Annual Supplement to Gastroenterology & Endoscopy

Crypt Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus: An Update Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Identifying High-Risk Patients

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Treatment Options for High-Risk Patients Treatment of Nonachalasic Esophageal Motor Disorders

Improving Bowel Preparation For Inpatient Colonoscopy: A Proactive Approach Comparison of 2021 IDSA and ACG Recommendations for Treatment of C. difficile Infection

SPOTLIGHT SECTIONS: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Scope Reprocessing and Infection Control GI Nutrition Emerging AI Applications In Gastroenterology

2022

gastroendonews.com

News •

Elevating the Standard

Visit medical.olympusamerica.com/getready

Pending 510(k); not available for sale in the United States. Olympus may not take orders that might result in contracts for the sale of the device until clearance is achieved.

9 Crypt Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus: An Update 15 Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Identifying High-Risk Patients 23 Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Treatment Options for High-Risk Patients 43 Treatment of Nonachalasic Esophageal Motor Disorders 53 Improving Bowel Preparation for Inpatient Colonoscopy: A Proactive Approach 89 Comparison of 2021 IDSA and ACG Recommendations for Treatment of C. difficile Infection SPOTLIGHT SECTIONS: 35 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease 63 Inflammatory Bowel Disease 75 Scope Reprocessing and Infection Control 82 GI Nutrition 93 Emerging AI Applications in Gastroenterology gastroendonews.com Annual Supplement to Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News • 2022 GASTROENDONEWS.COM4

GASTROENTEROLOGIST† RECOMMENDED Brands for Digestive Health FREQUENT HEARTBURN Recommend PRILOSEC OTC® For 24 Hour Relief With 1 Pill Each Morning^ * THESE STATEMENTS HAVE NOT BEEN EVALUATED BY THE FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION. THIS PRODUCT IS NOT INTENDED TO DIAGNOSE, TREAT, CURE, OR PREVENT ANY DISEASE. † Based on ProVoiceTM Surveys 2022. Prilosec OTC®: Frequent Heartburn Medicine / OTC Acid Reducer Category. Metamucil®: OTC Therapeutic Fiber category. Align®: Probiotic Category. ^ It’s possible while taking Prilosec OTC. Use as directed for 14 days to treat frequent heartburn. May take 1-4 days for full effect. DAILY FIBER SUPPLEMENT Recommend METAMUCIL® To Help With Occasional Constipation*. DAILY PROBIOTIC SUPPLEMENT Recommend ALIGN® to help with occasional:* · Abdominal discomfort · Gas · Bloating PSYLLIUM FIBER SUPPLEMENT ®

EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD

ANDREW ALBERT, MD, MPH Chicago, Illinois

MANOOP S. BHUTANI, MD Houston, Texas

BROOKS D. CASH, MD Houston, Texas

ALINE CHARABATY, MD, AGAF Washington, D.C.

AUSTIN CHIANG, MD, MPH Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

ALAN F. CUTLER, MD Farmington Hills, Michigan

SARAH ENSLIN, PA-C Rochester, New York

RONNIE FASS, MD, MACG Cleveland, Ohio

HARISH K. GAGNEJA, MD Austin, Texas

FRANK G. GRESS, MD New York, New York

VIVEK KAUL, MD, FACG, FASGE, AGAF Rochester, New York

GARY R. LICHTENSTEIN, MD Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

JENIFER R. LIGHTDALE, MD, MPH Worcester, Massachusetts

DANA J. LUKIN, MD, PH D, FACG New York, New York

PETER R. MCNALLY, DO Fort Carson, Colorado

KLAUS MERGENER, MD, PH D, MBA Tacoma, Washington

SATISH RAO, MD,PHD Augusta, Georgia

JOEL E. RICHTER, MD Tampa, Florida

DAVID ROBBINS, MD New York, New York

ELLEN J. SCHERL, MD New York, New York

PRATEEK SHARMA, MD Kansas City, Kansas

JEROME H. SIEGEL, MD New York, New York

ASHWANI K. SINGAL, MD, MS Sioux Falls, South Dakota

EDITORIAL STAFF

SARAH TILYOU Managing Editor smtilyou@mcmahonmed.com

MEAGHAN LEE CALLAGHAN Associate Editor lgray@mcmahonmed.com

LANDON GRAY Assistant Editor mcallaghan@mcmahonmed.com

JAMES PRUDDEN Vice President, Editorial

DAVID BRONSTEIN DONALD M. PIZZI Editorial Directors

ELIZABETH ZHONG KRISTIN JANNACONE Senior Copy Editors SALES STAFF

MATTHEW SPOTO Publication Director mspoto@mcmahonmed.com

DON POPOWSKI Account Manager dpopowski@mcmahonmed.com

CRAIG WILSON Sales Associate, Classified Advertising cwilson@mcmahonmed.com

JOSEPH MALICHIO Vice President, Medical Education jmalichio@mcmahonmed.com

ART AND PRODUCTION

MICHELE MCMAHON VELLE Creative Director

JEANETTE MOONEY Senior Art Director

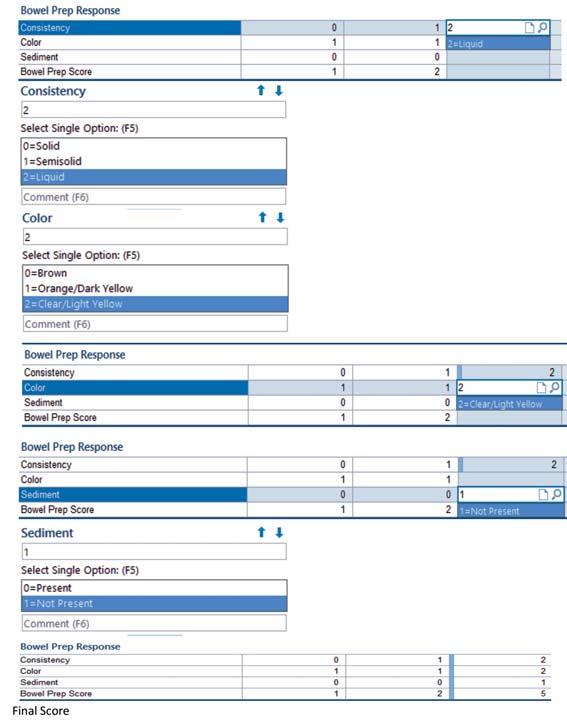

JAMES O’NEILL Senior Systems Manager

RON REDFERN Production Manager

ROB SINCLAIR Circulation Manager

MCMAHON PUBLISHING

VAN VELLE President, Partner MATTHEW MCMAHON General Manager, Partner

LAUREN SMITH MICHAEL P. MCMAHON MICHELE MCMAHON VELLE Partners

RAY AND ROSANNE MCMAHON Co-founders

DISCLAIMER—The reviews in this issue are designed to be a summary of information, and they represent the opinions of the authors. Although detailed, the reviews are not exhaustive. Readers are strongly urged to consult any relevant primary literature, the complete prescribing information available in the package insert of each drug, and the appropriate clinical protocols. No liability will be assumed for the use of these reviews, and the absence of typographical errors is not guaranteed. Copyright © 2022 McMahon Publishing Group, 545 West 45th Street, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10036. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form.

GASTROENDONEWS.COM6

Diagnose foodborne illness in minutes, not days Campylobacter results in 15 minutes with Sofia 2 Accurate, objective and automated results in 15 minutes for Campylobacter with Sofia 2 fluorescent immunoassay technology. Detects four of the most prevalent Campylobacter species including C. jejuni, C. coli, C. lari and C. upsaliensis with excellent performance compared to culture. Sofia 2 Campylobacter FIA • Simple, flexible workflow with dual mode testing • Various sample types including fresh, frozen, Cary Blair or C&S • LIS Connectivity • Room Temperature Storage For more information contact Quidel Inside Sales at 858.431.5814 Enhanced diagnostics featuring data analytics and surveillance AD20352100EN00 (02/22)

truFreeze RFA-F RFA-C Pre ProcedureImmediately Post Procedure48 Hours Post Procedure 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 1. Solomon, SS. et. al. Liquid Nitrogen Spray Cryotherapy Is Associated With Less Postprocedural Pain Than Radiofrequency Ablation in Barrett’s Esophagus: A Multicenter Prospective Study. Journal Clinical Gastroenterology. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb;53(2):e84-e90. © 2022 STERIS Corporation. All rights reserved. All company and product names are trademarks of STERIS Corporation, its affiliates or related companies, unless otherwise noted. Offer your Barrett’s Esophagus patients an ablation option that is proven to be less painful1... Pain intensity scores and the presence of dysphagia assessed for LNC vs. RFA1 For more information, visit www.steris.com/trufreeze. A recent multicenter prospective study shows patients undergoing Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) had at least 5 times greater odds of experiencing pain compared with the Liquid Nitrogen Cryotherapy (LNC) group.1 Clinically proven to reduce post-procedure pain when compared to other modalities of ablation for Barrett’s esophagus and cancer. Spray Cryotherapy System

Crypt Dysplasia In Barrett’s Esophagus: An Update

ZOE LAWRENCE, MD SETH A. GROSS, MD

NYU Langone Health New York, New York

ZOE LAWRENCE, MD SETH A. GROSS, MD

NYU Langone Health New York, New York

Endoscopic

surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus can help diagnose cellular changes and prevent progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Given that surveillance intervals are determined by the degree of dysplasia, an understanding of the significance of the findings is crucial.

