HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

How much do you know about Black history on campus and in Boca Raton?

SPRING 2023 STAFF

Editor-in-Chief

Savannah Peifer

SPECIAL ISSUE: VOL. 27 | #3

FEBRUARY 1, 2023

WANT TO GET INVOLVED AT THE UP?

Weekly meetings: Fridays at 2 p.m. in room 214 in the Student Union

Email: universitypress@gmail.com

UPRESSONLINE.COM

Facebook.com/UniversityPress

Instagram/Twitter: @upressonline

TO PLACE AN AD: Contact Wesley Wright wwrigh21@fau.edu

First copy is FREE, each additonal copy is 50 cents and available in the newsroom.

Art Director

Lance Plummer

News Editor

Jessica Abramsky

Student Life Editor

Melanie Gomez

Business Manager

Maddox Greenberg

Managing Editor Ma. Emilia Santander

Copy Desk Chief

Jasmine Die

Sports Editor

Cameron Priester

Lead Photographer

Nicholas Windfelder

Social Media Manager

Luisa Ortiz

Advisers

Wesley Wright

Michael Koretzky

Staff Writer

Mary Rasura

2 UNIVERSITY PRESS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FEATURE:

PEARL CITY: 108 YEARS OF RESILIENCE

FEATURE:

A PURPOSE DRIVEN

PIONEER: MARIETTA MISCHIA

STUDENT LIFE:

THE GROWTH OF THE UNIVERSITY’S HAITIAN COMMUNITY

FEATURE:

DIVERSITY IN STUDENT

MEDIA MIRRORS NATIONAL TRENDS

Long before FAU, even before the city itself was founded, Boca Raton was home to a vibrant, allBlack community which still stands to this day.

11 years after the Supreme Court’s ban on Jim Crow’s “Separate but Equal,” FAU graduated its first ever integrated class.

Florida Atlantic University is home to three organizations representing the Haitian community.

Mistrust and feeling misunderstood are some reasons Black students don’t join student media.

6-9 10-12 14-15

16-17

3 UNIVERSITY PRESS

AVÈK ANPIL MEN CHAY LA PA LOU

Jasmine Die | Copy Desk Chief

Growing up in communities with subpar schools and lack of access to opportunity, many immigrants and racial minorities struggle to overcome the barriers that come with navigating higher education – I have witnessed it firsthand.

There is a world of opportunity behind the barricade of accessibility for these underrepresented communities. While this institution may not have a perfect history, I believe that Florida Atlantic University has long acknowledged and served the ever-prevalent minority populations of South Florida.

As the daughter of two Haitian immigrants, I appreciated that our household never overlooked the importance of education. My parents were firstgeneration college graduates, both of whom earned their undergraduate degrees here at FAU. Their experience at the university has largely fostered opportunities for social mobility and contributed to their success.

This institution has long embraced diversity and blazed a trail in Florida, providing equitable access to education in ways no other public university in the state has. As Florida’s most racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse public state university, FAU is distinguished by its ability to retain and graduate Black students.

I have grown up on this campus, having attended FAU schools since I was four years old. I am grateful for the atmosphere of opportunity that the university has offered me, my family, the Haitian community, the Latin and Caribbean community, and Black students generally.

The UP wants to represent, serve, and protect the voices of all students. I hope that this issue will be part of a larger recognition and celebration of the diversity on campus. I implore minority students to get involved in student media.

The newsroom needs your perspective to serve the FAU community in a way that best represents the student body.

One student alone cannot rectify years of underrepresentation of Black students in campus media, but each student who chooses to get involved plays an integral part in ensuring we produce a well-rounded outlook of our campus in the news.

Growing up, my parents often repeated a Haitian proverb that says “Avèk anpil men chay la pa lou,” which translates to “With many hands the burden is not heavy.”

My desire is that we work together to amplify Black voices in student media and represent our rich and abundant culture on this campus.

EDITOR’S LETTER:

Diversity needs to be present in student media, and it takes all of us to make it happen.

HONORING OUR COMMUNITY

Cameron Priester | Sports Editor

Last December, Editor-in-Chief Savannah Peifer, Copy Desk Chief Jasmine Die, and myself met and decided to publish this special print edition to celebrate Black History Month. But more than that, to the three of us, this issue is a call of duty. Five years ago, the University Press published a similar issue highlighting six black students and staff members. Part of that issue reported on how from 2008 to 2016 FAU’s Black student body had grown considerably. According to the latest available Diversity Data Report, that percentage has only continued to grow. However, we haven’t published another Black History Month issue, or any issue of the sort. For reference, FAU has seen three different head football coaches in that span. Before the one in 2018, it had been more than 13 years since we had published a Black History Month issue— as far back as our records go.

In our most recent print issue, Savannah wrote in the opening line of her Editor’s Letter that the University Press was formed on the basis of serving the FAU community. That foundational principle was meant to extend to the entire FAU community. But, are we fulfilling that responsibility if we are allowing the stories that are important to the Black students on our campus to go unreported?

Our Black student body is a foundational part of what makes our campus so unique, and what allows us to call ourselves one of the most diverse universities in the nation. As the university’s most prominent studentrun news source, it’s our duty at the University Press to ensure that the stories near and dear to our Black students reach the forefront of our community’s mind.

So, yes, this issue is a celebration. But to us at the University Press, it is also the fulfillment of our duty as student-journalists: serving every single student at Florida Atlantic University

5 EDITOR’S LETTER:

As the University Press, our duty is not only to celebrate, but also amplify student voices at any time

FEATURE: PEARL CITY: 108 YEARS OF RESILIENCE

Long before FAU, even before the city itself was founded, Boca Raton was home to a vibrant, all-Black community which still stands to this day.

Cameron Priester | Sports Editor

Lot in Pearl City that has already began demolition and reconstruction.

Photo by Cameron Priester.

Cameron Priester | Sports Editor

Lot in Pearl City that has already began demolition and reconstruction.

Photo by Cameron Priester.

Today, the most notable stop along Old Dixie Highway, which cuts directly through the heart of Boca Raton, is the brand-new, $56 million Brightline station that opened in December of last year. But long before that was built, the busiest stop along that road was a vibrant, all-Black community that predates the city itself.

