TREE & SERPENT

Early Buddhist Art in India

A pioneering study of the emergence of Buddhist art in southern India, featuring vibrant photography of rare works, many published here for the first time

Named for two primary motifs in Buddhist art, the sacred bodhi tree and the protective snake, Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India is the first publication to foreground devotional works produced in the Deccan from 200 BCE to 400 CE. Unlike traditional narratives, which focus on northern India (where the Buddha was born, taught, and died), this groundbreaking book presents Buddhist art from monastic sites in the south. Long neglected, this is among the earliest surviving bodies of Buddhist art, and among the most sublimely beautiful. An international team of researchers contributes new scholarship on the sculptural and devotional art associated with Buddhism, and masterpieces from recently excavated Buddhist sites are published here for the first time—including Kanaganahalli and Phanigiri, the most important new discoveries in a generation. With its exploration of Buddhism’s emergence in southern India, as well as of India’s deep commercial and cultural engagement with the Hellenized and Roman worlds, this definitive study expands our understanding of the origins of Buddhist art itself.

344 pages; 322 illustrations; 3 maps; bibliography; glossary; gazetteer; index

TREE & SERPENT

TREE & SERPENT

Early Buddhist Art in India

John Guy

CONTENTS

Sponsors’ Statements 6 | Director’s Foreword 7

Preface 8 | Acknowledgments 10 Note to the Reader 12

Lenders to the Exhibition 13 | Contributors 13

MAPS

Indian Subcontinent 14

India’s Global Setting 15

Major Buddhist Sites Active in the Deccan, 200 bce–400 ce 15

BEGINNINGS OF BUDDHIST IMAGERY

Early Buddhist Landscape of Southern India 18

John Guy

CATALOGUE 26

John Guy

RELICS, STŪPAS, AND TEXTS

Stūpas, Footprints, and Imagination in Early Buddhism 76

Peter Skilling

Stūpas and the Cult of Relics 82

John Guy

Celebrating the Buddha in Early Southern India 88

John Guy

CATALOGUE 96

John Guy

MONASTIC BUDDHISM, COMMERCE, AND PATRONAGE

The Business Side of a Buddhist Monastery 118

Gregory Schopen

Buddhist Patronage and Monastic Institutions in Āndhra: Epigraphic Evidence 123

Vincent Tournier

Maritime Networks of Coastal Āndhradeśa 129

Himanshu Prabha Ray

CATALOGUE 132

John Guy

GLOBAL SETTING

Rome and Its Connections with India 160

Norman Underwood

Evoking the Buddha in Peninsular India, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia 166

Sunil Gupta

CATALOGUE 170

John Guy

THE BUDDHA REVEALED

The Development of Buddhist Image Worship in Early Āndhradeśa 198

Akira Shimada

Buddhist Narratives at Kanaganahalli 203

Monika Zin

The Buddhist Stone of Āndhradeśa 207

Federico Carò

CATALOGUE 210

John Guy

Early India: Chronology and Key Events 280

Gazetteer of Buddhist Sites, Principally in the Deccan 282

John Guy and Vaishnavi Patil

Glossary 290 | Notes to Essays and Catalogue 296

Bibliography 310 | Index 332 | Photograph Credits 343

SPONSORS’ STATEMENTS

It is our great joy and privilege to support the exhibition Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 bce–400 ce at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. At Reliance Foundation, we are committed to preserving and promoting Indian heritage and shining a spotlight on Indian art on the global stage. This exhibition traces the origins of early Buddhist imagery and showcases newly discovered and never before seen masterpieces of Buddhist art. In the “cradle of Buddhism,” the teachings of the Buddha are entwined with an Indian ethos, and continue to shape global thought, culture, and ways of life. We are excited to collaborate with The Met and John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia, and to celebrate this confluence of spirituality, religion, and art. Buddha’s message enlightens the hearts and minds of devotees around the world, and I hope this exhibition gives them and others an opportunity to immerse themselves in the philosophy of Buddhism.

Inspired and informed by interconnectedness, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Global supports programs in arts, culture, and Buddhism, and funds initiatives that enhance the well-being of humanity, wildlife, and the environment.

With our first major collaboration with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, we are proud to support Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 bce–400 ce, an exhibition closely aligned with our interest in activating art resources for broad, nonsectarian learning of Buddhism and Buddhist art on the worldwide level.

We are honored to support The Met in welcoming visitors from across the globe to learn and engage with Buddhist teachings and the origins of Buddhist art.

Nita M. Ambani Founder Chairperson, Reliance Foundation

Phillip Henderson Chief Executive Officer, The Robert H.

It is an honor to support The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s commitment to opening new vistas on the ancient arts of South and Southeast Asia, and the curatorial vision and groundbreaking research that John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia, brought us with Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia in 2014 and now with Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 bce–400 ce. I first met John almost twenty years ago in London while auditing lectures in the postgraduate diploma program in Asian art at the School of Oriental and African Studies, where I encountered a number of influential teachers. John and the inimitable scholar Pratapaditya Pal inspired me and so many other students of Asian art for decades, and I owe them an enormous debt. Congratulations to The Met for the courage in bringing us yet another transformative exhibition that will add much to our understanding of the origins of Buddhist art and the lessons of the Buddha, so relevant to our needs today.

Fred Eychaner Fred Eychaner Fund

6

N. Ho Family Foundation Global

DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD

With Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 bce –400 ce, The Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrates the extraordinary artistry of this early period in India and continues its commitment to presenting exhibitions that open new frontiers on the past for our visitors, both in terms of popular awareness and new scholarship. The message that the Buddha taught in the fourth century bce, and was memorialized in rock-cut edicts by the Mauryan emperor Aśoka in the mid-third century bce, remains starkly relevant to us today. His call to not slaughter the animals of the forests nor burn their habitats addresses contemporary agendas of environmental awareness and care for the planet under our stewardship. One of the Buddhist jātaka stories from this time tells of a king of Vārāṇasī who put the forest at Sarnath under his protection so that the deer could roam free of the fear of hunters, thus creating perhaps the first national park. Above all else, the Buddha’s message was compassion for all living creatures. The serenely beautiful art that was produced in service of Buddhism, and is presented in this exhibition and book, celebrates the outstanding artistic achievements of this time and addresses universal concerns principally through storytelling, a simple and accessible pathway that the disciples of the Buddha and their lineage descendants developed, following the Buddha’s example.

This exhibition and publication featuring the arts associated with the earliest Buddhist stūpas represent a monumental undertaking on the part of the Museum and an expression of trust and goodwill on the part of our lenders. This assembly of rare early Buddhist works of art includes a number of objects that have recently been excavated from monastic sites in India, and have never before been publicly exhibited. It is our privilege to present these outside India for the first time.

Foremost, I wish to express profound appreciation to the Government of India’s Ministry of Culture, thanks to whom we have been able to present so many extraordinary works of art from India, gathered from numerous museums and archaeological sites across multiple states. We express our deep gratitude to their governments: Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. The many individuals who generously assisted are listed in the Acknowledgments. I am delighted to also thank our lenders from Europe, notably the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Museum für Asiatische Kunst – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. In the United States, my appreciation goes to the Brooklyn Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena.

Exhibitions of antiquities of this kind are expensive undertakings, and we are indebted to the sponsors who generously stepped forward to help us realize this milestone in U.S.-Indian cultural cooperation. Tremendous thanks are owed to Reliance Industries Limited, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Global, and the Fred Eychaner Fund for making this exhibition possible. We are also grateful to the Estate of Brooke Astor, the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Exhibitions, the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation, the Lavori Sterling Foundation Endowment Fund, and Usha M. and Marti G. Subrahmanyam for their generous support. This wonderful catalogue is made possible by the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Publications, with additional funding from Albion Art Co., Ltd., and I gratefully acknowledge their support. The symposium is presented with the support of the Fred Eychaner Fund and organized in cooperation with the New York Center for Global Asia, NYU Shanghai Center for Global Asia, and the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute, Harvard University.

