Welcome to the summer 2022 edition of The Geographer. With Scotland’s census under way, and in response to letters from members, it felt like a good time to look at the general issue of population, to help us understand some of the big global trends and the pressures and policies this impacts. With ever-increasing population forecasts, it remains a key consideration in many geographical issues, and is a factor in everything from pandemics to sustainability.

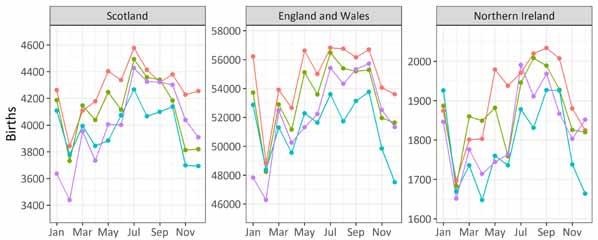

At the last census, in 2011, Scotland recorded its highest population ever, at 5,295,403 people. Within this figure, the number of people over the age of 65 exceeded the number of people under the age of 15 for the first time, underlining an ageing demographic, typical of many modern western countries. With a domestic population that was almost static between 2001 and 2011, most of the growth in population was attributable to immigration, which sat at around 6% of the population. Scotland, like many countries with ageing profiles, faces the problem of how to maintain services and economies if so few people are of working age, and is reliant on immigration to tackle this, at least in the short term. And whilst consumption remains the primary driver of worsening climate change, a burgeoning global population also plays a clear and significant role. What are the current trends in population? How do we minimise this impact and reduce this pressure? How do economies work with increasingly ageing populations? How does migration impact, especially when this is more likely in a climate-stressed world? And what is the outlook for Nature? This is especially pertinent with the United Nations Environment Programme’s Stockholm+50 event reflecting on the past 50 years of environmental efforts, and in the run-up to UN COP15 on biodiversity in Kunming later in 2022. And of course population is affected by war. With the awful invasion of Ukraine by Russia, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on the response from the geographical community and to express our sympathy and empathy for those affected and displaced. The beautiful front cover image was created by Scottish artist Evie Caldwell, and we are grateful to her for allowing us to use it here. And photographer Nicolas Economou has kindly provided some thought-provoking images of the people of Ukraine.

Alongside all of this, we have interviews with two of our newest postholders: RSGS’s new President, Professor Dame Anne Glover; and the newly-appointed Geographer Royal for Scotland, Professor Jo Sharp from the University of St Andrews. It’s another bumper edition and we hope you will find it informative, insightful and inspiring in equal measure.

Mike

Robinson, Chief Executive, RSGS

RSGS, Lord John Murray House, 15-19 North Port, Perth, PH1 5LU tel: 01738 455050 email: enquiries@rsgs.org www.rsgs.org

Charity registered in Scotland no SC015599

After serving as RSGS President for ten years, Professor Iain Stewart has now passed the baton on to Professor Dame Anne Glover, whom we are delighted to welcome to the role. Dame Anne is a biologist and academic, holding senior positions at the Universities of Aberdeen and Strathclyde, and is a previous President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. She served as the first Chief Scientific Adviser for Scotland (2006 11), and as Chief Scientific Adviser to the President of the European Commission (2012 14). Throughout her career, she has demonstrated how to take scientific knowledge from the laboratory to top decision makers and politicians in Scotland and in the EU, and has been a key ambassador for women in science. We greatly look forward to working with Dame Anne as our new President; see pages 38 39 for an interview in which she shares her enthusiasm for the role. And we are delighted that Iain Stewart has agreed to maintain his connection with RSGS by taking on a new position as a Vice-President.

We are delighted to say that our Fair Maid’s House Visitor Centre reopened on Friday 6th May 2022, for the first time since the start of the pandemic. Housed in the oldest secular building in Perth, the Fair Maid’s House is a geographical delight. Visitors can watch the planet from space and see the continents evolve in the Earth Room, or learn about the hottest and coldest places on Earth in the Education Room. In the Reception Room and Cuthbert Room, you can enjoy special displays of items from our collections, thanks to Margaret Wilkes and her Collections Team. And in the atmospheric Explorers’ Room, you can learn about maps and explorers, or just sit down with a fascinating book.

The views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the RSGS.

Cover image: Solidarity. © Evie Caldwell (www.eviegraceillustration.com) Masthead: SA Agulhas II. © Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust and James Blake

Over the summer, we plan to open the Fair Maid’s House from 1:00pm to 4:30pm every Thursday, Friday and Saturday. So please come along and visit us – we look forward to welcoming you all back to the Geographical Heart of Scotland!

Thursday, Friday, Saturday 1:00pm – 4:30pm

We are delighted to announce that Jo Sharp, Professor of Geography at the University of St Andrews, has been appointed as Geographer Royal for Scotland. Professor Sharp has been at the cutting edge of scholarship and public engagement around issues of inclusion and diversity for 25 years. See pages 16 17 for an introductory interview. With the position of Geographer Royal, Professor Sharp will adopt the tasks of promoting geography in Scotland, championing Scottish geography internationally, and better establishing ‘geographical thinking’ within public life. She is the sixth individual to hold the distinguished title, which was previously held (2015 21) by Charles Withers, Emeritus Professor at the University of Edinburgh.

With membership rates having remained unchanged since 1st August 2018, and to help counter the higher and still-rising costs that RSGS is facing – including for energy, professional services, travel, and now venues –the Board has recognised that it is necessary to increase membership subscription rates (there will be no change to the rate for School members). However, recognising that RSGS members and potential members are also facing many other cost-of-living price rises, it was agreed that any membership rate rise should be kept as minimal as possible, and certainly below the rate of inflation over the four-year period. Therefore, the Single rate has risen by only £2, to £50, and the Joint rate has risen by £3, to £75. Whilst we know any increase is unwelcome, especially in the face of rising costs across society, we are confident you will understand the need for this rise, and really hope you will continue to see this as great value for money. And with face-to-face talks returning this year, we are looking forward to welcoming so many of you back again, come the autumn.

The rates which will apply from 1st August 2022 are: Student/SAGT £21 School £30 Single £50 Joint £75 Life £1,320 Separately, we are looking at options for addressing the fast-rising cost of postage for those members who live outside the UK.

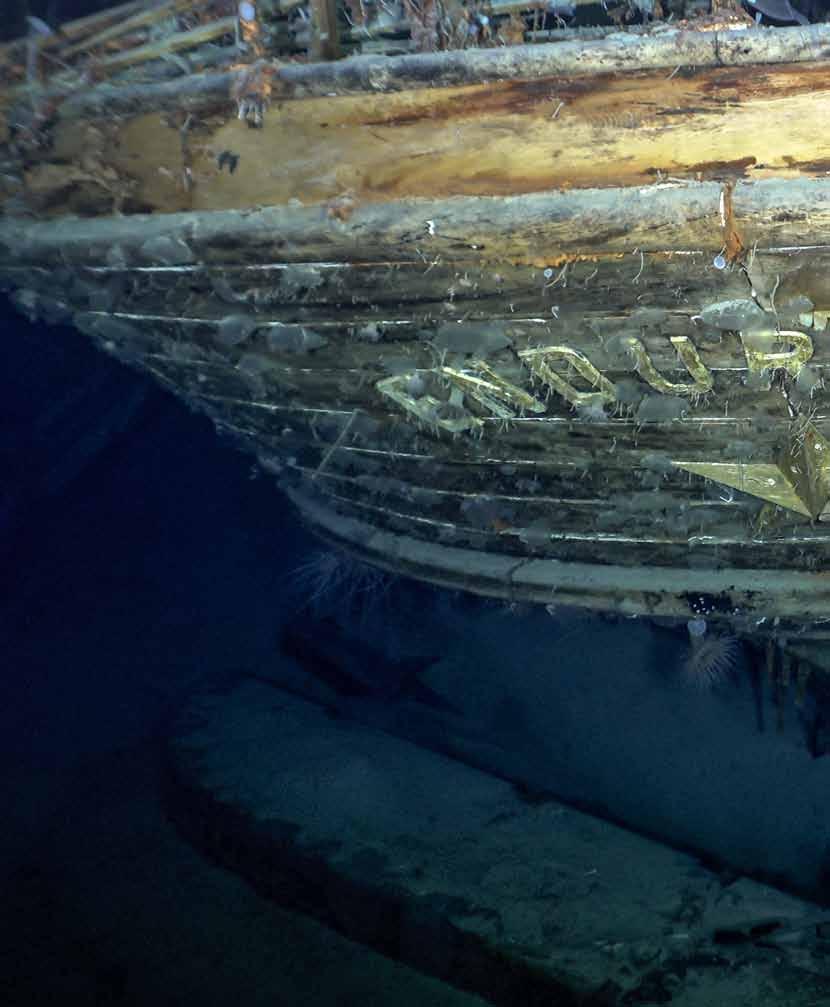

In May, at a private event at the Institut Français Écosse in Edinburgh, we were pleased to present our prestigious Shackleton Medal to Hugh Andrew, Managing Director of Birlinn Publishers, in recognition of his leadership and citizenship in Scottish publishing, and his role in exemplifying high-quality geographical works.

