A PUBLIC SQUARE FOR ALL TO LEAD • VOLUME 14 • ISSUES 3 & 4 • FALL 2022 • $16.00 JOURNAL THE klcjournal.com | PUBLISHED BY THE KANSAS LEADERSHIP CENTER

the story on page 74.

Canonecityhavetwolanguages Puedeunaciudad,tenerdosidiomas? Read

THE JOURNAL

(Print edition: ISSN 2328-4366; Online edition: ISSN 2328-4374)

is published quarterly by the Kansas Leadership Center, which receives core funding from the Kansas Health Foundation.

The Kansas Leadership Center (KLC) is a non-profit organization teaching that leadership is a skill that can be developed through learning and practice. The principles and competencies covered at KLC can help anyone hone the skills needed to confront problems that exist in organizations and communities.

KLC is different in that it focuses on helping people from all positions, backgrounds and sectors learn the same four competencies of leadership.

KLC MISSION

To foster civic leadership for stronger, healthier and more prosperous communities in Kansas and beyond.

KLC VISION

To be the center of excellence for leadership development and civic engagement.

THE JOURNAL’S ROLE

To build a healthy 21st Century public square for all to lead.

KANSAS LEADERSHIP CENTER

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

David Lindstrom

Overland Park (Chair)

Julia Fabris McBride, Matfield Green (Interim President & CEO)

Jill Arensdorf, Hays Tracey Beverlin, Pratt Gennifer Golden House, Goodland Ron Holt, Wichita

Karen Humphreys, Wichita Susan Kang, Lawrence Mary Lou Jaramillo, Merriam Peter F. Nájera, Wichita

Patrick Rossol-Allison, Seattle, Washington

Frank York, Ashland

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Chris Green 316.712.4945 cgreen@kansasleadershipcenter.org

CIVIC ENGAGEMENT MANAGER

Maren Berblinger 316.462.9963 mberblinger@kansasleadershipcenter.org

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS

Sam Smith 316.712.4955 ssmith@kansasleadershipcenter.org

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

Shaun Rojas 316.712.4956 srojas@kansasleadershipcenter.org

ART DIRECTION + DESIGN

Craig Lindeman lindemancollective.com

PHOTOGRAPHY

Jeff Tuttle Photography 316.706.8529 jefftuttlephotography.com

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Stan Finger

P.J. Griekspoor

Kim Gronniger

Jerry LaMartina

Joel Mathis

Mark McCormick

Amanda Vega-Mavec

Dawn Bormann Novascone

Michael Pearce Barbara Shelly Mike Sherry

Beccy Tanner Keith Tatum Mark Wiebe

COPY EDITORS

Bruce Janssen

Shannon Littlejohn Laura Roddy

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

Roxie Hammill

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

David Kaup

Luke Townsend

WEB EDITION

klcjournal.com

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Annual subscriptions available at klcjr.nl/subscribenow ($24.95 for four issues). Single issues available for $10 at kansasleadershipcenter.org/klcstore.

CHANGE OF ADDRESS

Update contact information or unsubscribe online at klcjr.nl/updateinfo.

KANSAS LEADERSHIP CENTER

325 East Douglas Avenue

Wichita, KS 67202 www.kansasleadershipcenter.org

JOURNAL THE

CONTRIBUTORS

KEITH TATUM Columnist

Keith is a native Kansan, born in Manhattan and raised in Topeka. He has dedicated his career to public service and empowering every voice within our community. He holds a master’s degree in public administration from the University of Kansas and a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Washburn University. He and his wife, Teresa, live in Topeka and have a blended family of 10 children and one grandson.

JOEL MATHIS Contributing Editor

JOEL MATHIS Contributing Editor

Joel is a freelance writer who lives in Lawrence with his wife and son. He is both a reporter and opinion writer who covers topics that include technology, politics and popular culture. He currently blogs at joelmathis.substack.com.

BARBARA SHELLY

Contributing Editor

Barbara is a veteran journalist and writer based in Kansas City, Missouri. She specializes in reporting on education and health care. Her work has appeared in the Kansas City Star, where she worked on staff as a reporter, columnist and editorial writer, and more recently KCUR public radio, Flatland, The Pitch, The Huffington Post, The Week and the Community College Daily.

Contents A PUBLIC SQUARE FOR ALL TO LEAD • VOLUME 14 • ISSUES 3 & 4 • FALL 2022 PUBLISHED BY KANSAS LEADERSHIP CENTER 2. Watching Our Mouths MANAGING OURSELVES TO IMPROVE POLITICAL COMMUNICATION. BY: CHRIS GREEN 4. A Different Kind of Animal Reaches a Crossroads WHAT’S THE FUTURE FOR KANSAS COMMUNITY COLLEGES? BY: BARBARA SHELLY 14. Extending a Hand FORGING HEALTHIER RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN ATHLETES AND COLLEGE TOWNS. BY: BARBARA SHELLY 20. Step by Step FOSTERING CONSENSUS ON RACIAL JUSTICE. BY: JERRY LAMARTINA 28. Kids and Guns Together for Good SCHOLASTIC TARGET SHOOTING PROVIDES AN OUTLET. BY: MICHAEL PEARCE 38. A Deadly, Evolving Problem LEARNING TO LIVE WITH BLUE-GREEN ALGAE. BY: MICHAEL PEARCE 52. Bigger and More Satisfying than Ever BEING IN ON THE JOKE AT FREDONIA’S SAUSAGE FEST. BY: BECCY TANNER 60. Saving More than Supper RURAL RESTAURANTS RETURN FROM THE BRINK. BY: BECCY TANNER 74. Embracing the Possibility of a Bilingual City CAN EMPORIA HAVE TWO LANGUAGES? BY: JOEL MATHIS 84. Upholding High Standards CAN A DATABASE HELP WEED OUT BAD COPS? BY: ROXIE HAMMILL 92. Ounces of Prevention A SCHOOL BOARD MEMBER ON PREVENTING THE NEXT UVALDE. BY: KEITH TATUM 92. The Back Page I’M REALLY PROUD OF KANSAS, BUT NOT WHY YOU THINK. BY: MARK MCCORMICK

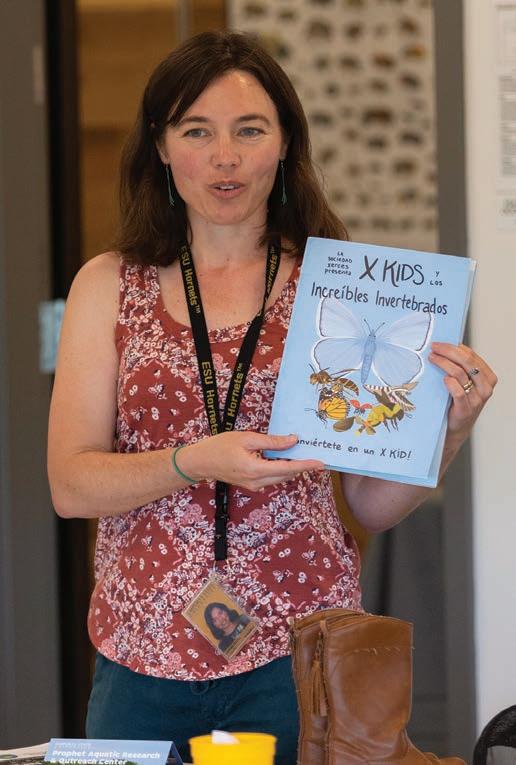

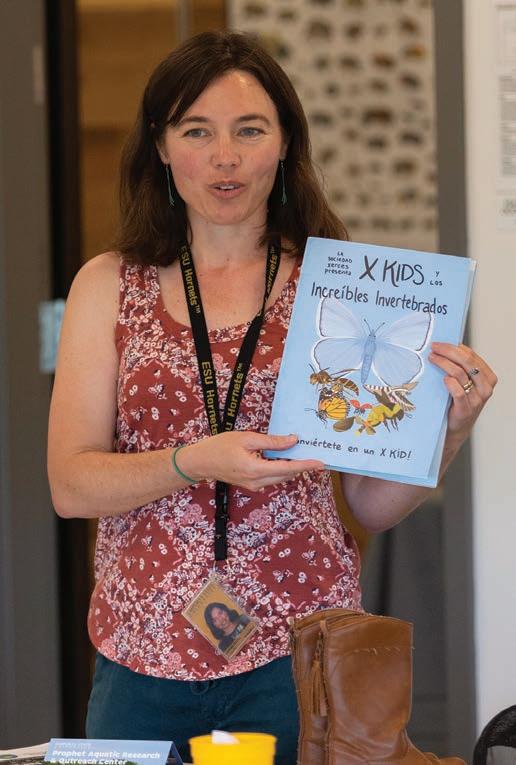

Watching Our Mouths

Words are not violence. But in these fraught political times, they certainly matter.

