Ministério da Cultura e Museu Paranaense apresentam:

Museu Paranaense

A exposição “Claudia Andujar: poéticas do essencial” marca a história do Museu Paranaense (MUPA), com a incorporação de fotografias de Claudia Andujar em seu acervo. Andujar é fotógrafa reconhecida internacionalmente pela sua produção ímpar e por sua profunda relação com o povo Yanomami. A entrada desses novos itens enriquece ainda mais o arquivo imagético do MUPA e sua coleção antropológica, histórica e artística.

Esta expansão de acervo insere-se em um movimento mais amplo, conduzido nos últimos anos pela instituição, em torno de um compromisso com as reivindicações sociais dos diversos grupos que compõem a sociedade. Dentro da metodologia de trabalho construída mais recentemente pelo MUPA, têm-se valorizado representações éticas sobre as populações que produziram boa parte dos itens de seu acervo e cujas histórias figuram nos projetos expositivos, com destaque às dos povos indígenas. O Museu buscou, em suas últimas ações, agregar pessoas e comunidades que integram os povos originários do país, tendo em vista a elaboração de novas narrativas em que suas vozes e saberes fossem os grandes catalisadores.

Apesar de Claudia Andujar não ser uma pessoa indígena, cada detalhe de sua obra e de sua atuação política foi elaborado a partir de uma postura de plena escuta em relação ao povo Yanomami. A fotógrafa e ativista baseou suas criações nos valores e reivindicações próprios das comunidades em que viveu e é reconhecida por eles como uma de suas mais relevantes aliadas. O esforço recente do Museu Paranaense é de seguir esses mesmos preceitos que permearam a

The exhibit "Claudia Andujar: poetics of the essential" marks an important moment in the history of the Museu Paranaense (MUPA): a set of photographs by Claudia Andujar, an internationally recognized photographer known for her unique work and deep relationship with the Yanomami people, joins the museum collection. The addition of these new items further enriches the visual archive of MUPA and its anthropological, historical, and art collection.

This expansion of the collection is part of a broader movement carried out by the institution in recent years, focusing on a commitment towards the social claims of the diverse groups that make up society. Within the recently developed working methodology of the MUPA, ethical representations of the populations that have been depicted in a significant portion of its collection are valued, and their stories featured in exhibition projects, with particular emphasis on indigenous peoples. Recent museum actions have made efforts to include individuals and communities representing the indigenous peoples of the country, in the quest to develop new narratives in which their voices and knowledge serve as major catalysts.

Although Claudia Andujar is not of indigenous descent, every detail of her work and political activism was crafted from a position of careful listening to and engagement with the Yanomami people. The photographer and activist based her creations on the values and demands of the communities in which she lived; she is recognized by them as one of their most important allies. The Museu Paranaense

vida e o trabalho de Andujar e reverberar as pautas das sociedades e sujeitos indígenas.

Nesse panorama, a imagem tem figurado como uma das mais relevantes ferramentas de reivindicação. Para os Yanomami, a beleza de sua cultura era um dos aspectos mais importantes a serem registrados e divulgados pelas lentes da câmera de Andujar. Entre tantos outros povos originários, a interpretação sobre a captura de retratos e cenas varia de acordo com suas mais diferentes concepções cosmológicas. Há cada vez mais um consenso, no entanto, sobre a relevância do alcance das linguagens artísticas e documentais visuais.

A entrada desta seleção de fotografias de Claudia Andujar para o acervo do Museu Paranaense é mais um passo na consolidação de uma atitude recente na história da instituição de quase 150 anos, que é confrontada com as práticas excludentes praticadas ao longo de nossa história e que se torna consciente do cenário de exclusão que vivenciou. O MUPA é um espaço que tem se dedicado a se reinventar e construir um novo papel para si, como um colaborador na reparação das perdas coloniais e na construção de uma sociedade que ofereça plenas condições para o florescimento dos modos indígenas de existir.

recent efforts follow the same principles that have shaped Andujar’s life and work, echoing the agendas of indigenous societies and individuals.

In this context, images have become one of the most important tools for advocacy. For the Yanomami, the beauty of their culture was one of the most crucial aspects that was captured and disseminated through Andujar’s lenses. The many different indigenous peoples of Brazil have their own takes on photography – on the portraits and scenes captured – which vary according to their diverse cosmological concepts. Yet there is a growing consensus on the significance of visual artistic and documentary languages in advocating for their causes.

The inclusion of this selection of Claudia Andujar’s photographs within the Museu Paranaense collection represents another step in consolidating a recently assumed attitude, new to the almost 150-year history of the institution. It confronts the exclusionary practices that the museum took part in over its long trajectory and propagates new awareness of the scenario of exclusion that the institution was accomplice to. The museum thus becomes a space devoted to reinventing itself. It takes on a new role, as collaborator in reparations for colonial damage and the building of a society that offers full conditions for the flourishing of indigenous ways of being.

Josiéli Spenassatto e Isabela Brasil Magno

Núcleo de Antropologia do Museu Paranaense (Museu Paranaense Anthropology Division)

Atravessando continentes e cidades, a extensa trajetória de Claudia Andujar cruza novamente Curitiba na nova exposição do Museu Paranaense “Claudia Andujar: poéticas do essencial”. Entre idas e vindas, o trabalho da fotógrafa ganha uma nova morada na capital paranaense.

A obra, assim como sua criadora, escapa às definições. Claudia Andujar recusa para si o título de artista, ao mesmo tempo em que seu trabalho não se resume a um simples esforço de documentação fotográfica. Em seus próprios termos, suas fotografias podem ser traduzidas como uma busca, uma procura. Preencher as ausências, que desde cedo permearam sua vida, levou Claudia a cruzar o Atlântico e experimentar diferentes linguagens que a ajudassem a compreender o outro e a si própria.

Foi no Brasil, na Floresta Amazônica, que entre desconhecidos, o povo Yanomami, a fotógrafa viu-se entre os seus. Em suas fotografias, através das fragilidades da vida que retratava, Claudia Andujar reconheceu a si própria, a garotinha de anos atrás devastada pelos horrores do nazismo que exterminou a maior parte de sua família.

Recorrentemente interpretada apenas por um viés negativo, a vulnerabilidade na obra de Andujar ganha outra nuance, construída

Crossing continents and cities, Claudia Andujar’s extensive trajectory emerges again in Curitiba at the new Museu Paranaense exhibit, "Claudia Andujar: poetics of the essential." Through comings and goings, her work finds a new home in the Paraná state capital.

The oeuvre, much like its creator, defies definitions. Although Claudia Andujar rejects the title of artist, her work is not merely limited to simple efforts of photographic documentation. In her own terms, her photographs can be translated as a quest, a search. Filling the voids that have permeated her life from an early age, Claudia crossed the Atlantic and experimented with different languages that could help her understand both herself and others.

It was in Brazil, in the Amazon rainforest, that among strangers - the Yanomami people - the photographer felt to be among her own. Through her photographs, amidst the fragility of the lives she portrayed, Claudia Andujar recognized in herself the little girl of many years ago, devastated by the horrors of Nazism which exterminated most of her family.

Often interpreted only from a negative perspective, vulnerability in Andujar's work

pela fotógrafa a partir de sua vivência com a sabedoria Yanomami. Para um membro desse povo se tornar xamã precisa passar por um ritual com os espíritos Xapiripë ou Hekurapë . Nessa cerimônia, ele fica estendido em meio à maloca, suscetível a essas entidades que fragmentam e remontam seu corpo com golpes de espada. Somente após se deixar à mercê de outros e ser fragmentado é que um indivíduo é capaz de acessar o mundo espiritual e mediá-lo para os demais. Assim como o ritual xamânico, o trabalho de Claudia Andujar revela que as quebras e a vulnerabilidade gerada por elas podem abrir as frestas necessárias para acessar outros indivíduos, povos e dimensões.

Se o livro “A Queda do Céu” é definido pelo antropólogo Bruce Albert como um relato de vida, autoetnografia e manifesto cosmopolítico focado na trajetória do xamã Davi Kopenawa, é possível dizer que a obra da fotógrafa e ativista Claudia Andujar é uma manifestação artística de objetivos muito semelhantes, a divulgação do modo de vida Yanomami. Divulgação essa que sempre teve dois vieses indissociáveis – político e estético.

Não foi superficial a intencionalidade política em seu trabalho, haja vista, por exemplo, seu pontapé no indigenismo como fotojornalista na revista “Realidade” (1971), a cocriação do fotolivro “Amazônia” (1978), uma espécie de

gains another nuance, constructed by the photographer through her experiences with Yanomami wisdom. For a member of the Yanomami to become a Shaman, they must take part in a ritual with the Xapiripë or Hekurapë spirits. In this ceremony, participants lie down in the middle of the hut, surrendering to entities that break apart and rebuild their bodies with the strokes of a sword. Only after relinquishing oneself to others and becoming fragmented can an individual access the spiritual world and mediate it for others. Akin to shamanic ritual, the fractures and vulnerability that Claudia Andujar’s work reveals can serve as openings to access other individuals, peoples, and dimensions.

