1 Contents Contents 1 Foreword by the Editor 3 Imogen Tozer (MA History) Understanding Prehistoric Maritime Activity Using Computational Modelling: The Late Bronze Age as a Case Study 4 Cal T. Pols (MA Maritime Archaeology), Archaeology Department Incorporating the Digital World into Museums: The Victoria and Albert Museum as a Case Study for Success 26 Libby Davis (MA Cultural Heritage Studies with Public History), Archaeology Department The Submerged Prehistoric Record of the Adriatic Sea and its Significance for Debates in Upper Palaeolithic Research 35 Samuele Ongaro (MA Maritime Archaeology), Archaeology Department Speaking to the Present, from the Past: History as a Dramatic Tool on the Elizabethan Stage 48 Catrin Ward (MA Cultural Heritage Studies), English Department Promoting the ‘Going Global’ of Taiwanese Films: The Case of the Taipei Cultural Foundation’s Film Support Policy 58 Yuetong He (MA Film & Cultural Management), Film Department The Eerie Sound of the Wind: David Lynch's Sound Dream in Mulholland Drive ..................... 68 Jiyan Wei (MA Film Studies), Film Department Entering a New Stage: An Analysis of the Main Drivers of the Growth of Korean cinema ........ 80 Mingyue Wang (MA Film & Cultural Management), Film Department An evaluation of Academic Interpretations of Vladimir Putin’s Image through visual sources . 90 Lydia Boniface (MA History), History Department Space and the ‘Feeling of Community’ in the context of the Gorbals Jews 98 Sam Beesley (MA History), History Department

2 The Design and Analysis of Three Speaking Tasks for Classrooms 110 Binxin Gong (MA ELT/TESOL Studies), Languages Cultures & Linguistics Department Approving Translanguaging as a Medium of Instruction in English as a Medium of Instruction Classrooms ......................................................................................................................................... 119 Yijia Wu (MA Languages and Cultures), Languages Cultures & Linguistics Department The Digital Conception and Realization of Musical Instruments in the Western Music History: The Barak Norman Bass Viol 124 Lei Qin and Wei Chen (MA Music Management), Music Department Assertability and the Paradox of Conditionals 135 Thomas Phillips (MA Philosophy), Philosophy Department Ignoring Practicality: An Infallibilist Conception of Knowledge 144 Connor Caw (MA Philosophy), Philosophy Department Authenticity In Musical Performance: Score Compliance versus Interpretive Freedom .......... 154 Cara Duttaroy (MA Philosophy), Philosophy Department

Foreword by the Editor

While working as Assistant Editor of the Southampton Journal of Undergraduate History in 2021-22, I received enquiries from postgraduate students studying other Humanities courses asking if they could be a part of the journal. From that interest, the Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities was created, and it is my absolute pleasure to be able to present the first edition.

This journal is a collaboration between seven different departments from the School of Humanities: Archaeology, English, Film Studies, History, Languages Cultures & Linguistics, Music, and Philosophy. We received 25 submissions and narrowing them down to the published articles was very difficult. These papers reflect the rich diversity of the School of Humanities, with topics ranging from the Elizabethan stage to Taiwanese cinema, prehistoric seas to language acquisition. They feature different perspectives, writing styles, and referencing systems, and together demonstrate the collective academic strength of Southampton’s Humanities students

I am incredibly grateful to the student markers who helped select the published articles: Annabel Chapman, Wei Chen, Wenzhao Gao, Katherine Masters, Megan Sheridan, Catrin Ward, and Emily Wright. Extra thanks go to the assistant editors, Lydia Boniface, Cara Duttaroy, and Sydnie O’Hara, for their invaluable contributions and effort throughout. The journal would not be complete without all your time and dedication, which has created a friendly sense of community amongst postgraduate Humanities students.

Many thanks also go to Dr. Eleanor Quince, for all her help in launching a brand-new journal, and to the wider School of Humanities for their encouragement. Personal thanks must also go to Will Clarke and Rosalind Baxter, for supporting me throughout the process

Thank you to all the students who submitted articles, even if they did not make it into the final journal. I’m very grateful to have received such high interest and so many submissions for a first issue, and you can all be very proud of the work you have produced.

Finally, a huge thank you to you, the readers! All the students have worked very hard on the journal, and we really hope you enjoy it.

Imogen Tozer Editor-in-Chief, 2022-2023

3

Understanding Prehistoric Maritime Activity Using Computational Modelling: The Late Bronze Age as a Case Study

Cal T. Pols

Abstract: Computational approaches have become widespread in archaeology and provide powerful tools to better understand our past. New developments in computer modelling techniques have improved our understanding of maritime landscapes and activities such as seafaring. This article presents the great utility of such approaches to deliver a nuanced understanding of maritime activity in the Late Bronze Age (LBA). New research was also completed that combined environmental (wind), human (time), and vessel performance to visualise seafaring routes in the Aegean during the LBA.

1. Introduction

Computational modelling has enabled archaeologists to theorise, investigate, and visualise human activity in the past. These applications, such as using Geographic Information Systems (GIS), have typically provided tools and analysis for terrestrial activity (Wheatley and Gillings, 2002; Conolly and Lake, 2006). More recently, computational approaches have been developed for use in understanding maritime landscapes and activities. Sophisticated models of maritime space and connectivity enable archaeologists to better understand what prehistoric seafarers may have experienced when engaging in maritime activities. These models can also visualise and quantify spatio-temporal patterns across maritime space that enables a more nuanced understanding of prehistoric seafaring.

Presented here is an evaluation of such approaches with a specific case study examining seafaring connectivity in the Late Bronze Age (LBA) Aegean. The LBA in the Aegean is a period roughly dating between c. 17000 – 900 BC (Iacono et al., 2022: 371). Previous modelling in the Aegean has tended to focus on earlier periods and on a more localised scale. This article presents new research and an approach that accounts for both human (time) and environmental (wind) factors and their impact on LBA seafaring on a broader, regional scale.

2. Computational Approaches in Maritime Modelling

Unlike terrestrial landscapes, upon which past human activities can leave their marks, the sea itself bears no trace of past activity on the surface (Berg, 2007: 389). The sea does not have the physical ‘cultural landscape’ that often provides information about routes, connectivity, and travel as in terrestrial landscapes (Van de Noort, 2011: 98). An important step in understanding ancient landscapes, as well as seascapes, is through visualisation from which recreating connectivity can be attempted

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 4

(Parker, 2001: 32). In the maritime landscape, it must be the seafarer’s perspective that we attempt to understand and reconstruct (Parker, 2001: 32).

Computational modelling offers ways of investigating seafaring in the past by estimating potential connectivity and experiences of maritime space. Sophisticated models can account for both environmental conditions, such as wind and currents, as well as human considerations such as time and energy (Leidwanger, 2013; Alberti, 2018; Safadi and Sturt, 2019). The visualisation of maritime connectivity and space, especially in a spatio-temporal approach, allows useful insights about the existing patterns in the archaeology to be extracted.

2.1 Maritime Space

Prehistoric seafaring was a complex activity and thus attempting to understand it is a challenging task (Berg, 2007). One reason for this is that our modern conceptions of space typically operate within a Cartesian paradigm, where space is absolute and is measured by distance. In the past, however, maritime space was likely not perceived in quantitative distances but rather through qualitatively experienced factors such as time and energy (Safadi and Sturt, 2019: 2).

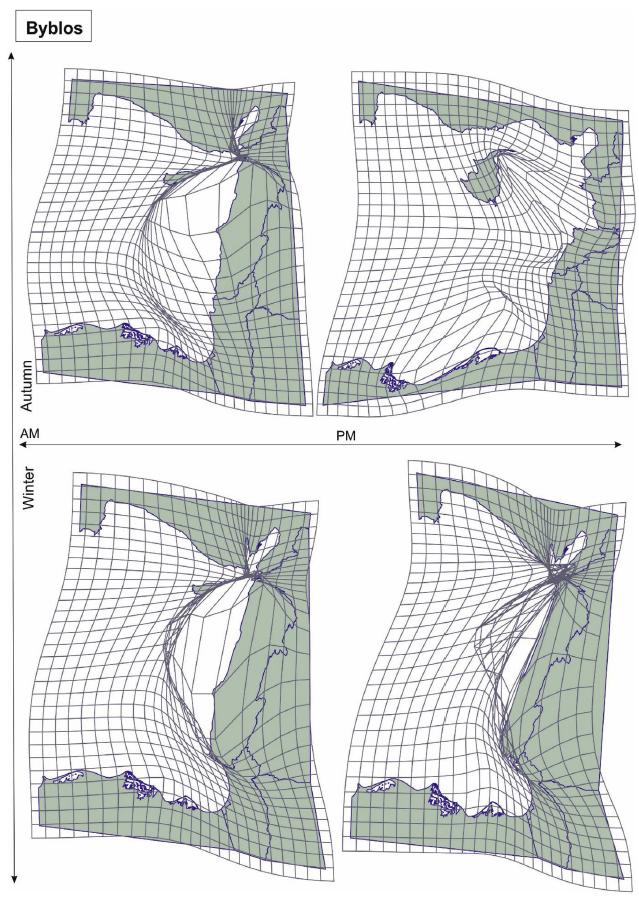

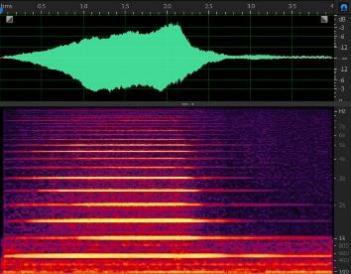

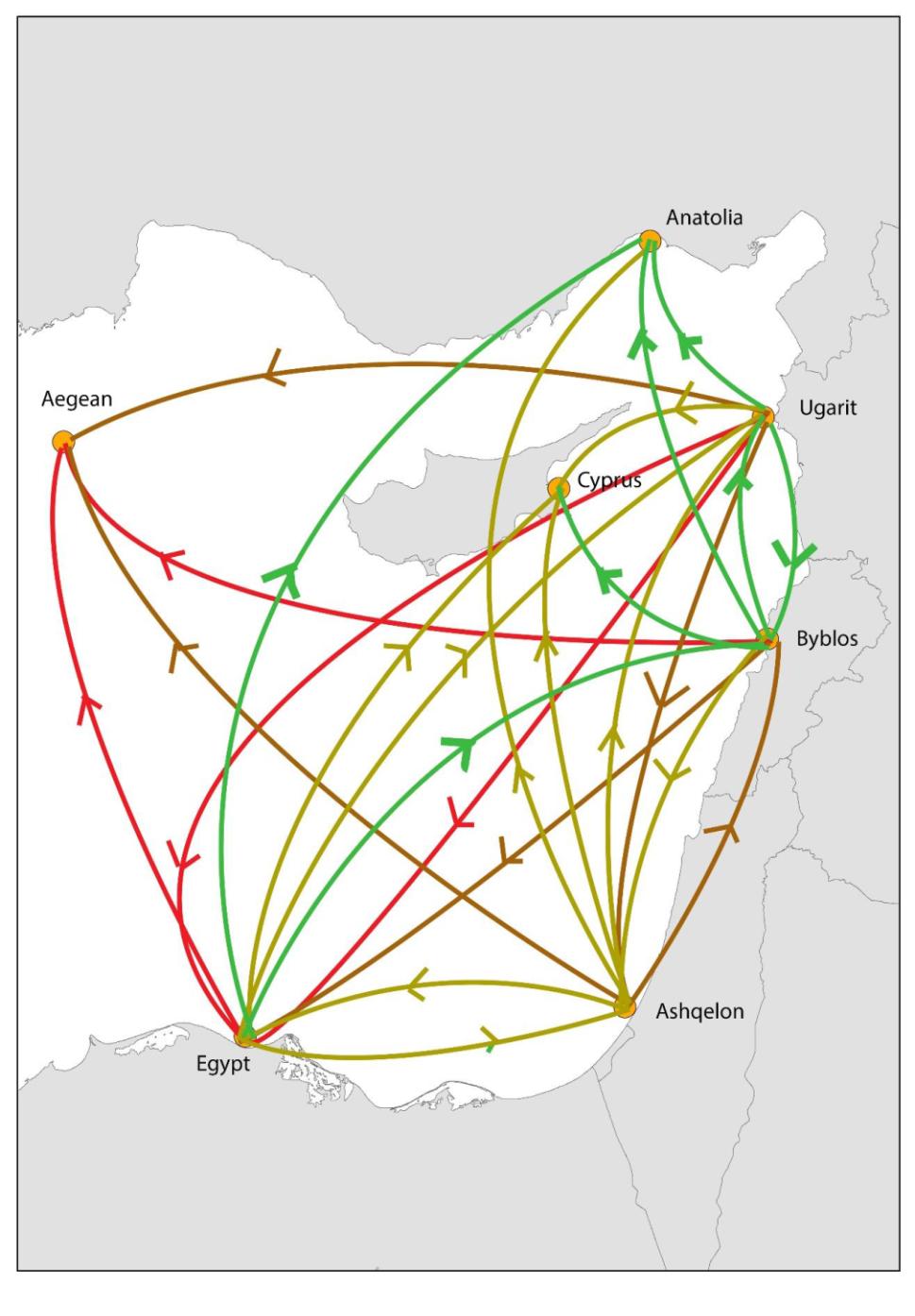

Computational modelling from Safadi and Sturt (2019) visualised how cognitive and experiential maritime space is closely linked with time in relation to seafaring. Using cartograms, they were able to show how maritime space can stretch and compress based on the journey time of seafaring activities from different locations in the eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age (Figure 1) (Safadi and Sturt, 2019: 6-7). This approach adds texture and complexity to maritime space that often is depicted as a single, flat colour.

Archaeology Department 5

2.2 Maritime Connectivity

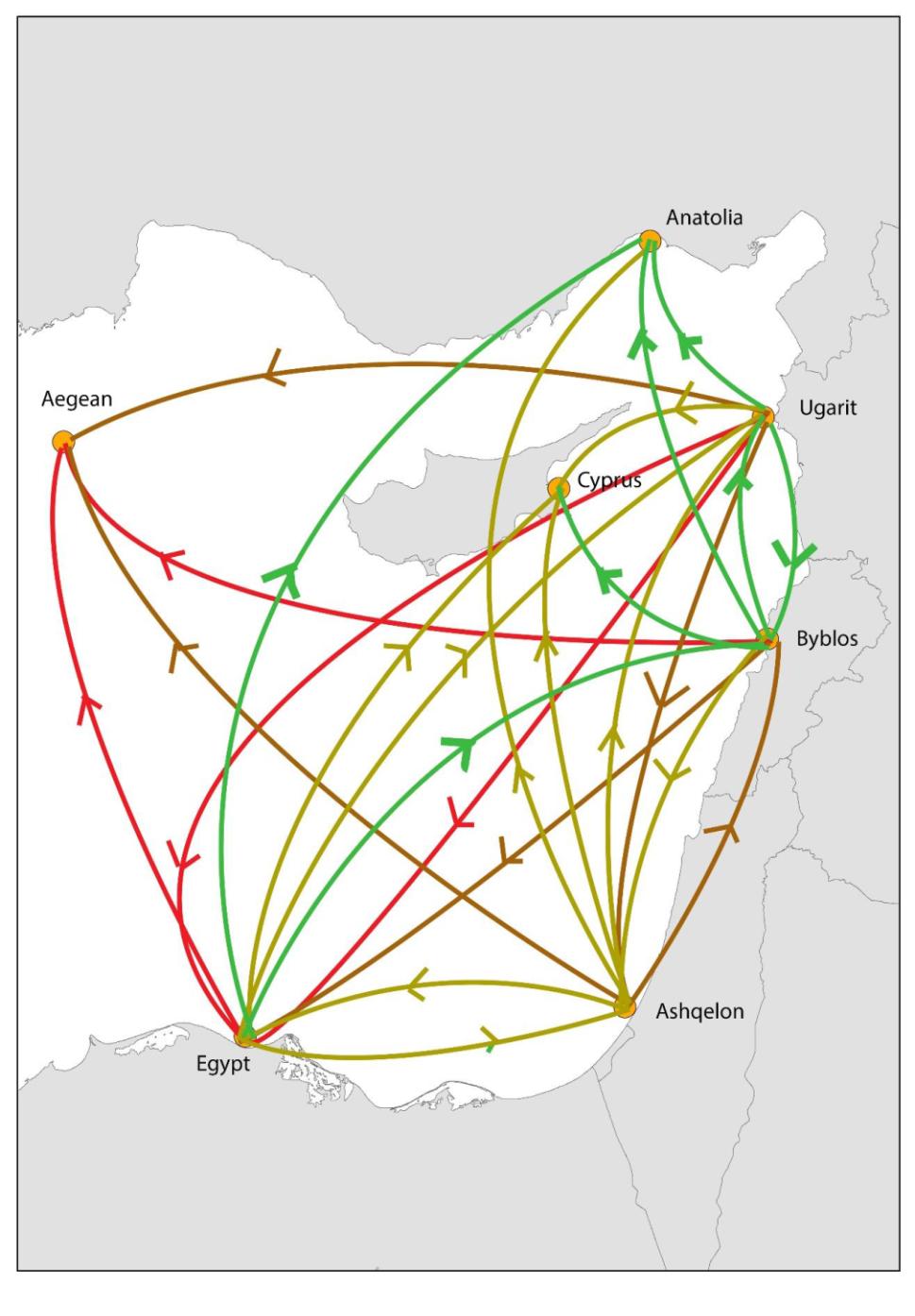

Conceptualising maritime space as the combination of distance and time (Mlekuž, 2014) also enables archaeologists to better understand maritime connectivity. By combining these approaches, accounting for a textured maritime space and human costs, potential seafaring connectivity can be visualised. Using computational modelling, Safadi (2018) was able to visualise the cost of maritime connection in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean (Figure 2). Analysing these patterns can lead to new insights into the distribution of material culture that may have been spread through maritime activity. Computational modelling by Leidwanger (2013) also assessed potential maritime connectivity using both human (time) and environmental factors (wind). Accounting for averaged wind conditions

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 6

Figure 1 - Distortions of maritime space-time visualised for departure points in the Eastern Mediterranean Bronze Age (Safadi and Sturt, 2019: 9).

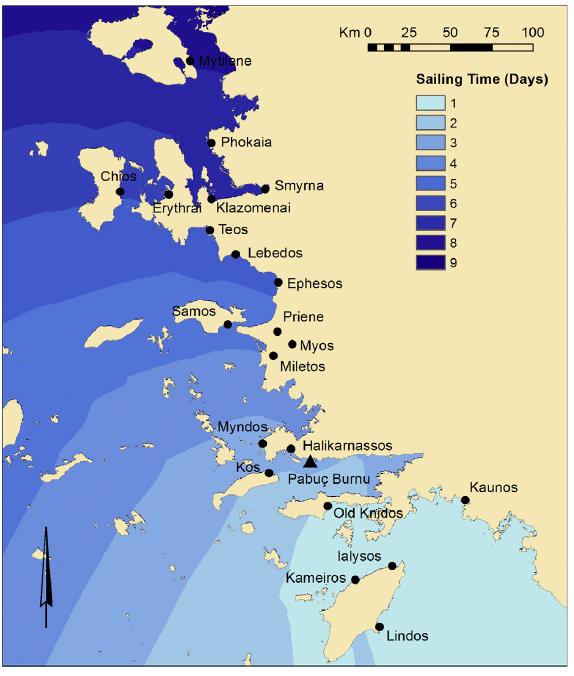

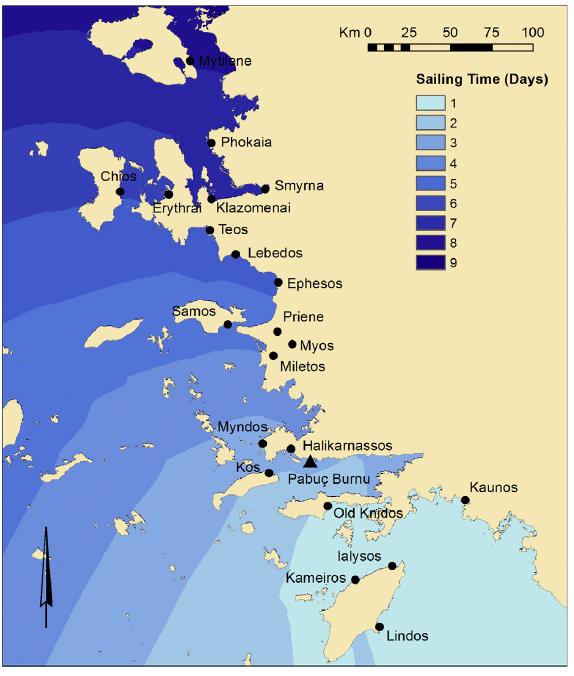

and the potential vessel performance of a Roman ship, Leidwanger (2013: 3304-3306) modelled sailing time from departure points in the eastern Aegean (Figure 3).

Department 7

Archaeology

Figure 2 - Potential maritime connectivity visualised based on the cost of travel (Safadi, 2018: 293).

2.3 Maritime Modelling of the Bronze Age Aegean

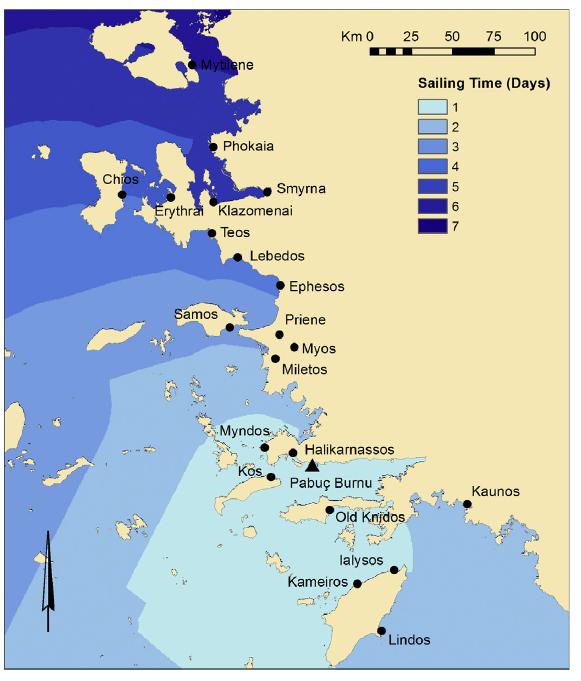

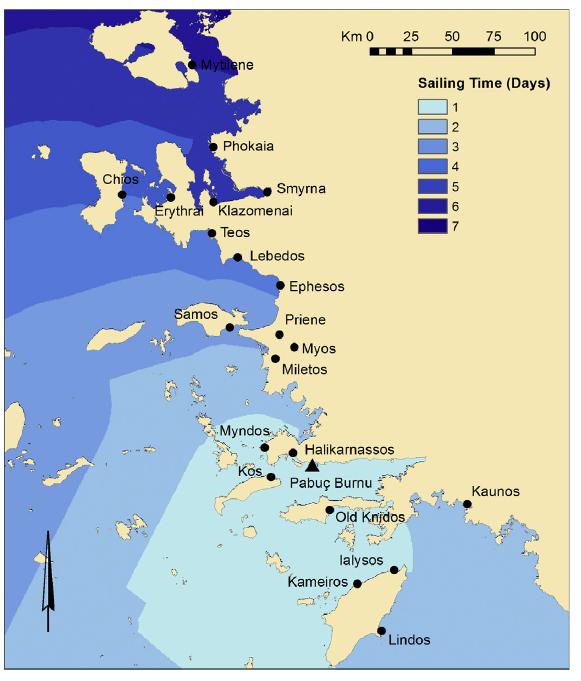

Earlier attempts to model maritime connectivity in the Bronze Age Aegean relied mainly on geographical distances (Jarriel, 2018: 56). While these may still provide useful insights and ways of thinking about the archaeological record, newer methods can provide more nuanced understandings. For example, Jarriel (2017, 2018) used GIS cost surfaces to model maritime connectivity in the Cyclades islands during the Early Bronze Age (EBA). This modelling incorporated environmental, archaeological, and technological considerations to estimate travel time from departure points in the central Cyclades (Jarriel, 2018: 52). Jarriel’s modelling used wind data and performance estimates of early BA vessels without sails in different conditions (Figure 4) (Jarriel, 2018: 59-61). One important element of this modelling was the temporal aspect: by modelling maritime connectivity across different months of the year, we can begin to understand the maritime activities of the past at a more nuanced, ‘higher resolution’ level.

A similar computational approach was undertaken by Thompson-Webb (2017), who modelled voyage time for rowed longships and sailed Minoan craft of the EBA from various sites in the southern Aegean. Thompson-Webb’s modelling, based on Leidwanger’s work (2013), examined the impact of the physical maritime environment conditions of networks of the early Bronze Age and how these

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 8

Figure 3 – Modelling of sailing time in the eastern Aegean; (left) Halikarnassos as departure point and (right) departure from Rhodes (Leidwanger, 2013: 3306).

changed over time as vessel performance developed from rowed to sailed craft (Thompson-Webb, 2017: 55-59).

Thus far, previous modelling approaches in the Aegean have been more localised and focused mainly on the Early Bronze Age. Taking a similar methodological approach to the prior modelling and applying principles established by Leidwanger (2013), Safadi and Sturt (2019), Alberti (2018), and Jarriel (2018), modelling was completed focusing on the LBA on a more regional scale. To do so, first the maritime context on the LBA in the Aegean must be understood and explored.

Archaeology Department 9

Figure 4 - Path distance modelling in the Cyclades of EBA (non-sailed) watercraft account for monthly changes in wind conditions (Jarriel, 2018: 65).

