The Architect's Newspaper

How are SO – IL, Lake|Flato, DIALOG, and David Baker Architects alike? page 7

Joan Davidson, philanthropist and preservation ally, dies at 96 page 8

The race is on to save Marcel Breuer’s Cape Cod cabin page 9

World-renowned professor, architectural historian, and curator Jean-Louis Cohen died suddenly on August 7. Read on page 8.

Admirable in Alief

Page and SWA Group deliver a new community center and landscape for a Houston neighborhood. Read on page 10.

MATERIAL MAGIC

Architects often work on existing buildings to deliver carbon-sensitive results. Four projects and an excerpt showcase adaptive reuse successes. Read on page 27.

Au Revoir, Jean-Louis Exhibit Columbus Astounds Hed Tkkt Back to School

The latest iteration of the Indiana design event opened on August 26. Read on page 11.

New academic leaders share their thoughts. Hear from Daniel Barber, Milton Curry, Julia Czerniak, Michael McClure, Quilian Riano, Mason White, and Heather Woofter. Read on page 16.

Three Ecocomments

Mark Jarzombek, Ersela Kripa, and Lindsey Wikstrom write about engaging the climate crisis. Read on page 18.

AN visits the Los Angeles studio of West of West page 12 14 Open House: BLDUS 20 Tech+ NYC preview 22 Q&A: Olivier Campagne 64 Marketplace 66 Comment: Martin Weiner

The Architect’s Newspaper 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10007 PRSRT STD US POSTAGE PAID PERMIT No. 336 MIDLAND, MI September 2023 archpaper.com @archpaper $3.95

Products and more. Read on page 39.

Sustainability COURTESY HEMPITECTURE CESAR BELIO MANDANARCH/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS/CC BY-SA 4.0 © ALBERT VECERKA/ESTO HADLEY FRUITS

Neolith, one of the most sustainable surfaces in the market, made with 100% natural raw materials.

NEOLITH.COM

CENTER

CHASE

/ San Francisco, USA

Pilkington

Spacia™

The thermal performance of conventional double glazing in the same thickness as a single pane for historical restoration. Bring your historical buildings up to code while keeping the same look and feel with Pilkington Spacia™.

1.800.221.0444

buildingproducts.pna@nsg.com

www.pilkington.com/na

Scan for more on historical restoration glass solutions

Keep the sash Upgrade the glass

How Architects Learn

CEO/Creative Director

Diana Darling

Executive Editor

Jack Murphy

Art Director

Ian Searcy

Managing Editor

Emily Conklin

Web Editor

Kristine Klein

Design Editor

Kelly Pau

Associate Editor

Daniel Jonas Roche

Associate Newsletter Editor

Paige Davidson

Contributing Products Editor

Rita Catinella Orrell

General Information: info@archpaper.com

Editorial: editors@archpaper.com

Advertising: ddarling@archpaper.com

Subscription: subscribe@archpaper.com

Vol. 21, Issue 7 | September 2023

The Architect’s Newspaper (ISSN 1552-8081) is published 7 times per year by The Architect’s Newspaper, LLC, 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10007.

Presort-standard postage paid in New York, NY. Postmaster, send address changes to: 25 Park Place, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10007.

For subscriber service: Call 212-966-0630 or fax 212-966-0633.

$3.95/copy, $49/year; institutional $189/year. Entire contents copyright 2023 by The Architect’s Newspaper, LLC. All rights reserved.

Why did Stewart Brand have to go so hard? His 1994 publication How Buildings Learn is full of insights about how buildings discount and misuse time. He studies how buildings adapt and change over the decades, or even centuries, of their existence. He rails against “magazine architecture,” beginning with the example of I. M. Pei’s MIT Media Lab, which defies adaptation: The building isn’t unusually bad; its badness is just the norm in new buildings overdesigned by architects. (Perhaps my fondness for the book is heightened by his regular references to MIT’s campus, where I was an undergrad.) He then laments the existence of architecture as art instead of craft and addresses the still-tricky problem of architectural photography, which is often created before people begin using the buildings. These photos then often go on to be published opposite language from the “‘prismatic luminescence’ school of wine writing.”

Throughout, Brand mentions responsive and humble approaches that we might today call “sustainable,” but the term’s only index-worthy appearance—as “sustainable design”—lands in the appendix: “ Sustainable is a buzzword, meaning ‘ecologically correct,’ but it does stimulate thinking toward durability and open possibilities,” Brand wrote. (This type of hardy, DIY realization was something he had been working on for decades at the time, at least since launching The Whole Earth Catalog in 1968.) Rather than architecture as “the art of building,” he suggests the practice of architecture should be reborn with a new definition: “the design-science of the life of buildings.”

Given current knowledge about the climate crisis, this would-be new vocation has everything to do with the subject of this issue of AN: sustainability. The topic permeates most of the contents that follow, including some appropriate criticism of its shortcomings. This is most clearly seen in our material-forward Focus section (page 39), which examines new bio-cements, hears from the Healthy Materials Lab at Parsons, interviews a decarbonization specialist, reviews an exhibition about low-carbon home design, and shares products to consider specifying in your next project.

Brand might appreciate the Poplar Grove residence designed by BLDUS, seen in the photograph above and covered by Nigel F. Maynard on page 14. (Astute readers may recall that AN published the architect’s sketches for the home in 2021.) In both its contextual placement as an alley house and in its construction using natural materials, it functions as a case study for

how to build thoughtfully and lightly. But its architecture can’t escape history. The plans summon both John Hejduk’s nine-square grid exercise and the Roman domus: The interior square is given over to a staircase, above which a compluvium admits daylight instead of rain.

Brand might also enjoy the features section of this issue (page 27), which focuses on adaptive reuse, an act that has always been a regular part of making architecture. Here we share an excerpt from Deborah Berke’s new book, Transform, written with Thomas de Monchaux and published by Monacelli Press, along with worthwhile projects by GOMA, PLY+, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects, and Bruner/Cott.

As a break, check out a few technology-focused spreads where you can preview AN ’s upcoming Tech+ conference on October 27 (page 20) and read my exchange with Olivier Campagne, a Paris-based digital-image maker who uses Midjourney to imagine new versions of the mechanical-minded worlds he’s been rendering for leading European architects (page 22).

This carbon-aware issue arrives at the end of a summer of climate disasters. Architects learn from nearly everything— education, mentorship, travel, observation, conferences, conversation, clients, and media—so this summer has been a master class in what might be our future. From floods in Vermont and India to fires in Canada and on Maui and the heat dome across the central U.S., it’s obvious that the effects of climate change are already here. This lived experience should spur action. Wider regulatory mandates are urgently needed, but regardless, architects can design buildings that use less carbon and might serve as refuge when climate change intensifies.

Writers need readers. Brand closed the acknowledgements in How Buildings Learn by listing his contact info to encourage people to get in touch with him “to make corrections for later printings and to make things happen in the real world.” Feedback still matters today.

See page 6 for a letter from a reader who was so incensed by a review published in AN that he procured a tour of the building in question and wrote to us with his own thoughts.

Following in Brand’s footsteps, I’ll leave you with my email address, should you want to make something happen in the real world: jmurphy@archpaper.com.

Jack Murphy

Vice President of Brand Partnerships (Southwest, West, Europe)

Dionne Darling

Director of Brand Partnerships (East, MidAtlantic, Southeast, Asia)

Tara Newton

Sales Manager

Heather Peters

Assistant Sales Coordinator

Izzy Rosado

Vice President of Events Marketing and Programming

Marty Wood

Senior Program Associate

Ethan Domingue

Program Assistant

Trevor Schillaci

Audience Development Manager

Samuel Granato

Events Marketing Manager

Charlotte Barnard

Events Marketing Manager

Savannah Bojokles

Business Office Manager

Katherine Ross

Design Manager

Dennis Rose

Graphic Designer

Carissa Tsien

Associate Marketing Manager

Sultan Mashriqi

Marketing Associate

Anna Hogan

Media Marketing Assistant

Wayne Chen

Please notify us if you are receiving duplicate copies.

The views of our writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff or advisers of The Architect’s Newspaper.

Corrections

The Decorative Glass page in last month’s Focus Section included the incorrect image for Pulp Studio’s DermaAR finish. The correct image for the product is reproduced above.

Studio Ma was founded by principals Christiana Moss, Christopher Alt, and Dan Hoffman. Its work on ASU’s Manzanita Hall was completed with SCB.

The founding partner at Marvel is Guido Hartray, not Hartnay; the photos of the office’s Rockaway Village are by David Sundberg, not Sunberg.

The Architect’s Newspaper TY COLE

4 Editor’s Note Masthead Info

COURTESY PULP STUDIO

Open Mail

Aesop

2-104 Palisades Village

1052 North Swarthmore Avenue

Pacific Palisades, CA 90272

Luxury cosmetics brand Aesop has debuted another serene architect-designed store at its new Palisades location. The company tapped Odami, a Toronto-based design studio, to realize an interior inspired by the lush natural surroundings of the Palisades’ rolling hills and valleys. (WORD Design x Architecture served as the architect of record.) Odami brought these site-specific ideas inside the store, starting with an even green palette with a slightly dusky tint to it. This tone is applied in rough brushstrokes to the walls and floors but also continues through leather upholstery details as well as floor-to-ceiling curtains that pleat softly along the back wall, concealing storage. Soft concrete forms emerge to make pedestals, washbasins, and recessed shelving nooks with custom insets for the iconic amber bottles. Finally, accents of dark wood further complement the play between dark and light.

