Spring 5784/2024

•

Vol.

84, No. 3

$5.50

It's More Than An Airline. It's Israel. FLY THE FLAG elal.com

54

COVER STORY

Hope Amid Crisis— A Symposium

How we can maintain a sense of hope and optimism in a time of tragedy

By Michal

Horowitz; Rebbetzin Dina Schoonmaker, as told to Barbara Bensoussan; Rabbi Larry Rothwachs; Rabbi Dr. David Fox; and Rabbi Dov Foxbrunner

Responding to Crisis: A Historical Approach

By

Dr. Henry Abramson

Celebrating Life in the Face of Pain: One Son Married, One Son Missing

By Toby Klein Greenwald

Of Faith and Fortitude:

How Devorah Paley Energized a Nation

By Yocheved Lavon

A Laughing Matter

In the aftermath of October 7, Orthodox Jewish comics have been finding ways to keep spirits high and make us laugh.

By Carol Green Ungar

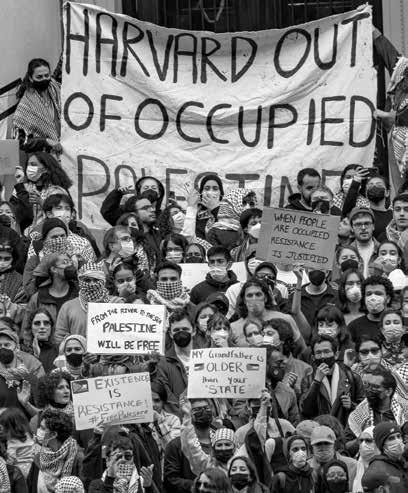

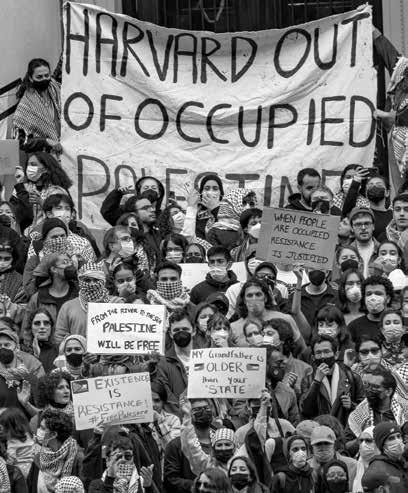

THE JEWISH WORLD Voices from Campus

By Gideon Askowitz, Rebecca Massel, Adin Moskowitz, Eitan Fischer and Isaac Ohrenstein

Chizuk on Campus

By Steve Lipman

How Students Are Responding to Antisemitism

In the wake of rising antisemitism on college campuses and in public high schools, a growing number of students are responding to antisemitism in a novel way—by embracing their Judaism.

By Tova Cohen

DEPARTMENTS

02 06

LETTERS

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

My Yarmulke

By Mitchel R.

Aeder

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

In Praise of Israeli Emunah

MENTSCH MANAGEMENT

How Do We Partner?

The Benefits of Shared Leadership

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

ON MY MIND

Yefashpesh B’ma’asav: PostTragedy Introspection

By Moishe Bane

IN FOCUS

Torah United

By Rabbi Moshe Schwed

LEGAL-EASE

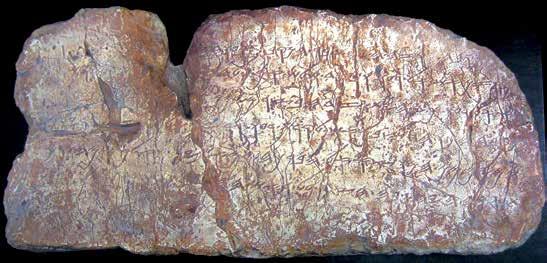

What’s the Truth About . . . Rashi Script?

By Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky

KOSHERKOPY

A No-Grainer: The Laws of Yoshon Simplified

By Rabbi David Gorelik

72

THE CHEF’S TABLE Pesach’s Forgotten Meal

By Naomi Ross

NEW FROM OU PRESS BOOKS

Kohelet: A Map to Eden—An Intertextual Journey

By David Curwin

Reviewed by Rabbi Reuven

Chaim Klein

REVIEWS IN BRIEF

By Rabbi Gil Student

LASTING IMPRESSIONS

Until When

By Nomi Gutenmacher

Cover:

Design: Bacio Design & Marketing

Cover photos:

Top center: Akiva Sheinberger for Chabad of Israel

Top right: Allison Bailey/NurPhoto via AP

Bottom left: Sipa USA via AP

Bottom right: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

1 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION Jewish Action seeks to provide a forum for a diversity of legitimate opinions within the spectrum of Orthodox Judaism. Therefore, opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of the Orthodox Union. Jewish Action is published by the Orthodox Union • 40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006, 212.563.4000. Printed Quarterly—Winter, Spring, Summer, Fall, plus Special Passover issue. ISSN No. 0447-7049. Subscription: $16.00 per year; Canada, $20.00; Overseas, $60.00. Periodical's postage paid at New York, NY, and additional offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Jewish Action, 40 Rector Street, New York, NY 10006. 42 INSIDE Spring 2024/5784 | Vol. 84, No. 3

FEATURES

20

36 42 50

58 71 72

10

80

85

16

83

88

92 96 100 102 104

54

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION jewishaction.com

THE MAGAZINE OF THE ORTHODOX UNION

jewishaction.com

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

A NOTE OF GRATITUDE

LETTERS

This is a long overdue hakaras hatov letter to Jewish Action for being the impetus for the creation of a program that has changed hundreds of lives—particularly my and my daughter’s lives.

Associate Editors

Sara Goldberg • Batsheva Moskowitz

Editor in Chief Nechama Carmel carmeln@ou.org

Rabbinic Advisor

Rabbi Yitzchak Breitowitz

Assistant Editor Sara Olson

Book Editor

Rabbi Gil Student

Literary Editor Emeritus

Matis Greenblatt

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Moishe Bane • Dr. Judith Bleich

Book Editor Rabbi Gil Student

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Goldberg

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Berel Wein

Contributing Editors

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein • Dr. Judith Bleich

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman • Rabbi Hillel Goldberg

Moishe Bane • Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Deborah Chames Cohen

Rabbi Sol Roth • Rabbi Jacob J. Schacter

Rabbi Berel Wein

Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz • Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Gerald M. Schreck • Dr. Rosalyn Sherman

Editorial Committee

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin • Rabbi Binyamin Ehrenkranz

Rebbetzin Dr. Adina Shmidman • Rabbi Gil Student

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Rabbi Avrohom Gordimer • David Olivestone

Gerald M. Schreck • Rabbi Gil Student

Copy Editor

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Hindy Mandel

Design 14Minds

Design Bacio Design & Marketing

Advertising Sales

Advertising Sales

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Joseph Jacobs Advertising • 201.591.1713 arosenfeld@josephjacobs.org

Subscriptions 212.613.8140

Subscriptions 212.613.8134

ORTHODOX UNION

ORTHODOX UNION

President Mark (Moishe) Bane

President

Mitchel R. Aeder

Chairman of the Board

Chairman of the Board

Howard Tzvi Friedman

Yehuda Neuberger

Vice Chairman of the Board

Vice Chairman of the Board

Mordecai D. Katz

Barbara Lehmann Siegel

Chairman, Board of Governors

Chairman, Board of Governors

Henry I. Rothman

Avi Katz

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors

Vice Chairman, Board of Governors

Gerald M. Schreck

Emanuel Adler

Executive Vice President

Executive Vice President/Chief Professional Officer Allen I. Fagin

Rabbi Moshe Hauer

Back in 2014, my daughter Dina Sheva attended a Yachad Shabbaton in Hollywood, Florida. Shortly after, Bayla Sheva Brenner, a former writer in the OU Marketing and Communications Department and Jewish Action contributor, called me and requested an interview with Dina Sheva for a Jewish Action article about Yachad, the OU’s organization for Jewish individuals with special needs. During the interview, I mentioned that Dina Sheva had no social life in South Florida other than Yachad events, and that she didn’t have anyone with whom to learn Torah. She had been learning parashah every week with various high school girls, but when the latest one went to Israel for gap year, I was unable to find a new parashah partner for her. Bayla Sheva enthusiastically said, “I’ll do it!”

At that point, I had been learning with my chavrusa Miriam from Partners in Torah for a few years. When Miriam’s daughter Zahava heard that Bayla Sheva and Dina Sheva were learning My First Parsha Reader over Skype, she decided that expanding this kind of learning program would be a great project for Partners in Torah. Together Bayla Sheva, Zahava and Rabbi Eli Gewirtz, national director, Partners in Torah, established a chavrusa program for Jewish individuals with special needs called Lev L’Lev.

