Published by W.D. Hoard & Sons Co. February 2023 hayandforage.com Water wars pg 10 Producer or farmer? pg 18 Be more drought resilient — Part 2 pg 26 This Missouri grazier promotes dairy worldwide pg 28

By Paul Schneider Jr., AG-USA (This is a paid advertisement)

Is there anything that farmers can do to retain moisture while at the same time get rid of compaction? Yes! Here is a good way to do just that.

Put fungi to work

A while back I traveled to Albertville, Alabama to attend the South Poll Cattle Association meeting. One of the speakers stated that it’s best to have a ratio of 50% bacteria to 50% fungi in the soil. In fact, fungi are key in helping us get rid of compaction and highly structuring the soil. Structuring it magnifies the soil’s ability to retain moisture.

The bad news is, fungi don’t normally thrive in farm land; they thrive in soils in wooded areas, where there is plenty of decaying wood to feed on. So, how can we get fungi to thrive where we farm? Easy! Just arrange for the plant to feed the fungi.

But how do we accomplish this?

● Remove toxins and salts that inhibit beneficial fungi.

● Bring nutrient balance to the soil.

● Empower the plant to sequester large amounts of sugars in order to feed mycorrhizal fungi.

MycorrPlusis a product designed to do all of these things, and more. It is a bio-stimulant that can:

● Help empower microbes gobble up toxins.

● Help flush salts from the root zone.

● Help balance soil nutrients.

● Help maximize the amount of sugars sequestered by the plant.

In short, MycorrPlus (my-core-plus) can help create a friendly environment in the soil where mycorrhizal fungi can feel at home.

Sequester more carbon, retain more moisture

Aerobic microbes require oxygen and moisture to thrive. With the right help, they will build incredible structure into the soil, one where oxygen circulates freely and moisture is stored efficiently.

Because oxygen-rich, highly structured soil is very beneficial to plants, they are more than eager to form a partnership with mycorrhizal fungi.

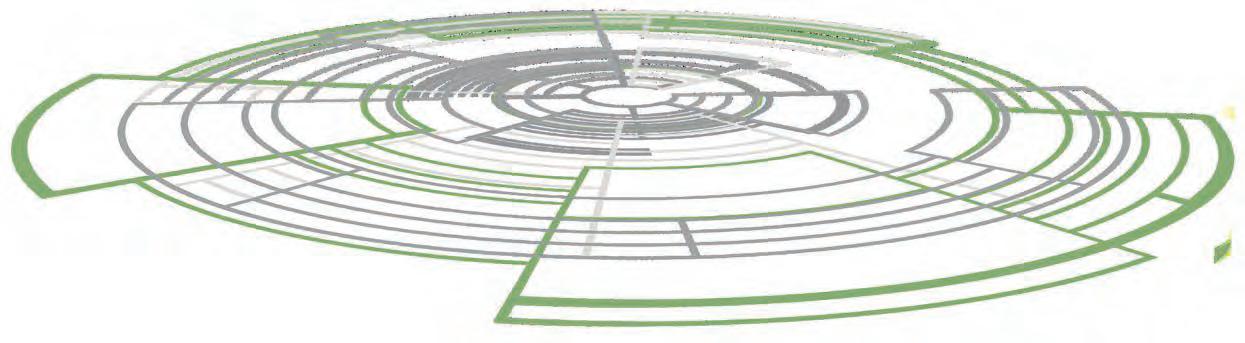

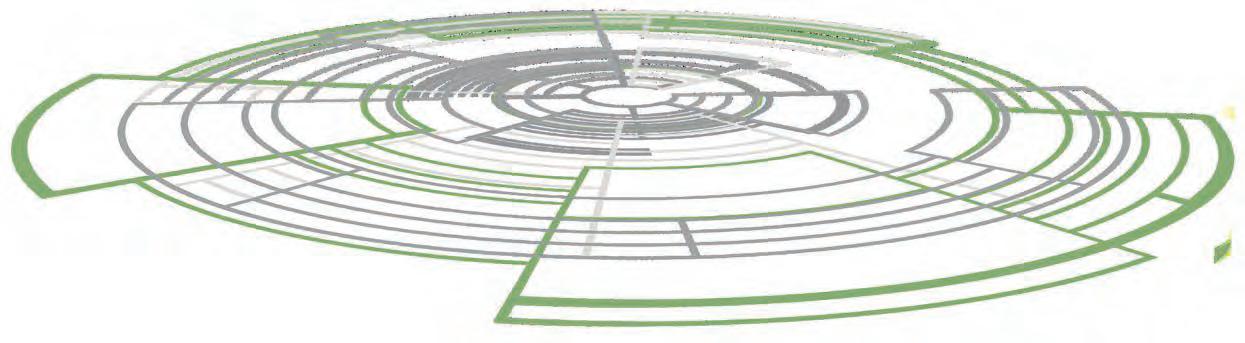

Can the microbes in MycorrPlus aerate the soil? Yes! As plants sequester sugars to feed the microbes, the microbes use the residues of these sugars as gums and glues to bind soil particles together, creating air compartments about 1/4” to 3/8” in size (see picture above).

As soil is highly structured, rain will soak deeply into the soil instead of just water logging the surface, making it possible for a farmer to more quickly get back in the field.

In the picture, in the soil on the left, can you see the small air pockets?

◊ The soil on the left is what soil can look like when it has been highly structured by MycorrPlus. It is aerated and crumbly.

● In the soil on the right, the dirt is tight and clumped together.

◊ In highly structured soil, when it rains, water soaks down into the air pockets and is stored until it is needed.

● In tight soil, the top 6” or so of the soil becomes water-logged and you will see water standing in the field.

● When the water evaporates, it leaves the soil dry and hard.

◊ In the highly structured soil, the microbes have created a moist, oxygenrich environment where they feel right at home.

● In the soil on the right, aerobic microbes don’t have enough air to survive, and anaerobic bacteria dominate the soil.

Plants will feed aerobic bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi because plants receive a lot in return from doing so.

Conclusion

MycorrPlus is amazing. By helping to switch on carbon sequestration, the soil will act like a sponge, soaking in rain and irrigation water.

Please call toll-free today and ask for a free information packet or contact our West Coast office!

Or go to: www.AG-USA.net

Conquer Nature by Cooperating with it

Like a center pivot for dryland farmers! Reduces the need for LIME and other fertilizers Plus

MycorrPlus is a liquid bio-stimulant that helps to remove compaction by highly structuring the soil. It creates something like an aerobic net in the soil that retains nutrients and moisture. It contains sea minerals, 70+ aerobic bacteria, 4 strains of mycorrhizal fungi, fish, kelp, humic acid and molasses. $20 to $40/acre.

To learn more, call (888) 588-3139 Mon. - Sat. from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. EST. Request a free information packet or visit: www.AG-USA.net Organic? Use MycorrPlus-O.

TM

National office: AG-USA, PO Box 73019, Newnan, GA 30271. (888) 588-3139 info@ag-usa.net West Coast office: Global Restoration LLC, 1513 NW Jackpine Ave., Redmond, OR 97756. (541) 788-8918 wcoast@ag-usa.net

Structured soil vs. Non-structured soil

Native grass pastures forged in fire

Tim and Annie Jessen control red cedar growth and enhance forage species diversity through controlled burns on their 2,400-acre Nebraska ranch. The couple contract grazes 350 cow-calf pairs each year.

MANAGING EDITOR Michael C. Rankin

ART DIRECTOR Todd Garrett

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Jennifer L. Yurs

ONLINE MANAGER Patti J. Hurtgen

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING John R. Mansavage

ADVERTISING SALES

Kim E. Zilverberg kzilverberg@hayandforage.com

Jenna Zilverberg jzilverberg@hayandforage.com

ADVERTISING COORDINATOR

Patti J. Kressin pkressin@hayandforage.com

W.D. HOARD & SONS

PRESIDENT Brian V. Knox

EDITORIAL OFFICE

28 Milwaukee Ave. West, Fort Atkinson, WI, 53538

WEBSITE www.hayandforage.com

EMAIL info@hayandforage.com

4 First Cut

12 Beef Feedbunk

14 Alfalfa Checkoff

16 Sunrise On Soil

20 Feed Analysis

25 The Pasture Walk

30 Dairy Feedbunk

Water wars

The recent rain and snow events in the West aren’t going to solve the water challenges. It’s going to require infrastructure and policy changes.

12 STOCKER SYSTEMS ARE AN ATTRACTIVE ALTERNATIVE

25

TO DRAG OR NOT TO DRAG?

