Electronic beatS conversations on essential issues N° 42 · SUMMER 2015

“I don’t owe anyone a pop record” Róisín Murphy

M.E.S.H. Lydia Lunch Michael Rother Dj Bone

04 – 05

sEpt

podgorica 02 – 03

oct

16 – 17

oct

06 – 07

nov

BucharEst BudapEst zagrEB

ElEctronicBEats.nEt

ElEctronic BEats city festivals 2015

EDITORIAL: preview with M.E.S.H.

“It’s important for people to feel like they have a stake in their culture.” A.J. Samuels: Knowing sufferers

of tinnitus and having struggled with it myself in the past, it recently occurred to me how strange it was that so few magazines and websites on electronic music address the issue. Which is why we’ve decided to bring together in conversation experimental musician Frank Rothkamm and therapeutic tinnitus app developer Jörg Land, both of who have developed two new, extremely different approaches for therapy. Have you dealt with tinnitus at all in the past?

M.E.S.H.: Yes, I started noticing I had mild tinnitus in my left ear after coming home from a six-hour DJ set in Switzerland. This club had the booth monitor right by my head and the monitor control dial on the mixer was broken. I didn’t realize I was developing it for a long time because whenever I would notice the tone in a quiet room, I assumed it was just some electronic device in the immediate environment creating high frequency sounds. I find it interesting reading the ways people try to quantify the volume and frequency of tinnitus symptoms that seem to be psychological. It made sense to me that certain treatments that seem very subjective or imprecise could have actual real results. Frank Rothkamm’s project makes intuitive sense to me—a mix of research and experimentation on his own symptoms, filtered through his artistic practice. I can imagine that listening to his Wiener Process box

Since this magazine’s shift in focus towards the voices of the artists themselves, we have attempted to broaden the scope of what’s important to thinking about electronic music. What’s relevant to the artists from their perspectives—in monologues, interviews and conversations—is relevant to us, which is why looking beyond the conventional framework of dance music towards literature, film, art and philosophy has become central to Electronic Beats. In our cover story on Róisín Murphy, our lengthy interview with novelist Richard Price, our tinnitus special and elsewhere, we ask: How does framing information change its value? What’s a frame? Is it the thing that tells you where art ends and walls begin? Is it the conceptual packaging that simplifies complex things? Avant-garde producer and guest previewer M.E.S.H. offers his perspective. A.J. Samuels Editor-in-Chief

set in full would attune the brain to perceive slight changes in tone at a finer granularity. Maybe the sound of the tinnitus just becomes a tone among many, and psychologically you become less irritated by it. The perceived volume decreases. AS: In our Recommendations sec-

tion, cybernetics theorist Oswald Wiener discusses his experiences making music together with Fluxus artist Dieter Roth, which often centered on tension-filled explorations and musical “failures”. An important goal was to break with conventional musical frameworks. How do you approach the possibility of failure in what you do?

M: I was interested to read about

how Oswald Wiener felt he had some kind of balancing effect on Roth, as well as Wiener’s description of the tension between pure abstraction and the listener’s desire for coherence. Roth’s extreme level of output seems intimidating without experiencing the context of the time he worked in. I think in the conditions we make music today, it’s more necessary to have a fear of adding extraneous signals into the environment. It’s often the case that working quickly and unselfconsciously leads to unconscious copying and falling into clichés. Perhaps because we’re sitting now on the archive of all recorded music. Even working improvisationally can lead to quotations and copied gestures. As listener

expectations become more normalized it becomes harder for artists to build a convincing language of their own. Personally, I like to create specific environments to work in, get things down quickly without editing, let it sit, listen, find connections between decisions I’ve made and build on those connections. It’s best if I can work instinctively and build up these tendencies into a sensibility. That way I can take the unexpected, the failure, and turn it into a semi-coherent system. AS: What about the club music framework? In our Bass Kultur feature, Venus X speculates about the future of her party GHE20G0TH1K, which has much stylistic overlap with the Berlin-based Janus collective, to which you belong. M: For Janus it’s been really impor-

tant to have resident DJs to set the tone and draw connections between the guest acts and develop something new. As Venus says, I think it’s important for people to feel like they have a stake in their culture and be the ones that get to introduce it to the rest of the world. GHE20G0TH1K was really influential because it was so unfiltered, had a diverse audience, and turned into a platform for new sounds that didn’t have a home. There are a lot of pretensions about the club being a liberatory space but most aren’t. GHE20G0TH1K is an exception. ~ EB 2/2015 3

The ayes have it with Adi Ulmansky, a fixture of our spring 2015 EB Festival season. In between working the photo booths, Adi delivered solo live sets of hook-filled R&B and electronics in Cologne, Warsaw, Prague and Bratislava. Read her recent backstage conversation with Róisín Murphy on electronicbeats.net. Photo: Martin Haburaj

4 EB 2/2015

Discover More on this page with the eb.tv App

EB 2/2015 5

6 EB 2/2015

Discover More on this page with the eb.tv App

At the EB Festival Bratislava, the silhouettes of hip-hop fan Ryan Lott, aka Son Lux, and drummer Ian Chang cast a psychedelic shadow reminiscent of A Tribe Called Quest’s classic The Low End Theory. In the past Lott has earned his keep writing music for commercials, but now boasts collabs with indie-pop media darlings Lorde and Sufjan Stevens. He’s also applied his song craft to soundtracks, including The Disappearance of Eleanor Rigby and this year’s Paper Towns. His sixth LP Bones is out now on Glassnote Records. Photo: Martin Haburaj EB 2/2015 7

8 EB 2/2015

Discover More on this page with the eb.tv App

Lights, camera, HORNS. It’s 2015, and brass is the new black. Here at the EB Festival in Warsaw, Kristoffer Lo of Norwegian popsters Highasakite wields not a trumpet or a cornet, but a flugabone. Yes, it’s the shiny old-world tool used mostly for heralding indie angels. And undeniably, grace abounds as Highasakite’s latest LP Silent Treatment topped the charts in Norway, where rustic pop comes in all shapes, sizes and beard styles. Photo: Hubert Zieli´nski EB 2/2015 9

Electronic Beats Magazine Conversations on Essential Issues Est. 2005 Issue N° 42 Summer 2015

Publisher: C3 Creative Code and Content GmbH Heiligegeistkirchplatz 1, 10178 Berlin Managing Directors: Rainer Burkhardt, Gregor Vogelsang, Lukas Kircher, Karsten Krämer, Jeno Schadrack, Burkhard Tewinkel, Dr.-Ing. Christian Fill Director Berlin Office: Stefan Fehm Creative Director Editorial: Christine Fehenberger Head of Telco & Commerce: Thomas Walter Conceptual Advisor: Max Dax

Editorial Office: Electronic Beats Magazine, Waldemarstraße 33a, Aufgang D, 10999 Berlin www.electronicbeats.net magazine@electronicbeats.net Editor-in-Chief: A.J. Samuels Editor: Mark Smith Managing Editor: Sven von Thülen Copy Editor: Karen Carolin Art Director: Johannes Beck Graphic Designer: Inka Gerbert

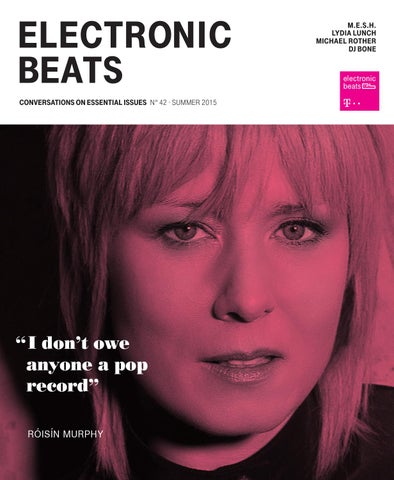

Cover:

Róisín Murphy, photographed in Berlin by Luci Lux.

