SPIRIT OF ST BARTH N10 / 2023

Milestones are always a special time for reflecting and taking inventory; an opportunity to glance at the goodness of the past, while paving a way forward. And for us, this 10th Anniversary issue is just that. It’s a time to look back at what puts the ‘spirit’ in Spirit of St. Barth and the many stories that have so generously brought it to life throughout the years.

Since the beginning our goal has always been to create more than just a publication, but an ongoing love story that pays homage to this beautiful island which has touched so many people with its beauty, its depth, and its inimitable charm. SOSB has been a destination where locals, longtime visitors, and newcomers alike can get a taste of what makes St. Barth truly unique through an interesting mix of history, education, photography, and of-the-moment finds.

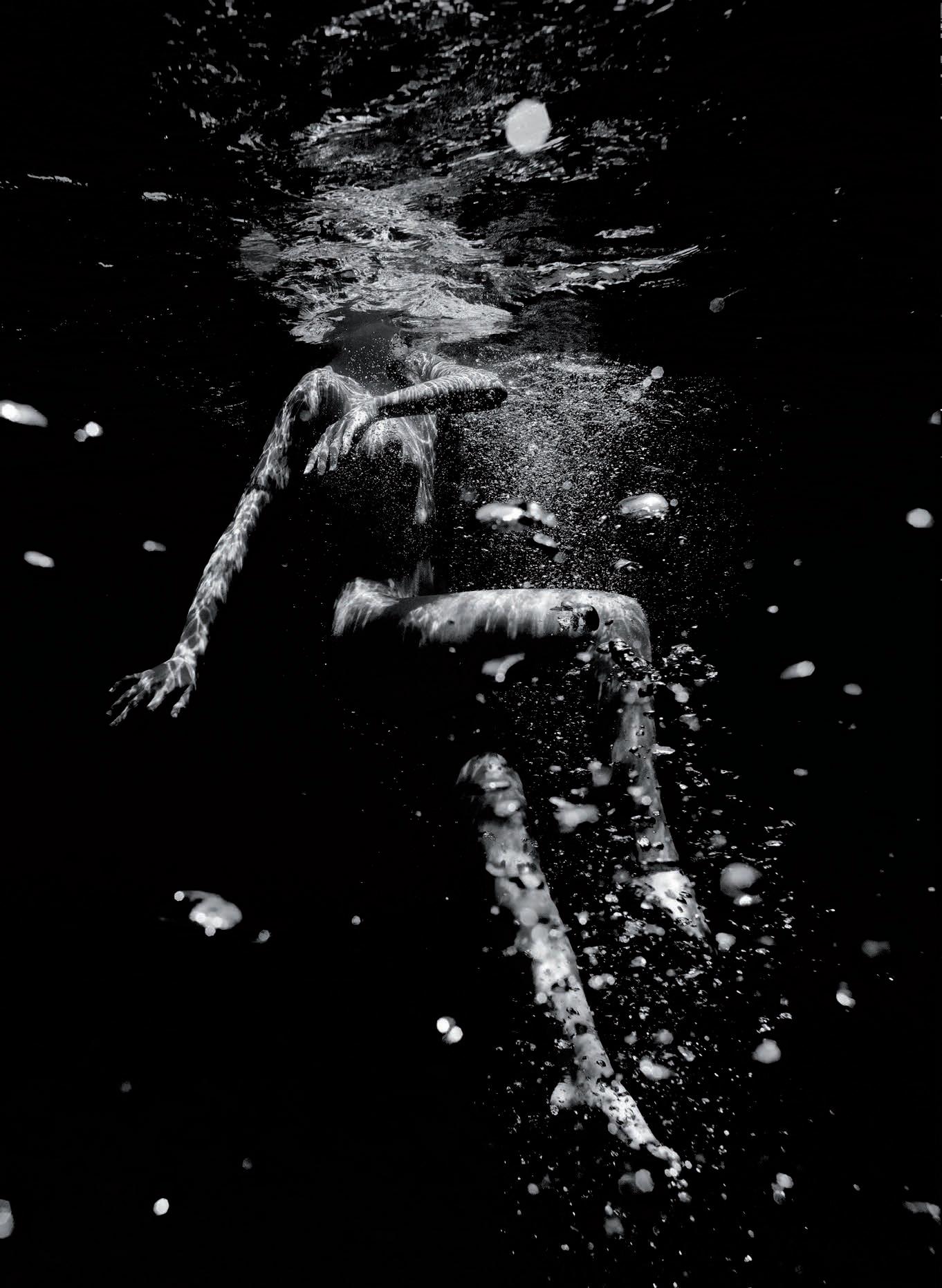

This year we’ve taken our favorite stories and photo editorials from past years to make a special 10th Anniversary issue for all of you. We invite you to journey with us – from a dive into the island’s origins to breathtaking underwater scenes to making acquaintance with our very smallest residents, the bees. We hope you enjoy the many sides of St. Barth.

Truthfully, and as is often the case with any labor of love, we never imagined making it to this place. But we are humbled and honored to be here, and look forward to bringing you more inspirational content and beautiful images in the years to come.

Sébastien Martinon

EDITOR’S LETTER

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

A Perfect Ten

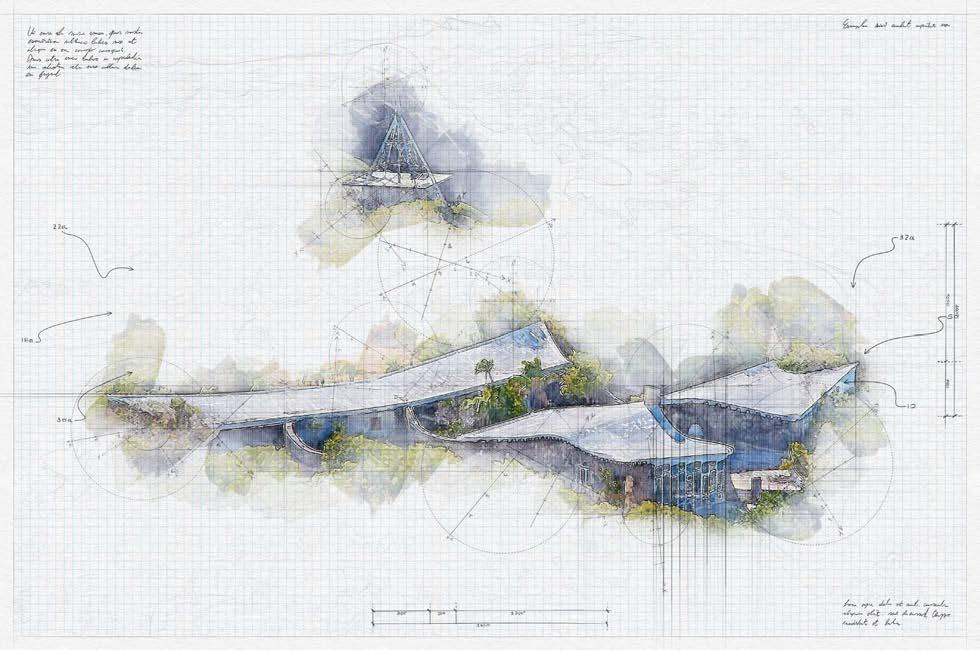

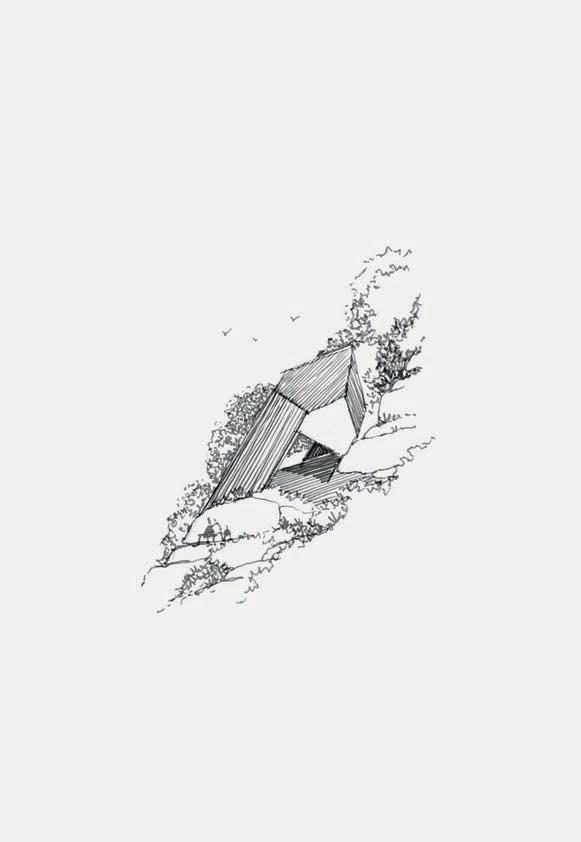

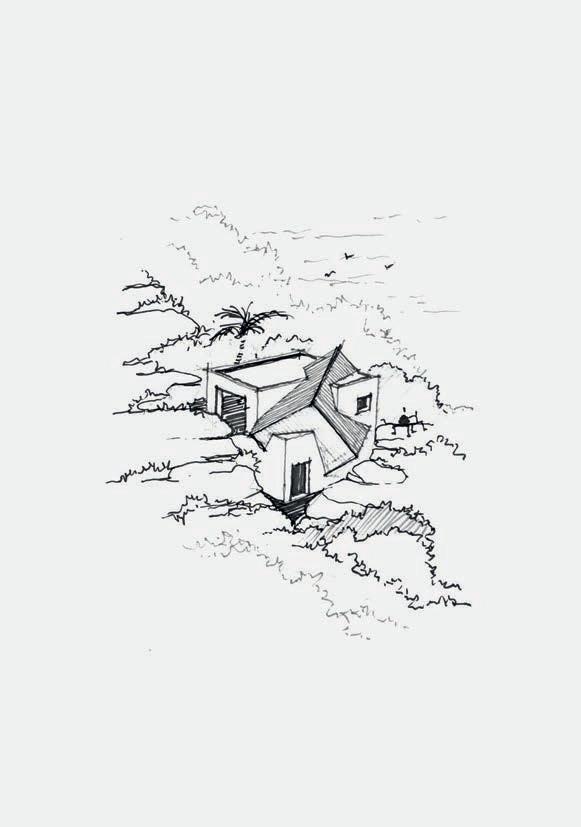

The fascination we derive from looking backward in time, from conjuring up memories of the past, is one of the most universal of human traits. We may recall happy times wistfully and times of hardship with sadness, but it all captivates our interest. It is with this sense of a shared passion, not for just the present beauty of our island, but for all the special and unique moments in her long history, that we mark the 10th anniversary of Spirit of St. Barth. In this milestone issue, we look back at how – in the magazine’s own brief history of one decade – we have chronicled and highlighted so much about the island’s past, as well as events and current realities that will become the past. Origin stories captivate us, so over the years we have explored the background of different facets of the island, sharing what we learn along with archival images that have fortunately been preserved: the history of the salt works at Saline, how the first pilot to land a plane on the savannah in St. Jean shaped the island’s trajectory, why the craft of straw weaving is such a valued St. Barth tradition, and how is it being preserved? Spirit of St. Barth has also turned attention to issues that connect our past to our future, by spotlighting architects working to integrate new construction more fluidly with nature, by featuring works by the island’s artists and artisans past and present, and of course by documenting the devastation wrought by Hurricane Irma and the true spirit of the people of St. Barth that enabled such a dramatic recovery. As you look through this anniversary issue No. 10 of Spirit of St. Barth, you will find a selection of these articles along with new art and photograph features.

12 | 13

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

N10 / 2023

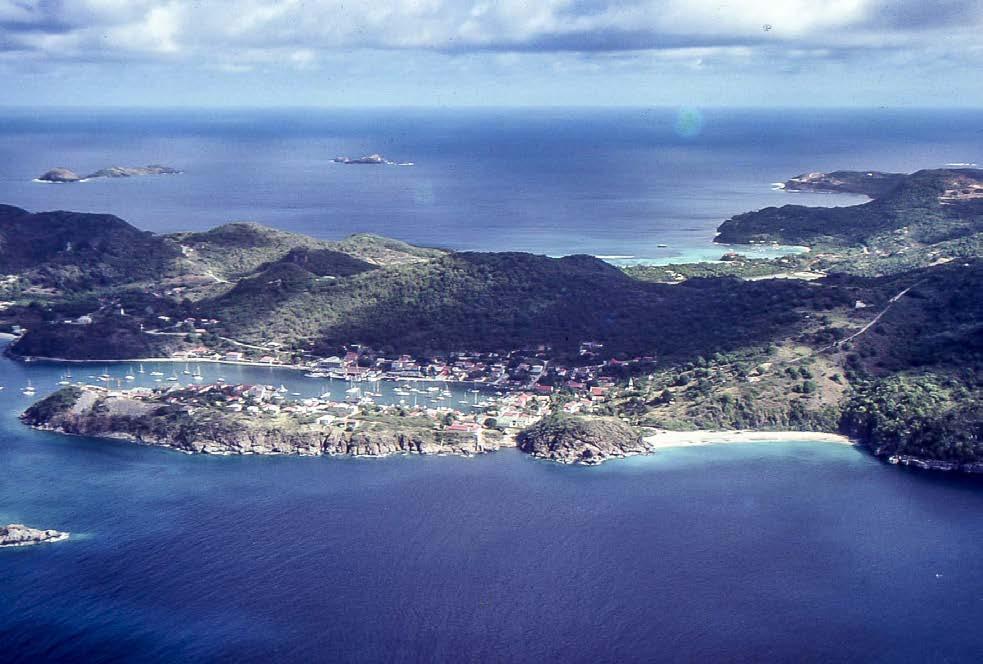

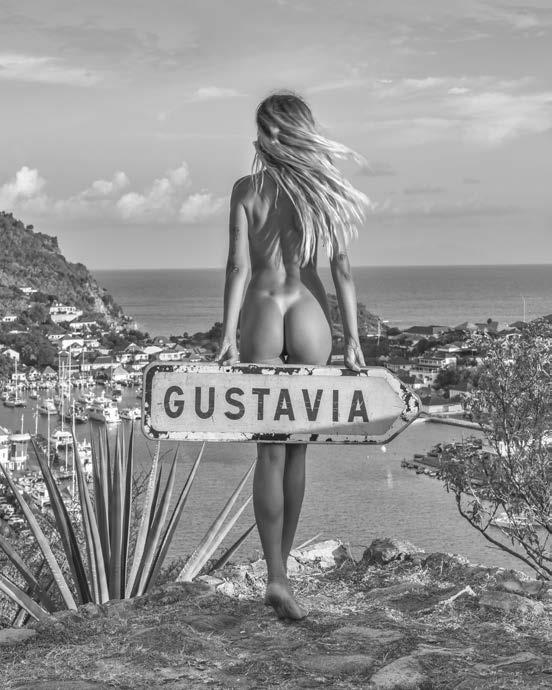

A glance at the island’s Swedish past Un regard sur notre passé suédois

36

Si vous avez passé un certain temps à St-Barth, vous avez certainement remarqué les vestiges persistants du passé suédois de l’île.

En effet, en 1784, le roi de France fut tenté d’échanger l’île de SaintBarthélemy contre des entrepôts dans le port de Goteborg, et, le 7 mars 1785 à Versailles, Louis XVI et Gustave III signèrent donc le traité qui scella cet accord.

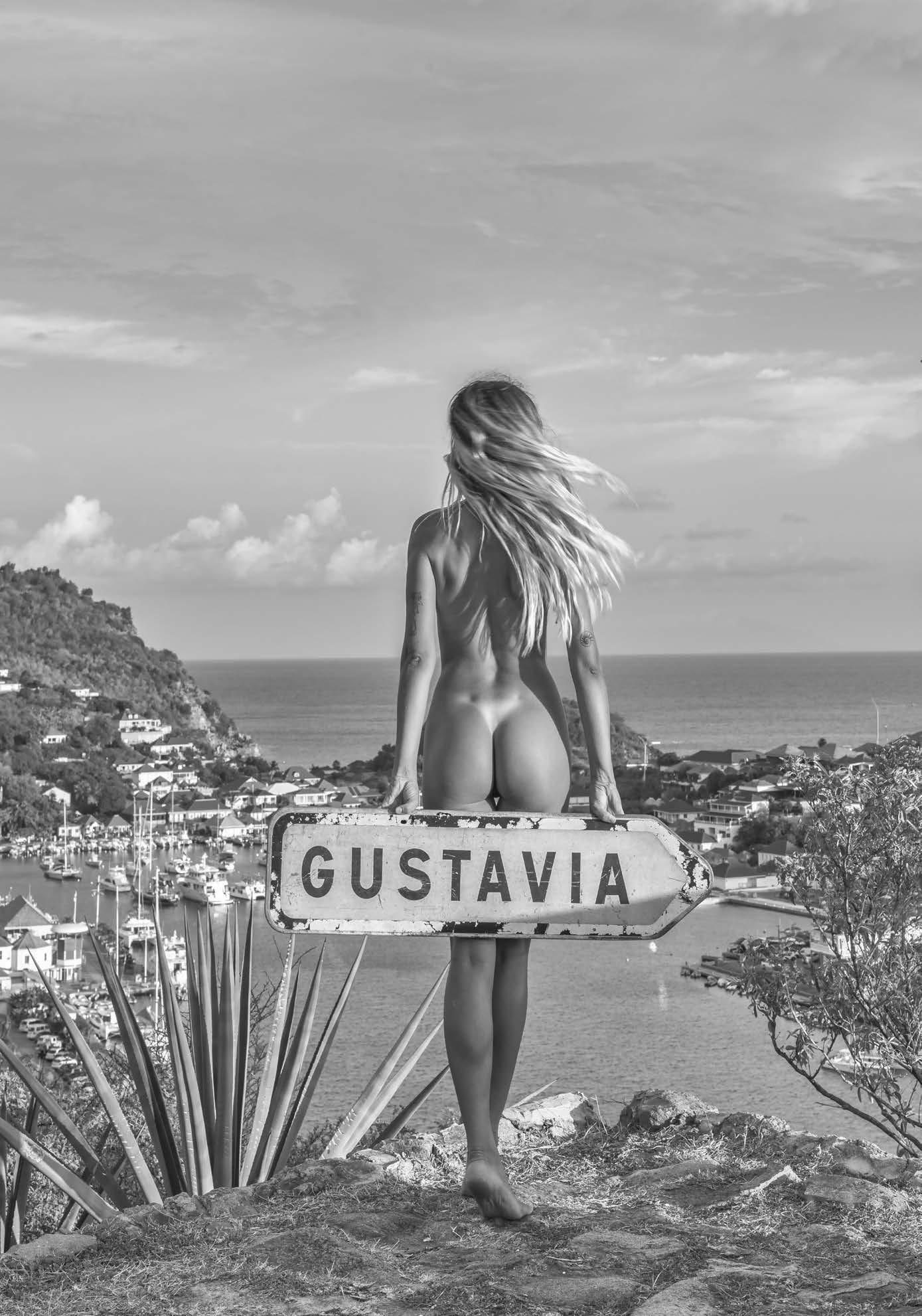

Le port de Carénage fut alors rebaptisé Gustavia par le nouveau gouverneur, Salomon Mauritz Von Rayalin, et ce fut le début de l’âge d’or de la capitale. L’île est déclarée port franc et plusieurs milliers de navires transitent alors chaque année par Gustavia, toutes les nations étant autorisées à entrer librement, exonérées des droits de douane.

De nombreux bâtiments furent alors érigés. Entrepôts et hangars sur la rive Ouest, connue sous le nom de La Pointe, pour les réparations navales, et, quais et maisons de style suédoissur le côté Est. Le port était alors animé de commerçants, d’aventuriers, d’étrangers et marins de tous bords pour une population totale d’environ 3880 habitants.

Les habitants de l’île, dont la seule source de revenus était la vente de coton, n’ont pas vraiment bénéficié pas de cette prospérité. Ils furent donc exonérés, par Gustave III, de payer des impôts.

ACID ISLANDS

Il n’y eut pas, ou peu, de mariages mixtes mais locaux et Suédois ont vécu en paix jusqu’à la Révolution française et, en particulier, un épisode tumultueux avec le gouverneur Berpstadt.

En effet, lors d’une émeute, le gouverneur ordonna de tourner les canons vers la ville, mais le sergent-major August Nyman refusa d’obéir aux ordres, jouant la montre dans l’espoir que la situation se résoudra d’elle-même. Cela fonctionna et la capitale fut épargnée. Nyman fut dès lors considéré comme un héros par la population. Après sa sa mort, une foule considérable accompagnait ses cendres, qui furent placées dans une belle urne au sommet de la colline surplombant le port. Cette urne est encore visible aujourd’hui au

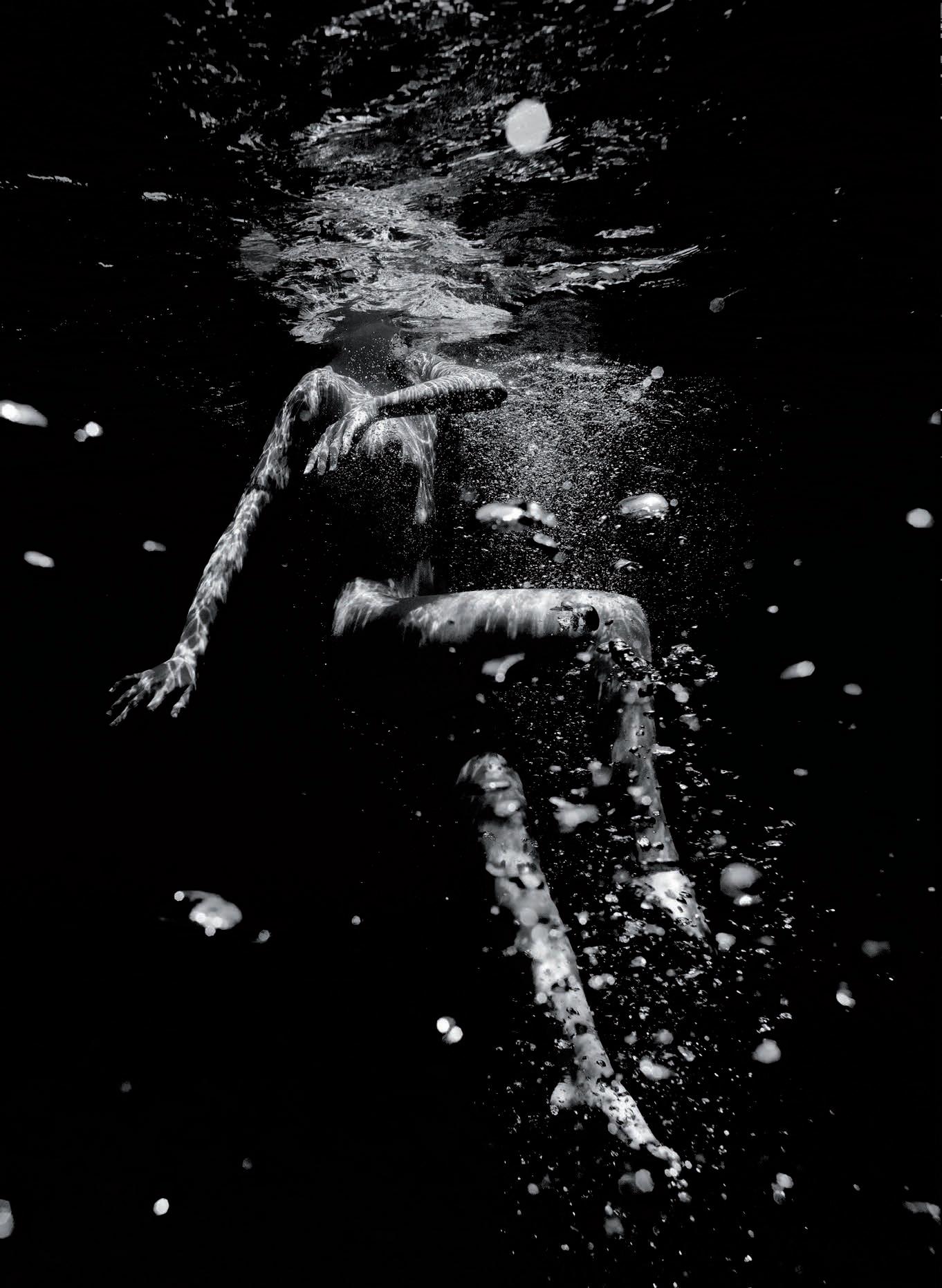

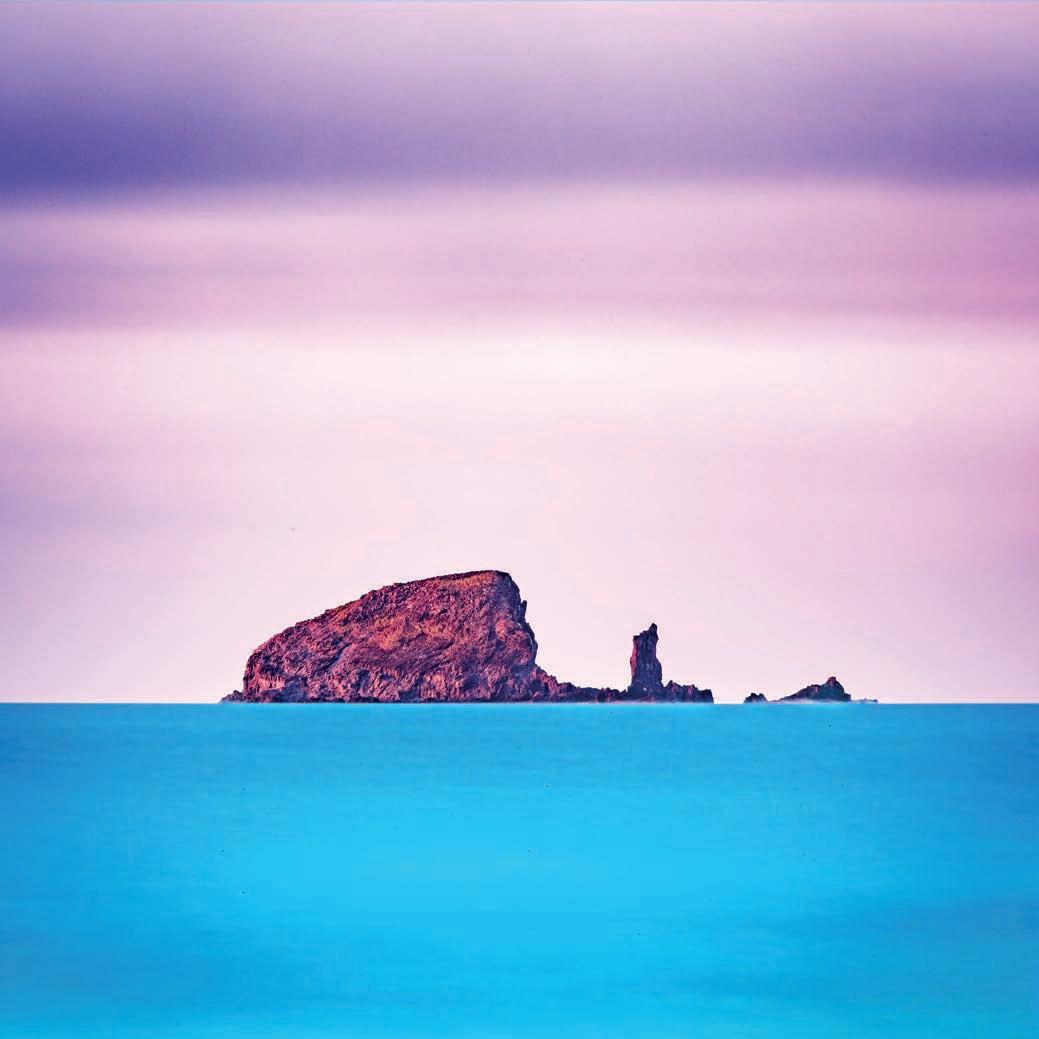

A psychedelic take on the ongoing Islands series Une version psychédélique de la série Islands 42

Bien que cette période semble aujourd’hui oubliée, il existe encore, principalement à Gustavia et alentours, de nombreux artefacts visibles de l’époque suédoise. La maison Dinzey, par exemple, construite entre 1822 et 1830 est classée Monument Historique le 17 avril 1990 par son propriétaire actuel, le consul honoraire de Suède.

