THE

CONTRIBUTION OF AGRO-PROCESSING TO AFRICA’S INDUSTRIALISATION STRATEGY

2022 Cape Town

THE AfCFTA AND TRANSFORMATIVE INDUSTRIALISATION WEBINAR SERIES

SUMMARY REPORT

Linkoping House

27 Burg Road

Rondebosch 7700

Cape Town

T +27 (0) 21 650 1420

F +27 (0) 21 650 5709

E nelsonmandelaschool@uct.ac.za

www.nelsonmandelaschool.uct.ac.za

Design: Mandy Darling, Magenta Media

1 Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 2 Important facts that emerged from the discussions are as follows: ......................... 2 Context ....................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of presentations .................................................................................................. 4 Introduction and opening remarks by Prof Faizel Ismail 5 SESSION ONE: The Competitiveness of the Agricultural Sector in Africa ......................... 7 Setting the Scene: The Competitiveness of the Agricultural Sector in Africa by Dr Noncedo Vutula .................................................................................................................... 7 The Competitiveness of the African Agriculture Sector by Professor Antoine Bouët 7 AfCTA as a potential game changer ................................................................................ 12 Sustainable Agriculture, Climate Change and Water resources to support agriculture in Africa by Professor Sylvester Mpandeli 13 Land Policy Framework in Africa as an Enabler for Africa’s Structural Transformation by Dr Jane Ezirigwe ................................................................................ 16 SESSION TWO: Regional Value Chain Case Studies .............................................................. 18 Introduction to the session by Dr Njongenhle Nyoni .................................................. 18 The Cassava Regional Value Chain by Dr Abiodun Ihebuzor ..................................... 18 Leather Production Regional Value Chain in East Africa by Mme Jennifer Gache 21 Soya Regional Value Chain in Southern Africa by Ms Grace Nsomba 22 Cotton/Textiles Regional Value Chain by Prof Lindsay Whitfield ............................ 23 Thank you and Closing Remarks by Professor Faizel Ismail 25 Policy Recommendations and Future Work .................................................................. 25

Executive Summary

The Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance at the University of Cape Town hosted a webinar titled “The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy’’ on 16 March 2022. This webinar is part of a series of webinars under the theme “The AfCFTA and Africa’s Structural Transformation Roundtable Series’’, which the Nelson Mandela School launched in 2020.

The webinar panel explored critical factors that are needed to transform the agricultural sector in Africa to make it more competitive. The panel also considered structural issues around the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) as well as climate change adaptation strategies which impact agricultural productivity and regional value chains. Similarly, the webinar panel focused on sector specific-factors that support the competitiveness of agriculture in Africa. These factors include climate change and water and land availability, as critical enablers of a competitive agricultural sector in Africa.

A select number of regional value chains were also discussed as catalysts for leveraging regional integration. These regional value chains can play an important role in alleviating knock-on effects caused by the continent’s dependence on commodity exports, and overreliance on imports of goods manufactured by global suppliers.

Important facts that emerged from the discussions are as follows:

The African agricultural sector has a comparative advantage in select commodities. These include cashew nuts, cut flowers, sesame seeds, and vanilla. A caution was raised about the focus of African countries on raw and semi-processed products. The panel also highlighted that the notion of

competitiveness can be applied to a particular product, sector or the entire economy.

There is noticeable diversification of export destinations for African agricultural products. The share of African agricultural exports to the European Union (EU) is decreasing and an increasing share is going to emerging and high-growth economies. The majority of African agricultural exports to these destinations are mostly primary and semi-processed products. However, intra-African agricultural trade is mainly processed products.

The main obstacles to Africa’s greater participation in global agricultural trade are nontariff measures (NTMs) and customs formalities. These obstacles inhibit intra-Africa trade as well as the participation of African countries in global agricultural trade.

The vast market offered by the AfCFTA is a game-changer and a milestone in Africa’s regional trade integration. However, while liberalizing 90 percent of Africa’s tariff income is critical for economic development and poverty reduction, this needs to be combined with efforts to reduce nontariff measures.

The African continent is one of the most vulnerable continents to climate change due to low adaptive capacities, which are exacerbated by socio-politico-economic issues such as unemployment, inequality, poverty, poor governance, and the low human and country-level capacity to respond to crises.

Although many African countries have climate adaptation and mitigation policies, these policies are formulated at the national level, creating a policy-scale disconnect between the national and household levels. These policies often lack consideration of interlinkages in biodiver-

2

sity, poverty, inequality, social cohesion and culture.

Sustainable, inclusive and resilient food systems require careful management of water for agricultural production as well as interface with biodiversity and people. Early warning systems are therefore critical for planning and preparedness. In dealing with climate and water-related challenges, the African continent needs to consider adopting a comprehensive approach that balances the water-food-nutrition-health nexus.

There is a need for the continent to elevate the role of biodiversity and ecosystem services in smallholder farming systems, particularly the contribution of this biodiversity to upstream and downstream water provisioning, and the potential for innovative non-conventional value adds to livelihoods. Such considerations include the use of technology in irrigation, early warning systems and geographic information systems. This calls for a greater overlap between science, policy and practice in order to create sustainable, resilient, and equitable food systems in Africa.

The historical land issue in Africa is a result of both colonization and the diversity and degree of persistence of indigenous and cultural forms of economic organizations. In addition, the African continent has approximately 600 million hectares of uncultivated arable land; this translates to approximately 60 percent of the world’s uncultivated arable land. Despite Africa’s vast tracks of uncultivated land, agricultural productivity remains low, further contributing to the rising food import bill.

In addressing land as an enabler for the competitiveness of agriculture in Africa, several issues – ranging from legal systems, land tenure, land use, management and environmental governance – need to be considered. In addition, contemporary processes of social organization and mobilization, including those derived from class, gender, region, culture, ethnicity,

nationality and generational segmentation of societies, have also been dominant in shaping access to, control and utilization of land. These also result in complex claims and conflicts over land resources. While these diverse contexts have led to variations in national approaches to land policy and land reforms, some commonalities and challenges have also emerged leading to similar responses in the design of new land rights regimes.