What brings me to finally express my appreciation? I have been learning with Chany, my Lev L’Lev partner with special needs, for eight years now. She just informed me that she will be coming to visit me in Florida! Thank you, Jewish Action, for being the catalyst for the special learning relationships that I, Dina Sheva, and so many others have enjoyed over the past few years.

Judy Waldman

Chief Institutional Advancement Officer

Executive Vice President & Chief Operating Officer

Arnold Gerson

Rabbi Josh Joseph, Ed.D.

Chief of Staff

Hollywood, Florida

Senior Managing Director Rabbi Steven Weil

Yoni Cohen

Managing Director, Communal Engagement

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Yaakov Glasser

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Chief Human Resources Officer

AN APPRECIATIVE READER

Josh Gottesman

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer Shlomo Schwartz

Chief Information Officer

Miriam Greenman

Chief Human Resources Officer Rabbi Lenny Bessler

Managing Director, Public Affairs

Maury Litwack

Chief Information Officer Samuel Davidovics

Chief Financial Officer/Chief Administrative Officer

Shlomo Schwartz

Chief Innovation Officer Rabbi Dave Felsenthal

General Counsel

Rachel Sims, Esq.

Director of Marketing and Communications

Gary Magder

Executive Vice President, Emeritus

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb

Jewish Action Committee

In general I’m an easygoing person, but I’ll admit that I’m a snob when it comes to a few areas in life: fonts (I can’t read anything written in Comic Sans), ice cream companies (nothing beats Häagen Dazs), and . . . Jewish magazines.

Jewish Action Committee

Gerald M. Schreck, Chairman

Dr. Rosalyn Sherman, Chair

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

Gerald M. Schreck, Co-Chair

Joel M. Schreiber, Chairman Emeritus

©Copyright 2018 by the Orthodox Union

And yet I find each edition of Jewish Action to be professionally compiled, thought-provoking, and interesting to read. The writing is of high caliber, and there is always a great selection of authors and topics. I read the articles cover to cover, and they always leave me feeling proud of my Judaism and determined to step up my Jewish practice and commitment. No exaggeration.

Eleven Broadway, New York, NY 10004

©Copyright 2024 by the Orthodox Union

Thank you for what you bring to the community. I’m already checking my mailbox for the next edition.

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

40 Rector Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10006

Telephone 212.563.4000 • www.ou.org

Twitter: @Jewish_Action Facebook: JewishAction

Sari Kopitnikoff Author and educator

New Jersey

That Jewish Moment | @thatjewishmoment

2 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

Facebook: Jewish Action Magazine X: Jewish_Action Linkedln: Jewish Action Instagram: jewishaction_magazine

RAV MOSHE: A LITTLE-KNOWN STORY

Editor’s Note: In Rabbi Yirmiyohu Kaganoff’s excellent brief biography of Rabbi Tzvi Pesach Frank (“Medinat Yisrael: Through a Torah Lens” [summer 2023]), he mentioned that upon Rabbi Frank’s passing, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein was offered the position of chief rabbi of Yerushalayim and considered it, but after consulting with “extended family members,” he did not accept the offer. We asked Rabbi Kaganoff to elaborate on this, which he did in the letter below.

It is fortuitous that I know the details of this story from its primary source. I once asked Rabbi Ephraim Greenblatt, a renowned talmid of Rav Moshe, if he knew any details about why Rav Moshe declined the position of chief rabbi. Rav Ephraim told me the following story:

After Rabbi Frank’s passing, Rav Ephraim, then still a student of Rav Moshe’s in Mesivtha Tifereth Jerusalem, was planning a trip to visit his parents in Yerushalayim for yom tov. (Rav Ephraim had been born in Yerushalayim’s Old Yishuv). Rav Moshe asked him to take care of a mission on his behalf, which he was not to divulge to anyone: to visit Rabbi Michel Feinstein, Rav Moshe’s nephew and a son-inlaw of the Brisker Rav, and ask him whether accepting the chief rabbinate position would provide Rav Moshe with practical authority over the rabbinate in Yerushalayim, and whether his authority would be accepted both by rabbanim of both the New Yishuv and the Old Yishuv.

Rav Ephraim sought out Rav Michel, who was living in Bnei Brak. Rav Michel responded that Rav Moshe’s authority would be more respected and adhered to if he remained in New York than if he moved to Eretz Yisrael to accept the chief rabbinate position.

Although Rav Ephraim told me that he had been sworn to secrecy over his mission, he felt that decades after Rav Moshe’s passing, this condition was no longer in effect and that for the sake of historical record it is worthy that people know.

GLUTEN-FREE DAIRY BREAD

I recently bought gluten-free bread marked OU-D, made with corn, potato and rice starches. However, the article entitled “The Kashrut of Bread: All You Knead to Know” in Jewish Action’s recent issue (winter 2023) states that bread should not be milchig or fleishig. The article makes it clear that there are some acceptable exceptions, like pizza crust, crackers or English muffins. I am confused since the gluten-free bread is marked OU-D. Can you advise?

Barbara Bolshon

White Plains, New York

RABBI ELI GERSTEN RESPONDS

Halachically, bread is only considered lechem if it is made from one of the five grains (wheat, barley, spelt, rye and oats), necessitating the berachah of Hamotzi. Gluten-free bread, while shaped to look like bread, is not halachically considered lechem as it is not made from one of the five grains, and therefore its berachah is Shehakol. Since it is not authentic bread, the halachot of dairy bread do not apply.

Rabbi Eli Gersten serves as an OU Kosher rabbinic coordinator and recorder of OU policy.

VOLUNTEERING FOR ISRAEL

I read “From Toothbrushes to Tourniquets” (winter 2023), and I loved Shelley and Ariel Serber’s activism in packaging and sending supplies for the IDF, as well as their ability to encourage others to help. My husband and I are traveling again to Pri Gan in southern Israel to do another round of picking tomatoes. We’ve harvested with families from Canada, Mexico, the US, South Africa and, of course, Israel. Not everyone can go to Israel to participate in the volunteering efforts. But like Shelley and her family, those in the Diaspora can find many ways to help. B’yachad nenatzeiach.

Donna Levin

Elkins Park, Pennsylvania

Transliterations in the magazine are based on Sephardic pronunciation, unless an author is known to use Ashkenazic pronunciation. Thus, the inconsistencies in transliterations throughout the magazine are due to authors’ preferences.

This magazine contains divrei Torah and should therefore be disposed of respectfully by either double-wrapping prior to disposal or placing in a recycling bin.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

To send a letter to Jewish Action, e-mail ja@ou.org.

Letters may be edited for clarity.

4 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

GO TO THE GO-TO > SERVING TOWN SINCE 1979 Welcome to our Town! ALL BRANDS • ALL MODELS • ALL BUDGETS LAKEWOOD 732-364-5195 • 10 S CLIFTON AVE. LAKEWOOD, NJ 08701 CEDARHURST 516-303-8338 EXT 6010 • 431 CENTRAL AVE. CEDARHURST, NY 11516 BALTIMORE 410-364-4400 • 9616 REISTERSTOWN RD. OWINGS MILLS, MD 21117 WWW. TOWNAPPLIANCE .COM • SALES@TOWNAPPLIANCE.COM NAT I O NWID D E L V E !YR

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE

MY YARMULKE

By Mitchel R. Aeder

By Mitchel R. Aeder

This is an article about clothing. Office fashion, to be precise.1

When I was a kid, we used to love to visit my father, a”h, at his accounting firm in downtown Manhattan. One time, he brought me to the office on a Sunday to pick up some documents. (This was pre-Google Docs, email, WFH, FedEx. . . .) On the way, he mentioned that Sunday is yeshivah day at the office. I soon understood his meaning, as nearly all the men in the office were wearing yarmulkes. Orthodox employees worked on Sundays to make up for time missed on Erev Shabbos. In those days, it was unheard of for men to wear yarmulkes in a professional setting. But on Sundays, it was acceptable for men to let their hair down (or put a lid on it), so to speak.

Fast forward to the mid-1980s. It was becoming increasingly common for Orthodox people to land jobs at New York law and accounting firms that once did not welcome Jews, but yarmulkes were still rare. Still, change

was in the air, whether for political, sociological or other reasons. As I began my search for a law firm job, I resolved to alternate interviews with and without a yarmulke—until I received a job offer “with”2 one. I was among the first cohort at my law firm to wear a yarmulke to the office and, ten years later, among the first at the giant accounting firm to which I switched. Then the floodgates opened. By the time I retired, our firm had literally dozens of employees who wore yarmulkes in the office, and it was no longer uncommon to see men sporting peyos or untucked tzitzis

Despite this, some Orthodox men (and not only “old timers”) continued to go bareheaded in the office.3 Some felt that they may be denied advancement opportunities with a yarmulke, others worried that a yarmulke might prejudice their clients (e.g., in a courtroom), and still others did not want a yarmulke to restrict their ability to socialize with clients. Some wore their yarmulkes in the office only during meals, and some mastered the trick of removing/donning their yarmulkes in the revolving door as they entered/exited the building.

