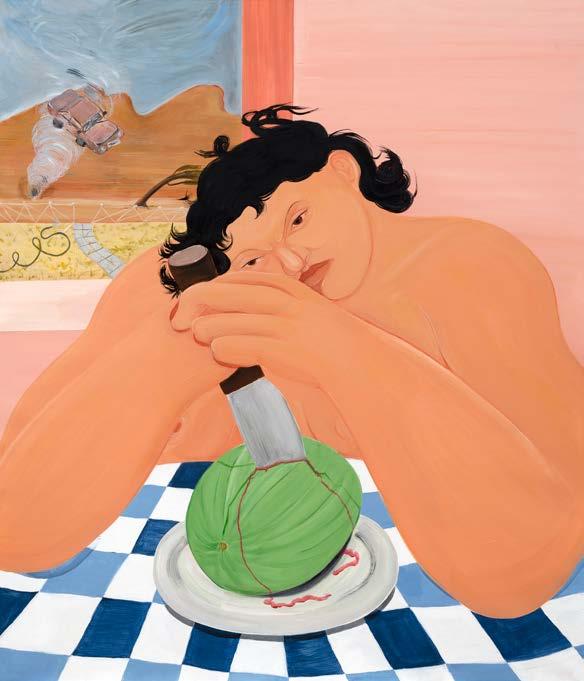

Alfredo de Stefano/México

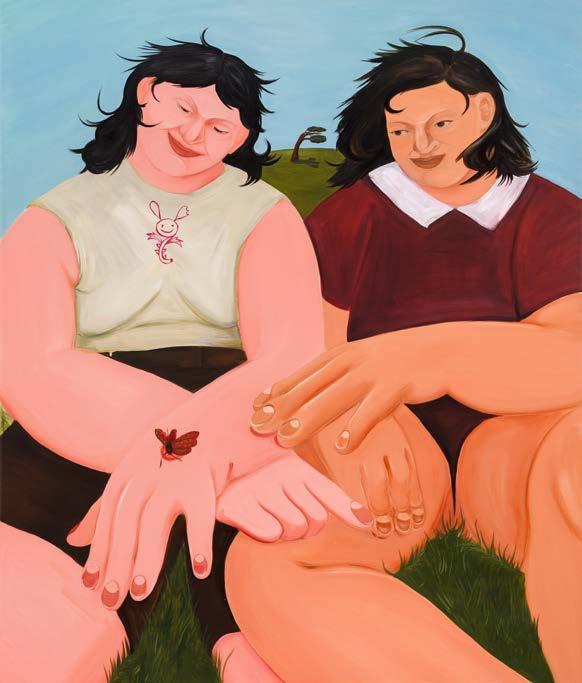

Raquel Bigio/Argentina

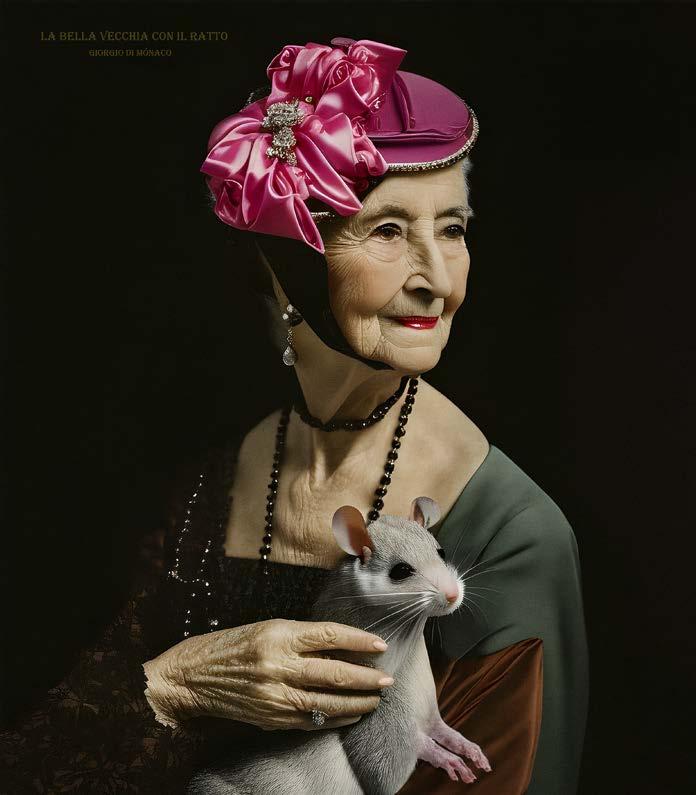

Ysabel Lemay/Canada

Matilde Marin/Argentina

Alfredo de Stefano/México

Raquel Bigio/Argentina

Ysabel Lemay/Canada

Matilde Marin/Argentina

ha pasado más de un cuarto de siglo, 26 años desde que comenzamos nuestra aventura en el arte. Hoy, luego de muchas historias, se concreta un hito importante en esta línea de tiempo que seguiremos escribiendo. Abriremos una nueva etapa en este proyecto de arte: un espacio expositivo, con más de 500 metros cuadrados. Este volumen arquitectónico busca aportar al mundo de las artes visuales y entregar un espacio a la comunidad con un objetivo claro, exponer y apoyar a los artistas que forman parte de la colección Arte Al Límite y a tantos otros que puedan exhibir en nuestro espacio.

Los años de trabajo han demostrado que los sueños se hacen realidad. La portada de este número muestra nuestro espacio, el que será confidente de obras de las artes visuales. Sin darnos cuenta, volvemos al mundo expositivo, pero desde otra mirada, no como galería, sino como museo inserto en el Valle del Aconcagua.

No ha sido fácil, el esfuerzo de muchos es necesario para lograr cosas grandes. Palabras para describir lo que se siente son muchas, pero una prevalece: determinación. El coraje de todo nuestro equipo ha sido fundamental para avanzar sin miedos, para avanzar al límite. “Arte Al Límite Museo” abrirá cargando en su ADN una misión clara: mostrar lo mejor del arte contemporáneo, para generar un aporte a las regiones de nuestro país, y sobre todo a Chile.

Por su parte, nuestra revista en formato físico seguirá difundiendo entrevistas exclusivas a artistas, con la intención de mostrar las obras de quienes tienen trayectorias emergentes, consolidadas y consagradas; a artistas nacionales e internacionales.

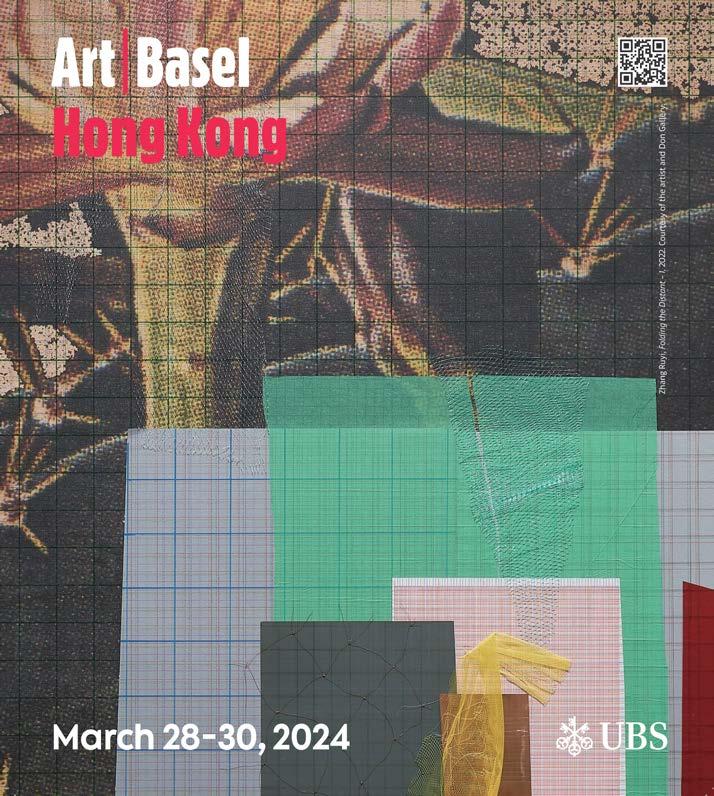

Este año se viene nuevamente intenso, el primer semestre, caracterizado por la Bienal de Venecia en Italia y las ferias de Arte Basel en Suiza; en Chile con la reapertura de la Bienal de Valparaíso y feria Ch.ACO, instancias donde esperamos abrir puertas con nuestra nueva institución. Pero esta gran apertura aún tendrá unos meses de descanso, porque el museo se inaugura el segundo semestre convocando a todos los agentes del arte y artistas que deseen participar de este momento único para nosotros y para muchos que han confiado en Arte Al Límite.

Queremos agradecer desde ya a todas las personas que han contribuido en nuestro proyecto, artistas de los más variados países, curadores y críticos, editores y periodistas de la revista; a nuestros equipos de diseño; a quienes han aportado en el sitio web y las redes sociales; a quienes trabajan en nuestros stands de las diversas ferias de arte; al nuevo equipo del museo; y a todos quienes con sus conocimientos y voluntades han hecho posible de este sueño, una realidad.

It has been over a quarter of a century, 26 years, since we started our adventure in art. Today, after many stories, we celebrate an important milestone in this timeline we are still building. We will open a new stage of our art project: an exhibition space with over 500 square meters. This architectural structure seeks to contribute to the visual art world and provide the community with a space and a clear objective: to showcase the work of the artists making up the AAL collection and that of many others who can hold exhibitions in our space.

Our years of work have proven that dreams do come true. The cover of this issue presents our space, which will be a confidant of visual artwork. Without even realizing it, we have returned to the world of exhibition, from a different perspective: not as a gallery, but rather as a museum embedded in the Aconcagua Valley.

It has not been an easy road; the effort of the many is necessary to achieve great things. Words abound to describe how it feels, but one prevails: determination. The courage of the entire team has been fundamental in making progress without any fears, in pushing the limit. The Arte Al Límite Museum shall open its doors with a clear mission imprinted in its DNA: to show the very best of contemporary art, to contribute to the regions of our country, and, above all, the entirety of Chile.

Our print magazine will continue to disseminate exclusive interviews with artists, aiming to show artwork by emerging, consolidated and celebrated artists, of both national and international origin.

