personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century

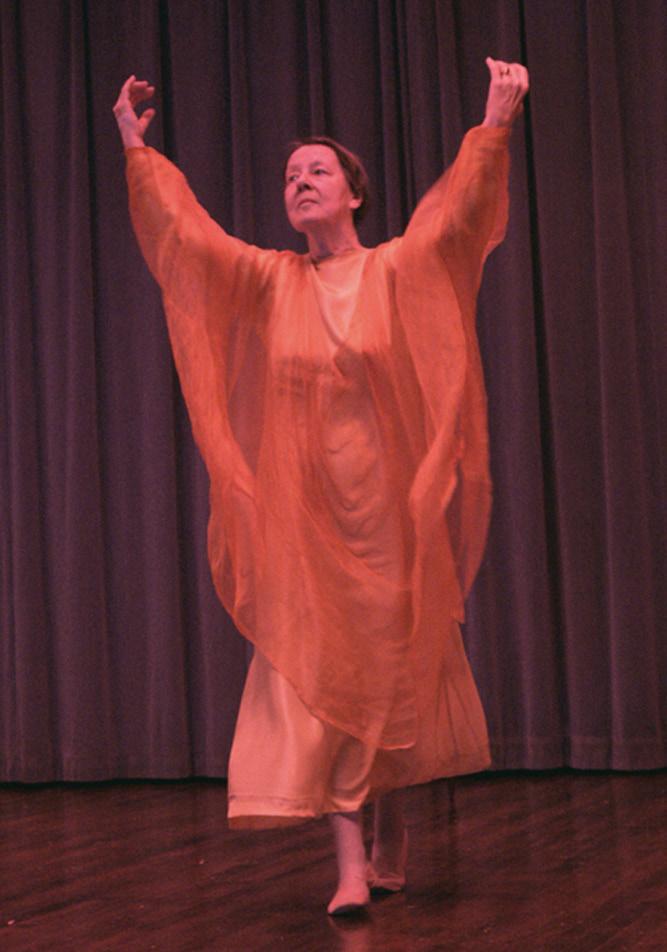

“Strong Angel” by Laura Summer

Aesthetic Thinking of the Heart

The Sin of Literalism

Preparing the August Conference: “That Good May Become”

personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century

“Strong Angel” by Laura Summer

The Sin of Literalism

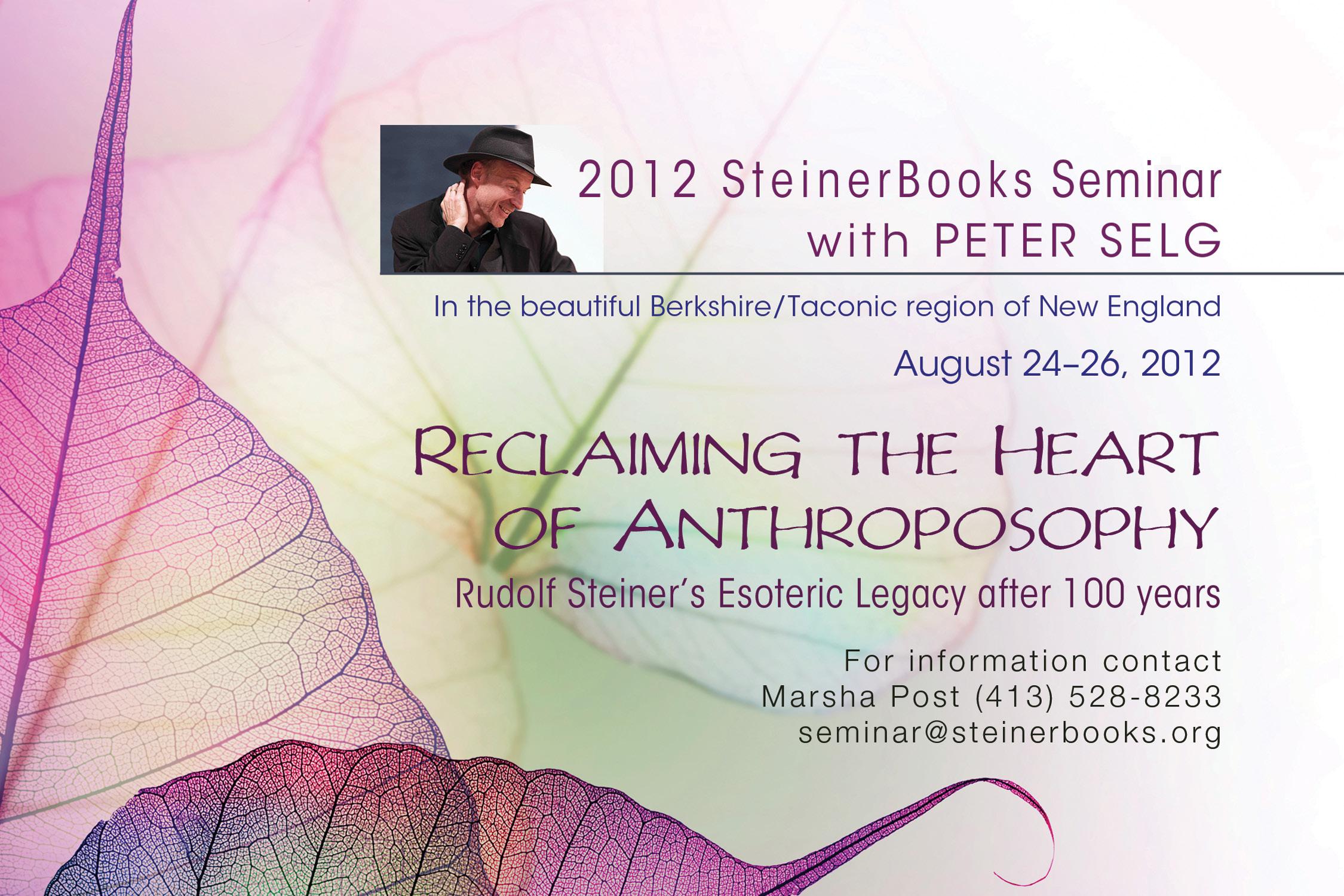

Preparing the August Conference: “That Good May Become”

Color & Music through the Circle of the Year Three courses with Manfred Bleffert

June 16-22 Instrument Building

The breathing process of the earth and of the cosmos as a musical base for the development of new instruments and musical form.

June 25-29 New Music Improvisation

July 2-6 Color & Tone in Relation to Rudolf Steiner’s Soul Calendar

Manfred Bleffert has dedicated his life to developing new music. His work includes a unique approach to graphic notation, composition and instrument building. His research is broad and profound. His compositions are improvisational and unique. He is a musician, a visual artist, and a dynamic and inspiring teacher.

July 14-18 Five Days of Experimental

Work with Color, Light, Music & Puppetry with Laura Summer, Nathaniel Williams, Faye Shapiro & Marisa Michelson

July 23-27 Seeing the Word through Painting A workshop with Laura Summer

Working with poems & stories, watercolor, pastel, charcoal, and collage, we will relax our expectations, playfully manipulate our media, and experience the realm of creation to develop skills for further work.

July 23-27 Orientation Toward an Inner Voice Vocal experimentation with composed and improvised music with Marisa Michelson & Faye Shapiro

ALL COURSES WILL BE HELD in Columbia County, NY, two hours north of New York City. The work of Free Columbia is based on an understanding of the importance of creating a free cultural space. There are no set tuitions, rather we offer suggested donation amounts based on what it costs to run courses. It is also possible to make a monthly pledge to support Free Columbia rather than making a one-time donation. In addition to the suggested donation, a commodity fee of $180 will be charged to participants in the instrument building workshop. This fee enables you to take home the instrument you build.

Five-day course suggested donation: $250 – $450

Instrument building fee: $180 All supplies are included but not housing or food. For information: Laura Summer at 518-672-7302

laurasummer@taconic.net www.freecolumbia.org

the New York Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in America

138 West 15th Street, NY, NY 10011 (212) 242-8945

“It’s a funny thing that the man with the most impressive holistic legacy of the 20th century remains almost unknown in holistic circles as a spiritual teacher.“

– Ralph White on Rudolf Steiner, in the New York Open Center blog

Anthroposophy NYC closes July 1st to September 7th. Visit asnyc.org for regional summer events and our fall schedule posted August 15th.

spirituality, health, education, social action, esoteric research, human and cosmic evolution

self-development, biography, therapies, rhythms & cycles, threefolding, economics

exhibits, workshops, talks, museum walks

Rudolf Steiner’s therapeutic art of sacred movement

music, theater, festivals, community celebrations

free, weekly and monthly, exploring transformative insights of Rudolf Steiner, Georg Kühlewind, Owen Barfield and others

Browse dozens of works by Steiner and many others on education, science, health, art, spirit, biodynamics. Open Tues-Wed & Fri-Sat, 1-5pm.

Serve the future by teaching the children of today through Waldorf Education. Become a Waldorf Teacher by completing a Part-Time Program in Waldorf Early Childhood or Elementary Teacher Education at Sunbridge Institute.

