designs for about one acre, on any of several sites. The HSA board accepted the project at their April 1967 meeting. Our special little seed had begun to germinate albeit very slowly. The committee developed a garden plan that included planting advice. It soon became clear, however, that The Society would have to provide the funds for construction.

Genevieve Jyurovat, HSA President from 1974-1976, was very knowledgeable about legal arrangements for a large public

United States.”

Our little seed again began to stir. The Society was fully committed to the National Herb Garden project and to all the many pieces involved in putting it together. Mrs. Jyurovat stated in the April 1976

and federal officials during her frequent trips to Washington on behalf of the herb garden. Mrs. Jyurovat was recognized for her huge contribution to this project when she was awarded a Certificate of Achievement in 1987.

Ultimately, a bill was sent to Congress that, for the first time, would permit the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to accept fully tax-deductible gifts on behalf of the National Arboretum. The Senate passed it on July 25, 1975 and the House followed on November 4. Meetings resulted in an agreement between The Society and the Agricultural Research Service (ARS).

Society President Genevieve Jyurovat and the First Vice-President Elizabeth 'Betty' Neavill signed the agreement January 21, 1976. It was approved by leaders of USDA and ARS in February 1976. The agreement states in part, “The parties to this agreement desire to make arrangements of the design, construction, development, maintenance and preservation of a National Herb Garden on the grounds of the United States National Arboretum located in Washington, D.C. for their mutual benefit and the benefit of the people of the

Department of Agriculture’s newsletter, Research News, “It is particularly appropriate to initiate such a Garden in connection with America’s Bicentennial. An Herb Garden at the Arboretum will sum up the long contribution herbs have made to America’s well-being, pleasure and commerce and serve as an introduction to their new role in science. It will be a teaching garden, an historic garden and a garden of the finest in design and planting. Above all, it will be a garden of inspiration and continuity and affection. Each ethnic group will discover something of its heritage here, and just as America brought a diversity of people together and enriched their lives by their being together, so will the National Herb Garden.”

The ARS chose a site next to the administration building at the arboretum. Because of this location, the designated garden site was a little more than two acres. The ARS agreed to provide utilities for construction and maintenance, to provide background plants as available, to arrange for the construction and supervision of these to assure completion of the garden, and to provide labor and other services for the maintenance of the garden. The Society

4 5 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

Lef T L–R 'Skip' March (Supervisory Horticulturist for the U.S. National Arboretum), Betty Rea, Dr. John Creech (Director of the Arboretum) and Tom Wirth (Landscape Architect for Sasaki Assoc) review the site plans for the National Herb Garden. A B O ve: HSA group placing the initial site location sign for the National Herb Garden (including edna Cashmore center)

shouldered the responsibilities for contributing funds for the construction and development of the garden; for consulting in the design, planting and construction of the garden (along with the ARS); and for selecting and paying a landscape architect. The architect’s charge was to prepare detailed plans, specifications, cost estimates, and a timetable for the completion of each stage of construction. A concept plan had been prepared for the garden by Elsetta Barnes, an HSA member and a landscape architect, who had designed the Western Reserve Garden. Unfortunately, she could not continue the project and The Society selected Thomas Wirth of Sasaki Associates in Watertown, Massachusetts.

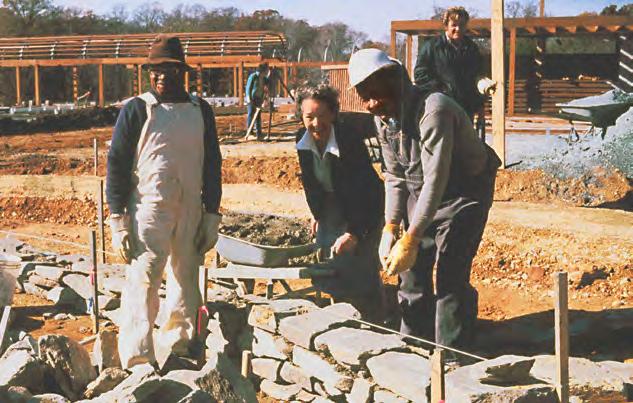

Katharine T. Patch., another member of Western Reserve Unit, chaired the committee to raise initial funds. Genevieve Jyurovat, Edna Cashmore and others attended a ground-breaking ceremony in June 1976. A job sign now identified the site as the future National Herb Garden, noting that this garden was a Bicentennial gift from The Herb Society of America to the nation. Our special seed had found its garden home.

At this time The Society presented a check for almost $18,000 to the Director of the Arboretum, Dr. John Creech. The initial proposed fund drive to raise $200,000, with a matching amount to be provided by the government, soon became woefully inadequate due to ever-rising costs. The Society agreed that fund raising should be organized by its members, avoiding paying large consulting fees to professional fundraisers. Booker and Mary Worthen became treasurers of the National Herb Garden Fund while Roland and Ruth Remmel assumed the task of raising $400,000. When nearly half this amount

Herb Garden fund.

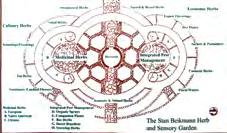

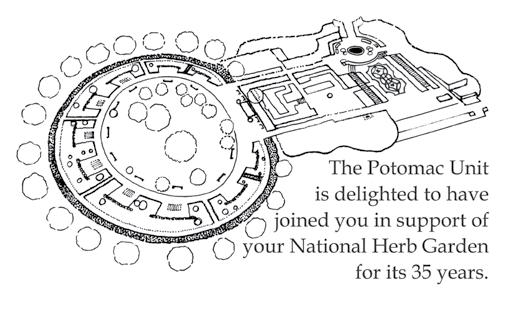

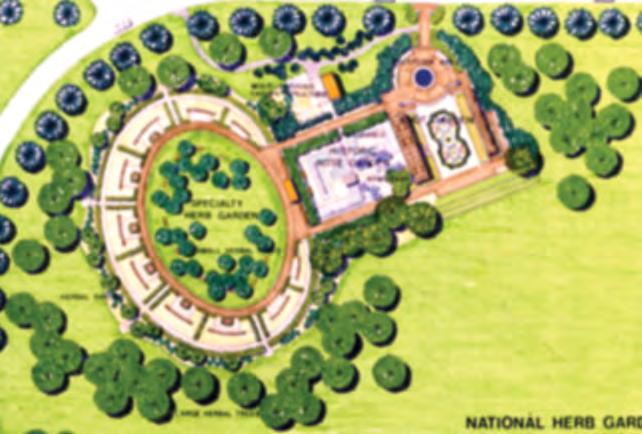

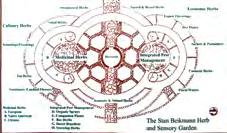

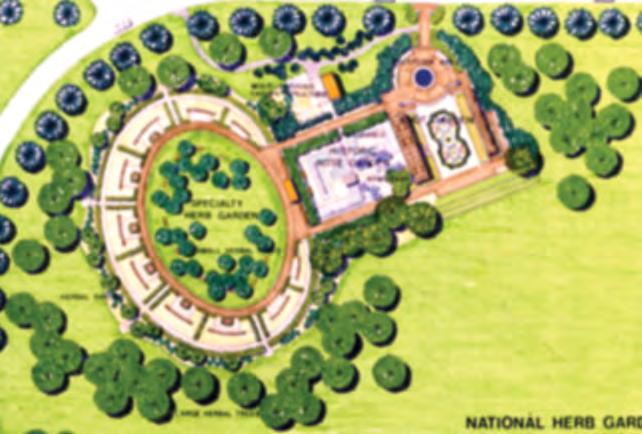

The garden plan is key-shaped— with specialty gardens forming the head, a historic rose garden the shank, and the knot garden with the reception area above, the bit. The key symbolically opens the door to education, beauty and the sharing of herbal knowledge.

had been raised, HSA went outside the organization and published articles in many newspapers and magazines throughout the country, raising more funds. HSA president Betty Rea met with the Secretary of Agriculture and, in March 1978, appeared before the Appropriations Subc ommittee of Agriculture, Rural and Related Agencies. This committee was chaired by Jamie L. Whitten, Congressman from Mississippi. The Society requested a government appropriation of $200,000 to match our contribution to the National Herb Garden. We had already raised nearly that amount. While the federal funds were a lready in the Agricultural Appropria-tions, they had been dropped due to President Jimmy Carter’s demands for economy and budget cutbacks. Enter the intrepid Mrs. Rea who regularly visited congressmen

a nd lobbied to have the funds restored. Armed with her basket of tussie-mussies (freely distributed), her ready smile and her charming gift of persuasion, she became known to the guards and was even given a temporary parking place at the Capitol.