14

IMAGING ALFALFA FIELDS PREDICTS YIELDS, FINDS PROBLEMS

26

WE NEED TO BE MORE DROUGHT RESILIENT

Making hay was a part of his flight plan

This South Carolina haymaker and former Marine pilot provides quality bermudagrass to his clients.

16

SEVERAL FORCES BIND SOIL

28

THIS MISSOURI GRAZIER PROMOTES U.S. DAIRY WORLDWIDE

18 PRODUCER OR FARMER?

ON

20 QUANTIFYING NUTRIENT DIGESTIBILITY STARTS WITH FIBER

30 MANY APPROACHES TO HIGH-FORAGE DIETS

Cattle at the Creek Plantation near Martin, S.C., graze pearl millet during the summer when perennial forage growth lags. The ranch is known for breeding and training cutting horses, but they also run 2,200 commercial cow-calf pairs and have a herd of registered Texas Longhorn cattle on the nearly 14,000-acre operation. Learn more at creekplantation.com.

February 2023 | hayandforage.com | 3

HAY & FORAGE GROWER (ISSN 0891-5946) copyright © 2023 W. D. Hoard & Sons Company. All rights reserved. Published six times annually in January, February, March, April/May, August/September and November by W. D. Hoard & Sons Co., 28 Milwaukee Ave., W., Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin 53538 USA. Tel: 920-563-5551. Fax: 920-563-7298. Email: info@hayandforage.com. Website: www.hayandforage.com. Periodicals Postage paid at Fort Atkinson, Wis., and additional mail offices. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: Free and controlled circulation to qualified subscribers. Non-qualified subscribers may subscribe at: USA: 1 year $20 U.S.; Outside USA: Canada & Mexico, 1 year $80 U.S.; All other countries, 1 year $120 U.S. For Subscriber Services contact: Hay & Forage Grower, PO Box 801, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538 USA; call: 920-563-5551, email: info@hayandforage.com or visit:

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to HAY & FORAGE GROWER, 28 Milwaukee Ave., W., Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin 53538 USA. Subscribers who have provided a valid email address may receive the Hay & Forage Grower email newsletter eHay Weekly. February 2023 · VOL. 38 · No. 2 6

www.hayandforage.com.

10

22

Photo by Amber Friedrichsen

31 EQUIPMENT LANDSCAPE REMAINS IN FLUX THE COVER

31 Forage Gearhead

38 Forage IQ

38 Hay Market Update

DEPARTMENTS

PHONE 920-563-5551

Forage on my mind

WINTER offers a lot of time for reflection, and for the editor of a hay and forage magazine, a lot of that thinking is devoted to . . . well . . . hay and forage, at least until baseball season starts. Lately, a lot of issues and concerns have surfaced in the forage world, so I thought I’d offer a rundown on a few of them that have consumed my modest amount of gray matter. Even though they may not all impact you directly, they should be on your internal radar, too.

Another drought

These past couple of years have been filled with information on drought reaction and planning. Drought conditions seem to be traversing the U.S. like the couple hell-bent on eating at every Cracker Barrel in the nation (Google it). Fortunately, drought likes to move around from year to year, and in 2022, the Southern Plains and western Midwest were subject to its wrath; it was the Northern Plains and Northwest region the previous year.

If I’ve learned nothing else in my less than illustrious agricultural career, it’s that drought years are bad, but a second consecutive drought year is a killer because excess forage inventories have been exhausted. Here’s hoping drought can find its way offshore in 2023, but be ready if it doesn’t.

More water woes

It’s one thing to not get rain when history dictates that you’re supposed to, but it’s an altogether different story when you rely on surface water for irrigation in the same way you rely on food for long-term survival. Yes, the recent deluge of rain and snow in the West is certainly beneficial; however, the water problems for those being served by the Colorado River and snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada Mountains isn’t going to be fixed by one good winter of moisture. Find out why this is the case in our “Water wars” article beginning on page 10. Millions of forage acres are being impacted.

Hay stocks and production

Yes, December 1 hay stocks were up in some areas that got hammered in 2021 and rebounded in 2022, but overall, the U.S. hay barn has been emptied to a level not seen since the early 1950s. Hay production was down again as well to the tune of 11% lower than just two years ago. Most of that production drop came from a decline in grass hay, although alfalfa has trended lower as well. The drought in 2022 hit some large

hay-producing states pretty hard. The current state of hay affairs, along with historically high input costs, does little to make one think that hay prices will retreat much in 2023. However, one good production year coupled with declining fertilizer prices could reverse the recent inventory trend. Even with higher input costs, hay has been a profitable crop. I’m not sure how high hay prices can go before even more users slam on the brakes and look to other alternatives or, in some cases, start producing their own hay.

Alfalfa at a crossroads

There hasn’t been a lot of great alfalfa news lately, but it’s important to keep things in perspective. It remains the dominant forage crop in a large chunk of the U.S. and actually seems to be gaining popularity in some Southeastern states. By now, most people have heard that a few major alfalfa breeding companies are either putting a halt on new variety development or looking to eliminate their alfalfa programs altogether. This could be good news for the couple that remain, but long term, there will be less private infrastructure for alfalfa improvement. Perhaps there will be opportunities for public institutions to develop alfalfa breeding programs. All this is happening with the recent good news that China is opening up its borders to the importation of glyphosate-resistant alfalfa.

Forage gurus

We’ve lost a lot of forage expertise in recent years, and that is worrisome. There have been two more recent retirements of extension forage specialists in Ohio and West Virginia, and a number more in the forage academic world are knocking on retirement’s door. It is heartening to see a few positions being filled or in the process of being filled, but they all are coming after long gaps in time without a forage person in place. Forage research and extension positions are critical to the industry if bright, young forage workers are to be trained and developed. So, that’s what I’ve been thinking about these past couple of months. Fortunately, baseball season will be here soon. •

Happy foraging,

FIRST CUT

Write Managing Editor Mike Rankin, 28 Milwaukee Ave., P.O. Box 801, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538 call: 920-563-5551 or email: mrankin@hayandforage.com

Mike Rankin Managing Editor

4 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

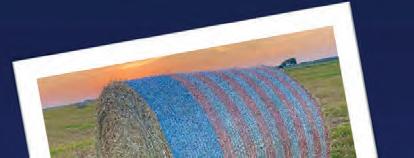

BALING WITHOUT COMPROMISE

KUHN offers the most efficient and versatile range of fixed and variable chamber round balers available on the market.

These round balers ensure consistent, perfectly shaped round bales and produce exceptionally high bale densities even in the most demanding conditions.

No matter if you’re baling dry hay, corn stalks, high-density baleage or anything in between, KUHN round balers are ready to work for you.

Visit our website to locate a Dealer near you!

www.kuhn.com

A BALER FOR EVERY OPERATION

INVEST IN QUALITY ®

FB Fixed Chamber Balers

VB 560 Variable Chamber Baler

VB 7100 Series Variable Chamber Balers VBP 3165 BalePack (Baler-Wrapper Combo)

VB 3100 Series Variable Chamber Balers

by Amber Friedrichsen

MOST farm fires are created by accident. Electrical sparks fly, engines run too hot, and wet hay spontaneously combusts. However, there is one instance when fires are planned for and set intentionally.

Prescribed burns are used to mimic the natural fires that once occurred on native prairies. They inhibit encroaching trees and weeds and preserve plant communities. This process is also a routine part of pasture management on Jessen Ranch located near Niobrara, Neb. Tim Jessen and his wife, Annie, use prescribed fire to control the native grasses on their property and maintain

a forage system that can support a large herd of grazing cattle — but Tim and Annie weren’t the first ones in their family to pioneer this practice.

Jessen Ranch was established by Tim’s grandfather in the 1940s in the northeastern part of the Cornhusker State, overlooking the Lewis and Clark Lake, which is a part of the Missouri River. Its address doesn’t register on a smartphone map, and the closest city is over 40 miles away. Needless to say, gas stations and grocery stores en route to the ranch are few and far between.

The Jessens’ homestead is surrounded by rolling hills dotted with patches of forest and gaping gullies resulting from previous soil erosion. When Tim’s father, Gene, began farming here in

1952, the tricky terrain wasn’t the only thing causing him trouble. Invasive red cedar trees were outcompeting the desirable forages.

To give the native grasses on the land a fighting chance, Gene began administering prescribed fires every spring. The fires eventually eliminated most of the red cedar trees and allowed sunlight to reach the soil and stimulate the growth of different forage species. In the 1980s, Gene also transitioned from continuously grazing cattle to a rotational grazing approach, which encouraged even more plant diversity.