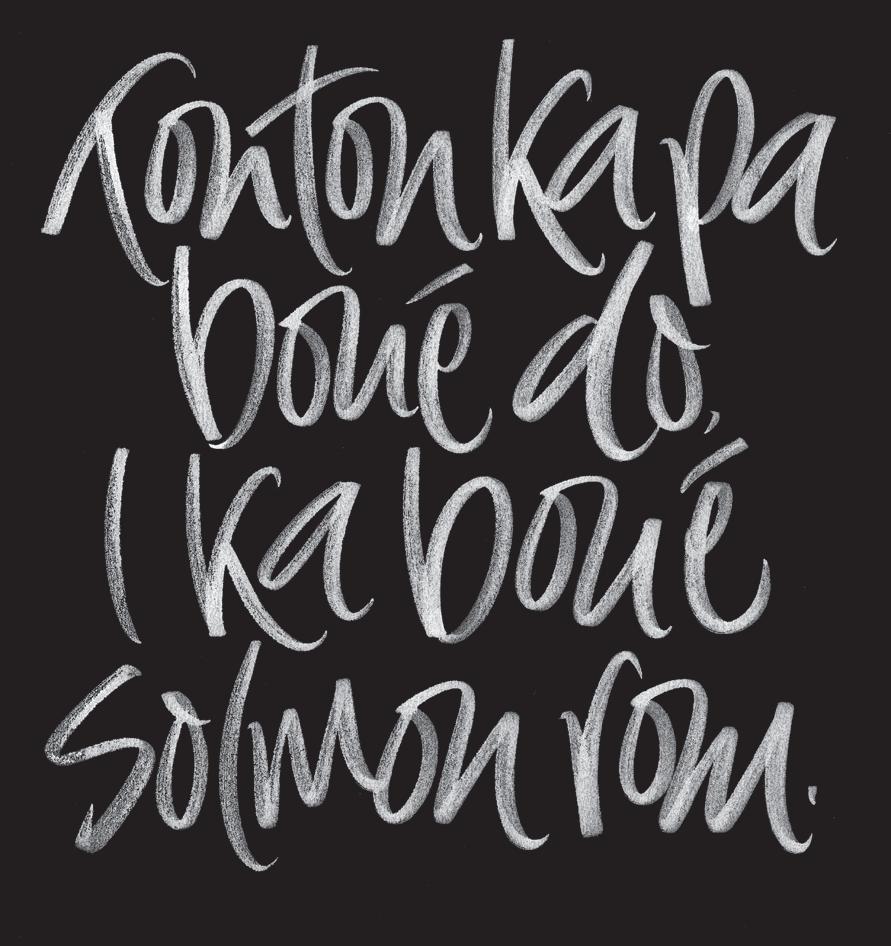

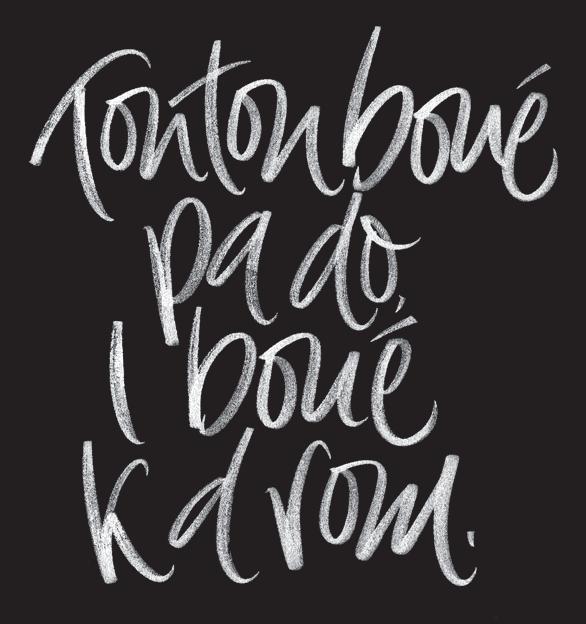

LIVING LANGUAGE

Vous pouvez aussi admirer le clocher suédois, construit entre 1796 et 1799, ainsi que l’une des quatre fortifications encore debout : le Fort Oscar, qui abrite actuellement la gendarmerie de St-Barth. D’autres, comme le fort Karl ou la batterie du fort Gustav III, ne sont plus que des ruines. Aussi, en parcourant certains sommets des collines entourant Gustavia vous pourrez observer d’autres vestiges et vous devinerez aisément la raison stratégique de ces emplacements.

A look into the origins and dialects of native St Barth speakers by linguist Julianne Maher Un regard sur les origines et des différents dialectes de St-Barth par la linguiste Julianne Maher

A suite d’une succession de catastrophes, dont un terrible incendie, des emmeutes, des ouragans, des sécheresses et enfin une épidémie de fièvre jaune, Oscar II de Suède decida de se débarrasser et de vendre de cette coûteuse dépendance. Cependant ni les États Unis d’Amérique ni l’Italie ne furent intéressés, et, le 10 août 1877, en vertu d’un nouveau traité, la Suède rétrocède St-Barth à la France.

46

TRADITION REVISITED

The particular heritage of straw weaving in St Barth L’héritage particulier du tressage à St-Barth

52

Nos lecteurs les plus curieux iront probablement découvrir par eux-mêmes l’une des nombreuses facettes fascinantes de St-Barth. 28 | 29

WOMEN OF THE ROCK

A homage to the women of St Barth Un hommage aux femmes de St-Barth

58

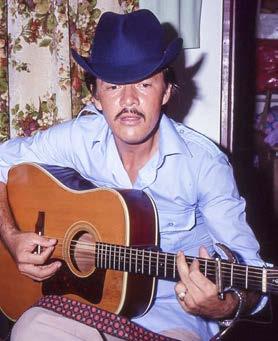

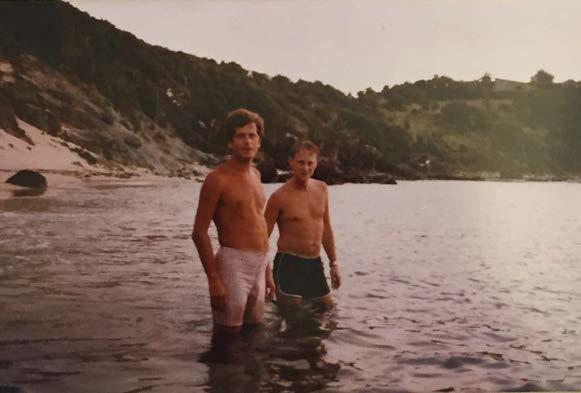

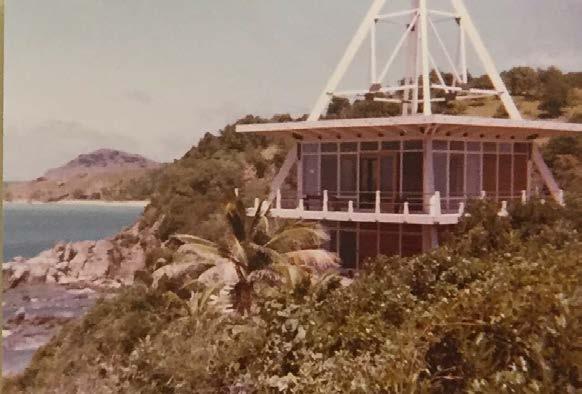

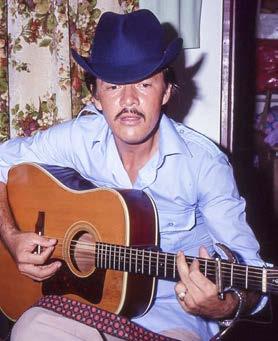

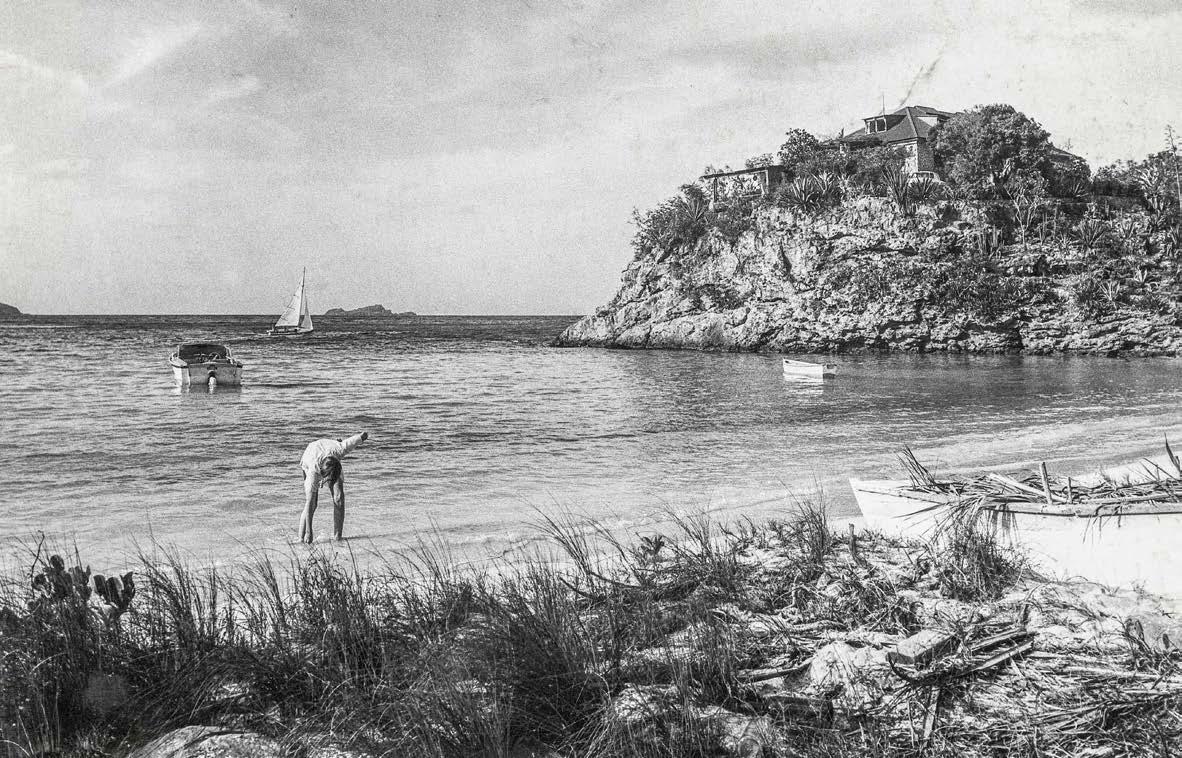

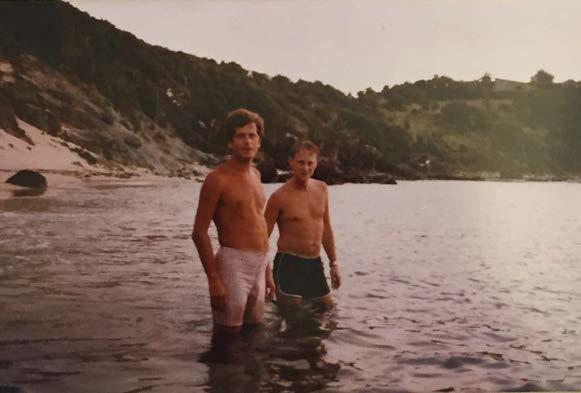

THAT WAS THEN

Life in St Barth during the late 70’s La vie à St-Barth à la fin des années 70

74

LES CASES ST BARTH

The history of the traditional ‘Cases’ St Barth L’histoire des cases traditionnelles

78

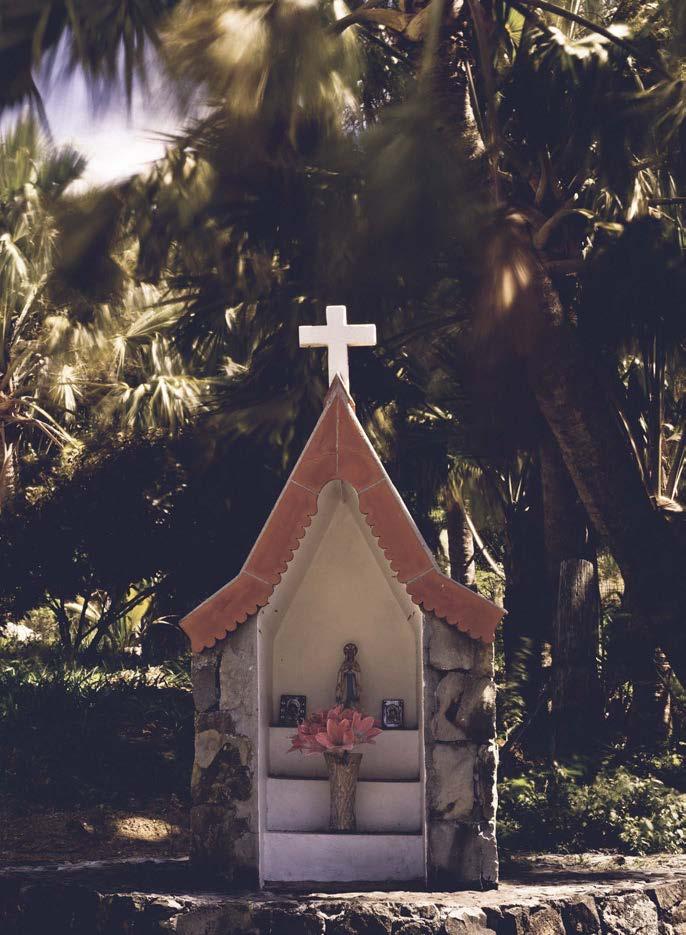

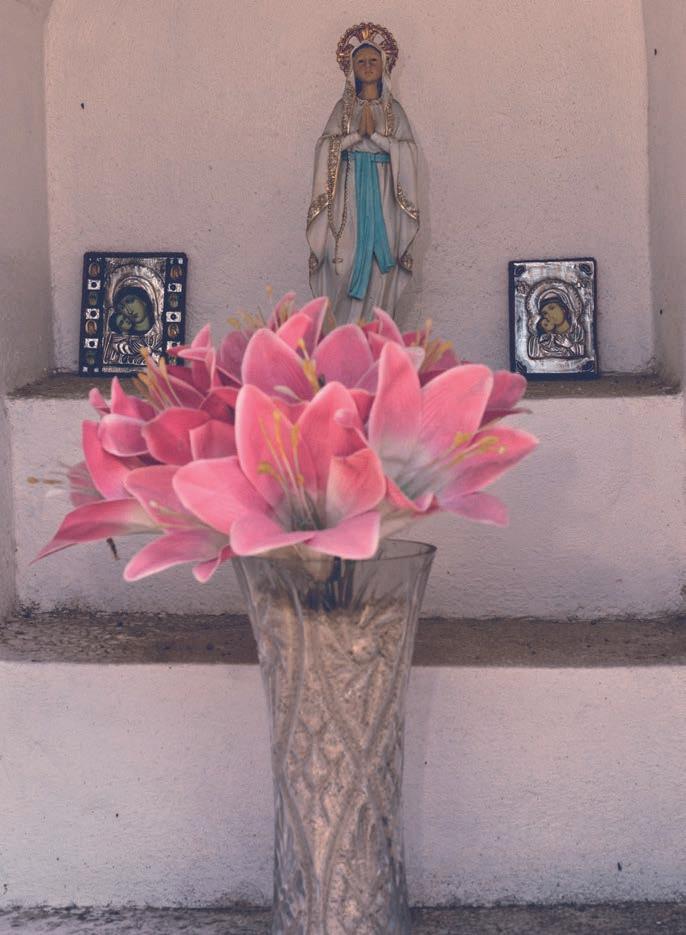

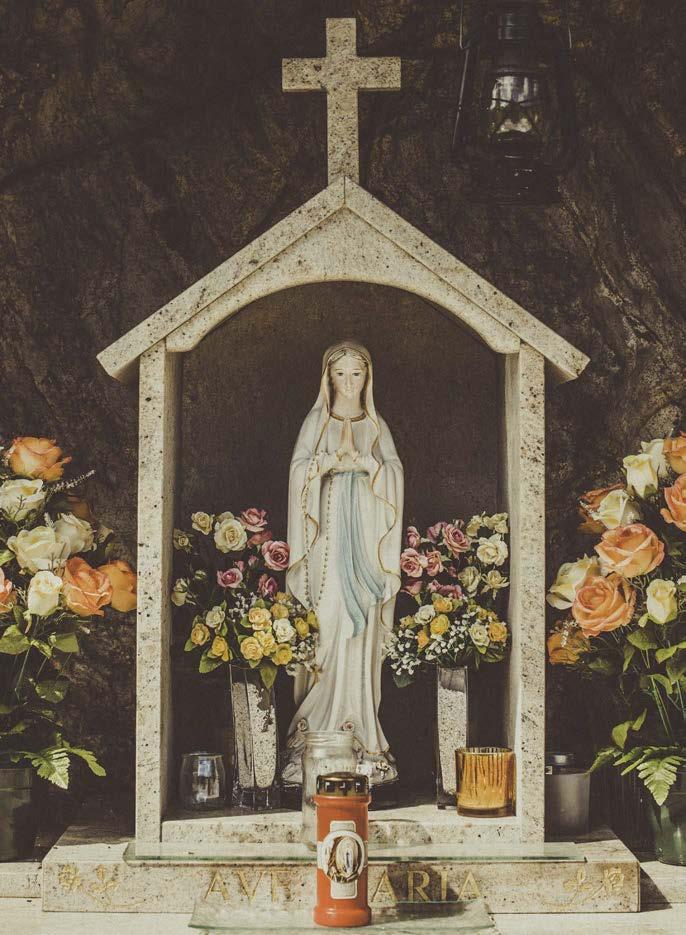

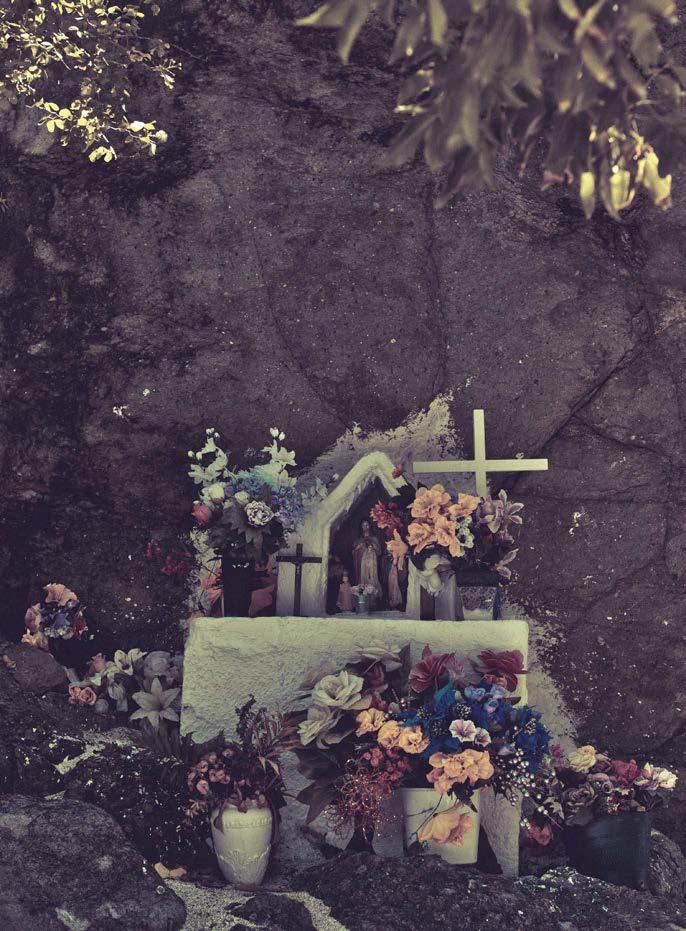

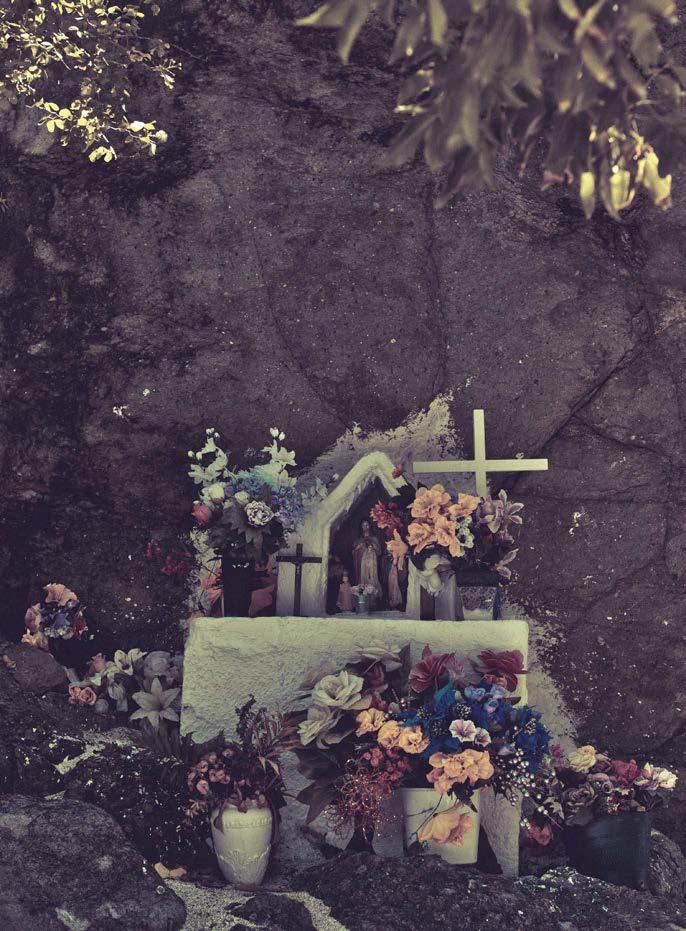

HEAVEN & EARTH

The roadside shrines in St Barth Les petites chapelles des bords de route à St-Barth

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

84

AN

ANCHOR STORY

The unusual story behind the famous anchor in Gustavia L’histoire insolite de la célèbre ancre de Gustavia

90

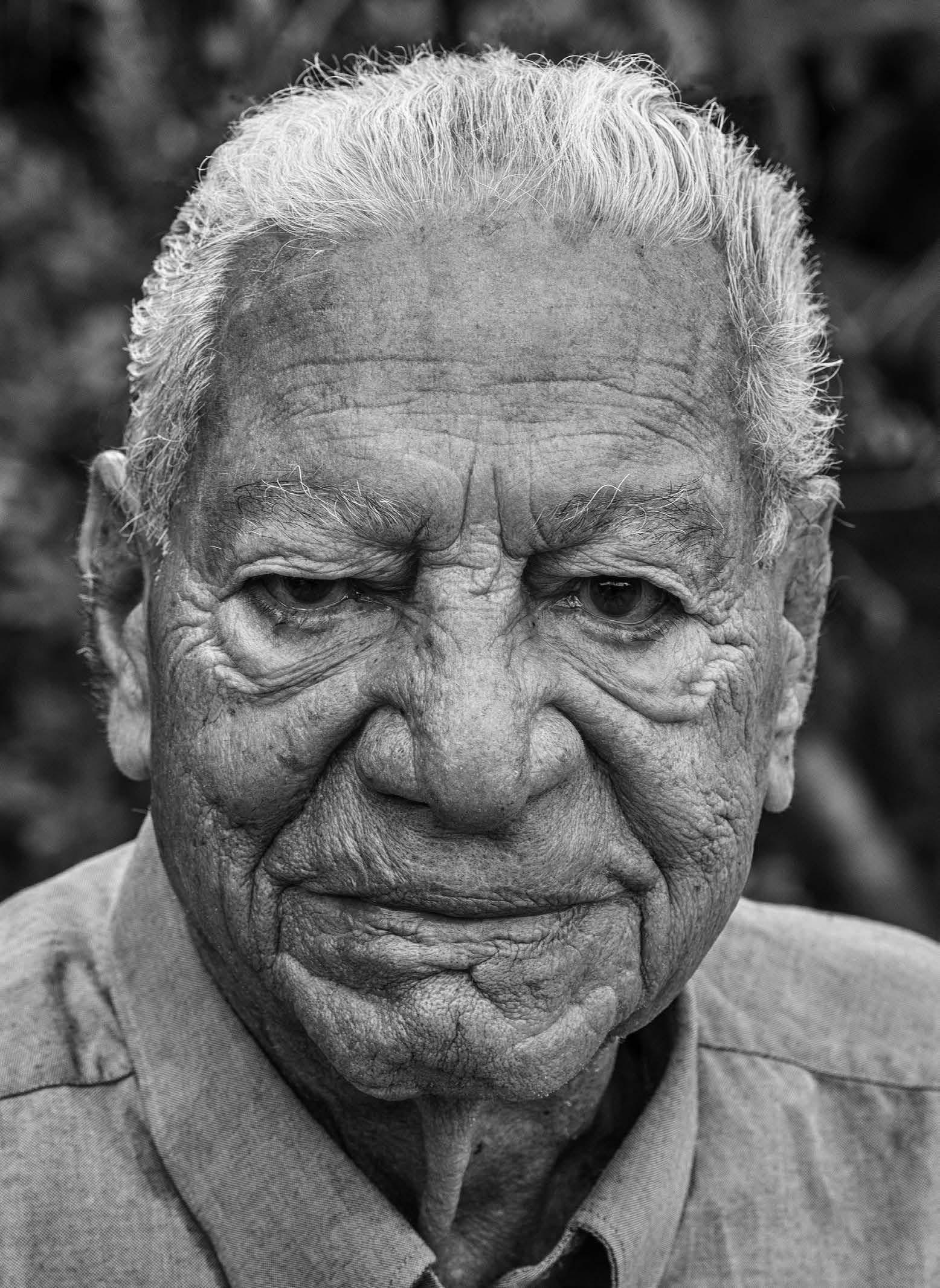

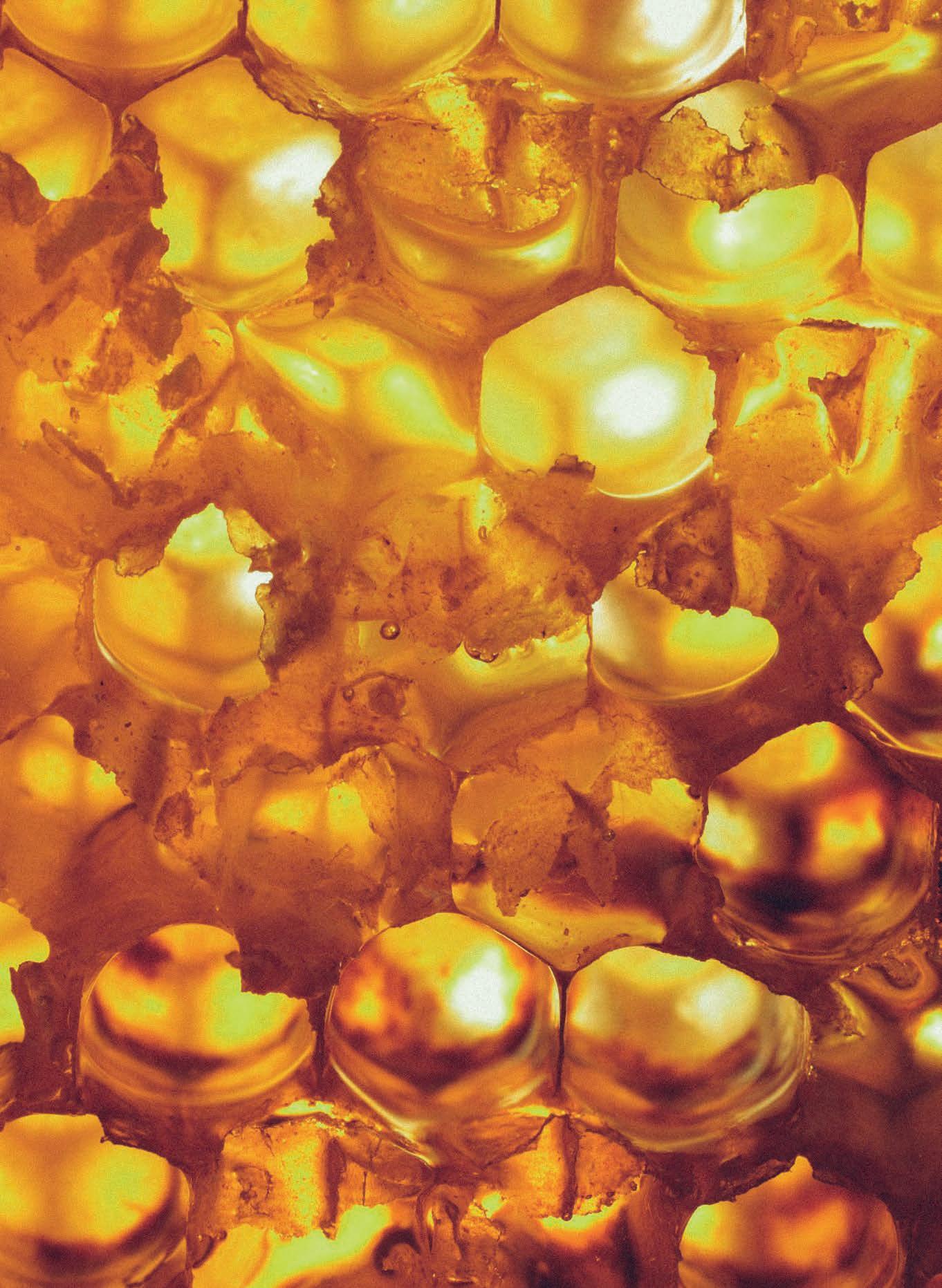

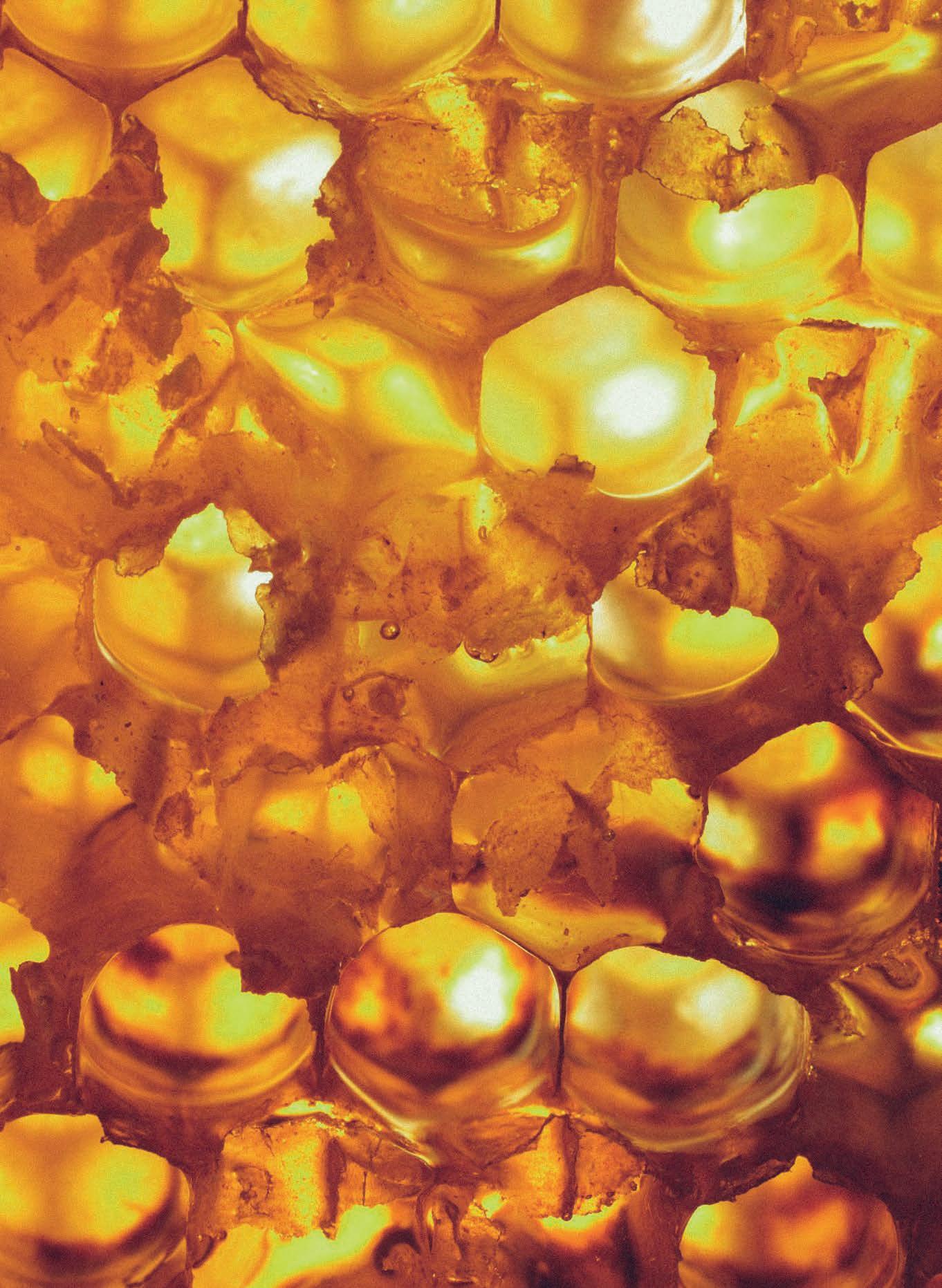

LIQUID GOLD

The personal story of bees in St Barth L’histoire intime des abeilles à St-Barth 96