Tree and Serpent was conceived by John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art, and realized over several years, extended by the interruption of the worldwide pandemic. His resolute commitment brought this exhibition and publication to fruition, in what became something of a Herculean challenge. Curatorship today requires a particular mix of scholarship, connoisseurship, and diplomacy to realize an exhibition of this complexity. Skilled teams of colleagues across the Museum came together in collaboration, and I thank them all for their dedication. The Department of Asian Art, led by Douglas Dillion Chair Maxwell K. Hearn, provided leadership as did Deputy Director for Exhibitions Quincy Houghton, along with Deputy Director for Collections and Administration Andrea Bayer. We are further grateful to the international scholars in the field of Buddhist studies who contributed texts to the present volume.

In a world of growing uncertainties, this exhibition and publication remind us of all that we share. Beyond the aesthetic experience and the quietude that this art invokes, it brings a deeper message built on mutual understanding and respect. India is the home of many faiths, including Buddhism, and in sharing this rich heritage it allows art to be its ambassador.

Max Hollein Marina Kellen French Director The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

7

PREFACE

Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India presents the story of the origins of Buddhist art in India. In so doing, it examines these sources through a less familiar lens, that of the art of the Sātavāhana and Ikṣvāku dynasties of southern India, who variously ruled the region from the first century bce to the early fourth century ce. To better understand the processes by which the Buddhist faith and culture were disseminated, the focus is shifted away from the heartland of Buddhism, the greater Magadha region of northern India where the Buddha was born, taught, and died, to the territories of the Dakṣiṇāpatha, the regions of the south, and the roads that led there. The southern region, the Deccan, was home to some of the greatest early monasteries of Buddhist India. Today, we turn to Bharhut, Sanchi, and Amaravati when we seek to understand the majesty of this architecture and its adornment. The enclosure railing at Bharhut, the ceremonial gateways at Sanchi, and the first copings at Amaravati are the earliest and best preserved of their kind from the early Buddhist world. They are rich in visual narrative, using their surfaces as tableaux for the storytelling that made Buddhism accessible to a wide community of believers.

The exhibition takes the stūpa (a dome-shaped structure originating as a funerary mound) as its central motif, embodying as it does the essence of Buddhism, the person of the Buddha (his relics), and his teachings (Dharma). The architectural components of stūpas provided the platform for Buddhist teachings, deploying auspicious signs and symbolic representations in narrative settings to convey the essential teachings. Almost all the works of art presented here once formed an integral part of the adornment of this pivotal Buddhist monument that emerged— lotus-like—from the earthen funerary mound that was the stūpa’s genesis. Two iconographic devices were privileged above all others in the adornment of the southern stūpa: the branching bodhi tree and the snake (nāga). Their ubiquitous presence in southern Indian stūpa decor prompted James Fergusson, an early student of Buddhist architecture, to title his 1868 publication Tree and Serpent Worship: Or, Illustrations of Mythology and Art in India in the First and Fourth Centuries after Christ. The present exhibition and publication seek both to recognize the pioneers in the field of Buddhist architectural and art historical studies, and to reposition the field going forward.

Two historical correctives are in order. The first is to give due recognition to the importance of southern Buddhism, here defined as that of the Deccan and its parallel life in Sri Lanka. Early Buddhist art history has long been focused on the art of Mathurā and Sarnath, along with other sites in the Gangetic Basin of northern India, and

the Gandhāra region of the northwest, present-day Pakistan, largely to the exclusion of the myriad developments taking place in the south. Recent studies, including those of scholars contributing to this publication, have begun to recognize the importance of the Buddhist Deccan, spanning from the rock-cut vihāras of the Western Ghats to the riverine and coastal monasteries along the Bay of Bengal.

The second corrective is to realign the study of the Buddhist legacy of the Deccan within the wider field of Indian Ocean studies and global history. Much that we need to learn about Buddhist India in the early centuries ce is increasingly recognized as being shaped by the dynamics of global exchange. The western Indian Ocean trade with the Red Sea and Mediterranean was a major factor, as were the less well understood exchange systems of the Bay of Bengal with Southeast Asia and China. The Romans prepared papyrus bills of loading for cargoes of ivory and pepper shipped from the Konkan Coast of western India to the Mediterranean (fig. 81). No such primary sources exist for Southeast Asia, but the recovery of Mauryan stone artifacts there makes clear that deep commercial—and cultural—engagements began much earlier than previously acknowledged (figs. 77–79).

This exhibition and publication are privileged to foreground two recently excavated stūpa sites that have redefined much of what we understand about Southern Buddhism. Both sites have been found relatively intact, a rarity in the Deccan, where natural and human attrition has taken a heavy toll. Kanaganahalli stūpa in northern Karnataka, and the hilltop monastic complex of Phanigiri in Telangana, have added two major sites to the already extensive corpus of Buddhist sites in the Deccan (see Maps). Sculptures from both stūpa complexes are presented here for the first time, along with masterpieces from such little-known sites as Pauni, Brahmapurī,

8

Fig. 1. A village elder at the entrance to the medieval Hindu temple at Chandavaram, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh. Two limestone panels with bodhi tree, stūpa, and Dharma-wheel design, removed from the nearby Sātavāhana-era stūpa site, are installed as doorway paving. Photographed in 2017

Dhulikatta, Dupadu, Jaggayyapeta, Chandavaram, and Goli. The important contributions made by the excavators of these two new sites, the Archaeological Survey of India and the Department of Heritage, Telangana, are here respectfully acknowledged.

The showering of mercantile wealth, built largely on interregional trade and by the stimulus of a burgeoning international exchange with the Roman world, resulted in much of the finest Buddhist art preserved in India. With the waning of that trade, support for the monastic communities also subsided, and Buddhism gradually faded from the Indian landscape. The monasteries were abandoned and their majestic architecture pillaged, the limestone adornments crushed and burned to produce lime and the brick core of the stūpas quarried for building materials. These practices are witnessed today at the village of Chandavaram in Andhra Pradesh, where two sculpted limestone panels from the nearby stūpa complex have been used to decorate the threshold of a local Hindu temple (fig. 1). At another village in the district, Velpuru, limestone āyāka pillars have been refashioned as Śaiva lingas. The appropriation and repurposing of religious sites and their architectural remains is not a new phenomenon in India; the sacred landscape has always been contested. The Buddhists were not shy in the propagation of their faith and, for more than a millennium, succeeded. But just as they appropriated and subjugated the nature cults of early India, so Buddhist sites were in turn either abandoned or given over to Hindu temples.

Early Buddhist art was also shaped in part by external stimuli, present across India from the Mauryan period as West Asian Hellenism and then Roman influences left their marks on the arts of the subcontinent. The participation of the ivory guild of Ujjain in the funding of a monumental stone gateway at Sanchi signals the importance of

the ivory trade to the economy of early India. This involvement is mirrored in a jātaka story popular in Sātavāhanaera art, the Chaddanta-jātaka. The disturbing tale of jealousy, revenge, cruelty, and remorse, is first told in the south at Kanaganahalli (fig. 2). Ivory traders would have been a familiar sight at the marts of the Konkan Coast, from where great quantities of ivory and luxury objects made from the material were shipped west, as witnessed at Pompeii (cat. 85).