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 9 PRINTER-FRIENDLY VERSION AVAILABLE AT GASTROENDONEWS.COM

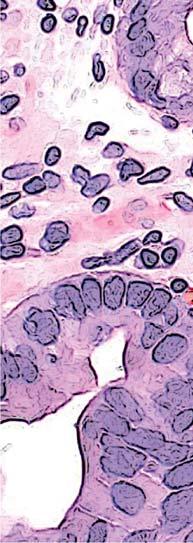

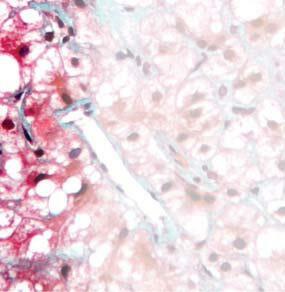

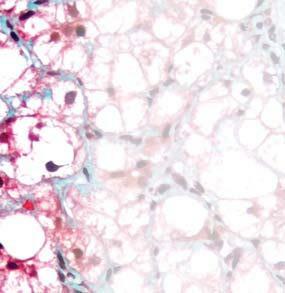

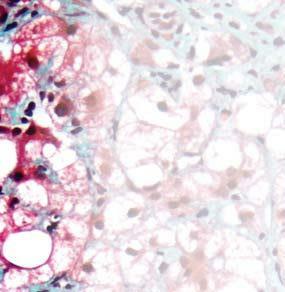

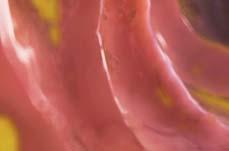

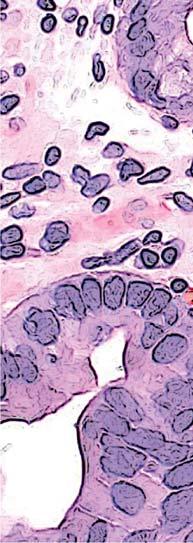

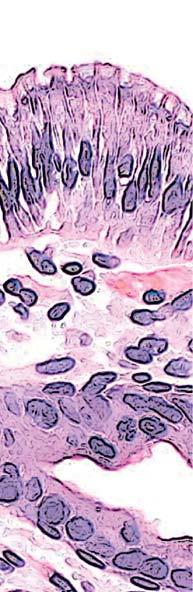

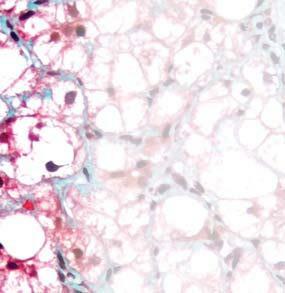

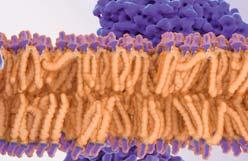

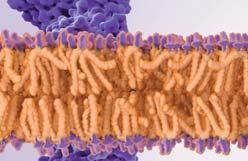

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is defined as the presence of columnar mucosa with intestinal metaplasia of at least 1 cm within the esophagus.1 Up to 7% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease have histologically confirmed BE, with prevalence highest in South America, followed by North America, and lowest in Asia.2 As a precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), BE represents a premalignant state.3 The pathway from a healthy esophagus to cancer includes progression from erosive esophagitis to nondysplastic BE, then to lowgrade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), adenocarcinoma in situ, and culminates with invasive adenocarcinoma (Figures 1-3).4 As the seventh leading cause of cancer-related death among men in the United States, esophageal cancer is the subject of much research, and the early detection of changes along this dysplasia-to-carcinoma sequence can be lifesaving.5

In 2021, there were an estimated 19,260 new cases of esophageal cancer diagnosed in the United States and approximately 15,530 esophageal cancer deaths.5 Surveillance of BE can help diagnose cellular changes and prevent progression to EAC, but guidelines on endoscopic surveillance intervals are dictated by the degree

of dysplasia identified.1 Thus, an understanding of the significance of the findings is required.

Under the microscope, dysplasia is characterized by architectural and cytological abnormalities. When dysplastic changes are seen in the crypt bases with preserved surface maturation, pathology will be labeled as basal crypt dysplasia or indefinite for dysplasia (IND).6,7 Significant research has gone into understanding the importance of crypt dysplasia, and we discussed the contributions to the literature on crypt dysplasia in a previous review ( Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News 2019;72[7]:1-4). In this current review, we discuss advances that have been made in the past 2 years that clarify the implication of these findings.

Inflammation Versus Dysplasia

The cellular abnormalities that define crypt dysplasia can sometimes be attributed to inflammation or technical issues with specimen handling. Crush artifact and heat damage, such as the damage sustained from cautery, can lead to lack of surface epithelium or damage to the surface and inability to accurately assess the surface maturation.8,9 Similarly, crypt dysplasia or IND will often be used when there is a background of inflammation. However, unlike true dysplasia, inflammation, granulation tissue, and mucosal erosion do not cause DNA abnormality or aneuploidy. Therefore, it has been proposed that DNA content abnormality can be used for the risk stratification when IND is diagnosed. Choi et al found DNA content abnormality in 21 patients with biopsy consistent with IND, 90.5% had normal DNA, and only 1 of those patients developed HGD. The other 9.5% had abnormal DNA and developed HGD or EAC within 2 years. The research demonstrates that evaluation for DNA abnormality can differentiate true crypt dysplasia from the cellular abnormalities caused by inflammation or technical issues.8

In addition to aneuploidy alone, mutational load, or the measure of genetic aberration and instability, can be used to risk-stratify patients with IND and differentiate between those with inflammation and those with dysplasia. In a retrospective study of 28 patients with baseline IND, 88% of those who progressed to LGD or HGD had a mutational load of at least 0.5. The sensitivity and specificity for identifying patients who would progress to HGD were 100% and 85%, respectively, when using a baseline mutational load of at least 1.5. Based on this research, mutational load also can help risk-stratify patients with IND.10

More specific investigation into the cellular abnormalities that may be present in dysplasia has included assessing the presence of abnormal tumor suppressor gene p53 via immunohistochemistry among patients with BE. Redston et al found that 90% of IND patients who progressed to advanced disease had abnormal p53 compared with just 15.4% of nonprogressors.11 Patients with abnormal p53 within IND samples progressed with similar rates to patients with LGD, whereas patients with IND and normal p53 had much lower progression

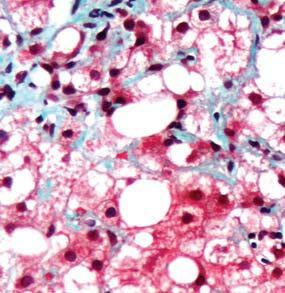

Figure 1. Basal crypt dysplasia. The surface is mature; however, deep glands have increased mitotic activity, cribriform architecture, and luminal debris.

Image courtesy of Yvelisse Suarez, MD.

GASTROENDONEWS.COM10

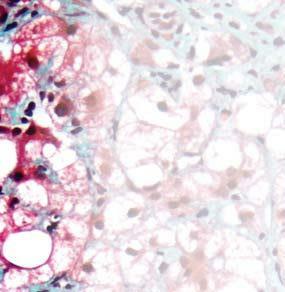

Image courtesy of Yvelisse Suarez, MD.

rates. Since abnormal p53, like high mutational load and abnormal DNA, would not be expected to be seen in nondysplastic inflamed or damaged tissue, its presence may help differentiate between those samples with IND that are on the pathway to progression versus those that are simply inflamed.

Updates to the Literature

Most of the recent literature on crypt dysplasia in BE consists of retrospective studies. One exception is a multicenter prospective cohort study from Philips et al assessing the risk for neoplasia among patients with IND.9 They found that 24% of patients with IND developed dysplasia. In this study, length of the BE segment was the only significant risk factor for progression to neoplasia. Similarly, Shaheen et al found a correlation between BE segment length and rate of progression from crypt dysplasia to HGD or EAC.12 In this study, of 128 patients with crypt dysplasia, 3 progressed to HGD or EAC, with a progression rate of 1.42% per patient-year. Henn et al found an annual progression rate of 0.98 cases per 100 patient-years from IND to HGD or EAC among a retrospective cohort of 107 patients with IND.13 However, all cases of HGD or EAC were discovered within 1 year of initial IND diagnosis, reinforcing

the need for surveillance EGD within 6 months of IND diagnosis. Among this cohort, 18.7% of patients developed LGD within a median follow-up of 2.39 years. Of note, patients with persistent IND on repeat endoscopy had a higher rate of progression, with 36% developing LGD.

One of the main challenges with understanding IND is determining whether it has a place along the metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence. One retrospective single-center Barrett’s registry showed that the rate of progression to HGB and EAC was higher among patients with IND than among those with nondysplastic BE, and was lower in patients with IND than those with LGD.14 This pattern suggests that IND may fall along this spectrum and perhaps represents a midway point between nondysplastic BE and LGD.