3. The Late Bronze Age Aegean

3.1 Prehistoric Context

The Aegean provides some of the earliest evidence of maritime crossings in the Mediterranean. Obsidian flakes originating on the island of Melos have been found on the Greek mainland and have been estimated in date to be c. 11,000 BC (Robb and Farr, 2005: 25; Dawson, 2013: 35). Similar evidence comes from lithic assemblages on the Ionian Islands, all of which through periods of lower sea-levels remained separate from the mainland (Galanidou and Bailey, 2020: 313). More generally, the wide-scale settling of islands in the Mediterranean and the coastal spread of stylistically consistent pottery during the Neolithic indicates the maritime capabilities present in the region (Robb and Farr, 2005; Ammerman, 2010; Farr, 2010). This shows not only the skills, knowledge, and technical capacity necessary for maritime crossings but also indicates the social processes involved (Farr, 2006, 2010).

3.2 A Maritime Bronze Age

The Late Bronze Age is a period that dates to c. 1700-900BC in the European Mediterranean (Iacono et al., 2022: 371). During this period, encounters between different groups and regions developed into a maritime network of relationships (Iacono et al., 2022: 372). The ‘Palatial Period’, starting around 1400 BC, saw the emergence of several ‘palace-based states’ such as Mycenae, Tiryns, Pylos, Thebes, and Messenia (Tartaron, 2017: 14). This period had an increase in shared material culture and development of communication in the ‘Mycenaean world’ (Tartaron, 2017: 17, 2018). For example, the considerable wealth accumulated at the central sites of Mycenae and Pylos indicates important contacts with Minoan Crete (Shelton, 2012: 141). At the same time, the Eastern Mediterranean became ‘increasingly interconnected by maritime networks’ (Tartaron, 2017: 20). These maritime networks involved Crete and Cyprus as well as the more distant eastern Mediterranean and Egypt (Iacono et al., 2022: 380).

Grave artefacts from mainland burials include precious materials such as metals, gemstones, and imported objects (Iacono et al., 2022: 379). These have been interpreted as evidence of a socioeconomic and political system in the LBA that was, at least in part, facilitated by maritime connections (Iacono et al., 2022: 379). Examples of materials that must have been acquired from outside the Aegean, as they do not naturally occur there, include lapis lazuli, ivory, and copper. The origins of these are likely Afghanistan, Egypt/Levant, and Cyprus respectively (Burns, 2012: 291). Alongside the potential economic element, there is also a likelihood of socio-political influences on maritime connections. The act of maritime movement itself as well as the acquisition of foreign objects may be activities that accrue prestige and status (Broodbank, 2000: 290; Van de Noort, 2011; Burns, 2012: 292).

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 10

3.3 Watercraft

There are less than 400 depictions of ships surviving from the Bronze Age in the Mediterranean (spanning c. 2,000 years) and their use to infer ship characteristics is challenging due to their difference in stylistic and artistic conventions (Tartaron, 2018: 37). Early iconographic evidence of watercraft in the Aegean appears only in the third millennium BC with the depictions of ‘longships’ on Cycladic frying pans (Wachsmann, 1998: 70-73). Minoan seals dating to the 2nd millennium BC also depict similar vessels, although the use of these depictions to estimate vessel characteristics is understandably debated (Whitewright, 2018: 29).

Additional depictions of Minoan watercraft appear in the Miniature Fresco in the ‘West House’ on Akrotiri (Thera) (Wachsmann, 1998: 86). Supplementing this iconography with shipwreck evidence, such as the Cape Gelidonya (Bass, 1967) and Uluburun wrecks (Pulak, 1998), reconstructing the characteristics of these vessels has been attempted. However, the performance of prehistoric (LBA) watercraft is a much-debated topic and one that likely does not have any definitive answers. The performance of watercraft is a combination of environmental conditions (winds, currents, visibility), human considerations (time, experience, skills, knowledge), and technical capabilities of the vessel (rig, hull shape, size) (Whitewright, 2011; Tartaron, 2017: 81-82).

4. Methodology

4.1 TRANSIT Toolbox

The methodology of this modelling was undertaken by using a toolbox in ArcGIS Pro created by Alberti (2018). The TRANSIT toolbox calculates the time it takes to sail from a specified input location based on three key variables: wind speed, wind direction, and a horizontal factor (Alberti, 2018: 511).

The horizontal factor is an estimate of how the ‘cost’ of movement increases or decreases based on the alignment to a flow, in this case, the wind direction (Alberti, 2018: 512). This is very important for the estimation of potential sailing routes, as it determines how well a vessel can perform in relation to the wind. The values used for the horizontal factor were taken from the estimated performance of ancient vessels with a square rig (Whitewright, 2011; Alberti, 2018: 515). While many complicated factors combine to determine how well a sailing vessel can perform, the three variables that underlie this model can be considered the most fundamental for sailing in ideal conditions.

As illustrated above, the passage of time was a key factor in prehistoric seafaring. As such, the theoretical approach underpinning this modelling is Least Cost Analysis (LCA). LCA assumes that humans act in ways to reduce the ‘cost’ of an action, such as the movement between two locations

Archaeology Department 11

(White and Surface-Evans, 2012: 2; White, 2015: 407). Taking time as the primary ‘cost’ of seafaring, potential sailing routes were estimated by calculating the ‘Least-Cost Path’ (LCP) between specified locations. An LCP is the path of least accumulated cost between an origin and destination (Wheatley and Gillings, 2002: 137-144; Connolly and Lake, 2006: 252-255; Herzog, 2020: 333-346). In terms of modelling seafaring, the LCP is the quickest sailing route between two given locations.

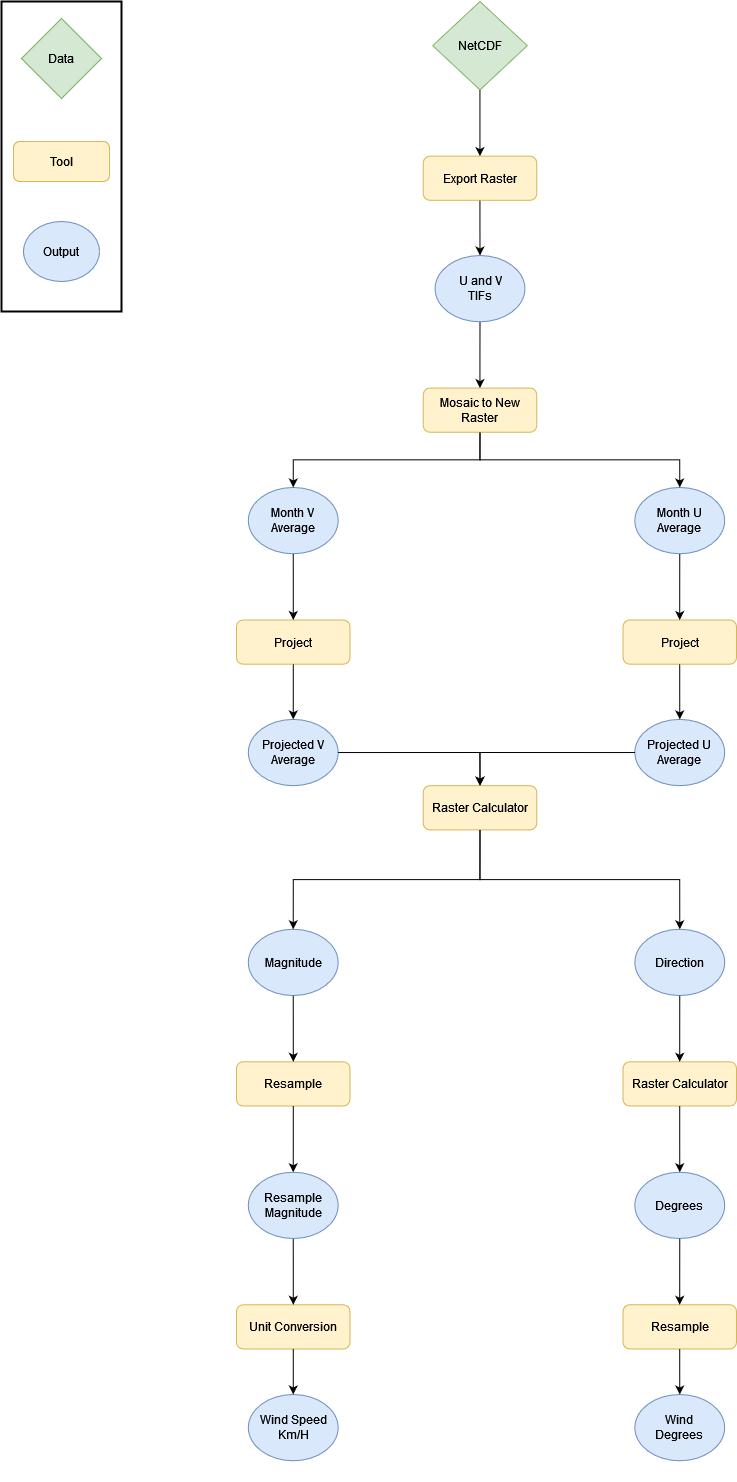

4.2 Data and Workflow

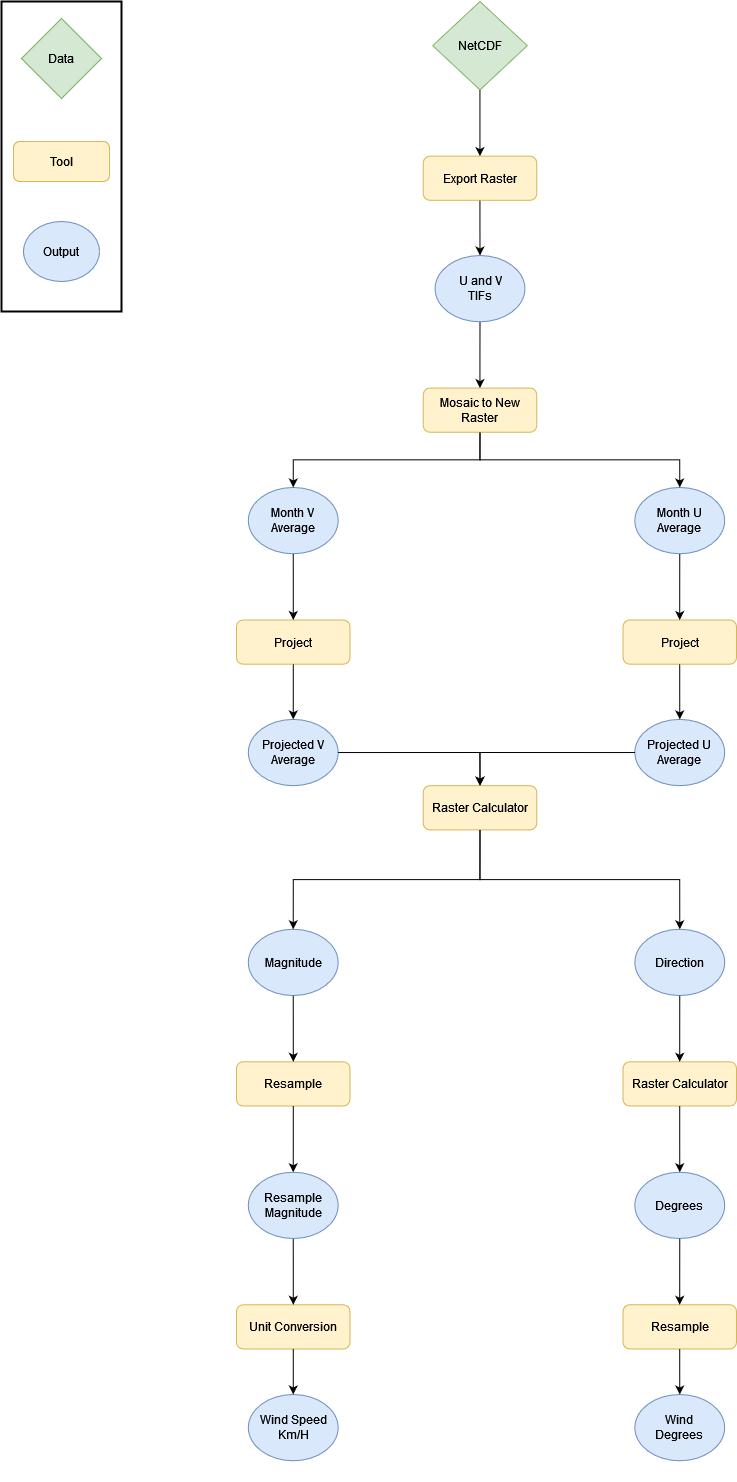

The wind data used for the modelling was hourly gridded reanalysis ERA5 U and V wind component data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (Hersbach et al., 2018). Time slices at 9.00am were taken from every other day for four different months (January, April, July, and October) over a five-year period (2017-2021). These months were selected as they are the second month of each season in order to act as a rough estimate for that season. These time slices were then averaged together to create a monthly average and was completed for five years’ worth of wind data. Modern wind data was used based on Murray’s (1987) conclusion about the comparability of ancient and modern wind conditions (see also McGrail, 2001: 89). Figure 5 outlines the overall workflow followed using ArcGIS Pro. Calculating wind direction in degrees and wind speed (magnitude) was completed using formulae from Safadi (2018: 258-259).

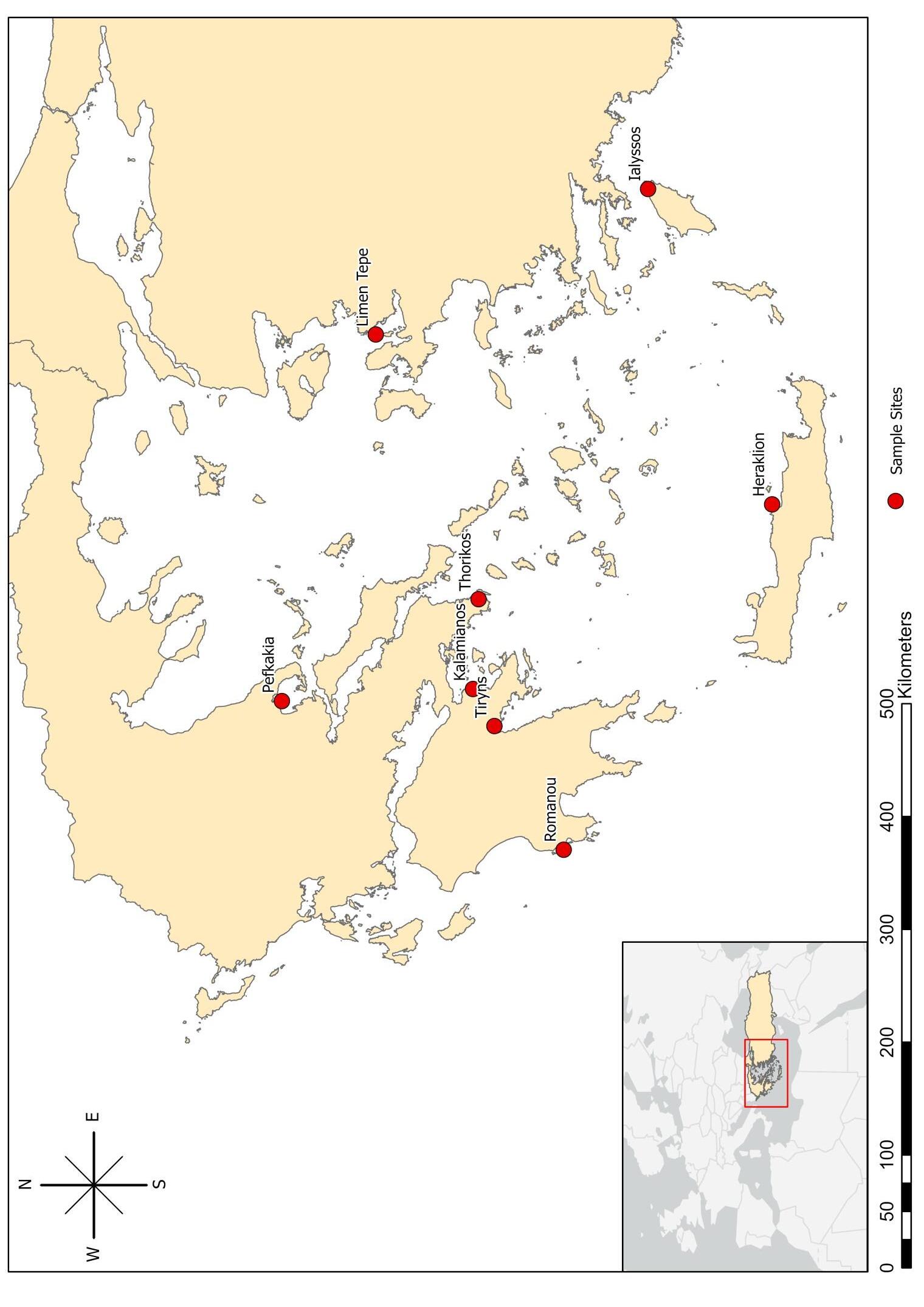

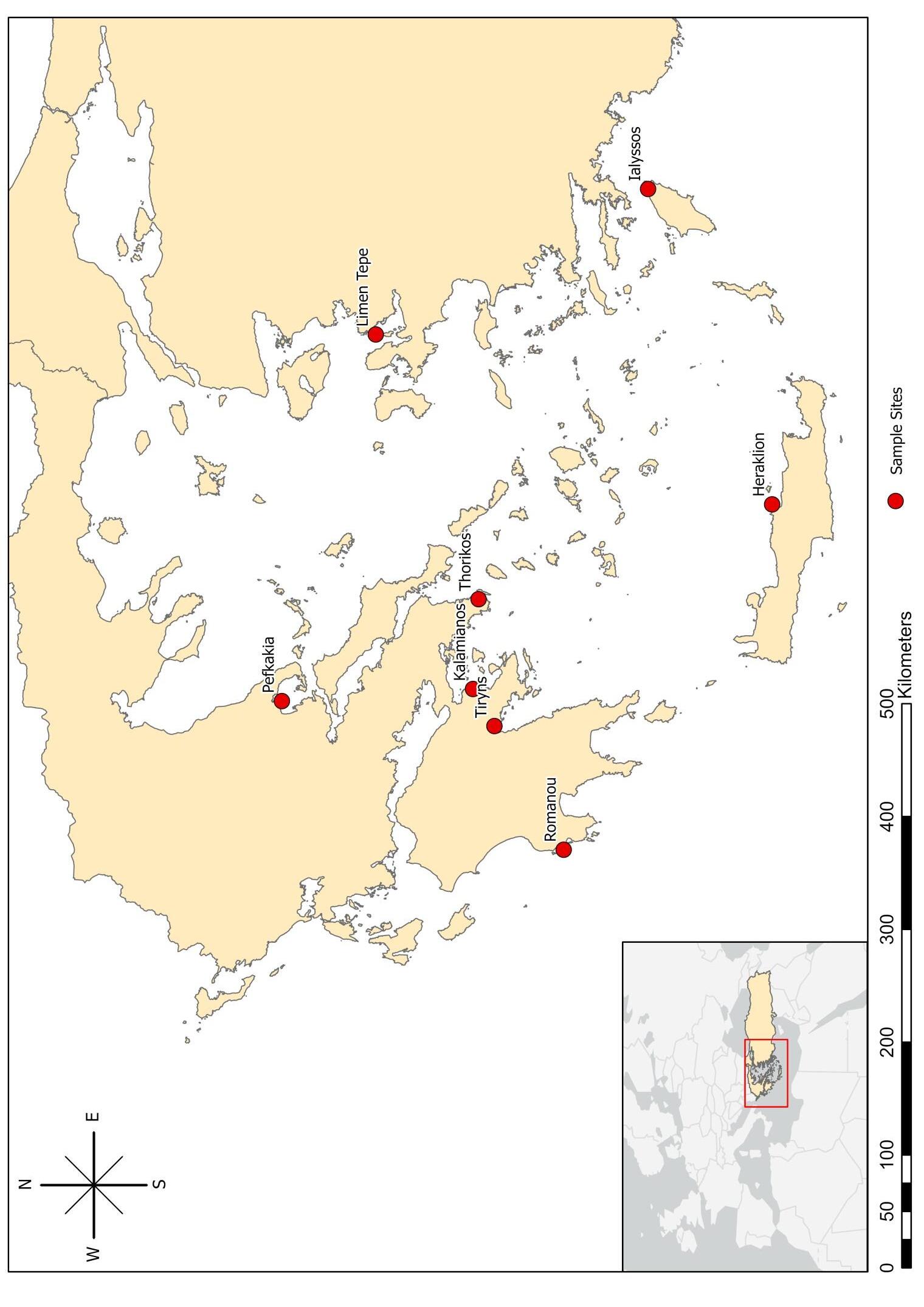

Origin and destination locations were then selected (Figure 6). The aim was to not reconstruct specific voyages per se, but rather to illustrate the potential maritime connectivity between different regions in the Aegean (Table 1). Out of the eight total locations, four were selected as the origin locations for the modelling; Kalamianos, Romanou, Heraklion, and Limen Tepe. Different origin locations had to be used due to the anisotropic nature of the modelling (Wheatley and Gillings, 2002: 137; White and Surface-Evans, 2012: 3). These origin locations were chosen to visualise how the maritime connectivity and sailing time changes from the different regions and bearings of sail, i.e. sailing east to west, north to south, and vice versa.

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 12

Table 1

Chosen Locations Region

Kalamianos Attica

Thorikos Attica

Tiryns Peloponnese (East)

Romanou Peloponnese (West)

Pefkakia Thessaly (North)

Heraklion Crete

Ialyssos Rhodes (Dodecanese Islands)

Limen Tepe Anatolia (West Turkey/ East Aegean)

Sites used in the modelling and the regions they represent (Source: Author).

13

Archaeology Department

–

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 14

Figure 5 – Overall workflow in ArcGIS Pro followed in order to process wind data (Source: Author).

Archaeology Department 15

Figure 6 – Map of the Aegean showing the sample sites used in the modelling (Source: Author).

