NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A RY RE VI E W ONLINE

2018

NORTH CAROLINA ON THE MAP AND IN THE NEWS

IN THIS ISSUE Reviews of books by writers who put North Carolina on the map

n

Fiction, Poetry, Essays, Literary News

n

and more . . .

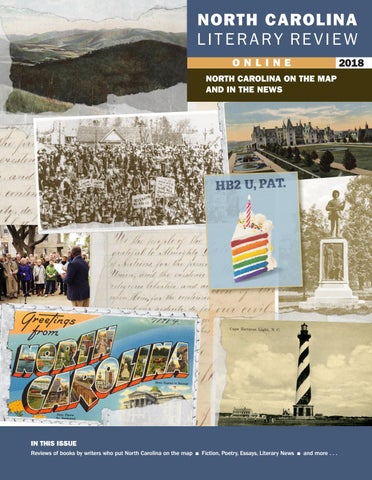

COVER COLLAGE DESIGN by NCLR Art Director Dana Ezzell Lovelace top left: Asheville, “looking up the Swannanoa Valley” (NC Postcard Collection, NC Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill) 2nd row: Loray Mill Strike in Gastonia (Associated Press), Biltmore House (Durwood Barbour Collection of NC Postcards, NC Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill)

Published annually by East Carolina University and by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association © COPYRIGHT 2018 NCLR

3rd row: Randall Kenan speaking at the March 2016 gathering of writers in Raleigh; also pictured, Allan Gurganus, second from left (photograph by Tom Rankin); birthday card to Governor Pat McCrory published by the Writers for a Progressive North Carolina in the News & Observer in October 2016 (courtesy of Boone Oakley; Creative Director David Oakley, copywriter Mary Gross, Art Director Eric Roch von Rochsburg); “Silent Sam” Confederate Monument on the campus of UNC Chapel Hill (Durwood Barbour Collection of NC Postcards, NC Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill) bottom row: one of many such North Carolina postcards (find the full NC Postcards collection here); and Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, 1908 (Durwood Barbour Collection of NC Postcards (P077), NC Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill

COVER DESIGNER NCLR Art Director DANA EZZELL LOVELACE is a Professor of Graphic Design at Meredith College in Raleigh. She has an MFA in Graphic Design from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. Her design work has been recognized by the CASE Awards and in such publications as Print Magazine’s Regional Design Annual, the Applied Arts Awards Annual, American Corporate Identity, and the Big Book of Logos 4. She has been designing for NCLR since the fifth issue, and in 2009 created the current style and design. In 2010, the “new look” earned NCLR a second award for Best Journal Design from the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. In addition to the cover, Dana designed the fiction in this issue.

ABOVE Asheville, “looking up the Swannanoa Valley” (NC Postcard Collection, NC Collection

Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC Chapel Hill)

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A RY RE VI E W ONLINE

2018

NORTH CAROLINA LITERATURE NORTH CAROLINA ON THE MAP INAND A GLOBAL CONTEXT IN THE NEWS IN THIS ISSUE 6 n North Carolina on the Map and in the News includes poetry, prose, book reviews, and literary news Karen Willis Amspacher Alton Ballance Margaret D. Bauer Robert Beatty Barbara Bennett David Blevins Teresa Bryson Wiley Cash James W. Clark, Jr.

Mae Miller Claxton EbzB Productions Julia Franks Barbara Garrity-Blake Allan Gurganus Leah Hampton Alex Harris Anna Dunlap Higgins-Harrell Vivian Howard

Joanne Joy Janet Joyner Kristina L. Knotts Randall Kenan Robert Morgan Savannah Paige Murray Rain Newcomb Reynolds Price Ron Rash

Terry Roberts Lorraine Hale Robinson Margaret Sartor Bland Simpson Leverett T. Smith, Jr. Walter Squire Ali Standish Zackary Vernon Daniel Wallace

54 n Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues includes poetry, prose, book reviews, and literary news Alex Albright Joseph Bathanti Christina G. Bucher Sally Buckner Kathryn Stripling Byer L. Teresa Church F. Brett Cox Mark Cox Thomas E. Douglass

Wilma Dykeman Annie Frazier Donna A. Gessell Garrett Bridger Gilmore June Guralnick George Hovis Sarah Huener Gene Hyde Danny Johnson

Glenis Redmond Rosalind Rosenberg Steven Sherrill Marty Silverthorne Shelby Stephenson Hannah Crane Sykes Gregory S. Taylor Eric C. Walker Gertrude Weil Emily Herring Wilson

John Kessell D.G. Martin Michael McFee Kat Meads Susan Laughter Meyers Lenard D. Moore Pauli Murray James Larkin Pearson Barbara Presnell

110 n North Carolina Miscellany includes poetry, fiction, book reviews, and literary news Margaret D. Bauer Christina Clark Gabrielle Brant Freeman Alice Fulton

Irene Blair Honeycutt Patricia Hooper Celeste McMaster Grace C. Ocasio

Laura Sloan Patterson W.A. Polf Nicole Stockburger Hannah Crane Sykes Michele Walker

n

Art in this issue

n

Alec Campbell-Barner David C. Driskell Jensynne East Rachel Elia Courtney Johnson

Phoebe Lewis Carol Retsch-Bogart Heather Evans Smith Donald Sultan Sallie White

4

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

North Carolina Literary Review is published annually in the summer by the University of North Carolina Press. The journal is sponsored by East Carolina University with additional funding from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. NCLR Online, published in the winter, is an open access supplement to the print issue. NCLR is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals and the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses, and it is indexed in EBSCOhost, the Humanities International Complete, the MLA International Bibliography, and the Society for the Study of Southern Literature Newsletter. Address correspondence to Dr. Margaret D. Bauer, NCLR Editor ECU Mailstop 555 English Greenville, NC 27858-4353 252.328.1537 Telephone 252.328.4889 Fax BauerM@ecu.edu Email NCLRuser@ecu.edu NCLRsubmissions@ecu.edu http://www.NCLR.ecu.edu Website Subscriptions to the print issues of NCLR are, for individuals, $15 (US) for one year or $25 (US) for two years, or $25 (US) annually for institutions and foreign subscribers. Libraries and other institutions may purchase subscriptions through subscription agencies. Individuals or institutions may also receive NCLR through membership in the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. More information on our website. Individual copies of the annual print issue are available from retail outlets and from UNC Press. Back issues of our print issues are also available for purchase, while supplies last. See the NCLR website for prices and tables of contents of back issues.

Cover design by Dana Ezzell Lovelace ISSN: 2165-1809

Submissions NCLR invites proposals for articles or essays about North Carolina literature, history, and culture. Much of each issue is thematically focused, but a portion of each issue is open for developing interesting proposals – particularly interviews and literary analyses (without academic jargon). NCLR also publishes high-quality poetry, fiction, drama, and creative nonfiction by North Carolina writers or set in North Carolina. We define a North Carolina writer as anyone who currently lives in North Carolina, has lived in North Carolina, or has used North Carolina as subject matter. See our website for submission guidelines for the various sections of each issue. Submissions to each issue’s special feature section are due August 31 of the preceding year, though proposals may be considered through early fall. Issue #28 (2019) will feature writing from and about North Carolina’s African American Writers. Read more about this topic on page 75 of this issue. Please email your suggestions for other special feature topics to the editor. Book reviews are usually solicited, though suggestions will be considered as long as the book is by a North Carolina writer, is set in North Carolina, or deals with North Carolina subjects. NCLR prefers review essays that consider the new work in the context of the writer’s canon, other North Carolina literature, or the genre at large. Publishers and writers are invited to submit North Carolina–related books for review consideration. See the index of books that have been reviewed in NCLR on our website. NCLR does not review self-/subsidy-published or vanity press books. Advertising rates $250 full page (8.25”h x 6”w) $150 half page (4”h x 6”w) $100 quarter page (3”h x 4”w or 4”h x 2.875”w) Advertising discounts available to NCLR vendors.