“Before the 1980s, Dad did like everybody else: Cows were in the pasture the first of June and rounded up in the fall,” Tim said. “When he got into rotating,

6 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

Prescribed burning on the Jessen Ranch was successful in controlling red cedar trees. It also helped encourage forage species diversity.

the diversity in the pasture increased — mostly in a positive way.”

Gene passed away in 2018, but his legacy of land stewardship lives on through Tim and Annie, who have since moved to the farm and started managing the 2,400-acre operation. Tim continues to demonstrate his father’s affinity for sustainable agriculture in combination with his own interest in raising beef cattle by custom grazing roughly 350 cow-calf pairs on Jessen Ranch each year.

Restoring and renting land

Prescribed burns are still carried out on Jessen Ranch; however, they aren’t required annually like they used to be. Tim surveys his pastures for red cedar

trees and decides to burn if there are enough popping up. He also considers the weather conditions to determine when it is safe to set a fire. In some years, Tim burns as early as February, whereas in others he will wait until May. Most of the time, burning takes place in late March or April.

The Jessens control the prescribed fires themselves and with assistance from neighbors. To prevent flames from crossing property lines, they backburn along shared fences. This technique is often used to curtail a wildfire’s path of destruction and involves setting smaller fires ahead of a larger one to expend any resources that could be used as fuel. But even with this protocol in place, the burn site must be monitored with a close eye.

“It’s stressful,” Tim stated. “The work really starts when the burning is done because for three or four days — or whenever you get moisture — you have to babysit the fire until it’s out. You have to worry about it spreading in the middle of the night.”

When the fire is fully extinguished, Tim custom grazes for a livestock producer who lives roughly an hour away. Cows and calves usually arrive sometime in April, along with a few bulls. The different classes of livestock ride separate trucks for ease of transportation and animal safety. Once they have been unloaded in the cattle yard near the Jessens’ house, it only takes two or three hours for most cow-calf pairs to reunite. Calves graze alongside their mothers for several weeks until they return to the cattle yard for weaning. After a couple of days of bellowing and longwinded moos, the calves are shipped back to their home farm. Then breeding season begins, which aligns well with plant growth.

Learning by doing

Most of the property is composed of warm-season grasses, offering an abundance of forage when cows’ energy requirements start to rise. Pastures are primarily based on little bluestem, big bluestem, and switchgrass, although Tim said an analysis from the Natural Resource Conservation Service showed more than 100 species of forbs and other grasses are present. This includes some cool-season grasses such as wild oats, Kentucky bluegrass, and different types of fescue that help extend the

grazing window.

The ranch is divided into 22 paddocks, using more than 15 miles of high-tensile electric fence on fiberglass posts. While temporary step-in fencing works well in many rotational grazing systems, Tim said the topography of his fields makes moving fences impractical. Instead, his fences are permanent or semi-permanent, and the materials used can withstand prescribed fires.

Permanent water tanks have also been installed. One main holding tank is filled with water from a nearby dam via underground water lines. Then the water is allocated to water tanks in the pasture, and one tank services two to three paddocks. This system is fully functional now, but there was some trial and error along the way.

“My mistake early on was making the water lots too small,” Tim admitted. “You would think if you made the tanks big enough to hold three-fourths of a herd, it would be fine. But we’ve had to make

them about four times the size of that.”

Cattle move through the paddocks quickly the first time around, completing a full rotation in a little over a month. Then as the summer progresses, paddocks receive longer periods of rest to ensure adequate recovery and regrowth. As a rule of thumb, cattle graze half of the available forage and the other half is left standing.

“When you get the winds that we have, leaving that thatch of grass on the ground keeps the soil from drying

continued on following page >>>

February 2023 | hayandforage.com | 7

Tim and Annie Jessen custom graze 350 cow-calf pairs on their ranch near Niobrara, Neb. In addition to their cattle enterprise, the couple also raise and train border collies.

out,” Tim said. “A lot of these ridges are just gravel and sand. If you take all the grass off and get a week of 100°F weather, it will just bake the roots.”

Over the years, Tim has observed grazing behavior that has helped him time his rotations. The herd tends to graze in a circular pattern as a single unit, with only a few outliers straying away from the group. He also noted not all paddocks are uniform in size, so some grazing circles in the grass are completed faster than others. Nonetheless, once the animals have made a loop, he moves them to the next section to prevent overgrazing.

Shorter occupation time not only prevents overgrazing, but it prevents pinkeye, too. Tim has found significantly fewer outbreaks of pinkeye when rotations only last three to five days. Flies that carry pinkeye-causing bacteria lay eggs in cow manure, so moving cattle before these insects have time to hatch minimizes the spread of infection.

In addition to grazing, a small portion of land is seeded to alfalfa. Even though the cows exclusively graze grass and are returned to their owner at the end of the grazing season, Tim makes sure to have some hay on hand in case something goes awry. For example, one year an unexpected snowstorm in the

fall prevented trucks from navigating to the farm. Tim kept the cows and fed them hay until the roads were clear and they could finally go home.

Calling for border collies

Moving cattle on Jessen Ranch is an undertaking. The steep slopes are difficult to summit in four-wheel drive, and the gullies are so deep that cows seem to get lost inside. Therefore, rather than wrangling cattle on all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), the Jessens rotate their herd with the help of border collies.

When Tim’s brother started raising border collies eight years ago, he paid him a visit one day and was inspired by what the dogs could do. Tim realized their talents would be instrumental to rotational grazing, and soon after, he and Annie acquired and began raising border collies of their own.

On the ranch, the young dogs begin by driving a group of steers in a lot close to the Jessens’ house. But their skills are truly put to the test in the pasture.

The canines know it is time to corral cows when they see Tim approach their kennels. They patiently wait for his command to jump up into the bed of his truck and are instantly on the lookout for their grazing subjects. Once the red and black cows have been spot-

ted against the green grass, the dogs eagerly enter the field and carefully listen to Tim’s directions. They know when to approach the animals, when to back away, and how to parade them through the gate and into the next paddock.

“It used to be being pretty hard to get the cattle to move, but now I just sit in my side-by-side drinking my coffee while the dogs move them for me,” Tim laughed.

As the dogs’ herding abilities heat up, the Jessens’ pastures continue to improve. With prescribed burning and rotational grazing, there is seldom a red cedar tree in sight. What is in full view, though, are the positive effects their practices have had on the land. Although Tim and Annie can successfully control a large fire, the passion they have for their farming lifestyle is one flame they just can’t put out. •

AMBER FRIEDRICHSEN

The author served as the 2021 and 2022 Hay and Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She currently attends Iowa State University where she is majoring in agricultural communications and agronomy.

8 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

The 2,400-acre Jessen Ranch consists of rolling hills that overlook Lewis and Clarke Lake, which is part of the Missouri River. Their grazing acres are divided into 22 paddocks.

John Deere Dairy Solutions & Support Your animals. Our solutions. Keeping your herd healthy and productive is your top priority. Helping you do it is ours. From tractors, balers and unrivaled dealer support, John Deere has the solutions and support for every need on a dairy farm. Contact your dealer or learn more at JohnDeere.com/Dairy.

by Mike Rankin

WHISKEY is for drinking; water is for fighting over. This is far from an original statement, but no truer mantra has ever been spoken.

The western U.S. is in all-out battle over water, and it’s being fought in localities, states, and nationally . . . all the way up to the Supreme Court. It’s a complicated war because the rules and water sources are so diverse. There are a plethora of treaties, compacts, and laws to consider, negotiate, or renegotiate.

Complicating the situation are widespread drought conditions across the West and urban expansion in cities such as Phoenix, Las Vegas, San Diego, and Los Angeles. It should be noted that much of the West is arid by nature, even without a drought. In some areas, environmental regulations that were put in place to improve the status of endangered aquatic species are further limiting water resources for human or agricultural use.

The situation is bad — very bad — and alfalfa along with pasture and other forage acres are in the crosshairs on the war’s front line.

“We are seeing a demonization of Western irrigated agriculture and, in particular, alfalfa production,” said Dan Keppen at the World Alfalfa Congress held in San Diego last November.

Keppen is the executive director of the Family Farm Alliance, which is an organization that advocates for family farmers, ranchers, irrigation districts, and allied industries in 17 Western states. Its mission is to ensure the availability of reliable, affordable irrigation water supplies to Western farmers and ranchers.

