MENTOR: JADE YUMANG

CURATORIAL GUIDANCE: JON SANTOS PRESENTED BY CUE ART

All artwork © Bhen Alan

Photos by Leo Ng

West 25th Street New York, NY 10001

CUE Art

137

Graphic design by Corinne Ang

CUE ART APRIL 4 – MAY 18, 2024

EXHIBITION MENTOR: JADE YUMANG

CURATORIAL GUIDANCE: JON SANTOS

CATALOGUE ESSAYIST: SASHA CORDINGLEY WRITING MENTOR: ANA TUAZON

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Sometimes My Accent Slips Out is a solo exhibition by Providence-based artist Bhen Alan with mentorship from Jade Yumang. The exhibition builds upon the artist’s ongoing investigation of the banig, an indigenous form of mat weaving in the Philippines that, for the artist, serves as a memory bank in the face of personal upheaval, new territories, and shifting cultural landscapes.

Sometimes My Accent Slips Out parallels the practice of mat weaving with the sociolinguistic impact of migration and personal transformation. Alan reflects upon his own ancestry, contemplating the significance of the banig to everyday life, spirituality, and culture in the Philippines. These mats—which are used for sleeping, eating, gathering, rest, and ritual—serve as extensions of the individual self and collective heritage, as objects that mediate birth and death, celebration and mourning. They serve as a material legacy of resilience and community, with their forms and techniques passed down from weaver to weaver despite centuries of colonization, globalization, and foreign imposition.

“Banig weaving does not start at the first fold of a reed over another, but with seeds that are planted and tended to until harvest [...] the banig is intimately entwined in a natural cycle of living and dying that is essential to human and nonhuman survival...a stark contrast to the ‘destroy, extract, exploit’ approach to the land’s resources in much of the West,” writes catalogue essayist Sasha Cordingley. “Taken altogether, banig is not just object, but a stand-in for a Filipino identity, which has firmly resisted the steamrolling of culture, memory, and tradition by colonial enterprises.

The banigs Alan creates are, in a sense, autobiographical. In emigrating from Cagayan Valley, Philippines to Canada and then to the United States, the artist struggled with his speech, compelled to code switch between accents and dialects in ways both subconscious and overt. Alan repositions the process of weaving as a proxy for this hybridity. In intertwining the material, the maker must balance the warp and weft of the mat, maintaining an even tension. In Alan’s banigs, he breaks and disrupts this grid, embracing inconsistencies and using his

3

body as a loom. Pushing beyond tactile representations of identity, his practice is a testament to the dynamic craft of communication. Accent serves as the warp in the fabric of speech, influencing the texture and quality of spoken language. The desire to be understood and accepted within new communities often becomes a pursuit to countervail inherited accents with acquired ones. Alan rejects this notion. Working within an intricate grid, he embraces the errors and glitches that fracture its borders, and in the process, he creates new ways of seeing—and of embodying—what is in between.

Through these explorations,

Sometimes My Accent Slips Out unravels the complicated legacies we navigate in an increasingly globalized world. Alan’s practice is a site of negotiation, a place of reconciliation

between multiple cultural and social identities. He employs a variety of weaving techniques, presented in brightly-colored works that drape the gallery in palm, abaca, and coconut leaves from his homeland, interwoven with cattails and other materials from North America. Positioned alongside these large-scale works are banigs of pandan, tikog, and buri from his recent Fulbright fellowship fieldwork in the Philippines, during which he collaborated with weavers in various regions of the archipelago.

Sometimes My Accent Slips Out is a celebration of our multiplicities and a declaration of presence. Alan embraces a wholeness that uplifts the nuances of cultural legacy, and activates future narratives of tradition that may be carried through generations and across geographies.

leaves, industrial fence.

Filipino. Pilipino., 2022-24. Woven

5

rattan, rattan, abaca, coins, dried fruits, coconut

Bhen Alan (b. 1993, Cagayan Valley, Philippines) is a visual artist, dancer, and educator who grew up weaving and learning traditional folk dances. He immigrated to Toronto, Canada, when he was 17 years old, before settling in the United States. He received U.S. citizenship in 2019. Alan’s work draws from his upbringing and diasporic experiences to incorporate multiple disciplines and mediums that reflect both his cultural heritage and recent contemporary investigations.

