A Concordia Seminary St. Louis Publication

Editorials Editor’s Note Erik H. Herrmann 5 An Exegetical Note Jeffrey Gibbs 7 An Extraordinary Way to Honor a Pastor James Brauer 12 Articles Translation and Syncretism Douglas L. Rutt 17 Translation Principles and Lessions for Translatros Vilson Scholz 31 Reading the Bible with Spiritists William D. Miller 39 Homiletical Helps Anatomy of a Sermon Sermon on Job 19:18–25 by Timothy Saleska Erik Herrmann 55 Reviews Featured Review T&T Clark Introduction to Spirit Christology By Leopoldo A. Sánchez M. 65 Volume 49 Number 2

Publisher

Thomas J. Egger

President

Executive Editor

Erik Herrmann

Dean of Theological Research and Publication

Editor

Melanie Appelbaum

Managing Editor of Theological Publications

Manager, Creative Operations

Beth Hasek

Graphic Designer

XiaoPei Chen

Faculty

David Adams

Charles Arand

Abjar Bahkou

Joel Biermann

Gerhard Bode

Kent Burreson

Timothy Dost

Thomas Egger

Joel Elowsky

Kevin Golden

Benjamin Haupt

Erik Herrmann

David Lewis

Richard Marrs

David Maxwell

Ronald Mudge

Peter Nafzger

Glenn Nielsen

Joel Okamoto

Jeffrey Oschwald

Philip Penhallegon

David Peter

Ely Prieto

Paul Robinson

Mark Rockenbach

Douglas Rutt

Timothy Saleska

Leopoldo Sánchez M.

David Schmitt

Bruce Schuchard

William Schumacher

Mark Seifrid

W. Mart Thompson

Jon Vieker

James Voelz

Exclusive subscriber digital access via ATLAS to Concordia Journal & Concordia Theology Monthly

http://search.ebscohost.com

User ID: ATL0102231ps

Password: concordia*sub1

Technical problems?

Email: support@atla.com

cj@csl.edu

correspondence should be sent to: CONCORDIA JOURNAL 801 Seminary Place St. Louis, Missouri 63105 314-505-7117

All

The fifty days of Easter have come and gone but Pentecost continues on. That’s not simply a liturgical observation about the church year. The Holy Spirit, who was so lavishly poured out on that first Pentecost, continues to fill God’s people with the comfort of his presence, the manifold gifts of Christ’s life, and the hope of an everlasting life in God’s bright and eternal country. The Spirit urges the church, leads it out into the world, and through it bears witness to the truth.

The work of the Holy Spirit in the life of the church is as manifold as his gifts. Our own professor Leopoldo Sánchez offered some beautiful reflections on the work of the Spirit in our individual lives in his book Sculptor Spirit (IVP, 2019). Sometimes descriptions of personal sanctification—being made holy—can remain a little abstract. Sánchez helpfully looks at the concrete and particular ways that the Spirit empowered and was active in Christ’s own life and ministry and then extends those themes to the Christian life. The things that Jesus “began to do and teach,” as Luke describes the subject matter of his Gospel, is ongoing through the work of the Holy Spirit in the lives of those who belong to Christ.

Of all the Spirit’s work, it is especially his presence in and through his word that stirs the life of the church—”nowhere [is the Spirit] more present and more active in than the holy letters themselves, which he has written.” (WA 7, 97, 2–3). By this word the church is made holy—“sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth” (Jn 17:17). The Spirit made known this truth at Pentecost in a profusion of languages; likewise, the church devotes itself to bring the truth of God’s word into every tongue and dialect, trusting that this same Spirit speaks and is active to “call, gather, and enlighten.”

Martin Luther believed this wholeheartedly and so he centered his entire reforming efforts toward the bringing of God’s word to his own people, in their own language. Luther’s translation of the Bible into German is one of the great literary and cultural achievements of western history, but for the life of the church it was a gift of God. Last fall we marked the 500th anniversary of his translation of the New Testament with an evening lecture on the significance of Luther’s translation and the work of biblical translation in general. One of the lectures was given by Dr. Vilson Scholz, visiting professor of exegetical theology from Seminario Concordia in Brazil and long-time translation consultant for the United Bible Society. We publish here his reflections on Luther’s approach to translation, which interacts both with the

Editorials 5

Editor’s Note

contemporary schools of translation and the theological conviction that God does indeed speak his word through every language.

Belief that the Spirit takes up human speech and language to communicate the gospel to all people, however, does not make the task of translation easy or simple. Human language and culture are not neutral vehicles but are shaped by myriad experiences, traditions, and Weltanschauungen. In his article, “Translation and Syncretism,” Dr. Douglas Rutt enters into the challenges that emerge when language is also embedded with theological and religious ideas that distort or undermine the Christian message. Bringing his own missiological experience and expertise to bear on the question, Rutt argues that translating God’s word into a people group’s “heart language” remains the goal: “the ability to communicate the message of the wonders of God so that it ‘cuts to the heart,’ in other words, it reaches the heart of a hearer, mandates translation of God’s word to the ‘heart languages’ of people.”

Taking up the challenge of contextualization along with the various approaches to translation—literal, dynamic equivalent, and functionalist—Rutt weighs the strengths and pitfalls of each for the purpose of faithfully conveying the message of the gospel.

Syncretism and accommodation is the context of our third article, by Dr. William Miller, pastor at Faith Lutheran Church in Lincoln, Nebraska. Based on his doctoral research, Miller introduces us to Brazilian Spiritism, especially as it was developed and systematized by the nineteenth-century French educator, Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail, writing under the name Allan Kardec. Both a Christian heresy and a philosophical/religious movement, Spiritism argues both for its continuity with the Bible and for additional sources of theological authority in experience, science, and mediumship. In this article, Miller examines its more popular elements, especially the operative assumptions and methods for how the Bible is cited and read to support the Spiritist doctrine.

As we continue to witness this season the greening and growth of the natural world around us, let us also be grateful for the emergence of our own green season, the growth and fruit that the Spirit awakens and cultivates in us. His work is an eternal work for our eternal spring.

Erik H. Herrmann Dean of Theological Research and Publications

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 6

An Exegetical Note

Precious or Costly? What is the death of his people in God’s sight?

(Psalm 116:15)

Some time ago, I realized that I didn’t know what Psalm 116:15 meant. The ESV’s translation is the standard one: “Precious in the sight of the LORD is the death of his saints.” You see this verse offered to express Christian sympathy and support at the death of a believer. It popped up on Facebook, I heard it in person, I saw it in writing.

I did not know, however, what the verse meant. On the face of it and apart from any context, Psalm 116:15 seems to say that God looks with approval when his saints die. (“Saints” is the plural of with 3 ms pronominal suffix, “his faithful ones, his devout ones.”)1 Read in isolation, the statement indicates that God likes the death of his people or that it pleases him; it is precious in his sight. In English, this would be the normal way of understanding verse 15 as a stand-alone statement. In addition, that would be the normal force of the Hebrew adjective that is fronted in the verse: “Precious in the sight of the LORD.”

The surrounding context provided by Psalm 116 itself, however, leads strongly in another direction. And, after developing my own very preliminary investigation, I learned that I was quite late to the exegetical party. The need to render in this verse differently than “precious” is widely acknowledged in commentaries and in at least a few English Bible versions and paraphrases. To state my conclusion up front, a more faithful, contextual rendering of this verse would be this: “Costly (or weighty) in the sight of the LORD is the death of his saints.” I’ll build the case for this on three major supports: (1) the semantic range available to the adjective ; (2) Psalm 116 as a whole and how it directs the translation in a certain direction; and finally (3) the book of Psalms in general and its attitude towards death. At the end, I’ll offer several ways to apply the verse in light of God’s work in Christ and our Christian life today.