Contributing Authors: Kathy Alberici, Mykki Blanco, Lisa Blanning, DJ Bone, Cakes Da Killa, Max Dax, Simon Denny, John Duncan, Roman Flügel, Brendan M. Gillen, Terri Hooley, Daniel Hugo, Finn Johannsen, Daniel Jones, Jörg Land, Suzanne Lavery, Tim Lawrence, Claire Lobenfeld, Lydia Lunch, Anthony McIntyre, M.E.S.H., Róisín Murphy, Richard Price, Michael Rother, Frank Rothkamm, Scuba, Lorenzo Senni, Adrian Sherwood, Dan Shipsides, Elissa Stolman, Eugene Ward, WIFE, Frank Wiedemann, Oswald Wiener, Ry X, Venus X

Contributing Photographers and Illustrators: Nick Ash, Erez Avissar, Günter Brus, Ron Galella, Martin Haburaj, Franz J. Hubmann, Fergus Jordan, Luci Lux, minus, Alex de Mora, Cornelius Onitsch, Björn Roth, Dieter Roth, Sarah Rubensdörffer, Katja Ruge, Andrew Savulich, Niko Solorio, Miguel Villalobos, Holger Wick, Isolde Woudstra, Hubert Zieli´nski

Electronic Beats Magazine is a division of Telekom’s international music program “Electronic Beats” International Musicmarketing / Deutsche Telekom AG: Wolfgang Kampbartold, Claudia Jonas, Kathleen Karrer and Ralf Lülsdorf Public Relations: Schröder+Schömbs PR GmbH, Torstraße 107, 10119 Berlin press@electronicbeats.net, +49 30 349964-0 Subscriptions: www.electronicbeats.net/subscriptions Advertising: advertising@electronicbeats.net Printing: Druckhaus Kaufmann, Raiffeisenstraße 29, 77933 Lahr, Germany

Thanks to: Christoph Adrian, Ian Anderson, Nicolina Claeson, Monika Condrea, Max Gassmann, Timur Gerbert, Peter Greenberg, Julia Hecht, Sarah Kaes, Seek Knive, Brad Samuels, Mary Jo Savulich, Logan Joseph Siff, Lorraine and Murray Smith, Nadine Söll, Paul A. Taylor, Dave Youssef

© 2015 Electronic Beats Magazine / Reproduction without permission is prohibited

ISSN 2196-0194 “If you’re given an outsider lemon, try and make some outsider lemonade.”

10 EB 2/2015

At the Leaf Audio DIY synth workshop held at the EB Festival in Bratislava, attendees repurposed defunct dial-up Telekom modems into 8-bit chiptune synthesizers. What in feudal times was known as “gleaning”—serfs collecting leftover crops from wealthy landowners—is today called upcycling, and it’s what the middle class do to the average man’s trash. Photo: Martin Haburaj EB 2/2015 11

Berliners had a chance to twiddle the knobs of history at the R is for Roland book release party at Echo Bücher this past May. R is for Roland features over three hundred pages on seminal Roland machines (like the System 100 seen here) and including interviews with the likes of Jeff Mills and Lee “Scratch” Perry. Read a review of the book in our Recommendations section by DJ, author and magazine editor Sven von Thülen. Photo: Holger Wick

12 EB 2/2015

Discover More on this page with the eb.tv App

CONTENT MONOLOGUES

Editorial ...................................... 3 Weltanschauung ...................... 4 recommendations .................. 16 Tim Lawrence, Oswald Wiener, Brendan M. Gillen, Finn Johannsen et al; on Grace Jones, Dieter Roth, Visonia, Conrad Schnitzler and more. Pop Talk on Taylor Swift; Music Metatalk with Mark Smith; Video Game Soundtracks with Daniel Hugo; DJ Bone dissects a festival DJ set

Interviews

Conversations

“I just don’t give a fuck anymore.” Max Dax meets RÓISíN Murphy .......................... 50 “A real addiction.” A.J. Samuels meets richard price ........................... 56

“A few drops and the smell of death was gone.” LYDIA LUNCH talks to MYKKI BLANCO ............................ 70 “Listen with your body in the zero gravity position.” TINNITUS SPECIAL! FRANK ROTHKAMM vs. JÖRG LAND ................................... 76 “Like a healing shower for the ears.” MICHAEL ROTHER talks to ROMAN FLÜGEL .......................... 80

BASS KULTUR ............................... 38 Lisa Blanning talks to Venus X about New York’s GHE20G0TH1K

Wanderlust 72 Hours in BELFAST ................... 86

ABC .................................................. 40 The Alphabet According to Adrian Sherwood

NEU: Simon Denny on Deconstructing NSA Aesthetics .... 98

Style Icon ................................... 44 How Scuba learned to love Prince

Three of our featured contributors: Richard Price

Venus X

Simon Denny

(* 1949) is an American novelist, screenwriter and master of gritty street dialogue. His most recent novel, The Whites, is now being adapted to the big screen. In this issue he talks about the formative influence of James Brown. Photo: Miguel Villalobos

(* 1987) aka Jazmin Venus Soto, is an American DJ and co-founder of New York’s GHE20G0TH1K party. In this issue she explains the origins and future of the party, and why celebrities shouldn’t be co-opting the underground. Photo: Erez Avissar

(* 1982) is a New Zealand artist whose work investigates the visual aesthetics of business, surveillance and technology. In this issue he discusses commissioning a former NSA art director for his installation at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Nick Ash

In this issue: Augmented Reality! Get access to tons of extras

with your smartphone in

simple steps.

Get the latest version of our EB.TV app for iOS. In case you already installed the app, run the update by scanning the QR code on the left. STEP Start the AR camera from the app’s main menu and watch for this sign: ------> Sweep over the pages indicated STEP with the logo to unlock videos, exclusive mixes, related articles and more. STEP

EB 2/2015 13

Monologues

POP talk: TAYLOR SWIFT’S 1989

2014’s best-selling album, Taylor Swift’s 1989, is still dominating pop charts in 2015. The record has earned countless accolades, and a week after Swift bagged eight Billboard Music Awards in May it reclaimed the second spot on the Top 100. Still, the album’s relevance in the mainstream seems worlds away from the underground. Are there points of connection? We’ve attempted to bridge the gap by tapping four artists to tell us how they feel about the megahit. Here, American rapper Cakes Da Killa, experimental trance composer Lorenzo Senni, Drum Eyes member/improvisational violinist Kathy Alberici and Tri Angle Records associate WIFE weigh in.

Rapper and New Jersey native Cakes Da Killa on why Taylor Swift writes songs for That Hoe Over There: With writing accolades from NYC to Nashville and a few Grammys in tote, Taylor Swift is America’s favorite girl next door. 1989 was made for the drunken karaoke smackdowns we later regret getting tagged in on Instagram, but it’s cute. “Blank Space” is clearly a candy-coated THOT [That Hoe Over There] anthem. Swift’s pen game is polished, but some of the hooks sound like commercial mind control, especially on “Shake It Off” and “I Wish You Would”, which I like because Taylor clearly wants to say, “I wish a bitch would!” in a cute way. “Clean” is my favorite, maybe because I’m love starved. Or because I need to do my laundry. The moral of the story is that Taylor Swift is lusty as fuck.

16 EB 2/2015

Dance music dissector Lorenzo Senni hears something in Coldplay that he doesn’t hear in Taylor Swift—something only an emoticon can describe: My brain has already digested singles like “Blank Space” and “Shake It Off”, and of course, I know a pop song doesn’t always need to be challenging. But we often underestimate how sensitive we are to sonic events. That sensitivity is what I’m interested in when considering things made by professionals in big studios. And because I listen to a lot of pop music, I have to say that I was a bit disappointed when I realized that 1989 does not provide that ubiquitous tranc-y feel—one that even Coldplay has in the form of an uplifting coda on “A Sky Full Of Stars”. A pop record needs just a couple of big hits to achieve really good results, but this won’t be enough to write history. ¯\_(``J )_/¯

Taylor Swift’s impressive, no-filler songwriting makes doom-psych maestro

Kathy Alberici

wish she were twelve again: It seems strange to write a review of a record that is already so omnipresent that I can hum the choruses of half the tracks on there. I played the album today in the car as I drove round the streets of Berlin anticipating the need to switch it off pretty quickly, but damn, it’s too catchy. There’s no fluff, no filler, just straight up joyful pop music making me wish I were twelve years old so I could dance on my bed miming with a hairbrush. Each song is a perfectly crafted piece of sing-a-long sunshine. And with that amount of music, we’re talking about a lot of sunshine. There’s nothing revolutionary about this music, just all the right ingredients for great pop: a girl who can actually sing, writes all her own songs, and pumps out enough hooks per track to make anybody believe they know all the words. Some people think it’s just pop music, but I know that it’s dangerous stuff.