N C L R ONLINE Editor Margaret D. Bauer Art Director Dana Ezzell Lovelace Poetry Editor Jeffrey Franklin Fiction Editor Liza Wieland Art Editor Diane A. Rodman

Founding Editor Alex Albright Original Art Director Eva Roberts

Graphic Designers Karen Baltimore Stephanie Whitlock Dicken Assistant Editors Christy Alexander Hallberg Sally F. Lawrence Randall Martoccia Editorial Assistants Michael Ryan Smith Omar Sutherland Interns Harley Beechner Amber Colbert Elizabeth Grimsley Samantha Grzybek Autumn Gunsley Hannah Hensley Melissa (Max) Herbert Kristen Williams

EDITORIAL BOARD James Applewhite Professor Emeritus, Duke University

Ronald Wesley Hoag Professor of English, East Carolina University

Laurence Avery Professor Emeritus, UNC Chapel Hill

Elizabeth Hudson Editor, Our State magazine

Christina Bucher English Rhetoric and Writing, Berry College

Paul C. Jones English, Ohio University

Paula Gallant Eckard College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, UNC Charlotte

Anne Mallory English, East Carolina University

Gabrielle Freeman English, East Carolina University

Joan Mansfield Art and Design, East Carolina University

Guiseppe Getto English, East Carolina University

Kat Meads Red Earth MFA program, Oklahoma City University

Brian Glover English, East Carolina University

Sean Morris English, East Carolina University

Rebecca Godwin English, Barton College

Amber Flora Thomas English, East Carolina University

Jaki Shelton Green SistaWRITE

Scott Romine English, UNC Greensboro

George Hovis Professor of English, SUNY Oneonta

Helen Stead English, East Carolina University Mary Ann Wilson English, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

5

6

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

The Notorious and the Noteworthy in the Old North State by Margaret D. Bauer, Editor Inspired by our state’s notoriety after nationally unpopular legislation, former intern Ellen Franks suggested this year’s special feature topic. In 2016, the North Carolina General Assembly passed House Bill 2, more commonly known (throughout the country) as the Bathroom Bill. ECU students are proud of our “Leadership University” and would prefer that the state lead in anti-discrimination rather than discriminatory legislation against transgender people. As professors sometimes do, I used the student staff members’ dismay over our state’s sudden national disrepute as a teaching moment, pointing out to them that, even in the middle of the darkest chapters of our history, we have much to be proud of here in North Carolina, including an incredible number of talented writers who use their pens (or keyboards) to fight back against discrimination. Have you been to an Allan Gurganus or Bland Simpson reading lately? They are among the many literary stars of the Old North State who take advantage of their time at a podium to call on the rest of us to resist threats to the reputation and well-being of North Carolina. Another notorious event in North Carolina to receive national news coverage, this one from the more distant past, the mill strikes of 1929 inspired many writers, most recently, Wiley Cash, whose new novel is reviewed here. Other reviews in this special feature section are of recent books by several writers who put our North Carolina homes “on the map.” North Carolinians can find writers to be proud of, to brag about, from the western end of the state that produced Robert Morgan and Ron Rash to Eastern North Carolina, where Reynolds Price was born and to which Vivian Howard returned to open her restaurant, produce her television show, and write her cookbook/memoir. After watching her PBS series, people from all over started mapping their route to Kinston, which they had very likely never heard of prior to viewing A Chef’s Life.

North Carolina is certainly on the map as a vacation destination as well, whether tourists are heading to the Biltmore in Asheville or the beaches of the Outer Banks, and as you’ll find in other reviews here, these places also inspire writers. Between the mountains and the coast, the first public university in the country to hold classes, UNC Chapel Hill, boasts Big Fish author Daniel Wallace, as well as Bland Simpson and Randall Kenan among its faculty, just to name those UNC writing professors featured here in reviews and award news. Read, too, about Allan Gurganus, who writes about a “place between places”; through his fictional Falls, NC (and his international reputation), readers the world over know Rocky Mount, his hometown. Some of our writers who have made the news recently are not (yet) so well known, but their successes assure us that the next generation of North Carolina writers will continue to make us proud, and their North Carolina–set stories will reach audiences beyond the state, as evidenced by some of the awards you’ll read about here. Former Doris Betts Prize winner Leah Hampton, for example, shares with us another award-winning short story, which we place in this section both because of the prestige of the award (her $50,000 prize certainly made the news) and because the history-making 2016 presidential election plays a role in the story. Here, too, we include a poem by second-time Applewhite Prize finalist Janet Joyner because she alludes to the nation’s crumbling “Infrastructure” (the title of her poem) and a Confederate monument, two subjects found “in the news” recently. Enjoy the reviews, literary news, fiction, and poetry in the pages that follow, and then subscribe or renew to receive the 2018 print issue, which will include interviews with Vivian Howard and Allan Gurganus, an essay by Bland Simpson inspired by a conversation with Dr. William Friday, and Margaret Maron’s reflection upon finishing her last Deborah Knott mystery – about how this series took her across the state to enjoy many of the state’s gifts that put us “on the map.” n

N C L R ONLINE

7

NORTH CAROLINA ON THE MAP

and in the News 8 Allan Gurganus: Two Tributes Homage to THE Allan Gurganus

by Margaret D. Bauer Celebrating Allan Gurganus, “Our Author” by Leverett T. Smith, Jr. 13 Crafting Local Souls: The Metafiction of Allan Gurganus by Zackary Vernon 19 Foodways and the Story of North Carolina

a review by Joanne Joy Vivian Howard, Deep Run Roots Randall Kenan, ed., The Carolina Table 23 Lift Every Voice a review by Walter Squire Wiley Cash, The Last Ballad 26 The Biltmore’s Unlikely Hero

a review by Teresa Bryson Robert Beatty, Serafina and the Black Cloak 28 Infrastructure a poem by Janet Joyner art by Carol Retsch-Bogart 30 With Eyes to See It a review by Zackary Vernon Ron Rash, Above the Waterfall

33 Redemption in the Imprisoning Mountains a review by Savannah Paige Murray Ron Rash, The Risen 34 Terry Roberts Receives James Still Award

37 Sea, Sand, and Human Hands a review by Alton Ballance David Blevins, North Carolina’s Barrier Islands Karen Willis Amspacher and Barbara Garrity-Blake, Living at the Water’s Edge 39 Bland Simpson Receives 2017 Caldwell Humanities Award

42 Boomer a short story by Leah Hampton art by Donald Sultan 47 Giving Fictional Shape to History a review by Kristina L. Knotts Robert Morgan, As Rain Turns to Snow and Other Stories 49 Wolfe Award Goes to Debut Novelist 50 Inside the Mind of Reynolds Price a review by James W. Clark, Jr. Alex Harris and Margaret Sartor, Dream of a House 53 Extraordinary Misadventures a review by Barbara Bennett Daniel Wallace, Extraordinary Adventures 54 North Carolina, My Kith, My Home by Ali Standish 56 Exemplary EbzB Team Receives Hardee Rives Award presentation remarks by Lorraine Hale Robinson 57 2017 Parker Award Winner Pays It Forward

35 In it for Life a review by Anna Dunlap Higgins-Harrell Mae Miller Claxton and Rain Newcomb, eds. Conversations with Ron Rash

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE 58 n Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues poetry, prose, book reviews, and literary news

103 n North Carolina Miscellany poetry, fiction, book reviews, and literary news

8

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

ALLAN GURGANUS:

TWO TRIBUTES

Adapted from tributes presented at the North Carolina Writers Conference Rocky Mount, 29 July 2017

COURTESY OF JANE HOLDING

Homage to THE Allan Gurganus by Margaret D. Bauer I am so honored to have been asked to pay tribute to one of the writers we Eastern North Carolinians boast about. “Where in North Carolina did I land?” my friends back home in south Louisiana might ask. Louisiana people go to Florida, not the Outer Banks, for the beaches, but a few like me might have gone to summer camp in the mountains. “No, it’s nothing like that where I live,” I tell them. “I moved to Eastern North Carolina, about forty miles from where the author of Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All is from.” Wherever you are in the US – and lots of places beyond, that title will ring a bell. So yes, indeed, I am proud to have been asked to be among the speakers to honor this world-widely beloved writer tonight. I’m not going to introduce to you a writer who needs no introduction, but I am going to remind you of some of his works that you simply have to read again, starting with the story this wonderful, sweet man read the first time I met him about twenty years ago now! When I was just a child professor, playing dress-up in Alex Albright’s too big to fill shoes as the new editor of the North Carolina Literary Review, Allan Gurganus – the Allan Gurganus who wrote Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All – came to speak at ECU. So awestruck in those days, before learning that my new home state was chock full of the literary stars of my reading pleasure, I probably didn’t say two words to him. My younger self, much like the old lady standing in front of you this evening, a selfconfessed writer groupie, would sit mesmerized during a reading, nodding my head and wearing a silly grin on my face, reflecting how much I relish these opportunities to hear the writer on a stage behind the voices on the