The adjective occurs in the Hebrew Old Testament thirty-five times, and twenty-two times it straightforwardly modifies literal possessions that are “precious, valuable”—frequently in the phrase, “precious stone(s)” (e.g., 2 Sm 12:30).2 This positive meaning also occurs in theological or relational contexts six times, modifying God’s mercy (Ps 36:7), wisdom (Prv 3:15), the faithful prophetic word (Jer 15:19), and various important or valuable people (Ps 45:10; Prv 6:25; Lam 4:2). Twice the

Editorials 7

context stretches or broadens this positive sense, referring to the “beauty” or “glory” of a pasture (Ps 37:20) or to the “splendor” of the waxing moon (Job 31:26). Context, of course, has this ability to adjust the meaning of an individual word.

Two other examples show that context can further adapt the meaning of in what might be called a more neutral direction. 1 Samuel 3:1 (ESV) reads, “Now the young man Samuel was ministering to the LORD under Eli. And the word of the LORD was rare ( ) in those days; there was no frequent vision.” The last clause of the verse influences the meaning of the adjective in the prior clause, moving it from “precious, rare” all the way to “rare, infrequent.” In addition, Ecclesiastes 10:1 (ESV) reads, “Dead flies make the perfumer’s ointment give off a stench; so a little folly outweighs wisdom and honor.” A more literal rendering of the last clause would be “weighty ( ) from [ of comparison] wisdom and honor is a little folly.” Citing this verse, BDB glosses the adjective with “influential”; the Dictionary of Classical Hebrew suggests, “weighty.” Here the meaning has journeyed from “precious, valuable” to “significant, weighty, influential.”3 Lexically these examples in the OT show how the adjective’s meaning can be changed by the context. This is the first point in the argument.

Second, it is precisely the context provided by Psalm 116 as a whole that makes the normal translation of verse 15 (i.e., “precious”) misleading at best. It’s simple enough to state the force of the context. Psalm 116, like many psalms, expresses the psalmist’s gratitude to God for preventing his death. The psalmist didn’t die, and he is thankful for it! Even a quick reading makes this clear. The psalm says (ESV), “The snares of death encompassed me; the pangs of Sheol laid hold on me; I suffered distress and anguish. Then I called on the name of the LORD; ‘O LORD, I pray, deliver my soul!’” (vv. 3–4). Further, “For you have delivered my soul from death, my eyes from tears, my feet from stumbling; I will walk before the LORD in the land of the living” (vv. 8–9).4 Immediately after verse 15, the psalmist declares (v. 16), “O LORD, I am your servant; I am your servant, the son of your maidservant. You have loosed my bonds.” How did God regard the death of the psalmist? It was something that needed to be prevented, and prevent it God did. In such a context, “precious” in the normal positive sense cannot be the meaning of 5

As I mentioned, the tension between context and the common translation in verse 15 is widely acknowledged among those who study Psalm 116. I consulted ten commentaries from a range of theological commitments as well as two scholarly articles. One of the articles and seven of the commentaries argue that the standard translation “precious” must be adjusted. The remaining sources acknowledge the difficulty but respond by (in effect) altering the meaning of the noun “death”! Two authors in this latter cluster of four assert that the verse means that the death and the life of God’s saints are precious in his sight.6 (Of course, the verse does not say that.)

A third writer advocated a more radical change, suggesting that for rhetorical effect

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 8

the word “death” in verse 15 has been deliberately interchanged with the word that really fits here, namely, “life.”7 The final writer (in this group of four) argues that the noun “death” ( ) is not in fact a form of the noun “death” at all; I am not aware that this view has convinced many.8

From the eight scholars who suggest a different rendering than “precious” for , Franz Delitzsch is typical: “The death of His saints is no trifling matter with God; he does not lightly suffer it to come about; He does not suffer His own to be torn away from Him by death.”9 More directly Derek Kidner says, “Precious could mean either ‘highly valued’ or, in a less happy sense, ‘costly’ . . . the singer’s rescue from death (3, 8) makes the second meaning more likely”10 I surveyed English translations using the popular website biblegateway.com. Although almost all English translations that I consulted offered the standard translation of “precious,” three (Common English Bible, Complete Jewish Bible, and Jerusalem Bible) offered “costly.” Moreover, quite a few “amplified” versions and/or paraphrases allowed the context to adjust their renderings. The Good News Bible offers, “How painful it is to the Lord when one of his people dies!” The Amplified Bible’s additions are, in my opinion, very helpful: “Precious (and of great consequence) in the sight of the Lord is the death of his godly ones (so He watches over them).”11

Third and finally, Psalm 116 exhibits a perspective on death that is widespread through the entire psalter. Here I will simply assert this as an obvious fact and trust my readers to examine the texts if they feel the need to do so. In psalm after psalm the authors speak in gratitude to God because death threatened to take them away from the land of the living, but God intervened and did not let the psalmists die. It is a little obvious; after all, the authors lived to write their psalms! The psalmists believed that embodied, created life lived in faith and service to the God of Israel is a great good; death threatens that good. The psalmists do not want to die, they don’t die (at least, not then), and they thank God for preventing their deaths. God cares about whether or not his servants die. Throughout the psalter, God saves his servants from Sheol. Their death is no small matter to him. It is weighty. It is costly—just as Psalm 116:15 says.

In brief fashion I’ve tried to show that (1) the lexical possibilities available to , (2) the context of Psalm 116 itself, and (3) the entire psalter’s prominent theme of giving thanks for deliverance from death combine to produce a translation of Psalm 116:15 along the lines of “Costly/weighty in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints.” I encourage my readers to their own further study of Psalm 116:15. In light of this brief presentation, the question of application immediately comes to the fore. Four sorts of applications (at least) are possible.

The first is christological. In many and various ways, the ministry of the Lord Jesus fulfills the psalms (cf. Lk 24:44). In my view, for instance, Psalm 110 is a prediction, applying only to the ascended and victorious Jesus and first claimed by

Editorials 9

him during Holy Week long ago.12 On the other hand, Psalm 22 applies to Christ’s work typologically; David’s suffering and deliverance is the type, and Christ’s is the infinitely greater antitype. In a way that is similar to Psalm 22, Psalm 116 can also be interpreted in light of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Christ’s death was costly to God his Father. God did not treat it lightly. And in answer to Jesus’s plea, the Father rescued him from death (Heb 5:7–10). He did so by breaking death’s hold, by raising his Servant-Son from the dead to walk in the land of the living . . . forever. Death no longer has mastery over Jesus (Rom 6:9). He is the Lord.

A second way for Christians to appropriate Psalm 116:15 is to pray as the psalmist did when our own lives are in danger. It is entirely appropriate to beseech the Lord to save us from death, to preserve our lives and lengthen our days. To walk before the Lord in the land of the living means greater, continued opportunity to offer the sacrifice of thanksgiving in the courts of the Lord’s house, in the midst of Jerusalem—that is in the midst of his holy Christian church.

Third, Psalm 116:15 validates the grief of Christians (and others) when their believing loved ones die. Death is not trivial to us because it is not trivial to the God who made all things; it matters to him. It is possible that John 11:35 (“Jesus wept”) describes how costly to the Lord Jesus himself was the death of Lazarus, even though the Lord knew he would rescue him from death that very hour. God’s good intention that we walk before him in the land of the living is attacked and temporarily negated when a believer dies. It is entirely Christian to grieve as needed when such a costly thing as death comes on the scene.

But not without hope. Fourth and finally, death only temporarily negates our good, creational existence in this fallen world. For the day will come when that cost no longer needs to be paid. Resurrection awaits the psalmist who sang Psalm 116. Resurrection signaled the victory of Jesus over sin, Satan, and death itself; he was delivered over because of our transgressions and raised because of our justification! Every believer can look death in the eye and say with confident hope, “I will walk before the Lord in the land of the living.” The day is coming when we will all know with unshakeable certainty just how true Psalm 116:15 has been ever since it was penned.

Jeffrey Gibbs

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 10

Endnotes

1 There are some small grammatical questions that arise in verse 15. One is the unusual form of the word “death,” which appears to have a he-directive appended. Also, the preposition precedes the noun “his saints.” If one were to woodenly render the verse, it would run “Precious in the eyes of Yahweh toward death for his saints.” The he seems not to be regarded as semantically significant by scholars, and the lamed that governs “his saints” likely expresses possession; on the many possible uses of see B. K. Waltke and M. O’Connor, An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax (University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns, 1990), 11.2.10.

