DISCOVER YOUR NEXT GREAT BOOK

APR 2022

ALSO INSIDE

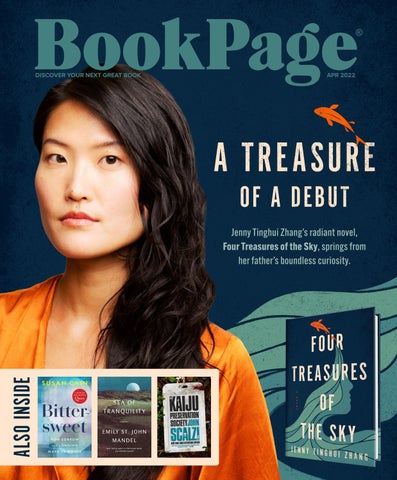

Jenny Tinghui Zhang’s radiant novel, Four Treasures of the Sky, springs from her father’s boundless curiosity.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Reader feedback helps us make BookPage even better. What do you love about BookPage? What would you like to see more of? Our Reader Survey is your chance to help shape our content and celebrate the books and features you love.

Take our Reader Survey for the chance to win these great prizes!

$500

FIRST PRIZE

SECOND PRIZE

THIRD PRIZE

1 winner $500 Visa Gift Card

2 winners Kindle Paperwhite

5 winners Book Bundle

Signature Edition ($189.99 value)

4–5 books (approx $120 value)

BookPage.com/survey No purchase necessary; see rules online. Take the Reader Survey by 5/1/22 to qualify for prizes.

@readbookpage

@bookpage

@readbookpage

bit.ly/readbookpage

BookPage

®

APRIL 2022

features feature | poetry. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

feature | earth day for young readers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Five writers work magic with the power of verse

Three picture books explore our connections with nature

feature | high fantasy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

meet | blanca gómez . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 Meet the author-illustrator of Dress-Up Day

Three epic sagas that aren’t afraid to ask difficult questions

q&a | john scalzi . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 The celebrated sci-fi author’s latest is a monster of a good time

reviews

feature | thrillers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

fiction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Loved HBO’s “The White Lotus”? Read these three books

nonfiction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

cover story | jenny tinghui zhang . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 A father’s spirit of exploration, a daughter’s artfully crafted novel

young adult. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

feature | inspirational living. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

children’s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Four authors share hidden paths to healing

interview | maud newton. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

columns

A debut that’s much more than a conventional family memoir

the hold list . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

feature | earth day. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

book clubs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Three nonfiction titles celebrate nature’s precarious beauty

well read. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

feature | asl fiction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 Two love letters to Deaf culture

romance. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

q&a | amanda oliver. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

whodunit . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

What it costs librarians to be the saviors of society

cozies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

feature | ya novels in verse. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

lifestyles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Writing LGBTQ teens back into history

behind the book | ashley woodfolk. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 Why her new YA novel is her most “emotionally honest” yet

PRESIDENT & FOUNDER Michael A. Zibart VICE PRESIDENT & ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Elizabeth Grace Herbert CONTROLLER Sharon Kozy

PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Trisha Ping

BRAND & PRODUCTION MANAGER Meagan Vanderhill

DEPUTY EDITOR Cat Acree

CONTRIBUTOR Roger Bishop

MARKETING MANAGER Mary Claire Zibart

ASSOCIATE EDITORS Stephanie Appell Christy Lynch Savanna Walker

SUBSCRIPTIONS Katherine Klockenkemper

EDITORIAL INTERN Jessie Cobbinah

audio . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15 Cover and pages 12–13 include art from Four Treasures of the Sky by Jenny Tinghui Zhang © 2022, designed by Vi-An Nguyen, used with permission from Flatiron.

EDITORIAL POLICY

BookPage is a selection guide for new books. Our editors select for review the best books published in a variety of categories. BookPage is editorially independent; only books we highly recommend are featured. H Stars are assigned by BookPage editors to indicate titles that are exceptionally executed in their genre or category.

SUBSCRIPTIONS

BookPage offers bulk subscriptions for public libraries and bookstores to distribute to their patrons. Single-copy subscriptions for individuals are also available. For more information or to subscribe, go to subscriptions.bookpage.com. Digital subscriptions are available through Kindle, Nook and Flipster.

ADVERTISING

For print or digital advertising inquiries, email elizabeth@bookpage.com.

All material © 2022 ProMotion, inc.

B O O K P A G E • 2 1 4 3 B E L C O U R T AV E N U E • N A S H V I L L E , T N 3 7 2 1 2 • B O O K P A G E . C O M

readbookpage

readbookpage

bookpage 3

the hold list

Under-the-radar reads We love it when a great book or hardworking author cultivates a huge following, but we also love cheering for an underdog. Here are five books we believe are deserving of the fireworks and fanfare typically reserved for the biggest blockbusters.

The Tenth Muse

The Promise Girls

Elsewhere

I am ready for Catherine Chung to become a household name, and I know that day is coming. Both of Chung’s novels, Forgotten Country (2012) and The Tenth Muse (2019), tell stories of female mathematicians questioning family roles and chasing down secrets. I fell especially hard for her second novel, not just because Chung is a strong storyteller (and indeed she is) but because of her narrative’s clean chronological structure, which embodies the precision and beauty of math itself. Over the course of the novel, protagonist Katherine reflects on her childhood as the daughter of a Chinese immigrant and a white American veteran of World War II. She reckons with her place in a male- dominated field, hedges her dreams against her relationship with an charismatic older professor, attempts to solve a famed hypothesis and, in the search for her family’s true history, follows the clues in an equation-filled diary. Chung unfurls these mysteries with all the formal elegance and unequivocal truth of a perfectly balanced equation. —Cat, Deputy Editor

One of Marie Bostwick’s novels had been on my TBR list for so long that I’d forgotten how it had gotten there when I finally started reading it sometime in mid-2021. By chapter five, I had downloaded the rest of Bostwick’s novels. Although I’ve loved them all, my favorite is The Promise Girls. The three Promise sisters were groomed to be artistic prodigies by their overbearing mother, Minerva. During a live televised performance, pianist sister Joanie intentionally blundered her signature piece, and Minerva slapped the girl. In the subsequent uproar, child protective services split up the family, and each sister closeted her creative pursuits and difficult childhood. Decades later, the sisters begin to reexamine their conclusions about their upbringing and artistic abilities. Bostwick creates worlds where we can trust that, with the support of loved ones and a healthy dose of creativity, good people will prevail. Her stories have been a refuge to me, and I know that many readers would find similar comfort in them. —Sharon, Controller

Gabrielle Zevin is best known for her 2015 bestseller, The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry, but her literary talents didn’t start there. In Zevin’s 2005 speculative novel, Elsewhere, 15-yearold Liz has been killed in a hit-and-run accident, and she wakes up on a cruise ship called the S.S. Nile that’s bound for the afterlife. When the ship arrives in Elsewhere, a place uncannily similar to Earth, Liz learns that she will age backward until infancy. Then she’ll be released into a river and sent back to Earth, where she will begin a new life. Utterly distraught, Liz spends most of her time at the Observation Decks, where one “eternim” buys her five minutes of Earthviewing time. On the brighter side, she’s taken in by her grandmother Betty, now 34, who died before Liz was born and currently works as a seamstress in Elsewhere. As Liz comes to grips with living her new life in reverse, Zevin executes a premise that’s unique and fully realized. You won’t be able to keep Elsewhere to yourself. —Katherine, Subscriptions

Light From Other Stars I love to look up at the night sky, so Erika Swyler’s second novel, Light From Other Stars, stole my heart. It’s beautifully written, easy to get lost in and powerfully heartfelt. With a light-handed approach, Swyler toes the line between factual science and science fiction to tell the story of Nedda Papas, jumping between her childhood in 1980s Easter, Florida, and her adventures aboard the spaceship Chawla decades later. Nedda’s childhood scenes introduce her father, Theo Papas, a former NASA scientist who’s reeling from the death of his son. When Theo creates an experiment that alters the life of everyone in Easter, Nedda and her mother form an unlikely alliance, and Nedda’s recollections of these earlier events help her solve a dire problem aboard the Chawla. Throughout this tale of time and loss, Swyler explores how people change, how relationships evolve, what happens to us when we die and just how far we’ll go to hold on to the ones we love. —Meagan, Brand & Production Designer

Each month, BookPage staff share special reading lists—our personal favorites, old and new.