Thank you to everyone who attended an Inspiring People talk over the winter, and for your ongoing support. We successfully hosted 24 talks, with more than 10,000 households in attendance over the season. Some of the highlights were our Explorers-in-Residence Luke and Hazel Robertson and Writer-in-Residence Jo Woolf, cave diver Jill Heinerth, Active Nation Commissioner Lee Craigie, Kenyan hiker Gitonga Wandai, polar explorer Myrtle Simpson, and mountaineer Stephen Venables, but we’re sure you will have your own favourite. Catch up on many of these talks at www.rsgs.org/videos.

We are now planning our programme for 2022 23, and are very excited to be returning to face-to-face talks hosted by our Local Groups. We look forward to welcoming you back! We also plan to retain some online talks when the season starts again in September.

We are pleased to have held public screenings of our documentary, Scotland: Our Climate Journey, organised and hosted by RSGS Local Groups in Edinburgh, Helensburgh, Kirkcaldy, Perth and Stirling. The film tells Scotland’s climate journey through the past, present and future, narrated by individuals from different sectors, offering different perspectives and all contributing in the battle against climate change. Many thanks to our Local Group volunteers, and to all who attended. Visit www. rsgs.org/scotland-our-climate-journey for details of any upcoming screenings. Contact enquiries@rsgs.org if you would like to organise a screening in your local community.

organise a screening

In March, a meeting was held in Geneva to discuss a global plan to tackle the world’s escalating nature crisis. Convened under the Convention on Biological Diversity, the meeting brought together government negotiators to debate the draft text of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, with the final plan set to be adopted at the COP15 biodiversity conference in Kunming later this year. Following limited progress and commitments made during the discussions in Geneva, it was announced that an additional set of talks would take place in Nairobi in June.

There has been plenty going on at RSGS during the early part of 2022, with a strong focus on nature and agriculture. We ran a conference with Perth City Leadership Forum, and another with the international geographical community (see pages 32-33), to see what greater role can be played to support the biodiversity crisis. We had a number of visitors, virtually and face-to-face, including Deputy First Minister John Swinney and Cabinet Secretary Marie Gougeon, with whom Mike Robinson is working closely through the Agriculture Reform Implementation Oversight Board which is considering a future farm payment system.

Mike Robinson spoke at a number of external events, including a Social Investment Scotland event, a YMCA Scotland conference, and a Perth Ambassadors breakfast meeting, and we ran a few film screenings of Scotland: Our Climate Journey. And we continue to develop our international connections, working with the Royal Canadian Geographical Society on their statement on Indigenous languages, with the International Geographical Union and the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) on a biodiversity conference, and with the Explorers Club of New York.

In March, we were pleased to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Devi Sridhar, Professor and Chair of Global Public Health at the University of Edinburgh, in recognition of her invaluable research contributions during the Covid-19 pandemic, and for being a critical voice in communicating to the public and advising the UK and Scottish Governments. In addition to media appearances, much of Sridhar’s important impact on the UK’s pandemic response has been behind the scenes. As part of her DELVE membership, Sridhar advises the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies. She is also part of the Scottish Government’s expert group which develops and improves the pandemic response plan.

We are very grateful to Philanthropy & Fundraising International, a highly-regarded professional fundraising consultancy, for their recent generous provision of access to two places on their acclaimed Great Fundraising Masterclass. The inspirational training course is now helping to inform the development of RSGS’s new strategic fundraising plan, and we hope it will help us in achieving a significant step-change to the Society’s levels of regular income, enabling us to deliver more and better outcomes for Geography in Scotland over the next few years.

The East Grampian Coastal Partnership (EGCP) has launched a new project to create four unique maps covering the Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire coasts. The maps will feature a wealth of interesting information about the coastline, including the people, history, environment and activities that make the North East of Scotland special. EGCP is collecting memories, thoughts and short stories of residents and visitors who have spent time in the area, for possible inclusion in the maps. See www.egcp.scot/discover-maps for more information.

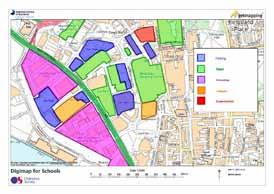

Digimap for Schools (digimapforschools.edina.ac.uk), created by Ordnance Survey (OS) and the University of Edinburgh’s data and digital expertise centre EDINA, gives teachers and pupils access to a wide range of OS’s authoritative data and tools. In recognition of the powerful effect mapping can have in bringing many academic subjects to life and supporting increased learning outcomes, OS will provide two years of free access to Digimap for Schools to any primary or secondary school in England with a low Ofsted rating.

David Henderson FRSGS, OS Chief Geospatial Officer, said, “Providing primary schools with an Ofsted rating of 3 or 4 free access to Digimap for Schools will help even more young people to experience the benefits of exploring their understanding of the world through maps. As well as being fun, the lifelong skills that stem from such enhanced geographical awareness are fundamental to solving some of today’s biggest challenges.”

During April, we were pleased to distribute copies of Horrible Geography of Stunning Scotland and James Croll and his Adventures in Climate and Time to all primary and secondary schools in Perth, as a free and fun learning resource! Horrible Geography teaches about the best (and most gruesome) of Scotland’s geography, from leaking lochs and roving rivers to groovy glaciers and vile volcanoes. James Croll tells the story of a brilliant-minded man from Perth who defied poverty and ill-health to become one of the world’s first climate scientists.

Both books can be purchased at our Fair Maid’s House Visitor Centre (open 1:00pm to 4:30pm, Thursday to Saturday), through our online shop at rsgs.org/shop, or by phone at 01738 455050.

We are sorry to report the death of one of our long-standing Vice-Presidents. Born and educated to Doctorate level in Belfast, Bruce Proudfoot was a Geography academic with a distinguished career that spanned universities in Belfast, Durham, Edmonton (Canada) and finally St Andrews. He served as RSGS Vice-President from 1993, and maintained a keen interest in the Society’s work, and in antiquities and archaeology.

Due to an unusual technical glitch, the title and byline of the article published on page 13 of the spring 2022 edition of The Geographer failed to appear. The article was entitled ‘Five million more

lost’ and it was written by Gordon Brown, former Prime Minister. We sincerely apologise for this error.

According to the United Nations, in late April at least 15.7 million people from Ukraine were in urgent need of humanitarian assistance and protection, and most of those had had to flee their homes. “Over five million people fled Ukraine to seek safety in other countries, and another 7.1 million have been internally displaced across the country,” said UN Assistant Secretary-General Amin Awad. “This represents more than 25% of the entire population of Ukraine.”

Since the Russian invasion on 24th February, civilian infrastructure has taken a huge hit, with more than 136 health facilities and an average of 22 schools a day coming under attack. Moreover, damaged water systems have left six million people without regular access. At the same time, humanitarians face tremendous challenges that often prevent them from delivering assistance to areas where people are in desperate need. And to add to the complexity, many people who have been displaced are now returning home.

The months of intense and escalating hostilities in Ukraine continue to have horrific repercussions for civilians, and continue to cause a grave humanitarian crisis. “It is remarkable how the humanitarian community here managed, in a few weeks, to expand from delivering assistance in two areas of eastern Ukraine to now operating across all 24 oblasts,” said Osnat Lubrani, UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Ukraine. “However, we are still not able or have been prevented from reaching areas where people are in dire need of assistance, including Mariupol and Kherson.”

