Colombia

Land of Rhythm, Rivers and Rich Diversity

• Magdalena and Megadiversity

• Colours, Cultures and Conservation

• Imagine a Country Winning Entries

• Climate, Coffee and Coca

• COP26 and Finland’s New Climate Targets

• The Passing of Our Patron

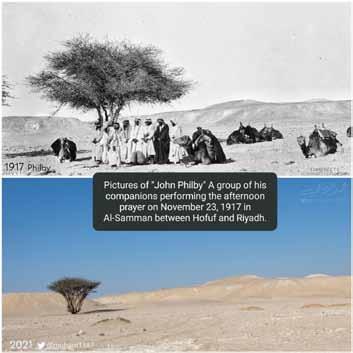

• Mungo Park, Libby Penman, Wade Davis

• Reader Offer: The World Atlas of Trees and Forests plus news, books and more...

Colombian proverb

“Poverty does not destroy virtue nor wealth bestow it.”

Winter 2022

The magazine of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society

The Geographer

The GeographerColombia

This edition of The Geographer is the result of a collaboration between RSGS and Colombian geographers at the University of the Andes, in response to their engagement in the international geographical society gathering we hosted in March. At the conference, Professor Andrés Guhl remarked that “Basic education around the importance of the natural environment to human societies is an urgent priority in order to tackle the serious threats to climate and biodiversity in Colombia, a country which is considered highly vulnerable in spite of relatively low emissions.” He asked us to help by increasing the profile of the country, and this magazine is our attempt to do that. With more than 10% of all living species on the planet, Colombia is famous for its biodiversity. So much so that this word barely does it justice: Colombia is often described as one of the most megadiverse countries in the world. It holds well over one in ten of the world’s plant, mammal and amphibian species, and is home to more species of birds (c1,900) than any other single country on Earth.

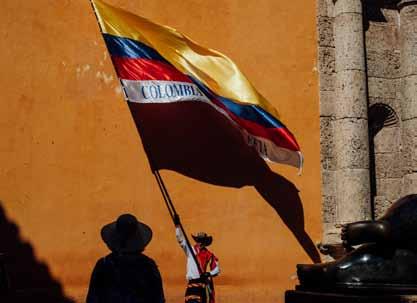

It is the crossroads of Latin America and the gateway to South America, reaching as it does from the Pacific coast via the Andes mountains in the west, to the Amazon rainforest and Llanos (plains) in the south and east, to the Caribbean coast in the north. As such it is also home to a multicultural population, and a great number of Indigenous communities. It is the only part of South America named after Christopher Columbus, reflecting the Spanish colonial history in the country. It was first invaded in 1499 and, fuelled by the European determination to seek out the fabled city of gold in the search for El Dorado, it remained part of the Spanish empire for more than 300 years. Although the nation celebrates its year of independence as 1810, it was another 12 years before it finally wrested control fully from Spanish resistance, in 1822.

Colombia is most famous for cocaine and coffee, but it is also a major exporter of oil, gas and gold. And yet, like many modern countries, it is also increasingly investing in renewable energy, with nearly 70% of domestic energy from hydroelectric. Although its environment is such an incredible jewel, and of global significance, it is struggling like many with the need to preserve this whilst developing its short-term national economy. So whilst it was one of the first countries in the world to grant a river (Atrato) its own legal status, it remains one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a human rights or environmental rights defender.

Colombia is an incredible country and deserves our attention and our help. We are grateful to Professor Guhl for all his help with this edition of The Geographer. We hope you enjoy it.

Mike Robinson, Chief Executive

RSGS, Lord John Murray House, 15-19 North Port, Perth, PH1 5LU

tel: 01738 455050

email: enquiries@rsgs.org www.rsgs.org

Charity registered in Scotland no SC015599

Four Decades Behind a Camera

Follow us on social media

The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the RSGS.

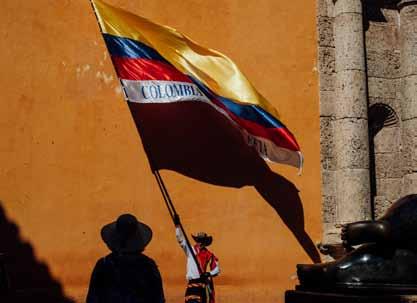

Cover image: Waving the Colombian flag in Cartagena during a running event. © Anna Pumer

RSGS: a better way to see the world

We are delighted that Mungo Park Medallist Doug Allan FRSGS will speak for RSGS at a special one-off event at Perth Concert Hall on Wednesday 21st December 2022. In a talk entitled Four Decades Behind a Camera, the Scottish wildlife cameraman and photographer, best known for his work in polar regions, will share some of his amazing experiences and spectacular images from his life and career.

book now!

Tickets are £17.50 for RSGS members, £12.50 for students and under-18s, and £22.50 for general admission, inclusive of booking fee. Please call 01738 621031 or book at www.horsecross.co.uk for a pre-Christmas treat!

Red Sea swim

Ahead of November’s UN Climate Conference (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh, endurance swimmer and UNEP Patron of the Oceans Lewis Pugh FRSGS completed the world’s first swim across the Red Sea (lewispughfoundation.org/ red-sea-2022). Over 16 days, he swam the 123km from Tiran Island, Saudi Arabia to Hurghada, Egypt, to highlight the impact of climate change on coral reefs, which support 25% of all ocean life and are the most biodiverse ecosystem on Earth.

When he rounded the southernmost point of the Sinai Peninsula at Ras Mohammed National Park, he described the sea life as spectacular. “There’s arid desert as far as the eye can see, but under the water, life explodes!”

The most challenging part of the swim was crossing the Gulf of Suez. “In all my years of swimming, I’ve never experienced anything like this. There were hazards coming at me from every angle. Extreme heat, high winds, big waves, sharks, oil tankers and container ships. I had to fight for every metre.”

Scientists warn that if we heat our planet by more than 1.5°C, we will lose 70% of the world’s coral reefs. If we heat it by 2°C, 99% of coral reefs will die. We are currently on track for at least a 2.2°C increase.

Masthead image: Drumming lessons for local children in Comuna 13. © Anna Pumer

21st December

Thanks to retiring Trustees

We were very pleased to have the opportunity, at a small private event in August, to thank recently retired Board members Tim Ambrose and Alister Hendrie for their many invaluable years as RSGS Trustees. Tim joined the Board as Treasurer in 2013, and has been incredibly generous with his expertise and time throughout. He has brought so much thoughtfulness and confidence to the Board, and has been instrumental in helping the Society develop. In recognition and sincere appreciation of this, we were delighted to present Tim with Honorary Fellowship of the Society.

Alister served on the Board for ten years, initially as the Local Groups Committee representative, and then, from 2015, as Vice-Chair of the Board. Throughout this time, he provided great expertise, knowledge and guidance, and we are grateful for his continued encouragement, help with strategic planning, and kindness.

We are extremely grateful for Tim’s and Alister’s contributions over the last decade; for their part in making the last few years as successful as they have been for the Society, allowing it to grow into what it is today.

SAGT Conference 2022

Alastair McConnell, RSGS Education Committee

In October, Geography teachers from across Scotland convened on Inverness Royal Academy for the first physical conference of the Scottish Association of Geography Teachers since the Covid pandemic pushed everything online. It was also the first conference to take place in the Highlands, allowing many to attend who would normally have to travel a great distance.

With a theme of one world, many stories, this was a perfect event for RSGS Writer-in-Residence Jo Woolf to give a keynote speech. She focused on information from the RSGS archives, with stories of exploration that captivated the audience. Her story of Mount Roraima in South America, the inspiration behind Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, was fascinating and the images from this unique location were stunning. RSGS also had a presence with a stall publicising our work. Delegates were able to collect copies of Horrible Geography of Scotland, the James Croll ‘Penny Magazine’, and The Geographer Feedback was all very positive.

The other keynote speaker was Bobby McCormack, Chief Executive of Developing Perspectives. He gave a very humorous talk about bringing stories to the classroom and making the pupil the centre of any lesson, rather than the teacher.

As well as the keynote speakers, an impassioned speech from SAGT President Iain Aitken on the future of our subject, and a lovely lunch, the conference included a range of workshops. Everyone in attendance was in no doubt about the importance of meeting in person, and the conference will be hosted next year at the same venue.

Inspiring People 2022-23

Face-to-face talks

Since September, it has been wonderful to see so many of our members and supporters once again attending face-to-face events hosted by our Local Groups across Scotland. We have enjoyed talks from Christopher Horsley, Professor Colin Ballantyne, Elise Downing, Alex Bescoby, Will Copestake, Cameron McNeish, Professor Stephen Peake, Colin Prior, Rebecca Lowe, Shahbaz Majeed and Lee Craigie.

Now we are looking forward to the amazing talks to come in 2023: polar explorer Craig Mathieson, talking about his Polar Academy and the challenges of running a charity during a pandemic; kayaker Callum Strong, recounting his ambitious expedition to paddle the length of the Panjshir River in Afghanistan; historical geographer Professor Charles Withers, examining the achievements, inspiration and ‘afterlife’ of Mungo Park; author Richard Clubley, sharing stories of life on Orkney, from its past to its future; explorer Jacki Hill-Murphy, reflecting on recreating Isabella Bird’s 150-mile trek through Ladakh; mountaineer Alex Moran, on his amazing feat completing the first ever Island Munros Triathlon; filmmaker Libby Penman, sharing stories from her years of filming epic wildlife in Scotland; adventurer Sue Stockdale, recounting highlights and challenges from her travels to over 70 countries; nature writer Tom Bowser, exploring the past, present and future of red kites in Scotland; explorer Alice Morrison, on her epic walk across Morocco with three guides and six camels; and kayaker Sal Montgomery, sharing stories and adventures from road-tripping around America and British Columbia.