During the hotly contested mid-term election, many of us were inundated with political communication. The political messages we give and receive these days are often strongly worded, designed to speak to lizard brains rather than rationality. Candidates and groups hoping to influence you know they’re often fighting a losing battle to hold your attention.

The problem happens when political hyperbole drifts into apocalyptic language or dehumanization. Partially because of that, we currently have a political system where Americans are less likely to tolerate political differences and have less faith in working things out through the ballot box. As many as 1 in 4 Americans, according to a poll released last January, say it’s sometimes OK to use violence against the government, with 1 in 10 saying violence is justified “right now.”

One way to counteract political propaganda is to pay heed to how our buttons are being pushed. You probably can’t help repeating your side’s talking points every so often. But you can manage your triggers and force yourself to hold and test multiple interpretations.

How do you know when political messaging goes too far? One tell is that a victory by the other side is equated to the end of the world. You might hear that if Democrats win, it will result in the shredding of the Constitution and the end of America. (More than one candidate who ran this fall said something along these lines.)

If you’re a Republican, you most certainly won’t like many of the governing choices being made if Democrats win. But the past two years haven’t ushered in a woke, socialist dystopia in the U.S. either. Facing considerable constraints, Democrats have sacrificed some of their liberal priorities to focus on items with broader appeal. And they may have to give up power anyway.

Another clue to look for is when a group gets caricatured. Perhaps you know someone willing to argue that all Republicans are racists. How anyone thinks they can see into the hearts of tens of

millions of voters to know exactly what they believe is beyond me. There’s no doubt many Republicans have different views on issues related to race, ethnicity and unity than many Democrats. But it’s also true that the views of both sides can resonate across racial and ethnic lines. It’s telling that President Donald Trump, despite withering criticism about some of his statements, increased his support among Black and Hispanic voters in 2020, compared with 2016.

That doesn’t mean that elections don’t have very serious consequences. Efforts to cast doubts on elections when we don’t like the outcome are troubling, as is continued insistence, despite evidence to the contrary, that the 2020 vote was decided by fraud. Kansas voters seemed to reject these concerns in the August primary in the race for secretary of state, but voters around the country could make different choices this November.

Through it all, remember that you can be a partisan and watch your mouth at the same time. Don’t fall into the trap of describing the other side in less than human terms or saying that a political party’s victory will usher in an apocalypse. The odds are it won’t, and there will be other elections in two years and four years, where fortunes can be altered again.

When we see exaggerated political language being used, we should call it out and encourage those expressing it to reframe their views. They don’t have to change too much. You can strongly criticize what you disagree with without demonizing the people with whom you disagree. And if we’re truly exercising leadership on this topic, then we should hold our own side accountable first. Saying that someone has the wrong ideas might not feel as gratifying as saying they are dangerous or evil. But it certainly makes it easier to contemplate living in a world where your side’s power ebbs and flows.

Sure, politics can be about getting what you want done. But unless it’s also about keeping our social ties strong amid change, our politics won’t serve anyone well for very long.

THE JOURNAL 2 3 THE JOURNAL

LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE EDITOR CHRIS GREEN

CHRIS GREEN EXECUTIVE EDITOR

WITH POLITICAL COMMUNICATION TENDING TO EXTREMES, MANAGING OURSELVES MATTERS MORE THAN EVER.

BY: BARBARA SHELLY

Cowley College was established in 1922 as Arkansas City Junior College. For 30 years, it existed in the basement of the Arkansas City High School. In 1950, Galle-Johnson Hall was built, the beginning of today's 15-acre campus in downtown Ark City.

CHANGES IN HIGHER EDUCATION: COMMUNITY COLLEGES

A different kind of animal reaches a

CROSSROADS

KANSAS’ 19 COMMUNITY COLLEGES OFFER A PATHWAY FOR 96,000 STUDENTS TO PURSUE POSTSECONDARY STUDIES. THEY HAVE LONG BEEN AN AVENUE OF OPPORTUNITY FOR FIRST-GENERATION AND IMMIGRANT STUDENTS, AND THEIR INVESTMENT IN ATHLETICS AND CAMPUS LIFE PUTS THEM ON THE CUTTING EDGE OF WHERE TWO-YEAR INSTITUTIONS MIGHT BE HEADED ACROSS THE COUNTRY. BUT PRECIPITOUS ENROLLMENT DECLINES, AGING CAMPUSES AND FUNDING STRUGGLES CLOUD THE FUTURE OF THESE INSTITUTIONS, WHICH ARE OFTEN ECONOMIC LINCHPINS IN SMALL CITIES.

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

If Joe Blake had followed family tradition, he’d have headed for the University of Kansas straight out of high school. His parents are KU graduates and his older brother and sister enrolled there as freshmen.

But when Blake graduated from Hutchinson High School in the spring of 2020, he drove south to Arkansas City and Cowley College, a community college whose campus fits into a few blocks of a sleepy downtown.

Blake had his reasons. He’d been a star tennis player in high school, and Cowley offered him a scholarship and the chance to continue competing. He also had his sights set on a sports broadcasting career, and Cowley has a strong mass communications program. Blake plans to complete his bachelor’s degree at KU’s School of Journalism.

As he finished up his time at Cowley, Blake had no regrets about first going to a rural community college with an enrollment of about 3,600 students.

“I ended up being the voice of Cowley soccer this year,” he says. “And the tennis has been phenomenal.”

Blake is one of about 96,000 students who connected with a Kansas community college last academic year for credentials that include associate’s degree courses or training certificates. His experience highlights why public two-year schools are popular and, for many students, essential, even as the schools face headwinds.

Lawmakers and others in Kansas are calling for affordable education opportunities beyond high school. Current and prospective employers depend on community colleges to equip workers with the training and knowledge to thrive in today’s economy. Lawmakers recently created and expanded the Kansas Promise Scholarship program, which provides a free education at community colleges and technical schools for qualifying students in high-demand fields.

Yet enrollment at Kansas community colleges has plummeted in recent years. Campuses are

aging and funding is a persistent headache. As the state’s community college network moves into its second century of providing affordable postsecondary education for Kansans, questions about its viability grow more acute.

“We need advocacy,” says Dennis Rittle, who served as president of Cowley College for seven years before departing the post in July for a job in Arkansas. “We’re always fighting for the crumbs and trying to make sure we can keep our doors open and our bills paid, versus really getting out there and changing Kansas in a positive way.”

KANSAS COMMUNITY COLLEGES ARE PLENTIFUL, RESIDENTIAL AND SPORTS-FOCUSED

The birth of community colleges in Kansas dates to 1919, when college-level programs were established as part of public school systems in Garden City and Fort Scott. A 1965 state law enabled two-year schools to operate

independently of school districts, with their own governing boards and taxing authority.

From the start, community colleges presented an option for high school graduates who weren’t willing or able to attend a more expensive fouryear university. Over time, the schools moved into the workforce domain, offering training and job certification to adults of all ages. Across Kansas and the nation, community colleges are a leading avenue of opportunity for low-income, first-generation and immigrant students.

Today, 19 public community colleges are scattered throughout Kansas, and most have multiple locations. In addition, the state has seven technical colleges, which offer workforce training but not, usually, general college courses.

Compared with nearby states, that’s a lot of schools. Missouri, with a larger population, has 14 public two-year colleges. The Association of Oklahoma Community Colleges lists 12 members.

Johnson County Community College, with a sprawling campus in Overland Park and a reliable stream of income from a sales tax in the state’s wealthiest and most populous county, served about 26,000 students in the 2021 academic year. That’s a larger head count than the Kansas Board of Regents reported for any of the state’s public universities.

But JCCC is an outlier. Most Kansas community colleges are located in rural areas and serve about 2,000 to 3,000 students on their main campuses.

And those schools are notably more residential and sports-focused than most of the nation’s community colleges.

