KULTYWATOR PRAGA

VOCATIONAL SCHOOL AS AN URBAN ACTIVATOR OF PRAGA WARSAW

Aneta Ziomkiewicz aneta.ziomkiewicz@gmail.com

Master of Architecture Academy of ArchitectureAmsterdam, August 2022 Comission: Wouter Kroeze (mentor) Jana JarrikCreponOuburg

Examination comission: Burton Hamflet Marc Reniers

KULTYWATOR PRAGA VOCATIONAL SCHOOL AS AN URBAN ACTIVATOR OF PRAGA WARSAW

1. A cultivator is a person who ensures that an element of culture is not forgotten and that it develops.

2. A cultivator is a tool or machine that is used to prepare the soil and kill weeds around growing plants.

table of contents introduction 7 context 19 characteristics of Praga-Północ 31 Różycki market 41 tenement typology 51 makers of praga 77 concept 87 design 107 reflections 187 index 190

INTRODUCTION

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

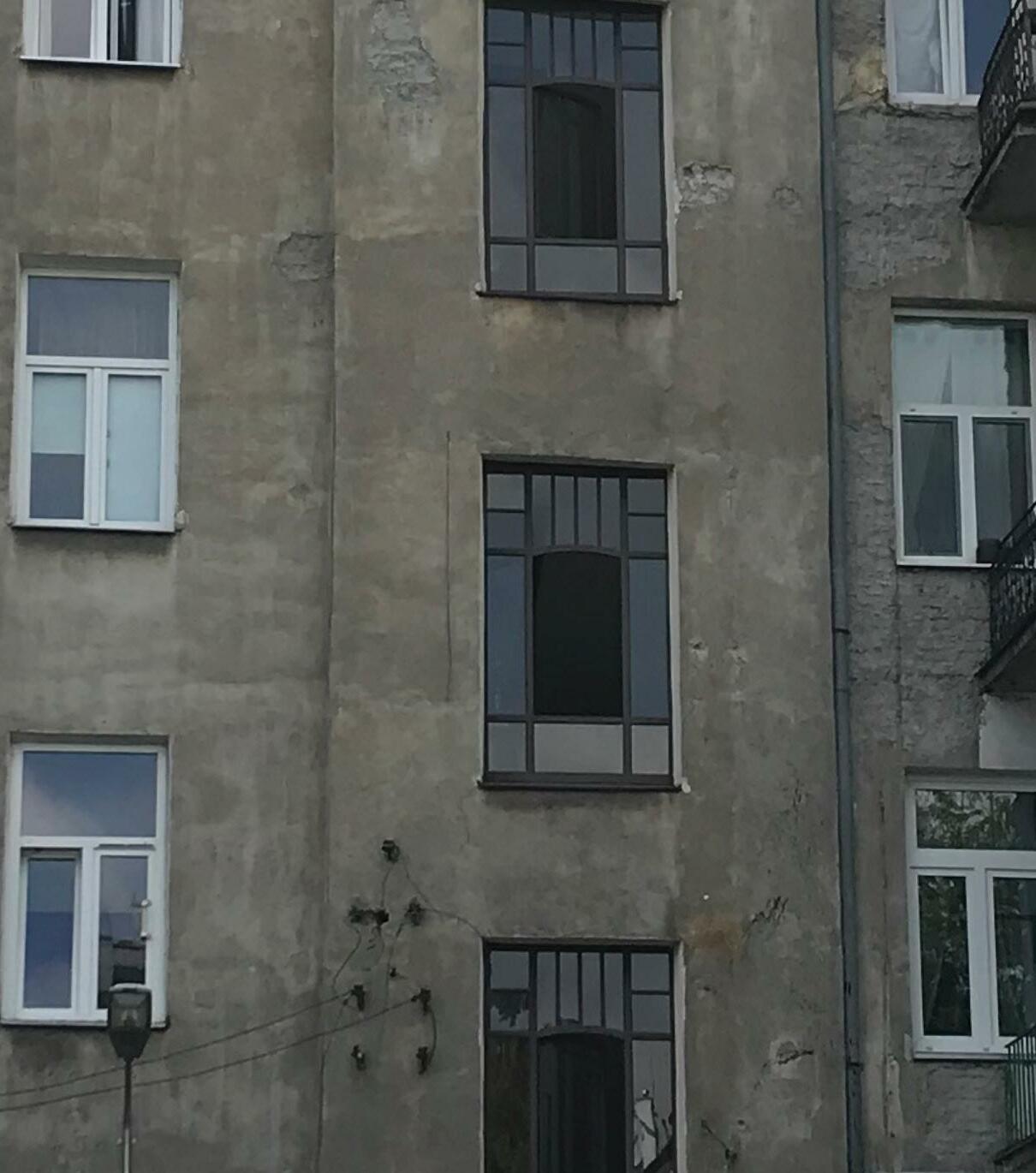

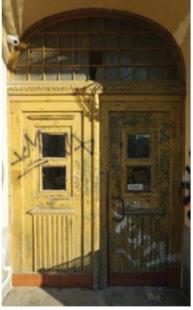

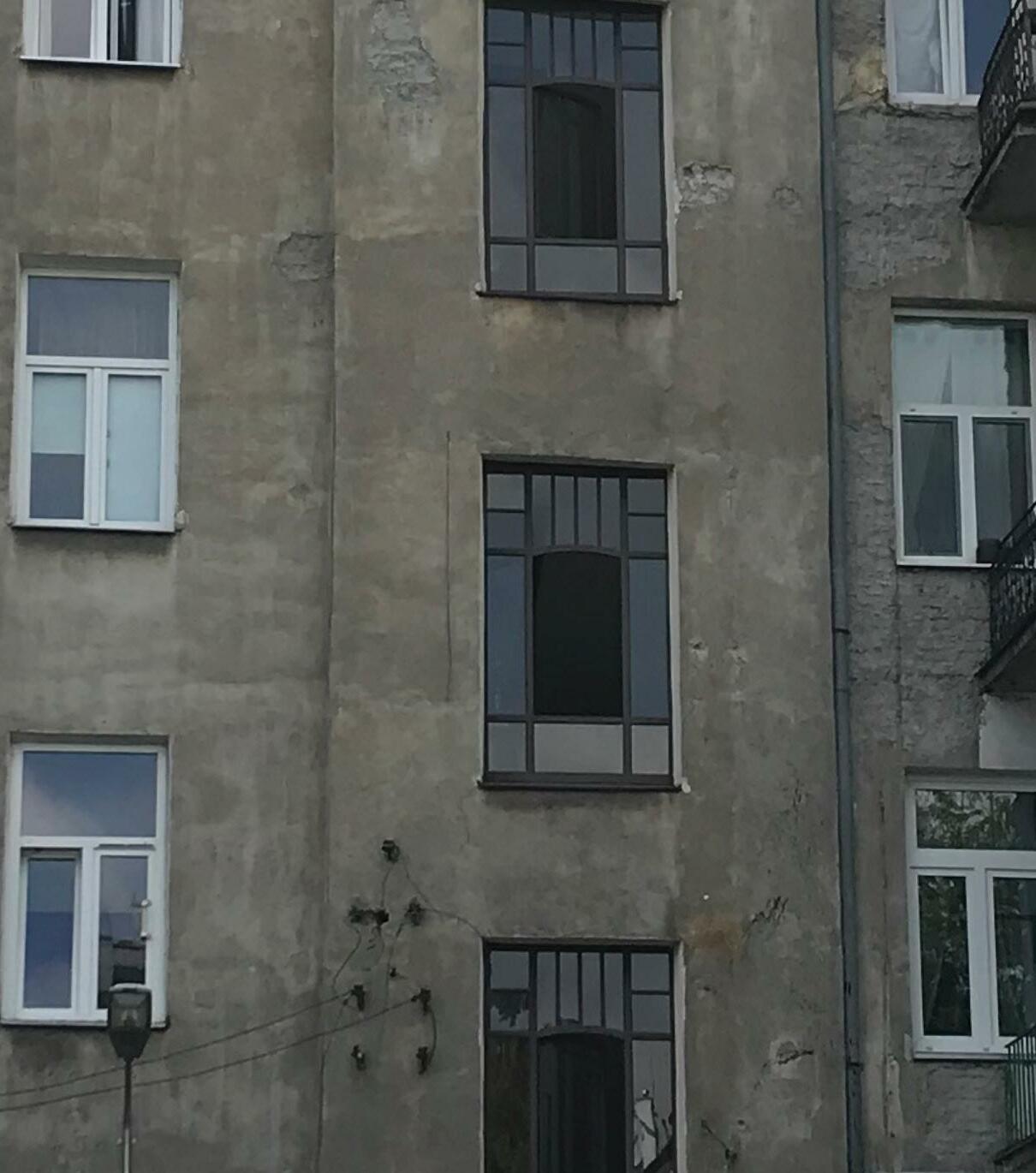

Praga-Północ is a special district on the map of Warsaw. It stayed almost untouched during the bombing of the city, where the rest of the city was destroyed by almost 90%. Around 500 pre-war tenement houses with entrance gates and courtyards have been preserved in the Praga North, however currently they often are neglected.

After 1989 when Poland regained its independence, tenements of Praga met a different fate. They often suffered in the course of clearances, demolitions or complicated ownership situations in the changing history of the country.

In spite of the unique character of the district, its undeniable architectural value is often underestimated by the city authorities and developers, who often allow these architectural gems to be demolished in order to erect buildings that are completely out of context.

15

introduction

16

Poznan Vienna

Warszawa Berlin

16

Poznan Vienna

Warszawa Berlin

The tenement typology (typology of enclosed blocks of flats) was a popular housing typology in many Eastern and Central European cities especially in the 19th century, where cities grew very rapidly. Nowadays, metropolises are becoming denser, but there are few ideas for revitalising the areas filled with them. My project attempts to answer with a site specific proposal for an urban block in Praga North in Warsaw.

17

introduction

CONTEXT

Warsaw is the capital of Poland and also its largest city. Its complex history over the centuries, especially after the destruction of World War II, has left the city long lost and in search of its identity, which is why it is still trying to reinvent itself today.