To highlight the urgency of the water situation, Keppen noted that there were 695,000 acres of land fallowed in the Central Valley of California during 2022. This region relies on reservoir fill from the Sierra Nevada Mountain’s winter snowmelt, which lately has been deficient. For the federal Klamath Irrigation Project straddling the California-Oregon border, farmers only received 15% of their normal water allocation. Some irrigators in Arizona decided to keep their fields fallow because of power costs. Electricity costs jumped because of lower reservoir levels while natural gas prices were also high during the past year.

“California is a hard place to farm right now, and other states are moving in the same direction,” Keppen said. “Currently, there are a multitude of environmental and labor regulations that have added significant compliance costs in the past 10 years.”

These regulations are exacerbating the natural drought. Keppen said that

the method that agencies are using to protect endangered fish species in places like California’s Central Valley and the Klamath Basin is taking water that was originally developed and stored for agriculture and allocating it for the benefit of certain species. “What’s frustrating is that there is no empirical evidence to suggest that the water reallocation is helping the targeted species,” Keppen shared.

River woes

If northern and central California’s water situation is thought of as critical, then the Colorado River Basin is even more dire. As background, the Colorado River provides irrigation water to seven Western states — Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. Lake Powell is formed by the Glen Canyon Dam, which is close to the Utah–Arizona border. Further downstream, Lake Mead is formed by the Hoover Dam. These lakes provide the region’s needed water reserves and are sources for hydroelectric power generation.

“I don’t see things getting much better, particularly in the Colorado River Basin,” Keppen said. “Urban areas are expanding rapidly, which hikes the demand for limited water. As a result, some interests are pressing to fallow thousands of additional farmland acres in 2023.”

10| Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

Many people, including Keppen, believe there is a very real possibility that Lake Mead water levels could get down to dead pool, the point at which water no longer flows through the dam. Even before that occurs, hydroelectric power generation will cease from a lack of adequate water pressure through the dam. A dead pool water level is also a justified fear for Lake Powell, where boat docks are already many feet from the water’s edge.

“Currently, the government is looking for ways to back water up to keep dead pool from occurring,” Keppen noted. “A part of their plan is to limit water to farmers and hopefully compensate them in return. Such a plan, if implemented in a way that solely relies on agriculture, would result in 1 million acres of farmland being fallowed to meet the targeted 2 to 4 million acrefeet of water cuts.”

Many entities and Keppen still believe that a workable solution and plan for the Colorado River Basin is attainable. “Answers can be found that do not pit urban and agricultural interests against each other,” Keppen said, “but the issues are complex.”

Adding to that complexity is that some of those with senior water rights are understandably reluctant to use less water for fear of permanently losing their allocation.

The stakes are high

The complexity of the water situation in the West is undeniable, but the stakes are higher than you’ll find on any Las Vegas casino floor.

“There’s probably never been a more important time to protect American food production,” Keppen said. “Western irrigated agriculture, including alfalfa and other forage production, has to be viewed as a priority in the context of national security. This statement is based on what we’re seeing in the world and in our country today.”

He referenced the war in Ukraine, which has landed a massive blow to world food production and created pockets of food deprivation. “Global hunger is back to record levels and is rising,” Keppen asserted.

According to the 2022 Global Agricultural Productivity (GAP) Report, Keppen said that total factor productivity (TFP), which rises when producers boost their output while using the same or fewer inputs, is at its lowest level of growth since the report was initiated

in 2010. The 2022 GAP report found that current efforts to accelerate global agricultural productivity growth are inadequate to meet future food needs.

“The western U.S. has been a longtime, proud agricultural powerhouse,” Keppen said. “Our country has consistently run an agricultural trade surplus, but that has changed in recent years. In 2019, the U.S. ran a trade deficit for the first time in 50 years. The USDA projects it will happen again in 2023. Imported Mexican fruits and vegetables are driving this deficit,” he added.

Fallowing vast acres of agricultural land, even if farmers are compensated, will significantly lower domestic production and make the country more dependent on imports. In some cases, it may shift production to other U.S. regions, which will dictate agricultural products be transported back to the West, raising consumer costs.

“Simply cutting off water will have a devastating effect on not only the farmers, but also the greater rural communities that depend on agriculture for their well-being,” Keppen explained. “In California’s Imperial Valley, there is no other water source above or below ground than the Colorado River. The residents of the valley rely solely on irrigated agriculture for their economic survival.”

Keppen noted that one of the silver linings to the drought is that it’s bringing heightened political and public attention to the needs of Western agriculture and rural communities. In the federal bipartisan infrastructure law, $8.3 billion was allocated for the Bureau of Reclamation. Previously, it was hard to draw enough political attention to get that level of funding, Keppen said. Also, the Inflation Reduction Act included $4 billion for Western drought mitigation, especially in the Colorado River Basin.

Alfalfa under fire

It’s not surprising that alfalfa is front and center in the water crisis discussion. A majority of the alfalfa hay produced in the U.S. comes from Western states. Most of this production is irrigated. Further, alfalfa, with its multiple cuts, generally needs more water annually than many other crops.

“The two big arguments being made are that alfalfa should be abandoned in favor of higher value crops or ones that use less water,” Keppen said. “The dissenters don’t realize that farmers will only grow crops that people will buy. Further, the Western agricultural

community was built on the local supply of feed and food. Relocating alfalfa production, for example, would increase fuel costs and greenhouse gas emissions. These reports also fail to mention that the Lower Colorado River Basin states have the highest alfalfa yields in the U.S.,” he added.

Another frequently heard argument regarding Western alfalfa is that hay export sales are the equivalent of shipping water overseas through field crops grown in Arizona and California. Keppen pointed out that this argument falls apart because it doesn’t address other export products that also use a lot of water or consider products that are imported and used by U.S. residents.

“Alfalfa has proved to be highly flexible and resilient in surviving droughts while sustaining productivity, even when as little as half of the water requirement is applied,” Keppen asserted.

A major research emphasis in the West has been to find ways to keep alfalfa profitable while reducing traditional water application amounts. These efforts include developing irrigation systems that reduce water application losses and, in turn, require less water to be applied. Government assistance for implementing these new technologies would help accelerate their adoption.

Deficit irrigation is also a practice that has been researched, promoted, and used for alfalfa where water is being limited. With this approach, alfalfa is fully watered early in the season to capture maximum yield and forage quality, then no water is applied during the hot mid-summer when both yields and forage quality are lower. The crop then goes dormant as it would during a Northern winter. When rains or irrigation return, alfalfa has the ability to break dormancy and return to full production. Grower adoption of these practices will no doubt need to increase in the years ahead as both agricultural and urban interests will need to make concessions.

Perhaps abundant winter precipitation will return to the West on a regular basis, but that’s not a bet we can afford to take. Finger pointing from either the urban or agricultural sides won’t get the water problem solved. There will need to be concessions across the board, but those concessions shouldn’t include completely shuttering the Western communities and businesses that were built and rely on irrigated agriculture for economic survival. •

February 2023 | hayandforage.com | 11

Stocker systems are an attractive alternative

WHEN we combine the beef cow inventory of Tennessee with Kentucky, the number of cows managed pushes these states into the top five beef cow-calf states. The beef cow-calf sector of the southeastern U.S. produces a significant number of feeder calves. Many of these feeders move to a stocker operation to add weight prior to feedlot entry.

As grain prices rise and the cost of adding weight in the feedlot spikes, putting that weight on calves with grass becomes more attractive. Stocker operations with payment arrangements based on gain are seeing positive returns with the current high grain prices. Maintaining a productive forage base is essential to keep stocker systems competitive.

Productive forage stands are a function of several factors. The recent high fertilizer prices have resulted in some producers pulling back or eliminating fertility applications altogether. In the short term, this may go unnoticed as most of the nutrients are deposited back on the fields; however, uneven distribution of feces and urine and the exportation of nutrients in the animals will begin to lower forage production. Routinely pull soil samples and consult with your county extension agent, crop adviser, or fertilizer dealer to discuss soil test results.

Do not overlook liming fields to ensure soil pH allows for the optimal production of forages and availability of nutrients. Without maintaining a proper soil pH, you may not realize the full benefit from fertilizer applications.

Adjust for forage availability

Arguably, the simplest forage management consideration to improve the profitability of a stocker operation is to ensure adequate forage is available. Overgrazing is the primary factor to suboptimal performance of grazing cattle. When forage availability falls below approximately 1,200 pounds of dry matter per acre, forage intake can be reduced, which lowers nutrient intake

and ultimately performance. Appropriate stocking rates need to be managed as cattle gain weight and forage growth changes over the growing season.

