A PUBLICATION OF THE OKLAHOMA VISUAL ARTS COALITION WINTER 2023

Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition PHONE: 405.879.2400 1720 N Shartel Ave, Ste B, Oklahoma City, OK 73103.

Web // ovac-ok.org

Executive Director // Rebecca Kinslow, rebecca@ovac-ok.org

Editor // John Selvidge, johnmselvidge@outlook.com

Art Director // Anne Richardson, speccreative@gmail.com

Art Focus is a quarterly publication of the Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition dedicated to stimulating insight into and providing current information about the visual arts in Oklahoma. Mission: Growing and developing Oklahoma’s visual arts through education, promotion, connection, and funding. OVAC welcomes article submissions related to artists and art in Oklahoma. Call or email the editor for guidelines. OVAC welcomes comments. Letters addressed to Art Focus are considered for publication unless otherwise specified. Mail or email comments to the editor at the address above. Letters may be edited for clarity or space reasons. Anon-ymous letters won’t be published. Please include a phone number.

2022-2023 BOARD OF DIRECTORS // Kirsten Olds, President, Tulsa; Diane Salamon, Treasurer, Tulsa; Jon Fisher, Secretary, OKC; Jacquelyn Knapp, Parliamentarian, Chickasha; Douglas Sorocco, Past President, OKC; Matthew Anderson, Tahlequah; Marjorie Atwood, Tulsa; Barbara Gabel, OKC; Farooq Karim, OKC; Kathryn Kenney, Tulsa; Drew Knox, OKC; Heather Lunsford, OKC; John Marshall, OKC; Russ Teubner, Stillwater; Chris Winland, OKC The Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition is solely responsible for the contents of Art Focus . However, the views expressed in articles do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Board or OVAC staff. Member Agency of Allied Arts and member of the Americans for the Arts. © 2023, Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition. All rights reserved. View the online archive at ArtFocusOklahoma.org.

3

CONTENTS / / Volume 38 No. 1 // Winter 2023

Support from:

ON THE COVER // Nathan Lee, The Existential Nature of Agony and Ecstasy, 2020, galvanized steel wire, recycled paper, acrylic paint, acrylic stain | Courtesy of the artist, page 14; MIDDLE // Carmen Huizar, Sin título, 2019-2022, oil paint on canvas | JS, page 10; BOTTOM // Gabriel Rojas, Fuera de Juego, 2022, acrylic, oil, fabric on raw canvas, 73" x 77" | Courtesy of the artist, page 18.

4 6 10 14 LETTER

THE EDITOR

Q&A For the Record // In the Studio with NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield OLIVIA DAILEY REVIEW De Casa a Casa // Notes on La casa que nos inventamos at Oklahoma Contemporary MIRELLA MARTINEZ FEATURE A Natural Evolution // 1515 Lincoln Gallery Breaks New Ground MEGAN ROSSMAN PREVIEW Painting the Wormhole // Gabriel Rojas and Michael Palazzo at Living Arts CASSIDY PETRAZZI REGIONAL REVIEW Rococo Revisited // Yvette Mayorga’s What a Time To Be at The Momentary DANNY R.W. BASKIN EKPHRASIS A Picture and a Poem SYLVIE MAYER AND Z. B. REEVES EDITED BY LIZ BLOOD OVAC NEWS // NEW AND RENEWING MEMBERS 18 22 26 29

FROM

JOHN SELVIDGE

ROBIN CHASE

Leaning into this new year, I’m impressed that so many people I know are beginning it on an optimistic note. I am too, but considering our mental habits these past few years—the ones that kept us braced for upheaval and tragedy during times of plague, violence, and terrible politics bordering on farce—enjoying a little blue sky above us almost feels suspect now.

But if the 21st century has taught us anything, it’s that our challenges will get weirder. That seems suddenly very true in the realm of art right now, as AI technologies raise fears that art-making, even our art spaces will be increasingly governed by algorithms more tuned to clickbait than human interest or reflection. But even on this point, I can find reasons for optimism because isn’t it art at its best that helps us reassert agency over our imaginative spaces (aka, our own minds) and break down the barriers set up between us? Maybe even far enough to reach one another?

Fittingly, each writer in this issue of Art Focus is concerned with making vital connections by mobilizing different legacies for the sake of new discoveries. That’s evident in artist Mirella Martinez’s reflections on Mexico and memory spurred by an exhibition at Oklahoma Contemporary (p. 10) as well as Cassidy Petrazzi’s take on different modes of collaboration among two Tulsa painters (p. 18), not to mention Danny R.W. Baskin’s account of Yvette Mayorga’s maximalist appropriation of Rococo (p. 22). Similarly, Olivia Dailey’s interview with NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield engages history and tradition in vibrant, uncompromising tones (p. 6), and Megan Rossman explores a new vista for art, conversation, and synergy at Oklahoma City’s recently launched 1515 Lincoln Gallery (p.14).

For my part, I’m honored to serve as Art Focus’s guest editor for 2023 and am eager to learn more as I go about the artists and artistic communities throughout my home state. Special thanks to outgoing guest editor Liz Blood, as righteous a truth-teller as you’ll find in Oklahoma, for showing me the ropes, as well as to Rebecca and the entire OVAC team. Together, I think we’re going to have a very good year indeed.

—John Selvidge

JOHN SELVIDGE is an award-winning screenwriter who works for a humanitarian nonprofit organization in Oklahoma City while maintaining freelance and creative projects on the side. His art writing, travel writing, and poetry have appeared locally, nationally, and internationally. He was selected for OVAC’s Oklahoma Art Writing and Curatorial Fellowship in 2018.

4

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

WINTER SESSION JAN. 16 – MARCH 12 okcontemp.org/StudioSchool Exhibitions | Classes | Camps | Performances 11 NW 11th St., Oklahoma City NEW YEAR. NEW SKILLS. Explore four- and eight-week classes or single-day workshops across a variety of favorite disciplines and creative new topics.

6

//

NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield, Based on Quinault Girl (1913), 2021, acrylic on canvas, 30" x 40" | Courtesy of the artist

FOR THE RECORD // IN THE STUDIO WITH NICOLE NAHMI-A-PIAH HATFIELD

By Olivia Dailey

NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield is an Oklahoma-based artist whose paintings are rooted in Native American traditions. Originally from Apache, she recently relocated from Enid to Norman. When I visited with her, she was in the process of setting up her new studio while maintaining a steady presence at Oklahoma art and craft events—like the Native American Art Market in Lawton and OKC Princess Holiday Craft Fair in Norman—where she sells her work, performs live paintings, and teaches workshops on subjects like the Plains Indians tradition of ledger art. She asked to begin our Q&A session with a greeting in Comanche:

Haa Maraweka! N u nahnia tsa Nahmi-A-Piah.

So to begin, what is ledger art?