4

We Sang You Home When I worked in an independent bookstore, a trend I noticed and loved was baby showers to which guests were encouraged to bring a book as a gift for the impending arrival. It’s never too early to start building a home library and sharing books with children! Board books are especially perfect for placing in the hands of the newest readers, because the thick cardboard pages are much harder to tear and can hold up to many readings (or nibblings). I loved sending folks out the door with Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett’s We Sang You Home, a spare, poetic meditation whose first-person plural narration encompasses many kinds of families and could be read by any caregiver, not just a birthing parent. I’ve read this book countless times and still choke up at Van Camp’s beautiful benediction: “Thank you for joining us / Thank you for choosing us / Thank you for becoming / the best of all of us.” What an extraordinary way to welcome a tiny new person to the world. —Stephanie, Associate Editor

book clubs

by julie hale

Books for Broadway lovers With Tom Stoppard: A Life (Vintage, $20, 9781101972663), British biographer and literary critic Hermione Lee delivers a captivating portrait of one of the world’s most beloved playwrights. Stoppard (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Arcadia, Shakespeare in Love) was born in Czechoslovakia in 1937. He and his mother fled the Nazis during World War II and eventually put down roots in England. He worked as a journalist before going on to write the plays, radio shows and screenplays for which he has won numerous awards and worldwide acclaim. Lee explores Stoppard’s works while tracking his remarkable life, diving deep into subjects like artistic reinvention and the creative process. Actor Leslie Jordan takes stock of his TV career (“Will and Grace,” “American Horror Story”), acclaimed stage work and unexpected Instagram success in How Y’all Doing? Misadventures and Mischief From a Life Well Lived (William Morrow, $16.99, 9780063076204). A Tennessee native, the 66-yearold Jordan writes with Southern These show-stopping nonfiction flair and plenty books explore life in the limelight. of humor, sharing family stories and fabulous anecdotes involving Dolly Parton and other stars. He also writes about serious matters, like the AIDS crisis and his struggles to make sense of his homosexuality. Questions related to the nature of celebrity and social media will inspire spirited reading group dialogue. Actor and singer Rachel Bloom, who created the musical comedy TV show “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend,” reflects on what it’s like to be an outsider in I Want to Be Where the Normal People Are: Essays and Other Stuff (Grand Central, $17.99, 9781538745366). Recalling awkward middle school years when she was bullied, sharing journal entries and opening up about her mental health, Bloom explores her enduring quest to feel “normal.” She’s modest and forthright in this funny, deeply personal collection. Book clubs can dig into a wide range of discussion topics, including individuality, conformity and the challenges of self-acceptance. In My Broken Language: A Memoir (One World, $18, 9780399590061), Quiara Alegría Hudes, an award-winning playwright and co-writer of the musical In the Heights, shares memories of her upbringing in a West Philadelphia barrio during the 1980s and ’90s. The daughter of a Jewish father and a Puerto Rican mother whose marriage fell apart, Hudes looks back on life with her family, her Ivy League education and her entry into the world of writing and theater. The art of storytelling and the importance of communication are among the many rich themes in this moving memoir.

A BookPage reviewer since 2003, Julie Hale recommends the best paperback books to spark discussion in your reading group.

BOOK CLUB READS FOR SPR ING THE DIAMOND EYE by Kate Quinn “Kate Quinn has brilliantly hit her mark—this is a stunning novel about a singular historical heroine.” —ALLISON PATAKI, New York Times bestselling author of The Magnificent Lives of Marjorie Post

NINE LIVES by Peter Swanson A heart-pounding story of nine strangers who receive a cryptic list with their names on it— and then begin to die in highly unusual circumstances.

ANGELS OF THE PACIFIC

by Elise Hooper “Absolutely riveting. This story of endurance and sisterhood will have you turning pages late into the night.” —LAUREN WILLIG, New York Times bestselling author of Band of Sisters

THE PROPHET’S WIFE by Libbie Grant A sweeping historical novel that tells the remarkable story of the Mormon church through the eyes of the woman who saw it all— Emma, the first wife of the prophet Joseph Smith.

t @Morrow_PB

t @bookclubgirl

f William Morrow I BookClubGirl

5

feature | poetry

New collections from celebrated voices Five poets work magic with the power of verse. National Poetry Month is a time for highlighting poetry as a platform for honoring everyday experiences and giving voice to our deepest, most vulnerable selves. For all readers who celebrate, we recommend the wide-ranging collections below, which offer poetic explorations of nature, identity and our need for connection.

H Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes To read Nicky Beer’s third collection, Real Phonies and Genuine Fakes (Milkweed, $16, 9781571315397), is to experience poetry as pageantry. In Beer’s hands, the poetic form is a staging place for spectacle, replete with provocative imagery and a brash cast of characters, including celebrities, magicians and eccentrics. “Drag Day at Dollywood” features “two dozen Dollys in matching bowling jackets, / Gutter Queens sprawled across their backs in lilac script.” Beneath their similar facades, the Dollys have distinct identities, which Beer hints at with expert economy. Across the collection, Beer teases out concepts of truth and self-perception. In “Dear Bruce Wayne,” the Joker—“a oneman parade / in a loud costume”—displays his genuine nature, while Batman keeps his virtuous essence under wraps: “don’t you crave, / sometimes, to be a little / tacky?” the narrator asks him. “Doesn’t the all-black / bore after a while?” Beer displays an impressive range, from full-bodied narrative poems to an innovative sequence called “The Stereoscopic Man.” Her formal shape-shifting and penchant for performance make this a magnetic collection.

Content Warning: Everything Content Warning: Everything (Copper Canyon, $16, 9781556596292), the first poetry collection from award-winning, bestselling novelist and memoirist Akwaeke Emezi, doesn’t feel like a debut. Emezi (The Death of Vivek Oji) shifts effortlessly into the mode of poet, exploring spirituality and loss in ways that feel fertile and new. Emezi favors flowing lines unfettered by punctuation, an approach that underscores the urgent, impassioned spirit of a poem like “Disclosure”: “when i first came out i called myself bi a queer tangle of free-form dreads my mother said i was sick and in a dark place.” A desire for release from the constraints of tradition and familial expectations animates many of the poems. As Emezi writes in “Sanctuary,” “the safest place in the world is a book / is a shifting land on top of a tree / so high up that a belt can’t reach.” From searing inquisitions of the nature of guilt and sin to radical reimaginings of biblical figures, Emezi operates with the ease of a seasoned poet throughout this visionary book.

Time Is a Mother “I’m on the cliff of myself & these aren’t wings, they’re futures,” Ocean Vuong writes in his second poetry collection, Time Is a Mother (Penguin Press, $24, 9780593300237). The line is one of the book’s several references to reaching an edge and then jumping or launching, with all the courage required by such an

6

act and the possibilities that await. Born in Vietnam and brought up in the U.S., Vuong (On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous) writes with keen precision about laying claim to his own authentic life. Identity is a prominent theme in poems like “Not Even”: “I used to be a fag now I’m a checkbox. / The pen tip jabbed in my back, I feel the mark of progress.” In extended prose pieces and short works of free verse, Vuong remembers his late mother, chronicles the search for connection and reveals a gradual emergence into true selfhood—a sort of rebirth: “Then it came to me, my life. & I remembered my life / the way an ax handle, mid-swing, remembers the tree. / & I was free.”

H Earthborn Earthborn (Penguin, $20, 9780143137016), the 14th book of poetry from Pulitzer Prize-winning author Carl Dennis, is a rich exploration of our relationship to nature in a time of environmental instability. Dennis addresses global warming in “Winter Gift”: “Now it seems right to ask / If winter, though barely begun, is spent, / So hesitant it appears, so frail.” In “One Thing Is Needful,” he enjoins us to act: “it’s time to invest / In the myth of a long-lost Eden.” Religion and mortality are recurring themes, as in “Questions for Lazarus”: “I know you may not be at liberty / To offer specifics,” Dennis writes, “but can you say something / In general about how dying has altered / Your view of life?” Dennis’ poems unfold at a relaxed pace, through long lines, considered and meditative, that accommodate a fullness of thought. As he examines both our lesser drives and finer desires, he holds out hope that we can be better humans and custodians of the planet, a sentiment that makes Earthborn a uniquely comforting volume.

Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head In Somali British author Warsan Shire’s first full-length collection, Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head (Random House, $17, 9780593134351), she brings personal history to bear in poems that focus on the plight of refugees and the realities of being a woman in an oppressive, patriarchal society. “Mother says there are locked rooms inside all women,” she writes in “Bless This House.” “Sometimes, the men—they come with keys, / and sometimes, the men—they come with hammers.” Shire writes about female genital mutilation—a common practice in Somalia—in “The Abubakr Girls Are Different,” a poem that balances beauty and brutality: “After the procedure, the girls learn how to walk again, mermaids / with new legs.” The poem “Bless Grace Jones” casts the singer—“Monarch of the last word, / darling of the dark, arched brow”—as a symbol of strength, a figure to be emulated: “from you, we are learning / to put ourselves first.” Indelible imagery and notes of defiance make Shire’s book a triumphant reclamation of female identity. —Julie Hale

well read

by robert weibezahl

H Keats John Keats exists in many minds as an effete, epigraphic nature lover (“A thing of beauty is a joy forever,” “Beauty is truth, truth beauty”) rather than the spirited, earthy man he was. The profile that historian and literary critic Lucasta Miller assembles in her engrossing Keats: A Brief Life in Nine Poems and One Epitaph (Knopf, $32.50, 9780525655831) is a welcome corrective that seeks a truer understanding of the life and work of the iconic British poet. Keats’ life was short (he died in 1821 at 25), and some of its details are scant (the exact day and place of his birth, for example, are sketchy), but as in her previous literary study The Brontë Myth, Miller doesn’t offer a full-fledged biography in Keats. Instead, as the subtitle plainly states, she looks closely at nine of his most representative works in chronological order, threading in literary analysis as she unspools the pertinent life events that may have inspired or unconsciously influenced each piece. Miller is an avowed Keatsian, but one of the strengths of this study is her refreshing willingness to call out the poet for some inferior writing just as often as she extols the brilliance of his more enduring masterworks. The Keats she presents here was a work in progress, cut off in his prime (or perhaps before), and Miller is quick to point out the peculiarities, and sometimes failures, of even his most revered Those seeking a truer understanding poems. This candor adds of the life and work of John Keats to rather than detracts from will welcome this invigorating the affectionate picture reappraisal of his short, tragic life she paints of and extraordinary, enduring poetry. a young man who alternated between ambition and insecurity: a poet who routinely compared his own work to Shakespeare’s yet wrote his own self-effacing epitaph as, “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water.” Keats embraced the pleasures of life and art while wrestling with childhood demons. He was born in the waning years of the 18th century, into England’s newly formed middle class, and his father died under suspicious circumstances when the future poet was 8. He was fully orphaned by 14 but was effectively abandoned by his mother years earlier, when she ran off with a much younger man. Keats may have been somewhat emotionally crippled by parental longing, Miller suggests, but he was also a full participant in day-to-day life, devoted to his brothers and sister as well as to a passel of equally devoted friends. The extraordinary language with which Keats fashioned his then-radical poetry percolates with striking neologisms and is laced with coded sexuality. Indeed, Keats himself could be profligate in matters of sex, drugs and money (he abandoned an apprenticeship to a doctor), and Miller sharply centers his life in the context of its time, detailing the moral ambiguities and excesses of the Regency period that would later be whitewashed by the Victorians. While the U.S. publication of this superb volume misses the 200th anniversary of Keats’ death by a year, it is never a bad time to revisit a poetic genius. Miller has given us a thing of beauty, indeed.

Robert Weibezahl is a publishing industry veteran, playwright and novelist. Each month, he takes an in-depth look at a recent book of literary significance.

romance

by christie ridgway

H Boss Witch A witch hunter is on the prowl in Ann Aguirre’s delightful Boss Witch (Sourcebooks Casablanca, $15.99, 9781728240190). Clementine Waterhouse, one of the owners of the Fix-It Witches repair shop, vows to save her family and coven by distracting Gavin Rhys, a sexy Brit who’s arrived in town to snatch away the power of any witch in the vicinity. Gavin and Clem quickly discover a powerful spark of sexual attraction between them, and it’s enough to keep them both bewitched, bothered and bewildered until reinforcements are called in from Gavin’s team. Can they craft a solution to an age-old enmity and find a forever love? Boss Witch may be a paranormal romance, but Gavin and Clem have problems every reader can relate to: meddling family, impossible expectations and fears of intimacy. There’s plenty of amusing whimsy piled into Aguirre’s imaginative story, made all the more charming by her energetic and vivid writing style. Boss Witch will make readers believe in the unbelievable, and wish for a little magic for themselves.

To Marry and to Meddle A couple finds their new marriage less than convenient in To Marry and to Meddle (Atria, $16.99, 9781982190484) by Martha Waters. For years, Lord Julian Belfry was satisfied with his scandalous reputation as the owner of an unsavory theater. He’s only a second son, after all, and not set to inherit any grand title. But respectability would certainly sell more tickets, and he thinks that marrying Lady Emily Turner will help him reach that goal. Emily agrees, as she’s more than ready for a married lady’s relative independence—and it doesn’t hurt that Julian is handsome and charming. But as the pair learns to live together, they must confront uncomfortable truths about themselves. Will these new revelations make or break their union? Waters’ prose harkens back to foundational Regency romance author Georgette Heyer, but Emily and Julian’s individual journeys of learning to like their authentic selves are timeless.

Going Public A workplace romance starts slow then burns hot in Going Public (Carina Adores, $14.99, 9781335500168), the second book in Hudson Lin’s Jade Harbour Capital series. Elvin Goh loves his job as assistant to Raymond Chao, a hotshot fixer and partner at private equity firm Jade Harbour, even if Elvin’s all-hours assignments mean he can’t ignore the many lovers who parade in and out of Ray’s bed. Elvin and Ray are already a great team, but sorting out a thorny, potentially dangerous problem in a Jade Harbour holding brings the pair closer together—and into a new kind of intimacy. Watching sweet, innocent Elvin and jaded playboy Ray navigate new waters will melt readers’ hearts. Lin excels at revealing the inner workings of her characters’ minds, and when they wear their feelings on the sleeve of a luxury business suit . . . well, the appeal is multiplied.

Christie Ridgway is a lifelong romance reader and a published romance novelist of over 60 books.

7

whodunit

by bruce tierney The Echo Man

The only thing in this line of work that gives me more pleasure than reading a killer debut novel is reading a serial killer debut novel. The serial killer in Sam Holland’s The Echo Man (Crooked Lane, $27.99, 9781643859910) tallies up an impressive body count, handily surpassing the known body count of any real-life serial killer in the U.K. Detective Chief Inspector Cara Elliott and Detective Sergeant Noah Deakin are investigating a series of murders, deaths they eventually realize are all evocative of different serial killers from history. Meanwhile, suspended cop Nate Griffin spends his downtime ferreting out his wife’s murderer, the same unauthorized inquiry that got him suspended in the first place. After joining forces with fugitive murder suspect Jessica Ambrose, who's been framed for the murder of her husband via arson, Nate essentially throws the rulebook out the window. They’re a rather formidable pair, unfettered by the constraints of on-duty police officers. As the tension mounts, Holland poses a creative and frightening question: When and how will the killer stop being a copycat and deliver his coup de mort, the deathblow that will cement his legacy in the annals of murder?