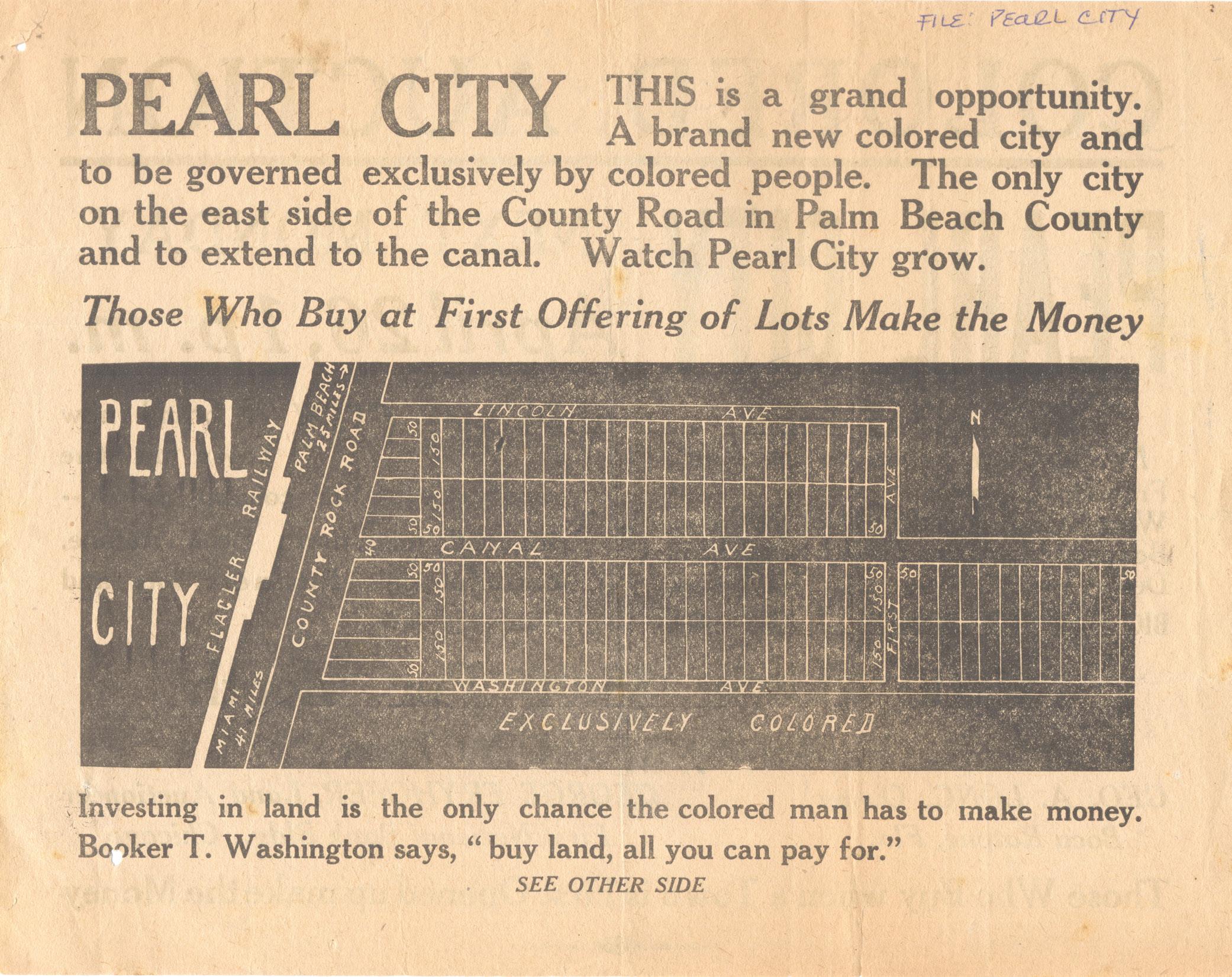

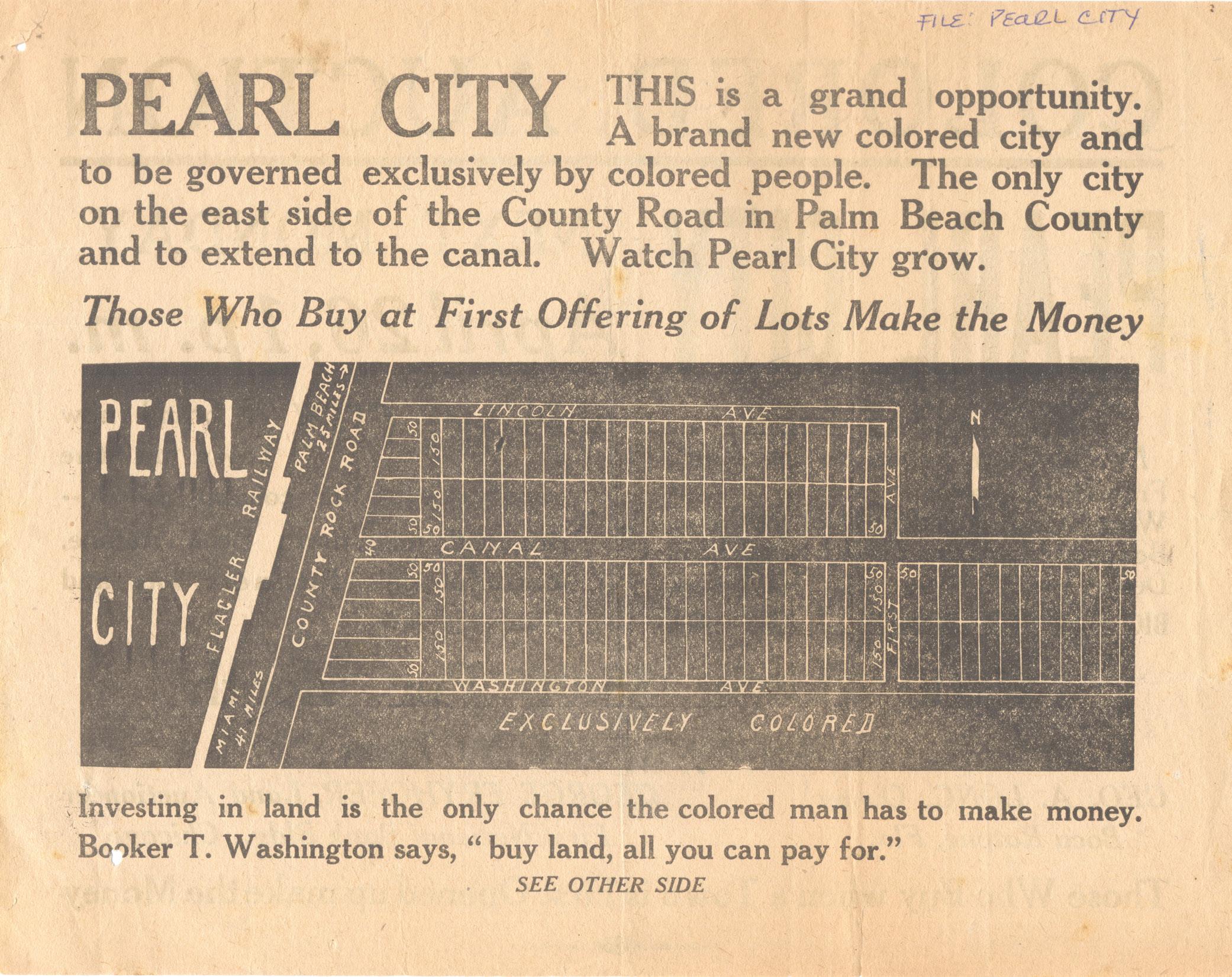

Nestled between what is now Federal and Dixie Hwy., and directly south of what is now Glades Rd., Pearl City was an all-Black neighborhood established in 1915, 10 years before the city itself had been incorporated, for the African-American sharecroppers working on the many farms in the area at that time.

“It is the oldest neighborhood,” said Dr. Candace Cunningham, professor of sociology at FAU. “It’s older than Boca Raton the city and it’s the only historically Black neighborhood, that’s very much part of the importance.”

It was originally proposed by George Long, an associate of railroad tycoon Henry Flagler, so that the workers wouldn’t have to make the daily trek from Deerfield to the pineapple farms where they worked— which is where the neighborhood is suspected to get its name, Hawaiian pearl pineapples.

After the community was approved, small parcels of land—ones that were smaller and more expensive than those offered to white families—went up for auction for a minimum down payment of five dollars. One by one, families began to move in.

Though it wasn’t an immediate process, before long, Pearl City’s three avenues, Lincoln, Canal, and Washington, were dotted with several family homes, primarily built in the long, thin “shotgun” style that was popular around the South in that era. The homes were small, humble abodes, most consisting of just a few rooms, with resident’s own crops and livestock often kept between each other.

Although it never grew considerably large in numbers, the neighborhood eventually blossomed into a self-sufficient community, independent of the white society they were ostracized from. Within a few years of its establishment, Pearl City eventually developed its own infrastructure; several businesses, a school, even entertainment, such as multiple dance halls, or “juke joints” as they were referred to.

“They were mom-and-pop type stores, but it became its own little commercial area,” said Susan Gillis, curator of the Schmidt Boca Raton Historical Museum. “They had to, because the Black citizens were not welcomed in the white areas.”

The community grew to become very tight knit, often gathering together at the neighborhood’s juke joints, or at the beach to enjoy eating freshly caught sea turtle, which was a frequently eaten meal at the time.

Marie Hester, one of 14 grandchildren of Pearl City pioneers Will and Belle Demery, called growing up in the community “a family affair.”

“It was like a village,” remembers Hester, who was born in the family home in Pearl City. “Everyone watched out for each other, we had to.”

However, what really binded the neighborhood together is the two churches that Pearl City is built both literally and figuratively around, Ebenezer Missionary Baptist and Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal; both of which still stand today.

In 1985, the Boca Raton Historical Society published an oral history on Pearl City in which an original resident of the neighborhood, Lois Dauphus Martin,

detailed the importance of the two churches.

“Well, we were all close because you had like two churches in here, Ebenezer Baptist and Macedonia,” remembered Martin. “The first and third Sunday you went to Ebenezer, the second and fourth you went to Macedonia, and that’s how we operated for years and years. [On Sundays] one church would close down and we would all be at the other church.”

Aside from being their place of worship, the churches were often the host of community gatherings and became a symbol of pride and community to the neighborhood.

Cunningham, who’s been heavily involved in the community, including helping organize a photo exhibit about Pearl City at the Boca Raton Art Museum, spoke to the importance of the churches to Pearl City.

“When you think historically to the role of Black churches in the Black community, they are not only centers of religion, but they are also centers of culture and where african-americans can sort of openly discuss social issues,” said Cunningham. “The Black church was often times the only spaces that were owned and operated exclusively by Black Americans. So that meant African-Americans could organize and openly discuss issues without the same sort of fear of repercussions.”

Ebenzer and Macedonia weren’t the only source of pride in their community however. Residents took great pride in the fact that their neighborhood was situated east of the railroad that runs directly through Boca Raton.

At the time, all-Black neighborhoods were usually built on the opposite side of train tracks as a way of physically, and symbolically, separating them from the rest of society, just as the all-Black communities in neighboring

7 UNIVERSITY PRESS

1915 advertisement for plots of land for sale in Pearl City. Courtesy of the Boca Raton Historical Society.

Fort Lauderdale and Palm Beach were. Pearl City, however, was not, and its residents took great pride in that fact.

“We prided ourselves on living on the east side of the railroad track,” said Hester. “

Despite the state of the rest of the South at the time, even at the height of segregation there was never much tension between the residents and the adjacent white neighborhoods, because the communities remained to themselves.

