Arena3Cover:Layout 1

22/2/12

10:24

Page 1

000 1Intro1:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:31

Page i

000 1Intro1:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:31

Page ii

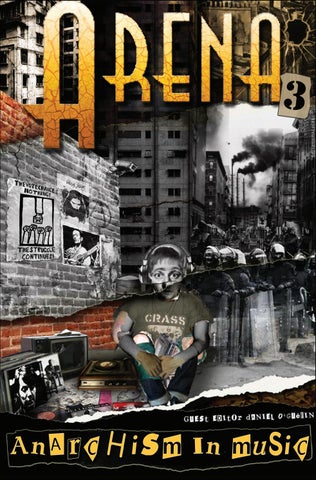

ARENA 3: ANARCHISM IN MUSIC Publisher: ChristieBooks Guest Editor: Daniel O’Guérin Cover: Sean Fitzgerald Copyright © the individual authors First published in the UK in 2012 by ChristieBooks PO Box 35 Hastings, East Sussex, TN34 1ZS ISBN-13: 978-1-873976-51-7

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data: A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. Distributed in the UK by: Central Books 99 Wallis Road London E9 5LN Email: orders@centralbooks.com

000 1Intro1:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:31

Page iii

Guest Edited by Daniel O’Guérin ‘I don’t know anything about music. In my line you don’t have to. ‘ — Elvis Presley ‘State Control and Rock ‘n’ Roll are run by clever men... it’s all good for business, we’re in the charts again.... —Vi Subversa ‘Somebody once said we never know what is enough until we know what's more than enough.’ — Billie Holiday ‘I would like everyone to understand that they can be creators, that they are creators. The context isn't important, it's to help a world to exist, to be born.’ — George Brassens (For Sal, and everyone else raising a voice....)

000 1Intro1:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:31

Page iv

000 1Intro1:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:31

Page v

CONTENTS Introduction 1 Daniel O’Guérin 1 1 Daniel O’Guérin What’s in (A) Song? An Introduction to Libertarian Music? 3 2 David Rovics 45 Busking Memories 23 3 Phil Strongman 45 No Future, Nature Boy 38 4 Petesy Burns 45 The Social Space 44 5 Robb Johnson 125 What I Do 52 6 Norman Nawrocki 45 From Rhythm Activism to Bakunin’s Bum 60 7 Boff Whalley 107 In Defence of Anarchy 71 8 Boff Whalley 143 Anarchism and Music: Theory and Practice 77 9 Penny Rimbaud 95 Falling Off the Edge 83

000 1Intro1:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:31

Page vi

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 1

INTRODUCTION In this third volume of the Arena series we gather around the proverbial camp fire where we might listen to tunes to make our toes tap and to words which might reach into our hearts and pull us into a future of wild possibilities, daring us to dream. These songs of freedom push against convention, sing of finding ways and means to move beyond the confines of staid convention and the litany of war, poverty and misery that are the direct consequence of the edifice of capitalism and those frightened elites who hide cowering behind it. In ancient Rome, after Constantine bent his knee to Christ (or at least saw the convenient propaganda in such a coat of many colours), the music of theatre and of festival dismayed the naysayers of the ascending Christian empire that grew in his wake; the frivolity and joyousness of celebrating life became anathema to the new social order bent on obedience to the will of God and, by divine right, those masters who perpetuated his will. And so they banned it. But in all cultures, despite the engrained social mores, you can discover the life-affirming music that fuels the carnival and the street parade, strips away the dogma and drudgery of life and makes the heart leap. Life should be for celebrating after all, a Mardi-Gras of moments; not a never-ending struggle up a steep dark hill. Music reflects the culture around it and ancient folk musics have melded and moulded themselves accordingly over time into a vast amalgam of expression. Latterly this has become a commodity and where once it was unhindered and organic, it is now shaped and packaged and available from all good participating stores. This is largely a Western phenomena and yet even within these boundaries there are still voices shouting over the walls and strains carried on the breeze and over the barricades of history. Anarchist music is perhaps an ill-fitting term. Robert Fripp, of the rock group King Crimson, who are renowned for their inventive approach to composition, describes Crimson, who consciously avoid accepted (commercial) forms of rock music, as ‘a way of doing things, which is in a sense anarchic’. Much in the same way that advances in other art forms were anarchic, when they broke the rules, such as The Goons or Monty Python who brought comedy kicking and screaming into modern times. It is this same approach which informs the 1

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 2

oON ANARCHIST MUSICn anarchist cinema and video

avant garde, that is to say, unhindered expression. It is this approach which could become the bedrock of a new culture. But form aside, whatever the medium or genre, there are still those voices singing or ranting against what they find wrong in this world of ours — some telling stories of those who tried to find a new world in their hearts, those who were not in the least afraid of ruins (for they knew they could rebuild from the ashes of the old); or those who sing words of encouragement and of defiance and of hope in desperate times; or who applaud the dispossessed and forgotten and celebrate their humanity while rallying against those spit on their misery. And who make us cry, and who make us feel angry, reminding us of what needs to be done - those who can make us laugh at the absurdity of it all, have us dancing in the streets, but who can also make us forget. In these pages, then, a small selection of musicians and lovers tell of their thoughts and experiences in putting across anarchism, not so much as rhetoric or propaganda, but as expressions and reflections; reminiscences of life-journeys outside of the box and even existentialism. These ideas may influence us, they may be enjoyable to experience but it is when we run with them into the streets and fields, when life again becomes the carnival, that we might crack open the cold edifice of what passes for culture and allow a few bright flowers to break through. Daniel O’Guérin, Spring 2012 Daniel O’Guérin is the editor of back2front magazine, a periodical journal which examines, promotes and critiques radical music, arts, politics and culture since 2003. He runs an independent music label and has also contributed to dozens of other publications since the 1980s when he had this daft idea that things could be much better.

2

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 3

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG? An introduction to Libertarian Music by Daniel O'Guérin (Back2Front zine) La Marseillaise was a tune adopted by many radicals due

to its association with the French Revolution of 1789 and would ironically became the national anthem of France. Just as a national anthem can bound a patriotic crowd to lofty, if largely false, ideals and emotions so too can other forms of music from a more honest libertarian perspective. The development of anarchist philosophy in Liberty Leading the People the late 19th century and its consolidation in the anarchist-communism of Kropotkin, Malatesta et al counted many artistic figures among its adherents and sympathisers. All art forms are expressions of human experience after all; signposts of sorts offering perspectives both in and out of context for those who come to appreciate them. Music, of all the arts, is perhaps the most powerful at inspiring a feeling or memory or in putting a statement across. Melody lingers; counterpoint causes pause and awareness while lyrics, particularly those that follow some kind of meter, are easily etched into the memory. In folk tradition music was often a way of celebrating the memory of common people standing up to authority. From the folk traditions of bygone ages to more modern examples such as the Rembetika which came out of the Greek underground at the turn of the 20th century or the hip hop tradition in working class America in the 1980’s we hear examples of class consciousness expressed through song. But Rembetika musicians a more radical tradition had begun to emerge in other times and places where the class war was in earnest. Joe Hill (18791915) was a Swedish-American migrant worker and member of the US syndicalist union the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). In times of high class struggle it was common for the bosses to send in the Salvation Army band to cover up the orations of Wobbly organisers (and to placate the crowd). Hill re-wrote the lyrics of the Salvation band’s Christian hymns so that workers could sing along to his expropriations. Joyce Kornbluh writing about Joe Hill comments: “He articulated the frustrations, hostilities, and humour of the homeless and dispossessed” (1) The IWW soon developed a tradition of folk songs and 3

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 4

ANARCHIST MUSIC

poems that aroused solidarity among workers in struggle or kept their stories alive around the camp fire. Perhaps the most well known tune from the IWW songbook is Solidarity Forever written by Ralph Chaplin in 1915:

Ralph Chaplin

‘Woody’ Guthrie

In our hands is placed a power greater than their hoarded gold, Greater than the might of armies, magnified a thousand-fold. We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old For the union makes us strong. (2)

Hill, along with Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) whose guitar famously had the slogan ‘This Machine Kills Fascists’ adorned along the front are credited as pioneers of the modern radical folk tradition in America. Influenced by traditional Irish folk music and Black Blues, Guthrie’s songbook included over 1000 songs related to tales of conscientious bandits and murdered anarchists (Sacco & Vanzetti); songs of youth and of old age; of woods, rivers and mountains and the distant plains creating a cultural focal point for the popular struggles of the moment. Guthrie and Hill would later influence the likes of Phil Ochs, Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan and the so-called singersongwriter genre which emerged around the Civil Rights Movement and the Anti-Vietnam war protests in mid-late 1960s America. Other early developments in the US included protest songs against the First World War such as Alfred Bryan’s I Didn’t Raise My Boy To Be A Soldier from 1916 while even earlier tunes such as Bread and Roses written by Caroline Kohlsaat and James Openheim at a textiles strike in Massachusetts were taken up by later movements. During the Great Depression folk singers like ‘Aunt’ Molly Jackson who penned The Poor Miner’s Farewell which she sang to striking coal miners in Kentucky in 1932 were potent reflections on an economically-decimated working class: Leaving his children thrown out on the street, Barefoot and ragged and nothing to eat, Mother is jobless, my father is dead, I am a poor orphan, begging for bread. (3)

‘Aunt’ Molly Jackson

4

A few years later in 1937 the Orson Welles-directed musical The Cradle Will Rock which depicted labour organisation against a backdrop of such corruption and greed was immediately shut down lest it encourage social unrest. (Welles and his team were locked out of the theatre and blockaded by armed

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 5

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

servicemen under orders from the federal government). A lyric from the musical goes: Well, you can’t climb down and you can’t sit still. That’s a storm that’s gonna last until the final wind blows, and when the wind blows...(4)

Of course throughout the early 20th century music began to change rapidly through cultural displacement and the merging of styles, while the influence of the romantic tradition led to more emotional forms of expression. The development of the phonograph and the gramophone and later the introduction of radio by 1906 did much to spread music, though the industry that grew up around it was (and remains) more concerned with commercial viability than artistic merit (and much to the chagrin of the latter). The performance of music had also become increasingly visual with the rise in popular cinema while music halls and show bands continued to be significant. We know that while many genres began to develop from the turn of the century; the blues and jazz scenes had their own radical traditions which lamented the conditions of workers but often tinged with hope. In these lyrics blues singer Lead Belly spoke for many: Some white folk in Washington, they know just how, call a colored man a nigger just to see him bow The home of the Brave, The land of the Free I don’t wanna be mistreated by no bourgeoisie. (5) ‘Lead Belly’

It is the merging of these various genres - blues, jazz, country and the various folk traditions that landed with US immigrants and other huddled masses that gave birth to rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s. Several people have commented that rock ‘n’ roll has had more cultural influence than anarchist philosophy though the comparison is both unfair and erroneous. While rock ‘n’ roll was challenging the sexual boundaries and social mores of the times it would eventually become subsumed within capitalism as its wider marketability and exploitation became apparent. The protest song was rarely heard within this new commercial medium as the commodification of teenage angst was initially slow to became a viable niche market, and only later the cornerstone of the 5

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 6

ANARCHIST MUSIC

business. But the folk/protest tradition, while also an entertainment per se, served as a genuine reminder of the economic reality of those workers who played, sang and listened, as well as a continual call to arms. As Ayerman and Jamison have commented: There is more to music and movements than can be captured within a functional perspective... which focuses on the use made of music within already-existing movements. Music, and song, we suggest, can maintain a movement even when it no longer has a visible presence in the form of organizations, leaders, and demonstrations, and can be a vital force in preparing the emergence of a new movement. Here the role and place of music needs to be interpreted through a broader framework in which tradition and ritual are understood as processes of identity and identification, as encoded and embodied forms of collective meaning and memory. (6)

Rock ‘n’ roll brought with it another perspective however - it offered a vague ‘freedom’ from 40 years in the field or on the factory floor and young people especially where drawn to the notion; increasingly terrified by the alternative prospect of wage slavery and toiling to make ends meet as their parents had done. Many young people fantasised about the life of the rock star and the ‘freedom’ it appeared to emulate while others were quick to capitalize on their dreams. The 1960s especially saw new and sometimes fresher perspectives on sex, drugs and libertarian ideas. But the threat of nuclear war, the debacle in Viet Nam and other social concerns provided materials for protest songs to draw upon within this commercial medium. A good example of the feeling of the times is from British rock band The Who: We’ll be fighting in the streets With our children at our feet And the morals that they worship will be gone And the men who spurred us on Sit in judgment of all wrong They decide and the shotgun sings the song I’ll tip my hat to the new constitution Take a bow for the new revolution Smile and grin at the change all around me Pick up my guitar and play Just like yesterday And I’ll get on my knees and pray We don’t get fooled again Don’t get fooled again Meet the new boss, same as the old boss... (7)

6

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 7

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

As rock music developed, however, it became more egocentric and commercialised as screaming fans attended huge arenas for a glimpse of the star, while any revolutionary tendencies became increasingly exploited, marketed and ultimately moribund. In other countries and traditions a similar development can be traced however we also begin to see a more explicitly anarchist outlook. In Italy radical poet Pietro Gori (1865-1911) penned several well known anarchist tunes such as Addio a Lugano Bella (“Farewell to Lugano”) and Stornelli d’esilio (“Exile Songs”). In 1887 Gori was arrested for his comments on the Haymarket Massacre when persons unknown threw a bomb at cops trying to break up striking workers (four were subsequently executed even though the prosecution conceded they had not thrown the bomb!) In France Léo Ferré (1916-1993) and Georges Brassens (1921-1981) were Chancon singers who broke free from traditional song structures and fused ideas of love, melancholy and moral anarchy with street slang and monologue. Brassens performed such cabarets ‘to prostitutes, delinquents and other disinherited since 1952’. Ferré was later involved with Radio Libertaire, an anarchist free radio station in Paris while Brassens was editor of the anarchist weekly Le Monde Libertaire in the 1950s and also a member of the Anarchist Federation. Reflecting on the events in Spain in the 1930s Ferré wrote “Les Anarchistes“.

Pietro Gori

Georges Brassens

The anarchists. They have a black flag at half-mast on melancholy hope that they drag through life, some knives to cut the bread of friendship, and some rusted weapons so they do not forget. (8)

Spain itself had developed a healthy tradition of anarchist music. The more autonomous regions such as Andalucía or the Basque country have long folk traditions with political themes, which in turn have been exported to Latin America. Perhaps the most famous song from the 1936-39 revolutionary period is “A Las Barricadas” (To the Barricades):

Léo Ferré

Black storms shake the sky Black clouds blind us Although death and pain await us Against the enemy we must go The most precious good is freedom And we have to defend it With courage and faith

7

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 8

ANARCHIST MUSIC Raise the revolutionary flag Moving us forward with unstoppable triumph Working people march onwards to the battle We have to smash the reaction To the Barricades To the Barricades For the triumph of the Confederation (9)

The anthem of the Spanish Mujeres Libres written by Lucía Sánchez Saornil in 1937 was a powerful statement for feminism at the time:

Lucia Sanchez Saornil

Fists upraised, women of Iberia towards horizons pregnant with light on paths afire feet on the ground face to the blue sky. Affirming the promise of life we defy tradition we mold the warm clay of a new world born of pain. (10)

In Latin America itself Rafael Uzcategui has written of the tradition which evolved there:

Rafael Uzcategui

8

Cappelletti — one of the historians of Latin-America’s libertarian ideals — asserts that anarchism has a wide tradition in our continent, rich in pacifist and violent struggles, manifestations of individual and collective heroism, in feats of organization, in oral, written and practical propaganda, literary works, stage, pedagogic, cooperative and community experiments. Its decadence — after the main role libertarians played between 1870 and 1930 — is attributed to three causes: The series of coup-d’états occurred around the ‘30s and the repression following each of them; the foundation of the Communist parties, that, thanks to the support of the Soviet Union, received material strength and a prestige lacking in the libertarian organizations and in third place, the apparition of national-populist currents, more or less linked to the armed forces. The anarcho-syndicalist groups developed a vast cultural work directed to the peasant and labour majorities during the first years of the 20th century. Soon after, the proclamations of newspapers and books were taken to the stage, to the plastic arts or turned into poems. In Argentina, libertarian “payadores” were the chroniclers and heralds of the agrarian struggles in the southern cone. Likewise, composers of tangos and milongas were activists of the ideal and immortalized the memory of successful labor struggles or of the consequences of bloody government repressions. In Mexico, Corridos, Zapatistas and Magonistas gave popular expression to demands for land, liberty and other demands of clear anarchist vein. (11)

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 9

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

In Italy during the Second World War anarchists sang of leaving their homes to avoid conscription, a song that had been written many years before, and this is an example of how such songs maintain and reinvigorate the tradition as Uzcategui suggests above. Farewell beautiful Lugano my sweet land, driven away guiltlessly the anarchists are leaving, and they set off singing with hope in their heart. It is for you exploited for you workers that we are handcuffed just like criminals. Yet our ideal is but an ideal of love. Anonymous comrades friends who remain the social truths do spread like strong people. This is the revenge that we ask of you. And you who drive us away with an infamous lie, you bourgeois republic will be ashamed one day. Today we accuse you in the face of the future. Ceaselessly banished we will go from land to land promoting peace and declaring war, peace among the oppressed war to the oppressors. (12)

In Makhnovist Ukraine between 1919-21 the anarchist insurgents of the Black Army also spread their propaganda against the Bolshevik deceit by song: Makhnovshchina, Makhnovshchina Your flags are black in the wind They are black with our pain They are red with our blood By the mountains and plains in the snow and in the wind across the whole Ukraine our partisans arise In the Spring Lenin’s treaties delivered the Ukraine to the Germans

9

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 10

ANARCHIST MUSIC In the Fall the Makhnovshchina threw them into the wind Denikin’s White army entered the Ukraine singing but soon the Makhnovshchina scattered them in the wind. (13)

Meanwhile the song Brüder, zur Sonne, zur Freiheit composed by Leonid Petrowitsch Radin had been a popular tune during the 1905 and 1917 Russian Revolutions. The German musician Herman Scherchen learnt the track while a Russian POW during the First World War, translated it into his native tongue and took it to Germany where it became an anthem for the German workers movement. Brothers, to the sun, to the freedom, Brothers get up to the light. Brightly out of the dark past, the future is shining through.(14)

This example shows the ability of music to break through international barriers and how songs written many years ago and still have an influence on future generations. Of course it wasn’t only song that presented revolutionary ideals. Instrumental music has also played a part. We note in passing composers such as Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978) whose 1954 ballet Spartacus is concerned with slaves rising against their masters. Benjamin Britten’s (1913-1976) War Requiem from 1962 examined the futility of war using texts by Wilfred Owen while Luigi Nono (1924-1990) and Hans Werner Henze (b. 1926) both wrote a variety of works that combined music with texts, theatre, and electronics relating to political issues viewed from a revolutionary Marxist perspective. The first explicitly anarchist composer however is perhaps John Cage (1912-1992). Richard Kostelanetz comments:

John Cage

In surveying his work in music and theater, in poetry and visual art, I have noticed that the American John Cage favored a structure that is nonfocused, nonhierarchic and nonlinear, which is to say that his works in various media consist of collections of elements presented without climax and without definite beginnings and ends. This is less a negative structure, even though I am describing it negatively, than a visionary esthetic and political alternative. In creating artistic models of diffusion and freedom, Cage is a libertarian anarchist. (15)

10

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 11

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

Cage himself confirmed his position: “I’m an anarchist. I don’t know whether the adjective is pure and simple, or philosophical, or what, but I don’t like government! And I don’t like institutions! And I don’t have any confidence even in ‘good’ institutions”. The Anarchic Harmony Foundation was established after Cage’s death in 1992 on the notion that “anarchic harmony is one arrived at through social situations that de-emphasize leadership and encourage voluntary cooperation between individuals and groups.” (16) The avant garde tradition itself has long had radical concerns and is tasked with the pushing of boundaries, especially political, within a particular idiom. However English composer Cornelius Cardew (1936-81), who himself argued for a “politically motivated peoples liberation music”, has argued that the often inaccessible atonal music of the avant-garde movement merely served to exacerbate the fragmentation of society rather than bringing the masses together. Returning to popular music we can comment on the differences between the more radical folk traditions and the commercial music industry which would occasionally amalgamate some aspects of the folk genre but only if it was commercially viable to do so. This is not to berate the artistic merits or entertainment value of popular commercial artists but to illustrate the influence of capitalism upon the music itself. The advent of rock ‘n’ roll brought several more adventurous bands to the fore. The Beatles, for example, brought songwriting back into vogue where it had previously been common practice for an artist to sing standards written by a professional song-writer. Corporations like Thorn-EMI were able to put their financial muscle behind bands like the Beatles while leaving others, as good if not better, out in the cold. Using tight legal contracts the Music Industry was able to dictate how a band should look, and ultimately how it should sound. Lyrics deemed to ‘rock the boat’ were often compromised and in this way artistic expression was effectively curtailed. The influence of large sums of money consequently affected an artist’s output in other ways. The bigger they were, the less effort they seemed to make and very few artists within the commercial vein have been consistently interesting. In 11

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 12

ANARCHIST MUSIC

Hawkwind

12

some instances the more famous an artist became, the bigger and more outlandish performances that ensued, while tales of wrecked hotel rooms and excess were common among the spoiled brats of the industry. We might note so-called radical bands like the Rolling Stones whose stars can be seen at the opera with politicians and bureaucrats. (Indeed in passing we might comment on the saccharine activity of self appointed martyrs like St Bono or Archbishop Geldof whose attempts to throw money at the poor merely cover up the reasons for why that poverty exists in the first place). The industry itself had begun to target specific audiences especially since the 1960s and used a developing music press to invent a rock terminology that when stripped of bullshit merely created genres within genres to establish specific marketing demographics for considered exploitation. Styles of dress and assorted brands became associated with particular genres as rock music became more and more excessive and hedonistic. By the 1970s however with stadium rock music the norm, bands played to huge crowds who could barely see their heroes creating a huge distance between the performer and the crowd, physically and culturally, creating false hierarchies and fake mythologies. Rock music had become elitist and snobbish. In the UK however the Free Festival movement, which had developed from the 1960s counterculture, advocated a non-commercial avenue for rock music. Bands such as Hawkwind and Here & Now often played free to audiences or offered their services to assorted benefits. The 1970 Isle of Wight festival, England’s answer to Woodstock in America, saw bands like Hawkwind set up outside the commercial event to play for free. (While never explicitly anarchist Hawkwind has contained several anarchists such as Robert Calvert and Michael Moorcock). In the late 1970s groups such as Henry Cow began the Rock In Opposition movement, ostensibly a statement against the exploitation of the music business. During the mid-1970s in Britain, however, there was a much bigger kick-back against the music industry with the appearance of punk rock. Malcolm McLaren, who’d been involved with the situationist group King Mob in London, introduced the Sex Pistols to the world and caused a bit of a stir.(17) Such was the beginning of the Punk explosion - torn clothes, spiked or coloured hair and bad attitude caused an

