NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE VI E W O N L I N E

FALL 2023

NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE OF NORTH CAROLINA

n

F E AT U R I N G n

Randall Kenan Prize Essay by Jane Haladay on Lumbee Children’s Literature n Poetry by Tonya Holy Elk n Essays by Brittany D. Hunt and Synora Hunt Cummings n Excerpts from the lumBEES’ Women of the Dark Water

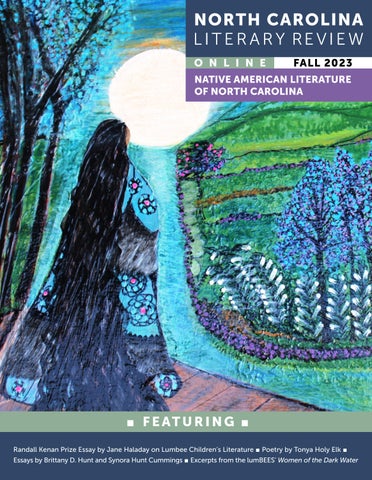

COVER ART Moon Dancer #1 (watercolor, textured media, and acrylic, 14x14) by Joan C. Blackwell After retirement from a career of many years as a Department of Defense classified management analyst in northern Virginia, JOAN C. BLACKWELL returned to her roots in Lumberton, NC, and completed a master’s in Art Education at UNC Pembroke, where she formerly earned her bachelor’s degree. As a recognized artist in the Lumbee Tribe community, she has been featured often in newspapers, on television, and has conducted art workshops for several National Art Education Association events across the US, as well as offering classes and events in her Lumbee community. Her work has been shown in numerous solo exhibitions and appears in many private and public collections.

COVER DESIGNER NCLR Art Director DANA EZZELL LOVELACE is a Professor at Meredith College in Raleigh. She has an MFA in Graphic Design from the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence. Her design work has been recognized by the CASE Awards and in such publications as Print Magazine’s Regional Design Annual, the Applied Arts Awards Annual, American Corporate Identity, and the Big Book of Logos 4. She has been designing for NCLR since the fifth issue, and in 2009 created the current style and design. In 2010, the “new look” earned NCLR a second award for Best Journal Design from the Council of Editors of Learned Journals. In addition to the cover, she designed the Haladay essay on Lumbee children’s books, the Katz and Powell short stories, and the Green Performance Poetry Prize story.

Produced annually by East Carolina University and by the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association © COPYRIGHT 2023 NCLR

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y RE VI E W O N L I N E

FALL 2023

NATIVE AMERICAN LITERATURE OF NORTH CAROLINA IN THIS ISSUE 6

n

Native American Literature of North Carolina includes poetry, prose, and drama Leslie Locklear Christina Pacheco Darlene H. Ransom Devra Thomas

Synora Hunt Cummings Jane Haladay Tonya Holy Elk Brittany D. Hunt

38 n Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues includes poetry, fiction, pedagogy, and book reviews

Cori Greer-Banks Michael Keenan Gutierrez Christy Alexander Hallberg Allison Harris Allison Adelle Hedge Coke Kimi Faxon Hemingway George Hovis Lockie Hunter Shelley Ingram Emily Alice Katz Randall Kenan Jon Kesler Kristina L. Knotts

Phillip Lewis Al Maginnes Joseph Mills Daniel Moreno Michael Parker Terry Roberts Josh Roiland Ann Rotchford Lee Smith Elizabeth Spencer Elizabeth Wellman Jesse Wharton Barbara Wright

J.S. Absher Joseph Bathanti Barbara Bennett Richard Betz Charles Waddell Chesnutt Jim Clark Marie T. Cochran Sharon E. Colley David Wright Faladé Charles Frazier Sarah Gaby Michael Gaspeny Jill Goad Sally Greene

104

North Carolina Miscellany includes poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and book reviews

n

Onyx Bradley Amanda M. Capelli Johnny Cate Keith Flynn Janet Ford Roxanne Henderson Mimi Herman

n North Carolina Artists

Joan C. Blackwell Bea Braveboy Gabriela Costas Bre Barnett Crowell Raven Dial-Stanley

Culley Holderfield James W. Kirkland Michael Loderstedt Dale Neal Alessandra Nysether-Santos Scott Owens

in this issue n Sharon Dowell Frank Holliday Alisha Locklear Monroe Evynn Richardson Jeremy Russell

Deborah Pope David E. Poston Gary V. Powell Cheryl Skinner Katherine Soniat Allan Wolf

4

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

North Carolina Literary Review is published annually in the summer by the University of North Carolina Press. The journal is sponsored by East Carolina University with additional funding from the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. NCLR Online, published in the winter and fall, is an open access supplement to the print issue. NCLR is a member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals and the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses, and it is indexed in EBSCOhost, the Humanities International Complete, the MLA International Bibliography, and the Society for the Study of Southern Literature Newsletter.

Address correspondence to Dr. Margaret D. Bauer, NCLR Editor ECU Mailstop 555 English Greenville, NC 27858-4353 252.328.1537 Telephone 252.328.4889 Fax BauerM@ecu.edu Email NCLRstaff@ecu.edu https://NCLR.ecu.edu Website

NCLR has received 2022–2023 grant support from the North Carolina Arts Council, a division of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, and from North Carolina Humanities.

Fall 2023

Subscriptions to the print issues of NCLR are, for individuals, $18 (US) for one year or $30 (US) for two years, or $30 (US) annually for institutions and foreign subscribers. Libraries and other institutions may purchase subscriptions through subscription agencies. Individuals or institutions may also receive NCLR through membership in the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association. More information on our website. Individual copies of the annual print issue are available from retail outlets and from UNC Press. Back issues of our print issues are also available for purchase, while supplies last. See the NCLR website for prices and tables of contents of back issues. Submissions NCLR invites proposals for articles or essays about North Carolina literature, history, and culture. Much of each issue is thematically focused, but a portion of each issue is open for developing interesting proposals, particularly interviews and literary analyses (without academic jargon). NCLR also publishes high-quality poetry, fiction, drama, and creative nonfiction by North Carolina writers or set in North Carolina. We define a North Carolina writer as anyone who currently lives in North Carolina, has lived in North Carolina, or has used North Carolina as subject matter. See our website for submission guidelines for the various sections of each issue. Submissions to each issue’s special feature section are due August 31 of the preceding year, though proposals may be considered through early fall. Issue #33 (2024) will feature NC Disability Literature, guest edited by Casey Kayser Issue #34 (2025) will feature NC LGBTQ+ Literature, guest editor James A. Crank Issue #35 (2026) will feature NC Mysteries and Thrillers, guest edited by Kirstin L. Squint Please email your suggestions for other special feature topics to the editor. Book reviews are usually solicited, though suggestions will be considered as long as the book is by a North Carolina writer, is set in North Carolina, or deals with North Carolina subjects. NCLR prefers review essays that consider the new work in the context of the writer’s canon, other North Carolina literature, or the genre at large. Publishers and writers are invited to submit North Carolina–related books for review consideration. See the index of books that have been reviewed in NCLR on our website. NCLR does not review self-/subsidy-published or vanity press books.