“They were very friendly and as far as I know, there were no problems to speak of,” wrote Pearl City resident, Louise Dolphus Williams. “Because you stayed in your community and you did your thing and they stayed in their community and they did their thing, as far as I know.”

Because there wasn’t much negative interaction between themselves and the white communities, residents of Pearl City didn’t take much part in the Civil Rights Movement that began swarming the nation in the 1960s.

“We really weren’t aware of all the things that were happening. Mostly because we didn’t have a television. We had a radio but we didn’t have freedom of the radio. So we really had no knowledge of it,” said Hester.

The Civil Rights Movement wasn’t a hot topic of conversation either. Hester added that her first time really learning any knowledge of Black history was on a trip to Washington D.C. as an 18-year-old in 1967.

“That was the most education I had received on civil rights and black history,” she recalled.

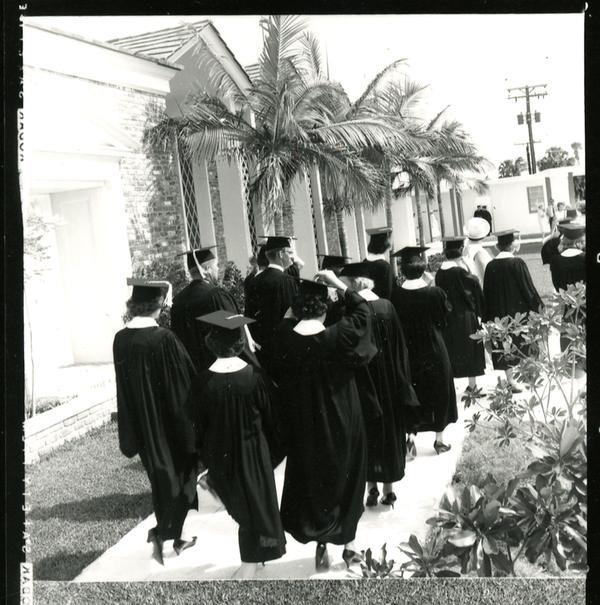

Some residents of Pearl City did, however, take part in the movement at least once. In 1965, students of Marymount College in Boca Raton, now Lynn University, gathered with residents of Pearl City to march in response to the “Bloody Sunday” marches led by civil rights trailblazer Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, Ala.

Though they sit just over a mile away from each other, FAU’s ties to Pearl City remained loose until a sociology professor decided to share the neighborhood’s story to the rest of the world.

In 1985, Arthur Evans, a professor of sociology at FAU who passed away in 2018, conducted a series of interviews with generational residents of the neighborhood, and shared the interviews in two publications. One of which was the Spanish River Papers, the other was a book Evans helped author titled “Pearl City: A Black Community”—which is the source of most of the historical society’s information on the community and all of their quotes from its residents.

Both Cunningham and Gillis credit Evans’ research with being one of the most important factors in keeping the stories of Pearl City alive.

“He did really important work in terms of helping to preserve that history and helping actually create a historical narrative that we wouldn’t have otherwise,” said Cunningham.

It was also Evans’ work that played a part in inspiring Cunningham to do her own research on the community, which took the form of oral histories she authored about Pearl City.

“What I wanted to do with my oral histories is get a sense of what has happened since its founding, and also get a sense of what is enabling citizens of Pearl City to retain their property and sense of community,” said Cunningham in an interview with PBS. “I think the importance of collecting those stories is that they’re now available for prosperity. But also, we know what those residents want in their future.”

In the wake of Evans and Cunningham’s research in Pearl City, student organizations on FAU’s campus have become heavily involved with the community, and the several events dedicated to its preservation.

The FAU Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has frequently done work in the community recently, and in years past. Chapter President Hannah Laguerre frankly described it as “heartwarming” to be able to help give back to Pearl City.

“It’s also so fulfilling because kids today don’t seem very interested in history. So being able to show there are still some who are interested in their history and giving back is so important,” said Laguerre.

In past years, the FAU chapter of the NAACP has worked in the community. This past June, with the help of Ebenezer Baptist, the NAACP held a youth rock-painting event for children. More recently, they assisted the community host their annual parade and community event in celebration of Martin Luther King Day.

8 UNIVERSITY PRESS

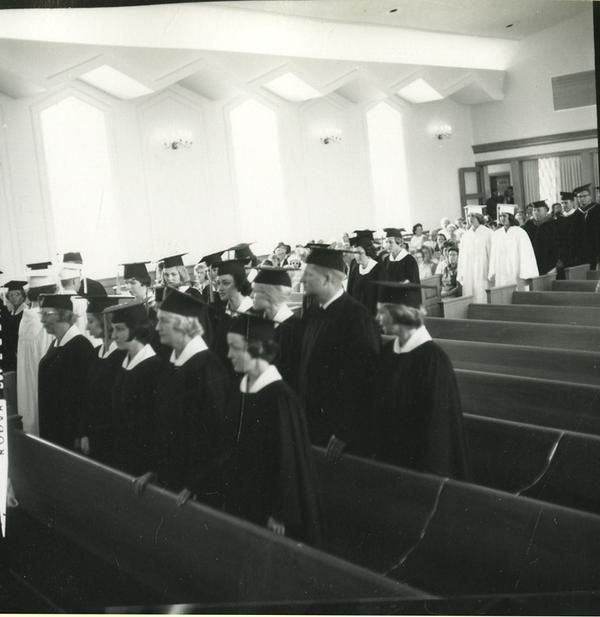

Students of Marymount College, now Lynn University, marching with residents of Pearl City in response to the “Bloody Sunday” marches in Selma, Ala., 1965. Courtesy of the Boca Raton Historical Society.

Memorial of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. which stands in front of Ebenezer Missionary Baptist church in Pearl City.

Photo by Cameron Priester.

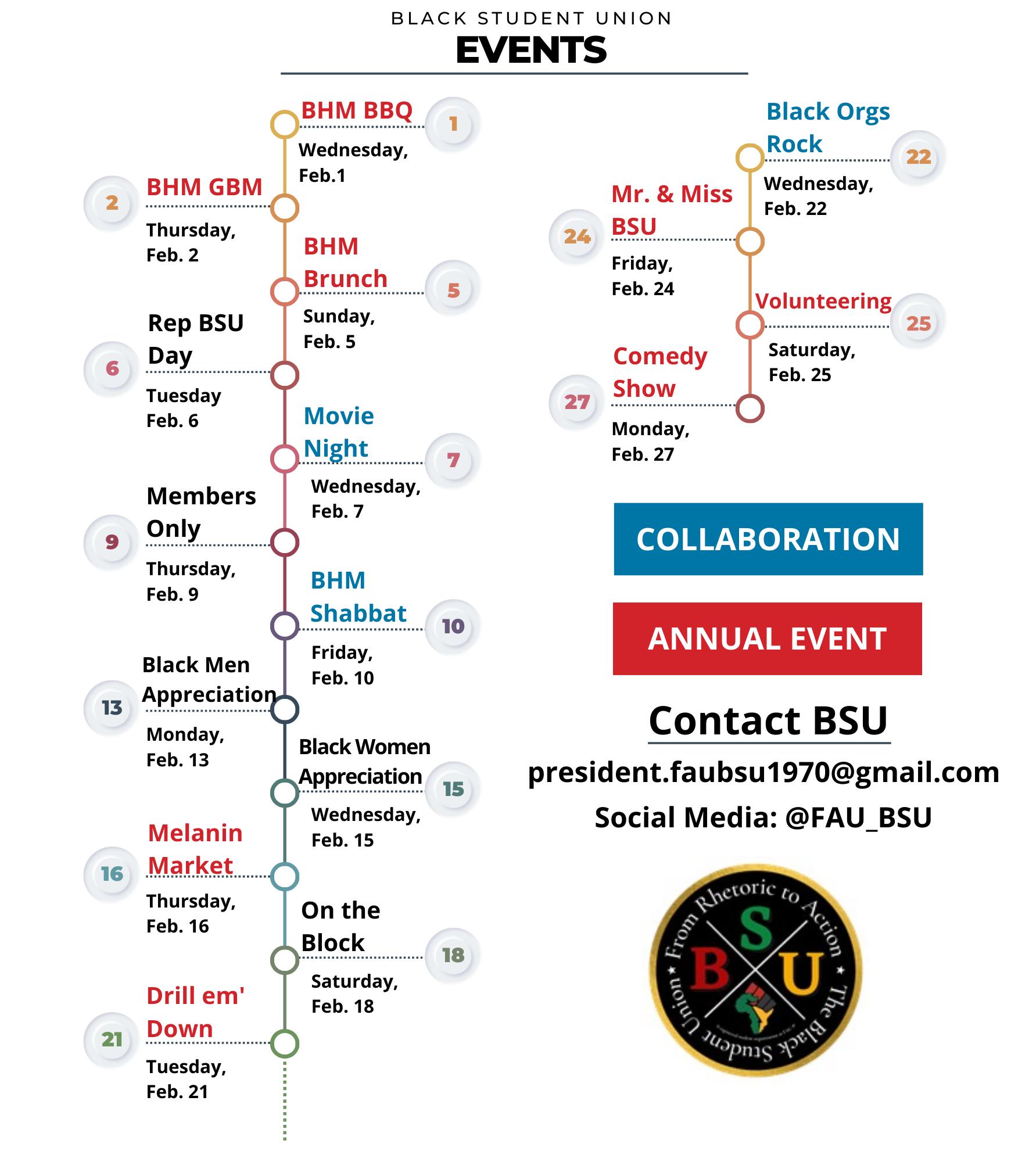

Other campus organizations have also been involved in the community, such as the Black Student Union, who hosted a field day for the children of Pearl City this past Labor Day.

