and the ORIGINS OF MADE IN ITALY

curated by Neri FadigatiG.B. Giorgini

and the ORIGINS OF MADE IN ITALY

curated by Neri Fadigati

INDEX /INDICE

- first - second - third - fourth - fifth - sixth - seventh - eighth - ninth - tenth - eleventh - twelfth

between → pp. 32-33 between → pp. 48-49 between → pp. 64-65 between → pp. 80-81 between → pp. 96-97 between → pp. 160-161

FOREWORDS

ROBERTO CAPUCCI

FERRUCCIO FERRAGAMO

President of Polimoda

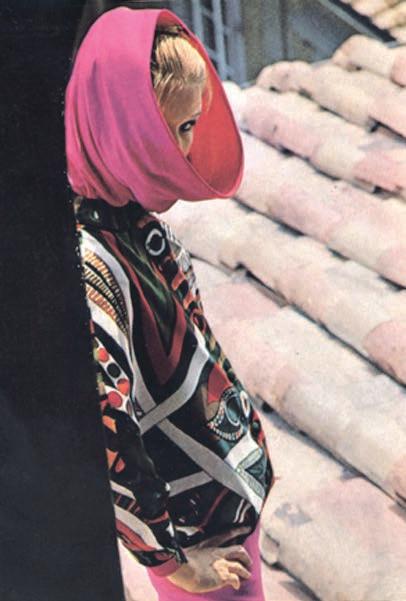

Taylor, artist, creator of sculpture gowns LAUDOMIA PUCCI

President of Emilio Pucci Heritage

INSERT ANTONELLA MANSI

Chairman of Centro di Firenze per la Moda Italiana

BRUCE PASK

Men’s Fashion Director - Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus

EUGENIO GIANI

President of Regione Toscana

→ p. 8 → p. 10 → p. 12 → p. 14 → p. 17 → p. 18

THE GIORGINIS, SIX GENERATIONS AT THE SERVICE OF THE COMMUNITY.

/ I GIORGINI, SEI GENERAZIONI AL SERVIZIO DELLA COLLETTIVITÀ.

by ROMANO PAOLO COPPINI

GIOVANNI BATTISTA GIORGINI, THE FAMILY TRADITION AND THE VISION OF THE FUTURE.

/ GIOVANNI BATTISTA GIORGINI, LA TRADIZIONE DI FAMIGLIA E LA VISIONE DEL FUTURO. → p. 22

→ p. 21 by NERI FADIGATI

ITALY AT WORK, FROM CRAFTSMANSHIP TO FASHION.

/ ITALY AT WORK, DALL’ARTIGIANATO ALLA MODA

by DANIELA CALANCA

THE AMERICAN REJECTION AND THE FIRST ITALIAN HIGH FASHION SHOW IN FLORENCE.

/ IL RIFIUTO AMERICANO E LA PRIMA SFILATA DI ALTA MODA ITALIANA A FIRENZE.

→ p. 40 by GIAN LUCA BAUZANO

THE SALA BIANCA AND THE TAILORS PROTAGONISTS OF SUCCESS.

/ LA SALA BIANCA E I SARTI PROTAGONISTI DEL SUCCESSO.

→ p. 56 by EVA DESIDERIO

THE ROLE OF THE UNITED STATES, THROUGH TRADE AND DIPLOMATIC CHANNELS.

/ IL RUOLO DEGLI STATI UNITI, TRA COMMERCIO E DIPLOMAZIA.

→ p. 82 by SONNET STANFILL

THE ITALIAN FASHION SHOWS AND THE AMERICAN PRESS: FASHION AND MARKETING.

/ LE SFILATE ITALIANE E LA STAMPA AMERICANA: MODA E MARKETING.

→ p. 158 by GRAZIA D’ANNUNZIO

THE EVENTS OF ITALIAN FASHION ABROAD.

/ LE MANIFESTAZIONI DELLA MODA ITALIANA ALL’ESTERO.

LIST OF FASHION HOUSES / LISTA CASE DI MODA

INSIGHTS / APPROFONDIMENTI CONTRIBUTORS

BIBLIOGRAPHY & SITOGRAPHY / BIBLIOGRAFIA & SITOGRAFIA

→ p. 178

→ p. 146 by NERI FADIGATI

→ p. 198

→ p. 206 → p. 218 → p. 220

THE VISION AND COURAGE OF GIOVANNI BATTISTA GIORGINI

I was 20 years old. I had graduated from art school in Rome and I was attending the Academy of Fine Arts, but my secret dream was to design clothing. I designed a lot of clothes, without having any experience as a dressmaker, but by translating my ideas into garments, as if they were sculptures or paintings. A creative trend that has accompanied me throughout my whole career. I designed a few outfits for my girlfriends and my cousin. They stood out because of their originality.

One day, a journalist who covered traditional craftsmanship, Maria Foschini, spoke to me about a Florentine gentleman, Giovanni Battista Giorgini, who was in the business of exporting objects of high craftsmanship mostly to the United States and had brought together Italy’s greatest names of fashion design to create an “ Italian style” by sending them down the runway at his residence, Villa Torrigiani, and inviting the most important American buyers who enthusiastically welcomed this initiative. He asked me to show him my drawings, for he wished to find and launch young talented fashion designers. And so, just like that, I found myself thrown into the great world of fashion, amongst the most illustrious names. Giorgini planned to send my creations down the runway at the 2nd Italian High Fashion Show held at Florence’s Grand Hotel. However, not everything went smoothly. The other designers taking part in the show were annoyed by not having been informed and consulted by Giorgini, who relied on the surprise factor, and got in the way. That seemed to be the end to it, but it was not so. Giorgini believed in me and did not want to spoil my chances. So, he invited me to the party following the fashion show and his wife and daughter wore the outfits I had designed for them. It was a huge success and I also met Oriana Fallaci. At the next fashion show, the first one held at the Pitti Palace, I was officially part of the team. My ‘senior’ colleagues welcomed me into their family and I established a real friendship with some of them, such as Simonetta Visconti di Cesarò. Those were wonderful years for me. The fashion shows, the photo shoots set in Florence and, above all, the tours all over the world: United States, South America, Europe, even the former Soviet Union. Italian fashion was seen as opposed to French fashion. Everything that followed was initiated in Florence on Via dei Serragli, on February 12 and 14, 1951, by the vision and bravery of a man: Giovanni Battista Giorgini. I will be eternally grateful to him for all he has done not only for me, but mostly for the Italian ‘fashion system’ as a whole. When Giorgini’s name was at risk of falling into oblivion, I greatly appreciated his grandson Neri Fadigati’s attempt to reverse the situation and do justice to his grandfather’s legacy. I was always available to help him out in any way, since the exhibition Le Origini del Successo, held in 2001 at Florence’s Ente Cassa di Risparmio, for which I created a sculpture-dress, which is now kept at the Giorgini Archives.

/ Avevo venti anni. Diplomato al liceo artistico di Roma cominciavo a frequentare l’Accademia di Belle Arti, ma il mio desiderio segreto era quello di creare abiti. Ne disegnavo tantissimi, senza avere alcuna esperienza sartoriale, tentando di tramutare in vestiti le mie idee, come fossero sculture o dipinti. Un trend creativo che mi ha accompagnato durante tutta la mia carriera. Facevo qualche abito per le mie amiche e mia cugina. Piacevano per la loro originalità. Un giorno una giornalista che si occupava di artigianato, Maria Foschini, mi venne a parlare di un gentiluomo fiorentino, Giovanni Battista Giorgini, che si era occupato fino a quel momento di esportazione di oggetti di alto artigianato, principalmente negli Stati Uniti. Giorgini aveva riunito le più importanti sartorie del tempo chiedendo loro di creare uno ‘stile italiano’ e aveva fatto sfilare i modelli nella sua residenza di Villa Torrigiani. Gli importanti compratori americani invitati, tutti clienti del suo buying office, avevano accolto l’iniziativa con entusiasmo. Mi propose di portargli i miei disegni, visto che era alla ricerca di nuovi talenti da lanciare. Mi ritrovai così proiettato nel grande mondo della moda, tra i nomi più importanti. Giorgini decise di farmi sfilare alla seconda edizione dell’Italian High Fashion Show che si svolgeva al Grand Hotel di Firenze. Non tutto però andò liscio. Gli altri partecipanti, contrariati dal fatto di non essere stati avvisati da Giorgini, che puntava sul fattore sorpresa, si misero di traverso. Sembrava tutto finito, ma non fu così. Il patron credeva in me e ci teneva a non bruciarmi. Così mi invitò al ricevimento dopo la sfilata e sua moglie e le sue due figlie indossarono gli abiti che avevo fatto per loro. Fu un successo e nell’occasione conobbi Oriana Fallaci. Mi ritrovai così la stagione successiva, la prima a Palazzo Pitti, ufficialmente inserito nel gruppo. I colleghi più ‘anziani’ mi accolsero tra loro e con qualcuno coltivai anche una sincera amicizia, come con Simonetta Visconti di Cesarò. Furono anni splendidi.