This year will be once again intense. The first semester will bring the Venice Biennale in Italy, the Art Basel fairs in Switzerland, the reopening of the Valparaiso Biennial, and the Ch.ACO art fair. We had hoped to make our way through these events with open doors in our new institution. However, the great opening will still have to wait a few months until the second semester, when we will summon all art agents and artists who wish to participate in this unique moment for us and for those who have trusted in Arte Al Límite.

We want to thank all the people who have contributed to our project in advance: artists from a wide array of countries, curators and critics, our magazine editors and journalists, our design teams, to all those who have contributed to the website and social media, those who work in our stands in several art fairs, to the new museum team, and to all those who, with their knowledge and disposition, have made this dream a reality.

DIRECTORES

Ana María Matthei

Ricardo Duch Marquez

DIRECTOR COMERCIAL

Cristóbal Duch Matthei

DIRECTORA DE ARTE Y EDITORIAL LIBROS

Catalina Papic

PROYECTOS CULTURALES

Camila Duch Matthei

EDITORA

Elisa Massardo

DISEÑO GRÁFICO

María Nestler

FOTOGRAFÍA PORTADA

Jorge Azócar

CORRECCIÓN DE TEXTOS

Javiera Fernández

ASESORES

Benjamín Duch Matthei

Ricardo Duch Matthei

Milagros Duch Matthei

Felipe Duch Matthei

REPRESENTANTES INTERNACIONALES

Julio Sapollnik (Argentina)

REPRESENTANTE LEGAL

Orlando Calderón

TRADUCCIÓN

Adriana Cruz

SUSCRIPCIONES

info@arteallimite.com

IMPRESIÓN

A Impresores

DIRECCIONES

Chile / Francisco Noguera 217 oficina 30, Providencia, Santiago de Chile. www.arteallimite.com

VENTA PUBLICIDAD

+56 9 99911933.

info@arteallimite.com

marketing@arteallimite.com

Derechos reservados

Publicaciones Arte Al Límite Ltda.

Por Julio Sapollnik. Crítico de Arte (Argentina) Imágenes del archivo de Arte Al Límite.

Lo que perdura en el tiempo Standing the test of time

en su relación con el arte, Ana María Matthei cometió un pecado de juventud: comenzó pintando paisajes y figuras humanas. Esta experiencia le permitió conocer las dificultades que atravesaban los nuevos artistas para exponer: “¡Me exigían un mínimo de tres exposiciones y no tenía una!”. Comprendió así, como algunas galerías preferían trabajar con artistas consagrados, disminuyendo la igualdad de oportunidades para conocer artistas emergentes. Tras las negativas, logró realizar una primera muestra en un Centro Cultural, gustó y vendió. Percibió que había un espacio para crear una galería de arte que trabaje con nuevos nombres y permita exponer a los artistas no conocidos de las diferentes regiones del país.

En 1998 abrió la galería Matthei, un cubo blanco, donde exhibía artistas no vinculados a las galerías tradicionales y, también, consagrados de regiones. Así, presentó al grupo “Bajo Techo” y el grupo “Grisalla” y a artistas emergentes en el Santiago de aquel entonces. A partir del segundo año comenzó a exponer artistas de Argentina, Europa y EE.UU.

Comprendió que debía dar a conocer la galería en el extranjero. La primera feria internacional de arte en la que participó fue ArteBA, en Buenos Aires y después Miami. Cuando comenzó a realizar exposiciones, percibió que el coleccionista norteamericano siempre preguntaba: “¿Dónde está el catálogo?, ¿en qué revista salió publicado el artista?, ¿me das su página web?”, “¡Nosotros no teníamos nada de eso!”, explica Ana María.

Así nació una primera publicación que no fue una revista, sino, un buen catálogo. “Allí publicamos entrevistas a los artistas que exhibíamos, también comentarios sobre la feria en Suiza en la que habíamos participado y publicitamos una agenda con todas las exposiciones que, a lo largo del año, se realizaban en Galería Matthei. La colección de Arte Al Límite comenzó desde el inicio de la galería”.

Revista Arte Al Límite. Los orígenes Grande fue la sorpresa al advertir que diferentes artistas llamaban a la galería para solicitar entrevistas. Así nació la idea de fundar una revista

In her relationship with art, Ana María Matthei committed a sin in her youth: she started painting landscapes and human figures. This experience allowed her to understand the difficulties that new artists face to exhibit their work: “I was required to have a minimum of three exhibitions, and I didn’t even have one!” Thus, she learned how some galleries rather work with established artists, reducing the equality of opportunities to discover emerging artists. After the rejections, she managed to have a first show in a cultural center, which was well liked and sold. She sensed there was some room to create an art gallery that worked with smaller names and allowed unknown artists from different regions of the country to show their artwork.

In 1998, she opened Galería Matthei, a white cubic space featuring the work of artists who were not affiliated with traditional galleries, as well as established artists from the regions. That is how she came to showcase the band Bajo Techo and the Grisalla collective and emerging Santiago artists at the time. During the second year, she exhibited artists from Argentina, Europe and the US.

She realized she had to promote the gallery abroad. The first international art fair that she participated in was ArteBA, in Buenos Aires, and later in Miami. When she held the first exhibits there, she noticed America art collectors always asked: “Where is the catalog? What magazine published this artist? Can I have their website?” “We had none of that!,” Ana María explains.

Her first publication came as a result: not yet a magazine, but a good catalog. “There, we published interviews with the artists we were exhibiting, commentary on the Swiss fair we participated in, and a calendar with all the exhibitions Galería Matthei held in the year. The Arte Al Límite collection started in the gallery’s early days.”

Arte Al Límite Magazine. The origins

It came as a shock when artists started calling the gallery to ask for interviews, which led to the idea of founding an art magazine.

de arte. La siguiente publicación se presentó en Casa Lo Matta, un centro cultural de la época colonial, de inicios del siglo XIX.

Buscar el nombre para la revista no fue fácil. O como cuenta la leyenda, las mejores ideas ocurren cenando en familia. En el caso de Matthei fue similar, estaba con su marido, su hijo Cristóbal y su nuera Catalina, quien fue la diseñadora de la revista desde el inicio y actual directora de arte, pasando las vacaciones de verano. Reunidos en una mesa, percibieron que las muestras en la galería Matthei cruzaban un límite: el público verdaderamente se asombraba, no quedaba indiferente. De inmediato surgió el nombre: “Arte Al Límite”.

La revista debía publicar artistas de trayectoria nacional e internacional y para alcanzar la mejor calidad debía incluir reportajes interesantes con mayor cantidad de páginas, críticas atrayentes y profundas. Y por sobre todas las cosas, sorprender con el diseño y la calidad de impresión. Así lo ha hecho.

Además, la necesidad de dar a conocer a los artistas de la galería la llevó a crear el sitio web arteallimite.com; después, el periódico Al Límite, que nació en 2005 llegando a publicar 114 ejemplares. Las diferentes noticias del hacer artístico nacional e internacional ayudaban a planificar actividades para un viaje, como bien lo experimentó este cronista. Con reportajes más cortos y una agenda actualizada, la información era vivaz.

El posicionamiento que ocupaba Arte Al Límite generó, en 2008, la organización de la I Feria de Arte Contemporáneo en Chile. Con la experiencia de recorrer más de treinta ferias internacionales al año, tomaron conciencia de que en Chile no se hacía ninguna. Era la posibilidad de mostrar el arte internacional y las obras de los artistas directamente a través de los artistas. Se realizó en Vitacura con el apoyo municipal así que la entrada fue liberada.

La motivación de Ana María Matthei y su equipo era enorme. No les bastó con: la galería, la revista, el periódico, el sitio web, la Bienal y los viajes para posicionar la revista en ferias internacionales; a ese momento sumaron la realización del Gallery Night: “Harto trabajo”, le gusta decir a Ana María.

The next publication was presented in Casa Lo Matta, a cultural center from the early 19th century colonial times.

Finding the name for the magazine was no easy task. Legend has it the best ideas come at the family dinner table. This was the case for Matthei. Once summer, she was having dinner with her husband; her son, Cristóbal; and her daughter-in-law, Catalina, who initially took the role of designer for the magazine, and current holds the position of art director. Gathered at the table, they came to the realization that the samples shown at Galería Matthei pushed the limits: the audience was truly struck by what they saw, they could not remain indifferent. Suddenly, the name came: “Arte Al Límite.”

The magazine had to publish artist with national and international trajectories and, to reach the best possible quality, it had to include interesting articles over more pages with captivating and deep critiques. However, above all else, it had to be striking in its design and print quality. And so it has been.

Additionally, the need to promote the gallery’s artists led her to create the website arteallimite.com and then the Arte Al Límite bullet-in in 2005, which managed to publish 114 issues. The different news in the national and international art world helped her plan out a whole journey, as I have come to learn. With shorter articles and an updated calendar, the information in the bullet-in was lively.

The momentum that Arte Al Límite gained was such that in 2008 Chile’s first Contemporary Art Fair was organized. After having visited over 30 fairs around the world a year, they couldn’t help but notice that Chile had none. This was an opportunity to showcase international artwork and highlight pieces directly though artists. The fair was held in Vitacura with the support of the municipality so admission was free.

Ana María and her team’s motivation was huge, so they could not settle just for the gallery, the magazine, the bullet-in, the website, the biennial, trips to be featured in international art fairs: they had to do Gallery Night as well. As Ana María likes to say it has been “a lot of work.”

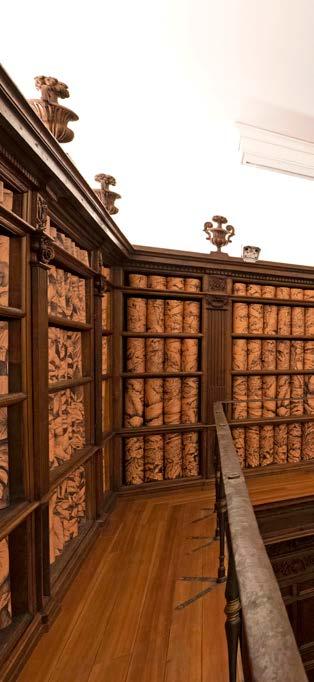

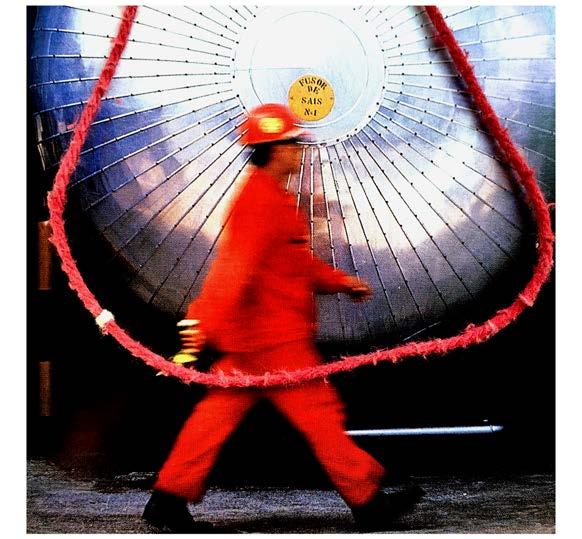

Fachada Norte Arte Al Límite Museo , 2024. Foto: Jorge Azócar.