To date, there is only 1 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the risk for progression in BE-IND. Pooling data from 8 studies with 1,441 patients, Krishnamoorthi et al found an incidence of HGD and/ or EAC of 1.5 per 100 patient-years.15 This rate is similar to the rate of progression in LGD, and the authors point out that, given the similar rate of progression as LGD, there may be a role for endoscopic therapy for IND in the future.

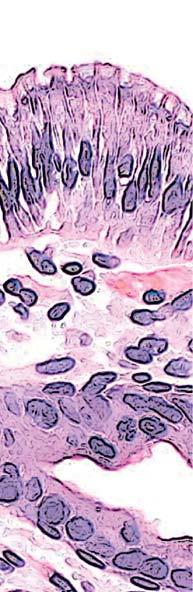

Figure 2. Low-grade dysplasia. Hyperchromatic nuclei extend to the surface, with maintenance of polarity.

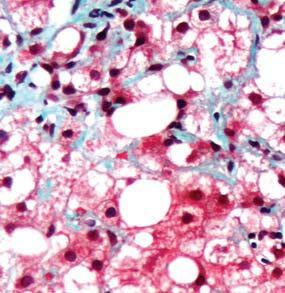

Figure 3. High-grade dysplasia. Crowded irregular glands with hyperchromatic nuclei extending to the surface, with loss of polarity.

Image courtesy of Yvelisse Suarez, MD.

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 11

Guidelines Recommendations

The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines for BE recommend that when pathology is indefinite for dysplasia, the patient should be started on twice-daily proton pump inhibitors and undergo repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) within 6 months.1 This recommendation has been modified from the 2015 recommendation to repeat EGD within 3 to 6 months.16 When IND is identified on the surveillance EGD within 6 months, repeat endoscopy should be performed annually.1

In comparison, patients with nondysplastic BE can wait 3 to 5 years for their next EGD, depending on the length of the segment of BE.1 This shorter interval means that patients with crypt dysplasia will have more surveillance endoscopies than those without dysplasia; although endoscopy is a safe procedure, it is not without risks, including the risks of anesthesia. Understanding of the significance of crypt dysplasia,

References

1. Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: an updated ACG guideline. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(4):559-587.

2. Eusebi LH, Cirota GG, Zagari RM, et al. Global prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer in individuals with gastro-oesophageal reflux: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2021;70(3):456-463.

3. Coron E, Robaszkiewicz M, Chatelain D, et al. Advanced precancerous lesions in the lower oesophageal mucosa: high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27(2):187-204.

4. Coleman HG, Xie SH, Lagergren J. The epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2018;154(2):390-405.

5. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33.

6. Coco DP, Goldblum JR, Hornick JL, et al. Interobserver variability in the diagnosis of crypt dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(1):45-54.

7. Lomo LC, Blount PL, Sanchez CA, et al. Crypt dysplasia with surface maturation: a clinical, pathologic, and molecular study of a Barrett’s esophagus cohort. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30(4):423-435.

8. Choi WT, Tsai JH, Rabinovitch PS, et al. Diagnosis and risk stratification of Barrett’s dysplasia by flow cytometric DNA analysis of paraffin-embedded tissue. Gut. 2018;67(7): 1229-1238.

9. Phillips R, Januszewicz W, Pilonis ND, et al. The risk of neoplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus indefinite for dysplasia: a multicenter cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc 2021;94(2):263-270.e2.

therefore, has downstream effects on patient safety and healthcare costs.15

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline for screening and surveillance of BE does not contain specific guidance regarding interpretation or management of crypt dysplasia, but it notes that patients with crypt dysplasia may be at a higher risk for progression and points out that further research is needed to clarify the natural history of crypt dysplasia.17

Despite additional research over the past several years, the role that crypt dysplasia plays in the metaplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence from BE to EAC remains ambiguous. It is clear that crypt dysplasia carries with it a risk for progression to HGD and EAC, and strides have been made toward understanding the nuances of this complex diagnosis. Further investigation and high-quality, prospective research on the significance of IND is necessary to elucidate the importance and management of this finding.

10. Trindade AJ, McKinley MJ, Alshelleh M, et al. Mutational load may predict risk of progression in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus and indefinite for dysplasia: a pilot study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6(1):e000268.

11. Redston M, Noffsinger A, Kim A, et al. Abnormal TP53 predicts risk of progression in patients with Barrett’s esophagus regardless of a diagnosis of dysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(2):468-481.

12. Shaheen NJ, Smith MS, Odze RD. Progression of Barrett’s esophagus, crypt dysplasia, and low-grade dysplasia diagnosed by wide-area transepithelial sampling with 3-dimensional computer-assisted analysis: a retrospective analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95(3):410-418.e1.

13. Henn AJ, Song KY, Gravely AA, et al. Persistent indefinite for dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus is a risk factor for dysplastic progression to low-grade dysplasia. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33(9):doaa015.

14. O’Byrne LM, Witherspoon J, Verhage RJJ, et al. Barrett’s Registry Collaboration of academic centers in Ireland reveals high progression rate of low-grade dysplasia and low risk from nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: report of the RIBBON network. Dis Esophagus. 2020;33(10):doaa009.

15. Krishnamoorthi R, Mohan BP, Jayaraj M, et al. Risk of progression in Barrett’s esophagus indefinite for dysplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91(1):3-10.e3.

16. Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(1):30-50; quiz 51.

17. Qumseya B, Sultan S, Bain P, et al. ASGE guideline on screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(3):335-359.e2.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Copyright © 2022 McMahon Publishing, 545 West 45th Street, New York, NY 10036. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form. GASTROENDONEWS.COM12

Which Barrett’s esophagus patient is likely to progress to high grade dysplasia or esophageal cancer?

Two non-dysplastic patients nearly identical by pathology and clinical risk factors

NDBE 4cm

Hiatal Hernia No Lesions

NDBE 3cm

Hiatal Hernia

Lesions

TissueCypher Score / Risk Class 3.6 / Low Risk

Five-year Progression Risk 2.1% Outcome Progression-free for 6.7 years

The FIRST and ONLY precision medicine test that:

•Predicts future development of esophageal cancer in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (BE)

TissueCypher Score / Risk Class 9.6 / High Risk Five-year Progression Risk 21.4% Outcome Progressed to HGD in 2.7 years following baseline

•Is an INDEPENDENT risk predictor from tissue histology and other clinical risk factors

•Transforms patient management by enabling upstaging or downstaging based on individual patient risk

Know your patient’s individual risk of progression to esophageal cancer

LEARN MORE AT TISSUECYPHER.COM

© 2022 Castle Biosciences. TissueCypher Barrett’s Esophagus Assay is a trademark of Castle Biosciences Inc.TC-015v3 – 042122

No

VELACURTRANSIENT ELASTOGRAPHY 2X MORE DEPTH 30X MORE VOLUME Volume SampledMeasurement Depth 15 12 9 6 3 0 100 cm3 80 cm3 60 cm3 40 cm3 3 cm3 0 cm3

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Identifying High-Risk Patients

ASHWANI K. SINGAL, MD, MS, FACG, FAASLD, AGAF

Professor of Medicine Department of Medicine University of South Dakota

Sanford School of Medicine

Transplant Hepatologist

Avera McKennan University Hospital Chief, Clinical Research Avera Transplant Institute Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Nonalcoholic

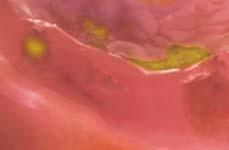

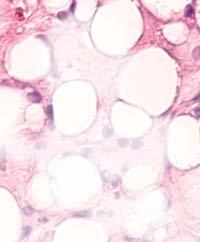

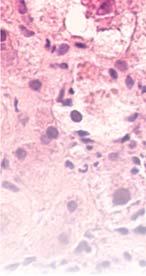

fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by excessive fat deposition in the liver in the absence of other causes of liver disease, including harmful consumption of alcohol.1 The disease spectrum ranges from nonalcoholic fatty liver or hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)—characterized by hepatic inflammation and steatosis with or without fibrosis—to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2-4

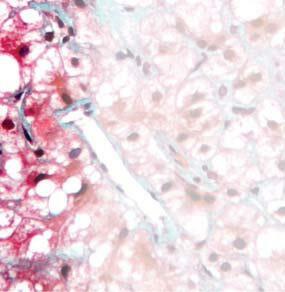

Fibrotic liver Formation of scar tissue within the liver

Cirrhotic liver Scarred tissue replaces healthy tissue in the liver

Liver cancer Formation of malignant tumor in the liver

Liver Steatosis Enlarged liver due to fat deposits

Fibrotic liver Formation of scar tissue within the liver

Cirrhotic liver Scarred tissue replaces healthy tissue in the liver

Liver cancer Formation of malignant tumor in the liver

Liver Steatosis Enlarged liver due to fat deposits

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 15

NASH is the second-leading indication for liver transplantation in the United States5 and likely will become the main indication in the future.6 It also is the fastest-growing reason for simultaneous liver–kidney transplantation, acute-on-chronic liver failure–related hospitalization, and HCC.7-9 NAFLD also is the most common long-term complication in liver transplant recipients.10

This review, part 1 of a 2-part series, focuses on NASH, given its clinical significance and greater effects on patient outcomes, discussing how to identify patients who are at risk for advanced fibrosis. Part 2 discusses ongoing clinical trials with new therapeutic targets (See page 23).