Le sfilate, i servizi fotografici ambientati nella cornice storica di Firenze, ma sopratutto le tournée in giro per il mondo: Stati Uniti, Sud America, Europa, perfino nell’allora Unione Sovietica. La moda italiana era una realtà in contrapposizione alla moda francese. Tutto ciò che è venuto dopo era nato a Firenze, in via de’ Serragli il 12 e il 14 febbraio del 1951, da una visione e dal coraggio di un uomo: Giovanni Battista Giorgini. Gli sarò sempre grato per tutto ciò che ha fatto non solo per me ma per il ‘sistema moda’ italiano in generale. Quando il suo nome rischiò di finire nel dimenticatoio ho molto apprezzato l’opera svolta da suo nipote Neri Fadigati mirata a ribaltare questa situazione e rendere giustizia all’immagine di suo nonno e mi sono sempre reso disponibile ad aiutarlo in questa missione, sin dai tempi della mostra Le Origini del Successo, che si tenne nel 2001 all’Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, per la quale creai un abito scultura che oggi è ospitato nell’Archivio Giorgini.

ROBERTO CAPUCCI

On July 22, 1952 the Sala Bianca of the Pitti Palace opened its doors to foreign journalists and buyers who had come to watch the Italian fashion shows, enshrining its success. Although the initiative conceived and organised by Giovanni Battista Giorgini was in its fourth iteration, this moment marked the true birth of Italian style, the point at which the fashions of the Bel Paese became inextricably associated with the Italian culture, art and craftsmanship that this place represented.

Giorgini’s intuition was the fruit of a long reflection that he had often shared with my father Salvatore Ferragamo, a friend for whom he had great respect. Both knew a lot about the American market, at which Italy’s products were targeted. Giorgini had begun promoting Italian art, antiques and crafts in the US in the 1920s. My father had become famous during these same years in California, opening a bespoke footwear store in Hollywood which had become a mecca for the divas of the nascent American film industry. In 1927 he had returned to Italy and settled in Florence, choosing this city precisely because it was regarded as the cradle of Italian art and crafts and synonymous with the culture of savoir faire and good living with which Italy was associated.

WHe had first got to know Bista, as Giovanni Battista Giorgini was known to his friends, in this period, and had been quite impressed with his class and intelligence. For this reason, he didn’t hesitate to accept his invitation to take part in the first Italian fashion show in his Florentine residence, Villa Torrigiani, open to an audience of journalists and buyers from the most important American department stores, on February 12, 1951. There were very few household names in attendance. Apart from Sorelle Fontana, Emilio Schuberth and Emilio Pucci, the designers present all represented new fashion houses. Established tailors were unwilling to put their reputations on the line in an enterprise which at that time looked like a shot in the dark. However, well aware of Giorgini’s extensive experience and credibility, my father was more than happy to help out his friend, creating special shoes for the occasion to go with the dresses of Schuberth. Called Kimo, the sandals were inspired by both renaissance footwear and the Japanese tabi shoes. They consisted of a kitten heel formed from strips of leather to be worn with a satin or leather sock in contrasting material and colour. My father’s dream of making Florence a hub of culture and fashion on a par with Paris had finally become reality. Not many people know that in 1949 Salvatore Ferragamo had talked to Christian Dior, while the latter was visiting Florence, about the possibility of creating a fashion palace in the city to host international fashion shows, because at that time the thought of there being an ‘Italian style’ was inconceivable.

Year by year Ferragamo continued to play an active role in Florence’s fashion shows, strengthening its long association with the arrival in the Sala Bianca, in January 1965, of the collections of my sister Giovanna, who had begun to dedicate herself to prêt-à-porter in 1959 and who would be a mainstay at the prestigious venue until 1982, the final year in which the Sala Bianca of the Pitti Palace opened its doors to the world of fashion.

Though the headquarters of women’s fashion later moved to Milan, Florence maintained its vocation for fashion thanks to the many Pitti Immagine initiatives in support of men’s and children’s fashion, the creation of a state museum dedicated to clothes and fashion at the Pitti Palace, where it all began, and in particular to the opening in the city of schools designed to shape the new creatives of the future. It makes me really proud then that one of these institutions, Polimoda, of which I am Chairman, has agreed to promote this book to celebrate, 70 years on, the genius of Giovanni Battista Giorgini and the Sala Bianca of the Pitti Palace, the venue tasked with spreading that aura of prestige which from fashion has become associated with all Made in Italy products, making them so special and coveted across the world.

I hope that these pages can be an inspiration to the younger generation and that, today just as yesterday, emerging talent and creativity can bring new impetus and dynamism to our industry.

THE IDEA DIDN’T COME TO FRUITION AT THIS TIME BUT THANKS TO GIORGINI’S PERFECT ORGANISATIONAL WORK AND DIPLOMACY IT WAS BECOMING A REALITY, ADOPTING A CLEAR MADE IN ITALY CONNOTATION AND LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR A VENTURE OF FAR GREATER SIZE AND ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE.

/ Il 22 luglio 1952 la Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti apriva le porte ai giornalisti e ai compratori stranieri venuti ad assistere alle sfilate di moda italiana, sancendone il definitivo successo. Sebbene l’iniziativa ideata e organizzata da Giovanni Battista Giorgini fosse già giunta alla sua quarta edizione, è solo in quel momento che nasce davvero lo stile italiano, quando l’immagine della moda del Bel Paese si lega indissolubilmente a quello della cultura, dell’arte e dell’artigianato italiano che quel luogo rappresentava.

L’intuizione che Giorgini aveva avuto era il frutto di una lunga riflessione che aveva spesso condiviso con mio padre Salvatore Ferragamo, di cui era estimatore e amico. Entrambi conoscevano bene il mercato americano, al quale la produzione italiana era diretta. Giorgini aveva iniziato negli anni Venti la sua attività di promozione negli Stati Uniti dell’arte, dell’antiquariato e dell’artigianato italiano. Mio padre era diventato famoso negli stessi anni in California, aprendo un negozio a Hollywood di calzature su misura che era diventato il punto di riferimento delle dive del nascente cinema americano. Nel 1927 era tornato in Italia e si era stabilito a Firenze, scegliendo questa città proprio perché era ritenuta la culla dell’arte e dell’artigiano italiano e sinonimo di quella cultura del saper fare e della piacevolezza di vivere che si riconosceva all’Italia. Già in quel periodo aveva avuto modo di conoscere Bista, come era chiamato Giovanni Battista Giorgini dagli amici, e ne aveva apprezzato l’ingegno e la signorilità. Per questo motivo non esitò a rispondere con entusiasmo al suo invito di partecipare il 12 febbraio 1951 alla prima sfilata di moda italiana nella sua dimora fiorentina, Villa Torrigiani, di fronte a una platea di giornalisti e buyer dei più importanti department store americani. I nomi conosciuti erano pochi. A parte le Sorelle Fontana, Emilio Schuberth ed Emilio Pucci, i sarti e le sarte presenti rappresentavano tutte giovani firme. Le sartorie affermate non avevano voluto mettere a rischio la loro credibilità in un’impresa, che appariva in quel momento un salto nel vuoto. Mio padre, invece, fu ben felice di dare una mano all’amico, di cui conosceva la grande esperienza e credibilità, creando per l’occasione delle calzature speciali da accompagnare agli abiti di Schuberth, dei sandali, chiamati Kimo, che richiamavano da un lato le calzature rinascimentali e dall’altro i tabi giapponesi. Erano caratterizzati da un sabot a listini di pelle da indossare con una calzetta abbinata in raso di seta o in pelle in colore e materiale contrastante. Mio padre vedeva finalmente concretizzarsi quello che era stato anche un suo sogno, far diventare Firenze un centro della creatività e della moda al pari di Parigi. Non molti sanno che nel 1949 Salvatore Ferragamo aveva ipotizzato con Christian Dior, in visita a Firenze, la possibilità di creare in città un palazzo della moda, aperto alle sfilate internazionali, perché in quegli anni non era neppure immaginabile uno stile italiano. L’idea allora non era andata in porto, ma grazie al grande lavoro di perfetta organizzazione e di diplomazia svolto da Giorgini, stava diventando realtà, prendendo una chiara connotazione Made in Italy e dando inizio a un percorso dalle proporzioni e dalle conseguenze economiche ben più ampie e significative.

Anno dopo anno l’azienda Ferragamo continuò a prendere parte attiva alle sfilate fiorentine, rafforzando l’antico legame con l’ingresso in Sala Bianca, nel gennaio del 1965, delle collezioni di mia sorella Giovanna, che dal 1959 aveva iniziato a dedicarsi al prêt-à-porter, e continuerà a essere presente nella prestigiosa sede fino al 1982, ultimo anno in cui la Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti accoglierà il mondo della moda. Nonostante la moda femminile abbia scelto in seguito di rappresentarsi a Milano, la vocazione di Firenze alla moda si è mantenuta intatta grazie alle tante iniziative di Pitti Immagine a sostegno della moda maschile e dell’infanzia, alla creazione di un museo statale dedicato al costume e alla moda a Palazzo Pitti, dove tutto era iniziato, e soprattutto grazie alla nascita in città di scuole dedicate a formare i nuovi creativi del futuro.

Sono dunque orgoglioso che proprio una di queste istituzioni, il Polimoda, che rappresento come Presidente, si sia fatto promotore di questo volume che ha l’obiettivo di celebrare a settant’anni di distanza il genio di Giovanni Battista Giorgini e la Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti, quale luogo deputato a diffondere quell’aura di prestigio che dalla moda si è propagata a tutti i prodotti Made in Italy, rendendoli speciali e desiderati nel mondo.

Mi auguro che in queste pagine i giovani possano trovare tanti stimoli e la riprova che in un continuum con il passato, il talento emergente e la creatività danno nuovo impulso al settore. Oggi come allora.

