Science Extension Journal

An Anglican community inspiring

To be a leader in Christian education that is characterised by a global vision that inspires hope

We acknowledge the Dharug, Darkinjung, Wonnarua and Yolŋu peoples who are the traditional custodians of the land on which Barker College, Darkinjung Barker, Ngarralingayil Barker and Dhupuma Barker stand. We pay respect to the Elders past, present and emerging of the Dharug, Darkinjung, Wonnarua and Yolŋu nations and extend that respect to other Indigenous people within the Barker College community.

Senior Editor

Dr Matthew Hill

Creative Direction

Mrs Susan Layton

Dr Matthew Hill

Research Supervisors

Dr Alison Gates

Dr Terena Holdaway-Clarke

Dr Matthew Hill

About the Scientific Research in School Journal

When the New South Wales Education Standards Authority announced a new course “Science Extension” to commence in 2019 we were thrilled that there was an opportunity for a formally-assessed capstone experience in Science for our students. From the perspective of the Barker Institute it was an exciting chance to support students doing academic research, alongside other subjects such as History Extension, Music Extension and English Extension 2.

Where many capstone project courses fail is the at final step of the research process – dissemination. Research is not merely the process of conducing an investigation and writing a report, but sharing it with the wider community so that people can learn, critique, have other student researchers at multiple schools build on the projects published. I am so glad to be able to publish this journal each year now celebrating 62 articles each representing genuine contributions to science.

Dr Matthew Hill Director of The Barker InstituteEvery day our students change the world through enriching the lives of those around them, and we are all beneficiaries. This publication demonstrates one way our students are impacting others; through contributing to academic research in the discipline of Science.

This year’s research projects demonstrate extensive scientific thought, rigour and communication.

It is with delight that I read of how our school laboratories have been used for research in medicine, rocketry, biology, sport science, and many other disciplines. I commend each of these reports to you.

I congratulate these students as authors and also recognise their role as collaborators, working with their parents, friends, teachers and university academics to produce such high-quality academic writing.

Barker Science aims to develop every student as scientific thinkers and communicators. Understanding Science allows young people to make good decisions for themselves and the world around them.

These 18 students have worked hard for many years to develop their skills, and under the guidance of a wonderful team of teachers as their supervisors, applied these skills to a collection of unique projects as part of the Year 12 Science Extension course.

I wish to congratulate Dr Matthew Hill, Dr Alison Gates and Dr Terena Holdaway-Clarke who have supported, inspired, instructed and nurtured these budding scientists.

It is with great pride that I share our brilliant students’ work. They are now academic writers, contributing knowledge to the scientific literature at a university level.

Mr Phillip Heath AM Head of Barker College

Mrs Virginia Ellis Head of Science

Once again, our students are changing the world through academia.

Science Extension is the capstone experience allowing our students to showcase all they have learned.

Research

Undertaking proper scientific research takes curiosity, capacity and commitment. These students found research questions that they were passionate about and worked hard to implement the scientific research process to answer them. They demonstrated a high capacity for scientific thinking, inquiry and communication resulting in these high-quality journal articles. It was a joy and a privilege to work with these fine young scientists. We are incredibly proud of them and we are excited to share their work with you in this journal.

Dr Matthew Hill Director of The Barker Institute

Dr Terena Holdaway-Clarke Biology Teacher

Dr Alison Gates Agriculture & Science Teacher Assistant coordinator STEAM

Dr Matthew Hill Director of The Barker Institute

Dr Terena Holdaway-Clarke Biology Teacher

Dr Alison Gates Agriculture & Science Teacher Assistant coordinator STEAM

Part 1: Environmental & Food Science

The use of edible fungi to digest oily waste

Eamonn Browning

Determination of the antifungal properties of polyphenols extracted from the common grape 13 (Vitis vinifera) Owen Ng

Stomata - the gatekeepers of life: the effect of Bonsai conditions on azalea stomatal density 23 Tegan Lee

Concentration of microplastics found in sediment from ocean beaches compared to estuarine beaches in Sydney 31 Olivia Marlin

The importance of fungi investigation in the effect of cullulose enzymes on the growth rate and fungal spore density with Pleurotus ostreatus

Sam Young

The effect of cations on Wallaby grass growth after germination

Dana Callaghan

Investigating the effect of ocean aciditification on sea monkeys (Artemia nyos)

Mia Vesey

Part 2: Physics

Grey matter matters: An investigation into the role of helmets in preventing force on the brain 69 Claire Kitching

Postprocessing of commercially available FFF thermoplastics by microwave annealing 79 Jack Wilson

Cost viability of coilgun-style kinetic launch system to place satellites in low earth orbit 87 William Bray

Did SpaceX get it wrong: a systematic evaluation of potential of a flyback return mode to increase performance 93 Rosco Jones

The effect of the curvature of a swimming paddle on the propulsion force 105 Jessica Hargreaves

Part 3: Pharmacological, Microbial and Applied Science

Ultrasonic deactivation of E. coli bacteria with a Zinc Oxide “hedgehog” sonocatalyst 117 Benjamin James

Enantiopure versus racemic antihistamines as antimicrobials 127 Sass Heerey

The anti-microbial properties of Australian scorpion (Urodacus elongatus) venom 135 Nilan Kumerage

Concentration wars: Ampicillin Vs Escherichia coli (K-12) 143 Luke Trevithick

Identification of potential 2-aminothiazole pharmaceuticals 153 Josh Tung

Are attractive people symmetrical? Facial symmetry and perceptions of beauty 163 Cassie Onikul

Environmental & Food Science

Some of the most complex challenges facing 21st century scientists lie in how we will feed the world’s growing population and how we will adapt to and mitigate against ever changing environments under pressure

Eamonn and Sam entered the realm of edible fungi, both looking at oyster mushroom cultivation in different conditions. Eamonn showed that cultivating mushrooms could simultaneously remediate oily waste present in the growing substrate: his work forms the basis for a win-win in food production and safe disposal of oily food waste. Sam was able to improve the yield of oyster mushrooms by applying cellulase to the growing fruiting bodies.

Owen’s work involved some clever thinking to achieve results in a high school laboratory. He was able to extract polyphenols from grapes and then to demonstrate their antifungal properties. The application of this new knowledge could be important for organic fungicides.

Olivia provided insight into methods available to students to investigate microplastics and a clever experimental design to consider the origins of these important pollutants around Sydney. We think that this project will be an important launching pad for future student projects at Barker.

Mia and Dana completed projects that help us to better understand the challenges of a changing climate. Mia’s work explored the effect of pH on the survival of sea monkeys (brine shrimp) and Dana explored the impact of salinity on the growth of a native pasture grass, Wallaby Grass.

It was wonderful to see Tegan’s interest blossom and develop from a Year 11 Biology Depth study. She investigated the impact of miniaturizing plants through the art of bonsai on stomatal density. This is an elegant way of exploring the impact of environmental stress and her findings are fascinating.

It has been a pleasure to watch these students grow and develop through their research projects and we look forward with great interest to their exciting careers as future scientists.

The use of edible fungi to digest oily waste

Eamonn Browning

Barker College

Purpose: This paper aims to investigate and determine the capacity of edible Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) to remove oil contamination from a growing substrate of coffee grounds and to examine the effect of this production method on the yield of the mushrooms.

Design/methodology/approach: Sterile coffee grounds were divided into two containers and mixed with different amounts of canola oil. A control group of coffee grounds did not receive any oil. The substrate mixture was inoculated with commercially prepared Oyster mushroom spawn. The amount of oil present in the substrate was measured before and after myceliation.

Findings: Substrates with no oil produced more mycelial growth than spawn bags inoculated with a low oil load. Spawn bags with low oil loads removed on average 73% of oil from the sample proving that mushrooms can effectively remediate the oil “contamination”. High oil load samples removed 57% of the oil

Research limitations/implications: Due to environmental conditions, the mushrooms did not properly fruit meaning that mushroom yield could not be calculated. Given the success of the oil removal, it would be very worthwhile to repeat this experiment and calculate mushroom yield.

Practical implications: Edible fungi are clearly able to remove oil from their growing substrate. This could be applied to the remediation of cooking oils before they are disposed of via waste. If this could be shown to also produce edible fungi, this would be an important step toward sustainable food production.

Social implications: This could be implemented in small scale food production systems and be used to help process waste and grow edible fungi.

Originality/value: The paper investigates mycoremediation of a vegetable oil and examines the extent to which it is effective against the amount of contaminant that is present.

Keywords: Mycoremediation, Oil, Fungi.

Paper Type: Research paper.

