The seminar is sponsored by CDLP, a project of TCDLA, funded by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals Course Directors: Parole, Prison, & Related Issues October 13-14, 2022 Gene Anthes, Bill Habern, & David O'Neil

PAROLE, PRISON, AND RELATED ISSUES

SEMINAR INFORMATION

Date October 13 14, 2022

Location Austin Southpark Hotel |4140 Governors Row Austin, TX 78744

Course Director Gene Anthes, Bill Habern, and Dave O’Neil

Total CLE Hours 13 5 Ethics: 1.0

Thursday, October 13, 2022

Daily CLE Hours: 8.0 Ethics: 1.0

Time CLE Topic Speaker

7:45 am Registration and Continental Breakfast

8:10 am Opening Remarks

8:15 am .75 Interviewing a New Parole Client

9:00 am .75 Evaluating a New Parole Case

9:45 am Break

10:00 am 1.0 Presenting a Parole Case

11:00 am 1.0 Parole Revocation Case Law

12:00 pm Lunch Line

12:15 pm .50 Lunch Presentation| Texas Voices

12:45 pm Break

1:00 pm 1.0 Presenting a Parole Revocation Case

2:00 pm 1.0 Ethics and Prisoner Grievances

Bill Habern and Gene Anthes

David O’Neil

Bill Habern

Gary Cohen

Bill Habern

Mary Sue Molnar

Sean Levinson

Robert Hinton Ethics

3:00 pm Break

3:15 pm 1.0 Minimizing Post Conviction Consequences of Plea Bargains

4:15 pm 1.0 Sex Offender Litigation

5:15 pm Adjourn

David O’Neil

Richard Gladden

PAROLE, PRISON, AND RELATED ISSUES

SEMINAR INFORMATION

Date October 13 14, 2022

Location Austin Southpark Hotel |4140 Governors Row Austin, TX 78744

Course Director Gene Anthes, Bill Habern, and Dave O’Neil

Total CLE Hours 13 5 Ethics: 1.0

Friday, October 14, 2022

Daily CLE Hours: 5.50 Ethics: 0 Time CLE Topic Speaker

7:30 am Registration and Continental Breakfast

7:55 am Opening Remarks

Bill Habern & David O’Neil

8:00 am .75 Unique Issues Women Confront in Prison Nicole Moore

8:45 am 1.0 Civil Commitment of Sexually Violent Predators Gene Anthes

9:45 am Break

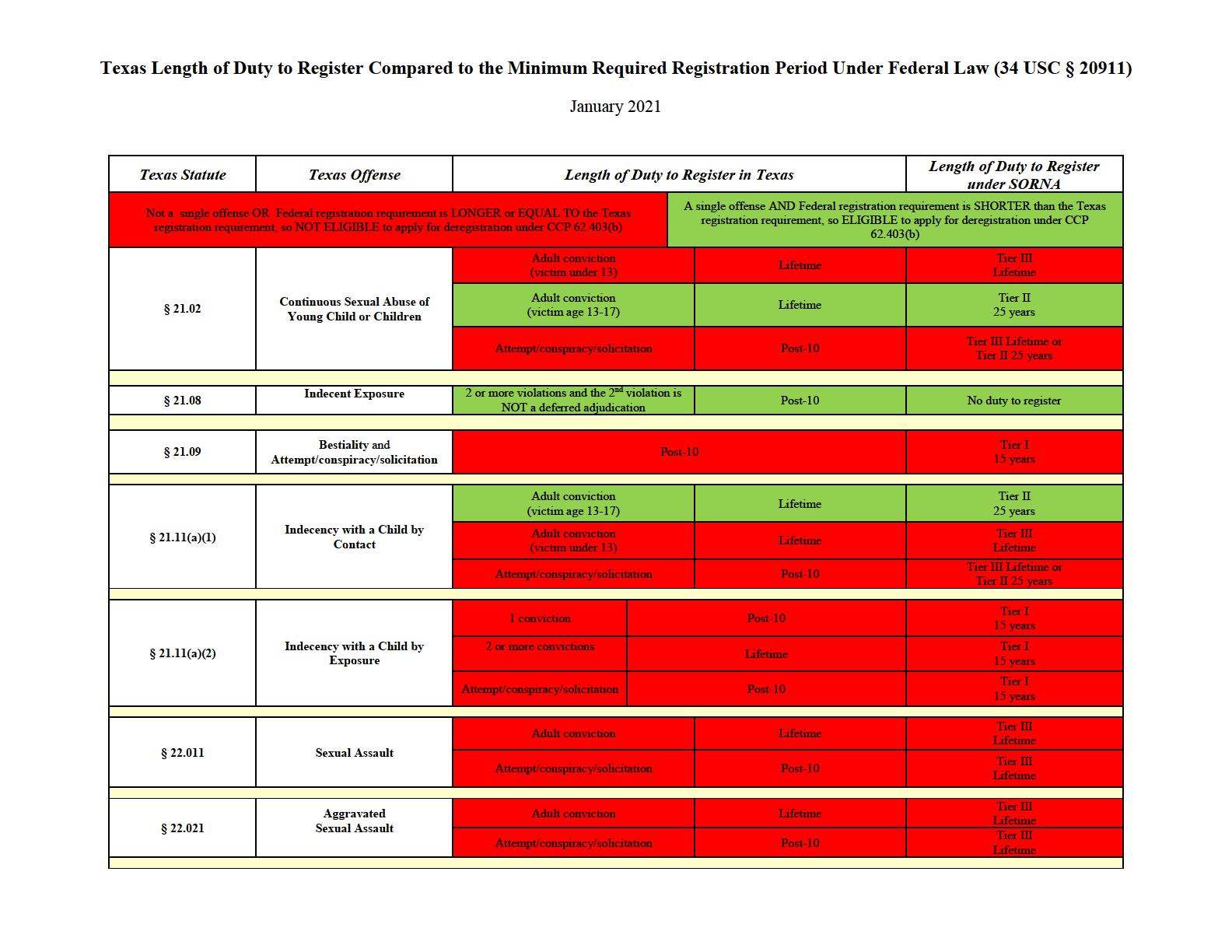

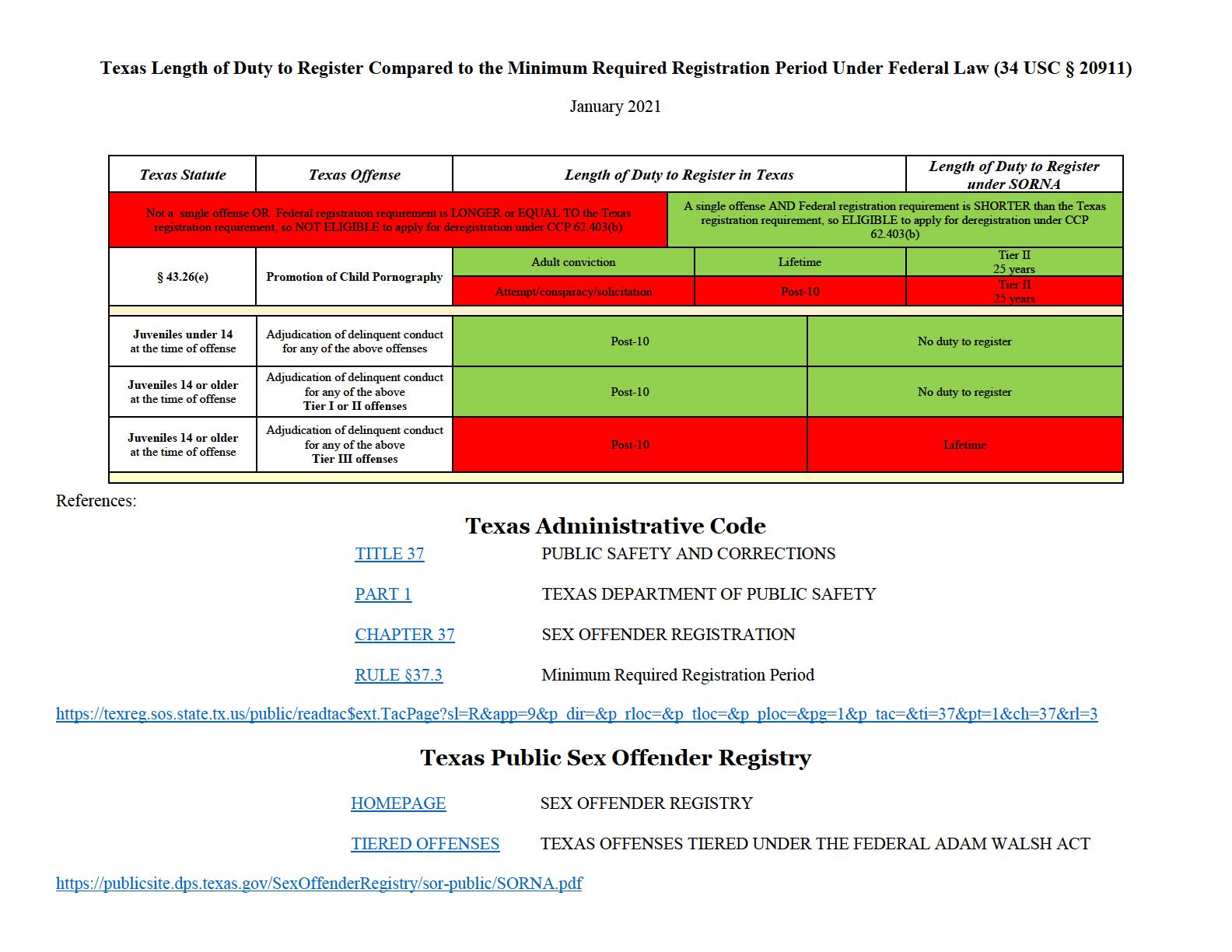

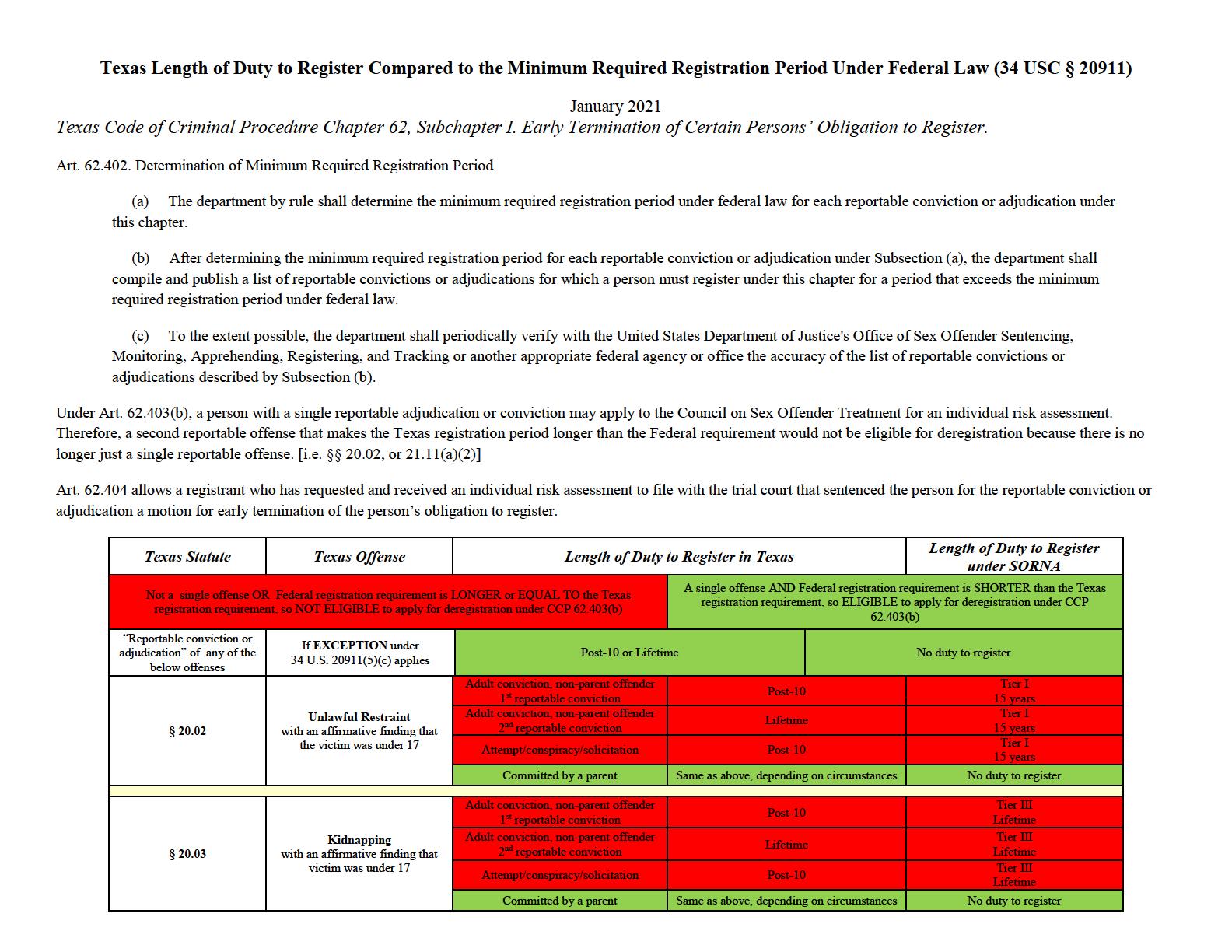

10:00 am .75 Sex Offender Deregistration

10:45 am Lunch Line

11:00 am 1.0 Lunch Presentation| From Free World to Prison and Back Again

12:00 pm Break

12:15 pm 2.0 Q&A: Things to Know about Dealing with TDCJ and the Texas Board of Pardons & Paroles

Scott Smith

John Flagg

Board Members with Tim McDonnell

TDCJ Personnel (TBA) with Gary Cohen and Allen Place as Moderators

2:15 pm Adjourn

Criminal Defense Lawyers Project

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

Table of Contents

speakers topic

Thursday, October, 13, 2022

David O’Neil Interviewing a New Parole Client

Bill Habern

Evaluating a New Parole Case

Bill Habern Parole Revocation Case Law

Mary Sue Molnar Sex Offender Residency Restrictions

Sean Levinson

Presenting a Parole Revocation Case

Robert Hinton Ethics and Prisoner Grievances

David O’Neil Minimizing Post Conviction Consequences of Plea Bargains

Richard Gladden Sex Offender Litigation

Friday, October, 14, 2022

Scott Smith

The Basics of Sex Offender De Registration

John Flagg Innovating for a Change

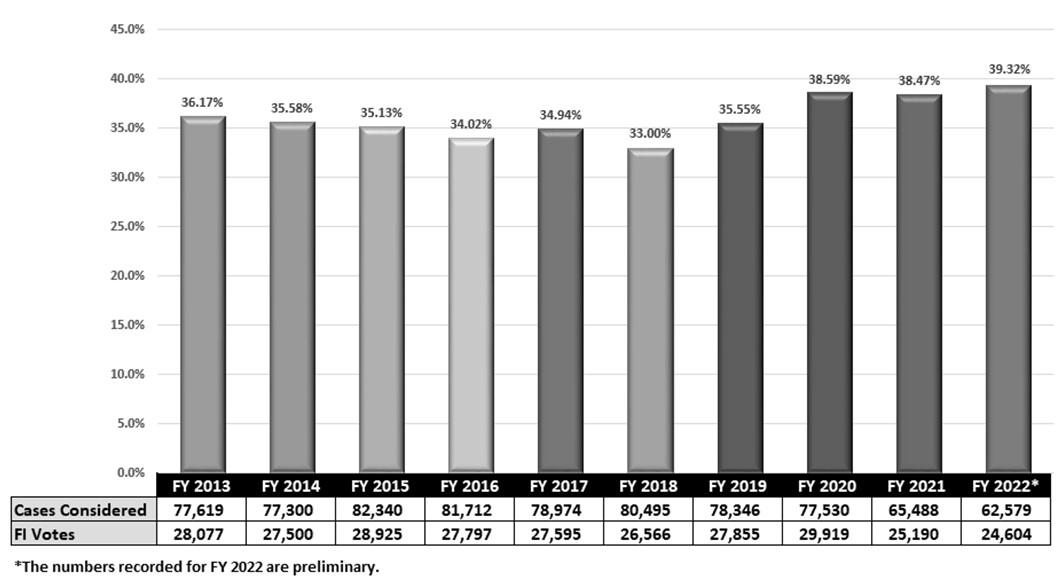

Tim McDonnell Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Criminal

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

13-14,

Southpark Hotel

Topic: Interviewing a New Parole Client

Speaker: David O’Neil

The Law Office of David O’Neil, P.C.

North Main Street Houston, TX 77009

phone

October

2022 Austin

Austin, Texas 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Defense Lawyers Project

3700

713.863.9400

832.879.2185 fax david@paroletexaslawyer.com email www.paroletexaslawyer.com website

PAROLE INTERVIEW WITH ___________________, TDCJ#____________, AT ________________, ON __________ 1. CONFIRM TDCJ OFFENDER INFORMATION, DOB ( ) & CITIZENSHIP ( ). TIMESHEET EXPLAIN: EVAL, BRIEF, PAROLE/MS PROCESS (IPO INTERVIEW, POSSIBLE PAROLE VOTES INCLUDING DETAINER ISSUES), PAROLE SCORE, PROTESTS, ATTORNEY PHONE LIST, RELEASE FORMS, AND, AS APPLICABLE, SB45, HB1914, CCSVP 2. PAROLE PLAN(S), HOME, JOB, SCHOOL IC ? DETAINERS? DEPORTATION TIES TO HOME COUNTRY AND ALTERNATE PLAN? 3. CSZs ?, LRP? SPECIAL CONDITIONS: C, M, R, S, SISP, T, V, X, Z, O.33. 4. ATTORNEYS WITH TRIAL FILE CIVIL SUITS? 5. IF A PRIOR BOARD CONSIDERATION REPRESENTED BY ATTORNEY? COPY OF PRESENTATION? PERSONAL INTERVIEW DETAILS 6. SPECIFICS OF SOCIOLOGY AND IPO MEETING. 7. DETAILS OF OFFENSE(S) & TRIAL/APPEAL/WRIT: CLIENT VERSION V. OFFICIAL VERSION, WITNESSES/VICTIM IMPACT STATEMENT/VICTIM MEDIATION/MEDIA REPORTS/PLEA OFFERS/PSI, POLYGRAPHS, PSYCH EVALS 8. DRUG/ALCOHOL HISTORY & INSTANT OFFENSE SA, REHABS (CERTIFICATES, RELEASES). 9. CRIMINAL HISTORY. IF ANY PRIOR SO ALLEGATIONS DISCUSS O.33 AND COLEMAN HEARING. 10. FREEWORLD JOBS, SCHOOLING, MILITARY (& Achievements) 11. PERFORMANCE ON BOND: JOBS, REPORTING REQUIREMENTS, COMPLIANCE

