About Island Press

Since 1984, the nonprofit organization Island Press has been stimulating, shaping, and communicating ideas that are essential for solving environmental problems worldwide. With more than 1,000 titles in print and some 30 new releases each year, we are the nation’s leading publisher on environmental issues. We identify innovative thinkers and emerging trends in the environmental field. We work with world-renowned experts and authors to develop cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental challenges.

Island Press designs and executes educational campaigns, in conjunction with our authors, to communicate their critical messages in print, in person, and online using the latest technologies, innovative programs, and the media. Our goal is to reach targeted audiences—scientists, policy makers, environmental advocates, urban planners, the media, and concerned citizens—with information that can be used to create the framework for long-term ecological health and human well-being.

Island Press gratefully acknowledges major support from The Bobolink Foundation, Caldera Foundation, The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, The Forrest C. and Frances H. Lattner Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The Summit Charitable Foundation, Inc., and many other generous organizations and individuals.

The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters.

Island Press’s mission is to provide the best ideas and information to those seeking to understand and protect the environment and create solutions to its complex problems. Click here to get our newsletter for the latest news on authors, events, and free book giveaways.

Also by Lorraine Johnson (A Selected List)

100 Easy-to-Grow Native Plants for American Gardens in Temperate Zones

Grow Wild! Low Maintenance, Sure Success, Distinctive Gardening with Native Plants

Tending the Earth: A Gardener’s Manifesto

City Farmer: Adventures in Urban Food Growing

The Real Dirt: The Complete Guide to Backyard, Balcony and Apartment Composting (co-authored with Mark Cullen)

Green Future: How to Make a World of Difference

The Natural Treasures of Carolinian Canada [ed.]

The Ontario Naturalized Garden

The New Ontario Naturalized Garden

Also by Sheila Colla

Bumble Bees of North America: An Identification Guide by Paul H. Williams, Robbin W. Thorp, Leif L. Richardson, and Sheila R. Colla