Emily Conklin

Emily Conklin

551 North Palora Avenue, Suite B Yuba City, CA 95991

According to legend, boba, or bubble, tea was introduced to the United States out of a shop in the San Gabriel Valley in the 1990s. It’s since become a gastro culture explosion, and Endemic Architecture, led by Clark Thenhaus, has designed a compact new shop in Yuba City, California, that shows just how far the treat has risen. The high-design concept of My Boba Spot updates the “boba aesthetic” and follows as a logical extension of Endemic’s “confetti urbanism” design ethos. Dustypink paint defines the doors and circulation of the space, and special consideration is given to the pickup window adjacent to the service counter. Still, the space is largely empty, except for a circle of paint that runs between the floor and wall: My Boba Spot may be, in fact, a singular confetto . A swing hanging from the ceiling within this singular confetto is the perfect venue for an Instagram snap while one enjoys the graphic treatments of Endemic Architecture’s interior. EC

CoZy Dental

1600 18th Street

San Francisco, CA 94107

Healthcare spaces tend to evoke images of beige walls, uncomfortable chairs, and stuffy, cramped environments. The spaces that house such essential services suffer not from the practice of caregiving but from an ignorance on the part of design. Luckily, things are changing. At CoZy Dental, a new healthcare space designed by Spiegel Aihara Workshop, there is no room for scratchy folding chairs or wrinkled magazines circa 2008. The result is a space that is at once vivid and cozy. The interior is punctuated by bright yellows and pinks, abundant potted plants, and a front desk setup that feels as if you’re walking into a cafe: A teakettle is ready and waiting to serve you while you wait. Design-y touches like mirrors lined with fun tubes of light and bright textiles—reappropriated building rainscreen house wraps—hang from a frame of warm wooden beams, adding a decidedly nonsterile feeling throughout. Overall, the space uplifts the notion that taking care and being cared for shouldn’t be things to dread or put off. Health begins with intentionally creating the right environment so that improvement becomes inevitable. EC

Re: (W)rapper

A reader responds to a Crit by Ryan Scavnicky from our June issue.

One of the most intriguing new buildings in Los Angeles is a highly sculptural and visually prominent new high-rise. There is nothing else like it around.

Given its unique appearance, I had been itching to find out more about it. Are those bands that wrap it really what’s holding it up? If so, how did its designers ever figure out (and build) that geometry? When the June 2023 issue of The Architect’s Newspaper arrived with a photo of it on the cover, I eagerly looked for answers.

Instead, I found a review by Ryan Scavnicky. I was so put off by its contents that I wanted to offer readers another opinion.

To start, an obvious error: Despite Scavnicky’s claim that the building is in South L.A., it should accurately be located in Culver City, an upscale municipality within “Near West” L.A. with thriving nightlife and restaurants, a vibrant arts district, and the (sur)real estate values that go with it.

Full disclosure: Before reading this Crit, I didn’t know who designed the building or anything more than one could glean at a distance, nor did I personally know architect Eric Owen Moss or anyone who works in his office.

If I was going to respond to an article, I want to be sure it made sense, so I called the office and requested a tour, which was graciously provided by Dolan Daggett, project director at Eric Owen Moss Architects. Now, after seeing it up close and experiencing the building within its surrounding context (notably the new adjacent mass-transit line), I am even more impressed.

Architecture is a public art—a social art. Unlike music or film, it can’t be switched off. It impacts its surroundings. Architecture, since it always defines mass, is invariably sculptural. There are architects who explore the sculptural possibilities within their commissions, whether the sculpture is a Miesian box or a Saarinen-like arch. And there are those who don’t... or can’t. As in any field, buildings (in L.A., at least) range from the mundane—like its unending rectilinear stucco dingbats—to the sublime, as in Frank Gehry’s masterful and free-form Disney Hall. As sculptors of the public’s environment, architects have a duty not only to their client to fulfill functional program requirements, but also at best to the public at large to make a positive contribution to the built environment. Usually, program, function, budget, and/ or a lack of imagination combine to create the mundane. On rare occasions, these factors combine to bring about boundary-breaking buildings.

Such is the case here. Moss and his team used every opportunity to express the building’s functionality in sculptural terms. An exoskeletal structure allows for large uninterrupted floors of varying heights; stairs cantilever out from the building, linking floors of similar height; and a large sculptural stairway connects the building lobby to the adjacent mass transit.

Is this building a too-esoteric dialogue with a too-limited portion of the public, as Scavnicky implies? He mentions the disparity between architecturally attuned opinion (“insiders”) and that of those who do not possess such

awareness (“outsiders”). Most innovations in any field of the arts are met with controversy: the more departure, the more controversy. The real issue isn’t so much about educated vs. uneducated taste, as he implies, as it is about those who welcome innovation and experimentation and those who feel threatened by the unfamiliar—by new forms and new ideas, which this building is all about.

Most rule-breaking buildings come about only from that all-too-rare combination of wealthy client willing to entrust a highly creative architect with his or her vision. And that was the case here. Moss, I learned, has worked with this developer/client for the last 25 years and has transformed the Hayden Tract, a large industrial land holding, into a veritable wonderland of highly original and sculptural architecture. Any architecture student, given the uninhibited and highly diverse exploration of architectural forms that populate it, would think he or she had landed in architectural heaven.

Contrary to Scavnicky’s assertions that the (W)rapper is inappropriate to the Blackmajority areas in which he (incorrectly) says it’s located, this building is artistically and functionally well suited both to the Hayden Tract—a reflection of its architectural adventuresomeness—and to Culver City as a whole and the entertainment and tech industries that have flocked to it.

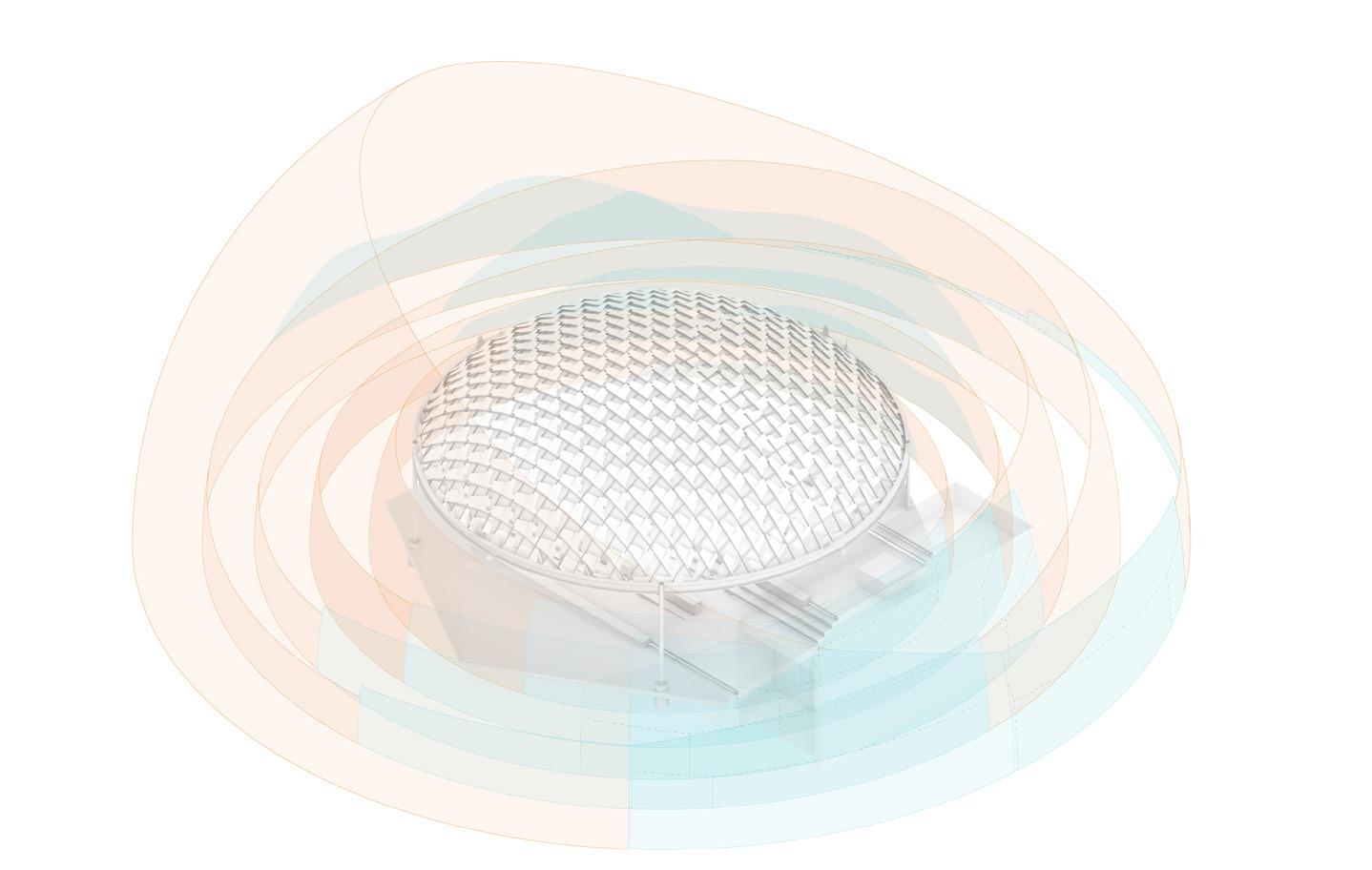

It is a remarkably innovative structure, from its visible steel-web structure to its isolation-pad foundations. How innovative is it? The structural system bears a visual resemblance to that of Herzog & De Meuron’s Bird’s Nest Stadium in Beijing. (Which building was conceived first depends on who one asks.) There is both logic and art in the structure’s configuration. Like the Beijing Bird’s Nest Stadium, the structure is derived with both function and aesthetic in mind, but it certainly isn’t “chaotic-looking,” as Scavnicky wrote.

Scavnicky presents a dark view of architecture’s future, claiming that this building “expresses its own Freudian death drive.” Why not instead recognize the life-affirming joy of designing buildings that save lives in the event of a major earthquake? Darker still, Scavnicky claims that working for firms that create new visions is essentially a dead-end professional street; that’s certainly not what I sensed during my tour with Daggett. I wonder if Scavnicky has ever felt the desire to transcend the mundane and be part of something extraordinary?

