PL AY! THE GAME CHANGING ISSUE #54

FEATURES 4 On My Mind 8 What’s New? 12 Bookshelf 14 Interview 22 Theme Text PORTFOLIOS 33 Rosana Paulino 49 Leonard Suryajaya 59 Kalev Erickson 73 Ivan Mikhailov 97 Lorenzo Vitturi 113 Alice Quaresma 125 David Fathi 137 Kay Kasparhauser 161 Mickalene Thomas 177 Charlie Engman & Hillary Taymour 189 Camila Falquez 201 Sheida Soleimani 225 Jimmy DeSana 239 Jos Houweling 249 Rolph Gobits 257 Pelle Cass 265 Sportification 289 Martine Syms 33 59 73 225 249 49 125 177 239 201 113 257 189 97 137 161 265 289

Play is one of the founding pillars that allows us to discover the world. To play is to learn how things work, how we behave, interact and how we can solve problems. It fuels our scientific thirst for experimenting, the enchantment towards the magic of discovery and the frustration of failure. It is also crucial to inform how we perceive and experience reality, and how we create a new, alternative one we might be able to control. Play investigates the powers at play in our society and its subversive, irreverent potential. It looks at its healing powers, the relief that comes from unlocking energy, creativity, and unexpected ghosts.

PL AY ! PLA y ! P L AY! PL AY! P LA y !

FEATURES

PLAYFUL APPROPRIATION AND THE ARCHIVE

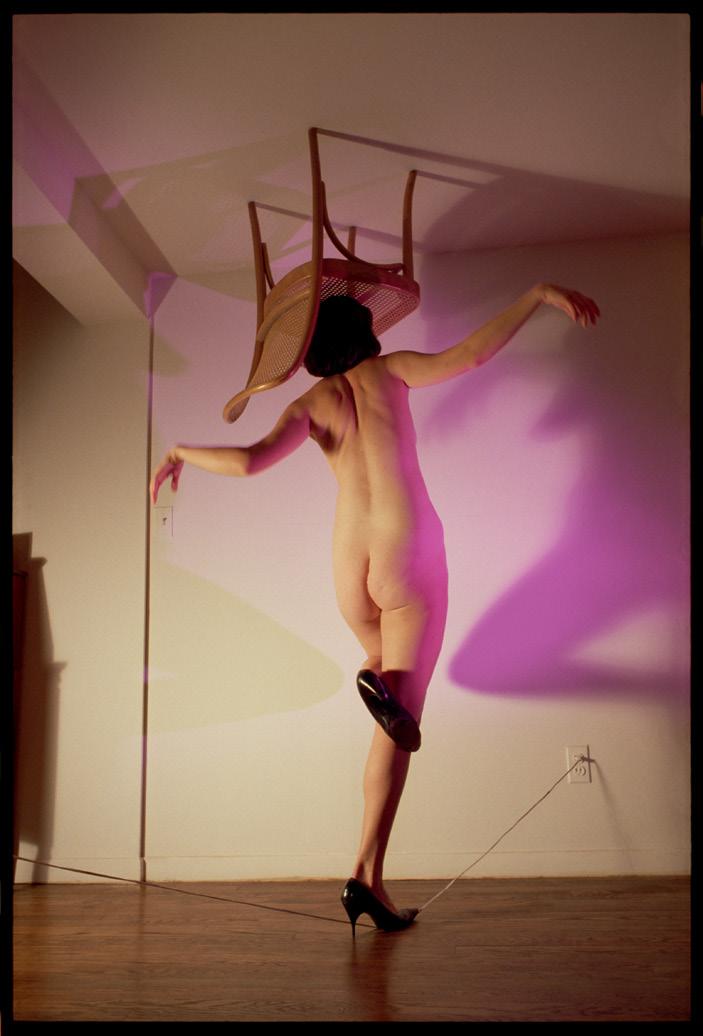

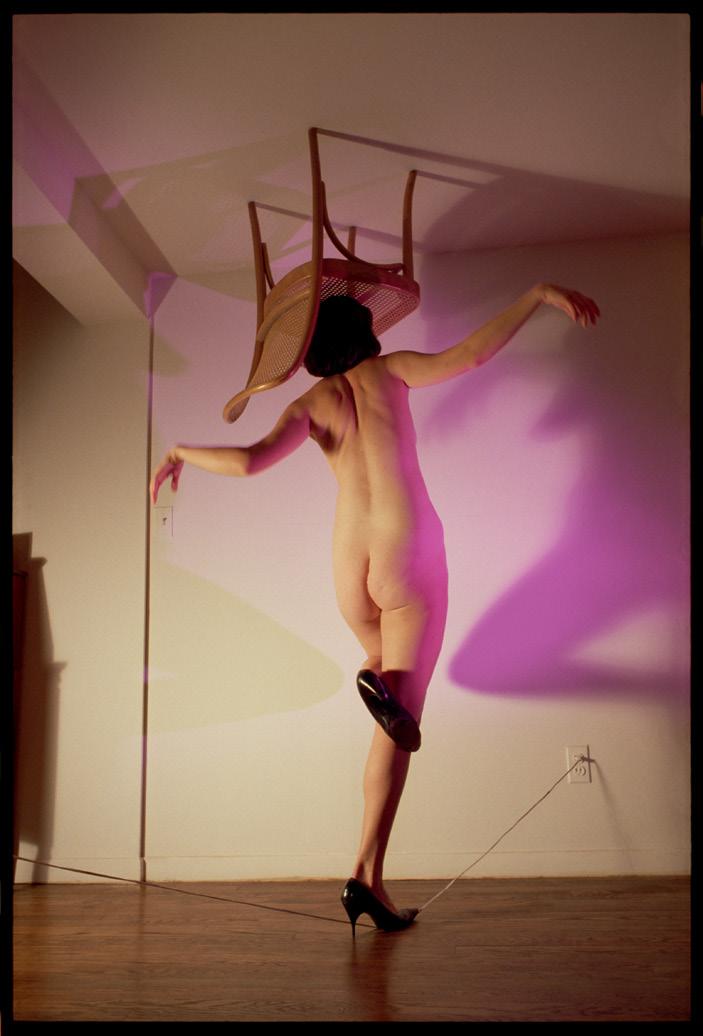

JIMMY DESANA

ON MY MIND

Mavis Staples Fiona Tan Deborah Willis Glenn Ligon

WHAT’S NEW

Laura El-Tantawy Mariam Medvedeva BOOKSHELF of Hans Gremmen

INTERVIEW

with William Kentridge by Dana Linssen PLAY!