Now Accepting Applications for Teacher Education Programs Enrolling Summer 2012

Now Accepting Registration for Summer Series 2012

Courses in Professional Development and Continuing Education

Details at www.Sunbridge.edu

We are a Rudolf Steiner inspired residential community for and with adults with developmental challenges. Living in four extended-family households, forty people, some more challenged than others, share their lives, work and recreation within a context of care.

Daily contact with nature and the arts, meaningful and productive work in our homes, gardens and craft studios, and the many cultural and recreational activities provided, create a rich and full life.

In collaboration with the University of the West of England we are delighted to announce the first Masters of Science in Practical Skills Therapeutic Education ©

Commencing 28 th August 2012, the MSc programme will delivered by the Crossfields Institute Hiram Education and Research Department. It will be based in the Field Centre a new bespoke campus for practical and academic education and research, Gloucestershire, UK (www.thefieldcentre.org.uk)

"The Field Centre represents an essential innovation in interdisciplinary, spiritually based research, teaching, and learning. By intention and design, it seeks to weave together an ethical relationship to the Earth with a deeply therapeutic education and an exploration of human consciousness as loc us for true freedom and ethical action grounded in love.

Self knowledge, stewardship of the Earth and care for each other will, at the Field Centre, become the three strands that, when braided together renew higher and further education."

Professor Arthur Zajonc, Amherst University Patron of the Field Centre.

This Masters of Science programme is designed for professionals in anthroposophic health and social care, curative and therapeutic education, arts, crafts and commerce. It offers specialism in the method of Practical Skills Therapeutic Education.

The programme offers 70% experiential, work based learning in 8 different locations across England and Wales. Individual modular and work based pathways and subject specialisation are available for professionals who wish to develop their practice in their workplace.

Aims and rationale

“There is no more beautiful symbol of human freedom than the human arm and hand.”

The MSc in Practical Skills Therapeutic Education aims to equip learners with the know ledge, understanding and skills to set up, manage and/or teach in organisations wishing to implement or integrate this method. The overall learning outcomes focus on the development of:

Rudolf Steiner quoted in Carlgren Education Towards Freedom.

1. A Practical Skills Therapeutic Education curriculum for people with special educational needs.

2. A therapeutic and educational residential care component .

3. Tools for leadership and management in organisations.

The rationale for the combination of these themes is to develop expertise in integrative and holistic education, care and management within special educational needs provisions.

“Today, trust, training and practising sense perception is st ill a quite new and challenging way of research. The Field Centre is dedicated to this path of research and it has the potential to become one of the centres of phenomenon based science in the western English speaking world. Therefore I support this projec t with my best thoughts and the warmth of my heart.” Johannes Kühl, Director of the Natural Science Section at the Goetheanum.

For further information on the programme structure, entry requirements, fees and accommodation, please contact Nick McCordall, Programme Coordinator, Crossfields Institute nick@crossfieldsinstitute.com ( ++44 (0) 1453 808118 www.crossfieldsinstitute.com/education_and_training/msc programme/

18 The Aesthetic Logic of the Heart, by Van James

21 The Sin of Literalism, by Frederick Amrine 25

7 being human digest

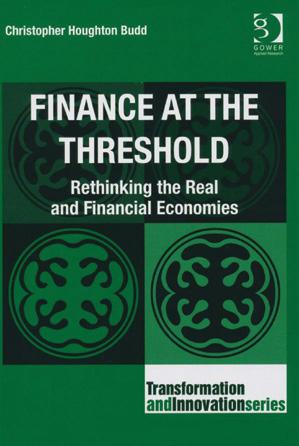

13 Christopher Houghton Budd’s Finance at the Threshold , review by Christopher Schaefer

14 Anglea Lord’s Easter: Rudolf Steiner’s Watercolor Painting, review by David Taulbee Anderson

15 Georg Kuehlewind’s The Gentle Will , reviewed by Joyce Reilly

38 What’s Happening in the Anthroposophical Society? by Marian León

General Secretary on the Road; WRC Visit to Seattle

Introducing Carla Beebe Comey; Manzanita Parzival

40 Celebrating Dorothea Mier at Eighty, by Michael Ronall

44 What’s Happening at the Rudolf Steiner Library? by Judith Soleil

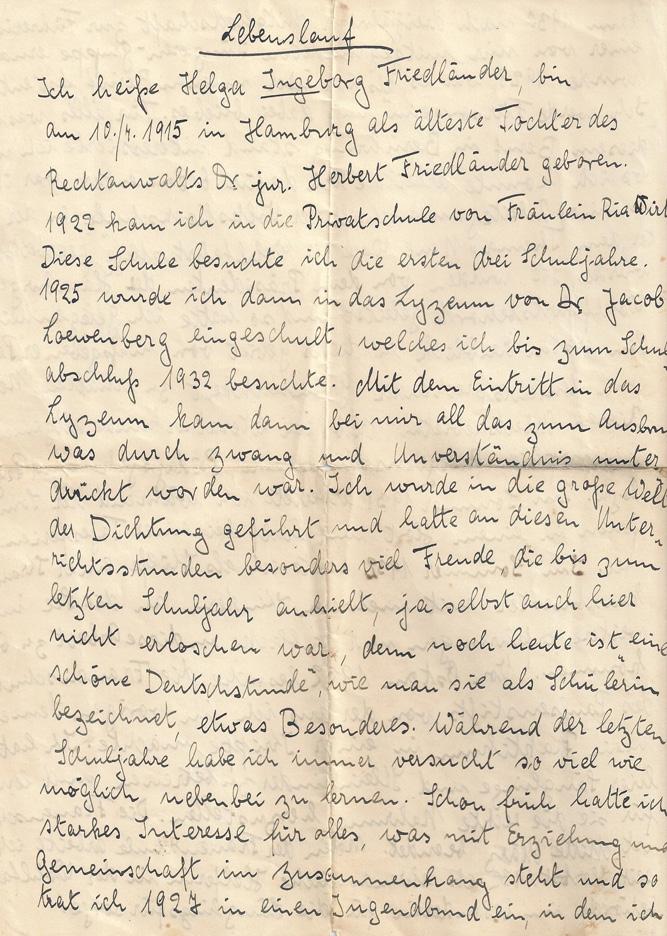

42 Inge Elsas: 1915-2012, by Margaret Runyon

43 Rudolf Binnewies: 1912-2012, by Mark Murray

41 New Members of the Anthroposophical Society; Members Who Have Died

You might have heard that this issue would have a 100th anniversary salute to Rudolf Steiner’s Calendar of the Soul . That’s coming in the Fall 2012 issue, so that we can digest some really wonderful material for you.

The main event of this issue is a dozen pages devoted to further preparation for the annual conference in August. Readers might be surprised at the degree of “letting it all hang out” that we are indulging here. It’s just a conference, right, and it’s just about future directions for this rather small organization, the Anthroposophical Society in America. Some people will come, perhaps quite a number; and then, on August 12th, it will be over. Right?

The conference planners, and the Society’s General Council, and the guests who are joining us from the Executive Council at the Gotheanum, are hoping for much more. What is sought is a real enlivening of the whole anthroposophical movement on this continent, with a permanent increase in the engagement and interaction of members and friends, and perhaps a significant change in the tone and robustness of our participation in current human conversations and social dialogues.

Naturally, we believe that anthroposophy matters: that it is a way of seeing, knowing, experiencing, and participating more consciously in human evolution. It has now reached the century mark, roughly speaking, when cultural movements either take hold or fade. We think that human civilization as a whole needs anthroposophical ideas, experiences, and initiatives if it is not to become terribly sterile and pervasively brutal. They may not come from anthroposophists, but certainly Rudolf Steiner saw to it that anthroposophists are aware of the stakes.

So come to the conference if you can, and join in this preparatory conversation if you won’t be in Ann Arbor physically in August. Serious work is being done to make the whole process open, stimulating, and consequential. And if some of the conversation about the history and be-

havior patterns of the Anthroposophical Society doesn’t resonate with you, let us add just a few words further about the history moment it is facing.

Anthroposophy arose in the late 19th century and was reaching a certain culmination just a hundred years ago. It was responding, like some other, better-known worldviews which have come and gone, to radical changes in human society and in human individuality. Anthroposophy rested, you might say, on the magnificent cultural achievements of the modern age of Europe to that date—but it anticipated the problems of mechanization, commercialization, and destruction of life forces in human health and in nature and even in culture which we have now experienced very fully.

And when Europe as a cultural force came crashing down in the “Great War” of 1914-1918, anthroposophy was left without its supporting platform. For our core questions, the 20th century was about survival. When it became, finally, “the American century,” and the strengths and weakness of US-Americans and our culture became dominant facts in the human future, it began to become clear that American anthroposophists would have to become more engaged. And in a way, this conference may be a real beginning of tht engagement. We hope that intrigues you!