At last, in October 1978, the appropriations bill was signed by President Carter, including the restored funds for the garden. A bulldozer, with a tussie-mussie attached to the mirror for luck and Mrs. Rea on board, broke ground for the garden. Our special seed had finally broken dormancy and was above ground!

As this was going on, the National Herb Garden committee met at the arboretum and decided on basic plantings and titles for the ten specialty gardens— Dioscorides, dye, colonial, Native American, medicinal, culinary, industrial, fragrance, oriental, and beverage. Using authoritative references, the plant lists give exact landscape descriptions and uses for the plants. The garden plan is key-shaped with specialty gardens forming the head, a historic rose garden the shank, and the knot garden with the reception area above, the bit. The key symbolically opens the door to education, beauty, and the sharing of herbal knowledge.

The National Herb Garden was dedicated on a lovely summer evening, June 12, 1980.

The U.S. Marine Band provided music, Dr. John Creech, Director of the Arboretum, greeted attendees, and Ann Burrage, one of the seven founders of The Herb Society of America, presented the National Herb Garden to the people of the United States.

Joan Mondale, wife of the Vice-President, accepted the garden for the American people. Mrs. Burrage said the occasion was “the Mt. Everest of my life.” Other speakers were two staunch supporters of the NHG,

The Honorable Bob Bergland, Secretary of Agriculture, and The Honorable Jamie L. Whitten, Congressman from Mississippi.

The final fund-raising report was submitted in 1982 after all pledges had been paid in full. The effort spearheaded by the Worthens and Remmels raised $419,361.69. What a monumental achievement under their leadership along with the support of many dedicated members and friends!

The Society has been so fortunate to work with the NHG Curators employed by the arboretum. There have been four— Holly Shimizu, Janet Walker, Jim Adams, and Chrissy Moore. Each has given their special expertise in caring for and planning the future of the garden. They have given lectures, workshops, answered countless questions from visitors, and corresponded with herb lovers around the world. They have visited many units and members at large making it possible for those who cannot visit the garden to still feel a part of it.

The curator cannot possibly maintain the garden alone. The HSA supports a garden fellow to assist the curator. This has been made possible through contributions to Friends of the National Arboretum (FONA) and to the HSA National

A fter partial contributions for some years the Fellow is now fully funded by contributions from members. Also key to keeping t he garden pristine at all times is a cadre o f volunteer s some from the local community, some HSA members at large, and some from the National Herb Garden committee composed of one member from each unit located within a day’s drive of the garden. Many members participate in “Under the Arbor” programs, given in good weather. These programs (described more fully elsewhere in this issue) may be demonstrations and/or hands-on herbal workshops. All are educational, very popular, and fun for visitors.

An article in The Herbarist of 1980 by Carolyn Cadwalader, then chairman of the National Herb Garden committee, states, “The National Herb Garden is the culmination of many years of cooperative effort from public and private sectors of the United

States. The Herb Society of America provided t he original drive, selected one of the top landscape designers in the country, raised most of the money from small contributions of interested individuals in The Society, and combined its collective knowledge in the growing and use of herbs, and in research and horticultural wisdom.” The previous year, HSA president Eleanor Gambee said, “To laud the few who initiated this project or those who struggled with its progress over the intervening years would be to discriminate against the hundreds of dedicated members who also have worked toward the achievement of establishing the finest herb garden in the world.”

Our special seed is now a flourishing herbal tree. Its branches are strong because of the dedication of our members; it is recognized around the world. Hopefully its seeds will germinate and develop into strong branches of herbal knowledge for generations to come.

In her 1983 garden chairman’s report, Henrietta Truitt summed up the feelings of HSA members for the National Herb Garden, “Our name, and our national and international image are represented in our Garden. We want to maintain it as we w ish it to be maintained and take pride in what it represents to the public. For, what is a garden? First, it is made of dreams and plans; second, it is the plants themselves, and last but not least, it is the one who loves and tends it.”

That would be the members of The Herb Society of America.

Happy 35th Birthday — From the HSA to the USA!

Sandy Salkeld de Holl has been an HSA member since 1981. She is a member of the Philadelphia Unit, where she served as chair, and the North Carolina Unit. Sandy was the first Mid-Atlantic District membership delegate and has chaired the National Herb Garden committee. To celebrate the NHG’s 25th anniversary she began a “25 for 25” campaign that, with the support of many units and members, raised over $25,000 for the National Herb Garden. for this effort she was honored with an HSA Certificate of Achievement. Sandy has been an active volunteer at The Philadelphia flower Show for over 40 years. She presently serves as Chair of Judges Activities. Her love of gardening follows her to North Carolina where she is a member of the Porters Neck Garden Club and the Cape fear Garden Club.

6 7 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

NHG circa 1979

NHG circa 2007

NHG today

Still Growing!

f om Left: Carolyn Cadwalader and Betty Rea

35 Years and

Value inthe Genes

Scott Aker

Most visitors to the U.S. National Arboretum come to see the beautiful gardens that we cultivate, to get some ideas for their own garden, or to enjoy a nice walk. Herb lovers might focus on the ways the plants we display are important sources of flavorings, medicines, beverages, and fragrances. Those with an environmental interest might visit to enjoy the birds and butterflies that live here. However, hidden in plain view among all of these things is the scientific value of the plant genetic resources in our gardens and collections.

both, providing a resource for education and plants that are valuable in research efforts.

The business of developing and maintaining the scientific resource in our gardens is not as straightforward as cultivating gardens for purely aesthetic or educational motives. To maintain plants with scientific integrity, we must carefully select our sources for plants and maintain detailed records relating to those plants.

Just a few years ago, the arboretum adopted a new Living Collections Policy to guide decisions relating to the plant collections at the arboretum. The Living Collections Policy is located at http://www. usna.usda.gov/Information/USNA CollectionsPolicy.pdf. It provides the broad parameters by which new plants will be incorporated in our gardens and collections. At the same time, it provides measures for evaluating existing plants in our collec-

almost never the same throughout its range, this may mean collecting many different accessions of the same species over a broad geographic range. This does not mean that species may only be obtained through the collecting activities of arboretum staff. Seed or plants obtained from other collectors may be used as long as the necessary data were recorded when the collection was made. Generally, this consists of a precise description of the area wherein the plant was collected; a description of the elevation, topography, soil type, and associated plant species at the collection site; digital images of the plant growing in the site, including distance and close up shots; and a dried pressed herbarium specimen of the plant. With all this information, scientists can return to the site to collect from the same population of the plant if needed and they can view morphological details on digital images and on the pressed herbarium specimen to resolve any identity issues that arise and ensure that the seeds from a collection are similar to the original plant when they are germinated and grown into mature plants.