One of the priorities of the AfCFTA is the development of regional value chains (RVC), aimed to boost the competitiveness of the continent through manufacturing and agro-processing. Different regional economic communities are involved in the development of regional value chains. Certain RVCs exist for food security purposes, while others are intended to boost the competitiveness of agriculture in Africa.

Leather production has been identified as a priority for the East African Community (EAC) towards developing a competitive domestic leather sector. Another objective is to make affordable quality leather products accessible to the EAC and to promote the regional leather industry as competitive and for job creation.

Although the leather production value chain has a huge potential in the EAC, this industry competes with an influx of cheap synthetic shoes and second-hand products from other countries. The availability of cheap imports deters investment, especially in the footwear manufacturing sector. The need to develop policies and incentives that encourage local production and discourage the dumping of imported cheap footwear has been identified as another priority.

Although soybean is a non-staple crop in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), it has huge potential as a commercial crop. Soybean has a wide range of uses such as in animal feed, as an alternative sauce of protein for human consumption, and as an industrial

3 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

raw material. Some of the most common products of soybeans are tofu, soy milk, soy sauce, textured vegetable protein and soy flour. In addition, approximately 85 percent of soybeans grown around the world are used to make vegetable oils for consumer and commercial use.

In the Southern Africa region, soybeans are cultivated in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The soybean industry has huge potential in the region as an alternative for proteins, animal feed and for soya oil. There is also a huge opportunity to expand production and participation in Eastern and Southern Africa. However, investments are needed, particularly in processing facilities.

The cassava value chain has been prioritized for food security purposes, and as an alternative staple food to reduce the dependence of Africa on imports of wheat and other staple foods. The African continent is a major producer of cassava and has a comparative advantage in its production. More investments are needed in the production and processing of cassava into other products such as cassava flour (which can be a substitute for wheat), cassava chips, garri and cassava starch.

Some countries, particularly in West Africa produce and export cotton. Within the context of African industrialization strategies, the cotton and textile regional value chain needs to focus on moving away from exporting cotton to processing cotton for textile industries locally. In addition, African countries need to integrate textile industries that can supply domestic regional and global markets.

Context

Agriculture plays an important role in Africa as it contributes about 15 percent of the gross domestic product in the continent. It also contributes approximately 30 percent of the value of African exports and employs more than 60 percent of the

population.

However, climate change poses a significant challenge to agriculture development in Africa. The increasingly unpredictable and erratic nature of weather systems on the continent places an additional burden on food security and rural livelihoods. Some parts of the continent have experienced the destruction of farms and homes through recent floods, while other parts of the continent have endured prolonged droughts. These changing weather patterns demonstrate the extent of the threat posed by climate change on the continent. These severe weather conditions will exacerbate Africa’s deepening food crisis, narrow channels of food access and slow efforts to expand food productivity. The African continent needs extensive climate change adaptation strategies to reduce and potentially eliminate the impact of climate change on many sectors, including the agricultural sector.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has lowered economic growth, increased poverty, and reduced trade flows, the AfCFTA presents an opportunity for significant economic gains at both the regional and continental levels. However, to fully seize this opportunity, tariff liberalization is necessary. There is also a need to improve Africa’s infrastructure and address non-tariff measures (NTMs) that impact Africa’s external competitiveness.

Summary of presentations

The webinar commenced with opening remarks and an introduction of the speakers. The webinar was comprised of two main sessions, which were organised to include presentations, discussions and questions/comments and final closing remarks. Participants asked questions in writing via the chat function on the webinar platform. Below is a thematic summary of the content from the various presentations.

4

Introduction and opening remarks by Prof Faizel Ismail

Prof Ismail welcomed the participants and speakers to the roundtable, which forms part of a continuing discussion on the theme, The African Continental Free Trade Area and Africa’s structural transformation. This particular roundtable focused on The contribution of agro-processing to Africa’s industrialization strategy.

In 2020, the Nelson Mandela School launched a series of public dialogues across the African continent on the broad theme of the African Continental Free Trade Area and Transformative Industrialization. Upon the completion of the negotiations on the free trade agreement and the beginning of its implementation, the Nelson Mandela School realized the necessity to broaden the discussion beyond trade as trade in

isolation will not deliver the benefits of economic development to all the countries on the African continent. The School, therefore, launched a program aimed at linking the AfCFTA to industrialization and at exploring how African countries could leverage their commodities (especially agriculture) to spread the benefits of the AfCFTA to the less developed countries on the continent, and further build its value chains.

Prof Ismail further shared that the Nelson Mandela School is aware that to truly benefit from regional integration, Africa will have to do more than simply open its markets; it will also have to address several challenges: facilitate technology transfer, build financial development institutions

5

that can support industrialization, eliminate non-tariff barriers, improve logistics and trade facilitation infrastructure such as transport (including rail and road and ports). All these matters will need to be addressed, simultaneously, with the implementation of the free trade agreement.

It is with this broad objective in mind that the Nelson Mandela School identified specific high-priority areas of focus for the roundtable series, which include: regional value chains, agriculture and agro-processing, cotton textiles and apparel, vaccines and pharmaceuticals, and renewable energy, among others. At the first discussion (November 2020), Prof Carlos Lopes did an excellent job of identifying some of the key challenges in agriculture on the African continent. Dr Noncedo Vutula took this discussion forward in this webinar, by particularly focusing on the competitiveness of the agricultural sector in Africa and enhancing food security in the context of climate change. She brought together an excellent group of experts from across the African continent, who have also worked in agriculture for many years, to contribute to the discussion.

6

SESSION ONE: The Competitiveness of the Agricultural Sector in Africa

Setting the Scene: The Competitiveness of the Agricultural Sector in Africa

by Dr Noncedo Vutula

Before introducing the panellists for the session, Dr Vutula briefly contextualised the topic. He shared that agriculture is a major income-generating sector for many African countries; it generates about 15 percent of the continent’s GDP annually. The sector also employs about 70 percent of Africa’s workforce, making it a significant income source for many households. However, agriculture and food trade is low, due to fluctuating commodity prices that have worsened since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and, more recently, the Russia/Ukraine conflict.