From the side of the Rudolf Steiner Library Newsletter, this issue features reviews of three very disparate books:

Easter: Rudolf Steiner’s Watercolor Painting, by Angela Lord, reviewed by David Taulbee Anderson, is a contemplation of Rudolf Steiner’s treatment of Christ’s deed of bringing the dead into the light of consciousness

Sample copies of being human are sent to friends who contact us (address below). It is sent free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/membership.html or call 734.662.9355).

To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104. To advertise contact Cynthia Chelius at 734-662-9355 or email cynthia@anthroposophy.org.

through His descent into hell on the Saturday after the Crucifixion. The reviewer, an accomplished artist himself, emphasizes the language of color and its function as a bridge between the dark unconscious and the light-filled resurrection forces of cognitive feeling.

Finance at the Threshold: Rethinking the Real and Financial Economies, by Christopher Houghton Budd, reviewed by Christopher Schaefer, PhD. Dr. Schaefer provides a thorough and detailed exposition of this book’s basic argument that “today’s financial crisis is the result of excess liquidity and the global economic system.” In the spirit of anthroposophy, the author sees crisis as opportunity and makes the suggestion—critical for the reviewer—that the economic system’s excess liquidity ought to be spent through gifting to young people and to the cultural sphere in vastly increased amounts. This was a solution first proposed by Rudolf Steiner as a means of restoring the economic and financial system to health. It is critical to recognize the relation between the economic life of the time and its spiritual life. The economic life is invariably “the shell which the spiritual life has thrown out,” and takes its form from the inner spiritual life.

The Gentle Will: Meditative Guidelines for Creative Consciousness: by Georg Kühlewind, reviewed by Joyce Reilly. The Gentle Will is the most recent of Georg Kühlewind’s books to be published in the US. In it, he explores the themes closest to him—meditation and attentiveness—through the prism of ordinary thinking, living thinking, cognitive feeling, and the “gentle will”—separated musically, as the reviewer points out, with four “preludes” mediating the progression. While The Gentle Will will meet the expectations of Kühlewind readers who have grown used to his showers of unexpected insights, the book is primarily practical. Meditation, attentiveness, and healthy consciousness are to be experienced and tested. In addition to 27 contemplations and meditations, the book contains 41 exercises to be performed by the reader. The Gentle Will is not about anthroposophy; it is working with anthroposophy.

Frederick J. DennehyOur “being human digest” covers news and ideas of interest from the wide range of holistic and humancentered cultural initiatives. Items are brief, suggestions are welcome. Please write editor@anthroposophy.org or “Editor, being human, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104.”

Since the late 1990s the small California group “People for Legal and Nonsectarian Schools” (PLANS) has waged a losing battle in the courts to prevent the Sacramento City Unified School District from operating a public charter school using methods based in Waldorf education. In May the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against PLANS’ latest appeal. From the beginning, PLANS had asserted that Waldorf education teaches anthroposophy, and that anthroposophy is a religion. Rudolf Steiner clearly stated that anthroposophy is not a religion, and that people of any or no religious affiliation could be anthroposophists. He also helped a group of priests and seminarians found a new religious group, the Christian Community: Movement for Religious Renewal, which would be superfluous if anthroposophy itself were a religion. He also made very clear that while anthroposophy should inform the methods of the teachers, it should not be part of the content of the curriculum. PLANS had agreed, repeatedly, that their case had no merit unless anthroposophy were shown to be a religion. They made no effective case on that basis, and the latest court ruling dismissed their appeal.

Charter schools have become a large part of the US educational landscape, and many educators are seeking through the charter schools to introduce new ideas in contrast to our increasingly standardized national curriculum. Charter schools do not have curriculum independence, nor are their teachers the final authority in the

Approach,” and another section takes up “Science Education” with multiple articles by Craig Holdrege and others. And it leads back to “Computers and Education” where the long-time IT researcher Stephen Talbott brings his fine and independent mind to bear.

schools; but this ruling removes a lingering cloud so that those aspects of Waldorf education which are possible in a public charter setting can be developed without fears of litigation.

With an extended and serious discussion of technology in education unfolding over the last nine months, beginning from the New York Times, a space has been opened for the idea that recent technology can be well mastered late in secondary education, but that its prevalence early on will at the very least crowd out other important experience and learning which will not be gained later.

A May 25 article in the UK’s The Guardian on expansion of state funding for Steiner schools (as they are generally known in the UK) does suggest, however, that another line of criticism may be reawakened: that Waldorf/ Steiner schools don’t teach “good” science. The movement has actually dealt with this question very extensively over the years. The observational and experiential approach to natural science which Waldorf fosters is clearly much closer to the pattern of the great research scientists’ experience than the abstracted hypothesis and simulations approach which relies on computing power and is now so common.

Those interested in anthroposophy’s approach to natural science have a great online resource at The Nature Institute (www.natureinstitute.org – note that there is no “the” in the address). The first of its content areas is devoted to “Seeing Nature Whole – A Goethean

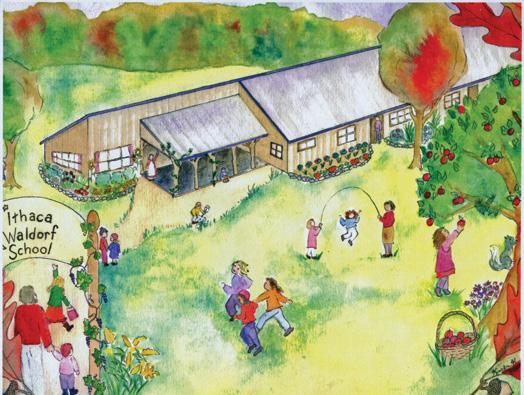

Lisa Turner has posted pictures at Picasa of the birth of the new building for the Ithaca (NY) Waldorf School. It’s a fine opportunity to live into this miraculous process. As Lisa says, “The interior work is coming along, but does not give such a dramatic image. Of course, the placement of the doors has changed since the floor plan was given to me, and the number of skylights, etc. We are very excited about this fairly miraculous project, and now must learn to care for it—a lot of mowing, trees to be planted. And fill it with children, and finance the repayment of the construction loan.”

It’s also a chance to illustrate something about anthroposophy’s approach to science (see the preceding item). The images show four different elements that allow this new school to come into being—four different “causes” for its existence. One is the building materials (top picture in group): they provide the substantial cause. Another is the workers and machinery (right): they are the effective cause. Today’s approach to science (with roots going back to Francis Bacon around 1600) likes to focus on these two kinds of causes, as ex-

clusively as possible, while minimizing the other two sorts of causes. One of those others is shown in the blueprints (left picture in group): this is a representation of the form of the school, which will take shape based on this form. The other is the intentional element (the “teleological” cause, from Greek telos which means purpose). It is shown here in the watercolor (bottom). That is what people really want here! Not just a building, but a space for certain kinds of joyful human interactions.

When it comes to human activity, we acknowledge the form and the purpose, even though the “bricks and mortar” and the workers and machinery seem more real, more visible, more tangible, more practical—than blueprints and dreams. When we turn to Nature, however, our philosophy of science has been wishing to leave out purpose entirely and make form a question simply of survival factors.

So consider, how would this incarnating Waldorf school be different without the blueprints and the watercolor-dreams? And then, how is Nature made poorer, and weaker, when we deprive it of half of the causes for its true being?

It requires a bit of imagination, but then it has a powerful impact: try to think away all the artificial (mostly electrical) lighting that accompanies modern civilization. Airplane lights, stadium lights, street lights, neon lights, house lights, car lights. Think your way back to gas lamps on the streets, and before that torches. Take it all back 200 years or so. And by the way, not so many of us were living in cities or even large towns then. Think back, and then, a couple of hours after a wonderful sunset, look up at the stars. Can you imagine what it was like to have a thick carpet of stars, dimly precise, texturing the sky—

instead of just a few bright ones standing out from a grayish mist?

If you’ve ever really seen a good dark night sky, you’ll understand the impulse for the Headlands International Dark Sky Park in Michigan’s upper peninsula. Anthroposophist and astrosophist Mary Stewart Adams is the park’s program director, and she recently helped Emmet County win a grant for a Dark Sky Discovery Trail at the park. Stories inspired out of humanity’s thousands of years of intimacy with the night sky will now be part of the park’s offerings. “While human beings have looked up in wonder at the night sky from time immemorial, and have built monuments and temples and created great works of art and literature to celebrate the mystery of our relationship to the planets and stars, in contemporary culture the information about this relationship is dominated by scientists using satellites, telescopes and computers,” Adams said. “Our intent is to tell the story using the humanities, from the perspective of the human beings involved in discovery, the mythological figures that have been associated with the night sky, and more. These stories are the fabric of our cultural life and when shared they enhance the sense of place and belonging in both the cosmic order and the community.”

The Headlands Dark Sky Discovery Trail will include 11 interpretive signs and life-size cut-out figures – cultural “docents” – that will allow the visitor to be engaged intellectually and imaginatively in the experience. Each Discovery Station will represent one of the planets, plus the sun and moon, and be accompanied by a sign detailing the person or object’s connection to the dark sky and the culture on Earth; a self-guided cell phone tour stop; and a specialized QR code for smart phone users to instantly scan and connect with the audio.