THEME TEXT by Elisa Medde ROSANA PAULINO

Text by Alecsandra Matias de Oliveira

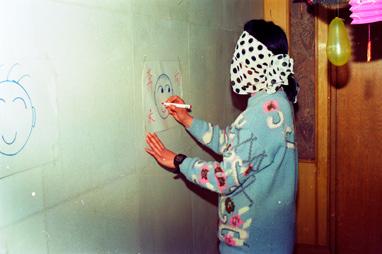

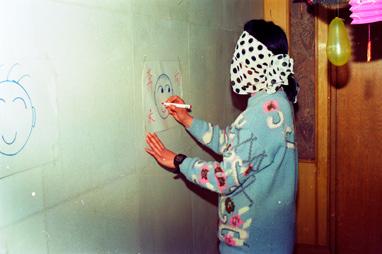

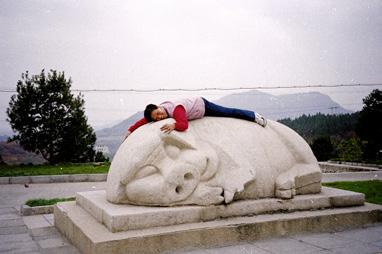

LEONARD SURYAJAYA

Text by Efrem Zelony-Mindell

KALEV ERICKSON

Text by Timothy Prus

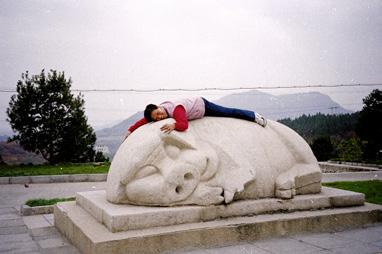

IVAN MIKHAILOV

Text by Anastasiia Fedorova

PLAYING THE SYSTEM

Text by Ben Burbridge

Text by Mariama Attah LORENZO VITTURI

Text by Kim Knoppers

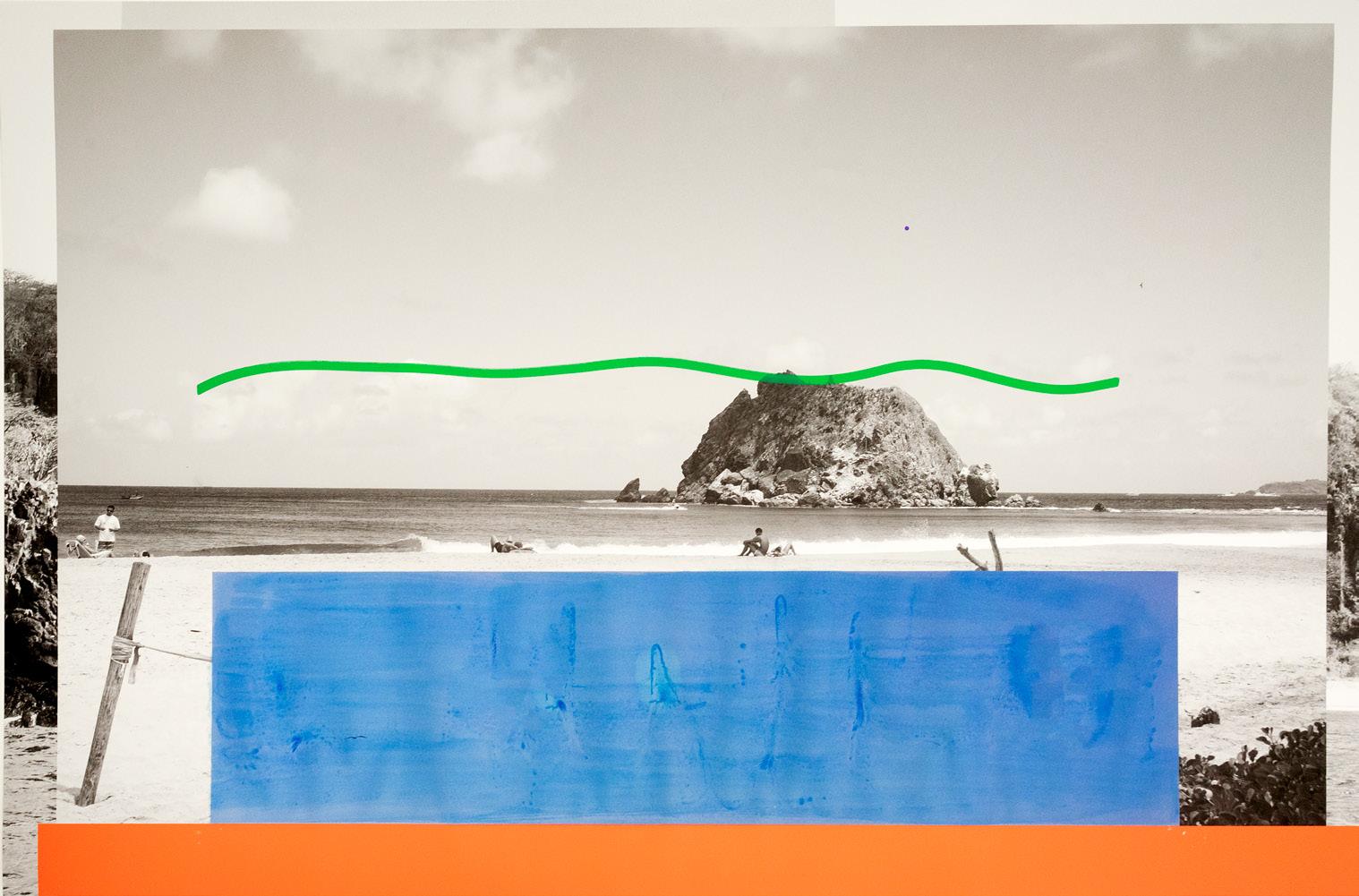

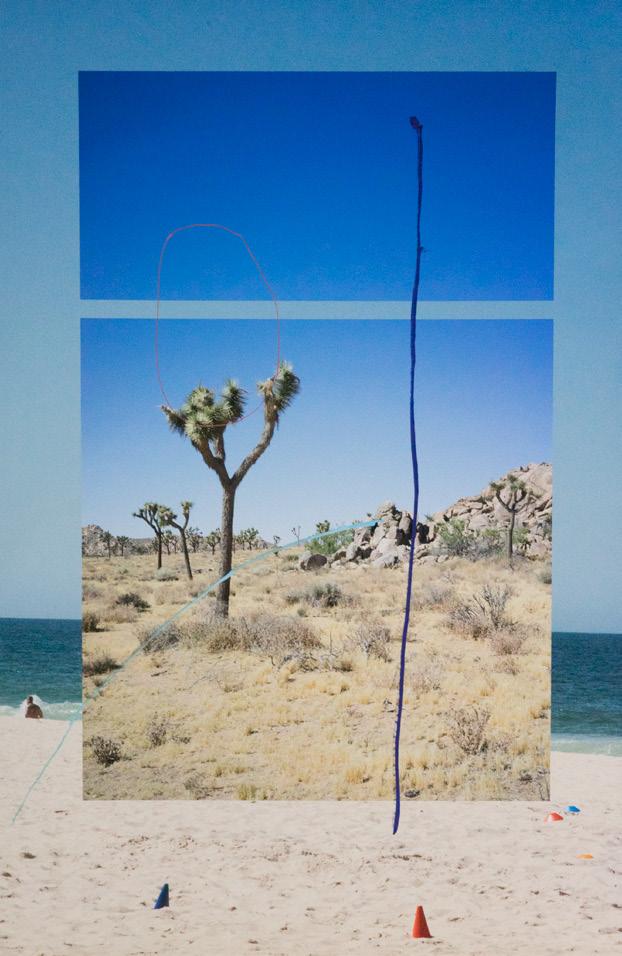

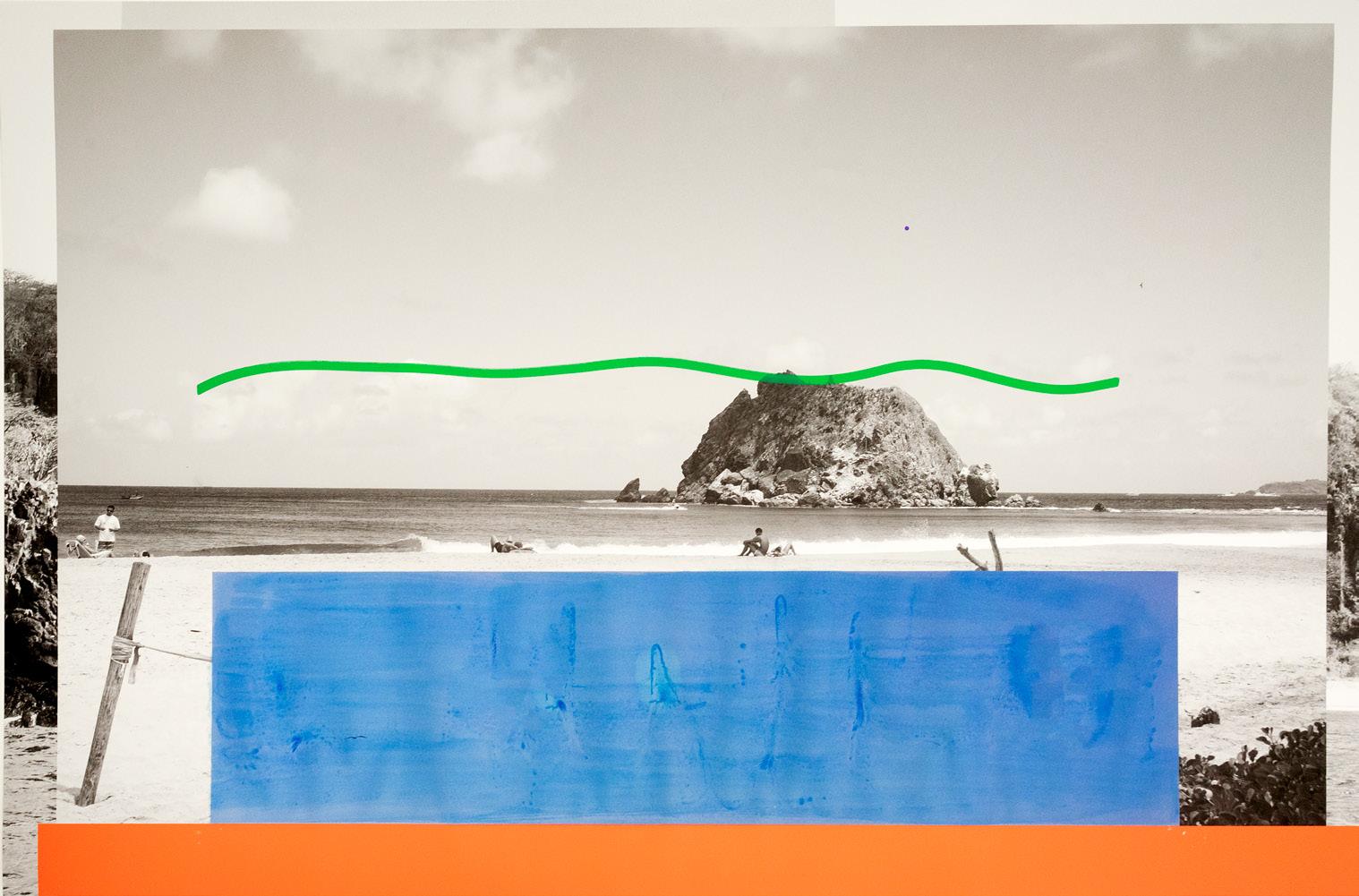

ALICE QUARESMA

Text by Cat Lachowskyj

DAVID FATHI

Text by Lewis Bush

KAY KASPARHAUSER

Text by Carly Mark HOMO LUDENS

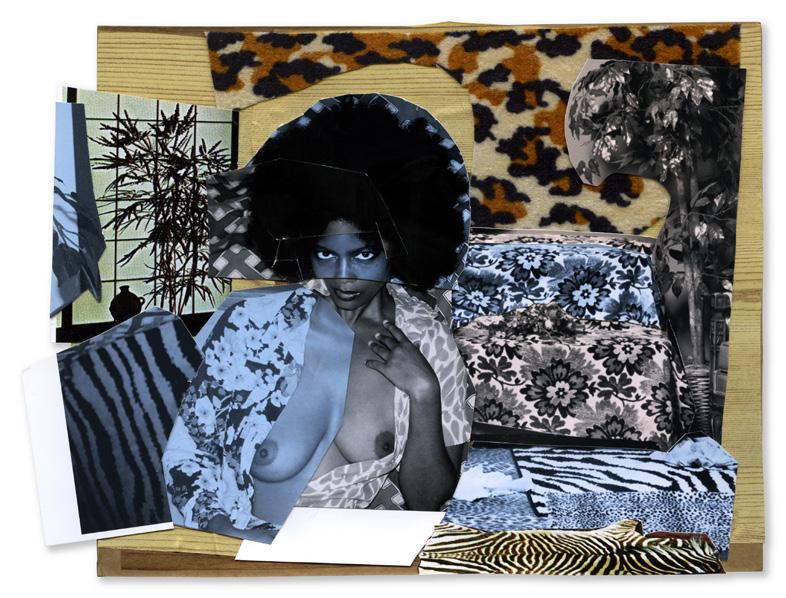

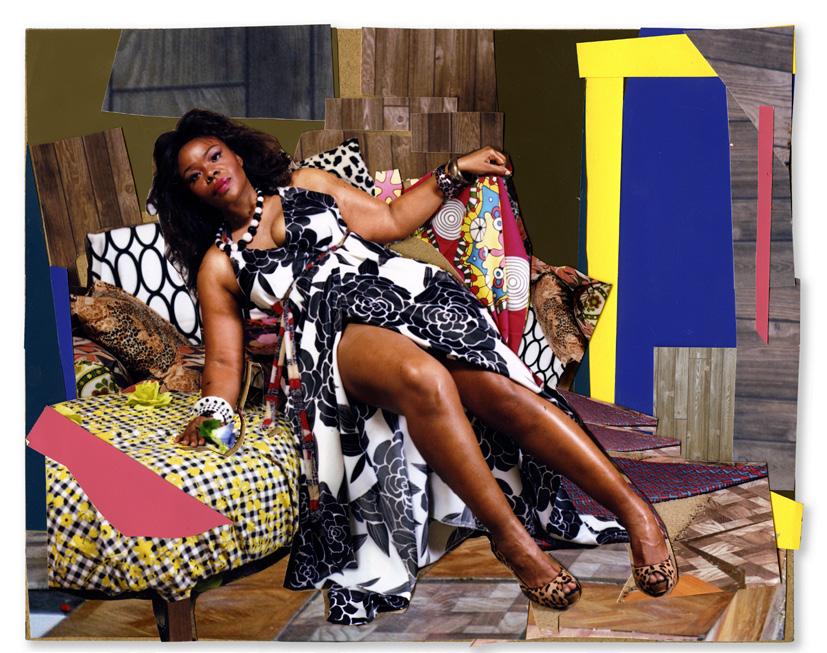

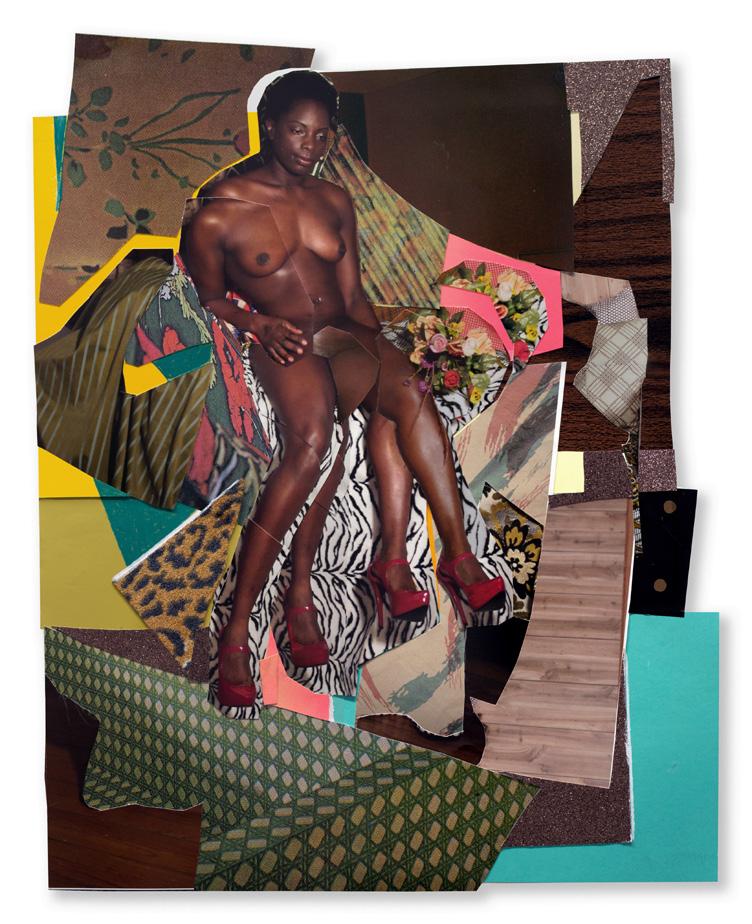

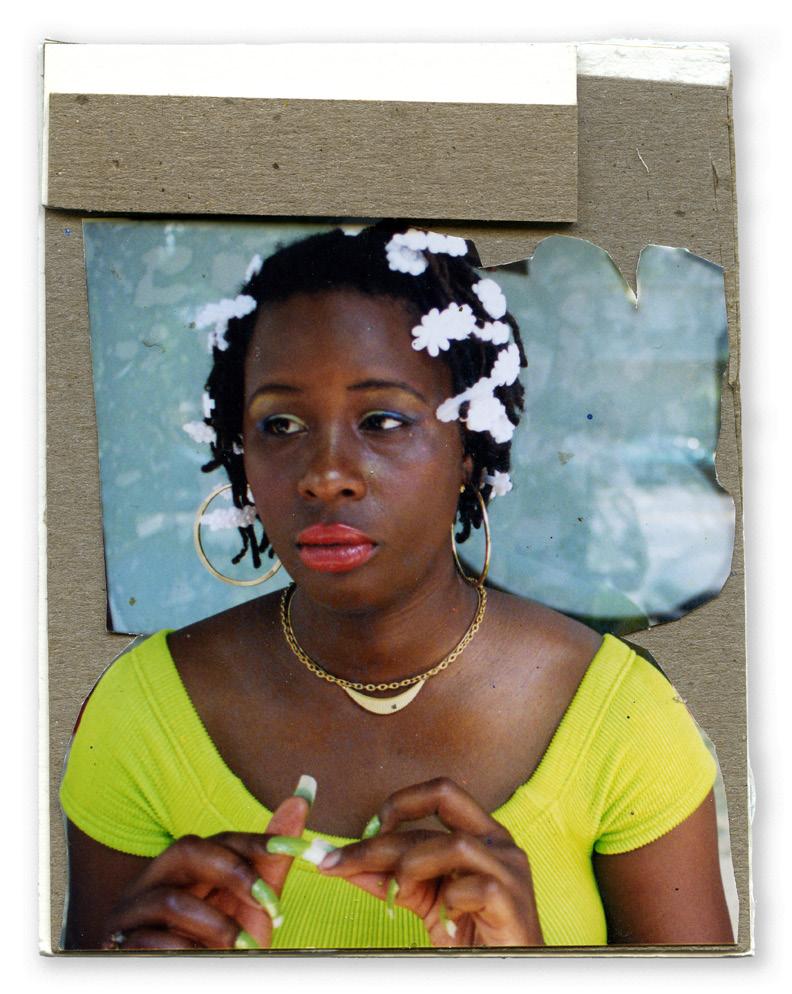

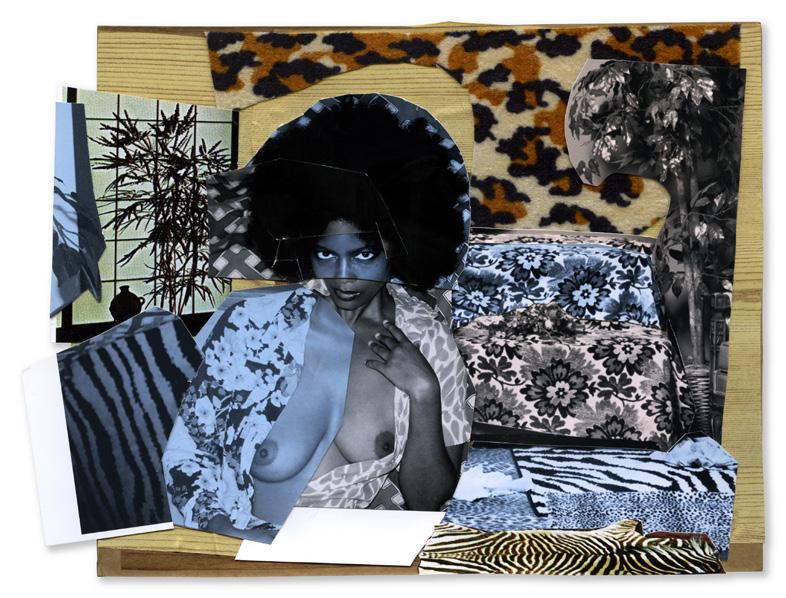

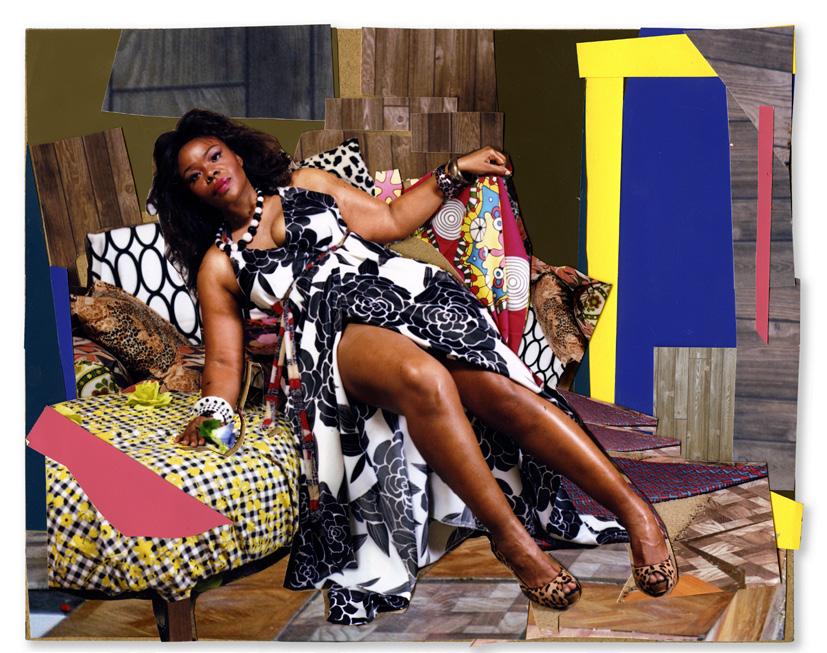

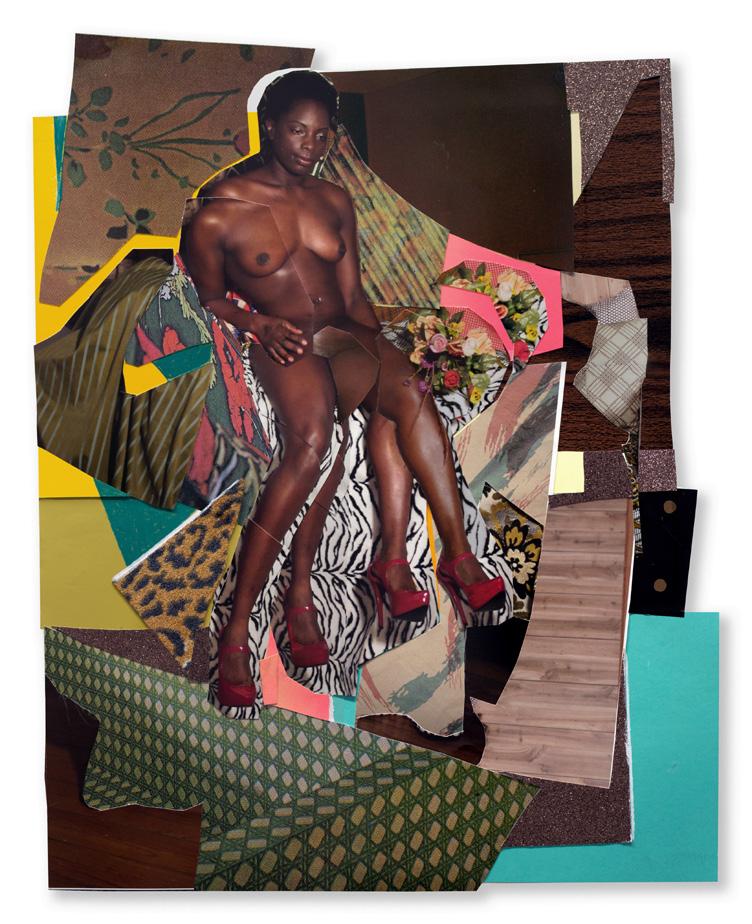

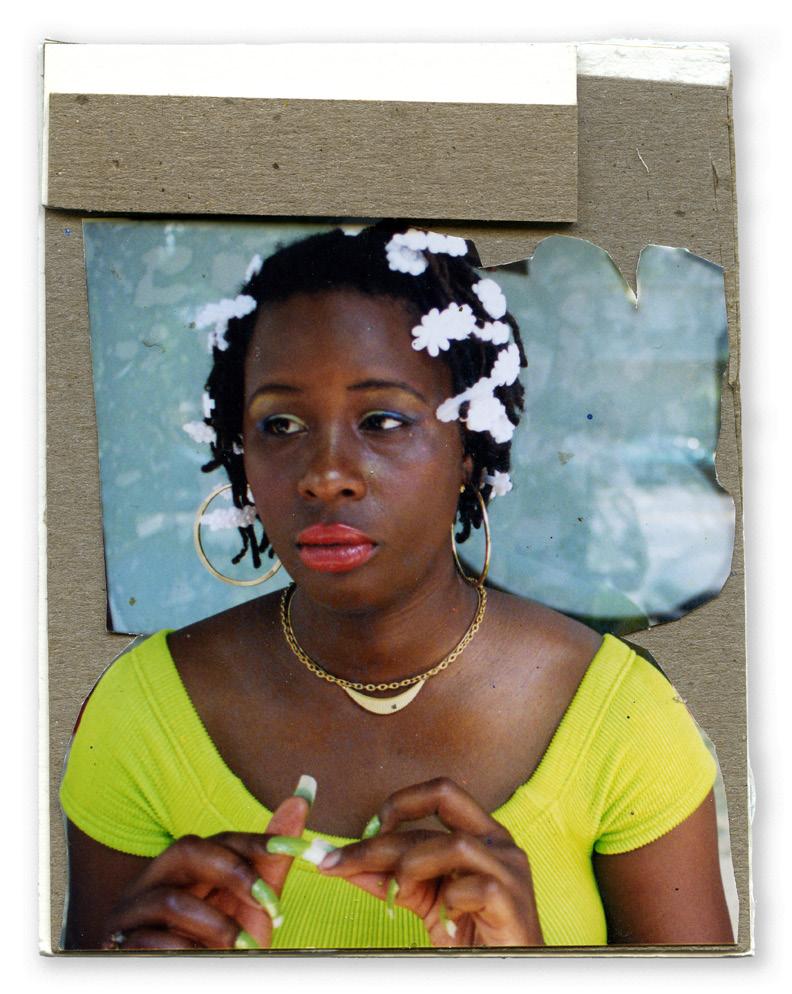

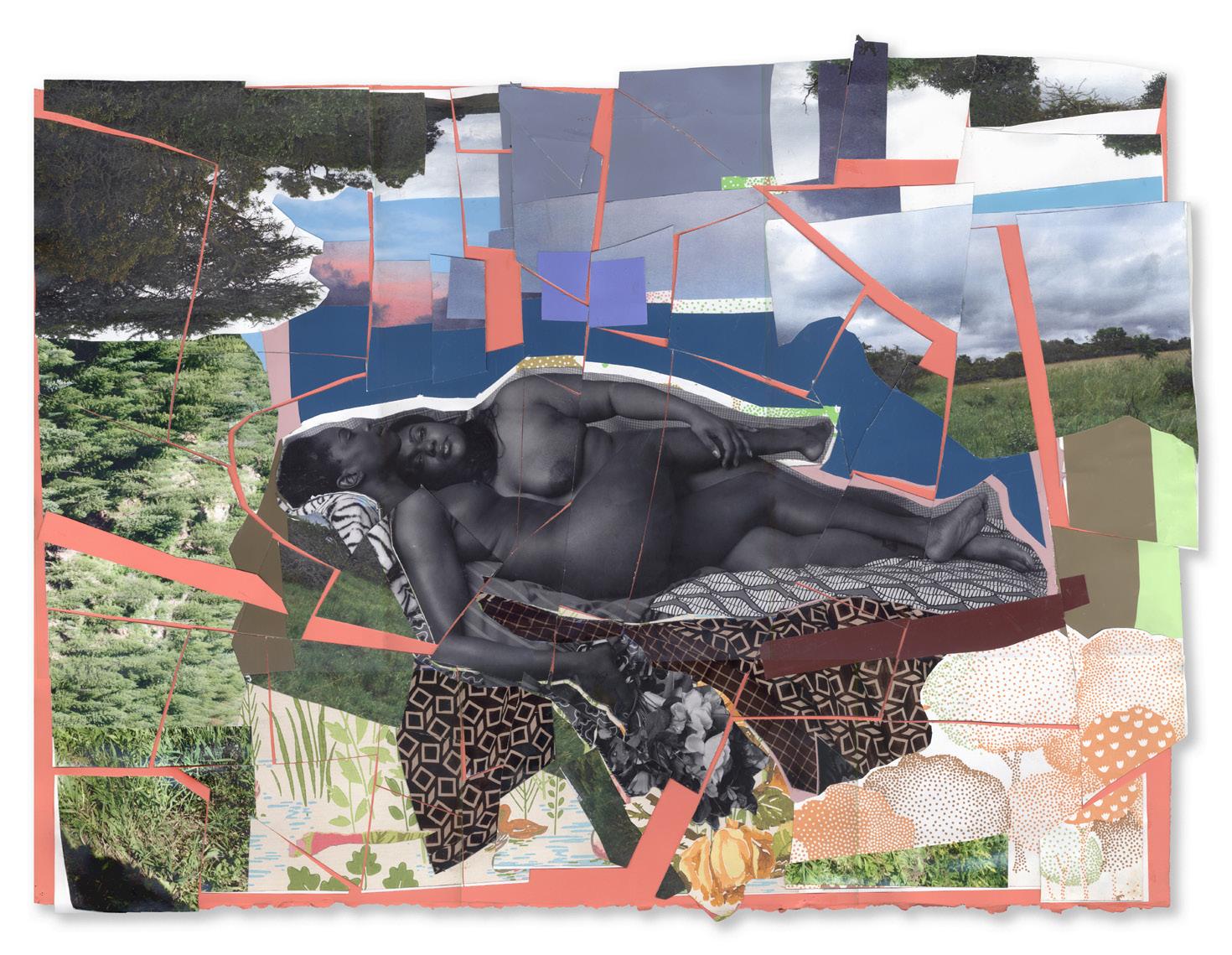

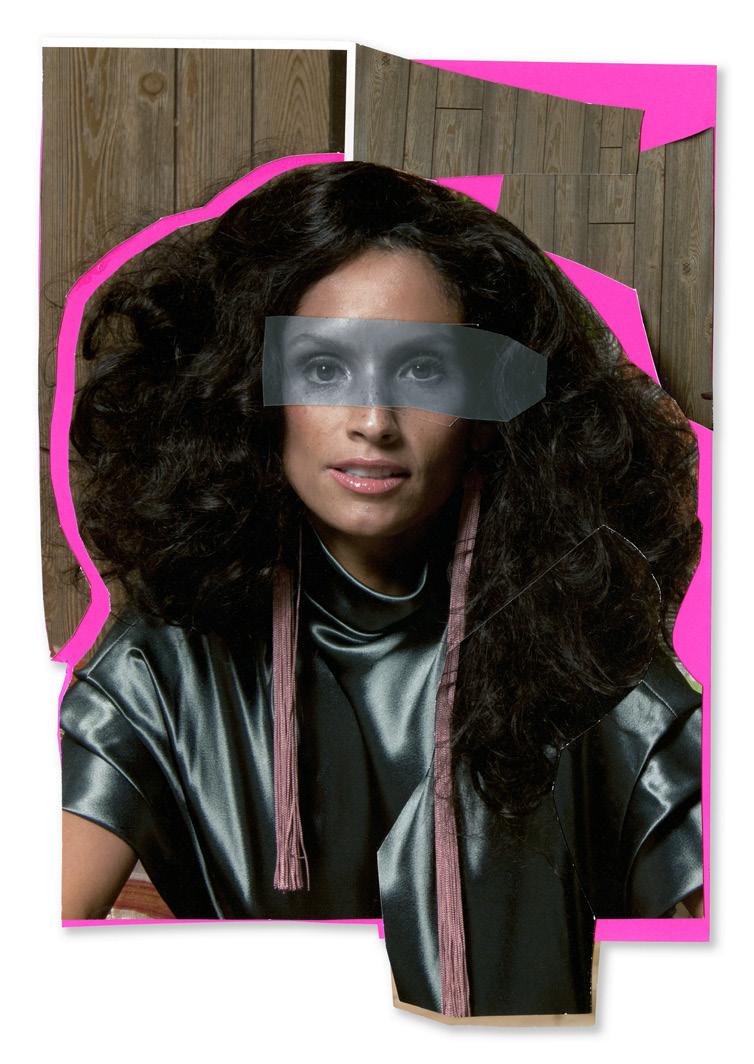

Text by Hinde Haest MICKALENE THOMAS

Text by Salamishah Tillet

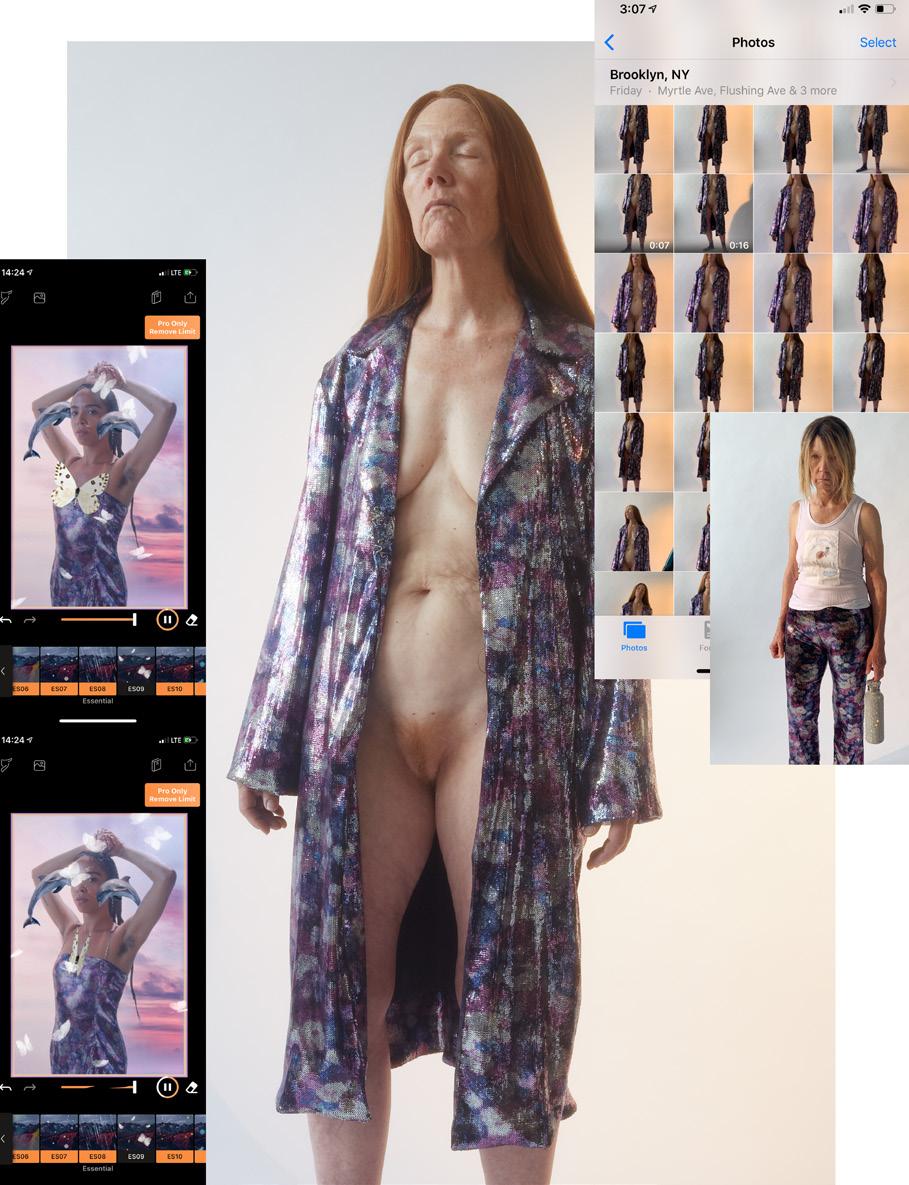

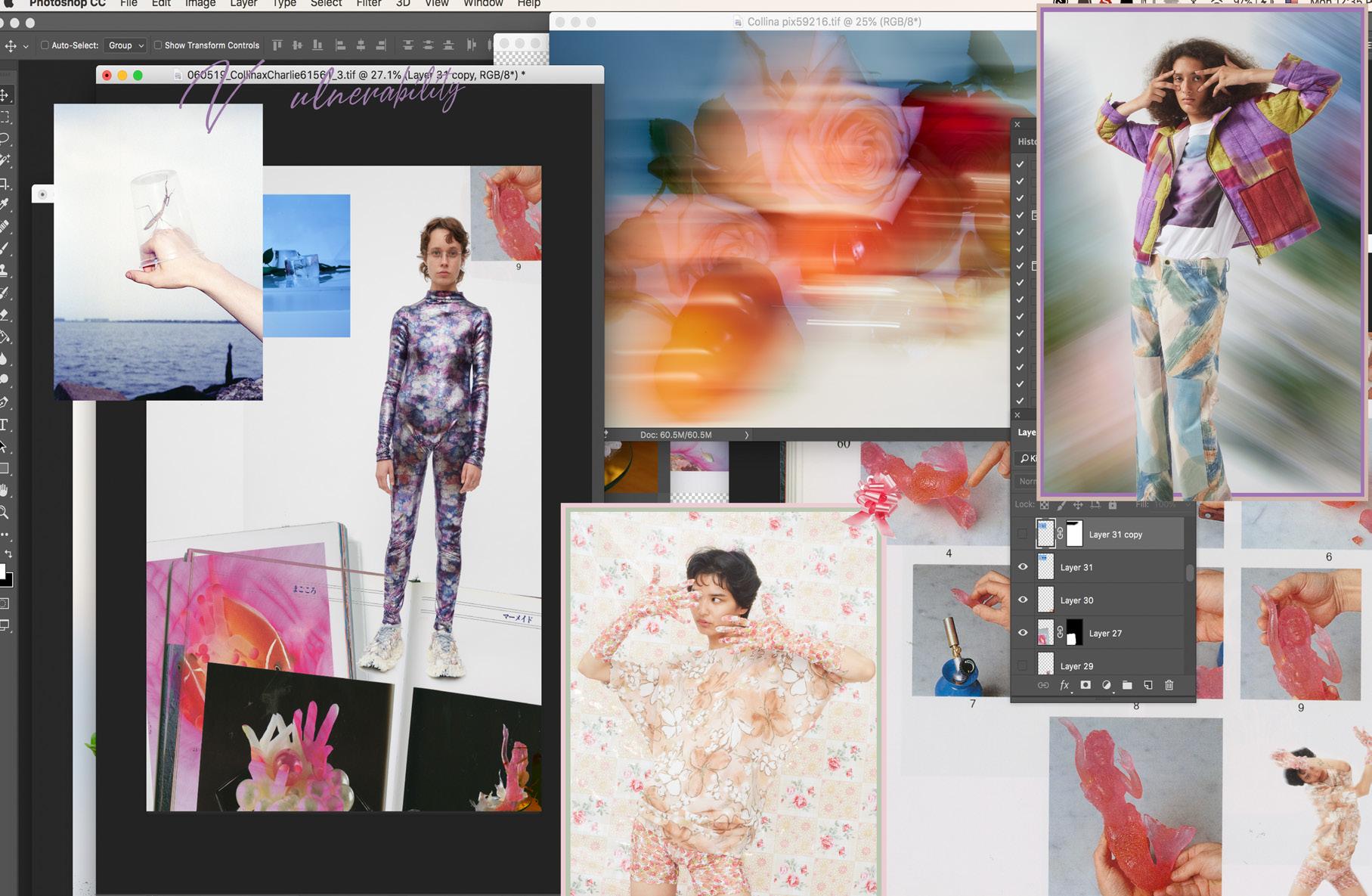

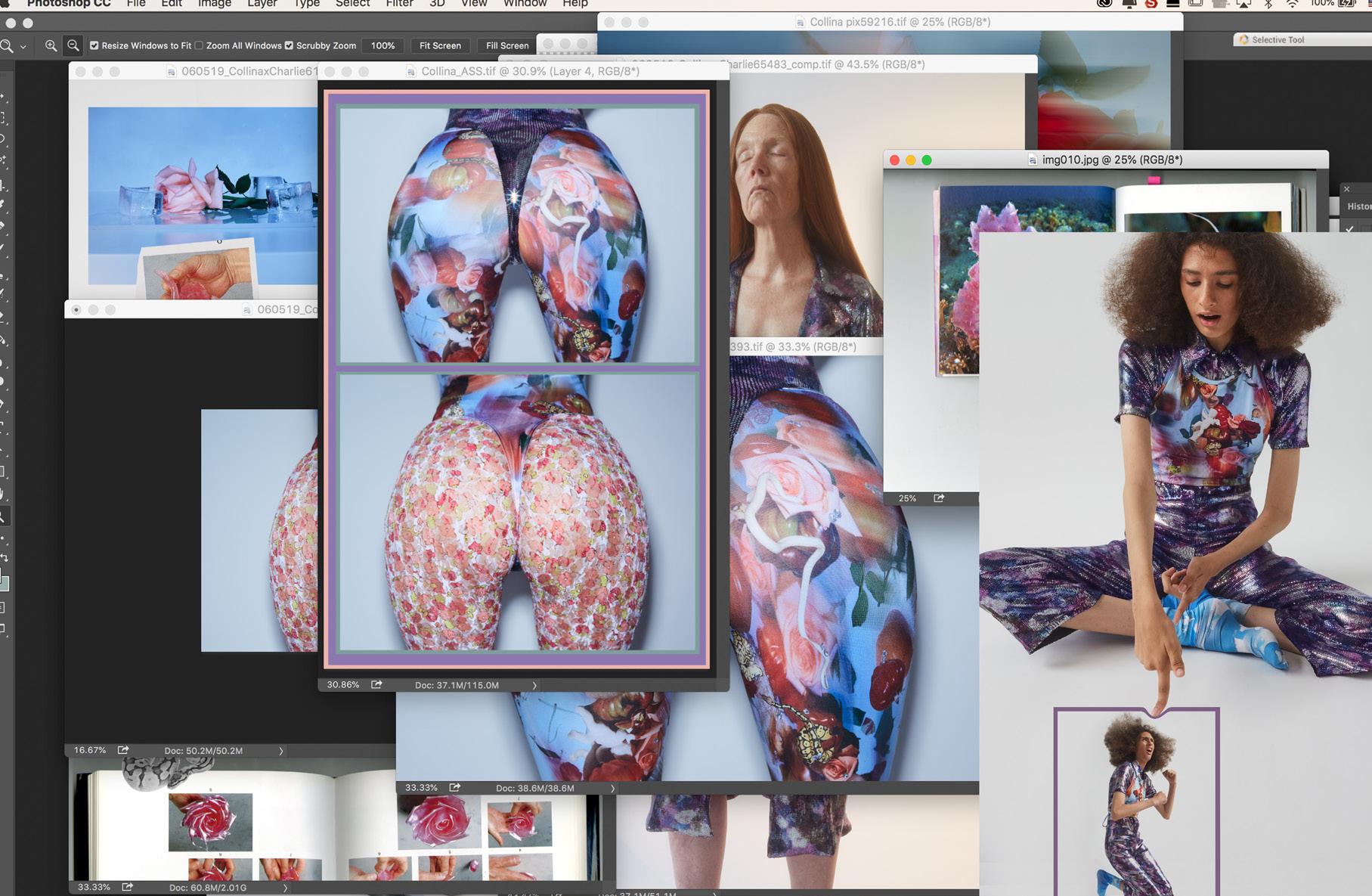

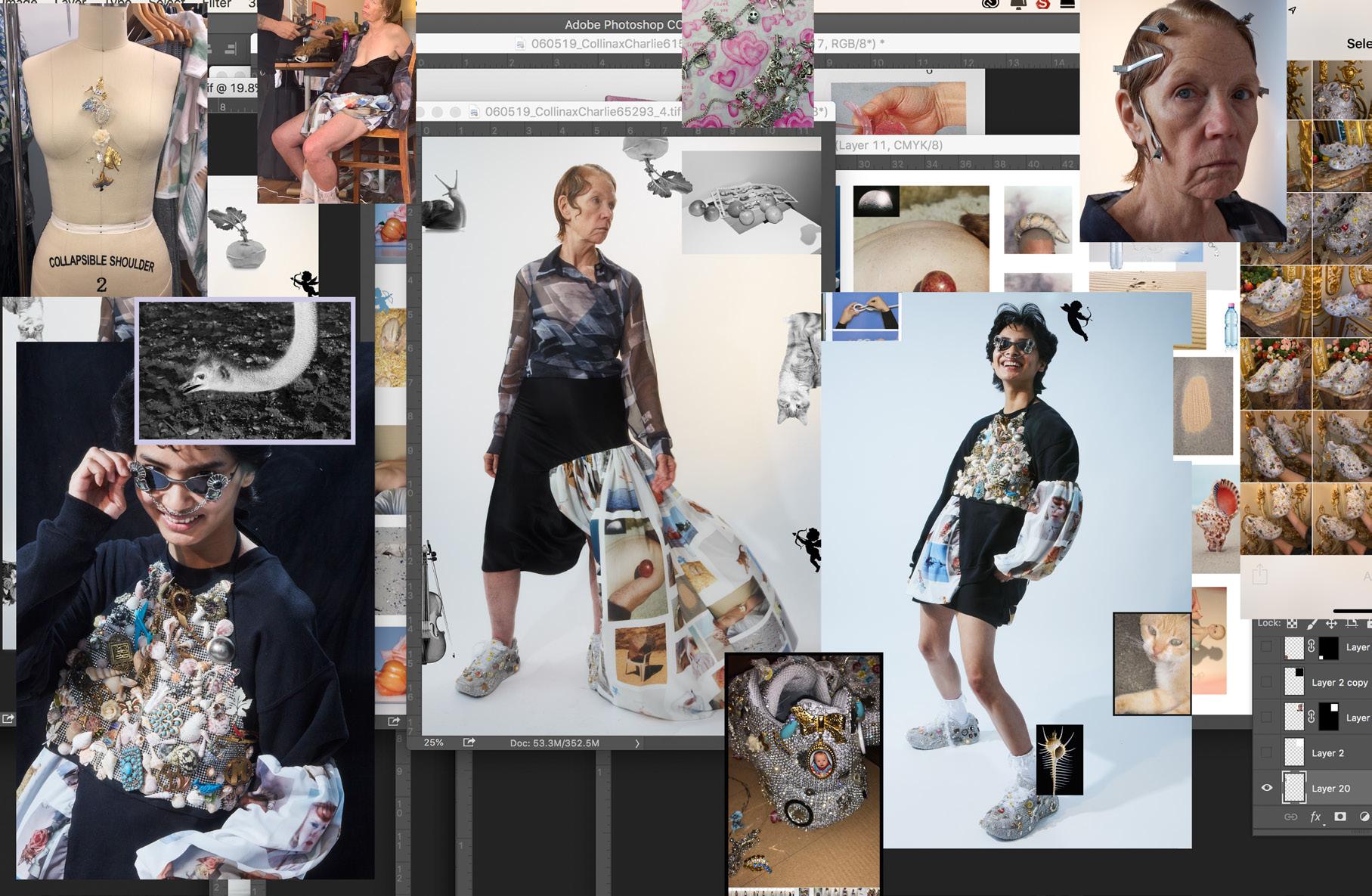

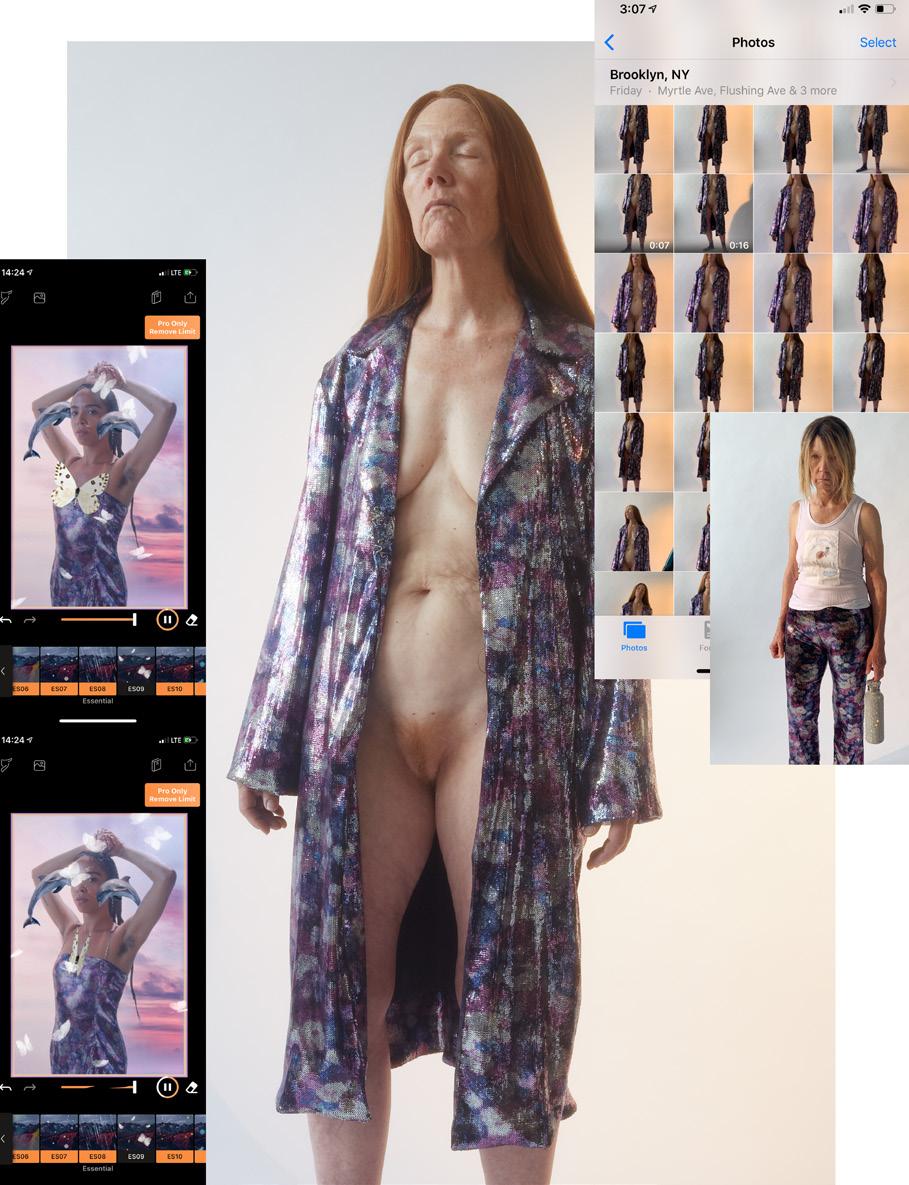

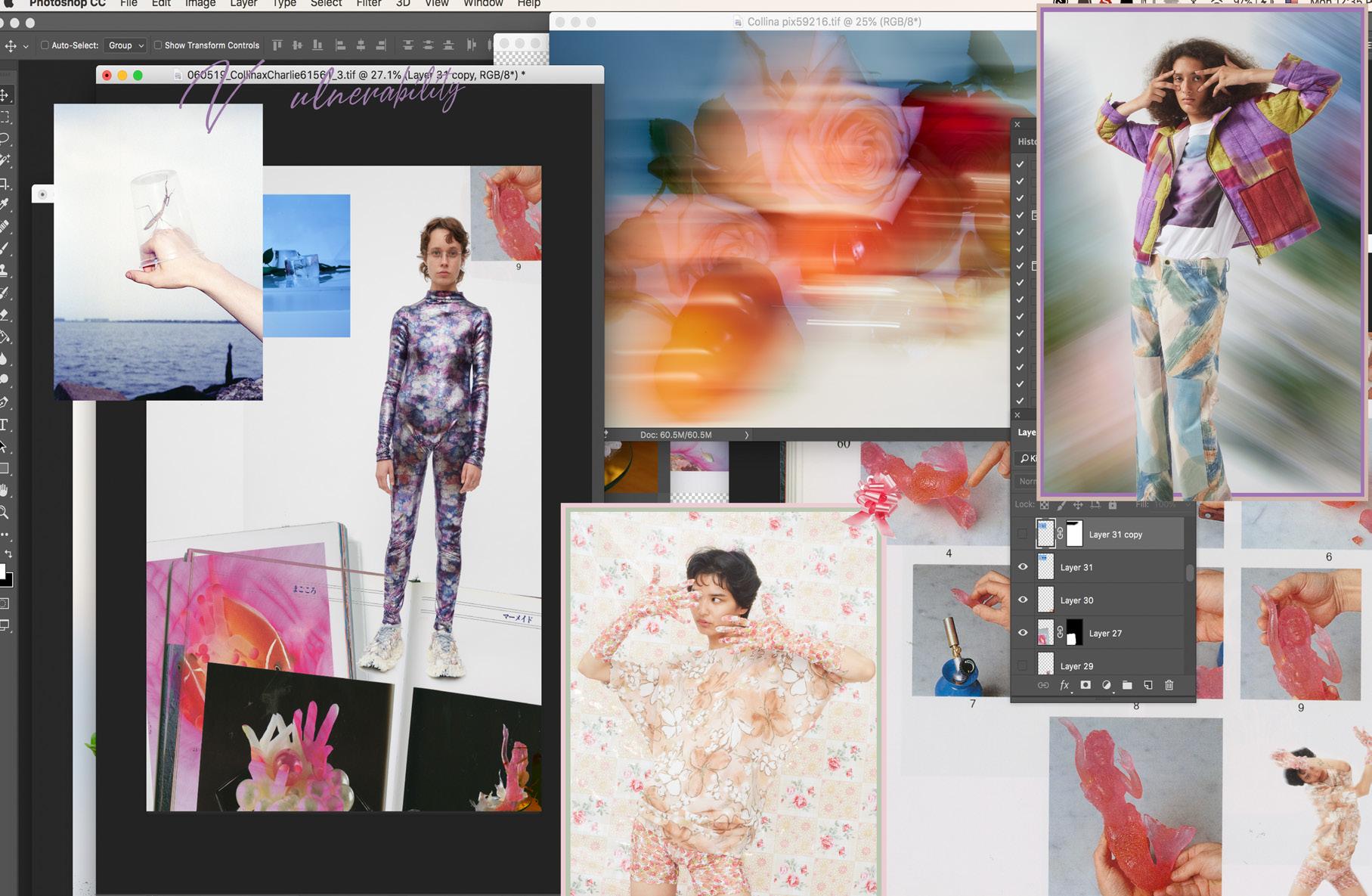

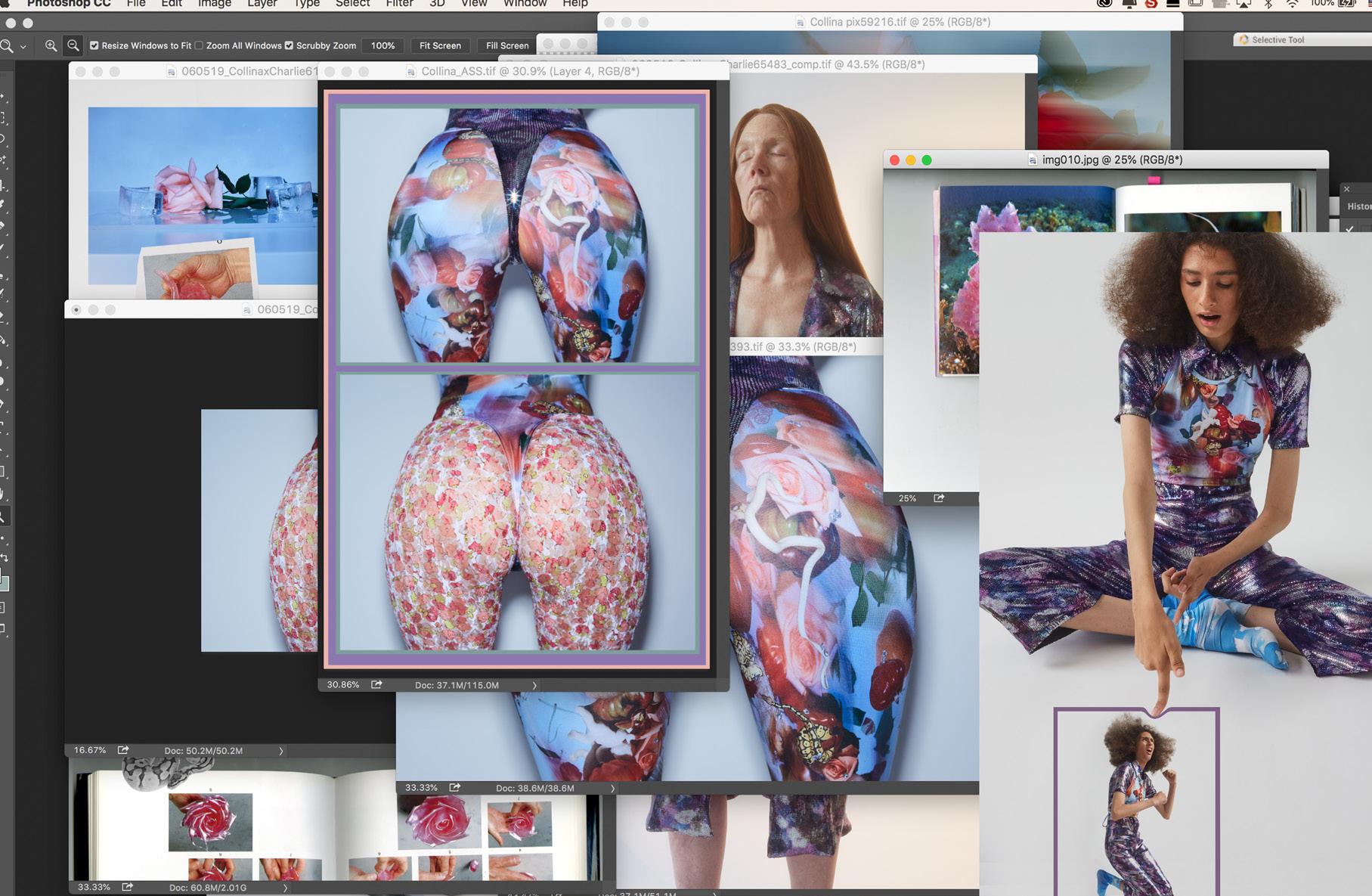

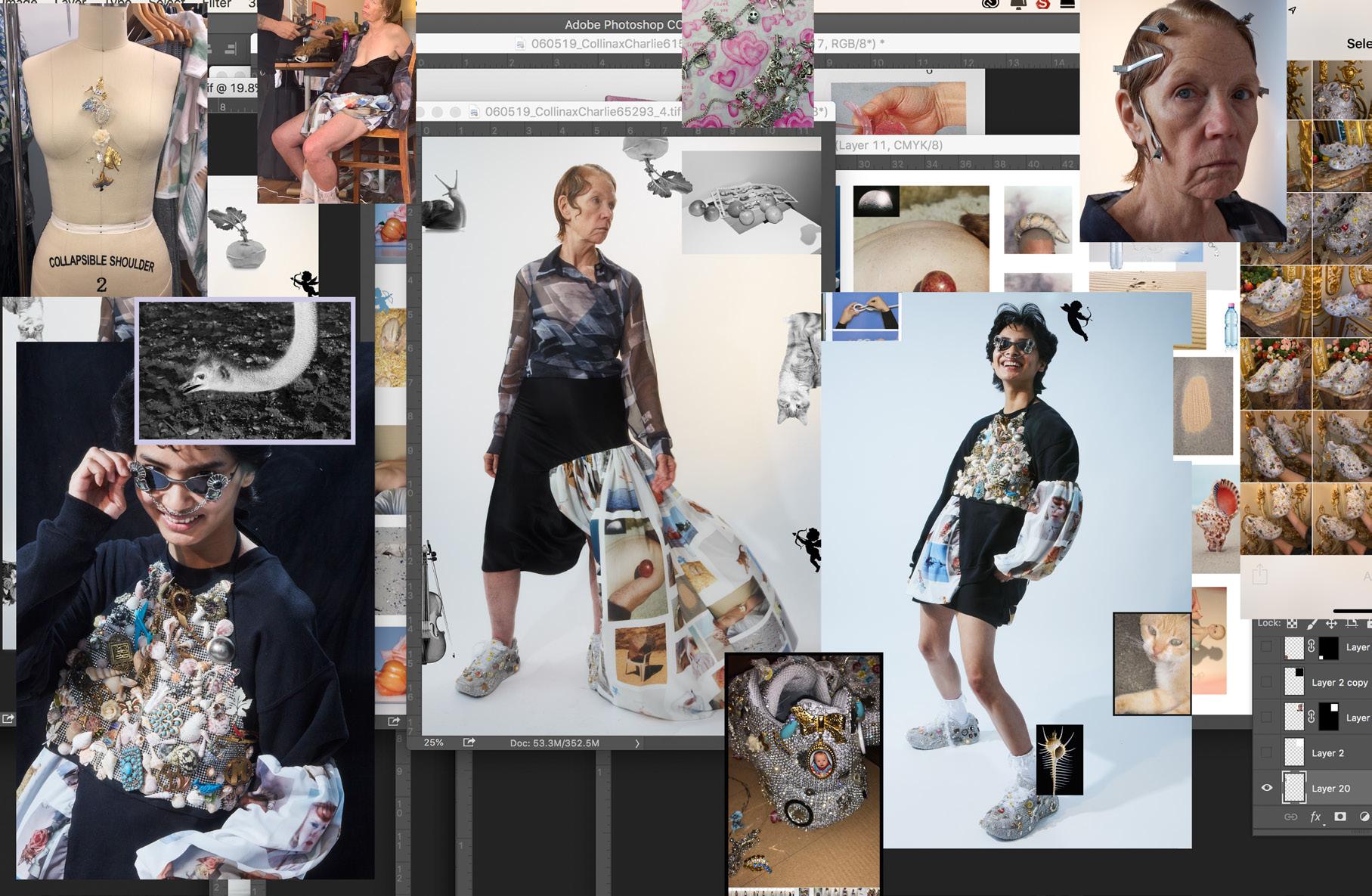

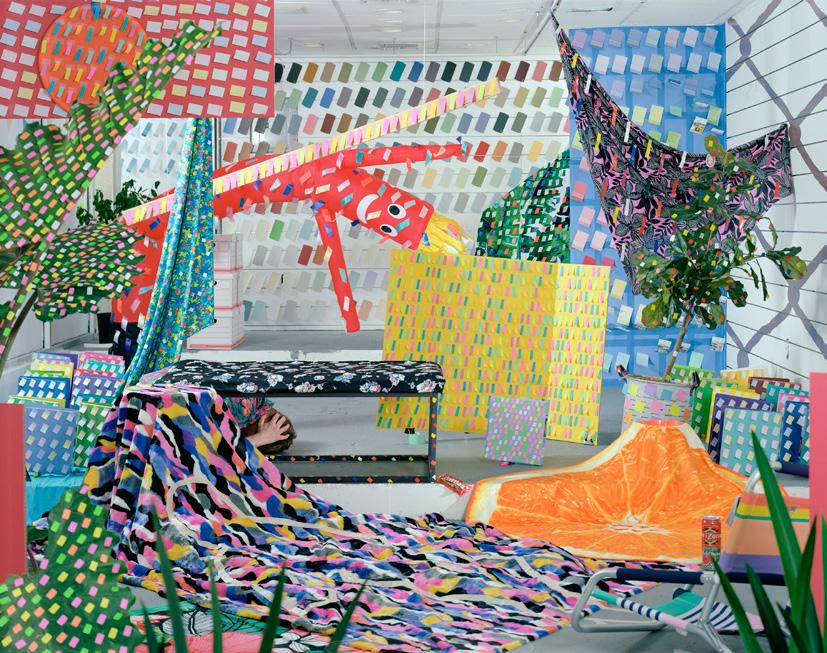

CHARLIE ENGMAN & HILLARY TAYMOUR

Text by Maisie Skidmore

CAMILA FALQUEZ

Text by Chiara Bardelli Nonino

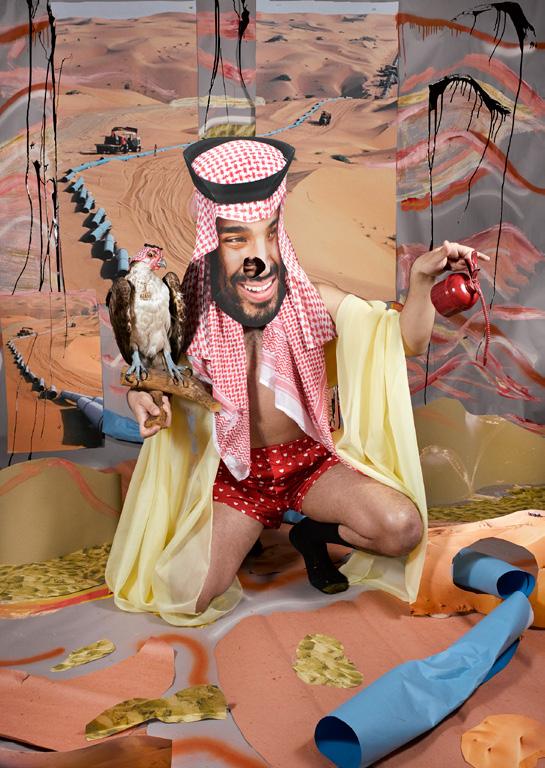

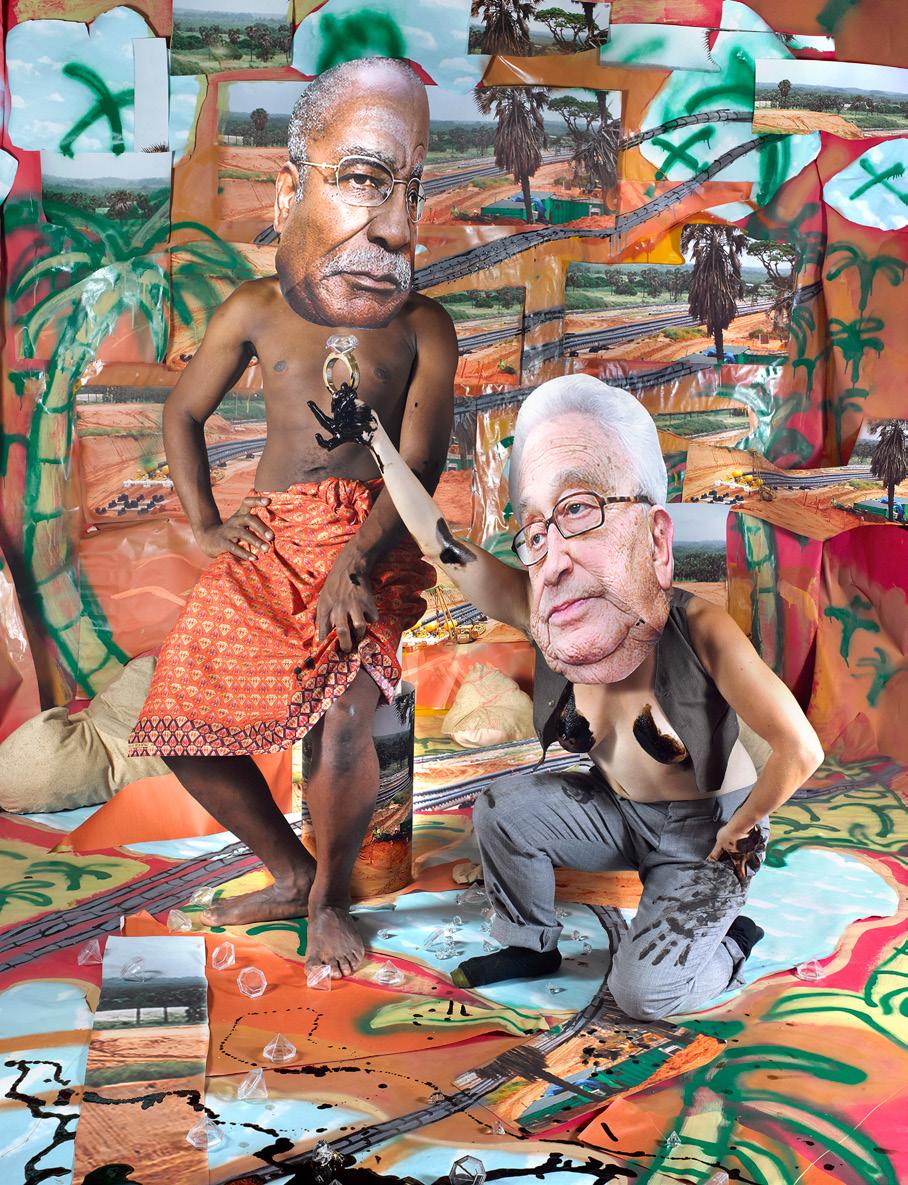

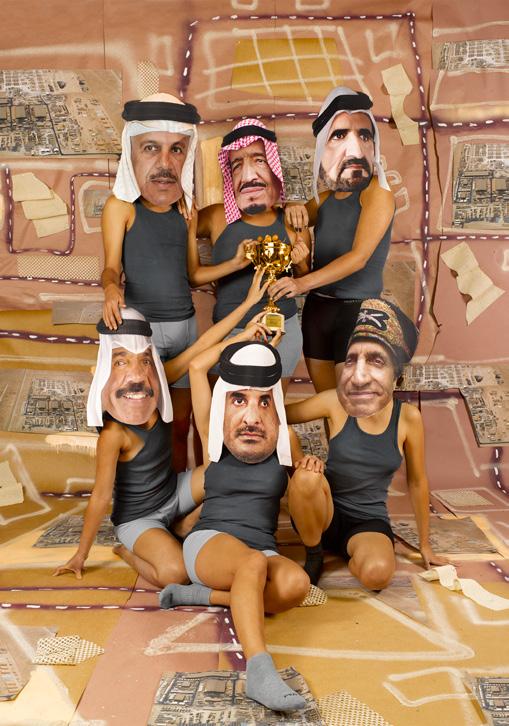

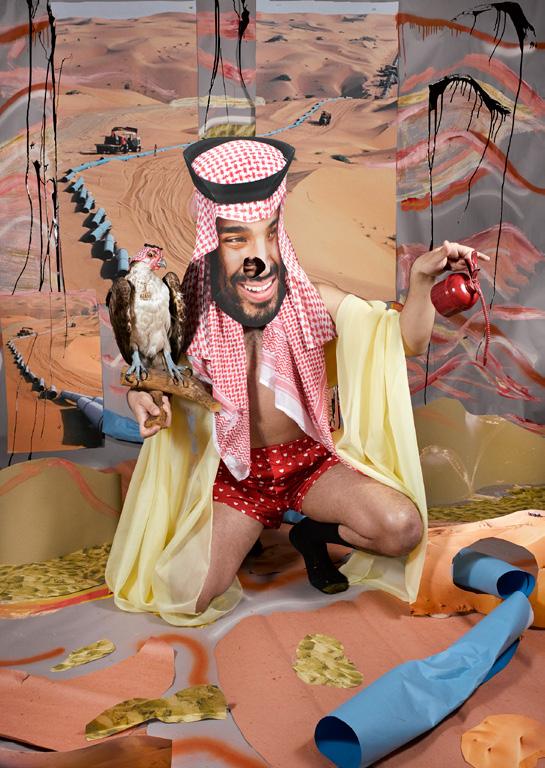

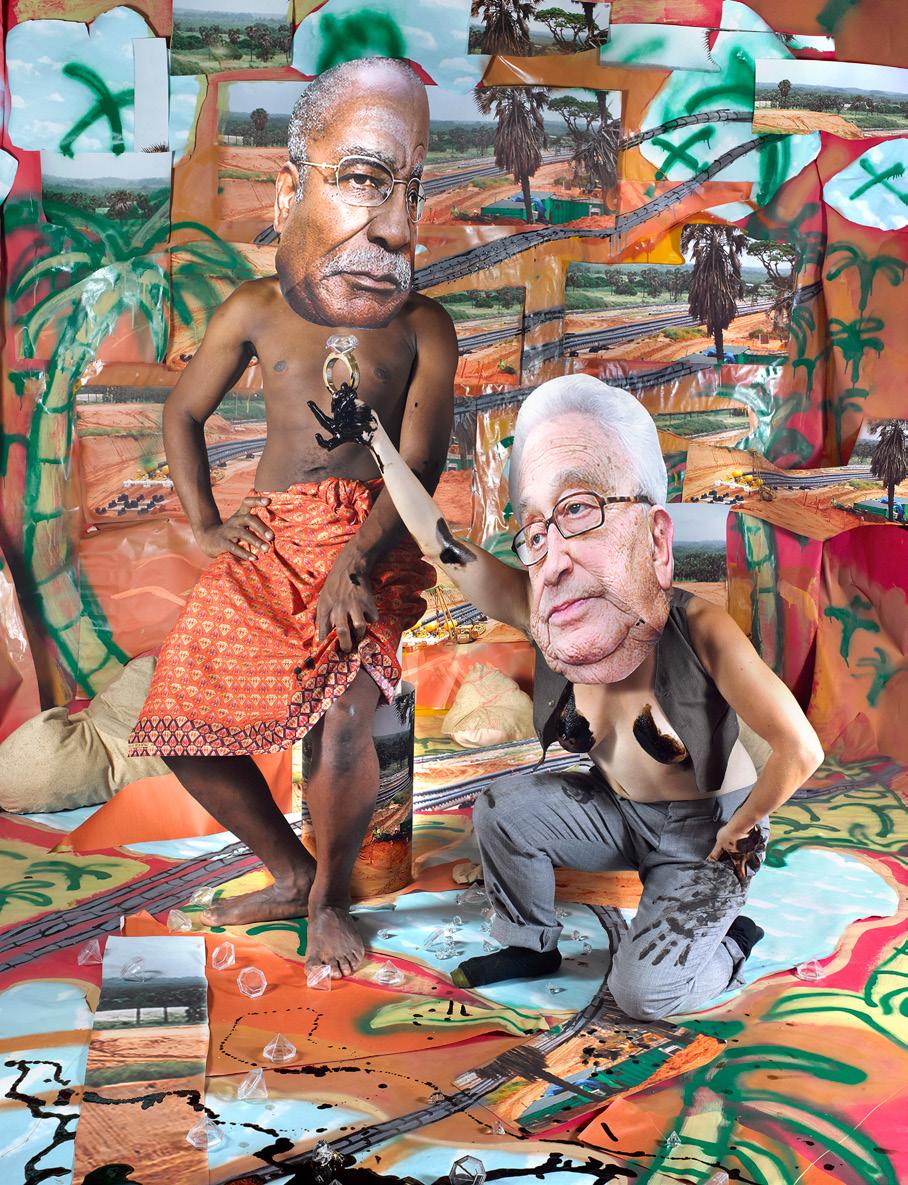

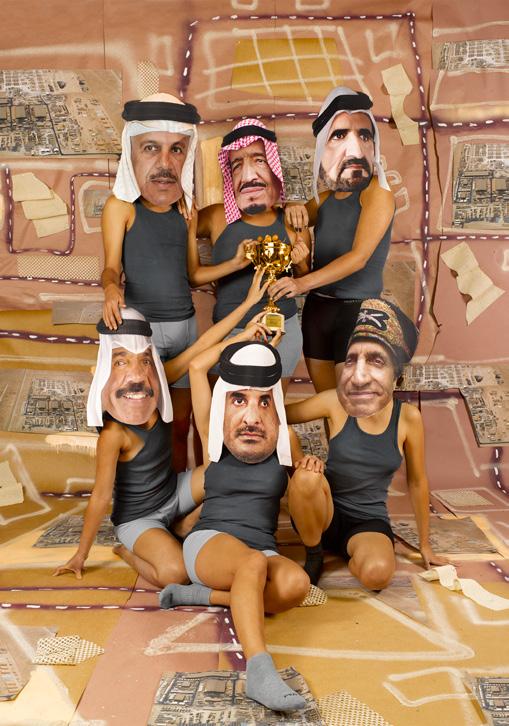

SHEIDA SOLEIMANI

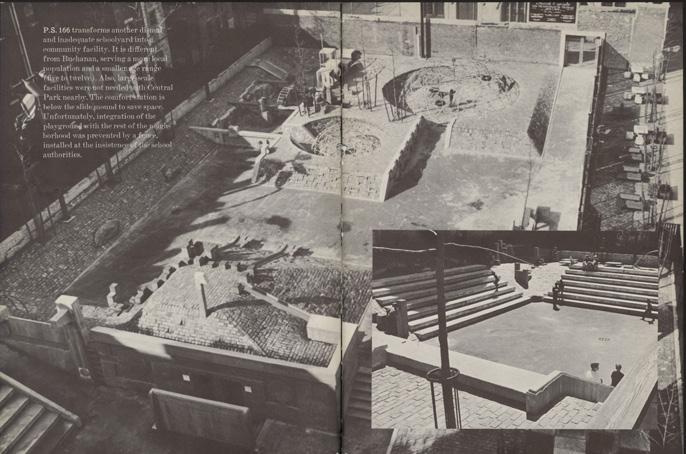

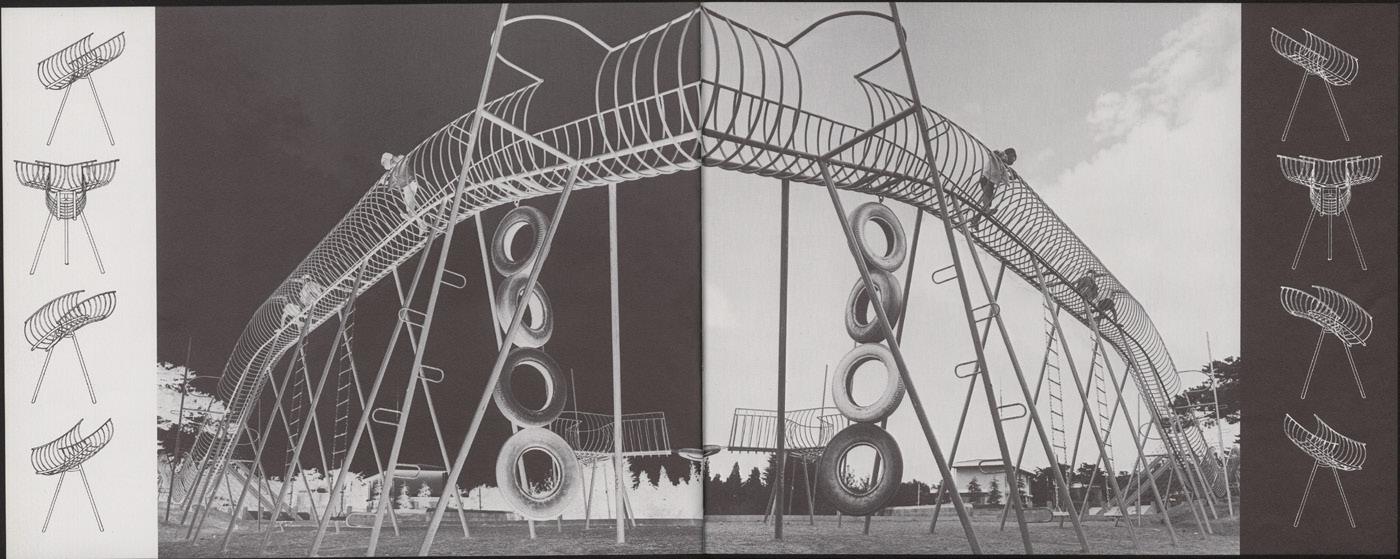

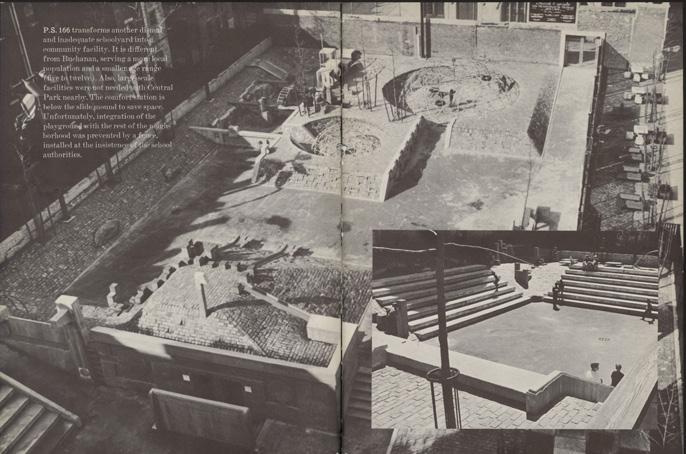

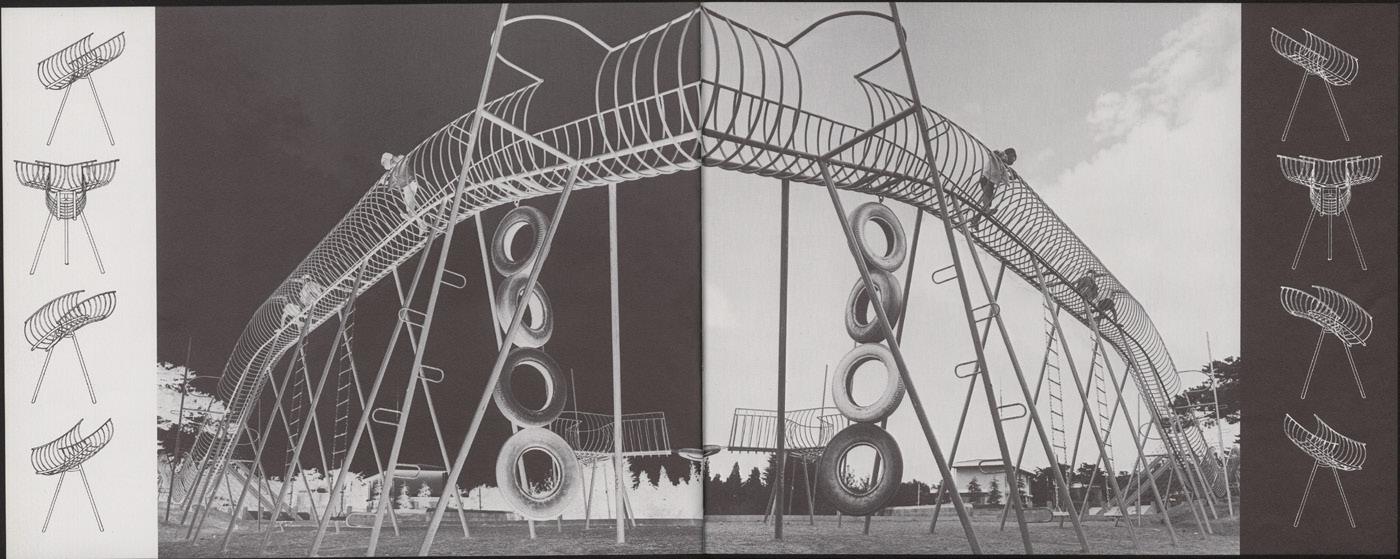

Text by Maitreyi Maheshwari THE PLAYGROUND PROJECT

by Gabriela Burkhalter

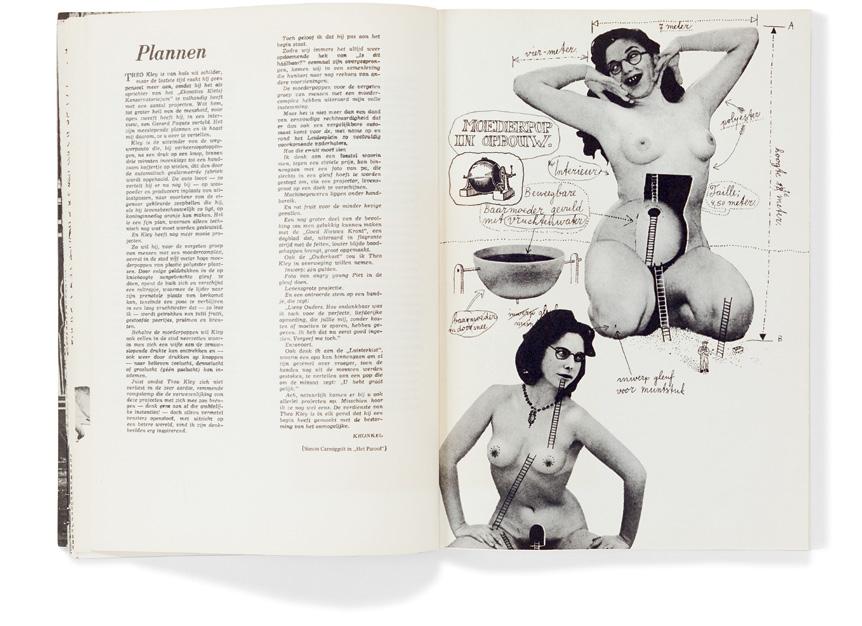

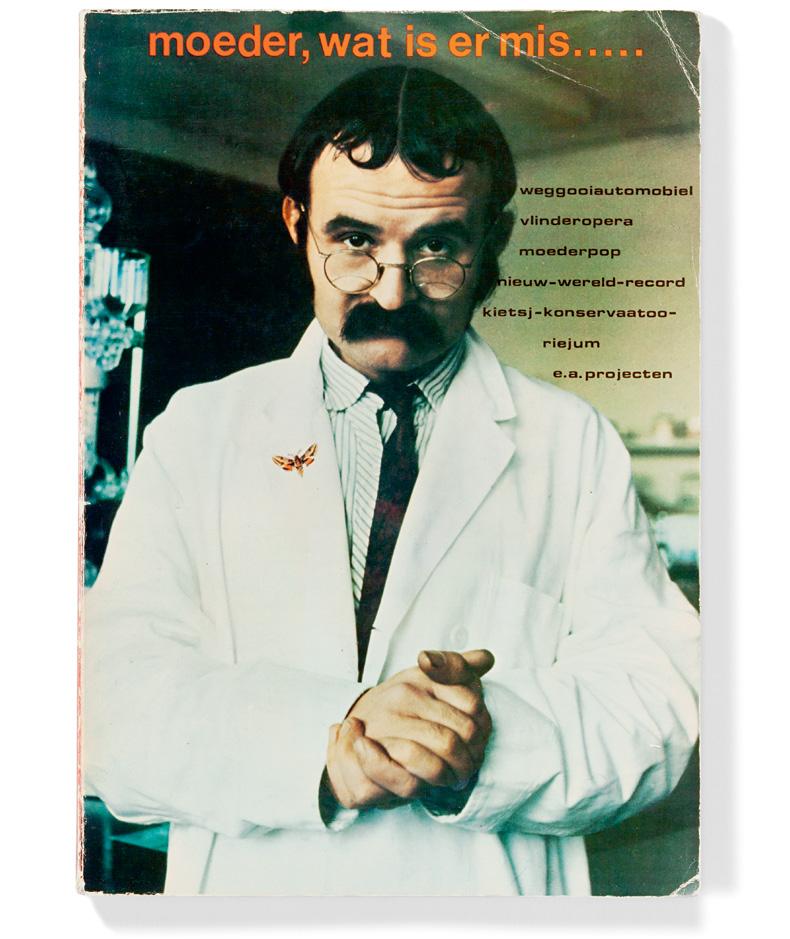

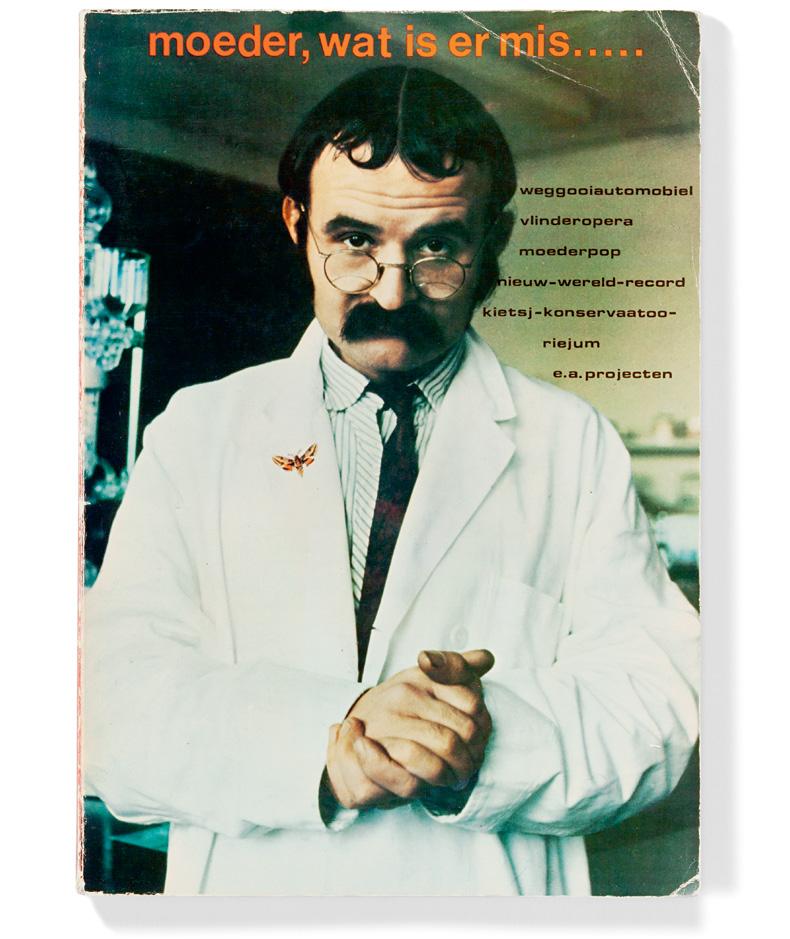

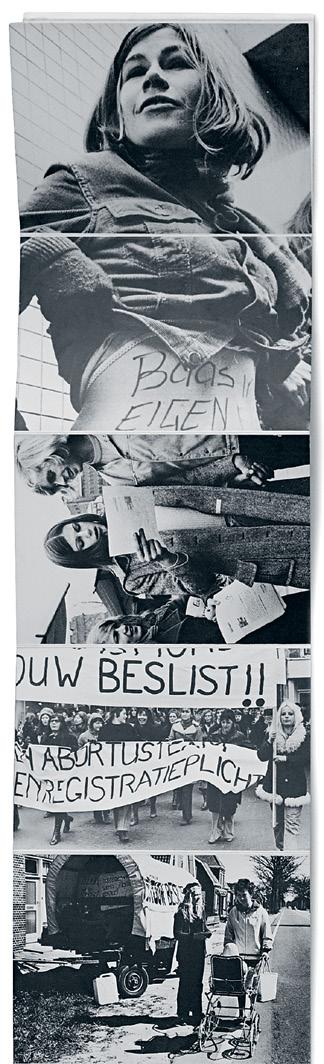

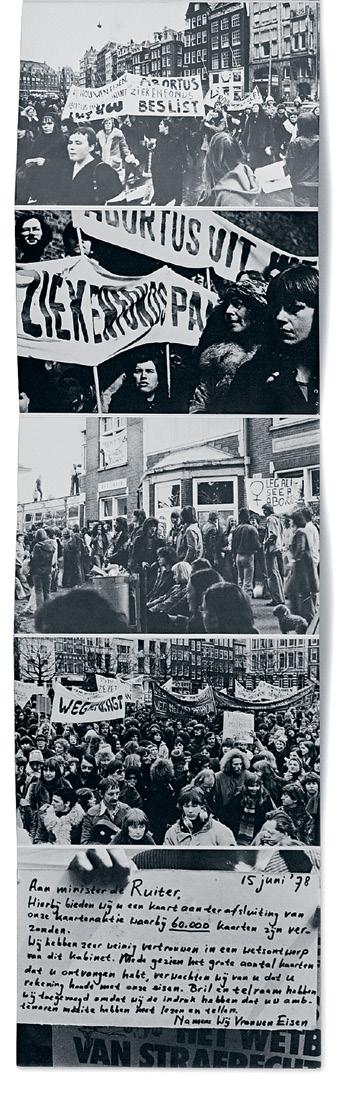

Text by Bryan Barcena JOS HOUWELING

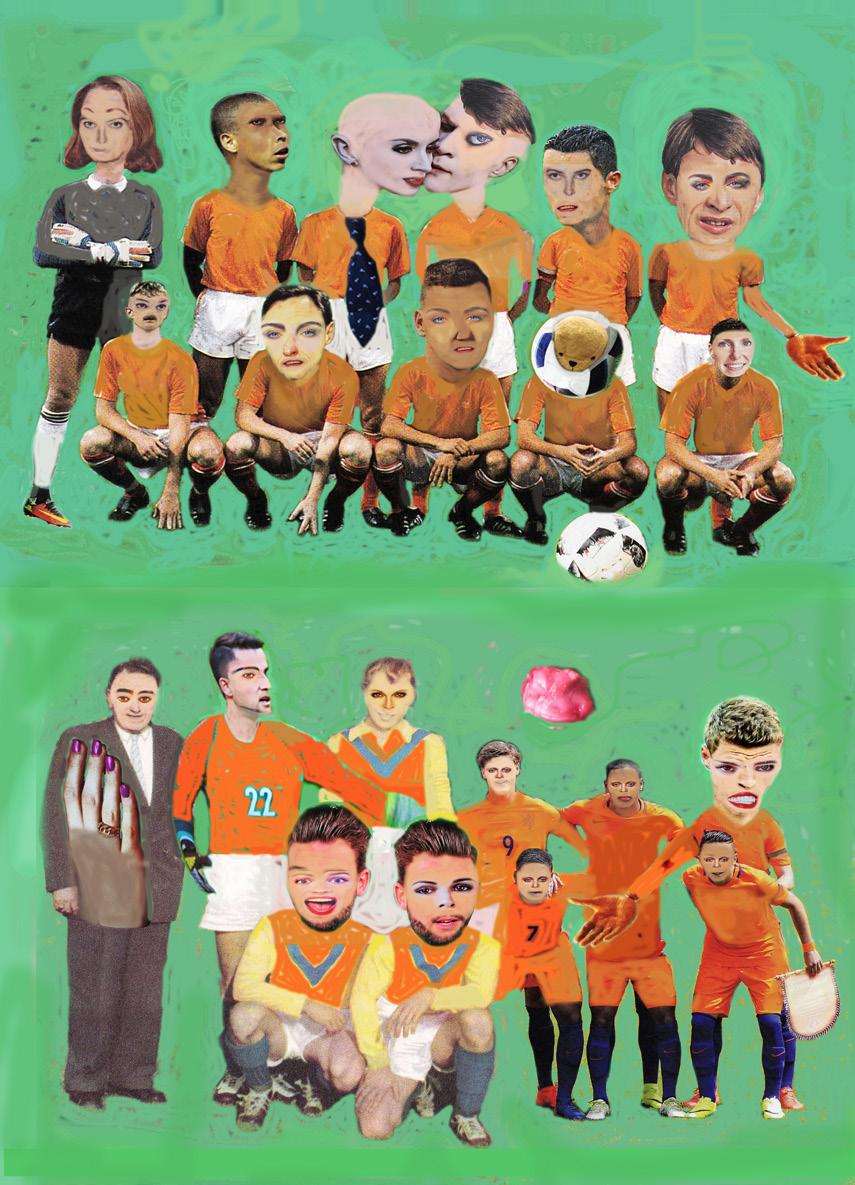

Text by Sacha Bronwasser ROLPH GOBITS

Text by Pim Milo

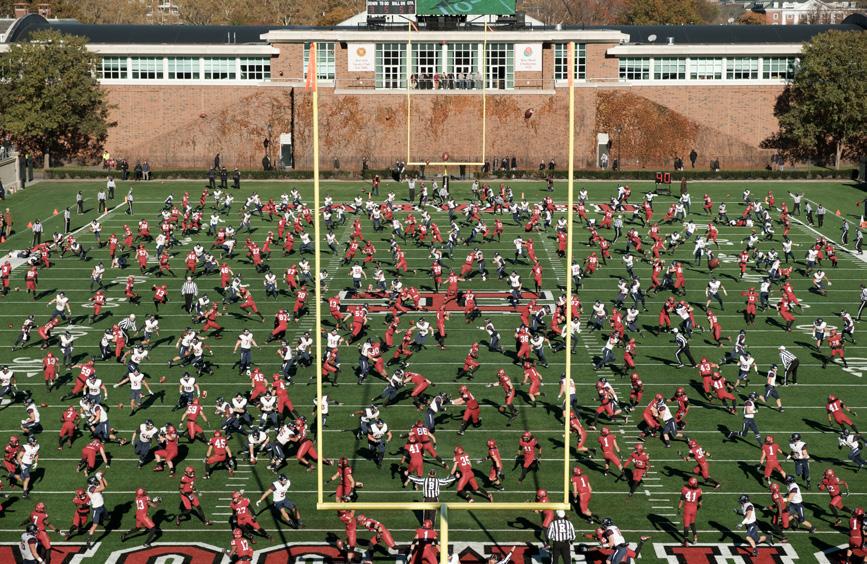

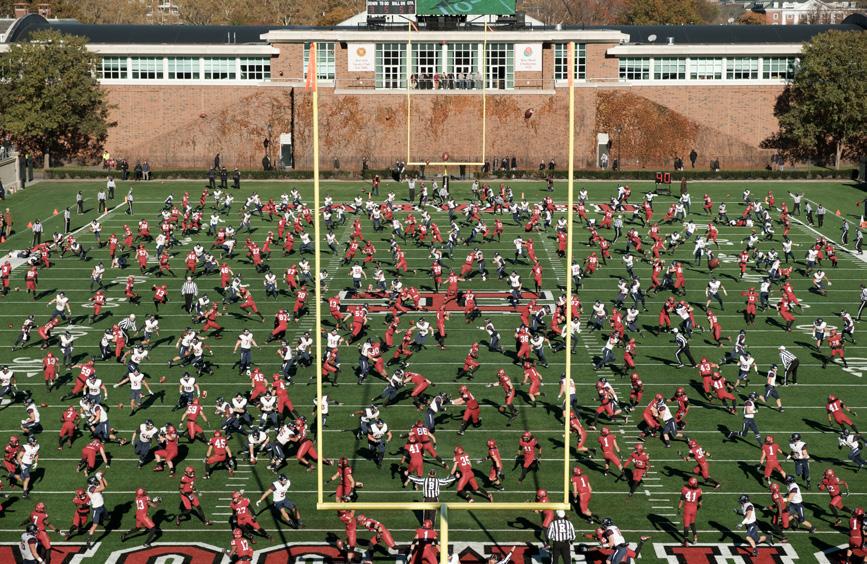

PELLE CASS

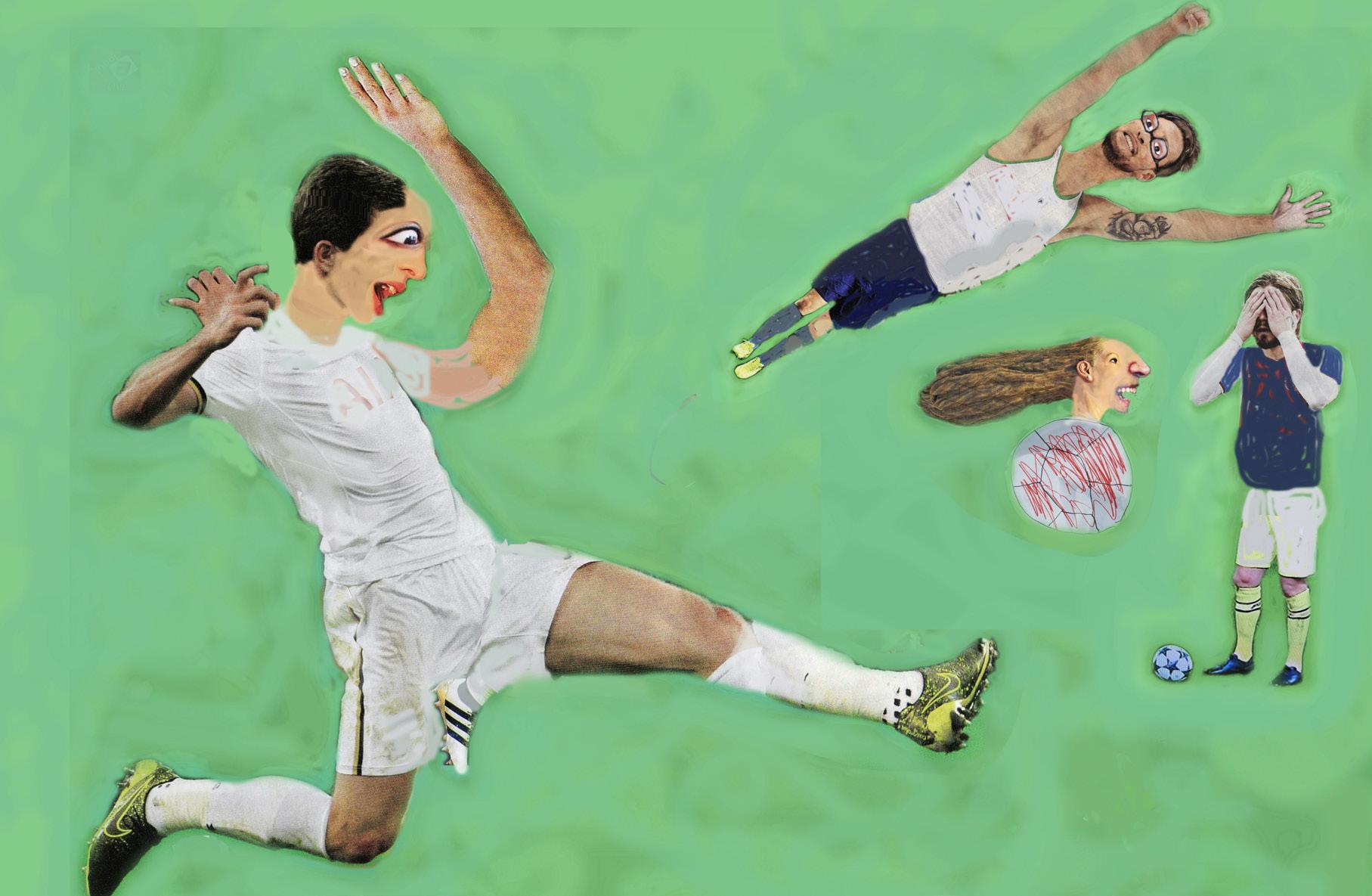

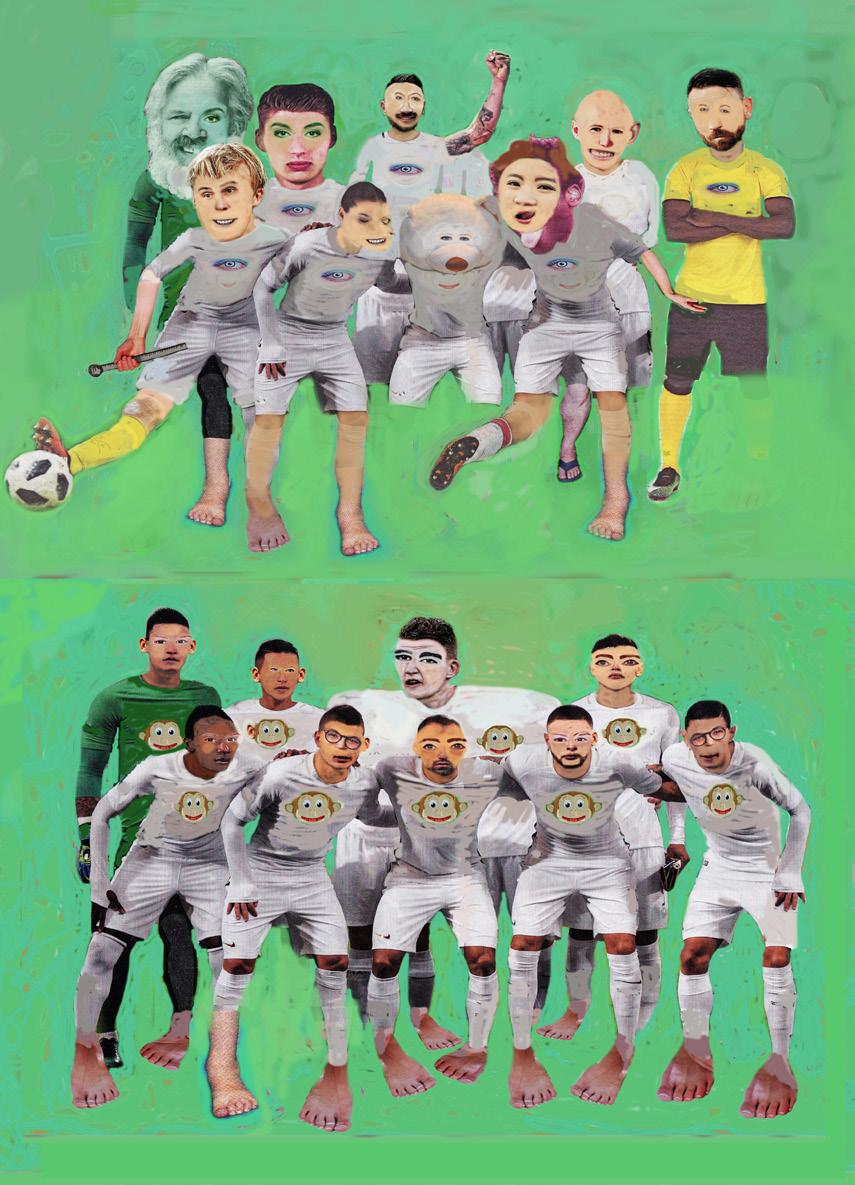

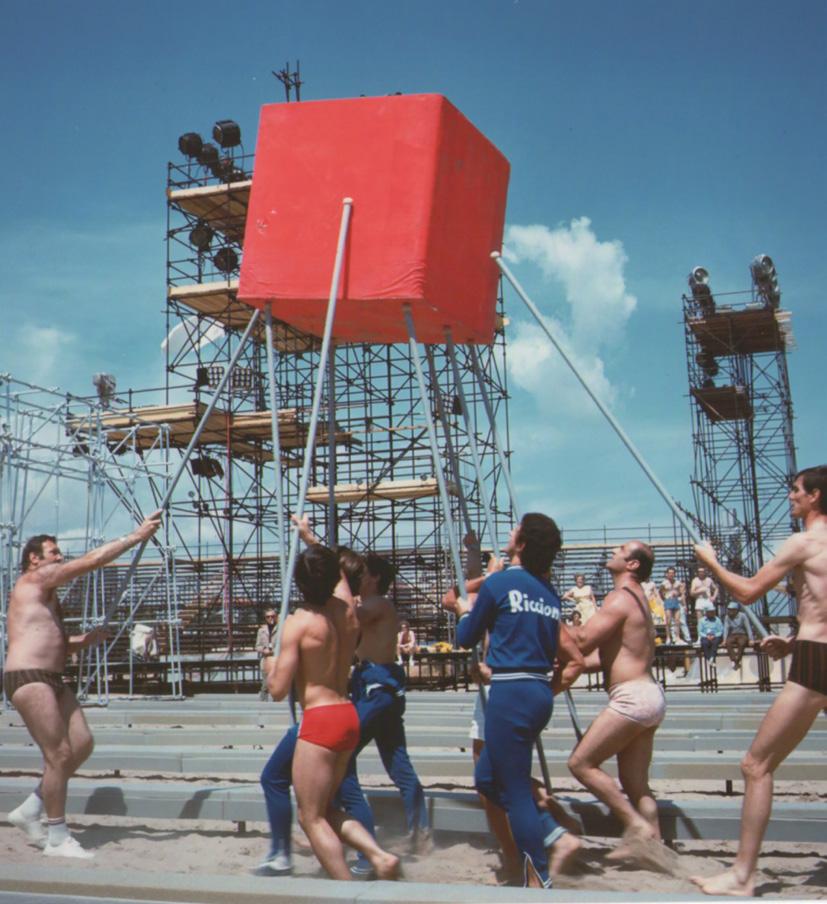

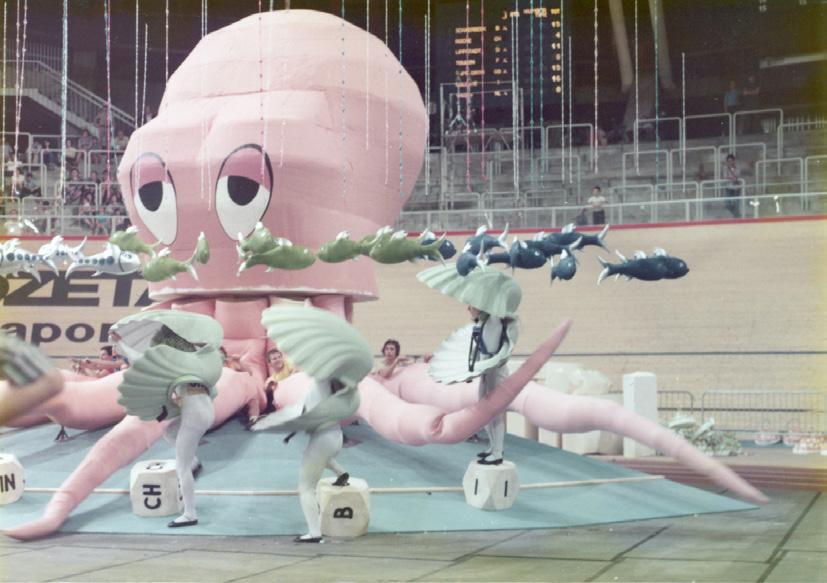

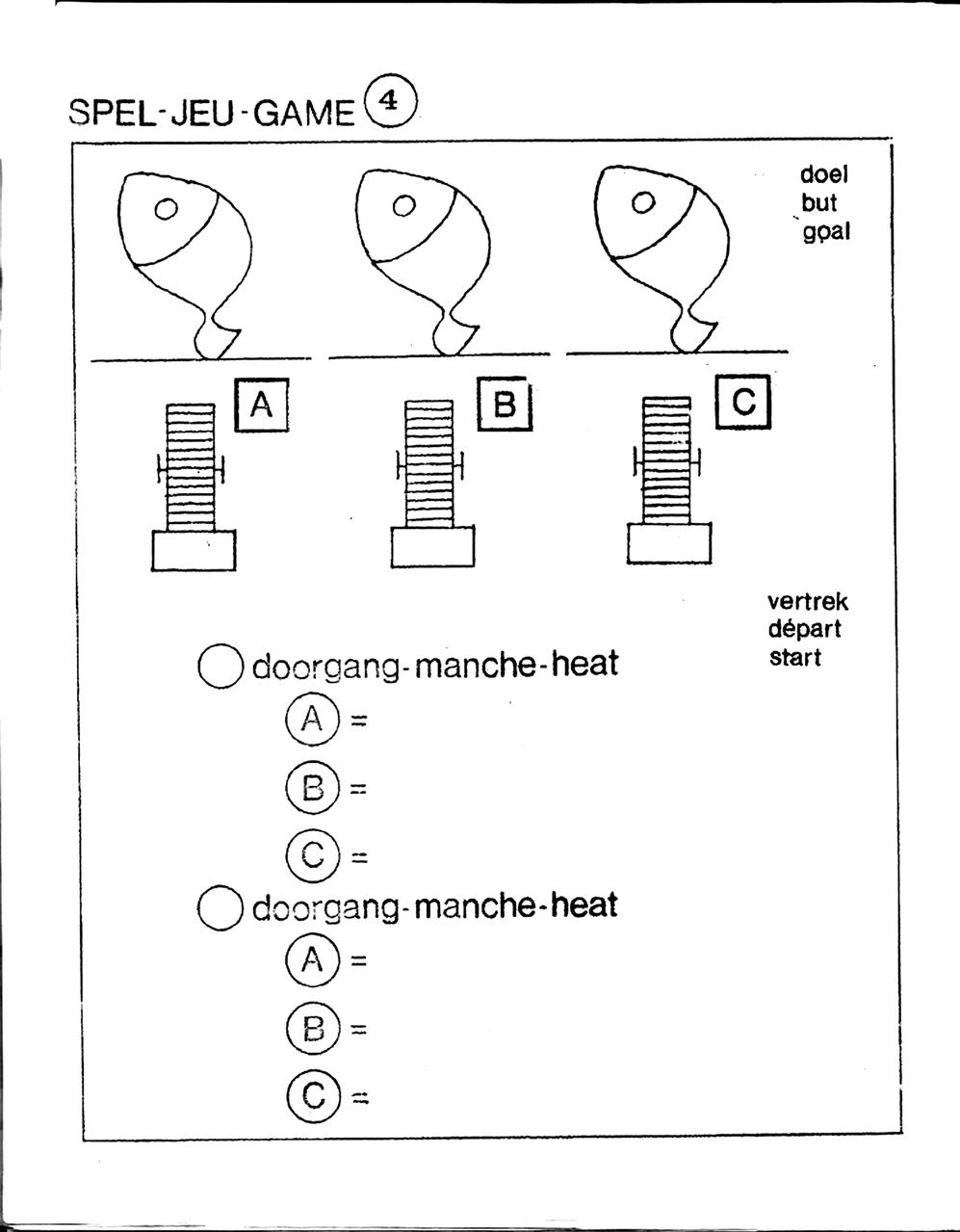

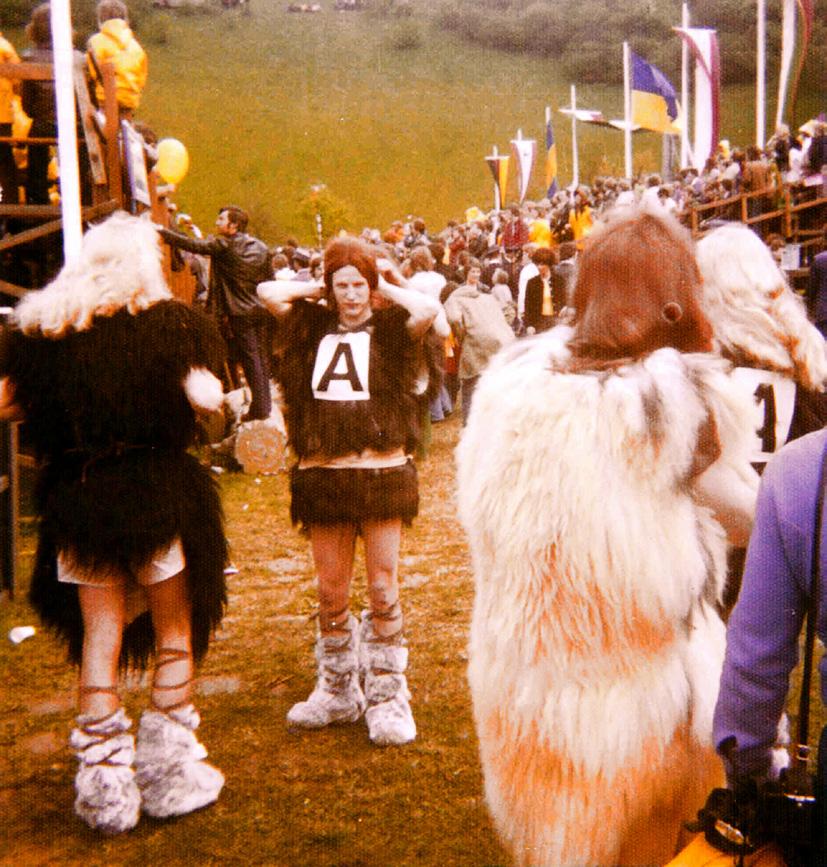

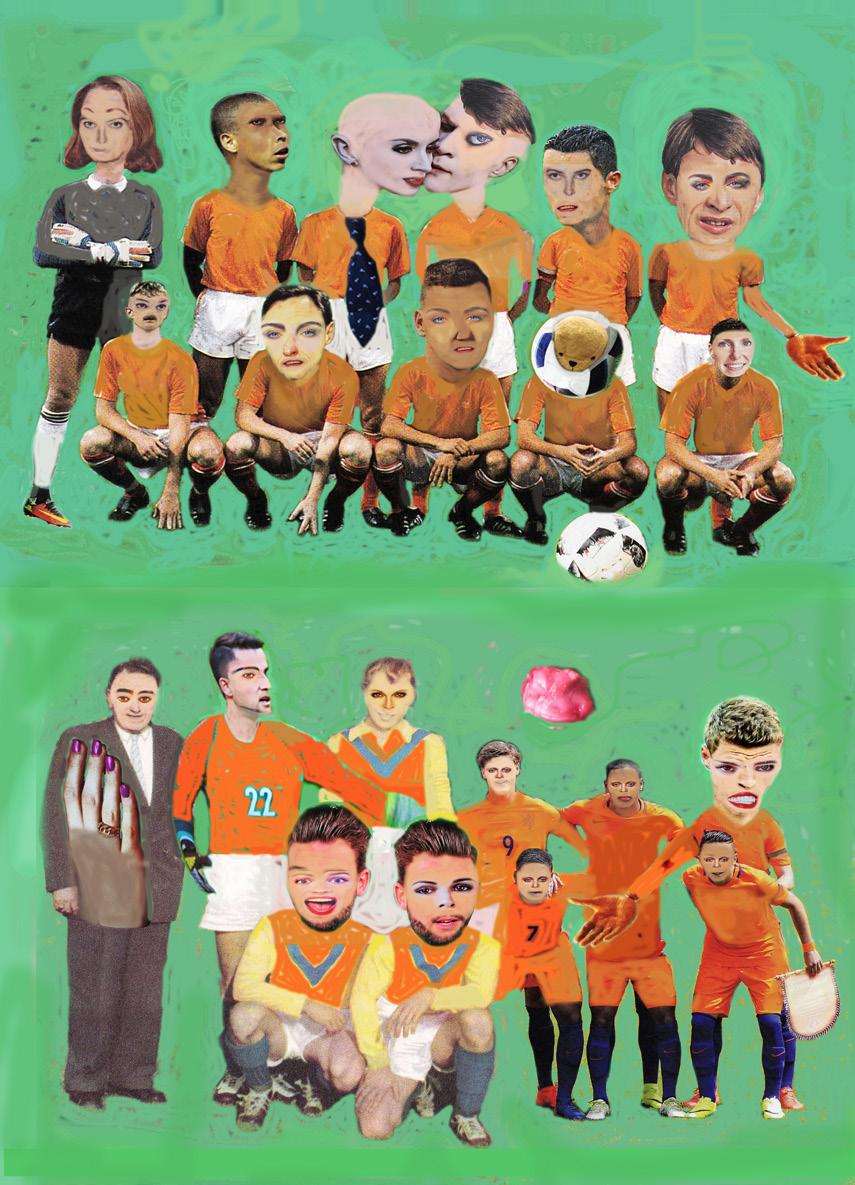

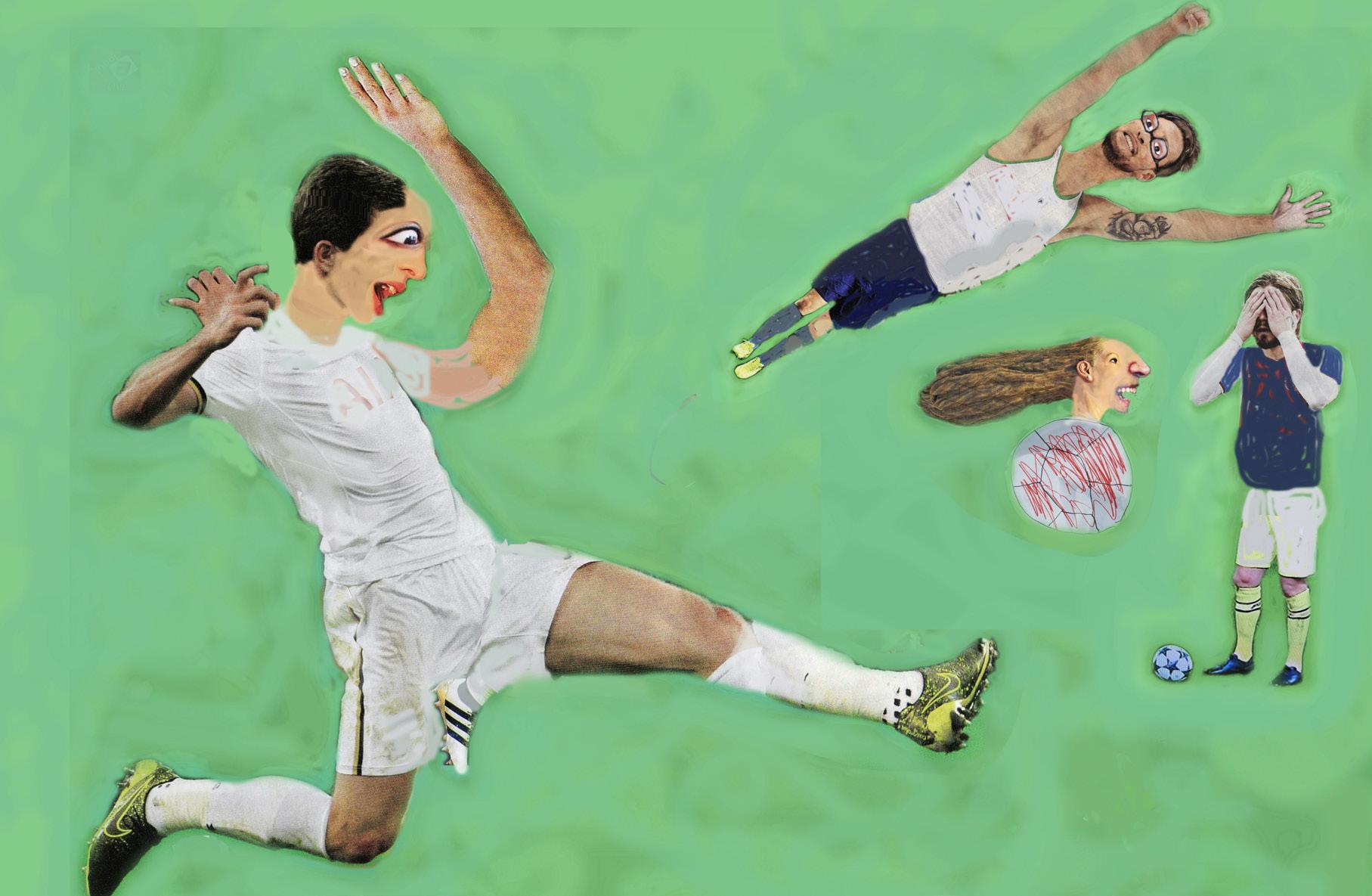

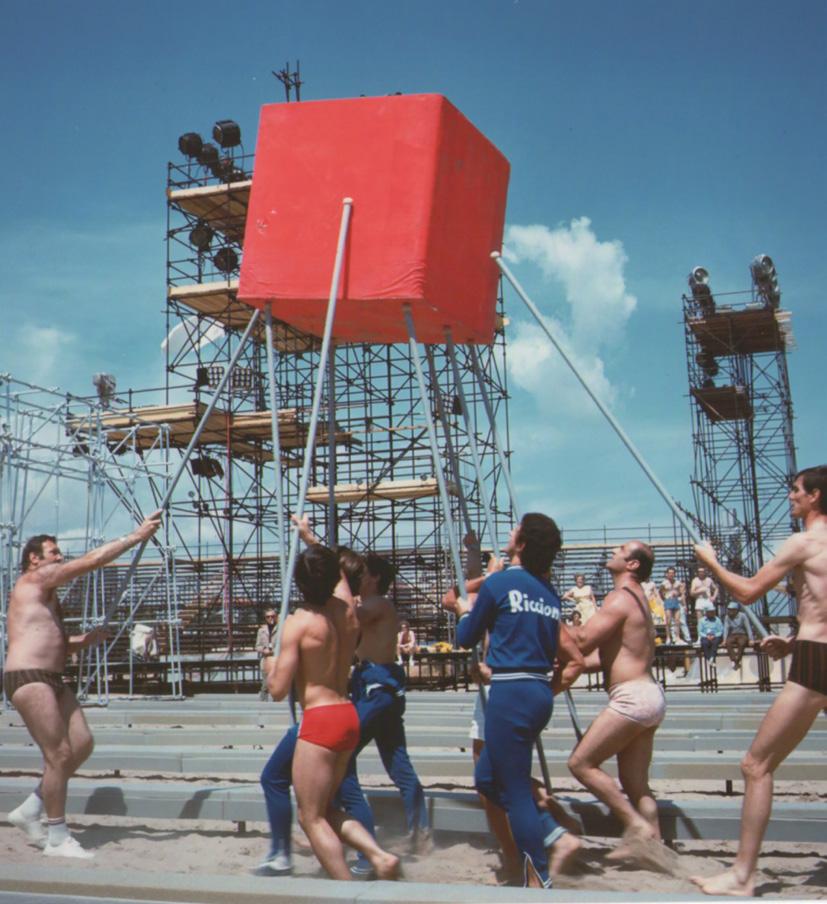

Text by Louis Kaplan SPORTIFICATION

Text by Franco Ariaudo & Luca Pucci BIOGRAPHIES CREDITS MARTINE SYMS

Text by chatbot

In his 1938 book Homo Ludens, Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga famously described play as the origin of all cultures. He believed the countless playful elements in our lives could not be explained purely by their biological benefits: the learning of skills, the release of tension, the acquisition of power and the establishment of hierarchies. Play was part of the nature of life itself, he believed, one that was reflected in extremely diverse cultural forms. If play makes you think primarily of squeals in the playground or a card game in the pub, then you underestimate the presence of play in our daily lives. To Huizinga, Homo Ludens was the basis of culture and cultural innovation. Culture does not merely arise out of play, it develops in and as play.

