book proposal by Douglas Bullis

Half the human population lives in the great arc of fifteen nations between Japan and Mongolia. In 2023 their national garment industries produced over $1.5 trillion in sales of products ranging from fast fashion to high couture. These fifteen countries are home to over 300 fashion designers and 44 trade associations with 45,000 members.

Some 263 accredited fashion schools have a collective attendance of over 1.1 million students aspiring to join the 282 brands presently sold in retail outlets. Over 70 Fashion Weeks each year are attended by thousands of trade buyers, media reporters, social influencers, film stars, and socialites. Over five million people a year view Fashion Week collections on television and YouTube, in which hundreds of talented designers showcase their latest ideas.

The Asian fashion market is half the world, yet there is not a single largeformat illustrated book that reveals this bonanza of beauty. The last panoramic survey of the Asia Fashion world was Fashion Asia published by Thames & Hudson released nearly a quarter-century ago. Enormous progress in style innovation, marketing acumen, and the technology of recycling throw-away plastics into unprecedented garment components have occurred since then.

It is time for a fresh look.

This is a tiny sampler of what they will see.

We make noise, not clothes.

I saw a Comme des Garçons show in Tokyo while I was a student. It opened my eyes to how iconoclastic fashion can be. It wasn’t long before Rei Kawakubo noticed my clothing line UNDERCOVER. Rei bought an MA-1 jacket from my very first show. We struck up a friendship. She told me, “Showing in Tokyo would only take you so far. You’ve got to go to Paris.” In 2002, I staged my first women's wear presentation in Paris. Kawakubo’s support also helped drum up interest from journalists and buyers. The night before the show, Kawakubo invited me

and my friends to dinner at Davé, a Chinese restaurant in Paris popular with the fashion crowd. Rei toasted me with the line, “To the beginning of Jun’s fame in Paris!.”

My office and work place are still located in the back streets of Harajuku, housed in a repurposed shipping container that appears to float above the ground. The black metal handle on the front door has crossbones and a lightning bolt etched above the words “Undercover Laboratories.” Without Harajuku, and without Tokyo, there is no UNDERCOVER. Every collection is designed by me from start to finish. My clothes are about revealing, not concealing.

I DO WHAT I DO BECAUSE I LIKE TO DO IT.

I’m almost like a father to this generation. We have the same spirit of mixing things up to turn them into something unexpected. Kids are very interested in what I do because I’ve been leading the Harajuku scene for so long. We share the same rebellious spirit.

I still make my clothes for Harajuku Street trendsetters. Even though I have nothing to prove anymore, I still have a lot to say about the dark stuff underlying human experience, and what the darkness reveals about us. I peel back the façade of the mundane to reveal the layers of the abnormal hidden behind it.

When I was little, I didn't know what fashion was. My Granny told me many stories about embroidery, what people wore in the palace, and I would fantasize about that. When I was eight, I asked Granny for a yellow dress. She said, “Yellow is forbidden." Yellow was the color reserved solely for the Emperor.

For me, each piece is imbued with a narrative, whether it is drawn from fairy tales or military history or dynastic times. It is not fashion; it is timeless art.

I express my emotions in my work. When I create, it is like beautiful music or paintings. I want you to look at them and feel the design touch your soul.

I don't court celebrity. I am happy to be at home with my family, upstairs in my design room where I sketch my ideas. That is my happiest place.

When I first came to Europe I met an

Italian designer who told me, “There are no fashion designers in China. When you speak to the media, don't say you are a Chinese designer. Say you are a designer whose nationality is China.” I answered that there are many designers in China who design because they love it.

When I see the work of our ancestors 200 years or 500 years ago, I am amazed by the amount of intricate, painstaking work they achieved. I hope my work will live longer than me, so future generations will look at it and appreciate our achievements today.

My greatest joys come when I achieve a breakthrough in design or technique. Roughly eighty percent of my designs are meant for people to wear. That work sustains me more than my museum-quality creations. The more responsibility a woman takes on in her life, the greater she becomes.

Many of my contemporaries embrace Western influences and aesthetic language. I take my design cues from my own heritage —various reinterpretations of the cheongsam, Chinese porcelain patterns, and the use of silk in all its variants. I am also inspired by the histories of different countries. My Spring 2017 couture collection titled Court was a couture play on Renaissance courtesan costumes. There is an underlying theme connecting my collections though: impeccable and uncompromising attention to detail.

Yang Enlan is an ethnic Miao from southwest China's Guizhou Province. She is head of the plantprotection station of Shuicheng District Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Miao women exercise relatively more independence, mobility, and social freedom. They are known to be strong willed and politically minded. They actively contribute to their communities in social welfare, education, arts and culture, and agricultural farming.

Miao women demonstrate great skill and artistry in their traditional clothing. From vests, coats, hats, collars, and cuffs, to full skirts and baby carriers, the patterns on their clothes are colorful but complicated, a complexity offset by the clean lines of the silhouettes. Starting about age seven, girls learn how to embroider from mothers and sisters. By the time they are teenagers, they are quite deft — which is said to enhance their spousal prospects.

Ms Yang’s distinctive headdress typifies the traditional “long-horn” Miao cloth head covering worn in twelve villages in the nearby Zhongshan District. Hill tribe Miao women prefer highly elaborate silver headdresses and jewelry. Miao garments are distinctive for their design, style, and intricate workmanship. A Miao saying goes, "Without embroidery, a girl is not a girl.”

cultural elements speak for themselves. Through fashion design, which is a mutual language like music, international audiences can gain a better insight into China.”

The cuff at the end of her sleeve derives from the Manchu-era mati xiu ( ) horse hoof cuff originally devised to shield warriors’ hands from cold winds during battle. Archers rolled the cuffs back when using their weapons. The hoof cuff became highly stylized in court dress, as from the inset image of a 1770 jifu coat used as informal daily attire in the Imperial court.

An elegant garment is ballet on the body.

When I was a young girl I came from very humble beginnings. I was the eldest in a family of seven children. I left school early to help my uncle’s business. He was a tailor in a tiny town outside Taichung City in Taiwan. I became quite nimble at needlework and embroidery, but I never dreamed of becoming a designer. Early training leaves deep footprints. I still insist on impeccable tailoring and craftsmanship.