Read more Pop Talk on electronicbeats.net

„Taylor Swift, I can‘t get used to this album.’ It is ist so genial konstruiert, dass es sich wie eine zeitlose Blaupause für die Zukunft des R&B anfühlt.“ Daniel Jones

He’s not twelve years old. He’s not a fan of the middle class. He is sick of heteronormativity. The man who calls himself WIFE doesn’t like a lot about 1989: I expected to like some of this record and thought it could at least hold a candle to some of Katy Perry’s best songs, but it falls very short. The tracks are catchy enough but none of them are outstanding . . . or even particularly good. What’s really difficult about listening to the whole thing is that it has the lyrical appeal of a prepubescent diary. Tay Tay’s anecdotes might seem reasonable when you are a twelve-year-old, but by the time you hit sixteen you know that it’s all garbage. It sounds like the pinnacle of the upper-middle class: too safe, too white. It’s drenched in nostalgia, but not that real nostalgia that comes from a human with a heart that feels real things. It’s the kind of nostalgia that is born of an eighty-minute romcom. Throughout the record I’m hearing a person without any emotional investment in what they’re doing. Anyone who has seen a man and woman on skates singing “A Whole New World” will understand that this record has a lot in common with Disney on Ice.

A Polaroid and a Sharpie is all you need to make your Number 1 record retro spiffy. EB 2/2015 17

recommendations

“DJs and dancers could start to freak out in a different way.” Tim Lawrence recommends Grace Jones’ The Disco Years box set Disco had its fair share of casualties, but for historian and writer Tim Tim Lawrence is an expert on New York City Lawrence, Grace Jones may be its ultimate dance music culture and has penned two survivor. Her first three authoritative music albums show disco in history tomes, Love its death throes and a suSaves the Day and the perstar in the making. Arthur Russell biogIsland

raphy Hold On to Your Dreams. He is also cofounder of the Lucky Cloud Sound System, a British offshoot of David Mancuso’s legendary long-running Loft party. His next book, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83, about the city’s post-disco club culture, is due out in 2016.

Opposite page: Selten gehörte Musik, Munich, 1974. Offset print. © Günter Brus. The poster by Viennese Actionist Günter Brus advertises a night of “Seldom Heard Music” performed by Brus, Dieter Roth, Oswald Wiener et al. All images are featured in the accompanying catalogue to the exhibit Dieter Roth und die Musik: Und weg mit den Minuten on now at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. 18 EB 2/2015

Disco started to go mutant before the backlash of 1979 compelled its producers to quit their exploration of punk, new wave, funk and dub combinations. As disco outsold rock for the first time during 1978, for instance, figures such as Arthur Russell, Michael Zilkha and Walter Gibbons were carrying dance music into dissonant territory as they added their left field touch to releases like Dinosaur’s “Kiss Me Again”, Cristina’s “Disco Clone” and Love Committee’s “Just As Long As I Got You”. But the shake-up arguably started even earlier, when Grace Jones recorded “I Need a Man”, “Sorry” and “That’s the Trouble” for the French label Orpheus between 1975-77. Admittedly, Jones didn’t set out with any radical intent, her main concern being to switch from modeling to music. Yet these releases stand out as early studies in disco juxtaposition thanks to the way her stiff, gravelly voice combines so uneasily with the standardized disco-backing track. DJs and dancers could start to freak out in a different way. Jones went on to release three disco albums with Island, Portfolio (1977), Fame (1978) and Muse (1979), all of them now reissued as part of an elaborate box set. Given that pioneering disco remixer

Tom Moulton produced all three, and given that Jones is now widely regarded as one of disco’s definitive divas, it’s easy to assume they amount to a landmark trilogy, with Jones now deemed by Island to have been a “natural choice” for Moulton following his work with The Three Degrees, MFSB and The Trammps. But whereas the gospel-R&B tradition produced what seemed like a small army of African-American divas who were able to connect with New York’s predominantly gay dance crowds through a sense of shared emotional hardship as well as a relentless will to survive, Jones cultivated an inverted diva persona

“Affectlessness, dominance and drag.”

Tim Lawrence

that combined affectlessness, dominance and drag. And while dance crowds loved her stage persona and style, relations with Moulton soon turned strained. “Grace became very grand when it was time to do the album,’’ Moulton told me. ‘‘I guess the success went to her head. I finally got so mad I said, ‘Grace, it’s amazing that with so little talent you can please so many!’” Chris Blackwell of Island picked up Portfolio once it had been completed and went on to release Fame and Muse, having heard about Jones through writer Nik Cohn, author of the article that inspired the making of Saturday Night Fever. “He was a friend of mine,” recounts Blackwell. “He said, ‘There’s this unbelievable

looking Jamaican girl in New York, you should check her out, she wants to be a singer.’” Ready to enter the disco market after making his name in ska, reggae and rock, Blackwell was all set to sign Jones based on her image. So he was pleasantly surprised when he listened to “La Vie En Rose”, a new track from the first album, and deemed it “unbelievable.” But the triple dose of musical covers that took up the whole of the first side were sonically insipid as well as ill-suited for Jones, whose voice seemed stiff when faced with the melodic-emotional demands of the form. “Do or Die” turned out to be the standout track on Fame yet fell short of Moulton’s finest work; the sequence of French language covers seemed to be made for lounge listening rather than dance floor play. Muse sank because of the backlash and also because it was the weakest of the three albums. While Jones fans and disco collectors will rightly welcome this reissue, history suggests that the releases were somewhat out of time, delivering an instrumental backdrop that was already beginning to sound generic and presenting an artist whose sense of discord was a little ahead of its time. Jones would find her ultimate expression on her next three albums, the Compass Point trilogy, when Blackwell took control of the studio. Dub, rock, soul, funk and disco swerved and clashed to create a new form of cacophonous bliss. Where other disco artists struggled to survive the backlash, Jones would relax into her mutant self. ~

EB 2/2015 19

“The presence of a non-musical tension.” Oswald Wiener on Dieter Roth und die Musik: Und weg mit den Minuten

Edizioni Periferia

Above: Splittersonate (Splitter Nr. 64 und 86), 1976-1994. 115 sheet, collage, Courtesy: © Dieter Roth Estate, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

20 EB 2/2015

Dieter Roth’s remarkable relationship to music has never been explored in detail—until now. Close compatriot Oswald Wiener looks at how the current exhibit and catalogue on Roth’s musical endeavors reflect a life that knew no boundaries. I saw the first installment of the Dieter Roth und die Musik exhibition a couple of months ago at Kunsthaus Zug in Switzerland. As Roth’s longtime friend and companion I can

surely say that trying to stage an exhibition that focuses only on his music is an undertaking that is almost doomed to fail for two reasons. First of all, his musical output was close to boundless, especially during the last years of his life. He died in 1998 at age sixty-eight and followed an exhausting work ethic that prized quantity over quality. Second, Roth is still first and foremost known for being an extraordinarily gifted concrete poet, graphic designer and Fluxus artist. I remember that when I first met him in Vienna in 1966 I was surprised that he

also made music. I was quickly stunned by his extensive musical knowledge and creativity, and we started recording music together. In fall 1972 I organized the Erster Berliner Dichterworkshop [The First Berlin Poetry Workshop] in my then restaurant Exil in West Berlin. We did it again in late 1973, which is when Dieter and I composed and recorded Selten gehörte Musik/Novembersymphonie [Rarely Listened to Music/ November Symphony] together with Georg Rühm in his studio. But apart from our on and off collaborations, Dieter

Read more recommendations on electronicbeats.net

composed and recorded almost obsessively on his own. Walking through the Kunsthaus Zug, I was reminded how many hours of music Dieter Roth actually had composed in his life—not to mention his massive Langstreckensonate #1 [Long Distance Sonata #1] from the mid-nineties, which is comprised of some 264 compact cassettes full of piano music. You could easily spend months and months listening to his late musical works, and you probably could fill even more than one museum show with his vast output. That’s why I remember asking myself why the curators of the Roth exhibition put on display as much as possible and only made it accessible via headphones. I mean, does it really make sense to randomly listen to twenty minutes of Langstreckensonate #1 and then miss the remaining 250-plus hours? Of course, on the other hand you also have to ask yourself whether it would really be enlightening if you would take the time to listen to the whole piece. Personally, I would consider myself a typical music listener. I don’t like abstractions that lead nowhere. And as such I sometimes have my problems with the nihilism inherent in Dieter Roth’s music because it deliberately neglects aesthetic categories such as arcs of suspense or dramatic composition. I prefer the music that I recorded with Dieter together as we balanced it and kept the nihilism out. Having said that, a major part of the music that was on display at Kunsthaus Zug and now in Berlin at the Hamburger Bahnhof was the result of collaborative efforts where Dieter sometimes only played a minor role. But it’s in these collaborative works where you’ll find the presence of a non-musical tension that his pure solo works often lack. When Dieter and I made music