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 13

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

initial furore as the new youth cult expressed its disgust at society; but punk rockers originally dressed for shock value and adopted imagery accordingly and thus the circled ‘A’ appeared alongside the swastika in a movement that was largely bereft of any real political meaning. In an essay White Punks on Bordiga published in 1995 in Organise #35 the author comments: How can content be dissolved into form? Well, punk, to me and many people, expressed anger, boredom, restlessness and a sickness of society and conformity - the clever trick is that the music is also characterised by its angry, restless, and nonconformist ‘form’. Lyrical content was either blasted out of existence by screaming rants, crashing drums, and thrashing guitars or twisted to poetic extremes as a protest against the stale lyrics of 1970’s love ballads and disco trash tunes (e.g. Buzzcocks and their cynical anti-love songs, or Joy Division and their gloomy soul dredging excursions). But punk was mainly angry, and anger characterised its form - this tradition continues to date, and for the record companies it is often the case of the angrier the better. The harsher the subject that forms the kernel of the lyrics (fascism, smack, prisons, state control, environmental rape) the more angry the lyrics, the more angry the accompanying form, the more the record becomes a ‘punk’ record, the more it sells to the punk market, the happier the record company. (18)

Punk was a virus that caught on quickly as both another exploitable fashion and latterly a political philosophy that identified with anarchism. The Clash, a much more incendiary band than the Pistols, had more of an inclination to social commentary. Although marketed by the CBS record company as the last gang in town and quickly becoming huge, front man Joe Strummer attempted to amalgamate radical politics with being a rock star, a contradiction that could never work. Called sell-outs for signing with the huge CBS company Strummer was nonetheless an influential and enigmatic spokesman for the disaffected youth of Britain. If you didn’t like The Clash, Strummer suggested, then form your own band! One person who took this idea to heart was Steve Thompson who changed his name, as was the trend of the day, to Steve Ignorant and together with avant garde poet Penny Rimbaud, who had been instrumental in the earlier free festival movement, founded the band CRASS. Although often overlooked by music historians who base their work on commercially successful artists the influence of CRASS was

The Clash

Steve Ignorant

CRASS — Feeding of the 5000

13

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 14

ANARCHIST MUSIC

Penny Rimbaud

massive in several ways. Initially they used the anarchy sign as a means of keeping both Left and Right political groups from adopting them as radical mascots, wanting nothing to do with either dogma yet from the outset they decided to take their politics very seriously. While many rock stars attempted to put over a radical message their ideas were often watered down by their celebrity or by the machinations of their record company. CRASS wanted none of it. In terms of anarchism, and the anarchist tradition, the individuals that formed the band/collective Crass knew where they were coming from. They envisaged punk as a useful vehicle for propaganda (taking the already established music form and adding visual and sound bytes), the propaganda being the broadening of an understanding and appreciation of anarchism. Crass carried on the punk tradition of anger and honed the lyrics down to sharp comments and questions on everyday life and the class struggle - at first assuming that listeners to punk music paid attention to the lyrics. Crass also made new ground in pulling together the elements that were being fostered - thus we saw the rise of cheap benefit gigs with no private organisers, the building of anarchist centres and prisoner support. They also began to consider the packaging of their records, using fold out sheets of montage, statements, essays and essential contact listings. (19)

They established their own label in 1978 and priced their albums at half the going rate which caused a stir, though the Clash were the first to attempt price restrictions. This was a clear and direct statement against the rock industry and an attempt to minimise the influence of capitalism on art. Young people were also attracted to the powerful artwork, by Gee Vaucher, and many of the CRASS records came with inserts and literature presenting various campaigns and dissemination of radical ideas. The CRASS philosophy was There Is No Authority But Yourself and DiY culture was subsequently encouraged and not just in the realm of music, but across communities. The first CRASS record was hugely successful and moreso for the fact that it’s shocking lyrics against church and state were meant from the heart: You’re paying for prisons. You’re paying for war. You’re paying for lobotomies. You’re paying for law. You’re paying for their order. You’re paying for their murder. Paying for your ticket To watch the farce.

14

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 15

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG? Knowing you’ve made your contribution To the systems fucked solution, To their political pollution. No chance of revolution. No chance of change. You’ve got no range. CRASS

Don’t just take it. Don’t take their shit. Don’t’ play their game. Don’t take their blame. USE YOUR OWN HEAD. Your turn instead. It’s not apologise. It’s not economise. It’s not make do. It’s not pull through. It’s not take it. It’s not make it. It’s not just you. It’s not madmen. It’s not difficult. It’s not behave. It’s not, oh well, just this once. It’s fucking impossible. It’s fucking unbearable. It’s fucking stupid. FUCKING STUPID (20)

CRASS began to use their notoriety to raise funds for numerous causes and to help other bands get a start. They funded a small group called GREENPEACE who would later become much bigger and reinvigorated CND who later distanced themselves, but they also caused a surge of interest in anarchism - taking it ‘out of the dusty bookshops’. They began a cottage industry from their collective space, an old farmstead called Dial House in the Essex countryside, which Rimbaud had occupied in the late 60s and run as a ‘free house’. By limiting their contact with the music press, who had often ridiculed them, they gave most of their interviews to fanzines, which in turn caused a revival in self-publication and printing. Hundreds of bands and fanzine writers sprung up as consequence throughout the UK, creating counter-cultural hubs which in turn began to organise within their communities in different ways. The music industry had latched onto punk very quickly and ‘designer rebellion and well-rehearsed anger’ were easily exploited. Punk had merely been a passing fashion yet the anarchist-punk milieu was its own beast. The bands that began to express themselves in such ways were often put down by the music press if they featured at all. CRASS themselves were 15

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 16

ANARCHIST MUSIC

debated in the House of Lords and accused of obscenity but it was their alignment with the ‘Persons Unknown’ trial in 1980 that brought them wider political attention. The trial at the Old Bailey was at the time the longest criminal trial in history and was in fact a conspiracy against anarchists in which ‘persons unknown’ were accused of ‘conspiring to cause explosions’ and, by implication, overthrow the State in a re-run of the Angry Brigade. After acquittal Ronan Bennett, one of the defendants, planned to establish an anarchist centre and with financial backing from CRASS and anarcha-feminist band Poison Girls the Autonomy Centre opened in Wapping in 1981. The short-lived centre was to close due to breaking the terms of the lease though they later adopted the Centro Iberico in Harrow Road, an old school house that had been squatted by Spanish anarchist refugees. These venues in combination with the rural free festival and traveller movement were signs of a new and far more militant counter culture. CRASS were soon being courted by everyone from the IRA to the KGB ( a prank by the band had been to create a conversation between Thatcher and Reagan and slip the tape to the media which resulted in the US authorities accusing the KGB before the truth came out) while the groups pacifist philosophy was summed up in the track “Bloody Revolutions” which appeared in Freedom at the time (21): You talk about revolution, well, that’s fine But what are you going to be doing come the time? Are you going to be the big man with the Tommy-gun? Will you talk of freedom when the blood begins to run? Well, freedom has no value if violence is the price Don’t want your revolution, I want anarchy and peace You talk of overthrowing power with violence as your tool You speak of liberation and when the people rule Well ain’t it people rule right now, what difference would there be? Just another set of bigots with their rifle-sights on me But what about those people who don’t want your new restrictions? Those that disagree with you and have their own convictions? You say they’ve got it wrong because they don’t agree with you So when the revolution comes you’ll have to run them through You say that revolution will bring freedom for us all Well freedom just ain’t freedom when your back’s against the wall You talk of overthrowing power with violence as your tool