The scientific literature clearly shows that as stocking rate increases to the point that forage availability limits selectivity, daily gain is reduced. However, the balance is to find the stocking rate that supports the desired individual animal performance and pounds of beef produced per acre. As an example, research on early season stocking rates on tall fescue in central Kentucky revealed that as stocking rates rise from 500 pounds to 2,500 pounds per acre, average daily gain declines linearly. The research summary states, “. . . high stocking rate is much riskier with adverse growing conditions.” This past year’s extremely dry June put many stocker operators in a pinch as forage production became limited by dormancy.

High quality needed

Forage quality is the next key element to maintaining performance of stocker calves. A variety of options exist from annuals such as small cereal grains like wheat, triticale, oats, or annual ryegrass to perennial forages such as bermudagrass, fescue, and native grasses.

In the Fescue Belt, interseeding legumes such as red and white clover or lespedeza can boost the protein and digestibility of the forage consumed by stockers, which improves performance. Additionally, recent research by the USDA Food Animal Production Research Unit in Lexington, Ky., has demonstrated that red clover offers improvements in animal performance beyond the simple dilution of the alkaloids present in the fescue. With high fertilizer prices, the interseeding of legumes offers a low-cost nitrogen option as well.

Early in my career, I worked with forage colleagues in Wisconsin to look at performance of stockers on nonendophyte-infected tall fescue, soft-leaf tall fescue, or orchardgrass interseeded

with either white or kura clover. At the time, corn prices were $2.10 to $2.30 per bushel, and given the yield of highly productive ground, I figured I could compete with row crops if we achieved 1,000 pounds of beef gain per acre. The University of Wisconsin’s Ken Albrecht and his student had previously achieved this with kura clover-grass pastures.

If the grazing season is 210 days, 4.75 pounds of gain per day is needed across the animals grazing — not on a per head basis. If the stocking rate is 2.5 head per acre in the early season, that means the target daily gain is 1.9 pounds per day per calf. Stocking rates must be adjusted as forage growth changes.

We reached just over 800 pounds per acre on the endophyte-free tall fescue two out of three years. Drought set in during the third year, limiting forage and beef production. Even in southern Wisconsin on the Arlington prairie, tall fescue was a performer and survived the heaving, grazing, and harsh winters. Kura clover was the only treatment that offered the potential to reach that lofty target of 1,000 pounds of beef per acre. Later, I learned that Garry Lacefield and colleagues at the University of Kentucky achieved 1,000 pounds per acre grazing alfalfa. Novel endophyte fescues and other forages from breeding programs have led to improvements in stocker production.

Stocker operators should be running budgets and considering management options that can improve forage production and quality to improve beef gain per acre. Here’s hoping that you have an early spring with just the right precipitation to keep forages growing all season long. •

12| Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

BEEF FEEDBUNK

by Jeff Lehmkuhler

JEFF LEHMKUHLER

The author is an extension beef specialist with the University of Kentucky.

Imaging alfalfa fields predicts yields, finds problems

Hay & Forage Grower is featuring results of research projects funded through the Alfalfa Checkoff, officially named the U.S. Alfalfa Farmer Research Initiative, administered by National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA). The checkoff program facilitates farmer-funded research.

LFALFA yields can vary tremendously within a field, with the highest-yielding area often three or four times that of the lowest-yielding area. Is that the result of soil limitations, fertilizers, or irrigation management? What about the effects of drought?

The effect of two irrigation systems — low elevation spray application (LESA) and mobile drip irrigation (MDI) — on alfalfa productivity under full and

unmanned aerial vehicles equipped with multispectral and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) sensors predicted alfalfa yield “accurately,” said Putnam. They were less successful in predicting forage quality.

Drought has been a major problem for Western alfalfa growers, who have been forced to cut back on water applications. This research, like other recent studies, shows alfalfa can be successfully deficit-irrigated. In this study, alfalfa plots were treated at full or 100% evapotranspiration (ET), 60% ET (summer cutoff), 60% ET (sustained drought), or 40% ET (severe sustained drought).

affected by treatments.

“The question then becomes, ‘How much yield would be lost under those partial-season irrigations?’” Gull said. Measuring yield is especially challenging in deficit-irrigated or droughty fields. “We often see a patchy drought effect, where the drought shows up on the sandy patches and parts of the field that have lower water-holding capabilities. Thus, it is difficult to measure over a whole field,” he pointed out.

water-deficit irrigations was studied in recent Alfalfa Checkoff-funded research at the University of California-Davis (UCD). The research was led by thenPh.D. student Umair Gull and Dan Putnam, UCD Extension forage agronomist.

They also examined the use of remote sensing technology to predict alfalfa yield and quality, particularly under drought conditions. Drones or

PROJECT RESULTS

1. LESA and MDI performed well. LESA sprinklers worked better with gradual deficits, and MDI performed better under sudden cutoff deficits.

2. Yields were reduced under water deficits, but partial-season yields were realized at 70% to 98% of fully watered yields depending on system and year.

3. Forage quality wasn’t greatly affected by irrigation or watering treatments.

4. Multispectral and LiDAR sensing both accurately predicted alfalfa plant height and yield. Prediction of quality was accomplished, but with less certainty.

Alfalfa yields were reduced under water deficits. But partial-season production totaled 70% to 98% of yields from fully watered plots over the twoyear study, proving partial-season irrigations of alfalfa can be done, Gull said. Forage quality was not substantially

Drone flights were tested using different cameras or LiDAR, a technique which measures plant height. Both methods were found to be very promising, and equations proved to be fairly robust in predicting yields over a larger area.

Helps find problems

Yield prediction equations could help determine yield losses if alfalfa growers must transfer water or fields suffer

14 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

YOUR CHECKOFF DOLLARS AT WORK

DAN PUTNAM Funding: $78,922

UMAIR GULL

YIELD MAPS CREATED VIA DRONES equipped with sensing technologies over multiple harvests (May through October) illustrate the variation in yield caused by differences in irrigation amounts.

from drought, Putnam said. “But one of the most useful things about imaging alfalfa fields is in diagnosing problems. In all fields, you’re going to have soil problems, damage from pests or traffic, maybe compacted soils or poor drainage, or an irrigation problem. Imaging can help you visually see the poor growth and translation to yield. If growers are not irrigating properly or are having irrigation problems, they can calculate

SUPPORT THE ALFALFA CHECKOFF!

Buy your seed from these facilitating marketers:

Alfalfa Partners - S&W

Alforex Seeds

America’s Alfalfa

Channel

CROPLAN

DEKALB

Dyna-Gro

Fontanelle Hybrids

Forage First

FS Brand Alfalfa

Gold Country Seed

Hubner Seed

Innvictis Seed Solutions

Jung Seed Genetics

Kruger Seeds

Latham Hi-Tech Seeds

Legacy Seeds

Lewis Hybrids

NEXGROW Pioneer

Prairie Creek Seed

Rea Hybrids

Specialty

Stewart

Stone Seed

W-L Alfalfas

actual yield losses in different areas, then determine if the problem is worth fixing,” he emphasized.

Sprinkler systems are used on alfalfa throughout much of the West.

The researchers used LESA and MDI systems because of their high efficiency.

“A lot of things can be done to improve sprinkler irrigation and LESA is one of them,” Putnam said. “It’s important to put sprinklers closer to the ground

and close together to get better coverage.” Sprinklers can also convert to MDI systems, which drip water on the soil surface, reducing wind losses and allowing for slow water infiltration.

LESA and MDI are known to reduce or eliminate wind losses, improve distribution uniformity, and can push water deeper into the soil profile as compared to mid-elevation, widely spaced overhead sprinkler systems.

February 2023 | hayandforage.com | 15 CERTIFIED QUALITY ISO 9001 T-L … LIKE NO OTHER. www.tlirr.com Contact T-L, your T-L dealer, or visit www.tlirr.com to learn more. 151 East Hwy 6 & AB Road P.O. Box 1047 Hastings, Nebraska 68902-1047 USA Phone: 1-800-330-4264 Fax: 1-800-330-4268 Phone: (402) 462-4128 Fax: (402) 462-4617 sales@tlirr.com · www.tlirr.com Tired of UNCERTAINTY? Want insurance and assurance all bundled into one reliable package? Time to invest in some long-term peace of mind and stability with a T-L Center Pivot — THE MOST RELIABLE SYSTEM IN THE INDUSTRY. Contact your local T-L representative to find the perfect fit for your irrigation capabilities and needs. LIKE NO OTHER. RELIABLE IRRIGATION PERFORMANCE WILL IT RAIN? OR MISS US AGAIN… TL-482I.indd 1 10/20/21 9:47 AM

•

Several forces bind soil

HAVE you ever wondered why clay soils have such a good ability to absorb water? And yet, these same soils can become muddied and are prone to standing water in wheel tracks from vehicles traversing a pasture. Some might call this an effect of soil compaction, and it might be, depending on the circumstances. However, we also need to consider another process that occurs in soil, and that is the process of soil aggregation.