Esta actitud de vivir adelantada a los nuevos tiempos la llevó a liderar un equipo que supo crear una plataforma digital e-commerce. Presentaban una sección dedicada a señalar el posicionamiento de cada artista, su rango, su ranking en relación a los demás, basado en exposiciones y colecciones a las que pertenecían. Cuando alcanzaron la máxima información, tomaron la decisión de vender. Sin embargo, no fue fácil mantener al artista dentro de la plataforma, fue momentos antes de que explotaran las redes sociales, así que los artistas vieron la oportunidad de independizarse.

Arte Al Límite nunca dejó de tomar riesgos. En el año 2017, para celebrar los años de trayectoria, presentó por primera vez la colección en el Espacio Cultural de la Fundación Telefónica en Santiago de Chile, la entrada era libre y gratuita. Junto a ello ocuparon otros 4 espacios de arte: Fundación Cultural de Providencia, Centro Cultural Estación Mapocho, Galería Posada del Corregidor, para mostrar la mayor cantidad de obras de la colección y demostrar su apoyo a los artistas con los que han trabajado hace años. Con curaduría de la argentina Marisa Caichiolo, religando fotografía, pintura, instalaciones y esculturas.

El artista cubano residente en Miami, Antuan Rodríguez, presentó Punching balls. Una instalación de bolsas para practicar boxeo que llevan impresos los rostros de Donald Trump, Vladímir Putin, Fidel Castro, George W. Bush, su vicepresidente Dick Cheney, la Secretaria de Estado Condoleeza Rice y Nicolás Maduro, entre otros. Los espectadores elegían a quien golpear con todas sus fuerzas. “Arte Al Límite se ha destacado por apostar por la carrera de artistas que de a poco se han ido consolidando en la escena regional. Mi obra fue portada de la revista en sus primeros años, por allá en 2004 y me sorprendió que se la jugaran por una imagen que no era fácil. Me gustó ese riesgo”, explicó Antuán en un reportaje del periódico La Tercera, en 2017.

Así cobró toda su dimensión el concepto “Al Límite”. Mostrar a los artistas que rompían esquemas y que no se los conocía a nivel internacional, fuese cual fuese su país de origen. Se exhibía a los artistas que cruzaban ciertos límites, antes que las redes o internet mostraran lo inverosímil.

This attitude of being a step ahead of the times drove her to lead a team to create a digital e-commerce platform. They included a section dedicated towards artist positioning, pointing out artists’ ranking in relation to others, based on their exhibitions and collections they were part of. At the height of that data collection, they decided to sell the platform. However, before the social media explosion it was hard to exalt artists on any platform, and artists took this as a chance to become independent.

Arte Al Límite never stopped taking risks. In 2017, to celebrate its trajectory, it presented its collection in the Fundación Teléfonica cultural space in Santiago, Chile, where admission was free of charge. The collection was also shown in 4 other spaces: Fundación Cultural de Providencia, Centro Cultural Estación Mapocho, and Galería Posada del Corregidor, aiming to exhibit most of the pieces in the collection and to show support for the artists AAL had been working with for years. Curated by Argentinean artist Marisa Caichiolo, the exhibitions merged photography, painting, installations and sculptures.

Miami-based Cuban artist Antúan Rodríguez presented Punching balls , an installation of boxing punching bags with the faces of Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Fidel Castro, George W. Bush, his Vicepresident Dick Cheney, Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice, and Nicolas Maduro, among others. The audience chose who they wanted to punch with all their might. “Arte Al Límite has stood out for betting on the career of artists who have been gradually becoming established in the regional stage. My work was featured in the magazine cover in its early days, around 2004, and I was shocked they took a risk with an image that was not easy. I like that risk,” Antúan explained in a news article published in La Tercera in 2017.

This is how the pushing art “to the limit” concept took on its full dimension: by showcasing artists who broke new ground and who were not well-known at the international level, regardless of their country of origin. Artists who crossed certain limits were exhibited, before the networks or the Internet came to show the far-fetched.

Antuan Rodríguez, Punching balls , Imágen cortesía del artista.

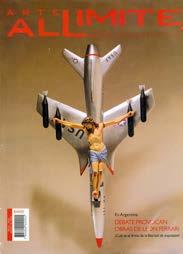

Quien escribe estas líneas, recuerda con gran estima la visita de Ana María Matthei a la ciudad de Buenos Aires a fines de 2004, poco tiempo después de que creara la revista. En ese momento, se exhibía una retrospectiva del artista León Ferrari (1921 - 2013), en el prestigioso Centro Cultural Recoleta. Allí se presentaba Civilización Occidental y Cristiana. Un objeto realizado en 1965, en repudio a la guerra de Vietnam, llamó la atención inmediata de Ana María: un Cristo de santería crucificado sobre la maqueta de un bombardero norteamericano F-105, cuyos materiales son óleo sobre yeso y plástico de 200 x 120 x 50 cm. Y con la intuición artística que siempre la caracterizó, al ver la obra de León, Ana María gritó: “Esta obra va a ser tapa de nuestra próxima revista”. Así salió.

Ante la fuerza que transmite la imagen, sin embargo, se encontró con una gran problemática: comenzaron a retirarse algunos auspiciantes y suscriptores. Les atraía la marca, no su contenido. Pero el tiempo le dio la razón a Ana María: En 2007, León Ferrari recibió el “León de Oro” al mejor artista en la 52ª Exposición Internacional de Arte Bienal de Venecia, Italia. En 2009, realizó una exposición en el Museo de Arte Moderno (MoMA) de Nueva York y en 2010, fue invitado de honor en Les Rencontres d’Arles, Francia, ocasión en la que presentó una gran retrospectiva de su obra. El diario estadounidense The New York Times lo nombró en aquel momento uno de los cinco artistas plásticos vivos más importantes del mundo.

Esta mirada que avizora, observa, vislumbra lo que está por venir, es una característica que unió a toda la familia Duch-Matthei en la concreción de los proyectos que surgían. La revista Arte Al Límite es codiciada por la calidad de artistas que publican sus trabajos, es deseada por los críticos para exponer sus ideas y admirada por los coleccionistas gracias a la información que reciben. Esta publicación convertida en un verdadero referente del arte latinoamericano, alcanza hoy la cantidad de 104 publicaciones.

Un nuevo museo

Para Ana María Matthei, la creación de un espacio que contenga la colección es la concreción de un sueño. Siempre lo pensó. Desde los primeros años en la galería y después con la revista.

In writing these lines, I fondly remember a visit Ana María paid me in Buenos Aires in 2004, a short time after she created the magazine. Back then, a retrospective of artist León Ferrari (1921-2013) was being shown at the prestigious Centro Cultural Recoleta, entitled Civilización Occidental y Cristiana . An object made in 1965, in condemnation of the Vietnam War, caught Ana Maria’s eye immediately: a 200 x 120 x 50 cm Santeria Christ crucified on the model of an American F-105 bomber, made of oil on plaster and plastic. With the artistic intuition that has always made Ana María stand out, when she saw León’s piece she shouted: “This piece is going to be the cover of our next magazine issue.” And so it was.

However, the strong visuals of the piece stirred up a big controversy: sponsors and members started pulling out; they were attracted to the brand, not the content. But Ana María was proven right in time: In 2007, León Ferrari was awarded with the Golden Lion to the best artist in the 52nd edition of the International Exhibition by the Venice Biennale, in Italy. In 2009, his work was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and in 2019 he was the guest of honor in Les Rencontres d’Arles, France, where a great retrospective of his artwork was shown. The New York Times named him one of the top 5 most influential artists in the world at the time.

This foresight, observation and vision of what is to come, is a characteristic that brought the entire Duch-Matthei family together in the realization of their future projects. The Arte Al Límite Magazine is cherished for the quality of the artists they publish, coveted by critics to convey their ideas, and admired by collectors due to the information they can get from it. This publication, turned a true reference of Latin American art, celebrates its 104th issue today.

For Ana María Matthei, creating a space for the collection is a dream come true. She always knew it. Since the early days of the gallery and then the magazine.

Portada edición N°12 Revista Arte Al Límite . Imágen de portada: León Ferrari. Imágen archivo AAl, Feria Internacional de Arte.

Las obras que adquiría la colección, debían permanecer juntas. Exhibirlas. Ese fue el compromiso que tomó con los artistas, las obras no se venden. También, tenía claro que no era Santiago el lugar de exhibición, sobre todo después de lo que le ocurrió en sus inicios como artista de regiones. Así, siempre intuitiva, encontró un amplio espacio en el valle del Aconcagua. La región de Valparaíso posee una cierta cantidad de ciudades chicas, rodeadas por viñedos imponentes. Esto hace que la ruta del vino sea un paseo concurrido por turistas. De esta manera la colección queda dentro de un camino elegido por sus bellezas naturales y ahora artísticas apenas a una hora de distancia de Santiago.

La curaduría del nuevo espacio es de la argentina Marisa Caicholo, quien vive en Los Ángeles, EE.UU. y conoce muy bien la colección. El acervo de Al Límite sorprenderá seguramente por la presentación tanto de obras nuevas como de artistas invitados. Un recorrido que comienza con algunas de las primeras obras que ingresaron a la colección hasta las de los últimos años. ¡Harto Trabajo! Exhibir las obras: pinturas, esculturas, instalaciones, dar acceso a nuestra colección de revistas y periódicos, programar los mejores videos sobre arte contemporáneo y así, como un museo vivo, desarrollar continuamente nuevos proyectos.