Literature Review

Fungi are responsible for converting dead matter into nutrients for the soil, and thus contribute to the environmental ecosystem (Stamets, 2010). Fungi can be very large organisms with the largest recorded Fungi measuring to 10 square kilometres, located in Eastern Oregon. It is the largest known organism and has an estimated age of 2,400 years (Casselman, 2007).

Fungi can grow in diverse environmental conditions. They are being studied in diverse applications within food production, packaging, and waste remediations (Pullano, 2020). Their ability to decompose organic materials has meant that mushrooms are increasingly being investigated for their capacity to breakdown environmental toxins and manage waste through a process of bioremediation, or more specifically, mycoremediation (Nikola, 2020).

At the same time, one of the most significant food waste problems is the disposal of used and excess cooking oils. Oils cannot be safely disposed of in water waste as they are toxic to marine and

freshwater ecosystems. Canola oil contains Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) which inhibit standard plant growth. Oil can be detrimental in landfill and soil/compost waste because PAHs alter soil grain size, blocking of pores preventing ventilation and water holding capacity of soil (Filho et al., 2017).

Edible Fungi

Oyster mushrooms can be grown in a laboratory setting using spawn bags and a substrate as a growing medium, mixed in with grain spawn. Coffee grounds are a suitable substrate and another form of cooking waste that can be utilised and remediated (Sayner, 2018). Through inoculating the coffee ground substrate with mushroom spawn, the mixture is then sealed in a spawn bag as seen in Figure 1., and placed in a dark environment as it allows the spores to reproduce (JayLea, 2022). After Mycelia networks have grown, slits are made in the bag, exposing the Primordial formations to the air, prompting mushroom fruiting, and the spawn bags are placed in a lit humid environment to encourage mushroom fruiting (MycoHaus, 2020).

Mycoremediation

Fungi species, including oyster mushrooms, (Pleurotus spp.) remove toxins from their environment through a process called mycoremediation (Greenberg, 2019; Mahan, 2015). Fungi use three main methods in decontaminating their environment; biodegradation, biosorption and bioconversion (Kulshreshtha et al., 2014). Biodegradation is a process which the fungi use to break down and recycle a complex molecule into its mineral constituents thus removing their toxicity to the surrounding ecosystem (Mahan, 2015; Ali et al., 2020). Enzymes including ligninase and cellulase excreted from the mycelial, breakdown chemicals into minerals that are less damaging to the soil substrate, thus stimulating more mushroom and plant growth (Akhtar & Mannan 2020). Secondly, biosorption is a process of active transportation and storage of minerals and compounds into the cell (Daccò et al., 2020). They can then be further broken down and recycled for the plant (Kapahi & Sachdeva, 2017). Lastly, the process of bioconversion utilises harmful waste in the cultivation of fungi to enhance gross yield and mushroom growth (Kulshreshtha et al., 2014).

An experiment conducted by Horel and Schiewer (2020) identified the extent to which fungi can bioremediate hydrocarbons over a 28 day period. The study utilised spawn bags contaminated with fish biodiesel. At the conclusion of the experiment, more than 48% of the fish biodiesel had been removed by the bioremediation processes. This investigation identified fungi's ability to remove hydrocarbons

from substrates. However, it lacked in effective graphical representation of the data to aid in identifying the type of trend. Another investigation examined the effect oil has on oyster mushroom growth (Chukunda and Simbi Wellington, 2019). Their research determined that with a 50% increase in oil contamination, there can be an expected 20% decrease in oyster growth. Whilst the experiment produced results that proved the hypothesis, no control was used therefore degrading the validity of the experiment. These investigations confirmed mycoremediation can be produced in a laboratory setting and with specific oil types. Practically, investigations into other cooking oils would be valuable as well as investigating bioremediation of high oil loads compared to low oil loads as well as its effect on mycelial growth.

Additionally, fungi can readily adapt to their environment, providing the ability to grow in harsh locations and under different stresses that other natural bioremediation agents cannot (Selbmann et al., 2013). When conditions become too harsh for plant growth, fungi focus on extremotolerance and change their biological processes to best adapt under environmental pressures (Gostincar et al., 2010). The application of this is by introducing an adaptive species with mycoremediation properties to a harsh and contaminated environment, the natural processes of the mushrooms will allow the soil to be alleviated from harmful toxins and theoretically produce a natural edible crop that yields nutrition at the same time (Selbmann et al., 2013). There is little found practical investigations into fungi extremotolerance that produces quantitative results that mushrooms can adapt to grow in environments with high oil concentrations, therefore there needs further research into the effect of high oil loads on the growth of fungi to determine their ability to grow in such conditions.

This research aims to overlay these two food production dilemmas and seeks to determine whether mushrooms can be used to bioremediate oily food waste. By using an edible mushroom species in the mycoremediation process, it may be possible to use the breakdown of food waste to produce another food source. All these effects combine to affect the diversity and population of beneficial microbes (Klamerus Iwan et al., 2015).

Scientific Research Question

To what extent can oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) cultivation decrease the concentration of cooking oil in the growing substrate?

Scientific Hypothesis

In determining the capacity of oyster mushrooms in removing oil contamination from a growing substrate of coffee grounds and examining the effect of the yield that different amounts of oil may have it is hypothesised:

1 That oyster mushrooms will remove greater concentrations of cooking oil from a soil substrate when the initial concentration of oil is lower.

2 In substrates with the greatest amount of oil, the mushroom yield will be lower than in a substrate with less oil contamination and the substrate with no oil will produce the greatest yield of oyster mushrooms.

Methodology

A greenhouse that could hold nine spawn bags was sterilized using a surface cleaner and constructed in the lab. From the clear plastic sides, a 30cmx30cm patch was cut out and replaced with screen material and duct taped in place to provide ventilation for mushroom growth (as seen in Figure 2). 6.75kg of used coffee grounds was collected over a two day period from a local café and was stored in the freezer immediately after collection to prevent mould growth (contamination). The coffee grounds were sterilised by evenly dividing and spreading out in batches onto baking trays lined with fresh baking paper and was placed in the oven in 170 degrees Celsius for 40 minutes as shown in Figure 3. After sterilization, the coffee grounds were poured into large sterile zip lock bags, sealed, and returned to the freezer to prohibit growth of mould.

Nine large containers were washed using detergent and dried. An electronic scale that measured to 0.00 grams accuracy was used to divide the coffee grounds into nine 750g samples as shown in Figure 4. 100ml of unused supermarket brand canola oil was added to each of 3 of the substrates and mixed thoroughly. In another 3 separate containers, 300ml of canola oil was added to each of the substrates and thoroughly mixed, whilst another 3 containers were left without oil contamination. 100ml and 300ml were determined to be a large enough difference to determine a comparison between low and high oil load when combined with 750g of coffee grounds in a spawn bag, providing enough room for mycelium growth within. 720 grams of commercially grown Pleurotus oyster mushroom grain spawn was separated into 9x 80g portions (as seen in Figure 4.). The grain spawn

portions were tipped into the substrates and thoroughly mixed by hand into each substrate ensuring that the grain was broken down and spread to the entire substrate mixture.

From each substrate mixture, one 6g sample of substrate was collected from the centre of the mixture and placed into a 15ml centrifuge tube. The tubes were labelled and placed into the freezer to inhibit mycelial growth. These nine samples would later be analysed as the “before” sample. The containers were emptied into mushroom spawn bags which were then labelled and sealed. Spawn bags were placed in a dry

dark environment to prompt myceliation for three weeks.

After three weeks, two bags were observed to have been contaminated by mould growth and were discarded from the experiment (see Figure 5). Unfortunately, these bags were both from the same group: the high contamination group. This meant that the high oil contamination group only had one bag in the treatment.

after 7 days as no growth was observed and placed in the fridge for 24 (cold shock) hours and returned to the greenhouse to shock the mushrooms into growing.

The spawn bags were removed after three weeks in the greenhouse. For each spawn bag, a test tube was used to collect a sample by plunging the open end through the middle of the substrate to the bottom of the bag, twisting and removing it. 6g of the collected sample was transferred using a sterile stirring rod into the 15ml centrifuge tube (see Figure 7). The foil was used to catch spilt substrate pieces and funnelled them into the centrifuge tube. The tube was then labelled with the amount of oil from the spawn bag the sample came from. This was repeated for all the spawn bag mixtures. Each of the centrifuge tube samples from before the mycelial growth and after the mycelial growth were filled with distilled water up to the top of the tube.

