Evolving News for

Members & Friends

a quarterly publication of the anthroposophical society in america including the rudolf steiner library newsletter

research issue 2010

Research not Revelation

The present issue has taken some time to reach you, but we expect it to be an annual feature, since the subject is so important. Research! A word that is so strongly associated with natural science for the last several centuries, and secondly with the new fields, the humanities, the human sciences, which blossomed as disciplines in the 19th century.

Research is also at the heart of Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophy. But anthroposophy does not see limits where natural science has placed them. It takes those limits as demands for enhancing human capacities. Our sophisticated mechanical instruments provide wonderful data, but first and last anthroposophy looks to disciplined human observation, imagination, inspiration, intuition. So it charts new paths in research in many directions, making much of very limited resources.

And despite the impression that anthroposophy all comes from Rudolf Steiner himself, we find both outstanding predecessors to whom he pointed, as well as a remarkable number of capable individuals and groups carrying on where Steiner left off. As detailed on subsequent pages, research generally begins in self-examination and meditation. It then evolves either in conversational settings like study groups and branches of the Anthroposophical Society, or in the very conscious activity of initiatives like Waldorf schools, biodynamic farms, Camphill villages, medical and therapeutic practices, social finance organizations, and countless artistic and community undertakings. And ideally it finds its way then into the work of sections of the School of Spiritual Science, an institution Rudolf Steiner created in 1924 for this purpose. For over two decades the school has had a unifying collegium in North America, and the good effects of this collaboration are being felt even with shoestring budgets.

Only a few segments of the range of anthroposophical research are represented in this one issue, but we hope it will allow you to begin to imagine the true scope of Rudolf Steiner’s intentions for anthroposophy: that it should seed the culture of our times with an abundance of living and healing impulses and thereby renew the consciousness of our humanity.

Expanding Communications

As we cannot do justice to the scope of anthroposophy’s research work in this one issue, so a quarterly printed magazine cannot contain everything that friends and members want to share. Nor is it satisfying to offer a largely one-way communication at a moment when the means for lively interchange get easier and easier. So we are beginning a policy of publishing much more on the society’s website, anthroposophy.org, and linking to it by way of the twice-monthly E-News communication. The many interesting and timely reports will be published more quickly. Comments can be shared. New and old items can be linked topically. The website will become a broader and deeper destination. And our choice of what to include here or leave out will be made less agonizing! So please sign up for E-News at anthroposophy.org to keep in touch with further developments.

— John Beck, Editor, Evolving News for Members & Friends

Serve the future by teaching the children of today with an unhurried, age-appropriate education rich in art and academics. Become a Waldorf Teacher B y comple T ing a par T T ime program aT Sun B ridge in ST iTuT e! Waldorf education, based on the work of rudolf Steiner, is the fastestgrowing independent school movement in the world. There is a constant need for Waldorf teachers (K-12) with hundreds of job openings every year for qualified men and women.

285

www.sunbridge.edu

2 Evolving News From the Editor

Hungry Hollow Road

Ridge, NY

Email: editor@anthroposophy.org info@sunbridge.edu

Chestnut

10977 845.425.0055 /

Plant the Seed of Imagination Become a Waldorf Teacher

Have an article, news, letter? Want to propose one?

Email editor@anthroposophy.org or write to the address below.

Was this issue passed along?

View or download previous issues at anthroposophy.org where you can also become a member. Or to receive the next printed copy, contact the society and ask to be added to the friends list.

Would you like to advertise? Call Cynthia Chelius at 734-662-9355 — or email editor@anthroposophy.org

Would you like to support this publication and at the same time make your service or product known to our thoughtful readers? Call soon to reserve space in the next issue. And if you have an existing ad or flyer but no design time to adapt it for us, we can usually work with what you have already created.

3 Research Issue 2010

p.6 p.9 p.23 p.48 p.7 p.12 p.27 p.60 Evolving News for Members and Friends is a publication of the The Anthroposophical Society in America, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Contents From the Editor 2 Letters to the Editor 4 What’s Happening at the Rudolf Steiner Library 5 Where on Earth Is Heaven? (RSL book review) 6 Ernst Katz, teacher of anthroposophy 7 Triskeles: Building the Positive Future 9 LA Karma Workshop: Tycho Brahe, Herzeleide, Emperor Julian 12 Feature Articles Research–a special section 13 Spiritual Research in the Branch 14 The Section for the Social Sciences in North America 15 A Resurgence of Research at Threefold 16 The Henry Barnes Fund for Anthroposophical Research 17 What Shall We Do About Ahriman? 18 The Seven Levels of Illness & Healing - a modern fable 21 Metamorphosis: Evolution in Action (book review) 23 Conference of the Natural Science Section in Chicago 24 The Nature Institute: Center of Excellence in Holistic Research 25 The Postmodern Revolution and Anthroposophical Art 27 Challenges Facing Waldorf Education 40 News for Members Freedom and Initiative: remarks by Torin Finser 42 “A New Impulse” Conference 45 Joan Treadaway (council member profile) 46 Michael Support Circle Report 46 Florida Groups Gather At The Spring Equinox 46 Stars, Stones & Mutuality: CRC Gathering 47 The Austin Centenary Celebration 48 The Reappearance of Christ in the Etheric 51 Where on Earth is Heaven? (second book review) 59 Thresholds Ronna McEldowney 60 Lorna Odegard 61 Members Who Have Died 61 New Members of the Anthroposophical Society 62

Letters to the Editor

On Elemental Beings

Regarding the letter by Jenny Hohmann about nature spirits, I would like to recommend Peter and Anneli’s Journey to the Moon published by SteinerBooks two years ago. In the catalog’s description major happenings in the book were ignored: the encounter of the children with the Spirits of Nature. (The translated verses are a bit clumsy—I am no poet!) The illustrations by the famous German painter Hans Baluschek are in themselves worth looking at.

Marianne H. Luedeking

Note: Ms. Luedeking translated the book in question. The original German cover is below:

progress, but on ‘the empathic evolution of the human race and the profound ways it has shaped our development.’ Empathy, Rifkin explains, is not a quaint behavior trotted out during intermittent visits to a food bank or during the Haiti telethon. Instead, it lies at the very core of human existence. Indeed, in this time of economic hardship, political instability, and rapid technological change, empathy is the one quality we most need if we’re going to survive and flourish in the 21st century.”

Notes/Notices

LA Library catalog online

people at Forest Row, East Sussex. Three program areas are active at this time: visual arts, foundation through the visual arts, sculpture training; biodynamic agriculture courses; and storytelling courses. Emerson is on the web at emerson.org.uk

Correction/Update

Summerfield Architect

In the article “Musical Instrument Building and Improvisation” mention was made of “architect and parent Steve”— which should have specified “Steve Sheldon, who designed the buildings at the Summerfield Waldorf School where the workshop had taken place.

Wiechert in Bay Area

again for a conference “Finding Balance,” February 24-26, 2011, in the San Francisco Bay area; bacwtt.org has details. Also, the picture of Christof used (below) should have been credited to BACWTT.

On Empathy

Because of your interest in my article on empathy [in the Sophia Sun newsletter], I thought you would like to see the article below. It’s really amazing to see positive proof of the evolving of human consciousness.

Kathleen Wright

Arianna Huffington’s article from the Huffington Post, Feb. 3, 2010 was attached. It begins:

“ For this month’s HuffPost Book Club, I have chosen Jeremy Rifkin’s The Empathic Civilization, which boldly sets out to present nothing less than—as Rifkin puts it—‘a new rendering of human history.’ This alternative history focuses not on the conflicts and power struggles that have marked human

From Rudolf Steiner Library & Bookshop in Pasadena: “The catalog of our library can now be consulted on the website of the Los Angeles Branch of the Anthroposophical Society – anthroposophyla.org. (On the home page click on Library & Bookshop, and on the following page click on Library Catalog.) You can search the catalog by book title, author, translator and subject. You can search for a specific Steiner lecture by date and/or place and run reports of all the books in our collection by Rudolf Steiner sorted by title or GA number. Books by other authors can be sorted by title, author or subject section. Reports include full particulars of a book, such as publisher, publishing year and GA number. At this time our library has 860 different Steiner titles, over 3800 Steiner lectures and about 2000 titles by other authors. Please direct inquiries to Philip Mees phmees@sbcglobal. net.”

