HIGHLIGHTING HISTORY OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE IN NH

Artistic Expression SHARING CULTURE THROUGH CREATIVITY

New Hampshire residents have been expressing themselves through crafts for thousands of years.

New Hampshire residents have been expressing themselves through crafts for thousands of years.

The day before I sat down to write this, I was at the finish line of the Boston Marathon with my youngest son. I didn’t get there by running 26.2 miles from Hopkinton this year (though I have run it a few times and can vouch for how epic the event feels to participate in).

We’d parked in Medford, taken the T into the city, and strolled through the throngs of excited spectators and volunteers to Boylston Street. Many of my New Hampshire friends were racing, and we were thrilled to have the opportunity to see them cross that iconic finish line.

We watched runners finish the race for the better part of the late morning and afternoon. Runners from all countries and backgrounds. Elite runners who run for a living and runners for whom this marathon was a first marathon, a bucket list, Mount Everest achievement. Athletes competing in streamlined racing wheelchairs and athletes running on prosthetic limbs, blind athletes running with guides.

The winner this year was Sisay Lemma, who finished in 2:06:17, which means he averaged 4:49 per mile for all 26.2 miles.

The last runner to finish was Gary Weiland. He crossed the line after 7 hours, 11 minutes and 6 seconds. Much of his race happened through the hottest parts of the day, and he ran it on a prosthetic leg. He’s a firefighter from Texas who lost his leg in 2018 and was running for the charity 50 Legs, which provides prosthetics to people who can‘t afford them.

The fact that Lemma, Weiland and every runner who finished in between (and some wheelchair division athletes who finished before Lemma) all compete in the

same race, on the same stretch of road, on the same day, says something about the inclusivity of running.

I’ll admit, as an avid runner and part of that community, I have a bias. But acknowledging that, I’d still say the road-racing community is incredibly welcoming. Perhaps because there is a good deal of physical discomfort, even suffering, involved in the sport, most runners seem happy to give credit for the effort put forth rather than just the finish time. In the pub after, telling stories of the race, the drama of cracking four hours is no less respected than coming in under three, if it was a well-earned time.

This egalitarianism, and inclusiveness, is illustrated perfectly by the Boston Marathon.

Boston is the only marathon in the world to offer prize categories in the Para division, according to Mary Kate Shea, senior director, professional athletes, at the Boston Athletic Association.

“We have more Para divisions at the Boston Marathon than the Paralympics have for their marathon,” she told a televi sion reporter after this year’s race.

This commitment to diversity is a powerful example of how principles of inclusion can work to make for richer experiences for all.

And it highlights the inaccuracy of the current canard leveled at diversity programs that a commitment to inclusiveness is somehow a negative for communities or organizations.

On the run from Hopkinton to Boston this April 15, nothing could have been further from the truth. 603

To illustrate the mission of 603 Diversity, Seacoast artist Richard Haynes has provided one of his recent designs to accompany our motto “Live Free and Rise.” We are selling T-shirts and other merchandise featuring Haynes’ design, or a design created by art student Chloe Paradis, to benefit the Manchester Chapter of the NAACP. Visit 603Diversity.com to buy one today.

The 603 Diversity underwriters provide a significant financial foundation for our mission, enabling us to provide representation to diverse communities and for diverse writers and photographers, ensuring the quality of journalistic storytelling and underwriting BIPOC-owned and other diverse business advertising in the publication at a fraction of the typical cost. We’re grateful for our underwriters’ commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion in this magazine, their businesses and their communities.

At Enterprise Bank, people and relationships come first. We encourage and foster a culture of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging, where everyone feels valued and respected. We are committed to a caring workplace that recognizes the importance of making a meaningful, positive difference in the lives of our team members, customers, and communities.

My career growth with Enterprise Bank has included management training, roles in learning & development, and my current role as DEIB Manager. The Bank has allowed me to create programs and events that are beneficial for our team members as well as our communities. I’m grateful for Enterprise Bank’s investment in the DEIB function and focus on building equality, equity, and belonging for everyone. “ ”

Sophy Theam Manager, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion | Enterprise Banker since 2005

EnterpriseBanking.com/NewHampshire 877-671-2265

I was hunting for deals. What I found was fraud.

AARP Fraud Watch Network® helps you recognize online shopping scams, so your money, health and happiness live longer. The younger you are, the more you need AARP.

Learn more at aarp.org/fraudwatchnetwork

Anne Jennison is a traditional Abenaki/Wabanaki storyteller and a historian with more than 30 years of professional experience. Additionally, Anne is the current chair of the NH Commission on Native American Affairs, a member of the Indigenous NH Collaborative Collective, an affiliate faculty member for the UNH Native American and Indigenous Studies Minor, and a co-creator of the “People of the Dawnland” interpretive exhibit about the Abenaki/Wabanaki peoples at Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth. Anne continues to act as a consultant for the museum’s ongoing Abenaki Heritage Initiative.

Vanessa Weathers is a devoted stay-at-home mom who has always been passionate about community and well-being. As a neurodivergent individual, Vanessa brings a unique perspective to her work. She created a digital community for Black women in NH that now has over 600 members and leads a committee dedicated to establishing a social club that prioritizes the needs of Black women, femmes and nonbinary individuals.

Dr. Wildolfo Arvelo is executive director of Cross Roads House, the second largest homeless shelter in New Hampshire. Prior to Cross Roads House, Arvelo served as director of the Division of Economic Development for New Hampshire. From 2007-2017, he served as president of Great Bay Community College in Portsmouth. Arvelo has a doctorate in educational leadership from the University of Massachusetts/Boston.

Emily Reily joined Yankee Publishing as an assistant editor with New Hampshire Group in September 2023. Emily writes for 603 Diversity, New Hampshire Magazine, and other Yankee publications. Her work has appeared in various local and national newspapers including New York Times for Kids and Washington Post Magazine. A former newspaper photojournalist and current music critic, Emily lives in Dover.

Alberto Ramos heads the recently formed Center for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Access at Plymouth State University. He serves as the chief diversity officer and affirmative action officer. He has partnered with PSU Black and Latinx student unions, PSU Pride, the Multicultural Club, faculty and staff to form a council of principal advisors and launched a Student Leadership Program. Ramos holds an M.A. in teaching English as a second language, and a B.A. in communication studies and travel and tourism.

Sarah Pearson is managing editor of custom publications for Yankee Publishing, which produces 603 Diversity and many other titles. She is an awardwinning editor and journalist who previously worked for a newspaper. She is a lifelong New Hampshire resident and mother of two boys.

Lisa Carter-Knight is a serial entrepreneur with a passion for building brands. As the owner and chief engagement officer of Drinkwater Marketing and Productions, she works with small businesses and large enterprises to develop brand, digital and event marketing strategies to drive revenue. Prior to launching Drinkwater, she spent more than 20 years in the corporate sector building product and brand strategies for top Fortune 500 companies such as The Limited Corporation, Timberland Footwear and Staples Inc.

James McKim, who was involved in the original plannng of 603 Diversity and has written essays for past issues, serves as managing partner of Organizational Ignition. He is driven by an intense need to help organizations achieve their peak performance through the alignment of people, business processes and technology. He is recognized as a thought leader in organizational performance, the uses of neuroscience and program management.

Raised in a diverse community in Boston, Massachusetts, Suzanne Laurent worked as a registered nurse for the Boston Head Start Program. She moved to Toronto, Ontario, in 1982, and unable to work as a nurse, Laurent pursued a career in photojournalism. She has been a resident of New Hampshire since 1987. She has an extensive award-winning background in journalism. She is also a juried photography member of the New Hampshire Art Association and a published poet.

Primary photographer for 603 Diversity is Robert Ortiz of Robert Ortiz Photography. Ortiz began his photographic career at 15, and has chronicled everything from local weddings and events to the lives of the native peoples of the Peruvian Amazon. He lives in Rochester with his wife and son and 15-year-old daughter, Isabella, who is currently in training as his photo assistant.

Advocate, coordinator and educator Yasamin

Safarzadeh, a native Angelino and current resident of Manchester, compiled our calendar and wrote the feature on “Echoes and Shifts.”

Safarzadeh hopes to secure a future for a more diverse young adult population in New Hampshire to ensure a more prosperous and effective future for all. DM her at phat_riot on Instagram.

Esmeldy Angeles was visiting her native country in the Dominican Republic when she decided to go outside and take some pictures.

She took a photo of herself with her phone, something she says she didn’t do very often, but that day, it struck a nerve with her.

“All of a sudden I thought, if this picture looks this good taken with a phone, what would it look like if I took it with a professional camera?” Angeles said.

When she returned to the United States, she started saving up and bought her first mirrorless camera.

“At the time, I thought the picture looked incredible. Looking back at it now, it seems like a regular photo,” Angeles said. “But I’m glad that it inspired me to make the decision to get a camera.”

Angeles recently completed an exhibit at Positive Street Art in Nashua, covered event photography for New Hampshire PBS and café owner Emmett Soldati, and is working on some new projects now.

Angeles immigrated from the Dominican Republic to Nashua in 2012, when she was 14 years old. From a young age, she was passionate about different types of art and practiced drawing and painting.

“I have always loved art in all its forms,” said Angeles, now 27.