ABOVE Margaret Bauer paying tribute to Allan Gurganus, sitting

here with Jane Holding, at the 2017 North Carolina Writers Conference (Read Holding’s tribute in the NCLR 2018 print issue.) Read about NCLR Editor MARGARET D. BAUER in the North Carolina literary award coverage elsewhere in this issue.

page. But unlike the old lady in front of you, I was far too intimidated to speak more than cliché pleasantries to these writers. – I have since learned to leap onto the stage before anyone else can get to him to beg for the privilege of publishing the story (and don’t get in my way or you might find yourself toppling off the stage). Anyway, I don’t remember if I had the nerve to say more than “thank you for coming, I enjoyed the reading” that night so many moons ago, but I do remember the story Allan read, “Nativity, Caucasian.”1 And I encourage you to reread that story first thing tomorrow – not tonight. You’ll get yourself all worked up with laughing and won’t be able to settle down to sleep. Here’s just the opening to remind you of what I am talking about, as well as to show you his genius for capturing a time and place. Just listen for how his selective (and hilarious) word choices reflect the post-world war two era’s attitude toward pregnancy.

1

“Nativity, Caucasian” is collected in White People (New York: Knopf, 1991); subsequently cited from this collection. The story was originally published as “Nativity, Caucasian: The Day Mother Nature Played Her Trump Card” in Chicago Tribune 6 Dec. 1987: web.

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

N C L R ONLINE

9

COURTESY OF JANE HOLDING

(“What’s wrong with you?” my wife asks. She already knows. I tell her anyway). I was born at a bridge party. This explains cer tain frills and soft spots in my character. I sometimes picture my own genes as crustless multicolored canapés spread upon a silver oval tray. Mother’d just turned thirty and was eight and one half months gone. A colonel’s daughter, she could boast a laudable IQ plus a smallish independent income. She loved gardening but, pregnant, couldn’t stoop or weed. She loved swimming but felt too modest to appear at the Club in a bathing suit. “I walk like a duck,” she told her husband, laughing. “Like six ducks trying to keep in line. I hate ducks.” Her best friend, Chloe, local Grand Master, tournament organizer, was a perfect whiz at stuffing compatible women into borrowed seaside cottages for marathon contact bridge. “Helen precious?” Chloe phoned. “I know you’re incommoded but listen, dear. We’re short a person over here at my house. Saundra Harper Briggs finally checked into Duke for that

My reading can’t do this story justice, but you know who can? Allan Gurganus. And when we decided to add an audio component to NCLR’s 2008 humor issue, “Nativity, Caucasian” was the story I asked Allan to read for us. By then, I was much less shy about asking than I might have been if this story had not already been published by the time I first heard him read it a few years before – in the Chicago Tribune no less, and then, of course, in his White People collection. I had learned in the decade since then something else about North Carolina writers – how incredibly generous they are. And the bigger the star, the larger the generosity (in most cases). Allan arranged for himself to go to WUNC to have a professional recording made of him reading this story, and now anyone who still has a CD player can experience what I did when he introduced that story to me. We call it lagniappe in Louisiana, for the story is, as Fred Chappell might put it, “an elegant sufficiency,” but hearing Allan read it, now that is lagniappe.2 As I say, after several years serving as NCLR editor, I got pretty good at those leaps to the stage to beg a writer for a story, poem, or essay, and as soon as Allan finished giving his keynote address for the Eastern North Carolina Literary Homecoming one year, I asked if we could publish it in NCLR. With his usual kind magnanimity, he responded something along the lines of, “Of course, my dear, I wrote it for NCLR.” Now think

radical rice diet? And not one minute too soon. They say her husband had to drive the poor thing up there in the station wagon, in the back of the station wagon. I refuse to discriminate against you because of your condition. We keep talking about you, still ga-ga over that grand slam of yours in Hilton Head. I could send somebody over to fetch you in, say, fifteen minutes? No, yes? Will that be time enough to throw something on? Unless, of course, you feel too shaky.” Hobbyists often leap at compliments with an eagerness unknown to pros. And Helen Larkin Grafton was the classic amateur, product of a Richmond that, deftly and early on, espaliers, topiaries, and bonsais its young ladies, pruning this and that, preparing them for decorative root-bound existences either in or very near the home. Helen, unmistakably a white girl, a postdeb, was most accustomed to kind comments concerning clothes or looks or her special ability to foxtrot. And any talk about the mind itself, even mention of her wellknown flare for cards, delighted her. So, dodging natural duty, bored with being treated as if pregnancy were some debilitating terminal disease, she said, “Yes. I’d adore to come. See you shortly, Chloe. And God love you for thinking of me. I’ve been sitting here feeling like…well, like one great big mudpie.” The other women applauded when she strolled in wearing a loose-cut frock of unbleached linen, hands thrust into patch pockets piped with chocolate brown. (All this I have on hearsay from my godmother, Irma Stythe, a fashion-conscious former nurse and sometimes movie critic for the local paper.) (47–48)

ABOVE Self-confessed writer groupie Margaret Bauer posing

with Allan Gurganus and Jane Holding after the tribute banquet

2

NCLR’s Mirth Carolina Laugh Tracks, the CD component of the 2008 issue, which focused on North Carolina humor, is still available for purchase. The Chappell quotation is from “The Beard,” which appears in I Am One of You Forever (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1985) and which Chappell allowed NCLR to publish in 1998.

10

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

can hear spoken by vacationers to our tourist attractions, brings his readers into the homes and churches and schools and stores and fields and streets they do not visit during their beach or mountain vacations. Like the many people who pass through the real North Carolina on their way to the beach or the mountains, I thought all of North Carolina was like the Western North Carolina camp I attended half a dozen summers of my youth – a cool escape from hot Louisiana. Where are the mountains? I wondered as my plane from Indiana, where I was teaching in spring 1996, approached the Pitt Greenville airport. Clearly, I was as ignorant about North Carolina as the tourists who come to stay in the mountains or on coast and don’t know about all we have between. I had always told my parents that someday I would live in North Carolina. And after a year in Indiana, where it was still snowing in March, arriving here to blooming azaleas that reminded me of my native Louisiana, I was ready to come “home.” No one warned me, as Allan’s naughty narrator is warned as she plans her move from Ohio to Florida in “My Heart Is A Snake Farm,” to “Be careful where you first settle. Danger is, once you’re sprung from these fierce [in my case Indiana] winters, the first place you find in the [Old North] State you will – like some windblown seed – take fast tropic-type root.” I have deep roots here now – they’ve been digging in for over twenty years, and I am so proud to say I am from Eastern North Carolina, birth place of such storytellers as Allan Gurganus, who calls it “the place between places that secretly becomes more a place because, stuck out on our own, we’ve found a way to impose high standards and to enjoy the hell out of whatever we could bring-up-by-hand here among ourselves out here amidst our fields and just that stone’s throw off the highways leading to the spots others founds important” (“Now” 12). I join you all today in thanking Allan for the gift of his stories, which introduced me and so many others to the backstory of this region, from the parlor and the kitchen, the street and the field. And Allan, I read some advice you gave to writers in a Daily Beast interview: “Read your work aloud daily. Read it once a week to your friends. Provide the wine yourself.”5 Well, I will provide the wine (or really good bourbon if you prefer) any time you need someone to listen to you read your work. n

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARGARET BAUER

about it – this is a writer who publishes in The New Yorker and The New York Times – you know, venues that pay. While we at NCLR have always depended upon the kindness of – well, let’s say strange writers who give their essays titles like his “Now the Feds Are Paying Us Not to Grow Our Best-Known Carcinogen, What?” Putting his “Now What” question another way in the subtitle, he asks, “What Shall We Eastern North Carolinians Export?”3 Storytelling is “what,” according to Allan, and I hereby declare him the Mark Twain of Eastern North Carolina – indeed North Carolina storytellers – with a twenty-first century bawdiness that might make the old riverboat pilot blush. I’m thinking here about Allan’s New Yorker story “My Heart Is A Snake Farm,” in which we witness a retired librarian’s transition into libidinous motel owner, undaunted by the possibility that Buck’s “prize Burmese python [might] wind up in [her] . . . Parnassus Palms dresser drawers.”4 But back to the essay I was lucky to land for NCLR, as in most of his fiction, that essay celebrates the region I now call home, Eastern North Carolina, to outsiders only “a series of piglet teat exits off a highway,” Allan points out, visited by people on the way to the Outer Banks, stopping only, “if they needed a hospital or gas or a cleanly restroom” (“Now” 8). So much of Allan’s writing, which has been translated into many of the different languages you

3

“Now the Feds Are Paying Us Not To Grow Our Best-known Carcinogen, What?; or, What Shall We Eastern North Carolinians Export?” NCLR 16 (2007): 7–14; quotations from this essay will be cited parenthetically.

