AND YOUR OWN. BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

WE INVITE YOU TO

ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA

AND YOUR OWN. BECOME A MEMBER TODAY!

WE INVITE YOU TO

ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY IN AMERICA

WELCOME! We look forward to meeting you!

Benefits of membership

• Connecting with

• The print edition initiatives, arts, ideas,

• Membership in the community founded Switzerland

• Borrowing and research the Society’s national

• Discounts on the and store items

• After two years for Spiritual Science,

Are there requirements Steiner’s work in the Questions? Contact

source development. the and wide Waldorf medicine, therapeutic insight

Name

JOIN ONLINE AT www.anthroposophy.org/membership

Street Address City, State, ZIP

Questions? Contact us at info@anthroposophy.org or 734.662.9355, or visit www.anthroposophy.org

Telephone

Occupation and/or Interests

Date of Birth

The Society relies on the support of members and friends to carry out its work. Membership is not dependent on one’s financial circumstances and contributions are based on a sliding scale. Please choose the level which is right for you. Suggested rates:

❑ $180 per year (or $15 per month) — average contribution

❑ $60 per year (or $5 per month) — covers basic costs

❑ $120 per year (or $10 per month)

❑ $240 per year (or $20 per month)

❑ My check is enclosed ❑ Please charge my: ❑ MC ❑ VISA

Card #

Exp month/year 3-digit code

Signature

Complete and return this form with payment to: Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Ave, Ann Arbor, MI 48104 Or join and pay securely online at anthroposophy.org/membership

MLS# 4397191

Seller will look at offers between $599,000 and $698,876. Historic Town Farm on over 63 private acres surrounded by conservation land. Ideal organic farm 3316 SF residence, barn, dance studio & greenhouse.

92

MLS# 4355361

$1,000,000

On 12.4 private acres abutting conservation land. Exquisitely crafted 6888 SF residence entirely of non-toxic materials & health promoting systems.

12 From the Classified Section of a Newspaper of 2407, by Christian Morgenstern, translated by Christiane Marks

13 A World in Need, editorial by John Beck 14

14

“Imagine the Potential”: reGeneration, by Shepha Schneirsohn Vainstein

17 Lakota Waldorf School Building, by Truus Geraets

by

General Council Members

Torin Finser (General Secretary)

Joan Treadaway (Western Region)

Dennis Dietzel (Central Region, Chair)

Virginia McWilliam (at large)

Carla Beebe Comey (at large, Secretary)

John Michael (at large, Treasurer)

Dwight Ebaugh (at large)

Marian León, Director of Programs

Deb Abrahams-Dematte, Director of Development

Katherine Thivierge, Director of Operations

being human is published four times a year by the Anthroposophical Society in America

1923 Geddes Avenue

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1797

Tel. 734.662.9355 www.anthroposophy.org

Editor: John H. Beck

Associate Editors:

Fred Dennehy, Elaine Upton

Design and layout: John Beck

Please send submissions, questions, and comments to: editor@anthroposophy.org or to the postal address above, for our next issue by 10/10/2015.

©2015 The Anthroposophical Society in America. Responsibility for the content of articles is the authors’.

Our spring issue was distributed to many of the member schools of AWSNA, the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America. A larger number of copies of this issue are being sent both for teachers and for parents. Many parents already get the wonderful Renewal magazine edited by Ronald Koetzsch. What Renewal does for the Waldorf world, being human tries to do for the core impulse of “anthroposophy” and the whole movement around it.

So what is anthroposophy? If you know something about Waldorf education, you can simply say that what Waldorf aims to do for school-age children, anthroposophy is offering to adults. Unlocking our fullest capacities as human beings. Understanding our times so that we can participate fully. Finding our ultimate authenticity and what Rudolf Steiner identified as the one place of real freedom: knowing what we truly love, and acting from that.

In Feb a y 2011 th the 150th anni e sa y of the b th o R do f Ste ne the quarter y pr n pub ca ion o he Anthroposoph ca Soc ety n Amer ca took on he b i g h Thi f f th p phy i d id ldeve opmen and the ur her evo u ion o human culture and soc e y and he co ce o a o us th the hu a fu u e Each ss e nc des fea e a t cles on inita

To stay in touch with being human please go to our web page: anthroposophy.org/bh

Around this luminous core there are initiatives of exploration, understanding, healing, creativity, and new community such as you see inside—the anthroposophical movement. And this movement, and the Anthroposophical Society working at the core of it, is at a threshold. Just one hundred years ago Rudolf Steiner was asked whether such efforts could break through to support a new culture. World history and its own history caused the anthroposophical movement to adopt a cautious stance, and that has become a bit of a habit. But Steiner’s tools are designed for a global, cosmopolitan world, and ninety years after his death much of anthroposophy is still avant-garde. Other great and good ideas have emerged to help, but so far nothing has proven broad and high and penetrating enough to open the doors of a new world culture. Meanwhile, those of us who know it well believe that anthroposophy provides the means to “be the change,” helping each individual to find the place where she or he really wants to take a stand.

Emai s preferred; arge attachments (10MB+) a e usua y rece ved i ho p ob em Add ess posta mai to John Beck Editor Anthroposoph cal Soc ety in America 1923 Geddes Avenue Ann Arbor MI 481041797 We w cons der engthy subm ss ons for alternat ve presen at on here on anthroposophy org n the A t cles sect on We try to respond to a subm ssions etters eedback and nqu r es promp ly but fee free to check back you do no hear rom us n a reasonab e amount o me

To stay in touch you can subscribe—just visit anthroposophy.org/bh; to explore membership in the Society visit anthroposophy.org/join (being human is part of your membership). Enjoy what you find here, and feel free to share your thoughts to editor@anthroposophy.org or to the address below.

John BeckCopies of being human are free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/join or call 734.662.9355). Sample copies are also sent to friends who contact us at the address below.

To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104.

In this issue we present three reviews (on pages 46 to 54). John Beck makes a survey of some of the books newly available from the Owen Barfield Literary Estate, whose editor in chief is Jane Hipolito. For those not familiar with him, Owen Barfield was arguably the most brilliant and engaging of all English speaking anthroposophists. The Literary Estate is publishing for the first time three works of Owen Barfield’s fiction, and reissuing the 1962 masterpiece, Worlds Apart. Worlds Apart is presented in the form of a conversation -- a drama of ideas – engaging the “watertight” disciplines of space science, physics, evolutionary biology, positivist philosophy, psychology, theology, language and, yes, anthroposophy.

Had Worlds Apart been written today one of its conversational protagonists might well have been a fictionalized version of Thomas Nagel, the author of a highly controversial refutation of contemporary materialist reductionism, (for which Nagel has been accused by a number of materialist thinkers of intellectual treason), entitled Mind & Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False. Frederic Amrine, in his review of the book, examines Nagel’s presentation of several crucial issues—life, consciousness, human reason, the lawfulness of the universe and moral values—as to which reductionism can only stammer at an explanation.

Mr. Amrine proceeds to scrutinize critically the scientific consensus against Nagel’s “emperor’s new clothes” assessment of neo-Darwinian reductionism. He then proposes his own view, distinct from Nagel’s, that the failure of reductionism as an explanatory principle does not so much call for an alternative form of causality as a new and more radical paradigm that embraces indeterminacy and complexity. He suggests that the fundamentals of such a paradigm already exist in the works of Rudolf Steiner.

Finally, I have reviewed Massimo Scaligero’s A Treatise on Living Thinking: A Path Beyond Western Philosophy, Beyond Yoga, Beyond Zen. Scaligero was an original (and highly demanding) anthroposophical writer and teacher of the practice of living thinking that may be realized in the authentic practice of contemplation and meditation. Scaligero had a powerful influence on the writings of Georg Kühlewind, who, in addition to communicating his own original understandings, transformed Scaligero’s insights into clear and accessible language.

I have also examined in this review a problem sometimes encountered with anthroposophical writers of the last century, i.e., how to reconcile the brilliance of what they say with the questionable record of how they have acted.