I met my husband and we already had two children by the time we decided to start our own business. The label Shiatzy Chen began life producing knitwear when I launched it in 1978. At first it was hard to balance both parts of my life — I often had a child in my arms while I worked. How to find the perfect balance between family and work is always a challenge for a Chinese women because society expects women to sacrifice a career to dedicate her life to family. I refused to give up work to be a stay-athome mom, never. I had to accept that there’s always going to be sacrifice. Over the years I gradually moved toward couture fashion and am by now referred to as “the Chanel of Taiwan.”

It took considerable courage to show at Paris Fashion Week in 2008, yet the results were amazing. In 2010 I became the first Chinese member of the Fédération Française de la Couture. In October 2023, I celebrated my twenty-sixth consecutive season at Paris Fashion Week. I now have a couture studio on the Avenue Montaigne in Paris, and seventy retail shops around Asia.

It is important for me to articulate my Chinese heritage through fashion. All we Asian designers have rich cultures to share, just as Coco Chanel shared her French heritage. Our subcultures are richly varied, which gives fashion designers a unique source of inspiration.

One year I wanted to contribute to a charity that supported the Miao peoples who live in the southern Chinese provinces of Guizhou, Hunan, Yunnan, and Sichuan. Their customary costumes inspired my fall-winter 2019 collection. Chanel and LVMH support the same charity, so the Miao people reached a world far larger than the villages where they hand-sew their clothing.

Another season I looked to calligraphy for inspiration. Every country leaves its cultural footprints. It is important for we artists of China to share our many cultures with the world — just as Coco Chanel bequeathed her French heritage to the world. We are the world’s cultural ambassadors just as politicians are ideological and economic ambassadors.

Every collection is an exercise in anxiety. As I watch the model part the curtain to walk out onto the catwalk, I always see some little detail in her garment that I might have done better. Were her earrings really the best to show with that garment? What if I had let the hemline fall to mid-knee instead of above it? What could I have done better? I wonder if I will ever consider myself successful. I ponder the legacy and status of brands like Prada and feel a pang that I have such a long way to go.“Progress, not perfection” is a hard taskmaster, yet when I hear the applause and take the flower bouquet at the end, I am as grateful for my discipline as I am the accolades.

The name Ika means “a thousand islands” in the Bahasa Indonesia that I learned as a child of Bali. Like my name, a single sketch can delight a thousand eyes.

Even as a child I paid attention to the way people choose clothes to express how they feel. I went to Europe to train in apparel design. There I learned more than technique. I learned humility. Germans did not use the word “designer.” They used the word “stylist.” I also learned at the outset that there is no alternative to hard work.

Yet the siren song of Asia drew me back. My family lives in Bali, but Hong Kong is where I produce what I dream at home. I located my business Butoni Limited there in the early 1980s. My career identity has never been “fashion designer.” My identity is how I articulate my life into physical reality day after day. I begin my work day with an inspiration. By the end of the day someone is wearing it. No two days are alike, and neither are the designs.

I cannot live a life of inspiration for its own sake. I have to pass it on. The women who buy my clothes get much of it. But inner satisfaction is more than outer sales figures. I have to nurture the young people, too. I give lectures, make YouTubes. I founded Bali Fashion Week in 2000 as a celebration not of lifestyle, but of Bali. Today the Bali Export Development Organization sustains hundreds of weavers, embroiderers, boutique owners and their staffs, budding entrepreneurs with a sense of social and environmental responsibility. That to me is success.

A typical Ika creation can be called “fashionable ready to wear.” I draw inspirations from my travels and meetings with people from all over the world. They are tiny sprinkles of creation that empower myself and my team in our constant search for new fabrics, new experiments, new ways of embroidering, leaping ahead of the curve of new technologies. Being creative means being different in every way.

Butoni isn’t a label that a woman wears. It is what the world means to her. A woman puts on her body what writers put into words and painters daub on canvas. No good artists repeat themselves or give in to the demand to become a money-making formula. That is why each of my designs has its own identity, its own one of a kind.

I appreciate four human traits above all. The first is resilience — never giving up. The second is ethos — the proper way to manoeuvre within the parameters of respect. The third is curiosity, the quest for the unknown.

The fourth is discovery. Only by turning over every leaf do we find all the treasures hidden underneath.

Two recent developments in the Asian apparel world gratify me deeply — reconfiguring traditional garments into modern styles, and deconstructing crudely made fast fashion to turn it into garments with lasting beauty. Both these movements turn the past into the future.

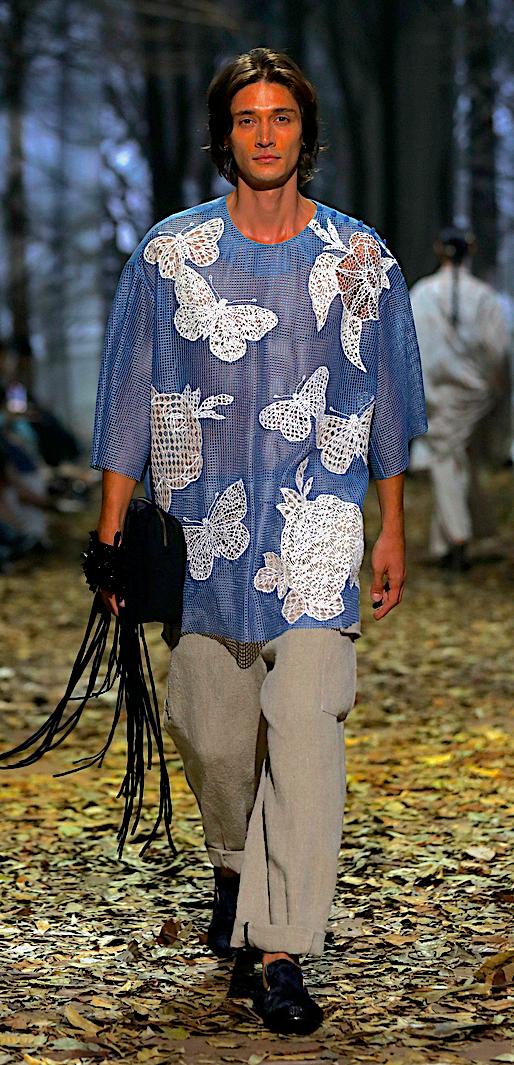

In 2012 I turned to the ancient methods of the Miao peoples who live along the southern coast of China and island of Hainan. I wanted to reinterpret the Miao methods using the textiles and decorative techniques of our own time.