While only about one quarter of the nation’s 936 public community colleges have on-campus housing, according to research by the American Association of Community Colleges, dorm options in Kansas are nearly universal. Only JCCC is exclusively a commuter campus.

And while about half of the nation’s two-year colleges have intercollegiate athletic programs, every community college in Kansas offers men’s and women’s athletics.

“Athletics is important to community colleges in Kansas,” says Carter File, president of Hutchinson Community College. “It’s one of the ways we can really integrate ourselves into the community and something the community can take pride in.”

In some ways, Kansas community colleges have existed for years as a model for what colleges in other states wish to become.

“What I have learned is that rural colleges really need two things – they need athletics and they need residence halls,” says John Rainone, president of Mountain Gateway Community College in Clifton Forge, Virginia, who just wrapped up a term as chair of the American Association of Community Colleges Commission on Small and Rural Colleges.

“If

really want students to think about us as a first option, I do think students are expecting

THE JOURNAL 6 7 THE JOURNAL

we

Former Cowley College President Dennis C. Rittle doesn't think the state's community colleges are meeting their potential:

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

“We’re always fighting for the crumbs and trying to make sure we can keep our doors open and our bills paid, versus really getting out there and changing Kansas in a positive way.”

that we have some of the amenities that fouryear colleges have,” he says.

On-campus housing and the chance to play sports bring students from around the world to small Kansas towns like Arkansas City, Parsons and Concordia. They provide activities and entertainment and youthful energy to aging rural communities.

But as Kansas’ experience demonstrates, sports and dorms alone aren’t enough to keep small community colleges relevant in a turbulent economy.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE STUDENTS?

Despite an ongoing push to enroll graduating high school seniors in some kind of postsecondary academic or vocational program, the overall enrollment in the state’s community colleges has been declining for at least 10 years.

In 2022, a total of about 96,000 students signed up for college credit or vocational courses at the

19 community colleges. That’s nearly 16% fewer students than in 2017, according to Kansas Board of Regents data. Some community colleges have seen enrollment drops approaching 30%.

The picture over 10 years looks even worse. Based on a report issued in March, community college enrollment dropped by 27%, while enrollment at the state’s public universities dipped by about 3%. The smaller technical schools fared much better, with a recorded increase in enrollment of 61%.

Community college enrollments have always been tied to economic trends, often to the schools’ advantage. Laid-off adults rushed to campuses during the Great Recession, for instance, seeking to upgrade their skills and credentials.

But that kind of bounce didn’t happen in the pandemic, when classes were remote and the federal government was offering generous unemployment benefits. And in the current economy, employers desperate to fill job openings are waiving education and training

requirements that students have traditionally obtained at community colleges.

“We hear all the time from our area industries, our regional industries: ‘I just need somebody who’s going to show up for work every day, and pass a drug test,’” says Marlon Thornburg, president of Coffeyville Community College.

The effects of the labor shortage are hitting some of the schools’ most popular programs, such as a collaboration between Coffeyville and Pratt community colleges that trains high school graduates to install and repair electrical power lines.

In just two years, for a little more than $25,000 in tuition, fees and living expenses, an in-state student can graduate with an associate’s degree and a certification for a job that pays a starting salary of nearly $50,000. After a fiveyear apprenticeship, earnings exceed $77,000, according to KSDegreeStats.org, a tool created by the Kansas Board of Regents.

But right now, many students aren’t staying for two years.

“The companies need workers,” Thornburg says. “After the first year of the lineman program, a lot of kids do an internship that first summer. And if they do well on their internship, those companies don’t want the kids to go back to school. They’re hiring them right now.”

SKEPTICS AND CHAMPIONS

The steady enrollment declines feed an undercurrent of discussion about the viability of Kansas’ system of small, independent community colleges and the way they’re funded. “Kansas has stagnant population growth, fewer Kansans in the workforce, shrinking rural communities and an overall aging population,” says Kansas Rep. Kristey Williams, a Republican from Augusta, who has questioned the cost and necessity of supporting 19 community colleges.

Community college sports teams across Kansas help with their schools' branding and reputation. This past season, Cowley College's baseball team defeated Kansas City Kansas Community College in the Plains District championship game – in which Ty Hammack, of Edmond, Oklahoma, got a round of low fives after hitting a home run – enroute to the NJCAA World Series. Photo by Jeff Tuttle

THE JOURNAL 8

9 THE JOURNAL

Williams, who responded to questions in an email exchange, notes that the two-year school in her district, Butler Community College, lost 30% of its enrollment in the past decade.

“Many students are moving to online options, which provides a source of revenue but doesn’t require the large footprint necessary when enrollment was in-person and growing,” she says.

Alan Cobb, president and CEO of the Kansas Chamber of Commerce, says he is frequently asked about the administrative costs of the community colleges.

“Obviously, Garden City is going to have some programs that are different from Johnson County Community College, so you need some flexibility,” Cobb says. “But do you need a president at every community college? I think we should ask that.”

Talk of mergers of community colleges, or of community colleges and four-year colleges, pops up every so often in legislative hearings or other forums. But because community colleges operate independently without any statewide governing authority, it’s hard to discern who besides a governor would initiate a conversation about consolidation.

“There are people who whisper in the halls. It’s very rarely discussed in a formal setting,” says Heather Morgan, executive director of the Kansas Association of Community College Trustees.

Skeptics and advocates agree on one point: They say the state’s system for funding community colleges is hopelessly outdated.

A cost model created in the early 2000s calls for the Legislature to pay roughly one-third of the cost of instruction and related services for community colleges. The remaining two-thirds is to come about equally from student tuition payments and local property taxes.

But the state hasn’t paid its share for years. In the 2020 fiscal year, state appropriations amounted to less than 20% of revenues for the community college system.

That leaves locally elected boards with the difficult choice of either raising tuition, increasing local mill levies or both.

The reliance on property taxes in particular bothers Williams. She notes that only about 20% of Butler Community College’s enrollment comes from the home county. Most students commute from neighboring Sedgwick County.

“Sedgwick County is the major benefactor of the property taxes paid by Butler County residents,” Williams says.

“I think the coolest part about the Kansas community college network and also the trade school programs is that a majority of them are located in rural areas.”

Many community college leaders say they, too, would like the Legislature to pick up a greater share of their funding and shift the burden off of property taxes. They’d also appreciate more state help with maintaining their buildings and financing new ones.

“Physical building issues are preventing us from educating more Kansans to meet the workforce demands that are acute across the state,” Morgan says.

Community colleges are somewhat hampered when it comes to making their case in Topeka. Few of them can afford lobbyists. Apart from Morgan, there is often no one to take up their cause.

Research has found that, while taxpayers were forking over $13.5 million in the 2016-17 fiscal year to Cowley College, the return on investment in higher lifetime earnings for Tigers alumni and increased business output, was more than three times that. Additionally, the school adds millions to the regional economy in jobs and spending by staff, alumni and collegians like sociology student Sierra Yourist of Ponca City, Oklahoma.

THE JOURNAL 10

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

Trisha Purdon

Kansas Office of Rural Prosperity

Each college is governed by an independent board of trustees. Unlike in most states, Kansas has no governing or regulating authority for two-year schools. While the Board of Regents governs the state’s six universities – hiring their presidents, setting tuition rates and approving contracts – community colleges make those decisions at the local level.

“The regents champion the universities,” says Rittle. “I’m not bashing them or saying they don’t care about the community colleges. But we don’t have that champion that says, ‘The only reason we’re here is to help you be successful.’”

“I think the coolest part about the Kansas community college network and also the trade school programs is that a majority of them are located in rural areas,” says Trisha Purdon, director of the Kansas Office of Rural Prosperity, a division of the state Department of Commerce.

“They really are the integral resource that these rural communities depend upon,” she says, “not just for new blood coming into the town, but also for ongoing training programs that really ensure that rural communities continually evolve and learn new skills.”

Researchers examined the 201617 fiscal year and found that federal, state and local taxpayers gave Cowley College $13.5 million in that period. The return on that investment, in higher lifetime earnings for students and increased business output, is projected to be $45.8 million.

DISCUSSION GUIDE

1. What barriers keep the factions (legislators, community college officials, local government officials, business community officials, etc.) from coming together to make progress on the health of the local community college?

Of course, plenty of people around Kansas are pulling for community colleges to succeed.