This digest offers brief notes, news, and ideas from holistic and humancentered initiatives. E-mail suggestions to editor@anthroposophy.org or write to “Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104.”

[www.anthroposophy.org/articles] Research of the life and times of Marion Mahony Griffin, including her understanding of her own and Walter’s contributions to the world, is continuing in Canberra with Laura Summerfield (+61-417 609 946, laura.summerfield@gmail.com) and Trevor Lee (+61 2 6291 3391, tlee@tpg.com.au). They are bringing insights to this from their own backgrounds in anthroposophy, biography work, architecture and psychology.

Australia’s most famous anthroposophist honored in her native Chicago

On 9 May 2015, Marion Mahony Griffin was honored by the naming of a park in the Chicago suburb where she lived for the last stage of her life. With her husband Walter Burley Griffin, Marion was co-designer of Australia’s national capital, Canberra, after a worldwide competition in 1912. Even before then, Marion had achieved prominence by graduating in Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1884 and becoming the first female licensed architect in the state of Illinois and among the first so qualified anywhere in the world.

Read the full report with links to her legacy online

Camphill Ghent is an anthroposophically inspired community for elders in rural upstate New York, near the quaint village of Chatham and close to an extensive cultural life. The community itself hosts an outstanding chamber music series, and a new on-site addition is an office of the Karl König Institute for Art, Science, and Social Life. A physician and founder of the Camphill movement, Dr. König was one of the most important anthroposophical thinkers and doers of the generation active after Rudolf Steiner’s death. The institute’s original office in Aberdeen, Scotland, began the work of maintaining an archive. Seven years ago the first volume of the New Edition of Karl König’s Works was published; recent and forthcoming volumes are Social Farming—Healing Humanity and the Earth and Nutrition from Earth and Cosmos.

“Karl König showed directions and ways towards the renewal of medicine, educational theory, curative education, psychology, inspired from anthroposophical life and research. This applies as well for many areas of practical life.” The international website is at www.karl-koenig-archive.net and contact in the USA is Richard Steel, Camphill Ghent, 2542 Route 66, Chatham, NY, 12037 (r.steel@karl-koenig-archive.net), or telephone (518)-721-8410.

In March the leadership and boards of the Alliance for Public Waldorf Education and the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America announced that “together we are forging a new relationship based on our common foundation and perspective on what is best for children. Today a license for the Alliance use of the term Public Waldorf was signed, as was a Memorandum of Understanding that affirms and articulates some of the many ways the two organizations and our respective members can collaborate. The license empowers the Alliance to use the mark ‘Public Waldorf SM’ with acknowledgement that it is a service mark owned by the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America and used pursuant to a license.” The agreement is posted on the Alliance website (www.allianceforpublicwaldorfeducation.org ).

The letter concludes, “Waldorf educators, whether they work in independent or in public schools, hold Rudolf Steiner’s goal for education to be eloquently expressed in this quote: ‘Our highest endeavor must be to develop free human beings who are able of themselves to impart purpose

A monthly international magazine for the advancement of Spiritual Science

Symptomatic Essentials in politics, culture and economy

Ask for free sample issues, also to help us reach out to others who might be interested and/or subscribenow.

Order form

❐ Single issue:

CHF 14.- / $ 15.- (excl. shipping)

❐ Trial subscription (3 issues): CHF 40.- / $ 43.- (excl. shipping)

❐ Annual subscription with air mail / overseas:

CHF 200.- / $ 214.- (incl. shipping)

❐ Free Sample Copy

Please indicate if Gift Subscription – with Gift Card.

The above prices are indicative only and subject to the current exchange rates for the Swiss Frank (CHF). For any special requests, arrangements or donations please contact Admin Office.

Name:

Delivery Address:

Tel./E-mail:

Invoice to (in case of Gift Subscription):

www.isisbiodynamic.com

Date:

Signature:

E-mail: PASubscription@perseus.ch

Phone number: +41 (0) 79 343 74 31

Address: Drosselstrasse 50, CH-4059 Basel

Skype: ThePresentAge

Website: www.Perseus.ch

and meaning to their lives.’ In all of Waldorf education lives the hope of providing new ideas for cultural and educational renewal in our communities. It is with tremendous excitement and hope that we look towards a future of working collaboratively in service to the children of North America.” The website for AWSNA is located at whywaldorfworks.org.

From June 22 through July 8, in Concord, Massachusetts, the Village University was convened. The name is inspired by a hope of Henry David Thoreau: “...That is the uncommon school we want. Instead of noblemen, let us have noble villages of men” and women.

The theme for the first week was: The Genius of Our Land in all her aspects, facets—which the conversations and gathering lived up to in many ways. The second week was devoted to the theme: Translating Transcendentalism into a Language for Our Time.

A detailed account of these remarkable gatherings is posted online (anthroposophy.org/articles), and you can find out more about the impulse at www.concordium.us. The moving spirit of this vision is Stuart-Sinclair Weeks, Founder, Center for American Studies, Concord, MA 01742 (stuartbweeks@gmail.com).

Theology was once a primary field of the studies now known as the humanities, but as localized in seminaries and committed to existing dogmas it is now a specialist field. Rudolf Steiner was a well-respected public intellectual in 1900, but when he began to speak dramatically about matters associated with theology, many turned away.

Steiner developed techniques to research consciousness and said he did that as his first step, looking at existing sacred texts and such only after finding his own way. To be understood, he then communicated his findings in known terms and concepts. Eventually he identified the archangel Michael as a primary inspirer of his work. Independent researcher Bill Trusiewicz has contributed a number of fine papers, under the title above, which are too long for being human to print. To four already posted we are adding a fifth now at anthroposophy.org/articles. It is wide-ranging and handsomely illustrated.

Recent issues have shared general and specific ideas and practices involved in anthroposophic medicine, and this issue includes the statement from the physicians’ association on vaccination (see page 29). Also in this issue is William Bento’s article about anthroposophic psychology (page 23). We recently asked Anthroposophic Nurse Specialist Elizabeth Sustick (esustick@gmail.com) for a thumbnail description of the nursing side. She replied:

“Anthroposophic Nursing (AN) is an expression of holistic care-giving, encompassing the physical and spiritual nature of the human being. Rudolf Steiner, PhD and Ita Wegman, MD collaborated in clinics in Arlesheim, Switzerland in the early 1900’s to develop a natural approach to medicine that would offer healing to the whole human being, body, soul and spirit. The nurses in their treatments work closely with the element of warmth as a bridge between the physical and spiritual being of their patients. This is of key importance in supporting and nurturing the patients’ own life-giving healing forces. AN practice includes external applications of therapeutic substances through teas, footbaths, compresses, embrocations (Einreibung ) and hydrotherapy. Nurses interested in AN have the opportunity to expand and deepen their nursing impulse in the art of healing and their own inner development through continuing education offered by NAANA. NAANA is affiliated with the International Forum for Anthroposophic Nursing (IFAN) at the Medical Section of the School for Spiritual Science, Goetheanum, Dornach, Switzerland.”

Online visit www.aamta.org/organizations/nurses/.

BD, Organic, Conventional soil compared ELIANT, European Alliance of Initiatives for Applied Anthroposophy (eliant.eu/en/news), coordinates the work by Steiner-inspired initiatives with complex regulatory structures, research, and information. A recent report, “Climate, Soil, and Effects of Herbicides,” notes that “the long-term trial comparing biodynamic (D), organic (O) and conventional (K) growing systems prove scientifically that organic and biodynamic agriculture produce soils with a significantly higher level of organic matter and humus than those of conventional agriculture.”

Beyond soil fertility, climate change make this important because “throughout the world the number of heavy rainstorms is increasing. Water that cannot be absorbed by the soil runs off as surface water... Agricultural land and villages are flooded and the damage and costs of reparation are huge.” All soil combines mineral content with organic matter, and it is “the organic matter in the form of humus and microbial biomass [which] can absorb and hold water.” Sterilizing the soil by use of herbicides and pesticides diminishes biomass.