ISSN: 2165-1809

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

5

Editor Margaret D. Bauer Art Director Dana Ezzell Lovelace Guest Feature Editor Kirstin L. Squint Digital Editor Devra Thomas Art Editor Diane A. Rodman Poetry Editor Jeffrey Franklin Founding Editor Alex Albright Original Art Director Eva Roberts

Graphic Designers Karen Baltimore Stephanie Whitlock Dicken Sarah Elks Senior Associate Editor Christy Alexander Hallberg Assistant Editors Desiree Dighton Anne Mallory Randall Martoccia Editorial Assistants Amber Knox Daniel C. Moreno Wendy Tilley Interns Dasani Cropper Megan Howell Abby Trzepacz

EDITORIAL BOARD Hannah Dela Cruz Abrams English, UNC Wilmington

Rebecca Godwin Emeritus, Barton College

Christie Hinson Norris Carolina K-12

Catherine Carter English, Western Carolina University

Marame Gueye English, East Carolina University

Angela Raper English, East Carolina University

Celestine Davis English, East Carolina University

Kate Harrington English, East Carolina University

Glenis Redmond Poet Laureate, Greenville, SC

Meg Day English, North Carolina State University

George Hovis English, SUNY-Oneonto

Amber Flora Thomas English, East Carolina University

Kevin Dublin Elder Writing Project, Litquake Foundation

Amanda Klein English, East Carolina University

Robert West English, Mississippi State University

Gabrielle Brant Freeman English, East Carolina University

Celeste McMaster North Carolina Writers’ Network

Brian Glover English, East Carolina University

Tariq Moore Department of Language and Literature North Carolina Central University

6

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

NCLR’s First Guest Editor Signing Off by Kirstin L. Squint, Guest Feature Editor

It is with mixed emotions that I introduce the 2023 fall online special feature section on literary production by the state’s Indigenous peoples, the final one in my term as the journal’s guest feature editor. The most prominent emotion I feel is pride at what the editorial team has accomplished and how we have been able spotlight so much incredible writing and artwork by Native American citizens from North Carolina’s tribes. The fall online feature begins with Jane Haladay’s important essay on the way she uses Lumbeeauthored children’s books (Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming Y’all: Nakoma’s Greatest Tradition, both published in 2020) in her service learning classes at UNC Pembroke to engage with local elementary schools. Haladay’s essay demonstrates the importance of representation and how meaningful it is for both Lumbee college and elementary students to see themselves in the pages of books authored by Lumbee tribal citizens, Brittany Hunt, Christina Pacheco, and Leslie Locklear. Haladay’s essay is the winner of the 2023 Kenan Prize for best essay on a new North Carolina writer, and though it is also included in the 2023 print issue, sharing the full essay here broadens the access to and impact of this important work. Haladay’s teaching materials are available through NCLR’s Teaching North Carolina Literature initiative, funded by a Community Research Grant through North Carolina Humanities. Complementing Haladay’s essay is a reflection by Brittany Hunt, author of

Whoz Ya People?. Hunt poignantly details how she came to write her story, which was a response to a professor who assigned a blatantly misrepresentational children’s book about Native peoples in a graduate-level course she took. Hunt articulates the love she poured into Whoz Ya People?, a nuanced tale of a Lumbee boy from Baltimore finding his community in Robeson County, explaining her purpose powerfully: “I grew up without any Lumbee children’s books. But now no Lumbee child will ever have to do that again.” Hunt is also the co-host of The Red Justice Project, a podcast dedicated to illuminating the stories of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples; my interview with her and her co-host, Chelsea Locklear, was included in the Winter 2023 online issue. Following Hunt’s essay, Lumbee citizen Synora Hunt Cummings reflects on her experience watching the new version of Paul Green’s well-known outdoor drama, The Lost Colony, which has been staged in Manteo since 1937, depicting the events surrounding the first short-lived English colony in North America. The production was changed significantly in 2021 when all of the Native American roles were played by Native peoples, rather than white actors in redface, for the first time, and Cummings tells about seeing her people finally represented on the stage. She also reminds us that the story is not one “of a colony lost in history”; rather, it is one of “Natives and settlers forging rapport and interrelation.”

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

7

NORTH CAROLINA

Native American Literature of North Carolina We are honored to include here, too, an excerpt of the play, lumBEES, Women of the Dark Water, which was staged in 2019 at Fayetteville’s Cape Fear Regional Theater. NCLR’s digital editor, Devra Thomas, attended one of the six sold-out performances, noting in her introduction that the play was remounted in 2022 at UNC Pembroke. Our excerpt here attempts to capture the play’s memoir and autoethnographical elements. Our guest feature section ends with a poem by Tonya Holy Elk, who has another poem in the print issue. “Women of the Red Earth” celebrates the strength of Indigenous women and their sacred role in relation to the natural world. The poem underscores these ideas through its use of quatrains that emphasize “the four corners, the four directions.” Alisha Locklear Monroe’s painting Symbolic accompanies Holy Elk’s poem, and the artist featured with Holy Elk’s print issue poem, Joan C. Blackwell, shares another Moon Dancer painting for this issue’s cover. You will find other Native artists’ works with the other content in this section (and throughout the other 2023 issues’ feature sections). I am thankful to Margaret Bauer for asking me to be NCLR’s first guest feature editor. This has been a tremendous journey, and it is my hope that NCLR will continue to receive work by and about North Carolina’s Indigenous peoples beyond the 2023 issues. Though this issue highlights work by Lumbee writers and artists, NCLR always welcomes submissions from all of North Carolina’s tribal nations. n

8 Coming Home: Affirming Community through Lumbee Children’s LIterature 2023 Randall Kenan Prize essay by Jane Haladay illustrations by Bea Brayboy, Raven Dial-Stanley, and Evynn Richardson 24 Whoz Ya People?: Musings from the Author on Her Lumbee Children’s Book an essay by Brittany D. Hunt illustration by Bea Brayboy 26 Living My Native Past in the Present an essay by Synora Hunt Cummings 28 lumBEEs, Women of the Dark Water a play excerpt introduced by Devra Thomas 37 Women of the Red Earth a poem by Tonya Holy Elk art by Alisha Locklear Monroe

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE 38 n

Flashbacks: Echoes of Past Issues

104 n

North Carolina Miscellany

poetry, fiction, pedagogy, and book reviews

poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and book reviews

8

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

2023 RANDALL KENAN PRIZE WINNER

COMING HOME

by Jane Haladay

AFFIRMING COMMUNITY THROUGH LUMBEE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

EVERY ASPECT OF INDIGENOUS EXPERIENCE AND CULTURE is deter-

distinctiveness through shared stories, language, and place are the themes of two recent Lumbee children’s books, each of which is simultaneously an engaging story and a space for Lumbee children in Robeson County and beyond to read their own stories into the lives of the young protagonists, Henry and Nakoma, whose names, faces, families, and speech allow all Lumbee children to see and hear themselves and their people joyfully represented in the boys’ experiences. The National Council of Teachers of English underscores the power of such representation in its 2015 “Resolution on the Need for Diverse Children’s and Young Adult Books,” affirming that “Stories matter. Lived experiences across human cultures including realities about appearance, behavior, economic circumstance, gender, national origin, social class, spiritual belief, weight, life, and thought matter.”1 Mr. Jim, the elder in Brittany D. Hunt’s

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

mined by being in relationship – with humans, with more-than-humans, and with places – and relationships are created and fortified through storytelling. Down in Southeastern North Carolina, in the Lumbee community of Robeson County, asking someone “Who’z ya people?” is both an invitation to discover and understand connections through kinship and place and a kind of vetting process for figuring out who someone belongs to, which stories might be shared or embellished between individuals, families, and the larger community. Belonging, kinship, and expressing cultural 1

JANE HALADAY is a Professor of American Indian Studies at UNC Pembroke, where she teaches Native American literature and other AIS courses that incorporate service learning, writing enrichment, and international Indigenous travel study. She has published a range of critical and creative work. Among other recognitions, Jane has received UNCP’s Excellence in ServiceLearning Award (2016) and the Outstanding Allyship Award from UNCP’s American Indian Heritage Center (2021).

“Resolution on the Need for Diverse Children’s and Young Adult Books,” National Council of Teachers of English 28 Feb. 2015: web.

I am grateful to Dr. Brittany Hunt, Dr. Leslie Locklear, and Ms. Christina Pacheco for sharing their time with me to discuss their books for this article. I continue to be extremely grateful to the dedicated third-grade teachers at Union Elementary School, including Ms. Katara Bullard, Ms. Ginger Brayboy, and Ms. Karen Revels, who always find time for service-learning in their busy teaching schedules, and always treat my students and me with kindness and positivity. I am in awe of the good work they do with their students and am honored to be in community partnership

Native American Literature of North Carolina

2

“As a child, I read a lot of books. I read constantly. I loved learning about new characters and exploring the world from my own house. The characters . . . might be adventurers, witches, wizards, doctors, lawyers, spies, explorers . . . However, there was one thing that they were not: Lumbee.” —Brittany D. Hunt (Author’s Note)

3

Jane Haladay’s service learning assignment is included among the “Teaching North Carolina Literature” materials on NCLR’s website.