Alan holds an MFA in Painting and a Certificate in Collegiate Teaching in Art and Design from the Rhode Island School of Design, and a BFA in Painting from the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. From 2022-23, he received a Fulbright scholarship to conduct artistic research in the Philippines, working alongside master weavers of indigenous tribes to research mat weaving culture.

His work has been exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (Boston, MA), Praise Shadow Gallery (Brookline, MA), Real Art Ways (Hartford, CT), 808 Gallery at Boston University (Boston, MA), Rhode Island School of Design (Providence, RI), Hunter Gallery (Middletown, RI), E.I.K. Gallery at Yale University (New Haven, CT), Culture Lab LIC (New York, NY), Providence Public Art Library (Providence, RI), St. Botolph Club Foundation (Boston, MA), John B. Aird Gallery (Toronto, Canada), Shockboxx Gallery (Hermosa Beach, CA), Providence Art Club (Providence, RI), Bowersock Gallery (Provincetown, MA), and New Bedford National Historical Park (New Bedford, MA), among many others.

8

ARTIST STATEMENT BHEN ALAN

In the Tagalog language, matingkad is used to describe colors or light. Its English translation, flamboyant, usually describes the character of a person. People have called me flamboyant due to the way I dress, my gestures, and how I approach my artmaking practice. I have learned to reclaim this identity, playing with the notion of flamboyance to draw out ideas of opacity and transparency.

Within the context of diaspora, where individuals are uprooted from their homelands and dispersed across the globe (by choice or not), the concept of visibility takes on profound significance in terms of culture and belonging. In my practice, I use weaving as a means of negotiating identity and expressing the multifaceted experiences of migration. Through camouflage, shapeshifting, and protection, I seek to underscore themes of resilience and adaptation in the face of displacement. Shapeshifting—the ability to adapt and

transform in response to changing circumstances—is exercised by immigrants across the globe. As I manipulate materials to create diverse patterns of vibrant color, I endeavor to engage in a process of reinvention, blending old and new influences to craft narratives of hybridity while simultaneously embracing error, discombobulation, glitch, interruption, and obstruction in form and structure.

In my work, I use materials commonly found in both the Philippines and North America (such as indigenous leaves and grasses, feathers, paper, rattan, plastics, recycled and found objects, fabrics, and fibers) to conjure works that break new ground in terms of form and expression. The works became generative, as if they are growing in scale, texture, and pattern.

9

My weavings, in particular, serve as a portal to home, ancestors, and spirituality. They function as a gateway, allowing me to explore my identity and create work that challenges easy understandings of tradition and culture. Weaving practices, grounded in generations of making

and creativity, serve a protective function and offer sanctuary to me and to my community. Woven works such as mats, baskets, and textiles serve as tangible embodiments of culture, carrying within their fibers the memories, traditions, and aspirations of people—and the places they call home.

10

Artist Bhen Alan at the opening reception of Sometimes

My Accent Slips Out , 2024.

11

Madapaka , 2022. Woven rice sack and canvas, fans, coconut leaves, abaca, sinamay, bamboo leaves, feathers, found yarn, found thread, fabrics, palaspas, rattan, and industrial plastic fence on stretcher bar.