Admission to face-to-face talks is FREE for RSGS members, students and under-18s, and £10 for others. Tickets are available through rsgs.org/events, or at the door (cash only).

Online talks

In autumn 2022, we were delighted to bring you online interviews with renowned explorers David Hempleman-Adams and John Blashford-Snell, and ecocide campaigner Jojo Mehta. Our online events will continue into 2023 with skier and adventurer Myrtle Simpson, endurance swimmer Lewis Pugh, and explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison

Tickets for online talks are FREE for students and under-18s, £2 for RSGS members, and £6 for general admission. Book now at rsgs.org/events

Francesco Sindico FRSGS

book online tickets now

In October, we were delighted to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Professor Francesco Sindico of Strathclyde Law School. Professor Sindico established and developed the Strathclyde Centre for Environmental Law and Governance (SCELG), which is now one of the leading centres in the UK in the field of environmental law. He has long supported and collaborated with RSGS, including by hosting medal presentation events, providing valuable platforms for our work, helping secure venues for talks, and consistently considering the Society through his work.

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 1 news

to a talk!

come along

Inspiring People Illustrated Public Talks Inspiring People 2022-2023 Illustrated Public Talks Open to everyone • £10 general admission • FREE for RSGS Members, students, U18s • Evening talks start at 7.30pm • Afternoon talks (Edinburgh & Glasgow only) start at 2.15pm (*Note Dunfermline talks have a 7pm start) David Hempleman-Adams FRSGS In his extraordinary lifetime of global expeditions, Sir David HemplemanAdams has battled against the elements in the harshest climates known to man, often steeling himself against illness and injury; and in doing so he has proved that, if you have a childhood dream of adventure, you should never let it go. John Blashford-Snell The legendary explorer and RSGS Livingstone Medallist, Colonel John Blashford-Snell, has led over 100 expeditions in almost every part of the world, join us as he shares some of his most unbelievable tales from a life of adventure. Jojo Mehta FRSGS Jojo Mehta as spokesperson and Executive Director of Stop Ecocide International has overseen the growth of the movement to criminalise ecocide; knowingly causing mass destruction to the environment through unlawful acts. She recounts her journey to environmental advocacy, and the potential of the crime of ecocide to change cultural norms. 2022-2023 "The best national talks programme in Scotland" 28 Inspiring Speakers • 96 Fascinating Talks • 14 Locations Photo by Geoff Makley Christopher Horsley, Marum Crater, Ambrym, Vanuatu Motivational stories of adventure Expertise on vital current issues Inspirational insights into people, places and planet Christopher Horsley Having explored some of the most active volcanoes in the world, adventurer Christopher Horsley is drawn to the fires that created our planet. Capturing the beauty of these naturally destructive creators has led him closer to the edge of volcanic craters around the world than most people would dare. From abseiling over 400 metres to collect fresh lava samples from some of the most inaccessible places in the world to encountering armed rebels on volcanic slopes for his recent TV series, Exploration Volcano, for BBC Earth, Chris works closely with Congolese volcanologists to supply and install live-stream Drawn to Fire Sal Montgomery A worldwide explorer, often found kayaking full-on whitewater rapids through unknown deep canyons in some of the world’s most remote locations, Sal Montgomery has led several world-first expeditions for TV documentaries and short films. 2019 saw a sudden transition, from living in the Amazonian jungle to working in a major UK hospital during a global health emergency. National lockdowns may have put this wild girl’s travels on hold, but that didn’t mean that her craving for adventure was dimmed. She shares her latest stories and adventures from road-tripping around America and Best Day Ever: Road-Tripping With a Kayak The Karakoram: Ice Mountains of Pakistan and Inspired Myrtle Simpson RSGS Mungo Park Medallist Myrtle Simpson is a Scottish mountain climber and polar explorer, and the tenth woman to receive the Polar Medal, 50 years after she became the first woman to cross Greenland’s polar ice cap. She has scaled Andean peaks, dragged a sledge across glaciers and sea ice, and attempted to reach the North Pole, amongst many other adventures. Lewis Pugh FRSGS RSGS Mungo Park Medallist Lewis Pugh has pioneered swims in the world’s coldest and most vulnerable climates, tying his passion for swimming with his advocacy for human rights and environmentalism as UN Patron of the Oceans. He was the first person to swim across the North Pole, and undertook a multi-day swim in the Polar Regions, across the Ilulissat Icefjord, to awaken people to the threat of melting sea ice. Robin Hanbury-Tenison As an explorer, author, filmmaker, conservationist, and campaigner, Robin Hanbury-Tenison has spent over fifty years exploring the world, has undertaken over 40 expeditions to some of the world’s remotest regions and saved over 500 minority ethnic groups through his charity Survival International and led multiple ground-breaking expeditions. 22 Nov 22 21 Feb 23 21 Mar 23 20 Sep 22 24 Jan 23 18 Oct 22 Lord John Murray House, 15-19 North Port, Perth, PH1 5LU Charity registered in Scotland No SC015599 Extra Online Talks Open to everyone - £6 general admission - £2 for RSGS Members - free to students, U18s - 7.30pm Tuesday evenings Join us for ‘An Interview with’ series... Join the RSGS and get the live talks for free, plus quarterly editions of The Geographer ! Annual membership rates are: • £21 Student • £50 Single • £75 Joint • £30 School To join, see www.rsgs.org or email enquiries@rsgs.org or phone 01738 455050 Join us today to start your geographical adventure! Colin Prior Acclaimed landscape photographer Colin Prior presents two different stunningly illustrated talks this season. In The Karakoram: Ice Mountains of Pakistan, he looks at a range that is so remote, each trip requires careful planning and miles of trekking with a team of porters and ponies. The reward is the ultimate mountain landscape: “sculpted by wind and ice into monumental spires, towers, cathedrals and pyramids, these rocks are a showcase of natural design and form.” In Inspired, he speaks about his sources of inspiration and how they influenced his work on assignments in over 50 countries, travelling around the world Extra Online Talks! www.rsgs.org

Ordnance Survey in Dubai

Rare Colombian hummingbird rediscovered

Dubai Municipality has signed two contracts with Ordnance Survey (OS), to harness geospatial data and expertise, accelerate innovation, and help develop fundamental services for citizens, residents and visitors.

Working with Dubai’s Building Regulation and Permits Agency (BRPA), OS will provide expertise to improve planning and construction processes. Paul French, OS’s Chief Commercial Officer, said, “Dubai Municipality is at an exciting time in expanding its capabilities. We are pleased to be contracted to support the organisation in transforming the construction sector.” Engineer Maryam Obaid Almheiri, Chief Executive of BRPA, said, “The agency aims to implement pioneering systems to serve the city, develop executive planning, survey and construction services. Our partnership with OS and other internationally recognized consultancy firms supports us achieving our goals.”

A second contract, with Dubai’s GIS Center Department (GISCD), aims to implement the geospatial development strategy over several years. Accurate and trusted geospatial data will be critical in helping to tackle a range of challenges which are facing cities across the world, including transport and mobility, net zero, planning and infrastructure, and health. Juliet Ezechie, OS’s Director of International, said, “Dubai is a city primed to be at the cutting edge of geospatial innovation. The city is now laying the strong foundations that will form the tenets of this immense potential, ensuring comprehensive geospatial data coverage.” Maitha Ali Al Nuaimi, Acting Director of GISCD, said, “Dubai is one of the fastest growing cities in the world and GISCD’s strategy will provide an up-to-date ‘digital twin’ of the Emirate. The long-term cooperation between GISCD and OS contributes to achieving these goals, in addition to enabling us to enhance the aspirations of the Dubai government in making Dubai the happiest city in the world.”

COP conference

In the run-up to COP27 held in Sharm el-Sheikh in November, RSGS and the Open University in Scotland held a COP26: One Year On conference to understand what signs of positive change had begun to take root since COP26, nationally and internationally, and what more needed to be done. The conference heard from 18 speakers from multiple sectors within the climate arena, and allowed key stakeholders fighting climate change to discuss, debate and prioritise the actions, campaigns, policies and innovations that need to be accelerated to ‘keep 1.5 alive’. See page 32 for more information.

A Critically Endangered hummingbird has been sighted and documented in Colombia after going missing for more than a decade. The Santa Marta sabrewing is only found in Colombia’s Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains, and was feared to have gone extinct after it hadn’t been spotted since 2010, with the tropical forests it inhabits having been largely cleared for agriculture.

It is only the third time the species has been documented: the first was in 1946 and the second in 2010, when researchers captured the first photos of the species in the wild. “This sighting was a complete surprise, but a very welcome one,” said Yurgen Vega, who made the rediscovery while working with SELVA, ProCAT Colombia and World Parrot Trust to study endemic birds in the region.