In addition to the charity that’s been done, there’s been much effort put into the preservation of Pearl City, from both the residents and outside entities.

Because of the neighborhood’s designation as a local historic district, the area can never be redeveloped for commercial use. Private development companies, however, have already begun buying up privatelyowned plots of land in Pearl City, many that have been passed down through generations, for demolition and redevelopment into modern residences; some of which are actively taking place. Federal designation, however, would add further protections from gentrification.

“Historical designation from the city essentially means that an area will maintain its characteristic as a residential area,” said Cunningham. “What that residential area looks like, and quite frankly, who is benefitting from that area could alter.”

The fight to maintain Boca Raton’s oldest neighborhood hasn’t wavered though.

In 1994, five members of Ebenezer Baptist helped found the Developing Interracial Social Change of Boca Raton (D.I.S.C.), a local nonprofit dedicated to “promoting justice in the community” according to their website. Now with Hester as President and with the help of several other groups, the organization has been leading the push to have Pearl City designated as a national historic district.

Hester explains that the federal government focuses on the stories when making a decision.

“I think we will receive the designation,” she said. “We have turned in the last of the information. We are just waiting to hear from them now.”

Gillis and Boca Raton Historical Society have been recently focusing their efforts on saving the Fountain family home. Built in 1925 and the oldest original home in Pearl City, the Fountain home is one of the last remaining physical pieces of history that we have left of the neighborhood, but has fallen into disrepair.

Residents don’t plan on stopping their fight to make Pearl City a federally recognized historic district. Nor do they plan on leaving the community that many of their ancestors built and lived in for over a century, anytime soon.

This unwavering sentiment was described perfectly by Martin.

“They have tried their darndest to get us out of here,” she said. “They have told us a million times that this is our choice property and for you all to be living on it when you could sell it for commercial and make all this money off of it, but what do we say to them? This is home.”

9 UNIVERSITY PRESS

Above: Photo of Macedonia African Methodist Episcopal Church which stands in Pearl City. Below: Photo of Ebenezer Missionary Baptist Church, which stands in Pearl City. Photos by Cameron Priester.

