SERPENTES

Michaelmas Term 2022

175 Anniversary Edition

The unexamined life is not worth living. Plato, Apology 38a

Senior Editor: RHW Kwok

Editors: ORJ Bryant, I Choi, D Donnelly-Trimble, CLP Napier, AFY Skrine Dons: SR, SB

Front Cover Image: A Detail from the Elgin Marbles – a collaborative drawing by some of the 6.2 Art students and Downe House

1 ὁ δὲ ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτ ὸς ἀνθρώπῳ

Table of Contents

The Shortest Ever War (and its long history and aftermath) –DingDing Zhou ......................................................................................... 3

Women, Life, Freedom – Sepehr Sardaat ............................................. 6

Stylistic Shift of Roman Portraiture and its Significance on Contemporary Society, Republic to Empire – Jeff Xi ......................... 10

In this modern world, has our societal desire and over-eagerness to become ‘woke’ been to the detriment of modern society, and if so, what effect does it have on the world at large? – Benedict Wateridge .................................................................................................. 14

UKSMC Brute Penetration Operation Guidelines – Kelvin Lam .... 17

What were the attractions to Plato or Xenophon of writing dialogues as a way of doing philosophy? – Anonymous ..................................... 23

Why human “Alpha males” and other male archetypes don’t exist, and the social implications of their fabrication. – Aaron Li .............. 27 Music and History: Interaction between the Second World War and Western Art Music via Shostakovich and Reich – Kim Chin ........... 31

“People who serve on juries are ill-informed, prejudiced, and not clever enough to avoid jury service”. Should we abolish Trial by Jury?

– Mikolaj Rutka ....................................................................................... 35

Is the distinction between past and future fundamental? – Hyunjo Kim .............................................................................................................. 39

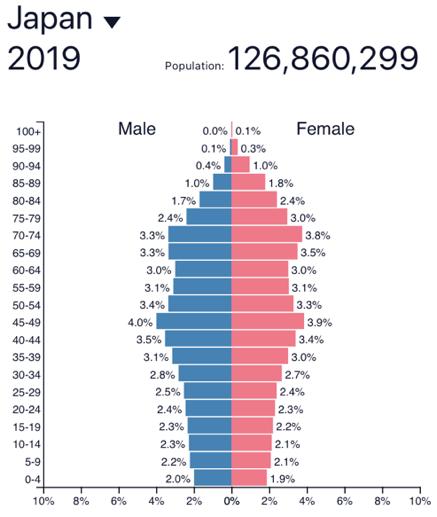

On ageing society and its concomitant economic impacts. – Tom Wang ........................................................................................................... 43

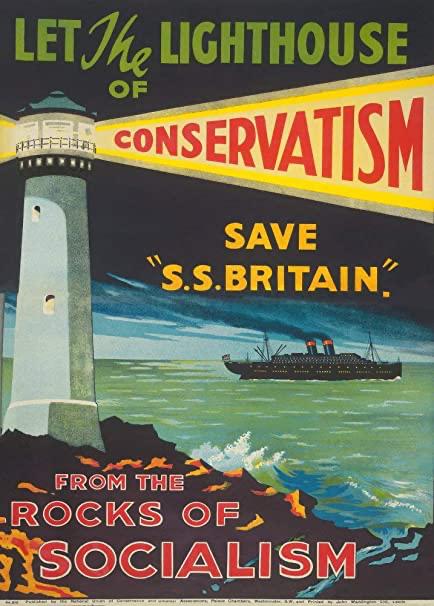

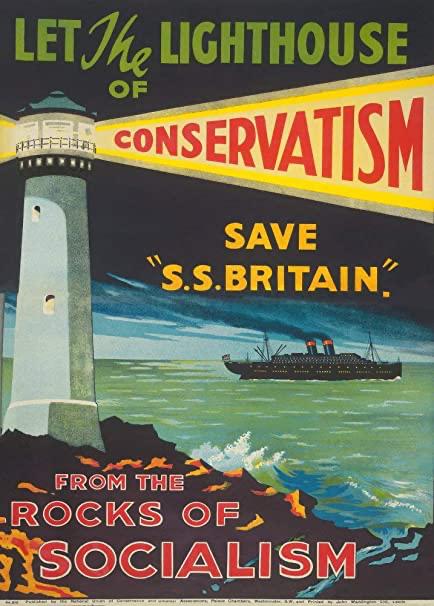

Conservative Party Conference Report – Napier, Lee et al. ............ 47

2

The Shortest Ever War (and its

DingDing Zhou

long history and aftermath)

The impacts of brief events on our lives tend to go unnoticed. Waking up early. Making a first impression. Saying thank you. But all of these brief events leave lasting impacts. This was the case with a brief war between Britain and Zanzibar 126 years ago. Lasting a mere 38 minutes, this war would lead to Zanzibar’s complete abolition of slavery, a new political system, and a Revolution leading to the formation of a new country. Although the shortest ever recorded war, a long history looms over and a long aftermath lies ahead.

19th Century Anglo-Zanzibar State of Affairs

The war took place on 27 August 1896. To understand why, we must return to the early 19th century, when Said bin Sultan ruled over Zanzibar from 1806-1856. Under his rule, Zanzibar was made the dominant power in Eastern Africa, the leading mercantile economy of the western Indian Ocean, and the biggest clove producer in the world. Slavery was thus prevalent as the many clove plantations needed a large, cheap labour force. To stop this, Britain formed a treaty with Said in 1822, preventing Arab traders, the main slaveholders in Zanzibar, from selling slaves to European powers. Yet in 1842, 15000 slaves were still imported annually, so another treaty was signed in 1845 to restrict Zanzibar’s slavery to its possessions in Arabia and East Africa. After Said’s death, Barghash bin Said came into power. In 1873, Britain and Zanzibar signed yet another treaty, the Kirk-Barghash treaty, which banned public slave trade markets. Although these treaties heavily curtailed slavery in Zanzibar, slavery was still not eradicated.

Later in 1890, Zanzibar became a protectorate of the British Empire, so the power of the Sultan was rendered purely nominal and subject to British interests. Unsatisfied with the treaties only reducing slavery, British authorities had a key aim for Zanzibar: the complete abolition of slavery.

A few Sultans’ deaths later, Prince Khalid bin Barghash, who claimed he should’ve been Sultan in 1888, saw his opportunity in 1893 and defiantly occupied the throne, opposing Britain’s desire for the more obedient Hamad bin Thuwaini to become Sultan. However, Britain was able to convince Khalid to stand down and Hamad was made Sultan. But just three years later, Hamad suddenly died on 25 August 1896, with speculations that Khalid had poisoned him. Within a few hours, Khalid seized the palace, declaring himself Sultan.

Knowing the British favoured another successor, Khalid immediately barricaded himself within the palace with 3000 of the Sultan’s personal soldiers, accompanied with a small battery of artillery and the armed royal yacht Glasgow to defend his self-proclaimed throne. Seeing this

3

as casus belli, Basil Cave, the chief diplomat in the area, issued an ultimatum to Khalid ordering him and his troops to surrender their weapons and the palace. Khalid ignored this and Cave telegraphed back to Britain requesting permission for military action to be taken. On the 26th of August, Cave received approval and issued a final ultimatum to Khalid demanding his surrender at 9 AM on the 27th of August or else the palace and his troops would succumb to full British firepower. Khalid believed this to be a bluff and refused.

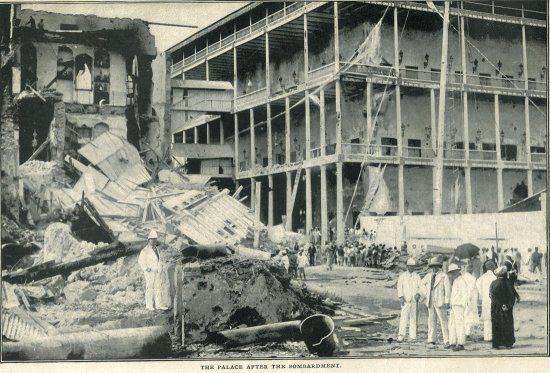

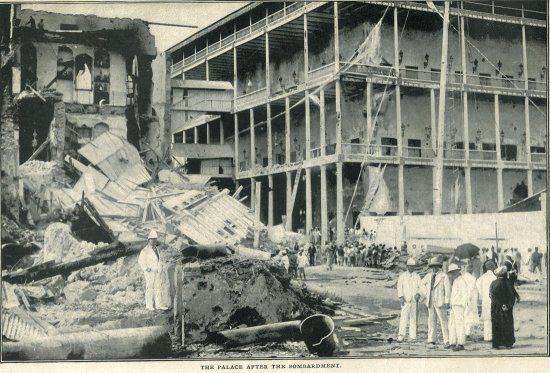

The 38 Minute War

And so the war began. At 9:00 AM, under the command of Rear Admiral Harry Rawson, three British Royal Navy vessels opened fire on the palace. After 38 minutes of artillery bombardment, the palace was destroyed, the Glasgow was sunk, and Khalid’s soldiers had suffered 500 casualties. Thus, Khalid surrendered. The war was over.

Just a few hours later, Hamud bin Muhammed, the British-favoured successor, was titled Sultan of Zanzibar. He swiftly complied to all British terms regarding his role as Sultan, becoming a puppet of Britain.

Stirring Up a Revolution

Britain’s victory in the Anglo-Zanzibar war meant the complete abolition of slavery in Zanzibar and the end of the Zanzibar Sultanate as a sovereign state. In 1897, Hamud, under British control, completely abolished the legal status of slavery in Zanzibar and was knighted by Queen Victoria for doing so. With the Sultanate now as a puppet government, Zanzibar started a period of heavy British influence. However, it’s rarely known that the Anglo-Zanzibar war also fuelled the Zanzibar Revolution.

Over six decades later, Zanzibar gained independence from Britain in 1963 as a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth. But, only one month after independence, a Revolution started. It was the most violent outbreak of anti-Arab violence in post-colonial African history. The roots of the Revolution can be traced back to 1840. Due to the wealth generated by the immense clove production, thousands of Arabs emigrated into Zanzibar, where there was already a substantial Arab population. Along with the Sultan, the Arab minority became the main slaveholders of Africans locals.

The roots lead on to 1896 when Britain won the Anglo-Zanzibar war. The war furthered the tensions between the Africans and Arabs because although slavery was abolished, the Arab minority continued to exploit the African majority. The Africans were also discontented that the government was still in Arab control despite the Sultan’s defeat in the war, and local African revolutionaries wished for more power.

As a result, when the formal declaration of Zanzibar’s independence was given on 10 December 1963, long-simmering racial, cultural, and economic tensions within Zanzibar were exposed.

4

The African majority could not envision any social progress whilst power remained in the hands of the Sultan and the Arabs. So, on 12 January 1964, they rebelled.

The Revolution was successful, starting with the overthrow of the Sultan by hundreds of local African revolutionaries, which sparked reprisals against Arabs in communities across Zanzibar. An estimated 17,000 people were then killed and thousands of Arabian refugees fled Zanzibar. Government policies in favour of Arabs were immediately dismantled and land belonging to the Arabs was redistributed. However, Zanzibar was faced with the threat of a weak economy as the population was less than 76,000. So, the new President of Zanzibar began working with political leaders in the neighbouring Tanganyika to form a union. The effort was successful so on 26 April of the same year, Zanzibar and Tanganyika formed the nation of Tanzania.