Jane Digby el-Mezrab: From Ballroom Conquests to Bedouin Camps: RSGS Writer-in-Residence Jo Woolf explores the remarkable life of Jane Digby, who inspired a new character in the recent BBC adaptation of Around the World in 80 Days The Covid Pandemic, Two Years In: RSGS Chief Executive Mike Robinson reflects on the Covid-19 pandemic and considers what has changed since the beginning of the outbreak.

In March, Mike Robinson received the Cairncross Trophy, given in recognition of outstanding citizenship. The award was for his contribution as RSGS Chief Executive, for his promotion of community sport and wellbeing through his Chairmanship of Live Active Leisure, “and for the many other services he willingly and freely gives to the community of Perth.”

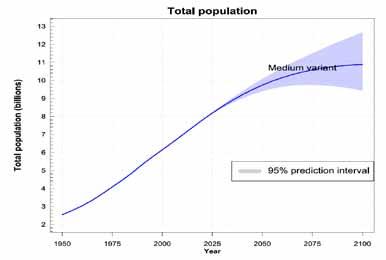

In 1950, five years after the founding of the United Nations, world population was estimated at around 2.6 billion people. It reached five billion in 1987 and six billion in 1999. In October 2011, the global population was estimated to be seven billion. In May 2022, it is estimated at over 7.9 billion. This dramatic growth has been driven largely by increasing numbers of people surviving to reproductive age, and has been accompanied by major changes in fertility rates, increasing urbanisation and accelerating migration. These trends will have far-reaching implications for generations to come.

See pages 8 9 for more information about world population growth.

Taking inspiration from the word-guessing game Wordle, there are now geographical versions. In Worldle (worldle.teuteuf.fr), you are asked to identify a country by its outline. You have six chances; if you guess incorrectly, you will be told in which direction the answer lies and how far away it is from the guessed country. In Globle (globle-game.com), you are asked to find the mystery country using the fewest number of guesses. Each incorrect guess will appear on the globe with a colour indicating how close it is to the mystery country; the hotter the colour, the closer you are to the answer.

We were delighted to appoint Alistair Cave and Matthew Edwards, from Mort&Pal Video Production & Editing Services, as the first RSGS Film Producers in Residence. We have already collaborated with Al and Matt on a number of exciting projects, including all of our online Inspiring People talks, our Chalk Talk online lessons, and interviews with John Blashford-Snell and Professor Iain Stewart. We look forward to continuing our work with Mort&Pal, and the film projects they will help us create in the future.

Many senior secondary school pupils will now be considering their options for university. Of course, the best subject for many will be Geography, as it offers such a wonderful breadth of subject matter, skills and experiences, leading to a wealth of career choices.

The University of Aberdeen, for example, offers both MA and BSc Geography subjects, with plenty of topics to offer in human and physical geography. The department specialises in subjects like sustainable development, rural and digital geography, paleoecology, water resource management, and glaciology. All teaching is research-led and investigates some of the most important problems facing the world today, ensuring that courses are current and exciting, and reflect the cutting edge of geographical research. For more information, visit www.abdn.ac.uk and search for ‘Geography’.

A flagship UN report on climate change which was published in April indicates that harmful carbon emissions from 2010 to 2019 were the highest in human history, and that as a consequence the world is on a ‘fast track’ to disaster. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report noted that greenhouse gas emissions generated by human activity had increased since 2010 across all major sectors globally, suggesting that we are on a pathway to global warming of more than double the 1.5°C limit that was agreed in Paris in 2015. Although there is encouraging work being done, the report calls for immediate reductions in emissions across all sectors to limit global warming.

In April, we were pleased to present RSGS Honorary Fellowship to Dr Richard Dixon, former Director of Friends of the Earth Scotland and WWF Scotland, in recognition of the huge role that he has played in developing Scotland’s environmental ambition over the last three decades, in injecting science into a wide range of policies in Scotland, and in sharing his deep knowledge and wisdom throughout the NGO community.

Martin Hurst, Emma Laurie, Chris Philo, Rhian Thomas, University of Glasgow

Following the sterling efforts by Dan Clayton and Charles Warren (University of St Andrews), the Scottish Geographical Journal has moved into the custodianship of a new editorial team based at the University of Glasgow. This new team combines expertise across human geography (Emma Laurie, Chris Philo) and physical geography (Martin Hurst, Rhian Thomas), and together we possess diverse cross-disciplinary linkages across to the Earth sciences, geospatial and mapping sciences, social sciences and humanities.

In line with the scholarly traditions of the journal, dating back to 1885, we will seek to ‘refresh’ the journal’s offering in various ways: chiefly by encouraging greater flexibility in the types and forms of contributions that we will publish, but also by seeking a greater range of ‘voices’ from both inside and beyond academia. The Scottish roots of the journal are crucial, and our ambition is to be publishing high-quality, topical and challenging pieces about and from Scotland, always seeing Scotland within a global panorama of changing environments and landscapes (natural, manufactured, political-economic and sociocultural). We encourage people to read our inaugural editorial, which will appear shortly, and to check out the journal website (www.tandfonline.com/journals/rsgj20). Fortuitously, the first hard copy issue to appear under the new editorship will carry a brand-new cover, graced by a lino-cut from the esteemed artist Nick Hayes.

Neonicotinoids were back in the news recently, so it was interesting to see a survey carried out by the Scottish Government’s Bee Health Team, with consultation and comments by members of the Bee Health Improvement Partnership. Participants provided information on measures they would like to see included in a new strategy to help improve the health of Scotland’s honey bees. Comments show education remains at the forefront of future work. Other suggestions included bans or restrictions placed on imports and pesticides, government funding for new beekeepers and local associations, more communication, introduction of compulsory registration, more research, more bee inspections, and protection for Varroa-free areas. The results of the survey, along with lessons learned from a review of the previous strategy, will be key in informing the new ten-year Scottish Honey Bee Health Strategy.

In late February, under the auspices of His Highness Sayyid Bilarab bin Haitham Al Said, the British Embassy and Outward Bound Oman celebrated a new partnership to equip 500 young Omanis with a broad understanding of the importance of sustainability, and the causes and impact of climate change, with a focus on solutions, mitigation and opportunity. Using Outward Bound Oman’s equipped training centres in the Sharqiyah Desert and Jabal Akhdar, the Climate Shapers programme builds upon COP26 outcomes and aims to equip young Omanis with the knowledge to positively impact, influence and inspire the communities around them. The celebratory event took place in Outward Bound Oman’s training centre in Muscat, attended by His Excellency Bill Murray, the British Ambassador in Oman, and other VIP guests. RSGS featured prominently, with a three-minute video clip featuring our Chief Executive, Mike Robinson.

A new Scottish Government report (www.gov.scot/publications/ blue-economy-vision-scotland) focuses on the sustainable use of ocean resources while preserving the health of marine and coastal ecosystems. It recognises that Scotland’s seas and waters have a key role to play in contributing to the nation’s future economic prosperity, especially in remote, rural and island communities, and that a healthy marine environment is essential to supporting this ambition.

Scotland has 617,000km2 of marine area, seven times greater than the size of the land, and 18,743km of coastline. The marine economy supports nearly 75,000 jobs, a sector that generated £5 billion in GVA in 2019. The blue economy approach requires a transition from ‘environment versus economic growth’ (the prevailing status quo in Scotland and globally) to ‘shared stewardship’ of natural capital that is facing common pressures.

The six outcomes are:

1 marine ecosystems are healthy and functioning;

2 Scotland’s blue economy is resilient to climate change and contributes positively;

3 established and emerging sectors are entrepreneurial and competitive;

4 to be a leader in healthy, quality, sustainably harvested and farmed Blue Foods;

5 thriving, resilient communities have more equal access to the benefits that ocean resources provide;

6 Scotland is an ocean literate and aware nation.

In 2020, writer Val McDermid and geographer Jo Sharp edited a book called Imagine a Country, which contained nearly 100 ideas for Scotland’s future from people across the country, and challenged readers to start imagining their future. RSGS is taking up this challenge with a writing competition for secondary school pupils in Scotland. The deadline for entries is 24th June 2022, and we hope to feature the winning essays or stories in the next edition of The Geographer. See rsgs.org/imagine-acountry for more information.