4

Institute of Education Sciences’ National Center for Education Statistics in the United States website for Union Elementary School’s data from the 2020–2021 school year. Of note in this data is the fact that of 403 enrolled students at UES during this school year, four hundred were eligible for the free lunch program, one indicator of children living in low income and/or food insecure homes in Robeson County. According to the NCChild.org website scorecard for Robeson County elementary students, only 24.9% of third graders countywide scored proficient in reading. These are some of the reasons my service-learning community partnership with the third-grade teachers at UES for the past nine years has been so meaningful to me, to the teachers at UES, and to the third-grade Union Eagles and UNCP Native Literature students.

5

For information on the eight state-recognized and one federally recognized American Indian tribes in North Carolina, see the Triangle Native American Society’s website. For a map of North Carolina tribal communities, see the North Carolina Department of Administration’s website.

Brittany D. Hunt, Whoz Ya People?, illus. Bea Brayboy (Independently published, 2020), unpaginated.

with them. I also thank Mr. Sandy Jacobs, the Director of the Office of Community and Civic Engagement at UNCP for his continued and unquestioning support of my service-learning activities with UES. Dr. Scott Hicks of the UNCP Teaching and Learning Center has long been my role model for best practices in service-learning, and he was the person who nudged me to take the plunge years ago, a step I have never regretted. A sincere miigwech to my writing pal, the author-scholar Dr. Carter Meland at the University of MinnesotaDuluth, for his suggestions on the original draft of this essay.

9

COURTESY OF THE AUTHORS

children’s book Whoz Ya People?, reminds the story’s protagonist of a people’s powerful connections when he tells him, “Henry, Henry, don’t you know / there’s much power in your kin? / And when we ask ‘whoz ya people,’ / we want to know who you are and who you’ve always been.”2 Themes of kinship, community belonging, and cultural affirmation are also the centerpiece of the service-learning assignment I included in my fall 2021 Introduction to American Indian Studies class and spring 2022 Native American Literature class at The University of North Carolina Pembroke (UNCP).3 While I have regularly taught this service-learning literacy assignment in some form over the past nine years, during the academic year 2021–2022, I used for the first time the two Lumbee children’s books Whoz Ya People?, by Brittany D. Hunt and illustrated by Bea Brayboy, and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! Nakoma’s Greatest Tradition, written by Leslie Locklear and Christina Pacheco and illustrated by Raven Dial-Stanley and Evynn Richardson. This service-learning collaboration takes place between my UNCP students and three third grade classes at Union Elementary School (UES) in Rowland, North Carolina, where the student population is approximately ninety two percent Lumbee.4 Authors Hunt and Pacheco are both Lumbee, as are all three of the wonderful third-grade teachers at UES – Katara Bullard, Ginger Brayboy, and Karen Revels – who have been my community partners in service learning for many years, along with other UES teachers. Author Leslie Locklear is Lumbee, Waccamaw Siouan, and Coharie, three of the staterecognized Native nations in North Carolina.5

N C L R ONLINE

10

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

. . . one student group’s writing prompt was, “If you had to pick one person to take with you to Lumbee Homecoming, who would you pick and why? What would you do with that person?”

Fall 2023

My experience using these two books in service-learning courses last year makes clear the tremendous power of tribally, regionally, and culturally specific representation in literacy education for both local Lumbee third graders and my own Lumbee university students, particularly, as well as for students of all heritage groups. The service-learning assignment I’ve developed has several elements, some of which have been modified over the past two years to accommodate a virtual format because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to spring 2020, my students always went to Union Elementary to teach the third-grade classes in person, but in 2021–2022, these assignments were taught virtually. (Happily, we returned to in-person teaching in fall 2022.) The UNCP students taught from video classrooms on campus, and the UES students participated from their three individual classrooms in Rowland, with their dedicated teachers negotiating troublesome tech issues to keep us all connected. The first step in my assignment with UNCP students is reading the children’s book aloud together in class, and I ask every student to read at least a line or two. We discuss the books and possible ideas for teaching them. I assign student groups to each third-grade class, and each group is responsible, based on my clear criteria, for creating a pre-lesson handout for the third graders that UES students complete with their teachers before meeting with my students, to help the younger learners focus on themes and events in the children’s book they’re about to hear. Next, each UNCP student group creates a lesson plan for the literacy activity that includes pre-reading questions based on the pre-lesson handout, reading aloud Whoz Ya People? (fall 2021) or It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! (spring 2022) to the third graders, checking for understanding and asking post-reading questions. The UNCP student groups (which I designate Corn, Beans, and Squash for important and sacred traditional Southeastern Indigenous foods, frequently referred to as “the three sisters”) then create a simple writing prompt for the third graders so each might connect personally to the story they just heard. An example of a writing prompt created by UNCP students for Whoz Ya People? in fall 2021 was “Describe what you remember from your first day of third grade or your first day at Union Elementary. Write at least two sentences.” This prompt connected third graders to Henry’s first day of school in Hunt’s book. For Locklear and Pacheco’s It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all!, one student group’s writing prompt was, “If you had to pick one person to take with you to Lumbee Homecoming, who would you pick and why? What would you do with that person?” The activity takes place on two separate days, during two UNCP class periods, working around the best times for the UES teachers. After the teaching activity concludes, my students are required to write a Reflection Essay on the servicelearning experience.6 6

Haladay’s Reflection Essay assignment is included among the “Teaching North Carolina Literature” materials on NCLR’s website.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

11

Both It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! and Whoz Ya People? are about different types of homecomings. It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y ’all! focuses on Nakoma, the book’s eight-year-old Lumbee protagonist, as he excitedly describes to his white friend, Spencer, the joys he anticipates at Lumbee Homecoming, the annual event that takes place in Pembroke, North Carolina, each July. Lumbee historian Malinda Maynor Lowery explains the significance of the fifty-three-year Homecoming tradition:

For a Lumbee boy like Nakoma, grape ice cream, the firetruck that tosses out candy during the parade, riding in golf carts, the strength and beauty of the powwow dancers, and the fireworks show are all highlights of Lumbee Homecoming.

The local [Robeson County] population swells by untold thousands for a wonderful cacophony of family reunions, beauty pageants, art exhibits, book readings, a powwow, a car show, and a gospel sing, among other events. Plenty of outsiders visit because it is simply one of the most entertaining happenings of the year in southeastern North Carolina. But it is far more family reunion than festival.7

ART ©2020 BY RAVEN DIAL-STANLEY AND EVYNN RICHARDSON

In Nakoma’s description of this atmosphere to Spencer, the authors effectively use the device of Nakoma explaining to his non-Lumbee friend the delights of Lumbee Homecoming to simultaneously celebrate this annual cultural event and to offer a model of inclusive, cross-cultural friendship between these eight-year-old boys. The book opens with Spencer asking Nakoma what his plans are for the upcoming weekend as the boys play at the park on “a hot July day.” Nakoma replies that he and his Grandma Etta will be “spending the whole weekend together” and “going to Lumbee Homecoming! All I can think about is my grandma, golf carts and grape ice cream. Good gah, I can’t wait!”8 When Spencer asks what Lumbee Homecoming is, Nakoma regales him with stories of the wonders of Homecoming, each of which is a cultural touchstone for Lumbee people and for all who attend Lumbee Homecoming. For a Lumbee boy like Nakoma, grape ice cream, the firetruck that tosses out candy during the parade, riding in golf carts, the strength and beauty of the powwow dancers, and the fireworks show are all highlights of Lumbee Homecoming. Grandma Etta likes her lemonade and a collard sandwich, a beloved Lumbee delicacy, and Nakoma likes his funnel cake (7). All of these events take place in the embrace of family and cultural community, the overarching theme of Locklear and Pacheco’s book. Homecoming for Nakoma, as for so many Lumbee people, is an “annual reunification celebration” (Lowery xii ). Nakoma tells Spencer that at the fireworks show, the final event of Homecoming, “Grandma always pulls me in close and Uncle Jerry smiles. This is the best part of the day” (13). The book

ABOVE Nakoma and Spencer, an

illustration by Raven Dial-Stanley and Evynn Richardson for It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all!

7

Malinda Maynor Lowery, The Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle (U of North Carolina P, 2018) 40; subsequently cited parenthetically.

8

Leslie Locklear and Christina Pacheco, It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all!: Nakoma’s Greatest Tradition, illus. by Raven Dial-Stanley and Evynn Richardson (Independently published, 2020) 1; subsequently cited parenthetically.