FERRUCCIO FERRAGAMO

President of PolimodaEmilioPucci 1953

I remember my father’s stories well about this extraordinary period in history for Italy. After the war there was a desire to start again, to rebuild. Those were the years of the Italian miracle, which came about thanks to men and women I consider true heroes. Men and women whose best years had been taken away by the war and who were ready to start again stronger than before with their great courage and enthusiasm. One of Giorgini’s biggest merits was to bring them together, calling upon some already established names such as my father’s, to act as a driving force and appeal for the American press. From that marvellous room in a palace still surrounded by rubble, these incredible figures supported one another to create an entire universe, Made in Italy, which has made Italy huge all over the world. I have always been fascinated by the complicity of the fashion shows in the Sala Bianca (everyone had their own vocation: some wore dresses, some hats, some shoes... my father’s own creations walked several times with Salvatore Ferragamo’s, who he was very close to) and the great ability to adapt and improvise. It is amazing to see what these men managed to do with what today would be considered very little resources, making progress in an Italy that still did not value fashion, viewing it at best as an imitation of Paris’ style. Confirming how fragile the concept of fashion still was, my father signed his first collections under the name ‘Emilio’ and only a few years later did his full name appear.

When Giorgini called him for the fashion show in 1951, he had already launched his collection in department stores in the United States three years prior and opened a boutique at Canzone del Mare on Capri called ‘Emilio Original Sportswear’. In 1947, in Zermatt, Harper’s Bazaar (USA) photographer Toni Frissell shot a young American woman wearing a ski suit my father had created for himself. And it was the editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland who, also in 1947, convinced my father to design a ski collection that would later be produced in America and sold to Lord & Taylor. Actually, my father was initially surprised by the request and replied to Diana ‘I don’t design collections, I am an officer in the Italian air force!’, but in the end she won him over. So, he soon returned to Florence where, even before the fashion shows, he opened a small workshop lured by the hands and great craftsmanship that had also inspired Giorgini. He was very happy to seize the opportunity that Bista gave him: to showcase Italy through his prints and his colours, through his voice and his style, a style unlike any other, which had nothing to do with prêt-à-porter or Parisian high fashion, bringing his ‘Original Sportswear’ to the Sala Bianca. They were brave visionaries who committed themselves to their work with passion and joy. I believe that the new generations can learn from a great lesson from their examples and they can be an important source of inspiration.

/ Ricordo bene i racconti di mio padre su quello che è stato un periodo storico straordinario per l’Italia. Superata la guerra c’era voglia di ricominciare, di riscostruire. Furono gli anni del miracolo italiano, avvenuto grazie a uomini e donne che considero dei veri e propri eroi. Uomini e donne a cui la guerra aveva portato via gli anni migliori e che erano pronti a ripartire più forti di prima, con grande coraggio e entusiasmo. Uno dei più grandi meriti di Giorgini fu quello di riunirli chiamando, tra questi, nomi già affermati come quello di mio padre, che facessero da traino e richiamo anche per la stampa americana.

Da quella meravigliosa sala, in un palazzo ancora circondato dalle macerie, queste figure incredibili, sostenendosi a vicenda, hanno creato un intero universo, il Made in Italy, che ha reso grande l’Italia nel mondo.

Delle sfilate nella Sala Bianca mi ha sempre affascinato la complicità - ognuno aveva la sua vocazione: chi gli abiti, chi i cappelli, chi le scarpe… le creazioni stesse di mio padre sfilarono più volte con quelle di Salvatore Ferragamo, a cui era molto legato - e la grande capacità di adattamento e improvvisazione. È stupefacente vedere cosa siano riusciti a fare questi uomini con quelle che oggi verrebbero considerate delle risorse molto ridotte, muovendosi in un’Italia che ancora non dava valore alla moda, vista tutt’al più come imitazione dello stile di Parigi. A conferma di quanto fosse ancora fragile il concetto di moda mio padre firmò le sue prime collezioni solamente con il nome ‘Emilio’ e solo qualche anno dopo comparì il suo nome completo di cognome. Quando Giorgini lo chiamò per la sfilata del ’51, aveva già lanciato la sua collezione nei department store negli Stati Uniti da 3 anni e aperto una boutique alla Canzone del Mare a Capri chiamata ‘Emilio Original Sportswear’.

Nel 1947, infatti, a Zermatt, il fotografo di Harper’s Bazaar (USA) Toni Frissell riprese una giovane americana che indossava la tuta da sci che mio padre aveva creato per sé. E fu l’editor in chief Diana Vreeland che, sempre nel ’47, convinse mio padre a disegnare una collezione da sci che sarebbe stata poi prodotta in America e venduta a Lord & Taylor. In realtà mio padre fu inizialmente sorpreso dalla richiesta e rispose a Diana “non disegno collezioni, sono un ufficiale dell’aviazione italiana!”, ma alla fine lei la spuntò. Così, in breve tempo rientrò a Firenze dove, già prima delle sfilate, aprì un piccolo laboratorio, attirato dalle mani e dalla grande artigianalità che avevano ispirato anche Giorgini. Fu quindi ben felice di cogliere l’opportunità che gli porse Bista: raccontare l’Italia attraverso le sue stampe, i suoi colori, attraverso la sua voce e il suo stile, uno stile diverso da qualsiasi altro, che non aveva niente a che fare con il prêt-à-porter o l’alta moda parigina , portando nella Sala Bianca il suo ‘Original Sportswear’.

Sono stati dei visionari coraggiosi, che si sono impegnati con passione e allegria. Credo che le nuove generazioni possano trarre dalle loro vite esemplari un grande insegnamento e un’importante fonte d’ispirazione.

LAUDOMIA PUCCI

Italian fashion - in its contemporary sense as a clothing industry and industry of beauty and lifestyle culture - originated in Florence in the 1950s with Giovanni Battista Giorgini. There are two symbolic moments in particular that everyone remembers: the exhibition of the first Italian collections to a small group of American buyers at Giorgini’s on February 12, 1951 and the first fashion shows in the Sala Bianca of the Pitti Palace on July 22, 1952. The fact that Giorgini had moved to Florence was certainly a contributing factor in the decision to hold this series of seminal events in the city, but it was not the only reason. In the post-war years, together with Rome and Venice, Florence was already known around the world as one of the symbolic cities of Italy, culture and Italian beauty. It had long hosted a network of craft workshops and small businesses that ‘constructed’ fashion. Therefore, even before the war, the city on the banks of the Arno had been home to important international buying offices and Giorgini’s professional experience in the US market began with one of these offices. Giorgini’s vision gave the fledgling Italian fashion industry an international vocation that it had previously never had, concentrating on replicating French models for domestic customers, in spite of the autocratic interlude that lasted about a decade. Giorgini’s direct experience in the USA made it possible for young Italian tailors and creatives to engage with the rich, dynamic and modern North American market from the outset. We must remember that in the 1950s France was internationally synonymous with high-quality fashion, understood almost exclusively as haute couture with a small target audience. In the book La Sala Bianca. Nascita della Moda Italiana (The Sala Bianca. The Birth of Italian Fashion - Electa, 1992), published to support the exhibition of the same name organised by Pitti Immagine in 1992, US fashion publishing magnate John B. Fairchild remarks: “Who would have thought then that one of the oldest and certainly most beautiful cities in the world would have given fashion an entirely new way of thinking and dressing, in a cheerful Italian style? What has always fascinated me about the Italians is that although they are traditional, they are very modern both in their way of thinking and in their creativity. Modern fashion - far from the musty odour of the antiquated French style - originated in Italy, in Florence.”

The post-war economic recovery sparked a widespread desire for innovation in culture and everyday life and the very idea of fashion began to change: it was no longer merely the preserve of the few; no longer just a traditional craft, but increasingly a modern industrial enterprise;

NO LONGER SIMPLY FUNCTIONAL PRODUCTION BUT INCREASINGLY A FORM OF CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE EXPRESSION.

This period,

between the 1950s and 60s, would see the gradual shift from the world of haute couture to that of prêt-à-porter; from the culture of the ‘tailor’ to that of the ‘designer’; from single artisan workshops to the construction of districts and a complete industrial supply chain. Giorgini was the person with an awareness or at least an intuition about these important combined processes of change. He was familiar with the North American market and understood its buyers’ psychology; he grasped the notions of marketing and communication: he knew that he was selling not only clothes, a better fit, functionality and technical and creative quality at lower costs, but also a new conception of fashion and standards of culture, beauty and quality of life that a city like Florence and all of Italy could convey.

Giorgini was also aware of a sociological change that had taken place in the USA following the war and the widespread employment of female labourers and office workers in American companies; the new social roles that had been created had radically altered the female wardrobe which, as well as dresses for social occasions and comfortable housewife outfits, also now included a range of stylish but functional options suitable for an active everyday life outside of the home and the country club. This change offered young Italian creatives an opportunity to assert their vision of a fashion that was less demanding and more responsive to these new female roles.

As the famous journalist Guido Vergani recalls: “The American market mirrored our future: women who worked, who were forced to use public transport and live outside the home from dawn to dusk, without compromising on style and elegance. They needed - just as we soon did - a less sophisticated and complicated fashion product than what Paris offered. The future was racing towards mass production and increasingly practical and youthful fashion”1

We can therefore certainly say that a vocation for innovation, culture and lifestyle is what distinguished Italian fashion from the outset. Perhaps little has been written about the risk taken by Giorgini in moving in a totally new direction, in a city other than Paris, at such a delicate time of post-war reconstruction. His ability to take risks, to stake everything on a group consisting largely of novices, marked the start of a success story that continues to this day. Giorgini’s great work led to the founding of the CFMI in 1954, with the City of Florence and other local institutions among the founding members.