Africa has been a net importer of food for over two decades, for the following main reasons: population growth; low and stagnating agricultural productivity; policy distortions; weak institutions; poor infrastructure; and changing consumption patterns. Ironically, most of the food imported into Africa can be produced locally at lower costs.

Consequently, the AfCFTA is expected to generate economic, trade and industrialization opportunities for the continent, namely in the agriculture and overall food sector, through the removal of tariffs on 90 percent of all goods traded between Member States. The AfCFTA is also expected to create opportunities for building partnerships and increasing investment in regional value chains, which will increase value addition on the conti-

nent. Agriculture and processing can be used as catalysts for economic transformation in Africa through the provision of raw materials and inputs for processing plants in the industry.

Dr Vutula concluded by stating that this webinar would tease out some of the concrete steps that can be taken to leverage the vast potential of the agricultural sector through the integration of value chains. She then introduced the speakers for the first session – Prof Antoine Bouët, Prof Sylvester Mpandeli, and Dr Jane Ezirigwe –and briefly shared their biographies.

The Competitiveness of the African Agriculture Sector by Professor Antoine Bouët

Prof Bouët is the editor of the African Agriculture Trade Monitor Report (AATM), a yearly publication of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). Prof Bouët joined IFPRI in February 2005 as Senior Research Fellow to conduct research on global trade modelling, trade policies, regional agreements, multilateral trade negotiations and informal crossborder trade. He leads the African Growth and Development Policy (AGRODEP), a trade and regional integration group. The AGRODEP is a modelling consortium which was established to assist with the analytical needs of agricultural development strategies, particularly the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) agenda.

7 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

About IFPRI

The IFPRI was established in 1975 and has a global footprint, being active in over 50 countries. It provides research-based policy solutions to sustainably reduce poverty and end hunger and malnutrition in developing countries. The IFPRI provides research in four thematic areas: Development Strategy and Governance (DSGD); Environment and Production Technology (EPTD); Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTID); and Poverty, Health, and Nutrition (PHND).

About the AATM

The AATM falls under the Markets, Trade, and Institutions (MTID theme. The 2021 AATM edition analyses continental and regional trends in African agricultural trade flows and policies. This edition highlighted that although African countries have diversified both their exports and trade partners over the last decade, African agricultural trade is still subjected to major structural

challenges as well as exogenous shocks. The report found that many African countries continue to enjoy the most success in global markets, especially with cash crops and niche products. At the intra-African level, countries are becoming more interconnected in the trade of key commodities, but there are still several unexploited trade relationship avenues.

The AATM report also examined the livestock sector and discovered that despite its important role in Africa, the sector is concentrated on low-value-added products that are informally traded. The report also examines trade integration in the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), which remains limited due to factors such as tariffs, nontariff measures, poor transport infrastructure, and weak institutions. Lastly, the AATM report elaborates and deliberates on the implications of two major events affecting African trade in 2020 and 2021, namely the COVID-19 pandemic and the implementation of the AfCFTA.

8

Most of the tables and diagrams used in the presentation by Prof Bouët are from the most recent version of this report (September 2021). Prof Bouët addressed two questions in his presentation: (1) the competitiveness of African agriculture, and (2) whether the AfCFTA is a potential game changer.

Competitiveness of African agriculture

Concerning the competitiveness of African agriculture, Prof Bouët confirmed that regional (agro-processing) value chains can increase the value-added and employment opportunities in Africa, as regional value chains have low trading costs. He highlighted that competitiveness is a concept that is difficult to define but commonly used in public debate forums. Competitiveness can narrowly be understood by comparing prices of the same commodity produced in two different places, or broadly, at the national level by taking into account not only trade costs but also exchange rates, institutions, and other economic factors. It is important to keep in mind that producers can compete

on price, quality, and degree of product differentiation.