And although play can of course be valuable as recreation and relaxation, it never comes free of obligations. To play a game well you have to conform to certain basic principles. There is usually a clearly marked out playing field, there are players, there is play time and there are the rules of the game. If you fail to adhere to the rules you disqualify yourself. So inventiveness, creativity and innovation are of value only if deployed within the strict framework of a specific game. A player’s freedom is limited by the boundaries of the game. Play is often disinterested; the player’s interests concern only the game, and it is the game that gives playing its

value and purpose. At the same time, the game exists only by dint of the fact that it is played. In a sense this is analogous to art, which is likewise free of any selfinterest on the part of the artist, achieving real value only within a shared concept of what art is, how it is understood, and how it is deployed within a culture. There are cultural rules, commandments and prohibitions here too, often slightly disguised.

In this issue of Foam Magazine we turn our attention to the game, to playing and to humans at play. Play is essential to everything that makes us human and an integral part of almost everything we do. In play we find relaxation, pleasure and community spirit. There is plenty of space for frivolity, faux naiveté, humour and hilarity, no matter how serious the undercurrents may be. There is room for science too, for example, which similarly depends on rules and conventions but can fully develop only by means of creativity and experimentation, and which needs people with the courage to cross the boundaries of the familiar and explore new, unknown territory. Playing also means daring to be unconventional, to see things differently and make fresh use of them, to give them a twist and transform them. Audacity, vision and an open mind are essential in moving the game forward and adding something to what already exists. In his own time, Huizinga saw an erosion of the game and attributed this partly to

technological advances. What would he make of our own day, with its internethumans and the complex interaction of online and offline life? A nourishing environment for Homo Ludens or a paradise for cheats and spoilsports? At any rate, ours is a time in which nothing is fixed, in which everything is always in motion, in which realities and identities are compiled at will and hybridity is a key word. The browsing, cut-and-paste player creates new and unexpected forms of play.

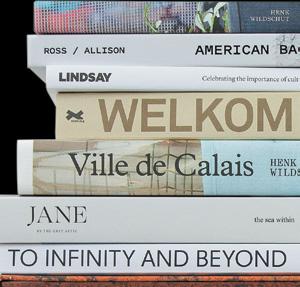

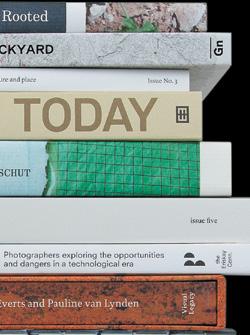

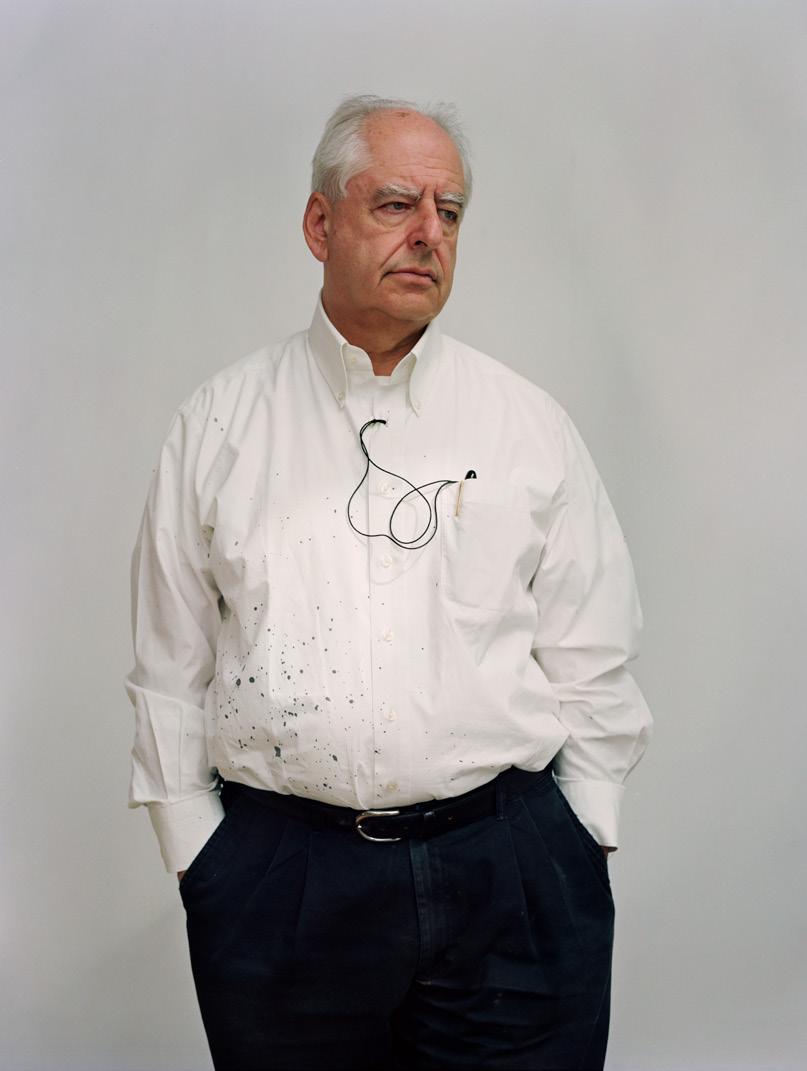

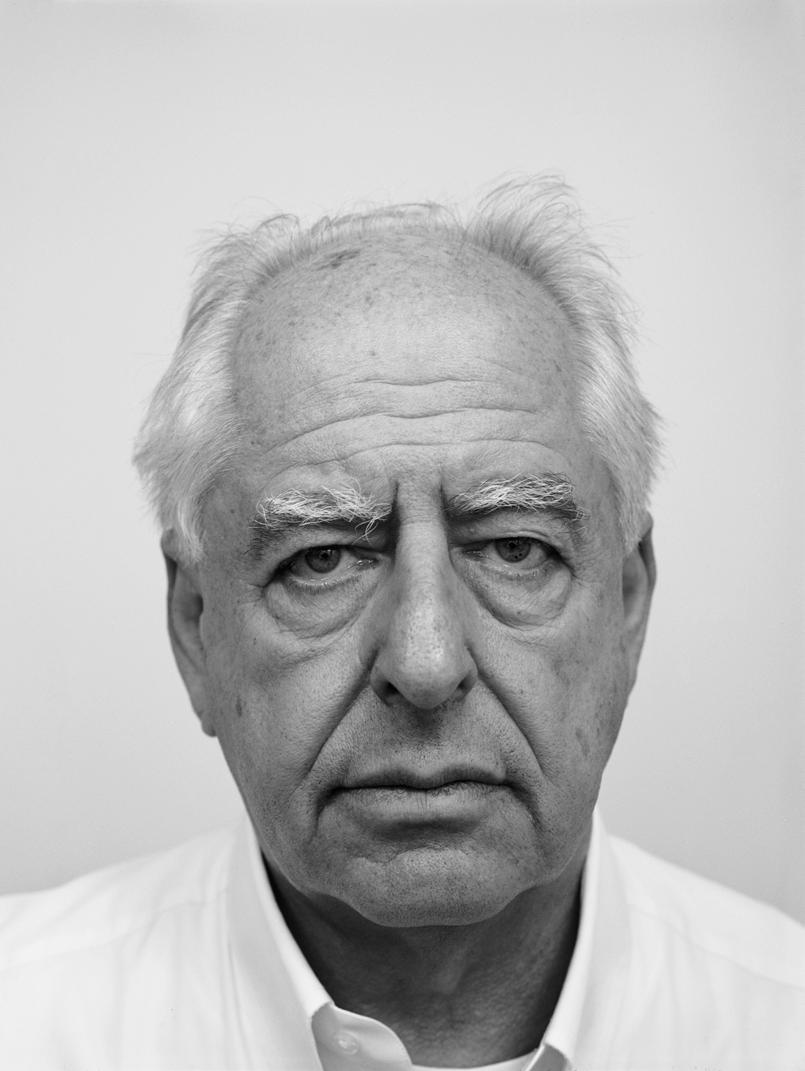

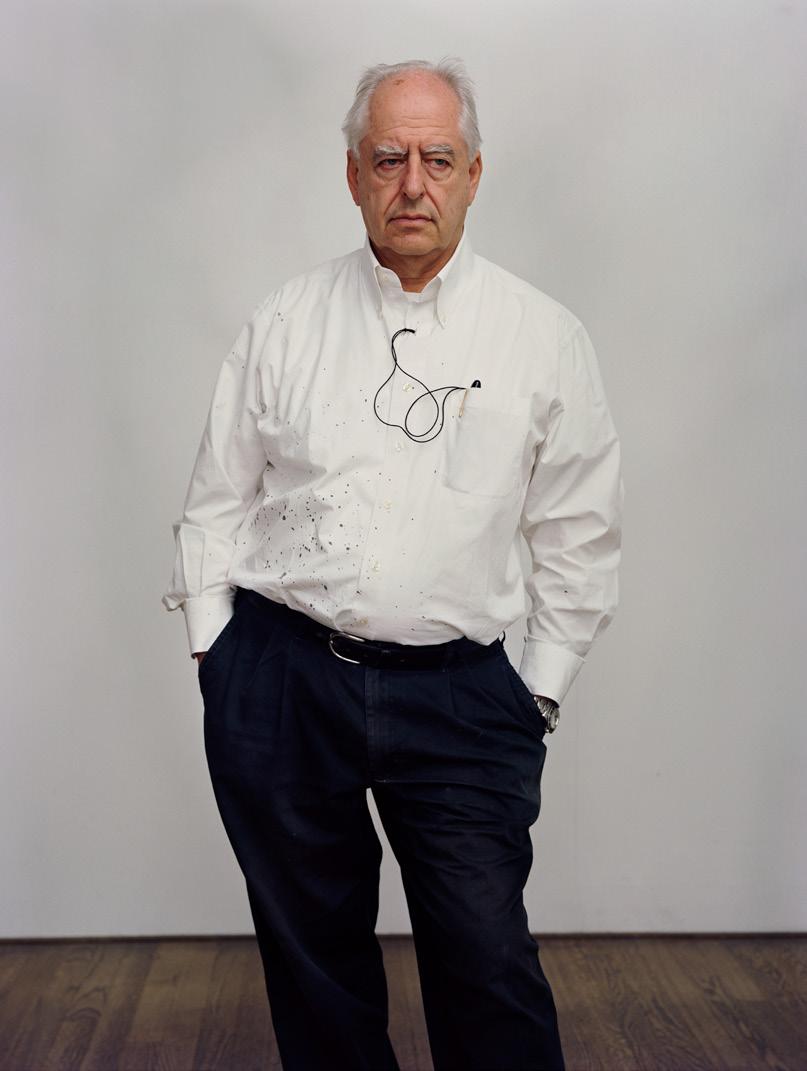

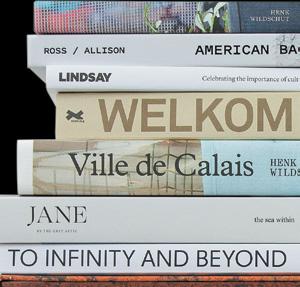

We are extremely pleased with this issue’s wide-ranging interview with William Kentridge (portrayed by Dana Lixenberg), a South African artist whose expressionist and engaged work is unmatched in its exploration of social themes, in which playfulness coincides with seriousness and gravity is combined with lightness of touch. We also look at a shelf of books put together by Hans Gremmen, graphic designer and creator of photo books whose astonishing book designs always emerge from his appreciation of craft. All in all, we hope this issue will prove itself a great playing field with a variety of players that will give you, whether a discerning reader or participatory player, a very great deal of pleasure.

And last but not least, as she leaves Foam after 18 years as Editor-in-Chief, we give a final salute to Marloes Krijnen.

2 3 MARCEL FEIL

CONTENTS

Editor-in-Chief

4

225 239

Editorial

8 12 14 22 33 49 59 73 81

249 257 265 277 279 289

Text

89 97 113 125 137 145 161 177 189 201 209

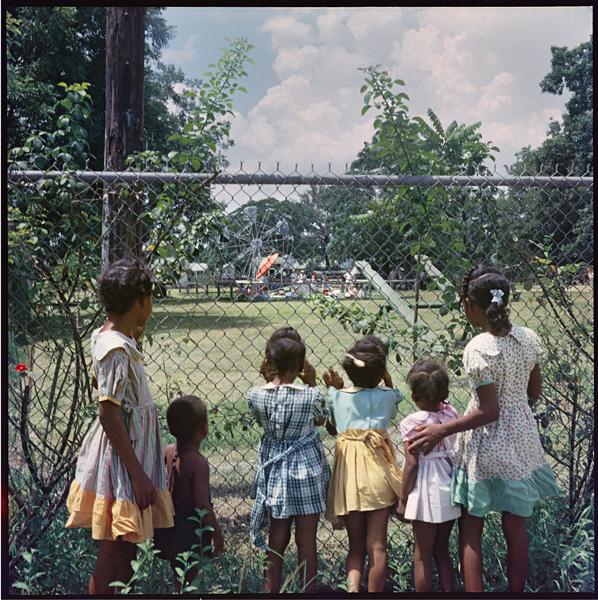

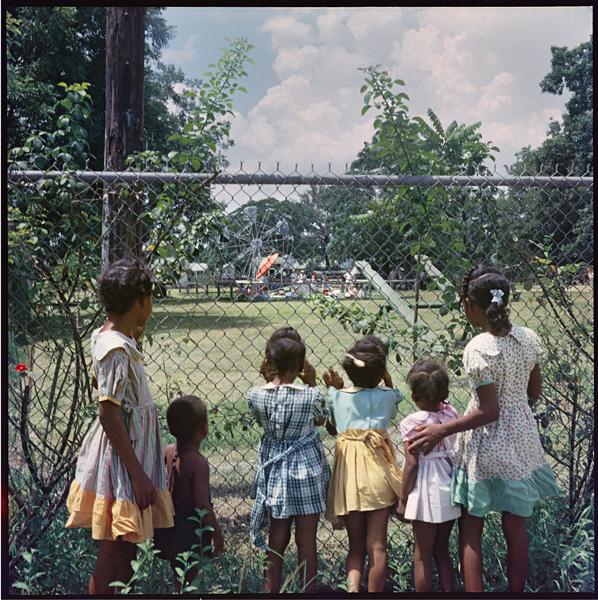

MAVIS STAPLES is an American rhythm and blues and gospel singer, actress, and civil rights activist. Staples was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1999 and the Blues Hall of Fame in 2017. In 2011 she won her first Grammy award for the album You Are Not Alone. Her latest release, We Get By, features the image Outside Looking In as the album cover.