If Davi Kopenawa’s, book "A Queda do Céu " ("The Falling Sky") is defined by anthropologist Bruce Albert as a life story, autoethnography, and cosmopolitical manifesto focused on the trajectory of a shaman, it is possible to say that the work of photographer and activist Claudia Andujar constitutes an artistic manifestation with very similar objectives: the dissemination of the Yanomami way of life.

This dissemination has always had two inseparable aspects, the political and the aesthetic.

manifesto contra a convenção da representação fotográfica, ao mesmo tempo que contra a ditadura e o desastre das políticas indigenistas, e a cofundação da ONG Comissão PróYanomami, em 1978, que foi fundamental nos processos que levaram à demarcação da Terra Indígena Yanomami, em 1992. E quão menos política seria a escolha de pesquisar, fotografar e publicar, também em plena ditadura, narrativas mitológicas contadas pelos próprios Yanomami (“Mitopoemas Yãnomam”, 1978)?

Foi na aliança entre evidenciação jornalística com uma sensível e inteligente produção estética que Andujar expôs a beleza cultural Yanomami. A maestria com a pouca luz de dentro de uma casa comunal (série “A Casa”, 1970-1976), a qualidade dos retratos (série “Catrimani”, 1971-1972), o esforço da criação/ captura do etéreo do pensamento Yanomami (série “Sonhos Yanomami”, 2002), a captura de volumes, texturas e tempos das relações humano/floresta (série “A Floresta”, 19721976) e, da mesma forma, a sagacidade dos enquadramentos e atenção às situações e composições das imagens que parecem fazer visíveis o que não se pode ver (série “O Reahu”, 1974-1976). E as reflexões que levantam a mescla dos retratos de intimidade – de sorrisos, de descanso –, com fotografias de recortes de jornal remetendo a cenas do garimpo ilegal e da malária, presentes na série “Genocídio do Yanomami” (1989), têm uma atualidade brutal que felizmente hoje aparece em evidência política e humanitária.

Expondo a beleza da cultura Yanomami, Andujar expôs também os tempos sombrios que se iniciaram com a invasão das terras desse povo na década de 1970. Nas séries “Genocídio do Yanomami”, “O Reahu”, “Catrimani”, “A Floresta” e “A Casa”, seu trabalho respeitou a vontade desse povo, que não queria ser retratado e divulgado para o mundo a partir das indignidades impostas a ele. Com sutilezas, a obra de Andujar denuncia, mas vai além. A delicadeza, lida tantas vezes como ausência de força, revela sua potência nas fotografias de Andujar, assim como as pequenas plumas brancas dos trajes de Xapiripë ou Hekurapë , que lhes conferem o poder dos trânsitos espirituais.

The political intentionality of her work is evident, as exemplified by her role as a photojournalist in "Realidade " magazine (1971) and her co-creation of the photobook "Amazônia" (1978), a manifesto against the conventions of photographic representation as well as against the dictatorship and the disaster of Brazil’s indigenous policy. She also co-founded the Pro-Yanomami Commission, in 1978, an NGO which played a key role in processes leading to the 1992 demarcation of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory. Amid a dictatorship, how much less political could her choice to research, photograph and publish the mythological narratives told by the Yanomami themselves ("Yãnomam Mythpoems", 1978) be?

It was through her alliance of journalistic evidence with sensitive and intelligent aesthetic work that Andujar depicted the cultural beauty of the Yanomami. This was executed through her mastery of low light inside a communal house ("The House" Series, 1998), her fine portraits ("Catrimani" Series, 1971-1972), her efforts to capture the ethereal nature of Yanomami thought ("Yanomami Dreams" Series, 1974-2003), her portrayal of volumes, textures, and the relationships between humans and the forest ("The Forest" Series, 1974) and the clever framing and attention to situations and compositions in images that seem to render visible that which cannot be seen ("The Reahu" Series, 1974-1976). The reflections raised by her juxtaposition of intimate portraits – people happy or at rest – and photographs of newspaper clippings depicting scenes of illegal mining and malaria, present in the "Genocide of the Yanomami" Series (1989), have a brutal relevance that, fortunately, is no longer ignored as political and humanitarian evidence.

By depicting the beauty of this indigenous culture, Andujar also exposed the dark times that began with the invasion of Yanomami lands in the 1970s. In her series "Genocide of the Yanomami", "The Reahu", "Catrimani", "The Forest", and "The House", Andujar’s work respected the will of the Yanomami people,

Na série “Sonhos Yanomami”, tênue também é a linha que separa e ao mesmo tempo interliga as diferentes existências entre pessoas, bichos e matas. As imagens cosmológicas Yanomami se contrapõem às grandes certezas, que formam o sólido e bravo ímpeto de destruição dos não indígenas. A compreensão da complementaridade que existe entre todas as formas de vida ocupa também mais uma etapa na busca de Andujar para preencher os próprios espaços do seu existir.

Mesmo com todo o experimentalismo e sensibilidade nos esforços tradutórios, a obra de Andujar deixa também o legado da reflexão sobre a produção das próprias imagens, neste caso feitas através de lentes muito específicas, material e culturalmente falando, que são as lentes ocidentais. A série “Minha Vida em Dois Mundos” (1974), por exemplo, nos arremessa para um lugar tensionado, não menos poético, entre a perspectiva sociocosmológica das sociedades hegemônicas, que fotografam para lembrar, e a perspectiva de um povo que foi fotografado, para o qual a lembrança, justamente por não depender de registros em “peles de imagens tiradas de árvores mortas”, é um valor que está no pensamento e na oratória, e por isso não envelhece. E fizeram parte do talento de Andujar justamente o amor e a coragem para fundir na fotografia aquilo dos Yanomami que não envelhece.

Esta exposição oferece ao visitante a oportunidade de, mesmo distante geográfica e culturalmente do povo retratado e da fotógrafa, se encontrar, reconhecer em si e nos outros, por meio e por dentro das diferenças, as diversas sensações que compõem o viver entre os mundos de Claudia Andujar.

who did not wish to be portrayed and revealed to the world through the indignities imposed upon them. With subtlety, Andujar’s oeuvre denounces, yet goes beyond denunciation. In her photographs, the gentle way of a people, often interpreted as a lack of strength, reveals its power, just as the small white feathers of the Xapiripë or Hekurapë costumes grant their bearers the power of spiritual transitions.

In the series "Yanomami Dreams", the line that simultaneously separates and connects different existences – people, animals, and forests – is also subtle. Yanomami cosmological images contrast with the certainties that form the solid and fierce impulse of destruction coming from nonindigenous peoples. Understanding the complementarity that connects all forms of life represents another stage in Andujar's quest to fill the spaces of her own existence.

Even with all the experimentalism and sensitivity in her translational efforts, Andujar’s work bequeaths a legacy of reflection on the production of images itself, in this case, made through a very specific lens, material and culturally speaking – the Western lens. For example, her series "My Life in Two Worlds" (1974) catapults us into a place of tensions, no less poetic, between the socio-cosmological perspective of hegemonic societies, which photograph to remember, and the perspective of a people that are photographed. For the Yanomami, remembrance, precisely because it does not depend on what is recorded as “the skin of images of dead trees” is a value that exists in thought and oratory and therefore does not age. Andujar’s talent includes just this: the love and courage to merge in her photography that which in the Yanomami does not age.

This exhibit offers visitors the opportunity –albeit geographically and culturally far from the people who are portrayed and from their photographer – to encounter and recognize in themselves and others, through and within differences, the diverse sensations that make up Claudia Andujar’s experience of living between worlds.

P. 14-25

Atravessando um riacho durante a colheita

(Crossing a stream during the harvest), 1974

Yanomami, 1974

Yanomami, 1974

Yanomami, 1974 P.30

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

P. 36

P. 37

P. 38

P. 39

P. 40

Catrimani, 1974

Yanomami, Catrimani, 1976

Yanomami, 1974-1976

Yanomami, 1974

Moradores da aldeia Xaxanapi entram na maloca dos Korihana Thëri com seus melhores enfeites, cantando e agitando flechas para iniciar os cerimoniais da festa, (Xaxanapi village residents enter the Korihana Thëri maloca with their best ornaments, singing and waving arrows to initiate festival ceremonies), Catrimani, 1974

P. 41

P. 41

P. 42

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Jovem em rede tradicional de algodão, planta que as mulheres aprenderam a cultivar e fiar, (Young person in a traditional cotton hammock, a plant that women learned to cultivate and spin), Catrimani, 1974

O xamã e tuxaua João assopra o alucinógeno yãkoan

(The shaman and tuxaua João blows the yãkoan hallucinogen), Catrimani, 1976

Guerreiro de Toototobi (Toototobi Warrior), 2002

Guerreiro de Toototobi (Toototobi Warrior), 2002

P. 48

P. 49

P. 50

P. 51

P. 52

Xirixana Xaxanapi Thëri mistura mingau de banana em cocho suspenso, capaz de armazenar até 200 litros de alimento para as festas (Xirixana Xaxanapi Thëri mixes banana porridge in a suspended trough, capable of storing up to 200 liters of food for celebrations), Catrimani, 1974

Tear (Loom), 1975

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Yanomami, 1974

Minha vida em dois mundos 2

(My life in two worlds 2), 1974

Minha vida em dois mundos 4

(My life in two worlds 4), 1974

Wakata-ú, Catrimani, da série "A Casa"

(from The House series), 1976

Minha vida em dois mundos 3

(My life in two worlds 3), 1974

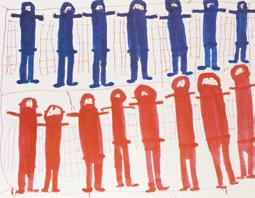

P. 60-67 Genocídio do Yanomami: morte do Brasil (Genocide of the Yanomami: death of Brazil), 1989 Detalhes de instalação composta por 228 imagens (Details of installation composed of 228 images).