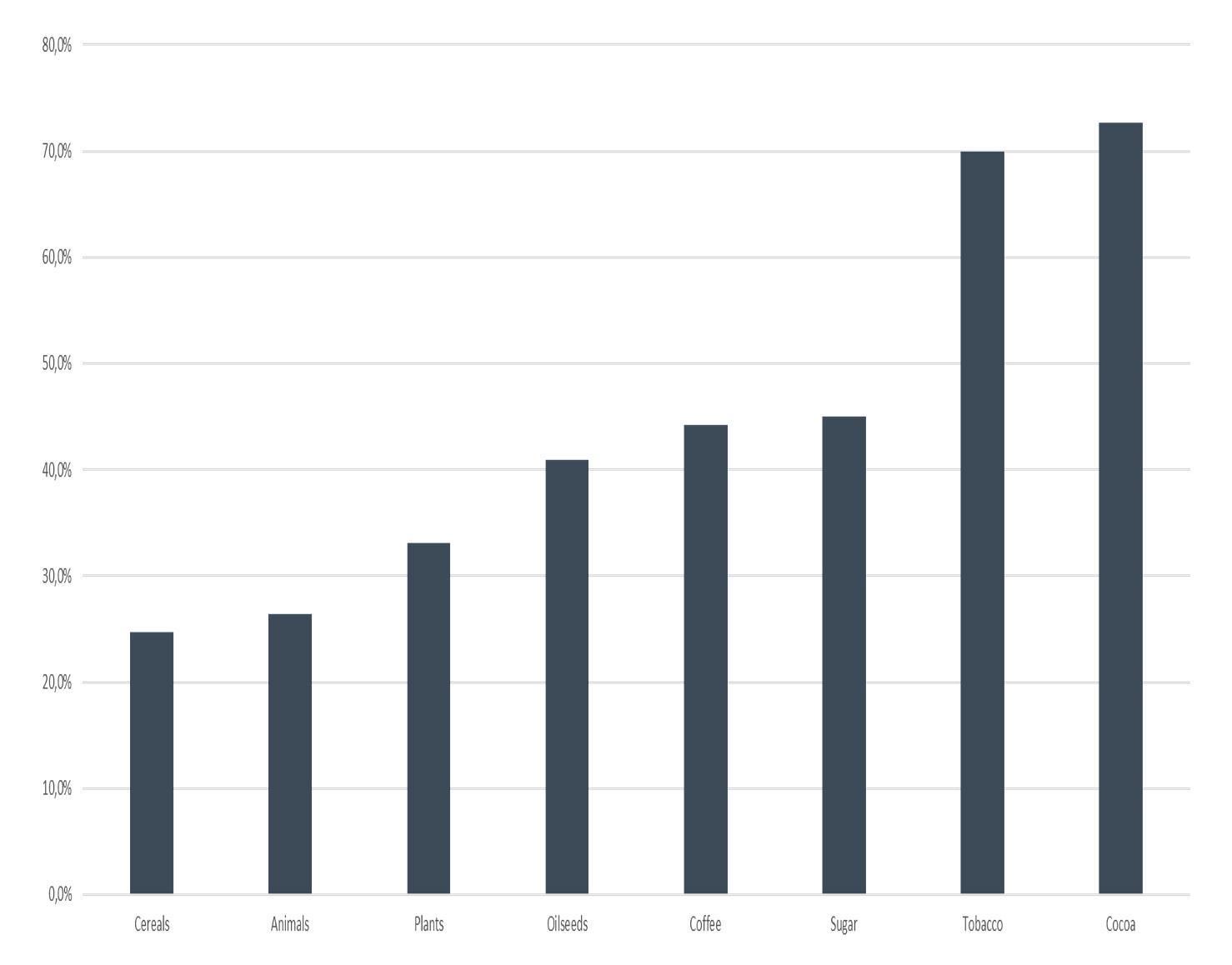

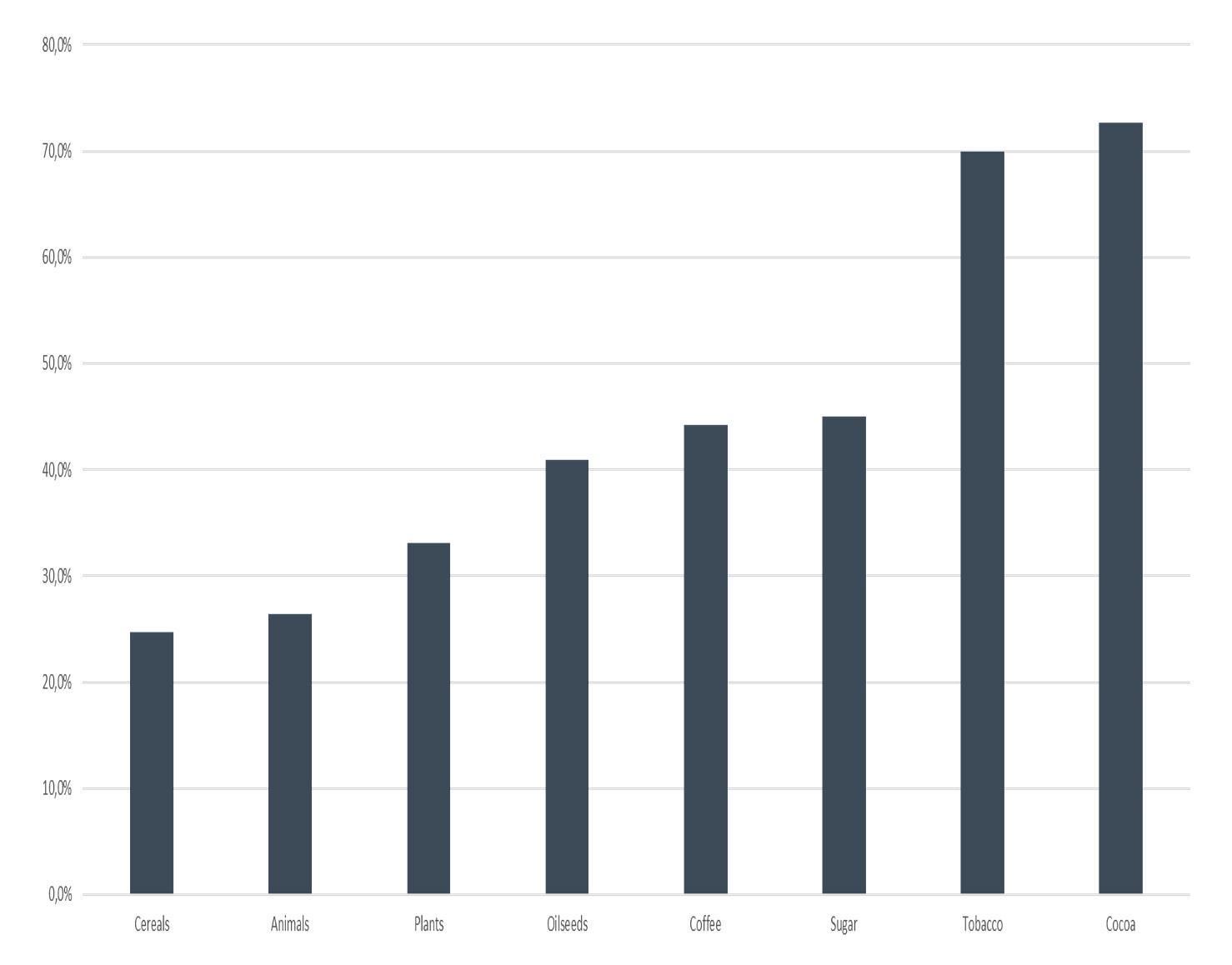

He referred to sections of the AATM report that focus on the competitiveness of several African export-oriented commodity value chains, particularly on export performance and trade flows. The commodities in which the continent has a comparative advantage include sesame seeds, cashew nuts, cocoa, cotton, tea, and grapes. He, however, highlighted that the comparative advantage of coffee is declining. Many African economies need to change their product specialization and increase their export share in pro-growth products. For example, Madagascar and Comoros need to focus on spices and vanilla. For Niger and Central African Republic, the focus should be on fresh fruits. He emphasized that an important feature of African agricultural exports to non-African markets is dominated (90 percent) by unprocessed or semi-processed products, whereas those within the continent are balanced: half of Africa’s intra-regional trade is associated with processed products, as reflected in figure 1 below.