December 20th 2015 - January 3rd 2016

Come with us, visit the sacred places of this ancient civilization and its Mysteries!

We will visit many of the famous and not-so-famous sites: The Sphinx and the Pyramids of Giza

The tombs of the Valley of the Kings

The great Temples of Luxor, Karnak, Dendera, and more

Visit the anthroposophically-inspired community of Sekem

Cruise the Nile in a traditional dahibiya sailboat

With informal talks and eurythmy

Please have no fear to visit Egypt at this historic moment!

For details, please contact Gillian:

610 469 0864

gillianschoemaker@gmail.com

WORKSHOPS TALKS STUDY GROUPS

CLASSES FESTIVALS EVENTS EXHIBITS

HEALING PLANTS (MONTHLY LECTURE)

Wed’s 7pm: David T. Anderson, 9/16, 10/14, 11/18, 12/16

STEINER & KINDRED SPIRITS

Robert McDermott, Thurs Sep 17, 7pm

ART OPENING: “NEW WORK”

by David Taulbee Anderson, Sat Sep 19, 2–4pm

TECHNOLOGY IN EVOLUTION

talk by Andrew Linnell, Thurs, Sept 24, 7pm

MICHAELMAS FESTIVAL & POT-LUCK

Sunday, Sept 27, 4pm to 7pm

EURYTHMY (MONTHLY WORKSHOP)

Mondays 7pm, Linda Larson: 9/28, 10/19, 11/16, 12/14

ROBERT FROST

Andy Leaf, Open Saturday, Oct 10, 2pm

WHAT MOVES THE BLOOD

Fri, Oct 16, 7pm: Branko Furst, MD, new research on the heart’s role in life & health

CYMATICS

Wed Nov 11, 7pm, the art, science, & therapy of sound’s visible effects; Jeff Volk, Gabriel Keleman

Plus Weekly & Monthly Study Groups

Programs and resources in visual arts eurythmy

music drama & poetry Waldorf education

self-development spirituality esoteric research evolution of consciousness health & therapies

Biodynamic farming social action economics

Open Mon-Thurs 1-5pm, Fri-Sat 11am-8pm, Sun 11am-5pm; call for latest: 212-242-8945

“The most impressive holistic legacy of the 20th century...”

— NY Open Center co-founder Ralph White on Rudolf Steiner

The New York Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in America – 138 West 15th Street New York, NY – (212) 242-8945 www.

spiritual,

world & ‘outsider’ art

August 5 !! Artificial Snowstorm in Thale (Harz Mountains) produced by Hotel Alpenrose utilizing the great Paper Scrap Snow Centrifuge owned by the American Nature Drama Imitation Company Brotherson and Sann.

American Agent seeks stuffed Noblemen. Paying top prices.

Resuming Tomorrow on a Daily Basis: Transformation of water into wine. Oysters, caviar, champagne, finest fruits for everyone, by a simple method!

Egon Schwarzfuss, Hypnotist (Across from the Ministry of Agriculture)

We invite the Society for Ant Games to gather tomorrow, the 17th , on Tempelhof Field to finish the great heap.

offers ant costumes in brown and black, all sizes, manufactured strictly to the specifications of the S for A (“Society for Ant Games”).

Aphid costumes in all sizes also available, complete with accessories.

announces that simulated burglaries are now officially allowed by the police. As always, subscribers enjoy considerable benefits. Subscribe for a whole year, and you receive one attempted murder free, in addition to the three burglaries. For further details, see our catalogues and prospectuses.

English Church, made of rubber; easy assembly, with its own carrying case. 1550 Marks.

Upcoming Event: Launching of the first German Aerial Newspaper!

Six tethered balloons anchor the screen, which measures 800 square meters. It will be installed on Kreuzberg every evening after dark, projecting the latest news in letters visible at a great distance.

There are specially-made binoculars available to subscribers, in addition to tickets for seating in the attics and on the chimneys of our headquarters and its branches. We call to your attention that only subscribers have access to the special events we are planning, the first of which will be the full-size projection of every subscriber born on a Sunday.

An official reward of 3,000 Marks is offered for the capture of the balloon pirate who took the tiles off of the roof of the Köpenick Courthouse on the night of Monday to Tuesday.

Signed: A. Bilz, Aerial Police Officer

The Executive Council of the Society for Technical Issues, Division of Transportation, invites the public to the September 12 continuation of the discussion on the subject of laying tracks on water.

is the best mouthwash! In addition to its cleansing power, it is highly nutritious! Its use replaces breakfast or supper! Testimonial: Very dear Sir: I have been using your Nutridentol regularly for two months now and during this period I have saved 4 kilos of butter. My headaches have totally disappeared, as well. My greatest thanks to you! Eleonora Hecht

For the Lonely: Memory-evoking fragrances, made up to your exact specifications by The Marketplace of Little Things to Make You Happy. Address telegrams to: Happiness House.

Diversion Apparatus: containing music, images, liqueurs, fireworks, brochures, lottery tickets, etc.

Tomorrow, Sunday: Grammophone-lecture by Professor Houston Shaw of the University of New Heidelberg, Massachusetts. Authentic proof that Henrik Ibsen, to whom the well-known dramas have been ascribed, is identical with Peer Hansen, former lecturer at the University of Christiania.

Seeking a Violinist –an excellent one – to play for my lizard.

Adele Süsskind , c/oThose who do not purchase an artificial head are simply fools. Your artificial head is put on over your natural head and offers the following advantages: a) Protection from rain, wind, sun, dust – in short, all negative outer influences which irritate the natural head no end and prevent it from carrying out its intended function – that of thinking. b) Sharpening of the natural senses: With your artificial ears you hear about 100 times better than with your natural ones; with your eye apparatus you see as with binoculars; with you A.H. you smell more keenly and taste more discerningly than with their predecessors. And yet you do not need to make use of any of this; you can adjust the head in whatever way you wish; so you can switch it onto “dead,” too. The A.H. makes possible a completely undisturbed inner life. Closed rooms, monks’ cells, vernal solitude, etc. have now become unnecessary. You may isolate yourself even when surrounded by the densest of crowds. The A. H. is tailored to you personally and is lightweight for comfortable wear. It includes a battery which prevents the unauthorized from touching it. Since it needs no hair, the skull area can be used for advertising. If you are smart and open-minded, you can easily recoup the cost of the A.H. by renting advertising space there to a business you find congenial. You can actually make money via your A.H. more easily than by means of your natural head.

Translator’s Note: Christian Morgenstern was born in Munich on May 6, 1871 and died in Merano, Austria, on March 31, 1914, of the tuberculosis which overshadowed his entire adult life yet never hindered his work or touched his optimism and love of all of humanity. These relatively early futuristic ads are usually included with his Galgenlieder (Gallows Songs), which were first published in 1905. They are not as well-known, but considerably more translatable than the exquisite humorous poems, which rely so heavily on rhyme, meter, puns, etc. The ads are funny, of course, but also foreshadow every technical device available today to seduce us into worlds of virtual reality, sensation and horror, and distraction generally. Their only inaccuracy lies in underestimating the speed at which technology has moved!

In the preface to the 1962 edition of Morgenstern’s letters ( Alles um des Menschen Willen) his life-long close friend, Friedrich Kayssler, reminds us that Morgenstern’s “humorous” and “serious” poems have always formed a unit. Morgenstern called humor “a certain hard-to-define quality that can probably only be found where life is at the same time regarded with an unshakably earnest eye, as with the heart-felt love of a child.”

— Christiane MarksI have rarely written editorials in seven years as editor of being human. I do so now for three reasons. First, despite tremendous power and material wealth, humanity is not in good shape. Second, anthroposophy and other holistic, spiritual, and globally-aware impulses have proven that they can engage the deficiencies of the modern world and bring forth better approaches. Third, the Anthroposophical Society in America has arrived at a place of decision in regard to acknowledging the far-reaching cultural intentions of anthroposophy—intentions which speak clearly to open minds and hearts.