We have now held ten Meet the Expert events, short online sessions in which individuals and organisations can hear from leading experts in the fields of climate change and sustainability. At an event in late April, we were joined by Professor Des Thompson, Principal Adviser on biodiversity and science at NatureScot, and Dr Deborah Long FRSGS, Chief Officer at Scottish Environment Link, to explore what the biodiversity challenge means for organisations, and what solutions exist.

Long-standing RSGS member and supporter Iain Rankin will have been known to many of you, most likely as the cheerful and dynamic Chair of the RSGS Aberdeen Group, a position he held for many years. Iain was a huge supporter of RSGS, alongside his many other charitable interests, and we miss him greatly. He volunteered in the Fair Maid’s House, promoted our work wherever he could, and even attended events on our behalf. One such was the Patron’s Lunch, a street party to celebrate the 90th birthday of our Patron, Her Majesty The Queen, held in The Mall in London in 2016, which Iain enjoyed with other long-standing members including Board member Lorna Ogilvie.

Iain was always incredibly enthusiastic about our activities, especially those which benefitted young people. Perhaps it isn’t surprising then that Iain’s generous spirit also extended to his legacy. When he died in 2018, he not only made sure that we received his map collection, but he also mentioned RSGS in his Will. And in late April we received a final notification that RSGS will receive c£15,000, for which we are extremely grateful. Gifts like these are really vital to our small charity, and we are indebted to Iain’s foresight and kindness.

If you would like to consider donating to RSGS in your Will, please do get in touch with Mike Robinson at the office in Perth.

For many of us, the population bomb is the ultimate ecological doomsday machine. All efforts to halt climate change, end extinctions and the rest are bound to fail, it seems, unless we can end the apparently unstoppable rise in human numbers in Africa, India and elsewhere.

Well, we should think again. For in the half century since the phrase was popularised by American ecologist Paul Ehrlich, in a best-selling book of the same name, the population bomb has gone a long way to being defused. What is replacing it is a consumption bomb.

Take India. It is about to overtake China as the world’s most populous country. But in November 2021, the government there announced that the number of children born to an average Indian woman had fallen from 5.9 back in the 1960s to just 2.0, slightly below the long-term ‘replacement level’ of 2.1 children per woman.

With two-thirds of India’s population under 35 years old, it will be a while before their numbers stop rising. But the country is primed for population decline from mid-century. It is far from alone. Only two of the world’s ten most populous nations still have fertility above 2.1: Pakistan and Nigeria. The rest – China, India, the USA, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, and most recently Bangladesh and Indonesia – are at or below replacement levels. Global average fertility is below 2.4 and falling fast. The trend to radically smaller families is near-universal now. In much of East Asia, as well as southern and eastern Europe, fertility has for years been closer to one than two. When in 2015 China abandoned its 35-year-old coercive one-child policy, there was no fertility uptick. Chinese women mostly only want one child now. Declining fertility typically goes fastest among the better educated and better off, and those living in cities. But “there is plenty of evidence that once fertility starts declining, less educated/poorer/rural people follow suit,” says Monica Das Gupta, a sociologist at the Maryland Population Research Center. The underlying reason is that, thanks to massively improved health among children, couples can decide their family size on the assumption that their babies will grow to adulthood.

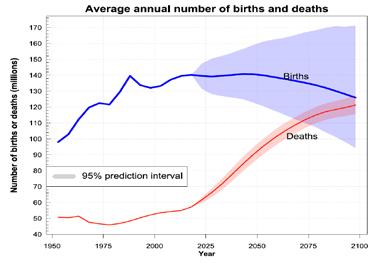

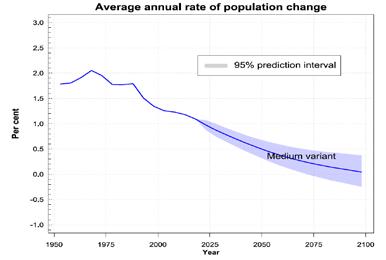

So, while the world’s population has more than doubled in the past half century, to around 7.9 billion today, it seems most unlikely to double again. UN demographers predict a peak of around 11 billion at the end of the century. Many demographers believe it will happen much sooner. Stein Emil Vollset at the University of Washington says numbers may peak in the 2060s, and slump to as low as 6.3 billion by the century’s end.

That may be over-optimistic. Women in sub-Saharan Africa still average 4.7 children, but even there the trajectory is downwards. In the 1970s, Kenya had the world’s highest fertility rate, at 8.1. Today, it is today down to 3.4. Vollset and others expect accelerated fertility declines, as the continent urbanises, education improves, and family planning becomes more available. But no coercion required. If Ehrlich’s demographic doomsday scenario is not playing out, his framing of the planetary crisis remains otherwise correct. He saw humanity’s impact governed by three factors: human numbers, rising per capita consumption, and the technology we use to produce what we consume.

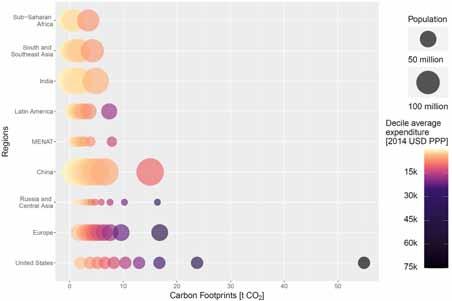

It is increasingly our consumption patterns that are driving climate change, our rising use of resources, and the destruction of nature. And that is with as many as a billion people going to bed hungry at night, and many more with degrading living standards.

To defuse the consumption bomb, we need of course to address the consumption patterns of the rich – and yes, that does include us – but also to embrace the third factor in Ehrlich’s doomsday equation. Here too there is at least a glimmer of hope.

To take three examples. We know the energy-generating technologies that can cut our carbon emissions by more than 90%. We know how to recycle most materials to reduce mining and simplify manufacture. And we know how to produce our food on a fraction of the land currently tilled, so giving land back to nature.

So here is an optimistic narrative. The doomsters are wrong. Demography is not destiny. But our ingenuity assuredly is.

“While the world’s population has more than doubled in the past half century, it seems most unlikely to double again.”

The profound impact of people on the planet is undeniable: 95% of the Earth’s surface and 87% of the ocean are affected by human activity. We’ve disrupted the climate to a degree that threatens all life on Earth. Our geological age was recently named the Anthropocene to reflect the devastating transformation being caused by a single species: our own.

Yet when it comes to the root of this ecological harm, people often choose sides with the fervour of football fans, blaming either population or consumption. But this is a match no one wins unless we recognise that population and consumption are two sides of the same coin.

We can’t meet climate targets or protect wildlife simply by slowing population growth while greenhouse gas emissions, animal agriculture, plastics production, waste, and pollution continue to rise on a steep curve.

And we can’t effectively mitigate climate change over the long term, stop deforestation, or end the extinction crisis as long as we continue adding 220,000 people to the planet every day. That’s nearly doubling the population of Glasgow each week – and every new person needs food, water, energy, and a place to call home.

Consumption and population combined create the pressure we put on the world around us.

By the end of 2022 or early 2023, there will be eight billion people in the world; more than twice as many as there were 50 years ago. In that same time span, wildlife populations have plummeted by more than two-thirds and wild spaces have been lost at an alarming rate. According to the Global Footprint Network, in 2021, humanity used up the resources the planet can replenish in a year by the end of July; five months too soon. We’re amassing ecological debt we won’t be able to repay.

Although the public discourse about environmental crises continues to be dominated by debates over rapid population growth versus unsustainable consumption, many people are beginning to understand this is a false dichotomy.

A recent survey by a US-based reproductive health company found that 58% of people were reconsidering having children because of the climate crisis. Another survey found that more than 96% of respondents were “very” or “extremely concerned” about their children growing up in the age of climate crisis, while nearly 60% were just as concerned

about the carbon footprint of their reproductive choices. As a result, people are deciding not to have children, to have fewer children, or to move to a city with fewer climate-related risks before getting pregnant.

We inherently understand that our family planning choices and the future of our children can’t be separated from how we use and exploit the environment.

The clock is ticking before the changes wrought by humanity are irreversible – not just climate catastrophe but the loss of irreplaceable biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. We don’t have time to argue about whether population growth or consumption is to blame, especially when the solutions are the same.

There are good reasons why people react to these issues with the passion of rivals, especially when it comes to the stigma around population growth. Historically, and even now, atrocities like forced sterilisation have been committed in the name of population control. One thing we can all agree on is that human-rights violations have no place in the fight for our future. Solutions must be based in justice, dignity, and empowerment. And those aren’t just the only acceptable solutions; they’re also the most effective.

