hayandforage.com

February 2024

Two sides of the silvopasture coin pg 8

Train your grazier’s eye pg 20

Sugar in horse hay: yea or neigh? pg 26

A corn silage primary debate pg 32

Published by W.D. Hoard & Sons Co.

Elevate Your Hay and Forage Operation with KRONE -The Hay and Forage Specialists! Dive

the

WEBSITE

to learn more about KRONE

into

full KRONE line and special offers in the featured product pages. KRONE

Scan

6

Pennsylvania’s Rodney Boll, a full-service custom forage harvester, can

bale into 21 small ones that are ready for transport in as few as five minutes. 21

MANAGING EDITOR Michael C. Rankin

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Amber M. Friedrichsen

ART DIRECTOR Todd Garrett

EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Jennifer L. Yurs

ONLINE MANAGER Patti J. Hurtgen

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING John R. Mansavage

ADVERTISING SALES

Kim E. Zilverberg kzilverberg@hayandforage.com

Jenna Zilverberg jzilverberg@hayandforage.com

ADVERTISING COORDINATOR

Patti J. Kressin pkressin@hayandforage.com

W.D. HOARD & SONS

PRESIDENT Brian V. Knox

EDITORIAL OFFICE

28 Milwaukee Ave. West, Fort Atkinson, WI, 53538

WEBSITE www.hayandforage.com

High-quality hay binding pays for itself

Choosing the correct type of net wrap or baler twine can prevent handling and storage issues down the road.

Restoring rangeland at Ritter Ranch

Mike Williams is determined to improve the perennial forage populations on his 12,000acre ranch in Southern California.

8

TWO

22 Dairy Feedbunk 32 Feed Analysis 38 Forage IQ 38 Hay Market Update

Alsike clover dominated this renovated pasture belonging to the Greenacres Foundation farm, a pasture-based operation located near Cincinnati, Ohio. Alsike clover is a short-lived perennial legume that offers good forage biomass but can cause phytotoxicity issues in horses. It’s identified by a lack of leaf variegation, the absence of pubescence, pinkishwhite flowers, and serrated leaf margins.

February 2024 | hayandforage.com | 3

HAY & FORAGE GROWER (ISSN 0891-5946) copyright © 2024 W. D. Hoard & Sons Company. All rights reserved. Published six times annually in January, February, March, April/May, August/September and November by W. D. Hoard & Sons Co., 28 Milwaukee Ave., W., Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin 53538 USA. Tel: 920-563-5551. Fax: 920-563-7298. Email: info@hayandforage.com. Website: www.hayandforage.com. Periodicals Postage paid at Fort Atkinson, Wis., and additional mail offices. SUBSCRIPTION RATES: Free and controlled circulation to qualified subscribers. Non-qualified subscribers may subscribe at: USA: 1 year $20 U.S.; Outside USA: Canada & Mexico, 1 year $80 U.S.; All other countries, 1 year $120 U.S. For Subscriber Services contact: Hay & Forage Grower, PO Box 801, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538 USA; call: 920-563-5551, email: info@hayandforage.com or visit: www.hayandforage.com. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to HAY & FORAGE GROWER, 28 Milwaukee Ave., W., Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin 53538 USA. Subscribers who have provided a valid email address may receive the Hay & Forage Grower email newsletter eHay Weekly February 2024 · VOL. 39 · No. 2

A one-of-a-kind baling approach

square

convert a large

24

SIDES OF THE SILVOPASTURE COIN 12 SOLVING WEEVIL RESISTANCE 14 IS YOUR FORAGE SYSTEM PULLING ITS WEIGHT? 16 BUILD DIVERSITY IN PASTURES 18 SIMPLE ROOTS MAKE SOIL LIFE COMPLEX 20 TRAINING YOUR GRAZIER’S EYE 22 DRY COWS ARE FORAGE SINKS 26 SUGAR IN HORSE HAY: YEA OR NEIGH? 28 THWART HERBICIDERESISTANT WEEDS WITH ALFALFA 32 A CORN SILAGE PRIMARY DEBATE

THE COVER

First Cut

Alfalfa Checkoff

Beef Feedbunk

Sunrise

Photo by Mike Rankin 20 The Pasture

ON

4

12

14

18

On Soil

Walk 21 Forage

Gearhead

DEPARTMENTS

EMAIL info@hayandforage.com PHONE 920-563-5551

Mike Rankin Managing Editor

Mike Rankin Managing Editor

Maintaining momentum

MOMENTUM is a wonderful thing. We’ve all seen how positive momentum can bring something or someone from the dregs of defeat or extinction to the top of the hill by merely exerting a little positive energy that, over time, manifests itself into a lot of positive energy. This occurs in all facets of life, including business entities, organizations, churches, politics, and sports. Success is rarely achieved without some degree of momentum, while failure is often the result of lost momentum.

Largely through the efforts of the National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA), which was formed by industry leaders in 2006, federal alfalfa research funding has grown significantly over the past 10 years. It’s been a study of the very definition of momentum. For example, the federal Alfalfa Seed & Alfalfa Forage Systems Research Program has grown from $1.35 million allocated annually, which was a fraction of some other commodities with far less value, to $4 million. Early efforts to boost research funding for alfalfa were often rebuked by policymakers because, unlike many other crops, growers had no “skin in the game.”

In 2016, the U.S. Alfalfa Research Initiative was created; it’s better known as the Alfalfa Checkoff Program. Without federal mandate, alfalfa seed brands voluntarily collect $1 for every bag of alfalfa seed sold. This money is then turned over to NAFA, which awards it to the nation’s alfalfa researchers on a competitive basis. It should be noted that 100% of the money collected is used for research with no administrative fees assessed. Most participating seed companies chose to simply add $1 to every bag sold rather than make the checkoff dollar a separate invoice line item. Alfalfa growers now had their skin in the game and were rewarded with annual boosts in federal research funding.

You see the partial benefits of this program in every issue of Hay & Forage Grower, where a completed checkoff-funded research project is highlighted. What may be less apparent to the greater alfalfa community are some of the indirect program benefits that have largely occurred in the past three years.

With the more than $3 million in checkoff funding collected since its inception, it has leveraged over $40 million in additional federal dollars for research. Moreover, university forage extension and research positions are now being filled, following years of vacancies in many cases. These days,

universities don’t fill positions unless adequate research funding is available from outside sources. With new hires, additional students are being trained in alfalfa breeding, agronomy, pathology, and extension. Further, the USDA-Agricultural Research Service has been able to bolster its alfalfa research presence with permanent position funding at several locations across the U.S.

Initially, nearly all of the major alfalfa seed companies signed on to voluntarily collect the checkoff dollar per bag. In the past year, 26 alfalfa brands have actively participated in the program. They are to be commended for that decision in seeing the potential value in return to the industry, with little effort on their part. Given that it doesn’t cost anything to participate, and every alfalfa entity benefits, it’s difficult to understand why a company wouldn’t be on board. Nonparticipation is extremely shortsighted, in my opinion.

To be clear, alfalfa growers are funding the program, not the companies. If a company decides to exit the program (as some have done) and not collect the extra checkoff dollar, I hope they also lower the cost of a bag of seed by a dollar. I’ve seen companies make claims such as “all-in on alfalfa” or “relentlessly driving the alfalfa industry forward.” If that’s so, it’s hard to justify not supporting a program that has been beneficial to both their company and the greater alfalfa industry.

The utility and effectiveness of agricultural commodity checkoff programs have long been debated in many arenas. I get it, but the millions of dollars and positions leveraged by the relatively small collection of funds generated by the still fledgling alfalfa checkoff program is indisputable. One of the consequences of a consolidated alfalfa seed industry is that it only takes one or two larger companies to kill the momentum gained to date, let alone the entire program. Big or small, it’s important that all do their part.

Finally, I would like to ask alfalfa growers, who benefit the most from the checkoff program, to encourage their seed supplier to participate and thank them for doing so. If they don’t participate, ask them why. After all, it’s your dollar per bag that will keep the momentum going and the program alive. •

Happy foraging,

FIRST CUT

Write Managing Editor Mike Rankin, 28 Milwaukee Ave., P.O. Box 801, Fort Atkinson, WI 53538 call: 920-563-5551 or email: mrankin@hayandforage.com

4 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

A one-of-a-kind baling approach

by Amber Friedrichsen

NOT all teenagers have a clear image of their careers, but a young Rodney Boll knew his would look like the view of a hayfield from the seat of a tractor. The self-starter from Mount Joy, Pa., purchased his first round baler the summer after he graduated high school and has been custom baling ever since.

Boll grew up on a farm and wanted to continue working with his family, so his father suggested he buy a baler to expand the operation and make his job a more sustainable one. Lucky for him, another custom baler in the area decided to scale back shortly after Boll started his business and he was able to acquire some of those clients. His customer base quickly grew by word of mouth, and over time, he started offering other types of custom work.

Now Boll has about 100 clients. In addition to baling hay and straw, he plants and harvests forage and chops corn silage for other farmers. Planting, harvesting, chopping, and baling sched-

ules tend to overlap throughout the summer, but rather than put all of his eggs in one basket, Boll prefers to be diversified. He takes pride in finishing every task and embraces the fast pace of custom work life.