Human circumstances today, globally, include many shortages and problems. Our media thrive on threats; do they ever give accounts of the immense assets and resources which are available to us? How much work and value is being created today by machines? How much free activity is supported by energy resources we have learned to harness? How much is humanity empowered by an ever-growing access to the world of ideas? With all this abundance mere survival should not be in question (though for so many it still is). So there are historically unprecedented resources available for culture. Properly used, culture liberates, empowers, inspires, heals, helps us grow wise. Many millions of individuals use their free cultural time well, but we endure saturation advertising for empty entertainments—things that have been clearly identified as sleep-inducing social drugs.

As Thomas Meyer wrote recently in The Present Age, Rudolf Steiner’s saw a basic shift in humanity’s relationship with mind and spirit (Geist) as the deeper cause of the First World War and the turmoil that followed. In 1899, a five-millennium process of darkening of human consciousness ended. Like a cosmic dawning, new streams of consciousness started pouring in. Locked into materialistic culture and its principle of enforcement, few people could engage this new light consciously; instead, it fueled conflict. Many more people are now seeing reality in this new light and acting in accord with the spiritual

principle of empowerment. With necessary trials and errors, these actions have had profoundly positive results, including the ambitious and penetrating initiatives out of anthroposophy. And these alternatives are being noticed.

If you have a light, you don’t hide it, you place it high to light the whole room. That ancient wisdom is the challenge anthroposophy is now facing. Rudolf Steiner gave us centuries’ worth of insights, questions, and projects. We need to keep renewing ourselves by engaging this gift, yet we must also try to make it available. Every human being today is making choices which will determine our individual futures—and humanity’s. Materialism toughens and hardens us; anthroposophy lights up interiors, builds capacities for healing, reawakens community.

For historical reasons, the Anthroposophical Society has been cautious in presenting its case to the world. German language and culture, highly appreciated in 1910, has been overshadowed by English. Special responsibility rests now on the Anthroposophical Society in America.

I find it a kind of signal from “behind the veil” that as the ASA has moved to shoulder these responsibilities we meet the financial challenges engendered by our past isolation. The ASA, a national organization concerned with all human needs, has a membership and budget suitable to a regional animal welfare league. We have overcome our traditions to start communicating more openly and to undertake stronger relationship building— the type of things that initiatives on the following pages like reGeneration and Heartbeet Lifesharing do so very well. And we are willing at last to say and to undertake “A Campaign for Anthroposophy in America.”

For decades I have been inspired by the astonishing ideas of anthroposophy and by its caring, creative, committed people. I can express that now in a few clear words: “anthroposophy is being more consciously human, becoming more fully human, and acting more humanely in all of life.” And I also know that this campaign will succeed as we begin to reach out with authenticity to each other, to others in our movement to create a worthy culture, and to all others who are trying to wake up into a better world.

Waldorf parent Shepha Schneirsohn Vainstein liked her school so much that she started organizing people to use Waldorf to create a better world.

People on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota think Waldorf can help sustain their whole culture.

In Vermont, Heartbeet Lifesharing has so many wise ways of making community that they now need a proper space for it.

The Avalon Initiative just organized an important gathering to work on rediscovering the fundamental inspiration of teaching.

The soul or psyche is the center of anthroposophy’s picture of the human being. The late William Bento has helped get anthroposophic psychology established in North America.

Every role an actor takes on is an initiative, and Maria in Steiner’s mystery dramas is a very special challenge.

What do anthroposophical doctors think about vaccination? Read their statement on page 29.

life, learning,

Waldorf alumna and teacher Karen Gierlach recently shared with Members of the Section for the Social Sciences a report from Shepha Schneirsohn Vainstein, president of reGeneration, on a Waldorf teacher training event in Palestine. We pass it along, prefaced by reGeneration’s vision statement, goals, and key activities, including its work in development of “social capital.” — Editor Vision. Children of all faiths growing up in the Middle East have a basic right to experience a wholesome environment that cultivates the empathic foundation, the motivational drive, and the personal and social resources to be able to create a sustainably peaceful, productive, and prosperous society as adults.

Goals. Contributing to the field of social change and equal access to education, reGeneration seeks:

• To back grassroots, interfaith and multicultural education with social technologies that fosters cooperation between Jews and Arab in Israel.

• To bring educational achievement among Arab citizens of Israel and Palestinians of the West Bank on par with Jewish Israelis through increasing access to high caliber education for all children; and,

• To cultivate a diverse cadre of interfaith supporters who use their financial and human capital to promote our mission.

Objectives:

• Support Ein Bustan, a joint Jewish-Arab Waldorf school in Israel

• Build the capacity of Tamrat El Zeitoun, the first Arab Waldorf School

• Introduce and facilitate the development of Waldorf education in Palestinian schools in the West Bank Strategy

• Organize Waldorf education workshops and training for Arab Waldorf teachers

• Support programs in California that focus on overcoming preconceptions and building bridges based on our common humanity.

Background and Strategic Context. On five continents there are over 1,000 Waldorf educational institutions, community epicenters fostering wholesome environments in the classroom and in the home. This growing global educational community is creating a ripple effect promoting UNESCO’s values of equality and tolerance, transforming families and ultimately society worldwide. In the Middle East, outside of an initiative in Egypt, there are no Waldorf schools in the Arab world.

“Seeding the Middle East with an educational philosophy that embraces

the arts, the earth and all the children.”In Israel the number of schools using Waldorf reGeneration Vice-President Noor-Malika Chishti ritually pours water over the hands of Shepha Schneirsohn Vainstein at the concluding ritual of Celebration of Abraham where the organization’s interfaith work and support of educational projects for Jewish, Christian and Muslim children in the MIddle East was honored at the Celebration of Abraham in Davis, California, in January. We each washed the other’s hands and the breaking of a loaf of bread together symbolized of respect and connection. Tamrat El Zeitoun—an Arab interfaith Waldorf school educating children from kindergarten through fifth grade in northern Israel.

educational techniques has steadily increased in the Jewish community since 1989 when the first school started with 13 children. Today there are more than 4,000 Jewish children in 16 Waldorf schools in every major city in Israel. Additionally, in Israel there are over 100 kindergartens using these methods and three Waldorf high schools opened in the 2009/2010 year. The annual student growth rate is over 10% per year.

Consistently each year approximately 60% or more graduates from the Waldorf high school in Israel sign up to perform an extra year of volunteer community service to work with Jewish and Arab individuals who are homeless, drug addicted, or orphaned—in comparison with 2% of Jewish high school graduates overall. Waldorf school graduates in Israel testify that the values they received in school had a major influence on their decision to do volunteer service benefitting the community.

reGeneration’s initial phase included conflict resolution training for faculty and teens in Israel, support for our Palestinian Teacher Training, and support for a high school peace leadership program in the Galilee. The high school program was a two-pronged educational model promoting Jewish and Arab coexistent participation in Israeli society while addressing the high drop-out rate and low performance for matriculation of Israeli-Arab high school students from a public high school. Though the high school program in itself was successful, we made two critical observations. One was that we saw that the educational gap between Jewish and Arab high school students was too large to try to effectively remediate at such a late stage of development.

From this observation we decided it was far more productive to support an equal education for both Jewish and Arab students from the earliest years. We also observed how important it was for the Jewish and Arab communities to share a common goal in which they could work together to achieve.

