This is the fourth volume of the Journal of the Kilbrittain Historical and images that appeal to many tastes. The topics span many different eras of history in our own region and beyond. This volume includes the history of Coolmain Castle, an article on Brehon Law, local evictions

IRA commander Charlie Hurley, the killing of RIC man Constable Bolger, several other fascinating articles on the War of Independence written by direct participants, ecclesiastical history, educational history in the area, the concluding part of the story of ‘Rebel Doctor’ Dorothy StopfordPrice, and a very special and poignant tribute to the local people who perished in the Tuskar Rock air disaster in their 50th anniversary year. Other items include personal histories, poetry, society trips, and superb images from local photographers.

Once again our contributors have displayed skill, passion and determination in their wonderful articles. Their commitment to unearthing and articulating the rich cultural heritage of the Kilbrittain region is a truly admirable pursuit that is to be highly commended. We salute them and thank them for preserving this unique record for future generations to enjoy and be inspired by. We trust that you, the contemporary reader,

Pictured

Pictured

above:

Coastguard Station at Howe’s Strand from the air by Michael Prior

Front

cover photo: Coolmain Castle and Old Head by Brian Madden

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY ARTICLES & RECORDS FROM THE PAST 2018/19 VOLUME 4 KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY | ARTICLES & RECORDS FROM THE PAST 2018/19 VOLUME 4 PRICE €10

KILBRITTAIN

ARTICLES & RECORDS FROM THE PAST

Produced by

The Kilbrittain Historical Society

Anybody that would like to contribute to future journals, please submit materials to the address below;

Email: info@kilbrittainhistoricalsociety.com www.kilbrittainhistoricalsociety.com

Find us on Facebook under Kilbrittain Historical Society

HISTORICAL SOCIETY

2018/19

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY COMMITTEE

L-R:

Sean O'Connor (P.R.O.), Niall O'Brien (Treasurer), Triona O'Sullivan-Enright (Secretary), Denis O'Brien (Chairperson), Micheal Larkin (Deputy Editor), Diarmaid O'Donovan (Editor), Con McCarthy (Vice Chairperson).

The Kilbrittain Historical Society would like to thank all who supported us during the year, including those who gave presentations and contributedmaterial for our journal.

Copyright Southern Star Ltd. Volume 4

Kilbrittain Historical Society

First Published December 2018 Published by Southern Star Creative Skibbereen, Co. Cork

The views expressed in each article are the author’s own, and do notrepresent those of the Kilbrittain Historical Society as a group.

MEMBERSHIP LISTING 2018

Kilbrittain Historical Society

Annual Membership Fee €20 per person/€25 per family.

Barry, Hugh & Family

Begley, Diarmuid

Brennan, Mary

Browne, Fergal

Cahalane, Denis

Calnan, Marie & Family

Cashman, Dominic

Cashman, Sheila

Chapman, Christine

Coghlan, Noel (Nollaig) RIP

Collins, Denis & Family

Coffey, John W., Nova Scotia, Canada

Condon, Liam

Cremin, Fr. Jerry 15. Crombé, Véronique 16. Cronin, Dan 17. Crowley, Eileen 18. Crowley, Ger 19. Crowley, Helen 20. Crowley, Kieran 21. Desmond, Ann Marie & Family 22. Dollard, John, Michelle & Family 23. Fallon, Eugene 24. Fitzgerald, Maureen 25. Frost, Rosemary 26. Hawkes, Alan 27. Hickey, Annette & John 28. Hickey, Fr. Pat 29. Hickey, Vincent & Family 30. Larkin, Michael & Peggy 31. Lordan, Jerome 32. Lynch, Mary 33. Mac Lellan, Anne 34. McCarthy, Con & Family 35. McCarthy Eamonn 36. McCarthy, Nan 37. McCarthy, Tim & Majella 38. Moloney, Marian 39. Moloney, Noreen 40. Murphy, Vincent 41. Northridge, Patsy 42. O’Brien, Frank, Denis & Family

