Electronic beatS conversations on essential issues N° 38 · SUMMER 2014

“Society waits for nobody” MØ

Wayne Shorter François K Inga Copeland RZA

ELECTRONIC BEATS LIVE 2014

12 .09. PODGORICA 18 .10. VIENNA 31 .10. BUDAPEST 08 .11. ZAGREB 21 .11. LEIPZIG ELECTRONICBEATS.NET #ELECTRONICBEATS

EDITORIAL

“You stick to formulas without becoming formulaic”

Max Dax: Hans Ulrich, you have

just released an impressive new book called Ways of Curating. In it, you write about the importance of rituals in your life, dedicating a whole chapter to taking the night train through Europe to meet as many artists as possible. You also elaborate on the importance of always confronting these artists with other fields of interest such as architecture, music, and, most importantly, poetry. For me, making magazines is the equivalent, not just because it means doing something on a regular basis. Rather, in Electronic Beats we exclusively publish interviews and monologues that are based on real conversations. The ritual for us is talking to people and transforming these exchanges into a larger discussion every three months. By the way, I also try to take the night train as often as possible. Hans Ulrich Obrist: My book is also based on conversations. I’ve always had them with artists and I have always been interested in the question of how to turn them into books. Studs Terkel is one of the great masters of conversation. He recorded more than 10,000 hours in his life and taught me how to bring the exchanges into book form. Rituals are important because

Dear Readers, In this issue, risktaking—be it in the form of harmonic and rhythmic deconstructions of pop music or fighting for gay rights in less than hospitable surroundings—was a central topic of conversation amongst artists, musicians and curators whose work is more than just a way to make a living. In sunny Malibu I was challenged by none other than Wu-Tang chief RZA to a game of chess—and lost bad. Also in Los Angeles, legendary saxophonist Wayne Shorter described to me his work in a single sentence of provocation: “Jazz means: I dare you.” In New York, Fatima Al Qadiri and Kenneth Goldsmith discussed the risks and intellectual rewards of copyright infringement. Read on, we dare you. Sincerely, Max Dax

they give structure to life: I go jogging every morning at 6 a.m. in the park, and I used to have a coffee drinking ritual, but I had to quit that. Oh, and I have the ritual of buying a book every day. MD: In your book you outline

that not only curating but also the way people visit exhibitions has evolved over the decades.

HUO: You can say that going to the museum is a twentieth and twenty-first century ritual. More and more people go and it’s a very different ritual than going to the theater or attending a music performance where basically you sit in a chair in front of the stage. Millions of people go to museums, but it is always an individual experience. Check out the texts by German scholar Dorothea von Hantelmann about it. MD: Like an exhibition, I think you

can actually draw a comparison between a museum visit and buying a magazine. Unlike a book, a magazine is current for only a couple of weeks. After that, the next issue replaces the previous one, which, over night, becomes a thing of the past. The great thrill therefore is figuring out how to imbue it with some kind of sustainability so people won’t throw your magazine

in the trash after reading it. This means that you have to make the magazine a real document of its time, because only then willl it have a lasting relevance. One of the ritualistic parts of making a magazine is that you always have to think in the same structures, the same columns, the same layout. And yet still you try to find new formats that could function with every new issue. Essentially, you stick to formulas without becoming formulaic. HUO: Did you know the Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bennekom, who do Fantastic Man and The Gentlewoman are also doing the corporate magazine for COS? It’s a great magazine and I read every issue cover to cover. MD: I love the COS Magazine because it seeks to redefine the concept of “branded journalism”. I think that Gert Jonkers, with whom we did an extensive interview together with Penny Martin from The Gentlewoman in our Fall 2011 issue, has understood that we should see corporate publishing as a chance to make exceptional magazines. People like Jonkers are changing the world of publishing for the better, because they understand the ritual of producing a magazine like curating an exhibition. ~

EB 2/2014 3

WELTANSCHAUUNG

“Science for a Better Life”1, “Make.Believe”2, “Connecting People”3, “Turn on Tomorrow”4—the track titles on Diamond Version’s stellar new LP CI (Mute) certainly have a familiar ring to them. But are Carsten Nicolai and Olaf Bender’s compositions really a critique of corporate culture or more a piss take? Did it still count as subversive when the two co-founders of avant-garde electronic imprint Raster-Noton played the Electronic Beats Festival in Prague this past March? It’s hard to say. Check out Stroboscopic Artefacts chief Lucy’s review of CI in this issue’s Recommendations section for some answers. Photo: Tomáš Martinek Bayer 2Sony 3Nokia 4Samsung

1

4 EB 2/2014

EB 2/2014 5

6 EB 2/2014

London-based newcomers Jungle powered through their show at the recent Electronic Beats Festival in Bratislava this past April. The group surrounding frontmen T (center, left) and J (center, right) have emerged from a cloud of mystery regarding their identity—one that wasn’t entirely uncontroversial. In their videos and early press shots, the group used black models and dancers to be the face of their sound, but the two bandleaders looked pretty white onstage . . . not that the music sounded any different. Photo: Eduard Meltzer EB 2/2014 7

8 EB 2/2014

Bathed in a blue glow, Dan Snaith, took to the stage in Bratislava as Daphni following an impressive performance by friend Kieran Hebden, aka Four Tet. Snaith’s eclectic DJ set included lots of sudden changes and a steep developmental arc, with entries and transitions both oblique and calculated—in other words: classic Daphni. Photo: Geoff Fibula EB 2/2014 9

It’s not hard to see how much of Warsaw has been rebuilt over the past seventy years and today, amidst a blooming cultural environment, a virulent form of turbo capitalism has real estate developers eager to capitalize on the city’s vast amount of empty space—large chunks of which can be found not far from the street ul. Złota pictured here. In this issue’s city report (p. 84), we spoke with artists, curators and musicians about why so much art from the city has become expressly political and how this will change their future. Photo: Luci Lux

10 EB 2/2014

EB 2/2014 11

Imprint Imprint Electronic Beats Magazine Conversations on Essential Issues Est. 2005 Issue N° 38 Summer 2014

Publisher: BurdaCreative, P.O. Box 810249, 81902 München Managing Board: Gregor Vogelsang, Stefan Fehm, Dr.-Ing. Christian Fill, Karsten Krämer, Jeno Schadrack Creative Director Editorial: Christine Fehenberger Head of Telco & Commerce: Thomas Walter

Editorial Office: Electronic Beats Magazine, Waldemarstraße 33a, 10999 Berlin, Germany www.electronicbeats.net magazine@electronicbeats.net Managing Director: Stefan Fehm Editor-in-Chief: Max Dax Editor: A.J. Samuels, Duty Editor: Michael Lutz, Editor-at-Large: Louise Brailey Intern: Joe Morgan Davies Art Director: Johannes Beck Graphic Designer: Inka Gerbert Copy Editor: Karen Carolin

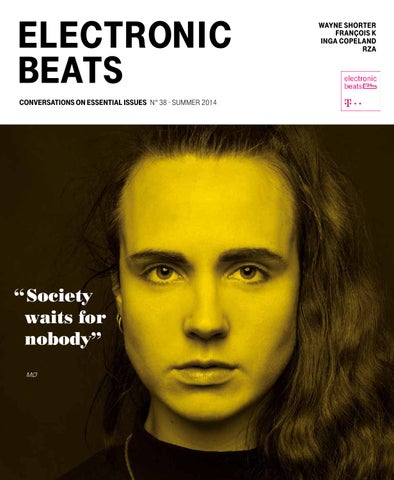

Cover: Mø, photographed by Frank Bauer in Munich. For our limited edition cover, Wayne Shorter was photographed in Los Angeles by Luci Lux.

