10 minute read

Verdy

Next Article

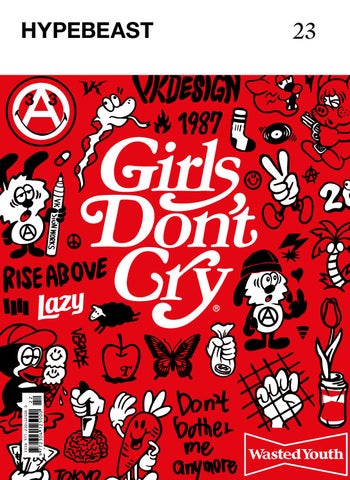

his hometown of Tokyo and throughout Los Angeles. Granted, the first thing GDC brings to mind is a Frank Ocean spin-off, but this simple graphic has proved to be potent, amassing a fanbase with all the hallmarks of a cult following. The work of the Japanese graphic designer has caught fire and spread from the Far East to the West Coast, to adorn musicians ranging from Lil Uzi Vert to A-Trak and Kehlani.

As public image becomes the essential weapon for self-preservation in the fashion and entertainment industries, designers construct personas out of necessity. The stage presence of the man or woman behind the brand almost eclipses the brand itself. Think what the ever-present Jerry Lorenzo is to Fear of God, or the multi-faceted Virgil Abloh is to Off-White. However, that’s not always the case, as seen with Tokyo-based designer Verdy and his freshly formed label, Girls Don’t Cry. Verdy looks almost nondescript compared to the aggressively groomed Lorenzo and the more affable, yet still impeccable, Virgil Abloh. Though Verdy isn’t flashy, he does have a signature aside from the black-rimmed glasses and baseball cap he wears almost every day: a smile stretching from ear to ear accompanied by two fingers, propped artlessly in a jovial peace sign.

Verdy’s graphics speak loud enough. The unmistakable lettering of his latest, Girls Don’t Cry, can be seen splayed across the backs of hoodies and tote bags in

Girls Don’t Cry began on the backs of a diverse range of individuals, a trio of words creating the only common element among an otherwise unlinked cast of characters. But, as Verdy explains, his brand has been built on relationships alone. He spends a lot of time talking about individuals who have helped launch his career, Hikaru from Bounty Hunter being first on the list for showing interest in his graphic artwork. Then, Paulo and Reggie of Rare Panther, who introduced him to the streetwear community in LA. GDC grew from the mutual curiosity that results from the meeting of cultures. If it were not for meeting lots of new people and making friends first, Verdy maintains, there would be no Girls Don’t Cry. The label also owes its birth to his wife. The designer initially designed a single GDC T-shirt to give to his wife as a present, one that would function as a mobile business card while she wore it. “They might even ask, ‘What brand is that?’” he jokes, mirth lighting up his features. According to Verdy, he’s made it this far only because of other people: friends, mentors and one very patient woman.

At 31 years old, Verdy looks like he will head down a path similar to that of Nigo and Jun Takahashi, as both designers single him out for collaborations and exclusive pieces. Having the support of this tight-knit, pivotal group whose opinion means the world—both to Verdy and to the world itself—has the happy-go-lucky designer poised to pick up a very large and very heavy baton in his homeland Japan, while his name continues to effortlessly spread in the US with Girls Don’t Cry.

something I thought was good. Wasted Youth’s concept is that there’s nothing in life that is a waste even though there are good and bad times, and that in the end everything you’ve come through has been necessary for you. This is the reason why youth culture, skate, punk and hard core—all of which I’ve been influenced by—are all mixed in the graphics. I chose the name Wasted Youth because I wanted people to think that those times they may have felt that their youth has been wasted, the struggles that they’re going through like I have, are what took them—thankfully—to where they are today.

Q&A

You’ve gained global attention most recently with Girls Don’t Cry, but before that you had Wasted Youth and Anarchy & Peace. Tell us about those two projects. The very first project was Anarchy & Peace. I first wanted to make a logo that expressed me the best; I mixed up the Anarchy logo, which relates to punk and is part of my roots, and the smiley face because I smile a lot. I was wondering how the two could work together. I tried putting them side by side, putting one on top of the other, and finally decided to change the yellow smiley face into white and draw an A. Not only was it expressing Anarchy & Peace well, it also represented me very well. I thought that logo was me in a nutshell.

After two or three years, I would go to LA and become good friends with Reggie, who designed the front cover of HYPEBEAST Magazine Issue 21. From him, I would learn how to create a brand and the discipline to work in art. I was always creating graphics for punk bands and there were times when I was apprehensive about making them. Wasted Youth was created at this time, when I wanted to express my feelings 100% and create

The latest brand of them all is Girls Don’t Cry. I wanted to create a project featuring my wife who would always be a great pillar for me. That’s how Girls Don’t cry made its debut; it wasn’t something that was supposed to be sold. One or two years ago in LA, there was a pop-up collaboration with Carrots, and I wanted to give my wife a T-shirt as a present. Well, there are many reasons for why it’s a T-shirt—like, when you meet someone for the first time and introduce yourself saying that “I’m in graphic design,” the conversation would end: “Oh, are you?” But if you have a wife next to you wearing the T-shirt you designed, it would be easier to follow up by saying “I’m designing things like this.” Or the person may even ask you, “What brand is that T-shirt?” So that’s the reason I thought a T-shirt would be a good choice.