“There is a sense of accomplishment when all of the balers come home at the end of the day and everybody was taken care of,” Boll affirmed. “Then we just have to get ready for tomorrow and we do it all over again.”

Small bales, big demand

The patchwork pattern of agricultural land in Lancaster County creates farms of many shapes and sizes, and Boll finds himself in fields that range anywhere from 1 to 100 acres. Although most jobs are relatively small, he covers an estimated 10,000 acres per season across planting, mowing, chopping, and baling.

“There are days we have 15 different jobs scattered across a 20-mile radius,” Boll said. “We will cover multiple acres multiple times a year. For example, we will mow a field in the spring, go in and merge the forage into a windrow, and

then chop it,” he added.

Since buying his first round baler in 1998, Boll has added Massey Ferguson 2250 and 2270 large square balers and three Massey Ferguson 1840 small square balers to his machine shed. He also upgraded to a Massey Ferguson 4160 round baler, gained three Samasz triple mowers, and has a Claas Jaguar 870 chopper. His equipment line-up allows him to meet a variety of customer needs, which ultimately revolve around their target markets.

Horse owners tend to buy small square bales since they are easier to handle than large ones, and there is also a demand for straw in and around construction sites for erosion control. With that said, small bales represent a large portion of Boll’s production; however, making and handling them can take up a large portion of his time. One way he overcomes this is by running two Marcrest Bale Barons, which make hay easier to collect and transport.

“When we small bale, we drop the bales on the ground and come through with the Bale Barons, which pick up the

6 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

Rodney Boll built an integrated conversion system in his hay barn to downsize large square bales into small ones. All photos Boll Farms

bales and package them into bundles of 21 that are essentially like a large square bale,” Boll explained.

From large to small

The Bale Barons enhance efficiency to an extent, but making small bales is still rather tedious. Baling large bales, on the other hand, requires much less time to cover the same area of ground.

About 10 years ago, Boll and his father began brainstorming ways to build a machine that could convert large square bales into small ones. Much to their surprise, such a contraption already existed.

“With small square balers, it takes four or five machines to do the same number of acres per hour as one large baler. It takes a lot more labor to be small baling in the field, and you are limited on how much you can do. We couldn’t do enough,” Boll said. “Then we stumbled across the Bale Converter, and with that we could harvest hay quickly with a large square baler, get it under cover, and then convert it to small square bales when we had time.”

The Bale Converter ultimately tears up large square bales so hay can be reconstructed into small bales. It was a game changer for Boll before a barn fire destroyed his machine in 2018. Despite the disaster, Boll went straight to the drawing board to make a blueprint for a new barn. The crafty custom baler designed a building for hay and straw storage that also had space for an integrated bale conversion system.

Boll bought another Bale Converter and put it on one end of the new barn where it sits at the right-hand side of the U-shaped conversion system. Large square bales are untied and pushed into the machine, and after the Bale Converter shreds the bales, the hay is fed directly into a Massey Ferguson 1840 baler. Hay is then reassembled into small square bales before it moves along a curved chute that is connected to a Bale Baron on the left-hand side of the conversion system that compresses them into packs of 21.

The task takes about five to eight minutes from start to finish — depending on forage species — which means Boll can rebale almost 300 small bales per hour. The Bale Converter, the baler, and the Bale Baron are all powered by electric motors.

“We knew what was working and we knew what we wanted, so we made this

makeshift system,” Boll said. “What the Bale Converter does is mimic a windrow in the field by tearing apart the hay and feeding it to the baler. It’s a unique thing that serves the niche market we have.”

Any hay that is lost in the process is collected by three in-floor augers that run under each leg of the conversion system. These augers, which are covered by steel crates for safety reasons, lead to a vertical auger that delivers chaff to the front of the baler, virtually eliminating waste.

Helping hands

The conversion system runs almost every day, and operating it is a full-time job. Boll converts many of the bales he makes for his customers, but he also converts bales for farmers who harvest their own hay. At least two of his nine full-time employees always stay back at the barn to feed the Bale Converter and move bales while the rest of the crew is in the field.

“People bring their product to us and hire us to convert it. We rebale far more than what we bale on our own,” Boll stated. “Some have their own trucks, and we do trucking for those who don’t. Either way, there are trucks coming every day.”

In addition to working in the field, converting bales in the barn, and truck-

ing hay on the road, Boll appreciates his employees’ assistance with maintaining and repairing equipment in the shop. He typically trades in his small square balers every year but decided to keep his large square balers and round baler in 2023 given high equipment prices. He was confident these machines were still in good condition going into the fall, and with a handy team and a reliable equipment dealer, breakdowns aren’t too concerning.

“We have a really good group of employees who make my job a lot easier. I’m grateful for all they do for us,” Boll said. “We do daily maintenance ourselves, but I will have my dealer service the balers every winter. They go over things with a fine-toothed comb and replace whatever they think is necessary. And if we do have a breakdown, he can usually get to us within a day, and often within a few hours.”

Among the team is his father, Jay; his wife, Heather, who manages bookwork; and his oldest son, Landon, who recently graduated from high school. Like Boll, Landon is eager to stay involved in the custom operation business and hopes to have a career in agriculture of his own. It was this resolve that led Boll to start baling years ago, and it will likely be what carries the custom operation into the next generation that also includes son Kadon and daughter Dori. •

February 2024 | hayandforage.com |7

In addition to a team of reliable employees, Rodney Boll is grateful for help from many family members. From left: Jay, Joan, Dori, Heather, Rodney, Landon, and Kadon Boll.

Brett Chedzoy

Brett Chedzoy

Two sides of the silvopasture coin

by Brett Chedzoy

SILVOPASTURING is the integrated production of trees, forages, and livestock that has been practiced in some corners of the world for many decades. However, in the mixed hardwood forests of the eastern U.S., silvopasturing has struggled to take hold.

Early foresters and conservationists recognized that farm woodlands were being treated as sacrifice paddocks and thus irreparably damaged and degraded from excessive livestock access. Therefore, the mantra “keep livestock out of the woods” discouraged the adoption of this agroforestry practice that has huge potential in the naturally forested Northeast.

Farm viability, heat stress, and a growing list of noxious plants that want to overrun the landscape are just a few

of the modern challenges for grazing farms that warrant a rethinking of livestock in the woods. With a much better understanding of rotational grazing principles and tools to manage the impacts in more positive ways, the past concerns about grazing in and around trees can be largely eliminated.

Cornell University Cooperative Extension’s work with silvopasturing inadvertently started in the early 2000s with the Goats in the Woods project that evaluated the effectiveness and feasibility of using livestock to control problematic plants in forest understories. That project gave rise to educational efforts on silvopasturing in both farm plantations and naturally occurring woodlands, as well as the opportunity to add multipurpose trees into open pastures.

Although there were some useful earlier experiences to draw from in places

like Missouri and the mid-Atlantic, the learning curve of silvopasturing in the humid and high-value hardwood forests of the Northeast was unique.

In New York alone, there are an estimated 2 million acres of degraded farm woodlands and invasive shrublands with potential for silvopasturing. There are another 2 million acres of pastureland that could be enhanced through the profitable incorporation of trees.

Even after filtering down those acres to suitable land that is accessible and operable by skilled and capable graziers, there is potential to implement environmentally-friendly livestock production in our own backyards. The following is a synopsis of experiences and challenges of establishing silvopasture.

Adding trees into pastures

For the trees into pastures pathway of silvopasture creation, one of the

8 | Hay & Forage Grower | Fabruary 2024

Young trees in silvopastures must be protected from grazing livestock and wildlife to minimize damage.

more important barriers is the cost of successfully establishing trees in a sod environment that is full of both domestic and wild herbivores.

Electric fencing is the tool of choice for protecting young, vulnerable trees from livestock, but additional protection may be needed to prevent deer, rodents, and rabbits from browsing and girdling the investment. Additional threats include pest outbreaks, drought stress, and smothering weeds and vines, to name a few. All of these are manageable with proper planning, preparation, and ongoing maintenance.

The initial high costs of establishing trees can be offset by the advantages of choosing trees that suit multiple objectives and are planted in functional designs. The book “The Grazier’s Guide to Trees” available at treesforgraziers.com is a good starting point for thinking through key considerations. If producers are new to tree planting, they should start small and seek out experienced people who can help reduce costly mistakes and wasted efforts.

From personal planting efforts of a quarter-million trees in the past 35 years on our family farms in New York and Argentina, here is some advice to anyone starting out:

• Don’t bite off more than you can chew. It’s a lot of work to plant trees, and even more work to keep them alive early on. Don’t underbudget.

• Hedge your bets against serious future pest issues with more species diversity, and match trees to their site requirements to promote long-term vigor and resilience.

• Don’t cut corners. Doing so will cost more in the end and possibly lead to a complete failure of the planting.

Adding pasture into trees

By contrast, adding pasture into trees utilizes existing trees, but the same caveats apply to forage selection and establishment. Successful forage establishment in existing woodlands is a three-step process.

• Reduce tree and understory shrub density. This will reallocate sunlight to the ground surface where it can be utilized by forage plants. In forestry, this is known as thinning, and it can be accomplished commercially through a timber sale if there is adequate volume and value or precommercially where there is a net cost to accomplish the necessary thinning treatment. The

services of a professional forester can be invaluable for planning and implementing tree thinning.