Conclusion

History just keeps surprising us. Caused by decades of ongoing political tension regarding slavery, the shortest ever recorded war, lasting 38 minutes, would result in the complete abolition of slavery in Zanzibar, the end of the Sultanate’s power, and the Zanzibar Revolution which would lead to the formation of Tanzania. No one would’ve guessed the extent of such a brief event’s impact back then. And it’s the same in our everyday lives now. Brief events often make the largest impacts, and these impacts are often concealed unless we pry into them. So we must further develop our curiosities for events happening around us, because a lot lies under the iceberg’s tip, and a lot can be impacted by it.

5

Women, Life, Freedom

Sepehr Sardaat

Given the recent world events, especially those concerning the women of Iran, I have felt obliged to write this piece in hopes of educating the reader and opening up a discussion about womanhood, freedom, and the history of Iran, all in one; to highlight the strength and character of women, in commemoration of Mahsa Amini and every brave woman who lost her life in the fight for freedom.

It must be noted from the very beginning, however, that this essay is a mere glimpse upon the unparalleled depth and breadth of the Iranian revolution and its consequences upon the lives of Iranian women in society. While women are only one of the hundreds of other groups who have suffered at the hands of the Iranian regime, they are the group that has suffered tenfold in history. There are a thousand and one things to touch upon when it comes to analysing any event in history, let alone subjects as big as a revolution and women’s lives, roles and rights within a society, which in themselves are deserving of a thousand and one books. This short report offers contextual illumination on the events which are taking place in Iran, and what the future may look like for women in Iran.

Scaling the Damavand of history

Swiftly after Iran’s Constitutional Revolution, the Iranian Women’s Rights Movement sprung up in 1910. During this era in Iranian history, women had little to no rights. Their role in society was confined to the home. Few women had the privilege of an education, and any education which the non-nobility could receive was either through religious schools (only reserved for men) or unregulated, private schools. Thus, seeing the lack of education that women of all classes suffered from, the early focus of this movement was upon the importance of education to the lives and emancipation of women. However, from 1914 to 1925, the discussions in women’s publications extended beyond education to child marriage; economic and social empowerment, and the rights and legal status of women. These early female activists were also part of a very divisive and controversial decree in Iranian history: kashf-e hijab (unveiling). This decree was issued by Reza Shah, who was heavily influenced by the reforms of Atatürk, in 1936 and banned all Islamic veils. However, this decree, while being popular with most women’s rights activists, was ill received by a considerably large part of the Iranian population who were still very religious. This was also because the unveiling was symbolic of Iran’s cultural and social advances towards the West, something which the clerics in Iran have been devout critics towards since its conception. Perhaps, one could argue that the popularity of the clerics in Iran was also because they were the only opposition to the “colonialism” of the western powers such as Britain, and their influence over Iran. The clerics’ stern opposition to these powers and the “westoxification” of Iranian society was something that has followed them to this very day –something which, as of recent, they have failed to battle despite their attempts.

However, despite the outcries of the clerics, Reza Shah did not pay them heed. It was, ironically, his son, Mohammed Reza Shah who often tried to portray himself as their allies by removing the ban on Islamic veils, and often visiting holy sites with his family in order to appease the

6

clerics. Albeit his reasons for this were clear: he wanted allies to protect him from the threat of other political parties like Tudeh Party of Iran (communist party) and the “Red Tyranny” that he called the Soviet Union while he tried to align himself ever further with the West. Yet despite this, women made their most important advances towards emancipation and gaining more rights under his reign. In 1959, 15 of Iran’s women’s rights organizations formed a federation called the “High Council of Women's Organizations of Iran” which focused on women’s suffrage. Despite the outcries of clerics, their biggest achievement was in 1963 wherein the women of Iran gained the right to vote and stand for public office under the Shah’s “White Revolution”. Due to their recent political emancipation, a coalition of women’s rights groups formed “The Woman’s Organisation of Iran” which was patroned by the Shah’s sister. These achievements were later followed by many more as women began to join every part of Iranian workforce, and in 1968 Farrokhroo Parsa was became the Minister of Education and the first woman to hold a cabinet position. In the meanwhile, the WOI had continued to fight for improvements in women’s lives and it did so through the setting up of branches and Women's Centres, which provided useful services for women – literacy classes, vocational training, counselling, sports, cultural activities and childcare. Arguably, however, their most notable achievements were the increasing of women’s literacy rate; legalising abortion, and the Family Protection Act of 1975 which granted women equal rights in marriage and divorce, enhanced women's rights in child custody, increased the minimum age of marriage to 18 for women and 20 for men, while practically eliminating polygamy.

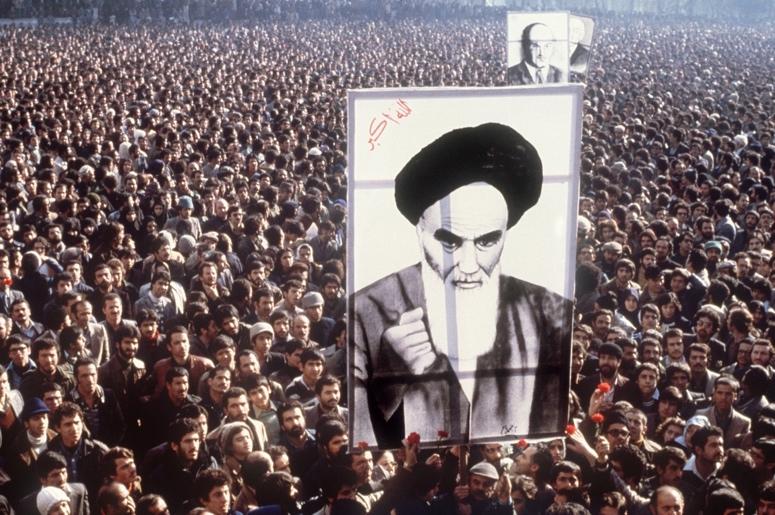

All this soon changed after the Iranian Revolution of 1979…

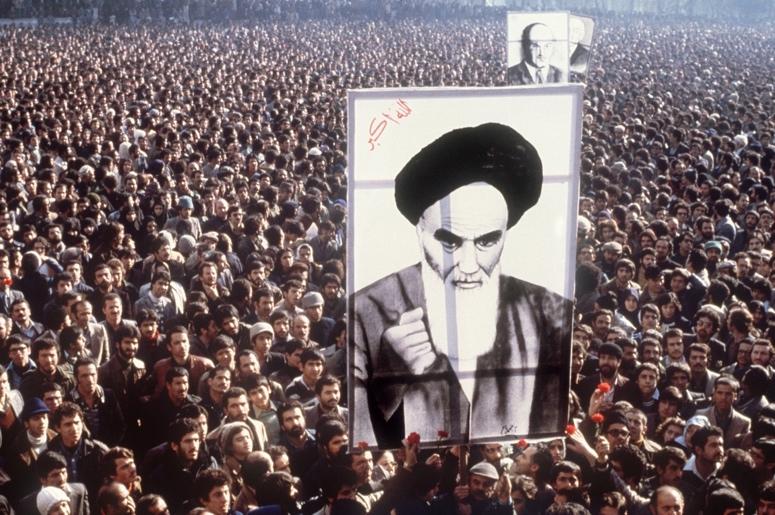

Women of Allah

When the Shah fled and Ayatollah Khomeini was declared Iran’s Supreme Leader, every right which women had fought over half a century for was evaporated seemingly overnight. Women’s role in politics, society and the economy was reverted back to what it was over a dynasty ago: the wearing of hijab was made compulsory; abortion was banned; the Family Protection Act was dissolved; the minimum age of marriage for girls was lowered to 13 (although a considerable amount began to be married off at 8 or 9); women could no longer divorce their husbands; women could be stoned to death; husbands could stop their wives from leaving the house; polygamy returned, and child custody was taken away from women. Moreover, influential women, such as Farrokhroo Parsa were executed. Women have been time and time again persecuted both legally and illegally in Iran, even in the form of brutal acid attacks due to “bad hijab”. While women still have the right to vote, can leave the house alone, have surpassed men in university entrances and can drive, they are still considered second class citizens under the legal system and considered dependent on men and the state to control them.

7

Additionally, the Islamic Penal Code sees the worth of a woman as half that of a man’s, meaning that the money paid for the injury or murder of a man is twice that of a woman. It is the same case for the testimonies in court, men’s testimonies hold twice the weight.

These reforms, and what I will call “submission” were rightly met with widespread protests throughout the years that the Islamic Republic of Iran has existed. These acts of protest, however, were not always in the form of demonstrations also but in the form of civil disobedience. For example, movements such as “My Stealthy Freedom” and “White Wednesdays” were two online movements started by famous Iranian women’s rights activist Masih Alinejad encouraging Iranian women to protest compulsory hijab. Other demonstrations and protests were like those of the “Girls of Enghelab Street.” However, women’s rights activists such as Nasrin Sotoudeh, Fatemeh Sepehri, and Narges Mohammadi, among many others, also voiced their opposition by supporting and representing political prisoners, who were often tortured and sentenced to execution, in court. It should be noted, however, that none of these activists (amongst the innumerous others that are not named in this article) have faced an easy time fighting for justice. Many of them have been imprisoned and some of them (such as Masih Alinejad) have survived assassination attempts from the regime.

There have been numerous outcries against various aspects of the Islamic Republic’s regime. However, any sort of protest, be it militant opposition to brutal crackdowns and ethnic oppression, to the 2019 protests in regards to rising inflation and a 200% increase to the cost of fuel (which saw the killing of over 1500 protesters in less than two weeks) have been unsuccessful. Thus, it comes as being quite unsurprising when the protests for women’s right, until now, have also been unsuccessful. Thus, to me and many other Iranians, the recent successes and the length of time for which the protests, ensuing Mahsa Amini’s murder, have carried on seems nothing short of miraculous!

Revolution?

One need only search her name on any platform to be bombarded with the most recent news about the protests in Iran. These protests have lasted over a month and have been met with unparalleled support from all communities, at home and abroad – this is something that has been unheard of in the Islamic Republic’s history and leads many Iranians to believe that a second revolution is tangible. In my opinion, the reason for which this uprising is different to all the rest is because it has no face; there is no leader to be killed or imprisoned – it is the brave women who are leading the people on and chanting “Woman, Life, Freedom!” and unless the regime decides to save itself by massacring its youth even more than it already is, an irreversible ideal of a better future has sprouted within the minds of the Iranian youth. A future where women are no longer killed over what they wear, a future where boys and girls can go to school and play together, a future where men and women can stand shoulder to shoulder in all rings of society.

However, it must also be noted that another reason for this revolution being hard to supress is that it is a social revolution. The 1979 revolution was a mere political revolution; a reform of government in which there was only a change in who ruled over the nation – all of people’s belief systems stood intact. Yet now, the government faces a social revolution, one which will

8

see the restructuring of the whole of Iranian society and how it functions, one in which, we all hope, tyranny is uprooted and liberty blooms in every garden of every home.