12. TDCJ CHRONOLOGY (INCLUDE ALL PRIOR INCARCERTIONS): UNITS, JOBS, PROGRAMS/PROGRAM REQUESTS, LINE CLASS, CUSTODY LEVEL, GANGS/MONITORED CLIQUES, CERTS., DAILY SCHEDULE, BOOKS.

13. DISCIPLINES (INCLUDE PRIOR INCARCERATIONS)

14. MEDICAL/PSYCH HISTORY PRIOR PSYCH EVALS/SO EVALS.

15. FAMILY INFORMATION: PARENTS, SIBLINGS, SPOUSE, CHILDREN (DOB, LOCATION, JOBS, ETC).

16. FAMILY VISITS

17. GO OVER BIO & OTHER HISTORY NOT COVERED IN BIO TO INCLUDE ANY NEGATIVE FAMILY ISSUES THAT COULD PRESENT PROBLEMS/PROTESTS

18. DISCUSSED LETTER TO THE BOARD, APOLOGY LETTER(S), SUPPORT LETTERS FROM FAMILY, FRIENDS PROSPECTIVE EMPLOYERS & TDCJ EMPLOYEES (SEND TO ATTY, “GUIDANCE ON WRITING SUPPORT LETTERS”).

19 PHOTOS FAMILY, FRIENDS, HOME, ACHIEVEMENTS (IDENTIFY PERSONS/PLACES)

20 WHO WILL ATTEND BOARD INTERVIEW (IN PERSON, ZOOM, TELEPHONE)

21 SOs: LSOTPs, POLYGRAPHS, “X”, SISP, CCSVP, COLEMAN EVALUATION, SOCC, PSYCH EVAL.

22. ADVISE TO PROVIDE ALL DOCUMENTATION IF HIRED, AND UPDATE (BY PHONE & LETTER).

23. DISCUSS TENTATIVE OPINION: CONCERNS, COA, SECONDARY OBJECTIVE, TIMETABLE.

WORDS OF ENCOURAGEMENT, MESSAGES FOR FAMILY

24

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

13-14,

Southpark Hotel

Topic: Evaluating a New Parole Case

Speaker: Bill Habern

The Habern Law Firm P.O. Box 130744 Houston, TX 77219 0744 713.942.2376 phone bill@paroletexas.com email www.paroletexas.com website

October

2022 Austin

Austin, Texas 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com Criminal Defense Lawyers Project

Criminal Defense Lawyers

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

13-14,

Southpark Hotel

Topic: Parole Revocation Case Law

Speaker: Bill Habern

The Habern Law Firm P.O. Box 130744 Houston, TX 77219 0744 713.942.2376 phone bill@paroletexas.com

www.paroletexas.com

October

2022 Austin

Austin, Texas 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Project

email

website

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

13-14,

Southpark Hotel

Texas

Topic: Sex Offender Residency Restrictions:

Effective or Counter Productive?

Speaker: Mary Sue Molnar

Founder and Executive Director

Texas Voices for Reason and Justice 9424 Old Corpus Christi Hwy San Antonio, TX 78223 210.414.5701 phone marysueintx@yahoo.com email www.website.com website

Author: Texas Voices for Reason and Justice

P.O. Box 23539 San Antonio, TX 78223 210.414.5701 phone www.texasvoices.org website info@texasvoices.org email

October

2022 Austin

Austin,

6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com Criminal Defense Lawyers Project

Laws and

Pursuing Rational

Policies Sex Offender Residency Restrictions: Effective Or Counter Productive? TVRJ, Inc. Texas Voices for Reason and Justice P.O. Box 23539 San Antonio, TX 78223 (210) 414 5701 http://TexasVoices.org

Texas Voices for Reason and Justice is a statewide, non profit, volunteer organization devoted to promoting a more balanced, effective, and rational criminal justice system. TVRJ advocates for common sense, research based laws and policies through education, legislation, litigation, and support for persons required to register for sex related offenses as well as for members of their families. We believe that sex offense laws and policies should be based on sound research and common sense, not panic or paranoia.

INTRODUCTION:

In recent years, restrictions against where registered sex offenders may live have become commonplace. These restrictions were created on the theory that proximity to areas where children congregate would tempt those convicted of sexual offenses into re offending. However, despite their popularity, residency and proximity restrictions have not shown to be effective. In fact, research has concluded that the imposition of these types of restrictions do not improve public safety and actually cause more harm than good

Current Texas Policy:

Texas does not have a state wide residency restriction law for registrants who have served their sentences, but many cities have enacted their own ordinances to limit where registrants may live.

Guidelines of Texas Parole and Probation Departments also restrict most registrants on supervision from living within specific distances of places such as schools, parks, day care centers, and other places designated as ‘child safe zones’ where an offense is already least likely to occur.