Through that artistic exploration, she found her way to photography.

“A part of me has always loved the power that photography has,” she said. “The ability to tell stories, evoke emotions and convey messages makes me so passionate about life.”

Angeles spent hours and hours doing research to teach herself

photography. She watched YouTube videos to hone her craft. And she practiced, trying new things and learning from her mistakes.

She took photos of her close friends and was receiving positive feedback.

“That is when I knew it was something I really wanted to pursue professionally,” she said.

Angeles’s art is focused on portraiture, and she hopes people feel a sense of empathy, curiosity and appreciation for other humans through her work.

“I strive to capture the essence of my subjects by emphasizing their facial expressions, body language, and the interplay of light and shadow,” she said. “I try to highlight the raw emotions and textures in each image.”

Like many who seek to pursue a career as an artist, depending on it for a stable income has been a challenge.

“I have struggled to sustain myself from art and have had to question if I should really keep going,” she said. “Nevertheless, I have learned to push forward and keep trying to pursue what makes me happy.”

“I hope that my art prompts reflection, sparks conversation, and inspires a greater appreciation for the beauty and diversity of the human spirit,” Angeles said. “Ultimately, I want people to feel moved, inspired and enriched by the power of photography.”

For those looking to learn more about her upcoming exhibits, you can find Esmeldy Angeles on Instagram @esmeldy_angeles. 603

Bernadette Uwimana showcases her sewing and design skills at her Manchester store.

Bernadette Uwimana showcases her sewing and design skills at her Manchester store.

In the vibrant melting pot of Manchester, cultural diversity thrives, and nowhere is this more evident than in the realm of fashion. Among the city’s diverse tapestry, one designer stands out for her eclectic and multicultural approach to fashion:

Bernadette Uwimana.

Hailing from the Republic of Congo, Uwimana infuses her designs with the vibrant colors, patterns and textures inspired by her African heritage. Her skillful blend of contextual fashion design and expert dressmaking has earned her recognition at prestigious events like at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

Despite facing challenges, including language barriers and single motherhood, Uwimana’s determination led her to estab-

lish her Manchester store in 2015. With a degree in sewing and a passion for design cultivated in her homeland, she brings a unique perspective to the local fashion scene. Uwinama has launched fashion design and sewing workshops. Students learn how to sketch, tailor, design and create their own fashion designs.

Uwimana’s work exemplifies the beauty of cultural diversity in fashion, showcasing how different influences can harmoniously coexist. Uwimana’s designs celebrate the fusion of cultures, resulting in visually striking and culturally rich creations that captivate the senses.

You can visit Uwimana Fashions by appointment at 96 Webster St., Manchester. 603

The Business Alliance for People of Color in New Hampshire has organized its inaugural Shades of Progress conference. The conference will be held May 22 from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. at the Grappone Conference Center.

The conference is designed to encourage advocacy, networking, community building and knowledge exchange between the Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) business community, those interested in launching a business, allies and other organizations.

“When we founded the Business Alliance for People of Color (BAPOC) in 2021, we felt that it was important to continuously build and create that community,” said Will Arvelo, BAPOC chairman. “Because BAPOC serves as a statewide organization for

BIPOC entrepreneurs and small businesses, we felt that a statewide conference would be important for us to come together to listen, learn, share, network and generally strengthen the community.”

The conference will be a forum for in-depth discussions to develop workshop proposals that delve into the challenges, successes and aspirations of the BIPOC business community in New Hampshire.

“The conference will have exciting speakers and BIPOC business owners as well as really interesting breakout sessions that will highlight the ‘Shades of Progress’ we have made over the last several years,” Arvelo said online. “We will also highlight several of our BIPOC businesses and their products in our ‘Market Place’ venue.”

BAPOC-NH, a NH nonprofit, has

organized to support, advocate for and promote businesses owned by people of color. They leverage local, state and federal resources to expand diversity, equity and inclusion. This will also include wealth building and social capital for the betterment of the state’s minority-owned businesses, underserved communities and economic vitality.

“Our BIPOC communities are here, growing, and engaged with the rest of NH,” Arvelo said online. “We love it here, and we want to contribute to the social and economic evolution and prosperity of NH.”

Registration for the event is $110 at eventbrite.com/e/shades-of-progress-abusiness-alliance-for-people-of-color-conference-tickets-805964721177. Tables of 10 are also available for reservation. 603

Compassionate, caring, and innovative employees are what makes this a great place to work!

At our core, we are caregivers who aspire to make our community a healthy and safe place for all who seek care from us, as well as for our staff. With our distinctive backgrounds, diverse races, ages, different sexual orientations, gender identities, and individual religious beliefs, we are dedicated to work together to care for everyone in our community. It is this mission that unites us as one. ExeterCareers.com

New Hampshire’s Abenaki people and their allies work to bring hidden history into the openn BY ANNE JENNISON PHOTOS BY ROBERT ORTIZ

“Does the Abenaki tribe exist today? What is the difference between Abenaki and Wabanaki? Are there Abenaki people in New Hampshire anymore? How many Abenaki are there?”

These are the kinds of questions you’ll see if you do a quick Google search for the word “Abenaki.” Well, the answers to those questions are complicated.

Yes, there are Abenaki people living in New Hampshire today. “Abenaki” and “Wabanaki” both mean “People of the East” or “People of the Dawnland.” Both names come from the same root words: “waban,” meaning “east,” and “aki,” meaning “land.”

No one really knows exactly how many Abenaki people live in New Hampshire, but the numbers are likely to be far greater than census numbers indicate, because the U.S. Census isn’t a reliable source for this information. There’s no place on the census forms

where Abenaki are asked to identify themselves and no compelling reason for Abenaki people to self-identify for the federal government, because there are no federally recognized Abenaki tribes in the United States. Did I mention this was complicated?

Although the Abenaki and their ancient ancestors have roots here that go back 12,800 years in New Hampshire, you might not be aware that today’s Abenaki descendants could be your neighbors, school teachers and local business owners, among many other possibilities. Today’s Abenaki people get up in the morning, drink their tea or coffee, and check their email just like everyone else. Cultures have to change and adapt over time in order to survive — and the Abenaki people are survivors.

“After the arrival of the people from across the ocean 500 years ago, the Abenaki lived on the societal edges of New Hampshire, along the marshes, the rivers and later on the ‘other side of the tracks,’” said Rhonda Besaw, an acknowledged master of traditional Wabanaki beadwork.

“The prevailing thought was that the Abenaki had all died out or had moved to Canada and never returned home. In spite of this, the Abenaki continued to dance upon the land, and their drums were not silenced. They continued to harvest the medicines, to greet the sunrise, to care for the land and fulfill their responsibilities to the elders and ancestors. Through the efforts of many in recent times, the beauty and vibrancy of Abenaki culture is beginning to be seen.”

Due to complicated historical factors, New Hampshire is the only state in New England without any state or federally recognized Native American tribes. However, there are currently three unrecognized Abenaki tribal groups in New Hampshire and two intertribal groups, many of whose members are Abenaki. Furthermore, there are many Abenaki descendants in New Hampshire who haven’t joined any of these organized Abenaki tribes or groups.

In addition to the Abenakis who live in New Hampshire, there are also four state-recognized Abenaki tribes in Vermont as well as two Abenaki reserves whose residents are recognized as a First Nations tribe in Quebec. Unsurprisingly, there are extended family relationships across state and international borders between all of these Abenaki peoples as well as the other related Wabanaki tribes: the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, M’ikmaq and Maliseet peoples.

Two more reasons that no one can say exactly how many Abenakis live in New Hampshire are intermarriage and acculturation. Intermarriage with the Scots, Irish, French, African slaves, free Blacks and the English during the colonial era and beyond impacted the Abenaki people.

Additionally, over time there was an understandable lack of willingness by Abenaki descendants to identify themselves as Abenaki for federal census records due to historic and severe colonial —

and later federal — anti-Indian policies of war, overt prejudice, removal by means of forced migration or slavery, removal of Indian children from their parents’ homes to be adopted by white families or sent to Indian boarding schools — and other policies of erasure that threatened the very existence of the Abenaki people in New Hampshire.

American attitudes about Native Americans, though, have been in a state of change that began in the late 20th century with the enactment of new federal laws giving more protections to Native Americans between the late 1970s and early 1990s. These new federal laws and a renewed, more positive, public interest in Native Americans — and in the Abenaki people — began during the years surrounding the 1992 Columbus Quincentennial.

Since that time, an entire body of scholarship has been developing around the history and cultures of Indian tribes in New England and also around what has become referred to as the Abenaki “Hiding in Plain Sight” phenomenon — the strategy used by the Abenaki from the late 18th century up through the late 20th century in order to protect their lives, their jobs, their homes and have access to education for their children — all without their neighbors knowing their Abenaki identities.

In fact, Abenaki people became so adept at blending into white society by acculturating and assimilating that many stopped speaking Abenaki at home and stopped passing their history and

actually sure they had Abenaki heritage, even though they may have heard snippets of family stories that referred to one or more of their great-grandparents or earlier ancestors as having been Abenaki or Indian.