5

Noah Charney, “Allan Gurganus: How I Write,” Daily Beast 16 Oct. 2013: web. ABOVE Allan Gurganus at the North Carolina Writers Conference,

Rocky Mount, 29 July 2017 4

“My Heart Is A Snake Farm,” New Yorker 22 Nov. 2004: web.

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

N C L R ONLINE

11

CELEBRATING ALLAN GURGANUS, “OUR AUTHOR”

I think I can best celebrate Allan Gurganus by telling the story of the publication of Allan’s Good Help by the North Carolina Wesleyan College Press in the months before Alfred Knopf published Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All nearly thirty years ago.1 In the summer of 1987 Wesleyan’s administration decided to sponsor a college press and asked me to direct it. In my plans for the Press, I had discounted the possibility of publishing work by Allan because of his ties to New York agents and his need to make money from his writing. We weren’t in a position to pay him what he could earn in New York. In addition, at the time Allan offered us the typescript of Good Help, the North Carolina Wesleyan College Press could hardly be said to exist. We had not yet published anything, and as its Director, I didn’t even know what I didn’t know about publishing. Publishing Allan’s story Good Help gave us a good shove toward being a Press. His gift was not just generous, it’s a good illustration of his affection for this area, what he called in a letter to me “my adored community,” meaning, I then supposed, the people who had nurtured him in Rocky Mount when he was growing up. For the NCWC Press, this gift was truly “Good Help.” Allan didn’t just hand us the typescript of Good Help and go home to New York. He stayed with it and worked at all aspects of its publication, from design to distribution, writing me letters of suggestion and complaint when he couldn’t be in North Carolina. As we planned the design of the book, we realized that Allan had skills as a visual as well as a literary artist. Consequently, and not knowing what we were asking, we asked him to provide a series of drawings that would enhance the narrative. Allan was enthusiastic about doing this, finding in doing the drawings “a personal revelation,” his ideas about “line and narrative now happily commingled.” This particular contribution made Good Help, along with Blessed Assurance,2 unique among Allan’s books, the text and drawings playing off one another. This produced a book that now seems a tribute to Allan’s skills in both the literary and visual arts. Poker-faced, the book’s title page simply reads “With Illustrations by the Author.”

1

2

Allan Gurganus, Good Help (Rocky Mount: North Carolina Wesleyan Press, 1988); quotations from this edition cited parenthetically; Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All (New York: Knopf, 1989).

Allan Gurganus, Blessed Assurance (North Carolina Wesleyan Press, 1990); later included in White People (New York: Knopf, 1991).

COURTESY OF ALLAN GURGANUS AND LEVERETT T. SMITH, JR.

by Leverett T. Smith, Jr.

Distribution was quite another problem. Did we have mailing lists? Well, sort of. There was a very general “Arts” mailing list at the college, but basically, we had little idea how to tell the world that we had a book to sell. Allan provided us with his mailing list, adding name after name, and to our delight, many wanted to buy the book. A mailing list started to form around these names. But Allan was never really happy with our efforts at distribution, complaining at one point that only his friends were learning about the book. Because he had many friends, we did sell out the edition, but the problem of distribution stayed with the press for the rest of its life. Our conversation about distribution did produce a keynote of the whole enterprise. In the midst of a page-long discourse on various methods of distribution, Allan stopped to ask, “We’re all making this up as we go, no?” We certainly were.

ABOVE A Blessed Assurance illustration by Allan Gurganus,

featuring Vesta Lotte Battle

12

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

COURTESY OF ALLAN GURGANUS AND LEVERETT T. SMITH, JR.

By 1988, the year Good Help was published, the title page described Good Help as “being a chapter from Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All forthcoming from Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.” Sensibly, the title page underlined the story’s relation to the novel. As Allan put it in a letter, Good Help was “an ambassador for my novel.” Just so, but clearly an ambassador for other things, too. Confederate Widow is a great bundle of stories, interconnected in one way by the voice of the narrator, Luci Marsden. Good Help in our edition was identified on the title page as one of these stories, but it is also an early G u r g a n u s n ov e l l a . This literary form that Thomas Mallon calls “the commercially perverse, neither-thisnor-that form of the novella,”3 has occupied Allan for some forty years. It has proven just the right vehicle for Allan’s stories and heroic storytellers within stories, Luci Marsdan and Maimie L. Beech the first of these. For Allan, the teller is always as important as the tale, if not more. Maimie L. Beech of Good Help is, among other things, one of Allan’s heroic storytellers. Here she is described: Till school spoiled things, Maimie might sit – with some beautiful picturebook opened in her lap, a living baby tucked snug under either arm and – free as air or water – spin out any tale she chose. It felt like swimming and walking at the self-same time – a promenade along some river’s glassy lid. Her lore was partly fairy tales like one about a poppa-king whose golden touch proved butterfingered.

Her lore was

partly Bible rehash, part neighborhood gossip from Baby

3

Thomas Mallon, “Big Talker: The Voices of Allan Gurganus,” New Yorker 7 Oct 2013: web. ABOVE A Good Help illustration by Allan Gurganus, featuring

Maimie L. Beech with Bianca

Africa downhill, partly whatever stepping-stone-footholds the pretty pictures gave. Her finger was careful to skim to and fro, fro and to – a dorsal fin keeping her afloat. (21)

Of course, heroic as Maimie is, it is Luci Marsden who is telling Maimie’s story, and the two are connected first by similarity of name and then by Luci’s concern for Maimie’s fate. In one of the few times Luci Marsden enters Good Help, she imagines Maimie’s watery end: “I imagine Maimie smelling the river, sighing many Psalms aloud, practically chugging them. I see her noticing the moonlight wavering on water like some flaming path or giant tongue. I imagine her good shoes testing water’s temperature. I hear Famous Maimie Beech saying to the river, to the night and world – ‘Open up. It’s me’” (56). Finally, the vast advertising campaign Knopf was mounting for Confederate Widow brings us to the question of Allan’s ambition. Before Confederate Widow, Allan had been a tenured college professor, a writing teacher, and had done his own writing on the side. He was, as he put it, “eager to be a full-time writer, not a hobbyist.” He wanted “to earn a living via writing.” As we worked on Good Help, Allan began to sign his letters to me “Your Author.” This was clearly to encourage me, but it was more than that. In calling himself “author” he also was trying a new role for himself. As the publication of Confederate Widow approached, so did the possibility of Allan’s “earning a living by writing.” And this entailed not just earning his living by writing, being an author, but being an authority, becoming a full-time investigator of and spokesman for that “adored community” he has since imagined so forcefully, both in his books and in his life. So, thank you, Allan, first of all for your generosity and your concern for the cultures of eastern North Carolina. Thank you for your multiple artistic talents, and your concern that they integrate and complement each other. Thank you for your long-time interest in the novella form and for showing us its possibilities. Thank you for being “Our Author,” for all your good help in service to your “adored community.” n

LEVERETT T. SMITH founded the North Carolina Wesleyan College Press in 1987 and served as its director until 1994. He is Professor of English at North Carolina Wesleyan College, where he is also curator of the Black Mountain College Collection. Read his interview with Jonathan Williams in the 1995 issue of NCLR.