5. Results

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 16

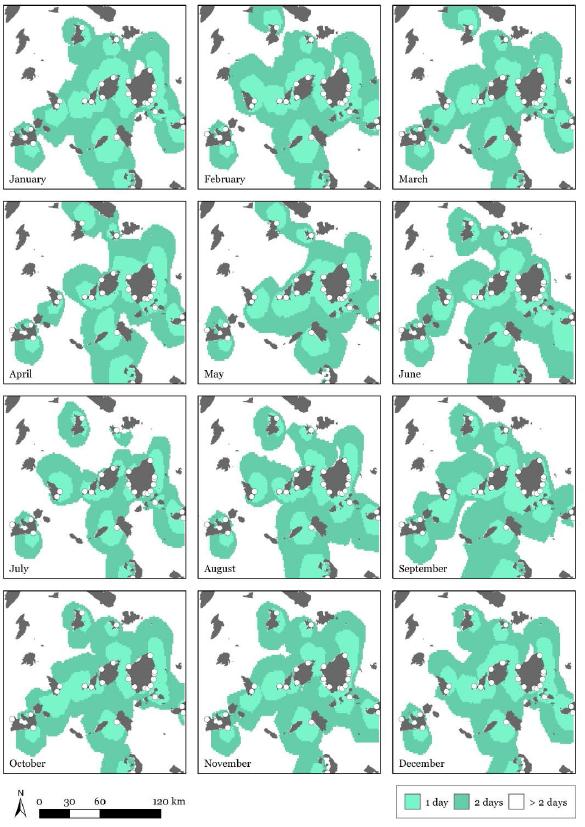

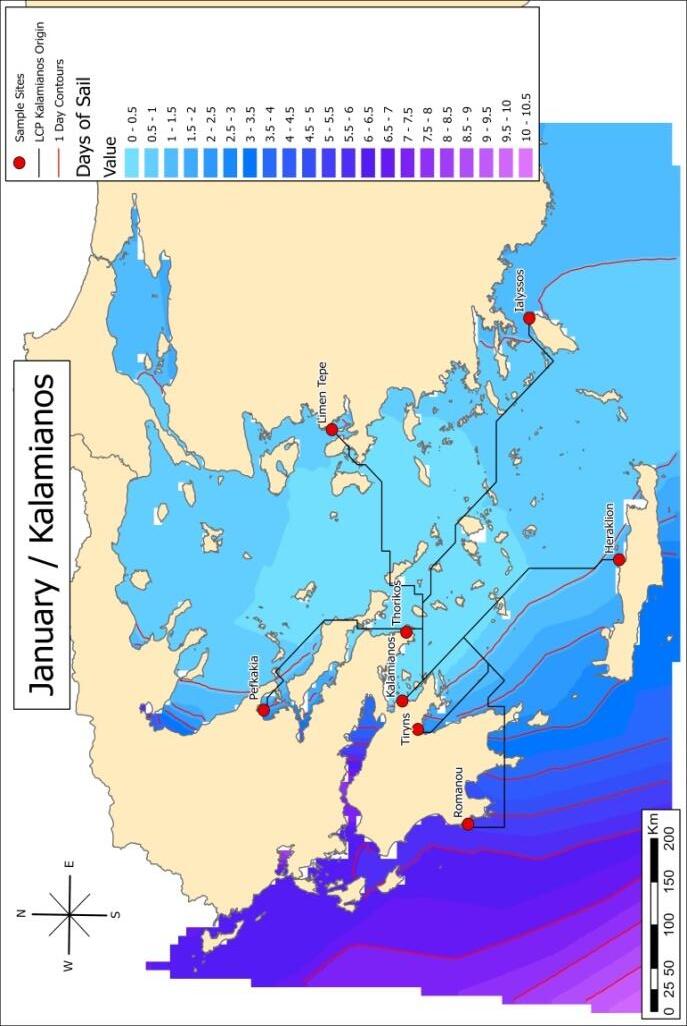

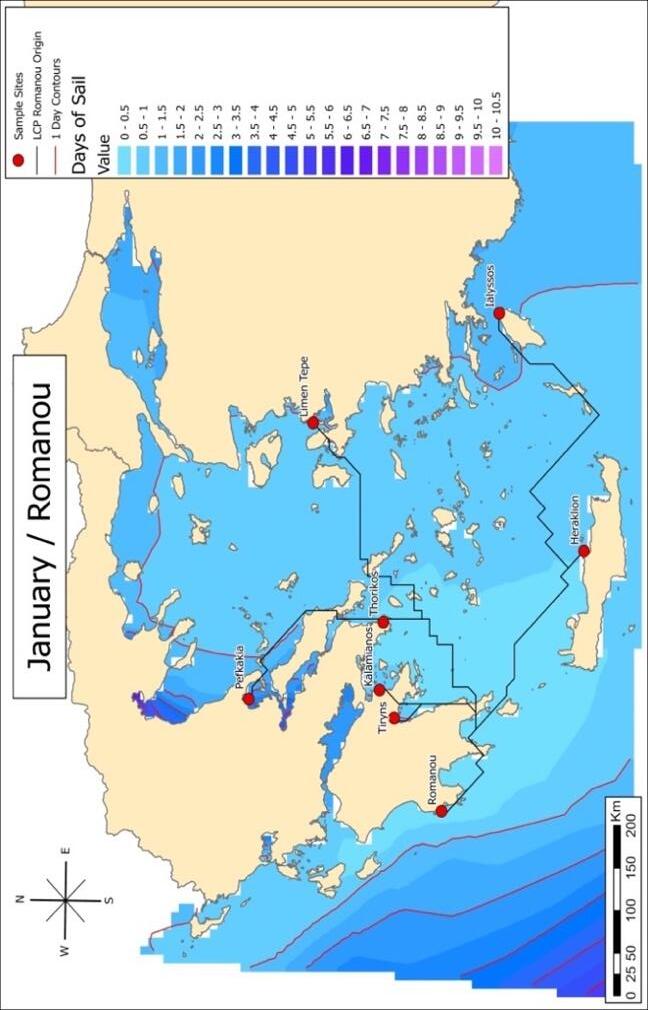

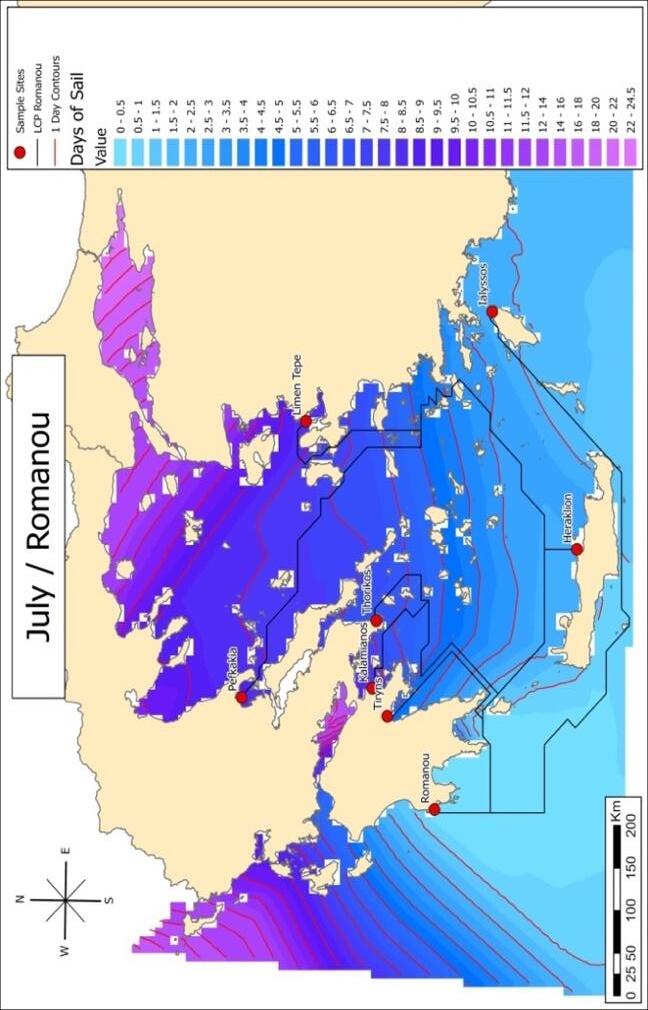

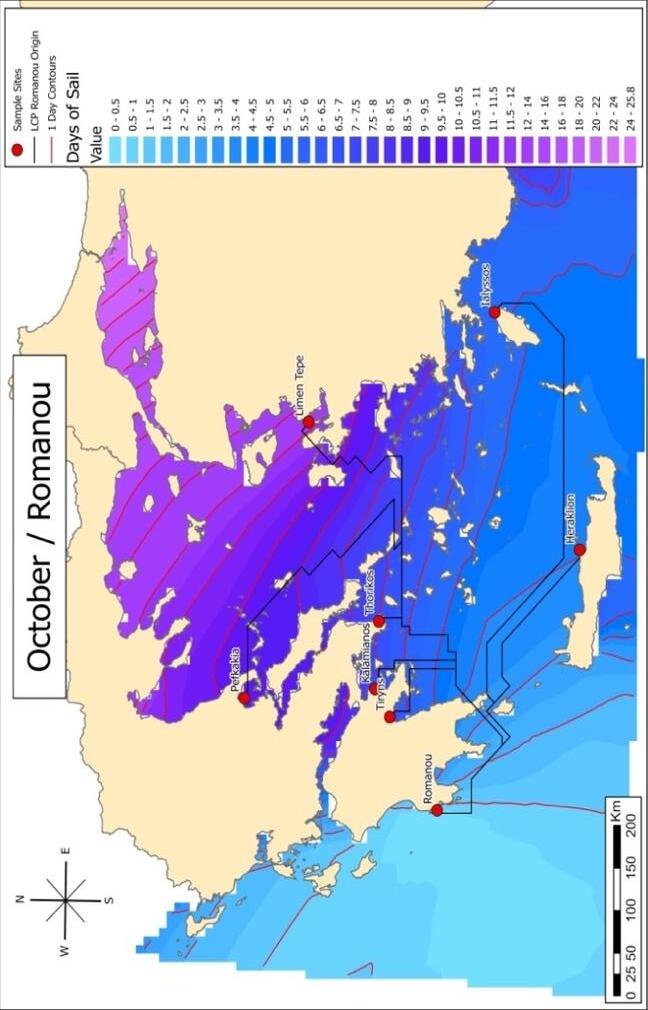

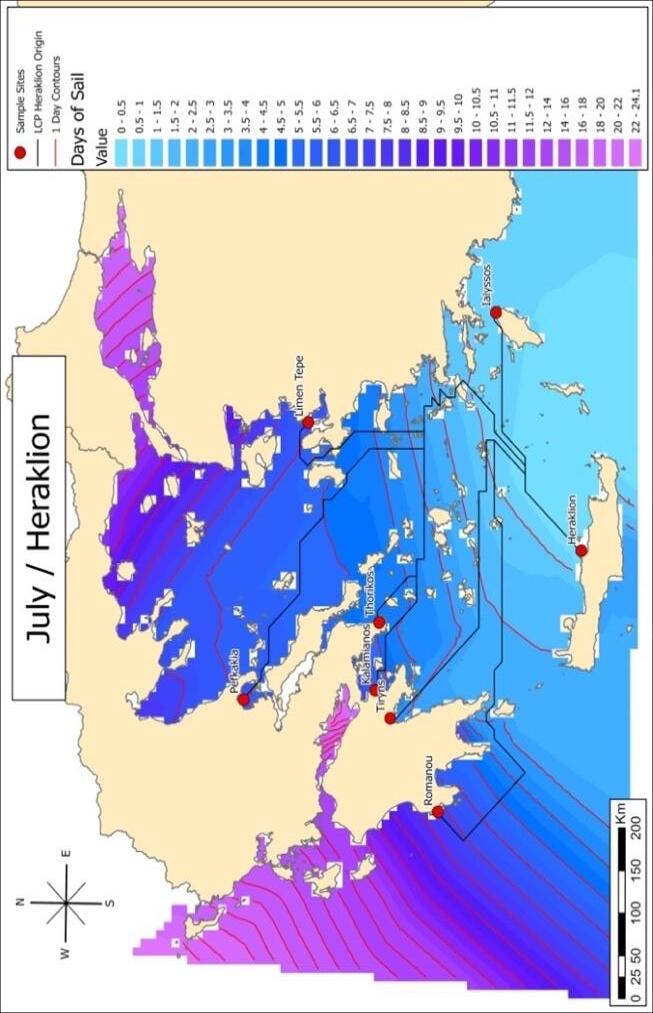

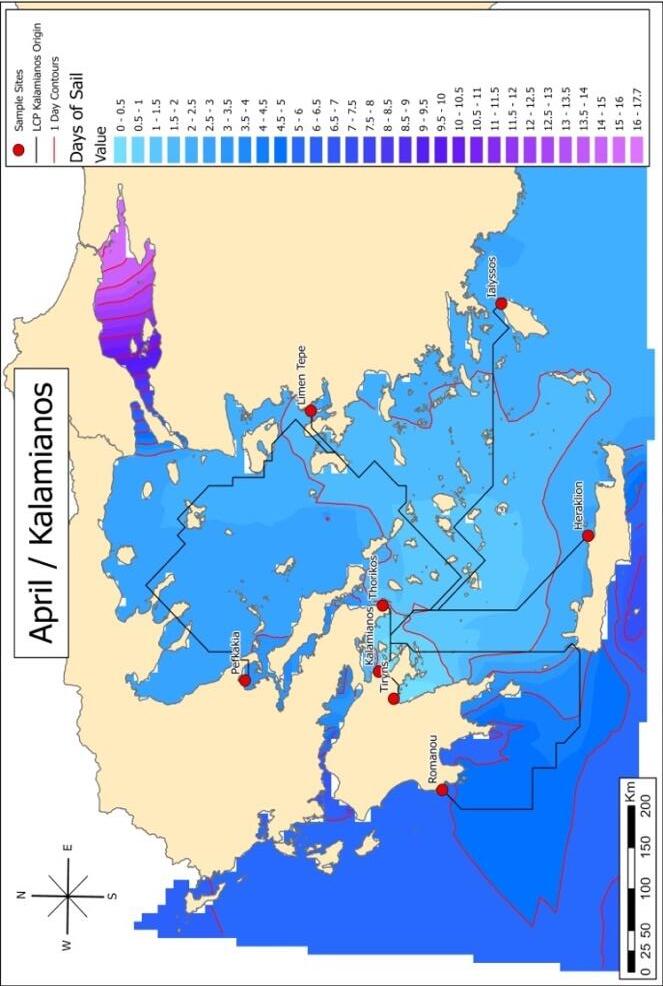

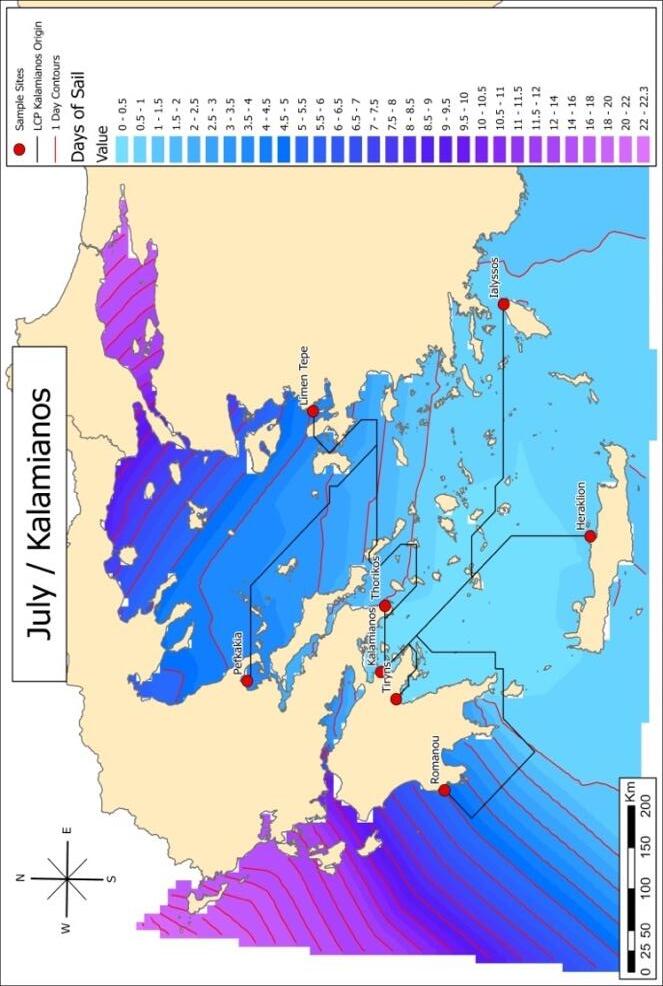

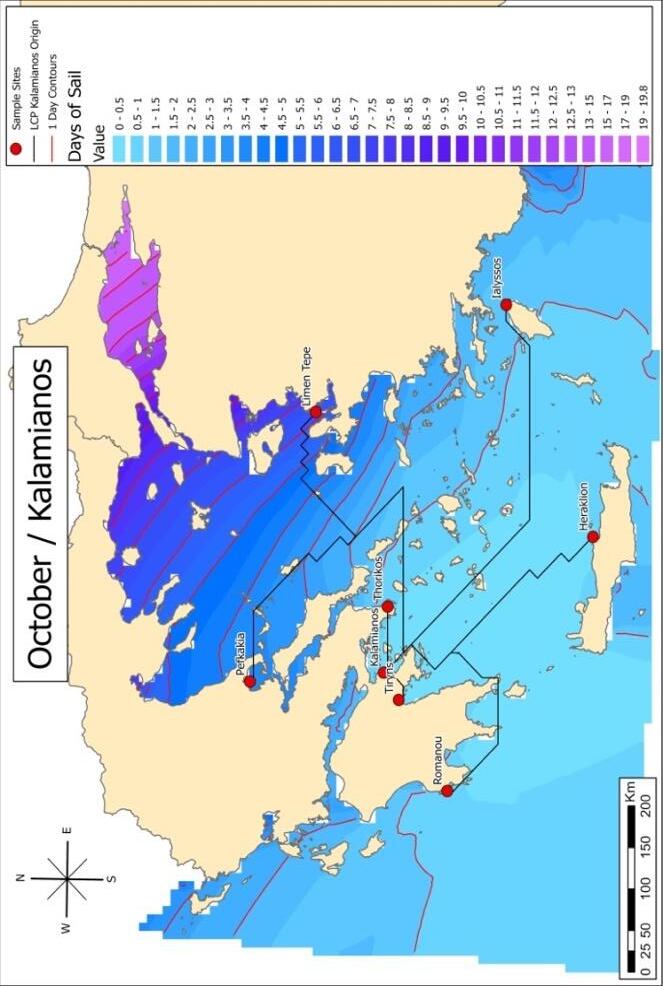

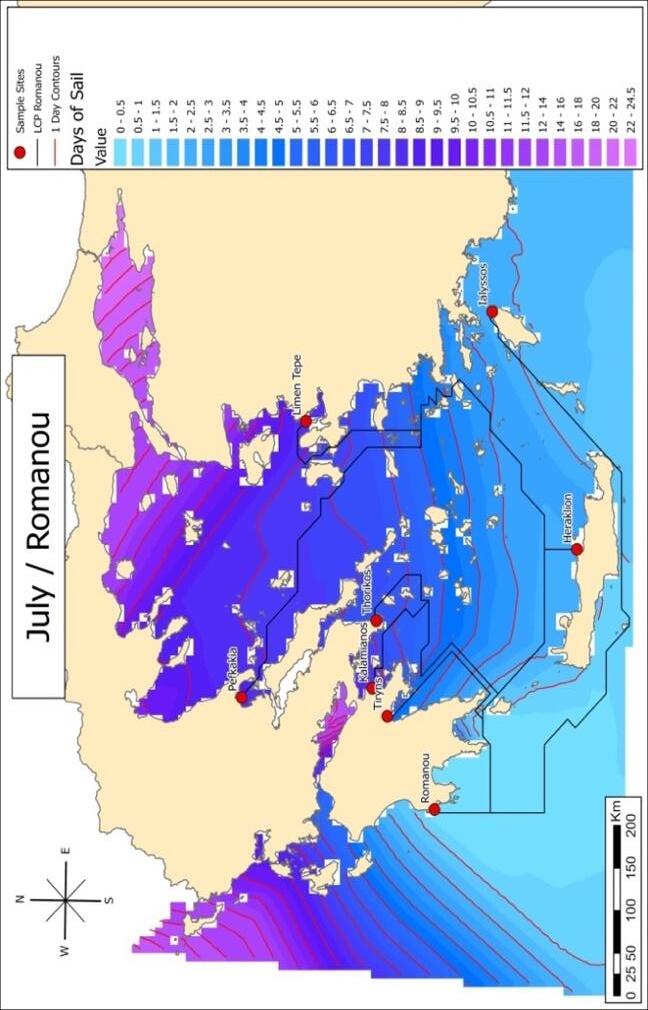

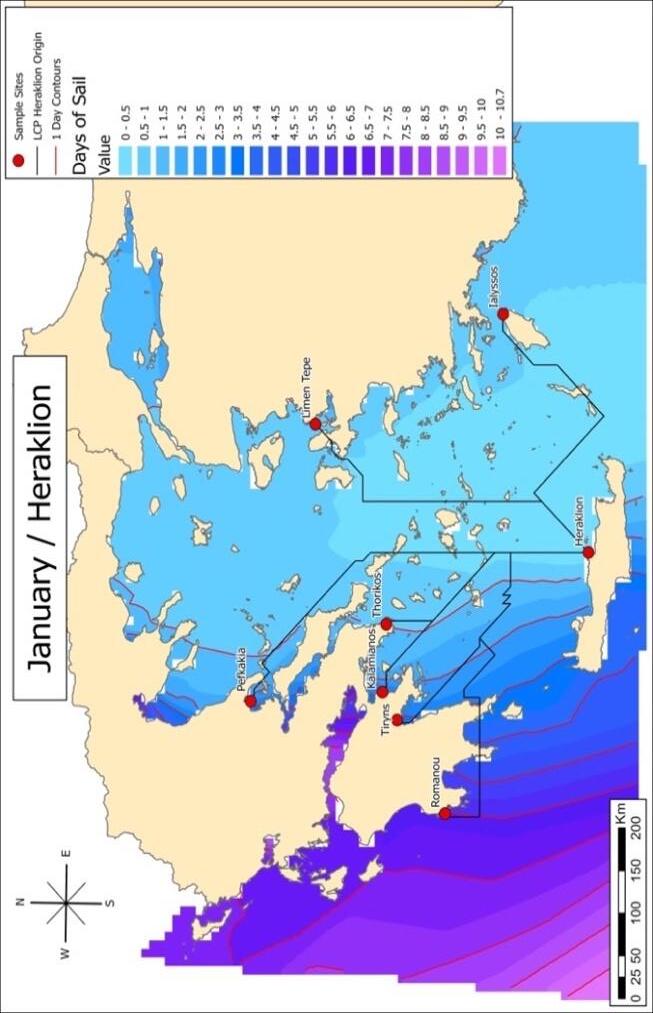

Figure 7 – Maps showing sailing time and LCPs using Kalamianos as the origin of departure

(Source: Author).

(Source: Author).

