SPRING

• Maturation: have the options improved?

• Aerial spraying of vineyards - never say never!

• Alternative packaging - should we move beyond the green bottle?

• Tasting: Field blend whites and other white blends

SPRING 2023 • VOLUME 38 NUMBER 4

INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION COLUMNS

10 AGW / WINE AUSTRALIA: :One Sector Plan to get us back on track

11 ASVO (Andy Clarke): New editor in chief for the Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research

WINEMAKING

12 RACHEL GORE: Maturation recap: have the options improved?

18 Understanding the effect of barrel-to-barrel variation on the colour and phenolic composition of a red wine

22 Consumer response to wine made from smoke-affected grapes

28 AWRI REPORT: Vintage 2023 - observations from the AWRI helpdesk

VITICULTURE

42 Aerial spraying of vineyards - why you never say never!

48 Advances in grapevine viral disease detection: use of optical imaging technology for virus surveillance in vineyards?

53 Managing botrytis sustainably: investigations of dsRNA silencing technology

54 Frost - causes and mitigation strategies for established vineyards

59 Future success in wine industry growth and sustainability relies on improved plant material

64 How does a variable and changing climate impact budburst timing of winegrapes?

67 ALTERNATIVE VARIETIES: Savagnin

BUSINESS & MARKETING

70 TOWARDS NET ZERO: Alternative packaging and wine: should we move beyond the green bottle?y

74 The journey to better understanding the direct-to-consumer channel

76 Top-line results from Vintage 2023

80 The consumer preference for lower alcohol: are there lessons from beer?

TASTING

88 Field blend whites, and other white blends

12 42 68 84 CONTENTS

Established 1985

Published quarterly

PUBLISHER: Hartley Higgins

GENERAL MANAGER: Robyn Haworth

EDITOR: Sonya Logan

Pvh (08) 8369 9502 Fax (08) 8369 9501

Email: s.logan@winetitles.com.au

EDITORIAL ADVISORY PANEL:

Gary Baldwin, Peter Dry, Mark Krstic, Armando Corsi, Markus Herderich

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS:

Kym Anderson

Peter Bailey

Eleanor

Bilogrevic

Sofia Catarino

Andy Clarke

Tory Clarke

Justin Cohen

Martin Cole

Ben Cordingley

Adrian Coulter

Peter Cousins

Geoff Cowey

Julie Culbert

Robyn Dixon

Marcel Essling

Kathy Evans

Natacha Fontes

Leigh Francis

Lucy Golding

Rachel Gore

António Graça

Markus Herderich

Kieran Hirlam

Tony Hoare

Matt Holdstock

Larry Jacobs

WenWen Jiang

Mark Krstic

Cindy Liles

Paul Lindner

Mardi

Longbottom

Samantha

McKee

Lee McLean Fabiano

ADVERTISING SALES:

Ph (08) 8369 9514

Andrew Everett

Email: A.Everett@winetitles.com.au

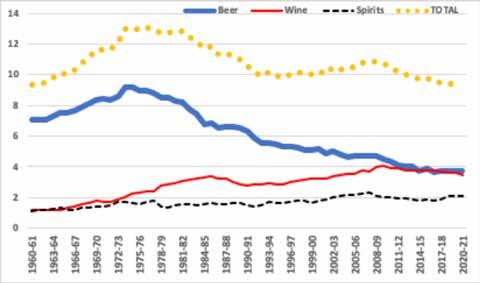

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION:

Tim Coleman

CREATIVE SERVICES:

Tim Coleman

SUBSCRIPTIONS:

One-year subscription (4 issues)

Australia $71.50 (AUD)

Two-year subscription (8 issues)

Australia $115.50 (AUD)

To subscribe and for overseas prices, visit: www.winetitles.com.au

Published by Winetitles Media

ABN 85 085 551 980

ADDRESS:

630 Regency Road, Broadview, South Australia 5083

TELEPHONE:

Ph (08) 8369 9500

EMAIL: General info@winetitles.com.au

Editorial s.logan@winetitles.com.au

Subscriptions subs@winetitles.com.au

Sonya

Logan, Editor

Minchella

Vinay Pagay

Jason Pallant

Mango Parker

Chris Penfold

Leonard Pfahl

Liz Pitcher

Jorge Ricardo-

da-Silva

Liz Riley

Sean Sands

Christa Schwarz

Neil Scrimgeour

Con Simos

Danielle Verdon-

Kidd

Yeniu Mickey

Wang

Eric Wilkes

As I write this editorial (late August), a series of workshops are being held around the country giving members of the Australian wine industry the opportunity to identify the collective challenges facing the sector and how they might be addressed. That feedback will be used to formulate strategies for a One Sector Plan (OSP), which is being jointly led by Australian Grape & Wine and Wine Australia in acknowledgement of the “perfect storm of issues” that have impacted the sector since 2020 and are being “felt by everyone in the community”.

Members of industry are also encouraged to complete a short online survey to put forward their thoughts on which of the following themes the plan should focus on: people, consumers, customers and communities, product and place, environmental, social and governance (ESG), markets or systems.

A draft OSP is expected by December 2023. In a joint column, Wine Australia CEO Martine Cole and Australian Grape and Wine CEO Lee McLean speak more about the One Sector Plan which you can find on page 10.

Underlining the challenges facing the industry that the OSP aims to address are the figures from the 2023 vintage (which Peter Bailey from Wine Australia takes a deep dive into on page 76) and the export stats from the 2022-23 financial year (see page 7).

Also in this issue of the Wine & Viticulture Journal, we present the fourth and final article in our Towards Net Zero series. With packaging and transport being such a significant contributor to the wine industry’s emissions, we asked the Australian Wine

Research Institute to compare the carbon footprint of different packaging options, and the technical considerations that producers should bear in mind when weighing them up.

Sticking with the theme of climate change, over in Viticulture, we are celebrating the return of former regular writer Tony Hoare who from this issue onwards will be providing a series of articles on managing extreme weather events. In keeping with the season, Tony’s first article takes a look at frost (page 54). Then we have researchers from the University of Newcastle revealing the results of their investigations into the influence of changing springtime temperatures on budburst across Australia’s wine regions (page 64).

With extreme weather events, such as fires, forecast to become more frequent and intense due to climate change, information to help guide producers on what to do with grapes that have been exposed to smoke from a nearby fire is paramount. While there has been significant inroads into understanding whether or not and to what degree a wine exposed to smoke will be smoke-affected, there has been little research into exactly how consumers perceive these wines. The AWRI has undertaken some research into the consumer acceptance of smoke characters in wine and present them in an article in Winemaking which starts on page 22.

Also in Winemaking, our regular scribe Rachel Gore reviews current methods for maturing wine, balancing their quality outcomes against their price (see page 12).

Enjoy delving into these articles and more in the following pages.

Advertising A.Everett@winetitles.com.au

WEBSITE: www.winetitles.com.au

Printed by Lane Print, Adelaide, South Australia. ISSN 1838-6547

Printed on FSC Certified Paper, manufactured under the Environmental Management System ISO 14001, using vegetable-based inks from renewable resources.

Conditions

The opinions expressed in Wine & Viticulture Journal are not necessarily the opinions of or endorsed by the editor or publisher unless otherwise stated. All articles submitted for publication become the property of the publisher.

All material in Wine & Viticulture Journal is copyright © Winetitles Media. All rights reserved.No part may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical including information and retrieval systems) without written permission of the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information, the publisher will not accept responsibility for errors or omissions, or for any consequences arising from reliance on information published.

Cover image: Wine Australia

WINE AUSTRALIA & Australian Grape and Wine 10 ASVO 11 AWRI REPORT 38 REGULAR FEATURES

D @winetitles

Q @winetitlesmedia C linkedin.com/company/winetitles-pty-ltd E @winetitlesmedia

ALTERNATIVE VARIETIES 68 VARIETAL REPORT 84

• •

• •

INDUSTRY STATISTICS

2023 DELIVERS SMALLEST VINTAGE IN A GENERATION

The Australian wine industry crushed an estimated 1.32 million tonnes in 2023, 26 per cent less than the 10-year average and the lowest recorded since 2000, according to the latest national vintage report released by Wine Australia.

Wine Australia manager, market insights, Peter Bailey, said the second consecutive smaller vintage would have a direct impact on grape and wine businesses.

“This smaller vintage, which will reduce the wine available for sale by around 325 million litres, is likely to have a considerable impact on the bottom line of grape and wine businesses all around Australia, at a time when the costs of inputs, energy, labour and transport have increased significantly.”