A PURPOSE DRIVEN PIONEER: MARIETTA MISCHIA

11

Jasmine Die | Copy Desk Chief

Jasmine Die | Copy Desk Chief

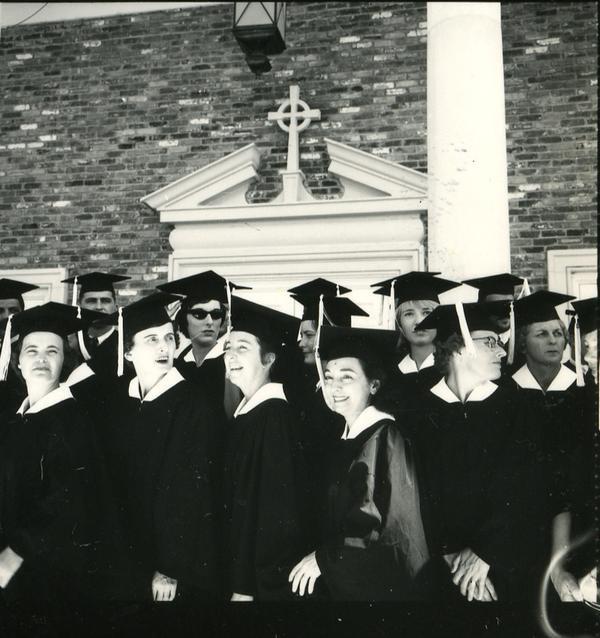

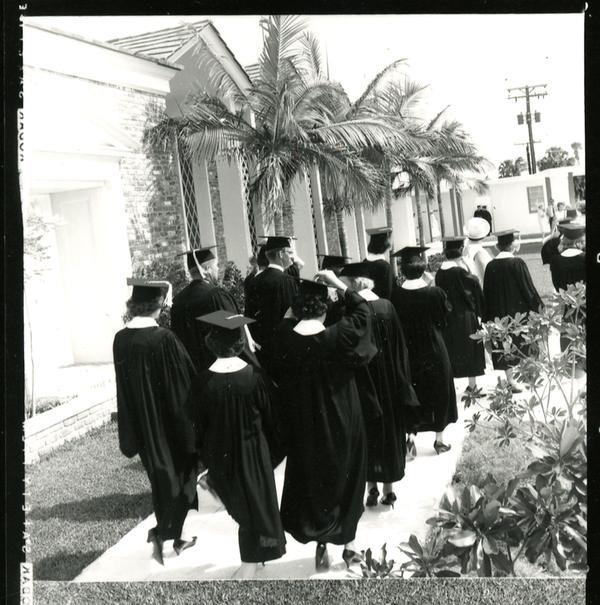

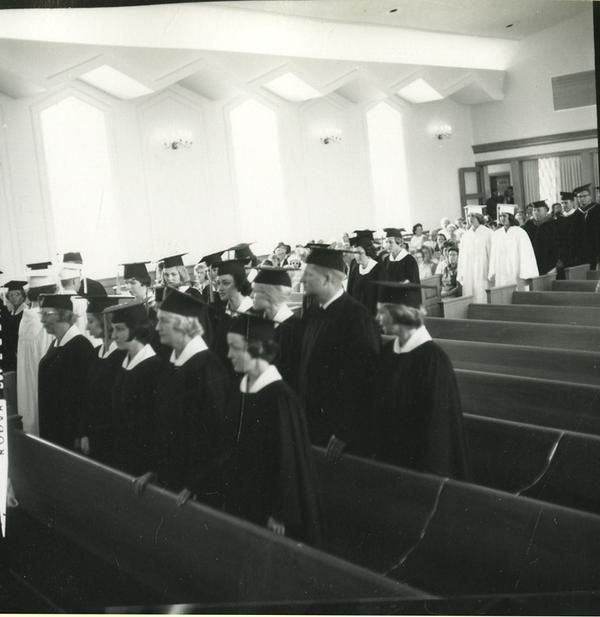

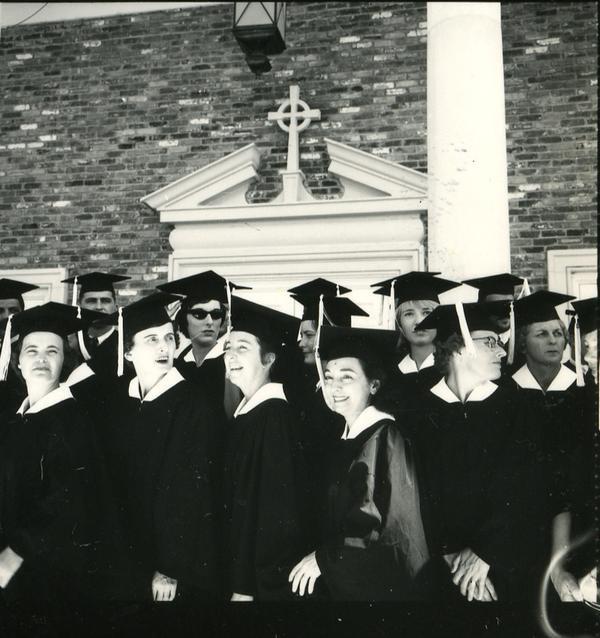

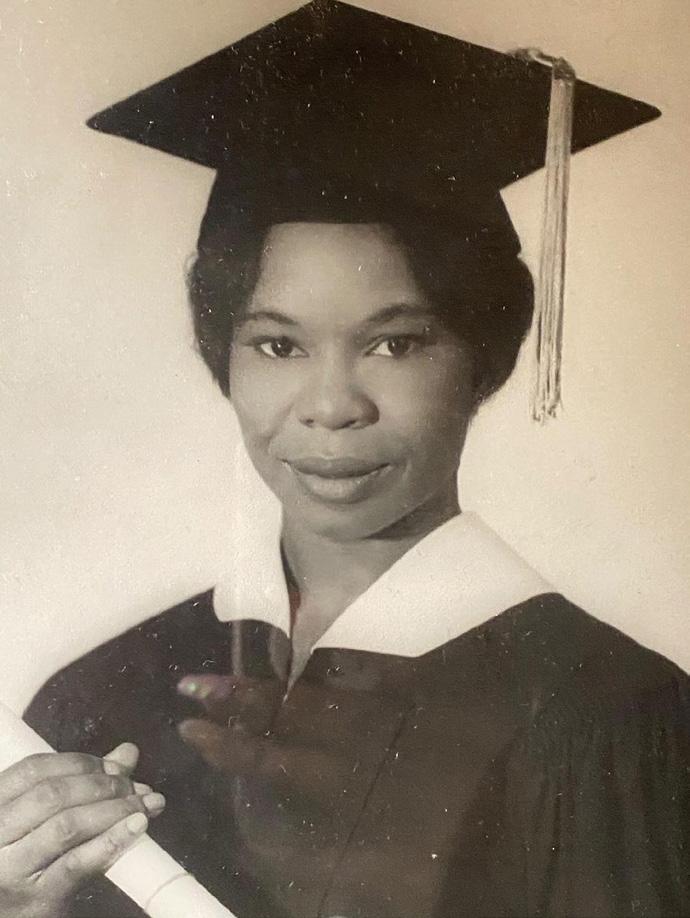

On April 24, 1965, Florida Atlantic University honored its first-ever graduating class at First Presbyterian Church in Boca Raton where two Black students, Marietta Cochran Mischia and Vera Wilson LeGrier, received their degrees alongside non-black students.

Mischia, a sharecropper’s daughter who came up from extreme poverty to attend FAU in 1965 is a story of perseverance and great success.

Even in its infancy, the university played an important role in supporting minority populations in Florida.

“FAU was the only [public state] university that accepted Blacks at the time,” Mischia said.

In the early 1960s, Black students at FAU fit into a much larger piece of history– nation-wide efforts towards desegregating higher education institutions.

Paradoxically, some of the most effective efforts towards desegregation took incentive from the Supreme Court’s legalization of segregation.

The Supreme Court ruling on the constitutionality of Jim Crow’s “separate but equal” in 1896 “Plessy v. Ferguson” prompted demands from Black Americans nation-wide for access to equal education and opportunity.

The court’s ruling gave Black Americans more reason to argue for integration as segregation in higher education inherently left them at a disadvantage.

The efforts to desegregate schools culminated May 17, 1954, in Topeka, Kan., where the Supreme Court abolished school segregation in the landmark case “Brown v. Board of Education”, putting a legal end to Jim Crow’s “separate but equal.”

This ruling, however, only marked the beginning of a decades-long struggle to integrate schools.

It was not until 1962 that James Meredith integrated a previously all-white higher education institution, the University of Mississippi.

Despite vehement opposition from students and faculty, Meredith earned a degree in political science. However, Meredith faced violent mobs and chaotic encounters. Governmental personnel eventually sent U.S. Federal Marshals and Guardsmen to protect him.

Further south in Boca Raton, Marietta Cochran Mischia and Vera Wilson LeGrier became the first Black Americans to be admitted to FAU, in 1963.

Unlike Meredith, Mischia recounts a rather positive experience at the university during a time when fair treatment of Black Americans in higher

10 UNIVERSITY PRESS FEATURE:

years after the Supreme Court’s ban on Jim Crow’s “Separate but Equal,” FAU graduated its first ever integrated class.

Left: Marietta Mischia (left) with young Shannon Cochran (right). Courtesy of Shannon Cochran.

Below: Gradution pictures of FAU’s Class of 1965. Courtesy of FAU Library.

When asked about discrimination and barriers to a safe and equal education, Mischia affirms she did not face any.

“There was a professor or two who seemed not to have high expectations of Black students, maybe because we were the first Black students in his class, but that was not indicative of all the professors,” Mischia recalled. “There were professors who were respectful, intelligent, and accommodating. I feel they wanted all students to achieve.”

She continues to express that to her knowledge no form of violence or repression was ever directed against her or Wilson, a close friend of hers during her time at FAU. When deciding what university to attend, she did not have many options at the time.

“It was a dream and endeavor of mine of a lifetime to attend any university, but FAU was the only state university open to Blacks at the time,” Mischia commented.

“In my childhood I was deprived of the experiences deemed necessary for a child to develop to the best of his ability socially, mentally, emotionally, and physically. Therefore, it was difficult to pursue my serious interest in reading,” Mischia wrote in an undated autobiography.

Yearning to have access to more books, Mischia determined that she would pursue a career in education– if permitted the opportunity to do so.

“I early determined that teachers had the access to all and any kind of books, hence I wanted to be a teacher,” she wrote.

However, Mischia wrote that her ambitions were restricted by the social and political circumstances at the time.

“After high school due to circumstances beyond my control (namely economics and segregation and discrimination laws) I was unable to continue my education,” she said.

The 1954 Supreme Court decision allowed Mischia to continue her

education, changing the trajectory of her life.

“I was able to continue my education, due to the decision of the Supreme Court, that Negroes could attend any Public Institution,” she recalled. “I suppose this was the most significant happening in my life.”

Living in Miami-Dade County, Mischia was approximately 50 miles away from the university. After her commute from Miami to Boca Raton via the Greyhound bus, Mischia would walk over a mile from the bus stop to the recently-opened university, which did not yet have a stop of its own.

“There was no paved road. There were just dirt roads and fields that I had to walk through,” Mischia said.

Nonetheless, she asserts this journey was her best option.

“It was convenient. They accepted me,” she said.

Mischia felt that activities during her time emphasized important values like hard work, perseverance, and inclusivity despite status and background.

11 UNIVERSITY PRESS

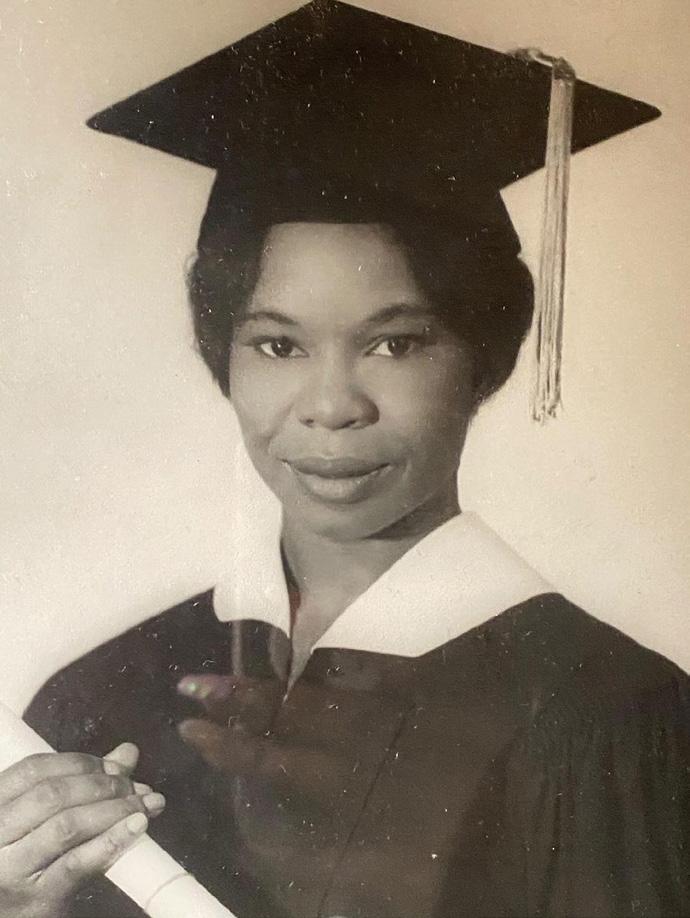

Graduation portrait of Marietta Mischia. Courtesy of Shannon Cochran.

Marietta Mischia receiving an award for her work as a distinguished Dade County educator. Courtesy of Shannon Cochran.

After graduating from the College of Education in 1965, Mischia went on to become a community leader in Miami-Dade County, working both in education and social services.