Thankfully, this was not my experience. I was blessed that my yarmulke did not adversely affect my career. On the contrary, it helped me avoid potentially uncomfortable situations especially in restaurants and other social situations. I had the sense that my colleagues respected that I was living according to a set of principles— which went beyond eating kosher and leaving early on Fridays to include honesty, business ethics and careful speech. Of course, that created added pressure, or incentive, for me to strive to live up to those principles, which undoubtedly is the point.

The word “yarmulke” is said to derive from the Aramaic “yarei malkah,” or fear of Heaven.4 The yarmulke is a constant reminder that we are standing before Hashem and should behave

Wearing a

yarmulke

or a Magen David suddenly became fraught in many American cities.

accordingly. This is especially important in a secular environment such as a university or office, where influences can be religiously toxic. In this regard, the yarmulke plays a similar (but not identical) role for men that dressing in accordance with halachic standards does for women. Rabbi Anthony Manning explains that a goal of tzenius is to develop a “life-changing awareness of being lifnei Hashem [which] applies equally to men and women.”5 Query whether a baseball cap has the same effect on its wearer as a yarmulke, even if it may satisfy halachic requirements.6 At the OU, I am now doubly blessed to be in an office environment where yarmulkes or hats are standard. Married women in the OU office wear a wide array of hair coverings as well. This gives the office something of the feel of a beis medrash and enhances the sense of standing and working lifnei Hashem I am surrounded by professionals who are passionate about serving the Jewish people. The sense of shared mission and service makes the office a special— almost holy—place, and office attire such as the yarmulke enhances this sense of holiness. Our environments affect our religious growth. As does our attire. We are all accustomed to considering the religious environment when choosing a community or a college; do we do the same when choosing a profession or a job?

Of course, public displays of yarmulkes and other Jewish outerwear and accessories have historically made Jews (especially Orthodox Jews) more easily identifiable targets of antisemites.

6 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

Mitchel R. Aeder is president of the Orthodox Union.

In the recent history of the United States, this ugly phenomenon was mostly limited to the Chareidi community, primarily in Brooklyn. That changed on Shemini Atzeres of 5784. Wearing a yarmulke or a Magen David suddenly became fraught in many American cities.

There have been two conflicting reactions in the Jewish community. Some have chosen to lay low and try to hide their Jewishness in public. Administrators at a Jewish day school in California recently instructed first graders (six year olds!) not to wear their kippot on a field trip, out of fear. Yes, we have to take reasonable precautions and employ security. But what message will children (and adults) internalize when their yarmulkes become a threat instead of a source of pride and inspiration?

Sometimes this attitude is taken to an extreme. In People Love Dead Jews, Dara Horn describes the unfathomable attempt in 2018 by the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam to prohibit an employee from wearing his kippah. Apparently, a Holocaust museum has no place for living, committed Jews. Never again?

But there has been another reaction to the antisemitism that has exploded since Shemini Atzeres. I recently met Ethan Hamid, an impressive junior at the University of Southern California (USC) who co-founded Kippahs on Campus in October. The grassroots organization has inspired dozens of students to proudly wear yarmulkes on campus for the first time. The OU’s Jewish Learning Initiative on Campus (JLIC) educators on other university campuses similarly report a noticeable increase in the number of students wearing a yarmulke or Magen David, and sometimes tzitzis! (Some are also walking around campus draped in an Israeli flag, as if to dare antisemites to start up with them.) Our NCSY/JSU staff have seen a similar phenomenon in public high schools: kids wanting to connect to their Jewishness and to other Jews by displaying yarmulkes and Jewish/Israeli shirts and jewelry. This is inspiring. Yarei malkah. We fear Heaven. [See “How Students Are Responding to Antisemitism” in this issue.]

David Efune beautifully gave voice to this reaction in the Wall Street Journal: “Publicly expressing one’s faith can be a life-threatening decision. For my part, I will wear the most prominent yarmulke I can find. The best way to honor the memory of those slain for being Jewish is not to sacrifice a scintilla of our Jewish identity but to express it in the extreme.”7

Our yarmulkes are more important than ever. May Hashem allow us to continue to stand before Him in all places with our heads proudly covered in awe and reverence and safety.

Notes

1. For the first thirty years of my professional career, my mother, a”h, did not trust me to buy a single item of work attire on my own. Except for my yarmulkes. Which makes me something of an expert, I suppose.

2. A law student a year ahead of me interviewed at sixteen firms. He wore his yarmulke to eight of the interviews, and received job offers only from the other eight.

3. This is in no way intended to be judgmental. See Iggeros Moshe, OC 4:2, CM 1:93. I am aware that Manhattan professional firms do not reflect society at large. There continue to be many industries and locations where one would not be comfortable wearing a yarmulke to work.

4. Growing up, we pronounced it “yahmaka.” I recall being shocked when I first saw it spelled. I chose to use yarmulke rather than kippah in this article, because it’s a much cooler word.

5. Reclaiming Dignity: A Guide to Tzniut for Men and Women (Beit Shemesh, 2023), 503. See more generally, part 2, chap. 2.

6. To the outside world, a baseball cap often announces “Orthodox” as much as a yarmulke does, especially when worn by men who are (1) over forty (2) wearing a sport jacket or suit or (3) have a beard and a belly.

7. “Give Me The Biggest Kippah You Can Find,” October 19, 2023. This headline was a reminder that the size of my own yarmulke has grown over the years. Some ascribe it to my hairline, others to my ego.

7 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Spring is a time for change. Switch to the Bank that puts your interest first. VISIT US BANK ONLINE Locations in the NYC area & the Hudson Valley. Use BerkOnline & BerkMobile to access your accounts anywhere, 24/7. ® Personal & Business Banking and much more, all with exceptional service MEMBER ADDED CONVENIENCE: EVEN MORE WAYS TO BANK WITH US. (212)802-1000 www.berkbank.com

at a Jewish day school in California

graders

to wear their kippot on a field trip, out of fear.

Administrators

recently instructed first

not

TAKES YOU TOURO THERE

TOURO IS HERE TO NURTURE YOUR ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE AND FUTURE CAREER. From our president, to your professors and peers, you'll find unwavering support in the classroom, on campus and beyond. With shared values and a commitment to your success, TOURO TAKES YOU THERE. touro.edu/poweryourpath

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI MOSHE HAUER

IN PRAISE OF ISRAELI EMUNAH

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

By Rabbi Moshe Hauer

When Israeli soldier Ori Megidish was rescued by the IDF after having been held hostage in Gaza for twenty-three days, footage released by her friends and family showed mitzvot they had performed in the hope of securing her safe return home. In one video that has been widely viewed, her mother can be seen with a group of women emotionally praying for her daughter’s return while performing the mitzvah of hafrashat challah. 1

Among the twenty-one soldiers who died in the building collapse in central Gaza in January was Master Sergeant (res.) Rabbi Elkana Vizel, thirty-five, a resident of Bnei Dekalim in southern Israel. Rabbi Vizel, a father of four and a teacher, had prepared a letter ahead of time in the event he would be killed in action. In the letter, he wrote: “When a soldier falls in battle, it is sad. But I ask you to be happy. Don’t be sad when

you part from me. Sing a lot, hold each other’s hands, and strengthen one another. We have so much to be excited and happy about. . . . We are writing the most meaningful moments in the history of our people and the whole world, so please be optimistic. Keep choosing life all the time, a life of love, hope, purity and optimism.”

Emunah, faith, is essential to how we as individuals and as a nation confront or embrace the challenges before us. It is the critical ingredient in inspiring stories like these, two of the many hundreds of moving accounts shared since Simchat Torah. And we, especially those of us not yet living in Israel, need to learn how to access it.

The events of October 7 and their aftermath have inflicted enormous upheaval on the Jewish people and on huge numbers of individual Jews. The range of those affected is vast, including the families and circles of the hostages and victims of terror, as well as of the fallen, wounded, and active-duty soldiers; additionally, there are the displaced, the economically impacted, and those around the world grappling with the tsunami of antisemitism. Klal Yisrael’s resilience is being tested as it experiences significant individual and collective trauma. Ground Zero of those traumas is in Israel, and it is there that stories and images coming across our information streams demonstrate the power of emunah in building our resilience.