The resulting lack of information and isolation between scattered pockets of Abenaki family groups and individual Abenaki descendants, especially in the southern parts of the state, contributed to the cultural disconnect. For example, I graduated from Portsmouth High School in New Hampshire in the early 1970s — at least 20 years before cellphones and the internet made it much easier to find and communicate with other Abenaki people. At the time, I never met anyone with Abenaki heritage anywhere in Portsmouth or the Seacoast (outside of my own family) until I happened to be sitting next to someone at a powwow planning meeting in 2019 and — comparing notes about our backgrounds — discovered that we’d been in the same Portsmouth High School graduating class and never met one another.

Increasingly user-friendly communication technology has helped overcome this isolation and has been a boon to Abenaki cultural revitalization. A growing use of videoconferencing, like Zoom, has allowed Abenaki language classes that used to take place only once a month near Burlington, Vermont, and occasionally during a week-long summer school, to take place online daily since 2020. A summertime Abenaki language immersion program is now part of the curriculum at Middlebury College in Vermont, directed by Jesse Bruchac, an acknowledged Abenaki language scholar.

After the late 1970s as it began to be safer to be publicly Abenaki in New Hampshire and New England, Abenaki descendants began to explore their own family histories to learn more about their Abenaki cultural heritage. Abenaki descendants began to reach out to find others with whom to share information and celebrate their heritage.

Initially, this took the form of Abenaki families and previously existing small Abenaki groups coming out of obscurity while new groups of Abenaki were formed or found one another. More cultural and historic information was shared. Annual powwows were initiated to celebrate Abenaki cultural heritage as well as the heritage of other Native Americans living in New Hampshire.

Those who were part of that early reawakening of Abenaki culture in New Hampshire comment on the process of cultural awakening that has seen tremendous change since the 1980s and 1990s. During those years many New Hampshire Abenakis who attended the powwows tended to wear bits and pieces of regalia that reflected the cultures of many other tribes, but especially the culture ways of the Lakota people from out West.

Abenaki/Wabanaki – Native American and First Nations Resources and Allies

annejennison.com/abenaki/wabanaki-native-american-firstnations-resources-and-allies

Denise Pouliot, Sag8moskwa (female head speaker) of the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People here in New Hampshire, remembers “the pan-Indianism times well. There was only one group of Abenakis dressing in culturally appropriate Northeast Woodlands clothing at the time. Now people are much more apt to be knowledgeable about what culturally appropriate traditional Abenaki clothing looks like and are wearing their regalia for special celebrations and powwows.”

In 1991, the Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum was opened in Warner by Bud and Nancy Thompson. From its beginning, the museum had a positive impact on New Hampshire Abenakis while it fostered respect for all Native American cultures. Over the years the museum became a nurturing cultural center, a source of information for the general public, and a place for Abenakis and members of other tribes to meet and learn from one another.

As time has passed and communications improved with the development of the internet, there has been, and continues to be, an efflorescence and revitalization of Abenaki culture in New Hampshire. Powwows and seasonal cultural celebrations are held year-round. Abenaki traditional dances, music, storytelling, clothing ways, foodways, beautifully crafted works of art and demonstrations of craft ways are shared with the general public. Everyone is welcome at powwows. New Hampshire Abenakis are celebrating the revitalization of their culture and also sharing their message that, “We’re still here.”

Through these last few decades of renewed and growing Abenaki identity, there have been several significant developments. In 2010, the New Hampshire Legislature created the New Hampshire Commission on Native American Affairs (NHCNAA). Since there are no state or federally recognized Native American tribes in New Hampshire, the commission has become the de facto point of

contact to act as a facilitator and liaison for information and issues relating to New Hampshire’s Native Americans.

In addition to the creation of the NHCNAA, there have been several other fairly recent positive developments relating to supporting and educating the public about New Hampshire’s Abenaki people.

In 2016, faculty members of the UNH Anthropology Department working in cooperation with the Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People formed a group of activist Indigenous allies called the Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective (INHCC). This group of mostly non-Indigenous students and professionals, working in partnership with Abenaki advisors, have undertaken many projects to help educate the public about the history, culture and ongoing presence of New Hampshire’s Abenaki people.

“As a person with Indigenous heritage in the Northeast Woodlands peoples, I greatly appreciate the inclusion, camaraderie, deep historical, archeological and scientific research which has helped bring light to the true story of the thousands of generations of Indigenous peoples who have called this land their home,” said Kathleen

Blake, former chair of the New Hampshire Commission on Native American Affairs. “It is so very helpful to work with others, Indigenous and not, who care deeply about truth, honesty and cultivating understanding.”

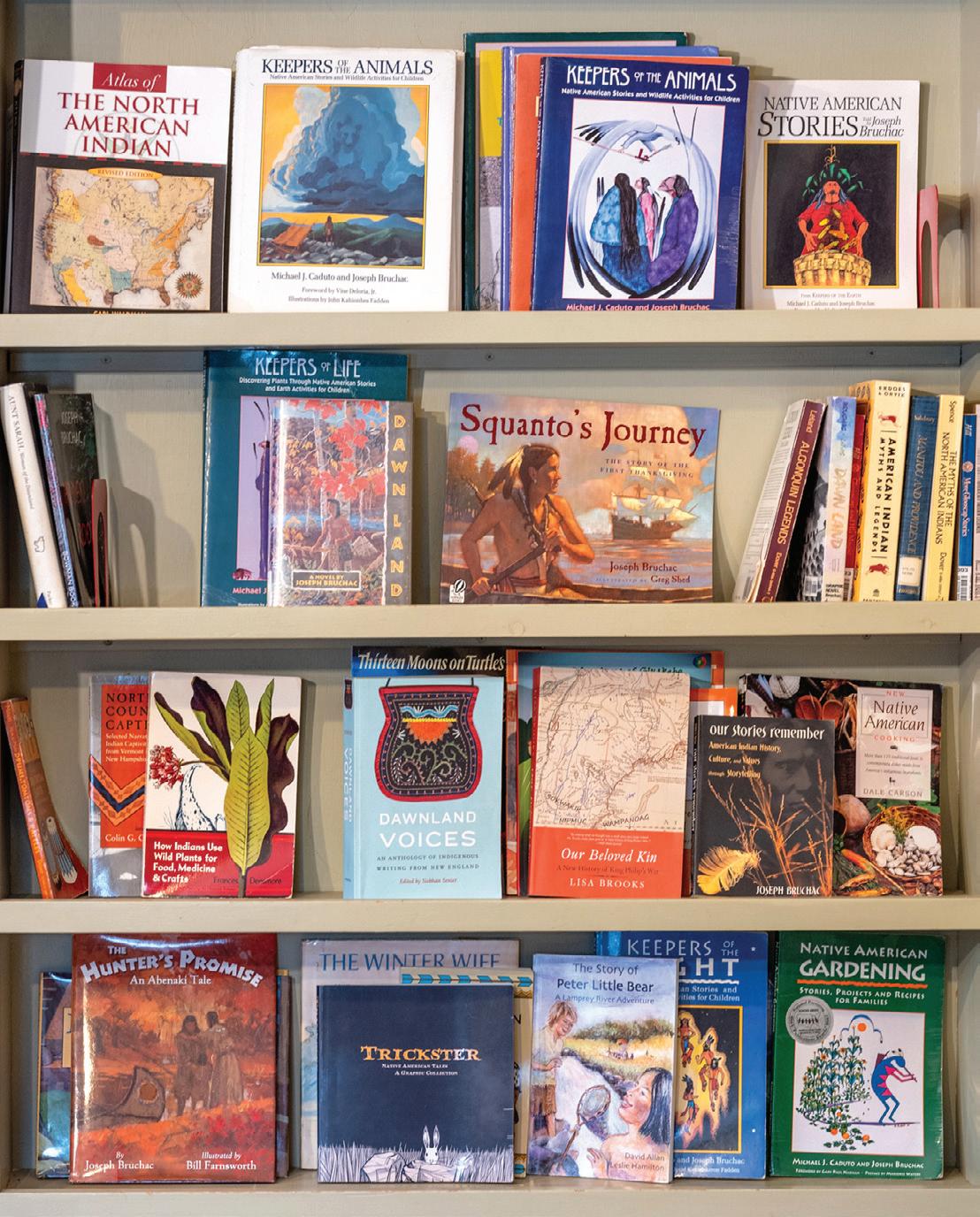

In keeping with its goal to educate the public about New Hampshire’s Abenaki people, the INHCC has created a set of curriculum materials and Teachers’ Guide about the Abenaki for New Hampshire educators to use with their students. The guide has a tremendous list of resources: books, websites, etc. that will be interesting to not only teachers, but for anyone who wants to learn more about the Abenaki/Wabanaki peoples.

The INHCC has also created several videos, blogs and a collection of written articles on topics ranging from land acknowledgements to Indigenous mascots, to environmental issues, and traditional Abenaki cultural information. The INHCC website makes all of these materials available at no cost.