2 Computer software generates two uses of the adjective (Prv 17:27 and Zec 14:6) that are actually examples of the adjective being confused with or , “cool, cold.”

3 J. A. Emerton, “How Does the Lord Regard the Death of His Saints in Psalm cxvi. 15?,” in The Journal of Theological Studies vol. 34, no. 1 (1983): 153, reports that it is “generally believed” (especially owing to the meaning of Aramaic and Arabic cognate verbs) that the Hebrew verb that is related to the adjective in question originally signified “to be heavy.”

4 In both verses 4 and 8, the ESV translates with “my soul.” As so often in the OT, this refers to the person, the self, as verse 3 shows, “The snares of death encompassed me.” The psalm does not refer to the “soul” as opposed to the “body.”

5 An indirect support comes from several uses of the Hebrew verb , as noted in Emerton, “How Does the Lord Regard,” 150. Psalm 72:14 (ESV) reads, “From oppression and violence he redeems their life, and precious is (form of ) their blood in his sight.” In both 1 Samuel 26:21 and 2 Kings 1:13–14, one or more persons (e.g., a ) are regarded as precious (form of ) in another person’s sight. What this means, of course, is that blood was not spilled, and life was not taken.

6 H. C. Leupold, Exposition of the Psalms (repr. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1969), 808; John F. Brug, Psalms, Volume 2 (Waukesha, WI: Northwestern, 1989), 183.

7 John Goldingay, Psalms Vol 3: Psalms 90-10 (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 346, says “Literally understood, v. 15 is an odd statement. The meaning of might have become stretched along lines parallel to those that apply to , so that it means heavy, grievous, or burdensome. But there is no other indication of this stretching, and it is easier to infer that v. 15 involves a hypallage, an interchange in the application of words. Prosaically put, the life of the people committed to him is valuable to Yhwh; or the people in danger of death who are committed to him are valuable to him” (emphasis added). This strikes me as unlikely. If the psalmist had wanted to say, “Precious in the sight of the LORD is the life of his saints,” he could have easily said that.

8 Michael L. Barré, “Psalm 116: Its Structure and Its Enigmas,” Journal of Biblical Literature vol. 109, no. 1 (1990): 61–79.

9 Franz Delitzsch, Psalms: Third Book of the Psalter (repr. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976), 219.

10 Derek Kidner, Psalms 73–150 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1975), 410.

11 In passing, let me mention one intriguing feature of the interpretation of Psalm 116:15. Quentin F. Wesselschmidt, Psalms 51–150 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2007), 293–296, cites selected Fathers on verse 15’s meaning, including Cyprian, Ambrose, Augustine, and Leo the Great. They seem to have retained the positive meaning of “precious,” while applying the verse to deaths of Christian martyrs. In a context of martyrdom, the normal translation would make tolerable sense; God is pleased when his martyrs die bearing fearless witness to him. Martyrdom, however, is not even on the radar in Psalm 116; the psalm does not rejoice in death, but in death being averted.

12 Jeffrey A. Gibbs, Matthew 21:1–28:20 (St. Louis: Concordia, Publishing House, 2018), 1158–1166.

Editorials 11

An Extraordinary Way to Honor a Pastor

There are many ways to honor a pastor’s years of service. Congregations may celebrate a pastor’s retirement or milestone with a service, social event, or gift. Rarely does an individual, who benefited from a pastor’s faithful delivery of the gospel, find a way to share the preacher’s story of service or some sermons. So, it is extraordinary that someone, even a family member, honors a pastor by creating a website that documents his ministry and shares his gospel messages. However, that is what my brother, Roger L. Brauer, has done for our father, Harold H. Brauer (1910–1998), a 1935 graduate of Concordia Seminary, St. Louis.

Perhaps what led my brother to this project was a deep interest in his family tree and a hope that sharing messages about Jesus might help even one person. Though he had high school level pre-ministerial training, in college Roger studied both mechanical engineering and psychology. Eventually, he earned a Masters and a PhD in engineering from the University of Illinois. During his career Roger continually researched his family genealogy through correspondence, interviews, newspaper archives, ship’s logs, web resources, and personal travel to sites in the United States and Europe. Over the years he collected several file drawers of data. After Harold’s death, Roger ended up receiving all of Harold’s sermon manuscripts (about 2,000) from ministry to congregations in Colorado (Julesburg, then Amherst), Utah (Ogden), and Wisconsin (Symco, then Green Bay). Along the way, he helped start three Christian schools and several parishes. In the final years of his ministry, he was the North Wisconsin District’s stewardship and mission counselor.

Since he had the biographical data and all of Harold’s sermons, Roger got the idea of creating a website to honor his father. (Keep in mind that Roger has little fear of big projects, as evidenced by building his own house while he was fully employed or writing a comprehensive, 672-page book, Safety and Health for Engineers, now in its fourth edition.) So, he organized his material and arranged for web developers and services, making sure that the site’s contents would be downloadable.

The website has two main parts. The first surveys Harold’s personal story: that his parents chose him to meet their pledge that one of their six sons would become a pastor, that by age eighteen he had completed grade school, high school,

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 12

and the two years of college which preceded seminary studies, that he had athletic accomplishments in tennis and basketball; that during World War II he held services for German prisoners of war and established a congregation for workers at a nearby navy supply center when they did not have enough rationed gasoline to drive to his Ogden congregation. The site includes considerable information: Harold’s autobiography, selected documents, photos, and news clippings related to his education, athletic participation, pastoral assignments, residences, and family. The second part has the sermons. Getting them onto a website was no simple task since some were handwritten and the typewritten ones were on single-spaced, double-sided half-sheets. No scanning process could make them easy to read. Through experimentation, Roger learned that the fastest method to get a legible text was to dictate each sermon, let voice-recognition software generate a text file, and then edit that version for posting to the web. The sermons are grouped into six categories: church year, Old Testament, New Testament, special occasions, radio sermons, and German sermons. For each category or subcategory, a user can view a list with the sermon title, biblical text, and date and place of delivery. Clicking on the sermon’s number in the list takes the user to a page with the sermon, its biblical text, title, and hymns used when it was delivered. The eleven radio sermons from1947–1948 were on 33 1/3, 16-inch platters that the station had recorded in advance so that they could be aired when Harold was not available for a live broadcast. Roger had these sound recordings converted to digital sound files so a web user could choose to read the text or hear the sermon as it would have sounded more than sixty years ago. The German sermon texts are posted, but not translated. Since some of the sermons are still being processed, the web collection is not yet complete, but it is up and running.

This is an extraordinary project, created by a pastor’s son, to honor a sainted servant of the Lord. To access this tribute to Rev. Harold H. Brauer go to MyLifeForChrist.org.

James L. Brauer Professor Emeritus

Editorials 13

Articles

Translation and Syncretism

Douglas L. Rutt

Douglas L. Rutt is provost and professor of practical theology at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis. He joined Concordia Seminary in July 2018 after serving as the executive director of International Ministries for Lutheran Hour Ministries. His areas of academic interest include homiletics, theological education and formation, Christian leadership, and missiology.

One of the most significant missiological issues that faces the church as it continues to expand throughout the world is the danger of syncretism. Renowned missiologist Gailyn Van Rheenen stated that the “largest vacuum” in mission theology and research today is the topic of syncretism. Further, he has said, “I am continually awed by the creativity of humans to mix and match various religious beliefs and rituals to suit their changing worldview inclinations.”1

The Perennial Challenge of Syncretism

Syncretism,2 simply put, is the mixing or comingling of beliefs and practices from non-Christian religions, values, worldviews, and ultimate commitments of a people, with the message communicated to us in God’s word, the truth of Holy Scripture.

