2022

fleeting nature of time confronting prejudice hyperfocus on change

publication of Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing

publication of Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing

a

glassworks Fall

featuring

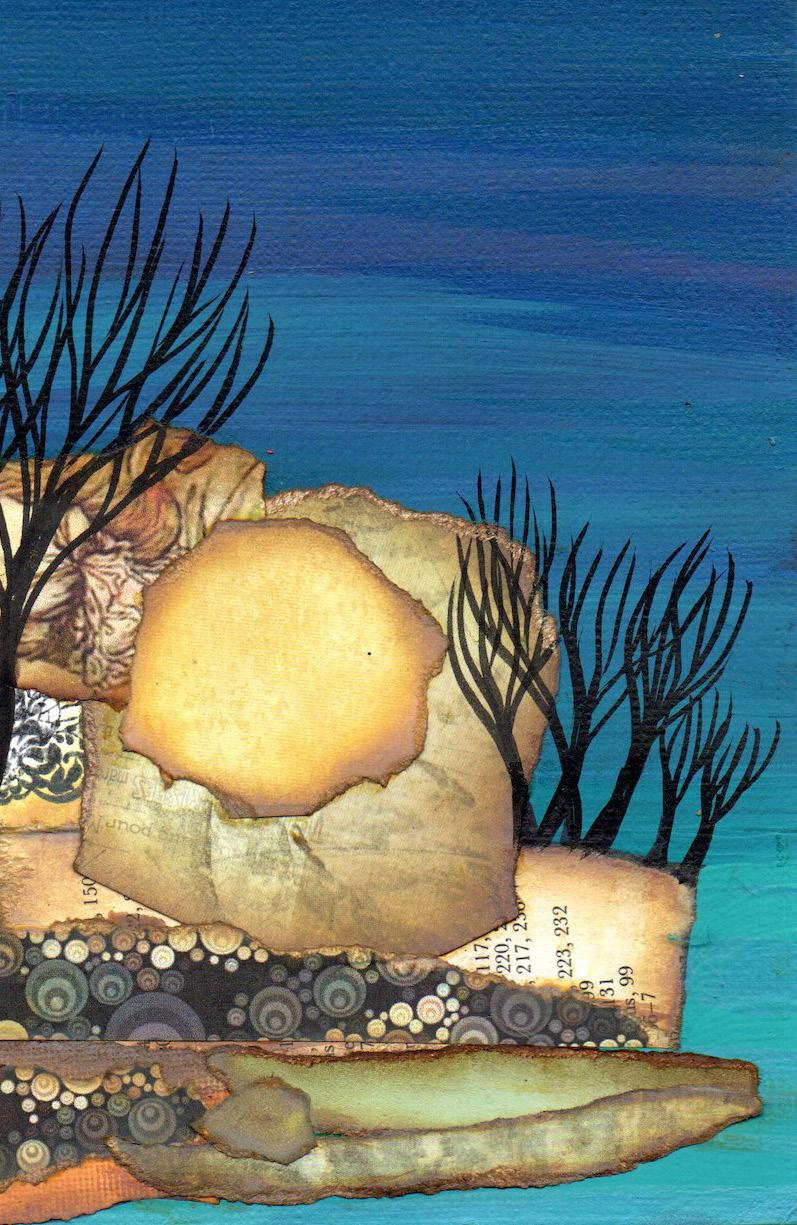

Cover art: “Entering the Dream” by Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad

The staff of Glassworks magazine would like to thank Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing Program and Rowan University’s Writing Arts Department

Cover Design & Layout: Katie Budris

Glassworks is available both digitally and in print. See our website for details: RowanGlassworks.org

Glassworks accepts literary poetry, fiction, nonfiction, craft essays, art, photography, short video/film & audio. See submission guidelines: RowanGlassworks.org

Glassworks is a publication of Rowan University’s Master of Arts in Writing Graduate Program

Correspondence can be sent to: Glassworks c/o Katie Budris Rowan University 260 Victoria Street Glassboro, NJ 08028

E-mail: GlassworksMagazine@rowan.edu

Copyright © 2022 Glassworks

Glassworks maintains First North American Serial Rights for publication in our journal and First Electronic Rights for reproduction of works in Glassworks and/or Glassworks-affiliated materials. All other rights remain with the artist.

EDITOR IN CHIEF Katie Budris

MANAGING EDITOR

Cate Romano

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Garret Castle

Skyla Everwine

Emily Nolan

Amanda Smera

Ariana Tucker

Eric Uhorchuk

Sean Wolff

FICTION EDITORS

Garret Castle John Castle Daria Husni

Ariana Tucker

NONFICTION EDITORS

Farah Bakri Ellen Lewis

Amanda Smera

POETRY EDITORS

Jake Amato

Aleksandr Chebotarev

Natalie Ritchie

MEDIA EDITORS

Billy Appelbaum

Emily Nolan

COPY EDITORS

Editing the Literary Journal

Fall 2022 students

glassworks

Fall 2022 Issue TwenTy-FIve

MASTER OF ARTS IN WRITING PROGRAM ROWAN UNIVERSITY

Issue 25 | Table of ConTenTs

arT

ChrIsTopher paul Brown, FaBrIC In The lIghT #1 | 12

FaBrIC In The lIghT #4 | 23

oormIla vIjayakrIshnan prahlad, enTerIng The dream | Cover The euCalypTus oCean | 17

sea and slumBerIng land | 56

BeTh younger, Through BuIldIngs under over TenTs IT Flows | 43

walkIng InTo vICTory | 6

waTerFronT songs meeT The CITysCape | 30

FICTIon

kaTharIne BosT, good moTher | 8 Carolynn mIreaulT, you have a FrIend In enosBurg | 44

nonFICTIon

graCe CornelIson, wasp | 32

jodI sCoTT ellIoTT, (engIneerIng) error | 57 lIor TorenBerg, on hunger | 18

poeTry

ChrIsTIne andersen, musIngs oF a sojourner | 60 summer oF mosquIToes | 61 marIa Barnes, lasT TrIp | 62 laurel BenjamIn, hydrangeas aT The Corner oF key and marIn | 26

selF porTraIT wITh Flesh | 28 m. d. Berkman, old BIrd | 54 despy BouTrIs, so mayBe I’m The leaky rooF | 53

sTeve Cushman, orange | 4 ZorIna exIe Frey, pee sTands For prejudICe | 40 alIson luBar, grIeF Is IT’s own CarnIval prIZe | 24

sonneT [mId]TransFormaTIon | 25 lea page, my FaTher ClaImed | 13 e.B. sChnepp, anoTher moon poem | 55 CarolIne n. sImpson, all I Can’T reCall From my grandmoTher’s FronT porCh | 14

dIanne sTepp, dInner parTy | 3 lIsa sT. john, relenTess sunrIse: golden shovel | 16 edyTTa wojnar, FaIled assIgnmenT | 39

john wojTowICZ, aFTer hours Flowers | 5

The hIsTory of Glassworks

The tradition of glassworking and the history of Rowan University are deeply intertwined. South Jersey was a natural location for glass production—the sandy soil provided the perfect medium, while plen tiful oak trees fueled the fires. Glassboro, home of Rowan University, was founded as “Glass Works in the Woods” in 1779. The primacy of artistry, a deep pride in individual craftsmanship, and the willingness to explore and test conventional boundaries to create exciting new work is part of the continuing spirit inspiring Glassworks magazine.

glassworks 2

DInner ParTy Dianne Stepp

I bring a medley of foil-wrapped cheeses arranged on a willow plate, and as I carry it from the car to the picnic table, a few leaves blow amid the silver packets–a russet oak leaf, crisp and dry, a toasty maple, several yellow leaves–birch or alder–fall among the shining squares and triangles. The six of us old friends, gray heads inclined together around the worn table, don’t seem to care if we eat at all. The wine glows in our glasses, the first bats flit like swallows. Sparks fly from the outdoor burner. Amid the bits of tinsel, leaves, like offerings.

glassworks 3

Steve Cushman

I could tell you about the man who planted seeds for this orange tree eleven years ago or about the one who picked the fruit, dropped it in a white plastic bucket, his eyes shaded from the Florida sun. Or the packer, the shipper, the clerk at Harris Teeter. All the hands that have touched this one Navel, here now on our kitchen counter. But for a moment, none of that matters, because all I see are Julie’s thin fingers as she peels the bright orange skin, breaks off a perfect little section, says open, and I do as she slides it in my mouth, aware, or maybe not, of what she is offering this snowy, January, Carolina morning.

glassworks 4

oranGe

afTer-hours flowers

John Wojtowicz

Fresh cut and tightly bundled with leftover ribbon.

Set out by the highway in a ten-gallon bucket half-filled with hose water.

5.00 scrawled across the front. Padlocked moneybox.

These are after-hours flowers, doghouse roses, home late with whiskey breath bouquets.

Forgotten anniversaries. Mother-in-law-troubles.