Contributing Authors: Fatima Al Qadiri, Sander Amendt, Black Cracker, Lisa Blanning, Inga Copeland, Kenneth Goldsmith, Ben Goldwasser, Heatsick, Daniel Jones, François K, Katarzyna Kołodziej, Magdalena Komornicka, Nina Kraviz, Claude Lanzmann, Steven Levy, Lucy, Martyn, Mø, Hudson Mohawke, Joanna Mytkowska, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Karol Radziszewski, RZA, Wayne Shorter, Jacek Sienkiewicz, Rosemarie Trockel, Stanisław Welbel, Anna Zaradny

Contributing Photographers and Illustrators: Robert Abbott Sengstacke, Curtis Anderson, John Barclay, Frank Bauer, Barry King, Guy le Querrec, Luci Lux, Tomáš Martinek, Eduard Meltzer, minus, Tim Peukert, Hans Martin Sewcz, Tim Soter, Miguel Villalobos

Electronic Beats Magazine is a division of Telekom’s international music program “Electronic Beats” International Musicmarketing / Deutsche Telekom AG: Claudia Jonas, Kathleen Karrer and Ralf Lülsdorf Public Relations: Schröder+Schömbs PR GmbH, Torstraße 107, 10119 Berlin, Germany press@electronicbeats.net, +49 30 349964-0 Subscriptions: www.electronicbeats.net/subscriptions Advertising: advertising@electronicbeats.net Printing: Druckhaus Kaufmann, Raiffeisenstr. 29, 77933 Lahr, Germany

Thanks to: Ian Anderson, Karl Bette, Reto Bühler, Adrienne Goehler, Jörg Hacker, Fallon MacWilliams, Andreas Reihse, Niko Solorio, Hayley Woolfson © 2014 Electronic Beats Magazine / Reproduction without permission is prohibited ISSN 2196-0194 “To me jazz means: I dare you.”

12 EB 2/2014

CONTENT Content M

o

no

logues

Editorial .................................................................................... 3 Weltanschauung ...................................................................... 4 Recommendations................................................................... 16 Music and other media recommended by Rosemarie Trockel, Hans Ulrich Obrist, Heatsick, Daniel Jones et al.; featuring new releases by Kreidler, Thug Entrancer, Ramona Lisa, Diamond Version, Arto Lindsay, Joey Anderson and more BASS CULTURE François K on Deep Space .................................... 28 ABC The alphabet according to Nina Kraviz .................................... 30 Style Icon Hudson Mohawke on Quincy Jones ............................. 34 Counting with . . . Black Cracker.............................................. 36

I nt

e

r v

ie

w s

“Society waits for nobody” Sander Amendt meets MØ ................................................................ 40 “Yeah! The dictator! Yeah!” Max Dax plays chess with RZA ......................................................... 46 “To me jazz means: I dare you” Max Dax talks to WAYNE SHORTER ............................................... 54 “Whatever was on TV” A.J. Samuels interviews INGA COPELAND ........................................ 68

C o nv

er s at

i

o ns

„You grew up in a place without Led Zeppelin?“ FATIMA AL QADIRI talks to KENNETH GOLDSMITH ............................................................... 76 Wanderlust: 72 Hours in WARSAW.................................................. 84 NEU: “It’s a red flag for snoops”..................................................... 98

Three of our featured contributors: Lisa Blanning

Rosemarie Trockel

Frank Bauer

(* 1975) is an American journalist and regular contributor to Electronic Beats. In this issue, she interviewed producer François K, as well as moderated a conversation between Kenneth Goldsmith and Fatima Al Qadiri. Photo: Luci Lux

(* 1952) is a German artist known internationally for her work on sexuality, feminism and the human body. In her first contribution to Electronic Beats, she recommends Kreidler’s ABC. Photo: Curtis Anderson. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers Berlin London

(* 1967) is a German photographer based in Munich. A regular contributor to Electronic Beats, in the past he has shot the likes of Bryan Ferry and Gerald Donald. In this issue he photographed our cover story, Danish singer MØ. Photo: Tim Peukert

EB 2/2014 13

M

o

no

logues

recommEndations “In contrast to fine art or literature, music needs no translation, no mediation” Rosemarie Trockel recommends Kreidler’s ABC

Bureau B

Rosemarie Trockel is a German conceptual artist internationally known for her work in various media dealing with themes of sexuality, the disconnectedness between fine art and craftsmanship, and female identity. She lives and works in Cologne, and teaches at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. This is her first contribution to Electronic Beats Magazine.

More than ten years ago I was introduced to Kreidler’s Andreas Reihse by Thea Djordjadze, an artist friend from Georgia. For several years we three were neighbors in Cologne’s Südstadt where we shared the same backyard and an old garage in which Andreas also produced music. In 2003 Thea, Bettina Pousttchi—another artist—and I had asked Andreas to create the sound for one of our installations, which turned out to be incredibly well fitting. Lucky enough we extended this kind of loose collaboration several times, for example for the theatre play “I WILL”, a collaboration with students of the Dusseldorf Art Academy, curator Marjorie Jongbloed and others, including Alex Paulick who has become Kreidler’s bass player in the meantime. In that sense I had super luck in having been Andreas’ neighbor. Over the years Kreidler’s music too became one of the best companions in

my life. Their two albums Eve Future and Eve Future Recall helped me through a winter, Tank I listened to non-stop when it was released, as I did with DEN. And now it’s happened again: I listen to ABC for breakfast, then in the car, and, actually I’m listening to it the whole day. I am jealous of musicians if they work the way Kreidler do. Among all the artists I think musicians happen to enjoy the most freedom. I’m not talking about economics. To make a living from music is a completely different issue. But how happy you must feel when your work can make other people happy? Music is immediate, it touches the heart directly and at the right volume you experience it with the whole body. You dance to music, you fall in love with music, music gives you comfort, and of course it inspires you. In contrast to fine art or literature, music needs no translation, no mediation.

It is not easy for me to pin down the secret of their new album ABC, what it “does” to you, what kind of a spell it casts on you. Perhaps it’s the temper of longing with comfort; then, what may sound light and easy, even sketch-like is, if you listen to it again, full of new swerves and curves, new depths and layers every time you listen. You will encounter a complexity that is never mannered and never ambient. There is always a driving moment, a carry-on that takes you by the hand, to get you up, to keep on keeping on. I like how each song on ABC responds to each other, all of them together become a big narration. And they even connect to songs on other Kreidler albums in a manner that earlier achievements are extended and become an entity in their very own everexpanding cosmos. In that sense, Kreidler’s music is equivalent to the most beautiful physics. ~

“Emerged from the eleven dimensions of string theory” Hans Ulrich Obrist recommends the David Bowie is exhibit and catalogue

V&A Publishing

16 EB 2/2014

“I am another.” This phrase by the French poet Arthur Rimbaud is key to understanding David Bowie not just as a person, but as a persona. Alternately, as the great Lebanese poet Etel Adnan has emphasized: “Identity is shifty. Identity is a choice.” Indeed, Bowie’s play with identity has been a bridge to his relationship with fashion, which is why the recent Bowie exhibition in the Victoria and Albert Museum

in London and accompanying catalogue has made an effort to include numerous outfits and costumes that underscore his permanently mutable façade, such as the artistically tattered Union Jack frock he designed together with Alexander McQueen. Of course, this also draws a connection to his various identities in films, such as the reptilianhumanoid alien with telepathic abilities and superhuman intel-

ligence in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth. There, Bowie’s character founds a billion dollar tech company in order to build a spaceship to return to his planet, but can’t get it done because of the superficiality and brutality of human civilization. All in all, a complex commentary on human identity on a more abstract level. Bowie famously studied music and design and accordingly can be considered a kind of

Above: Standing tall. Bowie’s beloved turquoise boots from 1973. © The David Bowie Archive Previous page: Union Jack coat designed by Bowie and Alexander McQueen for 1997’s Earthling. © The David Bowie Archive 18 EB 2/2014

Renaissance man with his multiple talents, which is reflected also in his variety of interests and which he treats as kind of parallel realities. This enables him to cover high and low culture, from pop to avant-garde—a kind of approach of cultural innovation reminiscent of early Godard as well as the experimental literature of nouveau roman—or even the famous MAYA principle—“most

advanced, yet acceptable”—which promotes aesthetic innovation only to the point that it doesn’t interfere with solving the problem at hand. Because ultimately, he changed the rules of the game, starting in 1969 with his entrance into the charts “Space Oddity” and eventual glam transition with Ziggy Stardust. Things turned more experimental with his Berlin years and trilogy of albums Low,

Lodger and Heroes before becoming a new romantic disco icon in a shiny blue suit and bleached blonde hair singing “Let’s Dance”. This chronology is also marked by long periods of alternating visibility and invisibility, unpredictability and erratic changes in appearance and presentation. Apparently he also didn’t visit his own exhibit, but he did come out with a new album last

year. As Cocteau und Djagilew said: étonne moi, surprise me. There are museums for architecture, science, literature and art, but there are almost no museums for sound. And yet it’s interesting to apply the medium of the exhibit to phenomena that lie outside of the art world.