Concerning the root cause, Van Rheenen put it this way:

Author’s note

This is an adaptation of a keynote address given at the Bible Translation Conference cosponsored by the Department of Mission Theology of the Ethiopian Evangelical Church

Mekane Yesus and Lutheran Bible Translators, June 17, 2022, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Syncretism occurs when Christian leaders accommodate, either consciously or unconsciously, to the prevailing plausibility structures, beliefs, and practices through cultural accommodation so that they reflect those of the dominant culture . . . so that Christianity loses its distinctiveness and speaks with a voice reflective of its culture.3

While syncretism is usually blamed on an accommodation of the message to the prevailing culture, I contend that it is not only the accommodationist approach to gospel communication that can lead to syncretism, but that also syncretism can appear due to a neglect or denial of the prevailing culture, where context, culture, and worldview are overlooked, as we will see later in this article.4

The continuous struggle of anyone attempting to bring the gospel to people who have not already been exposed to and shaped by the biblical message is to present the truth of God’s revelation in a way that confronts the culture and elements of the culture that are not consistent with the truth of God’s word, yet does not destroy the culture entirely. The challenge throughout the history of Christian expansion has been to discover how to communicate God’s word in a way that resonates with a certain people or cultural context without the message losing its core essence. When cultural behaviors and beliefs that end up altering or distorting God’s message are incorporated into “Christian” practice and teaching, syncretism takes place.

Some will argue that all expressions of Christianity in some ways are syncretistic or are threatened by syncretism. Syncretism is not always obvious, especially to those within a culture or tradition shaped by Christianity. That might be called “subtle” (but no less potentially insidious) syncretism. An example from US culture might occur when an American hears that there is “freedom” in the gospel. As Paul states: “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free” (Gal 5:1).

Americans have a unique idea of freedom, thinking that it implies that individuals are free to do whatever they want. That concept of freedom easily leads to moral relativism and even carnality. Rather, the freedom that Paul is speaking of is freedom from the burden of a guilty conscience before God—freedom from God’s eternal wrath. It has nothing to do with “you are free to behave as you wish.”

A more palpable form of syncretism is something I witnessed as a missionary in Guatemala. This form of syncretism has sometimes been called “Christopaganism”

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 18

The freedom that Paul is speaking of is freedom from the burden of a guilty conscience before God.

because of the mixture of ancient pagan beliefs and practices with elements of Christianity. The sixteenth-century conquest of the Americas by the Spaniards can be seen from various perspectives; however, besides the gold and silver, as well as agricultural products such as sugar, tobacco, and cacao, which were extracted from the continent, there were sincere, ongoing attempts to evangelize the aboriginal inhabitants of the Americas.

Within the Catholic church building in the market town of Chichicastenango, one can witness religious practitioners, curanderos, performing shamanistic rites and rituals, appealing to ancestors and other deities or spiritual powers from the ancient Mayan pantheon of precolonial times, in the very center aisle of the church building. Meanwhile, a Roman Catholic catechist will be preaching from the front, urging people to attend Holy Communion and have their children baptized. The contrast is startling. Another example is a deity and folk saint by the name of Maximón (sometimes referred to as “San Simón”). In the mind of the Guatemalan local people, he seems to be a mixture of Mayan deities and biblical figures, such as Judas Iscariot and Saint Peter, among others.5

Contextualization and its Relationship to Syncretism

How and why did this comingling of pagan and Christian practices happen? The missionaries who accompanied the conquistadores approached the challenge of communicating the Christian message to the indigenous communities, who previously had no known exposure to the gospel, in different ways. Dr. Rudolf Blank, in his book Teología y Misión en América Latina, speaks of two distinct methodologies. One he calls “tabula rasa,” literally “blank slate.” This approach displayed little respect for the cultures, religious beliefs, and ideas of the local inhabitants. According to the tabula rasa model, the only way to implant Christianity in the “New World” was to totally obliterate every vestige of the local religion and start anew in the hearts of the people.6

The conquerors were optimistic about the effectiveness of this methodology, even though today most would agree that it led to syncretism such as described above regarding the curanderos of Chichicastenango and Maximón in the Lake Atitlán region. It is not that easy to do away with people’s deeply seated assumptions and beliefs, even though outward artifacts and vocabulary have changed. It is widely understood today that ignoring the previous beliefs of the people and coercing them to adapt to new practices and dogma, only meant that the old practices were pushed underground; they were still at hand, none-the-less. It is often said that while the indigenous people of Central America may pronounce the name of a saint, in their heart they are invoking an ancient deity.

Blank describes the other approach to evangelization in the New World as “providential preparation.” According to this method, every culture has at least some residue of the truth. The work of the missionary is to look for similarities in

Rutt, Translation and Syncretism ... 19

the religious beliefs and practices of indigenous peoples that can be used as “points of contact” with the teachings of Christianity. The Augustinian monk Bartholomew Díaz used this tactic. As Blank says, “Instead of prohibiting the rites and dances of the natives, he permitted these ceremonies to be offered to the Eucharist instead of the sun. Native disguises and music were utilized in the celebration of Catholic festivals such as the Festival of Corpus Christi.”7

The danger of syncretism is present also in this approach if carried out uncritically. The line between making use of harmless cultural practices to help communicate the gospel and accommodating the message of the gospel to the point of its distortion can easily be crossed.

Approaches to Contextualization

These examples demonstrate different approaches to what missiologists sometimes call contextualization. Contextualization is a complicated idea with a controversial history, both in how it is defined and how it has been implemented. It is used in diverse ways, sometimes to mean something that goes far beyond what a person committed to the truth of Scripture could tolerate. What David Hesselgrave and Edward Rommen stated in the later part of the past century is true today: “There is not yet a commonly accepted definition of the word contextualization, but only a series of proposals, all of them vying for acceptance.”8

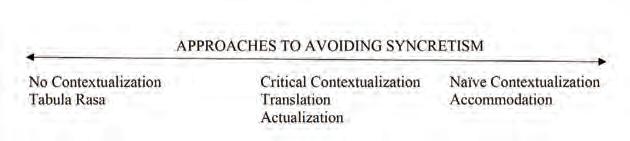

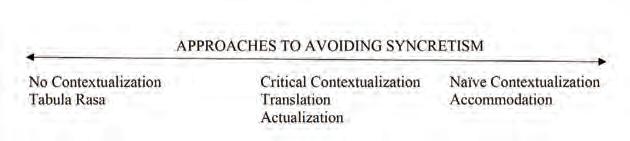

Dr. Paul Hiebert wrote of contextualization that will best avoid syncretism. He spoke of the period of “noncontexualization,” which would be akin to the “tabula rasa” approach described above by Blank. It is the idea that there is little within a non-Christian culture that can be built upon in communicating the gospel.

On the other end of the spectrum, he spoke about “naive contextualization.” This is where elements of the culture are absorbed uncritically or made use of in the transmission of the Christian message. Both approaches lead to syncretism, the former because it bypasses context and thus, essentially, bypasses the hearts of the hearers. The latter also leads to syncretism by causing confusion when the challenges of the gospel to a culture infected by sin (as are all cultures) are not fully communicated with impact.