Emerson College

Joann Ianniello wrote to be sure that we were aware of continuing life and activity at Emerson College in the UK, in the new context of “Emerson Village.” No doubt a great many people share her gratitude for time spent with remarkable

The article “Renewal” mentioned as upcoming an appearance by Christof Wiechert at the “New Impulse Conference” of the Bay Area Center for Waldorf Teacher Training in California that was already past (see p. 45). Christof will appear at BACWTT

Christof Wiechert will also return to the Renewal 2011 program in Wilton, NH, “Celebrating Rudolf Steiner’s 150th Anniversary.” One week courses run from June 26th-July 1st and July 3rd-July 8th. Other presenters include Virginia Sease, Van James, Christof Wiechert, Aonghus Gordon and craftspeople, and Dr. Tobias Tuechelmann. Email info@ centerforanthroposophy.org or call 603 654 2566.

Join us as we trace the threads of spiritual history in the landscape and soul-scape of Scotland.

Story, song, eurythmy & informal talks will guide us into the unique cultural climate of this beautiful and infinitely varied country. We will visit the Neolithic stone circles of the Outer Hebrides and Orkney, the glens and mountains of the Highlands, the sacred island of Iona, the social initiative of Robert Owen at New Lanark, the spiritual community of Findhorn, historic and beautiful Edinburgh, and much more. Tour leaders are native Scots:

Gillian Schoemaker, eurythmist, Camphill Special Schools, Pennsylvania, and Sean Gordon, Celtic scholar, storyteller and Waldorf teacher, Aberdeen, Scotland

4 Evolving News

Interested? For details of itinerary and cost, please contact Gillian: 610 469 0864 gillian_schoemaker@yahoo.com SCOTTISH ODYSSEY July 16th – August 5th, 2011

What’s Happening in the Rudolf Steiner Library

Judith Soleil, Library Director

Flying barcodes! Yes, the automation project proceeds apace. The library’s online public access catalog at http:// rsl.scoolaid.net now contains searchable records for nearly 14,000 items, about half the collection. When visiting the catalog online, be sure to check out the “News” section. We are posting book annotations on the page now as well as events we host at the library. Also check the “New Items” page, which lists monthly acquisitions.

Call for volunteer translators! The library subscribes to a number of Germanlanguage anthroposophical journals with intriguing contents: Das Goetheanum, Info3, Flensburger Heft, Der Europäer, Die Drei, Die Christengemeinschaft. We would love to share some of the articles from these journals with English speakers. Please let us know if you would like to collaborate with us on such a project; we will provide editorial assistance.

We are looking for back issues of the

British journal Anthroposophical Movement/News Sheet for Members of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain, and copies of the Rundbrief published by the Pedagogical Section. Contact us regarding specific dates needed.

Why books? Are books just a tired, inefficient, outdated medium (ouch!)? Digital resources are important, particularly in the sciences, where researchers rely on up-to-the-minute online journals and databases. Still, Robert Darnton, director of Harvard’s university library, predicts longevity for the book: http://harvardmagazine.com/2010/05/gutenberg-2-0

Book Reviews

by Frederick Dennehy

I believe that miso belongs to the highest class of medicines, those which help prevent disease and strengthen the body through continued usage. . . Some people speak of miso as a condiment, but miso brings out the flavor and nutritional value in all foods and helps the body to digest and assimilate whatever we eat. . .

In this issue we offer Keith Francis’s review of Metamorphosis: Evolution in Action, by Andreas Suchantke, one of the most important books on Goethean science to appear in years. Readers of this book (and, because it is so incisive and detailed, this review) are likely to come to a fresh understanding of metamorphosis as not only a concept, but as an imaginative activity. Suchantke emphasizes the need to “escape from the idea of a fixed spatial form” and cultivate an intuition of “the inner line, or, rather, the time-gestalt of the whole of evolution.” In a larger context, readers will be challenged to wean themselves from the mechanistic habit of focusing exclusively on what Aristotle termed “efficient cause” and to develop a sense for the neglected “formal cause” or “archetype.” Such a genuinely scientific approach yields a comprehension of living things and of

the process of change—metamorphosis— sharply distinguishable from a grasp of the finished world that physicists investigate. Also in this issue is my review of Where On Earth Is Heaven? by Jonathan Stedall, a warm, honest, and amateur—in the best sense—inquiry into the meaning of immortality. Readers will be intrigued (and instructed) by Mr. Stedall’s understanding of anthroposophy from the periphery of the movement, and an account of Rudolf Steiner not from the vantage point of a disciple, but from that of a sympathetic friend.

Book reviews are on p.6 and p.23.

Library Annotations

Brief descriptions of new books available from the library; annotations this time by Judith Soleil.

Anthroposophy—Rudolf Steiner

Astronomy and Astrology: Finding a Relationship to the Cosmos, compiled and edited by Margaret Jonas, Rudolf Steiner Press, 2009, 250 pgs. Includes notes and a bibliography.

“Although Steiner rejects the simplistic notion of the planets determining our lives and behavior, he makes a clear connection between the heavenly bodies and human beings…. This…anthology features excerpts of Steiner’s work on the spiritual individualities of the planets, the determination of human characteristics by the constellation at birth, the cultural epochs and the passage of the equinox, solar and lunar eclipses…and much more.” An excellent introduction by Margaret Annotations continue on p. 62

Rudolf Steiner Library’s borrowing service is free for Anthroposophical Society in America members; non-members pay an annual fee. Borrowers pay round-trip postage. Requests can be made by mail (65 Fern Hill Road Ghent, N.Y. 12075), phone (518-672-7690), fax (518-672-5827), or e-mail: rsteinerlibrary@taconic.net

5 Research Issue 2010

www.southrivermiso.com WOOD-FIRED HAND-CRAFTED MISO Nourishing Life for the Human Spirit since 1979 unpasteurized probiotic certified organic SOUTH RIVER MISO COMPANY C onway , M assa C husetts 01341 • (413) 369-4057

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

Where on Earth Is Heaven?

By Jonathan Stedall; Hawthorn Press, 2009, 566 pgs Review by Frederick J. Dennehy

Books describing an author’s spiritual journey generally tend toward an ending. Readers find themselves traveling along with the author and sense in the final pages that a “destination” of some sort will be reached.

Where on Earth Is Heaven? is not structured in that way. As Richard Tarnas aptly notes in his foreword, Jonathan Stedall’s book is more like a fireside chat. His account has the freshness and honesty of a friend’s impressionistic reminiscences, as well as the meandering and somewhat repetitious features of informal conversation.

Mr. Stedall’s original intention was to write very little about himself, and to focus on the people whom he had come to know and the ideas he had encountered that had influenced him spiritually. Readers of the first draft suggested that the book needed to be more autobiographical; consequently, Mr. Stedall, with some reluctance, extended his account to include moments from his “own bumpy journey—the downs as well as the ups.”

is simply between science and religion. Rather, the division is between those persons who sense and seek an intrinsic meaning and purpose in the world, and two other groups: (1) those who see any notions of meaning and purpose as the ephemeral projections of needy humans, determined by a combination of biochemistry and “contingency”; and (2) those who believe in the existence of objective purpose and meaning but think that these are destined to be realized elsewhere, in a “heaven” somewhere beyond Earth. That “somewhere” is often conceived to be on a “thinner” or disembodied plane that is subject nonetheless to “ordinary consciousness”—the same consciousness that regulates our experiences at ten in the morning on a not very exciting workday.

Editor’s Note: by separate routes we received two reviews of this unusual book. Since they are relatively short and different in character, we are publishing both. The second review, by Signe Schaefer, follows the continuation of this review, on page 59.

Mr. Stedall takes his stand unmistakably on the first side of this divide, but not as a combatant, a philosopher, or a systematizer. Instead, he reports to us as an observer of long standing who has seen and inquired into a vast range of human experience. A significant part of that experience is closely related to anthroposophy.

“Where on Earth is heaven?” was a question originally asked many years ago by the author’s then seven-year-old son. This book is Mr. Stedall’s effort, after a gap of twenty years and his encounter with serious illness, to answer it. Each of the thirtysix chapters is connected—directly or indirectly—to the possibility and meaning of immortality. The chapters loosely follow Mr. Stedall’s career as a BBC documentary film producer. His employer (hard to imagine this now!) allowed him to travel—geographically and spiritually—almost wherever his most burning questions dictated.