Genetic resources aren’t readily apparent since their essence lies at the cellular level in the DNA of the plants in our gardens and in the detailed records we keep behind the scenes. The U.S. National Arboretum is part of the Agricultural Research Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. As part of the nation’s premier plant research organization, we place great emphasis on the scientific value of the plants in our collections. When the arboretum was established by an act of Congress in 1927, it was created to provide education for the gardening public and conduct ornamental plant research and development. Our gardens do

t ions to ensure that what we already have provides the desired scientific value and for a deaccessioning process when they don’t. With new policy comes change, and the biggest change with the adoption of the Living Collections Policy has been the manner in which we obtain plants for our gardens and collections. The policy recognizes two broad categories of plants with regard to source requirements— species and cultivars.

The guidelines within the policy mandate that species to be added to the collection be collected from wild populations within the natural geographic range of the species. The goal here is to capture the true genetic resource of plants that have not been altered or selected in some way. Since the genetics of a given species are

In the National Herb Garden, a good example of a wild-collected plant is Artemisia frigida, collected in 2011 from a population growing in Thunder Basin National Grassland in Wyoming. It is growing in the Native American theme garden in the National Herb Garden, where it fits because of its use by the Lakota and other tribes as a medicinal plant.

Since cultivars are cultivated varieties of plants, it is not possible to obtain plants of cultivars from wild populations. Instead, the Living Collections Policy mandates that cultivars come from an originating source. This sounds simple enough when you consider some recent cultivars, such as Lavandula ×intermedia ‘Phenomenal’, introduced by Peace Tree Farms in 2012. It gets more difficult when you start talking about cultivars that have been around for decades. Lavandula angustifolia ‘Hidcote’ was introduced by Major Lawrence Johnston of Hidcote Manor in Gloucestershire, England around 1920. After the passage

8 9 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

in the

Our own Chrissy Moore (NHG curator) working in the field

Value

Genes

of all that time, it becomes progressively more unlikely that the original plant still exists. You might think that since cultivars are perpetuated through asexual means of propagation, such as rooted cuttings, that any ‘Hidcote’ would do if we need to add it to our collections. Unfortunately, there is the problem of cultivar drift. Nursery propagators tend to set aside the healthiest of the new plants that have been propagated for use as stock plants for next season’s cuttings, and with this, there is a tendency to select for more robust and vigorous mutations of the mother plant. The difference may be negligible at first, but after generations and generations of mother plants and cuttings, the progeny may be quite different from the original plant. In fact, there is now a cultivar known as ‘Hidcote Superior,’ introduced in 2001, that was selected from cuttings of ‘Hidcote.’ So, getting as close to the original source as possible is important if we are to maintain integrity in our collections.

Sometimes cultivars are nearly impossible to track down. A good example is the double form of tuberose, which is more common than the single form. Polianthes tuberosa ‘The Pearl’ dates back to 1870. It would be difficult to find information about the entity that introduced it, let alone locate the original plant.

Collecting plants in the wild comes with its own limitations. First, we must be able to locate and legally collect plants. Development throughout the world has placed pressure on plant species in the wild, and conversion of wild land into farm fields or homes erases the native flora of a given location. Climate change, invasive plants, diseases, and pests add to that pressure. In most instances, threatened and endangered plants may not be collected, and some may not be transported from point A to point B because of the threat of transporting diseases or pests that are known to be associated with that plant species.

The Convention on Biological Diversity established international regulations on conservation, sustainable use, and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from genetic resources. In short, plant and

animal genetic resources are the sovereign property of the country of origin, and access to them requires appropriate approvals and agreements on benefits sharing. Many signatory nations do not issue national permits, or make provisions for open access to collected plant material, and this has effectively ended plant collecting in some countries for us.

The arboretum has participated in collecting trips in China since 1980, as the principal botanical partner in the SinoAmerican Botanical Expedition, and later as part of the North America Chinese Plant Exploration Consortium (NACPEC) with other public gardens in the United States and Canada. The plants that were acquired gradually built up the holdings we have in the China Valley section of the Asian Collections at the U.S. National Arboretum. At last count, there are 366 wild collected accessions in China Valley. For the past ten years, we have not been able to participate in collecting trips to China because it hasn’t been possible to get the required permit, and we haven’t been able to add plants collected by other consortium members, since they have

Development throughout the world has placed pressure on plant species in the wild, and conversion of wild land into farm fields or homes erases the native flora of a given location. Climate change, invasive plants, diseases, and pests add to that pressure.

been collected with permission from local and regional officials, and not the appropriate national designates.

Even though we haven’t been able to do much plant collecting abroad, there is potential for collecting in our own country. Although we have some native herbs on display, primarily in the Native American theme garden, most of them are not wild-collected. Wild-collected plants can be used to replace species that come from unknown or nursery sources. It would also be good to grow a broader representation of native herbal plants that are native to parts of our country beyond the Mid-Atlantic region.

Why is it important to spend so much time and effort on our plant genetic resources? Having well documented plants is key to any breeding program, and knowing the details about the plants you consider using is key to deciding whether they may be useful in breeding efforts. Correctly identifying our plants is very helpful in studies to work out the genetic relationships between plants. Collecting efforts and careful source selection for cultivars will allow us to assemble a thoroughly documented genetic resource. Then we must preserve it to ensure that it will be alive and available when we need it, sometimes even for purposes we could never possibly anticipate. Our rosemary collection was used by one researcher investigating an antioxidant compound found in the plant to determine which varieties produce the highest amount of that compound. His research was part of a quest to find natural preservatives for meat that would not adversely affect flavor. Much later, in a visit to my local supermarket, I found rosemary extract listed as an additive on prepackaged meat, evidence that our collections played an important part in research that did benefit the general public.

Often we spend decades assembling and tending our plant genetic resources.

The National Boxwood Collection at the U.S. National Arboretum came about in the 1950s when Director Henry Skinner brought a great diversity of plants from his boxwood selection efforts at the Morris

Arboretum to the National Arboretum. It has been carefully added to and documented since then. The appearance of boxwood blight in recent years led to heightened interest in the collection, widely recognized as one of the most diverse boxwood collections in the world. Researchers now recognize it as a critical resource in efforts to breed resistant boxwood, and work is now underway at the arboretum’s Floral and Nursery Plants

Research unit to better understand the genetic relationship of different taxa as an aid to future breeding efforts.

The arboretum’s living collections, particularly wild collected material, are part of the Woody Landscape Plant Germplasm Repository (WLPGR) within the USDA’s National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS). Because of this, many of the arboretum’s plants appear in the Germplasm Resources Information Network

(GRIN), an online resource that anyone can use to find plants that the Agricultural Research Service maintains in its collections. Researchers, breeders, nursery professionals, and public gardens may request propagules through the internet. Quantities are limited, and distribution requests are reviewed by curators who make the ultimate decision as to availability. The plants listed in GRIN tend to be species collected in the wild or obscure cultivars plants that cannot be easily acquired from nurseries or seed dealers. There may be a long wait for seeds or cuttings, since seed may not be available or it may be the wrong season to take cuttings, and sometimes our holdings consist of a very small number of plants. The National Arboretum distributes material through the WLPGR to national and international cooperators, and this role will only increase as we strengthen our role in conserving plant genetic resources important to our nursery and landscape industries.

Who determines what kinds of plants we should have in our gardens and collections? One of the provisions of the Living Collections Policy is the formation of the Plant Collections Committee. Composed of various arboretum staff members, it provides oversight for the collections to ensure proper alignment with research, educational, and display priorities and the USNA Strategic Plan. Their work helps us to know which plants belong in which collections. One of their current initiatives has been writing C ollection Development Plans for each of the arboretum’s plant collections and gardens.