By some measures, investment in Kansas’ community colleges is a bargain. A 2019 economic impact study by labor market data company Emsi found that Cowley College adds $265 million to its region’s economy annually through jobs and the spending impacts of students, staff and alumni.

The same firm, Emsi, found that Kansas City Kansas Community College in Wyandotte County added $182.3 million to its local economy in a given year. That report estimates that students who attended KCKCC in the 2016-17 school year will earn a combined $186.3 million more in pay over their working lives because of the education and training they received at community college.

2. `What are the possible roles for senior authority in these situations? What are potential opportunities for leadership?

3. Leadership is risky. What is at risk for the community that doesn’t take action toward progress?

- By Kaye Monk-Morgan

Because of their scattered nature, many of the achievements of Kansas community colleges never become widely known.

In Concordia, Cloud County Community College was one of this year’s 25 semifinalists for the Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence. The Aspen Institute awards the honor every two years, based on metrics such as retention and graduation rates and success factors for lowincome and minority students. Although Cloud wasn’t one of the 10 finalists, it can still claim bragging rights.

“It’s a great time to be at Cloud, in my opinion,” says college President Amber Knoettgen, who obtained her associate’s degree at the school and played on its basketball team. “When we’re recruiting, we’re able to say that we’re one of the top 25 community colleges and technical schools in America.”

By mid-August, students were filling up dorms at Kansas community colleges and sports seasons had begun. Enrollments still looked low and finances still looked uncertain. But colleges remained secure of their place in their communities.

At Garden City Community College, plans were underway for a new building to expand John Deere ag tech training, and industrial maintenance and welding classes. Students from around the nation and world were coming to campus to play sports or take courses they can’t find at home. In the spring semester, 43 states and 90 nations were represented on campus, college President Ryan Ruda says.

Ruda, who has been at the college for 23 years and served as president since 2019, said he networks constantly in his community to try to make sure the school is responding to needs.

“We are a transfer institution. We are a technical institution. We provide fine arts and athletics,” he says. “Community colleges really try to be all things to all people.”

THE JOURNAL 12 13 THE JOURNAL

AN ESSENTIAL RESOURCE FOR RURAL COMMUNITIES

$1.2M Less than high school diploma $1.6M High school diploma/ GED $1.9M Some college $2 M Associate’s degree $2.8M Bachelor’s degree $3.2M Master’s degree $4 M Doctoral degree $4.7M Professional degree MEDIAN LIFETIME EARNINGS Source: “The College Payoff: More Education Doesn’t Always Mean More Earnings,” Georgetown University, McCourt School of Public Policy, Center on Education and the Workforce

COMMUNITY COLLEGES

Extending a hand

BY: BARBARA SHELLY

WHEN COMMUNITY COLLEGES RECRUIT A DIVERSE MIX OF ATHLETES TO THEIR CAMPUSES, IT CAN CREATE CONFLICTS AND MISUNDERSTANDINGS WITH THE MOSTLY WHITE LOCALS.

BUT IN HUTCHINSON, OUTREACH BY POLICE AND COLLEGE OFFICIALS TO STUDENTS COULD POINT THE WAY TOWARD HEALTHIER RELATIONSHIPS.

Members of the Hutchinson Community College Blue Dragons football team had just arrived on campus in July when the police chief paid them a visit.

If the athletes were expecting a law-and-order lecture, they received something altogether different. Jeff Hooper welcomed them to Hutchinson. He told players that, in his department, good police work is measured not by arrests but by positive encounters between officers and those they have the privilege to serve.

Hooper acknowledged that some of the athletes sitting before him, more than half of whom were Black, might not have a positive impression of the police. Some grew up in tough urban neighborhoods, others in small towns where people of color are closely watched and often harassed.

“Give us a chance,” Hooper said. “Allow us to talk to you and build relationships and connect with you on a one-to-one basis.”

The presence of minority student athletes, such as (at left) Micah Woods from Birmingham, Alabama, in mostly white towns like Hutchinson has led to some encounters with local law officers in which players felt profiled. With that in mind, Hutchinson Police Chief Jeff Hooper made it a point this summer to meet with Hutchinson Community College's football players, welcome them to town and explain that arrests are not how he measures good police work. Photos by Jeff Tuttle

15 THE JOURNAL

CHANGES IN HIGHER EDUCATION:

Hooper recalls some of the athletes were clearly skeptical, others suspicious. “Police are evil,” one player said.

Later, Hooper said he was not offended by the generalization. “One of the things I talk to my officers about is that our uniform carries with it baggage,” he says.

“And that baggage is made up of everything you’ve ever read, seen or heard about law enforcement.”

The chief asked the players to keep an open mind.

“I’ve never been Black, and I’ve never been from the inner city,” he said, recalling the conversation later.

“But you’ve never been a police officer and been on a call all by yourself at night where you get a report that an armed subject broke into a house and you have to enter that house on your own not knowing whether you’re going to go home to your family at the end of your shift.”

Hooper’s outreach to students, in collaboration with college leaders, could point a way toward better relationships in other Kansas cities where sports and other opportunities bring diverse groups of community college students to campuses and communities where the population is majority white.

THE CHALLENGES OF RECRUITING

Sports are huge at Kansas community colleges and have been for decades.

Kansas Rep. Kristey Williams, a Republican from Augusta, has asked the Kansas Legislative Division of Post Audit for a report on whether money from state and local taxpayers is used to subsidize athletes from other states or nations. The audit is ongoing.

Beyond the fiscal concerns, some people question why more roster spots aren’t given to Kansas athletes.

Carl Heinrich, commissioner for the KJCCC, says the conference limits teams to 55 out-ofstate football players on 85-player rosters. Other sports have no caps on out-of-state athletes.

campus lucrative for the colleges. Some community colleges offer scholarships to out-of-state and Kansas athletes that can come from fundraising, fees or other methods the schools come up with, Heinrich says. Scholarships are limited to tuition, fees and books, and sometimes room and board, depending on whether a college plays at the Division II or Division I level.

A MEASURE OF TROUBLE

File, president Hutchinson Community College

Athletes arrive in rural communities from around the nation and overseas. Some just want another year or two to be part of teams and play the sports they love. Others hope a good season at a junior college will lead to an offer to compete at a four-year university.

Talented Kansas athletes often have scholarship offers from four-year schools, Heinrich says. To be competitive, coaches have to look elsewhere.

“It’s a challenge for coaches to get their rosters filled every year,” he says.

International athletes often receive aid from their home countries to attend college in the U.S. and play sports, which makes their presence on

At a time when Kansas community colleges struggle with declining enrollments, sports programs guarantee a statewide presence of about 3,000 athletes on campuses, in classrooms and in residence halls.

But sports have also brought a measure of trouble to a few schools.

Hutchinson Community College President Carter File and his wife, Tracey, were on hand at Gowans Stadium in Hutch this fall as the Blue Dragons football team began its season with a 42-0 romp past Navarro College of Corsicana, Texas.

The chief’s welcome was a marked departure from the reception that athletes and other students of color at HutchCC, as the school is called, once experienced. Before Hooper’s arrival in 2018, Black students complained of routinely being stopped and questioned by police when they were out and about in Hutchinson, a city where nearly 80% of the population is white.

“In the past, it happened quite a lot,” says Darrell Pope, past president of the Hutchinson chapter of the NAACP. “We’re talking about being stopped while driving and walking. They’d be out somewhere, and the police would come and hassle them. Or they’d be in Walmart and someone would call the police.”

The Kansas Jayhawk Community College Conference (KJCCC) is one of the most robust chapters in the National Junior College Athletic Association, and Kansas teams routinely compete for national championships in multiple sports.

“For a lot of people, athletics is the lens they see the college through,” says Carter File, president of Hutchinson Community College.

File counts it as a plus that HutchCC’s sports programs draw students from all over. “One of the things we pride ourselves on is that we do introduce diversity into the community,” he says.

“We want to create the opportunity for students to interact with other students of different backgrounds.”

The far-flung range of hometowns on Kansas community college sports rosters does raise some eyebrows.

THE JOURNAL 16 17 THE JOURNAL

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

For a lot of people, athletics is the lens they see the college through.

" "

Carter

Twice in the last four years, football players died of heat stroke during practices. Fort Scott Community College, in southeast Kansas, shut down its football program after Tirrell Williams died there. The other death, of Braeden Bradforth, was at Garden City Community College in western Kansas.