Bailey said a third consecutive La Niña event produced the wettest year since 2011 and it was also Australia’s coolest year since 2012. Persistent winter and spring rainfall across much of South-Eastern Australia made access to vineyards difficult as well as causing flooding in some regions. The cool, wet conditions through spring and summer in some regions also led to lower yields, delayed ripening and challenges managing disease.

Further reducing the size of the crush were winery inventory pressures resulting in some yield caps being imposed, uncontracted grapes not being sold and/or vineyards being temporarily taken out of production.

Bailey said that it was impossible to determine what share of the overall reduction, compared with an average vintage, could be attributed to demand-driven effects as opposed to seasonal conditions.

“However, white grapes — which are in higher demand — were reduced by a similar percentage to reds, which suggests that seasonal effects were the main contributor to the reduction,” Bailey said.

The crush of red grapes in 2023 is estimated to be 711,777 tonnes — a 26 per cent reduction compared with 2022 and 25% below the 10-year average of 943,146 tonnes, while the white crush was an estimated 605,321 tonnes — a decrease of 22% compared with 2022 and 28% below its 10-year average of 839,013 tonnes.

South Australia retained its position as the largest contributor to the crush, with a 55% share of the total, despite its second-smallest crush since 2007. New South Wales was second-largest with 27% of the crush, followed by Victoria with 13%. Western Australia, which overall had a very good season, increased

its share to 3.5%, while Tasmania and Queensland each accounted for slightly less than 1%.

The main reduction in the crush came from the three large inland wine regions: the Riverland (South Australia), Murray DarlingSwan Hill (New South Wales and Victoria) and Riverina (New South Wales). The crush from these regions combined was down 28% per cent to 899,936 tonnes, whereas the crush from the rest of Australia’s 59 GI wine regions and 26 GI zones together was only down by 15% compared with 2022 at 417,162 tonnes. This meant that the large inland regions reduced their share of the national crush to 68 per cent, compared with the long-term average of 74 per cent.

The total estimated value of the 2023 crush at the weighbridge was $983 million, a decrease of $229 million (19%) compared with the 2022 vintage and the lowest since 2015. The decline in value was less than the decline in tonnes, because of a small increase in the overall average purchase value, driven by an increase in the average value and share of grapes from cool-temperate regions.

EXPORT VALUE CONTINUES DECLINE AS GLOBAL WINE MARKET WEAKENS

Australian wine exports declined by 10 per cent in value to $1.87 billion and 1% in volume to 621 million litres in the year ended June 2023, according to Wine Australia’s latest Export Report.

The decline in value was largely driven by a reduction in exports to the United States of America (US) as lower-priced packaged exports continued to decline. Exports to the United Kingdom (UK) also continued to decline, following the two years of elevated shipments due to pre-Brexit demand and COVID-19 related market impacts.

The latest export results are partially reflective of broader global trends reported by market research firm IWSR, with all wine consumption globally declining 3% in volume in 2022, but premium price segments bucking the trend with continued growth, albeit at slower rates than recent years.

Wine Australia manager, market insights, Peter Bailey said that more than half of the decline in Australia’s export value took place in shipments with an average value between $2.50 to $4.99 per litre free on board (FOB), which are generally wines exported in their final packaging and sold in lower priced retail segments.

“Wine consumption in mature markets is in decline, driven by decreases in the commercial price segments. This is impacting Australia’s export performance, especially in the US, as Australia is very exposed to the price segments in decline,” Bailey said.

In comparison to value, export volume was stable as a short-term, supply driven increase in unpackaged wine shipments, especially to Canada, was outweighed by declines in volume to many of Australia’s export destinations.

“The growth in unpackaged shipments comes as the shipping challenges of the past couple years have eased, allowing Australian exporters to catch up and ease pressure on inventory,” Bailey said.

The complete report can be downloaded at www.wineaustralia.com/market-insights/ australian-wine-export-report

INDUSTRY OUTLOOK

AUSTRALIAN WINE INDUSTRY ‘SWIMMING IN WINE’

Immediate removal of Chinese antidumping tariffs would not be enough to prevent Australia’s wine industry facing several years of oversupply, according to Rabobank’s Wine Quarterly Q3 2023 report.

Improving trade relations between China and Australia the recent removal of Chinese tariffs on Australian barley has led to hope that

6 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4 NEWS

removal of the tariffs placed on Australian wine in March 2021 may be imminent.

However, the report by Rabobank, a leading specialist in food and agribusiness banking, says even in a “best case scenario”, with tariffs removed this year and Chinese consumption of Australian wine recovering quickly, this would “not be a panacea”, with Australia’s wine industry still facing at least two years to work through its current wine surplus.

Report author, RaboResearch associate analyst Pia Piggott, said so large is the current oversupply, that Australia has the equivalent of 859 Olympic swimming pools worth of wine in storage.

“That’s over two billion litres of wine, or over 2.8 billion bottles of the wine,” she said.

Piggott said that when a slew of Chinese anti-dumping tariffs and soft bans hit various products exported by Australia in 2020-21, wine took the most notable hit, losing about one third of export value from its peak in 2019,” she said.

“Unluckily, the tariff coincided with an exceptional growing season and Australia’s largest crush on record.

“Wine production for the ’21 vintage increased 36 per cent year on year, which would have in any case caused an oversupply. This coincided with COVID, logistics bottlenecks and inflation which were major hurdles in the way of plans to grow and diversify exports. Thus, two plus years into the tariff, prices of Australian commercial red grapes have significantly declined, and oversupply issues remain,” she said.

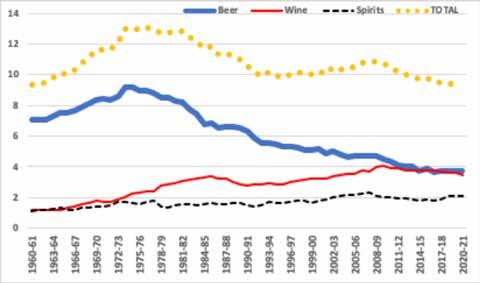

Piggott highlighted that the wine market in China has been contracting in recent years, with consumption more than halving from its peak in 2017 to just 880 million litres in 2022.

“Chinese consumers began transitioning away from wine as part of a broader decline in alcohol consumption on a per capita basis, however declines were greater for wine than beer and spirits,” she said.

“COVID lockdowns and the economic slowdown curbing discretionary spending have also played a role in declining consumption to levels not seen since the 1990s. Despite only Australia being hit by tariffs, the past five years has seen volume declines in imports from nine of the top ten supplying countries, as consumers become more price sensitive.”

Rabobank projects that China’s consumption reached the bottom in 2022, and while there is considerable uncertainty, there is upside potential for growth in imports as ontrade premises reopen and the urban middle class have more disposable income to spend wining and dining.

“Positively, some Australian brands have maintained brand awareness and presence on retail shelves in China throughout the tariff period by expanding their range of products from origins outside Australia,” she said.

The Rabobank report said despite competitive pricing, a valuable brand and quality product, it has been difficult for Australia to grow total exports in the absence of the Chinese market over the last few years.

“In a push to move volume, bulk wine has grown from 55% pre-tariff to over 60% of exports and as long as stocks need to be shifted as bulk shipments, prices will remain depressed,” Piggott said.

“In the United Kingdom, Australian imports have fallen from their peak in 2020 as off premise consumption of wine declines following COVID reopening.

“In the United States bulk wine has grown to represent 25% of imports from Australia, with increasing volumes and declining average value,” she said.

“In 2023 and onwards we expect the UK and US will remain key export markets for Australian wine, however some headwinds remain. In the UK, implementation of new alcohol duty rates will increase duties payable on a typical bottle of Australian wine by 20 per cent (750ml at 12.5 per cent alcohol).”

The Rabobank report said the Australian wine market will remain in oversupply for a considerable length of time.

“To return to balance and profitability, acreage needs to be reduced, thus over the next five years we will see rationalisation of assets throughout the supply chain,” it said.

Piggott said for vineyards, margin pressure from both ends will remain high for some time, particularly for uncontracted vineyards with a high mix of red varieties.

“For wineries, particularly those selling commercial wine, stocks will remain high for some time as businesses slowly work through selling inventory. While some brands have increased bulk shipments and been able to heavily discount stock, this will need to continue for some time to rebalance the market,” she said.