It comes from a traditional style that different Plains Tribes practiced a long time ago, before pictographs, on hide and rock. They passed down their stories through these images. It became ledger art when we began putting our images on different types of ledger paper in the later 1800s. It could have been from a grocery store, a doctor’s office, or a bank. It’s whatever we had available at the time. For my ledger art I go online and look for antique ledger paper from the late 1800s or early 1900s. I really like to create on ledger paper because it’s like a diary for me. I can take it anywhere. I can easily create whatever I’m feeling at the time.

I think it’s nice that you teach because you’re a selftaught artist. What are you currently exploring about your craft?

I’m always going back and forth between mediums. Recently, I painted a mural for the Chickasaw Nation’s Define Your Direction campaign, but instead of a wall, I

painted it on a big canvas sheet. I had to learn how to paint a mural on a new medium.

Tell me about the live paintings that you perform at some of these events.

When I first started doing art professionally, one of my main goals was to do live art—basically doing a painting in public within a given time frame. I’d seen several male artists do it, and I thought, “Oh, I can do this.” Hopefully, it’ll inspire other women artists to do live art. Boy, the first time I did live art, I got lost in it.

I love your style of portraiture with vivid colors.

I don’t know why I’m so drawn to portraits. I like to tell people’s stories through color and through their eyes, their facial features.

You also paint a lot of images of mother and child, like Forever Love, which almost seems like an artistic genre in and of itself.

As an artist, a little piece of us is always in whatever we create. It could be things that remind me of my mom or my grandma, or of me and my son. I want other mothers to relate to it, to see themselves in that image as well.

I want to recognize our women—our mothers and our grandmothers and our aunts—to let them know that we see you and we appreciate you.

You often work from historical photographs of tribal people. What makes you want to paint someone?

I find myself painting more of the women—those are my favorites. Most historical images of our women, the photographs, didn’t include their names. You didn’t know who they were, but you would often know who the men were. I like to recreate those pieces just to, again, recognize them and remind people who they were, that

7

CONTINUED

IN THE STUDIO

these women were also important. They were life-givers and would fight right alongside their men in the tribe.

What you’re describing sounds like a result of the Westernization of tribal people.

I’m glad you said that because, as tribal people, we know that. I know that our men knew who we were, that we fought alongside them, that we were equal to them. We knew our roles within the tribe. I want to show people that we were equal to the men.

What do you want your art to say about Native American culture, past and present?

I want people to see it through our eyes—how we see it. I want us to tell our own stories. Whether that’s in front of a camera or on canvas, I want us to be able to represent ourselves.

My goal is to contribute to keeping the tradition alive, to keep telling our story to our community, our tribal people, our youth. I want to teach my tribal youth that it’s not about material things, it’s about being rich with our culture and traditions—and that includes art.

If people outside our tradition see that and hear that, good. That’s in the back of my mind, too, because I don’t want people to think of us as these mystical creatures or what you see in the old movies. I have a duty to represent us truthfully.

You can view more of NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield’s art on her website nahmiahpiahart.com. Follow her on social media to learn more about her participation in upcoming events.

OLIVIA DAILEY has a BA in Journalism from the University of Oklahoma. She works as a media production coordinator in Norman.

IN THE STUDIO 8

TOP // NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield, Forever Love , 2022, prisma color and ink on antique ledger paper | Courtesy of the artist; BOTTOM // NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield in her studio | Richard Curtis

9

IN THE STUDIO

TOP // NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield, Kalispel Woman , 2022, acrylic on canvas, 36" x 36"; BOTTOM // NiCole Nahmi-A-Piah Hatfield, Based on Quanah Parker , 2022, acrylic on canvas, 16" x 20" | Courtesy of the artist

DE CASA A CASA // NOTES ON LA CASA QUE NOS INVENTAMOS AT OKLAHOMA CONTEMPORARY

By Mirella Martinez

An anxious mind, a car, expansive flat roads, and an unwavering desire to maintain a meditative state are all ingredients for long, aimless drives down rural backroads. It’s during these tranquil meanderings, against an Oklahoma backdrop, that I’m able to connect the dots between my experiences in Mexico and works from Oklahoma Contemporary’s La casa que nos inventamos: Contemporary Art from Guadalajara

We’re all familiar with the typical, manufactured version of Mexico. It’s the same version that’s been pushed on us for years as aerial images of a bustling city come into focus, then jarring, overly saturated, orange street-level shots, maybe even a close up of papel picado—the brightly colored tissue paper strung high and zigzagging in intricate patterns between buildings along a cobblestone street—followed by a disjointed sequence of prickly magueys that displays rows and rows of the towering plant. All this is a stark contrast to the Mexico I’ve come to know as well as the one presented to us by La casa que nos inventamos

Parallels can be drawn between Oklahoma City and Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco. While Guadalajara has already cemented itself as a flourishing artistic and cultural hub, artists in Oklahoma City—amidst a reset in terms of diversity and inclusion—are cultivating an awareness of their home’s potential to do the same. The rural richness that surrounds both metros involves similarly deep-rooted traditions concerning family, agriculture, and each region’s indigenous heritage.

La Casa’s nearly 50 artworks, all made by artists hailing from Guadalajara, give us insight into a much more complex, delicate, possibly even a romantic take on the city’s contemporary environment and its art community that extends to what life in Mexico can be. The show walks

a fine line between feelings of comfort, tension, familiarity, and even a hint of magical realism with moments of delicacy sprinkled throughout.

Alejandro Pereda’s work touches on the topic of abandonment through his piece El día cuandro el future no llegó (The Day When the Future Did Not Come). The crumbling island of rebar and concrete cacti conjures two strong associations from vastly different worlds: first, the exposed rebar left atop Mexican homes for when families decide to build additional rooms or floors onto what are typically multigenerational homes. The hope of a thriving future is a stark contrast to the other image that comes to mind, that of a dilapidated, long-abandoned structure frequently found alongside backroads. Two conclusions oppose one another—one that’s still a “maybe,” and the other simply discarded and left to decay.

Often, when I find myself driving on roads that seem to have remained untouched and unchanged for years, I think about the times I’ve returned to my family’s rancho in Mexico. On my many visits before it was decided the old house should be updated, repainted, or maintained with luscious flowerbeds, I used to look at the old family portraits and construct my own narrative of their intimate histories. I find this sentiment and longing mirrored in Julieta Beltrán’s works like Archivo Familiar: La boda de los abuelos a color de la memoria and Archivo prestado: Los Viajeros (los abuelos de alguien mas). These paintings’ extreme close-ups open upon someone else’s intimate and cherished moments to become a zone onto which we can project our own memories and desires. Drawing inspiration from her own family photos as well as those of others, Beltrán’s art doesn’t provide a replica of the image but gives us an isolated, almost disjointed look at a cherished moment instead.