• Pay attention to forage germination requirements and conditions. Soil scarification, seed-to-soil contact, adequate temperature and moisture, and sufficient soil pH are all critical factors that influence the germination and survival of young forage plants. Many farm woodlands have abundant soil seed banks of forage species that can thrive in the light shade of silvopastures, but supplemental and timely broadcast seeding can accelerate desirable stand development after initial thinnings.

• Use skilled grazing and other management tools where possible. Doing so will shift the understory composition in a positive direction. Clipping and spraying may not be options with trees in the way, so the use of intensive rotational grazing and adjusting grazing density to promote the growth of the desirable species while pressuring the undesirable ones will gradually influence forage quality, composition, and productivity.

For technical details on manipulating forest density to create silvopasture within existing wooded areas, search for the “Cornell Guide to Silvopasture in the Northeast,” which is available under the publications page of forestconnect.info.

Research is ongoing

More work is needed to develop shade

but a number of cool-season forages have already been observed to produce well in silvopastures where cooler, wetter conditions encourage prolonged growth periods to compensate for slightly reduced photosynthesis.

Orchardgrass, tall fescue, and reed canarygrass have some of the best documented shade tolerance, though most cool-season forages remain productive under well-thinned silvopasture canopies. Well-thinned is approximately 50% crown closure, which is also the point at which growth and competition is optimized amongst trees.

Additional work is also needed to document the economics of silvopasturing. Studies in New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Missouri have all shown significant economic benefits for silvopasturing over just timber production or grazing open pastures. Silvopastures have also been widely recognized to provide superior carbon capture and storage benefits, and emerging markets are developing for producers to market carbon from new tree establishment in silvopastures. •

The author is a regional extension forester and grazing educator with Cornell Cooperative Extension. He and his family own large grazing operations that extensively use silvopasturing in upstate New

February 2024 | hayandforage.com |9

BRETT CHEDZOY

Sign-up is free, fast and easy at hayandforage.com eHay WEEKLY • Headline News and Field Reports • Market Insight and Crop Updates • Original Features • Event Coverage Electonic Newsletter Direct to your inbox every Tuesday morning!

Solving weevil resistance

Hay & Forage Grower is featuring results of research projects funded through the Alfalfa Checkoff, officially named the U.S. Alfalfa Farmer Research Initiative, administered by National Alfalfa & Forage Alliance (NAFA). The checkoff program facilitates farmer-funded research.

LTHOUGH alfalfa weevils have developed resistance to pyrethroid insecticides, causing severe alfalfa losses in the Western U.S. and concern elsewhere, producers may still be able to utilize pyrethroids on a limited basis. They’ll need to alternate those insecticides with others using different modes of action as well as implement additional control options, according to Alfalfa Checkoff research by Kevin Wanner, Montana State University Extension entomologist.

The research also highlights the need to register new insecticides for alfalfa with different modes of action — critical for alfalfa weevil management, he noted.

In 2019, Western farmers and ranchers reported losing a majority of first cutting to alfalfa weevil defoliation after two or even three applications of pyrethroid insecticides. Weevil populations ballooned to high levels — 100 larvae per single sweep net sample, which is five times the economic threshold. “After talking to colleagues in other Western states, it was clear that alfalfa weevil resistance to pyrethroid insecticides was suspected across the region,” Wanner said.

The producer reports prompted a collaboration between Montana State University and the University of California–Davis to quantify the degree of pyrethroid resistance in the West and develop multi-state recommendations. That research led to Wanner’s Alfalfa Checkoff-funded project, which entailed on-farm research to support the registration of new insecticides for alfalfa.

“The majority of effective and available insecticides for alfalfa weevil control all contained pyrethroid active ingredients. It quickly became clear that forage alfalfa suffered from a lack of different active ingredients with different modes

of action that can be used in rotation to manage pyrethroid resistance in alfalfa weevils,” Wanner asserted.

The purpose of the project was to evaluate new insecticides, combinations of older insecticides, and the timing and rates of currently registered insecticides for control of alfalfa weevil. “We were able to take advantage of a USDA-NIFA-funded research project to maximize the results of NAFA’s Alfalfa Checkoff grant,” Wanner noted. “Good on-farm collaborations with regional producers and implementing consistent experimental procedures in three diverse

alfalfa-producing regions in Montana, Oregon/Washington, and Arizona proved to be a valuable approach.”

Wanner’s research showed, because of cross-resistance, all mode of action (MoA) 3A pyrethroid products registered for forage alfalfa become ineffective. Rotating the insecticide MoA and using noninsecticide strategies such as an early harvest, where applicable, are critical to preserving their usefulness.

“If you see ‘slipping’ control with pyrethroid insecticides — for example, needing maximum label rates to achieve the same level of control previously provided by lower rates — managing

PROJECT RESULTS

• All MoA3A pyrethroid insecticides were ineffective in areas with known alfalfa weevil resistance (control ranged from 40% to 80%), except Brigade (bifenthrin, registered for seed alfalfa).

• In these same areas, Steward (indoxacarb) was effective at the lower 6.7 ounce per acre rate (control was typically over 90%). Higher rates of Steward may be necessary when early applications and extended persistence are required.

• Older products: MoA1A Sevin XLR was not effective and produced phytotoxic yellowing of alfalfa; MoA1B Dimethoate 400EC provided promising results on its own in Montana and mixed with a pyrethroid in Washington.

• New products: Endigo and Actara (not registered for alfalfa) were effective at one of three sites.

• Af ter three years without using a pyrethroid, control provided by MoA3A Warrior increased from 0% to 80%.

12 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

YOUR CHECKOFF DOLLARS AT WORK

KEVIN WANNER , Montana State University Funding: $99,960

Treatment MOA Active ingredient Rate oz/acre Warrior II-low rate 3A Lambda cyhalothrin 1.28 Warrior II-high rate 3A Lambda cyhalothrin 1.92 Steward-low rate 22A Indoxacarb 6.7 Steward-high rate 22A Indoxacarb 11.3 Endigo ZCX 3A,4A Thiamethoxam, Lambda cyhalothrin 4.5 Actara 4A Thiamethoxam 3.46 Mustang Maxx 3A Zeta-cypermethrin 4.0 Brigade 3A Bifenthrin 6.4 Permethrin 3A Permethrin 8.0 Baythroid XL 3A ß-cyfluthrin 2.8 Sevin XLR 1A Carbaryl 48.0 Diamethoate 400EC 1B Diamethoate 16.0

Figure 1. Efficacy of Warrior (after three years without using a pyrethroid) and Steward

the resistance will prolong the usefulness of this valuable insecticide group,” Wanner said.

By conducting trials in the same commercial field in Montana for four consecutive years, Wanner and his team made a preliminary estimate of how quickly pyrethroid insecticides might regain their effectiveness. “Avoiding the use of pyrethroids for three to five years

in areas with high resistance may restore their efficacy, but resistance will return quickly when pyrethroid use is resumed. I’d recommend using MoA3A pyrethroids no more than once every three years, rotating with MoA22A Steward and noninsecticide options,” Wanner pointed out.

“The diversity of alfalfa production systems and the importance of custom-

izing alfalfa weevil management recommendations were reinforced by this project. A ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach will not work,” he said. •

For further information on results of Alfalfa Checkoff-funded projects, visit NAFA’s website at https://alfalfa.org/research.php

Dyna-Gro

Forage First

FS Brand Alfalfa

Gold Country Seed

Hubner Seed

Innvictis Seed Solutions

Jung Seed Genetics

Kruger Seeds

Latham Hi-Tech Seeds

Legacy Seeds

Lewis Hybrids

February 2024 | hayandforage.com | 13

CER IFIED QUALITY ISO 9001 T-L … LIKE NO OTHER. www.tlirr.com Contact T-L, your T-L dealer, or visit www.tlirr.com to learn more. 151 East Hwy 6 & AB Road · P.O. Box 1047 Hastings, Nebraska 68902-1047 USA Phone: 1-800-330-4264 Fax: 1-800-330-4268 Phone: (402) 462-4128 Fax: (402) 462-4617 sales@tlirr.com · www.tlirr.com Tired of UNCERTAINTY? Want insurance and assurance all bundled into one reliable package? Time to invest in some long-term peace of mind and stability with a T-L Center Pivot — THE MOST RELIABLE SYSTEM IN THE INDUSTRY. Contact your local T-L representative to find the perfect fit for your irrigation capabilities and needs. LIKE NO OTHER. RELIABLE IRRIGATION PERFORMANCE WILL IT RAIN? OR MISS US AGAIN… TL-482R.indd 1 1/23/24 1:19 PM Alfalfa Partners - S&W Alforex Seeds

Alfalfa Channel

DEKALB

America’s

CROPLAN

Fontanelle Hybrids

NEXGROW Pioneer Prairie Creek Seed

Rea Hybrids Specialty Stewart

Alfalfas SUPPORT THE ALFALFA CHECKOFF! Buy your seed from these facilitating marketers:

Stone Seed W-L

By Jeff Lehmkuhler

Is your forage system pulling its weight?