Fierce Poison In Victorian London, one fictional detective stands out from the others: Sherlock Holmes. But author Will Thomas gives a convincing account of why attention should be paid to two others, Cyrus Barker and Thomas Llewelyn, whose 13th adventure plays out in Fierce Poison (Minotaur, $27.99, 9781250624796). It starts off dramatically, when a rather unwell-looking man named Roland Fitzhugh enters their office, promptly slumps to the floor, implores, “Help me,” and then dies before their eyes. Senior partner Barker feels honor bound to investigate, especially after it is revealed that his new (-ly deceased) client was a member of Parliament. This is but the beginning of a rash of poisonings that terrorize the citizenry of England’s capital city: first, a young boy selling sweets outdoors, followed by his entire family, save for an infant girl. Then the poisonings get closer to home, targeting the two detectives themselves. On the suspect list are a gardener who maintains a plot of lethal plants, an herbalist well versed in the preparation of illicit potions and any number of people who disliked Fitzhugh, both in his political career and in his former life as a barrister. Narrated in the first person by Llewelyn, who serves as smart-alecky Archie Goodwin to Barker’s Nero Wolfe, Fierce Poison is cleverly told with humorous asides, period particulars and all the requisite red herrings.

Give Unto Others The COVID-19 pandemic hovers in the background of Donna Leon’s latest installment of the Commissario Guido Brunetti series, Give Unto Others (Atlantic Monthly, $27, 9780802159403). Tourism is down, crime is down and a kind of malaise seems to have settled over the city of Venice. So when an old acquaintance approaches Brunetti to look into a worrisome family matter, Brunetti accepts, albeit not without reservations. The concern is centered on Enrico Fenzo, an accountant who has been acting strangely of late. When confronted by his wife, he alludes to a “dangerous” situation and declines to say more. As Brunetti launches his clandestine inquiry into the situation, it appears that perhaps he is ruffling some feathers: A break-in takes place at the veterinary clinic run by the accountant’s wife, and one of the dogs lodging there is badly mauled, perhaps as a warning against further investigation into the accountant’s potentially illegal affairs. As is the case with most of the other 30 Brunetti novels that precede it, Give Unto Others is a largely character- and milieu-driven novel. There is a central mystery, to be sure, but the characters and their evolving relationships are the driving force of the series as it explores Venice, its history, its culture and, of course, its crime.

H The Sacred Bridge I was a big fan of Tony Hillerman’s Leaphorn/ Chee mysteries, so I approached Spider Woman’s Daughter, Anne Hillerman’s first book in the continuation of the series, with a bit of trepidation. Turns out, I needn’t have worried; Anne Hillerman so adeptly channeled her father’s narrative voice that 20 pages in, I had completely forgotten it was not a Tony Hillerman book. She also brought positive changes to the series, giving Jim Chee’s wife, police officer Bernie Manuelito, and Joe Leaphorn’s inamorata, anthropologist Louisa Bourebonette, larger roles in the story. In Hillerman’s latest installment, The Sacred Bridge (Harper, $26.99, 9780062908360), Leaphorn’s role is tangential but critical: He sends Chee to Arizona’s magnificent Antelope Canyon in search of a lost cave chock-full of awe-inspiring artifacts. But before Chee can locate it, he spots a dead body floating facedown in nearby Lake Powell. The deceased is Curtis Walker, a Navajo man who was an experienced outdoorsman and was particularly passionate about the area's ancient rock art. When the autopsy suggests foul play, Chee is called in to assist. Meanwhile, Bernie pursues a separate line of inquiry into a hemp processing plant on Navajo Nation land after witnessing a deliberate hit-and-run that killed a plant employee. Once again, Hillerman nails her father’s style, fleshes out the female characters and brings the glories of the Southwest to life on the printed page.

Bruce Tierney lives outside Chiang Mai, Thailand, where he bicycles through the rice paddies daily and reviews the best in mystery and suspense every month.

8

cozies

by jamie orisini

H Under Lock & Skeleton Key Under Lock & Skeleton Key (Minotaur, $26.99, 9781250804983), the enchanting first book in Gigi Pandian’s Secret Staircase series, flawlessly balances magic, misdirection and murder. After a performance gone wrong, stage magician Tempest Raj must move home to Hidden Creek, California, and contemplate working for her father’s company, Secret Staircase Construction, which adds whimsical details like sliding bookcases and secret rooms to homes. But at his latest job site, a body is discovered inside a wall. To make things even worse, the victim is Cassidy, Tempest’s former stage double. Hidden Creek is a truly delightful setting; the Raj family home abounds with hidden rooms and intricate locks, and also includes the dreamy treehouse where Tempest’s grandparents live. The mystery is engaging and full of crafty twists (sometimes literally, in the form of sleight-of-hand tricks), and Pandian's writing bursts with heart and hope.

DOESN’T STOP HERE.

Divided We Stand H.W. Brands In Our First Civil War, historian and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist during illuminates the intensely personal convictions of the Patriots and Loyalists the American Revolution.

A Deadly Bone to Pick Mystery fans and dog lovers alike will enjoy Peggy Rothschild’s A Deadly Bone to Pick (Berkley, $26, 9780593437087). Former police officer-turneddog trainer Molly Madison makes a cross-country move to Pier Point, California, with her loyal golden retriever, Harlow, at her side. On her first day there, she befriends a slobbery Saint Berdoodle (named Noodle) and volunteers to train him. But when her new charge digs up a severed hand on the beach, Molly quickly goes from new kid on the block to murder suspect. Readers will enjoy Rothschild’s fast-paced and well-plotted mystery, especially its small beach community setting filled with memorable characters. Molly’s lessons blend seamlessly into the central mystery, and animal lovers will appreciate seeing the reality of loving and living with pets depicted on the page.

Sign up to receive reading recommendations by email at BookPage.com/newsletters

Murder on the Menu After serving nearly 20 years with the London Metropolitan Police and undergoing a divorce, Jodie is ready to start fresh. She and her 12-yearold daughter, Daisy, move to Penstowan, the small village where Jodie grew up. There, she opens her own catering company, and her first client is Tony, a longtime friend and onetime ex-boyfriend who hires her to cater his upcoming wedding. But when the bride-to-be disappears and bodies start to pile up, Jodie takes off her caterer’s coat and dives into the investigation in order to clear Tony’s name. Author Fiona Leitch’s witty dialogue and tongue-in-cheek humor elevate each scene, and Leitch also ably explores the bittersweet nature of Jodie’s return: While she’s happy to live closer to her mother, Jodie’s also living in the shadow of her late father, who served the village as chief inspector. Murder on the Menu (One More Chapter, $12.99, 9780008436568) will delight cozy fans, especially those who want just a touch of melancholy amid all the crime-solving fun.

Jamie Orisini is an award-winning journalist and writer who enjoys cozy mysteries and iced coffee.

Get more ideas for your TBR list, in all your favorite genres: Audiobooks Biography/Memoir Children’s Books Cooking/Food/Drink Historical Fiction

Mystery/Suspense Popular Fiction Romance Young Adult and more!

@readbookpage

@bookpage

@readbookpage

bit.ly/readbookpage

9

feature | high fantasy

TARNISHED CROWNS Three high fantasy novels aren’t afraid to ask difficult questions. Readers who are eager for feats of magic and daring adventures but don’t want to retread the same old stories from decades past will be enthralled by these three novels, each of which strays outside of the traditional high fantasy playbook to great effect. Far from being simple tales of birthrights and inheritances restored, these books delve into heady questions about power, privilege and the consequences of political intrigue. And while each does this in a different way, they do have one thing in common: They open with a death.

The Amber Crown Jacey Bedford’s The Amber Crown (DAW, $20, 9780756417703) begins with the death of King Konstantyn of Zavonia, poisoned by an unknown assassin. His personal guards are immediately blamed for the death and executed by the new king. Valdas Zalecki, head of the king’s guard, was out of the palace on the night of the murder, and it is up to him to find out who killed his beloved king—and to find Queen Kristina, who’s gone missing. Mirza, a witch and healer with the power to speak with the dead, promises Konstantyn that she will avenge his death. And the last piece of The Amber Crown’s puzzle is Lind, the assassin who killed Konstantyn. Haunted by the specter of his abusive childhood, Lind finds that the murder of a king is not an easy thing to live with. As their stories collide, these three outsiders must work together to prevent Zavonia from falling further into chaos. Despite its conventional premise, The Amber Crown still represents a divergence from traditional high fantasy. The world building echoes Eastern Europe, with Zavonia serving as a fictionalized version of Poland. This allows Bedford to pull from supernatural practices of that region of the world, such as blood rituals and dream walking. And Bedford’s focus on marginalized and supposedly “unimportant” characters, rather than knights and princes, forces readers to reckon with the consequences of political upheaval outside of a royal court.