Also illustrated by Ann Sanderson

Canada’s Arctic Marine Atlas

Bees of Toronto: A Guide to Their Remarkable World

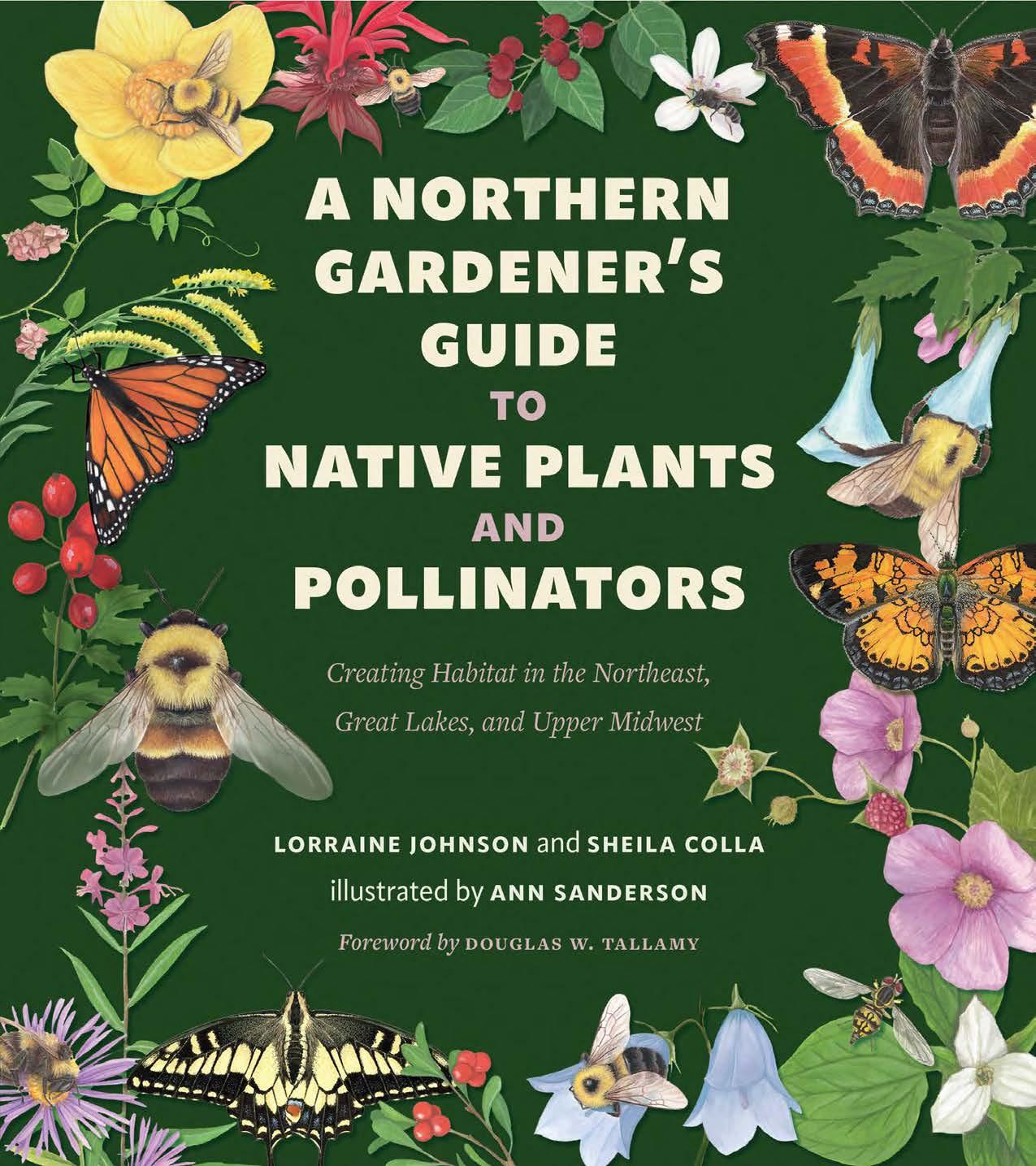

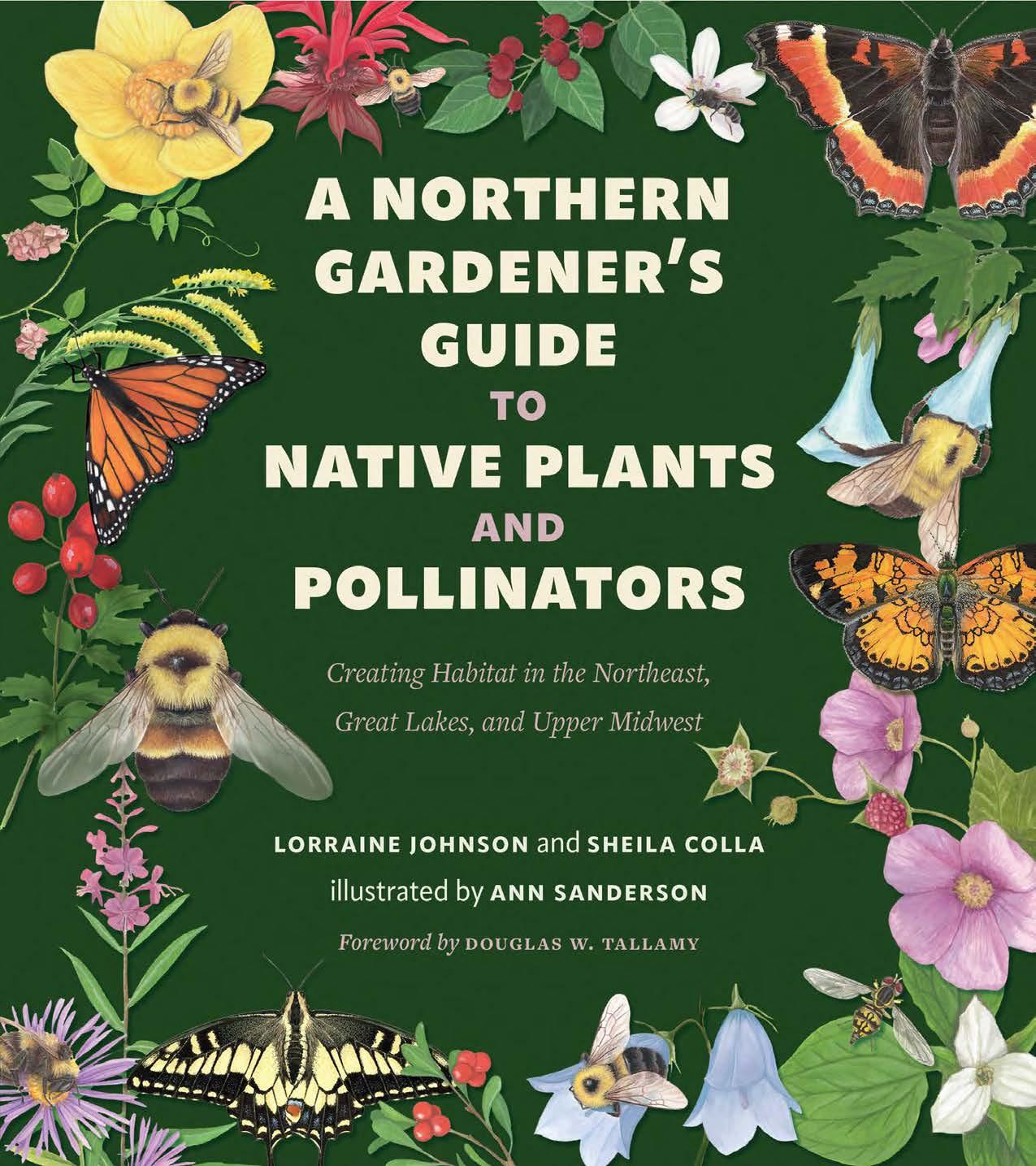

N G A rde N er’s Guide to N Ative Pl AN ts and Polli NAt ors

Creating Habitat in the Northeast, Great Lakes, and Upper Midwest

Lorraine Johnson & s hei L a C o LL a

Illustrations by a nn s anders on Foreword by Douglas W. Tallamy

A Norther

Text Copyright © 2023

Lorraine Johnson & Sheila Colla

Illustrations Copyright © 2023 Ann Sanderson

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 480-B, Washington, DC 20036-3319.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022948612

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Book interior design and layout by Libris Simas Ferraz.

Keywords: blooming periods, climate change, community gardens, conservation, container gardening, ecological diversity, endangered pollinators, flowering plants, garden designs, native grasses, rain and pond gardens, regenerating habitat, rusty-patched bumblebee

Douglas Tallamy vii

Contents Foreword By

introduCtion Pollinators Bring Life 1 1 The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators 2 A Primer on the Pollination of Flowering Plants 5 The Scoop on Honeybees 8 2 Native Plants Matter 1 2 Native Plants 14 But Don’t Non-Native Plants Attract Pollinators, Too? 15 All Green Is Not Green! 17 What About Cultivars of Native Plants? 18 Where to Find Native Plants 20 The Climate Change Connection 22 Diversity, Diversity, Diversity 23 3 Starting Your Garden for Native Pollinators 2 4 Site Preparation 24 Designing Your Pollinator Patch 27 Native Plants for Containers 29 Turning Lawns into Gardens 30 Planting Your Patch 31 Maintaining Your Patch 31 Native Herbaceous Plants for Pollen Specialists 35 As Your Garden Grows 36 Adding Native Plants to an Existing Garden Bed 36 From Plants…to Plant Communities 39 Beyond the Patch 40 Nesting Sites and Overwintering Habitat for Native Bees 44 Checklist for Creating a Pollinator-Friendly Yard and Garden 45