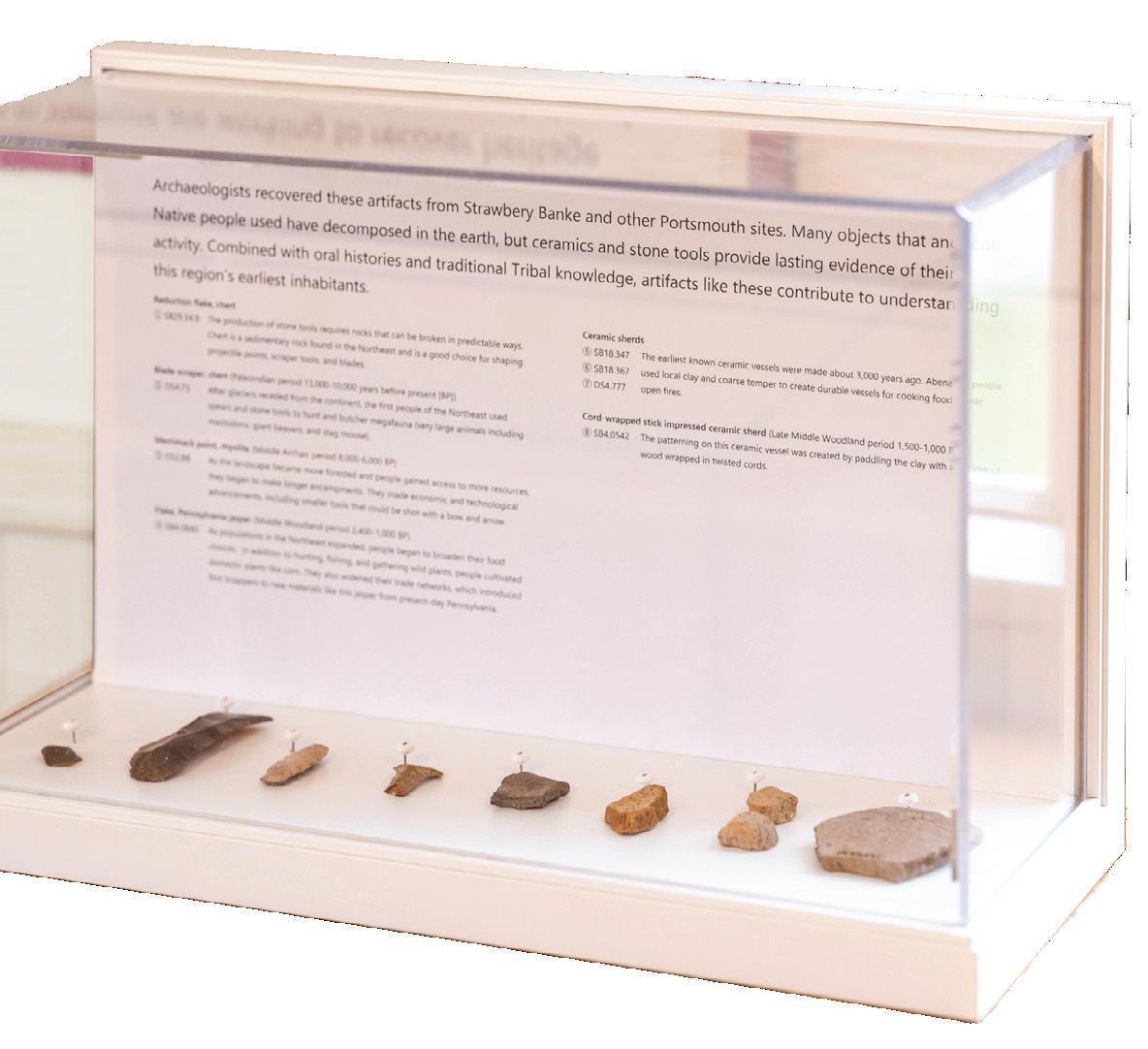

In 2017, the Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth began a modest Abenaki interpretation program that in 2019 grew into a permanent exhibit called “People of the Dawnland.”

In her role as the archaeologist at Strawbery Banke Museum and the coordinator of their Abenaki Heritage Initiative — which includes the permanent “People of the Dawnland” exhibit as well as the museum’s expanding Abenaki history and cultural programming — Alexandra Martin sees her work as an Abenaki ally “as an opportunity to work with Indigenous partners to decolonize the Abenaki history of New Hampshire and Northern New England.”

Martin notes that she “grew up in New Hampshire being fascinated with Abenaki history, but not getting much exposure to Abenaki people or current issues. Today, as a grown-up museum professional and educator, we have a responsibility to educate the public in an engaging way about events in the present as well as the past.”

She also noted that the museum, having committed to acting as an ally to Abenaki, Wabanaki and other Indigenous peoples, has expanded the “People of the Dawnland” exhibit from one room to two, and grown the Abenaki Heritage Initiative to include outdoor interpretation with a wigwam frame (2020) and a “Three Sisters” teaching garden (2021), an additional exhibit room and an intertribal powwow event (2023), as well as public presentations on Abenaki language revitalization efforts and a traditional Native American Storytelling Festival. All of these efforts have had far reaching impact.

In 2019, the University of New Hampshire in Durham created a Native American and Indigenous Studies Minor program that offers courses on a variety of Indigenous-related topics, including introducing the history of New Hampshire’s Abenakis. These and other new Abenaki public education initiatives around the state are far reaching.

Proof of the New Hampshire public is becoming much more aware of New Hampshire’s Abenaki heritage and the Abenaki people who are still living here can be seen in the queries that come in from schools, libraries, historical societies, museums and the general public, seeking accurate information about the Abenaki people.

There is still much that needs to be done, though, to educate about and support New Hampshire’s Indigenous peoples as their existence and their culture reemerge from obscurity. When speaking of what it feels like to be a New Hampshire resident with Abenaki heritage, Abenaki people will often share how disheartening it is to continually be told that they don’t exist because “there are no Abenaki people in New Hampshire anymore.” That erasure — be it intentional or just from the lack of accurate information — is deeply felt.

When asked how the public can be of help, a consistent message from New Hampshire’s Abenakis is that the place to begin is by acknowledging the Abenaki people who are living in New Hampshire now:

“Please don’t speak of us only in the past tense. We’re still here.” 603

Did you ever wonder what it would be like to be part of an archaeology dig, discovering objects from about 3,000 years ago?

The New Hampshire State Conservation and Rescue Archaeology Program (SCRAP), formed in 1978, is a public education program to train people to do archaeology in a responsible manner and to appreciate its benefits.

NH SCRAP, part of the Division of Historic Resources, is offering two sessions in June and July for participants to engage in excavation on a terrace of the Androscoggin River containing pre-contact Native American deposits focusing on an intact feature and an artifact concentration identified during previous field investigations. >>

and

Led by State Archaeologist Mark Doperalski, NH SCRAP team members will continue the work done at the site that uncovered three hearth features, primitive tools and other artifacts at Mollidgewock State Park.

The first hearth feature was discovered in 2020. Charcoal samples were collected, and then radiocarbon dated it at over 3,000 years old. A second hearth was found in 2022 and the third during last year’s excavation.

“The three radiocarbon-dated hearth features are significant, and so is the lithic (or stone tool) workshop,” Doperalski said. “It’s hard for me to pick what’s more important out of those.”

The site is a 46-acre park located at the confluence of the Androscoggin River and the north-flowing Mollidgewock Brook.

“Native Americans would have considered this site a prime location for an encampment, given its relatively flat, well-drained soil on a major transportation corridor,” Doperalski said.

When asked whether these Native Americans would have been Abenaki or Micmac, Doperalski explained that Indigenous peoples moved around a great deal.

“There is no evidence that the peoples who occupied this encampment were the ancestors of any one tribe who lived in New Hampshire,” he said. “And, of course, these findings are 3,000 years old.”

Only a small number of Native Americans, perhaps 10 or less, would have stayed at this encampment for a short amount of time, Doperalski added.

“Then they would have moved onto an-

other site. They not only made and sharpened tools, but almost certainly cooked or smoked fish and animals over their open hearth.”

One participant during last year’s excavation at Mollidgewock State Park, is Haylee Parr of Andover, New Hampshire. At just 21, Parr went alone to the first session and pitched a tent on the grounds of the dig. She began commuting daily to the site, but found the drive to be too much.

“Most of the group was older, and I was out of my element, but everyone made me feel safe and comfortable,” she said.

“There was no running water or electricity. So, we bathed in the river and took turns at the end of the day using the one power outlet in the camp office, about a half-mile away, to charge our phones.”

The New Hampshire State Conservation and Rescue Archaeology Program (SCRAP) is a public participation program for archaeological research, management and education.

The New Hampshire State Conservation and Rescue Archaeology Program (SCRAP) is a public participation program for archaeological research, management and education.

Parr is fascinated by archaeology. After graduation this May from Nashua Community College with an associate degree in political science and history, she plans to study archaeology and social anthropology at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

After her experience in the field last summer, Parr spent one day a week beginning in October 2023 at the state lab in Concord cleaning and cataloging findings.

“I do have some Micmac heritage, and this made it all the more meaningful for me — that maybe my ancestors left something here,” Parr said. “My grandfather asked me what I found most interesting, and I told him about the hearth that was found to be about 3,200 years old.”

The second oldest of five children, Parr is bringing her 18-year-old sister to both sessions this summer.

The two field sessions for 2024 are each two weeks long (June 17 – June 28 and July 1 – July 12). Fieldwork takes place daily on weekdays from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Participants must be 18 and older, but 16- and 17-year-olds can join with a parent or guardian. The group is usually limited to 20 participants.