20

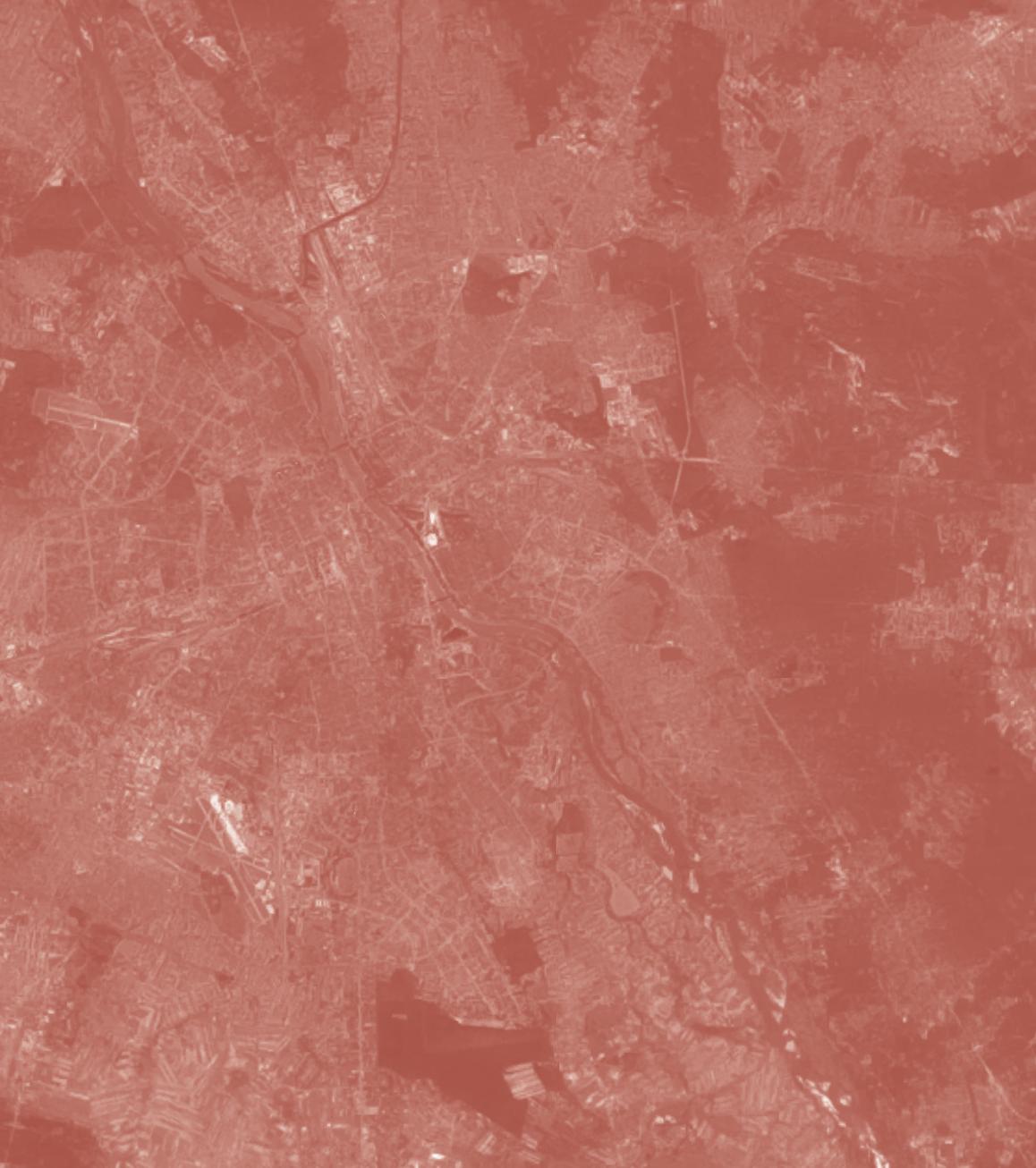

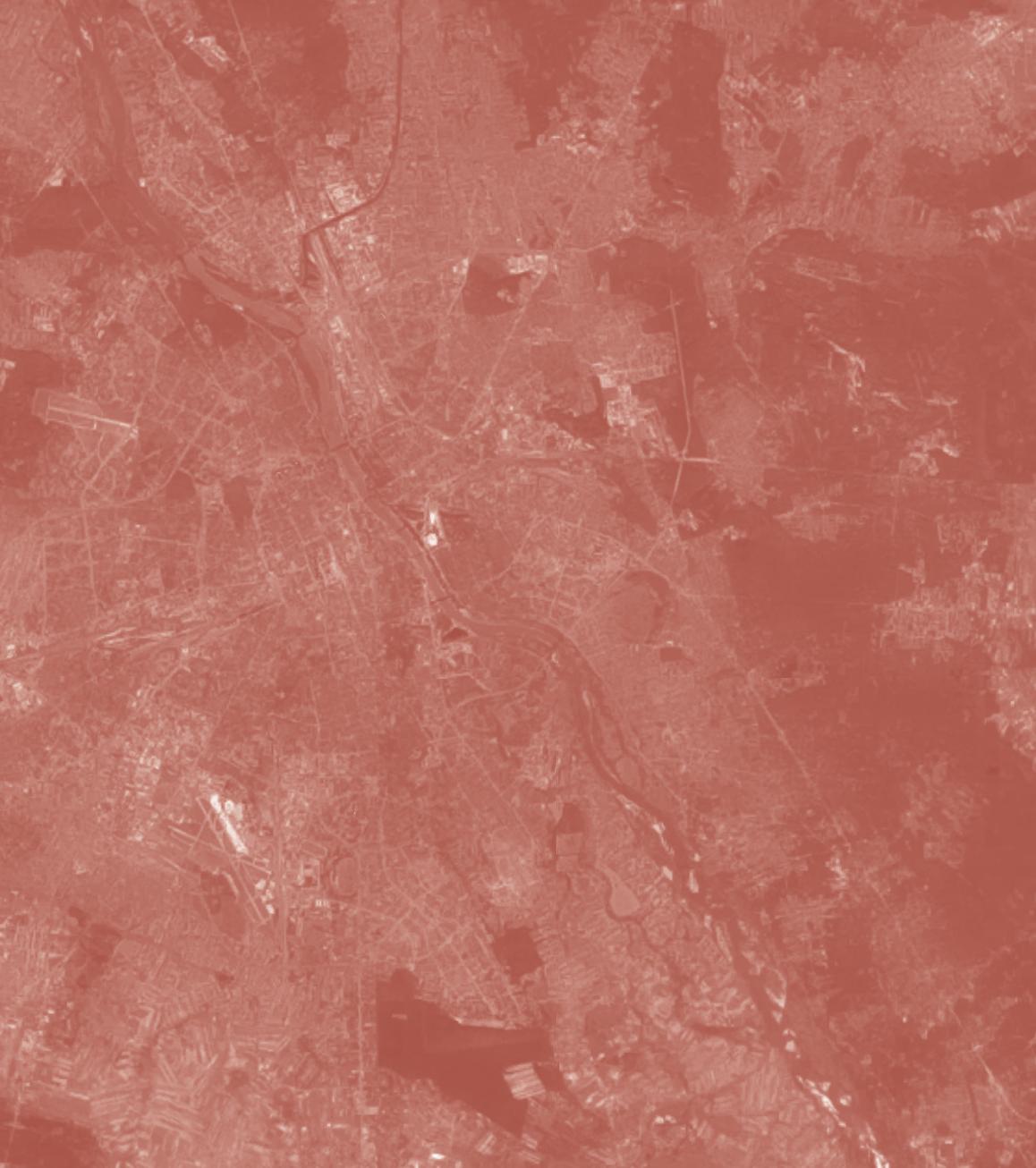

WARSAW

PRAGA NORTH

A district of Praga-Północ for a long time was a separate town and was only incorporated into Warsaw in 1791. Prior to that, it had been a separate settlement. Separated from the city by a river, it created its own distinctive folklore with a strong productive spirit (it had many factories, craft workshops, famous markets, gardens and orchards). Unlike the rest of the city, Prague was not severely damaged during World War II and is therefore now considered the most authentic part of the city.

21

location

Before Praga was granted municipal rights in 1648 by the king Władysław IV Vasa, more than a dozen villages were located here. For a log time the main occupation of its inhabitants was agriculture. In spite of progressive development, the landscape in this area was dominated by green meadows, orchards, gardens and forests.

22

B.Bellotto View of Warsaw from Praga, 1770

Praga, as the less devastated part of the city after the war, for few months became the main political and administrative centre of the country, in a kind of substitute role of the capital. However, when the reconstruction of the city began, the development of this district left to itself was long forgotten.

Praga was for a long time considered as an uninhabitable and unsafe district, a large part of the inhabitants of the left bank considered Praga to be the wrong part of Warsaw.

23

Warsaw Praga

Praga-Północ in a context of Warsaw

Praga first mentioned

Poland disappeared from the map forWarsaw first under Prussian (German) Russian occupation

construction of the first permanent bridgeKierbedzia bridge

construction of Terespol railway station

24 1648

Praga grantedwascity rights by King

Wladyslaw IV 1791 Praga

attachedwasto

Warsaw

as a borough

1794

Battle of Praga

1862

construction of the Petersburg Railway Station

1795 Third

Partition of Poland

1864

1867

1432

1914-1918

World War I

1939-1945

World War II, Warsaw Uprising

1989 Solidarity movement, collapse of communism regime inPoland

1990-1995 Poland suffered temporary declines in social, economic, and living

2004 Poland is becoming amember of European Union

for 123 years,(German) and then communist rule

1882

opening ofRóżycki Market

1915 destruction of the Kierbedzia bridge and the Petersburg and Terespol Railway Station by Russianevacuating forces

1944 administrative functions moved to Praga

1940-’s -1950’s development of large factoriesand construction of the National Stadium in Praga

?

25

2022

history of Praga

demolished buildings preserved buildings

26

German order for total destruction of Warsaw.

After the Warsaw Uprising failed for Poland on 9 October 1944, the Nazi Germans, in retaliation, ordered the complete destruction of Warsaw. By January 1945, valuable cultural monuments, religious buildings, residential and economic infrastructure had been destroyed.

At the beginning of 1945, the only area of old Warsaw that resembles the early city is a district of Praga, located on the right bank of the Vistula.

27 destruction of Warsaw during WWII

28

Warsaw city center before WWII

Warsaw city center after WWII

The post-war reconstruction of Warsaw was the first attempt in the world’s history to recreate the entire historical core of the city, and not just its most valuable monuments. However, the reconstruction of the rest of the city was aimed at creating a new socialist capital, and thus destroying the old face of Warsaw, or rather what was left of it. The future capital city of Poland was to be seen as a model socialist city, and this meant nationalising the land and demolishing many of the buildings that had survived the war.

This mainly involved tenements buildings from the turn of the 20th century, characteristic for pre-war Varsovian architecture.

29 reconstruction of Warsaw

CHARACTERISTICS OF PRAGA-PÓŁNOC

32

railways

The development of railway lines, connecting Warsaw with other parts of the Russian partition (Warsaw was then under Russian rule) had a significant impact on the formation and development of the whole district. Two new railway stations were built that time - the Petersburg Railway Station and the Terespol Railway Station. Praga was changing from a neglected suburb to a bustling and urban district.

of Praga

trade

Market traditions in Praga are very long and date back to the Middle Ages. Thanks to these exchanges, a settlement developed from which today’s district was created. Praga lay along several important trade routes and later was conveniently located near important railway stations connecting to the East.

architecture

The development of the Prague railway and markets contributed to the rapid growth of the district and the associated high demand for new housing. A large number of residential buildings were built during this period, among which the tenement typology dominated (kamienica czynszowa).

33

charcateristics

34

craftsman workshop markets factories train tracks and buildings orchards and gardens river flood terraces water buildings

35

productive activites ca.1900

36

craftsman workshop markets factories train tracks and buildings orchards and gardens river flood terraces water buildings

activites

37

productive

nowadays

38

why this site?

Różycki Market

rich trading and cultivating tradition of Praga, for a long time the most important market of Warsaw

tenement typology

one of the best preserved urban block in Warsaw with original pre-war tenement typology

makers of Praga a long-standing tradition of craftsmanship

39

fascinations_3 important elements of Praga

40

RÓŻYCKI MARKET

41

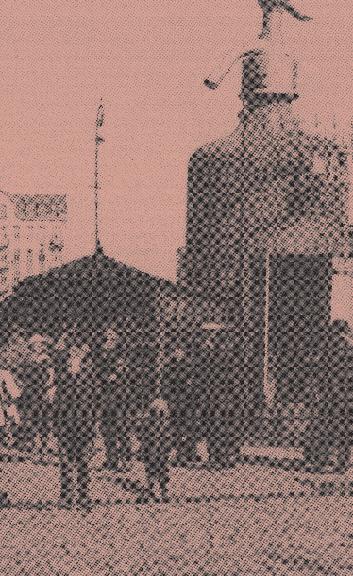

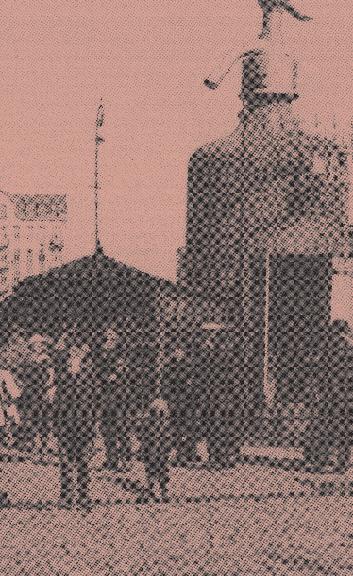

Julian Józef Różycki

The founder of the Różycki Market, a pharmacist from Warsaw, owner of several pharmacies and social activist

42

Targowa

Brzeska

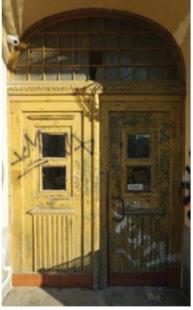

The area where the market is located was purchased in 1874 by Julian Józef Różycki (a pharmacist, owner of several pharmacies, investor). Later, he also purchased the surrounding plots (among others, plots located at Targowa Street 52 and 54, 8 and Ząbkowska 10 Street and Brzeska Street 23/25 ). He decided to establish a market on the area he owned, which was to become the commercial center of Praga.

The official opening of the market took place in 1882.

43 Julian Józef Różycki

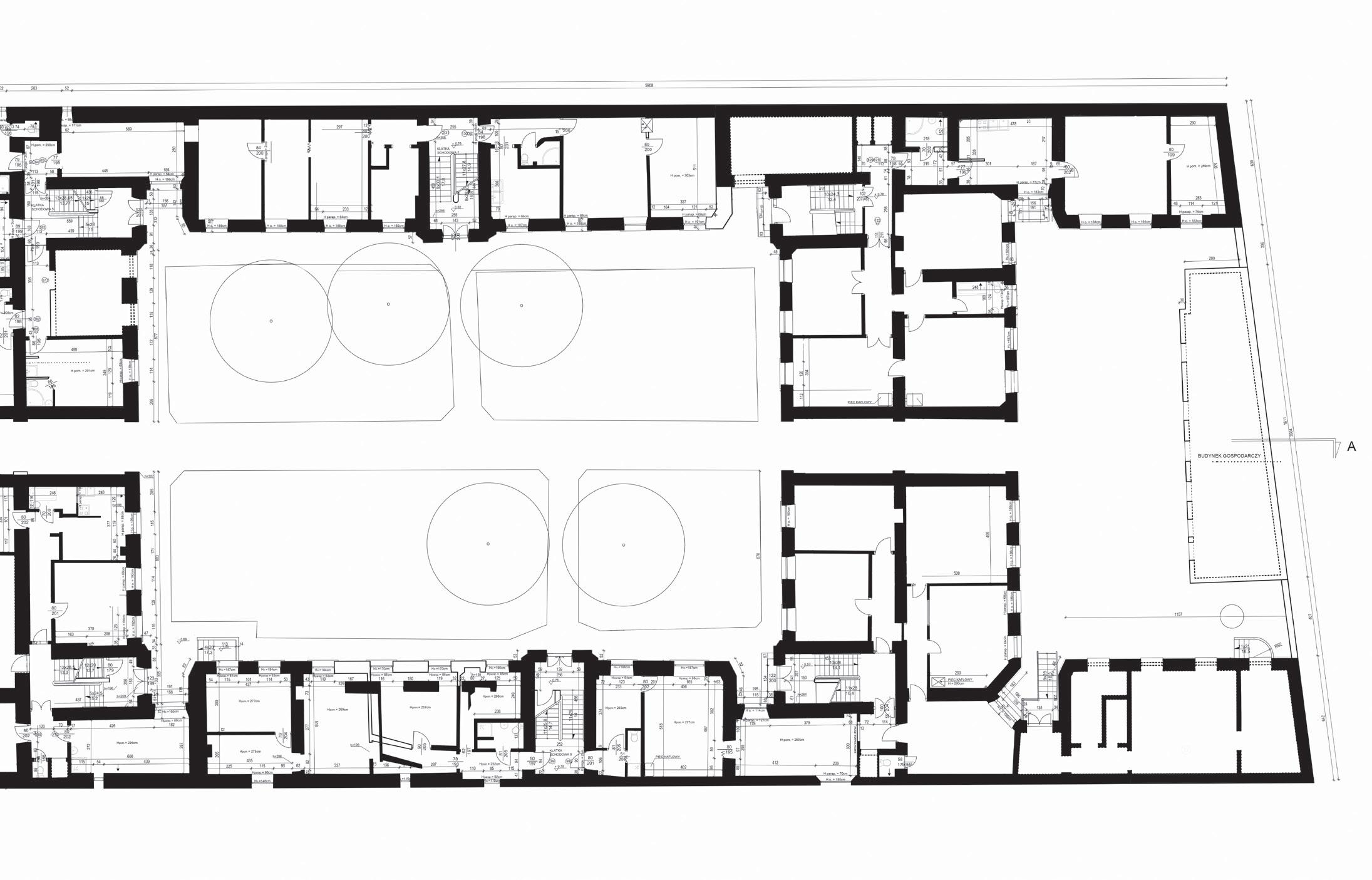

Różycki Market

44

the market

The market opened in 1882 and it quickly became the main shopping center in Praga.

Around 1901, the owner of the bazaar built a seven-meter-high kiosk at the gate from Targowa Street. It was quite disincitve blue siphon-shaped constructionthat housed a kiosk selling soda waters andsweets. Over time, the kiosk became a symbol of the market and an icon Praga district.

45

opening of

46

Shortly after the Second World War, the market began to grow rapidly, due to the smallscale sales that many were engaged in to make a living during difficult times. For this reason, almost anything could be bought at the market, from meat to illegal passports sales .

In 1950s, the bazaar was nationalised, but this did not eliminate private trade.

47

market after the WWII

48

Różycki market initially worked well in the early 1990s. Among the sellers were residents of the former USSR. Later, however, the market did not stand up to competition from the infamous Jarmark Europa at the 10th-Anniversary Stadium and quickly declined.

The early 1990s were associated with the development of non-flagging entrepreneurship in Poland, and Praga was one of the most dangerous districts. At that time, the market received an unfavourable reputation as a dangerous place and it is still regarded as such today.

The market in 2020 was in a very poor state of repair, in need of intensive maintenance. Only 11 market stalls remained on it (whereas 111 stalls in 2018 ).