THE cow-calf industry is set to see a few profitable years once again. The national beef cow inventory is at its lowest numbers in decades with USDA’s July 2023 count indicating a herd size 3% smaller than the previous year. The continued dry weather may have impacted the herd size, but based on the information from agricultural economists, it would seem herd expansion has not started at any significant pace.

The ranches and farms raising beef cows make decisions and investments into enterprises that are lower risk, and in most years, lower returning. Land ownership is a long-term investment with hope the land value improves over time. Yet, rising land values lead to higher taxes, which must be accounted for in the operation expenses.

Higher interest rates are also inflating operating costs for ranches and farms. A $50,000 loan paid over five years at an interest rate of 5% or 8% results in a $4,200 increase in interest paid. The cow-calf system must therefore be managed at a greater efficiency, balancing input costs with production responses.

The Standardized Performance

Analysis (SPA) data outlined the pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed was key for profitability in cow-calf systems. Many factors influence this production parameter.

Factors of profitability

The number of calves weaned and the actual weight at weaning are major overarching factors with each being impacted by several elements. Herd health has a direct impact on abortion losses, scours, and respiratory disease, all swaying both the number of calves weaned and their weight. Bull libido and fertility affect the number of cows that become pregnant, influencing the number of calves born and weaned. Are you managing everything at a function that provides a rate of return for the factors that impact the overall herd profitability?

Forage systems are foundational to this profitability index. Enhancing our beef production per unit of grazed and harvested forage is critical. Climate smart agriculture encompasses options such as rotational grazing, and preventing abortions and neonatal death losses through improved herd health lowers carbon dioxide and methane production

by increasing pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed. Essentially, every factor that plays a role in promoting overall herd profitability with more pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed will directly lower the carbon footprint of the cow-calf system. Thus, it is a winwin situation.

Strive for a better system

Forage availability is the first place to start. Recent years of high fertilizer prices have likely led to limited or no investment in fertilizer for forage acreage used in beef cow-calf herds, particularly in the Midwest and Southeast. Correcting soil pH is the first step and the lowest investment to improve soil fertility and subsequent forage production. Bringing soil fertility into a range that supports legumes can assist in capturing atmospheric nitrogen for greater forage production and quality.

Stand assessment following drought conditions will be helpful to determine the potential stand viability and risk of weed encroachment. Previous research conducted by a colleague sug-

Pounds weaned per cow

gests every pound of weed dry matter growing in a field lowers desirable forage production by a pound. Drought conditions often result in overgrazing of already stressed plants, reducing desirable forages.

As forage production is reduced from either summer dormancy or overgraz-

BEEF FEEDBUNK

14 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

Mike Rankin

Figure 1. The key to profitability in a cow-calf system is pounds of calf weaned per cow

ing, the maintenance energy expended by the beef cow goes up. Research has demonstrated lowering the plane of nutrition available to beef cows reduces milk production, which will directly lower calf weaning weight. Additionally, suckling calves rely on available forage to meet their nutritional needs for growth at an ever-increasing rate after 2 months of age. The normal lactation curve leads to reduced milk production after six to nine weeks, although calves require greater nutrients to support their body weight gain and genetic potential for growth.

Take soil samples to assess soil fertility and make plans to improve stands after determining nutrient losses in the pasture after drought conditions. Ensure soil fertility will promote the establishment of the forage species being considered. As an example, annual lespedeza does better on marginal soil fertility than red and white

clover. Though lower yielding, annual lespedeza can be another forage option that is less common than it was a few decades ago.

Consider new seedings

Are stands in poor shape? Is renovation inevitable? Thin Kentucky-31 endophyte-infected tall fescue pastures could be candidates for upgrading to novel-endophyte varieties. Novel endophytes provide plants with persistence while lowering or eliminating the production of detrimental alkaloids that impact animal performance.

Arkansas research revealed the conversion of 25% of pasture to novel-endophyte tall fescue can benefit cow-calf systems. Seeding bermudagrass varieties that are cold tolerant, or native forages, are other options to consider. Conversion of limited acreage to a warm-season species can provide forage when cool-season forages are dormant

or less productive.

Now is a good time to assess soil fertility and stand composition to develop a plan for improving your forage system. A variety of tools are available to help enhance your pastures and boost the pounds of calf weaned per cow exposed. These improvements can be implemented stepwise and do not require an all-in approach. Using different approaches, especially when considering new forage species, provides the opportunity to evaluate these changes under your management. •

JEFF LEHMKUHLER

JEFF LEHMKUHLER

February 2024 | hayandforage.com | 15 DELIVERING THE HIGHEST QUALITY FORAGE Oxbo 2228 Oxbo 2340 OXBO.COM Find out about how the new technology delivers the highest quality forage. POWERMERGE LEARN MORE AT

The author is an extension beef specialist with the University of Kentucky.

Build diversity in pastures

by Kim Cassida

IN THE northern United States, hayfields often consist of a single forage species like alfalfa, but single species pastures are somewhat rare. Most single species pastures will be annuals like sorghum-sudangrass that are used to fill temporary forage needs. Otherwise, permanent pastures are almost always seeded as a mixture of species. There are many good reasons for this.

The classic example is mixing a forage grass with a legume like red or white clover, birdsfoot trefoil, or alfalfa. Through symbiosis with beneficial rhizobia bacteria in root nodules, legumes are able to fix all the nitrogen (N) they need from the N present in air. Nitrogen is then recycled in soil when legume roots and shoots die, and about half of the N in plant protein that is consumed by grazing livestock is returned to the pasture as manure and urine. As a result, legume N cycles within a well-managed pasture and ultimately feeds the grasses.

Nitrogen from legume and manure sources is released over time because

it is gradually decomposed into available N rather than providing a pulse dose that is instantly available the way unstable fertilizer N is. This helps even out the availability of forage across the growing season because N is a primary driver for plant growth. It also helps reduce loss of N from the soil, which can happen whenever mineralized N is present in amounts greater than what the pasture plants need. Holding onto the N in the pasture saves producers money and helps prevent contamination of groundwater and surface water.

The rule of thumb is that a pasture containing at least 30% legume by weight of forage will provide all the N needed for adequate plant growth. While pasture growth may be further improved by adding N fertilizer, producers should take a hard look at whether that is cost-effective in their specific situation, especially when N fertilizer prices are high.

Adapt to differences

The second big reason for adding biodiversity to pastures relates to adaptation of species to microsites within a field.

Pastures rarely present a consistent set of growing conditions across the entire area. Soil types differ from sandy to heavy. The degree of slope and drainage potential varies. A north-facing slope will have different sunlight availability, temperature fluctuations across the season, and potential for winterkill than a south-facing slope. Soil fertility is certain to vary across a single pasture and can be greatly influenced by past cropping history and grazing management. While it is difficult to find a single forage species that works well across the board for all microsite combinations, graziers in Northern regions are fortunate to have a wide variety of species that grow well with each other and are welladapted to these different conditions. Most seed marketers sell pasture mixes designed to cover the bases for the typical microsites found in their service region. Many will also make custom mixes according to producer specifications. It is important to recognize that these mixes are not intended to create a pasture that has exactly the same proportion of species on every square foot. The species in the mix will

16 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

There are several advantages to seeding multiple forage species in a grazing system.

segregate to the microsites where they are best adapted and may not establish or persist at all on microsites where they are unsuited. This is normal.

Expensive seeding mistakes can be avoided with a little knowledge about your site. For example, if the site is sandy and prone to drought, it is pointless to buy a mixture that mostly contains species with poor drought tolerance. Likewise, if your pasture has questionable drainage for part of the year, don’t buy mixtures with a high proportion of species that hate wet feet. Good species for drought-prone sites or sandy soils include alfalfa, orchardgrass, smooth bromegrass, meadow bromegrass, and chicory. Heavier soils with marginal or seasonally wet drainage favor red and white clover, birdsfoot trefoil, Kentucky bluegrass, timothy, ryegrasses, tall fescue, meadow fescue, and festulolium.

Don’t hesitate to make use of species that volunteer, or seed themselves, into a pasture. As long as a pasture “weed” is not toxic and livestock will eat it, it is feed. Quackgrass, dandelion, plantain, and many others add diversity and are readily grazed and nutritious.

Consider growth curves

Lastly, pay attention to the compatibility of forage species. Choose species from different functional groups — cool-season grasses, legumes, and nonlegume forbs — where normal peak growth happens at staggered times of the year. This will help reduce competition for resources and ensure a more consistent forage supply over the growing season. Orchardgrass and Kentucky bluegrass tend to have early spring growth peaks, followed by fescues, then bromegrasses, with timothy and perennial ryegrass peaking late. Legumes also have the greatest growth in spring but tend to have a more even growth pattern than grasses over the rest of the growing season.

Producers often wonder about growing warm-season native grasses like bluestems, indiangrass, switchgrass, or prairie plants in mixes with improved cool-season grasses and legumes. Unfortunately, this rarely works well in Northern regions. The native warm-season plants have a relatively short growth window and slow regrowth after grazing, and they usually get crowded out by the fast-growing cool-season forages that have a much

longer growing season. Warm-season perennial mixes in the North are best established as summer pastures dedicated to these species only.