O começo do mundo 1

Céu rachou enorme, céu rachou todo.

Tudo acabou

Longe do céu pés. Céu escorado, o céu sobreposto.

Céu suspenso, longe céu, longe suspenso.

Céu perna enfincada, céu perna enfincou de pau.

Outra céu rachadura, céu encaixado.

Céu racha ainda, depois céu rachou. É nublado.

Tudo acabou completamente.

Mato não tem mais.

Mato fundo longe, longe muito foi.

Mato folha pequena, rachada no meio a árvore de nariz (tronco) curto (as árvores eram Yanomami) Água ainda alto.

O começo do mundo 2

Maloca pequena, longe alto. Tudo acabou.

Longe, longe choram. Tudo acaba.

Cipó, maloca pequena longe, alto.

Aquela perto: longe outra maloca fixaram.

Aqui minha maloca em cima.

Antigamente tudo acabou longe; de cima desce tudo.

Tapirí choram todos, hiima aflitos bateram.

Batiam muito, panela batiam.

Menino chora todo mesmo.

Céu escoram xamãs

xamãs céu sustentavam, céu sustentam escorando.

Céu devagar alto suspendem; suspendem baixo muito.

Mato céu outro, céu racha.

Outro fica.

Céu escora pajé grande, escora muito.

The beginning of the world 1

The sky split apart into an enormous rent.

Everything came to an end.

The feet of the sky are set wide apart.

And support the sky above them.

The sky is suspendend up on high,

Its wooden legs gripping the earth.

Then appeared another rent, this time framed in the shape of a fork.

Again and again the heavens split apart.

All is overcast.

Everything came to an end.

Gone is the bush.

The forest, falling asunder.

Dug a chasm in the earth and fell into its depths.

The tiny leafed trees.

With theis stunted trunks and with roots exposed

Split in two as they fell.

High in the heavens still water remained

The water of the rains.

The beginning of the world 2

The tiny hit high up in the sky.

Everything has brought itself to an end.

Far, far away the Yanomami are weeping.

Everything ends.

Tiny hut, high and far away.

Another hut built nearby.

This was the hut of my forefathers.

At the dawn of time, everything came to an end.

Everything fell from up above.

All the Yanomami, in their tapiri

Weep and beath the hiima in their grief.

Beating, beating, beating.

Beating at the cooking pots.

All the young boys are weeping.

The xamã are propping up the sky.

The xamã were holding the sky aloft.

Slowly they raise the sky,

Raising it just a little.

But a piece of tree-laden sky breaks away.

A piece of the heavens falls into its place.

(That piece we still can see today.)

The great xamã is propping up the sky.

He props it up a long time.

A moloca pequena no alto, no céu.

The tiny hut high up in the sky.

A mulher ficou grávida e os filhos dela eram pacas.

The woman became pregnant and all her children were pacas.

O fim do mundo

Tudo acaba.

Céu desaparecerá.

Com os napépe todos caem.

Tudo acaba.

Cai tudo, de cima desce.

Tudo acaba, longe irá para o fundo.

Cai, tudo acabará.

Aqui outro céu suspenso fica, céu pequeno (fino) suspenso, este céu descerá, céu longe, fundo.

Choram muito.

Napèpe todos caem.

Tudo acaba.

Depois Yanomami não.

Céu cai enorme muito.

Céu completo desce, todo desaparece. Yãnomam não dormem mais.

Céu os pés.

Lá céu fincado, lá céu fincado, lá céu fincado, longe, lá céu fincado é (indicando os quatro pontos cardeais)

Céu completo cai todo.

Choram todos.

Depois céu acabará.

Céu estruturas, céu estruturas suspendiam. Céu cai.

Tudo acaba.

Céu acabará, todo mesmo, longe.

The end of the world

Everything comes to an end.

The sky will vanish.

Along with the napèpe everything will fall.

Everything comes to an end.

Everything falls, tumbling down from on high.

Everything tumbles down and comes to its end.

That lovely layer of sky up there, that too will fall.

The sky will be swallowed up by the deep.

Everyone is weeping.

All the napèpe are tumbling down.

Everything comes to an end.

From that day forth there will be no more Yãnomam.

The huge sky falls down.

The entire sky crumbles and vanishes. There are no more Yãnomam.

The feet of the sky;

There, one of its feet is grappling down; There, another foot has grappled down; There, far, far away another foot has grappled down.

The heavens above are falling.

Everyone is weeping.

The heavens are going to come to an end.

The structures still support the sky.

Everything comes to an end.

Heaven will come to an end.

P. 78-79

P. 80

P. 81

P. 82-83

O começo do mundo 1 (The beginning of the world 1)

O começo do mundo 2 (The beginning of the world 2)

O começo do mundo 3 (The beginning of the world 3)

O começo do mundo 4 (The beginning of the world 4)

A moloca pequena no alto, no céu. (The tiny hut high up in the sky.)

Omam (Omam)

A mulher ficou grávida e os filhos dela eram pacas. (The woman became pregnant and all her children were pacas.)

O fim do mundo (The end of the world)

Fragmentos de poemas e desenhos originalmente publicados no livro “Mitopoemas Yãnomam”. Claudia Andujar e Emilie Chamie. Editora Olivetti. 1978.

(Poems and drawings originally published in the book “Mitopoemas Yãnomam”. Claudia Andujar and Emilie Chamie. Published by Olivetti. 1978.)

Depoimento e imagens publicadas originalmente em “Relação: homem pra homem”.

Jornal Ex-, São Paulo, n.14, p.19, setembro de 1975.

(Testimonial and images originally published in “Relação: homem pra homem”.

Jornal Ex-, São Paulo, n.14, p.19, September 1975.)

Era de manhã e sabia que de tarde viriam me buscar para me levar de jipe na cidadezinha de Caracarai. Primeira viagem por terra de volta ao outro mundo, o mundo tecnológico e compromissos diferentes. O mundo no qual nasci e cresci; onde aprendi que para ser respeitada tinha que me impor como pessoa sorridente, com a cabeça limpa, otimista.

Não me despedi formalmente porque não existe "até logo" entre os Indios; e se existisse, também não iria me despedir de qualquer jeito. Se despedir implica um fim; mas a vida é uma continuação eterna das coisas que se ligam, desligam e ligam de novo. Às vezes de jeitos diferentes. Tem mil maneiras de se separar e se juntar: é um processo molecular. As formas são infinitas, as combinações inúmeras, mas essencialmente sempre tudo continua; é o processo da vida. O mistério da existência. Vida, onde a morte é só um processo complementar, uma outra forma de continuar. Um processo de transfigurações de momentos em fluxo.

Embrulhei minha rede, saco para dormir, máquina fotográfica, canequinha, remédio para malaria, calça blue-jean, camisetas. Estava tudo pronto para deixar os meses de trabalho entre a família extensa do mundo Yanomami. Os Yanomamis que até pouco pensavam ser o único povo do mundo. Eles a "gente" e o resto, os "napê", os que não são Yanomami. A última coisa que fiz, como tinha feito tantas vezes, foi de dar remédio a um doente. Mil novecentos e setenta e quatro, o ano em que tiveram onze gripes e o sarampo, trazido pelos peões da construção da estrada (Manaus - Caracarai - Venezuela), e malária que não acaba mais.

E o jipe chegou. Havia três ou quatro Indios olhando com curiosidade minha parafernália. la embora. Falei pouco, era emocionada. Lá, estava em casa. Me sentia bem, era como se sempre tivesse estado lá, integrada. Esse pequeno mundo na imensidão do mato Amazônico era meu lugar e sempre será. Estou ligada ao Indio, à terra, à luta primária. Tudo isso me comove profundamente. Tudo parece essencial. E talvez nem entendo tudo, e não pretendo entender. Nem preciso, basta amar. Talvez sempre procurei a resposta à

It was morning and I knew that in the afternoon they would come to get me and take me in the Jeep to the small town of Caracarai. My first land trip back to the other world, the technological world with different commitments. The world in which I was born and grew up; where I learned that, to be respected, I had to present myself as a smiling person with a clear mind, optimistic.

I did not say goodbye formally because “see you soon” does not exist among the Indians: and if it did exist, I would not say goodbye anyway. Saying goodbye implies an end: but life is an eternal continuation of things that come together, separate, then come together again. Sometimes differently. There are a thousand ways of separating and coming together: it is a molecular process. The forms are endless, the combinations countless, but in essence everything always continues: it is the process of life. The mystery of existence. Life, in which death is merely a complementary process, another form of continuing. A process of transfigurations of moments in flux.