49

market nowadays (2020)

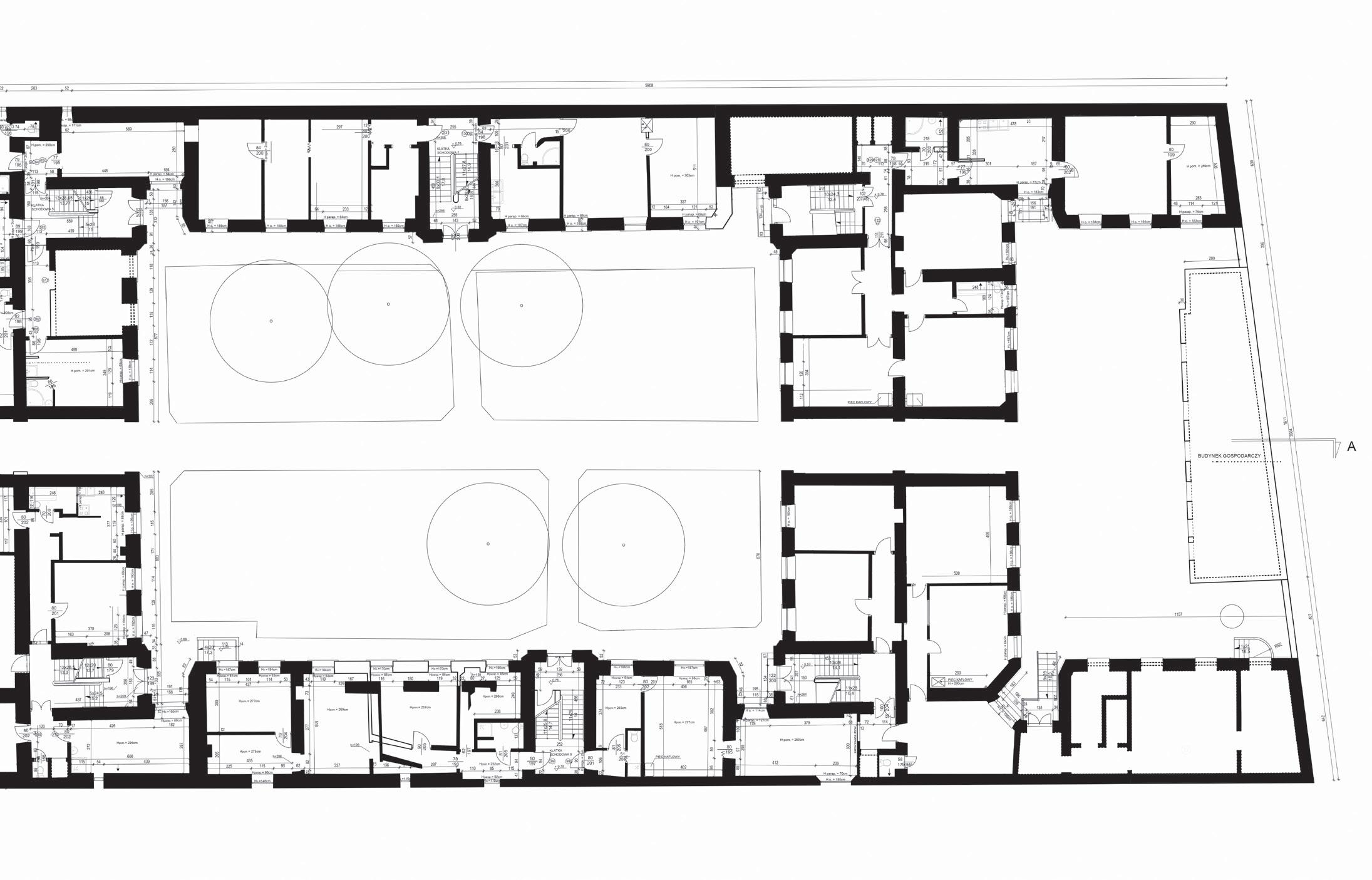

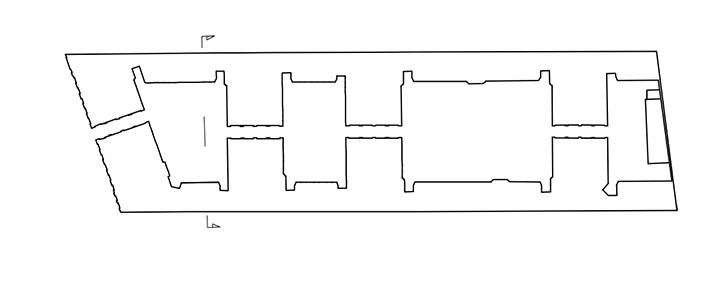

TENEMENT TYPOLOGY

52

Tenement house (pl. kamienica czynszowa) designed as multi-family housing, which emerged in the 19th century and was the basic type of housing in polish cities. From the architectural point of view, the word is usually used to describe a building that abuts other similar buildings forming the street frontage, in the manner of a terraced house.

The ground floor often consists of shops and other businesses, while the upper floors are apartments, oftentimes spanning the entire floor. Kamienice have large windows in the front, but not in the side walls, since the buildings are close together.

53

tenement house

54 parcel 200m 30 m parcelparcel

the typology

The city of Warsaw consisted of many long parcels. Buildng regulation applied to the height and quality of the facedes, however the interiors of the building were not regulated. State authorities did not want to build small streets, leaving investors to solve the issue of inner communication between buildings. This leaded to the cheapest solution which was to create a system of interconnected courtyards.

55

origin of

building

outbuilding

outbuilding

building

56 1. front

2. side

3. side

4. back

1 2 3 4

building order in the construction of the tenement

Originally, the tenement house consisted of several parts built along the parcel: the front building on the street side, the side outbuildings (on the right and left side of the courtyard) and the back building at the back of the courtyard. If the buildings consisted of more than one courtyard, then side and cross outbuildings surrounded them.

The order of construction in this typology was also important, starting with the front building, then the side outbuildings and the back buildings (and so on). However the further away from the street the buildings are located, the less valuable they become and the more difficult they are to access.

57

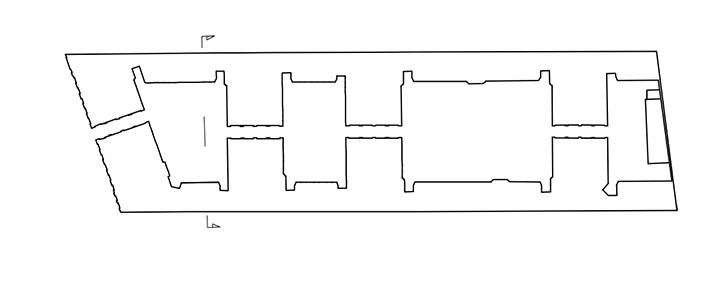

perfectly filled urban block

This drawing illustrates what an urban block would look like if all plots of land were built up with tenement house buildings.

58

real urban block- the site

However, most often the central part of the urban block was left empty, unfinished, often used as an orchard, garden or warehouse.

typology in an urban context

59

tenement

structurally independent buildings buildings structurally dependent on one adjacent wall buildings structurally dependent on two adjacent walls

60

Tenemant buidlings are “sharing” the wall The demolition of one of the building has an impact on their neighbours and can cause a destruction of the entire quarter.

Tenemant buildings (kamienica czynszowa) coexist and they created an integral urban ensamble only when in connection with other tenemants (side fireproofed walls, interconnected courtyards) .

61

“shared” wall

important development of Warsaw

XIX century was the time of big cities in the western world. At that time they developed very rapidly, especially in the fields like crafts, trade and industry. Many people moved that time to the urban settlements driven by improvment their quality of life.