While the Living Collections Policy was written over a period of many months with many opportunities for thought, review, and editing, it is considered to be a living document. While its terms intentionally limit what may be planted in a collection, it was never intended to be a roadblock that would prevent the development and refinement of our gardens and collections at the arboretum. When we began the design phase of our current project to renovate the Friendship

10 11 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

Rosemary Collection

Value in theGenes

Garden, we quickly realized that the requirement for original source cultivar material or wild collected plants would cause replanting of perennials in the renovated garden to be problematic. The Plant Collections Committee examined the problem and determined that some of these requirements could be relaxed with regard to herbaceous perennials. They clarified that while we should still do everything that we can to obtain plants from an originating source or from w ild populations, it is not an absolute requirement. As a minimum, we do need to be sure that we obtain plants from highly reputable sources that are very careful about properly labeling the plants they grow and sell.

How will the Living Collections Policy shape our collections in the future? Their development will be much more deliberate and more carefully planned, marked by a commitment to continuously work to refine the plants we have in them.

Plants that do not have adequate records and plants that cannot be definitively identified as to species or cultivar might have to be replaced by known entities. This will not be a drastic change over a short period of time, but will rather be a very gradual and subtle change done plant by plant over many years. This g radual approach will allow us to maintain the beauty and educational value of our collections while we steadily improve their scientific value.

Scott Aker is Head of Horticulture and education at the U.S. National Arboretum (USNA) in Washington D.C. He manages curators, technicians, educators, and horticulturists and provides oversight for some of the most notable plant collections in North America. Prior to serving in management, Aker was the horticulturist in U.S. National Arboretum. He earned his Master’s Degree in Horticulture from the University of Maryland and his Bachelor’s Degree in Horticulture from the University of Minnesota.

A native of the Black Hills of western South Dakota, Aker served for a short time with the University of Maryland Cooperative ex tension Service in Howard County, Maryland after completing his master’s thesis. Aker wrote Digging In a weekly garden question and answer column in the Washington Post. He now writes Garden Solutions, a column in The American Gardener.

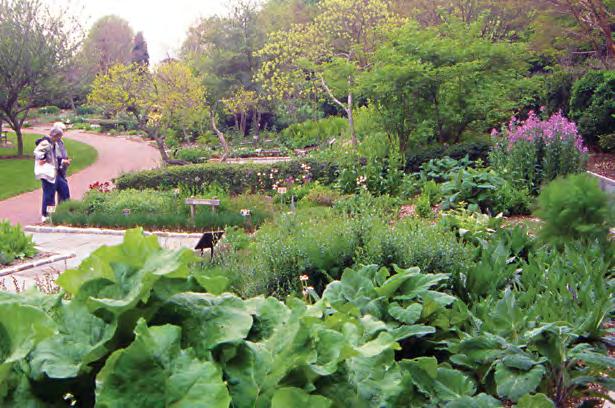

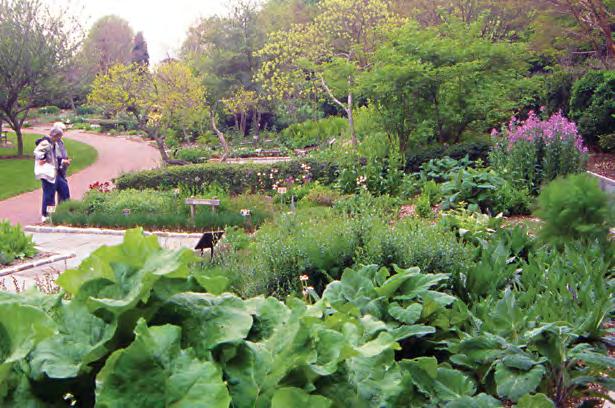

The National Arboretum website states that the National Herb Garden “is a captivating place to visit any time of the year.” This garden offers the resurgence of spring, the exuberance of summer, the colorful maturity of fall and the quiet dignity of winter. In these photographs we offer views of the nooks and crannies of the garden as well as garden activities across seasons, and across years. Stroll slowly through these images, whether this is your first visit or simply the most recent of many. Appreciate what this gift from The Herb Society of America is.

12 13 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

In FOCuS: THe nATionAl HerB gArDen

Value in theGenes Show me your garden, and I shall tell you what you are. — Alfred Austin Poet Laureate of the united Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1896–1913

Wild-collected Glycyrrhiza glabra from Azerbaijan

A BOv e L ef T Yellowwood (Cladrastus kentukea) in bloom in the entrance Garden (May 2010) A B Ove: White blooms of Rosa rugosa ‘Henry Hudson’ Be LOW L ef T Ornamental edibles display in the entrance Garden (Mar 2012) Be LOW C e NT e R early spring planting of tulips and strawberries in the entrance Garden (Mar 2012) B e LOW RIGHT: Wild-collected germander (Teucrium polium) from Azerbaijan (2009) BOTTOM L e f T: Rosmarinus officinalis ‘Logee Light Blue’ flowers (Mar 2012) BOTTOM RIGHT: Rosa ‘ v ck’s Caprice’ (Apr 2012)

14 15 The Herbarist issue 81 2015 In FOCuS: T H e nAT i onAl Her B gAr D en

A B Ove: Brick walk to the Theme Gardens (7 May 2009) Lef T: NHG sign accented by tulip cultivars and Allium alfatunense cv. (22 Apr 2010) Be LOW Restful bench in the rose garden (30 May 2014)

Spring

Lef T: ×Citrofortunella microcarpa (calamondin) in the entrance Garden (Apr 2012)

ABOve Papalo/yerba porosa (Porophyllum ruderale) in the Culinary Garden (July 2014) Be LOW: v ew of the Knot and entrance Gardens (July 2014)

A B Ove: entrance Garden fountain and herbal grasses display (July 2014) RIGHT: entrance sign with the Herb of the Year, Artemisia, in foreground (May 2014)

BeLOW: Basil cultivars and purple sugar cane in the Culinary Garden (July 2014)

16 17 The Herbarist

In

T H e nAT i onAl Her B gAr D en

Issue 81 2015

FOCuS:

Summer

A B O v e: Stand of Salvia leucantha ‘Midnight’ (Mexican bush sage) in the entrance Garden (Nov 2014)

Lef T: Herb of the Year basil around the Armillary in the Rose Garden (Sept 2003) BeLOW Lef T: vetiver grass (Chrysopogon zizanioides) and lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in the entrance Garden (Nov 2014)

A B Ov e: Asian Garden (Sept 2009) ABOve RI GHT: Pelargonium echinatum blossoms (Nov 2014) B e LOW L ef T: Asian Garden with Celosia argentea var. spicata flamingo feather’ in the foreground (Oct 2014)

B e LOW RIGHT: Purple amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus cvs.) and zinnias (Zinnia cvs.) in the Dye Garden (Sept 2009)

19 issue 81 2015

Fall

In FOCuS: T H e nAT i onAl Her B gAr D en

In FOCuS: T H e nAT i onAl Her B gAr D en Winter

A B Ov e: A resident mockingbird overlooks the Knot Garden (Jan 2015) L e f T: West arbor, the site of many Under the Arbor educational programs conducted by HSA members (feb 1999) B e LOW: view from the Colonial Garden looking out over the neighboring Theme Gardens (Jan 2015)

BOTTOM: A winter walkabout provides views through the Atlas cedars to the NHG beyond (Jan 2015)

A B Ove: A view into the snow-covered Rose Garden (8 feb 1997) ABOve RI GHT: Lindera umbellata (kuro-moji) leaves provide winter beauty in the fragrance Garden (Jan 2015)

BOTTOM RIGHT: The Armillary stands sentinel in the wintry Rose Garden (Jan 2015) BOTTOM

L e f T: view of the rosemary (Rosmarinus cvs.) collection and the Capitol Columns through the dwarf river birches (Betula nigra ‘Little King’ fOX vALLe Y ) (Jan 2015)

The National Herb Garden with its specialty beds, changing entrance garden and extensive collections is a testament to “the glory of gardening.” We hope you have been nurtured by this fabulous garden.

The glory of gardening: hands in the dirt, head in the sun, heart with nature. To nurture a garden is to feed not just on the body, but the soul.