The Miao people consider the butterfly to be the sacred mother of all living things. Butterfly Mother was impregnated by the froth of breaking waves. She laid twelve eggs amid the boughs of a sweet gum tree. Over the next twelve years, each egg hatched into one of the animals of the zodiac. She also gave birth to Jiang Yang and his sister, who in turn gave birth to the human race.

The Miao people believe that everything, animate or inanimate possesses a spirit — mountains, rivers, and creatures; even metals, plows, and drums. They embroider these elements onto bibs, handbags, pleated skirts, leg wraps, headgear, and baby slings on a simple indigo-dyed fabric. The result is a stunning palette of embroidery unique among decorative traditions. Combining the age old with the contemporary transformed the Butterfly Mother of Myth into the Butterfly Mother of Now.

Creative people draw inspiration from everything around us. Each seasonal collection is a saga told by me to my followers and the world around us.

When I was young I was very interested in art and acting, so I merged the two interests into fashion as a career. I learned the clothing business via a tailor friend who operated a small clothing alteration business. He offered me work assembling his garments. As the eldest son I had to support my family. My friend’s job paid enough money that I no longer had to skip meals to support my family. When I decided to make garments as a career, I took a second job in a clothing design institute. I designed jeans and business suits for a ready-made clothing company. After five years learning how to run a clothing business, I launched my LIE SANGBONG brand in 1985 in the Myeongdong district of central Seoul.

My duty is to inspire people to choose garments that express the art of the everyday.

I became internationally recognized in 1999 via designs that blended Korean hangul calligraphy into modern interpretations of our hanbok street clothing.

I showed that collection on my first visit to Paris. Everything was a new experience for me. I had to limit the total weight of my baggage, so I got on the plane wearing seven layers of my clothes and my only pair of shoes. When I arrived at my assigned booth in the showroom, the booth was flying the national flag of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea). The organizers didn’t know there were two Koreas.

Since then I have shown my collections in twenty-three Paris Fashion Weeks and have twenty shops all over Asia.

I am spectator in the world of imagination.

I have adopted modern technology like the non-woven textiles that our Korean scientists invent using computer technology applied to chemistry. An alternative to the weaving loom arrived with machinery that floats sheets of plastic that are thicker and more durable than the flimsy films that house painters use as drop cloths. Plastic fabrics can be cut into shapes just like woven textiles, but cut pieces made of plastic sheet can be overlain on other cut pieces, then fused together with heat to create patterned shapes that resemble paintings with multiple layers overlain on top each other. One cannot do that so easily with woven cloth because when numerous patterns and colors are layered the cloth becomes too heavy to wear or the drape is ponderous.

I used plastic fabrics in a collection inspired by “The Kiss” painted by Austria’s Gustav Klimt. The show interpreted Klimt’s eroticism, colors, and intricate decorative motifs using the cuts, drape, and surface designs of the material in the show. I blended multiple surface effects into looks unattainable any other way.

I hope to dispel the idea that a woman wearing a fashionable garment is all surface and no mystery. I structured the entire last third of my 2024 spring/ summer collection around the figure of an enigmatic shape that moves like a human wraith but is a total mystery beneath the surface — just as a real woman is a mystery beneath her outer identity.

My ties with Austria trace back ten years to when I staged a show in Vienna for the occasion of Korea and Austria’s fiftieth anniversary of diplomatic relations. For this show I adopted the theme of Gustav Klimt’s “The Kiss” because it so exquisitely expresses love. The pandemic had prevented people from kissing because a kiss involves skin on skin. People couldn’t do that with Covid masks in the way.

I decided to model my 2023 collection at the Belvedere in Vienna after the painting. The designs are not simply the “The Kiss” printed on cloth. I wanted to reinvent the craftsmanship of imagery using embroidery for the patterns and fur and leather to convey the sense of tactility.

I learned so much while studying Klimt’s painting. I contemplated deeply how I was going to reinterpret it into garments. I felt like it was my duty as a designer to upgrade the painting into a new form of artistic representation.

Traditional Korean hanbok isn’t as tight and body-aware as Western clothes. Korea was historically known for our many types of hats, but since industrial modernization, Koreans have moved away from traditional wear toward Western styles. In the 1980s and 1990s, designs became daring and avant-garde under the influence of European fashion. Then in the 2000s, the wheel returned to street style in which comfort was prized over form.

Today young people are into the derivative street clothes they see on their cellphones. International style icons can inspire, but it is we local designers who must reinvent local style to match the taste of the times by immersing it within our overall Korean world view. Korean fashion captures the personality of our subcultures more than any other art.

I tell stories using design. I orchestrate my catwalk shows to begin with street wear. The designs rise in sophistication as the show proceeds. The last pieces are one-of-akind couture worn only by a single buyer. Couture lives in its own ethereal world of concept.

I strive to reinvent traditional Korean garment shapes and patterns using the latest fabrics and color technology. When I use traditional textiles, I often choose silk.

My favorite decorative motifs are inspired by dancheong, the traditional Korean colors painted on wooden doors and window frames.

In one collection people compared my decorative designs to the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian. In reality, the designs were based on our traditional jogakbo patchwork cloth used to wrap gifts and items for storage.

I started at fifteen helping my mother work as a seamstress. I had no formal fashion training, yet three years later I was hired as the assistant designer of Cebubased fashion designer Nikki Crodua. After four years I opened my own shop. From the beginning I wanted to reveal the extraordinary nature of couture. In 2004 I won first place in my first show, the 2004 Philippine Fashion Design Competition. The piece was a terno inspired by the Philippine Pag-Asa eagle. I dyed jusi fabric to look like feathers. I sewed 5,000 eagle quills as a faux/real plumage on the dress. I received a standing ovation when the announcer revealed how I did it.

Beauty takes time. Ask any woman.

It takes a lot of work to turn imagination into reality. I sketch, shape, form, sample, decide on the techniques. Then my team comes in and works their magic. I am not afraid to put in the effort. I like the slow way of doing things, perfecting minute details and figuring out complexities.

I don’t work with fabrics, I subvert them — stiffen soft chiffon into sculptural shapes, turn contours into visual drama using precise pleating, emboss fabric into textured three-dimensional intricacy.

A designer must have an eye for beauty, but also be a strict editor. We have an urge to put everything we know into a design. We have to learn discipline and restraint.

We must balance weight, movement, restriction, and functionality. Beauty transcends mediums. It reveals itself in the details of a dress, a sculpture, or colors being mixed in startling ways. Beauty in its purest form evokes emotion as it gives delight.