I had the pleasure of meeting Gordon Parks when he was alive, and was honored by his Foundation in 2017 with the Gordon Parks Foundation Lifetime Achievement Civil Rights Award. When we started talking about cover ideas for my new album, one of the ideas was to include a photo by Gordon Parks.

My label sent over a few different ideas and the shot Outside Looking In struck me immediately. That was it — I needed to have that as my cover. The image reminds me of me and my family growing up. It was so powerful I didn’t even need to see any other options.

I’m so thankful that the Foundation let us use it for the cover. I can’t imagine having anything else.

Mavis Staples

FIONA TAN is internationally recognised for her photographic works, video and film installations in which explorations of memory and time are key. She represented The Netherlands at the Venice Biennale in 2009 and has participated in Documenta 11, and numerous other international biennials and exhibitions. Her work is represented in esteemed public and private collections. As the 2019 winner of the Spectrum Prize for Photography her work is currently on show in the solo exhibition Goraiko currently at the Sprengel Museum, Hannover.

As the fluorescent tubes flicker on, I am confronted by rows and rows of A5-format envelopes. I’m told that although this forgotten archive has been stored here in the museum depot for over 40 years, no one has ever really had a look at it.

I remove one of the orange A5 envelopes from a shelf at random. Attached to the front of the envelope is a small colour photograph, and above that a handwritten letter and number. The 6x6 original negative is stored inside. The image I’m looking at is a medium format shot of a woman posing with yellow flowers. This is clearly a staged photograph taken by a professional photographer. The woman’s expression is appealing but also disingenuous, managed. Although the resulting image is well lit, colourful, and professional, it’s also generic and impersonal. The image reminds me of the photos on my mother’s knitting patterns when I was a girl. What comes to mind is the word gaaf — colloquial Dutch for neat or perfect. What am I looking at? What is the photograph’s relevance today? And perhaps even more pertinently, what am I not seeing? The starting point for my photography exhibition — Gaaf — at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

4 5 ON MY MIND ON MY MIND

Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, 1956

© Gordon Parks, courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation

Fiona

Tan

Image from the Agfa Advertising Archive, 1950s/60s © Collection Museum Ludwig

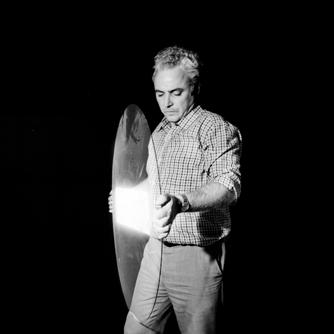

DEBORAH WILLIS is a photographer, teacher, curator and an author of books on photography. She teaches at New York University.

Mirror (_2100135), 2017

I first met Gordon Parks in 1974. Parks was assigned by LIFE magazine in 1949 to photograph in Rome, Italy and a two-page spread was published in the August 1 issue of the magazine. The article documented Via Margutta, a narrow cobblestoned street in Rome where artists and poets lived and worked. This photograph of the artist Pericle Fazzini (1913–1987) in his Via Margutta Studio inspired me to think more about Parks’ focus on photographing artists at work. Here we see the artist chiseling, moulding, and shaping a female form in wood. He is wearing a

shirt and sweater vest, a pipe is balancing delicately from his mouth. The studio floor is filled with wood shavings and wooden models shaped in the female form appear to be dancing or holding on to a moment that Fazzini imagined. Its lighting and soft focus invites the viewer into the space as we peer through the studio trying to find the reference for the current piece. I am intrigued with Parks’ love of life, real and imaginary, as he creates this flawless image. Parks appreciates beauty in all forms — beauty in life and beauty in work.

Deborah Willis

The photograph is a record of some activities that took place in front of a mirror. One of those activities was the taking of a photo. The others are left for the viewer to surmise.

The image is dirty. Rather, the mirror in which the scene is reflected is dirty; coated with dust that someone has partially wiped away, but whose hands have left their mark.

The word ‘darkroom’ has several definitions: one is a room for developing photographs, another is a space set aside in a nightclub or bar for sexual encounters.

GLENN LIGON received a Bachelor of Arts from Wesleyan University and attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study Program. In 2011 the Whitney Museum of American Art held a mid-career retrospective of Ligon’s work, Glenn Ligon: America, organized by Scott Rothkopf. Recent exhibitions include: Des Parisiens Noirs, Musées d'Orsay, Paris; Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions (2015), a curatorial project organized with Nottingham Contemporary and Tate Liverpool; Blue Black (2017), an exhibition Ligon curated at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis.

Is this image a self-portrait? The artist is in the centre of the composition, but the picture is not focused on him, it is focused on his entanglements. Sometimes a photograph is about what can’t be represented or what lies outside the frame.

A picture through a glass, darkly, so to speak.

6 7 ON MY MIND ON MY MIND

Glenn Ligon

Pericle Fazzini in Via Margutta Studio, Rome, Italy, 1949

© Gordon Parks, courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation

Darkroom

© Paul Mpagi Sepuya

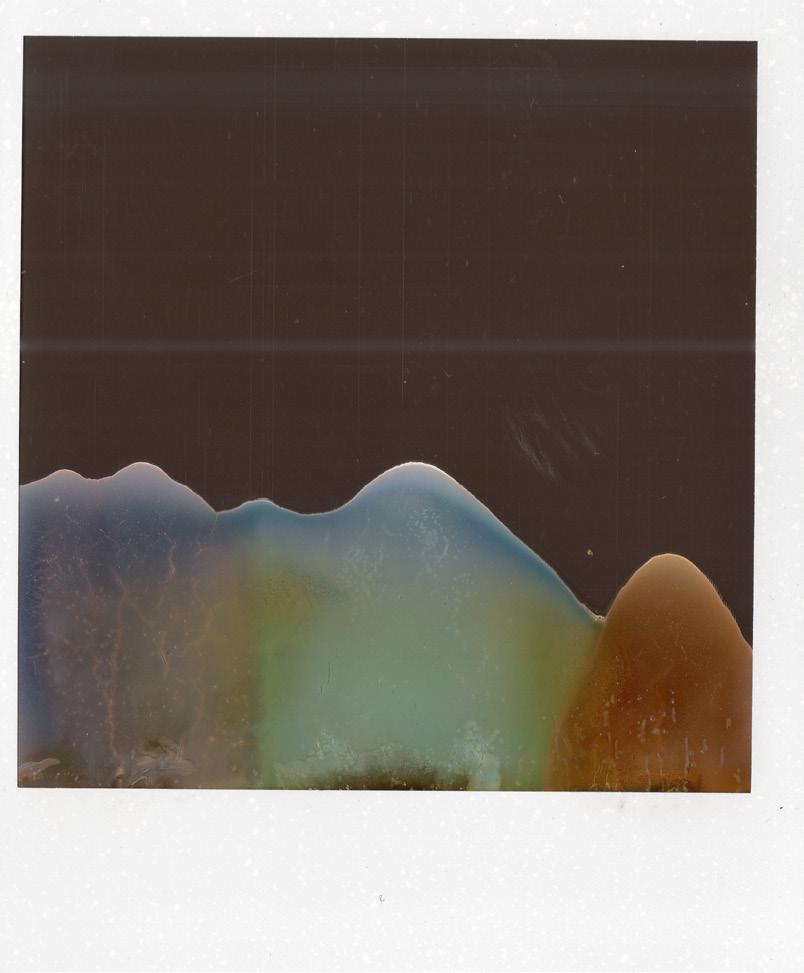

LAURA EL-TANTAWY

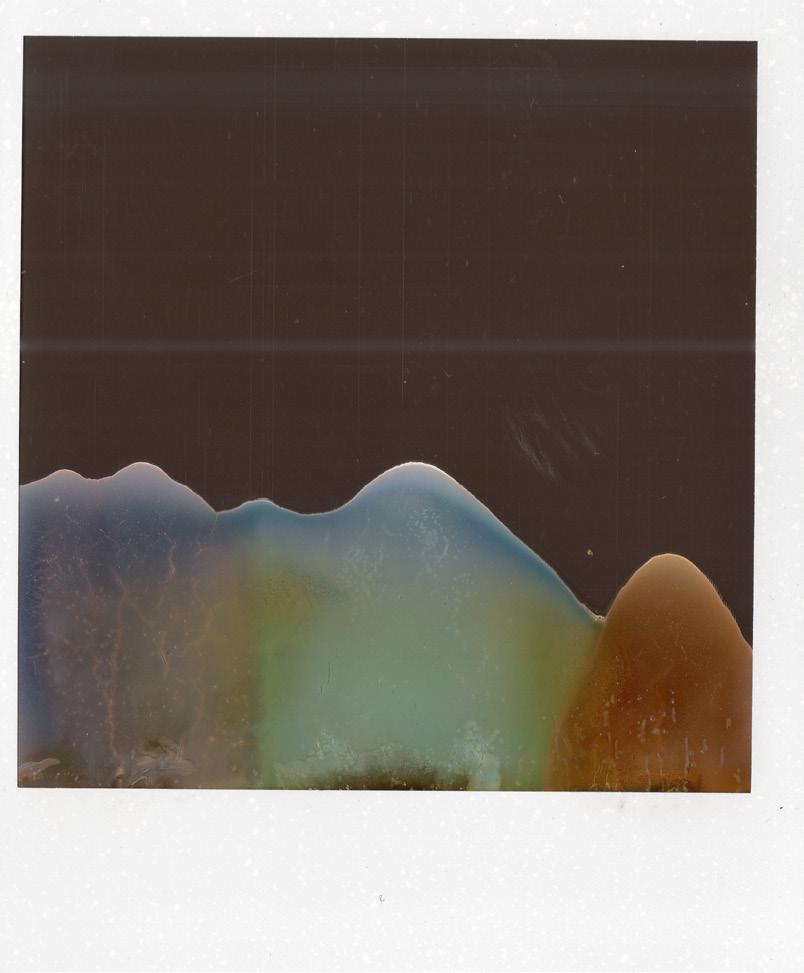

A Star in the Sea is an overture for embracing the unexpected. The photographs, text and title pertain to three independent, personal life events: a love story, my first and only trip to my place of birth in the UK, and a vision on a beach in Italy. It is inspired by a desire to redefine my relationship with the ideals of success & happiness. In this context A Star in the Sea is an opportunity to celebrate imperfection — an artistic gesture to have faith in the universe. The work takes on the form of a book. It is conceived as an artistic object demanding intimacy — something you want to protect and treat with care.

LAURA EL-TANTAWY is a documentary photographer, artful book maker and mentor. In 2015, she released her first title In the Shadow of the Pyramids a firstperson account exploring memory and identity. The publication was shortlisted for the prestigious Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize. She self-published three other titles: The People (2015), a newsprint celebrating the Egyptian Revolution of 2011; Beyond Here Is Nothing (2017), a meditation on home and belonging; and A Star in the Sea (2019), an artistic contemplation on embracing the unexpected.

8 WHAT’S NEW? 9 WHAT’S NEW?

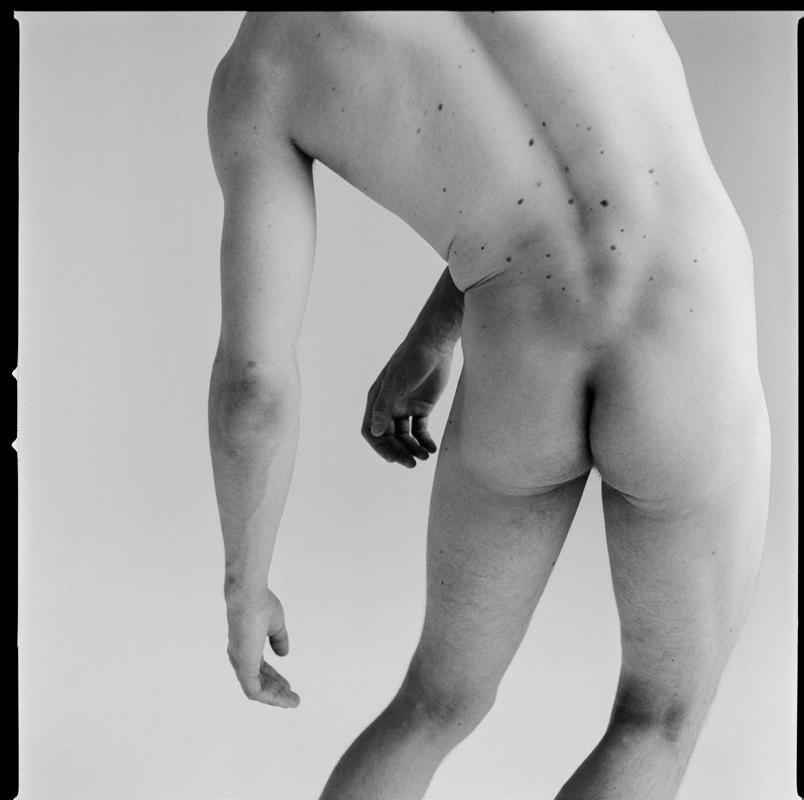

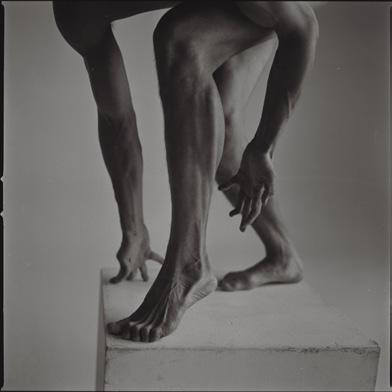

MARIAM MEDVEDEVA

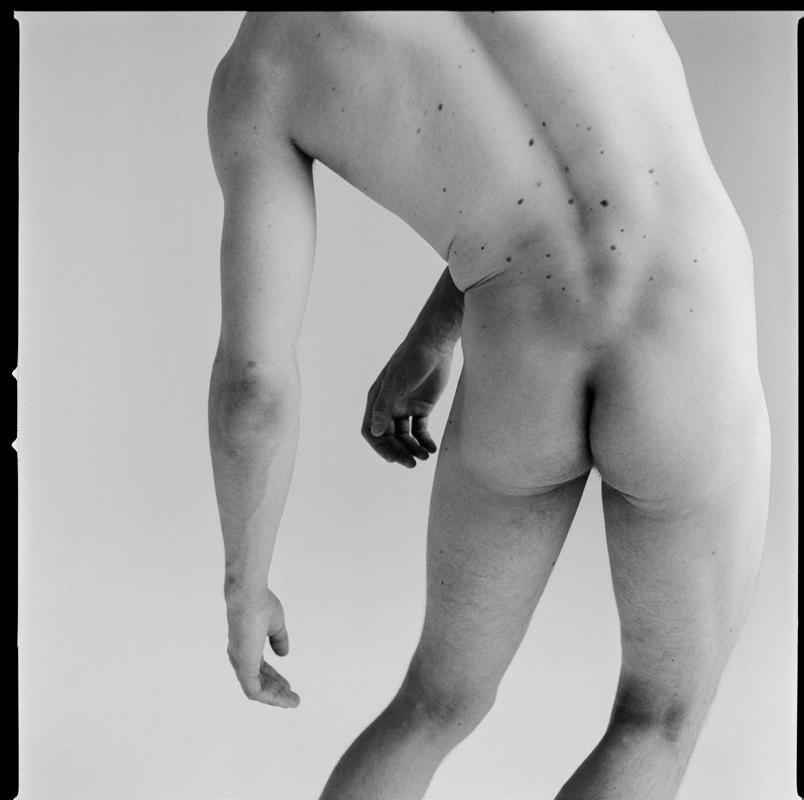

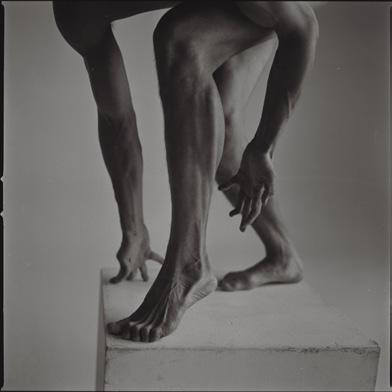

Male Figure Studies explores the nature of men through photography and performance. I use natural lighting to paint the body. No electricity or batteries, everything is natural as a human body. The grey colour gives a 3D experience and is the ‘zero’ for our eyes and light exposure readings. The nudity of men and women is asymmetrically presented in visual culture. I gain inspiration from classical sculpture and fine arts. At first glance, in antiquity, female and male bodies were presented in relatively equal proportions. On closer inspection we notice how men’s bodies received very special representation because of their muscles, attitude, and masculinity. This is what influenced my choice of subject. For the models, in becoming naked they are taking on their bodies, experiencing dialogue with it. It always becomes their own personal experience. I observe and save. At the end of each photoshoot I have disconnected myself. I am there only as an instrument, capturing moments one by one. It is fascinating to see God and the source in men.

MARIAM MEDVEDEVA is a photographer based in Paris and working worldwide. After ten years in in the art and culture sector, she completed a Master in Photography at Speos Photographic Institute in 2013. In recent years, Mariam has been working on long-term and personal fine art projects.

10 WHAT’S NEW? 11 WHAT’S NEW?

2

1

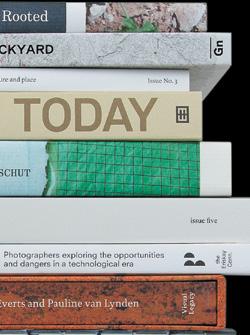

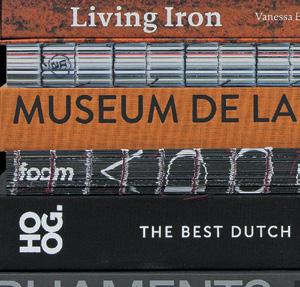

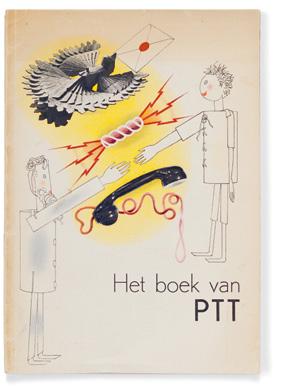

BOOKSHELF

3 4 5 30.

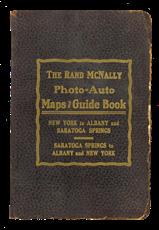

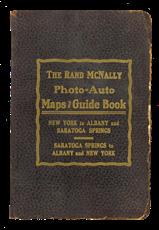

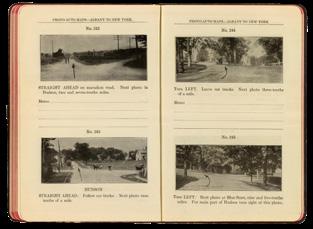

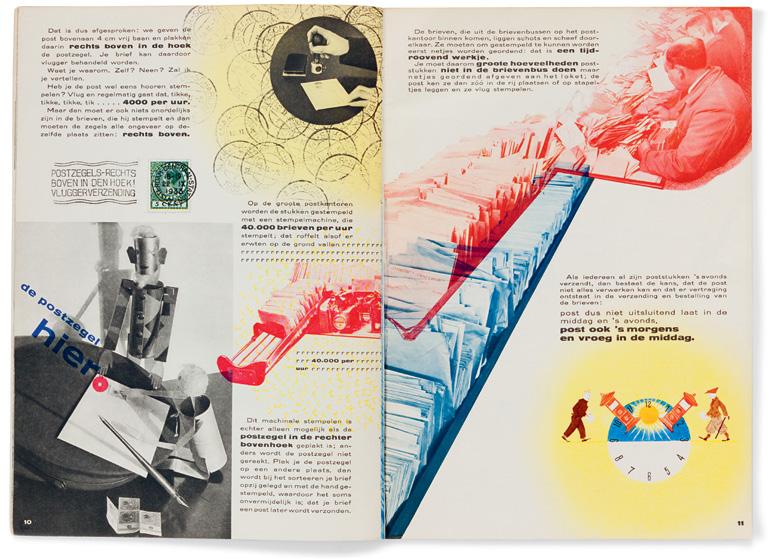

THE RAND MCNALLY PHOTO-AUTO MAPS AND GUIDEBOOK 1

The Motor Car Company Co., Chicago, 1907

Not really a photography book pur sang but the way photography is used to guide people on their way is very charming. In the same way, it is very naive because the book is useless after cutting that one landmark tree on page 45, for instance. Nevertheless this book is Google Street View avant la lettre The way the landscape is documented is interesting because of the objectivity: the concept determined what should be in the frame, which results in a very honest slice of the American landscape of the early 1900s.

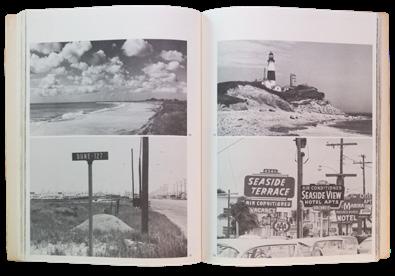

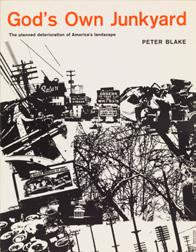

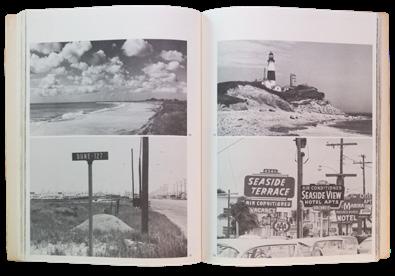

GOD’S OWN JUNKYARD — THE PLANNED DETERIORATION OF AMERICA’S LANDSCAPE 2

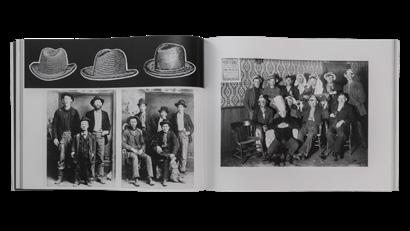

WISCONSIN DEATH TRIP

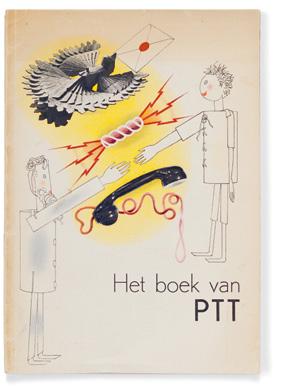

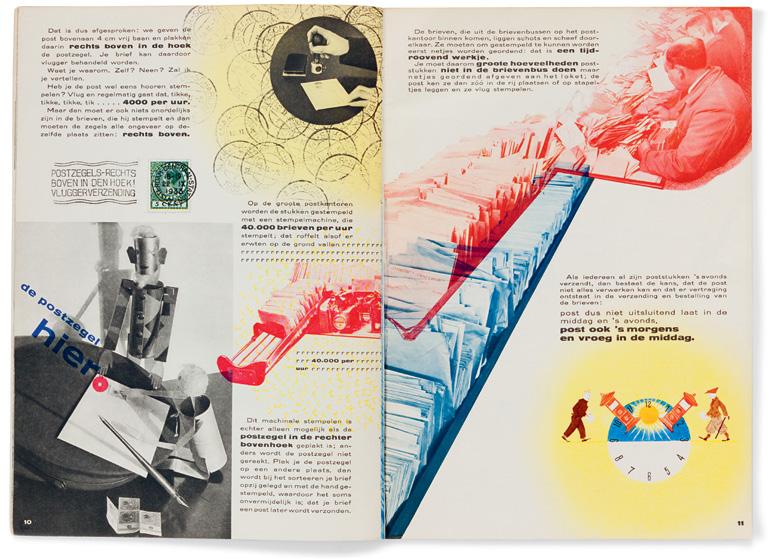

General note about my selection: this selection is my current state of mind; echoes from the near and distant past. When it comes to books, I like to surround myself with yesterday’s voices while I am working with friends on tomorrow’s books. The books are in chronological order.

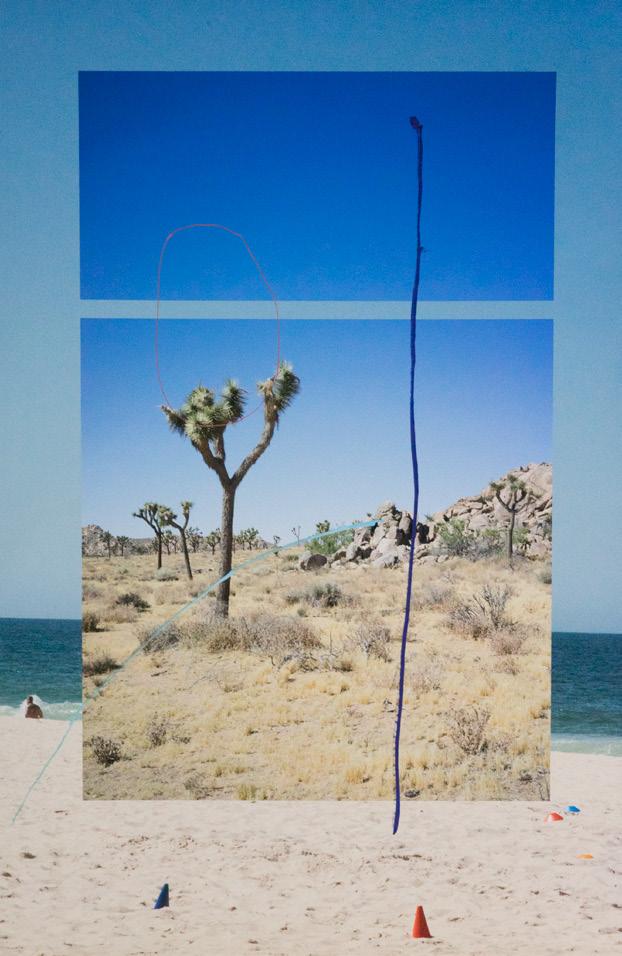

HANS GREMMEN is a graphic designer, and founder of publishing house Fw:Books. He has designed over 200 books, and won various awards for his experimental designs.

Among them a Golden Medal in the BestBookDesignfromalloverthe World competition, Leipzig.

Learning from Las Vegas by Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour from 1972 is one of my favourite books; shaping my ideas and love for the behind the scenes of a consumer driven market, and its effects in architecture and on the landscape. God’s Own Junkyard (published nine years prior) is in many ways the counter voice of Learning from Las Vegas It is a visual pamphlet which takes a stand against the ‘uglification’ of America. A strong example of manipulating found footage into a political statement. This book is a dystopian projection of the future, based on images from the past.

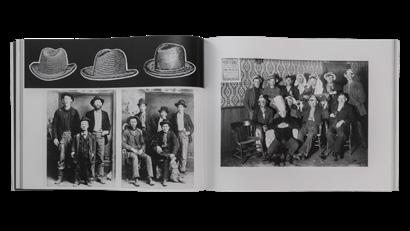

A brilliant book about the shadow part of the explorations of the frontier in the mid to late 1800s. The book contains historic images and is oblong in format. Both of these elements would, in 99 out of 100 times, make a super standard book which would most likely not leave a long lasting impression. But this book goes (way) beyond this issue: the mixing of texts, clippings, and images (many of them engravings) alongside photography comes together in such a good way, that time will never catch up with this book: it remains incredibly fresh and contemporary.

So far the far past.

In my two books from the recent past, picked two young photographers who both grew up in an era where the internet was already integrated into everyday life. This is reflected in their work in which they both balance on the thin line between reality, expectation and representation.

Google Street View is for both an important reference; it is a photographic tool, an incredible ‘new’ source of documentation of the world. Imagine how this will evolve in the next 20, 30, 60 or 100 years: being able to go back in time. At every location you can witness urban and social changes. Both photographers show their interest in the ghost in the machine by working with glitches of the system. This is an interesting and, in a way, a hopeful approach: within a world which seems more and more regulated, there will always be ways to wander, to be surprised and to create your own perspective on top of the image-drivenforced-cliché-thing-called-reality.

12 HANS GREMMEN’S

13 BOOKSHELF

Michael Lesy Pantheon Books, 1973

Peter Blake Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963

It

THIS WORLD AND OTHERS LIKE IT 5 Drew Nikonowicz Fw:Books with Yoffy Press, 2019 Drew Nikonowicz This World and Others Like It This World and Others Like

Drew Nikonowicz

GENERAL VIEW 4

Thomas Albdorf Skinnerboox, 2017

Thomas Albdorf

Skinnerboox

Damaged Utopias

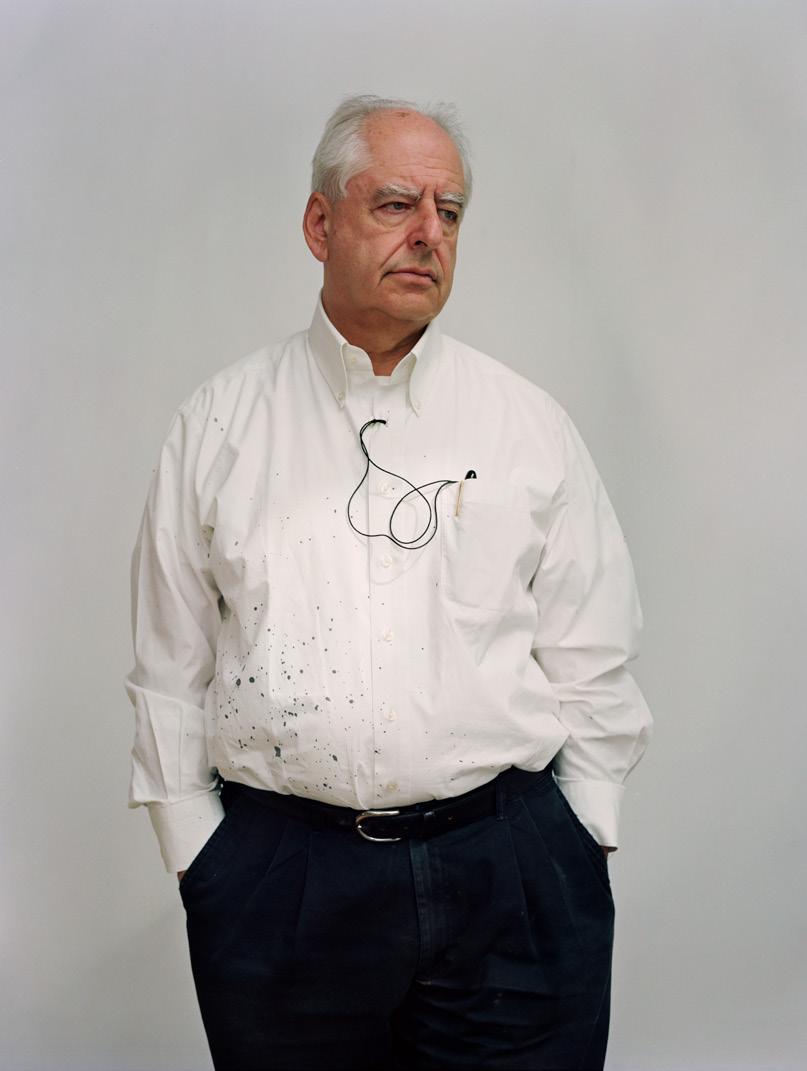

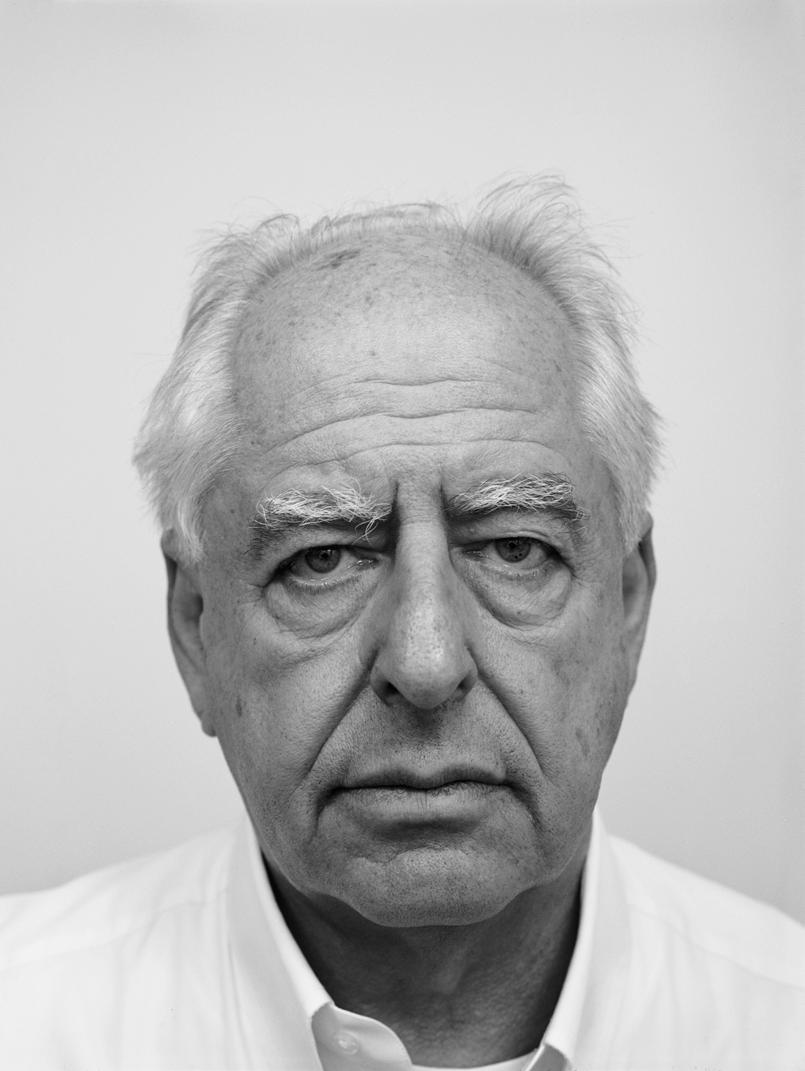

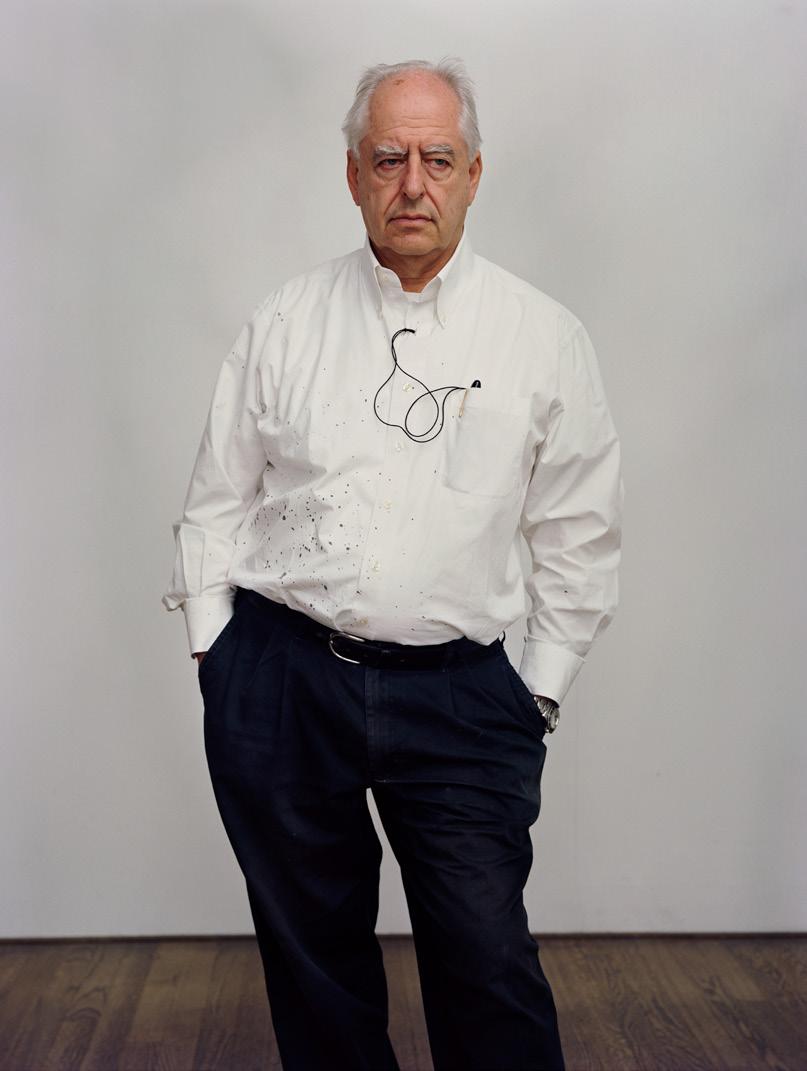

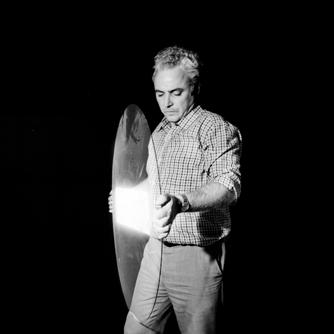

William Kentridge in conversation with Dana Linssen

14 INTERVIEW INTERVIEW

15

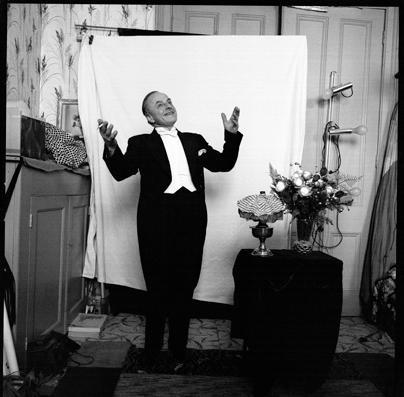

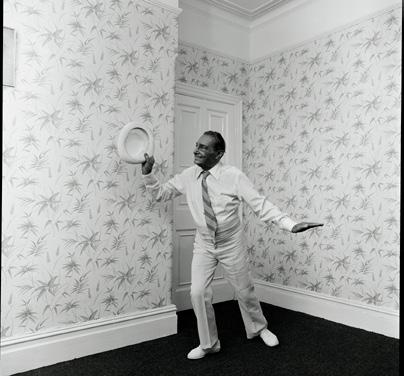

Portraits by Dana Lixenberg

This stratification of images and materials can be found in his sculptures and stage designs as well. But this procedure also reflects his thematic interests: hidden histories, selective social amnesia and recollection and reconciliation. Damaged utopias as he calls them are another of his ongoing fascinations. I spoke with the artist about the importance of inadequacy and provisionality in his works on the eve of the premiere of The Head & The Load at the Holland Festival in Amsterdam, where he was associate artist and presented a cross section of his recent stage works. Simultaneously an exhibition in the Eye Filmmuseum presented his Ten Drawings for Projection, documenting South Africa history of Apartheid and its aftermath and the installation O Sentimental Machine, a love story with a megaphone, in which Kentridge plays revolutionary Leon Trotsky.

DANA LINSSEN: O Sentimental Machine was originally commissioned by the Art Biennale of Istanbul, but I understand that some of the ideas originated in Amsterdam?

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE: While working on the previous exhibition I had here at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, More Sweetly Play the Dance / If We Ever Get to Heaven in 2015 I was already interested in a project on Trotsky in exile. The Eye has a distinction of being a film museum but is also the portal to the Dutch film archives and they showed me some wonderful pieces of archival material that I don’t think existed anywhere else, one of which was an eight-minute public oration that Trotsky gave in French. And my understanding, and I might be completely wrong with that, was that it was recorded on film with all the grand gestures as if he was talking to a crowd of thousands, because he did not get a visa to travel to France, so the only way his message could get to France was in this recorded speech. It is a very unremarkable speech. He doesn’t say anything new. He is so completely caught between wanting to defend what is happening in the Soviet Union and being against Stalin that he is left in a very weak position.

DL: Would you say that is politics at its best or at its worst?

WK: It is politics at its most tragic. But there is still a kind of optimism and hope in his voice in what he is saying that is kind of wonderful. So, it is a time capsule of that damaged utopian moment; even in that period it is already very compromised and damaged. I had already started

making that film in advance, in which I played Trotsky with a paper beard and moustache, and that is why I asked about that Trotsky footage. The film itself is a love story between a megaphone and Trotsky’s secretary. It has to do with the belief in the perfectibility of machines, that was a very strong Soviet and early 20th century idea and is not so far of the contemporary idea of artificial intelligence and machines that will think for us. Trotsky believed in humans being mechanical — if we could just solve that little bit of the human machine called psychology to construct the ideal revolutionary.

DL: One thing that is very characteristic for your work is the layering of images and their seemingly accidental quality. Can we break down the practice, process and the themes of your work from the perspective of accident and layering?

WK: The briefest capsule of my work is that it starts with drawing, with charcoal drawing. Charcoal is a medium you can adjust very easily, with a cloth or with an eraser. And so instead of making thousands of different drawings there are a few drawings in each film which get erased and redone many hundreds of times. And each piece of paper, each drawing is a record of that scene coming into being. Which means that of itself, without it ever having been a conscious decision, what is brought into the films is a sense of the passage of time. Because you see the trace of the previous frames and the erased and the grey erasure of the paper. It is always about inadequacy and provisionality in the sense that it can always be changed, it can always become something else. One has to find a strategy to allow these accidental moments to occur and become part of the work. The themes of that are time and erasure and memory and ghosts of things that are built into the image and the material and become part of the work. When we speak about the Ten Drawings for Projection, over the 30 years that these films have been made, they are not a direct history of South Africa, but they correspond to different key moments, from the end of Apartheid, to the AIDS epidemic.

DL: What came first, the practice of erasing and layering or your interest in the erasure of history, and issues of memory, recollection and trauma?

INTERVIEW

WK: It has to be both. There has to be a physical medium, whether it is charcoal or ink in which to think about the subject. But there is an impulse or a first image and then you rely on the physical work to suggest other images and gradually discover what the film is about, rather than knowing it beforehand. But they are never made with a script or a storyboard which makes them inefficient films, but that is the way that they have to be put together.

DL: You recently started to work in virtual reality and augmented reality too. What does that bring to your practice?

WK: They are generally still analogue performances captured by 360-degree cameras, which you then have to see in a virtual reality headset. It is a different way of making a theatre performance. You, the audience are right in the middle of it. And the voices are behind and around. It is the start of an exploration. I don’t think I’m so interested in deep virtual reality, when we would really recreate a world that looks like a drawing of mine. For now, I’m interested in having the drawing and looking at it from a different perspective. One of the problems of VR is that it is an isolated single person experience. The degree of immersion is frightening.

DL: Given your interest in the romances between men and machines, between drawing and the photographic images, what is VR giving you that other media and art forms haven’t been able to?

WK: Maybe the way scale changes. When you look at a drawing in the world there are many clues that set the scale for you, in relation to your body, or other objects in the same space. One of the things that VR does is that it completely loosens that sense of scale. It does things with that, and with the shocking feeling of presence that makes you aware how much your brain is doing constructing images. That is an ongoing fascination I have, how perception works, the work we do to make sense of images.

DL: Do you ever regret that due to the essence of your working methods most of your work is an irreversible process, that you can’t go back to a pre-existing image?

WK: You can, you just redraw it. You stop the film there and it won’t be exactly the same but that is ok. It maybe won’t be the same in a practical or factual sense, but also not in a philosophical sense, because time has passed. When I went from film to digital I did not change my practice. With animation in the digital camera there is a way that you can look back at what you have but I have a rule of never doing that, so that you are always thinking forward as you did with film, you couldn’t go back. So, it is always thinking the movement ahead and if you got it wrong you got it wrong.

DL: A question that comes forth of this practice is whether you prefer the concept of time’s arrow or time as a stratigraphy?

WK: Deep time I think of as geological strata, but current time either as an arrow if you want it to be immaterial but otherwise it is like a section of books on a shelf and the movement of time through all those pages, but it is a material that you are moving through naturally. No,

actually I don’t think of it as an arrow, because when you’re animating it is always stopped, everything is in a static moment, and accumulatively it gives you the movement of the arrow. So even if you are drawing a line and saying the arrow is moving, it consists of all these static moments.

DL: Can we take this as a starting point to talk a bit more about the themes of your work?

WK: There is a lot of geology drawn into Johannesburg’s history of mining, of going down into the ground. But I was realising I was working in a new film and there are certain sequences when there is a landscape when there essentially is a bird that moves from one side of the frame across to the other and in a way that is just drawing time, it could be anything, it’s just a movement. But the difference is that if you just draw a landscape and you have a static frame and you hold it for five seconds the time resides in the viewer. They are giving it the five seconds of watching. If there is some movement in it, suddenly the movement goes into the image. A lot of the drawing I have done in the last 10 years is on top of books. That has to do with the previous history that is being reinscribed. The same drawing on a blank sheet of paper or in a book has a different quality, partly because of the absorbency of the paper and partly because of the sense of grid of knowledge that lies underneath. The context becomes part of the drawing.

DL: When you are drawing over your own work you are actively erasing, so could we say that when you are drawing over a pre-existing text you are actively obscuring?

WK: That is a question that I would never ever ask myself in the studio. I think it is a belief in the fragment, and knowledge or meaning are always being made from a provisional combination of fragments, put together in a certain way to give a coherence we hope it holds. And when the fragments are rearranged in a different order the same information can give two different meanings. Which is then about the activity of making sense of the world. The collage makes you aware that you are making it coherent, because it wasn’t coherent to start with. The work in the studio is the demonstration of that. Because that is what happens for every artist in every studio, the act of creating is in itself a demonstration of how to make sense of the world.

DL: And when we expand this to the way you are not only returning to the history of South Africa in your work, and its interconnectedness with European histories of colonialism and the Holocaust, how do these themes create these tectonic shifts in your work, and keep erupting?

WK: Part of it has do with a set of images that sits in people. So, there is one film I did, The History of the Main Complaint (1996) where we see Soho, one of my returning characters, behind a curtain in a hospital. But a young black South African man told me: it is so fantastic that you’ve drawn a shack, with a corrugated iron roof. So, for him it was completely a drawing of a shack with a bowl of water outside and he loved it for that. Soho is always in his pinstriped suit, and some other viewers say: It is so interesting that Soho is wearing these striped concentration camp pajamas. Certainly, I was not drawing either of those. I think it is because of the roughness of

16 17 INTERVIEW

William Kentridge’s oeuvre is a landscape of layers: his animation films are produced during a process of drawing, erasing, and redrawing, putting one image over the other, often using existing backgrounds such as books, maps or photographs, creating visual sediments of time.

the drawings and their ambiguity which allows people to link in to images that they already have. I think that is what we always do, trying to make sense of things we don’t quite understand as if they might mean something we have seen. There is also a belief in the ability of other people to make imaginative leaps to understand other contents, even if they misunderstand, even if they misconstruct it. My intentions are always the least interesting part of it.

DL: But even without the artist’s intentions… if I as a spectator have a certain set of images in my mind, then you as an artist will have a certain set of images in your mind too that are returning in your work.

WK: Cultures are most lively when they are misunderstood and appropriated. Everything is enriched by people from outside the tradition. And the one thing that Apartheid taught us in South Africa was the destructive nature of identity politics. And I know that identity politics has become very important in gender relations and racial relations, but what I see each time is the damage of essentialism. And the falseness of trying to go back to an imagined tradition. Every tradition is a construction, the more desperately it is hung onto, the greater the falsity of it.

The only hope is a kind of bastardism, when things from different traditions are taken and meeting, and overlapping, and this is just a lesson from South Africa. Take someone like Gandhi, whose pacifist resistant politics relates back to a kind of Indian spiritualism of the Bhagavad Gita. But the last thing he got it from was from being a good Indian mystic. He got it from conversations with a Jewish South African architect he befriended who got him to read John Ruskin and Madame Blavatsky who used this kind of meta-fake Indian mysticism to justify her talking to dead people and through that he got back to the Bhagavad Gita and to Sanskrit and it is through that kind of mixture and these very circuitous causes that he arrives somewhere.

DL: Your sympathy for cultural appropriation could have been undisputed 20 years ago but is a controversial issue today. How do you discuss this with the new generation of South African artists that you work with, for instance in the Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg, where you support experimental, collaborative and cross-disciplinary arts projects?

WK: There are a lot of young black artists that are not interested in working with a white established artist. There is a much greater kind of separation than there was 20 years ago. But the people that I do work with understand the richness that comes from working with what comes from the meetings of different traditions, with stories and dances, and large parts of their histories that I know about that they have no idea about. In the opera The Head & the Load there is a lot of history that would be difficult to separate and say this is white history and this is black history. The whole point about colonialism is that everyone becomes complicit and the whole nature of the First World War was the schizophrenic desire to resist being part of the war and the demand to be part of it. And to take that and understand the real messy implications, so yes I am sure some people will hate the work for that, and with some people it will be possible to have a discussion about it and we also understand that rage is a current phenomenon and to even begin to have a discussion is to give in to the discussion. So I do understand that, but then there is nothing to be said.