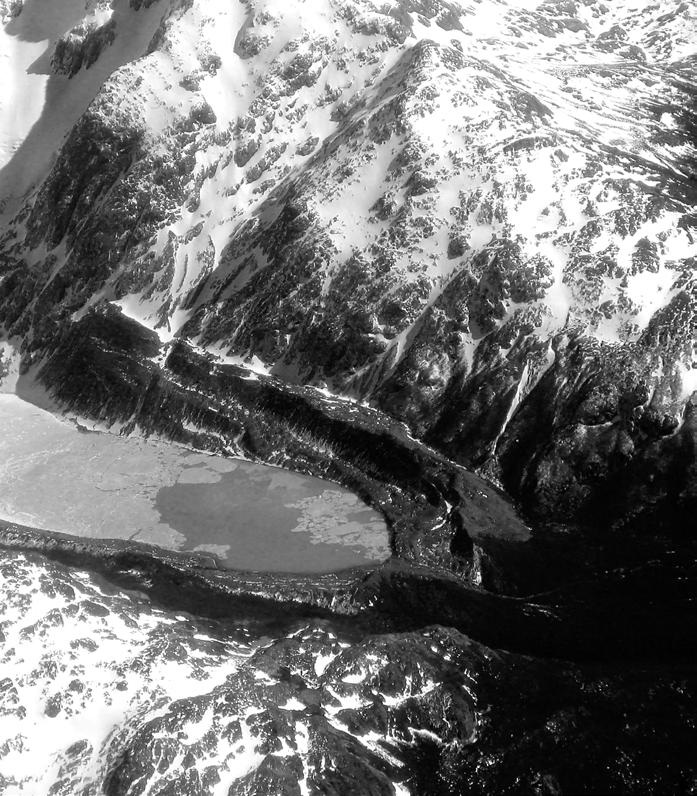

Una colección de arte en plena cordillera es sorprendente. ¿Cómo hace el visitante para separar la belleza de la naturaleza y vivenciar lo que propone el arte?

¡Que pregunta tan difícil! En muchos museos del mundo hay un entorno maravilloso que los rodea. Aquí también va a pasar esto. Los cerros, los pastizales y el paisaje van a estar siempre presentes aún estando dentro del Museo a través de las vidrieras. Para el ojo del visitante va a ser un diálogo constante entre arte y naturaleza. Salir para llegar a la sala de video caminando por una terraza de 350 mts2, ofrece contemplar también la maravillosa presencia de los árboles y el cielo. Vamos a distribuir esculturas al aire libre a escala “cordillerana”. Amplios espacios para recorrer y sorprenderse al encontrar piedras gigantescas junto a las esculturas “cuidadas” por altos árboles. Buscamos resaltar la diferencia con un espacio de la cultura en la ciudad,

The pieces she acquired for the collection had to remain together. They needed to be shown. That was the promise she made to artists, that the pieces would not be sold. She also knew that Santiago was not where they should be exhibited, especially after what happened at the beginning of her career as an artist from the regions. Thus, as intuitive as ever, she found a large space in the Aconcagua valley. The Valparaíso region is filled with countless small towns, surrounded by impressive vineyards. This is a very frequented area by tourists due to the wine route. This way, the collection will be in a tourist destination chosen because of its scenic and now artistic beauty, just an hour away from Santiago.

The curatorship of this new space is by Argentinean Marisa Caicholo, based in Los Angeles, US, who knows the collection very well. AAL’s collection will surely surprise with the presentation of new pieces and the guest artists. The tour starts with some of the first pieces that joined the collection and more recent artwork from up to the last couple of years. A lot of work! Exhibiting the pieces –paintings, sculptures, installations–, providing access to our collection of magazines and bullet-ins, planning the best videos on contemporary art and thus, like a living museum, constantly develop new projects.

A collection in the midst of the mountain range is surprising. How can viewers separate the beauty of nature and experience the artistic proposals?

What a hard question! Many museums around the world are surrounded by beautiful environments. This will also be the case. The mountains, the grasslands and the landscape will always be present, even within the glass doors of the museum. For visitors, there will be a constant conversation between art and nature. Exiting the museum to walk towards the video hall through a 350 m2 patio offers the opportunity to marvel at the wonderful presence of trees and the sky.

We will lay out sculptures outdoors at a “mountain range” scale. Vast spaces to roam around and be amazed to find gigantic stones next to the sculptures “guarded “ under tall trees. With this space, we seek to highlight the difference with urban

donde sabes lo que puedes encontrar. A menos de una hora de Santiago el público visitante tendrá la posibilidad de encontrar tanto artistas nacionales como internacionales. En el nuevo espacio “Arte Al Límite Museo”, todo va a ser distinto. Porque las obras exhibidas atraerán la mirada del espectador con tanta intensidad como el cambio de color en las montañas.

El museo es una gran sala con más de 500 m2 y una altura de 4 mts a los lados y 9 mts en el centro. Ese gran espacio estará dividido por paneles móviles. Esto nos va a permitir, en una exposición temporaria, por ejemplo, quitar los paneles y presentar la obra en planta única.

Este proyecto de abrir la colección al público provoca, en lo personal, una gran motivación ¿Cómo se sostiene la energía para hacer realidad un sueño de tantos años?

La respuesta está en el trabajo, en la perseverancia. Creyendo en el proyecto. Cuando uno hace lo que le gusta se vive con emoción: conocer a un artista, escucharlo hablar sobre su obra y después exhibirlas. Tengo muy presente cuando fue el momento en que entró cada obra a nuestro patrimonio. La obra no llega, sino que es seleccionada, elegida, pensada para la colección. Una colección que nació acompañada por toda la familia. Desde muy jóvenes mis hijos han participado en la galería, en la revista, con el periódico. Viajaron a una gran cantidad de ferias de arte, llevando para su difusión los últimos números de la revista y también para exhibir los libros que hemos editado, son cerca de 25. Entre todos conversamos sobre los criterios que debemos seguir para desarrollar nuestra marca y acrecentar la colección ¡Sola nunca hubiera podido! Siempre sentí el apoyo de mi marido, Ricardo, en unidad con toda la familia. Esto ha sido así desde los inicios y continúa con la familia unida hasta hoy. Esto es lo que me motiva, esto es lo que me gusta. Esto es lo que va a perdurar en el tiempo.

¡Bienvenidos a Arte Al Límite Colección y Museo!

cultures, excited about what you might find. Less than an hour way from Santiago, visitors will enjoy an encounter with both local and international artists. In this new space, “Arte Al Límite, the Museum,” everything will be different because all the exhibited pieces will captivate viewers as much as the changing colors of the mountains.

The museum is a big hall with over 500 m2 and a height of 4 m on the sides and 9 m in the center. The vast hall will be divided with movable panels, which will allow for rearrangement and removal of the panels in, for instance, a temporary exhibit where we want to show artwork in a single space.

This project of bringing the collection to the public is personally very motivating. How do you sustain the energy to make a longterm dream come true?

The answer is in the work, in perseverance. Believing in the project. When you do what you love, life is exciting: meeting artists, listening to them speak about their work and exhibiting that work. I remember the moment each piece came into our possession very clearly. Pieces do not just come, they are selected, chosen, and well-thought-out for the collection.

A collection that was born in the presence of the entire family. Since an early age, my children have participated in the gallery, the magazine, the bullet-in. They traveled to countless art fairs, took the latest issues of the magazine and the some-25 books we have published to disseminate them.

We all talk about the criteria we must follow to develop our brand and grow the collection. I couldn’t have done it on my own! I have always felt the support of my husband, Ricardo, along with the whole family. This started with the whole family united, and so it remains today. That is what motivates me, that is what I like. This is what will stand the test of time.

Welcome to Arte Al Límite, The Collection and Museum!

Por Elisa Massardo. Lic. en Historia y Estética (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía del artista.

Representado por Building Bridges Art Exchange.

The planetary garden, 2023, vista de instalación. Museo de las artes, Universidad de Guadalajara, México.

The planetary garden, 2023, vista de instalación. Museo de las artes, Universidad de Guadalajara, México.

“Prefiero susurrar hundiéndome en las profundidades”

consideremos el espacio como una proyección mental de una visión, así podemos inmiscuirnos en el trabajo de Pietro Ruffo, quien prefiere: “hacer que la gente entre en una dimensión que plantea preguntas, en lugar de ofrecer certezas”. Así es como en The Planetary Garden expone una reflexión sobre el presente con obras de gran formato que invaden las habitaciones donde se encuentran, en la que busca mostrar los 250.000 años de historia que han moldeado este clima y la morfología de este planeta, y de nuestro intento por domesticarlo, siendo que “ya ha visto cientos de especies surgir, dominar y luego desaparecer”, explica.

Su pasión por la naturaleza y su entorno comenzó cuando estudiaba arquitectura, ahí realizó sus primeras exposiciones y al graduarse, el arte visual entró en su vida de forma innata y para quedarse. Probablemente las influencias de su abuelo, quien era artista abstracto; de su padre, arquitecto; y de su madre, diseñadora de vestuario, fueron cruciales para desarrollar en él esta vocación transdisciplinar donde podemos observar cómo el dibujo, el diseño, las nociones espaciales e, incluso, el diseño de vestuario, se mezclan en su obra como si fuera una danza contemporánea de múltiples intérpretes que forman un solo cuerpo.

Como si fuera poco, las bases del artista se encuentran en los conocimientos de pintura que adquirió de adolescente, en sus estudios de

“I prefer whisper by diving down into the depths”

let us consider space as a mental projection of a vision and only then can we explore Pietro Ruffo’s work, who prefers to: “make people enter a dimension that asks questions, rather than provide certainties”. In The Planetary Garden, the artist presents large-scale pieces that reflect on the present. The pieces seek to evince the 250,000 years of history that have shaped the climate and morphology of the planet, as well as our attempts to domesticate it, despite the planet already having witnessed “hundreds of species emerge, dominate, and then disappear,” as the artist points out.

His love for nature and his environment started when he was studying architecture and had his first exhibitions. When he graduated, visual arts came to his life innately and to stay. The influence of his grandfather, an abstract artist; his father, an architect; and his mother, a fashion designer; were crucial for him to develop a cross-discipline calling where drawing, design, spatial awareness, and even fashion design intertwine in his work, as if in a contemporary dance of several interpreters shaping one body.