“I once witnessed how Dieter was crying while listening to a recording of a late Beethoven string quartet. He simply was overwhelmed by emotion. Has anybody ever considered that Dieter probably composed his complex of abstract and—as he would put it, “meaningless”— music in his later years to hide his emotional side?” Oswald Wiener

together with Günter Brus or Gerhard Rühm, you could physically feel our presence in the form of tension. In hindsight I would call it “music of emotions.” I would go so far to say that Dieter Roth only showed true emotion when he wasn’t trying to meet his own impossibly high musical standards, but rather when he would allow himself to be just one part of a larger group of musicians. I once witnessed how Dieter was crying while listening to a recording of a late Beethoven string quartet. He simply was overwhelmed by emotion. Has anybody ever considered that Dieter

probably composed his complex of abstract and—as he would put it, “meaningless”—music in his later years to hide his emotional side? I know that Dieter didn’t want to show his feelings. He felt embarrassed that I had seen him crying. In the early seventies I published a book of poems by Dieter Roth called Frühe Schriften und Typische Scheiße [Early Writings and Typical Crap] because I believe that he was a very good poet. Like with his music, he insisted that there was no meaning or significance in his writings. He believed in repetition. When he wrote poetry he often would repeat the same line by the dozen. I once asked him if he thought that this had to be taken as an invitation to emphasize each line in a different way. But he answered: “No. Each line has to be declaimed in the same way.” And I, on the other hand, couldn’t really tell if he really thought what he said or if he just wanted to contradict me. Clearly, the curators both in Zug and at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin have invested a lot in research. This becomes clear when studying the catalogue Und weg mit den Minuten [And Away with the Minutes], where the entire background to Dieter’s body of work becomes tangible. The complete edition even comprises seven books, a DVD and three vinyl records. The catalogue contextualizes the times, the places and the ideas of Dieter Roth and his various collaborators in much greater detail than we ever would have had the chance to experience, even having lived through those decades ourselves. Which brings me to what is probably the largest impact this exhibition has left upon me: We tried to understand the times we lived in as we went through them, but we were unable to reflect on the bigger picture. Today, it doesn’t matter that we don’t remember every detail—others have done the research instead. ~

Oswald Wiener is an Austrian artist, professor, cybernetician and former member of avant-garde literary circle the Wiener Gruppe. In 1968, he was sentenced to jail together with Günter Brus, Otto Mühl, and Peter Weibel for his participation in the Viennese Actionist happening Art and Revolution, which involved nudity, public masturbation, defecation and self-mutilation on a large Austrian flag while singing the country’s national anthem. As a result he fled to Berlin, where he ran the famous artist restaurant/hangout Exil, before becoming a professor of aesthetics at the Düsseldorf Art Academy in the nineties. This is his first contribution to Electronic Beats.

EB 2/2015 21

Recommendations

“Mesmerizing becomes propulsive.” Ectomorph’s Brendan M. Gillen recommends Visonia’s Nausicaa EP

Electronic Emergencies

Brendan M. Gillen, aka BMG, is one half of Detroit electro outfit Ectomorph, which he founded together with Drexciya enigma Gerald Donald before teaming up with producer Erika Sherman. Gillen has played a key role in defining the stark sci-fi sound of second wave Detroit electro, and continues to keep the spirit alive via his Interdimensional Transmissions label. This is his first contribution to Electronic Beats.

Electro has always had transportive qualities, but for Brendan M. Gillen, Visonia’s latest EP is an electronic journey of epic proportions. I first heard of Visonia, aka Chilean producer Nicolas Estany, via his inspired and somewhat haunting collaboration with Dopplereffekt on Last Known Trajectory a few years ago. What seemed like such an effortless balance between warmth and ice has only gotten better on his latest productions, with each new release bringing further developments in complexity and stylistic diversity. Which brings us to the current Nausicaa EP on Rotterdam’s Electronic Emergencies, a label distributed by Clone. The title is the name of the princess from the Odyssey who is angelically kind to Odysseus, the wandering hero enduring adventure after adventure on his way home to Ithaca after fighting in the Trojan War. Nausicaa is also the windriding princess in post-apocalyptic manga Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. I suppose who Estany is referring to depends on who you think the world’s greatest

storyteller is: Homer or Hayao Miyazaki. Either way, it’s clear that this is the soundtrack to some form of epic exploration. What I find so compelling in Visonia is the fusion of genres old and new. Inspirations come from many sources: the synthetic strings of John Foxx, Ultravox and Gary Numan, the soundtracks of Jan Hammer and Giorgio Moroder, percussion tricks of IDM and the Skam catalogue, early rave, deep hypnotic modern techno power, Detroit electro and classic EBM, to name a few. Yet through all the distinct influences a stable and unique voice emerges, inspired by the past but never nostalgic. It’s not thick analogue, but rather more soft synth modern laptop production. The beats are powerful when the song calls for it and ever dominant strings truly sing out, sometimes simultaneously in ethereal layers but more often as classical, almost new wave melody. For me, the EP functions as an album, since there are so many thoughts within. Or perhaps it’s more of a soundtrack, because like a good DJ set, it takes you on a journey. Some of the songs feel schizophrenic, like the opener “The Moon Doesn’t

Want to Look at You”, which initially balances angular eighties wave with “Crockett’s Theme” strings. Eventually it starts jumping in and out of sections that are simultaneously young Juan Atkins electro and Kevin Saundersoninfluenced UK rave. Long story short: these aren’t combinations you really ever thought you were going to hear, or believe would work if seen only on paper. The drama reaches its apex in the hall of “Blue Mirrors”. A sense of urgency takes over, and what was mesmerizing becomes propulsive, dark and luscious. I envision a bareback flight in a dystopian Never Ending Story. Perhaps that’s a contradictory image, but so is the music of Visionia. The journey ends with title track “Nausicaa”, which is full of suspense and a sense of longing. We find ourselves finally reaching home, only to realize that we lost a part of ourselves on our voyage. It’s important that albums like this continue to be made. That is, music not just built for the dance floor, or purely for the mind. This is a fusion of so many of the best ideas across genres, combined thoughtfully to tell a story. Not pure DJ music, but pure electronic music. ~

“This is the sound of no deadline.” Mark Smith recommends Ben Zimmerman’s The Baltika Years Mark Smith finds serenity in an album composed over a decade on obscure PC software. Software

22 EB 2/2015

When promotion materials for The Baltika Years began appearing online, there were two key selling

points: First, according to its creator Ben Zimmerman, the tracks were never intended for release, and second, the album is comprised of a decades worth of music laboriously built using an arcane PC called the Tandy 1000 RLX. It ran an operating system called Deskmate,

which is capable of sequencing three mono voices of user-generated or built-in samples. However, it could only record eighteen seconds of sample material at a measly 22 kHz, which is about half the industry standard for audio fidelity. To put this in perspective: modern

EB 4/2014 23

24 EB 4/2014

recommendations

music software running on a decent laptop can record hundreds of hours of audio at a sample rate over four times higher than the Tandy. According to Software label-head Daniel Lopatin, aka Oneohtrix Point Never, The Baltika Years articulates a belief that idiosyncrasy is inevitable, and that human affect and technology are linked. One helps the other express something mysterious about the world.” Immediately my interest was piqued. The idea that Zimmerman made his pieces free from the pressure of concrete goals posed some titillating questions: What could this possibly sound like? Is music best made without prior intent for distribution? Do we automatically assume that art will flourish when freed from the slings and arrows of The Audience and The Market? How much stock do we place in the idea that genius is best incubated alone? And does the notion of the lone genius automatically also imply an ivory tower from which he or she creates? As a result of these thoughts, I heard and judged The Baltika Years according to different criteria than most music. For me, this collection of tracks is something more like a

Read Mark Smith’s review of Indonesian noise band Senyawa on electronicbeats.net

longitudinal study than a collection you simply sit down and enjoy. This isn’t to say it’s not immediately enjoyable—I was hooked on first listen. But it’ll turn a lot of people off within a few seconds. The lowbit processing of the Tandy gives Zimmerman’s samples sharp, jagged edges and a uniform depth of field akin to the aesthetic of early video game music. If you’ve ever played on a vintage Nintendo or Sega, you’ll know what I mean—there’s something charmingly naive in that era of bright and blocky audio. What at first glance seems crude is offset by the baroque intricacy of Zimmerman’s sequencing, which teases out remarkable textural details from the shifting, crumbling timbres of re-pitched samples. The Tandy’s feeble processing powers give Zimmerman’s sound sources a unique morphing quality that’s simultaneously lo-def and packed with potential. Guitars on “For Mimi Pt. 1-5”, yapping voices on “Phyllis”, and wacky FM bell tones on “The Scream” all become marked by the Tandy sound. His sources often decompose in order to evolve, a process in full effect on tracks like “Housed!” and “Crystal Lake”. Zimmerman

appears to have arrived at a place of sonic abundance by moving towards extreme limitation. As a result, there’s something charmingly autistic in Zimmerman’s pieces, which are put together precariously like a musical Jenga tower. It’s also in the act of stacking compositions that a discernible whole appears. Taken in isolation each track comprises a disconnected oddity, be it a ten second miniature or a twentyminute opus. But they only break into full bloom in a sequence. Making such complex music on the Tandy must have been an extremely arduous process. This is the sound of no deadline, no release schedule, no concrete goals. I can hear the emancipation and, to be honest, that trumps for me any of the actual musical qualities of the record. Releasing music like this sidesteps typical forms of judgment and listening. The quality of the music recedes behind the fact that The Baltika Years operates outside of temporal cycles decided by anyone who isn’t Ben Zimmerman. That’s rarer than you think. But if you heard this in a vacuum, without the press release explaining how to hear it, would it come across in quite the same way? ~

Mark Smith is one half of improvisational techno duo Gardland. He is also an editor at Electronic Beats.