Mr. Stedall is not a scholar but a producer of films. He is not a man of personal visionary experience but a person of natural devotion and highly focused attention. In the words of Nicolas Malebranche, “attention is the natural prayer we make to inner truth in order that it may be revealed in us.”

This book takes its place on one side of a cultural divide whose fault lines have been visible for a long time and have been widening at an ever-increasing speed. The topography of that divide has also altered appreciably since it was delineated by C.P. Snow in The Two Cultures in 1961. The split is not so much between the scientific method and the humanities (Geisteswissenschaft), and it would be crude to maintain that it

Mr. Stedall returns again and again to Rudolf Steiner, as a philosopher, an esotericist, and the source for the creation of Camphill therapeutic initiatives and Waldorf education. Very little in these pages could be deemed to be “original” regarding Steiner, and a fair portion of the commentary is overtly mediated through secondary sources. Mr. Stedall was enormously impressed with the Camphill movement, which he encountered through his work documenting the Camphill community, Botton Village, and the school at Camphill Aberdeen. He was strongly influenced by his nine-month stay at Emerson College in England, particularly by the scientific method of founder and principal Francis Edmunds. During that same stay he boycotted all eurythmy classes. While he enrolled both his children in a Waldorf school, he found the experience there insufficiently flexible to accommodate the particular interests evinced by his children when they did not conform to the time frame expected by the teachers concerned.

But this is not a book for students of Rudolf Steiner or for participants in the daughter movements of anthroposophy who want to go deeper. Nor is it a book in which you will find the struggles and hurdles encountered by a man who at long last “finds” anthroposophy. What you will find is an intelligent, intensely curious, and candid thinker who experiences and digests the insights of Rudolf Steiner along with those of Carl Jung, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and many others, albeit with a partiality toward Steiner. You will find a man fascinated by the human side of great thinkers and doers. And so he places Steiner in both surprising and unsurprising company, along with Tolstoy, Gandhi, Sir Bernard Lovell, Malcolm Muggeridge, the poet John Betjeman, Laurens van der Post, and many

Review continues on page 59

6 Evolving News

Book Review / the Rudolf Steiner Library Newsletter

Ernst Katz, teacher of anthroposophy

Donald Melcer

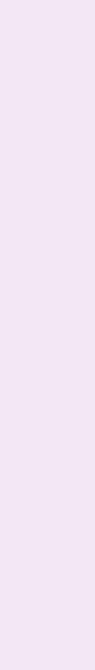

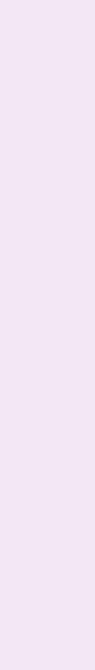

On September 3, 2009 one of the great teachers of anthroposophy crossed the threshold. Ernst Katz was 96 years old. He joined the society when he was 16, and was fully dedicated to anthroposophy as a way of life and for understanding man’s purpose on Earth for all those 80 years.

I first became acquainted with Ernst in 1962 when a series of his articles about the book The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity was published in the new journal (now defunct) Free Deeds I had been reading various works of Rudolf Steiner for about three years. Like many people, I had struggled to understand that particular book, as well as most of Steiner’s other “basic books.” Ernst’s articles were examples of extraordinarily clear thinking. I felt as though I had at last found a competent guide to the lofty ideas presented in The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. Every time the postman delivered a new issue of Free Deeds I felt a rush of anticipation for Ernst’s next article.

About five years later at a summer anthroposophical conference I met a young professor of German from the University of Michigan. Alan Cottrell told me about the Ann Arbor study group in anthroposophy led by physics professor Ernst Katz, and the wise guidance he provided. As a person who had studied anthroposophy mostly alone and had many unanswered questions, I was envious of those fortunate people who had such a teacher. Destiny responded kindly to my envy, for within a year I was offered a position at Michigan State University, just a fifty minute drive from Ann Arbor. I quickly broke my vow never live in a place where it snowed all winter, and we left sunny Austin, Texas for snowy East Lansing, Michigan.

The Ann Arbor study group held its meetings in the homes of several members. The presentation protocol was simple. A designated person would present a short recap of a preselected Steiner lecture which was followed by a general discussion. Attendance was typically 25 to 30 eager anthroposophists, and discussion was lively. I found Ernst’s behavior interesting. There was no doubt that he was the leader but he showed no inclination to display his superior anthroposophical knowledge. Often he made little or no comment about a question or topic. More typically the discussion would continue until a question arose that no one could explain adequately. The room would grow quiet as all eyes turned toward Ernst. He would then say rather quietly, “Yes, well...” and then give his thoughts on the question. We learned to have our notebooks and pencils ready at those moments.

Physics students at the university also recognized his extraordinary teaching skills and personal character. Once a group of students called on him during office hours and said something to this effect: “You know, Dr. Katz, we students gossip about our teachers, and we have noticed something different about you. Your courses are more alive and you seem genuinely interested that we

understand what you present in lectures. Can you tell us what it is that makes you different?” The students were quite correct in their perception, for Ernst believed that every human connection was an event of destiny, and he treated each one with respect and reverence.

Some years later, Ernst phoned the regular members of the study group and suggested that we buy an old abandoned fraternity house. The purpose was to create a dwelling for university students interested in spiritual development so they could have a common place to live and study. We responded, and the Rudolf Steiner Institute of the Great Lakes Area was formed as a non-profit corporation. The structure of the building was sound, but the interior had to be completely renovated. Much of the restoration work was done by local members who donated their weekends for at least a year. A central building was created where anthroposophical activities of all sorts could take place. Ernst and his wife Katherine soon sold their large home on the Huron river and bought a small house adjacent to the building now named Rudolf Steiner House. For many years they were overseers of the building and friends of the students and artists who lived there. After it’s mission had been served, the building was donated to the Anthroposophical Society in America and is now the society’s headquarters.

The University of Michigan allowed professors to teach what was called “Free Offerings,” full credit courses in their special interests. Course content was carefully screened by a special committee. Ernst applied to teach anthroposophical courses, and after intense scrutiny, was allowed to do so. As a result, he was one of the few university professors at that time—perhaps the only one in North America—who taught courses in both natural science and “spiritual” science.

One of the great blessings of a university teaching career is that opportunities for work are always greater than the time available to do them all. Boredom is never a problem. I saw that Ernst accomplished an amazing amount of work, yet never seemed rushed or anxious. How did he do it? I simply could not accomplish everything I wanted to, and decided to make a special trip to Ann Arbor to ask Ernst’s advice for improvement. Of course I hoped that he would give me a few clues as to how one accomplishes more work in less time.

7 Research Issue 2010

ANTHROPOSOPHY NYC

email: anthroposophynyc@yahoo.com

Lectures, workshops, art exhibits, festivals, study groups.

RUDOLF STEINER BOOKSTORE

features works of Rudolf Steiner and many others on spiritual research, Waldorf education, personal growth, Goethean science, Biodynamic agriculture, holistic therapies, the arts, and more

Fall/Winter Highlights

CELEBRATING 100 YEARS: ANTHROPOSOPHY IN AMERICA & NYC

Nov 20, Sat, 7:30pm – Mel Shrawder

Pax Vobiscum, a full length play

Nov 21, Sun – Vivian Gladwell

The Courage to Be, An Introduction to Clowning Conference & Workshop , 1-5:30pm; Performance, 7pm

Nov 22, Mon, 7pm – Linda Larson (eurythmy workshop)

Colors of the Rainbow (Dec 13: In the Advent Mood)

Dec 5, Sun, 5pm – Advent Garden Festival Celebration

Dec 8, Wed, 7pm – David Anderson (10-part series)

Essential Steiner: Steiner & Psychology (Jan 19: Projective Geometry; Feb 16: Chemistry)

Dec 9, Thu, 7:30pm – Dorothy Emmerson

Acting for Non-Actors (Michael Chekhov Techniques)

Dec 18, Sat, 2-5pm – Art Exhibit Opening

Jorge Sanz Cardona: Soulscapes

Dec 26–Jan 6: The Holy Nights & Epiphany

Phoebe Alexander, Walter Alexander, Cynthia Lang, Barbar Simpson, Keith Francis, Kevin Dann, George Centanni, Lenard Petit, Linda Larson, Erk Ludwig, Fred Dennehy; Jan 6 - Epiphany Dinner & Concert