TARGETED

Some images from the 2015 Bucket Regatta Airshow Quelques images du show aérien de la Bucket Regatta de 2015

102

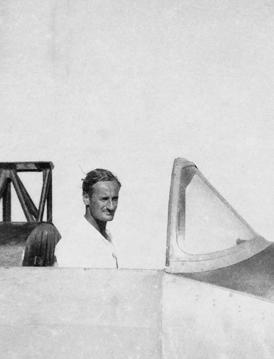

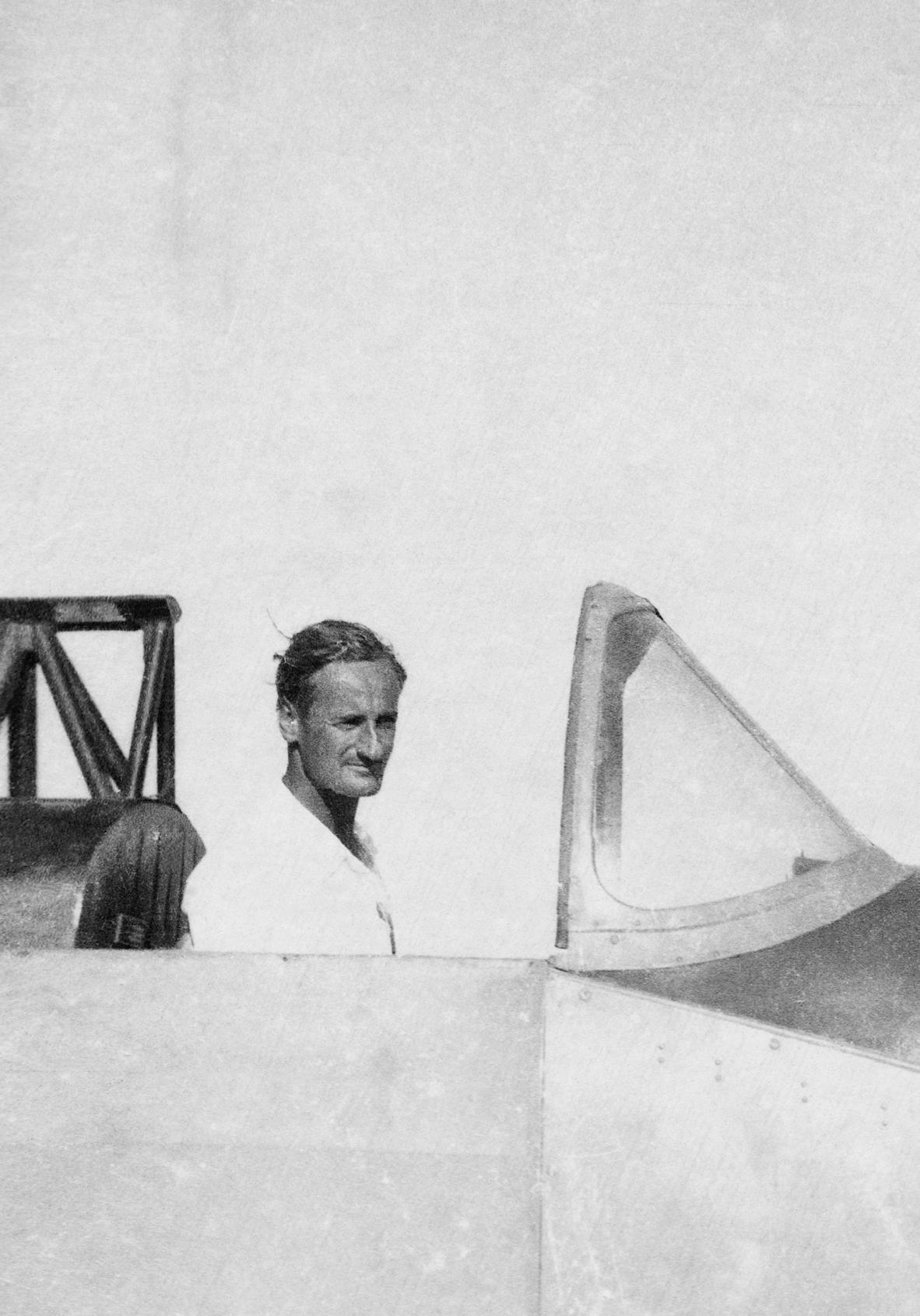

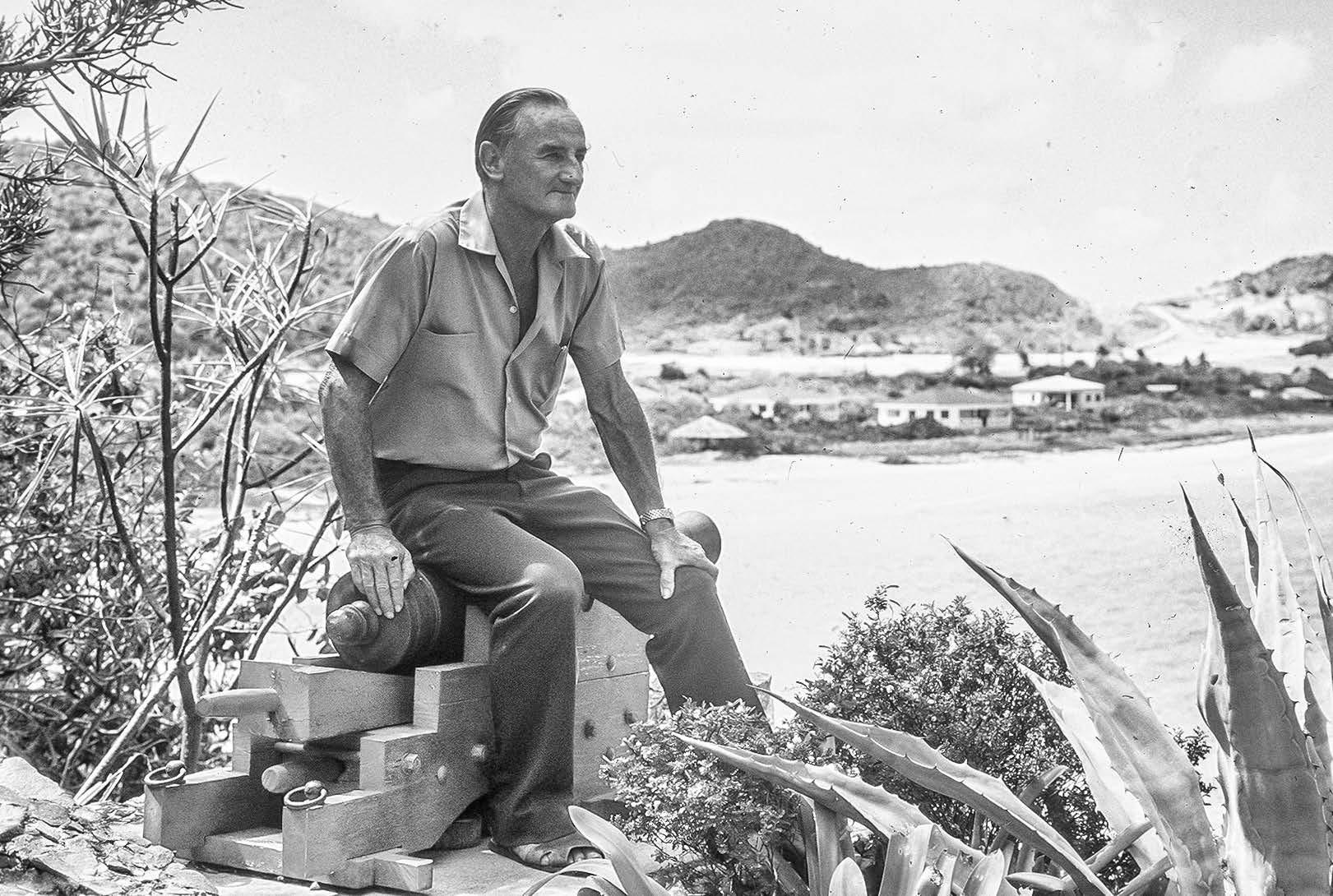

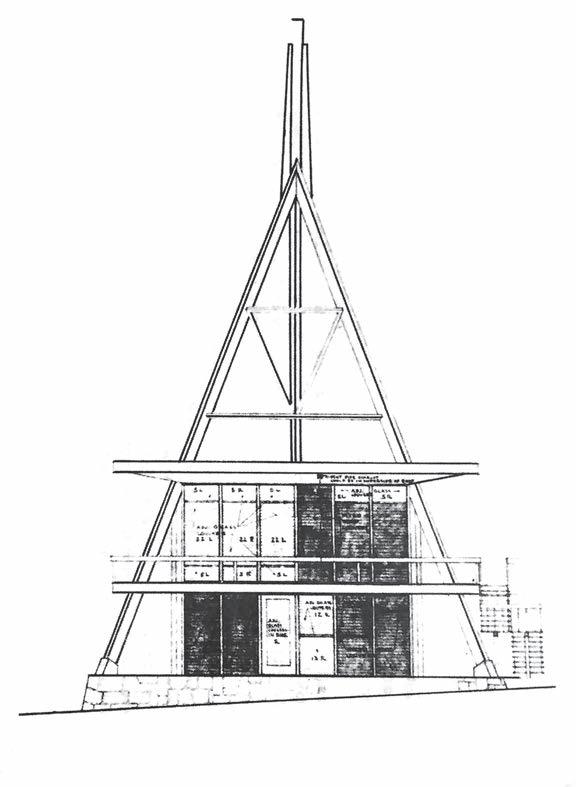

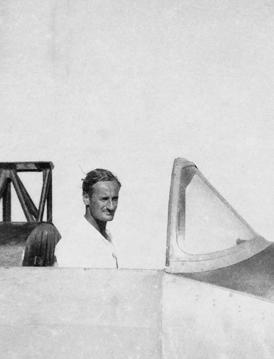

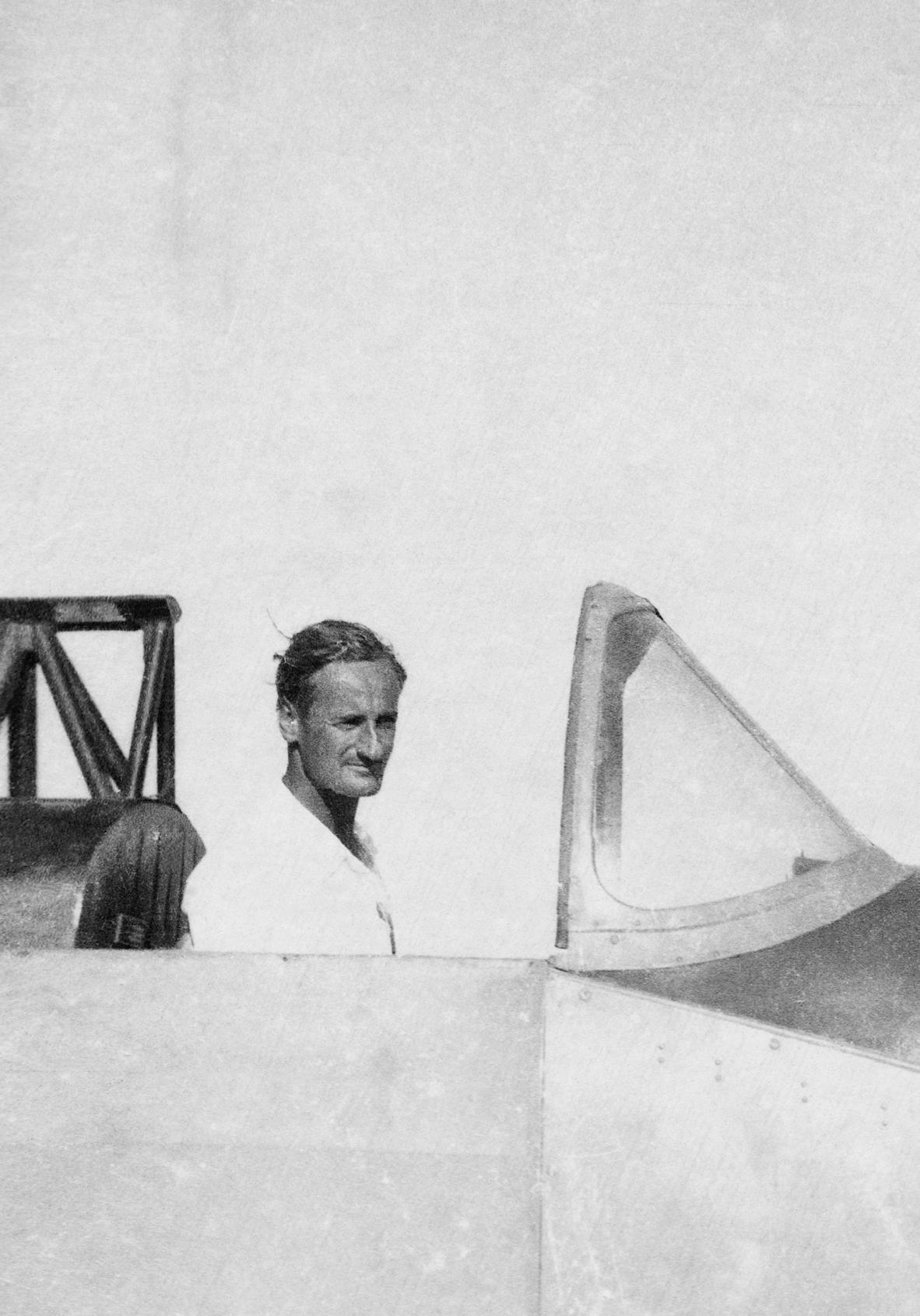

TAKING FLIGHT

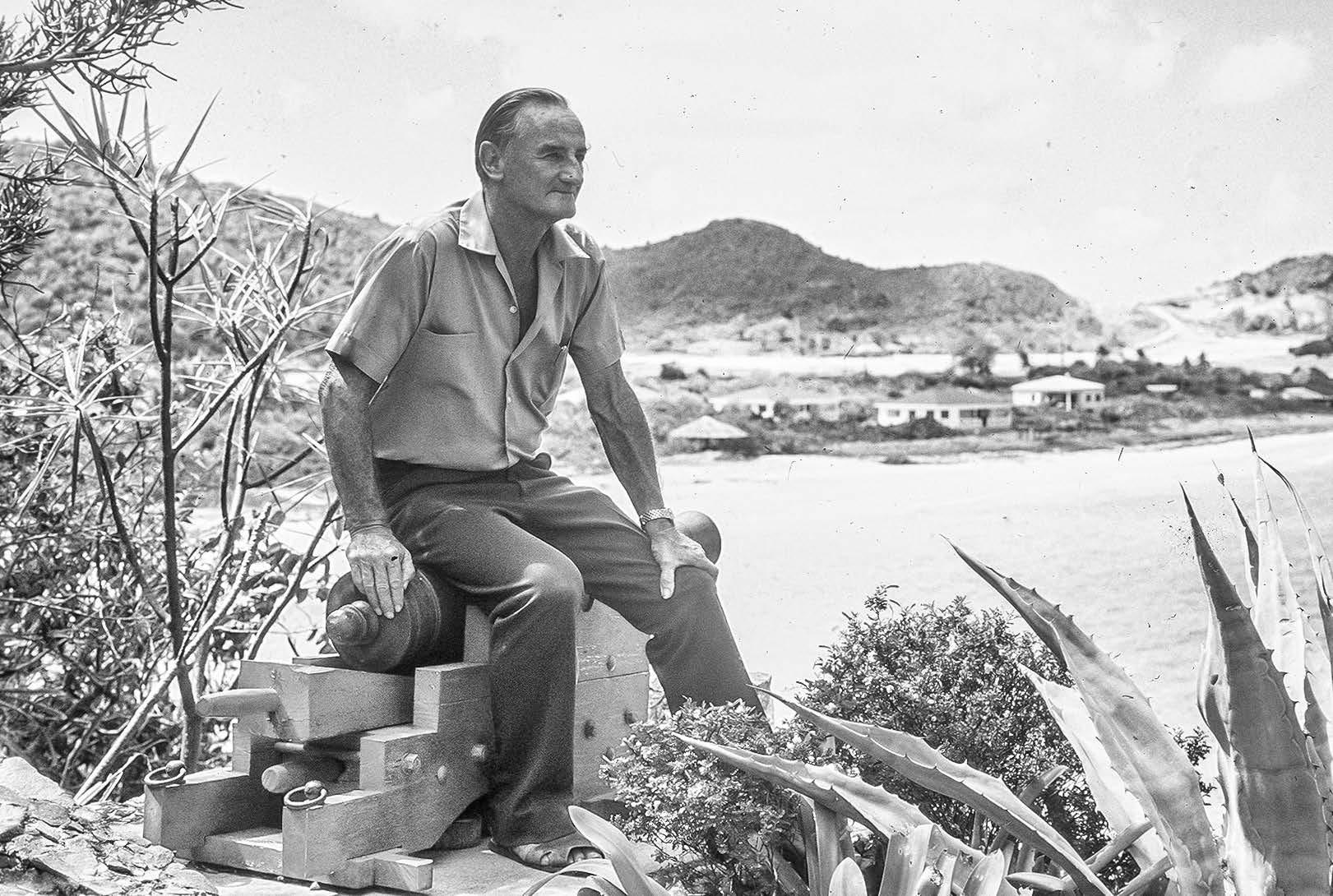

The story and legacy of Rémy de Haenen L’histoire et l’héritage de Rémy de Haenen

108

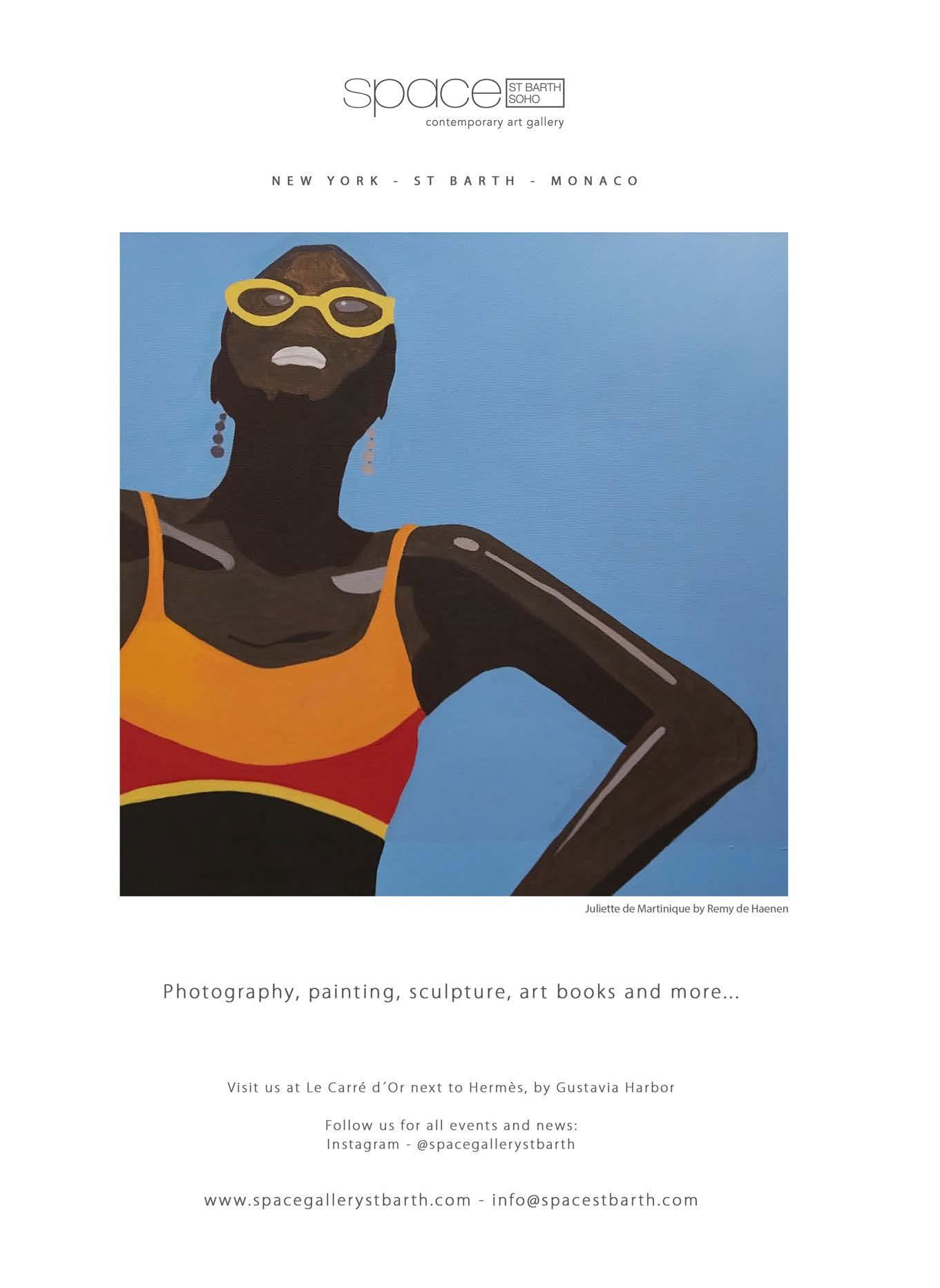

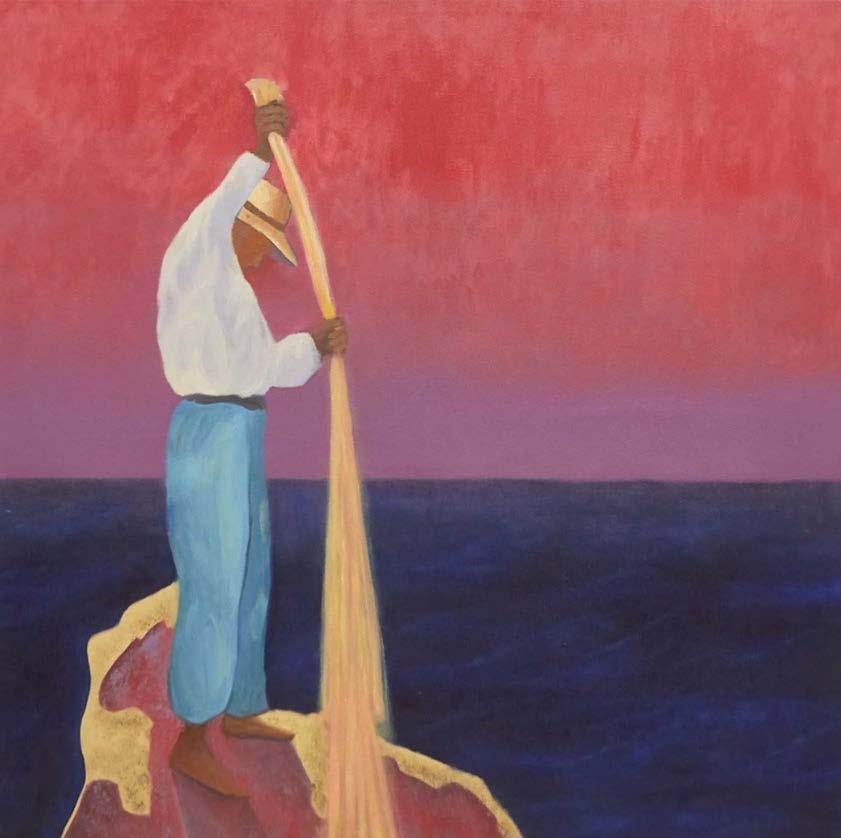

REMY

DE HAENEN

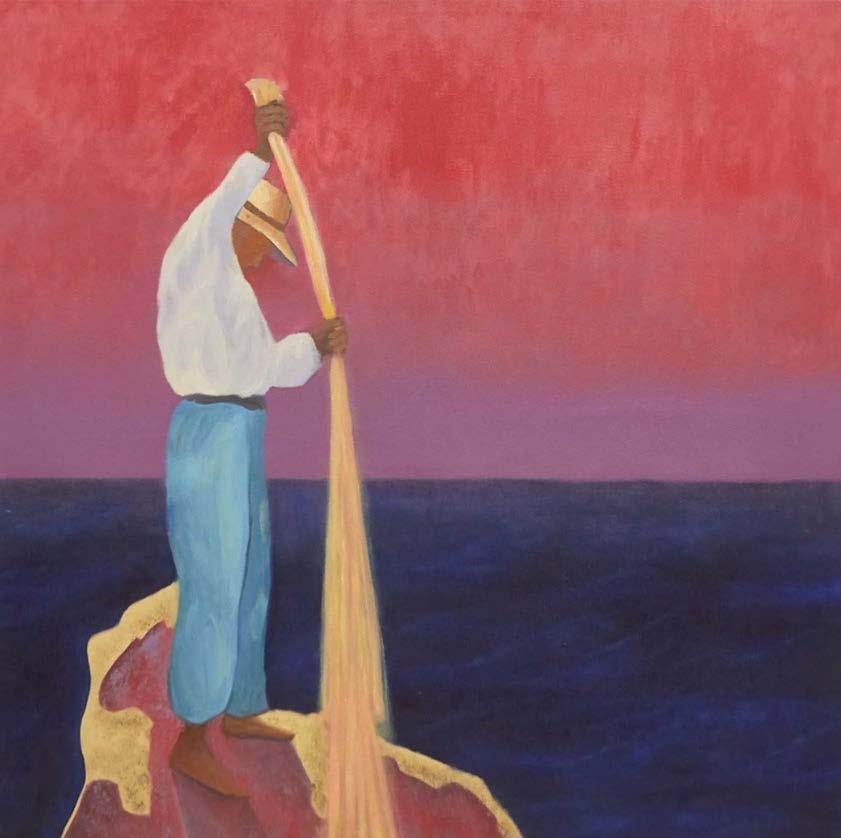

Discover the artworks of Rémy de Haenen, influenced by cultural diversity, freedom, colors, and nature Découvrez les oeuvres de Rémy de Haenen, influencées par la diversité culturelle, la liberté, les couleurs et la nature