DL: The Holland Festival opening production The Head & the Load about South Africa and the First World War is in fact the result of a very communal and collaborative process, could you describe how that went?

WK: We had a workshop of about 45 performers, of about 60 people in all. The music that comes out of the two composers Phillip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi is sort of a mixture between European high modernism and African cultural tradition. The form is a mixture of Dadaism and dance from the north of South Africa. It

18 19 INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW

Every tradition is a construction, the more desperately it is hung onto, the greater the falsity of it.

was a larger scale than other ones that I have done, but it is no different from a lot of theater that I have made in South Africa over the years. I’ve worked with many of the dancers before in the Centre for the Less Good Idea, or had seen them at work in different projects, the composers suggested musicians. The design team are people I have worked with for years.

DL: What do you recognise in them? Is it the same desire to reinvent an art?

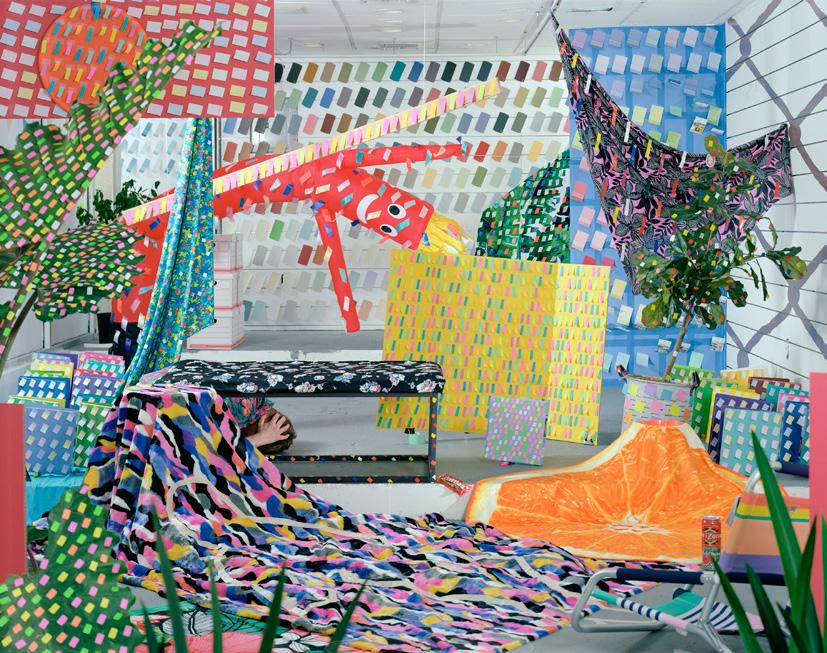

WK: I think so. In South Africa there is a huge pressure to write the political essay before the work is done. To say what the outcome is going to be. The Centre for the Less Good Idea is a release from that. A lot of the work we do is very political, but it is done without an agenda. And I think people are open to see what will emerge instead of what we will say in advance what it will mean. As artists we understand the gap between what happens when we are making something and the essay that either before or after tries to justify that. Oftentimes the things you make don’t say the things you expect them to.

DL: You just used the word ‘political’, how do you understand that term in relation to art?

WK: I understand the provisionality, the ambiguity, and paradoxes of politics. All attempts to make a work of political clarity are falling into the traps or authoritarianism, every stake certainty carries a big stick and beats everybody else into silence. So, the more ambiguous, the least clear, the most interesting they are. Paradox and ambiguity are central to my work, because they are often seen as the edges of knowledge that are in fact central to how we understand the world. Thats comes from my biography and my experience, from the work in the studio, from having seen all the political changes. At the end of Apartheid, it all seemed so clear, and it all seems so messy now. In a sense South Africa is a model for the rest of the world. Not a successful model, but a prescient image where the formal economy gets smaller and smaller and the informal economy where people have to get by and improvise, and informal settlements become larger than the highways, where you can divide the world into the 75 people that can get on Elon Musk’s rocket to Mars to start a new colony and the 7.5 billion that won’t. In that sense the disfunction of the society is kind of a key to where we’re going.

All images © Dana Lixenberg, 2019

WILLIAM KENTRIDGE is internationally acclaimed for his drawings, films, theatre and opera productions. His practice is born out of a cross-fertilisation between mediums and genres, and responds to the legacies of colonialism and apartheid, within the context of South Africa’s socio-political landscape. As an opera and theatre director, Kentridge has also collaborated with the Metropolitan Opera in New York, the Royal Opera House in London, and the Holland Festival in Amsterdam. His work has been featured in numerous solo and group shows, including Documenta, Kassel; Tate Modern, London; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Venice Biennale, and presently in exhibition at Eye Filmmuseum, in Amsterdam.

DANA LINSSEN is a philosopher and film critic. Since 1997 she has been working as a film critic for the Dutch daily newspaper NRC Handelsblad, and for more than 20 years she was the editor-in-chief of the Dutch independent film monthly de Filmkrant. In 2009, she won the Louis Hartlooper Award for Film Journalism. Dana has worked as a jury member for various festivals, including Berlin International Film Festival, Venice Film Festival and Cannes Film Festival.

DANA LIXENBERG is a photographer and filmmaker. She studied Photography at the London College of Printing and at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. Dana pursues long-term projects on individuals and communities on the margins of society. She lives and works between New York and Amsterdam. The series Imperial Courts 1993–2015 was awarded the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize in 2017.

20 21

INTERVIEW INTERVIEW

All Work a

by Elisa Medde

by Elisa Medde

23 THEME TEXT

No Play 22 THEME TEXT a ghost in sharp relief , from the series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40×28", 2019 © Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

nd

The moment we start working on a new theme for Foam Magazine normally begins with a blank board and a word. We write down a word, and then we press play. We start talking, and writing down all the words that appear to be somehow connected with the master word.

In a process very similar to cell division, a map, a word bubble appears, made of many different words, each with its own identity and projecting each towards a different direction. As if that master word was an entity in fieri, made by a semantic core that erupts from as many particles as it is made of: a dual process of creation (a cell that starts dividing and by doing so expands and enlarges its limits, its physical boundaries) and expression, with words like pollen erupting from a ripe plant on a windy day. It’s a tricky play with no fixed rules: easy to get carried away with spin-offs and side bubbles, or overexcited with hay fever. It’s a free play, that we try and struggle to structure and tame into a strong game – by means of large doses of improvisation. A big house of cards based on two very strong founding pillars: creation, and expression. Which is exactly what the core essence of the noun Play is based on, making it all very meta and kind of dizzying. In fact, what we mean when we use the word play is a range of activities, with the purpose of leisure, enjoyment, pleasure: it is a recreational activity. To play means to act, perform. Also, to play means to act creatively. And also, to play means to create.

On Play, its functions and meanings for human and non human children and adult specimens, quite a few theories have been elaborated. Since around 1850, we can count at least seven classic (or old) theories – Surplus Energy, Relaxation Theory, Pre-Exercise Theory, Recapitulation Theory, Growth Theories, Ego Expanding Theories – and four current theories – Infantile Dynamics, Cathartic Theory, Psychoanalytic Theory, Cognitive Theory. These theories all disagree on the majority of positions and facts, but yet all have one assumption in common: that creativity plays a fundamental role in whatever the reason is that we play, and that it has a very deep, thorough effect on our brain and therefore in our emotional and social intelligence.

The Oxford Dictionary also reminds us that to Play means to ‘engage in activity for enjoyment and recreation rather than a serious or practical purpose’, while as a noun stands for ‘Behaviour or speech that is not intended seriously’, often ‘Designed to be used in games of pretence; not real’. In our cognitive map, Play belongs to the universe of the unreal, close to the galaxy of magic and very much influenced by the magnetism

of absurd and paradox. A dimension normally belonging to children, and unrelated to anything remotely useful. Unless we talk about organised play – that is –game. As Play accommodates structure, rules, architecture and especially purpose it exponentially becomes pertinent to the world of adults too. As adults, we do keep playing ultimately because it makes us feel good, it’s satisfying. It is liberating – we notice it more when we lack it, rather than when we have it in our frantic daily routines. The adult-friendly versions of Play go under the nouns of sport, performance (musical or theatrical), video games. Arts.

So what kind of game are we playing here? And why? The link between Play and the arts, all of them and specifically visual arts, it’s an easy one, stemming from that founding pillar that holds the weight of so much we are concerned with: Creativity. Creativity moulds, stimulates and directs play in so many different ways they are countless. But it needs a trigger, that we call Inspiration. And inspiration is indeed a game changer. Abundant in children, becomes more scarce, complex and precious in adulthood, frequently teaming up with Motivation.

24 THEME TEXT 25 THEME TEXT

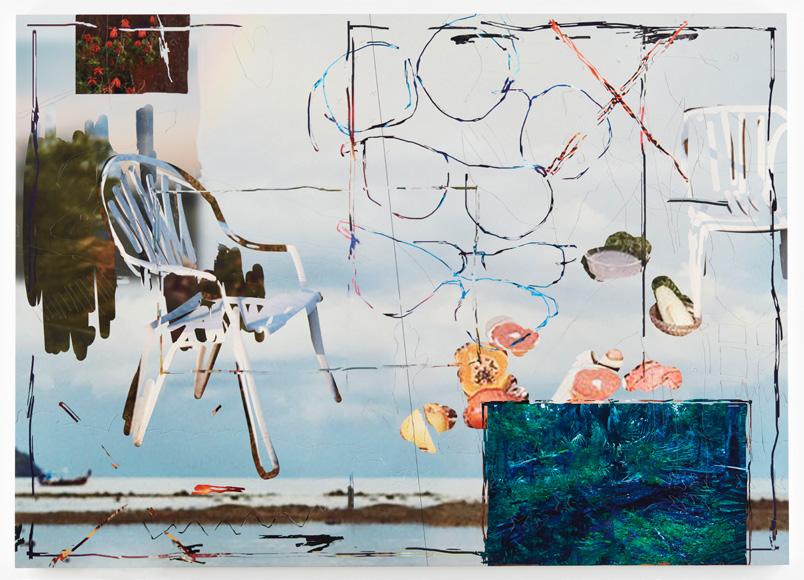

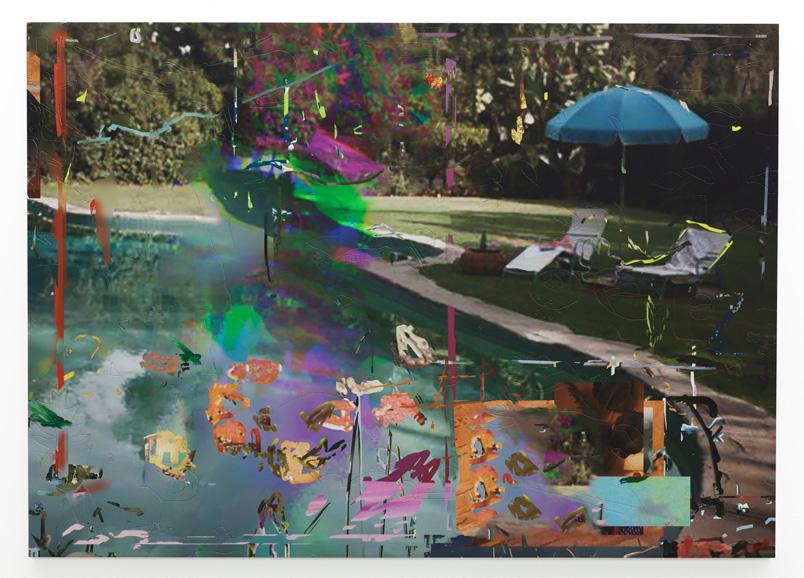

finally somewhere to sit , from the series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40×56", 2019 © Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

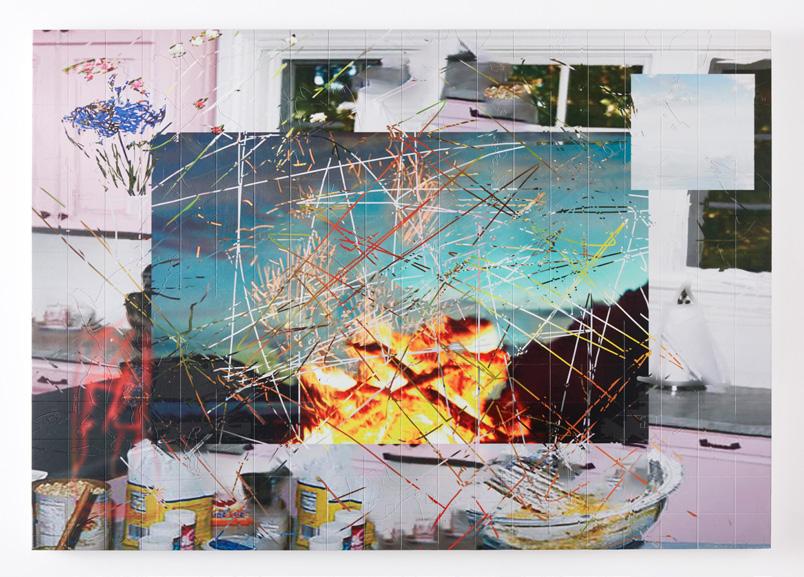

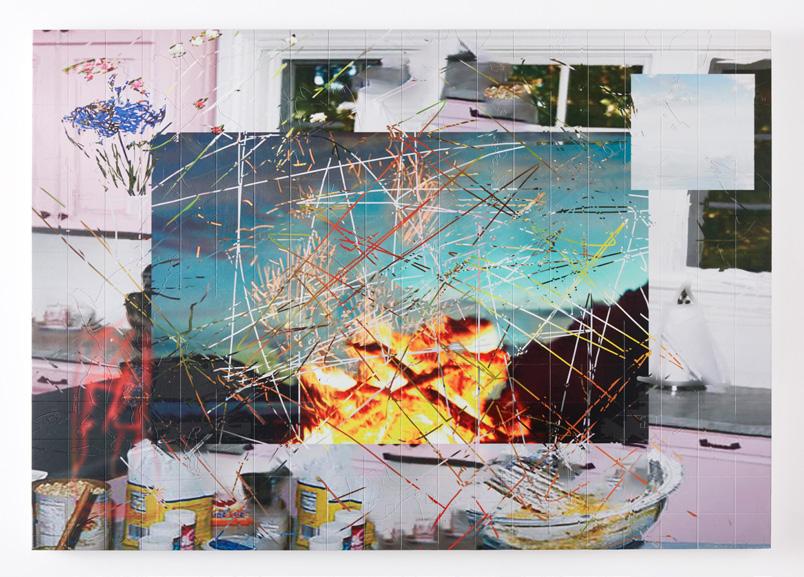

maybe we’re on fire , from the series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on carved hand-wood panel, 40×56", 2019

© Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

maybe we’re on fire , from the series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on carved hand-wood panel, 40×56", 2019

© Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

The creative process in adulthood often becomes a complicated one, drenched in struggle and horror vacui (especially the less we engage with it) until something unties the knot, plays the trick, and the magic begins. Everyone has their very personal and different relation with the creative act and the dynamic of it unfolding, but it is safe to say that the creative act releases a very strong and deep sense of liberation, a relief. Once this happens, and one finally starts playing the game, the possibilities are infinite.

If all artistic acts are playful, in a sense, some are more concerned and conscious than the others. If it can be said that any artist, or specific body of work, barely engaging with the medium itself is playing with it, there are plenty of cases in which Play becomes more central, sometimes crucial, to the core purpose of the work itself. It is one of the most important powers of art, to be able to catalyse, express and put the spotlight on acts and aspects that are absolutely central and fundamental in our everyday life – we are just too busy to see them, or feel them. Playfulness, leisure and performance all have a crucial role in building our personalities and our communities: we play and assume roles both on a personal and group level continuously, assuming stances and positions based on the extent in which we play by the rules or break them. Play is also one of the fundamental acts that allow us to discover the world. For babies, to play is to learn how things work, how we behave and interact and how we can solve problems – and this is an imitation game in which we all play a part.

Exactly the same attitude, can be argued, fuels our scientific thirst for experimenting the enchantment towards the magic of discovery and the frustration of failure. Science is often perceived, rightfully, as a very controlled form of play but it is one that requires an incredible amount of creativity to start with – to imagine what is not there yet, or perceive how processes might work and could be hijacked. Play is also crucial to inform how we perceive and experience reality and the events that create our everyday life. But also, how we create a new, alternative reality we might finally be able to control. Play also investigates the powers at play in our society and its subversive, irreverent potential: it will be a laughter that will bury you all. The spectrum includes also the healing power of play, the relief that comes from unlocking those hidden parts of our self through improvisation, rituals and the theatre of the absurd: a psychomagic act, as Alejandro Jodorowsky defined it.

When looking at photographic practices through this lens, each body of work amongst the ones presented in the issue of Foam Magazine you are holding in your hands assumes a specific role, performs its part in the precious ‘bag of seeds’ that we wish each issue of the magazine to be. After all, to play also means to willingly make room for a fertile ground that triggers and allows

more creativity – leaving us wondering if any of those theories mentioned before had a close look at the addictive nature of play. To Play, moreover, goes hand in hand with ‘to craft’. This is also a very important component of the artistic process, but also of the ‘activation’ mentioned above – to press play. This activation can also be seen as a fertile act that allows us to deal with incredibly difficult things such as tragedy, violence and oppression. Through art we can expose them, expose the power structure that allows their existence, and fight them – while at the same time we can finally start healing from them. This is the case, as an example, of the work of Rosana Paulino that we present here with a portfolio titled Atlântico Vermelho / Red Atlantic. The features that lie at the core of her artifacts – the craft itself, the manual labour involved, the reappropriation of images and symbols, and all the tools she employs to speak of her themes – slavery, diaspora, oppression and violence against women to only name a few – take the viewer by hand into an experience that resembles a ritual. A grieving ritual in which the evil, the pain and the suffering are faced, exposed, confronted, and then incapsulated in an act of love and healing.

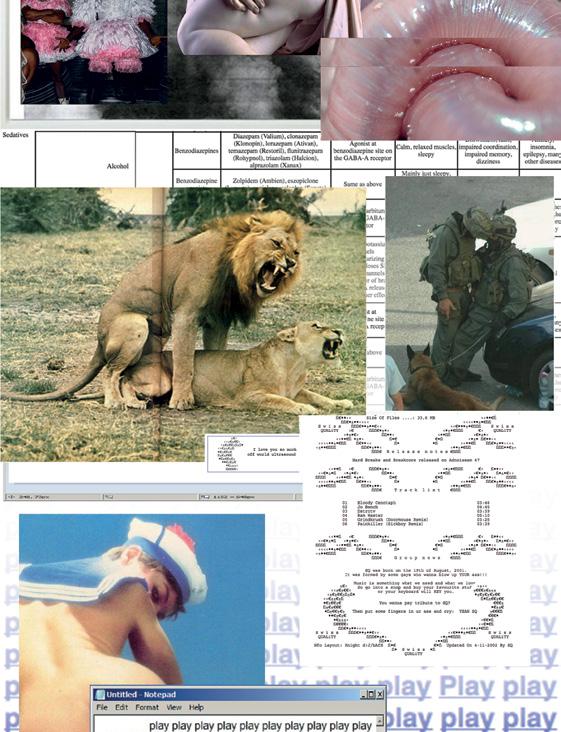

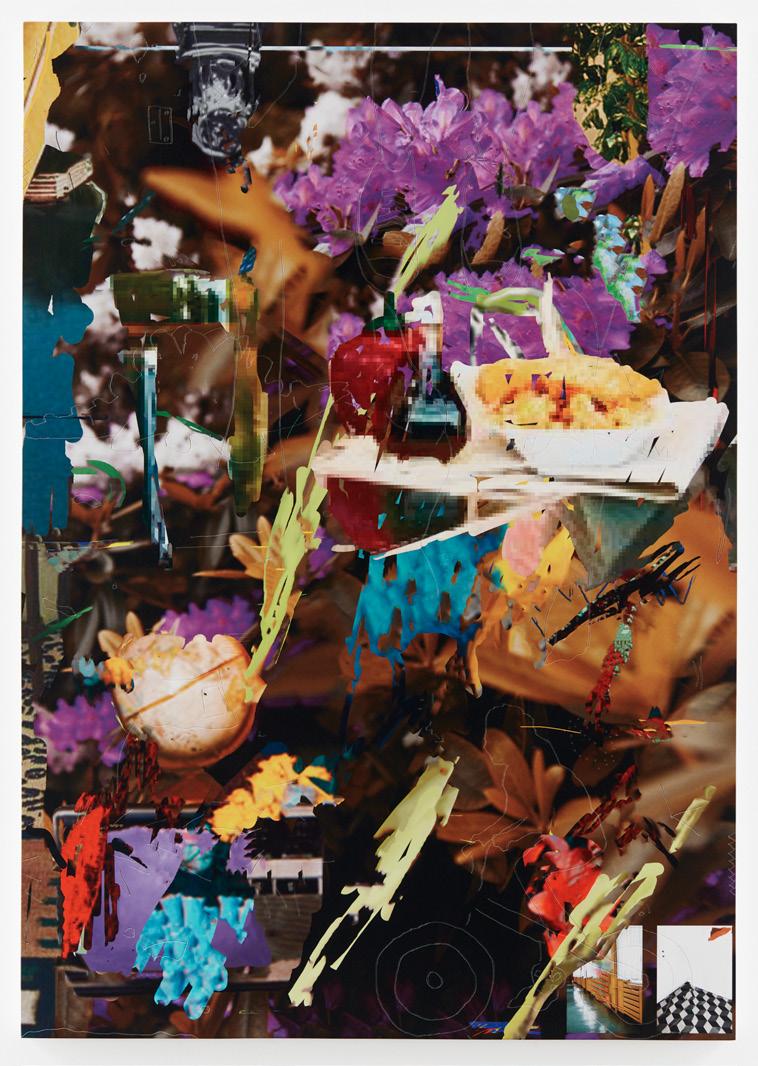

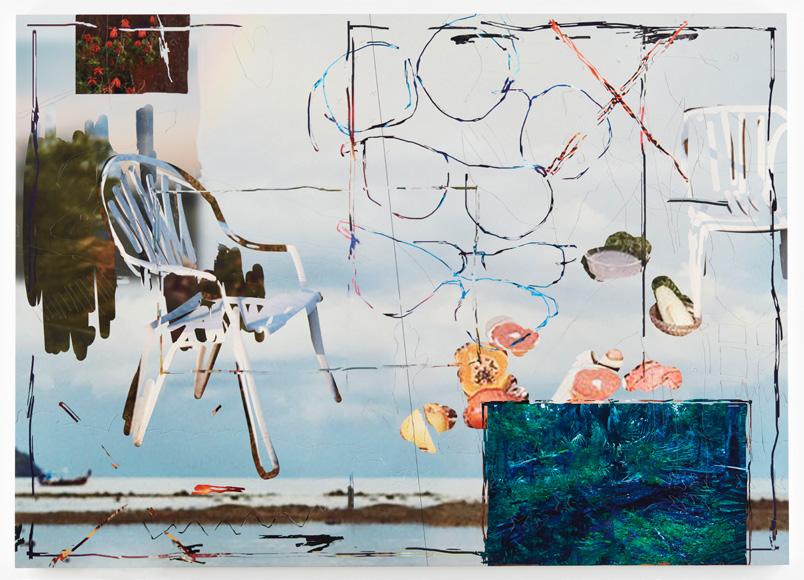

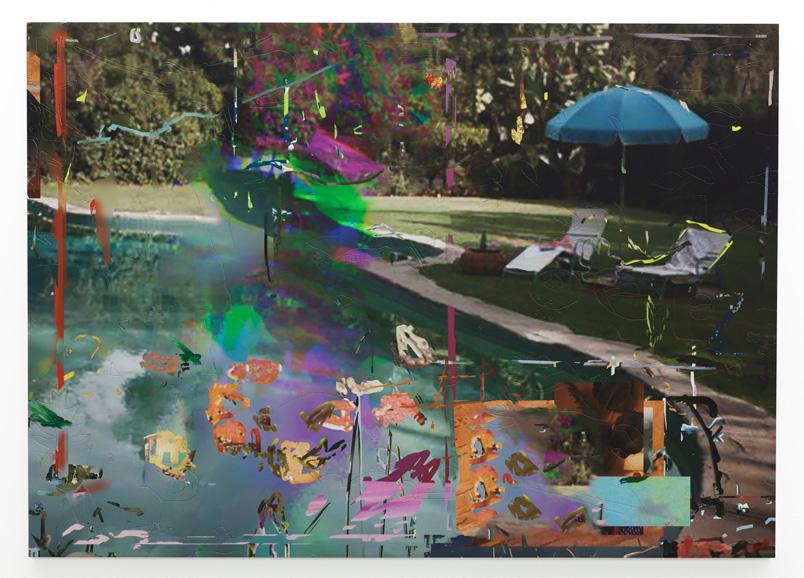

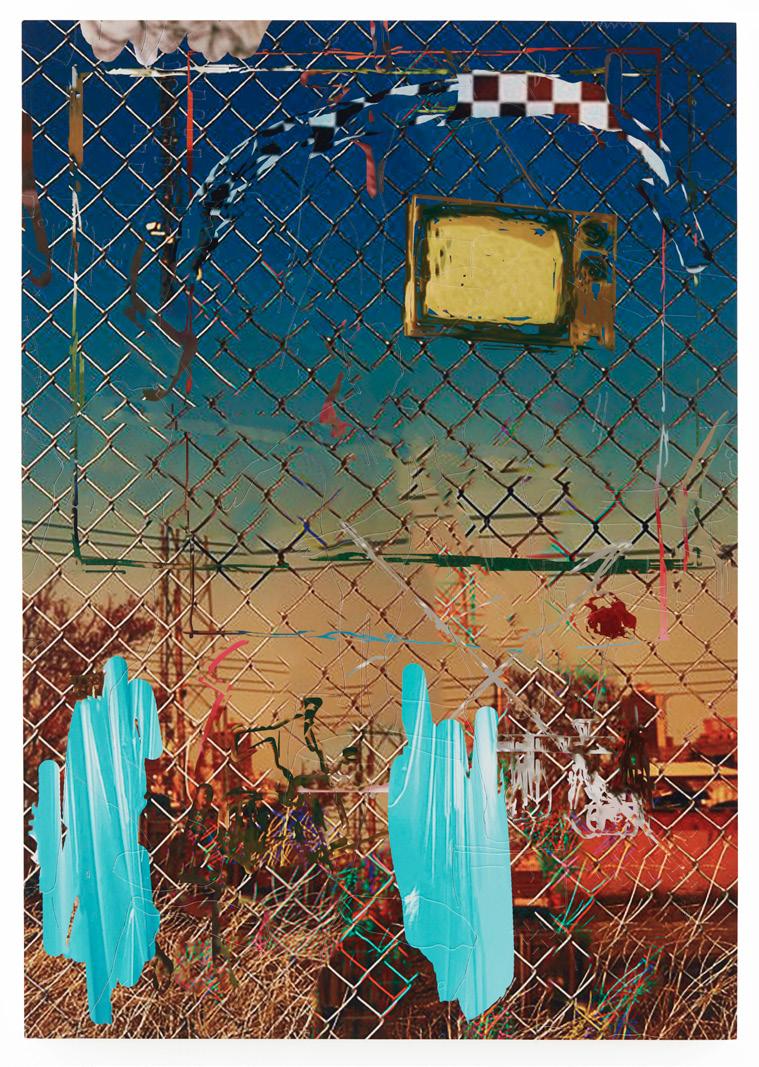

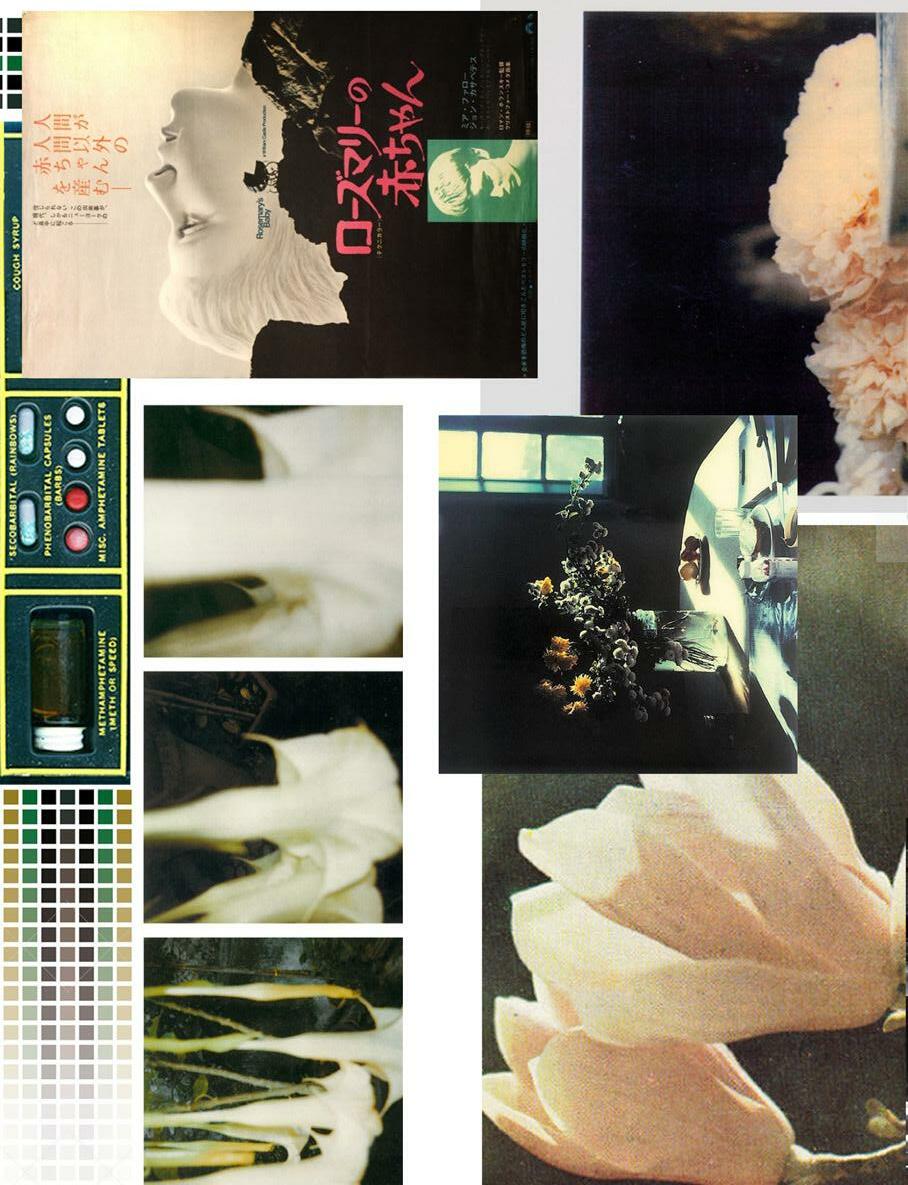

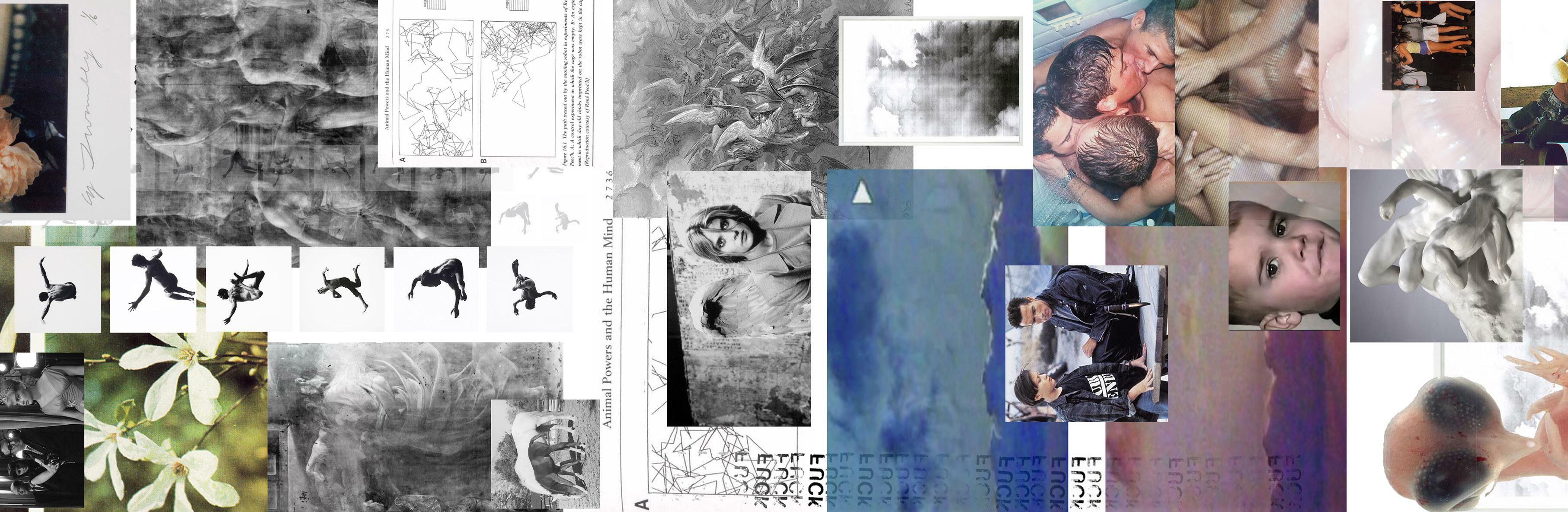

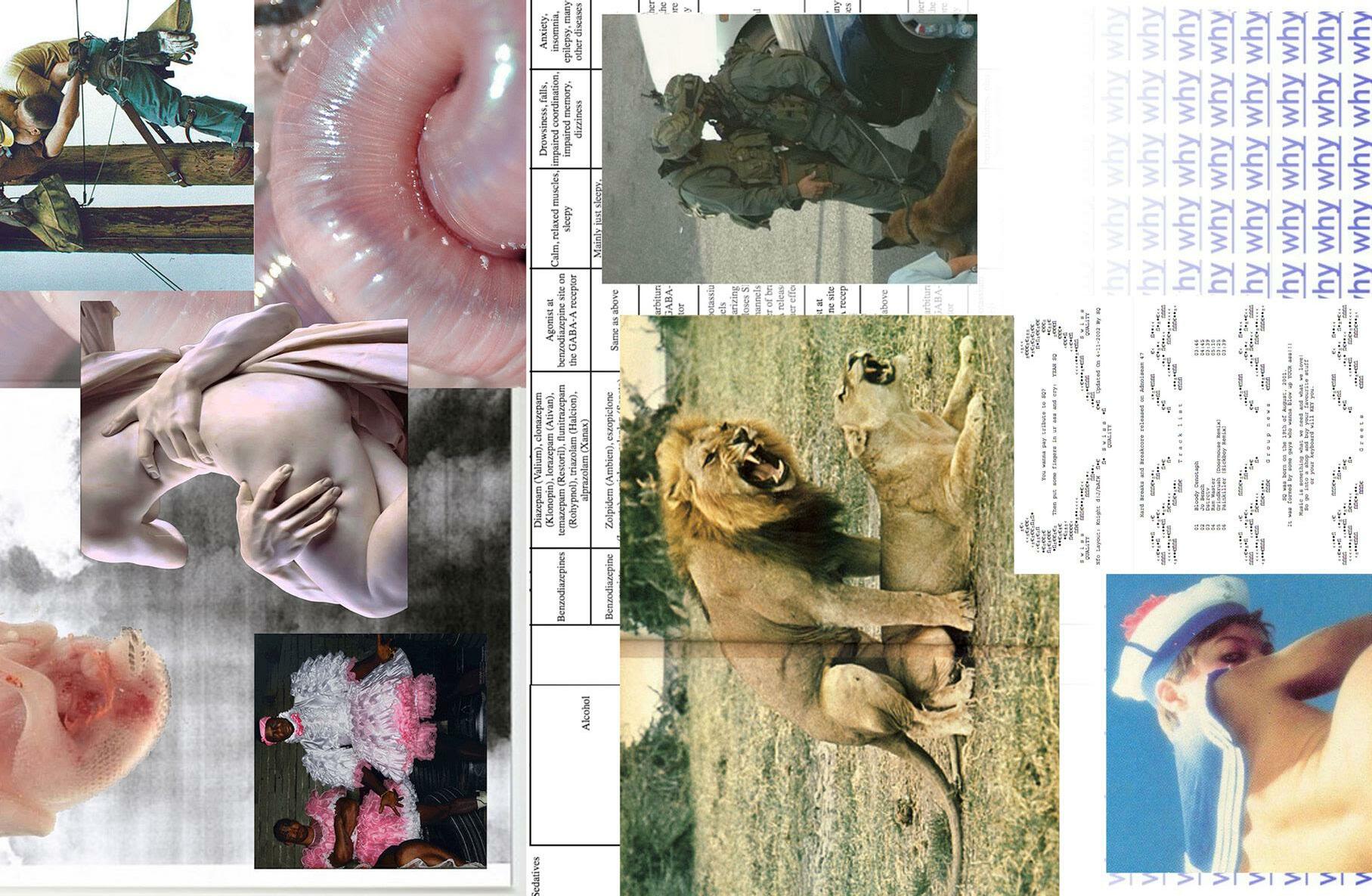

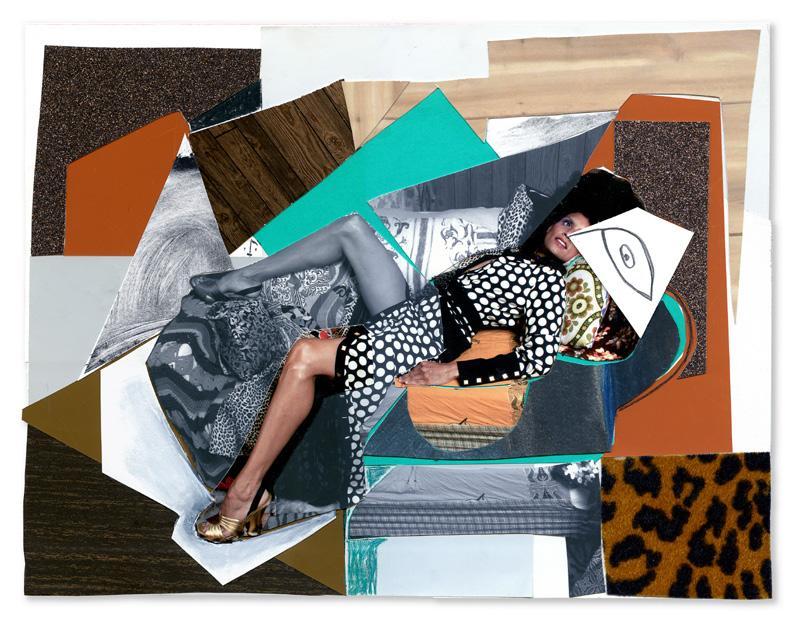

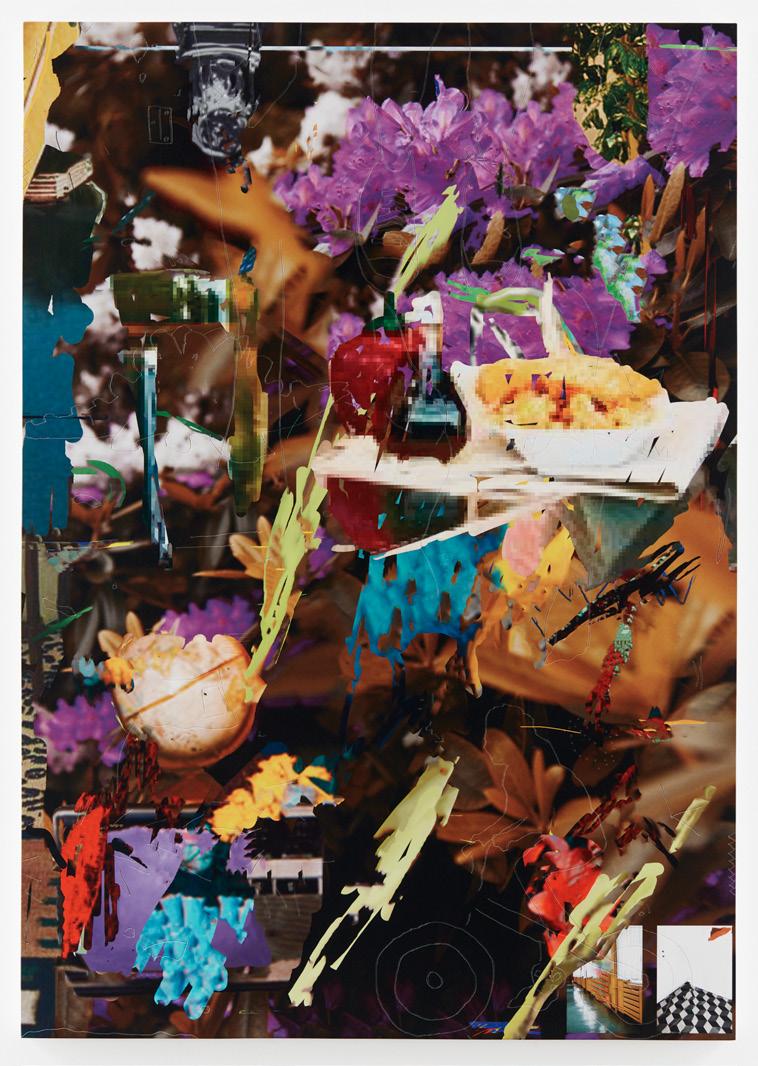

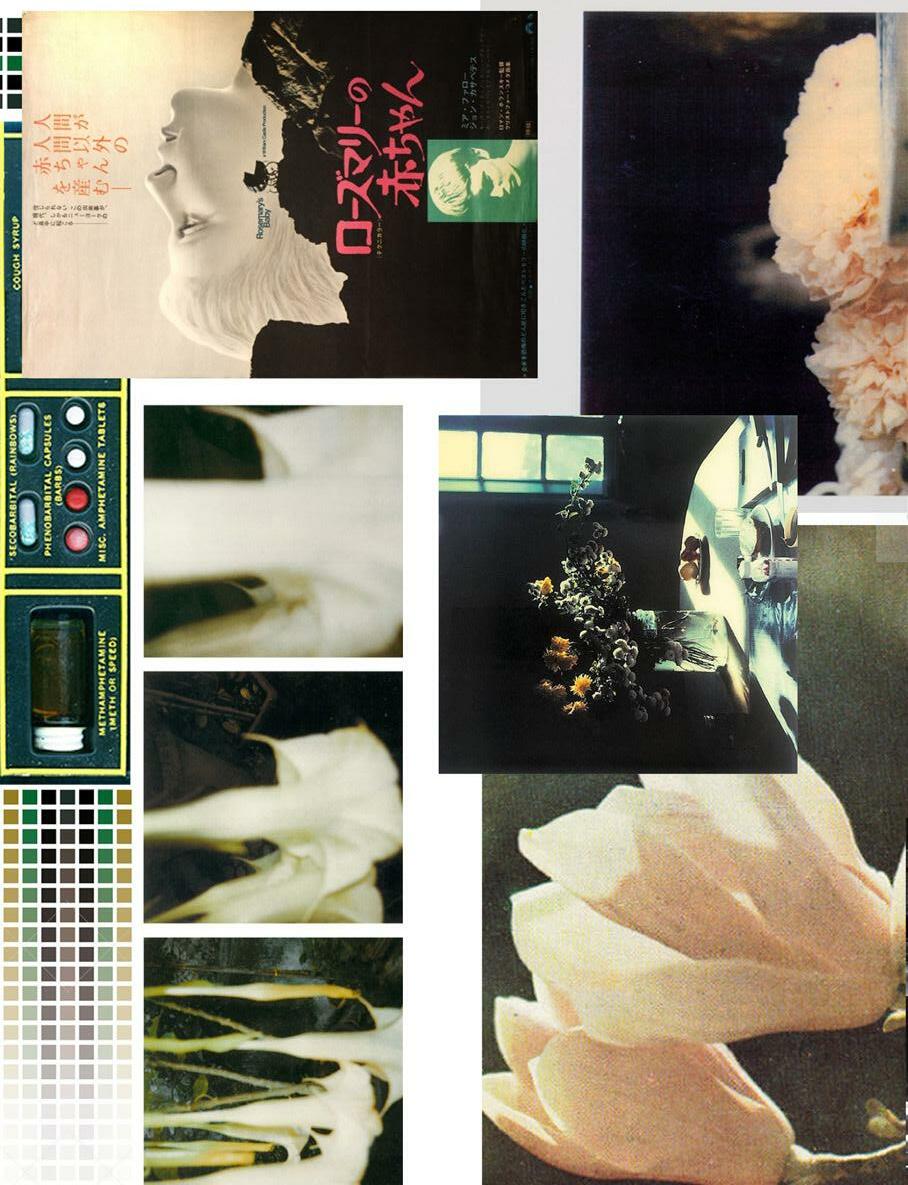

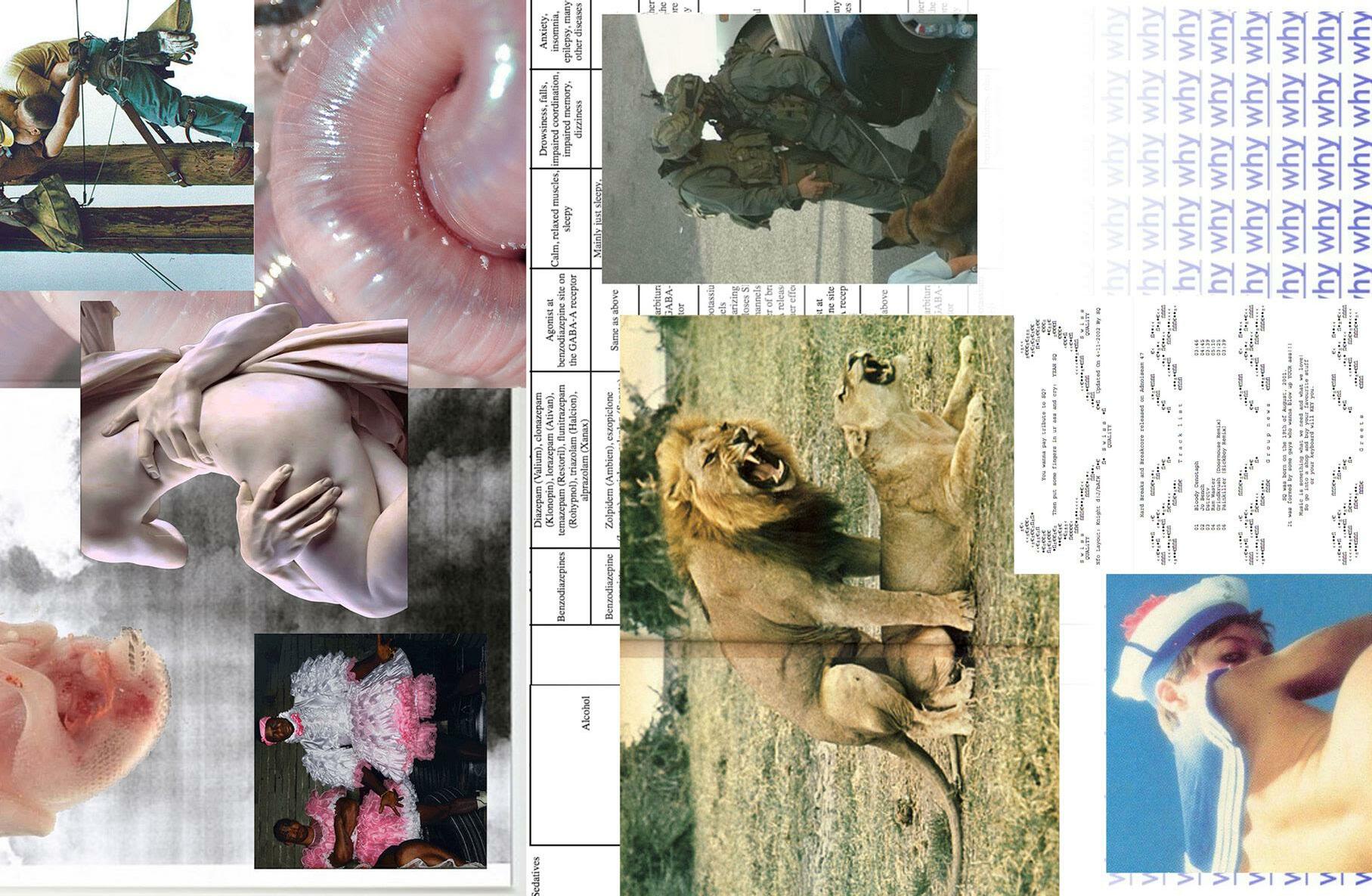

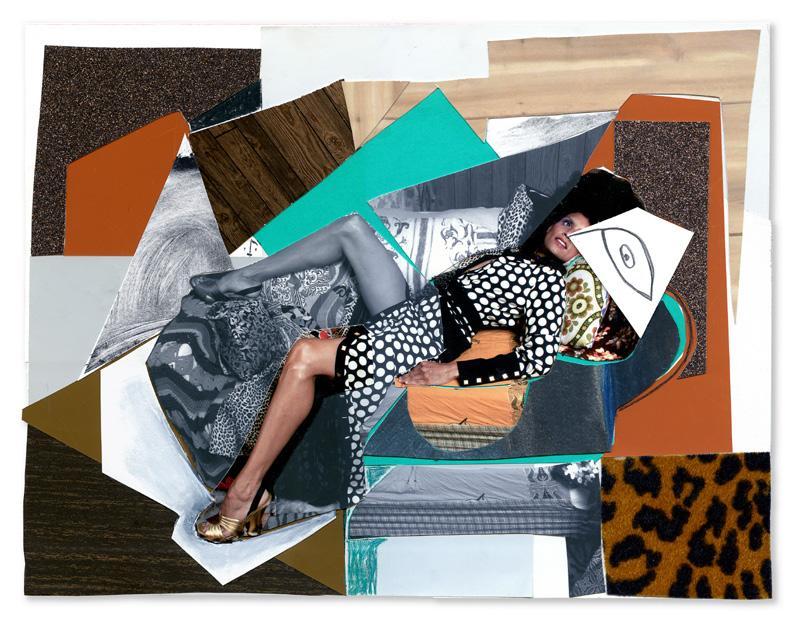

Kay Kasparhauser’s portfolio is a remastered close up of her project @wip.tba.001. Living as an in-progress Instagram feed, it’s an immersive experience on the pure nature of images, their connections and our neural pathways. She plays and engages with, and manipulates visual elements coming from the most disparate sources, from paintings to sculptures to movies and more, creating narratives that are both immediate and

28 THEME TEXT 29 THEME TEXT stay cool , from

series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40×56", 2018 © Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

Play is also crucial to inform how we perceive and experience reality and the events that create our everyday life.

the

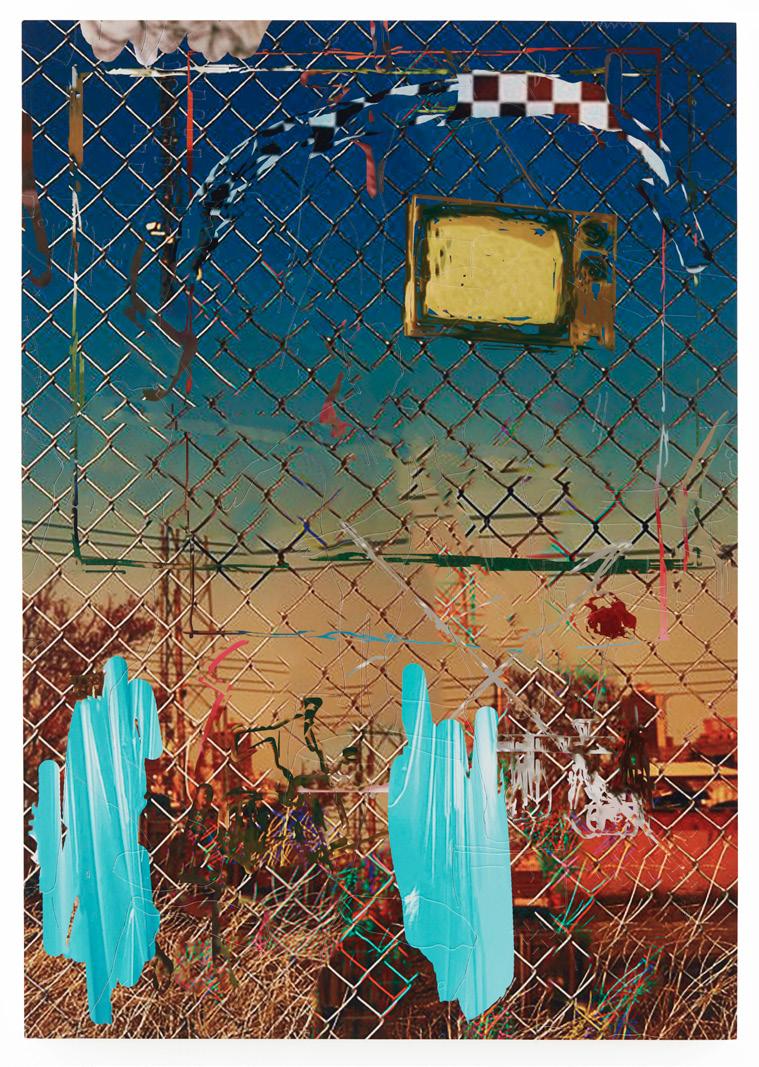

they will not die , from the series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 28×40", 2018 © Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery ↘ 31 THEME TEXT

looking for poison frog , from the series psychic pictures , acrylic and UV print on hand-carved wood panel, 40×28", 2019 © Zach Nader, courtesy of the artist and Microscope Gallery

articulated – with the devil hidden in the details and playing with ghosts. Each plate has also its own reason of being and is a micro narrative, unfolding in captions. A unique being with multiple personalities that acts as a modern Atlas of Mnemosyne.