There are several methods for enhancing forage species diversity in an existing pasture. Frost seeding, or broadcasting seed onto exposed soil in early spring, is an excellent method on heavier soils because freeze-thaw cycles bury the seed. Frost seeding is most successful with red or white clovers and birdsfoot trefoil, and it is an excellent way to add legumes to a pasture. It can also be used to seed some grasses, such as ryegrass and festulolium, although this doesn’t work as consistently as with legumes. I have also had frost seeding success with orchardgrass and chicory.

Almost any desired species can be no-till drilled into pastures. The best timing in the North is right before the pasture breaks winter dormancy. Overseeding during the growing season is risky because new seedlings may be overwhelmed by the rapid regrowth of established plants. This is one instance where some judiciously planned overgraz-

ing right before seeding can be helpful to suppress regrowth of existing plants long enough for seedlings to get started. Avoid overseeding in the middle of summer because seedlings will have little chance to establish when water is scarce.

Another low-tech option for adding species to pastures is bale grazing; however, feeding mature hay will add seeds to your pasture whether you want them or not. Make sure you are planting desirable forage seeds from your hay, not weed seeds like thistles.

Regardless of method used, building forage species diversity will pay off with better pastures that hold up under stress and grow more forage for your livestock. •

KIM CASSIDA

Sponsored and Funded by:

February 2024 | hayandforage.com |17

The author is an extension forage and cover crop specialist with Michigan State University.

John E. Baylor Memorial Forage & Livestock Scholarship For current undergraduate students majoring in a field related to growing/feeding forage to livestock. APPLICATIONS DUE: APRIL 1, 2024 afgc.org/fg-foundation/

GRASS UP TO YOUR SHOULDERS

CONSIDER THIS!

Simple roots make soil life complex

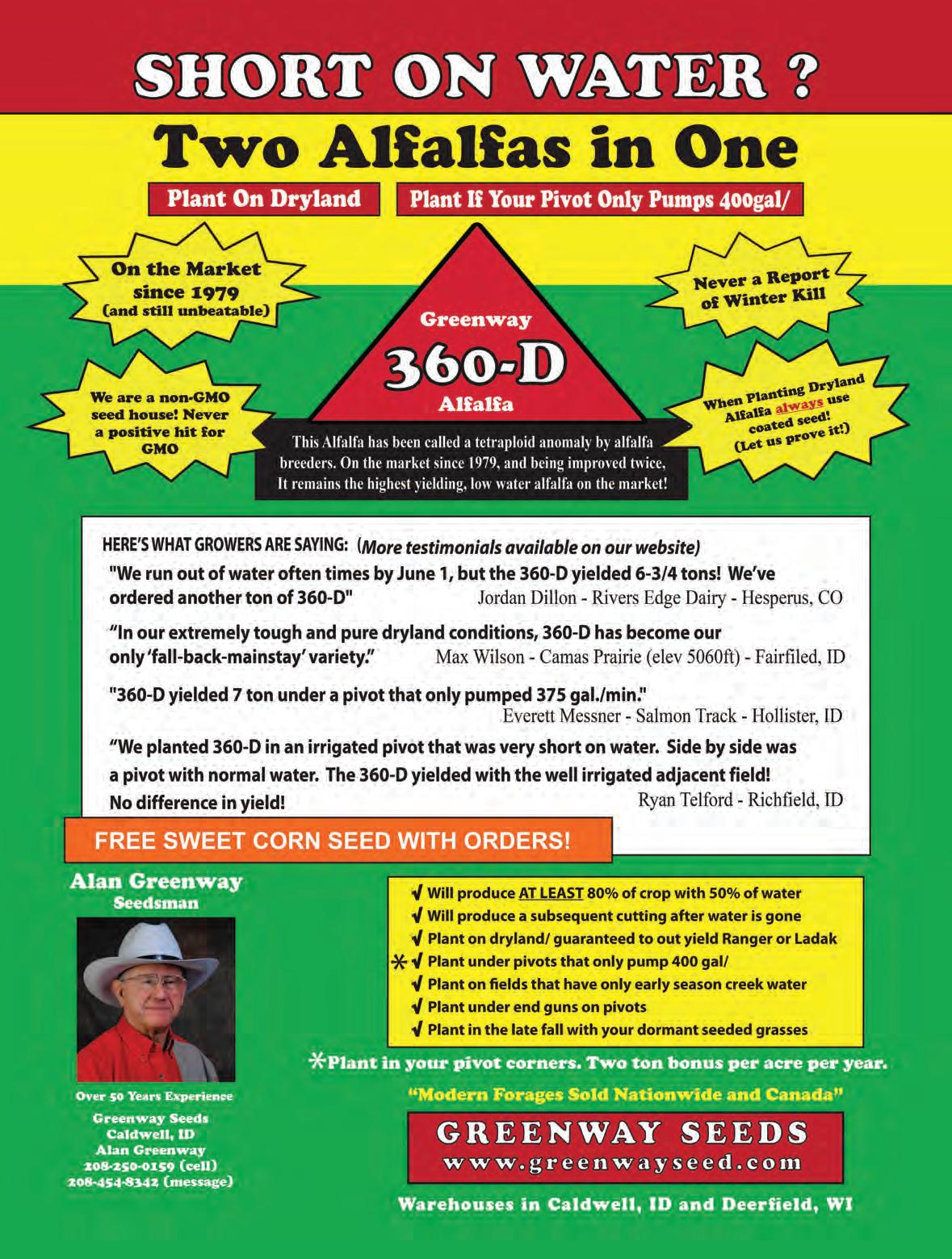

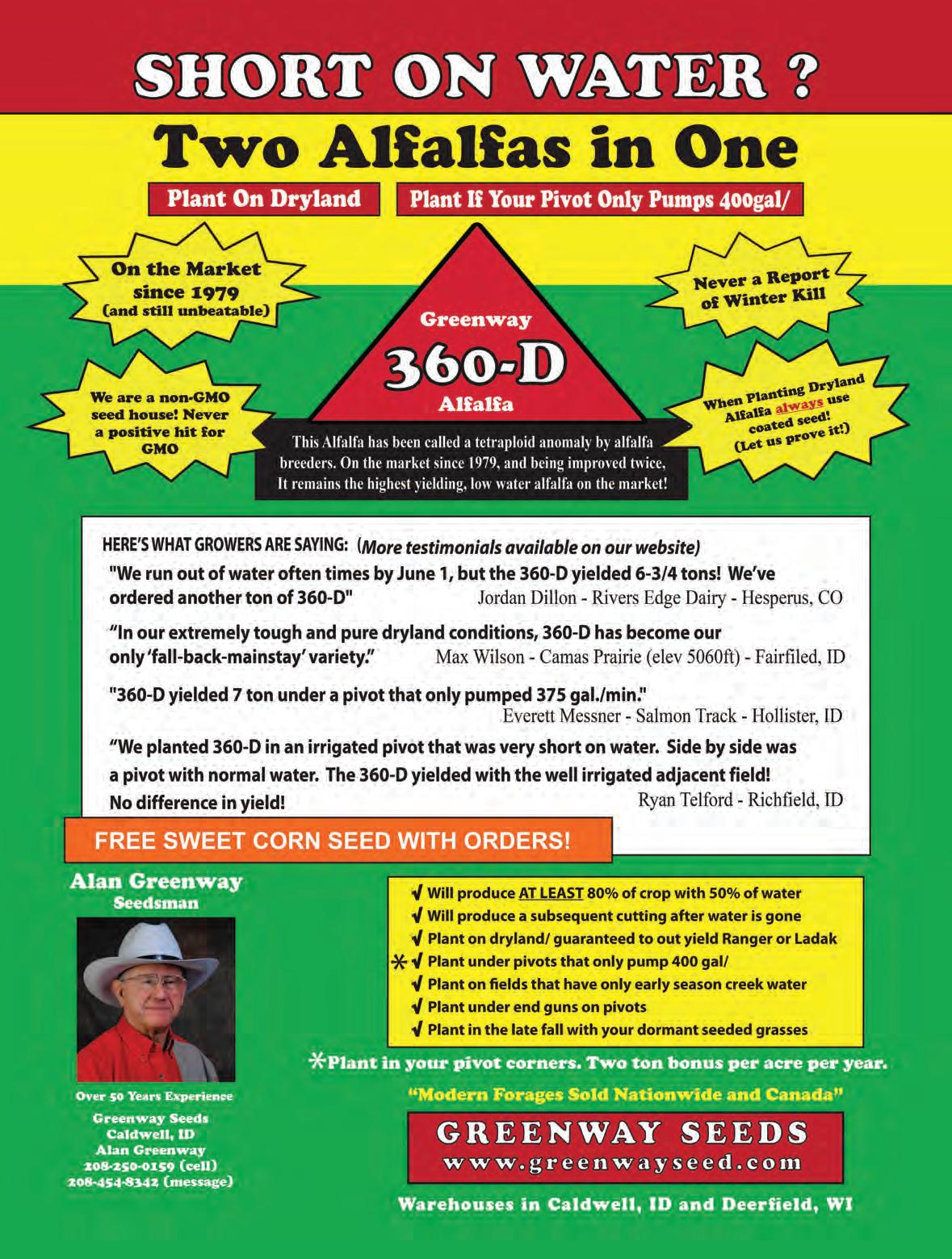

The cost to take out an old stand of alfalfa and re-establish a new stand is GREAT! What if you could plant a varity of alfalfa that would last 10 years and still test well?