10 REVIEW

CONTINUED

11 REVIEW

Alejandro Almanza Pereda, El día cuandro el future no llegó , 2021, concrete and rebar | JS

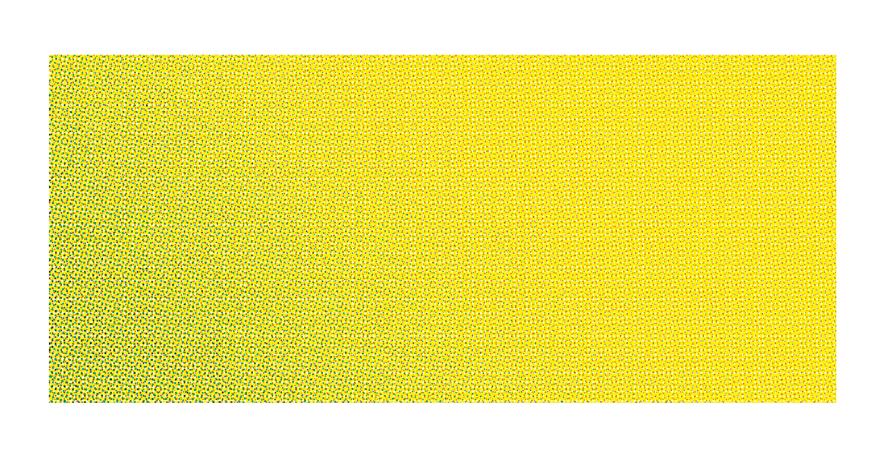

I also see this isolating, abstracting technique in Carmen Huizar’s Sín Titulo series where she isolates markings from the walls of her small Mexican town in a way that recalls the chipped, hand-painted flower pots and the exteriors of stores down the road from my grandparents’ house in rural Mexico. Huizar’s crisp geometric figures and blending of pastels are easy to digest, perhaps because these types of functional, mundane markings are easily dismissed or overlooked. These paintings ask us to reframe the way we view the marks and signs surrounding us, to not dismiss them but rather elevate and romanticize them.

Appropriately titled The fact of constantly returning to the same point or situation, Jose Dávila’s large, silk-screened linen panels remind me of visits to el rancho when, year after year, I returned eager to look for changes only to discover that I was the one who had changed. As figures compete for dominance over both of Dávila towering panels, one might think these works would instill a sense of chaos, but my eyes follow the thick, curved lines up and down their canvases in a soothing manner, and the visual tension between the bisected orbs and the bold, rhythmic lines creates an unexpected sense of harmony. These works of Dávila’s remind me of how we find peace when we return to a place that remains unchanged, whether a back road or family ranch, and the real chaos and tension resides solely in our minds, our anticipation.

La casa que nos inventamos contains several different conversations within its works, but what brought me back to see it were the quiet ones. Perhaps mere whispers at first, its subjects weave for me a net of complex emotions tied to memories as its other conversations explore topics of land, tradition and social commentary. Though Guadalajara and Oklahoma City are several hundred miles apart, La casa que nos inventamos brings their artists and audiences together for an insightful experience of the international contemporary art discourse. With its delightfully unexpected materials and the varying scales of the works displayed, the show touches on

TOP // Julieta Beltrán, Archivo familiar: La boda de los abuelos a color de la memoria, 2021, oil paint, guesso, and marble powder on MDF | JS; MIDDLE // Julieta Beltrán, Archivo prestado: Los viajeros (los abuelos de alguien más), 2021, oil paint, guesso, and marble powder on MDF | JS; BOTTOM // Alejandro Almanza Pereda, El día cuandro el future no llegó, 2021, concrete and rebar | JS

12

TOP

same

RIGHT // Carmen Huizar, Sin título, 2019-2022, oil paint on canvas | Mirella Martinez

many subjects. They’re the kind of topics one could mull over during long, aimless drives while the Oklahoma cotton-candy sky fades into a deep blue.

La casa que nos inventamos : Contemporary Art from Guadalajara can be seen through January 9 at Oklahoma Contemporary in Oklahoma City.

Born in Mexico, MIRELLA MARTINEZ immigrated to the U.S. with her family at a young age and grew up in Oklahoma. After attending Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida, she spent years traveling across the American west. She has been published in catalogs distributed nationwide and shown work in solo and group shows across the state. Currently based in Oklahoma City, she produces images, among other works, that question how we perceive and interact with the world around us. You can view her artwork at mirellamartinez.com.

13 REVIEW

// Jose Dávila, The fact of constantly returning to the

point or situation, 2021, silkscreen print and vinyl paint on loom-state linen, two paintings | JS;

A NATURAL EVOLUTION // 1515 LINCOLN GALLERY BREAKS NEW GROUND

By Megan Rossman

Anyone familiar with the geography of Oklahoma City likely is acquainted with the stately residences south of the state Capitol. Blocks of grand old homes, some dating back to statehood, line the streets that extend from Lincoln Avenue. In December, the local arts community found new sanctuary in one of these historic abodes at the opening of 1515 Lincoln Gallery—named for the address of the 6,000 square-foot villa it inhabits in the Wilson-Harn District.

This gallery is the latest project of Susan McCalmont, a longstanding force in the state’s creative scene. McCalmont, who’s lived in the neighborhood for the past five years, has owned and operated Objets Trouvés since 2019, where she featured work from contemporary artists and secondary art market pieces such as found art and objects. Antique Chinese scrolls, intricately detailed Japanese tea sets, colorful porcelain vases, and ceramic tableware were showcased alongside paintings, sculptures, and jewelry by more than fifty working artists whose locations span from Oklahoma to eastern Europe. 1515 Lincoln Gallery is both a continuation and new incarnation of that concept, providing more space for ideas and art to flourish.

“You’ve got air and light and you can breathe,” McCalmont says of the new location. “There isn’t really a gathering place in this part of town. I want people to be able to come together here and be surrounded by art.”

Prior to retiring from nonprofit work and opening her own gallery, McCalmont served in a number of roles, including the executive director of the Kirkpatrick Foundation for two decades, and in 2006 she founded Creative Oklahoma. Her love of art and its ability to connect people eventually propelled her into developing her own place for sharing that passion. In this newest venture, she hopes all will feel welcomed into the house on Lincoln.

Nathan Lee, 1515’s first artist-in-residence, arrived at his new home last year. The Oklahoma City native lives and creates onsite in a large garage apartment with a bright studio space. While many of his works are sculpture and paintings, he’s not confined to one medium. In addition to fine art and illustration, he’s written books, screenplays, and co-produced the 2013 feature documentary Transcend: 5 Black Artists by 5 Black Artists

“I want to be the Jim Thorpe of the art world,” he says.

Lee was among the founders of Inclusion in Art, an organization that promotes diversity in the city’s visual arts scene through exhibits and learning events. In November 2022, he earned the Michi Susan Award from the Paseo Arts Association, which is given annually to an individual who works to mentor and encourage Oklahoma visual artists.

In fact, Lee’s willingness to help guide others was how he and McCalmont were introduced. In 2008, he was a mentor for the ArtScience Prize, an international after-school program that fuses art and science with team-building skills that was adopted in-state through Creative Oklahoma.