Opposite page: Long before Jimi Hendrix burned his Strat, it was man vs. music for members of the Wiener Gruppe, pictured here laying waste to a grand piano for their performance 2 welten (2. literarisches cabaret), Vienna, 1959. Photo: Franz J. Hubmann, Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation, Vienna. © IMAGNO/Franz Hubmann.

“Projecting my Western perspective.” Eugene Ward recommends Nozinja’s Nozinja Lodge Eugene Ward is known for distilling diverse genres into a unified sound, but South African dance music don Nozinja proved something of a cultural curveball. I first heard about Shangaan, the South African genre in which Nozinja is arguably the central creative figure, not long after I had discovered footwork via

Massacooramaan’s blog. I was fast enraptured by footwork with its uncanny sampling, unprocessed drum samples and high speed. When Will Bankhead linked me to the Honest Jon’s compilation Shangaan Electro – New Wave Dance Music From South Africa, I was intrigued. But at the time, footwork held a kind of competing position in my mind and eventually “won out” as far as these two fast, tom-heavy genres go. I felt I knew how I wanted my tom

drums, and what’s more, footwork had recognizable samples such as Evanescence, Aaliyah or Lil Wayne distilled into new hooks and contorted around direct, aggressive drum work. As a teenager there wasn’t much that could compete with footwork for me, though my associating it with Shangaan was somewhat facile and dubious. Where the lyrics and cultural context of Shangaan escaped me, in footwork I felt I already had something ostensibly similar in the

Warp

EB 2/2015 25

Recommendations

Eugene Ward is a Sydney-based producer best known for his Dro Carey and Tuff Sherm aliases. With a rapidly growing discography of releases for the likes of The Trilogy Tapes and Berceuse Heroique, Ward is one of Australia’s most prolific and respected dance music producers of recent years. This is his first contribution to Electronic Beats.

drum palette, which drew upon on that familiar musical touchstone for a white male: American pop. I wouldn’t say I dismissed Shangaan at that point, but I did judge it unfairly and somewhat superficially by conflating it with the Chicago dance genre, considering Shangaan’s tempo and arrangement is entirely indigenous. And still, I find it difficult to escape my cultural bias. Listening to Nozinja Lodge, I catch myself projecting my Western perspective onto the apparent styles on the record. But the tracks on the LP, like those on any reasonably interesting electronic album, are not restricted to a single definable style. Here, they’re neither “all Shangaan” nor entirely high tempo.

Growing up on Japanese video game music, it’s hard not to associate the use of rapid-fire, impossibly accented electronic percussion with the rolls and fills of so many 16-bit adventures, though I don’t think Nozinja would have the same interest in the Sega Genesis sound chip as myself. This presents an interesting point, namely how completely different contexts can see creators arrive at the same point with their machines, at least with respect to drum programming. My favorite example of this is the album’s second track, “Mitshetsho We Zindaba”. Its chord progression, groove and instrumentation bring to mind Icehouse, or the more current purveyors of Australiana, Client Liaison. The fourth track,

“Xihukwani”, gives me this vibe as well. There is also a chant in “Mitshetsho We Zindaba” that is immediately recognizable: a semi-obscure but highly popular Roland sample heavily used by Atlanta producer Zaytoven and first prominently used on “Dilemma” by Nelly and Kelly Rowland. The use of this sample feels so indebted to my reference point that I think maybe, in that one sound, Nozinja and I are actually looking at the same thing. Nozinja Lodge is a well-paced, catchy album that feels truly innovative, whether measured against the criteria of Western dance music criticism or the cultural context it’s rooted in. As such it comes highly recommended, whatever it may connote or tell you. ~

“Pioneering musical eras are exciting precisely because nothing is settled.” Finn Johannsen on Conrad Schnitzler & Pyrolator’s Con-Struct

Bureau B

Finn Johannsen is a DJ, music journalist and vinyl enthusiast based in Berlin. He coruns the Macro label with Stefan Goldmann and is one of the key figures in Berlin’s renowned Hard Wax record store. This is his second contribution to Electronic Beats.

26 EB 2/2015

Conrad Schnitzler’s impact on electronic music is matched by the sheer depth of his discography. Finn Johannsen peers into an intimidating legacy to find a unique project of reconstructions planned by—and befitting of—the master himself. It’s been four years since the legendary German electronic music pioneer Conrad Schnitzler passed away, and I’m very sure that at this very moment a person, or more likely, several people are wondering just where to start with the gargantuan archive he left behind. From the late sixties until his death he pressed record more than most,

and his vast, officially released output is surpassed only by what has not yet graced the public’s ears. Every music consumer nowadays is forced to struggle with the sheer amount of music resurfacing from the past. Legions of thorough and not so thorough specialized labels are dealing with mostly manageable back catalogues. And then there is Conrad Schnitzler. In retrospect, you can take a whole lot of what we’re familiar with today in terms of electronic music, trace it straight back to what he was doing decades ago and slap a “proto” tag on it. From the very beginning until the very end, record for record. So how do you approach such a legacy? You need time, for sure. You need dedication, definitely. You need expertise, of

course. But you also need an idea of how to comprehensibly do justice to all the effort. Schnitzler himself is probably the only person to ever have heard everything there is, but thankfully he was also helpful in helping others wade through his oeuvre as much as he possibly could. When m=minimal label head Jens Strüver was granted access to Schnitzler’s audio library in the early 2000s, he invented the ConStruct series, in which Schnitzler’s archive would be constructed into new compositions by other musicians. And Schnitzler agreed to it. The first installment was handled by Strüver and Christian Borngräber, followed by Kreidler’s Andreas Reihse after Schnitzler’s death. Now, seminal krautrock/ kosmische label Bureau B are on

the case. And what a case it is. It’s important to note that the series is not meant to be a tribute to finished recordings by means of remixing. The history of electronic music is littered with unnecessary remix compilations. Don’t get me started. Of course, there are exceptions where the remix is as advanced as the landmark music it approaches. LFO’s version of Yellow Magic Orchestra’s “La Femme Chinoise” comes to mind, which is a fine example for the ideal combination of source material and the remixer’s own artistic signature. Both YMO and LFO have their merits, and together they

multiply. More often than not however, reworks are disrespectful to the original by being too respectful, thus watering down the originality of what they’re reworking. Luckily this is not the case with the ConStruct series, and Schnitzler surely wouldn’t have been content with just being flattered by other artists, however weighty his artistic persona. Which leads me to the third Con-Struct album, curated and rearranged by none other than Kurt Dahlke, aka Pyrolator. Dahlke, a former member of German electronic post-punk miracle Der Plan, is another seminal pioneer of electronic music in his own right. He knew

his Buchla and his numerous other synths and devices and what to do with them. I’m totally convinced that Dahlke’s historical impact should never be underestimated, and may later be con-structed itself. An inspired choice for Schnitzler’s recordings indeed. In Dahlke’s own words: “I wanted to present a side of Conrad which I had always heard in his music but which often goes unnoticed: a darker, technoid side. In my opinion, Conrad has always been one of the great pioneers of classic Berlin techno music.” Upon hearing the album, the word “proto” once again comes to mind, this time applied to techno. But it’s

Above: Dieter Roth, Postkarte an Dorothy Iannone, 1972, repainted polaroid photograph, Ahlers Collection. © Dieter Roth Estate, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

EB 2/2015 27

RECOMMENDAtIONS

not today’s club formula of drone plus kick thunder, but rather more of a nineties variety, when disparate sounds, both imported and home grown, permeated the scene. Pioneering musical eras are exciting precisely because nothing is settled within them. These eras are

defined by their explorative nature, an openness that both Schnitzler and Dahlke embodied several times throughout their respective careers. With the latest Con-Struct album, you have Schnitzler’s love of musical adventure combined with Dahlke’s selection, which reflects his own

musical preferences and signatures. Or as he put it: “I must admit, I could not resist the temptation to add one or two of my own ideas. The original tracks were so inspiring, I just had to.” I’m more of a Dahlke than a Schnitzler scholar, but I sense understatement. ~