FUTURE SPECIAL EVENTS

Feb 14, Mon, 7pm – Torin Finser

Freedom & Initiative:

Anthroposophy in the 21st Century

Feb 26, Sat, 7pm – Eugene Schwartz

Rudolf Steiner & the 21st Century

Mar 11-12, Fri/Sat – Steiner Books

Spiritual Research Seminar 2011

ANTHROPOSOPHY NYC

the New York Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in America

138 West 15th Street, NY, NY 10011

(212) 242-8945

www.asnyc.org

Instead, he told me how one of his colleagues, a famous scientist who received many requests for more information about articles he published, responded to all these inquiries—more than he could possibly answer. Ernst said, “He ignores the first and second request by any individual and only answers if there is a third. He figures that if a person asks the third time, he or she is really interested and will make good use of his reply.” That was Ernst’s quiet answer to my question. As I drove home to East Lansing I felt that he had not answered my question at all. I had expected a detailed answer describing how one goes about improving his output. After a time, the answer dawned upon me. Ernst had said in effect, “Here is how one man does it. You will have to develop the capacity and skills to accomplish what you want in your life—there is no simple formula.” Thanks, Ernst.

All of Ernst’s teachings, whether given to an individual, or published as essays for all to read, have this quality—they did not provide a ready answer to a particular problem, but required the person to think through the details and find his or her own solution. Ernst knew that we learn most profoundly through our own active thinking, and he was a master at stimulating such thinking. No wonder that his physics students perceived something different about him.

All his published anthroposophical essays will soon be available in a book titled Core Anthroposophy: The Teaching Essays of Ernst Katz to be published by SteinerBooks. Jannebeth Röell, James Lee, and I edited the book and found the work absolutely inspiring. Ernst’s composition is exquisite. One of the last questions I asked him before his death was, “How do you write these excellent essays?” This was not just a question of curiosity—I wanted to improve my own writing. I was hoping again for an answer in the form of step-by-step instruction.

His response was to mail me a copy of a letter by Sergei Prokofieff praising Ernst for one of his essays. Prokofieff is one of the current generation’s most respected anthroposophical writers. Ernst’s letter thanked me for my compliments about his writing and enclosed a copy of the Prokofieff letter. That was all. What was he suggesting?

Ernst was too modest to be calling attention to himself, so I knew the Prokofieff letter was not for that purpose. His response said in effect, “You discovered something about my writing that a writer we both highly respect also discovered.” I took that to be a very nice personal compliment, but the real lesson was, “If you will continue to study the essays carefully you will discover the method of my writing.” Then, of course, what I learn will come as my own effort in imaginative cognition, not by following a set of instructions that would likely produce a dull imitation. At that moment I felt deep thanks—thanks from the heart—for Ernst’s answer to my question.

Ernst intended all of his writings to be for both the present and coming generations. He would be pleased if you were to select him as one of your spiritual teachers. You won’t be disappointed if you do.

Donald Melcer, PhD, is professor emeritus at Michigan State University, a clinical psychologist, and a marriage and family therapist. He coordinates the Anthroposophical Foundation studies at the Austin, Texas, Waldorf School.

centerpoint

8 Evolving News

Building the Positive Future

A conversation with Clemens Pietzner on Triskeles

In 2002, Clemens Pietzner and a group of colleagues and board members created the Triskeles Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to youth, philanthropic services and community building. From 1984 to 2002, Clemens was executive director of the Camphill Foundation, a public foundation focused on serving communities caring for and supporting children, youth, and adults with developmental disabilities.

Working out of World Themes

» Evolving News — How did the Triskeles thought and approach develop?

Clemens Pietzner — Part of this was biographical, and some of it has to do with how I’ve had the privilege of being inserted into the world. Prior to Triskeles, I had 20 years of active engagement in various ways with Camphill. And prior to that, government work in three different state governments. I have always had an interest in social action, social justice.

Some key themes have been part of the formation of Triskeles. Those are not personal themes; they belong to all of us; they are world themes.

The first theme is: how do we build a positive future? That has always been a big question for all of us, with the emphasis on “positive.”

A second theme relates to the question of community and individual. How can I be my best independent self, standing free and fully conscious, and how can I—at the same time—be most connected and most engaged in my community—be that with my family, or my social organism? Connectedness and engagement are central to the second theme.

The third theme is: stewardship and ownership What can I truly own in this world? And what is it my practical and moral obligation to be a steward of? I don’t mean that only in terms of natural resources. But what kinds of forces do I need to steward, what kinds of relationships, and even how do I steward my own world and the social contract that I make with others?

And finally, the fourth theme is that of: money and intention Money is neutral, and it’s given value and movement through a series of our actions and oftentimes, arbitrary agreements that we generate collectively. A whole universe of activity emerges from that! In fact, money gains a certain kind of value, by what

it does. And it “does stuff” because we ask it to. So we give it intention when we buy something or when we give a gift. It bears something of our consciousness, and it gains movement through that. I’ve always been really interested in what money bears, what is inherent in the transactions of money and the forces connected to money.

These four themes were central to the formation of Triskeles. We chose to build our programs with those four themes in mind, because they are all intertwined. By working with young people, we are directly addressing a positive future. And, we chose to work with money and intentionality around the issues of investment and gifts. That was true also of the themes of ownership and stewardship in community.

So, these ideas continue to be very much at the core of what Triskeles currently does even as our programs continue to evolve, emerge, and grow.

Thought into Actions and Back into Thought

» EN — You’ve done some shaping of the organization, separating out the original foundation/philanthropic work, and you’ve certainly had a lot of success in the youth work. Where would you say it is going?

CP — All I can really speak to with accuracy is maybe the next three to five years. First of all, we are generating a lot of energy and excitement and programmatic effectiveness around youth employment, health, nutrition,

9 Research Issue 2010

all the issues around obesity, leadership training, social entrepreneurship, and philanthropy. Our “Food for Thought” program is becoming in some respects our flagship program, and it touches on all of those areas. So, we’ll continue to focus on and build that program.

Secondly, because we work with young people, we are finding a great deal of interest in the area of social entrepreneurship. Young people want to know about business, about money, about green projects and operations, sustainable organizations, and globalism in the best sense of the word. How do young people take those large ideas and apply them in their practical lives? We will continue to focus on the areas of social entrepreneurship for young people and youth philanthropy. I also think this is a huge area of opportunity for the Waldorf schools. Youth today are really interested in those topics and get inspired when they see people who “walk the talk” and are doing things that are connected to their ideals.

The third direction we are working towards has to do with alignment. More and more people understand the positive aspects of sustainable and socially responsible investing and are seeing more deeply that it’s productive to think about investing aligned with one’s values and aligned with one’s charitable intent. There have been significant leaders in this field who have demonstrated that there is, can, and should be effective alignment between those things. That’s where returns, not just financial returns, but returns

of impact and social importance, defined in a variety of ways, continue to be more and more important. This is what we strive for in our donor advised funding and related work in philanthropy. To be part of and helping initiate conversations on different levels around this issue of alignment, whether that be with financial planners or people who come at this from a very spiritual perspective and want to see how that streams into practical life, will be a factor in our growth.

We want to continue and expand the approaches that we have to our donor advised fund work and our philanthropic work. We definitely see our “Food for Thought” and our related programs growing. And we’re looking to further develop our green Sustainable Directions Internship Program in New York City. We will be adding board members and increasing infrastructure. We’re interested in youth entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurship, and philanthropy also with youth.

These are directions for further expansion. Of course, a particular challenge is finding resources. Can we find the resources to meet the demands and interests in our activity areas?

Engaging the Work of Triskeles

» EN — Then how can people step forward and help, work with you, and also benefit from your experience?