I started at fifteen and I’m now fifty-one. That’s a good full circle. I am delighted when I inspire young designers. I want to be remembered as a designer who was not merely popular but contributed to the elevation of the craft in terms of technique, construction, and design.

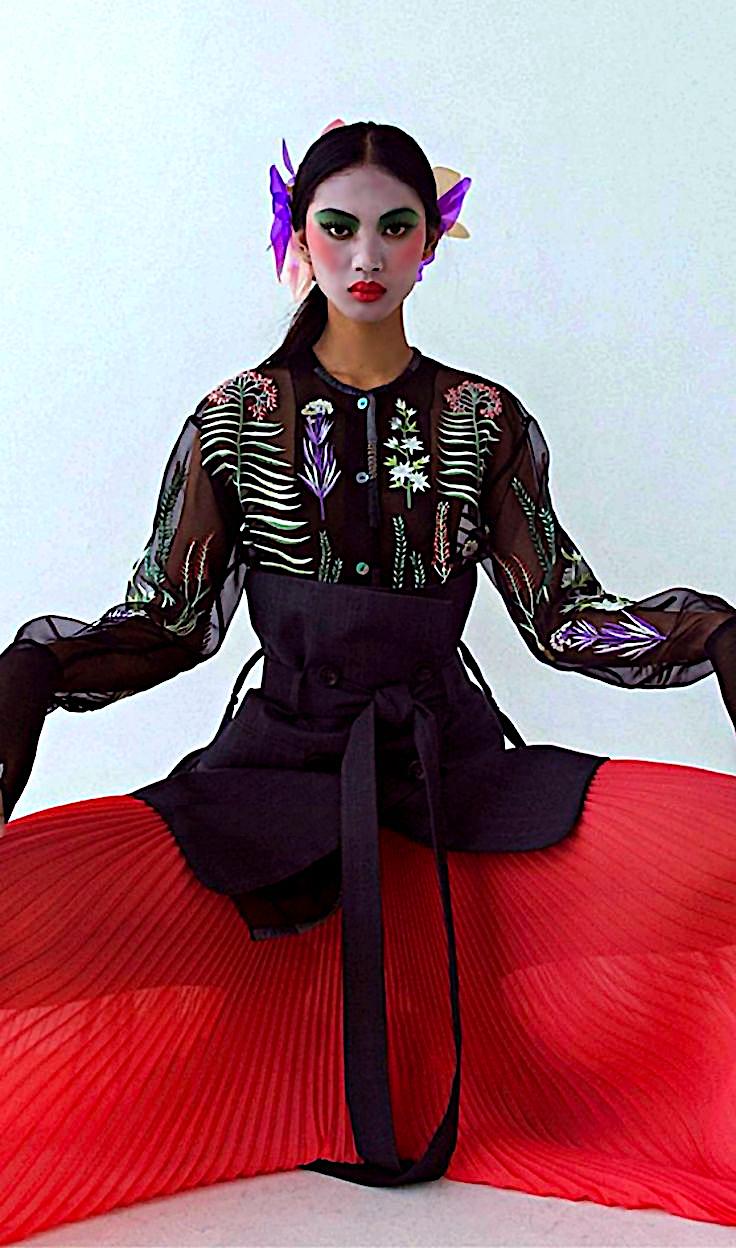

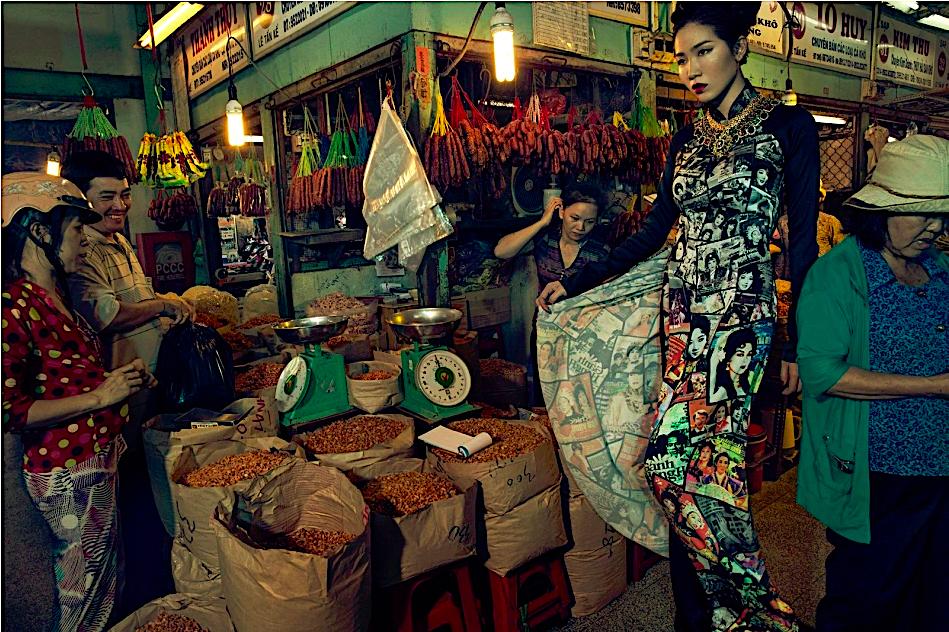

I am a self-taught fashion designer based in Ho Chi Minh City. As a graduate of Fine Arts from the Ho Chi Minh City University of the Arts, my selfintroduction to the Vietnamese fashion community came in 2000 when my “Green Leaves” fashion collection won First prize in the “New Ideas” category at Vietnam's Grand Prix.

I began to work with singers and celebrities in Vietnam, styling their photo shoots and constructing signature looks. As my work became more recognized, I launched a ready to wear brand named Kin by Cong Tri in 2009. In 2011 added a menswear line, KinConcept.

Today I personally teach at my atelier, where I create new designs from villagesourced fabrics, producing fashionforward designs that are infused with

tradition. My signature aesthetic and keen eye for detail combine both progressive and hand-made techniques, resulting in collections that feature laser cutting, interlacing, hand-ironed pleating, knitting, and hand painting. I place a particular emphasis on jewel and sequin embellishments.

As my brand grew in popularity and sales, my creations could become more avant-garde in the Haute Couture world. In 2013 I became the first Vietnamese designer to launch a design house dedicated to Haute Couture.

My hand-made garments are easily identifiable due to their traditional identity, imbued with an international contemporary spirit. I mentor emerging designers hoping to follow my path into the fashion industry in Vietnam.