Will a monarchy return? Will Iran split into different ethnic regions and be swallowed by its neighbouring countries? Will a true democracy one day reign over a unified Iran? All these questions, and many more plague the minds of every Iranian. To understand these concerns, it is important that we realise how ethnically diverse Iran is: Arabs, Turks, Kurds, Fars, Baloch, Lurs, and many more have lived together under the flag of Iran for millennia, yet now the possibility exists that some of these groups may seek independence or join the neighbouring countries. What is evident, however, is that it is in the best interest of its neighbours, such as the Arab world, that no Middle Eastern superpower such as Iran exists again for it would benefit them all, both economically and politically. The future is uncertain, yet in the future lies freedom, and no one can steal this dream from the people of Iran.

As I write this article today, on the 28th of October 2022, the news has just announced that the families of the Iranian government officials are fleeing Iran. Could this be the beginning of a hopeful future? Could this be what we have all been praying for? Could this be the end of a nightmare?

Editor’s Note (23/11/22): The Iranian Government has issued its first death sentences in response to the protests which have shook Iran. The nightmare, as mentioned above, may not be over yet. Many will lay awake wondering whether they will have the opportunity to sleep again. Why? Such is the price of freedom.

9

Stylistic Shift of Roman Portraiture and its Significance on Contemporary Society, Republic

to Empire Jeff Xi

Across almost the entirety of Roman history, from the Republican Rome to the Constantine Period, Roman Portraiture matured and evolved into a complex art form in its own right. However, one should hesitate to present the style of these works as one of linear progression. The stylistic shift of was one of constant alternation between the realistic and the idealised, the art evolving as the artist was subjected to a broad variety of cultural and societal changes underpinned by Rome’s expanding empire and volatile systems of government. Hence the often-dynamic art, in this case Roman portraiture in the form of death masks, busts, and sculpture, embodies the shifting attitudes of society and its subsequent cultural emphases. No other period in the history of Rome was this notion more prevalent than the transition from the Late Republic to the reign of Augustus, which saw both a flourishing of the arts and the critical change from Republic to Empire, thus this article seeks to explore the conception of art as an indicator of societal change through the lens of Roman portraiture of the Late Republic and the Augustan age, and in turn pose the question: does art hold intrinsic value to society?

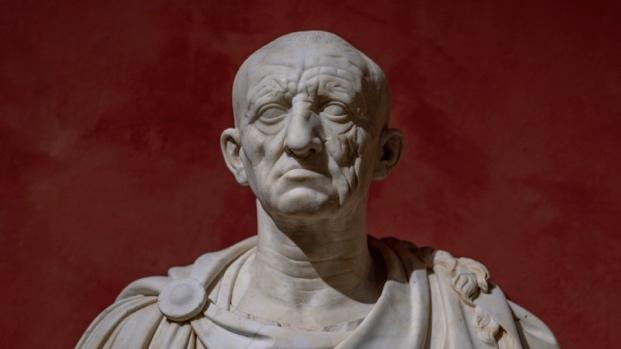

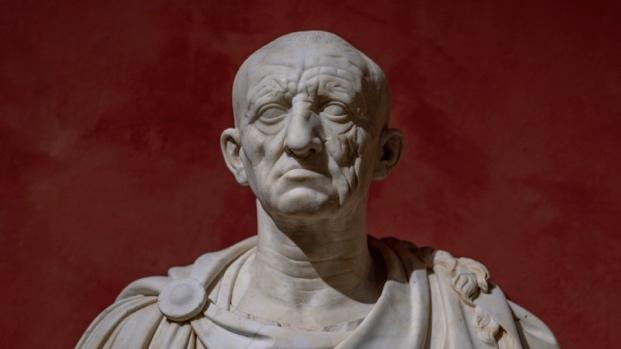

Throughout the late Republic (147–30 BC), portraiture often adopted themes of Verism, a style which explicitly displays the imperfections of the subject, often referred to as ‘warts and all’. A clear example of this style can be seen in Figure 1, where the Patrician’s deeply wrinkled face and furrowed brows stared expressionlessly ahead, devoid of any emotions. Indeed, Verism in Roman portraiture possesses a profound emphasis on the wrinkles and warts, seeking to create candid depictions of its subjects. Despite the ostensible implications that Verism focuses on realistic portrayal, its better described as a form of hyperrealism, often just as idealised and stylised as its classicising counterparts, albeit within a different visual parlance. When juxtaposed against the aesthetic beauty of Hellenistic sculpture, these veristic works can often be received as surprisingly grotesque. This uniquely Roman stylistic tendency is the result of a culmination of cultural influences. Roman funerary practices, which included the creation of ancestral imagines, or funeral masks, was arguably the source of the realism, and predisposed the Romans to Verism due to the imagines’ integral role in Roman social life. Polybius in his Histories briefly dwells upon these masks, writing that ‘After the burial… they place the likeness of the deceased in the most conspicuous spot in his house… a mask made to represent the deceased with extraordinary fidelity both in shape and colour… they display [imagines] at public sacrifices

10

Figure 1: Head of a Roman Patrician from Otricoli, c. 75–50 BCE, marble

adorned with much care. And when any illustrious member of the family dies, they carry these masks to the funeral, putting them on men whom they thought as like the originals as possible in height and other personal peculiarities’. The display of imagines of ancestors who have held public office or received honours in the atrium of Patrician households serve the purpose of reminding visitors (which for a prominent senator could be on a daily basis as he received his clients and guests) of his aristocratic lineage, an element key to political success in Rome. Hence the need for accurate portrayal arises, where these imagines cast directly from the features of the dead allowed a patrician’s prominent background to be easily recognisable, thus the realism of such masks in part laid the foundation for the flourishing of veristic portraiture. Verism was also formed in reflection of contemporary Roman core values. The wizened physical traits as demonstrated in Figure 1 is an embodiment of gravitas (seriousness and responsibility), severitas (sternness), and virtus (manliness), the essential virtues of Roman leadership. This in turn served to compliment the subject of the portrait and his qualities. The employment of Verism by the influx of ‘new men’ (those who lacked social background) on the political scene in the Late Republic was also responsible for the style’s contemporary popularity, as the adoption of an austere appearance provided the familial gravitas that these new politicians so direly lacked, affirming their commendable leadership qualities, and hopefully increasing the chances of his success.