The Florence Centre for Italian Fashion (Centro di Firenze per la Moda Italiana), which now heads a fully-fledged group of which Pitti Immagine is the most prestigious and significant operational component, has managed to resume its tradition of combining marketing (fashion shows and events) with artisan and industrial production chains, the most distinctive asset of our region, while giving particular priority to the international projection and promotion of Italian fashion.

Particularly at difficult times like the present, we must seek to emulate Giorgini’s propensity for risk, his vibrant embracing of change, his dynamism, perseverance and optimism, his understanding of the ever-changing connection that international fashion has with culture, art and all of the other creative industrial languages and sectors, and finally his vision of Florence as a place in touch with the spirit of the day, as reflected in fashion. 1La Sala Bianca. Nascita della Moda Italiana - Electa 1992

/ La moda italiana - nella sua accezione contemporanea di industria dell’abbigliamento e di industria della cultura del bello e del lifestylenasce a Firenze negli anni ’50 con Giovanni Battista Giorgini. In particolare, i momenti simbolici che tutti ricordiamo sono due: il 12 febbraio 1951 con l’esibizione delle prime collezioni italiane in casa Giorgini di fronte a un piccolo gruppo di buyer americani e il 22 luglio 1952 con l’esordio delle sfilate nella Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti.

Il fatto che Giorgini si fosse trasferito a Firenze aiuta sicuramente a collocare in città questa serie di eventi embrionali, ma non è l’unico motivo. Nel dopoguerra Firenze è già, con Roma e Venezia, una delle città-simbolo del nostro Paese, della cultura e della bellezza italiana nel mondo e a Firenze opera da lungo tempo una rete di laboratori artigianali e piccole imprese che ‘costruiscono’ la moda. Per queste ragioni la città in riva all’Arno diventa, ancor prima della guerra, la sede di importanti buying office internazionali e l’esperienza professionale di Giorgini nel mercato statunitense nasce proprio con uno di questi uffici.

La visione di Giorgini impone alla nascente moda italiana una vocazione internazionale che non aveva mai avuto fino a quel momento, concentrata sul replicare i modelli francesi per la clientela domestica, nonostante la parentesi autarchica durata circa un decennio. L’esperienza diretta di Giorgini negli USA fa si che i giovani sarti e creativi italiani si confrontino fin da subito con il ricco, dinamico e moderno mercato nord-americano. Non dimentichiamo che negli anni Cinquanta è la Francia il sinonimo internazionale di moda di qualità, intesa quasi esclusivamente come haute couture e con un pubblico di riferimento ristretto.

Nel volume La Sala Bianca. Nascita della Moda Italiana (Electa 1992) che esce a supporto della mostra omonima prodotta da Pitti Immagine nel 1992, il magnate dell’editoria di moda USA John B. Fairchild ricorda: “chi avrebbe detto allora che una delle più antiche e certamente più belle città del mondo avrebbe dato alla moda un sistema interamente nuovo di pensare e di vestire, in un allegro stile italiano? Ciò che mi ha sempre affascinato degli italiani è che pur essendo tradizionali sono molto moderni sia nel loro modo di pensare che nella loro creatività. La moda moderna - lontana dall’odor di muffa dell’antiquato stile francese - ebbe origine in Italia, a Firenze”. La ripresa economica del dopoguerra stimola una voglia diffusa di innovazione nella cultura e nella vita quotidiana e l’idea stessa di moda comincia a cambiare: non più solo una possibilità per pochi; non più solo un’attività artigianale tradizionale, ma sempre più un’attività industriale moderna; non più solo produzione funzionale, ma sempre più espressione culturale e comunicativa. È in questo periodo, tra gli anni Cinquanta e i Sessanta, che si passerà gradualmente dal mondo della haute couture a quello del prêt-àporter, dalla cultura del ‘sarto’ a quella dello ‘stilista’, dal singolo laboratorio artigianale alla costruzione di distretti territoriali e di una filiera industriale completa. Giorgini è la persona che ha consapevolezza o almeno l’intuizione di questi importanti processi combinati di cambiamento. Conosce il mercato nord-americano e capisce la psicologia dei suoi compratori, sa cosa sono il marketing e la comunicazione. Sa di non vendere solo abiti, una migliore vestibilità, funzionalità e qualità tecnica e creativa a costi più bassi, ma anche una nuova idea della moda e modelli di cultura, bellezza e qualità del vivere che una città come Firenze e tutta l’Italia possono trasmettere. Giorgini coglie anche un mutamento sociologico negli USA avvenuto in seguito allo sforzo bellico e all’impiego massivo di operaie e impiegate nelle aziende americane. I nuovi ruoli sociali impongono una mutazione importante al guardaroba femminile: non più solo abiti per occasioni mondane o comodi abiti da casalinga, ma una gamma di opzioni eleganti e funzionali, utili ad affrontare un’attiva vita quotidiana fuori dalla casa e dai country club. Questo mutamento offre ai giovani creativi italiani l’occasione per imporre la loro visione di una moda meno impegnativa, più rispondente a questi nuovi ruoli femminili. Lo ricorda bene il famoso giornalista Guido Vergani: “Il mercato americano era lo specchio del nostro futuro: donne che lavoravano, che erano costrette ad utilizzare mezzi pubblici, a vivere dall’alba al tramonto fuori casa, senza per questo rinunciare a un’esigenza di stile, di eleganza. Occorreva loro - e ben presto anche a noi - un prodotto di moda meno sofisticato e complicato di quello offerto da Parigi. Il futuro correva a grandi passi verso le confezioni in serie e verso una moda sempre più pratica e giovanile” 1. Possiamo sicuramente dire quindi che la vocazione all’innovazione, alla dimensione culturale e al lifestyle contraddistingue fin da subito la moda italiana.

Forse si è scritto poco sul rischio intrapreso da Giorgini nell’aprire una direzione totalmente nuova in una città diversa da Parigi, in un momento delicato come la ricostruzione post-bellica. Questa sua capacità di rischiare, di giocarsi il tutto per tutto facendo affidamento su un gruppo composto in buona parte da esordienti ha segnato un cammino e avviato una storia di successo che dura ancora oggi. Infatti, sulle basi del grande lavoro svolto da Giorgini, nel 1954 nascerà il CFMI, con il Comune di Firenze e altre istituzioni del territorio tra i soci fondatori. Il Centro di Firenze per la Moda Italiana, oggi a capo di un gruppo vero e proprio che vanta Pitti Immagine quale componente operativa più prestigiosa e rilevante, ha saputo riprendere il suo insegnamento di coniugare il marketing (sfilate ed eventi) con le filiere produttive artigianali e industriali, vera ricchezza identitaria del nostro territorio, e soprattutto di dare priorità alla proiezione internazionale della moda italiana e della sua promozione.

Di Giorgini - specialmente in un periodo difficile come l’attuale - dobbiamo saper riprendere la propensione al rischio, l’intelligenza vivace del cambiamento, il dinamismo, la perseveranza e l’ottimismo della volontà, l’idea forte della sempre mutevole connessione che la moda internazionale ha con la cultura, l’arte e tutti gli altri linguaggi e settori industriali creativi e infine una visione di Firenze che la veda al passo con lo spirito della contemporaneità di cui la moda è portatrice.

ANTONELLA MANSI

As a member of the Bergdorf Goodman fashion office I am extremely proud that our predecessors were one of five North American retail teams to accept Signore Giorgini’s generous invitation to attend the very first Italian high fashion show at his house in Florence. Neiman Marcus and Bergdorf Goodman have cultivated and established historic, long-standing relationships with innumerable Italian designers and manufacturers over the years that have become a vital part of our luxurious

offering.

/ Come rappresentante dell’Ufficio Stile di Bergdorf Goodman, sono molto orgoglioso del fatto che i nostri predecessori siano stati uno dei cinque department store nord-americani che accettarono il generoso invito del signor Giorgini a partecipare al First Italian High Fashion Show - la prima sfilata delle più prestigiose firme dell’alta moda italiana - nella sua casa fiorentina. Nel corso degli anni, Neiman Marcus e Bergdorf Goodman hanno coltivato relazioni storiche con innumerevoli designer e produttori italiani che oggi sono parte essenziale della nostra offerta di articoli di lusso. I nostri clienti, attenti e sensibili al buon gusto, amano l’abbigliamento e gli accessori Made in Italy, verso cui nutrono profonda ammirazione e rispetto. Per questo siamo lieti di portare avanti la tradizione e le relazioni fra i nostri due Paesi.

Cordialmente,

BRUCE PASK

Men’s Fashion Director - Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus

G.B.Giorgini & JuliaTrissel(BergdorfGoodman’sBuyer)

OUR DISCERNING CUSTOMERS HAVE A DEEP LOVE, RESPECT, AND DESIRE FOR CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES THAT ARE MADE IN ITALY AND WE ARE PLEASED TO CARRY ON THE TRADITION AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN OUR TWO COUNTRIES.