As mentioned, Scavnicky concludes with his assessment of the conflict between the cognoscenti vs. the uninitiated (my terms) and architecture’s “complicity with neoliberal capitalism.” He declares that the building is “pseudointellectual contortionism.” Given Moss’s reportedly “incoherent web” of metaphorical references and efforts to translate the language of architecture into words, I’m sure I would enjoy discussing architecture with Moss. With Scavnicky? I’m not so sure.

Roger Leib Los Angeles

The Architect’s Newspaper

6

My Boba Spot

ALANNA HALE

JUSTIN LOPEZ

RAFAEL GAMO

Duravit AG has plans to realize the world’s first climate-neutral ceramic production facility, designed by DAD Architecture/Design, in Quebec.

Noguchi Museum and Pratt Institute among 48 recipients of a $2.7 million grant from the Frankenthaler Climate Initiative.

The Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, a nonprofit founded by the abstract expressionist painter, announced this week the names of 48 institutions receiving grants of $2,500 to $100,000 to fight climate change from its climate-focused subsidiary, the Frankenthaler Climate Initiative (FCI). This year, the foundation also announced an increase in annual funding from $10 million to $15 million, accelerating the initiative’s “commitment to climate action in visual arts sector.” The 2023 recipients include the Noguchi Museum, Pratt Institute, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, SITE Santa Fe, the Wassaic Project in New York, and the

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. The funds support a myriad of sustainable projects, from upgrades to HVAC systems and installations of renewable energy sources to the implementation of green building envelopes and designing low-emission buildings. Lise Motherwell, director and board chair of the Frankenthaler Foundation, said in a statement that “these organizations have inspired us with their ingenuity and commitment to lower their carbon footprints.”

FCI is concurrently planning a special public program on September 22 during Climate Week NYC. DJR

Duravit AG, a German bathroom manufacturer, announced plans to build the “world’s first climate-neutral ceramic production facility” in Quebec. The new plant, designed by DAD Architecture/Design, will make ceramic sanitary ware in a roller kiln fueled by hydropower electricity. Duravit officials claim this strategy “will save around 11,000 tons of CO2 per year compared to a conventional ceramic factory.” The electric roller kiln was developed with SACMI.

“Canada will be the first country in the world to produce carbon-neutral ceramics!” said

Minister of Innovation, Science, and Industry François-Philippe Champagne.

This will be Duravit AG’s first factory in North America, and it’s part of a strategy to bring the company’s products to Canadian and American consumers.

The Canadian government provided a repayable contribution of $19 million and also issued an $11 million loan to facilitate the plant’s construction. Production at Duravit’s new location in Quebec will commence in 2025.

Daniel Jonas Roche

Ceramics Class Giving Back B Corps

More and more architecture firms are becoming certified B Corps: What are they, and what do they mean for architecture?

This summer, Lake|Flato became the 86th architecture, design, and planning firm to become a certified B Corp. The certification program is run by B Lab, a nonprofit that evaluates companies for sustainable and ethical practices in the following categories: governance, workers, community, environment, and customers.

The Texas firm joins a few other firms familiar to AN readers in the B Corp ranks, including SO – IL, DIALOG, and David Baker Architects. B Corp evaluations ask companies to disclose data on a wide range of categories, including basic standards like providing clean drinking water and toilets for workers— like those installing the work of landscape architects, for example. In a sense, B Corp designation is a way for small and midsize private businesses to signal their virtues when they do not have the disclosure responsibilities of publicly traded companies. As the buzzword circulated last year, other firms, including Perkins&Will, Stantec, Perkins Eastman, and Gensler, responded to their companies’ position within the Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) sphere. But if a firm’s practices are already ethically sound, chasing another corporate certification may not be the best use of resources—unless it is engaging

with a clientele that values such measures. For a firm like SO – IL or DIALOG, having the B Corp sticker might make their firm more appealing to potential clients. If this can win them work, and make some corporate practices more transparent, so be it. But it may not do much more than that.

Chris Walton was formerly an assistant editor at AN

September 2023

7 News

DAD ARCHITECTURE/DESIGN/COURTESY

DURAVIT AG

PRATT INSTITUTE LIBRARIES/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS/CC BY-SA 2.0

Green Thumbs Jean-Louis Cohen

New York Botanical Garden’s new Site Operations Center will be one of the first net-positive facilities in the Bronx.

The world-renowned architecture professor, historian, and curator died unexpectedly in France at 74.

Jean-Louis Cohen, New York University Institute of Fine Arts professor in history of architecture, died on August 7 due to an allergic reaction from a wasp sting. He was 74 years old.

Cohen’s death was confirmed by the Institute of Fine Arts. News of his death was initially shared online by Isabelle Regnier, a regular contributor to Le Monde about architecture. Tributes quickly followed from across the globe.

At the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), keeping the grass green and the flowers in bloom requires a lot of behind-the-scenes work, much of which happens at the Site Operations Center. This month, the NYBG announced it was a recipient of $2 million in funding from Mayor Eric Adams’s $117 million budget allocation for cultural projects in New York City.

NYBG will use this funding to support the design and construction of a new Site Operations Center by Mitchell Giurgola Architects that will be one of the Bronx’s first netpositive energy facilities. In order to achieve this, the building will be constructed of mass timber and feature geothermal wells and a roof

topped with photovoltaic panels to generate renewable energy, targeting LEED Platinum certification. It will also be clad with Ultra High Performance Concrete panels, depicted in a shade of brown in the renderings.

“The staff and Board of NYBG are passionate about making the Botanical Garden’s National Historic Landmark campus a welcoming, sustainable, and accessible place for the public to connect to the natural world,” said CEO and President Jennifer Bernstein, adding that the funds “demonstrate the Mayor and his team recognize the unmatched power of cultural organizations as drivers of economic strength and social vibrancy.”

Kristine Klein

Cohen was born in Paris in 1949. A trained architect and historian, he studied at the École Spéciale d’Architecture, the Unité Pédagogique No. 6, and Architecte DPLG, all in Paris. In 1985, Cohen earned his PhD in art history from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. After a series of appointments in academia and the French government, he left Paris in 1994 to join NYU as Sheldon H. Solow Professor of History of Architecture.

During his tenure at NYU, Cohen held visiting teaching appointments at Princeton University, TU Delft, and the University of Sydney, while lecturing at other prestigious institutions around the world. A polyglot, Cohen conducted research in and on Paris, Berlin, Moscow, New York, Algiers, and Casablanca. Notable among his long list of accomplishments and publications is his research on Le Corbusier: He’s widely considered one of the

world’s preeminent experts on the icon of modernism, and he is known more generally as an international authority on 20th-century architecture and urbanism. Cohen wrote numerous acclaimed books, including exhaustive monographs on Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, and organized lectures and exhibitions on diverse subjects ranging from Soviet constructivism, the radical Italian architect Bruno Zevi, Oscar Niemeyer’s work in Brazil, and international and French modernism.

Currently two exhibitions about the work of Paulo Mendes da Rocha co-curated by Cohen and Vanessa Grossman are on view at the Casa da Arquitectura in Matosinhos, Portugal, through February 25, 2024. Additionally, Cohen co-curated Paris Moderne 1914-1945: Architecture, Design, Film, Fashion with architect Pascal Mory and fashion curator Catherine Örmen, featuring exhibition design by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The show is on view at Shanghai’s Power Station of Art through October 20. Cohen contributed obituaries for Hubert Damisch and Claude Parent to AN. Most recently, he provided commentary about the Vkhutemas exhibition at the Cooper Union. DJR

AN is collecting stories and remembrances of Cohen from friends, students, and colleagues. If you would like to share a memory, please email it to jmurphy@archpaper.com.

Joan Davidson, 1927–2023 Derby City Dispatch

She was a much-loved, New York–based philanthropist who supported both preservation and publishing.

Joan K. Davidson died on August 11, aged 96, just a few weeks shy of announcing the 2023 Alice Award. Distinguished and admired, she understood and acted on the principle that architecture and design are integral to quality of life

Louisville, Kentucky’s Beaux Arts–style Speed Art Museum is a mainstay of the Kentucky art scene. Yet following its 2016 expansion by Kulapat Yantrasast of wHY architecture, it’s readying for yet another: In 2025, the museum plans to open Speed Outdoors, a three-acre public sculpture park.

Designed by Reed Hilderbrand Landscape Architecture with PLC Management, BOSSE Construction, and K Norman Berry Associates Architects, Speed Outdoors supports a growing collection of outdoor sculptures. But Louisville historically has had scarce access to public greenspace. The addition of Speed Outdoors not only adds to the art and culture scene of Kentucky’s largest city but also creates a place for respite and recreation.

“The Speed Outdoors represents our vision for a museum shaped by dedication to inclusivity, belonging, and boundless forms of creativity,” said Raphaela Platow, director of the Speed Art Museum.

A lacquered cast-aluminum bench by Zaha Hadid; Mark Handforth’s massive Silver Wishbone; a monolithic concrete installation from Sol LeWitt; and two chairs made of rocks and steel rods designed by Kulapat Yantrasast are among the inaugural pieces that will be sited within the new sculpture park. A $22 million capital campaign supported by the University of Louisville seeks to raise money for the park’s construction and its continued operation. It’s expected to open in 2025. KK

With her crest of white hair and commanding voice, Davidson was wonderfully intimidating but unstintingly generous to the causes dear to her. Born on May 26, 1927 in New York City, she received her Bachelor of Arts at Cornell and an Education degree from the Bank School. She gave grandes dames a good name: Her career was a productive matrix of progressive activism and social connectivity stretching back to an early job as a staffer in the office of Senator Lyndon B. Johnson in Washington, D.C. But philanthropy was her calling. She was inspired by her father, Jacob M. Kaplan, who redirected a fortune made in owning the Welch’s Grape Juice company (which he sold to employees in 1956) into the J. M. Kaplan Fund.