16

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 17

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG? You speak of liberation and when the people rule Well ain’t it people rule right now, what difference would there be? Just another set of bigots with their rifle-sights on me Will you indoctrinate the masses to serve your new regime? And simply do away with those whose views are too extreme? Transportation details could be left to British rail Where Zyklon B succeeded, North Sea Gas will fail It’s just the same old story of man destroying man We’ve got to look for other answers to the problems of this land You talk of overthrowing power with violence as your tool You speak of liberation and when the people rule Well ain’t it people rule right now, what difference would there be? Just another set of bigots with their rifle-sights on me Vive la revolution, people of the world unite Stand up men of courage, it’s your job to fight It all seems very easy, this revolution game But when you start to really play things won’t be quite the same Your intellectual theories on how it’s going to be Don’t seem to take into account the true reality Cos the truth of what you’re saying, as you sit there sipping beer Is pain and death and suffering, but of course you wouldn’t care You’re far too much of a man for that, if Mao did it so can you What’s the freedom of us all against the suffering of the few? That’s the kind of self-deception that killed ten million Jews Just the same false logic that all power-mongers use So don’t think you can fool me with your political tricks Political right, political left, you can keep your politics Government is government and all government is force Left or right, right or left, it takes the same old course Oppression and restriction, regulation, rule and law The seizure of that power is all your revolution’s for You romanticise your heroes, quote from Marx and Mao Well their ideas of freedom are just oppression now Nothing changed for all the death, that their ideas created It’s just the same fascistic games, but the rules aren’t clearly stated Nothing’s really different cos all government’s the same They can call it freedom, but slavery is the game Nothing changed for all the death, that their ideas created It’s just the same fascistic games, but the rules aren’t clearly stated Nothing’s really different cos all government’s the same They can call it freedom, but slavery is the game There’s nothing that you offer but a dream of last year’s hero The truth of revolution, brother................... is year zero. (21)

The anarchist-pacifist stance of Crass was not everyone’s cup of tea however and so more militant groups began to appear 17

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 18

ANARCHIST MUSIC

such as Conflict and Chumbawamba while many of the bands who came from the Crass camp were often poor imitations. This was all too apparent in vague lifestylist notions of what anarchism meant and in the contradictory politics of negation which made up most of the lyrics. There was debate at this stage between the emerging anarchist punk philosophy and traditional class struggle anarchists.

Ian Bone of anarchist punk band the Living Legends, who founded the newspaper Class War discusses the influence of Crass: Crass had found a way o f getting anarchist political ideas through to tens of thousands of youngsters. From the plastic A’s of Rotten’s ‘Anarchy in the UK’, Crass gave the circled A real political meaning. They had created an embryonic political movement. They’d reached punters in towns, villages and estates that no other anarchist messages could ever hope to reach. But what were they going to do with it? People were fighting back but Crass were s till telling them to turn the other cheek. They’d achieved something much bigger than I previously recognised but their influence had become reactionary. The time w as right to produce a paper aimed at the Crass anarcho-punks and soon after the first (Class War) paper hit the streets. (22)

Perhaps the most significant development which comes from the period was the Stop the City demonstrations in London in 1983 and 1984 organised by the anarchist group London Greenpeace and heavily promoted by CRASS which caused millions in damages, according to The Times, and became a precursor for the Reclaim the Streets and J18 movements and the later and international anti-G8 demonstrations. Throughout these times the anarchist-punk groups despite their unresolved political arguments and counter-arguments helped to fund many ongoing radical activities. CRASS played their last gig for striking miners in Aberdare, Wales in 1984. To some extent they felt they’d done all they could within the particular medium of punk. The influence of Crass should not be underestimated. Many others began to adopt some of their philosophies and set up in their wake across the UK and spreading to Europe, the US and beyond. The US punk scene had developed its own punk hybrid known as hardcore. In American cities and small towns hardcore scenes grew up around certain bands and 18

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 19

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

publications who had begun to tour, or print information about what was going on, but again it was another youth subculture concerned with vague tribal identity and it was bands like Dead Kennedys, Millions of Dead Cops and Canada’s D.O.A. who created a more anarchist leaning. Dead Kennedys’ front man Jello Biafra interviewed in the Anarchism in America documentary states: “Anarchy begins with the mind and American minds for generations have been programmed in the opposite direction.” (23) An example is given in these lyrics to the Dead Kennedys track Moral Majority:

Dead Kennedys

You call yourself the moral majority We call ourselves the people in the real world Trying to rub us out, but we’re going to survive God must be dead if you’re alive You say, ‘god loves you. come and buy the good news’ Then you buy the president and swimming pools If Jesus don’t save ‘til we’re lining your pockets God must be dead if you’re alive Circus-tent con-men and southern belle bunnies Milk your emotions then they steal your money It’s the new dark ages with the fascists toting bibles Cheap nostalgia for the Salem witch trials Stodgy ayatollahs in their double-knit ties Burn lots of books so they can feed you their lies Masturbating with a flag and a bible God must be dead if you’re alive (24)

Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, DOA and others toured small American towns and brought their ideas into rural backwaters creating a radical backdrop for many young people in the process. So it was the anarchist punk movement developed all over the world. It continues to play a role introducing many young people to libertarian ideas but in consequence it is a doubleedged sword. More often than not the anarchism espoused by punk bands was one of individualism. Bob Dylan has written that he stopped creating overtly political songs because he felt they had become a safety net. People merely identified with the message and bought the record or went to the gig as if this was somehow going to 19

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 20

ANARCHIST MUSIC

David Rovics

arrest the problems discussed in the lyrics. In punk rock small communities with conflicting ideas espoused lifestylist politics such as vegetarianism and consumer boycotts without seeming to grasp the implications of the wider class struggle. In consequence some see punk as a distraction from the work that really needs to be done. Although many of the original anarcho-punk bands no longer exist many of their individual members continue to put forward the Idea while others such as Oi Polloi, MDC and the Subhumans are still going to this day, and the movement is international. But while punk has latterly been the genre most associated with anarchism it is not the only one. The folk tradition has continued and will continue to carry the thoughts and deeds of those gone before across the centuries. Artists such as David Rovics and Utah Phillips (1935-2008) and bands like Chumbawamba have carried on a largely acoustic rendition of anarchist folk tales. In the UK in the late 80s and early 90s the rave/techno scene, itself inspired by the anarcho-punk movement, brought a green anarchist/ecological vision to the fore through illegal raves and parties in warehouses and secluded rural hideouts. In turn the State brought in the Criminal Justice Bill in 1994 shocked at the idea that people may actually be celebrating without paying for it, in an attempt to crush the movement. The punk ethic, rather than the style of music, has had a considerable influence on wider musical culture with politicised bands like Rage Against the Machine or System of a Down, and even in hip hop culture with bands like Consolidated, techno bands like Germany’s explicitly anarchist Atari Teenage Riot or the unclassifiable Negativland who’s ABC of Anarchism includes readings from Alexander Berkman. Of course outside of this there is an ongoing folk tradition which has always formed the bedrock of the protest song. The Zapatista movement, which created an autonomous peasant zone in Chiapas, Mexico have developed their own anthem: Our people demand an end To exploitation, now! Our hander istory says... now! To the struggle for freedom.