The story of the Giorgini family is full of big personalities that left an important mark all over Tuscany. Nicolao held numerous political roles in the Republic of Lucca, in the Duchy of the Bourbon and in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. His son Gaetano, engineer, was Rector of Pisa University and reclaimed large areas of the Maremma. His grandson, Giovanni Battista, jurist and senator after whom the eponymous Florentine piazza is named, was an eminent politician and advocate of the national unification law of 1861. Giovanni Battista’s great nephew - also Giovanni Battista, to whom this book is dedicated - is commemorated in the city with a plaque that I had the pleasure of mounting personally in via de’ Serragli, at the crossroads with Villa Torrigiani, where he once lived. He became internationally famous after the Second World War thanks to his key contribution to the economic recovery of the entire country. In particular, Tuscany benefitted from his skills as a promoter and exporter. It was he, at just 26 years of age, who promoted our finest crafts to American buyers for the first time, playing a leading role at the major Italy at Work exhibition in Chicago in 1949. From the artisans of the working-class districts of the city centre to the glassmakers of Poggibonsi, the shoemakers and leather industry of the Piana and the furniture manufacturers of the Valdarno, all product sectors saw their revenues rise exponentially thanks to their sales abroad. One particularly emblematic case was that of the alabaster industry which, from ancient artisan activity already practised by the Etruscans, became the speciality of the economy of Volterra. In fact, aware of the uniqueness of this material and the value of its craftsmanship, in the 1950s Giorgini sent his son-in-law - director of the export office - to Volterra to seek out high-level suppliers. The small number of manufacturers soon grew to number dozens. However, his most important intuition - the central theme of this book - was understanding that fashion would become the jewel in the crown of Made in Italy and that the headquarters of this industry could only be in Florence, as the presence of an international event like Pitti Immagine, whose origins stem from the work of Giorgini, still demonstrates today.

I would also add that as well as being a fine businessman, Giorgini had an important socio-political vision, viewing his work as a tool that could help drive the growth of the collective, something that has always struck a chord with me.

I am therefore delighted to join forces with Neri Fadigati, Polimoda and publishers Gruppo Editoriale in paying tribute to a fascinating man that contributed so much to the success of Italian fashion across the world.

/ La storia della famiglia Giorgini è ricca di grandi personalità il cui passaggio ha lasciato importanti tracce in tutta la Toscana. Nicolao ricoprì numerosi ruoli politici nella Repubblica Aristocratica di Lucca, nel ducato dei Borbone, fino al Granducato di Toscana. Suo figlio Gaetano, ingegnere, fu rettore dell’ateneo pisano e bonificatore di ampie zone della Maremma. Il nipote, Giovan Battista, giurista e senatore cui è intitolata l’omonima piazza fiorentina, fu eminente uomo politico cui si deve la legge di unificazione nazionale del 1861. Il suo omonimo pronipote, al quale è dedicato questo volume, è ricordato in città con una targa che ho avuto il piacere di apporre personalmente in via de’ Serragli, all’altezza della Villa Torrigiani, un tempo sua abitazione. La sua fama diventa mondiale nel secondo dopoguerra, grazie al suo fondamentale contributo alla ripresa dell’economica dell’intero Paese. La Toscana in particolare fu beneficiata dalle sue doti di promotore ed esportatore. Fu lui, a soli ventisei anni, a proporre per la prima volta ai buyer americani il nostro migliore artigianato, che così nel 1949 fu protagonista della grande mostra Italy at Work a Chicago. Dagli artigiani dei quartieri popolari del centro cittadino, alle vetrerie di Poggibonsi, ai calzaturifici e le pelletterie della piana, ai mobilifici del Valdarno, tutti i settori merceologici videro aumentare in modo esponenziale i loro fatturati grazie alle vendite all’estero. Un caso particolarmente emblematico fu quello dell’alabastro, che, da antica attività artigianale già nota agli Etruschi, divenne il punto di forza dell’economia volterrana. Negli anni Cinquanta del secolo scorso, infatti, consapevole dell’unicità del materiale e del valore della lavorazione, Giorgini mandò a Volterra il genero, direttore dell’ufficio esportazione, alla ricerca di fornitori di alto livello, tanto che le poche ditte produttrici diventarono decine.

La più cruciale delle sue intuizioni - che è infatti al centro del racconto di questo libro - fu però capire che la punta di diamante del Made in Italy sarebbe stata la moda e che il suo luogo d’elezione poteva essere solo Firenze, come dimostra ancora oggi la presenza di una manifestazione internazionale come Pitti Immagine, che proprio nell’opera di Giorgini affonda le sue origini.

Quello che tuttavia voglio aggiungere, perché lo apprezzo particolarmente, è che oltre a essere un valente uomo d’affari, Giorgini aveva un’importante visione sociopolitica che guardava alla propria attività come a uno strumento per la crescita collettiva.

Sono dunque lieto di unirmi agli sforzi di Neri Fagidati, del Polimoda e della casa editrice Gruppo Editoriale, nel rendere omaggio a una figura così affascinante e importante per il successo del costume italiano nel mondo.

EUGENIO GIANI

Regione Toscana

THE GIORGINIS, SIX GENERATIONS AT THE SERVICE OF THE COMMUNITY.

/ I GIORGINI, SEI GENERAZIONI AL SERVIZIO DELLA COLLETTIVITÀ.

Giovanni Battista Giorgini, born in 1898, to whom this book is dedicated, was given this name after his famous great uncle Giovan Battista (Lucca 1818 - Montignoso 1908), a university professor and member of the first parliament of unified Italy. Giorgini belonged to an illustrious family of government officials. His grandfather Nicolao had collaborated with the government of the Lucca Republic, with Elisa Bacicocchi’s Napoleonic government and with the restored Bourbonist dukedom. His son Gaetano, after having completed his studies at Paris’s Ecole Politecnique, worked for the House of Lorraine, leaving a lasting mark by planning the First Meeting of Italian Scientists, reforming the academic studies and reopening Pisa’s Scuola Normale. Giovan Battista had established connections with many distinguished personalities, including Vieusseux, Capponi, Ridolfi, D’Azeglio and Manzoni, whose daughter Vittoria he married in 1846. The wedding was celebrated in Nervi, at the magnificent Villa degli Arconati, and marked his entry into the highest cultural society of Northern Italy. Giorgini joined the University Battalion during the First Italian War of Independence, but he was forced to return to Pisa for health reasons. The re-establishment of the Grand Duchy, following 1849, caused the dismemberment of Tuscan universities, and so Giovan Battista, in order to keep his teaching job, had to move back to Siena with his wife and Vittoria’s sister, Matilde, who had joined the family. During the events of 1859, he supported the House of Lorraine’s entry into the war with the Piedmontese troops. When this plan failed and the Lorraine family left Florence, Giorgini, as member of the Tuscan Council and later of the provisional government presided over by Ricasoli, was instructed to draw up the document that provided for the annexation of Tuscany to the Kingdom of Sardinia. As soon as Giorgini joined the parliament, he was very busy: he wrote the paper that gave Vittorio Emanuele the title of King of Italy, thus ratifying the unification of Italy. As his father-in-law Manzoni before him, Giorgini wrote several works about the relations between the Italian State and the Catholic Church, always supporting a conciliation with Rome. Elected senator in 1872, he gradually retired from his political career, turning his attention to literary works and the translation of the Latin classics. Upon his death, his daughter Matilde published his works and important collection of letters. As this book well illustrates, Giorgini’s legacy was carried on by his grandnephew named after him and who, in the following century, kept Italy’s prestige high across the world.

/ A Giovanni Battista Giorgini, nato nel 1898, cui è dedicato questo volume, il nome fu imposto in onore del celebre prozio Giovan Battista (Lucca 1818 - Montignoso 1908) docente universitario poi deputato del primo parlamento dell’Italia unita. Giorgini apparteneva a un’illustre famiglia di funzionari. Il nonno Nicolao aveva prestato la sua opera nel governo della Repubblica lucchese, in quello napoleonico di Elisa Baciocchi e nel restaurato ducato Borbonico. Suo figlio Gaetano, dopo aver studiato all’École polytechnique di Parigi, fu al servizio dei Lorena, lasciando un segno duraturo attraverso l’organizzazione della Prima riunione degli scienziati italiani, la vasta riforma degli studi accademici, nonché la riapertura della Scuola Normale di Pisa. Giovan Battista vantava vaste relazioni con personalità eminenti come Vieusseux, Capponi, Ridolfi, D’Azeglio e Manzoni, con la cui figlia Vittoria convolò a nozze nel 1846. Il matrimonio fu celebrato a Nervi, nella splendida villa degli Arconati, segno dell’inserimento nel più alto ambiente culturale piemontese-lombardo. Partito col Battaglione universitario, durante la prima guerra d’indipendenza, fu costretto al rientro a Pisa da problemi di salute. La restaurazione granducale, dopo il 1849, comportò lo smembramento punitivo degli atenei toscani, così Giovan Battista tornò a insegnare trasferendosi a Siena con la famiglia, di cui faceva ormai parte anche la sorella di Vittoria, Matilde. Gli avvenimenti del 1859 lo videro fra i sostenitori dell’entrata in guerra dei Lorena a fianco delle truppe piemontesi. Fallito questo disegno e dopo che i Lorena ebbero lasciato Firenze, Giorgini, membro della Consulta toscana e poi del governo provvisorio presieduto da Ricasoli, fu incaricato di stilare il documento che chiedeva l’annessione della Toscana al Regno di Sardegna. Entrato a far parte del parlamento iniziò un’intensa attività: sua fu la relazione che attribuiva a Vittorio Emanuele il titolo di Re d’Italia, sancendo così l’unificazione nazionale. In linea col suocero Manzoni si produsse in vari scritti sui rapporti fra Stato e Chiesa, sostenendo una pronta conciliazione con Roma. Nominato senatore nel 1872, si allontanò sempre di più dalla lotta politica, preferendo dedicare i propri interessi alle opere letterarie e alla traduzione di classici latini. Dopo la sua morte, la figlia Matilde curò la pubblicazione dei suoi scritti e del suo importante epistolario. Come racconta il presente volume, il suo insegnamento fu ben messo in pratica dall’omonimo pronipote, che nel secolo successivo si spese per tenere alto nel mondo il prestigio dell’Italia.