CP — We are very interested in working with people who, through philanthropy, wish to take advantage of our donor advised fund services. We are always looking for new, positive relationships that might manifest as board membership or advisors, or as volunteers on the local level. We are looking for program support. Without question, all this will help us grow. Unfortunately, we are not always able to meet a very, very significant demand for our youth programs because we just don’t have the bandwidth at times to do that. And then if people wish to benefit from our experience, we also do advisory work for and with small projects and not-for-profits. We are not a grant-making organization in the traditional sense. It’s important that people understand that. We do have resources, but the funds that we have in the Triskeles Foundation are stewarded by us; we don’t have discretionary gift money. The

10 Evolving News

gifts we make are supportive of our donors’ intents. As a result, we have to disappoint people a lot, but that’s just how it works. Finally, we can serve smaller not-for-profits who are interested in a sustainable investment approach by working with their endowments or reserve funds. Sometimes endowments or reserve funds in organizations aren’t big enough to get the attention of money managers. We’re able to do that on their behalf. We can manage these funds in a socially-responsible, mission-related way, and the resources do not have to be huge. Those are a variety of ways that people could get engaged—and if you gave me another ten minutes I could think of a hundred more!

A Working-with-the-Whole Process

» EN — It seems an unusual combination, altogether, from understanding philanthropy through actual money management to all the human relationships. And these very specific needs of young people and their families, both the under-served and then young people looking to experience entrepreneurship. Is Triskeles fairly unique in this combination?

CP — I don’t know of any youth organization that actually provides programs that could potentially support a youngster from kindergarten through 12th grade. More specifically, I don’t know of other organizations that are focusing on the youth work around food and youth entrepreneurship and then also taking it all the way into philanthropy; not only for youth but beyond that. I don’t know of another organization that unifies all these pieces. In our “Food for Thought” program, for example, we’re making products like pesto or salsa with the youth. And we’re creating small business plans with them. Many of these youngsters are underserved kids, but Waldorf youth are important participants in these activities as well. We are creating small business plans around the food products that they have actually made. Then, we’re taking the products and youngsters to local farmers’ markets and shops in their neighborhoods where they are selling their products. From the money that we make with the youth, we put the money into a small youth donor advised fund. And then we guide the youth through a philanthropy process in which the young people are actually thinking, “What are the entities in our community that we use?”

“How can we support them?”

We lead the youngsters through a process in which they make choices about what local charities they want to support with the money that they’ve earned. Some of our board members have matched the youths’ gifts and sales. That is a long process. Again, I don’t know of any other group that is taking the process that far. There are many great youth groups around food, and there are great youth employment groups, but we seek to combine all of these pieces.

» EN — It’s real social-artistic work. I’d ask more but you’ve given a lot of time this morning.

CP —Triskeles has come a long way in these seven years, and it has been a great journey, hard sometimes, but joyful and very rewarding.

11 Research Issue 2010

Photos by Emilie McI. Barber.

LA Karma Exercises Workshop Tycho Brahe, Herzeleide, Emperor Julian

with Linda Connell, Jannebeth Röell, MariJo Rogers, Lynn Stull and Joyce Muraoka

June 25– 26, 2010 in Pasadena, CA

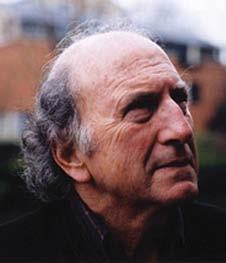

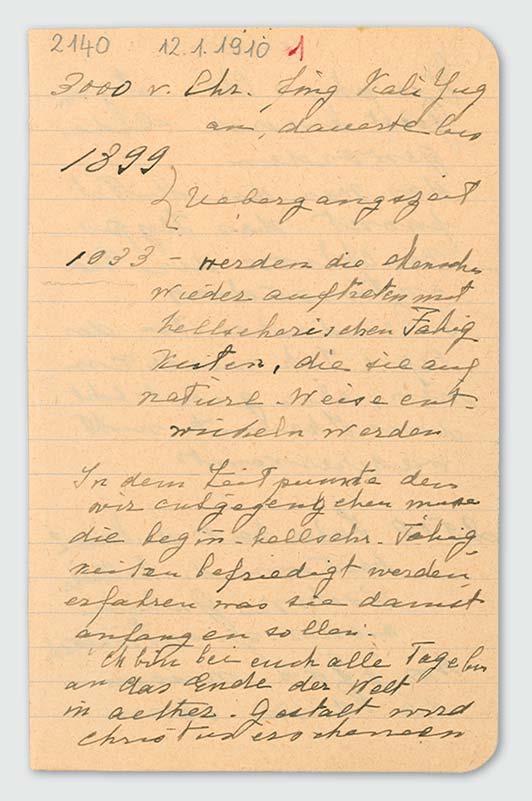

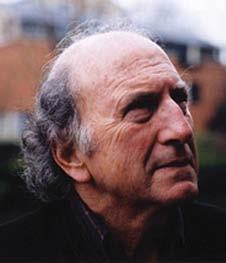

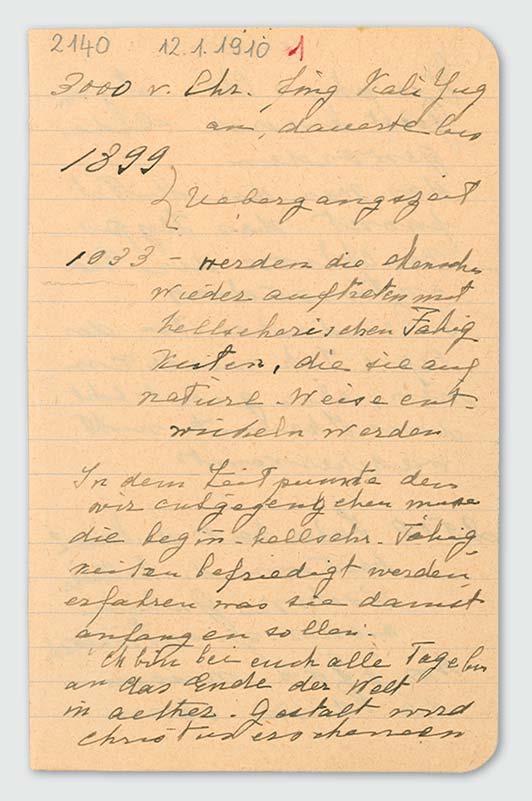

This excellent workshop should be subtitled, “An Evolving Method for Studying Karma.” Linda Connell, Jannebeth Röell, and MariJo Rogers (center, right, and left in the picture at right) shared with us the results of many months of their private endeavors to bring karma study to life through looking at the lives of Tycho Brahe (1546-1601, left), Herzeleide (9th century, pictured below watching a tournament) and Emperor Julian (Julian the Apostate, 331-363, two sculptures at lower right). They began with these three people because Rudolf Steiner gives a fairly lengthy description of their connection in Karmic Relationships, vol. 4 (lectures of 9/14 and 9/16/1924), describing something of the earthly life of this individuality in each incarnation as well as life between death and rebirth.

The workshop focused on the first karma exercise, the Saturn, Sun, and Moon exercise (Karmic Relationships, vol. 2, 5/4/1924), where you bring before your mind certain features and characteristics of a person and then “think them away” in order to arrive at deeper levels in the person’s life, and, ultimately, a picture of the person’s karma.

Jannebeth, MariJo and Linda had each done extensive research into the life of one of the three: Jannebeth studied Emperor Julian, MariJo pondered Herzeleide, and Linda researched the life of Tycho Brahe. After a brief introduction to the first karma exercise, each presented an extensive biography of the person she had studied. The basic method was to look initially at physical characteristics and constitution, including significant illnesses (moon level). Next, we heard about upbringing, family life, education, travels, work, significant people met, geographic settings, and relationships;

in other words, all that the person saw and heard and accomplished or attempted in life (sun level). Finally, a deeper look at what seemed to live as the tendency of the person’s life, the direction of the person’s thought (saturn level).

In the final session of the workshop, Jannebeth drew a grid on the blackboard: across the top¸ Julian, Herzeleide, and Tycho; along the left side, from top to bottom, “spiritual world”, saturn, sun, moon, making a grid of 12 squares. It was our turn to bring something to the workshop. What had we noticed, what stood out for us, what parallels might exist, what had surprised us, made us say “Aha!”? This collaborative work was challenging and very exciting. Among the observations: each person was born into a noble family; there were very strong themes of the sun in each life; there was a powerful connection between this individuality and Mani in at least the lives of Julian and Herzeleide; and each of the people at some point were within the same geographic areas in Europe. This was a beginning, a first tentative penetration into the themes of this fascinating and important personality.