Because of the unprecedented growth of Waldorf education in the Jewish community and the nascent development of this humanistic education within the Arab community, reGeneration decided that the most effective intervention for equal opportunities in education in Israel was to support two pilot education programs, Ein Bustan, the first Arab/Waldorf kindergarten in Israel and El Zeitoun, the first Arab Waldorf School in Israel. Both

of these programs, along with our Palestinian Teacher Training have a high potential for positively impacting society in the Middle East. Today we support an education in the Middle East that builds resiliency in Christian, Jewish, and Muslim children while promoting new capacities for this generation to shape a stable and sustainable future for all.

reGeneration is a member of Alliance for Middle East Peace (ALLMEP), a coalition of over sixty organizations, and the United Religions Initiative (URI), a coalition of grassroots interfaith organizations from over seventy countries around the globe. The two schools it co-sponsors in Israel, Ein Bustan and El Zeitoun, are affiliated with the Inter Agency Task Force on Israeli Arab Issues.

Last November a concert, “Together in the City of Angels,” launched the newly established Southern California Muslim-Jewish Forum. reGeneration worked with sixteen Jewish and Muslim organizations to establish the Forum as an umbrella body to strengthen MuslimJewish ties in the Greater Los Angeles area. Everything from the event committee to the performances are examples of Muslims and Jewish working together. Members of the forum are the Academy of Jewish Religion California; Bayan Claremont Islamic Graduate School; Beth Shir Shalom; Claremont Lincoln University; IKAR; Islamic Center of Southern California; King Fahad Mosque; Malibu Jewish Center and Synagogue; MECA Young Professionals; Muslim Public Affairs Council; New Ground; Pacifica Institute; reGeneration; Sufi Order International; Temple Emanuel of Beverly Hills; Valley Beth Shalom; and the Wilshire Boulevard Temple.

Letter from Shepha Schneirsohn Vainstein

Palestinian educators in Jenin in the West Bank are enthusiastically talking about their wonderful ten days at the recent West Bank Waldorf Institute [WBWI] held at Al Quds University’s Open Campus in Jenin from February 15 to February 25, where we were able to produce a West Bank version of the Public School Institute held at Rudolf Steiner College for the past twenty-three years.

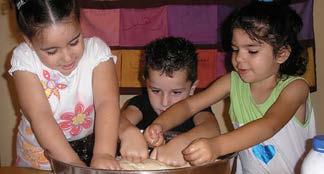

One hundred twenty eager Palestinian kindergar-

ten and grade school teachers came from throughout Jenin to be part of this immersive workshop. The WBWI was a window into how to provide an engaging and healing education for Palestinian children growing up under the chronic stress of conflict. The Palestinian educational community welcomed learning methods on how to educate children in a manner that promotes creative thinking while cultivating a culture of safety, peace, and respect in their classrooms.

The teachers learned about recent research showing powerful advantages that high quality early childhood education bestows, whose major benefits can emerge much later in the adult lives of their students. Palestinian kindergarten teachers began to learn how to create these environments for young children while grade school teachers learned how to give engaging lessons using the arts, movement, and singing games developing a multiplicity of skills.

In an overflowing room of 180 people, the program was emceed by WBWI’s Coordinator, Dr. Rola Jadallah, who recently had been inducted into the Women in Science Hall of Fame of the United States Embassy in Amman, Jordan. The opening ceremony included comments from the Governate of Jenin, Jenin’s Director of Education, the President of Al Quds University in Jenin, psychologist and Director of WBWI Dr. Wael Mustafa Abu Hassan, myself, and Rudolf Steiner College Chair of Early Childhood Education, Lauren Hickman.

With initial attendance way beyond the expected number, it turned out that word had spread throughout the Al Quds student body that a great class was being held on the top floor of their university so the first few days we had a huge number of unregistered drop-ins until we tightened our check-in procedures with our administrative assistants. Even then we had forty kindergarten teachers and eighty grade school teachers in attendance. It was very touching

It was deeply gratifying to see how we were connecting the Palestinian educational community to a global Waldorf educational community embracing all children, regardless of religion, race or nationality.

to be told how much people enjoyed the WBWI faculty who taught with great patience and such open hearts. Thankfully, filmmakers captured on video the first two days and the final three days of these historic moments. This footage will eventually become part of a documentary on Waldorf education in the Middle East, scheduled for release in 2017.

One of the highlights of the WBWI was to see how the Palestinian teachers cherished Aida Awad, the founding kindergarten teacher from Tamrat El Zeitoun, the Arab Waldorf school in Israel. The Palestinian teachers knew Aida had studied in Hebrew at a Jewish Waldorf Teacher Training in Israel and that she had transposed what she had learned into Arabic and the Palestinian culture. They appreciated her warm welcoming demeanor and were amazed by her ability to captivate children in such a magical and tranquil way. Also greatly appreciated by the Palestinian teachers were classes taught by Lauren Hickman of Rudolf Steiner College and nationallyrecognized Waldorf consultant Anna Rainville, who has taught at Rudolf Steiner College’s Public School Institute for the past twenty-three years. Waldorf alumna Karen Gierlach provided classes on adult development based on the reflection of each individual teacher’s own unique biography. Group singing was provided by Julia Anna Katarina, an English Waldorf graduate, musician, and opera singer who is fluent in Arabic. In addition, reGeneration’s Middle East Liaison and Way of Council trainer, Itaf Awad, worked with seventeen Palestinian school counselors giving them an experience of how the Way of Council can teach their students deep listening skills and build a sense of community. The work with Itaf was so valued by the school counselors that Itaf has made plans to continue to come from Israel to Jenin to work with them once a month. Before giving my own lectures on the developing brain of the young child, I met with Itaf’s group of Palestin-

ian school counselors who informed me that televisions are ubiquitous in preschools and kindergartens throughout Palestine. I there- fore included a talk on how the American Academy of Pediatricians has recommended absolutely no screen time for children under two and how recent research in brain development validates the holistic Waldorf approach to educating young children in a manner that physically helps the brain grow more primed for creative thinking and executive functioning. We all made a strong case for keeping television out of the kindergarten and Aida Awad highlighted the daily rhythm in her classroom as a model of how the Waldorf kindergarten’s calm and consistent routine serves as an important foundation, a healing environment for children growing up in stressful conditions.

It was deeply gratifying to see how we were connecting the Palestinian educational community to a global Waldorf educational community embracing all children, regardless of religion, race, or nationality. For further highlights please see West Bank Institute of Waldorf Inspired Education on Facebook [www.facebook.com/WBIWIE].

“What is next?” Although we are waiting for the results of our pre- and post-surveys, it already has become apparent that the Palestinian teachers hunger for more exposure to Waldorf methods for their students. Training to become a Waldorf teacher requires a significant time commitment and deep inner work to learn how to embody the Waldorf approach. We developed a Committee for Palestinian Waldorf Inspired Education to field applications from Palestinian kindergarten teachers who want Waldorf early childhood education training. We are in the midst of refining criteria for the selection of these teachers and soon will be developing the program and its accompanying budget.

It was extremely moving to see the faces of these Palestinian teachers glow in joy from what they were learning, knowing that these experiences were creating an educational foundation from which their own students will benefit. Something truly magnificent happened in the West Bank! If we are persistent, it can only bring something good and productive to the troubled Middle East.

Shepha Schneirsohn Vainstein co-founded re:Generation [regenerationeducation.org]. She received her Masters of Counseling Psychology from Pacifica Graduate Institute and is a psychotherapist practicing in Los Angeles specializing in trauma recovery and personal empowerment. She is a facilitator of Nonviolent Communication and the Way of Council. A long time Waldorf parent and advocate, she continues to volunteer at her local public Waldorf-Method school, the Mariposa School of Global Education in Agoura Hills.

It has been a miracle that some 150 people responded to send a message of support to the Lakota Waldorf School [www.lakotawaldorfschool.org ] and a check of $10,000 earmarked for building. We understand that building a new class room is now urgent, as a big recruiting drive will bring in many new enrollments, and because the school has now two buses to pick up children from further afield.

Our check, we hope, will stimulate bigger building grants from other sources. The administration is currently talking with a log cabin builder from the Black Hills, to make a proposal of building a tipi classroom out of wood. Another piece of good news is that an experienced Waldorf teacher by the name of Barbara Booth has committed herself for a year to be the mentor for the teachers.