It is in Israel that we regularly encounter among the masses— halachically observant or not— emunah peshutah, a pure and simple faith in a loving G-d Whose supportive presence ensures that we are not facing our challenges alone, “lo ira ra ki Atah imadi—I will fear no evil for

You are with me.”2 This is apparent in the bareheaded young soldiers wearing tzitzit, the songs of faith that have become alternate national anthems, and the embrace of mitzvot like the hafrashat challah of Ori’s mother. And it is in Israel that we also find many whose devotion and connection to G-d is not simple, but profound; individuals like Rabbi Vizel whose deep faith creates within them a determined, emunah-based sense of mission and purpose that fortifies them to experience and infuse every challenge with meaning. Emunah thus provides both support and meaning in confronting challenges, significantly impacting our resilience.

More fundamentally, emunah is the heart and soul of Judaism, the single principle that—according to the prophet Chavakuk—all 613 commandments can be drilled down to.3 It can hardly be considered a mitzvah hateluyah ba’Aretz, a mitzvah that can only be fulfilled in the Land of Israel, yet it seems to flourish there in ways that bear out the Talmudic statement that one who lives outside of Israel is like one who has no G-d.4 For the sake of our own continued strength and to build the place of emunah in our own lives, we need therefore to explore how to enhance both the emunah peshutah that defines our understanding of G-d and His supportive presence in our lives, as well as the dimensions of emunah that will inform the purpose and meaning we see in our own role in G-d’s world.

I. Man’s Faith in G-d: Elokei Ha’Aretz

“It [Eretz Yisrael] is the land that Hashem, your G-d, concerns Himself with; the eyes of Hashem are constantly upon it from the beginning of the year until the end of the year.”5 The holiness of the Land of Israel is predicated on its inherent connection to G-d, Who, as the Ramban often notes, retains an elevated degree of involvement there.6 While this is part of the inherent kedushat ha’Aretz, there is an aspect of Hashem’s presence in the land that is predicated on human behavior, which we must strive to replicate wherever we

10 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

Rabbi Moshe Hauer is executive vice president of the Orthodox Union.

The New Look of

are. Experientially, we feel Him more readily in Israel because G-d-speak is everywhere, Shem Shamayim shagur b’fihem 7 This G-d-speak makes a real difference—Rashi teaches that the way Avraham transformed G-d from an abstract concept, Elokei haShamayim, into a tangible presence on earth, Elokei haShamayim veElokei ha’aretz, was by making people familiar with G-d to the point that they mentioned Him regularly.8 That is the reality we encounter in Medinat Yisrael, and anyone who visits there can provide numerous illustrations of this.

A personal example. Several years ago, a group I was with visited one of the communities on the Gaza border. Our local guide took pains to note several times during the visit that this was not a religious community; yet, when showing us the concretereinforced children’s nursery, she explained how during rocket attacks the teachers bring all the kids into the safe space and for the ten or so minutes they must stay inside, they sing together the Israeli pop song “Mi shemaamin lo mefached—He who Believes.” The song, by Israeli singer Eyal Golan, includes this in its “secular” lyrics: “He who believes is not afraid of losing faith for we have the King of the Universe, and He protects us from them all.”

This is “secular” Israel: Shem Shamayim shagur b’fihem. It would be hard to replicate among strictly observant Jews in America the rich sense of faith and connection experienced at a Sephardic Selichot prayer with masses of traditional Israeli Jews. And do the observant Jews of America have anything that resembles the life of religious Israeli Jews, where a night out may consist of going to a holy place like the Kotel or Kever Rachel to daven? This past year, I had the privilege to visit the Kotel on the last night of Chanukah. It was astounding to see the thousands who streamed there to offer special prayers on Zot Chanukah, a virtuous practice noted in many mystical and Chassidic sources that goes relatively unnoticed among American Jewry. Shem Shamayim shagur b’fihem

Toward this end, we should consider how all of us everywhere can become more comfortable with G-d-speak, mentioning Him more regularly and building up our individual and communal emunah peshutah, simple faith and greater awareness of His presence in our lives. There has been meaningful progress in this area before and especially since October 7, with multiple platforms engaging people in ongoing prayer efforts, in spreading daily inspirational doses of emunah, and, of course, in saying “Thank You Hashem!” While these are not experiences of deep and profound theological or philosophical study, they bring G-d into our lives, which is always a good thing, but especially so in these times of challenge when the sense of His supportive presence ensures that we are not facing our challenges alone—lo ira ra ki Atah imadi

II. G-d’s Faith in Man: Chovato B’olamo

One of the most impactful educational innovations in the modern State of Israel is the Mechina pre-military academy. After seeing significant abandonment of observance among religious soldiers in the military framework, Rabbi Eli Sadan created the Bnei David Mechina Program in Eli, where students spend a year preparing for their army experience. A significant part of their daily schedule is dedicated to the study of emunah, but rather than address the theological questions of G-d’s existence or even the core principles of our belief in the Divinity of Torah and the afterlife, the curriculum focuses instead on the questions of “why”: why did G-d create the world and for what mission and purpose did He choose man?

Studying the thoughtful Torah works of Rabbi Yehudah Halevi, the Maharal, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch and Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, the students are given an emunah framework focused less on G-d’s role in the world and more on answering the existential questions of chovato b’olamo—what G-d seeks from us as the Jewish people and from the

It is in Israel that we regularly encounter among the masses—halachically observant or not—emunah peshutah, a pure and simple faith in a loving G-d Whose supportive presence ensures that we are not facing our challenges alone.

individual Jew here and now in Israel in the twenty-first century, as “we are writing the most meaningful moments in the history of our people and the whole world.” The result is a program that has consistently churned out students driven by a sense of mission to serve G-d and the Jewish people by assuming responsibility to protect and build the modern State of Israel in the vision of the prophets. Motivated to excel in serving their people, an inordinate number of graduates of Bnei David and its sister institutions are senior officers in the IDF and serve in combat units, while many have gone on to other realms of public service. They and their work are invariably defined by the deep faith that provides them with a sense of mission and purpose. This is the strand of emunah taught in one of the classic works of Jewish thought, the Derech Hashem (The Way of G-d) of Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato (the Ramchal). While the title of the book gives the impression that its subject will be an understanding of G-d and His ways, the book’s real focus is on clarifying the mission and purpose of man. The book’s name is thus appropriately derived from a verse that speaks of Avraham “teaching his children and household to keep the derech Hashem, the way of G-d, by doing that which is right and just.”9 In this context, the way of G-d serves as the template for how man, created in G-d’s image,

12 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

should conduct himself. More broadly, the book provides a brilliant and beautiful superstructure for G-d’s goals in Creation and in His ongoing providence. It is a work of emunah whose ultimate and most empowering lesson is on the role of man in G-d’s world, and those who absorb that lesson are transformed by it.

This sense of mission, as well, is more accessible in Israel, the center stage of Jewish life and the place where our history is being written. It is there that we encounter clear-eyed men and women living lives of emunah with the confidence of those who know exactly who they are and what they are here for. Yet all of us everywhere must work to strengthen and clarify our own sense of mission, building our emunah by considering, identifying, and ultimately being driven by chovato b’olamo, our purpose in the world, the “why” of our existence as individuals and as a nation.

III. Conclusion

The challenges the Jewish people are now facing are deep and profound, and we must confront and embrace them. We would do well to draw from the inspiring and instructive example of the great people of Eretz Yisrael, where emunah is the currency that carries a power and impact much richer than the faith we experience here. We must follow people like Ori’s mother to draw strength from beyond ourselves, from the G-d of our emunah peshutah, Whom we trust is with us, Who instructs His angels to accompany us wherever life takes us, and Whose eyes are constantly on us. And we must follow the inspiring example of Rabbi Elkana Vizel, identifying with G-d’s faith in us and finding the strength that must come from within ourselves and our emunah-driven clarity of the purpose for which He has granted us life on this earth, to write the next and

more glorious pages of Klal Yisrael’s history, of its return in peace to Tzion v’Yerushalayim.

Notes

1. See https://www.jpost.com/arab-israeliconflict/gaza-news/article-772496; https://www.instagram.com/aish.com/ reel/CzCIim_rZBM/.

2. Tehillim 23:4.

3. Chavakuk 2:4, Makkot 24a.

4. Ketubot 110b.

5. Devarim 11:12.

6. See, for example, Ramban to Vayikra 18:25.

7. See Bereishit 39:3, where Rashi explains that the Torah’s description of Hashem being with Yosef was based on Yosef constantly invoking His Name.