11

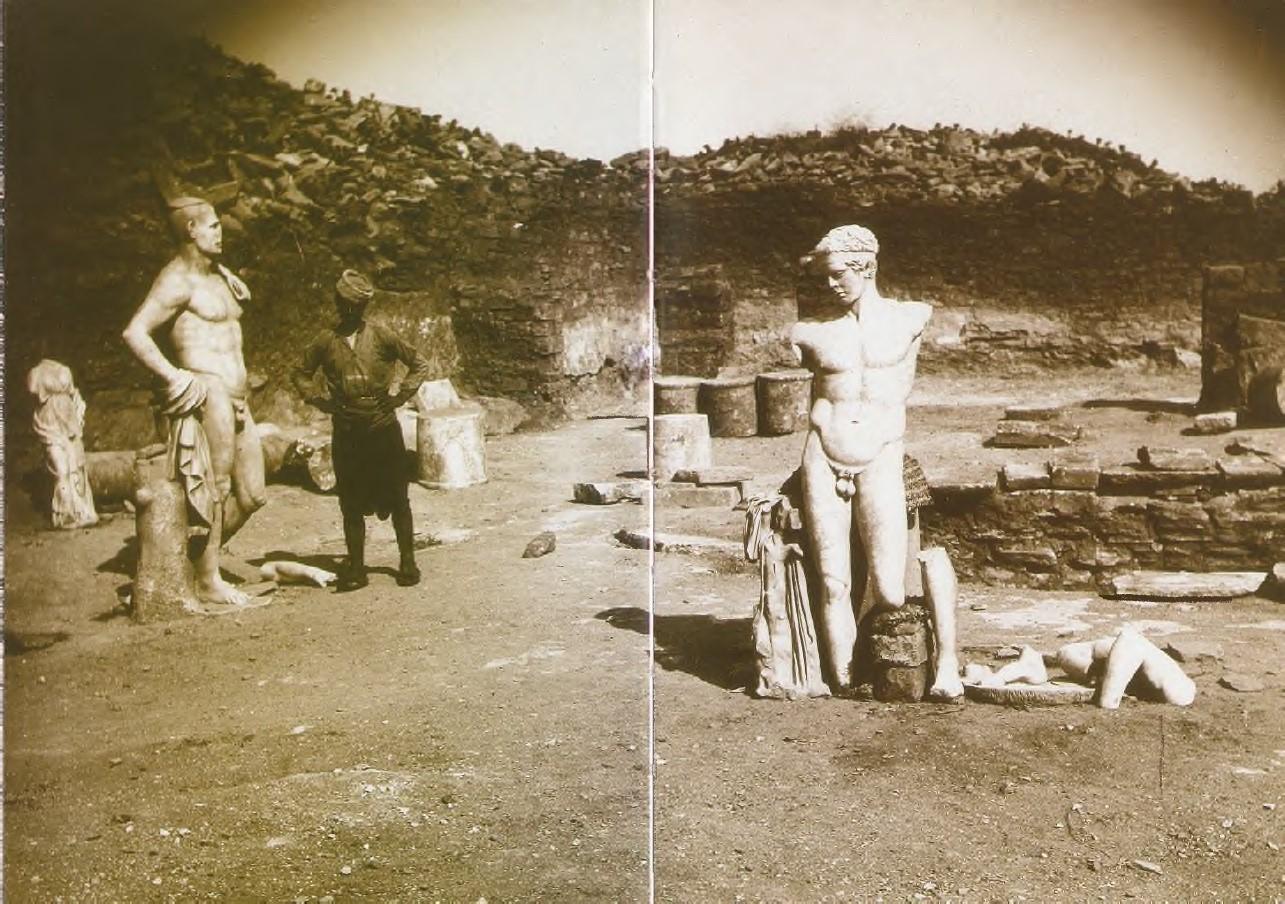

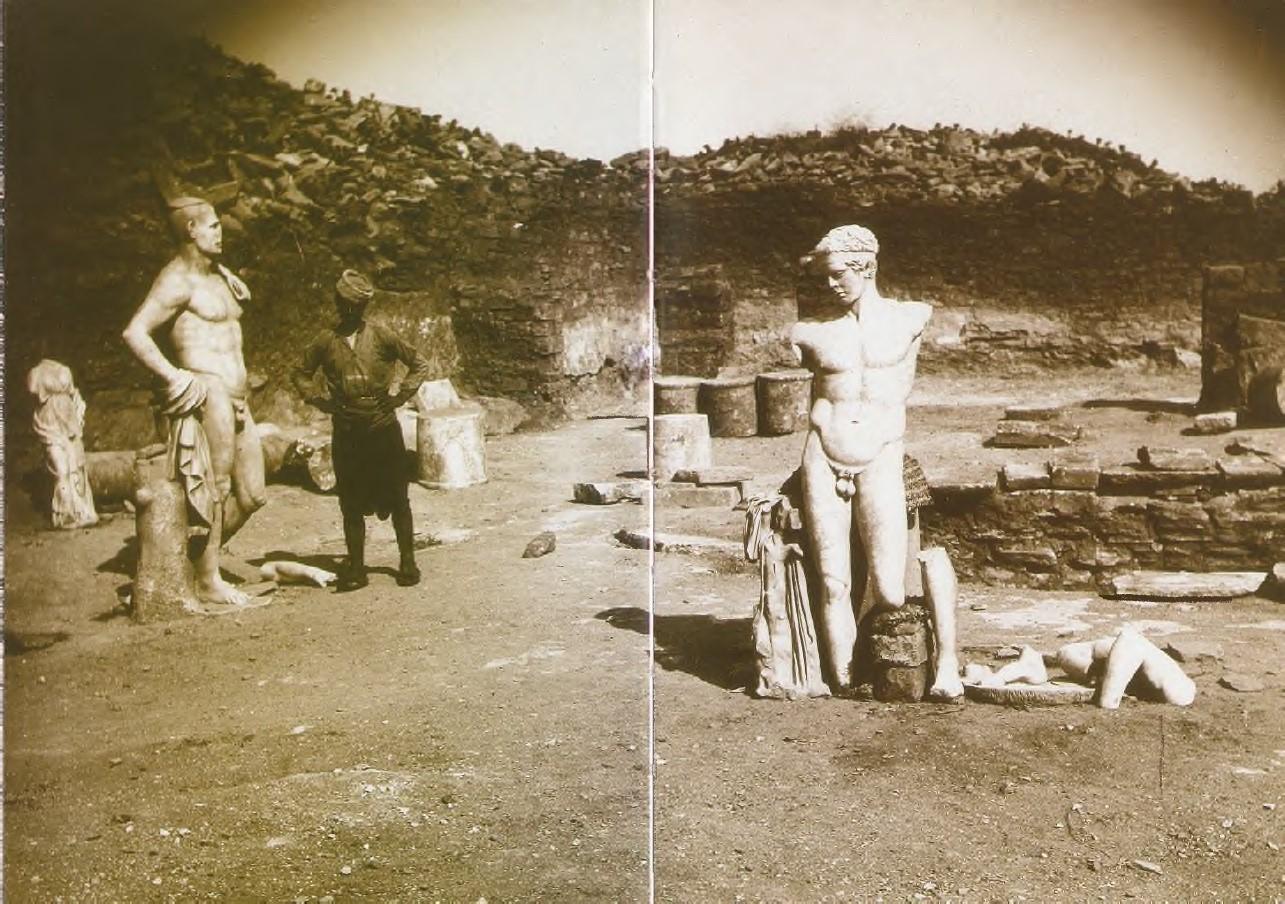

Figure 2: Pseudo-athlete of Delos (left), Diadumenos (right), shortly after their discovery in 1894

Although Verism thrived at the height of fashion throughout the late Republic, the style fell into disuse as Augustus’ reign began, where the idealised elements of Greek Classical sculpture were endorsed by the emperor. Augustus placed significant emphasis on a return to the Golden Age of Greece within the arts as he promised to bring about a Golden Age for Rome itself. This shift towards Classical sculpture was prefigured by the influx of Greek culture throughout the Roman conquest of Greece, especially after the sack of Corinth in 146 BC, where the rich Corinthian spoils inspired many artistically as they entered Rome. The relationship between the veristic and the classicising, which could also be perceived as the relationship between Greek and Roman cultural identity, was an undoubted complex one. The idealistic beauty of Classical sculpture began to undermine Verism even before Augustus came to power, where in the final years of the Republic the hyperrealistic style was mitigated by a renaissance of Hellenistic pathos which culminated in the classicising works of Augustan portraits. Despite the extensive influence of Greek sculpture on Roman works, the Roman adoption of Greek artistic styles, and more broadly their culture, is perhaps better described as a romanisation of Greek methods. This repurposing of Classical culture can be observed to be a subversion and critique of Greek decadence through the imposition of Roman ideals. This is best shown in the Pseudo-athlete sculptures of the late Republic, which combine a veristic head with a classical body, as shown on the right in Figure 2. The balding, wrinkled head of the Pseudo-Athlete of Delos is (perhaps grotesquely) attached to the idealised, athletic body standing in contrapposto, greatly influenced by the Diadoumenos (on the right in Figure 2), unearthed on the same site. The Diadoumenos was sculpted during the High Classical period in ancient Greece by the renowned Polykleitos, whose influence on Augustan portraiture will be elaborated upon in the next paragraph, as the notion of reappropriating Classical styles of sculpture with distinctly Roman ideals was not lost on the new Emperor.

The aforementioned reign of Augustus brought about significant changes for all aspects of Roman society. Although the transition from republic to empire saw surprisingly little structural change in the governing class, the cultural impact of Augustus was profound. Augustus came into power after a century of detrimental civil wars, and thus was eager for the Roman people to leave such memories behind and indeed forget his own role in the civil war as ruthless, young Octavian. He saw the arts as a method of ushering in a new golden age, bringing about an era of peace, the Pax Augusta, in which he refounds both Rome and his own public image, rendering portraiture to be a particularly effective medium for conveying ideologies amongst other forms of art. One of the most renowned Roman sculptures, the Augustus of Prima Porta (Figure 3) is a prime example of Augustan portraiture. When juxtaposed against the Head of the Roman Patrician from Orticoli, or even the PseudoAthlete of Delos, a stark contrast can be immediately observed. The

12

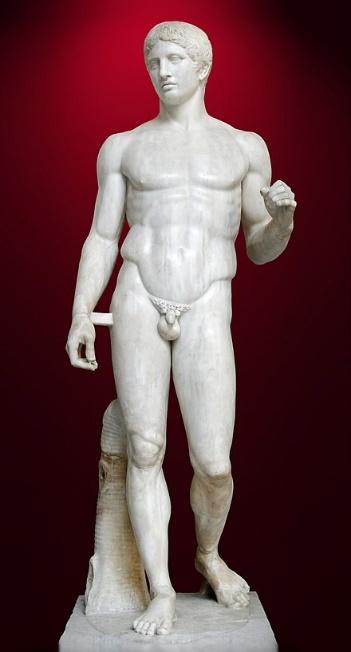

Figure 3: Augustus of Primaporta, 1st century C.E., marble

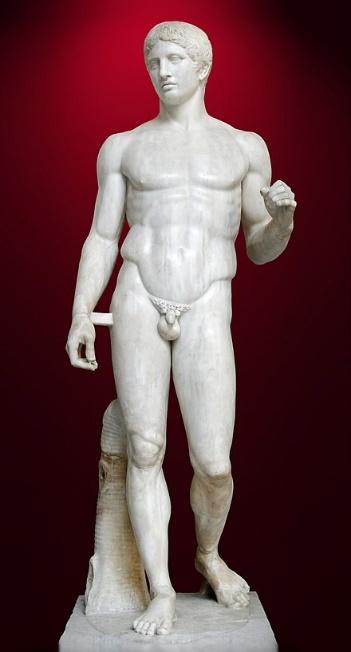

Figure 4: A well-preserved Roman period copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos

evidently idealised face and figure of Augustus echoes more of the Classical Greek sculptures than any of its predecessors from the Late Republic, the Augustus of Prima Porta bearing a heavy resemblance to the Doryphoros of Polykleitos (Figure 4), both possessing a similar contrapposto stance. This sudden shift in preference for idealised styles of portraiture by Augustus was a result of the heroizing qualities of Classical sculpture, which not only allowed Augustus to emphasise the youth and beauty of the new Julio-Claudian dynastic family but presented Augustus as flawless through association with the Doryphoros, which embodied the ideal male youth. However, the Augustus from Prima Porta was not a simple replica of Polykleitos’ sculpture, rather it was created with the same Romanising intention as the Pseudoathlete of Delos. In contrast to the Doryphoros, Augustus is depicted wearing both a senatorial toga and an elaborate breastplate with an upraised arm as if issuing a command, which affirms his role as ‘princeps’, or ‘first amongst equals’ as well as his political and military abilities. These differences convey that the ideal Roman man was not just one of beauty as the Greeks had supposed, but one who is capable in war and in politics, embodying core Roman values.

In conclusion, the transition from Republic to Empire saw an extensive shift in style from the veristic to the idealised, but the role of art never changed, as the stylistic tendencies of roman portraiture reflected the cultural emphases of the time; perhaps this role of art still has not changed even to this day. One could argue that the exigency of art for embodying if not determining the cultural identity of a society bestows a demonstrable value upon art.

13

Benedict Wateridge

The world is an enigma of social laws and modern justice. The way that society functions is constantly changing, as evidenced by the emergence of the word "woke", which has begun to be pervasive in modern social justice. In the West, the unjust and racist actions of the past have scarred us and act as a constant reminder of the mistakes that were made. Hence the creation of the word "woke". Originally, a just standard of fair behaviour and demeanour for society and individuals. However, in recent years, it has been hijacked by modern extremes. Wokeism is now being used as something that is dividing society and the world that we live in, causing more problems than it can solve, which leads to the question of whether our blind obedience to ‘woke’ has been toxic and detrimental.

To understand all that is going on with this term, we must first discern its true meaning and how it was intended to be used. Most dictionaries define "woke" as a perceived awareness of inequality and other forms of injustice. However, it can be more broadly described as staying aware of the facts and the true situation. This is a term that has been around since the 1960s and 70s, although the general idea has been around much longer. ‘Woke’ or Wokeism is a seemingly fair and honest ideology intended to help guide people to make better and fairer choices and decisions and to stand against the backward ways of oppression from the past. Nonetheless, in more recent years, we have seen this word and this idea degrade into an insult and a slur in today’s society.

We can see that ‘woke’ is polarising the modern world. It has been hijacked to silence justice and rights. ‘Woke’ is now used as an insult, a slur, and even as a joke. In the modern west, the term ‘woke’ has become symptomatic of a modern cultural war. We can see just how far this term and idea have fallen in recent years when we look to America, the ‘supposed’ land of the free. Yet in America's theatrical and febrile political atmosphere, the word is now used as a sardonic insult. Almost as soon as the word lost its initial sense, it found new meaning as an affront, becoming a byword for smug liberal entitlement, which left it open to mockery. "Woke" was eventually redefined to mean following an intolerant and moralising ideology. It is now being used to erode the principal freedoms of modern-day liberal democracies: the freedom of speech and freedom of choice. Wokeism is now used to attack and control people's beliefs and shut down ideas contrary to the ‘woke’ mob. It has become a weapon of the aggressor and is no longer the ‘enlightened’ idea

14

In this modern world, has our societal desire and overeagerness to become ‘woke’ been to the detriment of modern society, and if so, what effect does it have on the world at large?

that it once was, but a watered-down phrase with its true meaning lost in modern overuse. It has blinded many people’s ideologies and what they think of different affairs throughout the world. Instead of opening people's minds to other possibilities wokeism now polarises our views, creating intolerant and extreme communities across the globe. Modern culture and social media have and will continue to exaggerate and abuse the word and it’s true meaning.