Hiebert advocates for what he calls “critical contextualization.” Critical contextualization is when, in the efforts to bring a new word (God’s word) to people,

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 20

The line between making use of harmless cultural practices to help communicate the gospel and accommodating the message of the gospel to the point of its distortion can easily be crossed.

one takes culture and context seriously, recognizes that the process of accurate communication of the message must include listening for and searching for ways in which that message can be related to people within a certain context, and yet avoids the pitfalls of adapting to the culture in a way that distorts the message. In that way it is called “critical” contextualization because one does this work carefully, critically scrutinizing the way in which cultural elements can be made use of without compromising the message.9

Dr. Robert Kolb, in his book Speaking the Gospel Today, used two terms for what we mean by contextualization in its appropriate sense. Kolb speaks of actualization and translation, noting that it is crucial to avoid accommodation. 10

In summary, by “contextualization” we mean taking seriously the culture and context surrounding and impacting people’s lives and finding a way to communicate God’s truth into the hearts of people of that contextual situation. This would mean that two things are necessary: Exegesis of the word, and exegesis of the world. We must do all we can to try to understand God’s word, within its original context. That involves a careful reading of and reflection on the text of Scripture, preferably in the original language, to determine the meaning in its original setting. It would include an understanding of the historical and social situation of the text. It also includes an examination of the grammatical structures employed by the inspired writers. Sound exegesis, is, then, “the systematic process by which a person arrives at the reasonable and coherent sense of the meaning and message of a biblical passage.”11

Yet, as Kolb stated: “Genuine biblical teaching, doctrine, is not correct if it is merely flawless in content. It must also be accurately presented, aimed precisely at the situation of the contemporary hearer. It must be as effectively spoken by us today as it was effectively delivered to the prophets and apostles two millennia and more ago.”12

When the message of the gospel is accommodated to the culture, so that it loses its prophetic voice, its “saltiness,” even to lose its “offensive” character, then the message is distorted, the power of the gospel is undermined, and the result is syncretism. To put it another way, African theologian Tite Tiénou emphasizes the critical importance of contextualization to the life of the church:

Rutt, Translation and Syncretism ... 21

Contextualization is the inner dynamic of the theologizing process. It is not a matter of borrowing already existing forms or an established theology in order to fit them into various contexts. Rather contextualization is capturing the meaning of the gospel in such a way that a given society communicates with God. Therein theology is born.13

Again, people approach contextualization from a variety of postures, often depending on the theological position to which they ascribe. While almost everyone today understands that in some ways the message must be actualized or translated into the context of the hearers, there is a continuum in terms of which holds more weight in the process, biblical revelation or contextual, human elements. Hesselgrave and Rommen have provided a helpful diagram to illustrate how one’s theological commitments will impact how one approaches contextualization. While the entire endeavor is much more nuanced, in general terms one can see how things tend to shake out.14

By means of this chart, one can see how theological positions value the message of Scripture in their approach to contextualization. One could say that those who have a lower view of Scripture will emphasize the human elements in their interpretation of the message and will likely be ready to adapt the message more freely to the prevailing context. On the other hand, those who have a higher view of Scripture will tend to exercise more care in order to avoid conditioning or even distorting the message based on contextual/cultural norms.

Even so, true, appropriate contextualization, actualization, or translation requires serious attention to both the world and the word. It is not something that can be executed in a formulaic fashion. It involves human communication with complicated human beings with their biases, emotions, spiritual conditions, complex contextual experiences, and so on, and thus it is something one works toward and is ready to adjust along the way. Is contextualization a science, an art, or a skill? The answer is, “yes.” It really is all three.

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 22

Translation, “Heart Language,” and Contextualization

We have laid a foundation of “translation and syncretism” by looking first at contextualization because translation, especially translation of Scripture, is an essential component of any true contextualization or actualization of the message for a people group, and Bible translation work requires the same diligence in understanding human language as well as the message of God’s revelation. Every time we observe Pentecost, we remember a decisive event in the life and history of the Christian church, when it was made obvious that God’s message can be expressed in any language:

Now there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven. When they heard this sound, a crowd came together in bewilderment, because each one heard their own language being spoken. Utterly amazed, they asked: “Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language? Parthians, Medes, and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs—we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!” Amazed and perplexed, they asked one another, “What does this mean?” (Acts 2:5–12)

When the people heard this, they were cut to the heart, and said to Peter and the other apostles, “Brothers, what shall we do?” (Acts 2:37).

It is not only that these people from various language groups heard the “wonders of God” in their own language, but that the hearing in their own tongue was key to the message “cut(ting) to the heart.” While the Spirit may not work for us today as it did on Pentecost 2000 years ago, the ability to communicate the message of the wonders of God so that it “cuts to the heart,” in other words, reaches the heart of the hearer, mandates the translation of God’s word to the “heart languages” of people.

Rutt, Translation and Syncretism ... 23

The ability to communicate the message of the wonders of God mandates the translation of God’s word to the “heart languages” of people.

James Nestingen quipped, “Your heart language is the language your mama spoke to you when she was changing your diapers.”15 The impact of hearing something in your heart language is significantly greater than when hearing it in another language, even if you know that other language well. I visited a Lutheran congregation in Jamaica years ago, where everyone spoke English, yet the heart language of the people is Patois (Patwa). The service was conducted in English by an American missionary. Afterwards I asked a member of the congregation if she thought it would be good to use Patois in the service. Her face lit up and she said, “When the pastor uses a Patois expression, or when we sing a Patois hymn, it is . . .” She trailed off. All she could do was point to her heart. Hearing the wonders of God in her heart language was special, and she seemed to indicate that to hear God’s word in Patois has special significance beyond the English, which she understood perfectly.

Christianity has grown, and continues to grow, in Africa. In the year 1900, less than 10 percent of the people of Africa were Christian, by 2000, that number had grown to over 50 percent.16 Historian Mark Noll lists the growth of vernacular Bible translations as one of the most significant factors in the growth of Christianity worldwide, not only because people hear the message, but because of the impact of hearing it in their own language. He states

This wave of translations has also been liberating, especially because it has given to peoples all over the world a sense of being themselves the hearers of God’s direct speech. Thus, in a world where fewer and fewer can escape modern electronic technology and the reach of “imperial” languages associated with that technology—Chinese, French, Spanish and especially English—the chance to hear the Christian message in one’s own mother tongue takes on even greater significance.17

And yet, while the translation of the Scripture into the vernacular heart languages of the world is key to clear understanding of the message, there are differing approaches to translation, just as there are differing approaches to contextualization in general. While a given translation can lead to a clearer and true understanding of the message of Scripture, it can also lead to a misinterpretation or distortion of the original message if the translation work is not done carefully and critically.

Approaches to Translation and Syncretism

One approach to the process of putting the original text of Scripture into another language has been described as “literal,” “word-for word,” or “formal correspondence.” This is where the translator tries to follow the text of the original Greek and Hebrew as closely as possible, word-for-word, and in a similar word order. In English, the NASB and the ESV are modern examples. This approach to translation is founded on a high

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 24

view of Scripture, that every single word of the Bible is fully inspired by God, and thus a translation should follow the original as closely as possible. This is a noble idea, yet different languages have different structural, syntactical, and grammatical features that sometimes make it difficult if not impossible to follow the original so closely.

This is true of the difference between Greek and English. English simply does not have all the linguistic apparatuses to handle, for example, the very long, complicated sentences of Paul in the first chapter of Ephesians. You might argue that Ephesians 1:3–14 is really one, extremely long sentence in the original Greek.18 Greek is a language with a complex structure that has various tools to keep what one is talking about straight, such as three genders (masculine, feminine, neuter), number, case, the genitive absolute, and so on. Even a formal correspondence translation in English doesn’t attempt to follow the Greek completely. In English, the reader would simply get lost, and thus even the more literal ESV uses five sentences to translate that one Greek sentence, Ephesians 1:3–14.

A slavish word-for-word translation could lead to a lack of understanding, and thus open the door to syncretism. For example, no English translation actually describes the Lord as “long nostriled,” but that is exactly what the Hebrew phrase, means (Ex 34:6). The sense of “long nostriled” is not clear in English, and so English translations are likely to translate “long nostriled,” into something like “slow to anger,” or “long-suffering.”19

Recognizing shortfalls of literal translations, another approach to Bible translation was developed and articulated by people such as Eugine Nida, Jacob Lowen, and William Reyburn. This approach has been called “dynamic equivalent,” “meaning-based,” or “thought-for thought.” This is an over-simplification, to be sure, but this approach to translation tries to understand the impact on the original hearer of a particular phrase of Scripture and attempts to translate in such a way so as to produce the same impact upon the modern-day hearer. Proponents of this approach “say that the message, not the particular words, is what matters, and that their style of translation helps people understand that message more clearly.”20 In comparison with the more literal translation of the ESV, mentioned above, of Ephesians 1:3–14, the “dynamic equivalence” New Living Translation uses fifteen sentences to translate that one long Greek sentence.