The Discovery Stations will lead from the Headlands main entrance and to the designated Dark Sky Viewing Area at the Lake Michigan shoreline, about a 1.5 mile walk. They will be spaced relative to the planets’ locations and distances from each other in the solar system.

And what about the Venus transit, you ask? 700 people took part in the park’s programs around this event. Work on the Dark Sky Discovery Trail will begin immediately, with estimated completion by Labor Day. Updates will

be available on the county site [ www.emmetcounty.org/ darkskypark ]. Each month, Emmet County offers free monthly programs at the Headlands, with program details also available on the Web site. Plus, a biweekly video email blasts features Adams providing night-sky viewing tips, celestial highlights, program information and more. To register for the email blasts, contact Piehl [ bpiehl@ emmetcounty.org ]. Reported by The Sophia Sun

This being human is a small publication (48 pages including covers), issued quarterly, and potentially interested in all things human. To put it kindly, we leave out whole universes from every issue. More and more we will be publishing additional material at anthroposophy.org – where, under the “Articles” heading, we have just added reviews of two books by Reg Down (by none other than Nancy Parsons and Therese Schroeder-Sheker), a reflection by Neill Reilly on “Moral Imagination,” and a lighthearted piece by Michael Ronall called “How to Survive as a Man in Eurythmy School.” New articles will be there by the time you read this, so scroll down the list please!

I believe that miso belongs to the highest class of medicines, those which help prevent disease and strengthen the body through continued usage. . . Some people speak of miso as a condiment, but miso brings out the flavor and nutritional value in all foods and helps the body to digest and assimilate whatever we eat. . .

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director,

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director,

Threefold Educational Center CHESTNUT RIDGE, NEW YORK

www.threefold.org/research

Co-sponsored by the North American Collegium of the School of Spiritual Science

The Threefold Educational Center in Chestnut Ridge, NY, about forty minutes drive north of New York City, was a research center from at least the early 1930s. Threefold’s commitment to research continues today in many ways, highlighted by a yearly “living questions research symposium” close to Michaelmas. This year (September 20-23) brings “Toward an Arts and Science of Wholeness.” Details at www.threefold.org/research.

Least known of the national or continental anthroposophical institutions in North America is the Council of Anthroposophic Organizations. It was formed in the mid-1990s to bring to the leadership of the Anthroposophical Society in America a consciousness based in the

practical operations, planning, and strategic thinking of service organizations and functions based in anthroposophy. We will be highlighting the work of the CAO in our next issue and on line, but also want to mention it here in relationship to research: the kind of research that evolves from “hard experience” and the bringing of ideals to earth. This is a special region of research which speaks particularly to the practical orientation of US-Americans. The CAO is looking at some of our hardest questions, including bringing along next generations of workers in adult education and curative work, or training in such specialties as accounting as needed by anthroposophical initiatives. The CAO also is helping to fund the Leadership Colloquium and help support attendance at this year’s annual members conference in August.

Behind the active anthroposophical initiatives of schools and farms and medical practices and artistic groups there is the original research of Rudolf Steiner, the traditions and accomplishments of culture before him (think Goethe in morphology or Bronson Alcott in education), and the ongoing study, experimentation, and collaborative work that continues up to this day. Steiner launched an ambitious School for Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum in Switzerland to carry this work, and thirty years ago the work began to take on specific shape on this continent with its own leadership group, the North American Collegium. Sherry Wildfeuer brings us up to date:

“The North American Collegium of the School for Spiritual Science arose through the expressed need of some people in America to experience their work with the 19 Lessons of the First Class in the context of the School as a whole. All who have joined the School may consider themselves members of the General Anthroposophical Section of the School, but how can the pupils experience themselves as part of a school community? How do the vocational Sections relate to each other and to the whole? What is the research that is meant in the 9th Statute given by Rudolf Steiner for the Anthroposophical Society? When, with the blessing of the Goetheanum, the Interim Collegium was formed in 1994, these questions began to be explored and elaborated.

“The impulse to form the Collegium can be traced back to 1981 when the Executive Council of the Anthroposophical Society came to a conference in Spring Valley

and called for a “Goetheanum in the West.” The development of Section work on this continent was suggested as preparation and was subsequently taken up. Thus, from its inception the Goetheanum-building impulse belonged to the impulse of the Collegium.

“We studied the lives of the members of the first Vorstand of the Anthroposophical Society, mindful that the profound differences among those brought together in the School and Society need to find resolution if we are to be able to work fruitfully for the spiritualizing of our civilization. We recognize that a sufficiently active culture of research among the members of the School has not yet developed. What are our real questions? What can we offer out of anthroposophy to meet the needs of our time? How can the Collegium augment what the Class Holders do? We recognize the need to communicate directly with the members and are proposing a means of doing so.

“When members of different Sections work together, they enhance each other’s insight and effectiveness. Such multidisciplinary collaboration needs to be practiced and fostered. The Collegium itself is a model for such collaboration but we are limited by only coming together twice a year. Such collaborative work should be encouraged in locales where people can share their research with peers

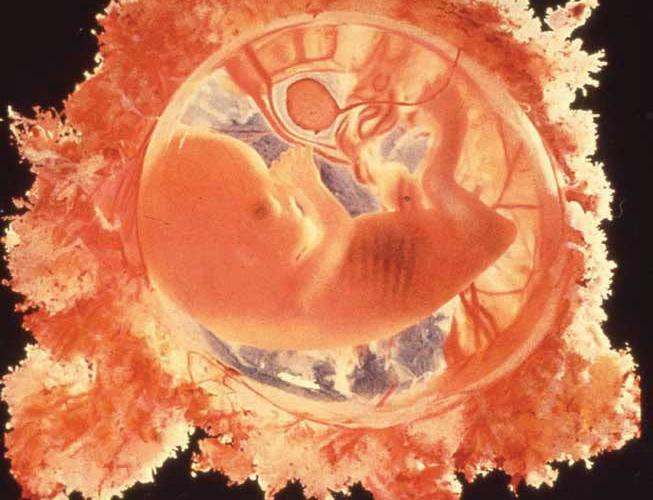

This seminar explores how human prenatal development expresses the essence of human spiritual unfoldment. Understanding the stages of embryological development provides a basis for therapeutic recognition of embryological forces in all later stages of life. This seminar is a rare opportunity to hear a world authority on modern embryology through a unique synthesis of scientific and spiritual principles.

and take up common themes from their diverse vantage points (“Local Collegia”).

“Rudolf Steiner expected members of the School to be ‘active members’ of the Anthroposophical Society. How can this aspect of the School be encouraged and supported? Collegium members are chosen by their Sections (with the exception of those for the General Section, who were chosen by the Class Holders) but they are not Section Leaders. The Collegium as a whole can be seen as carrying responsibility for the General Anthroposophical Section of the School on this continent. We are formed in the image of the Collegium at the Goetheanum. A way of working and mutual understanding has been built up over time through common work with the Class, study, artistic work, sharing of our individual research activity, and collaboration on specific projects and events. (Several conferences and the Henry Barnes Fund for Anthroposophical Research are examples of this.)

“The Councils of the Anthroposophical Societies of the US and Canada are also represented on the Collegium. We see the need for these Councils and a committee of the US Council, the Council of Anthroposophical Organizations, to be clear about their various tasks and work together. Perhaps it is helpful to recall the pre-earthly deed of Christ whereby the organs of the human body, which were each tending towards independence, needed to become sufficiently selfless to harmoniously perform their distinct and necessary functions in service of the organism as a whole. Something of this mood of service needs to prevail in each group as well as in our coming together, which of course is expensive and unwieldy and must be well prepared to be fruitful.

“The Collegium realizes that to serve the School it

needs to have a common picture of the School as a whole and a mutual understanding of roles with the Class Holders. Through Virginia Sease’s participation in our Collegium meetings as often as possible we have built good communication and trust with the Executive Council at the Goetheanum. This is essential, and we are deeply grateful for what she brings.”

More on the work of the School, its Collegium, and the Henry Barnes Fund for Spiritual Research will be appearing online at anthroposophy.org.

Except for having no funding to speak of, Frank Chester has been having a great time. Last year he spoke with cardiologists about the implications of his discoveries around the geometry of the heart. To the Goetheanum later in 2011 he brought his combined impulses: research, design, sculpting, architecture, geometry; creating a bit of a stir with his process and with a design for a Goetheanum building for North America. To the Rhode Island School of Design in early 2012 he brought a picture of arts-and-design with real depth of consciousness which brought students forward to ask if they could connect up with his institution. (Perhaps he is an institution, but he doesn’t have one you can join.) And a few weeks ago we were able to meet with him in San Francisco where he is based and connect some dots between “anthroposophy and contemporary philosophy” – such as the possible relationship between his unlocking of the condensed forms of geometry’s “ideal solids” and the Deleuzian philosophical notion of de territorialization and re territorialization.