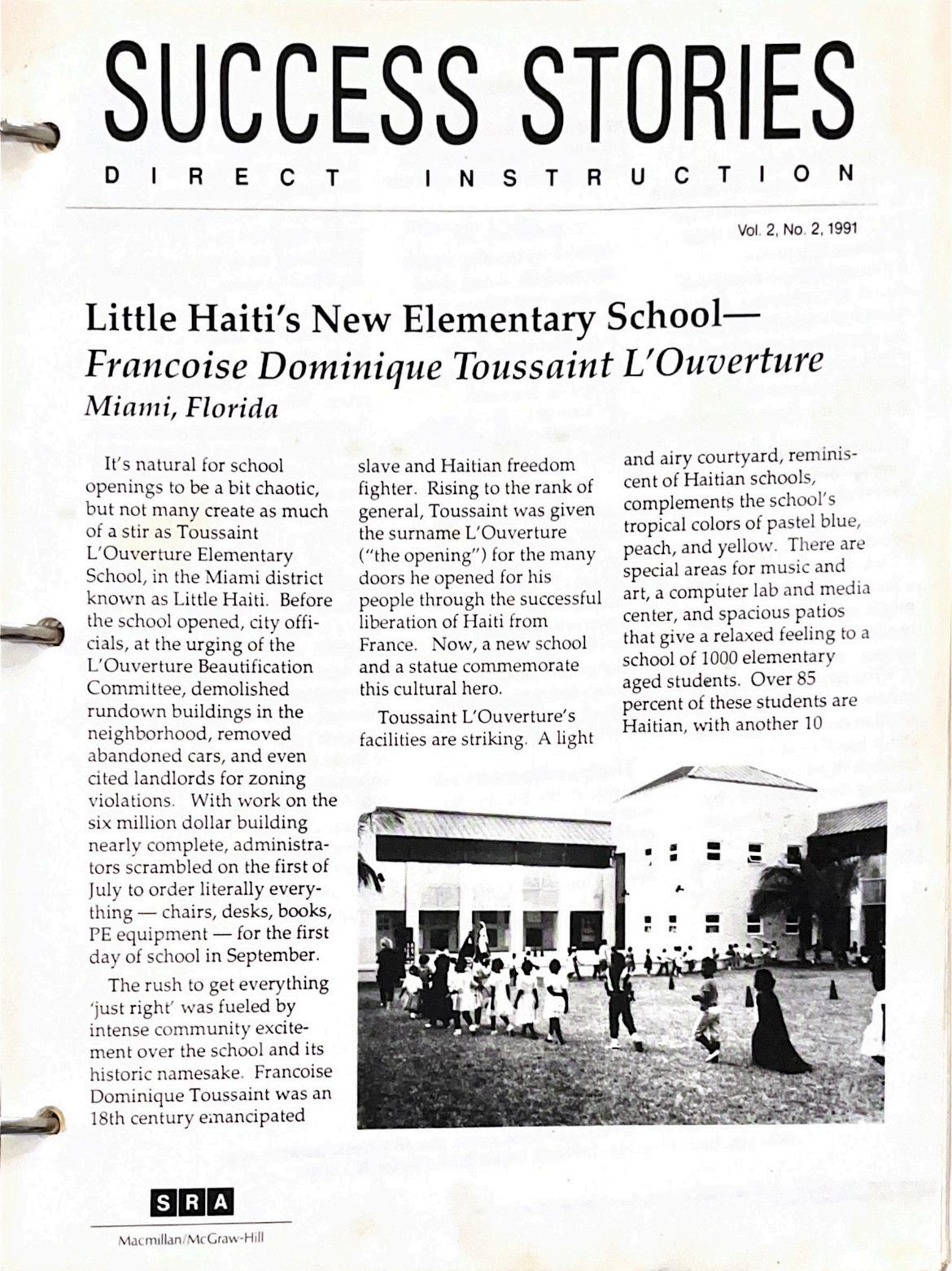

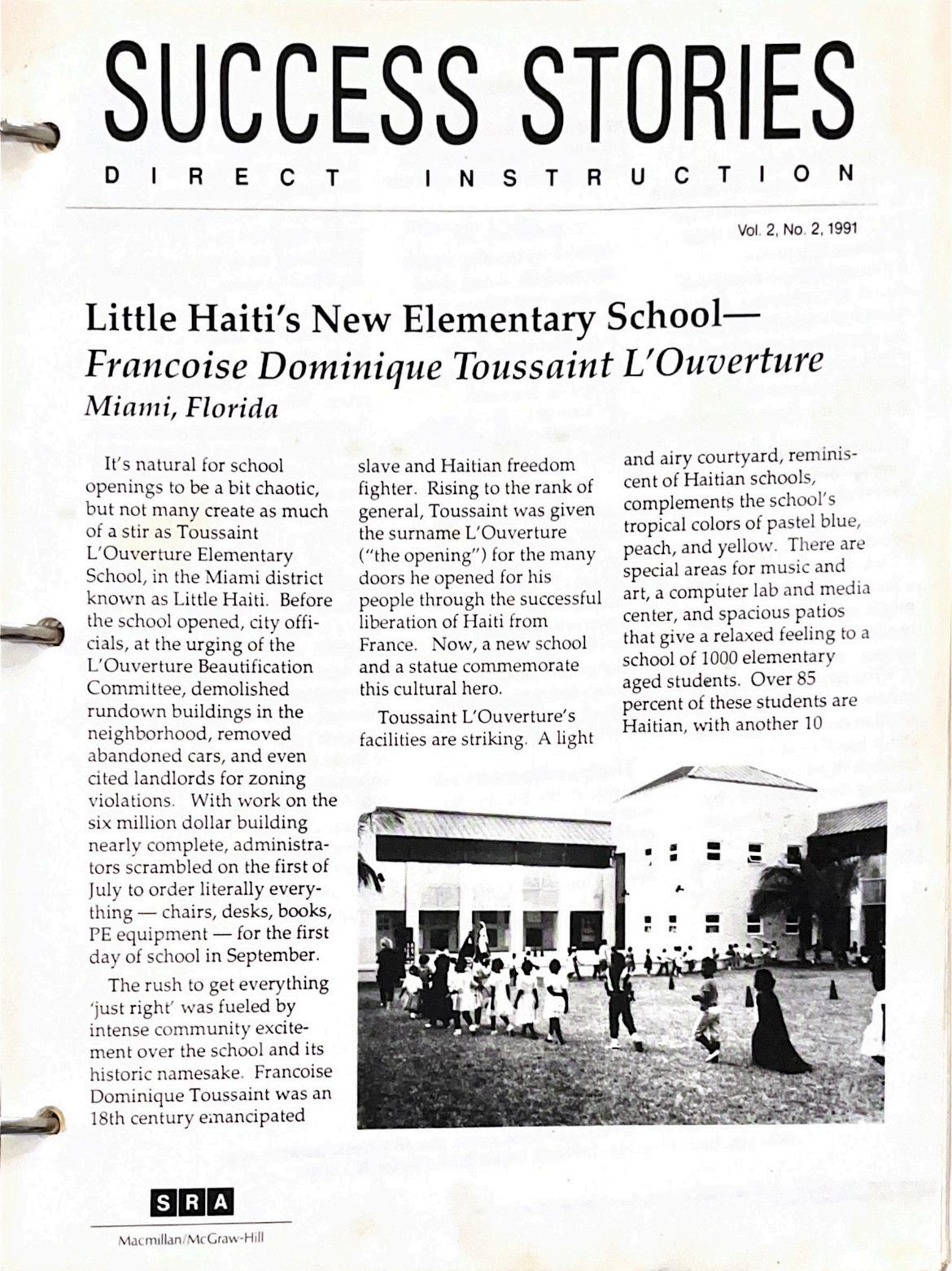

Following her principalship at Earlington Heights, in 1989 Mischia founded Toussaint L’Ouverture Elementary School, the first elementary school in Little Haiti, where she wore the title of both school principal and classroom teacher.

“I bought every piece of furniture for the school. I hired every teacher for the school,” she said.

Mischia mentions there were the challenges in running a school in Little Haiti at the time due to many students not having a “formal education,” but school was convenient due its proximity to their neighborhoods.

Under Mischia’s leadership, the school managed to employ a teaching staff of over 200 and be of service to Little Haiti’s underserved immigrant population with a student body of over 1,000.

Mischia went on to attain her Ph.D. in educational leadership at Nova Southeastern University in 1992.

Shannon Cochran, Mischia’s granddaughter, explains that her grandmother has been a great inspiration and influence for her success.

“My grandmother instilled the value of education in me at a young age,” she said.

Mischia would attend reading events at the local library and owned a tutoring center in Miami.

“My grandmother’s love and passion for education and the way she fearlessly achieved her educational goals in the face of adversity, racism and segregation taught me how to be tenacious, ambitious and resilient,” Cochran said. “Because I had someone to look up to as an example, I knew that I had the power to be succeeding in the field of education while also creating my own legacy.”

Mischia hopes to encourage individuals who feel they come from a disadvantaged background.

“No matter the obstacles, barriers, and misfortunes, persevere and develop a commitment for whatever your goal is and do your very best to achieve it,” Mischia said.

12 UNIVERSITY PRESS

Above: Macmillan/McGraw-Hill recognizes Toussaint L’Ouverture Elementary School’s success in 1991. Below: Gradution pictures of FAU’s Class of 1965. Courtesy of FAU Library.

Right:Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

Join the University Press Today

A free press can be good or bad, but, most certainly, without freedom a press will never be anything but bad.

-Albert Camus

STUDENT LIFE:

THE GROWTH OF THE UNIVERSITY’S HAITIAN COMMUNITY

Florida Atlantic University is home to three organizations representing the Haitian community.