62

popularity of tenement typology in the 19th century

it provided high-density solution for fast growing cities

a feeling of belonging for people who moved from the village to the city

63 seasonal-living more in tune with the weather

first floor

ground floor

64

65 study of exisitng tenementof Praga Północ

66

67 study of exisitng tenementof Praga Północ

68

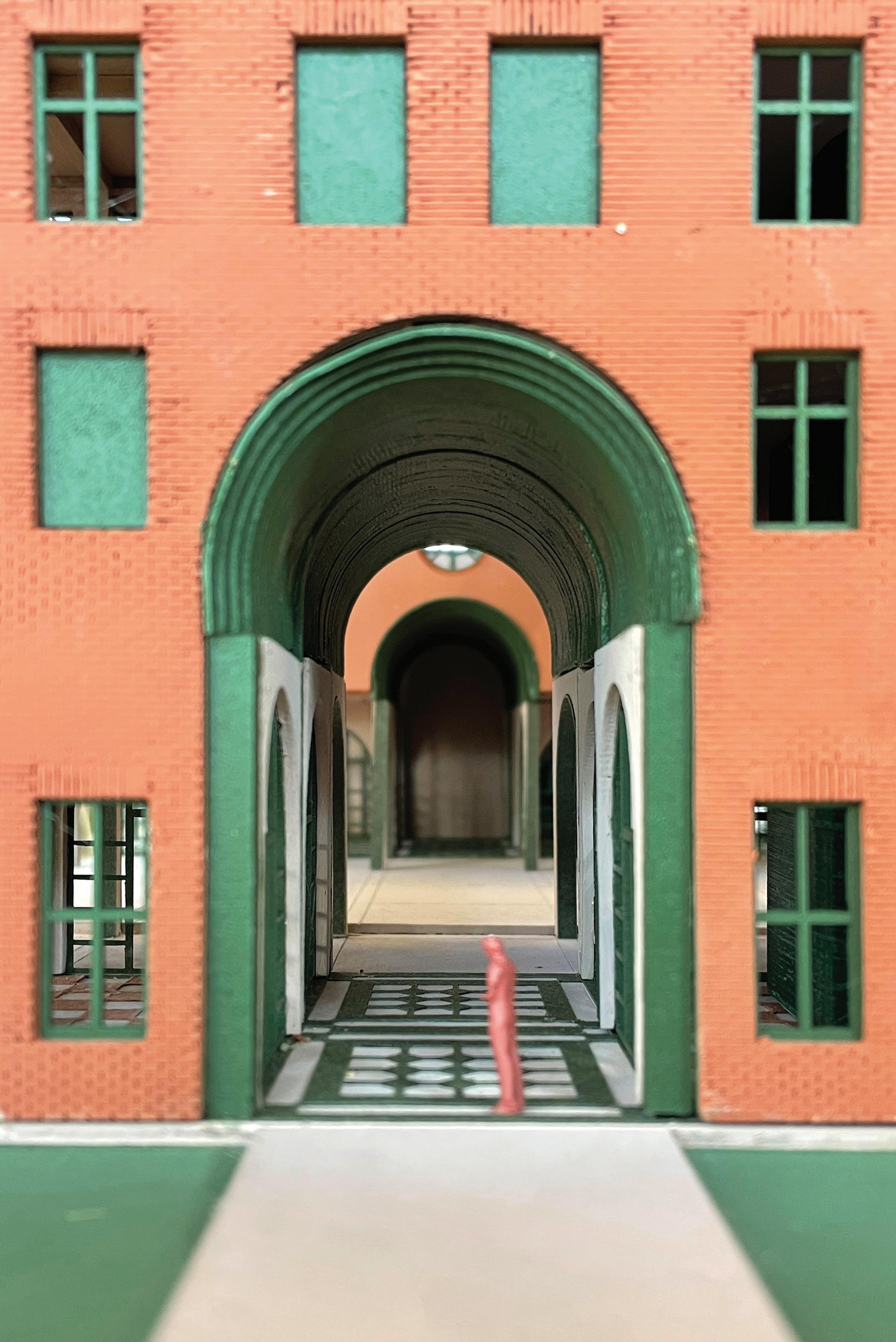

69 architectural elements gates and archways

70

71 architectural elements doors and window frames

72

73 architectural elements floor tiles and mosaics

74

75 stairs details architectural elements

MAKERS OF PRAGA

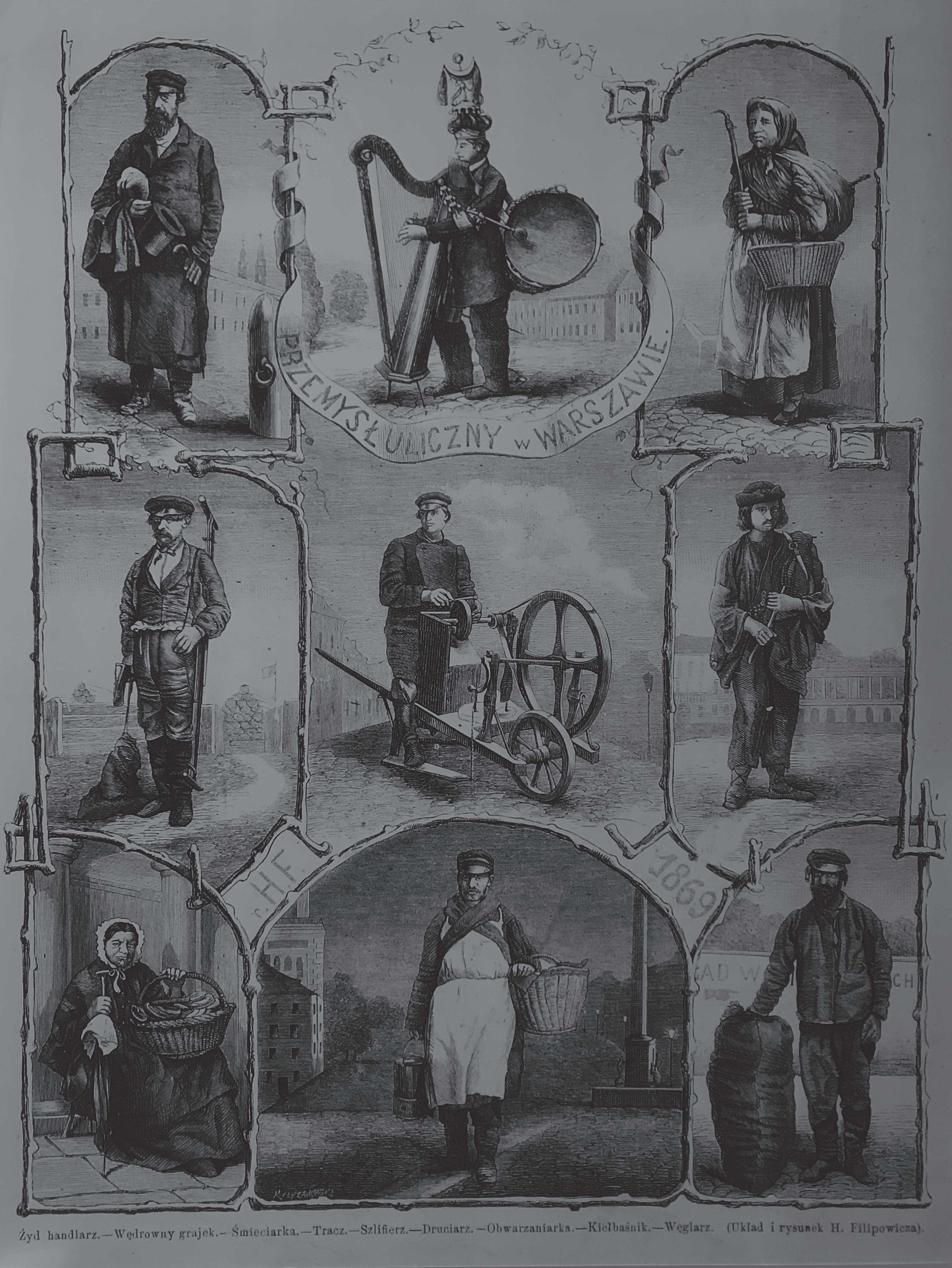

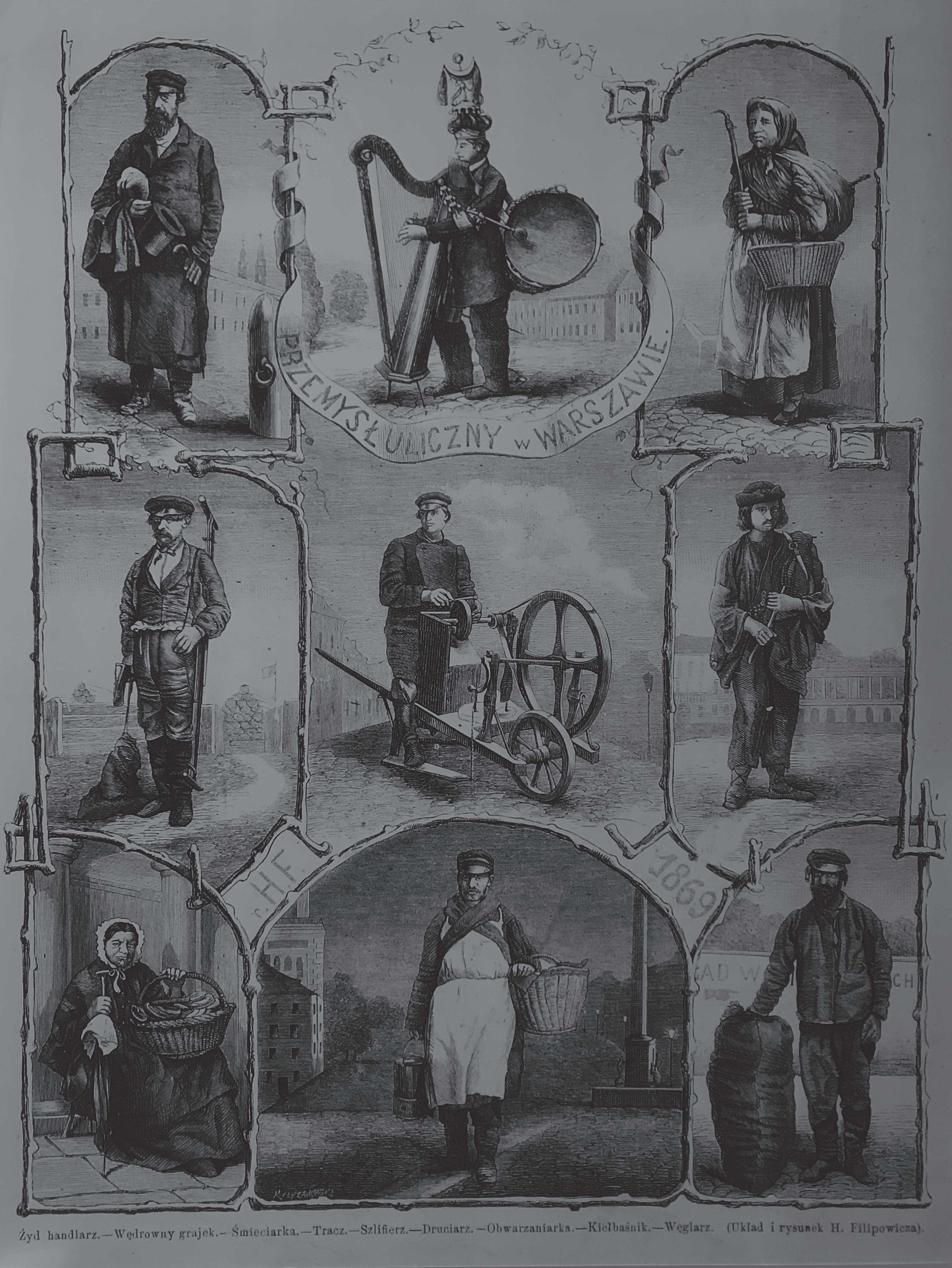

Praga before the war was a place where trade, crafts and industry flourished. People traded not only for money, but also for the products and services they produced.

trade of Praga at the end of 19th century

local

80

wandering musicain

knives sharpener

sausage man

garbage woman wireman coal dealer

Jew trader sawyer bagel woman

80

wandering musicain

knives sharpener

sausage man

garbage woman wireman coal dealer

Jew trader sawyer bagel woman

81 shoemakerbookbinder

upholster furrier

makers of Praga at the end of 19th century and

81 shoemakerbookbinder

upholster furrier

makers of Praga at the end of 19th century and

Today, Praga is also the craft centre of Warsaw. Crafts are becoming more and more popular, but most craftsmen are having difficulty finding successors to take over the workshop and the knowledge they have gained over many years of experience.

Praga

bookbinder shoemaker confectioners and bakers tailors watchmakers jewelers/engravers upholsters furniture renovation carpenter furriers glaziers opticians photographers unique metal related others

makers of

now

84

important elements in existing situation

85

mapping existing situation

CONCEPT

88

Różycki Market

The site I have chosen is predominantly built up with a typology of townhouses along the streets, with the middle of the block remaining empty.

What fascinates me is the porosity of this layout, which I wanted to preserve and create a project that clebrate this quality.

Particularly interesting are the unbuilt parts of the urban block, it is there that I think there is a lot of potential for densification and diversification.

As I mentioned earlier, the buildings in the middle of the city block are difficult to access, so the buildings in the depths of the parecel are now often abandoned.

My idea is to create a new street that cuts through this block in the middle and creates a new routing system, while creating new courtyards used for gardening and recreational purposes.

89 concept

making

selling

making learning selling

90

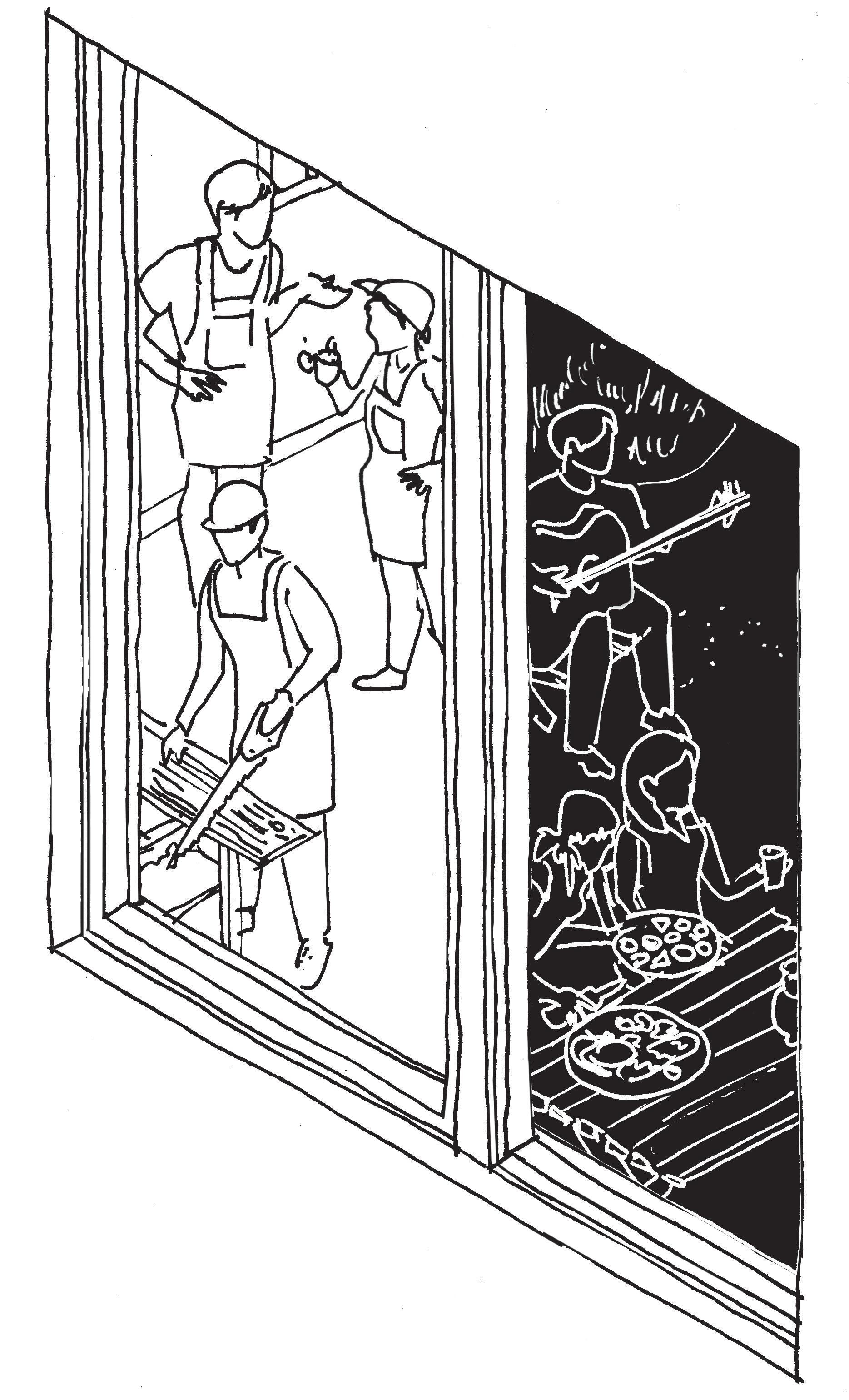

Although Praga has a rich tradition of craftsmanship that is still evident today, many of these crafts are slowly dying out because young people are not interested in continuing on this path. Many makers fear that when their careers come to an end, there will be no successors to take over their craft.

What can be done to activate and revive these traditions? What is missing here?

In my opinion, what’s missing is a place that inspires and also teaches young people who have a specific trade in their hands. My answer to this problem is the creation of a vocational school.

91 missing element

92

The end of Soviet dominance in 1989 brought many changes to the Polish educational system. The teacher and the student organisation demanded a complete restructuring of the centralized system and autonomy for local educational jurisdictions and institutions.

The main goal included creation of the pluralistic market of the curriculum and textbooks, which was not influenced by the communist ideology.

The educational reform from 1999 transformed the education system in Poland from two level to three levels of schooling.

One of the downsides of the change was a marginalization of vocational education.

93

vocational

education in

Poland

94

A reference to strong craft traditions of Praga, partly still visible today.

A reference to the past, where Praga was a green part of the city of Warsaw with plenty of orchards and gardens.

Cities are becoming more and more populated, and with them the demand for food. Is it possible to produce food closer to home?

Urban areas offer considerable potential for horticultural food production, but questions remain about how to do this in the most efficient way, as well as integrating them into the urban fabric.

95

vocational school’s origin

96

culinary art focused on plant-forward diet

two specialisation of the school: urban horticulture

“The way we eat in inextricably linked to social, political, economic and physical structures that govern our lives, which is what gives food its unparalleled complexity and potential.” 1

People living in cities are often disconnected from the food creation process, only encountering the final product chain, which is the supermarket product.

My idea is to create a school that sets an example of how sustainable food production can be carried out in the city and create new connections between people and the food they eat.

97 specialisation of the school

1 Steel Carolyn,Sitopia: How Food Can Save the World , London , Penguin Random House, 2020, p. 14

98

basic course retraining course for adults

The school consists of two types of courses: a basic course for people who have completed lower secondary school and would like to gain practical training, and a further training course for adults who would like to change their existing profession.

In this way I would also like to stimulate the development of the district

99

course types

100

from

Warsaw likewise many other European cities has a spacial and social disharmony between living and working conditions. The city is full of opportunities for high-skilled workers, however in the same time lacking so for low-skilled workers. This phenomena causes economical, social and transportation problems.

Moreover, new urban development projects often have housing as their main agenda. To break down this imbalance and make cities vibrant, more multifunctional neighbourhoods are needed. To break down this disparity and make cities vibrant, more multifunctional neighbourhoods are needed.

101

monofunctional to multifunctional

102

school market

gardens gastronomy

living working collective

“Neighbourhoods is a state of being in a relationship. More than anything, the human environment is about relationships; relationships between people and planet, relationships between people and place, relationships between people and people.”2

Today, in a rapidly changing and urbanising world, the word neighbour is more relevant than ever. In cities that are becoming denser, diversification is also very important, because it is the richness of diversity that creates opportunities.

My concept is to increase the diversity of Praga, specifically the site I am working on. In order to achieve this, I propose to make a new mixed used building in the middle of the urban block, which could become a new center of the neighbourhood.