Men struggle in the dark to decide which bunch bears the fragrance of forgiveness.

glassworks 5

walkInG InTo VICTory Beth Younger

glassworks 6

glassworks 7

GooD MoTher

Katharine Bost

My mother used to tell me, “Motherhood always starts out as a blessing.” She never revealed how it ended, but the implication was enough. To her, there was nothing more special than cradling a swad dled infant. But what happens when the infant grows? When they be come a toddler? A child? God for bid, a teenager? “The best thing you can do,” she would say, “is to be your idea of a good mother.”

The wooden box shifts on the table when I push it away from me. The contents roll around, clattering against one another. I don’t like it on the table, far away from me, though, so I place it on my lap. Finger the creases and nicks.

“What I want to know,” a girl with braids and a visor says, “is why the police haven’t arrested her yet.” She wipes down the hot sauce bar for the fifth time in the past hour. It is clean.

She’s speaking to one of her co workers, a wiry waiter with glasses thicker than the table I sit at. He has a face littered with freckles and pimples, some overlapping each other. Beside the girl with braids, he is short and scrawny. Probably used to get beaten up on the playground when he was in elementary.

Jamie might have looked like him.

“No evidence,” the boy says, and his deep voice contrasts the rest of

his squeaky demeanor.

They’re talking about me. It doesn’t matter to them whether I can hear their conversation or not. But it matters to me, so I fiddle with the paper my straw came in to keep from opening the box. I rip it in half at first. Then those pieces in half. Then those pieces in half. Then…

“Everyone knows she did it,” the girl says. Her nametag reads Rochelle, but the boy calls her Roch. She seems like the sort of girl Jamie might have admired. Tall, confident, outspoken without being arrogant. She might have been a good babysitter.

I have run out of paper to shred, and my fork is plastic—too hard to pull apart. If one of the servers comes by, I’ll ask for a napkin.

“Knowing she did it doesn’t hold up in court,” the boy says.

He is a smart child, and not just because he wears glasses. He’s smart because he has nothing else, no one else. No one to play with when he was young—likely an only child. So he surrounded himself with books, memorizing encyclopedias and dictionaries. At least, this is what I imagine his childhood was like.

I wonder what his mother thought—thinks—of him. Wheth er she’s proud that he spends his weekends working at Tijuana

glassworks 8

Typhoon instead of partying with his classmates.

“She should confess,” Rochelle says. “Save the city a bunch of money taking her to court. It’s a waste of taxpayer money.”

fancy restaurant, and you order at the register, but any conver sation with me is too much for them.

They don’t know me, but they knew Jamie. Rochelle did, at least. She had—has—a younger sister his age. It’s strange to think that in a few years, the sister may be working here. Maybe wiping down the hot sauce bar even though it doesn’t need cleaning. Maybe talking about strangers in corner booths with red mat ted hair covering their eyes and a wooden box in their laps.

The girl is barely sixteen and hasn’t had a taste of the stupid places that taxpayer money goes. Just five years ago, the whole city had to pool our money together to build a profes sional rugby stadium. State of the art, the mayor had said. We don’t want to be behind the times. So we brought a rugby team in, and it didn’t even last three years. No one went to the stadium, and the team won a grand total of two games. Now the multi million-dollar complex stands aban doned, rotting away like everything else in this town.

Like Jamie?

The difference between the stadium—Jamie—is that the peo ple in the town are alive. We’re alive and rotting.

Neither the boy nor the girl wants to approach me, though I will them to. Every night I come in they try to pass me off on the other. It’s not a

My hair is matted, and I push it off my forehead. It has been days since I’ve cleaned it. Grimy.

The boy and girl move to wipe down a table nearby, but they keep their distance. “I heard,” the boy says, his voice low but not too low that I can’t hear it, “that they found scratch marks on the outside of her car.”

“But you said there wasn’t enough evidence to prove in court,” the girl says, her eyes flickering in my direction.

I can see them through a mir ror on the wall opposite of me. They don’t know I’m watching them. They think…they have me figured out.

“They can’t prove they’re from him. But my cousin got a look at the car before they seized it. Said there are deep scratches, like the kid was clawing at it.

glassworks 9

“ The difference . . . is that the people in the town are alive. We’re alive and rotting. ”

Katharine Bost

| Good Mother

Trying to get back inside.”

When I look down, I see that my fingers have bent, stiff at the joints. They have formed claws without my permission. If I scratched my car with my hands like this, could I leave deep scratches, too?

“That’s awful.” She looks at me again, this time with a different expression. I meet her gaze in the mirror, but she doesn’t notice.

“What’s really awful,” the boy starts, but pauses to flip a chair over the table. It’s almost closing time. “What’s really awful is that they haven’t found his body. They don’t know what she did to it.”

“Him,” I say under my breath. “They don’t know what I did to him.”

If the two hear me, they don’t know I’m talking to them. They ig nore me, focusing on flipping the chairs onto the tables. They don’t like asking me to leave, so every night they will stare at me, hoping I take the hint and exit on my own. But I don’t.

I unnerve them. My fingers, still in their clawed shape, drag over the wooden box in my lap. My nails make a satisfying scratch, and I think of nails on metal. Nails slicing through acrylic enamel. A bump be neath tires. A crunch of…

boy has walked away to the cash reg ister. It takes several moments for her to approach me, and I pretend not to notice. I trace the lines of the box over and over and over. I count the days to his birthday. Start over. Count the number of years he was alive. Start over. Count the number of times I—

“Ma’am.” Her voice is shaky. “We’re, um, closing.”

I don’t answer at first. She twists the toe of her shoe on the ground. “I said we’re—”

“Do you want to see what’s in my box?” I ask, lifting it so it’s on the table.

The girl shakes her head. The con fidence from earlier—the one I had noticed and imagined Jamie would admire—it trembles. It crumbles beneath a façade of childishness. Naivety. She shakes her head.

“No—no thank you,” she says.

I smile at her. It was supposed to be nice, but the mirror shows it for what it truly is.

“Very well,” I say, and then I stand, taking my wooden box with me. I clutch it close to my chest, keeping it closed to respect the girl’s wishes. It isn’t until I’m outside the restaurant, after they’ve locked me out, that I retreat to a corner to gaze upon its contents.

“It could be anywhere,” the boy says, and then he nods at me. “It’s your night to tell her.”

The girl’s eyes widen, but she nods. She stands still, even after the

I held onto these gifts to remind myself of him. My Jamie. His fin gernails, torn and dirty. Two of his teeth, chipped down the middle. The rest of his baby teeth, rattling away glassworks 10

whenever the box so much as shiv ers, are intact. But I hold onto these because I hold onto him, and I won’t let him go. I won’t grab his hand, broken and bobbing above muddy river water, but I…hold onto what I have.

Because accidents happen, and I was a good mother.

Katharine Bost | Good Mother

glassworks 11

fabrIC In The lIGhT, kaTrIn Dohse 2017 #1 Christopher Paul Brown glassworks 12

My faTher ClaIMeD Lea Page

that coat hangers reproduce at night, tangled wire mocking him, mornings, when he opened his closet door. He preferred order—or I thought so, as much as a child thinks about anything at all. At our house, furniture was polished, no scratches, scores or scabs.

When I was eleven, he remarried into a family of free spirits, or, as some might have it, slobs. Platters of food were left out to feed the flies.

Dog shit calcified on the guest room rug. A pile of Bon Appetit magazines listed by the toilet, covers melded by ancient spills.

Bird guides, phone bills and obscure history abstracts collected under the couch. Broken appliances, small and large, were heaved outside to rust.

A fish pond filter, clogged with last year’s rotting leaves, lay forgotten on the back stair.

Once, on one of my weekends there, he shouted, in gratifying exasperation, I own all horizontal surfaces! Had he realized his mistake? He declared anything left on those surfaces was his to do with what he would, although, in the end, it turned out he wouldn’t. The mess stayed—grew, even. He stayed, too, and never said a word when I stopped coming.

I can’t say I remember him ever being uncertain, not even when he made up an answer— those hangers—but there is a fundamental mystery about what goes on when we close the door, turn our backs and look away.

glassworks 13

When I saw him in the paper, I was shocked, she said. We drank British tea in thin floral china, travel weary, stained by a bitter no milk could mask.

We’d already told her the week before—

He shouldn’t have smoked those cigarettes, as if an actor not a son had passed, as if it weren’t a fall and a hemorrhage.

I can’t recall the smell of the cigarette dangling from his fingers when he picked me up from elementary school, the day of the Great American Smokeout.

But I do the smell of my grandmother’s bony hugs— my cheek against hers, powder and blush a hint of candy, homesickness stale in crow’s feet.

I recall her scoffing at shortbread made with margarine

as she gazed into The Great War for “butter boats” arriving on the North Sea.

I don’t remember if she showed me the newspaper but his countenance sat with us on the front porch— proud and brave in two dimensions.

all I Can’T reCall froM My GranDMoTher’s fronT PorCh Caroline N. Simpson

glassworks 14

I know it must’ve been there, but I can’t recall the smell of cut grass in the humidity between us this last day she spoke of my father.