122

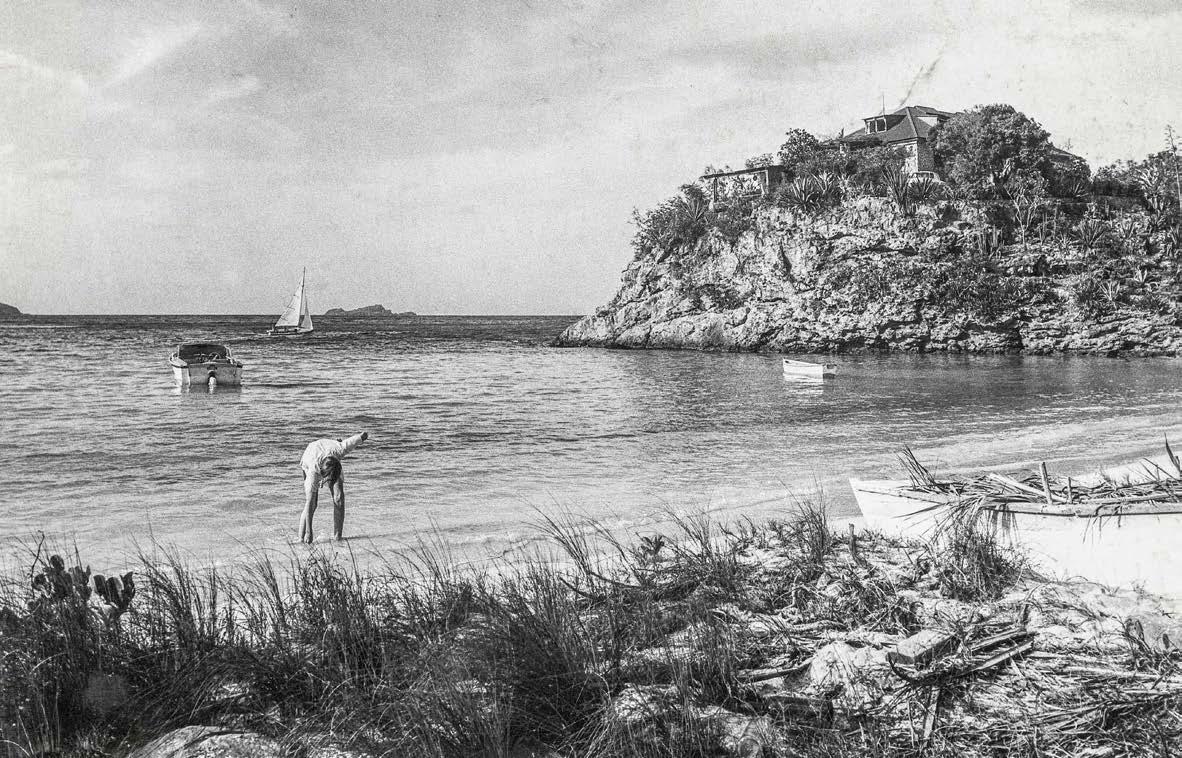

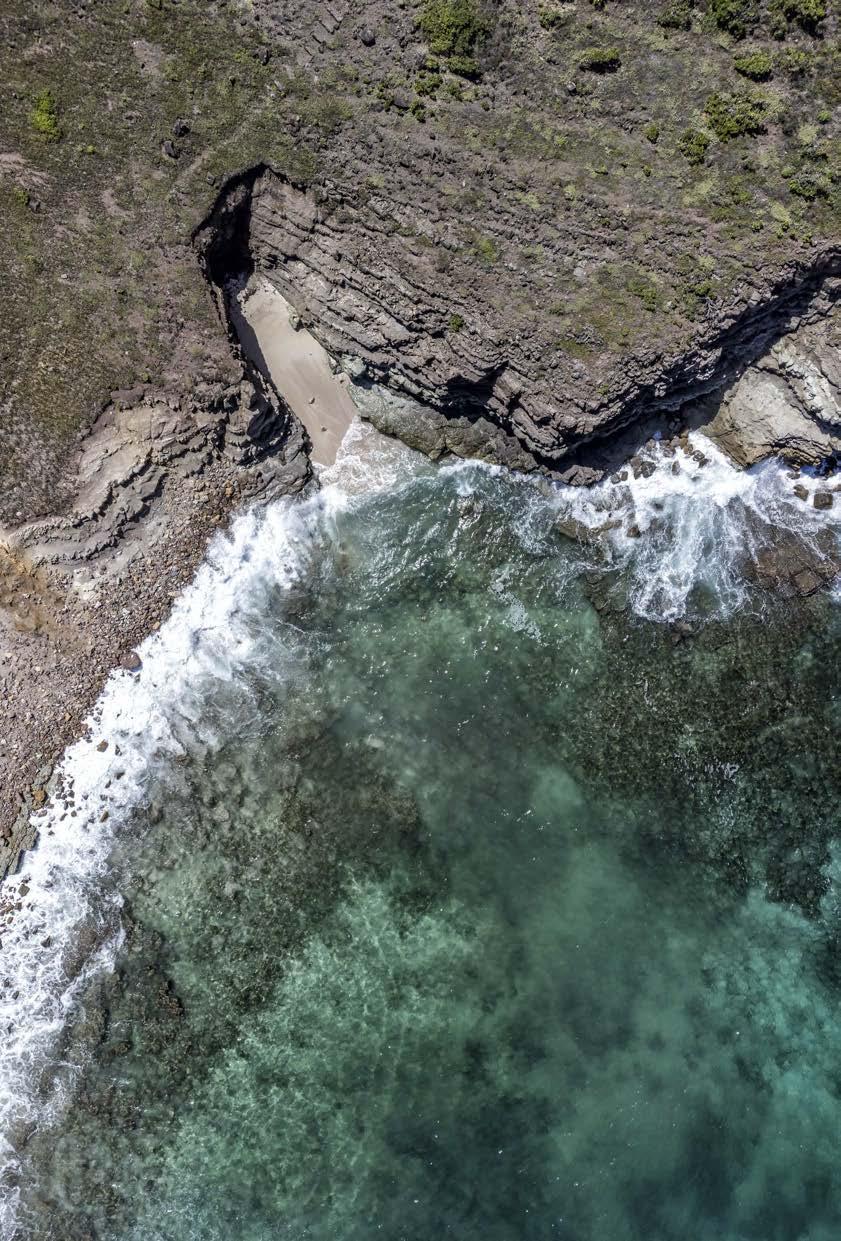

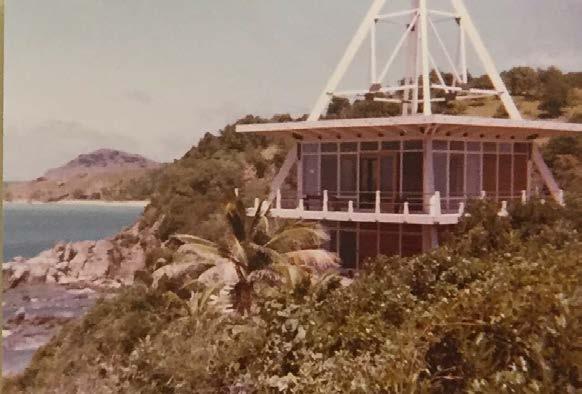

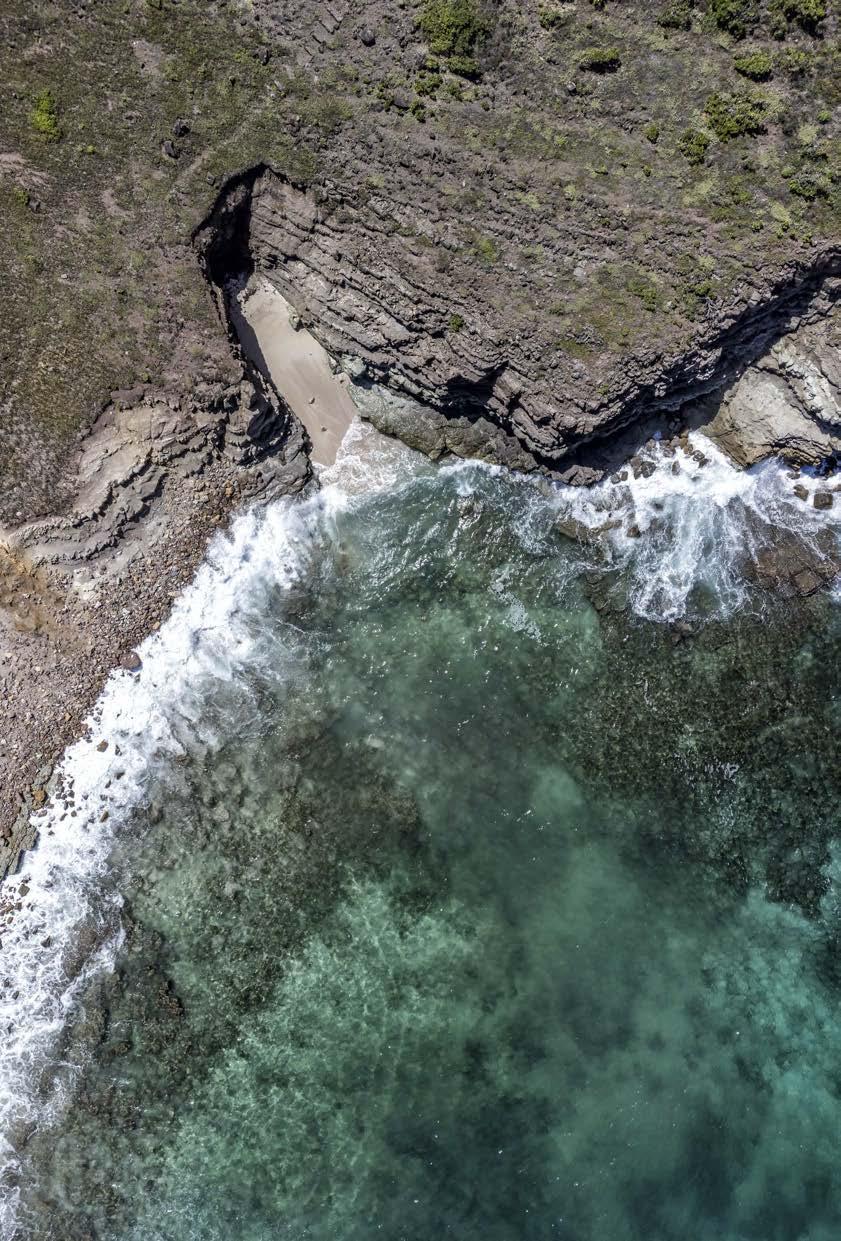

ROCKEFELLER

An intimate look into the Rockefeller estate in Colombier Un regard intimiste sur le domaine Rockefeller à Colombier 128

VISIONS OF ST BARTH

A photographic journey through the island of St Barth by Sébastien Martinon Un voyage photographique à travers l’île de St-Barth par Sébastien Martinon

150

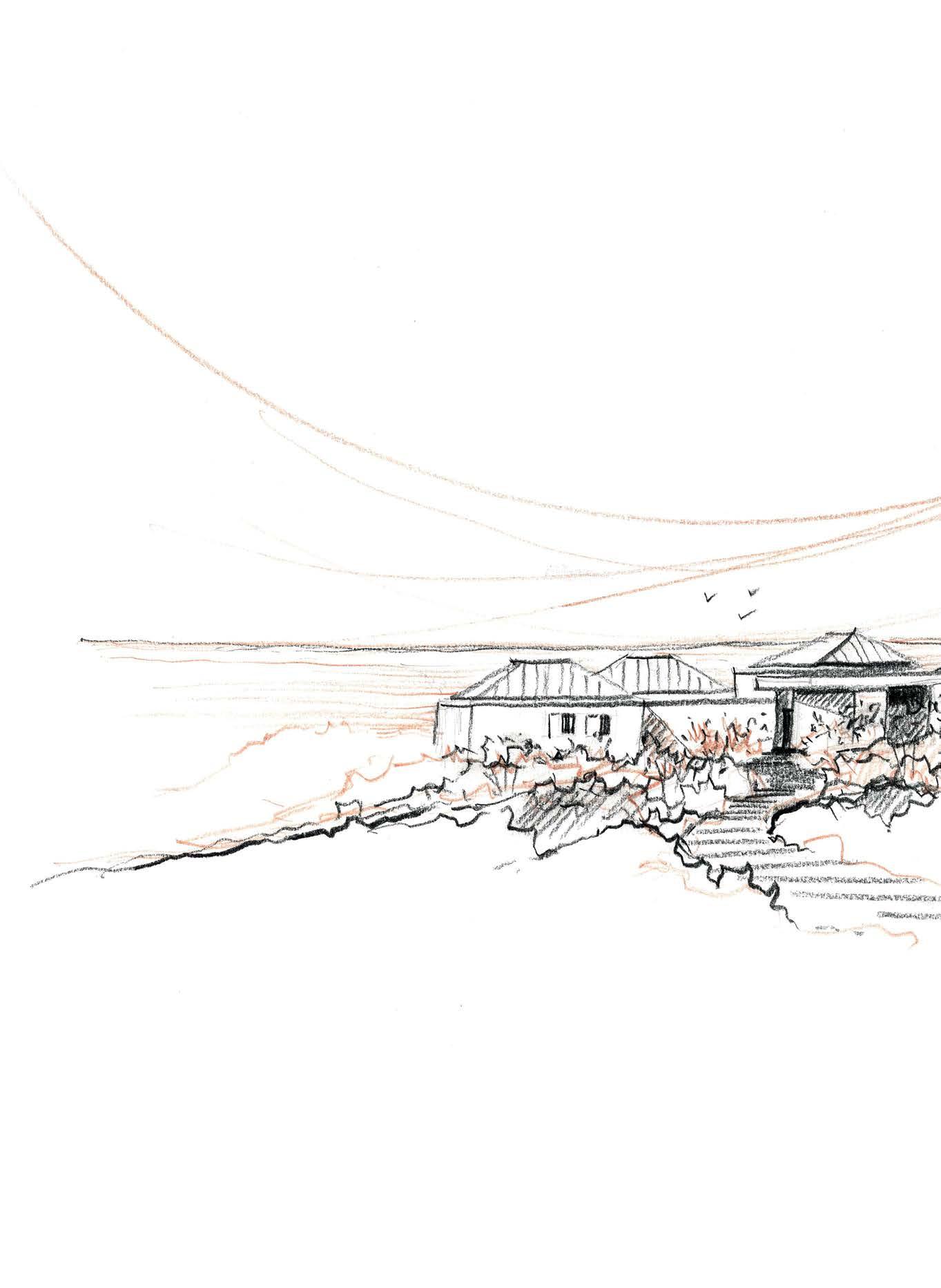

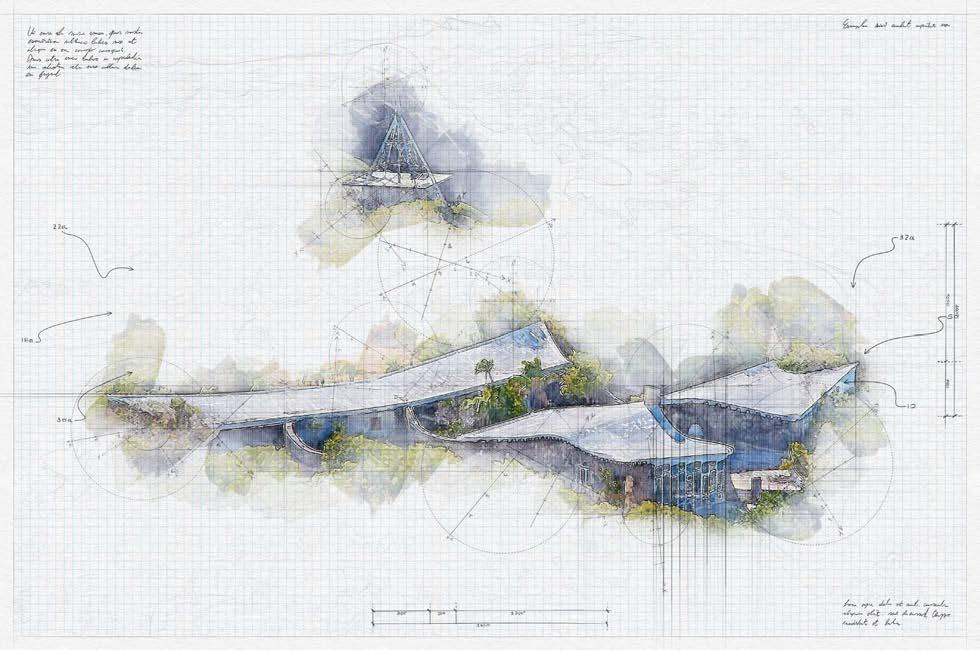

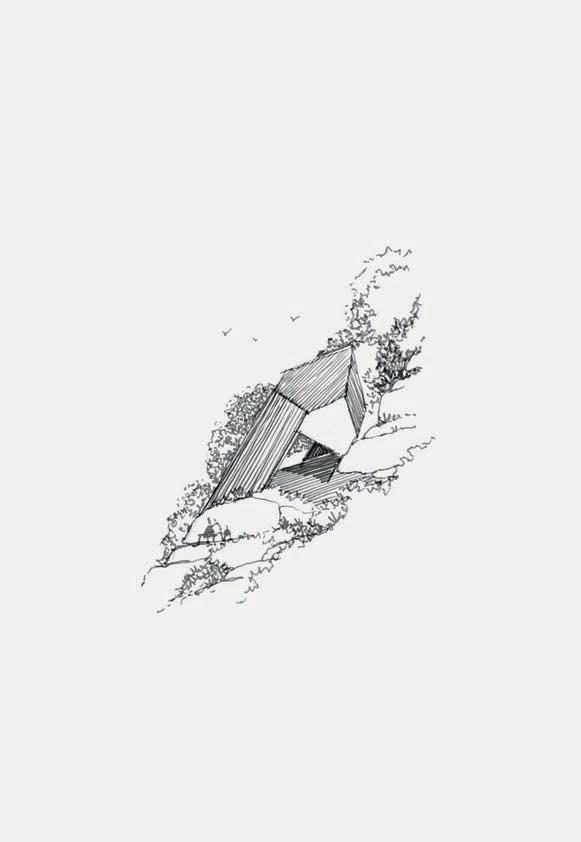

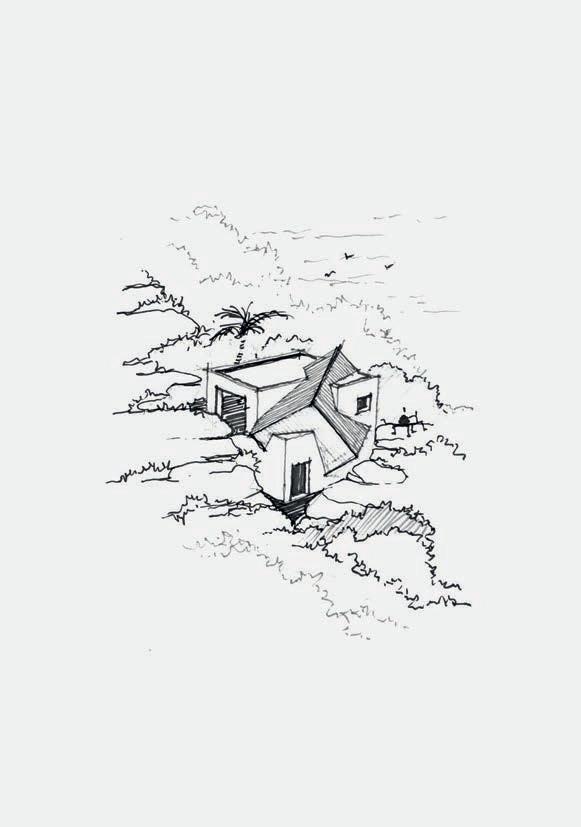

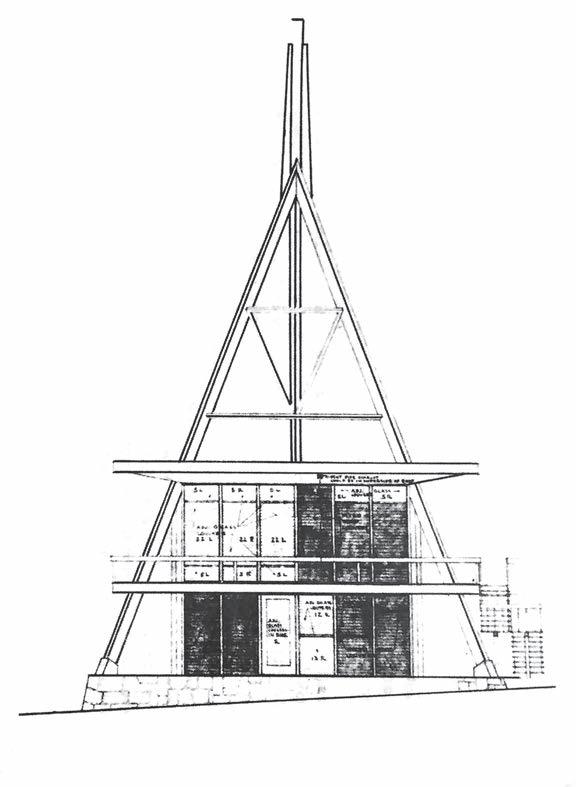

UTOPIA

A reflection on the future of construction in St Barth Une réflexion sur l’avenir de la construction à St Barth