Apart from the deaths, lawsuits filed in 2020 and early this year alleged that Black student athletes at Highland Community College in northeast Kansas were subjected to “rampant racial harassment and discrimination.”

The 2020 lawsuit, which the American Civil Liberties Union of Kansas filed on behalf of four athletes, alleged that members of the Highland Police Department, acting as security officers for the college, routinely searched vehicles and dorm rooms of Black student athletes. Police officers used their squad cars to trail Black students while they walked on and off campus, the suit also alleged, and disciplined Black students for offenses more than white students. Ultimately, the parties reached a settlement.

The college agreed to pay students and their lawyers $90,000. Security officers and housing personnel were ordered to take antidiscrimination training.

Still pending is another lawsuit, brought by three former Highland Community College coaches. The coaches contend the college fired them without cause and smeared their reputations because they protested the college’s treatment of Black players.

It also alleges that the school’s now former athletic director told the coaches to “recruit more players who the culture of our community can relate to.” The population of Doniphan County, where Highland is located, is 92% white. Its Black population is about 3%.

In an email, Highland President Deborah Fox said the college “intends to vigorously defend itself” against what she called “baseless allegations” by the coaches.

“Our communities that house the main campus (Highland) and other HCC locations have been extremely positive when interacting with our students,” she said, and added that the people in the community “understand how important all students are to our college and northeast Kansas communities.”

AN INTENTIONAL APPROACH IN HUTCHINSON

In Hutchinson, which also has a Black population of about 3%, leaders say that cultivating positive relationships for both minority students and residents requires an intentional approach.

The college opens its campus to civil rights events such as Hutchinson’s Emancipation Celebration’s gospel fest. And the spring semester begins earlier at HutchCC than many other colleges so that students can engage in local activities for Martin Luther King Jr. Day if they choose, File says.

Hutchinson’s faith community also reaches out to students. Soon after they arrived for training, the HutchCC football team was invited to a meal at one of the Black churches. Black players are shown the way to barber shops and other places where they can feel comfortable.

Pope, the NAACP leader, credits Hooper with creating a positive atmosphere in town. “He’s got a different philosophy,” he says.

Hooper says his philosophy begins and ends with relationships. In Hutchinson, he says, “there aren’t many people who don’t know me or haven’t heard me talk.”

But the community college constantly brings new faces into the community. “So every year we have to try to meet with those new students and try to break through those barriers,” Hooper says.

After the chief’s meeting with the football team, the athlete who had blurted out that “police are evil” trailed behind his teammates to talk to Hooper as he walked out to his patrol car.

“Hey chief,” the athlete asked, “can I ride in your police car?”

“Absolutely,” Hooper said. “Hop in.”

“I drove him back to the dorm,” Hooper says. “A lot of the kids were getting back by that time. He got out and said, ‘Yeah, I got a ride from the chief!’”

Hooper doesn’t know if the encounter will change the athlete’s perception of law enforcement.

“I do know that he’s seen my heart,” he says, “and when I see him on campus, we can have a conversation. He’s going to walk up to me or I’m going to walk up to him. That’s the only way I know how to change the world, is one relationship at a time.”

THE JOURNAL 18 19 THE JOURNAL

Before Police Chief Jeff Hooper’s arrival in Hutchinson in 2018, Black students at HutchCC complained of routinely being stopped and questioned by police. Photo by Jeff Tuttle

STEP

BY: JERRY LAMARTINA

CONVERSATIONS

ABOUT RACIAL JUSTICE AND EQUITY HAVE BECOME INCREASINGLY POLARIZED ALONG PARTY LINES. BUT A COMMISSION CHARGED WITH ADVANCING RACIAL JUSTICE AND EQUITY

AFTER THE MURDER OF GEORGE FLOYD HAS FOUND SUCCESS WITH POLICY PRESCRIPTIONS THAT TEND TO GENERATE CONSENSUS RATHER THAN CONTROVERSY.

The journey of a commission charged with addressing issues related to systemic racism began back in July 2020, a mere 60-some days after the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer.

In the months since Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly introduced members of the 15-member Governor’s Commission on Racial Equity and Justice, the group has convened nearly three dozen meetings and published three substantial reports totaling more than 250 pages in length.

The first, which came out in December 2020, dealt with policing and law enforcement. Two reports in 2021, one in July and one in December, dealt with the social determinants of health. With that last document, the commission’s work as a body formally ended.

But in many ways, the group’s leadership challenge was only beginning.

Since the summer of 2020, conversations about race have become increasingly polarized, with controversies erupting over programs to promote racial and social justice, especially in schools. One factor helping drive the flareups has been deep divisions, especially along partisan lines, over whether racism is a problem that mostly lies in the hearts of a few individuals or a societal challenge that requires changes in policy and culture.

The commission was mentioned this fall in a campaign advertisement attacking Kelly for “appointing a woke commission that pushed for anti-policing laws.”

Amid these upheavals, members of the commission have, in recent months, contributed to highly visible efforts to advance a slate of recommendations for actions that Kelly, the Legislature, local governments, law enforcement and other agencies and organizations could take to improve the criminal justice system and increase economic, educational, health, mental health and housing opportunities.

Through its efforts, the commission staked out a middle ground of sorts with legislative recommendations often designed to foster systemic change while transcending the most hot-button topics.

And this past session, despite a contentious political climate, they saw several bills with components related to their recommendations signed into law. A $16 billion budget that Kelly, a Democrat, approved April 20 included a provision extending KanCare’s postpartum coverage from 60 days to one year, a change federal officials eventually signed off on.

Other bills related to the commission’s recommendations didn’t become law but the Legislature discussed them, which gave them attention and started a dialogue, including state policies involving COVID-19, says Dr. Tiffany Anderson, the superintendent of Topeka Public Schools, who chaired the commission with Dr. Shannon Portillo, then a Douglas County commissioner, recently an associate dean of academic affairs in the University of Kansas School of Professional Studies at KU’s Edwards campus in Overland Park and a professor in the public affairs school on KU's Lawrence campus.

On a visit to the Topeka Center for Advanced Learning and Careers, 14-year-old Morgan Barrett got a chance to meet and visit with Tiffany Anderson, the superintendent of Topeka USD 501.The center, created through business partnerships, provides real work experiences through profession-based learning. Photos by Jeff Tuttle

STEP by

THE CHALLENGE OF ENGAGEMENT

Portillo, who left Lawrence for a position at Arizona State University this fall, says engaging the Legislature has been one of the commission’s “big challenges … to make sure the recommendations we put in front of them that have to do with racial equity make a meaningful difference in communities across the state. This work will be ongoing for years.”

But commissioners also view their engagement work more broadly, looking for ways to connect with more Kansans, including “those who don’t see themselves as criminal justice activists, to step up and play a role and ask how they can address behavioral health problems,” says David Jordan, a commission member and president and CEO of the United Methodist Health Ministry Fund, based in Hutchinson.

That includes people who may not know a lot about the issues, which requires commissioners to build support by working through others, whether they are stakeholder groups or individuals such as faith leaders, community influencers and business owners.

“If we’re able to address some of these longstanding inequities, we’ll be able to be living in a more just and prosperous state,” he says.

SUBTLE BUT SIGNIFICANT CHANGES

The legislation that has passed so far might not grab the headlines. But the support for the measures has been nearly unanimous, suggesting there is at least some space for common ground on topics that can be highly charged.

Still, not all stakeholders are excited to talk about even those areas that have produced consensus. Despite multiple attempts, efforts to reach Republican legislative leaders about areas of agreement on the subject of racial justice and equity were unsuccessful.

In a news release from the governor’s office, State Rep. Brenda Landwehr, a Wichita

Republican, lauded the expansion of postpartum coverage under Medicaid in July. But none of those quoted connected the policy change to racial equity.

“As a mother, I know how important the first year is and this enhanced period of care for Kansas mothers is vital for their mental health, their baby’s health and their families,” Landwehr said. “I am grateful to our state for taking this monumental step to improve maternal health across the state.”

But that doesn’t mean the impact won’t be significant.

Jordan said in a news release that the extended coverage would help 9,000 Kansas mothers a year by “reducing maternal mortality, improving health outcomes and reducing disparities.”

KanCare covers 31% of Kansas births, and 29 organizations signed a letter supporting postpartum coverage expansion, which the federal government allowed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The policy itself has nothing do with race or ethnicity. But it could have profound implications for racial equity nonetheless. Kansas has stark racial disparities when it comes to maternal and child health, according to the commission’s first report.