When I think of his obituary, I smell Silly Putty lifting the facts of his life, taking the creases of my palm.

glassworks 15

relenTless sunrIse: GolDen shoVel Lisa St. John

after “Cell” by Margaret Atwood

Relentless sunrises, now like fading bruises, look snidely, not objectively.

Their substance died with you.

Sullied hues, that’s all they have now. There is no color without light. To offer me more would admit that marigold moments are the chemotherapy chewing the cancer but, it’s really up to each cell to fend for its survival. Is there a cure for blindness toward the beautiful?

16

glassworks

The euCalyPTus oCean

Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad

Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad

glassworks 17

hunGer

Lior Torenberg

Growing up in an Israeli house hold, we fasted on Yom Kippur to remind ourselves of the suffering our ancestors experienced, from biblical times all the way up to the Holocaust. On my maternal side, my grandmother hid for years in a cave in Libya with her eight siblings, and my grandfather escaped Morocco by sneaking onto a boat to France. On my paternal side, my grand mother absconded herself in the woods of Poland, eating dead crows to stay alive, and my grandfather dug himself out of a concentration camp with a spoon only to be re captured and ultimately liberated at Bergen-Belsen in 1945.

This is all to say, Yom Kippur was a solemn day of respect and reflection, repentance and atone ment. It was also my birthday, and instead of a The Little Mermaid cake, I received a lesson in epigenetics, a transference of trauma—instead of food, we spooned terrors into each other’s mouths.

Whether because of the Holo caust or some other ancestral event lost to history, scarcity is ingrained in my family tree like a mossy gnarl. We are messy and wanting, chests overfull with our enlarged, hun gry hearts. Along this family tree are other ailments, crabapples that, while perfectly edible, taste of paper

and meal. My pick of the lot was anx iety (both parents), depression (both parents), gastrointestinal issues (mother), hypothyroidism (mother), and hypoglycemia (father). I imag ine this inheritance like the skin of a snake, shrugged off only to be in gested by another, smaller animal.

This is what a gastrointestinal episode feels like: I eat something, anything, and soon I feel the burble of noxious gasses in my stomach. This is the warning sign. I have less than an hour to get home before they double me over with their insistence, slicing at my rib cage to get out. I wish I had the type of trouble that sent me to the bathroom for relief, but instead, I lay in the fetal position for two to twelve hours waiting for the pillaging to stop in my gut.

I don’t think I’m going to die, but I want to. More than that, I don’t want to eat. Never again, and espe cially not out in public when I’m not sure if I can make it home. At work? Far too risky. Before a night out? Absolutely not.

These symptoms began in the winter of 2017. Before that, eat ing had never been something I associated with pain. But like many women, I had sometimes wished not to be so hungry. My appetite is large, you see. I say this now in a gener ous way, like I am a god. A hungry,

on

glassworks 18

insatiable, fleshy pink god. I have dirt under my nails, and I like to eat.

But there were times when I wished I wasn’t so hungry. Like when I was fourteen and my aunt told me that she weighed the same as me on her wedding day, and it sounded like an instruction. Like when my father dated women who weighed signifi cantly less than me, and it sounded like a condemnation.

over my hunger, or rather, my growing lack of it, and this obsession separated me from my suffering, as if my body were nothing more than a science experiment I could revisit day over day. What was causing my stomach pain? I stopped eating out, pared down my ingredi ents, cooked carefully with the precision of a scientist mixing unstable compounds. I took a bite of food, waited half an hour, and took another.

”

According to the Wiener Holo caust Library Collection, prisoners at Auschwitz-Berkenau were fed 700 calories a day. When I was sick, I ate less than that. I am not comparing my gastrointestinal distress to the horrors undergone by Holocaust victims, by my own grandparents. What I’m trying to figure out is how hunger, a signal that tells me that I’m alive, can also feel like death, and how its absence, sometimes, can feel the same way.

After I became sick, I obsessed

I saw one gastroenterologist. Two. Three. I tried cutting out spicy foods, caffeine, all raw fruits and vegetables, alcohol, gaseous foods like asparagus, beans, onions, and garlic. I swal lowed a strange liquid that would reveal if I was missing a certain enzyme. I took all matter of antacid and indigestion medica tion: from the candy-pink world of Pepto Bismol and Tums to the heavy hitters like Gaviscon and Prilosec, more common in pharmacies abroad.

My hair fell out from worry. All of it, all at once. I devel oped something called telogen effluvium, which is when a period of intense stress causes all the hair on your head to die. I was afraid to touch my hair, let alone wash it in the shower, or god forbid, brush it. I wore hats, and headbands. I stayed home, hidden among my sheddings.

“

What I’m trying to figure out is how hunger, a signal that tells me that I’m alive, can also feel like death, and how its absence, sometimes, can feel the same way.

glassworks 19

Lior Torenberg | On Hunger

And in the meantime, I lost weight. When my mother saw me for the first time since I became sick, she said that I looked like a Holocaust victim.

My mother, a lifelong yo-yo dieter who used to eat nothing in college but saltines and tuna salad in order to lose weight. Who did the South Beach Diet, the grape fruit-for-breakfast diet, the what ever diet. She looked at me like she wanted to cry.

How did you do it? people would ask me. And in the same breath: I’m wor ried about you.

my once prominent butt reduced to hard edges. I enjoyed the asexuality of my body, how I had less surface area to clean in the shower. And over time, my appetite diminished, and I wasn’t hungry anymore.

And no, none of this was glamorous. Aside from losing my hair, I became low energy, tetchy, and vulnerable. I isolated myself, more so in the summer, when I couldn’t cover up in baggy clothing. I went to work, took a lot of naps, and that was all.

I thought a lot about Eurydice during this period. In the musical

“ Eurydice . . . accepts death in order to avoid starvation. In doing so, she isn’t wishing to escape hunger, but rather to be full forever. To eliminate the inevitability, the dread of where her next meal would come from.

It’s complicated to be under weight. It’s complicated to even de fine what underweight means when BMI is just a number, and celebrities and models looked like I did when I was ill. Being a woman is difficult in this way. Being a man is difficult, too. It seems that the fact of being a person in a body is difficult.

I didn’t love how I looked per se, but there was a part of me that liked it in an aesthetic sense. My body felt simple to me, un-busy. I felt boyish, too. I had resented my curves grow ing up, and now I was flat chested,

”

Hadestown, she accepts death in or der to avoid starvation. In doing so, she isn’t wishing to escape hunger, but rather to be full forever. To elim inate the inevitability, the dread of where her next meal would come from. But she didn’t note the differ ence between the absence of some thing and its perfect satisfaction, and the former is what she received. She was dead, and so she never had to be hungry again. For Eurydice, this distinction, this everlasting absence, was Hell.

I wonder if any part of her was glassworks 20

ashamed to be found by her hus band, Orpheus, in Hades, ashamed of how far she had fallen, her dead eyes, gray skin. If she had become grateful, in a way, that she didn’t have to live aboveground again and subject herself to judgment for the person she had become.

The further I was in the gallows of my gastrointestinal illness, the more isolated I felt from the out side world, and the less able I was to rejoin it. I was afraid people would judge me, talk about me behind my back. My diminishing body was the only thing that I allowed to keep me company, a metronome by which I counted out my days.

And then one morning, two years after my troubles began, I fell asleep at work after eating a bagel. My co worker nudged me awake and sug gested that I could be gluten intoler ant like her. I eyed the paper plate on my desk, the stray sesame and pop py seeds. I’m good with gluten, I said. I tested for Celiac years ago.

Maybe you’re just intolerant, she said. It’s pretty common.

It was infuriatingly simple. I cut out all gluten from my diet and within two weeks, my stomach pain had disappeared. Within a month, the brain fog that had kept me dulled and dumb lifted. My friends marveled at my shiny new personal ity, my wit and energy, and I did too.

Yes, I was furious—years of GI appointments, thousands of dollars spent—but I was also overjoyed. On

numerous occasions, my new found energy and mental clarity brought me to tears. I was good at my job all of a sudden, and bright, and even funny. I had energy to do things like go to the gym and see friends after work. I could live aboveground again.

It took about a year to ful ly build back my appetite after that. And yes, sometimes my revived appetite scared me and I wished, again, that I wasn’t so hungry. What would it even take for me to feel full? I wondered. Would my appetite just contin ue to grow and grow by the day until I ate the whole world and my stomach exploded, like some insatiable god in a creation myth?

What would I create?

There’s fear, a lot of it. I get in the shower and there is more of me. Shaving my legs takes longer. My breasts are sizable un der my palms. This is different, and so it feels bad. It’s painful to be hungry because it’s painful to be alive.

But there are things that feel good, like communion. Eating and drinking with others, let ting people love me in this way, tethering ourselves to each other briefly over a dinner table again and again. This is the metro nome now, the cadence of living.

Since writing this, my appe tite has normalized. Reached a set point and fallen out of focus

glassworks 21 Lior Torenberg | On Hunger

entirely, become utterly uninterest ing. My stomach has stopped re volting against me and become just another organ, as simultaneous ly vital and mundane as my spleen or colon.