“We had so much in common, including the way that we looked at art as a communication tool,” he says of his friendship with McCalmont. “She’s always been supportive of my work and not pigeonholed me.”

With his ever-growing resume, it would be difficult for anyone to plausibly pigeonhole Lee. He’s been deeply involved in the evolution of this new space as well. The gallery will host his first show here this March, featuring many of his mixed-media sculptural pieces constructed with paper bags, fast food napkins, and

14 FEATURE

CONTINUED

FEATURE 15

ABOVE // Nathan Lee and Susan Calmont; BELOW // 1515 Lincoln Gallery interiors | Megan Rossman

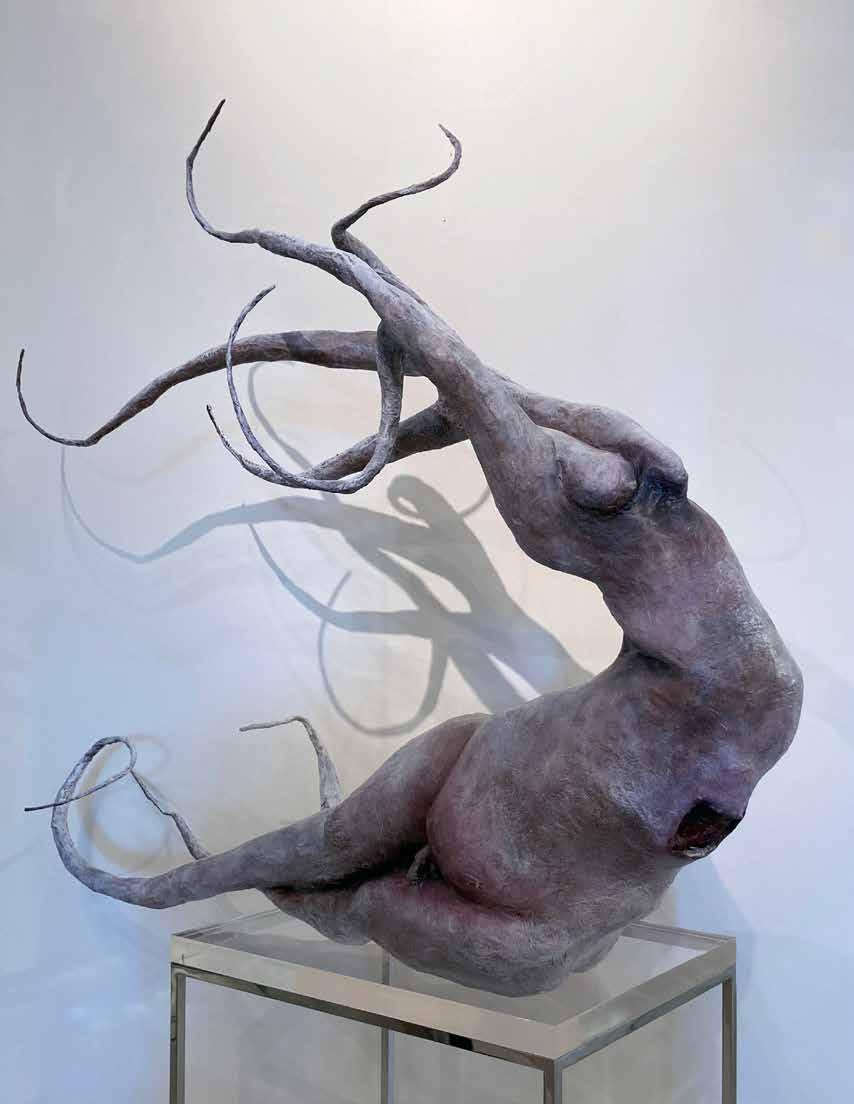

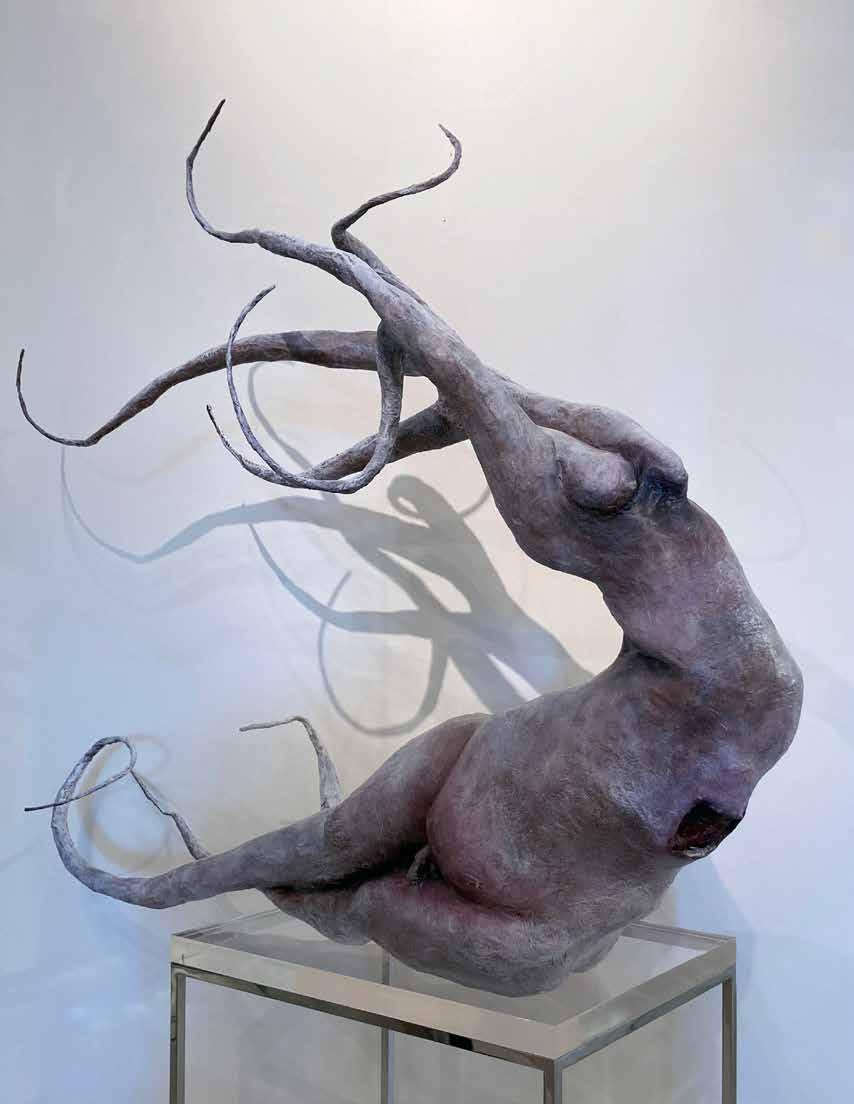

other reused materials that Lee molds over a wire base and paints. His biomorphic series comprises twisting forms like Fallacy of Achilles whose bulbous, humanoid figure sprouts sprawling, branch-like limbs. Abrasions on the surface might speak to the hidden wounds we carry. While rooted in nature, Achilles and its kin concern the similarities and fundamental connections between us as humans, Lee says.