Black, non-Hispanic women have pregnancyrelated mortality rates more than three times higher than those for white women. And infants born to Black women are more than twice as likely to die as infants born to white women.

Another new law, HB 2008, allows the state’s attorney general to coordinate training regarding missing and murdered indigenous persons among law enforcement agencies throughout Kansas in consultation with Native American Indian Tribes, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, the Kansas Law Enforcement Training Center and other appropriate state agencies. The effort is seen as a way to address the high rates of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls nationwide.

Other statutory changes included SB 127, which addressed driver’s license suspensions while HB 2026 created a drug treatment program for people on diversion.

Anderson sees both short-term and long-term actions that can lead to progress on many of the commission’s recommendations.

These include creating rural opportunity zones, expanding the types of businesses eligible for state tax credits, and providing affordable child care assistance. But she adds that changes requiring governments to spend more money, such as expanding Medicaid, have a fraught history, even though expansion would reduce spending from the state’s general fund on law enforcement and behavioral health.

The commission’s recommendations include data collection and analysis, partly done by the governor’s Office of Administration, Portillo says. Engagement of minority organizations such as the Kansas African American Affairs Commission and the Kansas Hispanic and Latino Affairs

THE JOURNAL 22 23 THE JOURNAL

“If we’re able to address some of these long-standing inequities, we’ll be able to be living in a more just and prosperous state.”

David Jordan, president of the United Methodist Health Ministry Fund, sees work of the Governor’s Commission on Racial Equity and Justice as more than just reporting to the Legislature but also connecting with a swath of Kansans. Photo by Jeff Tuttle

Commission also is important for reaching the commission’s goals.

“We can see some of this work spread out for the state,” Portillo says.

She says stakeholders are increasing public awareness of the commission’s goals using methods including social media, live-streamed informational presentations, community agency announcements, listening sessions with community groups, newspaper opinion pieces and editorials, making the commission’s reports available on government websites, learning sessions with law enforcement officials who are people of color, and conducting webinars on the commission’s recommendations “intended to inform and engage the public so they’re empowered to take the next step.”

LEADERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES

Floyd’s death, and the earlier deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor at the hands of police officers, prompted nationwide demands for racial equity reforms in the criminal justice system. But the road to creating substantial change can be long and difficult.

The commission’s strength and its opportunity to provide leadership grow from the diversity of its members’ expertise and their ability to share its goals with the people they serve to get them involved in the process, Anderson says.

An important part of the commission’s recommendations addresses “training and mindsets, transformational practices,” including anti-bias training, Anderson says. Unchallenged and unchanged mindsets “create barriers to transformation occurring.”

“I think that’s the largest barrier in any system,” she says. “It’s how you think.”

Anderson focused her doctorate on new school principals’ effective leadership styles. She says leadership can occur regardless of title and formal authority, which is foundational to the

commission’s efforts to involve all Kansans in working toward its goals.

Portillo says the broad range of topics the commission studied and made recommendations for is both exciting and one of the biggest challenges because of how many areas they address. Approaching the problems from the commissioners’ multiple disciplinary perspectives required them to ensure they were “speaking the same language” in making their recommendations.

Leadership opportunities to implement the commission’s recommendations, because they seek to address a wide range of long-standing, systemic and interwoven inequities, require “hard work, determination, focus and multiple partners and stakeholders,” Jordan says.

“The leadership challenge is facilitative to empower partners across the state to take leadership on these issues that resonate with them, that align with their interests and that they have talents and skills to address, and it’s also adaptive in nature,” he says. “The challenges are not technical or simple. They need collaborations to address emerging needs.”

Jordan says it is worth analyzing the Strengthening People and Revitalizing Kansas' executive committee, which oversees the state’s distribution of American Rescue Plan Act funding, with a race and equity lens. This lens can also be applied to all statewide policies.

Asked how the fractured political climate would affect the commission’s work, Jordan says challenges also bring opportunities.

“Not all will engage with all issues in these reports, but there’s an opportunity to engage as nonpartisan,” he says. “We can all work together to move forward recommendations at the local level, which is sometimes easier than at the state or federal level.”

Portillo says none of the commission’s work is partisan, but implementing the recommendations requires working across partisan divides. For example, the idea of

25 THE JOURNAL

When it comes to racial equity, unchallenged and unchanged mindsets

“create barriers to transformation occurring,” says Dr. Tiffany Anderson who co-chaired the Governor’s Commission on Racial Equity and Justice.

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

having public defender offices in the state’s most populous counties is nonpartisan and would increase economic efficiency. She cited data showing public defenders cost the state less than having appointed counsel.

“But it’s a topic that as we talk about organized public defense, people see it as ideologically leaning one way or the other,” she says. “We’re arguing that this is better for equity outcomes and more economically efficient for the state.”

CRIMINAL JUSTICE

Wyandotte County District Attorney Mark Dupree calls Kelly a visionary for creating the commission when “the criminal justice system as well as the community and state as a whole, and quite frankly, this country, needed it to happen.”

He says educating those in power is the key to a more equitable criminal justice system. The commission assembled experts in various fields, including criminal justice experts in law enforcement and the courts – “boots on the ground and those working with creating laws that would be more equitable for Black, brown and broke folks in the entire community, and then allow them to educate us.” Many of the commission’s recommendations grew from their learning about where systemic flaws are.

Dupree says the biggest obstacle to achieving the commission’s recommendations will be changing the minds of people who are removed from “where things are happening on the ground.”

“Though I’m law enforcement, there’s a difference in what I do and what officers do,” he says. “The disconnect that I had to deal with and humble myself and understand is that I may see things a little different from where I sit.”

Some legislators are “a tad bit removed from where a lot of those touchpoints are,” Dupree says. The task is to convince them less to accept the commission’s recommendations than to accept what the experts told the commission and then advance those recommendations.

Asked how to balance making the criminal justice system more equitable with the system’s responsibility to prosecute those who commit crimes, regardless of their race, Dupree says a holistic approach is needed.

“We historically haven’t had the whole picture in mind but only a case-by-case analysis, which is important to understand as a piece of the puzzle but not the entire puzzle,” he says.

The commission’s goal of a more equitable approach in criminal justice matches “what

we’ve always tried to do, which is pursue justice.”

The difference, though, is pursuing justice by considering all factors that affect it, the “underlying issues that bring individuals into the criminal justice system as well as what happens to them once they get in there.”

Mental health is a good example of those factors, Dupree says. Going back 20 to 30 years, most people disregarded mental health as a criminal justice factor. That view has changed because “now we understand that the vast majority of cases that we deal with in our criminal justice system is predicated on someone being diagnosed with a mental illness.” That translates to 80% of county jail inmates throughout the country having been diagnosed with a mental illness, he says.

DISCUSSION GUIDE

1. Who are the factions that might need to be engaged on this topic? How would you characterize their views, values, and potential gains and losses?

2. From your perspective, how might commissioners work to inspire a collective purpose among all Kansans?

3. How do you see the work of the commission benefiting the culture of Kansas and your life? In what ways might their work challenge you?

4. How might commissioners work to create a trustworthy process that can cross partisan divides?

5. The commission has reported on a variety of subjects, from policing to the social determinants of health. If you were on the commission, what would you choose to focus on?

- By Maren Berblinger and Brianna Griffin

Lacking conversations about the effects of mental illness on the criminal justice system prevents having informed conversations about recidivism, Dupree says. The same is true for drug addiction and drug treatment. Some people need treatment but others “need prison. But to say, ‘Let’s throw them all in prison’ really does a disservice to the pursuit of justice.”

That also applies to equitable treatment in the courts. Without considering race and historical racial disparities, “we’re trying to pursue justice without the whole picture.”

“I tell people all the time that the criminal justice system in our country is the best

criminal justice system in the world,” Dupree says. “However, in any system that’s run by people, since we are flawed, there will be flaws. And that’s OK as long as we’re willing to acknowledge those flaws, educate ourselves and then work to correct it and keep moving."

That notion undergirds the commission’s recommendations, especially in their early stages of implementation but also long term. Anderson says the commission’s reports provide “a bridge between the divisions across the state … because it offers conversations on topics of concern to everyone.”