This year on my birthday, on Yom Kippur, I will put my healthy body through a fast. Inhabit my ances tors’ suffering and even a little bit of my own. And when that fast is over I will celebrate the unending, ceaseless nature of things—trauma, hunger, love—and my place within it, as someone who has decided to live aboveground.

“

It’s painful to be hungry because it’s painful to be alive. ”

glassworks 22

fabrIC In The lIGhT, kaTrIn Dohse 2017 #4 Christopher Paul Brown glassworks 23

GrIef Is ITs own CarnIVal PrIze Alison Lubar

at the goldfish-toss: ping pong ball tok-toks to a hushed muffled tsisk in the grass, rests next to others like empty eggs. Once in a while, one tries to sing the bowl, kiss rim in ellipses, but whisks itself out. A win is a loss: this fish won’t last a week. But Gabriella clung to eleven years, less long than rotten love. If I can end this, bury her in a brown velveteen candy box, I will shoot my shot every time and still, always walk away winning.

glassworks 24

sonneT [MID]TransforMaTIon Alison Lubar

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2019

Her corners clipped from the collector’s loft, Munch’s Mermaid crowns a left-of-center room, waves brim with ambiguity: assume she still cannot claim anything she’s sought.

Her room is blue among Renoir, Manet, Lautrec, Degas, all spirited, they’re not stopped in an existential moment, caught: my siren lies half wet, fully delayed.

And so, myself in each age that we met [at ten, enchanted; seventeen, sanguine; but now by thirty two, a narrow world]

I see our moon’s hope tempered by regret, despaired in brackish limbo, stuck between, and neither turned to fish nor back to girl.

glassworks 25

hyDranGeas aT The Corner of key anD MarIn

Laurel Benjamin

One hundred edges entered the building. One hundred edges, glass shattered iridescent lavender of afternoon, damsel flies a wild dust dance intoxicating air as if someone opened a champagne bottle. But it was a man

driving a truck into our house, a cocoon broken as I stood up from the rocking chair, muscles in a sonata of their own, some moving one way, others blooms of new lilacs that would over time rectify. My ears did not hear traffic outside and I wondered if the packing I’d done for camping was sacrosanct, down in the garage. I found the cats under the bed. Closed the bedroom door. Grabbed my purse and took the back door outside.

I smelled licorice or was it blacktop pealed like someone would fold a sheet back before bed. Neighbors stood around. Police kept the intersection clear for the ambulances hauling away drivers. Firemen suited in black baggy pants and jackets with yellow fluorescent stripes routed under the new cavity like anthropologists looking for the next big dig, and others came with jaws to set the driver free from where he’d pushed beams of redwood taken from these hills seventy years before.

glassworks 26

And to me, the red bougainvillea crawling up the front porch were my own arteries bleeding, my own oxygen performing an arabesque of unassailable difficulty. The stench of smoke remained at the dining room window, a plume floating where it would go, and next to the truck lay the heads of hydrangeas chopped off at the point of impact, their silken purple skirts finally idle of chatter, their gossamer wings clipped.

glassworks 27

self-PorTraIT wITh flesh

Laurel Benjamin

Your hips are as wide as your grandfather’s said my mother, whose breasts pointed then sagged. She took to Overeaters Anonymous, no ice cream in the freezer,

and particular like her gloves, hard to find for small hands, she only liked butterbrickle or cashews with ribbons

of caramel bowed and unraveled, as she stood in front of the mirror. I inherited her gloves,

the hats I crocheted for her, her stockings, her skin a pale shade. And in her craving for order,

my mother frequented museums, perpendicular lines funneled into a next room,

each painting or sculpture with its own identity card describing details beyond the eye’s reach.

Each craving had its own purpose yet she had only one way out

after I was born, and she terminated the lump within her, unseeable from the outside, my father finding a doctor who would perform that task.

Women are bought and sold, our bodies argued in the highest courts, beyond flesh. Onlookers the deciders, each of us in our own portrait where one woman’s eyes bug out at the disgrace

glassworks 28

of ample flesh, another instead observing the small landscape for sale.

In a storefront window you can see me boxed in an ornate frame ready for sale. I’ve paid the price, stealing orange cake, crumbs dropping along sidewalk.

Across the street, the candy shop just opened but don’t be distracted by tiny chocolates—

look at my thighs, gloves not enough to cover.

Regard me as a portrait of skin and pulp, what’s inside unsacred.

glassworks 29

waTerfronT sonGs MeeT The CITysCaPe

Beth Younger

waTerfronT sonGs MeeT The CITysCaPe

Beth Younger

glassworks 30

glassworks 31

Grace Cornelison

White Anglo-Saxon Protestants, to which I regretfully belong, all said the same thing to me last Sunday.

The three of us had been sitting in a back pew (a compromise be tween my evasive, ungodly influence and their exhaustion over fighting me about the non-biblical specifics of church attendance). This meant that when the pastor finished the prayer after his sermon, paused, and asked to “call up the other elders of the church to pray together over George and Patricia Cornelison,” several hundred heads swiveled back to find us.

The only proper response to a sea of scrutinizing pale faces is in visibility or war, but war wasn’t an option, so I practiced controlling the wayward skin around my eyes and mouth that wanted to contract and grimace.

The pastor explained to the flock adorned in autumn colors and dehydrated hair about how “our foundational elder and his wife” would “be absent from us, as George undergoes extensive treat ment,” and “we are so thankful for his years of dedicated service to our congregation, and we just pray that the Lord….” It all became a buzzing frequency in the back of my head that was piously echoed after the service like a religious

Cards Against Humanity.

“My uncle had what your dad has, and the doctors gave him six months to live, and he only made it about two months, but I just know the Lord is watching over your father.”

“Come here a minute, honey, let me hold you and pray over you. Dear Jesus, we just ask that you wrap up sweet Grace in the palm of your hand and be with her while…”

~

My parents left the driveway and the city before the next morning’s sun had risen in the skyline. Be fore the sun had finished rising, before I had even let the two longlegged gray beasts outside to potty, I was on the phone with my mother bargaining about my undergraduate spring tuition.

“How are your grades looking this semester?” she asked dubiously. “Especially now that you’re not dating that boy?”

I looked down at the frail tabby purring himself to sleep in my lap, one of his claws still daintily stretched to knead my sweatpants.

“They’re great,” I insisted.

They were not great.

I had missed an assignment in Anthropology 1000 and gotten a 68% on the first exam, and I didn’t even know when the next assignments were due for my four

wasP

glassworks 32

other classes.

“Well. Tell me how midterms go, and then maybe we can make a decision. But I don’t know what you’re going to do if you don’t fin ish school, especially with all those animals. You will probably have to give them away.”

My dogs whimper in their sleep.

~

I don’t leave myself a generous amount of time in between that first alarm and leaving the house in time for an 8:30 a.m. lecture, so my friend’s first official invitation to ride horses, for this evening, is bouncing around the inside of my skull like an old Windows screensaver. I can almost feel the thoughts and mem ories the invitation collides against. The last time I was on a horse was so long ago, middle school, which is ages and ages for a college student. I don’t even remember if I rode a gelding or a mare, or if the saddle was pommelled and Western or sleek and English. Probably West ern. It was a friend’s birthday trail ride. Before that, I had only been placed upon the backs of my grand father’s dairy cows, which to me, had been as good as a horse.

I stare at the toothpaste collecting around the edges of my mouth and imagine myself on a mare with a rich mahogany bay coat.

Then the invitation bounces against a knot in my head: Dad, my mom, tuition, and what I will do if I can’t afford college mingles in the

same internal space with the future and care of my fourlegged friends. FAFSA considers me a dependent, and my Head of Household, my father, makes too much money for the of fered loans to cover even half of tuition. I understand the irony.

I don’t normally have conflict ing plans, or any plans. People at church stopped inviting me places because of my respons es to men, mostly. I’m not a “hand-wash the dishes while the college boys crack jokes about women in the kitchen and sit around drinking spar kling grape juice” kind of girl, I’m a “let me tell you why you’re wrong using a lifetime of con stant theological indoctrination while I pet the hostess’ cat” kind of girl.

I am thinking about all of this and definitely not texting and driving when I message Mandy back.

“I would love to.”

~

I’ve known Mandy since I was four and she was five, but I’ve never been to her house. It’s a whole-ass family proper ty, really, because her text says that her grandfather lives in the white trailer at the top of the driveway. Across from his four or so acres of meticulouslymowed grass and the Trump flag flying above the American glassworks

Grace Cornelison

33

| WASP

flag, there are roughly ten acres of fenced-in pasture sprawl on the right, starting on the other side of the driveway and continuing down under power lines. At the top of the pasture there is a white and rusting bumper-pull trailer and a short twenty-year-old pulling cinder blocks out from under the trailer hitch, which is already connected to the back of a shiny red Ford F-150.