103 ultimate use of the spaces

2 Sim David, Soft city: Building Density for Everyday Life, Washington, Island Press, 2019, p. 11

104

Outdoor spaces in the city provide additional living space in the often dense urban fabric. Here too, the greater the variety the better, in order to attract a diverse audience. Many of these spaces can be used during the day for functions other than in the evening, e.g. a garden that is used for growing plants during the day can become a meeting place in the evening.

use of the spaces

105 ultimate

DESIGN

108 Warsaw Wileńska Station

site drawing _ existing situation

109 existing situation 1:2000 Warsaw East Station exisitng

buildings

train stations buildings to demolish market stalls water Warsaw East Station

Warsaw Wileńska Station

train stations existing buildings buildings to demolish market stalls

water Warsaw

Wileńska Station

110 Warsaw Wileńska Station

drawing _ new situation

111 Warsaw East Station new situation 1:2000 exisitng buildings train stations new buildings gardens water Warsaw East Station train stations existing buildings new building green elements water site

main entrances

116

main entrance

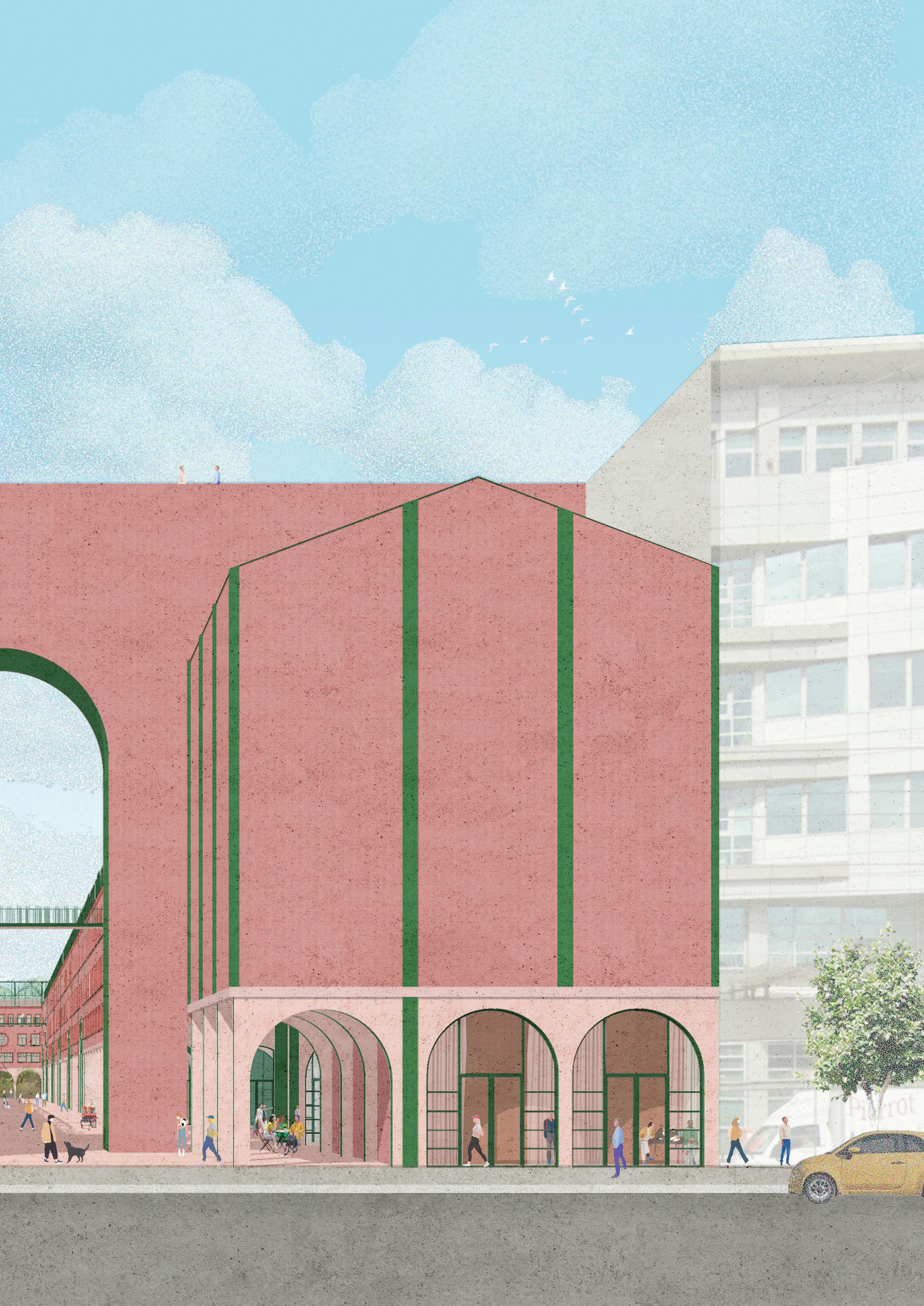

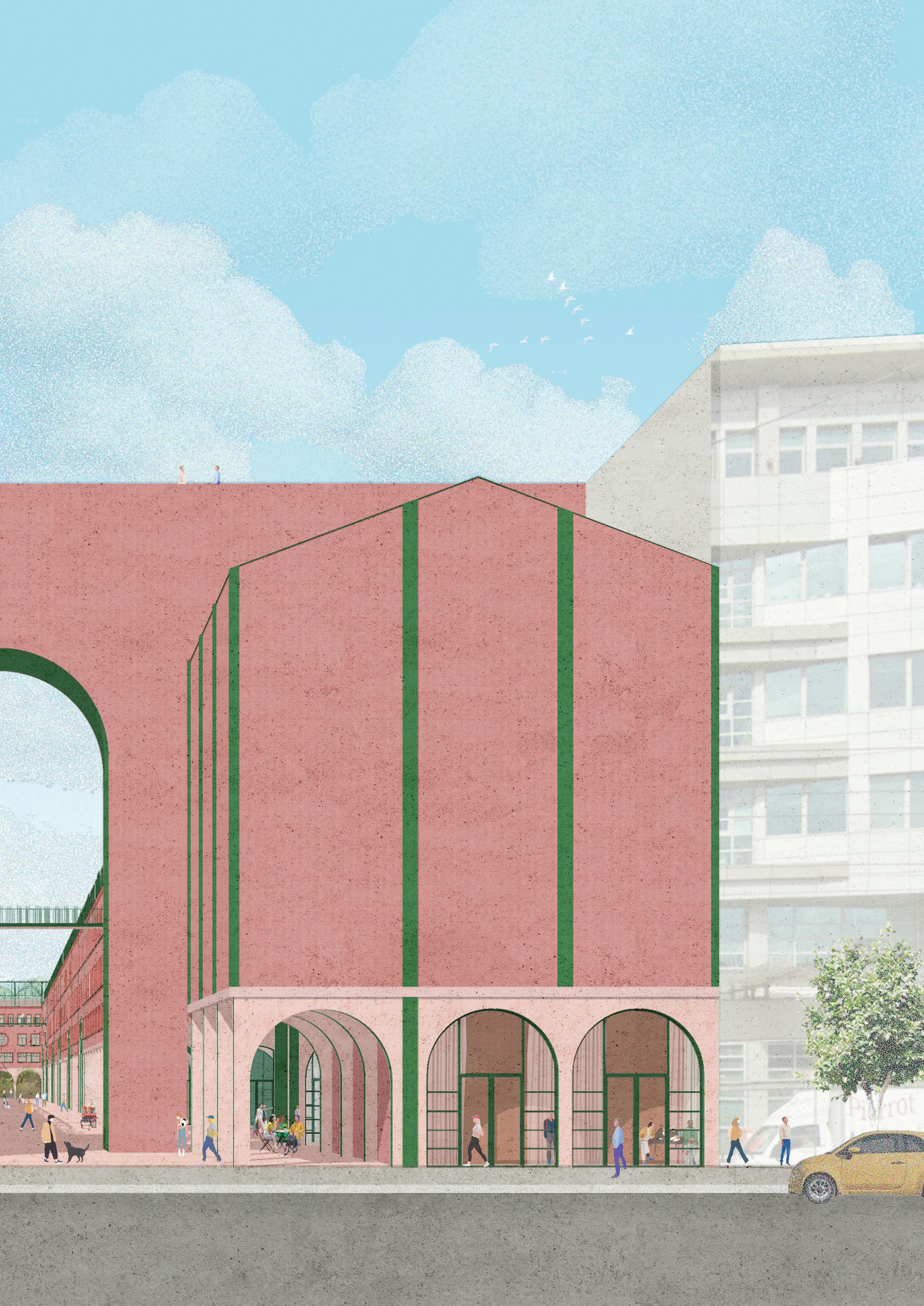

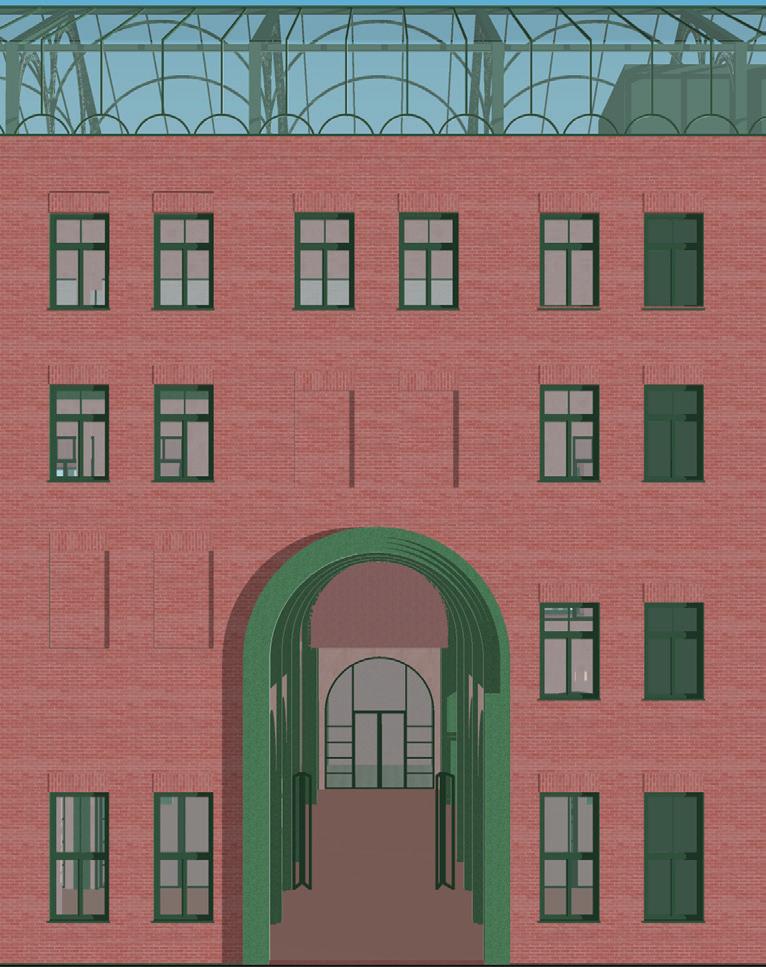

The main entrance is located along Białostocka Street. I chose this place because of the proximity of important public transport centres such as the railway station - Warsaw East Station.

park side entrance

It is a local entrance connecting the project with the rest of Praga, its entrance leading through a pocket park, which was created in the place of a market moved from there to the main building building of the project.

117

main entrances

118

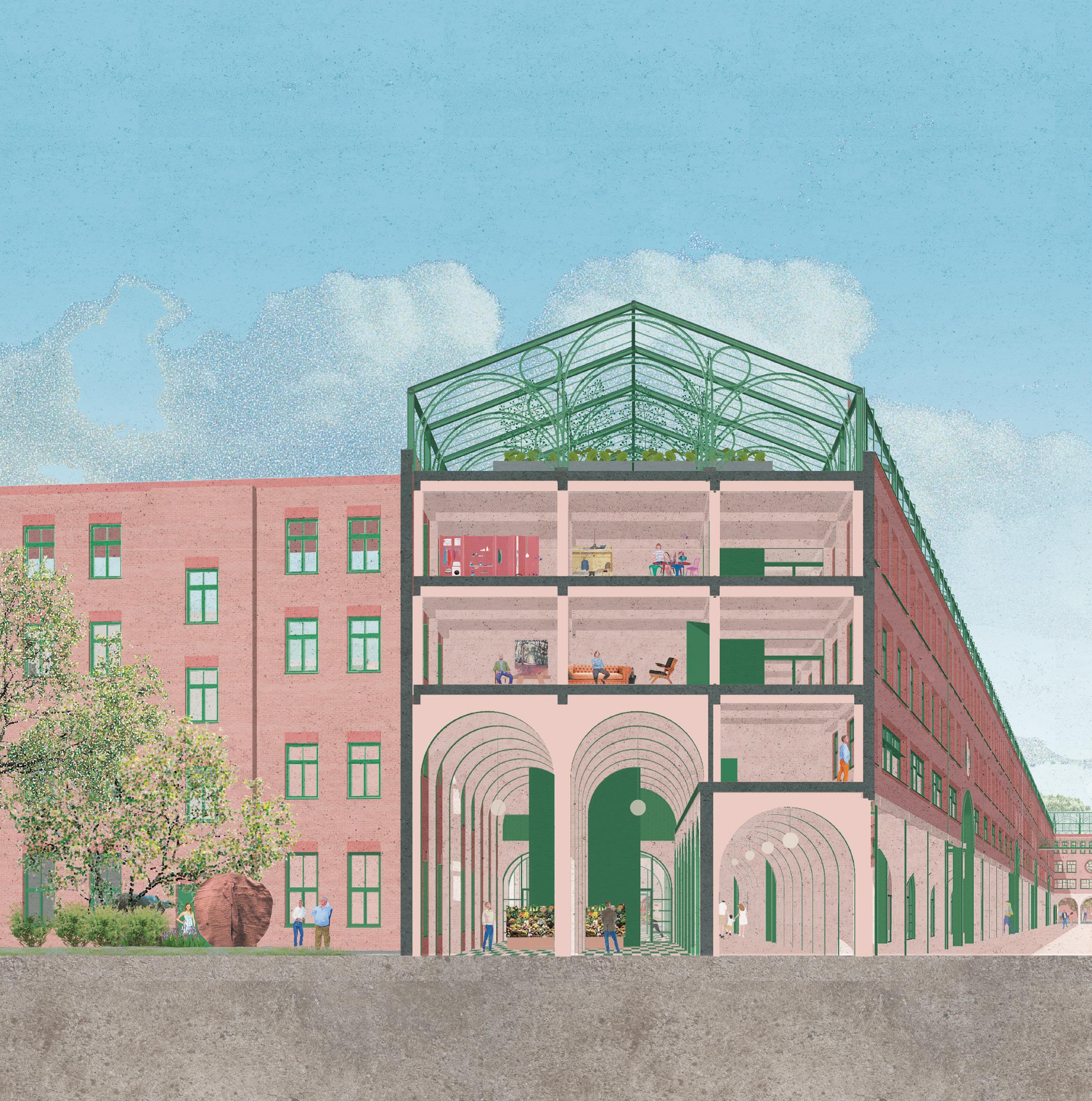

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

119 program

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

ground floor_program

122 678

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

floor_program

123345 2 1 first floor 1:500 regular housing student housing housing/work units work collective routing school gastronomy botanical garden green house bazaar first

124 678

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

floor_program

125345 2 1 second floor 1:500 regular housing student housing housing/work units work collective routing bazaar school gastronomy botanical garden green house second

126 678

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

127345 2 1 third floor 1:500 regular housing student housing housing/work units work collective routing bazaar school gastronomy botanical garden green house third floor_program

678

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

129345 2 1 fourth floor 1:500 regular housing student housing housing/work units work collective routing bazaar school gastronomy botanical garden green house fourth floor_program