The site has primitive camping available at the Mollidgewock State Park campground. Participants can make their own reservation by visiting the state park’s facility reservation website at newhampshirestateparks.reserveamerica.com

For an application for the two sessions, visit mm.nh.gov/files/uploads/ dhr/documents/scrap-field-school-flier. pdf

For more information, contact, State Archaeologist Mark Doperalski at (603) 271-6433 or email him at mark.w.doperalski@dncr.nh.gov.

Applications to the field school must be received by the NHDHR by May 10, 2024. There is a $50 participation fee to help the program defray costs of supplies and instructional materials. Successful participation at the field school will earn credit toward SCRAP certification for Survey and/or Excavation Technician status.

In addition to the summer field school, volunteers can participate in the state’s archaeology lab in Concord. There, they learn how to wash and catalog artifacts, maintain and organize field equipment, and share stories of adventures from field seasons past. The archaeology lab is generally open to

Haylee Parr of Andover participated in SCRAP during research at Mollidgewock State Park in Errol under the direction of State Archaeologist Mark Doperalski in June 2023. She’s returning this year with her younger sister. (Courtesy photos)

volunteer participation on Wednesdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. from October through May.

Individuals seeking to learn more about volunteer opportunities at the state’s archaeology lab, or wishing to be added to the lab volunteer email list, should contact the state archaeologist by emailing mark.w.doperalski@dncr.nh.gov or calling 603-271-6433. 603

As a center of learning for Native American life past and present, the Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum in Warner holds events and workshops throughout the year in addition to its regular museum programming. On March 16, it joined sugarhouses across the state in celebrating Maple Weekend. Volunteers at the muse-

um demonstrated the way Native people would have made maple syrup and acorn meal pancakes.

Madeleine Wright, a member of the Nulhegan Band of Coosuk Abenaki and a teacher, was on hand to share stories of the Abenaki people of New Hampshire.

Maple baked goods were available for purchase and visitors could also head inside the museum to learn from the art and artifacts on display.

The Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum is open for its regular season from May through October. Learn more at indianmuseum.org.

n BY EMILY REILY

n BY EMILY REILY

For generations, including before the pre-colonial era, tribes in New England like the Abenaki, Pennacook, Cowasuck, Passamaquoddy and Penobscot depended on the paper birch tree.

The deciduous birch, New Hampshire’s state tree, is a “pioneer” tree, one of the first to sprout after land has been cleared of vegetation or after a brush fire wipes the slate clean. The birch’s silvery white bark, scored with horizontal light pink scars, can be found throughout much of the state. A compound in the bark called botulin is known to protect the tree from harsh conditions.

For centuries, birch bark has been renowned by Indigenous people for its strength, flexibility and versatility. They used it daily making tools; wigwams, or homes; for crafts; for telling stories; for moose calls; for traveling on waterways and even cooking (birch sap makes good syrup). Birch bark baskets make collecting and carrying wild berries less difficult. Mothers and caregivers used the bark to assist during childbirth, since they believe it has sanitary and medicinal qualities.

Bill Gould of Warner is a citizen of the Nulhegan Tribe, which is recognized by Vermont.

“There is no path in New Hampshire law

for tribes to be recognized. Hopefully this will change in the future, as historically New Hampshire and Vermont were traditional Abenaki homelands,” he says.

Gould says any Indigenous tribe in North America with access to birch trees used birch bark, referencing knowledge passed down from elders.

Gould is constructing his fourth birch bark canoe, having learned the craft through research and direction from tribal members. He says they were made as far back as the 1500s, declining around the early 1900s as canvas canoes became cheaper to make.

“It was all handed down because it was a main form of transportation. Navigating these waterways was the quickest way to get anywhere and transport goods and furs,” he says.

Gould cites birch bark sturdiness and elastic properties as ideal for making canoes.

“It’s very strong, lightweight and durable. It’s pretty much the only boat that’s built from the outside in,” Gould says.

According to tradition, single pieces of

birch bark are scraped to remove loose pieces, then stitched together using spruce root. Gould uses cedar for the gunwales and planking, while the thwarts are made of hardwood.

He tests it by putting water in the bottom, stopping any leaks using a small patch of bark with just the right mixture of spruce gum and animal fat. Once it’s properly sealed, he takes it out on a pond on his property.

“It’s very strong, it’s flexible. And lasts and lasts and lasts,” says Gould, who has had his work displayed at the Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum in Warner.

A more unusual Indigenous art form is birch bark biting. The Ojibwe word mazinibaganjigan means “pictures upon the bark,” according to educator, oral historian, writer, dancer and North Dakota Poet Laureate Denise Lajimodiere, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band in Belcourt, North Dakota.

Lajimodiere has practiced the art for years, having learned from a practitioner in Michigan, Kelly Church. Her method of working with birch bark is also steeped in tradition.

In the spring, after performing a ceremony that thanks the birch tree’s spirit, Lajimodiere cuts the bark in a way that doesn’t damage the tree, and presses it flat. She then

peels and separates the layers until there’s just one “onion-skin-thin” layer.

The practice is similar to making a paper snowflake: The thin bark is folded several times, then the practitioner thinks about an image — something from nature. Lajimodiere often likes to imagine a dragonfly soaring through the air, for example.

Using her sharp eyeteeth, or canines, she makes indentations, “biting” an image into the folded bark, turning it as she goes. Since it’s created using the mouth, it’s impossible to see what it will look like until it’s complete.

“I can just see it in the darkness of my brain,” Lajimodiere says.

After the bark is unfolded, the tiny pinpointed imprints reveal a whimsical, symmetrical pattern that is illuminated once it’s held up to the light.

“That’s what’s cool about the biting. You don’t have to do anything, just bite it and open it up and, ‘Oh, there’s a star. There’s a flower.’ It’s really cool,” Lajimodiere says.

Denise Pouliot of Alton is an educator and head female speaker for the Cowasuck band of the Pennacook Abenaki people. Pouliot makes educational toys from birch bark as well as birch bark etchings and baskets using sweetgrass, black ash and birch bark.

“Birch bark was interwoven into our common practices and everyday lifestyle. It was really a tree that we’ve depended upon,” Pouliot says.

She says the birch bark’s thickness makes good material for baskets, dishes, bowls and trays. Besides canoes and wigwams and moose calls, birch bark was also used as a fire starter, Pouliot says.

Lajimodiere also agrees, saying oils in the bark makes it waterproof.

“If you’re out in the forest, and you’re in trouble, you can peel the bark off of the birch tree and start a fire, where the other barks will absorb the rain. It’s one of the many properties of birch bark that is quite amazing,” Lajimodiere says. People can also put a water-filled birch bark basket over the coals and cook fruit tree sap, or make tea with powder from the bark.

“Since it’s waterproof, we could bury the baskets that had our dried food in it into the ground. And it was a natural preservative,” Lajimodiere says.

“We use birch bark to build our houses, to store our food. We’d use birch bark to create maps. We would use birch bark to make baskets. It influences every aspect of Indigenous life. It was a food resource as well. I think people underestimate the use of birch within our culture. The tree has a lot to give,” Pouliot says.

Lajimodiere, who calls the birch a “medicine tree,” says its bark has a harmless, tasteless powder that she notices when biting it and says peeling the bark is calming and relaxing.

“When we do our beadwork, every bead is a prayer. So, when I do my birch bark biting, I am in a good way, spiritually and mentally peaceful. Then that that goes into our work. It’s a very peaceful, meditative type of work. I could peel for days and days. I love peeling,” Lajimodiere says.

Other uses include sacred scrolls documenting special ceremonies, or as maps.

“If you came to the reservation here, I would bite you a map of how to get to my

A lined “Makak” used as a food storage container (bread bin).

house,” says Lajimodiere, noting that it’s a “pre-contact” art, in use before Europeans came to North America. It’s also used as patterns for beadwork, and people have lately begun to add beads to their bitten creations.

For years, the art of birch bark biting seemed lost to time. Lajimodiere attributes the waning number of practitioners to “the boarding school era,” when parents and grandparents who attended boarding school as children were not allowed to practice ceremonies and crafts related to their culture.

“So many of this was forced to be put aside from forced assimilation. Now it’s coming back very strong,” Lajimodiere says.

Practitioners caution others not to remove bark from birch trees unless skilled in the process, but they are more than happy to teach others how to make crafts and artwork from the tree.

“I will give back to anybody wants to learn. It’s mostly done by women. But I’ve taught men also and teach anybody that’s interested in” birch bark biting, Lajimodiere says.

“The Passamaquoddy and the Penobscot seem to be building more canoes. Our tribe has gained an interest in it again, trying to pick it up again and learn it,” Gould says.

Gould is also doing what he can to keep the craft alive. He and his wife, Sherry, work often with the NH State Council on the Arts to pass on their knowledge to others. He’s working on an apprenticeship with the council to teach others how to make canoes for the first time. His grandson is helping as well.