4 Profiles of Native Plants 46 Spring-Blooming Native Plants 48 Summer-Blooming Native Plants 88 Fall-Blooming Native Plants 148 Native Grasses and Sedges 150 Trees, Shrubs and Woody Vines 162 Rain Gardens 224 Pond and Bog Gardens 225 Ask for Me—and Grow the Native Plant Movement 226 Boulevard (a.k.a. “hell-strip”) Gardens 228 Concerns…and Reassurances 229 Great Combinations of Native Perennials for a Pollinator-Friendly Garden 231 5 Sample Garden Designs 2 35 Balcony Garden 235 Community Garden 236 Public Patch 237 High-Density Residential 238 Residential Garden 239 6 Resources 241 Native Plant Ranges 241 Native Plant Groups 242 Native Plant Nurseries 243 Selected Books 243 Acknowledgments 245 Index 246 About the Authors 256

Confusing bumblebee (Bombus perplexus) and marsh marigold (Caltha palustris)

By Douglas Tallamy

You’ve all heard the expression “What happens in vegas staYs in vegas.” But this does not apply to our yards! From an ecological perspective, what happens in our yards does not stay in our yards. Everything we plant, or don’t plant, or apply to our yards, impacts the greater ecosystem and everything that depends on the ecosystem around us. For example, when we plant invasive plants, we are harboring ecological tumors whose offspring escape our landscapes, impacting our neighbors and the surrounding natural spaces. By pushing out the native plants that run our local ecosystems, invasive ornamentals drastically and negatively affect the ability of those ecosystems to supply the life support on which we all depend. When we manicure acres of lawn, we diminish the ability of that land to reduce stormwater runoff, compromising the watershed of everyone in the immediate area, as well as that of communities tens or hundreds of miles downstream. Large swaths of lawn also waste an opportunity to fight climate change; filling our yards with turf grass species notorious for their inability to sequester carbon is a lost opportunity— made worse every time we mow, which adds carbon to the atmosphere. “Lawn care” also pollutes local waterways with the fertilizers and pesticides we routinely apply to grass, and when we overuse turf grass, we eschew our responsibility to support the food web that supports local animals. Finally, what prompts me to invoke the Vegas metaphor here is that our plant choices, both in terms of species and amounts, determine how well our landscapes support the diverse communities of native bees required to pollinate the plants that comprise high-functioning ecosystems.