The foundations on which the artist stands lie in the knowledge of painting that he acquired during his study of architecture,

arquitectura que le permiten comprender la ciudad desde la sociedad que la conforma; además, realizó una investigación sobre Isaiah Berlin, en la Universidad de Columbia, cuyos análisis sobre la Guerra Fría y las repercusiones de la libertad americana calaron profundamente en el artista, al punto de que: “dio lugar a una serie de obras que investigaban el concepto de libertad, un tema que he investigado durante muchos años y que me llevó a diferentes partes del mundo para investigar cómo se percibe este tema”. Desde acá comenzamos una entrevista exclusiva que nos permite conocer más los conceptos que desarrolla a través de sus múltiples, inmersivas e impresionantes obras visuales:

¿Cómo definirías la libertad y la dignidad del individuo? Y, ¿por qué son tan importantes en tu trabajo?

La importancia de la palabra libertad radica precisamente en el hecho de que no puede definirse. Esta fue la gran trampa del siglo XX que destacó Berlin, cuando los dirigentes políticos pusieron en práctica definiciones de libertad formuladas por filósofos como Rousseau o Fichte, para crear regímenes autoritarios, imponiendo al pueblo una idea inequívoca de libertad que, de hecho, la invalidaba por completo. El término dignidad está estrechamente relacionado. Creo que Kahlil Gibran expresó claramente en su poema de 1923 On Freedom que la

which allowed him to understand cities from the perspective of the society that shapes them. Furthermore, he completed a research on Isaiah Berlin at Columbia University, whose analysis of the Cold War and its repercussions on American freedom deeply resonated with the artist, to the point that the inspiration: “gave rise to a series of works, which investigated the concept of freedom, an issue that I have researched for many years and which took me to different parts of the world to investigate how it is perceived”. In the exclusive interview that follows, we learn more about the concepts he develops through his diverse, immersive, and impressive visual artwork:

How would you define the freedom and dignity of an individual?

Why are these concepts important for your work?

The importance of the word “freedom” lies precisely in the fact that it cannot be defined. This was the great pitfall of the twentieth century highlighted by Berlin, when political leaders put into practice definitions of freedom formulated by philosophers such as Rousseau or Fichte, in order to create authoritarian regimes, imposing on the people an unequivocal idea of freedom that, in fact, completely invalidated it.

The term dignity is closely related. I think Kahlil Gibran made it

The clearest way, 2021, vista de instalación. Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, Vaticano. Foto: Emanuele Angelini.

The clearest way, 2021, vista de instalación. Biblioteca Apostólica Vaticana, Vaticano. Foto: Emanuele Angelini.

libertad debe buscarse dentro de cada uno de nosotros antes de exigirla externamente, pero es un ejercicio agotador, por lo que a menudo nos parece más adecuado salir a las calles.

En una entrevista anterior dijiste que por primera vez gritaste en vez de susurrar, ¿podrías explicarme la diferencia y qué temas consideras necesario gritar al mundo?

Como actitud prefiero estudiar y susurrar sumergiéndome en las profundidades de los asuntos. Creo que gritar es un esfuerzo inútil que se queda en la superficie. La historia siempre ha sido para mí un filtro para comprender el mundo que me rodea, una distancia que pongo entre mí y la complejidad de los acontecimientos cotidianos.

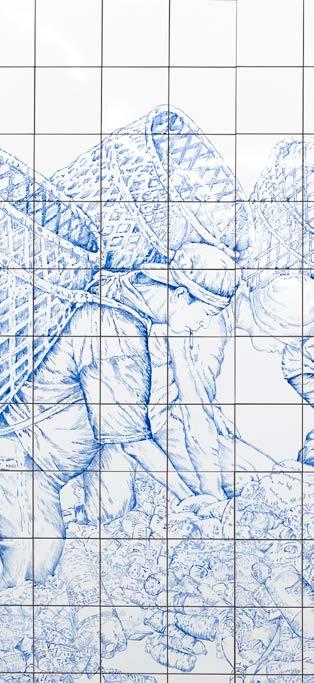

En 2020 creé una exposición titulada Tidal Wave pintando grandes paredes de azulejos que representaban escenas de la vida cotidiana, desde las migraciones hasta las manifestaciones de Fridays For Future. En estas últimas, los jóvenes que tomaron las plazas de todo el mundo gritaron su disconformidad y su entusiasmo, y su proyección de un mundo diferente me resulta fascinante.

¿Cuál es la importancia de los mapas en tus obras?, ¿de dónde proviene esta idea de trabajar con ellos?

clear with his 1923 poem On Freedom that liberty should be sought within each of us before demanding it externally, but this is a tiring exercise, and, thus, we often find it more fitting to take to the streets.

In a previous interview, you said that you shouted for the first time instead of whispering. Could you explain the difference? What topics do you consider necessary to shout to the world? As an attitude I prefer, to study and whisper by diving down into the depths of issues. I think shouting is a futile effort that remains on the surface. History has always been a filter for me to understand the world around me, a distance I put between me and the complexity of the daily happenings.

In 2020 I created an exhibition entitled Tidal Wave by painting large walls of tiles depicting scenes of daily life, from migrations to Fridays For Future demonstrations. In the latter, young people who took to the squares around the world shouted their dissent and their enthusiasm, and their projection of a different world fascinates me.

What importance do maps hold in your work? Where did the idea of working with them come from?

Noruwei and Pietro Ruffo, The planetary garden, 2023, vista de instalación, video 4:27 minutos. Diverse Los Angeles, Estados Unidos.

Noruwei and Pietro Ruffo, The planetary garden, 2023, vista de instalación, video 4:27 minutos. Diverse Los Angeles, Estados Unidos.

Lo que me intriga de los mapas es que representan una herramienta subjetiva que dependen de quién los esboza y, aún más importante, de quién los encarga. Leer mapas antiguos revela las tensiones y ambiciones de distintos pueblos. Cada mapa es un intento de dominar la inmensidad de un mundo que nos domina; es como si mirar un mapa nos situara en una posición de otro mundo que no nos corresponde controlar pero que nos halaga.

¿Ves un vínculo entre los mapas y las fronteras? Entendiendo que en tu obra también has trabajado el tema migratorio que ha sido tan conflictivo para Europa en la última década.

Somos la única especie que se impide migrar. Nos imponemos fronteras que no queremos que crucen los demás, aunque reivindiquemos el derecho a cruzarlas a nuestro antojo. Somos una de las especies más jóvenes del planeta, e intentamos controlar la migración con escaso éxito, trazando fronteras y definiendo enemigos que viven más allá de la misma.

Sin duda, necesitamos mucho más tiempo para encontrar la armonía con el mundo que nos rodea y con las personas que lo habitan. Nuestro frenesí es el propio de un niño muy joven.

¿Consideras que se pueden crear mundos posibles?, ¿cómo?

Creo que vivimos en el mundo más hermoso posible. No necesitamos crear otros, sino quizás cambiar nuestra percepción de este.

What fascinates me about maps is that they are a subjective tool that depends on those who draw them, and, more importantly, on those who commission them. Reading historical maps reveals the tensions and ambitions of different peoples. Each map is an attempt to dominate the immensity of a world that dominates us; it is as if looking at a map puts us in an otherworldly position that is not ours to command but that flatters us.

Taking into account your work on migration issues, which have been so troublesome for Europe over the last decade, do you see a link between maps and borders?

We are the only species that prevents itself from migrating. We impose borders on ourselves that we do not want others to cross, even though we claim the right to cross them at our whim. We are one of the youngest species on this planet, and we try to control migration with limited success, drawing borders and defining enemies who live beyond the border. We certainly need much more time to find harmony with the world around us and with the people who live in it. Our frenzy is typical of a very young boy.

Do you think that possible worlds can be created? How?

I think that what we live in is the most beautiful world possible, we don’t need to create others, perhaps to change our perception on this one.

Por Karla Siguelnitzky. Teórica del arte (Chile)

Imágenes cortesía del artista.

Brasil

La resistencia de la Amazonía a través del lente

The resilience of the Amazon through a lens

los sesgos sociales fraccionan e instauran una estructura jerárquica en el orden de la sociedad. Potencian el surgimiento de arquetipos y cánones que delimitan nuestro entendimiento sobre la multiplicidad de pueblos y etnias. Esta homogeneización ha obstaculizado la creación de una perspectiva más amplia que logre integrar la diversidad de razas. La obra de Rodrigo Petrella, llama justamente a reflexionar sobre esta temática mediante exquisitas composiciones, en las que el autor ejerce tanto el rol de artista como de testigo y etnógrafo, creando imágenes con un alto contenido crítico y artístico.

La carrera de Petrella se sustenta en varios años de investigación sobre las comunidades indígenas de la Amazonía brasileña. Sus fotografías revelan de manera sutil y cercana diversas prácticas y estilos de vida de dichas comunidades. Su obra nos invita a ser parte de esta realidad muchas veces opacada por el sistema occidental imperante, asimismo nos llama a ser conscientes del riesgo en que estas comunidades están sumidas debido al incesante avance del sistema neoliberal que antepone un crecimiento económico en vez de preservar, cultivar y conservar su ecosistema.

El surgimiento de las ciudades modernas ha desplazado y alterado la intrínseca relación entre naturaleza e individuo. Además, la sociedad actual se encuentra subyugada a constantes avances tecnológicos, olvidando el origen de nuestra existencia, ¿cómo crees que difiere la percepción que tenemos sobre la naturaleza frente a esta situación? Creo que gran parte de esto se debe a la revolución industrial, cuyo proyecto político-económico provocó un giro tremendo en la percepción del mundo y por encima de todo, en la relación con el tiempo de las cosas: time is money! Dio origen a una fiebre generalizada, una búsqueda del tesoro por minerales, fuerza del trabajo humano, recursos biológicos, guerras, fuentes de energía y operaciones de extracción y explotación a un nivel de intensidad nunca experimentado en la historia, tan grande que ha reconfigurado grandes partes del territorio global, sobre todo las ciudades.

Enormes volúmenes de riqueza han emergido y han sido transformados en otra cosa con el potencial de cambiar toda una geografía, fronteras, relaciones sociales y alianzas entre países. Todo esto, en cierto modo, ocurrió y sigue ocurriendo de forma violenta, con tal exuberancia y velocidad. Las sociedades se encuentran en un estado traumático, sin embargo, siguen buscando respuestas a este sentimiento de desplazamiento y alienación al mundo/ tiempo llamado natural.