This especially applies to the life and work of David Bowie, who, despite being primarily a musician has a relevance that was nothing less than culturally transformative. The Bowie exhibit does an excellent job in showing the different dimensions of someone who was not just a

songwriter, but also a producer, fashion icon, actor, painter and inventor of rituals and cults. I occasionally think of him as someone who emerged from the eleven dimensions of string theory and whose behavior cannot be predicted. No one knows what his next step will be. ~

Hans Ulrich Obrist is Co-director of Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery and a regular contributor to Electronic Beats Magazine.

“Carl Craig and RP Boo through neon dimension filters” Daniel Jones recommends Thug Entrancer’s Death After Life Thug Entrancer makes me respect house music. Don’t send me any prayers or worried emails; it’s not a long-running interest. In fact, this record is closer in content to a sub-genre-style juke. There’s a ghostly processor void looming over Death After Life that gives the album an otherworldly URL sheen, as though it were transmissions from another plane of audio. Indeed, I’ve been petitioning for years for post-life artist awareness beyond wishing Kurt Cobain happy birthday on Twitter. Did you know that in 2014, ninetyeight percent of teenagers continue to listen to living artists? If you are part of the two percent that believe the opinions of the living are void and worthless and that only the dead should be allowed to speak and grace our ears with wisdom, share this review with ten friends or Klaus Nomi’s ghost will come into your room when you’re at work and ruin your bed sheets. But back to my point about house music: Thug Entrancer, aka Ryan McRyhew, clearly has a love for the sounds of funky, paireddown Chicago. “III” in particular amps up the Larry Heard-like dance vibes, but removing the soul in favor of a kind of audio coleslaw: beats and snares are flung full-force at the listener’s ears, a sonic salad for the mind to digest. Thug Entrancer bears little aes-

thetic resemblance to McRyhew’s previous project Hideous Men, a collaboration with his partner Kristi Schaefer; the hip-hop tinged occultronic beats have been smoothed out into something more mechanical. I can’t say I’m particularly versed in Chicago’s musical flavors, having only been there

“Share this review with ten friends or Klaus Nomi’s ghost will come into your room when you’re at work and ruin your bed sheets.” Daniel Jones

once, but I can say that playing Whitehouse in the trap was not as cool as I’d hoped, unfortunately. The seasoned drug dealers were not having it, repeatedly referring to it as “demoralizing” and “this shit’. If they’d only had “IV” to layer them in John Carpenter synths, they might have been too creeped out to slap me and whack

my guts and make me stand on the corner with a sign that said “Fart Boss”. The Nancy Reagan advertisements were right: drug dealers are just bullies with cool tattoos and a lot of money. Indeed, Death After Life maintains a driving, after-dark juke flavor across the first half of the record, reminiscent of footwork minimalism; the second starts to get a bit more upbeat, chasing Excitebike soundtracks down a neon-lit racetrack on such skittering tracks as “VIII” and making my legs do the awkward shuffle most frequently seen in “Old Man Dances To ——” sort of videos. McRyhew, however, does make you think. His disruption of the traditional patterns embedded in each of these genres by decades of musicians is a result of loving care. Even as he dismantles, he rebuilds sibling structures on top of the ruins which echo our modern thought processes toward our past: a constant renewal, a fresh perspective on our dance roots to re-inspire or re-awaken tired ears. In a similar way as That’s Harakiri, another recent musical reconceptualization from Sd Laika, McRyhew uses broken patterns and repetitious audio phrasing to hypnotize the listener with both familiarity and discombobulation: the hand clap

Software

Daniel Jones is a music promoter and creator of the subculture reconceptualization tumblr formerly known as Gucci Goth, now BlackBlackGold. Since 2011 he’s also been a staff writer and editor for electronicbeats.net. In the last issue of Electronic Beats, he recommended HTRK’s Psychic 9-5 Club.

Listen to this issue’s recommendations on Spotify.com EB 2/2014 19

recommEndations

beat of “V” applauding itself, the Atari meltdown toward the end of “III”, the overall uncanny feeling of hearing acid-tinged footwork rhythms overlayed with eighties Dario Argento-wave cloaks. It’s messy and, at times, seemingly divergent: the aforementioned meltdown, for example, seems

more of an album closer than a three-deep ender. But that’s half the fun. Above all, Death After Life feels like the mutant art-kid split personality of modern house music’s more staid mannerisms. You can picture McRyhew bouncing around his equipment with a wide grin, running the likes of

Carl Craig and RP Boo through neon dimension filters and sweating it out as diodes. A flick of the hair and that techsweat is pouring on to your face and lips, just flying everywhere as the synth pulses laser light on the wall reading: MUSIC IS COOL. Which is the best part about music. ~

“It conveys real human emotion, and what kind of music does that these days?” MGMT’s Ben Goldwasser recommends Ramona Lisa’s Arcadia

Pannonica/Bella Union

Ben Goldwasser is a founding member of American psychpoppers MGMT along with singer and lyricist Andrew VanWyngarden. Based in New York City, the group’s most recent self-titled album was released in September 2013 and featured prominently in our cover story from the same time. This is his first review for Electronic Beats Magazine.

Right: Bowie’s bluegrey suit worn on his Diamond Dogs tour in 1974. Design by Fred Burretti. © The David Bowie Archive 20 EB 2/2014

I first met Caroline Polachek, aka Ramona Lisa, through Craigslist, of all places. In 2006, during the writing process for Oracular Spectacular, Andrew and I were searching for a practice space to flesh out ideas. Caroline and her band Chairlift posted an ad on Craigslist, looking for another band to share their room. We all became friends quickly and found that we had a lot of overlap in our musical tastes and a mutual desire to fuse pop music with more esoteric elements. On Arcadia, her first solo record, Caroline has accomplished this and more. A little over a year ago, a friend invited me to a secret performance of Caroline’s new music. I had no idea that she had recorded an entire album of her own material, and while she may have been nervous to share her project with the world for the first time, I was struck by how the performance presented something fully formed, as though she had been hard at work creating her own universe. Accompanied by haunting videos and choreography, the music seemed unapologetically new but at the same time it was hard to imagine that it had only just been written. The fact that most of it had been produced on a laptop while on tour made

it all the more impressive to me, given that that process can be really tedious. Unlike most music produced “in the box”, which lacks depth or falls too heavily on repetitive loops, Arcadia sounds rich and meticulously arranged and is constantly taking unexpected directions. There’s a great interview with Angelo Badalamenti where he describes how he composed the musical themes for Twin Peaks. While sitting at a Fender Rhodes trying out ideas, David Lynch guided him through the various images and moods of the show. I can imagine a similar visual approach to writing music when I listen to Arcadia. While

“Beyond just adopting whatever flavor-ofthe-month production tricks happen to be in vogue” Ben Goldwasser

most of the songs on the album stand well on their own, such as “Backwards and Upwards”, which is an outright jam, the entire album seems to guide you through a tangible fantasy world. There’s a great blend of old and new on Arcadia. I’m constantly reminded of other music that I like (for instance, I was tricked into thinking that I was listening to OMD at one point when “Avenues” came on when my phone was playing music on shuffle), but there’s always a novel sonic element or juxtaposition of styles that keeps the music from venturing too far into pastiche. It doesn’t hurt that her voice is a striking, singular instrument that she is in excellent command of. This is the kind of album that takes you by surprise. It doesn’t seem to come from any scene in particular, but it could easily further the opportunity for music to be accepted as “pop” while retaining a feeling of experimentation that goes beyond just adopting whatever flavor-of-the-month production tricks happen to be in vogue. Maybe most impressive is that through Arcadia’s strangeness and familiarity, it conveys real human emotion, and what kind of music does that these days? ~

recommEndations

“I became fascinated with the power of music in its relation to location and memory.” Heatsick recaps the music he heard on his recent world tour

Ghostly International

Above, top to bottom: Patrick Cowley’s School Daze (Dark Entries); John Barry’s original soundtrack to the 1965 James Bond flick Thunderball (United Artists Records); Black James’ im A mirAcle (FarFetched).