I park on the outside of the pas ture and don’t remember getting out of the car or locking it because there are fucking horses in that trailer, and I haven’t been on the back of one since attending a different friend’s birthday in middle school.

Mandy and I met at the piano studio where her older sister and my brothers and I took lessons from a severe Presbyterian woman. I’d brushed off Mandy’s small at tempts at friendship over the years because her Facebook posts were full of poser-tomboy-deer-hunting and what felt like a whole lotta false bravado and cheesy Bible quotes. Her biblical references were over used clichés that were always taken wildly out of context, like, “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me,” but the quotes had been less and less frequent over the years.

I still labeled Mandy off as your typical country Republican until I got that bona-fide invitation Friday morning with a date and time to be put in a saddle. My relatives are

all southern conservatives. I put up with them every holiday season. Ev ery Sunday with the congregation. I can put up with it today if it means horses are involved.

Mandy waves a flannel arm at me and adjusts her Georgia Bulldogs cap with the other.

“Hey, Gracie-girl! Long time no see!”

I didn’t realize her hair was even shorter than mine until she flips her ball cap off and over one hand in a move that looks like she practices it in the mirror, and she fluffs the curls on the top of her head with a hand that’s so twitchy, I wonder if she is the same nervous and awkward for mer homeschooler as me. Her eyes are the Hollywood kind of pierc ing blue underneath dark eyebrows, and her cheeks are flushed; she’s in sensible, thick, straight-legged jeans pulled over her leather Western boots. We’re both in flannels, but I have white-washed skinny jeans and Nike sneakers and this woman is the first person who has ever made me feel remotely like an actual city girl.

My tongue is tied until I hear the unmistakable noise of a horse blow ing hard out of its nostrils from in side the trailer, and then I give up on any sort of country-girl connection with Mandy because I’m squealing and almost bouncing despite myself. She flashes me a startled look, like, “is this girl okay?”

“Uhh…well, they’re all loaded up and ready to go,” she says, fiddling glassworks 34

with her belt buckle that has a shiny bronze “M” on it.

I ask if I can see them and she’s still facing me when she rolls her eyes and waves me on over to a door at the front of the trailer. It opens with a rusty squeak, and a mahoganycolored horse with a white strip

The truck is big and has pol ished-looking tan leather seats and is nicer than any of the cars Dad has ever bought, and once we’re finally driving, I have to ask Mandy to repeat herself con stantly because my neck is craned and my eyes are glued past the

down her face sticks her nose out and chuffs inquisitively at me. I already know her name is Jill be cause Facebook, my Weimaraner, and Mandy’s horses are the only rea son we’ve kept in any sort of contact after her older sister stopped piano lessons years and years ago.

She has liquid doe eyes peppered with fragments of honey and cedar, and she smells like hay and pasture and musky-earth-horse-dog. She has soft whiskers around her velvet nose, which is shiny, like Mandy oiled it.

Behind her is a sandy gelding Mandy tells me is twenty-nine, which apparently isn’t all that old for a rid ing horse. He is a palomino Quar ter Horse and his name, Corduroy, fits him perfectly. His eyes are even softer than Jill’s, and when he looks at me, the feathery whiskers around his eyes wiggle and dance like he is greeting an old friend.

rear window and onto the trail er, as if I could pierce through the aluminum metal or whatever like Superman and see the two horses inside.

Mandy finally shoots me a prickled look once we’re on the highway because I’m clearly not paying attention.

“They’re not gonna disappear out of the trailer, you know,” she says pointedly. Her mouth is almost in a pout, and she’s so childish for a moment that it’s al most cute, so I give my craning neck a break and try to make a concentrated effort.

We move from parents and delicate discussions of their health (her dad has a chronic heart condition and a perpet ually bum back from break ing it Jumping [motorcycles over several school busses] for glassworks

“

She has liquid doe eyes peppered with fragments of honey and cedar, and she smells like hay pasture and musky-earth-horse-dog. ”

Grace Cornelison | WASP

35

Jesus, and my dad is…you know) onto lighter things like church boys, and I fish around for any sense of progressiveness in her and am re warded with an explosive rant about racism and homophobia in southern churches. There’s enough fire and assessment behind her eyes when she looks at me and enough venom in her voice when she talks about church and boys for me to risk it.

I’m surprised when my throat tightens and my hands go cold. I look at her face and look away, and try to swallow my words, but I blurt it out anyway.

“I’m bi.” My neck jerks a little, like it’s trying to be arrogant from a pattern of self-defense at this disclosure.

“But I’ve actually never offi cially dated any of them,” I admit sheepishly.

Mandy’s smile is confident, dar ing, even. “That’s actually why I invited you today, after all those years mostly ignoring each other,” she admits, running a hand down the back of her head in a way that makes me want it to be my hand, my fingers, in her hair.

“I was seeing this girl, Rawen.”

“Rawen Johnson?” I demand, thinking there is no way the world is this small.

Her eyes almost bug out of her head.

“You know her? Well, she and me were supposed to go horseback riding tonight and she was s’posed

”

You don’t have a crush on me, do you?

You just haven’t met the right guy. If I were you, I’d be afraid my parents would find out.

“Same,” she says, and her grin is cocky but her eyes are nervous un til I make her take one hand off the wheel to give me the cheesiest highfive and we bond over hiding “really good friends” from our parents.

to spend the night, and then her mom found out.” There is a specific drawl seeping into her enunciation now, and it feels like childhood memories of aunts under pecan trees, red solo cups full of proper ly made sweet tea and boiled pea nuts, and scratching fire ant and mosquito bites around my ankles and feet.

“ My mom’s voice is full of reproach and condemnation, like she is in a pulpit speaking to a crowd of nonbelievers, like there is an immeasurable line between us, and it is my fault . . .

glassworks 36

I sympathize with her plight, and ask if there’s any chance Rawen’s mom would out Mandy to Mandy’s mom.

She says she doubts it, but her eyes twitch.

~

I spend the next month attempting to get my grades up in preparation for the midterm talk with my mom instead of saddling up the horses every time Mandy gets out of class or work. But we ride together almost every weekend, and on weeknights she asks me out to dinner after she gets off work and she pays for my pizza and Dr. Pepper. It’s effortless, like finding a mirror image of your self with the same experiences, the same parents, the same terrors.

We go to each other’s churches together often, and apparently enough people are talking at my church about the two girls with short hair for my parents to finally ask me “if I was hanging out with that girl Mandy,” at which point I have to dutifully and carefully diss the theology in Mandy’s church’s pulpit and talk about how nice it is to have someone to talk to while they’re gone in order to soothe their fears.

“I’m worried about your school,” my mom says over and over, and each time, I see my four-legged beasts behind cold bars and my stomach sinks to my hips.

“Your father and I aren’t going to pay for you to live in our house, you know, and you won’t be able to

afford rent on a minimum-wage job,” she reminds me. “Especially not with all your animals.” I look at the gray dog whose swan neck is arched over my thigh and rest ing against me, and I look at the two cats, all of whom have been my closest friends over the past few years, as my beliefs evolved and my church community dis integrated. Mandy’s face pops in my head, cheeks and parted lips flushed as she digs her heels into her mare’s sides and the two gallop across the dusty summer pasture like they’re starring in some fucking Disney film.

My mom’s voice is full of re proach and condemnation, like she is in a pulpit speaking to a crowd of nonbelievers, like there is an immeasurable line between us, and it is my fault, because she raised me better.

That month, Dad’s voice just got weaker and weaker and he couldn’t talk for long as his white blood cell count began to drop and the no-shit chemo infusions increased. My mom sent me selfies of her and Dad in N-95 masks in hospital waiting rooms and kept asking me about my as signments and grades. I told all of my professors that I had to leave my ringer on during class because I felt like I was perpetu ally holding my breath just wait ing for the worst phone call. I played catch-and-evade with my glassworks

Cornelison

37 Grace

| WASP

parents on the phone because I nev er knew if it would be the last time I spoke to Dad, but I had to lie ev ery time he asked me about “how it was going.”

It’s going kind of gay, Dad.

~

It’s another clear Friday evening and my legs are jello as I reach up to grab the leather Western saddle around the sides from Corduroy and hoist it over him. The stirrups gen tly smack his back, which is wet in the shape of a saddle and girth strap, and I set the saddle on top of the wooden fence.

Mandy walks over to Corduroy’s lead rope, tied by me in a daisy-hitch knot to the hitching post. She gives it a firm tug and shoots me an ap proving grin that starts at my eyes and lingers around my mouth.

“Guess the city girl can learn somethin’,” she teases.

I don’t even think until I have al ready bridged the sandy gap between us and we are sandwiched between horses breathing heavily and I can tell her throat is choking because of how thickly she swallows.

My breath washes over her face.

“Maybe you can teach me some thing else?”

We reach for each other’s faces at the same time and she cups my cheek and searches my eyes.

“You ready?” she asks, tilting her neck and leaning forward.