Administrator Isabel Stadnick’s own children, who grew up on the Reservation, are now both studying Waldorf education at the Goetheanum in Switzerland. The older one is presenting just now [April 2015] her thesis about the future of the Lakota Waldorf School, where high school students could learn trades in workshops and sell their goods in retail outlets. Also, how to make the Lakota Waldorf School an interesting destination for tourists. All this with the aim to make the Lakota Waldorf School ultimately self-sustaining.

Because it may take a few years to work towards the realization of this fantastic plan, let us continue to show them our support in keeping the ball rolling, the ball, which has already been pushed by so many people. We can’t thank you enough for that.

Truus Geraets (truus.geraets@gmail.com) is a eurythmist and social activist working through The Center for the Art of Living.

Heartbeet Lifesharing is the newest Camphill community in North America. I became aware of Heartbeet at the Anthroposophical Society’s fall conference in 2009 when Hannah Schwartz shared its story of community outreach and engagement.

Hannah grew up in Camphill, and just out of college she and her husband Jonathan Gilbert bought a farmhouse in Hardwick, in Vermont’s “Northeast Kingdom,” a beautiful region of small New England towns. Fifteen years later Heartbeet Lifesharing is a local institution and widely known for inspiring, youth-oriented conferences. After houses and a barn, it is now building a community and cultural center, “the heart of Heartbeet.” “It will be a venue for gatherings, concerts, festivals, plays, conferences, and many special events—a multi-purpose theater, seating 175 people, will be the core of the building.”

Out of $2.2 million there is just under $300,000 to raise. Hannah hopes that will be in place by year’s end so that the building can be finished by March. The fundraising “is beautiful work as it is all relationship building around something truly meaningful.”

The following is drawn from newsletters, pamphlets, and the Heartbeet website (www.heartbeet.org). Several pictures are from a fine video by Corey Hendrickson. — Editor

The Camphill impulse is multi-dimensional. An early mission statement described Heartbeet Lifesharing in part as “an initiative that recognizes the importance of interweaving the social and agricultural realms for the healing and renewing of our society and the earth. We fully acknowledge and live out of the understanding that every human being is unique and unrepeatable. In light of this insight, our mission is to offer both a vacation and respite program and a permanent residential program for developmentally disabled individuals that focus not on a person’s disability but rather on his or her capacities.”

Today, Heartbeet is a vibrant lifesharing Camphill community that includes adults with developmental dis-

abilities. Working from a philosophy of social therapy, Heartbeet has become recognized as an innovative model of care for individuals with special needs. It is a fully licensed Therapeutic Community Residence.

“In Camphill you approach who you meet in a very different way. We’re not care-givers, we’re caring for each other. So really we’re recognizing each human being as having a destiny to fulfill.”

— Heartbeet co-founder Jonathan GilbertFive extended-family homes form a supportive environment that enables individuals to discover and develop their unique abilities and potential. Heartbeet provides work and artistic opportunities, which help adults with special needs participate in the community in a meaningful way. This means:

• healthy and fulfilling adult relationships

• building practical and artistic skills

• meaningful vocational experiences

• integral membership of a caring community

• love of lifelong learning

• openness for new experiences

• social and self-awareness

• mutual trust and respect.

Independence & success flourish. It is a place where differences fade and diversity is celebrated!

Because of Heartbeet, the hopes that we had for Max at his birth—of a happy and productive life surrounded by loving family—have been restored.

Rachel Schwartz (now Rachel Knauf) was prime mover in ten years of twice-yearly Heartbeet Youth Conferences. Themes included “The Whole Human Being in Relation to Karma” and “Learning the Signs of Destiny through Thinking and Artistic Experience.” Three conferences explored, four at a time, the experience of the twelve sense identified by Rudolf Steiner: lower senses of touch, life, movement, and balance; middle senses of smell, taste, sight, and warmth; and the upper senses, hearing, word, idea, and perceiving the “I” of the other.

Conference #20 was “Know Yourself and Change the World”: finding the courage to begin (Joan of Arc for inspiration), making connections between inner work and social justice and transformation, karma and reincarnation, the new clairvoyance, and more. The coordinating role passed to Annie Volmer with the next conference, “Encountering Thresholds: The Courage to be Vulnerable.” Annie wrote, “Heartbeet remains committed to the destiny of these very special events. We are working hard to fill Rachel’s shoes!”

In fall 2014 a new direction came: an International Camphill Youth Conference. As Haleh Wilson reported to being human , “Nearly eighty attendees came together to frame important questions about prevailing dynamics between the generations of Camphill. After four days, such questions had been identified, parsed, and refined, and participants had struck new friendships of the kind that serve increasingly to knit Camphill together as an international community.”

This year the Second International Camphill Youth Conference offers “An Anthroposophical Initiative: At the Altar of the Present Moment—An Exploration of Selfless Collaboration.” It welcomes those, young and old, who will to carry the spiritual impulse of Camphill into the future. The organizers write:

Since parting from the last conference, members of the planning committee have been mindful of the deep suffering of humanity on a world scale as well as in our communities, our relationships, and our selves.

We’ve been led to ask what it might mean to become a selfless collaborator in our time—to learn to gently ask the healing questions for our brothers and sisters in pain, and to cultivate vulnerable spaces wherein we give of our listening and our compassion. The last conference brought us down a path much like Parzival’s, where we came, each in our own way, to recognize our individual failures and the failures of our communities and of modern humanity. What happens when that self-knowledge is given over to the healing forces of the Christ who spoke, “Where two or more are gathered in my name, there shall I be”? How do we take up this sacred responsibility for the altar of the present moment which exists between human beings? Have we advanced far enough in our inner striving that we can offer our own suffering at this altar, that it may be transformed through Community into the courage to meet others in the present moment, and to hold—as conscious, selfless deed—their suffering as our own?

Can [the Parzival] story encourage our own intergenerational collaboration? We have a sacred responsibility for one another. This thought will be at the heart of our explorations together.

“To strangers I think it will be interesting for them to learn what Heartbeet is about. It’s up to them if they want to come and support, it’s up to them, it’s their own calling if they’re ready. Being supportive means to bring of your utmost self, and I think that’s important.”

— Annie Jackson, residentWe see so much promise in Max’s future now. His life at Heartbeet is a dream come true.

— Amy Gleicher, parentA view of Vermont’s “Northeast Kingdom” [photo: Patmac13, CC 3.0, Wikipedia]

Six years ago Per Eisenman wrote, “Our temporary conference community…has been coming together faithfully for nine years. The Heartbeet Lifesharing community hosts us and grows around us, like a time-lapse movie of a growing flower. Every six months there is a new development, a new home, new barn, new coworkers.” But this unfolding was interrupted in January, 2013: “Heartbeet Lifesharing’s new home, Sophia House, nearing the end of construction, was destroyed as a result of a chimney fire. We are deeply thankful that no one was hurt! Our hearts are heavy, but we are slowly getting off our knees. Although this is a tremendous setback, we are working hard to continue embracing the vision and enthusiasm that has filled the air at Heartbeet over the last year.”

Out of the ashes of Sophia House came the impulse to build a community center. Reporting from last fall’s meeting Haleh Wilson wrote, “On September 20, 2014, 101 years since the laying of the Foundation Stone of the First Goetheanum, a Heartbeet ceremony incorporated conference participants in a poignant visual reminder of Camphill’s basis in anthroposophy and the legacy of Rosicrucianism. A vast cross [of ashes] was laid on the site where Heartbeet will soon commence construction on its Community Center. Participants joined Heartbeet community members to form a circle around the site while seven bunches of red roses were laid in the circuit that appears on the Rose Cross, a symbol that urges us toward renewal. ... Certainly in the moment of that September 20th ceremony, the Rose Cross image seemed to speak to the events of today’s Camphill movement, a call for renewal in the face of forces seeking to change us: the cross on the Earth, the wide circle around it, people joining hands, voices lifted in song.”