12

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

The authors of It’s

ends with Nakoma and Spencer standing on the playground facing each other, smiling. Nakoma tells Spencer, “It’s Lumbee Homecoming,” while Spencer, thoroughly won over by Nakoma’s stories of this magical event, asks, “Wow can I come?” (15). The authors of It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! use Nakoma’s repetition of what he’s looking forward to about Homecoming to emphasize key themes: “Grandma, golf carts, and grape ice cream. Good gah, I can’t wait,” is repeated three times in the book, and a fourth time with a slight variation when Nakoma thinks about “Miss Lumbee, golf carts and grape ice cream. Good gah, I can’t wait!” (10). The alliteration in the G sounds and the cadence of these repeated phrases – especially when read aloud – animate this story with Nakoma’s excitement. A lively, colorful illustration shows Spencer and Nakoma sitting on the back of a golf cart facing readers, with Spencer’s eyes drawn in spirals and his tongue out in a lickyour-lips revery as five imaginary grape ice cream cones form a fan above his head (8). Throughout the book are Dial-Stanley and Richardson’s illustrations of significant and familiar Pembroke landmarks that are some of the locations embedded in Lumbee Homecoming happenings, including Berea Baptist Church and The University of North Carolina Pembroke. It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! was born from Locklear and Pacheco’s idea that, as elementary educators in Robeson County, they wanted to see literacy materials for Lumbee students that reflected Lumbee children’s contemporary experiences, recognizing the way they dress, eat, speak, play, and celebrate traditions. To find such a book, these authors realized they had to write it themselves. Like many inspirations, this book grew out of a casual conversation between Locklear and Pacheco as they discussed the lack of Lumbee representation in children’s literature. Pacheco explains that after a conversation with a colleague, “I walked over to Leslie’s office, I said, ‘Hey, we should write a book.’” Locklear emphasizes Pacheco’s central role in lighting the flame that would bring their book into being. “So I truly credit her with . . . being the [visionary] because I was like, Oh, this is a cute little book,” Locklear explains. “And then Christina [said], Yeah, I already communicated with Amazon, this is how we’re going to [do it]. And I was like, Whoa, she’s for real. Like, she’s for real for real.”9 The energy of these author-educator collaborators and friends in creating what Locklear calls their “passion project” is evident in both the book itself and in the conversations I have engaged in with them about the book and its work in the world. Locklear visited my UNC Pembroke Native American literature class in spring 2022 to read her book to my students, who would be teaching it during service-learning the following week.

Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! use Nakoma’s repetition of what he’s looking forward to about Homecoming to emphasize key themes: “Grandma, golf carts, and grape ice cream.

COURTESY OF LESLIE LOCKLEAR COURTESY OF CHRISTINA PACHECO

ABOVE TOP Leslie Locklear ABOVE BOTTOM Christina Pacheco

Fall 2023

9

Personal interview with Christina Pacheco and Leslie Locklear, 4 May 2022; quotations from these women, aside from those from their book, are from this interview.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

13

Although my students and I had previously read the book aloud together in class, experiencing Locklear’s animated, elementary educator reading/performance brought the story fully to life. UNCP students had a chance to ask questions of the author, during which time Locklear explained that while It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! was written for any reader, it was also written with Robeson County elementary educators in mind, because “as an elementary educator [herself ], [she wasn’t] seeing this kind of material in the classroom and [she] heard the same thing from other elementary educators.” To this end, the book includes a page titled “Digging Deeper Educator Resources,” followed by a page with a short history of Lumbee Homecoming. The “Educator Resources” page includes questions for “Whole Group Discussion” and a prompt for a “Writers Workshop” in which teachers might ask their students to “Tell me about your favorite family tradition.” One group discussion topic points out the phrase “good gah” as one that students might not be familiar with and asks them to speculate on what it might mean, without providing an answer. Brittany D. Hunt’s Whoz Ya People? tells the story of a different kind of Lumbee homecoming. In Whoz Ya People?, which is written in rhyming verse, we follow the story of eight-year-old Henry (named for the Lumbee hero and Confederate conscription resistor Henry Berry Lowry) and his family, who return to their Robeson County home place from Baltimore, Maryland, where young Henry was born and raised. Baltimore isn’t a random reference, of course; a large and vital Lumbee community lives in East Baltimore, which formed after many families moved there after World War II seeking work.10 Thus, although Henry in Hunt’s book is presumably leaving a familiar Lumbee community in Baltimore to return to the original homeland of his Lumbee people, he is still “nervous as could be” on his first day of school, when the story’s events take place. Before he arrives at school, Henry asks, “Mama, Daddy, / what do I do if no one talks to me?” His parents reassure him that will certainly not

One group discussion topic points out the phrase “good gah” as one that students might not be familiar with and asks them to speculate on what it might mean, without providing an answer.

10

See Maynor Lowery (130–31) and Stephanie Garcia, “A UMBC professor Is Documenting the History of the Lumbee Indian Community in Baltimore,” Washington Post 13 Dec. 2020: web.

14

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

be the case, and it isn’t. The remainder of the story details Henry’s encounters with the many teachers, school staff, students, and cousins, all of whom know – or are – his “people,” which quickly solidifies his deep, immediate connection to the Robeson County Lumbee community and puts Henry increasingly at ease. Hunt includes names in the story that are familiar to all Lumbee people, including Henry’s teachers, Ms. Locklear (who may or may not be related to the Locklears of Locklear’s Collards in Locklear and Pacheco’s book) and Ms. Oxendine. The janitor, Mr. Sam, tells Henry he knew Henry’s Grandma Hazel (who “sewed the finest quilts”), his Grandpa Jerry (who “made the best cornbread”), and that once a long long time ago, I took your Aunt Rhoda on a date.

ARTWORK ©2020 BY BEA BRAYBOY

But please don’t tell your Uncle Earl, boy, he might kill me out. But son, it’s sure good to see you. You’ll do good here, I have no doubt.

Aunt Rhoda, Hunt told me, is named in honor of Henry Berry Lowry’s wife, Rhoda Lowry, another historical reference Lumbee people will recognize.11 In this scene with Mr. Jim and Henry, illustrator Bea Brayboy depicts Mr. Sam talking to Henry while mopping the school hallway. The illustration is framed on two sides by four thought clouds with scenes of Grandma, Grandpa, Aunt Rhoda and Mr. Sam on a date at the Pembroke McDonald’s, and Aunt Rhoda with Uncle Earl, his weightlifting biceps bulging, letting readers know that Mr. Sam has a point about keeping his long-ago date with Aunt Rhoda a secret. These image clouds are not directly connected (as thought bubbles often are by a succession of smaller bubbles) to either Mr. Sam or Henry, making readers wonder whether these are Mr. Sam’s memories or Henry’s imaginings of what Mr. Sam is describing. That these images are likely both is an effective visual device for strengthening the growing ecosystem of relationships we see Henry coming to understand as he learns who his people are. The last page of Henry’s story shows his nuclear family, Lumbee historical figures, and the new relatives and friends he met at school that day in an arch behind his smiling, blue-eyed face. He is “so amazed” reflecting on his day, thinking to himself, “these really are my people, / they know me and I know them.” Like Locklear and Pacheco, Hunt’s book emerged to address a lack of representation – and also out of personal academic frustration. Hunt recalls “a very specific moment” that spurred her to write the book. She explains that “I actually had to write it because I took

These image clouds are not directly connected (as thought bubbles often are by a succession of smaller bubbles) to either Mr. Sam or Henry, making readers wonder whether these are Mr. Sam’s memories or Henry’s imaginings of what Mr. Sam is describing.

ABOVE Mr. Sam and Henry,

illustrated by Bea Brayboy for Whoz Ya People?