This brief essay is merely an introduction into the relationship of anarchist and libertarian ideas with music; there is so much territory to cover and so many stories to tell that we might 20

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 21

WHAT’S IN (A) SONG?

only glance at a few examples along the way. I have indicated the influence of the corporate music industry and its exploitation of the protest song, and touched upon a few critiques. Central to these critiques is that political rock music can provide a form of escapism which provides a safety net that can detract from actual mobilisation. Folk music is the more genuine idiom, it is older and far less contrived, yet within this narrative we are here to celebrate the diversity and passion of radical expression, the influence it has brought to bear and the constant reminder of the need to work together to overcome our oppressors. Let the chorus soar. Notes 1. 0Kornbluh, Joyce L., Rebel Voices: An I.W.W. Anthology, University of Michigan Press, 1964 2. 0Lyrics from Solidarity Forever, composed by Ralph Chaplin, 1915 3. 0Lyrics from The Poor Miner’s Farewell, composed by Molly Jackson, 1932. See also Archie Green, Only a Miner: Studies In Recorded Coal-Mining Songs, Urbana, IL, 1972 4. 0Lyrics from the libretto for The Cradle Will Rock composed by Mark Blitzstein, 1937 5. 0Lyrics from The Bourgeois Blues, composed by Leadbelly (Huddie Ledbetter), 1937 6. 0Ron Ayerman and Andrew Jamison, Music and Social Movements, Mobilizing Traditions in the 20th Century, Cambridge Cultural Social Studies, 1998 7. 0Lyrics from Won’t Get Fooled Again, composed by Pete Townshend, 1971 8. 0Lyrics from Les Anarchistes, composed by Léo Ferré, 1966 (translation by Caleb Smith) 9. 0Lyrics from A Las Barricades translated by Ilsa Barrea and Rachel Voland ,1998 10. Lyrics from the Anthem of Mujures Libres, composed by Lucia Sanchez Saornil Valencia, 1937 11. Rafael Uzcategui, The Tradition of Libertarian Singers, See online http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/anarchism/songs.html (also a major source for this essay) 12. Lyrics from Addio A Lugano, composed by Pietro Gori, 1898 (translated by Davide Turcato) 13. Lyrics from La Makhnovtchina, author unknown. See online http://perso.club-internet.fr/ytak/ (translated by Dan Clore) 14. Lyrics from Brüder, zur Sonne, zur Freiheit, composed by 21

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 22

ANARCHIST MUSIC

Leonid Petrowitsch Radin (Translation from the German by Jan Hoesemans) 15. Richard Kostelanetz The Anarchist Art of John Cage, 1993. See online: http://www.sterneck.net/john-cage/kostelanetz/index.php http://www.anarchicharmony.org/

16. The Anarchic Harmony Foundation. See online: 17. McLaren died in 2010 and his last words were “Free Leonard Peltier”. Peltier was the Native American activist framed for his political outlook by the authorities in 1977 still in custody. 18. See the essay White Punks on Bordiga along with several other articles on the anarcho-punk movement from a critical perspective at: http://www.uncarved.org/music/apunk/ 19. ibid 20. Lyrics from You Pay by CRASS, 1978 21. Lyrics from Bloody Revolutions by CRASS, 1980 22. Ian Bone Bash the Rich, True Life Confessions of an Anarchist in the UK, 2006 23. Joel Sucher & Steven Fischler Anarchism in America, documentary, 1983. Also contains interviews with Murray Bookchin and Paul Avrich. A sequel is apparently in production. 24. Lyrics from Moral Majority by Dead Kennedys from the album In God We Trust, Inc

CLASS WAR CD OUT NOW Ian Bone has recorded some new material with Andy Martin and ‘UNIT’, including the new track ‘FUCK OFF GORDON BROWN’, a 7.5 minute reading of ‘TO TRAMPS’ by Lucy Parsons and Durrutti’s famous ‘ We are not in the least afraid of ruins’ speech, plus a reading of the Mansfield miners rally from Bash The Rich. UNIT added another 13 new tracks of their own and the entire LIVING LEGENDS back catalogue (21 tracks from Swansea, Cardiff and Bristol) PLUS the CLASS WAR single Better Dead than Wed featuring the dulcet tones of Martin Wright. This makes for a wopping double CD of 42 tracks in all including such faves as TORY FUNERALS and THE POPE IS A DOPE. The CD, entitled CLASS WAR featuring UNIT and THE LIVING LEGENDS. can be had for a cheapo tenner from Andy Martin at: UNIT HQ PO BOX 45885 LONDON E11 LUW unitunited@yahoo.com

22

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 23

BUSKING MEMORIES David Rovics, anarchist and Wobbly, is a political singersongwriter who travels the world raising political and social consciousness, and making incisive social commentary wherever he performs. As David explains, he began his career busking in Seattle. by David Rovics ‘In that Wobbly tradition of sharp social commentary, David is a master.’ —The Industrial Worker ‘Listen to David Rovics.’ — Pete Seeger ‘New York-born Rovics is a folk protest musician for the modern day. With songs titles like Who Would Jesus Bomb? and Lebanon 2006, he’s not out to replicate the poetic undercurrent of Blowin’ in the Wind like Dylan...’ —Time Out

David Rovics by André Lyagen

Some recent experiences over the past few months have brought me back to my youth, or at least my young-adulthood, much of which I spent as a professional street musician. For many, busking is a marginal profession at best. For others, it’s a good living. These days there are large parts of the world, particularly in the US and Canada, where you can travel for hundreds of miles without seeing a busker. In much of the world, though, and in some parts of North America as well, the buskers are an active subculture that anyone who uses mass transit or frequents pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods has daily contact with in one form or another. Ever since anybody has been paid to play music, there have been buskers. In other words, it is a tradition that goes back at least as far as the first market town. And as sure as busking is as old as civilization, it has also always been the number one profession of travelers of many kinds, and of the newest migrants to any place, along with other forms of day labour. Although the tradition is old and has a timeless quality to it, it’s also profoundly influenced by things like laws, urban planning (or lack thereof), and the state of popular culture (that is, Clearchannel, Sony, Time-Warner, etc.). From the time I was in my late teens I guess I was pretty sure I wanted to be a professional musician. I tried my hand at busking in various cities as a youthful vagabond, but for years it was only an occasional preoccupation that only supplied me with a very supplemental income in terms of what I needed to come up with every month in the perennial effort to keep a roof over my head and food in my belly. In my early busking 23

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:46

Page 24

ANARCHIST MUSIC

efforts I don’t think I ever made much more than $4 an hour on average, and I could make three times that much money doing temp jobs for Kelly Services and the like. Back then, in the 1980s, someone who could touch-type and knew how to use a primitive word processing program was in high demand. I could (and did) live somewhere for a few months just to check it out, knowing I had a skill that could keep me more or less gainfully employed in any major city or college town. By the early Nineties, though, I developed an unmistakably nasty case of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, and typing for a living was no longer a viable option unless I were just resigned to the problem getting worse, which I wasn’t. I stopped typing for a living and never looked back. Faced with the need to make a living doing something else, I started busking again. I also took a couple jobs in cafes, but it became clear that I could make just as much money per hour busking, so I never worked the cafe jobs more than on a very part-time basis. I quickly discovered that there were ways I could make quite a bit more money busking. But I never intended to be a professional busker — I wanted to be a professional musician, making a living performing mostly original material, or at least covers of really obscure leftwing artists. I knew this kind of material wasn’t ideal busking material, unless you're busking near a protest or something, but I didn’t care. I had a plan, and busking was to be part of it. The plan was to become a really good musician, and then to become a really good songwriter. I viscerally recognized the truth in the advice I had received somehow or other from Utah Phillips, I believe it was — that in order to be a good writer of any kind, you first had to steep yourself in the tradition. Whatever tradition you're into, you have to have it in your blood. At the Pike Place Market in Seattle there was a young woman one day handing out fliers about what it meant to be a bard. It said a bard needed to be able to make up a song on any subject on the spot, and a bard should have at least three hundred songs memorized at any given time. I never worked too hard at on-the-spot songwriting — although one of Pike Place Market’s regular buskers, Jim Page, was and is a master at that art — but I thought memorising three hundred songs seemed like a good plan. Although I had lost the worker’s comp claim against my former employer due to a new law passed by the state of 24