I packed my hammock, sleeping bag, camera, mug, malaria medicine, blue jeans, T-shirts. Everything was ready for leaving behind the months of work among the extended family of the Yanomami world. The Yanomami people, who until recently thought they were the only people in the world. Them, the “people” and the rest, the “napê”, those who are not Yanomami. The last thing I did, as I had done so often, was to supply medicine to an ill person. The year 1974, marked by eleven cases of flu and measles, brought by the workers on the Manaus-Caracarai-Venezuela highway, and the never ending malaria.

And the Jeep arrived. There were three or four Indians looking curiously at my paraphernalia. I was leaving. I said little, overcome with emotion. There, I was at home. I felt good, it was as if I had always been there, integrated. This small world in the immensity of the Amazonian rainforest was my place and forever will be. I am linked to the Indian, to the land, to the fundamental fight. All of

razão da vida nessa essencialidade. E fui levada para lá, na mata Amazônica, por isso. Foi instintivo. A procura de me encontrar.

Me acho nas longas caminhadas pelo mato. Fiz várias. Me lembro do suor pingando do nariz, queimando os olhos. Caminhamos horas. Homem, mulher, criança, criança recém-nascida, nas costas da mãe, o macaco da noite agarrado no cabelo da India, as redes, as panelas, o essencial, tudo caminhava. O homem na frente com arco e flecha para defender a mulher e a criança, ou pronto para qualquer caça. Seguindo a trilha, um caminho estreito, coberto de um tapete de folhas. Igarapés, paus caídos, mil dificuldades, um mato virgem. O mato que para o Indio é como uma cidade para nós. Ele conhece cada cruzamento, supera-os como nós atravessamos as ruas.

Eu me senti cansada, de horas de caminho. E o mato todo, monótono, não enxergava mais. E nós ainda estavamos andando. De repente me desliguei. Sei que estava caminhando, seguindo o outro, colocando um pé em frente do outro, e meus pensamentos foram longe. Me vi criança na Europa. Uma Europa na guerra, uma criança que tenta desesperadamente se ligar a alguém. Amar e ser amada, compreendida, era o desejo da minha infância. E não consegui. Fui para Nova York e procurei a mesma coisa, ainda criança. Gostava de passar horas no campo, nos parques, no cemitério com árvores, porque eram lugares quietos e solitários. Passava horas em igrejas vazias conversando sozinha. Me senti só na grande metrópole.

Mas ainda estava andando no mato Amazônico com os Indios, uma marcha que virou automática. E senti que a vida estava tomando conta de mim. Era uma caminhada que limpava. Limpava tudo que era dentro de mim. O calor, o suor, a fadiga, o ruido surdo dos passos.

Me senti integrada com migo, com o mato, não importava onde ía, quantas horas caminhava. Sabia que me tinha encontrado. Me encontrei no senso de ter encontrado o essencial. São momentos raros que a gente sente às vezes, que resumem tudo. E a gente se sente integral. Dura pouco, são momentos só. E me lembro

this moves me deeply. Everything seems essential. And perhaps I do not understand it all, and I do not intend to understand. Nor do I need to, loving is enough. Perhaps I have always sought the answer to the meaning of life in that essentiality. And I was taken there, in the Amazon forest, because of that. It was instinctive. In search of myself.

I find myself during the long treks through the forest. I have done several. I remember the sweat dripping off my nose, burning my eyes. We walked for hours. Men, women, children, newborns on their mothers’ backs, a night monkey clinging to a woman’s hair, the hammocks, pots, the essentials, everything moved. The man in the lead with a bow and arrow to defend his wife and child, or ready for an eventual hunt. Following the trail, a narrow path, covered with leaves. Igarapés, fallen branches, a thousand difficulties, a virgin forest. The forest that is to the Indian like a city to us. He knows every crossing, crosses them the way we cross streets.

I felt tired from hours of trekking. And in the monotonous forest I could no longer see. And we kept on walking. Suddenly, I zoned out. I know I was walking, following the person ahead of me, putting one foot in front of the other, but my thoughts were far away. I saw myself as a child in Europe. A Europe at war, a child trying desperately to hold on to someone. To love and be loved, understood, was the desire of my childhood. And I failed. I went to New York and sought the same thing, still a child. I enjoyed spending hours in the countryside, in parks, in cemeteries with trees, because they were quiet and solitary places. I would spend hours in empty churches talking to myself. I felt alone in the metropolis.

But I was still trekking through the Amazonian jungle with the Indians, a march that became automatic. And I felt that life was taking charge of me. It was a trek that cleansed. Cleansed everything inside of me. The heat, the sweat, the fatigue, the muffled sound of our footsteps.

I felt united with myself, with the jungle, it did not matter where I was going, how many

que suava tanto nesta caminhada, que era toda molhada. A sede me apertou. Quis parar e beber, mas não podia porque era apenas uma entre outros acostumados a andar como se anda numa grande avenida. E se parasse e ficasse para trás, o mato iria me engolir. Então andava e me perdia nos pensamentos. Essa minha primeira viagem no mato durou uns cinco dias. Os Indios foram caçar e pescar. O destino geográfico da viagem me era desconhecido, só sabia que era uma procura de comida e queria entender o que significava isso. Tinha dias em que andávamos horas, outro pouco. O que me levou era o desejo de entender essa busca pelo alimento tão essencial nessa sociedade. Cada tarde, nós limpávamos o mato para acomodar para a noite. Pendurávamos as redes entre as árvores, cobrindo-as com um teto de folhas de sororoca (banana selvagem). A noite chegava cedo. No mato onde o sol penetra pouco, a obscuridão da noite é total. Pelas sete horas todos estavam na rede e só se enxergavam as luzes das fogueiras e dos vaga-lumes. Deitada escutava as risadas, as conversas dos Indios e os barulhos do mato. Porque o mato raramente é silencioso. Dormia e acordava. O Indio de vez em quando levantava para alimentar o fogo. As noites eram compridas, os barulhos misteriosos. Às vezes me dava medo e ficava escutando o barulho dos passos de bichos ou um pássaro noturno a cantar. Às vezes ouvia um jato bem longe em cima do mato passar e pensava no passageiro, rota Nova York-Rio-São Paulo, tomando seu último whisky que a aeromoça servia. Me sentia entre dois mundos, um bem longe em tempos e mentalidade e um outro perto que queria pegar entre as mãos e entender.

Na época não me importava não entender a língua dos Yanomami. Nós nos entendíamos com gestos e mímica. As respostas encontrava no olhar. Não sentia a falta de troca de palavras. Queria observar absorver para recriar em forma de imagens o que sentia. Talvez o diálogo iria até interferir. Só mais tarde, quando acabei de fotografar, eu procurei a comunicação verbal. Fotografar é processo de descobrir o outro e através do outro si mesmo. No fundo por isso o fotógrafo busca e descobre novos mundos, mas acaba sempre mostrando o que

hours we walked. I knew that I had found myself. Found myself in the sense of having found the essential. There are rare moments that we sometimes experience, which sum everything up. And we feel whole. They are brief, just moments. I remember sweating a lot during that trek, and how wet everything was. I felt thirsty. I wanted to stop and drink, but I could not because I was only one among others accustomed to moving as one would move on a wide avenue. And if I stopped and fell behind, the jungle would swallow me. So I walked and lost myself in thoughts. This, my first trip through the forest, lasted five days. The Indians went out to hunt and fish. The geographical destination of the trek was unknown to me, I only knew it was a search for food and that I wanted to know what that meant. There were days when we walked for hours, on others, only a few. What drove me was the desire to understand why the search for food was so essential to that society. Each afternoon, we would clear an area to accommodate us during the night. We would hang the hammocks between trees, covering them with a roof of sororoca leaves. Night would come quickly. In the forest, where the sun barely penetrates, darkness at night is total. Around seven o’clock, everyone was in their hammocks, and all one could see was the lights from the campfires and the fireflies. Lying down, I listened to laughter, the Indians’ conversations, and the sounds of the forest. Because the forest is seldom silent. I would fall asleep and wake up. From time to time an Indian would get up to tend to the fire. The nights were long, the noises mysterious. At times I felt afraid and listened for the sound of animal footsteps or the song of a nocturnal bird. Sometimes I would hear a far-off jet passing over the forest and thought about the passenger on the New York-Rio-São Paulo route having the last whiskey the stewardess served. I felt myself between two worlds, one very distant in terms of time and mentality, the other nearby, which I longed to grasp in my hands and understand.

At the time, it did not bother me not to understand the language of the Yanomami. We made ourselves understood through

tem dentro de si. Minha busca da interligação homem-terra estava dentro de mim antes de ter ido na Amazônia e as caminhadas no mato só serviam como catalisadores para reforçar o que estava fundamentalmente lá.

O medo da morte me perseguiu muitos anos. É um pensamento que trouxe da infância; sem dúvida sentimento de culpa. Durante a guerra, meu mundo foi arrasado de um dia para o outro. Fiquei viva enquanto os outros morreram. Morreram meu pai, morreu minha avó, minhas amiguinhas e um amiguinho que me emocionou e me acordou dos sonhos da infância.