Focused largely on New York, the Kaplan Fund has long been an advocate for preservation efforts, including Carnegie Hall, New York Garden Markets, the South Street Seaport Museum, and Westbeth’s 383 rent-controlled live-work spaces for artists. In 2022, she initiated Carriage House Events where people could come, she said, “to listen, see, think, agree, disagree, and have fun”—in other words, to partake in her recipe for a good life.

Public remembrances of Davidson are being collected on the website of the Kaplan Fund.

Julie Iovine was the executive editor of The Architect’s Newspaper from 2007 to 2013. She now lives in upstate New York.

The Architect’s Newspaper 8 News Obit

Louisville, Kentucky’s Speed Art Museum announces Speed Outdoors, a new sculpture garden to be designed by Reed Hilderbrand.

CREDIT TKTK

MITCHELL GIURGOLA ARCHITECTS

REED HILDERBRAND LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

Read more at archpaper.com.

SAMIRA BOUAOU/COURTESY EPOCH TIMES

Clock’s Ticking…

Marcel Breuer is known for iconic midcentury modern buildings around the world, but the Bauhaus-trained, Hungarian American architect spent his summers on Cape Cod, in Massachusetts, at a lesser-known, modest cottage of his own design, completed in 1949. But this month, the Cape Cod Modern House Trust (CCMHT) rang the alarm bells: The cottage may soon be demolished.

CCMHT is under contract to purchase the cottage, but the group has a little under one year to raise the funds to save this “cultural gem,” and donations are needed: $1.4 million, actually.

Breuer’s cottage contains the late architect’s books, furniture, art, photographs, and ephemera, and according to Peter McMahon, founding director of CCMHT, “It’s basically a repository of Breuer’s life.” McMahon also notes that the cottage is historically significant for a few reasons: “Breuer was really interested in the Cape’s local vernacular design, its oyster shacks, and covered bridges. And this cottage was the first time he developed what’s become known as the ‘Long House,’ which is basically a long house on stilts. It’s a New England cabin melded with a modern European design that uses pilotis made up of local wood materials.”

Preservationists and modern art lovers have good reason for concern. In 2022, Docomomo US broke the news that Breuer’s Geller House, on Long Island, was demolished overnight to make way for a new “superfluous tennis court.” Docomomo has since paired up with CCMHT to save this cottage.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to protect such an important home and make it open to the public,” said Liz Waytkus, executive director of Docomomo US. To get involved, go to ccmht.org. DJR

September 2023 9 News

There are just under 365 days left to save a timeless classic in Cape Cod designed by Marcel Breuer.

modulararts.com 206.788.4210 made in the USA

MARTA KUZMA Ventanas PANEL ©2019 modularArts, Inc. Shayle PANEL ©2023 modularArts, Inc. Breeze™ PANEL @2022 modularArts, Inc. Ziggy BLOCK ©2012 modularArts, Inc.

Zephyr

BLOCK ©2012 modularArts, Inc.

Seamless Feature Walls in Modular, Glass-Reinforced Gypsum. Over 60 designs!

News A New Civic Hub

A neighborhood center in southwest Houston designed by Page and SWA Group supports the lives and health of local residents.

Drivers crossing through southwest Houston on Bellaire Boulevard encounter a continuous flow of unpredictable urban elements. After passing under two of the city’s three beltways, the characteristically Houstonian thoroughfare arrives at a complex that is different. The Alief Neighborhood Center, nestled behind foliage on the corner of Bellaire and South Kirkwood, stands out. The effort dates back to 2014, when Alief’s local government dedicated itself to providing a facility that serves and embodies the diverse community’s values.

Designed by Page Southerland Page, the Alief Neighborhood Center opened in January and is a testament to community design. (The project was originally led by EYP, and finalized design efforts were completed by Page

Landgrab

after its acquisition of EYP last year.) Despite initial resistance, extensive outreach meetings during the schematic design phase allowed the community to voice its needs and desires: This project had been 30 years in the making.

“They were referred to as District F, for forgotten,” Jonas Risén, lead design architect and associate principal at Page, told AN. The first few meetings with community members were fraught with what he described as “frustrations and grievances for the way things had been handled previously.”

The result of these meetings and design schemes is a brand-new, 70,000-squarefoot community center that looks like it could be at home on a research university campus. It sits on the site of an older, much smaller

“Vulture agents” are trying to buy up real estate in Hawaii for pennies on the dollar.

Last month, Maui residents and Hawaii’s governor, Josh Green, called attention to predatory developers trying to buy up properties in parts of Maui impacted by wildfires. An official press release from the governor’s office stated that residents “are being approached about selling fire-damaged home sites, by people posing as real estate agents who may have ill intent.” Green said he’s currently working with Hawaii’s attorney general to issue a moratorium “on any sales of properties that have been damaged or destroyed.”

Hawaii has the highest cost of living in the country, and Maui has long struggled with rising rents and land values. The wildfires are

only exacerbating this: Now, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has reported that 4,500 people in Maui need shelter.

“Realtors are calling families who lost everything, offering them to buy their property and their home for pennies on the dollar,” said Paele Kiakona, a Lāhainā resident.

Since the wildfires began, Maui resident Tiare Lawrence has been an outspoken critic of the developers on her personal Instagram, using her platform to warn Hawaiians and raise donations.

“Maui is not for sale,” Lawrence told MSNBC. “It is important that the multigenerational families that come from Lāhainā get to continue to live in our hometown.” DJR

community hall. There are now new facilities for a public library branch, new parkland, and health departments, along with a complex for outdoor sports. Lifted above the floodplain in response to post–Hurricane Harvey concerns, the building sits atop an artificial hill, a plinth that conceals a parking garage.

The center spatially separates the health department from the parks department on the first floor, while the second floor houses the library department and “tech link” spaces. Despite hosting separate departments, these areas maintain a seamless connection within the building to enhance work efficiency and facilitate the use of shared meeting rooms. Conveniently located closest to the entrance, the health department sees a significant daily influx

of visitors. “We have [around] 1,200 people a day coming in,” Risén said. Elevated above the park’s tree canopy, the library offers an open view of the outdoor facilities to the south.

The outdoor scope of the project further adheres to the idea of community interaction. SWA Group’s landscape effort establishes the site as a civic gathering place for the Alief community and seizes the chance to establish a fresh, resilient development model for Houston post–Hurricane Harvey. The design intentionally shapes the parkland to absorb floodwaters while simultaneously offering essential recreational facilities: a planted seating area; courts for basketball, tennis, and a soccer field; a pool; and a skate park. Tree canopies and curved pathways lead people through the site, and sport courts are distanced—and therefore acoustically separated—from gathering spaces and playscapes.

Fittingly for its roadside context, one of the most prominent aspects of the community center is its sign. Larger-than-life lettering sits prominently on the front facade, providing an immediately visible and already-iconic boost of neighborhood pride. Five 16-foot-tall aluminum letterforms read ALIEF. The welcome sign doubles as a shade structure for the entry patio, making it “the biggest front porch in Texas,” as Risén told Texas Monthly. The space is functional, open, and surprisingly cozy.

To celebrate Alief’s diversity and community, art pieces adorn the center and its grounds. Outside, connected to the curving paths near the main entrance, stands Windbloom , an artwork by Falon Mihalic, a Houston-based multidisciplinary artist and landscape architect. Windbloom resembles an elevated, colossal flower and serves as both an overhead shading device and, from a distance, a “supersized flower map.” Inspired by the coastal prairie, it portrays prevailing winds with colorful resin “petals” set on a framework of painted carbon steel, firmly rooted in the center’s butterfly garden.

As we know, the excitement of a new building can be as brief as the scent of freshly poured concrete. But a well-designed building only gets better with time and use, outliving the initial hype. My visit to the Alief Neighborhood Center showed that the facility is actively beloved, with people of all ages running, jumping, rolling, and reading, among other actions. Page’s Alief Neighborhood Center, an emblem of local pride and inclusivity, should be a model for community centers throughout Houston.

Rodrigo Gallardo is a Houston-based designer. His writing has been featured in Texas Architect and Cite: The Architecture and Design Review of Houston