Soil aggregation is the clustering of the smallest soil particles — clay and silt-sized particles that would often be too small to see as individual particles — into larger soil crumbs that resemble small stones or pebbles. These clusters of soil particles are bound together by a variety of organic and inorganic gluing mechanisms.

Historically, soil science has focused on inorganic glues that bind soil particles by electrostatic forces, chemical bridges, and chelating agents. However, soil biological mechanisms can be equally important in cementing soil particles together into stable crumbs that create a diversity of soil pore sizes between these crumbs but also keep their strong cationic attraction forces.

Root of attraction

Plant roots often find their way through soil by exploring the path of least resistance, following water and nutrients in the spaces between soil crumbs (or aggregates). These growing roots deposit water-soluble and other by-products of growth onto and between soil crumbs. Earthworms and other soil animals might also push soil particles to the side to consume soil and organic resources deposited in soil.

All of this tugging and pushing, along with the deposition of fecal pellets and various reworked soil and carbon substrates, leads to a dynamically structured soil. Soil fungi and bacteria are consuming these root-derived inputs continuously, but they are also leaving behind some of the glues that bind soil particles together. Further, as soil dries and rewets over and over, it becomes more structured over time.

The activity of soil microorganisms

and roots are key elements of soil aggregation. Since these factors are most active near the soil surface, soil aggregation is also strongest near the soil surface. One way to measure the impact of soil management on aggregation is by determining the soil stability index. This index measures the average size of aggregates following a short period of immersion and oscillation in water relative to the average size of aggregates following light crushing of dried soil.

A grassland advantage

Vigorously growing forage plants produce an abundance of roots to extract water and nutrients. They are also secreting carbon substrates that feed soil microorganisms to glue soil particles into aggregates. In a recent survey of paired land uses across 25 sites in North Carolina, soil stability index was 94% under grassland fields. This meant that nearly all dry aggregates were stable in water and did not fall apart. The index was the same as soil under undisturbed woodlands. Croplands had lower stability index values, falling to 75% when managed with no-till and only 62% when managed with conventional disk tillage.

Land management effects were stronger in fine-textured soils (more clay and silt), but the positive impact of conservation management with grass roots

occurred even in coarse-textured soils (more sand). Therefore, forage-based agriculture can improve soil aggregation in a variety of soils.

Stable soil aggregation means that soil is functioning to allow rapid water infiltration when it rains, thereby lowering water and nutrient runoff and storing more water in soil. It also means that communities of microorganisms living within these aggregates are protected from their neighbors seeking to consume them, which ultimately leads to more stable nutrient cycling. Excessive trampling, tillage, and vehicular traffic during wet conditions are forces that can degrade soil aggregates, so make pasture management decisions accordingly to preserve and enhance soil aggregation. •

For more detailed information on soil aggregation and its determination in agricultural systems, scan the QR code.

ALAN FRANZLUEBBERS

The author is a soil scientist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Raleigh, N.C.

16| Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

SUNRISE ON SOIL by Alan Franzluebbers

Water-stable aggregates > 1 mm

YOUR SUCCESS IS ROOTED IN YOUR SPIRIT. We’re America’s Alfalfa. ® Our pledge of allegiance is to your success. Selected for their yield and quality characteristics over the past decades, our varieties produce agronomically sound, winter-hardy and disease-resistant alfalfa. Ask us how our UltraCut™ disease package can help you grow a healthy alfalfa crop even in fields susceptible to tough Anthracnose and Aphanomyces disease strains. Experience more flexibility and freedom in your fields with America’s Alfalfa seed. Increase your independence with innovative traits. ©2023 Forage Genetics International, LLC. America’s Alfalfa,® HarvXtra,® and UltraCut™ are trademarks of Forage Genetics, LLC. Roundup Ready ® is a registered trademark of Monsanto Technology LLC, used under license by Forage Genetics International, LLC. HarvXtra® with Roundup Ready ® Technology and Roundup Ready ® Alfalfa are subject to planting and use restrictions. Visit ForageGenetics.com/legal for the full legal, stewardship and trademark statements for these products. Talk to your local America’s Alfalfa dealer, call 800-406-7662 or visit AmericasAlfalfa.com today.

PRODUCER OR FARMER?

by Greg Halich

WHEN I was about 5 years old, I desperately wanted to become a farmer like my grandfather and uncle. At that time, my family was living in the suburbs outside a large metropolitan area, and I longed for the trips back to the family farm in Steuben County, N.Y. I understood even at that young age what a farmer was in a general sense and what they did. The same could not be said about most of the adults I knew in the suburbs. As the years passed, my understanding of the two worlds became deeper, particularly related to community and purpose. My conviction was that I wanted to live and work in a real place. I wanted to be a farmer.

Fast forward years later when I started working in extension, and it quickly became clear that farmers were no longer referred to as “farmers,” but as “producers.” My bubble was burst: Never once had I dreamt of being a producer!

So thorough was the avoidance of the word by most of my colleagues that I assumed it must be considered an insult to use it and was somewhat shocked by this realization. This made no sense to me, but being new, I didn’t try to rock the boat. At the time, I didn’t give too much thought into the reasoning for this new verbiage, but I never stopped recoiling, just a little bit, every time I heard the word “producer.”

Fifteen years later, it still bothers me, and over the last few years I have started thinking about the change and the possible causes for it. Why did the land-grant system, along with the USDA and private industry, stop using the word “farmer,” and why was it replaced by “producer?” One potential reason is simply that producer implies efficiency. The livestock producer produces cattle. The grain producer produces corn. The

vegetable producer produces produce. And so forth. The land-grant system is all about trying to be efficient, so this word fit very well with that image.

Another potential reason was an attempt by the land-grant system to add legitimacy and importance to those producing or growing our food. Based on earlier experiences in my life, there was a segment of society that looked down on farmers. This was before the era of the local food movement where the general public had been given a better understanding of the importance of farming and farmers. A subtle shift away from “farmer” to a new term that implied modernization, such as “producer,” was potentially a way to move past this bias. If this was the primary reason for the change in terms, it was done with good intentions.

Another reason?

I believe there is a more likely reason for the change in names. Traditional methods of farming and hence the word “farmer” had become synonymous with an outdated way of thinking in the agricultural research community. During the second half of the 20th century, the land-grant system was taking a more scientific approach to agricultural production. Previous methods of farming were based largely on community knowledge and tradition. The new system would be driven by science and the experts who understood it. A new term was needed, and “producer” was born.

What had previously been a healthy mix between art and science was usurped by a focus mainly on scientific prescriptions. Moreover, the scientific approach, to a large degree, required isolating specific questions or variables. It was difficult, if not impossible, to answer broad, systems-level research questions with this approach. Consequently, agricultural research went from understanding systems to focusing on the parts of those systems.

British agriculturalist Sir Albert Howard in discussing this transformation in agricultural research wrote: “The natural universe, which is one, has been halved, quartered, fractionized, and woe betide the investigator who looks at any segment other than his own!” What is amazing is that

this was written nearly 75 years ago, and I can assure you the isolation of these various segments has only gotten worse. I can also personally assure you there is a very real “woe betide” price to be paid for stepping outside, or even peering outside, your allotted academic silo.

With the transformation of agricultural research, it was believed there was not just an E=MC2 for agriculture but a functional equation solution for each of the fractionized parts. It was believed that the same approach that worked for physics and mathematics to build the atomic bomb and get us to the moon would work equally well where human, cultural, physical, chemical, and biological components were combined into one interdependent system.

Equations implied a scientific approach, and a scientific approach implied rigor. Agriculture, as well as many other fields at this time, desperately wanted to be considered a hard science and rewarded faculty that pulled their departments in that direction. Statistics were further incorporated into agricultural research as well as other fields to imply confidence or certainty of results, and hence add validity to the prescriptive recommendations for soil fertility, pest control, and animal health. It was hoped that agricultural research would now be on equal footing as mathematics, physics, chemistry, and engineering, and it would finally be seen as a true science.