Increasing access to reproductive healthcare and education for women and girls improves equity and wellbeing, which make it easier to cope with environmental disasters. Women who are educated and empowered to make their own family planning decisions are also better able to participate in muchneeded solutions to climate change, pollution, habitat loss, and other ecological problems. Healthcare and education also happen to be the key to slowing population growth.

Transitioning to renewable energy reduces pollution and climate risks that harm reproductive health and justice, making it easier for people to choose if and when they want children and to raise their families in a healthy environment. Transforming food and agriculture to increase access to sustainable diets and farming practices improves human health outcomes, particularly for pregnant people and children, and reduces pressure on wildlife and habitat.

To address the environmental crises that define our lifetime, we need to find solutions to both population growth and overconsumption by expanding human rights and creating a fairer, healthier future for everyone.

“We’re amassing ecological debt we won’t be able to repay.”

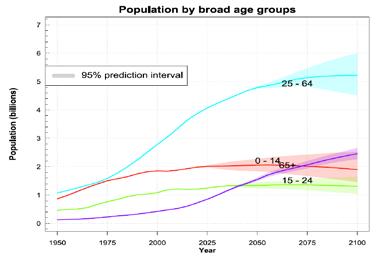

The world’s population is expected to increase by nearly two billion persons over the next three decades, from 7.9 billion currently to 9.7 billion in 2050. A report published by the Population Division of the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects 2019, population. un.org/wpp) concluded that the world’s population could reach its peak around the end of the current century, at a level of nearly 11 billion. The report also confirmed that the world’s population is growing older due to increasing life expectancy and falling fertility levels.

Growth rates vary greatly across regions. The number of countries experiencing a reduction in population size is growing, while the population projections indicate that nine countries will make up more than half the projected growth of the global population between 2019 and 2050: India, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, the United Republic of Tanzania, Indonesia, Egypt, and the United States of America (in descending order of the expected increase). China (1.44 billion) and India (1.39 billion) remain the two most populous countries of the world, representing 19% and 18% of the world’s population,

respectively. Around 2027, India is projected to overtake China as the world’s most populous country.

The population of sub-Saharan Africa is projected to double by 2050 (99% increase). Growth rates for other regions include Oceania excluding Australia/New Zealand (56%), Northern Africa and Western Asia (46%), Australia/New Zealand (28%), Central and Southern Asia (25%), Latin America and the Caribbean (18%), Eastern and SouthEastern Asia (3%), and Europe and Northern America (2%).

The global fertility rate, which fell from 3.2 births per woman in 1990 to 2.5 in 2019, is projected to decline further to 2.2 in 2050. A fertility level of 2.1 births per woman is needed to ensure replacement of generations and avoid population decline over the long run in the absence of immigration. In 2019, fertility remained above 2.1 births per woman, on average over a lifetime, in subSaharan Africa (4.6), Oceania excluding Australia/New Zealand (3.4), Northern Africa and Western Asia (2.9), and Central and Southern Asia (2.4).

“The world’s population is growing older.”

The world’s population is growing older, with the age group of 65 and over growing the fastest. By 2050, one in six people in the world (16%) will be over age 65, up from one in 11 (9%) in 2019. Regions where the share of the population aged 65 years or over is projected to double between 2019 and 2050 include Northern Africa and Western Asia, Central and Southern Asia, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean. By 2050, one in four persons living in Europe and Northern America could be aged 65 or over. In 2018, for the first time in history, persons aged 65 or above outnumbered children under five years of age globally. The number of persons aged 80 years or over is projected to triple, from 143 million in 2019 to 426 million in 2050. The falling proportion of the working-age population is putting pressure on social protection systems. The potential support ratio, which compares numbers of persons at working ages to those over age 65, is falling around the world. In Japan this ratio is 1.8, the lowest in the world. An additional 29 countries, mostly in Europe and the Caribbean, already have potential support ratios below three.

A growing number of countries are experiencing a reduction in population size. Since 2010, 27 countries or areas have experienced a reduction of 1% or more in the size of their populations. This drop is caused by sustained low levels of fertility. The impact of low fertility on population size is reinforced in some locations by high rates of emigration. Between 2019 and 2050, populations are projected to decrease by 1% or more in 55 countries or areas, of which 26 may see a reduction of at least 10%. In China, for example, the population is projected to decrease by 31.4 million (c2.2%) between 2019 and 2050.

Migration has become a major component of population change in some countries. Between 2010 and 2020, 14 countries or areas will have seen a net inflow of more than one million migrants, while ten countries will have seen a net outflow of similar magnitude. Some of the largest migratory outflows are driven by the demand for migrant workers (Bangladesh, Nepal and the Philippines) or by violence, insecurity and armed conflict (Myanmar, Syria and Venezuela).

Dr Phoebe Barnard, Chief Executive, Stable Planet Alliance, USA

Dr Phoebe Barnard, Chief Executive, Stable Planet Alliance, USA

We can no longer avoid it: humanity is in advanced ecological overshoot. Our overexploitation of resources exceeds ecosystems’ capacity to provide them or to absorb waste. Global society has failed to meet the goals of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). We face an epochal crossroads.

Solutions are rooted in the two fundamental drivers of ecological overshoot: population growth and consumption growth. Consumption is, of course, non-linearly but inextricably linked to population. Global population is now roughly ten times the relatively stable levels prior to 1750. And global consumption is massively greater than this; disproportionately so. The 80+ million net new people added to the planet each year (which is ten million more people than in the entire United Kingdom in 2021) and their associated consumption undermine solutions to our environmental and societal crises.

Climate instability, extinction, famine, social and political instability, unprecedented suffering – all our good works to forestall these are made almost impossible simply by needing to cut the ‘pie’ into an additional 80 million pieces each year.

Population and consumption are the two fundamental ‘threat multipliers’. And managing these threat multipliers, not to mention the threats that are multiplying, requires changing both public perception and public policy. This is the first step. The next step is significantly increasing investments in ethical and empowering health, education and economic programmes supporting women and girls, men and boys. These can already start to bend the global population curve by the middle of the century, or even sooner. Bold actions are required in the next five to eight years, at all scales. Yet the ‘demographic transition’ that made such progress in the 1960s and 1970s slowed in the past 20 years. Investment in family planning programmes faltered over the past 25 years, despite continued population growth. Globally, births per woman fell by more than one in the 1970s, but by only 0.1 in the 2010s. There are twice as many women of childbearing age as 50 years ago. Much more deliberate action is needed.

Society is changing fast anyway, everywhere. Women are increasingly choosing smaller families, to better provide for their children and balance family life with economic opportunities. Small families are one of the best ways to reduce human impacts. Many young people also question the ethics of bringing children into a world so fraught with crises. For citizens of rich countries, having fewer children is the single most effective way to individually reduce future greenhouse gas emissions. For those of poor countries, increasing economic and educational advancement and urbanisation are rapidly changing birth rates, although they sometimes increase consumption. Many countries are currently perversely trying to increase birth rates, through ill-founded fears of the economic impacts of an ageing population. Such misconceptions contribute to chronic underfunding of reproductive health and family planning services, and growing numbers of women with

unmet needs. Fulfilling these needs could avoid 21 million unintended births globally per year, while saving $3 on maternal and newborn health care for each dollar spent on contraception. The economic stimulus from slowing population growth repays the investment more than one hundredfold within a few years.

Despite 25-year shortfalls in intergovernmental support for family planning programmes, some non-profit- initiatives are effective in reaching under-serviced communities and transcending cultural barriers. For example, Population Media Center’s serialised TV/radio dramas in local languages in 50+ countries change attitudes toward women’s roles, family violence and contraception. Adequate funding for these normshifting programmes is an essential investment in planetary and social wellbeing.

Other good news is the proliferation of Population-HealthEnvironment (PHE) projects. Few environmental or livelihood programmes in the past linked population growth and environmental stress, but this is changing. PHE projects integrate community health and family planning alongside resource management and livelihoods, often with greater community engagement and enthusiasm than single-sector projects. Linking environmental health with population pressure improves men’s support for family planning. Scaling up and funding such projects would steadily reduce pressure on our planet and climate.