— Alfred Austin Poet Laureate of the united Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1896–1913

Pat Kenny, a member of the Potomac Unit, has been a member of The Herb Society of America since 1979. She has been very active on the National Herb Garden committee. Her career as a medical illustrator carried over to botanical illustration as well as nature photography. She received the Helen de Conway Little Medal of Honor, the highest award given by The Society, in 2015. An apt description of Pat stated: Her “adherence to plant nomenclature and accuracy in depicting in art are balanced by a gardener’s pragmatic instincts and a scholar’s tenacity in seeking out truth.”

20 21 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

i n T egri T y & o u T r e ACH:

Building A Strong Foundation For The National Herb Garden

Chrissy Moore

The National Herb Garden (NHG) resides on 2 ½ acres of prime real estate at the U S National Arboretum in Washington, DC Its high profile location puts it in the public eye and also invites professional scrutiny In such a situation, the pressure to maintain quality collections and educational opportunities guides many of our decisions . To assist staff in collections maintenance, the National Arboretum adopted a new Living Collection Policy in 2012 that delineates numerous parameters to which each garden or collection must conform to uphold its integrity and accuracy within the scientific plant community . (See Scott Aker’s corresponding article)

First Things First: Primary Source Challenge

The Arboretum’s Living Collection Policy strongly encourages— and in some cases, mandates— the acquisition of plant material from known primary (original) sources. For species, this means collecting them within their native range, and for cultivars, this means obtaining plants from whoever introduced or named it. This

can be a challenge in the NHG as many herbs currently in cultivation are so far removed from their native wild origin that tracking down an herb’s primary source is nearly impossible. Additionally, because so many herbs are easily propagated and passed along, finding the original source for any given cultivar can be difficult at

best. While identifying herbal progenitors is a key component of the primary source dilemma, an even more pressing concern is proper identification and deciphering correct nomenclature.

Throughout the herb world, accurate nomenclature is a problem made worse by the situations alluded to above. In order to

accurately source your plant material, you absolutely need to have a correct name; otherwise, we you have no idea whether we are talking about the same plant or what plant you are identifying. In the NHG, a plant without a correct name is of no use to us, and thus, is removed. Efforts are then made to reacquire the plant material with adequate documentation. In some cases, new cultivars or hybrids can be easily traced to their original sources if the breeder made a point of promoting it the introduction. Lavandula ×intermedia ‘Phenomenal’ introduced by Peace Tree Farm in 2012 is a recent example. Oftentimes, though, the information is not w idely disseminated or is published in limited print outlets. Perhaps a plant’s only mention was in a nursery’s catalog or on a website. Web searches can aid the process, but this means has only been a relatively recent addition to the botanist’s or taxonomist’s research toolbox. At times, our botanist in Plant Records has had to search documents from the 19th and 20th centuries just to find a plant’s first mention in the nursery trade. Frustratingly, this is not an unusual occurrence as legitimate documentation of nomenclature or provenance for an herb can be quite rare. Gene banks, such as those of the National Plant Germplasm System of the U.S. Department of Agriculture— which includes the U.S. National Arboretu m— collect, store, document, and distribute a broad spectrum of plant genetic resources, including some herbal material. This material, and associated information, is available through the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN), making this database one of numerous good resources for nomenclature and provenance cross-checking, but it is by no means all-inclusive. Alternatively, there exist genera-specific registrars, which focus attention on key plants, also facilitating nomenclature checks. For popular landscape or garden genera such as Rosa or Acer, registrars exist to document the introduction of new cultivars or varieties, as well as wildcollected material. Unfortunately for herbs, there are no such registrars or other

official outlets documenting an herb introduction, which leaves the gardener, breeder, scientist, or curator at the whim of individual mental recall or even worse, the telephone game: “What was the name of that plant you gave me? I think I’m going to take cuttings of it to sell at next year’s plant sale. Did you say it was ‘Fabulous’ lavender? Okay, yeah, that’s close enough. No one will really notice. I’m sure it will be a hit because it really is a fabulous plant!”

Mm hmm… we know the rest of that story

This lack of a centralized database begs for the establishment of such an entity. And while HSA has the Plant Collections Committee, which collates information from various members’ holdings, it does not serve as a nomenclature clearinghouse. Given these challenges, the curator must do his or her best to locate original source material for those herbs where it is possible, and for the rest of the plants, a good faith effort is made using reliable sources for acquisitions. When new

the arboretum’s database system, as well as on the garden’s signs.

For the most part, due diligence is the best we can hope for. Unless the herbs are wild-collected or received directly from the introducer, primary-source material is often not obtainable. We have to put a lot of trust in the nurseries and seedsman we use to provide accurately identified material to us. Even with those measures in place, the NHG has, on occasion, received seed that was incorrectly labeled. The curator, therefore, must vigilantly root out such cases of mmistaken identity to maintain the integrity of the collection.

Cleaning House: Collection Integrity

The NHG’s main goal is to facilitate a richer understanding of herbal plants through aesthetically pleasing garden displays and signage. The language we use in the NHG to describe an herb is “any plant that enhances people’s lives through flavorings, fragrances, medicines, coloring agents, and additives in industrial pro-

material is brought in, the names are vetted through the arboretum’s Plant Records Office. Our botanists search the literature for documentation of names, as mentioned above, and if possible, the origination of the plant material. Due diligence is done wherever possible, but the appearance of new—and sometimes old—information may arise through continued literature searches or through subject matter experts. When corrections need to be made, changes are reflected in

ducts, with the exclusion of those plants used strictly for food.” The garden houses more than 800 taxa in ten theme gardens, a heritage rose garden, a knot garden, and other miscellaneous garden beds.

The curator of this garden is not merely a guardian or caretaker, but is also a researcher, interpreter, and manager of plant material, resources, time, and people. The first— plant materia l— is the foundation on which the other elements rest; without the plants, there is no garden. Since the

22 23 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

Interns are essential in conducting investigations and gathering data in the garden

plants in the garden have the aforementioned requirement of being useful to humans, this is the deciding factor by which any inclusion in the garden is measured. People often ask me how I come to decide what plants are grown in the garden, so I explain that I look for at least three reliable references for each plant’s use. If a plant seems to be questionable for any of a multitude of reasons, I will make the call as to whether it stays or goes.

A number of years ago, I asked the NHG Committee members if their respective units would be willing to engage in a project for the garden aimed at researching and updating each theme garden’s plant list. I felt strongly—and still do—that each theme garden should undergo periodic review to determine which plants should remain and which plants may need to be removed. Alternatively, there may be plants that have not been included previously that should be included based on new research. Things change over time, after all, thus abolishing the notion that what has been must always be. Even in an historic setting where management of an historic landscape is relatively static, change is sometimes inevitable.

The participating units were assigned one of the ten theme garden’s plant lists to research and review and then report back their findings to the NHG staff. We set up parameters by which plants were given priority status. Those plants that were deemed highly useful were given primary importance (first tier plants) and, thus, are always included in the garden unless there are overriding factors such as

availability of plant material or invasiveness. Plants of secondary importance (second tier plants) are also included in the garden but are not given as much weight or consideration as those in the first tier. Third tier plants have much weaker references for their use and may either be eliminated from the plant list altogether or may be included if there is space in the garden. Using this evaluation system frees the curator to make educated decisions regarding a plant’s status in the garden rather than feeling obligated to maintain a plant just because it’s always been there. An example where such a review was helpful appeared while reviewing the various trees planted throughout the garden. A Malus halliana ‘crabapple’ was growing in the garden for years even t hough it had no defensible herbal use. In 2014, this tree was removed from t he collection, making room for a new, truly herbal tree. In other cases, certain plants, such as Artemisia vulgaris ‘mugwort’, have become invasive in the g arden. Though the plant might be highly useful, its presence has become an environmental nuisance, which overrides any argument for its inclusion. In another scenario, some plants are just too challenging to keep alive because they cannot grow well in our climate or soils and, therefore, do not justify the expenditure of resources necessary to maintain them. Sometimes a suitable substitute is worth the effort. One such example is Taxus brevifolia ‘ Pacific yew’ , the original source of taxol, a chemotherapy drug. Pacific yew does not grow well in the Mid-Atlantic climate, but other species of Taxus do. These species contain variable quantities of the active chemical as well, so making the switch to a species more amenable to the NHG’s environmental conditions—with an explanation for the substitute in the signage—is a reasonable accommodation.