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:46

Page 25

Busking Memories

Massachusetts under the Republican governor at the time that said any worker’s comp claims had to be approved by the employer of the injured worker, thereby making most claims by folks like me completely pointless, Aetna kept on sending me worker’s comp checks by accident. They were supposed to only send them for 6 weeks, but they kept coming for eighteen months. I was receiving a whopping $160 a week for eighteen months, and I savoured every bit of my newly-found liberation from wage-slavery. I used the time methodically, living in the tiny little efficiency apartment in Seattle I had moved to. Every day I spent several hours learning songs and practising them, committing them to memory. I had a songbook I made from photocopied pages of other songbooks, and lots of lyric transcriptions I had made myself for songs of artists without songbooks such as Jim Page, John O’Connor, Utah Phillips and others. Once I had a batch of songs memorised I’d spend an afternoon busking at Pike Place Market, then I’d go back to the woodshed and work on learning more songs. Life continued like this until Aetna rudely stopped sending me checks. I then briefly and abortively pursued higher education a bit more in late 1993 and early 1994, before picking up with a band called Aunt Betsy, for whom I played bass guitar, recorded an album, and did a Midwest tour. Soon after that was over I found myself once again living in Boston, where I had originally gotten Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. This time I wasn’t typing for a living, I was busking, pretty much five or six days a week, four hours a day (until my voice was hoarse, which took four hours generally), mostly in the Boston subways — The T, as it’s known. Although I spent most of three years as a full-time busker in Boston, I was still looking at it as an opportunity to pay the bills while honing my craft. By this time I had learned well what sorts of acts make significant money on the streets, and I was not doing most of the things I should have been doing if I were trying to really master the specific craft of busking. My goal by then was to become a good topical songwriter and a good musician, and I was still working at it. Particularly on the streets — the tourist spots like Faneuil Hall or the neighborhoods where people go when they’re ‘out on the town’ such as Harvard Square — the buskers who make serious money are generally very talented people who tend to fall into one of three categories: the exotic, the 25

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:47

Page 26

ANARCHIST MUSIC

extravagant, and the familiar. People who combine these qualities often do the best. For those of us who possessed none of these qualities, those of us doing a more subtle kind of thing, such as telling an unfamiliar story or singing an unfamiliar song in a way that wasn’t particularly flashy, our best bet was always the subways, rather than the streets, and the Park Street T stop, middle platform of the Red Line, became my home. Usually Monday through Friday, 11 am till 3 pm or so. On the streets people are walking around from place to place, going somewhere, and if they’re going to stop and listen to a street musician or watch a street performer of some other kind, the performer has no more than a few seconds to catch their attention. In the subways it’s different — people are standing on the platform waiting for the next train. If it’s not rush hour, the trains might be coming once every ten minutes. This means that most of your audience is going to be on the platform, within earshot of you, for one full song. If the trains are running late, maybe they’ll catch two or three. (Those were the best days.) In this situation you have a bit more to work with, you have a chance to suck them into your story — nothing too impressive required other than a good, solid narrative. Until last fall I hadn’t really done any busking since 1997. I often think of the years when I spent much of my time on most days somewhere underground, though, and sitting in a bus a couple weeks ago really brought it all back to me in a more physical way. Sitting in a bus is also something I haven’t done much since those days, for better or worse, and sitting in my seat, looking at the advertisements and the poetry and the diverse bunch of people crowded onto that bus, I remembered all those mornings, many hundreds of them I guess, taking the Orange Line from the second-to-last stop, where I lived in Jamaica Plain, to Downtown Crossing, where I’d take the Red Line one stop to my spot at the Park Street T stop. I guess it was the closest thing to a regular full-time job I ever had. Each weekday morning I’d put my guitar on my back and pack my battery-powered amp, mike stand, mike and assorted cables onto a little wheelie thing and I’d walk to the Green Street T. The commute from there in JP to downtown was 45 minutes each way on the Orange Line. I became quite disciplined about reading a book during the commute, so I was spending 1½ hours each day reading a book in those 26

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:47

Page 27

Busking Memories

days, and I got more book-reading done during my Boston busking years than ever before or since. The subway line I was riding on every day only exists due to a struggle waged by the local residents against a planned highway that would have essentially wiped the neighbourhood off the map, like so many others around the country before it. People mobilised and the government ultimately cancelled their highway plans and replaced them with an extension of the subway instead. Above the subway in JP is a long, thin park, and on this park every year people involved with a local institution called Spontaneous Celebrations hold a small festival — in part to commemorate the victory of the neighborhood in defeating plans for a new highway. In a place like Boston it doesn’t take very long to get to know all the regular street performers. Some of them come and go, but by and large it’s pretty much a few dozen people who are full-time buskers, at least among those whose main stomping grounds were the T, like me. I quickly discovered that for the sort of music I was doing, the mid-day train schedule worked best. Fewer people coming through, but they have more time on the platform. I made a living, just barely, but in a decidedly unambitious way. The more ambitious performers did popular covers, or had a really eye-catching shtick of some kind, and in the subway they played during rush hour, when the maximum number of people are going past them or waiting on the platform near them, and when the trains are coming every few minutes — too fast for most commuters to even hear an entire song. The plus side of being unambitious was there was rarely any competition for my favorite spot — at least by the time I got to it. Before I got there there would often have been someone busking for hours, taking advantage of the rush hour. Two of the regulars at that spot other than me were a cantankerous blues musician from New York with the stage name of Roland Tumble, and a cantankerous blues and folk musician from West Virginia named Nathan Phillips, who later took up the moniker of Bullfrog. Many of the other musicians would drop by on their way to another spot, sometimes checking in to see if my spot was already taken. It was a major stop for switching from one major line to another (Green to Red or vice versa) so they would often have been coming through anyway, and when you ride the subway 27

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:47

Page 28

ANARCHIST MUSIC

enough you know where to get on so when it stops at Park Street you’ll be near the area where the buskers usually busk when you step out of the train. Some of the best musicians I know, who I have recorded and performed with on and off since then, I first met in the subways. Eric Royer was one of them. I don’t remember if we met when I was listening to him busk or when he was listening to me, but whenever I was lucky enough to come across him on the street or in the subway somewhere I’d listen for a good spell. He was and is a crazy musical phenomenon, with a vast repertoire of traditional old-time and bluegrass songs in his head, all delivered on a five-string banjo that he plays with consummate skill, and when it comes to most of the bluegrass numbers, with the blinding speed and technical accuracy that the genre usually calls for. But in addition to the fine singing and banjo-playing, Eric also accompanies himself with the most sophisticated one-man band setup I have ever seen or heard of, which basically involves playing a two-string bass, a four-string guitar and a cow bell using an intricate, medieval-looking invention of his that allows him to play different chords, complete with an alternating bass line, using pedals controlled by his feet. The highlight of many different afternoons of busking was when Eric would stop by on his way somewhere, get out his banjo, and play along with me for a few songs. Eric is a fairly shy sort who probably didn’t enjoy a lot of the attention he’d get while busking, but his craft was clearly destined for the profession. The blistering banjo solos are a real attentiongetter, and combined with the wild one-man band setup it’s irresistible. Eric made more in an hour than I’d generally make in a day — this despite the fact that he hardly ever did a song that anybody other than a serious traditional music fan would recognise. If he did bluegrass, one-man band versions of Aerosmith songs he probably would have made many times as much money, I’d guess. One of the legendary buskers of Harvard Square in the 1980s — a few years before my time as a professional busker, but he would very occasionally make an appearance during my time on the scene — was a guy named Luke. I don’t know his last name — I heard many people refer to him by his first name and never once heard anyone mention any other name. He was a very precise, energetic performer with an impressive vocal range and very solid guitar skills, and he did nothing but 28