While climate change may not motivate everyone to have smaller families, the improvement of family and community wellbeing may. Smaller families improve women’s health, infant nutrition, and access to schooling and employment prospects, while easing pressure on the environment. After a few decades, the lower population trajectory becomes a dominant determinant of sustainable wellbeing.

Like planting a forest, our slow start only increases the urgency of our predicament. How we normalise lower birth rates in this decade will make the difference between having 12 billion or seven billion people to sustain in 2100. While accelerating the decline in fertility won’t contribute much to phasing out fossil fuels by 2050, it will affect our trajectory for ending and reversing deforestation. This is vital for achieving net-zero emissions. Earth in overshoot cannot sustain even the current 7.9 billion without unacceptable trade-offs. It’s time we acknowledge this.

“Managing these threat multipliers requires changing both public perception and public policy.”

Approximately 80 million people are added to the global population annually. That is the equivalent of ten New York Cities, or a single Germany, added to our planet – each year. Our planet’s finite geography has been transmogrified by humanity’s constant march to delete or further burden our planet’s unique ecoregions that support basic human life. This has finally led to a global discussion on how we, as a global community, might set aside 30% of our planet for nature by 2030, on our quest to set aside at least half of the planet for wilderness over the long term, as the famous ecologist E O Wilson called for in his final book Nature Needs Half in 2016. Population is not the only issue at play here, but the days of ignoring population dynamics as the inconvenient truth that we prefer not to discuss are now over.

Humanity long ago exceeded our planet’s longterm ecological carrying capacity, and has been accumulating ecological debt at an alarming and unsustainable rate – a debt that will come due in a horrific manner if not paid down aggressively in the near term. Human population and consumption dynamics have been driving us closer and closer to climate catastrophe, ecological destruction and untold human suffering each year. Yet we should not necessarily be discouraged. Our ability to bend these curves, lighten the human footprint choking our planet, and avert such catastrophes is nigh.

The energy transition is already afoot, and could easily be accelerated. Ideally we would achieve not only net-zero emissions but zero emissions, and far less profligate use of energy. Transitions in our consumption patterns, particularly those of the wealthiest nations, are also finally being discussed in earnest. Done properly, this transition could help many of us lighten our individual human footprints, while also allowing billions from the developed world to transition into the global middle class without emulating the kind of ecological footprint we in the developed world have historically foisted on our planet. We should not kid ourselves; much is left to be done on both these counts. But, it is the demographic transition that must be accelerated, receiving particular attention, if we are to live within the limits of our finite planet. We cannot continue adding 80 million people each year and think our progress on

energy and consumption transitions will have a meaningful effect, particularly since we are buried so deep in the ecological debt that generations of humans have already accumulated. Many forget that a demographic transition has been afoot for decades, as women and girls have been educated, empowered, integrated into the workforce, and given access to family planning technologies. The overall fertility rate of the world has dropped from five children per woman in 1950, to below 2.5 in 2020, which means that women today are having half the number of children that women did 70 years ago. The Population Research Bureau reported a global fertility rate of 2.3 in 2021. We are so close to achieving the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. Many countries have demonstrated that this demographic transition leads to prosperity, not the other way around, with some of the most prosperous countries (and certainly many of their urban centres) demonstrating fertility rates of 1.5 or below. South Korea reported a fertility rate of 0.8 in 2021. Scotland is now below 1.29 total fertility rate. How much would we need to invest in women and girls over the next decade to accelerate this demographic transition so that globally we achieved a fertility rate of 1.5 by 2030 –using empowering strategies and shunning coercive means? That is the question we should be asking ourselves and our leaders. If we achieved that goal, and if we accounted for the natural demographic momentum built into the system, by 2050 we could have fewer people on the planet each year instead of more. We could safely avoid a peak of nine billion humans, and glide to three billion humans soon after 2100, all the while paying down centuries of ecological debt. Some (economists in particular) will invoke baby bust alarmism, questioning how the economy could work in such a scenario. I suspect if the great Scottish economist Adam Smith were alive, he would explain the mechanisms by which our economy could be resilient in the face of this challenge; certainly more resilient that it will be in the face of climate catastrophe, ecological annihilation, and the resulting human displacement, conflict and suffering.

In A Planet of 3 Billion, Dr Tucker decrypts the complex story of how we have come to burden the finite geography of our planet in unsustainable ways.

“Many countries have demonstrated that this demographic transition leads to prosperity.”

Half a century ago, in the summer of 1972, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment opened in Stockholm. It was a historic meeting. It led directly to the establishment of the Brundtland Commission, whose report triggered a succession of international meetings, beginning with the UN Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, and its successors, in Johannesburg in 2002 (Rio+10) and Rio again in 2012 (Rio+20), and finally the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in New York in 2015, which adopted the Sustainable Development Goals.

In June 2022, the fiftieth anniversary of Stockholm is being marked by another UN meeting, ‘Stockholm+50’, again in Stockholm. This is pitched as a commemoration of the 1972 meeting, a celebration of “50 years of global environmental action,” and an opportunity to address the “triple planetary crisis” of climate, nature, and pollution. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) hopes it will “act as a springboard to accelerate the implementation of the UN Decade of Action to deliver the Sustainable Development Goals.” That is a lot to hang on a two-day meeting.

The 1972 Stockholm Conference had predecessors, including the UN Scientific Conference on the Conservation and Utilization of Resources in 1949, and the Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth symposium in 1955. That included contributions from geographers (Darby, Gourou, Glacken, Mumford, Sauer, the list is long) and helped give human-environment relations a central position in the growing discipline of Geography.

More immediately, Stockholm drew inspiration from the Biosphere Conference in Paris in 1968, and discussion of the environment by the UN’s Economic and Social Council. The Swedish ambassador to the UN proposed a conference on the human environment in July 1968.

The worries that brought Stockholm into being were primarily those of western environmentalism, about issues such as nuclear and chemical waste, acid rain and industrial

pollution. Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s ground-breaking critique of the pesticides industry, had been published ten years earlier, and Paul Ehrlich’s neo-Malthusian The Population Bomb in 1968. Environmental movements were growing fast, particularly in Europe and North America. The governments of many developing countries (many recently independent), mistrusted this environmentalism. Faced with deep poverty, environmental problems caused by industrialisation seemed remote. They feared that environmental protection would hinder economic development.

A meeting of the Stockholm Conference ‘Preparatory Committee’ in 1971 adopted the idea of sustainable development to circumvent these fears, suggesting that development and environmental protection could go together, that industrialisation without environmental harm was possible. This kept the conference on track. The scope of the conference was also expanded to include issues of particular concern to developing countries such as soil erosion, desertification, water supply and human settlement.

The Stockholm Conference itself was attended by the governments of 113 countries, although (unlike the Rio Conference 20 years later) by only two Heads of State (Indira Gandhi for India and Olaf Palme from the host country).

Issues debated included not only environmental problems, but nuclear weapons testing and the Vietnam war. Delegates from developing countries argued that environmental issues must not restrict opportunities for economic growth. Mrs Gandhi made a famous speech framing the fundamental challenge facing the world as one of inequality, arguing that the environment could not be improved while some countries and people remained poor.

The Stockholm Conference agreed 26 Principles, which ranged from the safeguarding of renewable and nonrenewable resources and ecosystems and the prevention of pollution to nuclear weapons and human rights. The conference’s greatest achievement was to place the idea of sustainable development onto the international agenda,

“Stockholm+50 is an exercise in peaceful multilateralism to tackle environmental crisis.”Stockholm. Image by Tommy Takacs from Pixabay

although only eight of 109 Recommendations for Action referred to development and environment specifically. This was more a statement of faith than a plan.

Fifty years later, UNEP (which itself arose from Stockholm 1972) is asking us to look back to 1972, and draw inspiration for tackling the profound challenges of the 21st century. How has the world changed over five decades of debate about sustainable development? What remains the same?