If he doesn’t have big grants, Frank has great support in his online presence (tip of the hat to Seth Miller). Go to www.frankchester.com and, after bookmarking the site, plan to spend an hour a day there for at least a week. There are videos, diagrams, booklets: all as beautifully done as the work itself.

By Christopher Houghton Budd. Gower, 2011, 239 pgs. Review by Christopher Schaefer, Ph.D.

By Christopher Houghton Budd. Gower, 2011, 239 pgs. Review by Christopher Schaefer, Ph.D.

Christopher Budd is well known to students of anthroposophy as a writer and lecturer on associative economics, accounting, and finances. Finance at the Threshold: Rethinking the Real and Financial Economics, published by Gower, is a very stimulating effort to integrate Rudolf Steiner’s economic ideas into the mainstream economic debate about the current financial crisis. The book is meant to give Steiner credibility as an economist among an academic audience not familiar with his ideas. It does this in two main ways: first, by using Steiner’s economic insights as a way to understand the present crisis; and second, by suggesting fundamental solutions to the problems of the financial system based on his work. The book is full of intriguing ideas and challenges to mainstream economics. Its basic argument is that the financial crisis is the result of excess liquidity in the global economic system. Budd suggests that in the same way cathedral building in the Middle Ages siphoned off surplus capital, today, gifting to young people and to cultural life in vastly increased amounts could restore the economic and financial system to health by using excess capital productively, a solution first proposed by Rudolf Steiner in World Economy.

The author sees the financial crisis as global, and as representing a new, defining moment in human history that calls into question both our ways of acting and our understanding of economic life. He relies on an image provided by Rudolf Steiner to make this case: “The economic life of a particular time, and the spiritual life of a particular time, hold the same relation as a nut to its shell; the economic life is invariably the shell which the spiritual life has thrown out. It takes its cast from the spiritual life. Today’s is, therefore, the product of an abstract spiritual life.” (World Economy)

From this basic insight Christopher Houghton Budd suggests:

1. The world economy has been global since the beginning of the 20th century, but our behavior and our

understanding have not until now recognized this.

2. The financial crisis is due to excess capital seeking ever-increased returns at a time when there are no new markets as such, since most areas of the globe, including the Islamic countries, operate under conditions that allow the free movement of capital and goods. The growth of the international financial market is not only due to the mistaken leverage of assets such as housing stock, but also through the vast sums available to capital markets through pension, mutual, and investment funds.

3. People’s consciousness and economists’ understanding of the international economy is too abstract; their sense of what is really happening is inaccurate. The efficient-market hypothesis of the Chicago School claims that the market will always do the best job of determining true price. But this approach, based on abstract mathematics, assumes that people act rationally and that there are clear cause-and-effect relationships in economic life. As Steiner noted long ago: “Economic processes are distinguished by the fact that we ourselves are within them, therefore we must see them from within. We must feel ourselves inside the economic processes, just as a being would do who is inside the chemist’s retort.…” (World Economy) Here Steiner anticipates George Soros, who argues that the economic and financial system is reflexive in nature, and that there are no independent variables for determining either price or behavior. The author cites Soros approvingly, “Let us examine the main assumptions of the theory of perfect competition. Those that are spelled out include perfect knowledge; homogeneous and divisible products; and a large enough number of participants so that no single participant can influence the market price… The assumption of perfect knowledge is suspect because understanding a situation in which one participates cannot qualify as knowledge.…” Furthermore, “The shape of supply and demand curves (which supposedly determine price) cannot be taken as independently given, because both of them incorporate the participants’ expectations about events that are shaped by their own expectations… Nowhere is [this] more clearly visible than in financial markets.…” Steiner also noted that a calculation of true price depends on whether one is a producer, trader, or consumer, suggesting that there are really three different equations for determining price.

It was from this insight that he suggested the importance of an associative economics that would bring consumers, traders, and producers together in associations in order to arrive at an approximation of true price.

4. The author makes five basic recommendations for renewing and transforming the international financial system. The first is to recognize that the world economy is global and will require an international reserve currency, such as John Maynard Keynes suggested with the creation of the “bancor.” Such a suggestion rests on the understanding that money is an agreement among people about a medium of exchange, and is based on the economic activity of a society made visible through loan and purchase transactions. Secondly, the international economic and financial system will need to be self-administered by associations of consumers, traders, and producers. Thirdly, as one would expect given the author’s previous work, he advocates that the financial system needs to rely much more on accounting, and in particular, double-entry book-keeping, to connect individuals to economic life (micro-economics) and to the broader field of macro-economics. Greater reliance on accounting would create a self-balancing economics, as those who required liquidity would need to be balanced by those offering liquidity, so that all accounts would sum to zero. The fourth recommendation, articulated rather poetically, is a plea to recognize the existence of a “choir of cultures” (free cultural life); a group of states (rights life); and a global world economy, each of which needs to be independently administered according to its own inherent principles. The last proposal, previously mentioned—and to my mind, critical—is to recognize the need to spend the economic system’s inevitable excess liquidity through gifting to youth and to educational and cultural life.

Finance at the Threshold is an intriguing and stimulating book. Its limitation, besides its high price, is the author’s understandable use of academic language and mode of presentation. I do wish that a simpler, shorter, and cheaper version of this book would be published in paperback, because as a trained economist and social scientist also interested in bringing Steiner’s social and economic ideas to a broader audience, I find Christopher Budd’s examples and conceptual discourse compelling. Many chapters deserve special study: for example, chapter 2, “When the Banks Stopped Lending to One Another,” features many interesting quotes from both liberal and conservative economists; and chapter 4, “It’s the Epistemology, Stupid,” raises basic questions about our current

understanding of economics.

For a new edition, I would suggest a deeper look at how the present financial and economic system has created distortions and suffering in the United States and Great Britain, since in these countries economic and financial elites have determined political discourse and government decision-making for the last three decades with devastating consequences for their own citizens and for the world.

I would also recommend that readers look at Martin Large’s book, Common Wealth: For a Free, Equal, Mutual and Sustainable Society (Hawthorn Press, available from the Rudolf Steiner Library), for a complementary presentation on the ways in which threefold perspectives are alive in many efforts at social reform. I can also suggest Gary Lamb’s recent study, Associative Economics: Spiritual Activity for the Common Good , (AWSNA, available from the Rudolf Steiner Library) for its comprehensive presentation of Steiner’s ideas on economics. At a time when the limitations of both socialism and capitalism have been made abundantly clear, all three books should be read and worked with as a way of enlivening a new imagination of society appropriate to our time and our consciousness.

Rudolf Steiner’s painting, Easter, is taken as the subject of meditation for this book. The author, who has worked with the Easter motif as a painter for many years, approaches the picture out of her experience with color and her research into anthroposophical and other sources on the esoteric significance of the Mystery of Golgotha. A history of the crucifixion as a theme in art leads us into our contemplation. Other references are the apocryphal gospels that illuminate the picture’s theme, which is the descent of Christ into hell on the Saturday after the crucifixion. The author explores what took place in the realm of the dead from many angles, and also discusses how the twenty-third psalm is related to the picture, using it as a means of understanding its depths. Other references are Rudolf Steiner’s Soul Calendar, and an account of the ancient Adonis festival.

Part 2 leads us into the most significant means of understanding the picture, color itself. The author dem-

onstrates how the powerful polarities of above and below, and light and darkness, are mediated by the rainbow bridge of colors. She explores the activities of the individual colors and their expressions in a way that draws the reader into their being and essence, so that they become a language that can be read by the soul through heightened feelings imbued with meaning. The section concludes with Rudolf Steiner’s rainbow meditation.

Part 3 examines the background of the Mystery of Golgotha and its cosmic aspects, particularly the sun and moon, since Easter as a movable festival is determined by the interplay of these two planets. The author also looks at the other planets and their related colors. Finally, she invites readers to delve more deeply into this important subject by suggesting possible ways to paint the motif oneself as a means of entering into the life of the theme.

Christ’s deed of bringing the dead into the light of consciousness was not only important for the actual deceased individuals—patriarchs and prophets—who had been held captive in the underworld in a dampeneddown condition of consciousness, but for us, too, here in our earthly lives. The underworld part of our consciousness that is submerged in darkness can also be given new forces of life, or resurrection forces. Color is the bridge into these dark realms, and it is our feeling that uses color as a vehicle for going beyond the realm of dead abstractions. The author shows how the third hierarchy, which includes the angels, creates the world of color in which imaginative pictures appear. It is possible to go through these pictures, glowing in color, to the darkness behind them where inspirations sound toward us and living meaning fills us from a world that was previously dark and unconscious.