The Architect’s Newspaper

10

HAWAII NATIONAL GUARD/FLICKR/CC BY 2.0

CREDIT TKTK

© ALBERT VECERKA/ESTO

Process as Project

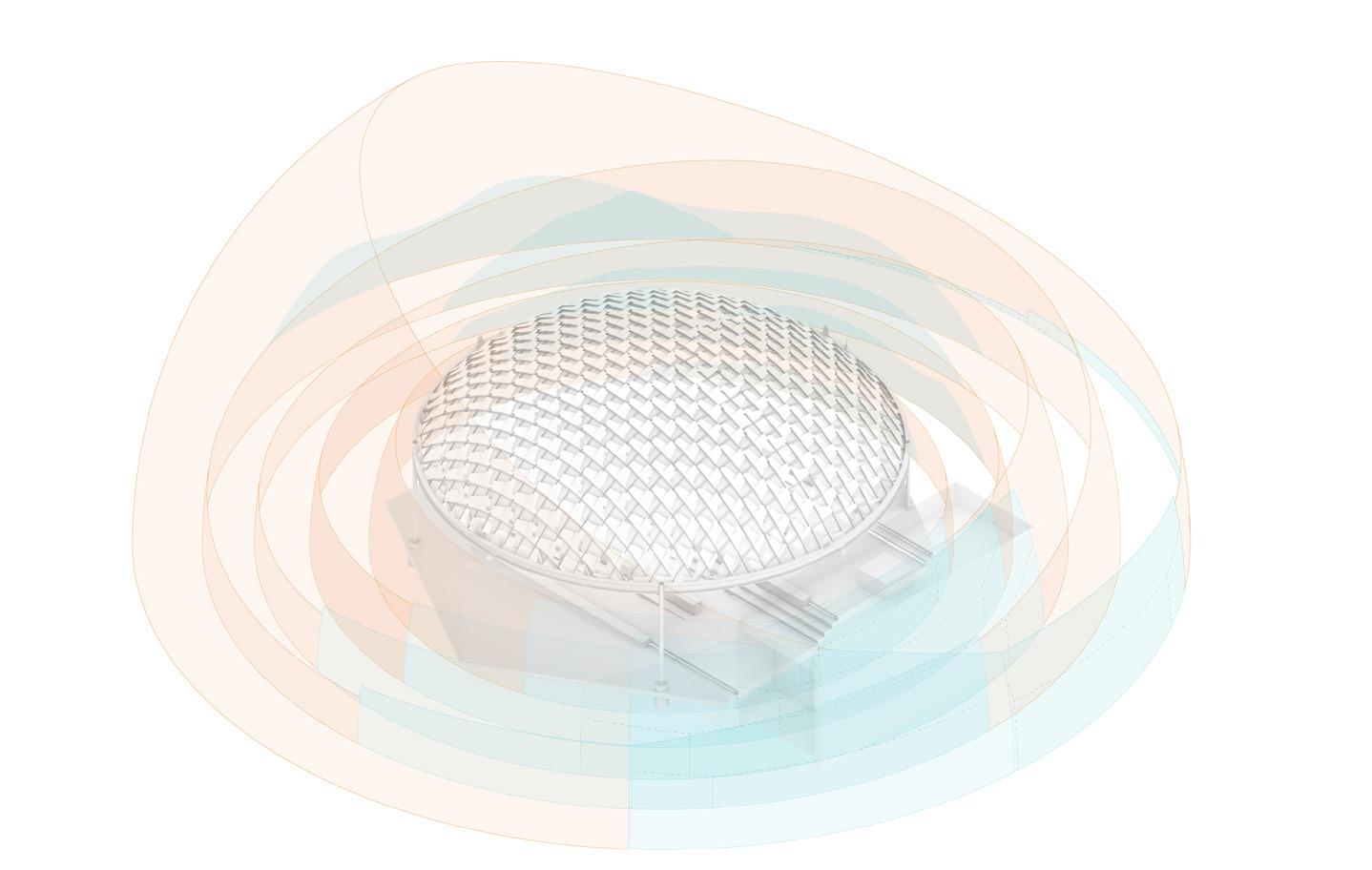

This year’s Exhibit Columbus raises the bar for design expositions looking to partner with local communities.

Since 2014, Exhibit Columbus has activated the small eponymous Indiana city, home to about 45,000 people. Since the mid-20th century, it has been regarded as a hotbed of architectural innovation, from iconic and formally exciting structures to experimental ways of living. The exhibition, now in its fourth iteration, offers a platform for architecture’s rising stars to display work alongside established legends.

The word on the tip of everyone’s tongue this year at Exhibit Columbus was “community.” The 2023 exposition is called Public by Design which focuses on centering the perspectives of local Columbus residents to inform 11 installations spread throughout the city. According to Exhibit Columbus executive director Richard McCoy, designers were tasked with making “meaningful connections in public space” alongside local community leaders. To that end, each of the four recipients of the J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize paired up with various city departments for their projects.

Harlem-based Studio Zewde collaborated with Columbus’s department of parks and recreation for their piece, Echoes of the Hill, located in Mill Race Park, an early Michael Van Valkenburgh project. The Mexico City firm Estudio Tatiana Bilbao’s installation, Designed by the public, posited new social potentials for local libraries in dialogue with staffers from Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, designed by I. M. Pei. New York’s PAU (Practice for Architecture and Urbanism) built InterOculus, a steel rotunda designed for dancing located at a prominent Columbus intersection, in collaboration with the department of public works. PORT, an office with locations in Chicago and Philadelphia, designed The Plot Project together with members of the Mill Race Center, a community center for active adults on the edge of Mill Race Park.

“We were part of Exhibit Columbus

from the very beginning,” said Beth Stroh, who owns Viewpoint Books, an independent bookstore that opened in 1973 on Washington Street, Columbus’s main thoroughfare. “Downtown businesses like mine were asked about what we wanted to see. The way Exhibit Columbus leadership engaged with us made us feel like valued partners in this process. It just makes our community feel alive, activated, and welcoming.” Stroh worked with local high schoolers on their pavilion, Machi, which created a “new living room for all of us to be in community” in downtown Columbus. She told AN, “We can’t wait to see what kind of programming happens. We’re already planning storytimes there.”

Communications design by Chris Grimley was beautiful and clear, and brought home the public design motif. Grimley told AN that Exhibit Columbus’s graphic identity this year built off the original design by Rick Valicenti, and that the 25 brightly colored signs planted around town orienting pedestrians were an “homage to the playful patterns and shapes of Ray Eames and Alexander Girard.”

Alongside the four Miller Prize winners were seven University Design Research Fellows who also displayed works. These included Joseph Altshuler and Zack Morrison (Could Be Architecture); Esteban Garcia Bravo and Maria Clara Morales (Purdue University); Jessica Colangelo and Charles Sharpless (Somewhere Studio/ University of Arkansas); Deborah Garcia (MIT Belluschi Fellow); Molly Hunker and Greg Corso (SPORTS/Syracuse University); Katie MacDonald and Kyle Schumann (After Architecture/UVA); Ohio State’s Halina Steiner, Tameka Baba, and Forbes Lipshetz and Iowa State’s Shelby Doyle.

Located in a sunken brick terrace outside I. M. Pei’s Cleo Rogers Memorial Library, Responder by Deborah Garcia was a family affair. In collaboration with

Propeller, a local production outfit, and MIT students, the piece was assembled on site by a herself, a team of local volunteers, and her two sisters, Ana and Sara. “My sisters have helped with all of my exhibitions,” Garcia told AN

On display until November 26, Responder is a throne that doubles as a boom box sheathed in gorgeous, charred wood panels. A nighttime sound performance on August 26 at Garcia’s installation gave Columbus the experimental feeling of a dissident noise show. Over the course of several months, Garcia recorded ambient noises from the Pei-designed library’s easily overlooked elements—its elevators, mechanical equipment—to compose a symphony, or “sonic register” with the building that John Cage would have appreciated. On opening night, viewers laid down on the subterranean plaza at Cleo Rogers Memorial Library after a long day of walking to take in the ambient music and observe the brutalist building in a new light.

A second happening came later that evening at Prisma by Esteban Garcia Bravo and Maria Clara Morales, an illuminated installation across the street from Kevin Roche’s Cummins HQ building. Prisma featured glowing tubes that lit up the night sky, augmented by an experimental DJ set by Liv Mershon, a Chicago-based artist originally from Columbus. A pickup truck parked in the middle of the road made it safe for viewers to sit on the asphalt and consume the sights and sounds, giving the high-art packed evening Dazed and Confused vibes.

“It was wild playing in my hometown, seeing it from a totally new perspective, and playing my totally bizarre music for an entire hour,” Mershon told AN. “What was so joyful was, as I was playing, people came inside the installation by Esteban and Maria and danced inside of it while I was performing. It became almost a collaborative experience,” Mershon said. “It felt

weird because in the 90s and early aughts, I felt like I needed to escape my hometown to explore the weirdness that’s inside of me. But it was really cool to discover that that weirdness is supported in the town where I grew up.”

Could Be Architecture’s installation, A Carousel for Columbus, was also musically inclined. A local high school garage band shredded on top of the spinning carousel decorated with a deliciously polychromatic mural by Altshuler and Morrison. A self-described “locomotive love letter,” A Carousel for Columbus builds on the duo’s track record of experimenting with bold patterns and building artful public spaces. “Taken together, the carousel, supergraphics, and performances offer a locomotive landscape that celebrates the power of shape, color, character, and sound to generate a public platform by design,” the architects said in their project statement.

And then for some, the 2023 Exhibit Columbus meant coming full circle. “Twenty-six years ago I made a pilgrimage to the design mecca of Columbus, Indiana after my then–architecture professor, Stanley Saitowitz, had completed beloved follies in Mill Race Park,” said PAU founder Vishaan Chakrabarti.

“Ever since it’s been a lifelong dream to build there, so the fact that PAU’s first built design, InterOculus, now stands proudly at the heart of downtown Columbus as a canvas for community convening is both humbling and gratifying, particularly given the extraordinary multicultural dance that launched it,” he told AN. “At a cultural moment when society feels like it is spinning apart, an architecture of urbanity can pull us together to address the big issues of our day, from climate change to inequity to the social isolation driven by technology.”

DJR

September 2023

11 News

AN is a media partner for Exhibit Columbus.

PORT’s The Plot Project became a hub for people to gather and rest. Tatiana Bilbao Estudio’s Designed by the public posited new social potentials for public libraries, itself located just outside of the Cleo Rogers Memorial Library.

HADLEY FRUITS

HADLEY FRUITS

Alleviating Alienation

“When I am in California, I am not in the West. I am west of the West,” declared Theodore Roosevelt at the turn of the 20th century. The potential for self-reliance implied by Roosevelt was felt at that time by countless western settlers, who together transformed California—particularly its southern half—into a sea of low-rise development and automobile infrastructure within a matter of decades. Yet an alternate reading of Roosevelt’s proclamation, which envisions limitless potential for new modes of living and working, became both the inspiration and namesake for West of West. A young Los Angeles–based architecture firm that responds to the western landscape of the 21st century, the studio offers fresh approaches to community building through novel design practice.

Cofounders Clayton Taylor and Jai Kumaran resist operating as a top-down design practice. Following their shared early-career experience at Morphosis Architects, they intentionally seek input from all ten people in their office throughout each step of the design process.

How do they maintain the levels of patience and humility necessary for creative equity?

“Don’t be an asshole,” Kumaran told me. We were sitting in the West of West studio space, set within a sunbaked shopping center in L.A.’s Chinatown. “We hire people who know things we don’t know, people who notice details that go over our heads.”