8. Rashi to Bereishit 24:7, based on Bereishit Rabbah 59:8.

9. Bereishit 18:19.

13 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

NATIONWIDE SERVICE: New York Tri-State • Philadelphia • Florida • Chicago • California • New England • Washington, DC Area • Toronto • Montreal WE KOSHER FOR PASSOVER! PROMPT SERVICE Overwhelmed? No time? Moving? Relax and leave the koshering to us. We do it all and make it a pleasure. 1.888.GO.KOSHER I GOKOSHER.org Rabbi Sholtiel Lebovic, Director I rabbi@gokosher.org Go-Kosher KOSHERING SERVICE KOSHERING AMERICA’S KITCHENS, ONE AT A TIME™ • Full Kitchen Koshering • Instructions and hands-on demonstrations • Full toiveling service • Can arrange kosher affairs in hotel/restaurant of your choice • Available for groups, seminars and schools Ad Design: Julie Farkas Graphic Design • julie@juliefarkas.com ד"סב

HOW DO WE PARTNER?

THE BENEFITS OF SHARED LEADERSHIP

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

By Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph

As I prepared to write this next installment of Mentsch Management (thank you, readers, for your continued positive feedback), I suffered loss in a way I had never experienced before. I found out that Sergeant First Class (res.) Yakir Hexter, a fighter in the 8219 Engineering Battalion, fell in battle in the southern Gaza Strip.

On the day Yakir was to be born, I drove his parents to the hospital. His mother, Chaya, encouraged me to slow down so that we could survive the foggy, dark roads from the Gush to the hospital. His father, Josh, was my chavruta at Yeshivat Har Etzion. He was not just my partner, but my teacher too. He still is— including the day he spoke at the funeral of his twenty-six-year-old son, Hy”d Yakir had a special chavruta, Sergeant First Class (res.) David Schwartz, Hy”d, who was also taken from us in battle in Gaza, at the same moment as his learning partner. They were study partners in the very same yeshivah where Josh and I had studied.

What is it about partnership—whether in study, at home or at the office—that makes it work?

At the funeral, Josh described Yakir as “a mentsch, a young man of integrity, honor and kindness.” Yakir was many

things: smart, talented, funny, a runner, truly a golden boy; he was studying to be an architect. And what made him a great man was his mentschlich approach to everything he did. And that’s what it takes to be a partner.

This essay is dedicated in memory of Yakir Yamin ben Rav Yehoshua Hexter, Hy”d

Leadership teams have long included members who play complementary roles. Homer’s history of the Trojan War not only highlights the strength of King Agamemnon but also the warrior heroics of Achilles, Odysseus’s strategic approach, and Nestor’s diplomacy and management of the team. Each of them played a role and played it well, which led to victory.1

And yet many a team has also failed at the art of partnership, especially at senior levels. Our question, then, is: How do we partner with others?

Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin (the Netziv) notes that in Shemot 6:26–27, the names of Moshe and Aharon— leaders, brothers, partners—are presented in different orders:

Verse 26: “Hu Aharon uMoshe asher amar Hashem lahem hotzi’u et Bnei Yisrael me’eretz Mitzrayim al tzivotam—It is the same Aharon and Moshe to whom Hashem said, ‘Bring forth the Children of Israel from the land of Egypt, troop by troop.’”

Verse 27: “Hem hamidaberim el Pharaoh melech Mitzrayim lehotzi et Bnei Yisrael miMitzrayim hu Moshe v’Aharon—It was they who spoke to Pharaoh, king of Egypt, to bring the Children of Israel out of Egypt; these are the same Moshe and Aharon.”

Why is Aharon before Moshe in the first verse, and then Moshe before Aharon in the second? Rashi explains that this implies that they were of equivalent stature. The Netziv disagrees, for as great as Aharon was, Moshe

has a special place in our history. He suggests that the order depends on whose perspective is being represented. Verse 26 presents the perspective of Bnei Yisrael (i.e., “taking Bnei Yisrael out of the land of Egypt”). They knew Aharon as he had stayed in Egypt. Perhaps they didn’t yet fully appreciate Moshe’s value, because he had grown up in the palace and then fled to Midyan.

Verse 27, on the other hand, is presented from the perspective of the palace of Pharaoh, as it says “Hem hamidaberim el Pharaoh.” In Pharaoh’s eyes, Moshe was greater. He already knew Moshe’s name and his wisdom, but he didn’t know Aharon. This may be because Pharaoh knew Moshe since he had grown up in the palace. Or it may indicate the lack of Israelite leadership while Moshe was away, and thus the need for a new voice, one that was at one time rooted in the local leadership but also familiar with the palace.

Furthering his analysis, the Netziv points to the phrase “al tzivotam” in verse 26. Based on Iyov 7:1, “Halo tzava le’enosh alei aretz v’chiymei sachir yamav—Is not man on Earth for a limited time, his days are like those of a hireling,” he translates “tzava” not just as a limited time but as a specific purpose. Thus, al tzivotam implies that each leader had a specific purpose.

In verse 27, in the war of words with Pharaoh (“Hem hamidaberim”), Moshe was greater than Aharon. What was Moshe’s purpose, his lane, his superpower, his strength and identity? He represented the paradigm of Torah, the metaphorical sword protecting Bnei Yisrael. The fight with Pharaoh had to come from Moshe, so he is listed first in the verse that reflects Pharaoh’s perspective.

Aharon, on the other hand, represented the sustaining power of tefillah. The work of Aharon and his

Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph is executive vice president/chief operating officer of the OU.

16 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

MENTSCH MANAGEMENT

There are many ways to support Israel and its people, but none is more transformative than a gift to Magen David Adom, Israel’s emergency services system. Your gift to MDA isn’t just changing lives — it’s literally saving them — providing critical care and hospital transport for everyone from victims of heart attacks to rocket attacks.

Join the effort at afmda.org/give or call 866.632.2763.

17 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

IN

afmda.org

NO ONE SAVES MORE LIVES

ISRAEL IN TIMES OF CRISIS.

descendants—korbanot, the Mishkan, and ultimately the Beit Hamikdash—is what brought about sustenance for the Jewish people. Even before the Jews went out of Egypt, when they would daven for sustenance, Aharon was the leader. The people trusted him and turned to him. Targum Yonatan on Parashat Chukat (20:29) states that when Aharon died, Moshe called him “Amud tzelos’hon d’Yisrael—the pillar of Yisrael’s prayers.” And this is what made Aharon special. Bnei Yisrael’s sustenance was dependent on Aharon, and therefore Aharon is listed before Moshe in verse 26, reflecting the perspective of the Children of Israel.

Moshe and Aharon serve as a paradigm of a balanced partnership. Their respective strengths of protection and sustenance were both needed to effectively lead Bnei Yisrael.

How do we partner with others? In “Is It Time to Consider Co-CEOs?” (Harvard Business Review, July-August 2022), authors Marc A. Feigen, Michael Jenkins and Anton Warendh studied 2,200 companies listed in the S&P 1200 and the Russell 1000 from 1996 to 2020. They found only eighty-seven companies that were led by co-chief executives: . . . [D]uring that period, especially in times of stress, some of those jointly led companies performed notably poorly. . . . Many observers don’t find this surprising. Installing two decisionmakers at the top, the theory goes, almost invariably leads to trouble, in the form of conflicts, confusion, inconsistency, irresolution, and delays.

Marvin Bower, who built McKinsey, famously warned Goldman Sachs not to have co-CEOs. “Power sharing,” he said, “never works.” Except that it often does.

Feigen, Jenkins and Warendh found that the co-led companies performed well—they had an annual shareholder return of 9.5 percent, 3 percent better than their competitors—and that co-leadership didn’t negatively affect longevity for the leaders themselves.

The key, they found, was to set the right factors for successful partnership— something that resonates in my own partnership with Rabbi Moshe Hauer, my OU chavruta. Though they listed nine factors in total,2 including conditions like willing participation, board support,

shared values and an exit strategy, of note is their inclusion of “complementary skill sets,” which can then yield clear responsibilities. Similarly, Stephen A. Miles and Michael D. Watkins, in “The Leadership Team: Complementary Strengths or Conflicting Agendas?”

(Harvard Business Review, April 2007),3 highlight four ways in which complementary leadership manifests, including complementarity in tasks, expertise, cognition and roles. Underlying each of them is a clarity of responsibilities, lanes, capabilities and styles. When leaders divide responsibilities into clear lanes, such as one managing the external relationships and the other concentrating on the internal ecosystem, the inherent risks in shared leadership can be managed through trust, communication and coordination.

Moshe and Aharon each had their complementary strengths. What emerged from their relationship, through the lens of the Netziv, are three possible steps that might help others when thinking about how to share leadership:

1. We must know ourselves. What are our strengths? What do we bring to the equation? What is our sense of where we can really add the most value?

2. We must appreciate, know and have an understanding of our partner’s

strengths. What do we need him to be great at?

3. We have to understand when and how to stay in our own lanes at the appropriate times. When is one person the focus, and when is the other person the responsible party?