“This year he’s taken an interest in it, so I’m hoping he’ll learn it and stick with it,” Gould said, “And then he can teach his kids.” 603

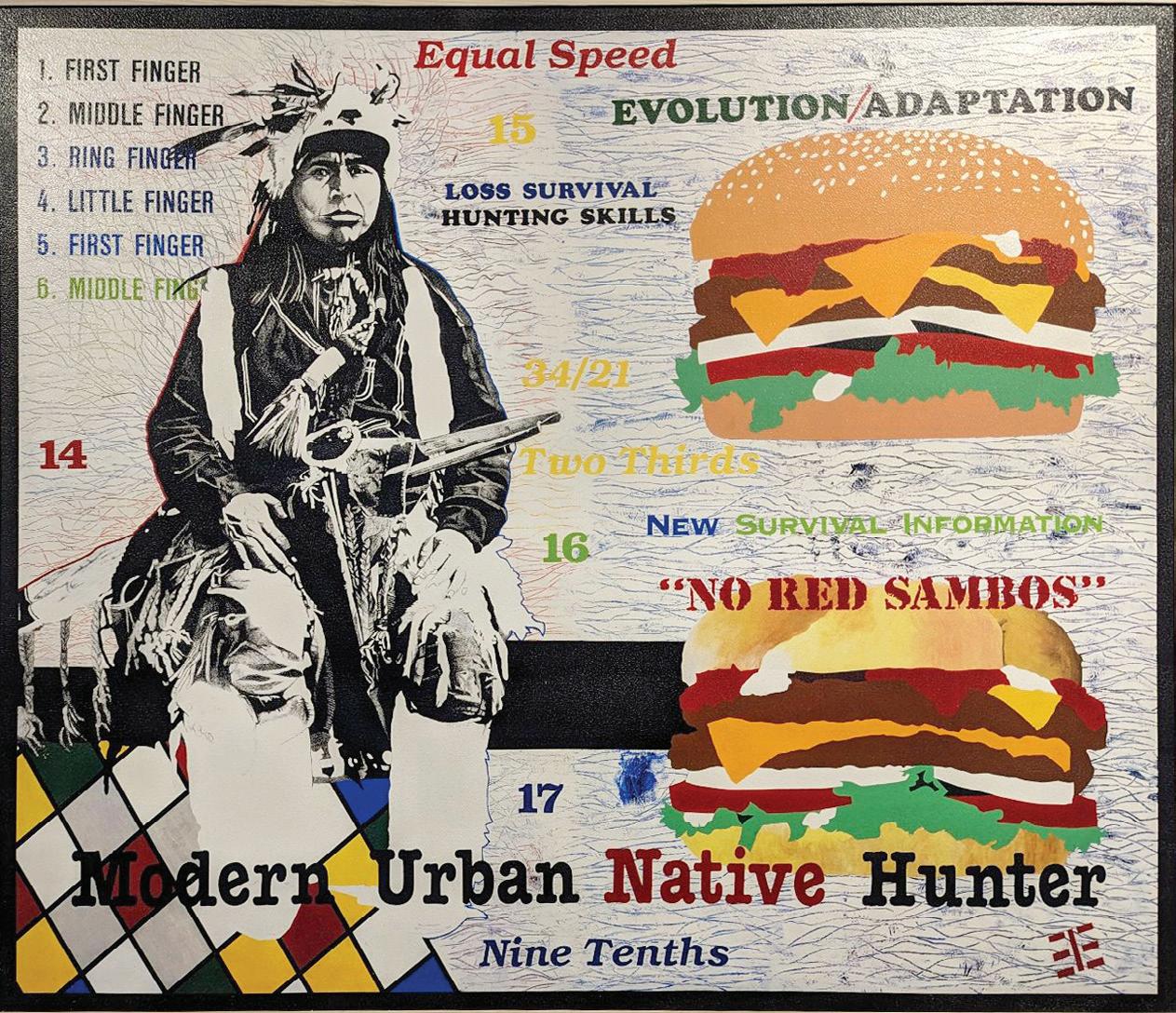

INDIGENOUS ARTISTS CHALLENGE THE NARRATIVE OF CONTEMPORARY NATIVE ART

Margaret Jacobs’ family exercises silence with a keen sensibility that there is no weight in long pauses.

I am sitting at Elly and Mark Jacobs’ house devouring the classic American fare in Akwesasne, a sovereign Mohawk nation, located on the border of the U.S. and Canada.

I am uncomfortable in the silence and thinking to myself, “Please don’t say anything stupid. Don’t ask about Thanks giving. Don’t talk about ‘Reservation Dogs.’”

My name is Yaz, as many people call me, and I am on a mission to befriend Jacobs in order to foster a relationship to establish a continuous art exhibition that communicates

Subtle and Strong by Margaret Jacobs.

Subtle and Strong by Margaret Jacobs.

Saltbottle,

with exhibitions nationwide, something on the beat of the pulse of the nation.

After a year, we will have conceived and birthed the show called “Echoes and Shifts,” an international Indigenous exhibition hosted on two sites in Manchester (at Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce) and Nashua (at Positive Street Art), encompassing a throughline of identity in artists who grapple with the duality of multiple nationhood and disrupted genealogies.

The other artists involved in this endeavor actively challenge stereotypes within the narrative of contemporary Native art, pushing the boundaries in their field and offering a multiplicity of voices, perspectives and narratives which broaden the understanding of contemporary Native art.

With this exhibition, “Echoes and Shifts” aims to challenge dominant discourses around Indigenous art and creative practice in New England. Jacobs, myself and the crew at Positive Street Art believe this exhibition will help to break stereotypes and misconceptions about Native peoples and share accurate and authentic narratives.

At the dining table at Mark and Elly’s house, I’m trying not to inhale the food too quickly, but Elly has the ability to speak to my love language which happens to be my palate.

Jacobs is their daughter and a Haudenosaunee metalsmith. She tells stories through sculptures and jewelry, keeping alive the practices of the visual traditions of her people while innovating metalsmithing techniques pioneered by the Haudenosaunee (Mohawks) as early as the 1880s. These skills were integral in building the financial capital of America, New York City.

Jacobs says her artistic practice “concen trates on creating art objects that highlight botanicals and relationship objects — items that hold cultural, personal and familial impor tance — as a way to have conversations around utility objects, historical and cultural narrative, materiality and value systems as humans.”

To speak truth, the metal work, when I first encountered it, was elegant yet terrifyingly brutal. It was natural in the symbolism, yet was made of iron. I did not have the context of the work, but knew that there was something in it all I wanted to showcase; Jacobs was up to some thing and I wanted everything to do with it.

As the curatorial and special projects coordi nator at Positive Street Art, I have been working with Jacobs on this real-life representation of Indigenous works mostly in the vein of the Haude nosaunee, for over a year and a half.

Cecilia Ulibarri and Manuel Ramirez are the co-founders of Positive Street Art, an organiza tion dedicated to building stronger communities through educational workshops, placemaking en deavors and beautification of the urban landscape with the visual expressions of New Hampshire’s overlooked and under-resourced communities.

Amid the need for a venue change, I asked if PSA would host the Akwesasne exhibition, Ulibar ri paused for what seemed like massive swaths of time before saying, “I was wondering when you were gonna reach out.”

Sponsorships and grants associated with the earlier venue were lost with the shifted location. Prospects were looking less than fortuitous. But no one has ever assumed a child of exiles, a child of the First Nations People and a single mother who started her career out of transitional housing with two children could ever be held down. This would not stop Jacobs either. These types of misfortunes are par for the course in the careers of artists and curators who are working-class people of color.

Ulibarri and I called Jacobs after the

Old Growth Series: Blueberry by Margaret Jacobs. (Courtesy of PhillipsX)

Old Growth Series: Blueberry by Margaret Jacobs. (Courtesy of PhillipsX)

JUNE 13

• 5-7 P.M.

Opening reception with Margaret Jacobs at Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce Gallery. Light refreshments served.

JUNE 10-13

Youth mural led by Akwesasne Youth Leader, Ansley Hill.

JUNE 14

• 3-5 P.M.

VIP event with West High School.

• 6-8 P.M.

Opening reception at Positive Street Arts, Nashua. Reception will include performances, curatorial introductions, light food and refreshments.

JUNE 15

• 2-5 P.M.

Black Ash Basket Weaving Workshop with Carrie Hill, master basketmaker and exhibiting artist from Akwesasne.

JUNE 17

Private tour of sites for youth programming.

TBD: Artist Talk with Co-Curators

exchange, exclaiming that the show still has a home! And one for future years to establish the reality of Indigenous voices in the Granite State.

When Jacobs and I linked up on the phone or in person, the parallels and shared tribulations sauntered us into a fast kinship. I asked her why she left New Hampshire.

“I hit the glass ceiling, and there was no place else to grow and achieve my potential,” Jacobs said.

I sent silent acknowledgements, like a quiet prayer, to the people and organizations who stood up and helped shift this programming over to PSA and keep the momentum alive when I had reached similar heights.

In this new reality of New Hampshire, with a growing number of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) organizations and companies, the people stood alongside programming and exhibitions like this.

The second time Jacobs and I got together was at her homestead in Central New York. This space was fascinating in that it was an incredibly working-class, predominantly white community, with smatterings of transplant artists and art connoisseurs who had made their career fortunes in other fields in Boston, Chicago or Manhattan and began twilight careers in the arts in rural regions of the country.