30 THEME TEXT

Ghosts are nothing more than traces, presences, carved in the memories of what was once. In 1924, art historian Abu Warburg started to work on his seminal (and unfortunately unfinished) work called the Atlas of Mnemosyne. This consisted in a series of 79 thematic plates (of which only 69 were effectively realised) in which Warburg arranged and rearranged black-andwhite photographs reproducing art-historical works and cosmographical images. In his words, it had to be a visual map ‘On the influence of the ancient world. This history is magical – to be dissembled. A ghost story for the full grown up’. Influenced by the studies on the nature of memory and its ‘physical’ location in the brain by Richard Semon, his aim was to ‘map the afterlife of antiquity’, that is ‘how images of great symbolic, intellectual, and emotional power emerge in Western antiquity and then reappear and are reanimated in the →

art and cosmology of later times and places, from Alexandrian Greece to Weimar Germany.’ Called phatos formulae (phatosformeln), the pathways illustrated in the panels formed a cartograph to investigate the origins, the histories of western visual culture and the movements and migrations of its elements through the centuries and cultures. A visual association game based on very rigid rules, the Atlas of Mnemosyne sought also to playfully create a method through which we could practically see the invisible threads that connect images, so to create a big puzzle that could ultimately help us understand something about our visual universe, and ultimately about us.

The images accompanying this text are made by Zach Nader, and are part of a series called psychic pictures. His work stems from Flusser’s idea that images both program and are programmed by our world in an endless feedback loop. Each image is a wood panel that is gessoed and painted white, carved into, and then printed over with a UV printer.

Everything in this set of work is made from existing advertisement imagery, imagining ‘these idealized situations and bodies combining, looping through our world, crumbling, and creating new things’. Again with his words, ‘think of the carvings as chunks of images, in this case also idealized situations and the place where I make the body visible again – as more of a ghost. They require the viewer to consider their distance and relationship to the object as they shift from appearing as a faint line into a physical mark’.

It is this physical mark making, whether through imagination or photography, that allows us to visualise play and its performative elements. Through learning and creativity, we can discover various ways of pressing Play, triggering our sense of discovery and learning and fueling our appetite for adventure. Play is also a call to arms: a resistance against passive entertainment, and the commodification of our attention. An ode to the energy sparked by a new adventure about to start, and the infinite possibilities it could unfold. WAAARRIORS!

32 THEME TEXT * The Warriors (1979)

COME OUT TO PLAY-AY! *

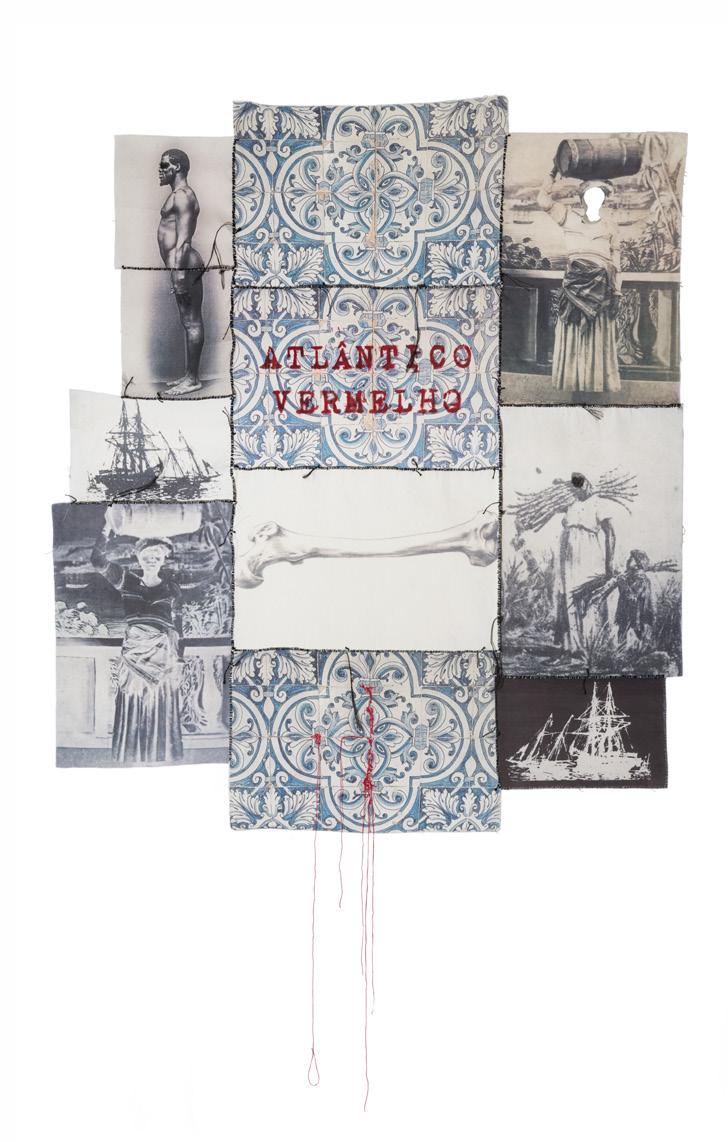

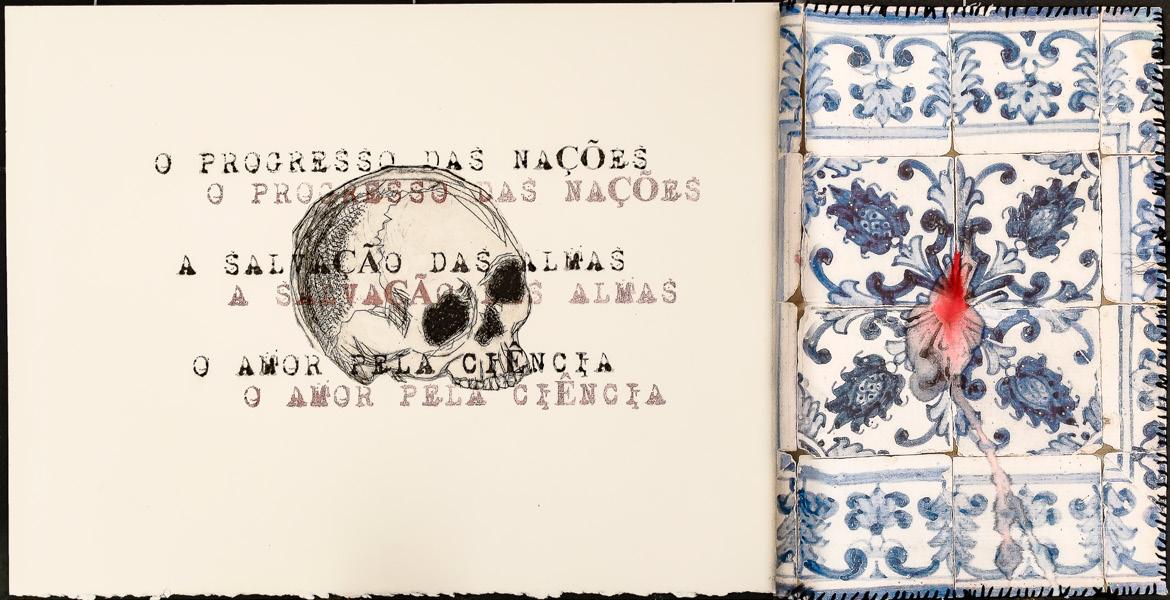

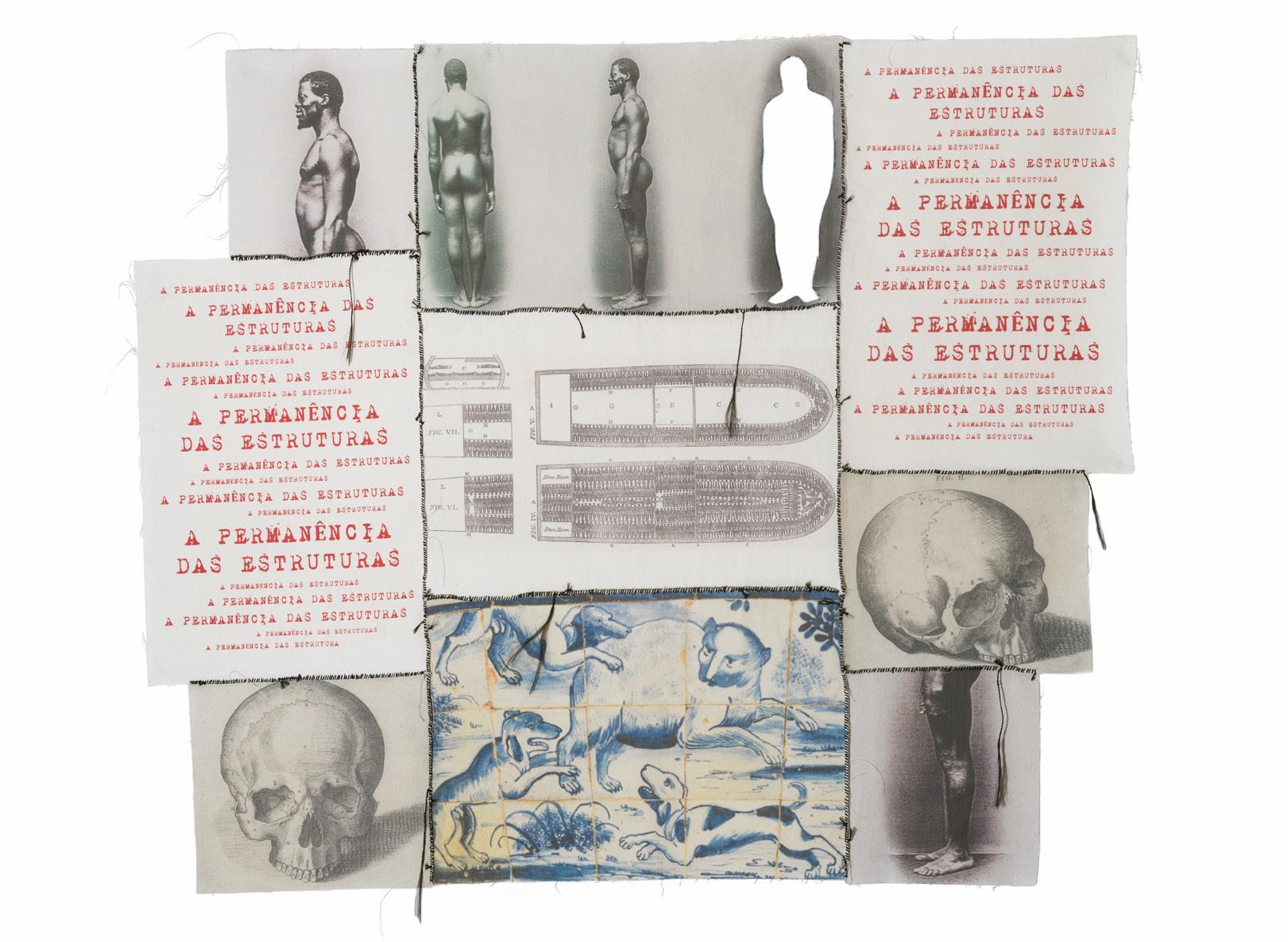

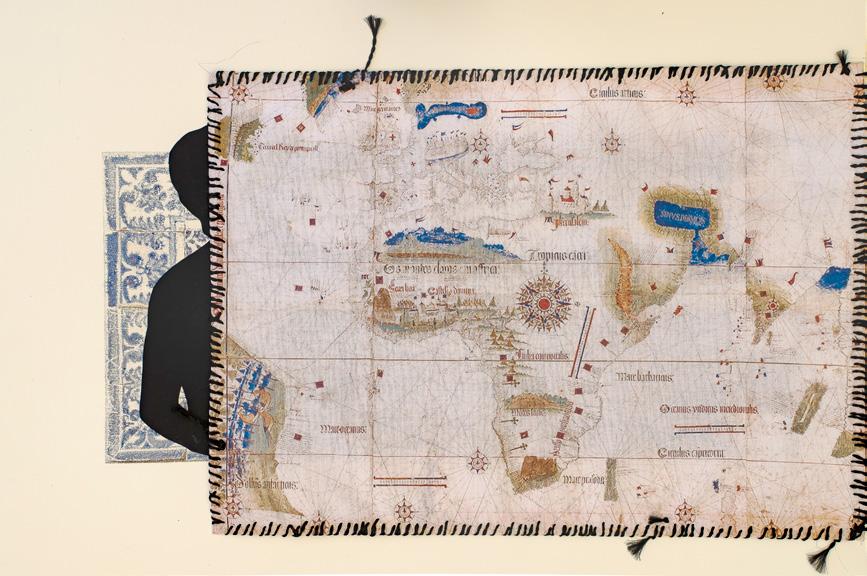

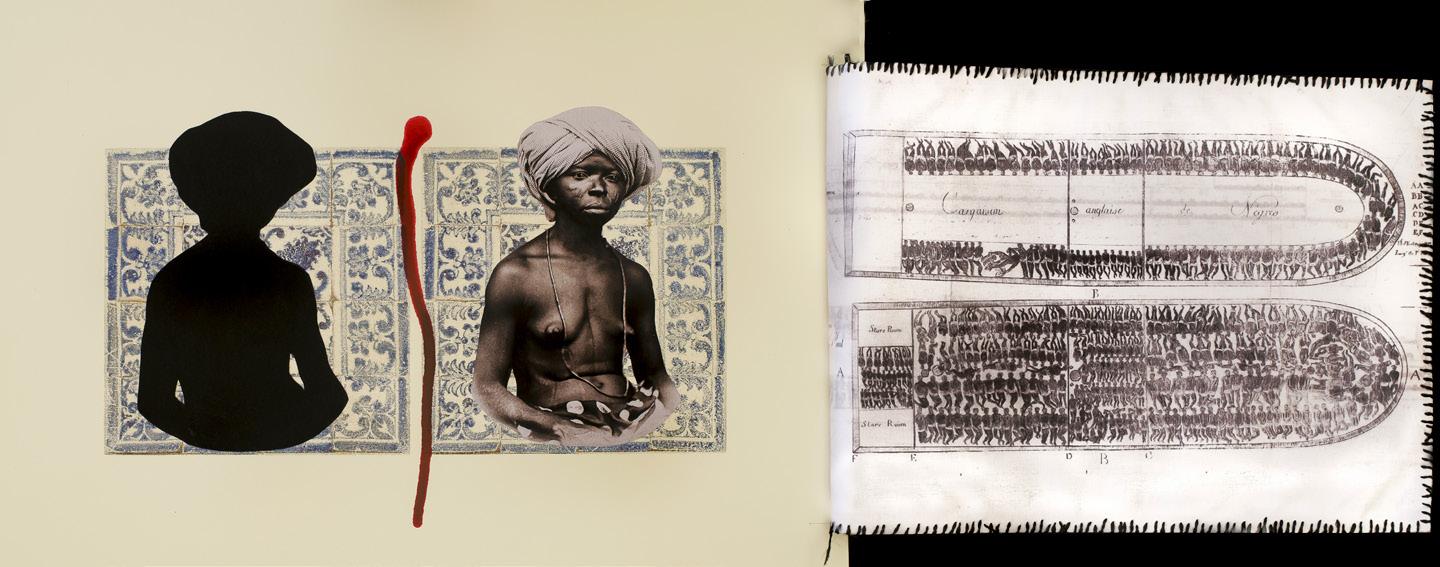

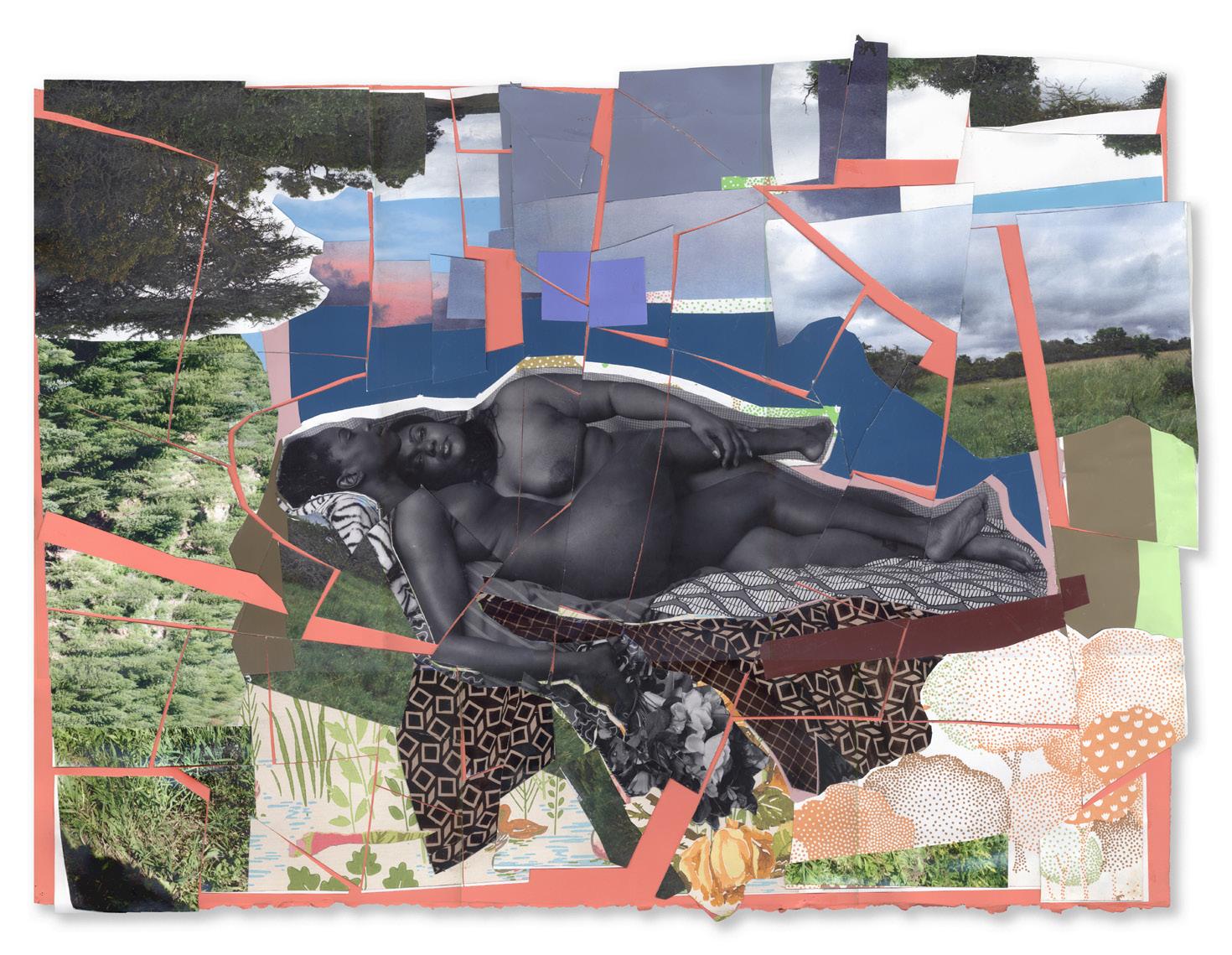

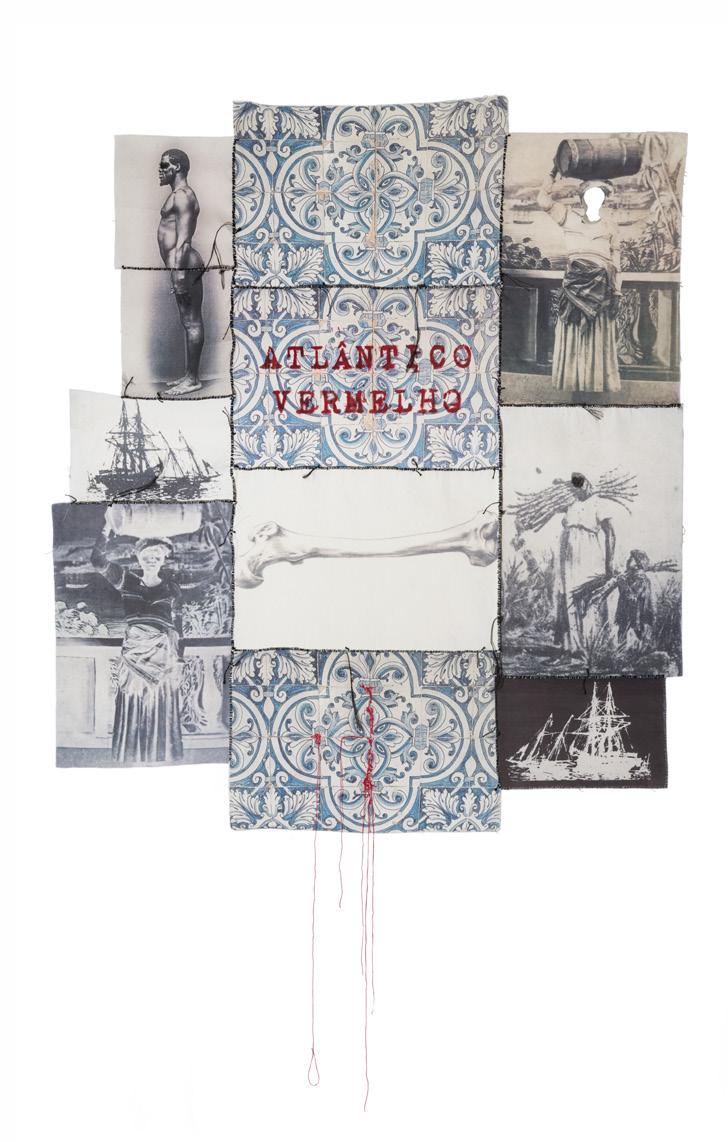

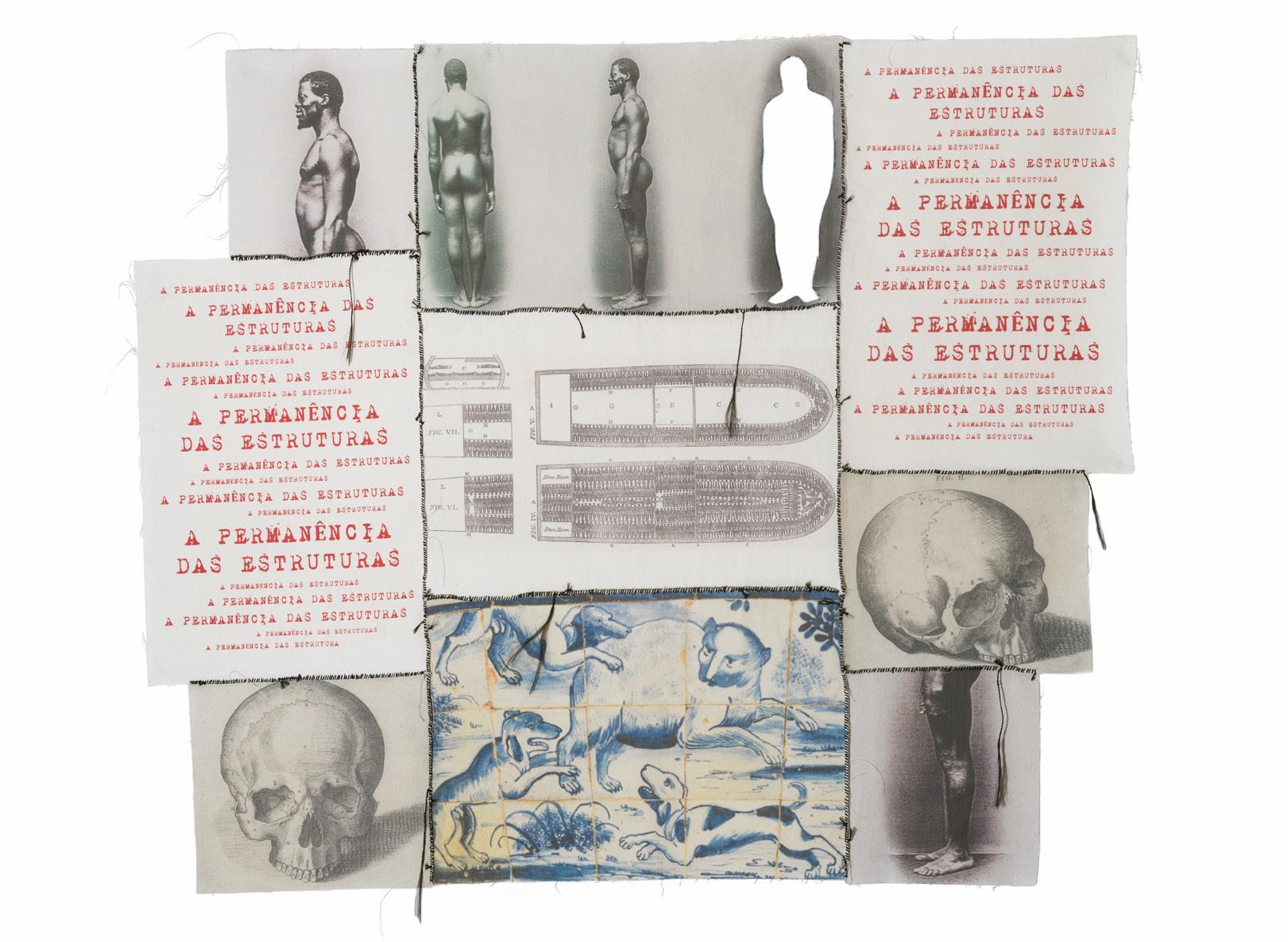

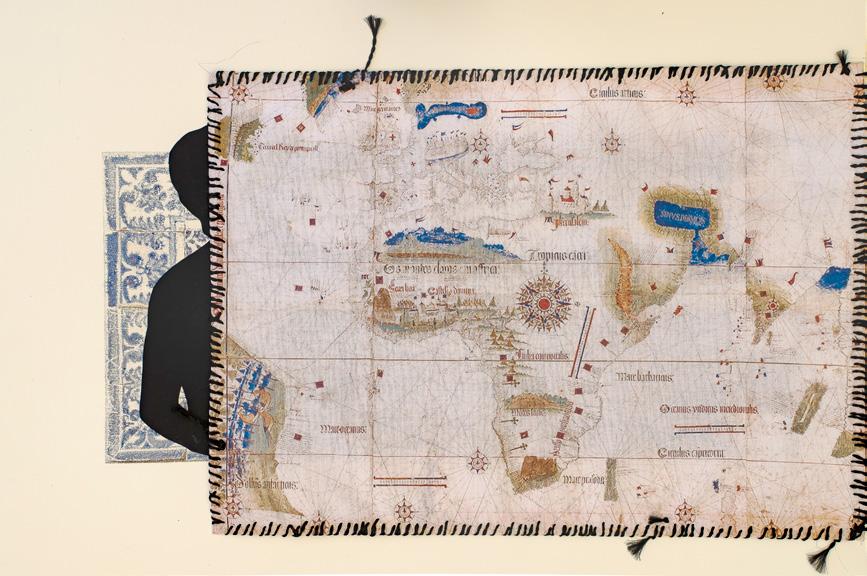

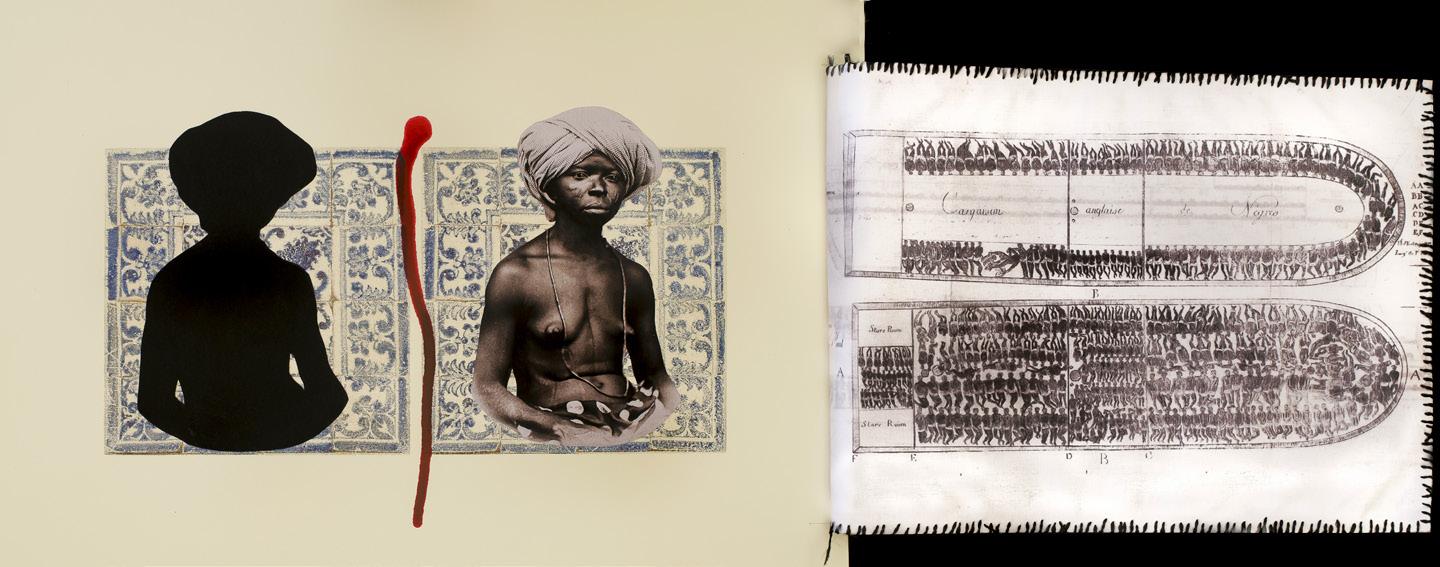

ROSANA PAULINO

Atlântico Vermelho / Red Atlantic

33

make the scanned background same as page background (Rich Black)

make the scanned background same as page background (Rich Black)

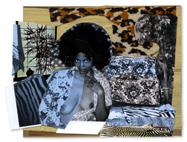

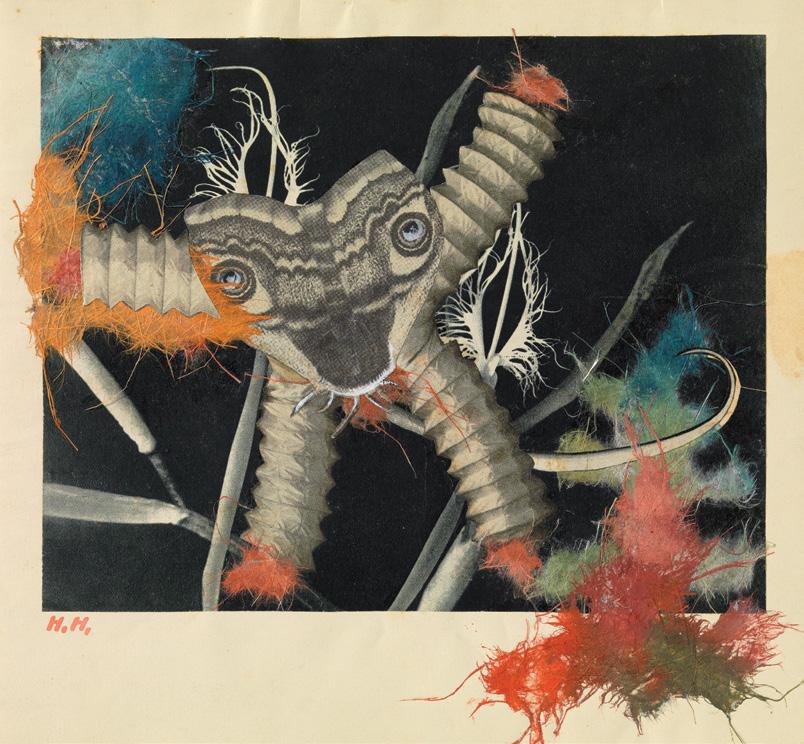

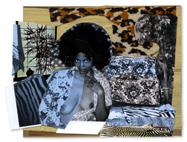

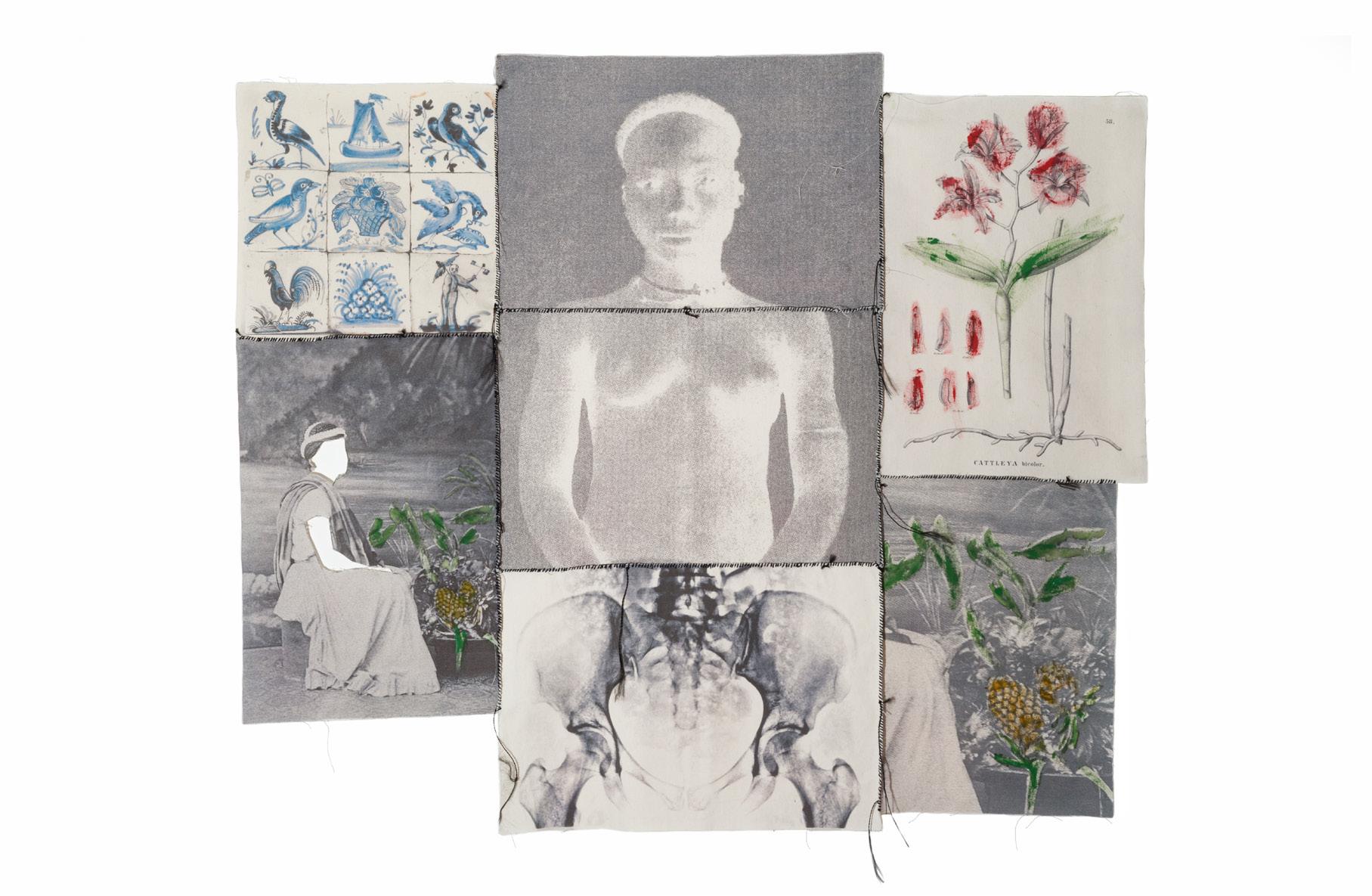

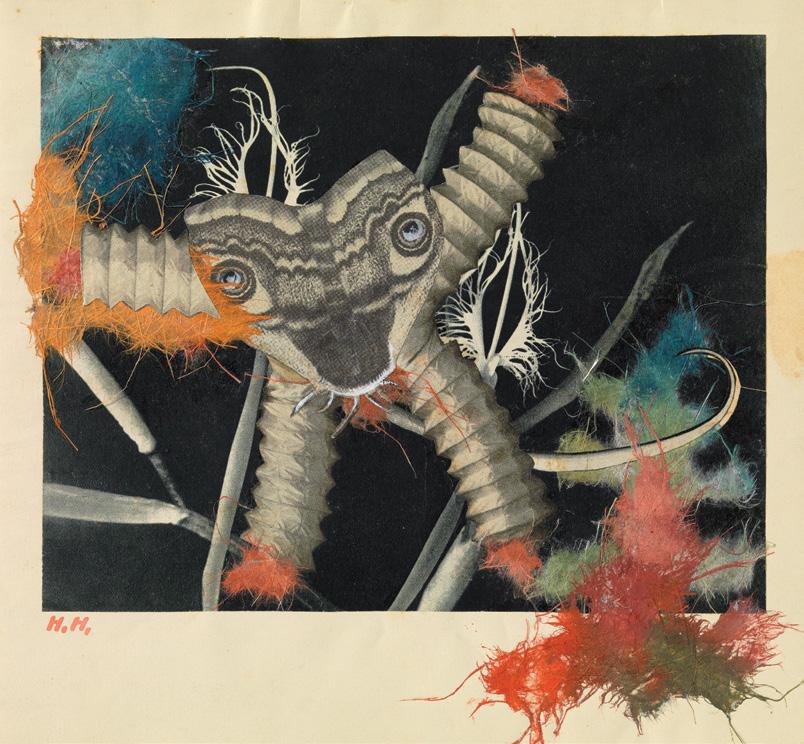

Rosana Paulino opts for addressing sensitive topics such as social, gender and racial issues, playing with various images and different techniques. This ranges from the simplest (coming from the domestic world) to the most sophisticated (requiring technology and experimentation). How to expose the scars of slavery, for example, in a delicate and poetic way? There are many solutions, however, the artist chooses the path of affections, memories and stories that emerge from the bricolage.

