RICKER EST. 1953

#F8B3AC #2266AA PERCEPTION VOLUME III PART II

#F07341

#F9BC17 #0A856E #A094C7

#534985

#56C7F0 #FB3640

COULD BE ARCHITECTURE ANDREW KOVACS BEN GROSSER

HIMALI SINGH SOIN

MIMI ZEIGER

BLAIR SMITH

MAURICIO ROCHA MARK RAYMOND

PROJECTS OF DECENTERING

From playfulness and algorithmic bias to emptiness and decolonization, the following issue of the Ricker Report aims to explore and challenge our understanding of the normal and the everyday. This publication is designed to illustrate the values of our featured artists, architects, and curators but also the integral role of perception in the construction of our reality. The experiences of our lives define our perception of the world, but the way we perceive the world also defines our experiences.

In the context of our ever-changing social, political, and economic climate, we present these notions of perception as a form of agency to construct new and other worlds. We truly believe that a future built on the foundations of justice begins with an understanding of those with a different perspective. Through whatever form our world may take on, we see our newest installment of the Ricker Report as an opportunity to learn and embrace the views of others.

As the world moves towards a “new” normal, the Ricker Report will continue to develop as a platform for both criticism and change. We will continue to stand as a reminder that things are not always as they seem to be. It is only a matter of perception.

The Ricker Report Team

Editor-in-Chief

Shravan Arun

Director of Operations

Mila Lipinski

Director of Outreach

TJ Bayowa

Editors

Diego Huacuja

Delnaaz Kharadi

Kriti Chaudhry

Hannah Galkin

Andrew Cross

Phoebe Glimm

Michelle Mo

Alejandro Toro

Defne Ergün

Graphic Designers

Sneha Patel

Rachita Ranjit

Asher Ginnodo

Zach Michaliska

Adam Czapla

Eliza Peng

Jerry Rodriguez

Ishita Anand

Could Be Architecture

Joseph Altshuler and Zach Morrison

The Architectural B-Side

Andrew Kovacs

Demetrification, NFTs, and MORE

Ben Grosser

we are opposite like that Himali Singh Soin

The Optimistic Critic

Mimi Zeiger

Blair Smith

The Art of Emptiness

Mauricio Rocha

Homemade, with Love analōg

Mark Raymond

Canon and the Projects of Decentering

Soumya Dasgupta and Emilee Mathews

6 20 34 48 60 84 70 110 132

Could Be Architecture

COULD BE ARCHITECTURE 6

Could Be Architecture is a Chicago-based design practice directed by Joseph Altshuler and Zack Morrison that designs seriously playful spaces, things, and happenings. They work across scales, including designs for buildings, interiors, installations, scenographies, exhibits, furniture, costumes, and publications. As practitioners and academics, their work is equally invested in built pragmatics and speculative research. As citizens and artists, their work is committed at once to public engagement and aesthetic ambitions. They aim to create architecture that tells stories, builds audiences, resonates with people’s emotions, and instigates enthusiasm around the activities and imagery that it stages. Their work positions architecture as an active character in the world, enacting a future full of wonder, humor, color, and delight.

9 COULD BE ARCHITECTURE

COULD BE ARCHITECTURE

In conversation with Joseph Altshuler and Zack Morrison

How did the story of Could Be Architecture begin?

Zack (Z): It started with our story “Oscar Upon a Time”. It was the first project we worked on collaboratively and before naming ourselves as a collective entity. We met at Rice University, and, through getting to know each other, we became aware of our shared interest in the way that we looked at the world and architecture. This was also the first year of the Fairy Tales Competition. We partnered with Mari, Joseph’s partner, to write a story, and “Oscar Upon a Time” was the result of it.

Joseph (J): On one hand, we hope that it’s a fun and engaging story so that people who don’t have a background in architecture can still enjoy and engage in spatial ideas. On the other hand, it is also a foundational narrative for our practice and research agenda. The story is about how we can have a meaningful, friendly, and companionable relationship with architecture at many different scales. From the

scale of an object to the scale of buildings and cities, architecture has a capacity to be our companion and friend. In all the work that we do, we look to find ways in which people can relate to buildings less as objects and tools that serve our needs and more like a subject that could actually be our friend. Maybe a nonhuman friend but our friend, nevertheless.

Z: In a lot of ways, we keep returning to that story through the overall idea of how we amplify architecture’s presence as a companion in our lives. The story allowed us to explore form, color, and scale in whimsical ways because it was a story that was only ever going to be a story. It allowed us to investigate things we were and are still interested in.

How has your architectural fairy tale “Oscar Upon a Time” grown alongside your practice’s ethos?

Z: In some ways, the story was very specific.

COULD BE ARCHITECTURE 10

J: Oscar, the human protagonist, has the same ontological status as the architecture he interacts with. In the story, Oscar is gifted four abstract architectural “objects” on his fourth birthday. As Oscar grows, his architectural companions grow with him. By the time he’s a young adult, his architectural companions have grown big enough to become the rooms of his house, and by the time he is an old man, they’ve grown to the extent that they are actually buildings in the city. The themes of Oscar remain relevant to our practice today, and we are still playing them out. Just like Oscar, we are slowly scaling up the kind of projects that we are working on. They may be growing at a different rate than us as well. In many ways, Oscar is our avatar as we seek to make architectural friends in the world.

Z: As a work of fiction, and a fairy tale in particular, the story indulges in whimsy and magic. Although the story isn’t something that is meant to be built literally, our practices

continue to grow with built work. We use the story as guide to envision how to embed the magic of whimsy and play into more practical, built projects.

J: The story sets up an agenda, and the practice enacts it into the world.

Where does Could Be Architecture find itself in the larger stories of practice, pedagogy, and curation?

J: We operate between all three of these different vectors. We are, first and foremost, a professional practice with real clients, but we also both teach. Our curatorial practice tends to go between the world of academia and practice. So, all three of those vectors are important to us. We believe that they mutually enhance each other.

We also believe that our active professional practice makes us better teachers. Similarly,

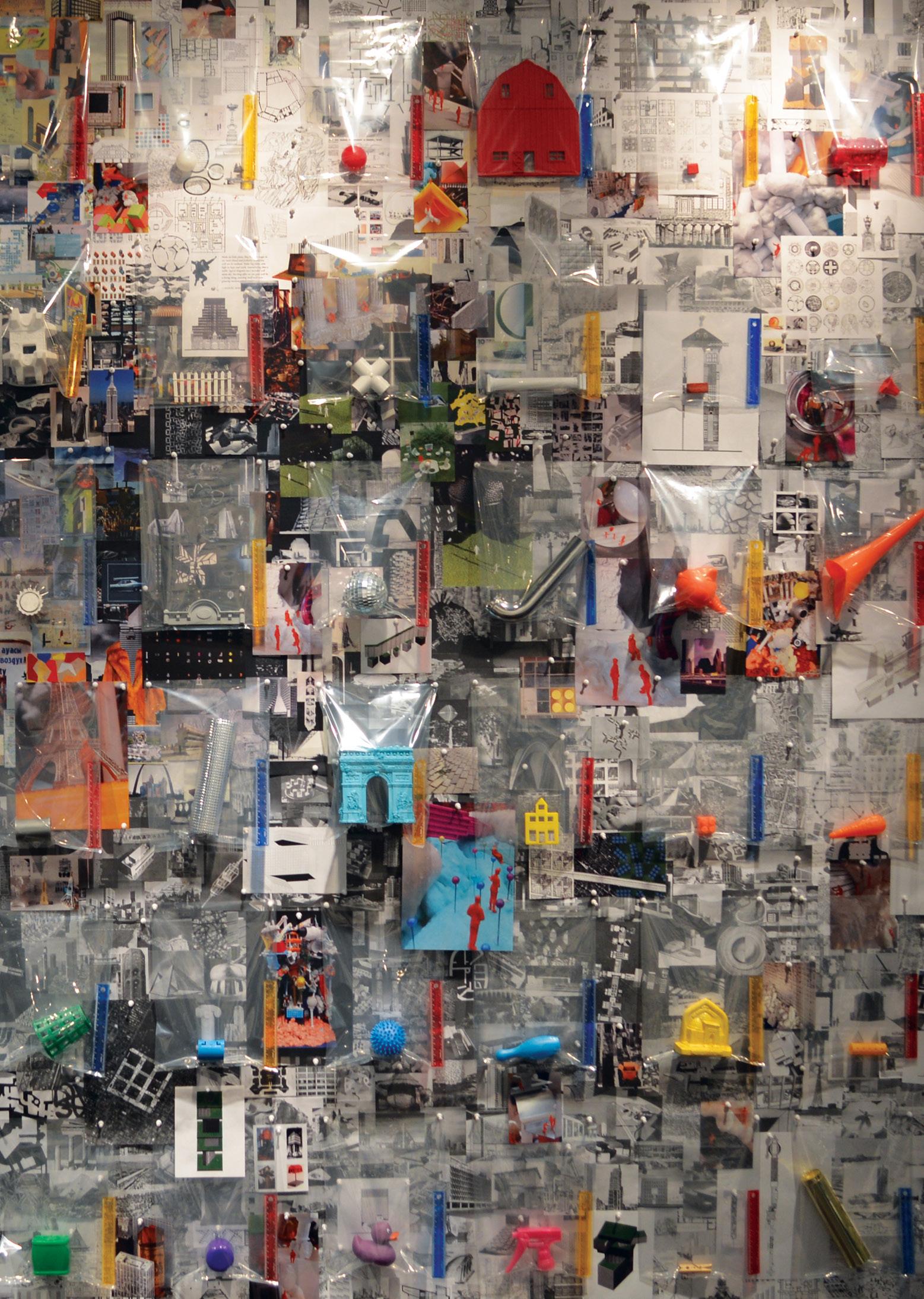

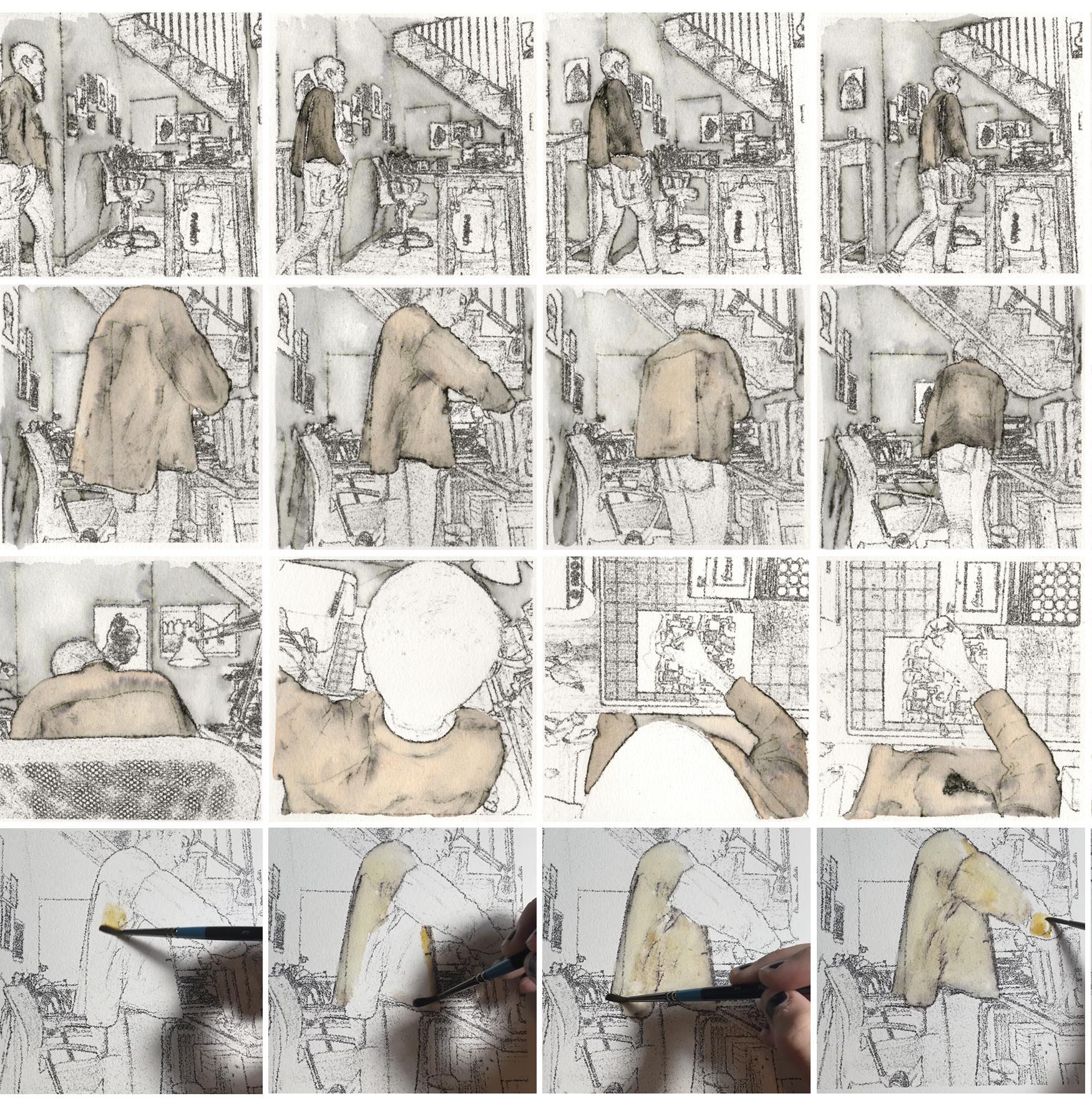

Deviant Dwellings Courtesy of Could Be Architecture

Deviant Dwellings Courtesy of Could Be Architecture

I think the fact that we are teachers makes us practice in a way that allows us to be more accessible and more approachable. It allows us to also bring certain qualities of the discipline and a discourse of the discipline into its practical application. There is a mutual relationship between these things, and sometimes there are literal crossovers as well.