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:47

Page 29

Busking Memories

Beatles songs. He only ever busked in the same storefront in Harvard Square, and whenever he’d set up to do his thing he’d attract an adoring crowd of tourists, students and street kids who’d stick with him until he packed up for the night. If he wasn’t around on a warm weekend night when people figured he’d probably show up, many of the street kids could be heard asking, where’s Luke? With Luke there was something intoxicating about the way he used the Beatles as a unifying factor for all of society. It turns out pretty much everybody loves the Beatles — they transcend age, class, ethnicity, etc. Their music was just so popular and so infectious that it just managed to get into the broad fibre of society, and people would sing along actively, often in harmony. It was a very participatory thing. But if Luke represented the positive side of using popular culture for good purposes, you might say Manny represented the dark side. He was always an impeccably nice guy, and extremely industrious. He had learned many things about doing street music over the years, growing up somewhere in the Boston area, with his unmistakable, working class Boston accent. He knew the basic elements, or some of them, of how to make decent money at the craft: a good spot with room for lots of people to gather, a good sound system, a knowledge of songs that people are familiar with. He may have known that he could make even more money if he were a better musician, but this was unclear. I heard the stories from many people who attempted to have a chance to busk in Manny’s very prime spot there in the middle of Harvard Square on Brattle Street. Whatever time of the morning they’d get there — and for the best spots you had to get there hours early and hold the spot until the good busking time came around — Manny would be there. It seemed he often got there before dawn, riding to the Square on his bicycle, home-made wooden trailer attached to the back of it, with his mixing board, speakers and guitar. What he lacked was the ability to deliver anything but the most lifeless renderings of only the most over-played, overbusked songs ever written. Like a broken record, visitors and locals alike would be accosted every day to many hours of Cat Stevens, Neil Young and the Rolling Stones — but only their very most popular songs, none of the other ones, ever. Workers at the local businesses had to suffer interminably repeated unvaryingly stillborn renditions of Heart of Gold and 29

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:47

Page 30

ANARCHIST MUSIC

The Sound of Silence, quietly wishing Manny would one day be silent, their wishes dashed with every new dawn, as they found Manny holding down his spot when they came to open their businesses. And then there were artists who had an even better, more souped-up battery-powered sound system than Manny’s, complete with a variety of effects pedals, but who were masters of their craft. One such busker in Harvard Square for many years was Ned Landin, aka Flathead. He was, in fact, slightly Neanderthal-looking, with long hair coming out of a balding head and big, hairy eyebrows. I assume that’s where he got the stage name, I don’t know. More notable than his appearance was his mastery of the guitar and his poignant songs. He’d do a lot of his own songs, not so much familiar stuff, but despite this and the fact that he was just another white guy with a guitar, he had a loyal following in the Square because he was just so damn good. Flathead originated in Minnesota, and he could often be seen busking in Harvard Square in the middle of winter, when most buskers were either in the subway, busking in some warmer part of the world for a few months, or doing something else for the winter. Just to emphasise the point, he would plant his big amp on top of a nearby snow bank. He told me once that if the temperature went down below 25 degrees Fahrenheit he’d stop for the day, not because he had a problem playing the guitar in such weather, but because people wouldn’t stop and listen when it was that cold. Weekends were the best time to busk in a place like Harvard Square, and many people only came out to busk on weekends, such as Mike, the juggler and tightrope-walker extraordinaire, who set up his tightrope in one of the few parts of the Square where there’s a wide enough public space to set up a tightrope without getting hit by a car. This happened also to be within earshot of Manny’s perennial spot, so the juggling and tightrope-walking inevitably had to happen to the tune of yet another sad performance of ‘Wild World’ or ‘Down By The River’. A bunch of us regular street performers once had a meeting to try to figure out a system so people wouldn’t have to get up at dawn to hold down a prime spot, which is generally the default procedure when a better system isn’t agreed upon, but if I recall, Manny didn’t show up to the meeting, and we gave up soon thereafter. Sometime after that 30

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:47

Page 31

Busking Memories

Flathead abdicated his position as a fixture of Harvard Square and moved to Los Angeles. I couldn’t believe a Minnesotan who had lived for years in Boston could find a happy home in LA, but he’s still there last I heard, so I guess he likes it. At the Harvard Square T Stop — easily the most popular place on the T to busk, the Inbound platform, specifically — a system had been agreed upon by all the regular buskers, called ‘the flip’. This happened every morning at 7 am, and I believe it still does today. Every morning at 7 anyone who wanted to busk on the spot at some point during the day would show up, and the spot would be randomly allotted via the flip of a coin to three performers, who had dibs on morning, afternoon or evening. I never wanted the morning slot and I was damned if I was going to get up at 5:30 so I could be on the other side of the Boston area by 7, just so I could hang around somewhere or other in order to have the afternoon spot I wanted. But I did show up for the flip on more than a few occasions, somehow or other. During one of the time periods when I was showing up for the flip we had an entertaining little problem in the form of a Polish accordion player, an older man who had probably very recently immigrated to the US, and spoke no English. The flip is, of course, just a convention established by the community of street performers — nothing legally binding or anything. So if someone gets there before 7 am and doesn’t want to play by the rules, there’s no predetermined method for dealing with this. So for several mornings in a row, an assortment of musicians showed up for the flip and encountered this stern-looking, very large Pole with a massive accordion protruding from his very large belly. Each morning we’d all attempt to explain to him through some combination of English and sign language what the deal was, and each morning he’d look at us with an expression that at first appeared to be confusion, and later looked more like annoyance. By the second morning, Roland, who was cantankerous to begin with, suggested we break the accordion player’s fingers. The rest of us, exasperated though we were by the situation, all thought that this was a shockingly violent idea, especially coming from a fellow musician who used his fingers for a living in very much the same way as the accordion player. Along with me and Roland, Grant was there every morning. Grant was a very good classical guitarist from 31

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

ON

22/2/12

09:47

Page 32

ANARCHIST MUSIC

somewhere in England who was one of the most regular occupants of the spot there on the Inbound platform of the Harvard Square T. Finally, after four or five days of this, a young classical violinist from Russia came to the flip, and the conflict was resolved immediately and amicably. Amazing what a little verbal communication can do when it’s in the right language. The Pole spoke Russian. The violinist explained, in Russian, how the flip works. The accordion player understood. Starting that very morning he started participating in the flip and playing by the established norms henceforth. In all the years I was busking in the Boston area I hardly ever played an original song. I was actively writing them by then, but I felt like they were still collectively works in progress. I also couldn’t bear exposing my own songs to the harsh subway environment, really, it was more an emotional thing than anything strategic in terms of my musical evolution, though that was also part of it. In any case, what I sang down there was almost entirely obscure songs from the past and present that only hardcore fans of topical folk music might recognise — and even most of them wouldn’t, either. In my years living in Seattle I became a huge fan, as well as friend, of Jim Page. Left-wingers in Seattle and people who frequent certain places like the Pike Place Market know his music, but in Boston, and most other places, this is not the case. While in Seattle I went to many of Jim’s shows. Many of his songs I couldn’t find in recorded form I found by befriending other Jim Page fans who had recorded some of his live shows. I copied their recordings and transcribed every word of every song on them. Then I set out to figure out how he played the guitar parts. That part was harder — I never learned to fingerpick anything like Jim, nowhere near that good, but I did learn to mimic his flat-picking style, as well as his idiosyncratic singing style, which he has since pretty much abandoned, but he used to fancy a certain vocal trick that made him sound perpetually like a teenage boy whose voice was changing. So I’d stand there deep under the streets above, singing the songs of Jim Page, Phil Ochs, Utah Phillips, Woody Guthrie, and loads of old anonymously-written songs I had found in books like Songs of Work and Protest or The Little Red Songbook. There were many conclusions I could effectively draw from years singing those songs in the Boston subways. For one, the overwhelming majority of people riding 32

ArenaMusic:TBOG4c

22/2/12

09:47

Page 33

Busking Memories