I shudder every time I hear the media justify concern for bees by claiming they pollinate one-third of our crops. May Berenbaum, Chair of the Department of Entomology at the University of Illinois and one of the most respected entomologists in the country, recently wondered where the one-third statistic came from. After considerable sleuthing, May was unable to track down any study that supports the one-third claim. So she made her own estimates. By Dr. Berenbaum’s calculations, only one-seventh of our crops depend on animal pollination, and in the typical American diet, which is based heavily on corn and wheat (both wind-pollinated crops), only one-twelfth of our crops are pollinator-dependent.

What bothers me, though, is not that the media has inflated the importance of pollinators to agriculture, but that they imply that the only value of species such as pollinators is how they directly serve humans. That level of anthropocentrism misses the real impact of pollinators, not just on humans but on most other earthlings as well. Regardless of their importance to our crops, pollinators are essential

vii

Foreword

to life as we know it: they pollinate 80 percent of all plants and 90 percent of all flowering plants, the very plants that turn the sun’s energy into the food that supports all animal life on terrestrial earth. If we recklessly landscape in ways that do not support pollinators, we will lose the species that support 80 to 90 percent of all plant species. That is not even close to an option if we humans plan to continue inhabiting Planet Earth.

Fortunately, the Las Vegas metaphor works both ways. The way we landscape our yards can just as easily export ecological benefits instead of costs. We can liberally use plants that support the highest numbers of species of pollinators, both specialists and generalists, as well as the caterpillars, grasshoppers, and other insects that feed our hungry birds. We can reduce our lawn to cover only the areas on which we regularly walk, or in strips that serve as cues for care, demonstrating to our neighbors that we are actively and purposefully gardening, even if our aesthetic choices are not mainstream.

We can add dense plantings of woody and herbaceous plants that hold rainwater on site and sequester tons of carbon while doing so, and we can control mosquitoes with benign biocontrol of larvae rather than through the wide-scale carnage wrought by mosquito fogging.

Private landowners hold enormous conservation potential because there are so many of them. In the United States, 135 million acres are now in residential landscapes. The good news is that hundreds of millions of people live in, and thus manage, those landscapes. With a little education, all of us can come to realize that sustainable earth stewardship is not something we can ignore or practice only if we feel like it. It is essential. And the care of life around us is a responsibility we all hold. I say that with certainty, because each one us depends on the quality of local ecosystems for our continued well-being. Landscaping in ways that eliminate nature is a fool’s errand, and we can do better. And that is what Lorraine and Sheila will help you do. Protecting and enhancing pollinator populations is one of the best ways to ensure our future, and the future of the life around us. There is no better resource for this noble task than the book you now hold.

viii Foreword

Rusty-patched bumblebee (Bombus affinis)

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

native, or “ Wild” Bees—that is, Bees that occur naturallY Within a region— are some of the most misunderstood creatures around. Popular misconceptions are that they all make honey, they’re all black and yellow, they all sting and they all live in hives. But the majority of the region’s native bees don’t live in hives (they are solitary), are not black and yellow (they are a variety of colors, including blue and green!), do not sting—and none of them make honey. There are more than 4,000 different bee species in North America. Types of native bees include bumblebees, sweat bees, mining bees, cuckoo bees, leafcutter bees and cellophane bees, among others. And there are more to discover. In 2007, bee expert John Ascher found a species—in New York City—that had never before been described to science: Lasioglossum gotham. Consider that for a moment: a bee species found…in the middle of the largest city in the country…described to science and named for the first time…just over a decade ago. Urban habitats are, in many ways, quite hospitable for bees, with a diversity of plants for nectar and pollen and an array of habitats for nesting, mating and shelter. Anywhere we live can provide habitat, whether it’s in a big city, a small town or a suburb or on a farm. But some species of native bees are in trouble. Take the rusty-patched bumblebee, for example. As recently as the 1980s, it was abundant—one of the most common bumblebee species in its range. Its extensive historical range spans from the eastern United States west to the Dakotas, north to southern Ontario and south to Georgia. However, by the early 2000s, it had all but disappeared from Canada and much of the United States.