Moshe and Aharon both brought remarkable strengths to each other and to the leadership of the Jewish nation, teaching us important lessons on how we partner with each other. As we approach Pesach, may we utilize these pointers on being a mentsch in the management of all sorts of complementary partnerships— whether in our personal lives with spouses or family members or at work: to understand what we bring to the table, what others bring, and how to appreciate when the other is primary, ultimately yielding optimal results for us and all of Klal Yisrael.

Notes

1. See the opening of Stephen A. Miles and Michael D. Watkins, “The Leadership Team: Complementary Strengths or Conflicting Agendas?” Harvard Business Review, April 2007, https://hbr.org/2007/04/the-leadership-team-complementary-strengths-or-conflicting-agendas.

2. See the full list at https://hbr.org/2022/07/is-ittime-to-consider-co-ceos.

3. https://hbr.org/2007/04/the-leadership-team-complementary-strengths-or-conflicting-agendas.

18 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

Sergeant First Class (res.) Yakir Hexter, twenty-six, from Jerusalem (left), and Sergeant First Class (res.) David Schwartz, twenty-six, from Elazar were killed in action in Gaza in January on the same day. This painting by artist Tanya Zbili Katz, entitled “Chavrusas in Shomayim,” depicts Hexter and Schwartz, H”yd, learning bechavruta at Yeshivat Har Etzion, based on a 2019 photo taken by the young men’s mutual friend Yehuda Moskowitz. Explore more of Tanya Zbili Katz’s work on Instagram @Tanyazbiliart and on her website www.Tanyazbiliart.com.

Could You Really Extend Your Life?

REVISED&EXPANDED

Interview with Author

Michael Kaufman

Am I My Body’s Keeper?

The Way of Torah and Science

Be Healthy & Fit • Lose Weight • Live Years Longer

Why did you write “Am I My Body’s Keeper?”?

To inform people that they could live longer — years longer, and healthier. That they could increase their health span and their lifespan just by changing their lifestyle.

How many years longer?

On average, as much as 12 years (men), 14 years (women).

That’s incredible! What do we need to do to live a dozen years longer?

To start, just 5 easy behaviors: Don’t smoke, eat healthily, exercise 30 minutes a day, drink alcohol only moderately, and maintain a proper weight. A long-term Harvard study of 123,000 people found that those who kept these 5 healthy habits were 82% less likely to die from heart disease and 65% less from cancer — the two most frequent causes of death.

But isn’t our lifetime determined on High?

It is. But Torah and Chazal cite many ways that you can extend your life. The Torah directs hishtadlus — take good care of yourself. If you don’t, or you cross the street against a red light, you could cut your life short.

Which of the 5 life-prolonging behaviors is most important?

Exercise. It’s the best medicine on the planet. An amazing — and free! — drug provided by Hashem. Eating healthily is essential. Food is the body’s fuel. However, as the Rambam says, nothing can substitute for exercise to keep you strong, healthy, and fit. Science agrees. If exercise was a drug it would be a miracle cure. Sitting, you write, is the new smoking. But smoking kills. How can just sitting kill us?

An American Cancer Society study found that those who sit 6 hours or more a day have a 20% to 40% higher death rate than those who

sit 3 or fewer hours. Scientists agree that sitting causes more ill health than smoking. Humans are built to move. The 100 trillion cells in our body must move. Once they stop, we’re dead. But we must sit. What should we do? Stand up every 30 minutes. And move. Use a shtender when you daven. And when you learn. Place a computer on it when you work. Walk

“A masterpiece that can change people’s lives forever!”

¦ Prof. Petachia Reissman MD Director, Dept. of Surgery Shaare Zedek Hospital, Jerusalem

Haskama by Rav Osher Weiss א"טילש

when you can. Avoid the elevator, use the stairs. Get Up! Why Your Chair Is Killing You by Dr. James Levine, and Sitting Kills, Moving Heals by Dr. Joan Vernikos are good books on the subject.

You advise not exercising on a treadmill or bike. Why? Aren’t they effective?

They are indeed — for exercising your legs. On the treadmill and bicycle — and exercycle — your

legs move, but only your legs. When you’re finished you’ll need to then exercise the rest of your body. Elliptical trainers and rowing machines work out the entire body. So does energetic walking while swinging your arms. As does swimming — a terrific exercise.

Is it too late for a long-time “too busy” person to change to a healthy lifestyle?

It’s never too late to start living a healthier lifestyle. Like ceasing to smoke, the moment you stop, the body starts to improve.

Why do you caution in your book not to wish anyone to live to 120?

Because the brocha is restricting. The astounding success of science in discovering the means Hashem provided to conquer disease after disease has almost doubled life expectancy since 1900. Not surprisingly, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, and other gedolim maintained that a brocha to live to 120 is a request to curtail a person’s lifetime. How about wishing people instead to live chaim aruchim, chaim tovim, ve’chaim shel beracha — a good, long, and blessed life?

To help you attain that good, long, and blessed life, I wrote Am I My Body’s Keeper?

Michael Kaufman is the author of ten books. He lives in Israel where he does research on the latest scientific studies on health and fitness while standing at his shtender desk. In his 90s, he maintains an active, energetic schedule which includes daily fitness workouts, and brisk walks around Jerusalem.

19 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

For Sale at Amazon Main Distributors: Israel Bookshop 732-901-3009

How we can maintain a sense of hope and optimism in a time of tragedy

20 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024 COVER STORY

As we write these lines in February, the war in Gaza is still raging and more than 100 hostages still remain in the hands of Hamas. It is our fervent hope and prayer that by the time you read this, the hostages will be home and peace and security will be restored to Am Yisrael and Eretz Yisrael.

The TENACITY of Our Nation

Since Shemini Atzeres 5784— what has become known as the infamous day of “October 7”—our beautiful nation, our Holy Land, our beloved Medinat Yisrael have been in the throes of a catastrophe on a scale not seen since the cursed days of the Shoah.

The magnitude of the damage, the terrible and staggering loss of life and the existential threat to our State are well known. As Prime Minister Netanyahu said in one of his first addresses to the nation, “We are fighting our second War of Independence.”

How can we, as individuals, as communities and as a nation, maintain hope and optimism in the face of catastrophe?

Michal Horowitz teaches Judaic studies classes to adults of all ages, nationally and internationally. Her weekly parashah shiur, “Contemporary Parshanim,” is posted on the OU's AllParsha app, and she delivers many shiurim for the OU Women’s Initiative.

I remind myself often of the words we sing at the Pesach Seder: “And it is this that has stood for our forefathers and us, that not one alone has risen up to destroy us, but in every generation they arise to destroy us, and Hashem saves us from their hands.” The truth of this declaration rings loud and clear. From Eisav to Amalek, from Pharaoh to Haman, from the Crusades to the Inquisition, from Tach V’Tat to the blood libels of Europe, from pogroms to the death camps.

Astoundingly, miraculously, beyond all natural explanations and reasonable possibilities, Toras Yisrael, Am Yisrael and Eretz Yisrael are alive, well and thriving. This alone is the greatest chizuk and hope for challenging times.

My grandparents were all Holocaust survivors, and three of them had been married with families. Between them, they lost five young daughters in the flames of the Shoah. In his memoir entitled In Seven Camps in Three Years (published in the Yizkor book of his hometown Krasnik, Poland) my maternal grandfather Yitzchak Kaftan, z”l, wrote:

By Michal Horowitz

By Michal Horowitz

I still remember several names of those killed: Reb Yehoshua Asher Weinberg, Reb Peretz Feder. I remember my uncle, Moishe Markovitches, a boy of about thirteen years. Handsome as a tree in bloom—he was also among those who were shot, may G-d avenge his blood. Reb Peretz Feder and I slept on one pallet and talked continually about the murderers, that they were sent by G-d and that their end is near. “We suffer now so that Mashiach will come. Whoever will survive this hell will see a Jewish state.”

The faith of my grandfather astounds and encourages me and lifts me up in difficult times. As he lay on that pallet in hell, he professed the purest faith in G-d, His Redemption and a Jewish state, which for that generation was only a fantastic dream. A former student of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, my grandfather wrote with emunah in Hashem and faith in the eternity of our nation.

A number of years ago, I attended a talk by the well-known Israeli educator and public speaker Miriam Peretz, whose two sons were killed while serving in the IDF. She spoke about the

21 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

Miraculously, beyond all natural explanations and reasonable possibilities, Toras Yisrael, Am Yisrael and Eretz Yisrael are alive, well and thriving. This alone is the greatest chizuk and hope for challenging times.

losses of her two sons, Uriel and Eliraz, Hy”d, the loss of her husband from a broken heart and her unwavering faith in Hashem and His nation. Miriam related that since the fall of her firstborn, Uriel, her personal statement is: “For your brokenness is as vast as the sea, who can heal you?” (Eichah 2:13).