PESTS & DISEASES

SA ACCEPTS MORNINGTON PENINSULA AS A PHYLLOXERA EXCLUSION ZONE

South Australia’s Department of Primary Industries and Regions (PIRSA) has reclassified the Mornington Peninsula as a Phylloxera Exclusion Zone (PEZ) from a Phylloxera Risk Zone (PRZ) for the purposes

MEET THE FISCHER FLEX1 FLEX2 WEEDING SYSTEM & NEW FISCHER TORNADO Fischer FKT-420 RSO CANE RAKE sales@fischeraustralis.com.au FITS 12 UNIQUE UNDERVINE MANAGEMENT DEVICES V38N4 WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 www.winetitles.com.au 7 NEWS

of imports into the state, Vinehealth Australia announced to industry this morning.

Entry requirements for regulated phylloxera risk vectors from the Mornington Peninsula have therefore changed according to South Australia’s Plant Quarantine Standard.

The Victorian Government gazetted the Mornington Peninsula as a PEZ in March 2022. PIRSA’s recognition of the region as a PEZ brings South Australia into line with other states and territories.

Vinehealth is mandated under the Phylloxera and Grape Industry Act 1995 to assess the relative threat to South Australia’s vineyards posed by phylloxera and has been encouraging PIRSA to place a moratorium on endorsing the upgrade of any Phylloxera Management Zone until the completion of a review into the National Phylloxera Management Protocol (NPMP).

According to Vinehealth, improvements in science have shown that the surveillance, detection, and disinfestation procedures in the National Phylloxera Management Protocol, including the rezoning procedure, are “not sufficiently effective” and are therefore “inadequate as the basis for rezoning to give sufficient confidence in the absence of phylloxera in the surveyed area”. Vinehealth also feels that historical movements between Phylloxera Infested Zones and the Mornington Peninsula are not adequately accounted for.

“The detections of phylloxera in Victorian vineyards this year have further emphasised that there is a considerable delay between time of infection to time of detection, and that detection is difficult,” Vinehealth said in its notice to industry.

“Vinehealth’s and PIRSA’s risk appetites and viewpoints on this decision [to recognise the Mornington PEZ] vary but are both valid,” Vinehealth advised.

“Vinehealth understands there can never be zero biosecurity risk associated with interstate trade, and that many South Australian wine businesses are reliant in some capacity on direct or indirect interstate trade. Therefore, there is a need to balance maintenance of trade with minimising the risk of a pest introduction to the state.

“Given the risks inherent with serious pests such as phylloxera that are difficult to see and detect, slow to show impact in the vineyard, and are spread by a range of vectors — the best protection for all vineyard owners and industry personnel is to ensure your own biosecurity measures are in place.”

COMPANY NEWS

KARADOC WINERY TO CLOSE

Treasury Wine Estate’s commercial winery at Karadoc, near Red Cliffs in the Murray Darling, will close in mid-2024, the company announced in July.

Operating since 1973, the winery currently makes wine for various TWE brands including 19 Crimes, Lindeman’s, Wolf Blass, and Yellowglen. These brands will continue be made with long-standing local TWE winemaking partners Zilzie Wines and Qualia, and at TWE’s Barossa winery in South Australia.

TWE said a number of factors had led to the decision to close its Karadoc winery, including the global decline in commercial wine consumption, rising costs and under-utilised capacity at the site.

“Making the decision to close a site is something we take very seriously and is a last resort after we’ve looked at all other possible options,” said TWE’s chief supply officer Kerrin Petty. “Globally, the wine industry is seeing consumers shift away from commercial wine (less than $10AUD a bottle).

“Over the coming years, we expect commercial volumes at Karadoc to continue to decline and volumes to be at around 60 per cent of the capacity that the site is built to process. Given 70 per cent of costs at Karadoc are fixed, processing less volume means the cost of running the site is substantially higher.

“Combine this with rising costs and unfortunately as a result, we’ve made the difficult decision to close our Karadoc winery from mid-2024, which is hard news to share with our loyal team, the local community and partners.

Approximately 60 TWE workers will be impacted by the closure of the winery.

“We’re committed to assisting our team members to find future employment and continuing to support the local winemaking industry,” Petty said.

The company also plans to divest its commercial vineyards in Lake Cullulleraine, in north-west Victoria, and Yankabilly, in south-west New South Wales.

“We continually review our global vineyard assets to ensure they’re in the best possible places to grow our premium and luxury portfolio,” said Petty.

“A number of factors contribute to our shifting vineyard footprint including changing consumer trends and wine preferences as well environmental changes such as higher temperatures and reduced access to water.

“This has meant divesting some of our vineyard assets but also looking at opportunities to expand our footprint in new locations for future growth.

“Last year we acquired Beenak Vineyard in Victoria’s Yarra Valley, as well as Château Lanessan in Bordeaux, France, and we hope to share further updates in this space soon,” he said. WVJ

8 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4 NEWS

A One Sector Plan to get us back on track

By Dr Martin Cole1 and Lee McLean2

The Australian grape and wine sector is undoubtedly sick of the word ‘unprecedented’, but the perfect storm of challenges facing winegrape and wine producers has frankly never been seen before.

When Australian Grape & Wine developed Vision 2050, in collaboration with Wine Australia, we set out to achieve goals that would be of the greatest benefit to the sector and to the planet — creating a more sustainable, profitable and inclusive grape and wine community.

While the principals of Vision 2050 remain the same, the roadmap to get there has changed significantly. We need to act now to address the immediate challenges of significant wine tariffs, supply chain disruptions and increasing commodity costs.

Wine Australia and Australian Grape & Wine have teamed up to develop the One Sector Plan, a strategy to be co-designed with the sector that identifies the collective challenges facing our sector and how they can be addressed.

To seek everyone’s input on the One Sector Plan, we commissioned ACIL Allen to run a national survey and program of workshops throughout August and September, 2023. While we’re aiming to have a plan drafted by the end of the year, feedback will remain open into the new year to ensure everyone has an opportunity to contribute.

The plan will consider the nuances of different regions and will reflect the organisations’ different roles (including industry-wide advocacy and labour laws), while working together to achieve a collective vision for the broader grape and wine sector.

Workshops are being held across the country so that consultation can be thorough and consider the varying priorities of stakeholders operating in different regions, markets and segments.

Outside of these workshops, we encourage everyone to complete our brief online survey to ensure we have broad representation across Australia’s grape and wine communities.

The co-designed plan will reflect the collective strategic priorities of the sector, recognising the common themes and concerns of growers, makers and exporters, and will have clear objectives about how those concerns can be addressed in the immediate future.

The plan will clearly outline the key challenges and opportunities and provide strategic direction across the sector to provide guidance for the industry to face problems that impact everyone.

While there are differences between the various groups across our sector, there are also key points of collaboration, and the plan will be adaptable to the entire sector’s needs and operating environment.

Navigating different views and priorities naturally has its challenges but we hope to provide alignment on the overall strategic intent of the plan, while allowing for autonomy at local and regional levels.

We encourage anyone who has ideas about how we can face the sector’s challenges to complete the national survey and attend a workshop. The key questions we will be asking in the workshops will explore what the sector’s key priorities are, how those priorities can be addressed through research and innovation, marketing or policyadvocacy; what existing opportunities can be leveraged from existing initiatives, and where the points of collaboration are.

For more information about the One Sector Plan, visit https://www. wineaustralia.com/ one-sector-plan WVJ

Chief Executive Officer, Wine Australia

Chief Executive Officer, Australian Grape & Wine

10 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4 WINE AUSTRALIA & AGW

1

2

New editor in chief for the Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research

By Andy Clarke, President, Australian Society of Viticulture & Oenology

By Andy Clarke, President, Australian Society of Viticulture & Oenology

The Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research (AJGWR) has a new editor-in-chief following the retirement from the position of long-serving Dr Terry Lee OAM.

Professor Stefano Poni was an outstanding choice for the role. He is an experienced editor, with high integrity, superb judgement and a real affinity with the AJGWR and our purpose. I’m thrilled he will be leading the AJGWR and its talented editorial team.

Professor Poni takes up the role of editorin-chief from Terry Lee who stepped down at the end of June 2023 after a highly successful 11 years in the role.

On behalf of the ASVO board, I’d like to thank Dr Lee who has been an outstanding leader, seeing the AJGWR through considerable change. He has made a tremendous contribution to the publication, the grape and wine community and industry. His pre-eminent publishing achievements led to an all-time high impact factor, and he leaves the AJGWR in strong shape. During his tenure, he upheld the highest quality standards of a leading journal and significantly increased the AJGWR profile and reputation.