The rusty-patched bumblebee had the unfortunate distinction of being the first native bee to be officially designated as e ndangered in both the United States and Canada. One of the authors of this book, Sheila Colla, was the last person in Canada to identify this bee in the wild, in 2009, by the side of a road in Pinery Provincial Park. Sheila had spent every summer since 2005 searching for the rusty-patched bumblebee in places where they had previously been recorded. On that summer day in 2009, she had found none and was on her way out of the park when, from the passenger window of the car, she

2 1

Rusty-patched bumblebee (Bombus affinis)

spotted the distinctive rusty patch of a lone specimen. This sighting was the last known in Canada. The causes of this bee’s rapid and catastrophic decline have not yet been confirmed, but speculation centers on several negative factors: loss and fragmentation of habitat, including nesting and foraging opportunities; disease and competition from non-native honeybees and managed bumblebees in greenhouse and field crops; pesticides; and climate change. Given the dramatic speed and geographic extent of bee loss, conservation scientists believe a new disease brought in by managed bees is the main driver of decline. In the United States, some recent populations have been found in the Midwest and in the Appalachians, but the species seems to have declined from most of the northeastern and central parts of its historic range. The widespread loss of a formerly common species is a phenomenon echoing around the world. In Europe, approximately half of bumblebee species are in

Planting gardens full of a diverse range of native plants helps to support pollinators throughout their life cycle. © Mathis

Natvik

Natvik

3

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Rusty-patched bumblebee (Bombus affinis) and common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca)

This community pollinator garden in a public park was designed and built by volunteers from the group Blooming Boulevards. Resilient native plants such as asters and goldenrods, planted in raised beds, flourish in this public site.

What Pollinators Need

• Areas with diverse flowering plants, from spring to fall, with accessible pollen and nectar

• Plants on which to lay their eggs, or nesting areas in which to lay their eggs

• Areas that are free of pesticides

• Patches of bare ground in which to burrow and build their nests

• A diverse array of plant and landscape features, such as rocks, dead wood, dead stems, leaves, mud, oils and resins that support the various habitat and nesting needs of diverse pollinator species

decline, and only a few are increasing. Of the 25 known bumblebee species in the United Kingdom, three are considered extinct, and at least seven have undergone significant declines. In North America, IUCN Red List assessments suggest at least one-quarter of the 46 native bumblebee species are at risk of extinction. For example, the relative abundance of the American bumblebee, a once-common species, has fallen dramatically—by 89 percent between 2007–2016 and 1907–2006. Other once-common bee species now rarely seen through much of their historic ranges

4

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

© Jeanne McRight

in the United States and Canada include the yellow-banded bumblebee, the yellow bumblebee and the bohemian cuckoo bumblebee. Reversing this trend, and ensuring that common species remain common, will take committed action at all levels of government and by everyone. And one important place for individuals to start is by creating and regenerating habitat gardens—connected landscapes full of diverse native plants known to provide nectar, pollen and habitat for native bees, maintained using practices that support the pollinators necessary for all life on Earth.

A Primer on the Pollination of Flowering Plants

For many flowering plants to reproduce, pollen (the plant equivalent of sperm) must move from the “male” part to the “female” part of the flower. Some plants have the male and female parts within the same flower; some have separate male flowers and female flowers on the same plant; and some have male flowers and female flowers on separate plants entirely. Some can fertilize themselves, while others need another mate nearby for cross-pollination. Some plants that have both male and female flowers on the same plant have features that ensure cross-pollination (for example, the females are receptive to pollen only