Spawn bags were removed from the dark environment and X shaped slits were made with a sterile scalpel where the mycelial growth had pressed against the edge of the spawn bag to allow mushroom growth outside the spawn bag. The bags were placed in the greenhouse shown in Figure 6. Bags were numbered and placed randomly on different shelves to account for the proximity to the humidifier in the chamber. The greenhouse was sealed, and the humidifier placed on a low setting, placed on a 15 minute on/off timer. The intent of this was to maintain a stable environment to produce maximum results. Spawn bags were taken out of the greenhouse

Table

Oil layer in centrifuge tube

Oil

Oil

Oil

oil load A

oil load B

oil load C

Low oil load average High oil load

The tubes were loaded into the centrifuge and spun at 4000rpm for 60 minutes. The layer of oils in the centrifuge for the sample before mycelial growth was compared to the centrifuge sample of after the mycelial growth, both from the same spawn bag substrate by using callipers to measure the thickness of the layer in mm. Observations were made on the amount of mycelial growth in the control spawn bags with no oil, the bags with low oil load of 100ml of inoculated canola oil and bags with high oil load of 300ml of inoculated canola oil.

An online t test calculator was used to compare the means of amount of oil from the sample before and after mycelial growth to test the hypothesis and determine if a significant difference exists between them. The amount of oil before and after mycelial growth between the samples from the low oil load and the high oil load were averaged and placed in a column graph on the horizontal axis and oil layer in centrifuge (mm) on vertical axis, completed in excel. Error bars were calculated and graphed using excel.

Results

The oil layer in centrifuge tube before mycelial growth and after mycelial growth in the 100ml contaminated spawn bags labelled as the low oil load, and the 300ml contaminated spawn bag labelled as high oil load is shown in Table 1. The average for the low oil load before and after mycelial growth was calculated whilst the absence of more than one set of data for high oil load meant that no average could be calculated. This was then plotted in a column graph showing standard error in Figure 8 Figure 8 shows a general trend of an oil loss after the mycelial growth.

There was a 73% oil loss between the oil layer in the sample from before the mycelial growth compared to after in the low oil load average and a 57% decrease in oil from the samples with high oil load.

Figure 8: Amount of oil (mm) in 6g sample before and after mycelial growth

A t test was used to compare the mean of the low oil load before mycelial growth and the low oil load after mycelial growth to determine whether the two resulting samples are significantly different. The null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference between the means. The alternative hypothesis is that the means are significantly different. The alpha value was 0.05. The t value is 5.5. The test was a one tailed hypothesis. The P value was 0.002664 and the result is significantly less than the alpha value of 0.05. As the P value is greater and the alpha value, there is a significant difference in the mean amount of oil in each sample.

Observations were made on the amount of mycelial growth in each of the spawn bags and the ability to produce mushrooms. Control spawn bags with no oil contamination had more vigorous mycelial growth, producing primordial formations that protruded out from the bag. Spawn bags introduced with 100ml of oil contamination had mycelial growth however lacked substantial primordial growth. Spawn bags with 300ml of oil contamination showed far less mycelial growth showing splotches of exposed substrate where there was no growth and patches of mould growth as shown in Figure 9.

Discussion

The first hypothesis tests whether oyster mushrooms can effectively bioremediate (remove) different amounts of canola oil from a growing substrate. The result from this experiment proves that there is a significant decrease in oil results from mycelial growth. Using a student t test, the p value was found to be less than the alpha value of 0.05 (p=0.02664). The null hypothesis is that there is no significant difference between the mean amounts of oil. The alternate hypothesis is that there is a significant difference between the mean values. As the p value was found to be less than the alpha value, therefore, the null hypothesis can be rejected, and the alternate hypothesis is accepted. Thus, it can be reliably concluded that mycelial growth removed oil from the substrate, reducing the oil load. The second hypothesis could not be tested because the fungi did not fruit properly. As this crop failure happened across all test and control groups this can be assumed not to be a result of the oil treatment.

Figure 8 shows that a low oil load had a larger oil loss than the higher oil load, therefore, proves the hypothesis true and that mushrooms will remove cooking oil from a coffee ground substrate more efficiently when the initial concentration of oil is lower. Low oil load average had a 73% removal, and the high oil load had a 57% oil removal. 16% difference confirms that Oyster mushrooms were more effective at bioremediating oil concentrations when the oil contamination was lower than when there was a high oil concentration. Therefore, mycoremediation of oil by Oyster mushrooms would be more effective if there is a greater amount of mushroom spawn over contaminant amount.

This is consistent with findings from other research. For example, research on the effects of crude oil on the growth of Oyster mushroom (P. ostreatus), found that high concentrations of oil resulted in a decrease in the fungi’s natural processes and functions, and thus inhibited its growth (Chukunda and Simbi Wellington, 2019). Ultimately, they concluded that fungal ability to transform PAHs into reusable products decreased as the concentration of PAHs increases, due to inability to obtain other resources from the substrate and environment. This is consistent with the findings of this study and therefore likely to be true of vegetable oils as well as petroleum.

Observations of mycelial growth determined that in substrates with a greater amount of oil, the mycelial growth was lower than in substrates with little to no oil contamination. The spawn bags with no oil contamination developed primordial formations which would later develop into the mushrooms. The spawn bags with low oil loads did develop large amounts of mycelial growth; however, did not produce primordial formations. It is therefore concluded that the presence of oil delayed or inhibited mushroom growth. There is no research to indicate a direct explanation for this; however, it is plausible that the oil delays the mushroom development and that with more time, the mushrooms might develop in substrates with oil present. High oil load bags did not produce much visible mycelial growth. Repetition of the experiment over a longer time frame may be one possible direction for future research.

One key and unexpected outcome was that the experiment was unable to produce any fruiting bodies (i.e., mushroom yield). Despite an attempt to cold

shock the spawn bags, no fruiting occurred. This was mostly likely due to environmental factors rather than the experiment because the control bags did not fruit either. The timing of the experiment meant that it was conducted during late autumn. Unseasonably cold conditions and an error with the laboratory thermostat meant that the laboratory temperature was dropping too low during the overnight period. This meant that the initial intention to measure the yield of the mushrooms (through mass of the fruiting bodies) was unsuccessful and the control for the experiment that would have been used to compare the yield produced, was less effective in comparing the end results for the loss of oil. However, it was still possible to qualitatively observe the extent of myceliation through measuring the difference between substrate before and after (the difference was assumed to be mycelial growth). From this it was concluded that in substrate containing low concentrations of oil, mushroom growth was inhibited; however, mycelium was still able to develop, whilst in high oil loads, mycelial growth was inhibited.

In two of the high oil load spawn bags, unwanted mould growth developed and needed to be discarded. Whilst this contamination is strictly a non result, it is highly suggestive that the Oyster mushroom was being inhibited, allowing other fungi to flourish. Out of the nine spawn bags produced, contamination only occurred in bags with the high oil load. Therefore, I hypothesise that high concentrations of oil made the environment more susceptible to fungal growth as the desirable mycelia is inhibited by the oil, however undesirable species were able to survive.

The experiment was limited in the amount of time to let the spawn grow in a dark environment and a limited time to allow them to grow in the greenhouse. Therefore, if the experiment was conducted over a longer period, there may have been primordial formation growth in spawn bags with low oil loads, and therefore would have concluded that presence of oil delays growth of those formations and not inhibit it.

Due to the lack of mushroom growth, measuring the yield of mushroom growth had to be adapted to observing the mycelial growth, thus turned finding quantitative data into recording qualitative data, and thus limited the capability of solidifying the relationship with a t test.

Future directions of research would involve repeating the experiment and extending the growth time to test

for mushroom yields. Furthermore, extending that research to testing the safety and edibility of the mushrooms, thus contributing to the application of the research and investigation, wherein bioremediation can also produce food for impacted communities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this experiment showed that the amount of oil in a substrate is decreased through mycelial growth using the natural process of mycoremediation. It showed that as the amount of oil in a substrate increased, there is a decrease in the effectiveness for Oyster mushrooms to remove the contaminant from the substrate and furthermore, increases in oil meant a decrease in mycelial growth and a susceptibility to mould growth.

The method employed in this research task was an effective way to determine if the active process of mycoremediation was present, wherein it showed the relationship between the amount of oil before and after mycelial growth. However, the experimental period impacted the methodology so that it had to be changed to produce a result in yield to test the hypotheses. This could be adjusted in the future to accommodate more time to the mycelium to grow and thus, as future research, the yield of mushroom production would be invaluable towards practical uses of this research.

The application of this research conforms to addressing vegetable based oil pollution, where environments impacted with similar oil contaminant can be bioremediated using Oyster mushrooms; however, to be successful would require a high proportion of mushroom grain compared to contaminant for it to be effective.