Professor Poni is the Professor of Viticulture at the Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environmental Sciences at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Piacenza, Italy. He is also director of the one-year Master VENIT and is coordinator of the Master of Science in Sustainable Viticulture and Enology. He has authored over 320 scientific publications, 159 of which were edited in international refereed journals. His H-index is currently 41 in the Scopus database.

Poni has been an invited speaker at 55 international congresses, he was awarded with the Perdisa Prize in 1994, the ‘Enotecnici’ Prize in 2004, and the Rudolph Hermanns Foundation Prize in 2011. He also won the prize for the best paper published in 2013 in the viticulture section of the American Journal of Enology and Viticulture (AJEV). Poni has been an associate editor for the AJEV since 1 January 2006 and associate editor for the AJGWR since 1 January 2012.

“It is indeed a great honour and privilege

to be appointed as editor-in-chief of the prestigious Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research,” Poni said. “As a representative of Old World viticulture, the link to Australia as a New World viticulture and oenology leading country is such a stimulating task. My effort will primarily be to attract even more original scientific work about the challenges that the wine chain is facing, starting with climate change-related issues. Moreover, I will try to add further motivation to all actors involved in the process of submission-evaluation-decision for improved interaction between the quality of the selected research and speed of publication.”

ASVO 2023 AWARDS FOR EXCELLENCE

The annual ASVO Awards for Excellence is a prestigious event to promote industry excellence, foster leadership and encourage innovation and sustainability in the Australian wine industry.

The awards have a long and proud history of recognising individuals in the Australian grape and wine community who are champions of change and are willing to go the extra mile to help others.

The Awards for Excellence event includes presentations of the ASVO Viticulturist and Winemaker of the Year, the Wine Science and Technology award, recognition of the best viticulture and oenology papers from the AJGWR, presentation of the Dr Peter May award for most cited paper from the AJGWR in the last five years and an announcement of new ASVO Fellows.

The 2023 awards will be held at the National Wine Centre, Adelaide, on Wednesday 8 November. For more information on this year’s event and to register

visit https://www.asvo.com.au/events/2023awards-excellence

ASVO 2023 AWAC SCHOLARSHIP RECIPIENT

The ASVO board of directors is delighted to reveal that the winner of the 2023 ASVO scholarship for Advanced Wine Assessment Course (AWAC) is Emma Shaw from the Canberra wine region.

Emma is the general manager at Collector Wines and also runs her own business, Pique-Nique, which offers wine appreciation classes and events to encourage consumers to develop their understanding of and comfort with wine, and their appreciation of Canberra wines. Emma also volunteers her time with industry associations across the broader region and is close to completing a Bachelor of Wine Science at Charles Sturt University.

Emma was an outstanding applicant for the scholarship, with her very clear passion for teaching others how to appreciate wine.

The ASVO exists to foster excellence in viticulture and oenology, and a key element of this is to encourage and facilitate education to the highest standard. The AWAC scholarship covers the fees for one ASVO member each year to receive this formal education in wine tasting which will not only further the recipient’s career but also contributes to excellence in the Australian wine industry.

The AWAC was founded in 1992 by the Australian Wine Research Institute. It is an intensive four-day course designed to provide training to potential new wine show judges by developing the sensory analysis capabilities and vocabulary of Australian wine industry personnel at an elite level. The scholarship covers the course fee which in 2023 is $5390.

“I am thrilled,” said Emma when told the news. “I am sure the AWAC course will push my knowledge of wine assessment to new heights. Receiving support by way of a scholarship is greatly appreciated. Thank you to the ASVO board for selecting me amongst the many deserving applicants.”

V38N4 WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 www.winetitles.com.au 11 ASVO

WVJ

Stefano Poni, the new editor-in-chief of the Australian Journal of Grape and Wine Research, and Emma Shaw

Maturation recap: Have the options improved?

By Rachel Gore, Director and Principal Consultant, Free Run Consulting

Rachel reviews existing methods for maturing wine — both barrels and alternatives — in light of the current squeeze on capital expenditure and reflects on how quality expectations can be achieved at a cost-effective price.

Given today’s financial pressures that seem to be squeezing us from every direction, is now the right time to reassess our winemaking protocols to see whether we can achieve the same quality parameters but in a different way? We now have access to an array of maturation options that have improved substantially over the last decade so there’s no time like the present to take a closer look.

Wines that have had some influence from oak are, in general, preferred by many wine consumers around the world, however, the practice of barrel maturation is costly due to the price of oak barrels and the extended period of time that the wine must stay in them. To save money and shorten the period of time in contact with wood, the use of cheaper

alternatives, now more than ever, have become more popular.

Wines are normally aged in oak wood barrels for the purpose of improving overall sensory attributes. During the maturation process, wine undergoes many changes due

to the reactions between wine components, the oxygen that slowly diffuses through the oak barrel surfaces and the compounds that are released from the oak itself. Barrels have been used for centuries for preserving and ageing wines, acting as storage vessels that are capable of releasing compounds that affect and improve a wine’s individual characteristics. During the period of maturation in oak, wine undergoes oxidative processes that alter its composition and organoleptic profile due to the transfer of oxygen, phenolic and aromatic compounds from oak to wine. While oxidation usually involves negative implications, the term ‘oxygenation’ suggests the liberation of oxygen and its contact with wine — a technique used in winemaking to improve colour, aroma and texture.

12 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE

SPRING 2023 V38N4 WINEMAKING WINE MATURATION

JOURNAL

“Ten years ago you could taste the ‘plankiness’ in a wine and could identify that alternatives had been used. These days the sourcing has improved and the focus on the quality of the raw material has really progressed.”

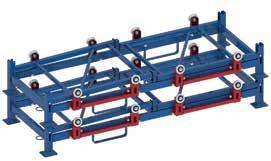

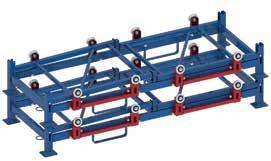

Foldable stillages for wooden barrels

ARMT18/1

Pallet for wooden barrels

A foldable steel pallet with a load capacity of 750 kg. Stacks into a 5-level rack with a height of 5m .

In the ARMT18/1 variant, the barrels rest on rollers. This allows you to conveniently rotate the barrels in order to, for example, wash them inside. Powder coating to any RAL color.

• Capacity: 2 barrels 225Lt or 300Lt

• Weight: 54 kg

• Outside dimensions: 1.8 x 0.8 x 1.0m

• Stacks into a 5-level rack with a height of 5m

• Folding design for optimised transport and intralogistics flexibility.

Quoted and shipped directly from the manufacturer!

ARCOM Sp. z o.o. ul. Brzeska 3, 32-765 Rzezawa, Poland arcom.net.pl email: info@arcom.net.pl

In the case of oak barrels, the level of oxygen transferred through the ‘breathing mechanism’ of a barrel depends on the oxygen transfer rate (OTR). In a recent study, it was shown that wines aged in barrels with a high oxygenation rate had a greater ability to consume oxygen, resulting in an increase in colour intensity1. The parameters that will determine the necessary quantity of oxygen include the presence of sulfur dioxide, the initial wine composition (anthocyanins/tannins/ varietal/vineyard and vintage) and the ultimate destiny of the wine. In the case of oak barrels, the OTR will depend on the chosen species, its geographical origin or barrel manufacturing process1. These characteristics will result in a different porosity of wood (coarseness or grain) and also in the degree of oxygen transfer.

Could there be alternate methods of ageing that replicate oxygen diffusion that could be used in conjunction with oak alternatives or additives to produce the same affects?

In this article I will delve deeper into the hidden costs of oak, the use of microoxygenation in conjunction with tannins, oak alternatives and the comeback of the ancient wine vessel amphorae but at what cost?

BARRELS

Barrels have functions beyond serving as a storage vessel. Barrels, in all of their different formats and sizes, allow for the separation of sediment as lees from the wine over a period of time. They provide tannins, allow oxygenation and assist in the stability of colour in red wines. During the ageing process of a barrel, the wood releases compounds into the wine that contribute to an improvement in its organoleptic properties. All of this contributes to the ageing of wine by adding complexity, flavour and longevity, therefore, the wine barrel acts as an active vessel that releases chemical compounds into the wine, improving its physical, chemical and sensory properties.