9 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

Figure 1: Trends in intra-African agricultural trade, 2003–2019 (US$ billions)

The presentation also highlighted areas where Africa has defensive trade interests in the agricultural value chains. One such area is in the cereals sector, where Africa has a big trade deficit. He also emphasized the importance of identifying the countries in the continent that have low competitiveness for cereals as well as those that have some comparative advantage. Additionally, it is important to determine whether Africa is uncompetitive in all stages of the cereals value chain, or whether there is a comparative advantage at certain stages of production. The above-mentioned aspects are necessary for building regional value chains. It is also important to know whether Africa’s trade imbalance in the agricultural sector is as significant in its intra-regional component as it is in its extra-regional relations.

While a few African countries are among the largest producers of cassava, especially Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Ghana, the global market for this crop is significantly smaller than that of maize, rice, and wheat. No African country is featured among the 10 largest producers of these three cereal crops. On the other hand, China, India, Ukraine, and the United States are often among the largest producers.

The semi-processed stage of these crops yields flour, groats, and starch, while the processed stage includes food preparations using these cereals. These include bread, pasta, couscous, tapioca, cereal products, biscuits, waffles, and so on. As it is not possible to distinguish among food preparations based on cassava, maize, rice, and wheat, the processed stage is essentially the same for each cereal.

10

Figure 2: Percentage of products with Africa’s Revealed Comparative Advantages, 2017–19 Average

In addition to cereals (wheat, maize, rice) where African economies have a defensive interest, other value chains of interest include the cassava, sugar, and vegetable oils value chain. The focus on these value chains is mainly influenced by their high import bill. Also, these three value chains are major foods in terms of kCal/person/ day in four populous African countriesEgypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa.

It is also important to note that during the period 2003–2018, economic and population growth was stronger in Africa than in the rest of the world. This led to higher demand for food staples imports in Africa. Similarly, the current increasing food import bill is due to rapid domestic demand growth, as a result of higher economic growth, increasing population growth and increased urbanization.

Of importance for African governments to note is that the high food import bill is a missed opportunity for the continent, as the African agricultural sector is missing out on growing markets. Additionally, the high level of imports is exposing the continent to additional risks, as agricultural markets regularly undergo significant volatility cycles.

Non-tariff barriers (NTBs) are high in Africa; a trend that is similar to other parts of the world. However, NTBs can have a more restrictive impact in Africa since low-development countries meet more difficulties when subjected to these barriers. These NTBs can be in the form of export restrictions, import duties applied by the importer, time lost for border compliance, the cost for border compliance, and the cost for documentation compliance.

Many intra-African traders consider NTBs to be the biggest obstacle to achieving the objectives of the AfCFTA and deepening integration in the Regional Economic Communities (RECs).

In addition to the high trading costs in Africa, intra-African trade of agricultural

11 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

products is regionally segmented. There is a very small trade share between African regions. Moreover, the areas where Africa has a comparative advantage are mostly for unprocessed or semi-processed products. Africa also specializes in niche products (berries, essential oils, etc.) for which the value in the global market is very low.

AfCTA as a potential game changer

In relation to whether the AfCFTA is a game changer, Prof Bouët highlighted that positive trade reform must be based on trade with countries with large trade volumes. The AfCFTA can stimulate regional value chains and agro-food processing but this reform needs to be ambitious. It must not only address tariffs but also infrastructure improvements. Technical trade barriers also need to be addressed. The AfCFTA, therefore, has the potential to significantly boost intra-regional trade and break Africa’s longstanding dependence on foreign

countries as export destinations and sources of imports and investment.

Diversifying exports, accelerating growth, competitively integrating into the global economy, increasing foreign direct investment, increasing employment opportunities and incomes, and broadening economic inclusion are some of the positive economic outcomes that the AfCFTA can facilitate.

Professor Sylvester Mpandeli from the Water Research Commission made a presentation on Sustainable Agriculture, Climate Change and Water resources to support agriculture in Africa.

About the Water Research Commission

The Water Research Commission (WRC) aims to contribute towards an improved quality of life for the people of South Africa, by promoting water research and the application of research findings. This is accomplished by promoting coordination,

12

Figure 3: Trends in intra-Africa and intra-regional agricultural exports, 2003-2018

communication and cooperation in the field of water research; establishing water research needs and priorities; funding research on a priority basis; and promoting the effective transfer of information and technology. Since its formation in 1971, the WRC has been successful in promoting a significant expansion and upgrading of expertise in the South African water industry.

Sustainable Agriculture, Climate Change and Water resources to support agriculture in Africa by Professor Sylvester Mpandeli

Prof Mpandeli contextualised his presentation by stating that Africa is facing a triple challenge of poverty, unemployment and inequality. Malnourishment or food insecurity is another big challenge, therefore, the continent has the responsibility to produce sufficient and nutrient-dense food. At least 75 percent of smallholder subsistence farmers produce most of the region’s food, however, they are threatened by climate change and consequently insufficient water supply.

He suggested that Africa is the most vulnerable continent to climate change, due to its low adaptive capacities; this is worsened by the legacy of socio-political-economic issues. Policies also lack the consideration of interlinked issues such as local biodiversity benefits, poverty, inequality, social cohesion and culture – which play out at the household unit. Embracing collaborative processes is key so that stakeholders in policy governance can co-design and co-produce pathways to tackle these intractable societal challenges. Sustainable development approaches need to be embraced, as agriculture as a whole is on the decline. Fit-for-purpose, sustainable, inclusive and resilient food systems should be underpinned by agricultural water management, biodiversity and a peopledriven approach.

13 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

Prof Mpandeli highlighted the mismatch between health and the food policy, which causes the large gaps that still exist between food supply and nutritional requirements as reflected in figure 4 below.