130 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4

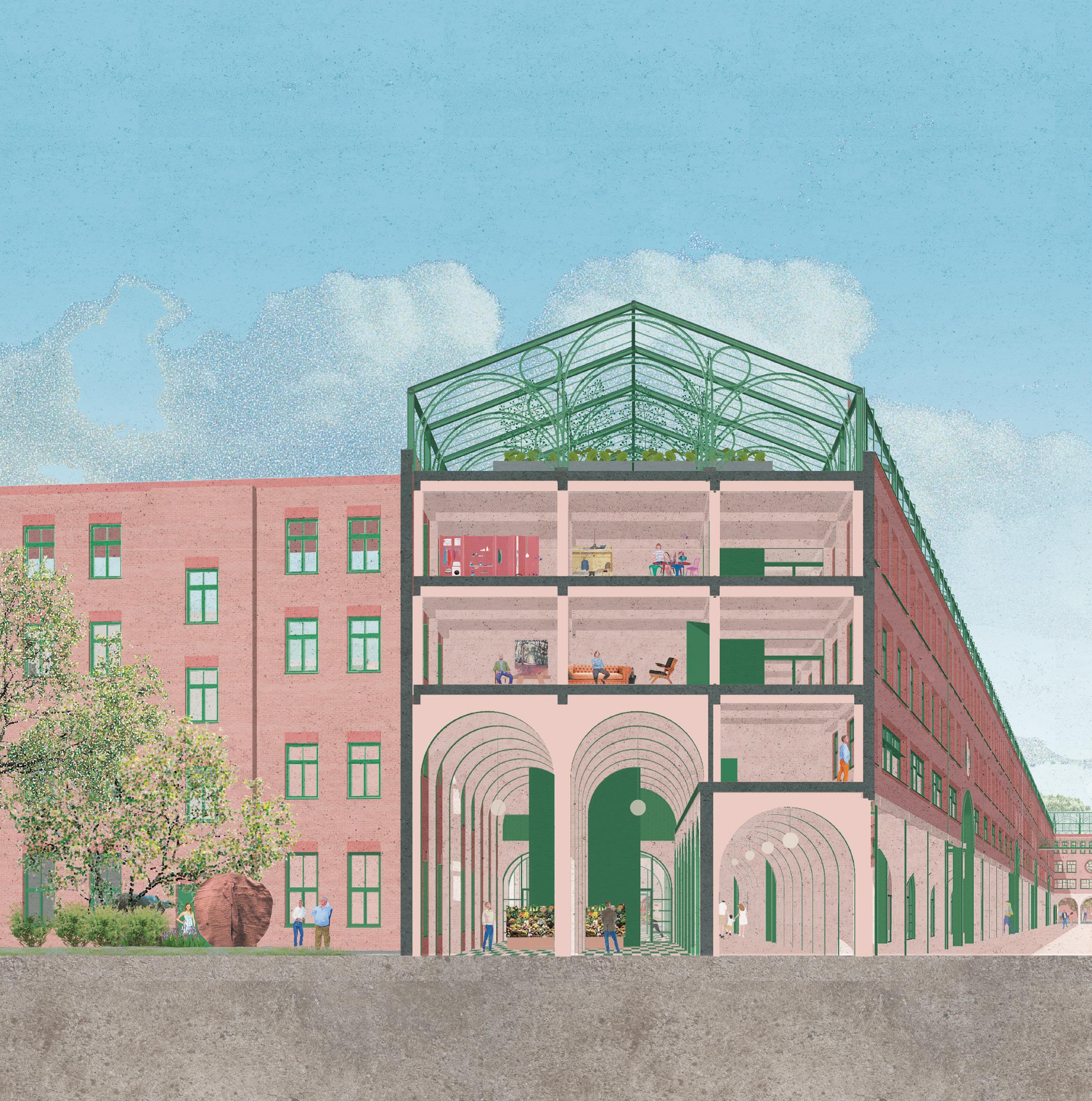

People’s lives in the city are changing, but also the city or neighbourhood itself is changing all the time. If a place is to be truly resilient, its form must be responsive and able to change. It must adapt to changing demographic and economic cycles, population densities, as well as new functions.

Kultywator Praga aspires to be a resilient place thanks to the flexibility of its layout, which can easily be changed in the future when the function inside the building changes.

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

131

cross-section _program

132 5 6 7 8 5 6 7 8

school market gastronomy botanical garden green house student housing regular housing housing/work units work collective routing

133

cross-section _program

136

137 floorplan in the context

138

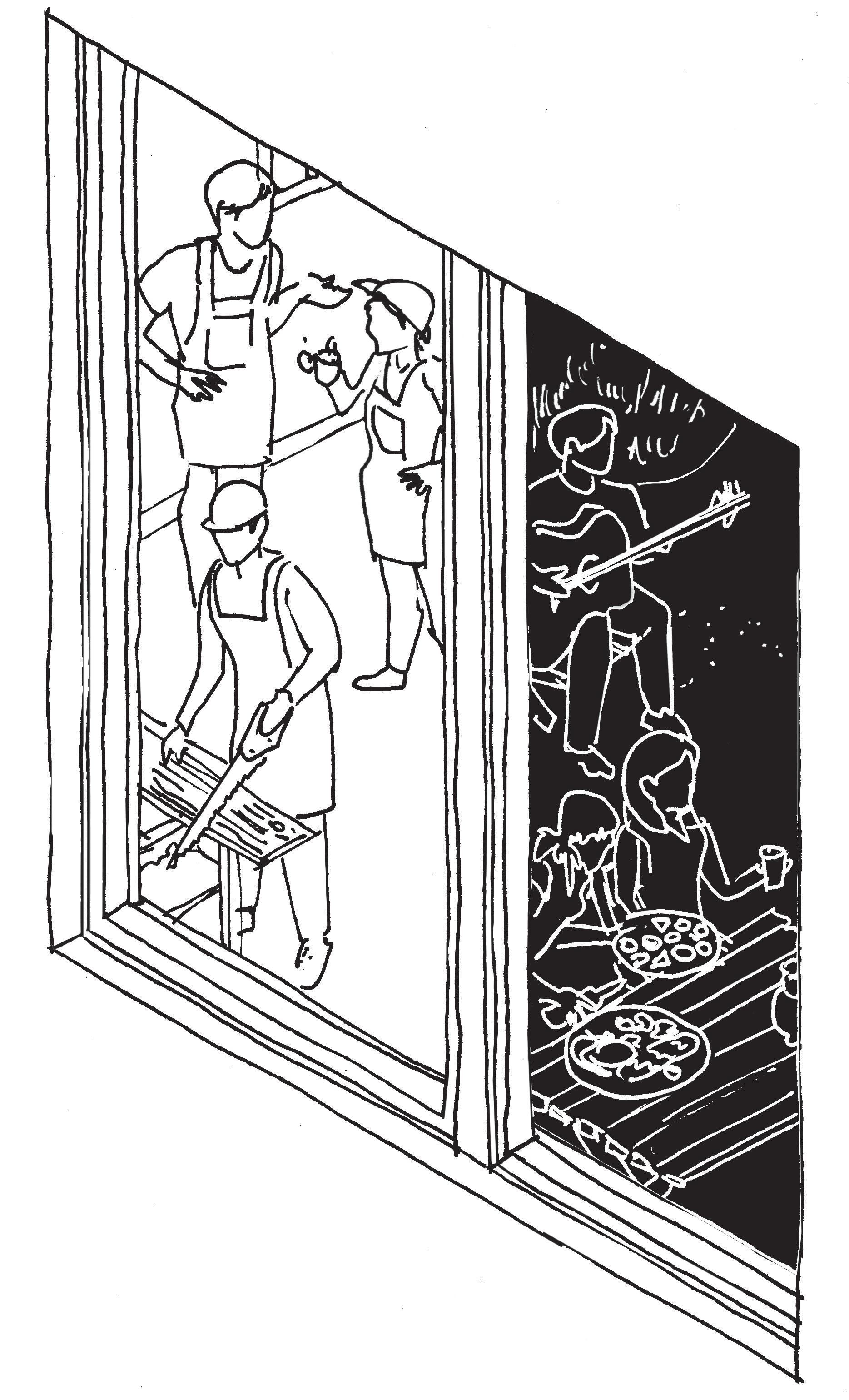

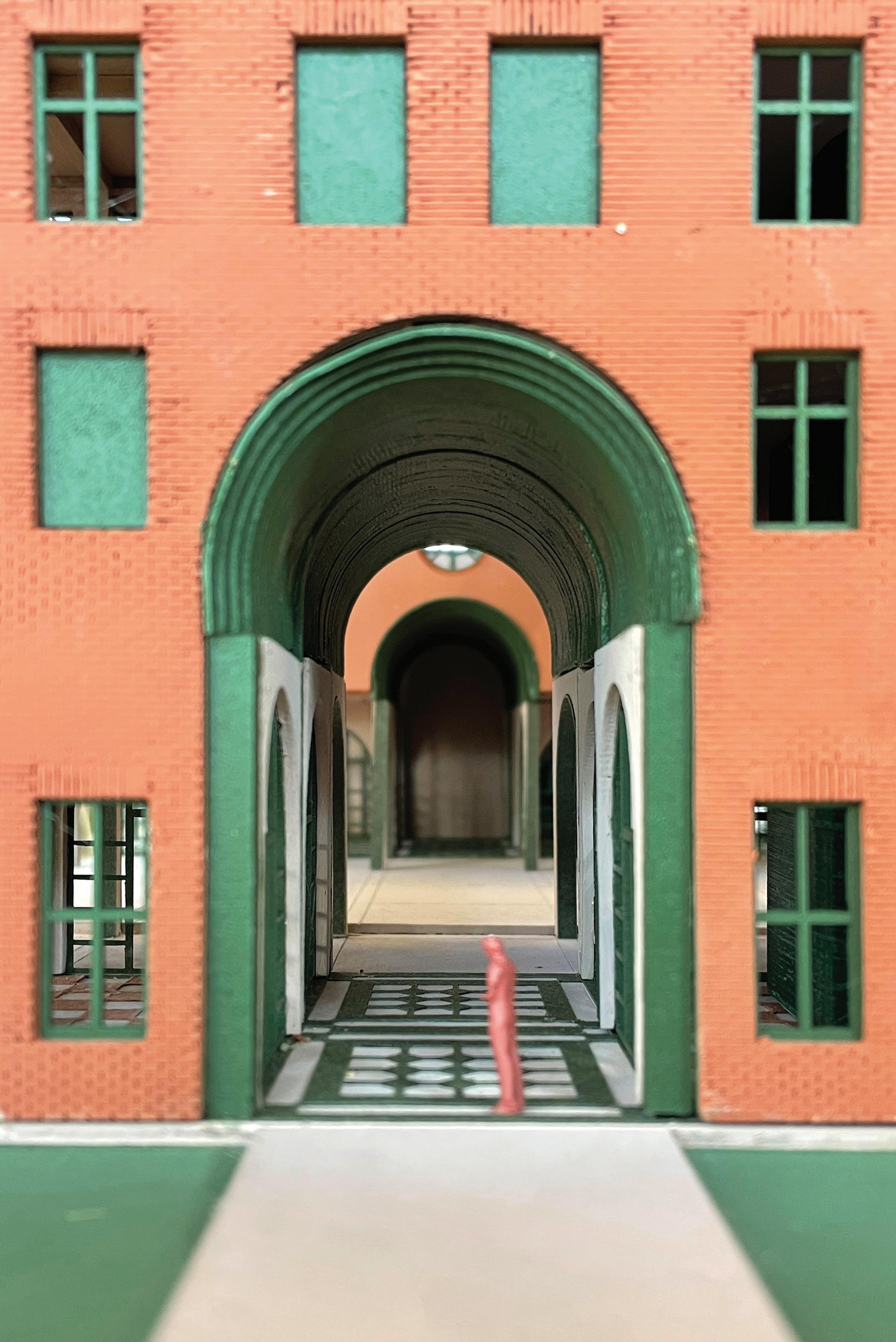

In the tenement house typology, the fronts and backs of the buildings form two different worlds: outside, public life is vibrant, facing the street, while the courtyard lives at a different, quieter pace.

What is also important in my interpretation of this typology is what happens between these spaces, the arcades that buffer life inside and life outside and archways that leads from one space to another.