Os anos passaram. Era madrugada; exausta de dores, apoiei a nuca no travesseiro com gelo na testa. Me senti deslizar no limbo. Estava passando muito mal, com a malária. Descobri que a dor era mais terrível que a morte. Meu único desejo era que a dor parasse. E um dia parou; perdi o medo da morte. As folhas podres no solo da floresta, as caminhadas no mato fechado, o encontro com migo nos momentos raros que a vida me propôs num momento de entrega, é o que está com migo, está no meu trabalho. Trabalho que pode se resumir na fotografia, no tratar de um doente, na comunicação, em mil coisas, todas interligadas, porque sou sempre a mesma pessoa com a mesma procura.

O jipe chegou, me levou. Durante a viagem para Caracarai me acalmei, sabia que o que tinha feito era certo. Certo para os demais que deixei para trás e certo para mim.

gestures and mimicry. Answers were in the gaze. I did not miss the exchange of words. I wanted to observe, absorb, in order to recreate in the form of images what I was feeling. Perhaps dialogue might even interfere. Only later, when I was done photographing, did I look for verbal communication. Photography is the process of discovering the other and, through the other, oneself. Intrinsically, this is why the photographer seeks and discovers new worlds, but in the end always shows what is inside oneself. My search for the man/land interconnection was inside me before I went to the Amazon. And the treks through the forest only served as catalysts to reinforce what was basically there.

Fear of death pursued me for many years. It is a thought that goes back to childhood: without a doubt, a feeling of guilt. During the war, my world was destroyed overnight. I lived while others died. My father, my grandmother, my girlfriends, and a male friend whose death deeply disturbed me and who woke me from the dreams of childhood.

The years passed. It was late at night: exhausted from pain, I rested my head on the pillow and applied ice to my brow. I felt myself drifting into limbo. I was suffering greatly with malaria. I discovered that pain is worse than dying. My only wish was for the pain to cease. And one day it did: I lost the fear of death. The rotting leaves on the forest ground, the treks in dense jungle, the self-revelation that life offered me in the rare moments of respite, is what remains with me, it is in my work. Work that can be seen in the photography, in the treatment of the ill, in communication, in a thousand interconnected things, because I am always the same person with the same pursuit.

The jeep arrived, took me away. During the journey to Caracarai I became calmer, knowing that what I had done was right. Right for those I left behind and right for me.

Fotografar. Filmar. Contar. Compartilhar. Refletir experiências e refratar o vivido.

Em diferentes partes do que se costuma chamar de território brasileiro – necessariamente marcado pelas presenças, historicidades e pertenças indígenas –, Denilson Baniwa e Patrícia Ferreira (Pará Yxapy) conversaram acerca do trabalho de Claudia Andujar em conjunto com os Yanomami. Falaram também sobre a atuação profissional plural de Patrícia, a percepção Guarani da imagem e possíveis leituras a respeito da fotografia e do cinema indígena no Brasil presente.

Transpassados por temporalidades e geografias múltiplas, Denilson e Patrícia, Baniwa e Guarani, trocaram perguntas e óticas por meio de áudios enviados com smartphones, em diferentes dias do mês de julho de 2023. Em uma troca que instiga o pensar sobre as tantas formas do dialogar e do criar conjuntos; sobre a contemporaneidade e a nãolinearidade da História; sobre a arte e o que vai além dela; vemos mais do que dois agentes falando sobre si e sobre Andujar.

Vemos o que há de essencial na poética. Sentimos o que há de poético no essencial.

Denilson Baniwa é amazônida de origem na nação Baniwa. Tem como base de trabalho a pesquisa sobre aparecimentos e desaparecimentos de indígenas na História Oficial do Brasil, ao mesmo tempo em que busca nas cosmologias indígenas e suas representações artísticas um possível método de compartilhar conhecimentos ancestrais e ao mesmo tempo criar um banco de dados com essas cosmologias como modo de salvaguardá-las.

Patrícia Ferreira Pará Yxapy é cineasta e professora. Nasceu na aldeia Kunha Piru, na Província de Misiones, Argentina, e atualmente mora na Aldeia Ko’enju, em São Miguel das Missões, no Rio Grande Sul, Brasil. Em 2007, fundou o Coletivo Mbyá-Guarani de Cinema e começou a participar do projeto "Vídeo nas Aldeias", elaborando vários documentários. Fez residência artística no Canadá, em 2014 e 2015, com cineastas indígenas Inuit. Participou de diferentes festivais de cinema, nacionais e internacionais, sendo referência como mulher cineasta indígena.

Denilson Baniwa 13/07/2023

Oi, Patrícia. É muito bom estar conversando com você sobre seu trabalho e também sobre o trabalho da Claudia Andujar para essa exposição no Museu Paranaense. Então, quero te fazer algumas perguntas sobre como você vê a tua ação enquanto cineasta, fotógrafa, e também a tua visão, a partir da tua vivência, em relação ao trabalho da Claudia, que claro, tem uma importância muito grande. A construção da imagem e a percepção de não indígenas mudou a partir do trabalho da Claudia. A gente sabe que o trabalho da Claudia foi essencial para a proteção dos direitos e da visibilidade dos temas relacionados aos Yanomami. Bom, eu quero te fazer algumas perguntas. Primeiro, quero que você se apresente. Fale quem é você, de onde você vem e qual a tua ação no momento. Tua atuação enquanto cineasta, fotógrafa. Quais filmes você já fez, quais prêmios e como você se relaciona com o cinema e a fotografia.

Patrícia Ferreira 19/07/2023

Eu me chamo Patrícia Ferreira. Na verdade tenho dois nomes. Patrícia Ferreira é o que está escrito no meu RG, mas meu nome verdadeiro em Guarani é Pará Yxapy. Eu moro aqui nas missões, no Rio Grande do Sul. Município de São Miguel das Missões, Tekoa Koenju. Faz bastante tempo que eu trabalho com cinema. Atualmente trabalho como professora. Na verdade, quando eu comecei a trabalhar com audiovisual eu já atuava como professora aqui na minha aldeia. Eu sempre tentei levar as duas coisas, os dois trabalhos, como prof. e como cineasta, mas era um pouco complicado, porque não batia muito o tempo, como educadora e como realizadora. Porque para realizar alguns filmes, alguns trabalhos com audiovisual requerem algum tempo, né. Tempo de pensar, tempo de realizar, tempo de analisar o trabalho. E trabalhar com educação, no caso com as crianças na escola, também requer muito tempo. Educar as crianças, repassar o conhecimento dos seus antepassados e preparar para o futuro. Mas sempre insisti para levar isso, que eu pudesse trabalhar junto o audiovisual dentro da educação. E hoje eu posso dizer que de alguma forma eu estou conseguindo trabalhar a educação junto com o audiovisual.

Eu faço parte de um coletivo Guarani de cinema. Como coletivo a gente já fez uns sete filmes. E os filmes que a gente realizou foram mostrados em vários países, em vários lugares do Brasil e festivais. Já ganhamos alguns prêmios como reconhecimento. O primeiro filme que foi feito foi o "Duas Aldeias", no qual eu só participei na tradução, de língua guarani para português. Esse é o primeiro filme do coletivo. Depois veio "Bicicletas de Nhanderu". Depois o "Tava e Desterro Guarani". E para crianças, "Mbya Mirim" e "No Caminho com Mário". E depois fui fazendo em parceria com outras pessoas, como o "Teko Haxy" que eu fiz com a Sofia e o "Nosso Espíritos Seguem Chegando", que é o mais novo que eu participei também. São esses filmes que a gente fez e circularam bastante.

Bom, a segunda pergunta é sobre como você entende a construção da imagem a partir da fotografia e do cinema. Você, enquanto uma pessoa indígena, como você entende a fotografia e o cinema? Se a construção da imagem ajuda a repercutir temas importantes para a tua comunidade, mas também de maneira geral para todos os povos indígenas do Brasil.

Bom dia, tudo bem? Eu to aqui no Amapá, na terra dos Oiampi e o acesso é bem difícil. E por isso não te respondi antes. Hoje eu estou num lugar que pega, mas depois eu vou para outro lugar, aí acho que vou ficar sem internet. Peço mil desculpas, além de não ter celular, estou em um lugar de difícil acesso.

Falando da minha própria experiência, de quando a gente começou com o audiovisual, lá em 2007, 2008. Eu acho que o audiovisual, tanto a fotografia como o vídeo, com certeza repercutiu muito, principalmente pensando na minha realidade que é a aldeia Koenju, e os municípios que a gente pertence. Antigamente, antes da gente trabalhar com isso, as pessoas daquele município não tinham quase nenhum entendimento sobre qual povo morava naquela região. Mesmo vivendo num lugar turístico que é do próprio povo Guarani. Que foi construída aquela igreja e tudo mais e usufruindo daquele lugar como lugar turístico. E desde que a gente trabalha com cinema isso mudou bastante. O olhar é diferente, o reconhecimento. Eu acho que, de alguma forma, ao trabalhar com audiovisual o nosso objetivo é esse, né, mudar uma construção, de menos preconceito, para ir construindo as pessoas, construindo pensamento. De forma geral, acho que cada povo que trabalha com isso, com fotografias, com audiovisual, ajuda muito a repercutir, em cada lugar, o problema que existe. Não necessariamente para melhorar, mas de alguma forma ajuda que todas as pessoas de fora vejam isso e que mesmo que isso demore para ter alguma solução, nunca é imediata, mas de alguma forma isso nos ajuda a levar os problemas para fora, para poder depois, em algum momento, receber o retorno positivo.