We were supported in this endeavor by the nourishing eurythmy brought by Lynn Stull. With Joyce Muraoka speaking, they presented “The Stars Once Spoke to Man,” a verse presented by Rudolf Steiner to Marie Steiner, three times throughout the workshop, which helped us deepen our appreciation of the theme. We also had a eurythmy session with Lynn, with a wonderful collaborative effort to choreograph and perform one section of the verse.

This workshop takes up the important question of how we can study karma. Rudolf Steiner gave us his karma research as a precious legacy and an incentive to take up this essential work. Using his work as a scaffolding, Linda, MariJo, and Jannebeth have begun to construct a practical method for taking up this task. If any other branch is interested in having this workshop, please email any of the presenters:

Linda Connell ( linconnell@sbcglobal.net); Jannebeth Röell ( jannebeth@mindspring.com); MariJo Rogers (marijo.rogers@hp.com).

Marcia Murray

Pasadena, CA

12 Evolving News

Anthroposophy as developed by Rudolf Steiner a century ago is distinguished by truly holistic breadth and by commitment to a path of objective, scientific research. It does not accept the so-called “limits to knowledge” which still mark off the boundaries of modern natural science— specifically the limits to our understanding of “matter” and “consciousness.” These are not real, unsurpassable limits, Steiner insisted, but stage-markers in human development which are calling for new techniques based in the cultivation of the potentials of human consciousness.

Rudolf Steiner’s own life path is filled with new approaches and new beginnings in the search for real knowledge and experience. Gifted in childhood with what Hollywood has popularized as the ability to “see dead people,” Steiner turned away from this spontaneous gift and sought to find a path to the same and further experiences by methods appropriate to the Western scientific tradition. An early discovery was that the true contemplation of geometric forms involves a “sense-free thinking.” Lines without width and planes without depth, the stuff of geometry, are no more perceptible to the physical senses, and no more materially real, than human beings who have left their bodies at death; but they can be known in contemplation. Steiner continued with intensive studies in Vienna which for its time would equate to a course at MIT or Cal Tech today. He learned to review the most uncongenial and dogmatic lectures over and over again— backwards. In that way he discovered how their hidden logical failures could unlock more living insights.

In the years before 1900 Steiner explored many paths: psychological phenomenology (which became essential to 20th century philosophy); the dynamic morphological and evolutionary science of Goethe (still slowly being recognized as fundamental to true ecological and life sciences); the esoteric wisdom of a “simple” folk herbalist; and the popular occult spiritualistic streams like Freemasonry and Theosophy. He engaged the most serious scientific research of a triumphant time which had unlocked the vast force fields of electromagnetism, unrolled the time dimension of life in biological evolution, and opened the doors of the unconscious mind. He also immersed himself in the arts and humanities, and in the intense social questions arising at the end of aristocracy. Most importantly, however, he was developing capacities for introspection, meditation, and contemplation, until he arrived at the little understood point of “initiation.”

As he described it just short of a century ago, “We must gradually accustom ourselves to the necessity of submitting our ideas, concepts and modes of thought to a certain change before we are able to form correct ideas of the higher worlds beyond the senses.... Anyone really pursuing the practical path into the worlds opened by initiation, anyone having actual experience of life beyond the sense world,

knows well that one must not only transform many things in oneself...but also lay aside many habits, representations, and concepts before one can enter the higher worlds.” (Lecture of August 27, 1912)

So the path of anthroposophical research is at the same time a process of personal growth and transformation. And everyone who undertakes this challenge is immediately faced with the rather overwhelming abilities and accomplishments of Rudolf Steiner himself. How could he know so much, critics ask, and why has he had no equals? The first question can be met by pointing to persons of unique gifts in many fields. For the second, the answer lies in human evolution itself, the evolution of consciousness which is both an individual matter and an aspect of the life of humanity. There are many researchers following Steiner, but anthroposophy recognized that we are all becoming, never finished. And so the very most essential requirement for this path of research may simply be humility. In T.S. Eliot’s phrase, “Humility is endless.” Submitting ourselves to humility’s power, we become capable of attempting whatever needs doing.

The following pages, then, offer some aspects of the present work of research among anthroposophists today. What we do not capture at all in this first look is the working of the three emerging higher senses for which Rudolf Steiner used the names Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition. He meant them in a specially disciplined and intensified form, but imaginations and inspirations and intuitions such as we all have give us a clue: private, intimate moments of wonder, fresh perception, insight, realization. Experiences of that sort are contemplated and then perhaps taken into the conversations of study groups and branches, into the teachers’ circles of schools and the life of all kinds of initiatives. With special intention they are also shared in the work of the sections of the School for Spiritual Science, established by Rudolf Steiner in the last months of his life.

And so what is won individually and humbly is shared, heard, pondered; and it becomes, in Michael Howard’s phrase in an article we will publish in the next issue, vital threads in a living fabric — The Editor

13 Research Issue 2010 Research

a

special section

Living with and Sharing Questions in the Twin Cities: Spiritual Research in the Branch

by Dennis Dietzel, Roseville, MN

Branch activity in the Twin Cities has waxed and waned over time, but in the last five years we have consistently met on the third Wednesday of each month with ten to fourteen people. Our current activity is largely due to the hard work of a few people, particularly Becky Streeter, who has been our Branch contact in recent years.

About five years ago we started follow ing a three-part meeting format, inspired by Rene Querido:

1. some content related to anthroposophy / spiritual research,

2. branch business and reports from local initiatives,

3. current events in the light of anthroposophy. As we have worked with this form, we have gradually moved to a two-part meeting preceded by a social time where we share a potluck meal.

During the first part of the meeting, we strive to build an awareness of local anthroposophical initiatives and attempt (in words inspired by Robert Karp) to build a vessel that weaves together the spiritual intentions of the different initiatives. We are blessed with many anthroposophical initiatives—three Waldorf schools, two life-sharing/CSA farms, Camphill Village Minnesota, some medical related work,—and through our shared experience we hear about the various initiatives and their activities. We then hold them in silence for a few minutes, sending our best thoughts for their efforts. This part of the meeting is our vesselbuilding work and takes 30-45 minutes.

The second part of the meeting is devoted to sharing the spiritual research of members. We approach this in a very humble way, encouraging the person to share their research at whatever level they are. We keep the definition of “spiritual research” broad enough so that people do not feel intimidated or that they have to match up to Dr. Steiner’s standards. The format is up to the presenter, but generally he or she speaks for 20-30 minutes followed by conversation and questions (up to an hour). “Minnesota Nice” prevails here, so we tend to not be overly critical of each other, striving to listen and respect each others’ opinions. Following are some examples of recent presentations:

Albert Linderman is involved professionally as an organizational development consultant. He has studied the work of Otto Scharmer (www.presencing.com) and taken a workshop on Theory U, Otto’s approach to group decision making. Albert described Theory U, which takes a group through a transformative process of open mind/heart/ will to presencing, allowing solutions to come from the future. Although Otto is presenting his work in

the main-stream as a lecturer at MIT, it happens that he grew up on a biodynamic farm in Germany. He does not speak about anthroposophy in his written work, but his work reveals many inspirations from this fount.

John Fuller recently attended the Economics of Peace conference in California. John shared this work with us and related it to anthroposophical principals of threefolding. After presenting a sober picture of our current economic situation, John shared from the many inspiring presentations of people he heard at the conference (www.economicsofpeace.net).

Our next meeting will focus on the work of Shona Terrill, who is working on her masters degree at Antioch College. She will lead a session on the topic of her dissertation, which is “Moral Education.” Shona describes her work thus:

I explore observations of past societal crises and reveal how these relate to education through the prism of five moral pillars: sympathy, benevolence, reason, equity, and self determination. I also use these pillars to examine modern day social and educational theory. By studying three local schools of differing educational streams, I explore how contemporary society puts moral education into practice.

We have found this sharing of research to be fruitful for the group and a way for the researcher to deepen his/her own work. It does take extra effort to put ones’ ideas in front of other people, but the payback is the insight gained from the input of others.

Reprinted from the Winter-Spring 2009-10 edition of The Correspondence, the newsletter of the Central Region. Dennis Dietzel serves on the Central Regional Council and joined the General Council of the Anthroposophical Society in America representing his region.