Heatsick, aka Steven Warwick, is a British musician and visual artist based in Berlin. His work encompasses technology, hybridization, performance, sculpture and film. He is a regular contributor to Electronic Beats. 22 EB 2/2014

I have just returned from a fivemonth tour around the world. To say I have been feeling displaced is a massive understatement. Being in so many non-places such as airports and without a home, I really started to drift. And I learned to love it. However, the longer I was without a fixed location, the more recordings and books I amassed. Perhaps this is a psychological need to root down to something. Either way, I became fascinated with the power of music in its relation to location and memory. This first happened when I was on a stopgap stay in London over winter at a party of a friend of my partner’s. “Do you like John Barry?” I was asked by another partygoer. “Well, yes, I like his Bond soundtracks, but I’ve never really sat down and listened to them.” Cue a Bond soundtrack! Maybe it was the prosecco and the serendipity of it all, but I was thrown back into watching a forgotten Bond film, with a flashback more intense than any I’ve ever encountered, each note triggering more cinematic details. I felt I realized the power of soundtracks—their subliminal effect on cinematic memory and how deeply embedded in one’s consciousness they can become. I couldn’t recall the soundtrack name, but I distinctly remembered one song, its woozy flutes and eerily hypnotic scale snake charming my mind. I had to hunt it down. After several failed YouTube attempts, I decided to instead watch every bond film until I found said piece of music. After three movies, I found it on Thunderball, Bond’s fourth. The track in question

was “The Bomb”, which played over and over again my mind. After that, I watched as many Bond films as I could before I got bored. I got to Live and Let Die. I was reminded of the sheer ideological overload of cold war paranoia, the transparent sexism and racism on view. I wanted to rewatch with adult eyes, my anchor to childhood in an otherwise strange drift, which was to last for many months of my tour. After that, I was off to America for a month, basing myself in L.A. but traveling all over for six weeks. A city without a center, L.A. was the perfect environment to reside in. Driving around the city with a friend, we listened to so much

“A lo-fi soundtrack made for a gay porn flick, but the music is quite different to the bombastic Hi-NRG productions he’s known for and what I would have expected.” Heatsick

music and eventually realized just how much time we spent in a car. Indeed the car for me was a home itself, with its own ecology and lifestyle built around it. I found out that cassettes are still currency in the U.S., and in several cities they were placed in my hand. In St. Louis, I had the fortune to play with Black James, a bizarre all-girl project best described as GRM style tape collage of popular song, with homothug girls voguing and projecting webcams onto multi-video channels in the background. It was one of the most baffling things I saw and I wondered how it would translate onto recordings. Actually, the image proved impossible to shake, as I am stuck with this memory no matter what I hear on their cassette. In Philadelphia I was given tapes by self-styled American rager M ax Noi Mach, most of which were somewhere between power electronics, ghetto tech and state of the world addresses. In San Francisco I was given several records from the Dark Entries label, including the School Daze soundtrack by Patrick Cowley, San Francisco’s legendary Hi-NRG disco producer, who made classics with Sylvester and a notoriously psychedelic remix of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love”. The Cowley record was a lo-fi soundtrack made for a gay porn flick, but the music is quite different to the bombastic Hi-NRG productions he’s known for and what I would have expected. These tracks are a lot more experimental and introspective, showcasing another side of

Cowley that I greatly endorse. This record also started to soundtrack my own journey around America in the opposite way to the Bond, in that I was listening to the music having not seen the film and trying to imagine how it would work together. I was reminded of the Fred Halsted film LA Plays Itself, which is part porn, part social critique of the changing state of Los Angeles

and soundtracked with bizarre tape collage music. Which is to say that it is completely at odds with the desired effect to arouse. But back to Cowley: A track that I became particularly fond of is “Mocking Bird Dream”, with its dissolving liquid synths and delicate circular melodies. I DJ’d it in the Tenderloin district in a record store which was very close to a series of apartments that

rehouse struggling addicts. They were milling around and when I played Cowley a bunch of them ran inside screaming in recognition and starting partying hard. Afterwards my friends took me to legendary dive bar Aunt Charlie’s where they played wall-to-wall Hi-NRG. The crowd was mostly drag queens and cell phones were banned. Oh, and whiskey was four dollars. I was home. ~

“Makes me want to go straight back to the beginning” Martyn recommends Joey Anderson’s After Forever There are two things that fascinate me about the New Jersey house music producer Joey Anderson. Recently I came across a few YouTube videos that featured Joey dancing. Yes, you read that right, a house producer actually DANCING to music. Through his years as a competitive dancer, Anderson was eventually introduced to DJing and making his own music. In the videos, Joey’s movements are fluid and beautiful; they look invented on the spot and in the moment, nothing seems planned or contrived. In total alignment with the rhythm, his moves feel random but in the best sense of the word—like how water always finds the easiest way down stream. Anderson approaches making music in much the same way. My second moment of fascination with Anderson was when I heard his track “Auset”, which was released last year on his Above the Cherry Moon EP for Avenue 66. Many people, including myself, were introduced to Anderson’s music through Levon Vincent’s Fabric 63 mix CD but it was “Auset” that proved to me his virtuosity as a musician. The track starts with a menacing synth riff filtering in and out with several other elements added to it before it all breaks down midway, leaving

us with just a kick drum. The tension builds and fading in from the distance is an entirely new riff that catapults the music to a new level of darkness. Then, when a frantic piano theme accompanies it, you’re truly in another world. This is not a techno track, but a story; with an end that is different from its beginning; with a development that captures the listener, picks you up, and puts you down in a different place. Anderson’s debut LP After Forever released on the Dutch Dekmantel label, captures the natural fluidity of his dancing in sound, as well as his exquisite skill of transforming a techno track into an almost meditative moment. After the beatless opener “Space Between Curtains”, the album really kicks off with “It’s A Choice”, which is rhythmically the most adventurous of them all. A Mooglike lead guides you through the song almost hesitantly and without leading to any sort of climax, the song’s easy progression becomes infectious. “Maiden Response” and “Amp Me Up” do similar things, establishing a rhythmical foundation with interesting patterns of leads on top. They develop slowly without doing anything majorly different. It’s meditation, you get into the zone, and you

stay there. I’ve heard Anderson’s music described as psychedelic and “trippy”, but I think those are unfair categorizations. These songs are not just little themes that happen to sound better when on hallucinatory drugs. They’re much more than just that. These are entry points to a Zen-like state. That said, Anderson does not always hit home runs. His music is a very fine balance between getting the movement and development of a track just right or sounding a bit noodle-y. The middle part of After Forever, with “Keep the Design” and “Brass Chest Plate” have good rhythmic ideas and interesting sounds, but it all gels together a little less than some of the rest. By no means are these bad songs; they just have less focus. Anderson gets back into gear on “Archer’s Ceremony” and “Sky’s Blessings”, with the latter a sort of redux of the former but in a more energetic fashion as “Heaven’s Archer”. This triptych brings a very strong ending to the album, and makes me want to go straight back to the beginning of it all, which is an obvious sign of quality. A debut album always defines an artist’s main direction and sound as a continuation of a range of singles. Perhaps it’s

Dekmantel

Dutch producer Martyn, aka Martijn Deijkers, is a pioneer in fusing dubstep, jungle and techno. He’s released numerous 12-inches as well as two critically acclaimed LPs, 2009’s Great Lengths (3024) and 2011’s Ghost People (Brainfeeder). His new album, The Air Between Words (Ninja Tune) is out in June 2014. This is his first contribution to Electronic Beats Magazine.

EB 2/2014 23

recommEndations

possible to explore your sound a little more in the space of sixty minutes but the main focus of an LP should be to define who you are. In Anderson’s case, After Forever shows that he is

in no rush. He is at peace with the elements he has to construct the songs and nothing comes in too soon or stays in too long. It is all meticulously put together. You can trust his craftsmanship

and that’s what makes listening so enjoyable. His combination of meditating on sound and the fluidity of progression make After Forever one of the key albums you need to listen to in 2014. ~

“As if attempting to reverse the brainwashing process of the barrage of proscriptive mottos” Lucy recommends Diamond Version’s CI

Mute

Lucy, aka Luca Mortellaro, is a Berlin-based DJ and producer. He is also the founder of dark, noisy techno label Stroboscopic Artefacts where he has released two LP’s, 2011’s Wordplay for Working Bees and 2014’s Churches, Schools and Guns. This is his first contribution to Electronic Beats Magazine.