Depending on its origin, age, thickness of staves, uses, toasting and the time spent in the barrel, the acquired properties are different. As the compounds that can be extracted from oak are finite, factors such as the composition of the wine, maintenance of the barrels and fermentation affect the life of the barrel, decreasing the extraction rate over time. Oak is the most extensively used wood in barrel manufacture due to its hardness, permeability and characteristics. French oak is typically more expensive than American oak due to the

losses involved as a result of its irregular grain and greater porosity. This characteristic means that the wood has to be divided instead of sawn which leads to a lower yield from the wood2

There is a large array of barrel sizes and oak origins now available, with many different formats, for example, barriques, hogsheads, puncheons and oak tanks, all of differing sizes and shapes.

In a small to medium sized winery, each barrel, regardless of the size, is a significant cost and can represent a substantial portion of the winery’s budget. In a larger winery, the individuality of a specific barrel can be lost amongst the sheer volume of oak, therefore, it still represents a substantial expense although the hidden cost of time and labour taken to care for a barrel can often be overlooked.

In order to keep a barrel in a condition fit for winemaking, there is much labour involved. A barrel isn’t something to be bought once — barrels are expensive to buy but they also require constant maintenance that is necessary to maintain their value. The decision on what oak to purchase is sometimes made not on what is the most suitable type of oak for the wine but more with an eye on price. This, along with the lack of understanding around just how much it will cost to maintain a barrel, can sometimes result in a barrel program that is detrimental to the final wine quality which could then jeopardise the long-term viability of the wine’s sale.

The cost of a barrel can be considered an annual expense or a capital investment. Most wineries think of barrels as capital investments meaning that the ‘cost’ of a barrel is not all accounted for at once but is depreciated over a predetermined timeframe.

If a barrel is allowed to dry out, if the hoops are not kept tight or if it isn’t adequately and regularly soused, it becomes worthless. Fill, empty, clean, stack, top, gas, maintain — these operations all add up to a sometimes-hidden cost to the winery.

A barrel will impart oak characteristics for four to five years after which time it starts to become more of a storage vessel. However, there are options to extend the useful life of a barrel using the process of ‘re-shaving’ or ‘refiring’. This is traditionally a labour-intensive process that takes the barrel out of production for some time and requires dismantling the barrel in order to access the inner staves. Another option is the use of a chemically-inert slurry that ‘sands’ the internal surfaces of the oak barrel without the need to pull it apart. The process is suitable for all used red or white barrels up to 12 years old that have been kept in reasonable condition.

OAK ALTERNATIVES

There are definite cost savings when using oak alternatives, but the real savings are in the lack of labour required to maintain an oak storage vessel throughout its lifetime.

As with oak barrels, there seems to be a multitude of options when it comes to oak alternatives — from staves to chips, from beans to liquids — and the products are not only beginning to catch up to barrels in terms of quality, but they are more sustainable and, most importantly, cost effective. The oak alternative industry is constantly coming up with

14 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4 WINEMAKING WINE MATURATION

“In a larger winery, the individuality of a specific barrel can be lost amongst the sheer volume of oak, therefore, it still represents a substantial expense although the hidden cost of time and labour taken to care for a barrel can often be overlooked.”

Photo: Frances Andrijich/Wine Australia

new and innovative ways to closely mimic the impact of barrels. Some of the most recent products include ultra-premium sourcing of oak, new flavours, toasts and blends as well as tools to make the production process quicker, easier and more efficient without sacrificing quality. Ten years ago you could taste the ‘plankiness’ in a wine and could identify that alternatives had been used. These days the sourcing has improved and the focus on the quality of the raw material has really progressed.

Another alternative is the application of oak extracts in a liquid form. These provide winemakers with the ability to make controlled additions and adjustments to complement their wine at any stage of the winemaking process and provide the wine with the benefits of natural oak tannins as well as building the desired flavour profile. Liquid tannins have been very popular, especially during fermentation and at the finishing stages of winemaking. At fermentation, winemakers are replacing solid pieces of oak with liquid products because they are much easier to use. The quality of the finishing tannins gives winemakers the freedom

to make additions in many different forms and for a variety of reasons, whether it is oak, seed or skin tannin that is required to make improvements to the wine.

It should be noted that although phenolic and aromatic compounds present in oak are released during contact between wine and oak alternatives, the oxidative process that occurs in the barrel does not take place in tanks. For this reason, the use of oak alternatives is often combined with micro-oxygenation.

MICRO-OXYGENATION

Micro-oxygenation, or MOX for short, is the controlled addition of oxygen during the winemaking process that attempts to simulate, in a tank, the low uptake of oxygen that occurs in barrels over a long period of time. The technique involves treating a wine with well controlled sub-saturation doses of oxygen over short periods of time and can result in improvements in red wine structure and fruitfulness.

eter Steer - 0423 318 555 | Neville Fielke - 0407 993 387 *versatility enhances traditional barrel programs, avoids barrel variation, 3X lower cost, 5X lower carbon per Ltr, 25yr life, pre-set OTR choice Wine excellence that doesn't cost the earth Be Barrel-Smart. Elevate barrel performance* Proven, long life, large barrels - masters control & consistency for ageing success Affordable new top barrel oak every vintage - suits a variety of price points & styles Synergises oxygen & oak - performs like new top-end French barrels annually Barrels that nurture nature & save water - reduces the winery carbon footprint Increases quality, lowers cost - more flexibility & control for barrel-smart winemakers elevagebarrels.com © 2023 V38N4 WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 www.winetitles.com.au 15

WINE MATURATION WINEMAKING

The stage at which micro-oxygenation is started can influence the rate and quantity of oxygen added to wine. It is typically begun at the end of alcoholic fermentation and prior to malolactic fermentation.

An article by Del-Alamo-Sanza and Nevares (2018) indicated that the natural rate of permeation into new French oak barrels is between 1.66mL/L/month and 2.5mL/L/ month. It is important to note that the age of the barrel will affect the oxygen diffusion rate — the older the barrel, the slower the oxygen diffusion rate since most of the wood pores will contain wine sedimentation.

Dose rate and oxygen quantity are the most critical aspects of successful MOX to ensure that wine does not accumulate dissolved oxygen. The stage of wine production at which micro-oxygenation is started can also influence the recorded rate and quantity of added oxygen.

MOX treatment alone does not improve flavours or ellagic tannins that contact with oak can provide. When used in conjunction with either oak alternatives or liquid tannins, however, the results can be highly successful.

It is interesting to note that a New Zealandbased company has entered the market with a new technology for micro-oxygenation users, in conjunction with oak alternatives, that offers wineries portable units that connect to tanks and update automatically every 15 minutes to ensure precise addition rates. The unit uses a different type of diffusion technology that helps get an even dispersion of oxygen throughout the wine volume and better mimics the oxygen exchange in a barrel. It moves around inside the tank rather than simply dropping it in the top, resulting in improved oak integration and stabilisation of colour, decreased astringency and reductive aromas and a more balanced mid-palate structure.

AMPHORAS

An amphora is an ancient Greek or Roman jar or vase made of clay with a large oval body and a narrow cylindrical neck, originally used for transporting and storing grapes, olive oil, grain and other supplies. Because clay is porous, the vessel allows oxygen to penetrate the vessel which helps soften tannins and flavours in the same way that barrel maturation and micro-oxygenation work. Since the clay is a neutral material, the presence of oxygen enables wine to develop without imparting any additional flavours. In addition, clay is an excellent thermal conductor which releases the heat from fermentation so there is normally no need for temperature control. The wine evolves slowly, preserving the primary fresh fruit characters of the wine and giving it a deep rich texture. The presence of oxygen also softens tannins and accelerates tertiary aromas.

Amphoras come in a wide range of sizes and shapes. Most are made with clay but others have been made with sandstone and concrete, however, these are not normally referred to as ‘amphora’.

Due to the nature of these ancient vessels, if cared for correctly they can last for decades, making them financially and environmentally attractive unlike oak barrels that must be replaced every four to five years. The initial outlay, however, is considerable – generally prices begin at around $8000 whereas a stainless-steel tank can be anywhere from $500 for a small variable-capacity tank while an oak barrel can range in price from $1200 up to many thousands of dollars. Concrete tanks that offer benefits similar to amphorae may cost tens of thousands but whilst both concrete and

clay vessels represent a significant investment, those who use them say the benefits are worth the expense.

Before purchasing one, buyers should consider how much oxygen the wine needs, the ease of sanitation of the vessel, the thermal insulation properties and the safety and durability of the vessel. If purchasing from overseas, freight must also be carefully considered as this can be considerable given the weight and shape of the vessel.