In conclusion, this research has produced promising results to provide a scientific basis for growing edible fungi on coffee grounds that have been spiked with oily food waste. This could be an inherently sustainable food production system where waste (coffee grounds and cooking oil) is converted to an edible product (mushrooms) and the remaining substrate is much more compostable and environmentally inert than the original materials.

Acknowledgements

Dr Alison Gates mentored and assisted in the design of the project, from the apparatus, practical work,

resources, report writing guidance and is acknowledged for her efforts and involvement in this investigation.

Mrs Lucy Pitkin assisted, aided, and supported the methodology, specifically through her efforts in showing and teaching how to care for the mushrooms. Furthermore, her best efforts in aiding in getting the mushrooms to produce fruit bodies.

References

Abdel Shafy, H.I. and Mansour, M.S.M. (2016). A review on polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source, environmental impact, effect on human health and remediation. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum, [online] 25(1), pp.107 123. doi:10.1016/j.ejpe.2015.03.011.

Akhtar, N. and Mannan, M.A. (2020). Mycoremediation: Expunging environmental pollutants. Biotechnology Reports, [online] 26, p.e00452. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S22150 17X19307003

Ali, S., Gupta, S.G. and Pathak, B. (2020). ABATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL POLLUTANTS. [online] Elsevier: Candice Janco, pp.127 149. Available at: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/62558053/Abateme nt_of_Environmental_Pollutants20200330 107049 1wkoc1w with cover page v2.pdf?Expires=1642826624&Signature=FD2DOR4Wre6 8w5RLWby3 YMcxgELRW 0t~N~PKiyjj9sUxscNmoaoH46Jlbg8Cl3cz4q16VWXm53 dQQOuHF6OureajJlhY3dXN4CT9IO4vGhKWxajHeFaly DPAUzffrMl

CY8Ys0DMpInEmp783yO2H3K32ojXqCuW5ntTrENm N6zp3p0VlZ6G7TS9fq16lX73enKn7sEHiUS2tuMyWAl bhpAhQB4cF~no58ob4l4Zho8ipkW4NhUlU5ZevANFoC zsldj1yvdfl4OHY9TjE0l9VcaH6OBVvzQpL6vHg48Q0H sy8b3KkhIUhXzTzTApQTUaKQdC3GmtEKo7qCA28qu w__&Key Pair Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA#page=140 [Accessed 22 Jan. 2022].

Casselman, A. (2007). Strange but True: The Largest Organism on Earth Is a Fungus. [online] Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/strange but true largest organism is fungus/ [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Chukunda, FA and Simbi Wellington, WS. (2019). Effects of Crude Oil on the Growth of Oyster Mushroom; Pleurotus ostreatus. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: file:///C:/Users/61490/Downloads/Effects_of_Crude_Oil_ on_the_Growth_of_Oyster_Mushr.pdf [Accessed 4 Feb. 2022].

Daccò, C., Girometta, C., Asemoloye, M.D., Carpani, G., Picco, A.M. and Tosi, S. (2020). Key fungal degradation patterns, enzymes and their applications for the removal of aliphatic hydrocarbons in polluted soils: A review. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, [online] 147, p.104866. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2019.104866

Gostincar, C., Grube, M., De Hoog, S., Zalar, P. and Gunde Cimerman, N. (2010). Extremotolerance in fungi: evolution on the edge. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, [online] 71(1), pp.2 11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574 6941.2009.00794.x

Greenberg, S. (2019). Mycoremediation: Definition, Current Trends and Market Opportunities. [online] Bccresearch.com. Available at: https://blog.bccresearch.com/mycoremediation definition current trends and market opportunities [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

JayLea (2022). Do Mushrooms Need Light Or Sunlight? The Facts Explained. [online] Flourishing Plants. Available at: https://flourishingplants.com/do mushrooms need light or sunlight/#:~:text=Mushrooms%20don’t%20need%20light %20except%20during%20their%20fruiting%20period,pre venting%20it%20from%20getting%20dry. [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Kapahi, M. and Sachdeva, S. (2017). Mycoremediation potential of Pleurotus species for heavy metals: a review. Bioresources and Bioprocessing, [online] 4(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643 017 0162 8

Klamerus Iwan, A., Błońska, E., Lasota, J., Kalandyk, A. and Waligórski, P. (2015). Influence of Oil Contamination on Physical and Biological Properties of Forest Soil After Chainsaw Use. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, [online] 226(11). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270 015 2649 2

Kulshreshtha, S., Mathur, N. and Bhatnagar, P. (2014). Mushroom as a product and their role in mycoremediation. AMB Express, [online] 4(1). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4052754/ #:~:text=Mycoremediation%20relies%20on%20the%20ef ficient,types%20of%20substrate%20and%20pollutants.&t ext=However%2C%20sometimes%20they%20absorb%20 the,consumed%20due%20to%20absorbed%20toxicants

Mahan, J. (2015). Mushroom Cultivation. [online] The Permaculture Research Institute. Available at: https://www.permaculturenews.org/2015/07/03/mushroom cultivation/ [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

MycoHaus. (2020). All in One 5 Pound Spawn Bag, Rye & Compost Mushroom Grow Kit. [online] Available at: https://www.mycohaus.com/products/all in one 5 pound spawn bag rye compost grow kit#:~:text=Simply%20inject%20your%20favorite%20spo res,or%20place%20in%20a%20terrarium. [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Nikola (2020). Mycelium: Using Mushrooms to Make Packaging Materials Materials and Engineering Resources Matmatch. [online] Materials and Engineering Resources Matmatch Get the latest in materials science and engineering news, educational content and material use cases. Available at: https://matmatch.com/resources/blog/mycelium using mushrooms to make packaging materials/ [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Selbmann, E.Egidi, Daniela Isola (2013) Plant Biosystems An International Journal Dealing with all Aspects of Plant Biology. (2013). Biodiversity, evolution and adaptation of fungi in extreme environments. [online] Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/11263504.2 012.753134 [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Pullano, N. (2020). 9 mushroom uses: Surprising uses for the fungus that improve your life. [online] Inverse. Available at: https://www.inverse.com/science/mushroom burial suits and vegan leather 9 uses for mushrooms [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Sayner, A. (2018). Growing Mushrooms In Coffee Grounds. [online] GroCycle. Available at: https://grocycle.com/growing mushrooms in coffee grounds/ [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Schiewer, S. and Horel (2020). Microbial Degradation of Different Hydrocarbon Fuels with Mycoremediation of Volatiles. [online] MDPI Microorganisms. Available at: file:///C:/Users/61490/Downloads/microorganisms 08 00163 v2.pdf [Accessed 4 Feb. 2022].

Sérgio Thode Filho, Laudelina, J., Heider Alves Franco, Daniel Vidal Perez and Regina, M. (2017). Environmental impacts caused by residual vegetable oil in the soil plant system. Ciência e Natura, [online] 39(3), pp.748 757. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/4675/467553545021/html / [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Stamets, P. (2000). Growing Gourmet & Medicinal Mushrooms. Thrid ed. [online] RANDOM HOUSE US, p.82. Available at: https://library.uniteddiversity.coop/Permaculture/Growing _Gourmet_and_Medicinal_Mushrooms.pdf [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Stamets, P. (2010). The Petroleum Problem. [online] Fungi Perfecti. Available at: https://fungi.com/blogs/articles/the petroleum problem [Accessed 19 Jun. 2022].

Owen Ng Barker College

Purpose: This research aims to determine whether polyphenolic compounds extracted from grapeseeds (Vitis vinifera) are able to inhibit the growth of common grape fungi (Botrytis sp) and thus to consider their suitability as an organic fungicide in grape production.

Design/methodology/approach: A method for extracting polyphenols in a secondary school laboratory was developed. The extracted compounds were tested via well diffusion on agar plates lawned with Botrytis sp against a control of potassium bicarbonate, a compound used widely in viticulture enterprises as an antifungal.

Findings: A positive linear association was found between concentration of polyphenols and inhibition. However, it was also observed that polyphenols are less effective than that of the potassium bicarbonate control.

Research Limitations/implications: This research was primarily focused on the polyphenols present in seeds, which may not reflect the composition and antifungal nature of other parts of the grape such as the skin. A larger sample size and more sophisticated laboratory analysis could improve the reliability of this research.

Practical/social implications: If successful, this may allow for the development of new, ecologically friendly organic fungicides and sustainable horticultural practices in the future to meet the growing demand for mass produced food in a growing global food crisis.