A outra pergunta é como o povo Guarani entende a imagem. A gente sabe que, para muitos povos, a imagem é passageira. Não existe sentido na catalogação ou no arquivamento de imagem. Então, como o povo Guarani, o teu povo, se relaciona com a imagem? Fotografada ou gravada em vídeo, antigamente e atualmente.

Eu vou falar um pouco mais da minha experiência como cineasta, e como eu ouvi as pessoas mais velhas falarem sobre a imagem. Quando a gente começou a trabalhar com audiovisual, muitas pessoas, principalmente as mais velhas, tinham um pouco de resistência de serem fotografadas e filmadas. Por dois motivos. Um era por uma desconfiança,

Revista Continente, ano 2017, no 196 Pelo direito de existir

P.F. 24/07/2023

porque como a gente mora numa cidade turística, muitos não indígenas vinham e tiravam fotos sem autorização. Muitas vezes levavam isso. Algumas vezes pedem pra fazer filmagens e muitas vezes a gente não sabe para quê e por que que foi filmado, não tem retorno do resultado. Então, quando a gente começou a trabalhar com isso, uma das preocupações era essa. Como que a gente ia tirar a imagem? Pegar a imagem dos mais velhos para transformar em que? Como a gente ia trabalhar? E se vai ser um trabalho dos não indígenas? Isso era com um entendimento de que a gente tá roubando a imagem pro nosso trabalho. Então a gente teve que explicar muito que era importante esse olhar de dentro. Principalmente filmar as coisas da nossa realidade para mostrar para os não indígenas. O que a gente tá passando, qual é a nossa necessidade. Uma das coisas era isso.

E outra questão de não querer ser fotografada ou filmada também é que quando a gente capta uma imagem de uma pessoa mais velha a gente tá tirando o espírito daquela pessoa, mais ou menos nesse sentido, né. Eu lembro que uma das pessoas mais velhas falou assim: “ah, e quando eu morrer?”. Porque pra gente, quando uma pessoa falece a gente tem essa lembrança da fala, mas a gente não quer ver mais a imagem do que já foi. Então, nesse sentido, quando eu partir desse mundo, como vocês ainda vão ter a imagem de eu falando? Por esse motivo, quando a pessoa falece já não é pra estar junto com a gente. Já tá bom no outro plano, então não pode mais estar com a gente. Mas na imagem a gente ainda vai ter ele conosco. Então isso também era uma coisa que não achavam muito bom. Porque a imagem vai ficar para sempre. Então eles não querem ficar presos naquela imagem quando partir. Nesse sentido, tinham resistência de filmar. Mas a gente falou que era importante ter esse conhecimento. A gente sabe que hoje em dia a nossa cultura vai se perdendo muito rápido. A gente explica isso, que a nossa intenção é preservar nossa cultura, nossa memória e fortalecer o que a gente ainda tem. E nesse sentido a gente fez o trabalho com os mais velhos através dessa compreensão.

E a outra pergunta que eu queria te fazer é se você conhece o trabalho da Claudia Andujar e como que você vê a atuação de fotógrafos não indígenas na ajuda aos povos indígenas em suas lutas. A gente, claro, sabe que a Claudia foi uma importante aliada dos Yanomami, mas você também tem outros fotógrafos que são aliados de populações indígenas, e como você vê a atuação dessas pessoas?

Eu conheço o trabalho da Claudia pela internet. Eu vejo as fotos, que ela é fotógrafa e trabalhou com os povos Yanomami, faz um tempo. Mais do que isso não, mas eu sei da importância do que ela fez tanto para os povos Yanomami, quanto os povos de fora, que são os não indígenas.

D.B.

13/07/2023

P.F.

24/07/2023

Então, eu acho que cada um que trabalha assim, sejam indígenas ou não indígenas, com a questão do audiovisual, fotografias, com certeza isso soma a nossa luta, na nossa luta do dia a dia, na nossa luta pelas demarcações de terra. Principalmente para nós, Guarani, que os não indígenas nos acompanham, eles de alguma forma estão sempre nos auxiliando, ajudando a levar e repercutir nossa luta. Acho que por isso hoje a gente tá mais visível que antigamente. A catequização quis nos apagar, né. Então hoje a gente está voltando a ser visível, mas de forma mais lenta, através da nossa luta, através da nossa espiritualidade. Acho que é isso.

A última pergunta é relacionada a como você vê o cenário brasileiro agora nesse momento. Que ainda tem esses fotógrafos aliados não indígenas, mas também tem grande movimento de fotógrafos e cineastas indígenas no Brasil. Como você vê esse movimento, e como você imagina que vai ser daqui pra frente, o futuro da fotografia e do cinema indígena no Brasil?

Bom, são essas perguntas que eu queria fazer, mas se você quiser contribuir, falar um pouco mais de alguma coisa que seja de seu interesse, ou que você queria que eu tivesse te perguntado, ou que você queria falar, fica à vontade que temos espaço pra falar o que você quiser, tá bom? É isso. Muito Obrigado. Aguyjevete.

Hoje os fotógrafos e cineastas indígenas estão aumentando de alguma forma, porque a gente sabe da importância desses equipamentos que a gente tem. Produzir esses arquivos, esses audiovisuais, para nós, ajuda muito. Tanto para nós povos indígenas, quanto povos não indígenas, a gente sabe da importância dessas ferramentas que estão chegando nas aldeias. Hoje, por exemplo, eu tô aqui nos Oiampi para dar continuidade na formação dos jovens Oiampi, para trabalhar com audiovisual. É dessa forma que a gente vai alcançando os povos não indígenas para poder reconhecer a importância da nossa existência. Eu acho que hoje eu posso dizer que estão começando a entender a importância do audiovisual.

Realidade, ano 1971, no 67 Editora Abril (org.), Amazônia

Photographing. Filming. Narrating. Sharing. Reflecting experiences and refracting the experienced.

In different parts of what is commonly referred to as Brazilian territory – necessarily marked by indigenous presences, historicities, and belongings – Denilson Baniwa and Patrícia Ferreira (Pará Yxapy) discussed Claudia Andujar's work in collaboration with the Yanomami. They also talked about Patrícia's diverse professional engagements, the Guarani perception of image and possible interpretations of indigenous photography and cinema in present-day Brazil.

Transcending multiple temporalities and geographies, Denilson and Patrícia, Baniwa and Guarani, exchanged questions and perspectives through audio messages sent via smartphones, on several days in July 2023. In an exchange that provokes musings on the many forms that dialogue and collective creation may take, on contemporaneity and the non-linearity of History, on art and what lies beyond it, we see more just than two people speaking about themselves and about Andujar.

We see the essential within the poetic. We sense the poetry within the essential.

Denilson Baniwa is an Amazonian from the Baniwa nation. His work is based on researching the appearances and disappearances of indigenous peoples in Brazil's Official History, while seeking within indigenous cosmologies and their artistic representations a possible method for sharing ancestral knowledge and creating a database with these cosmologies, as a means to safeguard them.

Patrícia Ferreira Pará Yxapy is a filmmaker and teacher. She was born in Kunha Piru village, in the Province of Misiones, Argentina, and currently resides in Ko’enju Village, São Miguel das Missões, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. In 2007, she founded the Mbyá-Guarani Indigenous Cinema Collective and began participating in the Video in Villages project, producing several documentaries. She conducted artistic residencies in Canada in 2014 and 2015, collaborating with Inuit indigenous filmmakers. She has taken part in various national and international film festivals and is a reference as an indigenous woman filmmaker.

Denilson Baniwa 13/07/2023

Patrícia Ferreira 19/07/2023

Hi, Patricia. It's great to be talking to you about your work and also about Claudia Andujar's work for this exhibit at Museu Paranaense. So, I want to ask you some questions about how you view your role as a filmmaker, photographer, and also your perspective, based on your experiences, on Claudia’s work, which is of course very significant. The construction of the image and the perception of non-indigenous people has changed due to Claudia's work. We know that Claudia’s work was essential for protecting the rights of the Yanomami and for the visibility of issues related to them. Well, I want to ask you a few questions. First, please introduce yourself. Tell us who you are, where you come from and what you’re currently involved in. Your role as a filmmaker, photographer. What films you've made, any awards and how you relate to cinema and photography.

My name is Patrícia Ferreira. Actually, I have two names. Patrícia Ferreira is what is on my ID, but my true name in Guarani is Pará Yxapy. I live here in the 'missions ', in Rio Grande do Sul. Municipality of São Miguel das Missões, Tekoa Koenju. I've been working with cinema for quite some time. Currently, I work as a teacher. In fact, when I started working with audiovisuals, I was already a teacher in my village. I always tried to balance both roles, being a teacher and a filmmaker, but it was a bit complicated since the timing didn't always match – being an educator and a filmmaker. Because making films, audiovisual projects requires time, you know. Time to think, time to create, time to analyze the work. And working in education, especially with children in school, also requires a lot of time. Educating children, passing down the knowledge of their ancestors and preparing them for the future. But I have always insisted on combining them, so that I could integrate audiovisual work into education. And today, I can say that in some way, I'm managing to work on education alongside audiovisual work.