The Roman trade with India in the early centuries ce is increasingly regarded by modern Roman historians as a crucial factor in sustaining the expansive campaigns of the Roman Empire. Arguably, this trade is what we are witnessing in a fourth-century apse mosaic decorating the luxury Villa Romana del Casale in Piazza Armerina, Sicily (fig. 3). A goddess, flanked by an elephant and tigress, displays a cornucopia-like tusk and is surrounded by black pepper plants and a tree that is likely the aromatic agarwood. She wears a diaphanous garment suggestive of Indian muslin, a favorite in Roman couture, and may be identified as the personification of India. While her identity may be contested, what is indisputable is the role that Sātavāhana trade in ivory, pepper, aromatics, and cotton goods played in the Mediterranean world. Likewise, the wealth it engendered in India, especially in the Āndhradeśa territories of the Deccan, contributed to a boom period in the patronage of Buddhist monasteries when much of the sculptural art was added in the form of new encasement panels and enclosures. It is this chapter of early Buddhist art that is celebrated here.

John Guy

John Guy

Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

9

Fig. 3. Mosaic depicting an unnamed goddess, probably the personification of India, displaying ivory, pepper, aromatic wood, and textiles, and commanding an elephant and tigress. South apse, Villa Romana del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily, 4th century ce

Fig. 2. Ṣaḍdanta-jātaka (of the elephant “Six-Tusks”) drum panel depicting the hunter Sonuttara presenting the tusks of Chaddanta, the king of the elephants and the bodhisattva in disguise. Inscribed: Chaddanta-jātaka. Kanaganahalli, Sannati, Gulbarga district, Karnataka. Sātavāhana, 1st century bce . Limestone

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This exhibition and publication could not have happened without the support and vision of the director and leadership of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, who entrusted me to develop two major exhibitions that would extend the boundaries of scholarship in the field of Indian and Southeast Asian art history. The first was Lost Kingdoms: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast Asia, mounted in 2014, and the second, prepared with the unstinting support of Marina Kellen French Director Max Hollein, is Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 bce–400 ce, presented here. Deputy Director for Collections and Administration Andrea Bayer and Deputy Director for Exhibitions Quincy Houghton have further helped sustain our commitment to this exhibition in many ways. I am grateful to them all.

The field research that underpins this exhibition and publication took place over an extended period, commencing in earnest in 2014. I returned to India repeatedly thereafter, investigating the many stūpa sites that mark the monastic landscape of ancient Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The associated sculptural remains are dispersed in museums spanning the country. In the course of this fieldwork I enjoyed the generous support of numerous colleagues who facilitated access to museums and storerooms, and at times accompanied me to the more remote sites.

To colleagues in India, I begin by expressing my deep gratitude to the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Shri G. Kishan Reddy; Hon. Minister of State for External Affairs and Culture, Smt. Meenakashi Lekhi; Secretary of Culture, Shri Govind Mohan; and Joint Secretary Smt. Mugdha Sinha. They are responsible for the guardianship of India’s heritage, and their support was central to the success of this cultural cooperation between India and the United States. The Indian Ambassador to the United States, HE Taranjit Singh Sandhu, and the Indian Consul General in New York, Randhir Jaiswal, are owed special mention for their vision and steadfast support. I thank Smt. Lily Pandeya, Director General of the National Museum, New Delhi, for her support, along with her exceptional team in the International Exhibitions Department, led by curators Zahid Ali Ansari and Visetuonuo Kiso. They have been pivotal in managing the loans from India and are thanked for their professionalism and grace. I am grateful to Jawhar Sircar, the former Secretary of Culture under whose benevolent eye this project began, and to Venu Vasudevan, former Director General of the National Museum, New Delhi.

The Archaeological Survey of India, charged with the enormous responsibility of protecting more than three thousand heritage sites throughout India, is among the oldest such organizations in the world. I extend my deep

appreciation to the Director General, V. Vidyavathi, along with Joint Director General M. Nambirajan and many other colleagues there, including D. N. Dimri, Sanjay Kumar Manjul, N. K. Sinha, Anil K. Tiwari, and Vinay Gupta. I also note with gratitude the support of retired Directors Generals Rakesh Tewari and B. R. Mani, both of whom gave essential support in the formative phase of this project.

Beyond New Delhi, we have engaged with, and are indebted to, seven state governments and the numerous museums and archaeological sites that are under their watch: The Government of Andhra Pradesh: Hon. Chief Minister Shri Y. S. Jagan Mohan Reddy; Dr. Mukthapuram Harikrishna of the Chief Minister’s Office, Velagapudi; Hon. Minister of Tourism, Culture & Youth Advancement Smt. R. K. Roja; Principal Secretary to Government (Sports & Youth Services) Dr. G. Vani Mohan, also Commissioner of the Department of Archaeology & Museums; that Department’s Assistant Director Shri R. Phalguna Rao; and the Department’s staff. The Government of Bihar: Hon. Chief Minister Shri Nitish Kumar; Principal Secretary of Art, Culture and Youth Affairs Shri Ravi Manubhai Parmar; Director General of the Bihar Museum Shri Anjani Kumar Singh; Additional Director Shri Ranbeer Singh Rajput; and their curatorial team. The State Government of Maharashtra: Hon. Chief Minister of Maharashtra Shri Eknath Shinde; Additional Chief Secretary Shri Bhushan Gagrani; Principal Secretary of Tourism and Cultural Affairs Shri Saurabh Vijay; Director of the State Directorate of Archaeology and Museums Shri Tejas Garge; and Kolhapur Town Hall Museum curator Shri Amrut Patil. The State Government of Tamil Nadu: Hon. Minister for Industries, Tamil Official Language and Tamil Culture and Archaeology Shri Thangam Thennarasu; Principal Secretary for Tourism, Culture and Religious Endowments Shri B. Chandra Mohan; Director of the Government Museum, Chennai, Shri Sandeep Nanduri; Assistant Director Shri K. Sekar; and curator Shri S. Paneerselvam. Thanks also to former Director Ms. Kavitha Ramu. The State Government of Telangana: Hon. Chief Minister Shri K. Chandrashekar Rao; Secretary of Youth Advancement, Tourism, Culture & Sports Shri Sandeep Kumar Sultania, also Director of the Department of Heritage, Telangana; that Department’s Deputy Directors Shri Bavandla Narayana and Shri P. Nagaraju; and Assistant Director Ms. V. Nagalaxmi.

Thanks are also extended to former advisor of the Chief Minister, Shri B. V. Papa Rao, and to the former Director of the Department of Heritage, Telangana Shri N. R. Visalatchy. The Government of Uttar Pradesh: Hon. Chief Minister Shri Yogi Adityanath; Allahabad Museum

10

Director Shri Rajesh Prasad; along with retired Director Shri Sunil Gupta; Assistant Curator Shri Waman Wankhede; and Financial Officer Shri Raghavendra Singh. The State Government of West Bengal: Hon. Chief Minister Ms. Mamata Banerjee; Shri Arijit Dutta Choudhury, Director-in- charge of the Indian Museum, Kolkata; along with Ms. Nita Sengupta; Shri Sayan Bhattacharya; Shri Satyakam Sen; and former Director Shri Jayanta Sengupta.

The United States Embassy in New Delhi and its consulates throughout India have Generously assisted and facilitated this project throughout its long life. Special thanks goes to former Ambassador Kenneth I. Juster, who embraced the importance of the exhibition while on his first visit to Amaravati. I am also grateful to Chargé d’Affaires A. Elizabeth Jones and colleagues at the embassy and consulates, including Karl Adam, Gloria Berbena, Jennifer Bullock, Katherine Hadda, Scott Hartmann, Brindha Jayakanth, Salil Kader, David Kennedy, Lauren Lovelace, David Moyer, Ratna Mukherjee, Melinda Pavek, Judith Raven, and Madhuri Sehgal.

For loans in Europe, The Met is indebted to the British Museum, London, in particular Director Hartwig Fischer and Keeper of the Asian Department Jane Portal; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and Director Tristram Hunt, Keeper of the Asian Art Department Anna Jackson, and curator Nick Barnard; the Museum für Asiatische Kunst – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, its Director Raffael Dedo Gadebusch and curator Martina Stoye; and to the National Archaeological Museum, Naples, and its Scientific Director Marialucia Giacco. In the United States, the Cleveland Museum of Art has been a generous lender under Director and President William M. Griswold and with support from George P. Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art Sonya Rhie Mace, as has the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, thanks to President Walter W. Timoshuk and Chief Curator Emily Talbot.