One big thing that has changed is the recognition of the importance of anthropogenic climate change. Climate barely got a mention in 1972. It began to climb up the agenda only with the World Climate Conference in 1978, the work of the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) from 1988, and the UN Framework Convention signed at Rio in 1992. Now, climate change dominates every list of environmental threats. A second thing that is different in 2022 is the size and complexity of the international machine created to bring about a transition to sustainability. In 1972, many governments did not want the environment on intergovernmental or UN agendas. The so-called ‘Brussels group’ (including the UK and the USA) opposed the whole idea of the conference. That has changed utterly. Despite wobbles (President Trump’s withdrawal of the USA from the Paris Agreement comes immediately to mind), the web of international agreements, commitments and targets has got ever stronger and denser. Descriptions of Stockholm+50 link it to the Food Systems Summit, climate COP26, the High Level Dialogue on Energy, UNEA5.2, UNEP@50, climate COP27, and biodiversity COP15. Stockholm+50 is one tiny element in a huge diplomatic sustainability machine, a bureaucratic monster whose gaze will only momentarily linger on Stockholm this June.

On the other hand, much remains the same fifty years after the first Stockholm Conference. Most obviously, perhaps, 2022 brings a sense of déjà vu about the way politics frames international discussion of the environment. In 1972, the USSR and Warsaw Pact countries refused to attend the conference in protest that East Germany could not participate (neither East nor West Germany were members of the UN at the time), and China condemned US policy in Indochina (the Vietnam war was at its height). In 2022, Stockholm+50 takes place in the shadow of the savage Russian invasion of Ukraine, and superpower rivalries and domestic populist politics shape possibilities for progress. Stockholm+50 is an exercise in peaceful multilateralism to tackle environmental crisis, but in 2022 we have arguably moved away from international détente of the 1990s towards a world of new cold and hot wars.

It is also an unfortunate fact that many of 1972’s threats to the environment are still with us. Nuclear power is undergoing a renaissance as part of a decarbonised future (especially, for Europe, one not reliant on Russian gas). Yet there is still no credible plan for dealing with nuclear waste, and decades of efforts to separate weapons from civil power generation once again look problematic. Pesticides are also controversial again, with the impacts of neonicotinoids on honeybees and wild pollinators looking like an uncanny (and unhappy) sequel

to Silent Spring. Concern at the impacts of technological advance on the environment is again widespread. To take one example, novel genetic technologies and synthetic biology offer a step into the unknown, with attendant opportunities, risks and controversy.

Poverty and inequality also still characterise the world, despite progress in reducing numbers in absolute poverty. As Covid revealed, the world is profoundly unequal, and highly dysfunctional. The book written for the first Stockholm Conference by Barbara Ward and René Dubos, Only One Earth (1972), recognised the hard inheritances of colonialism and exploitative trade, and this critique is still valid. To it we can add the power of for-profit non-state actors to maximise profit and minimise costs, outsourcing environmental and social impacts down labyrinthine supply chains and avoiding taxation.

Perhaps most worryingly, the world economy is still utterly unsustainable. In a world in which sustainability targets and roadmaps abound, the direction of travel is still wrong. The Global Footprint Network calculates that ‘Overshoot Day’ for the Netherlands fell on 12 April this year. Most industrialised countries followed soon after. By any measure, our economies (global, national, and often local) demand more of the Earth’s natural systems than they can sustain. The classic critique of conventional growth strategies, Limits to Growth, was published in 1972. Neither the Stockholm Conference in that same year, nor its many successors, addressed the fundamental challenges of resource consumption, and the changes required to live sustainably on Earth. Our international meetings rearrange deckchairs on the Titanic, hoping we do not have to change course.

The 1972 Stockholm Conference began a debate on the human environment that is still raging, and is as urgent as ever, fifty years later. The challenges of sustainability transitions remain scarily difficult. The alternative is unthinkable.

Bill Adams’s book with Kent Redford, Strange Natures: conservation in the era of synthetic biology, was published by Yale University Press in 2021.

“The world economy is still utterly unsustainable.”

One of the challenges of every Geography teacher in Scotland is to try to ensure that all young people are secure in the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) outcomes associated with this subject by the time they are 14, as well as interested in continuing their geographic studies into S3. We have only two years as subject specialists to develop pupils’ passion for all things that are Geography, and have to do so within the current CfE constraints as well as having only a couple of contacts a week in which to teach our courses.

With such limited time and so much to cover, inevitably each of us has to prioritise certain curricular themes over others, and design courses that will attract young learners to continue their geographic journey for a few more years. With this in mind, Population Geography can be easily overlooked, not because it lacks importance as an area of geographic knowledge, but because it can easily be perceived as very dry, data driven, and less likely to attract students in what has increasingly become a very crowded landscape of subjects.

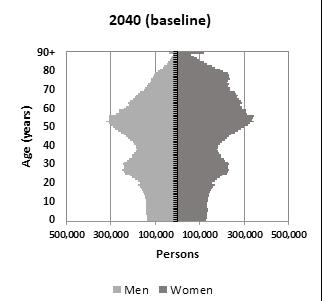

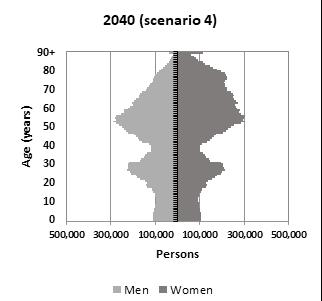

The Curriculum for Excellence programme dictates that all young people in Scotland be able to “compare the population structure of Scotland with a contrasting country and express informed views about the future implications for these societies,” (CfE, Level 4, Experiences and Outcomes). It is therefore incumbent on educators to shine a lens on this at some point, but this is, more often than not, done so rapidly. As a consequence, many of our young people do not really gain an appreciation of the changing demographics at play both in Scotland and internationally, as well as the impacts of population change across the globe. Nor do they get the time to develop some of the analytical

skills that the study of demographics could help develop. So why is demography so important and how can we engage 12- and 13-year olds in its study? The first area that needs to be addressed is to get young people engaged with the key language of demography, fertility rates, life expectancies and other key population indicators. This is more than just teaching a vocabulary; this is about enabling young people to compare and contrast data for countries at different stages of development. For example, is a life expectancy of 70 good or bad? If a country has a fertility rate of five, is this high or low? To do this, I have adapted the popular Top Trumps game from my youth and created my own deck of population Top Trumps cards where students need to select a population characteristic on their card to try to beat the value on their opponents’ card. It does not take long for students both to understand what each indicator means and to compare countries according to their data, whilst having fun!

Now that I have my students primed and excited by data, we move onto another key skill in this area of Geography: the ability to describe patterns. Population Geography lends itself perfectly to this skill; however, it can also be very dry. To get around this, I get students to extract life expectancies of each African country, input the data into a Google spreadsheet, and then we use the thematic mapping function in this spreadsheet to map the data. This can be done for any population data, but what is key is that the students engage with the data. The process of extracting data and inputting it into a table allows them to see the variations between countries and when they map it they very quickly pick up the geographic patterns at play and the language that comes with describing patterns.

“We use the thematic mapping function in this spreadsheet to map the data.”

Next up is developing an understanding of how development over time impacts on changing demographics. This is introduced to my students through the Jelly Baby game, where each student starts the game with their own population of jelly babies where each colour represents a segment of their society, for example the pink jelly babies represent the babies. Through selecting cards during the game, their population changes according to the instructions on the card. For example, their country may experience mechanisation in agriculture, and as a consequence they lose one of their pink jelly babies to represent a reduced dependency on children in agriculture. It takes very little time during the plenary to this game to get pupils to understand what factors caused their population to change during the game and, when they are asked to explain in detail the factors that can cause populations to change, they are able to give thoughtful insights into what happened to their country as if it were a real country (and do so whilst consuming their population).

Once students have grasped why populations change, they are ready to investigate population pyramids. These graphs are bread and butter to any Geographer, but to a 12-year old they have a certain smell of Maths about them. It is here that I make use of the digital resources available, especially www.populationpyramid.net which takes one-dimensional static graphs and brings them to life. The students get to explore the population of any country using this tool and investigate how they change over time. They are set certain challenges to investigate selected countries and try to determine what has happened to them in relation

to recent and historical population changes. For example, why in 1990 did China have a very small proportion of 4549-year olds, or why does the UAE have a huge proportion of 25-35-year-old males in 2020. These graphs allow the students to explore data in a way that was not available in the past, as well as connecting it to the personal stories of each country on Earth in relation to its own demographic changes. The end of the population journey for my 12- and 13-year olds is to consider the impacts of the population changes they have been studying. To do this they explore issues relating to Scotland’s ageing society and contrast those with Malawi and its youthful expanding society. This is the central theme that I have been building up to across the entire course, but by the time they arrive at it, they are fully invested in this subject matter and can converse using the language of demography when discussing the differing challenges of our two societies.