THE JOURNAL 26 27 THE JOURNAL

Shannon Portillo, here conversing with KU Endowment's Scott Zerger, says none of the commission's work is partisan, but implementing its recommendations requires working across partisan political divides.

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

KIDS AND GUNS

Ayoung gunman’s appalling murder of 19 students and two teachers at a grade school in Uvalde, Texas, horrified Kansas teacher Victor Mercado and parent Matt Onofrio. Like so many, both miss the pre-Sandy Hook days when active shooter drills weren’t part of a student’s educational process.

Both also hope people can look past such unspeakable tragedies and see the amount of good that can come from programs that safely bring students and firearms together. Onofrio and Mercado are coaches for clay target shooting teams at Kansas high schools. A fast growing scholastic sport in America, it is also proving safe, according to John Nelson, USA Clay Target League president.

“What those kids did in Texas and Buffalo were terrible tragedies, but they’re so very rare compared to the number of students who benefit from these kinds of programs,” says Onofrio, head clay target shooting coach at Kapaun Mt. Carmel High School. “For every bad kid we read or hear about, there are thousands of success stories with young (target) shooters in Kansas and probably millions across the country.”

Mercado says Maize High School has had as many as 48 students on his school’s clay target shooting team. He’d like to see many more benefit from the program.

“I love to see kids get involved in anything outdoors,” says Mercado, who teaches Spanish and an outdoors education class that introduces students to such pursuits as fishing, camping, hunting and target shooting. “That’s especially true of clay target teams. They have so much to offer.”

He also touts “life-lesson skills” that go beyond what students can learn in a classroom. Mercado’s students learn not only firearms safety and awareness, but respect for others and

themselves, the importance of determination, working as a team and mental toughness.

Most scholastic target coaches say such traits help youth mature into good adults and help keep them from being caught up in the rising tide of teen gun violence.

“I don’t worry about those kids at all for that,” Todd Robinson, a 17-year law enforcement professional, says of the young people he coaches on a shooting team in Concordia. “They’ve learned to understand and respect firearms. They also have something they belong to, a place, the trap range, where they know they’re welcome and included. It’s when kids don’t have that, that we can have some serious problems.”

Opportunities for such “target busting educations” have spread quickly across Kansas and have become amazingly popular.

A FAST GROWING SCHOOL SPORT

Kansas got into high school clay target competitions back in 2016, with 29 schools and 321 shooters. Josh Kroells, the USA Clay Target League Kansas state director, says the recent spring season saw 108 Kansas high school teams put about 2,200 students out on ranges, busting clay targets with shotguns. Another six Kansas schools, with about 170 shooters, who can be as young as sixth graders, have teams within the Scholastic Shooting Sports Foundation. Some teams include students from several schools because not all schools host the activity.

Nationally, the USA Clay Target League began in 2007 with a few Minnesota schools. Now, it’s in 34 states with about 32,000 students participating. Some states, such as Minnesota, have stunning levels of participation.

Participants on Augusta High School's sporting clays team often look as adept as Taylor Gresham even though 40% didn't have access to a shotgun when they started. Coaches have discovered a variety of options

“In Minnesota we have more students shooting clay targets than boys and girls on high school hockey teams combined, and Minnesota is so known for hockey,” Nelson says. “We have 12,000 student athletes shooting targets on about 400 teams.”

29 THE JOURNAL

FOR

GOOD DEADLY SCHOOL SHOOTINGS SUCH AS THE ONE IN UVALDE, TEXAS, POWERFULLY SHAPE PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS ABOUT THE DANGERS OF GUNS IN SCHOOLS. BUT ACROSS KANSAS, A GROWING INTEREST IN SCHOLASTIC TARGET SHOOTING IS SHOWING THERE’S ANOTHER SIDE TO THE STORY. HERE’S HOW THE SPORT IS BLOSSOMING WITH AN EMPHASIS ON SAFETY, SUPPORT AND INCLUSION.

TOGETHER

BY: MICHAEL PEARCE

to outfit members.

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

Nelson says participation is growing at a rate of about 20% annually across the nation. State clay target championships can draw more participants than many other sports.

Most Kansas teams have been started by students, a faculty member or parents. Kroells says schools must approve a program before it can be accepted into the USA Clay Target League. Administrative approval allows a team to use the school’s name and mascot. School financial support varies greatly, but is never enough to cover all costs. Money also comes through team dues, donations and fundraisers. Clay target team participants are subject to all school sports rules such as maintaining good academic and attendance records. School policies forbidding guns and ammo on school grounds are strictly enforced.

Mercado says he’s gotten no negative comments from the Maize High School administration or faculty.

“Our administration is supportive of the shooting team because it gets kids involved in an extracurricular activity,” he says. “They know when kids get involved in a school activity, it gives them a sense of pride that they belong to something. Shooting sports is just one of many activities our school offers.”

Some coaches did face initial challenges when creating a shooting team. Augusta High School just finished its first year of target shooting competitions. Andy Hall, team coach, says it took three years to get the team started.

“We had a principal who didn’t believe in any kind of shooting. We’d make a presentation asking to start a team and we’d get an immediate ‘no’ from her, even though we had an athletic director and several teachers supporting us,” says Hall. “Eventually we got a new principal who was big into youth involvement. We took him and the school superintendent out to shoot some clays and things got rolling. The school board approved our team 7-0. Some members asked why we hadn’t had a team earlier.”

Nelson says some high schools that experienced past school shooting tragedies now embrace their high school teams. Minnesota’s Rocori High School had two students murdered by another in 2003. They’ve had a clay target team for several years. Last spring the school’s team fielded 74 students, says Nelson.

Coaches like Mercado and Hall say they’ve occasionally heard from parents who were leery of anything that combined kids and firearms. Some even had kids on their team. Mercado told of an 18-year-old student who purchased his own

shotgun and parents said he couldn’t bring it into their house. Hall had a parent who was very outspoken, both against her child shooting and the shooting team concept.

“Once she (the parent) really took the time to understand what was going on, and how things were working, she changed her mind,” says Hall. “She’s now a huge supporter of the team.”

“That means we had over 130,000 rounds fired in two days, and nobody got hurt,” says Kroells.

“But that’s not a surprise, because these kids are so well trained as per gun handling and following safeguards.” Nelson says the safety record of the state competition mirrors that of the sport nationally, where millions of rounds are fired annually.

It took Andy Hall, the coach of Augusta High School's clay target team, three years to get the OK from the school's administration to form a team. But that was the big hurdle. School board approval was unanimous.

In both cases, the coaches invited the parents to come see how the team practiced and operated. Those parents eventually became supporters of the programs. The overall safety of the sport has been the deciding factor for many, say Mercado and Hall.

SAFETY FIRST, MANDATORY ACCREDITATION, ZERO INJURIES

On June 18 and 19, the Kansas State High School Clay Target Championship was held at the Kansas Trapshooting Association’s Ark Valley Gun Club, a few miles north of Wichita. Kroells says teams came from 84 schools, totaling 1,363 students. Each shot at least 100 clay targets. Mercado, Kroells and others say the event went very well.

Kroells added that teams have a high ratio of coaches to students. Head coaches must go through training before they can coach with a team.

Paradoxically, injuries in a sport that involves weapons are all but nonexistent when compared with traditional athletic activities.

Jennifer Rolland has two daughters, Emma, 15, and Anna, 13, on Baldwin City’s interscholastic teams.

“You know, we’ve come home from (cheerleading practice) with a couple of concussions,” says Rolland. “They’ve never come home, after four years, from clay target practice with any kind of injury. These kids, and their great coaches, know what they’re doing.”

Kroells and Mercado say no other school sport has better safety preparation.

THE JOURNAL 30 31 THE JOURNAL

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

Jake Hall, a member of Augusta High School's clay target team, competed in August at a youth tournament on a sporting clays course at the Sportsman's Training Center near Augusta.

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

All student target shooters must attend and pass an approved, hands-on hunting/shooting safety course to be admitted to a team.

“It’s the only high school sport in America with mandatory safety certification,” says Nelson. “The safety of the participants is always of first and foremost importance.”

Coaches say participants take what they’ve learned to heart.

“The responsibility is not lost on them,” says Mercado. “If someone does slip up, another kid almost always gives them a polite reminder before I can say anything.”