156

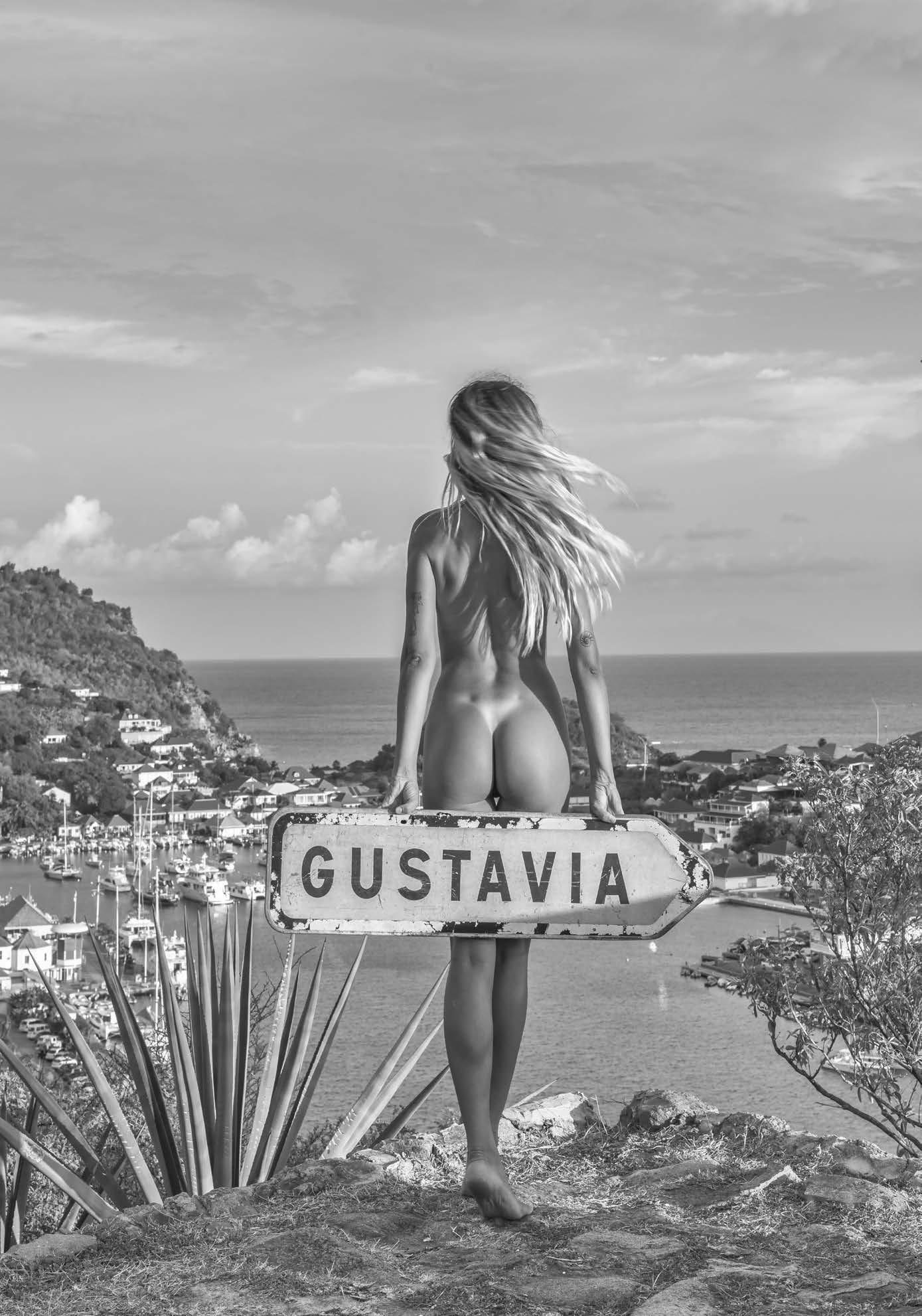

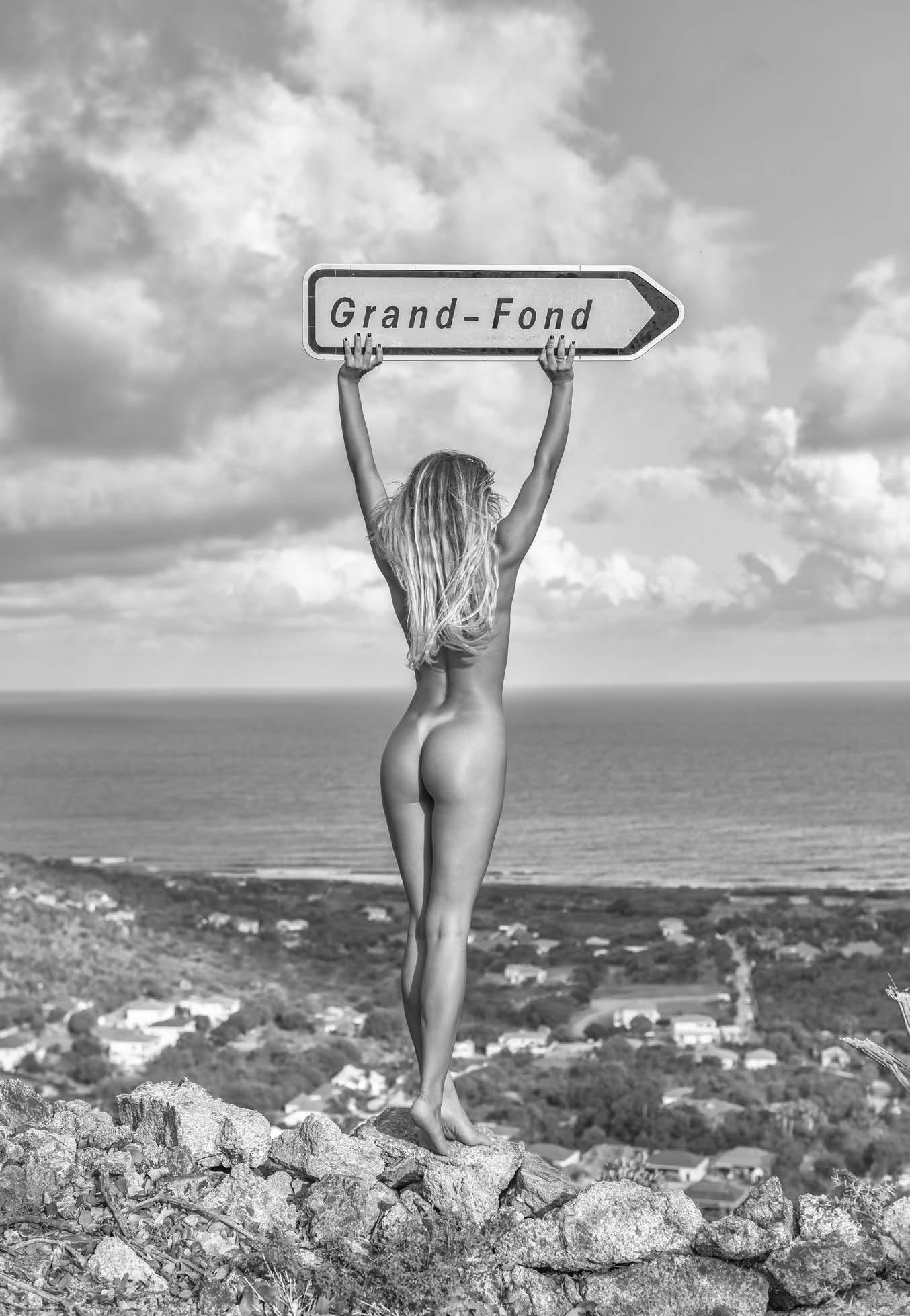

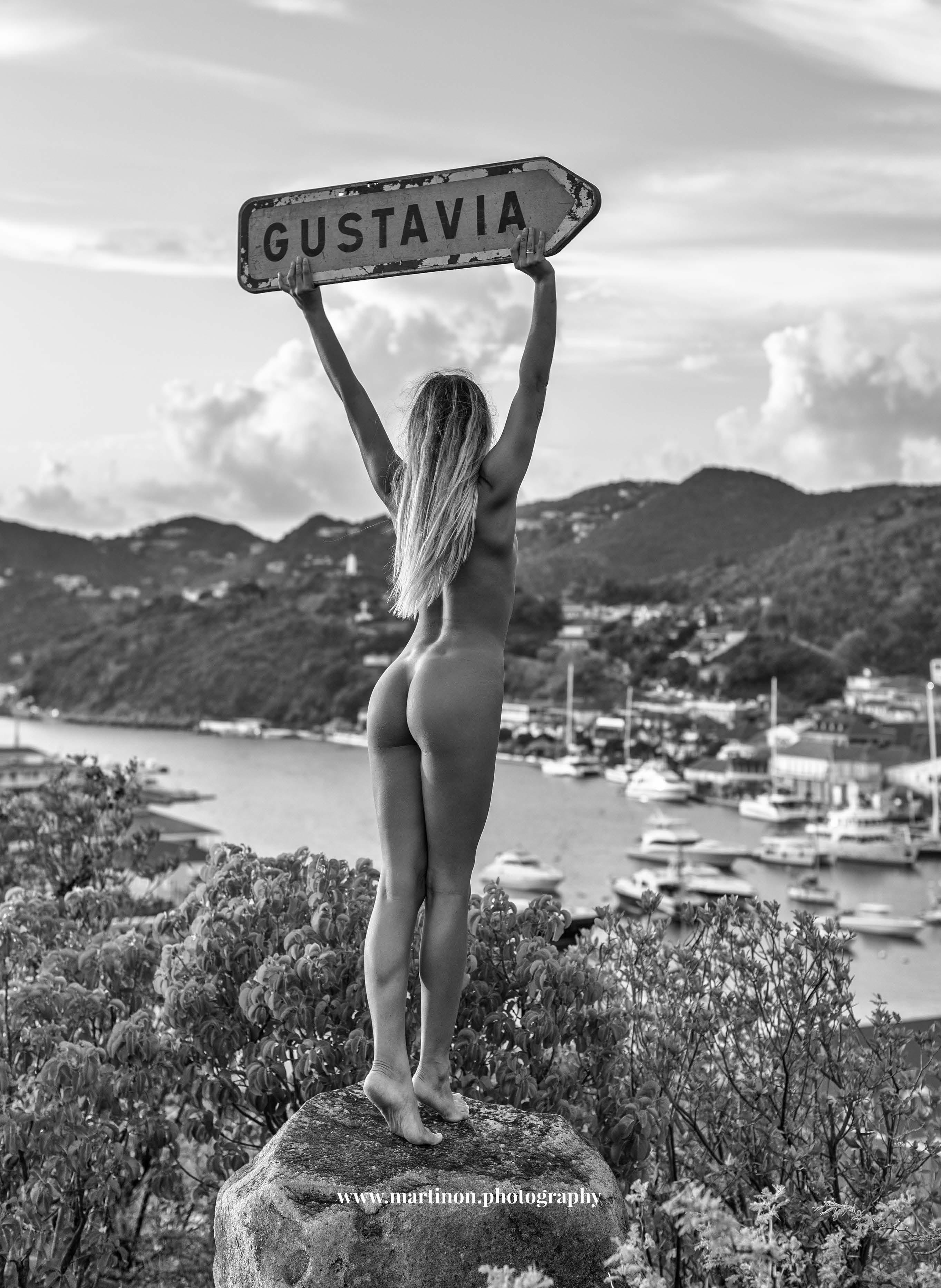

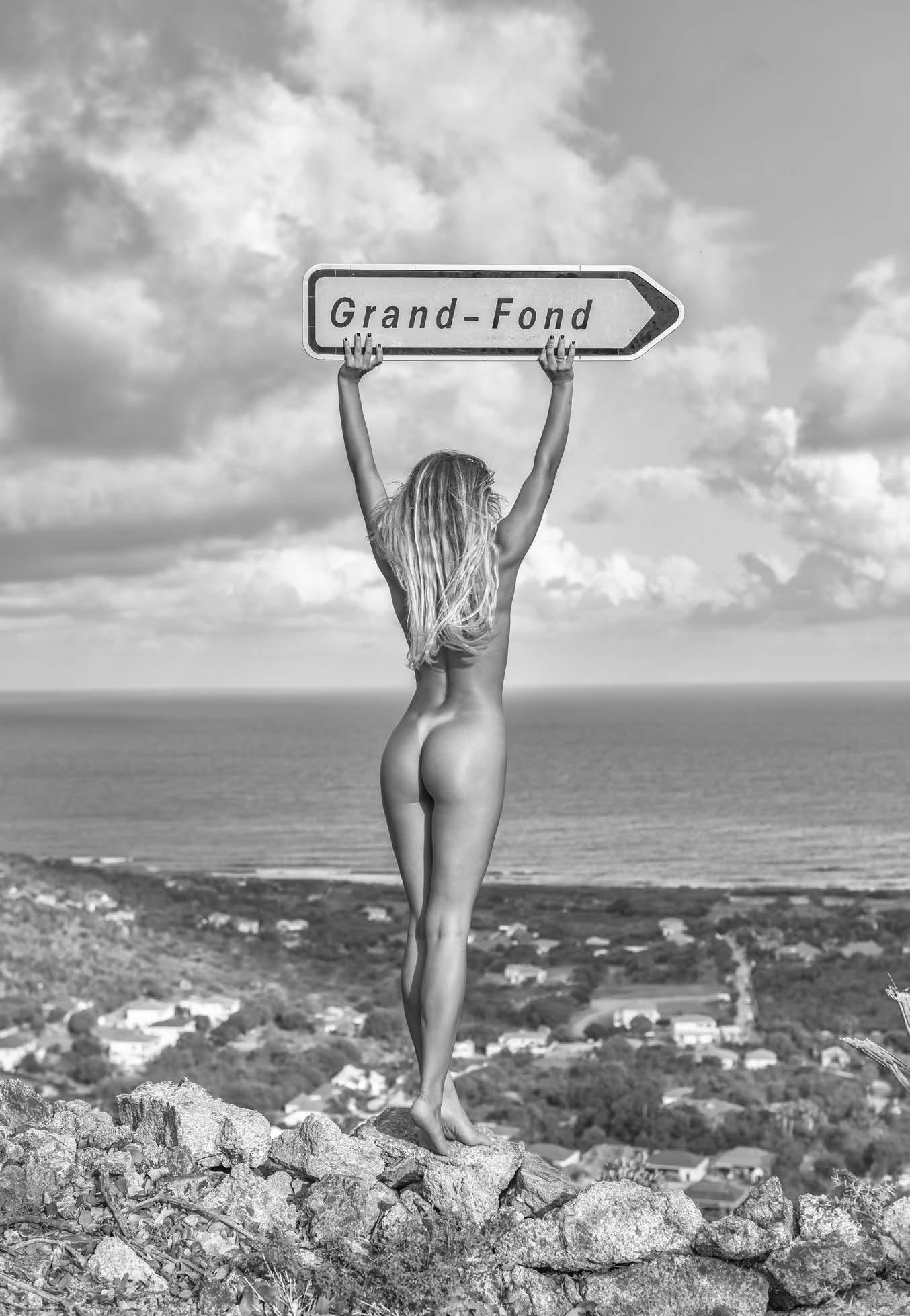

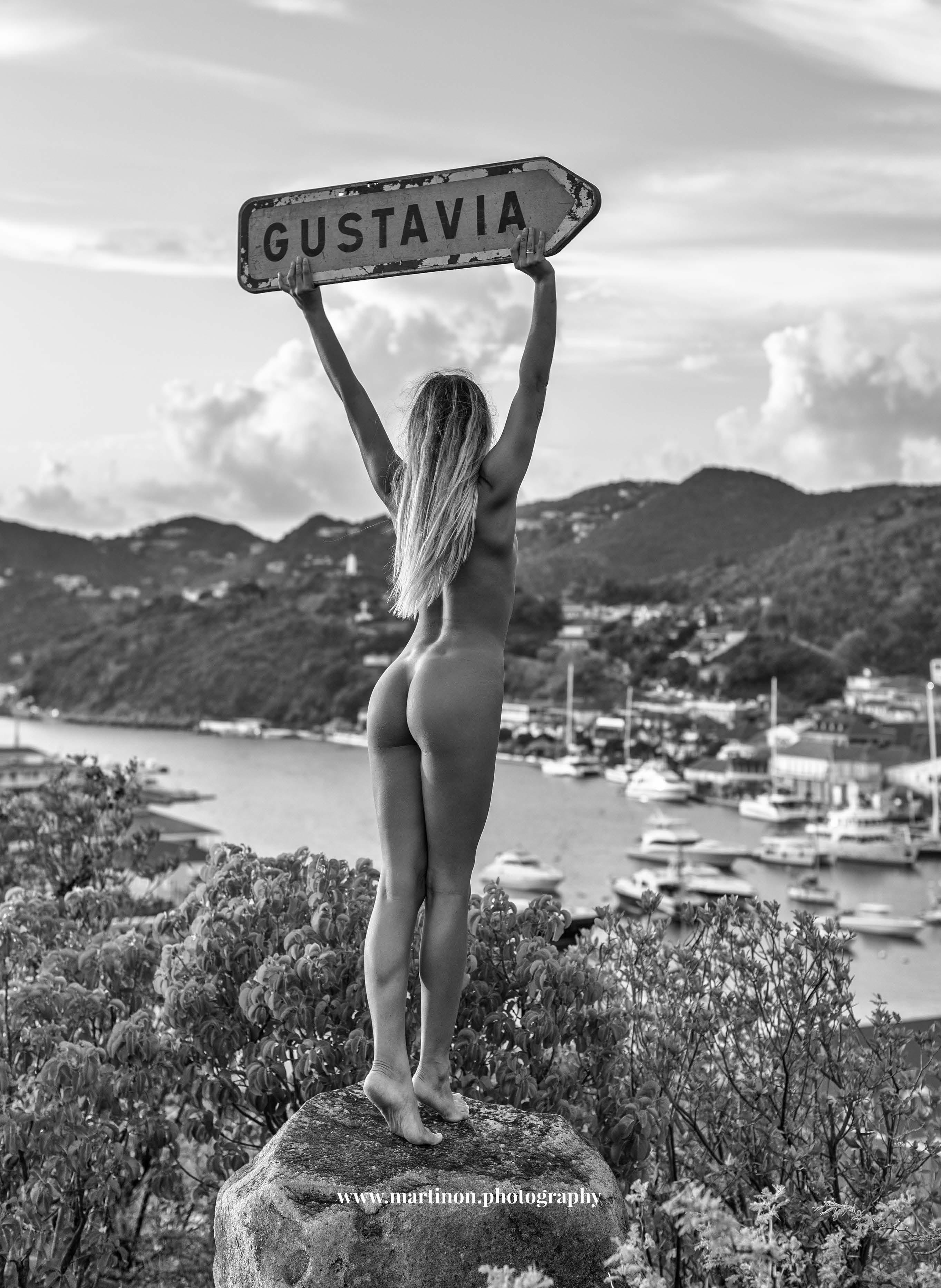

ROADSIGNS

An original guided tour Une visite guidée originale

16 | 17

Spirit Of St Barth N10 Saison 2023 Magazine gratuit

N° ISSN 2271-5185

Dépôt Légal Décembre 2022

Directeur de publication Sébastien Martinon

Raison Sociale

OUANALAO Studios S.A.S.U BP 311 Gustavia 97133

Saint-Barthélemy

La reproduction de tout ou partie de cet ouvrage sur un support quel qu’il soit est formellement interdite.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH est une marque déposée.

Contact seb@spiritofstbarth.com

Rédacteurs Bianca Connolly Ray Parish Sébastien Martinon Jasmine Martinon

Photos de Couverture Sébastien Martinon

Photographies & Illustrations Sébastien Martinon Sarah Maycock Cara Hornett Mathurin Brin Pascal Gademer

Design Studio BOWDEN

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

Name That Island

The indigenous island names as collected by Raymond Breton in 1640

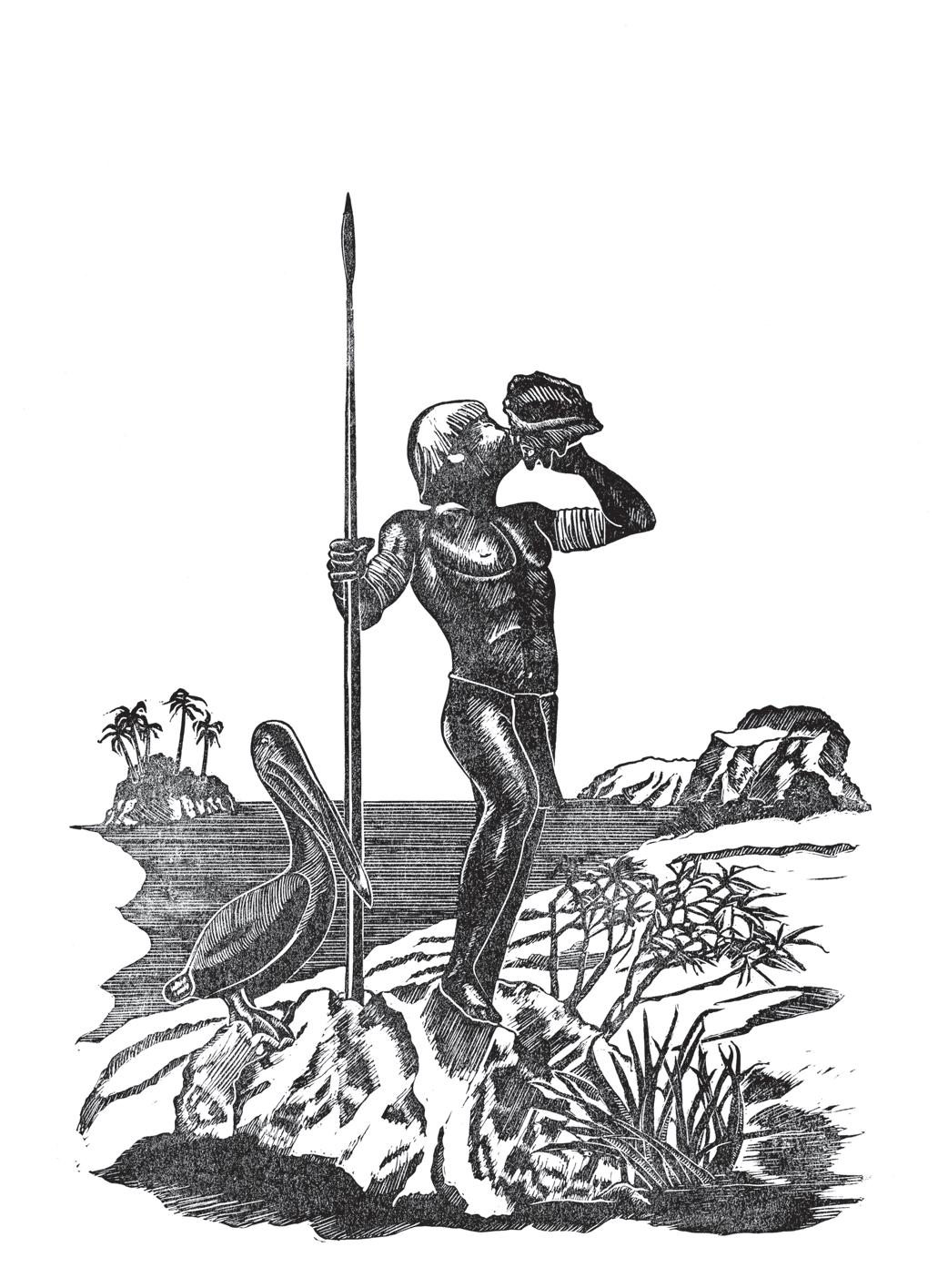

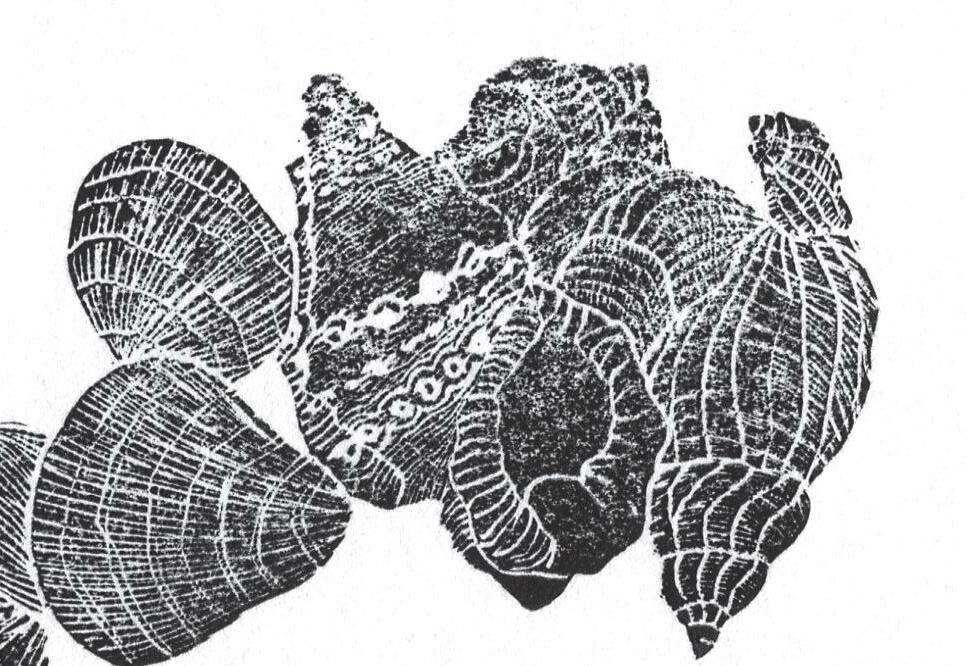

Words Bianca Connolly Illustration Cara J Hornett

18 | 19

When Christopher Columbus first 'discovered' the Caribbean in 1492 he was not the first to set foot in the area. While there’s very little recorded information before this time, it is estimated that the first tribes to inhabit the islands came from South America circa 1600 BC. These original Amerindians were the Arawaks and the Kalinagos (also known as Caribes).

As the European countries began colonizing around 1635, the Amerindians refused to work as their laborers and signed a treaty, the Treaty of Fort. St. Charles, to give them the status of 'National entity', that was meant to protect them. However, their population slowly declined during the following two centuries, most likely due to disease and poor treatment. Today, the last descendants can be mainly found on the island of Dominica.

Take a trip back in time with this illustrated map of the Caribbean islands, featuring their original names.

Lorsque Christophe Colomb a découvert les îles des Caraïbes en 1492, il n'était, en fait, pas le premier homme à y mettre le pied. Bien que nous ayons très peu d'informations datant de cette époque, on estime que les premiers habitants des îles sont venus d'Amérique du Sud vers 1600 avant J.C. Ces tribus amérindiennes étaient les Arawaks et les Kalinagos (également connus sous le nom de Caraïbes).

Alors que la colonisation européenne se développe intensivement à partir de 1635, les anglais et français accordent aux Amérindiens (qui refusent alors de travailler comme esclaves ou ouvriers) le status "d'entité nationale” en signant un traité au Fort St-Charles de Basse-Terre en 1660. Malgré cela, leur population déclinera au cours des deux siècles suivants en raison de la maladie et des mauvais traitements. Aujourd'hui, leurs derniers descendants se trouvent principalement sur l'île de la Dominique.

Faites un voyage dans le passé grâce à cette carte illustrée des îles des Caraïbes reprenant leurs noms d'origine.

Malliouhana (Anguilla)

Oüalichi (St. Maarten / St-Martin)

Amónhana (Saba)

Oüanálao (St. Barthélemy)

Aloi (Statia)

Liamáiga (St Kitts)

20 | 21

Jamaich (Jamaica)

Cuba (Cuba)

Cuba (Cuba)

Aïtij (Haiti / St. Domingo)

Borrinken (Puerto Rico)

Malliouhana (Anguilla)

Oüalichi (St. Maarten / St-Martin)

Iáhi (St. Croix)

Liamáiga (St. Kitts)

Amónhana (Saba) Aloi (Statia) Oüaliti (Nevis)

Oüanálao (St. Barthélemy)

Oüahómoni (Barbuda) Oüaladli (Antigua)

Allioüágana (Monserrat)

Caloucaéra (La Guadeloupe)

Aïchi (Marie-Galante)

Oüaitoukoubouli ( Dominica)

Ioüanacéra (Martinique)

Ioüánalao (St. Lucia)

Iouloümain (St. Vincent) Becouïa (Bequia)

Camáhogne (Grenade)

Ichirougánaim (Barbados)

22 | 23

— Confucius

“The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name.”

Origins

WORDS BIANCA CONNOLLY | ILLUSTRATIONS CARA HORNETT 24 | 25

It can be difficult to imagine St. Barth as anything other than the glimmering, cosmopolitan hub it is today. A place equal parts bohemian and glamorous, known for its famous clientele and almost other-worldly vibe. But everything starts somewhere else, and this land’s story is no exception. The island’s heart and soul, strength and vigor, originated in a far different reality from that of present day. Here, an ode to the foundation on which this paradise was built.

The island receives its first batch of visitors — a group of French settlers from the neighboring island of St. Christopher (now known as St. Kitts). They stumbled upon the shores of St. Barth, but were disinterested in the rocky, arid land, and made no attempt to colonize.

Phillippe de Lonvilliers de Poincy, Commandeur de l’ordre de Saint Jean de Jérusalem, nommé Capitaine general des iles d’Amérique, makes the first attempt to inhabit the island, sending 50 settlers led by ‘Le Sieur Gente Jaques’, along with a few slaves. At this point the terrain was not terribly different from what it had been in 1629, but despite the barren land and poverty, these settlers made St. Barth their home for eight years, setting the tone for the strength and perseverance still characteristic of the island’s locals today.

C’est Philippe de Lonvilliers de Poincy, Commandeur de l’Ordre de Saint Jean de Jérusalem, nommé Capitaine général des îles d’Amérique, qui sera le premier à s’y installer, envoyant 50 colons conduits par ‘le Sieur Gente Jacques’, ainsi que quelques esclaves. A ce moment-là le terrain était peu différent de lors de sa découverte en 1629. Cependant malgré l’aridité et la pauvreté ces colons s’y établirent pendant huit ans, imprimant à jamais la force et la persévérance qui caractérisent encore aujourd’hui les habitants de cette île.

L’île reçoit sa première vague de visiteurs, un groupe de colons français en provenance de l’île voisine de St Christopher (connu maintenant sous le nom de St Kitts). Venus par hasard sur ces côtes ils ne s’attardèrent pas à la vue de cette terre rocheuse et aride.

1629

1648

Imaginer St Barth d’aujourd’hui autrement qu’un lieu cosmopolite et fascinant peut s’avérer difficile. Un endroit où se côtoient le bohème et le glamour, connu pour sa clientèle de célébrités et son atmosphère si particulière. Mais toute chose a ses origines ailleurs et l’histoire de St Barth ne fait pas exception à la règle. Son âme ainsi que son cœur, sa force et sa vigueur sont nés à la faveur d’une réalité bien autre que celle d’aujourd’hui. Voici une ode à ce qui aura permis à ce paradis de se construire.

On a fateful day in 1656, a ferocious, cannibal tribe of Caribbean natives from Central America lands on shore under the cloak of darkness, massacring almost every resident, save a few who managed to escape by raft to St. Christopher. It is said that the Caribs mounted the victims heads on poles and used them to decorate Lorient beach. Not surprisingly, it took the Gouverneur de Poincy three years to convince a group of 30 brave souls to inhabit the island again. Most came from Brittany or Normandie, and lived in such a state of poverty that the real risks of autonomous living on a virgin island didn’t deter them.

From 1671 – 1681, the island’s population increases by 43, along with an increase in cattle. The oldest written proof that documents the first settlers by name can be found in the Rolle des Habitants, created on July 18th, 1681. This document’s importance is paramount, as it presents the list of names of the first settlers, 22 years after they arrived on the island.

De 1671 à 1681, la population humaine (43 âmes) et celle du bétail de l’île augmentent. Le Rolle des Habitants, un document d’une importance capitale, avec les noms des premiers colons, et créé le 18 juillet 1681 (22 ans après leur arrivée) atteste de la véracité de ce développement.

Un jour funeste de 1656, une tribu d’indigènes des Caraïbes d’Amérique centrale, cruelle et cannibale, débarque sur les côtes. A la faveur de l’obscurité ils massacrent presque tous les habitants, quelques uns réussissent à s’enfuir en radeau vers St Christophe. La légende veut que les Caraïbes mirent les têtes des victimes sur des piques pour les faire trôner sur la plage de Lorient. On n’est pas surpris d’apprendre que le Gouverneur de Poincy mit trois ans pour convaincre un groupe de 30 braves de repeupler l’île. La plupart venaient de Bretagne ou de Normandie. Etant donné la misère où ils vivaient, ils étaient prêts à tenter l’aventure sur cette île encore vierge.

It’s not until 1724 that further information is presented about the island’s population, found in the parish registers. These allow us to have an accurate read of the population, 40 years after the Rolle des Habitants of 1681.

Il faudra attendre 1724 pour trouver dans les registres de paroisses plus d’informations sur la population de l’île. Quarante ans après le Rolle des Habitants de 1681 ces registres permettent d’avoir une bonne mesure sociologique.

1656 1724

1681

THE FIRST SETTLERS OF ST BARTH LEFT FROM THE FRENCH TOWNS OF ROUEN (QUESTEL), LES SABLES D’OLONNE (GRÉAUX), CHATEAU-CHINON (BERNIER), SANSAIS (LÉDÉE), SAINTES (VITTET), BORDEAUX (BERRY/LAPLACE) AND TOULON (AUBIN).

28 | 29

These documents give us a clear picture of who was named as Les Habitants de Saint-Barthélémy in 1730: 180 people living on the island from 1724 – 1730. These numbers closely follow the list written by Champigny on June 17th, 1730, which counted 192 residents and 129 slaves, for a total of 321 people.

There were only 11 families in the Rolle des Habitants of 1681: Aubin, Bernier, Duboc, Faverel, Gréaux, Hode, Masson, Mutrel, Pottier, Tardieu and Vittet. During the next 50 years these families would be joined by: Berry, Brin, Laplace, Ledée, Magras, Maye, Questel and Quinquis.

The island continues to grow both in population and magnitude, but the thing that really sets it apart from so many other beautiful locales is its genuine spirit. There was not much economic gain, therefore St Barth’s was basically abandoned and left to itself for two whole centuries. Its early settlers did not have it easy fending for themselves, and most likely could not have fathomed what it would become fast-forwarding to 2018, but their determination, courage and steadfastness made this island what it is today. And that makes all the difference.

Ils permettent de savoir clairement qui étaient les habitants de Saint-Barthélémy en 1730, entre 1724 et 1730 on en compte 180. Ce chiffre se rapproche de celui établi par Champigny le 17 juin 1730 avec un total de 321 habitants, avec 192 résidents et 129 esclaves.

Sur le Rolle des Habitants de 1681 on ne compte que 11 familles dont voici les noms: Aubin, Bernier, Duboc, Faverel, Gréaux, Hode, Masson, Mutrel, Pottier, Tardieu et Vittet. Durant les 50 années suivantes viendront les familles Berry, Brin, Laplace, Ledée, Magras, Maye, Questel et Quinquis. L’île continue sa croissance en population et en ampleur, mais son authenticité est ce qui la distingue de beaucoup d’autres endroits tout aussi magnifiques. Comme il y avait peu d’enjeux économiques l’île de St Barth fut abandonnée à elle-même pendant deux siècles entiers. Ce n’est pas sans mal que ses premiers habitants réussirent à s’implanter, jamais sans doute n’auraient-ils pu imaginer ce qu’elle deviendrait jusqu’à nos jours, mais leur détermination, tout autant que leur courage et leur persévérance ont fait de cette île ce qu’elle est aujourd’hui. Voilà ce qui fait la différence.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

I.

CENSUS LIST OF 1671 (336 INHABITANTS, OF WHOM 290 WERE WHITE)/ LISTE NUMÉRIQUE DE 1671 (336 HABITANTS DONT 290 BLANCS).

— 85 Maitres de cases — 47 femmes mariées — 53 Garcons — 43 filles — 15 serviteurs artisans — 8 serviteurs blancs — 36 servantes blanches — 25 nègres — 15 nègresses — 6 négrillons et négrites

Le cheptel etait composé de 16 boeufs, 60 vaches, 25 veaux et UNE bourrique.

LIST OF SETTLERS OF THE ROLL OF INHABITANTS ON JULY 18TH 1681 (379 INHABITANTS, OF WHOM 295 WERE WHITE)/ LISTE DES COLONS DU ROLLE DES HABITANTS DE 18 JUILLET 1681 (379 HABITANTS DONT 295 BLANCS).