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

N C L R ONLINE

13

COURTESY OF ALLAN GURGANUS

Crafting Local Souls:

The Metafiction of Allan Gurganus by Zackary Vernon

On at least two occasions, I have heard Allan Gurganus say, “I rewrite to be reread.” Re-reading some of his fiction in the past few weeks has not only been a great pleasure, but has also made me reflect on what it means to rewrite and rewrite and rewrite, what it means to craft prose that is deserving of careful scrutiny time and time again. Gurganus is often referred to as a “writer’s writer.” The meaning of this, on one hand, is clear if one peruses the many laudatory reviews by fellow authors published in top magazines and journals or if one reads the ebullient endorsements from heavyweight writers that appear on the covers of his books. On the other hand, though, I think Gurganus is a writer’s writer because he often writes about writing – not in how-to nonfiction pieces for aspiring writers, but in the fiction itself.

ABOVE “Halloween’s Herald of Democracy” Allan Gurganus, as Zackary Vernon calls him in his

essay about the author’s “legendary Halloween show” (in NCLR 2014), Hillsborough, NC, 2017

14

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

These metafictional narratives, therefore, offer fiction about fiction, stories about the art of telling stories.

Gurganus’s latest book, Local Souls, for example, is comprised of three novellas, all of which reflect on how exactly one goes about crafting literature. These metafictional narratives, therefore, offer fiction about fiction, stories about the art of telling stories. This theme has gone largely unnoticed by critics, except for a few passing references, for instance in Jamie Quatro’s glowing review of Local Souls in the New York Times or in William Giraldi’s illuminating essay in the Oxford American.* That Local Souls is a metafictional book becomes immediately apparent once one begins reading. In the beginning of the lead novella, “Fear Not,” the first-person narrator describes going to a high school production of Sweeney Todd with a friend whose child is in the play. The narrator, we soon learn, is a writer who has just finished and sent to a New York agent his epic Civil War novel. (This should sound familiar.) Having completed the epic, the writer says that he needs “another project . . . a new subject,” particularly after, in his words, he has “shot [his] bolt on the Civil War” (16, 21). The narrator and his friend Jemma soon see in the audience an attractive and visibly flirtatious young couple, an anomaly among the otherwise sullen, aging parents. This immediately opens the floodgates of the writer’s imagination; his “narrative capacity” is not apparently as “exhausted” as he had assumed after finishing his Civil War tome. “[A]ren’t all real writers always writing?” he queries (17). This short narrative – a writer intrigued enough to explore a stranger’s life – serves as the frame for the novella. What follows is a fifty-page story, told in third-person, comprised of our writer-frame narrator speculating about the life circumstances that led this energetic, striking young couple to be at this particular production of Sweeney Todd. So from the beginning we know this novella is metafictional – a writer writing about a writer who is writing a seemingly true story in order “to understand this better.” And the narrator assures us that the story of the young couple is true, well researched, and comes “as close to Documentary as any trained liar ever dares go.” This near-documentary is, according to the narrator, “at least 81% . . . true” (21–22). The story concerns a woman who is reunited with a son that she put up for adoption after having him eighteen years earlier when she was only fifteen. The woman and her long-lost son, once reunited, seem to enter into an incestuous affair. If you haven’t read this novella, you should; it’s so darkly, so deliciously, so salaciously tragic that it feels downright Greek. It also has, as the story suggests, a sense of Russian literature’s determinism; Fate, in this narrative, comes with a capital F.

form ABOVE AND OPPOSITE RIGHT From the author’s illustration of Falls, NC, which appears inside the cover of Local Souls

* Allan Gurganus, Local Souls (New York: Liveright, 2013); subsequently cited parenthetically; Jamie Quatro, “Talk of the Townies: Local Souls,” New York Times 11 Oct. 2013: web; William Giraldi, “The Dead Give Him Stories,” Oxford American 82 (2013): web.

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

Allan Gurganus deserves his reputation as a writer’s writer, first for the beauty and depth of his stories, but also, I would argue, for the writerly advice embedded in books like Local Souls.

N C L R ONLINE

15

But what is the point of all this? Why write a novella about a writer speculating about incest, a tale that seems to come from “ancient texts and hillbilly legends” (84)? What is Gurganus positing here about fiction, about literature? The writer-narrator suggests that his task is to try to breathe “real life into these local souls” (22). The language here is biblical; and the writer is, therefore, within his own world, a godlike figure. I see no narcissism in this, though, and that’s not the point. The point is that we are, in a sense, all gods of our own imagination. We are, regardless of life circumstances, free to imagine what we will. The narrator of “Fear Not,” anticipating his next project, states, “I already sit imagining a hundred ways one person might tell another such a saga. So many questions live hidden in it. First, you’d gather all known facts. Once grasped, those might offer you a new way of knowing. After documenting, you must imagine inward, capturing some fraction of the costs to them, the reward of it” (84). The message that I think Gurganus wants us to take away is that narrative, whether in literature or simply in the content of our daydreams, leads to an empathic capacity. It is increasingly difficult to judge others’ choices if we can imagine ourselves capable of the same victories, the same burdens, and even the same shortcomings. The next novella, “Saints Have Mothers,” continues in this metafictional vein. Although there are no such immediately obvious writers writing about writing in this novella, the theme continues in subtler ways, in characters’ thoughts and conversations. The novella’s first-person narrator Jean is an intelligent divorcée who once published a single poem in The Atlantic. Jean’s daughter Caitlin is altruistic to a fault, precocious and often pretentious in her drive to always do good unto others, even going so far as to give her mother’s shoes away without permission. The crux of the drama in “Saints Have Mothers” occurs when Caitlin is presumed dead while on a summer trip to Africa. Following her daughter’s apparent death, Jean seems to find new meaning in her own life, playing the grieving mother and honoring a daughter who she often found impossibly self-righteous. In this regard, “Saints Have Mothers” is similar to the previous novella in that it investigates taboo topics: the first novella is about how incest might transpire quicker than we would have imagined, and the second novella is about how parents can resent and even dislike their children more than they would care to admit. In one scene in this novella, Jean pilfers through Caitlin’s room and discovers one of her daughter’s to-do lists, which includes a rather heady series of questions: “Are novels even valid this late in human history? Can the simply Personal be separated now, teased out, from the general warp-woof of utter Globalism? Fantasy, always a distortion? Argue Escapism’s morality, pro-con” (100). In other words: are novels relevant anymore? Has the personal and the local been superseded, eclipsed by the global? Is literature anything more than an escapist’s retreat from the real world?

16

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

[O]nce published, the stories no longer belong to and can no longer be protected by the writer; they exist in and of the world, for readers and critics to do with what they will.

The answers to Caitlin’s questions eventually come from her mother Jean. Contemplating poetry and comparing her own to her daughter’s, Jean decides that the best work must contain form and content, style and substantive ideas. Jean’s poetry had always gotten stuck on the aesthetic. The most profoundly important work, though, she suggests, must “[make] shapes from the worst of the mess of the world” (111). Thus, it is the function of literature to give artistic shape to the mess that surrounds us, while also bringing us pleasure in and insight into that mess. Local Souls’ final novella “Decoy” also frequently ventures into the terrain of metafiction. “Decoy” is told, like the other two, in first-person, in this case through the perspective of Bill, an insurance salesman with a heart defect who spends much of his time obsessing over his relationship with the town’s doctor. After Doc retires, he neglects friends such as Bill in favor of pursuing his new hobby, carving duck decoys. Bill, who is married but clearly also in love with Doc, records Doc’s meteoric rise to fame in the niche market of professional decoy carving. Throughout the narrative, Doc’s making of decoys becomes an elaborate metaphor for writing fiction. Doc’s decoys are perfect replicas of the ducks that are native to his little corner of North Carolina, not unlike the writer in the opening novella who “trie[s] breathing real life into these local souls” (22). The parallels between sculpting ducks and writing people become especially apparent when Bill ponders why Doc’s only subject is ducks: “Me, now, if I could sculpt or write, as a subject, only people would interest me. Why they do stuff! There’d be so much to know! But, making decoys, hadn’t he just been doing further xerox copies of known imitations of what started as pure waterbirds? With human portraits, no two can ever look alike” (311). Despite their simulacratic qualities, Doc’s decoys become so good, so life-like that they eventually capture the attention of New York agents, and rather than selling his decoys locally, they are all promised to far away metropolitan collectors and museums. This trajectory to duck decoy greatness parallels the careers many writers wish they could obtain; the end literary product, based on the local, is ideally bound for New York success.

empathy

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

N C L R ONLINE

17

However, before they can make their flight north, Doc’s masterpiece ducks are lost when a flood devastates the town and takes with it all of Doc’s decoys, swept out of his workshop and into the raging river. The decoys, no longer safe in the artist’s studio, are then destroyed by the elements, ravaged by the world. This flood and the loss of Doc’s best decoys parallels the sending out of a writer’s dearest stories, his most agonized-over words. And, of course, once published, the stories no longer belong to and can no longer be protected by the writer; they exist in and of the world, for readers and critics to do with what they will. Doc’s decoys are not kindly received following their alluvial birth into the world. The few that actually come back to him return utterly destroyed, and as a result Doc becomes increasingly unhinged. Bill notes, “people who love something too much, live at greater risk. And yet, that’s bound to be the one sane way forward. Surely our determination to never lose what we’ve made to love, that, in itself, means an early sort of decoy death” (315).