Right: Assymetrical knit onesy designed by Kansai Yamamoto for the 1973 Aladdin Sane tour. © The David Bowie Archive 24 EB 2/2014

I’ve been listening to the output of Raster-Noton for the past nine years and aside from an appreciation of the kind of electronic music they put out, I have also felt a kinship for it in regards to the general approach of the label: the music and the accompanying atmosphere of many of their releases is rooted in subversion and in the opposition to any form of mainstream dogmas. The label has embraced a fundamental belief in the idea that electronic music and what can be considered art are part of the same ensemble. Accordingly, Diamond Version, the collaboration between label founders Carsten Nicolai and Olaf Bender is an especially interesting project for me. Subversion is at the fore of what they do, both musically and conceptually. This is clear first and foremost in the song titles of their new album CI: “Science for a Better Life”, “Make.Believe”, “Feel the Freedom” are all examples of corporate slogans. Being aware of the power of words, I as a listener felt the titles provided a framework in which I could move within, specifically restraining the freedom of interpretation to a specific kind of thought process. Equally as interesting, however, is the fact that this conceptual framework applies not only to the track list or album title but also to the sound aesthetics. I can feel throughout the whole LP

a clear intention to play around with what I like to call “archetypes” of mainstream music and corporate sound. Unlike their solo releases as individual artists, Carsten Nicolai and Olaf Bender use simpler rhythmic patterns and song structures. They borrow the basic shapes from mainstream culture and reframe them, thereby turning them into something completely different. The result is remarkably disorienting with the sounds pushing the listener to focus more intently what’s being said and what this kind of deconstruction of corporate culture means.

“Nicolai and Bender seem to draw a connection between the mindlessness of some extremely popular EDM and the numbing repetition of advertising” Lucy

Accordingly, its with deceptively simple means that Diamond Version manage to reveal some of the dark sides of corporate identity, as if in an attempt to reverse the brainwashing process of the barrage of proscriptive mottos. I’m talking about simplicity and sarcasm, audible for example on “Were You There”, which features Pet Shop Boys’ Neil Tennant singing a childlike version of the classic Christian hymn. Here you can clearly hear Diamond Version’s attempt to not only recontextualize church music by placing it next to songs about branding, but also to appropriate the more common sounds you might hear on an EDM track and spit them back out as something darker and more threatening. In doing so, Nicolai and Bender seem to draw a connection between the mindlessness of some extremely popular EDM and the numbing repetition of advertising—of course, with a healthy dose of sarcasm. In contrast to mainstream EDM however, the music is treated in very subtle ways: Nothing is too in-your-face everything is very carefully layered and masterfully articulated in space. This paradoxical formula is the group’s bread and butter, and the collaboration with Japanese light artist and musician Atsuhiro Ito pushes the envelope of contrast even further, with Ito’s hazy, distorted light-blasts

recommEndations

and oscillations bellowing under the almost clinically precise electronic music production. Which brings us to the reason why we find this coming out on Mute and not on Raster-Noton. The history of Mute is filled with

bands who are immersed in pop culture but also seek to transgress pop values. This is, in a sense, the same thing, just the other way around: a band immersed in anti-pop culture playing with pop dogmas. But importantly,

it’s not only about making fun of pop: transgressing corporate values by using their own tools translates into an incredibly stimulating experience for the listener. To sum it up, this is a boiling kettle ready to explode. ~

“Like an encyclopedia we see not one but all forms of the work presented” Max Dax recommends Arto Lindsay’s Encyclopedia of Arto

Northern Spy Records

Max Dax is editorin-chief of Electronic Beats Magazine and electronicbeats.net

26 EB 2/2014

For the occasion of Michael Jackson’s fiftieth birthday in 2008 while I was editor-in-chief of the German pop cultural magazine Spex Magazine, I commissioned a laudation by Arto Lindsay on the King of Pop. What I got back from him a few days later was, in my opinion, one of the landmark texts that’s been written on Jackson. One of Arto’s observations that stuck with me was that every time he heard Jackson’s voice, he “smelled blood.” In developing his own bellowing rock voice, Lindsay wrote, Michael Jackson’s music became a metaphor for a lion that hunts down his prey, knowing that he would always get what he wants. When Arto released his first solo album in 1997, it was the first time you heard him sing tenderly, and it’s about as close as music comes to poetry, with lyrics that were at once minimalistic, harmonically complex and beautiful. Until then, he was primarily known as a noise musician, and a very influential one, too. There is a whole legion of bands, from Sonic Youth to Einstürzende Neubauten, that claim him and his former band DNA as a major influence and inspiring force in their artistic work. Encylopedia of Arto is a twoCD-set, with the first part comprised of a collection of Arto’s personal best-ofs spanning the years 1996 – 2004 off of his solo records,

from O Corpo Sutil to Salt. These string of albums are breathtakingly imaginative and heavily fueled by his particular brand of post-bossa nova deconstruction. The second CD on Encyclopedia is a photonegative of the first, consisting of live recordings from two Berlin shows held in 2011 at the Berghain and .HBC respectively. There, he recomposed his original songs on stage using only his guitar, a distortion pedal and voice, raising them into

“Listening to Encyclopedia makes me wish more musicians would leave their comfort zones and confront themselves and their audiences with new and unexpected situations” Max Dax

sonic behemoths and risking the chance of real failure in front of a live audience. In the vein of Miles Davis or Bob Dylan, Arto actively seeks on these recordings to reshape the concept of the concert as such, with the music a kind of elegant dance on thin ice. The only remnants of the originals are the very general frameworks, harmonies, and certain chord changes, which he proceeds to dissect in the very moment they’re being presented. Hitting a “wrong” note, his reaction is to ask, musically speaking, “What is a wrong note?” When a performer is able to embrace mistakes, he or she can, like an aikido master, turn them into something inspiring. You don’t have to tame improvisation. Knowing Arto for years now, he sometimes appears to me as a man from the future whose antennae are tuned to sounds that have yet to leak into the public consciousness. Listening to Encyclopedia makes me wish more musicians would leave their comfort zones and confront themselves and their audiences with new and unexpected situations, putting their craft at stake, be it on stage or in the studio. In that sense, the biggest achievement of this double LP is that it lives up to its name: like an encyclopedia we see not one but all forms of the work presented—that is, their place in pop culture and the avant-garde, the radio, and on the next level. ~

BAss Culture

“When I step in front of the crowd there, I am actually striving to give them my soul” François K on his clubnight Deep Space at Cielo, N.Y.C. François Kevorkian may have been born in France, but he’s inextricably linked with the sounds of New York disco and house. Coming up with the likes of Larry Levan and David Mancuso at such dance music institutions as the Paradise Garage and Studio 54, his nearly forty years in the city that never sleeps saw his star rise quickly as a producer and remixer, working with artists as diverse as Loleatta Holloway, Kraftwerk and Depeche Mode, while also becoming a revered DJ at his Body & Soul party, held together with veteran selectors Joaquin “Joe” Claussell and Danny Krivit. Having celebrated his sixtieth birthday this year, Kevorkian could easily rest on his laurels. Instead he has taken his now elevenyear-old dub-inflected clubnight Deep Space at Cielo in Manhattan to new heights. Here, for the uninitiated, François K takes you to Deep Space in his own words. Opposite page: Happy trails. Revelers at Deep Space, photographed by Tim Soter. 28 EB 2/2014