12

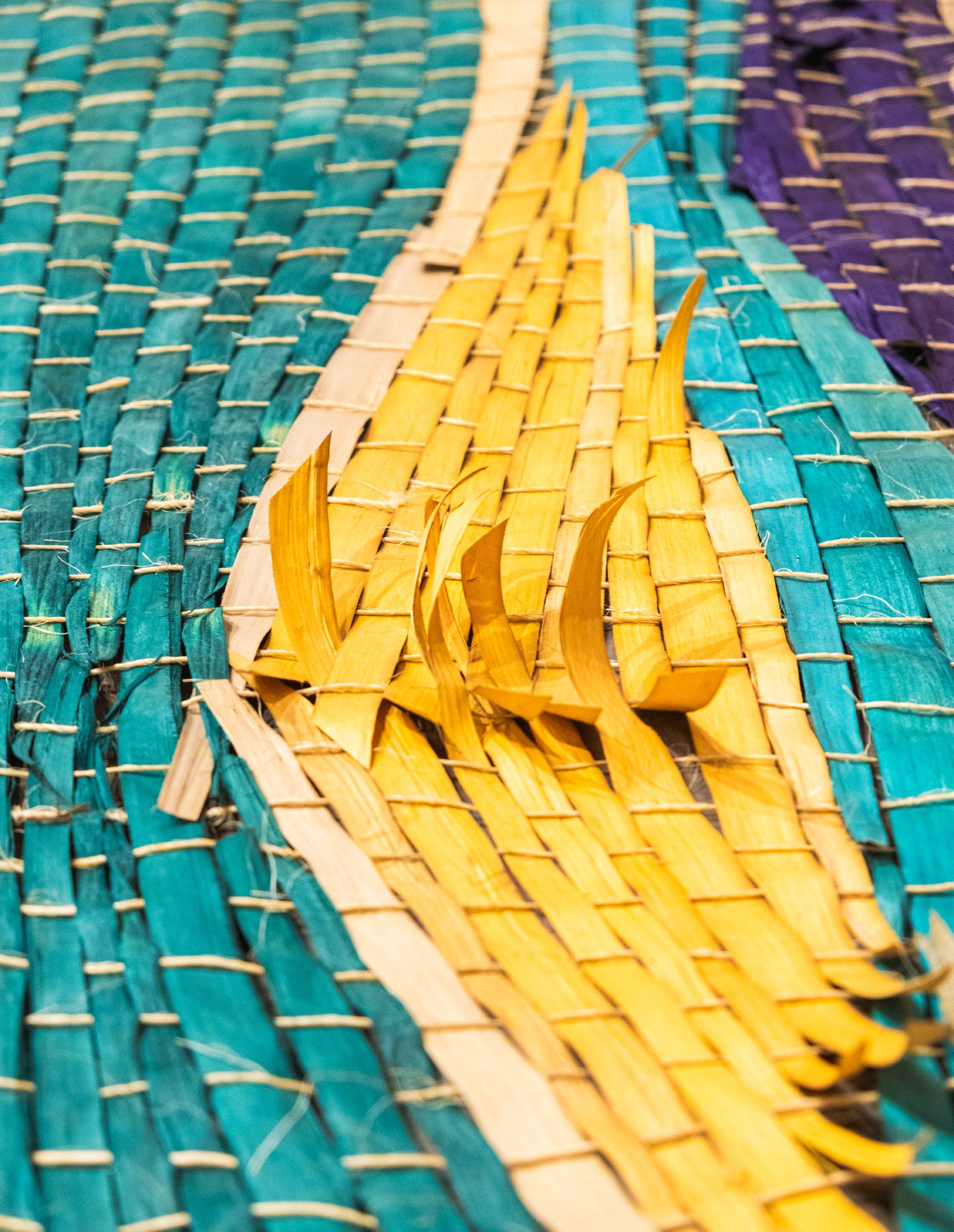

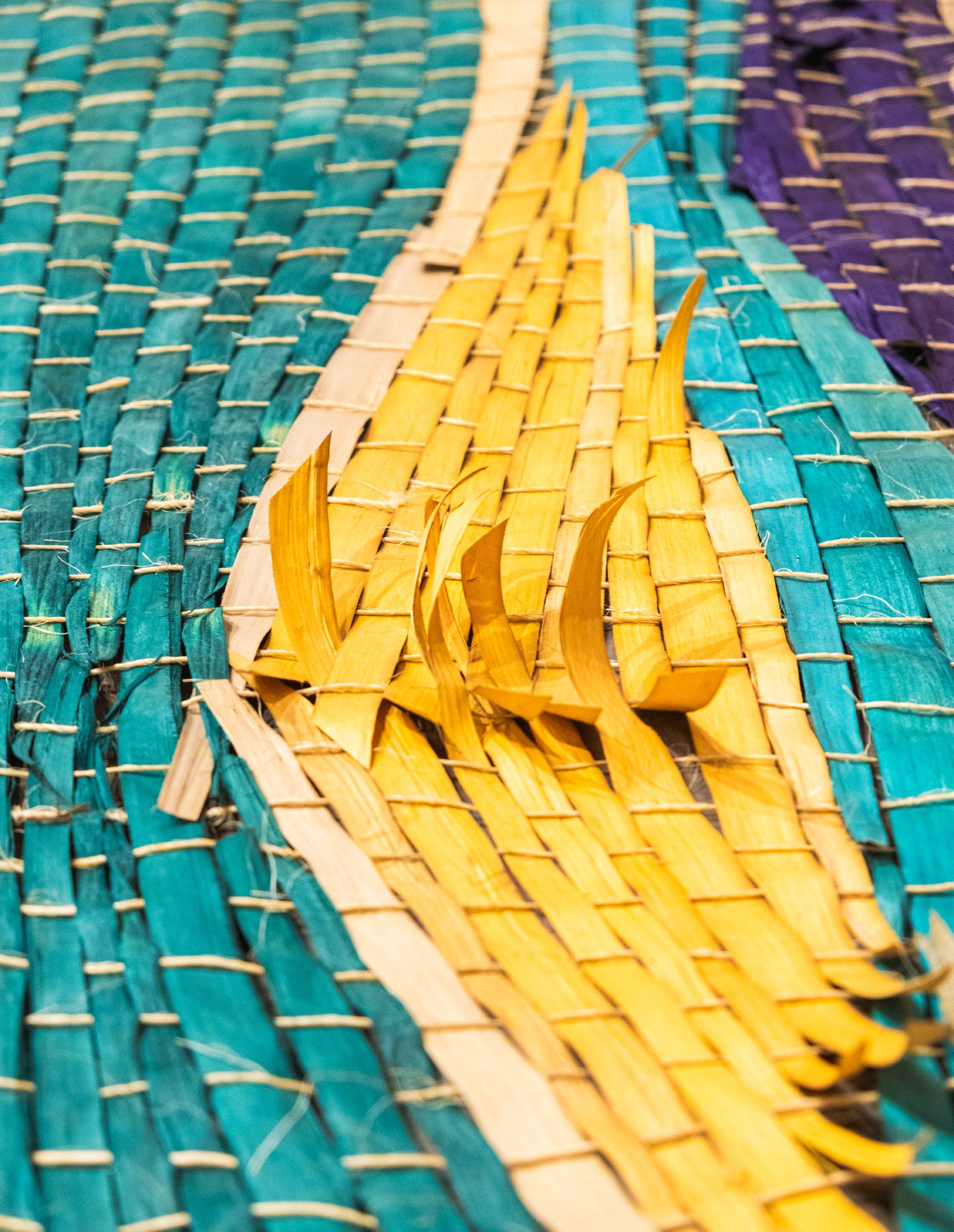

Detail of Mother Tounge , 2023. Cattails, palm leaves, pandan leaves, yarn, and twine.

Jade Yumang (b. Quezon City, Philippines) grew up in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; immigrated to unceded Coast Salish territories in Vancouver, Canada; and currently lives in Chicago, IL, which sits on the traditional homelands of the people of the Council of Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa, as well as the Menominee, Miami, and Ho-Chunk nations.

Jade received an MFA at Parsons School of Design with Departmental Honors in 2012 and a BFA Honors at the University of British Columbia in 2008. Jade has shown nationally and internationally in several museums and galleries, such as the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, the Museum of Arts and Design, Craft Contemporary, the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, the Des Moines Art Center, Western Exhibitions, and ONE Archives. Jade is a recipient of several grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the BC Arts Council, and is an Associate Professor in the Department of Fiber and Material Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

14

SHARP TONGUE JADE YUMANG

I speak your language, but sometimes my vowels are elongated, and I get my Fs and Ps mixed up.

My mom would tell me it’s okay to be in touch with your peelings.