This project’s sponsors recognized the importance of this endeavor, and I sincerely thank them for their investment in this work. Reliance Industries Limited, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Global, and the Fred Eychaner Fund make the exhibition possible. My appreciation goes to the Estate of Brooke Astor, the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Exhibitions, and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation for their major support, as well as to the Lavori Sterling Foundation Endowment Fund and Usha M. and Marti G. Subrahmanyam for their additional generosity. The Fred Eychaner Fund also makes possible the exhibition’s scholarly symposium, organized in cooperation with New York Center for Global Asia, NYU Shanghai Center for

Global Asia, and the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute, Harvard University. Finally, the beautiful book you now hold is made possible by the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Publications, with additional support from Albion Art Co., Ltd.

Foremost at The Met I must thank my colleagues in the Department of Asian Art, who have long supported this project with good humor. I am indebted to Douglas Dillion Chair Maxwell K. Hearn, who has been a steady guide and staunch ally. Stephanie Kwai, Senior Manager of Administration, Operations, and Collections, has been a pillar of strength, stepping forward even before one knew help was needed. Collections Manager Alison Clark has ensured that order prevailed, along with Mary Hurt, Inae Rurup, and Edmon Zhou. Technicians Beatrice Pinto, Imtikar Ally, Sooyoung Jeon, and Djamel Haoues handled and installed the works of art with skill and graciousness. This project benefited from the dedication of several research assistants, whom I thank: Maud LeClair, Vaishnavi Patil, and Kalyani Ramachandran. In preparing the Gazetteer of Buddhist Sites, Principally in the Deccan, I was ably assisted by interns Jovanna Abdou, Tarini Gandhi, Dhwani Gudka, Ottilie Lighte, Kaira Mediratta, Raagini Pareek, Mallika Ramachandran, and Gillian Scholz.

In the Exhibitions Department headed by Quincy Houghton, Senior Manager of Exhibitions Gillian Fruh and Touring Exhibitions Project Manager Jason Kotara navigated the many challenges of this exhibition. Vinod Daniel served as project manager in India, skillfully facilitating and guiding in equal measure. The Registrar’s Office has played a pivotal role, with Senior Associate Registrar Allison Barone at the helm, with Meryl Cohen, Mehgan Pizarro, and Sarah Kraft, as did Amy Lamberti, Associate General Counsel in the Office of the Secretary and General Counsel. The staff of Star International in India and Masterpiece International in New York are due thanks for their logistical expertise. The Design Department, led by Head of Design Alicia Cheng, with the brilliant design team of Senior Exhibition Designer Patrick Herron and Associate Design Manager Mortimer Lebigre, ensured that the curatorial vision for the exhibition was beautifully and evocatively realized. Special mention should be made of the Buildings Management team responsible for installing the works safely, led by Taylor Miller, with Michael Doscher and Matthew Lytle. Likewise, I am grateful to the Lighting Designers, guided by Amy Nelson. The Department of Objects Conservation, led by Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge Lisa Pilosi, brought its formidable experience to this project, and I thank Vicki Parry, Carolyn Riccardelli, Frederick Sager, and Marlene

11

Yandrisevits. I am further grateful to Research Scientist Federico Carò in the Department of Scientific Research.

The Department of Institutional Advancement worked closely with the curatorial team in expertly securing funds for this project, and I am grateful to Stephen A. Manzi, John L. Wielk, Jason Herrick, Kimberly McCarthy, and Evie Chabot. In the External Affairs Department, Stella Kim led the press and media promotions, working closely with the Digital Department’s team, headed by Douglas Hegley. The Education Department, led by Heidi Holder, Frederick P. and Sandra P. Rose Chair of Education, placed talented interns and developed a rich array of programming, for which I thank Francesca D’Alessio, Elizabeth Perkins, Marianna Siciliano, and Sherri Williams.

Members of the Publications and Editorial Department are to be thanked for their usual professionalism in seeing this book to fruition: Publisher and Editor in Chief Mark Polizzotti; Associate Publisher for Production Peter Antony; Associate Publisher for Editorial Michael Sittenfeld; Senior Editor Elizabeth L. Block, with Sarah McFadden; Senior Production Manager Christopher Zichello; Image Acquisitions Specialist Josephine Rodriguez; Editor Elizabeth Benjamin; Associate Editor Cecilia Weddell; designer Laura Lindgren; and bibliographer Amelia Kutschbach. Yael Shiri provided expert proofreading of the Middle Indo-Aryan and Sanskrit terminology. The publication is greatly enhanced by the photography of Thierry Ollivier,

NOTE TO THE READER

Abbreviations

ASI Archaeological Survey of India

Unless otherwise noted, catalogue entries are written by John Guy.

Note on Translation

Unless otherwise noted, translations of quotations are by the authors.

Note on Transliteration

Dealing primarily with art of the Indian subcontinent, many of the terms and toponyms discussed in this book originate from a variety of Indic languages and their spelling in English can therefore vary. Some of these terms, such as Buddha or Dharma, have entered common use in contemporary English. However, in order to offer consistency and clarity but also to be as loyal to their original pronunciation as possible, many of these words have been transliterated.

whose extraordinarily beautiful photographs were produced often in the most challenging of circumstances.

The contributors to this publication deserve special mention: Shailendra Bhandare, Pia Brancaccio, Federico Carò, Parul Pandya Dhar, Sunil Gupta, Himanshu Prabha Ray, Gregory Schopen, Peter Skilling (Bhadra Rujirathat), Akira Shimada, Elizabeth Rosen Stone, Vincent Tournier, Norman Underwood, and Monika Zin.

On a personal note, I extend thanks to Romila Thapar, Kesavan Veluthat, Oskar von Hinüber, Harry Falk, Naman Ahuja, and Suchandra Ghosh for their scholarship and friendship over the years. Akira Shimada served as an advisor to this project and on occasion an agreeable travel companion in the Andhra territories. I thank him on both counts. Arlo Griffiths and Vincent Tournier generously shared their groundbreaking contributions to Andhra epigraphy, along with contributors Stefan Baums, Emmanuel Francis, and Ingo Strauch, in the Early Inscriptions of Andhradesa (EIAD) online project. Thanks are due to Annette Giesecke on matters botanical and to William Dalrymple for his encouragement. The generous support of our sponsors is detailed above, but I wish to record my personal appreciation to Anita Chung and Fred Eychaner for their belief in this project. Finally, I am indebted to colleagues in India for their extraordinary acts of kindness to me on this project. These friendships are the bedrock of international cooperation and understanding.

John Guy

Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia

Place names in particular posed a challenge as they occur in various forms in the available literature, and modern place names have become invariably associated with their ancient history. In this book, places of archaeological significance as well as ancient toponyms have been transliterated, while for other place names they have been omitted.

The transliteration of words in Devanagari and related Indic scripts has been rendered with diacritics, to indicate a diversity of phonetic sounds not always reflected in Latin script, following the ISO 15919 Romanization standard established by the International Organization for Standardization (2001). For consistency, when a term or proper name can occur variously in different languages, the Sanskrit spelling was prioritized over others. All nonEnglish terms appear in italics. At times, the book makes use of epigraphic evidence, in which cases the inscribed spelling of proper names and toponyms was preserved. As for the names of rulers, whose names have been spelled in epigraphic records in various ways, a standardized spelling was used throughout. In the case of the Sātavāhana dynasty, a standardized Prakrit spelling has been opted for.