ABOVE The author’s illustration of

Falls, NC, which appears inside the cover of Local Souls

18

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

reception LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION PHOTOGRAPH BY MARGARET BAUER

Following the metafictional current of the novella to its close, Gurganus seems to suggest that after sending one’s treasured work out into the world, we must know that it will run the risk of being mistreated, of being destroyed. And yet this risk is worth it, the “one sane way forward” being the most dangerous – putting one’s work out into the world, despite the fear of how it will be received once it leaves the safety of the studio, the sanctum of the workshop. To conclude, these are the literary lessons that, as I understand them, Gurganus offers in Local Souls’ three novellas: One, empathy is inevitably engendered by narrative, and narrative is inevitably engendered by empathy. Judgment becomes increasingly difficult to maintain when one has inhabited the minds of others. Two, form must never be sacrificed for content, and content must never be sacrificed for form. The two must exist concurrently, the one buttressing the other. Three, the reception of one’s work by the world is a gamble, but one worth pursuing, a game worth playing. To not would mean a lack of vitality, a life not truly lived, a career unchallenged, and thus a certain kind of death. In short, the three novellas taken together seem to suggest: this is what literature does (inspire empathy); this is what literature looks like (a marriage of form and content); and this is how it feels to send one’s well-wrought darlings out into the unknown (lost to you and subject to the all-too-often cruel whims of the world). Allan Gurganus deserves his reputation as a writer’s writer, first for the beauty and depth of his stories, but also, I would argue, for the writerly advice embedded in books like Local Souls. It’s all there: why to write, how to write, and what to expect once one has written. n

ABOVE Zackary Vernon delivering this essay

at the North Carolina Writers Conference, Rocky Mount, NC, 29 July 2017

ZACKARY VERNON is an Assistant Professor in the English Department at Appalachian State University. Read his interview with Ron Rash and Terry Roberts, along with an essay on Allan Gurganus in NCLR 2014. In 2015, Vernon received the premiere Alex Albright Creative Nonfiction Prize for “Boone Summer: Adventures of a Bad Environmentalist,” which was published in NCLR 2016. This essay was delivered on a panel at the 2017 North Carolina Writers Conference in Rocky Mount, NC, after which he interviewed Allan Gurganus for the print 2018 issue of NCLR.

STEPHANIE WHITLOCK DICKEN has been designing for NCLR since 2001 and served as Art Director 2002–2008. For this issue, she designed this essay and several of the tributes and award stories. Her designs of the book reviews and sidebars in back issues of NCLR Online are now used as models for the student staff members to have the opportunity to work on layout. She teaches graphic design at ECU and Pitt Community College. For twenty years, she has also designed books for both independently and traditionally published authors.

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

FOODWAYS AND THE STORY OF NORTH CAROLINA a review by Joanne Joy Vivian Howard. Deep Run Roots: Stories and Recipes from My Corner of the South. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2016. Randall Kenan, editor. The Carolina Table: North Carolina Writers on Food. Hillsborough, NC: Eno Publishers, 2016.

JOANNE JOY has an MA in English from UNC Charlotte and a certificate in Technology and Communications from UNC Chapel Hill. She is currently working on a project to document and preserve recipes in North Carolina. VIVIAN HOWARD, originally from Deep Run, NC, is a chef and television personality. She is the star of A Chef’s Life, which is currently in its fifth season. In 2016, Howard won the James Beard Award for Outstanding Food Personality and a Daytime Emmy for Outstanding Directing in a Lifestyle/Culinary/ Travel Program. In 2017, she was named a Tar Heel of the Year by the News & Observer. Read more about her in the 2018 print issue. RANDALL KENAN’s books include A Visitation of Spirits (Grove Press, 1989), Let the Dead Bury Their Dead (Harcourt, Brace, 1992), and Walking on Water: Black American Lives at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century (Alfred A. Knopf, 1999). Among his honors are a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whiting Writers Award, the Sherwood Anderson Award, and the North Carolina Award for Literature. In 2018, he will be inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame. Currently, he is a professor in the English and Comparative Literature Department at UNC Chapel Hill. Essays featuring Kenan can be read in NCLR 2006, 2008, 2011, and 2012, and he was interviewed for NCLR Online 2017.

Southern food is trendy. Across the country, highly praised establishments from San Francisco to Brooklyn serve up Southern culture through staples like fried chicken, greens, and biscuits. Southern food is iconic and its widespread popularity offers the opportunity to tell the stories of the people who claim diverse traditions across the region. Arguably, food born of the South is linked to a profound sense of place and identity. Likewise are the foodways specific to the regions of North Carolina. Two new books – in very different genres – shed light on what food traditions mean to the people of the state. The collection of essays in The Carolina Table: North Carolina Writers on Food, edited by award-winning fiction and nonfiction writer Randall Kenan, gives us an expansive view of North Carolina food culture and identity, while highly acclaimed chef Vivian Howard of Kinston, NC, zeroes in on her community in Lenoir County and Eastern North Carolina through the lens of foodways in her cookbook/memoir, Deep Run Roots: Stories and Recipes from My Corner of the South.

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste; Or, Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy, 1825, trans. M.F.K. Fisher, 1949 (New York: Knopf, 2009) 15.

19

identity in The Carolina Table: North Carolina Writers on Food. This collection of personal narratives is a healthy exploration of how food and memory are inextricably woven into the fabric of individual and regional identity. Edited by Randall Kenan, the collection, penned by diverse writers, cooks, and scholars with ties to North Carolina, is a testament to the notion that foodways are truly transformative. The thirty essays are not just stories about food. Rather, as Kenan notes, each narrative embodies “The story of the Tar Heel state through food” (7). As the writers recall personal experiences, food is the vehicle for celebrating formative relationships: Marianne Gingher and her cakebaking grandmother, Ruth; Nancie McDermott and her chicken pie-toting great aunt Julia; Wayne Caldwell’s mother, Ruby, who equated his fullness with being “safe and loved” (30). As journalist John Egerton wrote in his iconic book, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History, “Because it is such an integral part of the culture, Southern food provides an excellent entree to the people and their times.”2 Whether intentionally or not, each writer makes profound connections between the ingredients or dishes and the experiences with the people in each of their lives. Many of the essays, like Crook’s Corner chef Bill Smith’s “Hard

“Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are.” This sentiment, thrust into the English vernacular by celebrated writer, M.F.K. Fisher in her 1949 translation of The Physiology of Taste,1 describes how food facilitates 1

N C L R ONLINE

2

John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (New York: Knopf, 1993). A well-respected journalist in the South whose career spanned decades, John Egerton organized members of the Southern food community to found the Southern Foodways Alliance at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in 1999. His founding mission, to document and preserve the foodways of the South, became the foundation for further study of race, class, gender, ethnicity, and social justice of the region through the lens of food.