Joan Allen, who just passed away and designed many

if not all the Camphill Halls in the USA, planted a further seed in conversation with Hannah Schwartz. “The idea was to have something that pre-dates the materialistic nature of our times, or came before its full onset, built into this inevitably modern building. I was coming home at high speed from a long trip when through the trees the colors called me to turn around.” On display in an antique store was an 1830s stainglass window from a church in New Haven, Connecticut. “The window itself is mostly a deep blues and reds with golds, Tiffany-style with motifs of a swan and the lamb as well as a special cross between the two big panels.”

There are many powerful things happening in Hardwick but the one I am most excited about is Heartbeet. The sheer humanity that is practiced there every day is an antidote to what is wrong with the world at large.

— Mateo Kehler, Co-Owner of Jasper Hill Farm and a new board member of Heartbeet

The new community hall will be a powerful, integrating space, in service to Heartbeet, the “Northeast Kingdom,” the international Camphill community, and the anthroposophical movement. The benefits, including cultural, educational, economic, and environmental one, have been carefully planned out.

For Heartbeet itself the Community Center answers the need for more space. “Our growing community is squeezed to capacity. With five lifesharing homes, we can no longer comfortably meet under one roof or welcome the local community to the extent that we would like. The ability to gather together is essential to building community life, and keeps everyone connected through shared experiences.”

Heartbeet has a limited number of designated building sites, so the Community Center is multi-faceted, with a multi-purpose theater, seating 175 people, as the core of the building. It also houses therapy rooms, a community library, a bakery and processing kitchen, and ad-

Hannah Schwartz writes, “In January we thought we were finished planning, but we needed to go back to the drawing board to keep the building within budget. Now, with the help of our tireless advising team, we are excited to say that we love the final building plans, and feel that we have just what we need and not an inch more.

“The building will soon start its material manifestation! We hope to break ground in late summer, though the exact date will depend on permitting. Imagine with us the festivals, plays, group meals, life celebrations, music and art that will fill this space! It will bring relationships, joy, inclusion and understanding that will resonate within Heartbeet and far beyond.

ministrative offices. Paper-making, weaving and felting workshops can expand into the old administrative spaces. Massage therapy, fitness classes, art exhibits, quiet study space, and computer access are available on site! Baking and food processing for the entire community take place in the Community Center kitchen, providing a training workshop for Friends with special needs.

The most important thing that Heartbeet brings to our area is a broader perspective on diversity. I love watching friendships develop, discomfort melt away, as Heartbeeters integrate into the community, spreading their own brand of love and joy. Every town needs a Heartbeet.

— Pete Johnson, owner of Pete’s Greens

— Pete Johnson, owner of Pete’s Greens

From its beginning Heartbeet has participated in the annual town dinner, and for the last four years family and friends have gathered at a local church to celebrate a Passover Seder.

“In the new center there will be space to host regular community meals together, and expand our ability to connect and host other Camphill communities and anthroposophical events. There will be an inclusive, noncompetitive environment for a broad range of quality arts events, including plays, concerts, dance performances, contradances, readings, and lectures. It expands opportunities for collaboration with local artistic, cultural, and educational groups.”

“We are all living and breathing with anticipation of the community center. This building will be the bridge to allow the gifts and treasures cultivated within our community to reach the surrounding extended community and will make collaboration possible with the many already interested parties that have approached us. Once construction has started we will begin formalizing plans for upcoming activities, and I hope that within the next year you will come and see some of these dreams and initiatives underway in this amazing new space! To date we still need the last $300,000 to get us across the finish line. A profound and humble thank you to all who have brought us this far!”

Hannah Schwartz (hannah@heartbeet.org) is Executive Director of Heartbeet Lifesharing, on the internet at www.heartbeet.org and

On Saturday, April 25, at the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, New York, a few more than 60 people from different arenas of education gathered together to discuss how to recapture the imagination of teaching as a vocation, student assessment as something other than a test, and education as an art, not a technical delivery system.

The Avalon Initiative [edrenewal.org ], a research project of The Research Institute for Waldorf Education [waldorfresearchinstitute.org ] in collaboration with the Hawthorne Valley Association’s Center for Social Research [thecenterforsocialresearch.org ] sponsored and formed the day’s work. We accidentally met hot on the heels of the recent round of Common Core testing in New York and the successful “Opt Out: Refuse the Test” effort. Up to 200,000 families opted out and kept their children home or requested that their children stay at school in study halls on the testing days. This number is up from 60,000 in the last round and is a statistically significant slice of the 1.1 million school-age children in New York.

Public, charter, independent schools, homeschoolers, and Waldorf school teachers and administrators were involved all day in lively presentations and discussions of vital imaginations for the future of education and cultural renewal in education.

A panel comprising Katie Zahedi, PhD, assistant professor at SUNY New Paltz and former principal at the Red Hook Middle School, Heinz-Dieter Meyer, PhD, Associate professor at SUNY Albany, and Carol Bärtges, doctoral candidate and teacher of comparative literature at the New York City Rudolf Steiner School, launched the day with vibrant ideas about a new approach to teaching, learning, and accountability in America. Gary Lamb acted as primary convener and moderator for the day with Patrice Maynard acting as facilitator.

Katie spoke of the success of the Opt-Out

movement, which she helped to energize and foster in New York State; and of the sacred relationship between teacher and student, unmeasurable with technology-driven testing. Heinz-Dieter Meyer spoke, as he has all over the world, and with particular clarity in India and in his classes in the United States, of his vision of the administration of education in which teachers play a pivotal role in determining appropriate assessments and accountability measures with politics and economic interests uninvolved. Carol Bärtges spoke of her years of experience in the classroom and how she assesses students using her own intuitive capacities and expertise in her Waldorf school. Carol also spoke of research being published by Academica Press, Assessment for Learning in a Waldorf School , chronicling the means of assessment used in Waldorf schools without a single, standardized test (available from www.waldorfpublications.org ).

One highlight of the day’s activities was the presentations by four eighth and ninth grade students who read their poetry about their experiences taking the language arts state tests. Poised and clear, these young people gave a chilling description of what the tests do to children during the test-taking hours. One of the members of the support team from Omega cried when she heard them rehearsing. She has been a teacher herself and appreciated deeply the eloquent expression of despair, anxiety, boredom, and wishes these students captured in their poetry.

We all left with new understanding of how the artificial barriers of “public and private,” “us and them,” “Republicans and Democrats,” are distractions from the high vocational calling of “teacher” that we, who teach or support teachers, all share. The day was remarkable and important for the future of education in America.

Patrice Maynard (patrice@waldorf-research.org) is Director of Publications and Development at the Research Institute Education.In recent years, William Bento worked with distinguished colleagues to establish a professional presence and training in North America for a psychology imbued with the insights of anthroposophy. The article that follows is one of his last; he passed on from a stroke on June 5th. — Editor

I will attempt to give an abbreviated view of the context out of which Rudolf Steiner brought forward his ideas in the Berlin lecture series of 1909, 1910 and 1911, now published and entitled, A Psychology of Body, Soul and Spirit. Its former title was Anthroposophy (wisdom of the body), Psychosophy (wisdom of the soul), and Pneumatosophy (wisdom of the spirit). If one lives with the idea that Steiner was taking every opportunity to address the origin, nature and destiny of humanity, many developmental aspects of his talks fall into place.

If one lives with the idea that Steiner was always taking every opportunity to address the origin, nature and destiny of humanity, many developmental aspects of his talks fall into place.