Mary Rasura | Staff Writer

Haitian immigration has been constant through the history of the United States since the colonial era, both as enslaved and free people. Dec. 12, 1972, marked the largest immigration movement of Haitians to South Florida seeking political asylum from the prosecution of dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier. Florida Atlantic University was founded a little more than a decade earlier in 1961, with Haitian migration developing alongside the university’s growth. Haiti is less than 1,000 miles from FAU, making you closer to Haiti than California.

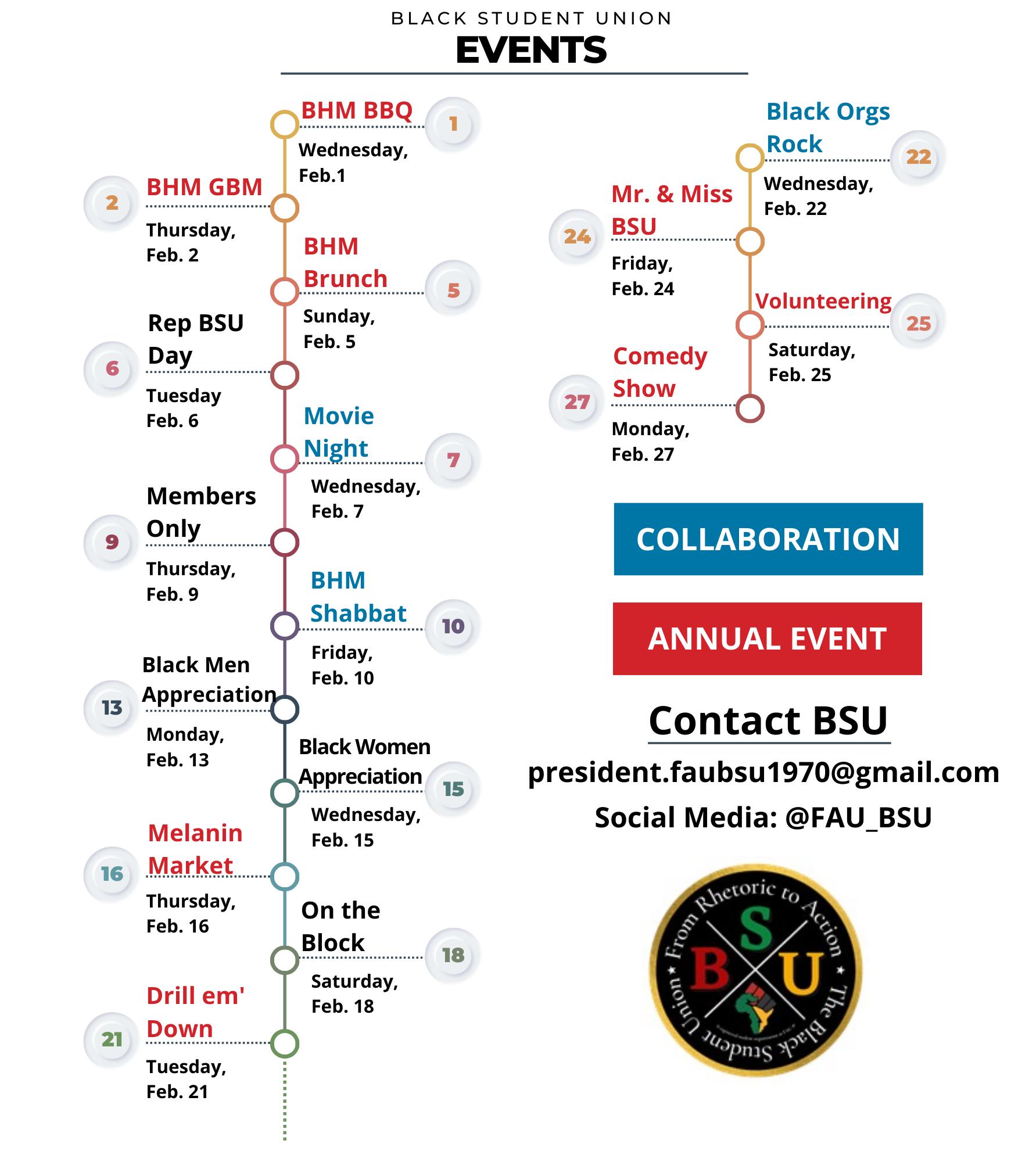

Today, FAU is home to three Haitian student organizations: Konbit Kreyol focuses on all Haitian students, Neg Kreyol, Inc., is focused on Haitian men and Fanm Kreyol, Inc., is focused on Haitian women.

Vania Bocage is a Haitian-American member of the Boca Raton House of Representatives and a senior public management major. She plans to join Konbit Kreyol this semester and stated that her main connection to Haiti is through her Haitian father’s ancestry.

“I would say when I was younger, I wish I had more of a connection because when you’re not fully something, the people that are, they want to know ‘why aren’t you in tune with your heritage? Why don’t you know much about the language, the food, the culture?’” Bocage said. “And a lot of that made me feel sad, and I didn’t really have a place.”

Going to a university in the U.S. can be a tool for social mobility, and immigrant parents are aware of this when raising their children.

“Being from an immigrant family, as a child they raise you in a certain type of way to where you’re expected to achieve success. Haitian parents worked extremely hard to be able to provide their children, their American children, a certain lifestyle to be able to be successful in America,” Bocage said.

Jasen Santerre, a senior business management major and member of Neg Kreyol, Inc., feels similarly as a Haitian-American first-generation college student. He acknowledges that his parents were unselfish in leaving their country behind for the U.S.

14 UNIVERSITY PRESS

Members of Neg Kreyol, Inc., a FAU student organization for Haitian men. Courtesy of Neg Kreyol, Inc.

Santerre believes the level of opportunity present in the U.S., that isn’t present in other countries, leads to his parents wanting him to succeed. He says that he understands and respects why his parents, and Haitian parents in general, have high expectations.

Jacqueline Charles is a longtime Miami Herald journalist who has reported on Haiti and the English-speaking Caribbean for over a decade. Migrating from Haiti to the U.S. is a treacherous journey, she said.

“Today, we are in an ongoing crisis of Haitians fleeing, taking to the sea by boats, dangerous boats in order to escape,” Charles said. “They’re not just escaping the economic and social breakdown in the country but they will tell you that they are escaping for their lives. They’re risking their lives to save their lives.”

One of the most well-known natural disasters that affected Haiti was the 2010 earthquake. At the time, Haiti was in the news showcasing the devastation, leading to young people wanting more nuance in media representation.

“You had a lot of young people that sort of just wised up to Haiti, but they really wanted to push the beautiful beaches and the beautiful culture and the delicious food, and this rich history of former slaves defeating their colonizers, the French, to become the first black Republic,” Charles said.

Bocage believes Haiti offers more than what is typically covered in the news.

“The news media has portrayed Haiti, they’ve portrayed Haiti to be a poor, developing country. We’re just full of diseases and malnourished children and things like that,” Bocage said. “While there are some cases of it, the media makes that the full scope. And from what I’ve been told by family members and other people, Haiti is actually a beautiful country. Beautiful language, amazing, delicious food and just rich culture, and I wish more people would be able to experience that.”

Abigail Augustin, a junior exercise science major and the president of Konbit Kreyol, is also a Haitian-American first-generation student. She is additionally a member of Fanm Kreyol, Inc., and the vice president of TriAlpha First-Generation Honors Society. Augustin is a scholar in the Kelly/ Strul Emerging Scholars Program, a mentorship program that helps lowincome first-generation college students finish their FAU degree in four or less years, debt-free.

“When you’re first generation, you might not know where to go or what to do. Whatever question I had, I would just ask the director or the assistant director [of Kelly/Strul Emerging Scholars Program],” she said.

Augustin states that she is grateful to have the opportunity to pursue her college education when her parents did not.

“I’m put in a situation where now I’m able to have the connections and I have the educational tools for furthering my career and things like that and they didn’t have that opportunity,” she said.

Annabelle Lanoue is a sophomore health science major and HaitianAmerican. She was raised mainly by her Haitian grandparents and Creole is her native language. She is also a first-generation college student and joined Fanm Kreyol, Inc., for the relationship it would provide with other Haitian women.

“There’s many organizations that recognize and bring women together,” Lanoue said. “But when you find something that’s specifically for your culture, where you get to bond with a sisterhood with women from your culture, and you guys get to encourage each other and get each other to your goals and where you want to be in life. I thought it would be a wonderful thing for me to join Fanm Kreyol.”

Lucas Endicott is the regional director of Course Study at Saint Paul School of

Theology and a longtime researcher of higher education in Haiti. He wrote last year an academic article entitled “Educated for Somewhere Else: Borderlands and Belonging in Caribbean Haiti” where he interviewed nine educational leaders in Haiti who had each received a degree outside of the country.

According to the article, only 2% of the total population in Haiti has received a professional or technical education. However, 81.73% of secondgeneration Haitians in the U.S. attained some college education. The article states this is demonstrating higher education achievement than other immigrant groups.