139 public _ semi-public _ private

140

141 public _ semi-public _ private

142

143 from public to privatearchways

144

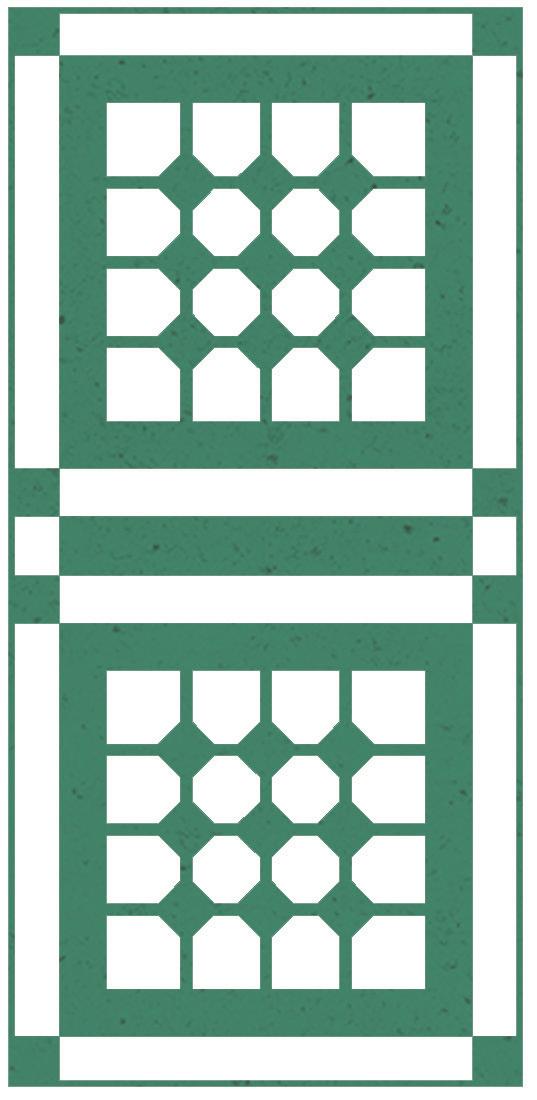

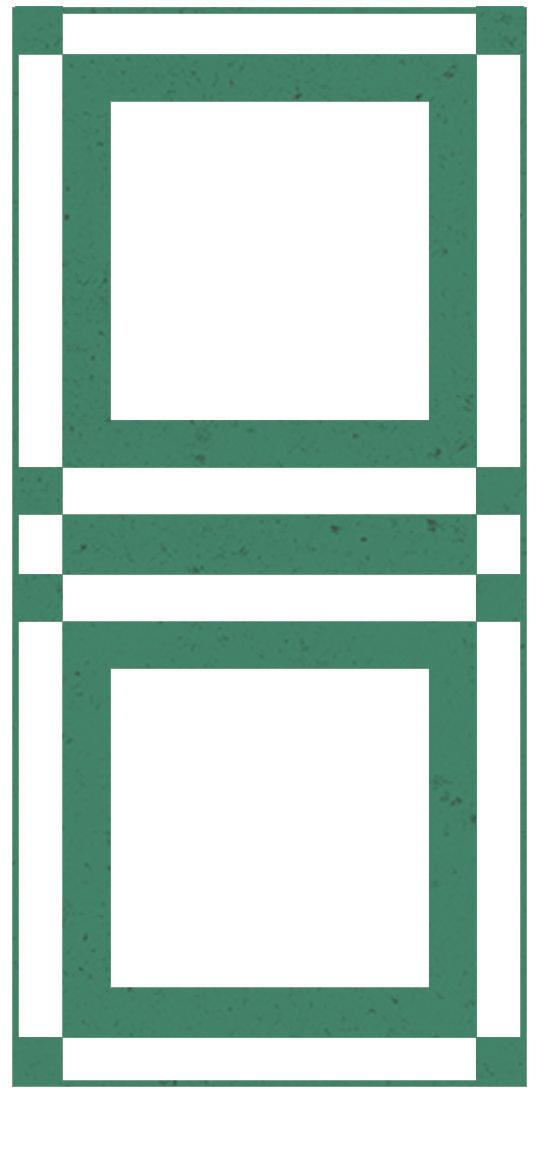

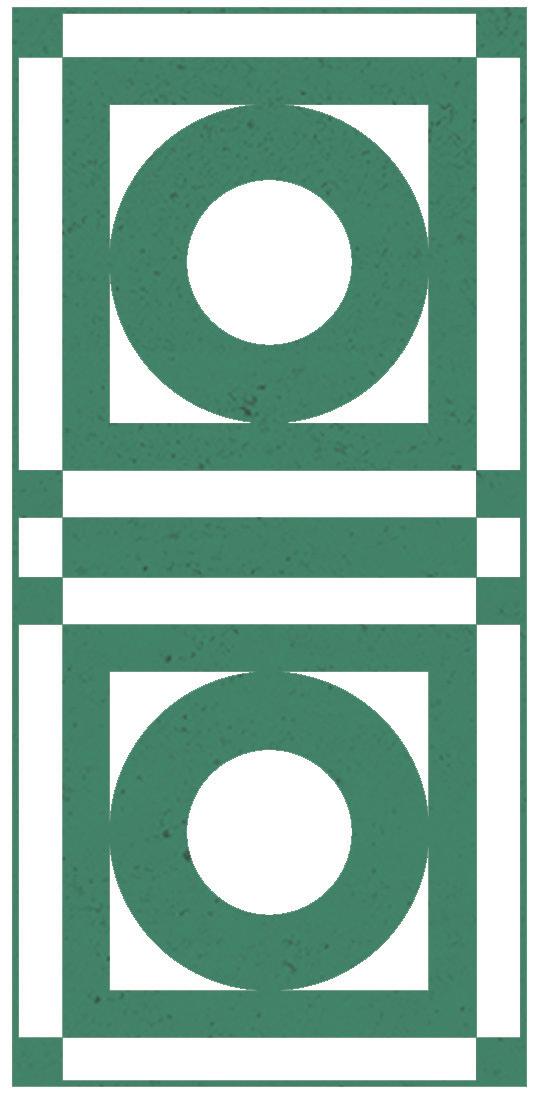

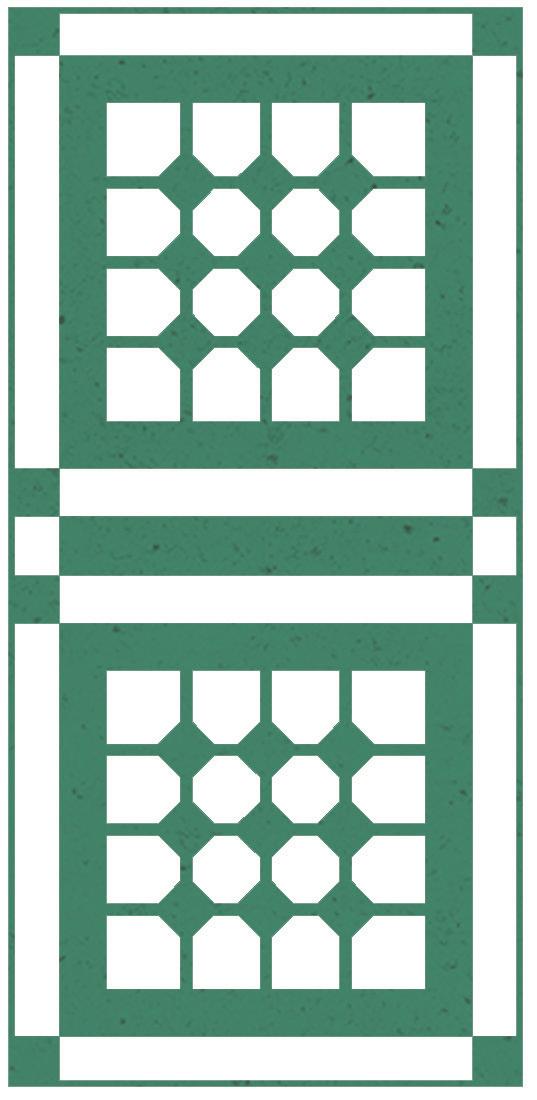

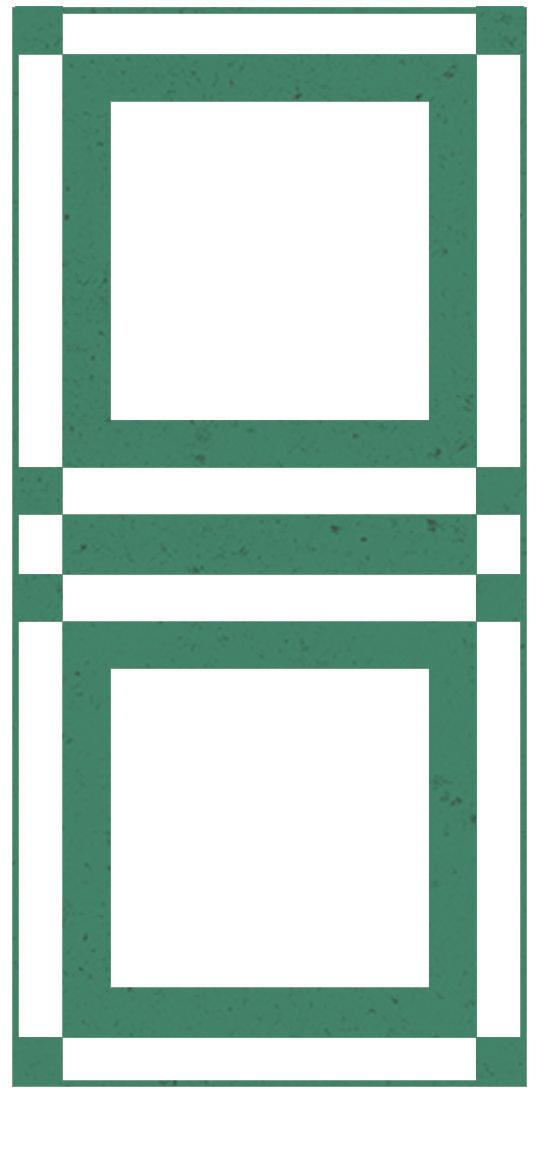

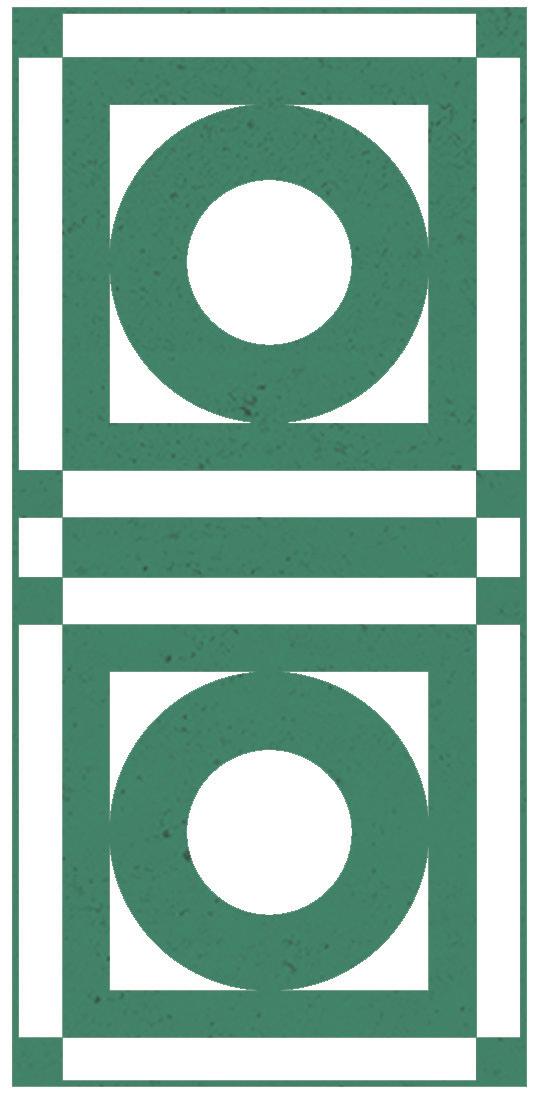

There are 16 entrances to the inner world of the urban block from the main building, which is 300 meters long. In order to make it easier for visitors to find their way around, I have decided to assign a different floor pattern for each entrance.

between public and private_floor patterns

145 transition

146

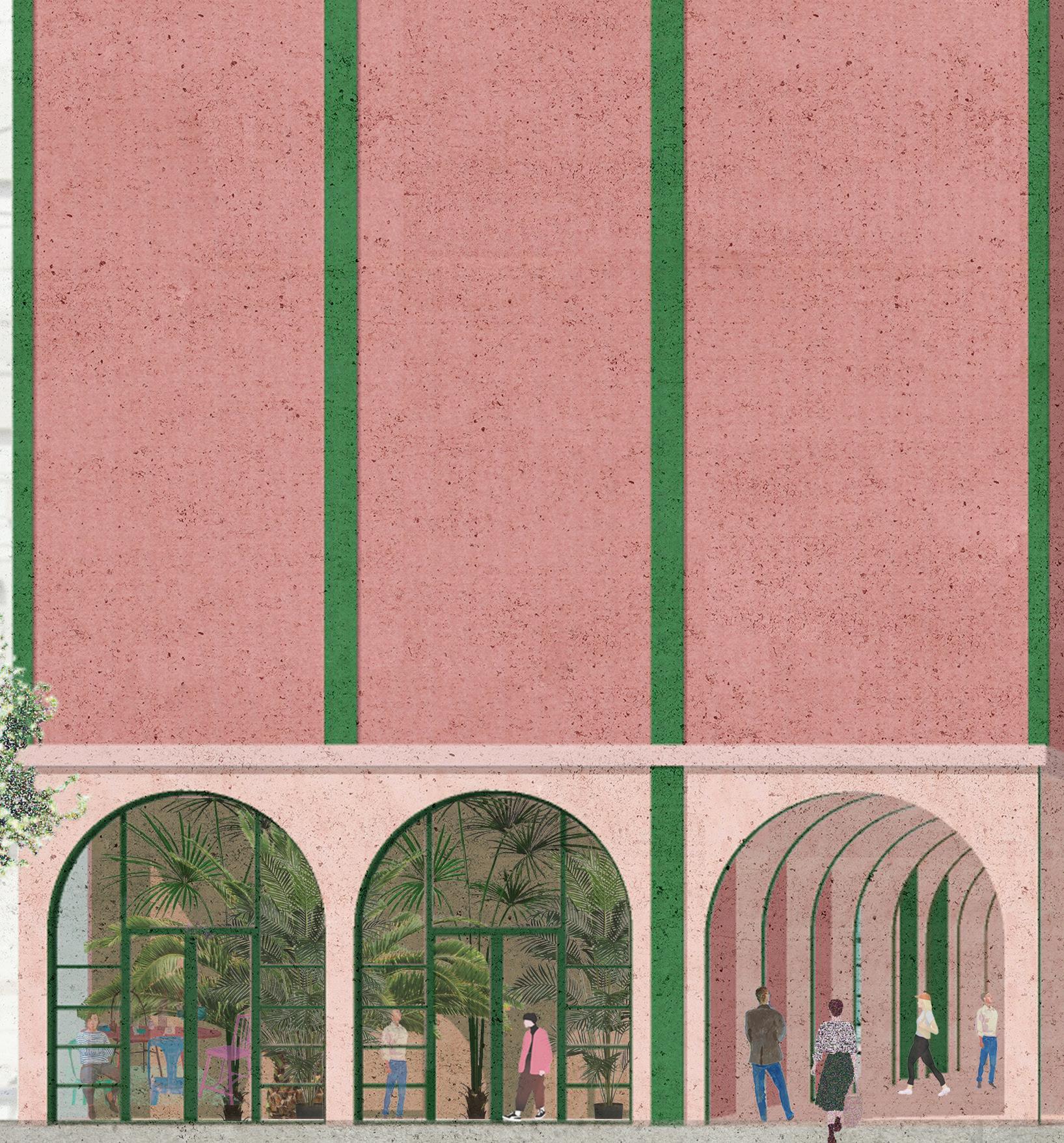

Warsaw’s pre-war townhouses are rich in detail. Their scale was human-friendly, and the division into floors and staircases visible on the façade made it possible to guess what was inside. When creating the project, I was inspired by this and wanted to contrast a radical urban plan with architecture that was friendly to human scale.

147 human scale

human scale

human scale

150

productive purpose

productive or recreational purpose

Praga in the past was full of gardens and orchards, many of them located in the courtyards of tenement houses.

My project draws on this tradition, tenement houses do not exist without courtyards and I want to bring them back to their former glory by making them green and liveable again. Some of them are used for the productive purposes - cultivating plants (part of the vocational school) and some for recreational purposes serving inhabitants and the whole neighbourhood.

Due to the amount of space required for growing plants, I have decided to designate also the top floor of the main building for this purpose. Due to the amount of space required for growing plants, I have decided to designate also the top floor of the main building for this purpose.