Though Miriam lives with the unfathomable reality of two sons buried just a few meters apart from each other on Har Herzl, she is a woman of great strength and tremendous courage. She draws inspiration from our sifrei kodesh, which teach her how to continue on with tenacity and an unbreakable spirit during the hardest times in life. Miriam said that the portion of Tanach that

speaks to her the most is from Shmuel II 12:16-23:

[When King David’s son was sick] he fasted and lay on the ground all night. Though the elders of the household tried to raise him from the earth, David would not rise, nor would he eat. And on the seventh day, the child died. And the servants feared to tell David. But David understood . . . and he said to his servants, “Has the child died?” “He has died,” was the reply. Vayakam David mei’ha’aretz—and David arose from the earth! And he washed, and anointed himself, and changed his clothing; and he came to the house of Hashem, and worshipped; then he came to his own house; and they set bread before him, and he ate.

Bitachon During Crisis

During these times of crisis, we need to strengthen our emunah and bitachon more than ever. The benefits of doing so extend well beyond the usual sense of feeling secure in the knowledge that Hashem is running the world for our benefit.

We read in Tehillim (32:10), “Haboteach BaHashem, chesed yesovevenu—One who trusts in Hashem will be surrounded by kindness.”

Rabbeinu Bachya interprets this to mean that one of the benefits of bitachon is that a person who possesses it will be surrounded by chesed, because his deep faith naturally attracts it. The Chafetz Chaim, however, sees this pasuk as a

And his servants asked him: “What is this matter you have done? When the child was alive, you fasted and cried and now that the child has died, you have arisen and you eat?” And David replied: “When the child was still alive, I fasted and cried, for I said, perhaps G-d will be gracious and the child will live. But now that he has died, for what purpose shall I fast? Can I bring him back? I shall go to him, but he will not return to me.” With her unshakeable faith, Miriam said: “After the death of his son, King David arose—he got up! I, too, go to my sons Uriel and Eliraz; I go to them on Har Herzl. I, too, rose up then, and continue to rise up every day since their deaths.”

This is the tenacity of our nation, the hope of our people, the victory within our souls and the courage of a Jew. Even after all we have endured, through the millennia of galus and the horrors of October 7 and its aftermath, we continue to rise, with emunah, courage, fortitude, simchah and hope. We continue to build. We continue to do good. And we continue to wait each and every day for the coming of the Mashiach and though he may tarry, nevertheless we will wait for him with each passing day.

By Rebbetzin Dina Schoonmaker

As told to Barbara Bensoussan

directive: If you want to strengthen your bitachon, you have to surround yourself with kindness, meaning that you have to actively look for Hashem’s chasadim around you in this world even when things are hard. While we’re going through difficult times, we have to bear in mind that Hashem has something good in store at the end of the process and that our suffering has a purpose.

22 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

Rebbetzin Dina Schoonmaker has been teaching in Michlalah Jerusalem College for over thirty years. She founded the women’s vaad workshop for personal development for women in Israel and worldwide.

Barbara Bensoussan is a frequent contributor to Jewish Action

The Chafetz Chaim offers the analogy of a sick person who needs medicine or surgery. Surgery is painful, and medicine is often literally a bitter pill to swallow, but we endure it because we know the suffering is in the service of a good outcome. When you focus your mind on Hashem’s chasadim in the midst of pain, the Chafetz Chaim says, it’s as if you take the bitter pill and turn it into a capsule, coating the medication and protecting you from its bitterness.

Some of my students are mothers with sons serving in Gaza and the North, which is emotionally very trying. But they work on being ba’alei bitachon and keeping in mind that Hashem has something good in store at the end. Together we try to look at Hashem’s chasadim, the good things we have in our lives despite the challenges: the amazing stories of hashgachah pratis, the beautiful achdus that has been generated, a breathtaking sunset— anything that brings perspective and balances out the pain.

To stay positive, I’m careful about the sources I look at for news. I try to look only at psychologically clean news, through outlets that have a good perspective. There are apps reviewed by professionals to ensure they aren’t overwhelming or pessimistic and don’t include sensationalism or graphic detail. Many of my students signed up for “good news only” chats.

We all want to be nosei be'ol, to share in the suffering of our fellow Jews. But the way we go about it has to work for each person individually. Some people will look at war pictures because they want to share the pain other Jews are feeling. They’re like Moshe Rabbeinu, who used his eyes to see and his heart

to feel the suffering of Klal Yisrael. He would lift bricks with them, and eventually killed an overseer who abused a Jew.

For other people, seeing pictures of the war’s brutality is so overwhelming that their emotional health suffers and they feel like they can’t get out of bed. These people may do better sharing the suffering through some type of physical expression or tangible reminder, like not shopping for luxury items; aveilus often manifests by refraining from certain activities, like during the Three Weeks and the Nine Days.

You always have to balance nosei be'ol with emotional resilience. Since this is an ongoing situation, you have to keep taking your psychological temperature to make sure whatever approach you’re taking allows you to remain emotionally intact.

Nosei be'ol can also be proactive. While some people may stop eating out in restaurants as a sign of solidarity, others will look around at displaced people who need food and will organize a meal train. This is a win-win. It raises spirits, releases endorphins and gives them a way to contribute to the war effort. At the same time, their fellow Jews receive material help and chizuk This is part of the chesed yesovevenu, the chesed surrounding the ba’al bitachon, that Tehillim 32:10 refers to. When you see material and spiritual help coming to Israel from both inside the country and all over the world, the bitter pill takes on a coating that makes it easier to swallow.

Not everybody is built to be an organizer, an ish tzibbur. But there are also many people doing quiet private acts within the reach of their abilities and talents: the student who learns extra hours in the beis midrash with the protection of a soldier in mind, or the young adult who recites an extra chapter of Tehillim. On the home front, it’s important for all of us to be soldiers by doing our utmost to create and maintain shalom within our families, even when it takes an extra measure of selflessness or courage. According to the Netziv, there’s a difference

between being in a difficult situation because of a natural disaster—like an earthquake or hurricane—and being in a difficult situation because of a human tormentor. When the source of the trouble is a human tormentor, he says, we need to invest extra effort in improving our behavior bein adam lachaveiro.

Our enemy is waging a psychological war as well as a physical war. For every person who is killed, they hope to kill the spirit of his loved ones and his nation. That gives them a second victory. We have to show them we are a strong nation, as we read in Tehillim (20:9), “They dropped to their knees and fell, but we arose and encouraged each other.” Look at the way our chayalim encourage each other, the way they sing and bond. We must stay strong! We must hug our loved ones, create new relationships and remember to keep the atmosphere in our homes positive. I find it helpful to have a mantra that I repeat daily to anchor me. Mine is “Haboteach BaHashem, chesed yesovevenu.” Each person has to find the right path to support his fellow Jews and share their pain, while retaining the awareness that Hashem has a good plan in mind for us. Keep your eye on His chasadim, and pay them forward as best you can.

24 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

24 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

Did you know?

Ashkenazi Jewish men and women are 10 times more likely to carry mutations in their BRCA genes and have increased risks for various cancers.

Know your risk so you can be proactive about your health. Screen for BRCA and over 70 other hereditary cancer genes. Order an at-home CancerGEN kit at jscreen.org and use coupon code JewishAction36 for $36 off.

25 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION 25 Spring 5784/2024 JEWISH ACTION

How to Build Hope

By Rabbi Larry Rothwachs

In the face of tragedy, we often find ourselves suddenly grappling, in desperate search of hope, optimism, faith and resilience. During the relatively tranquil course of day-to-day life, these features of inner strength typically receive little attention or cultivation. It is only when faced with life’s inexplicable and most challenging moments that we urgently seek understanding and engage in a search for faith. This reactive approach leaves us scrambling to develop the emotional and spiritual resources we have until then neglected. While it is never too late to foster a more hopeful, optimistic and faith-based outlook, it is crucial to recognize the importance of nurturing these qualities during our better days. Doing so not only enriches our everyday experiences but also fills a reservoir of inner strength that we may then draw from in times

Rabbi Larry Rothwachs serves as senior rabbi of Congregation Beth Aaron in Teaneck, New Jersey, and director of professional rabbinics at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary. In January 2023, Rabbi Rothwachs was appointed as the founding rabbi of Meromei Shemesh, a new community currently under construction in Ramat Beit Shemesh.

of adversity. A proactive approach to personal growth ensures that we are better prepared not just when tragedy strikes but throughout life’s journey.