— 71 hommes — 59 femmes mariées dont 2 veuves — 91 garçons — 74 filles — 23 nègres — 30 nègresses — 24 négrillons et négrites

30 | 31

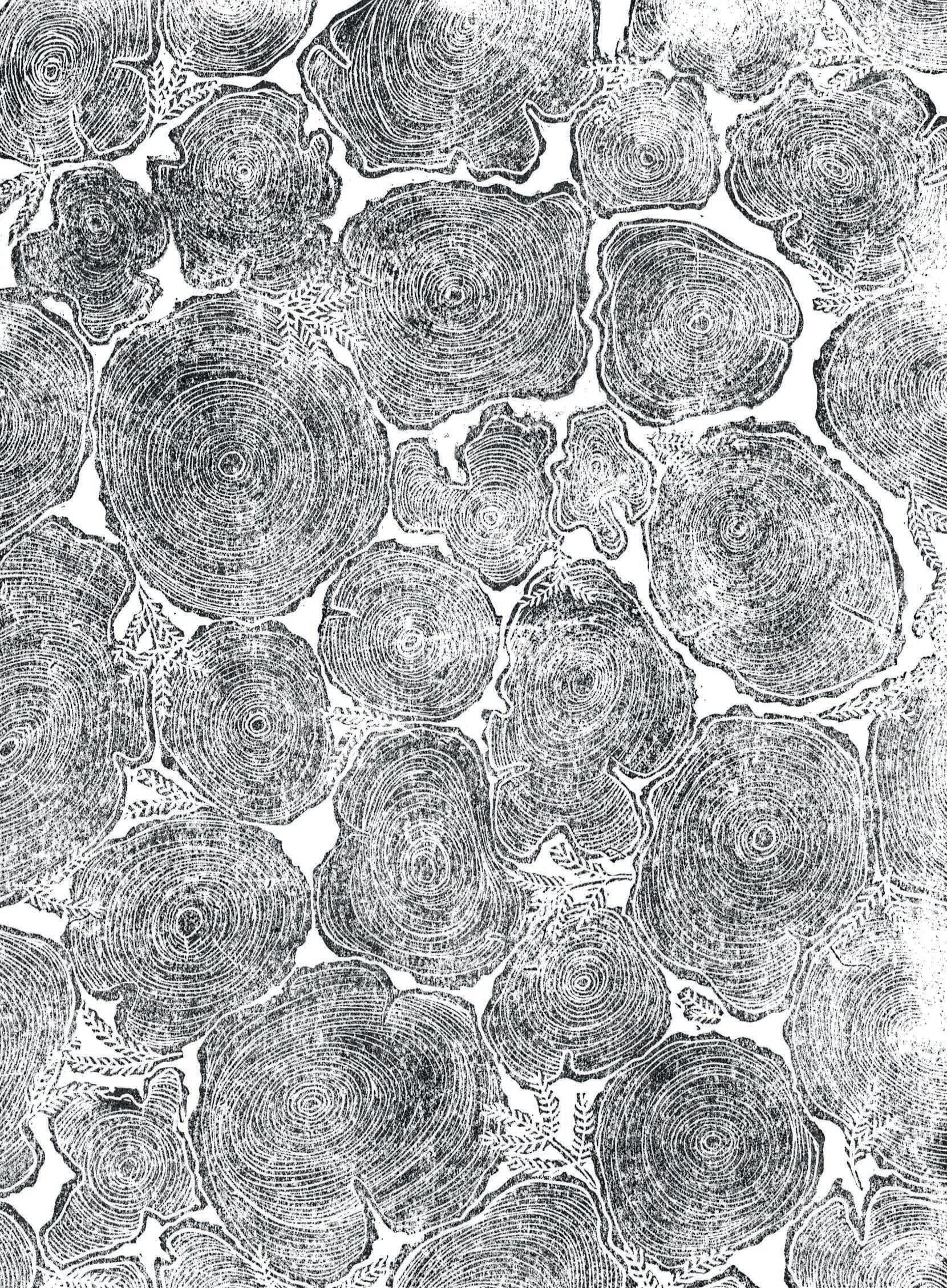

A glance at our Swedish past

WORDS SÉBASTIEN & JASMINE MARTINON ILLUSTRATIONS CARA HORNETT

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

If you spend enough time in St Barths, you cannot help but notice lingering vestiges of the island’s Swedish past.

Indeed, in 1784 the king of France was tempted by a swap for some warehouses in the port of Goteborg in Sweden in exchange for the island of St Barts. On March 7th 1785 in Versailles, Louis XVI and Gustave III signed the treaty that sealed this agreement.

The port of Carenage was renamed Gustavia by the new governor, Salomon Mauritz von Rayalin, and this was the beginning of the capital’s golden age. Each year, several thousand ships passed through Gustavia. The island was declared a free port and all nations were allowed to enter freely and exempted from customs dues. Hundreds of buildings were erected on both shores. Warehouses and sheds, in particular for naval repairs, were situated on the west bank known as La Pointe and on the eastern side the streets were lined with proper quays and Swedish style houses. The port became a strange bustling hub of shopkeepers, adventurers, foreigners and sailors, and around this time the population of the islands was around 3,880. The island’s locals remained unaffected by Gustavia’s prosperity, their only source of revenue were their patches of cotton. Gustave III decided that they were so impoverished they would be exempt from paying taxes. There were no mixed marriages but the local inhabitants lived in peace with the Swedes until the french revolution and a turbulent episode with the Governor Berpstadt.

During a riot, the governor turned his cannons on the town, but Sergeant Major August Nyman refused to obey orders, playing for time in hopes that the situation would resolve itself. And it worked, Nyman was considered a hero and the capital was spared. After his death, a huge crowd accompanied his ashes, placed in a beautiful urn, atop a hill overlooking the port. This urn is still visible today in the Gustavia museum.

The Swedish period was not all smooth. After a succession of disasters, including a terrible fire of unusual violence in the town of Gustavia, hurricanes, droughts and finally an outbreak of yellow fever, Oscar II of Sweden was trying to get rid of this costly nuisance. The United States of America and Italy wanted nothing to do with the island and in 1877, under the treaty of August 10th, Sweden handed St Barths back to France.

Though this period seems forgotten, many artifacts from the Swedish era are still visible in the island’s capital. The Dinzey house, which was built somewhere between 1822 and 1830, and now owned by the Honorary Consul of Sweden, was listed as the first historic monument in St Barth on April 17th 1990. You can admire the Swedish steeple which was built between 1796 and 1799, as well as one of the four citadels built during the Swedish period, Fort Oscar, which is currently the gendarmerie of St Barths. As for the others, such as Fort Karl and the battery of Fort Gustav III, you will only find the base and rumbles of their ruins. If you visit the hill tops where they once stood you can guess why they were built at these locations.

Hopefully some curious readers will explore these for themselves and discover one of the many fascinating facets of St. Barth’s.

Left GUSTAVE III OF SWEDEN THE ISLAND WAS DECLARED A FREE PORT AND ALL NATIONS WERE ALLOWED TO ENTER FREELY AND EXEMPTED FROM CUSTOMS DUES. HUNDREDS OF BUILDINGS WERE ERECTED ON BOTH SHORES. THE PORT BECAME A STRANGE BUSTLING HUB OF SHOPKEEPERS, ADVENTURERS, FOREIGNERS AND SAILORS. 32 | 33

Si vous avez passé un certain temps à St-Barth, vous avez certainement remarqué les vestiges persistants du passé suédois de l’île.

En effet, en 1784, le roi de France fut tenté d’échanger l’île de SaintBarthélemy contre des entrepôts dans le port de Goteborg, et, le 7 mars 1785 à Versailles, Louis XVI et Gustave III signèrent donc le traité qui scella cet accord.

Le port de Carénage fut alors rebaptisé Gustavia par le nouveau gouverneur, Salomon Mauritz Von Rayalin, et ce fut le début de l’âge d’or de la capitale. L’île est déclarée port franc et plusieurs milliers de navires transitent alors chaque année par Gustavia, toutes les nations étant autorisées à entrer librement, exonérées des droits de douane.

De nombreux bâtiments furent alors érigés. Entrepôts et hangars sur la rive Ouest, connue sous le nom de La Pointe, pour les réparations navales, et, quais et maisons de style suédoissur le côté Est. Le port était alors animé de commerçants, d’aventuriers, d’étrangers et marins de tous bords pour une population totale d’environ 3880 habitants.

Les habitants de l’île, dont la seule source de revenus était la vente de coton, n’ont pas vraiment bénéficié pas de cette prospérité. Ils furent donc exonérés, par Gustave III, de payer des impôts.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

Il n’y eut pas, ou peu, de mariages mixtes mais locaux et Suédois ont vécu en paix jusqu’à la Révolution française et, en particulier, un épisode tumultueux avec le gouverneur Berpstadt.

En effet, lors d’une émeute, le gouverneur ordonna de tourner les canons vers la ville, mais le sergent-major August Nyman refusa d’obéir aux ordres, jouant la montre dans l’espoir que la situation se résoudra d’elle-même. Cela fonctionna et la capitale fut épargnée. Nyman fut dès lors considéré comme un héros par la population. Après sa sa mort, une foule considérable accompagnait ses cendres, qui furent placées dans une belle urne au sommet de la colline surplombant le port. Cette urne est encore visible aujourd’hui au musée de Gustavia.

A suite d’une succession de catastrophes, dont un terrible incendie, des emmeutes, des ouragans, des sécheresses et enfin une épidémie de fièvre jaune, Oscar II de Suède decida de se débarrasser et de vendre de cette coûteuse dépendance. Cependant ni les États Unis d’Amérique ni l’Italie ne furent intéressés, et, le 10 août 1877, en vertu d’un nouveau traité, la Suède rétrocède St-Barth à la France.

Bien que cette période semble aujourd’hui oubliée, il existe encore, principalement à Gustavia et alentours, de nombreux artefacts visibles de l’époque suédoise. La maison Dinzey, par exemple, construite entre 1822 et 1830 est classée Monument Historique le 17 avril 1990 par son propriétaire actuel, le consul honoraire de Suède.

Vous pouvez aussi admirer le clocher suédois, construit entre 1796 et 1799, ainsi que l’une des quatre fortifications encore debout : le Fort Oscar, qui abrite actuellement la gendarmerie de St-Barth. D’autres, comme le fort Karl ou la batterie du fort Gustav III, ne sont plus que des ruines. Aussi, en parcourant certains sommets des collines entourant Gustavia vous pourrez observer d’autres vestiges et vous devinerez aisément la raison stratégique de ces emplacements.

Nos lecteurs les plus curieux iront probablement découvrir par eux-mêmes l’une des nombreuses facettes fascinantes de St-Barth.

34 | 35

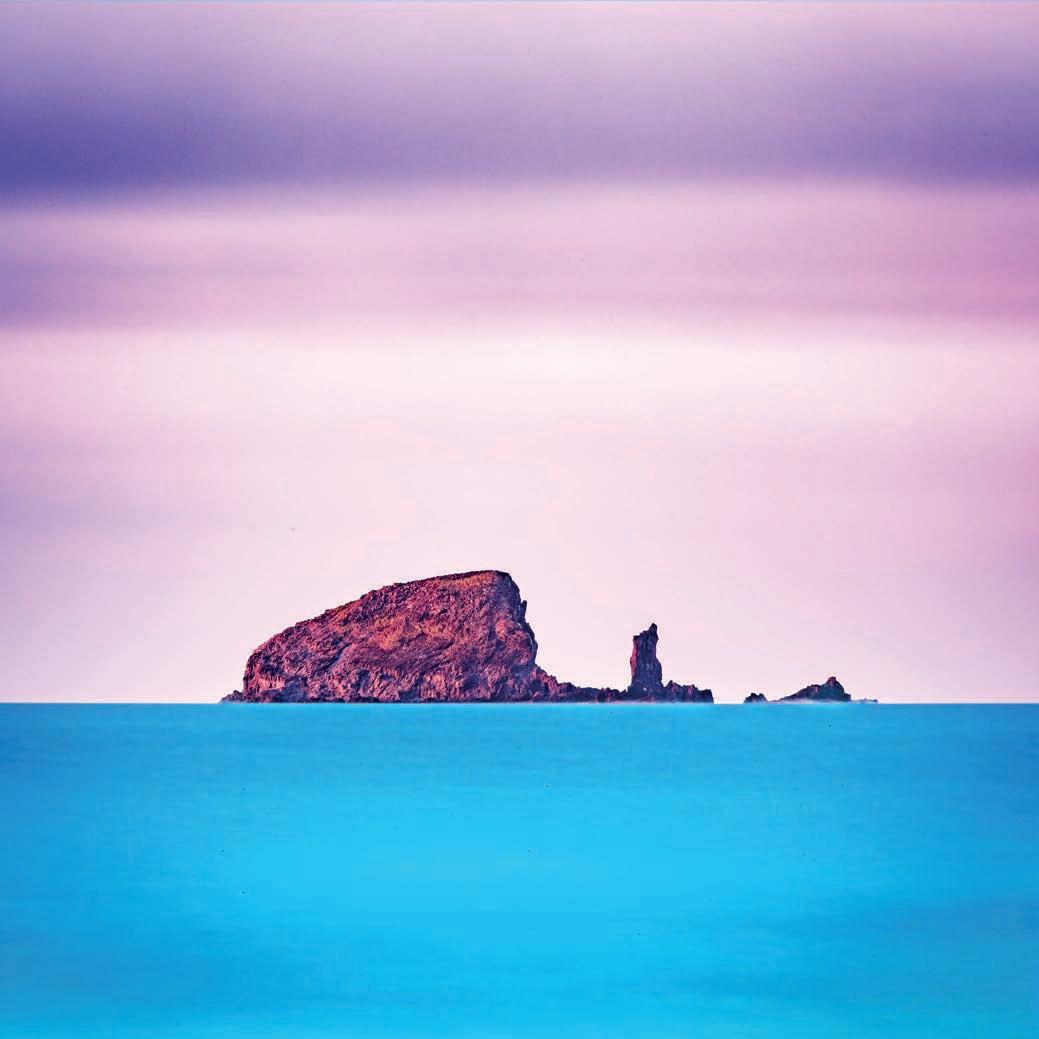

Acid Islands

PHOTOS SÉBASTIEN MARTINON WWW.ISLANDS.PHOTO

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

LE BOULANGER 36 | 37

PAIN DE SUCRE SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

TORTUE 38 | 39

TOC VERT SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

COCO 40 | 41

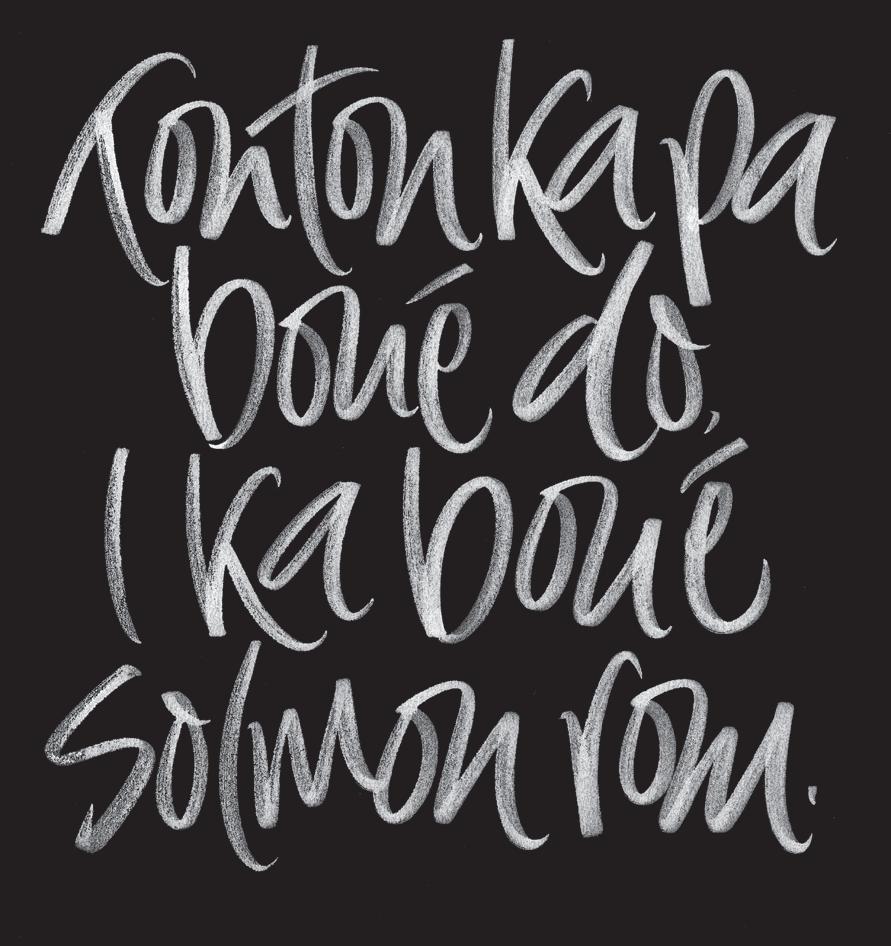

LIVING LANGUAGES

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

Words Ray Parish/Laurie Pinto Illustration Rachel Yallop

The island’s spoken word is as varied as its topography. Between 1986 and 2009, linguist and author Julianne Maher conducted extensive research into the nature of the languages and dialects used by native St. Barth speakers. She published her work in 2013 as The Survival of People and Languages (Brill). Building on earlier sociological and linguistic studies, Maher’s scholarly work sheds light on the puzzling nature of languages on St. Barth. How did four distinct languages come to be used on such a small island? Why is bilingualism between St. Barth’s two predominant tongues so rare? How did English take hold in Gustavia? What are the origins of Saline French?

Even in the time that Maher was conducting her research, rapid social transformation on the island altered St. Barth’s linguistic makeup. She reports in the book’s epilogue that Saline French may already be extinct, and that St. Barth Creole is fading. St. Barth Patois is increasingly recognized as a valuable element of the island’s cultural heritage, and so may resist the rising tide of standardized French.

“The important thing is that local people remain aware of these languages,” explains Maher, “so that it’s not just crazy linguists who come along and discover these things. It’s deeply embedded in the culture of St. Barth. This is their patrimony.” Maher hopes that The Survival of People and Languages will inspire more interest in the subject, with planned French and paperback versions bringing the work to a wider audience.

ST. BARTH CREOLE

Spoken predominantly in the island’s windward region, this tongue is related to the creoles of Guadeloupe, Martinique, Dominica and St. Lucia. It is linguistically distinct from other French creoles such those found in Haiti and Louisiana. By analyzing the records of exodus and return of the island’s populations during the 18th century, Maher determined that St. Barth Creole most likely grew out of the Martinican French spoken by families returning to the island from St. Vincent in the late 1700’s. These settlers lived mainly in the Windward region. Unlike the island’s patois, the creole is more associated by its speakers with Caribbean identity. “Eh ben, mwen té ka renmasé li, té ka mété li dan ti panyé …”

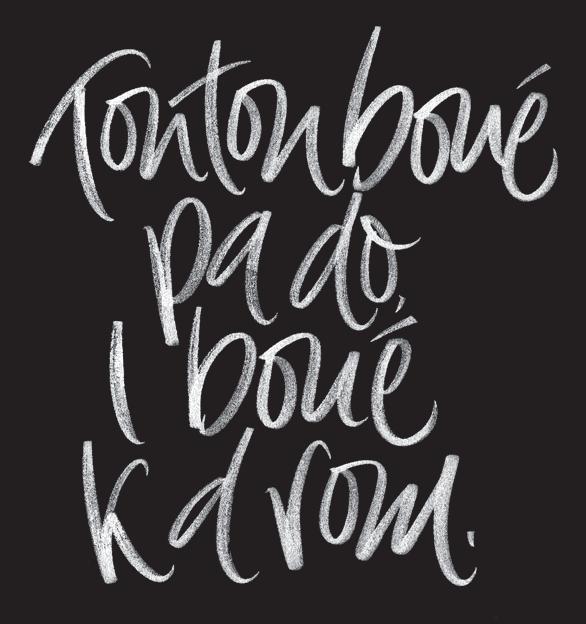

ST. BARTH PATOIS

Along with a French dialect spoken by St. Barth transplants in St. Thomas, St. Barth Patois is regarded by Maher and other linguists as the oldest form of West Indian dialectical French still used today. The tongue shows Norman influence, in that some words typical to French spoken in Normandy are seen in St. Barth Patois, such as amique for “when.” It also borrows from English, using variants of words and phrases such as “boy,” “bucket,” and “black eye.” The patois is more associated by its speakers with France and French identity, and may even be a precursor to creole in the Caribbean – a linguistic “living fossil” offering a glimpse of what spoken language was like here centuries ago. “Parler mwe twe …”

SALINE FRENCH

The form of French once spoken in the region around the salt ponds in Grand Saline is one of the island’s greatest linguistic mysteries. Maher describes the dialect as bearing some resemblance to both St. Barth Patois and Creole, but with an “unusual pitch contour” and nasality that led other St. Barth people to call the dialect “crazy.” This peculiar tongue was often unintelligible to outsiders. Maher speculates that it is a variant of the island’s original colonial French, perhaps influenced by the creole of neighbors in the windward region. If it is not already extinct, it is nearly so, and thus its origins may never be known for certain. “I fo je travayré du matin o swer pou lé sogny, eu. Mwa avwer sé térin la sa …”

GUSTAVIA ENGLISH

The puzzling use of English in St. Barth is sometimes attributed to contact with St. Kitts in the 1600’s, but Maher finds that unlikely. Wars between England and France during the 1700’s would have made it difficult to be an anglophone in Gustavia. More likely is that English speakers came to Gustavia from neighboring islands during the openness of the Swedish period. A newspaper published in Gustavia from 1803 to 1819 was, according to Maher, “essentially in English,” indicating that the language had taken hold in the daily activities of the port. Today, English has been largely replaced by French in town, with many families switching to facilitate their children’s success in school. “An’ de ship tro me off, an’ ah flew out in de air, in de sea. Everybody was goin’ crazy on board …”

42 | 43

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

Le langage parlé sur l’île est aussi varié que sa topographie. Entre 1986 et 2009, Julianne Maher mis en place un nombre considérable de recherches concernant la nature et les origines des différents langages et dialectes utilisés par les St Barth natifs. En 2013, elle publia son travail intitulé ‘La survie de la population et du langage’ dans lequel elle se basa sur des études sociologiques et linguistiques sur le sujet. L’étude de Maher clarifia la nature tant variée que déconcertante des langues vivantes de St Barth. Pourquoi 4 langues bien distinctes sont-elles utilisées, à différents niveaux, sur une ile de si petite envergure ? Pourquoi le bilinguisme entre les deux langues les plus utilisées de St Barth est-il si rare ? Comment les Anglais se sont-ils installés à Gustavia ? Quelles sont les origines des Salines Françaises ?

Au moment où Maher menait sa recherche, de nombreux changements sociaux et économiques eurent un impact direct sur la composition du langage de St Barth. Dans l’épilogue de son livre, Maher explique alors que la Saline Française pourrait être amené à disparaître, tout comme le créole St Barth. Le patois St Barth est quant à lui de plus en plus reconnu comme l’unique et seul héritage culturel de l’ile, ce qui peut expliquer pourquoi il continue de s’opposer au français standard.

LE CRÉOLE ST BARTH

Parlé principalement dans la région venteuse de l’île – Lorient, Camaruche, Marigot, Vitet, Cul de Sac/Toiny, Grand Fond – cette langue est liée au créole de Guadeloupe, Martinique, Dominique ainsi qu’à celui de St Lucie, Grenades et Trinidad. Elle est cependant très différente d’autres patois créoles français comme ceux parlés à Haiti ou en Louisiane. En analysant les archives historiques en rapport à l’exode et au retour des populations des iles durant le 18ème siècle (dus aux attaques fréquentes des anglais), Maher réalisa que le créole St Barth semblait s’être développé à la fin des années 1700 en relation au français martiniquais parlé par les familles après un séjour à St Vincent. (j’ai pas réussi à mieux traduire cette phrase qui me paraît longue et compliqué) À leur retour à St Barth, ces colons s’étaient alors principalement installés dans la région venteuse de l’ile. Contrairement au patois St Barth, le créole est plutôt associé à l’identité caribéenne au sens large par ceux qui le parlent. “Eh ben, mwen té ka renmasé li, té ka mété li dan ti panyé …”

LE PATOIS ST BARTH

Tout comme le dialecte français parlé par les St Barth transplantés à St Thomas, le patois St Barth est vu par Maher et d’autres linguistes comme la plus vieille forme de dialecte amérindien français toujours fortement employé dans la région. Cette langue révèle également des influences normandes par l’utilisation de certains mots caractéristiques du langage parlé en Normandie comme amique qui signifie quand . Ce patois s’est par ailleurs aussi inspiré de l’anglais puisqu’il utilise diverses variantes de mots et phrases comme boy , bucket , et black eye . Cependant, le patois est davantage associé par ses locuteurs à la France et l’identité française. Il pourrait même s’avérer être un précurseur du créole dans les Caraïbes, un fossile vivant en terme de langage qui offre un aperçu rare de ce à quoi le langage parlé pouvait ressembler plusieurs siècles auparavant dans les Antilles. ‘Parler mwe twe’.

LA SALINE FRANÇAISE

Le type de langue française qui était jadis parlé dans la région qui entoure les mares salées de la Grande Saline est un des plus grands mystères linguistiques de l’ile. Maher décrit ce dialecte comme une consonance mélangeant à la fois le patois et le créole St Barth avec un ton et une texture inhabituels ainsi qu’une nasalité qui amenaient les autres habitants à définir ce dialecte comme fou . Cette langue particulière n’était pas toujours compréhensible pour les locuteurs créoles ou patois. Maher avance que ce langage est une variante du français colonial originel de l’ile potentiellement influencé par les voisins créoles de la région venteuse. Si ce patois n’a pas encore disparu, il n’en reste pas plus utilisé, et ses origines resteront à jamais un mystère difficilement élucidable. ‘I fo je travayré du matin o swer pou lé sogny, eu. Mwa avwer sé térin la sa.’

L’ANGLAIS À GUSTAVIA

À St Barth, certaines théories attribuent l’utilisation de l’anglais aux rapports qu’entretenaient l’ile avec St Kitts dans les années 1600. Maher pense cependant qu’une telle assertion reste peu probable étant donné que les guerres entre l’Angleterre et la France durant les années 1700 n’auraient pas réellement permis à un anglophone de s’installer à Gustavia. Il serait alors plus plausible que les locuteurs anglais soient arrivés à Gustavia en provenance des iles voisines durant la période de transparence suédoise. Selon Maher, un journal publié essentiellement en anglais à Gustavia entre 1803 et 1819 indique que cette langue s’était dès lors répandue de manière significative dans les activités quotidiennes du port. De nos jours, l’anglais a été largement remplacé par le français dans la ville, beaucoup de familles ayant pour désir de faciliter la réussite de leurs enfants à l’école. ‘An’ de ship tro me off, an’ ah flew out in de air, in de sea. Everybody was goin’ crazy on board.’

44 | 45

THE IMPORTANT THING IS THAT LOCAL PEOPLE REMAIN AWARE OF THESE LANGUAGES,” EXPLAINS MAHER, “SO THAT IT’S NOT JUST CRAZY LINGUISTS WHO COME ALONG AND DISCOVER THESE THINGS. IT’S DEEPLY EMBEDDED IN THE CULTURE OF ST. BARTH. THIS IS THEIR PATRIMONY.

TRADITION, REVISITED

Words Bianca Connolly Photography Sébastien Martinon Stak Photo

Words Bianca Connolly Photography Sébastien Martinon Stak Photo

It may not be immediately apparent today, but at the heart of St. Barth’s worldrenowned reputation lies a rich history in beautiful straw works. From hats to baskets to children’s toys, these intricately braided creations became both a symbol of cultural heritage and a vital source of income for the island. Thousands of straw hats were exported every year, and unlike souvenir versions of similar styles in other locales, the famous St. Barth straw hat needed no indication of origin – it was the original Panama hat. While the entrepreneurial spirit of successive generations carried the island’s economy into modernity, today a small group of St. Barth women carry on the special tradition of this painstaking craft. The complex movement of the long straw plaits between the fingers of these talented artisans serves as a remembrance of a once-vibrant industry that reached international popularity.

History

The simple craft of weaving existed in St. Barth as a form of handiwork practiced at home from the time of the earliest settlers, and by the late 19th century, dried leaves of the Latania palm tree were being imported from other Caribbean islands for a large sum. In 1890, Pere Morvan completely changed the game, eliminating the need for imports by bringing seedlings to St. Barth and planting them near Corossol and Flamands. Poor families living in these neighborhoods saw in this new development a way to prosper, and hat-making quickly brought unprecedented activity to previously idled areas. International traders would stop by to place large orders, and all family members had to do their part, sometimes weaving late into the evening guided only by candles or moonlight. St. Barth’s straw-weaving industry gained even more ground in 1925, when Blanche Petterson, a skilled craftswoman from St. Martin, brought to the island an improved method of hat-making, greatly elevating the quality and introducing various decorative braiding techniques.

Botany

The Latania, also known as the Latan Palm, is a slow-growing, single trunk palm that can reach as tall as 30 feet when mature. It is recognizable by its wide, fan-shaped fronds. The Latania’s high tolerance to both drought and salty air allowed it to survive in St. Barth’s frequently harsh conditions. Like other palms, it is naturally adapted to the challenges of tropical storms and hurricanes, so while high winds might denude a plant of its fronds, it would survive to produce more.

Method

The process of preparing the palm fronds includes several steps. The Latania leaves must first be dried, then carefully prepared for plaiting (or braiding) into the uniform and usable strands . During the drying process, it’s necessary to make strands that are as flexible and pale as possible in order to ensure malleability and the finest color. Only the youngest fan-shaped leaves near the top of the tree are used, and only before they have opened. The fronds are each cut by hand, unfolded and the leaflets are separated from each other. They are then hung outdoors to dry in the sun for two weeks, taken in every night to protect from possible rain – moisture would cause them to become brittle and change color.

46 | 47

Once the leaves are dried, the strands are plaited in one of seven ways, each of which gives the ultimate product a particular look. To ensure uniformity when creating the strands, the thick edges of the frond are removed and what remains is cut into long, equally sized strips running the length of the leaf. Once plaited, they are kept in rolls until needed for a specific creation. Though the process has been honed and improved, the work of today’s rare artisans on St. Barth is fundamentally the same as in generations past – a living reflection of a valuable and cherished heritage.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

La fabrication artisanale d’objets et accessoires en paille marqua l’histoire de St Barth. Bien que cette réputation ait perdu en notoriété, les chapeaux, paniers et autres créations aux tressages complexes étaient à une époque un moyen important de gagner sa vie sur l’île. Chaque année, des milliers de chapeaux de paille étaient exportés et reconnus pour leur qualité et originalité. Le chapeau de St Barth ou chapeau Panama fut imité mais jamais égalé malgré les tentatives de reproduction. Le tressage de paille évoque ainsi non seulement la culture et l’histoire de St Barth mais également une industrie bourgeonnante qui a atteint une popularité internationale. Même si les nouvelles générations se sont depuis tournées vers d’autres activités plus modernes, une minorité de femmes se prête toujours à ce travail minutieux, perpétuant une tradition d’exception reflet de l’ambiance authentique de St Barth.