Curation isn’t all about purging, although sometimes it appears that way. Acquisition

of new plant material is also a major activity. After researching the various themes in the garden with the HSA units, we found that there are numerous plants that should be included in the garden, but for whatever reason, have not been or were lost over time. One example is Citrus bergamia ‘ bergamot’, whose fragrance and flavor gives Earl Gray tea its characteristic appeal. This plant was not included in the Fragrance Garden’s or Beverage Garden’s plant lists, so it was added to those gardens as a notable example of a plant used for both fragrance and flavor.

As gardeners know, things are always in flux, so periodic review of the plant material should always be on the curator’s priority list. Plants are not the only element in the garden that needs attention, though. The plants we grow in the garden also need to provide useful educational opportunities as well.

Get the Word Out:

Educating the Masses

One of The Herb Society’s key values— and by extension, the National Herb Garden’s—is providing opportunities for education about herbs (http://www. herbsociety.org/about/vision-missionstatements.html). While the NHG is part of the U.S. National Arboretum, which has its own educational mandates, the NHG also takes many of its cues from The Society. To that end, the garden is not merely a collection of pretty, or even tasty, plants but is a deliberate and thoughtful outreach vehicle for disseminating information about the usefulness of plants.

A few of the plants’ uses are known almost worldwide, but most are not. In an effort to provide information education to the public about a plant’s use, the NHG employs various modes of communication information. The first and most commonly encountered is signage. Basic signs include the scientific and common names, family name, and native range.

In the theme gardens more complex information labels add the habit of the plant (perennial, annual, etc.), a description of how the plant is used, and on newer versions, the plant’s accession number. The

inclusion of accession numbers on the sign allows visitors to access information using their mobile device about a particular plant via the Arboretum Botanical Explorer on the arboretum’s website.

The basic name labels are more straightforward to produce since they follow a standardized format. The information labels, on the other hand, require significantly more work. As mentioned earlier, each

to produce text no more than 150 words in length and be at an eigth grade reading level. This may seem like an easy task, but I can assure you, it is not! All labels are, again, vetted through the Plant Records Office to assure that the nomenclature is correct and to verify the text information. When all is deemed correct, the text is engraved on permanent labels and mounted on stakes for display in the garden.

1. An accession number is a unique number assigned to individual plants to differentiate them from others. The metadata with each number may include, but is not limited to, correct taxonomic name, location of plant in the garden or collection, when the plant was received, and source.

plant’s use must be documented in at least three reliable references, which may require considerable research. Once the use is verified, the label’s author (the curator, assistant, or intern) must distill that information down to include the use(s) of greatest importance and that are ( hopefully) the most relevant and/or interesting to the general visitor. The information must then be whittled further still

Labels are one means of getting the message out, but the NHG also utilizes displays and programs to further expand the educational outreach. Displays may include seasonal plantings of a particular theme coupled with appropriate signage. A recent example was intern Seth DeNoble’s breakfast, lunch, and dinner beverages plant display in the Entrance Garden. Displays may also take the form of interpretive panels in the display case area of the garden that cover various topics of interest, such as chile peppers. Both of these displays require multiple levels of research, development, verification, and interpretation to meet our criteria for accuracy and relevance. An equally important avenue for information dissemination is through public pro grams, including tours of the garden led by docents or NHG staff, and the ever-popular Under the Arbor series. The Under the Arbor series is the main opportunity units—generally those within driving distance of the NHG—have to participate

i n educational outreach in the garden. The Society members have extensive herbal knowledge and expertise to share with the public, and I feel strongly that it is one of curator’s foremost jobs is to link such entities to our visitors whenever and however possible. Just as there are multiple learning styles for individuals, so too, are there multiple styles of educational outreach that can be utilized in the garden to expound on the usefulness of plants.

Over the past 35 years, each curator has contributed his or her own expertise to the development of the garden. Regardless of stylistic differences, two elements are constant for any NHG curator— collection integrity and educational outreach. In both of these areas, challenges present themselves regularly. But a capable curator takes them in stride utilizing his or her resources to work through the issues and ultimately present a garden of herbal excellence to the world.

Chrissy Moore is the curator of the National Herb Garden. She is a member of The Herb Society of America, Potomac Unit. She is also a certified arborist with the International Society of Arboriculture. She attended St. Mary’s College of Maryland. Having completed two horticulture internships at the U.S. National Arboretum, she was hired by the education and v sitor Services Unit at the USNA in 1996. She served as the National Herb Gardener’s gardener from 1998 until 2007, when she accepted her position as curator.

24 25 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

i n T egri T y An D o u T re ACH: BuildingAStrongFoundation

Garden Design and Maintenance

A Conversation with Past Curators of the National Herb Garden

The Herb Society of America has been very fortunate in not only having extremely knowledgeable and personable curators for the National Herb Garden but also curators who had long tenures in the garden! We asked Holly Shimizu (1979–1988), Janet Walker (1988 –1997) and Jim Adams (1997–2008) to reminisce for us about their garden experiences.

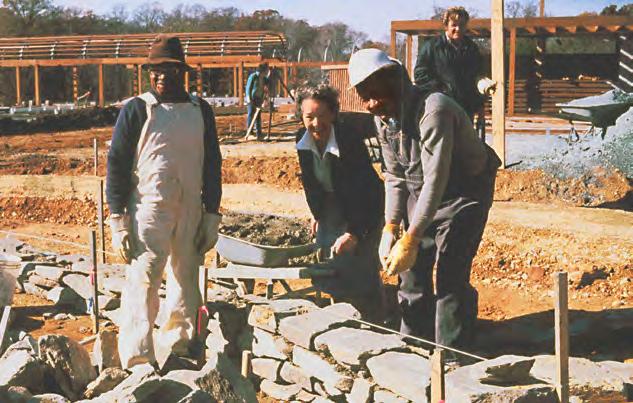

Holly: Being selected as the first curator of the National Herb Garden was such an amazing opportunity and learning was a constant. During the planning stages, while the Garden was still under construction, we met often with Tom Wirth, the landscape architect employed by Sasaki Associates of Boston, Massachusetts. We had some major surprises — the soil was terrible, heavy clay and did not drain at all — not an ideal setting for herbs. We were able to arrange for some compost from the National Zoo, which was referred to as “zoo-doo.” Occasionally exotic and bizarre weeds would appear, which we attributed to some of the exotic animals at the National Zoo. We worked with many of the HSA units that had been tasked with designing the specialty gardens and then I set to work locating many of the plants listed — it proved to be rather tough. When the plants came in they were often tiny little rooted cuttings or seedlings. For some of the larger plants, such as the boxwood and herbal trees, we traveled to nurseries to handpick our selections. Of course we were committed to t rying to get the labels done correctly although the headaches of trying to figure out what the plants really were proved to be a never-ending challenge. We struggled to get the Knot Garden details exactly right and then setting

the Armillary Sphere proved to be more complicated than expected in order to get it set true north. The garden opened on schedule but the plantings were admittedly underwhelming—thank goodness, as gardeners, we all knew the plants would grow, fill in, and the Garden would be wonderful in a few years.