This insight offers a deeper understanding of the pasuk in Yirmiyahu (17:7): “Baruch hagever asher yivtach baHashem v’hayah Hashem mivtacho—Blessed is the one who trusts in Hashem, whose confidence is in Him.” At first glance, this pasuk appears to be repetitive: it states that those who have faith in Hashem are blessed, and then mentions confidence in Him. However, this seeming redundancy holds a deeper meaning. The Sefas Emes interprets this pasuk as a charge, encouraging us to develop a deep faith and trust in Hashem, particularly during life’s more tranquil moments. At times during which the challenges we face seem manageable and the blessings in our life more apparent, we should seize the opportunity to focus, deliberately and intentionally, on Hashem’s abundant kindness and compassion. By doing so, we will hopefully succeed in building a strong foundation of faith upon which to stand during life’s tumultuous and challenging times. This proactive approach fills us with a healthy reserve, ensuring that we have a robust spiritual support system to draw from when we need it most. It enables us to

enter a “fortress of faith” built during calmer times, rather than frantically seeking shelter during a storm.

The reality, however, is that life often presents moments for which we find ourselves unprepared. Despite our best intentions, we frequently find ourselves caught off guard, struggling to maintain our equilibrium. In times of unforeseen adversity, how can we anchor ourselves to Hashem and fortify our spiritual resilience, especially when our prior preparations to build a foundation of emunah may have been less than ideal?

Our daily recitation of Shema constitutes a profound method for cultivating faith, particularly during challenging times. The ritual practice of covering one’s eyes is well-known. The common understanding is that this act aids in concentrating our focus, shielding us from distractions as we affirm our devotion to Hashem. Yet one could ask: why is this gesture not applied to mitigate distractions during other prayers? To answer this, we need to explore the meaning behind this practice within the broader context of prayer and faith.

Through our experience of this world, we often encounter apparent injustices: we see good people suffering and wicked people prospering. As devout Jews, we understand that surface appearances can be deceptive.

26 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

JEWISH ACTION Spring

The MOST WEAPON Against Hamas

ISRAELI SOLDIERS

HAVE COMMITTED TO WEARING TEFILLIN FOR THE REST OF THEIR LIVES. WE’VE ALREADY GIVEN 4,600 SOLDIERS THEIR VERY OWN SET OF TEFILLIN. LET'S SUPPORT MORE SOLDIERS AND GET THEM THE TEFILLIN THEY'RE ASKING FOR.

GIVE OUR SOLDIERS THE MOST PROTECTIVE GEAR >

WWW.THECHESEDFUND.COM/ISRAELSELECT/TEFILLIN SCAN TO DONATE

The MOST WEAPON Against Hamas has helped soldiers going to the battlefield with the mitzvah of putting on tefillin. In addtion, they have distributed sets of tefillin to those who committed to keeping this mitzvah every day.

6,000SOLDIERS X $500/TEFILLIN = $3,000,000 BE A PROUD SUPPORTER!

We hold a deep-seated belief that Hashem’s actions, though often incomprehensible to us, serve a higher purpose and are ultimately for the greater good, aligning in ways beyond our understanding. We understand that while we cannot always decipher the justice in events unfolding before us, there is a cosmic equation where “the numbers all add up.”

Our physical senses, especially our sight, frequently confront us with images that have the potential to undermine our faith. While our vision appears to offer a clear, unfiltered view of the world, it exposes us to harsh realities that can be overwhelming.

These visual experiences often narrate a story that clouds our capacity to perceive and believe in the underlying purpose of the events unfolding around us. The dichotomy between what we see and what we believe tests our ability to maintain faith amidst the complexities of the physical world. We cover our eyes during the moment of kabbalas ol malchus Shamayim, which is what the first paragraph of Shema is all about, to create a symbolic severance from our physical senses, a deliberate choice to forgo our reliance on our natural windows to the world. By obscuring our physical vision, we open ourselves to a higher level of perception,

The Psychology of

Hope

In our homeland and throughout the world, the Jewish nation is in grave distress. We are under attack, and we are at war. Throughout this long exile, we have suffered through the Crusades, the Inquisition, pogroms and the Holocaust . . . and now, we are targeted and threatened in every corner. Can we remain hopeful? Does hope help us cope with terror and tragedy? Are there any psychological tools that can enable us to transition from a sense of helplessness and hopelessness to optimism and hope?

Let’s understand hope by studying a bit of brain science. Human beings have elaborate brains, in

which thoughts, emotions, physical sensations and behavioral activity operate concurrently. During moments of intense pain or fear, the consciousness is engulfed in anguish, despair and anxiety, and the overwhelmed brain can descend into a helpless, hopeless state. The constant barrage of horrible news, atrocious images and existential threats we are currently experiencing has resulted in a feeling of hopelessness for many people. Our brains are in a state of shock and cannot think or feel much else.

How do we get past hopelessness? Consider what we generally do when we are frightened or in despair. We might daven that our suffering stop. We might exercise our bitachon,

acknowledging that there exists a reality far greater than what our eyes can see. This gesture is especially significant during times of crisis or tragedy, when the perceivable world offers little hope. It serves as a powerful reminder of our enduring belief, an affirmation that despite the darkest times, the sun will rise again. Covering our eyes reinforces our understanding that true insight and hope lie beyond the scope of our five senses, in the realm of unwavering faith in Hashem.

By Rabbi Dr. Dovid Fox

By Rabbi Dr. Dovid Fox

reminding ourselves that Hashem is the true source of salvation. Praying for a positive outcome and having faith that it will materialize are religious practices. But these actions are not hope. So what is hope and what does it accomplish in a person who is overwhelmed with distress? Is hope nothing more than denial gift-wrapped? Is it merely a deferral of despair? Is it donning a Pollyanna-like optimism to avoid crashing in pessimistic resignation to the horrid reality?

Psychologically healthy individuals are able to be hopeful, but not because they deny or suppress their feelings of anxiety or stress. In fact, it’s quite the opposite: achieving hope is a process that begins with self-awareness—i.e.,

28 JEWISH ACTION Spring 5784/2024

A Tradition of Excellence from Generation to Generation

THE ROTHSCHILD LEGACY

As the legend goes, Reb Mayer Anschel Rothschild (‘744–’812), received a bracha for wealth and hatzlocho from his renowned rebbe, Harav Zvi Hirsh from Tzortkov zt”l.

Rothschild became a banker and, with his family, established the largest private banking business in the world. Hundreds of years later, the family interests range from financial services and real estate to energy, agriculture and successful winemaking.

Today, the Rothschild family owns over 15 wine estates around the globe including in France, North and South America, South Africa and Australia. Of particular note are the Château Mouton Rothschild and the Château Lafite Rothschild which are classified as Premier Cru Classé — “First Growth” in English. This coveted classification proves the grapes were grown in the Bordeaux region of France and that they are among the highest quality in the world.

Rabbi Dr. Dovid Fox is a forensic and clinical psychologist, graduate school professor, author and director of Chai Lifeline Crisis and Trauma Services. He is rav of the Hashkama Minyan of Young Israel Hancock Park, Los Angeles and serves as a dayan on the batei din of Jerusalem and other communities. Among his rabbinic scholarly works are the Conversion Readiness Assessment, the Mikvah Checklist for Managing OCD, and teshuvos on the four chalakim of the Shulchan Aruch, including publications in Otzar HaPoskim. He is frequently consulted by rabbinic leaders and organizations on mental health halachah.

recognizing the anxiety and the stress. Research shows that when you are feeling a sense of hopelessness, you must look it in the eye, acknowledge your distress, and identify the ways in which that distress is affecting you.

How do you come to this selfawareness? Breathe slowly and deeply. Ground yourself, which means taking a few moments to find a quiet, comfortable posture that feels calming and familiar. Then observe the thoughts and ideas associated with your distress, the emotions that are present, and even your bodily sensations, such as your

breathing, tension, pain or weakness. Pay attention to how you feel as you focus inward, e.g., restless, agitated, numb. Observing and identifying your range of thoughts and emotions, your physical state, and your overall behavior allows for mindfulness and fuller consciousness of yourself and your experience. This leads to something very important: the ability to define and thereby limit your negative feelings.

You might have noticed a pain chart hanging in a doctor’s office or hospital, which consists of a series of cartoon faces with varying expressions depicting pain ranging from mild discomfort to unbearable. Doctors will often ask patients to refer to the chart to describe the level of pain they are experiencing. The purpose of the chart is to help the doctor understand how much pain you are experiencing, but it is also a way for you to rate your own discomfort. Once you define your level of pain, your mind has externalized the pain, making it an objective experience, rather than only a subjective one. The pain is this much, but not that much; for example, it is moderate, which means it is not severe. Setting a parameter for your distress, as well as naming the

experience within, helps mitigate the uncomfortable sensations. You know what it is and what it is not.