Prof Mpandeli advocated for a holistic and integrated approach that incorporates nutrition into aspects of crop and water productivity to effectively tackle food insecurity as well as malnutrition. A better understanding of the role of biodiversity and ecosystem services in smallholder farming systems is needed. Particularly, the contribution of biodiversity to upstream and downstream water provisioning, and the potential for innovative and non-conventional value adds to livelihoods.

Prof Mpandeli also spoke about the Water Commission’s work on digitalization in the agricultural sector as well as risk-informed early action, with the specific intention to

empower women and youth in the sector. He also spoke briefly about the need for transformational change and nexus planning, as an alternative toward sustainability by 2030; and the need to embrace the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). Prof Mpandeli shared that he is happy to report that most of the water management projects happening across the African continent are multi-disciplinary.

African leaders have a responsibility to find and implement different approaches to securing food and nutrition for all. Africa needs fair and equitable partnerships within the research, education, extension services, and private sectors. This includes the contribution of Africa’s agrobiodiversity and indigenous knowledge systems to food security, healthy diets, income generation, agricultural diversification and social cohesion.

14

Figure 4: Agriculture, health, and food policy mismatch

15

Land Policy

Framework in Africa as an Enabler for Africa’s Structural Transformation

by Dr Jane Ezirigwe

Dr Ezirigwe started her input by defining structural transformation as the transition from low productivity and labour-intensive economic activities to higher productivity and skill-intensive activities. She stated that her input aimed to address how land policy frameworks in Africa will help the continent transition out of low productivity and labour-intensive agricultural practices. She went on to state that Africa is underutilizing its land and continues to depend on food imports. She highlighted the need to link land policy frameworks to the regional value chains.

The land issues in Africa are historical, stemming from the colonization experienced in various regions, and the diversity

of and degree of persistent reliance on indigenous and cultural forms of economic organizations. This situation also has its origins in geo-political, economic, social and demographic factors more recently compounded by emerging global and strategic imperatives. These factors have given rise to a variety of legal regimes relating to land tenure, use, management and environmental governance. In addition, contemporary processes of social organization and mobilization, including those derived from class, gender, region, culture, ethnicity, nationality and generational cleavages, still dominate in shaping the access to, control and utilization of land, resulting in a complex basis of claims and conflicts over land resources. While these diverse contexts have led to variations in national approaches to land policy and land reforms, it is also the case that some commonalities and challenges have emerged leading to similar responses in the design of new land rights regimes.

16

Her situational analysis of the land framework across Africa further included the following points, which she briefly touched on:

• No one size fits all – there are nuanced differences across regions;

• Land ownership inequality (white minorities, gender);

• Access to credit;

• Poor Land Governance (land grabs, inefficient land admin, delays, conflict);

• Unsustainable patterns of use (pastoralism) – conflict;

• Poor linkages between urban & rural lands – limited market integration.

Some fundamental considerations for land policy frameworks that can lead to structural transformation in the agricultural sectors must consider big investors, smallholder farmers and local communities. These initiatives need to be inclusive of women and youth. Issues on environmental protection need to be taken into consideration, together with land use and agricultural technologies such as genetic engineering and precision farming. Further considerations include:

• Access to both farm and industrial land;

• Agriculture as an intermediate good – produces raw materials for food production;

• Frictionless trade & movement between urban and rural economies – road networks.

Dr Ezirigwe recommended that policymakers adopt a “people-centred development” approach that is consistent with ecological, economic and social realities. The land policies adopted should:

• Support new agricultural technologies and intensive livestock production;

• Promote investments both by and with smallholder farmers;

• Promote partnerships (long leases

versus outright sales);

• Inclusive access for women and black people;

• Safeguard against the dispossession of legitimate tenure right holders;

• Minimize environmental damage;

• Use tax to discourage ownership of large pieces of unused land above a certain threshold and to discourage its retention;

• Land planning should include linkages between designated farm and industrial land to include agro-processing activities.

She concluded her input by saying that COVID-19 has affected the global trade of food and agricultural goods, impacting both the exports & imports of African countries. The AfCFTA can trigger trade-led industrialization and opportunities for participation in regional value chains.

17 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

SESSION TWO: Regional Value Chain Case Studies

Introduction to the session by Dr Njongenhle Nyoni

Dr Nyoni highlighted some of the insights shared from the previous session: that Africa has competitive advantages, however, there are also gaps; intriguing statistics on regional trade; regional value chains and how to stimulate the African economy; and the various land issues that need to be confronted for the continent to make a positive transition regarding its value chains. He indicated that this session would delve deeper into regional value chains, considering a few case studies within the continent. Dr Nyoni then introduced the speakers for the session – Dr Abiodun Ihebuzor, Mme Jennifer Gache, Ms Grace Nsomba and Prof Lindsay Whitfield – and briefly shared their respective bios.

The Cassava Regional Value Chain by Dr Abiodun Ihebuzor

Dr Ihbuzor began his presentation with a background of NEPAD in relation to the AfCFTA. He presented NEPAD’s newest tools to tackle the shortcomings and failures of previous plans to strengthen the continent and to re-engage the goals of African development and integration. He highlighted that the cassava value chain has been prioritised in Africa as far back as 2005 through NEPAD, which introduced the Pan Africa Cassava Initiative (NPACI), mandated to co-ordinate CASSAVA development and promote the crop for food security purposes. The NEPAD initiative also covered market access, the organising of cassava producers and private sector investment across the cassava value chain.

More than 50 percent of the world’s cassava crop is cultivated in Africa (6,486,000 hectares), with Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as its major producers. Nigeria is the world’s largest producer of cassava, with 19 percent of the total world production – estimated at 45 Mt. Nearly 90 percent of the cassava produced in Sub-Saharan Africa is used for food, and in the DRC cassava constitutes 54 percent of the total energy intake and 16 percent in Nigeria. Apart from its use as a staple food – either fresh or processed – animal feed is the second largest market for cassava. An estimated 25 percent of the global cassava production is used as a feed ingredient for livestock, poultry, and fish farming.