In Surabaya where I grew up, nature and beauty were the same. To me the beauty of nature and the beauty of the human body were life itself.

I didn’t consider fashion design as a career until my first year in an architecture program at a college in Germany. I was always attracted to visual crafts, so I switched my career to fashion design. In 1977 I entered the Müller & Sohn Privat Mode Schule in Düsseldorf, Germany. When I graduated in 1982 I entered the London College of Fashion

The different ways of life in Germany and the U.K. inspired the idea that merging the best ideas of different cultures

I am a romantic poet disguised as a fashion designer.

can create innovative fashion and fashion can change people’s lifestyles. I developed the idea further by staying another year in Florence, Italy.

Exciting as all this was, Indonesia is where my heart lives. The world is getting smaller and more accessible as it becomes borderless. Over the years many Asian designers have modernized ancestral designs without losing their essence. As the world grows smaller, Asian fashion grows larger.

I find inspiration in the rich heritage that surrounds me. My forte is sculpting the richness of our culture into modern wearable designs. I am not much for talk, so I let my work do the talking.

When I need inspiration I go to art galleries, a world very different from the fashion world. One day I was struck by a tiny feature on a huge portrait of a woman in a gallery. She was almost completely hidden beneath multiple layers of fabric. Her sole adornment was a single, perfect rose. That tiny detail all but leaped off the canvas. It inspired my theory that fashion is a splendid jewel on a plain dress. The elegance of the rose and the elegance of the woman confirmed my vision that beauty in nature and beauty in a person are the same.

My designs for women start with respect for the female figure. Femininity

accentuates body curves, but a good design must be subtle and respectful, attractive without flaunting their allure.

The hard work, perseverance, and dedication to the fashion industry are not in vain. The Biyan brand appears in shops in Paris, Miami, Santa Fe, Hong Kong, Dubai, to say nothing of all the major cities in Asia.

Yet no one can do this alone. I rely on dozens of people who have worked with me over the years. I celebrate their talents, cry with them when times are tough. We thrive together despite the ups and downs of the fashion world career.

We South-East Asian designers are lucky — we don’t have seasons. In most climates fashion shows have to think one season ahead, so every year they design a Spring/Summer collection in the winter and an Autumn/Winter collection in the summer. But for us, every day is summer. That is why our ancestral garments clothes were airy and light. I want people to feel like they can move freely about in the same way I moved freely as a child. That is why my clothing restricts body movement as little as possible.

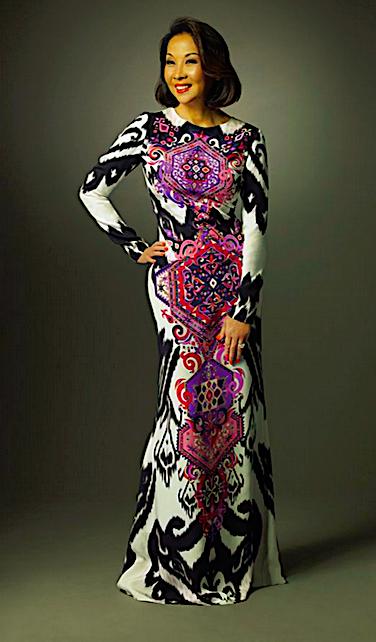

I presented my luxury ready-towear line titled Humba Hammu, meaning "Beautiful Sumba”, in South Jakarta.

The collection was the first in my career to showcase only traditional handwoven fabrics. The Sumba collection was composed entirely of locally woven ikat textiles. I transformed the traditional handwoven fabrics into luxurious pieces with opulent embroideries and patterns paired with jacquard silk outerwear.

I collaborated with 150 ikat weavers, thirteen of whom were brought over for the fashion show to show their work at a night market accompanying the event.

Traditional culture is an invaluable treasure that we must preserve. I hope my work will inspire ikat weavers to continue their work preserving Indonesia's textile traditions.

Before self-powered ships, the telephone, and television, island peoples in Indonesia and the Philippines developed richly varied subcultures because transport was slow and economies were poor.

Some islands like Borneo and Sulawesi have steep mountain ranges, which means deep river valleys. Each valley developed its own unique decorative art. On Borneo alone we have the Dyaks, Iban, Budiah, Bidayuh, Tedayan, Orang Minik, Bakong. Dalek, Biatahs, Singgais, Jagoi, Lara. There are so many weaving and decorative traditions that we designers can’t keep up with them all.

When I visited the island of Sumba in East Nusa Tenggara, I fell in love with the local ikat designs. We can do amazing things when we are in love. That happened with this collection. I planned to create forty looks, but I fell so much in love with the Sumba ikats that I ended up creating ninety looks.

I hope my effort improves the livelihood of the Sumba weavers by attracting international attention to their designs, attracting more tourists to visit and buy them.

The decorative drape and embellishments on today’s Muslimah modest wear hijab headwear and kebaya upper garments were invented in Malaysia and Indonesia but are now sold all over the Middle East.

Someone once called me l’enfant terrible of the Singapore fashion industry. You can decide for yourself whether I’m an enfant, but the terrible part is true. I have an insatiable passion for beauty and am fearless when it comes to doing something daring.

Twenty-five years in the fashion business have not jaded my love for high drama, the flamboyant, the glamorous. My couture designs and my relentless pursuit of beauty are one and the same. Brides seem to think so: I’ve been named “The Best of Singapore” three times by Singapore Tatler magazine. Imagination takes us to a world that never was so we can have a world that always is.

I create garments that reflect moments and dreams rather than worrying about the next best-selling commercial design. I create to ignore conventions, celebrate individuality and diversity, do away with the rituals of seasonal demands.

I make clothes for the woman who is seductive, confident, and feminine. She is enchanted by new ideas. There is never a dull moment in her life.

I turn catwalk shows into surreal installations where the clothing and the models are part of the theatrics.

There is an incredible amount of talent and creativity here in Singapore. There is no reason why the next hub of fashion should not be Asia. In the past couple of years our local market has seen a huge increase in the number and quality of home-grown fashion labels. They are the seeds of emerging indigenous fashion identity. As the economy improves, so does the market for fashion. The Singapore fashion scene is booming because of our emphasis on the consumers.

There is something beautiful about the creative process, the birth of an idea and the commitment to creation. I am always curious about the world, balancing a complex life with the desire to contribute.