The creations of Lee and others have a pristine backdrop in the recently renovated house. With offices and storage on the second story, the sprawling first floor serves as a showcase and gathering place for arts and culture and the people who thrive on them. A small gift shop near the entrance offers keepsakes and other unique items. Consigned artists’ work is displayed throughout the entire level with special exhibits that rotate every six weeks. The Spaces In Between and Nature’s Cathedral, an exhibition of two Oklahoma artists, opened on December 8 and runs through January 14 and highlights mixed media pieces by Paul Medina and wearable art by Sheridan Conrad. But 1515’s mission expands beyond its galleries. McCalmont wants this to be a place for people to slow down and have a conversation. She wants visitors to feel free to linger at the community table and have a glass of wine or a cup of coffee while they share ideas and inspiration in a beautiful and inviting setting.

“I want it to be joyful,” she says.

FEATURE 16

TOP // Various works and works in progress in Nathan Lee’s studio at 1515 Lincoln Gallery; LEFT // Lee with his sculpture Fallacy of Achilles | Megan Rossman

With collaborator Scott Hale, who owns and operates Southwest Art Appraisals and Southwest Wine Appraisals and offices upstairs, they plan to offer wine tastings and dinners, public talks, a music series, and more programming to be determined as the year progresses. An expansive backyard patio provides more space for events to spill out into the open air of the surrounding neighborhood.

The excitement of those who’ve been instrumental in the establishment of 1515 Lincoln Gallery is palpable. The impetus to foster a sense of community and belonging here through creativity underscores their necessity in an increasingly fragmented society. Art may not solve all the world’s problems, but its perennial power to bring people together is self-evident. As Lee says, “A lot of conversations outside of art will happen here, but art will be the catalyst.”

For more details, visit 1515lg.com.

MEGAN ROSSMAN currently serves as photography editor for Oklahoma Today magazine as well as photography manager for the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department. In 2018, she was selected to participate in OVAC’s Oklahoma Art Writing & Curatorial Fellowship. Although generally she leaves it to the professionals, Megan enjoys making her own art as well. She lives in Oklahoma City.

17 FEATURE

TOP // Exterior view of 1515 Lincoln Gallery; ABOVE // Paul Medina, Waterfall, 2022, mixed media, low-fired clay, steel, copper, and nylon cord, 60" x 28" x 9" | Megan Rossman

PAINTING THE WORMHOLE // GABRIEL ROJAS AND MICHAEL PALAZZO AT LIVING ARTS

By Cassidy Petrazzi

We often think of collaboration in the most straightforward way: people working together to produce something. With concurrent solo exhibitions in January at Living Arts in Tulsa, artists Michael Palazzo and Gabriel Rojas each recast what collaboration means through the artistic lenses of their own work.

For Rojas, painting has always provided a framework for activating the processes of memory. Through a method that involves stream of consciousness and a fast and lively production of works, Rojas manifests a non-linear language of form and abstraction that comes into being on its own terms. Often, he finds tension in his paintings, sometimes an appearance or feeling of disconnectedness, but through the volume of work he makes in his studio, he has been able to take a wider view of his paintings as a whole and note the forms, stories, or memories that consistently pop up. Though the abstracted imagery in one painting may appear to be disjointed, overall Rojas presents a visualization of experiences, memories of specific objects, songs, food, childhood bedtime rituals or stories—things communal or shared—that he weaves throughout his work. Through the active visualization of memory and shared experience, Rojas collaborates with family and community by reaching back to them.

Los Árboles Guardianes, on view at Living Arts, demonstrates Rojas’ practice of collaboration. As he tells the story, Rojas brought a folded, just-bought canvas back to his studio and laid it on the floor. After developing some process rules (think Sam Gilliam or Helen Frankenthaler) and considering ways he might begin, he noticed that the creases in the canvas where it had been folded formed a grid. The structure of a painted quilt soon revealed itself, and within each square Rojas drew scenes from childhood

and familial memories. On a subsequent visit to his family’s house in Tulsa, he found a tablecloth whose border matched the colors in the painting. Thinking formally, he cut off the tablecloth’s border and edged his painting with it. As Rojas recalled, “this collaborative act transformed the painting into a collective memory of family.” Furthermore, the trees painted throughout the work recall a bedtime prayer that his mother recited to him each night and provides the work’s title, which translates to “the guardian trees.”

If, for Rojas, collaboration is found in tradition, collective and personal memory, and through the partnership he strikes with a work’s physical materials, the genesis of Michael Palazzo’s turn to painting is collaboration through remembrance and commemoration. His current body of work is concerned with visual and corporeal experiences electrified through a discernably physical push and pull of vibrant, expressionistic color. Though abstract, Palazzo wants to make paintings people can relate to—that they can recognize and perhaps collaborate with in terms of their own experience. And so sunsets became a major inspiration for his recent body of work, though his sunset paintings are devoid of the saccharine sentimentality that often gives the genre a bad name.

Many of Palazzo’s canvases can be recognized as landscapes or skyscapes. Viewers might see pink clouds and what seems to be a mountainous landscape in Looking left while traveling through the event horizon, while other works like Attempting to touch the surface might capture the experience one could have if whizzing by or suspended within a changing sky.

Painting for Palazzo began in a meaningful way after his first year of college. After a traumatic loss, Palazzo says

18

CONTINUED PREVIEW

19 PREVIEW

ABOVE // Gabriel Rojas, Los Árboles Guardianes, 2022, acrylic, oil, fabric on raw canvas, 79" x 79"; RIGHT // Gabriel Rojas in his studio | Courtesy of the artist

that “I started to find myself again and it was through painting. It was like I couldn’t speak, but painting was doing it for me.” Though one might see evidence of Palazzo working though something deeply felt and personal, his work does not seem at all confessional. While remaining abstract formally, Palazzo’s works at Living Arts demonstrate a retrospective and reflective act of collaboration with memory, family, and love. When asked what he wants the exhibition’s visitors to walk away with, Palazzo replied, “deep pockets of silence where one can learn and grow.” One might assume Palazzo seeks to achieve the same through the act of painting.

Living Arts’ hosting of these two shows seems appropriate because the spirit of collaboration is alive and well at this nonprofit art space founded by a group of multidisciplinary artists in the 1970s. From its inception, Living Arts has been (and still is) a place for artists and the larger Tulsa community to experience and learn about art from an interdisciplinary perspective through the group’s presentation of exhibitions, films, workshops, lectures, performances, and direct community engagement.

Michael Palazzo and Gabriel Rojas’ concurrent solo exhibitions can be seen at Living Arts in Tulsa from January 1 through January 20.