Hay muchas percepciones, muchos intentos de explicar. Es un caleidoscopio de ideas y teorías desde puntos de vista muy distintos, pero todas se enfrentan a una realidad disimulada, compleja, cambiante y ante todo, opaca. Quizás, en otras palabras: el paraíso tiene muchas salidas, pero ninguna entrada.

s ocial prejudice establishes and divides the hierarchical structure of societal order. It encourages the formation of archetypes and standards that limit our understanding of the diversity of peoples and ethnicities. The homogenization brought about by this bias has prevented the establishment of a broader perspective that successfully integrates racial diversity. Rodrigo Petrella’s work urges us to ponder this very topic with his exquisite compositions, where he plays the role of artist, witness and ethnographer, creating images rich in critical and artistic content.

Petrella’s career has been built on the foundations of several years of research on the indigenous communities in the Brazilian Amazon. His photographs subtly and intimately unveil the many practices and lifestyles of these communities. His work invites us to partake in this reality, so often overshadowed in the reining Western system. Likewise, it raises awareness of the risks these communities face due to the relentless advancement of the neoliberal system, which prioritizes economic growth instead of preserving, cultivating, and protecting their ecosystem.

The advent of modern cities has displaced and altered the intrinsic relationship between nature and individuals. Current society is also subject to constant technological advancements that cause us to forget the roots of our existence. How do you think this has impacted our perception of nature?

I think most of this is attributable to the Industrial Revolution and its political-economical project that brought about a tremendous shift in our perception of the world and, above all, of our relationship with time: time is money! This created a widespread feverish state, a quest to find treasured minerals, human labor, biological resources, wars, and a historically unprecedented exploitation of energy sources that is so large-scale that it has reconfigured large portions of the global territory, especially cities.

Huge volumes of riches have emerged and been transformed into something with the potential to change the whole of geography, borders, foreign affairs, and alliances between countries. In a sense, all this happened and continues happening in a violent, exuberant, and rapid fashion. These societies are in a state of trauma, but they continue to seek answers to these feelings of displacement and isolation from the so-called natural world/time.

There are many perceptions and many attempts to explain this situation. There is a kaleidoscope of ideas and theories from very different points of view, all facing a hidden, complex, changing, and, above all else, non-transparent reality.

Perhaps, in other words, paradise has many exits but no entrances.

El canon occidental ejerce un ideal de belleza que limita la inclusión de otredades. Estos ideales producen arquetipos de individuos seriados y categorizan de forma jerárquica el origen y raza. Al respecto, y teniendo en cuenta tu trayectoria como fotógrafo de moda, ¿cómo percibes la convivencia de estas dos realidades?, ¿crees que ha surgido tanto desde el arte como de la sociedad una perspectiva más inclusiva referente a la belleza?

What ever happened to beauty? Gone with the wind Me parece que actualmente, con la explosión de las redes sociales y el alcance de los movimientos políticos descentralizados (e.g. #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter), que promueven programas ideológicos instantáneos a escala mundial a través de Internet, quedó claro que lo que antes se catalogaba como ‘canon occidental’ era un proyecto cultural estrecho, pensado por unos pocos y, probablemente, para unos pocos.

Basándome en esto, me pregunto: ¿dónde se queda la China, la India, para solo mencionar dos países, en esta historia?

Es posible que esta paleta de tonos de piel demasiado pálida para el momento actual, prejuiciosa en sus orígenes, se haya visto finalmente como algo insuficiente, corto en su alcance para servir de máscara a la representación general de las muchas alteridades emergentes.

Puedo señalar que, por un lado, la respuesta vino a través de la hipernormalización del consumo de la moda, por la globalización de las muchas marcas de lujo que han tomado la iniciativa de ensalzar el carácter universal del dinero y del buen gusto. Pero, ¿no sería este un nuevo hombre serializado?

Por otro lado, algo más surgió. Un canon alternativo de origen difuso y bordes indefinidos. Algo un tanto provinciano, de alguien que se vio amenazado por las muchas exigencias feministas, poscoloniales y por un nuevo mundo compuesto por nuevas jerarquías en los estratos de la pirámide social. Este sujeto también reaccionó, aunque en forma de prejuicios y teorías conspiratorias (e.g. fake news -QAnon), hechas de viejas ideas y nacionalismos, donde los espejos estéticos son seguros y la imagen reflejada no causa incomodidad.

La construcción de un relato vivo y auténtico se funda en el carácter íntimo y profundo de la representación, ¿cómo logras establecer dicha intimidad y qué factores son fundamentales para su construcción y desarrollo?

Este me parece el quid de la cuestión: ¿quién habla?

Más allá de intentar establecer una intimidad, aunque a veces es necesario mantener una distancia, en general, procuro y trato de dialogar, sensibilizar y construir los dispositivos narrativos que desarrolla la obra junto con los propios sujetos. Sin embargo, cada serie es un universo diferente y malheureusement no existe una fórmula mágica. Todo momento histórico tiene su propia contingencia, urgencia y necesidades específicas que moldean y dan forma al trabajo.

Western culture fosters an ideal of beauty that limits the inclusion of otherness. These ideals create archetypes of replicated individuals and hierarchically categorize origin and race. Bearing in mind your experience as a fashion photographer, how do you perceive the coexistence of these two realities? Do you think a more inclusive perspective of beauty has emerged both in art and society?

What ever happened to beauty? Gone with the wind I feel that now, with the explosion of social media and the scope of decentralized political movements (e.g. #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter) that promote instant ideological causes on a global scale through the Internet, it has become clear that what was previously called “Western ideals” were a narrow cultural project, conceived by and for a select few. Based on this, I wonder: Where do China or India, just to name two countries, fall into this history?

Possibly, these currently in vogue pale skin tones, which are prejudicial from their inception, have finally been seen as insufficient, as falling short in their scope to serve as the mask of general representation in the diversity of emerging otherness.

I can note that the response came from the hypernormalization of fashion consumption and the globalization of luxury brands that have taken the initiative to promote the universal nature of money and good taste. But wouldn’t this be a new form of a replicated individual?

Something else emerged as well: an alternative standard with vague origins and blurred lines. This somewhat provincial new standard stemmed from feeling threatened by the demands of feminists, post-colonialism and a world order made up of new hierarchies in the social class pyramid. Although this new ambiguous standard gave rise to prejudice and conspiracy theories (e.g. fake news, QAnon) made up of old ideas and nationalist feelings, it also made it so that when holding up a mirror to its image, it felt safe and did not cause any discomfort.

The construction of a sharp and authentic narrative is based on the intimate and deep nature of representation. How do you manage to establish this intimacy? What factors are fundamental in building and developing it?

To me, the crux of matter is: whose narrative is it?

Beyond trying to force intimacy, I generally try to make sure to engage in a conversation, become more aware, and craft the narrative devices to develop pieces alongside the subjects themselves, even though it is sometimes necessary to keep a distance. However, every series is a different universe and, unfortunately, there is no magic formula. Every historical moment has its own specific impact, urgency, and needs that mold and shape my work.

Yo no creo, además, que pueda haber un sujeto y un objeto ficticiamente separados por un aparato mecánico llamado cámara. Siempre hay una persona inmersa en un grupo de personas, interactuando constantemente y viéndose afectada dentro de todo este sistema. Como campos de fuerza procedentes de muchos cuerpos que interfieren entre sí, donde unas veces se anulan y otras se intensifican, mediaciones que ocurren al azar y dan origen a la estructura íntima y única de cada obra.

Incorporó las causalidades y posibilidades por muy contrarias que sean o que se presenten, ya que apuntan a soluciones estéticas válidas. De alguna manera intento exponer el proceso que se convierte en parte de la obra, pues la obra es también un proceso abierto, un proceso que busca la conciencia.

El poder crítico y la facultad discursiva de las imágenes impulsa y fortalece el rol del artista como activista. La representación de minorías e ideales opacados por el sistema imperante es clave respecto al factor de cambio que ejerce la cultura y las artes, ¿crees que como artista debes asumir un rol activo y contestatario sobre las problemáticas actuales?

Desde una perspectiva personal, que al cabo de años tomó forma, asumí que había hecho una investigación sistemática en cuestiones relevantes, de urgencia perturbadora, al menos a mis ojos, como testigo en este amanecer planetario del diseño industrial de residuos contaminados, de relaves que producen cambios ecológicos en los biomas y que han servido y siguen sirviendo a estas empresas. A través de este trabajo comprendí que este modelo sirve para ilustrar la actual forma de ocupación de la Amazonía: el encuentro entre la motosierra y el bosque.

En estos sitios reprimidos del panorama mental y visual común, como los fantasmas, tienden a regresar transfigurados, es casi un experimento científico, heterodoxo, que, tras coagularse, da vida a un nuevo paisaje, Frankenstein. Aunque insostenible desde el punto de vista medioambiental, de los pueblos nativos que por ahí circulan, esta realidad fluida y fluctuante que no está basada en lo local, en la comunidad y que no es propia de las necesidades físicas de automantenimiento y equilibrio de la tierra, sigue.

No sé los otros, pero mis obras pretenden construir una imagen del futuro que se materializa en una maqueta del pasado. Una especie de pastiche de paisajes destruidos, montañas de basura, agentes contaminantes y personas que nunca imaginaron ni se preocuparon por cómo sería el futuro actual.

Besides, I do not think subject and object could be fictitiously separated by the mechanical device we call a camera. People are always among others, constantly interacting with and being affected within the system. Just like the force fields of different bodies interact with one another, sometimes canceling each other out, other times becoming stronger, these mediations happen at random and they create the intimate and unique structure of each piece.

I incorporate all coincidences and possibilities, even if they seem contradictory, because aim at valid aesthetic solutions. I somewhat try to evince the process that is part of every piece, as it is also an open process, a process that seeks awareness.

The critical and narrative power of images boosts and strengthens the role of artists as activists. Representation of minorities and ideals overshadowed by the ruling system is key in culture and art as agents of change. Do you think as an artist you must assume an active and contesting role towards current issues?

From a very personal perspective, which I have shaped over some years, I felt I have conducted systematical research on relevant issues of a disturbingly pressing nature, at least in my eyes, I have been a witness to the dawn of mass-produced contaminated waste, mine tailings that affect the environment of biomes and that have worked and continue to work for the benefit of some companies. Through this work, I understood that this model illustrates the current state of occupation of the Amazon: the encounter between chainsaws and forest.

In the repressed areas of the common mental and visual landscape, these places are transfigured upon their return, like ghosts, and almost like a heterodox scientific experiment that, after coalescing, brings a new landscape to life, a Frankenstein.