As a part of my teaching role at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I’m also the curator of a gallery space that’s dedicated to architecture, interior architecture, and designed objects. When we are designing and fabricating installations for this gallery, our practice, pedagogy, and curation converge.

Z: I also think that it goes back to our ambition for architecture to be a more open and encompassing practice. We are conscious that we are not trying to specialize in any particular typology. We work on traditional architecture projects but also teach and curate exhibitions. In this sense, our practice seeks deliver architectural ideas through multiple modes.

J: Yeah, it is a super intentional ambition to be a generalist practice. We wear a lot of different hats to not necessarily become experts in one particular thing but rather to have a very intentional exchange among the different sectors and disciplines.

Speaking on the multidisciplinary and generalist nature of Could Be Architecture, what is SOILED magazine, and what role does it play in your practice?

J: SOILED predated our practice. I started SOILED after my graduation from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. At the time, there were limited outlets for multidisciplinary cultural exchange within or around

the architecture school. It was something that frustrated me during school, and I graduated with a craving to create opportunities for conversation, for discourse, and for cultural exchange in and among architecture. It is so delightful and refreshing to see the Ricker Report now taking on this kind of charge for cultural exchange—I wish you were around when I was an undergraduate student.

SOILED is a very direct and explicit platform to bring new audiences into architecture via literary techniques. The publication is a mash up of a literary journal and an architecture magazine. We play matchmaker to connect writers and other folks from the literary world with architects. We invite writers to create either works of fiction, poetry, or other kinds of storytelling that provide new entry points into architects’ work. Oftentimes, the architecture comes first. We reach out to architects that interest us or have exciting work along a particular topic of any given issue. Then, we’ll invite writers to respond through the written word. The writers create flash fiction, poetry and other kinds of content that help people who may not be able to read the drawings in the way that architects do. The goal is to enter the stories in an engaging, accessible, and entertaining way. Humor and enjoyment are very much a part of the agenda. SOILED has now been in production for 11 years.

The publication is a part of our effort to think about the audience(s) that is engaging with architecture and, more specifically, to engage audiences that may be left out. We believe that children are one of these groups that aren’t taken seriously enough by architects. Our most recent issue was an anthology of illustrated children’s stories akin to picture books that are either about architecture or, even more excitingly, stories that are told through architectural representation.

13 COULD BE ARCHITECTURE

Left: SOILED #8 Onceuponascrapers

Photographs by Sarah Gunawan

We launched this issue with a read-aloud for families and for kids at the Chicago Cultural Center during the last edition of the Chicago Architecture Biennial. It was a way to fully manifest this goal of engaging children with architectural ideas. SOILED neatly folds into our practice’s larger mission of building, creating, and challenging audiences in and around architecture.

How does Could Be Architecture challenge the more traditional narratives of architecture and its modes of production?

Z: To piggyback on the SOILED conversation, our practice seeks fun and entertainment in architecture. A core of our practice is to bring playfulness, a term that we use seriously, into the built environment. Most of our projects have an ambition to be realized into the world and bring a sense of play. They amplify particular characters in our built environment to engage the public. Most buildings are primarily occupied by non-architects. Architects walk into buildings and look at them differently than the general public because we’ve been trained to look at buildings in a particular way. An ambition in our projects is to find ways to invite the general public into that conversation so that the project becomes more accessible than a traditional architecture or magazine might permit.

J: Part of the ambition of our name – Could Be Architecture – is to challenge things that are outside of the neat confines of architecture with a capital “A”. We suggest that other things could be architecture if they are taken seriously by architects. That is one of many ways we look to invite new audiences into the discourse. An example of this is seen in a 5K run we organized a year and a half ago. Typically, you don’t think of a 5K running race as something that is within the purview of an architect. In many ways it isn’t, but we were interested in how a 5K race could be different if architects were the people organizing it. How can a 5K race be

different if architectural ideas underpinned its underlying organization and agenda? In the case of this project, it was an effort to bring new audiences into a particular neighborhood in Chicago. The race took place in the historically Black neighborhood of Bronzeville. This neighborhood is full of rich and vibrant architecture but is typically off of the most mainstream tourist paths of the city. Although it was not the most efficient or easy to follow route, its goal was to connect the greatest amount of significant architecture within the precise, predetermined distance of a 5K run (3.1 miles). In doing so, it invites the audience of athletes and culture to both meet and intersect. We hosted this event during the 2019 edition of the Chicago Architecture Biennial. We like to use the Chicago Architecture Biennial as an excuse to experiment with new audiences and modes of making architecture. In the end, the goal was not to convert runners into architecture lovers or to convert architects into runners. Rather, we wanted to diffuse the binary distinction between going to an athletic event or going to a cultural event and open it up to a non-binary spectrum of intersecting interests and affinities.

How does your work aim to amplify the narratives already told by the built environment?

Z: I think it goes back to working within the confines of the built environment. There is a certain amount of building standards in the United States that are manifested in codes and material qualities. In an effort to produce designs that have particular character embedded in them, we have to find ways to manifest that through the material standards themselves. I think we’re always trying to find ways to misuse or push the boundaries of the default materials we use to amplify architecture’s role in our narrative. Paint, plywood, and drywall are all things that are rarely questioned in their formal logic, but we’re trying to use these everyday materials to enact a livelier expression to spaces and the way

COULD BE ARCHITECTURE 14

Twisted Hippo

Photograph by Matthew Messner

Twisted Hippo

Photograph by Matthew Messner

HEY, THIS IS A MAGICAL MOMENT HEY, THIS IS A MAGICAL MOMENT

people use these spaces.

J: To briefly expand on that, we believe in the power of the familiar found not just in materials but also the familiar forms, familiar tropes, and familiar formats that we see in the built environment. In a lot of our work, we try to take those familiar nuggets of character and rearrange them in ways that people automatically recognize. People can hopefully start to see their built environment in ways that helps them understand that they have agency and power to change them.

The world as it exists in its most familiar state is not a “natural” condition. It is not necessarily the way it has to be. Only by amplifying these conditions of the familiar can we start to reveal the imaginative underpinnings of even the most ordinary context. Even the most mundane brick wall has some kind of ideology or value system behind it. And because architecture is all around us all the time and because it is the material manifestation of our reality, it sometimes hides the imagination, the ideology, the politics that underpin it. I think a lot of the other arts are liberated from this constraint. When you go to a play, you know the story that is happening on stage is another possible world. It’s not the world as it has to exist. You freely suspend your disbelief and accept that the rules that exist in that play are different than the rules of your existing everyday life. When you go to a museum and see a work of art on a gallery wall, the frame of that piece of art allows you to suspend your disbelief and believe that anything is possible within that frame.

Architecture doesn’t always have that luxury because appears “normal.” It’s all around us. It’s everyday. We don’t often question it. So, we look for playful and sometimes humorous ways to de-familiarize the built environment. A recent speculative project called Deviant Dwellings

provides an example. It’s a photographic, montage project that looks at very familiar housing typologies in Chicago and the surrounding suburbs, and it starts to make little tweaks and deviations to them. There’s still something very familiar about the underlying base architecture that we’re playing with, but we try to render it as something a little stranger. We do this so that people will take a closer look when they walk down the street, so that people start to embrace the fact that the world is subject to our dreams and imagination. We don’t have to rehearse the world exactly as it exists.

Z: One outcome of this ongoing pandemic is that I’ve been taking more walks with my daughter in the stroller. It’s allowed me to wander around the neighborhood and witness the beautifully strange things happening in the built environment that often go under the radar of Architecture with a capital ‘A’. With residential architecture, people add pop tops to their houses or ornament their buildings in peculiar ways, and I think an ambition in our practice is to point to those things and say, “Hey, this is a magical moment.” We should just turn the volume up on these moments so it’s not just me and my daughter in the stroller noticing it, but it’s amplified enough so that more people pause and delight.

What piece of advice would you give to aspiring architects, designers, artists, and storytellers?

J: Especially for architecture students, school is a really great time to take stock of where in your creative work you find pleasure and delight. Think about how you can turn your pleasure and your obsessions into careers. Figure out how to not just have fun around the architecture studio but actually have fun in the act of drawing, in the act of modeling,

17 COULD BE ARCHITECTURE

Left: Bronzeville Bustle 5K

Photograph by Katanya Raby

and in the act of producing a publication. Find what are the really specific tasks and actions that give you inner pleasures because those are the kind of things that you want to organize a practice around. If you’re not having fun there’s no point. People produce the highest quality work and cultivate the highest and most meaningful ethics when they’re having the most fun.

Z: Ditto. I couldn’t have put it any better. From our position as teachers, it’s super evident when a student is into a project because they’re finding joy in it. I think our role is to help people find that. It’s also incumbent on the individual to recognize when they enjoy an aspect of a project. I’m going to push whole heartedly on that. Happy people make the world happier.

What are you looking forward to in the next chapter of Could be Architecture?

J: In the next chapter, we look forward to expanding the scope of our practice. We hope to deliver a seriously playful way of thinking to the world. To date, our work spans a lot of different scales, but it doesn’t often operate on the biggest end of the spectrum.

We tend to do more installations, exhibits, commercial interiors, and small residential work. The ultimate goal is not to scale up. I’m not interested in some kind of unconditional growth in either the size of our practice or the size of the projects we’re working on. I don’t think scale or size of project is correlated with impact. I think some of the smallest projects can be extremely meaningful to the public and expand the kinds of audiences we’re interested in. While I firmly believe that, I’m also curious about what we can do on a bigger scale building project. I don’t have an immediate answer on how we will operate within that kind of scale and scope, but I’m curious, eager and optimistic about what we might lend to that realm of practice.

Z: I think that we are also trying to find new ways of collaborating. We don’t have ambitions to run a 200-person studio because we like to be intimately engaged in the act of drawing, model-making, and rendering. In order for us to explore bigger projects, it requires us to collaborate with other designers. We’re really excited to diversify our portfolio and who and how we work through strategic collaborations and alliances with other small firms, for example.

Happy people make the world happier.