The word was first coined by William Melvin Kelly, a black novelist, in an article in the New York Times published in 1962. He defined it as someone who was "well informed and up to date," especially when relating to ethical and racial subjects. I believe the true meaning of the word began to be tarnished when it entered mainstream society and spread into Internet culture, where the usage of "woke" quickly began to change. It went from activist to passé and soon found meaning as an insult, a linguistic process called pejoration. Consequently, ‘woke’ represents an intolerant and elitist ideology.

Since the change in meaning, it has begun to affect society, which is evident all around us. To a certain extent, it controls what we do and it implements societal rules. For example, traditional views on marriage are now deemed outdated, despite them being held from time immemorial. On a global scale, we can see that wokeism has been detrimental to America during the Black Lives Matter campaign. The police were under huge pressure as evidence of racist police brutality and killings emerged. While increasing awareness of these crimes is undoubtedly a good thing for bringing about reform, the vicious power of the ‘woke’ mob came to play. Instead of trying to put sensible rules and laws in place to prevent this level of brutality from happening again, many attempted to defund and defame the police. As a consequence, policing took a huge hit, which is a factor as to why there were record numbers of murders in U.S. cities, and even now there is a wave of crime hitting America's suburbs. Whilst it can be said that these issues are more culturally embedded and deep-rooted, we can still see the implications and the multitude of problems that have been created by wokeism.

Wokeism, as in the case of the Black Lives Matter movement, radicalises these calls for justice and takes them beyond what is necessary, corrupting these pleas for positive change into an angry storm that destroys our institutions. Perhaps this polarisation brought about the anger which motivated Trump supporters to storm the Capital. Social media allows the ‘woke’ extreme to spread further and indoctrinate and polarise the next generation. Today, if you venture onto any form of social media, you don’t have to look far to find suppressive videos of ‘woke’ extremists. Wokeism now imposes itself upon our fundamental freedoms of expression, suffocating views and ideas contrary to its fickle dogma.

15

Hopefully, we can acknowledge that the word "woke" is not inherently damaging and evil. However, it is, like many things, misunderstood and misused. It is not a tool for destruction and social chaos, but rather something that has been sullied by the modern world, and its meaning and uses have been co-opted by the Left. If anything, the story of ‘woke’ must show us that we cannot let the good be perverted by extremes. We must all understand that the crimes of the past cannot be allowed to happen again. However, with the way that everything has transpired, we must be able to see that we need to let sensible decision-making guide our choices, and we mustn’t rush into things as we have done with our blind desire and over-eagerness to be and become "woke". Perhaps, we could apply Chesterton’s Fence to our political behaviour, which is a public policy philosophy, that states that changes should not be made until we understand why the status quo happened.

I hope that as a global community we learn not to be impetuous, but to be patient and to see the issue as it truly is, not with the judgemental modern lens that we so often observe through. It can be said that those who benefit from the status quo will stand against change. However, ‘Woke’ isn’t a tool of those who are genuinely good but a weapon of virtue-signalling aggressors. The pejoration of ‘woke’ has not benefited society positively, nor is it being used to help understand people’s problems. Finally, I reiterate my conclusion. Our willingness to become ‘woke’ has been to the detriment of the world at large. It has divided people to the extent that these wounds still await reconciliation. Despite this, just because this term and idea has lost its meaning and effect doesn’t mean that it cannot be found again, and this time in a more sensible and controlled course of action, in a manner that will not act against us, but for us.

16

UKSMC Brute Penetration Operation Guidelines

Kelvin Lam

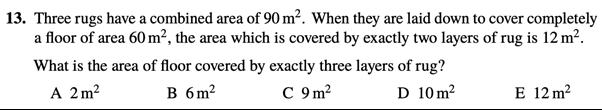

UKSMC, which stands for the UK Senior Maths Challenge, is the first major obstacle faced by most mathematicians in our country. However, the threshold of about an 85% score to get into the BMO seems to be demanding (even for most 6th formers!). Therefore, here I am going to provide some advice for every contestant with minimal advanced knowledge and ingenuity to make a sensible guess at the answer based on past questions, some data and just a bit of mathematical theory.

Think before you roll the pencil…

We first start with the less sophisticated technique - simply guessing the answer. When a contestant attempts to guess an answer for a difficult question, he tends to suspect his choice repeatedly, considering the evenness of the distribution of answers.

I have to admit, it is a bit embarrassing for many people to fall into a black hole of doubt, which ultimately affects not only their mental status and self-confidence, but also loses time for doublechecking or grabbing more marks by attempting the remaining questions. More importantly, this unnecessary process makes no difference from choosing an answer randomly. According to the rules of UKSMC, everyone starts with 25 out of 125 marks, while a correct answer grants 4 marks and a wrong answer deducts 1 mark. This means that, with a random guess, one’s score is expected to drop by 1 × 80% - 5 × 20% = -0.2, implying that this choice to guess randomly is not wise at all. To make a profitable guess, we must exclude at least 2 wrong answers so that the expected mark we get from each guess would be higher than 0. Then, what should we do in the unfortunate situation when all options seem plausible? Of course, leaving it blank is an option, but my advice may help you to do better than that.

I gathered the option distribution of the paper every year from 2010 to 2022 in order to maximise the accuracy of the investigation and also the plausibility of my method, on which I later elaborate.

The result is as follows:

17

We can make a few observations from this chart:

First of all, it is obvious that the options A and E appear significantly less than the other options. Although it might seem coincidental, it can be explained by the purpose of this competition. It aims to create a smooth transition between school and Olympiad Maths, and therefore the questions which require a specific answer follows a similar format. That is, it requires only the correct answer, rather than any proofs. The numerical options within UKSMC are usually in ascending order, and so hiding the answer within the options B, C or D can force the contestant to (at least) find a tight enough bound from both sides, which in theory increases the difficulty of guessing the answer. Hence, I would recommend you not to guess A or E, unless there’s a good reason to do so. However, the option distribution has been more even in recent years. In particular, no option could appear more than 6 times or less than 4 times from 2018 and this is the case for most other years thereafter. This slight change is for preventing both the strategy of guessing the same option for all the remaining answers or assuming the distribution is completely even. Therefore, I would recommend you to consider other possible options in the case that some letters have appeared 6 times already and give the rarest option a try.

Of course, we can’t rely on this technique all the time, owing to the nature of the previous method being entirely based on experimental probability and past data, and not at all on any mathematical reasoning.

One

answer for all cases; All cases for one answer

Therefore, the first mathematical method that I shall introduce is trying special cases by substituting simple numbers for unknowns. Usually, this method works when the questions are simplified to contain multiple unknowns while the question itself asks for the relation between some (or all) of the unknowns. This method always converts unknowns into actual numbers, with which we can work with more easily owing to its more obvious resemblance of school maths - a UKSMC question is often rather obscure in appearance, but not too bad in essence This method is also relatively efficient: most of the time, we can filter out the correct answer in a single try if all the values are different, and this happens especially often when we plug in slightly obscure values. On a probabilistic level, since most algebraic expressions given as options are in the form of polynomials, it is unlikely that a single substitution will not suffice, as, for this not to be the case, the values substituted must be one of the few instances when the two polynomials coincide. In any case, if we only vary one of the unknowns each time and keep the others unchanged, the maximum possible tries would be equal to the sum of highest degrees of the varying unknowns in the options because an n-degree polynomial only has at most n real roots by the fundamental theorem of algebra.

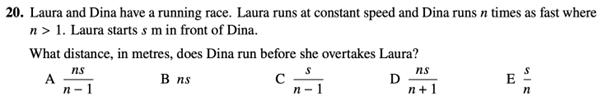

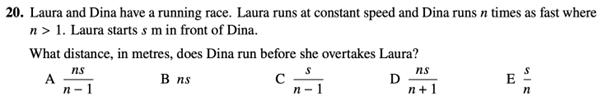

Perhaps this appears rather abstract and puzzling. Trust me, it’s not that difficult. Here is an example of an application of the technique in UKSMC 2021 Q20:

18

Some of the contestants might be struggling to deduce the general formula for this question. Fortunately, what we can do is plug in a simple but distinguishable n into all of these options such that no two options are identical for all s.

n = 3 is one good example to simplify the options as follows:

A. 1.5s B. 3s C. 0.5s D. 0.75s E. ⅓ s

Note that a general formula for the answer must satisfy all cases, so we can consider vLaura = 1 m/s, which implies vDina = 3 m/s. Now it is easy to figure out that, for the first second, their distance would be shortened by 2 m, meaning s = 2. We combine the fact that Dina runs 3 m in 1 second to catch up, and so the answer should be the one which ends up being 3 after substituting n = 3, s = 2, and so the options become:

A. 3 B. 6 C. 1 D. 1.5 E. ⅔ .

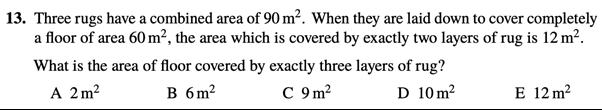

This implies the answer is A. Sometimes unknown are not given directly to the question, but the question can be simplified to apply the same method. Another example from UKSMC 2022 Q13 is shown on the next page.

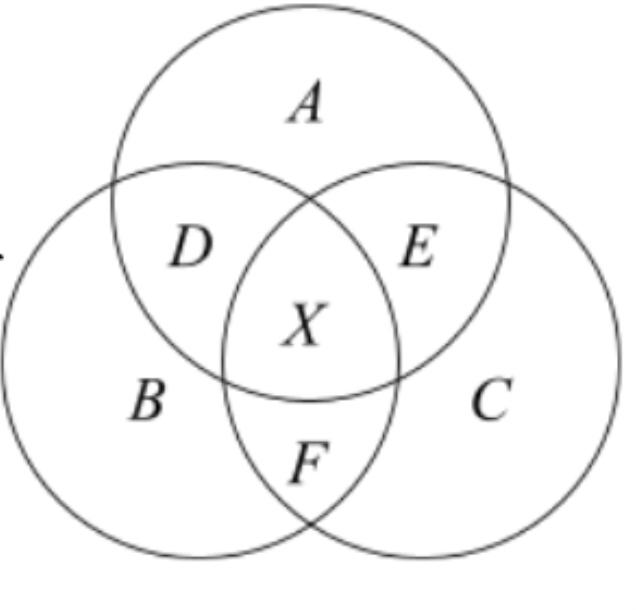

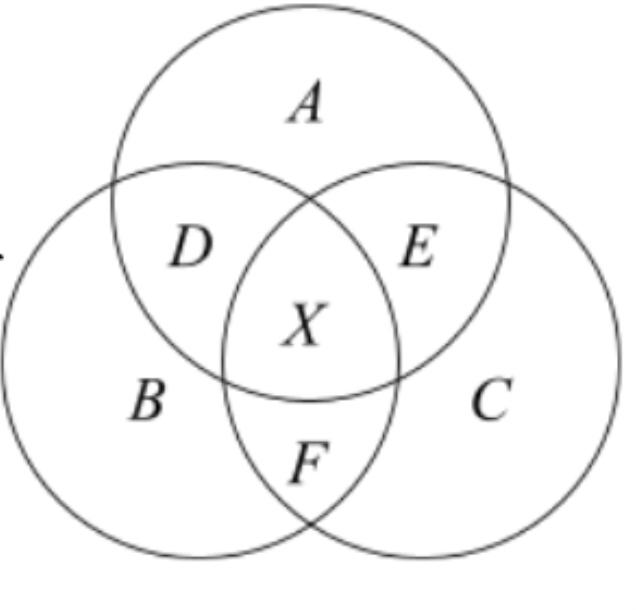

We convert statements into unknowns using a Venn Diagram on the right:

From the third sentence of the problem, D + E + F = 12, and therefore we can use a special case of (D, E, F) = (3, 4, 5). As A + B + C = 60 - 12 - X = 48 - X, we can also consider the special subcase where (A, B, C) = (48 - X, 0, 0). At this point, the question becomes even easier - we can just add up the values of 3 circles to get:

(A + D + X + E) + (B + D + X + F) + (C + E + X + F) = (48 - X + 3 + X + 4) + (0 + 3 + X + 5) + (0 + 4 + X + 5)

19

= 55 + 8 + 9 + 2X = 72 + 2X = 90 → X = 9, by what is formally known as the principle of inclusion and exclusion.