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice

1

http://Texasvoices.org

Because empirical evidence has shown that residency restrictions are ineffective, counterproductive, and costly, Texas Voices for Reason and Justice is opposed to laws and policies restricting where a person required to register may live.

The Facts:

Residency restriction laws and policies have no empirical support. They create instability, harm families, and waste resources. Research consistently shows that these type of restrictions do not reduce sexual re offense, do not reduce the rate of new sex offense cases, do not stop or reduce child sexual abuse, are not based on facts and evidence, and do not contribute to public safety.

Residency Restrictions:

Are not a feasible strategy for reducing sexual offenses. The vast majority of sex offenses occur in the home or by someone known to the victim.

not enhance public safety but they do create instability, harm families and waste resources

Can cause offenders to become homeless, to change residences without notifying authorities of their new locations, to register false addresses or to simply disappear.

Cover a broad range of offenses imposing the restriction on many offenders who present no known risk to children in the restricted locations.

Have been shown to increase both absconding and criminal recidivism.

Summary:

There are no statistics, there are no studies, there are no reports, and there is no evidence supporting the theory that residency restrictions protect children or the public at large.

In fact, countless studies show that these types of restrictions are nothing more than a comfort factor and may do more harm than good.

2 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

Do

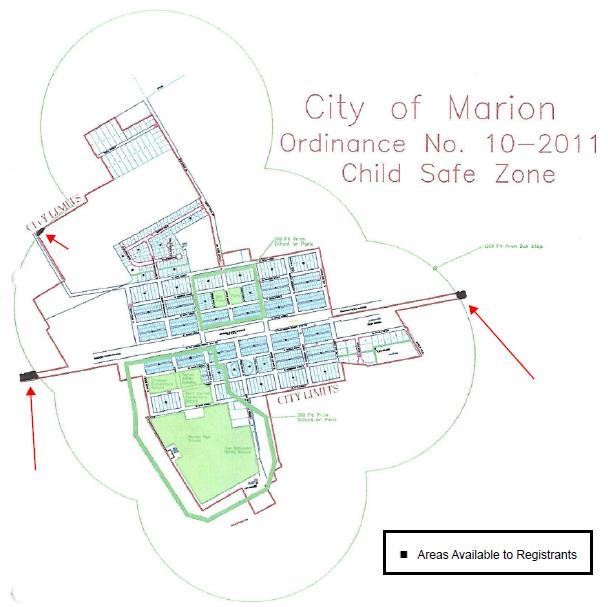

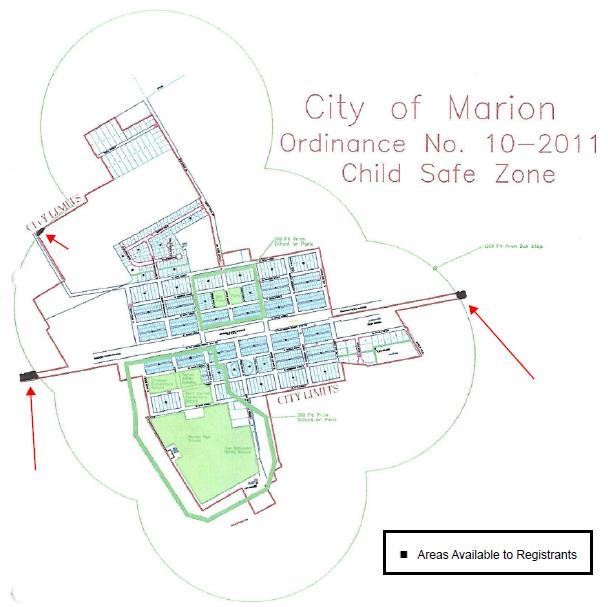

Example of 1000 foot Residency Restrictions in small towns

The exclusionary effect of the ordinance (before being repealed), in the town’s own map, is graphically shown above. Only a few tiny areas, if habitable at all, are available for Registrants. The intent to banish is clear.

3 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

Quotable Quotes:

“

One of the most concerning aspects of the implementation of residence restrictions is the passing of policy and law without consideration for research, best practice, and effective methodology. This often results in unintended counterproductive consequences which negatively impact community safety”. Colorado Sex Offender Management Board Residence Restrictions, 2009

“

ATSA supports evidence-based public policy and practice. Research consistently shows that residence restrictions do not reduce sexual reoffending or increase community safety. In fact, these laws often create more problems than they solve, including homelessness, transience, and clustering of disproportionate numbers of offenders in areas outside of restricted zones. Therefore, in the absence of evidence that these laws accomplish goals of child protection, ATSA does not support the use of residence restrictions as a feasible strategy for sex offender management.” ATSA (Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers) Excerpt from Public Policy brief, August 2014

“Because residency restrictions have been shown to be ineffective at preventing harm to children, and may indeed actually increase the risks to kids, the Jacob Wetterling Resource Center does not support residency restriction laws. Such laws can give a false sense of security while sapping resources that could produce better results used elsewhere.” Jacob Wetterling Resource Center Website

“We have 98 percent compliance,” said Lester, commander of Amarillo’s Detective Division and supervisor of the squad working offender registration. “Ninety-eight percent of the people, we know exactly where they live, where they’re working. And then, the other 2 percent we’ve either got warrants issued on them or haven’t found them. I don’t see that we have a problem that the ordinance addresses.”

Amarillo.com. December 2011 http://amarillo.com/news/local-news/2011-12-10/opponents-urge-caution-aboutpitfalls-proposed-restrictions

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice

http://Texasvoices.org

4

“

Research shows that there is no correlation between residency restrictions and reducing sex offenses against children or improving the safety of children. Research does not support the belief that children are more likely to be victimized by strangers at the covered locations than at other places.

Residency restrictions were intended to reduce sex crimes against children by strangers who seek access to children at the covered locations. Those crimes are tragic, but very rare. In fact, 80 to 90% of sex crimes against children are committed by a relative or acquaintance who has some prior relationship with the child and access to the child that is not impeded by residency restrictions. Only parents and caretakers can effectively impede that kind of access.

There is no demonstrated protective effect of the residency requirement that justifies the huge draining of scarce law enforcement resources in the effort to enforce the restriction.”

Iowa County Attorneys Association Statement on Sex Offender Residency Restrictions in Iowa, December 2006

“Housing restrictions appear to be based largely on three myths that are repeatedly propagated by the media: 1) all sex offenders re offend; 2) treatment does not work; and 3) the concept of “stranger danger.” Research does not support these myths, but there is research to suggest that such policies may ultimately be counterproductive. The resulting damage to the reliability of the sex offender registry does not serve the interests of public safety.”

Kansas Department of Corrections Website Statement

“California Coalition Against Sexual Assault (CALCASA) opposition to Jessica’s law is based on [the fact that] residency restrictions for sex offenders don’t make communities safer. Residency restrictions don’t reduce recidivism, don’t improve supervision of offenders, and ultimately do not protect children from sex offenders. Moreover, residency restrictions are having unintended consequences that decrease public safety. For example, Iowa Department of Public Safety statistics show that the number of sex offenders who are unaccounted for has doubled since a residency restriction law went into effect in June 2005.”

California Coalition Against Sexual Assault Statement Concerning Jessica’s Law

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice

5

http://Texasvoices.org

Across the States: KANSAS

Currently, the state of Kansas has no law that mandates where an offender can or cannot live, work, or go to school, nor does Kansas law allow for local jurisdictions to have such laws: however, this may be a condition of parole or probation. http://www.doc.ks.gov/publications/CFS/sex offender housing restrictions

MARYLAND

Maryland does not have any residency restrictions. Information put out by other states has shown that residency restrictions do not help to prevent sexual offenses from occurring because the victims and the offenders, in most situations, know each other. Some states, such as Iowa and Florida, have found that residency restrictions can make it very difficult to track sex offenders who have become homeless. Homeless sex offenders are also more difficult to register and without an address the registry is unable to tell the public where the offender lives.

PENNSYLVANIA

Pennsylvania’s Megan’s Law does not restrict where a sexual offender or Sexually Violent Predator/Sexual Violent Delinquent Child may reside. However, an offender may be restricted from residing near a school, park, daycare center, etc. if the registrant is on parole or probation. http://www.pameganslaw.state.pa.us/FAQ.aspx?dt=

FLORIDA

There is no bigger example of the negative impact of sex offender residency restrictions than the Julia Tuttle Causeway sex offender camp in Miami, where registrants were forced to live under a bridge in Miami, Florida. With few options, offenders still often sleep in cars, tents and in the open. http://www.npr.org/2014/10/23/358354377/aclu-challenges-miami-law-on-behalf-ofhomeless-sex-offenders

6 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

In The Courts:

In addition to the vast amount of research, a growing number of courts, cities, counties and states that once favored these laws are looking to reform or abolish residency restrictions altogether.

August, 2015

Mass. Supreme Court strikes down residency laws; Compares them to Japanese internment camps

“

The justices also warned that laws segregating sex offenders pose "grave societal and constitutional implications."

“Except for the incarceration of persons under the criminal law and the civil commitment of mentally ill or dangerous persons, the days are long since past when whole communities of persons, such Native Americans and Japanese-Americans may be lawfully banished from our midst,” the decision reads.

Boston Globe

Read the court’s decision: http://www.mass.gov/courts/docs/sjc/reporter-of-decisions/new-opinions/11822.pdf

February, 2015

New York Court tosses local laws on sex offender residency

ALBANY, New York Local communities cannot enact laws restricting where sex offenders may live, New York State’s highest court ruled on Tuesday. The Court of Appeals ruled that the state’s regulatory framework set up in the 1996 Sex Offender Registration Act, the 2000 Sex Assault Reform Act, the 2007 Sex Offender Management and Treatment Act and other modifications of Executive and Social Services laws – must prevail. Municipalities cannot enact laws where the state already regulates, the court found.

Philly.Com http://www.recordonline.com/article/20150217/News/150219388

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

7

March, 2015

CA court rules San Diego sex offender law unconstitutional

“The California Supreme Court ruled on Monday that San Diego County's "blanket" enforcement of the state's sex offender residency laws was unconstitutional, a decision that could open the door to wider challenges of the statute.”

"The residency restrictions place burdens on registered sex offender parolees that are disruptive in a way that hinder their treatment, jeopardizes their health and undercuts their ability to find and maintain employment, significantly undermining any effort at rehabilitation," Justice Baxter wrote.

"Blanket enforcement of residency restrictions against these parolees has ... infringed on their liberty and privacy interests, however limited, while bearing no rational relationship to advancing the state's legitimate goal of protecting children from sexual predators," Justice Marvin Baxter wrote in an opinion for the court.

Reuters

http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/03/02/us usa california sexoffenders idUSKBN0LY2BL20150302

May, 2011

PA high court strikes down a county's Megan's Law residency restrictions

“

In a ruling with statewide ramifications, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court on Thursday invalidated an Allegheny County law that restricted where convicted sex offenders could live, saying the ordinance would banish offenders to "localized penal colonies" with little access to jobs, support, or even their families.

The seven justices concluded that the Western Pennsylvania county law was at odds with the state's "Megan's Law," which requires convicted sex offenders across the state to report their residency so that nearby residents can be notified, but does not restrict where offenders can live.”

Philly.com http://articles.philly.com/2011 05 27/news/29590250_1_residency restrictions offenders megan s law

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

8

Newspaper Investigative Reports:

Hundreds of convicted sex offenders missing in Tulsa area

BY MAUREEN WURTZ THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 11TH 2016

TULSA According to Tulsa Police, there are hundreds of convicted sex offenders missing in the Tulsa area. However, just because they're missing doesn't mean they're gone, said Sgt. John Adams with the Tulsa Police Department. “The only thing we want to know and the only thing the public wants to know is where these guys are?" said Adams.