There are many ways to get the creative juices flowing. I design based on the concept I have in my mind. It usually springs when I am relaxed. I sketch my subconscious thoughts on paper. It’s always a surprise to see how the design develops. Sometimes the idea takes over and I am no longer in charge. I have worked hard to master the technical side so I know what is possible and how to do it right. I want to understand every part of the process, from the foundation to the finishing touches.

There is nothing more important than the artistic integrity of the design. Originality excites me while I work, but quality is the boss.

Many great fashion designers have inspired and influenced my work. Top of my list is the Spanishborn French couturier Cristobal Balenciaga. He was revered as the couturier of couturiers. He created astonishing collections with his mastery of cuts. I love the integrity of his creative ideal.

The first rule of Couture is that it cannot be rushed.

I was seventeen when I created my first design in 2007. I was a clueless teenager with no idea what I was getting into. I entered a Singaporean competition and won first place for a cheongsam-inspired gown. That design won the Designer of the Year contest. Then it dawned on me why designing was in my blood: My mother wore Emilio Pucci when I was growing up. I would see her receive socially prominent women who came to our home to commission one-of-a-kind dresses.

Later I learned that was the definition of “couturier.”

Nine years after that I founded The Melium Group, a portmanteau of international luxury fashion and lifestyle brands — Hugo Boss, Emilio Pucci, Givenchy, MCM, Stuart Weitzman, Tod’s. Melium made me an international fashion pioneer in Malaysia. I have been at it three decades now. It is not just a business, it is a journey to discover what I’m made of and what kind of legacy I want to leave.

Melium always meant more to me than a luxury fashion label. I began with a dream of curating beautiful fashion pieces and accessories for men and women who could truly appreciate them. I admire designers like Azzedine Alaïa and Hubert de Givenchy, Maticevski, and Jonathan Simkhai. They were architects of fabric, texture, and design that transcended the mundane. They designed dreams people could wear. Melium introduced unexpectedness to Malaysian fashion awareness. While the media and technology have changed beyond recognition, our passion to design dreams has not.

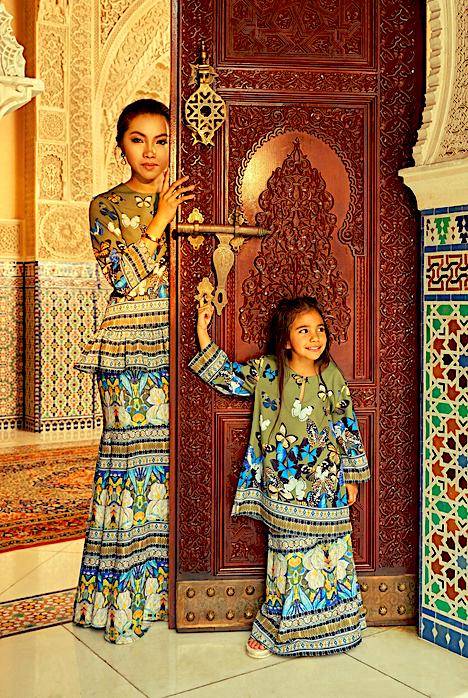

Then in 2015 a visit to Marrakech in Morocco prompted me to introduce couture to my repertoire.

A couture dress is a story, a narrative, an experience that can take two to three months to complete. There will be at least two fittings to take the basic measurements, and later alterations for exact size and fit. Slight adjustments — for example, changing a V-neckline to a rounded one — must be anticipated because a significant number of my clientele hail from the Middle East where there can be strict definitions of discretion in women’s clothing.

In couture dressmaking it is fundamental that the client be truly pleased with her piece. Couture is a commitment to an exquisitely memorable occasion. Fashion is my passion, but it can be a very stern taskmaster when you have to live with shifting demands every day.

The keynotes of a Farah Khan dress are their body-conscious shape and embellishments that set it apart from all others. How do I make a consistent look out of those two parameters?

First, there is the base fabric, a stretch net.

Layered on top of it is a second fabric which gives shape to the body beneath.

For the embellishments and accessories I work with South East Asian artisans who have honed their technique for years.

Over the years fashion has evolved. Couture retains its refined, elevated status, but streetwear has turned into a trend-chasing business, following events rather than leading them. When I began, the designer was the brand. Today brand is like a mall escalator that designers use to move from floor to floor. Fast fashion has become musical chairs in an overcrowded lobby.

I moved from the Melium retail collection into couture design in 2015 when I launched beautifully embellished evening wear inspired by a visit to Marrakech. Marrakesh is one of the most beautiful Islamic cities in the world. The architecture, culture, and design of all things there truly captures the beauty and harmony of Islam.

My visit inspired a collection based on two iconic locales there. One was the Jardin Majorelle, a botanical garden with a blue Cubist villa in the middle of it. I was so enchanted by the villa’s unique shade of blue that I made it the principal hue of the collection.

The other landmark was the Ben Youssef Madrasa. In years past it was the largest Islamic college in all of Morocco. The Madrasa’s intricate mosaic patterns inspired a collection that became such a success that it was reprised in Versailles, Cannes, London, and Jakarta.

I was born and grew up in Bangkok. Both my parents were visual artists. Much of my childhood and youth was passed visiting galleries and listening to my parents’ friends at get-togethers. I attended an unremarkable high school. Then I was accepted the Royal Academy in Antwerp. I received a Bachelor’s degree in fashion arts in 2015 and a Master’s the following year.

Two years later I launched my label SOI SA:M. The identity I project is contemporary luxury wear of uncompromising beauty. I hand-make my women’s wear, shoes, and accessories, focusing on sophisticated silhouettes, distinct color

combinations, and painstaking fabrication. I enjoy creating collections with a strong narrative story line behind them. In the beginning visual research is key. I freesketch multiple ideas into shape, colors, and styles into an attitude. Sketching defines the direction of the collection. In “The Wild Bunch” collection I knew from quite early on how I wanted the progression of the first few looks to propel the narrative line. It starts out with simple white pieces. They symbolize the Victorian-era ideal of purity. Gradually the garments mutate into dreamscape of modernity — vivid, wild, free.

For me the goal of fashion is to create fiction. Done well, a garment reveals the story of someone who constructs their own world. Taking a departure point from Peter Weir’s 1975 mystery-drama “Picnic at Hanging Rock,” one collection follows a group of Victorian school girls who dare to trust their instincts and venture into the wild rugged landscape of a place called Hanging Rock. Their mysterious disappearance prompts viewers to ask where they could have ended up.