12

alt. alternate anc. ancient mod. modern lit. literally Skt. Sanskrit Tib. Tibetan var. variant

LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION

INDIA

Government of India, Ministry of Culture

Archaeological Survey of India, Archaeological Museum

ASI, Amavarati, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh

Archaeological Survey of India, Kanaganahalli Archaeological Site ASI, Sannati, Gulbarga District, Karnataka

Archaeological Survey of India, Nagarjunakonda, Archaeological Museum ASI, Nagarjunakonda, Andhra Pradesh

Government of Andhra Pradesh, Amaravati Heritage Centre and Museum, Department of Archaeology and Museums

Government of Andhra Pradesh, Baudhasri Archaeological Museum, Guntur, Guntur District, Department of Archaeology and Museums

Government of Bihar, Bihar Museum, Patna

Government of Maharashtra, Town Hall Museum, Kolhapur, Department of Archaeology and Museums

Government of Tamil Nadu, Government Museum, Chennai

Government of Telangana, Karimnagar Archaeology Museum, Department of Archaeology and Museums

Government of Telangana, Phanigiri Stūpa Site, Department of Heritage Telangana, Hyderabad

Government of Telangana, State Archaeology Museum, Department of Heritage Telangana, Hyderabad

Government of Uttar Pradesh, Allahabad Museum, Prayagraj

Government of West Bengal, Indian Museum, Kolkata

National Museum, New Delhi

EUROPE

Museum für Asiatische Kunst – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The British Museum, London

Nick Gilbey and Mrs. Thomasin Nares

National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Private collection

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Brooklyn Museum

Cleveland Museum of Art

Norton Simon Foundation, Pasadena

Private collections

CONTRIBUTORS

AUTHOR

John Guy, Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

CONTRIBUTORS

Shailendra Bhandare, Curator of South Asian and FarEastern Coins and Paper Money, Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, England

Pia Brancaccio, Professor of Art History, Drexel University, Philadelphia

Federico Carò, Research Scientist, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Parul Pandya Dhar, Associate Professor of Art History, University of Delhi, New Delhi

Sunil Gupta , Former Director In Charge, Allahabad Museum, Prayagraj. Ministry of Culture, Government of India

Himanshu Prabha Ray, Professor, Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

Gregory Schopen, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Los Angeles

Akira Shimada , Professor, Department of History, State University of New York at New Paltz

Peter Skilling, Adjunct Professor, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, India

Elizabeth Rosen Stone, Independent Scholar, New York

Vincent Tournier, Professor of Classical Indology, Institut für Indologie und Tibetologie, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

Norman Underwood, Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, New York University

Monika Zin, Professor of Art History and Asian Studies, Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities and Leipzig University, Leipzig

13

BEGINNINGS OF BUDDHIST IMAGERY

Early Buddhist Landscape of Southern India

JOHN GUY

JOHN GUY

Buddhism in southern India cannot boast of a single holy site visited by the Buddha Śākyamuni in his lifetime. Yet within a period of less than two hundred years after the Buddha’s death, about 400 bce to the Mauryan emperor Aśoka’s reign (ca. 268–232 bce), Buddhism disseminated into the Dakṣiṇāpatha, the great region south, and especially in Āndhradeśa, the lands of the southern kingdoms bracketed by the Godavari and Krishna river systems. It claimed the possession of true relics housed in funerary mounds— stūpas—of spectacular scale and adornment. Its monasteries (vihāras) were among the most splendid, celebrated for the beauty of their natural settings, typically situated close to a river, as at Amaravati, or on high ground overlooking a river, as seen at Jaggayyapeta and Phanigiri (fig. 4). This remarkable Buddhist transformation of the southern lands was the product of two powerful forces, the appeal and authority of the Buddha’s message, and the patronage of the increasingly wealthy mercantile and artisan classes who sustained the faith and furthered its propagation, funding new stūpas and monasteries in places where none had been before. In so doing they were venturing deep into territories that belonged to other gods, where nature spirits and demigods presided. It was a contested religious landscape, and the early Buddhists had to compete for spiritual allegiance. This essay explores how Buddhism came to understand and control this landscape. Two leitmotifs are preeminent, the use of tree imagery and of serpents attending the stūpa . These two motifs are so pervasive as to be the defining features of Southern Buddhism. Their relationship to the Buddha’s world shaped the early Buddhism of southern India and its art.

The historical Buddha, born as the Bodhisattva (Buddha-to-be) Prince Siddhārtha, of the royal household of the Śākya clan of today’s Bihar, in northern India bordering western Nepal, came to be known as the Buddha Śākyamuni, the “wise-one of the Śākyas.” 1 He was revered in

his lifetime for preaching an ascetic path to secure release from the endless cycles of rebirth (saṁsāra) fundamental to the prevailing orthodoxy. 2 Following his parinirvāṇa (“complete-extinction”) about 400 bce, over the course of the next three hundred years, four Buddhist Councils were held, according to Theravāda sources. The first was convened within months of the Buddha’s death to commit to memory his teachings, the sutta (Skt. sūtra), and the monastic rules of conduct, the Vinaya. These are understood to have been promulgated by the Buddha himself and are therefore canonical. Monastic recitation specialists (bhāṇaka) were responsible for memorizing the Buddhist canon and transmitting it as an unbroken oral tradition. It was only about 50 bce, as best we know, that this knowledge was given written form on palm-leaf folios, at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka.3 The later Councils appear to have been largely preoccupied with attempting to resolve, ultimately unsuccessfully, more substantive doctrinal differences that had emerged, resulting in sectarian schisms that remain to this day.

The Buddha’s utterances, often prefaced with the phrase “Thus Have I Heard” and recorded in the form of discourses that became the core of Buddhist canonical literature known as sūtras, embody the Buddha’s teaching and instructions for monastic practice. Commentaries followed, as did a hagiographic literature built from fragmentary accounts of the life events of the Buddha embedded in the sūtras and Vinaya. Seminal events in the Buddha’s life became vehicles for conveying his ethical teachings, like those recounted in the Lalitavistara, Buddhavaṁsa, and Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita . Further life stories of the Buddha appear in the Pāli jātaka Nidānakathā and in the Vinaya, such as the Mahāvastu 4 Added to this corpus of teachings and commentaries were two other bodies of Buddhist literature, both of which have their origins, in part at least, in folktales that likely predate the Buddha’s era. These are

18

the jātaka tales that relate the life stories of bodhisattvas belonging to past lifetimes, and the avadānas, stories that similarly serve as vehicles for sharing Buddhist teachings, blending popular folk idioms with profound Buddhist discourse.5 The latter two sources, along with the Buddha’s biography, became important fountainheads for the narratives given form in the visual arts of early Buddhism.

Pāli was one of the many vernacular Middle IndoAryan languages of northern India and favored for the transmission of early Buddhism. The historical Buddha taught in Māgadhī, the spoken language of the territory of Magadha that he traversed in his lifetime. In regions where the Theravāda tradition thrived, most especially in Sri Lanka, Pāli was the language in which the canonical texts were preserved and in which commentaries were composed. Other vernacular languages were used in other regions, depending on the cultural setting of the commentator. Over time these became increasingly Sanskritized, as classical Sanskrit, which began as an exclusive sacred language of Vedic ritual and Brahmanism, prevailed across Indian literary society.6 By the second century ce such leading Buddhist scholars as Aśvaghoṣa were composing works of preeminent beauty in Sanskrit.