11

Personal interview with Brittany Hunt, 3 Jan. 2022; all unattributed quotations from the author are from this interview. See Lowery, The Lumbee Indians for details about Henry Berry Lowry’s reputation, resistance to conscription, and the formation of the Lowry Gang.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

15

“As I grew older, I wondered why there were not more Native children’s books or Native characters in children’s books. In most children’s books that do have Native characters, the way we are depicted is extremely inaccurate and outdated.” —Brittany D. Hunt (Author’s Note)

COURTESY OF BEA BRAYBOY COURTESY OF BRITTANY HUNT

ABOVE TOP Bea Brayboy ABOVE BOTTOM Brittany D. Hunt

a multicultural children’s literature class [in] my PhD program, and so we had to write a children’s book as a part of the class.” While most of her classmates composed their books using digital clip art, Hunt wanted original illustrations and invited Bea Brayboy to draw them. Hunt describes writing the book as “like a boom, like a resistance.” She elaborates:

[I]t was a really problematic class for me. . . . We were reading all of these wonderful books by Black authors and by Hispanic authors. And then once we got to the Native book week, that book was written by a white author. . . . I was so disappointed in my professor for choosing a book by a white author when there are so many different examples of Native children’s books that have Native authors. . . . And the book also was not even a good book. It was full of stereotypes, and it had like buffalos and tipis and like this . . . mysticism that people always associate with Native identity so much. . . . I wanted [my] book to be very much rooted in modernity and also in Southern culture as well, because most people [don’t associate] Natives with being Southern, and that’s a very big part of Lumbee identity. . . . I wanted a book that was super Southern and super Lumbee and super modern to kind of exist in contradistinction to the ways that my professor was trying to portray us . . . from the perspective of the white gaze [rather than] the perspective of, you know, actual indigeneity.

The book that resulted in collaboration with Brayboy’s illustrations is one that Hunt is extremely proud of. Like Locklear and Pacheco, authentic visual representation of Lumbee characters in Whoz Ya People? was important. Hunt’s characters were modeled after her own relatives, including Hunt’s Grandpa Jerry and her niece and nephew, Peyton and Paxton, to whom she dedicates Whoz Ya People? Also significant, according to Hunt, Henry’s long hair reflects how Brayboy’s grandson wears his own hair. Hunt, who has lived outside of Robeson County for years and will be living in Blacksburg, Virginia, beginning in 2023 when she

16

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Born in Lumberton, Hunt explains that “going home” will always mean going back to Robeson County. The same isn’t true of Henry in Hunt’s book. The fictional Henry was born in Baltimore, and so feels nervous “coming home” to Robeson County for the first time.

COURTESY OF RAVEN DIAL-STANLEY COURTESY OF EVYNN RICHARDSON

ABOVE TOP Raven Dial-Stanley ABOVE BOTTOM Evynn Richardson

12

Fall 2023

begins her faculty position at Virginia Tech, describes Henry’s story as one way she worked to reckon with her mixed feelings about calling Robeson County home but believing she is unlikely to ever live there permanently again. Born in Lumberton, Hunt explains that “going home” will always mean going back to Robeson County. The same isn’t true of Henry in Hunt’s book. The fictional Henry was born in Baltimore, and so feels nervous “coming home” to Robeson County for the first time. Although this aspect of his story isn’t Hunt’s experience, she explains that this is true for many Lumbee children who were born and raised outside of Robeson County. “And so [I’m] kind of reckoning with this belief that even if you’re not from there, you can always find home there,” Hunt states. “And I think that’s a major tenet of Lumbee homecoming celebrations as well. Like, even if you live in California or Iraq or England, you can always come home to where your people are and your people are going to accept you, or they should at least accept you.” Hunt elaborated on this latter aspirational aspect of envisioning Lumbee people’s acceptance of those who have lived away through Henry’s very positive experience in Whoz Ya People?: “I’m trying to write Lumbees in a way that I wish we could be all the time,” she admits. “Lumbees at certain points in history have been very accepting and at other points have not been. And so I’m trying to also reckon with those feelings, I think, of frustration as well.” Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! Nakoma’s Greatest Tradition are currently the only two children’s books that feature Lumbee kids in contemporary contexts.12 These books were written to honor today’s Lumbee children, to let them see themselves in books about “Indians” who don’t live in tipis or have grandmas with long silver braids; to see themselves as rural kids riding in golf carts or relocating to the country from distant cities. Like Hunt’s characters who mirror some of her own relatives, Locklear emphasizes that she and Pacheco: got very particular, as [illustrators Dial-Stanley and Richardson] were detailing out the photos, about what we wanted to see, even the hairstyle. . . . So even when we thought about the grandma, . . . my Aunt Claire . . . does not have this long gray hair. She’s got that short hair that a lot of our grandmas in our community kind of transition to in older age, because that was just common for us. And she’s not like a super skinny grandma. She’s a pretty meaty grandma. And we were like, okay, we want that representation because that is what we see.

Locklear and Pacheco’s and Hunt’s books stand alone as telling stories specifically about contemporary Lumbee boys in Robeson County. Other books published by Lumbee authors for children and juvenile readers include Arvis Boughman’s Chicora and the Little People: The Legend of Indian Corn (Aeon, 2011), Legends of the Lumbee (and some that will be) (Boughman, 2014), and the picture book How the Oceans Came to Be (7th Generation, 2022); Adolph L. Dial’s The Lumbee (Indians of North America) (Chelsea House, 1993); and Charlene Hunt’s You Don’t Look Indian To Me (Charlene Hunt, 2011).

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

17

Christina agrees, adding that the act of authentically representing Lumbee people as they are today “creates this connection of kinship” so that

when a reader or someone reads the story, they can say, Oh, man, that skin tone resonates with my family. That hair texture resonates in my family. . . . So changing up the representation just a little bit and giving people a different perspective of not all Native Americans, Indigenous people look the same. And like I said, just to kind of continue building on the relationship of kinship. . . . Oh, that looks like me in that book. I can see myself and I have those similar experiences.

COURTESY OF JANE HALADAY

Karen Revels, one of the UES third-grade teachers whose students participated in last year’s service-learning activity, echoed Pacheco’s words almost exactly when I spoke with her and the other UES third-grade teachers during our virtual debriefing meeting in December 2021. After using Hunt’s Whoz Ya People? in fall semester with my Intro to AIS class of mostly first-year students, I asked the three elementary educators how their students had liked Hunt’s book. Revels said that her students enjoyed Whoz Ya People? for many reasons, but primarily

because there were names in the book that they could relate to. Some of the kids had the same last name [it was a] name they knew. . . . It helped . . . them make a connection to what they were hearing. So we really enjoyed it, you know. And we could say that the author is, her family is from this area. She knows exactly what you’re going through. She probably knows some of your family. So, that connection, it helped them to really enjoy what they were listening to.13

During this interview, I asked Revels, Bullard, and Brayboy if teaching Lumbee-authored books was even more of a “hook” for their students – who are always engaged when “the college students” come to visit – than the other books I’ve used for our service-learning

“Some of the kids had the same last name. . . . It helped . . . them make a connection to what they were hearing. So we really enjoyed it, you know. And we could say that the author is, her family is from this area. She knows exactly what you’re going through.” —Karen Revels, Elementary School teacher

ABOVE Several students in Jane Haladay’s

2022 UNC Pembroke class and the Union Elementary class they worked with

13

Personal interview with Katara Bullard, Ginger Brayboy, and Karen Revels, 15 Dec. 2021. Other quotations from these teachers are from this interview.

18

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

collaboration. All agreed this was definitely true. Ginger Brayboy added, “Yes, I told them in fact, I went to high school with Brittany’s dad. And they thought that was interesting, that I knew her on that level.” Katara Bullard told us, “And see, Brittany [Hunt] and I are sorority sisters; we crossed at the same time. So I told them I knew her and they were like, ‘How?’And, you know, that brought up another discussion.” Bullard added that Leslie Locklear, author of It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all!, is “another sorority sister and is my husband’s first cousin, so it’s like, I’m connected with all of them.” She waved her hand in a circle of inclusion in the air in front of her on Zoom in a truly “Whoz ya people?” moment of interrelatedness. Hearing these books read aloud provides yet another way that the third grade Union Eagles (the UES school mascot) are able to recognize themselves in Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y ’all!. In addition to the familiar names and faces of those they know and love and the places they live, work, play, and pray in Robeson County, linguistic representation is also written into each of these stories, proudly announced in each book’s title with the words “whoz,” “ya,” and “y’all,” and within the speech of the stories’ characters. Through Nakoma’s eager expression, “Good gah, I can’t wait!,” Locklear and Pacheco privilege Lumbee English and community language, as Hunt also does in Whoz Ya People?. The rhythm, cadence, and sound of the Lumbee language is not monolithic but varies according to which community or city someone is from, their age, and, at times – as in Henry’s story in Whoz Ya People? – by how much time they may have spent living outside of Robeson County. The distinctive rhythm, cadence, and sound of the Lumbee language is one way Lumbee people immediately recognize each other, whether their paths cross in Wilmington or Seattle, Raleigh or New Orleans. While recognizing these variations in Lumbee speech, linguist Walt Wolfram affirms that “The facts of Lumbee English demonstrate how community members define themselves and are defined by others through their language. . . . Study of Lumbee

In addition to the familiar names and faces of those they know and love and the places they live, work, play, and pray in Robeson County, linguistic representation is also written into each of these stories, proudly announced in each book’s title with the words “whoz,” “ya,” and “y’all,” and within the speech of the stories’ characters.