His view on cosmology was both anthropocentric and Christ centered. He wished to reveal the esoteric beginnings of humanity from the standpoint of the cosmos. Each time he told the cosmological story layers of insight were added to his book, Esoteric Science: An Outline. The telling of the story compelled the listener to enter into picture building, imagining what cannot be seen by the sensible eye. In fact, it prompted one’s “I” to develop an organ of supersensible cognition. We can simply refer to it as imaginative cognition. I need not elaborate on how Steiner refuted the “Big Bang Theory.” Rather than to speak of abstract forces Steiner brought the living being-ness of the Cosmos by introducing the many beings of the Spiritual Hierarchies who served the Godhead. Hence the origin of the human being does not begin in some primal soup, but within the imaginative powers of the Godhead wherein all manner

of beings cooperated in a unity and for a divine purpose. Civilizations of our forefathers always told the stories of their relationship with the Cosmos, honored the many spiritual beings that participated in the human creation, and conducted rituals and ceremonies to invoke their continued participation in human evolution.

In this particular series of lectures Steiner addresses the nature of the Human Being, as he can be understood from the standpoint of the senses and from the phenomenological view of the soul. There is very little borrowing of ancient ideas about the soul nor is there much reference to modern concepts and formulations of the anatomy of the soul. Steiner attempts to bring a descriptive narrative of soul processes in which we are involved all the time. It is presented in a form that accentuates our own experiences and places them in a cohesive developmental context. And as such it bypasses the thorny dilemmas of theoretical and philosophical debates about the human soul. In today’s world there is a great deal of confusion, skepticism, and delusions about the nature of the human soul. The term “psyche” used by Freud had the meaning of soul . This term meant something much larger than the narrow meaning it has today. Soul meant a dimension that was both sacred and at the core of one’s character. Unfortunately, soul as used by Freud was translated into English as merely being mind . Although mind was in vogue in the Western world at the turn of the 20th century, it left out the greater dimension of the soul and its relationship with the cosmos. The whole birth of psychology suffers from a loss of a genuine understanding of soul. It has as a consequence been fraught with an intellectual convention of materialism. Fundamentally the soul has been abstracted from the spirit and driven deeper into the mechanisms of the body. In an approach to Anthroposophic Psychology realignment between body, soul, and spirit is sought for. This search is not for a new set of concepts to illuminate the realities of soul life, but to reinstate the heart of psychology. To state it succinctly, psychology offers us a path of knowing what lives as soul warmth and soul light when we take interest in each other’s lives. Psychology must not be relegated to an individual affair. It is a collective responsibility to create healthy conscious community that connects us to each other, to the endowment of the resources of the Earth, and to the wonders of the Cosmos. Emphasis on the “I” as the spiritual executor of the

soul is given a high premium in an anthroposophic paradigm. The “I” becomes the bearer of one’s destiny. It navigates through the karmic conditions set up by previous lives and contributes to the future course of humanity. But most important of all is its responsibility for imparting meaning to our individual development. In the realm of psychotherapy the “I” is the great transformer of our soul life. There the spirit must be found and be engaged with at the most profound level. Soul wisdom must be united with love for the spirit. When this attitude is fully embraced psychotherapy no longer becomes an intervention to alleviate pain and suffering, it becomes a means to bear and transform pain and suffering into wisdom and love. The path of Anthroposophic Psychotherapy and Counseling becomes a path of initiation, a path of self-education in the fullest sense of the word educare, to draw out one’s sense of destiny.

In The Riddle of Humanity (1916) Rudolf Steiner offers a schema that connected the twelve senses and seven life processes to the zodiac and the planets respectively. In the last 99 years there have been research and therapeutic practices within the anthroposophical movement that have given these correlations validity. And we can take heart that this work has been done. As we stand one year from the centennial of the lectures of The Riddle of Humanity we may take hope that a more thorough approach to applying this schema to the human soul may take place. Not in a prescriptive manner, but as a map to navigate the ever evolving terrain of the soul.

Ancient wisdom practices always had the cosmos in mind when any attempt at restoring health or intervening in a healing process was undertaken. But today, in world that has ignored the cosmos and relegated it to mere superstition and myth, we must rediscover the reality of living within the cosmos. Not only as we can determine it as the vast celestial space that enfolds us but as the dynamic realm of living forces that permeates the interior space within us. In the Psychosophy Seminars that took place from 2001 to 2004, preceded by five years of annual conferences exploring the mental health paradigm from an anthroposophical viewpoint, a group of us attempted to facilitate an experiential and cognitive learning of the innate relationship between cosmology and psychology.

The two individuals who were primarily responsible

for crafting the Psychosophy Seminars curriculum went on to obtain higher accredited degrees and licensure in the field of psychology. James Dyson, MD, went through training in one of the foremost schools of Psychosynthesis in London and graduated with a Master’s degree, and I attended the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology and graduated with a PhD in clinical psychology, procuring a license to practice in 2006. From the culmination of the Psychosophy Seminars to the present we have continued to collaborate on researching ways in which an Anthroposophic Psychology could fructify the mainstream psychologies, and particularly the transpersonal approaches to psychology that have acknowledged the spiritual nature of the human being. Although another cycle of Psychosophy Seminars could not take place there were a number of gatherings under the title of the Psychosophy Circle, wherein alumni met to support each other’s continued studies and research. Each meeting was followed by public workshops. Dr. Roberta Nelson, who attended and facilitated groups in the Psychosophy Seminars, joined Dr. Dyson and myself in copresenting content. These events would not have been nearly as successful were it not for the insightful guidance of our eurythmists, Karen Derreamuax and Gillian Schoemaker, also graduates of the Psychosophy Seminars. As time went on a most remarkable event occurred at a Medical Section conference in September 2012 in Dornach, Switzerland. A report on this conference can be found in full text at APANA [apana-services.org ]. The conference addressed anthroposophical approaches in psychiatry, psychotherapy, and psychosomatics. During this time a group of psychotherapists met under the guidance of Ad and Henrietta Dekkers from Holland. At the conclusion of these meetings the International Federation of Anthroposophic Psychotherapy Associations was founded. I was fortunate to be in attendance and a founding member of IFAPA. It was not long after this event that I recognized the time for an accredited and/or certified training in Anthroposophic Psychology had come, a dream held by Dyson, Nelson, and myself. As destiny would have it a core group of individuals rallied around the emerging task and agreed to make the ideal a reality. as two other anthroposophically inspired psychologists committed to form the Anthroposophic Psychologists Association of North America with

Psychology must not be relegated to an individual affair. It is a collective responsibility to create healthy conscious community that connects us to each other, to the endowment of the resources of the Earth, and to the wonders of the Cosmos.

us. These two individuals are on the core faculty of APANA: Dr. David Tresemer, one of my most significant collaborators in the research and development of New Star Wisdom, and Dr. Edmund Knighton, a fellow graduate of the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology and a talented psychologist in the field of teaching psychosomatics. I hope having shared context to the emerging relationships involved in the APANA initiative, the reader may gain a sense for the guiding ideals in this endeavor.

In the word itself cosmology reveals its study. It etymologically means the logical order of the origin and development of the Cosmos. Embedded in the meaning of the word cosmology is the sense of a teleological significance to the purpose of existence. Is there a higher study than this? With the loss of a consensus cosmology in Western civilization we have fallen into an abyss of abstractions. The Big Bang Theory is a perfect example of this. The theory itself suggests we are all here by chance without any higher purpose. Such a view coupled with the vast array of stars in our known galaxy can give rise to a feeling that the human being is an insignificant creature. It also lends itself to the argument that there is no moral world order to abide by. In this perspective any assertion that there is a moral world order is viewed as mere speculation or a myth at best. The very idea that for millennia men and women have believed and prayed to a God, whether known and unknown, has been dismissed as an aberration instead of being seriously considered that the need for a God is a central factor in man’s search for meaning.

There is an existential terror in living with the notion that the culmination of one’s life is nothing more than a pile of ashes. Although most people do not give much thought to this popular belief, it nevertheless impacts a majority of people even though it is below the surface of consciousness. It is astounding that so few professionals in the field of mental health ever give much attention to a client’s world outlook and how it shapes their soul’s disposition. In America we are so mesmerized by a culture of amusement and distraction that little time is spent in serious reflection on the values and purposefulness of our