I think of Dad in his hospital bed, and my mom’s voice when she

threatens my future with tuition control, and how the church foyer on Sundays may as well be empty rather than full. Something is slip ping away from me and I am sud denly aware that cicadas have begun humming, and songbirds are calling out to their mates as they settle in their nests, and it is the golden hour as the sun begins to set, and the light is making the horse hairs floating in the air catch on fire, and the scent of sweat and hay from Mandy is filling my nose and my head.

The horses whicker softly when I pull her face towards mine and close the space between our lips. She is softer than any mouth mine has ever felt, and there is no slopping doglike tongue reaching out for mine. She tastes like salt and peppermint and green energy drinks.

Mandy pulls back and inhales deeply and I realize I haven’t been breathing, either.

Her eyes are startled, electrified, and a red flush is creeping up her neck and cheeks.

“Are we really going to do this?” she insists, hand still cupping my cheek.

I pull her forehead towards mine and wrap my fingers around her short curls. We breathe into each other softly, settling like two mares bedding down for the night together.

glassworks 38

faIleD assIGnMenT Edytta Wojnar

In my story, I lie about my characters & steal identities of people I know who appear plain & increasingly pitiful on paper. I need to change them, make them three-dimensional, introduce peril, so I make the woman kiss her man & hiss

“pack your stuff & leave”

then I wonder if he will, who will keep the house & tend to the garden, & I decide she does, but they split the dogs, dishes, & photos & shuffle the children who become unruly & anxious. In the end

I don’t know how to arc this plot without killing at least one of them.

glassworks 39

Pee sTanDs for PrejuDICe

Zorina Exie Frey

1. Circa 2015

My coworkers and I Uber to happy hour in Coral Gables. Nobody and everybody’s hood. Cuban. Haitian. Turkish. Mexican. Arab. European. African? American?—me.

Tapas chased down with White Russians & reggaeton beats. Slurred speech accompanies laughter & selfies. Bar hopping adventure.

Blonde hair & Blue eyes strides into America’s alley to pee with no tissue. I, with a full bladder lookout for the nearest proper public facilities.

2. Circa 2005

My coworker and I drive to a garage party in Niles, Michigan. White people playing rap music Cheers’ing beer bottles Pabst Blue Ribbon testosterone surveys Africa’s rolling plains.

Their eyes hunt my gazelle legs, my caramel-continent skin, my sand-kissed lips, my inner-fight. The lioness considering…

Blue & grey eyes scowling Move, bitch! Get out the way!

Ludacris booms through whitewashed speaker boxes. My music betraying me.

It’s ok. You’re with me.

Now, I’m the white girl in her hood. Walking me back to my hatchback She relieves herself in shrubs. America’s front yard, with no tissue.

glassworks 40

3. Circa 1983

We played Luke, Han, Leia, and Godzilla. Eric had the Millennium Falcon.

He lived further down my white block. Far enough for me to ask to use his bathroom. He refused.

I can’t. My father says because you’re Black. To which I replied with a swinging closed fist. A reflex.

Since it’s frowned upon for me to pee in a bush I rode my Big Wheel home to relieve myself.

Eric’s father berates my momma on her doorstep flexing white privilege, Eric had a bloody lip. Look what your daughter did! He hissed.

My mother’s 1930s mentality kicked in. She picked a twig to whip me. A crime now. Legal when whites did it.

4. Circa 1980

My block occupies all white folks. My friends, Mark & Amy live around the corner playing Star Wars with baby dolls.

When I used their bathroom, I wasn’t allowed to close the door. They watched to see if I pee’d black.

When they found it to be yellow, Mark wiped the toilet seat with white tissue Erasing my existence.

[cont.] glassworks 41

5. Circa 1974

I live in between two different worlds. Once Black. The other white. My mother’s light-skinned melanin tells me Yankee blood swims beneath the bedrock of our family river where some people pee.

glassworks 42

ThrouGh

unDer oVer

Beth Younger

ThrouGh

unDer oVer

Beth Younger

glassworks 43

buIlDInGs

TenTs IT flows

you haVe a frIenD In enosburG

Carolynn Mireault

Daisy, a fraud, had never opened Steinbeck and could not solve a regular Rubik’s cube, much less the hexagonal one she carried. She did not have a license, nor a permit to drive, but a few days later took her older sister’s brown Sonoma to the intersection of Main and Cedar. She waited for close to an hour, staring at the distant Sunoco sign, and thought that maybe she was too late. Then a car pulled up and idled until another came soon after, and one girl got in the other’s car, and Daisy followed them through town. Trying to keep her distance without losing them, Daisy talked to herself.

“No one’s going to notice,” she said. “She said I could come. She said I could come if she had it. Bright star, would I were steadfast as thou art—” They turned down one backroad then another, and the ice was loud under her tires. “Not in lone splendor hung aloft the night—”

She parked the Sonoma behind them, joining a curtain of cars lead ing down a dirt driveway. In the dark, Daisy could just make out the flickering, yellow windows of a mod est house. She waited for the girls to get up to the front door, where they let themselves in, then she followed suit.

Inside, blue carpeting had been poorly installed, indicated by deep wrinkles across the dining room. It came up like monkshood on the baseboards. The students in attendance seemed to self-segre gate in accordance with who had or had not yet had their eighteenth birthday. The still-seventeen-yearolds hovered by the cupcake table while the eighteen-year-olds stood near decanters of noir, waiting for permission.

Mrs. Roth, who had grown dysmorphic, drifted among them in a shapeless, red frock and a goldembroidered scarf flipped over one shoulder. After losing her cat to a house fire years earlier, she lit only flameless candles which twinkled amber on every surface. She was in her late seventies and the school was putting pressure on her to retire.

“This could be the last one,” she said to everyone she greeted. “This could be the final year.”

She noticed Daisy almost imme diately who, despite the snow, wore a raincoat, and after taking off her shoes, was deciding where she be longed. She’d had her eighteenth birthday but considered that the still-seventeen-year-olds might be self-conscious enough to provide better cover. She saw Mrs. Roth heading her way and she picked up

~

glassworks 44

a chocolate cupcake.

“Merry Christmas,” she said.

“Hello, Daisy,” said Mrs. Roth.

“Thanks for having me.”

“Yes,” she said.

Daisy did not understand Mrs. Roth’s dislike for her. It derived from an unfortunate misconception, in which Mrs. Roth firmly believed it had been Daisy who had left a pack of adult diapers on the roof of her car at the drugstore since she saw her in a neighboring aisle.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Roth, “enjoy.” She walked back toward a herd of parents, and Daisy lingered by the students at the cupcake table who were more dressed up than her. One of them, Katie Cricova, wore a black velvet miniskirt with a green geomet ric blouse tucked into it. Her tights had runs, which were there on purpose, in pale veins up her thigh.

Mireault

“Good cupcake,” she said.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Roth.

Mrs. Roth wore no makeup except for black pencil liner, tight around her waterline and smudged on the outer corners. This was the first time Daisy had ever seen her without glasses, which were always perched on her nasal bridge in thin wire frames. Daisy, realizing she had complimented Mrs. Roth on the cupcake before taking a bite, licked some frosting off its loin and nodded.

“Really good,” she said.

“Where are your parents?” she asked Daisy.

“I don’t know,” she said. “They couldn’t come.”

“My mom’s flirting with all the dads,” said Katie.

You Have a Friend in Enosburg “

“I like your skirt,” said Daisy.

“What?”

“Your outfit,” she said.

“Oh, thanks.” Katie looked at Daisy, searching for a feature to compliment, but between the brown frizz and checkered jeans, all she said was, “You, too.”

Mrs. Roth stood up on a couch cushion, holding a glass of wine and balancing her self with a hand on one of the mother’s shoulders.

“Good evening!”

Everyone fell silent. For the first time since arriving, Daisy could hear the faint Claude Debussy playing off a speaker one room over.

“As we do every year,” said Mrs. Roth, “and you all know very well, let us hear a recitation

After losing her cat to a house fire years earlier, she lit only flameless candles, which twinkled amber on every surface. ”

Carolynn

|

glassworks 45

of one of the greats.”

The silent room waited for her finger to land on one of them. The parents curbed their smiles, hop ing with eighteen years of love and might that their perfect Greg or ac complished Molly would be chosen.

“Daisy Routledge.”

With two years of preparation, Daisy was practiced and felt that she finally belonged. For a moment, she believed Mrs. Roth had chosen her not to embarrass her, but to recognize her as part of the elite group—this particular one—for which she had always squirmed in longing. Mrs. Roth reached out her hand, removing it from the mother’s shoulder, and Daisy walked over to her, stepping up on the other couch cushion. Mrs. Roth smelled like the woodstove and freesia, like a true Vermont widow, and Daisy could only think of her grandmother, who also lit her own fires, and smelled that same way.

“Would you like to begin?” asked Mrs. Roth. “What will it be?”

“‘Bright Star,’” said Daisy. “Ah,” said Mrs. Roth.