H The Bone Orchard Sara A. Mueller’s debut novel also begins with the death of a monarch, this time an emperor. In The Bone Orchard (Tor, $26.99, 9781250776945), Charm is a prisoner but a well-kept one. Taken from her home when her kingdom of Inshil was conquered and colonized by the Boren Empire, the necromantic witch has been confined to Orchard House for decades. Charm is surrounded by her children, of a kind: boneghosts who are grown (and often regrown) from the fruit of the bone-producing orchard. Charm and her boneghosts—Justice, Pain, Pride, Shame and Desire—serve the

10

powerful men of the capital city of Borenguard as entertainers, masseuses and sex workers. Charm is mistress to the emperor himself, bound by a neural implant that keeps her magic in check and keeps her loyal to him. But when Charm is called to the emperor’s deathbed, she’s given a chance at freedom. If she finds the person who killed him, she will be free of the magic that keeps her bound to the crown. While the mechanics of Charm’s bone orchard and the empathic power that some citizens of Borenguard wield are certainly magical, other aspects of The Bone Orchard evoke classic sci-fi tropes. Charm’s boneghosts harken all the way back to Frankenstein, and the oppressive, fascist Boren Empire is straight out of Fahrenheit 451. But despite these nods to foundational works, The Bone Orchard still feels fresh and ambitious. Charm enjoys access to power while still being marginalized herself, a contradictory position that Mueller analyzes to endlessly fascinating effect. It may be an otherworldly, genre-bending fantasy, but The Bone Orchard is still intensely human at its heart.

In a Garden Burning Gold In a Garden Burning Gold’s (Del Rey, $27, 9780593354971) opening death is not so much a murder as it is a sacrifice. Young adult author Rory Power’s first novel for adults centers on twins Rhea and Lexos, siblings gifted with immense power and responsibility. Rhea is the Thyspira, tasked with taking—and then sacrificing—a new consort each season to keep the world lush and the provinces that owe fealty to their father, Vasilis, in line. Lexos is their father’s second, trained from near birth to assist Vasilis in his political machinations and keep stability in the land. When Rhea’s latest suitor-cum-sacrifice is revealed to be embroiled in an independence movement that threatens the stability of the family’s demesne, the twins must scramble to maintain control and protect all they hold dear. Set in a world patterned after ancient Greek city states, In a Garden Burning Gold dives deep into family love, political intrigue and filial duty. It’s rare to find a main character whose powers engender so much ambivalence as Rhea’s abilities do for her. She offers little in return to the families and communities from whom she has stolen a life, other than the continuance of the status quo. Power makes Rhea a compelling and often likable character, while never losing sight of the fact that, in the end, she always lives and her consort always dies. That imbalance compels readers to ask whether the sacrifice is really worth it, and whether that sort of power should sit in any one person’s—or family’s—hands. A grown-up version of Encanto mixed with a political thriller, all set against a dazzling Mediterranean backdrop, In a Garden Burning Gold is a strikingly original and thoughtful fantasy. —Laura Hubbard

Art from In a Garden Burning Gold © 2022. Reproduced by permission of Del Rey. Jacket design and illustration: Faceout Studio/Tim Green.

Let’s get ready to rumble

© JOHN SCALZI

q&a | john scalzi

An out-of-this-world job comes with some big perks. After wrapping up the Interdependency trilogy, sci-fi author John Scalzi planned to write a weighty and serious novel. Instead, he had a monster of a good time. The Kaiju Preservation Society (Tor, $26.99, 9780765389121) is an adventurous romp that follows onetime delivery driver Jamie, who lucks into the job of a lifetime working for the titular organization, studying and protecting enormous monsters who live in an alternate dimension. We talked to Scalzi about the book he calls “as much fun as I’ve ever had writing a novel.” There’s nothing like a good monster book to shake things up. What drew you to writing a story about Kaiju? Well, I was actually writing another novel entirely—a dark and brooding political novel set in space—and it turns out that 2020 wasn’t a great year to be writing a dark and moody political novel, for reasons that will be obvious to anyone who lived through 2020. That novel crashed and burned, and when it did, my brain went, screw it, I’m gonna write a novel with BIG DAMN MONSTERS in it. It was much better for my brain, as it turns out.

feature | thrillers

Shocking reads for fans of ‘The White Lotus’ Money may not necessarily be the root of all evil, but privilege certainly leads to peril in three exciting new thrillers.

Cherish Farrah

to pretend that the characters have no concept of Big Damn Monsters, and that opens up a lot of narrative opportunities. The dialogue in this book positively crackles with life. How do you approach writing dialogue? Dialogue is one of the things I “got for free”—which is to say, something that was already in my toolbox when I got serious about writing. That’s great, but that also means it can be a crutch, something I fall back on too easily, or get sloppy with because I know I can do it more easily than other things. So, paradoxically, it’s something I have to pay attention to, so that it serves the story.

You mention in your author’s note that The Kaiju Do you see yourself as a Jamie? Ready to believe, Preservation Society is “a pop song . . . meant to optimistic, quick with a joke? be light and catchy.” Did it feel like that to you You’ve hit on something, which is that Jamie is meant while writing? to be someone whom the readers can see themselves Not going to lie, writing Kaiju was as much fun as in, or at least could see themselves relating to. There’s I’ve ever had writing a novel. Some of that was in a little of me in Jamie, sure. There’s also some of me contrast to the unfinished in Jamie’s friends. They each “Self-honesty is important, have qualities that help them novel before it ; anything work together. would have been easier than especially when some that one, given the subject and year I attempted it in. creature wants to eat you.” OK, real talk: What weapon But most of it was just giving would you reach for first if myself permission to feel the joy of writing, and of you were face to face with a Kaiju? creating something expressly to be enjoyed. If I’m being real, I’m going to remember what the weaponmaster in the book asks the characters, There are many homages to sci-fi and monster which is, basically, “Are you competent enough for movie tropes in this book. What preexisting audithat weapon?” Self-honesty is important, especially ence expectations served you best? when some creature wants to eat you. In which case, All of the preexisting expectations served me! One I’m going for the shotgun: widespread, low level of of the important things about world building is that difficulty to use. Perfect. And then, of course, I’ll run like hell. the characters are in on the joke—they’ve seen all the —Chris Pickens Godzilla movies, they’ve watched Pacific Rim and Jurassic Park, and so all the tropes are on the table Visit BookPage.com to read an extended for them and the book to lean into, to refute and to version of this Q&A and our review of play with, depending on the circumstances of the The Kaiju Preservation Society. plot. No one, not the characters nor the readers, has

A toxic friendship between a wealthy girl and her less fortunate classmate is at the heart of this hypnotic story from Bethany C. Morrow. Cherish Farrah (Dutton, $26, 9780593185384) tips from slow-building suspense into over-the-top horror as it immerses readers in a singularly unsettling worldview.

The Younger Wife Beyond the twists and turns of Sally Hepworth’s The Younger Wife (St. Martin’s, $28.99, 9781250229618) lies an exploration of trauma and its aftermath, and a subtle examination of how wealth can color relationships and self-worth.

The Club Wealth is practically a main character in The Club (Harper, $26.99, 9780062997425) by Ellery Lloyd. This clever murder mystery provides a pointed and cleareyed cautionary tale about the downsides of money and fame. Is all the jockeying for power and catering to terrible people (while, one assumes, trying not to get murdered) worth it? —Linda M. Castellitto Visit BookPage.com to read our full feature.