RELIGIOUS SEEKERS

The Buddha, along with the historical founder of Jainism, Mahāvīra, were but two of many religious seekers in the territory of “Greater Magadha” in the Gangetic Basin, broadly defined as the territory extending from the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers at Prayagraj (Allahabad) in Uttar Pradesh east to Rājagṛha in Bihar (see

Maps).7 In the time of the Buddha this was home to a number of competing kingdoms whose rise was aligned with the urbanization witnessed in the historical sources as the sixteen large cities, mahājanapadas. Śrāvastī, a favored location for the Buddha to reside post-Enlightenment, was the capital of the Kośala kingdom, and Rājagṛha the capital of Magadha. The Buddha experienced his awakening at Bodhgaya, a mere fifty-six kilometers from Rājagṛha, and meditated and preached at Vulture Peak (Gṛdhrakūṭa) overlooking that city. Mahāvīra also lived for fourteen years at Rājagṛha. Patna (ancient Pāṭaliputra) emerged in the fourth century bce as the capital of the Nandas and, about 320 bce, as that of their successors, the Mauryas, the first imperial power to unify vast tracts of northern India into an administrative entity (see Early India: Chronology and Key Events). The ruling household of the Nandas appear to have been “zealous patrons of the Jains,” as was their usurper Chandragupta Maurya. 8 Others, including Chandragupta’s successor Bindusāra, were followers of the Ājīvikas, another ascetic movement (śramaṇa) whose founder was a contemporary of Mahāvīra and perhaps the Buddha.9 The Barabar Caves, located about forty-eight kilometers west of Rajgir, are their principal legacy (fig. 46). The rock-cut interiors are devoid of decoration, a suitable setting for the performance of the extreme austerities for which they were renowned. They contain Mauryan Brāhmī inscriptions, including two recording the support of Chandragupta’s grandson Aśoka in his twelfth regnal year.10

Aśoka, who is the best documented of all the Mauryan rulers, owing to the many rock-cut and pillar edicts he

EARLY BUDDHIST LANDSCAPE OF SOUTHERN INDIA 19

Fig. 4. Aerial view of the hill-top monastic complex of Phanigiri, Suryapet district, Telangana. Courtesy of Department of Heritage, Telangana