None of the information in this article is particularly new or innovative, however, now more than ever, winemaking costs must be scrutinised and the product market must be kept in full and visible site. If quality can be achieved by using alternate methods of ageing and oak integration at a more cost-effective price, why would you not investigate all options!

FOOTNOTES

1Sánchez-Gómez R.; del Alamo-Sanza M.; Martínez-Martínez V. and Nevares I. (2020) Study of the role of oxygen in the evolution of red wine colour under different ageing conditions in barrels and bottles. Food Chem. 328:127040.

2Waterhouse, A.L. and Towey, J.P. (1994) Oak lactone isomer ratio distinguishes between wine fermented in American and French oak barrels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 42:1971-1974.

REFERENCES

Del Alamo-Sanza, M. and Nevares, I. (2018) Oak wine barrel as an active vessel: a critical review of past and current knowledge. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 58:2711-2726.

Boulton, R.B.; Singleton, V.L.; Bisson, L.F. and Kunkee R.E. (1999) Viticulture for Winemakers. In: Principles and Practices of Winemaking. Springer, New York, NY, USA, pp.13-64.

16 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4

WINEMAKING WINE MATURATION WVJ

“…if cared for correctly [amphora] can last for decades, making them financially and environmentally attractive unlike oak barrels that must be replaced every four to five years. The initial outlay, however, is considerable…”

Photo: Bouchard Cooperages

Cooperages 1912 adds Maison Moussié to Collection of Premium Wine Barrel Brands

Tanunda (July 20, 2023) – Cooperages 1912 is growing their collection of premium wine barrel brands with the addition of Maison Moussié. Made with a noventique style – which combines innovation and authenticity – Maison Moussié creates luxury barrels positioned for high-end wines. Founded by Thomas Moussié, the company was acquired in September 2022 and will be the fifth premium barrel brand in the Cooperages 1912 collection.

Maison Moussié is best known for their Petra Collection. These barrels are toasted with a unique and patented heated stone toasting technology. The non-combustion process uses natural stones and water elements combined with heat to create barrels that are evenly toasted and consistent. Currently, lava rock and natural jade are being utilized for toasting material.

“Thomas Moussié has a unique approach to innovation, which can be seen in his heated stone toasting technology, that speaks to the innovative approach we’ve taken for decades at Cooperages 1912” said Mark Roberts, General Manager. “Innovation allows us to respond to the present and future needs of customers whose wine styles have continued to evolve. I believe Maison Moussié is an ideal fit with our current collection of wine barrel brands.”

Maison Moussié barrels are crafted in Bordeaux, using a specific wood supply that is seasoned in a dedicated area at the company owned mill in the North-East of France. From the exceptional forests of Tronçais, Bertranges and Bercé to the Centre-France region as well as other famous French forests, Maison Moussié sources the finest forests and tightest grains to craft their high-quality oak barrels.

“In aligning with Cooperages 1912, Maison Moussié will benefit from their exceptional savoir-faire and strong organization to accelerate its growth in Australia,” said Moussié.

Learn more about Maison Moussié from a Cooperages 1912 account manager or by visiting the website www.maisonmoussie.fr.

Cooperages 1912 offers a comprehensive collection of premium wine barrel brands:

Tonnellerie Quintessence, Tonnellerie Tremeaux, Maison Moussié, Heinrich Cooperage and World Cooperage. The Cooperages 1912 team consults directly with winemakers to ensure an optimal pairing between wine and barrel.

(ADVERTORIAL)

cooperages1912.com.au Cooperages 1912 59 Basedow Rd Tanunda SA 5352 +61 8 8563 1356

Understanding the effect of barrel-tobarrel variation on the colour and phenolic composition of a red wine

By Leonard Pfahl1,2, Sofia Catarino1*, Natacha Fontes3, António Graça3 and Jorge Ricardo-da-Silva1

Barrel-to-barrel

Ageing in oak barrels is a traditional and widespread practice in winemaking worldwide. Alternative containers, such as stainless steel tanks, concrete vessels, or polyethylene tanks, surpass barrels in some respects, like price, hygiene and material homogeneity. Nevertheless, barrels are still firmly established in quality wine production due to their positive influence on the organoleptic quality and complexity of wine1,2.

Various phenomena related to the physical and chemical characteristics of oak are directly responsible for these effects. First, there is water and ethanol non-negligible evaporation due to the porosity of the wood3, as well as some wine absorption by the wood (especially in new barrels).

Second, there is the transfer of extractable compounds, such as ellagitannins and volatile substances, like guaiacol, eugenol, ethyl- and vinyl-phenols, as well as oak lactones (ß-methyl-y-octalactone) and furfural (-derivates)4. The total amount, though, is limited and quickly reduced by the extraction process into wine5. The extracted substances influence sensations, such as astringency and mouthfeel, and increase aroma intensity and complexity.

Third, moderate oxygen permeation and diffusion through the wood promote different reactions of oxidation, polymerisation, copigmentation and condensation, involving anthocyanins and proanthocyanins, which stabilise the colour and reduce astringency. Storage in barrels accelerates the natural sedimentation of unstable colloidal matter, thus contributing to wine stability and limpidity2

Barrels are made from a natural product, wood. The most commonly used species are Quercus petraea (sessiliflora oak), Quercus robur (pedunculated oak) and their hybrids, and Quercus alba (white American oak). Locally, alternative botanical species, other than oak, may also be used6. Wood composition and the production process underlie a variation7

The main influencing factors are the oak species and origin of wood8, the seasoning and its location9, and the toasting process in the cooperage5

Barrels influence wine phenolic composition and colour development during ageing. For this reason, phenolic compounds are likely to be affected by barrel-to-barrel variation. This variation is widely known to winemakers, resulting in tastings and analytical control of individual barrels. Despite these facts, there is little to be found in the literature regarding barrel-to-barrel variation.

Variation of barrel influence can be problematic for analyses of barrel lots as it bears the potential of misinterpretation of results. This study aimed to shed light on the variable influence of barrels on wine colour, pigments and phenolic composition of woodaged wine. This trial stands out due to its practical background with a wine produced at winery scale. The large number of 49 barrel samples from four cooperages resulted in robust results (Figure 1).

EFFECT OF COOPERAGE ON BARREL-TOBARREL VARIATION

The Principal Component Analysis (Figure 2, see page 20) revealed overlapping areas

for all cooperages. It’s therefore consistent that no significant differences were found between the cooperages A, C and D for almost all analysed parameters.

However, for some analytical parameters cooperage B revealed significant differences between just one or two of the other cooperages but also, in a few cases, to all other cooperages1. Why cooperage B showed slightly different characteristics might originate in a smaller oxygen uptake through the wood and rifts between the staves9. Hence, this might be related to the cooperage’s production techniques and oak wood selection. To conclude, the wine aged for 12 months in different barrels varied in its phenolic and chromatic characteristics, but the cooperage of an individual barrel could not explain these variations.

Furthermore, it was checked if the cooperage had an influence on the barrelto-barrel variation by comparing the average coefficient of variation to the barrel-to-barrel variation of each cooperage.

The standard deviation ranged from 0.5 percent for general physical-chemical parameters, over 1.2% for most phenolic parameters, to 3.1% for pigments and 7.9% for anthocyanin-related parameters1. Due to the small standard deviations, it can be concluded that the cooperages do not differentiate from each other with practical relevance in their internal variation for most parameters analysed in this trial, with the exception of pigments and especially anthocyanin-related parameters.

18 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4 WINEMAKING WINE MATURATION

1Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food Research Centre, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal 2DLR – Dienstleistungszentrum Ländlicher Raum Rheinpfalz, Neustadt an der Weinstraße, Germany 3Sogrape Vinhos S.A., Portugal *Corresponding author: sofiacatarino@isa.ulisboa.pt

variation is familiar to winemakers, yet there is little in the literature regarding the phenomenon. Portuguese researchers set out to shed light on the influence of this variation on wine colour, pigments and the phenolic composition of a red wine produced at industrial scale from the grape variety Touriga Franca which was used to fill 49 new French oak barrels from four different cooperages with medium toasting levels.

HARVEST of Touriga Franca (Vitis vinifera L.), PDO Douro, Portugal, 2017 vintage

2 CONVENTIONAL RED WINEMAKING at industrial scale (28°C alcoholic fermentation; spontaneous malolactic fermentation)

3 BARREL FILLING

49 new barrels, 4 cooperages (Quercus petraea), medium toasting

4 12 MONTHS OF AGEING

T.: 15-18°C Humidity 75-85% S02 corrections were carried out periodically in order to keep a free S02 level of 40 mg/L, combined with topping up the barrels with wine of the same batch stored in a stainless steel tank.