This faith in others extends into many of the types of projects West of West has secured over the past eight years. Operating in a city known for single-family houses, the office has amassed a portfolio of multiunit housing projects that “sneak” density into low-rise neighborhoods. Design strategies like outdoor circulation paths and spacious communal facilities help projects succeed in unexpected places by inspiring human connection and collaboration. Even when working on building types often associated with social alienation, such as the ever-daunting office campus or bank tower, the studio similarly instills opportunities for interaction through well-placed community amenities amid warm materials.

The Architect’s Newspaper 12 Studio Visit

4

West of West finds opportunity for social interaction in places with little supply.

COURTESY WEST OF WEST

Before Garrett Leight became synonymous with upscale sunglass design, he and Kumaran were college friends with disparate passions. Taylor and Kumaran’s design sensibilities are visible on the smooth, undulating surfaces of their flagship for Garrett Leight California Optical, the first of many designs West of West would complete for the sunglass company. The interior was conceived as a habitable billboard: It’s large enough that motorists speeding down La Brea Avenue can peer into its expansive glass facade. The billowing wall along the

shop’s interior is visually propped up by sinuous plywood built-in cabinetry to match the clean yet relaxed aesthetic of Garrett Leight’s sunglass line. The wall is additionally broken up by a field of plywood pegs that serve as supports for shelving that can be easily modified, depending on changing collections and product quantity. The design scheme was so successful that West of West was invited to translate the same sweeping language to the brand’s SoHo, Manhattan, location later that same year.

In East Austin, West of West recently completed Eastbound, a 230,000-square-foot creative campus with a number of design details that distinguish it from the typically alienating office park. The campus consists of two large industrial buildings with precast square paneled facades punctuated by newly punched square windows. Inspired by the functionalist industrial buildings across the way from the three-acre site, the treatments retain their gritty character while new interventions bring copious natural light into

expansive open floorplans. “The outdoor pathway that runs in between the two buildings is wide enough to host opportunities for socializing,” said Kumaran, “but also narrow enough to receive regular shade from the bordering facades to beat the hot inland Texas weather.” Along the pathway, the wraparound glass facade of the ground floor appears to be lifting up the concrete mass above with the assistance of dramatically tilted concrete columns.

Though it is one of the first commercial office buildings in Los Angeles to combine cross-laminated timber (CLT) with steel framing, 6344 Fountain does not wear the trendy material on its sleeve. When commissioned to add a 50,000-square-foot addition to an existing two-story commercial building in Hollywood, California, West of West chose to draw inspiration from the unique culture of the neighborhood. The result is a pile of cubes with contrasting cladding materials scattered across the block in a manner reminiscent of early Frank Gehry. While the ground floor of

the addition is visually broken up by thoughtful landscaping, the upper floors of the addition are composed of interweaving office and terrace spaces with views of the Hills to the north. “Everyone in Hollywood wants a view,” Kumaran joked as he explained how the luxuriant outdoor spaces entice technology and film companies to lease spaces.

Steep slopes have been the mothers of residential invention in Los Angeles since single-family homes were first placed in the Hollywood Hills more than a century ago. When tasked with designing a five-unit housing project on a site with two distinct elevations in Echo Park, West of West devised a “slow stair street” that gently weaves the units together along a common meandering path. Like Sunset Steps, a multiunit housing project currently in the works in San Francisco, Echo Park Co-Living resolves several issues with low-rise development with a single solution:

“We wanted to reimagine how sites typically designated for single-family homes could both increase housing density while also benefiting the surrounding neighborhood through community amenities,” said Kumaran. While each stand-alone unit includes its own rooftop deck—an amenity that is far less common among homes across Southern California than it should be—each unit’s ground floor remains in dialogue across the site.

September 2023 13 1 3 2 4

LAWRENCE ANDERSON

DANIEL COURTESY WEST OF WEST

HERE AND NOW/PAUL VU

CHASE

Shane Reiner-Roth is a lecturer at the University of Southern California.

1 Garrett Leight Los Angeles 2015

3 6344 Fountain 2023

2 Eastbound 2022

4 Echo Park Co-Living 2022—

14 Open House Urban Sustainability

BLDUS designs an infill home that’s loaded with high-performance features.

Washington is a city of sandstone, marble, and red brick, so the Poplar Grove residence is the last house you’d expect to see in the nation’s capital. Andrew Linn and Jack Becker, principals in the firm BLDUS, eschewed traditional materials and instead clad Linn’s own single-family home in poplar bark, cork, and modified radiata pine. And yet, the material decisions aren’t the most interesting thing about the home. It’s also located in an alley. All of these surprising details come together for the design duo and tell their unique story.

“The history of alley houses is that there were thousands and thousands of units in the District. Many of them were informal, and many of them were lower-income,” said Linn, who lives in the house with his wife, Hannah, and their young son. “In the ’30s and ’40s, the wife of one of the presidents had a big push to improve the alleys. And the alley ‘improvement’ was slum clearance.”

But times change. In 2016, Washington revamped its zoning regulations to permit alley housing. For Linn and Becker, this was an opportunity to add thoughtfully designed single-family houses to the city’s urban fabric. Poplar Grove is part of that effort and is the first in a series of projects the firm has in various stages of completion.

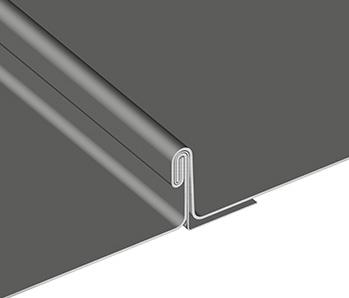

Linn and Becker designed the structure with a number of high-tech sustainability innovations, which amounted to a highly insulated building envelope: An energyefficient HVAC system, energy recovery ventilator, and triple-glazed windows create an efficient base for the entire home. On top of that, low-flow plumbing products save water, and a heat pump–fueled hot water tank works like a refrigerator in reverse—the unit pulls heat from the surrounding air in the house to generate hot water and conserve energy.

A final consideration was the inclusion of an automatic transfer switch in case Linn and his wife decide to add solar panels in the future.

But despite all the state-of-the-art green tech embedded in the home, the designers’ most important sustainability move was their decision to use BamCore, an exterior wall framing system made up of bamboo, eucalyptus, and other sustainable woods designed to save installation time and level up the efficiency. Delivered to the job site as a kit of parts, the panelized system comes with cutouts for doors, windows, outlets, and access panels, and each includes a cavity that accepts any type of insulation. Because it eliminates traditional studs, the system reduces thermal bridging by up to 90 percent. The duo has used the system on multiple projects. “We love it,” said Linn, a professor of practice at Virginia Tech College of Architecture. “It’s basically like making a passive house without thinking too much about it. Because you’re eliminating the thermal bridges, you get a tightly sealed home that’s more efficient.”

Set on a tiny lot among traditional row houses on all sides, the 2,500-square-foot house is a perfect 33-by-33-foot square with a zero-lot line on the east side, a five-foot

Above: The home as seen from the alley.

Left: The entrance, defined by a setback in the fence.

Above, right: The front door is set in a small front yard.

Facing page, top photograph: Interiors are all about light, sustainably-sourced wood.

Facing page, center photograph: Playful concepts like a lofted hammock extend the designer’s use of netting.

Facing page, bottom photograph: The main stair incorporates wood and net.