Karen Darke FRSGS, Explorer-in-Residence

In October, we were delighted to welcome Karen Darke FRSGS as an RSGS Explorer-in-Residence! Karen is a British Paralympic cyclist, Paratriathlete, adventurer, author, and RSGS Mungo Park Medallist. Just some of her amazing feats include becoming a Silver Medallist in the London 2012 Paralympics, and a Paralympic Champion in the Rio 2016 Paralympics. She has hand-biked the Carretera Austral through Chilean Patagonia, hand-biked from Canada to Mexico through the Pacific Coastal Trail, sea-kayaked from Canada to Alaska, sit-skied across Greenland, and scaled El Capitan, all whilst being paralyzed from the chest down. We now look forward to supporting Karen through her future expeditions.

Doors Open Day

We had a brilliant time at Doors Open Day in September, as we welcomed over 120 visitors of all ages from all over the world ‒ Australia, the United States, Canada, Hungary, Spain, France, Wales, England and Scotland ‒ to the Fair Maid’s House. The special display put together by our volunteers, titled Roots, Routes and RSGS, highlighted our remarkable Visitors Book and the potential storylines it hides in its pages, and was greatly enjoyed.

Amongst the visitors, we were delighted to see four RSGS Glasgow Group committee members, led by their Chair, Frank Norris, and popular mountaineer, writer and speaker Dr Hamish Brown FRSGS, who kindly brought the gift of some rare French maps of the Atlas Mountains and a very interesting Indian artefact to add to our collections. Thank you to them, and to all of our wonderful volunteers who helped organise and host the event.

Winter 2022 2 news

Colombia

The similar-looking Lazuline sabrewing. © Tom Friedel, BirdPhotos.com

Juliet Ezechie, Director of International at OS, and Maitha Ali Al Nuaimi, Acting Director of GISCD, sign the contract.

Cost-of-living crisis

Fellowships for Climate Solutions team

In October, Perth City Leadership Forum hosted a lunch for a group of local charities (including RSGS), organisations and individuals to discuss the cost-of-living crisis in Perth, specifically for those facing poverty. The event was a chance to hear more from the frontline organisations that are dealing with this issue every day, to hear ideas of how to reach more children and families, and to explore what organisations needed in order to scale up their efforts, tackle the crisis, and build collaboration.

Digital map transcription projects

In early 2022, the National Library of Scotland (NLS) initiated a set of new collaborative projects to transcribe features and text from old maps. With support from several hundred volunteers, NLS and its partners worked to transcribe details from the Roy Military Survey maps of Scotland (1747‒55), Ordnance Survey (OS) six-inch to the mile maps of Scotland (c1900s), and OS 25 inch to the mile maps of Edinburgh (1892‒94).

Roy Military Survey Project, in collaboration with the British Library: all 33,517 Roy placenames and their accompanying OS placenames have been transcribed, so that for the first time it is now possible to search all the names on this uniquely important 18th-century map covering all of mainland Scotland.

Scotways Historic Footpaths Project, in collaboration with Scotways: over 104,000 footpaths, spanning over 37,000 miles across Scotland, have already been traced, helping to facilitate Scotways’ work in researching the backgrounds of footpaths today and safeguarding them as rights of way.

OS 25-inch Edinburgh Transcriptions Project, in collaboration with the Machines Reading Maps team at the Alan Turing Institute: all 30,043 transcriptions have been recorded, edited and regrouped, allowing 21,950 placenames and related information on real-world features to be searched and viewed.

See maps.nls.uk/transcriptions for more information and links to search pages.

In August, we were pleased to present RSGS Honorary Fellowships to three members of the Climate Solutions team, for their contributions over the last six years in developing and delivering the courses. Their hard work allowed Climate Solutions to get off the ground, and helped make it so successful; the fact that we now have over 100,000 people signed up is a testament to their skills and effort. They were instrumental in creating the courses, and their contributions particularly stand out, not just for the expertise they shared, but for their personal commitment above and beyond what was required.

Galina Toteva, a PhD candidate in Carbon Management at the University of Edinburgh, is sole author of the Accelerator course, co-author of the Professional course, and lead author of the Student course. David Geddes, Director and Founder of Jump Digital, was instrumental in involving the company and producing a high-quality, easy-to-use system that can be rolled out universally. Robert Fleeting from Jump Digital was responsible for much of the technical build of the courses, and ensuring that they were delivered on time.

Dying to save the land

A report by non-governmental organisation Global Witness found that c200 environmental and land defence activists were killed around the world in 2021. More than threequarters of these killings took place in Latin America, particularly in Mexico, Colombia, Brazil and Nicaragua, with victims fighting resource exploitation and land disputes. “Most of these crimes happen in places that are far away from power and are inflicted on those with, in many ways, the least amount of power,” the report said. Global Witness also considers its report a baseline, noting “Our data on killings is likely to be an underestimate, given that many murders go unreported, particularly in rural areas and in particular countries.”

Butterflies in decline

Colombia

Butterfly Conservation’s annual citizen science project to monitor butterflies and some day-flying moths found numbers at the lowest on record for the third year in a row, despite a summer of persistent sunshine. The fine weather meant that the Big Butterfly Count in July–August missed the early peak emergence of some common midsummer species, but it was still a disappointing result once taking this into consideration. Some things that we can do to help include practising wildlife-friendly gardening, keeping long-grass areas in gardens, allotments and parks, and planting specific plants for some species, such as alder buckthorn for the brimstone butterfly.

Volunteer coffee morning

In October, we were delighted to host a coffee morning with Fair Maid’s House volunteers to say ‘thank you’ for all their hard work over the year. Volunteers were invited for tea, coffee and cake, and had the chance to reflect on our first open season since the start of lockdown. Many thanks again to all of our volunteers!

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 3 news

L-R: Robert Fleeting, David Geddes and Galina Toteva.

All three projects, blending together around Edinburgh.

Blog tales

With new content every week on our online blog (rsgs.org/ blog) there’s always something of interest. Recent additions include:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes: looking for clues in the RSGS archives: Writer-in-Residence Jo Woolf investigates links between renowned crime writer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, his characters, and RSGS.

By Railroad Through the Golden State: one night in September 1873, whilst travelling on the US Transcontinental Railroad, Isabella Bird rolled up in the town of Truckee, stepping out of her train carriage and straight into the hotel whose saloon was full of rowdy, gun-toting lumberjacks…

Thor Heyerdahl: six men, one balsa raft and 4,300 miles of Pacific Ocean: in celebration of the birthday of Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl, Writer-in-Residence Jo Woolf reflects on his life and the renowned Kon-Tiki expedition of 1947.

read the stories at rsgs.org/

blog

Three-norths point

In November, geospatial history was made as the three ‘norths’ combined over Great Britain for the first time. The point made landfall at Langton Matravers in Dorset, and will slowly travel up the country before finally leaving the land at Fraserburgh around July 2026.

Howie Firth, Tivy Education Medallist

Professor Roger Crofts CBE FRSGS, RSGS Vice-President

Professor Roger Crofts CBE FRSGS, RSGS Vice-President

At the 2022 Orkney International Science Festival, at an event hosted by Orkney whisky producer Highland Park in their excellent shop in Kirkwall, we presented our Tivy Education Medal to Dr Howie Firth MBE for his outstanding educational leadership over many decades. I welcomed the audience, saying that “Howie Firth established the Orkney Science Festival… and has grown it to become the international ‘gold standard’… He is a gifted communicator and educator, a broadcaster and a leading light in Radio Orkney. He is a true Orcadian polymath, demonstrated, for example, in his outstanding book Orkney. His insightful opening essay, An Orkney Panorama, demonstrates what only the most gifted scientists, cultural historians and educators can do.”

Formally presenting the Medal and Honorary Fellowship, Erica Caldwell, a previous recipient, reminded all that it is awarded, inter alia, for “exemplary, outstanding and inspirational educational work”, perfectly fitting Howie’s achievements. Howie responded, “Thank you for the huge honour of this presentation. It is amazing to be awarded something as special as this, and I am still absorbing it all. It is also inspiring me for the future.”

The ‘special line’ where magnetic north will join true north and grid north.

As expert map-readers will know, there is a difference between magnetic north (where the compass points, and which moves continually due to natural changes in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by changes in the flow of iron in the liquid outer core), true north (the lines of longitude that all converge at the North Pole) and grid north (the vertical blue grid lines shown on OS maps, which all but one need to vary from true north as they reflect the curve of the Earth).

Mark Greaves, Earth Measurement Expert at Ordnance Survey, said, “This triple alignment is an interesting quirk of our national mapping and the natural geophysical processes that drive the changing magnetic field.” Dr Susan Macmillan of the British Geological Survey, which makes detailed measurements of the magnetic field at 40 sites around the UK, said, “This is a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence. Due to the unpredictability of the magnetic field on long timescales it’s not possible to say when the alignment of the three norths will happen again.”

See www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/newsroom/news/three-norths-aligngreat-britain for more information, including an illustrative YouTube video.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has reported that, in 2021, the cultivation of coca (from which cocaine is extracted) reached a historically high level in Colombia. The area of coca cultivation increased by 43%, from 143,000ha in 2020 to 204,000ha in 2021. The potential cocaine production also reached a historical record high, increasing by 14% to 1,400 metric tons. The difference between the percentage increases is partially explained by the planting of new fields that have not yet reached their most productive age.