Opposite page: Dieter Roth and Björn Roth, Keller-Duo, 1980-1989, Dieter Roth Foundation, Hamburg. © Dieter Roth Estate, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

“Back in the nineties, every sound was a sonic mystery to unravel.” Sven von Thülen recommends R is for Roland Roland has created some of the twentieth century’s most influential instruments. Sven von Thülen remembers a time when their hallowed machines were a puzzle to the originators of Berlin techno. I’m not particularly prone to gear porn, nor am I the most technical producer. But luckily enough, I’ve been able to share a studio with friends who’d fallen hard for analogue machines of all kinds. So over the years I had the chance to test much of the classic equipment that defined house and techno, the genres that fascinated me the most. A whole lot of that gear was built by Roland, a company whose impact on dance music is difficult to overstate. For that reason, R is for Roland, a new illustrated book by Tabita Hub, Florian Anwander and Michal Matlak, is a timely and loving homage to the Japanese manufacturer. Aside from quality pictures for fans, it also includes interviews with pioneering artists such as Jeff Mills, Robert Hood and Mark Ernestus, who share their thoughts on their favorite Roland devices.

When I first got my hands on these machines they were already considered classics that had defined more than one sonic canon. Maybe that was one of the reasons that when Felix Denk and I began interviewing the historical protagonists of Berlin’s techno scene for our book Der Klang der Familie, the geek in me was curious to hear how those early producers found out about the machines responsible for the sounds they loved so much. Because back in the nineties, every sound was a sonic mystery to unravel, both in terms of its source and how you could reproduce it. So it came as no surprise when René Löwe, aka master dub techno producer Vainqueur, told us that, to his ears, Detroit techno sounded like it was made with lots of gear. It was only through

“They were already considered classics that had defined more than one sonic canon.” Sven von Thülen

his exchanges with Detroit producers like Eddie Fowlkes and Juan Atkins, who made their first trips to Berlin to play at Tresor, which helped Löwe realize that the secret of the sound wasn’t an expensive studio. Another early Berlin producer was Mijk van Dijk, who was working for the short-lived Hype Magazine back in the day. He too was searching for sonic clues: “When I interviewed Baby Ford or Kevin Saunderson, I always asked how they made their pieces. That’s how I learned about the 303. Before, it was always only the “Chicago” machine to me. And then there was the “Detroit” machine. That was the 909. The first time I played a 909, I came close to tears over how easily you could program the drums.” The irony is that all of these analogue synths and drum machines attained iconic status at a historical junction in electronic music, namely when they had to make room for digital equipment. As a result, they were discontinued or even considered to be commercial flops. Thirty years later, the love and fetishization of a TR-808 or a System 100 is more present than ever. R is for Roland is undoubtedly proof of that. ~

Electronic Beats

Sven von Thülen is an author, DJ and producer based in Berlin. His most recent book Der Klang der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the Wall is an oral history covering the rise of Berlin dance music during the build-up and in the aftermath of German reunification. He is also managing editor at Electronic Beats.

Read more about R is for Roland on electronicbeats.net.

EB 2/2015 29

Recommendations

“We fetishize the incomprehensible end.” Daniel Jones recommends HEALTH’s Death Magic

Loma Vista

Daniel Jones is a music promoter and creator of the subculture reconceptualization tumblr formerly known as Gucci Goth, now BlackBlackGold. He is a regular contributor to Electronic Beats.

30 EB 2/2015

Precarity, austerity, anxiety, fear. With civilization entering a new era of free fall, Los Angeles noise group HEALTH provides writer Daniel Jones with the perfect soundtrack for turning the end into a new beginning. This is how he peels away the layers and dives into the purifying blasts of Death Magic. “We have no words any longer to say to one another. Your mouth opens and: nihil, nihil, nihil.” – Current 93 We live in a time of great uncertainty. Systems fall around us. Mass economic disparity, social injustice and a dying planet are the legacies we leave for future generations. A deluge of information bombards us daily, there to be seen, liked and then forgotten. The boot stamping on our faces isn’t that of an oppressive government, but rather the concrete realization of our own neglect. We, the human race, love to terrify ourselves on a daily basis with the thought of our own annihilation. We fetishize the incomprehensible end because we fear it. Approached with a pair of tweezers and a microscope, it’s a strange fascination, one that fulfills mankind’s attempt to place itself outside the natural order of things. How do we maintain this obsession without devouring ourselves like an ouroboros? What we need now, perhaps more than ever before, is a post-nihilism that embraces entropy and fear and then enfolds it into the secondary routine of nightlife pleasures: death reshaped into dance magick. Heralding this musical memento mori, HEALTH

have returned with a collection of anthems for a crumbling world. Violence and noise have long been staples of the celebrated Los Angeles group, whose live shows rank among some of the loudest and most intense I’ve ever experienced. But it’s with Death Magic that they’ve crafted a definitive statement for Generation Fear. The cacophonous guitars have been shaped into concise industrial dance perfection, while Jake Duzsik’s vocals achieve something akin to pop emotion. On “New Coke”, the album’s bombastic lead single, Duzsik’s wail bombs and destructs with the aid of thudding kick drums and chainsaw synths. Standout cut “Stonefist” details love like an uncertain atheist invoking god: in a dismissive and derogatory way, but obsessively in their thoughts. It’s music tinged with a sadness of something half-remem-

“Some of us don’t know what we want, or where we’re going, or even if we’ll be alive next year. This is our reality. But it doesn’t have to be a mental dead end, a downward spiral or even a negative.” Daniel Jones

bered, yet perpetually just out of reach: “We’re never going backwards. We’re never growing young.” While these themes are prevalent throughout the album, it’s hard to necessarily call Death Magic a celebration of them. Like contemporaries Crystal Castles, HEALTH’s musical evolution finds them acting as bitter commentators on the state of the world for an audience more attuned to getting their news and views in the form of entertainment. It’s easy to imagine “Flesh World”, one of the most enthusiastically rave-friendly tracks on the album, burning up the same indie discos where Crystal Castles’ “Crimewave” once made hearts race. Yet underpinning the hammering beats are lyrics that speak of isolation in a crowd and a psychology that, beneath a veneer of apathy, is screaming at itself to regain control: “Follow your lust /There’s no one here to judge us /Do all the drugs / We die, so what?” As necessary as it sometimes feels to me to embrace the macabre, surrounding myself with images of death often functions like carving a large-scale jack-o’lantern display: creating totems to scare off the real bogeyman. In every musical explosion or reverbdrenched shriek I’m drawn to, I sense the extent to which the unknown terrifies me. Some of us don’t know what we want, or where we’re going, or even if we’ll be alive next year. This is our reality. But it doesn’t have to be a mental dead end, a downward spiral or even a negative. In this sense, the music on Death Magic suggests that, even as we revel in deathworship, one day we’ll maybe be able to shrug it off and resurrect. ~

Illustration: minus academy

music metatalk by Mark Smith

Becoming an RBMAde Man:

What do you see in this image? Over the past seventeen years, Red Bull Music Academy has become one of the most important incubators for up and coming dance music producers and artists. Magazine editor and Gardland member Mark Smith recounts his struggle with the application process for acceptance in electronic music’s ivy league.

W

hat’s the title of your autobiography?

What’s lying next to your bed? When was the last time you cried? You’re undergoing a psychological examination. Look inside yourself and answer 32 EB 2/2015

truthfully, lest you render the results void. Look further through these seventeen pages and you’ll see a Rorschach blot. Is that France? Or two flying warthogs? Coincidentally, this year’s Red Bull Music Academy is going down in Paris. Attending the Academy is a grand way to launch a music career, or sure up a flagging one, if you’re lucky enough to be chosen. In two two-week sessions you attend lectures with very famous and often interesting and sometimes inspiring musicians. You also go into the studio to collaborate with fellow academy participants. Myself being on the lower tier of everso-slightly successful electronic artists with no future prospects in sight, I considered myself a perfect candidate for this year’s academy, which is why I was following instructions like: This is where I am in

relation to the musical universe. Please draw us a map! Here I drew a stick figure being inexorably sucked into a swirling void labeled “music industry”, guarded by space junk and comets labelled “ego”, “money” and “time”. Hold up, I’m actually trying to get these people to bestow the coveted honor of Academy Participant upon me. I scribbled my drawing out and realized I had no space to draw another. So what exactly do they want? Is it me? My initial instinct was: hell no! I needed to come up with a character that fits my idea of what I think they want. Or rather, their idea of what I think they want . . . or something. And of course, the only way to ascertain what they may want is via the questions in the application. So I’d sit for way too long mulling over how best to answer questions like: What’s the one thing

you’d never put on Twitter? Well, it could be any number of things, but I was only interested in the answer they find most attractive. I got that old insectoid feeling of a cool kid sussing you out. You’re a nerd auditioning to be a cheerleader, and they humor you politely while scribbling cruel aphorisms on their notepad. I just want to be friends, be liked, and maybe even respected—just a little. I never thought that perhaps a completely uncynical response would be successful. Heck, I didn’t even get that far. I was maybe half way through before I started feeling deflated after thinking too long about this question: Who is your favorite Asterix character and why? What’s his or her name in your language, and what does it mean? I asked my girlfriend, “Should I even bother?” She said no, so I stopped. ~

Images from The Vanishing of Ethan Carter.