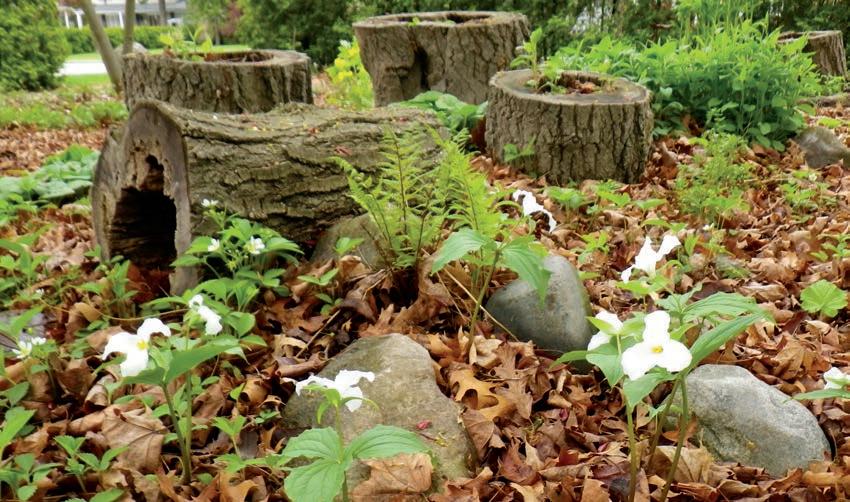

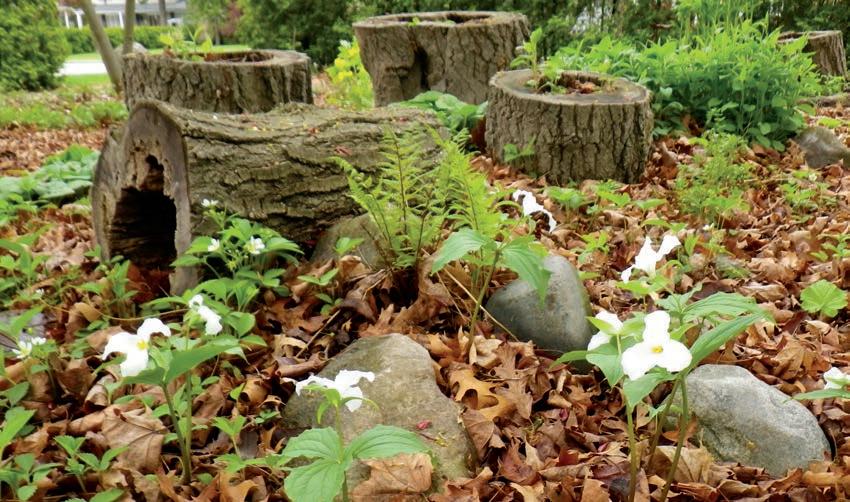

Pollinators need habitat. A diversity of native plants and natural features such as old logs, dead leaves and rocks ensure that gardens support the insects that support all life. This woodland planting restores and celebrates engagement with the natural world of which we are a part and the relationships between all creatures. © Shawn

McKnight, Return the Landscape

McKnight, Return the Landscape

5

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Lemon cuckoo bumblebee (Bombus citrinus) and fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium)

Buzz Pollination

Bumblebees, along with some mining, sweat and leafcutter bees, practice buzz pollination. Inserting its head into a flower and grasping the anthers (the part of the flower that contains pollen), or simply holding on to parts of the flower, the bee vibrates its flight muscles and shakes the pollen free. In this way, buzz pollination is a very efficient and effective way for bees to release large amounts of pollen from flowers, which have evolved to ensure that their preferred pollinator accesses their flowers. The native lowbush blueberry is an example of a plant that has evolved this system and depends on native insects capable of buzz pollination in order to release its pollen. Honeybees are used in industrial agriculture to pollinate crops, but in addition to blueberries there are many foods, such as tomatoes, melons, squashes, apples, cranberries, eggplants and peppers, that are best (and, in some cases, only) pollinated by native bumblebees and other types of bees, not honeybees.

after the males have already released their pollen). In other words, there’s lots of variation and specificity.

When fertilized, the female part produces fruits or nuts containing seeds, which, after dispersal, germinate to produce new plants.

Some plants (conifers and grasses, for example) are wind-pollinated—that is, the pollen moves from the male part to the female part by wind. The pollen-like structures in moss may be transferred in water. But most plants—approximately 80 percent—have pollen that is transported by animal pollinators, including insects, hummingbirds, bats and others.

Bees are the main pollinators of many flowering plants in North America and other temperate regions, though wasps, flies, beetles, hummingbirds, butterflies and moths are also pollinators. The pollination “services” that insects provide are in fact a by-product of an entirely different intention. These insects are visiting flowers most often to feed on nectar and pollen (though sometimes, they may be collecting resin or scents to attract mates) and, in the process, pollen sticks to their bodies and is transferred to other plants they visit. It is important to note that diverse wild bee communities are more efficient and effective pollinators than non-native honeybees, due to native bees’ hairiness and often electrostatic charges. As well, native bees exhibit a trait known as floral constancy, which means that they tend to repeatedly visit a particular species of plant on their individual foraging trips and, hence, efficiently cross-pollinate that species.