Archaeology Department 17

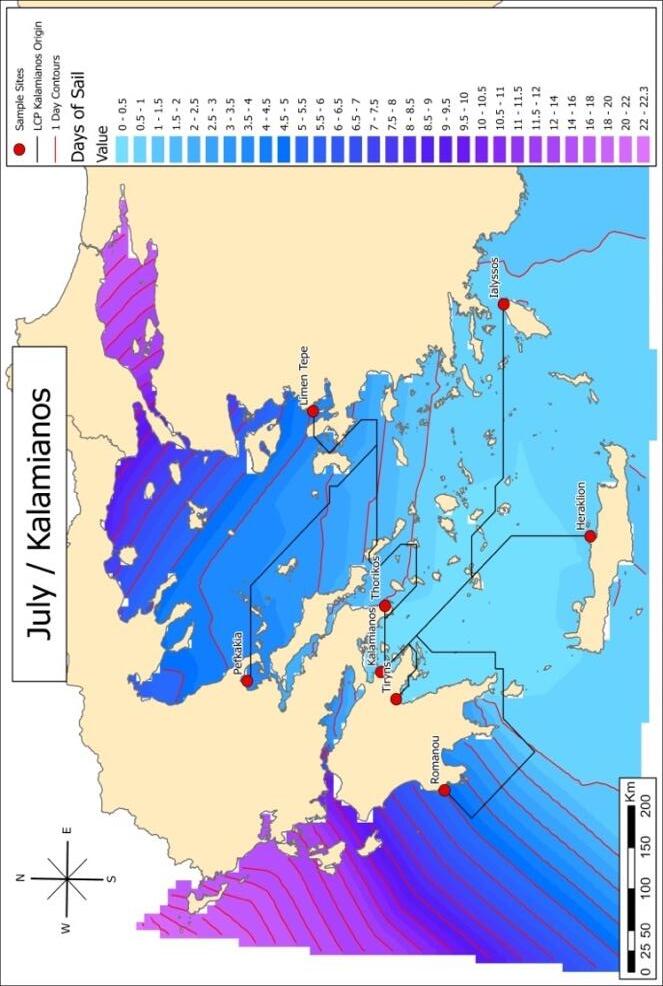

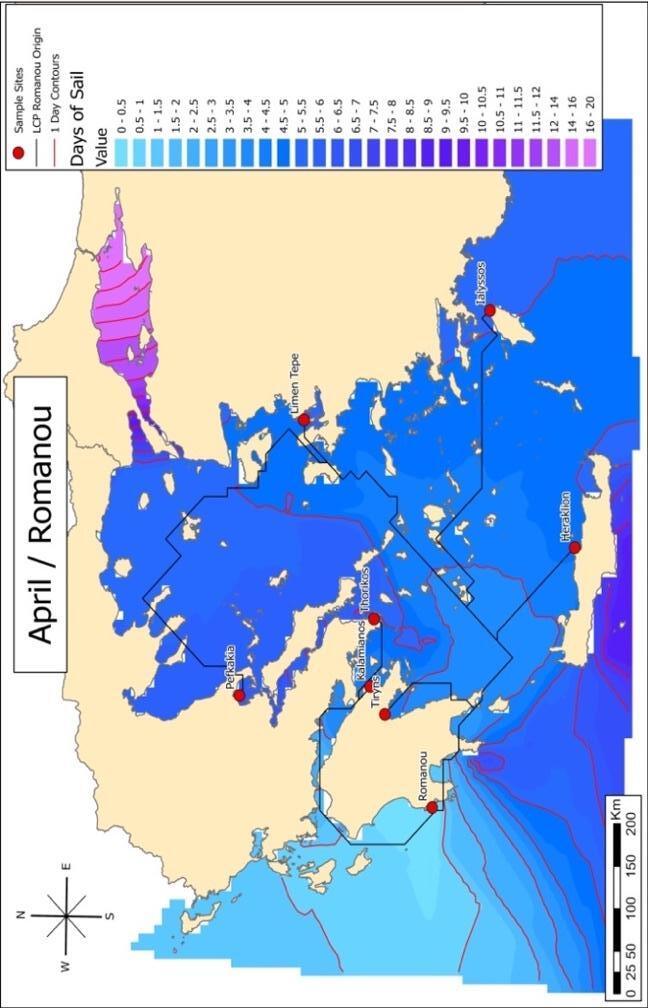

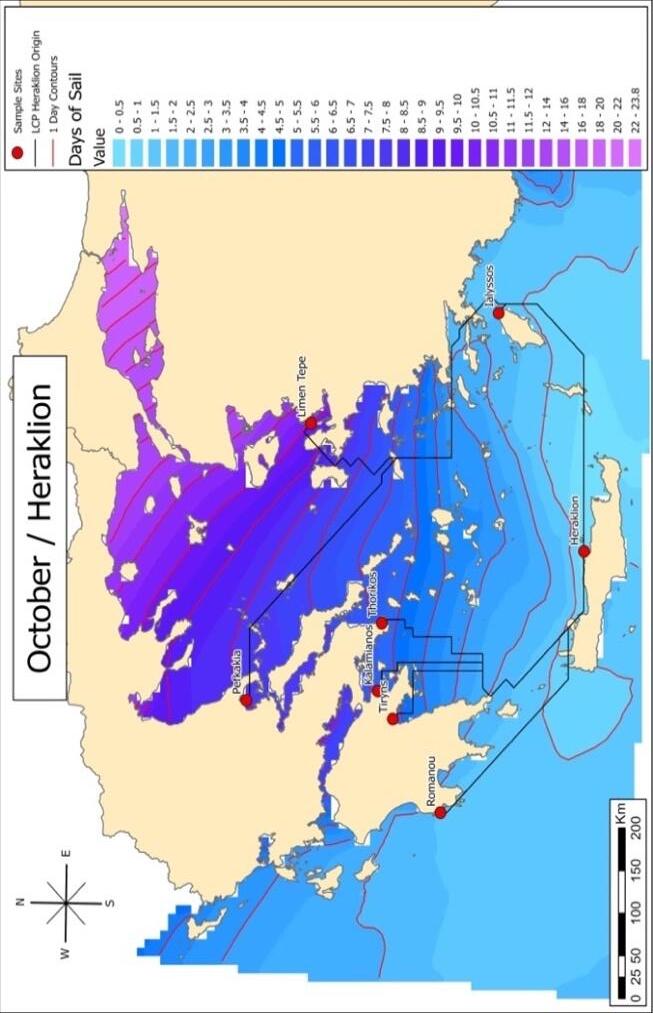

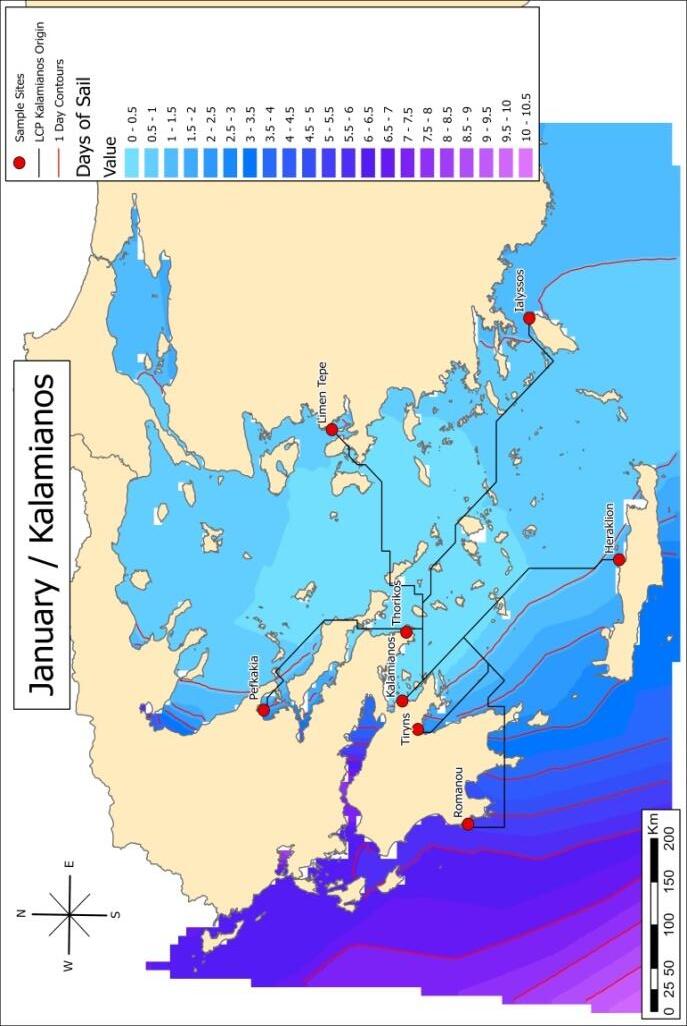

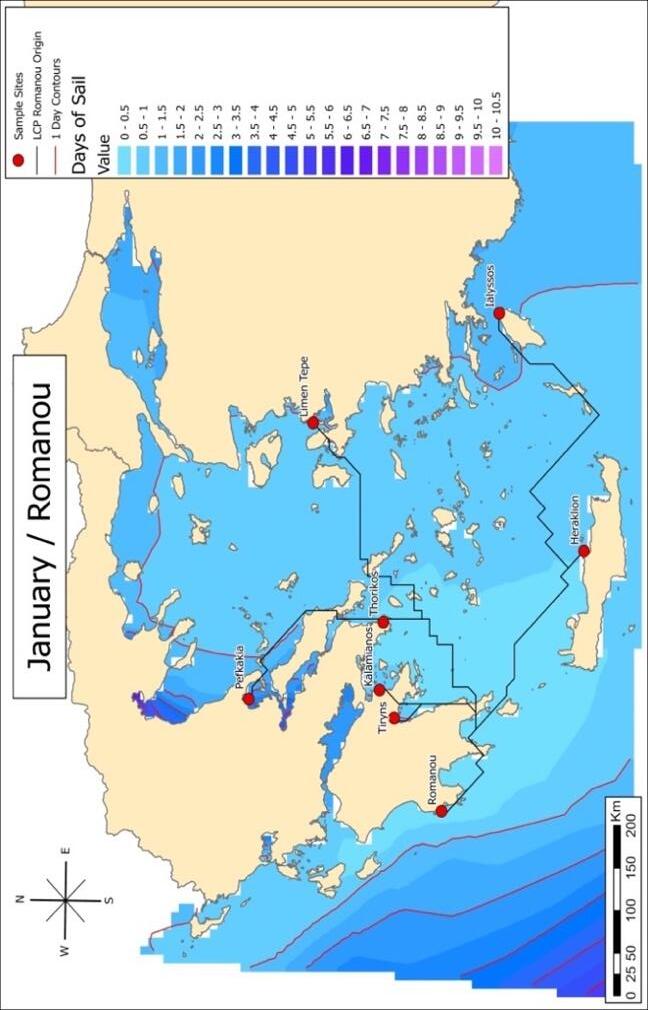

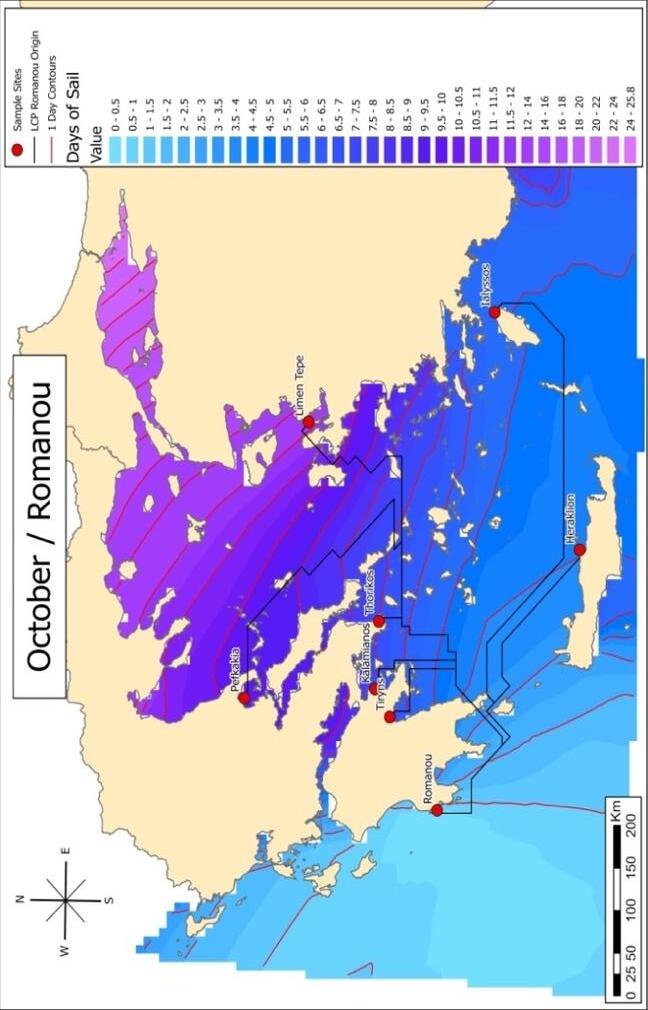

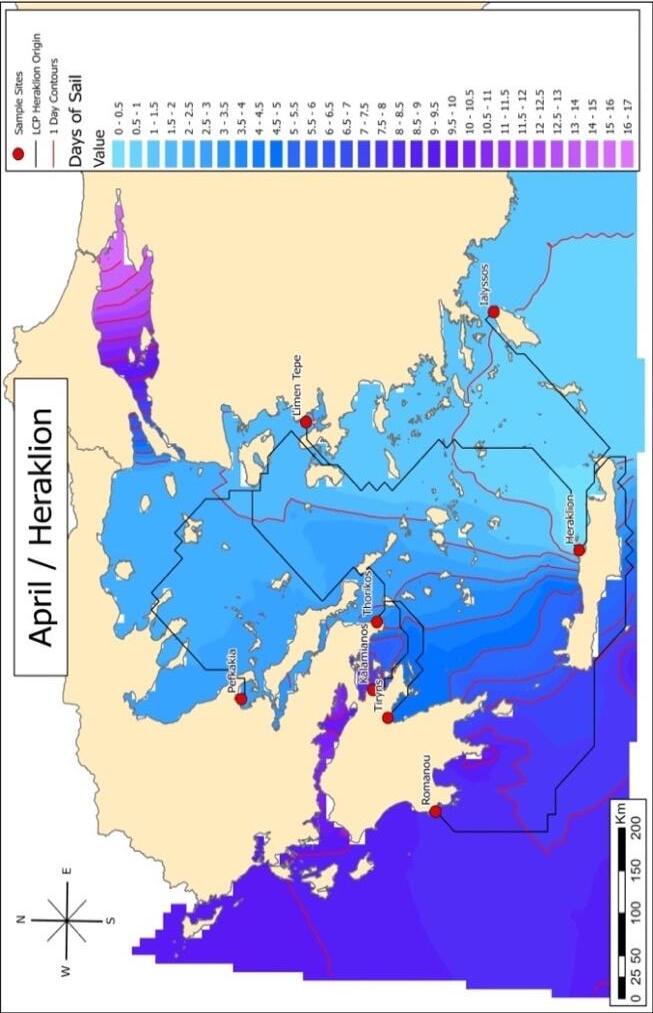

Figure 8 – Maps showing sailing time and LCPs using Romanou as the origin of departure

(Source: Author).

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 18

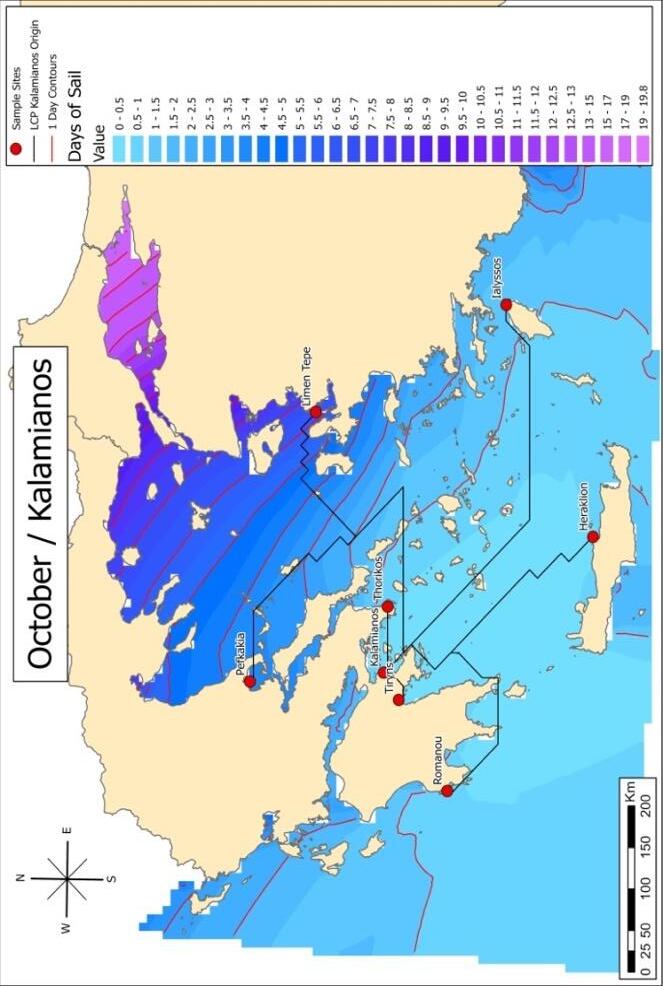

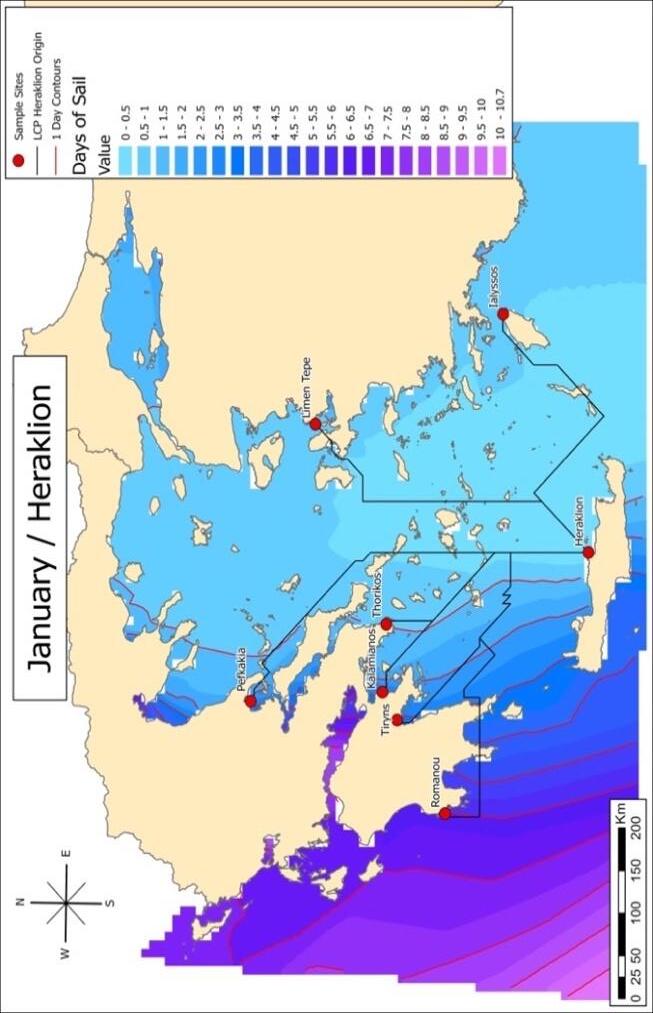

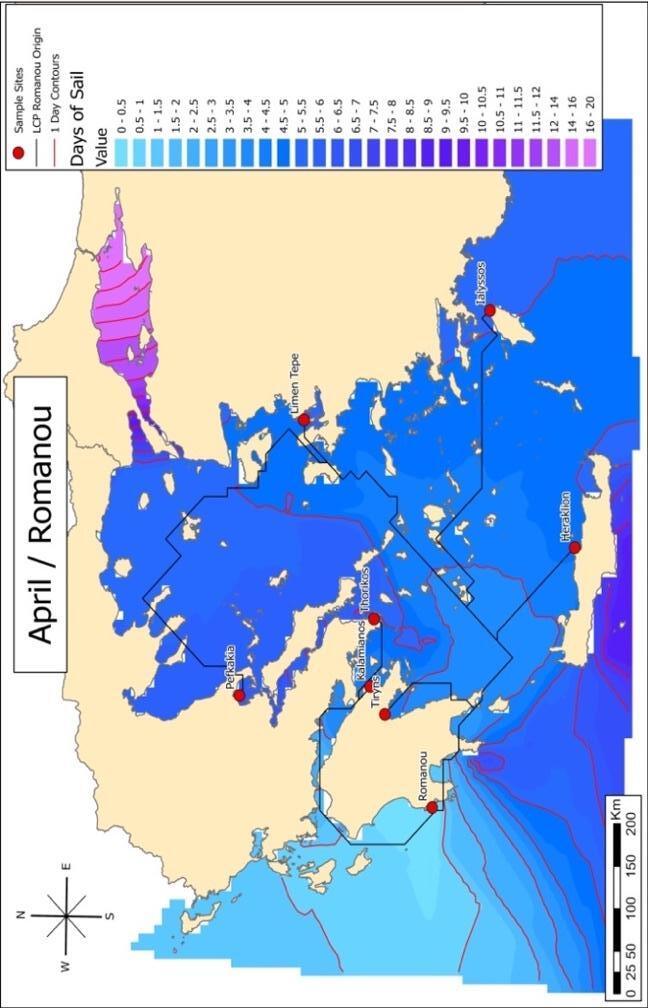

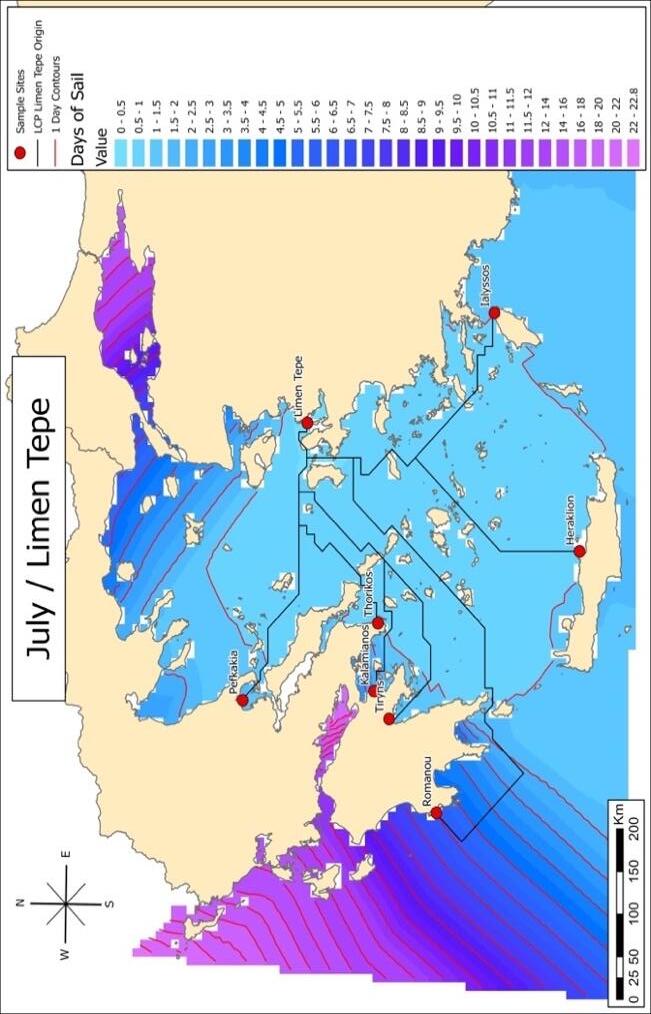

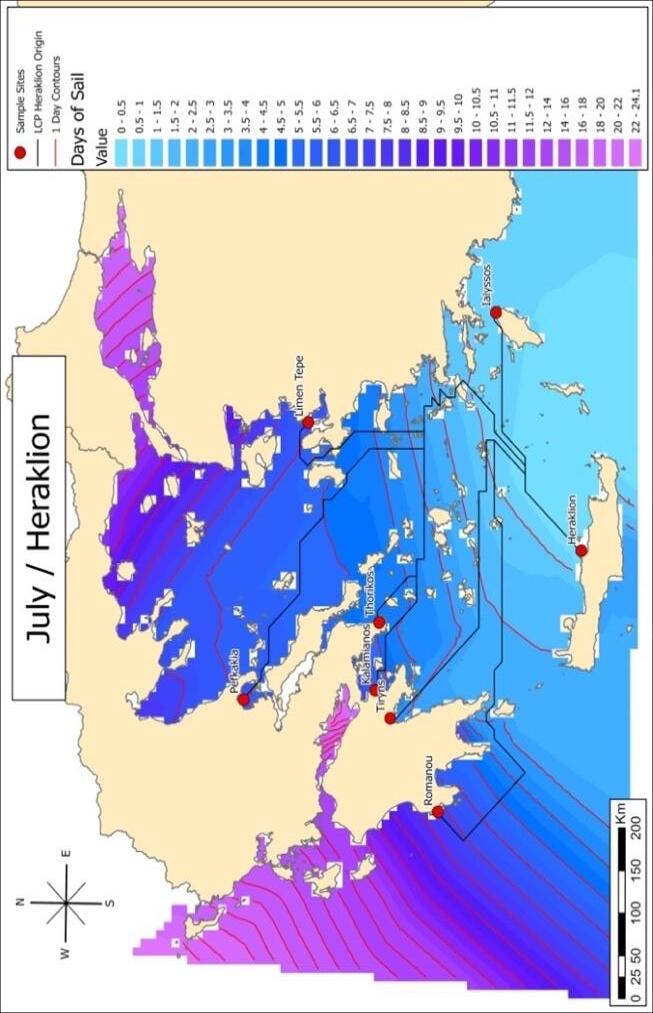

Figure 9 – Maps showing sailing time and LCPs using Heraklion as the origin of departure