ABOVE Detail from Whoz Ya People? bookcover

Native American Literature of North Carolina

“In an important sense, language reflects the status of the Lumbee people, who defy conventional stereotypes while at the same time maintain a resolute sense of who they are as Indian people.”

N C L R ONLINE

19

English indicates that it is a robust, distinctive dialect that embodies important dimensions of a community-based culture.”14 Like all communities with culturally distinct languages, Lumbee people also code-switch, as Hunt discussed with me during our interview. “Maybe you don’t have the accent,” she said of some Lumbee people. “And for me, I do have it. I don’t have it right now talking to you. It shifts. But when I’m home and talking to my family, it immediately morphs back into a very distinctive Lumbee dialect like I’m sure a lot of your students have.” Importantly, there is no code-switching in either Whoz Ya People? or It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! Like other Indigenous authors who write their languages into their texts, readers of the same Native community understand what they’re reading and hearing, and those outside those communities are welcome – and expected – to work to learn those meanings. Wolfram explains, “In an important sense, language reflects the status of the Lumbee people, who defy conventional stereotypes while at the same time maintain a resolute sense of who they are as Indian people” (vii). When Henry’s art teacher, Ms. Oxendine, asks him, “Boy, whoz your people?” and he tells her, she responds, “Them Hunts in Fairmont you said? Off Five Forks? / Boy, them Hunts down there’s a mess.” Lumbees in Robeson County will recognize the Hunt name, the Fairmont community, and where Five Forks is, as well as understand that in calling Henry’s people “a mess,” Ms. Oxendine (and the author) are using a common Lumbee phrase to affectionately tease, not criticize, Henry’s kin while establishing connections: “I’m real good friends with your Daddy’s folks.” Acoma Pueblo author Simon J. Ortiz has also recognized Indigenous people’s resistance in having claimed imposed colonialist languages “and used them for their own purposes.” Ortiz insists, “This is the crucial item that has to be understood, that it is entirely possible for a people to retain and maintain their lives through the use of any language. There is not a question of authenticity here; rather it is the way that Indian people have creatively responded to forced colonization. And this response has been one of resistance; there is no clearer word for it than resistance.”15 Resistance to erasure through cultural and individual relatability, one of the themes I discuss with my UNCP students in both the Intro to AIS and Native American Literature classes, was clear to my students through reading and teaching these two Lumbee children’s books during service learning. Reflecting on teaching Whoz Ya People? in our fall Intro to AIS class, one student, Kendall Chavis, wrote that he felt the book worked well for service learning at UES

—Walt Wolfram

14

Walt Wolfram, Clare Dannenberg, Stanley Knick, and Linda Oxendine, Fine in the World: Lumbee Language in Time and Place (U of North Carolina P, 2002) 78; subsequently cited parenthetically.

15

Simon J. Ortiz, “Toward a National Indian Literature: Cultural Authenticity in Nationalism,” MELUS 8.2 (1981): 10.

20

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

because it “allowed students to feel familiar within the book as it referenced people and places that the students were accustomed to. The students specifically responded positively to the places in the book like Maxton and Saddletree. They also showed interest in knowing familiar last names such as Locklears.” Relating Lumbee language both to herself and to the third graders her group was teaching, Kaya Carter (Lumbee) observed, “The way [Hunt] used our ‘lingo’ and ‘slang’ helped me, our group[,] . . . understand and relate to it more. I feel it being written in that way made it [easier] for anyone to understand at any level.” Students in my spring Native Literature class reflecting on It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! observed similar reactions of excitement and connection by the UES third graders during their teaching lessons: “It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y ’all! is a great book and I am glad that I was introduced to it in this class,” wrote Brittany Best (Black), a student in that spring class, continuing, “I love how specific Dr. Locklear and Christina Pacheco were in their characters because they understood the power of representation.” Brittany noticed “how relatable [the book] was to the kids. . . . That goes to show that books like these are needed in schools. When children are given the opportunity to see themselves, their cultures, and traditions it gives them a sense of pride and encouragement.”16 Thoughtful educators and members of historically underrepresented communities know well that “Representation Matters.” This sentiment is much more than a social media hashtag. To those who have long been rendered invisible, silenced, or have remained chronically unrecognized in the artistic productions of majority culture, including children’s literature, “Representation Matters” is a rallying cry demanding the right to be seen and heard, a declaration of dignity that insists upon opportunities to express one’s identity and the collective cultural or national identity of one’s people through stories authored by members of those communities. The nonprofit We Need Diverse Books (WNDB) reports “2019 statistics from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center [showing] that the percentages of children’s books depicting main characters from diverse backgrounds” identified only “11.9% of main characters are Black/African, 1% are Native/First Nations, 5.3% are Latinx, 8.7% are Asian/Asian American, .05% are Pacific Islander, 41.8% are white, and 29.2% are animal/other.” Of children’s books whose author/illustrators who have the same “race or ethnicity” as the characters they are writing about, “The percentage . . . is 68.2% for Native/First Nations, 46.4% for Black/African, 80% for Pacific Islanders, 95.7% for Latinx, and 100% for Asian/Asian American.”17 Thus, it is clear that books like Hunt’s

“It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! is a great book and I am glad that I was introduced to it in this class.” —Brittany Best, student

Books like these are needed in schools. When children are given the opportunity to see themselves, their cultures, and traditions it gives them a sense of pride and encouragement.

16

17 The cited students’ names, heritage self“What are the Statistics Supporting identification, and quotations are used (here the Dearth of Diverse Literature?,” and later in this essay) with permission. We Need Diverse Books, 2022: web.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

21

The impact of these two books to promote positive models of Native boyhood extends beyond the third graders and the UNCP students who were involved in these service-learning lessons with them, creating new sets of relationships through reading.

COURTESY OF THE AUTHORS

ABOVE Detail from It’s Lumbee

Homecoming Y’all! bookcover

Whoz Ya People? and Locklear and Pacheco’s It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! are fulfilling a compelling community need for both Lumbee cultural expression and literacy education in Robeson County. Additionally, the fact that both Henry in Hunt’s book and Nakoma in Locklear and Pacheco’s book are eight-year-old Lumbee males is yet another intentional act of representation. Locklear explained that as professional educators, she and Pacheco gave a great deal of thought to what they observed as “a lack of American Indian male representation in any positive light, but also in terms of American Indian male literacy rates.” Therefore, they pondered “a way to build positive representation for American Indian males” and “spent a lot of time talking about character development.” The impact of these two books to promote positive models of Native boyhood extends beyond the third graders and the UNCP students who were involved in these service-learning lessons with them, creating new sets of relationships through reading. Ahelayus Oxouzidis (Kwakwaka’wakw), a student in my fall Intro to AIS class, felt that Whoz Ya People? “was a good choice for these third graders because it teaches some of the values as Native peoples we learn in class, [and] it also is a book made by one of their tribal members that speaks on their own nation[.] I love these kinds of books and I even recently bought a few just so I can read them and read them to my siblings.” In her reflection on teaching It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! with the third graders, Native Lit student Makaylie Jacobs (Lumbee) noticed that “All of the children, except for one, had been to Lumbee Homecoming. I think that this book made them feel seen.” She considered what having a book like It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! would have meant to her as a Lumbee third grader to “have had a book like this when I was younger.