Note that the above method only works when there are infinitely many configurations that point towards the same answer for the problem. Unfortunately, sometimes, we may get some mainly algebra or geometry questions in which only a few non-trivial cases satisfy the conditions of the problem. In this case, we need to find a more practical way to find out the answer in case we can’t solve it directly. This occurs increasingly frequently in later questions, which may pose a problem for average contestants if they have an ambition for securing their qualification in BMO.

Take measures legally; See the answer directly

Try to draw a diagram that is as accurate as possible. For this, I strongly recommend you to bring a pair of compasses to the paper. Learning to illustrate the actual situation of problems is very important because this helps you make sensible conjectures that are likely to let you get the right answer, even if you are not able to prove it. This is very similar to scientists when they have to experiment to support their hypotheses.

We talk about the algebraic application of this method first. Normally, there are at least 2 to 3 questions about graphs of some functions. A typical problem would ask you for the number of intersections of the function to the x-axis, the y-axis or another function that is defined. Remember that your goal to survive in UKSMC without extensive skills is to convert everything into school maths that you are familiar with. Yes, calculators are forbidden, but I am sure that the arithmetic required is manageable. As long as you choose some simple values that won’t overload yourself, you can almost always generate a table of values. Yes, rulers are also forbidden, but you don’t need to worry about that either! Linear function can be easily solved even for set 8 shells (perhaps this is a stretch!), while nonlinear functions in UKSMC almost always end up in a complete curve which renders the use of the straightedge minimal. In addition, you can also create a “unit” by yourself using your compasses. Also, using the distance between the pin and the pencil attached could be a good idea. After that, your job is no more than paying attention to if the function has asymptotes. Also, the functions involved are always continuous due to the past resources in the context of UKSMC whose function problems almost always belong to one of the following. With all this information, everyone can draw a graph that reasonably accurately represents the situation of the problem. Although this method has no 100% guarantee that you will get the correct answer, the probability that you would get the answer right would increase when the coefficients inside one of the functions have an extreme ratio to each other, which actually happens frequently as the question writers tend to put the year number within one or two coefficients of the functions…

Take this question, for example.

20

We can tidy the equation up and we have to then draw y = x2 - 2022 and x = y2 - 2022. Both of these are parabola, with the latter one being a horizontal parabola, which is easy to draw with just GCSE knowledge. We first identify the vertices of the function being (0, -2022) and (2022, 0) respectively. Then we find the x-intercept of the former one to be (±√2022, 0), meaning that the y-intercept of the latter one would be (0, ±√2022). Here it is - you can determine the answer to be E just by looking at your graph even if it is somewhat inaccurate.

A similar tactic can be applied for geometry questions to find the relationship between lengths as well. In this kind of question, the success rate of this method is even higher because the question would always lead you to draw an accurate diagram that only consists of circles and lines. The only major drawback of this method is that you probably have to use a whole A4 sheet for your diagram in case the options are close enough to the extent that it becomes that it becomes extremely hard to measure area accurately in a small space.

This problem is from UKSMC 2022 Q20. I was panicking about this until I thought of drawing an in-scale diagram with 1 cm representing 1 unit in the question. We treat √2 ≈ 1.4 and we approximate π as 3.1, which reduces the options to the following:

A. 35 B. 36 C. 36.6 D. 40 E. 42

It is easy to see that such a square whose centre is located on the bisector of the sector angle must have an area maximized. You can try to construct another rectangle inscribed inside the quadrant to believe this fact, which is essentially a variant of the well-known theorem that for fixed a + b, ab has the largest value if a = b (the AM-GM Inequality, formally).

I believe you can easily eliminate the first three options by your first attempt to draw the inscribed square because I got a measure of 6.3 cm in my first three tries, giving the area of the square is at least 6.32 = 39.69 cm2, which suggests that the answer should be D.

It may be that this is not immediately obvious. Indeed, some measurement error produced by factors such as the width of the trace of pencil used to draw the square and the interval of measurement given limited material of my compasses (remember that ruler is banned) is inevitable. While you can definitely do some more construction of the same problem to increase your confidence in your answer, I have another argument that supports my guess without using the proper way of proving the answer. Note that option E is irrational because of its √2 part in it, but this is just the area of a square, so the length of the square would be √(30√2), a number nested under 2 square roots! Frankly, no irrational number is provided inside the question itself, and the syllabus of UKSMC on geometry only includes GCSE knowledge such as triangle angle chasing techniques and circle theorems… and Pythagoras’ Theorem! The crucial point is that this theorem always squares first to give the hypotenuse. Therefore, if there is no initial

21

information with square root, the greatest number of square roots within the expression of any fixed sides in the image would be 1.

Last Words

All these techniques combined should help you to solve at least 80% of the problems from almost all UKSMC papers according to my own attempt on UKSMC 2016 and 2017 papers. Finally, here is my last advice - don’t panic! The time limit for UKSMC can be a burden for people who haven’t received any proper maths Olympiad training, so being stuck in a mid-tier question for too long may hinder your chance of getting at least some of the later mark if you are not even giving them a try. On the other hand, the threshold of getting into BMO is actually not that difficult to achieve - you only needed 108 out of 150 marks to get into BMO 2021, implying that even if you guess all the questions you can’t do, getting 22 out of 25 questions is enough for the qualification; losing a tree is better than losing the whole forest by a lack of time. At last, I leave with this one ambition: that one day, students become more willing to try their absolute best in UKSMC, and that a whole classroom of Radleians could sit a BMO paper.

22

Anonymous

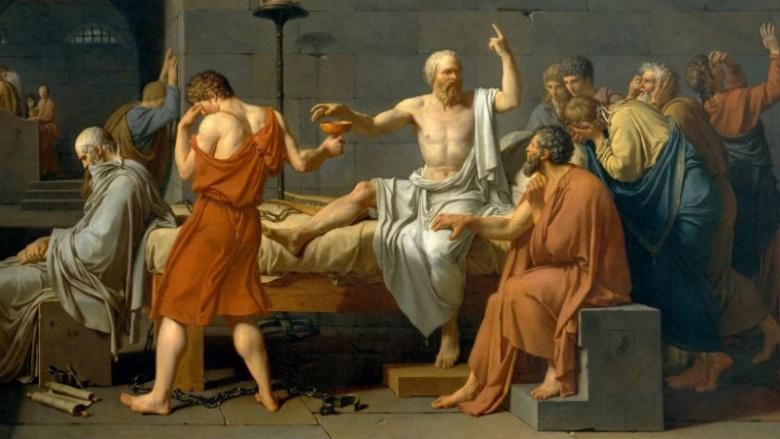

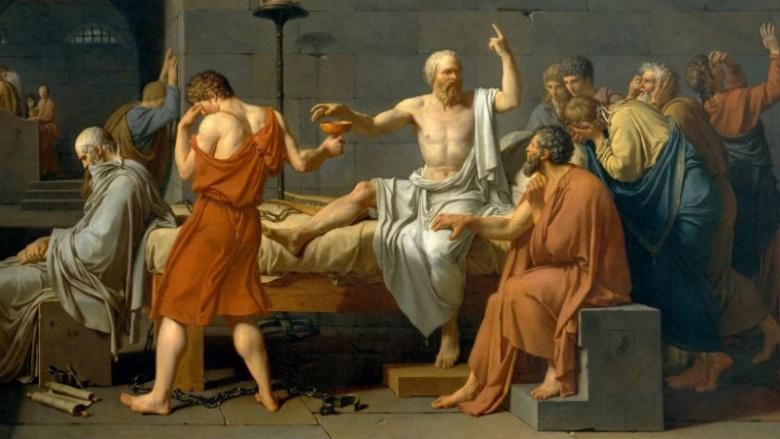

The dialogues of Plato and Xenophon are the last extant members of the distinctive genre of sokratikoi logoi, although we know of works by other followers such as Atisthenes and Simon the Shoemaker. I will examine principally the Platonic dialogues because Plato reveals more of his thought throughout his works, and the conclusions will be able to be adapted to Xenophon as well – they were, after all, both students of Socrates who were influenced by his thought, not least his ideas about writing. Socrates himself disdained written work due to three main reasons, as seen in Phaedrus 275a-e. Firstly, writing will produce forgetfulness as memorisation will no longer be needed. Secondly, texts are unable to answer any further queries the reader might have. Thirdly, others may misconstrue or even bandy its arguments around. The existence of these Socratic dialogues, written works, seem to contradict the aforementioned criticisms of Socrates, and this can only be resolved through the dialogue form. Although this may sufficiently justify the use of dialogue, I will also demonstrate how the genre is in fact essential for Plato and Xenophon’s philosophical purposes through logographic necessity (Phaedrus 264b-c).

We will apply Socrates’ first objection from Phaedrus. There is no need to examine the criticisms themselves as we are discussing the motives of Plato, who presumably agreed with them, as he had recorded and attributed them positively to his teacher, Socrates. This point attacks the most obvious form of philosophical writing: the treatise, used by pre-Socratics such as Empedocles and Anaximander, and is still currently the dominant genre for philosophy. The most fundamental form of a treatise is simply a collection of propositions listed in logical order, which a Socratic dialogue certainly is not. Firstly, there is no clear set of axioms or dogma in these dialogues, which means that the reader is unable to return to them as a reference source. Instead of causing forgetfulness, by shaping philosophy as a discussion, they require one to philosophise in order to understand them. Plato is entirely aware of this and so his corpus contains many apparently contradictory statements. The misunderstanding is that each dialogue needs to be considered individually, with consideration of the situation and circumstances (Jowett & Campbell, 1894), a level of thinking which treatises do not need to be concerned with. There is no uniform underlying Platonic motive expressed in these dialogues,

23

What were the attractions to Plato or Xenophon of writing dialogues as a way of doing philosophy?

as Plato does not even participate as a character is any of them, but only Socrates’ musings. He speaks through the characters with many different opinions, which allows Plato to subtly direct the course of action according to his preference and encourages the reader to enter into the discussion in a very personal way. In fact, Jacob Klein even suggests that without participation, the Platonic dialogue does not even occur (Klein, 1965). The entire concept of philosophical dialogue is far deeper than any other genre, because it also involves the soul; the entirety of the humanity of a person is involved, not just reason itself, but due to the different characters and the interaction of the reader which can be called ‘an interplay of souls’, where ‘because dialogue is a thinner world than daily life we can be forced to find ourselves’ (Lieb, 1963). Therefore, we can see that Plato’s choice of dialogue excludes its use for dogma, but instead as a point to stimulate discussion, which is the sine qua non of philosophy.