Originality/value: Rather than predict potential antifungal properties with radical scavenging molecules, this study uses live samples of Botrytis cinerea to determine antifungal properties in a practical manner. In addition, through a rigorous process of trial and error, this research outlines a reliable method for extracting polyphenols in a secondary school laboratory. This is not a trivial contribution since it could be used to develop interesting, engaging laboratory learning experiences for secondary chemistry students.

Keywords: Botrytis cinerea, Polyphenols, Inhibition Paper Type: Research paper

Literature Review

Botrytis cinerea is an airborne, necrotrophic fungus frequently observed on soft fruits such as grapes and can be found in virtually all environments (Kan, Shaw & Grant‐Downton 2014). Since 2015, B. cinerea has cost the global wine industry between USD 10 100 billion per year (Brito et al. 2021), which is up to 23.8% its total market size (Huron, Behm & Helmus 2021). Able to infect over 1000 crop species (Fillinger 2016), it can destroy up to 80% of any given harvest, making it one of the most prolific plant fungal pathogens globally (Petrasch et al. 2019).

According to Williamson et al. (2007), plants infected by B. cinerea will begin to exhibit necrosis, as parenchyma tissues collapse and fill with water, presenting brown lesions up to 15cm long and soft rotting of aerial plant parts. The compromised plant is now more susceptible to opportunistic pathogens such as Aspergillus niger or Penicillium expansum

that can further damage the crop. Prolific grey conidiophores become present post necrosis and can infect a neighbouring plant within 12 hours, or live on its surface for 3 months (Reignault et al. 2000).

Figure 1: Inhibition of fludioxonil, iprodione and other antifungals on B. cinerea conidial germination (Source: Kim et al. 2016).

Currently, the most common treatment for B. cinerea is the use of anti Botrytis fungicides known as botryticides, which currently represent 10% of the

Determination of the antifungal properties of polyphenols extracted from the common grape (Vitis vinifera)

global fungicide market (Dean et al. 2012). Some botryticides, such as fludioxonil and iprodione, are already known to inhibit between 93.7 100% of mycelial growth at 0.1 and 1 μg/ml respectively per figure 1. While such treatment is effective, botryticides (a form of diazole) also contain toxic, corrosive and carcinogenic chemicals such as chlorothalonil or pyrimethanil, which are harmful to humans if ingested at concentrations higher than 1.5mg/kg and therefore not desirable to applications in food crops. (Arena et al. 2018).

An alternative treatment to chemical fungicides is the introduction of organisms that inhibit the growth of B. cinerea through parasitic relationships between the pathogen and organism. For example, mycoparasites such as Pythium periplocum can be used to feed off and destroy invading pathogens such as B. cinerea (Karlsson et al. 2017; Paul 1999). However, the aforementioned mycoparasite is also the cause of Pythium root rot, which causes the decay of plant roots and water soaked lesions to appear on exposed surfaces (Sutton et al. 2006). Thus, while mycoparasites are not harmful to humans, maintaining a balance between the two pathogens for effective treatment remains a significant economic and horticultural challenge.

Recent studies, such as those undertaken by Yang et al. 2019, are beginning to explore the potential uses of plant derived compounds as antimicrobial agents. Naturally, most eukaryotic plants synthesise secondary metabolites, organic compounds not directly involved in the reproduction of the plant, to aid in abiotic stress or pathogenic response (Guerriero et al. 2018). According to Ali et al. (2009), the two primary secondary metabolites are terpenoids and polyphenols. Terpenoids, while already used in the medical industry for their antimicrobial properties (Cox Georgian et al. 2019), have a relatively low presence (804 μg/L) in grapes and are thus not suitable for the study (Cox Georgian et al. 2019). Further, high concentrations of terpenoids have been shown to cause central nervous system complications and gastrointestinal problems and may not be suitable for horticultural use (Mbaveng, Hamm & Kuete 2014).

On the other hand, polyphenols, the other secondary metabolite, can be found abundantly in concentrations between 300 to 16,650 mg/L in the leaves, pomace, skin or seeds of V. vinifera (Hornedo Ortega et al. 2021). Polyphenols synthesised in the leaves and pomace are yet to be extensively studied and their anti microbial

properties have not been elucidated. For example, some flavonoids, a type of polyphenol, present in grape leaves include quercetin 3 O glucuronide (76.5%) and quercerin 3 O glucoside (12%) (Bouderias et al. 2020) which are yet to exhibit any anti microbial properties (Razavi et al. 2009; Park et al. 2016). However, polyphenols extracted in the seed and skin of V. vinifera have already demonstrated both in vitro antifungal and antimicrobial properties against gram positive and negative bacterium including various Candida species (Teodoro et al. 2015; Bouarab Chibane et al. 2019). Specifically, the seeds, which contain 60 70% of the total extractable polyphenols, has exhibited the potential to protect food contamination through the restriction of pathogen growth (Lorenzo Rodríguez et al. n.d.).

Currently, there is no safe and cost effective method of B. cinerea prevention or treatment without the use of synthetic pesticides with harmful environmental and toxic side effects. Other solutions such as mycoparasites also present difficulties in horticulture as plants must be constantly monitored to maintain a balance between two or more harmful pathogens. With recent studies revealing the mechanisms behind natural pathogenic responses in plants, a natural solution to B. cinerea may involve the use of secondary metabolites. With the knowledge that V. vinifera contains a high concentration of polyphenols, a prominent secondary metabolite used in pathogen response, a naturally occurring anti microbial agent could potentially be realised. Using V. vinifera as an example, this study seeks to examine the effectiveness of polyphenolic compounds as an inhibition agent for B. cinerea, and if it is a viable alternative for synthetic pesticides on a theoretical level.

Method Culture of botrytis

Vitus vinifera (var. Mirindee seedless) grapes were washed to remove residual pesticides, halved with a scalpel and placed face down on an ampicillin spiked malt agar petri dish. These were left in an incubator without sunlight at 25°C for three days until grey conidiophores were visible on the surface.

Under a fume hood, a bunsen flame was lit to create an updraft of air. A petri dish was carefully opened under the flame and a loop of fungal mycelium was collected with a sterile inoculating loop. This was cultured in a malt nutrient broth in an incubator at 25°C.

The broth was sampled onto a microscope slide and covered with a cover slip. The slide was then observed for morphological traits such as hyaline conidia and rounded, apical cells to confirm that B. cinerea was grown. A malt agar plate was cultured from the broth to check that the sample was not contaminated.

Once positive, 5 10mm of infected skin was removed from the grape under the Bunsen and placed in a nutrient broth. This was left for 3 days at 25°C to produce a pure culture of B. cinerea

Extraction of polyphenols

Extraction

1kg of V. vinifera grapes were deseeded using a scalpel and the seeds left to dry in a dehydrator at 40°C for 2 days. The dry seeds were then removed and grinded into a fine powder with a mortar and pestle.

According to Nilüfer et al. (2018), the following conditions optimised the yield of polyphenols by ultrasound assisted extraction. In a beaker, 61.75mL of pure ethanol was mixed with 38.2mL of distilled water. This was repeated once to produce 200mL of 61.75% ethanol solution.

1.6g of grapeseed power was added to 50mL of ethanol solution in a 200mL conical flask. The flask was then fixed with tape in a 2L ultrasonic bath, filled with 1.3L of distilled water, heated to 50°C and a frequency of 28Hz. After 20 minutes, the flask was removed and cooled in room temperature water where it was filtered through Whatnam 40. filter paper.

As ethanol is an antimicrobial, it needed to be removed by heat as both solutions are soluble in water. In a separate beaker, 200mL of distilled water was heated and maintained at 90°C on a heating plate. The filtrate was measured in a measuring cylinder before being transferred to a smaller beaker. This was partially submerged in the hot water until its contents reached 85°C and left to evaporate for 10 minutes. The water temperature was continually monitored to ensure it was below 90°C, preventing the denaturation of any polyphenols present. The beaker was then removed and left to cool at room temperature. The contents were transferred again to the same measuring cylinder, which confirmed the expected volume of ethanol had evaporated.

Test for presence

5 drops of the treated solution and ethanol solution were placed in two separate test tubes. 3 drops of FeCl3 was added of each test tube. Polyphenols present in the treated solution underwent a complexation reaction

The iron phenol complex caused an immediate colour change to a dark green to be observed, confirming the presence of polyphenols. The control test tube of ethanol solution remained a very feint yellow.