19 COULD BE ARCHITECTURE

Left: Studio Portrait

Photograph by Steven Koch

The Architectural B-Side

ANDREW KOVACS 20

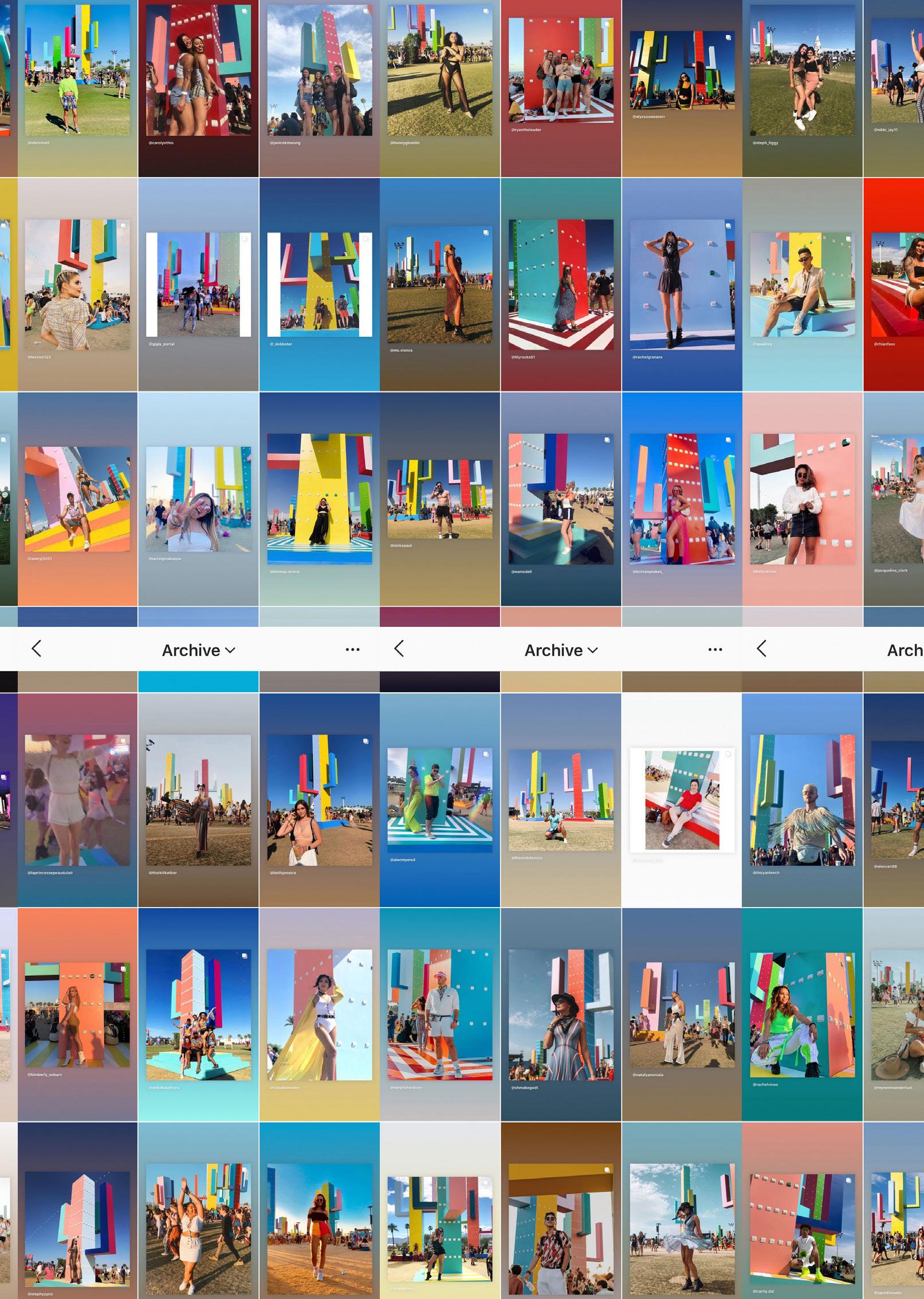

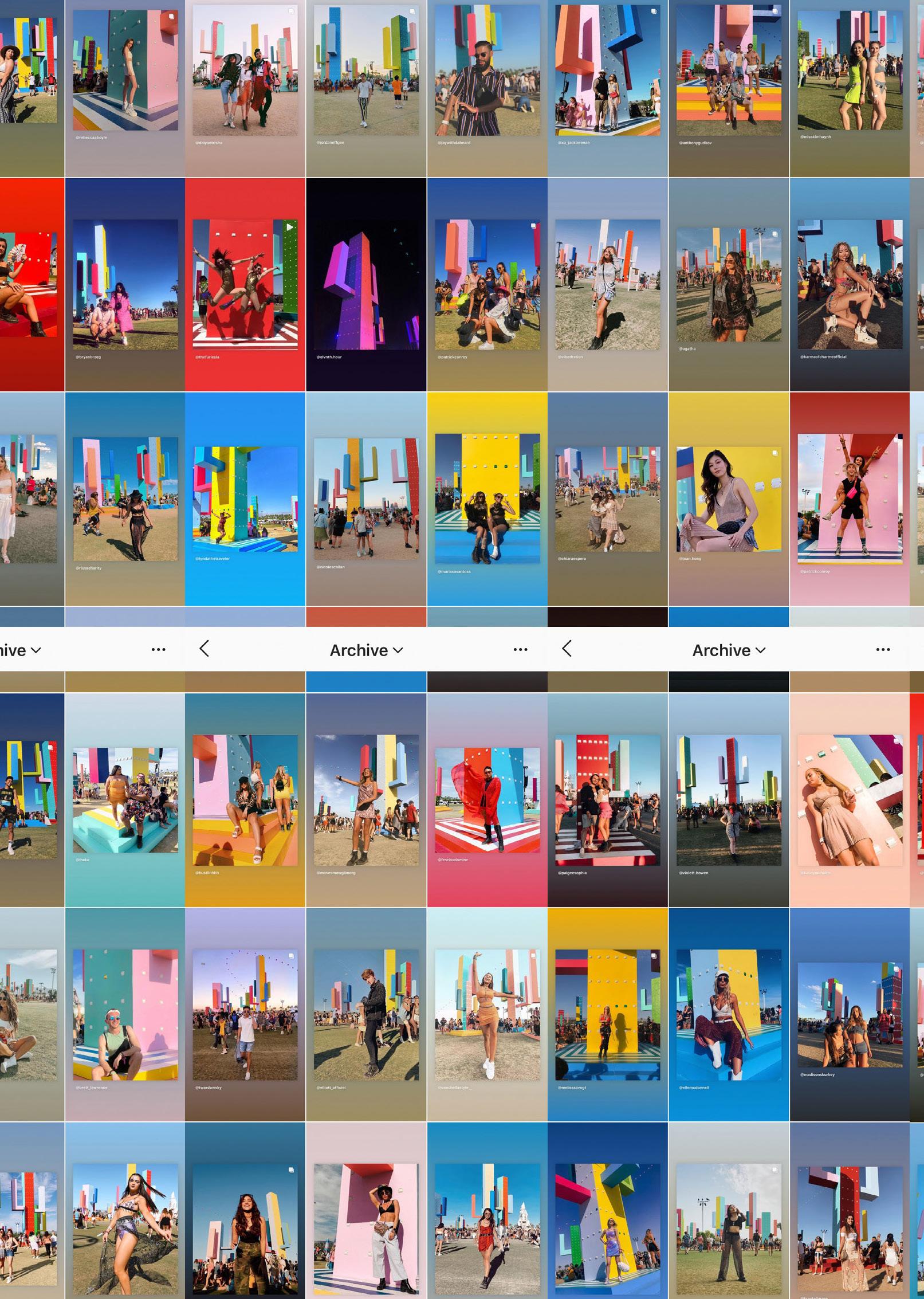

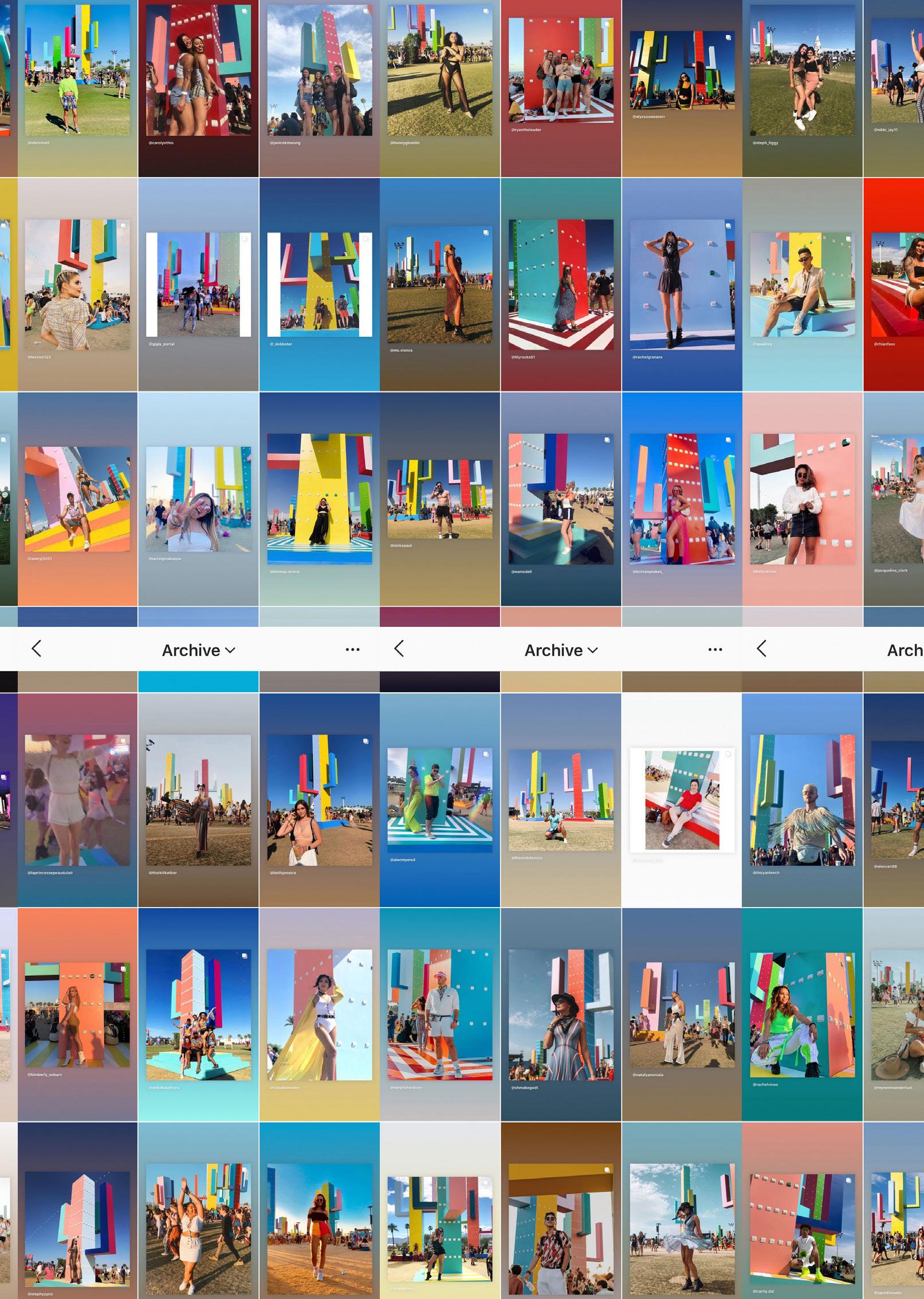

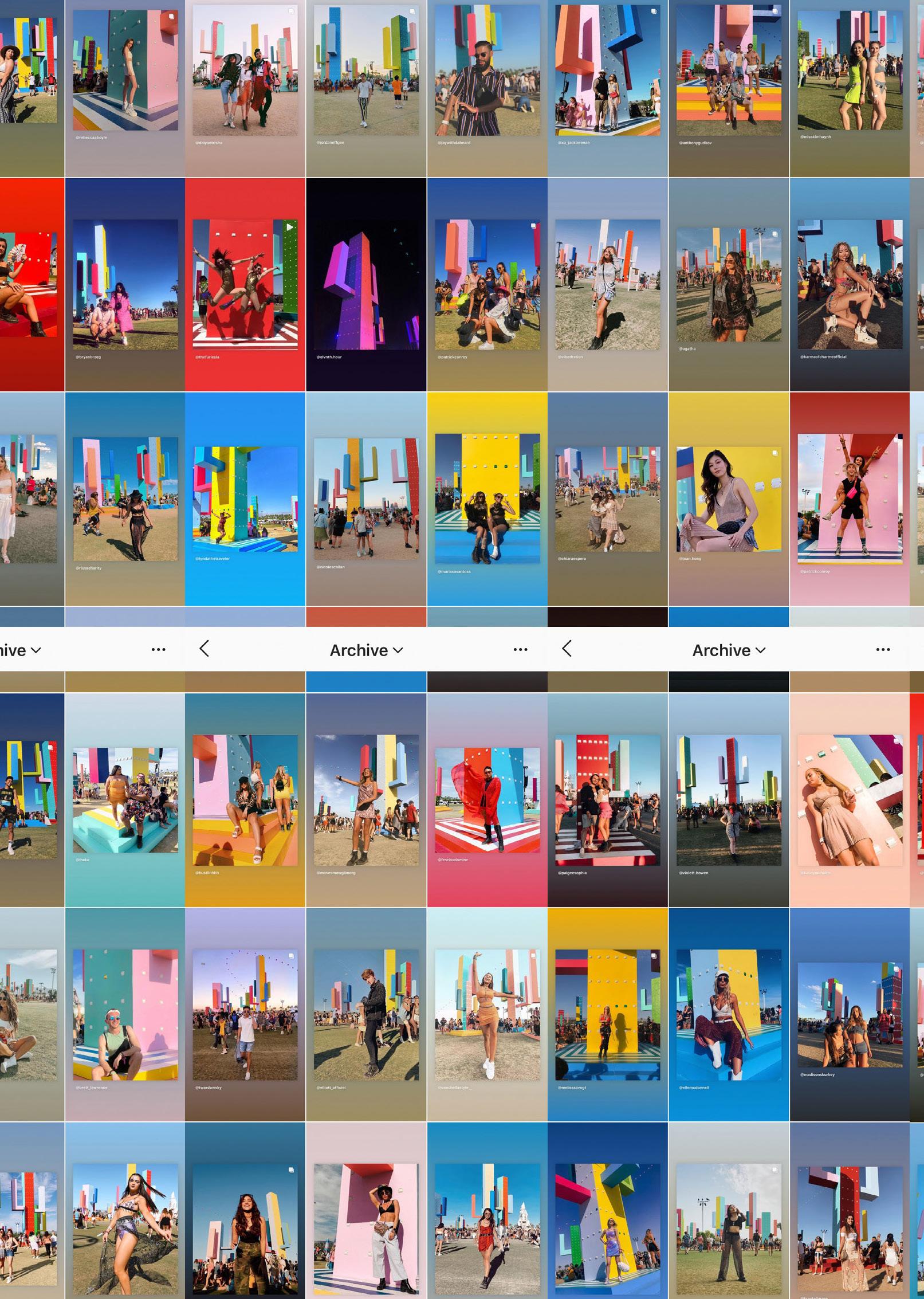

Andrew Kovacs is a Los Angeles based architectural designer and educator. Kovacs’ work on architecture and urbanism has been published widely including The New York Times , A+U , Pidgin , Project , Pool , Perspecta , Manifest , Metropolis , Clog , Domus , and The Real Review . Additionally, Kovacs is the creator and curator of Archive of Affinities, a widely viewed social media feed devoted to the collection and display of architectural b-sides. In 2015 Kovacs published the book Architectural Affinities as part of the Treatise series organized and sponsored by the Graham Foundation in Chicago. Kovacs’ design studio, Office Kovacs works on projects at all scales from books, exhibitions, temporary installations, interiors, homes, speculative architectural proposals and public architecture competitions. The recent design work of Office Kovacs includes a large-scale installation entitled Colossal Cacti at the Coachella Valley Arts and Music Festival and an experimental camping pavilion in the Morongo Valley Desert.

23 ANDREW KOVACS

THE ARCHITECTURAL B-SIDE

In conversation with Andrew Kovacs

What is the Archive of Affinities and the Architectural B-Side?

Archive of Affinities is an image collection project. When I was a graduate student, there was a shift in how I looked and collected images. Rather than simply downloading images from the internet, I began to upload images to the internet. This was basically the early start of Archive of Affinities. This is where I started to think about this idea of the Architectural B-Side. I was thinking about projects that were not necessarily part of the canon of architecture, but projects that you could still somehow incorporate into the discipline of architecture. For me, these projects became interesting because they were on the edge or the periphery of the discipline. You could think of it as work made by people that were trained as architects but did not actually practice as architects or artists whose subject matter was architecture.