I'm part of a Guarani cinema group. As a group, we've made about seven films. These films have been shown in various countries, different parts of Brazil and at festivals. We've received some awards in recognition. The first film we made was “Duas Aldeias ” [Two Villages] in which my only role was the translation, from Guarani to Portuguese. That was the group’s first film. Then came “Bicicletas de Nhanderu ”. After that, “Tava” and “Desterro Guarani” [Guarani Uprooting]. For children, “Mbya Mirim” and “No Caminho com Mário ” [On the Road with Mario]. Later, I collaborated with others, like “Teko Haxy”, which I made with Sofia, and “Nosso Espíritos Seguem Chegando ” [Our Spirits Continue Coming], the most recent one I also took part in. Those are the films we’ve made that have been shown widely.

D.B. 13/07/2023

Well, the second question is about how you understand the construction of the image through photography and cinema. As an indigenous person,

how do you perceive photography and cinema? Does the construction of images help to highlight important themes for your community and, more broadly, for all indigenous peoples of Brazil?

Good morning, how are you? I'm here in Amapá, in the land of the Oiampi, and [internet] access is quite difficult. That's why I haven't gotten back to you sooner. Today, I'm in a place with service, but I'll be moving on to another spot later, where I might not have internet. I apologize a thousand times; besides not having a cell phone, I'm in a remote area.

Speaking from my own experience, from when we began audiovisual work – back in 2007, 2008 – I believe that audiovisual media, both photography and video, definitely had a significant impact, especially considering my reality which is the village of Koenju, and the municipalities we belong to. Before we started our work, people from those municipalities hardly had any understanding of the peoples living in the region. Even though it’s a touristy area belonging to the Guarani people themselves. In which the church and everything else was built and the place used as a tourist attraction. Since we’ve been working with cinema, a lot has changed. Perspectives are different, recognition is different. I think that, somehow, working with audiovisual media, our goal is to change the constructs, reduce prejudice and build people’s understanding and thinking. In general, I believe that each indigenous group that engages in photography and audiovisual work helps greatly to highlight the issues that exist in their respective areas. Not necessarily to solve them, because solutions are never immediate, but in some way, it helps us bring those issues to the outside world so that eventually, at some point, we might get positive returns.

The other question is about how the Guarani people perceive images. We know that for many peoples, images are transient. Cataloging or archiving images has no meaning. So, how do the Guarani people, your people, relate to images? Whether photographed or recorded on video, both in the past and present.

I will share a bit more about my experience as a filmmaker and what I’ve heard older people say about images. When we started working with audiovisual media, many people, especially the elderly, had some resistance to being photographed and filmed. There were two reasons for this. One was distrust, because as we live in a tourist town, many non-indigenous people came and took photos without permission. Often, they would take these images back with them. Sometimes they’d ask to film, but many times we wouldn’t know why we were being filmed or what it was for, and there was no feedback on the results. So when we began this work, one of the concerns was how we would approach

images. How would we take the images of the elders and transform them? How would we work? And if non-indigenous people would be involved. There was this idea that we were taking their images for our work. We had to explain thoroughly that our insider perspective was important. Especially filming aspects of our reality to show to non-indigenous people. What we are going through, what our needs are. That was one of the considerations.

Another reason for not wanting to be photographed or filmed is that when we capture an image of an elder, we’re ‘taking away their spirit’, more or less in that sense. I remember an older person saying, “What about when I die?”. Because for us, when someone passes away, we remember their voice, but we don't want to see the image of what they once were. So, in this sense, when I depart this world, how will you still have an image of me speaking? That’s why when a person passes away, they're no longer supposed to be with us. They're fine in the other realm, so they shouldn't be with us anymore. But in images, we still have them with us. That’s another reason why they weren’t very fond of being filmed. But we explained that having this knowledge was important. We know that our culture is being lost very rapidly nowadays. We explain that our intention is to preserve our culture, our memory, and strengthen what we still have. In that sense, we conducted our work with the elders under this understanding.

D.B.

13/07/2023

P.F.

24/07/2023

And the other question I wanted to ask is if you're familiar with Claudia Andujar’s work and how you view the role of non-indigenous photographers in aiding indigenous peoples in their struggles. We know that Claudia was a significant ally to the Yanomami, but there are other photographers who are allies to indigenous populations. How do you see the role of these individuals?

I'm familiar with Claudia's work through the internet. I see her photos, [see] that she’s a photographer who worked with the Yanomami people for some time. Beyond that, not much, but I understand the importance of what she did, both for the Yanomami people and for non-indigenous people.

So, I think that anyone who works in this manner, whether indigenous or non-indigenous, with audiovisual media, photography, undoubtedly contributes to our fight, to our daily struggles, to our fight for land demarcation. Especially for us, the Guarani, who are accompanied by non-indigenous people, they’re somehow always assisting us, helping spread awareness about our struggles. I believe that’s why today we are more visible than before. The process of colonization aimed to erase us, right? So today we’re becoming visible again, albeit slowly, through our struggle, through our spirituality. I guess that’s it.

P. 107

D.B. 13/07/2023

P.F. 19/07/2023

The last question is related to how you perceive the current Brazilian scene. There are non-indigenous photographers who are allies, but there's also a growing movement of indigenous photographers and filmmakers in Brazil. How do you see this movement, and how do you envision the future of indigenous photography and filmmaking in Brazil?

Well, those are the questions I wanted to ask. But if you’d like to contribute, talk a bit more about something of your interest, or if there's something you wished I had asked or want to discuss, feel free. We have space to talk about whatever you'd like to. Okay? That’s it. Thank you very much. Aguyjevete.

Nowadays, indigenous photographers and filmmakers are growing in number, because we recognize the importance of the tools we have. Creating these archives, these audiovisual works, is a great help for us. It's beneficial for both indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. We understand the significance of these tools that are reaching the villages. For instance, today I’m here with the Oiampi people to continue training the young Oiampi in audiovisual work. This is how we gradually reach non-indigenous people and make them realize the importance of our existence. I believe that now they’re beginning to understand the importance of audiovisual media.

Télérama, ano 2020

Luc Desbenoit, Les yeux de l'Amazonie

Realidade (p. 202), ano 1971, no 67 Editora Abril (org.), Amazônia

Revista Arte!Brasileiros, ano 2015, no 31 S. Persichetti, Pela lente do amor

ACERVO / COLLECTION MUSEU PARANAENSE

SÉRIE "CATRIMANI" ("CATRIMANI" SERIES), 1971-1972

Claudia Andujar

Catrimani, 1971-1972

Políptico composto por 10 impressões em jato de tinta sobre papel Hahnemühle Photo Rag® Baryta 315gr. (Polyptych composed of 10 inkjet prints on Hahnemühle Photo Rag® Baryta 315gr paper)

SÉRIE "A FLORESTA" ("THE FOREST" SERIES), 1972-1976

Claudia Andujar

Yanomami, 1974

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Yanomami, 1974

Atravessando um riacho durante a colheita (Crossing a stream during the harvest), 1974

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Yanomami, 1974

Ampliação analógica feita com gelatina e prata sobre papel fibra Ilford Multigrade Classic fosco, banho de preservação a base de selênio. (Analogue print, gelatin and silver on Ilford Multigrade Classic matte fiber paper, selenium-based reservation bath.)

SÉRIE "O REAHU" ("THE REAHU" SERIES), 1974-1976

Claudia Andujar

Yanomami, 1974 - 1976

Moradores da aldeia Xaxanapi entram na maloca dos Korihana Thëri com seus melhores enfeites, cantando e agitando flechas para iniciar os cerimoniais da festa (Xaxanapi village residents enter the Korihana Thëri maloca with their best ornaments, singing and waving arrows to initiate festival ceremonies), Catrimani, 1974

Jovem em rede tradicional de algodão, planta que as mulheres aprenderam a cultivar e fiar (Young person in a traditional cotton hammock, a plant that women learned to cultivate and spin), Catrimani, 1974

Yanomami, Catrimani, 1976

O xamã e tuxaua João assopra o alucinógeno yãkoan

(The shaman and tuxaua João blows the yãkoan hallucinogen), Catrimani, 1976

Yanomami, 1974

Catrimani, 1974

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Ampliação analógica feita com gelatina e prata sobre papel fibra Ilford Multigrade Classic fosco, banho de preservação a base de selênio. (Analog print, gelatin and silver on Ilford Multigrade Classic matte fiber paper, selenium-based preservation bath.)

SÉRIE "SONHOS YANOMAMI" ("YANOMAMI DREAMS" SERIES), 2002

Claudia andujar

Guerreiro de Toototobi (Toototobi Warrior), 2002

Impressão em jato de tinta sobre papel Hahnemühle Photo Rag® Baryta 315gr.

(Inkjet print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag® Baryta 315gr paper.)

SÉRIE "A CASA" ("THE HOUSE" SERIES), 1970-1976

Claudia Andujar

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Xirixana Xaxanapi Thëri mistura mingau de banana em cocho suspenso, capaz de armazenar até 200 litros de alimento para as festas (Xirixana Xaxanapi Thëri mixes banana porridge in a suspended trough, capable of storing up to 200 liters of food for celebration), Catrimani, 1974

Tear (Loom), 1975

Yanomami, 1974

Sem título (Untitled), 1974

Wakata-ú, 1976

Ampliação analógica feita com gelatina e prata sobre papel fibra Ilford Multigrade Classic fosco, banho de preservação a base de selênio.