The dynamic equivalent approach to Bible translation has been the predominant methodology used by Bible translators for the past fifty years. Its value and usefulness are plain to see. Yet, as we have said for contextualization, it must be done critically. For this approach to work well and to faithfully convey true biblical meaning, a profound level of analysis of the original language and a deep understanding of modern vernacular language in its contemporary setting is essential. There is nonetheless a risk of syncretism with this approach if the translator does not fully understand how the intended audience might interpret the translation of God’s word.

Rutt, Translation and Syncretism ... 25

While these two philosophies of Bible translation have been seen as competing approaches, in truth, both methodologies require, at times, literal translation, and, at times, more of a paraphrase of the biblical text. Moreover, both an overly literal and an over-zealous dynamic equivalence approach can lead to misunderstanding of God’s original message, and thus lead to syncretism because of incomplete transfer of meaning from one language to another.

Functionalism and the Challenge of Syncretism

A third philosophy postulated in recent years, which is gaining traction even among Evangelicals, is called “functionalism.” Functionalism is an attempt to avoid the literal versus dynamic equivalent dichotomy, recognizing that sound translation will involve both approaches. Functionalism advocates that the defining factor in an approach to Bible translation is the function that the translation supposes to achieve. In other words, the way in which something is translated depends primarily on the function or the purpose of the translation. Purpose, called the skopos, is the controlling factor.

This approach advocates that translators should sit down with the local Christians and church leaders and work out the kind of translation that the people want and what needs and expectations they have for the translation. While it is true that local Christians and stakeholders should be a part of any translation project, some would say that this approach, if taken too far, can lead to syncretistic translations that put the needs and expectations of the community above the message that God would bring to those people. As in any approach to contextualization, the proper balance between the weight placed on the prophetic and challenging word of God and the needs and expectations of the people should be sought. Fidelity to God’s word should not be sacrificed by accommodating the message to meet the perceived needs of a community. If the biblical writers were to discuss it with them, the Jews of Pentecost certainly would not have asked for a word from God that was going to condemn them for putting his Son to death.

There are important positive aspects to the functionalist approach, especially the emphasis on community involvement. The importance of community “buy in” to a translation project is an absolute necessity. However, with all transcultural communication, it is not without pitfalls.

Seth Vitrano-Wilson raises legitimate concerns about the functionalist approach, especially as it has been employed to influence the translation of key dogmatic truths within the context of “insider movements.” This has led to serious controversies and division within the linguistic, Bible translation community. So much so, that major organizations have come to loggerheads and even division over the issue.

At issue is that certain translators recognize that within Muslim communities, it is offensive to describe Jesus as the “Son of God,” and to describe the relationship between the first and second persons of the Trinity in terms of Father/Son.” Islam for

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 26

sure has a problem with this in that it implies a sexual relationship between God the Father and Mary, a serious obstacle. Thus, some translators working in predominantly Muslim contexts advocate for using other, non-familial, terminology to describe the relationship between Jesus and the Father.

It is beyond the scope (skopos?) of this article to discuss all the ins and outs of this controversy, and how diverse groups have attempted to address it.21 To my untrained eye, however, it seems problematic not to speak of the relationship between the Father and the Son in the terms expressed in Holy Scripture. Is it offensive? Yes, it is. It was offensive to the Jews of biblical times. Saint Peter describes Jesus as a “rock of offense” and the “stone which the builders rejected” (1 Pt 2:7–8). This is not to say that the Muslim community should not be approached carefully and thoughtfully so as not to create an obstacle from the very beginning on this matter; however, one must question whether taking the “needs and expectations” of the receptor group as the primary determining factor in a Bible translation could not lead more readily to a syncretistic understanding of the message. Vitrano-Wilson argues that once one accepts the tenets of functionalism, it becomes nearly impossible to argue against these translations. After all, if the “local church” (defined however Insider Movement proponents choose to define it, and excluding anyone they deem as too far “outside the context”) wants a certain translation choice—if it fulfills the skopos that have for the translation—what can anyone else say about it? Ideas about “meaning” or “faithfulness” become completely relativized to what serves the purposes of the Insider Movement and the outsiders who promote it.22

The other obvious factor that will impact Bible translation efforts, which can lead to syncretism, or at least misunderstanding and doctrinal error, is the question of bias. Everyone has biases, that, even unwittingly, can and will condition the message as it is being translated according to their theological and other presuppositions. This is widely recognized, and one can see the different biases being injected into translations, especially to languages like English, which is said to have more than 450 translations of the Bible, each with its intended purpose.

An example of bias from a Spanish-language Bible can be found in its rendering of Matthew 28:19–20. A literal-grammatical translation of this passage from the Greek would come out something like this: “As you go (or, “wherever you go”), disciple all nations by baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and by teaching them to observe all things I have commanded you.”23

The relatively new and widely used Reina Valera Contemporánea, back translated into English, would read something like this: “Therefore, go and make disciples of all nations, and baptize them in the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy

Rutt, Translation and Syncretism ... 27

Spirit. Teach them to fulfill all things that I have mandated.” The difference is subtle, to be sure, but the newer version of this Spanish translation seems to emphasize a “believers’ baptism.” In other words, someone becomes a disciple first and then, as a believer, is baptized.

The Spirit of God

In all that we have discussed, it becomes readily apparent that faithfully moving the message from one context or language to another is fraught with challenges and pitfalls. From a human perspective, the whole enterprise seems overwhelmingly complex with so many chances of missing the mark. While I am convinced of the crucial need to bring the truth of God’s word to people in their heart languages, as did the Spirit on Pentecost, I recognize that the entire endeavor requires care, intense study, preparation, and attentiveness to human contexts and biblical absolute truth.

The great African theologian, Lamin Sanneh, devoted his life to describing how the Christian message is translatable into any language. Indeed, for Sanneh, its translatable nature is essential for there to be a genuine African assimilation and expression of the truth of God’s wonders. He didn’t underestimate the risks involved, but he also knew that God’s Spirit would and has worked mightily through such translations, as imperfect as they have been.24

Translating the message in a way that will prevent syncretism or mistaken understandings is a serious endeavor, and the reality is that humans will never be able to do it perfectly. This is not to say one involved in this work should not prepare him or herself in the various fields related to the task, such as biblical interpretation, anthropology, linguistics, psychology, communication theory, and so on; however, it is important to remember that behind it all is the power of the Spirit of God, which works in the hearts of those who hear the word to produce true repentance and faith in Christ Jesus. Sometimes the translation may not be particularly good, just like sometimes a sermon may not be particularly good, yet the Spirit can and does work through both to melt hearts and turn them to God. Jesus himself, in is “farewell discourses” (Jn 14–17) makes it abundantly clear that a “Helper” would come, who would help the disciples understand and assimilate things that even in the presence of their Lord Jesus they were not capable of understanding yet. We can be confident that in our efforts to produce translations that will clearly communicate the wonders of God, that same Spirit works and does his work in spite of the shortcomings of our efforts. The true hedge against syncretism, in the end, is the work of the Spirit.

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 28

Faithfully moving the message from one context or language to another is fraught with challenges and pitfalls.

Endnotes

1 Gailyn Van Rheenen, “Syncretism and Contextualization: The Church on a Journey Defining Itself,” in Contextualization and Syncretism: Navigating Cultural Currents, ed. Gailyn Van Rheenen (Pasadena, CA: Evangelical Missiological Society, 2006), 1.

2 The word syncretism is said to be derived from two Greek words, syn, which means “together with,” and kretizein, “to lie like a Cretan” (cf. Ti 1:12). This theory suggests that Cretans were constantly at battle with one another, but when faced with a common enemy, they would lock elbows and join forces to face the outside enemy together.

3 Gailyn Van Rheenen, “Contextualization and Syncretism,” Missiological Reflection #38 (blog), Missio Dei Foundation, January 1, 2011, http://www.missiology.com/blog/GVR-MR-38-Contextualization-andSyncretism/.