Daniel Hugo on Video game Music

Don’t Choose Your Own Adventure:

The Vanishing of Ethan Carter First-person mystery games are increasingly taking on more complex forms of storytelling—and their scores are reflecting it. What do nonlinear narratives sound like?

F

or many years now, the worldwide revenue of the video game industry has towered over that of print. In many respects, the immense popularity and economic success of video games has left classic forms of storytelling sustaining themselves on the slim pickings offered by a stubborn old-world cultural landscape. It seems fitting then, that some games would then turn to meditate upon the writer that it has helped make disappear. Indeed, every disappearance is a mystery, and every mystery has its own detective

34 EB 2/2015

inspecting the case. In The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, a first-person mystery game, players become the hard-boiled detective Paul Prospero, who traverses crime scenes that dot the noirish, bucolic topography of Red Creek Valley. The area appears as a kind of relic, with its abandoned mineshafts, houses, forests and train tracks. Prospero is investigating the disappearance of Ethan, whose strange and prophetic short stories alert his attention to a disturbing narrative intertwined with the town’s economic collapse. Littered throughout the world Prospero must explore, the stories become allegories that are clues moving us closer to Ethan’s disappearance, while also remaining abstract. The supernatural and mystical density of the game is amplified by its stunning graphics and sound design. The gameworld bristles with details

like pastel-colored skies, dust floating in cylinders of light, snatches of reflections caught in running water—all woven together into a wonderfully intricate and varied landscape that is near psychedelic in its hazy realism. The sheer magnitude of the valley, its aliveness, bears down and emphasises its own desertedness, generating the game’s creepy tone throughout. Only through Prospero’s paranormal ability to animate past events by correctly linearizing them in the present through a series of puzzles do we ever “see” other people in Red Creek’s vibratory surroundings. By largely avoiding dominant and clichéd evocations of fear, the sound design and score are perfectly measured in building the disturbed, tense atmosphere. Layered within its plaintive strings are a manifold of bizarre envelopes of sound, with chokes, gargles and rattles

emerging and disappearing as Prospero enters new areas of the map. The sceptical tone of the pieces prevents the story from being overloaded with any clear emotional content. Where other soundtracks demand and, in turn, direct attention, this one works through the detached coloring of a plot that always wants to avoid simple resolution. Ultimately, The Vanishing celebrates the power of the story. It champions what might be called a narrative surplus, where storytelling exceeds complete story understanding. Which is to say: What happens when, where and how can remain mysterious, as long as we’re intrigued by how we encounter the events and the way in which they slip into other stories. Because of this, every story is a mystery, and every mystery needs a detective. And detectives are in the business of creating as much as uncovering. ~

played out

Boned and Rethrowned PLACE: Bloc. Weekend, Minehead TIME: 7:28 p.m. Sunday - festival closing night If you’ve ever had doubts about the expressive potential of turntables and vinyl, look no further than Detroit native DJ Bone to teach you the truth. The painfully underrated selector, producer and label owner mixes with three or four decks at once, morphing classicist techno into something unfamiliar and genuinely exhilarating. Here, he unpacks the method and philosophy behind his charging whorl of sound, taken direct from a Sunday night set at Bloc. Weekend festival in England. 1. DJ Bone - “Detroit is . . . Hard” This is my current peak time favorite. It’s a banger, but the sentiment comes straight from the heart. I went into my studio, expressed myself and this was the result. I played this to give the crowd a glimpse into my vision of Detroit. It references what Detroit is—not only for me and many of my peeps, but also for the music fans around the world whose basis for techno stems from Detroit electronic music. It bangs hard but there’s a melodic key line and vocals of dedication to offset the heavy drums.

While the percussive elements of the remix battle it out with the beautiful strings and piano, I fade in the aptly titled “Distracted” by Ø [Phase]. This of Life” while the two previous tracks continue. Don’t forget I’m queazy, hypnotic track floats well on top of “Strings”. using three decks here! I cut faders in and out to introduce 4. Ø [Phase] - “Distracted” different elements while makThis came out on Token Records in ing sure I maintain the beat. I 2013 but I still find myself drawn to it. finally remove everything but Ø [Phase] has made sev“Strings” eral tracks that convey certain moods very well. when that “Distracted” has a wanpiano line dering, seasick synth line drops. but it never goes too far out. This sort of sound is a perfect way to disrupt a typical four-to-the-floor loving crowd. I use this track as a transition from one mood to another. It seems to hang in mid-air.

Heat, mood and intensity are my gauges in the mix. To take things even higher I needed a dark, charging follow up.

The next mix brings together two very bouncy tracks that really swing. A sort of giddy-up vibe is created.

Left: DJ Bone, photographed in Amsterdam by Isolde Woudstra.

2. Planetary Assault Systems - “Rip the Cut” Luke Slater, aka Planetary Assault Systems, is a master of his craft. This track is complete mayhem! It has that tribal feel that I love and fades into sinister territory while remaining funky. It’s very deliberate, almost like it’s in a hurry to reach its destination. Luke has this form of expression in some of his tracks that’s truly amazing. Honestly, my intention was to go from “Detroit is . . . Hard” to “Rip the Cut” in order to tear the roof off the place.

Fade in my remix of “Strings

new school, preserving an important piece of history for me and remaining true to the roots.

3. Rhythim is Rhythim - “Strings of Life” (DJ Bone Remix) This is an unreleased remix I made of Derrick May’s “Strings of Life”. There have been so many remixes but I wasn’t feeling any of them. I felt this classic needed an aggressive update. I introduced organic percussion and chants that get things popping, only to have it all drop out for the infamous piano line. It’s a yin and yang thing here. Old school becomes

5. Ben Sims featuring Paul Mac - “Can’t You See?” I received this gem from Mr. Sims quite a while back and have been running it non-stop ever since. I’m not sure if or when it had a proper release. Also, the title may have been changed. It’s a very hypnotic track with a disco essence to it. It’s the choppy sample edits that give it its soul. These relentless, unapologetic twists and turns fit my style of DJing perfectly. ~

EB 2/2015 37

38 EB 2/2015

Bass Kultur by lisa blanning

“It’s about people having authorship over their youth experience.” Venus X on the future of New York’s most influential party, GHE20G0TH1K. What started as a fiercely local club night fusing R&B and rap with regional forms of dance music has become New York’s key incubator for autonomous youth culture. With the forces of capital baying at the gates, founder Venus X tells us how to protect what’s real. In 2009, my friend was working at a bar and gave me an off-day monthly. At first it was called Deathwish, but people were calling it Ghetto Goth because that was what we were using to describe it. By the fourth month, it was Ghetto Gothik. It went through a few different spellings—it’s a lot about disruption and being elusive, not wanting people to find us online. Why would we make it easy to spell? I was young, brown, growing up in New York and gay. When you grow up in any of the black or Latino neighborhoods and you’re gay, everybody knows each other. But there were local punks, steampunks and hardcore kids who DJ’d with me, too. So we kind of created a crossroads where everybody could meet up, which didn’t exist before. It was a really open format. Within six months we started doing parties at a bar in the Lower East Side, maybe one hundred sixty capacity in the basement. They were the best parties. It was me, [Hood By Air designer] Shayne [Oliver], Physical Therapy, a lot of people who are now on Fade To Mind, and a lot of New York all-star instrumental-