Jacobs shares her home with Justin O’Rourke and handfuls of chickens. They have what looks like a post-apocalyptic scrapyard with studios made out of cargo shipping containers and myriads of tools for the chemical and physical mutilation of metals. Walking through the sculptures and gorgeous old-school cars, one begins to get a sense of the organization and method in all the production which takes place throughout the homestead.

During this trip, friends and I stacked wood for the couple, finishing a task which could have taken weeks in the span of hours. Thus, the friendship was immortalized in the strange transactions that exist due to social etiquette and

norms. After this episode, the tumultuous journey of curating an exhibition through such uncertain terrain became the show which would take place without a shadow of doubt.

Ulibarri, Jacobs and I fused our networks and talents to ensure firm footing in this year’s first exhibition of “Echoes and Shifts.” Thus far, we have secure finances through the generous private donations of New Hampshire artists and curators and nonprofits which provide grants to organizations and peoples who bring unique enrichment activities to underserved populations. We have submitted for grants and continue to do so.

The immense talents from Akwesasne and artists therein will participate in this year’s show because they believe in Jacobs and her work. Longtime mentor and friend George Longfish will lend his work, though the man’s caliber is that of the Smithsonian and his work has been in some of the biggest museums nationwide. Due to familial relations and a belief in this project, he deigns to be shown again with Jacobs.

Some of the other talents New England can look forward to seeing at this year’s show are as follows:

Carrie Hill is a Haudenosaunee woman from Akwesasne Mohawk Territory and owner of Chill Baskets. In 2014, she left her position at the Mohawk School in Hogansburg, New York, to pursue basket-making full time. The tradition of weaving Black Ash Splints and Sweetgrass goes back many generations of Hill’s family, and her first teacher was her aunt. Weaving felt natural to her and she fell in love with the entire process — she was soon creating her own unique pieces. Her work has been sent all over the world including an entire collection representing the Haudenosaunee People for the U.S. Embassy in Swaziland, Africa.

AKWESASNE MOHAWK

Ansley Hill is an emerging artist, student and youth leader. She comes from a creative family and has been making work since she was young. She has shown her work in exhibitions such as the Akwesasne Art and Juried Market as well as the Heard Market in Phoenix, Arizona.

George Longfish began his career in Chicago working at the first all Native American high school in the country. As an art teacher, Longfish described the beginnings of his educational career as taking “everything (he) learned and passing it on” to the students. Fighting against spaces disinterested in engaging Indigenous art, his first true foray into academia was at the University of Montana the following school year.

Immediately stepping into an administrative role, Longfish pioneered a program that traveled the country exposing students of the Indigenous art program to various styles of American Indigenous work. With just three weeks’ notice to the beginning of the following school year, he was contacted by UC Davis in 1976 to establish an Indigenous art curriculum from the ground up once again. Longfish created the school’s Native American Art Studies program and began a 30-year career there. He continued to pursue creative ventures and exhibitions all over North America.

AKWESASNE MOHAWK

Marjorie Kaniehtonkie Skidders has a career which spans multiple fields and now she sits at the intersection of all these life’s work. She has a bachelor’s degree in art and has created a decades-long career in education as a teacher, director Indigenous content curriculum writer and a school principal. Her work captures moments in the vivacity of tradition and performance in the Indigenous world. The photographs are almost cinematic in their placeness and color scheme.

ONEIDA NATION OF THE THAMES

Katrina Brown Akootchook is an artist and educator who works with beads and printmaking and design. Carrying intergenerational teachings, she innovates and melds with contemporary making and interjects humor and the decolonized perspective into each relic she renders. Often her work speaks to this perspective and the rights and autonomy of youth and young adults.

Erin Lee Antonak is an artist and curator. A graduate of Bard and SUNY New Paltz, she has curated shows all across North America, Europe and Asia. She has also been the board chair of the Indigenous Women’s Voices Summit. She blends the traditional craft-making of the Iroquois with a bold and humorous sensibility, bringing these relics to a duality of placeness and leaving the viewer in an entirely new universe.

There are still opportunities to support programming and exhibition costs. Please contact yasamin@positivestreetart.org for details, and don’t forget to check out the show openings in June! 603

A journalistic look at our state of diversity from the reporters at the Granite State News Collaborative.

A Portsmouth teenager accused of repeated acts of vandalism, including spray painting a temple with a swastika, has agreed to pay fines and do community service.

Loren Faulkner, 18, was accused of violating the state’s Civil Rights Act on three separate occasions in 2022 and 2023. That included targeting Temple Israel in Portsmouth, as well as multiple businesses that showed support for LGBTQ people, and a Black Heritage Trail sign.

Under the terms of a consent decree, Faulkner will pay $2,500 in fines, attend counseling and perform 200 hours of community service. If he violates any terms of the consent decree, his fine will increase to $50,000.

“The court found that Mr. Faulkner’s actions were motivated by hostility towards people because of their race, national origin, religion, sexual orientation and gender identity,” the New Hampshire Attorney General’s office said in a statement. “The court also found that Mr. Faulkner, through his actions, attempted to interfere or did interfere with the lawful activities of others including their ability to worship freely and engage in free speech or free expression.”

An attorney for Faulkner declined to comment when reached after the sentencing.

In addition to the financial penalties, the consent decree requires Faulkner to enroll in an educational or vocational program or seek employment.

The vandalism spree shook the Seacoast community and led to an outpouring of support for those targeted. According to the state’s Civil Rights Unit, there were a record number of complaints alleging hate or bias in New Hampshire last year.

— TODD BOOKMAN, NEW HAMPSHIRE PUBLIC RADIO

A former York High School special education teacher has settled her lawsuit against the school department that alleged she was discriminated against because she is a lesbian.

Michele Figueira filed the federal lawsuit last July alleging the York School Department violated Title VII, which prohibits employers from discriminating against an employee based on sexual orientation. She claimed she was discriminated against during her employment with the school district from 2018 to 2021 because she was a lesbian. When she complained, she alleged the administration created a retaliatory environment and did not renew her contract in 2021.

Figueira and the school district reached a settlement March 13 in federal court. Figueira’s attorney, Laura White, said she and her client could not comment on the settlement.

York Superintendent Tim Doak, who was hired after Figueira’s departure from the school, said he could not comment on the terms of the settlement but that both sides were satisfied.

“After Wednesday’s court mediation, the parties reached a settlement agreement to their mutual satisfaction and will not provide further comment,” Doak said in an email. He said a copy of the settlement agreement could be provided at a later date when the school district receives a copy from the court.

Figueira was a special education teacher for nearly 20 years when she filed the lawsuit with the York School Department alleging discrimination based on sexual orientation. She alleged her supervisor, who no longer works at the school district, made inappropriate comments about her being a lesbian.

— MAX SULLIVAN, PORTSMOUTH HERALD“It is a large community that considers itself one big family — family being one of the most important things for our culture,” said Keene native Nick Chakalos of the Greek community in the area.

Chakalos, 56, spent a significant part of his childhood attending Greek school in the city at St. George Greek Orthodox Church, learning the language and mingling with other Greek kids and families.

“I love Keene and the community we have, and have many fond memories of the people here,” said Chakalos, who now lives in Greater Boston.

He is the son of the late Timoleon N. “Lindy” Chakalos, a lifelong Keene resident known for Lindy’s Diner and Timoleon’s Restaurant, and Kiriaky “Kiki” Chakalos.

“Our grandparents and parents came to this country in order to make a better life,” he said of the reasons people emigrated from Greece to the United States.

He and others of Greek descent spoke to The Sentinel during Greek American Heritage Month in March. They told the stories of their families’ migration, their early lives in the Keene area and the importance of the Greek Orthodox Church in keeping the community glued together.

While Greek people are known to have been living in what would become the U.S. since the 1500s, there was mass Greek migration in the 20th century, when many people arrived as laborers during American industrialization, according to the Hellenic American Project.

“At an early age my father decided to come to America to seek new opportunities,” wrote Mary Booras, of Keene, in the book “In Their Own Words: Memoirs of the Members of St. George Greek Orthodox Church.”

Her father, John. A Booras, moved to Keene after leaving Palamari, a small village in the hills of Arcadia in southern Greece in 1904, and lived in a stone house in a family of 10 children.

“Dad was not able to bring many things with him. He had $20 in his pocket and his other possessions were wrapped in a blanket made of cotton yarn woven by his mother,” Booras wrote.

— MRINALI DHEMBLA, THE KEENE SENTINELIn March, the New Hampshire Senate Committee on Executive Departments and Administration heard testimony on CACR 13, a proposed state constitutional amendment that would outlaw slavery in all its forms in New Hampshire.

State Rep. Amanda Bouldin, D-Manchester, the bill’s prime sponsor, told the committee that the proposal seeks for the exception clause for the abolition of slavery in the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which allows slavery as a punishment for a crime where someone was duly convicted within the United States or any place in its jurisdiction, to be prohibited under New Hampshire law.

Bouldin and others who testified before the committee indicated that this exception was put in place as a method for slave owners to continue slavery by incarcerating former slaves with newly enacted laws through a racially biased criminal justice system that disproportionately disenfranchises people of color to this day. While she added that New Hampshire’s correctional system generally does not force prisoners to perform tasks against their will, she noted that they can receive punishments if they refuse to engage in certain activities outside of physical or mental health exceptions.