Janet: Ah, the Knot Garden! The biggest challenge I had to deal with was the chronic ill-health of the original Knot Garden, which just didn’t seem to be loving life and hence required more than its fair share of TLC and plant replacements. The plants exhibited

classic failure-to-thrive symptoms, as if they were standing with their feet in water, which I was assured just could not be the case. Eventually my boss gave the go-ahead to “check anyway.” We got my volunteering husband to dig a deep post-hole in each of the four corners of the garden, which promptly filled with water to within a foot or so of the surface grade and stayed that way, week upon week, even during one of our more severe summer droughts.

Problem diagnosed!

The remediation involved the complete

excavation, reconstruction and replanting of the Knot Garden. I learned t hat the original subsurface drainage tiles had been installed upside-down. They trapped irrigation water rather than draining it. Obviously the new tiles were reversed. Problem solved! Jim: Ah, irrigation in the garden! In November 1998, after more than a year of preparation, the Herb Garden was closed to visitors for its first major renovation since it was built. The renovation included a complete redesign of the irrigation system, removing the metal edging throughout the garden and replacing it with different edging solutions such as brick or block, adding night lighting to the garden, and most importantly, making the garden accessible by federal accessibility standards. This included removing the stone paths in the rose garden and in the theme gardens and replacing them with bluestone. It also meant grading the path along the rose garden to the knot garden so that it would have a more gradual slope. To prepare for the renovation, all of the plants within about two feet of the all the garden edges had to be removed. After making sure all of the plant records were up to date for those plants, when the garden closed, they were moved to a temporary holding nursery by the old M Street Entrance Gate. Because the holding nursery was in kind of an out of the way location at the Arboretum, we wanted to make sure the plants were protected. We installed a chain link fence around it with a locked gate. The nursery then was dubbed “the plant jail!”

The Herb Garden re-opened in the spring of 1999 with a big celebration called A Garden for All, calling attention to the fact that it was the first f ully accessible garden at the Arboretum. The event was co-sponsored by the Arboretum, The Herb Society of America, and the Friends of the National Arboretum. The event drew quite a crowd and was attended by

27 issue 81 2015

H olly Shimizu J anet Walker J im Adams

H E RBARIST

The Knot Garden at NHG

dignitaries from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Ward 5 of Washington, DC, and The Herb Society of America.

Favorite Garden Sections

Holly: It’s hard for me to pick a favorite as we were installing all of them! I think the roses. For the Antique Rose Garden we worked with Charlie Bell, a heritage rose person who was a part of the Potomac Rose Society. The garden was all planted in excellent soil, the plants located from a variety of private and public gardens as well as nurseries. I worked with Dr. Frederick Meyer, the botanist for the U.S. National Arboretum, to be certain that our roses were all correctly labeled in preparation for a large rose convention that included a visit to the garden. Well, I remember that day well. One of their authoritative members came into the garden and, with her cane in the air, she declared “all of these roses are labeled incorrectly.” The group spent days (perhaps months or years) arguing about the origins and identities of the roses in the Garden. I suggested that once they were clear and confident about the answers to these questions they should let me know so I could take it back to Dr. Meyer for review.

Janet: I also especially loved the Rose Garden. During the long peak of its season, I think it was among the loveliest places on earth, particularly once we had established the companion plants: opium poppy, cardoon, larkspur, feverfew, columbine, and foxglove, to name a few. Early and late in the day, and even in the hazy heat while the sun was still high, you could stand there between the rail fences and imagine yourself in some ethereal countryside of fragrant cozy lanes, yet all encompassed within the space of a typical urban backyard.

Jim: I have two different parts of the garden that were my favorites. I love the theme garden area. I really like the diversity of plant material in the gardens. There are so many beautiful and interesting plants with fascinating histories and stories.

I also really loved the sage collection. It was always so colorful, texturally rich, and alive with insects. I used to enjoy being at work late in September and October, when

the sun was lower in the sky and the rays of sunlight would cut straight through the border, backlighting all of the flowers. It is a magical sight. One of my most favorite sights in the garden.

Special Visitors to the Garden

Janet: A few months into my job as National Herb Garden curator this would have been in early fall of 1988 I had my first uneasy encounter in the garden. I worked from 7:00am to 3:30pm each weekday, and I was alone in the garden at about 7:10am making my early-morning rounds. I always enjoyed this time because I had the garden all to myself. But on this one day there was a 60-ish man out in the Specialty Gardens whom I didn’t recognize. I was a bit alarmed since we didn’t open until 8:00am. I had my radio (and pruning shears if I needed them) so I could call for help and I think I said, “Can I help you?”

Without preamble or apology, the strange man launched immediately into an extended and focused discourse on herbs and their uses which was absolutely fascinating. It was quite a bit over my head as a horticulturist who was still largely ignorant of herbs, but I could feel the curtain lifting then and there on a hidden and marvelous stage. He illustrated his presentation by baring the insides of his forearms, both of which were impressively reddened and blistered with a poison ivy rash, but one conspicuously less so than the other. He eagerly shared proof that jewelweed did indeed have an ameliorative effect on self-inflicted ivy poisoning. A rather startling visual aid, but pungent and hard to argue with!

This was my introduction to the “mad scientist” of herbs—the legendary ethno-

botanist Dr. James A. "Jim" Duke, who had purposely arrived early that day for a meeting in the Administration Building so he could spend some quality time beforehand in one of his favorite places. I quickly “got it” that this was an extraordinary person, and he became one of my mentors, always willing to impart his vast knowledge which seemed to pour out of him like a fountain.

Jim: There were many famous people who came to the Herb Garden for the Friends of the National Arboretum Cookout every June. Some that come to mind are Paul McIllhenny, Sandra Day O’Conner, and Christine Todd Whitman, Governor of New Jersey. Not famous, but worked for famous, was a crew from Martha Stewart Living magazine who came to photograph all of the different mints in the garden for a story about the genus. They came in June 1999 and it was the same day we started a renovation of the Colonial theme garden. We worked very hard that very hot day digging and dividing plants in the garden. At the end of the day, the gals from “MSL” said they were astounded at how hard the volunteers worked on such a hot day and how much they got done.

Holly: I remember that whenever we were going to have special visitors, Betty Rea would let me know. We would make tussie-mussies and picnics for our guests — this became our habit and proved to be an excellent way to introduce the Garden to potential donors and friends.

Rewarding Days in the Garden

Janet: What can I say about the most rewarding day in the Garden? There were so many! The day of the annual Friends of the National Arboretum al fresco fundraising event was a recurring high point in early June. We always got a spectacular turnout of staff and volunteer help beforehand to groom the Garden to perfection. For one day, and one day only, there wasn’t a hair out of place.

Holly: That sounds so familiar! After three years the Garden really began to look quite beautiful, plants had settled in to their spaces and as long as we had enough rain, the garden was quite enchanting as

well as highly educational. Having classes, tours, and herbal programs that were always well attended and popular helped us get out the word about this amazing new Herb Garden.

Jim: What I found most rewarding was working with the volunteers, the HSA units, and the National Herb Garden committee. Working with all of those folks was the hardest thing to leave. Working with such a dedicated group of people who freely gave their time and talents was the

most rewarding part of the job.

“What have you never been asked?”

Jim: What’s my favorite time of year in the garden? It’s autumn! Autumn is the most awesome time in National Herb Garden. All the plants are so big and have so much to offer. The colors are richer that time of year too. It was no coincidence that my most favorite program in the garden was the Bewitching Tour held at

Halloween time. It was so much fun to put on and the people on the tour seemed to really enjoy it.

Janet: I changed the garden, but how did the garden change me? My eight years as curator were a personal journey and evolution, something I would not have predicted. Herbs took a hold on me and the more I learned about them, the more I wanted to learn. I could grow them, sure, but knowing about their history, uses, powers and lore made them magical. The connection felt with everyone throughout time who has used a plant for a reason is thrilling, and very real. This must be what binds us all together.