Throughout my career, especially when I started going in the studio somewhere around 1978, I found myself very attracted to a lot of production techniques that clearly came from people using a lot of effects processing and delays and things. Whether it was more like traditional dub records from Jamaica or experimental records that came from krautrock in Germany, or whether it was some of the avant-garde free jazz that incorporated elements of tape music, like the Teo Macero productions of Miles Davis. All of these things, they had a confluence: astute producers were making heavy use of electronic music production techniques to enhance the live playing, whether it would be jazz, reggae, rock or whatever else. It was immediately clear in my work in the studio, and I became quickly known for being one of the people within the “dance music” or “disco” world that could deliver the trippy elements and exaggerated processing. Others were great at extended versions of songs or transforming them into something that had more muscle for the dancefloor. For me, it was the dub element— be it more electronic like my work with Yazoo, Kraftwerk or Jean-Michel Jarre, or on a more traditional reggae tip like with Black Uhuru, Jimmy Cliff, or Bunny Wailer. But as far as the people who were hiring me to do these remixes, this idea of the dub was always the thing on the side, rather than the main A-side version they were usually after. Then, in the early 2000s, I was approached by the owner of Cielo, Nicolas Matar, and he offered me

a night. We were close friends, and being a DJ himself, he dug what I was doing. It was pretty much with the understanding it was going to be something related to house music. I think they were really surprised when I came back and said, “First of all, I don’t want to do a big night, like the weekends. I want to do something as obscure and out of the way as possible. Monday sounds great.” Because when you do that, you’re guaranteed that the big weekend crowd and fistpumping advocates are going to be at home getting ready for their job the next day during the week. In the context of what the club looks like and how incredible everything is there—the sound system, the intimate setting that allows for a lot of seating around the dancefloor area for people not to feel awkward if they don’t dance—I figured I wanted to focus on trying to do something that was going to be totally unique and in some respect related to dub. Even though dub had been an integral part of my career and what I was doing since the beginning, it was never an acknowledged thing. It was just like a bonus. But I felt that was the time for things to change. Instead of just starting another night where I would play authentic Jamaican reggae from 1975 by Lee “Scratch” Perry, King Tubby, and Niney the Observer, it was more going to be about trying to showcase and connect the dots for people to incorporate that dub aesthetic into all sorts of different backgrounds. Or in conjunction with that, to take songs that would be

otherwise very ordinary and to actually do whatever processing and treatment to them—sort of an abbreviated version of what I’m doing in the studio, but live and in front of people. We courted dub poets, DJs, or other artists who we felt were compatible with that aesthetic and somehow would accept to do, say, “special” sets around this point of view. In that sense, another turning point, even though we were already established, was somewhere around 2006 when we started hearing all of these rumblings from London and all these strange new types of music that no one had ever heard before, like Digital Mystikz and dubstep; it took time, and I needed to get people’s ears used to that new sound. Deep Space has made me realize how much I value improvisation, the instant of creation, that moment where you’re standing in front of a crowd and there’s thirty seconds left to play on the record. You haven’t yet decided what you’re going to play next, and you have to look through all of your records and find something and put it on, mix it in, and make it all sound effortless and entertaining. It’s an unbelievable amount of pressure. What comes out is the one thing that you know you should be playing because, really, if you’re a DJ, you know what that is. Sometimes things that came from that voice are crazy, completely strange, totally odd. But I needed to defer to that voice and not stay focused on logic. When I step in front of the crowd there, I am actually striving to give them my soul—not some pre-programmed, pre-packaged, pre-digested slice of predictable fodder that might make them feel good at that very moment, but that they’ll have forgotten about ten minutes later. ~

Three records selected by François K on rotation at Deep Space (Top to bottom): Objekt – “Agnes Demise” off Objekt #3, white label self-release, 2013: “One of those songs I can fit into everything.” Special Request – “Soundboy Killer” off Soul Music, Houndstooth, 2013: “The mood of the junglist music from the mid-nineties but completely updated.” Jon Hopkins – “Open Eye Signal”, Domino, 2012: “Dark and brooding, distorted melodies and bass.”

EB 2/2014 29

ABC

The alphabet according to Nina Kraviz In 2011, when “Ghetto Kraviz” pounded its way through Europe’s clubs with a barrage of kick drums, it forcefully showed—with some help from a resurgent interest in footwork— how a single word repeated endlessly could be as catchy as any melody. But Nina Kraviz’s path to techno stardom wasn’t entirely smooth: Following the release of her self titled debut LP, the Siberian-born DJ and producer ruffled more than a few feathers last year in her controversial bathtub video interview for Resident Advisor, though ironically (predictably?) most of the naysayers were men. Unfazed by accusations of playing up her looks, Kraviz has continued doing what she does best, namely drop one sold out record after the next on such esteemed imprints as Rekids, Underground Quality and Efdemin’s Naif. Here’s what’s been on her mind lately, in alphabetical order. Opposite page: Nina Kraviz, photographed by Hans Martin Sewcz in Berlin. 30 EB 2/2014

A

as in Acid: When I first heard an acid house track by Armando on the radio I thought it was a message from outer space. It went straight into my veins. It’s been a while since that day but every time I hear a proper 303 bass line I feel like a spaceship is on its way.

B

as in Lake Baikal: The deepest lake in the world holds about twenty percent of the world’s fresh surface water and is located in Siberia between two tectonic plates, not far from my home city of Irkutsk. If you look at Russia, this is exactly that charming blue object that you find on the right side of the map next to Mongolia. This place is truly special and I feel very connected to its magic.

C

as in Chicago House: Chicago house, along with Detroit techno, has been one of my biggest inspirations. From melodic song-structured hip-house and mental acid grooves to the badass ghetto house of Dance Mania.

D

as in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep: This science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick served as the basis to the 1982 film Blade Runner. Postapocalyptic, dystopian future L.A. Watching Harrison Ford testing androids for lack of empathy is oddly relaxing. I also really like the soundtrack by Vangelis, where even saxophone, the instrument in pop music that I appreciate the least, sounds elegant. One little part of the movie’s original conversation was so inspiring to me that it appears in my own “Pain in the Ass” monologue.

E

as in Exaggerated Emotional Coherence: Also known as the “halo effect”. This is a psychological phenomenon in which our brain makes it easier for us by generating a certain representation of the world that is simpler and more coherent than it really is. The tendency to like or dislike everything about a person or a subject—including things you have not necessarily observed—is a part of it. This common bias helps us to create myths. It also helps with building up marketing strategies, creating superficial generalizations and jumping to conclusions. What it really doesn’t help with is recognizing the truth.

F

as in FM Intergalactic: Online radio station founded and curated by I-F, to which I owe half of my musical education. It’s comprised of four channels with the most choice music, from ambient soundtracks and Italo and Chicago house to the most obscure forms of electro and techno. The greatest thing is that you can always see the title and the artwork of the original record. The only problem is that half of the records played are hard to find and cost a fortune.

G

as in Gear: I think vintage synthesizers retain the spirit of their previous owners, which is pretty psychedelic.

EB 2/2014 31

H

as in Hypnotic moments and a state of flow: One of the most exciting things that a DJ can experience. It happens occasionally and cannot be predicted. Feels like magic. The crowd, the DJ, the place and the music become one thing and somehow both the music and the technical aspects of its deilvery are no longer consciously controlled. The DJ reaches a phenomenal closeness to the people and continues only as mediator, transmitting energy to the crowd and receiving it back.

I

as in Intellect: One of the most important aspects of humanity. It’s about the ability to create an idea. This is a gift from above. It never ceases to amaze me how infinite the possibilities are, how many incredible things we can learn and do and how there are not many things that we actually can’t do. In combination with a true spirit it is the essence of humanity. A lack of intellect on the other hand is the saddest thing. It restrains progress and development. But let’s not talk about that.

32 EB 2/2014

J

as in Jesus Christ: Besides the fact that he is God, he also used to be human. For me, he is a role model of a great human being.

K

as in Kosmos: “Space” in Russian. It also means: planets revolving around stars, asteroids and black holes. This was my favorite subject in school after biology. The Andromeda Galaxy is just 2.3 million light years away. There’s cosmic dust all over the place. It reminds me of my “Kosmos” dessert at a cafe in Irkutsk—vanilla icecream with crushed walnuts and frozen honey, sprinkled with a little bit of dark chocolate powder. Sputnik. Stunning pictures of Soviet spacecraft Mir with Earth in the background. Our earth is so beautiful in pictures from space, much more appealing than, say, Mars. Did Neil Armstrong actually walk on the moon? Belka and Strelka were two lucky dogs that flew to cosmos and actually came back. Many of their predecessors didn’t.

L

N

M

O

as in Love: All my favorite songs are about love. The same goes for books and films. It’s also quite a popular word. For centuries, people have been discussing same old thing and strangely never get tired of it. This is incredible. It never ceases to amaze me that the same word can be applied to carrot cake, children, hotdogs, flags, parents, perfume or an evening dress. Surprisingly, when it comes to loving somebody for real, most people fail. Let’s blame it on all our love for cookies.

as in Mens sana in corpore sano: Latin for “A sound mind in a healthy body.” This was the first Latin phrase that I learned in medical school while studying to be a qualified dentist. A very true saying.

as in Neurotics: Mostly very creative people that don’t fully stand on their own two feet and are in search of balance. That is, in between breakdowns, delusions, biting their nails, writing the most amazing books, making records, designing clothes and making irrational decisions that strangely help them remain in history. Neurotics are extremely sensitive and are never sure about anything. They run away from those who love them right after messing up their life. But other than that, they are lovely people. I’ve always been attracted to them.

as in Oxymoron: So far my entire life has been one big oxymoron. I’ve been a sad optimist, a naughty nerd, an impulsive introvert, an outgoing social phobic, an intellectual cover girl, a modern orthodox, a DJ-dentist, altruistically egocentric, enjoying superficial things while searching for a deep meaning, strongly fragile, narcissist and caring, focused in my own chaos. Some people don’t get how such opposites can exist in one person. I understand.