Although unsustainable from an environmental standpoint and from the viewpoint of native peoples that inhabit these places, this fluid and fluctuating reality prevails, even if it fails to consider local or community concerns and it is not conducive to the Earth’s physical needs of self-sustainability and balance.

I do not know about other artists, but my work aims to build an image of the future that materializes through a mock-up of the past: a sort of hodgepodge of deconstructed landscapes, mountains of waste, pollutants, and people that never imagined or worried about what the future would hold.

Por Ricardo Rojas Behm. Escritor y Crítico (Chile).

Imágenes cortesía del artista.

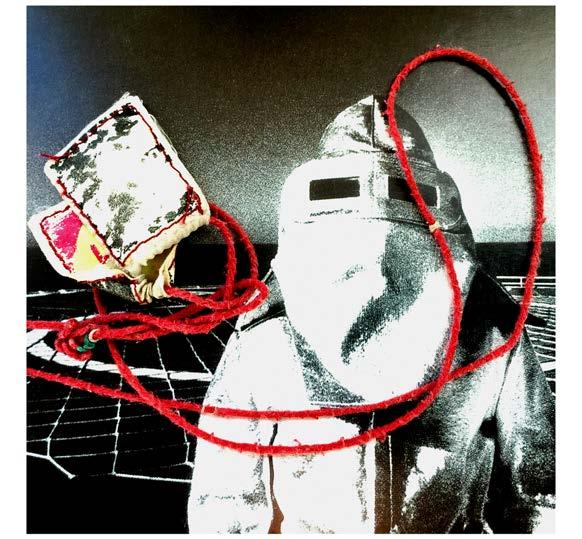

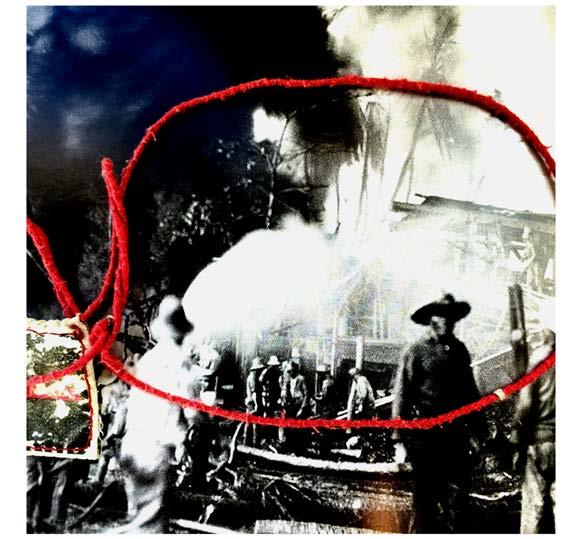

tantas veces nos vemos obnubilados por un flashazo de nombres que resplandecen en nuestra memoria como reconocidos. Pero, ese anquilosamiento instalado a perpetuidad no hace otra cosa que demostrarnos que en paralelo existe un número importante de artistas que viajan por otro carril, que no se entrega a lo comercial, lo complaciente, lo tradicional, lo esperado, o lo conformista, y no escatiman esfuerzos por encontrar múltiples formas de abordar el arte, legitimando nuevos códigos que modifiquen el orden de las cosas. En ese escenario está Muu Blanco, quien recuerda que todo responde a una serie de motivaciones que lo impulsaron a ser un artista multidisciplinario. Desde su bisabuelo, el escritor y poeta Udón Pérez, a ser nieto de Antonio Angulo Luzardo, primer artista abstracto de su país. Por eso realizamos una entrevista exclusiva, para abordar más sobre su obra y sus motivaciones.

¿Qué otros referentes o lecturas, músicas y paisajes, gatillaron ese motivación inicial?

El conocer la filosofía punk en los 80’s por medio de las letras de las bandas británicas, a la vez de descubrir las vanguardias del siglo XX, el futurismo de Luigi Russolo, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, los Dadaístas Hugo Ball, Tristán Tzara, Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp y los situacionistas Rosa Luxemburgo y Georg Lukács,y por supuesto el Arte sonoro de John Cage (FLUXUS) y muchos más de una extensa lista. Aunque, vivir en Caracas en esa época de los 90’s con 5 museos, la cinemateca, el movimiento musical en vivo y mi contexto familiar, su biblioteca ecléctica, la libertad de pensar y hacer cosas sin un sentido definido, ver por la ventana y estar en otra dimensión mental, del disfrute de las posibilidades creativas sin límite.

En ese sin o al límite, ¿Cómo confluyen el dada, el pop o la filosofía punk en ese hacer lo que quieres, hacer sin estar informado o deconstruir y volver a desarrollar?

Es algo natural, al comienzo era un joven desinformado, pero para el 2000 ya estaba inmerso en esta forma de producción de arte, que yo denomino ‘sistema de representación de arte contemporáneo, práctico y crítico’. Es una manera de creación muy sencilla que se va complejizando según el río en que me introduzca, viene de las conversaciones, de internet (imágenes-música-películas-lecturas), de su algoritmo que no solo te propone productos, sino temas que escuchamos cotidianamente; lo mismo sucede en YouTube y en servidores de música donde paso muchas horas al día recopilando cascadas investigativas que vienen de situaciones vividas a diario. Esos significativos descubrimientos son, para mí, la manifestación del arte que se divide en muchos tentáculos como medios expresivos.

Entrecruzando esos tentáculos ¿Cuál es el nexo entre la escuelita Federico Brandt en San Bernardino, y tu estudio de Coconut Grove?

Estudios libres, donde comencé por la historia del arte contemporáneo

we are often blinded by the bright flashes of names that light up our memory in familiarity. However, this deeply rooted stagnation only proves there is a significant number of artists who tread a different path and do not surrender to commercialization, complacency, tradition, expectations or conformity. These artists spare no effort in finding different methods of approaching art, thus legitimizing new codes that shift the established order. This is the stage where Muu Blanco operates, remembering that everything answers the myriad of motivations that led him to become a multi-disciplinary artist. He is the great-grandchild of writer and poet Udón Pérez and the grandchild of Antonio Angulo Luzardo, the first abstract artist in his country. In this exclusive interview, we address his work and his motivations.

What references, texts, music, and landscapes led to that initial motivation?

Learning about 80s punk ideology through British band lyrics, while discovering 20th-century avant-garde; Luigi Russolo’s and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s futurism; Dadaists Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Max Ernst, and Marcel Duchamp; situationists Rosa Luxemburg and György Lukács; and of course, sound art by John Cage (FLUXUS); as well as many others in a lengthy list. Living in Caracas in the 90s also influenced me. Back then, it had 5 museums and a bustling film and live music scene. My family context played a role as well, with its eclectic library, freedom of thought and of doing things without a specific purpose, looking out the window and being in a different mental space, and the enjoyment of creative possibilities without any limits.

In that creativity with or without limits, how do Dadaism, pop and punk ideology come together in doing what you want, creating while uninformed or deconstructing and redeveloping?

It is something natural. I was uninformed when I was young, but by 2000 I was already very much involved in that way of creating art, which I call a “critical and practical contemporary art representation system”. It is a very simple method of creation that becomes more complex depending on the waters I’m exploring. It comes from conversations, images, music, films and texts from the Internet and its algorithm that not only serves products, but also topics from everyday life. The same thing happens with YouTube, where I spend many hours in the day compiling waves of research stemming from daily situations. For me, these significant discoveries are artistic manifestations divided into the many tentacles of the means of expression.

Intertwining those tentacles, what is the link between the Federico Brandt Institute in San Bernardino and your Coconut Grove studio?

I started studying the history of contemporary art on my own, and from

de allí al dibujo, que fue un corrientazo que me despertó de nuevo el espíritu creador que desde los 12 años abandoné por andar vagando por Caracas con la banda de Ska “Desorden público”, luego 30 años de libertad creativa de mano de mi mejor amiga -la computadora portátil-, y en Miami, desde hace 9 años, he tenido 3 espacios de creación, uno público “Espacio Saltamantis”; y dos privados: mi casa estudio, en Design District, y ahora un garage bunker en Coconut Grove, donde estoy más activo que nunca conceptualmente para armar los próximos portaviones con lo que atacaré el mundo del arte desde el “Pantano de las Vanidades”, Miami City, mi nuevo hogar, ya que desde octubre del 2023 soy naturalizado estadounidense.

Existen abstracciones paisajísticas, torsiones de la realidad y proyectos sonoros ¿Hasta qué punto eso sigue siendo tu motor?

Las abstracciones paisajísticas están presentes desde el 2002, este mes edité mi cuarto foto libro y es de los primeros 10 años de esta investigación desde su nacimiento en las calles de Caracas hasta el 2012, cuando cerré ese ciclo en mi ciudad natal para emigrar. Con respecto al paisaje sonoro tengo archivos de muchas locaciones, las más recientes publicaciones sonoras son una serie de 4 sencillos de ambiente sonoro y flauta grabado en vivo en un jardín del centro cultural la Trinidad (Caracas, 2013) Nueva Poética Venezolana Vol’s 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 (NPV), a nivel global en el servidor de música de tu preferencia. Y, hace unas semanas, fui invitado a presentar una instalación sonora en la primera Doral Internacional Art Fair (City of Doral, Florida), donde realicé una curaduría de historia del arte sonoro desde el futurismo al paisaje sonoro con 100 años de historia, en 5 módulos, donde puedes escuchar 59 tracks de unos 30 artistas representantes del sonido en el arte.

¿Cuál es el concepto que moviliza tu trabajo como artista venezolano fuera de tu país?

Desde hace nueve años no dejo de editar y exponer todas las investigaciones maduradas de mis primeros 30 años de carrera artística en Venezuela, es una carga personal muy presente, la mayoría de mis investigaciones vienen desde ahí y tú pregunta me lo pone enfrente, incluso mi primera investigación que no tiene que ver con ser venezolano, ya que es un trabajo documental del 2020-2022, es mi supervivencia en este periodo de la pandemia y sus años siguientes, pero lo que busco es realizar arte centrado en el aquí y el ahora, sin dejar de lado mis referencias históricas personales. No soy un artista que tiene un arraigo folk venezolano, aunque sí estoy influenciado por pensadores y por su arte contemporáneo. Es lamentable, pero el perfil de artista venezolano no me favorece, eso es lo que me ha tocado vivir aquí en USA.