Our culture today, which is still dominated by dead thinking that lacks imagination, can benefit from cultivation of the type of willing-feeling-thinking that characterizes this study. The book can help readers develop the sensitivity needed to overcome the type of thinking that is bound to physical processes and matter. The Easter event can be a force in our lives that draws us out of the tomb of materialism and allows us to participate in the life forces that mold our world. Through this participation, we learn to experience directly the upbuild-

ing and coming-into-being of existence and truly live in the springtime of the world. Easter takes us on a journey where we must courageously face the underworld of the dead to find new life, eternal, springing up from the resurrection forces that Christ implanted into the depths of hell. This is not a book to be read casually; rather, it can be used as a means of finding the living wells that must be worked for. Just as Virgil served Dante as a guide through the Inferno, so Angela Lord is an excellent guide for modern people to take that necessary preliminary journey before entering the realms of the blessed.

The book features many beautiful color illustrations: Steiner’s original painting and versions of it by the author, Robert Lord, and Gerard Wagner are reproduced along with related material.

On the cover of the Lindisfarne Press edition of Georg Kühlewind’s The Gentle Will there is a lovely photograph of hands poised at a keyboard. The long slim fingers are touching the keys, but not yet pressing down—the music is all in potential, the keys await the music. The fingers are transferring the pianist’s intention, and are about to become instruments themselves. This expressive moment shows us the essence of what we are to encounter and work through in the one-hundred-plus pages of this slim and powerful book: the essence of the gentle will and its power to create, respond, repair, and express. This photograph becomes even more touching when we learn that the hands at the instrument belong to Georg’s grandson, and that in his own early life Georg had a passion to perform at the piano.

The book is itself organized musically, with four “preludes” framing the content and a progression in subject from thought to thinking; from thinking to feeling; and from feeling to willing; ending with the cosmic background of the will. In each section, Kühlewind as-

from What Is Felt to Feeling, from What Is Willed

sumes that we are there to be engaged not as mere readers or spectators, and he invites us to practice what he illuminates in his preludes in a particular form. There are sections entitled “Contemplation” that are meant to be thought through, pondered, and exhausted on the level of everyday thinking. Then there are parts called “Contemplation/Meditation, “where the reader is invited to use the contemplations as a means to enter into real bodyfree thinking, into the meditative path. This is perhaps a unique feature of Kühlewind’s work, that he repeats ideas from his earlier works and practical advice on how to achieve what he is speaking about, treating his books as a means rather than an end, almost as workbooks rather than pure text.

Michael Lipson’s translation is clear and elegant, and his long association with Kühlewind is such a help here. In his workshops, Georg often compared studying meditative texts in a state of ordinary consciousness, as if they were ends in themselves, to confusing the runway with the flight! To study like that is like grasping a magnifying glass with head down, testing the strength of the surface, and perhaps raising our head to calculate the wind’s velocity, without realizing that the runway is only the preparation for our own earth-free journey, our sense-free flight. This is both an amusing picture and a sad one, and Georg made it his life’s work to help free us of constraints so we could enter the world of spirit.

The first line of the “First Prelude” is: “We live in a world of meanings, though we are convinced that we live in a world of things.” This sentence alone could summarize everything that Kühlewind brings us, in this book and in so many others. It also relates to his endeavor to understand the experience of the small child, and his conviction that the trauma of birth is not the arduous process of emergence from the maternal body (traumatic for the mother, perhaps!) but the realization that we have emerged from the spiritual world of meaning into the material world of things. We knock up against that which has form but is hollow, and must elevate and infuse our experience with meaning ourselves, through our own effort of will. We then begin the work of the book—that is, we start to contemplate and meditate, at first around the theme of how we think. The outcome of these exercis-

es—that we begin to experience the I am, that we know ourselves to be an eternal, spiritual being rather than a complex of outer circumstances and inner reactions—is valuable enough to justify the whole book. The further benefit of this section, when it is worked through—that we begin to experience the objects that we use for concentration exercises as meaningful, sacred things—gives us entrance into the world from which we came.

The “Second Prelude” takes us from thinking to feeling, and, of course, by “feeling” Kühlewind is not referring to emotion, but to the feeling that leads our thinking, that guides our logic, which he calls cognitive feeling Kühlewind elucidates this difference, as well as the difference between the I and the Me, and prepares us for the next “flight.” These exercises lead us quietly yet dramatically away from the ordinary experience of emotion to the world of feeling; to differentiation in feeling; and then to meaning—and along the way we begin to realize our freedom. We begin to experience our inner world as “purified” of forms, and our outer “sight” as clarified and exact. Again, we could stop here and be infinitely enriched, but we are urged to go on.

The “Third Prelude” begins again with the thought that we do not know how we think, but now the emphasis is on the will: we do not know the connection of our thoughts to our will. We are used to exercising our will in action, but are not aware that everything that is formed has will, is formed with will. We can be awestruck by great art or music, by science and architecture, as well as by the majesty and ferocity of nature—and there we can directly experience a forming will, a will that is not mine, a will that is beyond anything I can imagine and therefore alerts me to the world beyond my experience. This momentary lapse in our egotism can lead to a moment of receptiveness, to a feeling of thy will not my will—which can also be experienced as grace. This receptive will is also the basis for our earliest learning, for the possibility to imitate, for the possibility to be imprinted with the first hundred words—with all that surrounds us as infants. In this section, the purification of the will becomes a possibility as we move into exercises for the will, and realize the importance of relaxation! We then confront speaking, remembering, imitating, reading, and the body, and our exercises bring us into touch with the gentle will itself. We are now ready for the “Fourth Prelude.”

The importance of this book lies in the realm of the gentle will. Kühlewind states that whenever we do not know how we do something, we receive a gift. We work

very hard at our exercises and in our everyday life, we increase our attentiveness and our awareness in each moment that we can—and then we are able to reflect, to be attentive, to be in tune with what we are doing, and so on: is this of our own making, or is this a gift? And through this gift, the whole objective world is revealed to us. Why is this not universally recognized? Why do we need to lay claim to our thoughts and ideas, as if we were not being allowed to participate in the spiritual world? Kühlewind points to this misunderstanding as a basis for much of our suffering. At this point, we are eager to go further.

In the fourth section, Kühlewind begins tracing the spiritual or cosmic origins of the will. Far from a flight without a runway, he takes us back to the essence of our humanity—our attentiveness. He states that the profaning of human life began when religions siphoned meaning into their own domain and left everyday life on a different plane. Everyday life began to be all about usefulness, manipulating the world of things, with an inevitable slide into commodification, and human life became simply a part of this useful thing-ness. The exercises in this section begin with silence and progress to meditation itself. The author presents different types of meditation: on a sentence or an image; perceptual meditations; and ends with meditation that poses a question, or meditative research. We are now at the moment when the gentle will can be seen as the fruit of all our efforts, and we are freed to be instruments—of art, of knowledge, and most importantly, of “the peace,” according to St. Francis. One is reminded here of the saints in their purest attitudes, such as St. Catherine: “All the way to God is God, for has he not said, ‘I am the Way?’” and of the words attributed to St. Francis: “Always and everywhere preach the gospel. If necessary, use words.” We have now reached the point where the exercises mean to take us: to freedom of, or gentle, will.

The rest of the book contains further exercises and meditations, and several sections that could be studied on their own but are probably best realized after the work of the earlier chapters has prepared the reader to take them up actively. In the appendix titled “Reversal of the Will and Encountering the Power of the Logos,” Kühlewind speaks about the difference between thinking or thought

and the experience of thinking, and the will and the experience of willing, with direct references to Rudolf Steiner’s Riddle of Humanity and The Philosophy of Freedom. He ends with quotes from Dante and Rilke, two of his most cherished writers. In the appendix, “Art and Knowledge,” he explores what are at first seemingly obvious differences between the two; unpacks these ideas and brings us to a childlike and playful, “gentle-willing” experience of both; and then emerges with us into a field where we are both more aware of the origins of ideas and creative expressions, and know ourselves to be capable in these realms. Indeed, the future health and existence of our world relies on our ability to be in a state of gentle willing.

Kühlewind is, above all, a teacher, guide, and traveler who stops along the road and waits for us to catch up with him. In all his books, as here, one finds not only his own careful journey explained, but also his deep respect for his readers, his conviction that we are all capable of being in a state of non-duality, neither everyday nor spiritual, simply— here. Kühlewind does not hand us anything completed, but opens a door—and sometimes puts out a hand to bring us over the threshold. If you are looking for a definition of will, or of anything else, you will be frustrated by this book—you will be asked to have an experience rather than seek definitions, and you will be invited, but not coerced. If you have the patience—and, indeed, the will—to take this journey, you will be more than pleased. I feel a sense of connectivity, of community, when I think of others across the world reading this book, working through its content, and consulting with each other about the experience—its difficulties, its joys. Indeed, in each of the many languages it may be translated into it will have a slightly different flavor, but no matter. This community of striving human beings, creating itself through individual commitment and mutual trust, may be small and not yet recognized as mighty. Perhaps this is the answer, seed-like as it is, to the question Kühlewind poses at the beginning of this book: In the face of human folly and suffering, what is to be done? We must answer that question with him.