I portrayed their innocence and youth using pure yellow dresses. As the collection progressed down the catwalk, the clothes injected an increasingly dark, sinister appearance. Perhaps the girls had entered into a parallel reality which tore off their picture-perfect surface to reveal hot-blooded eroticism that eventually consumes them. To translate this into fabric, I introduced increasingly discordant colors and frayed the edges of the garments until they looked like they were falling to pieces.

The Hanging Rock collection shifts from a proper Victorian look of frilly fragility toward a sensual, sexy, unsuppressed eroticism. The girls reveal their formerly concealed wild and urgent side. Their emotional fragility morphs into wanton desire. I accomplished this by pairing colors and textures that at any moment might fall apart completely.

Achieving the collection’s florid animallike look brought me to seek out new ways of expression using unexpected materials.

This interpretation of a well-known story became an entire line of garments meant for women who dare to roam through their own personal wild, dangerous dreamscape.

I create garment identities based on the stars of my favorite films. One collection was a dream sequence inspired by the photo montages of the German avant-garde photographer Grete Stern. Another collection derived from the monumental installations of the American artist Sarah Sze in which she turns found objects into otherworldly landscapes.

I am also inspired by the cinematic atmospheres of the directors Wes Anderson and Peter Weir, by the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, and the photomontages of David Hockney.

Characters and scene settings appear in collages along with other visual references, all translated into garment designs. Unusual techniques combine contrasting materials and bold color combinations to heighten the garments’ allure.

I want my garments to convey a sense of spontaneity and freedom wrought in a sophisticated way.

My Bangkok shop SOI SA:M is an art exhibition space which doubles as the showroom for my latest collections. The setup for this space changes with each new collection depending on the theme of that season. I invite other artists and creators to build an art installation alongside my garments. For “Cloudbusting” (2020), the artists Montis Songsombat and Naraphat Sakarthornsap created works that responded uniquely to the torn-to-shreds theme of the collection. Their sensibilities and mediums were very different, combining video, photography, and flower arrangement into one coherent whole. The common thread is the search for beauty.

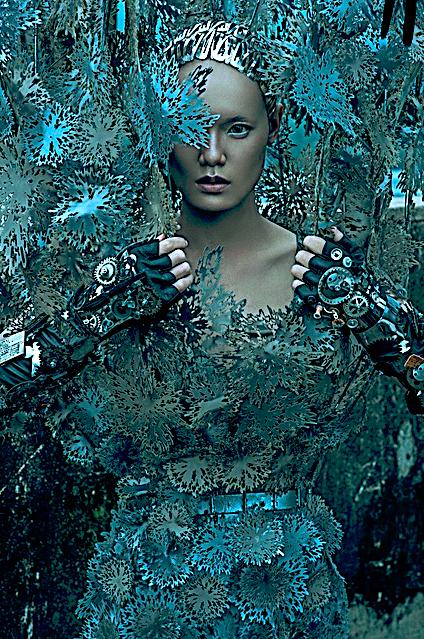

I was born into a family of research scientists and engineers. My ideas about form and structure took shape by observing my father and uncles working on engineering projects. I was fascinated by the aesthetics of complex mathematical blueprints. Computer-aided design could easily assemble structural shapes and intersecting curved surfaces that would be impossible using traditional drafting — a design technology that inspired the architects Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid to build the most visually arresting buildings in the world.

Even as a child I would mimic my father’s drawings with colored chalk on the walls of my house. But a career of stepping into my father’s shoes just did not resonate with me. When I regarded the sarees, lehenga, and shalwar khameez garments Indian women wore on the streets and to fancy functions,

Change something. Then change it again.

I was struck by their monotony. Their weavers and seamstresses had to rely on surface design and unusual color matching to project the wearer’s sense of individual taste. One day the thought arose, “Why not make those clothes using structural shapes like architects and sculptors?”

The limiting factor was that traditional textiles and weaving methods could not make fabric thick yet slippery enough to hold a shape without the human body to give it shape.

I loved drawing sketches of the clothes women wore. A cousin who was pursuing fashion design noticed my youthful sketches of seemingly impossible clothing designs. My cousin helped me apply to the National

Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) in Delhi, in 1999. I participated in many student competitions and got the chance to travel to Japan, London and Italy. Those travels gave me a taste of what fashion was like in different cultures. I met and interacted with design students from around the world, and sat in on in lectures and discussions with fashion experts and other people from the industry.

After I graduated in 2002 I apprenticed with two Russian couturiers, Seredin and Vasiliev, as a design assistant and pattern cutter for Paris Couture Week 2003. It was a wonderful feeling to see my first designs march down the catwalk.

Then one day I got a call from Tarun Tahiliani to join his ready-to-wear design team. He is one of the most highly regarded designers in India. I accepted at once. It was one of the best decisions I have taken in my career. There I learned the business side of garment making — meeting clients, dealing with shop owners, show producers, and media influencers. Under Tarun’s wing I learned that craftsmanship and marketing were both essential for success.

Then I met Shiv Agarwal, design director of the Creative Group. During our conversations the idea of launching an avant-garde brand of garments using unusual materials like coconut fiber and the leaves of certain bananas. He raised enough money to open a workshop aptly named Morphe. As the creative director I attended textile production conventions and became familiar with the big picture of global fashion.

All of these experiences culminated in the creation of my own Amit Aggarwal couture label. I finally had the freedom to create an independent design language that agreed with my understanding of the science of textile fabrication.

The key to my couture lies in moulding and freezing amorphous forms into wearable structures. Industrial materials are thoroughly transformed into intricate garments that hold their shape on their own, which further beautifies a woman’s figure.

One day I passed a landfill with mountains of waste plastics from onetime-use products — plastic bottles, shopping bags, and other use-and-forget products. Plastic materials do not degrade like cloth, metal tins, or wood. Burning them was out of the question given the levels of pollution in Indian cities. Then I learned that plastics melt if carefully heated, and the resulting viscous liquid can be shaped into flat sheets of varying thicknesses or extruded into long fibers which then can be woven or braided. Recycled plastic can also be heat-molded into curved patterns in the same way as sheet metal.

The bright light went on: deconstruct industrial waste into its original raw material, then reconstruct the new material into something entirely different. Every garment you see on these pages was made out of recycled

plastics. Their silhouettes, cut, and malleability are impossible using other materials. Neither are the sweeping curves, bows, floral motifs, and other elements.