11

cover story | jenny tinghui zhang

SEEING AMERICA THROUGH MY FATHER’S EYES A father’s spirit of exploration leads to a daughter’s artfully crafted first novel.

had the potential to turn into a permanent position. My mother and I waited Jenny Tinghui Zhang makes her debut with Four Treasures of the Sky, a in Oxford, hoping that this would be the one. He called and spoke about the spirited tale of Chinese calligraphy and one girl’s journey of self-acceptance in late 19th-century America. Zhang, a Texas-based Chinese American writer, holds an weather, how the job was going, the mountains that braced the city. I was always MFA in nonfiction from the University of Wyoming, and she is now a prose editor worried he wouldn’t make it back home. at The Adroit Journal. Her first novel reveals storytelling In the end, my father got that job. His company skills both vast and specific, bringing shadowy history “My father overcomes hills, moved us to Austin, where we upgraded to a nice twoto light while also displaying a remarkable talent for bedroom apartment right across from the Barton Creek skips down valleys, sensory detail. Mall. When my mother and I visited him at his office, Zhang was inspired to write this incredible story after my father proudly showed us the break room, where cuts through the trees.” receiving a request from her father, a man of boundless we could grab handfuls of free coffee creamer and play curiosity who has explored nearly every inch of his adopted country. Once Zhang pool. He looks unstoppable, I remember thinking as I watched my father hold court in that break room. completed the book, her father returned to the site where the novel’s finale occurs. A few years later, that same company let my father go in a series of layoffs. I came home from school one day and was confused to see him already there. In 2014, my father was driving through the Pacific Northwest for work. One “Your dad got laid off today,” he told me, smiling wide. It was a maniacal evening, while making his way through Idaho, he passed a small town called kind of smile; there was no joy behind it. Over the next two years, my father Pierce. His headlights caught a historical marker on the side of the road. He would stay rooted at the computer, scrolling through job sites and updating saw, in those lights, the words “Chinese Hanging Tree.” The marker detailed his resume. When the phone rang occasionally, he would leap up to take calls from recruiters. I always felt an oppressive hope an event in 1885 when five Chinese men were hanged by white vigilantes for the alleged murder during these calls—maybe this would be the one. of a local white store owner. But things never worked out for him, whether it My father carried that story with him all the was because he lacked the skill set, or the English, way back to Texas. During one of my visits home, to make the final rounds. With our finances and my college attendance he told me about the marker and asked if I could write it into a story so he could figure out what on the line, my father accepted a job at Time really happened. His research online had yielded Warner Cable as a field technician. He spent his days driving around Austin and climbing poles, few results, he lamented. I took the request as a joke. My father has helping old ladies with their cable boxes, fixing always entertained many curiosities. He’s an wires and signals. It wasn’t the job he dreamed Aquarius, a perpetual fixer, a man who reads of having with his engineering degree, but it was something. books about the universe and math and string theory for fun. When he was a child, my father had My parents moved out of Austin years ago, but I the kind of mischievous and inquisitive energy remain here. When they come visit me, my father that eventually matured into a certain genius. always speaks about the city with a familiarity He refused to sit and ride the bus, preferring to that can only come from having crawled every hang off the back and balance on the bumper. inch of it, for better or worse. Your dad did a job He played clever pranks on his parents. In high there, he tells me about Montopolis, Anderson school, he joined the high jump team—back Lane, Travis Heights. The gated neighborhoods when the conventional jumping form was to do of West Austin. The now-gentrified pockets so headfirst. of East Austin. I wonder if he is telling me, or When my parents immigrated to Oxford, reminding himself. Mississippi, for graduate school in the early 1990s, Today my father has a different job, one that there was no room for that kind of man. They takes him all over the United States—places that lived in a cramped one-bedroom apartment in most folks only ever pass through to reach their the married graduate student housing section final destinations. His job is to seek out these on the Ole Miss campus, just down the way forgotten, overlooked places in order to determine from the fraternities. They attended where the signal for his company’s radios falters. classes and worked multiple jobs It sounds lonely and excruciating to me, and I that paid as little as $2 an hour. often worry about his safety out in these primarily And they tried to raise me. rural areas, but my father loves it. His job has Four Treasures of the Sky allowed his curiosities to grow, unrestricted Our tenure in America and Flatiron, $27.99, 9781250811783 by the walls of a cubicle. He makes pit stops the fulfillment of their to inspect strange roadside attractions, takes American dream—all of Historical Fiction pictures of the mountains in Oregon, orders that would be hopeless without a job following my parents’ graduation, beers at steakhouses in Virginia. He shares these artifacts and stories with me the responsibility for which rested on my father’s and my mother, leading us down long, meandering thought experiments of shoulders. At one point, he flew out to San Jose, what really happened and wouldn’t it be funny if. When he is out there, driving California, for the trial period of a job that through the endless fields, hills and forests, I know that there is all the room in

•••

12

the world for the kind of man he is, the one who was put aside in my family’s desperation for a stable foothold in America. It was this exploration that led him to that historical marker in Pierce. Just another pit stop. Another curiosity along the way. My father asked me to write out the story of what happened, and I did. It turned into my debut novel, Four Treasures of the Sky. I took the story he told me and worked my way backward to an imagined beginning. What I didn’t realize was that the story was not really about what happened in Pierce. It turned out to be about a girl named Daiyu who is kidnapped from her home in China and shipped across the ocean to America before making her way back home through the American West. This journey is not without struggle, as you can imagine. Faced with the threat of bad men and women, anti-Chinese racism and the question of fate, Daiyu pushes forward, traversing strange landscapes and lonely days. Her journey takes her to places I have never wandered, but places I imagine my father has and will. Perhaps unconsciously, I am thinking of him when I think of her.

Right before the COVID-19 pandemic, my parents decided that they would start traveling more for pleasure. They went to Rome—the first trip abroad they’ve ever taken in their 30 years in America, not counting all the trips back to China to care for their parents. We were never able to travel much during the years when my father didn’t have a job, but for the first time, they could imagine Paris, London, Washington, D.C. They wanted to visit New York City, having worked there as a delivery runner and a hostess during their grad school years. This time, they would experience it as tourists, not two people trying to survive. When the pandemic hit, all of those dreams disappeared. Instead, my mother began accompanying my father on his work trips. It’s a good deal: When my father is done with his job assignment, he turns into a tour guide of sorts, taking my mother to the roadside attractions, national forests and waterfalls he finds on Google Maps. My mother is a good adventure partner. They wander together, propelled by my father’s curiosities. Last summer, my father got another job assignment in Bend, Oregon. My mother went with him, and after the job finished, they drove over to Idaho, to Pierce. I had begged them not to—I was afraid that they would be attacked, given what was in the news lately. But my parents went anyway. They walked through the town, all 0.82 square miles of it, and documented their journey, sending me videos and pictures of the historical markers, the inns, the fire department, the old courthouse. They walked to the woods nearby, back to the historical marker that started it all. In the videos, taken by my mother, my father walks ahead, charting the course for the Chinese Hanging Tree. The forest floor is lush and verdant.

review | four treasures of the sky Jenny Tinghui Zhang’s spirited first novel, Four Treasures of the Sky, follows a girl’s epic three-year journey from her provincial home in northern China to San Francisco’s Chinatown and then to the mountains of Idaho. Born in the late 19th century, Daiyu is named for a mythological beauty who dies tragically when her lover is forced to marry another. Throughout her story, Daiyu struggles to overcome her namesake’s fatalism and discover a more purposeful, loving self. She must also cope with the poverty and prejudice that shape her daily existence. After her parents abruptly disappear and her doting grandmother can no longer support her, 13-year-old Daiyu is sent to the city to fend for herself. She assumes the identity of a young boy,