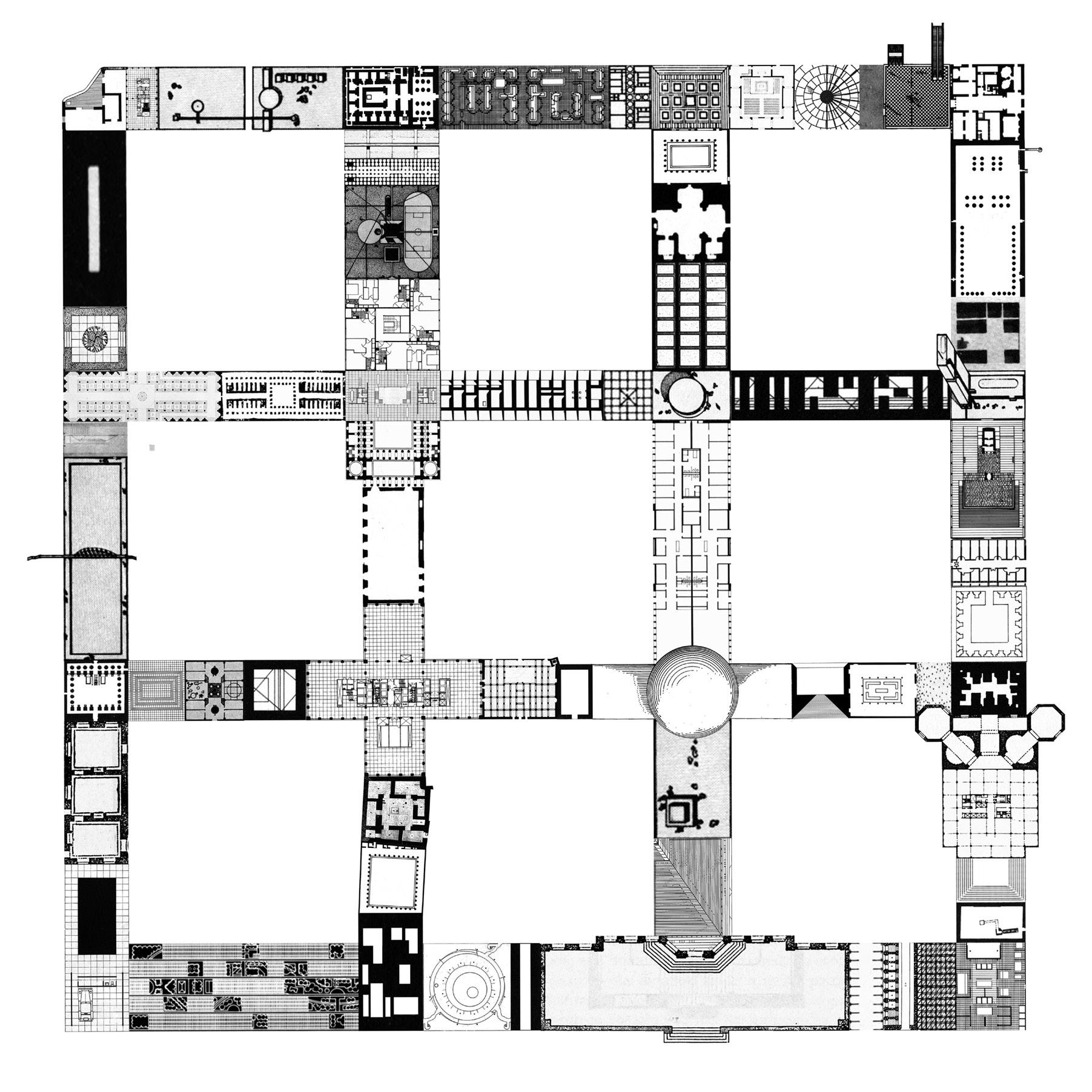

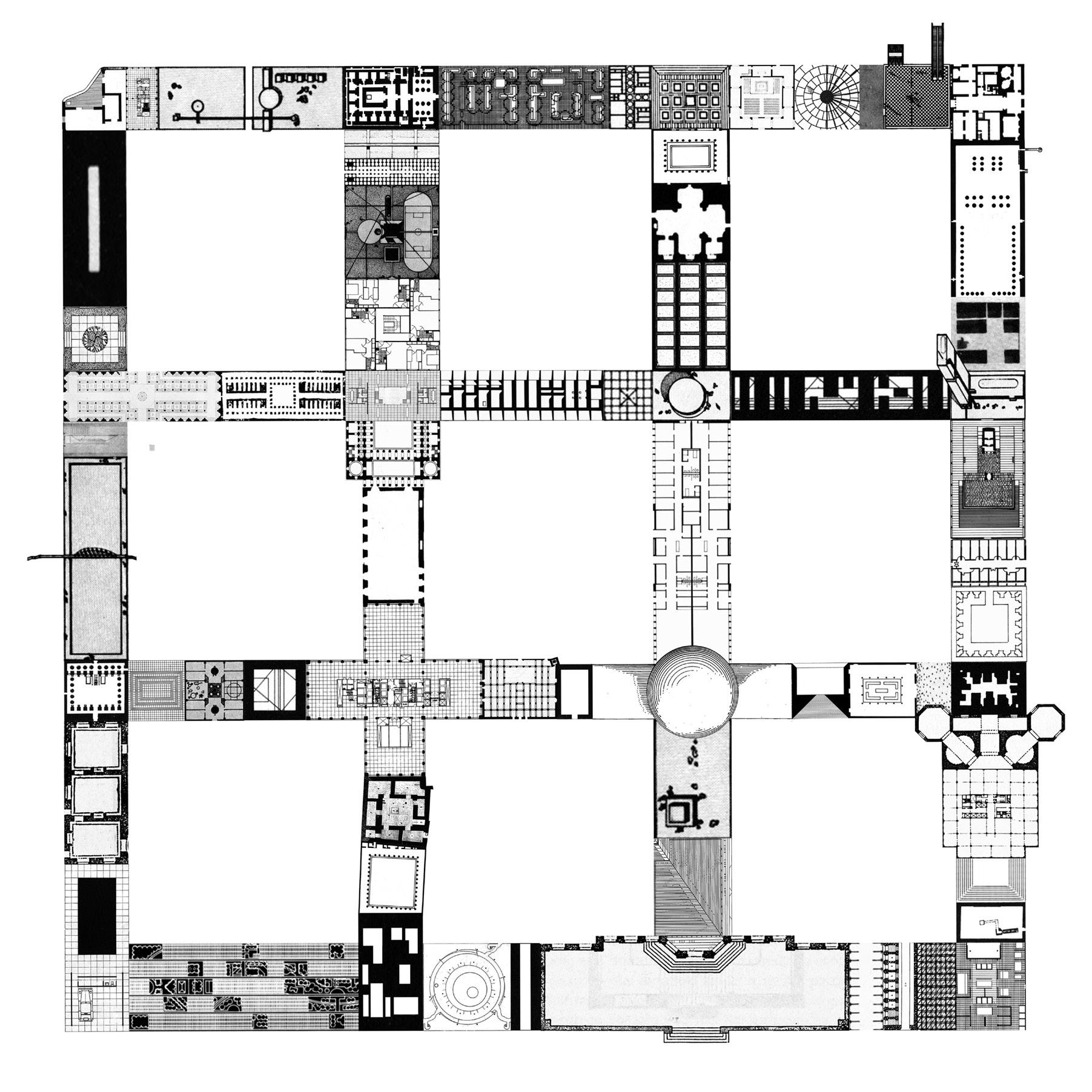

Then, the material that I was collecting for

Archive of Affinities reached a certain quantity. From this collection, I started to make speculative projects. At some point, I had collected a large quantity of floor plans. I would take those floor plans and reassemble them into speculative floor plans. This was probably the start of Office Kovacs. Another way to think about it is as a methodology of collection and production that Archive of Affinities facilitates. This project started off as collecting images and it is still an image collection project but I also collect physical objects as well.

What is the role of serendipity in your work? How do you find things when you do not know what you are looking for?

I love the idea of serendipity because the things find me. You can browse the internet, but it is hard to come across something a little more random with social media feeds that might be different than one another. But if you go to a physical library, you can easily stumble across something that you might not be looking for. I

ANDREW KOVACS 24

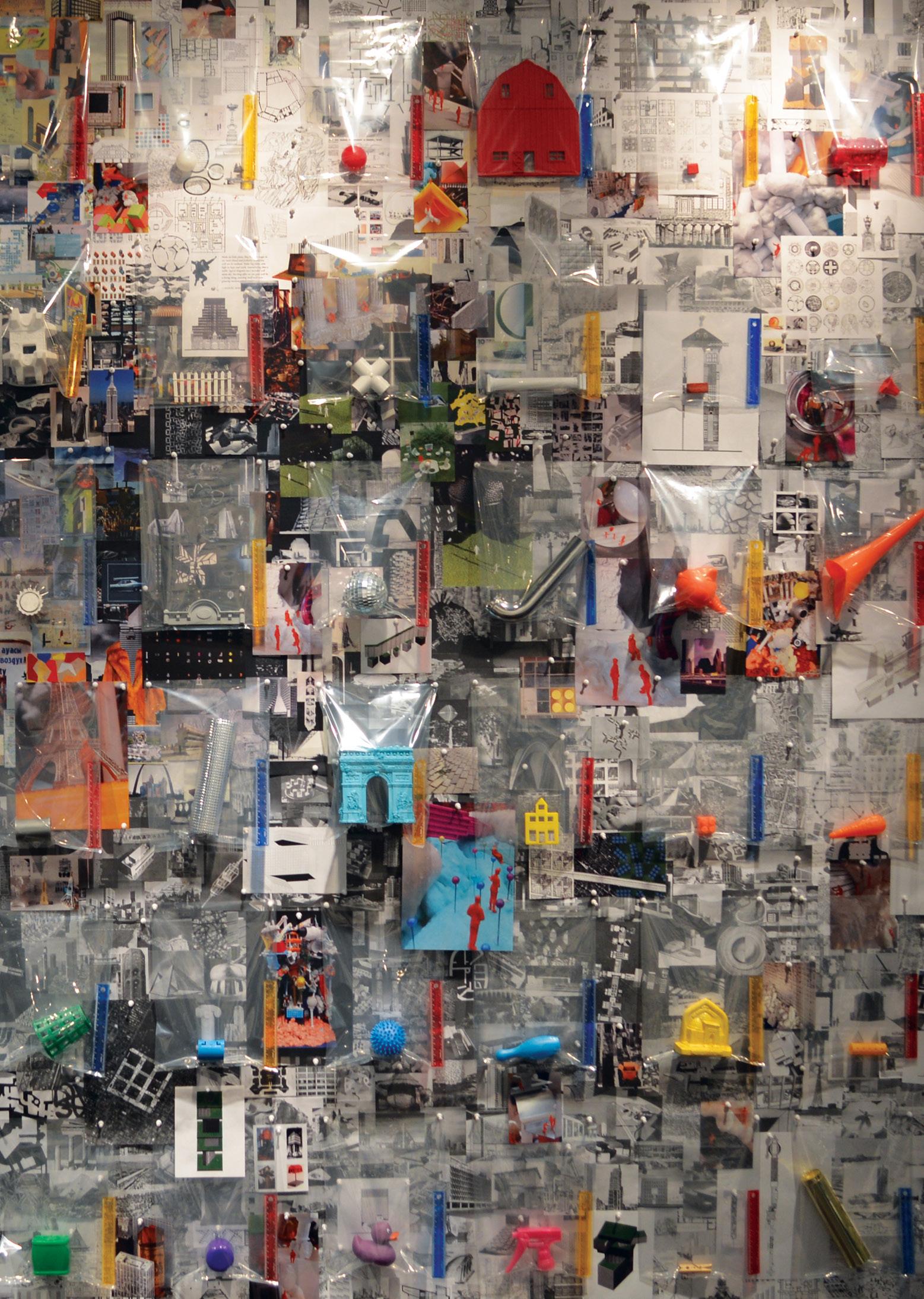

Architectural Multiverse Courtesy of Office Kovacs

Architectural Multiverse Courtesy of Office Kovacs

ANDREW KOVACS 26

Above: Plan for a Nine Square Grid Courtesy of Office Kovacs

Next Page: Colossal Cacti Courtesy of Office Kovacs

think serendipity is an interesting idea. Another way I would think of it is to have a kind of looseness when approaching design projects.

I find that the idea of social media feeds and the internet are quite interesting in the context of your work. Do you believe that the internet has shaped its own perception of architecture?

On one hand, the internet and social media instantly increase the audience for architecture to anyone with an internet connection. Also, you start to get different approaches to how people might share content in relation to how they think about architecture on the internet and social media.

An office might have its own Instagram account that only shares images of their projects, but then there are other accounts like the architecture meme accounts. These accounts use social media and the format of memes to generate architectural criticism. I find the way they broaden architecture’s audience to be very interesting. The broadening of this audience also determines how this audience might participate in architecture as well.

Knowing that social media algorithms curate what we see on our feeds, how might these feeds impact how people perceive architecture?

I think it really depends on the different social media accounts and what they are trying to achieve. For me, Archive of Affinities was a personal project. The format of different social media feeds was very helpful as a way to gather and collect those images. Even before I put Archive of Affinities on social media, I saved and organized images with folders on a hard drive. Thinking about this idea of an architect’s image bank, before the internet, you might have had postcards or even slides of images. For me, the image bank is a tool that architects can use not only for reference material and inspiration but also as a place where you can

chart connections between different architects and themes.