According to Adams, the places where a registered sex offender can live in Tulsa have been greatly restricted since 2006.During that year, Oklahoma lawmakers passed a 2,000 law, stating sex offenders can't live within 2,000 feet of a school, park, or any place where children live or play.

"2006 just turned our world upside down, prior to that we had 15 to 20 (failure to register) violations a year," said Adams. “Since that we have hundreds of violations a year”. Adams said because of the way Tulsa is laid out, there are almost no options for sex offender to legally live. Many areas available for sex offenders to live are either industrial areas, wealthy neighborhoods, or undeveloped areas.

"Legislators felt that if we put all of this off limits, they'll just move out of state. That didn't happen, they just stopped registering," said Adams.

Before 2006 they had around 680 registered sex offenders and now, Adams says they're less than 400.

"We're an outcast, a huge outcast, so we kind of take into each other. We know- we understand what each other is going through," said one convicted sex offender. He wanted to hide his identity, so for the purposes of this article, his new name is 'Ben.' Ben has been living out of his car ever since getting out of prison. Each week, he goes to the sex offender registry office and registers as a 'homeless sex offender.' Homeless sex offenders are required by law to register each week and let police know where they'll be staying. “I’m grounded to this spot, if I'm not here, we're going to come and arrest you why I'm freezing? I have to choose between life and death to follow the law," said Ben.

9 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

Adams said the weekly registering sets up sex offenders, like Ben, for failure.

"I agree, that if there is a danger, a person that is a danger, this can set them into their cycle to re offend," said Ben.

Homeless shelters in Tulsa aren't allowed to take sex offenders like Ben, because of how close they are to schools or parks. "We feel horrible when someone comes in and we find out that they are a sex offender and we just say we can't help you- you can't be here," said Sandra Lewis, with the Tulsa Day Center.

Adams said he's brought up his concern to lawmakers several times. He said, in private they'll agree, but in public no one wants to be the champion for the sex offender.

"Now, a third of the offenders- we have no idea where they're at. You're actually less safe because you can't tell your child stay away from the brown house with the green trim because that's a sex offender. You don't know because we've lost so many," said Adams.

Adams said they department receives grants from the state to help search for missing sex offenders, however without those grants, they don't have the man power.

He said he knows one way that Oklahoma can fix the problem.

"Get rid of everything and start all over. Get a legislative study, bring law enforcement in on the ground, and let's get something that works for everybody," said Adams.

As for now, Adams said, they'll continue to do the best they can to keep tabs on the offenders they do know.

http://ktul.com/news/investigations/hundreds-of-convicted-sex-offenders-missing-intulsa-area

10 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

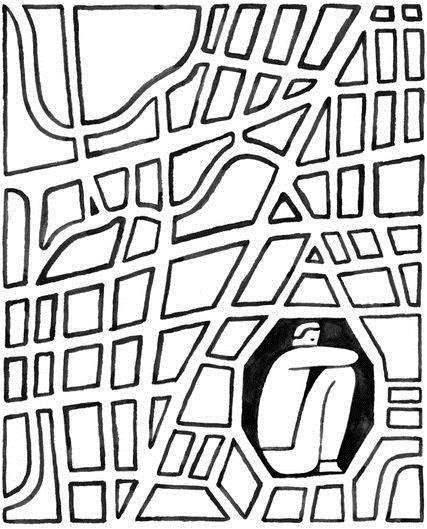

The Pointless Banishment of Sex Offenders

By THE EDITORIAL BOARD SEPT. 8, 2015

It’s a chilling image; the sex predator skulking in the shadows of a swing set, waiting to snatch a vulnerable child.

Over the past two decades, that scenario has led to a wave of laws around the country restricting where people convicted of sex offenses may live in many cases, no closer than 2,500 feet from schools, playgrounds, parks or other areas where children gather. In some places, these “predator free zones” put an entire town or county off limits, sometimes for life, even for those whose offenses had nothing to do with children.

Protecting children from sexual abuse is, of course, a paramount concern. But there is not a single piece of evidence that these laws actually do that. For one thing, the vast majority of child sexual abuse is committed not by strangersbut byacquaintances or relatives. And residency laws drive tens of thousands of people to the fringes of society, forcing them to live in motels, out of cars or under bridges. The laws apply to many and sometimes all sex offenders, regardless of whether they were convicted for molesting a child or for public urination.

Lately, judges have been pushing back. So far in 2015, state supreme courts in California, Massachusetts and New York have struck down residency laws.

The Massachusetts ruling, issued on Aug. 28, invalidated a residency restriction in the town of Lynn — and by extension, similar restrictions in about 40 other communities statewide in part because it swept up so many offenders, regardless of the actual risk they posed. Acting against a whole class presents “grave societal and constitutional implications,” the justices wrote. That unanimous ruling was based on the State Constitution.

11 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

The California Supreme Court went further,holding that a San Diego residencyrestriction, which effectively barred paroled sex offenders from 97 percent of available housing, violated the United States Constitution.

Far from protecting children and communities, the California court found, blanket restrictions in fact create a greater safety risk by driving more sex offenders into homelessness, which makes them both harder to monitor and less likely to get essential rehabilitative services like medical treatment, psychotherapy and job assistance.

Residency laws often lead people to live apart from their families, obliterating what is for many the most stabilizing part of their lives.

If the state wants to block someone from living in certain areas, the California court said, it must make that decision on a case-by-case basis.

The United States Supreme Court has not yet weighed in on residency restrictions, although a 2003 ruling upholding mandatory registration for sex offenders suggested that such laws may violate the Constitution.

It is understandable to want to do everything possible to protect children from being abused. But not all people who have been convicted of sex offenses pose a risk to children, if they pose any risk at all. Blanket residency restriction laws disregard that reality and the merits of an individualized approach to risk assessment in favor of a comforting mirage of safety.

Story Link: The Pointless Banishment of Sex Offenders

12 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

By ASHBY JONES Nov. 30, 2014

Cities and Towns Scaling Back Limits on Sex Offenders

Officials Say Buffer Zones Don’t Prevent Repeat Offenses and Make Predators Harder to Track

When Palm Beach County, Fla., was sued earlier this year over its housing restrictions for registered sex offenders, its attorneys took an unusual approach: They suggested the county relax its law.

The county’s commissioners prompted largely by the lawsuit brought by a sex offender who claimed the limits rendered him homeless voted in July to let such offenders legally live closer to schools, day-care centers and other places with concentrations of children.

“We realized the law was costing the taxpayer’s money [for services for the homeless] and was causing more problems than it was solving,” said county attorney Denise Nieman.

In the mid 1990s, states and cities began barring sex offenders from living within certain distances of schools, playgrounds and parks. The rationale: to prevent the horrible crimes sometimes committed by offenders after their release. In October, for instance, officials charged sex offender Darren Deon Vann with murdering two women in Indiana. Mr. Vann, who is suspected of killing several others, pleaded not guilty.

Now, a growing number of communities are rejecting or scaling back such limits— out of concern that theydon’t prevent repeat offenses, and, in some instances, may make sex offenders harder to track.

Before Palm Beach County shrunk its buffer zones, only small pockets of the county were open to sex offenders, said Mark Jolly, the head of the unit at the county sheriff’s office charged with tracking sex offenders. “They’d either just become homeless or they’d tell us they were homeless, then would move into housing within a restricted zone,” he said. “It became a nightmare to track these guys.”

Mike Rodriguez, the executive director of the county’s criminal justice commission, estimates that the change in the law increased the area in which sex offenders could live by about 70%.

13 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

In August, the Dallas City Council considered a proposal to adopt residency restrictions for Dallas’s nearly 4,000 sex offenders. Jerry Allen, a council member, said he “looked for research” to support the idea, but came up empty. So Mr. Allen persuaded the council to shelve the proposal.

A 2013 Justice Department study that examined Michigan’s and Missouri’s statewide restrictions showed they “had little effect on recidivism.” Other studies have found the vast majority of sex offense cases involving children are committed not by strangers but by family members or others with established connections to the victims, such as coaches or teachers.

About 30 states and thousands of cities and towns have laws restricting where sex offenders can live, while others are adding them. In March, a 1,000-foot buffer from parks took effect in San Antonio. In July, Milwaukee passed a law banning sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of a variety of places where children gather.

In October, the City Council in Elkhorn, Wis., population 10,000, passed an ordinance requiring offenders who move into town to live at least 2,000 feet from places such as schools and parks. The move was prompted by an influx of sex offenders released from the nearby county jail, many of whom had begun to congregate in the town’s business district, said Mayor Brian Olson. After the vote, he said he got several calls and letters from residents thanking him. “I think people were afraid to speak up on the issue, and that there was a bit of a sigh of relief,” Mr. Olson said. We’re just trying to keep our kids safe, and just did what a lot of other communities around the state have done,” he said.

Critics, however, say such moves do little more than score lawmakers political points and give an area’s residents a false sense of security. Some argue they can make communities less safe, by making it hard for offenders to find stable housing.

David Prater, district attorney of the county that encompasses Oklahoma City, said he and other state prosecutors have tried to get the state to relax its 2,000 foot buffer, to no avail. “No politician wants to be labeled the guy who lessens restrictions on sex offenders,” he said.

The police chief in Greeley, Colo., Jerry Garner, said he started having doubts about the restrictions when, a few years ago, Greeley officers discovered a registered sex offender living in his car, partly, recalls Mr. Garner, because he was “boxed out” of so much of the city. “Because of the restrictions, he was basically living as close to children as he wanted to,” said Mr. Garner. At his urging, in February Greeley slashed the size of the restricted areas for its 265 registered sex offenders from 1,000 feet around places like schools to 300 feet.

In October, three residents of a Miami outdoor encampment sued Miami-Dade County in federal court, claiming that sex-offender residency restrictions in the county rendered

14 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

them “unable to locate stable, affordable housing,” thereby forcing them and “hundreds” of others into homelessness.

A Miami Dade County spokeswoman declined to comment on the suit.

Miami-Dade County has come under fire for its residency restrictions before. In 2006, an encampment that ultimately grew to include more than 100 homeless sex offenders developed under a Miami freeway, largely as a result of the county’s residency restrictions. Four years later, to alleviate the problem the county eliminated some of its 2,500-foot buffer zones for sex offenders.

Some smaller towns are chucking restrictions, partly in the name of public safety. De Pere, Wis., a town of 23,000 south of Green Bay, tossed out its 500 foot buffer last year after reviewing data on its effectiveness, said several council members. The issue was reopened by some townspeople several months ago, when a convicted sex offender moved across the street from a school for children with special needs. But the council didn’t budge.

“You track where they live, you check in on them, but you let them live at home, where they’re comfortable and stable,” said Scott Crevier, a DePere city councilman. “I feel we’re actually safer than a lot of other towns in the state that have them.”

http://www.wsj.com/articles/cities-and-towns-begin-scaling-back-limits-on-sex-offenders1417389616

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice

http://Texasvoices.org

15

Lubbock Avalanche Journal

Sex offender residency restrictions: What does the research say?

Josie Musico

January 29, 2015

Earlier this week, I reported Muleshoe could set an ordinance restricting registered sex offenders from living near schools, playgrounds and daycare centers. Some of our online commenters suggested City Council consider more research on the subject before they take action. As always, thank you for your feedback. But what does the research say? Searching for studies that seemed as objective as possible, here is some of what I found:

About 93 percent of sex crimes are committed by an offender already acquainted with the victim, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics. Personal observation covering sexual-assault cases in the South Plains supports this statistic. I have not yet covered a case in which an offender attacked a stranger on a playground, but that does not mean it couldn’t happen.

A 2007 studybythe Minnesota Department of Corrections that reviewed 224 cases of sexual-offender recidivism determined those repeat offenders committed the attacks more than a mile away from their homes. The researchers summarized, “Not one of the 224 sex offenses would likely have been deterred by a residency restrictions law ... Even when offenders established direct contact with victims, they were unlikely to do so close to where they lived.”