P

as in Polaroid: I like the concept of capturing the beauty of the moment and enjoying immediate emotional response. Right here, right now. All that was in and around that moment is soaked by the paper, even your thoughts. It is what it is and there is no need to correct anything. That is probably the nearest analogy to what I feel when I record my music.

Q

as in Quantum physics: Extremely interesting branch of physics that I didn’t give enough attention to at university. But I am eager to correct this mistake.

R

as in the Russian language: I am very lucky that Russian is my native language and I can enjoy Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Nikolai Gogol without a dictionary. Incredibly rich, complex, colorful and melodic when properly spoken. Russian allows you to express every little nuance in the most accurate, elegant way. Without knowing Russian it seems impossible to convey the essence of Russian culture. It is truly a great language and if I wasn’t born Russian I would definitely have learnt it as a foreign language. Living outside of Russia, I really miss being surrounded by my language. Especially saying “я люблю тебя”, or: I love you.

S

as in Simulacra: An old term that has multiple interpretations and a core idea of Jean Baudrillard. It comes to my mind when I see something pretending to be something else. For example, what nowadays gets called “deep house” in popular electronic music.

T

as in Techno made in Detroit: Mysterious music from a mysterious city that gave me the proper direction in life.

U

as in UBS or Ultimate Bullshit: Abbreviation that I came up with to describe outrageous forms of nonsense, ignorance and stupidity in combination with an unstoppable will to share the result of this unnecessary evil in public.

V

as in Vinyl: When my friends go normal shopping, I go record shopping. Many years have passed since that first George Duke 12-inch but crate digging remains my biggest addiction. Record stores are where I feel most at home, where I lose sense of time and sometimes reality. Vinyl is everywhere in my house. I love putting them in order and sorting out the mess in my bag after a long set. I can spend a whole day going through dusty boxes with used vinyl in the hope of finding a hidden gem. Then when the gem is found, I can’t wait until the next opportunity to share it with people.

W

as in the What is it that the artist delivers? Their personality? Or maybe a message? In any case there should be something behind the artist.

X

as in Χρόvoς: Greek word for time, certainly one of the most interesting things for me to explore. I have no clear picture about time. It has this mystical effect on me. But even though I don’t know much about it, I sense that time extends far beyond our ability to measure it.

Y

as in Y: Why compare?

Z

as in Zeppelin, Led: My world doesn’t exist without this band. One the most vivid memories from my childhood is my father and I listening to “Whole Lotta Love” instead of doing my homework. Robert Plant looks like my future man. I love the nerve, the drama, the theremin, the tape echo on Led Zeppelin, and the fact that they recorded my favorite album ever in just thirty hours. ~

EB 2/2014 33

HUDSON MOHAWKe On Quincy Jones

Mr. Style Icon

I had the pleasure to work with Quincy Jones in his Los Angeles studio last year where he produced Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall. During the process he explained to me that he and Michael had created the studio to spec, and for me the most impressive thing were the speakers installed in the roof. The idea was that Michael and Quincy could lie on the floor and listen to the sound come at them from the ceiling. This is exactly what Quincy and I did as well: create, lie down, listen. The whole experience was extremely inspirational—I mean Michael is obviously The King of Pop, but also in the process of collaborating, I realized that some of my favorite productions of Quincy’s were his solo work, which for some people is more obscure. For example, I am a huge fan of funk stuff like The Dude, which more people should know because it did win a bunch of Grammys and even features legendary jazz harmonica player Toots Thielemans. Anyhow it’s from 1981 and has a kind of early rapping on it, which is funny and kind of ironic considering his strong opinions about hip-hop. I actually used samples from The Dude for the Pusha T record I helped produce last year. Honestly, I can’t say I was ner34 EB 2/2014

Scottish-born producer Ross Birchard, aka Hudson Mohawke, has successfully made the difficult leap from boy wonder to man of the music world. As the youngest ever finalist in the UK DMC DJ competition, his aggressive sampling pastiche impressed on 2009’s Butter and his most recent EP Satin Panthers (both Warp). In 2012, Mohawke signed to Kanye West’s GOOD Music exclusively for production duties, providing the likes of Kanye, Pusha T and Drake with musclebound psych-trap. Here, he discusses working with musical style icon, the man behind the man in the mirror, Quincy Jones. Right: Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones at the American Music Awards, 1988. Photo: Barry King/Corbis.

vous meeting Quincy for the first time. I approach artists and producers I work with, no matter how big they are, as people. It’s a person-to-person thing. It was the same when I worked with Rick Rubin: you just can’t get caught up with the back story or heritage of it all, otherwise it will get in the way of being creative. That is, despite being surrounded by barefoot guys drinking kale smoothies, which was the case when I worked together with Rubin in Bob Dylan’s old studio in Malibu, Shangri-La, which he now owns. That said, when I think back to Quincy’s studio, it was a bit challenging at times to not be impressed. He actually has Michael Jackson’s framed lyric sheets on the wall. That’s the first thing you see. I was like, “Fucking hell, I’m walking into history.” And then I remind myself not to get caught up in it. We didn’t talk a lot about Michael Jackson as a person, though I have in the past with Kanye. With Quincy, Michael was always discussed in revered musical terms: nobody has anything but the utmost respect for Michael, and Quincy Jones is obviously a huge part of that. I suppose that speaks for itself. ~

EB 2/2014 35

Counting wiTH . . .

Black

Cracker

Rapper, producer, trans-man and poet Ellison Renee Glenn, aka Black Cracker, recently dropped his impressive debut LP Poster Boy via Gully Havoc. How dope is the life of the globetrotting MC? Let him count the ways. Photo: John Barclay.

one

memorable line in a song:

“Damn homie, in high school you were the man homie / What the fuck happened to you?” 50 Cent – “Wanksta”

two

decisions I regret:

--5 a.m. Bushwick, Brooklyn. A bicycle. A curb. Too many whiskey rocks. Too much confidence and “youth.” Hit concrete head-on. Knee buckled with full weight. I have been walking with a slight to often pronounced limp and shattered ligaments ever since. (No insurance for all of my twenties.) --Not understanding what publishing was prior to hearing lyrics and production I contributed to an Android commercial. Full rotation, multiple channels.

three

sets of people that should collaborate:

--Military strategists and amusement park designers. --Laser light controllers and Southern Baptist preachers. --Soup kitchen fundraisers and porn stars.

four things I haven’t done yet:

--Met my father. (Though I doubt this will ever occur.) --Had more than $100 in the bank for more than three months. --Done yoga. --Sold out a solo show.

five

things I used to believe:

--Getting over heartbreak was quick, painless and as easy as catching a glimpse of a rainbow in a misty rain. --Hard work and originality would overcome hype and superficiality. --A smile is the ultimate weapon,

36 EB 2/2014

both in defense and offense. --Drinking coffee would make my skin darker, or so my great grandfather said. --I would be dead by now.

six

hours ago . . .

. . . I realized my second flight to Paris within 72 hours was not a day later but rather in thirty minutes. I made it, though I packed no pants.

seven albums everyone should own:

Antony and the Johnsons – I am a Bird Now Lil B – Red Flame Mike Ladd – Welcome to the AfterFuture Diane Cluck – Countless Times Wu-Tang Clan – Wu-Tang Forever Badawi – Bedouin Sound Clash Eckhart Tolle – A New Earth (book on tape)

After

eight

p.m.

Haribo. A bath. Her risotto. AKG 240’s pressed tight. MPK49 triggering Komplete through a Pro Tools instrument track. A silly melody and infinite wit, in an ideal world. Sky filled with holograms walking backwards through the sand.

nine My

lives . . .