Testing for a zone of inhibition

The polyphenolic solution was added in 0.5mL increments to 9 test tubes from 1 4 mL in volume. An 9th test tube was left empty as a control. Each test tube was then made up to 5mL in volume with distilled water. 9 small circles of filter paper, 10mm in diameter, were cut out and one was placed in each test tube in contact with the solution. This was repeated 3 times.

The agar plate was divided into 3 sections with a permanent marker. Pure B. cinerea culture was then applied evenly on the plate with a spreader. A KHCO3 disk (an industry standard antifungal) and a filter paper disk of polyphenol solution was placed in each section of the plate, while the third was left blank. This was repeated for the remaining 26 agar plates. The plates were left in a dark area at room temperature for 5 days and results were tabulated.

Scientific Research Question

Do polyphenolic compounds extracted from grape seeds have anti fungal properties?

Scientific Hypothesis

That the polyphenolic compounds extracted from grape seeds will exhibit a zone of inhibition around a well on a malt agar plate.

Results

Concentration and inhibition have a positive linear association

The raw data of the area of inhibition together with the independent variable is shown in Table 1. This

illustrated as a scatter plot and shown in Figure 2a. To examine the association between inhibition diameter in millimetres and concentration, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient was first calculated (r = 0.93) between inhibition and concentration.

2a illustrates this relationship as a scatter plot where a strong positive correlation between concentration and inhibition zone was observed including a clear upward trend. Next, a linear regression model was fitted to estimate the least square regression line and the fitted line is expressed as

0.017

a corresponding ��������2 of 0.87. Even though the ��������2 is high, the residuals vs fit plot (Figure 2b) showed a non random curvature pattern which indicates that it may be better to fit a non linear relationship between concentration and inhibition.

Piece wise linear association to model the relationship between concentration and inhibition

approaches were attempted to capture the non linear relationship between concentration and inhibition. The first involves a log linear model and the second involves a piece wise regression where a regression line was fitted to the non zero inhibition data. For the log linear model, a log transformation to the variable inhibition was performed and the fitted log linear regression model with the corresponding scatter plot shown in Figure 3a. However, residuals vs fit plot (Figure 3b) still showed a non random curvature pattern which is likely due to the zero values in the lower concentration data. Thus, the second approach fitted a linear model to the non zero inhibition data and the piece wise linear model is expressed as

the corresponding scatter plot shown in Figure 3c. The goodness of fit statistic for part of the linear regression ��������2 is 0.92 and no pattern was shown in the residual vs fit plot (Figure 3d).

Figure

(a)

scatter plot showing the level of inhibition (y axis)

concentration (x axis). The actual values are shown as black dots and the line of best fit (least square regression line) is shown in blue. The shaded regions show the confidence bound associated with the line of best fit. (b) A diagnostics plot showing that the residuals between the fitted and real values of concentration and inhibition

random.

Figure 3. (a) A scatter plot showing the log transformed level of inhibition (y axis) against concentration (x axis) with the line of best fit (blue) represented by equation �����������������������������������������ℎ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� � = 3 45 + 0 004 ���������������������������������������������������������������� . (b) A diagnostics plot showing that the residuals versus the fitted values. (c) The piece wise linear model with break point at concentration 51. (d) Diagnostic plot of the non zero where ���������������������������������������������������������������� > 51

The inhibition of poly was similar to the control KHCO3

The hypothesis was tested by determining whether the slope of the concentration for ���������������������������������������������������������������� > 51 was significantly different from zero. The estimated coefficient of ���������������������������������������������������������������� in the linear model was 0.246 with a corresponding t statistic of 9.304 and a p value of 0.003. The QQ plot (Figure 4a) shows an approximate normal distribution, indicating the assumption behind the t statistic is valid. Despite a positive non zero coefficient which indicates a significant positive relationship between concentration and inhibition, the level is still less than the inhibition of the positive control (������������������������ ��������3 ). Even at 100% concentration, the inhibition area of the polyphenols was 1.3mm at its maximum, while the positive control consistently inhibited 3.5mm see Figure 4b).

Discussion

In this study, the antifungal properties of polyphenols extracted from V. vinifera were examined by plating the polyphenols on a plate of B. cinerea. The results revealed that polyphenolic compounds extracted from V. vinifera did have an inhibitory effect on B. cinerea. However, the size of this effect was marginal compared to the positive antifungal control of ������������������������ ��������3 , potentially limiting the use of polyphenols as an effective method to inhibit B. cinerea.

Figure 5: Chemical structure of resveratrol (Source: Gambini et al. 2015).

Figure 4: (a) A scatter plot showing the level of inhibition (y axis) against concentration (x axis) compared to the positive control ������������������������ ��������3 . The actual values are shown as black dots and the piece wise function is shown in black. The ������������������������ ��������3 is shown in red. (b) A diagnostics plot showing the similarity between residual values and a normal distribution to validate the t test

Polyphenols contained in V. vinifera, such as resveratrol, have a unique structure allowing it to inhibit the growth of most fungi. This is consistent with the data which showed a positive correlation (r = 0.93) between polyphenol concentration and B. cinerea inhibition. This is likely due to the presence of resveratrol (a stilbene), which is a well known phytoalexin and has already been used to successfully inhibit the growth of B. cinerea at concentrations between 60 140 μg/mL (Abedini et al. 2021). These properties can be attributed to its structure, as resveratrol (3, 5, 4’ trihydroxystilbene) is the product of substituting phenyl groups for hydroxyls at 3, 5 and 4’ (Perrone et al. 2017, Figure 5). These hydroxyl groups mediate the production of other reactive oxygen species in the cell such as peroxides and hydroxides, leading to the activation of caspase and the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, triggering cell apoptosis in fungi and the destruction of the pathogen (Redza Dutordoir et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2014).

While some polyphenolic compounds such as resveratrol have exhibited anti fungal properties, other polyphenols such as Flavonoids are ineffective as anti fungal agents. Thus, if the proportion of ineffective polyphenols are high, polyphenols will be less effective at inhibiting B. cinerea. This can partially explain that while polyphenols from grapes inhibit B. cinerea growth, the most concentrated polyphenols mixture that was generated had a lower inhibition zone (1.3mm) than the positive control KHCO3 (3.5mm). One possible explanation for this trend is that fungal cell walls, comprised of multiple layers of polysaccharides and lipids, are difficult to penetrate (Garcia Rubio et al. 2020). Thus, for a polyphenolic compound such as Flavonoids, which

rely on the exploitation of weak cell walls to destroy pathogens, are likely to be ineffective against B. cinerea (Al Aboody et al. 2020; Mohammad et al. 2020). Specifically, B. cinerea’s cell wall undergoes extensive covalent cross linkage during growth between polysaccharides (Cantu et al. 2009) and it secretes a complex layer of triacylglycerol as part of its extra cellular matrix (Doss 1999), making it resistant to certain types of antifungal agents such as Flavonoids (Figure 7) (Nawaz et al. 2006; Singh et al. 2015).

Figure 6: Chemical structure of Flavonoids (Nishiumi et al. 2011). The polar ketone in the second carbon group interacts with porin protein on the cell membrane of B. cinerea to inhibit the transport of glucose, preventing further growth of both gram positive (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus, Xie et al. 2014) and gram negative bacteria (e.g. Escherichia coli,) (Source: Xie et al. 2017).

Liang and collegues (Liang et al. 2014) have shown that Flavonoids are the predominant polyphenolic compound in V. vinifera and are found in concentrations roughly 15x higher than resveratrol. Given the estimated low proportion of resveratrol in the tested samples, the results show non zero inhibition levels (between 0.03 1.3mm) which

strongly indicate the potential of polyphenols as anti fungal in the right concentration. In absence of an exact concentration, an inhibition area equal to that of industry standards (such as KHCO3 ) can be achieved by increasing the maximum concentration of the initial generated samples by 2.5 fold. If successful, this opens a new avenue for sustainable applications of fungicides in horticulture, as compounds sourced from food products may pose lower health risks for surrounding ecosystems.

This experiment was primarily limited by equipment, the total yield by mass of the polyphenols could not be determined or optimised. The seeds of the grape were used as literature has shown grape seeds contain in the highest concentration of polyphenols (60 70 wt%) in V. vinifera (Nawaz et al. 2006). However, Xie et al. (2010) observed that polyphenols extracted in the seed usually consist of proanthocyanins, epicatechin or other flavonoids, while resveratrol is primarily found in the skin. Thus, it is likely that the level of inhibition may be significantly greater when extracting polyphenols from the skin due to a greater presence of resveratrol. Furthermore, it was impossible to delineate between types of polyphenols present in the solution, such as resveratrol or flavonoids, limiting the generalisability of this study.