Read more here: http://www.csom.org/pubs/MN%20Residence%20Restrictions_0407SexOffenderReport-Proximity%20MN.pdf

16 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

A 2008 study from Lynn University, the University of New Mexico and the University of Nevada researched recidivism rates among Florida sex offenders. It did not find a correlation between the offenders’ homes in proximity to schools and playgrounds and their likelihood of reoffending.

The study concluded, “Sex offenders who lived within closer proximity to schools and daycare centers did not reoffend more frequently than those who lived farther away ... The time that police and probation officers spend addressing housing issues is likely to divert law enforcement resources away from behaviors that truly threaten our communities in order to attend to a problem that simply does not exist.”

The Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers supports alternatives to residency restrictions as mental health treatment and access to housing and employment.

http://www.atsa.com/pdfs/Policy/2014SOResidenceRestrictions.pdf

Sex offender notification laws and residency requirements began growing in popularity in the 1990s. Now, more than 30 states and hundreds of cities nationwide hold some form restrictions on where sex offenders are allowed to live.

‘I was actually a bit apprehensive with this blog because all the research studies I found seemed to point in the same direction, and I hope it doesn't make me look biased. If I can find any studies that indicate these ordinances are effective at preventing recidivism, I will definitely link them too. Have a great day.’ Josie Musico http://lubbockonline.com/interact/blog-post/josie-musico/2015-01-29/sexoffender-residency-restrictions-what-does-research

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice

http://Texasvoices.org

17

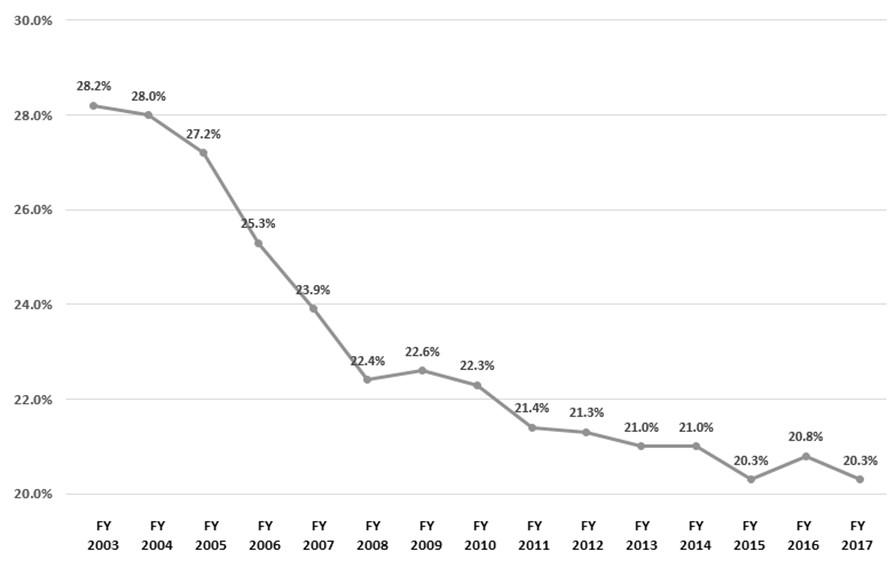

Low Recidivism for Sexual Crimes-The Facts

People convicted of a sexual crime seldom repeat the offense. Government reports and empirical studies consistently show the rate of repeated sex crime to be much lower than the general public believes. The most widely cited report was published by the U.S Department of Justice in 2003.1 It compared recidivism rates among prisoners released in 1994 over a three-year follow-up period. Sex offenders (SO’s) were rearrested for another sex crime at a rate of 5.3% 1.8% per year. Non-SO’s were rearrested for ordinary crimes (burglary, robbery, drug dealing, etc.) at a rate of 68% 22.6% per year. SO’s repeat their crime at a lower rate than any type of crime other than homicide. It is in that context that SO’s are understood to be at low risk to re offend.

Several other studies can be cited to illustrate the widespread understanding about the low recidivism rate among former sex offenders.

A) The pivotal meta-analysis by Hanson & Bussière (1998), from which the Static-99 actuarial scale was developed, found 13.4% of their 23, 393 sample re offended sexually within 5 years of release (approximately 3% per year). 2

B) The Texas Criminal Justice Policy Council (1997) tracked SO’s released from prison and found, after 3 years, 4% (1.3% per year) had returned to prison for another sex crime.3

C) The Washington State Institute for Public Policy found a 4-year recidivism rate of 2.7% (0.68% per year). 4

D) The California Prison System, (Marques, et al, 2005) found, among 649 released SO’s, a sexual recidivism rate of 23.1% over an average of 8.5 years (2.7% per year). 5

E) A U.S. Department of Justice Report (Zgoba, et al, 2012) surveyed 4 states (FL, SC, NJ, MN) and found an average 10 year sex offense recidivism rate of 9.9% (0.99% per year). 6

F) The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (2012) reported that, during a 3-year period, 1.9% of sex offenders on the public registry (including both those who had been to prison and those who had not) were arrested for another sex crime 0.63% per year. 7

G) A Bureau of Justice report surveying 9 states (AK, AZ, DE, IL, IA, NM, SC, TN, & UT) found an average 3-year sex offense recidivism rate of 3.4% -- 1.1% per year. 8

These statistics describe a broad, general category sex offenders. There are important distinctions to be made between types of offenders that would show large segments at extremely low risk of recidivism. The reports cited here are representative of a large body of literature. These descriptive studies make it clear that the great majority of SO’s have a very low likelihood of repeating their crime. Legislation and policy making that assumes otherwise is misguided and counterproductive.

18 Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

REFERENCES:

1. DOJ, 2003. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rsorp94.pdf

2. Hanson, R. K. & Bussière, M. T. 1998. “Predicting Relapse: A Meta Analysis of Sexual Offender Recidivism Studies,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66 (2) 348 362

3. Eisenberg, M. 1997. “Recidivism of Sex Offenders: Factors to Consider in Release Decisions,” Criminal Justice Policy Council.

4. Washington State Institute for Public Policy, 2005. “Sex Offender Sentencing in Washington State: Recidivism Rates,” http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/908/Wsipp_Recidivism Rates_Recidivism Rates.pdf

5. Marques, J. Wiederanders, M., Day, D., Nelson, C. & van Ommeren, A. 2005. “Effects of a Relapse Prevention Program on Sexual Recidivism: Final Results From

California’s Sex Offender Treatment and Evaluation Project (SOTEP),” Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 17 (1).

6. Zgoba, K., Miner, M., Knight, R., Letourneau, E., Levenson, J. & Thornton, D. 2012. “A Multi State Recidivism Study Using Static 99R and Static 2002 Risk Scores and Tier Guidelines from the Adam Walsh Act,” National Institute of Justice, DOJ, Document # 240099.

7. “2012 Outcome Evaluation Report,” California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/adult_research_branch/Research_Documents/ARB_FY_0708_R ecidivism_Report_10.23.12.pdf

8. Orchowsky, S. & Iwama, J. 2009. “Improving State Criminal History Records: Recidivism of Sex Offenders Released in 2001,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice.

Texas Voices For Reason and Justice http://Texasvoices.org

19

Criminal Defense

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

13-14,

Southpark Hotel

Topic: Presenting a Parole Revocation Case

Speaker: Sean David Levinson

Levinson Law Firm

Spicewood Springs Rd., Ste. 200

TX 78759

October

2022 Austin

Austin, Texas 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Lawyers Project

4810

Austin,

512.467.1000 phone 512.485.2844 fax seandlevinson@gmail.com email www.bettercallsean.com website

PresentingaParoleRevocationCase

Parole,Prison,andRelatedIssuesSeminar

TexasCriminalDefenseLawyers

Association,October13, 142022,Austin,Texas

SeanDavidLevinson,J.D.,LL.M

BetterCallSean®

LevinsonLawFirm

4810SpicewoodSpringsRd.,Suite200

Austin,TX78759 (512)467 1000 www.BetterCallSean.com

SeanDLevinson@gmail.com

Duringthecourseofanycriminaldefenselawyer’scareer,therewillcomeatime whentheirclientisaccusedofanewoffensewhilealsoonparolesupervision. The purposeofthispaperistodiscussthetypicalissuesthatlawyersmayencounter whendealingwithparolerevocations.

Parole Revocation Caselaw

ParolerevocationcaselawstartswiththelandmarkSupremeCourtdecision Morrisseyv.Brewer,408U.S.471(1972). InMorrissey,theCourtheldthatparole revocationsarenotpartofacriminalprosecutionandthusthe“fullpanoplyof rightsdoesnotextendtoparolerevocations”. TheCourtdidholdthatparole revocationhearingsdocallfor“someorderlyprocess,howeverinformal”. The Morrisseyholdingestablishesthefollowingminimumrightsofdueprocessin parolerevocationhearings:

• Writtennoticeofclaimedparoleviolations,

• Disclosuretotheparoleeofevidenceagainsthim,

• Opportunitytobeheardinpersonandtopresentwitnessesand documentaryevidence,

• Therighttoconfrontandcross examineadversewitnesses(unlessthe hearingofficerspecificallyfindsgoodcausefornotallowingconfrontation),

• A“neutralanddetached”hearingbodysuchasatraditionalparoleboard, membersofwhichneednotbejudicialofficersorlawyers,and

• Awrittenstatementbythefactfindersastotheevidencereliedonand reasonsforrevokingparole.

ForthepurposeofthisarticleitisimportanttonotethatinTDCJlanguage,aclient onparoleisgenerallyreferredtoasanoffender. Therefore,wewillusethis terminologygoingforward. Thefirststepinrepresentinganoffenderforaparole revocationhearingistoregisterwithTDCJ-ParoleDivision(“ParoleDivision”).

Next,allattorneysrepresentingoffendersmustfileafeeaffidavitwiththeParole Division. Thisformshouldbeforwardedtotheparoleofficerresponsibleforthe caseandalsotenderedtotheHearingOfficeratthehearing.

Unliketherighttocounselinacriminalcase,thereisnoautomaticrighttocounsel inparolerevocationhearings. However,theParoleBoardcanappointanattorney incertainsituations. TheBoardmayappointanattorneybasedonthefollowing factors:whethertheoffenderisindigentandwhethertheoffenderlackstheability toarticulateorpresentadefenseormitigationevidenceinresponsetothe allegations;and,thecomplexityofthecaseandwhethertheoffenderadmitsthe allegedviolation.1 Thisrequestforanattorneycancomefromtheoffender,parole officer,orhearingofficer. Inmyexperience,theParoleBoarderrorsonthesideof cautionandwillnothesitatetoappointanattorneytoanoffendertheybelieve cannotadequatelyrepresentthemselves,usuallydotolowIQormentalillness. Offendersarealwaysfreetohireanattorneythemselves.

Blue Warrant Issuance

Firstandforemost,alloffendersaregivenparoleconditionsthattheymustabideby whenreleasedonparole/discretionarymandatorysupervision(“DMS”). Failureto abidebyofanyoftheseconditionscouldresultinaviolationbeingfiledandaparole warrant(akaBlueWarrant)beingissued. TheseBlueWarrantsareNOBAIL.

Offenderswhoareonparole/DMSmaybesubjecttoBlueWarrantsfortechnicalor newoffenseviolations.

Technicalviolationstypicallyinclude:

• Failuretoreport

• Delinquentparolefees

• Positivedrugtests

• Failuretoresideinanapprovedlocation

• Homemonitoring/curfewviolations

Newoffenses

• ClassCandupoffenses2 .

Traditionally,aBlueWarrantwillbeissuedanytimeanoffenderisaccusedofa technicalornewoffenseviolation. Recently,inOctober2021,thereweresome changestoBlueWarrantissuance.

ThenewchangesinBlueWarrantsgenerallyonlyaffectNewOffenseViolations.