ROMANO PAOLO COPPINI

Pisa University ← G.B.Giorgini inhisstudio withaportrait ofhisfamousgreat-uncle withwhomheshareshisname photobyAGI

- SO, FROM DIPLOMACY TO COMMERCE. TWO KEYWORDS IN THE STORY OF GIORGINI, WHOSE PRIVATE LIFE AND PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES OVERLAPPED FOR 50 YEARS ON A ROLLERCOASTER OF SUCCESSES AND DIFFICULTIES, THROUGH UNTIL THE TRIUMPHANT POST-WAR PERIOD. [...] GIORGINI WASN’T SO MUCH AN EXPORTER AS A PROMOTER OF THE ITALIAN BRAND, OR RATHER ITALY ITSELF. A MISSION RATHER THAN A JOB. -

/ Dunque dalla diplomazia al commercio. Due parole chiave della parabola di Giorgini, dove vita privata e attività lavorativa si sovrapposero per cinquant’anni in un unico corso che vide alternarsi successi e difficoltà, fino al trionfo del dopo guerra. [...] Giorgini non fu solo un esportatore, ma piuttosto un promotore del marchio Italia o meglio dell’Italia stessa. Più che un lavoro, una missione.

GIOVANNI BATTISTA GIORGINI, THE FAMILY TRADITION AND THE VISION OF THE FUTURE. / GIOVANNI BATTISTA GIORGINI, LA TRADIZIONE DI FAMIGLIA E LA VISIONE DEL FUTURO.

“Bista, I leave you my name, honour it”. Our story begins with these words, spoken by a 90 year-old man, Giovan Battista ‘Bista’ Giorgini, still lucid yet close to the end.

As Romano Coppini explains, the old man was a patriot and a senator, advocate of the national unification law approved on March 17, 1961 by Turin Parliament.

On the receiving end of this burdensome bequest was his 8-year-old great nephew Giovanni Battista ‘Bista’ Giorgini, taken by his parents to say his last goodbye to the old man at the family home in Montignoso (later donated to the Municipality, which is now headquartered here). The child was so affected by the legacy that had been passed onto him that he immediately made it his mission in life to follow in the footsteps of his illustrious ancestor and honour Italy. As he explains himself.

Not yet 20, the young ‘Bista’ (nicknames were par for the course in the family) kept a detailed diary in little black notebooks. Having been lost over the years, fortunately some of them were rediscovered at an antiques market and generously handed over to the Giorgini Archive which conserves his memoirs.

An officer cadet in Piedmont, he anxiously waited to join his elder brother Carlo at the front during the First World War. Recalling this period, he continues: “I can’t wait to honour him and my country, Italy, which I love before all else”. Unable to achieve this aim on the battlefield - the War finished soon afterwards - he planned to do it by pursuing a diplomatic career.

The premature death of his father Vittorio put an end to this idea, forcing him to take care of the family businesses, particularly the marble quarries, opened in 1860 on Monte Altissimo by his grandfather Carlo, brother of the ‘Senatore’. The company was also a supplier of finished works, sculptures and garden furniture.

“Bista, ti lascio il mio nome fagli onore”, con questa frase, pronunciata da un uomo di novant’anni, ancora lucidissimo e prossimo alla fine, Giovan Battista ‘Bista’ Giorgini, inizia la storia raccontata in questo libro. Come spiega Romano Coppini, il vecchio signore era stato patriota e senatore, relatore della legge di unificazione nazionale, approvata il 17 marzo 1961 dal Parlamento di Torino. Destinatario del non facile compito era il pronipote Giovanni Battista ‘Bista’ Giorgini, all’età di otto anni portato dai genitori a dare l’ultimo saluto al vegliardo nella casa di famiglia a Montignoso (poi donata al Comune che oggi vi ha sede). Il lascito si impresse a tal punto nell’immaginazione del bambino che da quel momento capì quale sarebbe stata la missione della sua vita: ripercorrere le orme dell’illustre antenato onorando l’Italia. È lui stesso a spiegarlo. Non ancora ventenne, il giovane Bista (i soprannomi erano di regola in famiglia) teneva un fitto diario su quei piccoli quaderni neri con le righe rosse usati fino alla metà del Novecento. Andati perduti, alcuni di essi sono stati fortunosamente ritrovati sulla bancarella di un mercatino antiquario e generosamente consegnati all’Archivio Giorgini che custodisce le sue memorie. Allievo ufficiale in Piemonte attendeva con impazienza di raggiungere il fratello maggiore Carlo sul fronte della Prima guerra mondiale. Ricordando l’episodio prosegue: “non vedo l’ora di fargli onore, a lui e al mio Paese, l’Italia, che amo più di ogni altra cosa”. Non potendo mettere in pratica il proposito sul campo di battaglia - la guerra finì poco dopo - l’avrebbe voluto fare intraprendendo la carriera diplomatica. La prematura morte del padre Vittorio glielo impedì.

Dovette occuparsi delle attività di famiglia, in particolare delle cave di marmo, aperte nel 1860 sul monte Altissimo dal nonno Carlo, fratello del senatore.

TEXT BYThe art director was painter Filadelfo Simi, close friend of Vittorio.

NERI FADIGATI

To spend their holidays together they had built two houses on the slopes of Monte Procinto, above Seravezza.

The one belonging to the Giorginis, La Silvana, is a mountain refuge today. Among the projects they were commissioned was the creation of the monument to Garibaldi for the city of Porto Alegre in Brazil.

L’azienda si dedicava anche alla fornitura di opere lavorate, sculture e arredi da giardino. Il direttore artistico era il pittore Filadelfo Simi, amico fraterno di Vittorio. Per trascorrere insieme i periodi di villeggiatura si erano costruiti due case alle pendici del Monte Procinto, sopra Seravezza.

Quella dei Giorgini, La Silvana, è oggi un rifugio. Tra le commesse ricevute vi fu la realizzazione del monumento a Garibaldi per la città di Porto Alegre in Brasile.

On the previous pages, the family reunited.

/ Nelle pagine precedenti, la famiglia riunita.

Bista soon recognised that exporting works of art and luxury crafts could be a way of realising his dream.

Having left his brothers to manage the business, which had relocated to Massa where it is still headquartered today, he moved to Florence, centre of the craft production chain and logistical crossroads for goods destined for the foreign markets thanks to its proximity to the port of Livorno, where the American government had opened its first consulate in Italy in 1794.

In the meantime, he had married Zaira Augusta ‘Nella’ Nanni, whom he met in Savona during his period of military service. They had become engaged via letter having met just once, as he recounts in his diaries, although he had felt a slight sense of guilt when expressing his feelings given the possibility that he might soon find himself under enemy fire. In the meantime, in 1922 their first child, Graziella, was born in Forte dei Marmi, and she was followed in 1926 by Vittorio, known more for his theories on ‘morphological architecture’ than his creations, and in 1928 by Matilde, his closest collaborator, who he would remain very close to for the rest of his life.

So, from diplomacy to commerce.

Two keywords in the story of Giorgini, whose private life and professional activities overlapped for 50 years on a rollercoaster of successes and difficulties, through until the triumphant post-war period. In fact, when we talk about backchannel diplomacy we mean a country’s ability to strengthen its economic and geopolitical position using tools like exportation and the spread of its culture. Giorgini wasn’t so much an exporter as a promoter of the Italian brand, or rather Italy itself.

A mission rather than a job.

In fact, in the United States, the foreign policy of soft power, based on the gentle imposition of one’s social models, was widely practised in the 20th century.

Bista was one of the first to understand that our past guaranteed us an advantage in a period in which competition between nations was growing as the process of internationalisation loomed closer.

There were three main cornerstones to his success.

The first, encapsulated in the phrase mentioned at the beginning, regards the ability to ensure your actions stand the test of time, lasting well beyond your own lifetime.

Bista si rese così conto che l’esportazione di oggetti d’arte e alto artigianato poteva essere un valido strumento per la realizzazione del suo sogno.

Lasciato ai fratelli il compito di gestire l’attività, spostata sul versante di Massa, dove si trova ancora oggi, si trasferì a Firenze, centro della filiera artigianale e sede di smistamento della merce destinata a mercati esteri, grazie alla vicinanza del porto di Livorno, dove il governo americano aveva aperto la prima sede consolare in territorio italiano nel 1794.

Si era nel frattempo sposato con Zaira Augusta ‘Nella’ Nanni, conosciuta a Savona nel periodo del servizio militare. Il fidanzamento era avvenuto per lettera dopo un unico incontro, come racconta sempre nei suoi diari, non senza provare un certo senso di colpa nell’esprimere i propri sentimenti, vista la possibilità di trovarsi presto sotto il fuoco nemico.