I would like to think that the use of social media feeds totally explodes the architects’ image bank into many different directions, sensibilities, and ideas that might have shared relationships between different feeds and audiences.

Over time, we have seen our digital and physical worlds shift and overlap. Where does the Archive of Affinities find itself in both the digital and physical world?

I am interested in realizing or making things in the physical world; but whether it is sharing material on social media or using the internet to purchase things, I still operate within the digital world. I am not so interested in necessarily making work to just exist on the internet but rather using the internet to help me make things in the physical world. I think it is a really important to think about how the distance between what is digital and what is physical collapses more and more every day.

You mentioned that the Archive of Affinities has the potential to transform into something in the physical world. How is the Archive of Affinities used as a means of production, and how has your practice evolved alongside the Archive of Affinities?

Archive of Affinities is a project that I do almost every day. It in itself is a kind of practice that exists with no deadline, no client, and no budget. It is something that I really do for myself as a project of pure passion and fun.

In this instance, it can be seen as something that mobilizes the idea of an image bank. It takes things that are collected and uses them to produce something else. This idea is particularly interesting for me because I like to make collages. Whether I am using digital or physical parts, I am interested in the idea of

27 ANDREW KOVACS

collage or assemblage in architecture. In some sense, Archive of Affinities acts as a reservoir of these parts, a place where they might be stored or collected.

I could easily go on the internet and collect several different floor plans, but they might be poorly labeled or have different resolutions. This is why I use a book scanner to document many or almost all the material on Archive of Affinities. It allows me to know the sources of things and have them at the same resolution. The book scanner acts as a way to remove or flatten things from their context but also to have some kind of consistency across the things I collect.

and boring to not enjoy what work you are making. It is important to have fun and some sense of looseness in terms of producing work that still makes sense.

For example, I am very interested in the work of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, and how they famously theorized the duck in relation to the decorated shed. The duck is something that I find to be both super humorous and fascinating in architecture. It has a long disciplinary history, like architecture parlante, speaking architecture, and roadside American architecture. Like, you might see a shoe repair shop building shaped as a shoe. There is something kind of every day about it,

Looking more into what images compose the Archive of Affinities, how have notions of fun and humor played into your understanding of architecture?

I like thinking about fun and humor because it also comes with thinking about using things that are recognizable to get a larger audience interested in architecture. One of the things that I am certainly interested in is creating or reaching a much larger audience that’s not just made up of architects. Although architecture is something that shapes the world around us, the discipline of architecture and architecture academia suffers from having a very narrow audience. In a way, I find this to be an ironic contradiction. For me, elements like humor or fun, or even thinking things like pop art, are ways to reach a broader audience. That being said, I take what I do seriously, but I also like to have fun while I am doing it. It would be drab

but I appreciate the play of scale found in these types of projects. We obviously know the shoe is not a real shoe, but it is still building materials in the form of a shoe.

To me, projects like roadside architecture are inherent within the discipline. They already reach or attempt to reach a broader audience while still being about putting a physical building together. In an inherently humorous kind of way, I feel like I’m drawn to these types of things because it’s just funny when you see a big shoe.

I want to make the point that these are examples of architecture. For example, the artist Claes Oldenburg proposed everyday objects as being colossal. He made things like screws and fire hydrants colossal. He is an example of an artist whose subject matter is architecture.

ANDREW KOVACS 30

I take what I do seriously, but I like to have fun while I am doing it.

Thinking about your models for Coachella and the Chicago Biennial, what is the role of fun and modeling in your design process?

I like to make physical models. In my first year of architecture school, everyone was still learning how to draw by hand and make physical models. I learned how to design through physical modeling instead of designing something on the computer and 3D printing it. The model for the Chicago Architecture Biennial was a kind of freestyle model. We kind of just designed and made it as we went. This type of modeling is just fun to do. It relates a little bit to the way that I use collages or assemblages as a way of working. The model for the Chicago Architecture Biennial is, at one level, a speculation and, at another, just a physical model in an exhibition setting. However, if somebody had the ambition and the money, they could probably realize something like that in the world. It would probably be very expensive and time intensive, but it could be possible.

One way to think of something like Colossal Cacti, our installation at Coachella, is that it is just a piece or a part that is removed from the model at the Chicago Architecture Biennial. At an event like Coachella, which is the sort of an adult Disneyland, it is all about entertainment, fun, and music. Even the way I approached that project was through physical modeling. These models started off pretty extreme but were then paired down in a way to meet the safety constraints and other demands of Coachella.

What is the future of the Archive of Affinities?

When I started it, there was no idea of a future for it. It was something that I was doing that eventually became important for me as a designer. It was something that I was doing to maybe fulfill or expand my curiosity for architecture and design. I am always looking for things that I haven’t seen. So, I think I will

probably always be interested in collecting images and things to make other images and things.

In that sense, the project of the Archive of Affinities, just because I have been doing it for so long, is something that I will probably keep doing. There is no super defined idea about what role it should take in the future. I feel like that is okay for me because it really is this kind of personal project, ultimately, in terms of searching for things and then sharing it with an audience.

Are there any projects that you look forward to working on?

In one sense, I would love to realize some of the more speculative models as real projects. I have not found a client with the will, determination, and finances to realize some of these projects but there are different ways that I might approach this.

There is this one project which I have tried to do a few times, but it has not happened at all. It was supposed to happen but was canceled because of COVID-19. This makes sense because it was part of an event. The project deals with turning the materials collected via the book scanner into a physical art installation.

I am always trying to figure out ways to do work that is at the intersection of art and architecture and that goes back to some of the origins of Archive of Affinities. I am intrigued and interested in generating new types of engagement with a broader audience. This might be through sharing content on social media feeds, but I think something like the Coachella project, which was basically a mosh pit of selfies, is also a way of generating or using architecture to generate new types of engagement. It was awesome.

31 ANDREW KOVACS

Proposal for Collective Living II Courtesy

of Office Kovacs

of Office Kovacs

Demetrification, NFTs, and More

BEN GROSSER 34

Ben Grosser creates interactive experiences, machines, and systems that examine the cultural, social, and political effects of software. Recent exhibition venues include the Barbican Centre in London, Museum Kesselhaus in Berlin, Museu das Comunicações in Lisbon, and Galerie Charlot in Paris. His works have been featured in The New Yorker, Wired , The Atlantic , The Guardian , The Washington Post , El País , Libération , Süddeutsche Zeitung , and Der Spiegel . The Chicago Tribune called him the “unrivaled king of ominous gibberish.” Slate referred to his work as “creative civil disobedience in the digital age.” Grosser’s artworks are regularly cited in books investigating the cultural effects of technology, including The Age of Surveillance Capitalism , The Metainterface , Critical Code Studies , and Technologies of Vision , as well as volumes centered on computational art practices such as Electronic Literature , The New Aesthetic and Art , and Digital Art .

Grosser is an associate professor in the School of Art + Design, cofounder of the Critical Technology Studies Lab at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, and an affiliate faculty member with the School of Information Sciences and the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory, all at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA.

37 BEN GROSSER

DEMETRIFICATION, NFTS, AND MORE

In conversation with Ben Grosser

What inspired you to work with the social implications of software and social media’s fascination with metrics?

This goes back to my early social media days. Given my age, the platform of choice at that time was Facebook. After I joined Facebook in 2007, when the news feed emerged as a new feature on Facebook, I started to become aware of my own obsession with the numbers that were littered throughout the interface. For example, I noticed that I was focusing on how many likes I got more than who liked it, or on how much someone commented on my post rather than what they said. I began to track how many notifications I had when I logged in, or how many seconds ago something happened. The numbers—or metrics—were everywhere. I started to question how these numbers impacted me. Why do I care about them? Why am I so focused on them? If I’m so obsessed with these numbers, who benefits from this obsession? One way I thought about these questions was in theoretical terms. At

the time, software studies was emerging as a subfield of new media studies, reinforcing theoretical investigations into the cultural effects of software. But as an artist, even when I think about things theoretically, I always start by making something. The work I made in response to this realization was a piece I call the “Facebook Demetricator”. It’s a free and open source browser extension that hides all of the numbers throughout the interface. It was really just a way to let myself and others experience the platform without the numbers. It allowed us to see how their absence changed our experience. As I continued to create more demetricators for a variety of platforms, I was inspired to think more critically about what’s happening when users are interacting with a piece of software. Even with the best of intentions, software unavoidably comes embedded with all kinds of ideologies and biases from the people who directed its production. These have effects on how we think about ourselves, how we think about others, what we think is possible, and what we

BEN GROSSER 38

think is impossible. This helped me focus my work on software because every aspect of life is increasingly getting reinforced, recreated, and reimagined through software. This past year is a great example of this because the pandemic, with almost no warning, made us move everything we could onto digital platforms. It’s important to think critically about what’s happening in a user’s relationship with their software — who’s in control, who’s not, who benefits, and who doesn’t.

I feel that users do not realize that there are people that make these social media platforms. It is almost as if they believe that it is magic.

With metrics in particular, it seems hard for a lot of people to think about their presence

as being a deliberate design decision. If I go back fifteen, twenty years and told a joke at a party, if someone asked afterwards “how many people laughed at your joke?” I probably wasn’t carrying that number around in my head. I didn’t use to track how many friends I had or how many people were interested in me. Nowadays, ask a Twitter user how many followers they have and they have a pretty close idea. They track that number. This also shows how cultural trends to quantify and commodify everything extends into software as well.

What is “software recomposition”, and how does it challenge traditional notions of digital consumption?

Software recomposition is a term I coined to talk about the method of treating of existing

39 BEN GROSSER

Facebook Demetricator Courtesy of Ben Grosser

websites not as fixed spaces of consumption and prescribed interaction but instead as fluid spaces of manipulation and experimentation. Essentially, it addresses the idea that when we encounter a piece of software, our default reaction is to conform to it and to do things in the ways that it asks us to do them. Software recomposition goes in the opposite direction, treating software as something that we can manipulate. In some cases, that could simply mean giving a platform things that it doesn’t expect or posting the kinds of content that don’t achieve platform success. In my case, it often also includes the programmatic manipulation of existing platforms. A lot of my artwork takes the form of code-based browser extensions that manipulate platforms in real time. “Facebook Demetricator” sits between the user and the system, watching Facebook as it loads, finding all the metrics, and then hiding them from you before you can see them. The idea is that this allows me as a user and anyone else in the world to see these platforms differently from what the creators originally intended. I’ve used software recomposition for many works that programmatically manipulate

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok, but you don’t have to know how to code to subvert the intentions of these platforms. For example, though my “Go Rando” extension uses code to obfuscate how you feel on Facebook, it could be done manually. How it works is every time you click the like button, it randomly selects one of the seven reactions for you. The idea is that the noise generated from these random reactions does not let Facebook have access to an accurate profile of your emotions or personality. While the browser extension handles this for you, there’s no reason a user without any coding experience couldn’t just randomize their reactions manually. For me, this is a concept that calls on anyone who uses software to treat these platforms as places to experiment rather than to conform.

How does the abstraction of software inform the user of the software’s original

purpose, intent, or effect?

The most abstracting browser extension I’ve written is a work called “Safebook”. It hides all content across the Facebook interface as a

BEN GROSSER 40

way of posing the question: what would it take to make Facebook “safe?” This work’s answer is to hide all content across the interface, leaving only the boxes, the dropdowns, and pop-ups. It leaves Facebook as a fully usable piece of software, but you are not able to see any images or text. When you boil a complex platform like Facebook down to a series of functions without any content, it starts to reveal all kinds of things about what the software really is. First of all, you can pretty quickly see that Facebook is almost nothing without everything that we contribute to it. It’s a container for our data, and once we realize that, it starts to invite people to ask questions about who benefits from the generation of this data, whose labor is going into this, and who’s making money on the other side. I’m not making any money from contributing data to Facebook even though I do it all the time. It also reveals how homogenizing Facebook’s interface is. When we do insert data into the platform, it fits us all into its boxes, both literally and figuratively. Conceptually, it’s really sticking us into these preconceived ideas of what a profile looks like, what a user is supposed to do, and how we’re supposed to act within the platform. The extension also shows how much we internalize these platforms. Even without any of its content, I am still able to navigate Facebook because it’s so ingrained in my brain. “The Endless Doomscroller” is another project that works with the abstraction of software. It’s a very simple web interface in a social media feed style that presents an endless series of bad news headlines. No matter how fast you scroll or how long you scroll, you could never get to the bottom of this list of bad news. I made this project after realizing how hard it was for people to step away from media during the pandemic. I wanted to emphasize that these platforms are built to produce engagement and not to inform.

How has your art grappled with topics such as algorithmic bias and algorithmic transparency?

It’s important to know that everything that appears on a social media feed — every item, every object — is the result of years of algorithmic development and tuning by developers that want to create an environment that is difficult for you to step away from. Social media platforms do this on a personalized basis. As they figure out who you are and what keeps you engaged, they try to give you more of that. If it’s bad news about the pandemic, you’re going to see a lot of it. If it’s cat videos, you’re going to see a lot of that. Whatever it is that activates you as a user, it’s going to give you more of that. This is part of a lot of the problems that have emerged into the public consciousness. Social media platforms like Facebook have been weaponized and used to manipulate voting in the 2016 presidential election and, more recently, to help organize the insurrection at the United States Capitol. There are multiple ways in which the design of trying to make things as engaging as possible allows individual bias to thrive. The ways that software companies think, the way that Silicon Valley thinks about the world in general, is through accumulation and getting as much as possible. They desire more because capitalism desires more and because Silicon Valley ideologically is organized around the imperative of growing as quickly as possible. That gets embedded into these systems and starts to make us think in those ways too. We start to feel like we have to maximize our friend count. If we post a picture of our latest project on social media and it gets three likes and then we post a picture of something we don’t care about as much and it gets a hundred likes, it starts to make us think that the latter is most valuable. In terms of transparency, we all are

41 BEN GROSSER

Left: Go Rando Courtesy of Ben Grosser

constantly internalizing — trying to, anyway — a picture of how these algorithms function.