That variety is Greenway 360-D. It has been on the market over 30 years, and we know it’s longevity. If you plant 30 lbs/acre, 360-D will test well. It’s Proven!

OUT of sight, out of mind! This adage can certainly apply to our view of soil and the organisms that live in it. So, let’s uncover a key organism in soil — plant roots! Indeed, roots are the hidden half of plants, but they are necessary to perform many vital functions for the forages that help feed our families.

I-84 (Westbound) - Farewell Bend, OR - 150

Here’s What Growers Are Saying:

Roots give plants the structural footing to withstand the tempest wind and the pouring rain. Roots are the conduits for water and nutrients absorbed from soil. Roots are sometimes energy storage repositories for continued growth on a cloudy day. But did you know that roots are also the comforting home and food pantry for many microbial pilgrims that become the necessary allies for flourishing forages?

“We planted 30lbs/acre of 360-D. It tests well, and after 5 years, it is our highest yielding pivot on the hay ranch.”

Small zone big benefits

Kennon Forester - Railroad Valley Hay Co., Nyala, NV

“We planted 360-D back in the 80’s. To the best of my recollection, it lasted between 12-14 years.” Clare Olson - Corral, ID (Camas Praire)

Taking a deeper look into roots and their role in plant health, we should recognize the vital frontier of root exploration in the soil environment. The rhizosphere is a zone only a few millimeters distant from each root boundary. This zone becomes a hotbed of complex interactions that mostly benefit the plant, but it also contains dangerous villains that can cause disease.

“Our area has been in drought for several years. Everyone here is short on water. We only pump 400 gal. on 120 acres. That’s why we planted 360-D. Under that short water, we still yield near normal and the quality is excellent because we plant 35lbs/acre” Dan Sawyer - Clarendon, TX

FREE SWEET CORN SEED WITH ORDERS!

Sweet corn seed with orders!

Over

Alan Greenway Seedsman

Over 50 Years Experience

“The Macbeth did extremely well! We take only one cutting and graze the rest, but it always cuts 3 1/2 ton which is excellent for 6,200 ft.-elev. We normally put 2 windrows together for bailing, but could only bale one windrow on the Macbeth.”

Greenway Seeds Caldwell, ID

Alan Greenway 208-250-0159 (cell) 208-454-8342 (message)

The rhizosphere has several orders of magnitude greater microorganisms than bulk soil. This includes a greater microbial biomass, potentially more microbial diversity, and greater microbial activity. This is because readily available carbon substrates are exuded and slough off from growing plant roots at a high speed, and these foodstuffs feed a frenzy of microbial life. Close association of plants and soil microorganisms is exhibited in grand fashion at this interface.

A wealth of carbon

“Modern Forages Sold Nationwide And Canada”

GREENWAY SEEDS

www.greenwayseed.com

James Willis: Willis Ranch Cokeville, WY

Warehouses in Caldwell, ID and Deerfield, WI

“Modern Forages Sold Nationwide and Canada.”

Microbial growth in the rhizosphere is intense because easily degraded carbon substrates are freely available for short periods of time; therefore, the microbial community present in the rhizosphere is often composed of rapid feeders. Ecologically, we consider them r-strategists that proliferate where organic carbon resources are abundant. In contrast, a more stable community of microorganisms (considered k-strategists) will eventually take over once resources diminish because they have to be diligent in working with more limited and difficult to decompose organic carbon resources.

The bacterial phylum Proteobacteria appears to be the most dominant in the rhizosphere. Other fungal phyla of Ascomycota and Glomeromycota are also key groups engaged in a diversity of root-soil-microbial interactions.

Plant communities, or types of grasses, forbs, legumes, trees, and inherent soil properties, such as texture, pH, and cation exchange capacity, have a large influence on which microbial communities proliferate in the rhizosphere. These factors not only affect the composition and structure of the rhizosphere but also its functional attributes.

Further, the microbial community will change from the

SUNRISE ON SOIL 18 | Hay & Forage Grower |February 2024

FREE

Acres

Greenway Seedsman

Alan

50 years experience!

Seeds Caldwell, ID

Greenway 208-250-0159 (cell) 208-454-8342 (message) GREENWAY SEEDS greenwayseed.com Warehouses in Caldwell, ID and Deerfield, WI Some choose to add 360-D dryland alfalfa for its’ 10–12 year longevity. 5 1/2 Ton/ 1st Cutting (AND WE’RE SHORT ON WATER!) We run out of creek water about June 1, and Macbeth still kicked out the tons. We had to raise the swather to get through it! Of the five meadow bromes on the market, Macbeth is the only one that excels on dryland or low water. A meadow brome will always be your highest yielding grass! Macbeth will have leaves about as wide as barley. *Jerry Hoagland, Seven High Ranch, Reynolds Creek, Owyhee Co, Idaho MACBETH MEADOW BROME GRASS UP TO YOUR SHOULDERS Alan Greenway Seedsman Over 50 Years Experience Greenway Seeds Caldwell, ID Alan Greenway 208-250-0159 (cell) 208-454-8342 (message) GREENWAY SEEDS www.greenwayseed.com “Modern Forages Sold Nationwide And Canada” Warehouses in Caldwell, ID and Deerfield, WI 5 1/2 Ton/1st Cutting (AND WE’RE SHORT ON WATER!) *Jerry Hoagland, Seven High Ranch, Reynolds Creek, Owyhee Co, Idaho MACBETH MEADOW BROME We run out of creek water about June 1, and Macbeth still kicked out the tons. We had to raise the swather to get through it! Of the five meadow bromes on the market, Macbeth is the only one that excels on dryland or low water. A meadow brome will always be your highest yielding grass! Macbeth will have leaves about as wide as barley.

Greenway

Alan

by Alan Franzluebbers

CONSIDER THIS!

intense period of rapid growth when a root tip passes by a particular micro-geographic coordinate in soil to a more diverse community when organic carbon resources are consumed and by-products of decomposition become the more stable organic carbon resource. That is until the next root tip begins to search for nutrients it desires from the decomposition of these shifting microbial communities. It becomes a never ending underground dance of shifting population.

A dynamic environment

CONSIDER THIS!

The cost to take out an old stand of alfalfa and re-establish a new stand is GREAT! What if you could plant a varity of alfalfa that would last 10 years and still test well?

The cost to take out an old stand of alfalfa and re-establish a new stand is GREAT! What if you could plant a variety of alfalfa that would last 10 years and still test well?

That variety is Greenway 360-D. It has been on the market over 30 years, and we know it’s longevity. If you plant 30 lbs/acre, 360-D will test well. It’s Proven!

The rhizosphere is a narrow region of soil (1 to several mm) surrounding most plant roots. It is particularly important as a biologically enhanced region near the tips of actively growing roots. The schematic magnifies the rhizosphere, containing saprophytic (decomposers) and symbiotic bacteria and fungi. Schematic courtesy of Ripley Tisdale, Raleigh, N.C.

That variety is Greenway 360-D It has been on the market over 30 years, and we know it’s longevity. If you plant 30 lbs./acre, 360-D will test well. It’s Proven!

CONSIDER

I-84 (Westbound) - Farewell Bend, OR - 150 Acres I-84 (Westbound) - Farewell Bend, OR - 150 Acres

Here’s What Growers Are Saying:

“We planted 30lbs/acre of 360-D. It tests well, and after 5 years, it is our highest yielding pivot on the hay ranch.”

Kennon Forester - Railroad Valley Hay Co., Nyala, NV

Here’s What Growers Are Saying:

“We planted 30 lbs./ acre of 360-D. It tests well, and after 5 years, it is out highest yielding pivot on the hay ranch.”

“We planted 360-D back in the 80’s. To the best of my recollection, it lasted between 12-14 years.” Clare Olson - Corral, ID (Camas Praire)

The cost to take out an re-establish a new stand is could plant a varity of alfalfa years and still test well? That variety is Greenway the market over 30 years, ty. If you plant 30 lbs/acre, It’s Proven!

“Our area has been in drought for several years. Everyone here is short on water. We only pump 400 gal. on 120 acres. That’s why we planted 360-D. Under that short water, we still yield near normal and the quality is excellent because we plant 35lbs/acre” Dan Sawyer - Clarendon, TX

Kennon ForesterRailroad Valley Hay Co., Nyala, NV

FREE SWEET CORN SEED WITH ORDERS!

“We planted 360-D back

“Our area has been in drought for several years. Everyone here is short on water. We only pump 400 gal. on 120 acres. That’s why we planted 360-D. Under that short water, we still yield near normal and the quality is excellent

Here’s

“We planted 30lbs/acre of 360-D. highest yielding pivot on the Kennon Forester

The rhizosphere has all of the dynamics experienced at the field and global levels, only in miniature. Major disruptions can occur daily with growth of new roots that deposit sugary molecules, more structural carbon molecules, and even signal molecules. Gaping holes can be bored into nearby pores from earthworms burrowing their way to a daily food fest.