. . . are hanging by a strand of lightning, pulled by a spider between a liter of expired milk and triumphant sun.

ten

I wouldn’t touch it with a -foot pole:

Any amount of greed and ego-centric fame with only self-serving ambition. ~

connectinG the DiGital StartuP ecoSYStem with DeutSche telekom. lY P P a / m o .c m u a r b u h : it become Part of hubraum.com

facebook.com/hubraumberlin

twitter.com/hubraumberlin

I nt

e

r v

ie

w s

Sander Amendt talks to MØ

“ Society

nobody

waits for

Karen Marie Ørstedt, better known as MØ, has moved beyond her initial, foul-mouthed Peaches-esque productions into the terrain of soulful, pop-trap accessibility. On her debut LP, No Mythologies to Follow, the former hobby-squatter turned to producers Ronni Vindahl and Diplo (the latter initially an Internet acquaintance) to help her pimp her metamorphosis. Indeed, shifting identities comes naturally to the native of Odense, Denmark, who was raised on point and click self-discovery. Left: Karen Marie Ørstedt, aka MØ, photographed by Frank Bauer in Munich

EB 2/2014 41

K

aren, you were one half of the punk band MOR before you went electro with your new band MØ. How long have you been a punk and what does punk mean to you?

I grew up very isolated in the suburbs of the Danish city Odense on the Baltic Sea. I remember my upbringing in the best possible ways. My parents are great, I love my brother, our house was nice, we even had a piano. But when I became a teenager I suddenly became rebellious against everything my parents stood for. I just suddenly had this urge to be an outsider. I remember that my classmates thought I was mentally ill because I started to wear black one day, including mascara. They would wear colorful clothes and my style must have seemed so weird to them. In hindsight this seems so distant and so strange to me. You know, I was a tomboy before, a boyish girl, but they didn’t tease me. It all started when I began to wear black. And from there it was a small step to becoming a punk. And then?

I actually would like to rewind a bit. It all started with the Spice Girls. I had fallen in love with Sporty Spice. I was seven years old and I had this epiphany watching the Spice Girls on TV. I have them and only them to thank—or to blame—for becoming a singer. Watching them on TV was the first time ever that something really appealed to me. Don’t get me wrong: Every little girl at that time went mental because of the Spice Girls. But I took it really, really serious. And that’s why I started to make music as a teenager. I started to write songs because of the Spice Girls. By doing so, I learned to let off steam. Writing songs became my platform for expression. You are a man and you probably saw it differently, but for me as a teenage girl, the world hadn’t really opened up yet. And I didn’t know how to handle it. How old were you when you started smoking and drinking?

I was fourteen. That was when the hormones came through. From one day to the next things really started to change inside my head. What books did you read then?

In all honesty, I didn’t read that many books. I never did. I am a slow reader. But certain music would trigger me. I started to get hooked on Sonic Youth, Black Flag, Bikini Kill and other bands. Sporty Spice basically got replaced by Kim Gordon. I began to print out the lyrics of all the Sonic Youth songs on my parent’s computer. Actually I printed out all the lyrics of all the songs that somehow have touched me. From the Sonic Youth lyrics alone I could have made a book. I mean, it didn’t even occur to me that they may have released a songbook of their own. I just needed to print everything out immediately because it was accessible on the Internet. My brother on the other hand was playing computer games all the time when he wasn’t roleplaying Tolkien scenarios in the forest. And my brother had this friend who was always wearing black trench coats and had black hair. All I remember is that I wanted to look like him. I was listening to “Youth Against Fascism”, and my classmates thought I was mentally ill. Tell me about the squats you frequented at the time.

It all started when I changed to a school in the city. And there were other people who also dressed like me. I started smoking with them and they took me to their punk places. Suddenly it was 42 EB 2/2014

all about left-wing politics, anti-fascist engagement and drinking in squats. All these different groups were gathering there. There were feminist groups too, but first and foremost anti-fascist groups. Why? Were there a lot of neo-Nazis around?

No, not that many. But I was against them anyways. I soon started to get into the squatter’s environment and finally I started this punk band called MOR—Danish for “mother”—together with my friend Josefine. We immediately had what we’d define as success: We played in squats all over Denmark, Europe and even in New York. We had recorded music and would shout and perform to our self-made playback show. You’re from Berlin, aren’t you? Yes, why?

Well, we played at this squat Köpi in Berlin. We were drunk for five years, played every weekend in squats—basically we were being young, I guess. We just felt this huge energy. From the stage we’d preach about political things that were important to us. And be it a stupid slogan like, “Fuck the government!”, “Fuck Nazis!”, fuck everything. I mean, we were only seventeen. What counted for us was the fact that we were seeing the continent and that we had an audience. I think it’s important to always balance out the seriousness and the overreaction. Some of the political bands that I appreciated at that age were annoyingly serious. So it was a pretty quick development from Sporty Spice to Kim Gordon.

Well, for me as a seven-year old, Sporty Spice for sure was the Kim Gordon among the Spice Girls. Growing up and remembering my childhood fascination for the Spice Girls, it surely helped to inject pop ideas into my music. I mean, I still love perfect pop music. And everything suddenly made perfect sense when I went to Fynske Kunstakademi—the Funen Art Academy. I realized that I could combine everything and form some kind of an artificial character who is part me, part Kim Gordon and part Sporty Spice. After all, Kim Gordon went to art school too before she founded Sonic Youth, didn’t she? I started MØ during my time in art school in 2009. Actually, my alter ego then was rapping. Everybody thought I was crazy. But the fact that I could think and act conceptually liberated me. It has an ironic edge to it so that I called it MØ, which means “virgin” in Danish. I liked the idea that my alter ego had a bizarre name and was constantly agitating. It wasn’t about letting off emotional steam anymore. Everything had changed. And now you have a proper band.

I have to admit that I have since dumped the rapping alter ego. It was a progression. I started to sing more and more. And this led to another coincidence. Ever since then I have been working together with the producer Ronni Vindahl. He always liked me, but he never liked my sick raps. When he noticed that I had started singing he immediately asked me if I could record some vocals for him. He then produced some music around it, and we called the track “Maiden”. Eventually we’d constantly be exchanging files. I remember receiving his first email with music when I was doing an internship in New York. That moment changed everything. I liked the idea of becoming a pop musician, and that also meant that I had to form a band, play Roskilde, play the game. But that’s what it is: a game.

EB 2/2014 43

What kind of internship did you do in New York?

I heard you are a fan of Jonathan Meese.

I was helping JD Samson of Le Tigre. She’s the girl with the moustache. So, me and Josefine were JD Samson’s interns—interns in girl power and feminism.

Yes I am and I would love to meet him one day.

It’s one of the blessings of our times that you can effortlessly send music files back and forth to collaborate. Do you agree?

Absolutely. And that’s exactly the way Diplo works. I really like it that you don’t have to necessarily meet in person to do music nowadays. I grew up with this idea that I can do music in every hotel room, in every train or friend’s apartment. I don’t listen to the people who say that this way of making music is supposedly impersonal. I don’t think that way. To me it’s totally normal. Hans Ulrich Obrist has a project called 89+. It features the thoughts and opinions of the generation that was born in 1989 or later—basically the generation that grew up with the Internet, that doesn’t know a world before the Internet age.

Damn! I was born in 1988. You can always say you were born in 1989.

Not if you print this. Anyhow. As I said, I embrace these times. And you could call Twitter impersonal too. But a Twitter post actually led to Diplo and me finally meeting in reality. Someone must have read an interview in which I mentioned Diplo and how much I adore his music and tweeted it to Diplo. But he had heard of MØ before. He contacted me, and we met. And for me it paid off that he is so open-minded. He’s really into new sounds and new people, constantly traveling and collaborating. We ended up writing the song “XXX 88” together in 2012. In that sense I’d say our times are sick in a good way, no matter what the people say. Do you remember a time before the Internet?

You probably just have to get more famous. Or someone has to give him a copy of our conversation . . .

That would be so great! I really like the way he agitates. I discovered his performance work in art school. I admire him for the irony he shows in his performances. And I heard that he got sued for performing the Hitler salute. That’s true, but they closed the case. The court rightfully judged that the freedom of expression in art is more important.

That’s good to hear. I love him because he is crazy. But besides Jonathan Meese, my biggest idols are from North America. I love Grimes, I love Karen O. and I love Kim Gordon. They all stand for a kind of posture that I admire. I generally adore people who stay true to themselves, who are building something up over the course of several years. I think the real person manifests themselves in such efforts. And I’m saying this also because I was always bad in school. I couldn’t concentrate. And that’s why I basically felt so attracted to music. Have you ever met any of your idols?