(Analogue print, gelatin and silver on Ilford Multigrade Classic matte fiber paper, selenium-based preservation bath.)

COLEÇÃO DA ARTISTA ARTIST'S COLLECTION

Claudia Andujar

Genocídio do Yanomami: morte do brasil (Genocide of the Yanomami: Death of Brazil), 1989

Instalação composta por 228 cromos digitalizados e impressos com tinta mineral pigmentada, Epson Ultrachrome sobre papel Hahnemühle Photo Luster 260gr. Coleção da artista. Cortesia Galeria Vermelho. (Installation composed of 228 digitally scanned chrome prints. Pigmented mineral ink, Epson Ultrachrome on Hahnemühle Photo Luster 260gr paper. Artist's Collection. Courtesy of Galeria Vermelho.)

Claudia Andujar

Minha vida em dois mundos 2

(My life in two worlds 2), 1974

Minha vida em dois mundos 4

(My life in two worlds 4), 1974

Minha vida em dois mundos 3

(My life in two worlds 3), 1974

Ampliação analógica feita com gelatina e prata sobre papel fibra Ilford Multigrade Classic fosco, banho de preservação a base de selênio. Coleção da artista. Cortesia Galeria Vermelho.

(Analog print, gelatin and silver on Ilford Multigrade Classic matte fiber paper, selenium-based preservation bath. Artist's Collection. Courtesy of Galeria Vermelho.)

Claudia Andujar e George Love

Amazônia, 1978

Editora Praxis, edição 1a, ano 1978

Fotolivro, 30x21 cm. Coleção particular. (Publisher: Praxis, 1st edition, year 1978 Photobook. Private collection.)

Realidade, Editora Abril (org.), ano 1971 - no.67 Amazônia Revista brochura, 324 páginas, 24x30 cm. (Publisher: Editora Abril, year 1971, No. 67 Amazônia, Paperback, 324 pages.)

New York Times Magazine, ano (year) 1968.

Revista ARTE!Brasileiros, ano 2015, no. 31. Persichetti, Simonetta. Pela lente do amor. (year 2015, No. 31. Persichetti, Simonetta. Through the lens of love.)

Revista Continente, ano 2017, no. 196. Pelo direito de existir (year 2017, No 196. For the right to exist.)

Télérama, ano 2020. Desbenoit, Luc. Les yeux de l'Amazonie (year 2020, Desbenoit, Luc. The eyes of the Amazon.)

SÉRIES EDITORIAIS EDITORIAL SERIES

Claudia Andujar e Emilie Chamie

Mitopoemas Yãnomam

Contém textos e ilustrações de Koromani Waica, MaAmokè Rorowè e Kreptip Wakatautheri. Publicação fotograficamente ilustrada. Brochura com capa dura com sobrecapa. Editora Olivetti, 1978.

Coleção da artista. Cortesia Galeria Vermelho.

(Texts and illustrations by Koromani Waica, MaAmokè Rorowè and Kreptip Wakatautheri. Photo- illustrated publication. Hardcover booklet with slipcover. Publisher: Olivetti, 1978. Artist's Collection. Courtesy of Galeria Vermelho.)

Photo International, ano 2020. Hess, H.-E. Kampfen uber das Urleben (year 2020, Hess, H.-E. Struggle for survival.)

Governador do Estado do Paraná

Governor of the State of Paraná

Carlos Massa

Ratinho Junior

Secretária de Estado da Cultura State Secretary of Culture

Luciana Casagrande

Pereira

Diretora-Geral da SEEC General Director of SEEC

Elietti de Souza Vilela

Diretor de Memória e Patrimônio Director of Memory and Heritage

Vinicio Costa Bruni

Coordenador do Sistema

Estadual de Museus Coordinator of the Museums State System

Marcos Coga da Silva

Assessoria de Comunicação Communication Consulting

Dani Brito

Fernanda Maldonado

Assessoria de Design Design Consulting

Rita Solieri Brandt

SOCIEDADE DE AMIGOS DO MUSEU PARANAENSE

Conselho Deliberativo

Presidente President

Guilherme M. Rodrigues

Secretária Secretary

Barbara Fonseca

Membros

Members

Cristine Elisa Pieske

Amélia Siegel Corrêa

Juliana F. de Oliveira

Diretoria

Presidente President

Manoela Guiss

Vice-presidente Vice President

Felipe Vilas Bôas

Secretária Secretary

Francielle de Souza

2o Secretário

2nd Secretary

Richard Romanini

Tesoureira Treasurer

Josiéli Spenassatto

2a Tesoureira

2nd Treasurer

Mariana Souza Bernal

Conselho Fiscal

Presidente President

Gabriela Bettega

Membros

Members

Christianne L. Salomon

Gabriela Martello

MUSEU PARANAENSE

Diretora Director

Gabriela Bettega

Diretor Artístico Artistic Director

Richard Romanini

Gestão de Conteúdo e Comunicação Content Management and Communication

Beatriz Castro

Heloisa Nichele

Núcleo de Arquitetura e Design

Architecture and Design Division

Gabriela Martello

Juliana F. de Oliveira

Estagiárias (Interns)

Isabella Barbosa de Melo

Marina Montenegro Ikuta

Núcleo de Antropologia

Anthropology Division

Coordenadora (Coordinator)

Josiéli Spenassatto

Residente técnica (Technical resident)

Isabela Brasil Magno

Estagiária (Intern)

Pamela Cristina Laguna

Núcleo de Arqueologia

Archaeology Division

Coordenadora (Coordinator)

Claudia Inês Parellada

Residente técnico (Technical resident)

Giovanni A. Cosenza

Assistente (Assistant)

Fernanda B. Ferrarini

Estagiários (Interns)

Felipe Schwarzer Paz

Maiara Fabri Maneia

Núcleo de História

History Division

Coordenador (Coordinator)

Felipe Vilas Bôas

Estagiários (Interns)

Daiana Marsal Damiani

Gabriella Perazza

Felipe C. de Biagi Silos

Núcleo Educativo

Educational Division

Milena Aparecida Chaves

Roberta Horvath

Marília Alvez Abreu

Estagiários (Interns)

Lucas Plaza da Rosa

Marina Sarat Suttana

Renata S. Oliveira

Gestão de Acervo

Collection Management

Denise Haas

Laboratório de Conservação

Conservation Laboratory

Esmerina Costa Luis

Janete S. Gomes

Segurança (Security)

José Carlos dos Santos

Supervisor de Infraestrutura

Infrastructure Supervisor

Rogério Rosário

EXPOSIÇÃO

CLAUDIA ANDUJAR: POÉTICAS DO ESSENCIAL

Concepção, projeto e curadoria

Concept, project and curatorship

Museu Paranaense

Texto crítico

Critical Text

Josiéli Spenassatto

Isabela Brasil Magno (Núcleo de Antropologia do MUPA)

Revisão

Proofreading

Mônica Ludvich

Tradução

English Version

Lucas Adelman Cipolla

Miriam Adelman

Montagem

Exhibition Installation

Raul Fuganti

Iluminação

Lighting

Iluminarte

Laudos de estado de conservação

Condition Reports

Jozele Penteado

Aline Pestana

CATÁLOGO DA EXPOSIÇÃO

Concepção Concept

Museu Paranaense

Coordenação editorial e gestão de conteúdo

Editorial and content management

Beatriz Castro

Heloisa Nichele

Fotografia da exposição

Exhibition views

Eduardo Macarios

Revisão

Proofreading

Mônica Ludvich

Tradução

English version

Lucas Adelman Cipolla

Miriam Adelman

Design editorial

Editorial Design

Juliana F. de Oliveira

Richard Romanini

Impressão

Printing

Ipsis

Créditos dos textos

Apresentação

Foreword

Museu Paranaense

Claudia Andujar: poéticas do essencial

Claudia Andujar: poetics of the essential

Isabela Brasil Magno

Josiéli Spenassatto

Depoimento

("Era de manhã [...]")

Testimonial

("It was morning [...]")

Claudia Andujar, publicado em “Relação: homem pra homem”. Jornal Ex-, São Paulo, n.14, p.19, set. de 1975.

Entrevista Interview

Denilson Baniwa

Patrícia Ferreira

Pará Yxapy

Créditos das imagens

P. 14 – P. 67

Imagens das séries "Catrimani", "Sonhos Yanomami", "A Floresta", "O Reahu", "A Casa", "Minha vida em dois mundos" e "Genocídio do Yanomami: morte do Brasil"

Claudia Andujar (Cortesia de / Courtesy of Galeria Vermelho)

P. 70 – P. 77

Imagens extraídas do livro “Amazônia”, Editora Praxis, Edição 1a, ano 1978

Claudia Andujar e George Love

P. 78 – P. 83

Desenhos e poemas extraídos do livro "Mitopoemas Yanomãm", Editora Olivetti, 1978

Claudia Andujar e Emilie Chamie, com textos e ilustrações de Koromani Waica, MaAmokè Rorowè e Kreptip Wakatautheri

P. 88 – P. 94