20

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

ABOVE Some of the goats raised by

Tom Rankin and his wife, Jill McCorkle

through her work at the community college and the family newspaper, Parker’s childhood experiences at the family table were a reminder that sometimes it’s “who” we eat with, instead of “what” we eat, that matters. Jaki Shelton Green reminds us in “Singing Tables” that food creates community for her in other ways as she professes, “I am surrounded by generations of cooks, their wisdom, their laughter, and their flawed and perfect recipes lifting my hands and heart” (13). While some of the narratives connect an ingredient or dish to a memorable moment in time, like Green, many recall those who came before. Past generations molded and shaped not just culinary expertise, but as Jill McCorkle suggests in “Remembering the Cake,” unbreakable ties to home and the people we love, long after they have passed. In her essay, McCorkle draws a clear line between her first memory of her grandmother and the failing memory of her own mother. The pound cake she brings on most visits to her mother in a nursing facility facilitates a connection to the past for her mother. Notable in this collection are not only the ties to memories of the Old South, but also the inclusion of experiences in the New South. Food influences from outside the state’s borders facilitate connections in surprising ways.

Sophia Woo sums it up best in her telling of her food truck adventures in “Vulnerability.” A North Carolina native, Woo’s frequent trips to visit family in Taiwan led to her decision to buy a food truck to bring the richness of community through the food of her ancestry to people in America. She recounts her realization that “[f]ood is our way to connect to our surroundings and connect with people” (83). After winning the national “Great Food Truck Race” contest, Woo and her business partner continue their mission to connect with people in the Triangle through traditional Asian fare. In “On Food and Other Weapons,” Diya Abdo recalls the connection between food and love in her own Palestinian heritage and how the same sentiments translate for the Syrian refugee family that she sponsors. Tom Rankin writes of raising goats that largely supply a growing immigrant population of Spanish-speakers, Africans, and Asians and of the meticulous art of Halal processing. In his essay, “Raising Goats to their Rightful Place,” Rankin contemplates the PHOTOGRAPH BY TOM RANKIN

Crab Stew,” include heirloom recipes to root themselves in place across the diverse landscape of North Carolina. The process of catching, cleaning, and cooking crabs near Smith’s homeplace on the Outer Banks goes hand in hand with the sensory pleasures of the place itself: “Late in the afternoon there comes a moment when the sun is still hot, but the wind starts to come in off the sea. Heat radiates up from the sand as the breeze cools you at the same time. When this happens, tension magically leaves my neck and shoulders for a second. I feel like I am where I belong” (73). While there is no recipe included in “Orange You Glad,” Emily Wallace describes her place through her own food traditions, simultaneously giving us a history lesson on Nabs while schooling us on the Down East rural traditions of tractor brand loyalty: “We were solidly an Allis-Chalmers and Kubota family because we were an orange family, one sustained on the likes of pimiento cheese, cheese puffs, and Cheez-Its” (88). The common thread among all of the essays is that there is no singular experience – the “where” and the “what” are communal. Community can also be found at the North Carolina table in nontraditional ways. In “Let’s Cook, EXCLAMATION POINT,” memories like Michael Parker’s developing fondness for Hamburger Helper in the 1970s remind us that while regional foodways and resulting traditions can be formative, our associations between food consumption and loved ones are powerful. With a mother who, rather than cooking elaborate weeknight meals, instead served

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

ABOVE The Bar-B-Q Center in Lexington, NC

PHOTOGRAPH BY AUTUMN GUNSLEY

hierarchy of animals and the status of goats with meaningful metaphoric undertones. Paul Cuadros invites us in to share in the story of his love of Peruvian chicken in “Pollo a la Brasa Keeps Turning in North Carolina.” The well-received spread of this cuisine allows food to become a vehicle for expression and shared experiences between cultures. Each of these narratives highlights how influences from outside the South continue to contribute to the region’s evolution through exposure to diverse cultures and enriching personal experiences. Several essays laud the iconic foodways of leaders across the state. Professor of American Studies at UNC Chapel Hill William Ferris pays tribute to the long-standing traditions of Mildred “Dip” Council of Mama Dip’s in Chapel Hill and her influence on the region. For Ferris, Mama Dip represents both the connection to the Southern food of the past – things like fried chicken livers, sweet potatoes, biscuits, and sweet tea – and to the history of life in the South. And, of course, no conversation about North Carolina foodways is complete without the mention of (and often debate about) barbeque. Daniel Wallace’s essay, “The Mesopotamia of Pork,” celebrates the traditions of barbeque in the Piedmont. The Bar-B-Q Center in Lexington is a family-owned institution that has been slow-roasting pork shoulders since 1961. Housed in the same simple brick building that Wallace claims belongs next to Julia Child’s kitchen in the Smithsonian, its longevity is a testament to the community’s commitment to the long-standing food traditions of the region while also embracing the new.

Each region of the state is well represented as Kenan describes the breadth of experiences in the collection and the geography that it covers: “We feel that our toes are digging into the beach sand while our heads are peering over Mt. Mitchell” (8). Each narrative paints distinct, yet collective, pictures about what the state gives to each author in the form of sustenance, both body and soul. A common theme across the essays is evident: The foodways of North Carolina and its people are formative and rich with experiences. While exposure to the diverse experiences from Murphy to Manteo gives us a bird’s-eye view of what life through food is like across the state, the focus of a single region, or even a single county, is an opportunity to tell a deeper story. Chef Vivian Howard does just that in her acclaimed, nearly six-hundred-page book, Deep Run Roots: Stories and Recipes from My Corner of the South. With a writing style that

N C L R ONLINE

21

feels like she is talking to us across the kitchen table, Howard captures the essence of the foodways of Lenoir County and Eastern North Carolina and how they are inseparable from the people in the region. Her true journey began with the smell of “rank feet and rotten roughage” (417). Howard’s bold move from her big city life in Manhattan back to her roots in Eastern North Carolina to open a restaurant has taken unexpected turns, both to her benefit and to the region’s. She has said that opening an upscale restaurant like Chef and the Farmer in one of the most unlikely places in the world – the economically depressed Kinston, NC – was a risk. Initially, the food she wanted to cook, recipes inspired by her training in New York, was not the food that the community necessarily wanted. It took her some time to find her “voice” through food by finally honing in on local ingredients. Since she learned to connect with her community through food, she has become an ambassador for the way of life of the people of the region, to celebrate the local ingredients and food traditions, along with the people who cultivate them. That smelly sandwich bag of collard kraut that Howard describes in the introduction to the “Collards” chapter sent her headlong into an exploration of her native foodways. Her curiosity eventually inspired the award-winning PBS documentary, A Chef’s Life, which she co-created with childhood friend, producer Cynthia Hill. Not surprisingly, the cookbook has already earned Howard several prestigious nods, including a nomination for the James Beard

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

throughout Deep Run Roots is on target with Howard’s description of life in Eastern North Carolina. The images of the people are colloquial, and the photos of the ingredient arrangements are successfully rustic. Notable, too, are the paintings of each ingredient that introduce the chapters. One of the most personal and compelling visual presentations is one of her mother, who has been afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis since she was a child, making deviled eggs. The four close-up frames of her mother’s deformed hands performing this tedious task are a powerful testament to the importance of the dish in the community. Howard has said that she wanted to exalt her mother by including her and this recipe in particular. True to Howard’s unconventional ways, the book signing tour was an event in itself, with more than forty stops across the eastern United States in a food truck. The ticketed events included both the book and a small meal – a sampling of dishes from the cookbook like the Party Magnet cheese ball, pimiento cheese grits, and traditional sausage-stuffed pig’s appendix called a Tom Thumb. Her work in telling the story of Eastern North Carolina through food traditions, both on A Chef’s Life and in her prose, is formidable and important. As Howard has said, “By raising our food traditions up, shining a light on them, and validating them, we’ve been able to give people a pride in the place they come from.”3 Like many of the writers in The Carolina Table who make connections between identity and their own experiences with food and memory, through her collection of recipes and narrative voice in Deep Run Roots, Howard successfully tells her own story. n

PHOTOGRAPH BY ANGIE MOSIER

22

Foundation Book Award and top honors in the International Association of Culinary Professionals Award (IACP), cookbook awards in four categories, including best cookbook for 2016. Those praises are well deserved. While technically in the cookbook genre, the book feels like the autobiography that Howard has had lurking deep within her soul for years. The passion she carries for the people of her community and the foodways that they celebrate emanate from her writing. The fifteen-page introduction, which she encourages the reader not to skip, includes a healthy explanation of her journey in writing the book, along with side notes and instructions for things like preparing a canning bath. The well-crafted narratives that anchor each ingredient chapter, along with the expansive headnotes in every recipe, are personal and informative.