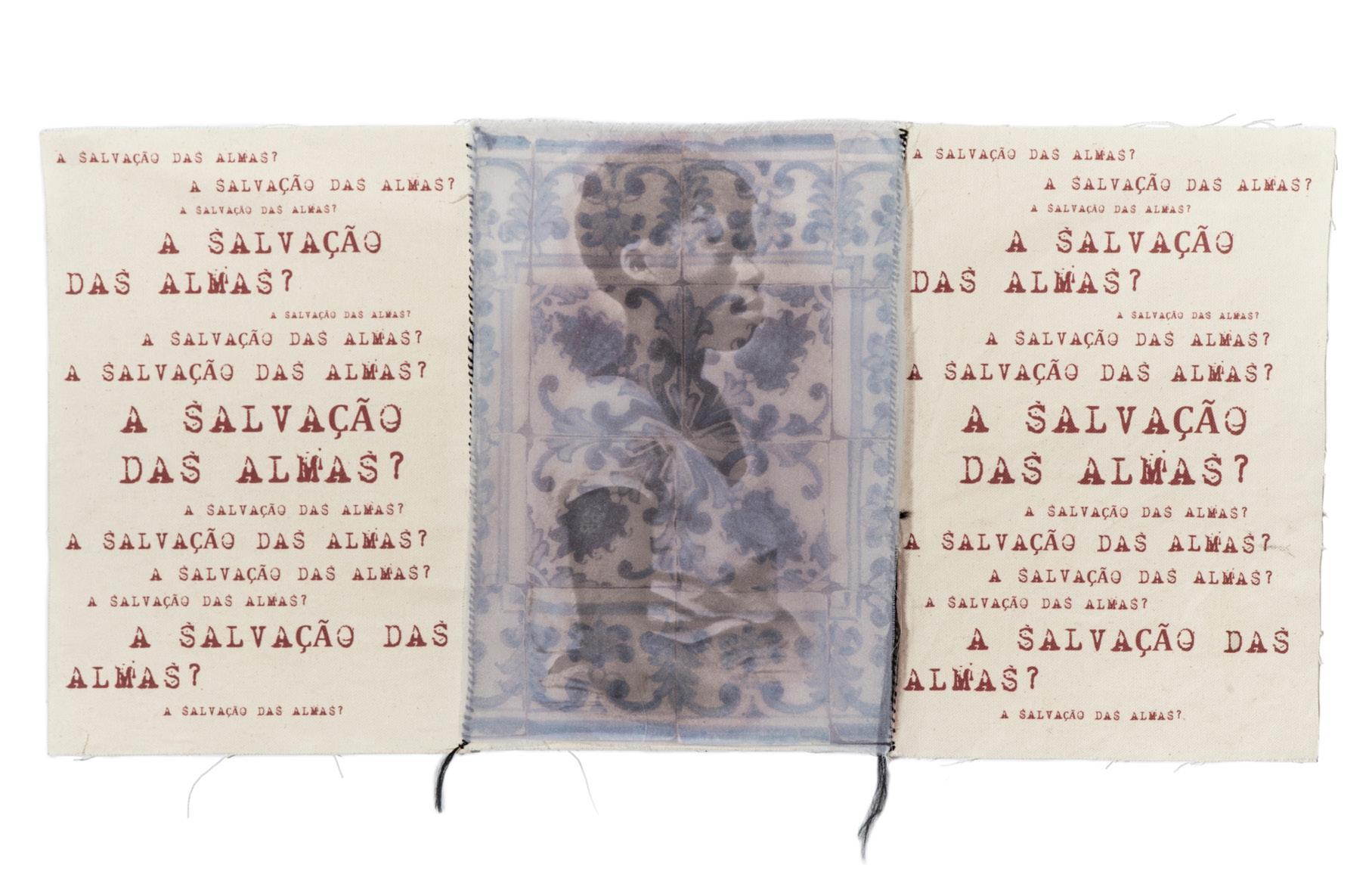

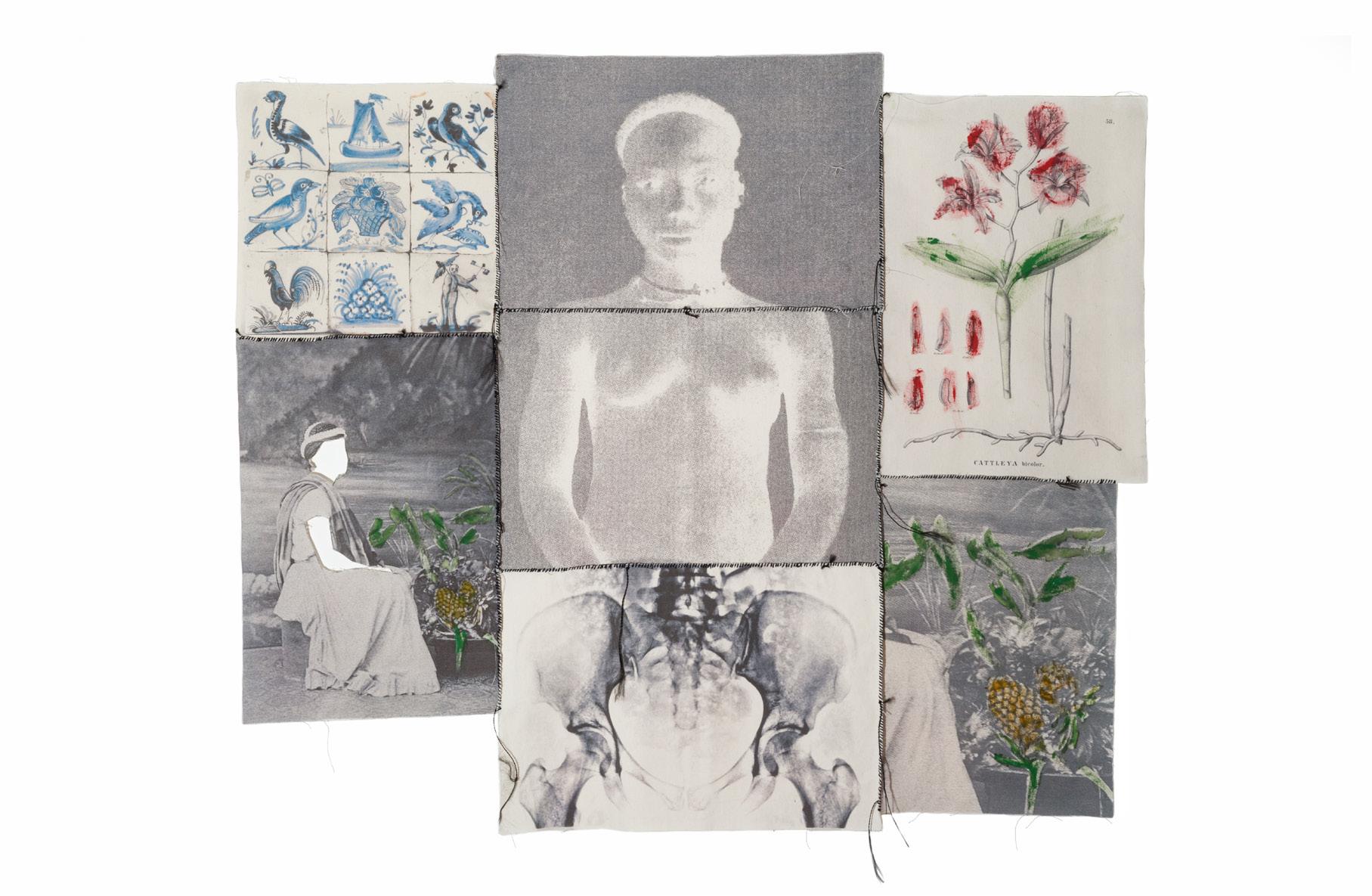

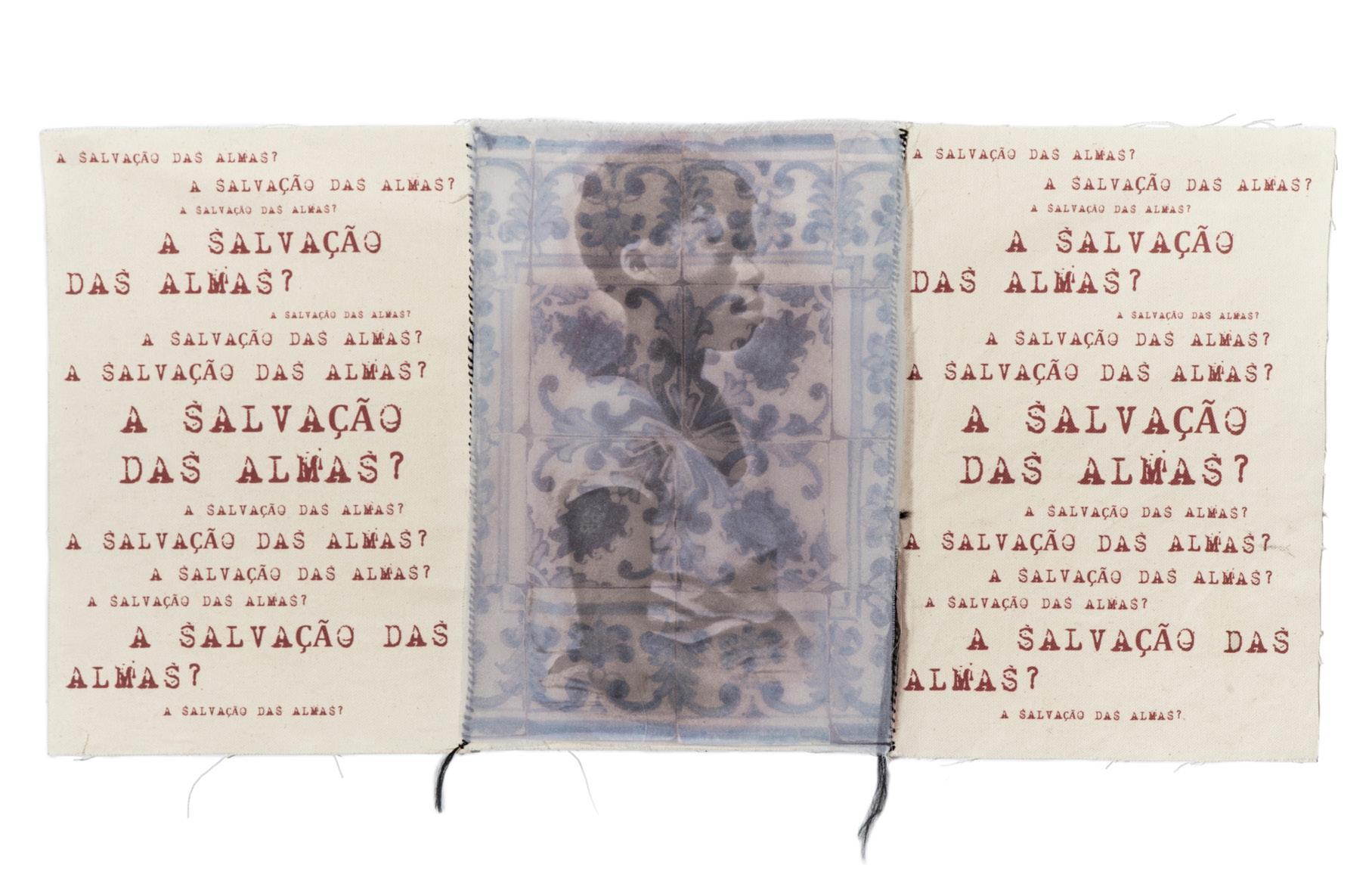

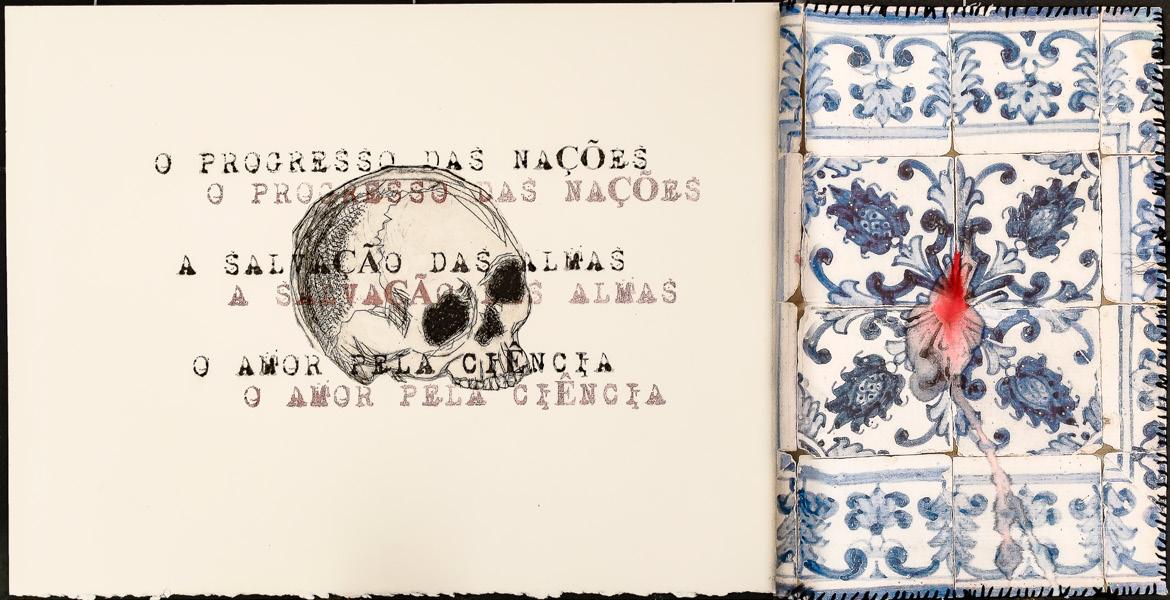

By employing drawing, engraving, weaving and photography, she places the colonial past and, above all, slavery, into the debate of our days. Yet, this is without apparent aggressiveness, it values the playful instead. In every work, there is a game of cut and paste as if it were fragmented and reassembled memories that stir up sensitivity and give new meanings to her works. These images bring the ‘anthropological photography’. The record of the fauna and flora of the ‘new land’, crude sutures, and disconcerting collages all these elements together recount memories silenced by the official history. In a special way, we evoke two works full of playthings: Red Atlantic and ¿História Natural?

Red Atlantic refers to the work of Paul Gilroy, the Black Atlantic: Modernity and

Atlântico Vermelho / Red Atlantic

Double Consciousness (Harvard University Press, 1993). In the book, Gilroy addresses a black Atlantic culture with African, American, British, and Caribbean roots. Rosana’s work is beyond cultural assimilation; it converges on one of the most sensitive metaphors for Afro-descendants: the crossing (the diaspora). Sea and caravels brand this imagination, however the voyage of a tomb ship through the unknown definitely marks the deprivation of the enslaved. Her Atlantic is red, tinged by the blood gushing between Africa and Brazil. The writings are red, as are the marks on the beautiful Portuguese tiles. For three centuries, the capture and sale of men and women deprived them of humanity, casting them into the category of ‘natural things’. In the composition of the images, these men and women emerge faceless, with their eyes covered or even overlaid by icons that transition between remembering and forgetting what is human. Flowers and exotic animals, colourful and exuberant, share the work’s surface with the black-and-white engravings and photos breaking its roughness.

As for ¿História Natural? (just like that, as a question) it is an artist’s book with 12 boards that refer to encyclopedic volumes recognised by the attempt to

categorise the animal and vegetable kingdoms. Motivated by the understanding of the colonialist logic, Paulino devoted herself to the research of the classification of races theories; she subverts and sutures images and arguments and shows the insides of this speech all from a soft perspective. Through engraving and collages, the artist offers blurred and dirty images as if showing us that that history, legitimised by moral, religious and pseudoscientific discourse, is false; it became a great cheating.

In short, these works, by the recombination of images, words and sutures, question, in an affective and lyrical way, the history instituted by the Brazilian patriarchal society. Through the game of memories, her works denounce that prejudice is the result of a construction and as such, can be deconstructed. It has been centuries of learning under the playbook of racism, and now comes the inevitable review of history and social roles.