Targeting High-Risk Patients

Patients with NAFLD usually are asymptomatic.11 The most common clinical presentations include incidental elevations in aminotransferases, steatosis on imaging, or a new diagnosis of cirrhosis.12 About 15% to 20% of NAFLD patients who develop NASH are at risk for progression to cirrhosis and liver-related mortality.13 Hence, identification of these patients is crucial so they can be targeted for close follow-up and treatment.

Clinical predictors of NASH are advancing age,

adiposity, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).11 Aminotransferases may be normal in

obesity, visceral

Table. Pooled Performance of Serologic- and Radiological-Based Noninvasive Assessment of Fibrosis for NAFLD Test Significant fibrosis (F2-F4) Advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) Cirrhosis (F4) Cutoff valueAUC Sensitivity/ specificity, % PPV/ NPV, % Cutoff valueAUC Sensitivity/ specificity, %PPV/NPV Cutoff valueAUC Sensitivity/ specificity, % PPV/ NPV Serologic biomarkers APRI 0.43-1.50.759/7768/–0.540.98 0.7569/7361/900.54-2.00.75 56/8438/–FIB-4 0.373.25 0.7564/7073/–1.241.45 0.8 78/7140/851.92-2.480.8576/8239/–NFS –1.10.7266/8382/––1.4550.7873/7450/92–0.0140.8380/8143/–BARD 20.8144/7050/6520.8875/6238/8930.8352/8425/ 94 HFS 0.470.8574/9776/92 ELF 0.570.9 45/9585/–1.6450.9330/–87/–NANANANA MLA 0.90.9970.989 Radiological biomarkers TE 6.7-7.00.8274/5963/857.6-8.00.8689/7743/9610.3-11.30.9483/8647/ 98 ARFI/ pSWE 0.8474/900.9592/910.9792/91 2D-SWE 2.7-9.40.8990/9288/933.010.6 0.9190/9288/933.360.92100/8655/ 100 MRE 3.4-3.620.8873/9183/86 3.6-4.80.9386/9171/93 4.2-6.70.9287/9353/ 99 MEFIB 0.90 APRI, AST–to-platelet ratio index; ARFI, acoustic radiation force imaging; AUC, area under the curve; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; MEFIB, MRE+FIB-4 combination; MLA, machine learning algorithm; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; NFS, NAFLD fibrosis score; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SWE, shear wave elastography; TE, transient elastography. Modified from reference 53. GASTROENDONEWS.COM16

more than half of patients with NASH and elevated in NAFLD patients without NASH.14

Liver Biopsy

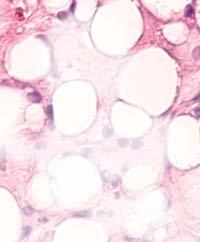

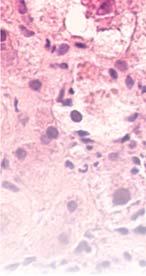

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for accurate diagnosis of NASH. A NAFLD activity score (NAS) is calculated based on liver histology, with evaluation of steatosis grade (0-3), acinar inflammation (0-3), and cytologic ballooning (0-2).15 A NAS of less than 3 excludes, and 5 or higher confirms, a diagnosis of NASH.15 Liver biopsy also allows assessment of fibrosis stage, the main determinant of outcomes in NAFLD.16 The METAVIR score is one method often used to score fibrosis stage on liver biopsy, with stage F0 correlating with an absence of fibrosis and stage F4 with cirrhosis.17 The Ishak score is another method, using fibrosis stages F0 to F6, with stage F5 equivalent to early cirrhosis and stage F6 indicating established cirrhosis.18

Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Disease

Liver biopsy has been considered the standard to stratify the disease spectrum in patients with NAFLD.13,19 However, biopsy is associated with potential complications: Pain after biopsy is almost universal, bleeding occurs in approximately 1 in 500 liver biopsies, and death occurs in 1 in 10,000.20 In addition, liver biopsy is not an ideal reference and is limited by sampling error, with inaccurate fibrosis staging occurring in up to 33% of cases and interobserver disagreement in up to 30% of cases.21 Liver biopsy also is limited in research studies and clinical trials, with a requirement of at least a 15-mm length of liver tissue with at least 10 portal tracts, a standard not observed frequently in clinical practice.21

Over the past couple of decades, several blood-based and imaging-based biomarkers have been developed for noninvasive assessment of liver disease (NIALD) (Table).

Blood-Based Biomarkers

Blood-based biomarkers to assess fibrosis in NAFLD can be categorized into indirect biomarkers (using patient demographics, standard-of-care laboratory values for liver chemistry, and platelet counts) and direct biomarkers (using specific laboratory tests measuring extracellular matrix deposition and turnover).22

NAFLD Fibrosis Score

This measure incorporates age, the presence of hyperglycemia, body mass index (BMI), platelet count, serum albumin level, and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio. In the pivotal study, NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) of 1.455 or less had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.88 (0.85-0.92), with a negative predictive value of 93% to exclude F3 to F4 fibrosis.23 As with many other NIALD biomarkers considering platelet count (see below), NFS is not accurate in patients who have undergone transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement or are asplenic.24 Similarly, NFS and other tests, including AST and ALT tests, lose accuracy when they are calculated

during acute-on-chronic liver injury because aminotransferases can be elevated acutely.

Fibrosis-4

This test uses age, AST and ALT levels, and platelet count. In a pivotal study of 832 biopsied patients with HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection, a cutoff of greater than 3.25 had a positive predictive value of 68% and specificity of 97% in the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis.25 Based on the lower and upper cutoffs of 1.30 and 3.25, respectively, Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) allowed avoidance of 71% of liver biopsies. The test also was found to be useful in diagnosing advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in NAFLD patients, with an AUC of 0.8 and 0.85 at cutoff values of 1.24 to 1.45 and 1.92 to 2.48, respectively. However, FIB-4 is less specific in patients older than 60 years of age.26

AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index

This index was developed in patients with HCV, with an AUC of 0.83 (95% CI, 0.78-0.88) and 0.90 (95% CI, 0.86-0.94) for predicting significant fibrosis and cirrhosis, respectively.27 The utility of the AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) in NAFLD patients was validated with an AUC of 0.77 and 0.91 at cutoff scores of 0.43 to 1.5 and 0.54 to 2.0, respectively.24

BARD Score

This score is the weighted sum of 3 variables (BMI ≥ 28 kg/m 2 =1 point, AST/ALT ratio ≥ 0.8=2 points, diabetes=1 point). In a pivotal study of 827 patients with NAFLD, a score of 2 to 4 had a 17-fold odds of indicating the presence of advanced fibrosis, with 96% accuracy in excluding this condition.28

Hepamet Fibrosis Score

This score consists of age, sex, homeostatic model assessment score, diabetes mellitus status, AST, serum albumin, and platelet count. The Hepamet Fibrosis Score has a better accuracy than FIB-4 and NFS and does not require adjustment for patient’s age.29

FibroTest (FibroSURE in United States)

This test uses total bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alpha2-macroglobulin, apolipoprotein A1, and haptoglobin, corrected for age and sex. In an initial NAFLD validation study, FibroTest showed an AUC of 0.88 (95% CI, 0.82-0.92) in predicting F3 to F4 fibrosis, proposing cutoff values of 0.3 and 0.7 to maximize negative predictive value (90%) and positive predictive value (73%), respectively.30 Conditions different from NAFLD affecting bilirubin (eg, Gilbert’s syndrome), haptoglobin (eg, hemolysis), alpha2-macroglobulin (eg, inflammatory condition), or GGT (eg, alcohol ingestion) may result in an inaccurate estimation of fibrosis.21

Enhanced Liver Fibrosis Score

This measure, which uses matrix metalloproteinase 1 (tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1),

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 17

hyaluronic acid, and amino terminal peptide of pro-collagen III, shows an AUC of 0.90 for distinguishing F3 to F4 fibrosis.31 Caution is advised when interpreting enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) score results in patients with other diseases associated with increased collagen turnover (eg, interstitial lung disease).31

A meta-analysis comparing serologic markers in the assessment of fibrosis in more than 13,000 patients showed NFS and FIB-4 to be the most accurate, with a pooled AUC of 0.84 and negative predictive value of greater than 90% for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis.32 One of the limitations of these blood-based biomarkers is that approximately 20% to 30% of patients can fall into an indeterminate category.24

Machine Learning Algorithm

This test consists of body mass index, Pro C3, type IV collagen, and AST-to-GGT ratio.33

Imaging-Based Biomarkers

Although liver biopsy often is needed, imagingbased NIALD can be used to improve accuracy and reduce the need for biopsy.24 In general, imaging techniques are more accurate than serum biomarkers,34 but many of them are not widely available.