“The man who lives his life artistically has his brain in his heart.” — Oscar

WildeConsider three different people’s thoughts on the subject of heart thinking. First; Dr. Paul Pearsall, American author of sixteen best selling self-help books says, We’re a brain culture as distinct from a heart culture. We want to quantify everything. If we can’t weigh it and measure it objectively, it simply doesn’t exist for us. The Hawaiians have always believed that it is through the heart that we know the truth. For them, the heart is as sentient as the brain. We find this same belief with the Hopi Indians in New Mexico, and with the Chinese; within many cultures the heart chakra is the key to healing.1

Second; when in 1925, the well known Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung went to Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, he met the Native American, Chief Ochwiay Biano. Biano told Jung that according to his people, the Whites were uneasy, restless, and “mad” people, always wanting things. Jung asked him why he thought this was, and the chief replied that it was because they thought with their heads, a sign of mental illness among the pueblo peoples. Jung asked Biano how he thought and the chief pointed to his heart. The response plunged Jung into a deep introspection that enabled him to see himself and his culture from a new perspective.2

Third; In the early twentieth century, Rudolf Steiner spoke of the important step needed in human development as a transition from our present brain-bound, intellectual thinking to a future, heart-felt thinking. This forming of heart thinking he connected directly with the aesthetic or artistic transformation of our spiritual capacity for thought. In 1919, three decades after the publication of his book The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, he said of this work: “I wanted to show that the realm otherwise dealt with only by the artist in imagination

must now become the serious concern of the human race, for the reason that it represents the stage mankind must reach to lay hold upon the supersensible that the brain is incapable of grasping.” 3

The art of weighing and measuring qualities—colors, tones, forms, words, and gestures—is a process in which the artist is constantly engaged. In fact, we are all doing this, artist or not, all the time. This weighing up of qualities is what Aristotle considered to be a virtuous, moralbuilding faculty: “Virtue is the human capacity, aided by skill and reason, to determine between the too little and the too much.” In Rudolf Steiner’s terms this faculty for virtue is referred to as moral imagination and ethical individualism (The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity). Just as the words art and heart literally intertwine, so too the artistic process and the development of cognitive feeling or heart thinking are interrelated and even synonymous.

In former times and in many cultures, heart wisdom

Figure

was acknowledged in various ways. The primeval Egyptian god, Ptah, is said to have created the world first in his heart before he spoke it into existence. To the ancient Egyptians the heart was the seat of emotions, thoughts, soul and life itself. One of the most important “spells” in the Egyptian Book of the Dead was the Weighing of the Heart (fig. 2). In this threshold trial, the deceased, led by the jackal-headed god of death Anubis, observed by the gods above, watched as his heart was weighed upon the scales of Maat, goddess of truth. If the heart was lighter than Maat’s feather of truth and not weighted down with sins and transgressions from the life just lived, then

the deceased was able to pass on to join the higher gods. Spells asking the heart not to bear witness against the deceased refer to the heart as though it were a conscious, living being. “Oh my heart…do not be my enemy in the presence of the guardian of the balance…Do not tell lies about me in the presence of the great god...” 4 The heart was the only internal organ allowed to remain in the mummified body of the deceased, while all other organs were removed and preserved separately, or in the case of the brain, discarded as unworthy.

While the weighing of the heart was a crucial step in the Egyptian mortuary cults, the weighing of the soul was emphasized in medieval Christian times and practices (fig. 1). Many depictions show the Archangel Micha-el selecting souls for their further journey by means of the scales (fig. 3). Weighing up the virtues or sins of the soul was pictured in terms of lightness or heaviness on the balance. Micha-el’s seasonal cycle as an archangel occurs each year in autumn, the time of Libra, the balance beam. As a Time Spirit or archai, Micha-el’s reign began at the end of the nineteenth century and is now fully underway in the 21st century. Rudolf Steiner said: “The Age of Michael has dawned. Hearts are beginning to have thoughts.” 5 In Steiner’s words, Micha-el’s threefold task is that, “He…liberates thought from the sphere of the head; he clears the way for it to the heart; [and] he enkindles enthusiasm in the feelings, so that the human mind can be filled with devotion for all that can be experienced in the light of thought.” 6

However, heart thinking does not just come about by itself. It requires a schooling in logical thinking, for in logical thinking we experience the consequential necessity of one thought connecting to another. Although logical

thinking will not serve us in supersensible realms, a kind of logical conscience develops from it and “a general feeling of responsibility in our soul for truth and untruth” 7 begins to take shape. So intellectual, logical thinking leads to a conscience that serves as a foundation for heart thinking. “Spiritual fervor now proceeds not merely from mystical obscurity, but from souls clarified by thought.” 8 In this way one comes to a grounded, spiritual idealism.

A visionary picture of “spiritual fervor,” originating in the “mystical obscurity” of an earlier era can be seen in the image of the sacred flaming heart from the French Order of the Visitation of Our Lady, c. 1673 and 1675 (fig. 4). Celebrated on the first Friday of every month and throughout the month of June according to Roman Catholic tradition, the flaming sacred heart of Jesus is venerated according to the visions of Jesus Christ described by a humble nun, later beatified as St. Margaret Mary Alacoque. “Flames issued from every part of His Sacred Humanity, especially from His Adorable Breast, which resembled an open furnace and disclosed to me His most loving and most amiable Heart, which was the living source of these flames.” 9 Although relegated by critics to the purgatory of Catholic kitsch art, the sacred flaming heart is a real symbol, not only of religious devotion, piety, passion, courage and love, but also of the future development of a true organ of heart thinking. Although sentimentalized in most pictures, it is an imagination of the etheric organ of the heart chakra (wheel), with its turning spokes, flowing lotus petals or radiating flames, depending on the cultural metaphor one chooses. Old Testament recognition of this spiritual organ and center of virtue is noted in Samuel:

“…The Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.” 10

Contrast this view with the late Christopher Fry’s declaration in The Sleep of Prisoners,

“The human heart can go the length of God…”

A 20th century visionary picture and artistic embodiment of the living heart forces may be seen in the Representative of Humanity, a thirty-foot tall wood sculpture created by Rudolf Steiner and often referred to as The Group. This monumental carving is a study in convexity and concavity, with a composition of figures in asymmetrical balance (fig. 5). The central figure, described by Steiner as the representative of a “spiritualized, inwardly deepened humanity,” 11 stands as the fulcrum and balance

beam of a dynamic, living scale. It is a contemporary, artistic imagination of the weighing of the heart, as this representative of spiritualized humanity strides between forces of opposition and extremism, expressing a middle position in freedom and love. This representative of the inwardly deepened human being was imagined by Steiner as showing in what streams out from its eyes as “pure compassion,” and what is shown through its mouth, “not designed for eating but for uttering true words that express conscience,” 12 the revelation of the “I am I.”

The weighing and balancing functions of both our heart and our thinking might be considered, in their essence, a form of art. The opposite of the word aesthetic is anaesthetic, which means numb, lacking feeling, and inability to respond. Aesthetic, on the other hand, means enlivened being, heightened experience, and response-ability. This response-ability is at the same time a responsibility in that it calls on us to be more aware of what we respond to and how we react and respond to it. In artistic activity, as in the training of practical thinking, we develop a faculty for conscience and we learn to take responsibility for our actions, our feelings and our thoughts. This builds an aesthetic logic and conscience that leads to the forming of heart thinking—to the aesthetic logic of the heart.

1. Hal Bennett, “The Thinking Heart: An Interview with Paul Pearsall,” www.mightywords.com.

2. Suma Varughese, Moving from Head to Heart, 9/2005. www.lifepositive.com.

Based on talks given originally as part of the inauguration of The Barfield School in Spring Valley, NY, on January 7, 2006, and then later that same year in Ann Arbor, MI.

Surely one of the greatest paradoxes of our enlightened age is the irrational tenacity of religious fundamentalism. The case against literalism is so strong and so straightforward that one is tempted to call for a summary judgment. The Bible offers conflicting accounts of the creation of the world, the creation of Adam and Eve, and the genealogy of Jesus, and they are sometimes internally inconsistent as well: for example, Genesis claims that God performed certain actions on three “days” that preceded the creation of the Sun and the Moon – bodies that are clearly integral to any literal sense of the word “day.” In the Gospel of St. John, Christ declares Himself to be among many other things a vine, a road, a door for sheep, and a “beautiful shepherd,” none of which was literally true. Only a psychotic could say such things and mean them literally, and only a militant atheist could countenance such a conclusion. The Bible may be true, but it cannot be literally true. Case closed!

If only it were so easy.

The fundamentalists have powerful allies. Literalism may seem today to be the province of the unsophisticated, but in the past, even the most sophisticated interpreters of the Bible, such as Augustine and Aquinas, insisted that the Bible is literally true. Moreover, literal interpretation is buttressed by the widely held assumption that literal, “lexical” meaning is primary, while figurative meaning in all its forms (metaphor, irony, parable, etc.) is at best secondary, derived ultimately from the literal meaning. Here also the fundamentalists have powerful allies: many modern philosophers and literary theorists have criticized figurative language as mistaken, unstable, unreliable, nonsensical, and even “diseased.” These prominent philosophers and literary theorists may have no use for fundamentalists, but such arguments play right into their hands.