1 TexasAdministrativeCode,Title37,Part5,Rule146.3.

2 NewOffensesdonotneedtobefiledincourt. Merelyanallegationmadetothe paroleofficerofacriminallawoffensemaybeenoughtotriggerabluewarrant.

TechnicalviolationswillstillcontinuetoresultinBlueWarrants. Thosehearings willbeconductedwithin41daysofthebluewarrantbeingexecuted.

NewOffenseviolationsarenowsubjecttonewruleswhichinmanyinstances actuallyhelpoffenderswhoareaccusedofanewoffensewhileonparole supervision. Historically,likewithtechnicalviolations,themerearrestofan offenderwouldtriggeranautomaticBlueWarrant. Underthenewrules,theParole Divisionwillnolonger“automatically”issueBlueWarrantsduetoanewoffense violation.

BlueWarrantsfornewoffenseswillbeissuedaccordingtowhatIrefertoasatier system.3

Offensesinthefirsttierthemostaggravatedoffensessuchasmurderandsexual assaultwillresultinBlueWarrantsautomatically.Thosecaseswillhaveboth preliminaryandrevocationhearingswithin41daysifthecaseisunindicted. Ifthe caseisindictedthengenerallyonlyapreliminaryhearingwilltakeplacewithin41 days. Ifprobablecauseisfoundatthepreliminaryhearingtheoffenderwillremain incustodyuntilthecriminalcaseisresolvedandthenarevocationhearingwilltake place.

Allotheroffenses(secondandthirdtier) will not resultinanautomaticwarrant issuance. Thesecondtiertypicallydealswithoffensessuchasrobberyand aggravatedassault. ThesecaseswillbestaffedtodetermineifaBlueWarrantshall issue. Thethirdtiergenerallyincludesmostlynon violentoffensessuchasdrug possession,theft,etc.

Ifawarrantisnotissued,thoseoffenderswillbefreetopostbondontheirnew offenseandresumeparolesupervision. Oncethosecasesareindicted,theParole Divisionmaystaffthosecasestodetermineifawarrantshallbeissued. IfnoBlue Warrantisissued,theoffenderwillcontinueonsupervisionuntilthecaseis adjudicated. Uponadjudication,theParoleDivisionmayissueawarrantand proceedtoahearing.4

PleasebecarefulwiththesesituationsinvolvingaBlueWarrantandanewcriminal charge. ManytimesaclientwillbondoutpriortotheBlueWarrantissuance. This usuallyhappenswhenanoffenderisarrestedonaweekendandtheBlueWarrant doesn'tissueuntilMondaymorning(forthoseoffensessubjecttoautomatic warrant). Iftheoffenderislatertakenintocustodyontheparolehold,theywillnot be“incustody”onthenewcriminalcase. Aconsiderationshouldbemadeinto raisingtheirbondonthecriminalcasesotheclientgetscreditforboththeparole caseandthenewlawviolation.

3 Theoffenseslistedunderthetiersystemarenotanexhaustivelist.

4 Asthisnewpolicyhasrecentlytakenplace,wedonotknowunderwhatconditions aBlueWarrantwillissueafteradjudication.

Hearing Logistics

OnceaBlueWarrantisexecuted,thepreliminary/revocationhearingwilltakeplace inthecountytheclientislocated,notnecessarilywheretheviolationsoccurred. Thatis,thecountythewarrantwasexecutedindetermineswherethehearingwill takeplace. SoaclientwhoisreportingtoparoleinDallasbutwasarrestedin Houston,willhavetheirhearinginHouston. (IfthebasisfortheBlueWarrantwas foranewcriminaloffense,theclientmaybe“benchwarranted”backtothecounty wherethecriminaloffenseispending).

Who is present at the hearing?

Hearingsarepresidedoverbyhearingofficers,whoareemployeesoftheTexas BoardofPardonsandParoles(“ParoleBoard”), not theTexasDepartmentof CriminalJustice(“TDCJ”). Thehearingofficersconducthearingstodetermine whetheraviolationoccurredandmakerecommendationstotheParoleBoard. In thesehearings,thehearingofficerpresidesoverthecasemuchlikeajudgeina courtroom.Hearingofficersexaminewitnesses,ruleonadmissionofevidence,and makerulingsregardingmotionsandobjections,amongotherduties.5 Theparole officer,employedbytheParoleDivision,actsmuchlikeaprosecutorinacourtroom. Theoffenderispresentatthehearingalongwiththeirattorney,ifonehasbeen appointedorretained. Asmentionedearlier,theHearingOfficermayexamine witnessesinadditiontotheparoleofficerandoffender/attorney.

Who gets a hearing and when do they get the allegations?

Everyoffenderaccusedofaviolationisentitledtoahearing. Theoffender(and attorneyifappointed/retained)mustreceivethehearingpacket(akadiscovery) within3daysofapreliminaryand5daysbeforearevocationhearing.

Priortoschedulingahearing,theoffenderwillbeaskediftheywanttohavea hearingorwaiveit. As a general rule, it is advisable to never waive a hearing.

What types of hearings are there?

Therearetwotypesofhearings:preliminaryandrevocation.

Apreliminaryhearingwilltakeplaceifanoffenderisaccusedofanewlawviolation. Theburdentosustainanallegationislow:probablecause. Ifprobablecauseis found,thecaseisusuallycontinuedtoalaterdatetoholdarevocationhearing after thecriminalcaseisadjudicated.6 Theclientwillremainincustodypendingthe outcomeofthecriminalcaseandthesubsequentrevocationhearing.

5 TexasAdministrativeCode,Title37,Part5,Rule147.2.

6 Inthecaseof“automatic”BlueWarrants,theRevocationHearingwillbelikely scheduledimmediatelyafterthePreliminaryHearingwithinthe41daytimeframe ifthecaseisunindicted

Revocationhearingsareheldfortechnical onlyviolationsandfornewoffense violationsthathavebeenadjudicatedincourt. Atthishearing,theburdenis preponderanceoftheevidence. Pleasenote,thatjustbecauseacriminalcasewas dismissed,DOESNOTmeantherewillnotbearevocationhearing. The burden is preponderance, not beyond a reasonable doubt!

What are the Preliminary and Revocation hearings procedure?

Bothpreliminaryandrevocationhearingshavetwoparts,afact findingandan adjustmentportion.

Thefirstpartisconsideredthefact findingportion,muchlikeatrial. Documentary evidenceistenderedtobeadmittedasevidence. Testimonyistakenfrom witnesseswhoaresubjecttocross examination. Likewise,objectionscanbemade tointroductionofdocumentsortestimony. Theoffendercantestifyiftheyso chose.

Inpreliminaryhearings,theparoleofficerusuallysubmitstheProbableCause affidavitasevidencetosupporttheirburden. Clientsshouldbewarnedthatany testimonytheygiveisunderoathandcanbeusedagainstthemasimpeachmentat trial. Therefore,mostofthetimeitisinadvisableforaclienttotestifyat preliminaryhearings.

Duetothelowburden,successatpreliminaryhearingsisgenerallylow. However, offenderscancallwitnessestothehearing. Thesewitnessescouldincludelaw enforcement,eyewitnesses,andeventheallegedvictim(s). Asalltestimonyisunder oathandrecorded,thiscouldbeusefulforimpeachmentatasubsequenttrial.7

Iftherequisiteburdenisnotmetateithertypeofhearing,thecasewillnotadvance anyfurther. ThiswouldbeakintoaDirectedFindingatatrial.

Iftherequisiteburdenismet,thehearingwillmoveontotheadjustmentportion, whichisakintoasentencinghearingatatrial. Duringthispart,theparoleofficer willtestifyastotheoffender’sadjustmentduringsupervision. Theywilladvisethe hearingofficerastotheoffender’soverallcompliancewithparoleconditionssuch aspriorwarrants,employmentstatus,drugtestresults,andhomeplanverification.

Offenderscanalsotestify,submitdocuments,andpresentlivewitnesstestimony duringthisstage. Mostcasesarewonorlostatthisstage.8 Icannotstressenough howimportantadjustmentevidenceisatarevocationhearing. Eventhoughthere maybeafindingastoanallegationatarevocationhearing,theevidencepresented

7 Theattorneycanrequestacopyofthedigitalrecordingofthehearing. 8 Adjustmenttestimonyistakenduringpreliminaryhearingseventhoughtherewill likelybearevocationhearingtakingplacelater. Inmostsituations,adjustment testimonyisthereforemoreimportantattherevocationhearing,asadecision whethertorevokeornotisbeingmadeatthattime.

atthisstagemaymakethedifferencebetweenarevocationandalesssevere punishment. Itisvitaltopresentmitigatingfactorsduringtheadjustmentportion. This is the only opportunity the hearing officer will have to gather information about the offender’s life, hardships, accomplishments, and lessons learned.

Mitigatingfactorsmightinclude:

Client’scharacter

Goodmoralstandinginthecommunity

Jobskills

Employmenthistory

Family

Education

Mentalhealthconcerns

Medicalissues,etc.

Futureeducational,professional,andpersonalgoals

Attheconclusionofthehearing,theparoleofficerwillmakearecommendation. Thehearingofficerwillthenconcludethehearingwithoutmakinga recommendation. Thehearingofficerwilllatertypeupareportandsendittothe localParoleBoardwiththeirrecommendation. AParoleBoardanalystreviewsthe fileandmakestheirrecommendationtothelocalParoleBoardwhothenissues theirdecision. AparoleofficerlatertenderstheBoard’sdecisiontotheoffenderin person.

What are the possible outcomes?

TheBoardhas30daystoissuearulingonthecase. Amajorityofthe3votersfrom thelocalBoardOfficeisrequiredforaruling. TheBoardcanthen:

• Acceptthefindingsfromthehearing(mostcommon)

• Overrulethefindings,or

• SendthecasebacktotheHearingOfficerforfurtherdevelopmentoffactual orlegalissues.

IftheBoardacceptsthefindings,theywillthendeterminewhatsanctiontoimpose. Generally,theParoleBoardtakesagraduatedsanctionsapproachtoviolations. Onceagain,theimportanceofmitigationevidenceduringtheadjustmentportionof thehearingiscrucial. Thepossibleoutcomesfromarevocationhearingare:

• ReturntoSupervision(possiblywithnewormodifiedconditions)

• IntermediateSanctionFacility(ISF)

• SubstanceAbusePunishmentFacility(SAFP)

• Revocation

Can you appeal the results?

YoucanonlyappealaBoard’sdecisionifthevotewastoREVOKE. Ifso,youhave 60daysfromtheBoard’sdecisiontofileaMotiontoReopen. Thismotionmustbe basedon:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Newlydiscoveredevidence,

• Findingsoffactarenotsupportedbypreponderanceofcredibleevidenceor arecontrarytolaw,or

• ProceduresfollowedinthehearingareviolativeofthelaworParoleBoard Rules.9

What happens after the Parole Board’s decision?

Ifoffenderisreturnedtosupervision,theywillbereleasedfromcustodyand resumeparolesupervision. IforderedtogotoISForSAFP,theywillwaitinthe countyjailuntilabedopensupandthenbetransferred. UponcompletionofISFor SAFP,theoffenderwillresumeparolesupervision. Eventhoughoffendersordered toattendISFandSAFPwillbehousedinprisontocompletetheirprogram,thisis notconsideredarevocation. Foroffenderswhoarerevoked,theywillremaininthe countyjailuntiltheyaretransferredtoTDCJ.

What about street time credit for those who are revoked?

IftheoffenderissentencedtoISForSAFP,theywilleventuallybereturnedto supervisionuponsuccessfulcompletionoftheprogram. Ifclientisrevoked, however,thestakesaremuchhigher. Mostoffendersareworriedaboutlosingtheir streettimeifrevokedforparole.Certainly,offenderswhoarerevokedwillgetcredit forthetimetheyspentincustodypriortobeingparoledandanytimetheyspentin custodyafterthebluewarrantwasexecuted. However,theymaynotkeeptheir streettime.