5 SAMPLING

51 samples

6 CHEMICAL ANALYSIS

• General physical and chemical analysis (FTIR)

• Chromatic characteristics (CIELab parameters: H*, L *, C*, a* and b*)

• Anthocyanin-related parameters

• Total phenols

• Flavonoids and non-flavonoids phenols

• Tanning power

• Copigmentation

• Flavanol monomers, oligomeric proanthocyanidins and polymeric proanthocyanidins

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Principal components analysis (PCA), Variance analysis (ANOVA)

Investigates the relationships between barrels and assesses cooperage and individual barrel effect.

Coefficient of variation (CV )

Shows the degree of variability in relation to the population average. Identifies the variation from barrel to barrel and between the cooperages.

Required barrel samples

Can be seen as a translation of the observed variation of a parameter into a number of samples of a barrel lot needed to retain results of a certain reliability.

V38N4 WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 www.winetitles.com.au 19 WINE MATURATION WINEMAKING

1

7

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the ageing assay1 .

EFFECT OF BARREL ON BARREL-TOBARREL VARIATION

Chemical characteristics analysed in this experiment showed individual barrel-tobarrel variation with a range from 0.01% to 37.2%. General physical-chemical parameters showed the lowest barrel-to-barrel variation in the trial (always less than 2%).

Exceptions were volatile acidity and residual sugar; however, this variation is likely to originate in different microbiological activity and is not necessarily linked to the influence of the barrel. It can be concluded that the effect of barrel ageing on general characteristics, like density, alcoholic strength or total dry matter, is either small or similar, with less than the individual barrels2

The same is true for chromatic characteristics to a certain degree. On the other hand, the change from blue to yellow notes was prone to a higher variation, which is likely related to the variation found for anthocyanins. The observed variation for total pigments and polymerisation index led to the conclusion that polymerisation reactions are probably influenced by the barrel, most likely by a variance in the permeation of oxygen.

In summary, these findings indicate that the effect of barrel-to-barrel variation on the chemical parameters of a red wine depends on each specific parameter and is not uniform. In particular, anthocyanin content shows high variation between barrels in general and is, to a lesser degree, impacted by a cooperage1

BARREL SAMPLE REQUIREMENTS

Upon analysing a barrel lot filled with the same initial wine, one can ask, “How many barrels need to be analysed to get reliable results representative of all the wine in the different barrels if hypothetically racked and joined together in a big tank?”

The characteristics of this hypothetically racked wine from all the barrels is referred to as the “true barrel lot mean”.

Reliable results are a point of discussion as not every situation requires the same exactness of results. More analyses usually translate to increased accuracy but require more resources too. Therefore, for practical reasons, a compromise is often necessary. To be able to make this decision, it is beneficial to know the link between the analytical parameter in focus, the necessary number of barrel samples and the resulting accuracy of results.

The analytical parameter to be analysed plays a critical role as variation from barrel-to-barrel changes with different parameters, and the greater the variation, the more samples of a batch are needed to determine, in their average, the true barrel lot mean.

To investigate this link, a backwards calculation based on the high number of samples of this trial was conducted. The calculation requires a predefined desired precision for the results, which has been set at 2%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20%1. For better understanding, a precision of 10%, for example, means all results will be inside a range of 5% above and 5% below the true barrel lot mean.

The results revealed that all phenolic and chromatic characteristics, except for the tannin fractions analysis and anthocyaninrelated parameters, can be analysed with only two barrel samples per barrel lot at 20% accuracy. When increasing the exactness, more analytical parameters require larger sample numbers per barrel lot. At a 10-percent range around the true barrel lot mean, several analytical parameters require more than two barrels per lot, for example, total pigments and polymerisation index. At a 5% range around the true barrel lot mean, only clarity, tonality and

colour due to copigmentation, as well as most physical-chemical parameters, can be analysed with up to two barrels per lot.

General physical-chemical parameters required the smallest samples due to low barrel-to-barrel variation. To achieve reliable results (5% around the true barrel lot mean) for the analysis of general wine characteristics and wine colour, in most cases between one to three barrels per barrel lot are sufficient. Analytical parameters influenced by wine maturation, such as the formation of polymeric pigments, polymerisation of phenolics and especially anthocyanin-related parameters, require more samples per barrel lot; otherwise, a reduction in the accuracy of the results needs to be accepted.

LIMITS OF THE STUDY

This experiment included only new barrels with the same toasting level while for barrel lots of different age and toasting levels, a qualified statement cannot be made. The number of barrel samples needed to analyse volatile acidity and residual sugar in a barrel lot should be calculated with care because these parameters are influenced not only by the barrel but by many other factors.

20 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 V38N4 WINEMAKING WINE MATURATION

Figure 2. Principal Component Analysis performed on wines aged in oak barrels from the cooperages A, B, C and D and bottle-matured wine in a total of 50 wines. The wines are represented in the plane of the two first components which express, respectively, 49 percent and 18 percent of the total variation.

Therefore, in practice, analyses of these two parameters might need different barrel sample amounts.

CHEMICAL PARAMETERS DIFFER IN THEIR VARIATION

It could be shown that the influence of an individual barrel on barrel-to-barrel variation on wine phenolics and pigments was greater than the influence of the manufacturing cooperage. The chemical parameters analysed in this study were prone to barrel-to-barrel variation at individual levels, overall ranging from almost 0% up to 37%. Parameters related to anthocyanins in particular were found to have a high barrelto-barrel variation.

Barrel-to-barrel variation of a chemical parameter influences the required sample size needed per analysed batch. Detailed recommendations on the required sample size for certain chemical parameters at different levels of accuracy were calculated

and can be used as an aid to generate measurements involving barrel lots.

REFERENCES

1Pfahl, L.; Catarino, S.; Fontes, N.; Graça, A. and Ricardo-Da-Silva, J. (2021) Effect of barrel-to-barrel variation on colour and phenolic composition of a red wine. Foods 10(7):1669, https://doi.org/10.3390/ foods10071669

2Waterhouse, A.L.; Sacks, G.L. and Jeffery, D.W. (2016) Understanding Wine Chemistry; 1st ed.

3Ruiz De Adana, M.; López, L.M.; Sala, J.M. and Fickian, A. (2005) A Fickian model for calculating wine losses from oak casks depending on conditions in ageing facilities. Appl. Therm. Eng. 25:709-718, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2004.07.021

4Towey, J.P. and Waterhouse, A.L. (1996) Barrelto-barrel variation of volatile oak extractives in barrelfermented Chardonnay, Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 47:17-20, doi: 10.5344/ajev.1996.47.1.17

5Chira, K. and Teissedre, P.L. (2013) Relation between volatile composition, ellagitannin content and sensory perception of oak wood chips representing different toasting processes. European Food Research & Technology 236:735-746, doi:10.1007/ s00217-013-1930-0.

Cooperages 1912 names Mark Roberts as new General Manager

Tanunda (June 20, 2023) – Cooperages 1912 announces the appointment of Mark Roberts as general manager, starting from July 1, 2023. He will be taking over management responsibilities for Patrick Schwerdt who served as a General Manager from 1997 to 2023. Patrick will now be selling spirit barrels.

With over 21 years’ of experience working for Cooperages 1912, Mark Roberts was an account manager for Oak Solutions Group, a sister company offering innovative oak products and tannins to winemakers and distillers. With his new position, Mark will be leading both wine barrels and oak products sales management activities in Australia. As General Manager of Cooperages 1912, he will also be responsible for overseeing all aspects of operational functions of the company, including the local production of Heinrich Cooperage barrels. Leading a team dedicated to elevate experiences, Mark Roberts and the Cooperages 1912 employees will work together to deliver high-quality products and services to the winemakers.

Commenting on his promotion, Mark Roberts said: “I am excited to be leading our Australasian team into the future. In this day and age, you need to rapidly evolve, be dynamic and adaptive to succeed. I feel that Cooperages 1912 has been on this trajectory of evolution to be ahead of the curve.”

“We are very pleased to have Mark Roberts and Patrick Schwerdt moving to these new positions and have them representing Independent Stave Company on both the wine and spirit sides,” said Franck Renaudin, Director of Artisan Cooperages and International Sales. “This will benefit both our company and customers, as the need for high-quality oak barrels and other cooperage products continues to grow”.

Before embarking on his career with Cooperages 1912, Mark completed vintages in Australia and overseas before graduating from Adelaide University studying Wine Marketing. Currently, Mark is studying an MBA at Adelaide University.