Although not as effective as synthetic fungicides, the results suggest the potential of polyphenols as an organic antifungal agent due to the correlation between inhibition and concentration. However, further research needs to be conducted regarding the presence of polyphenolics such as resveratrol hypothesised in the discussion. Testing other parts of the grape such as skin, with potentially high contents of resveratrol, may continue to validate polyphenols as a potential fungicide

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated a positive linear association between the concentration of polyphenols extracted from V. vinifera and inhibition against B. cinerea. These results indicate that the hypothesis can be cautiously accepted. However, results also show that the efficacy of polyphenols are significantly less than industry standard fungicides such as KHCO3. This trend may be explained by the low presence of antifungal compounds in V. vinifera and the structural adaptations of B. cinerea has developed to resist plant based pathogen responses.

Rather than inferring the antifungal properties of polyphenols with radical scavenging compounds, this

study used live samples of B. cinerea to test the level of inhibition on a practical level, which remains critical in the search for an alternative to synthetic and ecologically damaging fungicides. Further, research into the presence of compounds such as resveratrol in other parts of V. vinifera and its potential as an antifungal agent may reveal new mechanisms in plant pathogenic response, forming new frontiers in molecular biology and biochemistry.

Amidst the growing global food crisis, efficient and safe horticultural practices remain critical in the maintenance of the global food supply chain. Further research identifying the structure and mechanisms of plant derived secondary metabolites such as polyphenols are required to balance the demands of an exponentiating population with the harmful side effects of modern agriculture.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Alison Gates for her insightful contributions during the writing and practical components of this study. I would also like to thank the Barker College and the lab staff for providing the adequate equipment to perform the experiment.

References

Abedini, E, Khodadadi, E, Zeinalzadeh, E, Moaddab, SR, Asgharzadeh, M, Mehramouz, B, Dao, S & Samadi Kafil, H 2021, ‘A Comprehensive Study on the Antimicrobial Properties of Resveratrol as an Alternative Therapy’, in W Hu (ed.), Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2021, pp. 1 15, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC798742 1/>.

Al Aboody, MS & Mickymaray, S 2020, ‘Anti Fungal Efficacy and Mechanisms of Flavonoids’, Antibiotics, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 45, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC716812 9/>.

Ali, K, Maltese, F, Choi, YH & Verpoorte, R 2009, ‘Metabolic constituents of grapevine and grape derived products’, Phytochemistry Reviews, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 357 378, viewed 9 January 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC292844 6/#CR114>.

Arena, M, Auteri, D, Barmaz, S, Bellisai, G, Brancato, A, Brocca, D, Bura, L, Byers, H, Chiusolo, A, Court Marques, D, Crivellente, F, De Lentdecker, C, Egsmose, M, Erdos, Z, Fait, G, Ferreira, L, Goumenou, M, Greco, L, Ippolito, A & Istace, F 2018, ‘Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance chlorothalonil’, EFSA Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, viewed 24 May 2022,

<https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.2903/j.ef sa.2018.5126>.

Bouarab Chibane, L, Forquet, V, Lantéri, P, Clément, Y, Léonard Akkari, L, Oulahal, N, Degraeve, P & Bordes, C 2019, ‘Antibacterial Properties of Polyphenols: Characterization and QSAR (Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship) Models’, Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 10, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019. 00829/full>.

Bouderias, S, Teszlák, P, Jakab, G & Kőrösi, L 2020, ‘Age and season dependent pattern of flavonol glycosides in Cabernet Sauvignon grapevine leaves’, Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598 020 70706 7>.

Brighenti, E, Casagrande, K, Cardoso, PZ, Pasa, M da S, Ciotta, MN & Brighenti, AF 2017, ‘Total polyphenols contents in different grapevine varieties in highlands of southern brazil’, in J M Aurand (ed.), BIO Web of Conferences, vol. 9, p. 01024, viewed 10 January 2022, <https://www.bio conferences.org/articles/bioconf/full_html/2017/02/biocon f oiv2017_01024/bioconf oiv2017_01024.html>.

Brito, C, Hansen, H, Espinoza, L, Faúndez, M, Olea, AF, Pino, S & Díaz, K 2021, ‘Assessing the Control of Postharvest Gray Mold Disease on Tomato Fruit Using Mixtures of Essential Oils and Their Respective Hydrolates’, Plants, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 1719, viewed 21 May 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC840141 5/>.

Cantu, D, Carl Greve, L, Labavitch, JM & Powell, ALT 2009, ‘Characterization of the cell wall of the ubiquitous plant pathogen Botrytis cinerea’, Mycological Research, vol. 113, no. 12, pp. 1396 1403, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19781643/>.

Cox Georgian, D, Ramadoss, N, Dona, C & Basu, C 2019, ‘Therapeutic and Medicinal Uses of Terpenes’, Medicinal Plants, pp. 333 359, viewed 24 May 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC712091 4/#:~:text=This%20plant%20contains%20many%20medi cinal,2001).>.

Dean, R, Van Kan, Jal, Pretorius, Za, Hammond Kosacj, Ke, Di Pietro, A, Spanu, Pd, Rudd, JJ, Dickman, M, Kahmann, R, Ellis, J & Foster, Gd 2012, ‘The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology’, Molecular Plant Pathology, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 414 430, viewed 10 January 2022, <https://bsppjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10. 1111/j.1364 3703.2011.00783.x>.

Doss, RP 1999, ‘Composition and Enzymatic Activity of the Extracellular Matrix Secreted by Germlings of Botrytis cinerea’, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 404 408, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC91039/>

Fillinger, S 2016, Botrytis the Fungus, the Pathogen and its Management in Agricultural Systems, ResearchGate, Springer, viewed 22 May 2022, <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287645053_Bo trytis_

_the_Fungus_the_Pathogen_and_its_Management_in_Ag ricultural_Systems>.

Gambini, J, Inglés, M, Olaso, G, Lopez Grueso, R, Bonet Costa, V, Gimeno Mallench, L, Mas Bargues, C, Abdelaziz, KM, Gomez Cabrera, MC, Vina, J & Borras, C 2015, ‘Properties of Resveratrol:In VitroandIn VivoStudies about Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Biological Effects in Animal Models and Humans’, Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, vol. 2015, pp. 1 13, viewed 11 June 2022, <https://www.hindawi.com/journals/omcl/2015/837042/>.

Garcia Rubio, R, de Oliveira, HC, Rivera, J & Trevijano Contador, N 2020, ‘The Fungal Cell Wall: Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus Species’, Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 10, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019. 02993/full>.

Guerriero, G, Berni, R, Muñoz Sanchez, J, Apone, F, Abdel Salam, E, Qahtan, A, Alatar, A, Cantini, C, Cai, G, Hausman, J F, Siddiqui, K, Hernández Sotomayor, S & Faisal, M 2018, ‘Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Examples, Tips and Suggestions for Biotechnologists’, Genes, vol. 9, no. 6, p. 309, viewed 24 May 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC602722 0/>.

Hornedo Ortega, R, Reyes González Centeno, M, Chira, K, Jourdes, M & Teissedre, P L 2021, ‘Phenolic Compounds of Grapes and Wines: Key Compounds and Implications in Sensory Perception’, Chemistry and Biochemistry of Winemaking, Wine Stabilization and Aging, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/72677>.

Huron, NA, Behm, JE & Helmus, MR 2021, ‘Paninvasion severity assessment of a U.S. grape pest to disrupt the global wine market’, viewed 27 May 2022, <https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.19.452 723v3.abstract>.

Kan, JAL, Shaw, MW & Grant‐Downton, RT 2014, ‘Botrytis species: relentless necrotrophic thugs or endophytes gone rogue?’, Molecular Plant Pathology, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 957 961, viewed 9 January 2022, <https://bsppjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111 /mpp.12148>.

Karlsson, M, Atanasova, L, Jensen, DF & Zeilinger, S 2017, ‘Necrotrophic Mycoparasites and Their Genomes’, in J Heitman, TY James & PW Crous (eds), Microbiology Spectrum, vol. 5, no. 2, viewed 6 January 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28281442/>.

Kim, J O, Shin, J H, Gumilang, A, Chung, K, Choi, KY & Kim, KS 2016, ‘Effectiveness of Different Classes of Fungicides on Botrytis cinerea Causing Gray Mold on Fruit

and Vegetables’, The Plant Pathology Journal, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 570 574, viewed 9 January 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC511786 6/>.

Lee, J & Lee, DG 2014, ‘Novel Antifungal Mechanism of Resveratrol: Apoptosis Inducer in Candida albicans’, Current Microbiology, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 383 389, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25413604/>.