— Text by Alecsandra Matias de Oliveira

False Idol

48 ROSANA PAULINO LEONARD SURYAJAYA

49

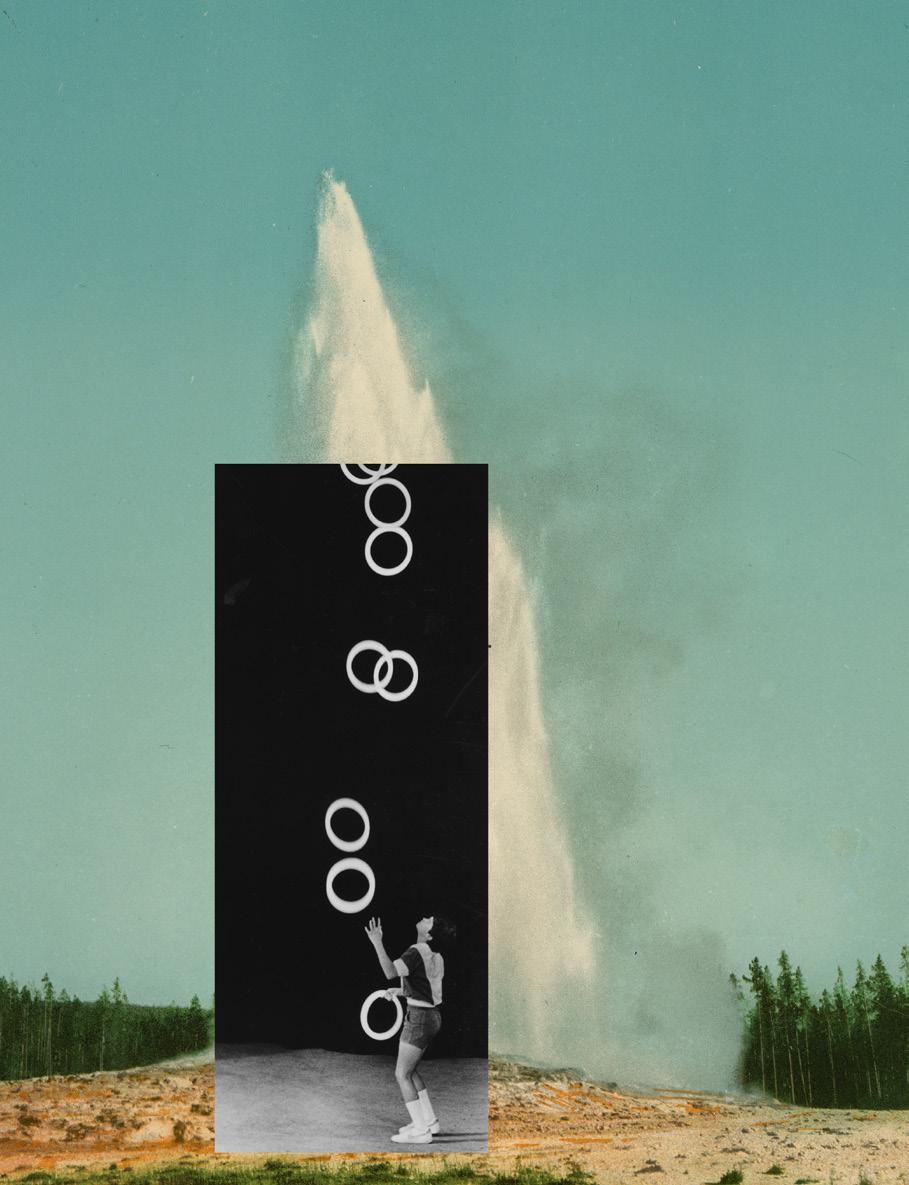

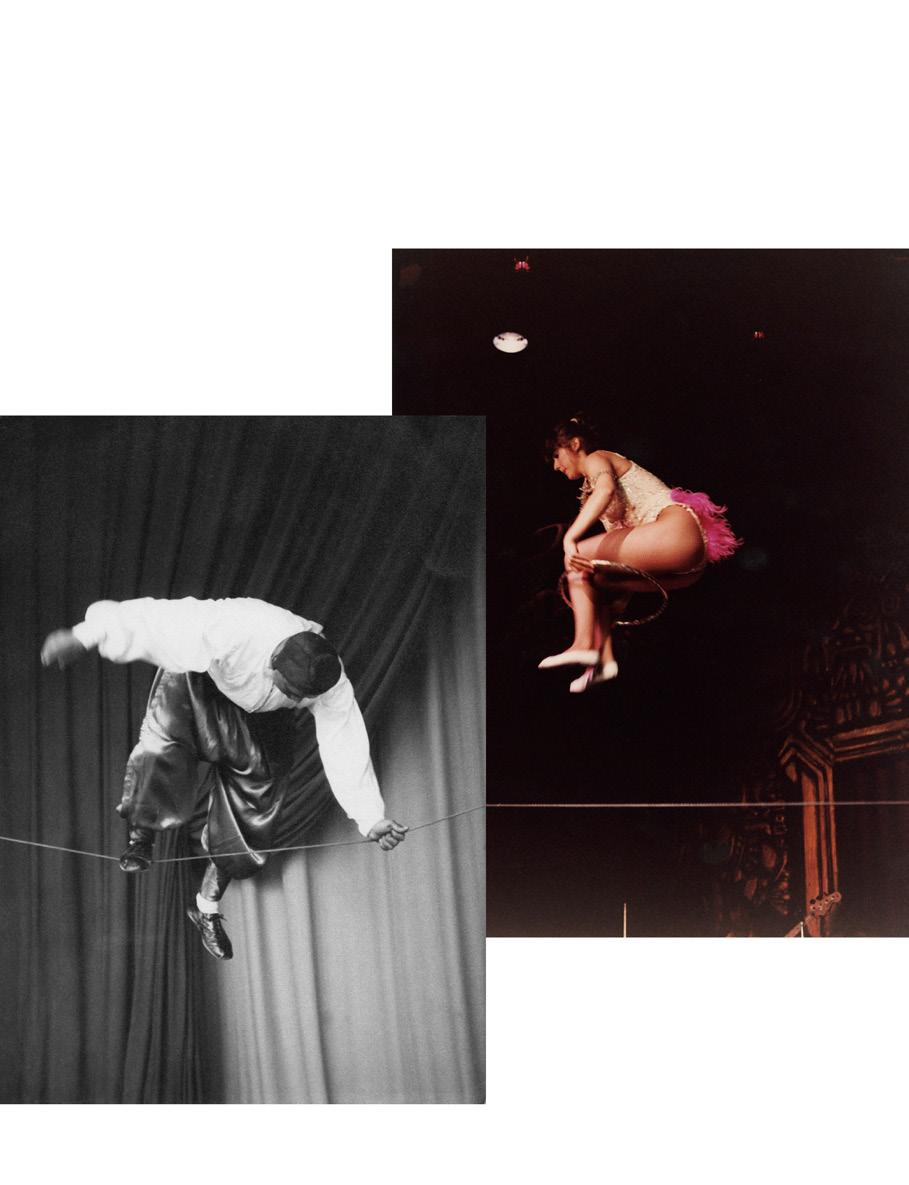

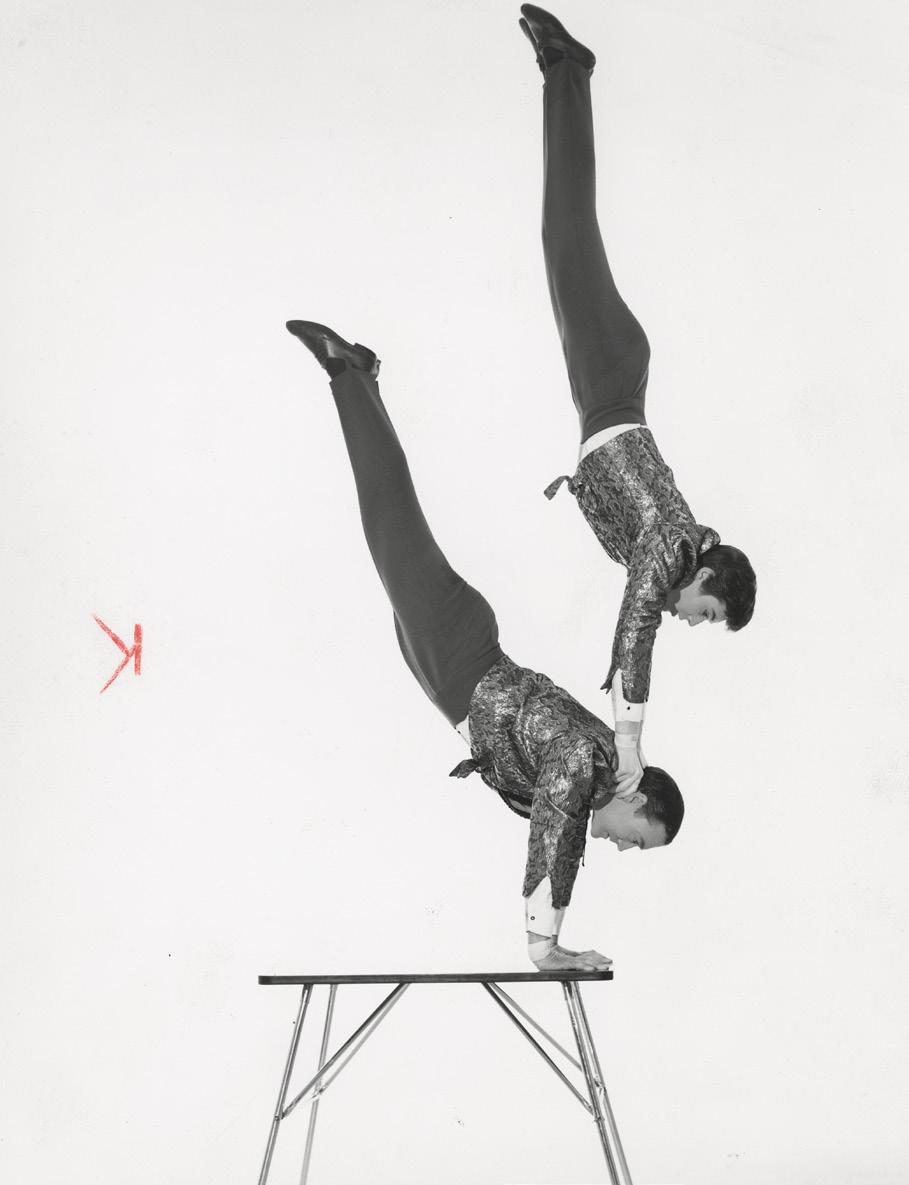

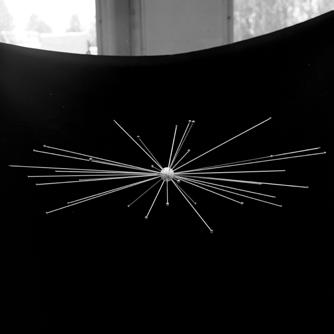

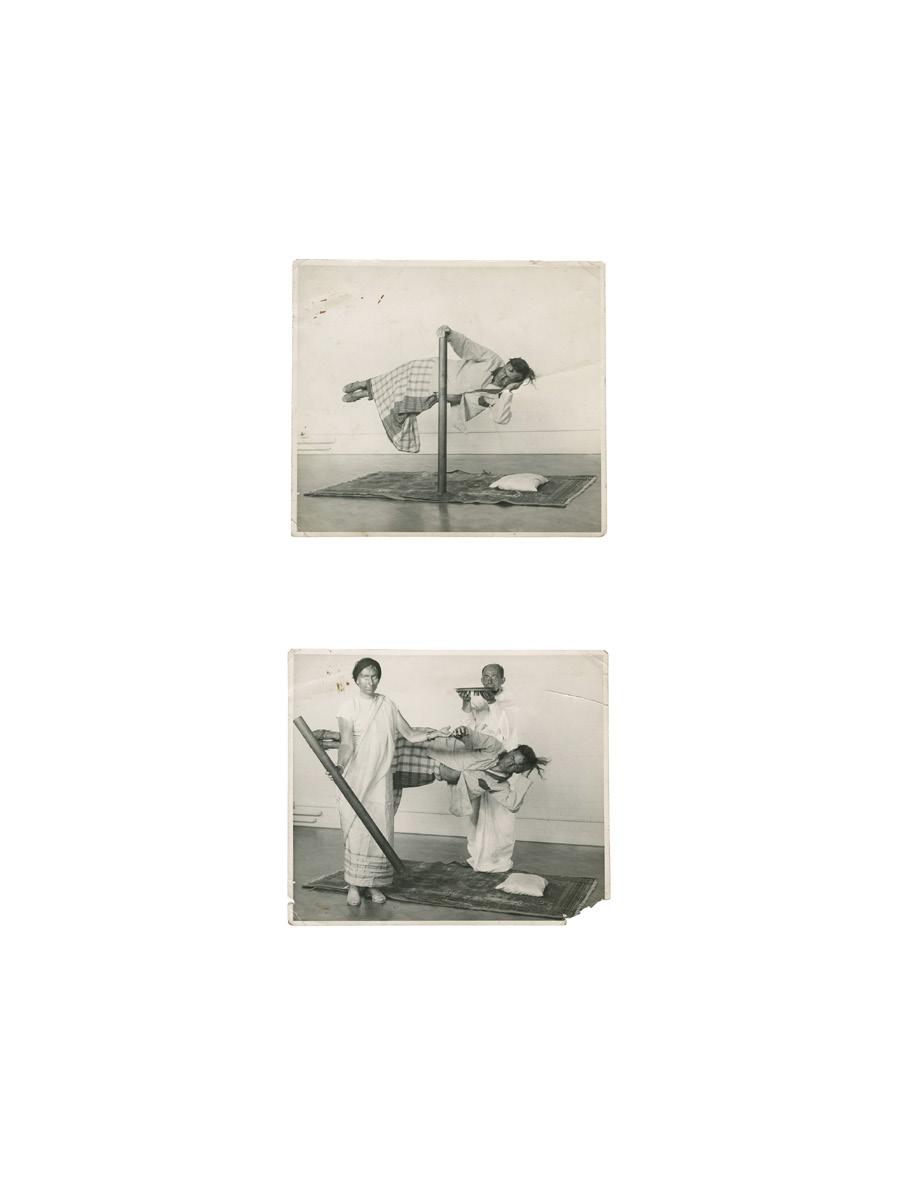

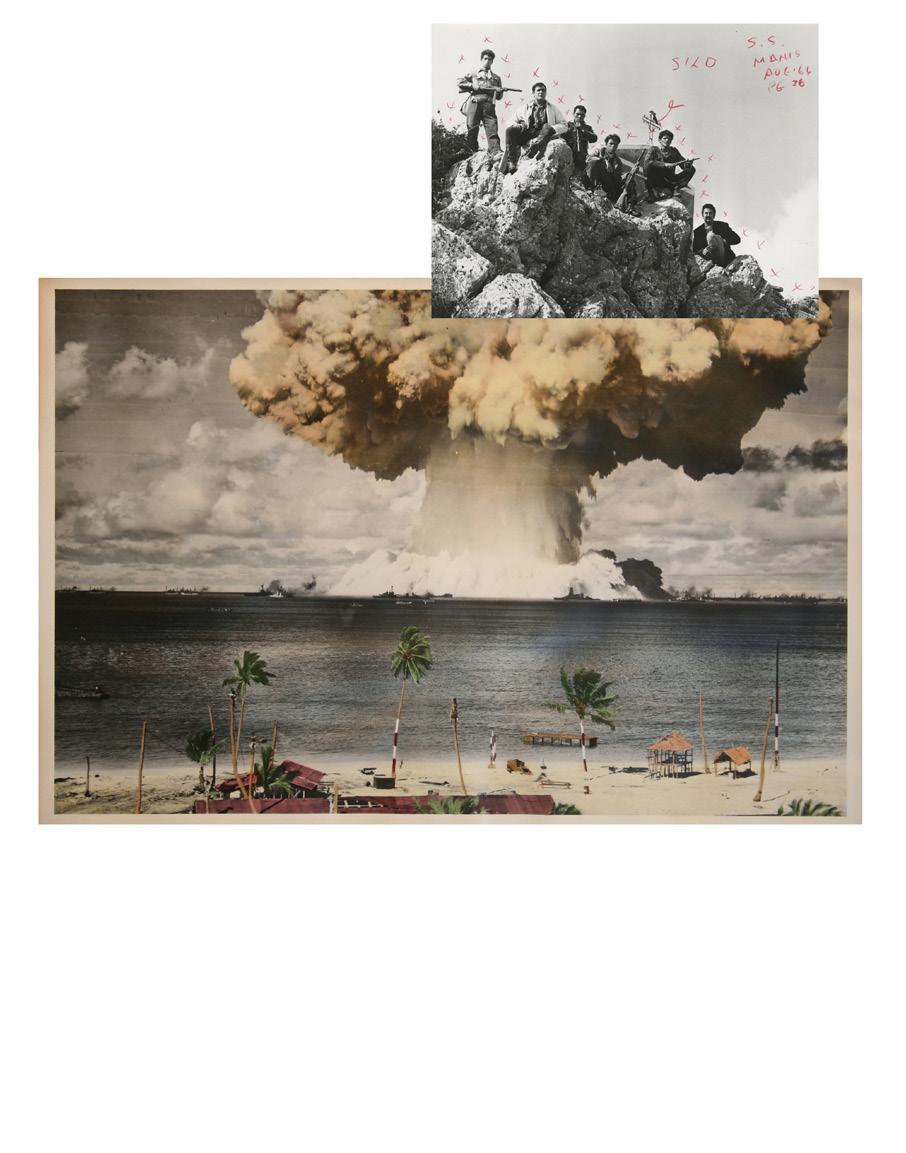

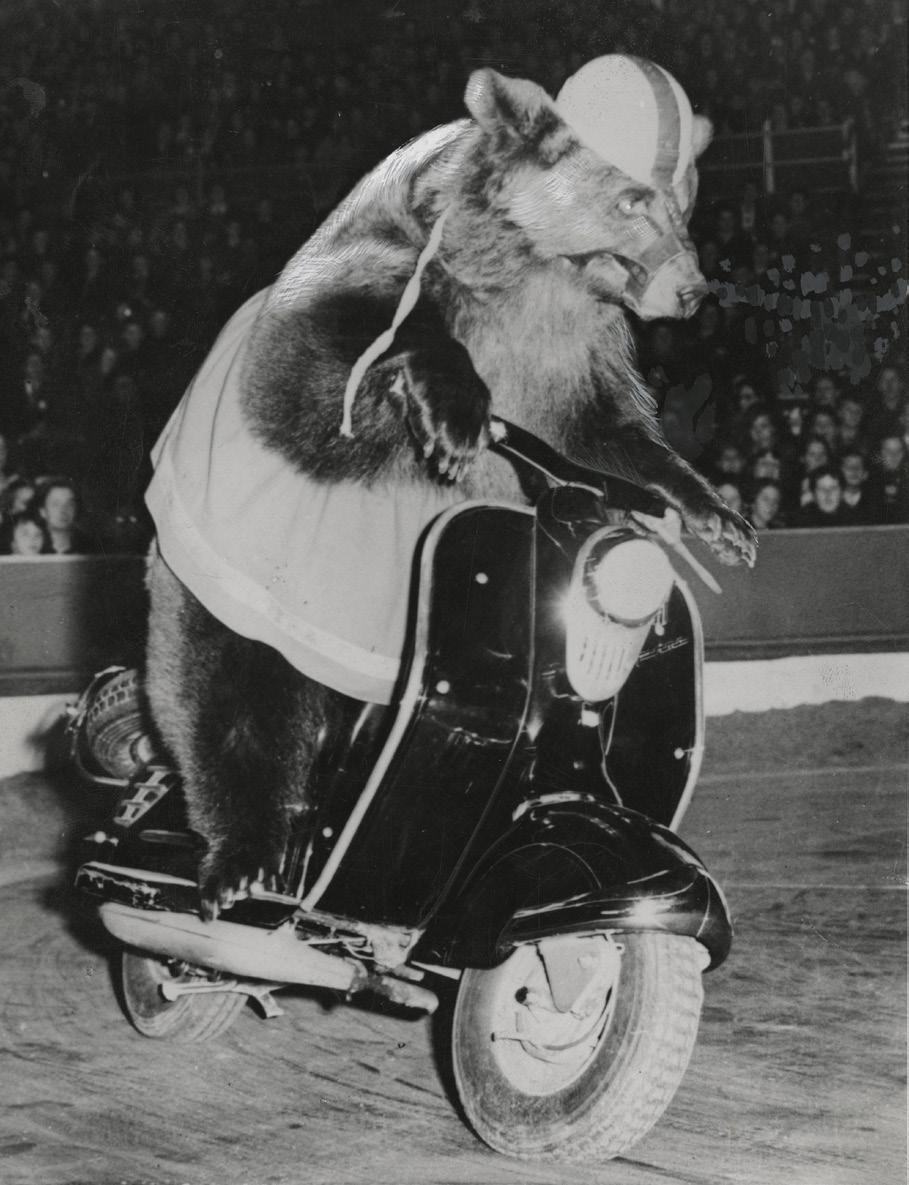

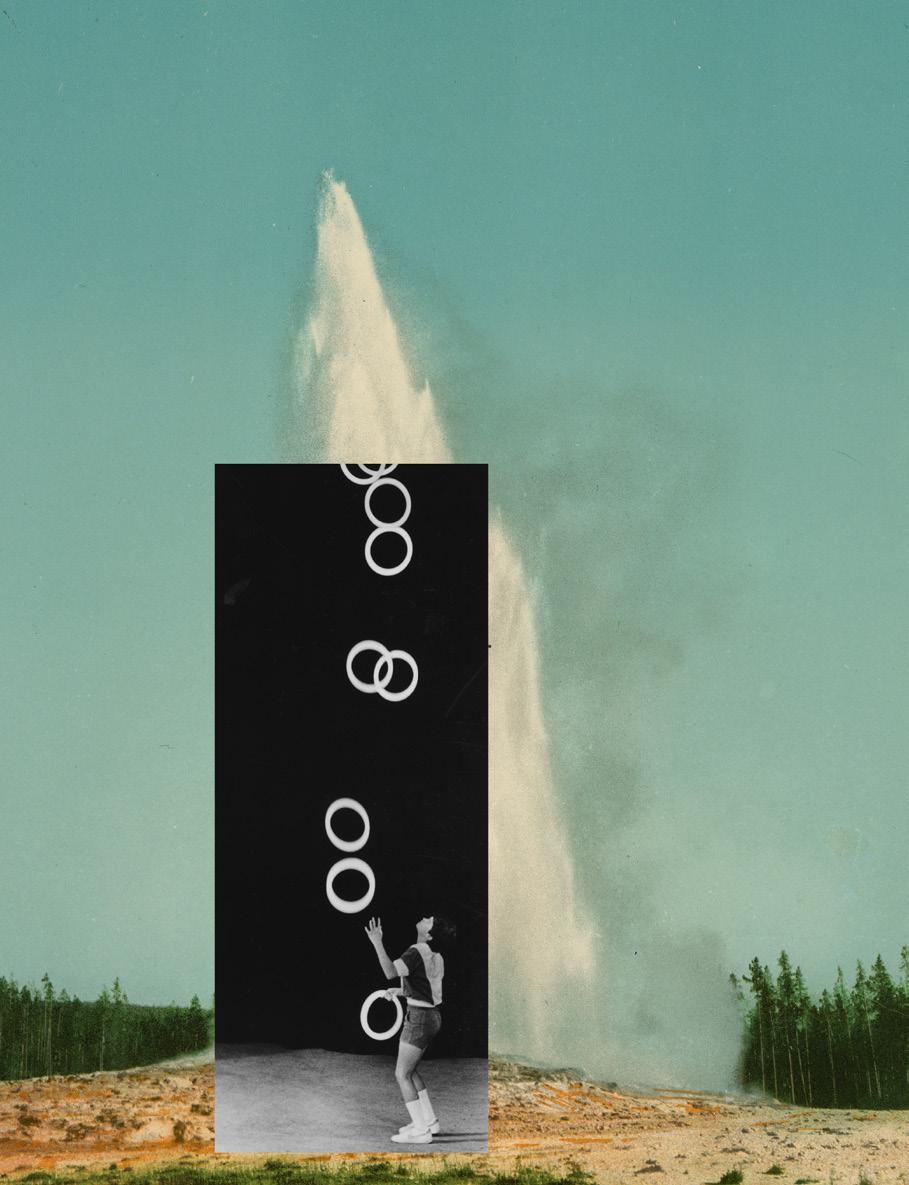

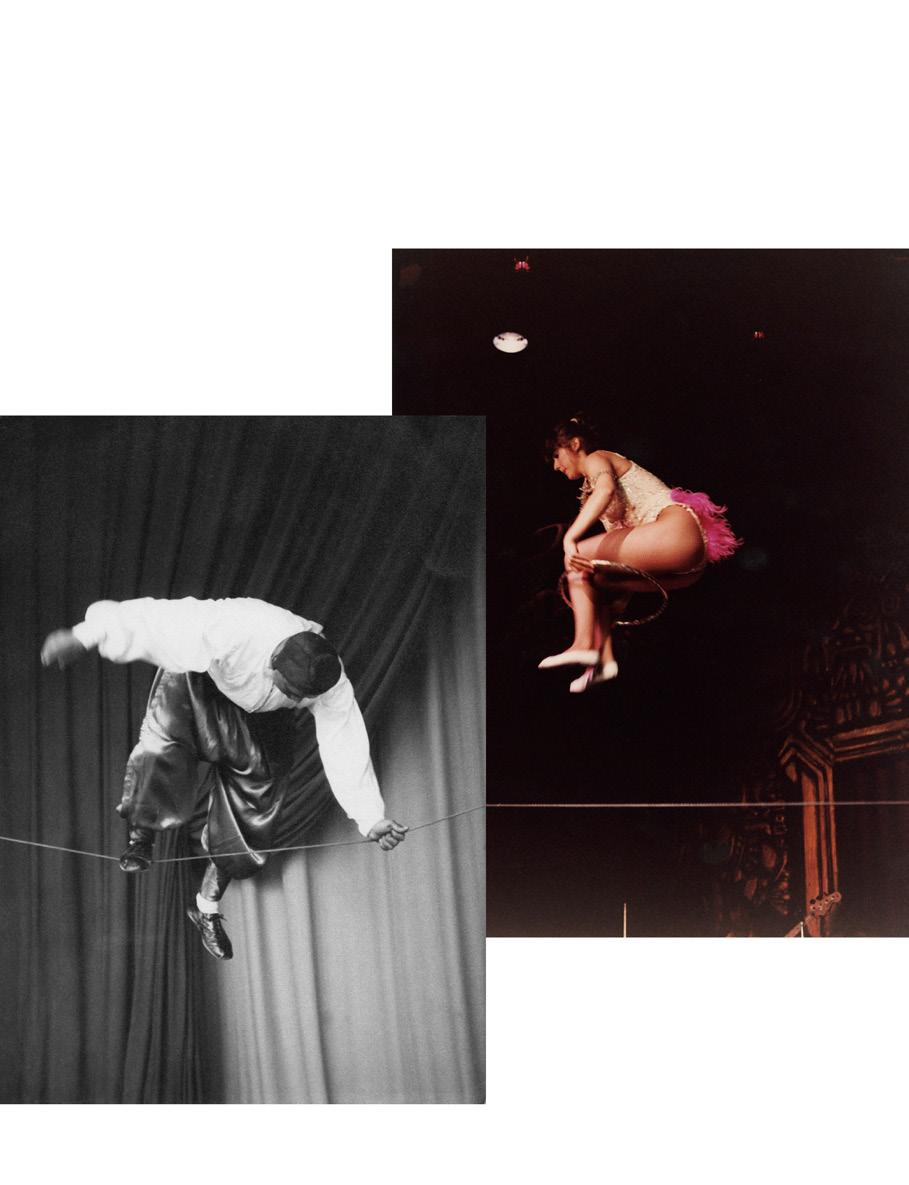

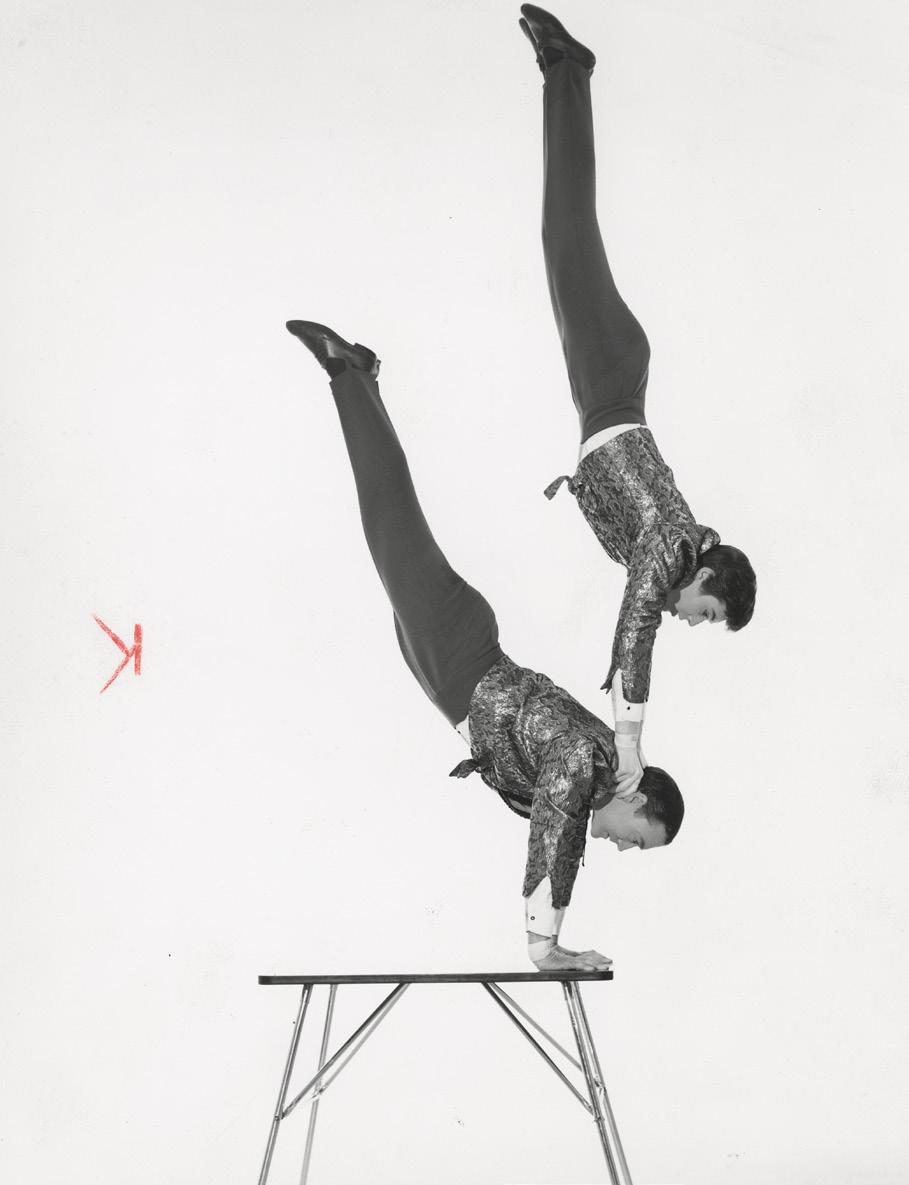

KALEV ERICKSON

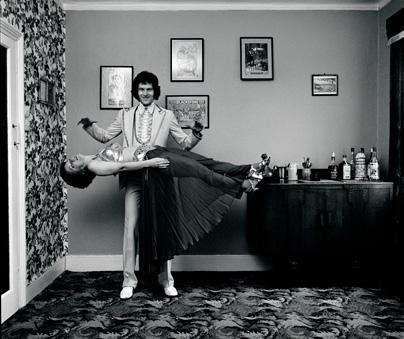

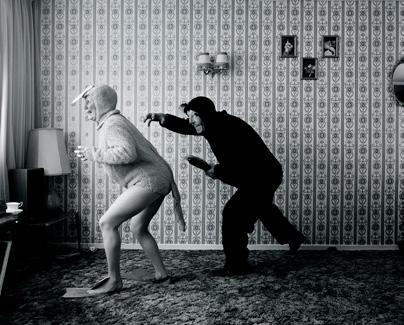

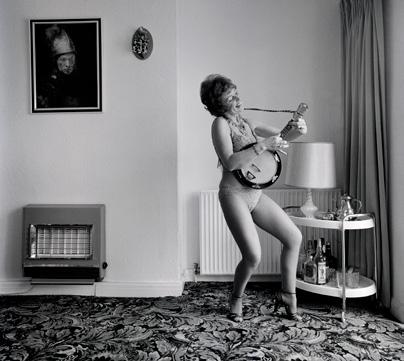

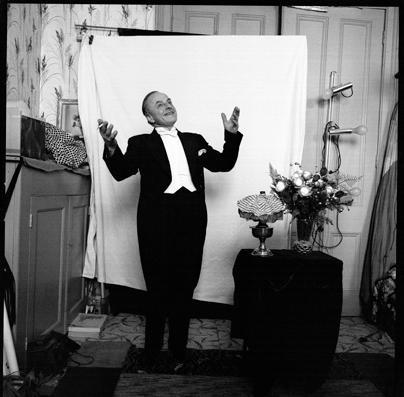

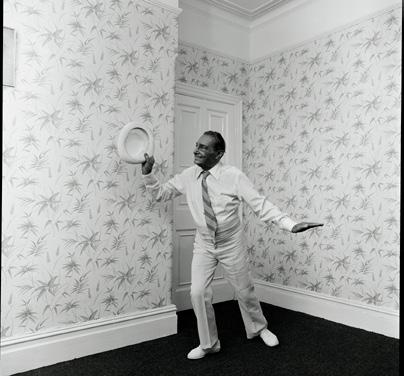

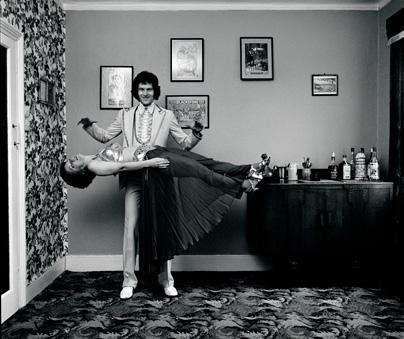

The Greatest Show on Earth

59

The Greatest Show on Earth

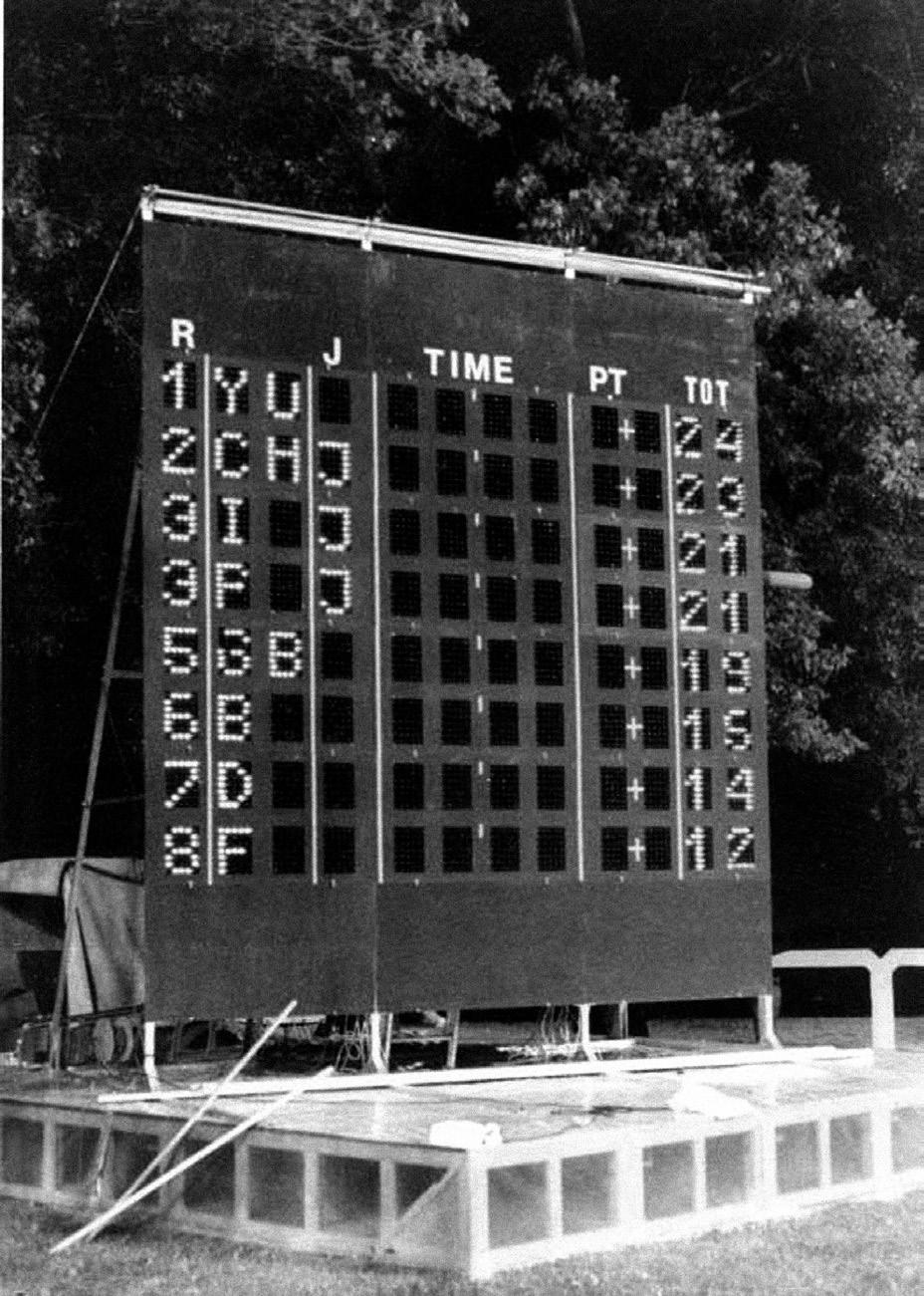

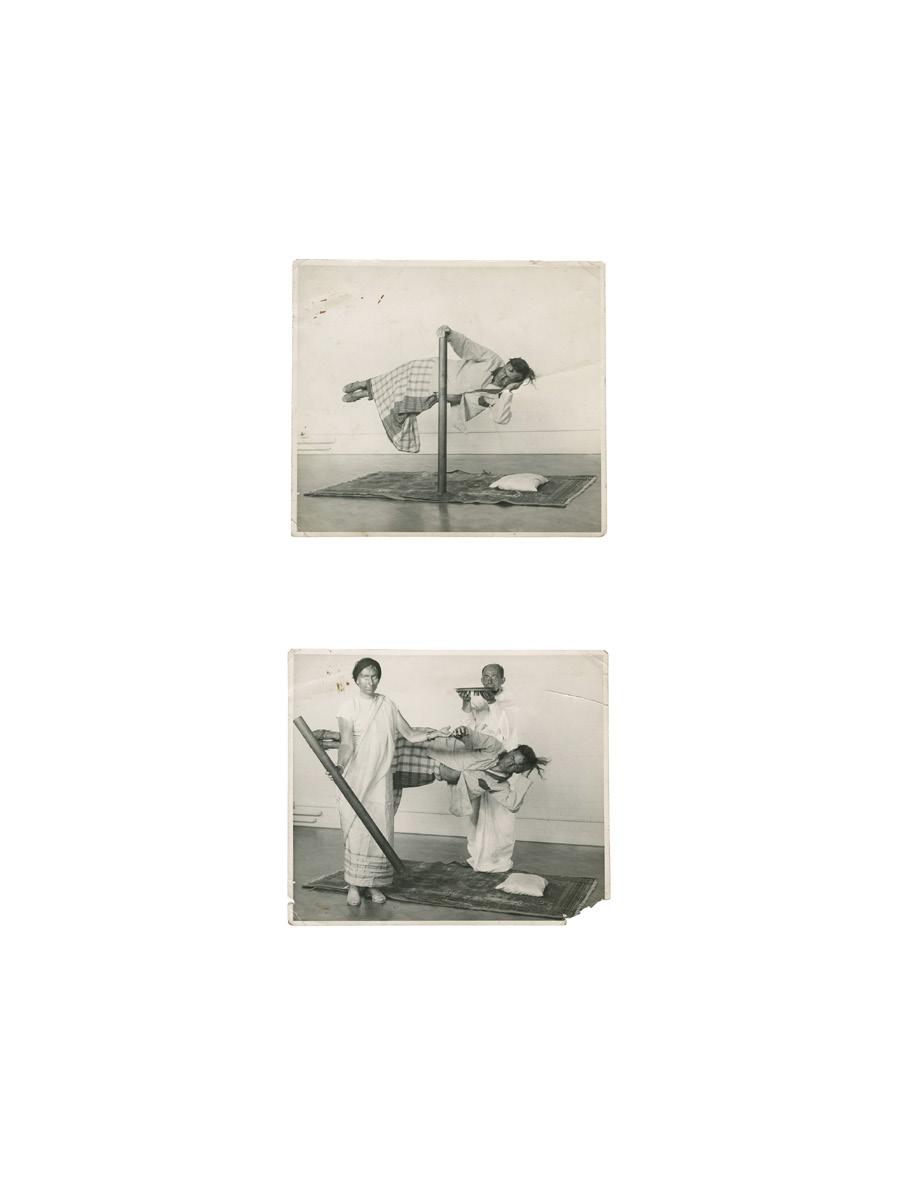

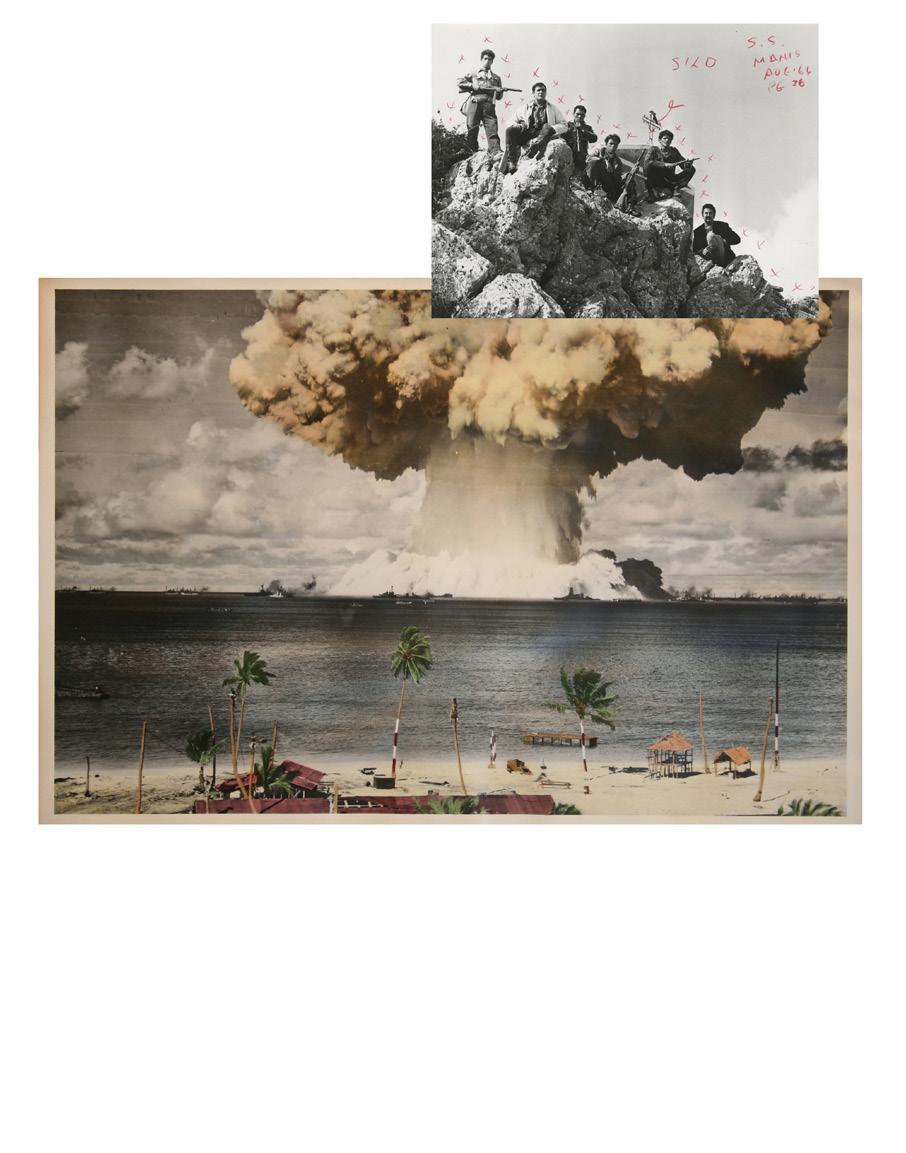

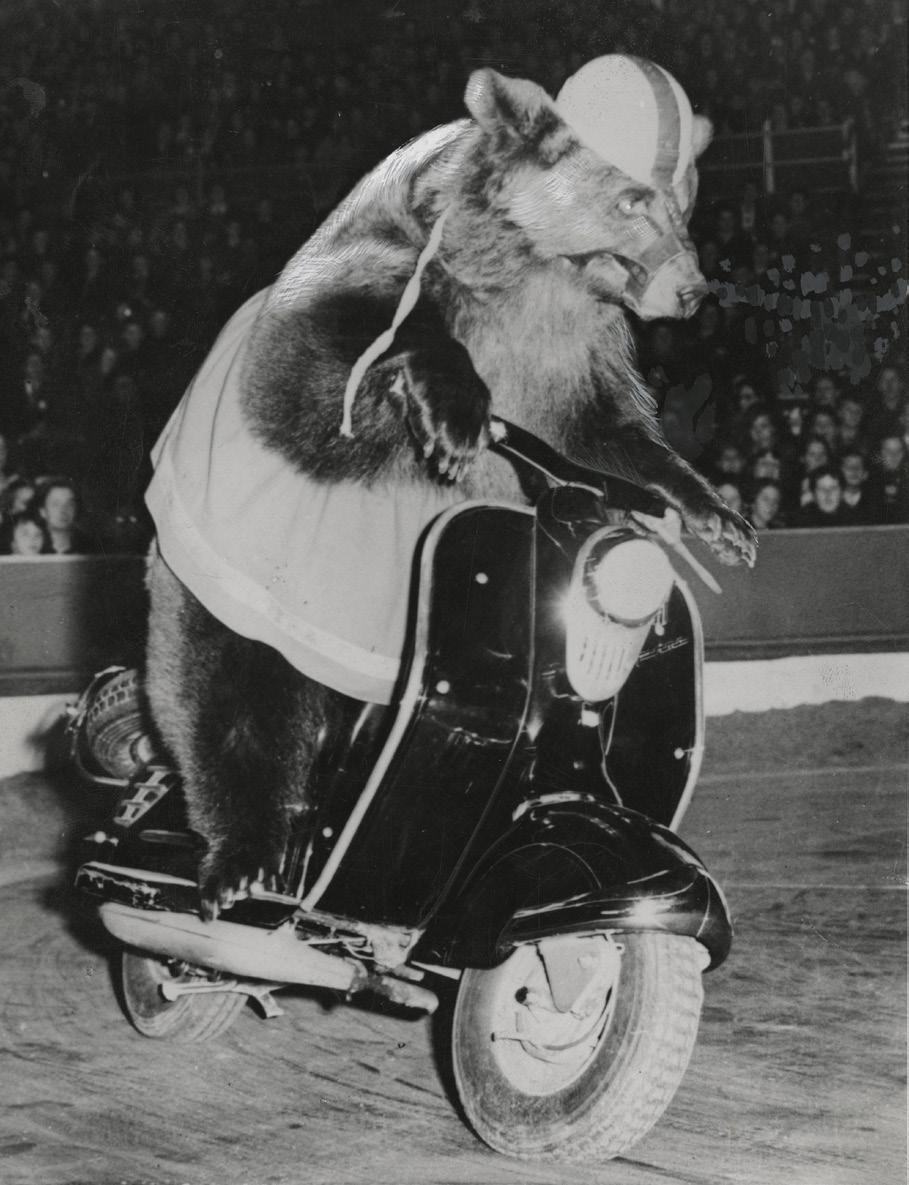

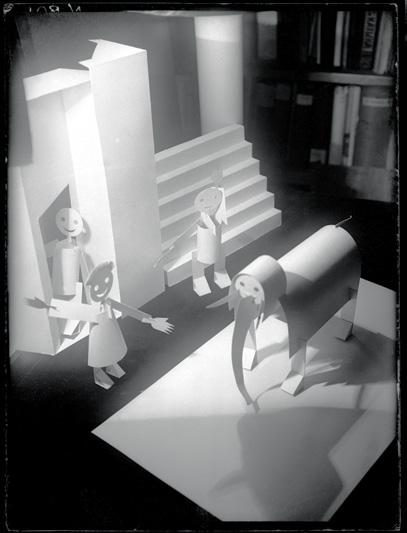

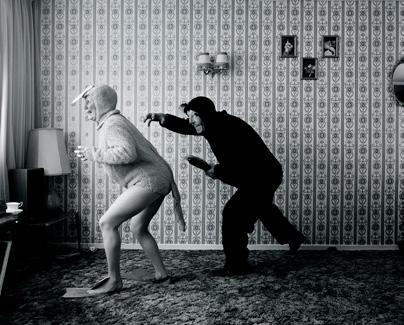

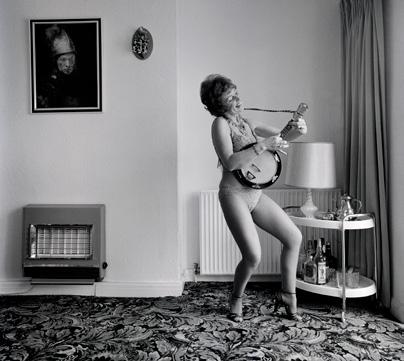

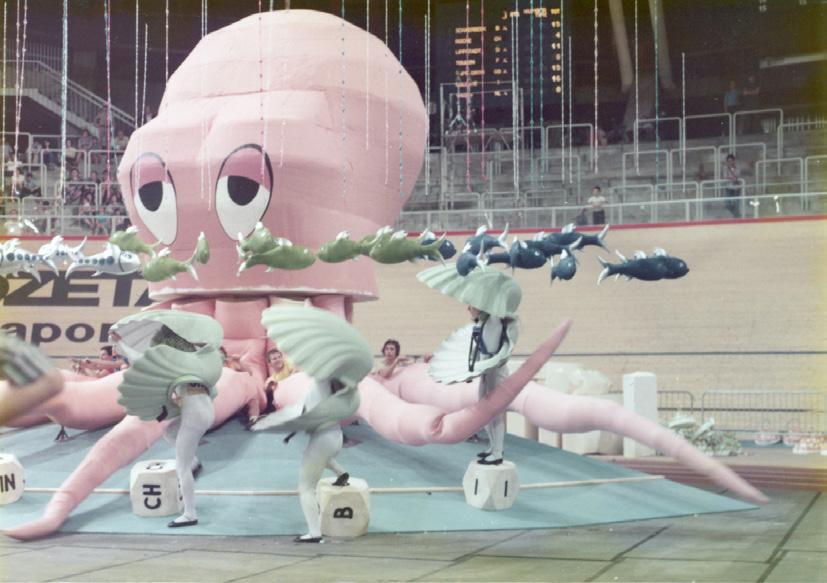

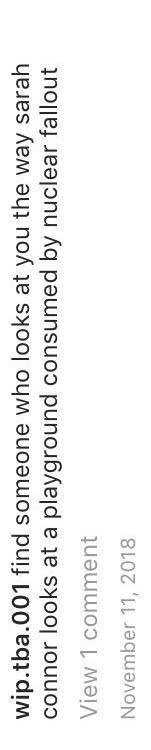

P.T. Barnum the 19th century circus impresario, and one of the greatest curators ever, was once heard to comment, ‘All the world’s a stage and life is a bloody circus’. No one knows for sure what he meant, but it seems in keeping with the spirit of Kalev Erickson’s The Greatest Show on Earth, which was exhibited at Photo España in 2018 as El mayor espectãculo del mundo and celebrated as Issue 13 of the Archive of Modern Conflict Journal AMC.

Photography has had to deal with the idea of spectacle almost since its invention. Ever more so as shutter speeds increased, and capturing the action shots of weird and wonderful events became a major thread in reportage. Now we have all become vicarious participants in the commercialisation of that ‘hold your breath’ moment.

The big top, that circular marquee of dreams, that disordered roundhouse has the most ancient of roots: the Greek and Roman amphitheatres where plays and games enthralled their audience. The life and death performances of gladiators evoked many of the same emotions as the

circus of the 20th century. Exploring the relationships between humankind and the rest of the animal world was a key feature of both. The incipient violence captured attention. A dangerous spectacle will most often transform the onlookers into a single organism. Sharing of fear, passion, hope and relief becomes addictive and acts as a chemical trigger in our brains. Agony and ecstasy have been shared by crowds and mobs since crowds and mobs began. This union gives us release from the constraints of our own individuality. We become one with each other.

Sexualised morphologies and narratives are intimately linked with a wide spectrum of spectacle. The Greatest Show on Earth doesn’t minimise this aspect and instead plays to the populace. Scantily clad bodies hanging upside down or flying through the air, squirting geysers, atomic bombs, ladies taming lions, speaks volumes about the metaphors in play. Spectacle and audience become complicit and co-dependant. It is interesting to note the dolphin training image; Erickson

believes that for years he has been pursued by libidinous extra-terrestrial dolphins.

Ritualised spectacle goes back further than the ancient world where Apollo and the trapeze artists forged a lasting duality with the wild anarchic clowns of Dionysius. Sex, and just as importantly, business are embedded in this rich and complex history. The animal and insect kingdoms are brimming with ritualised display. No doubt the dinosaurs had their own theatre. Erickson, with a deft touch, has massaged the surface of the phenomena. All we need to do is suspend belief. Not really a tall order. We then become player and performer in this magically created adrenaline rush that will transform our consciousness. Whatever else are photography exhibitions for?

— Text by Timothy Prus

Playgrounds

72 73

KALEV ERICKSON IVAN MIKHAILOV

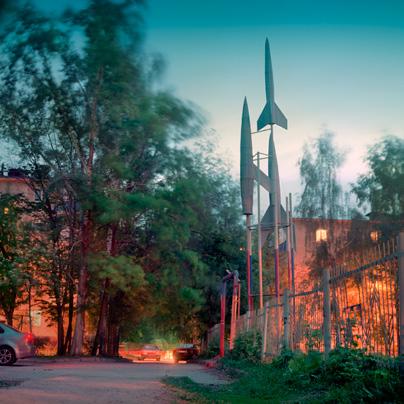

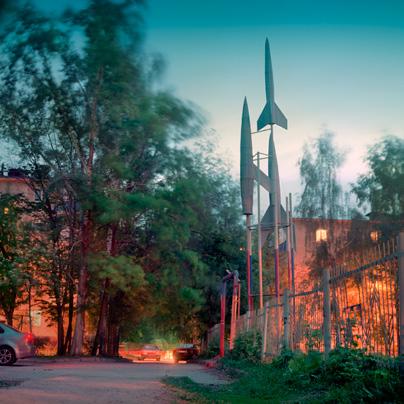

Playgrounds

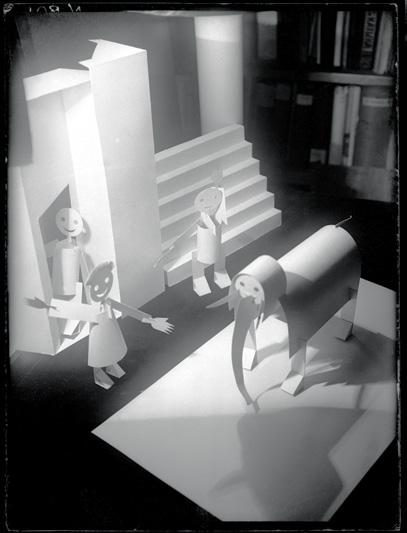

Looking through the images of playgrounds by Russian photographer Ivan Mikhailov, it’s hard not to feel a slight tingle of nostalgia. It takes you back to childhood, when the world was small and usually confined to a couple of blocks yet limitless like the possibilities of life stretching out ahead. Back then, play transformed everything: sandpits and clunky metal constructions of local playgrounds transformed into far-away lands where adventures unfolded every afternoon. At the same time, Mikhailov’s Playgrounds offers more than one type of time travel: it’s also a journey into the history of Soviet Russia, where even child’s play was shaped by grand utopian visions.

Ivan Mikhailov was born in 1981 in Novocheboksarsk, a town on the southern bank of the Volga River, just over 600 kilometres east of Moscow. Growing up, he remembers the rocket-shaped slides and playhouses. He was one of many boys and girls inspired by Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova, Soviet cosmonauts who were the first man and woman in space, in 1961 and 1963 respectively. In the minds of millions of Soviet kids, space travel was not just a distant fantasy but a viable career option. Since the 1960s, space dominated

children’s books and cartoons, and the broader Soviet propaganda; building communism was a mission not confined to the limits of our planet. These stories were reflected in urban planning through several space-themed playgrounds for kids. In Novocheboksarsk alone, Mikhailov spotted around 40 playgrounds.

If you have ever visited a Russian city, you will have noticed that the structure of residential areas is frequently the same: a children’s playground with a few trees standing at the centre of a housing estate, surrounded by towering apartment blocks. The glow from their many windows can be spotted in Mikhailov’s photographs: evidence of cosy day-to-day life juxtaposed with the almost otherworldly charm of cosmic playgrounds. Shot on medium format in a very static manner, these photographs are a testament to the private side of Russian life, but also its history, shaped by the grand, but also standardised way of thinking. If a relatively small town of Novocheboksarsk has more than 40, it’s hard to imagine how many of these tin rockets are scattered throughout such an enormous country.

At the same time, Playgrounds is much more than just a documentary project.

There is a certain magic to how these Earth-bound rockets look under the luminous night skies. A lot of them are now rusty and dilapidated, but previously possessed lightness, aspiration and dreams their creators wanted to pass on to the future generations. Notably, there are no people in the photographs, which places these constructions in the realm of imagination, separated from a boring mundanity.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many things changed, including stories and dreams. Bringing communism to the interstellar civilisations was not a priority anymore. These playgrounds are among the many relics left behind by Soviet utopian thinking, alongside modernist architecture and Lenin monuments. The rocket-shaped slides might soon be replaced by something else, signifying the country’s change of aspirations, but for now, they remain a part of children’s play and a crash course in history.

— Text by Anastasiia Fedorova

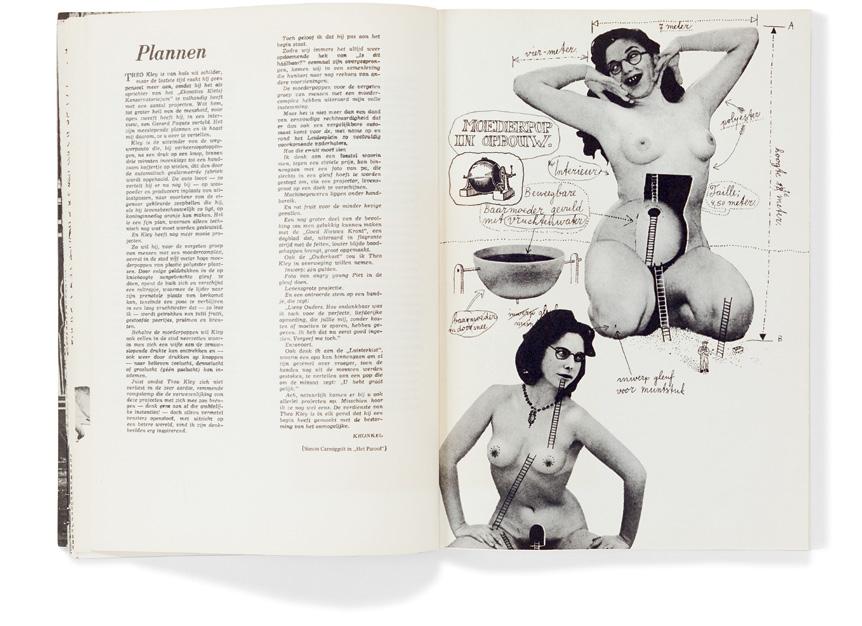

Playing System the

Essay by Ben Burbridge

80

IVAN MIKHAILOV

81 FOCUS ESSAY

Advances in machine learning and AI mean computers are becoming better at ‘seeing’ the visual content of images. Online interactions with photographs are subject to constant algorithmic surveillance, allowing everyday behavioural patterns to be identified, and likely future behaviours predicted, in ways that exceed the cognitive and perceptive capacities of any individual or group.

Digital media scholar Seb Franklin links the wider epistemic regime in which computational photography is enmeshed to a reconceptualisation of ‘the human as a computing machine’: ‘cognition, attention, communication and creativity’ are increasingly assumed to be ‘fully intelligible and representable as digital systems’. Sociality is understood in quantitative and statistical terms. Individual subjectivity is subsumed into datadriven probability models. Discussing social media platforms, artist Erica Scourti observes how, ‘algorithms ... do the number crunching to be able to predict what you might buy, and hence who you are, not because anyone cares about you particularly, but because where you fit in a demographic ... is useful information and creates new possibilities of control.’

Commentators sometimes query the role of the visual, or visually bound thinking, when approaching the social and political implications of computational

photography. An essay by Trevor Paglen suggests we may have to set aside ‘traditional visual theory’, along with our ‘meat eyes’, in order to truly appreciate what is at stake in an era of machineseeing. But if an engagement with photographs onlyasimages limits our understanding of photography as data, then does any parallel effort to attend to photography only as data risk reversing the current imbalance? Andrew Dewdney believes that the ‘global condition of the algorithmic image continues to function within the field of representation, precisely because it remains as yet the humanly understandable surface of communication operating within common sense’. We need ‘to understand the interface between mathematical and cultural coding’.

Images make data legible to humans as something other than data. The resulting interactions make humans legible to machines. Perhaps the most pressing challenge is to reverse that dynamic, using the content of images to develop the forms of critical legibility through which the operations of the network become clearer to humans. By recognising the types of images we are encouraged to upload and share, along with the forms of behaviour it is assumed our interactions with photographs will exhibit, can we also begin to understand thelogicofthesystems in which human sociality is entwined? By doing something that looks like, but is nonetheless significantly different from, those prescribed behaviours, can we start to play with the systems in ways that remain invisible to power? My colleague Micheal O’Connell describes this as ‘artificial stupidity’.

The pictures in A.M. Worthington’s 1908 book, A Study of Splashes, provide an early example of highspeed flash photography. Sequences of photographs depict a ball bearing as it descends into liquid surfaces and the delicate forms that result. Pictures are arranged in chronological order from left to right, sometimes from top to bottom, encouraging western audiences to ‘read’ them in much the same way they would a written text. One sequence, now held in the Science Museum Collection, London, consists of 23 photographs: two documenting the ball bearing as it falls; 21 depicting the splash as it forms, breaks, a jet rises, falls, and creates further, smaller splashes.

The main challenge faced by Worthington was how to make a series of very short exposures in quick succession in order to photograph the same fastmoving object multiple times. 20 years earlier, Eadweard Muybridge had produced sequential studies of human and animal locomotion using a bank of cameras with fast shutter speeds triggered by trip wires. His contemporary, Étienne JulesMarey, chose instead to use a rotating disk containing a small hole. A single exposure was made every time the aperture passed the camera lens, depicting figures multiple times on a single photographic plate as they traversed the space in front of the camera. The comparatively small size of the object that Worthington wanted to photograph, and the level of detail he desired, made similar methods untenable.

Machines today, we are told, can perform an increasing number of tasks almost as well as, often much better than, human beings.

‘Instantaneous Photography of Splashes’ Spark photographs of splashes by Arthur Mason Worthington, FRS, circa 1900 © National Science & Media Museum / Science & Society Picture LibraryAll rights reserved 83 82 PLAYING THE SYSTEM FOCUS ESSAY

Instead he worked in darkness with the camera shutter open, using the flash produced by spark discharges to create very short exposure times. It was not yet possible to produce a number of flashes in quick succession, however — this was a much later innovation normally associated with the stroboscopic photography of Harold ‘Doc’ Edgerton. Worthington opted instead to restage the same experiment multiple times, making a single photograph on each occasion and timing the spark to occur fractionally later and later as the process progressed. The series in the Science Museum Collection does not depict the uninterrupted descent of a ball bearing and the forms it created as the sequencing of the images encourages viewers to assume. It represents the ball bearing descending on two different occasions, and 21 different splashes, arranged in such a way that we ‘read’ them as constituent parts of the same event. The singularity of the event is a fiction, presented as though fact.

There are at least two ways to think about Worthington’s visual deception. The exactitude with which he went about the reenactment speaks to what science historians Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison identify as the virtuous character ascribed to mechanical objectivity in the latter 19th century. The increasing importance attributed to machinemade recordings in scientific investigations was driven as much by a puritanical distrust of the subjective distortions associated with human observers as it was a faith in the capacities of machines. While Worthington could not make his photographic sequence of a single event mechanically, he went to extraordinary lengths to internalise the operational logic of the machine: controlling constants and variables, timing each exposure with great precision, repeating the procedure to compensate for mistakes whenever required.

Alternatively, we could focus on the fact of the deception itself; on all that the camera does not see, but which was nonetheless crucial to the production of the series. The exposures are not separated by a fraction of a second, as their presentation encourages us to assume, but presumably by several minutes, as Worthington rearranged the apparatus, prepared the camera, waited for the liquid surface to still, all to produce an illusion. His mimicry involved thought and imagination.

The second possibility aligns Worthington’s photographs with a curious strand of early investigative photography, which utilised the assumed objectivity of the camera to veil or obscure more creative interventions. Photographic historian Marta Braun suggests that Muybridge misled viewers about the timing, order or content of up to 40 percent of his plates. On at least one occasion he combined elements from different picturetaking sessions and passed them off as though components of a single event. Where Worthington was responding to the irrevocable limits of the technology available at the time, it seems that Muybridge was lazy and/or conscious of the expense involved in restaging

PLAYING THE SYSTEM

an entire sequence, as even a single smashed plate or faulty shutter would have demanded.

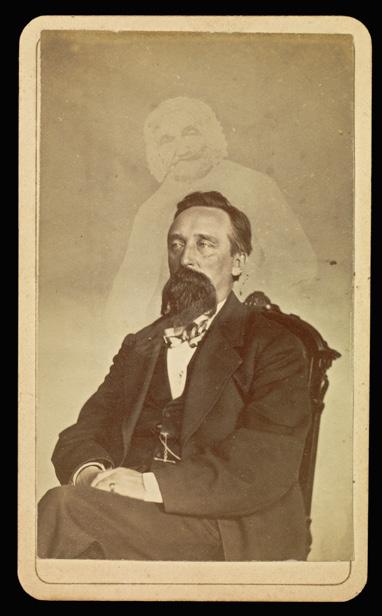

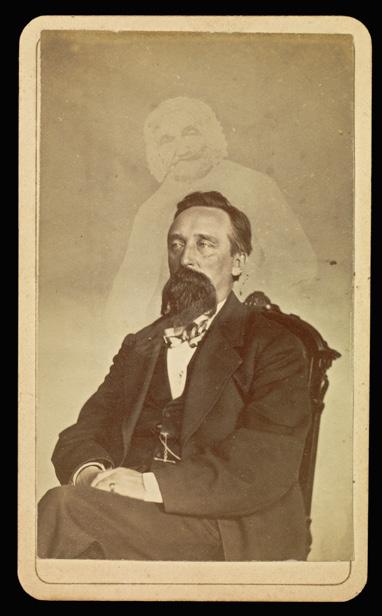

Spirit photography pushed that logic to captivating extremes. Portrait sitters at William Mumler’s New York studio were reportedly awestruck when their photographs contained a translucent apparition. The photographer encouraged them to believe this to be the ghost of a departed loved one, ‘visible’ only to the camera, not the result of deliberate double exposure. Mumler played with assumptions regarding the production of photography, along with audiences’ lack of familiarity with a novel technology, to obscure actions through which the photographs actually came into being. This proved to be a highly lucrative venture, particularly in the aftermath of the American Civil War when the desire to connect with departed loved ones reached an understandable peak.

Curator Corey Keller has written about the disorientating impact that scientific photography of hitherto unseen phenomena had on 19thcentury audiences. To see the inside of a human hand in xrays, rapid movement frozen as still images in highspeed photography, minute organisms enlarged in exquisite detail by photomicroscopy was ‘exhilarating, novel ... and fundamentally disturbing’. As audiences had no way to verify the truth of what the photographs were purported to show, reception involved a leap of faith. This fuelled photography’s associations with wonder, even with magic, sparking the imagination of early audiences. It also created room for imaginative forms of illusionism, fiction, and trickery. The changing relationship between these factors, and the meanings it has been assigned, provides an interesting route through the histories of photography.

Muybridge’s work provided a major source of fascination for conceptual artists in the latter half of the 1960s, who were drawn both to the potential of its gridded

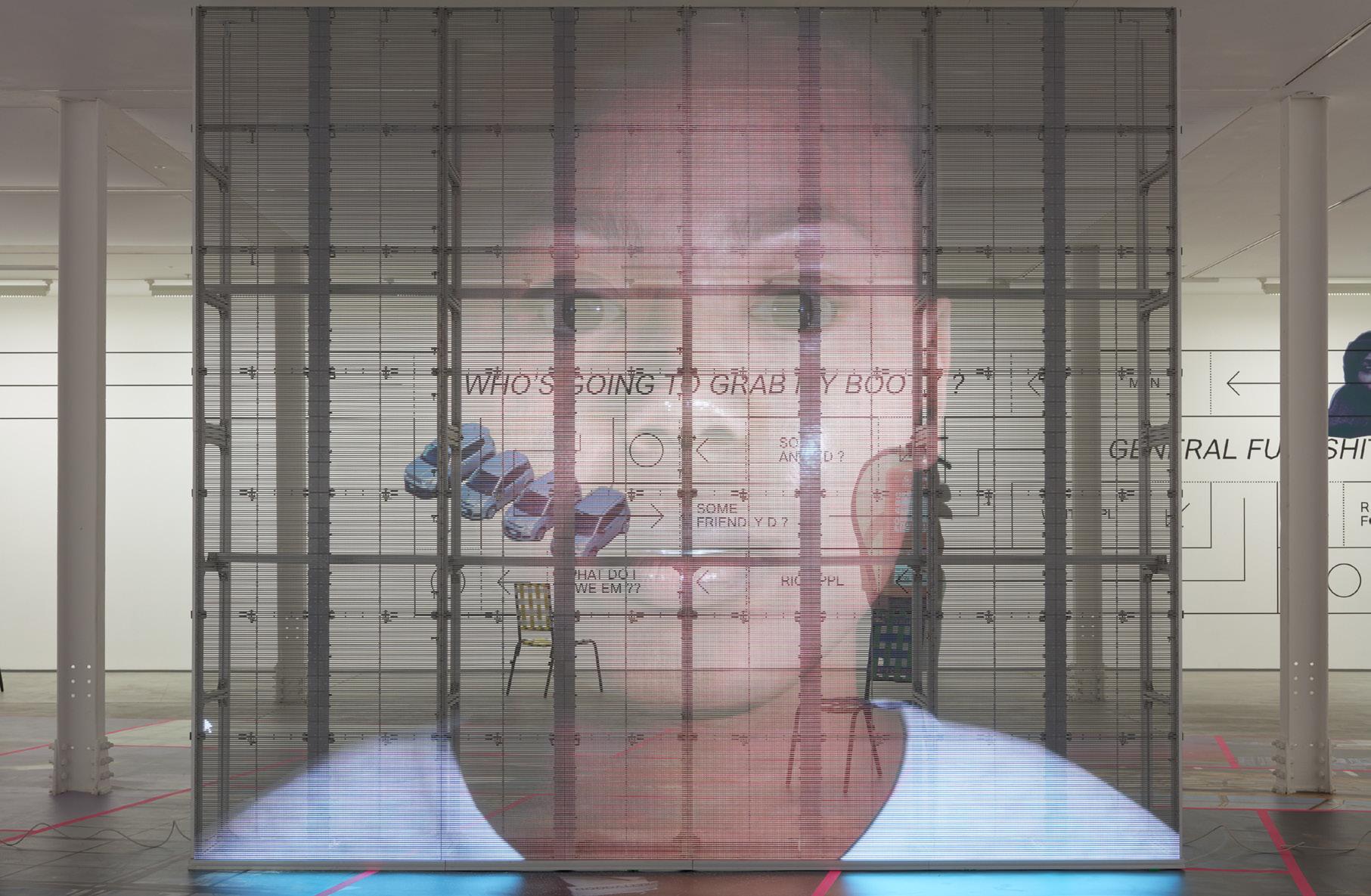

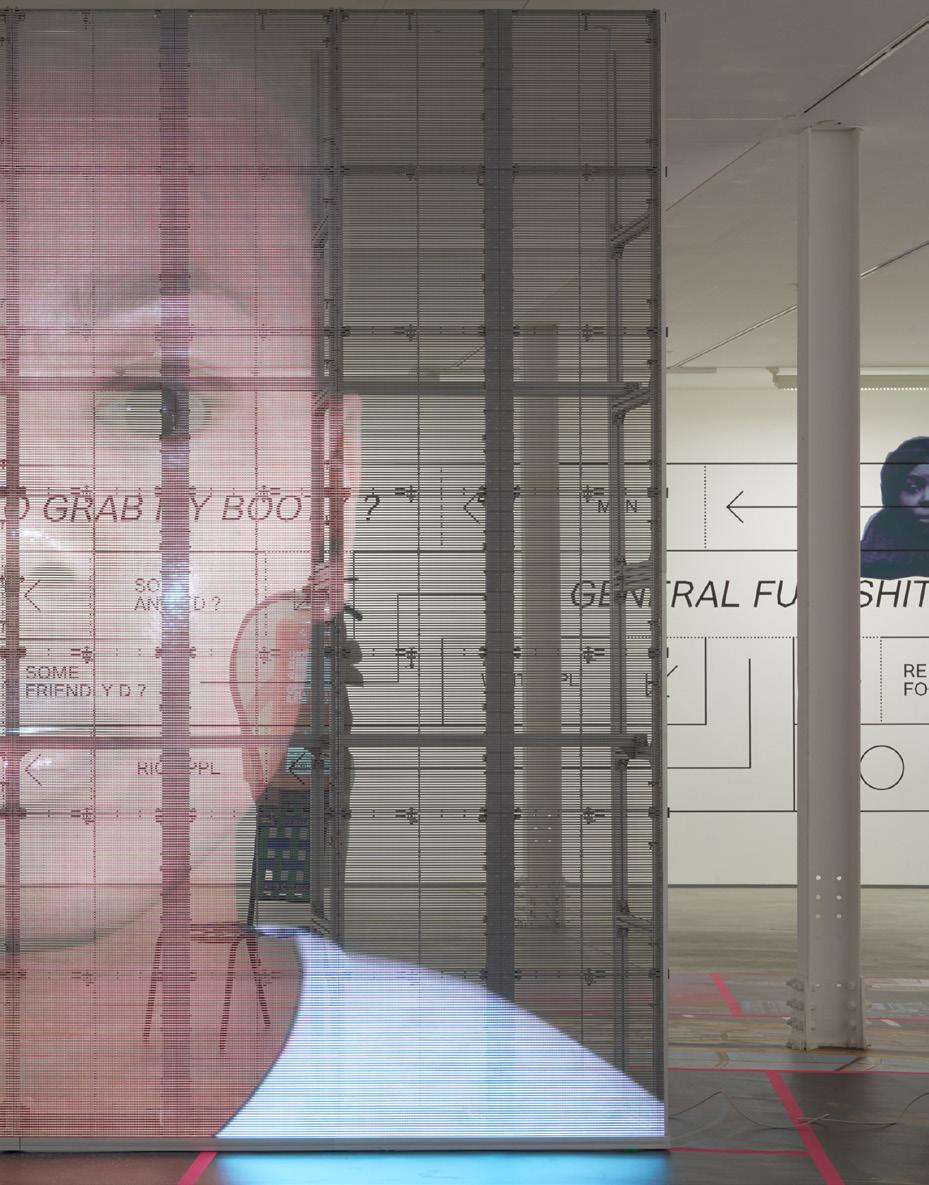

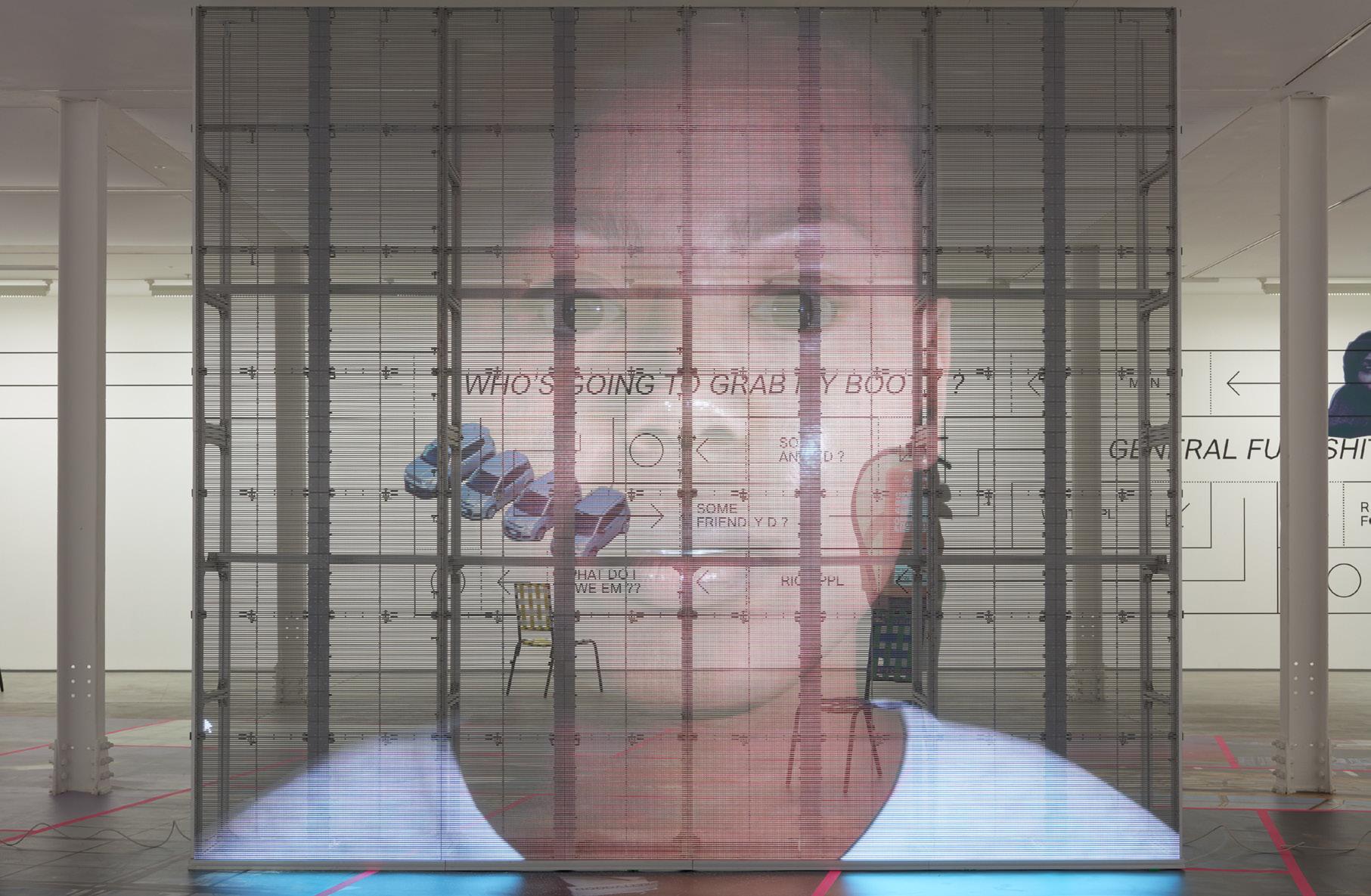

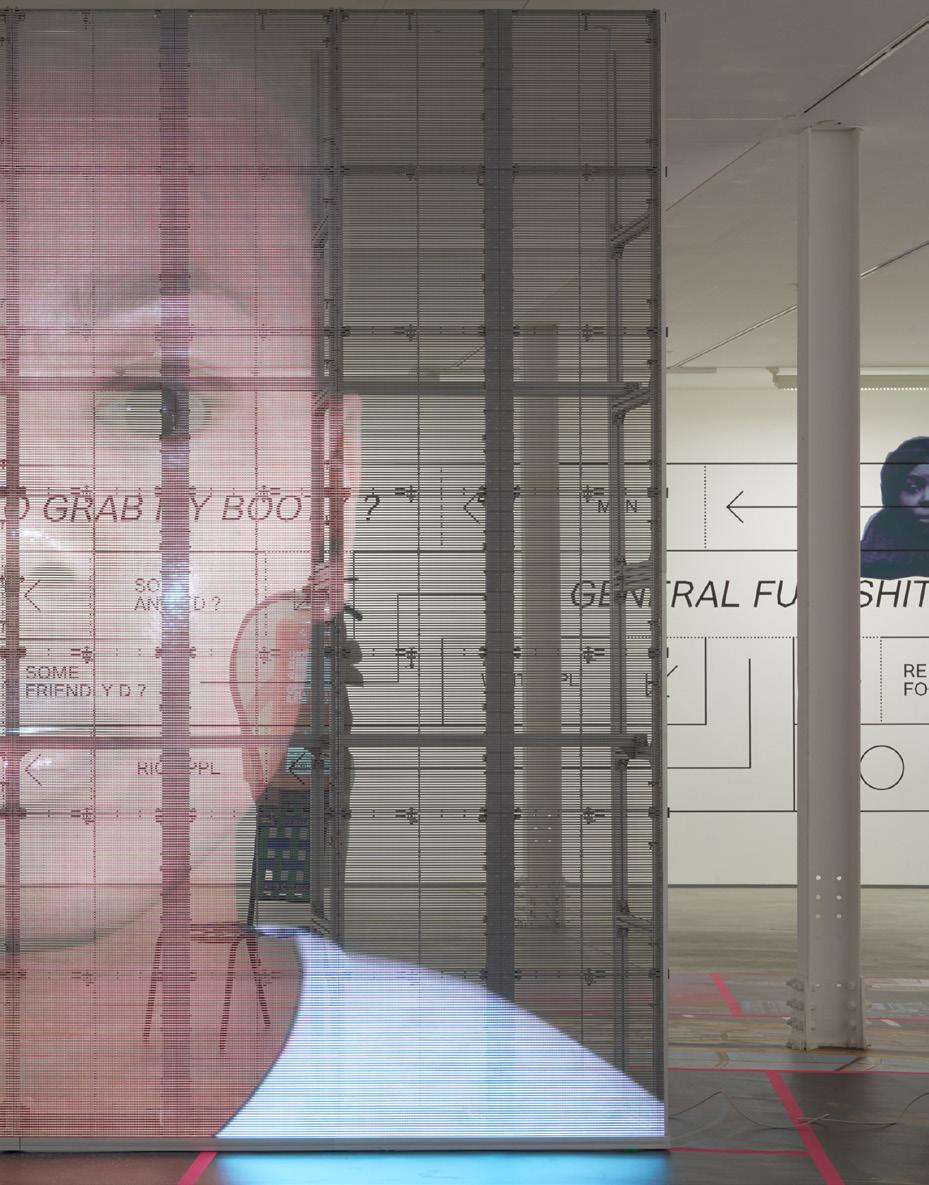

format and to those ways in which the serial presentation of images could deceive. SelfBurial by Keith Arnatt is a series of nine photographs in which the artist appears to gradually descend into a pile of earth. Hollis Frampton and Marian Faller’s Apple Advancing (Variety: Northern Spy) shows an apple that seems to move progressively closer to the camera, as though capable of moving independently. Exploding Paintbrush, a 1975 diptych by Robert Cumming, depicts a paint brush suspended in midair; then again with damaged bristles and surrounded by lively splatters, as though it had exploded spontaneously.

Speaking in 1977, Arnatt explained how, at that time, he had ‘become aware of the unreliability of photographic evidence and began to play with that feature’. He ‘felt that what a photograph could not tell or show might be just as significant as what it could.’ Artists’ playful science fictions opened up what art historian David Alan Mellor calls ‘a domain of comic absurdity inside the technique of willed amateur factualism’.

The production and reception of the 19thcentury images makes sense in the context of a wider belief in machines, both in terms of a capacity to negate the distortions of human subjectivity and to surpass the limits of humans’ own perceptive apparatus. When investigators such as Worthington, Muybridge and Mumler played with the operational logic of mechanical objectivity to create their convincing fictions, their work traded on, and in some important ways reenforced, the wider epistemological framing of machines as superior to humans.

Artists in the 1960s, by contrast, used similar tactics to reassert the imaginative and cognitive capacities of a subjective human presence, one capable of recreating movement based on a series of still images, but also of recognising signs of mimicry and play. The sentiments that underpin that work speak, in turn, to a wider disdain felt towards the rationalisation of the

As audiences had no way to verify the truth of what the photographs were purported to show, reception involved a leap of faith. This fuelled photography’s associations with wonder, even with magic, sparking the imagination of early audiences.

85 84 FOCUS ESSAY

William H. Mumler (American, 18321884) John J. Glover, 18621875, Albumen silver print. Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program

work place and the monotony of massproduced consumer culture. It is a high cultural manifestation of what sociologists Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello describe as an ‘artistic critique’ directed at the ‘poverty of everyday life…the loss of autonomy, the absence of creativity ... the different forms of oppression in the modern world.’

Both the tactics deployed and the specific photographs critiqued indicate an important shift in society’s relationships to photography. By that time, the medium was more than a century old: its systems were better understood as a result of increased exposure and lived experience. The hopes previously invested in machine seeing had started fade, particularly once photography was enlisted as a vital component within consumer culture more broadly. Due to its uses in advertisements, celebrity portraits, as a commodity consumed by the suburban middle classes, photography’s mechanical reproduction had, in the words of art historian Blake Stimson, ‘become camp’. The medium was robbed of its investigative potential, its political promise, and its wonder. Artists like Arnatt and Cumming project a resulting scepticism back in time, towards the earlier revelations of photographic history and all they appeared to promise. High speed photographic series are no longer exhilarating and disturbing, but programmatic and thus capable of malfunction.

In more recent times, photography’s mass practice has been operationalised anew based on the logic of an attention economy. Photographs are no longer only images that encourage us to buy stuff, or an opportunity to make images that we buy. They provide the basis for social interactions that are surveilled, harvested and in various ways traded by powerful entities, including the state and multinational corporations. What economist Shoshana Zuboff calls ‘surveillance capitalism’ involves ‘the unilateral claiming of private human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data’.

Recent analyses of relationships between the politics of the network and political resistance often converge around a similar set of principles. Robert Jackson suggests algorithms be understood not as ‘monolithic, characterless beings of generic function, to which humans adapt and adopt’, but as complex, fractured systems to be negotiated and traversed.’ We must creatively navigate computational systems and develop different ‘modes of traversal’. Finn Brunton and Helen Nissenbaum describe the potential of ‘obfuscation’ — a tool ‘for evasion, noncompliance, outright refusal, deliberate sabotage, and use according to our terms of service’, reliant on the creation of false, deceptive and misleading content to create strategic cover. For Caroline Bassett, metaphorical communication possesses important potential: an encoded meaning, ‘produced by, but nevertheless separate from and irreducible to the truth and the lie it combines’, it is the form of language ‘furthest from coded instruction.’

Those perspectives cast interesting light on contemporary artists’ engagement with networked image culture. Think, for example, of Ed Fornieles’ 2011 project Dorm Daze, a Facebook sitcom set at the University of California. It used information ‘scalped’ from the existing social media profiles of Berkeley students as inspiration for a cast of characters, whose lives were performed on Facebook by the artist’s friends according a semiscripted narrative. Over time, the characters deviated from stereotypes: a basketball star became involved with a violent drug gang; an emo and a jock explored the joys of sadomasochistic sex; a yogalover became involved with Occupy and blew up a bank; the father of a rich kid was discovered to be harvesting human organs in Cambodia.

The requirement to present a single, stable identity is essential to the effective monetization of our online