Long-term factors associated with this upward trend include changes in the dynamics and relationships of illegal armed groups, an increased supply of goods and services in populated places near coca-growing areas, and a concentration of cultivation in efficient agro-industrial hotspots. Short-term factors include less crop reduction intervention, positioning of new criminal groups, and worsening of socio-economic conditions due to the pandemic.

Two-thirds of the increased cultivation was seen in and around existing coca hotspots, but in new areas the increase was sudden and concentrated, leading to fears that northern Chocó and Cauca could quickly become hotspots. Over half of coca cultivation is in special management zones: Afro-descendant communities, forest reserves, Indigenous reserves, and National Natural Parks; the coca cultivation, and the manufacturing of cocaine, can affect the ecosystems in these zones.

news Winter 2022 4

Dr Howie Firth FRSGS (centre) with RSGS VicePresidents Erica Caldwell and Roger Crofts.

The Energy Crisis: Chief Executive Mike Robinson considers some of the burning questions concerning the looming energy crisis, including what we can expect, and what we can do to help. Colombia

Colombian coca cultivation

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (1926-2022) Patron of RSGS (1953-2022)

The end of an era

Jo Woolf FRSGS, RSGS Writer-in-Residence

With the sad announcement of Her Majesty The Queen’s death on Thursday 8th September, a long era in world history came to an end. The Queen’s reign was extraordinary for so many reasons: she was the longest-lived and longest-reigning British monarch, and she must surely have been one of the best-loved, having only recently celebrated her Platinum Jubilee amid outpourings of public celebration. For the generations who grew up knowing no other monarch, and listening to her words of calmness and strength during times of crisis, it is hard to believe that her smile, always radiant, is now a memory.

It is interesting to consider The Queen’s message during her Christmas broadcast of 2019. She said that, as a child, she never imagined that one day a man would walk on the Moon; yet, that year, we were celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. This was, she believed, a timely reminder of the positive things that can be achieved when people set aside past differences and come together in a spirit of friendship and reconciliation. Looking to the future, she reflected, “It’s worth remembering that it is often the small steps, not the giant leaps, that bring about the most lasting change.”

To echo a tribute to King George VI which appeared in the Scottish Geographical Magazine of 1952, “We record our homage to the memory of a beloved Sovereign.”

Remembering an amazing life

Professor Roger Crofts CBE FRSGS, RSGS Vice-President

The outpouring of shock, sadness and grief at the death of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II should be of no surprise to any of us. We hoped that she would always be with us through smooth and turbulent times. Well, hopefully she will be, as her life and its constancy, dedication and devotion to duty will live on not only in our memories but, as he has stated, in her son His Majesty King Charles III.

I had the privilege of representing RSGS at the Motion of Condolence at the Scottish Parliament, when we heard tributes from the First Minister and three of the other political party leaders. In response, The King made clear his commitment to following in his mother’s footsteps.

I only had the privilege of meeting The Queen once, when she presented me with an honour at Holyrood Palace. She was surprisingly small in height, but the greatest in stature of anyone in my lifetime. Her constancy and dedication to

her role, and her devotion to God, the established church, and her people are well known. So many words have been written to reflect on her lifetime of service.

What strikes me, in particular, has been her role internationally. She was an apolitical world figure par excellence. She straddled the world stage with dignity, composure and authority. Her knowledge of people and places was astounding, resulting from her diligence in preparation and her first-hand experience of travelling to so many countries, and at home and abroad meeting so many people from diverse backgrounds and persuasions. Her ability to choose the right moment to use the native tongue of the place visited, and to use her astute judgement to address long-standing issues, were her hallmarks. There are so many lessons our leaders around the world, and indeed us ordinary citizens, can learn from her example. May her legacy lead to a better world.

Reflections on a funeral

Mike Robinson, RSGS Chief Executive

It is not surprising that so many people are saddened by the death of Her Majesty The Queen. She was a constant figure in our lives, a visible public face in every aspect of life in this country, and around the world. She represented continuity and longevity and, for many, a solid ‘anchor’ to the ups and downs of regular existence. It is understandable that so many people feel sadness, not just for The Queen as an individual and for the era she represented, but because living so much in the public eye she was a thread in the tapestry of so many people’s lives.

It was then an especial honour for me to attend the funeral in Westminster Abbey on behalf of RSGS, and to witness such a moment of history first-hand. Within the Abbey itself I felt the mood was not sad, as I had expected, but rather respectfully uplifting. In amongst the pageantry, the prayers, the hymns and the beautiful music were some thoughtful reflections which cast the spotlight more on the legacy of The Queen and the other leaders present.

Her Majesty The Queen understood the importance of charities in our society, and they played a huge part in her day-to-day interests. As a representative from one of the many charities that enjoyed her patronage, it was the reading by the Reverend Canon Helen Cameron whose words struck the greatest chord for me. “Grant to [this nation’s] citizens grace to work together with honest and faithful hearts, each caring for the good of all.”

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 5

“Her knowledge of people and places was astounding.”

“She was a thread in the tapestry of so many people’s lives.”

“The Queen’s reign was extraordinary for so many reasons.”

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II visited the RSGS office in Edinburgh in 1984, in celebration of the Society’s centenary.

Colombia: a little bit of everything, from rain to snow, from deserts

Professor Andrés Guhl, Department of History and Geography, University of the Andes

When one thinks about Colombia, usually coffee comes to mind, but there is a lot more to this country. The 2022 edition of the Natural Beauty Report (www.money.co.uk/loans/ natural-beauty-report) puts this South American nation as the third most beautiful in the world. With over 1.1 million square kilometres, about 0.7% of the world’s land area, it is home to about 10% of the planet’s terrestrial biodiversity.

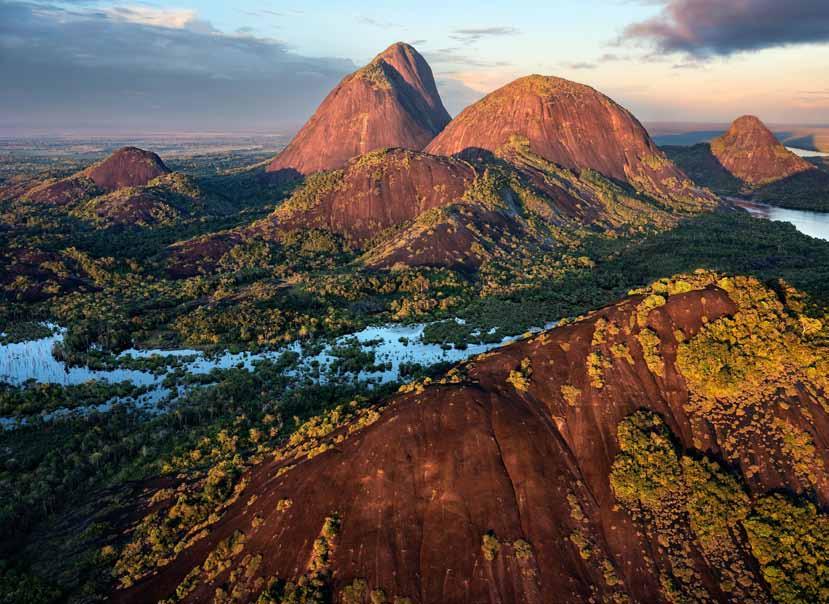

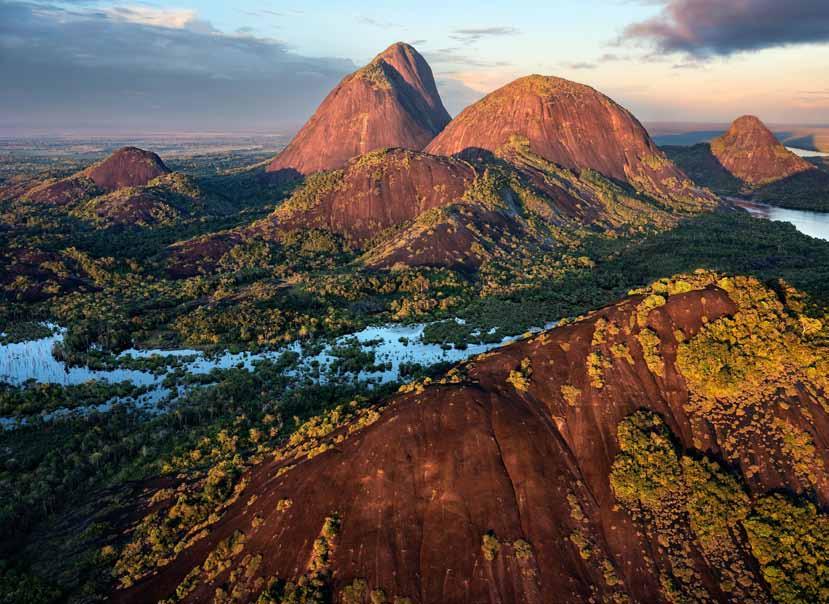

It is located in the north-western corner of South America, where the Nazca, South America and Caribbean tectonic plates converge. Tectonic activity contributed to the rise of the Andes, and divides the country in two different areas. The eastern part of the country corresponds to the oldest, most stable part of Colombia, characterized by relatively flat terrain and underlain by some of the oldest rocks on Earth, the Guiana Shield. The western half, on the other hand, is characterized by mountainous terrain and seismic activity. This is where the majority of the population lives.