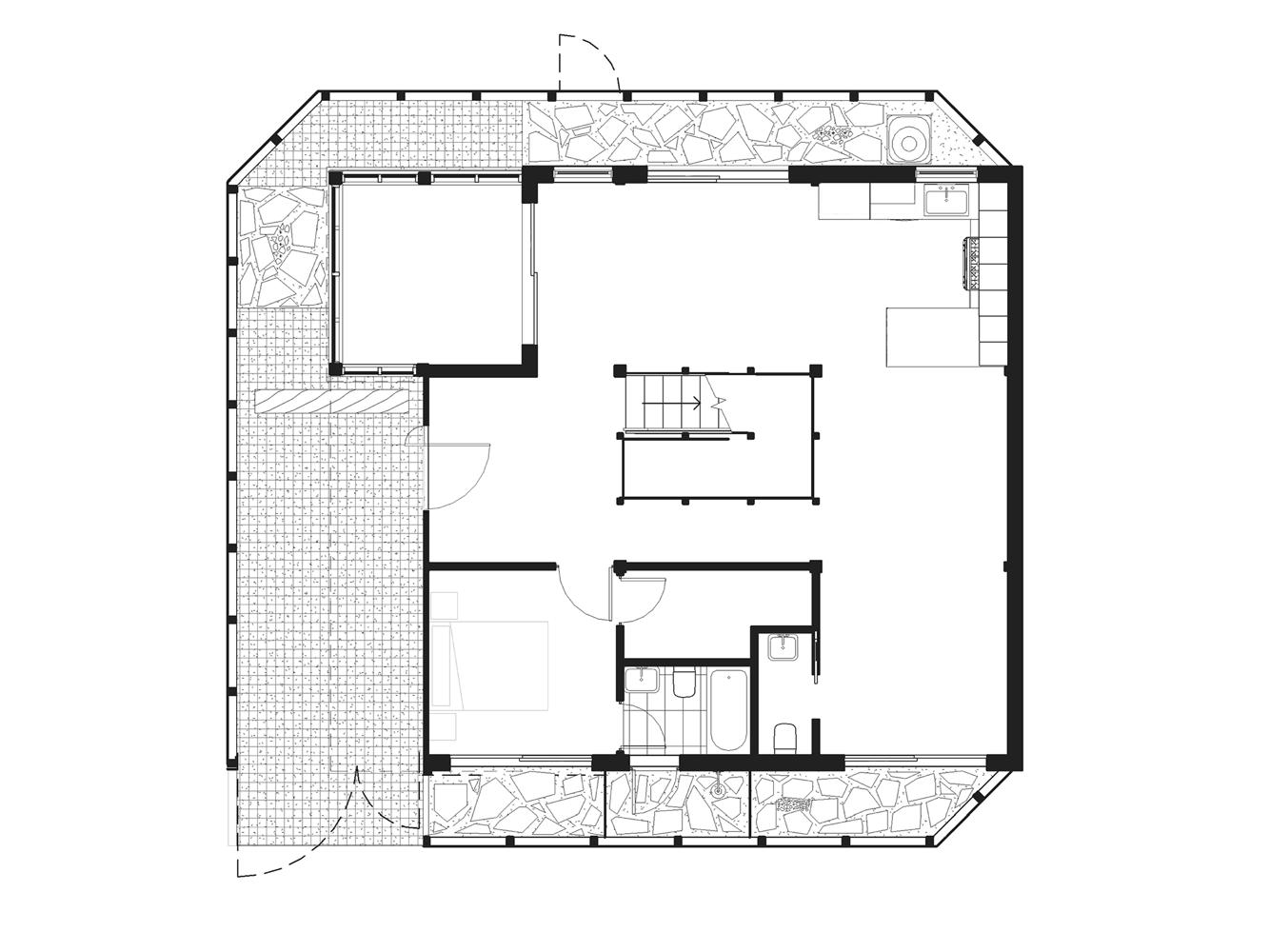

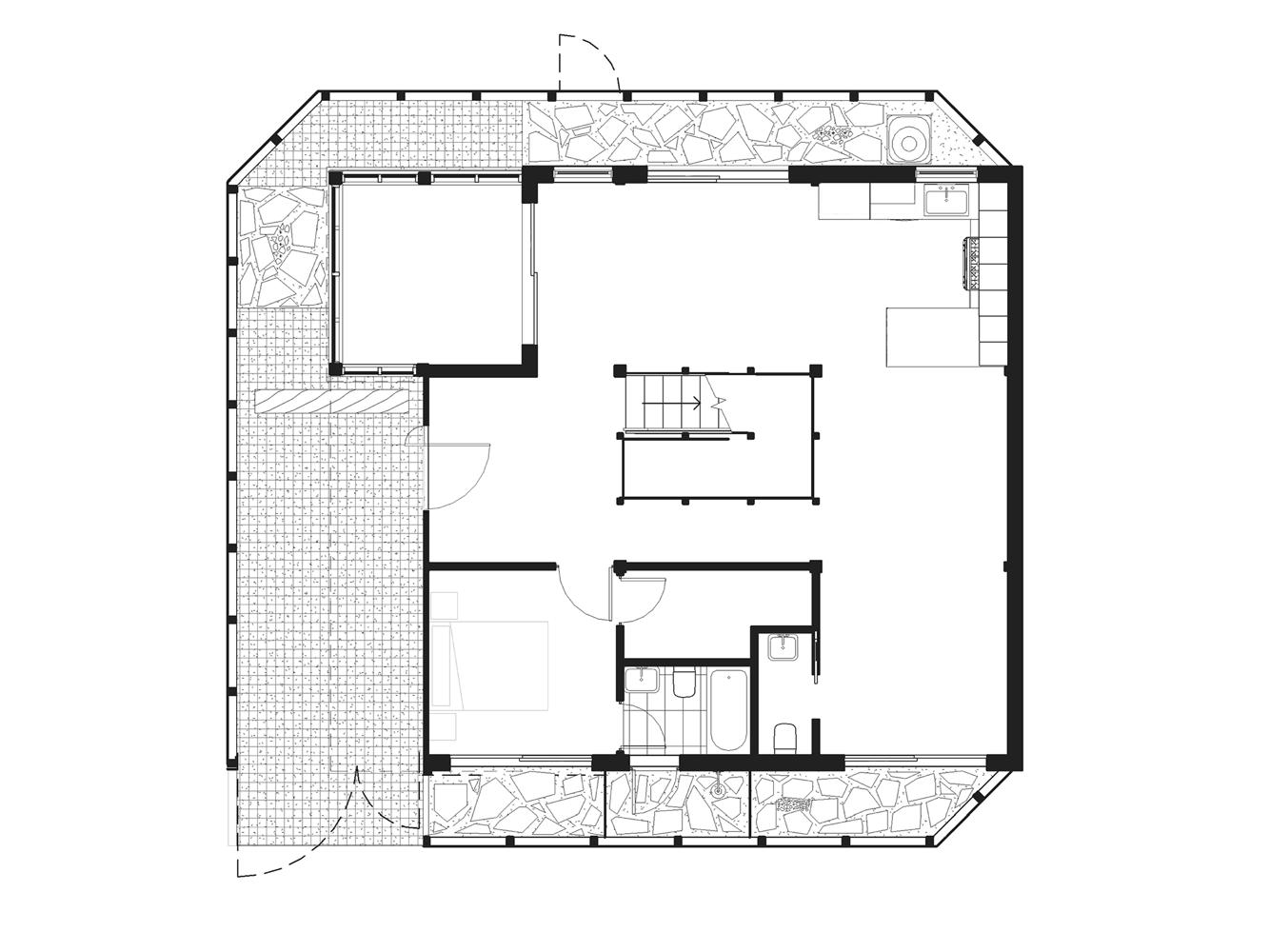

Facing page, top drawing: The second floor of the home in plan.

Facing page, bottom drawing: The ground floor of the home in plan.

The Architect’s Newspaper

TY COLE TY COLE TY COLE

setback on the north and south sides, and an extra 5-foot cantilever on the home’s second floor that creates an entry courtyard. The first floor is organized into three 11-foot bays: An office, dining room, and kitchen occupy the left side, while a foyer, stairwell, and living room take the middle. Bedrooms and bathrooms are to the right. Upstairs, the master bedroom floats above the kitchen and dining room, while guest bedrooms and baths are on the other side.

“The primary goals for this house were maximum privacy plus maximum light, which are counterintuitive,” Linn explained. “But the fences and these small side yards give us the required setbacks on this side. They’re just 5 feet, but that 5 feet gives us a grill and a place for mechanical units, for drainage and planters, and of course for trash and recycling. And we have an outdoor shower on the other side. It’s a very small but highly programmed yard.”

Linn and Becker designed the interior with a restrained hand, using simple materials in an honest way. They chose exposed poplar timber for the main structural supports, poplar plywood wall panels and kitchen cabinets, concrete countertops, and concrete floors. The inspiration behind the generous use of concrete was some collected scrap pavers Linn salvaged from a renovation at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum.

One whimsical but highly practical feature of the interior is the architectural netting installed over the entire living room, which promotes light penetration and provides extra lounging space. “We use the net all the time— for naps, morning cuddles, and afternoon

games of catch. I’ve even slept in it through the night a few times,” Linn said. “The net also illuminates the space more than if there was no net, since it’s white and catches the light.”

Strategically placed awnings over the home’s casement windows create privacy but also allow the family to move throughout the house with no artificial illumination. Skylights over the central stairwell bring in sunlight that’s free from visual noise, looking only to the sky. Additionally, the designers used generic LED strips set within the structural framing, so the house gets ambient illumination through recessed design, rather than unpleasant direct lighting throughout the home.

It turns out that living in a highly insulated, high-performance home is even more beneficial when it’s located in a dense city environment. The design choices literally allow the family to sleep longer, Linn said. “It feels better, the air feels better, it’s quieter, and it allows for living to be a pleasurable experience at every turn.”

September 2023

15 TY COLE TY COLE COURTESY BLDUS TY COLE

Nigel F. Maynard is an architecture and design writer based in the Washington, D.C., metro area. He has edited Custom Builder, PRODUCTS, Residential Architect, and BUILDER.

Back in Session

It’s the start of the 2023 –24 academic year, so that means a new crop of leaders are beginning the semester.

To check in, AN spoke with a set of leading educators about their roles. Each answered a septet of questions; a limited set of their responses appear below.

1. What are your goals and ambitions for your new role?

2. What are the most urgent topics and challenges for architectural education today?

3. How has the COVID-19 pandemic changed your thinking about being a leader in higher education, if it has?

4. What are you optimistic about as you create the future of architecture and architectural education?

2. Decarbonization, decolonization, and equity. Our fields are being challenged to transform radically. A more efficient building is not enough—we need to look at sufficiency principles as we consider our interventions in the built environment. Indigenous knowledge and the imperative for reparations resonates strongly across our fields. Modes of production and representation in architecture, as much as the buildings produced, have often been a medium of colonization and oppression. We need to be thoughtful of and focused on how to insist on other values. This includes training our students to insist on an ethical workplace. It is a whole new world.

4. For decades or longer, there has been heightened discussion about the agency of the architect. Can architects change the world? Our approach is pragmatic (the world is changing already, daily and dramatically). How, where, and when we can be most effectively involved. And how can we train our students and educate ourselves on the practical skills and critical attitudes most appropriate to these new challenges? Our ambition is to lead this process of professional transformation, provide avenues to catalyze change, and work together with partners to build a more equitable world, to put it optimistically.

three lessons that we gleaned from the past several years coinciding with the pandemic. Lesson 1: The pandemic showed us that low-wage workers and their dignity, equitable treatment, and fair pay are all critical to making our economy and our universities work. Lesson 2: The mental health of all our employees and students must be at the core of how we think about human resources and our culture in academia. Lesson 3: The pandemic taught us that the United States has a subpar social safety net whereby excess supply—of hospital beds in the case of the pandemic—is not present because it is not in the business interests of hospitals to finance it. If we extend this neoliberal logic to homelessness, affordable housing, or parks, we find the similar scenarios of either underinvestment or relying on philanthropy to meet the gap of what government and for-profit sectors are willing to provide. Architects must be more proactive in providing services that are at the front end of these policy debates so that we can see a pathway toward implementation.