Cooperages 1912, a subsidiary of Independent Stave Company, offers a comprehensive collection

6Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV) International Code of Oenological Practices; Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin (OIV): Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 9791091799737.

7Mosedale, J.R.; Puech, J.L. and Feuillat, F. (1999) The influence on wine flavour of the oak species and natural variation of heartwood components. Am. J. Enol & Vitic. 50:503-512.

8Miller, D.P.; Howell, G.S.; Michealis, C.S. and Dickmann, D.I. (1992) The content of phenolic acid and aldehyde flavour components of white oak as affected by site and species. Am. J. Enol. & Vitic. 43:333-338.

9Martínez, J.; Cadahía, E. and Fernández De Simón, B.; Ojeda, S. and Rubio, P. (2008) Effect of the seasoning method on the chemical composition of oak heartwood to cooperage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56:3089-3096, doi:10.1021/jf0728698.

This article was originally published in the May 2023 issue of the US-based Wine Business Monthly and is a summary of a much larger peer-reviewed article published in the scientific journal Foods, https://doi.org/10.3390/ foods10071669. WVJ

of premium wine barrel brands: Tonnellerie Quintessence, Tonnellerie Tremeaux, Maison Moussié, Heinrich Cooperage and World Cooperage. Cooperages 1912 also offers innovative oak products and tannins with sister company Oak Solutions Group as well as ISC spirit barrels.

Cooperages 1912

59 Basedow Rd, Tanunda SA 5352 +61 8 8563 1356

cooperages1912.com.au

(ADVERTORIAL)

V38N4 WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING 2023 www.winetitles.com.au 21 WINE MATURATION WINEMAKING

Consumer response to wine made from smoke-affected grapes

By Eleanor Bilogrevic, WenWen Jiang, Julie Culbert, Leigh Francis, Markus Herderich and Mango Parker, The Australian Wine Research Institute, Urrbrae South Australia 5064

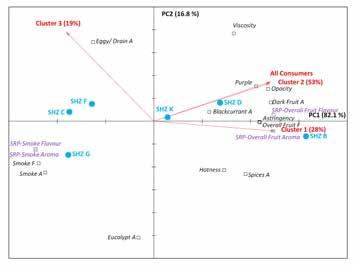

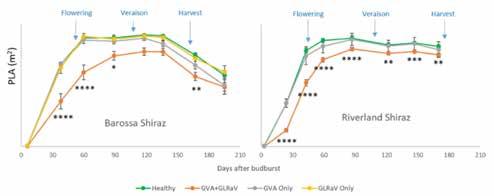

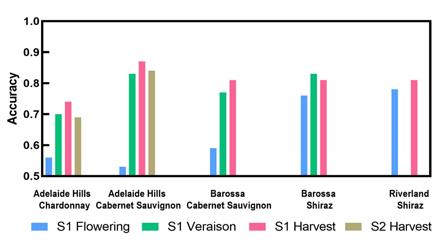

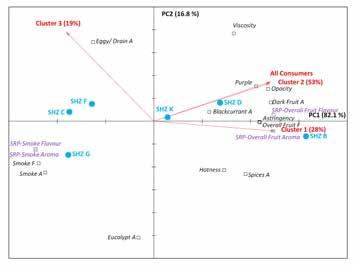

Consumer studies using three different sets of smoke-affected wines have delivered a clearer picture of the consumer acceptance of smoke characters in wine. The data will help producers make informed decisions about how best to manage smoke-affected wines, taking into account likely consumer responses.

IN BRIEF

INTRODUCTION

The increasing frequency of wildfires and total area burned globally has been linked to climate change as the main driver (Canadell et al. 2021, Richardson et al. 2022). Wine produced from grapes in vineyards exposed to smoke from nearby grass or forest fires can exhibit strong smoky aromas and flavours due to orthonasal and retronasal smoky odours (Parker et al. 2012). Commonly referred to as ‘smoke taint’, these characters are considered highly undesirable by winemakers. The losses to the Australian wine sector due to smoke from wildfires and prescribed burns have been estimated at $1.4 billion AUD since 2003 (Krstic et al. 2021).

The issue is also a challenge for the global wine industry and has caused significant quality defects and economic impacts in recent years throughout Europe, California and South America (Mirabelli-Montan et al. 2021).

There are a broad range of descriptors attributed to smoke taint in wine, such as smoky, medicinal, campfire ash, plastic and burnt aromas; and ash tray, drying and bitter and a lingering ashy aftertaste on palate (Krstic et al. 2015, Parker et al. 2012, Ristic et al 2011). Some smoky flavour can also be found in wines that have not been exposed to smoke, due to other processing and maturation steps, notably the use of oak barrels that have been toasted or charred using a flame (Francis and Williamson 2015, Koussissi et al. 2009, Prida and Chatonnet 2010). Toasted oak can impart volatile phenols to a wine, particularly guaiacol,

4-methylguaiacol and syringol (Chatonnet et al 1999), which are produced during oak toasting from the same lignin degradation process that occurs when wood smoke is generated (Pollnitz et al. 2004, Spillman et al. 2004). Other common wine flavours that can be present in non-smoke-affected wines and can be confused with smoke taint have been described as medicinal, burnt rubber and leather, which are generally considered negative attributes (Lattey et al. 2010, Wedral et al. 2010).

The chemical basis for the smoky characters in wildfire smoke-affected wines is complex, with a large number of compounds implicated. The compounds most associated with smoke-affected wines are volatile phenols (originating from smoke) and phenolic glycosides (produced in grapes by the addition of sugar units to the volatile phenols).

These volatile phenols impart smoky aroma and flavour, and include guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol, o-cresol, m-cresol, p-cresol, syringol and 4-methylsyringol (Parker et al 2012).

A large number of phenolic glycosides have been identified in smoke-exposed wines (Caffrey et al. 2019, Hayasaka et al. 2010), and routine markers for smoke exposure of grapes include syringol gentiobioside (SyGG), methylsyringol gentiobioside (MSyGG), phenol rutinoside (PhRG), guaiacol rutinoside (GuRG), cresol rutinosides (rutinosides of o-cresol, m-cresol and p-cresol) (CrRG), and methylguaiacol rutinoside (MGuRG) (Hayasaka et al. 2013). Beyond their role as biomarkers

■ Three studies assessing sets of Pinot Noir rosé, Chardonnay and unoaked Shiraz wines with varied smoke flavour were conducted to investigate whether consumers respond negatively to smoky attributes.

■ Detailed data analysis revealed wine consumers fell into three categories: highly responsive to smoke, moderately responsive, and a smaller group of non-responders.

■ Overall, wines rated high in smoke flavour were less liked compared to non-smoke-affected wines.

■ Independent of wine type, there was a strong negative correlation between smoky flavour and overall consumer liking.

■ This information can guide assessments of risk from smoke exposure of grapes and potential for quality defects in wine, as well as identify and benchmark management options for wine producers.

indicating smoke exposure, the phenolic glycosides can also contribute to the flavour and lingering aftertaste of smoke-affected wines, by releasing odorants in-mouth during consumption or during extended periods of storage (Mayr et al. 2014, Parker et al. 2020). While the concentrations of volatile phenols and phenolic glycosides are regularly compared to concentrations found in nonsmoke exposed wines to determine whether

22 www.winetitles.com.au WINE & VITICULTURE JOURNAL SPRING

V38N4

2023

WINEMAKING

SMOKE TAINT

Scan here to see more information about Sumitomo products www.sumitomo-chem.com.au ® Registered trademarks. ™ Trademark. DiPel BIOLOGICAL INSECTICIDE ® H E R B I C I D E

there is evidence of smoke exposure (Coulter et al. 2022), the exact relationship between chemical composition and concentration, and the intensity of smoky flavours in wine is complex (Parker et al. 2023). Highly smokeaffected grapes can result in wines with strong smoky flavours and high concentrations of volatile phenols and/or glycosides.

For wine made from mildly smoke-affected grapes, smoky flavours are not always evident. A recent study based on over 60 unique smoke-affected Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Shiraz wines found that statistical models based on guaiacol, o-cresol, m-cresol, p-cresol, and some glycosides gave good predictions of smoke flavour intensity, with a slightly different optimal model for each cultivar (Parker et al. 2023). In the absence of robust chemical models for predicting smoky flavours in other cultivars and wine styles, sensory analysis remains a critical tool to determine whether a wine has quality defects or is acceptable.