De hecho, el año entrante estoy llevando a Madrid un video que es una metáfora de cómo los artistas venezolanos estamos atrapados en el mercado del arte abstracto geométrico, si no estás en esa línea difícilmente tienes éxito como venezolano en el exterior. Ese video es una loop infinito de mi cuerpo caminando hacia adelante y hacia atrás dentro de una obra de Julio Le Parc y una vectorización traslúcida de una pieza de Jesús Rafael Soto.

there I began drawing. That rush reawakened my creative spirit, which I had abandoned at the age of 12 to wander around Caracas with the Ska band “Desorden Público”. From there, it has been 30 years of creative freedom alongside my best friend –the laptop. In Miami, I have had 3 spaces of creation over the last 9 years: one public, Espacio Saltamantis, and two private ones, my home studio in the Design District, and now a garage bunker in Coconut Grove, where I am more conceptually active than ever. This has led me to assemble the next aircraft carriers with which I plan to attack the art world from “Swamp of Vanities,” or Miami, which is my new home, as I have been an American citizen since October 2023.

Your work has featured abstract landscapes, reality distortions, and sound projects. To what extent are those still your driving force?

Abstract landscapes have been present in my work since 2002. This month, I edited my fourth picture book encompassing 10 years of research, from its inception on the streets of Caracas to 2012, when I closed that chapter in my native land to migrate. In regards to soundscapes, I have files from many places. My most recent sound publications are a series of 4 ambient sound singles with flutes recorded live at the garden of La Trinidad Culture Center (Caracas, 2013) entitled Nueva Poética Venezolana Vol. 1, 2, 3, 4 (NPV), available worldwide in your favorite music streaming platform. A few weeks ago, I was invited to exhibit a sound installation in the first edition of the Doral International Art Fair (Doral, Florida). I curated pieces from 100 years of the history of sound art, from futurism to soundscapes, and arranged them in 5 modules, where listeners can hear 59 tracks by around 30 representative artists.

What is the concept that drives your work as a Venezuelan artist away from your country?

For 9 years, I have not stopped editing and exhibiting all my fully developed work from the first 30 years of my career in Venezuela. This is a very present personal load; most of my research comes from there and your question makes me face it. In fact, my very first research project that has nothing to do with being Venezuelan is a documentary work from 2020-2022 addressing my survival of the pandemic and the years that followed. In it, I aim to create art focused on the here and now, without casting aside my personal and historic references. I am not an artist who is rooted in Venezuelan folk, but I am influenced by its thinkers and contemporary art. Unfortunately, being labeled as a Venezuelan artist does not work in my favor, that is what I have experienced here in the USA.

As a matter of fact, next year I will be taking a video to Madrid that serves as a metaphor of how Venezuelan artists are trapped in the geometric art market. If you do not fall into that category, you can seldom succeed as a Venezuelan abroad. The video is an infinite loop of my body walking forwards and backwards inside a piece by Julio Le Parc and a translucent rendering of a piece by Jesús Rafael Soto.

La feria es un punto de encuentro anual clave en el mundo del arte moderno y contemporáneo latinoamericano. Pinta PArC exhibe y potencia el intercambio cultural y la promoción de las artes visuales en la región.

- 5 invitados internacionales

- 45 galerías de 14 países

- Auditorio | Foro.

25 al 28 de Abril, 2024

Casa Prado

Av 28 de Julio 878, Miraflores

Lima, Perú

IT´S MORE THAN A FAIR, IT´S A CONCEPT

parc.pinta.art

PintaArtofficial

El reino de los mundos invisibles

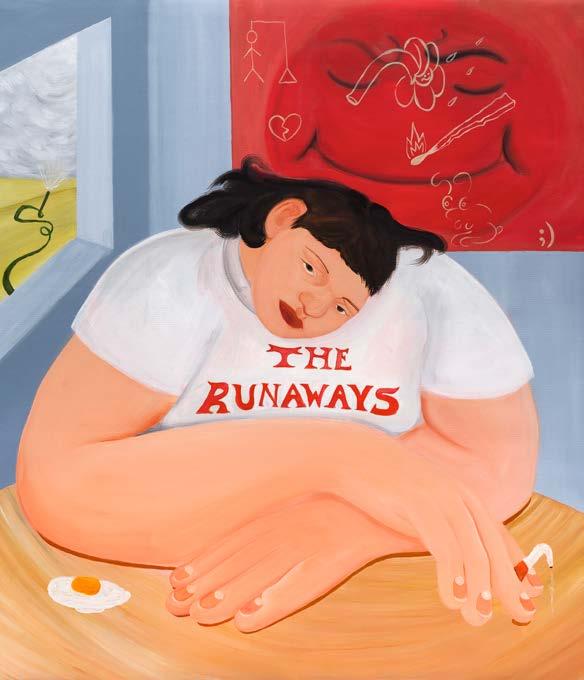

BLUSH,

BLUSH,

Plantas, hongos, flores, naturalezas imposibles en el mundo orgánico, paisajes digitales que no distinguen entre un océano y un bosque son creadas a partir del tratamiento digital de sus propias fotografías, creando imágenes que mezclan el mundo real con la ilusión de un paraíso.

Su conexión con la naturaleza se fortaleció durante su crianza en Quebec, en Canadá, donde su familia tenía una cabaña próxima al norte salvaje de la provincia. Tras su formación profesional en Diseño Gráfico y Comunicaciones, vendrían quince años de trabajo en la industria de la publicidad que marcan un sello distintivo en su visualidad. La búsqueda por hallar gratificación en el trabajo creativo la llevaría a estudiar un programa de pintura independiente, para luego imaginar un mundo en base a la fotografía que la ha llevado a tener una exitosa carrera donde, además, ha explorado el hiper-collage digital, la escultura y los NFT.

Ha sido reconocida internacionalmente por las obras que conceptualiza como panoramas de hiper-collage: “Un término que utilizo como una característica con la que defino la intensidad y complejidad de mi trabajo. Propone una visión distinta de la composición digital tradicional. La descripción de un panorama es una vista despejada o compleja de una zona. Pretendo ofrecer esa complejidad en mi obra porque así es como percibo la naturaleza.” El proceso del hiper-collage es altamente instintivo, permitiendo a cada pieza dictar su propio destino. Desde un punto de vista singular y simple –como una imagen, un color o una emoción–, Ysabel sigue un proceso meticuloso. Primero, aísla y extrae elementos de sus fotografías, los cuales le permiten entrar en contacto con la esencia y la individualidad de cada planta. Todas ellas tienen su propio impacto energético y provocan emociones particulares. Finalmente, entrelaza esos fragmentos entre sí mediante intrincadas composiciones.

La cita de Albert Einstein “Observa profundamente la naturaleza y entonces comprenderás todo mejor”, le resulta inspiradora. En ese sentido, su proceso creativo es “orgánico y fluido”.

Plants, fungi, flowers, natures impossible in the organic world, and digital landscapes that do all but distinguish between an ocean and a forest are created through digital manipulation of her photographs to deliver images that merge the real world and the illusion of a paradise.

Growing up in Quebec, Canada, she bolstered her connection to nature at her family’s cottage in the northern wilderness of the province. After studying graphic design and communications, fifteen years of work in the advertising industry would follow, shaping her distinctive visual signature. The pursuit of more fulfilling paths for her creative work landed her in an independent painting program. Later, this led her to imagine a world based on photography that has given way to a successful career in which she has also explored digital hypercollage, sculpture, and NFTs.

She is internationally renowned for pieces she calls hypercollage landscapes: “a term I use as a characteristic to define the intensity and complexity of my work. It proposes a distinctive view of traditional digital composite. The description of a panorama is an unobstructed or complex view of an area. I intend to offer that complexity in my work because this is how I perceive nature.” The process of hypercollages is instinctual and organic, allowing each piece to dictate its own destiny. From a single, simple starting point —an image, a color, an emotion— Ysabel follows a meticulous process. First, she isolates and extracts elements of her photos, enabling her to connect with the essence and individuality of each plant. All of them have their own unique energy and elicit specific emotions. Then, she intertwines the fragments in intricate compositions.

Albert Einstein’s quote, “Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better”, inspires her. Thus, her creative process is “organic and fluid”.

EDEN, 2022, composición digital, 91.44 cm.

Le gusta saber que ella es parte del mismo tejido de la vida que crea todas las cosas. Ve la naturaleza a través de sus lentes holográficos. Primero, es afectada por su esplendor. Luego, conecta con el campo energético, el cual abre la puerta de la información y el conocimiento donde se manifiestan los pensamientos creativos: “Al dejar que su energía fluya a través de mí, primero percibo y luego demuestro visualmente la magia del mundo vivo. Mi interacción con la naturaleza me permite comprender más profundamente mi comunión con esta y con los demás, y creo que su poder primordial puede ayudar a elevar nuestra conciencia colectiva”, explica.

Sus piezas han circulado en más de 135 exhibiciones en distintos países, también han sido adquiridas por colecciones públicas, corporaciones y museos. Quizás, una de las formas más innovadoras en que su obra ha circulado ha sido la venta de Flower of Sentience (2023), a través de su página web, como NFT, tecnología que representa la propiedad de elementos digitales coleccionables, únicos e intransferibles, conservando los registros de propiedad intelectual.

A pesar de lo anterior, se muestra crítica respecto al uso de inteligencia artificial en el arte contemporáneo. A inicios de 2023 tuvo la oportunidad de sumergirse en el mundo de la IA, siendo comisionada para crear veinte retratos basados en fábulas. Durante esas semanas, sintió una inmensa atracción hacia la dirección opuesta del encargo recibido. La naturaleza la estaba llamando de vuelta, de manera fuerte y clara. LeMay considera que en la actualidad vivimos en dos mundos diferentes en el planeta, por un lado, el mundo de la IA; por el otro, el mundo de la naturaleza: “Tomé personalmente la decisión de profundizar en mi relación con el mundo físico y el espíritu de la Madre Tierra. Ya se abrió la caja de Pandora con la IA. Está influyendo profundamente en nuestra forma de crear y trabajar. Rápido… muy rápido.”

She relishes in knowing she is part of the very fabric that creates all things. She sees nature through her holographic lens. First, she is moved by its splendor. Then, she connects to the energy field that opens the door for information and knowledge leading to creative ideas: “By allowing its energy to run through me, I first perceive and then visually demonstrate the magic of the living world. My interaction with nature allows me to understand more deeply my communion with it and others, and I believe its primordial power can help lift our collective consciousness,” she explains.