Trap is the main sport for the scholastic target teams. The rules of the game, and the trap courses, are designed for optimal safety. Targets are launched remotely from a single trap house, away from the shooters. Shotguns are loaded one shell at a time and only when it’s a shooter’s turn to try a target. Only one shooter has their gun loaded at a time. They call to get a target thrown when they’re ready.

Shotguns must remain unloaded, and open in a way that would make firing impossible, until it’s a student’s turn to fire at a target. Muzzles are always pointed in a safe direction, even when not loaded. It’s a very regimented and time-honored system (the modern version of trapshooting dates back to the 19th century) that is almost foolproof. Eye and hearing protection are mandatory. Most competitions are held virtually, with scores added online to determine winners, so there’s not a lot of traveling with guns.

ANYONE CAN SHOOT WELL

In addition to being safe, scholastic clay target shooting is an uncommonly inclusive scholastic sport. Athletic or physical skills aren’t needed to succeed.

“We have kids out there, succeeding, who’ve never had a desire to wear a football helmet or baseball glove,” says Hall, the Augusta head coach. “We have kids of all shapes and sizes on

the team. This gives all kids a chance to be part of a high school team and spend some time outdoors.”

Hall tells of being approached by a father of an athletic teen made a paraplegic in a motocross accident, asking about possibly joining the team. They worked to get the boy situated at the shooting line.

“He hit, I think, 12 out of 25 targets. It was something,” says Hall. “He looked at me with a smile I’ll never, ever forget.”

Nelson says that nationally, 39% of clay target league student athletes don’t participate in any other sports. Unlike many school sports, there is no “making the team.” All who go out get to be on the team and shoot at every practice and competition. Practice is more important than pre-team experience. Coaches like Hall say even those who’ve never shot before can quickly become competitive, through good coaching and repetition in as many practices as possible.

Alex Nold shoots for the Piper High School team in Wyandotte County. As an eighth grader, he helped form the team despite having no organized trapshooting experience. When he graduated in May, Nold was among the elite shooters in Kansas.

“It basically comes down to who shoots enough shells, and practices enough to be good,” says Nold. “This is one of the few co-ed sports. Boys and girls compete together. Our top five always had one or two girls in it.”

Hall and Matt Farmer, another coach of Concordia’s team, say teams are open to students of any financial means. Their programs are largely supported by a variety of fundraising events, like chili feeds and raffles. Farmer says kids on the Concordia team earned points based on participation in those events. Those points equaled free ammunition or other needed equipment.

The coaches say money from the fundraisers paid for things like a season’s worth of targets, range fees (if not donated by others), and ammo. Hall says manufacturers sell shotgun shells to

33 THE JOURNAL

Kenny McCoy joined a Kansas Big Brothers Big Sisters hunting and recreational shooting program at age 13. While the program drew protests from other programs around the nation, McCoy says he learned about the importance of respect for nature, others and himself.

Photo by Jeff Tuttle

teams in bulk, at rates far below retail prices.

About 40% of Hall’s shooting team didn’t have a shotgun when practices began. A variety of options makes sure all on the team get to shoot. Many find a relative or family friend to lend them a shotgun. Conservation groups, like Ducks Unlimited, have donated shotguns to programs as have individuals. Farmer said most coaches own several and gladly loan them to team members.

Many students who decide to stick with the team soon get a shotgun of their own. Sometimes the students, themselves, find ways to fund a purchase.

“At least four of our boys were out mowing lawns or doing whatever they could, and saving every dollar, to buy a (inexpensive) shotgun,” says Hall. “It doesn’t take anything fancy to shoot trap. It’s good to see a kid breaking targets with something they worked to get. They can also still be using that same shotgun in 50 years.”

LIFE LESSONS AT THE SHOOTING LINE

Rolland says her oldest daughter, Emma, has benefited in several major ways. The first time she shot, the sixth grader hit five of 25 targets.

“She really struggled at first, and I thought that was great,” says Rolland. “Facing a challenge is good. Now, she usually shoots around 20 out of 25. That’s taught her so much about perseverance.”

That average score places her high on the Baldwin City team, a solid competitor with the best of the boys.

“She’s always wanted to be a firefighter and this should give her confidence she will be able to make it in a male-dominated world,” says her mother.

Shooting trap is largely repetitive. Coaches say once a shooter masters the basics, it becomes a game of focus and an individual’s mental state.

“This sport teaches these kids mental toughness,” says Farmer, the Concordia coach.

“If they’re in a slump, they have to just shoot and shoot until they work it out. Eventually all these kids do work through those kinds of things. That does so much for their self-esteem and selfconfidence.”

Young shooters who work hard enough can get the same school athletic letter as awarded in other sports. Colleges with shooting teams offer scholarships.

YOUTH SET EXAMPLE FOR ADULTS TO “KEEP IT CLASSY”

In another difference with what has sadly become common in youth sports, shooters generally compete within a culture of encouragement.

“I’ve never heard anything negative or any kind of taunting. They all get along. Kids that don’t know each other will start talking,” says Robinson.

“Kids who before didn’t feel like they belonged anywhere, now know they have friends at the trap range. That’s huge for a kid, to know they have that.”

Sarah Barlow, who participated in many sports at Lansing High School, is particularly appreciative of the bonhomie among trapshooters. She joined the team at Piper High School because Lansing did not have a team. She was immediately accepted and welcomed.

Kroells says most Kansas scholastic teams welcome students from schools that, at the time, don’t have teams.

“It’s more laid back in a lot of aspects,” says Barlow, who just graduated from Lansing. “I know like in softball, some of the girls get pretty mean. Everyone is nice and considerate on the trap team. People on other teams keep it classy too.”

Rolland says it’s a joy for parents to attend shoots because parents are as well behaved as the shooters.

“You don’t have parents screaming at an ump or heckling a coach,” she says. “It’s fun to see hundreds of parents, well, acting like adults at a sporting event. No conflicts. People are talking and sharing things. It’s a welcome change.”

THE JOURNAL 34 35 THE JOURNAL

Augusta High School's Gavin Kiser sharpened his skills for the upcoming clay target season in August at the sporting clays course at the Sportsman's Training Center near Augusta. Photos by Jeff Tuttle

EMBRACING RECREATIONAL SHOOTING, HUNTING

Getting youth involved in target shooting is far from new in Kansas.

Ray Bartholomew, Kansas 4-H interim shooting sports coordinator, says 4-H has sponsored youth shooting programs for at least 30 years in Kansas.

A Kansas chapter of Big Brothers Big Sisters was the first within the organization to embrace hunting and recreational shooting for youth and mentors more than 20 years ago.

The Wichita-based group did so in 1999 largely to attract more outdoors-loving Kansans as mentors, says Mike Christensen, past director of the chapter’s outdoor mentoring program.

The decision drew protests from many Big Brothers Big Sisters programs around the nation.

He's proud to say the program has largely silenced many who criticized the idea of firearms and kids.

Before their first hunt or trip to a target range, participants must pass the state hunter/shooting safety course. They are mentored closely at ranges and hunting locations.

“You can really see these kids change after they’ve been out a few times,” says Christensen. “They learn a lot they never would have learned staying home or in the cities.”

Kenny McCoy, a past Little Brother, joined the program in 2009, when he was 13.

“Man, every time I went out, it was something new and great in a great place,” says McCoy, now 26. “I can tell you straight up that’s what probably made a good man out of me. I learned the right things about firearms. I learned the importance of respect for nature, others and myself. Once you get a kid out there in the field, they do not want to leave.”

McCoy is currently an avid volunteer/mentor for the program. While helping coach a target team and mentoring on hunts, he works at recruiting youth from Wichita’s African American community.

As with scholastic clay target shooting, the safety record of the program is unblemished.

“We put probably 1,200 kids through the course, and we still haven’t had our first injury from hunting or shooting,” says Christensen. “It’s always the No. 1 priority.” He says it’s also not an anomaly.

VOLUNTEERS, OPPORTUNITIES A PLENTY

School shooting coaches happily acknowledge the support they get from parents and the local shooting community with fundraising, clerical work, range maintenance and coaching. Many coaches came to the sport when a child joined the team, then stayed after they graduated. Some past students have returned to coach.

have all these shootings, and so many people wanting to ban guns. I’ve thought if they’d come and watch these school teams shoot, they might look at guns differently.”

DISCUSSION GUIDE

Ican tell you straight up that's what probably made a good man out of me. I learned the right things about firearms. I learned the importance of respect for nature, others and myself.