However, there were critics warning about this new process. In particular, that the emphasis and overreliance on statistical methods as the main driving force for prescriptive recommendations would result in investigators divorcing themselves from real-world agriculture. It was feared that recommendations based solely on small plots and statistics, without being tempered by practical verification in real-world settings over a period of time, would be misleading. There were also warnings that secondary effects that were outside experimental boundaries (for example, soil biology changes caused by cattle wormers) would be missed by this research paradigm that attempted to isolate one or two variables and, in the process, exclude other important components of the overall system.

18| Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

GREG HALICH The author is a grass-finishing cattle farmer in central Kentucky and an agricultural economist at the University of Kentucky. He can be reached at Greg.Halich@uky.edu.

Why the change from farmer to producer? I believe a producer was seen as someone who would be willing to follow expert prescriptions, without too much questioning of the methods used to justify them — or their practicality. However, a farmer is by nature a problem solver.

Critical thinking

Farmers historically faced much uncertainty, and hence had to adapt quickly and often. Very little was under their direct control. This required critical thinking skills to solve the myriad of new problems that were bound to occur. Most people who consider themselves “experts” do not want their clientele questioning their recommendations. They want them to follow. In short, farmer was no longer a good match for modern-day agricultural research and producer was a suitable replacement.

It is unfortunate that the word “farmer” has become largely shunned by the land-grant system. Thomas Jefferson would be dismayed by this change, as well as the resulting overreliance on expert advice. This founding father realized and went out of his way to make clear the importance of having farmers and citizens who were independent and critical thinkers. In more recent times, Wendell Berry brought up similar concerns in his pivotal book “The Unsettling of America.”

Producer or farmer? — which is better for long-term, permanent agriculture? Which is better for vibrant, rural communities and an independent country? Do we want citizens who have critical thinking skills, or do we want voters who will toe the party line and follow prescribed beliefs? I suspect I know which Thomas Jefferson had in mind almost 250 years ago, and I suspect I know which our two main political parties prefer today.

The final potential reason for the move away from “farmer” has nothing to do specifically with farming itself, but is a much broader societal issue. Once individuals or communities cede most of their important decisions to experts, they start losing their capacity for critical and independent thought. Once critical and independent thought is lost, we become more vulnerable to manipulation: commercially, culturally, and politically. Bread and circuses become the paramount issues of our

stand guard against weeds and grasses

Velpar

Apply on dormant, established stands to manage weeds and grasses with the highly effective, proven mode of action, hexazinone (Group 5).

VelparAlfaMax™ and VelparAlfaMax™ Gold

The one-two herbicide punch of hexazinone and diuron (Group 7) enhances herbicidal activity in two different ratios.

February 2023 | hayandforage.com | 19

your alfalfa crop, and improve the quality of your hay with the proven portfolio of NovaSource weed control solutions: Always read and follow label instructions. NovaSource®, Velpar®, Velpar® AlfaMax™, Velpar® AlfaMax Gold™ are registered trademarks of Tessenderlo Kerley, Inc. ©2022 Tessenderlo Kerley, Inc. All rights reserved. Learn more at novasource.com

Protect

WEED CONTROL INCREASE LONGEVITY OF THE STAND

Quantifying nutrient digestibility starts with fiber

I’VE recently opted for a diesel truck, primarily to step up the range between fuel stops. It’s got a 33-gallon fuel tank, but the range equation is more than just a larger fuel tank. Both tank size and fuel conversion efficiency are needed to project distance to empty. Sorting out energy value in your forage analysis is similar.

Nutrient content and digestibility measures are needed to project the energy value of forage. Nutrient amount is like the fuel tank size, then measuring nutrient digestibility is like the miles per gallon in the energy value equation.

Measuring and reporting forage nutrient digestibility began with neutral detergent fiber (aNDF) decades ago. Fiber, sugar, and starch each contain the same calorie potential, but the energy released from fiber by dairy or beef cattle is roughly half that of starch or sugar due to limited digestibility. Fiber digestibility is also related to how much forage dairy or beef cattle can consume. Hence, growers, feeders, and nutritionists have focused on fiber content and digestibility initially to better quantify forage energy value.

Forage testing laboratories use in vitro rumen techniques to assess fiber digestibility. These biological assays are complex. The short method explanation is that living rumen microorganisms are collected from cannulated donor cows via rumen fluid, and the fluid is used to inoculate and digest a feed sample on a lab bench. The term for this approach is in vitro, meaning simulated rumen.

Expanded measures

The undigested fiber amount (uNDF) is measured after a designated time period. Laboratories began with a 48-hour in vitro rumen incubation and have expanded to report many more digestion time periods. The common fiber digestibility measure (NDFD) is actually a calculated value. Laboratory technicians measure total fiber and undigested fiber and then calculate

NDFD. This has been a confusing topic, with forage reports listing both uNDF and NDFD on forage reports. For clarification, the math is as follows:

• uN DFX, % DM = undigested fiber after X time period, as a % of feed dry matter

• NDFDX, % aNDF = (aNDFuNDFX) / aNDF x 100

Initially, a NDFD48 was a good and simple start, but the aNDF digestibility section within the feed analysis report has grown to be exceedingly complex over the past decade. The following NDFD time points are now reported for different feeds: 12, 24, 30, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 240 hours. Further, Cornell University researchers noted that fiber contains a bit of ash contamination. Thus, fiber digestibility measures are now reported on an organic matter basis as well. The math is as follows:

• uN DFXom, %dry matter = uNDFX minus residual ash, as a % of feed dry matter

Less repeatable

Consider the following points to aid in fiber digestibility data interpretation. Laboratory NDFD is a biological measure, originating from living cattle. We readily understand that cattle and farms are quite different from one another; hence, a lab assay originating from an animal’s rumen should be recognized as less repeatable relative to lab measures like crude protein or starch, which rely upon standard chemical reagents.

Further, forage testing laboratories also utilize multiple different wet chemistry fiber digestion methods such as a rumen fluid standardization protocol (standardized) or a traditional rumen fluid protocol (traditional). In general, fiber digestion results should not be compared between different laboratories or methods.

Beyond NDFD48, NDFD30 has become more popular with nutritionists and incorporated into the relative forage quality (RFQ) index. The RFQ is a more robust forage quality rank-

ing than the relative feed value (RFV) calculation, partly because it accounts for NDFD. These feed index calculations are covered in more depth by Dave Mertens and me in previous columns originally published in the April/May and August 2020 issues.

In addition to NDFD30 or 48, the 12to 72-hour measures have been brought online to estimate fiber digestion over time and calculate digestion rate in nutrition models. Think of this like how your truck measures fuel consumption per mile over a trip to calculate fuel conversion efficiency.

Similar to rebar

Then the 120- and 240-hour measures have been brought onto the report to quantify the lignified and indigestible fiber. Think of this fraction as equivalent to the rebar in concrete. The uNDF240 measure has become useful to benchmark different crops and make forage to concentrate adjustments within farms. In general, compare your forage uNDF or NDFD results to laboratory and method benchmarks and within time point and laboratory measures.

Lastly, the 24-, 30-, 48-, and 240hour in vitro rumen measures have been integrated into a total tract NDF digestibility (TTNDFD) measure, which the University of Wisconsin’s Dave Combs spent roughly a decade investigating and verifying. The TTNDFD equation is similar to that used by advanced nutrition models, accounting for both lignified fiber and digestion rate. It is comparable between forages, and, in general, the TTNDFD goal is 45% or greater. •

JOHN GOESER

The author is the director of nutrition research and innovation with Rock River Lab Inc, and adjunct assistant professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Dairy Science Department.

20 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

FEED ANALYSIS by John Goeser

“When we first discovered Rezilon® herbicide and used it for the first full season, it virtually eliminated our early grass and weed problem and made our first cutting a sellable product.”

Rezilon® herbicide stops weeds before they start

Growing clean, high-quality hay can seem like a season-long battle against weeds. With Rezilon ® herbicide, you’ll see cleaner hay cutting after cutting. It stops weeds from emerging and stays active on the soil surface, giving you long-lasting weed control.* And that means you can raise high-quality hay — and your reputation.