I peeled back layers of myself to belong, and now I am weaving them back together so I can understand who I am.

“While the aesthetic practices of queer diaspora reorient us away from the straight and narrow, they do not instead offer recourse in the fictions of stable identity, narratives of linear progress, or the security of homecoming. Rather, they demand that we dwell, perhaps uncomfortably, in the space of disorientation that they open up.” —Gayatri Gopinath, “Queer Disorientations, States of Suspension”

When I was asked to mentor Bhen Alan, who was born in the Philippines, moved to Canada,

and is now living in the US, I had to take a second look, as I have experienced a similar winding road. I am grateful that the Executive Director of CUE, Jinny Khanduja, made our paths intersect.

In Bhen’s work, both structure and beautiful unruliness coexist. The work serves multiple purposes, re-performing and recrafting new ways of being seen. Its ever-evolving formations are not fixed, but rather loosely tethered into gridded structures of weaving that are flexible instead of rigid. Bhen’s approach allows for constant change while remaining steadfast due to the tension required to create pliable forms.

In diaspora, one thinks and speaks in layers. An accent can quickly summon your mother tongue while you are speaking another language. Worlds collide through

15

conversations. As Gayatri Gopinath asserts, this creates a space that is dizzying and full of possibilities.

My mom would tell me that she speaks adobo English: salty, sour, sweet, with surprise bites of whole black peppercorns—for the sharpness—so they don’t know what hit them.

Bhen’s work is characterized by language fraying on its edges. The largest piece in the show, which cannot be ignored, stands out like a tongue. Bhen mixes materials of different origins and weaves them together through the “overs” and “unders” of weaving, a tradition that is universal yet distinct in different cultures. In this work, Bhen references the banig, a

form of mat weaving that relies on the body rather than a loom. By directly imprinting the weight of the body, the pattern tells a story and leaves bodily residue to patina the work. Unlike a loom, which typically creates a rectilinear form, Bhen’s work spreads out in all directions, pointing you in new and unexpected ways. The layers of banigs on the floor bring your body back to the ground, inviting you to rest as you encounter dynamic wall pieces that unravel from their edges, that beg you to continue with the story. The pieces finish each other’s sentences, saying “see you later” rather than “goodbye.”

Whatever world Bhen opens next, we’re all ears.

Details of Banigs 1 through 11 , 2022-2023. Various materials, including: pandan leaves, tikog leaves, buri leaves, and fire soot. Made in collaboration with weavers in the Philippines.

17

Sasha Cordingley (she/they) is an arts and culture writer from the Philippines, born in Hong Kong, and residing in Brooklyn, NY. She currently works as a Press Officer and Writer at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Her writing has been published in Hyperallergic, Art Papers, ArtAsiaPacific, C Magazine, The Strategist, and Dirt. She is the recipient of C Magazine’s New Critic Award and the Henry Moore Institute Dissertation Award.

Ana Tuazon served as a mentor for this essay. Tuazon is a writer and educator based in Brooklyn, New York. Her writing on art, culture, and collectivity has been published in print and online; most recently in Track Changes: A Handbook for Art Criticism (Paper Monument, 2023). She was an Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grantee in 2021, and a 2019-21 Critical Studies Fellow in the Core Program at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She currently teaches part-time at Parsons School of Design.

This text was commissioned as part of the Art Critic Mentorship Program, a partnership between CUE and the AICA-USA (the US section of the International Association of Art Critics). The program pairs emerging writers with art critic mentors to produce original essays about the work of artists exhibiting at CUE’s gallery space. For more information about the program, visit the ACMP page on CUE’s website at www.cueartfoundation.org. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior written consent from the author.

18

IN THE FOLDS SASHA CORDINGLEY

When I ask Filipino artist Bhen Alan about the purpose of the banig, he offers an extensive list: it is a site for gossiping, eating, dance, and rest, he shares, and goes on to extol it as a vessel for life and death. His admiration for the hand-woven mat and its connection to the life cycle is understandable; its slick surface welcomed him—as it had many of his antecedents—in birth, and just two years afterward, the plaited fibers of the same banig were wrapped around his father’s body after he drowned in the village river.