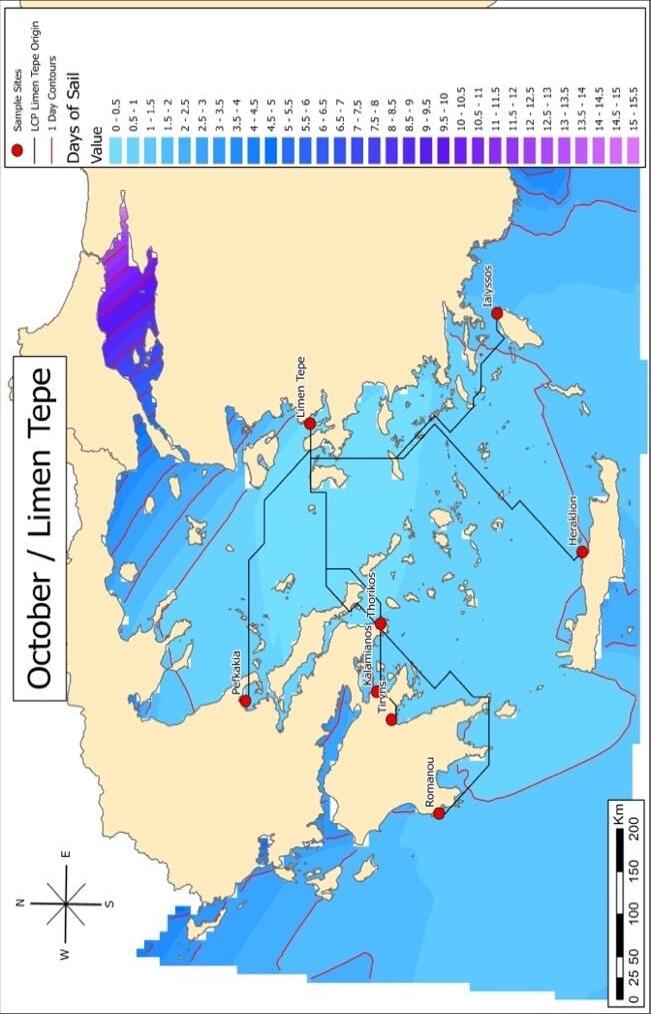

6. Results

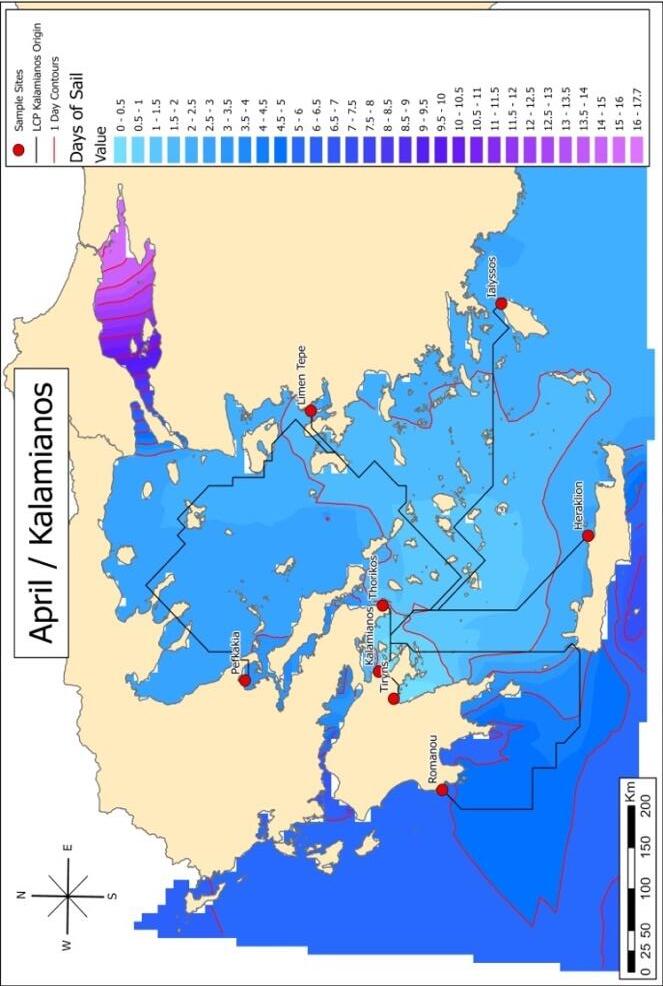

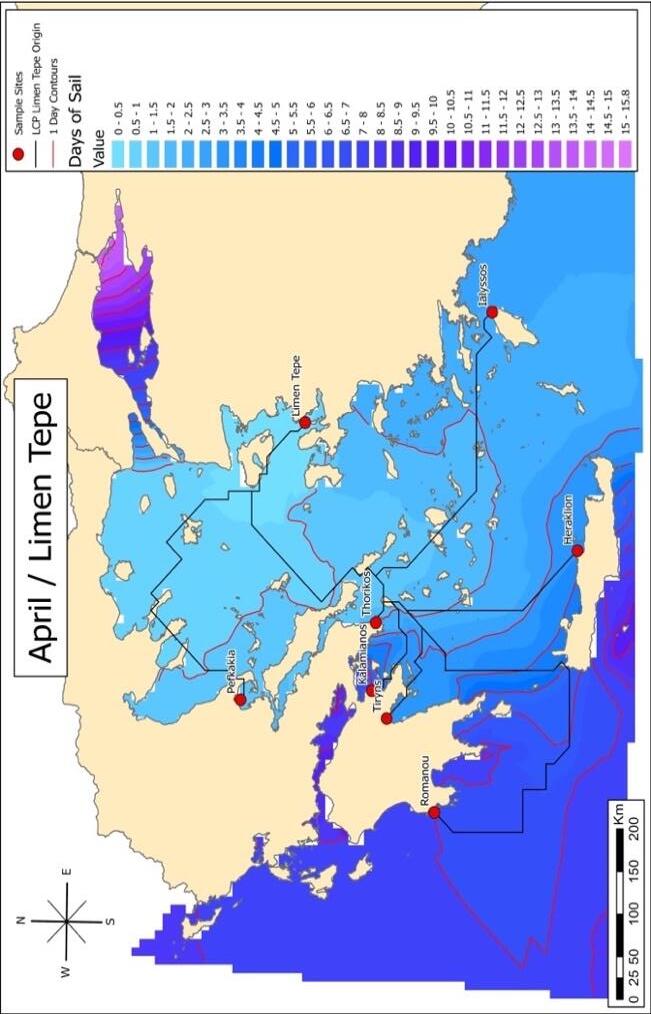

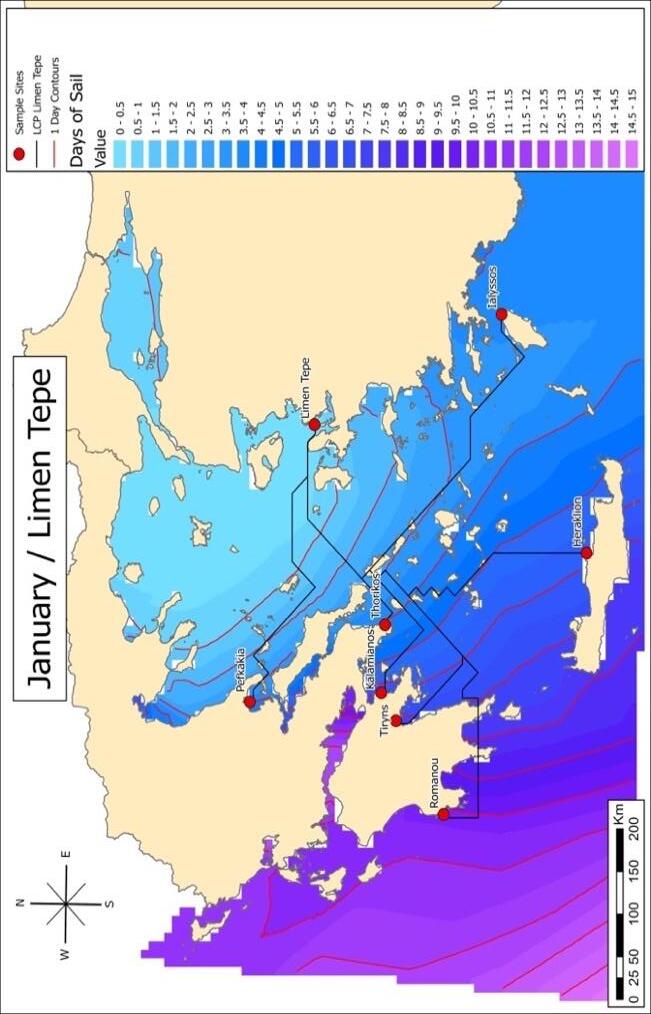

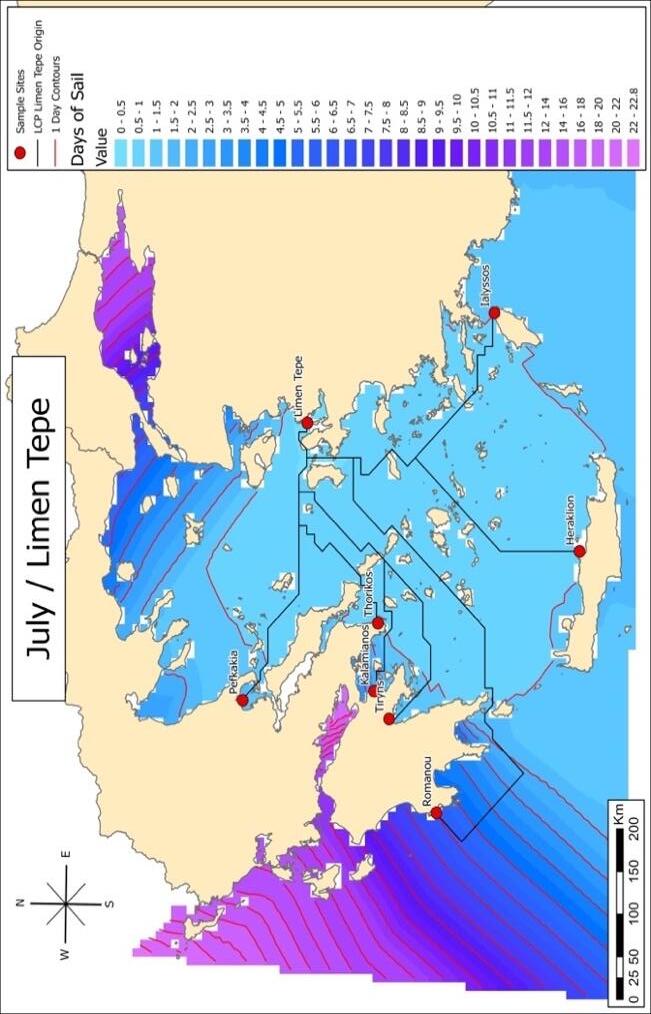

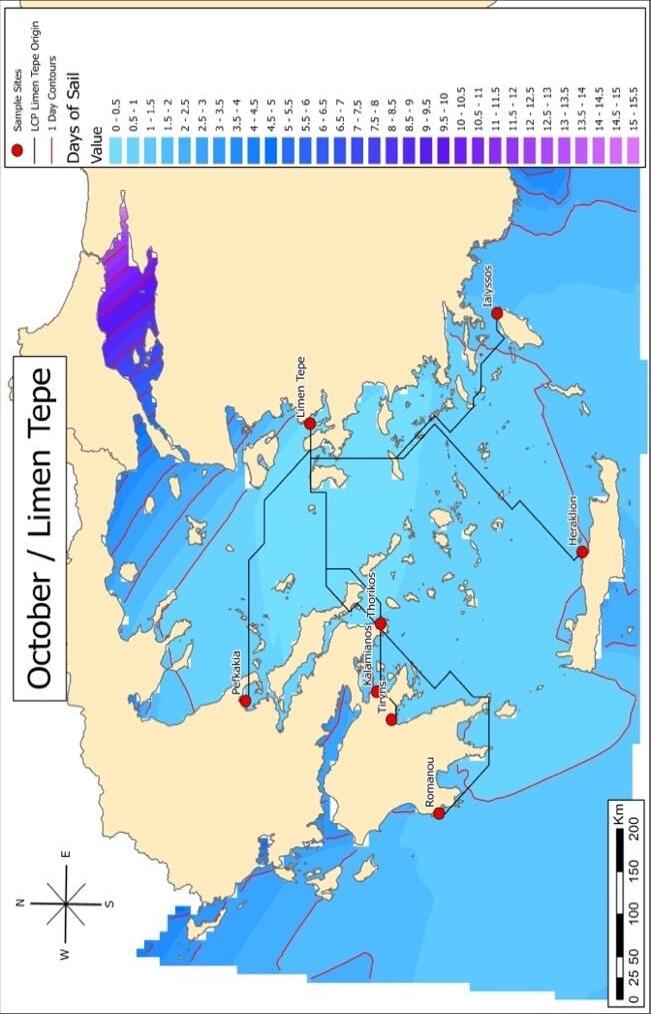

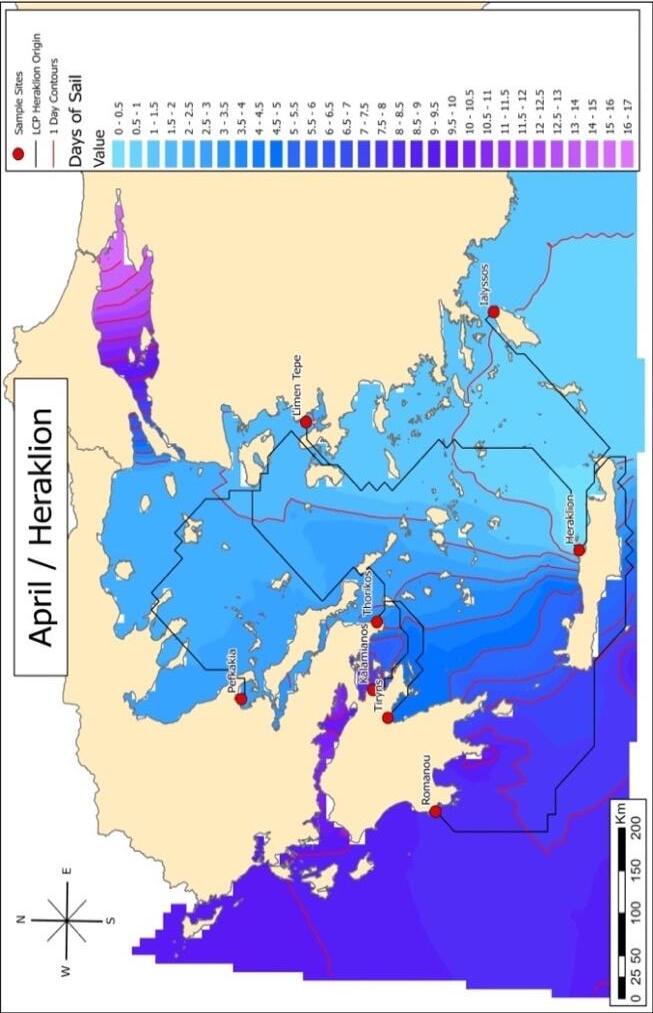

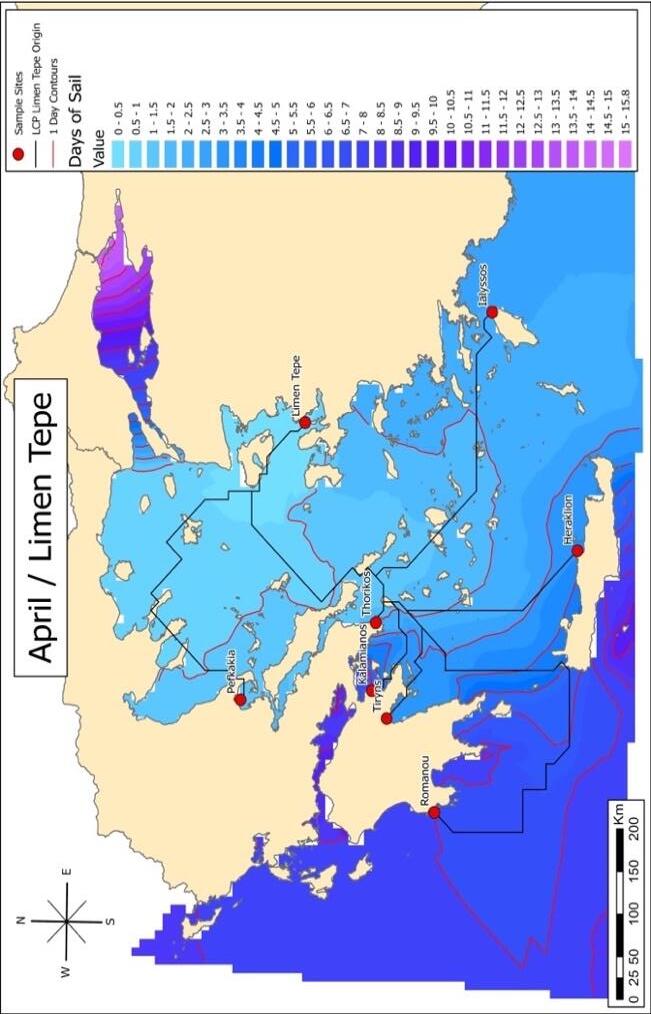

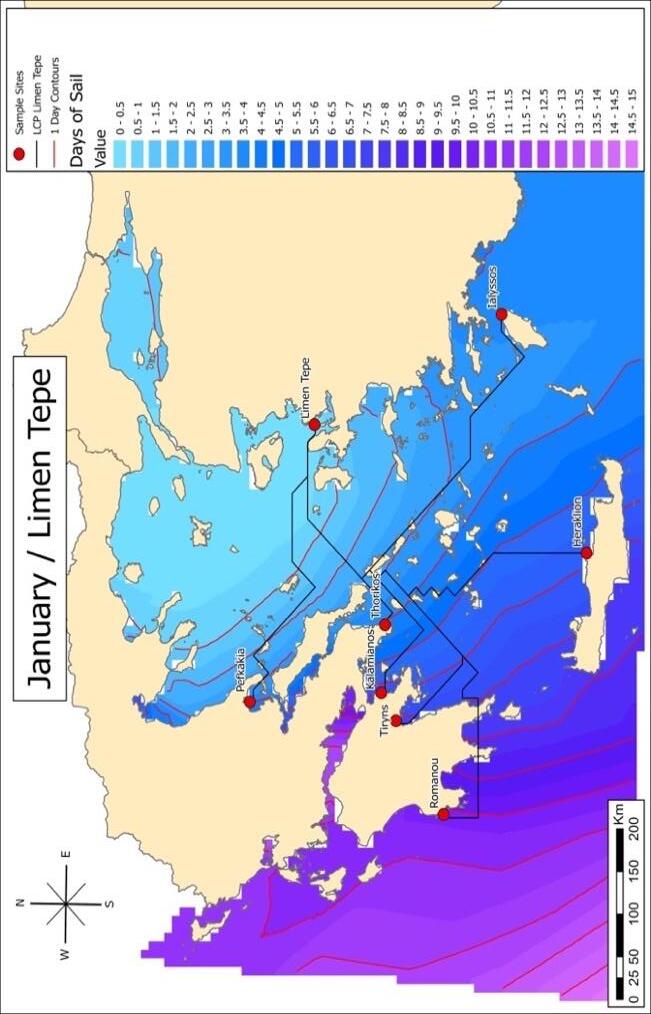

6.1 Overview

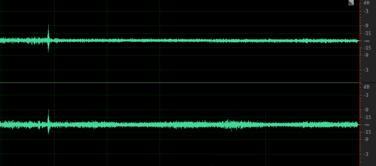

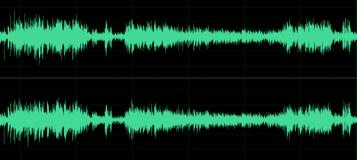

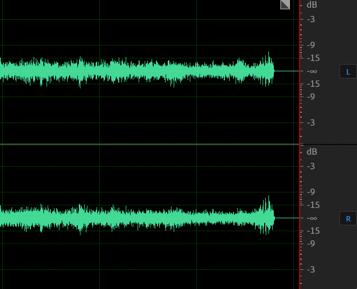

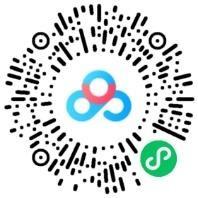

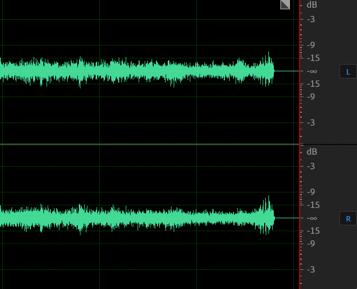

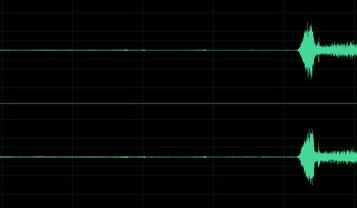

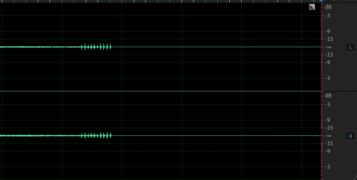

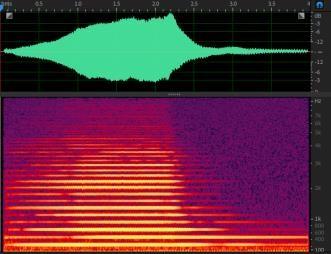

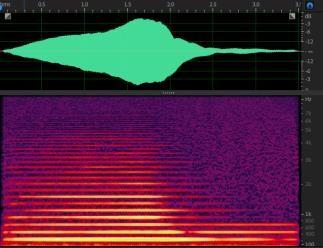

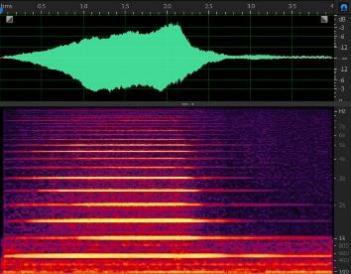

The modelling produced a series of 16 maps, 4 maps for each origin location run for the 4 months (Figures 7-10). Black lines are the generated LCPs: the quickest route between selected locations. Due to the resolution of the wind data (10km), the exact location of the LCP is likely not precisely accurate. Instead, it is better to see the LCPs as areas within which a vessel may sail and to look at the overall patterns and changes of the routes (coastal versus open water). Red lines are 1 day contours: sailing between two red lines corresponds to 1 day (24hrs). The background colour represents time in days of sail, where light blue is the fastest to purple/pink which represents the maximum time for that month. Each of the origin locations will be examined in turn below.

6.2 Kalamianos

January is the quickest month to sail, with the central Aegean, most of the Cyclades, and even east to the Turkish coast being reachable with 0.5 days of sail. In January, within one day sailing can reach from the northern Aegean, southeast corner of Crete, and across to Turkey. There are longer sailing times in July and October, particularly when sailing north towards the Bosporus. In general, routes are more coastal in January and October while the routes in April and July are more open water. There is an interesting route in April sailing to Pefkakia in the north, which goes southeast into the Cyclades before turning and bearing NE until reaching the Turkish coast and sailing up to approach from the north.

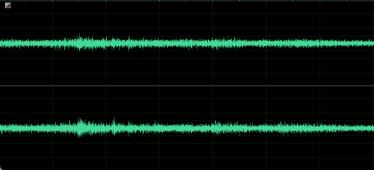

6.3 Romanou

January is the fastest month to sail, particularly sailing east; within one day the Aegean could be crossed and reach the Turkish coast. The quickest sailing in April is westward, towards Italy, a pattern repeated in October. July shows the quickest sailing is in a southward direction towards Crete and beyond. Again, sailing north in July and October is much slower than January and April. LCP routes tend to be more coastal in January, July, and October although there are exceptions. In April, routes east (Ialyssos and Limen Tepe) pass through the Cyclades.1 There is an interesting route in July to Ialyssos which sails south around the south of Crete.

Archaeology Department 19

1 Note: there is an error in the LCP route from Romanou to Kalamianos in April, which sails over the Isthmus.

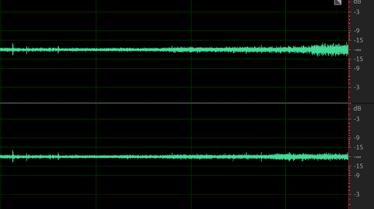

6.4 Heraklion

January again is the fastest month to sail the Aegean in: within 1 day of sailing a majority of the central Aegean can be reached. It is however much slower to sail west in January. July and October have longer sailing times, with very slow progress west in July and north in October. In all the months, there is faster sailing south or east (as far as Rhodes in January, April, and July). Routes in January appear more direct, sailing north into central Aegean, compared to October where routes are typically coastal. An interesting approach to Greek mainland sites (Thorikos, Kalamianos, and Tiryns) is taken in April, which starts by reaching the Turkish coast near Limen Tepe before crossing west and maintaining a coastal approach. All the routes in July start with a northeast bearing, some even reaching the Turkish coast, before crossing west to the Greek mainland.

6.5 Limen Tepe

As a change, October is the quickest month to sail in departing from Limen Tepe: within 0.5 days it is possible to reach the Greek mainland (for example Thorikos), within 1 day Crete (Heraklion) can be reached, and nearly as far west as Romanou. July also has relatively quick access to the Greek mainland and Crete, which are both in 1 day of sail. It is much slower to sail south during January. LCP routes are more coastal in January and October, April is a mix of both coastal and open water, and July shows more direct/open water routes. There is an interesting change in the route sailing to Ialyssos: in January and April, routes cross west to the Greek mainland before bearing southeast, while in July and October the route follows the Turkish coast.

7. Discussion

Computational modelling can be seen as a part of a wider attempt to understand the past. As has long been recognised, maritime landscapes are complex and multi-layered landscapes (Westerdahl, 1992; Parker, 2001). Conceptualising this landscape as separate entities (sea, islands, and coastscapes) rather than an interconnected whole can limit our understanding of maritime activities (Berg, 2007: 389).

This modelling has attempted to consider both environmental and human considerations involved in prehistoric seafaring for the LBA Aegean. It can be seen as a baseline, upon which the modelling can become increasingly sophisticated. For example, by layering cost surfaces such as calculations of fetch, currents, and political associates, the model starts to become more nuanced and, potentially, more accurate. Once this is established, it would be interesting to compare these LCPs to known shipwreck locations.

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 20

Naturally, there are methodological limitations, assumptions, and simplifications inherent within any model (Leidwanger, 2013: 3303). This model does not account for currents or wave height, and diurnal wind patterns. Moreover, it was run estimate time of purely sail-driven vessels with a square sail. While LBA vessels were likely square-rigged, depictions in iconography also show them in conjunction with oars and rowing, which the model does not account for (Wachsmann, 1998; Wedde, 2000).

Humans also do not necessarily act in a ‘least cost’ way – there was likely a variety of complex reasons a particular route may be chosen. For example, commercial interests, political affiliations, or ritual passages and stops may have played a role in route selection. Moreover, calculated risk -taking is a part of any seafaring activity (Adams, 2001: 293). This may mean that people would sail in riskier or sub-optimum conditions because the benefits or rewards of the voyage were worth the increased cost. Although strict phenomenologists provide a justified critique of computer-based approaches, these methods can still provide useful tools and ways of thinking about the past (Sturt, 2006; Lilley, 2012). Both the strengths and weaknesses of computer modelling need to be recognised, as well as integrating these approaches within the wider corpus of archaeological approaches for them to reach their maximum potential.

8. Conclusion

This article has highlighted the valuable role of computational approaches in understanding maritime activities in the past. Using the Late Bronze Age as its case study, it has shown how modelling of seafaring can provide nuanced understandings of maritime space and potential connectivity. New modelling was attempted for the LBA Aegean which aimed to account for both human and environmental factors relating to seafaring. It visualised and quantified how potential seafaring and connectivity can change greatly over time and space. These spatio-temporal insights into prehistoric seafaring are important steps to understanding the rich maritime experiences from the past.

Archaeology Department 21

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 22

Bibliography

Secondary Literature

Adams, J. (2001) ‘Ships and boats as archaeological source material’, World Archaeology, 32(3), pp. 291–310.

Alberti, G. (2018) ‘TRANSIT: a GIS toolbox for estimating the duration of ancient sail-powered navigation’, Cartography and Geographic Information Science, 45(6), pp. 510–528.

Ammerman, A.J. (2010) ‘The First Argonauts: Towards the Study of the Earliest Seafaring in the Mediterranean’, in A. Anderson, J.H. Barrett, and K.V. Boyle (eds) The Global Origins and Development of Seafaring. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 81–92.

Bass, G.F. (1967) ‘Cape Gelidonya: a Bronze Age shipwreck’, Transactions of American Philosophical Society, 57(8).

Berg, I. (2007) ‘Aegean Bronze Age Seascapes – A Case Study in Maritime Movement, Contact and Interaction’, in S. Antoniadou and A. Pace (eds) Mediterranean Crossroads. Athens: Pierides Foundation, pp. 387–415.

Burns, B.E. (2012) ‘Trade’, in E.H. Cline (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 291–304.

Conolly, J. and Lake, M. (2006) Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology).

Dawson, H. (2013) Mediterranean Voyages: The Archaeology of Island Colonisation and Abandonment. Walnut Creek: Taylor & Francis Group.

Farr, H. (2006) ‘Seafaring as social action’, Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 1(1), pp. 85–99.

Farr, H. (2010) ‘Island Colonisation and Trade in the Mediterranean’, in A. Anderson, J.H. Barrett, and K.V. Boyle (eds) The Global Origins and Development of Seafaring. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp. 179–190.

Galanidou, N. and Bailey, G. (2020) ‘The Mediterranean and the Black Sea: Introduction’, in G. Bailey et al. (eds) The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 309–319.

Hersbach, H. et al. (2018) ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1959 to present, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). DOI: 10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (Accessed: 7 December 2022).

Herzog, I. (2020) ‘Spatial Analysis Based On Cost Functions’, in M. Gillings, P. Hacıgüzeller, and G. Lock (eds) Archaeological Spatial Analysis: A Methodological Guide. London: Routledge, pp. 333–358.

23

Archaeology Department

Iacono, F. et al. (2022) ‘Establishing the Middle Sea: The Late Bronze Age of Mediterranean Europe (1700–900 BC)’, Journal of Archaeological Research, 30(3), pp. 371–445.

Jarriel, K. (2017) Small Worlds after All? Landscape and Community Interaction in the Cycladic Bronze Age. PhD Thesis. Cornell University.

Jarriel, K. (2018) ‘Across the Surface of the Sea: Maritime Interaction in the Cycladic Early Bronze Age’, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 31(1), pp. 52–76.

Leidwanger, J. (2013) ‘Modeling distance with time in ancient Mediterranean seafaring: a GIS application for the interpretation of maritime connectivity’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 40(8), pp. 3302–3308.

Lilley, K.D. (2012) ‘Mapping truth? Spatial technologies and the medieval city: a critical cartography’, Post-Classical Archaeologies, 2, pp. 201–223.

McGrail, S. (2001) Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mlekuž, D. (2014) ‘Exploring the topography of movement’, in S. Polla and P. Verhagen (eds) Computational Approaches to the Study of Movement in Archaeology: Theory, Practice and Interpretation of Factors and Effects of Long Term Landscape Formation and Transformation Berlin: De Gruyter, Inc., pp. 5–21.

Murray, W.M. (1987) ‘Do Modern Winds Equal Ancient Winds’, Mediterranean Historical Review, 2(2), pp. 139–167.

Parker, A.J. (2001) ‘Maritime Landscapes’, Landscapes, 2(1), pp. 22–41.

Pulak, C. (1998) ‘The Uluburun Shipwreck: An Overview’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 27(3), pp. 188–224.