Cassidy Petrazzi is an art historian, arts writer, and art enthusiast who works and lives in Tulsa with her husband, twin boys, and dachshund. She works as the director of operations at The Synagogue – Congregation B’Nai Emunah. Petrazzi received her MA in Art History from Oklahoma State University and her BFA in Expanded Media from Alfred University.

TOP LEFT // Michael Palazzo, Looking Left While Traveling Through the Event Horizon, 2022, oil and acrylic on raw canvas, 30" x 40"; MIDDLE // Michael Palazzo in his studio; BOTTOM // Michael Palazzo, Attempting to Touch the Surface, 2022, acrylic, oil, house paint, and aerosol on canvas, 36" x 36" | Courtesy of the artist.

21

ROCOCO REVISITED // YVETTE MAYORGA’S WHAT A TIME TO BE AT THE MOMENTARY

By Danny R.W. Baskin

Pink everywhere. It starts on paintings seemingly made of cake frosting and spreads like kudzu to the walls and sculptural installations scattered through the cavernous warehouse space of The Momentary in Bentonville, Arkansas. This old building, formerly a Kraft cheese factory, now houses a contemporary art and performance space across town from the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The Momentary opened in early 2020 as an offshoot of Crystal Bridges, a massive institution that showcases more than 200 years of American art history. With a top-floor bar that overlooks the small city and a beautifully terrazzo-covered coffee shop on the first floor, The Momentary functions as a hipper, more experimental space trying to cater to a younger audience. Walking up to the main doors, visitors are met by large glass and concrete expanses of grey tones. It’s cold and mechanical, industrial, in keeping with its factory character of decades before. But upon entering the current exhibition, Yvette Mayorga’s solo show What a Time To Be, the space becomes warmer, more welcoming, bubbling with joy and family and life.

Once the shock fades of moving from steel and rust to bubble-gum pink and baroque gold, viewers are left to examine Mayorga’s massive, intricate works that often depict the artist’s family members in poses plucked from Rococo-era paintings of royalty and wealth. These paintings, some around eight feet wide, are created by thick, intricate piping of acrylic paint that recalls the icing of lavish cakes or pastries, flattened and stretched out. The longer one looks, however, the more there is to discover. Mayorga’s use of 90s kid culture is what grabs me first: emojis and toy cars. Fake nails and sneakers.

Butterflies, Betty Boop, cell phones, and selfies. I move on to notice hidden objects scattered throughout the works: a photo of the earth on fire stuck onto a painted cell phone, or a Hello Kitty doll painted uniformly pink and blending into the background.

Zooming out, it takes longer to process the overall scenes themselves. While central figures lounge in classical bourgeois poses, the tableaux they inhabit are birthday parties and living room hangouts—relaxed moments from an unassuming childhood that feel familiar and nostalgic. These memories of childhood, some replete with white picket fences, showcase the middle-class American dream while the wealth and rampant excess depicted in them extend that dream. The hope for more, for everything, seeps outward in the form of classical vases, elaborate antique gowns, and tiered fountains. Tucked into a side gallery, one of the more spectacular installations is titled Bedroom After the 15th, a nearly full-size replica of a child’s bedroom with added whimsy and fantasy and covered in floor-to-ceiling pink, just like everything else. A bed, side table, laptop, and TV can be seen in the room, itself somewhat like a film set. Its wallpaper features faceless figures in 18th century garb, reminiscent of porcelain figures found at a thrift store, but scattered throughout this motif are cartoon eyes, wide open, perhaps taken directly from Daffy Duck after a big surprise. A playlist of popular hit songs from 25 years ago plays in the background. This is a fairytale space, a room that shows what little girls in 1990s America were told to want and often were not allowed to have. Femininity is showcased in full within the display, or at least a televised dream of femininity—the cartoonish

22 REGIONAL REVIEW

CONTINUED

23 REGIONAL REVIEW

Yvette Mayorga, Bedroom After the 15th, 2022, acrylic piping on Disney TV, purses, shoes, lotion, wooden shelves, lamp, ceramic, book bag, sneakers, Hello Kitty bubble blower, clock, faux books, mirrors, wood, pillows, wall paintings, nightstand, acrylic piping on bike, and acrylic piping on canvas | Danny R.W. Baskin

pink “girliness” that holds tight to so much of our society, almost plucked from a sitcom. There are fake eyelashes and elaborately framed hand mirrors hiding throughout the installation, seemingly referencing beauty standards placed onto children.

A sadness permeates this bedroom—so fake and uncomfortable with its sharp, 90-degree corners, yet relatable, familiar. As our generation currently grapples with breaking the bonds of gender binary, I cannot remove this conversation from the childhood bedroom on display. Nor can I ignore the truth that this kind of lavish femininity has historically not been allowed in museum spaces. In this way, the room and the exhibition as a whole can be read as a bold and decadent explosion of power and strength.

Within all of Mayorga’s work is the idea of wanting. From the exhibition’s first visible wall text, we learn that the artist is a first-generation Mexican American, whose family was often unable to afford what was considered by many the “standard” lifestyle of the American 90s dream—even if it was statistically far from standard. The

hope to belong is everywhere, as is the question of what it actually means to belong. Images of Mayorga’s actual family gatherings evoke happiness and acceptance while the baroque aesthetics surrounding them suggest an unattainableness. It’s art concerned with what it means to be a part and apart at the same time.

Yvette Mayorga’s What a Time To Be can be seen through May 21, 2023, at The Momentary in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Based in the Ozarks, DANNY R.W. BASKIN is an arts facilitator who has worked to write about, curate, and present art in contemporary galleries and museums throughout the region. He currently works as Museum Manager at the 21c Museum Hotel in Bentonville. Otherwise, Baskin is a furniture maker who focuses on historical craft, Judaica, and feasting traditions. He has a dog and four chickens.

24 REGIONAL REVIEW

Yvette Mayorga, Palma 2, 2022, fiberglass, wood, acrylic nails, sneakers, plastic nail charms, faux roses, collage, Astroturf, and acrylic piping | Danny R.W. Baskin

TOP LEFT // Yvette Mayorga, The Reenactment with Nike Air Jordans, After “The Last Supper”, 2022, acrylic nails, Nike shoes, false eyelashes, collage, plastic ring, plastic gummy bears, cherry nail rhinestones, rhinestones, car wrap vinyl, and acrylic piping on canvas | JS

BOTTOM LEFT // Yvette Mayorga, Digital collage study for The Reenactment with Nike Air Jordans, After “The Last Supper”, 2022 | JS

TOP RIGHT and BOTTOM RIGHT // Details of Yvette Mayorga, Bedroom After the 15th | JS and Danny R.W. Baskin

25 REGIONAL REVIEW

26 FEATURE

SYLVIE MAYER is an artist and teacher from Rhode Island, currently based in Oklahoma City. Her work focuses on moments of transition, processing grief, and contending with change. She received a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2018 and currently teaches painting and drawing at several locations around Oklahoma City.