6

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Allergic to Stings?

Only female bees are capable of stinging. Native bees rarely sting humans—non-native species of wasps are usually the culprits. However, bumblebees and non-native honeybees will sting if they are trapped or stepped on or if their nest is disturbed. When bees are foraging in flowers, it’s safe to enjoy watching them without fear.

If you are allergic to bee stings, you can still create a pollinator garden. Simply exercise caution around bees, the majority of which are gentle creatures that aren’t capable of stinging.

Most native wasp species are solitary and specialize on certain insect prey. You likely have not even noticed them, as they tend to stay away from humans.

There’s lots in the news about “Africanized honeybees” (a hybrid, non-native species) and “murder hornets” (an introduced species). Africanized honeybees are in a few US southern states and murder hornets have been found on the west coast—so there’s no need to fear being stung by them in the northeast, Midwest or Great Lakes regions.

Although some male bees feed on pollen, it is only the female bee that gathers pollen in order to take it back to provision her nest, where she lays her eggs and where the developing larvae will feed on the pollen. Many female bees have a “pollen basket” on their hind legs, abdomens or stomachs in which they store pollen before transporting it back to the nest. If you watch bees closely, you’ll be able to see, without need of a magnifying device, pollen grains on their bodies, giving them a colorful glow. Female bees mix pollen and nectar into a loaf called “bee bread,” which the larval bees eat.

While a particular bee species might depend on the pollen of a particular plant species, genus or family, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the plants themselves depend on that bee species for pollination. Other, generalist bee species (polylectic bees)—those that collect pollen from a broad range of species—can also pollinate the plant.

Bees utilize a wider variety of plant species for nectar than they do for pollen. However, the physical traits of various bee species (the length of their

7

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Black and gold bumblebee (Bombus auricomus) and apple (Malus domestica)

The Native Ecology Learning Garden at the Equinox Holistic Alternative and Roden Public schools (shown here before and after planting) is a place where students, staff and parents build their relationships with the land and give back to the earth. Planted by students and tended by families and neighbors, the garden helps to create a sense of community centered around experiences with nature and natural processes.

© Carrie Klassen

© Carrie Klassen

mouthparts, for example) do affect their ability to extract nectar from certain flower shapes, such as deep flowers.

The Scoop on Honeybees

There’s lots in the news about the loss of honeybees, Colony Collapse Disorder, Varroa mites and the dire consequences for the food we eat. Industrial agriculture— the system of large, mechanized monoculture farms—depends on the pollination services of non-native and managed honeybees, trucked long distances across the continent to pollinate crops.

When we hear about the mysterious deaths of honeybee colonies from unknown causes, a trend that shows no signs of abating, it’s easy to feel that we are in the midst of a crisis. And we are.

We need to find out why honeybees are dying—to continue to investigate what is wrong with our industrial agriculture system and any other factors that are causing honeybee colonies to die in massive numbers—but it’s important to note that honeybees are not an endangered species at risk of extinction. They are among the most common species in the world, introduced to many countries outside of their natural ranges. (There are no native honeybee species in North America.) When a honeybee colony dies, a new colony can be started with a new queen, readily available for purchase. This does not diminish the seriousness of

8

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Attracting Pollinators

Plants have evolved to attract pollinators in a number of different ways. Some plants have bright-colored flowers. Some have landing platforms. Still others produce fragrance, in effect advertising their nectar reward to insect visitors. Some plants have nectar guides—radiating lines, for example—that direct insects to the nectar source. These guides may be visible to the human eye or, in some cases, are visible only to bees, flies or other insects that can see color in the ultraviolet spectrum.

honeybee deaths, the economic consequences of honeybee deaths for the industrial agriculture system or the beekeeper, or the impacts on the bees themselves and their genetic diversity and conservation where they are native.

However, the focus on managed honeybee hive losses has eclipsed the fact that m any native bees, such as the rustypatched bumblebee, the American bumblebee, the yellow-banded bumblebee, the Macropis cuckoo bee and othe rs, are in serious trouble. And when native bees disappear, they disappear forever.

There has been a lot of interest in keeping honeybee hives as a way to help pollinators. However, starting a honeybee hive does not help save wild bees any more than keeping backyard hens helps save wild birds, or throwing non-native invasive carp into one of the Great Lakes will help native fish populations. A growing body of science documents that non-native honeybees are negatively affecting native bees. Current research finds that increases in honeybee foraging adversely

9

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Fernald’s cuckoo bumblebee (Bombus flavidus) and aster (Symphyotrichum sp.)