Histoire

À la fin du 19 ème siècle, les feuilles séchées des lataniers (palmiers exotiques) étaient importées des îles caribéennes environnantes pour une somme d’argent considérable. En 1890, Père Morvan changea la donne lorsqu’il fit l’acquisition de jeunes pousses pour les planter aux alentours de Corossol et de Flamands. Dès lors, l’importation devint obsolète. Les familles pauvres qui vivaient dans ces quartiers virent en cet avancement un moyen de prospérer. La fabrication de chapeaux se transforma rapidement en une véritable industrie et motiva du même pas les classes populaires à travailler davantage. Des collectionneurs internationaux venaient alors passer commande et chaque membre des familles St Barth s’impliquait dans le processus de création. Il leur arrivait parfois de tisser tard le soir avec pour seul éclairage celui des bougies ou du clair de lune. Blanche Petterson, originaire de St Martin, arriva sur l’île en 1925. Cette artisane aux nombreux talents initia alors les St Barths à une nouvelle méthode de création de chapeaux, rendant meilleure leur qualité. Elle leur transmit également son savoir-faire en matière de tressage ornemental.

Botanique

Le Latanier est un palmier à la croissance lente mais dont le tronc peut atteindre une dizaine de mètres de hauteur une fois arrivé à maturité. On le reconnait à ses grandes feuilles en forme d’éventail. Cet arbre s’adapte bien à la sècheresse ainsi qu’aux embruns, ce pourquoi on le retrouve souvent aux abords des plages de St Barth.

Méthode

Plusieurs étapes sont nécessaires à l’utilisation de la paille. La première implique la déshydratation des feuilles de palmiers. Durant cette phase, il est important de faire des torons (assemblages de feuilles pour former un cordage) extrêmement flexibles et pâles pour obtenir une bonne malléabilité et de jolies couleurs. Seules les nouvelles feuilles au sommet de l’arbre sont utilisées. Chaque feuille est coupée à la main puis triée, les plus petites sont départagées. Elles sont finalement exposées au soleil pendant 2 semaines et protégées des averses - l’humidité changerait en effet la couleurs des torons et les rendrait fragiles.

Lorsque les feuilles sont séchées, elles sont tressées de différentes manières avant d’être moulées et d’obtenir leur forme finale. Les rebords épais sont enlevés et le reste est coupé de manière à former de longs cordages. Une fois tressés, les torons sont gardés sous forme de rouleaux jusqu’à ce qu’ils soient prêts à être utilisés. On compte 7 types de tresses, chacune donne à son objet un look différent. Les tresses basiques sont cousues ensemble afin de produire une multitude de créations complexes.

50 | 51

Women of the rock

WORDS: BIANCA CONNOLLY/FRANÇOISE GRÉAUX

ILLUSTRATION: SARAH MAYCOCK

“Here’s to strong women! May we know them. May we be them. May we raise them.”

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

It’s hard to imagine a St. Barth without the creature comforts and worldrenowned style that’s made it one of the premier destinations in the world. It’s just as hard to imagine the treacherous challenges of an untamed island and the sacrifices that inevitably had to be made. But these were all realities for the first inhabitants, every day partnering in a slow dance with the unknown.

As we look back at the beginnings of St. Barth, one group stands out as a shining beacon of strength: the women. Hardworking, pioneering, life-giving women whose struggle and unwavering will helped to set the foundation for the enchanting island we know and love. This is a remembering of their goodness and grit, an homage to the gangan-n 1, the mothers, the big sisters, the tantantes2, and the totos3 who led the way.

These women wore many hats, stretching themselves to fit the demands of each day (or decade). They were: — Wives of sailors and fishermen, mothers, and friends pulling the seine4 to bring back the few coulirous5 to be dried and serve as sustenance for their large family. — Stoic women who lived each day managing the wrath of the sea – a sea that sometimes separated them from their fathers, husbands, and children. —

Women who during the droughts, carried huge buckets of water on their heads, barefoot on steep, unpaved paths. — Women who labored in the salt ponds, covered head-to-toe in thick fabrics to protect themselves from the sun’s harsh reflection off the salt crystals. — Women who endured torn, burnt skin from the pineapple fields, cacti, and endless barrage of the sun as they searched for wood with which to cook. — School teachers, religious teachers, and nurses who dedicated their lives to the betterment of others. — Women who pushed for the construction of a school, a cistern, and a Chapel in order to create a solid future for generations to come. — Single women and widows who took jobs doing the hard labor their husbands would normally have done.

And in spite of the hardships, these women built a remarkable community. They helped each other with childrearing and childbirth. Mothers made little carriers for their babies out of recycled flour bags, which they also used to make undershirts for the men and outfits for the children. As they had very few ways of making money, they wove straw into baskets, hats, and other creations which they traded for flour and a few coins. This tradition has been passed down from generation to generation, and for years was

one of the artisanal goods that St. Barth became known for.

There was only one midwife on the island who would move from village to village delivering babies. She would pass her knowledge onto other untrained women who filled the position with nothing more than their learnings and life experience. Yet somehow, this seemed to be enough. Perhaps with less worldly distractions, they were more in touch with their intuition and maternal instinct. Perhaps necessity helped them rise to the occasion and then rewarded them for their bravery.

This is a story of courage, of perseverance, of valor that lives on in every square inch of this land. We know it’s always a choice to put our best foot forward – to let our souls lead the way to the greater good. These women not only knew it, they lived it – working hard and facing the most trying of circumstances, but doing so with absolute grace and gratitude. Despite everything, they were happy with the life they had. Their example reminds us of the greatness that lies in simplicity and the beauty of a humble life.

1 Grandmothers 2 Aunts 3 Great-aunts 4 A type of fishing net 5

52 | 53

Our focus turns, in particular, to the pioneering women whose dedication built the foundation for the enchanting St. Barth of today.

A type of small fish similar to sardines

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

Il est difficile d’imaginer Saint-Barth sans le confort et le style raffiné qui en font une destination touristique de renommée mondiale. Il est tout aussi difficile d’imaginer les défis innombrables d’une île sauvage et les sacrifices qui ont inévitablement dû être faits par les premiers habitants, flirtant chaque jour avec l’inconnu.

Lorsque l’on repense à cette période compliquée, les prouesses et la bravoure des femmes d’alors s’impose. Des femmes travailleuses, pionnières et vivifiantes dont la lutte quotidienne et la persévérance ont contribué à jeter les bases de l’île que nous connaissons et aimons aujourd’hui. Au souvenir de leur bonté et de leur courage, voici un hommage aux gangan-n1, aux mères, aux grandes sœurs, aux tantantes2 et aux totos3 qui ont ouvert la voie.

Ces femmes, blondes, brunes, rousses ou metis se dépassant chaque jour pour s’adapter aux exigences d’un quotidien difficile. Elles étaient : — Ces épouses de marins et de pêcheurs, ces mères de famille et amies tirant la senne4 pour rapporter les quelques coulirous5 qui, séchés, aideront à nourrir leur famille nombreuse. — Ces femmes qui avaient le double rôle de père et de mère lorsque les maris devaient s’expatrier sur d’autres îlesnotamment à Saint Thomas - pour travailler de

longs mois. — Ces femmes stoïques qui devaient subir la colère de la mer qui les séparait parfois de leurs pères, maris et enfants. — Ces femmes qui, pendant les sécheresses, transportaient d’énormes quantités d’eau sur la tête, pieds nus sur des chemins rocailleux et escarpés. — Ces femmes qui travaillaient dans les étangs salés se couvrant de la tête aux pieds de tissus épais pour se protéger de la morsure du sel. — Ces femmes qui ont parcouru, la peau brûlée par le soleil, les champs d’ananas ou de cactus afin de chercher du bois pour cuisiner. — Ces enseignantes, ces religieuses et infirmières qui ont consacré leur vie au bienêtre de la communauté. — Ces femmes qui ont poussé à la construction d’une école, d’une citerne ou d’une chapelle afin d’aider les générations futures. — Ces femmes célibataires et ces veuves qui ont dû prendre en charge les travaux difficiles que leurs maris auraient normalement dû faire.

Elles s’entraidaient pour l’éducation des enfants et les accouchement. Les mères fabriquaient des petits porte-bébés avec des sacs de farine recyclés, (qu’elles utilisaient également pour confectionner des maillots de corps pour les hommes, des tenues pour les enfants ou des petits hamacs). Comme elles avaient très peu de moyens, elles tissaient la paille pour en faire des paniers, des chapeaux et d’autres objets utiles qu’elles

échangeaient contre de la farine ou quelques pièces. Cette tradition, transmise de génération en génération, fit, pendant des années, la renommée de l’île de Saint-Barth à travers toute la Caraïbe. Il n’y avait qu’une seule sage-femme sur l’île qui se déplaçait de en quartiers pour les accouchements ou des soins. Elle transmettait souvent cette responsabilité à d’autres qui faisaient de leur mieux avec ce maigre apprentissage et leur expérience de la vie. Pourtant, d’une manière ou d’une autre, cela semblait être suffisant. Sans les distractions mondaines et modernes, elles étaient alors plus à l’écoute de leur intuition et plus en phase avec leur instinct maternel. La nécessité du moment ne leur laissant souvent pas le choix. C’est une histoire qui parle de courage, de persévérance et de bravoure qui rayonne aujourd’hui dans chaque centimètre carré de cette terre. Ces femmes travaillant dur et faisant face aux circonstances les plus difficiles le faisaient, non seulement avec courage, mais également avec une grâce et une gratitude absolue. Malgré tout, elles étaient heureuses et leur exemple nous rappelle la grandeur qui réside dans la simplicité et la beauté d’une vie humble.

1 Grand-mères 2 Tantes 3 Grandes-Tantes 4 Un filet de pêche

5 Petit poisson ressemblant à une sardinea

Au souvenir des femmes dont la lutte quotidienne et la persévérance ont contribué à jeter les bases de l’île que nous connaissons et aimons aujourd’hui.

54 | 55

There was only one midwife on the island who would move from village to village delivering babies. She would pass her knowledge onto other untrained women who filled the position with nothing more than their learnings and life experience.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

56 | 57

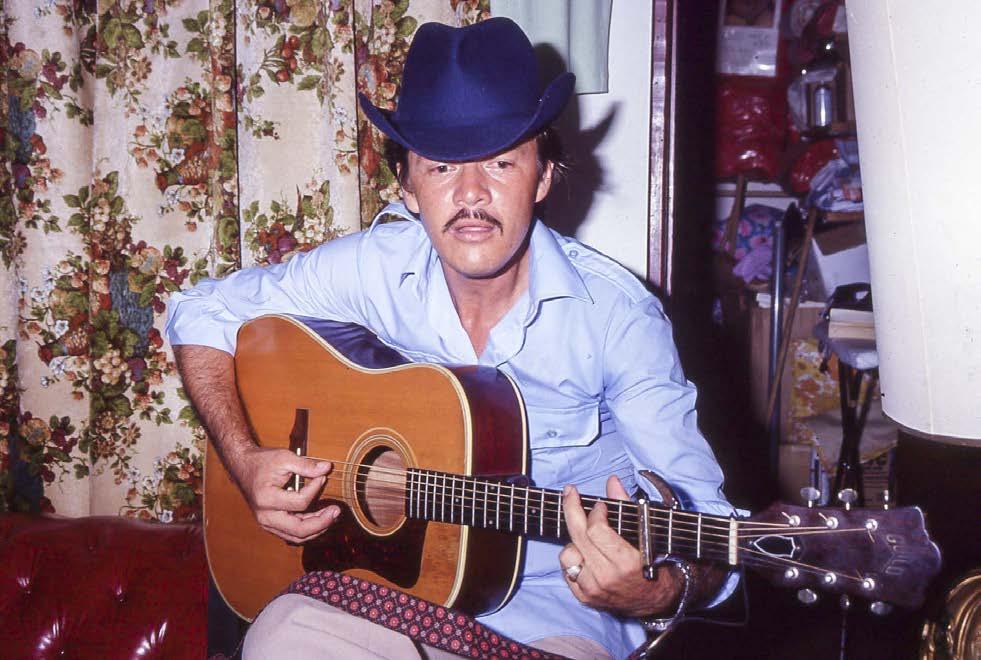

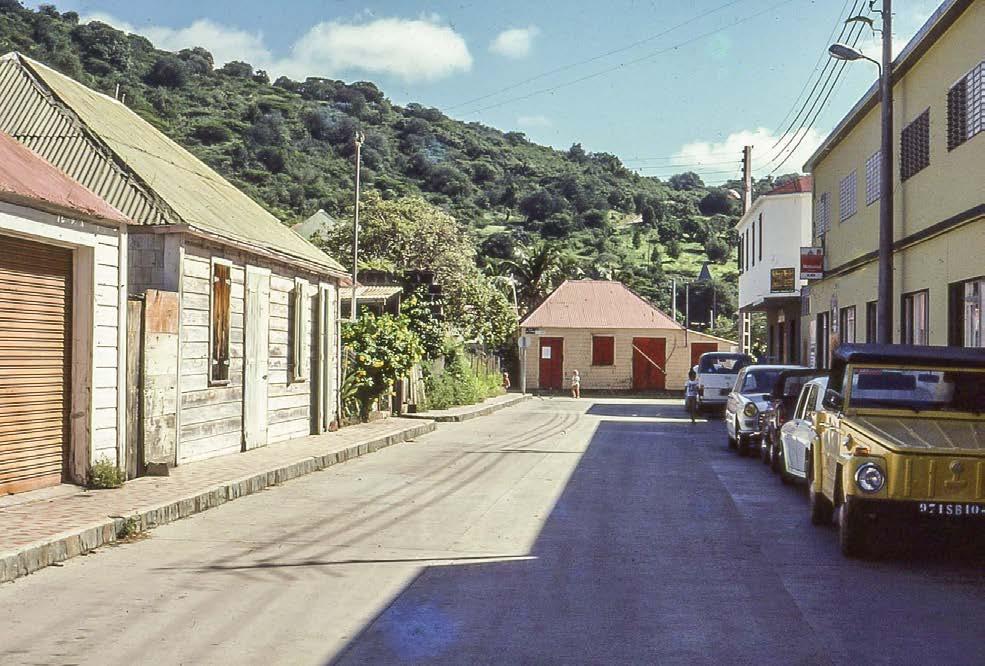

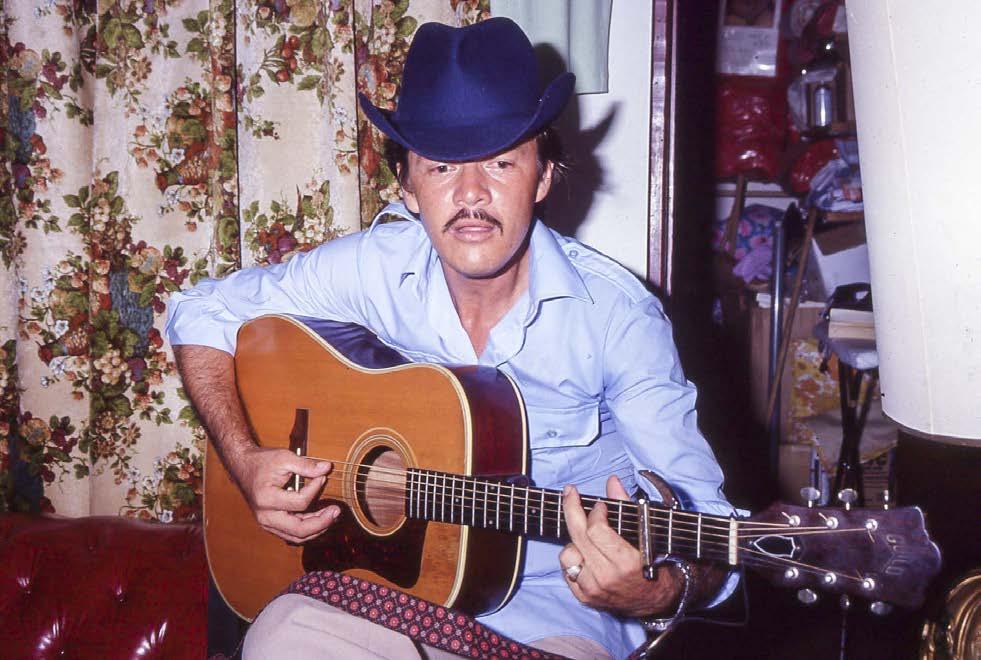

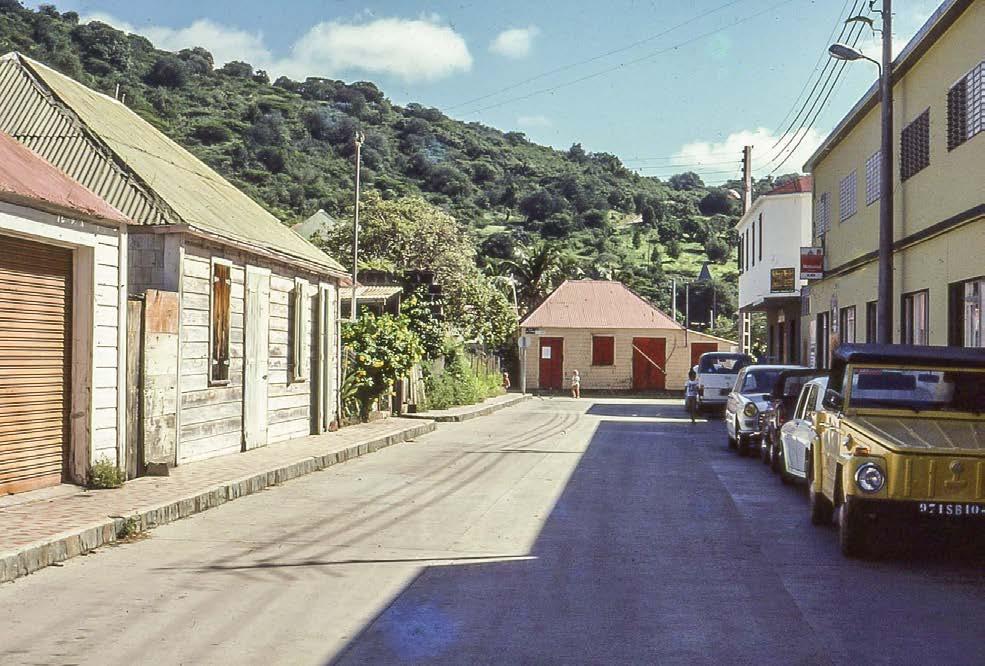

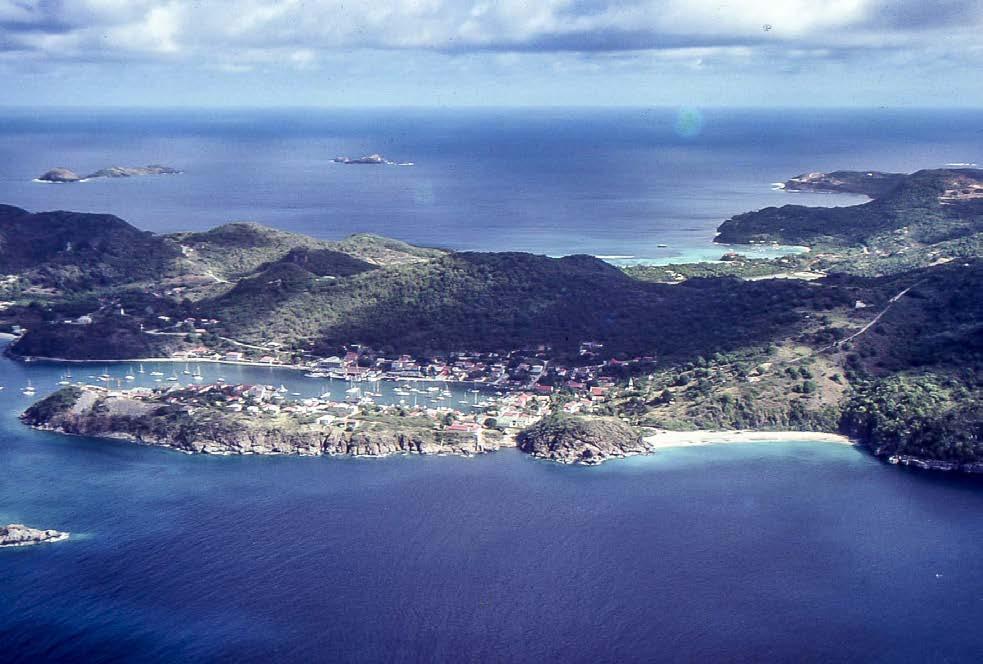

That Was Then

PHOTOS P. GADEMER

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

58 | 59

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

60 | 61

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

62 | 63

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

64 | 65

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

66 | 67

68 | 69

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

70 | 71

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

72 | 73

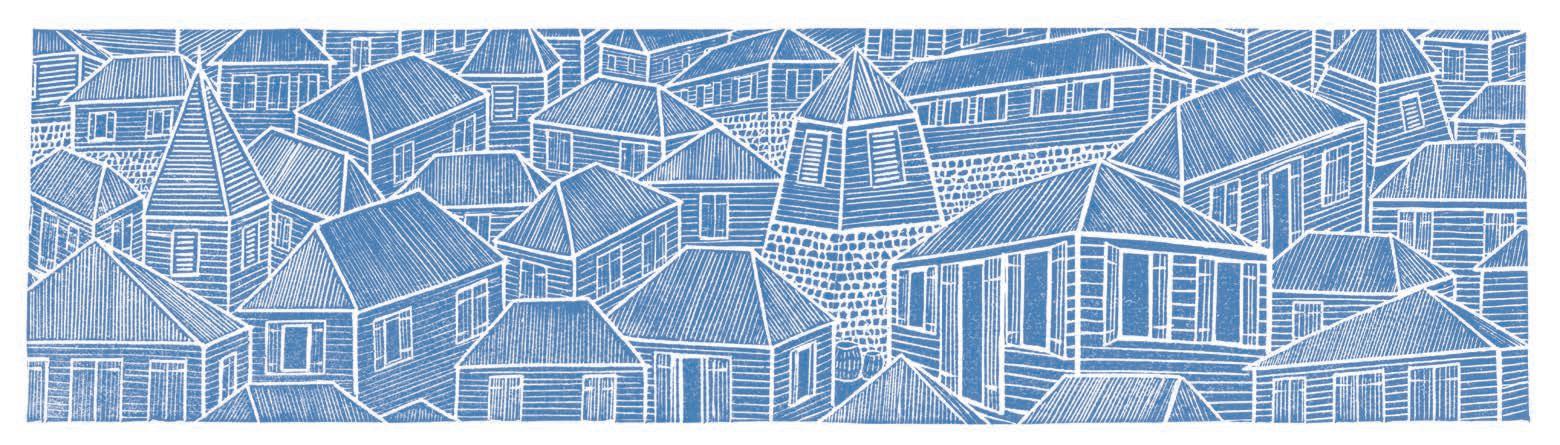

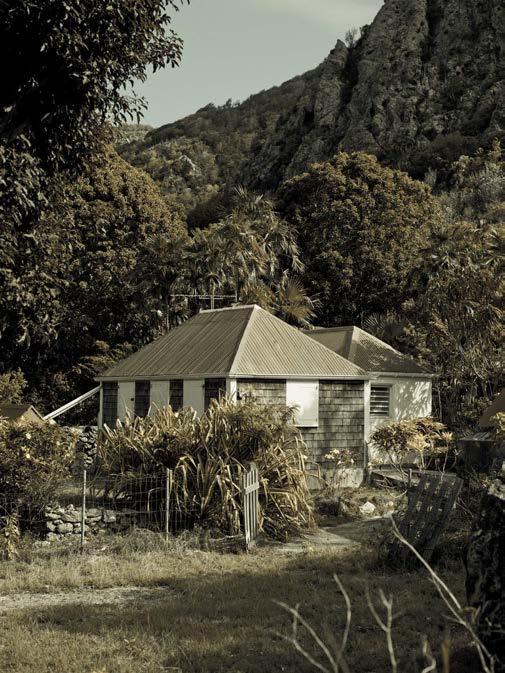

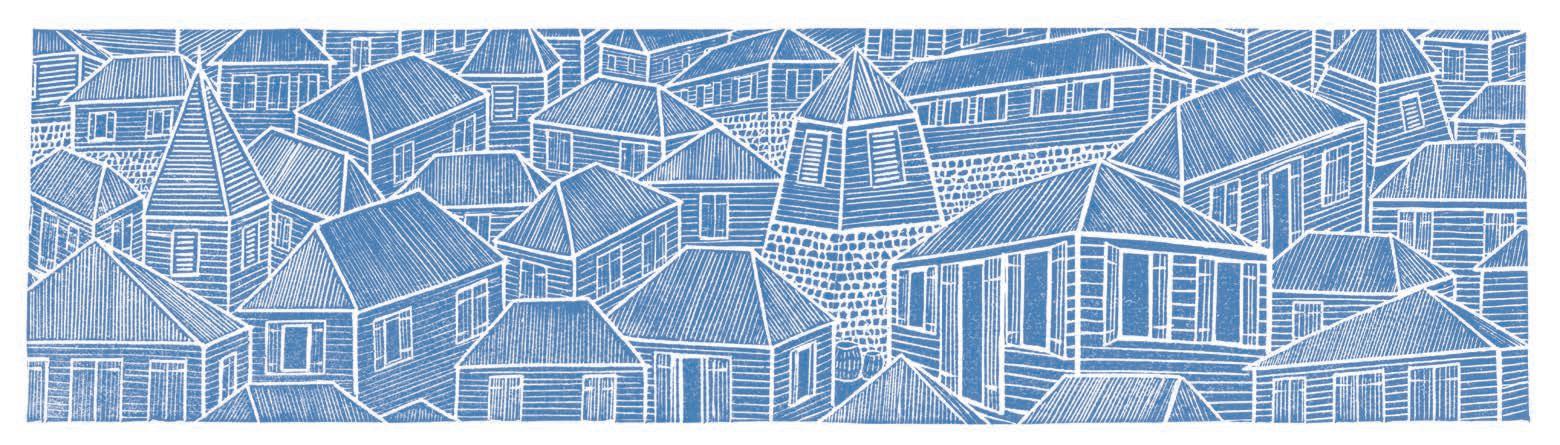

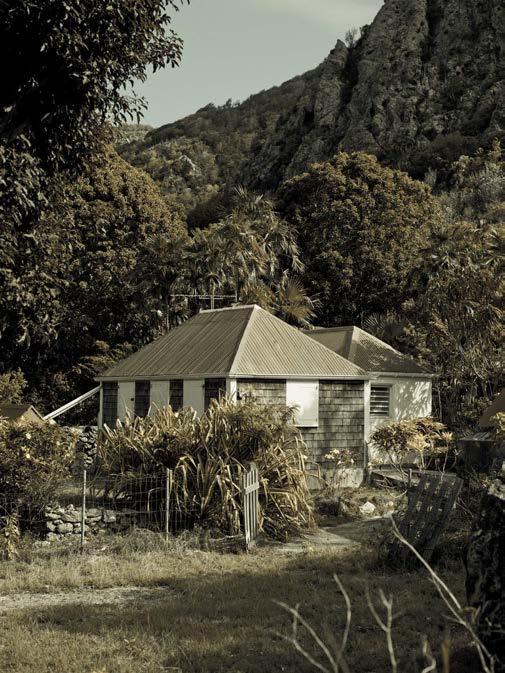

THE ST BARTH ‘CASE’ LA CASE ST BARTH

Text Miguel Berry Photography Sebastien Martinon

Within a few decades, the island of St Barthélemy became the scene of a considerable development evolving from the strictest destitution, to, sometimes ostentatious ostentation. Nevertheless, the soul of the island which also makes its beauty, and its picturesque charm knew was preserved over the passing years.

The traditional “Cases” St Barth, recognizable with their typical architecture, marked with simplicity and authenticity, testify of this almost recent past when the roughness of the former days’ life, contrasts with the opportunities which are offered in today’s everyday life.

If sun, crystalline water, and soft trade winds accompany the simple evocation of “St Barthélemy, heavens, over the centuries, were not always clement and by its fulgurances, lavished their cruel learnings. Hurricanes, earthquakes and of course dryness, established de facto major architectural criteria of these “Cases” St Barth.

Any boy reaching man’s age, according to implicit principles of honor, responsibility, had for initial project the construction of his “Case” in order to welcome his home. No matter if we are from “Sous le vent” or from “Au vent” coast-a geographical demarcation for two different communities by the language - the choice of the housing environment’s location was determined by the requirements of the climate and the ground’s topography. No matter if the coast is protected from the wind or, animated by the east wind, we found everywhere the same hot sun, the same seismic or cyclonic risks, and of course, everywhere the same water shortage.

With the absence of any drinkable water’ source, it was vital to store the inestimable rainwaters. Showing ingenuity, the old ones adapted themselves! Gutters modelled straight from

the built allowed the recovery of the rainwater which ran out in whose contents were infinitely more precious than an oil barrel. Afterward, and according to the earth’s quality, the cisterns, half buried – half only painful work could not resort to the earthwork or to hope for the assistance of tracto shovels - were built near the housing environment and allowed to keep a bit of freshness. Today still and in spite of the accessible tap water for all, it is very rare to plan a building without integrating a cistern in its lower part.