22

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

“When books are removed or flagged as inappropriate, it sends the message that the people in them are somehow inappropriate. It is a dehumanizing form of erasure. Every reader deserves to see themselves and their families positively represented in the books in their schools.” —”Letter from 1,300 Children’s and YA Book Authors on Book Banning”

When I was little I saw barely any accurate representations of myself in books and movies. . . . I think a very positive thing about them listening to this book was that they had experienced Lumbee Homecoming and the characters represented them and the things they enjoy and connect with.” These observations by Makaylie, Ahelayus, Brittany, Kaya, and Kendall connect directly to Hunt’s, Locklear’s, and Pacheco’s purposes and intentions in writing these books, and illustrate the success of both books in achieving their authors’ goals Even as students and educators at UNCP and Union Elementary School celebrate the impact of Hunt’s and Locklear and Pacheco’s Lumbee children’s literature, and the longstanding representational void their stories have begun to fill, we are witnessing growing energy by some to see books like these banned. Nationwide, conservative lawmakers, local school boards, and some parents are ramping up their xenophobic efforts to pull from school libraries books that, as Learning for Justice authors Coshandra Dillard and Crystal L. Keels state, “challenge white-centric narratives and offer more honest retellings of history.” In May 2022, a “Letter from 1,300 Children’s and YA Authors on Book Banning” was published by We Need Diverse Books, pointing out, “This current wave of book suppression follows hard-won gains made by authors whose voices have long been underrepresented in publishing,” and raises alarm about the fact that “[w]hen books are removed or flagged as inappropriate, it sends the message that the people in them are somehow inappropriate. It is a dehumanizing form of erasure. Every reader deserves to see themselves and their families positively represented in the books in their schools.”18 The powerful testimony of the Robeson County educators, authors, and students whose voices I share in this essay amplify the statements of these thirteen hundred authors that the need for specific Indigenous literary representation for Lumbee

“I wish I would have had a book like this when I was younger. When I was little I saw barely any accurate representations of myself in books and movies. . . . I think a very positive thing about them listening to this book was that they had experienced Lumbee Homecoming and the characters represented them and the things they enjoy and connect with.” —Makaylie Jacobs (Lumbee)

18

“Letter from 1,300 Children’s and YA Book Authors on Book Banning,” We Need Diverse Books, 19 May 2022: web.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

23

ARTWORK ©2020 BY BEA BRAYBOY

elementary children in books like Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! is crucial. Hunt, Locklear, and Pacheco have other children’s books in the works, stories that Lumbee children in Robeson County and all of us can look forward to. The work these Native women author/educators do every day to write, teach, and share their people’s stories show their resistance to those who would silence Lumbee voices by suppressing authentic media representations of their community. The American Indian Studies students in my UNCP classes and the UES third graders who come together through service learning to hear, read, and discuss the stories of Henry and Nakoma also support the ongoing resistance to Lumbee erasure in children’s literature that Hunt, Locklear, and Pacheco have spearheaded. The simple act of reading a children’s book is, of course, not a simple act. All of us, by buying, reading, teaching, and sharing books like Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! are helping ensure that contemporary Lumbee children have positive role models to identify with. This type of literary affirmation is a daily homecoming for Native children, like Henry’s return to Robeson County from Baltimore and Nakoma’s cuddles with Grandma Etta and Uncle Jerry under the exploding summer night sky during the fireworks finale at Lumbee Homecoming. Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! invite Lumbee children to come on home to their people, at least for a bit, from wherever they are, wherever they’ve been, and wherever they may be going next. n

The simple act of reading a children’s book is, of course, not a simple act. All of us, by buying, reading, teaching, and sharing books like Whoz Ya People? and It’s Lumbee Homecoming, Y’all! are helping ensure that contemporary Lumbee children have positive role models to identify with.

ABOVE Detail from Whoz Ya People?

Eric Gary Anderson wrote explaining his selection of this essay for the 2023 Randall Kenan Prize: I loved this report from the field, detailing how and why the author’s UNCP students teach local, mostly Lumbee, third-grade students. The author skillfully balances discussion of literature, culture, literary criticism, pedagogy, and the all-important, thriving community partnerships between the University and local public schools. The service-learning assignments are well designed and sure to be useful for teachers, students, and other stakeholders not just in Robeson County but across the country. The closing discussion of recent efforts to ban books from public schools is timely. And the stories of Lumbee teachers meeting a clear need by writing their own Lumbee-centered Young Adult books is downright inspiring.

24

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

WHOZ YA

PEOPLE?: by Brittany D. Hunt

Musings from the Author on Her Lumbee Children’s Book with art by Bea Brayboy

As a kid, I remember being transported through the wardrobe to Narnia, and from Platform 9 ¾ to Hogwarts, and into the dystopian future through books like The Giver. Books provided a portal to new worlds and alternative realms that fascinated me. These worlds and realms, however, were often unequivocally white, and I rarely if ever had books that reflected my own life experience as an Indigenous girl. Throughout school, the books assigned told of Gatsby or Raskolnikov or Valjean, and I was captivated and enraptured by these tales. But again, time after time, book after book reflected experiences foreign to me in most ways, while my white peers relished unknowingly in the simplicity of representation. Of being the forever main character. This problem followed from K-12 to undergrad, to grad school, and to my PhD program in 2019 when I signed up for a multicultural children’s literature class. As a part of the requirements of the course, we had to buy several children’s books to read and

discuss in class. The books were generally diverse, reflecting the experiences or histories of Black, LGBTQ+, and Latinx communities, to name a few; all of these books were by members of the community they represented. There was also one book whose name I have purposefully forgotten that was meant to reflect Indigenous people. This book was written by a white author. It featured pictures of teepees, buffalo, and other imagery considered stereotypically Native. How could a multicultural children’s literature course assign a book about Indigeneity that was written by a non-Indigenous person? Wasn’t the point of the class to be more representative of the experiences of diverse people and of the perspectives of diverse authors? Why was the only non-BIPOC author chosen for the course the author of the Indigenous-themed book? I was not shocked that this professor had made this choice since he had made several uninformed comments about Indigenous people in past classes, but I was disappointed that he didn’t take the time to choose a children’s book by an Indigenous author, especially when this is not difficult to do. I made sure to voice my concerns in front of the entire class and I refused to read the book. Later in the course, we were assigned with writing our own children’s book. This task felt so monumental to me – to not only correct the ignorance of my professor, but to correct a lifelong journey of exclusion of Indigenous perspectives from books and media in general. I knew that this was not just a class assignment for me, but an opportunity to create something for my com-

BRITTANY D. HUNT is an Assistant Professor of Education at Virginia Tech and the owner of Indigenous Ed., LLC, co-host of the podcast The Red Justice Project, and the author of the Lumbee children’s book Whoz Ya People?. She is a graduate of Duke, UNC Chapel Hill, and UNC Charlotte.

BEA BRAYBOY, a member of the Lumbee Tribe, is the illustrator for Hunt’s Whoz Ya People, and the illustration here is from this book. She earned a BA in Spanish from UNC Pembroke and taught Spanish in North Carolina and South Carolina public schools for thirty-six years before retiring.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

munity to be proud of. And so, while my professor babbled on in class, I am proud to say that I ignored every word and instead wrote my children’s book. The idea for Whoz Ya People? was already in my heart. I knew I wanted to create something that was unabashedly Lumbee, which is the tribe I belong to. I wanted it to be about community, love, and our incredible history. And so I started with Henry, named after a notorious Lumbee/ Tuscarora man from my community named Henry Berry Lowry (you should look him up immediately!). In the book Henry, an eight-year-old Lumbee boy, has moved from Baltimore, Maryland, where there is a pretty large Lumbee community, back to Robeson County, North Carolina, where his parents are from. He’s nervous about beginning his first day of school and not knowing anyone or making any friends. But as soon as he steps foot in the door, he realizes his teacher and his momma are old friends. And then later, he meets the janitor who knows his aunt. He plays with his cousins on the playground. He meets an elder who tells him he’ll see him at church or for supper on Sunday.