Transient Elastography or Vibration-Controlled Transient Elastography

This techniquehas the advantages of beingofficebased, reproducible across centers, available as a point-of-care tool, and easy to operate and interpret. The results can be affected by fed state, so patients are advised to fast for at least 3 hours before the test.35 Morbidly obese individuals with a skin-to-liver capsule distance of 25 mm or greater will require an extralarge (XL) probe.

The test is a liver stiffness measurement (LSM) and is reported in kilopascals (kPa). Transient elastography (TE) is 94% to 100% accurate in ruling out F3 to F4 fibrosis at a cutoff of 8 kPa. The sensitivity and specificity are 85% and 82%, respectively, for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis (stage F3) and 92% and 92%, respectively, for the diagnosis of cirrhosis.36 The AUCs for diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis do not differ with the standard M probe and the XL probe (0.87 vs 0.86 and 0.92 vs 0.94, respectively).37 TE is limited by lack of parenchymal assessment and inaccuracy in patients with ascites, cholestasis, inflammation from acute hepatitis, and heart failure. In addition, accuracy depends on operator experience.35 TE also has a technical failure rate of about 5% in patients who are morbidly obese.38

Figure. Proposed clinical care algorithm for NAFLD. a If MRE is unavailable. FIB-4, Fibrosis-4 score; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography.

Patients with

NAFLD (steatosis on imaging and other causes ruled out) FIB-4 LSM ≤8.0 kPa LSM >8.0 kPa MRE Consider liver biopsya FIB-4 <1.3 • Follow-up by primary care physician • Check liver chemistry every 6-12 mo • Lifestyle modifications: diet and exercise FIB-4 ≥1.3 Transient elastography assessment GASTROENDONEWS.COM18

Shear Wave Elastography

This test can be performed using acoustic radiation force imaging (ARFI), also known as point shear wave elastography (pSWE) or 2-dimensional SWE (2DSWE).39 ARFI measures the ultrasound attenuation and velocity of spread of shear waves expressed as meter per second (m/s) and has shown an accuracy of 95% for the diagnosis of significant fibrosis.39,40 Like TE, 2D-SWE measures liver stiffness in kPa, with the added advantage of assessment of hepatic parenchyma, and it has shown an accuracy of 92% for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD.41 Both ARFI and 2D-SWE are becoming widely available, and despite differences in cutoff values across manufacturers, high operator dependability, and limited experience (eg, few prospective studies), the accuracy is comparable to that of TE, and these methods are good alternatives for patients needing an anatomic ultrasound.42

MR Elastography

This technique involves phase contrast imaging, which measures liver stiffness depending on mechanical wave propagation. With this method, mechanical waves generated in a drum device over the liver are imaged for about 15 seconds in end expiration, and the device automatically provides a color-coded liver stiffness map. MR elastography (MRE) has the unique ability to assess regression and progression during the course of disease or in response to treatment.43 The accuracy of 2D-MRE for diagnosis of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, which has been documented in a recent meta-analysis, is independent of BMI, sex, and degree of inflammation.43 Although 3D-MRE is more accurate than the 2D technique, it takes more time, and experience with this approach is limited.42 MRE is more accurate than TE because it is less operator dependent, and it also is more useful for patients who are morbidly obese or have ascites. However, this method is not appropriate for patients with implanted metallic devices, claustrophobia, severe steatosis, or hemochromatosis, and it is further limited by high cost and lack of widespread availability.

Assessment of Steatosis

This review primarily focuses on assessment of high-risk NAFLD patients with fibrosis, but it is worth mentioning noninvasive imaging assessment of steatosis because the standard technique of ultrasonography fails to quantify steatosis, a relevant important assessment, especially in ongoing clinical trials targeting steatosis. 44 In addition, ultrasound assessment can provide false-negative results, leading to diagnosis of steatosis in patients with morbid obesity and/or renal disease.45 In the absence of more widely available and validated methods, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of Liver Diseases recommend ultrasonography to diagnose steatosis.13,19 Techniques for quantifying steatosis are discussed below.

Controlled Attenuation Parameter

This novel ultrasound-based technique to quantify steatosis is incorporated into TE equipment. It is easy to perform, widely available, affordable, accurate, and reproducible. The pivotal study assessing this technique showed AUCs of 0.91, 0.95, and 0.89 for the diagnosis of mild, moderate, and severe steatosis, respectively. In a recent meta-analysis, these respective AUC values have remained at 0.82, 0.86, and 0.88 at cutoffs of 248, 268, and 280 dB/m, respectively.46 However, the tool is limited in patients with morbid or severe obesity or ascites. In a limited evaluation of the XL probe versus M probe, controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) showed no difference in accuracy in quantifying fat.42 Some adjustments in CAP results are needed based on degree of obesity and in patients with NAFLD and diabetes.

MRI Proton Density Fat Fraction

This approach depends on the ability of MRI to separate water and fat tissue signals, using MR-based spectroscopic examination. MRI protein density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) reliably quantifies hepatic steatosis and is useful for following patients on treatment.47 The technique is superior to CAP for quantifying hepatic fat, with an AUC of 0.99 versus 0.85 for CAP.48 MRI-PDFF has excellent concordance with liver biopsy–based quantification of liver fat.49 MRI-PDFF also has been shown to be a surrogate for histologic improvement, with a 30% or greater relative decrease in hepatic fat being associated with a 2-point reduction in NAFLD activity score, NASH resolution, and improvement in fibrosis.50 However, the technique is limited by lack of widespread availability, high cost, expertise required, and other disadvantages of MRI-based assessment.

Prospective NAFLD Studies Using Noninvasive Assessment

Besides providing cross-sectional assessment of fibrosis stage, noninvasive imaging and serum biomarkers of fibrosis have been shown to predict liver-related outcomes and mortality.51,52

Approach to NIALD for Patients With NAFLD in Routine Practice

Considering the accuracy of NIALD techniques validated against liver biopsy, we proposed a clinical care algorithm (Figure). Of the serum biomarkers, NFS and FIB-4 are favored, having the highest accuracy in excluding advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.53 Of the imaging-based techniques, TE allows point-of-care clinical decisions and is the favored first-line imaging technique to stratify risk for fibrosis.53 These tests can be used in a simultaneous or sequential fashion. With a simultaneous approach, biopsy can be used for discordant results. With a serial approach, the second test reclassifies patients with indeterminate results on the first test, reducing the need for liver biopsy.54 If a biopsy is not obtained, continued follow-up and

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 19

monitoring are recommended for patients with indeterminate results.

Patient BMI, race, steatosis, and presence of diabetes need to be considered when using the algorithm in routine practice, and these variables affect NIALD. In this regard, CAP values are reduced by 10 dB/m for patients with NAFLD and T2DM. Similarly, CAP values are increased or reduced by 4.4 dB/m for every unit change in BMI above or below 25 kg/m2, respectively.46 As an example, in a patient with NAFLD, BMI of 29.5 kg/m2, and T2DM, a measured CAP value of 320 dB/m (severe steatosis) will translate to an adjusted value of 277 dB/m (moderate steatosis). Similarly, in

References

1. Sayiner M, Koenig A, Henry L, et al. Epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States and the rest of the world. Clin Liver Dis 2016;20(2):205-214.

2. Kanwar P, Kowdley KV. The metabolic syndrome and its influence on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis 2016;20(2):225-243.

3. Calzadilla Bertot L, Adams LA. The natural course of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(5):774.

4. Teli MR, James OF, Burt AD, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: a follow-up study. Hepatology 1995;22(6):1714-1719.

5. Patel V, Sanyal AJ, Sterling R. Clinical presentation and patient evaluation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2016;20(2):277-292.

6. Benedict M, Zhang X. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an expanded review. World J Hepatol. 2017;9(16):715.

7. Singal AK, Hasanin M, Kaif M, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for simultaneous liver kidney transplantation in the United States. Transplantation 2016;100(3):607-612.

8. Axley P, Ahmed Z, Arora S, et al. NASH is the most rapidly growing etiology for acute-on-chronic liver failure-related hospitalization and disease burden in the United States: a population-based study. Liver Transpl. 2019;25(5):695-705.

9. Pocha C, Xie C. Hepatocellular carcinoma in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—one of a kind or two different enemies? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:72.

10. Mikolasevic I, Filipec-Kanizaj T, Mijic M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver transplantation—where do we stand? World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(14):1491-1506.

11. Karim M, Al-Mahtab M, Rahman S, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—a review. Mymensingh Med J 2015;24(4):873-880.

12. Salt W. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a comprehensive review. J Insur Med. 2004;36(1):27-41.

13. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328-357.

14. McNair A. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): why biopsy? Gut. 2002;51(6):898; author reply 898-899.

15. Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011;53(3):810-820.

a patient with NAFLD at a low BMI of 21 kg/m2, a CAP measurement of 235 dB/m (no steatosis) will translate to an adjusted value of 252.5 (mild steatosis).

Summary

The current perspective on identifying high-risk NASH patients is transitioning away from liver biopsy, with the availability of several noninvasive, simple serologic and radiological biomarkers. However, given that the use of these biomarkers for following patients and assessing response to therapeutic intervention needs to be validated in clinical trials, liver biopsy remains a significant tool in patient selection and follow-up.

16. Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, et al. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(4):643-654.

17. Goodman ZD. Grading and staging systems for inflammation and fibrosis in chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2007;47(4):598-607.

18. Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22(6):696-699.

19. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), and European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obes Facts 2016;9(2):65-90.

20. Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, et al. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49(3):1017-1044.

21. Duarte-Rojo A, Altamirano JT, Feld JJ. Noninvasive markers of fibrosis: key concepts for improving accuracy in daily clinical practice. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11(4):426-439.

22. Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, et al. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology 2004;127(6):1704-1713.

23. Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Anstee QM, et al. Diagnostic modalities for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and associated fibrosis. Hepatology. 2018;68(1):349-360.

24. Xiao G, Zhu S, Xiao X, et al. Comparison of laboratory tests, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance elastography to detect fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66(5):1486-1501.

25. Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, et al. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1104-1112.

26. Boursier J, de Ledinghen V, Leroy V, et al. A stepwise-algorithm using an at-a-glance first-line test for the non-invasive diagnosis of advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2017;66(6):1158-1165.

27. Wai C-T, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38(2):518-526.

28. Harrison SA, Oliver D, Arnold HL, et al. Development and validation of a simple NAFLD clinical scoring system for identifying patients without advanced disease. Gut. 2008;57(10):1441-1447.

29. Ampuero J, Pais R, Aller R, et al. Development and validation of hepamet fibrosis scoring system—a simple, noninvasive test to identify patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(1):216-225.35.

GASTROENDONEWS.COM20

30. Ratziu V, Massard J, Charlotte F, et al. Diagnostic value of biochemical markers (FibroTest-FibroSURE) for the prediction of liver fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6(1):6.

31. Guha IN, Parkes J, Roderick P, et al. Noninvasive markers of fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: validating the European Liver Fibrosis Panel and exploring simple markers. Hepatology. 2008;47(2):455-460.

32. Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, et al. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med. 2011;43(8):617-649.

33. Feng G, Zheng KI, Li YY, et al. Machine learning algorithm outperforms fibrosis markers in predicting significant fibrosis in biopsy-confirmed NAFLD. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2021;28(7):593-603.

34. Fedchuk L, Nascimbeni F, Pais R, et al. Performance and limitations of steatosis biomarkers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(10):1209-1222.

35. Vuppalanchi R, Weber R, Russell S, et al. Is fasting necessary for individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to undergo vibration-controlled transient elastography? Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114(6):995-997.

36. Buzzetti E, Hall A, Ekstedt M, et al. Collagen proportionate area is an independent predictor of long-term outcome in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(9):1214-1222.

37. Staufer K, Halilbasic E, Spindelboeck W, et al. Evaluation and comparison of six noninvasive tests for prediction of significant or advanced fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7(8):1113-1123.

38. Barr RG, Ferraioli G, Palmeri ML, et al. Elastography assessment of liver fibrosis: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference statement. Radiology. 2015;276(3):845-861.

39. Kennedy P, Wagner M, Castéra L, et al. Quantitative elastography methods in liver disease: current evidence and future directions. Radiology. 2018;286(3):738-763.

40. Liu H, Fu J, Hong R, et al. Acoustic radiation force impulse elastography for the non-invasive evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a systematic review & meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0127782.

41. Herrmann E, de Lédinghen V, Cassinotto C, et al. Assessment of biopsy-proven liver fibrosis by two-dimensional shear wave elastography: an individual patient data-based meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):260-272.

42. Castera L, Friedrich-Rust M, Loomba R. Noninvasive assessment of liver disease in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5):1264-1281.e4.

43. Singh S, Venkatesh SK, Loomba R, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography for staging liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a diagnostic accuracy systematic review and individual participant data pooled analysis. Eur Radiol 2016;26(5):1431-1440.

44. Paige JS, Bernstein GS, Heba E, et al. A pilot comparative study of quantitative ultrasound, conventional ultrasound, and MRI for predicting histology-determined steatosis grade in adult nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Roentgenol 2017;208(5):W168-W177.

45. Sasso M, Miette V, Sandrin L, et al. The controlled attenuation parameter (CAP): a novel tool for the non-invasive evaluation of steatosis using Fibroscan. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012;36(1):13-20.

46. Karlas T, Petroff D, Sasso M, et al. Individual patient data metaanalysis of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) technology for assessing steatosis. J Hepatol. 2017;66(5):1022-1030.

47. Ajmera V, Park CC, Caussy C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging proton density fat fraction associates with progression of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2018;155(2):307-310.e2.

48. Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography vs transient elastography in detection of fibrosis and noninvasive measurement of steatosis in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152(3):598-607.e2.

49. Caussy C, Reeder SB, Sirlin CB, et al. Noninvasive, quantitative assessment of liver fat by MRI-PDFF as an endpoint in NASH trials. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):763-772.

50. Tamaki N, Munaganuru N, Jung J, et al. Clinical utility of 30% relative decline in MRI-PDFF in predicting fibrosis regression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2022;71(5):983-990.

51. Boursier J, Vergniol J, Guillet A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and prognostic significance of blood fibrosis tests and liver stiffness measurement by FibroScan in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65(3):570-578.

52. Lombardi R, Petta S, Pisano G, et al. FibroScan identifies patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular damage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(2):517-519.

53. Altamirano J, Qi Q, Choudhry S, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:31.

54. Petta S, Wong V W-S, Camma C, et al. Serial combination of non-invasive tools improves the diagnostic accuracy of severe liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46(6):617-627.

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 21

FUTURE OF NASH WITH FIBROSIS

A liver disease with

• Patients with NASH have

• Once a patient develops

consequences – including mortality1-5

disease, cirrhosis, decompensated

carcinoma2,4,6-10

the risk of liver-related mortality

•

- F2 and F3 patients are at ~10-17x

is

risk of mortality compared to F0 patients11

patients with significant fibrosis* as it is a strong

*Fibrosis stage F2 or F3 as defined histologically.12,13

F0=liver fibrosis stage 0; F2=liver fibrosis stage 2; F3=liver fibrosis stage 3; NASH=nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

References:

of patients with

TA, Yerian L, Lopez R, Zein NN, Feldstein AE. The inflamed liver and atherosclerosis: a link between histologic severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and increased cardiovascular risk. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(9):2644-2650. 3. Hagström H, Nasr P, Ekstedt M, et al. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy-proven NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):12651273. 4. Targher G, Tilg H, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multisystem disease requiring a multidisciplinary and holistic approach. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(7):578-588. 5. Koyama Y, Brenner DA. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(1):55-64. 6. Stepanova M, Younossi ZM. Independent association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease in the US population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(6):646-650.

7. Zhai M, Liu Z, Long J, et al. The incidence trends of liver cirrhosis caused by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via the GBD study 2017. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):5195. 8. Loomba R, Adams L. The 20% rule of NASH progression: the natural history of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis caused by NASH. Hepatology. 2019;70(6):1885-1888. 9. Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology. 2014;59(6):2188-2195.

10. Stine JG, Wentworth BJ, Zimmet A, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis compared to other liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48(7):696-703. 11. Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;65(5):1557-1565. 12. Kanwal F, Shubrook JH, Adams LA, et al. Clinical care pathway for the risk stratification and management of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol. 2021;1-13. 13. Ratziu V, Bellantani S, Cortez-Pinto H, Day C, Marchesini G. A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol. 2010;53(2):372-384.

IT’S TIME TO EXPLORE THE

severe

Learn more about the risks starting at F2 and how to identify these patients11 Visit NASHexplored.com/4 today and stay informed ©2022 Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Inc. All rights reserved. Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, 200 Barr Harbor Drive, Suite 200, West Conshohocken, PA 19428 US-00006 05/22

an increased risk of cardiovascular

liver disease, liver transplant, and hepatocellular

significant fibrosis*,

increases substantially1,11

higher

It

important to identify and actively manage

predictor of liver-related mortality1,11

1. Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver fibrosis, but no other histologic features, is associated with long-term outcomes

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroentrology. 2015;149(2):389-397. 2. Alkhouri N, Tamimi

Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Treatment Options for High-Risk Patients

ASHWANI K. SINGAL, MD, MS, FACG, FAASLD, AGAF

Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine Transplant Hepatologist

Avera McKennan University Hospital Chief of Clinical Research Avera Transplant Institute Sioux Falls, South Dakota

Themanagement of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) involves treatment of liver disease and its complications, control of risk factors, disease stabilization, and prevention of fibrosis progression. Although the only consistently proven treatment is lifestyle modification, development of drug targets to treat NASH has undergone rapid growth over the past several years, with several active clinical trials.

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 23

This is part 2 of a 2-part series on NASH. This review discusses ongoing clinical trials of new therapeutic targets for the treatment of NASH. Part 1 discusses how to identify patients with NASH who are at risk for advanced fibrosis (See page 15).