4 For this discussion, I rely heavily on my paper, “Contextualization in Evangelistic Conversation,” Missio Apostolica, 14, no. 1 (May 2006): 58–65. Also available at www.LutheranMissiology.org.

5 There are various investigations and reflections on the interesting interplay between the American indigenous, pre-conquest religious practices and beliefs and Christianity. Perhaps one of the most significant missiological publications on the topic is Christopaganism or Indigenous Christianity? Albeit produced some years ago, as the result of the William S. Carter Symposium on Church Growth at Milligan College in 1975, ed. Tetsunao Yamamori and Charles R Taber (South Pasadena Calif: William Carey Library).

6 Rudolf Blank, Teología y Misión en América Latina (Saint Louis, Concordia Publishing House, 1995), 30–35.

7 Blank, Teología, 35–37.

8 David J. Hesselgrave and Edward Rommen, Contextualization: Meanings, Methods, and Models (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1989), 85.

9 Paul G. Hiebert, “Critical Contextualization,” International Bulletin of Mission Research 11, no. 3 (July): 104–112.

10 Robert Kolb, Speaking the Gospel Today: A Theology for Evangelism (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1995), 17.

11 Richard Ascough, “Guide to Biblical Exegesis,” Queen’s University (blog). Accessed July 22, 2005. No longer available online.

12 Kolb, Speaking the Gospel, 18.

13 Tite Tiénou, “Contextualization of Theology for Theological Education,” in Evangelical Theological Education Today: Agenda for Renewal, ed. Paul Bowers (Nairobi: Evangel Publishing House, 1982), 51.

14 Hesselgrave and Rommen, Contextualization, 148.

15 Personal recollection, LCMS global theological conference in Peachtree, Georgia, November 2010.

16 In real numbers, it is estimated that in 1900 there were 9 million Christians in Africa. By 2000, that number grew to 500 million.

17 Mark Noll, The New Shape of Christianity: How American Experience Reflects Global Faith (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009), 24–25.

18 The original Greek manuscripts did not contain punctuation and spaces between words and sentences. It was up to the reader to figure out when one thought ended and another began.

19 Seth Vitrano-Wilson, “Functionalism: Why the New Dominant Paradigm of Bible Translation Makes Syncretism Inevitable,” Journal of Biblical Missiology (May 17, 2021). https://biblicalmissiology. org/2021/05/17/functionalism-why-the-new-dominant-paradigm-of-bible-translation-makes-syncretisminevitable/.

20 Vitrano-Wilson, “Functionalism.”

21 A brief summary of the controversy can be found here: https://www.christianpost.com/news/wycliffeassociates-split-global-alliance-father-son-of-god-arabic-translations.html.

Rutt, Translation and Syncretism ... 29

22 Vitrano-Wilson, “Functionalism.”

23 “Por tanto, vayan y hagan discípulos en todas las naciones, y bautícenlos en el nombre del Padre, y del Hijo, y del Espíritu Santo. Enséñenles a cumplir todas las cosas que les he mandado,” Mateo 28:19–20, Reina Valera Contemporánea (United Bible Societies, 2011).

24 Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2009).

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 30

Luther’s Septembertestament Translation Principles and Lessons for Translators

Vilson Scholz

Bible translation has been around ever since pre-Christian times when the biblical message began to be translated into Aramaic (the Targums) and Greek (the Septuagint). In Christianity, translation has become so to speak, second nature, and it has been so from the beginning. Jesus spoke Aramaic, but his words have been preserved in Greek. To us he speaks English, Spanish, Cheyenne, French, Portuguese, and some 2,500 other languages worldwide. For us, the Bible is a translated text. We naturally refer to our English versions as “the Bible.” Pastors don’t usually say, “Open your translation of the Bible.” It is the Bible!

In the Gospels, all words spoken by Jesus in Aramaic were immediately translated into Greek, and this by the writer of the Gospel himself. As St. Jerome pointed out in his letter to Pammachius, “we read in Mark of the Lord saying Talitha cumi and it is immediately added ‘which is interpreted, Little girl, I say to you, arise.’ The evangelist may be charged with falsehood for having added the words ‘I say to you’ for the Aramaic is only ‘Little girl, arise.’ To emphasize this, and to give the impression of one calling and commanding, the evangelist has added ‘I say to you.’” Mark was not a literalist. He preferred a rendering that is more emphatic or rhetorical, and understandable!

Bible translation has a long history, and one of the most interesting chapters is the one on Luther. What Luther did is more meaningful if compared to what St.

Vilson Scholz is a visiting professor of New Testament exegesis at Concordia Seminary. He comes to us from Seminario Concordia, Brazil. He has many years of experience as a translation consultant with the Brazil Bible Society. Currently he is working on a commentary on 2 Corinthians.

Jerome did. Jerome is the translator of the Vulgate (the date is AD 404), and the Vulgate is “the” Latin translation. Being older than Luther’s translation—and more widespread and influential in Western Christianity— the Vulgate is an important point of reference. Jerome, the translator, had to defend his method of translating, just as Luther had to do eleven centuries later. Jerome does it in “Letter 57: To Pammachius on the Best Method of Translating,” written in AD 395. The method that came under fire is what we know as “dynamic translation” or “semantic translation.” At one point Jerome writes, “I have not deemed it necessary to render word for word, but I have reproduced the general style and emphasis. I have not supposed myself bound to pay the words out one by one to the reader but only to give him an equivalent in value.” This is, simply put, dynamic equivalent translation. In his defense, Jerome appeals to the practice of classical and ecclesiastical authors, and to New Testament writers as well. And yet, Jerome’s Vulgate is anything but a dynamic equivalent translation. In fact, it is one of the most literal translations of the Bible that was ever made. Perhaps only interlinear translations are more literal. Jerome was able to keep the Greek word order. He did not translate the Greek article, because Latin does not have a definite article. For example, in the Lord’s Prayer, the petition, “Thy kingdom come,” which in Greek is elthétoo he basileia sou (“come the kingdom yours”) is translated as veniat regnum tuum (“come kingdom yours”). Such a literal and, sure enough, meaningful rendering is possible in Latin. But why is the Vulgate so literal? This has to do with Jerome’s famous exception, as I call it. In Letter 57, he writes, “For I myself not only admit but freely proclaim that in translating from the Greek (except in the case of the Holy Scriptures where even the order of the words is a mystery) I render sense for sense and not word for word.” The Holy Scriptures are an exception, says Jerome. It must be rendered word for word. And Jerome has had a lasting influence. Even on Germans, despite of Luther. For example, Luther translated the beginning of the Lord’s Prayer as Unser Vater (“our Father”). However, since before Luther’s time and to this very day German speaking people say, Vater unser. In this they are most certainly following the Latin Pater noster, which follows the Greek Páter hemon.

As for Luther, he translated the Bible literally most of the time. Unless there was a reason for doing something different—a reason that in most cases has not been made public—Luther would favor a literal translation or what we would call a

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 32

Unless there was a reason for doing something different Luther would favor a literal translation or what we would call a “formally equivalent” translation.

“formally equivalent” translation. In many instances one is left wondering why he did not prefer a more dynamic translation. In his Open Letter on Translating, written in 1530, Luther says, “I have not just gone ahead anyway and disregarded altogether the exact wording of the original.”1

An interesting and important example is Philippians 2:5–8. This text is commonly read as if it were dealing with Christ’s incarnation, which is then seen as his humiliation. Modern versions tend to favor such a reading. The New King James Version is a case in point: “Let this mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus, who being in the form of God, did not consider it robbery to be equal with God, but made Himself of no reputation, taking the form of a bondservant, and coming in the likeness of men. And being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself and became obedient to the point of death, even the death of the cross.” Luther scholars probably will confirm that the reformer never used the Philippians 2 text in reference to Christ’s incarnation. Luther’s translation of Philippians 2 has a dynamic touch here and there, but in general clings to the Greek and avoids unnecessary connections or paraphrasing. Here is what it says, in a somewhat literal translation into English, with parenthetical comments and the retention of the slashes that are part of his Septembertestament:

Each one be minded (Luther uses the singular because he is translating a reading found in the Majority Text published by Erasmus) / as Jesus Christ also was (Paul uses “Christ Jesus” a lot, but here and there Luther changes this to “Jesus Christ,” apparently because it is easier to pronounce) / who even though he was in divine form / he did not consider it a robbery / to be equal to God / but he emptied himself / and took on the form of a servant / became the same as another human being (this is clearly a Catholic or Lutheran reading, which assumes that this text has nothing to do with incarnation, only with humiliation) / and in appearance found as a human being / he humbled himself and became obedient unto death / yea unto death on the cross.