The eastern half can be further divided into a northern part that is characterized by savannah vegetation, and a southern section covered by the Amazon rainforest. The mountainous area includes the northernmost sections of the Andes. In Colombia, this mountain range divides into three separate branches that go roughly from south to north. These mountain chains are separated by deep valleys where two rivers flow to the Caribbean: the Cauca and the Magdalena, which are perhaps the most important in the country in terms of economic activity and historical significance.

The mountain ranges can reach more than 5,000 metres, meaning that one can find tropical lowland environments and snow-covered peaks in a small geographical space. The country still has six snow-covered mountains, but the permanent snowline is retreating due to climate change. The interaction of topography and wind patterns results in a wide range of climates, going from extremely dry to very rainy conditions that result in a stunning variety of ecosystems. When people think about biodiversity in tropical South America, the Amazon rainforest comes to mind. However, not too many people realize that the Andes, due to the diversity of climates and soils, are more biologically diverse than the Amazon rainforest.

Colombia is also a water country: it is among the top ten countries with the most renewable water in the world. Located along the Intertropical Convergence Zone, this means that there is abundant rainfall during the year. In addition, the Chocó stream, a low elevation wind stream flowing from west to east from the Equatorial Pacific Ocean, generates orographic rainfall on the Pacific coast lowlands. In this area, rainfall can reach more than 10,000mm per year, which is about 14 times the yearly rainfall amount Edinburgh receives. However, rainfall and humidity are not evenly distributed throughout the country. Many parts of the country receive little rainfall. For example, the northern tip of Colombia is a desert, and large portions of the Magdalena and Cauca basins are relatively dry.

On the western half of the country, the mountain ranges transition to a relatively flat area along the Caribbean coast. As the mountains disappear, the Cauca and Magdalena rivers create a seasonally flooded area characterized by river runoff, seasonal flooding and permanent lakes. Further north

of this region, smaller and lower mountains emerge. The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is located in this area. This massif reaches nearly 5,800m, making it the highest coastal mountain range in the world. As the crow flies, it is possible to go from sea level to 5.8km in about 50km.

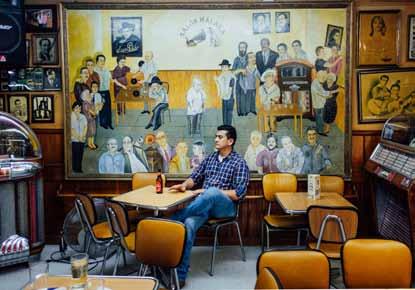

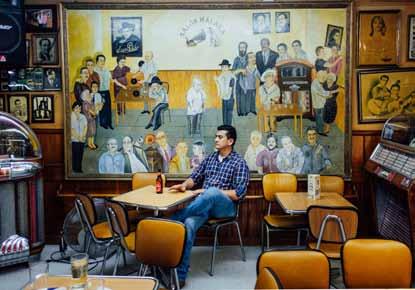

The diversity of Colombia is also cultural. There are still more than 60 Indigenous languages in use, mostly in remote areas. Although many of these languages are threatened, most communities across the country are proud of their Indigenous heritage and are trying to revitalize their languages and traditions. But Colombia is also a cultural melting pot. The present population of the country is the result of the mixture of Spanish, African and Indigenous peoples. The way in which these groups are present in the country is not homogeneous. The Andean area is mostly a mestizo population, while both coasts exhibit traits of African tradition. Indigenous groups are present throughout the country, but are dominant in remote areas. Music, food and handicrafts, among others, reflect this cultural mélange.

Colombia is a country of great biophysical and social diversity in a relatively small geographic space, and it is a great opportunity for people interested in geography: pack your bags, and do not hesitate to come!

Winter 2022 6

“The Andes are more biologically diverse than the Amazon rainforest.”

deserts to lush forests

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 7

Nevado del Huila, from Los Coconucos. © Andrés Guhl

Small-scale colonization of the rainforest. © Andrés Guhl

Indigenous hut, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. © Andrés Guhl

© Gabriel Eisenband

Creating national unity in Colombia

Chris Fleet FRSGS, Map Curator, National Library of Scotland

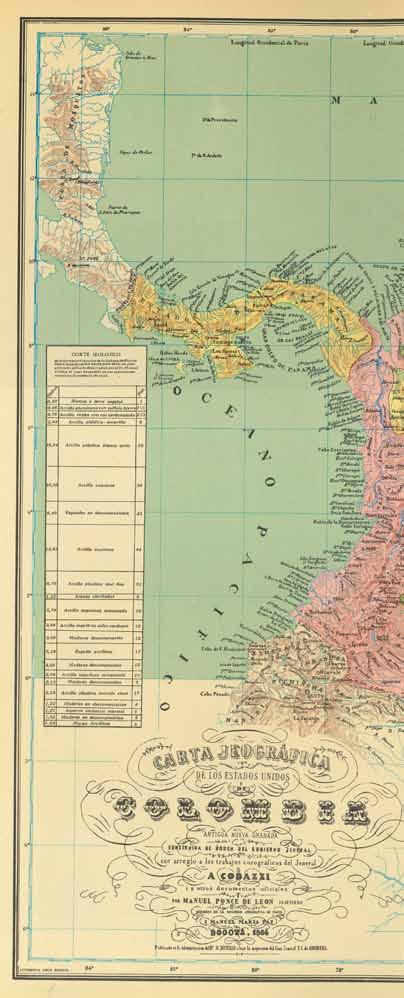

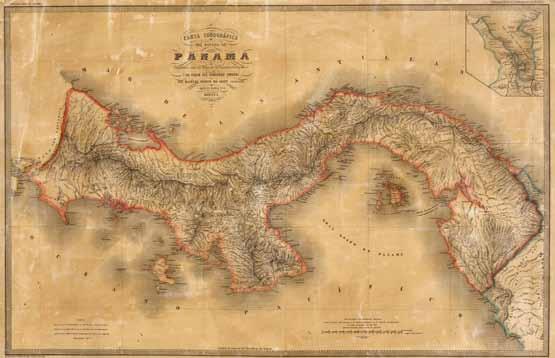

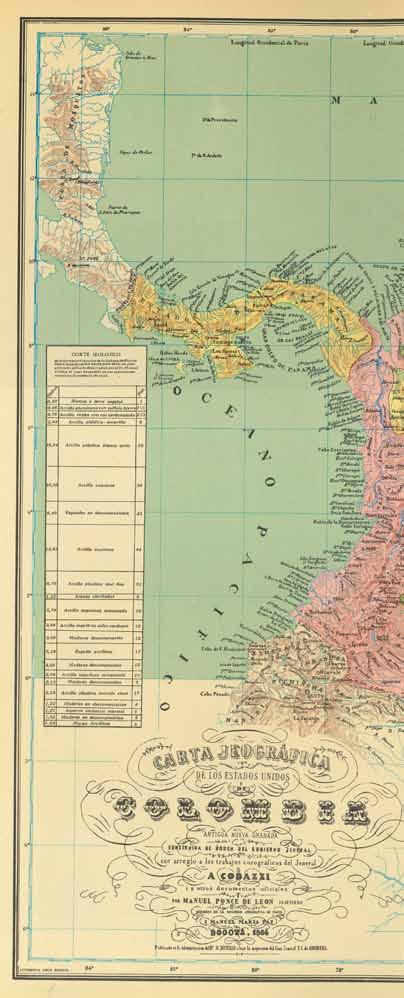

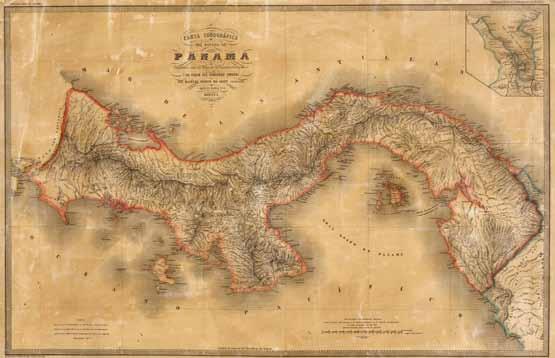

This map commemorates Agustín Codazzi (1793–1859) and his work to foster national unity and identity in Colombia.

Born in northern Italy, Codazzi was impressed by the ideals of the French Revolution, and he trained as a military engineer, going on to fight with Simón Bolívar to liberate Venezuela from Spanish control. Over the next two decades, Codazzi excelled in mapping and military work in Venezuela, before escaping to Colombia, where he continued his geographic and cartographic work with Comisión Corográfica.

The map shown here brings together the work of this interdisciplinary scientific project, involving both observation and description of the various inhabitants of the regions, as well as a survey of natural resources and economic infrastructure, also creating a series of regional maps.

Following Codazzi’s death in 1859 from malaria, he was honoured in many ways, including the naming of Colombia’s national geographic and cartographic institute after him.

Codazzi’s maps were published in his Atlas fisico y politico de la República de Venezuela (1840), and his Atlas de los Estados Unidos de Colombia (1865). These are our two earliest national atlases of these South American countries, and both works promoted these newly-independent states.

As well as being early examples of atlas lithography – both volumes were lithographed in Paris, creating full-colour plates as shown here – the maps included thematic physical, political and historical themes, with introductory text and indices. They reflected the growth of nationalism, imperialism and national identity that accelerated through the 19th century; during the 20th century, many countries sponsored their own monumental national atlas projects.