There are, however, larger pieces of uncultivated land in Africa, that could be used to grow cassava and contribute to Africa’s GDP. The World Bank forecasts that farmers and agribusiness in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have the potential to create a US$1 trillion industry by 2030.

The global trade in cassava products grew rapidly from the 1970s to the late 1980s, largely driven by European policy to discourage cereal and feed grain imports, which did not apply to pelletized cassava and financed the expansion of that trade, especially from Thailand.

China imported 9.3 million tons of dried cassava chips and pellets in 2015 for US$2.1 billion, with the chips mostly used for ethanol production, and mainly originated from Thailand and Vietnam. There was a decline in Chinese imports to 7.7 million tons in 2016 (FAOSTAT) mainly due to Chinese domestic policy switching

18

to emphasize increased use of corn for ethanol and feed, rather than preventing it.1

He also highlighted global trends in cassava production, which show that Africa has a comparative advantage in the production of cassava. Latin America has an advanced cassava food industry that is led by Brazil and processes several industrial cassava derivatives. Asian countries are the most advanced in processing non-food cassava derivatives. The bulk of cassava products outside Africa are not consumed directly as food. Most of it is intended for industrial purposes, and for feeds. In West Africa, cassava commercialization has centred on marketing prepared cassava-based convenience foods. The emerging cassava markets in South-eastern Africa have centred on fresh cassava, low-value-added cassava flour, and experimentation in the

1 https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

industrial processing of cassava-based starches, biofuels, and feeds (Haggblade et al 2012). Thailand is the world’s largest exporter of cassava products; overall, it accounted for 75 percent of global exports of dried cassava products by value in 2016 (FAO-STAT)2. Thailand exports cassava chips (about 60 percent of Thai cassava exports by volume), cassava native starch, and modified starch. The latter two categories are food and drink, paper, textiles, cosmetics and medical products. Thailand’s earnings from the export of cassava products reached nearly US$2.9 billion in 2016, having grown by about 15 percent annually since 2010. Thailand processes 40 percent of production into starch for both domestic and export markets. Vietnam exported US$1.5 billion in cassava products in 2015.

Dr Ihbuzor then proceeded to discuss how

19

2 ibid

cassava can be used to industrialize Africa. Cassava production is still a task for rural families, with virtually no organized plantations. This is one of the main obstacles to building a sound cassava industry since the high perishability of the root limits any initiative towards processing if a stable and permanent supply of raw material is not ensured. There is a need for an extensive and robust logistics system; including adequate and well-equipped storage, an efficient transport network to collect the product through the production zones for aggregation, and to maintain the product in good condition until it is processed to a more stable form.

Dr Ihbuzor then highlighted the following areas needing development, for cassava to be used to eradicate poverty on the continent: equipment, extensive service, agri-inputs, tractor hiring services, trading, cassava production and processing, packaging and international trade. Special Agro-industrial Processing Zones (SAPZ) are also key for the industrialization of

cassava in Africa. SAPZs are designed to concentrate agro-processing activities within areas of high agricultural potential. They enable agricultural producers, processors, aggregators and distributors to operate in one vicinity, thus reducing transaction costs and sharing business development services for increased productivity and competitiveness.

Dr Ihbuzor proceeded to share a case study of cassava processing in Nigeria and a SAPZ in Gabon. He further shared that accessibility, availability and affordability are key for building reform in global value chains. Dr Ihbuzor finally shared the lessons learnt and thereafter issued a call for action:

• The use of the value chain approach will accelerate the pace of the agro-industrial revolution and deliver powerful impacts. The differences in the resource structure will be better managed through Value Chain tools. Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) are diminishing hence African governments need to take charge in

20

removing constraints that hamper Cassava

Value Chain Development.

• Providing the appropriate policy environment is fundamental to attracting investment into the sub-sector. The AfCFTA exists to enable the efficient allocation of resources to spur growth and development, hence, the need to offer more opportunities to industries and market players in a bid to build a more resilient and robust landscape.

• The absence of legislative policy supports will frustrate the gains already made in Cassava Value Chain Development.

• With potential investment opportunities across all sectors (health, education, agriculture etc.), the time for the African continent to devise a competitive strategy is now. Especially for the non-formal sector and the MSMEs operators locally (this has the potential of unlocking significant value and developing the market economy).

Leather Production Regional Value Chain in East Africa by Mme

Jennifer Gache

Mme Gache shared that the East African Community (EAC) in 2017 directed the Secretariat to “Put in place mechanism/s that support leather manufacturing ... The mechanism/s should prioritize the development of a competitive domestic leather sector to provide affordable, new and quality options for leather products to EAC citizens. The mechanism/s should promote leather industries in the region, make the region more competitive and create jobs.”

Currently, countries in the region are struggling to move upward in the value chain; the region has only succeeded in the primary processing of hides and skins up to wet blue leather (a raw material), with 80-90 percent of the wet blue leather being exported and only 10 percent remaining for processing to finished-leather goods

(particularly footwear). The region also faces stiff competition from Asia and Europe in the global leather market.

Significant wastage of leather takes place at family, village and town market slaughters, affecting the number of hides and skins the region is able to process and sell to the global market. The region currently derives most of its value from the processing of wet blue; it hardly exports any finished leather products due to the quality of production. The local market, however, only consumes a fraction of the leather goods.

Consequently, the economic importance of the industry has been modest, and declining. The decline is attributed to several factors including the lack of diversified markets and low production differentiation. Other challenges along the value chain include value leakage, low quality/ unusable hides and skins, underutilization of tanneries, lack of affordable finance for tanneries and growth of SMEs, and inadequate collaboration along the value chain.

The region still strives to “be a regionally and internationally competitive leather producer and leather products industry, sustainably contributing to the socio-economic development and transformation of the EAC region, through value addition and retention”. To this end, the EAC has set the following development targets:

• Intra-EAC trade of leather and leather products increases from the current 1.5 percent to 10 percent by 2029;

• Increase GDP contribution from the current 0.28 percent to 4-5 percent by 2029;

• Increase exports to the global market by 20 percent on an annual basis, from the current US$131.2 million to US$700 million by 2029;

• Create employment opportunities along the value chain to the tune of 500,000 direct jobs by the end of 2029; and

• Train and support SME entrepreneurs.