Robb, J.E. and Farr, R.H. (2005) ‘Substances in Motion: Neolithic Mediterranean “Trade”’, in E. Blake and A.B. Knapp (eds) The Archaeology of Mediterranean Prehistory. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 24–45.

Safadi, C. (2018) The Maritime World of the Early Bronze Age Levant Through Space and Time. PhD Thesis. University of Southampton.

Safadi, C. and Sturt, F. (2019) ‘The warped sea of sailing: Maritime topographies of space and time for the Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean’, Journal of Archaeological Science, 103, pp. 1–15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2019.01.001

Shelton, K. (2012) ‘Mainland Greece’, in E.H. Cline (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 139–148.

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 24

Archaeology Department

Sturt, F. (2006) ‘Local knowledge is required: a rhythmanalytical approach to the late Mesolithic and early Neolithic of the East Anglian Fenland, UK’, Journal of Maritime Archaeology, 1(2), pp. 119–139.

Tartaron, T.F. (2017) Maritime Networks in the Mycenaean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tartaron, T.F. (2018) ‘Geography Matters: Defining Maritime Small Worlds of the Aegean Bronze Age’, in C. Knappett and J. Leidwanger (eds) Maritime Networks in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 61–92.

Thompson-Webb, C. (2017) From Sea to Screen: GIS Modelling of Bronze Age Ships in the Cyclades. Master’s Thesis. University of Liverpool.

Van de Noort, R. (2011) North Sea Archaeologies: A Maritime Biography, 10,000 BC - AD 1500. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wachsmann, S. (1998) Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Wedde, M. (2000) Towards a hermeneutics of Aegean Bronze Age Ship Imagery. Mannheim: Bibliopolis.

Westerdahl, C. (1992) ‘The maritime cultural landscape’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 21(1), pp. 5–14.

Wheatley, D. and Gillings, M. (2002) Spatial Technology and Archaeology: The Archaeological Applications of GIS. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

White, D.A. (2015) ‘The Basics of Least Cost Analysis for Archaeological Applications’, Advances in Archaeological Practice, 3(4), pp. 407–414.

White, D.A. and Surface-Evans, S.L. (2012) ‘An Introduction to the Least Cost Analysis of Social Landscapes’, in D.A. White and S.L. Surface-Evans (eds) Least Cost Analysis of Social Landscapes: Archaeological Case Studies. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 1–7.

Whitewright, J. (2018) ‘Sailing and Sailing Rigs in the Ancient Mediterranean: implications of continuity, variation and change in propulsion technology’, International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 47(1), pp. 28–44.

25

Incorporating the Digital World into Museums: The Victoria and Albert Museum as a Case Study for Success

Libby Davis

Abstract: The incorporation of digital platforms into museums is an essential way for institutions to maintain cultural relevance. This article examines the approaches of digital incorporation, using the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) as a case study to recommend digital approaches to museums considering utilising digital platforms. It identifies three approaches: social media, online exhibitions, and digitally inspired exhibitions. The article explores the success of these methods, using empirical data from the V&A’s past exhibitions to highlight and compare the most successful approaches. These will then be compared to present a strategy recommendation for museums looking to incorporate the digital sphere into their own institutions. It finds that the inclusion of digitally popular topics into museum exhibitions may be the most successful and pragmatically achievable method for digital incorporation in museums.

Introduction

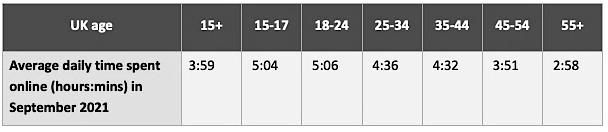

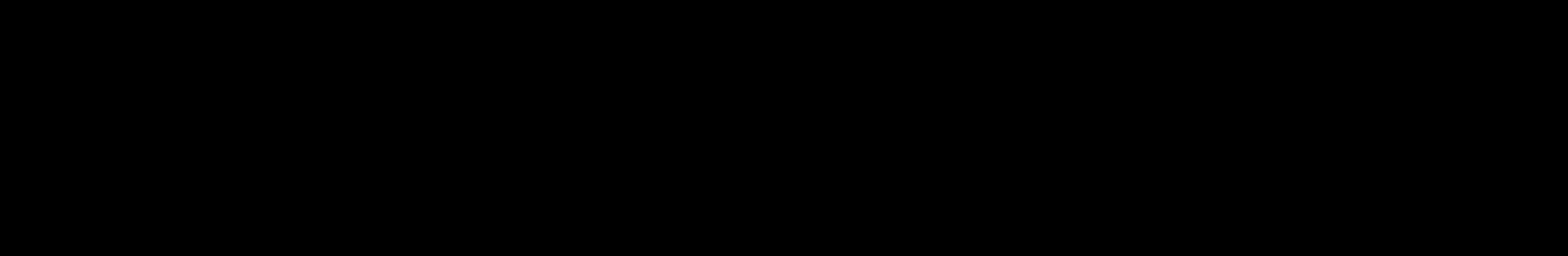

The modern world is ‘growing up digital’ (Flanagin and Metzger, 2008, p. 6.). Digital interest in culture grew through the pandemic, with content creation under the hashtag ‘museums’ on social media platform TikTok growing by 200% (Styles, 2021). The importance of the evolving digital world is undeniable. Museums have an opportunity to understand and utilise this to evolve alongside the 21st century, whilst engaging with an ever important and increasingly digitally engaged younger demographic (Figure 1) – an audience which museums have statistically struggled to attract (Statista, 2020)

Figure 1: Table from Ofcom report: ‘Average time spent online across computers, tablets and smartphones, per UK adult visitor per day (hours: minutes)’

18-24 year olds in the UK are spending an average of 5 hours and 6 minutes online per day, more than any other age group. (Ofcom, 2022, p. 5).

This paper explores the approaches museums can use to incorporate this digital world. These methods have been individually discussed in scholarly research, and this paper primarily uses the

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 26

Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London as a case study. Throughout history, the V&A has been one of the first museums to engage with new forms of media, as outlined by French and Runyard who highlight the V&A’s quick understanding of changing media in the 1970s (2011, p. 12.). The V&A continues to be at the forefront of utilising media and is a notable example of having used three key media approaches to incorporate the digital world: posting on social media platforms, hosting online exhibitions, and curating exhibitions inspired by the digital sphere. As an example of a museum using all three approaches, we can compare the methods with one another to establish the most successful way of incorporating the digital world.

To standardise judgement of these approaches, this paper applies a set of criteria, drawn from the mission of the V&A. Two of their key missions are expanding their international reach and the provision of a learning experience (V&A, no date). A final mission of museums in general is continued interest in the museum and, as a solely digital presence contributes little revenue to a museum, it is essential for continued maintenance and collection of their exhibits.

As a result, the criteria against which this study judges the approaches are as follows:

Criteria One: Engagement with a wider audience

Criteria Two: Opportunity for a learning experience

Criteria Three: Encouragement of continued interest in a museum, ideally resulting in revenue.

This paper suggests that when these approaches are compared, social media and online exhibitions are most successful when working in conjunction, and digitally inspired exhibitions can be successful as a stand-alone method.

Social Media

One method of incorporating the digital world into museums is by utilising one of the most popular digital platforms: social media. 16-24-year-olds globally are spending on average over 3 hours per day on social media platforms (Digital Information World, 2018). As has been discussed and supported by a wide range of researchers (Fletcher and Lee, 2012; Kist, 2020), it is a huge digital platform for museums to successfully utilise and the V&A have enthusiastically engaged with it. This article will focus on two content sites used by the V&A and are generally acknowledged as two of the most popular for 16-25-year-olds: TikTok and Instagram (Statista, 2022). TikTok and Instagram are platforms for short and engaging videos, with TikTok videos limited to 3 minutes and Instagram ‘Reels’ limited to 90 seconds. Algorithms show the videos to anyone, regardless of whether they are subscribed to the channel, creating the potential for a wide-ranging audience.

Archaeology Department 27

The view counts of the V&A’s videos speak to their success. A recent TikTok making use of a trending sound and video style on their account currently has 26.6 million views (Vamuseum, 2022), and an Instagram reel of Harry Styles’ jumper on display at the museum has 466,000 views (Vamuseum, 2022). This social media involvement clearly demonstrates criteria one, with high engagement levels across a wide audience. It is an excellent opportunity to present some aspects of museums to a young audience and engage with their interests. The museum presents itself through short videos that cater to the style of the platform. The V&A has achieved engagement success by using trending topics, but the videos are only a few seconds long, with information limited to a video of an object on display, without any further textual information or learning opportunities. This fails to fully demonstrate criteria two, as it is a platform that can only teach briefly in a limited way. Additionally, there is little evidence that these short videos encourage further interest within museums. Whilst 26 million people viewed the aforementioned TikTok (Vamuseum, 2022), the V&A account has only 74,300 followers (Vamuseum, 2022) which is 0.27% of the number that viewed the video. As a result, we cannot assert that the V&A’s social presence successfully achieves criteria three.

The V&A’s use of social media suggests that, while it is an important part of the digital sphere and a useful tool to engage a wider and younger audience, using social media alone does not provide the opportunity for in-depth learning experiences or further interest in museums. It may instead be a jumping-off point, useful for surface-level engagement with a wider audience and provision of small amounts of information.

Online and digital exhibitions

Making exhibitions available online is another way of incorporating digital media into museums, and such digitalization was especially prevalent during the Covid-19 pandemic when museums were required to close to the public. Research has been conducted into this method, giving credence to the success of online exhibitions in general (King, 2021; Burke, 2020).

The use of online exhibitions within the V&A can be seen through their ‘Curious Alice’ reality experience, which enabled visitors to download a digital landscape of the exhibition and interact with recreations of Alice in Wonderland at home (V&A, 2021). The exhibition’s immersion in virtual reality created an extensive opportunity for audiences to consume information about the world of Alice in Wonderland and learn from it, fulfilling criteria two. The V&A took this further by having an in-person exhibit alongside their digital exhibition (V&A, 2021). In doing this, the V&A successfully hit criteria three, providing the opportunity to take the digital exhibition further in visiting the museum for a nextlevel experience of the exhibition, thus encouraging further interest with the museum and the possibility for future investment.

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 28

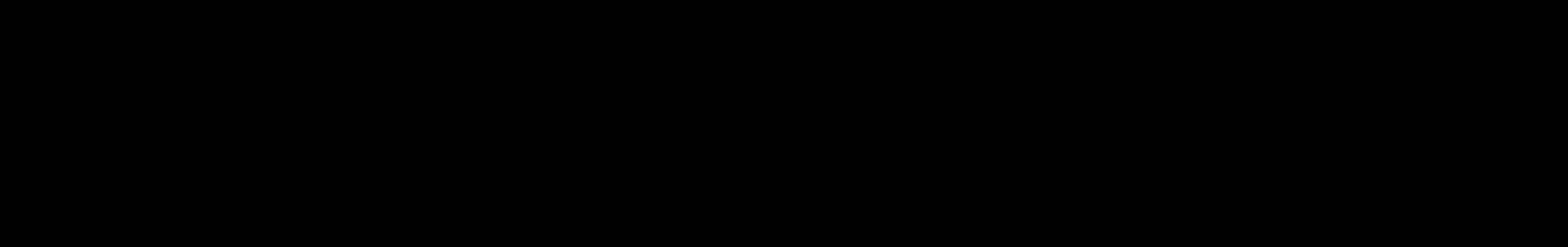

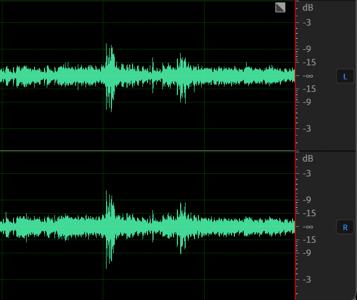

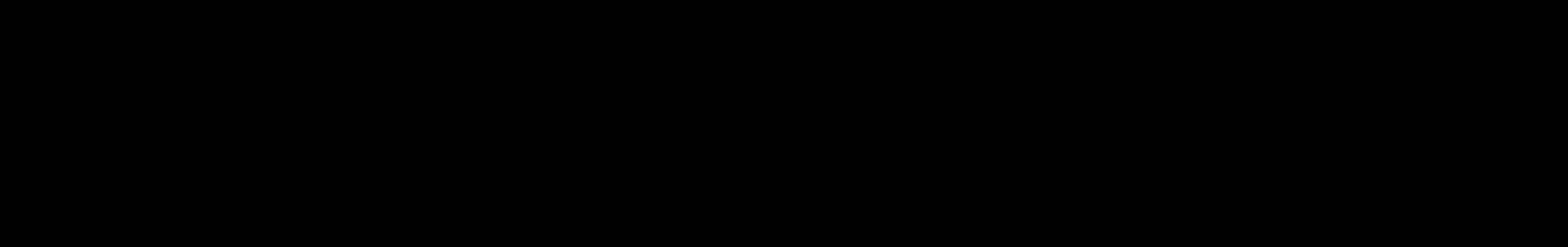

As a result, when examined as an exhibition in its own right, ‘Curious Alice’ is successful in criteria two and three, as a digital exhibit providing online learning experiences and having connections with the in-person exhibit, potentially encouraging visitors to engage with the museum further. However, the exhibition is set on the V&A’s website, which is not innately engaging a wider audience and may primarily be accessible to those already familiar with the museum. To tackle this, the V&A utilised their social media presence to make this online exhibition meet criteria one in engaging with a wider audience. The V&A went ‘live’ on TikTok ahead of the launch of their ‘Curious Alice’ exhibition (Styles, 2021). They hired a TikTok influencer to engage in ‘influencer marketing’, an industry worth $10 billion in 2020 which uses the fan following of a popular social media creator to successfully promote a product (Haenlein et al, 2020, p. 5.). In this case, the V&A built on the aforementioned success of their TikTok account along with a content creator with 600,000 followers (Hannah Lowther, TikTok) to promote their new exhibition. This promoted their digital exhibition among a social media audience likely already familiar with the V&A’s account. This combination of digital approaches resulted in 84,000 engagements with ‘Alice’ exhibition-based social media content and 78,000 people viewing the exhibition online (V&A, 2022, p. 17.). The in-person exhibition was the most visited of 2021, as seen in Figure 2

Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser was the most visited exhibition, with second place taken by an exhibition that ran for longer, eliminating the concern for unbalanced running lengths in numerical visitor data. (V&A, 2022 )

While a direct correlation between use of social media and visitor engagement cannot be asserted, other exhibitions did not incorporate the same digital aspects, so it is fair to say that the overall digital aspect of the exhibition contributed in some level to its success, considering the difference in visitor numbers. However, a cohesive use of digital approaches was required to achieve this success. Successful achievement of all three criteria came by utilising social media alongside online exhibitions.

Archaeology Department 29

Figure 2: Table of exhibition visitor numbers at the V&A 2021-2022.

Combining digital with reality: A digital inspiration

A final way that the digital world can be incorporated into museums is through the influence of the digital sphere, rather than the direct use of digital platforms. The concept of using popular culture to attract a different demographic has been briefly discussed by Golding (2013), who aligns the appeal of popular culture and youth in museums.

The V&A has used this approach with their new exhibition ‘Hallyu! The Korean Wave’, an exhibition on the increasing popularity of Korean culture (V&A, 2022). The K-culture phenomenon has been primarily influenced by the ability for a worldwide audience to access Korean culture on social media (Jin, 2016, p. vii.). Korean culture is now one of the most popular topics in the digital world. The V&A’s curation of an exhibition based on a topic so digitally popular is a different way of incorporating the power of the digital world into their museum. As this is an in-person museum, immediately criteria two is met, as people experience the exhibition in person and are provided with extensive information on the topic. Furthermore, there is a clear opportunity to succeed in criteria three. This exhibition draws people to the museum, spiking their interest, whilst also increasing revenue for the museum by charging £20 for entrance (V&A, 2022). This is the most expensive of their exhibitions, most of which are free whilst others average around £15. (V&A, 2022). This likely feeds into a desire for knowledge of Korean culture and its general popularity. The Korean pop-music (K-Pop) industry possesses a huge consumer market, with the average K-Pop fan spending up to $1,422 on merchandise per year (Meicheng, 2021). The V&A have capitalised on this, charging a little more for entry, knowing that fans will be willing spend more in order to see displays such as the outfit worn by one member of the K-Pop boyband BTS worn during a show (Vamuseum, 2022).

Criteria One is met in an alternative way, as by directly curating a museum of interest to the digital sphere they are engaging a digital audience. ‘Curious Alice’ as a museum is not of direct interest to a digital audience, so more work was needed to promote it through social media. However, ‘Hallyu’ directly appeals to an audience of digital consumers and is likely to encourage a wide range of visitors. As this is an exhibition still in progress, we are yet to see the visitor numbers, but the positive discussion across digital platforms, including Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, (Vogue, 2022; Harper’s Bazaar, 2022) neither of whom commented on ‘Curious Alice’, suggests there is a clear interest across the digital world.

If the exhibition is as successful as evidence suggests, this digital inspiration for in-person exhibits could be the most fruitful way for museums to incorporate the evolving digital world, hitting all three criteria in one approach. However, museums may be wary of waiting until confirmed visitor numbers for this exhibition are released in Spring 2023, to see evidence of the success of this approach.

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 30

Conclusion

What we can establish is that within the V&A the most successful form of digital incorporation is likely digital inspired in-person exhibitions, as these meet all of the success criteria with one method. Social media and online exhibitions do not reach all three success criteria alone, but the combination of the two can make the incorporation of digital media platforms successful.

It is challenging given the brevity of this article to establish whether these incorporations of the digital world in the V&A can apply to other museums. However, it could be said that smaller museums, perhaps with fewer resources to invest in all three approaches to digital incorporation, could focus on one method of digital incorporation: curating exhibitions that could appeal to a digital market, such as the V&A’s ‘Hallyu’ exhibition. This is perhaps the most beneficial means as it is the most likely to meet all of the success criteria and uses only one approach. However, more research into this topic should be conducted before museums consider committing to this approach, especially as the final outcome of the V&A’s exhibition is yet to be seen, and the effect of this method on smaller museums has currently not been widely researched.

31

Archaeology Department

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Digital Information World (2019) How much time do you spend on social media? Available at https://www.digitalinformationworld.com/2019/01/how-much-time-do-people-spend-social-mediainfographic.html (Accessed 15 November 2022).

Harper’s Bazaar (2022) Inside the new Korean wave exhibition at the V&A. Available at: https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/culture/culture-news/g41328048/korean-wave-hallu-exhibition-vand-a/ (Accessed 14 November 2022).

Lowther, H. (2022) [TikTok]. Available at: https://www.tiktok.com/@hannahlowther8?_t=8XQ2lHyD3GX&_r=1 (Accessed: 14 November 2022).

Ofcom (2022) Online Nation: 2022 Report. Available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/238361/online-nation-2022-report.pdf (Accessed 16 November 2022).

Statista (2022) Global social networks ranked by number of users. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

Statista (2020) Museum attendance UK by age. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/418323/museum-galery-attendance-uk-england-by-age/ (Accessed: 15 November 2022).

V&A (no date) About us: Our mission. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/info/about-us#ourmission (Accessed: 14 November 2022).

V&A (2021) Alice: Curiouser and Curiouser. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/alicecuriouser-and-curiouser (Accessed: 14 November 2022).

V&A (2021) Curious Alice: The VR Experience. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/curious-alice-the-vr-experience (Accessed: 14 November 2022).

V&A (2022) Hallyu! The Korean Wave. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/hallyu-thekorean-wave (Accessed: 14 November 2022).

Vamuseum. (2022) ‘He’s a 10 but…’ [TikTok]. 6 September. Available at: https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMFawYe6Q/ (Accessed 12 November 2022).

Vamuseum. (2022) ‘There’s a K-Wave Exhibition at the V&A’ [TikTok]. 12 October. Available at: https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMFaKYb54/ (Accessed 12 November 2022).

Vamuseum. (2022) [TikTok]. Available at: https://www.tiktok.com/@vamuseum?_t=8XQ1oHsTlzh&_r=1 (Accessed 12 November 2022).

V&A (2022) Victoria and Albert Museum: Annual Report and Accounts: 2021-2022. Available at: https://vanda-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/2022/07/22/11/22/36/a0c26b56-5b8e-4d97-bda6e9dd7c182010/VARPT22-220718-accessible.pdf (Accessed 13 November 2022).

V&A (2021) What’s on. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/whatson?type=exhibition

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 32

Archaeology Department

(Accessed: 14 November 2022).

Vamuseum. (2022) ‘Worn by Harry Styles, loved by you’ [Instagram]. 26 October. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/reel/CkLKyd-sgT1/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y= (Accessed 11 November 2022).

Vogue (2022) Inside Hallyu!, The V&A’s Playful Exhibition Celebrating Korean Fashion & Culture. Available at: https://www.vogue.co.uk/arts-and-lifestyle/article/hallyu-korean-wave-exhibitionreview (Accessed 14 November 2022).

Secondary Literature

Burke, V. et al. (2020) ‘Museums at Home: Digital Initiatives in Response to COVID-19’, Norsk museumstidsskrift, 6(2), pp. 117-123. Available at: https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2464-2525-2020-0205

Flanagin, A. J., and Metzger, M. J. (2008) ‘Digital Media and Youth: Unparalleled Opportunity and Unprecedented Responsibility’, in J. Miriam, & A. J. Flanagin (eds.) Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 5-28.

Fletcher, A. and Lee, M. J. (2012) ‘Current social media uses and evaluations in American museums’, Museum Management and Curatorship, 27(5), pp. 505-521., Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2012.738136

French, Y. and Runyard, S. (2011) Marketing and Public Relations for Museums, Galleries, Cultural and Heritage Attractions. Abingdon: Routledge.

Golding, V. et al. (2013) Museums and Communities. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Haenlein, M. et al. (2020) ‘Navigating the New Era of Influencer Marketing: How to be Successful on Instagram, TikTok, & Co.’, California Management Review, 63(1), pp. 5-25. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125620958166

Jin, D. Y. (2016) New Korean Wave: Transnational Cultural Power in the Age of Social Media. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

King, E. et al. (2021) ‘Digital Responses of UK Museum Exhibitions to the COVID-19 Crisis, March – June 2020’, Curator: The Museum Journal, 64(3), pp. 487-504. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12413

Kist, C. (2020) ‘Museums, Challenging Heritage and Social Media During COVID-19’, Museum & Society, 18(3), pp. 345-348.

Mason, A. et al. (2021) ‘Social media marketing gains importance after Covid-19’, Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1870797

Meicheng, S. (2021) Commentary: Why do K-Pop fandoms spend so much money? Available at: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/why-kpop-fans-spend-money-bts-united-nations2208521 (Accessed 13 November 2022).

Shaw, A. and Krug, D. (2013) ‘Heritage Meets Social Media: Designing a Virtual Museum Space for Young People’, Journal of Museum Education, 38(2), pp. 239-252. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/10598650.2013.11510774

33

Styles, D. (2021) TikTok offers worldwide museums tour with first ever livestreamed #museummoment event. Available at: https://advisor.museumsandheritage.com/news/tiktok-offersworldwide-museums-tour-with-first-ever-livestreamed-museummoment-event/ (Accessed: 13 November 2022).

Tovaglieri, F. (no date) Post Covid-19: What’s next for digital transformation? Available at: https://hospitalityinsights.ehl.edu/what-next-digital-transformation (Accessed: 13 November 2022).

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 34

The Submerged Prehistoric Record of the Adriatic Sea and its Significance for Debates in Upper Palaeolithic Research

Samuele Ongaro

Abstract: One of the largest palaeolandscapes in Europe, now lost to sea-level rise, was the Great Adriatic Plain, which at its maximum extent during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) covered almost half of the Adriatic Sea. This vast grassland area, crossed by numerous rivers, would have provided an attractive environment to humans, who would have moved through and settled in this landscape. Nevertheless, very few submerged prehistoric sites dated to the Palaeolithic have been found, although indirect evidence suggesting a use of this landscape by humans abounds. Therefore, this article will discuss two relevant issues of Upper Palaeolithic Research which not only could be solved by looking at evidence underwater, but also indicate the potential for Palaeolithic submerged sites to be present in the area. The first will be the Uluzzian Debate, which sees scholars interpreting this transitional industry found in Italy and Greece as the evidence for a Homo sapiens coastal migration route and early occupation of these areas. The second issue will be the use of the Adriatic region as a refugium for human populations during the LGM, which would explain the considerable evidence for contacts between different populations across the basin.