Deposition of fecal pellets rich in enzymes and unique growth-stimulating biomolecules might occur randomly from beetle larvae or springtails. Water saturation of pores can suddenly create a drowned aftermath of dead critters following an afternoon deluge or tropical storm.

Ecological engineering at the root level is an active area of research. One idea is to use ecological principles to obtain the most suitable management of an ecosystem. This may be to preserve a condition, such as high fertility and a microbial community able to resist pathogenic invasion, or to restore a condition of historical value and even to create new ecosystems of specific function.

Prospects abound for ecological engineering to engage humanity with its natural environment for a more sustain able future; however, daily life on the farm can be sim ply nurturing the complexity of soil life that masterfully abounds in the presence of a diversity of roots. •

“We planted 360-D back in lasted between 12-14 years.”

“Our area has been in drought water. We only pump 400 Under that short water, we excellent because we plant Alan

ALAN FRANZLUEBBERS

The author is a soil scientist with the USDA Agricultural Research Service in Raleigh, N.C.

February 2024 | hayandforage.com | 19

Greenway Seedsman Over 50 Years Greenway Caldwell, Alan Greenway 208-250-0159 208-454-8342 FREE SWEET CORN SEED WITH Greenway Seeds Caldwell, ID Alan Greenway 208-250-0159 (cell) 208-454-8342 (message) GREENWAY SEEDS greenwayseed.com Warehouses in Caldwell, ID and Deerfield, WI 360-D (Dryland/Low Water Alfalfa)

Training your grazier’s eye

ONE of the tools I have used to assist my grazing management decisions is the pasture inventory. Like any other product inventory, a pasture inventory is a snapshot in time of what forage you have available for grazing on your farm or ranch. In productive environments, such as those with high natural rainfall or irrigated pastures, I like to do a pasture inventory every two weeks. On rangeland, I suggest a monthly inventory.

There are two basic ways to do a pasture inventory. The way I was first taught, back in the 1980s, was based on measuring dry matter yield in the pasture. The most accurate way to estimate yield is to clip a reasonable number of small sample areas, bag the clippings, weigh them, dry them, and then weigh them again. That is the way we did it in research trials.

The sample quadrats we clipped were 2.5 square feet. We cut five to 10 quadrats per sample area. Then we weighed and dried a lot of paper bags of grass clippings. It was tedious, expensive, and not nearly as accurate as we would have liked to believe. The whole process is fraught with opportunities for error. I don’t encourage anyone to actually do this process.

Over the years, we also developed methods of measuring height to estimate yield. Yes, there is a basic relationship that the taller the pasture is, the greater the yield is likely to be. This process led to the creation of the “sward stick.” Since any of these height by yield relationships have to be calibrated to clipping yields, more errors are compounded.

An easier way

The second way to do a pasture inventory is much simpler. It is based on visually estimating how much feed is available in the field. The unit of measure we use is animal-unit days per acre (AUD/A). The standard animal unit is a 1,000-pound animal at a moderate level of performance. If we use 2.6% of body weight as a standard measure of daily intake for moderate production, an animal-unit day is 26 pounds of dry matter of forage consumed. Take the total live weight and divide it by 1,000 to determine the

number of animal units in the herd.

For example, if we have 100 cows weighing an average of 1,200 pounds, and they have 100 calves weighing an average of 300 pounds, we have a total herd weight of 150,000 pounds. Our herd consists of 150 animal units.

You might wonder how a visual estimate can be more accurate than clipping quadrats. Accuracy in visual estimation is based on calibrating your eye based on actual grazing events. You can train your eye to be most accurate if you are doing daily moves with your herds or flocks. You can be fairly accurate with up to weekly moves. Any longer grazing periods and your accuracy will be compromised by the variable recovery rate of the pasture being grazed. Here is how you train your eye to visualize forage availability.

Make repetitive estimates

We look at the pasture and estimate there are 50 AUD/A available. Available in the pasture means we can feed 50 animal units appropriately and leave an adequate amount of postgrazing residual standing in the paddock. We’ve already determined our herd consists of 150 animal units. Simple math says we should give them 3 acres for a one-day grazing period (150 AU divided by 50 AUD/A = 3 acres per day). Using a measuring wheel or a mapping app on our phone, we set up our polywire paddock to be exactly 3 acres.

We come back tomorrow at the same time of day and assess the results of our

first daily allocation. If there are only 2 inches of grass left and we were expecting there to be 4 to 5 inches, we guessed too high. There was more likely only 30 AUD/A available, so now we set up our Day 2 allotment to be 5 acres (150 AU divided by 30 AUD/A = 5 acres per day).

Once again, we come back tomorrow at the same time of day. Now we find we have 6 to 7 inches of grass left in the pasture. Dropping our estimate down to 30 AUD/A was too great of a correction. On Day 3, we estimate there to be 40 AUD/A available so we set up a 3.75acre paddock and check our results the next day.

If this process is repeated, soon we find our pregrazing estimate AUD/A and our corresponding paddock size are giving us the results we are looking for. Back in the 1970s, New Zealand researchers determined 30 repetitions of the process would create a grazier’s eye that was statistically as accurate as the best instruments we have available for measuring pasture yield.

Why is this process so accurate?

Because it is completely based on what actually happened in the pasture. •

JIM GERRISH

The author is a rancher, author, speaker, and consultant with over 40 years of experience in grazing management research, outreach, and practice. He has lived and grazed livestock in hot, humid Missouri and cold, dry Idaho.

THE PASTURE WALK by Jim Gerrish

20 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

Mike Rankin

High-quality hay binding pays for itself

THE offseason is a time of year when you can get unexpected phone calls and possibly a few visits from sales people who are trying to pedal their agricultural wares. After all, it’s the slow season for them, too. However, we often have our days already planned out. So, I’m a firm believer in scheduling a meeting with customers, and I expect my manufacturer sales reps to do the same with me.

Anything could be on the table when a salesperson pulls into your yard: seed, chemicals, fertilizer, twine, net wrap, plastic, and products that might fit the “snake oil” category. There are actually a few things on this list that are worth visiting during the fall and winter. Prepurchasing items can lead to some big savings in comparison to buying during the season.

In this issue’s column, I want to talk about input items that evoke a number of opinions: net wrap, twine, and plastic wrap. We all have the experience by now of finding the “best deal” available. After the purchase, we regret this decision due to the poor quality of a cheaper product. I once saw a stack of dry hay on the side of a field with no visible net wrap on any of the 70 bales in the row. When I asked the farmer what had happened, he went on a cussing tirade. He told me everything was fine the day they baled and

moved bales to the edge of the field, but after sitting in the Georgia sun for four months, all the bales started breaking open because the net had deteriorated. Talk about a nightmare!

Know what you’re buying

There are various brands and grades of net wrap. It is important to do your homework and research the brands you are getting prices on. If you can examine the net wrap before you purchase it, that’s a big plus as well. You might be able to get by with a lower quality net when you are putting up baleage and wrapping it in plastic because it’s the latter that is holding the bale together. You just need enough net on the bale to get it from the baler to the wrapper. Also, I do not think that edge-cover net wrap does as much good when wrapping in plastic. In my mind, you are just wasting money on a 51-inch roll when a 48-inch roll would suffice.

When putting net wrap on dry hay or straw, it’s a different story. This is where the cheaper material can get you in trouble. You should take into consideration how many times you are going to handle these bales before they are fed. Also, where will they be stored and for how long? The answers to these issues will affect what net wrap you purchase and how many wraps should

be put on a bale.

We’ve had some hay bales sold off our farm that had a spear stuck in them seven times before they made it to the cows. Needless to say, good-quality wrap is needed in that situation with several wraps on each bale. Another thing we found is that we preferred the 48-inch net wrap on bales stored inside versus a 51-inch product. This is mainly due to the cover edge always tearing off. We stacked our bales four-high on the flat, and when we took the stack down, the edge would tear and always be in the way.

The twine that binds

Twine can cause the same binding issues as net wrap, though in a different way. Most of the time you have trouble with cheaper twine while you are baling. This mainly translates to knotter issues, and on a hot day, that can make some tempers flare. We chose to always stick with a higher quality twine on our two-tie balers, and we also found that once we stepped up from 130 to 150 or 170 knot strength twine, we had fewer issues. This boils down to the knots not holding on the lower strength twine when the bale left the chamber. This same problem can occur on big square bales. With dry hay and straw, you will tend to have fewer issues with a high-strength twine. You are simply not stressing the twine to its limit on each bale. Perhaps just as important, you are also not stressing your baler operator as much.

We have upgraded several of our customers to high knot strength twine and high-quality net wrap. Yes, it was more expensive, but all have said that they have had less downtime and better bales, so the few pennies more that it costs is well worth it.

Take time this offseason to research your net wrap and twine. Prices have settled a little bit compared to last year, so this may be a good time to upgrade, if needed. I think you’ll see and experience the difference. •

ADAM VERNER

The author is a managing partner in Elite Ag LLC, Leesburg, Ga. He also is active in the family farm in Rutledge.