I began this article with the idea that Population Geography is often overlooked during the junior phase of Secondary education because of its perceived lack of interest to young people. With so many engaging geographic contexts available to us educators, who would take the risk of using up significant curriculum time when we are mindful that these students are soon going to be making their subject choices? What I have found is that by turning Population Geography into the central plank of my curriculum in first year and then building other curriculum themes like Climate Change, Environmental Issues, Development, Urbanisation and Global Tourism around key themes introduced during the Population topic, I have made the study of Population Geography one of the areas of the course that the students most enjoy.

“Each student starts the game with their own population of jelly babies.”Image by Eak K from Pixabay

What is it about Geography that you think is important? What can Geography offer to the world?

Geography is just such a vibrant subject. It is the opposite of narrow vision. A geographical education provides a wonderful range of skills to make sense of the world around us; asking us why the world looks the way it does, why there are differences between people and places, and what needs to change to make it better. It is pretty clear that the most difficult challenges we face just now – climate change, the emergence of new infectious diseases, growing poverty, and so on – can only be tackled from a perspective that recognises the interdependence of human and physical processes.

What are the challenges for geographers today? How do you think Geography is faring as a subject?

The subject does face challenges. There is a popular perception that Geography is all about memorising facts and figures about places, and this has meant that some have a lifelong aversion to the subject. Another perception is that it is all about exploration and travel, creating a perception that it’s for privileged students who can afford to explore the world in their gap year.

I don’t think that the Curriculum for Excellence has helped here, because it has eroded the visibility of Geography at school, and so there is less chance to challenge inherited views about the subject. I have recently been involved with redrafting the Quality Assurance Agency’s Benchmarks for Geography, and we were keen to highlight the diversity of ways that Geography can be studied, ensuring that the subject is welcoming to all.

Academically, I do think the subject is being taken seriously in a way I haven’t seen before in my career. I think it’s in part due to a growing realisation that many of the most challenging issues we face today are not things that can be fully understood from any single perspective. There is a vibrancy to Geography that comes from the diversity of approaches, methods and concepts that we draw on which is starting to be recognised.

What does RSGS do that you think more people need to know about?

RSGS has changed so much in the last 10 15 years. It has positioned itself as a leading voice in environmental issues, and seeks to help guide Scotland through the transition to becoming a more sustainable country. The Society does this through involvement with education, whether the Education Committee which connects school teachers across the country, or The Geographer which is a great source of information about all things geography for any interested reader. If you want ideas for what you can do to help make Scotland a greener country, or have ideas you would like to share about this, RSGS is your first stop!

How did you first get interested in the subject of Geography?

Like so many people, I first got interested in Geography because of the enthusiasm of a wonderful teacher, Kenny

Maclean at Perth Academy. His classes embodied a curiosity about the world that has stayed with me. I loved the way the subject brought together a variety of topics and approaches, theories and methods. I was interested in lots of subjects at school and struggled with the idea of narrowing my study, so the diversity of Geography always appealed. What have you done so far within the subject of Geography, and where has this taken you thematically and globally?

At Cambridge I was fortunate to take classes on political geography from Graham Smith. In my final year, his class started as The Geography of the Soviet Union and concluded as The Geography of Russia. It was a fascinating time to be studying this and I was determined to continue my study of political geography for my PhD. I had found John Agnew’s work on place and politics inspiring while writing my undergraduate dissertation (on the politics of the Shetland Movement), and so applied to study with him in Syracuse University in upstate New York. After my PhD, I started work as a lecturer in Geography at the University of Glasgow in 1995.

At Glasgow, I also had the opportunity to get involved in collaborative and interdisciplinary research projects. First, I was invited by John Briggs to join the Wadi Allaqi project, which was a collaboration with botanists and chemists at South Valley University in Aswan, to study a protected area in the south-eastern desert of Egypt. The building of the High Dam in Aswan in 1970 had created a large lake in this desert environment, and we were interested to understand the changes this had created. John had been leading work with Bedouins who lived in the area, to get at their understandings of the environment and the resources it offered to ensure that conservation efforts in the area took account of their voices. I led a team to work with Bedouin women to understand the particular challenges that they faced in living in such an extreme environment. While we wrote up much of this work for academic publication, I am most proud of the other outputs of the project, including the development of farms led by Bedouin women, and the introduction of literacy programmes.

In the last 15 years, I have been involved with another interdisciplinary project, this time focused on zoonotic diseases in norther Tanzania. The project started because a medical researcher, John Crump, who was based at the referral hospital in Kilimanjaro Region, noticed that a lot of people were arriving at the hospital with a fever and were being treated for malaria, but weren’t getting better. Using gold standard tests, he and his team discovered that less than 2% of people did have malaria. Around a third of them had bacterial zoonoses, like leptospirosis or brucellosis. These are generally not life-threatening conditions, but they can produce quite debilitating chronic conditions in humans and can reduce productivity and fertility in livestock, so it is a challenge for societal development. We put together an interdisciplinary team to look at the different sorts of landscapes where people and animals came together, and to

“It is pretty clear that the most difficult challenges we face just now can only be tackled from a perspective that recognises the interdependence of human and physical processes.”

understand where disease was most prevalent, who was at risk, what was driving disease outbreak. What do you hope to achieve as Geographer Royal?

I want to share my enthusiasm for Geography. I think in the Geographer Royal role I can help to amplify some of the excellent work that is being spearheaded by RSGS in education and public communication. Initially I will take time to meet with different parts of the geography community to find out what I can do to support them. For instance, there could be better communications between school and university-based geographers in Scotland. Secondly, I want to use the platform to find ways to promote the skills and insights from geographers to policy-makers. We have the benefit in Scotland of being relatively closer to decision-makers, but the work that RSGS has been doing to connect up geography societies across the globe gives us the chance to have influence beyond Scotland too. And finally, I want to try to increase public awareness of Geography. I am currently organising a schools’ essay competition for RSGS that I hope will be promoted at the Edinburgh International Book Festival in August.

“I first got interested in Geography because of the enthusiasm of a wonderful teacher.”Professor Jo Sharp at St Andrews beach. L-R: St Andrews University Principal Professor Sally Mapstone, Professor Jo Sharp, RSGS Chief Executive Mike Robinson.

Putin’s war in Ukraine is deplorable on every level, and our thoughts and prayers are with the people of Ukraine who need our compassion and practical support as a matter of urgency, as do their neighbours and allies.

It is desperately sad to watch the invasion of a sovereign nation, and the heroism and the statesmanship of Ukraine’s leadership is breath-taking. So is the heroism of the many in Russia who oppose this war, risking their own lives and positions to protest the invasion and the regime that drives it. Many Russians have taken to the streets, academics have posted a critical open letter (since blocked by the Russian state, of course), and journalists have tried to reveal what is going on. This feels like Putin’s war, not Russia’s. Many Russians have also sought sanctuary overseas, fearful of the repercussions and censorship.

Putin sowed the seeds of this invasion in 2014, invading Crimea and destabilising eastern provinces of Ukraine. He was angry that the Ukrainian people rejected the Ukrainian President Yanukovych, whom he viewed as a staunch ally and friend to Russia. The populus, though, were sickened by the corruption they observed in high office, from all sides. During the Maidan Revolution in 2014, they chose the promise of European democracy over Russia’s kleptocracy and corruption, as a way to liberate their economy and democracy and escape their dependency on Russia. But by choosing to turn to Europe they turned their back on Russia, and Putin simply saw the creeping encroachment of NATO and the European Union closer and closer to Moscow.

This is a tragic and awful time for Ukraine. It is a hugely worrying time for Europe as the threat of escalation is ever present. But these are very high stakes and it is also potentially the end game for Putin’s regime, as Russia risks becoming increasingly isolated and politically divided.

As corresponding members of the International Geographical Union, we are wholly in support of its Declaration on the Ukraine crisis.

“The International Geographical Union notes with dismay the alarming situation in Ukraine and finds the invasion of a sovereign democratic nation by Russian forces senseless and unacceptable. These actions are undermining global security and stability and have led to deplorable human suffering and loss of life. In the interests of peace and stability in international relations, we call for an end to the hostilities and for a resolution

that respects the sovereignty of Ukraine and all its people.