Intanto, nel 1922 a Forte dei Marmi, era nata la primogenita Graziella, che sarà seguita nel ’26 da Vittorio, noto più per le teorie sull’‘architettura morfologica’ che per le realizzazioni, e nel ’28 da Matilde, la sua più stretta collaboratrice, che gli resterà vicina per tutta la vita.

Dunque, dalla diplomazia al commercio. Due parole chiave della parabola di Giorgini, dove vita privata e attività lavorativa si sovrapposero per cinquant’anni in un alternarsi di successi e difficoltà, fino al trionfo del dopoguerra. Del resto con diplomazia parallela si intende la capacità di un Paese di rafforzare la sua posizione economica e geopolitica usando strumenti come l’esportazione e la diffusione della propria cultura.

Giorgini non fu solo un esportatore, ma piuttosto un promotore del marchio Italia o meglio dell’Italia stessa. Più che un lavoro, una missione. L’espressione inglese corrispondente, soft power, indica la politica estera, basata sull’imposizione ‘dolce’ dei propri modelli sociali, ampiamente praticata dagli Stati Uniti nel Novecento.

Bista fu tra i primi a capire che il nostro passato ci garantiva una posizione di vantaggio in un periodo in cui la competizione tra le Nazioni cresceva con l’approssimarsi del processo di internazionalizzazione.

Gli elementi alla base del suo successo furono sostanzialmente tre.

Il primo, racchiuso nella frase riportata all’inizio, riguarda la capacità di inserire il proprio operato in un orizzonte temporale molto ampio, che va ben oltre quello personale.

1961 BistaandNella athome photobyAGI →

On the left page find Bista during the game “pass the apple”.

/ Nella pagina sinistra trovate Bista durante il gioco “passa la mela”.

He was well aware that the legacy that had been bequeathed on him as a child would be passed down to others.

Once again, he says so himself in a passage in which he dedicates his efforts to the future generations. The second also regards the education he was given, which taught him that the greater good came before individual interests. The public interest is a value that comes before all others, to be pursued at all times, with respect for the institutions regardless of whoever these may temporarily be occupied by. Third aspect: place great importance on personal contacts, something that enabled him to build a vast network of relations in which work went hand in hand with friendship.

In July 1952, sat in the front row of the Sala Bianca, in front of the 20-metre long T-shaped runway, another Florentine invention, was Mrs. Churchill. She was surrounded by the editors of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, and correspondents from all of the biggest newspapers in the world; alongside them were buyers from the biggest distributors in the West, I. Magnin, Macy’s, Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus. Over the years Giorgini received visits from director Alfred Hitchcock and famous actresses like Gloria Swanson and Olivia de Havilland, among others. His fame across the pond is confirmed by a curious photo taken on board an ocean liner and published in Our Land Our People, a Look Magazine book dedicated to Americans, in the chapter “… of our pleasures”, with the caption: “pass the apple”. The book was given to him by designer Gianni Baldini with a dedication: “Bista, they’ve completed adopted you”. There were undoubtedly external factors that helped create favourable conditions for him, particularly in the post-war era. Giorgini was in the right place at the right time as Italy became central to the strategic vision of the US government, busy implementing what we can describe as the second phase of the Marshall Plan.

His role was so appreciated in the United States that Harry Truman decided to pay him a visit during a trip to Europe following the end of his presidency. He was the only person that the former President met with during his stay in Florence in 1955.

It had all begun many years earlier. His membership of the Waldensian denomination, following in his Swiss mother’s footsteps, brought him closer to his

Sapeva bene che il testimone ricevuto da bambino sarebbe passato in altre mani.

Di nuovo è lui stesso a dirlo in uno scritto dove dedica i suoi sforzi alle generazioni future. Anche il secondo riguarda l’educazione ricevuta, che anteponeva il bene collettivo a quello individuale. L’interesse pubblico è un valore superiore a ogni altro, da perseguire sempre, nel rispetto delle istituzioni, indipendentemente da chi temporaneamente le occupa. Terzo aspetto: dare molta importanza ai contatti personali, cosa che gli permise di costruire una vasta rete di relazioni in cui il lavoro andava di pari passo con l’amicizia.

Nel luglio del 1952 in Sala Bianca, davanti alla passerella a T lunga venti metri, altra invenzione fiorentina, era seduta in prima fila la signora Churchill. La circondavano le direttrici di Harper’s Bazaar e Vogue, e i corrispondenti di tutti i grandi giornali del mondo. Accanto a loro i compratori dei maggiori distributori dei Paesi occidentali, I. Magnin, Macy’s, Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus. Giorgini ricevette nel corso degli anni le visite tra gli altri del regista Alfred Hitchcock, di famose attrici come Gloria Swanson e Olivia de Havilland.

La sua notorietà oltreoceano è confermata anche da una curiosa foto scattata a bordo di un transatlantico, pubblicata su Our Land Our People, volume di Look Magazine dedicato agli americani, nel capitolo …of our pleasures, con la didascalia: “pass the apple”. Il libro gli fu regalato dallo stilista Gianni Baldini con la dedica: “Bista, ormai ti hanno adottato completamente”.

Sicuramente nella sua vicenda, soprattutto nel periodo del dopoguerra, sono presenti elementi esterni che concorsero a creare condizioni favorevoli.

Giorgini si rivelò essere la persona giusta, nel momento in cui l’Italia divenne un Paese centrale nella visione strategica del governo americano, impegnato a portare avanti quella che potremmo definire la seconda fase del piano Marshall.

Il suo ruolo fu a tal punto apprezzato negli Stati Uniti che Harry Truman, durante un viaggio in Europa compiuto al termine del mandato, volle fargli visita. Fu l’unica persona che l’ex presidente incontrò durante la sua sosta fiorentina nel 1955.

Tutto era cominciato molti anni prima. L’osservanza Valdese, dovuta alla madre svizzera, Florence Rochat, lo avvicinava ai suoi interlocutori commerciali e istituzionali.

(Continues on page 32 / Continua a pagina 32)

↑

L’Europeo02/01/1959 Giorginireadstheopinionsof criticsonItalianfashion, articlebyO.Fallaci

▷Giovanni Battista Giorgini, the family tradition and the vision of the future.

/ Giovanni Battista Giorgini, la tradizione di famiglia e la visione del futuro.

↑

L’Europeo02/01/1959 Giorginireadstheopinionsof criticsonItalianfashion, articlebyO.Fallaci

▷Giovanni Battista Giorgini, the family tradition and the vision of the future.

/ Giovanni Battista Giorgini, la tradizione di famiglia e la visione del futuro.

To read the transcript of the original telegram, turn the page, you will find it on the right.

/ Per leggere la trascrizione del telegramma originale, gira la pagina, lo trovi sulla destra.

commercial and institutional interlocutors. His continuous travels across the United States enabled him to gain an in-depth understanding of a country whose economic, social and political prospects enthused him. Having overcome the crisis of 1929 and muddled through the following decade, in the post-war years Giorgini set about making good use of the capital he had accumulated over the previous 30 years. Driven by his unlimited and contagious belief in Italy’s potential he tailored his fashion shows to the needs of the customer. Everything took place in a unique environment, the cultured surroundings being a complete novelty for the time. He rediscovered the qualities that bewitched foreigners, forgotten following the dictatorship and the war. There was no shortage of material, from the splendour of the Florentine Renaissance to that of 18th century Venice.

In 1954, Fay Hammond of the Los Angeles Times, one of the best-known fashion journalists of the time and a close friend of Giorgini, wrote that merely walking through the city centre to the Pitti Palace was a delightful experience and that once you got there you could get a real taste of Italy’s wonderful hospitality. That year, for the 8th show, there were buyers from 81 companies. Everyone had to leave a 200,000 lira deposit for their purchases.

Nine years later, Molly Ballantyne, buyer from the Ogilvy department store in Montreal, sent a telegram to her city newspaper in which she pulled no punches in her comparison between Florence and Paris. “Fashion week in Paris is like feeding time at the zoo but here in Florence it is like a gala dinner”.

The idea, new for the time, of supplementing the presentations with cultural events was developed to the max. Parties, carnivalesque masquerade balls and reconstructions of historical events with guests in costume were held in the city’s most beautiful venues, from Palazzo Vecchio to the Boboli Gardens, from the Pitti Palace to Forte Belvedere.

I continui viaggi attraverso gli Stati Uniti gli permisero di formarsi una profonda conoscenza del Paese di cui condivideva le prospettive economiche, sociali e politiche. Superata la crisi del 1929 e attraversato non senza difficoltà il decennio successivo, nel dopoguerra Giorgini mise a frutto il capitale accumulato nei trent’anni precedenti. Sostenuto da una fiducia illimitata e contagiosa nelle possibilità italiane costruì le manifestazioni della moda intorno alle esigenze dei clienti. Tutto avveniva in un contesto unico, con un contorno mondano assolutamente nuovo per l’epoca. Riscoprì le qualità che affascinavano gli stranieri, dimenticate dopo la dittatura e il conflitto. Il materiale a disposizione non mancava, dagli sfarzi del Rinascimento fiorentino a quelli del Settecento veneziano. Fay Hammond del Los Angeles Times, una delle più seguite giornaliste di moda dell’epoca, che aveva con lui un forte legame di amicizia, scrisse nel 1954 che solo raggiungere Palazzo Pitti attraversando il centro della città, era un’esperienza meravigliosa e una volta arrivati si poteva avere una prova della fantastica ospitalità italiana. Quell’anno, per l’ottava manifestazione, erano presenti compratori in rappresentata di ottantuno aziende. Ognuno doveva lasciare un deposito per acquisti di duecentomila lire.