Endicott discusses in the article how there are more students graduating from secondary school in Haiti than there are spots in universities, with 47% of students in 2009 not gaining a space in Haiti’s public universities.

“It’s pretty amazing how few spaces there are for as many students who want that,” he said. “And so then those students are compelled to do one of three things: either they go someplace else, so they primarily go to the Dominican Republic to college or university there, or they wait for their spots, or they enter a job market.”

The article states students entering directly into the job market are doing so “for better or for worse.” In his research, Endicott found that pursuing higher education outside of Haiti is looked upon favorably.

“One thing that they mentioned was that if you go somewhere else, you get a certain amount of respectability,” Endicott said. “Because now your degree is from France, or from Canada, or wherever it may be, or from Florida Atlantic. And you come back to Haiti, and you’re perceived now as more valuable as when you left.”

15 UNIVERSITY PRESS

“Because our parents didn’t have the opportunities and resources to be as successful as we have in the U.S. We have all these tools, resources to make us great, but in other countries, they don’t have that. So it makes sense why the expectation, why the bar is so high.”

-Jasen Santerre

Members of Fanm Kreyol, Inc., a FAU student organization for Haitian women. Courtesy of Fanm Kreyol, Inc.

IN STUDENT MEDIA MIRRORS NATIONAL TRENDS

Mistrust and feeling misunderstood are some reasons Black students don’t join student media.

Jessica Abramsky | News Editor

Minorities have been underrepresented in the media. The cause of this can be attributed to different reasons: education, lack of opportunity, and even racism.

The University Press decided to look into disparities of diversity in newsrooms and student media at FAU.

National Data in Media

The Associated Press, a major news organization, reported that 76% of its full-time news employees in the U.S. are white, 8% are Latino, 7% are Black, and 6% are Asian; news management staff is 81% white.

An article by Pew Research shows that American adults — Black, Hispanic, and white — feel that the media does not understand them, but for very different reasons.

Pew reports that Black Americans are more likely than Hispanic and white Americans to feel that the media does not understand them due to their race or another demographic trait.

Owl

discuss upcoming events

need

Above: University Press holds its first meeting after the Fall 2022 Student Media Open House.

Below: Owl TV holds their first general meeting of the Spring 2023 semester after the Student Media Open House. Photos by Nicholas Windfelder.

“Among Black adults who think the news media do not understand people like them, about a third (34%) say the main way they are misunderstood is their personal characteristics. This is far higher than the 10% of white adults and 17% of Hispanic adults who say the same,” the article states.

FAU’s Diversity Data Report for 2019-2021 shows that 19.8% of the student population is Black.

Tamia Fowlkes, a National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) student representative, Columbia Journalism School graduate student, and USA Today digital producer, believes that “journalism is all about finding and telling people’s stories and in providing space to offer insight into issues that haven’t been explored before.”

NABJ is an organization that assists Black journalists with their education, internships, and job opportunities.

16 UNIVERSITY PRESS FEATURE:

DIVERSITY

Radio holds a staff meeting to

that

coverage for recaps, music, or headlining. Photo by Nicholas Windfelder.

“We have a student membership program,” Fowlkes said. “I think it’s about $40 to join and that offers students opportunities to apply for scholarships, oftentimes up to like $10,000 to support their academic studies, or other internship opportunities and things like that, but specifically function to serve NABJ students.”

FAU Student Media

The station managers of Owl TV and Owl Radio believe their staffs are more diverse, as the UP currently has two Black editors out of eight.

Pete Gordon, a Black student and Owl TV’s station manager, said the organization has been predominantly Black and Latino since he joined in 2019.

“As FAU is known for its diversity, I don’t think I would get that sense if it wasn’t for Owl TV. The past five station managers, including myself, have been people of color,” Gordon wrote in a statement.

Luke Campese, station manager of Owl Radio, shares that the staff at the station includes an array of different people.

“The staff at Owl Radio is very diverse. Addiel, the director is Latino, the business manager is an international student from Brazil, and our promotions director is Black, as well as our head deejay,” wrote Campese in a statement.

Current UP adviser Wesley Wright is the only Black UP editor-in-chief in the last 25 years. He believes that some students might be skeptical of the media and others don’t feel understood by reporters.

“There’s this distrust between media institutions, and Black Americans more broadly, just because of shoddy journalism over the years and even

Tamara Buck, professor and chair of the Department of Mass Media at Southeast Missouri State University, and former student media adviser, agreed with Wright.

“There are very few students and it’s typically a lack of opportunity that comes around, we persons of color experience when we enter mostly white newsrooms,” Buck said. “But when you enter mostly white newsrooms, you find yourself challenged, in many ways, because your perspective is different as to what is news and your perspective is not always welcomed and understood.”

Buck said when editors do not understand someone’s perspective and opinions, they are forced to constantly explain themselves and why their idea is newsworthy.

“All of those explanations over time can develop frustrations,” Buck stated. “Which will take talent away from your newsroom. It’s something honestly, a lot of white leaders in the newsroom don’t have to experience and so they don’t recognize it. It’s a problem.”

Emily Bloch was Wright’s managing editor and attended FAU from 20122016. She currently works at The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Bloch said Wright was well respected by the staff. She said that Wright made her job easy because staff relations were “calm and amicable” while he was editor-in-chief.

17 UNIVERSITY PRESS

Top: Photo of Hannah Burrell, Editor-in-Chief of The Paradigm Press, a Black student run newspaper at FAU. Photo by Nicholas Windfelder. Left: Kennedy McKinney, founder of The Paradigm Press. Courtesy of McKinney.

“I don’t think we did a perfect job [reporting on diverse issues], but it’s something that we had discussions about, but it was very apparent that over the years, student media’s relationship with underrepresented communities, including the Black student community, was fractured or strained,” Bloch said. “And I think you can see that in some of our coverage. We were working to gain that trust from Black student representation.”

Kennedy McKinney, who graduated in Fall 2022, founded The Paradigm Press in 2020 under the impression that the UP did not adequately represent the Black community.

“I started the Paradigm Press to give a voice to the minority community at FAU,” McKinney wrote. “The paper serves as a place for us to express our concerns and celebrate our accomplishments.”

Hannah Burrell is a Black multimedia journalism major and current editor-in-chief of the Paradigm Press. She said she joined the organization because of her journalism background and being a part of her high school newspaper.

Burrell says that anyone in the FAU community can write stories for the UP or The Paradigm Press, as it is a journalist’s job. However, she says there are differences between the UP and the Paradigm Press.

“The difference is that Paradigm Press and UP have cultural differences in terms of what they want to publish in the press. UP covers general topics at FAU whereas Paradigm Press writes stories that pertain specifically to our culture,” Burrell wrote in a statement. “It is a safe space for minorities — in terms of writing about social and cultural issues within the Black community as well as celebrating our accomplishments in the community and at our school.”

Gordon believes that Black students should join student media organizations because it allows them to make more friends, and for some, it provides a sense of belonging.

Gordon figured he would struggle to make friends in college because he isn’t a “super film nerd,” in comparison to other film majors. He credits Owl TV for allowing him to easily make friends with common interests. He doesn’t think he would still be attending FAU without student media.

“Another reason is that it gives us the chance to tell our stories that other people won’t tell, and it allows us to tell those stories right,” Gordon wrote. “Whether it be highlighting black student organizations and events, or giving light to issues or stories that should be talked about more, joining student media gives us the power to speak on subjects that are often left unspoken on.”

Ways to diversify student media

Buck urges student media leaders to recruit students by going into classrooms, talking to students around campus, critiquing publications, and conducting culturally inclusive discussions and training amongst the staff.

Ryan Lynch is a current reporter at the Orlando Business Journal, and he was a staff writer during Wright’s time in the university. Lynch believes recruiting in classes is very important for student media because it will get more people involved and provide more opinions and ideas in the newsroom. “You can always do better on the recruiting side, and that’s saying just in a general sense, like, [student media leaders] will say ‘Oh, I’ll do a better job recruiting’ but you know, it’s about going into classes and clubs but it can also be a perception,” Lynch said.

Fowlkes agreed, claiming student news organizations many times may not be immediately aware of where they can better their efforts.

18 UNIVERSITY PRESS

Tamia Fowlkes, NABJ representative, Columbia Journalism School graduate student, and USA Today digital producer. Courtesy of Fowlkes.

“Sometimes our biggest blind spots come from being within the same group of people and not always seeing where we’re missing an opportunity to connect with new people, or new groups, or people who might be intimidated by the prospect of joining an organization,” Fowlkes said.

Cameron Priester | Sports Editor

Lot in Pearl City that has already began demolition and reconstruction.

Photo by Cameron Priester.

Cameron Priester | Sports Editor

Lot in Pearl City that has already began demolition and reconstruction.

Photo by Cameron Priester.

Jasmine Die | Copy Desk Chief

Jasmine Die | Copy Desk Chief