The second objection concerns whether the reader can ask further questions about the subject, which treatises and many other forms of literature are unable to satisfy, and only can answer with ‘one and the same thing’ (Phaedrus 275d). Plato resolves this tension through the participation of the reader as mentioned above. They are encouraged to put forward queries which characters in the dialogue may or may not be able to answer. This may not seem like a satisfactory response to Socrates’ criticism when the question is unanswered, but there are multiple arguments going around, especially evident in examples like Lysis and Euthyphro, where no firm conclusion is formed (aporia), and everyone resolves to find the truth another time. The participation is the aim of the dialogue, and ignorance is an essential part of philosophic discovery, without which there is no desire for the aim of the dialogue, wisdom. There are no official intertextual positions of Plato himself evident – though there are certainly shared themes and concepts – visible from the incongruous statements Socrates makes, so the curiosity of the reader is augmented, and he is encouraged to continue discussing it. This is true of later Platonic dialogues and especially in Xenophon’s dialogues, like Laws and Memorabilia respectively, where conclusions are made through questioning different views, but it is untrue to say the text answers with ‘one and the same thing’; the setting and characters will inform more concerning the discussion, and even the circumstances of the reader will change his interpretation. Moreover, Socrates claims that writing is entirely dependent upon its ‘father’, the author, for answers, but Plato has no need to defend his philosophy or further explicate it, as it is not his philosophy (as he asserts in Epistles

24

2 314c, 341c1). He is merely directing a discussion in which the reader is invited to participate and interact with the text, which will start bearing the fruit of philosophy – wisdom. Socrates’ third objection to writing is that the information will get into the wrong hands where it may be misused or misinterpreted. The danger is that the author could be accused falsely of some doctrine or cause harm to the lives of his readers who are not philosophers and so do not understand his teachings. The genre of historic dialogue means that there is no person whom a controversial point can be attributed, as Plato and Xenophon are not present and other characters had no say in writing the dialogue. Many may have died by the time of writing –most notably Socrates. Also, heterodox opinion is often opposed in the dialectical space which dialogue offers, so any accusation about the contents within would not have much basis. The second danger is overblown as well, because the degree of harm misuse may cause is very low – the uneducated reader would not understand the ideas within very well. There are multifarious viewpoints, and the many views of Socrates (the most eminent of the characters and hence most likely to be believed) require profound thought before it would affect the lives of the reader, like reincarnation and the ideas of Diotoma (Hyland, 1968). In fact, Socrates also uses irony often in Plato, to shield what others cannot grasp for those who are philosophically capable. This is less so with Xenophon, who is more conservative in his philosophical campaign for traditional values like enkrateia (Tredennick & Waterfield, 1990), and so can evade the objection. Theoretically there is potential for harm, but realistically, it is unlikely, which satisfies the objection sufficiently.

A key point frequently addressed above – the setting and characters– deserves to be elaborated on, as they set the foundation on which the dialogue can be built. Plato recognises that there is nothing extraneous in a good piece of writing (Phaedrus 264b-c), and so the dimensions in which the dialogue is portrayed is crucial for understanding the philosophising he is trying to promote (Moors, 1978). The selection of interlocutors is important, as seen in Crito. Socrates is known for listening to every argument fairly and responding accordingly in all the dialogues; indeed, in Apology 23b-c, he sees it as a command from Apollo’s oracle. In Crito 54d, however, Socrates acknowledges that he is ignoring the other’s arguments. This unusual behaviour can only be explained by the context; Crito is a rich friend, but not a philosopher, who attempts to help Socrates escape, so the latter denies his aid due to the risk to Crito’s soul. It seems possible that the act would persuade him to think that when justice cannot be reached legally, one should find it regardless, such as through bribery, which is unvirtuous and reflective of disobedience to the state (Tarrant, 1993). Likewise, the location affects the dialogue significantly – especially because it is the sole element which does not change – as seen in the wrestling school which provides the subject matter of friendship for Lysis and the banquet that shows the comparative freedom of speech

25

in Symposium, enabling Aristophanes’ and Socrates’ more unusual opinions. In treatises, one is deprived of the use of characters and environments in this profound and precise way, meaning that the philosophic experience is altered, and the individuality of philosophy is lost. In fact, this shows that only dialogue can provide the necessary tools for Socratic philosophy, where exposure to the pursuit of truth is at least equally important in the love of wisdom.

Plato’s intention concerning bringing people to philosophise themselves has been made clear, but the dialogue form further emphasises it. Socratic philosophy is not made up of a set of propositions, but involves the experience of it as well, which definitively cannot be put in words; the only method is through philosophical experiences where it can be understood without being specified (Hyland, 1968). Art is seen as an imitation of reality in the Republic, and so similarly dialogues can be seen as imitations of philosophical situations. In fact, dialogue scrutinises and compares arguments, where things can be separated based on value; so, this, unlike art or poetry, does not fall to Socrates’ criticism of imitation (Republic 393c-d) that both good and bad are sanctioned implicitly. Xenophon does this more so than Plato and comes to conclusions more often (Tredennick & Waterfield, 1990). Those capable of philosophy can thus be drawn to it through an authentic portrayal of what it is like, which the genre uniquely offers due to its inherently dialectical form. The dialogues bring the reader closer to the truth through analysis of different arguments particularly through Socratic elenchus, and on when it appropriate, as what is potentially dangerous is normally shielded by ambiguity and irony that can be grasped only by the subtle and philosophical. This can be done only in the form of a discussion, as treatises are unable to utilise the esoteric details which logographic necessity provides so fully for in dialogue. Such unclarity of dogma is perhaps the reason for sokratikoi logoi and the Socratic method, where the philosophy only begins when opinions are removed, and knowledge is gradually found.

Plato chose dialogue as his form for writing principally to stimulate discussion, teach the philosophic experience and preserve wisdom safely for those who could understand it. The genre has the potential to utilise every detail for a purpose (setting, characters etc) and imparts an imitation of philosophising where the good and the bad can be seen but will draw anyone who is ready for it to philosophy, which consists not solely of propositions but also of an inexplicable experience. Perhaps Xenophon was less concerned about concealing ‘dangerous’ knowledge, but there is undoubtedly greater subtlety in dialogue than in treatise, where both the exoteric and esoteric can be conveyed. Even where conclusions are made, it is justified and can still be challenged through the dialectics of dialogue. Nevertheless, it cannot be emphasised enough that to Plato, it is not what is conveyed which is essential, but when someone actively participates in the dialogue and begins to seek the truth; when the person ‘is brought to birth in the soul on a sudden, as light that is kindled by a leaping spark, and thereafter it nourishes itself.’ (Epistles 7 341c-d)

26

Aaron Li

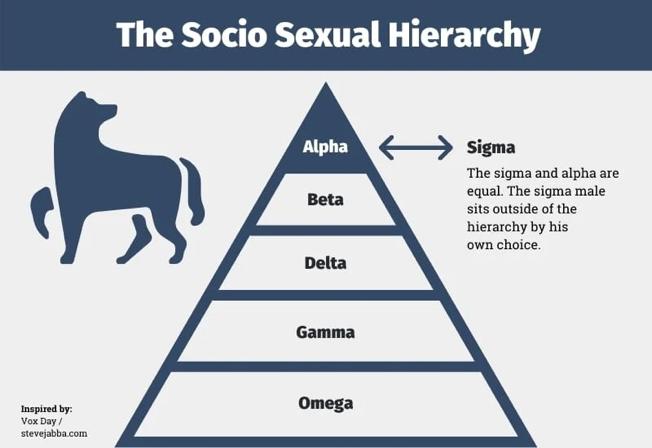

Most people now are probably familiar with the concept of an “alpha male”, owing to its rapid embedment throughout popular culture, and even working its way into colloquial language. If you go onto Amazon and search for “alpha male”, it will come up with countless self-help guides of how to achieve “alpha status”, and YouTube is just as littered with guides to what are considered “alpha male traits”. To begin, I would like to define what will be meant by an alpha male in this article. The Cambridge dictionary defines alpha male as a ‘strong and successful man who like to be in charge of others’. Basically, the “alpha male” is the ‘leader’ of a group of weaker men: “beta males” and is most attractive to women, achieving the most sexual partners, driven by his aggressive and commanding personality and facilitated by his immense social skills.

Origins

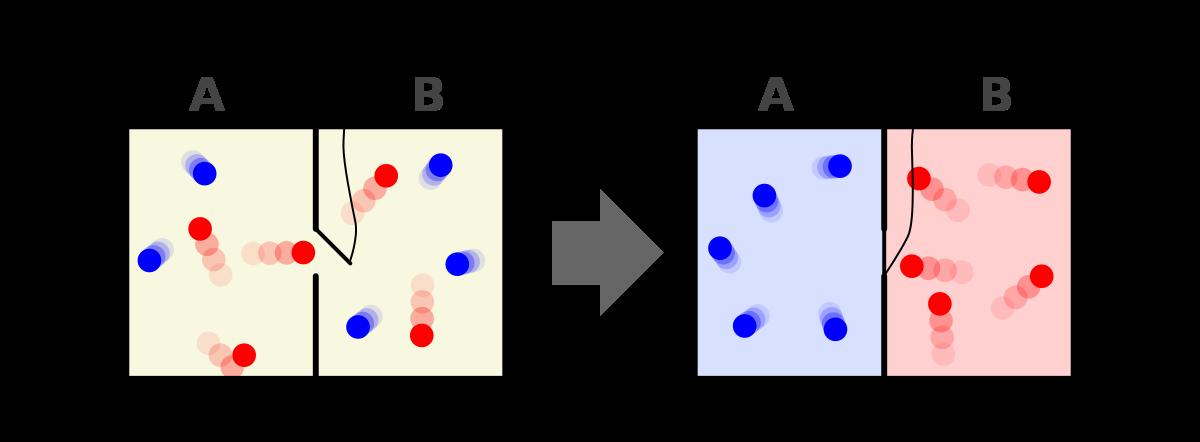

The term alpha male originated in studies of wolves, with the idea of a dominant male in a pack of wolves birthed in study conducted by R. Schenkel in 1957, titled ‘Expression studies on wolves - captivity observation’. Within this article, Schenkel describes what he saw as a formed hierarchical structure in the wolves which he observed in the Basel Zoological Garden and Zurich Zoological Gardens, in an attempt to ensure a range of conditions so that behavioural patterns were not accidental. He observed ‘two sex orders of precedence when either sex was in a majority’. They ‘govern the total life management of the pack’ as well as deciding ‘ownership of sexual rights’. ‘By incessant control and repression of types of competition, both of these “alpha animals” maintain their social status’.