© MARY INHEA KANG

•••

The pines shoot upward. My father overcomes hills, skips down valleys, cuts through the trees. He is wearing a pale blue polo and baseball cap. His hands are at his waist. When they reach the site of the hanging, my parents stop. The camera points upward, to the ceiling of branches and leaves, and what little sky can manage its way through. It catches my father in this shot: He is looking around, breathing hard. “It’s just here,” he murmurs. There is no sentimentality in his voice, no grand gesture of reunion. Just acknowledgment and the respect of observation. The true pleasure of his exploration, I realize as I watch the video, is in sharing it with those he loves. His stories are not simply just thought experiments; they are reminders that no matter where he is, he is always thinking about us. In a way, Four Treasures of the Sky is my attempt to tell him a story, too. The camera points back down, this time stopping at my father. “Now that we’ve seen it,” he says, “we can go.” He turns, plodding his way through the brush, making his way toward whatever curiosity comes next. —Jenny Tinghui Zhang

naming herself Feng, and scavenges for food and odd jobs. Eventually she is taken in by a calligraphy master, who teaches her the discipline of ink brush, ink stick, paper and inkstone—the Four Treasures of the Study, which are mirrored in the novel’s four main sections. The practice of calligraphy continues to inform Daiyu throughout her perilous journey, and a recurring pleasure of the novel is Daiyu’s meditations on the shape and meaning of Chinese ideograms as they apply to circumstances in her life. In a food market one day, Daiyu is kidnapped. When the kidnapper discovers Daiyu’s female identity, he hides her in a barrel and ships her to a brothel in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The descriptions of this trip are terrifying. Equally as visceral are Zhang’s depictions of brothel life: the food, the feel of the rooms, the rivalries and friendships of the prostitutes, the subterfuges and

cruel economics that make these places possible. In these moments, the author’s skill for sensory detail shines. The brothel is the first place Daiyu comes face-to-face with American anti-immigrant racism. Recent laws have forbidden Chinese women from being admitted to the country, while male laborers are still allowed in, so a secret trade of trafficking young girls has emerged. Daiyu is eventually able to escape and, disguised as a boy once again, travels to Pierce, Idaho, where a coal-mining boom has attracted Chinese miners. There the novel comes to its startling conclusion. Though Daiyu’s story is shaped by true historical inequities, Four Treasures of the Sky comes to life through her journey to selfdiscovery and self-acceptance. —Alden Mudge

13

feature | inspirational living

KEEP GOING Four authors share hidden paths to healing. The losses continue to mount as we enter year three of the COVID-19 pandemic. While this specific grief is still new, weathering sorrow is as old as humanity. Four nonfiction titles offer comfort, empathy and wisdom to those who are reeling.

H Bittersweet Like Quiet, Susan Cain’s bestselling book on introversion, Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole (Crown, $28, 9780451499783) eschews American cultural norms like mandatory happiness and productivity in favor of other more fertile traditions, such as Aristotle’s concept of melancholia. Cain asks provocative questions like, “What’s the use of sadness?” and seeks answers through academic studies, insightful interviews and vulnerable self-reflection. A standout example is her interaction with Dacher Keltner, a psychologist who helped Pixar understand the crucial role of sadness in Inside Out. Sadness, he says, is what brings people together and adds depth to joy. Bittersweetness is both a feeling and a disposition. (The book includes a quiz for readers to determine if they are bittersweet by nature.) Experiencing bittersweetness heightens life’s poignancy, opens the door to transcendence and helps people acknowledge the impermanence of existence. It is reasonable to be sad, Cain explains, when one is deeply aware that life can change in an instant. Grief and trauma may even be inherited. But when we explore these bittersweet feelings, we begin to see ourselves and our world a bit differently, with more depth, and can finally find new paths forward. As one of Cain’s sources Rene Denfeld put it, “We have to hold our losses close, and carry them like beloved children. Only when we accept these terrible pains do we realize that the path across is the one that takes us through.”

Grief Is Love Marisa Renee Lee focuses on how grief is actually a painful expression of love in Grief Is Love: Living With Loss (Legacy Lit, $26, 9780306926020). When Lee was 25, her mother died of cancer in her arms. Afterward she held a beautiful memorial and started a nonprofit in her mother’s honor, yet she found herself unable to deal with the gnawing grief that clouded her inner life. Every big moment reminded her of her mother’s absence, especially her wedding and her miscarriage. Healing came, but all too slowly. Grief Is Love is organized around 10 lessons related to grief, touching on topics such as safety, grace and intimacy. Lee carefully considers the impact of identity (gender, race, sexuality, class and so on) on mourning, noting at several points how society’s expectations of Black women—that they’ll be strong and keep their pain to themselves—slowed her own grieving process. Readers of this memoir will get a clear sense of how Lee’s grief rocked her world at 25 and continued to reverberate well into her 30s, but they’ll also appreciate the ways of coping she’s found since then—ones

14

she wouldn’t have allowed or even recognized during those early days of trying to manage and contain her feelings. Lee describes the long haul of loss and speaks directly and compassionately to those who are experiencing it. She also takes comfort in her faith and even imagines her mother and unborn child meeting in heaven.

The Other Side of Yet Media executive and former television producer Michelle D. Hord explores the twin griefs for her mother and her child in The Other Side of Yet: Finding Light in the Midst of Darkness (Atria, $28, 9781982173524). Hord pulls the word yet from the book of Job, which was a lifeline following her daughter’s horrific murder by Hord’s estranged husband, the child’s father. The Bible describes how Job lost everything and yet still believed. This describes Hord, too, who treasures her “defiant faith.” In The Other Side of Yet, Hord offers readers a framework for facing life after a traumatic event using the acronym SPIRIT (survive, praise, impact, reflect, imagine, testify). Though Hord’s book is not organized around these directives, her own story does follow this path. To read Hord’s memoir is to witness a mother who lost everything and yet stood to tell the tale and dared to remain vulnerable.

Take What You Need Jen Crow’s life also fell apart, but not because she lost someone beloved. Instead, the sudden tragedy of a house fire provided the impetus for Take What You Need: Life Lessons After Losing Everything (Broadleaf, $24.99, 9781506468617). Crow, a Unitarian minister, may seem an unlikely candidate for a spiritual guide: She loves tattoos and the open road and spent years defying anyone who got in her way as she ran from her difficult childhood. After settling down and finally feeling safe, a literal bolt of lightning changed her life in an instant. Almost immediately after the fire, Crow realized that the way she and her wife talked about the tragedy would impact their children. “I wanted them to hear our gratitude, not our fear,” she writes. So they took special care in framing the story they told about the fire, never describing it as a form of punishment or as “proof that hardship never ends.” As Crow searched for a better way to interpret their situation, she found herself learning from her children, who comforted each other instinctively, crawling into bed together and crying. Observing them, Crow considered that grieving might be as natural to people as any other process in life, and that they might already possess the things they need to persevere. Across these books about suffering and healing, there is a practical and poetic need to surrender to what is overwhelming. Each book points to the power of faith and spiritual traditions to guide people outside of their own perspectives, where they can finally see themselves with lovingkindness, accept their losses and keep going. —Kelly Blewett

lifestyles

by susannah felts

audio

H Refuse to Be Done I’ve been following writer and professor Matt Bell on social media for years, eagerly tuning in for the wisdom he shares from the many (many) books and author interviews he has read, and frankly awed by his fierce, upbeat dedication to his writing practice. Bell’s new guide for aspiring novelists, Refuse to Be Done: How to Write and Rewrite a Novel in Three Drafts (Soho, $15.95, 9781641293419), gathers his wealth of knowledge and motivational zeal into a volume that deserves a spot on every writer’s desk. He advocates for a three-draft approach, while recognizing that “draft” can mean many different things. His chief goal is to keep you from giving up—to provide the fuel and structure to get you through the inevitable slog of novel-writing. As I embark upon another revision of a novel I’ve been working on for years, I’m thankful to have this book riding shotgun.

Anna Spiro It’s been a minute since we’ve featured the work of an interior designer. Anna Spiro: A Life in Pattern (Thames & Hudson, $60, 9781760762131) turned my head with its springy, floral-print linen cover, just the thing to spiff up a side table. Inside, the fun continues: The photographs are spirit-lifters one and all, awash in bold colors, textures and, as is Spiro’s trademark, pattern on pattern on pattern, with glorious examples of how to avoid being matchy and yet make everything harmonize. Fans of the ebullient mix-and-matching of Justina Blakeley will also delight in Spiro’s maximalist, vibrant style. If you’ve had a hankering to try a pop of wallpaper, this book will take your face between its hands and say, “Go for it, friend!” Do you love being surrounded by your precious things? Spiro understands, and she encourages shaping your personal style around those beloved objects. “Above all, your goal should be to create an environment that is reflective of you, your life and taste,” she writes. “Collect art, furniture and other items that have meaning to you.”