Z. B. REEVES is a poet and writer whose work has appeared in Art Focus, Tulsa People , and Oklahoma Today, among others. He holds an MFA in creative writing from The New School and is currently editing a manuscript of poetry titled “Tender the Storm.” You can find him on Instagram and Twitter at @zbreeves.

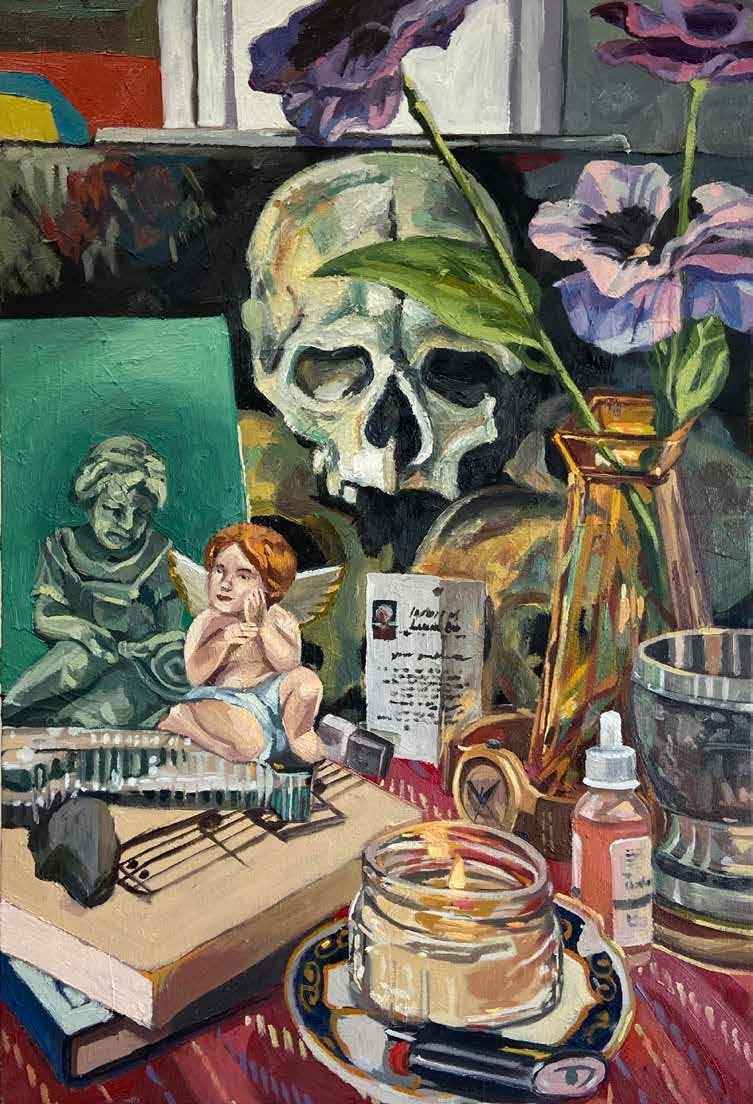

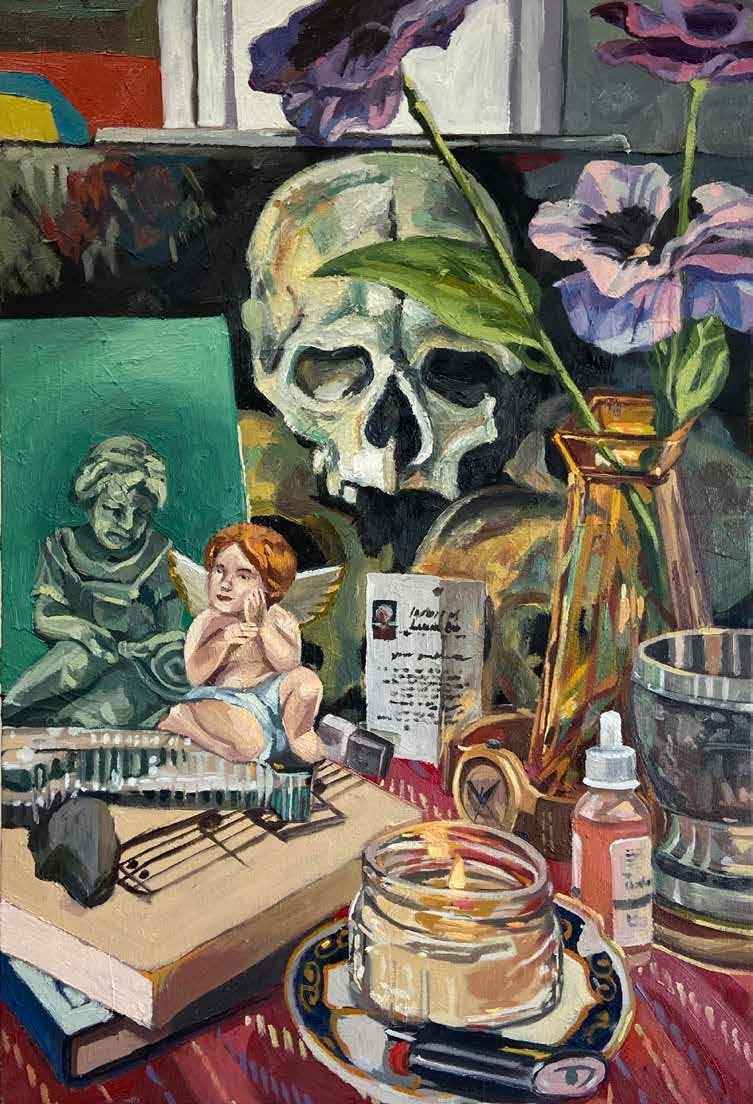

OPPOSITE // Sylvie Mayer, Vanitas (candle, lighter, #1 dad glass curio, rock, angel statue, child with snail statue, Cézanne, lactic acid serum, goblet, fake pansies, broken wooden watch with anchor), 2022, oil on canvas, 30" x 20"

EKPHRASIS

Edited by Liz Blood

Ekphrasis is an ongoing series joining verse and visual art. In each installment, a poet responds to an artist’s visual work.

Grandmother’s Living Room

By Z. B. Reeves

Above all I remember: being fed tomato soup and grilled cheese on white bread, Larry King and potpourri in the air as the grandfather clock strikes the hour—

between the words and lavender candles, the bowls with their saccharine hard candies— now, when no one’s looking, I sneak outside to wrestle with the angel in the night,

for even though my days of testament are numbered, my body knows it is meant for revelation; my body knows death is what even the best of us have left

as the angel breaks me upon the ground like bread is broken, like fragrance, unbound.

27

FEATURE

Rogers State University pursuing a Bachelor's degree in Studio Art. At RSU, they work at the campus gallery and previously had the opportunity to be a museum intern at the DACOR Bacon House Foundation in Washington, D.C. These experiences gave Fields insight that there is a whole world of art outside of just creating it. They discovered a passion for developing an environment where art can thrive. Putting artwork in places that will enhance its story, build relationships between other pieces, and keep spectators looking is something Fields finds special. As a working artist, they believe it's an honor to play such a unique role in how artwork is perceived and are excited to connect to the work on a different level than just viewing it.