What are the background concepts behind the actual logo designs? Like the Wasted Youth logo, for example. The reason it was a can of liquor is because you think a lot when you drink. Like, there would be times when you make mistakes because you drank too much or maybe think that the result of something might’ve changed had you had more liquor when you were young. So I thought liquor and drugs were a good reflection of what seems to be a waste but is actually not.

Fragment Design. Have you ever gotten inspired by Japanese street fashion brands? I’ve always been influenced by him. Even now, I’d read all the articles in which my senpais [teachers] I look up to are featured. Ever since I came to LA three years ago and became good friends with many people, I always thought that youngsters in LA are constantly keeping an eye on key people such as Hiroshi [Fujiwara], Nigo, Jonio [Jun Takahashi], Hikaru, Takizawa [Shinsuke], Sk8thng. This is only my personal view; Tyler [the Creator]’s generation was the one that witnessed Nigo and Pharrell collaborate and do something. That’s why I started going over to LA and felt the longings the world gave to them. As I experience and grow more, my respect towards my senpais is growing as well.

What is the background that forms you? How do you think that leverages your style of working in the fashion industry? I wanted to become a graphic designer when I was in junior high school. I didn’t really have enough money to buy clothes, but I saw through magazines when Ura-hara was at its peak, Hiroshi Fujiwara, Nigo, Jun Takahashi, Hikaru from Bounty Hunter… and I thought they were so cool. So that’s how I started to get interested in graphic design, and at first, I copied punk bands’ logos and jackets. I was also in a band. I had someone I knew from the studio that I used to practice at, who was really knowledgeable about ʼ80s hard core. He was the guy that introduced me to some of my favorite bands: Bad Brains, Black Flag and Circle Jerks, whose music and artworks are also nice.

Your style is in some way somewhat similar and has something that reflects Hiroshi Fujiwara’s

You had many collaborations with popular names such as Union, Undercover, Undefeated and Emotionally Unavailable. How did you get to collaborate with them and what were the reasons behind the decision to work with them? To tell you the truth, for Undercover, I heard rumors that “Mad Store” was going to hook up young artists; I thought “I’d have to go! I wanna do it!” So I approached them. I really thought about it every day for a long time. Even my wife, who had to listen to me go on and on about it, can explain everything [laughs].

So, there are times when people approach me and vice versa. However, even when I can feel there’s potential, if I have even the slightest anxiety imagining myself doing the collaboration, I would try to stay away from it as much as I can, because I feel that you can tell, when you’re at the point of deciding whether or not to do it, if it’s something that both parties would feel was worth doing.

How did you introduce your projects to the American market? Did you have anyone to help you out? Of course, timing was one. Whenever I went to LA to start something three years ago, I would stay at Paulo [Calle]’s. I went to so many parties and he would introduce me to lots of people. He would be like, “He’s Verdy, a Japanese designer.” After many conversations, I would tell them that I was throwing a pop-up; I had

I think that it’s easy for the younger generation in Japan to just go overseas and communicate with the people there. For my generation, I feel like people were more hesitant to go. Things such as values, the way of printing graphics, how to find your way of expression—things that I could not move forward with in Japan—would dramatically change in America. I can’t promise a change to everyone who’s reading this, but since I changed, there may be a chance for it.

Do bear in mind that, in the end, cool brands and people are cool regardless of whether they’re in Japan or America, and things that are not cool are just not cool. People who actively share opinions and people who do interesting things will inevitably connect; I believed in this all the more when I went abroad.

a lot of people come to the venue. I think my brand was well received because I went to LA where the culture is open and I talked to people first, instead of introducing my brand right off the bat.

Not to mention it’s very important to have friends that support you. You only succeed when you receive many supports, and in my case, I was lucky to have so many friends in LA, including Paulo, who would upload my stuff on Instagram and introduce HYPEBEAST to me.

Do you think the ties between America and Japan are strong in terms of street fashion and culture? Every young American is interested in Japanese culture, but they seem to have a store in mind already, such as Dover Street Market, F.I.L from Visvim, Undercover, Bape, Neighborhood—oh, and don’t count out Kuumba and Gr8. Kapital is also popular.

Who or what drives your desire to create? To begin, I believe, more than anything, in not forcing it. I would jot down things that I felt and try to reflect it on my next graphic work. It’s difficult to calm yourself down when you’re angry, or try to be angry when you’re not angry; it’s not easy to control your emotions. That’s why I write things down, like my feelings and things that I notice during a certain event in my life. Then I would discuss with my colleagues and friends how I want to express those feelings in a particular set of graphics. It’s good if the message is easy to understand, but it’s not good if it’s too easy. So I would subtly continue adjusting [until I feel it’s right].

I always have feelings to create every day, but I would not force myself to do it. It has to happen naturally.

What are your prospects for Girls Don’t Cry? What kind of future do you see in it? The pace has been really fast, and there is an increase in collaborations, but if Girls Don’t Cry gets too busy, I’ll have less time with my wife, and the original idea was that it’s a gift to my wife so it’s defeating its purpose. So I’d wish to continue at a pace where my wife wouldn’t feel lonely [laughs].