Scan to find out more *4-6 months of anticipated control per application. ALWAYS READ AND FOLLOW PESTICIDE LABEL INSTRUCTIONS. Environmental Science U.S. LLC., 5000 CentreGreen Way, Suite 400, Cary, NC 27513. For additional product information, call toll-free 1-800-331-2867. www.envu.com. Not all products are registered in all states. Envu, the Envu logo and Rezilon ® are trademarks owned by Environmental Science U.S. LLC. or one of its affiliates. ©2023 Environmental Science U.S. LLC. VM-0123-REZ-0006-A-1 REZILON

Lee Reynolds Hay Producer Shorter, AL

MAKING HAY WAS A PART OF HIS FLIGHT PLAN

by Amber Friedrichsen

S THE son of two sharecroppers, Jim McClain grew up picking cotton and cutting tobacco in the sticky heat of South Carolina. Fields were cultivated by mules pulling plows, and crops were planted and harvested by hand. The long days of tedious work molded him into a disciplined young man, but he still yearned for adventure.

McClain was fascinated with flying, and he fixated on anything with wings, from airplanes to birds to June bugs. In fact, he used to capture these iridescent insects and tie strings around their legs like makeshift kites so he could analyze their aviation. With flying and farming defining his formative years, McClain had two distinct goals for his future: To learn how to fly and to be a cowboy.

The former was accomplished when he became a pilot in the Marine Corps after graduating from college. McClain

and his fellow pilots were nicknamed flying leathernecks because of stiff leather collars on the original uniforms Marines wore to protect them from cutlass slashes by the enemy. After serving in two wars, making countless flights across the country and overseas, and eventually settling down in California to raise a family, McClain retired from the military in the early 1990s. But he wasn’t finished pursuing his dreams.

In 1993, McClain uprooted his life in California and moved back to his home state when his wife, Linda, a real estate appraiser, found a farm outside of Orangeburg, S.C., that was up for foreclosure. Even though the house was falling apart at its hinges and the rest of the land was shrouded with shrubs and trees, she was eager to close the deal on her husband’s behalf. Becoming a cowboy — or haymaker — was finally in his reach.

While Linda repaired the house, McClain cleared the land, installed

fences, built a barn, and constructed a shed. The U.S. military veteran turned the place into a fully functioning farmstead and named it The Flying Leatherneck Ranch to signify the promises he made to himself when he was just a kid.

Self-taught student

During McClain’s renovations, he established 600 acres of Coastal bermudagrass across multiple fields; however, he didn’t have any experience growing forage. He devoted countless hours to studying different production practices and was determined to implement some of the strategies he observed when he lived in the West. By applying the problem-solving skills he strengthened in the service, McClain essentially taught himself how to make hay.

“I come from a world of technology, so I made comparisons as best as I could,” he said. “I spent a great amount of time in Arizona and California, and even though they grow a different kind of

22 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2023

All photos Amber Friedrichsen

The skills Jim McClain gained in the Marine Corps have proved useful in building a successful hay business.

hay there, the equipment is the same.”

McClain was also intrigued by agriculture in other countries, so he invested in many of the haymaking machines he saw in Germany when he traveled there as a Marine. With a mower, a tedder, a rake, a small square baler, a round baler, and two stack wagons, McClain was prepared to tackle production.

There were many avid equestrians in his area of the Palmetto State, creating a constant demand for premium hay with high crude protein and fiber digestibility. McClain started selling hay to a stable owner, and word of his new business quickly spread. He now produces over 45,000 small square bales and 3,500 round bales every year, and his clients recognize the consistent quality of his product that results from his meticulous attention to haymaking details.

“My customers love their horses, and I love them for loving their horses,” McClain laughed. “They want the best hay they can afford in terms of nutrition, and my hay meets their standards.”

An unusual approach

Coastal bermudagrass is ideal for horse hay because of its fine stems and palatability. The perennial warm-season species tends to break out of dormancy in late February to early March, and first cutting occurs in mid-May once plants are 18 to 24 inches tall. McClain can get two to three cuttings from fields without irrigation each season, whereas his irrigated fields are harvested four to five times, or every 28 to 30 days.

Many producers irrigate hay in the West, but it is not a common tactic in the Southeast. Nonetheless, McClain has center pivot irrigators in two of his largest fields that account for nearly one-third of his total acreage. Instead of relying on irregular rainfall, ground water is pumped to the pivots at the push of a button. To maximize cost-efficiency, McClain programs the systems to run between 10 p.m. and 10 a.m. when electricity rates are lowest.

“Irrigation is extremely expensive, but it was an easy choice,” he stated. “It doesn’t always rain when you need it to rain, but when you have a customer base that is depending on you to provide them with product, irrigation mitigates liability.”

With the help of two part-time employees, McClain cuts hay with a John Deere 956 MOCO that has an impeller conditioner, which is crucial to facilitate dry down in the humid

climate. The impellers remove the waxy surface of bermudagrass stems to promote faster dry down times. Hay is then tedded to accelerate drying even further, and later raked into windrows with a Claas 680 carousel rake after three or four days.

To make small square bales, McClain has a Massey Ferguson 1840 in-line baler and a New Holland 575 baler. These machines have sensors that signal the application of propionic acid if forage is more than 16% moisture. Bales are then loaded onto a self-propelled New Holland bale wagon, which is McClain’s favorite piece of equipment. It only takes about 10 minutes to pack 163 small square bales on the platform and haul them to the barn. The unloading process is hands-free.

in humans. Therefore, McClain always cuts hay in the morning to keep the sugar concentration below a horse’s threshold, which is one of his major selling points.

McClain sends hay samples to a lab in New York that specializes in forage analysis for equine diets and receives results within a week. He then shares this information with his customers to justify an asking price, but with recent inflation, he is not willing to negotiate.

McClain applies a nitrogen-sulfur liquid fertilizer to his fields after each cutting, but the product he uses was double the cost in 2022 compared to years prior. Diesel fuel has also been extremely expensive, so he has bumped up his hay prices and started charging buyers a delivery fee.

“I’m very candid with my customers. I tell them what I am dealing with and explain why I cannot sell my hay for what I did last year,” McClain asserted. “I can’t absorb these costs. They have to be shared.”

Because of the caliber of his product and his transparency, business has remained steady. Many buyers contract bales in advance, but McClain doesn’t collect payment until they receive their order. He is confident he can supply the quantity and quality of hay to meet their needs, which speaks to his diligent approach.

“The stack wagon is my pride and joy. I’m the only one who operates it,” McClain beamed. “Small square bales are so labor intensive. I couldn’t do business if I didn’t have it.”

McClain uses a John Deere 459 baler and a New Holland 7060 baler for round bales. He has another bale wagon designed to carry 14 round bales at a time, and these bales are stacked fourhigh in the same barn. One of his horse customers buys nearly 1,000 round bales a year.

Horse-approved hay

McClain delivers small square bales himself on the back of his pickup or on a flatbed trailer. Face-to-face deliveries build good rapport with clientele, but they also offer McClain an opportunity to promote his hay’s premium quality. Bales typically have 13% to 15% crude protein, and he aims to keep sugar content low. Horses are susceptible to insulin resistance, and they can develop a condition similar to diabetes

In addition to hay, McClain also has a herd of 150 Black Angus cow-calf pairs. He allocates about 150 acres of bermudagrass pasture for grazing, which is divided into 18 paddocks. Pearl millet is also seeded for summer grazing, and each paddock is complete with a water tank and ample shade. McClain sells grass-fed beef direct-to-consumer with intentions of educating others about where their food comes from and how his animals were raised.

A word of advice

Even though he doesn’t wear a widebrimmed hat or throw a lasso, McClain considers himself the cowboy he always aspired to be. When he isn’t tedding, raking, or baling hay, he can most likely be found in the stack wagon, moving cattle, or making deliveries. He doesn’t take any of these tasks for granted because each of them is a chance to live out his childhood dreams.

With that said, McClain still flies whenever he can. He owns an airplane

continued on following page >>>

February 2023 | hayandforage.com | 23

and takes it on joyrides several times a week. Although he spends most of his time in the air alone, his grandchildren occasionally come to visit and accompany him in the cockpit. McClain takes advantage of these moments to teach them about the aircraft and make them his mini co-pilots. He hopes he can instill the desire to farm and fly in his grandchildren, but more importantly, he hopes his story encourages them — and the rest of the next generation— to follow their own trajectory.

“I want people to know that where they come from in life has little bearing on their final destination,” McClain said. “Anyone can make a future for themselves with a lot of hard work and dedication to the final goal.” •

AMBER FRIEDRICHSEN

The author served as the 2021 and 2022 Hay and Forage Grower summer editorial intern. She currently attends Iowa State University where she is majoring in agricultural communications and agronomy.