14 Evolving News

Research–a special section

As it did for Rudolf Steiner, the research process may begin with our own experiences and insights. These will commonly be shared first in a branch or study group.

“Sections” of the School for Spiritual Science founded by Rudolf Steiner serve medicine, pedagogy, agriculture, the social sciences, visual arts, performing arts, literary arts and humanities, natural science, mathematics and astronomy, and the spiritual striving of youth.

The Life of a Research Section

In any Section of the School of Spiritual Science, not all members work on a single theme; rather, each individual generally works on the issue or issues that present themselves in life. This can allow us to research and be active in areas that we love.

The Section for the Social Sciences, by its very nature, includes a particularly wide range of interests: members work in and represent research and activities touching on every realm of social life. As described on the Goetheanum website:

The Section for Social Sciences is concerned with human relationships in the three spheres of social life: economic, legal and cultural/spiritual. Depending on the sphere different fundamental questions arise:

How are the basic needs of the world’s population to be met? What responsibility does a citizen bear for the common good? What does a human being need from the world in order to reach his or her potential?

With such questions in mind the Section conducts research, pursuing insight and creative forms in a range of areas including: family culture, biography work, conflict resolution/peace studies, addiction, economic questions and the science, practice and politics of law.

The Section for the Social Sciences in North America was founded in June 1987; over time, eight points emerged, eight areas which, we believe, continue to indicate the Section’s scope:

1. to foster and encourage individual and collaborative research at local, regional and national levels with a focus on social lawfulness and the threefold nature of social life.

2. to work toward a deeper understanding of the spiritual beings connected to social life.

3. to recognize that the sacrament of human encounter is an essential task for this section.

4. to do what we can—humanly, socially, and spiritually—to encourage and support the initiative and research capacities of members of this section, and to cultivate collaboration with other sections of the School for Spiritual Science.

5. to provide local support in the branches of the Anthroposophical Society.

6. to foster consciousness of world events in a spiritual context.

7. to encourage associations of individuals and groups sharing common interests.

8. to create forums of meeting to help heal social ills and relationships.

A mighty set of tasks! One can see how work in the Section for the Social Sciences cannot but interweave with that of other sections. And one can wonder: How does this set of guideposts play out in a practical way? How does life within the Section for the Social Sciences manifest?

The section itself consists of about 140 members. Within the section, a Traveling Collegium meets with geographically scattered groups—generally twice a year—and sponsors a twiceyearly newsletter, providing members a forum of colleagues. The North American section maintains a close connection with that at the Goetheanum and was happily able to send two Collegium members to a Section for Social Sciences meeting in Dornach in November 2009. That year also saw cosponsorship of a public conference in Spring Valley and a “Round Table on Economics” at the Annual General Meeting of the Anthroposophical Society. At both the latter events younger friends were visible and active.

The heart of the section lies in the initiative of members. In some areas—the Northern California and Berkshire-Taconic groups come to mind—Section members meet regularly to study and share work-in-progress. Members who work with youth groups, offer workshops on social threefolding, work in social finance, provide mediation, or otherwise offer special services, bring their section perspective to that work.

Mention of a few recent articles in the section newsletter may give some flavor of the nature and variety of endeavor: Alexander Cameron described a “collaborative research in study,” an epistemological study with a (non-anthroposophical) colleague; Denis Schneider wrote of “developing community through art” in the form of writing workshops; Meg Gorman asked “What Shall We Do About Ahriman,” an article also published in Das Goetheanum; Chris Schaefer offered practical advice on things we can do relating to our very own financial institutions; Richard Rettig has brought a three-fold perspective to such contemporary issues as same-sex marriage and the liberal-conservative divide in politics; Stephen Usher delved into presentday world events in “The Present Crisis: The Surface Explanation and the Deep One;” Luigi Morelli described weaving the seven life processes into nonviolent communication and social technology modalities; Addie Bianchi described peace activities in the Israel-Palestinian area; Carl Flygt expanded his work on “Goethean conversation;” and so on …

A final quote from the Section at the Goetheanum may characterize a key aspect of the Section for the Social Sciences:

Of primary importance is the conversation between the various members of the section who are doing scientific research. Today one can no longer undertake any research on the social level in some ivory tower—exploratory conversations and exchange with others is essential.

For further information, please contact Shawn Sullivan, (California) 916-965-6553, shawnjs1@pacbell.net or another Collegium member:

Meg Gorman (New Mexico), 206-325-5520, pelicanmeg@earthlink.net

Kristen Puckett (Colorado), 970-689-3902, kristen.puckett@gmail.com

Bette Shertzer (New York), 212-877-1094, bshertzer@aol.com

Claus Sproll (Pennsylvania), 610-469-6292, claus@sproll.net

15 Research Issue 2010

The Section for the Social Sciences in North America

A Resurgence of Research at Threefold: Frank Chester, the 2010 Threefold Visiting Researcher

Bill Day

Thirty years ago, Henry Barnes called on every anthroposophical institution to set aside resources to support research. Of “the urgent need for research arising from anthroposophy,” Henry wrote: “We must find the way to work for future values (the purpose of all genuine research), while meeting the needs of today, tomorrow and the next day.” Henry was inspired by Rudolf Steiner’s call at the 1924 Christmas Foundation Conference for the establishment of research institutes that could support and carry forward spiritual scientific research. Through the work of these institutes, Steiner said, the insights of spiritual science will penetrate the general culture.

Today, anthroposophy has proven its ability to foster (for example) beautiful schools and productive farms that freely acknowledge Rudolf Steiner’s spiritual research as the basis of their work. But even the most prosperous and stable anthroposophical institutions still devote most of their resources to simply keeping the wheels turning, paying the bills, and staying alive for the next school year or planting season. Our people are busy just doing their jobs, we say, and there’s hardly enough money even to meet our immediate needs.

At the same time, who can deny that the need to discover our “future values” feels more urgent than ever?

With that in mind, Threefold Educational Center has created a Visiting Researcher program to bring together innovative researchers, motivated students, and Threefold community residents and guests.

The inaugural Threefold Visiting Researcher is artist, sculptor and geometrician Frank Chester. This fall, Frank brought his studio to the Threefold community, where a select group of research fellows have joined him in conducting investigations into the properties of new geometric forms.

Fellows entered the program on one of two tracks. Those in the Apprenticeship Track are working on projects assigned by Frank Chester, while Fellows in the Research Track brought an existing project or question to the Fellowship, with the aim of applying research methodologies they are learning from Frank Chester. Fellows in both tracks received intensive, hands-on instruction in Frank’s methodology. They will then have the opportunity to apply those methods to previously uninvestigated forms, with completely unpredictable results. Through their guided experience of one researcher’s methods, fellows will develop unrealized capacities and unexpected insights.

The 2010 residency has been structured in three parts:

September 19-25: Frank and his research fellows work together at Threefold. This intensive week-long gathering included morning lectures, work with projective geometry and orthographic studies, geometric net development, two- and three-dimensional drawing, perspective, form studies, basic construction techniques, and group discussions. Frank provided instruction on his research methodology, assigned research projects to fellows in the Apprenticeship track, and guided fellows in the Research track as they apply the methodology to their own research question.

September 26-October 23: Fellows work independently, on their own projects or on the forms and elements assigned by Frank. This independent research can be completed anywhere – fellows can return home or stay on at Threefold, where studio facilities are available. Each fellow will have at least one personal phone consultation with Frank during this time to check on progress and ask questions.

October 24-30: Frank and fellows reconvene at Threefold. This second group session will include presentations of independent work and a group compilation and reporting of research findings. An exhibition in Threefold Auditorium will feature the work of the research fellows, and time will also be devoted to exploring how the research methodology might be applied to each fellow’s own life questions and themes.

In early November, after the Visiting Researcher program is completed, the Threefold community will host a research symposium co-sponsored by Threefold Educational Center and the Collegium of the School of Spiritual Science. This event will include contributions from researchers of long standing, and be a fitting cap to a season marking a resurgence of research at Threefold.

In shaping the Visiting Researcher program, we at Threefold have worked hard to ensure that it is adequately funded and appropriately structured so that it can achieve the Christmas Conference ideal of institutionalizing spiritual-scientific research. As we work, continuous dialog with the Collegium of the School of Spiritual Science is intended to ensure that Threefold’s work harmonizes with the Collegium’s efforts in the same direction. We are striving to temper our enthusiasm and sense of urgency with a commitment to ensuring that the 2010 Residency is the first of many for the years to come.