Todetermineifanoffenderwillkeeptheirstreettime,wemustlookattwothings: theircriminalconvictionsandhowlongtheyhavebeenonparole. Offenderswill getcreditforstreettimeuponrevocationif:

• Theyhavenocurrentorpreviousconvictionsforoffensesin508.149ofthe GovernmentCode(DMSdisqualifyingoffenses), and

• Theymusthavebeenonparole/DMSforatleast½oftheirsupervisionterm atthetimetheBlueWarrantwasissued.

To be clear, if an offender is currently on parole for or has ever been convicted of a 508.149 offense, the will NEVER be eligible to “keep” their good time upon revocation now or in the future!

Therefore,itisvitaltoknowyourallofthefactssurroundingaclient’scriminal history,currentsentence,andhowlongtheyhavebeenonparolesupervision. Any attorneyrepresentinganoffenderforaparolerevocationhearingshouldadvise theirclienttheramificationsofarevocationandlossofstreettime.

9 TexasAdministrativeCodeTitle37,Part5,Rule146.11

Criminal Defense Lawyers

Parole, Prison, and Related Issues

13-14,

Southpark

Topic: Surviving the Texas Lawyer Disciplinary Process

Speaker: Robert C. “Bob” Hinton, Jr.

Robert Hinton & Associates, P.C. 3300 Oak Lawn Ave., Suite 700 Dallas, TX 75129 214.219.9300 phone 214.219.9309 fax Hinton.law@airmail.net email http://www.hinton law.net/ website

October

2022 Austin

Hotel Austin, Texas 6808 Hill Meadow Dr :: Austin, Texas :: 512.478.2514 p :: 512.469.9107 f :: www.tcdla.com

Project

TEXASCRIMINALDEFENSELAWYERSASSOCIATION PAROLE,PRISON&RELATEDISSUES SEMINAR 13-14October,2022 Austin,Texas SURVIVINGTHETEXASLAWYER DISCIPLINARYPROCESS Robert C. "Bob" Hinton, Jr. 3300OakLawn Ave.,Suite700 Dallas,Texas75219 (214) 219-9300-Office (214) 244-5375- Cell Hinton.law@airmail.net

EducationandEmployment

PROFESSIONAL BIOGRAPHY Of RobertC.Hinton,Jr.

.

J.D.,UniversityofHouston;April1973

•AssistantCriminalDistrictAttorney,DallasCounty,TX;April1973-1977

•Partner:Burleson,Pate,&Gibson;August1977-June1992

•RobertHinton&Associates,P.C.;June1992-Present

Member

•TexasCriminalDefenseLawyersAssociate(Director:1988-1995,Officer:1995-1999, President:2000-2001)

•NationalAssociationofCriminalDefenseLawyers;1979-Present

•DallasCriminalDefenseLawyersAssociation(formerDirectorandOfficer)l977-Present

AppointmentsandHonors

•Member:StateBarGrievanceCommittee,1979-1987(ViceChair)

•SpecialAssistantDisciplinaryCounsel,TexasCommissionforLawyerDiscipline,19922004

•Martindale-Hubble"A-V"rating,fromeligibilityin1978-Present

•2019InducteetoHallofFame,TexasCriminalDefenseLawyersAssociation

LicensedtoPracticebyandBefore

•StateBarofTexas

•UnitedStatesDistrictCourts,Northern,Western,Southern,andEasternDistrictsof Texas,WesternDistrictofLouisiana

•UnitedStatesCourtofAppeals,5thDistrict

•UnitedStatesTaxCourt

•UnitedStatesSupremeCourt

AreasofProfessionalActivitv

•FederalandStateCriminalDefense

•RepresentationofLawyersandotherLicensedProfessionalsinDisciplinary&Licensing matters

•FrequentContinuingLegalEducationAuthorandSpeaker

TABLEOFCONTENTS

I. TOGRIEVEORNOTTO GRIEVE

A. NoStandingorPrivityRequirement

B. Lawyer'sMandatory DutytoReportMisconduct orFitnessof Another Lawyeror Judge

II. ONE SIDE OFTHE STORY-THE CLASSIFICATION PROCESS

A. Classification

B. Dismissalas anInquiry

C. UpgradetoaComplaint

III. DEVELOPING THESTORY- THEINVESTIGATION PROCESS

A. Confidentiality

B. Investigation

C. SummaryDisposition Panel- ASecond ChanceforDismissal

D. Just Cause

IV. TELLING THE STORY-ADJUDICATION

A. Procedural Rules

B. InvestigatoryPanel

C. Evidentiary Panel andaProperQuestion

D. Timeframes and Venue

E. Published CaseLaw

F. AppealofanEvidentiaryJudgment

V. SANCTIONS

A. Sanctions

B. GrievanceReferral Program

C. Reinstatement

VI.ANOTHERGENRE-COMPULSORYDISCIPLINE

A. Intentional Crime

B. PleasThatTrigger Compulsory Discipline

l

I.TOGRIEVEORNOTTOGRIEVE

A.NoStandingorPrivityRequirement

Agrievanceisdefinedas"awrittenstatement,fromwhateversource,apparently intendedtoallegeProfessionalMisconductbyalawyer,orlawyerDisability,orboth receivedbytheOfficeoftheChiefDisciplinaryCounsel."Consequently,anypersonor entitymayfileagrievanceagainstalawyer,whoislicensedinTexas,regardlessof standingorPrivity.TheStateBarofTexas'OfficeofChiefDisciplinaryCounsel(CDC) receivesapproximately7,000grievanceseachyear, becauseanyonecanfile-agrievance andallegeanything,whetherornottheallegationinvolvesaviolationoftheTexas DisciplinaryRulesofProfessionalConduct(TDRPC),roughlytwo-thirdsofthe grievancesaredismissed;although,thesefiguresvaryannually.Agrievancethatis dismissedisreferredtoasaninquiry.Agrievancethatisupgradedforinvestigationis calledacomplaint.

B. Lawyer'sMandatoryDutytoReportMisconductorFitnessof AnotherLawyerorJudge

Rule8.03oftheTDRPCaddressesalawyer'sdutytoreportmisconductorfitness ofanotherlawyerorjudge.AsCommentltotherulenotes:"Self-regulationofthe legalprofessionrequiresthatmembersoftheprofessiontakeeffectivemeasuresto protectthepublicwhentheyhaveknowledgenotprotectedasaconfidencethata violationoftheseruleshasoccurred.Lawyershaveasimilarobligationwithrespectto judicialmisconduct."

However,noteveryviolationbyanotherlawyerorjudgefallsunderthereporting requirementsof8.03(a)&(b).Comment4emphasizesthattherule"...limitsthe reportingobligationtothoseoffensesthataself-regulatingprofessionmustvigorously endeavortoprevent.Similarconsiderationsapplytothereportingofjudicialmisconduct. Ameasureofjudgmentis,thereforerequiredincomplyingwiththeprovisionsofthis

THEGRIEVANCEPROCESS

Rule.”

Consequently,underthemandatorydutytoreportanotherlawyerorjudge,the reportinglawyerneedstohave:(1)actualknowledgeoftheprohibitedbehavior,which(2) raisesasubstantialquestionofeither(a)thelawyer'shonesty,trustworthinessorfitnessas lawyer;or(b)thejudge'sfitnessforoffice.

Theterm"substantial"referstotheseriousnessoftheallegedmisconductand "notthequantumofevidenceofwhichthelawyerisaware."Forexample,alawyer whomisuseshisorherclient'strustaccountfundswouldmeetthedefinitionof substantial,becauseoftheresultingfinancialharmtotheclientand/orthirdperson, andtheprofession.

Theterm"fitness"isdefinedinterminologyprecedingoftheTDRPC."'Fitness" denotesthosequalitiesofphysical,mentalandpsychologicalhealththatenableaperson todischargealawyer'sresponsibilitiestoclientsinconformitywiththe[TDRPC]. Normallyalackoffitnessisindicatedmostclearlybyapersistentinabilitytodischarge, orunreliabilityincarryingout,significantobligations.”

Rule8.03(c)allowsalawyertosatisfythemandatorydutytoreportafitness issue,resultingfromsubstanceabuseormentalillness,byanonymouslyreportingthe lawyerorjudgetoapeerassistanceprogram,suchastheTexasLawyersAssistance Program(TLAP.)Thenameofthepersonwhoreportsanotherlawyerorjudgeiskept confidential.

II.ONESIDEOFTHESTORY-THECLASSIFICATIONPROCESS A.Classification

Thestorybeginswithawrittengrievance.Thegrievanceisonlyonesideofthe storyaboutanindividuallawyer,butitisthecruxofhowlongthestorycontinues.The screeningofagrievancetodeterminewhetherornotitallegesaviolationofthe disciplinaryrulesiscalled,classification.LawyersattheCDCinAustinclassifyallof thegrievancesforthestatewithin30daysofreceipt.

B.DismissalasanInquiry

Agrievanceclassifiedasaninquirymaybeappealedbythecomplainanttothe BoardofDisciplinaryAppeals(BODA)within30daysfromreceiptofnoticeofthe CDC'sdetermination.TherespondentlawyerwillalsoreceiveanoticefromtheCDC, explainingthatagrievancewasfiledandwasclassifiedasaninquiry,andthe complainanthasarighttoappeal.Respondentisalsoprovidedacopyofthedismissed grievance.IfthecomplainantappealsandBODAaffirmstheinquiry,thedecisionis final.TheCDCrefersinquirestotheStateBarofTexas'Client-AttorneyAssistance Program(CAAP)forvoluntarydisputeresolution.

Inthe2017-2018baryear,BODAaffirmedapproximately90percentofthe appealsofCDCclassificationdecisionsitreceivedasinquiries.Subsequentgrievances bythesamecomplainantallegingthesamemisconductareclassifiedasresjudicata.

InquiriesaretreatedasconfidentialbytheCDC,whichcannotdisclosethemtopersons requestingsuchinformation.However,theCDCmaydiscloseinquiriestoauthorized agenciesorcommitteesandlawenforcementasdescribedinRule6.08oftheTexas RulesofDisciplinaryProcedure(TRDP).Thelawyer,whowasthesubjectofan inquiry,doesnothavetodisclosethedismissedgrievance.Complainants,ontheother hand,maydiscloseit.

C.UpgradetoaComplaint

IfBODAreversestheCDC'sdismissal,thegrievancebecomesacomplaint.A complaintisanygrievancethatisupgradedforinvestigationduringtheclassification processoranyinquirythatisreversedonappeal.Boththecomplainantandrespondent arenotifiedthatthegrievancehasbeenclassifiedasacomplaint.Therespondent receivesacopyofthecomplaintwithademandtorespondinwritingtotheCDC within30daysofreceiptofthenotice.

Theimportanceofarespondentpreparingawell-writtenresponse(essentiallya rebuttal)withsupportingevidencecannotbeunderstated.Infact,thefailuretoprovide anykindofwrittenresponsetotheCDCviolatesTDRPC8.04(a)(8).Lawyershave beendisciplinedforafailuretorespondevenwhentheunderlyingdisciplinarycase

mayhavebeenproperfordismissalbyasummarydispositionpanel.Thelessonhereis forthelawyernottobetooproud,toobusy,ortoolazytorespond;evenifthe complainantwastheworstclientintheuniverse.Arespondentshouldneverignorea demandbytheCDCforawrittenresponsetoacomplaint.

TheCDChastoconcludeitsinvestigationin60daysorlessfromthedeadlineforthe respondent'swrittenresponse.Inaddition,thecomplainantbecomesafactwitness, becausethepartyprosecutingthecomplaintistheCommissionforLawyerDiscipline (Commission).TheCommissionistheCDC'sclientandgivestheCDCtheauthorityto pursueappealsandagreetosettlements.