151 green elements

152

apple orchard

park

pear orchard

students garden students garden living courtyards

hops garden

productive green recreational green

153

sculpture garden botanical garden

main school’s courtyard study courtyard living courtyards

green elements

and new

exisitng

156

157 second floor 1:200 second floor_fragment

lecture hall

lecture hall

160

161 fourth floor 1:200 fourth floor_fragment

rooftop green house

rooftop green house

164

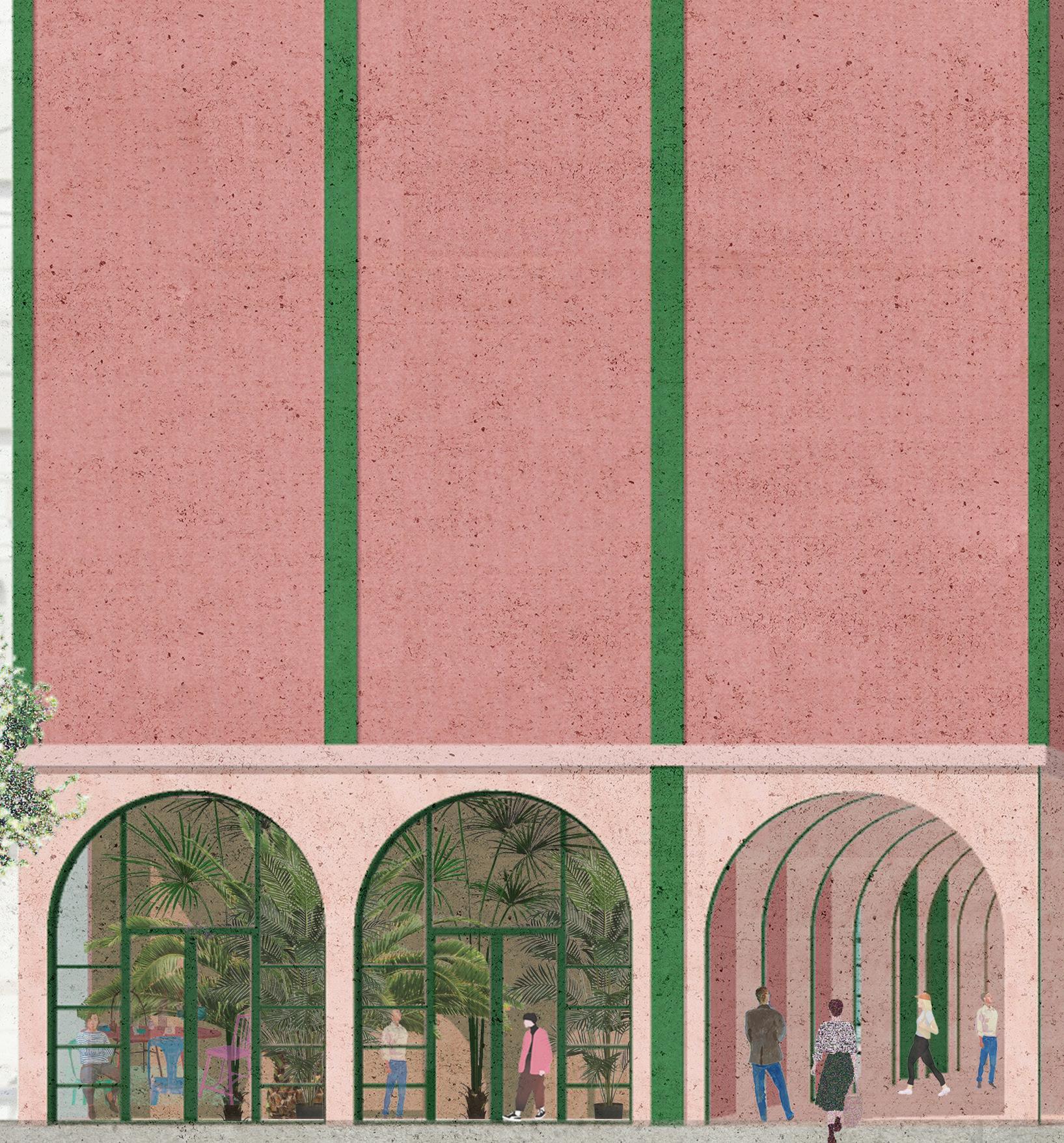

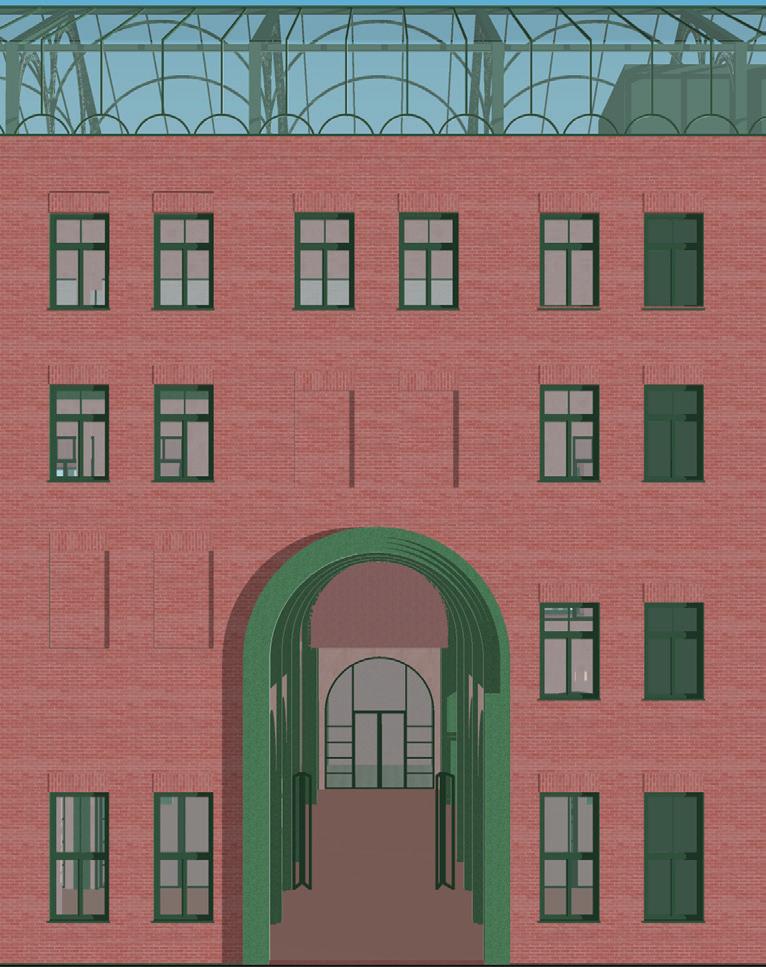

1. plaster covered facade

2. brick facade

3. steel frame facade

The facades of the tenement houses in later 19th and early 20th century took often form of city palaces with very richly decorated, plastered facades, high floors and beautiful interiors.

However, after the war, the decorations were torn down and the plaster was damaged due to the lack of restoration of the buildings. This exposed the rough, brick walls of the tenements, now typical of most Praga’s tenements.

It was important for me to carefully study the building traditions of Praga’s tenement houses and create a design that celebrated them. I created the design principles for the project’s facades.

The main facade facing the street was historically housing the most important functions and was also the richest in its decorations, while the side facing the courtyard is much more modest and practical, with very little decoration. I have applied a similar principle to my design, where the facade of the building facing the central street is covered with plaster, while the internal facades facing the courtyard continues the walls of the existing buildings, which are made of brick.

The exception to this are the buildings, require more light coming into them such as winter garden or botanical garden. There I have used a steel-framed facade inspired by 19th century botanical gardens.

types of facades: plastered brick steel frame

165 facade’s types

plastered facade

plastered facade

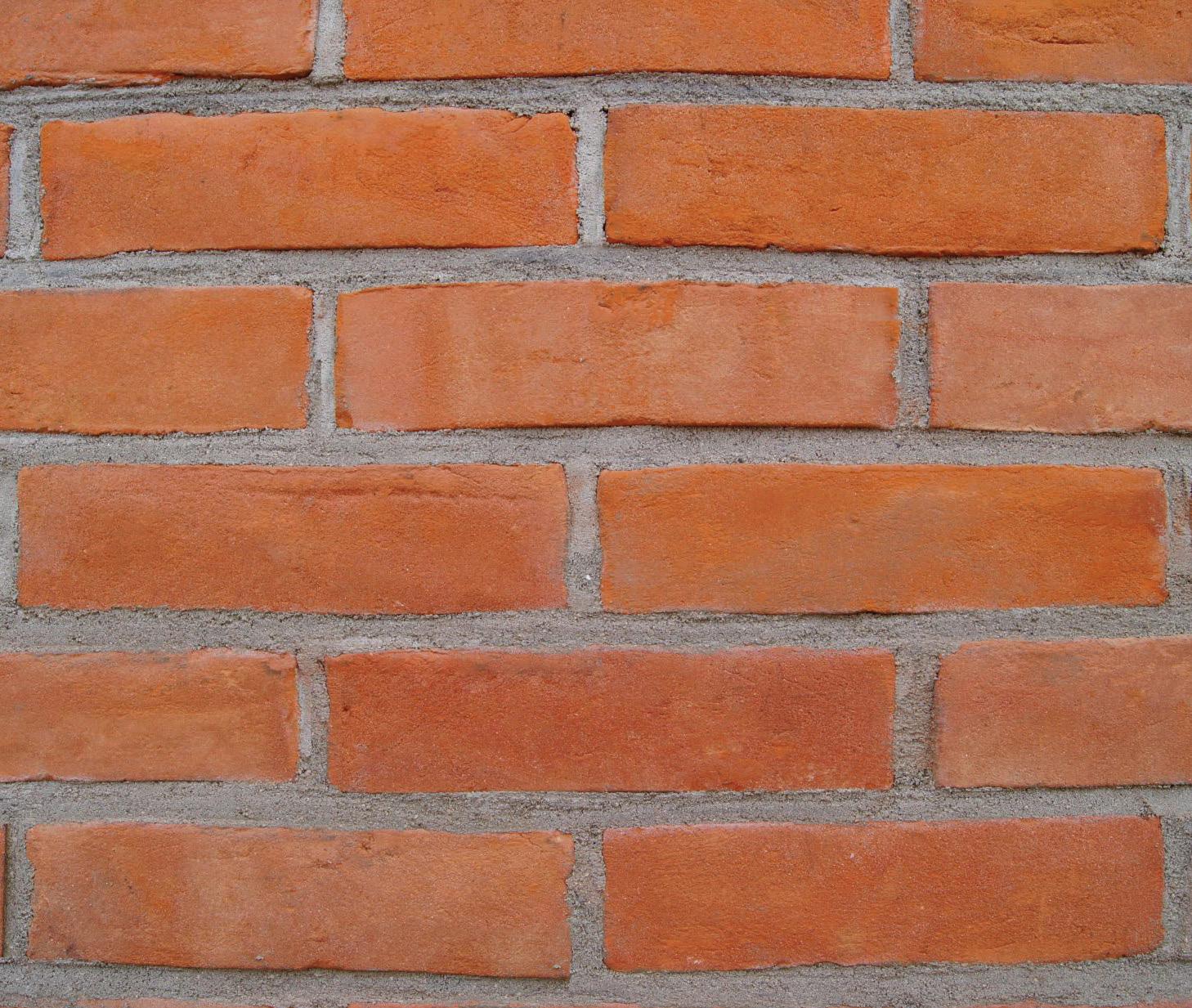

169 brick facade

171 steel frame facade

brick facade

Tenements were originally build from soli brick walls. The project in some parts uses brick from Krasnik close to Warsawcegielnia Trojanwoscy with a standart for Poland RF size (250x120x65 mm).

172

Tenements of Praga are usually covered with plaster, so that the main facades of the buildings are also covered with it in order to achieve coherence with the existing buildings. It is, however, an interpretation of a classic style with different, modern patterns.

173

plastered facade

materials

174 250 70 250 320

175 coss-section

school

class rooms and library

178

botanical garden

180

181 botanical garden

182

183 botanical garden

184

185 botanical garden

REFLECTIONS

188

approach architecturally and culturally sensitive toward the existing building environment

making cities more liveable and diverse with an attention to the human scale think globally, act locally

189

reflections

bibliography

Chudzyńska-Szuchnik, Katarzyna. Zręczni: Historie z warszawskich pracowni i warsztatów. Muzeum Warszawy, Warszawa 2019

Głowacka, Karolina. Echa dawnej Warszawy:Praga. Skarpa Warszawska, Warszawa 2019

Groyecka, Dorota. Gentryfikacja Berlina: Od życia na podsłuchu do kultury caffé latte. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Katedra. Gdańsk 2014

Łupienko, Aleksander. Kamienice czynszowe Warszawy 1864-1914, Instytut Historii PAN, Warszawa 2015

Porozumienie dla Pragi, Poradnik dobrych praktyk architektonicznych: Praga- Północ. Warszawa 2019

Steel, Carolyn. Sitopia:How Food Can Save the World. Penguin Random House. London 2020

190 INDEX

images

p.17, 21/ A.Krystyniak,1973-75, ul. Brzeska p.20 / B.Bellotto, 1770, View of Warsaw from Praga p.24 / unknown, The destruction in Warsaw after World War II p.25 / audiovis.nac.gov.pl / NAC p.25 / S.Braun, reproduction by D.Staga, 1944 p.26 / Google Earth p.29,30 / Muzeum Warszawskiej Pragi p.31 / unknown, 1908; R. Marcinkowski, Ilustrowany Atlas Dawnej Warszawy p.36, 60 / J.Raczyński, 1910, Krakowskie Przedmieście Street in Warsaw p.40 / S.Kazikowski, 1893 p.66-73 / Piotr Stryczyński, 2019, Poradnik dobrych praktyk architektonicznych. Praga-Północ.

191

acknowledgments

I would like to thank the people who supported me during the creation of this project. Without their help, this publication would not exist. Many thanks.

Commission:

Wouter Kroeze (mentor) Jana Crepon Jarrik Ouburg

Vibeke Gieskes

Artjom Morozow Angelina Hopf Bart Jonkers

Esther Bentvelsen Iris Lunenburg Kiwa Miyahara Marta Sołtys Magdalena Stańczak Niels Geerts

Orsolya Erdei

Stephanie Idongesit Ete

Zsófia Török

My Mum&Dad

My sister Iwona

Dariusz Bartoszewski Jacek Grunt-Mejer

193

Project by Aneta Ziomkiewicz (2020-2022)

Master of Architecture Academy of Architecture, Amsterdam

Copyright © Aneta Ziomkiewicz

16

Poznan Vienna

Warszawa Berlin

16

Poznan Vienna

Warszawa Berlin

80

wandering musicain

knives sharpener

sausage man

garbage woman wireman coal dealer

Jew trader sawyer bagel woman

80

wandering musicain

knives sharpener

sausage man

garbage woman wireman coal dealer

Jew trader sawyer bagel woman

81 shoemakerbookbinder

upholster furrier

makers of Praga at the end of 19th century and

81 shoemakerbookbinder

upholster furrier

makers of Praga at the end of 19th century and

human scale

human scale

lecture hall

lecture hall

rooftop green house

rooftop green house

plastered facade

plastered facade