If you ask a regular person, “How do you get something to get a lot of likes on platform X?”, they’ve got some ideas. They also probably click on things and like certain things not because they love those posts but because they hope that it might signal the algorithm to affect their feed in a positive way in the future. The truth is, these are all proprietary systems that are making big decisions about what everyone sees in the world. Increasingly, people’s picture of the world is based largely on their social media feed and what’s in it. The idea that a corporation such as Facebook, with one human who has the ultimate decision over everything, is making decisions about what 3 billion people on the planet see of the world every day is a problem because we don’t know what their algorithms are doing or what decisions they’re making. I would point to just a couple of people, but there’s so many we could talk about in terms of algorithmic bias. We can turn to Safiya Noble’s work in Algorithms of Oppression , looking at the way that racism is encoded into the way that Google thinks about data and shows you what you might want to see when searching for something. I’d also point to the book Black Box Society by Frank Pasquale. This book examines the whole spectrum of all of the different kinds of decision-making that happens out in the world through algorithms. These decisions can be anything from what loan you can get or what healthcare options you have. Finally, a couple faculty from our campus who have done some important work on algorithmic bias and algorithmic auditing are Karrie Karahalios from Computer Science and Kevin Hamilton from Art + Design (also currently Dean of FAA).

What is the “ORDER OF MAGNITUDE”, and how does it aim to critique the desires of social media corporations?

“ORDER OF MAGNITUDE” is what I refer to as an epic supercut. It’s a video project that draws

on every publicly available video recording of Mark Zuckerberg speaking, from his first recording in 2004 to the end of 2018. I treated these recordings as an archive and mined it for every time he spoke about one of three things: the word “more”, the word “grow”, and every time he utters a metric like “one million” or “two billion”. When I first had the idea, I thought that I’ll just make these into a supercut and it’ll probably be longer than most people would be willing to watch, maybe five or ten minutes. That is a pretty long supercut in the YouTube world. I started going through the videos, capturing snippets, and assembling the film. Pretty quickly, I got to that five or ten minute mark, but I wasn’t anywhere close to done. I kept capturing and editing, and, by the time I was done, the supercut was 47 minutes long. The scale of this project is reflective of Silicon Valley’s obsession with growth. Grow at all costs. More is always better than less: more users, more data, and more profit. That’s really the formula that drives these platforms and the companies that make them.

In regards to Mark Zuckerberg, I think the film uncovers some things. You get to see change over time, such as how he talks about the company (and how that does or doesn’t change). You get to see how the company’s technology changes over time. You also get to see him end up in front of Congress having to defend Facebook in the wake of the 2016 presidential election. For me, this supercut was a way of examining not only Zuckerberg as the quintessential Silicon Valley CEO, but also more broadly the emergence of Silicon Valley’s obsession with growth. This idea of growth is what got us to where we are right now, a time where more and more people spend their time absorbed into these platforms, giving them data in the form of our consumption or literally entering data more explicitly into these systems. Most of my work has been about manipulating software systems, using software recomposition like we’ve talked about, but with this work I really wanted to take a step back and think about who makes software and how

BEN GROSSER 42

43 BEN GROSSER

Endless Doomscroller Courtesy of Ben Grosser

Tokenize This Courtesy of Ben Grosser

Tokenize This Courtesy of Ben Grosser

it comes to be the way that it is.

How has your art evolved alongside social media corporations’ want for “more”?

Sadly, perhaps, there’s always a new platform, or there’s always another platform that I can take on that is obsessed with the concept of more. Certainly, a lot of my projects try to examine this from a variety of perspectives. The “Facebook Demetricator” is a fundamental project for me because it launched a lot of the work that came after. Future works have taken on surveillance, the proliferation of computational reading, and the algorithmic examination of everything we post on the internet. As software changes, I keep watching, thinking, and playing with it to try and enact these ideas of software recomposition both as a user but also as an artist.

What are your thoughts on non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and the tokenization of digital art?

I feel like cryptoart and NFTs have only been in the public consciousness for the last three or four weeks. Although I work with software art, a subset of digital art, I have seen how digital art has benefited from distancing itself from the more conventional art market because it is not something that people typically buy or collect. In these conventional art markets, people with a lot of money buy artwork as investments and just stick them in warehouses where nobody can see them. NFTs transform the conventional notions of ownership. One of my initial critiques of the frenzy that has emerged around NFTs is that the idea that a JPEG, or really just a certificate of ownership for a JPEG, is now a thing that creates a $69,000,000 payout for one particular artist. This approach threatens to change the focus and production of the digital art world. All of a sudden it makes all of these digital artists wonder how they can be that one-in-a-million that makes a lotto-level profit off of their digital art. The truth is that

NFTs and the platforms that make their sales possible are already complicit in reified systems of inequality. If we have Beeple, a digital artist, at $69,000,000, then you know that 99.9% of everyone else is down at the bottom making $20 or paying $200 to mint their NFT that never sells. It threatens to reconfigure the kind of work that digital artists are making. They start creating work that’s easily salable and that looks like “art” to the speculative finance crowd. If it’s going to gain immediate sale, it has to, to someone, look and feel like what people already think art should be. That means that there’s a lot less room for people who are focused on the cryptoart market to make work that doesn’t look like art—and some of the best art in history didn’t look like art when it was first made. There’s also a very active critique on the ecological costs of crypto-art and just how much energy is needed to even mint a single NFT.

The frenzy around NFTs led me to make a piece called “Tokenize This”. Readers can see it at tokenizethis.link . It’s a website that, if you go to it, it presents you with what it calls a ‘unique digital object’. This object is really just a box with a random color gradient and a unique code imprinted in it; a unique ID that isn’t reproducible and will ever reoccur. There’s also a URL that links to this unique object, but the thing is that it only lasts as long as you look at it. The moment you try to copy that URL and put it in a new tab, share it with a friend, or mint it as an NFT, the unique object disappears. It’s essentially destroyed the second it’s created. It’s a way of thinking about artificial scarcity, and making a work that resists what NFTs are trying to produce.

How does your art interact with or dictate your work in research or pedagogy?

In terms of research, the art that I make and the art that we’ve been talking about is my research. I also write papers, go to conferences, and do more traditional academic activities, but

45 BEN GROSSER

for me, the largest component of my research is making works, putting them out in the world, interacting with people who use them, seeing what happens, and following the things we’ve been talking about. As a professor, this work is in constant conversation with how I think about what the classroom environment is and how I help students to become more critical of the world around them. How do we see our environment as a set of systems? How do we think about who decided that a system should be the way it is? How did they come to think that it should be this way and not some other way? What does it mean culturally, socially, politically, for the decisions to have been made in those ways? In my classes, we deep dive into the analytical framework of software, helping students develop a set of skills and a critical frame through which they can go into a variety of media-focused spaces in the world. I encourage my students to look at the different ways in which software can influence users in negative ways so that wherever they end up, they can be that voice in the room that sees things differently. So for me, research and pedagogy are intertwined. I’m constantly showing work in class from the artists and scholars I know across the world. We talk about their work and have them in class to answer some questions. Research and teaching is, intentionally, kind of a blurry mess—in a good way.

What technologies or platforms do you look forward to working with next?

I have an exhibition coming up in London this summer. I’m working with TikTok for this exhibition because it is a fascinating new player amongst the other social media platforms. It’s the current obsession and has grown tremendously during the pandemic. As a user myself, I’ve been fascinated with how long I can get lost in its feed. It’s such a regular experience of the platform that there’s a TikTok meme for getting lost looking at TikTok. I’m very interested in the effects of the platform’s algorithmic feed and how it changes the way we think as users. I have a work out there called “Not For You”. It is an “automated confusion system” that manipulates TikTok’s feed so that you can see things that have nothing to do with how you feel or how they think you feel. On the other hand, I’m also working on my own social media platform prototype, a new social media platform we can all play with. I can’t solve all of the world’s platform problems as a single person making a prototype, but I do hope to focus in on and radically reconsider aspects that are common to most every platform we’ve seen so far. Although this is being made for my exhibition in London, it will also be made available for everyone in the world. Keep your eyes peeled for that. More broadly, most of my work comes out of my position as someone looking at and thinking critically about the world of technology and software. I let my own obsessions, my own ways of feeling, and my own use of software guide where I go next.

How do we think about who decided that a system should be the way it is?

BEN GROSSER 46

47 BEN GROSSER Not For You

Courtesy of Ben Grosser

we are opposite like that

HIMALI SINGH SOIN 48

Himali Singh Soin is a writer and artist based between London and Delhi. She uses metaphors from outer space and the natural environment to construct imaginary cosmologies of interferences, entanglements, deep voids, debris, delays, alienation, distance and intimacy. In doing this, she thinks through ecological loss, and the loss of home, seeking shelter somewhere in the radicality of love. Her speculations are performed in audio-visual, immersive environments.