I WANTED TO CREATE SOMETHING THAT WAS

UNABASHEDLY

LUMBEE

Henry quickly realizes that to be Lumbee in this community means you are never really alone; you are surrounded by your kin and by people ready to embrace and love you. The titular phrase Whoz ya people? is a common Lumbee colloquialism. It’s a phrase often used when two Lumbees are meeting for the first time to establish connection. It is contradistinct from American culture’s greeting of “what do you do?” – which is or can be a fundamentally hierarchical question. When people in my community ask me, “Whoz ya people?,” I often share that I am the granddaughter of Sonja and Jerry Hunt of Fairmont and Hazel and Haywood Johnson of Lumberton, and the daughter of Cordelia Chavis

N C L R ONLINE

25

and Ron Hunt. Typically, another Lum (short for Lumbee) will know at least one of my family members, and then they will share with me who their people are and what communities they are from. It is a fundamentally Indigenous way of communication that establishes relationality and kinship. Audra Simpson notes similar relationality methods amongst her own Kahnawà:ke people: “Who are you?” There is always an answer with genealogic authority - “I am to you this way . . .” ; “this is my family, this is my mother, this is my father”; “thus, I am known to you this way” . . . [T]he webs of kinship have to be made material through dialogue and discourse. The authority for this dialogue rests in knowledge of another’s family, whether the members are (entirely) from the community or not. “I know who you are.” Pointe finale. We are done; we can proceed.*

Throughout my storybook, several people ask little Henry who his people are, or they come up to him without needing to ask and mention knowing his family. This is a great source of comfort for Henry and for many Indigenous people more generally, who are also seeking to be known in a world hellbent on erasure. Also, the book features the use of Lumbee dialect throughout, mentions Lumbee foods, and Lumbee art forms. My own niece and nephew, Paxton and Peyton, are featured in the book (which is dedicated to them). Throughout the school year, the book is read in several schools in Robeson County, where most Lumbees live. This book is one of the things I’m most proud of creating. As Indigenous people, sometimes the path before us was already paved by some brave ancestor, or maybe our own mother or father. But sometimes there is no path at all, and we must be that person for someone else. I grew up without any Lumbee children’s books. But now no Lumbee child will ever have to do that again. I want to end this essay in thanks to all of the Lumbee children who inspired me to write the book, but also to all Lumbee adults who were once children and had to live in a world where Indigenous characters never made it into their books; Whoz Ya people? is my love letter to all of you. n

SARAH ELKS designed this layout. A graduate of Meredith College, * Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across she is based in Raleigh, NC, and works as a graphic designer with the Borders of Settler States (Duke UP, 2014) 9. Liaison Design Group.

26

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

Living My

NativePast Past Native

in the Present

by Synora Hunt Cummings Photographs by Cindy McEnery Photography; courtesy of The Lost Colony

The night has beckoned me here to this amphitheater as a spectator of the longest running outdoor drama, Paul Green’s The Lost Colony. Rain clouds hover against the sky, offering cool crisp air on a summer’s evening. The atmosphere is clear and inviting. The tar-top path meanders into rows of stadium seating. The set glows, as if beaming with pride at the birth of this acculturation. The crowd is not so large, and I find much solace in that. It is a mixed crowd: those who view the storyline as past tense and those who feel it in the present. Because there are fewer people here tonight, a presence of peace swaddles me and the meaning of this play is able to rest gently against my soul. Taking a seat, I am excited to be among my people as each character breathes life into this history. The characters of this drama are my people, the people of the Lumbee, are the people of the pine, people of the dark waters, rich with tannins, that lap against the knees of cypress trees. My people are the survivors of tribes whose cultures and rituals intertwined with the English colonizers who are being portrayed here. My people are part of the history put into motion long before “CRO” was carved into a tree. And on this night, my people live to tell the story of how we came to thrive along the present-day Lumber River.

Having grown up in Johnston County, North Carolina, not so far removed from my own community of Natives, though just far enough to feel ostracized both in The face of my the place where I lived and from people matters. the home that I longed for, I feel the palpable connection between the characters on the stage and the observers. It took many years before the painted red face no longer suited this play’s script. It has previously been a disappointment to look upon the cast and not see a face reflecting my own. The face of my people matters. Change has come. Native actors now portray the Native characters. Now, I see my own face and hear my own voice as the story pulses through my veins. I am Lumbee, a descendent of

. . . on this night, my people live to tell the story of how we came to thrive along the present-day Lumber River.

ABOVE Kat Littleturtle, a member of Snipe Clan,

representing her Kahtehnuaka Tuscarora people as the 2023 season narrator Born in Lumberton, NC, SYNORA HUNT CUMMINGS is an enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. She lives in Johnston County with her husband and three children where she works as a school counselor and volunteers in her Native community. This is her first publication.

Native American Literature of North Carolina

N C L R ONLINE

27

I am joyful seeing my Native people cast as the ancestors who fought against toil and trouble.

the Croatoan peoples. My DNA emerges from lines, scenes, and monologues. I am more than an observer. It is now my face the observer sees, my voice the observer hears, and it is my story being shared. Watching the story unfold feels like triumph. I am joyful seeing my Native people cast as the ancestors who fought against toil and trouble. Each is as familiar as my mother’s rocking when she caressed me against her bosom, humming songs of comfort in the soft light of the moon. My people represent me, and each face is glorious. My people, the descendants of this history, shatter the boundaries of representation. This performance is not about a colony lost in history, but rather one that was birthed beneath this sky and of these estuaries, inscribing a heritage of its own. Natives and settlers forging rapport and interrelation. This is an account that gives rise to the opportunity to thwart misrepresentation with heartbeats that keep time with our sacred drum. This is an account that raises our fists against red

face and embraces the raw reality of “we are still here.” We are still here. Paul Green’s The Lost Colony is a story of my people. The story of who we are intertwines like needles of long leaf pine in the fabric of English colonists, our histories seaming together to create panels of resilience, affability, and fortitude. There is not just one side to this story. One cannot exist without the other. One cannot be represented without the other. My people were cultivated from the very grains of this sand, harvested, and replanted in soil as red as their souls. The breath of my people filled the lungs of this narrative. The heart still beats with the rhythm of the drum. Every footstep continues to stir up the dust of our ancestors. The strength of our men remains as tall as the trees, and the hum of our mothers continue to beckon in the still of the night. This story, one of an English colony mingled among the Natives of this land, is certainly not lost on me. It touches my soul. n

ABOVE TOP One of the custom puppets designed by

Emmy-nominated puppet and theatrical designer Nicholas Mahon ABOVE BOTTOM Two of the Lumbee actors during the

2023 season

This essay will appear in Paul Green: North Carolina Writers on the Legacy of the State’s Most Celebrated Playwright, edited by Georgann Eubanks and Margaret D. Bauer, forthcoming in 2024 from Blair.

28

NORTH CAROLINA L I T E R A R Y R E V I E W

Fall 2023

lumBEES,

Women of the Dark Water Directed by Bo Thorp Produced by Darlene H. Ransom introduced by Devra Thomas

PHOTOGRAPH BY PAUL RUBIERA

North Carolina’s rich literary culture includes its long history of local-penned dramas. In 2009, the North Carolina Literary Review featured North Carolina drama and has run an occasional short play in other issues over the past thirty-plus years, as well as a few essays about dramatic works. Recently, we were delighted to discover we could include the following excerpts from a staged performance within the 2023 special feature on Native American Literature of North Carolina. The summer of 2019 had several momentous occasions for members of the Lumbee Tribe: in addition to the annual Homecoming Celebration held in Robeson County, Lumbees were able to celebrate their stories in music in Raleigh at the Governor’s Mansion as part of the “Music at the Mansion” series and on stage at Cape Fear Regional Theatre (CFRT) in Fayetteville with the original show lumBEES: Women of the Dark Water – A Memoir with Music. The theatrical show started because Darlene Holmes Ransom lived next door to CFRT’s founding artistic director, Bo Thorp. So when Ransom had an idea for a Lumbee women–inspired performance while watching a play Thorp was directing, she went back stage to tell her neighbor about her idea and ask if she would direct it. Old friends, the two got to talking about Ransom’s experience as a Lumbee woman, growing up in North Carolina. Thorp agreed to help shape the story for theatrical purposes. Starting in 2014 and over the course of several years, Ransom invited five other women to share their stories with the community. Given her extensive theater background, Thorp provided direction and dramaturgy, and renowned writer and filmmaker Georgann Eubanks provided scriptwriting assistance. The women sharing their lived experience with Ransom, The BEES as the women came to call themselves, were Roberta Bullard Brown, Dolores Jones, Jinnie Lowery, Jo Ann Chavis Lowery, and Della Maynor. “Traditionally, our people transmitted their ABOVE lumBEES (left to right) Della Maynor, Darlene