The cookbook is organized untraditionally by twenty-four ingredients that are local to the region. The account of her life unfolds with each one. Howard writes that the organizational result is “driven by story” more than any other reason, but there are three additional ways a reader can choose a recipe: a standard, well-illustrated table of contents, a recipe guide organized by food categories, and an index. Many of the recipes are simple, featuring the ingredient of the chapter. Many are traditional Eastern North Carolina fare that introduces the reader to the customary foodways of the region. True to Howard’s gifts as a chef, the majority of the recipes elevate the simple ingredients and timehonored recipes to make the dishes her own. Each recipe is well written and easy to follow. Imagery is always an important component of a good cookbook. The photography and styling

ABOVE Introduction to Howard’s Deep Run Roots

3

Vivian Howard, “The First Lady of Carolina Cooking: How 500 Pounds of Blueberries – and Returning Home to the South – Gave New Life to Chef Vivian Howard,” Saveur 21 July 2016: web.

North Carolina on the Map and in the News

LIFT EVERY VOICE a review by Walter Squire Wiley Cash. The Last Ballad: A Novel. New York: HarperCollins, 2017.

WALTER SQUIRE earned a PhD in English from the University of Tennessee, specializing in American literature and critical theory. His 2001 dissertation on “The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction” included a chapter on the Gastonia mill strike novels, adapted from his 2000 NCLR essay on the female authors of these books. He taught at UNC Charlotte for almost a decade before joining the faculty at Marshall University in 2010 where is an Associate Professor of English and Director of the Film Studies program. His other publications are on American mad scientist films, cinematic depictions of teachers, Disney adaptations, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. WILEY CASH grew up in Gastonia, NC, and lives in Wilmington. He earned a BA from UNC Asheville, an MA from UNC Greensboro, and a PhD from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He is the author of two other novels, New York Times bestseller A Land More Kind than Home (HarperCollins, 2012) and This Dark Road to Mercy (William Morrow, 2014; reviewed in NCLR Online 2015). Read more about him in an interview published in NCLR 2013.

Events live on beyond their historical moment in language, whether through speech or the written word. Perhaps second only to the trial, conviction, and execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, the 1929 strike at the Manville-Jenckes owned Loray Mill textile mill in Gastonia, NC, is the most (in)famous event in American labor history, in large part due to the words produced during and immediately after the strike. Despite the significant attention devoted to the Loray Mill strike of 1929, conditions were not considerably different than those at other Southern textile mills and during other textile mill strikes. One significant difference between other 1929 strikes and the one at the Loray Mill, however, was the presence of organizers, led by Fred Beal, from the Communist Party-affiliated National Textile Workers Union (NTWU). The Communist Party publications Daily Worker and Labor Defender made the events of the Gastonia strike national as well as international news, leading to coverage of the strike by such mainstream periodicals as Harper’s and the New York Times. Significantly, with the exception of the Gastonia Daily Gazette, which decried the actions taken by striking workers, almost all press accounts expressed sympathy for the striking workers and later the trial defendants, regardless of political orientation. One of the journalists to come to Gastonia during the strike was veteran labor reporter Mary Heaton Vorse. Vorse subsequently wrote the first novel to be based on the strike,

N C L R ONLINE

23

Strike! (1930), completed even before the jury reached a verdict in the trial of union members. Strike! was followed by Sherwood Anderson’s Beyond Desire (1932), Olive Tilford Dargan’s Call Home the Heart (1932; written under the pseudonym Fielding Burke), Dorothy Myra Page’s Gathering Storm (1932), Grace Lumpkin’s To Make My Bread (1932), and William Rollins’s The Shadow Before (1935). These six novels are collectively known as “the Gastonia novels,” for they are based upon events during the Gastonia Loray Mill strike, even though The Shadow Before takes place in Massachusetts and Beyond Desire in Georgia. In the four novels written by women, though, women’s organization of and participation in the strike come to the forefront. Those written by Southerners – Dargan, Lumpkin, and Page – begin with women deciding to move their families to the mill towns. The family labor system within the mills gets much attention in these novels, leading to women with children to agitate for schools in the mill towns. Foremost among the organizers in these novels are those based upon the actual historical figure Ella May Wiggins. Although best known now for her ballads, such as “The Mill Mother’s Song” (posthumously known as “Mill Mother’s Lament”),1 she was instrumental in organizing African American workers in Bessemer City, where she worked as a spinner at American Number Two mill. Each of the Gastonia novels written by women, with the exception of Dargan’s, include versions of “The Mill Mother’s Song,” and they all provide accounts of Wiggins’s murder.

1

NCLR included the lyrics of “The Mill Mother’s Lament” in NCLR 2000, within the layout of Walter Squire’s essay on the Gastonia mill strike novels.

2018

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE V I E W

PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE GASTON GAZETTE

24

While the previous Gastonia novelists commemorated Ella May Wiggins, Wiley Cash places her on center stage, beginning The Last Ballad with her voice, her history. Whereas the Gastonia novelists of the 1920s and 1930s were primarily concerned with class consciousness, through the voices of Ella May Wiggins and other characters, Cash highlights place, race, gender, and relationships, in addition to class. We see Wiggins before she becomes class conscious, and yet she already highlights the burdens placed upon her by her gender and class, and through those burdens she unites with her African American neighbors long before she hears any northern organizer making an argument for the necessity of racial equality. In fact, the historical Wiggins was murdered not for being a ballad singer but for her unionization of African American workers. The Last Ballad is an amazing novel, with chapters told from the perspectives of numerous characters, including Ella May Wiggins; her now elderly daughter, ABOVE Ella May Wiggins (1900–1929)

Lilly; a mill owner, Richard McAdam, and his daughter, Claire, and wife, Katherine; and Hampton Haywood, an African American labor organizer, among others. If there’s one flaw to the novel, it’s that Cash intrigues us with the voice of a character but then shifts to a new character who intrigues and onto yet another character who intrigues so that we are left wanting more from voices he has at least momentarily abandoned. This approach, however, highlights that any moment, any place is a collection of voices, people, and experiences, complicating the position-driven nature of contemporary media, which can manifest itself in historical studies, too. Cash’s implicit suggestion that every voice is important, especially those least frequently heard, produces much needed empathy. The earlier Gastonia novelists used literature as a means of political persuasion, perhaps with the desire to boost workers into class-consciousness, but, considering the time, economic, and educational constraints placed upon workers, much more likely the intended audiences were middle-class readers upon whose sympathies the texts preyed. Cash instead uses literature to build bridges of compassion. This is perhaps best demonstrated in the relationship between Ella and Katherine McAdam, the wife of a mill owner who seeks out Ella, develops a friendship with her, and assists her in helping the African American organizer Hampton Haywood escape town. Katherine never develops class consciousness, nor does she meditate upon how her wealth is dependent upon the exploitation

of mill laborers, not to mention white supremacist hierarchy, but she does feel intensely for Ella, her empathy inspired by their shared experience of having lost children. That reaching across class divide on the basis of shared experience extends Ella’s bridging the racial divide through her sharing space with her African American neighbors and co-workers. The effect of the multiplicity of voices is that The Last Ballad achieves a dialogic polyphony akin to what the literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin saw operating in the novels of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Rather than the diverse expressed thoughts, backgrounds, and experiences culminating in a synthesis, Cash’s characters retain complications and contradictions that reveal their full humanity. Figures in the proletarian Gastonia novels of the 1930s tend to fall within neat moral categories – the noble labor organizers and striking mill workers, corrupt mill owners and other members of the bourgeoisie, and, in between, residents held under the sway of a capitalist and racist system that doesn’t benefit them. However, mill owners in The Last Ballad are offered the chance of redemption, as when Richard McAdam participates in Hampton Haywood’s escape. In other cases, owners are shown to be victims themselves, and organizer and worker prejudices display an incomplete radicalization. The Goldberg brothers who run the mill where Ella works escaped European anti-Semitism to awake their first morning in North Carolina “to the orange glow of the six-foottall wooden cross afire in their front yard” (12). The Protestant power structure of Bessemer City situates the Goldbergs as “white but not American” and compels them “not to treat their workers OPPOSITE RIGHT The surviving children of

Ella May Wiggins

North Carolina on the Map and in the News