Luther, however, did not feel obliged to follow Jerome’s “notable exception,” by which the Latin translator argued for a literal rendering of the Scriptures. Luther would rather follow Jerome’s rule and go dynamic whenever necessary. In the Open Letter on Translating, Luther says that “the literal Latin is a great hindrance to speaking good German.”2 (The same holds true, of course, for “literal Greek.”) A few paragraphs earlier in his Open Letter, Luther is more specific: “We do not have to inquire of the literal Latin, how we are to speak German. . . . Rather we must inquire about this of the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the marketplace. We must be guided by their language, the way they speak, and do

Scholz,

Septembertestament ... 33

Luther's

our translating accordingly. That way they will understand it and recognize that we are speaking German to them.”3

Luther did not lose sight of the reader (and the hearers) of the text. He was aware of possible misunderstandings. He felt that Kirche (“church”) would be misunderstood in the sense of a consecrated building. People would not primarily think of an “assembled group of people.” Thus, in the New Testament, Luther never translates ekklesia (church) as “church,” using the word Gemein(d)e (“community”) instead—the Lutheran preference for “congregation” and, in areas with stronger German influence, “community” (Gemeinde).

Luther has been called a “creative translator,” an epithet apparently created by Heinz Bluhm. To be creative, Luther had to let go Jerome’s “notable exception.” The classic example is Matthew 12:34: “For out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks” (RSV, ESV). This is as literal as it could be. But what is “the abundance of the heart”? Luther has Wes das Herz voll ist, des gehet der Mund über, that is, “That of which the heart is full, of this the mouth overflows.” The New Jerusalem Bible is very idiomatic: “For words flow out of what fills the heart.” As simple as that.

Philippians 1:21 is one more example of creative translation. The Revised Standard Version and the English Standard Version are strictly literal: “For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.” Luther’s translation creates the poetic proverb: Denn Christus is mein Leben, und sterben mein Gewinn, that is, “For Christ is my life, and dying, my gain.” Note how he handles the single “to me” in the Greek: he doubles it, saying “my life,” “my gain.” Splendid! And dynamic. And Leben (“life”) and sterben (“dying”) rhyme in German. In English, a better-sounding version, with the same number of syllables, is, “For Jesus is my life / and dying is my gain.”

Luther becomes intently dynamic when dealing with words and themes that were high on what we may call his “Reformation agenda.” It is here that one can notice that it is indeed Luther’s Bible. What he did would certainly not be allowed to an interconfessional translation team or to a team working with Lutheran Bible Translators. Nowadays, your translation cannot be “denominational.” But Luther did not care. He said, “This is my translation.” Take the example of “preaching.” In Luther’s translation, “the voice of one crying in the wilderness” (Matthew 3:3 and elsewhere) is not just a voice of “someone crying”: it is “a voice of a preacher in the wilderness” (eine Stimme eines Predigers in der Wüste). (However, it must be added that the “preacher” was brought in later; in the Septembertestament Luther has just ein rufende stimme, that is, “a calling voice.”) At Pentecost (Acts 2:4), those who were filled with the Holy Spirit began to preach, and not just speak, in other languages. Romans 10:17 is classical: “So faith comes from what is preached (aus der prediget)” and not from what is heard, as most translations render the Greek word akoḗ

A famous example is Romans 3:28. It is well known that Luther did not simply say that a person is justified by faith; he said, “by faith alone.” But Luther did more.

Concordia Journal Spring 2023 34

He changed the order of the phrases, so that the emphasis falls on “by faith alone,” which he puts at the end of the sentence. Instead of “for we hold that a person is justified by faith apart from works prescribed by the law” (New Revised Standard Version), Luther says, “So then we hold / that a person is justified / without doing the work of the law / by faith alone.”

Luther translated Romans 3:23 in a way that nobody else dared or dares to translate. Instead of “all have sinned (past perfect) and fall short (present tense) of the glory of God,” Luther translated the Greek aorist as a present tense, which is strange, but not necessarily wrong. As a result, the verse is speaking about a human condition, not a past event. Luther’s translation says, “they are all (together) sinners.”

And what about “righteousness of God?” This is a good example of the so-called holy ambiguity, involving the Greek genitive. Translators the follow Jerome’s “notable exception” will always leave it the way it is in the Greek: “righteousness of God.” And so, it can mean that “God is righteous or just,” that “God bestows righteousness,” that “righteousness comes from God,” and so on. Yet, Luther was no fence-sitter. He settled for “the righteousness that counts before God” (die gerechticheyt die fur got gilt). This is unabashedly “forensic justification.” And this is in no sense a literal translation.

Does this mean that Luther is the creator of the “dynamic translation” model? No. This would be anachronistic, to say the least. Luther anticipated some of the features of our dynamic equivalence type of translation, but he was not interested in founding a Lutherische Dolmetschschule, that is, a “Lutheran Translation Model” or “Luther’s Way of Translating.” He did not intend to set right the clumsy German translations that had been published before his time. (We are told that eighteen translations had been published before Luther came on the scene.) Luther’s translation is not programmatic, for it does not follow an overall program or theory. Luther defends himself, gives reasons for translating this or that passage in such and such a way, but he does not teach how to translate the way he did. At the end of the day, Luther’s translation is one of a kind. One may even say that Luther’s way of translating did not win the day (or was not followed by other translators) because it is too idiosyncratic or unique. Luther is not just a translator; he is a preacher. In the same way as the gospel came clear to him, his desire was to preach this message to all his readers as well. Nobody could (or would) translate like Luther. And after him (just think of the King James Version), to play it safe, the basic rule was “translate literally.” Jerome got the upper hand or prevailed.

Scholz,

Septembertestament ... 35

Luther's

Luther becomes intently dynamic when dealing with words and themes that were high on what we may call his “Reformation agenda.”

Before giving a list of things Bible translators can learn from Luther, it may be important to answer the question, “Do English speakers have access to Luther’s translation of the Bible?” The answer is: “Not directly.” The “Luther Bible” in its entirety has never been translated into English or any other language, and, quite frankly, it is not a good idea to translate a translation of the Bible. In the case of this translation, however, scholars could be interested in having a larger portion in their own language. One place to go for additional examples of Luther’s translation is the Book of Concord, particularly the Formula of Concord. Here, many Bible passages are taken from Luther’s German translation. And whenever Luther’s translation is somehow unique, Luther’s text is translated into English. For example, in Article V of the Formula, which deals with law and gospel, the confessors (FC, SD, V, 22) cite the text of 2 Corinthians 3:9: the letter (or law) as “the ministry of condemnation” (in literal translation). In the Formula of Concord, it says that the law is a ministry (an office) that preaches condemnation. The confessors are quoting Luther’s translation (das Amt, das die Verdamnis prediget), and the English translator kept this rendering. Once again, Luther unpacked the Greek genitive (ministry of condemnation becomes ministry that preaches condemnation). His translation is anything but strictly literal. A more promising source (quantity wise) is Miles Coverdale who gave us the first complete printed translation of the Bible into English. Coverdale, “in addition to subscribing to the principles underlying the German Bible, has a very large number of definitely Lutheran formulations. He himself indicated as much when he said on the original title page of the first edition of 1535 that his version was ‘faithfully and truly translated out of Douche and Latyn.’”4

So, then, what can a translation agency or a translation team learn from Luther?