1. Introduction

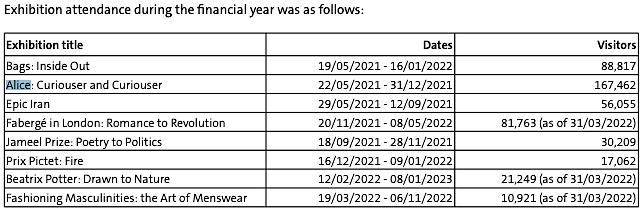

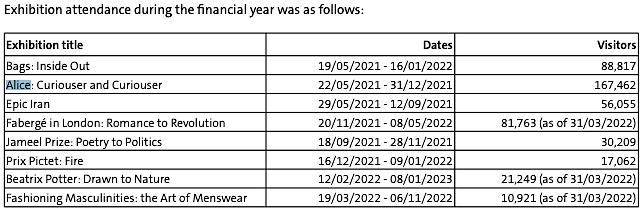

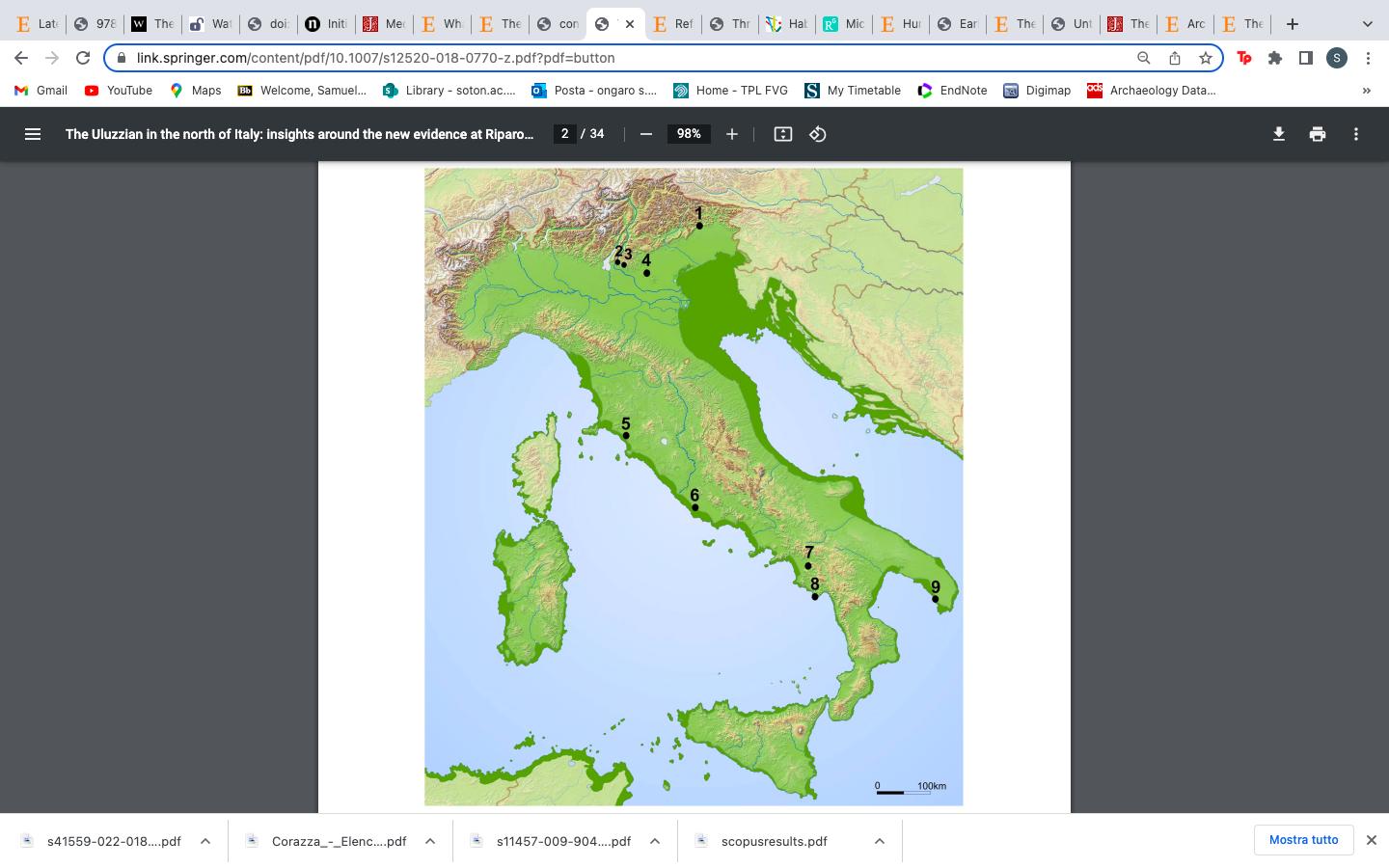

The field of submerged prehistory has recently witnessed a considerable increase in interest, given the potential of underwater sites to answer questions concerning various themes, such as human dispersals and maritime adaptations (Bailey et al 2020: 20-21). Nevertheless, the Palaeolithic, compared to more recent periods, has only seen limited involvement in this trend. Yet, numerous studies have highlighted the existence of submerged Palaeolithic sites and the potential of undiscovered ones. In fact, human settlement would have focused on coastal and lowland areas n ow underwater, where a more temperate climate compared to the drier continental interior would have been present together with an abundance of aquatic resources, especially near estuaries and rivers (Cohen et al 2012; Bynoe 2018). In Europe in particular, there are vast areas that at times of lower sea-level would have provided hominins with both links between isolated regions and habitats to settle (figure 1). Among these, the Great Adriatic Plain has produced very limited evidence, but can offer considerable insights on two important issues of Upper Palaeolithic research, namely the early dispersal of Homo sapiens into Europe, and human occupation of Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) refugia. Therefore, this article will analyse the potential for the submerged Adriatic Palaeolithic record to answer these questions, arguing for the decisive significance of this submerged landscape. Despite the lack of sites, the discussion will follow a theoretical and speculative approach based on indirect evidence, also demonstrating the need for further underwater investigations.

Archaeology Department 35

2. Paleogeographic Context

Since the discussion will focus on a landscape that does not exist anymore, it is important to understand how the Great Adriatic plain would have looked in the upper Palaeolithic. The main factor to take into account is sea-level: this has been fluctuating in correlation with the glacial-interglacial cycle for the last 2.5 million years, and it is affected not only by the amount of water in the oceans

eustatic sea-level

but also by the land uplift following ice sheets’ weight release

glacial isostatic adjustment – and by tectonic activity (Bailey & Flemming 2008: 2153-2159). However, reconstructing sea-level in this period of time is not straightforward. In fact, due to a lack of bathymetric data, problematic dating, and inaccessibility and inadequate preservation of suitable deposits, accurate geophysical models of sea-level evolution in the Mediterranean are only available since 20 kya (Benjamin et al 2017: 39). For the Adriatic, the picture is relatively less problematic only because of the presence of sea-level indicators like speleothems from the karstic coast of Croatia (Benjamin et al 2017: 40), and marine terraces from Apulia (De Giosa et al 2019). Thus, it has been deduced that sealevel was about 60 metres lower around 50 kya, until it reached -80 metres at 29 kya and a lowstand of

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 36

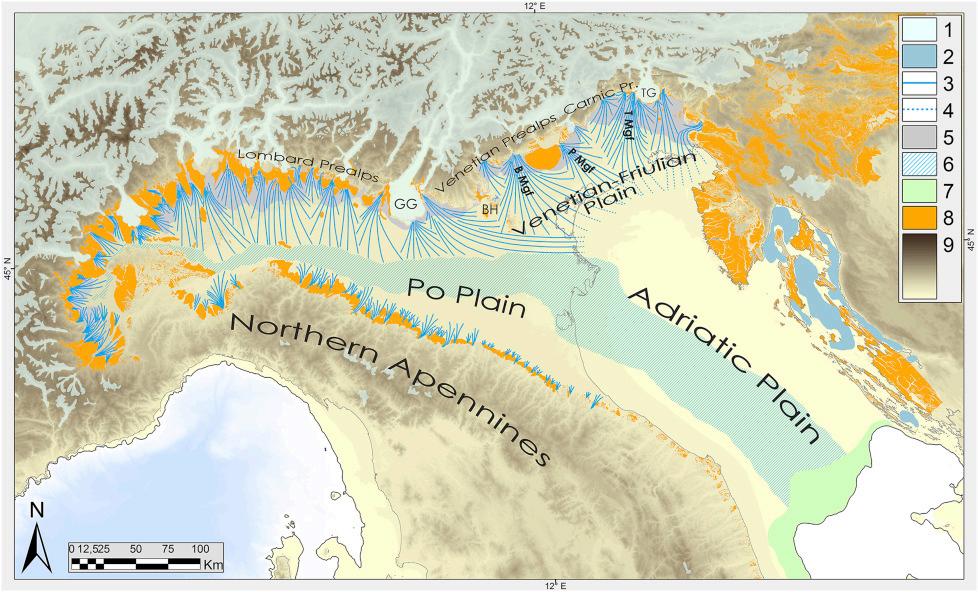

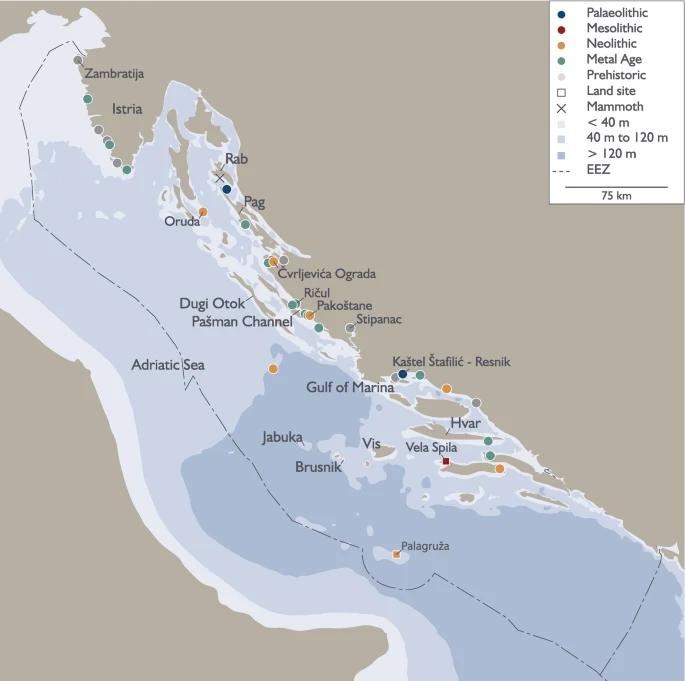

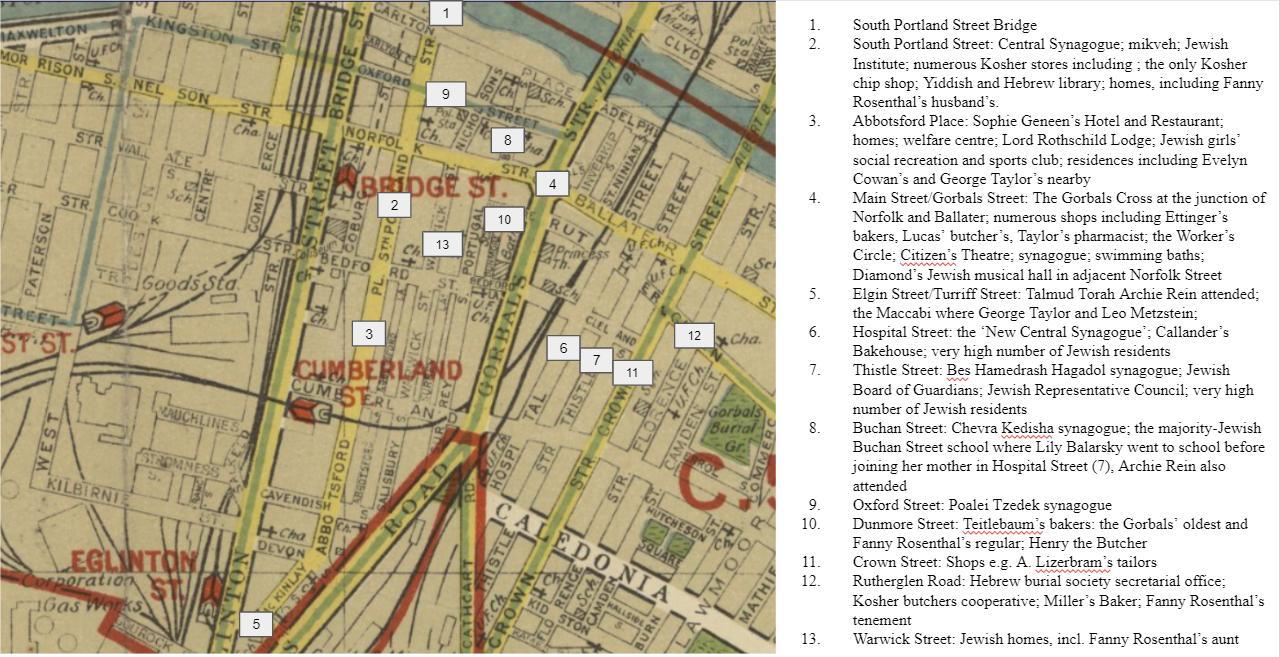

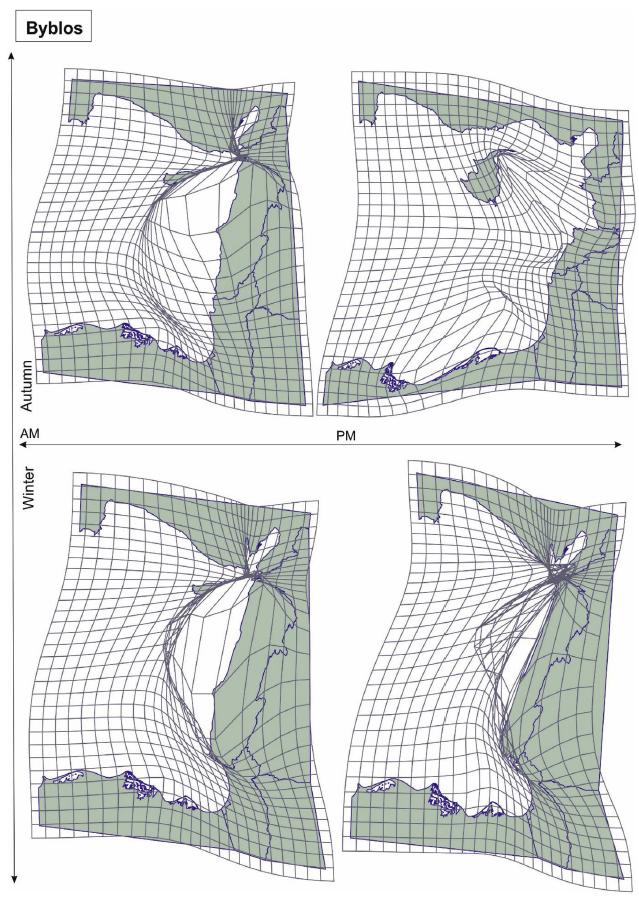

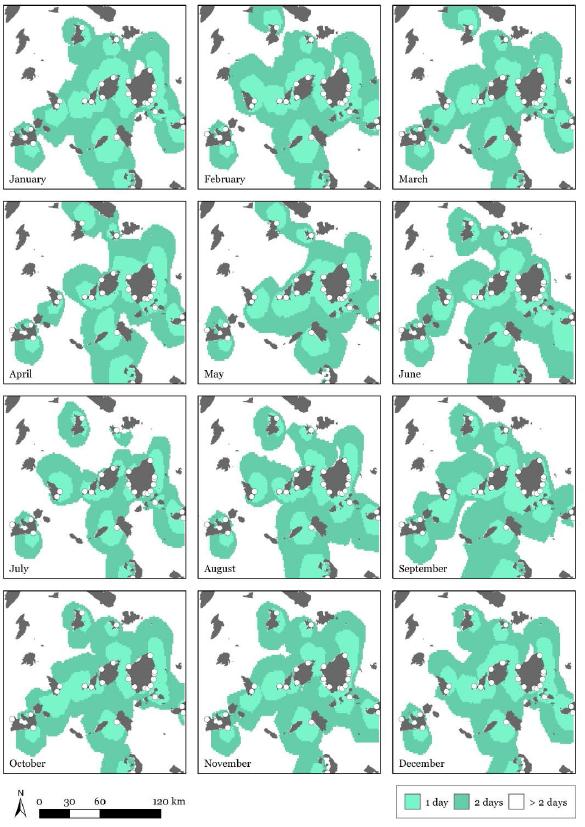

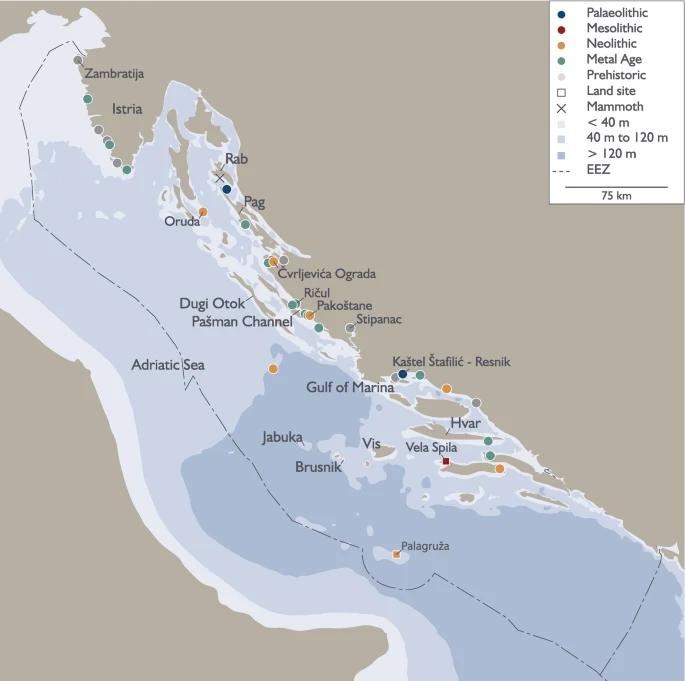

Figure 11: Emerged areas during the LGM around Europe: 1) Doggerland, English Channel and Bristol Channel, 2) France Atlantic Coast, 3) Portugal Atlantic Coast, 4) Catalunya and Valencia Coast, 5) Gulf of Lion, 6) Great Adriatic/Po Plain (the focus of this article), 7) Northern Black Sea Coast and Sea of Azov, 8) Other areas, 9) Northern European Ice sheets, 10) Mountain glaciers, 11) Rivers and lakes (image from Peresani et al 2021: 130).

–

–

–

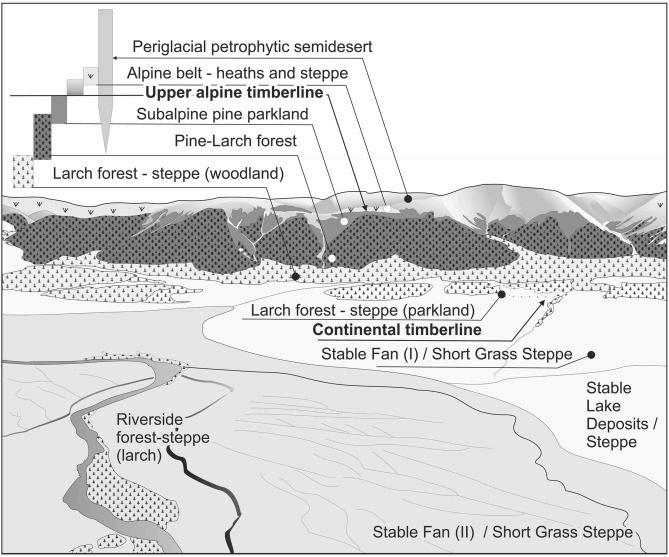

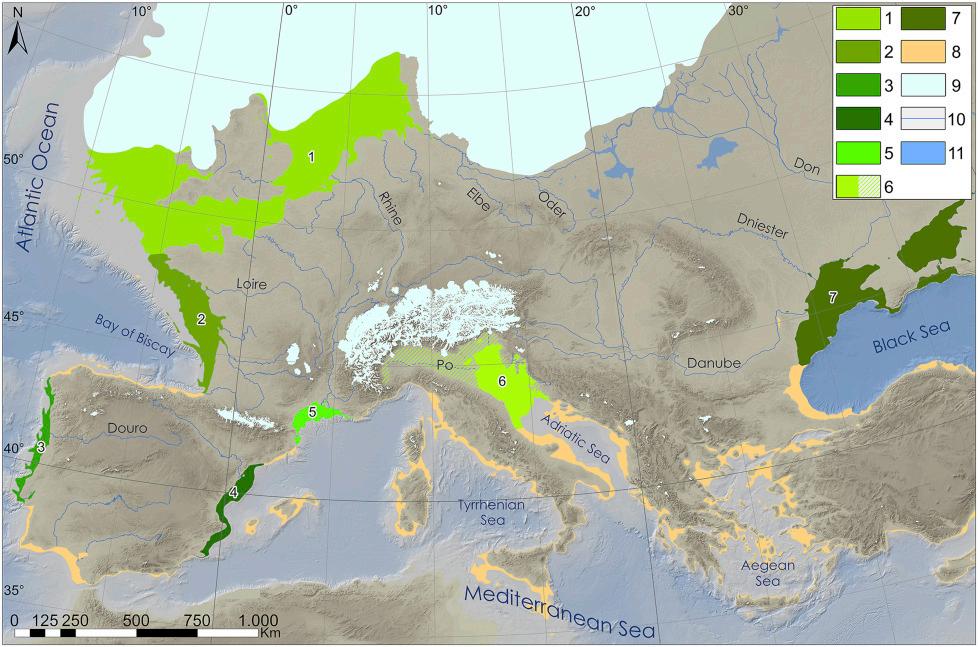

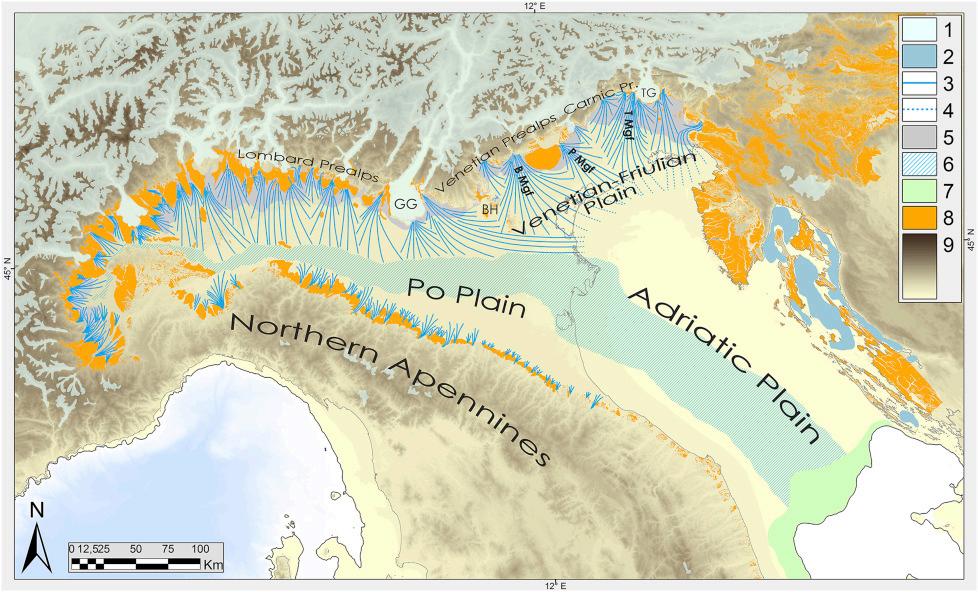

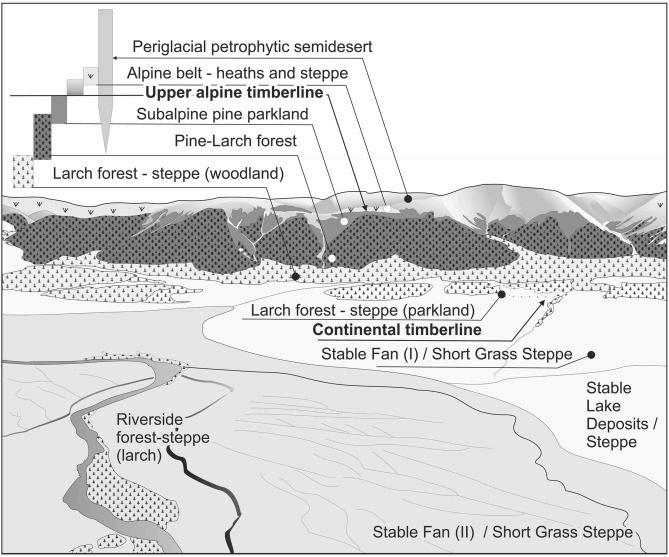

-120 to -140 metres at 21kya (figure 2) (Benjamin et al 2017: 40). From a paleogeographic point of view, the region was abundant with waterbodies, from the large fluvial valleys flowing through the former plain, to the system of lakes off the coast of Croatia and in the pre-alpine area (Peresani et al 2021: 133-134). Moreover, at least during the LGM, the environment seems to have been characterised by herbs and shrub-dominated steppes, swamps and marshes, and open boreal forests, with trees developing mainly on the alpine border and along rivers (figure 3) – similarly to the modern-day steppemountain border in the Altai region (Peresani et al 2021: 135-136). This picture of a ‘productive parkland steppe’ would be confirmed by the pre-LGM pollen record from Istria, which shows the presence of maple, alder, pine and larch along steppe taxa (Miracle 2007: 44-45), and also by the LGM one from the Adriatic Sea, indicating an herb-dominated grassland mixed with pine and oak (Antonioli et al 2017: 364). Therefore, now that a concrete image of the Great Adriatic Plain has been painted, it is possible to also imagine humans moving around and exploiting this vivid landscape.

Archaeology Department 37

Figure 12: Indicative paleogeographic map of the Great Adriatic/Po plain region during the LGM: 1) Glaciers, 2) Lakes, 3) & 4) Rivers’ megafans, 5) Upper proximal megafan belt, 6) Po River floodplain, 7) Po River delta, 8) stable surfaces supporting deeply weathered soils and loess, 9) DEM (image from Peresani et al 2021: 131).

3. A Marine Route into Europe?

The first issue that will be discussed is the possibility of a coastal dispersal into Europe by Homo sapiens around 45 kya, and the role of submerged landscapes in the Adriatic. Throughout the years it has become obvious that humans must have used coastal corridors for a quick dispersal into Asia and the Americas, and sea crossings must have been involved to reach places like Australia possibly earlier than 50 kya (Sturt et al 2018: 669-675). Yet, some scholars have doubted that similar coastal routes were used to reach Europe, as accessing the dry ‘island-poor Levant’ would not have required any maritime adaptation, meaning that populations crossing into Western Eurasia would have taken more time to generate a marine-oriented lifestyle (Broodbank 2013: 112-113). Thus, a continental route hypothesis is usually favoured, with humans moving from the Levant into Anatolia and then across the land-bridge available through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, as well as by crossing north of the Black Sea, quickly spreading into the whole continent through the Danube corridor (Broodbank 2013: 113; Gamble 2013: 264). Traditionally, this dispersal event was associated with the Aurignacian, yet this technocomplex seems to have appeared 5,000 years earlier in Europe than in the Levant, as the site of Geißenklösterle in Germany dates to 43 kya (Gamble 2013: 262). Besides, the oldest evidence for Homo sapiens in the continent at Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria, dating between 47 and 45 kya, lacks any association with Aurignacian tools (Hublin et al 2020). Therefore, it might be argued that, in order to

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 38

Figure 13: 3D schematic representation of the ecoclimatic gradients of the Altai region (Russia) which provide an analogue for the Great Adriatic/Po plain area (image from Peresani et al 2021: 136).

find any trace of a marine route into Europe, dispersals associated with Mediterranean technocomplexes predating the Aurignacian in the region must be investigated.