Achieving Treatment Goals

The goals in managing patients with NAFLD include treatment of liver disease and its complications, stabilization of disease, control of risk factors for the disease, and prevention of progression of fibrosis.1 Lifestyle modification with diet, exercise, weight loss, and control of the components of metabolic syndrome is the only consistently proven treatment for NAFLD. The best data on the beneficial effects of weight loss in NAFLD come from paired liver biopsy evaluation in patients undergoing bariatric surgery.2 Weight loss of at least 7% has been deemed necessary for histologic improvement.3 Practice guidelines recommend a goal of at least 7% to 10% weight reduction to improve both fibrosis and inflammation, but a 3% to 5% weight loss has shown success in improving steatosis.1 Given the difficulty in achieving this weight loss goal in the clinical setting, it is recommended that patients with NAFLD be managed by a multidisciplinary team that includes dietitians, physical activity supervisors, and psychologists.1 More frequent clinic visits are associated with greater weight loss in patients with NAFLD.4 Novel approaches, such as text-messaging weight management programs, can help patients achieve meaningful weight loss.5 Restricting calories to 25 to 30 kcal/kg per day to achieve a 10% weight loss over 6 months is desirable; rapid weight loss can worsen NAFLD.6 The Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce hepatic steatosis and improve insulin sensitivity in nondiabetic patients with NAFLD.7 Combining dietary changes with exercise is more effective than either intervention alone. There is a clear benefit of exercise on hepatic steatosis, even in the absence of weight loss.8 Resistance training may be preferable to aerobic training and is associated with significant improvement in NAFLD parameters.9

Management of diabetes and achievement of optimal glycemic control with a target hemoglobin A1c of less than 7% is desirable. Use of statins to treat dyslipidemias is imperative, with a target low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level of less than 100 mg/dL to decrease cardiovascular mortality.10 Atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, pravastatin, and simvastatin have been assessed in randomized controlled trials and were found to be safe for patients with NAFLD.11 Omega-3 fatty acids and fenofibrate are safe and effective for managing hypertriglyceridemia. Control of blood pressure, with a target below 140/90 mm Hg, is imperative.12 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are preferred, especially in patients with diabetes because they have been shown to improve insulin sensitivity.1 Heavy use of alcohol is associated with progression of fibrosis and worse prognosis,13 although light to moderate drinking has been shown to have a protective

effect in the development of NAFLD.14 Progression to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma occurs in only 2.5% of patients with NASH, and usually it is slower than with other chronic liver diseases.15

Many pharmacologic options have been studied, but no FDA-approved drug exists for the management of NAFLD. Vitamin E (800 IU per day) was better than placebo in clinical trials, with a higher proportion of patients showing improved histologic features of NASH (43% vs 19%; P=0.001).16 However, vitamin E did not improve liver fibrosis and did not gain FDA approval for the treatment of NAFLD or NASH. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases supports consideration of vitamin E for nondiabetic patients with biopsy-proven NASH.1

Liver transplantation is a definitive treatment for NAFLD patients with cirrhosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure, those with end-stage liver disease, or those with hepatocellular carcinoma. After surgery, these patients often develop an increase in body weight, subsequent insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and malignancy.17 Outcomes in patients with NASH after transplant are similar to those for other etiologies, with a lower risk for liver-related mortality.18

Novel Therapeutic Targets

Drug development of targets to treat NASH has undergone rapid growth over the past several years, with more than 100 registered clinical trials currently in different phases. Based on the pathophysiology of NASH, therapeutic targets are categorized into 3 groups related to their anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, and antifibrotic activity. Several drugs in trials exhibit more than 1 of these 3 activities. Several molecular targets are in later stages of clinical development (Table 1).

Peroxisome Proliferator–Activated Receptors

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs) (alpha, gamma, and beta/delta) are ligand-activated transcription factors of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily,19 which regulate metabolism and energy homeostasis. Thiazolidinediones (PPAR-gamma ligands) are effective in patients with diabetes, yielding improvements in steatosis, steatohepatitis, and hepatic fibrosis.16,20 However, these agents are limited by adverse effects, including weight gain, osteopenia, and fluid retention. Elafibranor (Genfit), a liver-targeted dual PPAR-alpha/delta agonist, improved metabolic (including cardiometabolic) features of NASH in a post hoc analysis of a phase 2b trial.21 The phase 3 RESOLVE IT trial evaluating elafibranor did not identify any safety issues but was prematurely terminated due to lack of efficacy (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02704403). Other examples are saroglitazar (Zydus Therapeutics)22 and lanifibranor (Inventia Pharma).23

Thyroid Hormone Receptor-Beta Agonist

Thyroid hormone receptor signaling regulates organogenesis, growth and differentiation, metabolism, and energy homeostasis.24,25 Its beta subunit, expressed in

GASTROENDONEWS.COM24

the liver, regulates metabolic function, and two agonists— MGL-3196 (resmetirom; Madrigal) and VK2809 (Viking)— are being evaluated in NASH. In a phase 2, 36-week trial, MGL-3196 improved steatosis as measured by MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF), liver enzymes, and fibrosis biomarkers.25 The greatest effect on NASH occurred in participants with 30% or more body fat. In a phase 2, 16-week trial, VK2809 improved low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels by more than 50% compared with placebo (8.9%).26 MGL-3196 is moving forward in a phase 3 clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03900429), and a phase 2b study is recruiting for VK2809 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04173065).

Bile Acids and Their Pathways

Bile acids are synthesized from cholesterol in hepatocytes and regulate metabolism, inflammation, and liver fibrosis. Nuclear (farnesoid X receptor [FXR]) and transmembrane (Takeda G protein–coupled receptor clone 5) bile acid receptors have been exploited with the development of agonists of these receptors.27

In the phase 2 FLINT study of NASH patients without cirrhosis, 72 weeks of treatment with obeticholic acid (OCA; Intercept) resulted in improvement in insulin sensitivity, increased fibroblast growth factor (FGF 19) levels, and improved liver histology compared with placebo.28,29 However, OCA was associated with increased low-density and decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, as well as severe pruritus requiring drug discontinuation in about 10% of patients.28 Atorvastatin safely helps control these adverse effects.29 These results were replicated in a phase 3 study of NASH patients with stage F2 to F3 fibrosis treated for 18 months with OCA30; 7-year follow-up results are awaited (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02548351). Caution is warranted in patients with cirrhosis due to reported episodes of decompensation in those with primary biliary cholangitis taking higher than recommended doses.

Tropifexor (TXR; Novartis), a non–bile acid agent with high affinity for the FXR, was evaluated in a phase 2 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02855164).31 The interim analysis of this 48-week study showed that TXR decreased liver fat content (by MRI-PDFF) and improved aminotransferases compared with placebo.32 Considering that TXR has an adverse effect profile that is similar to that of OCA, it is suggested that it be used based on body weight (with therapeutic effect greater in patients with a lower body mass index).33 Another non–bile acid FXR agonist, cilofexor (GS-9674; Gilead) resulted in improvements in fat content and aminotransferases in a phase 2, 24-week, placebo-controlled trial in patients with NASH and stage F1 to F3 fibrosis.34 The drug did not result in changes in lipid levels or pruritus especially at a lower dose of 30 mg.

FGF-19, secreted by the intestine and a downstream target of FXR, regulates carbohydrate metabolism and bile acid synthesis, with improved insulin sensitivity.35 In a phase 2 study, the parenteral FGF-19 analog NGM282 (NGM Biopharmaceuticals) given for 12 weeks reduced

liver transaminases, with improvement in all components of NASH and fibrosis on liver histology.36 The drug was safe except for increased serum cholesterol, which was controlled with adjuvant use of rosuvastatin. The molecule has been evaluated in a phase 2b, randomized, placebo-controlled, 24-week study, but the results of this study have not been posted or published yet (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03912532). Many other analogs of FGF-19 and FGF-21 are being investigated as therapeutic targets for NASH (Table 1).

Antagonism of C-C Chemokine Receptor Types 2 and 5

Hepatic inflammation activates monocytes and macrophages and causes upregulation of cytokines and chemokines, which cross-talk with hepatic stellate cells to lay down collagen, resulting in liver fibrosis.37 Cenicriviroc (Allergan), an antagonist of C-C chemokine receptors 2 and 5, was evaluated in a phase 2b clinical trial in patients with NASH and stage F1 to F3 fibrosis. Relative to placebo, cenicriviroc improved liver fibrosis but not NASH at 12 weeks; no improvement was seen at 24 weeks.38 The phase 3 AURORA study recently completed in patients with NASH and stage F2 to F3 fibrosis was terminated for lack of efficacy based on planned interim analysis (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier: NCT03028740).

Apoptosis Signal–Regulating Kinase 1 Inhibitor

Oxidative stress in hepatocytes activates the apoptosis signal–regulating kinase 1 inhibitor (ASK1), with phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase, leading to regulation of apoptotic pathways, with hepatic inflammation and myofibroblast activation.39 The ASK1 antagonist selonsertib showed beneficial activity in a phase 2 study in combination with the lysyl oxidase–like 2 inhibitor simtuzumab (Gilead). 40 However, the drug showed no efficacy in a large phase 3 trial41,42 and is not recommended for further evaluation in the landscape of NASH drug development. Caspase inhibition with emricasan (Pfizer) is an attractive option, but 2 studies in F1 to F3 fibrosis and cirrhosis with portal hypertension were negative.43,44 In the first study, emricasan did not meet any of the FDA-approved primary end points of improvement in fibrosis by at least 1 stage without worsening of NASH or NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis. In the second study, emricasan did not improve hepatic venous pressure gradient in participants with NASH cirrhosis and severe portal hypertension (gradient ≥12 mm Hg).