Codazzi’s work is important to the history and geography of Colombia, as well as illustrating the very significant role of map-makers in promoting nationalism.

Winter 2022 8

Carta Corográfica del Estado Soberano de Boyacá, from the Atlas de los Estados Unidos de Colombia, 1865. See commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Atlas_ de_los_Estados_Unidos_de_Colombia_1865 for maps of individual states.

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 9

A Codazzi, Carta jeográfica de los estados unidos de Colombia (1864). Image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

“The maps reflected the growth of nationalism, imperialism and national identity that accelerated through the 19th century.”

The possibilities of peace: new opportunities for Colombia

Professor Andrés Guhl, Department of History and Geography, University of the Andes

Colombia has experienced one of the longest civil wars in the world. For more than 50 years, different groups (left- and right-winged) have fought against the Colombian government, mostly in remote areas of the country. In 2016, after several years of negotiations, the Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia (FARC), the largest rebel group, and the Colombian government signed a peace agreement in a very hopeful moment for the entire country. Although there are still other rebel and criminal groups fighting the State, the disarmament and demobilization of the FARC generated hope, and a very welcome change in parts of the country where conflict and fear had become the daily routine.

When the civil war ‘dissolved’, many regions that were out of bounds for most Colombians became attractive spots in many ways. There are many examples of how this process took place, and how it created new opportunities and challenges. In the first place, the civil war meant that wild ecosystems were relatively unaltered in many areas, and the peace agreement opened them up to travel. For example, Caño Cristales (Crystal Creek), also known as the river of five colours, was an area in a municipality where the FARC had a very strong presence, and now it is a very popular ecotourism destination. The same can be said about many other locations in the country. Areas that were closed are now open, and people come to enjoy their natural wonders and the hospitality of their inhabitants. However, as in many areas of the world, the success of ecotourism can be its greatest enemy: overcrowded sites and degradation.

The changes brought in by the peace agreement also bring opportunities to former FARC guerrilla men and women. They lived in these remote areas for a long period of time, and their former lives in the forest as rebel fighters mean they know the birds, plants, insects and animals in these isolated areas. Many of them have been trained as ecotourism guides, and now they can share with travellers their specific natural history familiarity with these previously conflictive lands. In other parts of the country, former guerrilla fighters have become involved in restoration efforts. But instead of trying to transform the landscape back to a former ‘pristine’ state, they are trying to transform an

agricultural frontier area, where deforestation is widespread, into sustainable landscapes, where patches of forest and other wild ecosystems are interspersed with agricultural fields and pasture, while trying to preserve the ecological functions of the forest through landscape corridors and other connectivity and management measures. Although this kind of intervention will never restore the original ecosystems, it is expected that these lands will become a landscape that can accommodate humans and wildlife, maintaining some of its ecosystems and functions, and reducing pressure to deforest elsewhere because of the benefits of keeping a mixture of agricultural fields, pasture and wild ecosystems. However, this has not been easy, as large holders and investors want to transform these native ecosystems into agro-industrial areas, replacing more heterogeneous and beneficial landscapes for homogeneous monocultures, as has happened in many areas of the Brazilian Amazon.

Another benefit of the peace agreement is related to scientific knowledge of Colombian biodiversity. Through a government initiative that began in 2016, the BIO expeditions try to study places that were previously out-of-bounds areas, the remnants of wild ecosystems in regions that have been heavily altered by human activities, or locations that were the stage of conflict. As well as bringing together researchers from different parts of the country, the BIO expeditions also engage local inhabitants, many of them former FARC rebels, so the status of different species and ecosystems can be assessed. In these scientific expeditions, many new species have been discovered, and the knowledge they generate contributes to better management, conservation, and sustainable use of Colombia’s biodiversity.

But the peace agreement also brings challenges to many regions of the country. The disappearance of the FARC armies, the de-facto government in many areas of Colombia, has meant that groups of people are trying to grab these lands since the Colombian government has yet to reach the most remote parts of the country. Most of these lands are not titled, and people living there do not have deeds. Large, unscrupulous investors are injecting enormous amounts of money to deforest large swathes of forest and other ecosystems so they can claim ownership of these lands. It remains to be seen how the Colombian State can maintain its most valuable asset: biodiversity.

Winter 2022 10

“Many regions that were out of bounds for most Colombians became attractive spots.”

Hoatzin, San José del Guaviare. © Andrés Guhl

Image by Richard Brunsveld from Unsplash.

A river with rights

To think of a river as a person may be a strange concept, but for the Atrato River in Chocó, Colombia, it may be its saving grace. In 2017, it became just the third waterway on the planet to be granted its own legal rights. Such is the river’s significance that it also has its own Guardians who dedicate their lives to its protection and rehabilitation.

Whilst Chocó is not part of the Amazon biome, it has many similarities. Chocó is a richly biodiverse rainforest ecosystem, dominated by large rivers and thick forest cover. Just like the Amazon, Chocó is culturally diverse too, with a largely Indigenous and Afro-Colombian population. Like the Amazon, the Chocó region is rich in natural and mineral resources, and communities face an ongoing battle to protect their land and resources from outside interests. In Colombia, this means living within the midst of an ongoing internal armed conflict. Chocó’s five Indigenous tribes have lived there for thousands of years, and its Afro-Colombian communities, which make up the vast majority of the region’s population, trace back to the African people brought to the country by the Spanish as slaves.

The Atrato River and the Chocó region in general face many challenges, including environmental and social devastation; and face destruction by illegal gold mining. Consequently, communities are losing their traditional livelihoods as the region’s resources are depleted and degraded. When you add into the mix the presence of illegal armed actors, community life becomes precarious.

SCIAF has worked in Chocó since 2006, since identifying it as the poorest region of Colombia and one of the regions most affected by the conflict. To this day, it is the focal point of our Colombia Country Strategy. Through our local partners, we work with local Indigenous, Afro-Colombian, and Mestizo rural communities and their organisations, strengthening their capacity to defend, protect, and make sustainable use of their natural resources.

Colombia remains the world’s most dangerous country to be a human rights defender, meaning many community leaders are targeted for speaking out about the plight of their communities. Sadly, whole communities across Chocó have been forced to make the life-changing decision to leave behind the life they know to live in cities and towns, in search of safety and financial security.

We have worked to help communities gain legal rights and full access to their ancestral territories, develop plans for the sustainable use of their resources, and implement livelihood projects within their territories. We also work to ensure

local voices are heard loud and clear within Chocó, and at national and international level. We do this by strengthening leadership skills, helping new leaders find their voice, and adding our voice to the demands and campaigns of local organisations and partners.

The Atrato River is vital to people’s everyday lives: they fish the river, use it for transport, they bathe and wash their clothes in it, and it provides a livelihood.

In 2016, we worked with our partners to help them bring about a landmark case in the Colombian courts: the Atrato River court ruling. The voice of local communities was crucial to ensuring a positive result. The court ruled in favour of the Atrato River, granting the river the right to be protected, maintained, conserved and restored alongside the biocultural rights of its riverine communities. The Atrato River is only the third river in the world to be recognised in this way.

One of the river’s proud Guardians is Maryury Mosquera Palacios, who visited Glasgow in 2021 as part of COP26. She said, “The river is so important for the communities who live alongside it. The river is our washing machine. It’s our recreational centre. It’s our tourist centre where we have fun. Our economic source of our wealth, our economy. It’s our transport system. And we use it for cultural activities. Being a River Guardian and environmental activist is quite dangerous in Colombia. The River Guardians were created by the court ruling in 2016, but we have always been guardians of our homelands.

“The river is like a young child, and we are the adults who must care for its interests. Rights defenders run a lot of risks in Colombia, especially in vulnerable departments like Chocó. Right now, I don’t feel so much personal danger from the work I do. This doesn’t mean that the danger isn’t there, and I may face difficulties in the future. Some colleagues have had threats and situations carried out against them. But instead of focusing on the dangers to us, we must focus on what we’re doing for our communities. In favour of ourselves, but also in favour of future generations. So I never focus on how dangerous my work may be, but rather on who I’m doing it for.”

SCIAF Project Manager Mark Camburn said, “I am just in awe of the people we work with. Knowing the risks that they face, and yet they are prepared to take that risk for the greater good of their communities, for the good of their river, their forests. It’s really inspiring.”

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 11

Claire Cook, Senior Marketing and Communications Officer, Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund (SCIAF)

“I never focus on how dangerous my work may be.”

© SCIAF

Maryury Mosquera Palacios. © SCIAF

Protected areas: a security and peacebuilding approach

Sandra Valenzuela de Narvaez, Executive Director, WWF Colombia

Sandra Valenzuela de Narvaez, Executive Director, WWF Colombia

As the second most biodiverse country, Colombia plays a key role in preserving global natural resources. The country’s commitment to conservation is reflected in its National System of Protected Areas (SINAP, after its Spanish name), which covers 31 million hectares, equivalent to 15% of the country’s territory. The protected areas included in the system provide essential ecosystem services to local populations, including water provisioning and regulation. Protected areas produce the necessary water to generate 50% of Colombia’s hydro-energy (estimated at $502 million) and provide drinking water for more than 25 million people (an annual value of $491 million). In an average year, water provision and regulation services from national parks are expected to add at least $2.3 billion to the gross domestic product.