26 TREE & SERPENT

Catalogue

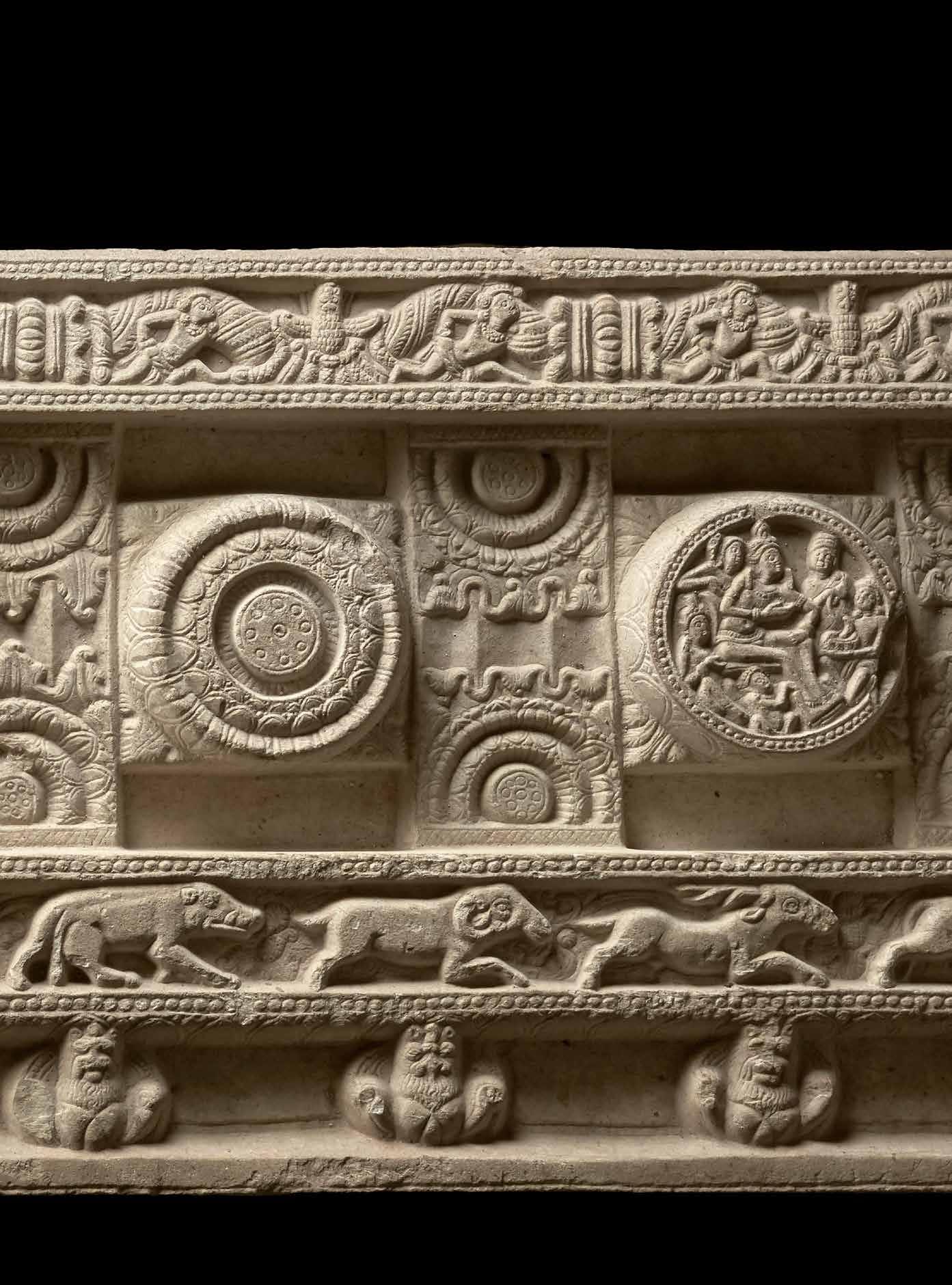

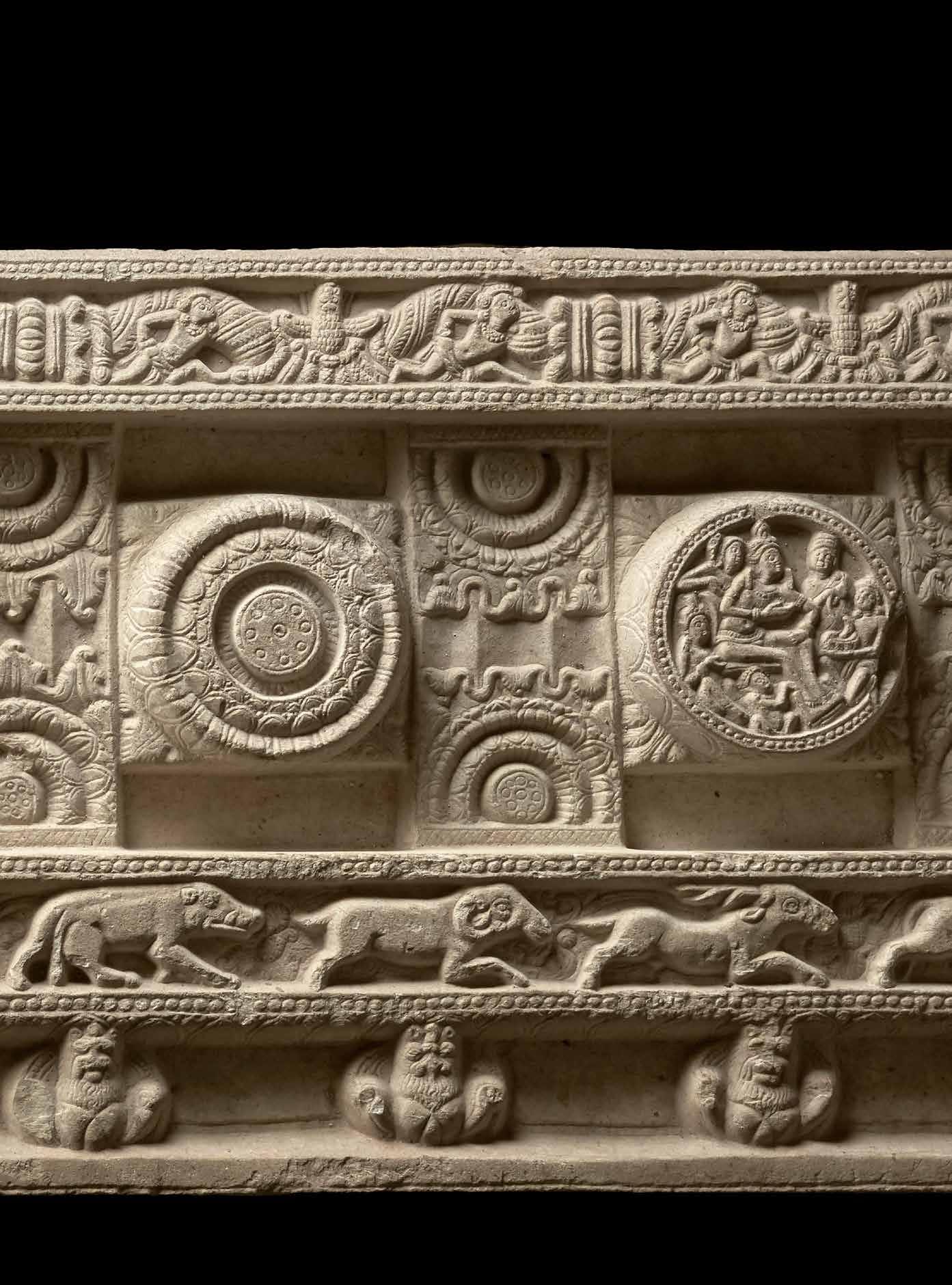

Kanaganahalli mahācaitya, Karnataka Sātavāhana, 1st century bce Limestone, approx. 393/8 × 551/8 × 77/8 in. (100 × 140 × 20 cm)

Kanaganahalli Site Museum, Archaeological Survey of India, Sannati, Gulbarga district, Karnataka

PUBLISHED: Poonacha 2011.

Of singular importance to the art and archaeology of early Buddhism in India has been the excavation of the stūpa mound at Kanganahalli in northern Karnataka.1 Extensive excavations were undertaken at the mahācaitya between 1994 and 2002. 2 Kanaganahalli overlooks the Bhima River, a tributary of the Krishna River, and is in the vicinity of Sannati, a Buddhist and urban center that in 1989 yielded fragments of several Aśokan edicts, establishing the location of Mauryan foundations. Earthworks and brick foundations identified a fortified city and citadel, along with traces of several Buddhist monasteries, marked by Sātavāhana-era Brāhmī inscriptions.

The substantially complete stūpa remains excavated at Kanaganahalli date from the first century bce through the third century ce. It has the most intact sculptural program of any stūpa excavated in Andhra Pradesh to date, and is preserved in remarkable condition. The first three centuries of the stūpa’s sculptural evolution are a rich tableau of jātaka tales and Buddha life stories, with the Buddha represented only in aniconic form. The Buddha depicted in human form appears in the last phase of renovation, mostly in the third century ce

A corpus of more than three hundred inscriptions has been identified on the limestone panels that encased the great stūpa . They provide the contemporary name of the stūpa , Adhālaka-mahācaitya , along with identifying glosses for most of the narrative scenes depicted and the names of numerous lay donors, including the prominently featured Toda family, described as bankers.3 A series of prominently positioned portraits of regal figures named as historic kings of the Sātavāhana royal lineage is unique to the history of Buddhist monastic architecture. As the Sātavāhanas were not Buddhists but rather devout Śaivas, their presence in the sculptural program at Kanaganahalli raises challenging questions. Only at the rock-cut royal cave at Naneghat in the Western Ghats

does a comparable royal lineage of the Sātavāhanas appear, with inscribed images, now largely obliterated. What these two sites of early Sātavāhana patronage have in common is an interest in protecting commercial trade routes, the former descending to the Konkan Coast of the Arabian Sea, the latter benefitting from riverine connectives to the Bay of Bengal. Evoking past Sātavāhana kings at Kanaganahalli presumably impressed lay patrons with the authority of a ruling order that ensured the safe passage of people and goods.

The abundance of Buddhist narratives depicted at Kanaganahalli is unrivaled. A dozen jātakas are presented, along with seminal scenes from the life of the Buddha. It is the richest surviving array of sculpted panels enlivening a mahācaitya . Traces of painted lime mortar in concealed surfaces demonstrate that

the monument was brilliantly painted, a radiant spectacle for worshippers to behold. Ubiquitous in stūpa depictions in Āndhradeśa is the prominence given to two motifs, both dedicated to honoring the Buddha relics within, the tree and the serpent. The nāgas seen here envelop the dome, their bodies entwined protectively and their hooded heads raised to strike. Above is a spectacular canopy of umbrellas honoring the relic, and in their branch-like proliferation, they mimic the bodhi tree that sheltered the Buddha at his awakening. On the flanking pilaster is a royal personage, accompanied by his wife carrying garland offerings in a basket. The protective presence of the nāgas tells us that this is not a generic stūpa , but rather is the Rāmagrāma, the stūpa that housed the eighth portion of the original division of the relics.

CATALOGUE: BEGINNINGS OF BUDDHIST IMAGERY 27

1. Nāgas protecting the Rāmagrāma stūpa, worshipped by a royal devotee

Fig. 10. Rāmagrāma stūpa guarded by nāgas. Amaravati mahācaitya. Ikṣvāku, 3rd century ce Amaravati, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh. Government Museum, Chennai (inv. 53)

MONASTIC BUDDHISM, COMMERCE, AND PATRONAGE

60. Nobleman and son at worship

Amaravati mahācaitya, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh

Sātavāhana-Sada, ca. 100–50 bce

Excavated below the pradakṣiṇāpatha pathway on the northeast side of the mahācaitya, January 1882

Limestone, 57 × 33 in. (144.8 × 83.8 cm) Government Museum, Chennai (inv. 181)

Not in exhibition

PUBLISHED: Burgess 1887, p. 99, pl. LI, fig. 2; Bachhofer 1929, p. 29, pl. 109; Sivaramamurti 1956, p. 159, pl. XVIII, fig. 1; Stern and Bénisti 1961, pl. VII, fig. a; Shimada 2013a, pp. 105–6, pl. 54; Kannan 2014, p. 44.

This sculpture is perhaps the most celebrated of the early phase panels produced for the adornment of the Amaravati mahācaitya . It depicts a man of high rank who we may assume played a leading role in the funding of the stūpa’s renovation in the first century bce. He is depicted, together with his son, offering bouquets of flowers; the untraced adjacent panel presumably depicted a stūpa , the subject of their piety. James Burgess recorded the precise location of the panel’s discovery:

“Among the stones dug up in January 1882, from under the general level of the procession path, was one from the north-east, measuring 4 feet 9 inches by 2 feet 9 inches, but broken across.” 1 Such a grand subject would have been given a prominent location in the first phase of the monument’s decoration, about 100–50 bce. In a subsequent renovation, it was thrown down and used as filler beneath a new pavement.

The panel depicts a regal male figure, richly attired with an elaborate headdress with a large frontal bun. He wears massive earplugs (kuṇḍala), one cylindrical and probably of ivory, the other square with a rosette with pearl border design, likely of gold. The eyes are attenuated and sharply defined, as is the deeply cut brow giving a stern intensity to the gaze that resonates with Bharhut figurative reliefs (cats. 26, 27). He wears a multistrand necklace likely of braided gold wire, with square medallions with hatching. Triple-band bracelets are worn on each forearm, and a heavy waist-sash with large toggles secures his skirt-cloth. The accompanying boy, presumably the worshipper’s son, participates in the making of offerings. He is more simply dressed and wears only cylindrical earplugs and a torque with radiating petals. In many respects, the

dress mode, jewelry detailing, and threequarter profile representation bear close comparison to the near-contemporary murals preserved at Ajanta in Cave 10, which provides portraits, of extraordinary fidelity, of Sātavāhana nobility and commoners alike (fig. 24). These are the oldest paintings to survive from ancient India.