Although most are familiar with the banig in the context of its domestic uses, its function as casket, midwife, or sacred grounds can be traced to the Philippines’ pre-colonial era, before the Spanish Empire arrived bearing rosary and cross, or the imperial arm of the United States instituted its own systems of education and governance. Antonio Pigafetta documented the banig

in Primo viaggio intorno al mondo (1525), a personal chronicle of Ferdinand Magellan’s proselytizing voyage to the Philippines’ Visayan Islands in the 16th century. The scribe wrote, “When we came to the town we found the King of Zzubu [Cebu] at his palace, sitting on the ground on a mat made of palm, with many people about him.”1 He recorded matrilineal customs, too: “[The women] do not work in the fields but stay in the house, weaving mats, baskets, and other things…from palm leaves.”2 Even the queen partook in the laborious folding that characterizes the banig, and its indigenous applications traversed hierarchies and functions alike.

Despite its longevity, the banig has scarcely been documented in the manuals and archives of the Philippines’ material history. Alan tells me that it is a tradition passed directly from one weaver to another,

19

transmitted through communities that are already attuned to the specific bends and splices of the palm, pandan, or tikog leaves that they employ. Techniques and designs are often held close— rarely leaving the boundaries of a barangay—for the simple fact that each community—and each weaver—retains distinct color schemes and pattern designs, ones that reflect local or personal narratives, ideologies, and beliefs. What they do share is the collective understanding that banig weaving does not start at the first fold of a reed over another, but with seeds that are sewn and tended to until harvest.

Many of these communities live in intimate relationship with the surrounding ecosystem, and tending to the land is an integral function of daily life. The Molbog people, for example, are nestled in the remote mountaintops of Balabac, Palawan; their isolated barangay lacks a cellular network, electricity, or access to clean water. Employment is scant. Yet, banig weaving persists as a viable source of income precisely because the community continually invests in the full life cycle of the pandan plant. For the Molbog, the banig is intimately entwined in a natural cycle of living and dying that is essential to human and nonhuman survival, wherein one cannot exist without the other; it is a stark contrast to the “destroy, extract, exploit” approach to the land’s resources in much of the West. Taken altogether, banig is not just an everyday object, but an emblem of Filipino

identities—of people who have firmly resisted the steamrolling of culture, memory, and tradition by colonial enterprises.

Bhen Alan’s practice of abstracted sculptural banigs makes this explicit. Madapaka (2022) is a burst of tousled fabrics in dazzling yellow and orange, pockmarked by dehydrated palm leaves, knotted fibers of yarn, and a slew of embellished fans. A close look at the work reveals dangling rosaries impersonating strands of thread, hidden amongst the torrent of material. They may look like haphazard additions, but the shrouding of the sacrament alludes to the Spanish Empire’s wielding of Catholicism and so-called cultural enlightenment as a means of seizing land across the Philippines from 1565 onward. Surrounding the rosaries are a number of intricately detailed multi-colored fans. Alan tells me he used to be a folk dancer, and that fans are often used in the dances of his community as an extension of the arm, marking the limits of bodily movement through swift flicks and circumvolutions by the dancer. In the work, the fans protrude like the feathers of a peacock, amplifying its presence. Their use suggests a prevailing native body and the traditions it enacts, informed by colonial presence yet unwilling to be suppressed by its afterlife.

Mother Tongue (2023) unfurls from the ceiling and splays out like a mouth stretched open and seized mid-sentence. It is a scroll of bound horizontal palm and pandan leaves in sage, turquoise, red, beige, yellow, and purple, and its

Detail of Madapaka , 2022. Woven rice sack and canvas, fans, coconut leaves, abaca, sinamay, bamboo leaves, feathers, found yarn, found thread, fabrics, palaspas, rattan, and industrial plastic fence on stretcher bar.

20

edges jut out in provocation. Lodged throughout the work are bushy patches of cattails gathered from the lakes of the artist’s adopted home in New England. They stand tall like weeds emerging from gravel, refusing to warp to the linear arrangement of the work’s principal textiles.