ists, like Dutch E Germ from Gang Gang Dance. Since then we’ve been on and off in both disgusting and great warehouses, and sometimes Santos and SOB’s. Musically, the party says two things specifically about our youth now: it’s very local and it’s also very Internet. So it’s from here but it’s also from nowhere. Everyone can co-exist here in New York because it’s so fast-paced and crazy. No one is going faster than us. So the music is local: vogue, which is happening in Midtown, and Jersey club. as well as a lot of producers from the Bronx and all over New York. But at the very beginning it was actually punk and industrial, really dark hip-hop and nineties Memphis murder music, like Three 6 Mafia. There was a time when we had a lot of great gothic rap that no one ever called goth, and it was reinterpreting what that was. We were trying to be obscene, we were trying to be fixers of history, we were trying to say, “Fuck you,” to a lot of people. This aggressive reinterpreting is now going into vogue culture, Jersey club, kuduro and juke. I don’t see the problem with understanding women’s history and sexual politics and also playing rap music. When you’re living it, it’s a much more dynamic thing. I was really militant when I was in my late teens. I was studying African studies, more specifically the political economy of race. I was squatting, hanging out with kids that were extremely radical. Then, by the time I was twentythree, I had gone back to school. I developed more into an adult that could sustain the pressures of capi-

talism and I wasn’t just angry. So how do I actually participate in the world that I like, which is a fashionable world, a world of complex social dynamics where sexuality is not just a thing of power play and abuse? Part of it is avoiding or working around male culture: a male-dominated nightlife, male-dominated fashion industry, a male everything. Now the party has been on and off for a few years. When there’s great venues, we’re not going to stop a party. But when there are no venues, and shit is hitting the fan, you realize some people are just using the party for the aesthetics. They don’t get that it’s about people having authorship over their youth experience. No celebrity can co-opt that. It’s not allowed, which is why GHE20G0TH1K was shut down for a few months when the whole Rihanna thing happened [Rihanna, who never attended the party, hashtagged #ghettogoth in a series of Instagram posts over a year ago]. This city is about money, it’s about greed. I’m not going to fight a celebrity, and I’m also not going to fight a system that’s organized in the service of rich people and corporate situations. Kids getting this organized to make an impact in so many different genres, from so many different backgrounds, doesn’t happen very often. And Rihanna is just an archetype for the whole system, which constantly says, “I’m going to take it from you even though you created it.” And it’s just like, “No, it’s 2015. We’re not doing this shit again.” ~ Photo: Erez Avissar

Three GHE20G0TH1K Classics: Joswa In Da House - “El Me Gusta (Fra Fra)”: “Explicitly gay Dominican dembow was crucial to the sound of GG.” B. Ames/Nicki Minaj - “Ra Ra Ha (Roman’s Revenge)”: “Unrealistically aggressive beat. Love the way B. Ames chopped the animal sound.” MC Bin Laden - “Bololo Haha”: “Baile Funk’s not dead.” Opposite page: Venus X (center) flanked by Nguzunguzu’s Asma Maroof (left) and guest MC Ian Isiah. EB 2/2015 39

ABC

The alphabet according to

Adrian Sherwood

as in African Head Charge African Head Charge was a psychedelic dub band I first produced back in 1981. Consider it an attempt to inject some “holy voodoo” into dub. The line-up changed a lot over the years but it’s centered on percussionist Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah. There was a lot of talk of African influences in Jamaican music during the seventies and eighties, but the heavy Afro percussion that Bonjo specialized in wasn’t so common. Most Jamaican roots tunes tended to use lighter percussion like repeater and bongo drums. With Head Charge we emphasized heavy beats, samples, chants, down-tuned vocals and backward-mixed tape. By Jamaican standards we made tracks that were pretty whack. Still, I stand by them to this day.

40 EB 2/2015

In the early eighties Afro-Caribbean roots music was being dubbed into another dimension. Producers like Englishman Adrian Sherwood stretched the music’s rich cultural fabric into new frames of time and space. Dub, industrial, electro, hip-hop and synth-pop became part of the same musical conversation, especially under the auspices of Sherwood’s label On-U Sound. There, dub cornerstones of bass weight and uncluttered space came to define the producer’s style, whether he was remixing Bim Sherman or Nine Inch Nails. His wide-open sound was most recently featured on Late Night Endless, a hi-def collaboration with Bristolian dubstep producer Pinch. Here’s an ABC cataloguing Sherwood’s sprawling history, from drinking tea with Björk to movie nights with Johnny Rotten. Opposite page: Adrian Sherwood, photographed in Ramsgate, UK by Alex de Mora.

as in British foreign policy God alive! It’s clear that British foreign policy is anything but just British, especially in light of “our” peace envoy Tony Blair’s criminal foreign policy adventures.

as in Dynamics There’s a dearth of dynamics in modern music. What’s more important are dynamic people and relationships.

as in English dub production The originators are untouchable but time marches on. The Jamaicans have a saying: “Each one teach one,” and many producers in the UK—and the entire world over for that matter—have been attentive students who learned from the best. They understood the lineage and pushed dub into the future.

as in Cultural cross-pollination Pollination is essential. Stop poisoning the bees! Cultural cross-pollination is great in music if the ingredients are properly seasoned.

as in Fatherhood The best productions I’ve ever been involved in are my children.

Discover More on this page with the eb.tv App

EB 2/2015 41

as in Gravity and groove Both are strong forces that pull you about and lift your feet off the ground.

as in High Wycombe What can I say? It’s a small satellite town west of London where I spent my formative years and forged lifelong friendships that have shaped me to this day. Glad I left when I did though.

as in Imported wax from the Caribbean and Africa Like receiving messages sent from another planet.

Illustrations by Cornelius Onitsch 42 EB 2/2015

as in Jah Shaka The pre-eminent sound system warrior and producer. I’ve been listening to him for over forty years. Most people don’t know that he’s a jazz aficionado as well as a dub master. I still marvel at his ability to work his sound system non-stop for twelve hours straight. When Mark Stewart and I first started working together, the first thing he did was play me a cassette of a Shaka dance. The cassette was heavily distorted, like most live Shaka recordings, but Mark’s tape was particularly hot. I thought he wanted to record tracks in the vein of Shaka’s steppers rhythms but I soon realized that he really wanted his record to sound like Shaka’s sound system blowing up.

as in Kukl We often crossed paths with the Icelandic post-punk band at John Loders’ Southern Studios in London. We would wait for whoever was in the studio to finish, be it Crass, Exploited, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Subhumans or Minor Threat. Only then could we get our own sessions started. In the meantime we’d have funny chats in the kitchen over cups of tea with Björk and the rest of that strange and lovely crew.

as in Lydon, John I first met the former Sex Pistol with Viv Goldman. I came across him later on through Ari Up while I was staying at her mum’s house. Ari was the daughter of John’s girlfriend, who later became his wife. I really liked John. He had a video player, something I’d never seen before. I spent a few nights with him watching films like A Clockwork Orange.

as in Meditate on bass weight I’ve always thought the bass line is as important as the melody. Most of my favorite tunes are all about the bass line.

as in Nostalgia Being nostalgic is all well and good, but when you’re making music and pine for a time gone by or for things to be or sound a certain way, you better be careful as it can spell the end for you.

as in Overdue payments An issue in all our lives.

as in Pinch aka Rob Ellis, dubstep pioneer and head of Tectonic records. He’s genuine, intelligent, funny and I’ve just made a great album with him!

Discover More on this page with the eb.tv App

favorite producers are those whose style you can recognize instantly.

as in Quality control at a record label I’ll relate this to the old music business. When they were minted it seemed that large record labels didn’t have much of a policy regarding quality control. These labels were often run by tone deaf A&R people and business men who seemed to think that being financially successful meant they had quality acts. Anyway I guess quality, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

as in Where is political music today? Good question! Sadly, I don’t think artists are as political as they should be. With the exception of Sleaford Mods I can’t think of many articulate, angry new bands coming up.

as in Teenage years Not the best years of my life, probably because I was stoned and unable to speak for most of the time. Now I remember those years fondly because that’s when I discovered Jamaican music.

as in Xciter App A new app for your phone that’s supposed to enhance the sound of compressed MP3s. I’d like to have a go with it, certainly sounds interesting. It’s just another tool but possibly a great one considering that most people listen to low quality digital files these days.

as in Uncluttered space A very important musical tenet. Carving out a specific place for each instrument and sound effect is what I love to do best. I like being able to isolate each part so I can grasp how one element plays off the other. I think this comes from my early experiences recording multiple musicians in a single room at the same time. Even after overdubbing, I made sure that everything could be clearly heard in a dynamic, three-dimensional field. Uncluttered space is vital to many modern productions. Tracks these days have become super minimal, though they’ve never had so much sonic power.

as in Racial tension It’s stirred up over and over again to stop us fighting the real dogs.

as in Signature sound Something to strive for. Most of my