III.DEVELOPINGTHESTORY-THEINVESTIGATIONPROCESS

A.Confidentiality

Thetreatmentofacomplaintisconfidentialduringtheclassificationand investigationphases.Confidentialitycontinuesifjustcauseisfound,andthedisciplinary caseisadjudicatedbyanevidentiarypanel.Eventhoughtheevidentiaryhearingprocess isconfidential,recordstotheproceedingbecomepubliclyaccessibleoncearespondent receivesapublicsanction.Publicsanctionsincludeapublic reprimand,suspension,disbarment,andresignationinlieuofdiscipline.Ifarespondent receivesaprivatereprimand,therecordswillremainconfidential.Ofcourse,ifa respondentchoosestohavehisorhercaseheardindistrictcourtbyavisitingjudge,itis notconfidential.

B.Investigation

ACDCinvestigatorandadministrativeattorney,whoareassignedtoa particularcomplaint,begintheinformation-gatheringprocess.Theinvestigation typicallyincludestalkingwithwitnesses,complainant(s)andrespondent;reviewingthe respondent'swrittenresponse;researchingcourtfiles;andobtainingotherinformation. TheCDCcanrequestaninformalhearingbeforeanInvestigatoryPanelof

theGrievanceCommittee.Attheconclusionoftheinvestigation,afindingmustbemade

ofwhetherjustcauseexiststoprosecuterespondentforprofessionalmisconduct.

C.SummaryDispositionPanel-ASecondChanceforDismissal

Ifthereisnofindingofjustcause,theCDCmustrequestasummarydisposition panel(SDP)toreviewthecomplaint.Venueforasummarydispositionisinthecounty wheretheallegedmisconductoccurred,ifitoccurredinTexas.Otherwise,venueisin thecountywheretherespondentresidesor,inthealternative,inTravisCounty.The SDPmeetswithoutthepresenceofcomplainant,respondent,orwitnesses.IftheSDP agreeswiththeCDC'sfinding,itwilldismissthecomplaintasaninquiry.Acomplaint dismissedbytheSDPisfinalandcannotbeappealedbythecomplainant.Duringthe 2009-10baryear,97percentofthecasespresentedforsummarydispositionwere dismissed.However,theSDPmayvotetoproceedtojustcasebasedonitsownanalysis oftheevidence.

D.JustCause

TheTRDPdefinejustcausetomean:"...suchcauseasisfoundtoexistupon reasonableinquirythatwouldinduceareasonablyintelligentandprudentpersontobelieve thatanattorneyeitherhascommittedanactoractsofProfessionalMisconductwhich requiresthataSanctionbeimposed,orsuffersfromaDisabilitythatrequireseither suspensionasanattorneylicensedtopracticelawintheStateofTexasorprobation."

Whenadeterminationofjustcauseismade,therespondentisnotifiedinwriting of:(1)thejustcausefinding,(2)theallegedruleviolations,(3)theallegedactsor omissionsleadingtothoseviolations,and(4)givenachoice(orelection)betweenthe complaintproceedingtoanevidentiaryhearingordistrictcourt.Respondent'selection mustbeinwritingandservedupontheCDCnolaterthan20daysfromthedatethe respondentreceivedthejustcausenotification.Ifrespondentdoesnotmakeanelection, thecomplaintproceedstoanevidentiaryhearing.

Inrecentyears,lessthan10percentofrespondentselecteddistrictcourt. Respondentstypicallychooseanevidentiarypanelhearingbecauseitoffersthe possibilityofreceivingthelowestsanction,calledaprivatereprimand,whichisnot availableindistrictcourtproceedings.Respondents,whodonotmakeanelection,

defaulttoanevidentiarypanelhearing.Additionally,atrialindistrictcourtispublic, whileanevidentiaryhearingisconfidential.

Arespondentwhoelectsdistrictcourtmay,ofcourse,chooseajuryorbench trial.Ineithercase,theTexasSupremeCourtappointsanactivedistrictjudgewhodoes notresideintherespondent'sadministrativejudicialdistricttopresideoverthecase.

IV.TELLINGTHESTORY-ADJUDICATION

A.ProceduralRules

Sinceapproximately90percentofcomplaintsareheardbyanevidentiarypanel ofgrievancecommitteemembers,thispaperwillfocusprimarilyonevidentiary hearings.Trialindistrictcourtproceedsasanyothercivilcaseandtherighttoappealis throughthestateappellatecourtsystem.

Regardlessoftheadjudicatorysetting,therearetwosetsofproceduralrulesthata lawyer,whoisrepresentingrespondentsorisarespondent,shouldbeknowledgeableof: (1)TheTexasRulesofDisciplinaryProcedure(TRDP)and(2)theTexasRulesofCivil ProcedureexceptasvariedbytheTRDP.

B.InvestigatoryPanel

TheCDCcanrequestaninformalhearingbeforeanInvestigatoryPanelofthe GrievanceCommittee.

C.EvidentiaryPanelandaProperQuorum

Foranevidentiarypaneltoconvene,itmusthaveaproperlyconstitutedquorum ofgrievancecommitteemembers.Anevidentiarypanelistypicallymadeupofsix grievancecommitteemembers,fourofwhomareTexas-licensedlawyersandtwoof whomarepublicmembersornonlawyers.Allgrievancecommitteemembersare volunteers.Insomerespects,therelianceofthedisciplinarysystemonvolunteersis astounding.Eachyear,atleast400dedicatedlawyersandnonlawyersdonatetheirtime toserveasgrievancecommitteemembers.Inaddition,therearesixlawyersandsix publicmemberswhoserveasvolunteersontheCommissionforLawyerDiscipline. Eventheappellatebody,BODA,whichhasoriginalandappellatejurisdictionoversix

typesofdisciplinarycases,ismadeupoftwelvelawyerswhovolunteertheirtime. AproperlyconstitutedquorumisthesubjectofTRDPandcaselaw.Generally, foreverygroupoftwolawyermembers,theremustbeonepublicmemberonthe evidentiarypanel.Forexample,iftherearetwolawyerspresent(whichequalone groupingoftwo),therehastobeonepublicmember.Butiftherearefourlawyers present(whichequaltwogroupings),theremustbetwopublicmemberspresentforthe hearingtoproceed.

Thepanelpresidingoveranevidentiaryhearingmustalsohaveamajorityofthe membersappointedtothepanelbepresentinordertohaveaquorum.Additionally,the quorumhastoremainproperlyconstitutedduringtheentireevidentiaryhearing.Asa result,aproperlyconstitutedquorumwill(1)representamajorityofmembersappointed totheevidentiarypanel(2)withtheproperratiooflawyermemberstopublicmembers (3)duringtheentireproceeding.

D.TimeframesandVenue

Fifteen daysafter theCDC receives the respondent's election (or the day following theexpiration of the respondent's right to elect) the grievance committee chair must appoint committeemembers to an evidentiary panel.Evidentiary panels usually are insix-member ofthree-member panels,depending on the sizeof the committee.Venue isin thecounty where respondent's principal place ofpractice is maintained; or in the alternative, the county where respondent resides. Other venue choicesmay include the county wherethe professional misconduct allegedly occurred if respondent doesnot maintainaplaceofpracticeorresidence;or,insomecasesTravisCounty.

TheCDChas60daysfromreceiptoftherespondent'selection(orthedeadlinefor electionifnoelectionismade)tofileitsevidentiarypetitionwiththeevidentiarypanel. Respondent'sdeadlineto fileanansweris5:00p.m.onthefirstMondayfollowingthe expirationof20daysafterreceivingserviceoftheCDC'spetition.IfRespondentdoesnot timelyfileananswer,thenadefaultisentered,andtheevidentiarypanelconductsahearing onsanctions.

Anevidentiaryhearingmustbeheldnolaterthan180daysafterthedatethe answerisfiled,butnosoonerthan45daysaftereachpartyreceivesnoticeofthe

hearingdate(unlesswaivedbyallparties).

Eitherpartymayservearequestfordisclosureupontheotherwithin30days beforethefirstsettingoftheevidentiaryhearing.Apartyhastoprovideawritten responsetotherequestwithin30daysafterreceivingservice.Afailuretorespondtothe requestfordisclosuremaypreventthepartyfromintroducingwitnessesorevidencethat wasnotdisclosedintheenumeratedlistprovidedlnTRDP2.17(D).Inaddition,the partiesmaynotraiseanobjectionorassertionofworkproductinordertoavoida requestfordisclosure.TRDP2.17(E)outlinesalimiteddiscoveryplanandstatesthatthe discoveryperiodbeginswhentheevidentiarypetitionisfiledandcontinuesuntil30 daysbeforethedayoftheevidentiaryhearing.Althoughtheevidentiaryhearingisless formalthanadistrictcourttrial,itissimilarinmanywaystoothercivilcases.

Theevidentiarypanelmustissueajudgmentwithin30daysofthehearing.The judgmentmustincludefindingsoffact,conclusionsoflawandthesanctiontobe imposed.Attheconclusionoftheevidentiaryhearing,theevidentiarypanelmay:(1)find thatprofessionalmisconductoccurredandimposesanctions;or(2)dismissthecase;or(3) findthattherespondentsuffersfromadisabilityandforwardthatfindingtoBODA. Foracompletesetofproceduraldeadlines,thelawyershouldconsulttheTDRP.

E.PublishedCaseLaw

CaselawregardingTexasdisciplinarycasesmayhefoundintheSouthwest Reporter,FederalReporter,andattheBoardofDisciplinaryAppeals'websiteat http;//www.boda.org/.

F.AppealofanEvidentiaryJudgment

AllappealsfromanevidentiaryhearinggotoBODA.Thenoticeofappealmust befiledwithin30daysafterthedateoftheevidentiaryjudgment.However,whena motionforanewtrialoramotiontomodifythejudgmentisfiled,thedeadlinetofilethe noticeincreasesto90days.Appealsarereviewedunderthesubstantialevidence standard.Inaddition,BODApromulgatesitsownproceduralrulesforthepartiesto follow.AnappealfromBODAistotheTexasSupremeCourt.

V.SANCTIONS

A.Sanctions

Boththeevidentiarypanelandthedistrictcourtjudgemay,attheirdiscretion,hold bifurcatedhearingsonsanctionswhenprofessionalmisconductisfound.

Someofthefactorsthatthetrieroffactmustconsiderwhenimposingsanctions(in noorder)are:

•natureanddegreeoftheprofessionalmisconductcommittedbyrespondent, forwhichheorsheisbeingsanctioned;

•seriousnessofandcircumstancessurroundingtheprofessionalmisconduct;

•lossordamagetotheclient;

•damagetotheprofession;

•assurancethatthosewhouselegalservicesinthefuturewillbeinsulated fromthetypeofprofessionalmisconductfound;

•profitstotheattorney;

•avoidanceofrepetition;

•deterrenteffectonothers;

•maintenanceofrespectforthelegalprofession;

•conductofRespondentduringtheProceeding;and

•Respondent'sdisciplinaryrecord,includinganyprivatereprimands.

Sanctionsmayrangefromaprivatereprimandtodisbarment.Arespondentwho facesasanctionasseriousasdisbarmentmaychoosetoresigninlieuofdiscipline.In addition,therespondentmaybeorderedtopayrestitutiontothecomplainantand attorney'sfeestotheCDC.

Aprivatereprimandisthelowestsanction,followedbyapublicreprimand.Next aresuspensions,followedbydisbarment.Anysanction,otherthanaprivatereprimand, isconsideredapublicsanction.

Thereareseveral types ofsuspensions that may be imposed assanctions.A suspension can be active,probated, or partially probated.Whena lawyer hasanactivesuspension (formally called, suspension for a term certain), heor shecannot practice law. A probated suspension allowsthe lawyer to practice lawand istheequivalentofthelawyerbeingonprobation.A partiallyprobatedsuspensionisahybridbetweenanactivesuspensionandaprobated suspension,becausethefirstpartofthesuspensionisactive,andthelawyercannot