Action is directed to the viewer’s right. The panel would have been positioned to flank a major scene in which the Buddha’s presence was evoked. No figurative depictions of the Buddha appear in this period. The exceptionally large scale of this panel and its simple scene of piety make a powerful statement regarding the prominent role of sponsors of Buddhist monastic architecture. The family members each offer flowers, the adult a bouquet of sāla flowers, and the boy a lotus. If indeed this personage is a major donor and likely royal, then it has added significance in the context of early Buddhist patronage patterns, which, according to the inscriptional record, are overwhelmingly female, and in this early phase, non-royal. 2 The early period Brāhmī script Prakrit inscriptions at Amaravati typically speaks of the donor as a family (or clan) leader, and of his or her relatives. Others are either communal (“Gift of the city [nagara] of Dhānyakaṭaka”) or associated with men of property ( gahapati ), such as wealthy merchants or men of rank (“A pillar of General Mudukutala”).3 This panel of pious worshippers has no surviving inscription to enlighten us as to the social position of those depicted. However, several early inscriptions at the Amaravati mahācaitya demonstrate that local rāja families and their officers were active patrons, and the recently retranslated memorial stone inscription from Mukkatraopet, Karimnagar district, Telangana, states that it was erected at the instigation of a familial group of higher noblewomen (ahimarikā s), each of whom is named. 4

The Amaravati panel has its nearest parallel in another remarkable and rare survivor from the early phase: a freestanding sculpture of a male worshipper standing erect, his hands clasped and holding a lotus bloom to his chest. It bears a damaged inscription in Brāhmī script incised between the folds of the waistcloth.5 Recent reexamination of

the inscription suggests a reading of “Gift of . . . Gotami’s [Skt. Gautamī] mother.” 6 It is distinguished by flat modeling, shallow linear detailing, and a somewhat rigid frontality, a style that can be broadly characterized as archaic. Close comparison can be made with the father-and-son panel, especially in the shared treatment of the garments, the oversized hands, double-ring nipples, and the four-pointed star treatment of the navel. The musculature of the chest and hips are also treated in a like manner. In sum, these shared features points to these two sculptures belonging to the same workshop and produced by the same generation of artists, or their immediate followers.

Further comment should be made of a highly important relief panel from Garikapadu, a major stūpa site located midway between Amaravati and Kesanapalli, that is now untraced. This panel is known only from an unpublished photograph taken during the survey by Alexander Rea in 1889.7 Rea reported that the stūpa, measuring about twenty-four meters in diameter, had around its circumference “spaces for 90 slabs, of which only six are completely gone. Others have little more than their bases remaining, but some are in very perfect preservation.” He concluded, “The finest slab is a complete one . . . carved with a jeweled raja standing by a horse.” 8 This majestic image has all the hallmarks of a royal commission, yet the figure’s identity is not immediately clear. However, the splendidly attired man and caparisoned horse suggest a person of high office. The man wears a magnificent turban and massive ear ornaments and holds a staff, perhaps a fly whisk. His horse wears a large plumage and is fitted with a harnessing of linked rosettes. This unknown figure is unquestionably regal: a local rāja , perhaps, or a regional governor? No records exist to locate this magnificent panel in the stūpa drum sculptural program of which it was once a part. Yet we may assume that it, too, like the fatherand-son panel from Amaravati, depicts an important sponsor of the once important stūpa at Garikapadu. The proximity of Garikapadu to Amaravati, located due west, raises the strong likelihood that they shared the same pool of sculptors, ensuring a stylistic unity across the two sites. Bhattiprolu, renowned for its spectacular reliquary deposit discovered by

140 TREE & SERPENT

GLOBAL SETTING

This catalogue is published in conjunction with Tree and Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 bce–400 ce, on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from July 21 through November 13, 2023.

The exhibition is made possible by Reliance Industries Limited, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Global, and the Fred Eychaner Fund.

Major support is provided by the Estate of Brooke Astor, the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Exhibitions, and the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation.

The catalogue is made possible by the Florence and Herbert Irving Fund for Asian Art Publications.

Additional support is provided by Albion Art Co., Ltd.

First published in India in 2023 by Mapin Publishing

Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Mark Polizzotti, Publisher and Editor in Chief

Peter Antony, Associate Publisher for Production

Michael Sittenfeld, Associate Publisher for Editorial

Edited by Elizabeth L. Block, with Sarah McFadden

Designed by Laura Lindgren

Production by Christopher Zichello

Bibliographic editing by Amelia Kutschbach

Image acquisitions and permissions by Josephine Rodriguez

Maps by Adrian Kitzinger

Photographs of works in The Met collection are by the Imaging Department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, unless otherwise noted. Principal photography for works in India is by Thierry Ollivier. Additional photography credits appear on page 343.

Typeset in Freight Text Pro and Rational

Printed on Perigord, 150 gsm

Separations by Professional Graphics, Inc., Rockford, Illinois Printing and binding coordinated by Ediciones El Viso, Madrid

Jacket illustrations: front, Stūpa panel with nāgarāja Mucalinda protecting the Buddha, cat. 5; back, Congregation hall pillar celebrating the Great Renunciation (detail), cat. 128.

Additional illustrations: frontispiece, p. 2: King Puḷumāvi surrenders the city of Ujjain, cat. 63; pp. 16–17: Coping railing with forest dwellers scaling or quarrying a rock face (detail), cat. 10; pp. 74–75: Coping stone with railing pillars (detail), cat. 44; pp. 116–17: Āyāka panel (detail), cat. 131; pp. 158–59: Coping fragment with lotus bloom meander, cat. 9; pp. 196–97: Āyāka cornice with four narrative roundels, cat. 123; p. 279: Yakṣa (detail), cat. 132.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art endeavors to respect copyright in a manner consistent with its nonprofit educational mission. If you believe any material has been included in this publication improperly, please contact the Publications and Editorial Department.

Copyright © 2023 by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10028 metmuseum.org

Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd

706 Kaivanna, Panchvati

Ahmedabad 380006 INDIA

T: +91 79 40 228 228 • www.mapinpub.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

isbn 978-93-94501-16-4

ART Tree and Serpent

Early Buddhist Art in India

John Guy

344 pages

322 illustrations and 3 maps

9 x 12.25” (228 x 344 mm), hc

ISBN: 978-93-94501-16-4

₹3950 | $65

July. 2023 • South Asia

John Guy is Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia in the Department of Asian Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Jacket illustrations: front, Stūpa panel with nāgarāja Mucalinda protecting the Buddha, Dhulikatta stūpa, Karimnagar district, Telangana, Sātavāhana, 1st century BCE; back, Congregation hall pillar celebrating the Great Renunciation (detail), Phanigiri, Suryapet district, Telangana, Ikṣvāku, 3rd–4th century CE

Jacket design by Laura Lindgren

printed in india

www.mapinpub.com

“Brilliant in conception, the publication Tree and Serpent brings together scores of stunning works of art from the beginnings of Buddhist art in India, many never seen before. Through the pieces he assembles and the text he provides, John Guy makes it clear that we cannot understand the Buddha until we see what surrounds him. In Tree and Serpent, the Buddha comes back home.”

Donald Lopez

Distinguished Professor of Buddhist Studies University of Michigan

Donald Lopez

Distinguished Professor of Buddhist Studies University of Michigan

www .mapinpub.c om ISBN 978-93-94501-16-4 ₹3950 | $65

John Guy

John Guy

JOHN GUY

JOHN GUY