4. The future is in great hands. Our students today are more diverse, more culturally open, and open to change. That allows educators to broaden and deepen the forms of intellectual engagement that we cocreate. Podcasting, broadcasting ideas via social media, utilizing video and other forms of media to communicate ideas—these offer extraordinary opportunities to use our talents and our training to reach a broader community than just connoisseurs. I find this to be a very exciting time to both reimagine architectural education and to be an architect working as what I have called a “citizen architect” engaged in public and civic actions, activations, and imaginings.

think, how to make, and how to communicate the value and impact of what we do, as well as address the environmental and social complexities of the 21st century. How we educate students in our fast-moving, informationsaturated, expanding fields is an ongoing dance between teaching architecture’s “internalities” (i.e., disciplinary knowledge) and engaging its “externalities” (i.e., issues in our world). Paying attention to activist movements for social justice and equity will continue to inspire us to reexamine what we teach, how we teach it, and by whom.

3. The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us that crises can happen quickly and—despite enormous challenges—catalyze exciting change. We felt the challenges of shifting coursedelivery modes broadly across the university community. Nonetheless, most of us have experienced some positive outcomes from these transitions. I am thrilled to see how faculty have expanded their classrooms to include national and international colleagues, catalyzing new alliances for research and creative work. I look forward to thoughtful discussions about the entangled issues of future teaching and learning modalities that will engage not only educational benefits and pedagogic possibilities but also issues of economics, equity, and politics.

4. Architectural education is a project of hope, and educators have a role to play in combating eco-anxiety by imaginatively engaging with our planet’s sometimes overwhelming issues and by showing and sharing the impact of architecture’s innovations.

Daniel Barber Head of School, School of Architecture Faculty of Design Architecture and Building, University of Technology Sydney

1. At the School of Architecture at the University of Technology Sydney, we have begun to frame three major focus areas of research, teaching, and public discourse: decarbonization and biodiversity, designing with country and valuing Indigenous knowledge, and equity and housing affordability. They are all interconnected. We are approaching openly, asking the question “What else would an architecture school do?”

I recognize that these three issues frame searing, existential questions for our field. Yet in the academy, we have the opportunity to experiment, test, consider, reflect on, and engage with these challenges. This is about a changing social role for architecture and working through the pedagogy, research, and public discussion needed to best contribute to the larger socio-ecological transformation in progress.

I am also focused on how we operate as an institution: insisting on an equitable workplace and transparent decision-making, and developing processes and frameworks that allow for consultation and engagement not only with our faculty but also adjuncts and professional staff. Pursuant to a new union contract, we are working to convert a number of casual positions to full-time roles.

Milton Curry Senior Associate Dean, Cornell University College of Architecture, Art & Planning

1. I will be engaged in expanding the College of Architecture, Art, & Planning’s influence and reach by supporting research, interdisciplinary work across campus, arts-integrated education, and online education platforms. The college, under Dean J. Meejin Yoon’s leadership, is maturing and becoming more connected to the university’s leading initiatives, including Cornell Tech in New York City and the new Department of Design Tech, co-located in Ithaca and New York City.

2. Embracing the political, socioeconomic, and cultural present that we find ourselves in. We must defend the democratic egalitarian space of the university and better understand the repair that is owed to those who have been wronged by failed policies of the past. Architecture, urban design, and planning must be leading the conversation about how to build, sustain, and maintain social order through equitable and diverse city design and urban development. Technology will not solve social, cultural, political problems without a proper humanistic lens. Architecture education provides a simultaneous humanistic and aesthetic/spatial lens from which to cohere new socialities. Architecture education, then, offers itself as a field that seeks to make the world better and more humane.

3. I don’t believe that online education will ever be the dominant delivery system for higher education, though I believe it will become an ever more important component of our pedagogical ecosystem. There are

Julia Czerniak Dean, University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning

1. I see a deanship as a leadership position with a disciplinary project that engages, inspires, supports, and advocates for the school, university, and city. Buffalo has a rich culture of architecture, landscape, and planning that spans centuries, and with such a legacy, I want to build a school of creative, talented, and intelligent people who discuss provocative ideas, do meaningful work, and collectively advance timely and serious projects. Buffalo, as a climate refuge city, is a fantastic environment in which to experiment. I look forward to working with such a multidisciplinary faculty on imagining the possibilities landscape architecture can bring to the existing disciplinary mix of architecture, planning, real estate, and historic preservation in the school.

2. What is so wonderful about a design education is that it moves between knowledge in the STEM disciplines, the humanities, and the arts. However, it is increasingly difficult for faculty to balance teaching students how to

I recently had two opportunities where I gained a better grasp of this aspiration. The first was a recent studio I co-taught as part of the Envision Resilience Challenge, where students learned—despite alarming predictions of sea-level rise—that strategies of retreat allowed them to see that brighter futures were indeed possible, despite overwhelming odds. Another opportunity arrived this June, when I co-taught a field studies course in the Galápagos Islands. The course studied the relationship between biodiversity and design through reimagining simple systems of infrastructure— sea walls, road crossings, shade structures— for multiple species, not just people. Students departed the islands with an entirely new way of seeing not only our discipline but our world, a more-than-human world. What we do is imagine futures. Can you get more optimistic than that?

Michael McClure Dean, Kansas State University College of Architecture, Planning & Design

1. My immediate goals are to get to know the people, programs, and aspirations of the college better so that I can join the team already in place. That understanding of where we are and where we are going is the foundation for meaningful and impactful leadership. To envision a more vibrant future, we must start with a base understanding. My goal is to provide leadership

The Architect’s Newspaper 16

Q&A

Architectural educators in new leadership positions share their thoughts.

DAVID MOJI/PIXOGRAPHY

COURTESY CORNELLA AAP

COURTESY JULIA CZERNIAK

COURTESY KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY

that is collaborative, participatory, and visionary. My ambitions for the college are that we work together to leverage our current success toward an even more vibrant future. I’m ready to fully engage with the university’s Next Generation Land Grant initiative. We will continue to work toward even more vibrant, inclusive, and socially involved design professions.

2. In order to create an architecture curriculum for the 21st century we need to make connections between the studio and the streets, between the academy and the public, and encourage engagement with the world and its problems. We are optimistic and realistic. We are collaborative. We believe in a better future, and we are equipped to bring our visions into reality.

And this is why design professions are uniquely poised to be at the forefront of addressing the most pressing challenges facing society today. At APDesign//K-State we understand that the best work is the result of inclusive, critical, and collaborative design processes that seek to solve problems and provide solutions to the communities we serve. Because we want our professions to be more relevant to society and to offer more robust solutions, we are committed to creating professions that represent the communities we are serving.

3. The COVID-19 pandemic has had an immense impact on society. Its effects on academia will be the subject for research and discussion for generations. In design education, it broke us out of some really bad habits, and as a leader, I am committed to remembering the lessons learned and to use what we have learned to improve design education. We should celebrate our teaching and learning methods, but we need to stop conflating longer hours working with excellence in outcomes. We need to stop confusing “rigor” with unhealthy habits and biased language. Finally, as architects and designers, we need to make sure that we leverage the attention society now has to the physical and built environment. We should not squander the trust given to us as the leaders in shaping that environment.

4. The life of an architect, planner, and designer is a wonderful one. We get to make the world more beautiful, more meaningful, and more useful. Not only do we get to study an extremely wide range of issues, we get to make propositions on how to reframe, reimagine, and improve the world for all its inhabitants. We don’t have to choose between the scientific method and the creative method. Almost always, our job is to consider “‘both,” and in that way, we are inclusive by nature. We have to believe in a better future in order to envision it. It is a privilege to get to engage with society as an architect, planner, and designer. It is a privilege to be able to guide and mentor the next generation of creative leaders.

1. We are just coming out of a month in which multiple heat records were broken. In fact, there are now cities that are becoming uninhabitable without air-conditioning, and the effects of this global climate crisis are being felt by the most vulnerable communities. In my new role, I am looking forward to supporting ongoing research by faculty and students, to look at our past to see practices we can bring back to our fields, and to bring in new and diverse voices to help with these important tasks.

2. Architectural education is being challenged to show its value in a larger moment of uncertainty and change. The moment is pushing education and practice to become even more collaborative as design professionals continue to learn to work with others as well as diverse communities.

3. Being in different administrative and leadership positions during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown me that empathy is an increasingly important tool. We are all responding to this moment by refiguring our priorities, and a leadership that responds empathetically to address the changing needs of multiple constituencies can help.

4. I am very excited to see the energy of students and faculty. Many of the challenges we are facing, as per your previous questions, require this energy and acceptance. Leadership becomes easier when there is a grassroots desire for it, which I feel right now. Together we can tackle labor, environmental, and social justice issues.

knowledge, and re-asserting the importance of live discussions and healthy debate. I am trying to wean the culture of design education away from a consumption-based pedagogy mindset, often encouraged by asynchronous learning. A true design education requires direct participation and engagement with each other; it cannot be passively consumed.

4. So many exciting things are unfolding in real time and show promise for an even greater future in design education. I am most excited about new models of practice, and how education can create space to expand not only what issues design can address but, equally importantly, how we address them. Experiments in methods and modes of practice are creating powerful nonhierarchical forms of collaboration and design tools, as well as exciting new ways for designers to work with communities, nature, and technology.

3. The pandemic was a poignant, historic moment where many lost loved ones, colleagues, and community members. We were held in collective grief and, paradoxically, felt the sharpness of record-pace problemsolving. The motivation to solve problems dissolved many barriers across the university and the greater community. And, in the face of a complex, ever-changing situation, we learned to be inventive, agile, and resilient— the skills we continue to foster in ourselves and our students.

Design and planning fields understand the world is interconnected. (No building stands alone.) We also understand that our success relies on the work and well-being of others. Our charge as educators is to foster that sense of community among students as we face the reality that we are a whole, living, and related system. As neighbors helping neighbors, we experience happiness in supporting others. Likewise, we need to encourage students to consider well-being in balance with an ambitious spirit.

Quilian Riano Dean, Pratt Institute School of Architecture

Mason White Director of Master of Urban Design and Post-Professional programs University of Toronto, Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design

Mason White Director of Master of Urban Design and Post-Professional programs University of Toronto, Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design