Liang, Z, Cheng, L, Zhong, G Y & Liu, RH 2014, ‘Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Twenty Four Vitis vinifera Grapes’, in G Pintus (ed.), PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 8, p. e105146, viewed 11 June 2022, <https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/jour nal.pone.0105146>.

Lorenzo Rodríguez, J, Ruiz, D, Pasqua, G, Simonetti, G & Pasqua, G n.d., In: Grape Seeds ANTIMICROBIAL AND ANTIVIRAL ACTIVITIES OF GRAPE SEED EXTRACTS, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://www.novapublishers.com/wp content/uploads/2018/10/978 1 63484 578 6_ch10.pdf>.

Mbaveng, AT, Hamm, R & Kuete, V 2014, ‘Harmful and Protective Effects of Terpenoids from African Medicinal Plants’, Toxicological Survey of African Medicinal Plants, pp. 557 576, viewed 6 January 2022, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780 128000182000194>.

Mohammad & Suresh Mickymaray 2020, Anti Fungal Efficacy and Mechanisms of Flavonoids, ResearchGate, MDPI AG, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338849298_An ti Fungal_Efficacy_and_Mechanisms_of_Flavonoids>.

Nawaz, H, Shi, J, Mittal, GS & Kakuda, Y 2006, ‘Extraction of polyphenols from grape seeds and concentration by ultrafiltration’, Separation and Purification Technology, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 176 181, viewed 18 June 2022, <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1 383586605002169#:~:text=The%20percentage%20of%20 the%20total,8%20wt%25%20%5B9%5D.>.

Nilüfer Vural, Özge Algan Cavuldak & Rahmi Ertan Anli 2018, Multi response optimisation of polyphenol extraction conditions from grape seeds by using ultrasound..., ResearchGate, Taylor & Francis, viewed 9 January 2022, <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323563110_M ulti_response_optimisation_of_polyphenol_extraction_co nditions_from_grape_seeds_by_using_ultrasound_assiste d_extraction_UAE>.

Nishiumi, S, Miyamoto, S, Kawabata, K & Terao, J 2011, Dietary flavonoids as cancer preventive and therapeutic biofactors, ResearchGate, unknown, viewed 11 June 2022, <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51174448_Diet ary_flavonoids_as_cancer preventive_and_therapeutic_biofactors>.

Park, J Y, Lim, M S, Kim, S I, Lee, HJ, Kim, S S, Kwon, Y S & Chun, W 2016, ‘Quercetin 3 O β D Glucuronide Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide Induced JNK and ERK Phosphorylation in LPS Challenged RAW264.7 Cells’, Biomolecules & Therapeutics, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 610 615, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC509854 0/>.

Paul, B 1999, ‘Pythium periplocum, an aggressive mycoparasite ofBotrytis cinereacausing the gray mould disease of grape vine’, FEMS Microbiology Letters, vol. 181, no. 2, pp. 277 280, viewed 9 January 2022, <https://academic.oup.com/femsle/article/181/2/277/7359 85>.

Perrone, D, Fuggetta, MP, Ardito, F, Cottarelli, A, De Filippis, A, Ravagnan, G, De Maria, S & Lo Muzio, L 2017, ‘Resveratrol (3,5,4′ trihydroxystilbene) and its properties in oral diseases’, Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 3 9, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC548848 4/>.

Petrasch, S, Silva, CJ, Mesquida Pesci, SD, Gallegos, K, van den Abeele, C, Papin, V, Fernandez Acero, FJ, Knapp, SJ & Blanco Ulate, B 2019, ‘Infection Strategies Deployed by Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium acuminatum, and Rhizopus stolonifer as a Function of Tomato Fruit Ripening Stage’, Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 10, viewed 17 April 2022, <https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2019.00 223/full>.

Razavi, SM, Zahri, S, Zarrini, G, Nazemiyeh, H & Mohammadi, S 2009, ‘Biological activity of quercetin 3 O glucoside, a known plant flavonoid’, Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 376 378, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19621057/>.

Redza Dutordoir, M & Averill Bates, DA 2016, ‘Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species’, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) Molecular Cell Research, vol. 1863, no. 12, pp. 2977 2992, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27646922/>.

Reignault, Ph, Kunz, C, Delage, N, Moreau, E, Vedel, R, Hamada, W, Bompeix, G & Boccara, M 2000, ‘Host and symptom specific pectinase isozymes produced by Botrytis cinerea’, Mycological Research, vol. 104, no. 4, pp. 421 428, viewed 27 May 2022, <https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/mycological research/article/abs/host and symptomspecific pectinase isozymes produced by botrytis cinerea/886E65DB76B4AF1A9DD7E829BE68C843>.

Robinson, S, Scholefield, P & Morison, J 2010, Prepared for : GWRDC EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ‘Assessment of Economic Cost of Endemic Pests & Diseases on the Australian Grape & Wine Industry’.

Singh, CK, Liu, X & Ahmad, N 2015, ‘Resveratrol, in its natural combination in whole grape, for health promotion

and disease management’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1348, no. 1, pp. 150 160, viewed 11 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC455311 3/>.

Sutton, JC, Sopher, CR, Owen Going, TN, Liu, W, Grodzinski, B, Hall, JC & Benchimol, RL 2006, ‘Etiology and epidemiology of Pythium root rot in hydroponic crops: current knowledge and perspectives’, Summa Phytopathologica, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 307 321.

Teodoro, GR, Ellepola, K, Seneviratne, CJ & Koga Ito, CY 2015, ‘Potential Use of Phenolic Acids as Anti Candida Agents: A Review’, Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 6, viewed 4 January 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC468507 0/#:~:text=Phenolic%20compounds%20isolated%20from %20natural,known%20antifungals%20are%20still%20sca rce.>.

Valero Jiménez, CA, Veloso, J, Staats, M & van Kan, JAL 2019, ‘Comparative genomics of plant pathogenic Botrytis species with distinct host specificity’, BMC Genomics, vol. 20, no. 1, viewed 6 January 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC641707 4/>.

Williamson, B, Tudzynski, B, Tudzynski, P & Van Kan, Jal 2007, ‘Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease’, Molecular Plant Pathology, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 561 580, viewed 24 May 2022, <https://bsppjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111 /j.1364 3703.2007.00417.x>.

Xia, E Q, Deng, G F, Guo, Y J & Li, H B 2010, ‘Biological Activities of Polyphenols from Grapes’, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 622 646, viewed 11 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC285285 7/#b30 ijms 11 00622>.

Xie, Y, Chen, J, Xiao, A & Liu, L 2017, ‘Antibacterial Activity of Polyphenols: Structure Activity Relationship and Influence of Hyperglycemic Condition’, Molecules, vol. 22, no. 11, p. 1913, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC615040 9/>.

Xie, Y, Yang, W, Chen, X & Ren, L 2014, Antibacterial Activities of Flavonoids: Structure Activity Relationship and Mechanism, ResearchGate, Bentham Science Publishers, viewed 10 June 2022, <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266029486_An tibacterial_Activities_of_Flavonoids_Structure Activity_Relationship_and_Mechanism>.

Yang, Y, Jin, G J, Wang, X J, Kong, C L, Liu, J & Tao, Y S 2019, ‘Chemical profiles and aroma contribution of terpene compounds in Meili (Vitis vinifera L.) grape and wine’, Food Chemistry, vol. 284, pp. 155 161, viewed 6 January 2022, <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30744840/#:~:text=Sev enteen%20terpene%20glycosides%20were%20quantified, 40.1%20to%2059.7%20%CE%BCg%2FL.>

Tegan Lee Barker College

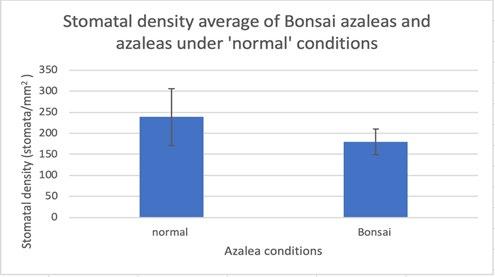

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to determine the effect of Bonsai conditions on the stomatal density of azalea plants.

Design/methodology/approach: A leaf imprint was viewed under a compound light microscope and the stomatal density was calculated.

Findings: An independent t test compared the means of the stomatal densities of the azaleas under ‘normal’ and Bonsai conditions and determined that the results are not significant as P>0.05.

Research limitations/implications: This paper is limited by the timeframe provided; without this boundary the sample size could have been increased for example more samples per leaf and more leaves overall. If this occurred then the outliers would have implicated the results less, providing more consistent results.