Holly: I think the question would be “has the garden grown in the way you expected? Absolutely! The garden was a leader then and continues to be an inspiration in the ever-expanding interest in herbs across America. The National Herb Garden has played a big role encouraging further herbal study and use in both public and private gardens.

Holly Shimizu, after studying horticulture at Pennsylvania State University, worked in a number of gardens in europe before being selected as the first curator of the National Herb Garden from 1980–1988. She went on the work at the U.S. Botanic Garden in Washington, D.C. and the Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden in Richmond, virginia. Most recently, she was the e xecutive Director of the U.S. Botanic Garden. She is a lecturer, writer, and the recipient of many awards, including the Nancy Putnam Howard from The Herb Society of America. Currently, she serves on the advisory board of the Las Cruces Biological Station in Costa Rica, the board of directors of the American Horticultural Society and the board of the friends of the National Arboretum.

Janet Walker had the good fortune to grow up surrounded by gardeners in Washington, and knew a good thing when she saw it. After working for years as a landscape contractor, she took over as curator of the National Herb Garden from 1988–1996 and, thereafter, as the Head of education and visitor Services at the U.S. National Arboretum. She later worked as Director of Horticulture for the American Horticultural Society’s River farm, followed by a second stint as a director of education and visitor services, this time for Bok Tower Gardens in Lake Wales, f orida. She currently is visitor Services Manager for the Smithsonian American Art Museum and National Portrait Gallery. When she’s not at work, she can usually be found outdoors.

Jim Adams began his career with internships at Michigan State Horticulture Gardens, Chicago Botanic Garden, Longwood Gardens and the Scott Arboretum of Swarthmore College. He has worked at the U.S. National Arboretum where he was assistant to the curator of fern valley Native Plant Collections and then curator of the National Herb Garden for nine years. He was Head Horticulturist for the British Ambassador to the U.S. before obtaining his current position with the U.S. National Park Service as Supervisory Horticulturist.

28 29 The Herbarist issue 81 2015

Carolyn Cadwalader and Holly Shimzu in the NHG circa 1979

A Conversation with Past Curators of the NHG

Left: Janet Walker in 1990 Above: (L) Intern Amy forsberg and Jim Adams

Under theArbor An Educational Series at the National Herb Garden

At an HSA board meeting in 1966, President Edna Cashmore announced her idea for a national garden of herbs that all Americans could see, admire and learn from.

— The Herb Companion, October/November 1993, p. 44

The Herb Society of America in fact did give our nation an herb garden fourteen years later. Local, national, and international visitors to the National Herb Garden (NHG) have been able to do those very things; “see, admire and learn”. The garden has been the site of many educational programs or events over the years. In more recent years the annual Under the Arbor (UTA) series has enthusiastically continued to educate. Janet Walker, second curator of the National Herb Garden, started an educational program called Discovery Carts. There were different cart themes based on six of the theme gardens: dye, medicinal, fragrance, culinary, beverage, and Native American. Trained volunteer docents from the National Arboretum worked on Saturday and Sunday afternoons, talking with the public about the topic of the day. Each topic had a discovery kit that included items or props displayed on the cart. These props became the talking points for the docents to engage visitors. Some of the kits included hands-on

activities that visitors could participate in (e.g., identifying different mints by scent), while other kits required the docents to demonstrate something, such as the dye kit where the docents actually dyed yarn or fabric with plant material.

The Discovery Carts program took place from May through October. Over time, it became increasingly difficult to staff the carts with arboretum volunteers, especially for both weekend days for many months. Eventually the program ceased altogether. Some years later the National Herb Garden committee members discussed the re-introduction of educational programming in the garden. It was clear that asking arboretum volunteers to staff such a program for so many days was not feasible in the long run, but we didn’t want to completely abandon the concept of an educational program in the garden. Chrissy Moore, current NHG curator, had an additional concern that many of the units were not as involved in the garden as hoped. She wanted all units to feel part of the garden, but knew that the more distant units could not be actively involved. The geographically closer units would be more accessible to the garden and possibly have members more willing to come for a Saturday afternoon presentation. The NHG Committee brain-stormed the idea and came up with a spin-off of the Discovery Carts program, the Under the Arbor series. The title derives from the flourishing arbor that is a focal in the National Herb Garden. There are three differences between the Discovery Carts program and the Under the Arbor program. First, in the Under the Arbor program, we limit the events to just Saturdays during peak visitation months (May, June, September and October) and do not schedule every weekend. Second, instead of using arboretum volunteers, we use HSA unit members and members

at large as educational ambassadors. This is a great way for the members to stay connected and involved in the NHG, as well as to share with the garden’s visitors some aspect of their herbal expertise. Third, the presenters are not limited to just the overall topics of dye, medicinal, fragrance, etc. They can choose any herbal topic to discuss. We’ve had everything from the ‘Herb of Year’ to herbal butters and cheeses, herbal teas to colonial herbs. The choices are somewhat unlimited; it all depends on the creativity of the HSA volunteer presenters. Each year the ‘Herb of the Year’ is highlighted at some point. In 2011, the NHG committee and garden curator Chrissy Moore decided to expand at least one of the Under the Arbor events. Because the garden has such a magnificent chile pepper collection, the committee chose to schedule a Chile Pepper Celebration in October, when the peppers are at their best. This was an opportunity to show off the beautiful chile peppers and the fall herb garden at the same time. This year we will be enjoying our fifth year of this celebration, where the public can enjoy the various displays and food samplings. The demonstration tables abound with chile pepper tablecloths and chile pepper decorations. We have given away packets of chile pepper seeds and sampled different types of chiles.

Attendees have tasted chile pepper hot chocolate, hot chili, chile pepper soups, chile peppers in appetizers and desserts, and of course, chile pepper ice cream and sorbets! Each year, as the word gets out, we have had more and more people attend. Even rainy weather has not forced us to cancel we just move to the classroom trailers!

The original National Herb Day, developed by the International Herb Association, is scheduled in the fall. While the NHG staff and volunteers wanted to do something to honor the day, many of the presenters could not make themselves available at that time of year. The NHG Committee chose to celebrate Herb Day in June, the month of the NHG’s actual birthday. Members of a number of units from the Mid-Atlantic area come for a spring work day in the garden on Friday and stay through to Saturday to do the UTA. At the first few Herb Day events each unit did its own display. More recently all the displays have focused on the same herbs, roses and lavenders. In 2015 we celebrated the actual birthdate of the NHG, June 12, with herbal cakes. All of the Herb Day celebrations have been very popular, with about two hundred people usually coming by to peruse the demonstration tables.

Elizabeth Kennel, a long-standing

31

Issue 81 2015

1. References to the ‘Herb of the Year’ and ‘National Herb Day’ are often included in articles in The Herbarist Both are public awareness campaigns initiated by the International Herb Association (International Herb Marketers and Growers Association). for more information visit: www.iherb.org

H E RBARIST

Billi Parus and Chrissy Moore

Pat Kenny P H OTO Lois Sutton

fresh herbs to touch and smell, thanks to Potomac Unit volunteers P H OTO Lois Sutton

Some of the themes participating units have presented during Under the Arbor programs

Potomac Unit The Potomac Unit has presented a wide variety of topics over the years, ranging from growing herbs in pots to edible flowers, lavender, crafts, and ‘Herb of the Year’. This year their topic is soap making.

South Jersey Unit Though this unit has done colonial herb presentations, their topic usually relates to lemon herbs. Their display always includes a vase of assorted fresh lemon herb samples, lemon herb infused liqueurs and waters, cookies, and candied lemon peel. Their handout includes the recipes. Usually four to six unit members attend and make a weekend trip of it, stopping to shop, tour, and check out great restaurants along the way. They love talking to people about the lemon herbs!