I have now shown my recycled-waste garments in numerous collections at Fashion Weeks in India and the West. My Luxury Pret collection is fabricated entirely with metallic textiles and sells in shops all over the world.

Many of the unusual shapes and design patterns were inspired by the Harjuku street clothes of Japan and of course, Frank Gehry’s buildings. My collections are a collage of various subtle and flamboyant influences. Plastics and artificial rubber can be manipulated via cutting, folding, even steaming into totally new forms. That explains the fluid, flower-like flounces and flat panel shapes that you see in the designs.

I have now shown my recycled plastic couture at Paris Fashion Week over the past ten years. The Amir Aggarwal brand is sold in 18 countries outside India such as Kuwait, Germany, Panama, London, and Dubai.

Over the past few years my understanding of form and function has come closer. The exaggerated but mostly theatrical form that still appears in my couture has slipped into my the ready-to-wear lines.

I enjoy exploration when I create garments. I imagine a shopper who doesn’t stick to an ideology and is open to the unexpected. My garments reflect traditional Indian silhouettes, but, the designs are very visually daring. My ideal customer is someone who dares to be different.

We make clothes that evoke romance, fairy tales, and feminism. From the very beginning our intention was for the company to grow. That goal is still the same. But the market and practices have changed quite a bit since we started the label fifteen years ago. Today, people no longer change their wardrobe every six months. Compared to the generation of our parents, the level of discretionary spending is much higher. Hence demand is higher too. Technology has changed so many things. We can make larger number of garments faster. Our garments are prized possessions because each dress is hand-crafted The availability of sales outlets all over Asia has really taken off. Fifteen years ago our market was just two or three stores. Today we are stocked all

Get it right when you change one thing, and you change everything.

over the world. There are multiple fashion weeks serving large numbers of designers too.

Our growth has been phenomenal. When we formed the label, the fashion week movement had just begun and the industry was in a nascent stage. People used to work on a consignment basis, We wouldn’t get paid till three or four months after a sale. Today there are multiple platforms and they pay on purchase.

We have grown far beyond our dreams when we first started. The first few years we had only four craftsmen. Today we have large teams, each specializing in just a few parts of dress assembly.

The market has also changed dramatically. Fifteen years ago a label would advertise in a magazine. Today we

are on the social media and attend celebrity appearances. We spend a million Sri Lankan rupees on marketing, and it works.

The first five years for any new designer are tough. The market is cut-throat but there is always room for good people.

We were best friends in college and go a long way back. Like all long-term business partnerships, we don’t let differences of opinion get to the point where we throw shoes at each other. The label is bigger than all of us as individuals. We are responsible for the entire team.

I have been interested in fashion for as long as I can remember. Even in secondary school I was sketching my own designs and sewing my own clothing.

My brand name Torgo is the Mongolian word for the material used in our traditional cloaks, which we call Deel. Torgo is a luxury material that implies elegance and high class (as distinct from high social status) to the Mongolian people.

I was an amateur in the fashion world when I began. My first collection named Torgo Show was shown in Irkutsk in 2015. It spurred excitement but also anxiety despite my pride in my design ideas.

The feedback was very positive. I was

astonished that my collection was better known abroad than in Mongolia.

I was a fresh voice in the eyes of the established Asian fashion centers. That encouraged me no end. I was surprised at so much interest in Mongolian textiles and designs — and in Mongolia itself — after my presentation.

Being a Mongolian Torgo designer, is challenging. I am inspired by the traditional garments of our long-lived Mongol culture. I translate these ancient styles into modern designs that are uniquely Mongolian yet world-aware as well. It takes time and perseverance to research the fashion of the past. The challenge comes in creating modern designs that are innovative yet retain the historical and traditional look.

The traditional horse-hoof cuffs on the sleeve ends were devised to protect herder’s hands when obliged to work without mittens in winter’s icy gales. Archers would roll the left cuff back when using their bows and arrows.

I am inspired by the idea of blending our traditional clan-leadership formal wear with Qing Dynasty court dresses from 1650 forward. Garment ideas that once graced the Forbidden City become contemporary wearable art under my design label Torgo, which I founded in 2003. I am fascinated by merging multiple layers of traditional Chinese silhouettes with contemporary deel taffeta embroidered with ancient totemic images of interlinked geometric shapes, formless clouds, and intricate knots.

My ideal garment seamlessly blends the timeless with the timely.

My father was the author Nwe Kya Thaing. I grew up surrounded by interesting, thoughtful people. Many of them told me that artists have to create their own success. I could not ride on my father’s coattails. I enrolled in a fashion design course in 2005, uncertain whether it was really my best career choice. It turned out to be as natural for me as a fish swims in the sea. I was such a quick learner that I was able to open my own design studio. I inspired so many women that two years later I began training other young women how to create their own careers.

Most of my customers order either traditional or modern outfits but not both. There is also a steady stream of orders for bridal gowns. When I go abroad to show my work, I show traditional Myanmar designs updated with modern textiles and surface designs. My last Hong Kong Fashion Week show featured rich black fabric with intricate hand-stitched gold and silver patterns. The outfits were in the traditional Myanmar style but they oozed modern off-the-shoulder styles and trailing skirts. Myanmar demand and international demand are two very different sides of the coin.

I am particularly proud of the handstitched embroidery in my outfits. I stitch ornately detailed sketches of Burmese women onto traditional skirt silhouettes. Each dress takes hours of painstaking patience. I was surprised when I received an overwhelmingly positive response to those dresses at the international fashion shows.

Trends come and go, but beauty is steadfast. In Myanmar, the demand for traditional Burmese designs has never waned. The most notable change across the years has been easier access to multinational fabrics and accessories.

My most famous creation is merging paintings of flowers with tapestry on cotton. This innovation became very popular in Myanmar because it was culturally traditional but artistically creative.

International recognition came when I

received the Best in Vogue accolade at the 2019 Myanmar Pride Awards.

Flying abroad for an international fashion week may sound glamorous, but those events are only a small part of my career. Designing and making garments is only half my job. The other half is teaching other women how to design and make clothes in my workshop in the Thuwunna district of Yangon. My classes cover everything — cutting, design, tailoring, keeping the finances in order. Many of the students are from rural villages. They see my designs on television or a magazine and want to learn how to make more interesting clothes than they can buy locally.

The part of my job that truly brings joy is watching students go back to their home towns and make a successful fashion design business all their own.