51 HIMALI SINGH SOIN

HIMALI SINGH SOIN 52

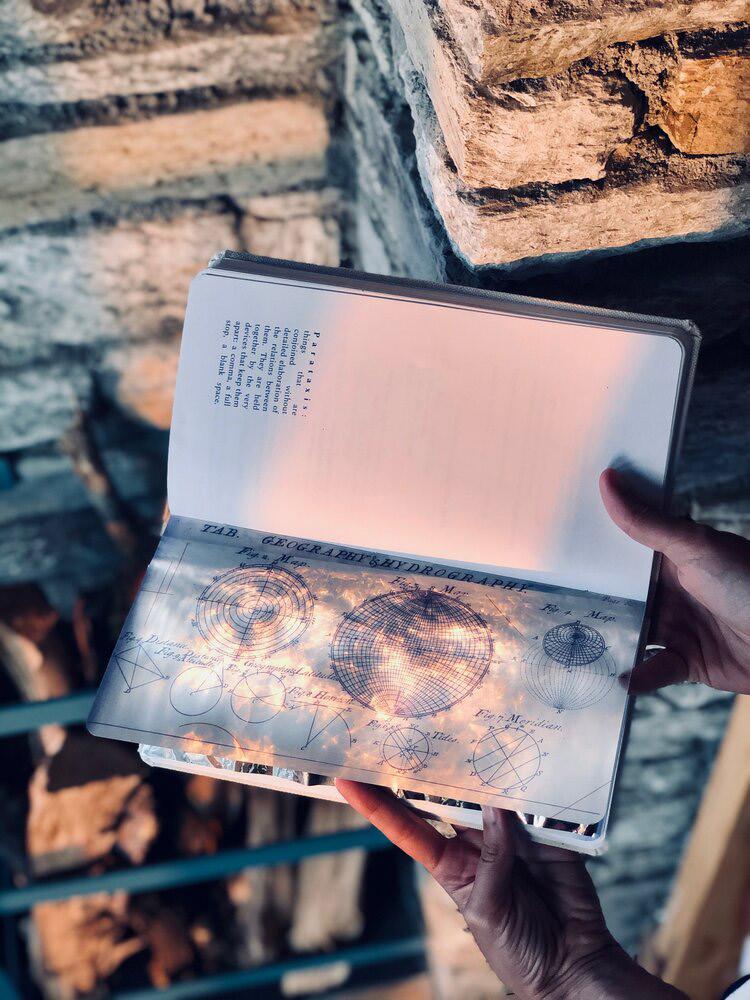

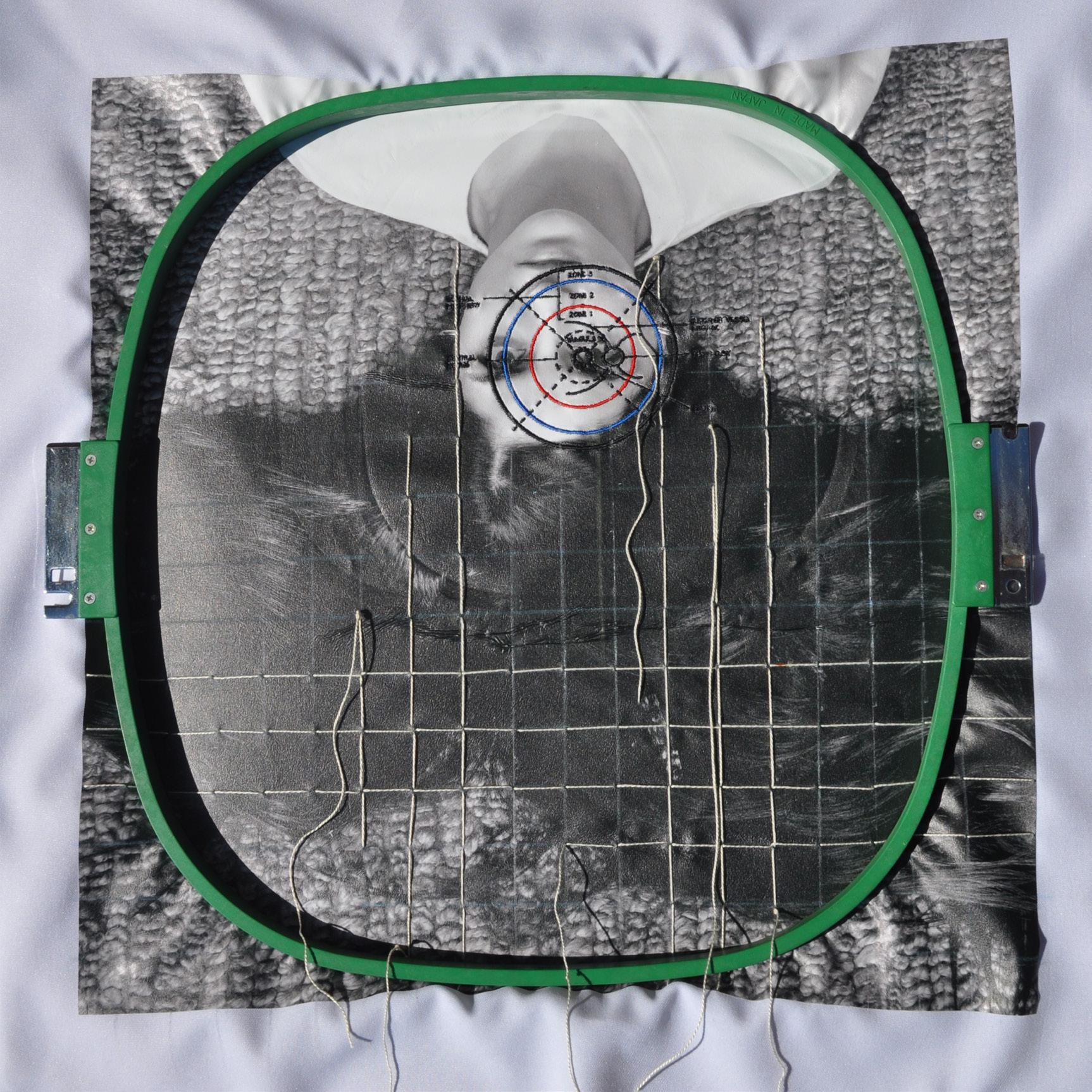

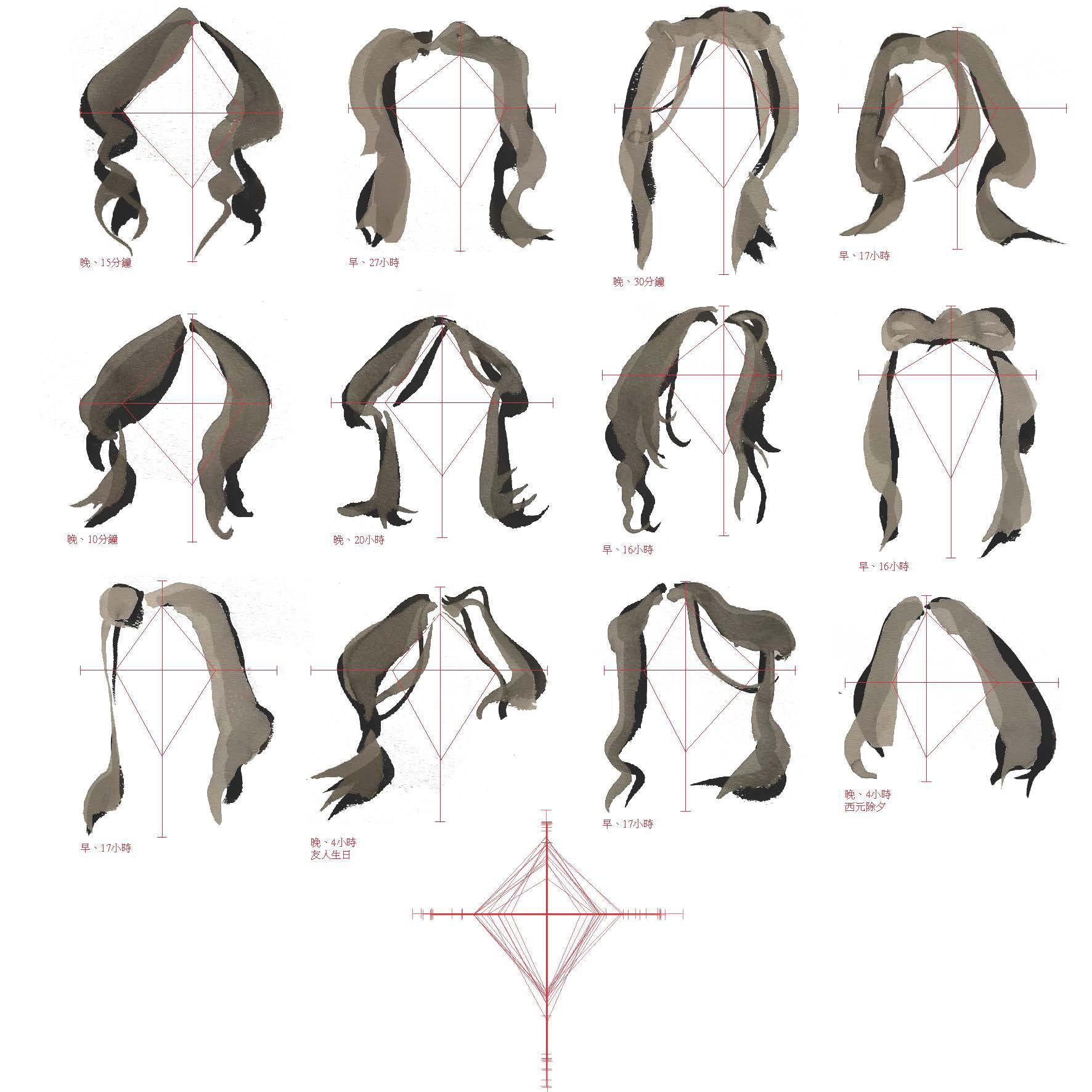

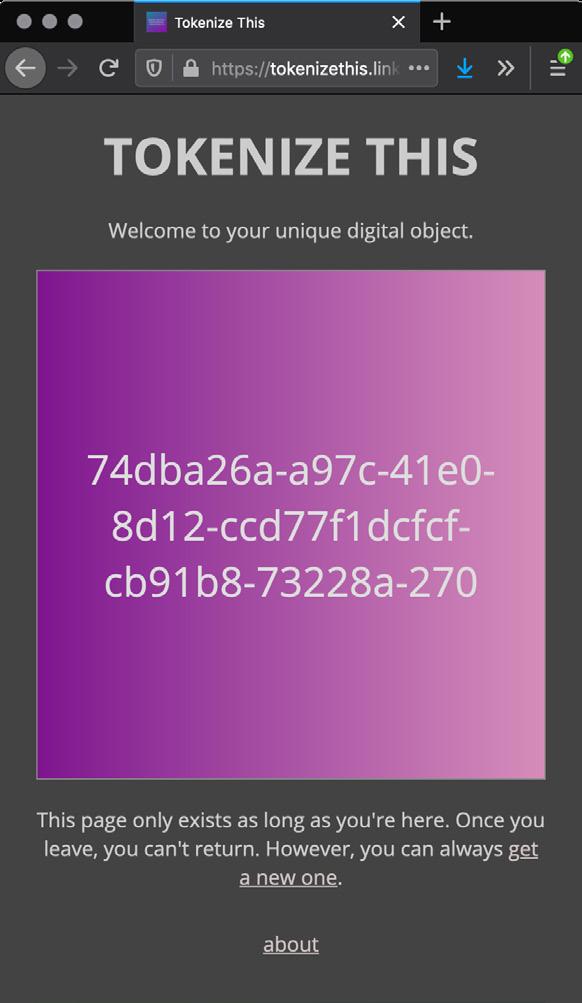

we are opposite like that Courtesy of Himali Singh Soin

The following excerpts are from the book we are opposite like that by Himali Singh Soin

we are opposite like that is ongoing series of interdisciplinary works that comprises mythologies for the poles, told from the non-human perspective of an elder that has witnessed deep time: the ice. It beckons the ghosts hidden in landscapes and turns them into echoes, listening in on the resonances of potential futures.

53 HIMALI SINGH SOIN

HIMALI SINGH SOIN 54 PAGE NO. -175 SPECIAL BLUE SPECIAL RED

55 HIMALI SINGH SOIN PAGE NO. -174 SPECIAL BLUE SPECIAL RED

HIMALI SINGH SOIN 56 PAGE NO. -171 SPECIAL BLUE SPECIAL RED

57 HIMALI SINGH SOIN PAGE NO. -170 SPECIAL BLUE SPECIAL RED

Images tracing the myth of an equatorial being in an extraterrestrial landscape. An intuitional cosmology in a world governed by arbitrary rules of reason.

HIMALI SINGH SOIN 58

we are opposite like that Courtesy of Himali Singh Soin

59 HIMALI SINGH SOIN

The Optimistic Critic

MIMI ZEIGER 60

Mimi Zeiger is a Los Angeles-based critic, editor, and curator. She was co-curator of the U.S. Pavilion for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale and curator of Soft Schindler at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture. Currently, she is the co-curator of 2020-2021 Exhibit Columbus. She has written for the New York Times , the Los Angeles Times , Architectural Review , Metropolis , and Architect and is an opinion columnist for Dezeen Zeiger is the 2015 recipient of the Bradford Williams Medal for excellence in writing about landscape architecture. Zeiger is author of New Museums , Tiny Houses , Micro Green: Tiny Houses in Nature , and Tiny Houses in the City , and editor of the LA Forum Reader , Dimensions of Citizenship catalog, Made Up: Design’s Fictions . In 1997, Zeiger founded loud paper , an influential zine and digital publication dedicated to increasing the volume of architectural discourse. She is faculty at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) and in the Media Design Practices MFA program at Art Center College of Design.

63 MIMI ZEIGER

THE OPTIMISTIC CRITIC

In conversation with Mimi Zeiger

How did you navigate your path as an architecture critic, writer, and curator? Have you always aspired to be a critic or is it something that happened along the way?

It is something that happened along the way. I first got my Bachelor’s in Architecture at Cornell, worked for a couple years in the Bay Area, and then went back to graduate school at SCI-Arc. While I was getting my M.Arch at SCIArc, my thesis project was a small publication called loud paper . Initially, I published three issues of loud paper for my thesis, but it continued for many years. I never had the same rate of publication after that, but that was when I first started writing about architecture in a serious way. The evolution of becoming an architectural critic was pretty long. When I was doing loud paper , I thought of myself as an architect who writes, and then at some point I thought of myself as someone who writes about architecture. Ultimately, I felt like I had enough experience under my belt to call myself a critic.

You have previously stated that “we need to place ideas, not gender, front and center.” How has the maledominated nature of architecture impacted architecture curation and criticism? What are some ways that we can dismantle this notion in the future?

That is a huge question. I have inherited a lot of the ways that architecture has been practiced through a western male epistemology, so I operate within that. And yet, even when I was in undergrad, the ways of expressing gender within that system felt really important. This was in the 1990s, which was the beginning of work done on the relationship between architecture and feminism. Critical work on how gender was operating within space was being done by Beatriz Colomina and others.

Sexuality & Space was Beatriz Colomina’s pivotal work, and it had a big influence on me. My undergraduate thesis had to do with ideas of the male gaze. I was playing with how the body interacts and what is seen and what is

MIMI ZEIGER 64

revealed. If I take a big jump forward to the work that I did on Dimensions of Citizenship for the U.S. Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, I sat down with my collaborators Ann Lui, Niall Atkinson, Iker Gil to think about who we wanted to invite and who we wanted to represent architecture at that moment in time. We asked, just kind of putting it out there, “What if we invite mostly women and people of color?” It was never an intent to make this a show about women. But when you have so many excellent designers like Amanda Williams, Jeanne Gang, Liz Diller, Teddy Cruz, and Fonna Forman, it was about creating a platform for the best ideas to come through. When we were given a choice between a white, male designer or a designer that was a person of color, it wasn’t a difficult choice to make. This past year, so many women were represented in the architecture and computation conference, ACADIA. It had

female programmers and an incredible group of speakers. Sometimes it’s about thinking about the questions that we are asking and then answering them. A lot of times when women are asked to participate in something, they are either siloed or seen as a check box. This is why I say we need to place ideas, not gender, front and center. It’s because we need to make platforms where ideas are expressed at their highest level with the people who are really thinking about them. We also need to make a clear decision about featuring non-cis white men. That decision has to be made.

In your article “Breaking Ground book on buildings by women is ‘both needed and problematic’”, you talk about how the women in the book are brought into this narrative of the sole genius. Could you talk more generally about how women in architecture are represented in media?

Mimi Zeiger Courtesy of Mimi Zeiger

Mimi Zeiger Courtesy of Mimi Zeiger

Sure. Let’s talk about women in architecture primarily being represented in media throughout the later part of the 20th century to today. Within media culture, women are represented generally in comparison to Zaha Hadid, the best-known female architect. We talk about them as female architects, as lady architects, a little older term, or the wife of. Denise Scott Brown is an example of “the wife of”. Ada Louise Huxtable, a really powerful critic and woman in New York, even wrote about Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi, husband of Denise Scott Brown, as the Venturis. The conventions of marriage and the conventions of sexuality are really baked in.

Gehry and others here in LA, outspoken to the nth degree, said, “Listen, I don’t want to talk about being a woman as a commonality. I’m more interested in talking about California.” The minute she said that, all the designers opened up about what was inspiring to them. It wasn’t about the burdens of needing daycare or being female, all very important topics, but it was really about what drives their work. I think that we have to understand how we perceive architects who are women as these creative professionals, how we perceive them as people who are bringing forth all of these rich bunches of ideas, and not just set up a platform where they have to talk about what they juggle in order to make it work. I am not saying that those things aren’t important, but I, as a reader, want to hear what makes them tick.