In our conversation, Alan tells me how his assimilation into North America is at times interrupted by his inability to fully assume the English language. Words dissipate upon recollection, and the intonations of his mother tongue inflect as he speaks. Rather than force the expected dialect of the region’s primary language, Alan indulges his linguistic ruptures by letting

them linger, mis/translating them through the entropic composition of his banigs. He draws upon these dynamics of language in The Difference between P and F (2024), composed of bundles of tangled yarn that clump and droop across asymmetrically adjoined stretchers, and Filipino. Pilipino. (2022-24), in which coiled strips of rattan loop around and through each other against a gridded brace, as if tripping over tonguetwisters in a new language or grasping at tip-of-the-tongue recollections.

Particularly striking about this latter work is the artist’s use of whole sheets of woven rattan, which are found on many of the

21

The Difference between P and F, 2024. Yarn on stretcher bars.

22

Philippines’ white sand beaches. Rattan is often woven by locals into chaise lounges, handbags, placemats, and coffee tables. The same is true for the banig; its forms and processes have taken on the shape of yoga mats, coasters, and sun hats by will of tourists seeking supposedly authentic souvenirs. Some communities in the archipelago have even lost their traditions of weaving as a direct result of the commodification of the craft. Although acutely aware of the onerous economic conditions that engender the banig as marketable product, Alan resists this outcome as the mat’s final form.

It is undeniable that much of the archipelago’s post-colonial culture today maintains remnants of the Spanish and American empires: there are basketball courts and

churches in every barangay, and military bases aplenty. The banig, however, has endured. By foregrounding the woven mat in his practice, Alan reclaims the object as a tactile archive that has survived rounds of cultural erasure by colonial regimes, one that narrates stories not just of the artist, but of communities that for centuries have gossiped, eaten, danced, rested, lived, and died— all on the ubiquitous banig.

Endnotes

1. Stanley, Henry Edward John and Antonio Pigafetta. The first voyage round the world by Magellan. London: The Hakluyt Society, 1874. Sabin Americana: History of the Americas, 1500-1926. 2. Ibid.

CUE Art is a nonprofit organization that works with and for emerging and underrecognized artists and art workers to create new opportunities and present varied perspectives in the arts. Through our gallery space and public programs, we foster the development of thought-provoking exhibitions and events, create avenues for mentorship, cultivate relationships amongst peers and the public, and facilitate the exchange of ideas.

Founded in 2003, CUE was established with the purpose of presenting a wide range of artist work from many different contexts. Since its inception, the organization has supported artists who experiment and take risks that challenge public perceptions, as well as those whose work has been less visible in commercial and institutional venues.

Exhibiting artists are selected through two methods: nomination by an established artist or selection via our annual open call. In line with CUE’s commitment to providing substantive professional development opportunities, each artist is paired with a mentor—an established curator or artist who provides support throughout the process of developing their exhibition.

To learn more about CUE, visit us online or sign up for our newsletter at www.cueartfoundation.org.

26

ABOUT CUE ART

STAFF

Jinny Khanduja Executive Director

Jasmine Buckley Gallery Associate

Keegan Sagnelli Communications Associate

Ninoska Beltran Gallery & Production Intern

Evelyn Sislema Development & Communications Intern

Jocelyn Guzman Intern

SUPPORT

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Theodore S. Berger, President

Kate Buchanan, Vice President

John S. Kiely, Co-Treasurer

Kyle Sheahen, Co-Treasurer

Lilly Wei, Secretary

Amanda Adams-Louis

Marcy Cohen

Blake Horn

Thomas K.Y. Hsu

Steffani Jemison

Aliza Nisenbaum

Gregory Amenoff, Emeritus

Programmatic support for CUE Art is provided by Evercore, Inc; ING Group; The Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation; The William Talbott Hillman Foundation; and Corina Larkin & Nigel Dawn. Programs are also supported, in part, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, in partnership with the City Council; the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Kathy Hochul and the New York State Legislature; and the National Endowment for the Arts.

27

30 CUE Art 137 West 25th Street New York, NY 10001