“Bright star,” she began, “would I were steadfast as thou art—”

“I was thinking ‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci,’” said Mrs. Roth. “O what can ail thee—you know it— knight-at-arms—”

She stopped and nodded for Daisy to continue. With the whole room staring, now Debussy sound ed louder—even deafening—and

the attentive eyes grew mocking. The mother to Mrs. Roth’s left, who had leant her shoulder, said, “Sarah knows it,” (supposedly her daugh ter), “I’ve heard her recite it and it’s very strong.”

“Wonderful!” said Mrs. Roth.

The girl who must have been Sarah came up to the couch by her mother, and Daisy stepped down.

“O what can ail thee, knight-atarms,” went Sarah.

Daisy saw Katie Cricova by the front door, putting on her shoes and waving her over. She joined her, stepping back into her boots from the pile of shoes dripping with mire and felt her jacket pocket for the keys to the Sonoma.

“That was bullshit,” Katie said.

“I guess,” said Daisy.

“No, it was,” she said. “Are you coming to the lacrosse party?”

“I don’t know,” said Daisy. “Where is it?”

“The squirrel’s granary is full!” went Sarah.

“A house near the falls,” said Katie. “You can follow me.”

In a small, red house, all the seniors were drunk. Some of the boys wore Santa hats and the girls wore dangling snowflake earrings. Daisy left her raincoat in the truck and shivered in her tank top; they had the backdoor propped open and smoked out of it. Two redhaired boys took up the couch and debated.

~

glassworks 46

“Then, you have to ask—fuck, it’s cold in here—where does morality come from?” asked one boy.

“Are we moral?” asked the other.

“The Bible.”

“Those who are moral, are moral despite the Bible,” said the other.

“I’m a Jainist,” said the first one.

“You don’t kill spiders?”

“Are they really having this con versation?” Daisy asked Katie.

“What?” she asked. “Come on.”

Katie pulled her toward the kitch en with such confidence that Daisy guessed she had been here many times before, had even grown up here, and that somewhere on a near by door jamb were pencil-ticked measurements of her growing up inch by inch. The kitchen was less hectic than the living room, hav ing no boys, and delicate girls sat on the linoleum passing rum. Katie took a sip then handed it to Daisy, who took two. They sat down on the floor with everybody else and Daisy wondered if Katie was gay and would reach for her checkered jeans or propose a kissing game.

Daisy had been to one other party in the past, having overheard the de tails in the art room, and had arrived just as a neighbor drove over from his property and said his horses were spooked, and the party listened, and all went home.

Sarah—‘La Belle Dame Sans Merci’—walked in with a box of san gria. She was heavyset and balancing on a tiny pair of red wedges. She

had a bookbag on her shoul der, which functioned as a sort of purse, and she put the san gria and an elbow on the island to lean.

“What time are we going back?” she asked.

“Don’t know,” said one of the girls. “Have to wait until later.”

“She probably goes to bed early,” said Sarah. “She’s old.”

“Go back where?” Daisy asked Katie.

“Mrs. Roth’s,” said Katie.

“Jake said there are eggs in the fridge,” said another girl on the floor.

“Can you believe she put you on the spot like that?” asked Katie. “She’s such a—”

“How many eggs?” asked another girl.

“That’s the charm of the party,” said Daisy. “That’s the tradition, is Keats.”

“She’s a—”

“Three dozen,” said the first.

“Keats at random,” said Daisy. “She could’ve picked anybody.”

“Fucking bitch,” said Katie. “I went as a joke.”

“My mom made me go,” said Sarah. “Roth wrote me a letter of rec.”

Shocked, Daisy scanned the room, but they were all in agreement. These were the peo ple she had always pictured at Mrs. Roth’s funeral in a room filled with flameless candles,

Carolynn Mireault | You Have a Friend in Enosburg glassworks 47

delivering Dylan Thomas into a cordless microphone.

“What are you guys going to do?” she asked.

“Nothing major,” said Katie. “Egg the outside, baby powder the inside.”

“The inside?” asked Daisy. “You’re going to break in?”

“She left the spare in plain sight,” said someone else.

Between the faux dark maple cabi nets, on the door of the black fridge, was a set of four magnets: bright blue dolphins in different colored shirts and coordinating sunglasses, lined up an inch apart. The one in yellow had a flipper up, like he had a question about the plan. The one in red’s fluke was entirely missing, per haps pulled off by a child, or broken off when knocked to the floor.

“I should go home,” said Daisy.

“You’re not coming?” asked Katie. “She literally humiliated you tonight.”

“I have my sister’s truck,” said Daisy. “I have to get it back before she sees.”

The trees bent over the road, occasionally dropping snow onto her windshield, and she listened to These Are Special Times, Celine Dion’s Christmas album, and did not sing along.

“Or gazing on the new soft fallen mask of snow upon the mountains and moors,” she recited, “no—yet still steadfast, still unchangeable.”

She pulled into the driveway, which sloped down toward the poorly cleared walkway, and silenced Dion with the turn of a key. Hold ing her raincoat over her forearms, as if hanging it there, she went up to the door and knocked. Mrs. Roth answered, having just shooed away the last of the desperate parents and stared at her.

“You did not say goodnight,” said Mrs. Roth.

“Because I was coming back,” said Daisy.

“It’s late,” she said. “Everyone’s gone home.”

Daisy looked past her where a ta ble flowered with uneaten cupcakes.

“Can I come in for a few minutes?” asked Daisy.

Mrs. Roth kept a hand on the front door but said all right, and they went inside where the wine was warm from the fireplace and the kettle clamored on the burner.

“Would you like some tea?”

“Can I have wine?” asked Daisy.

“No,” said Mrs. Roth.

“Sure, I’ll have tea.”

“And another cupcake?” she asked.

“Sure,” said Daisy.

Mrs. Roth gestured to the table for Daisy to sit, and she did. Mrs. Roth peeled the liner off a cupcake and placed it on a crystal tea plate. She poured boiling water into a fine bone cup and brought it to her.

“Now, you can have whichev er kind you’d like,” said Mrs. Roth, glassworks 48

~

“but this is what I’m having.” She held up a wooden tea box filled with Belgian Mint and put it under Daisy’s nose. “Isn’t that delightful?”

“Hook me up,” said Daisy.

“Excuse me?”

“I’ll have that one, too,” she said.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Roth.

Mrs. Roth, who loved baking for others—chocolate cookies, apple pies, blackberry croissants—had not eaten anything herself in six days. More and more, she found herself needing to sit down, and her vision coming and going, and the skin split ting on her hands and lips. The thick wood dining table shifted in the heat by the woodstove and made horrible noises of carpentry.

the living room were fur blan kets over the backs of chairs, and a small mahogany cabinet— polished beyond reason—where inside she supposed was a ste reo or old television. She looked back down at the dining room floor, where her feet wormed in dirty socks. The blue carpet, still so badly installed, somehow appeared even worse than it had earlier at the Christmas party. She imagined it floured with baby powder.

“Well,” said Daisy.

She pictured it on everything: graying that gleaming mahoga ny, coating the windows, where yolks of eggs would burst on

”

Their teas steeped and they sat across from each other. Mrs. Roth was letting the woodstove die down and had turned off three of the flameless candles. Daisy noticed for the first time the black pendant light which came down over the table like a microphone.

“Would you like anything else?”

Daisy hesitated, turning her head to see the small living room with its blush carpets, a stark transition from the dining room’s blue ones. Also in

the other side. It would look like ashes on the carpets. It would look like cocaine on the kitchen counters. Mrs. Roth cocked her head.

“Well?”

“I know something about to night,” said Daisy, “and, just so you know, I have nothing to do with it.”

“What do you mean?” asked Mrs. Roth.

She looked back at the carpet

You Have a Friend in Enosburg

“ She pictured it on everything: graying that gleaming mahogany, coating the windows where yolks of eggs would burst on the other side.

Carolynn Mireault |

glassworks 49

where fibers shed like the beige one in her parents’ basement. It must have been brand new. Her hands went up under the box apron and she pinched the table as hard as she could.

“Daisy?”

“Okay,” she said, “so, they’re going to egg your house.”

“Who?” asked Mrs. Roth.

“And they’re going to come in,” said Daisy.

“Who is?”

“And they’re gonna baby powder the inside,” she said. “All of this.”

“Who?” Mrs. Roth asked again.

“Everybody,” said Daisy.

“Who’s everybody?”

“Everybody, I don’t know,” said Daisy. “Everyone who was at the party.”

“The people who were here?” asked Mrs. Roth, pointing down at the dining table like it stood for her whole home and everyone she knew.

Daisy nodded, took her tea by the tag, and dunked it repeatedly into the fine bone cup. Mrs. Roth sat up straighter.

“Thank you,” she said.

“Should we call the police?” asked Daisy.

“Would you like to bake some thing?” asked Mrs. Roth.

“What?”

Mrs. Roth stood and went to the woodstove, which she opened and added short logs with a bare hand. She blew on the flames then closed the iron door.

“Would you like to bake a pie?”