Bouldin also noted that many individuals within New Hampshire’s correctional system are not actually incarcerated, but are awaiting trial and were not convicted of a crime.

State Sen. Sharon Carson, R-Londonderry, who provided a majority of the questions from the committee, said that she opposes slavery, but was uncertain if requiring prisoners to perform duties met the definition of that word and that the state constitution required clarity. She also questioned if this legislation was needed if prisoners in New Hampshire were generally not forced to do work against their will.

This sentiment was challenged by Dennis Febo, lead organizer for the Abolish Slavery National Network.

“If you feel like slavery is necessary, then you argue for it. Don’t ask us to define it. It’s already defined,” he said. “Getting us stuck in the weeds, I don’t think it’s fair. I think it’s insensitive.”

CACR 13 passed the New Hampshire House of Representatives by a vote of 366-5 earlier this year.

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.

What does New Hampshire value? Our motto is “live free or die.” But does everyone really want to live into that motto?

Historical trauma, genocide, colonial legacies and current forms of structural racism and violence continue to affect the health and well-being of American Indian/Alaska Native populations.

Cultural erasure, forced removal of children from families into boarding schools, eugenics and forced sterilization are some of the atrocities faced by those communities. The Abenaki people in New Hampshire, part of N’Dakinna, their traditional homeland, have faced violent colonial legacies that have significantly impacted their population.

In the housing market, people of color, including Native Americans, continue to experience discrimination leading to displacement, exclusion and segregation. This systemic inequality further exacerbates the challenges faced by Indigenous communities. The lack of state recognition for the Abenaki people highlights a broader issue of invisibility and lack of acknowledgment of Indigenous rights and sovereignty.

Despite centuries of displacement and marginalization, Indigenous communities in New Hampshire have persevered to maintain their cultural heritage. The history of New Hampshire is closely intertwined with the Indigenous peoples who inhabited the region for thousands of years, primarily characterized by various Algonquian-speaking tribes collectively known as the Abenaki. The arrival of European settlers in the early 17th century brought significant challenges and changes, leading to conflicts over land, diseases introduced by Europeans and disruption to their traditional way of life.

But the lack of state recognition for federally or state-recognized tribes like the Abenaki tribe in NH further exacerbates the marginalization experienced by Indigenous communities. Efforts to address this disparity include initiatives aimed at promoting Indigenous rights, cultural education and historical awareness. Various organizations and projects have been established to preserve and revitalize native languages, traditions and tribal governance systems

in an attempt to acknowledge and honor the contributions of Native Americans.

Efforts to address these disparities include initiatives like Savanna’s Act aimed at responding to cases of missing and murdered Indigenous persons and improving data collection. However, challenges persist, such as the exclusion of urban areas — like Manchester, Concord and Portsmouth — from federal jurisdiction under Savanna’s Act and the need for Indigenous data sovereignty to empower tribal nations in addressing missing persons cases.

The systemic marginalization of Indigenous people in New Hampshire has had far-reaching consequences, impacting the state as a whole. The marginalization of Indigenous people in New Hampshire and beyond has significant implications for non-Indigenous individuals and communities as well. By understanding and addressing the systemic issues faced by Indigenous populations, there is an opportunity to create a more just and inclusive society that benefits everyone.

Some key impacts on non-Indigenous people:

1. Social cohesion: The marginalization of Indigenous communities can lead to social divisions and tensions within society. Addressing these disparities and promoting equality can foster greater unity and understanding among all residents.

2. Historical awareness: Recognizing the injustices faced by Indigenous peoples can enhance historical awareness among non-Indigenous individuals. This awareness can lead to an understanding of the state’s history and the impact of colonization on Indigenous communities.

3. Cultural preservation: Efforts to support Indigenous cultural heritage and identity benefit not only Indigenous peoples but also non-Indigenous individuals. Preserving diverse cultural traditions enriches the overall cultural tapestry of the state and promotes intercultural dialogue and appreciation.

4. Environmental sustainability: The protection of Indigenous lands and resources is crucial for environmental sustainability, benefiting all residents

of New Hampshire. By respecting Indigenous land rights and involving them in conservation efforts, non-Indigenous people can contribute to a healthier environment for everyone.

5. Legal justice: Upholding the rights of Indigenous peoples in legal systems sets a precedent for justice and equality that extends to all members of society. Ensuring fair treatment and representation for Indigenous communities reinforces the principles of justice for all individuals.

The NH Department of Health’s Office of Health Equity plays a crucial role in promoting authentic community engagement and ensuring equitable access to quality services for all populations, with a specialized focus on racial and ethnic minorities. By addressing the underlying structural determinants of inequity and working on social determinants of health, the state aims to improve overall health outcomes in NH communities.

But the Office of Health Equity cannot address this issue alone. And the marginalization of Indigenous people in NH is not just a concern for these communities. It is a detriment to the entire state. It perpetuates cycles of inequality, hinders social cohesion and undermines the well-being of all residents. Recognizing and addressing the systemic marginalization of Indigenous people is crucial for fostering a more inclusive society where all individuals can thrive regardless of their background or heritage.

By acknowledging the historical injustices faced by Indigenous communities and working toward rectifying these disparities, New Hampshire can move toward a more equitable future that values and respects the rich cultural heritage of its native inhabitants. 603

Many of you know that I’m Mr. Collaboration. Systems change is difficult, if not impossible, to accomplish without collaboration and partnership. Not that it happens without starts and stops, and jerkiness, and sometimes it just does not happen.

I’m always excited when a new opportunity presents itself. I always see the possible, not the impossible. Particularly if it has some potential for benefiting our underserved, and Black, Indigenous and other people of color (BIPOC) communities.

On Nov. 22, 2023, there was an attack on Mamadou Dembele, a prominent business person within our Seacoast community. His attackers were not arrested, and what followed was four months of questions and uncertainty. Dembele was injured both on a physical and mental level, but the uncertainty also caused further harm.

Recently, warrants for the arrests of his attackers were issued, and the process of seeking justice for Dembele is now winding its way through the court system.

As the chair of the Business Alliance for People of Color (BAPOC-NH), it was important for BAPOC to step up and support Dembele through this challenging time and to advocate for justice on his behalf. We immediately came together, and with organizations such as Black Lives Matter, Seacoast NAACP, Manchester NAACP, Black Heritage Trail of NH, NH Center for Justice and Equity, and New England BIPOC Festival, we put on a demonstration at the African Burying Ground in Portsmouth on a cold and rainy Sunday. We had great turnout from the community and local media.

The day of the demonstration, we formed a coalition of sorts. Over the next four months we met, communicated and wrote letters to the

state police and the attorney general’s office. We have expressed our concerns to state authorities about process and timelines in collegial and respectful ways. In return, state authorities have opened their doors to us and have been as transparent as possible without any compromise to their investigation. In this process, we have been able to serve as a group of concerned citizens and organizations pursuing justice and well-being for Dembele.

What has resulted is the recognition that in unity there is strength.

This is nothing new. For all of human history, structural and systemic change has occurred when people have come together to rectify an injustice and make progress. In New Hampshire this is particularly important because our communities of color are newer, and they are in areas where the population is growing.

By coming together as a coalition of BIPOC-serving organizations, we can work with communities and state leaders to ensure that we are getting the resources, protection and justice guaranteed to all communities. We are thankful to all the BIPOC nonprofit organizations and leaders mentioned here that see the wisdom in acting together. Through this process we hope to set up strong lines of engagement and communication for the long-term benefit of our communities.

We look forward to working with state authorities to engage, listen and inform those across the state willing to engage in civil conversations with us. As we continue to build this coalition, we hope that others engaged in this important work of social and economic justice will also join with us, because on some level we are all Mamadou. 603

At NH Mutual Bancorp, diversity, equity and inclusion are at the core of who we are. We value the diverse and unique individuals who live and work in our communities, embrace all differences and strive to create a culture where everyone is welcomed and valued.

We are committed to dedicating our efforts; including leadership focus and investing our financial resources, to promote diversity, equality and inclusion across our work environment and within the communities we serve. Doing so, we believe, makes us a stronger, more successful and sustainable organization over the long-term.

https://www.nhmutual.com/careers/

Iam the first generation in a long line of African Americans to be born and raised outside of the southern United States. Although I was born in Ohio, I consider New Hampshire to be my home. I grew up in Nashua and have lived in Manchester my entire adulthood.

Culturally, I was raised southern African American, midwestern African American and midwestern white. I experienced culture shock when I moved to NH in the 1980s. Not only was I a cultural/ethnic minority but also a racial minority. I couldn’t help but feel othered even by what should be my own people, other Black people.

While the place I lived in Ohio was predominantly white, there was a community of African Americans with a strong sense of solidarity among us, so I was perplexed when I moved here and tried to befriend other Black people only to realize they didn’t consider themselves Black and identified more with their ethnicity (like Dominican, Haitian or Jamaican). This rejection was hard for me to process and understand.

Consequently, I stopped trying as hard to connect with other Black people and ended up with majority white friend groups. It wasn’t until I was an adult and began my own journey toward decolonizing my beliefs and unpacking my own anti-Blackness that I realized that these other Black ethnicities had also been indoctrinated with white supremacist beliefs toward other Black people, especially against African Americans. We needed a lot of healing as individuals and as a community.