Despite these efforts, Colombia’s landscapes and seascapes are facing unprecedented ecological and climate-related pressures. Having endured five decades of armed conflict until a peace agreement was signed in 2016, the country is confronting a new wave of deforestation and significant alterations of terrestrial socio-ecological systems, leading to increased emissions and further compromising the ability of these ecosystems to adapt to climate change. In this case, deforestation is mainly caused by illegal activities, which are attractive as they generate income and have low or non-existent punishment. Studies have shown how post-conflict settings in key conservation areas are affected by the territorial control of armed groups and population dynamics of colonization. The interaction of such issues results in land grabbing, agricultural expansion of monoculture and illegal crops, extensive ranching, illegal mining, illegal infrastructure, and illegal wood extraction, which are the main drivers of deforestation and destruction of biodiversity.

Nowhere are these pressures more pronounced and complex than in and around vulnerable forested areas in SINAP.

As highlighted in a recent study conducted in Colombian National Natural Parks and National Nature Reserves using an open-access global forest change dataset, 31 of the 39 protected areas in the country (79%) have experienced increased deforestation in the post-conflict years. This can be seen in a dramatic and highly significant 177% increase in the average deforestation rate between the two three-year periods before and after the peace agreement. This postconflict setting not only has deforestation consequences, but also requires connection with the peacebuilding initiatives (both local and national) included in the peace agreement which have been implemented under the territorial security approach.

A territorial peace and security approach with peacebuilding interventions includes dimensions such as: (i) socio-economic

inclusion and wellbeing opportunities (addressing and solving objective causes of conflict, such as human needs, poverty, land tenure, marginalization, and livelihoods development); and (ii) enhancing collaboration, collective action and conflict management, including transforming conflicts over natural resources access into collaboration, agreements and collective actions to enhance territorial governance, rights, security and innovative governance structures and schemes for decision making. In sum, it is transforming tensions through dialogue in a giving territory. Nowadays, protection and conservation goals and management have evolved and are considered as a window of opportunities to include a broader range of social and environmental targets, understanding local communities as part of a well-functioning ecosystem. Recent studies have found that proximity to conserved areas delivers health and income co-benefits to populations. Thus, the contributions of conservation areas to prevent or solve conflict and consolidate peace are among these social and environmental benefits, minimizing the risk of conflict associated with natural resource access or deterioration or scarcity, and providing alternatives to illegal or unsustainable economies.

WWF Colombia is strengthening more than 80 natural resources community enterprises located in the surrounding zones of 30 protected or conserved areas with Afrodescendants, farmers, and Indigenous communities. These initiatives are based on agreements to resolve conflicts and land tenure problems, focused on the promotion of agroforestry systems with coffee, cocoa and nontimber natural products, and fisheries management. These processes are based on environmental zoning, are associated with ecological restoration processes, and include improving market access for producers and green financial mechanisms.

In sum, this territorial security approach aims to support the Government of Colombia in the quest for strengthening peacebuilding and conservation efforts by providing strategies aimed at involving local communities in conserving biodiversity, through improving their livelihoods and addressing land-related conflicts and property rights around national parks, promoting dialogue between different stakeholders, tackling the root causes of the conflict, and moving towards a comprehensive agrarian reform. This comprehensive territorial security approach will help in reducing deforestation and soil degradation and promoting the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem services while communities’ wellbeing is improved based on a licit local economy.

Winter 2022 12

“Proximity to conserved areas delivers health and income co-benefits to populations.”

© Simon de Man

Biodiversity, inequality and Indigenous peoples

Mariana Tafur-Rueda, Oxfam Colombia

Mariana Tafur-Rueda, Oxfam Colombia

In Colombia there are 115 Indigenous groups, of which 93 are native; the remaining 22 are newly recognised ethnic groups from border areas. Indigenous communities are found throughout the entire landscape of Colombia. In the Orinoquía and Amazon regions they represent more than 40% of the total population, but they also have an important presence in the Pacific and Andean regions, as well as the Caribbean coast. There is a smaller presence in the Insular region, which is mostly populated by the black Raizal community.

Although Indigenous peoples still suffer today from multiple forms of discrimination and inequality, a broad regulatory framework exists to protect them. It’s only since the 1991 constitution that the doors opened to protect the diversity of Indigenous peoples, and to recognise their rights, such as free informed prior consultation appropriate to ethnic communities in Colombia, collective rights, and autonomy and selfdetermination in their territories. However, despite this broad legal framework, the Colombian state has not managed to guarantee full enjoyment of the rights of these peoples. Not only because of a search for economic development based on the indiscriminate exploitation of natural resources (mining and agribusiness), but also because of private economic interests, illegal activities, and illicit crops, which involve the presence of illegal armed groups who are part of the conflict.

In addition to the effects of the armed conflict, such as forced displacement, the inequalities suffered by Indigenous peoples in Colombia are reflected in areas such as health and education. Compared to 4.5% of the national total, 13% of the Indigenous population do not have formal education. Though official figures report almost 100% coverage in health, the reality is that there are great difficulties in accessing services. Health centres are almost entirely unavailable in these areas, so people need to travel great distances to get medical support; there is a lack of disaggregated data; and even where healthcare is available, there is no guarantee of quality care due to the lack of capacity in the system.

Added to this is the fact that the territories of Indigenous peoples are usually of great ecosystem and geopolitical importance, as in the case of the Amazon, and are usually

adjacent to, or even part of, protected areas. The ethnic communities of Colombia assume responsibility for the preservation of these ecosystems in line with their traditional beliefs. They believe that they must care for the planet and that conservation of nature is an essential part of caring for oneself, for one’s family, and for collective life with whom we share the planet. Unfortunately, this position of ‘caretaker of nature’ puts them at risk in cases of dispute, not only in Colombia, but throughout the world.

Hence, Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world to defend environmental rights (for the second consecutive year), as well as being the second most biodiverse country on the planet. This privileged geography puts Colombia under the magnifying glass of extractive interests due to its ecosystemic and natural wealth, adding to the crisis sustained by deep inequality, massive migration, and the growth of a few fortunes versus a lot of poverty. This is caused not purely by issues at a local level, but also by the extractive companies, rarely national, that use both legal and illegal strategies to achieve their goals. In other words, it is not only the responsibility of Indigenous peoples to defend environmental and territorial rights; the international community must also bear responsibility.

Indigenous women play a key role due to their relationship with the land and with nature, owing to their physical and spiritual view of the world. For Indigenous women, defending nature is defending life. For this reason, they have developed deeply embedded resistance and survival strategies as part of their daily lives, despite the fact that they are putting themselves at constant risk.

If the economic development model is put above nature and those who protect it, not only are human rights and multiple international agreements being violated (in addition to denying the value of human diversity) but life is also being endangered. This is not a problem for just a few nations in the world to solve. It is a problem for all of us who inhabit the Earth, and we must be aware of that responsibility to make better decisions individually, in the community and, above all, in the public sphere.

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 13

“For Indigenous women, defending nature is defending life.”

Colombia’s Pacific lowlands: an ‘adopted Glaswegian’ geographer’s

Dr Ulrich Oslender, Department of Global and Sociocultural Studies, Florida International University

In March 1995 I travelled for the first time to the Pacific coast region of Colombia. By then, I had already spent four months in Colombia on a year-abroad study programme. I was pursuing an undergraduate degree in Geography and Hispanic Studies at the University of Glasgow at the time. As part of the Hispanic Studies section of the programme, students were sent away for a year to a Spanishspeaking country to become fluent in their language skills. My choice back then fell on Colombia. Why? I am not so sure anymore. Colombia is a crazed fútbol nation, of course. Their flamboyant style with the likes of René el scorpión Higuita, el Pibe Valderrama, and Freddy Rincón seduced many during the FIFA World Cup in 1990, when Colombia held West Germany to a dramatic 1:1 draw (with Rincón scoring the equalizer in the 93rd minute). This surely was a convincing pull factor.

Or maybe it was the sheer exuberance of a tropical geography that attracted me. Colombia is the only country in South America with coastlines on both the Atlantic and the Pacific Ocean. The massive Andean mountain range, which runs along the South American continent, suddenly seems to split as it reaches Colombia. It is as if it could not make up its mind where to go next. This topographic indecision has resulted in three distinct mountain ranges: the Western, Central and Eastern Cordillera. Deep valleys separate the ranges, notably those of the two great rivers, the Cauca and the Magdalena. Climatic variation is determined by this extremely diverse topography. The higher up you are in the mountains, the colder it gets. The further down you go, the hotter it becomes. Year-round. It’s not time that dictates these temperature patterns, but space.

The region that would hold my fascination for the next three decades is known as the Pacific lowlands. Stretching from Ecuador to Panama, with a coastline of 1,300 kilometres, it covers an area of almost ten million hectares of tropical rainforest. Separated from Colombia’s interior by the Western Andean mountain range, and sparsely inhabited by around 1.3 million people (some 3% of Colombia’s national population), the lowlands have been characterized by their physical and economic marginality in relation to the rest of the country. Initially of interest to Spanish colonizers for its rich alluvial gold deposits, the region’s economy has been dominated by ‘boom-and-bust’ cycles. During relatively short time spans, natural resources have been exploited intensively, before a decline in external demand led to a rapid decrease and collapse of these economies. Both tagua (ivory nut) and rubber exploitation in the first half of the 20th century followed this boom-and-bust logic.