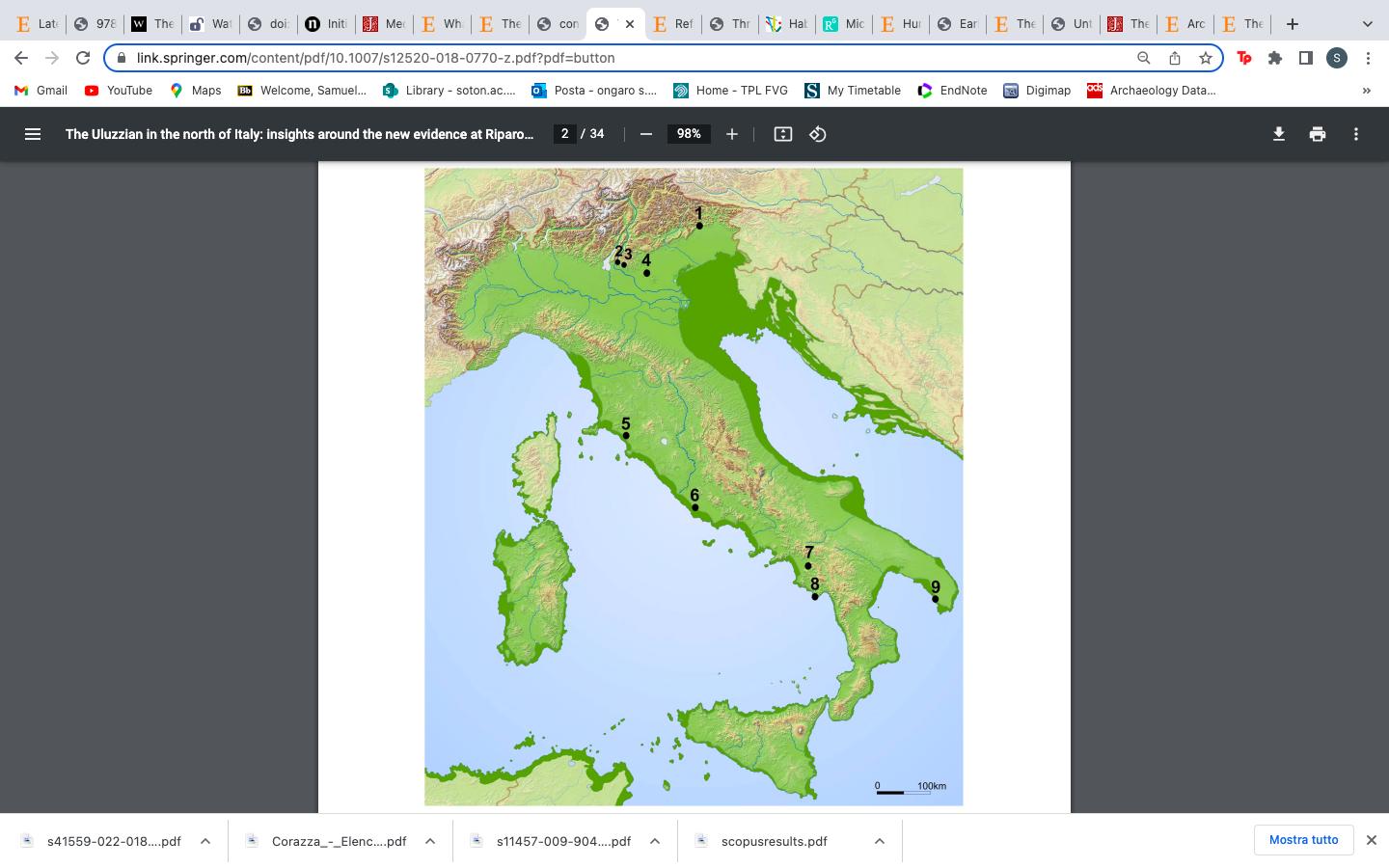

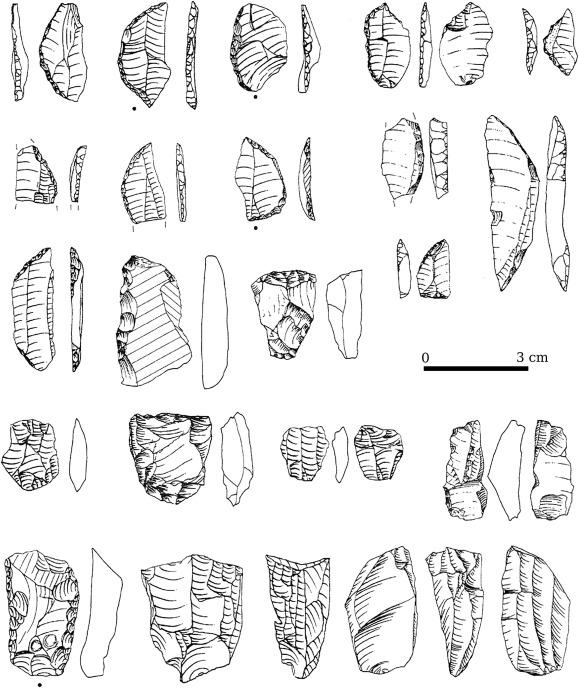

3.1. The Uluzzian Debate

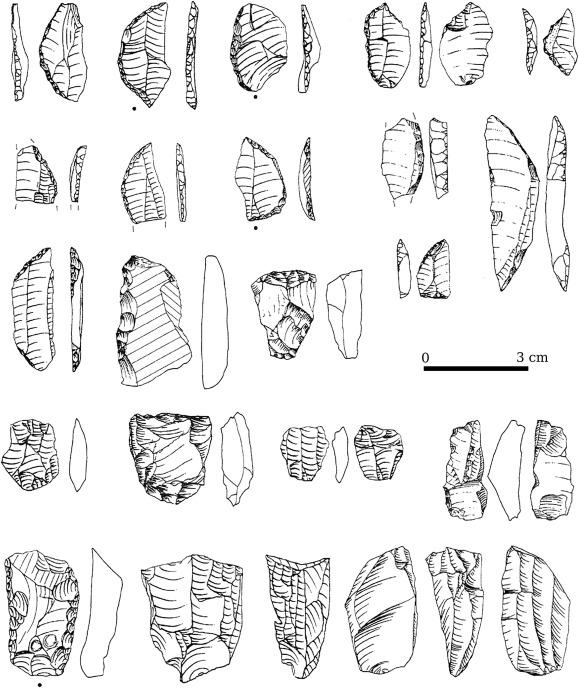

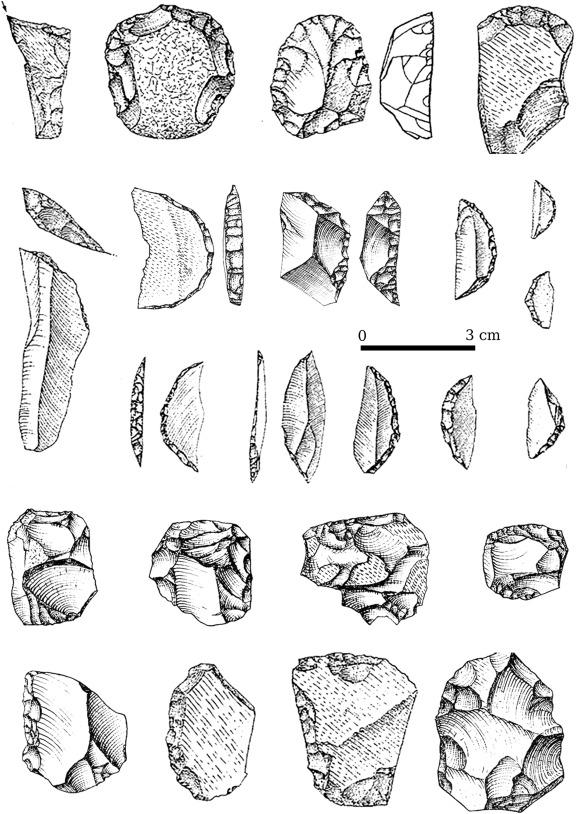

The main evidence for a coastal dispersal into Europe comes from a route starting in Greece and continuing along the Adriatic towards Italy, which is associated with the Uluzzian industry (Papagianni 2009: 130). This technocomplex is mainly found on the Italian peninsula, as testified by sites like Grotta del Cavallo in Apulia and Grotta Fumane in Northern Italy (figure 4) dated respectively to 44.3-43 kya and 44.8-43.9 kya (Moroni et al 2013: 29), but it has also been detected in Greece. In fact, at Klisoura Cave in the North-Eastern Peloponnese, a transitional assemblage (figure 5) dated around 40 kya has been found in a deposit between a Mousterian and Aurignacian layer bearing no similarities with either of these assemblages, but yielding arched back blades and splintered pieces that are typical of the Uluzzian (Papagianni 2009: 125). However, it has been argued that the industry of Klisoura is much more blade-oriented than the standard Italian Uluzzian (Papagianni 2009: 130-131), which, based on the lowermost levels of Grotta Fumane, has been defined more as a flake industry, with typo-technological elements in common with the Mousterian (Peresani et al 2016: 51). Nevertheless, other scholars have asserted that there are considerable differences between the Mousterian and the Uluzzian, which especially at Grotta del Cavallo (figure 6) is focused on small blades’ production (Moroni et al 2018: 8-17), while it is also true that even at Fumane innovations –namely the arched backed and splintered implements – are more evident in the upper layers (Peresani et al 2016: 52). The problem with the Uluzzian-Mousterian association is that this would imply that the industry was manufactured by Neanderthals, rather than migrating Sapiens Besides, underpinning the possibility of an Uluzzian coastal route along the Adriatic is also the fact that typical Uluzzian tools appear only sporadically in North-Western Greece and are absent in the Balkans (Papagianni 2009: 131). However, if the Uluzzian appearance really reflects a coastal migration, it is not surprising that evidence has not been found along the supposed Adriatic route, given that the coast at that time would now lie submerged, making the known sites only a pale reflection of what was happening closer to the sea.

Furthermore, the association of the technocomplex with Homo sapiens is confirmed by the human molars found in the Uluzzian levels at Grotta del Cavallo (Moroni et al 2018: 17-19). Moreover, evidence from shell-beads might also contribute in favour of the coastal-Uluzzian model. In fact, based on the assumption that symbolic artefacts might provide a plausible indicator for ethnic groups – as their meaning would have to be transmitted from one generation to another – Vanhaeren and d’Errico (2006) have established clusters of sites with similar bead types, and one of these incorporates assemblages from Greece and Italy as they share particular Mediterranean shells. Although this study was conducted on Aurignacian sites, a similar situation of shared shell-beads is witnessed in the

Archaeology Department 39

Legend:

1. Grotta Rio Secco

2. Grotta Fumane and Grotta Ghiacciaia

3. Riparo Tagliente

4. Riparo Broion

5. Grotta La Fabbrica

6. Grotta Fossellone

7. Grotta Castelcivita

8. Grotta La Cala

9. Grotta del Cavallo, Grotta Bernardini, and Grotta Uluzzo

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 40

Archaeology Department 41

Figure 15: The ‘Transitional’ industry of Klisoura Cave (Greece), possibly belonging to the Uluzzian technocomplex

–

compare with figure 6 (image from Moroni et al 2013: 38).

Figure 16: The Uluzzian industry from Grotta del Cavallo (Italy) – compare with figure 5 (image from Moroni et al 2013: 31).

4. An Adriatic Refugium

Another relevant issue, this time more academically recognised, is one of glacial refugia, and the possibility that the Great Adriatic Plain constituted a refuge zone around 20 kya. In fact, during the LGM, while the climate was increasingly turning colder and drier around Europe, the area surrounding the Mediterranean offered relatively improved conditions: in Italy, pollen records and charcoal indicate the survival of various tree-species in Sicily, Liguria, and Tuscany, including oak, elm, and birch (Broodbank 2013: 120). Besides, while the Alpine ice-caps isolated Italy from the rest of Europe, genetic data suggests that an event known as ‘Villabruna replacement’, in which gene-flow from the Near East entered the Italian gene pool, happened at the end of the LGM, as early as 19 kya (Aneli et al 2021: 1418-1419). Such gene-transmission could have happened only through the Great Adriatic Plain, which linked the Balkans and the rest of South-Eastern Europe with Italy. Moreover, contacts between different sides of the Adriatic are attested also by the use of Apennine lithic raw materials both along the Eastern Alps and in Croatia (Peresani et al 2021: 147-151). Thus, it might be argued that the region was occupied to an extent which allowed considerable connections – which are required especially for such a marked genetic event – making the Adriatic a lost glacial refugium.

Nevertheless, there are debates on the nature of this submerged landscape: various scholars have described the Great Adriatic Plain as a highly productive array of lowland, estuarine, and coastal environments, rich in game, water and other resources (Miracle 2007: 41-42). However, Mussi, using the Po valley as an analog, has argued that the region was a cold wind-swept steppe, where the boggy and gravelly landscape would not have sustained resources for human occupation (2001: 309-313). Yet, if Istria is used as a model for the Great Adriatic Plain, quite the opposite is demonstrated: faunal remains from various caves dated to multiple periods around the LGM show not only the strong, constant presence of grassland species like horse and red deer, but also the permanent existence of open and dense vegetation areas, the former associated with hare and aurochs, the latter with boar and roe deer (Miracle 2007). What is even more interesting is the pattern of human presence, as, while during the LGM occupation is scarce all along the Istrian and Dalmatian coast, both before and after the area sees an increase in sites, which has been interpreted as an ‘optical illusion’ reflecting the shift of human presence to and from the plain during the harshest period (Miracle 2007; Broodbank 2013: 132). Finally, that the former coastline was visited is also demonstrated by perforated marine shells typical of t he lower Adriatic found at sites along the Apennines and in Northern Italy (Peresani et al 2021: 151). Therefore, it is clear that the area must have been occupied even during the LGM, when it was used as a refugium from harsher conditions on the edges of the Adriatic.

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 42

5. The Role of Submerged Prehistory

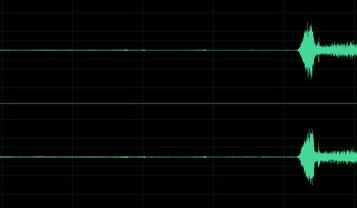

Taking everything into account, it is now evident that there are some missing pieces in the issues described above, which hinder a complete and correct interpretation of the European Upper Palaeolithic. The focus of these debates around the Adriatic region might suggest that the evidence needed is located on areas now submerged, yet, the state of submerged Palaeolithic archaeology in the basin does not look promising. Overall, there is a severe lack of sites, as only two localities – both along the Croatian coast

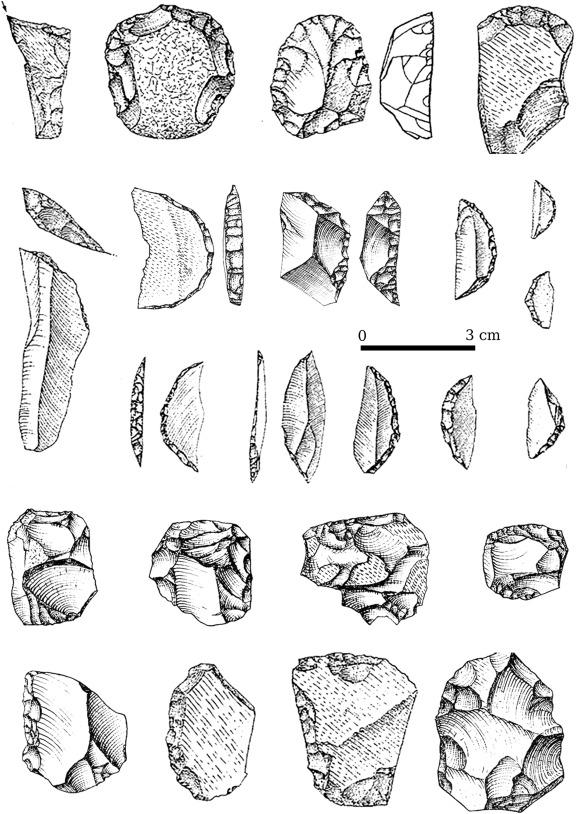

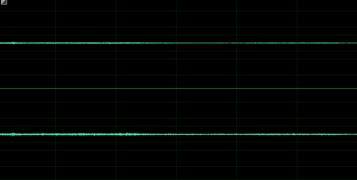

have yielded relevant archaeological material (figure 7). While one comprises only a single Mousterian tool, the other, Kaštel Štafilić-Resnik, has yielded several Mousterian cores and side scrapers (figure 8), and possibly some Upper Palaeolithic tools (Rossi et al 2020: 354). However, not enough information is available to determine whether these finds could be linked to a ‘transitional’ assemblage – and thus if they could be relevant to the Uluzzian debate. In fact, as already suggested above, the only way to confirm the correlation of this technocomplex with a coastal dispersal event from Greece into Italy is to find evidence of this route, which would have run along the lower plains of the Adriatic, now lying underwater. Besides, the fact that the Adriatic is the missing element in the Uluzzian model is confirmed by new sites being discovered in North-Eastern Italy (Peresani et al 2019), at the edge of the supposed dispersal route. Instead, the debate surrounding the role of the Great Adriatic Plain as an LGM refugium seems more settled towards a positive connotation of this landscape, although the area is a complete blank in terms of submerged Palaeolithic sites, which raises some doubts regarding the interpretation proposed in this article. Nevertheless, the lack of evidence should not be seen as proof for the region’s inhospitality – especially when all the indirect indicators presented above demonstrate the contrary – but rather as a sign of the poor state of research in the Adriatic: sufficient attention to submerged prehistory in the Adriatic has only been witnessed in the past decade (Rossi et al 2020: 348). Therefore, it is clear that more work should be conducted to find the evidence needed to gain a further insight into both the debates discussed here.

Archaeology Department 43

–

Southampton Journal of Postgraduate Humanities 44

Figure 17: Map of submerged prehistoric sites in the Adriatic (they are all located in Croatia): two palaeolithic sites are known, Kaštel Štafilić-Resnik (marked on the map) and a single Mousterian tool found off the island of Pag (image from Rossi et al 2020: 349).

Figure 18: Mousterian tools from Kaštel Štafilić-Resnik, including a core and two flakes (image from Rossi et al 2020: 355).

6. Conclusion

In summary, it has been demonstrated that the submerged Adriatic landscape has a significant role in debates which are crucial for Upper Palaeolithic research. On one hand, the possibility of a Homo sapiens’ coastal dispersal into Europe from Greece to Italy is associated with the Uluzzian hypothesis, which requires the lower plains of the Adriatic as a route, and thus can only be confirmed by submerged sites located along this corridor. On the other, since it has been established that the region was a human refugium during the LGM, it holds the potential to reveal several submerged Palaeolithic sites. Therefore, there is a need to further investigate the area and to finally rediscover a lost part of the Upper Palaeolithic record, opening a new chapter for submerged prehistory.

Archaeology Department 45

Bibliography

Secondary Literature

Aneli, S., Caldon, M. Saupe, T., Montinaro, F. & Pagani, F. 2021. Through 40,000 years of human presence in Southern Europe: The Italian case study. Human Genetics, 140: 1417-1431.

Antonioli, F., Chiocci, F.L., Anzidei, M., Capotondi, L., Casalbore, D., Magri, D. & Silenzi, S. 2017. The Central Mediterranean. In N.C. Flemming, J. Harff, D. Moura, A. Burgess & G.N. Bailey (eds) Submerged Landscapes of the European Continental Shelf: Quaternary Paleoenvironments, pp. 341376 Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell.

Bailey, G.N. & Flemming, N.C. 2008. Archaeology of the continental shelf: marine resources, submerged landscapes and underwater archaeology. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27 (23-24): 21532165.

Bailey, G.N., Galanidou, N., Peeters, H., Jöns, H. & Mennega, M. 2020a. The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes: Introduction and Overview. In G.N. Bailey, N. Galanidou, H. Peeters, H. Jöns, & M. Mennega (eds), The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes: 35 (Coastal Research Library), pp. 1-23. New York: Springer.

Benjamin, J., Rovere, A., Fontana, A., Furlani, S., Vacchi, M., Inglis, R.H., Galili, E., Antonioli, F., Sivan, D., Miko, S., Mourtzas, N., Felja, I., Meredith-Williams, M., Goodman-Tchernov, B., Kolaiti, E., Anzidei, M. & Gehrels, R. 2017. Late Quaternary sea-level changes and early human societies in the central and eastern Mediterranean Basin: An interdisciplinary review. Quaternary International, 449: 29-57.

Broodbank, C. 2013. The Making of the Middle Sea: A History of the Mediterranean from the Beginning to the Emergence of the Classical World. London: Thames & Hudson.

Bynoe, R. 2018. The submerged archaeology of the North Sea: Enhancing the Lower Palaeolithic record of northwest Europe. Quaternary Science Reviews, 191: 1-14.

Cohen, K.M., MacDonald, K., Joordens, J.C.A., Roebroeks, W. & Gibbard, P.L. 2012. The earliest occupation of north-west Europe: a coastal perspective. Quaternary International, 271: 70-83.

De Giosa, F., Scardino, G., Vacchi, M., Piscitelli, A., Milella, M. Ciccolella, A. & Mastronuzzi, G. 2019. Geomorphological Signature of Late Pleistocene Sea Level Oscillations in Torre Guaceto Marine Protected Area (Adriatic Sea, SE Italy). Water, 11(11): 2409. Available at: <https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112409> [Accessed 9 January 2023].

Gamble, C. 2013. Settling the Earth: The Archaeology of Deep Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

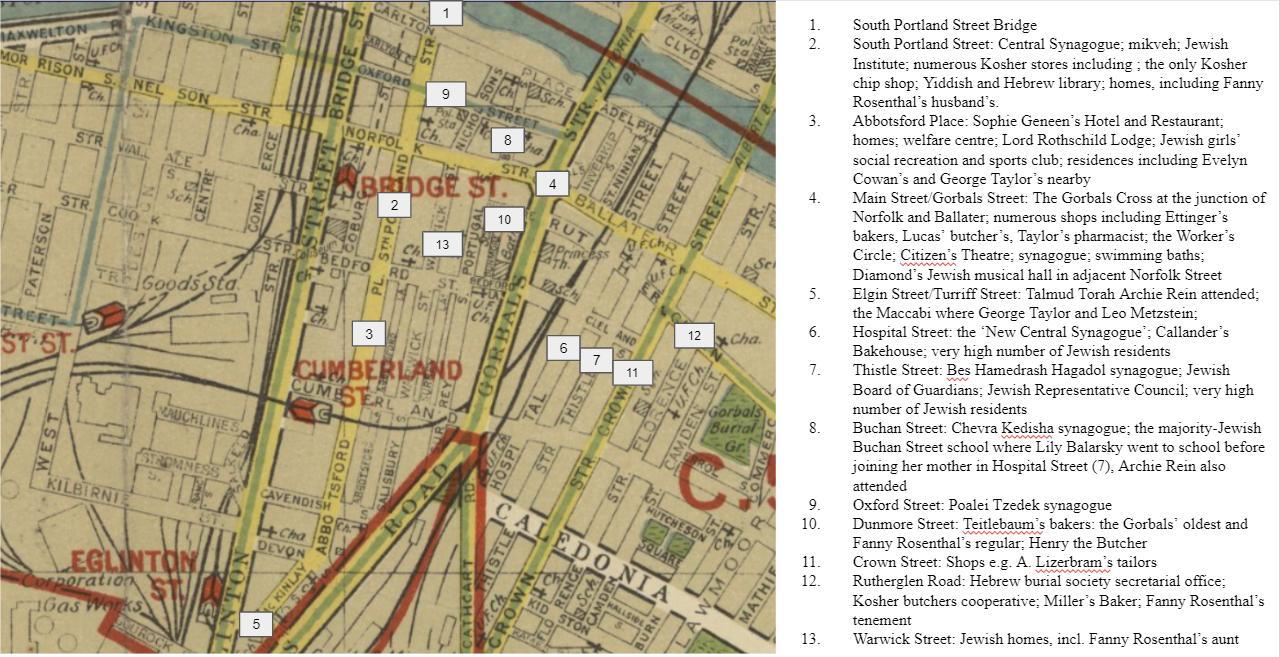

Hublin, JJ., Sirakov, N., Aldeias, V., Bailey, S., Bard, E., Delvigne, V., Endarova, E., Fagault, Y., Fewlass, H., Hajdinjak, M., Kromer, B., Krumov, I., Marreiros, J., Martisius, N.L., Paskulin, L., Sinet-Mathiot, V., Meyer, M., Pääbo, S., Popov, V., Rezek, Z., Sirakova, S., Skinner, M.M., Smith, G.M., Spasov, R., Talamo, S., Tuna, T., Wacker, L., Welker, F., Wilcke, A., Zahariev, N., McPherron, S.P. & Tsanova, T. 2020. Initial Upper Palaeolithic Homo sapiens from Bacho Kiro Cave, Bulgaria. Nature, 581: 299–302.