Looking at the composition of walls, dry stones, mainly volcanic origin were used. The binder was made of ground and water, the whole roughcasts with a filler of lime. The lime was prepared according to a St Barth’s knowledge, unique in the Antilles. The men dived to collect “cayes à chaux” (reefs with lime), well-known on the island. Associated with the sap of mancenilliers, this “cayes à chaux” was the object of a slow combustion, whose ashes constituted the relatively fragile basis of the rough coats, which it was advisable to maintain regularly. The lime was mostly transported on the head of the women, and sometimes had as undesirable side effect, the fall of the hair.

In the corners of the house it was frequent to find a gaïac or bois de rose completely integrated into the structure, so offering by its grounded roots, a solidity appropriate to support the torments of the weather. In a more symbolic way the same roots represented certain anchoring of the family for this dry ground which had seen them being born.

Raised on a solid base being able to support the telluric sudden starts, the body of the building was constituted with wood. Simple thatched roof in its debuts, the typical roof with four sides,

gradually evolved to be composed of essentes, following the example of the dressing of facades, then of sheet steels according to the availability of the present materials.

The kitchen which sheltered the “fouilleu” (the hearth) was built near the main house building for landing in particular fire risks. As conveniences a simple hole aside was enough for the needs for the family.

Whateveer of guingois or little academic, these traditional “Cases” (houses) whose undeniable charm continues to influence the architects, give evidence of the respect of their inhabitants for the nature a unique local knowledge and constitute by their humility, a real identity of the island of St Barthélemy through time.

Nowadays, the “Collectivité” impose for new constructions, roofs with four sides (as before) and a maximal height of 6m50 (formerly, the highest building did not have to exceed the top of palm trees), to guarantee to the attentive glances a certain harmony and preserve the authenticity of the island.

Because of the exiguity of the territory, of an increasing population whose requirements are not any more the same as the ones of former days, these “Cases” (houses) become more and more rare and disappear gradually from the landscape. In order to guarantee the conservation of this heritage, wouldn’t one have to think of classifying them as historic monuments?

In the meantime, in order to, sometimes, remember the good old memories “antan lontan” and to allow its imagination to wander at leisure on the traces of old, you can simply let yourself rock in the hollow a good hammock.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

74 | 75

ANY BOY REACHING MAN’S AGE, ACCORDING TO IMPLICIT PRINCIPLES OF HONOR, RESPONSIBILITY, HAD FOR INITIAL PROJECT THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIS “CASE” IN ORDER TO WELCOME HIS HOME.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

En l’espace de quelques décennies, l’île de St Barthélemy est devenue la scène d’un développement considérable évoluant du dénuement le plus strict au faste parfois ostentatoire. L’âme de l’île qui en fait aussi la beauté et le charme pittoresque a su au fil des années être néanmoins préservée.

Les cases traditionnelles St Barth, identifiables à leur architecture typique, empreinte de simplicité et d’authenticité, témoignent de ce passé presque récent où la rudesse de la vie d’antan contraste avec les facilités que nous offre aujourd’hui le quotidien.

Si soleil, eau cristalline, et doux alizés accompagnent la simple évocation de “St Barthélemy”, les cieux aux cours des siècles ne se sont pas toujours montrés cléments et par leurs fulgurances ont prodigué leur cruel enseignement. Les ouragans, séismes et bien évidemment la sécheresse, constituaient de fait des critères architecturaux majeurs de ces cases St Barth.

Tout garçon atteignant l’âge d’homme, selon des principes implicites d’honneur et de responsabilité, avait pour projet initial la construction de sa case pour y accueillir son foyer. Que l’on soit de “sous le vent” ou de la côte “au vent” - une démarcation géographique pour deux communautés distinctes par le langage - le choix de l’emplacement de l’habitat était déterminé par les exigences du climat et de la topographie du terrain. Que la côte soit protégée du vent ou animée par le souffle d’est, on retrouvait partout le même soleil torride, les mêmes risques sismiques ou cycloniques, et bien sûr, partout, la même pénurie d’eau.

Il était vital, en l’absence de toute source d’eau potable, de récupérer les inestimables eaux pluviales. Faisant preuve d’ingéniosité, les anciens s’adaptaient! Des gouttières modelées à même le bâti permettaient la récupération de l’eau de pluie qui s’écoulait dans des jarres dont le contenu était infiniment plus précieux qu’un baril de pétrole. Par la suite, et selon la qualité du sol, des citernes à moitié enfouie - à moitié seulement car le pénible travail ne pouvait recourir au terrassement ou espérer l’aide de tracto pelles- étaient construites à proximité de l’habitat et permettaient de garder une certaine fraicheur. Aujourd’hui encore et malgré l’eau courante accessible à tous, il est bien rare de planifier la construction d’un bâtiment sans y intégrer une citerne en dessous.

Du coté de la composition des murs, des pierres sèches, majoritairement d’origine volcanique, étaient utilisées. Le liant était à base de terre et d’eau, le tout crépit avec un enduit de chaux. La chaux était préparée selon un savoir-faire St Barth, unique aux Antilles. Les hommes

plongeaient pour recueillir des cayes à chaux, bien connues sur l’île. Associées à la sève des mancenilliers, ces cayes faisaient l’objet d’une lente combustion, dont les cendres constituaient la base du crépis relativement fragile qu’il convenait d’entretenir régulièrement. La chaux était le plus souvent transportée sur la tête des femmes, et avait parfois comme indésirable effet secondaire la chute des cheveux.

Aux coins de l’habitation il était fréquent de retrouver un gaïac ou du bois de rose totalement intégré à la structure, offrant ainsi par ses racines au sol, une solidité propre à supporter les affres du temps. De manière plus symbolique les mêmes racines représentaient un ancrage certain de la famille pour cette terre aride qui les avait vu naître.

Elevé sur un soubassement solide pouvant supporter les soubresauts telluriques, le corps du bâtiment était constitué de bois. Simple toit de chaume à ses débuts, la toiture typique à quatre pans, a progressivement évolué pour se composer d’essentes, à l’instar de l’habillage des façades, puis de tôles selon la disponibilité des matériaux présents.

La cuisine qui abritait le “fouilleu” (l’âtre) était édifiée à proximité de la case principale pour palier notamment les risques d’incendies. En guise de commodités un simple trou à l’écart suffisait aux besoins de la famille.

Qu’elles soient de guingois ou peu académiques, ces cases traditionnelles dont le charme indéniable continue d’influencer les architectes, attestent du respect de ses habitants pour la nature, d’un savoir faire local unique et constituent par leur humilité, une réelle identité de l’île de St Barthélemy à travers les temps.

De nos jours, la Collectivité impose pour les nouvelles constructions des toitures à quatre pans (comme auparavant) et une hauteur maximale de 6m50 (jadis, le plus haut bâtiment ne devait pas dépasser la cime des palmiers), afin de garantir aux regards attentifs une certaine harmonie et préserver l’authenticité de l’île.

En raison de l’exigüité du territoire, d’une population croissante dont les exigences ne sont plus celles d’antan, ces cases se font de plus en plus rares et disparaissent progressivement du paysage. Afin de garantir la préservation de ce patrimoine, ne faudrait-il pas songer à les classer au titre de monuments historiques?

En attendant, il suffit parfois pour se rappeler aux bons souvenirs “d’antan lontan” et permettre à son imagination de vagabonder à loisir sur les traces des anciens, de vous laisser simplement bercer au creux d’un bon hamac.

TOUT GARÇON ATTEIGNANT L’ÂGE

D’HOMME, SELON DES PRINCIPES IMPLICITES D’HONNEUR ET DE RESPONSABILITÉ, AVAIT POUR PROJET INITIAL LA CONSTRUCTION DE SA CASE POUR Y ACCUEILLIR

SON FOYER.

76 | 77

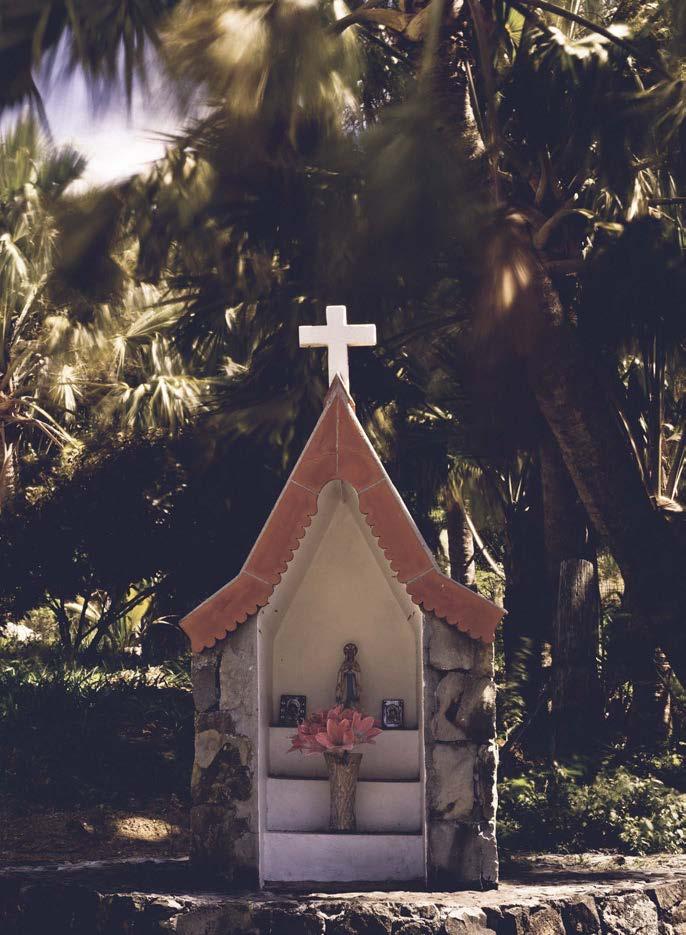

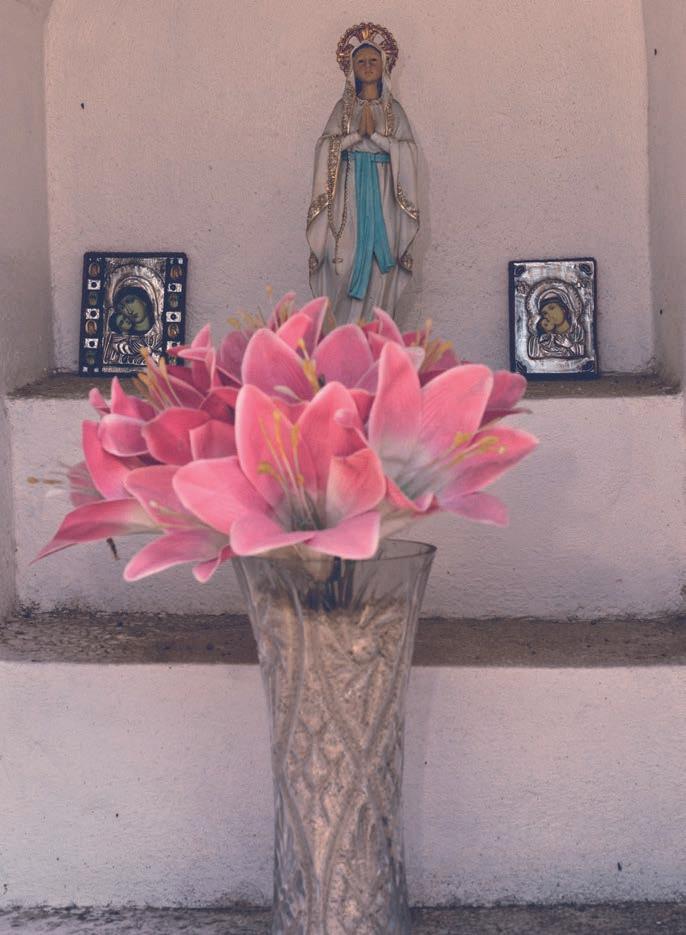

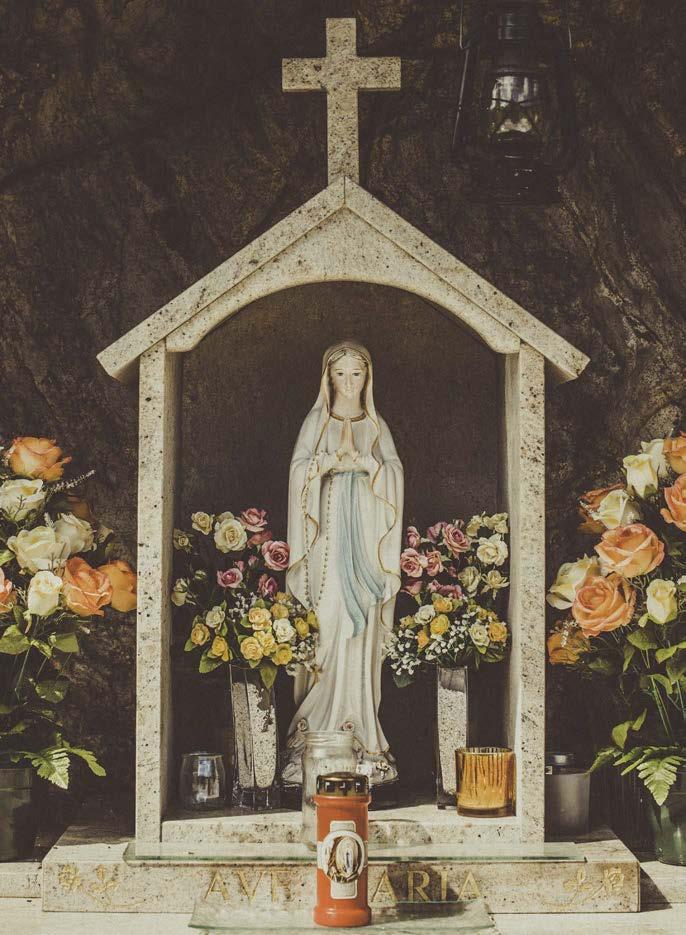

Heaven & Earth

WORDS BY RAY PARISH PHOTOGRAPHY BY SÉBASTIEN MARTINON

WORDS BY RAY PARISH PHOTOGRAPHY BY SÉBASTIEN MARTINON

78 | 79

If you spend enough time in St. Barth, you cannot help but notice the respect that the island’s local families have for tradition, ceremony and religion. More reserved than the exuberant celebration of spirituality seen elsewhere in the Caribbean, observance in St. Barth tends to be subdued. The notable exceptions are wedding parties – which make noisy tours from Gustavia to Lorient and back – and the year-round profusion of colorful silk flowers that decorate the island’s cemeteries.

St. Barth’s roadside shrines are a special form of cultural expression combining the island’s natural beauty with the reverence of the people who call it home. They are seen in virtually every neighborhood on the island, sometimes prominently placed at an overlook above the sea, sometimes hidden away beside a palm grove at a curve in the road. They are not meant for those going quickly from place to place; they are there for those who walk, who take the time to pause and reflect.

Not to be confused with roadside floral displays commemorating the lives of victims of traffic accidents, the shrines of St. Barth are solid constructions designed to be more permanent. Typically built of cement or stone, they often shelter crucifixes, statues, and candles and letters of offerings or prayer. Many were first built a century ago to offer prayers for the protection of sons gone off to war. Some have served as places of daily worship for those unable to make the trek to church. Families in the neighborhood of Grand Fond gather several times a year for prayer services at the shrine in the heart of the valley, a serene and meticulously kept sanctuary where an oil lamp burns perpetually above a statue of the Virgin Mary.

Though we often speed by these shrines several times daily on the way from here to there, they are worth a pause in a hectic day. Their simplicity and sincerity can provide a well-needed antidote to the overload of modern life, and they offer the comfort of permanence on an ever-changing island.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

Previous GRAND FOND Right top SALINE Right bottom GRAND FOND

Ceux qui auront passé suffisamment de temps à Saint-Barthélemy auront remarqué le respect que ses habitants portent à la religion et ses traditions. En contraste avec les célébrations exubérantes de leurs voisins antillais, et, à part quelques exceptions notables comme l’abondance de fleurs qui ornent les cimetières ou bien les processions bruyantes des fêtes de mariages qui résonnent parfois entre Lorient et Gustavia, les St-Barth expriment leur foi avec plus de discrétion.

Les autels de St-Barth combinent l’expression spirituelle des habitants avec la beauté naturelle de l’île. Ils sont présents dans pratiquement tous les quartiers, en évidence sur une corniche dominant la mer ou bien cachés au détour d’un virage. Les gens pressés ne les remarqueront pas, seul le promeneur attentif pourra les apprécier.

À ne pas confondre avec certaines compositions florales que l’on peut apercevoir au bord de la route et qui sont destinées à rendre hommage aux victimes d’accident, ces autels sont en général construits de manière permanente, en pierre ou en ciment. Ils abritent souvent des crucifix, des statuettes, des bougies et parfois des lettres de prières. Certains furent construits il y a près d’un siècle afin de pouvoir y prier pour la protection d’un être cher parti à la Grande Guerre, d’autres afin d’offrir un lieu de culte à ceux qui ne pouvaient se rendre à l’église. Plusieurs fois par an, les familles de Grand-Fond se réunissent encore au cœur de la vallée, devant un paisible autel soigneusement entretenu où une lampe à huile illumine toute la nuit une statue de la vierge.

Alors que nous passons devant plusieurs fois par jour, nous gagnerions certainement à nous y arrêter, ne serait-ce qu’un instant, afin d’échapper à la superficialité de la vie moderne et d’y trouver une source de réconfort et d’apaisement dans un monde en permanente évolution.

Left top TOINY Left bottom GRAND CUL DE SAC 82 | 83

An Anchor Story

TEXT MIGUEL BERRY PHOTOGRAPHY SÉBASTIEN MARTINON & ROMON BEAL

84 | 85

Romon Beal also has his own anchor story - like the one of Christophe Colomb (or at least from the same era) - which anchor is placed in the garden at the entrance of his house. Romon B found it in 1943 in Tortola while he was looking for his own anchor he had lost in the same seas.

An anchor which is even better known by the local people and, of course, by the tourists who never miss an opportunity to take a photography of it, is the imperturbable one facing Gustavia harbour.

In 1980, Romon Beal was then the harbour pilot; ensuring the entry of the tugs and barges in St Barth. One day of August, he had to ensure the entry of a container barge from the US Virgin Islands. The captain indicated him that he had hooked by the line of the trailer, from Charlotte Amalie to St Barth, something really big and which slowed it down during all the crossing. “I picked something at St Thomas I was not able to get ride of. And then nothing “. The “thing” had come off near the entrance of the port of Gustavia. Romon, whose curiosity was thoroughly aroused, naturally thought about a shipwreck which could have regrettably attached itself on the barge.

When he went to collect the traps (pots) on the following day, he decided, to be sure, to go and observe the “thing” that clandestinely hooked the barge. In this way, he had intuitively taken his “marks” which indicated, thanks to very precise spots, its exact position. D. Blanchard, his son-in-law and emeritus diver, was given the mission (and he accepted it) to descend 20m. What a surprise he had when he discovered huge chain links which were to lead him to an even more impressive anchor.

After the failed attempt of a modest trailer which did not succeed in moving it an inch, he requested the help of the Delgrès which was able to lift up to fifteen tons. The anchor was then lifted from the water, revealing a piece of extraordinary size and mass. An ebony emtek of 5m32, a chain of 30m weighting about 2 tons; and the anchor in itself measuring 4m69 and weighting about 10 tons. Briefly, a phenomenal discovery!

Clearly bearing the inscription “Liverpool... Wood...London”, Daniel Blanchard investigated with several existing Marine museums. The museum of London gave him some indications, appreciating the anchor manufacturing between 1750 and 1820. It possibly fitted (without any assured confirmation from the United Kingdom Ministry) a british warship named Wood, a freebooter with 70 canons based in Liverpool. The vessel would have deliberately cut the chain and its anchor on december 4th 1828 near to St Thomas, in order not to be reached by the canons coming from a brasilian privateer ship.

This anchor, of priceless historic value and still keeping its secrets, was delivered to the Community. Nowadays exhibited on a pedestal in Gustavia, it represents a clear additional tourist at traction for St Barthélemy, for the greater enjoyment of visitors which rarely leave without a souvenir picture.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

WHAT A SURPRISE HE HAD WHEN HE DISCOVERED HUGE CHAIN LINKS WHICH WERE TO LEAD HIM TO AN EVEN MORE IMPRESSIVE ANCHOR.

86 | 87

Des histoires d’ancre, Romon Beal en a aussi. Comme celle de Christophe Colomb (ou du moins datant de cette époque) placée dans le jardin à l’entrée de sa maison. Romon B la repéra en 43 à Tortola alors qu’il recherchait la sienne, perdue dans les mêmes eaux.

Une ancre encore plus connue de la population locale et bien sûr des nombreux touristes qui ne perdent jamais l’occasion de la photographier, est celle qui, imperturbable, trône face à la rade de Gustavia.

En 1980, Romon Beal était alors pilote du port, il assurait l’entrée des remorqueurs et des barges à St Barth. Un jour d’août, il dut faire rentrer une barge porte-conteneurs en provenance des îles vierges américaines. Le Capitane lui indiqua qu’il avait accroché par le filin de remorque, depuis le port de Charlotte Amalie jusqu’à St Barth, un objet très imposant, de nature à le ralentir durant toute la traversée. “J’ai ramassé quelque chose à St Thomas, je n’ai jamais pu m’en débarrasser. Puis, plus rien”. L’objet s’était alors détaché près de l’entrée du port de Gustavia. Romon, dont la curiosité fut piquée, songea naturellement à une épave qui aurait pu se fixer malencontreusement à la barge.

En allant ramasser les casiers (nasses) le lendemain, il décida toutefois, pour en avoir le cœur net, d’aller observer l’objet qui s’était clandestinement accrochée à la barge. A cet effet, il avait pris intuitivement ses “marques” qui indiquaient, grâce à des repères bien précis, sa localisation exacte. Son gendre D. Blanchard, plongeur émérite, eut pour mission (et il l’accepta) de descendre par 20 m de fond. Quelle ne fut pas sa surprise en découvrant des maillons de chaines immenses qui allaient le conduire vers une ancre encore plus impressionnante.

Après une tentative infructueuse d’un modeste remorqueur qui n’arriva pas à bouger d’une once l’objet imposant, le Delgrès qui lui était en mesure de soulever une quinzaine de tonnes fut alors sollicité. L’ancre fut alors hissée hors de l’eau révélant une pièce de taille et de masse exceptionnelles. Un madrier d’ébène de 5m32, une chaîne de 30 m pesant environ 2 tonnes et l’ancre proprement dite de 4m 69 pour une dizaine de tonnes. En deux mots, une découverte phénoménale!

Avec pour inscription apparente “Liverpool... Wood... London”, des recherches furent menées par Daniel Blanchard auprès des divers musées existants de la Marine. Celui de Londres apporta quelques éclairages, estimant la fabrication de l’ancre entre 1750 et 1820. Elle aurait équipé (sans confirmation certaine du ministère britannique), un navire anglais de guerre dénommé Wood, un bateau flibustier de 70 canons basé à Liverpool. Le vaisseau aurait délibérément sectionné l’ancre et sa chaîne le 4 décembre 1828 à proximité

du port de St Thomas, afin de se mettre hors d’atteinte des canons d’un navire corsaire brésilien.

L’ancre, offerte à la Collectivité, d’une inestimable valeur historique et qui garde encore ses secrets, est aujourd’hui exposée sur un socle à Gustavia. Elle ajoute indéniablement un attrait touristique supplémentaire à l’île de St Barthélemy, pour le plus grand bonheur de ses visiteurs qui repartent rarement sans une photo souvenir.

QUELLE NE FUT PAS SA SURPRISE EN DÉCOUVRANT DES MAILLONS DE CHAÎNE IMMENSE

QUI ALLAIENT LES CONDUIRE VERS UNE ANCRE ENCORE PLUS IMPRESSIONNANTE.

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH 88 | 89

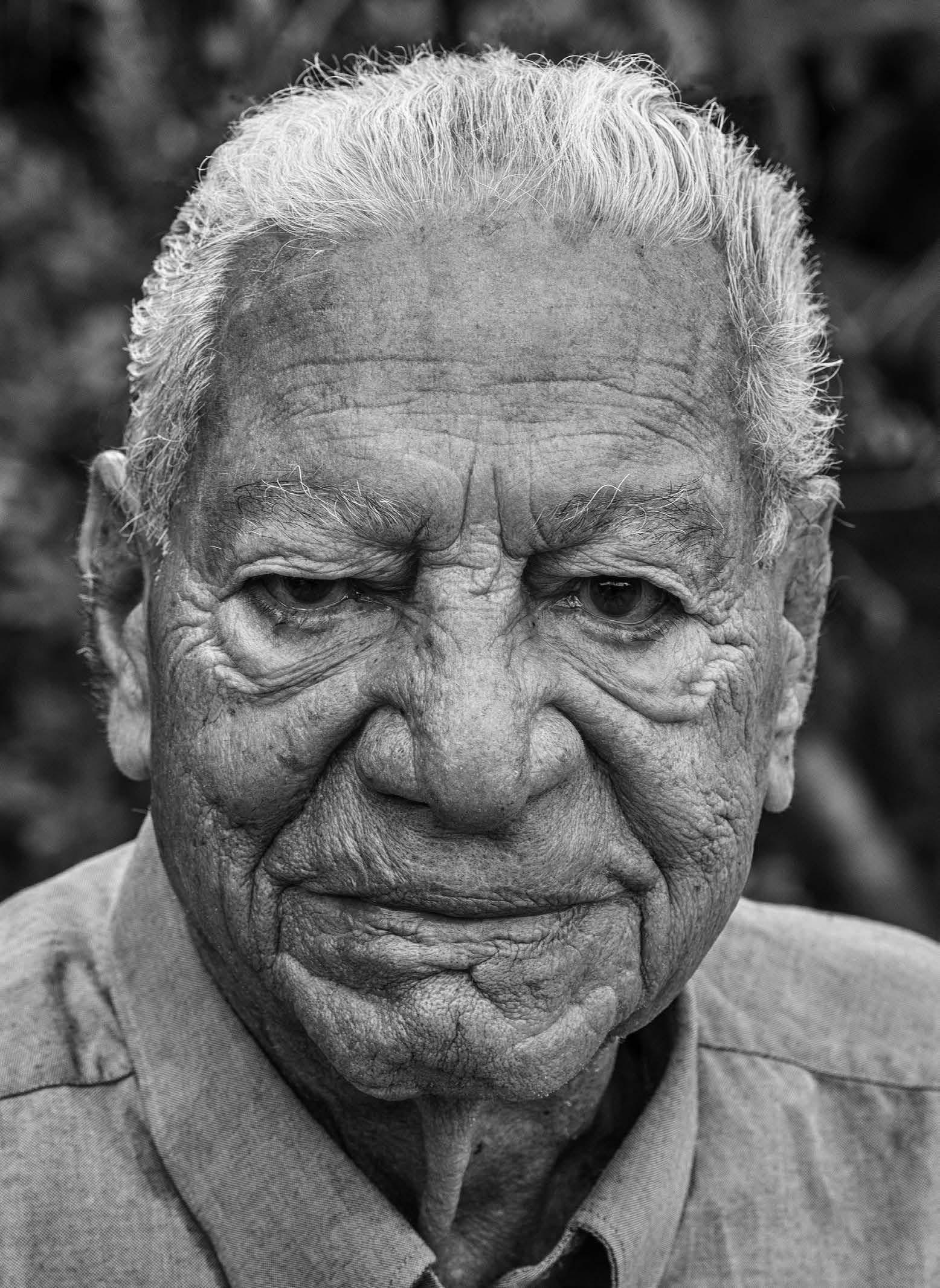

Liquid Gold

PHOTOS SÉBASTIEN MARTINON, FLORIANA, MATHURIN BRIN

SPIRIT OF ST BARTH

WORDS BIANCA CONNOLLY

The honey bee may very well be one of the most controversial members of the animal kingdom. It gets shooed and swatted away, and sends many running in fear of its potent sting, but it’s also a critical pollinator that plays an important role in maintaining life as we know it. As an added bonus, it also happens to produce the most delicious, golden liquid on the planet—and not without feat. The average worker bee makes about one-twelfth of a teaspoon of honey in its lifetime, which can last anywhere from three to six weeks. It takes approximately 556 worker bees to make just one pound of honey, with each bee collecting nectar from roughly two million flowers. It’s the production of a masterpiece as painstaking as they come.

Honey itself has its own place in history – bees have been producing it for tens of millions of years. In addition to being mentioned in the Vedic texts, and Sumerian and Babylonian cuneiform, it has been used for medicinal purposes throughout the world. In Ancient Egypt honey was not only utilized as a sweetener, but also as a tribute or form of payment. And so, honey garnered its unique, regal qualities.

90 | 91

S t. Barth has an intimate relationship with the honey bee, and the delicious fruits of its labor, though it has been an inhabitant of the island for only 40 years. Mathurin Brin first brought the bees over via plane from Curacao in the 1950s, carrying them in makeshift boxes, which he held on his lap. Following Hurricane Donna in 1960, Mr. Brin retired in St. Barth, where he was able to pursue his beloved beekeeping as a full time occupation after much convincing from his family and help from his son-in-law, Antoine Laplace.