Can we talk about women in architecture without foregrounding their femaleness?

Can we talk about women in architecture or women and architecture without foregrounding their femaleness? The subjectivities of white women and BIPOC women are hugely important, but how do we understand them as architects. One of the key things that got me thinking that ideas, not gender, needs to be foregrounded is when I was interviewing a number of designers and architects here in Los Angeles. I talked with Gere Kavanaugh, who is an interior designer and textile designer, Deborah Sussman, a graphic designer who has since passed, Annie Chu, an architect here in LA, and also April Greiman, a brilliant graphic designer, on a panel called the “Divas of Design”. We were all kind of cringing at the title, and I felt that it led us to talking about what it was like to be a woman. Gere Kavanaugh, a powerful designer who worked alongside Frank

Definitely. You don’t see posters or online forums for white male panels. That isn’t a thing. When we only invite women to panels about women, we do not do justice to the work that they are actually doing in the field of architecture.

I think the subjectivity that comes with womanhood and other diverse backgrounds are distinct. I want to make sure that we hold on to that, but that we hold on to that through the lens of the work and ideas that these great people produce. I think that we have come to a point where we have carved out spaces for women to create solidarity and to express the kinds of conditions that were holding them back. Now I really think that we have to see how this operates across race, class, and

MIMI ZEIGER 66

different sexualities. I think we can hold on to that intersectionality but as something that is part of a whole person who has ideas and dreams as well.

In your article “It’s time to abolish the architecture critic”, you explain that education is an important factor in developing diverse perspectives. How must institutions change to be more accessible?

I think if we dismantle some of its barriers, we begin to see the institution’s problems as structural. People are not aware of the privileges that have helped them go to elite schools, work for elite publications, and even hold elite positions as architecture critics. I

structural connections happen. They give you access to editors and a starting point to jump into a very competitive field.

Coming from my own background, I am hugely supportive of inventing your own platform. I think there are so many free tools that are available to get into criticism and to start writing. Part of the thing is, writing really comes from practice. The more you write, the more you develop a voice, and the more likely that it will get noticed. For those who are getting started in the field, sometimes it is really important to just start your own thing and develop a voice. If you are familiar with “McMansion Hell”, Kate Wagner’s determination to be a critic came from her starting her own platform. Some of these models can be harder

think institutions need something like the Ricker Report , a place where people can experiment and get experience early on. That is an incredible step. When that step isn’t there, it’s about inventing platforms. So, when I was a graduate student, I invented a platform.

These platforms do not always have to be publications. They could be something like Dank Lloyd Wright. It can be a meme platform on Instagram which expresses the kind of critique that you need. Criticism isn’t exactly taught in institutions, although there are a few places in the United States like Columbia’s CCCP (Critical, Curatorial, and Conceptual Practices in Architecture) program and a design research criticism program at the SVA (School of Visual Arts). I’ve taught at the one in SVA, and these programs try to make some of these

than others, but again, it could easily just be your Instagram account. You start there and keep growing.

As a lot of your work and mission is around increasing the amount of discourse on architecture, how do we make architectural discourse something that is more of an everyday kind of conversation?

I think in some ways it’s about who is writing and also about who is reading. I have found that you are not going to get everybody. If you look across publications that are out there in the world, Curbed versus Log for instance, they have very different ways of looking at the built environment. If the majority of work is

67 MIMI ZEIGER

The more you write, the more you develop a voice . . .

sort of more general interest and then there’s other things that plug in that are a little bit more specific, that captures the readership. Something like an academic journal, that is much more specific and highly curated, is going to attract a very particular readership. Part of it is about the scale of readership for certain ideas, just sort of sliding that back and forth till you find sort of the right fit. For me, with loud paper , it was about setting forth a kind of mission statement.

Now that you do a lot with curation and criticism, how has your perception of architecture and architectural education changed?

Being a curator and a critic who is thinking about questions of gender and racial equity, I think it puts a lot more pressure for me as an educator. It puts more pressure on me to make sure that my syllabi and projects are reflective of the things that I am calling out in my criticism. By the same token, when I do curate, if I have brought something up in criticism around questions of gender and racial equity, I also need to be responsible to it in my own curatorial work.

Because of my background at Cornell and SCI-Arc, I have baggage. I have to recognize when those are useful and also when they can be blinders to my work. There are also many people that are working to expand the canon of architecture. Mabel Wilson, Charles Davis II, and Ana Maria Leon are just a few people who are doing huge work to help us rethink the Western perspective and understanding of architecture. So, I am constantly learning as well. I am not always the expert; I am someone who has to do research and recognize my privilege.

In regards to the future, what is the role of curation and critique in various understandings of architecture?

I’d like to think that both curation and critique are really good at looking at what’s happening now. This is not like a technofuturist agenda but it’s about asking, “What are the ideas that are operating within culture, first and foremost, and then within architecture and design culture?” And then we have to figure out how we put those forward, whether it is something that I am critiquing or whether that is something or someone whose work I am interested in and am curating. For example, we cannot not look at questions of climate crisis. How do we do it through work that is happening in the present because we cannot invent work. Whose work is speaking to those concerns or what other writers can we also help support platforms that are doing that? As a critic I often look to other writers, Rebecca Solnit, Donna Haraway, or Anna Tsing who wrote The Mushroom at the End of the World . I will use inspiration from something they have written and ask: How do I bring that into architectural discourse and make it relevant?

I cannot predict the future, but I can hope for the future. I can hope that the speculative ideas that we are looking at now, or that I am seeing emerge now may change what happens. For being a critic, I am quite an optimist, and I would not be in this if I really thought architecture was screwed. I would have just pulled the plug long ago.

What projects or ideas do you look forward to working with next?

I’m currently working with Iker Gil and the folks at Exhibit Columbus on a cycle of projects for Exhibit Columbus 2021 and we are calling it “New Middles: from Main Street to Megalopolis: What is the future of the middle city?” It is about looking forward. The projects that we have started to see in the design presentations are dealing with some really necessary subjects. Iker and I have framed this topic around “What is the middle?” and we are defining the middle through the lens of the Mississippi Watershed, which includes Urbana-Champaign.

MIMI ZEIGER 68

By doing that we’re thinking about what environmental and the climactic issues are at play there. We also are doing this under a pandemic and racial revolutions and new understandings of complicity within architecture.

The folks that we’ve invited to be part of this are bringing up ideas about architecture for different species, from Joyce Hwang’s work, or questioning the idea of Columbus in general as a figure. We are working with Dream the Combine, who are thinking about all the different places that are named Columbus Colon, Columbo, or Columbia, critiquing our vocabularies of colonialism and then building an architecture out of that. Sam Jacob from London is looking at how we understand utopia, especially in a place like Columbus, Indiana, which is the ‘Athens on the Prairie’ and embodies the utopian vision of Modernist architecture. These are all ways that are percolating up through the work.

That is one of the biggest projects I am working on. A lot of it has to do with a kind of visibility, and maybe even perceptions, and changing that perception. If we think about how Columbus has a kind of brand identity as this Modernist Mecca, our hope is to question that as a singular narrative and bring forth other narratives that have actually existed in the city. Future Firm out of Chicago is looking at the people who work the night shift and

what happens when we change our perception of time. The New York based artist-architect Olalekan Jeyifous is looking at the architectural archive, and he has found several moments in Columbus’s history where African and Black artists have been celebrated through exhibitions, symposia, and other cultural events. He’s bringing that forward. He is unarchiving and revealing something within the city’s history, asking, “How does finding things in the past change us?”

I am quite optimistic around the threads of visibility, ecology, and ways of understanding colonialism. These are all important issues that can be discussed and talked about through design. How do designers begin to interpret these things? That is the huge project, and I am smack in the middle of it right now. Every time it is a test about how these ideas will be legible, be perceived by a public audience. Yet, Iker and I really feel like we have to pursue these ideas. There is no way around it.

The challenge is not to make people uncomfortable. The challenge is to show how interconnected we really are. We’re all very human. If the pandemic has shown us anything, we are all subject to the same fragilities. From that perspective, you have a real kind of sense of being just a precarious human being on planet Earth. We can think about these ideas in new ways.

69 MIMI ZEIGER

The challenge is to show how interconnected we really are.

Homemade , with Love

BLAIR SMITH 70

Blair Smith loves to rigorously play and make Black girl sounds, spaces, lands, planets, and galaxies with Black girls and those who love them. Her artist-scholar-curator dreams and praxis emerge where Black girlhood as a creative and relation building life force with Black girls/women, Black feminist poetics, sound, and alternative modes of cultural work and production meet. Her work previously explored poetics and sound as practiced with Black girls and collective Saving Our Lives Hear Our Truths (SOLHOT), a space to envision Black girlhood and our world anew, locally and galaxy-wide. Blair is a post doc fellow in art education with the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2019-21). Her curatorial and artistic praxis is focused on Black girl celebration, Black feminist poetics, sound art, and design with Black girls locally and worldwide.

73 BLAIR SMITH

HOMEMADE, WITH LOVE: MORE LIVING ROOM

In conversation with Blair Smith

As the title of the exhibition references J. California Cooper’s notion of homemaking, what does it mean to be “Homemade, with Love”?

To be homemade with love is about the work done with Black girls and by those who care about them. It is a legacy and continuation of Black girlhood celebration as practiced with a space-making collective called Saving Our Lives, Hear Our Truths (SOLHOT) in ways that feel truest to me and those who show up/ will show to make space for Black girls. It is to putting effort towards curating space with Black girls that they might see as theirs and something that sparks their creativity and dreams. It is about being together and using our hands to make things from what we have and with who is there.

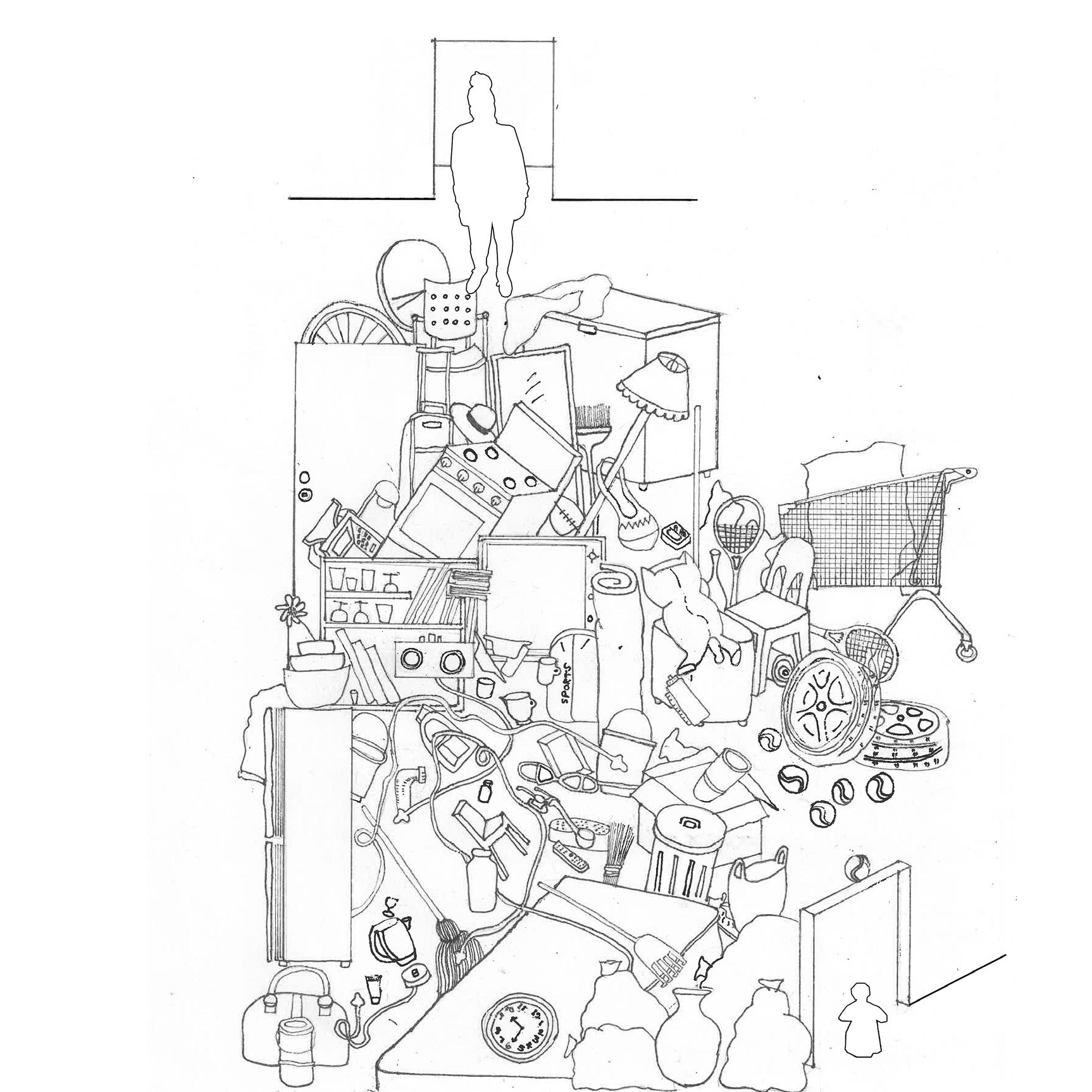

The power felt from the space you have made is generated from everyday objects typically found in our homes. What was the process of selecting the

objects you brought into this space? Was it a highly methodological process or more instinctive?