Mrs. Roth zested two lemons into a blue glass bowl. She rolled them on the counter, pushing her weight into them, sliced them down the middle and juiced them. She juiced four more then added that to salt and sugar in a saucepan. Next came cornstarch—“more than usual for the sake of time and texture”— and the whipping of a whisk. She separated five eggs, passing the yolks back and forth in their shells. She put the saucepan on a burner and kept stirring to thicken. Lightheaded, the room came and went, and she took hold of the countertop.

“Daisy,” she said, “will you con tinue stirring?”

Daisy went to the stovetop to keep whisking while Mrs. Roth got in a dining chair and took a few breaths. Her eyes closed and opened again.

“Am I doing it right?” asked Daisy. “Kind of fast, right?”

“Thank you,” said Mrs. Roth.

After a few minutes, Mrs. Roth rose and leaned over the counter to instruct Daisy.

“You want to add it slowly to the eggs,” she said. “To the yolks, carefully.”

Daisy brought the saucepan to the yolks and added some of the lemon mixture.

“Slowly,” she said. “Whisk as you go.”

“This is hard,” said Daisy.

“Yes,” said Mrs. Roth. “This is glassworks 50

~

a very difficult pie.”

Under instruction, Daisy put the whole blend back in the saucepan, on heat, and continued stirring.

“Now the butter,” said Mrs. Roth, “and take it off the heat.”

She had pre-baked a homemade butter crust the day prior, which was set in a glass pie dish. Daisy folded the mixture into the crust.

“You’re supposed to refrigerate that for quite a few hours,” said Mrs. Roth, “preferably overnight. But I won’t tell if you won’t.”

“What do we do?”

“Freezer,” said Mrs. Roth, “and we’ll do the meringue.”

~

“

Daisy went upstairs to the only bathroom, which was mostly taken up by a chicken-colored clawfoot tub. A sheer vinyl shower curtain wrapped around it on a metal track. Daisy, who had never been vaccinat ed, recalled the mass of her broth er’s body and head coming from her mother’s thighs in a bathtub just like this one.

As she washed her hands, she no ticed Mrs. Roth’s eyeliner pencil on

the sink beside the bar of soap. Carefully, she picked it up and, in Mrs. Roth’s bathroom mirror, applied it to her lower waterline, smudging it at the corners.

She went downstairs and, in the kitchen, Mrs. Roth had the egg whites and cream of tar tar turning slowly in an electric mixer. Sugar and water heated on the stovetop.

“You want to start slow,” she said.

The whites were frothing, so she added sugar and increased the mixer’s speed. She brought the saucepan over and slowly drizzled in the sugar water, then vanilla extract.

“And let it cool,” she said. She took the pie out of the freezer. “What’s the time?”

“About twelve,” said Daisy. “About midnight.”

“Do you mind getting some dishes?” she asked, spooning the meringue on top of the pie. “Cabinet next to the sink. Make sure they match, please.”

Daisy pulled down a set of pink, clanking plates. Mrs. Roth used a small cooking torch to brown the peaks of meringue.

“It didn’t weep,” she said. “Nice job.”

They brought their slices to the dining table and sat side by side facing the windows. Mrs. Roth turned out the lights, “so they’ll think I’m sleeping,”

Carolynn Mireault

a Friend in Enosburg

Then they came like rain, smashing and bleeding chalazae on the windows. ”

| You Have

glassworks 51

and left only a handful of flameless candles lit, by which to eat. The first egg was loud, and Daisy jumped, then watched the yolk run down the pane in a sequence of shell frag ments. Then they came like rain, smashing and bleeding chalazae on the windows. Mrs. Roth took a bite—her first in six days—of that rushed, yellow pie, and thought how wonderful it was to have company for dinner.

glassworks 52

so Maybe I’M The leaky roof Despy Boutris

of this apartment, always inviting in what ruins. Maybe I’m water, what threatens to drown us all.

I might be a moonless night— no light, invisible stars. Lately, my skin puckers at any touch:

a raindrop pearling my jaw, or a hand on the nape of my neck.

Maybe I’m meant to be a cicada, always keening into the uncaring air. Maybe it’s time I turn into the lake glistening golden. Maybe I need to learn to bear this life: the local news, hands fisting hair, breath shuddering out like sin.

Maybe I’m that mountain of fog, wanting to swallow everything. Underfoot, the crack of gravel,

a fallen receipt. Maybe I’m the mutt racing through the grass. Maybe I’m the twig caught in its craw.

glassworks 53

bIrD M. D. Berkman

Fishing the gulf at five am, empty pint of bourbon bobbing beside me, my gut half full of plastic already, eyes crusty, scaling up scales, sorting out sheens, hooks rusty, old lines unravelling, old chest unruffling sharp-beaked waders ready for me to fail, only the sun more insistent, only the night less willing to let go.

olD

glassworks 54

anoTher Moon PoeM

E.B. Schnepp

for L.

I’m reminded of Li Bai reaching into the deep end of a pool for a reflected moon, drunk on rice wine or constellations or his own desire. He was so sure she came down just for him, but it was a trap, a trick, or honest mistake [I can’t remember the difference between murder and manslaughter and the other one, their varied degrees]. She drowned him and looked so lovely the world simply stared at her, complimented her evening gown and dimples and no one noticed he’d passed for a year. There’s a precedent in Greece or maybe Rome where death row women show their breasts to the judge, the jury, the executioner all pardon and proclaim how could someone so lovely commit such a crime? I haven’t decided, yet, how I want her to do it, to murder me, which lake I want to be in when I watch the moon fall only for me—I long for the anonymity of an ocean, flirt with the notion of being Jonah and swallowed by something so impossibly large. We would follow the moon, her tides, I and my host, singing off key, to the tune of wolves instead of whales and we would be lonely together, hungry together, moon worshipping. Like this I could become myth with Li Bai and the moon, another of her harem desperate enough to drown.

glassworks 55

Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad

Oormila Vijayakrishnan Prahlad

sea anD sluMberInG lanD

glassworks 56

(enGIneerInG) error

Jodi Scott Elliott

We calculate new lives for our selves in his car, rewriting old equa tions and solving for possibility. Together it seems we can engineer any aspiration, and the sprawling city echos our ambitions with her own promises. It’s magic. Headlights, taillights, and the neon sign hanging in the doughnut shop window glit ter like stars in the night. When he’s driving, there’s even glamour in the gutters and the sidewalks and the auto shops. And for the first time since I moved down here, I finally understand the charisma of all these palm trees.

And yet, this abundance of palm trees lining so many boulevards, conjuring a tropical oasis, do not normally thrive in such an arid climate. No. The trees require more water in the soil. Water not naturally found anywhere near Los Angeles. Water self-taught civil-engineer William Mulholland had to find in Owens Valley 233 miles away. Water William Mulholland siphoned through the Los Angeles Aqueduct at 5,311 gallons per second. And if Mulholland hadn’t, the city wouldn’t be the recognizable inspiration we pass by from neighborhood to neighborhood.

These long tours of the city only have one catalyst, his phone call to me—but not mine to him.

And I never know what time or day or with what unknown variables he’ll call, so I abandon my last pack of cigarettes. I cannot discourage the compression of his lips to mine.

I also forgo lacy or silky underwear. He doesn’t like the idea that I might be willing before he’s had a chance to convince me, so I wear cotton girlie panties, something so whole some it feels like they’re not sup posed to be seen by anyone but my mother. Those are what excite him.

When William Mulholland first turned the valve for the aqueduct, he told Los Angeles residents, “There it is. Take it.” And so they did. Rows and rows of thirsty little orange saplings shot up from the ground and grew into an army of capitalist soldiers. Los Angeles swelled with miles of asphalt, lush lawns, kid ney shaped pools, studio lots, and celebrities. All the while Owens Lake shrank and shriveled and puckered into mud and then turned into dust.

I don’t pull my hand away from his when he shifts into reverse or back into drive. My knuckles turn erogenous under the friction of his thumb, as he figure-eights around their tiny peaks. I don’t tell him this. It’s my innocence he finds sexy. He wants to be the one to sully it. It’s no fun to sully something already dirty.

glassworks 57

Yes, William Mulholland brought water to the desert and transformed the landscape into a metropolis, but the city wasn’t about to use all that water all at once. No. Though residents still wanted it waiting and ready. They didn’t want to have to think about water until the mo ment they found themselves thirsty. So Mulholland started building the concrete walls of St. Francis Dam, modestly at first, but then he was always susceptible to ambition. He

Wherever they’re going is always more important than where we’re going. But to be honest, I’m a little afraid to get to where we’re headed. I suspect it’s not somewhere I actually want to be.

St. Francis Dam complained with loud, ominous creaking. Small fissures and leaks had the operator concerned, but William Mulholland found nothing wrong at his inspec tion. Twelve hours later, the reser voir collapsed. Twelve billion gallons

”

raised the walls higher to hold more water but not any wider for the ad ditional pressure of all that weight. And then he went and raised them again even higher.

of water rushed the fifty-four miles to the Pacific Ocean and claimed 431 lives along its way. An inquest concluded that the failure resulted from an error in judgement.