Nove anni dopo, Molly Ballantyne, buyer del grande magazzino Ogilvy di Montreal, inviò un telegramma al giornale della sua città in cui il confronto Firenze-Parigi era impietoso.

“A Parigi la settimana delle sfilate di moda è come l’ora del pasto al giardino zoologico, ma qui a Firenze è invece simile a un gala”.

L’idea, nuova per l’epoca, di accompagnare le presentazioni con eventi mondani fu sviluppata al massimo.

Lists start on page 198.

To understand the amount of organisation that went into the Florence fairs all you need to do is take a look at the fashion show programmes.

Feste, balli in maschera in stile carnevalesco, ricostruzioni di eventi storici con gli ospiti in costume si tenevano nei più bei luoghi della città, da Palazzo Vecchio ai Giardini di Boboli, da Palazzo Pitti a Forte Belvedere. Per capire la portata organizzativa delle fiere fiorentine basta esaminare i programmi delle sfilate.

/ Le liste iniziano a pagina 198. (Continues on page 36 / Continua a pagina 36)

↑ BellezzaSeptember1952 accessories

byValentino forVanna

↑ BellezzaSeptember1952 accessories

byValentino forVanna

Transcription from the original text translated from English by the organization. / Trascrizione dal testo originale tradotto dall’inglese dall’organizzazione.

On July 19, 1963 -

A Parigi la settimana delle sfilate di moda è come l’ora del pasto al giardino zoologico, ma qui a Firenze è invece simile a un gala. Per cominciare, le sfilate si svolgono nella Sala Bianca di Palazzo Pitti che, dovete ammetterlo, è uno scenario splendido. Poi molte si svolgono alla sera e tutti vi partecipano vestiti con la massima eleganza ed applaudono con entusiasmo. Le sfilate sono seguite da ricevimenti durante i quali parliamo tutti insieme in mille lingue ed accenti. Questo stimolante insieme di divertente fantasia e duro lavoro si prolunga per tutta la settimana finché si parte per Parigi. A Parigi però la dura realtà del commercio, le scomode seggioline e i dollari sonanti che siamo costretti a versare per assistere a ogni singola sfilata, fanno di quella settimana un periodo di fatica, tensione e nervosismo. Contrariamente all’atmosfera allegra e scintillante di Firenze.

Qui per assistere basta versare un deposito di 645 dollari, mentre a Parigi costa dai 250 ai 2.000 per sfilata. Il deposito viene dedotto naturalmente dagli acquisti, ma se non trovi nulla che ti piaccia perdi il denaro. Debbo affermare che la grande sensibilità dei creatori di moda italiani è stata ancora una volta brillantemente dimostrata durante questa settimana,come avrete già letto sulla nostra stampa specializzata e come potete rendervi conto voi stessi quando vedrete le nostre collezioni di autunno. -

In Paris, fashion week is like feeding time at the zoo, but here in Florence, it is like a gala. To begin with, the fashion shows take place in the Sala Bianca of the Pitti Palace which, you have to admit, is a beautiful backdrop. Then many others take place in the evening and everyone joins in, dressed in the most elegant manner and applauding enthusiastically. The shows are followed by receptions where we all converse in a thousand different languages and accents. This stimulating mix of fun fantasy and hard work continues throughout the week until we leave for Paris. In Paris, however, the harsh realities of the trade, the uncomfortable seats and the hard-earned dollars you are forced to pay to attend every single fashion show make you feel tired, tense and nervous. This is a contrast to the lively and glittery atmosphere in Florence. Here, a $645 deposit is required to attend, while in Paris it costs between $250 and $2,000 per show. The deposit is obviously deducted from what you buy, but if you do not find anything you like, you lose the money. I have to say that the great sensitivity of Italian fashion designers was once again brilliantly showcased this week, as you will have already read in our trade press and as you will realise when you see our autumn collections. -

▷Giovanni Battista Giorgini, the family tradition and the vision of the future.

/ Giovanni Battista Giorgini, la tradizione di famiglia e la visione del futuro.

Telegram sent by Molly Ballantyne (buyer of the Ogilvy department store in Montreal), to The Gazzette from Montreal.In detail on page 198. / In dettaglio a pagina 198.

The great dressmakers left almost immediately, believing they were strong enough to break away and present their collections in Rome.

They returned in 1957 when Giorgini managed to make Florence the national fashion capital, receiving the political support of President Gronchi who sent his wife Carla to the Sala Bianca.

The number of businesses in the Sportswear & Boutique sector grew year on year. From the offset a specific space was created for the presentation of hats, the Millinery Show, sponsored by Cappellificio La Familiare, and for men’s fashion with the debut of Brioni. Textile Promotion, the combination of a designer and a textile industry, served to strengthen Giorgini’s position, thanks to the alliance with the big factories of the North. Wanda Roveda specialised in teenage fashion. In 1962 a collection of female underwear was presented.

The same year saw the debut of Valentino, who had been designing accessories since the early 1950s. One of the many young talents unearthed by Bista.

From the first fashion show buyers understood the enormous commercial potential of Italian designs. Wearable was the adjective used to describe the clothes. Even the prices were competitive compared with those in France. The Fairchild News Service revealed that a 30-dollar Mirsa dress could be sold for 100 dollars by Bonwit Teller in New York.

The case of the Galliate knitwear factory was a classic example.

Olga de Gresy, a woman of great talent and close friend of Bista, had presented her designs in Paris back in 1949 under the Annie Blat label, knowing that the American public wanted French clothes.

The entrepreneur, whose work was inspired by an ethical approach towards her employees, over five hundred in the 1960s, was one of his biggest supporters.

The success of the Florence event could be seen in the increase in sales.

Once again, the Fairchild News Service reports the following figures in a note in January 1957 (in millions of dollars): accessories, 1950 - 2, 1955 - 15, 1956 - 22; fabrics, 1950 - 6, 1955 - 15, 1956 - 18.

In 1962, year of major expansion, 18 high fashion and 28 ready-to-wear labels presented their designs. There were 600 buyers, compared with 440 the previous year.

I grandi sarti lasciarono quasi subito, pensando di essere abbastanza forti da potersi affrancare, presentando le collezioni a Roma.

Ritornarono nel 1957, quando Giorgini riuscì a rifare di Firenze la capitale della moda nazionale, con il sostegno politico dell’allora presidente Gronchi che mandò la moglie Carla in Sala Bianca.

Il numero delle aziende alla voce sportsweare & boutique crebbe di anno in anno.

Fin da subito furono creati due spazi specifici, uno per la presentazione di cappelli, il Millinery Show, sponsorizzato dal Cappellificio La Familiare, e uno per la moda uomo, con il debutto di Brioni.

La Textile Promotion, abbinamento tra uno stilista e un’industria tessile, servì a rafforzare la posizione di Giorgini, grazie all’alleanza con le grandi fabbriche del nord. Wanda Roveda si dedicò alla moda per adolescenti.

Nel 1962 venne presentata una collezione di intimo femminile.

Lo stesso anno debuttò Valentino, che disegnava accessori fin dai primi anni Cinquanta. Uno dei tanti giovani talenti scovati da Bista.

Dalla prima sfilata i compratori si resero conto dell’enorme potenziale commerciale dei modelli italiani.

‘Portabile’ fu l’aggettivo più usato per descrivere gli abiti.

Anche i prezzi erano concorrenziali rispetto a quelli francesi. Il Fairchild News Service segnalava che un abito di Mirsa da trenta dollari poteva essere venduto a cento da Bonwit Teller a New York. Il caso del maglificio di Galliate è esemplare.

Olga de Gresy, donna di grande talento e intima amica di Bista, presentava i suoi modelli a Parigi già nel 1949 con l’etichetta Annie Blat, sapendo che il pubblico americano desiderava capi francesi.

L’imprenditrice, il cui lavoro si ispirava a principi etici nei confronti dei dipendenti, oltre cinquecento negli anni Sessanta, fu una delle sue maggiori sostenitrici.

Il successo fiorentino è testimoniato dall’aumento delle vendite.

Sempre il Fairchild News Service nel gennaio del 1957 riporta in una nota questi dati (in milioni di dollari): accessori, 1950 - 2, 1955 - 15, 1956 - 22; tessuti, 1950 - 6, 1955 - 15, 1956 - 18. Nel 1962, anno di grande espansione, sfilarono diciotto case di alta moda e ventotto di moda pronta. I compratori furono seicento, erano stati quattrocentoquaranta l’anno precedente.

Have a look to the Fairchild telegram on the insert ‘eighth’ / Vedi il telegramma di Fairchild dell’inserto ‘eighth’./

The companies present came from the following countries: Germany 53; USA 41; GB 27; Switzerland 18; Netherlands 5; Austria, Denmark, France, Belgium, Finland, Argentina, Uruguay 1.

There were 130 foreign journalists and 80 Italian journalists, including a young but already determined Oriana Fallaci. For RAI the fashion shows were covered by Bianca Maria Piccinino and Beppe Modenese who, introduced to the fashion world by Giorgini himself, would later take over his mantle, reviving in his Milan that which had begun to flag in Florence.

Around the aristocratic figure of Bista - the family had been part of Lucca’s nobility since the end of the 18th century - revolved a group of young professionals guided with charismatic elegance.