Love and Justice Model, actor and activist Laetitia Ky has amassed a significant Instagram following over the past several years, posting images of her incredible hair sculptures. She twists, bends and shapes her own hair into faces, animals, bodies, trees, breasts and other body parts, and much more. This hair art is striking at face value, but in Love and Justice: A Journey of Empowerment, Activism, and Embracing Black Beauty (Princeton Architectural, $27.50, 9781648960529), Ky frames her sculptural work within personal narratives that dig into issues of mental health, internalized misogyny, African heritage, sexism, self-care, Black beauty and other themes close to her heart. As a member of a new global guard of young creatives who refuse to separate their work from their beliefs and values, Ky is poised to become a strong role model for young people finding their way in the world.

Susannah Felts is a Nashville-based writer and co-founder of The Porch, a literary arts organization. She enjoys anything paper- or plant-related.

H African Town In African Town (Listening Library, 7 hours), co-authors Charles Waters and Irene Latham use a series of first-person narrative poems to tell the story of the Clotilda—the last American slave ship—and to reveal the fates of the enslaved passengers and their captors. Each character’s perspective unfolds in a particular poetic structure that reflects their personality, and the audiobook cast members incorporate the cadence of these poems into their performances without ever sounding forced or contrived. It’s an emotionally complex, searingly honest and extremely rewarding experience for teen and adult listeners alike. —Deborah Mason

Sign up for our audiobooks newsletter at BookPage.com/newsletters.

How to Be Perfect In How to Be Perfect (Simon & Schuster Audio, 9 hours), Michael Schur, creator of “The Good Place,” explores philosophical questions about how humans define goodness and how to achieve it. The audiobook is read mostly by the author, whose well-paced, attentive narration keeps his humorous, personality-driven (albeit sometimes meandering) content clear and engaging. Actors from “The Good Place” comprise the audiobook’s remaining cast, with Kristen Bell, D’Arcy Carden, Ted Danson and others bringing distinctive tones, attitudes and comedic gravitas to their performances. —Autumn Allen

I Came All This Way to Meet You Novelist Jami Attenberg invites readers to join her in reflecting on relationships, creativity and the nature of home in her first essay collection, I Came All This Way to Meet You (HarperAudio, 6.5 hours). Attenberg’s vulnerability in these essays, paired with narrator Xe Sands’ quiet, confident voice, makes this an intensely personal listening experience. It’s like sitting down with a clever friend to hear stories over cups of tea—nostalgic, conspiratorial and comfortable. —Tami Orendain

H All About Me! Mel Brooks—the multiple Tony, Academy Award and Emmy Award-winning comedian, writer, filmmaker and Broadway showman—has found reasons to laugh all his life and, thankfully, has shared that laughter with the public. Now he’s doing it again, this time with his memoir, All About Me! (Random House Audio, 15 hours). It’s easy to hear that Brooks had fun telling these stories, which clearly hold a distinct place in his heart. They’ll find a way into yours, too. —G. Robert Frazier

15

interview | maud newton

Shaking the family tree Maud Newton’s debut is much more than a conventional family memoir.

© MAXIMUS CLARKE

According to an article in the MIT Technology Among the most memoReview, by early 2019, more than 26 million people rable characters in her famhad added their DNA to the four leading commerily line are her maternal ninth great-grandmother, Mary Bliss cial ancestry and health databases. That level of Parsons, who faced multiple alleinterest cries out for an in-depth examination of genealogy’s broad appeal, and Maud Newton gives gations of witchcraft in 17th-century us just that in Ancestor Trouble: A Reckoning Massachusetts, and her maternal grandfather, and a Reconciliation, a thoughtful investigation Robert Bruce, who reportedly married 13 times. (So far, Newton has only been able to document 10 of genetics and inheritance as viewed from the marriages, though she’s still searching.) Another is branches of her own family tree. Charley, Robert’s father, who was accused of murSpeaking by FaceTime from her home in Queens, dering a man in downtown Dallas with a hay hook New York, the red-haired and bespectacled Newton Visit BookPage.com to read our starred is relaxed and cordial as she sits in front of a wall of in 1916. He died in a Texas mental hospital, but review of Ancestor Trouble. Newton became so engrossed glass-enclosed bookshelves. She speaks thoughtfully but with eviin his story that she purchased a dent passion about a project that tombstone to mark his previously regularly. I objectively think they’re highly probhad its genesis some 15 years anonymous grave. lematic, and on a personal level, I continue to be seduced by the tools that they offer.” ago, when she started researchFor Newton, the most probing her family on Ancestry.com. lematic aspect of her ancesNewton’s comprehensive approach also led her But it wasn’t until 2010, when try concerns her family’s conto explore different ancestor veneration practices, she received her 23andMe DNA nections with slavery and with such as Tomb-Sweeping Day in China and the Day test results, that her interest in efforts to expel Indigenous peoof the Dead in Mexico. As she studied these rituals ples from their native lands. On the subject took off. Even then, throughout history and the world, she came to realshe admits, she was “puzzled by her father’s side, that history ize that “we in the contemporary West who do not hardly came as a surprise; he my obsession with it. I wasn’t venerate ancestors or minister to them in the afterreally sure exactly what I was was, after all, obsessed with the life are the aberration, not the other way around.” trying to get at.” Confederacy. But Newton was That intriguing and moving investigation, she says, A 2014 cover story for Harper’s dismayed to discover that some provided her with “a spiritual connection now, a Magazine on “America’s Ancestry of her mother’s ancestors also healthy connection to my ancestors, including to enslaved people and particiCraze” led to a book contract some of the ancestors who were problematic when and launched Newton, a writer pated in genocide against Native they died, with whom I had difficult relationships in life.” In the end, she says, “it’s less important or and former book blogger who Americans. “It was an unpleasbriefly practiced law before ant surprise, but ultimately a interesting whether there’s some objective realAncestor Trouble her literary career began, on a healthy and useful one,” Newton ity to this feeling that I have of connection to my Random House, $28.99 long and sometimes circuitous says, “to recognize that it wasn’t ancestors. What’s important to me is the healing 9780812997927 path through subjects like the possible for me to divide my potential that this inquiry can have.” heritability of trauma and the family into the part that enslaved Readers will connect with many aspects of Memoir spiritual importance of ancesNewton’s vivid story, but there’s one—what she people and that I didn’t relate to tors in various cultures. “As a layperson, my abilas much, and the part that I related to more that calls “acknowledgment genealogy”—that she hopes ity to understand the deep science was limited,” didn’t have this history. It was on all the sides.” will especially resonate. This encompasses, as she Though her family history is rife with material, she says, “but I really wanted to do my best.” The puts it, “personal harms that we can acknowledge broad reading list reflected in her book ranges from Newton wanted to write a book that was more than within our own family or larger harms that relate to ancients like Aristotle and Hippocrates to the work a conventional family memoir. “The only way I the systemic problems that we’re facing now as a of contemporary writers such as Dani Shapiro and wanted to write it country. . . . If each “Making it personal is the most Alexander Chee. was if I could . . . of us can feel a little look at it through At the core of Ancestor Trouble is Newton’s comcomfortable powerful force we have for change.” more these different plex, often difficult family story. She describes her coming forward birth as a “kind of homegrown eugenics project,” lenses, both through my own family history and and recognizing these harms and thinking about writing that her parents “married not for love but in the larger historical, sociological, scientific, philthem and feeling about them in a larger context,” because they believed they would have smart chilosophical and religious history context,” she says. she says, “we’ll move a lot further along as a country dren.” The union between her father, a MississippiThat broad perspective magnified Newton’s restoward the kind of conversations and healing that we born lawyer and unabashed racist, and her mother, ervations about online DNA research websites. “I need.” Newton believes this and brilliantly reflects a Texas native who later in life became a fundamenam very skeptical and very concerned about the it in Ancestor Trouble. After all, she says, “maktalist minister who conducted exorcisms in the famdata those sites are collecting and the lack of coning it personal is the most powerful force we trol we have over what is done with that data,” she ily living room, lasted only 12 years but left Newton have for change.” with a colorful, at times painful lineage to explore. —Harvey Freedenberg says. “And I also continue to use both of those sites

16

Art from Ancestor Trouble © 2022. Reproduced by permission of Random House.

feature | earth day

Forces of nature Three works of nonfiction balance a rousing celebration of nature’s beauty with a somber appraisal of its precarious future. David George Haskell, Eugene Linden and Juli Berwald engage all of the senses as they offer caution and hope about the Earth’s imperiled landscapes.