Acetyl Coenzyme A Carboxylase Inhibition

Lipotoxicity from accumulated fatty acids in NAFLD as a result of de novo lipogenesis and increased influx from peripheral adipose tissue contributes to NASH, with downstream effects of inflammation and fibrosis.45 Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC), the rate-limiting step in de novo lipogenesis, with ACC1 in cytoplasm and

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 25

Table 1. Landscape for Compounds Targeted to Treat NAFLD and NASH

DrugTargetIndication Clinical trial namePrimary outcome(s) Current status

FXR agonists

Obeticholic acid (INT-747)1 FXR agonistNASH F2-F3REGENERATE NCT02548351

NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis; fibrosis improvement without worsening of NASH (on histology)

NASH F4REVERSE NCT03439254 Fibrosis improvement without worsening of NASH (on histology)

EDP-3052 NASH F2-F3NCT04378010Change in ALT; change in liver fat content

MET642NASH and liver fat ≥10% NCT04773964Safety and pharmacokinetics

Tropifexor (TXR, LJN452) Nonsteroidal FXR agonist NASH F1-F3FLIGHT-FXR NCT02855164 Change in transaminases and fat fraction on MRI

Phase 3: Histologic improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH (interim analysis)

Phase 3: Active but no data available

Phase 2: Reduction in ALT and liver fat

Phase 2a: Active but no data available

Phase 2: Improved liver chemistry and fat content

Cilofexor (GS-9674)3 NASH F1-F3GS-9674 NCT02854605 Overall safetyPhase 2: Improved liver chemistry, serum bile acids, and liver fat content

PPAR agonists

Elafibranor (GFT-505)4 PPAR-alpha/ delta agonist NASH F1-F3Golden NCT01694849

Resolve-IT NCT02704403

NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis

Phase 2b: Resolution of NASH without worsening of fibrosis

Phase 3: Terminated; did not meet predefined primary surrogate efficacy end point, no safety issues identified; no effect on resolution of NASH

PioglitazoneT2DM and NASH NCT04501406NASH improvement without worsening of fibrosis

Phase 2b: Recruiting

Saroglitazar5 NAFLD with ALT>50 IU/L EVIDENCES VI NCT03863574 ALT and liver fat contentPhase 2b: Improved ALT, liver fat, and metabolic profile

NASH with fibrosis NCT05011305NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis

Lanifibranor6 NATIVE NCT03008070 Decrease of ≥2 points in SAF score without worsening of fibrosis

Phase 2: Recruiting

Phase 2b: ≥2 points SAF score improvement higher with 1,200 mg dose vs placebo (55% vs 33%; P=0.007)

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DGAT2, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2; FASN, fatty acid synthase; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; HVPG, hepatic vein pressure gradient; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; MRI-PDFF, MRI proton density fat fraction; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; SAF, steatosis, activity and fibrosis score; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; THR, thyroid hormone receptor.

GASTROENDONEWS.COM26

Table 1. Landscape for Compounds Targeted to Treat NAFLD and NASH

DrugTargetIndication Clinical trial namePrimary outcome(s) Current status

Fibroblast GF analogs

Efruxifermin7 Pegylated FGF21

Pegbelfermin (BMS-986036)

NASH with fibrosis NCT03976401Liver fat by MR-PDFFPhase 2a: Improvement in liver fat content (2b ongoing)

NASH F3 FALCON 1 NCT03486899 Improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH

NASH CCFALCON 2 NCT03486912 Improvement in NASH without worsening of fibrosis

NASHSafety and liver fat by MR-PDFF

Aldafermin8 FGF19NASH F2-F3ALPINE 2/3 NCT03912532 Improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH

NASH CCALPINE 4 NCT04210245 Safety and improvement in ELF score

Phase 2b: Completed but no data available

Phase 2b: Completed but no data available

Phase 2: Recruiting

Phase 2b: Safe but did not meet primary end point

Phase 2b: Active but no data available

GLP analogs

Liraglutide9 GLP-1 analogNASH F0-F4LEAN NCT01237119

Improvement in NASHPhase 2: NASH resolution on histology

Semaglutide10 NASH F2-F3NCT02970942NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis Phase2b: Higher % of patients with NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis NASH F2-F3ESSENCE NCT04822181 NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis; fibrosis improvement without worsening of NASH; time to first liver-related clinical event

Phase 3: Recruiting TirzepatideDual GIP and GLP-1 agonist NASH F2-F3SYNERGY-NASH NCT04166773

NASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis Phase 3: Recruiting Efinopegdutide (MK-6024) NAFLD >10% liver fat content

IONIS DGAT2Rx11 DGAT2 inhibitor Type 2 diabetes and NAFLD

DapagliflozinSGLT2 inhibitor Type 2 diabetes and NASH

NCT04944992Safety; decrease in liver fat content by MR-PDFF

Phase 2: Active but no data available

NCT03334214Safety; liver fat content by MR-PDFF Phase 2: Safe and reduced liver fat content

DEAN NCT03723252 NASH improvement on histology Phase 3: Recruiting

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DGAT2, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2; FASN, fatty acid synthase; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; HVPG, hepatic vein pressure gradient; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; MRI-PDFF, MRI proton density fat fraction; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; SAF, steatosis, activity and fibrosis score; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; THR, thyroid hormone receptor.

GASTROENTEROLOGY & ENDOSCOPY NEWS SPECIAL EDITION • OCTOBER 2022 27

Table 1. Landscape for Compounds Targeted to Treat NAFLD and NASH

DrugTargetIndication Clinical trial namePrimary outcome(s) Current status

THR agonists

Resmetirom (MGL-3196) Selective THR beta agonist

NASH F1-F3 NCT0291226012

Change from baseline in fat fraction on MRI-PDFF (Histopathology with paired biopsy at 36 wksecondary end point)

NASH F2-F33-MAESTRO NCT03900429 NASH resolution on histology; all-cause mortality and liver-related events

VK2809THR beta agonist NASH F1-F3VOYAGE NCT04173065

Fatty acid synthesis inhibitors

Firsocostat (GS-0976)11 Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase inhibition

Phase 2: Improved fat fraction and lipid profile, liver chemistry, and NASH histology

Phase 3: Recruiting

Liver fat content and LDLPhase 2: Recruiting

NASH F1-F3NCT02856555Overall safety/adverse events Phase 2: Improved liver fat content, liver chemistry, and serum markers of fibrosis

Aramchol13 SCD1 inhibitorNASH F0-F3ARREST NCT02279524

Change in liver on MRS Phase 2b: Reduced liver fat, improved histology, and liver chemistry

TVB-2640FASN inhibitor NASHFASCINATE-1 NCT03938246 Liver fat contentPhase 2a: Improvement in liver fat content

PXL065MPC inhibitor NCT04321343

Phase 2: Active not recruiting

TesamorelinGHRH analogNAFLDNCT03375788Phase 2: Recruiting

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents

CenicrivirocChemokine receptor 2/5 antagonist

NASH F1-F3CENTAUR NCT0221747514

NASH F2-F3AURORA NCT03028740

Improved NASH without worsening of fibrosis; improvement in fibrosis without NASH worsening

Improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH; time to first liver-related event

Phase 2b: No improvement in NASH, but improved fibrosis without worsening of NASH

Phase 3: Terminated early; lack of efficacy on planned interim analysis of Part 1 data

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DGAT2, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2; FASN, fatty acid synthase; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FXR, farnesoid X receptor; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; HVPG, hepatic vein pressure gradient; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; MRI-PDFF, MRI proton density fat fraction; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors; SAF, steatosis, activity and fibrosis score; SCD1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; THR, thyroid hormone receptor.

ACC2 in mitochondria, is an attractive therapeutic target for patients with NASH. The liver-targeted inhibitor of ACC1 and ACC2, GS-0976 (firsocostat, Gilead), reduced de novo lipogenesis after 12 weeks of treatment and showed improvement in steatosis based on MRI-PDFF and markers of liver injury.46 Phase 2 studies using firsocostat in combination with the FXR agonist cilofexor (Gilead) in NASH recently completed and results are awaited (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03449446) (Table 2). Other drugs targeting hepatic fat accumulation

are aramchol (inhibitor of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1-1),47 TVB-2640 (fatty acid synthase inhibitor),48 and PXL065 (mitochondrial pyruvate carrier inhibitor) (Table 1).

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Analogs

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogs are approved for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and have the added advantage of resulting in weight loss and reductions in cardiovascular events.49,50 In a small phase 2 study, a 1.8-mg subcutaneous injection

GASTROENDONEWS.COM28

Table 1. Landscape for Compounds Targeted to Treat NAFLD and NASH

DrugTargetIndication Clinical trial

namePrimary outcome(s) Current status

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agents (continued)