FORAGE GEARHEAD by

February 2024 | hayandforage.com | 21

Adam Verner

Mike Rankin

By Gail Carpenter

DRY COWS ARE FORAGE SINKS

IN THE face of rising feed prices, dairy producers are seeking opportunities to feed low-cost forages now more than ever. When working with producers to determine options for incorporating different forages into their dairy diets, dry cows and heifers provide a convenient sink for some lower quality forages. It is crucial to emphasize that the term “lower quality” refers to forages characterized by poor fiber digestibility and low nutrient value, not high levels of molds or toxins. Care should be given during harvest and storage to keep the feed clean and free of mold growth.

Establishing the groundwork for a successful lactation begins with ensuring the proper nutrition of dry cows. There are as many ways to feed and manage dry cows as there are dairy farms; however, there are three key features of successful dry cow feeding:

• Avoid overconditioning dry cows

• Promote feed intake during the transition period

• Ma nage the calcium demands of the fresh period

Lactating dairy cattle have a heightened demand for energy, especially before and around peak lactation, and thus require high-quality forages with limited undigestible fiber. However, the scenario shifts for dry cows, particularly far-off dry cows more than three weeks out from expected calving. At this point, the emphasis shifts to “filler” forages, with straw being a common example. Filler forages are characterized by low fiber digestion and typically lack significant protein or starch. Their primary function is to provide rumen fill and satiety without contributing excessive energy that could lead to gains in body condition.

Keep an eye on intake

When feeding filler forages to dry cows, keep the second rule of successful dry cow nutrition in mind: Promote feed intake during the transition period. The amount the cow is eating is equally as important as what she is eating out of a total mixed ration (TMR). Like the lactating cow diet, a perfectly balanced

dry cow ration loses its efficacy if cows sort through it. Manage feed to minimize sorting to best utilize filler forages in the diet, and ensure cows are able to access the feedbunk at will.

Strategies for minimizing sorting are especially important when using filler forages, including alternative forages, because these lower quality forages will often be stemmy, making it easier for cows to sort around them. Grinding these feeds is typically recommended because they are tougher and may not break down adequately in the wagon during mixing.

Routinely monitor the TMR for long particles in dry cow diets. While less than the width of a cow’s nose is a common rule of thumb for maximum particle length, chopped forages as short as 1 inch can provide sufficient effective fiber while minimizing sorting behavior. Additional techniques to reduce sorting include incorporating liquids like water or molasses into the diet and consistently pushing up feed throughout the day.

DAIRY FEEDBUNK

22 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

Mike Rankin

Beyond feed management, facilities also impact feed intake by dry cows. Dry cows must always have access to the feedbunk, and animals should not be overstocked, particularly in the last three weeks before calving. Remember that heavily pregnant dry cows require more bunk space. Dry cow facilities must be designed and managed such that cows have cooling, clean bedding and water, and secure footing. Anything introducing a psychological barrier to a cow’s comfort during feeding ultimately hampers her feed intake during this critical period.

Calcium is key

Preventing milk fever by meeting the calcium demands of the fresh period starts before calving. Often, this is accomplished by feeding a negative dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD) in the last three weeks before expected calving. Calculating DCAD is done by adding the major cations (potassium and sodium) and major anions (chloride and sulfur) in

the diet and subtracting the anions from the cations. Anions are often incorporated into the diet to achieve a negative value in the equation.

Forages are major contributors of various minerals to the diet, including the ones that are important for managing calcium, such as calcium itself. Potassium in particular is often high in many forages, which will improve the dietary anions that counterbalance dietary cations. Therefore, understanding the mineral contributions of forages is critical for managing calcium around calving.

I had the opportunity to feed switchgrass hay to dry cows through a grant funded by the Ontario Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Rural Affairs, to study the inclusion of alternative forages into dry cow diets. We compared a TMR with switchgrass hay as the filler forage to a similar dry cow diet that included straw. We ground both the switchgrass hay and the straw to relatively short particle lengths (1 to 2 inches).

Part of the success we had when feed-

ing switchgrass hay was that there was minimal spoilage. Switchgrass hay also had an advantage over straw because it was lower in potassium, making it easier to achieve a negative DCAD.

Taking a broader perspective, switchgrass is cheaper than straw, it can grow on marginal land, and it improves soil health. This example highlights the potential of creative and informed utilization of alternative forages in dry cow diets. By adhering to foundational principles and embracing innovative approaches, dairy farmers can effectively control feed costs while safeguarding cow health and welfare. •

February 2024 | hayandforage.com | 23

GAIL CARPENTER

FIRST THING I’VE GOT TO DO IS SQUIRREL. AND THEN I’VE GOTTA SQUIRREL. AND AFTER SQUIRREL, I NEED TO SQUIRREL. WE HAVE YOUR BACKS, BARNS AND BOTTOM LINES. *Rozol ground squirrel bait is a restricted use pesticide Ground

distracting you from your daily to-dos? Minimize the squirrel moments with

REGISTERED FOR USE IN: CA, ID, MT, ND, NV, SD, UT, WA & WY

The author is an assistant professor and extension dairy specialist at Iowa State University.

squirrels

Rozol Ground Squirrel Bait.*

Restoring rangeland at Ritter Ranch

by Amber Friedrichsen

FROM the ripe old age of 5 years old, Mike Williams knew he wanted to be a rancher. The U.S. Army veteran grew up on a farm in Idaho, and after serving in the military for nearly a decade, he moved to Southern California to work as a cowboy. Then Williams and his wife, Lynda, established Diamond W Cattle Company when they started raising cattle of their own.

The couple used to rent property outside of Ventura before the Thomas Fire swept through and scorched the area right before their lease expired in 2017. Rather than resign the contract and try to recover the range, Williams turned his attention to another piece of land just a few miles west of Palmdale.

Ritter Ranch comprises more than 12,000 acres that stretch up the San Andreas Fault and peak at approximately 5,000 feet above sea level. It is named for the first homesteaders who settled there in the late 1890s to grow

grapes, keep bees, make hay, and graze cattle. The property was later purchased by a development company and essentially abandoned until Williams started renting it and running his herd there.

The topography of Ritter Ranch poses some challenges from a grazing perspective, and the consistent drought conditions in an already arid climate put a major damper on plant growth. Nonetheless, Williams is gradually updating infrastructure by repairing permanent fences and installing solar water pumps across the pastures, and he is learning how to implement lowstress cattle handling and strategic forage management to transform a rundown ranch into productive rangeland.

A push for perennials

Instead of a permanent pasture base of perennials, Ritter Ranch is primarily covered in cool-season annuals. Legumes like filaree and rabbitfoot clover pop up between stands of wild oats and soft chessgrass. The forage greens up in late winter and early spring after

the area receives most of its annual rainfall, but then plants go dormant for the rest of the year.

“Our real forage growth begins at the end of February when it starts to warm up,” Williams said. “Then you have March, and by April, the forage starts to dry out. It’s a pretty short growing season, and it can vary. But generally speaking, you get what you get during that time.”

Cattle readily graze these annual species, and Williams has found the plants provide adequate nutrition for cows to maintain body condition through most of the summer. But forage doesn’t regrow once it is defoliated, and cattle only pass through each part of the pasture one time during the year-long rotation. Come fall calving season, animals struggle to consume enough energy to support lactation and rebreeding.

“A dry cow can maintain herself through fall and into the winter here, but not a lactating one,” Williams said. “I was fall calving in Ventura, but I am switching to spring calving after

24 | Hay & Forage Grower | February 2024

Amber Friedrichsen

figuring out that wasn’t a good strategy. I didn’t start calving until the beginning of 2023, and I’m going to try and move that date back into February, and eventually March.”

In addition to shifting his calving schedule, Williams wants to encourage the establishment of more perennial species to ensure greater forage availability for his cattle. To do this, he has been letting animals overgraze the rangeland during each rotation to reduce ground cover. This, in combination with the extremely dry growing conditions, has seemed to improve the success rate of natural reseeding of plants like purple needlegrass.

“Believe it or not, I think the drought is actually helping establishment a little bit,” Williams shrugged. “When there is not as much forage available, the cows will graze until there is hardly any thatch. Perennials tend to grow better when they don’t have to try as hard to compete with the chessgrass and other cool-season annuals.”

Herding habits

Williams does not have a comprehensive system of cross fences to divide his property into rotational grazing paddocks, but because of the way he handles his cattle, he doesn’t need them. He practices a low-stress herding technique that relies on animals’ fight-or-flight instincts. The approach is inspired by the teachings from cattle handling expert Bud Williams, which the curious rancher read about in a book called “Stockmanship: A Powerful Tool for Grazing Lands Management,” by Steve Cote.

“Using Bud’s principles, Cote found if you handle animals carefully and gather cattle in a more practical way, they will stay where you move them. They associate the journey with the place,” Williams said. “You know how well you herded cattle by how well they stayed together when you come back to check on them the next day.”

On horseback, Williams calmly corrals cattle by riding in the opposite direction he wants them to go. This allows animals to move forward on their own as opposed to feeling forced if Williams followed them from behind. As long as they have a positive herding experience, animals don’t retreat to the previous part of the pasture, and they tend to stay where they were placed for two to three days. This tactic has made cows easier to manage, especially during

calving season and weaning. Williams has also noticed the herd grazes forages more evenly, which is ideal for promoting more perennial species.

“Herding pays off in your cattle, and it pays off in your pasture,” he said.