Bill Day is Development Coordinator at Threefold Educational Center. For more information, contact Rafael (Ray) Manaças, Executive Director of Threefold Educational Center, at 845-352-5020 x12 or rafael@threefold.org. Learn more about Threefold Educational Center at www.threefold.org

16 Evolving News Research–a special section

Though underfunded by any measure, the sections at the Goetheanum, in Dornach, Switzerland, begun by Rudolf Steiner, provide an international focus for research.

The on-going need for institutional support and funding for research in North America is a large one. In the USA, the Threefold Educational Center, originally the “Threefold Farm,” was already a center in the 1930s. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer (right, with colleague Sally Burns) had a laboratory there. The North American Collegium of the School for Spiritual Science was glad to announce, earlier this year, a new fund named for Henry Barnes, a leader of anthroposophical work for many decades.

The Henry Barnes Fund for Anthroposophical Research

The North American Collegium of the School for Spiritual Science is pleased to announce the Henry Barnes Fund for Anthroposophical Research. This has been made possible through a generous gift to the Collegium for the purpose of furthering and supporting research in the realm of the spirit.

To foster a culture of research within the School for Spiritual Science and the Anthroposophical Society, the Collegium will award grants to individuals who are nominated by their peers within the Sections of the School based on their work with research and its methods. The completed research will be presented through publications, exhibitions, performances and other forms of sharing with groups who express interest.

In addition, the Fund will support events such as symposia, lectures, conferences and workshops that focus not only on the content of research but also on the paths of inner activity leading to enhancement of our human capacities as described by Rudolf Steiner.

In order to recognize and support anthroposophical research activity beyond the scope of the original gift, we plan to cultivate an ongoing gift stream to sustain the Fund.

For the first year, beginning July 2010, a total of $25,000 will be available for distribution as grants of varying amounts.

Criteria for Awarding Grants:

a) As a rule, nominated researchers will be active members of one or more Sections of the School for Spiritual Science in North America (the United States and Canada).

b) Researchers are to be nominated by their peers, typically by their Section Council.

c) Grants will be awarded on the basis of previous research activity grounded in anthroposophy. However, a perceived potential to advance some aspect of anthroposophical research will be a deciding factor.

d) Both the need for the research topic itself and the need for financial support for the research will be considered.

e) The Collegium assumes there is a spectrum of kinds and levels of research in the realm of the spirit. Grants will be directed primarily towards research that exercises organs of perception and cogni -

tion beyond conventional sensory and intellectual faculties. Therefore grants will not be awarded for conventional academic forms of research on spiritual matters, but rather to support what is also known as Goethean scientific or Goethean artistic research, as well as imaginative, inspirational and intuitive forms of spiritual scientific research.

The Nominating Process

The Councils of the Sections of the School for Spiritual Science are invited to nominate one or two individuals active in their Section in recognition of their anthroposophical research and its further potential.

In nominating an individual, the Section Council—or an individual requested to act on behalf of the Section Council—will submit a two to five page statement that expresses why they believe the individual should be awarded a grant relative to the criteria outlined above. This will include some history of the nominee’s previous research activity and an outline of intentions for future research.

Part of the acceptance process will include a written agreement concerning the following: 1) Researchers will document their research activity in an appropriate manner, such as an article, performance or exhibition. This will include a discussion of their method and ways of developing the faculties of perception and cognition necessary to the research. 2) Researchers will agree to present their research in 1- 3 events arranged in collaboration with the Collegium. Honoraria for such events would be in addition to the original awards.

The Henry Barnes Research Fund Committee will also consider applications for financial support of events such as lectures, workshops or conferences that advance the understanding and practice of anthroposophical research. To qualify, such events are to be sponsored by a Section of the School, or by two or more members of the School who consider themselves active in the General Anthroposophical Section.

The Award Granting Committee currently consists of two members of the Collegium, Sherry Wildfeuer and Helen Lubin.

Please address questions or nominations to:

Sherry Wildfeuer or Helen Lubin

PO Box 1045 PO Box 1384

Kimberton, PA 19442 Fair Oaks, CA 95628

sherrywlf@verizon.net

helenlubin@gmail.com

17 Research Issue 2010

Modern social sciences rarely address whether ultimate reality is founded in “things” or in “beings.” Religions, spirituality, and one wing of today’s ecological thinkers take for granted that humans, animals, and plants are not the only “beings” in the cosmos. Hard sciences and rationalists disagree, and seem uncomfortable sometimes even with the beingness of humans. So anthroposophy is challenging in its aim to be both genuinely scientific and at the same time fundamentally concerned with beings not perceptible to physical senses. Three “principles” who are experienced as “principals” are known by historically familiar names of Lucifer, Christ, and Ahriman. The first two entered fully into a human life experience in the past; the third is preparing for such an incarnation in our times, Rudolf Steiner reported. Lucifer provided access to freedom, supports idealism, and tempts us to abandon the earth. Christ provides the power to become a real individual, balancing other powers and serving the needs of the earth. Ahriman brings abstracting intelligence and technical power, and is presently seeking to dominate human beings with an ideal of mechanization. What do we do about that?

Meg Gorman presented this work to fellow members of the Section for the Social Sciences in Spring Valley in August 2009 and subsequently brought it to the Goetheanum. It was translated and published in the News from the Goetheanum

Rudolf Steiner tells us “...there is only one book of wisdom.” The challenge of our time is to determine whether or not this wisdom is in the hands of Ahriman or the Christ. Dr. Steiner then says, “It cannot come into the hands of Christ unless people fight for it.”1

How shall we do this? How can the goals of human evolution be realized in the middle of the Ahrimanic forces pouring into our times. What can we, mere individuals, do to impede Ahriman and better serve Michael and the Christ? Dr. Steiner tells us that there is much we can do. “People must learn from spiritual science to find the key to life and so to be able to recognize and learn to control the currents leading towards the incarnation of Ahriman.”2

Ahriman and Lucifer are alive and well in each of us, in the anthroposophical movement, and in the world. The more we do our work well, the more we may find ourselves attacked by negative forces. When Jesus of Nazareth received the Christ into his being at the baptism of John, he is first recognized by Lucifer and Ahriman in the temptations in the desert. Where the Christ is active, these forces will show up to undo our work. Thus, we are all fair game. The task is to stay awake and identify these influences, especially in ourselves. As my colleague, Denis Klocek says, once we can see these forces working in us, we need to tell them, “Thank you for sharing, please sit down.”

The bad news, in one sense, is that Ahriman is coming, and there is nothing we can do about it. In addition, collective humanity is helping his incarnation and that of his henchmen. This is not new information for anthroposophists. On the other hand, there is good news: through human activity, it is possible to help Ahriman serve humanity. We do not have to endure him only; we can work to make Ahriman a helper of human beings. Aside from the obvious reality of materialism in our time, Rudolf Steiner gives us many other hints on how we are preparing for Ahriman‘s activities. It is important to be conscious of these in ourselves and in our work.

First comes the BAD NEWS. At the risk of being superficial and overly organized, I list below some of the ways in which we make Ahriman‘s job easy. When deeply considered, each of these can also become a tool for discernment in living the “examined life.” The following, in no particular order, are helping Ahriman‘s incarnation: Disregarding weightiest truths. Ignoring or discounting our spiritual selves and our destinies in the world and in human evolution create the greatest bridge for Ahriman.

Denying or ignoring the spiritual nature of the human being. The idea that we are only our biology permeates much of the world today. As higher animals, some say we bear no spiritual responsibility for one another. Ahriman delights in this.

Seeing the world as a “great mechanism” only and maintaining this scientific superstition.

1 The Influences of Lucifer and Ahriman 65-66

2 The Incarnation of Ahriman 69

18 Evolving News

Meg Gorman

>What >Shall >We >Do >About >Ahriman :( ?

Research–a special section

This makes science into a new religion and creates “scientific superstition as a prevailing dogma.” When we think mechanistically, we create disharmony in our waking and sleeping. We see this today in the enormous rise in sleep disorders, especially among our teenagers.3 Getting caught up in fears like anthrax, swine flu, and global warming without understanding the science behind them is a great help to Ahriman. Believing that science will save us from ourselves is equally helpful to him.