Here you can clearly see the inspiration for our current “alpha male”. However, unfortunately, Schenkel was wrong with this article. The idea which he had seeded was then greatly popularised by zoologist David Mech in the 60s, aided by his book ‘The Wolf’. Later, Mech tried to reconduct this experiment within the wild, producing a very different conclusion. He noted that in the wild, ‘most wolves disperse from their natal packs and attempt to pair with other dispersed wolves, produce their own pups and start their own pack’. In other words, in the wild the perceived ‘alpha male and female’ weren’t dominant individuals, but rather the parents of the pups. Thus, to project this idea of “alpha” individuals would be similar to saying that the mother and father are the dominant members of a pack (a family). Mech notes that the only use of ‘alpha’ may apply if there is occasionally a large pack made of several litters, whereby the older parents may become a form of ‘alpha’. Mech comments that Schenkel’s study was ineffective as studying the sociology of wolves in captivity was comparable to studying the

27

Why human “Alpha males” and other male archetypes don’t exist, and the social implications of their fabrication.

sociology of humans by studying a ‘refugee camp’, whereby all the members have arguably been thrown in in unusual circumstances and are forced into each other’s company.

Even if there were “alpha members” in a wolf pack, it would not be justifiable to compare our social structure to wolves at all, prominently due to the increasing interconnectedness of our world, and the blending and blurring of definitive social groups, whilst a wolf pack is a defined bordered group which doesn’t make frequent interactions outside their group.

Existence of alphas?

Despite what has just been discussed, ‘alpha’ individuals do exist within some species. The greatest popularisation of the term alpha is arguably a result of the book ‘Chimpanzee Politics’ by primatologist Frans de Waals. Within this book he describes the social structure of chimpanzees, in which there is, in a sense, a defined “alpha male”. The alpha chimpanzee in a group has mating rights, and has to patrol the territory and keep peace within the group. In the book, Waals makes a direct comparison between the similar tactics used by human politicians and chimpanzees in order to ‘campaign’ for leadership, or alpha status. This includes generosity, forming coalitions, and creating a good image of oneself. This is reflected by the fact that in chimpanzee hierarchy, it isn’t always the strongest and most aggressive individual that becomes “alpha”, but sometimes the ones that do the most favours for other members of the group such as grooming. Waals insists that humans have the wrong idea of what an alpha male is, with our media portraying the ideal “alpha male” as being controlling and aggressive. It can still be argued that by Franz’s definition, our equivalent of an “alpha male” is more like our political leaders, dethroning the concept of social “alphas”. ‘Alpha’ in the context of biology is a leader, a form of status, not a social trait, displayed in the fact that not all alphas have the aggression and dominance by how we define them socially. Thus, these two terms are barely interchangeable and our perceived idea of a natural born male with an ‘alpha personality’ is fabricated.

Other archetypes

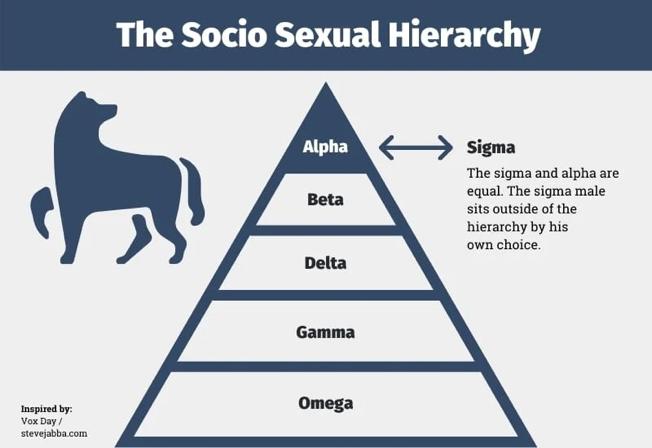

The term “alpha male” has subsequently birthed many other “types of men” in popular culture. These include:

- “Beta males” - The original male archetype created alongside the alpha. They are the “nice guys” who are generally submissive under the control of alpha males.

- “Sigma male” - The “lone-wolf” archetype. The “sigma male” is just as attractive to women, but does not care about social ideals.

- “Delta male” - A newer archetype. “Delta males” tend to be more reserved, perhaps due to a negative past which caused them to “transform”.

- “Gamma males” - A newer archetype. They are adventurous and fun-seeking, but do not fare well romantically, which is unfortunate, as they are romantics.

28

-

“Omega males” - The opposite of an “alpha male”. This is demonstrated by their immaturity and lack of social skills

An alternative version, the “socio sexual hierarchy” was a pyramid created by Vox day, in which “alpha” males resided at the top, and “omega” males resided at the bottom. “Sigma” males reside at the level of alpha males, but exist off of the pyramid. Some of his other views include accused white supremacy, and misogyny.

Why are these archetypes harmful?

The establishment of this supposed hierarchy would encourage men to aspire to become an “alpha male”, as they seem to enjoy the most benefits, socially, financially, and romantically. However, many of the traits which the media and popular culture are associating with “alpha males” are harmful and promote a toxic masculinity which pushes towards post-feminism. A popular YouTube channel, links their idea of an “alpha male” back to the picture of a “bad boy”. They promote qualities of “bad boys” such as ‘being selfish’ and ‘not giving a f****’ which “women would perceive to be attractive”. They also commented on how women preferred aggressive men over submissive men, who were aggressive in the ‘protection of their partner’ and ‘aggressive in the bedroom’xi. Another non-satirical source has a positive idea of “alpha males”, but comments that in relationships they are: ‘control freaks’, ‘always have to be right’, they put themselves first, objectify women, prioritise their goals over their partner’s and requires their partner to be submissive. They then follow this by describing it as the ‘prototype for real men’ and praising Donald Trump as being a powerful “alpha male”.

These archetypes can also drive anxiety in younger audiences, fuelling insecurities over fake archetypes which is leading to real life problems. Preceding the horrific 2014 Isla Vista killings, which led to the death of 7 people and injured 14 others, 22-year old Elliot Rodger had written a 137- page-long manifesto detailing his upbringing, planning the attack, and choosing the targets. He described his jealousy towards other men who had more success with women, towards couples, and condemned women for not finding him attractive. He then uploaded a series of videos on YouTube, the last being added one day before the killing spree, titled: ‘Elliot Rodger’s final retribution’. In this video, he reinforces his hatred towards the ‘popular kids’, and details his plan. Within this he comments: ‘You will finally see that I am in truth the superior one, the true alpha male’.

29

In the original wolf studies, both alpha male and female were present in wolf packs. Therefore, why isn’t it that the same archetypes have developed for women, but have solely become the male “socio sexual hierarchy”? This could either reflect the fact that the term was popularised by ‘Chimpanzee politics, in which the social structure of the described animal featured prominently alpha males. Do alpha females exist in nature? Well, yes. In fact, our joint closest living relative (to the chimpanzee), the bonobo, is one of the few primate species to feature a matriarchal structure. On the other hand, it could reflect a world still hiding undertones of inequality and gender expectations. The “alpha” is portrayed as a natural and successful leader. The reflection of an absence of an “alpha female” could reveal that society is still uncomfortable with the idea of female strength. “Alpha males” also are seen as having many romantic partners but difficult to tie down in a long-term relationship. The absence of “alpha females” therefore also alludes to the double standard when it comes to the number of romantic partners considered acceptable.

The original two archetypes were the “alpha” and “beta” males, with “alphas” having all the positive traits and “betas” having a complete set of negative traits. This creates the impression that the term “alpha” was only created for self-validation, by creating a separate class which also doubled a derogatory term that “emasculated” others. This probably reflects on some feeling of male insecurity, which is supported by the fact that the emasculated “betas” lead to the formation of a distinctly worse class: “omega”. The existence of a “sigma male” directly draws upon the human feeling of superiority which derives from uniqueness, created almost as a way to be more masculine than the “alphas”, owing to the idea that “sigmas” have “risen above” or “left” the “social hierarchy” on their own will. Finally, the newer members of the “hierarchy” (“delta” and “gamma”) were likely added in order to protect the class system, by making it seem more scientific and credible, drawing it closer to other personality classification systems, which have still been criticised as pseudoscience, but are also more recognised (E.G. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator).

Final thoughts

This article wasn’t written to attack anyone who self-indulges in these terms. It was written in order to educate and prevent aspirations to this generally unpleasant trope and reduce the fabricated male expectations which may put pressure onto this generation. If anything, maybe the term ‘alpha’, once it shifts away completely from self-identifying as a product of science, could become a much more positive archetype which could drive good.

30

How does the existence of these archetypes reflect on our society and human nature

Music and History: Interaction

between the Second World War and Western Art Music via Shostakovich and Reich

Kim Chin

Abstract

This essay explores the effects that the Second World War (1939-45) had on music and the effects vice versa. I acknowledge that the peripheral arts (such as folk tunes and oral traditions), though equally significant, are not examined in this essay but only on the central Western art music, especially those that are in the ‘canon’ are considered, Shostakovich’s “Leningrad” Symphony (1941) and Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988).

Introduction

Society and its culture are by definition, interlinked. In the world of arts, we observe a constant conversation, and with it, an evolution between music and history. Music is a product of its surroundings; through works from different eras, we gain insights into the world where they live. In fact, it is only the different societies that works lived through which gives them different perspectives – in a way, any given artwork is always living, via the people around it and their opinions.

Background

The Second World War broke out in an age of electronically mass distributed music. This is among the first times where music is so easily widely distributed, and in some cases, centralised. This put what was an art form right into the centre of warfare, as the states had the power to determine what songs were performed. In America, military bands were used for patriotism and nationalism. God Bless America, written by Irving Berlin was the nation’s first patriotic war song of WWII (Winkler, 2013). In Germany, the Nazis had a strong obsession with controlling and promoting culture. This stroke people back to the folk culture, after the movements of expressionism, modernism, jazz and other more dissonant, modern music (Wikipedia contributors, Role of music in World War II, 2022). Modernist composers such as Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Hindemith were targeted. Hindemith fled the Third Reich because of musical persecution (Wikipedia contributors, Role of music in World War II, 2022). Hindemith was publicly criticised by Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels as an “atonal noisemaker” (Reisman, 2006). On the other hand, composers with more conventional approaches like Carl Orff and Richard Strauss were allowed to stay (Wikipedia contributors, Role of music in World War II, 2022). In Russia, Stalin’s censorship and the socialist realism movement led to different reactions – a notable example is Shostakovich’s style of subtly ironic music.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No.7 (“Leningrad”), 1941

This symphony was written at a time of worldwide struggle in the city of Samara. Its Leningrad premiere took place on 9 August 1942 (Schwarm, 2017), with the city having been under siege for nearly a year. Under famine, the city struggled to find a complete ensemble, with orchestra

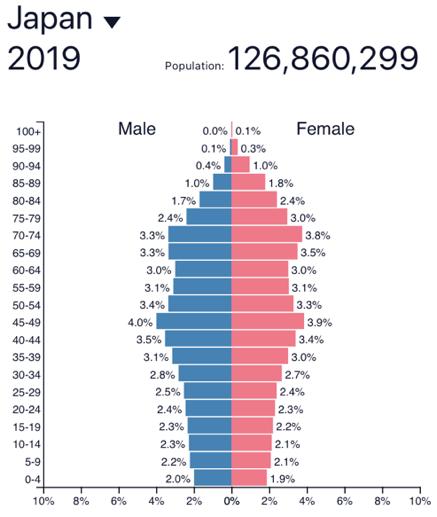

31