21 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

Soya Regional Value Chain in Southern Africa by Ms Grace Nsomba

Ms Nsomba’s presentation focused on the production of soya beans as a value chain for cooking oils and animal feed (which has a direct impact on the value chain for poultry, livestock and fish). The CCRED’s (Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development) research has found that small market participants are getting bad deals, small farmers get too low prices for their crops, small processors get charged too much for grain, and consumers are paying high prices for soybean products. There is, therefore, a strong case for regional competition advocacy and enforcement.

Growth and inclusion are being undermined by a lack of competitive markets with effective regulations – especially, on a regional basis. Many dispersed farmers have limited access to information on market prices (price takers) and are therefore undercut. Few large traders, with vast customer networks, storage and knowledge of prices across place and time (market makers), and are linked to large processors, are able to charge higher prices. Smaller agri-businesses who have to buy from these large traders may get charged high prices Dispersed consumers with limited bargaining power (price takers) also pay higher prices.

In terms of production, CCRED found that South Africa is a significantly larger producer of soybean compared to other countries in the region; however, it remains an importer of soybean and oilcake. Malawi and Zambia are significant exporters of soybean, with the ability to export within and outside African borders. However, despite its demand for soybean, other African countries (such as Malawi and Zambia) still do not export to South Africa; indicating that markets in Africa have not formed effective trade networks of soybean.

22

Climate change effects are compounded on markets that are not collaborating, with severe implications for soybean production, trade and regional integration. Weather patterns in Africa are especially unpredictable with long spells of drought and heavy rains.

Further impacting the processing of soybean to oil and animal feed is the significant travel distances between producing and consuming areas, resulting in transport costs within and across borders which exceed that anticipated. There are significant price changes from the purchase at harvest, to later months when large traders sell at supra-competitive margins (estimated excess profits of US$320 million). In addition, prices have been driven up in Malawi and Uganda, while prices in Nairobi & Dar es Salaam are far above fair import costs from the within region or the Deep-Sea region. This has led to animal feed producers closing down, thus reversing the development needed.

There is a huge opportunity to expand production and participation in Eastern and Southern Africa if markets worked better.

Cotton/Textiles Regional Value Chain by Prof Lindsay Whitfield

Prof Whitfield shared about the cotton and textile regional value chain in the context of African industrialization strategies, particularly, how the continent can move away from exporting cotton to processing for local textile industries.

She stated that not much cotton is processed into textiles in Africa, although there are apparel sectors that largely import their textile. There is a need for more integration between agro-processing and manufacturing in this value chain. Looking forward, Africa needs to consider building integrated textile sectors in the context of the 21st century. Furthermore, the conti-

23 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT

nent should not think about regional value chain participation separately from global value chain participation. When global market participation is considered first, the development of value chains will follow because export markets allow for access to a larger demand, which is necessary to achieve economies of scale in capital-intensive industries. It is important to reach that level of international competitiveness by building up the capabilities required through accessing foreign knowledge and frontier technologies.

She continued that for African countries to build integrated textile industries that can supply domestic, regional and global markets, the continent needs to understand global markets. African leaders need to also understand the local vision and also have an in-depth understanding of the global fashion industry. There are really important trends that are emerging relating to the types of textiles that are in demand, current technological innovations, and the transition towards sustainability. This emerging sustainability shift in the global fashion industry creates windows of opportunity for African countries.

The global fashion industry accounts for 6-8 percent of greenhouse gases and 20 percent of water pollution. Global apparel brands and retailers are now increasingly seeking to reduce the climate impact on their global supply chains by changing the raw material base of clothing. There is a move towards organic cotton, hemp, manmade cellulose fibres and recycled materials.

Prof Whitfield argued that when the continent thinks about how to create vertically integrated textile industries in African countries, innovation is necessary and to think beyond cotton. She added that if African producers persist in producing cotton, then it should rather be along the lines of producing organic cotton, alternative fibres and recycled fibres.

The second global trend that is providing

an important window of opportunity for African countries is nearshoring. Buyers are revamping their models to reduce over-stocking and shorten lead times, and they want to source from countries which are within close proximity. Nearshoring is proving challenging due to a lack of production capacity; which creates another opportunity for African countries.

Prof Whitfield concluded that there are great opportunities to build integrated textile industries in Sub–Saharan Africa. This can be done at regional levels, with the support of the AfCFTA. As such, Africa needs to stop thinking about competition among countries, and instead focus on collaboration between countries and regions in West Africa, East Africa and Southern Africa, and on building agglomerations of vertically integrated textile clusters. She further suggested that the continent needs to target collaborations with buyers as they are most capable to convince their foreign suppliers to buy local products.

24

Thank you and Closing Remarks

by Professor Faizel

Prof Ismail thanked the facilitators, speakers and participants for attending the session, and Dr Vutula for organising the webinar.

Policy Recommendations and Future Work

The focus of regional value chains should focus on areas where Africa has a competitive advantage.

The AATM report has identified cereals as an area where the African continent has low competitiveness. A possible collaboration with AATM, IFPRI and AKADEMIYA2063 could be beneficial in identifying the steps required to improve the competitiveness of cereals as well as vegetable oils for cooking and industrial use.

The high food import bill in Africa is worrisome and has exposed the continent’s dependency on imported food. The disruptions in food supplies caused by the war in Ukraine have not only exposed the deep reliance of Africa on food imports, but also highlighted the need to develop alternative sources of staple foods. The development of the cassava value chain as an alternative to imported grains can assist in reducing the dependency on global producers. The vast research that has been done in these areas could assist in developing a paper.

Given the importance of NTMs in Africa, the focus of the next webinar/roundtable will be on Trade Facilitation.

Ismail

25 The Contribution of Agro-Processing to Africa’s Industrialisation Strategy • SUMMARY REPORT