SPOTLIGHT ARTISTS:

www.momentumoklahoma.org @ovac_ok Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition VISIT:

Nguyen "Happy Family Dish" colored pencil, 2022, 48’’x48"

Childers, "Spill the Tea", White Stoneware, Decal and Luster, 2022, 21”x18”x18”

Dixon "Agni", oil on canvas, 2022, 4'x3'

NINA NGUYEN MARISSA CHILDERS CHRISTIAN DIXON

Nina

Marissa

Christian

The Momentum exhibition features Oklahoma artists 30 and younger working in a variety of media

It’s been an incredible year at OVAC, and now we are looking forward to all 2023 has to offer—including new exhibition opportunities, the next cohort of the Oklahoma Art Writing and Curatorial Fellowship, Artist Survival Kit (ASK) training sessions as well as panels, workshops, and much more.

With the Winter 2023 issue of Art Focus, we are honored to welcome John Selvidge as our new guest editor. John brings more than 20 years of experience as a writer and editor and has written for a variety of media, genres, and publications, including several times for these pages since he became one of our Oklahoma Art Writing & Curatorial Fellows in 2018. We know you will enjoy the unique perspective he brings to the magazine. Welcome, John!

Soon enough, we will host Momentum 2023 March 10-12 at Sailor and the Dock in OKC, and we are excited to welcome Coka Treviño as the exhibition’s Guest Curator. Momentum’s Emerging Curator will be Bayliegh Fields, and this year’s Spotlight Artists are Nina Nguyen, Christian Dixon, and Marissa Childers. We hope you’ll join us as we feature over 100 works by dozens of emerging artists 30 years old and younger.

The 24 Works on Paper exhibition, featuring art by contemporary Oklahomans, travels to The Wigwam Gallery

in Altus January 16February 24. You can also view the works and learn more about the exhibition on OVAC’s website through educational videos from the artists that focus on experimentation and observation in art-making.

Kinslow, Executive Director

Upcoming ASK programs will explore topics like Non-Fungible Tokens (NFT’s) and their influence on digital art, how to prepare artwork for display, and simple packing methods for delivering your works as well as many more professional development opportunities designed to help artists succeed.

To keep up with OVAC’s latest news, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter—and if you want to know more about our upcoming programming or how to get involved, please visit our website at ovac-ok.org. Wishing you health, joy, and prosperity in the new year!

Warm Regards, Rebecca Kinslow, Executive Director

AND RENEWIN G MEMBERS

A Jeweler’s Art

Ashley Adams

Melody Allen

Marilyn Artus

Martha Avrett

Breannah Banks

Patricia Battese

Cheyenne Baughman

Rachel Benbrook

Andy Boatman

Karin Cermak

Jack Chapman Dayton Clark

Carlos Colin Alyssa Coogle

Mackenzie Cooper

Angela Cozby

April Dawes

Shyanne Kay Dickey

Julia DuBreuil

Liz Dueck

Elizabeth Eagleton

Chase Earles

Meagan Elferink

Oliver Ellington

James Epperson

Janene Evard

Jean Ann Fausser

Bayliegh Fields

Joey Frisillo Kaitlyn Graham

Tyler Griese

Martin Hallren

Christina Harmon

Suzanne Henthorn

Steve Hicks

Lydia Jeffries

Renee Jones

Kalee Jones

Izzi Kienzle

Jacquelyn Knapp

Alyona Kostina

Carley Laird

Amanda Lawrence

Tina Layman

Tim Long Harolyn Long

Heather Lunsford

Sylvie Mayer

Chelsea McConnell

Cortney McConnell

Nathan McCullough

Joseph McGlon III

Lisa McIlroy

Richard McKinstry

Madeline McMenamin

Madison Moody-Torres

Connie Moore

JP Morrison

Austin Navrkal

Donna Newsom

Nina Nga Nguyen

John O’Neal

Kirsten Olds

Dustin Oswald

George Oswalt

Erin Owen

Denise Paglio

Kim Pagonis

Brandon Pascua

Brittany Phelan

Larry Pickering

Catherine PinneyShrouder

Alexis Piper Alondra Resendiz

Kendall Ross

Judy Rudin

L.A. Scott Ashley Showalter

To join or renew your membership, visit ovac-ok.org/membership-form or call 405-879-2400, ex. 1.

Thomas Shupe

Janetta Smith

Kelly Smith

Krystal Solis

Sally Stites

Jennifer Thompson

Shel Wagner

Clara Wiebe

Therese Williams

Mahogany Woods

Summer Zah

SEPTEMBER

THROUGH NOVEMBER

29

MEMBERS NEW

2022

2022

OVAC NEWS OVAC NEWS

Rebecca

BECOME AN OKLAHOMA INSIDER.

Get events info and behind-the-scenes stories about Oklahoma’s food, travel, events, and culture sent to your inbox.

Sign up for Oklahoma Today’s newsletters at Newsletter.OklahomaToday.com.

30

organization to help take fundraising to the next level. Take donations online, over the phone, via ACH, or in person.

Heartland has full service solutions for your charity or nonprofit organization to help take fundraising to the next level. Take donations online, over the phone, via ACH, or in person.

Discover what Heartland can do for you.

Are you ready to take the next step?

Heartland has full service solutions for your charity or nonpro organization to help take fundraising to the next level. Take donations online, over the phone, via ACH, or in person.

Discover what Heartland can do for you.

take fundraising over the phone, CREATE, COLLABORATE, COMMISERATE Two Art Galleries | Gift Shop | Photography Studio 10 Artists’ Studios | Art Workshops 3024 Paseo, Oklahoma City, OK 73103 thepaseo.org/PACC 405.525.2688 Tues-Fri 11am-5pm Sat Noon-5pm

ἔξοδος exodus an examination of a church experience Mel Hamilton January 13 - February 3, 2023 Gallery Hours: Thurs 5-8pm and Sat 1-5pm and by appointment Opening Reception Friday, January 13, 5-8pm 314 S Kenosha Ave, Tulsa, OK 918.694.5719 LiggettStudio.com/exodus

Liggett Studio presents paintings and conceptual art by

Heartland REGIONAL REVIEW

Non Profit Org. US POSTAGE P A I D Oklahoma City, OK Permit No. 113 1720 N Shartel Ave, Suite B Oklahoma City, OK 73103 Visit ovac-ok.org to learn more. 1/12 Photo Studio 1/15 Grants for Artists Application Closes 1/16 - 24 Works on Paper 2/24 The Wigwam Gallery in Altus 1/28 ASK Workshop: Exhibition Ready 3/10- Momentum 2023 Exhibition 3/12 3/30 ASK Workshop: Demystifying NFT’s UPCOMING EVENTS //