Native bees, in all their diversity, are the main pollinators in this region, but other insects including flies, wasps, butterflies (such as Milbert’s tortoiseshell, shown here), moths and beetles are also pollinators, as are hummingbirds.

Syrphid flies not only pollinate plants when they visit flowers for pollen and nectar, but the larvae of many syrphid species also control aphids and other softbodied insects considered to be agricultural pests. The eastern calligrapher fly (shown here), like many syrphids, is a bee and wasp mimic, but without a stinger.

The Benefits of Insects

For too long, many gardeners have treated all insects as “foe” rather than friend. And yet the majority of insects that visit plants in your garden are beneficial, carrying out important, useful functions that contribute to ecological health. Pollination is one obvious, crucial “service,” but there are many others, some we are only at the beginning stages of understanding. For example, syrphid flies (hoverflies, a.k .a. flower flies) actually control pests in the garden: adults lay their eggs on plants with aphids, and then when the syrphid fly egg hatches, the developing caterpillar-like maggot kills the aphids, sucking them dry. Other pest-controlling insects—tachinid flies and some types of wasps—are parasitic, laying their eggs directly inside aphids and caterpillars. The eggs hatch into larvae that eat and kill their hosts. Creating a habitat garden that welcomes pollinators will ensure that you are participating in the natural cycles that keep ecosystems in balance.

Yellow bumblebee (Bombus fervidus) and blue flag iris (Iris versicolor)

impact native bumblebee foraging and that native bumblebees are not as likely to return to a foraging site for a second time if honeybees are competing for floral resources at the site. Some research even suggests that the presence of honeybees negatively affects the reproductive and developmental success of native bees. As well, there is concern that diseases and pests of managed honeybees are spreading to native wild bees, and new exotic diseases might be introduced to native species that have not co-evolved with them. A 2019 study found that two viruses infecting honeybees are transferring to wild bumblebees, particularly those bumblebees foraging near apiaries. The research suggests that honeybees shed the viruses on flowers while foraging, and that the pathogens are then picked up by wild bees. Ironically, the flowers become “hotspots for disease transmission,” as the study puts it. As well, honeybees can “taxi” diseases that infect wild bees, hoverflies and other insects, potentially leading to drastic declines, such as

10

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Wasps

Wasps are important pollinators, though they are less well studied than bees. While a few species, such as yel low jackets and paper wasps, are familiar, the diversity of wasp species is much less well known, perhaps because they tend to avoid human contact. Wasps are predators (feeding on insects and spiders) and parasitoids (laying their eggs in or on their prey). As adults, wasps visit plants to feed on nectar, fruit and sap and, less often, on pollen. Like bees, the habitat requirements of solitary wasps include nesting sites below ground, in vegetation, in cavities, under rocks. Wasps have floral preferences and many have specific relationships with a narrow range of prey species. These relationships demonstrate fascinating webs of connection and symbiosis. For example, not only do wasps protect plants from herbivorous insects (by consuming them!), but wasps are rewarded by some plant species for this pest-control service: some plants with extrafloral nectaries (away from the flower) produce more nectar in these nectaries when they’re being eaten by caterpillars, and this attracts wasps, which in turn eat the caterpillars. Your habitat garden will support the crucial role that wasps have within ecosystems. To learn more about these diverse and fascinating, under-appreciated insects, Heather Holm’s book Wasps is fantastic, as are the fact sheets on her website, www.pollinatorsnativeplants.com.

The relationships between species are complex, fascinating and unique. Ichneumonid wasps, such as the Megarhyssa species shown here, use their long ovipositors to lay their eggs into their host (horntails, a treeburrowing and -eating sawfly), which the wasps can detect through the bark of trees!

we saw with the rusty-patched bumblebee. On the plant side of things, honeybees might pollinate introduced, weedy species they’ve co-evolved with and disrupt the native pollinator-plant relationships of native species. Although the peer-reviewed literature is clear, it is poorly studied in situ; hence, there are knowledge gaps in this growing field of study. However, following the precautionary principle, we recommend that if you want to help native bees and protect endangered pollinators, instead of starting an urban honeybee hive, plant native plants and create habitat in your yard, on your balcony, on the grounds of your apartment building or in a public space such as a community garden, local school or boulevard.

11

The Rusty-Patched Bumblebee and Other Native Pollinators

Natvik

Natvik

McKnight, Return the Landscape

McKnight, Return the Landscape

© Carrie Klassen

© Carrie Klassen