Fortunately, help is available. Readers who are well-

versed in the writings of Owen Barfield will recognize my title as an allusion to a chapter in one of his last works.1 Here as elsewhere, it is Barfield, following Rudolf Steiner, who gives us profound answers to our dilemmas. The first arrives in Ch. XIII of Saving the Appearances, where he argues that, since the Middle Ages, human consciousness itself has changed fundamentally, and with it the meaning of “literal.” Barfield’s star witness is Thomas Aquinas, who begins his Summa Theologica by distinguishing four different levels of biblical interpretation, three of which he terms “spiritual:” the allegorical or typological (e.g., episodes in the Old Testament prefiguring counterparts in the New Testament); the tropological or moral (every passage is a moral lesson for us); and, from Greek words meaning “upward leading,” the anagogical (the text has the power to transform and lift up our souls). But underlying these three spiritual senses is the literal sense or sensus parabolicus. The bare term is already puzzling for us: parables are prime examples not of literal but of figurative language. But then Aquinas’ example is doubly puzzling: The parabolical sense is contained in the literal, for by words things are signified properly [literally] and figuratively. Nor is the figure itself, but that which is figured, the literal sense. When Scripture speaks of God’s arm, the literal sense is not that God has such a member, but only what is signified by this member, namely, operative power. Hence it is plain that nothing false can ever underlie the literal sense of Holy Writ.2

For Aquinas, the “literal” sense is not the lexical meanings of the unmodified tenor and vehicle 3 (here, “God”

1 “The Sin of Literalness,” in Owen Barfield, History, Guilt, and Habit (Wesleyan, 1981). The change from “-ness” to “-ism” was meant to catch some of the reverberations of contemporary political debates, but my strategy worked too well: the otherwise handsome poster advertising my talk in Spring Valley came back from the printer with the title: “The Sin of Liberalism”!

2 Summa Theol., First Part, Q1, Article 10.

3 Editor : Regarding “vehicle” and “tenor”: I.A. Richards introduced new expressions for the parts of a metaphor (The Philosophy of Rhetoric, 1936): The tenor (whose Latin meaning is “holder”) anchors the metaphor, while the vehicle takes our understanding of tenor somewhere new. For “King Richard was a lion on the battlefield,” Richard is the tenor, lion is the vehicle

and “arm”), but rather the new, expanded meaning that results from the interaction between the tenor and the vehicle (God’s “operative power”)—i.e., just what we usually mean by “metaphorical”!

Barfield goes on to argue that Medieval consciousness is fundamentally figurative as such, and he concludes that “Our ‘symbolical’ therefore is an approximation to, or a variant of, their ‘literal’” (87). Which is to say, when Augustine and Aquinas wrote “literal,” they meant what we call “figurative.”4 Our modern literal-minded experience of language and thought is simply unknown to them

Barfield addresses the second dilemma succinctly in his essay “The Meaning of Literal;” a fuller version of the argument is offered in Poetic Diction 5 Language is born poetic. If one traces the history of language backwards in time, it becomes ever more poetic, but one finds no trace of “literalness” in our modern sense. There is no such thing as “born literalness.” Our “literal” (as opposed to Aquinas’ and the Evangelists’) is not primary, but rather derivative, and the derivative cannot be fundamental.

An archetypal example of “born poetry” would be John 3:8, “The wind bloweth where it listeth…So is every one that is born of the Spirit.” “Wind” and “Spirit” are both translations of the same Greek word, pneuma . But over time this innately poetic word lost its tenor and degenerated into the literal English term “pneumatic”; Spirit gave way to air pressure. Its Latin counterpart, spiritus, died as a metaphor by losing its vehicle. The living metaphors pneuma and spiritus have split into separate, literal components, and it turns out that these words are not at all exceptional: it is true of language generally that meaning is born metaphorical, but the metaphors eventually die into prose, which Emerson has aptly termed “fossil poetry.” The literal meaning is not primary, but rather the end-product of a semantic death-process – the antithesis of spirit. But we knew that: St. Paul already warned that “the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life” (2 Corinthians 3:6). The dead letter is neither fundamental nor spiri-

4 Steiner’s paradoxical claim in his first cycle of lectures on the Gospels (GA 103, the Hamburg cycle on John of 1908) that they are “literally and profoundly true” likewise turns on a different experience of the “literal” as already figurative, for he immediately adds that one must first learn the alphabet – i.e., learn how to read language of Imagination imaginatively. In this key cycle Steiner also asserts that all the events in the Bible are simultaneously historical and symbolic. Only when this statement stops feeling like a paradox have we begun to read the Bible aright.

5 Owen Barfield, “The Meaning of ‘Literal’,” in The Rediscovery of Meaning and Other Essays (Wesleyan, 1977), pp. 32-43; Poetic Diction: A Study in Meaning, 3rd edn. (Wesleyan, 1984).

tual. So much for the authority of the literal.

Alas, further difficulties remain. When one asks how it is that figurative language signifies, the answer is enigmatic. Consider Isaiah 40:6, “All flesh is grass.” “Flesh” and “grass” here cannot refer to empirical flesh and empirical grass. Hence the “is” of this short sentence clearly cannot be the logical copula, as in “Red is a color.” Somehow, flesh both is and is not grass. What this simple sentence is really saying is something like: “Flesh [isn’t really but in some sense that I can’t express in words might be like] grass.” “Is” cannot mean “is” in this sentence, and yet it signifies to us. Isn’t all this just patently illogical?

Indeed, great philosophers have tried for centuries to wrap logic around metaphor, without success. Hence it comes as no surprise when analytic philosophers of the twentieth century (Barfield’s bêtes noires) declare figurative language to be instances of “deviant denomination” or “deviant predication.” For them, metaphor is a tumor that spreads within the healthy body of lexical meaning, a “disease of language” that only their logical surgery can cure. Any sense of meaning we might have is entirely illusory.

Barfield spent his life countering this baleful conclusion, and he was not alone. An equally important contribution was made by the French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, especially in his magnificent essay, “The Metaphorical Process as Cognition, Imagination, and Feeling.”6 Ricoeur describes the metaphorical process as a suspension of ordinary referentiality leading to a semantic collapse, a cognitive ruin out of which a new “semantic pertinence” – a new meaning – is miraculously resurrected. Metaphor brings together two images, but they never coincide, or even touch. (Tellingly, in the Hebrew original of Isaiah 40:6, the word “is” – isn’t. There is no verb, just the juxtaposed images: “All the flesh the grass.”) We step into the mental space between the two icons, close our eyes, and something jumps the gap. We hear an “unspoken word,” which delivers the new meaning via the juxtaposition of the images. New meaning is not created from the bottom up, by rearranging the counters of the lexis ; nobody makes metaphors by randomly juxtaposing images until something interesting happens. Rather, an otherwise ineffable meaning seeks a way of expressing itself, finds, and then brings together appropriate images. The new meaning is always already formed and always already in movement. Metaphors are little threshold experiences.

The making of meaning, the semantic resurrection, happens on the other side of the threshold, and we pull it back into normal consciousness.

Experienced students of anthroposophy will have begun to notice a striking parallel between this process and the meditative path described by Rudolf Steiner, leading from Imagination to Inspiration: juxtapose images (e.g., the Rose Cross) that do not refer to the sense-world, then meditate on them until they come alive. Once Imagination has been achieved, practice until one can erase these living images at will and enter into that gap. We experience emptiness; the ground is pulled out from under our feet; we hover over a void until Inspiration arrives as the unspoken words, the toneless music, of higher beings.

Steiner repeatedly stresses that this experience of Inspiration requires courage, and the same is true of its little brother, the search for meaning within the semantic void of true metaphor. If not the same degree, figurative language nevertheless requires the same kind of courage at the threshold as higher stages on the path of initiation. We have reached a moment of radical freedom – but at the cost of dangling over an abyss. Metaphor demands a trip through the eye of the needle, and that eye is, from the perspective of everyday referential consciousness, utter meaninglessness. No wonder so many balk.

The ground beneath our feet has given way, and we feel ourselves falling. Do we ever hit bedrock? The uncomfortable truth is: never. It won’t do to say, for example, I am (figuratively) “born again” because Jesus is (literally) the Son of God. And it may be that when the Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong calls on us to free the Bible from “the Babylonian Captivity of the fundamentalists,” we cheer.7 (I do.) But, once free, where do we take it? For the Bishop, the only alternative is total relativism.

Spong poses the Gretchenfrage 8 of the liberal theologian: “Is the Bible true?” And his startling answer is: “No.” Spong quotes approvingly Edward Schillebeeckx’ admonition that there are “no ghosts or gods wandering around in our human history” (143), and he insists that “We mortals live with our subjective truth in the constant anxiety of relativity. That is all we can do” (169). He doesn’t come right out and say it, but implicitly, in every line of his book, Spong denies the supernatural as such. If

7 Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism (HarperCollins 1992).