Since the 1960s, the region has been an important source of the country’s timber supply. This has led to high levels of deforestation that pose a threat to traditional lifestyles. In the 1990s, the region began to attract attention in national development plans with a view to conserving its biodiversity. This conservationist trend has recently been sharply curtailed by an aggressive return to extractive economies, such as mechanical gold mining and agro-industrial exploitation, most dramatically seen in the sweeping plantations of oil palm monocultures. Throughout these changing development paradigms, a resilient local population – overwhelmingly made up of people of African descent – has continued to practise a diversified subsistence economy in the rural areas, based on fishing, hunting, agriculture, gathering, and smallscale artisanal gold panning for their everyday needs.

That was just about all I knew about this region back in February 1995, when I got off the small plane at the airport in Tumaco, the Pacific Coast’s third largest town. As a geographer-inthe-making, I was generally interested in conservation, biodiversity, and sustainable development. The Pacific lowlands seemed an exciting place, where these notions overlapped in complex ways with an emerging identity politics of the region’s Afrodescendant population. In the capital Bogotá I had met a US American woman who worked with the World Bank-funded biodiversity conservation program Proyecto Biopacífico I didn’t hesitate when she extended an invitation to accompany her to

Winter 2022 14

“Maybe it was the sheer exuberance of a tropical geography that attracted me.”

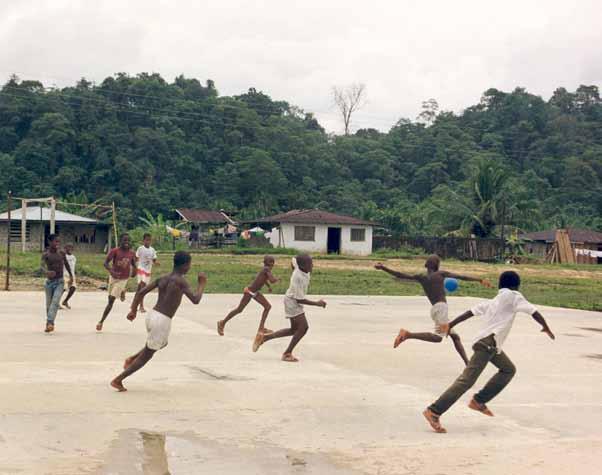

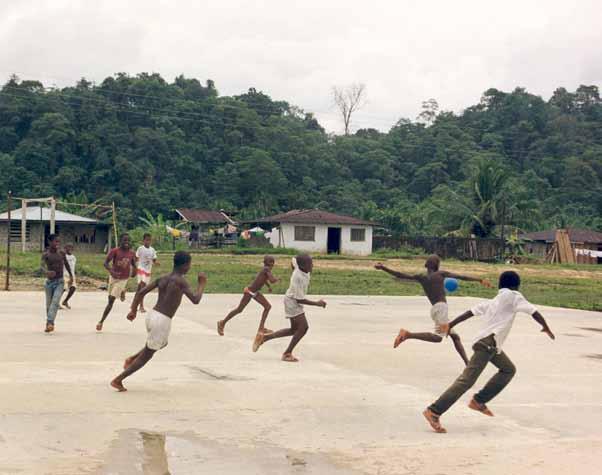

Fútbol in San Antonio.

geographer’s trip down memory lane

Guapi, a small coastal town some 150 kilometres north of Tumaco, where she needed to deliver equipment to Proyecto Biopacífico’s regional office.

This speedboat trip was a first taste of travelling through the maze of mangrove swamps that make up the southern coastline of the Pacific lowlands. Our captain suggested we should travel por dentro, slowly threading our way along the numerous meandering brooks and channels that cut through the mangrove landscape. He warned against navigating por fuera, on the open sea, as the Pacific Ocean was rough that day.

It was midday by the time we set off from the Bay of Tumaco. The sky was overcast, humidity near 90%, it was hot. I didn’t understand why we had waited so long. It was going to be a lengthy journey.

“Who are we waiting for?” I asked the captain, who had said something about esperando la marea.

“When is Marea coming?” …

Laughter all around. That was one of these silly gringo questions, of course. Marea means the tide. Apparently, there wasn’t enough water in the mangrove channels, and we had to be patient and wait for high tide to set in. Later I would realize how this seemingly mundane routine, the daily tidal changes, impacted everyday life patterns in a thousand and one ways. Travelling schedules are set according to the tides, calculating water availability not only in the coastal mangrove swamps but also further up the rivers. The alluvial plains have such a low gradient that the tidal impact can be felt up to 20 kilometres upstream. High tide also pushes salt water far up the rivers – a bad time for washing clothes or fetching drinking water from the river.

more than merely adaptive responses. The discourse of adaptation maintains those boundaries of culture and nature that seemed to dissolve in practice in front of my eyes. In 1999, I would spend many evening hours in the halfcovered courtyard of the house I rented on Calle Segunda, accompanied by Doña Celia Lucumí Caicedo, a traditional healer and midwife, with whom I shared this living space. As the rains pummelled the rooftops, generating a thunderous noise that drowned out all possibility of conversation, we just stared ahead watching sheets of rainwater hammering the patio’s tropical plants. These were moments of great peace and inner calm. There was nothing I could possibly miss out on. No one in Guapi left their homes during these deluges. No conversation could be had for the deafening roar of Changó’s fury unleashed on the rooftops of Guapi. It seemed we all became one with the rain.

Sitting in her rocking chair, Doña Celia was also lost in her thoughts back then, smoking pa’ dentro, with the lit end of the cigarette inside her mouth. A custom of many years, this enabled her to smoke while navigating her dugout canoe, come rain or shine. With both hands holding her paddle, the lit cigarette end was safe from wind and water in the navigator’s mouth. “A mi río, no lo olvido,” Doña Celia would murmur. “I don’t forget my river.”

I have since returned many times to Guapi and the Pacific lowlands. Doña Celia passed away in 2013. Other things have changed too. Illegal cultivation of coca was introduced to the region by outsiders, often forcing local peasants to cultivate this crop, which is turned first into coca paste and then cocaine, to be shipped to North American and European consumers. Unimaginable violence has accompanied those transformations in peoples’ everyday lives. Cocaine, make no mistake, is a blood-soaked white powder.

Sitting at the landing steps in Guapi the next day, I took in the majestic leisureliness with which the Guapi River descended to its meeting with the Pacific Ocean. It was there, where I spent innumerable hours in years to come, that the idea of the ‘aquatic space’ began to take shape. Anthropologists and geographers have described the interactions of rural populations with the tropical rainforest in terms of human adaptation to an often-unforgiving natural environment. Yet, sitting at the landing steps in Guapi, overlooking the busy activities – canoes arriving, women washing clothes on the river’s edge, children playing in the water, travellers awaiting embarkations to upstream locations – I felt that these were

Yet, the rivers still descend from the Andean foothills, carving their way calmly through the alluvial plains to their eventual encounter with the majestic Pacific Ocean. Locals still depend deeply on ‘their nature’, formed over hundreds of thousands of years, and shaped by human habitation and custom. And somewhere, in her little dugout canoe, Doña Celia is still digging her paddle into the river’s waves, smoking pa’ dentro, making her way upstream to her birthplace. Because, as everyone in Guapi knows, the ancestors are part of these landscapes, too.

FURTHER READING

Oslender U (2016) The Geographies of Social Movements: Afro-Colombian Mobilization and the Aquatic Space (Durham: Duke University Press)

West R (1957) The Pacific Lowlands of Colombia (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press)

“The daily tidal changes impacted everyday life patterns in a thousand and one ways.”

14Winter 2022 The Geographer 15

Dad and daughter.

Doña Celia smoking pa’ dentro

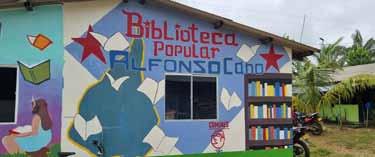

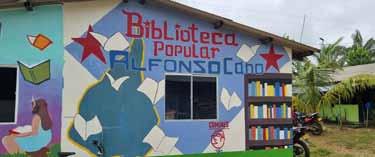

The cartography of empowerment: the Ecobarrios of Bogotá

Valeria Borrero-Ramos, Luis Sánchez-Ayala, University of the Andes

Valeria Borrero-Ramos, Luis Sánchez-Ayala, University of the Andes

The urban growth of Bogotá (the capital of Colombia) was marked by a process of rapid and extensive urbanization that took place throughout the 20th century. During this time, a large number of internally displaced people arrived in the city, escaping the atrocities of the armed conflict. Most of these people settled in the outskirts of the city, where the ‘vacant’ lands were not suitable for urbanization, without any type of infrastructure and basic services. This scenario gave way to the construction of a landscape of inequality in Bogotá, divided by the contrast between the informal neighbourhoods in the peripheries and the planned city of the elites with access to public services.

This is the case of Manantial and Triángulo Alto neighbourhoods in south-eastern Bogotá. Two informal neighbourhoods that, today, decades after their creation, are now declared by the authorities as high-risk zones due to possible landslides. This declaration was followed by a resettlement programme that forces the community to leave their homes and neighbourhoods. In response to such state policies, the community decided to initiate the process of creating the ‘Ecobarrio’ (Econeighbourhood).