43. O’Brien, Ian & Family 44. O’Brien, Jerry & Catherine 45. O’Brien, Niall & Noreen 46. O’Brien, Ollie 47. O’Brien, TimJoe & Kay 48. O’Connor, Eugene 49. O’Connor, Seán, Liz & Family 50. O’Donnell, Shane 51. O’Donoghue, Dermot 52. O’Donovan, Diarmaid 53. O’Donovan, John, Jan & Family 54. O’Driscoll, Willie & Family 55. O’Mahony, Barry 56. O’Mahony Family, Maryborough 57. O’Mahony, Mary & Family 58. O’Mahony, Neil 59. O’Mahony, Patrick 60. O’Neill, Kathleen & Family 61. O’Neill, Helen & Family 62. O’Sullivan, Barry 63. O’Sullivan, Cormac 64. O’Sullivan, Joanne 65. O’Sullivan, Mary 66. O’Sullivan Enright, Trióna & Family 67. O’Sullivan Couse, Yvonne & Family 68. Quinlan, Pat, Margaret & Family 69. Quinlan Family, Bawnleigh, Ballinhassig 70. Richardson, Sr. Cora 71. Ryan Helen & Family 72. Ryan, Noel & Chris 73. Ryves, Martin & Yvonne 74. Sexton, Brian, Mary & Family 75. Sexton, Lawrence & Joan 76. Shanahan, Róisín & Grania 77. Sheehan, Anne 78. Thorne, Joan & Jonathan 79. Twohig, Michael 80. Twomey, James (Jimmy) 81. Walsh, Annette, Aidan & Family 82. Whelton, Michael, Catherine & Family 83. Whooley, Donal

Kilbrittain Historical Society would like to extend our deepest sympathy to the family of former member and article contributor Noel (Nollaig)Coghlan who passed to his eternal reward during November 2018. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

CHAIRPERSON’S ADDRESS

Dear all,

Welcome to the fourth volume of the historical journal from Kilbrittain this publication makes for informative and enjoyable reading.

To date the previous volumes of historical journals have produced a wonderful variety of personal recollections, some tragic and some joyful, of the people of Kilbrittain and its surrounding West Cork hinterland. As a small rural place, Kilbrittain punches above its weight where heritage is concerned. For those reading this volume in different parts of the world, I hope you enjoy Kilbrittain's history and especially the history of its diaspora. If you have never been to Kilbrittain, perhaps the lush scenery and historical sites of this tranquil place will entice you to visit sometime.

We aim to publish as much information as we can but where this is not possible in this volume, information submitted will be used in future journal volumes. A bank of information is vital in keeping this series of journals alive so we welcome your continuing contributions. One society goal in us in archiving local history so that future generations have a wide scope of local heritage and community knowledge to treasure. Young or old, whatever the topic, all material is of great interest to the society.

I want to take this opportunity to thank everybody involved in the making of this journal, from article contributors who freely gave of their time, family stories and photos, to our members, and especially the Kilbrittain Historical Society Committee.

I would also like to thank all our guest speakers this year. I wish to thank all our members who attended our historical lectures and tour outings throughout the year. We welcome you to contact us with outing/lecture suggestions and give us feedback to make each historical society year better and better.

Finally, new members to our society are always welcome, both within and outside the Kilbrittain area. Perhaps this journal will persuade you, the reader, to make that choice. Yours Sincerely, Denis O’Brien

PROGRAMME OF EVENTS

10th April 2018 Society Annual General Meeting

24th April 2018

Place Names Along The Kilbrittain Coast –Speaker: Jerome Lordan

8th May 2018

15th June 2018

Castles of West Cork including Kilbrittain Speaker: Tony McCarthy.

Courtmacsherry Bay Boat Tour/RNLI Life Boat Station Talk Speakers: Diarmuid O’Mahony, Jim Crowley & Pat Lawton

12th July 2018

Guided Tour of Beal na Blath / Kilmurry Museum Speakers: Tim Crowley / Deirdre Burke.

15th August 2018

Parish Tour from Argideen to Harbour View Speaker: Michael Larkin

14th September 2018

Tour of Castle Salem, Rosscarbery Speaker: Tony McCarthy

23rd October 2018 Cork and the Great War Speaker: Gerry White

1st December 2018 2018/2019 Journal Launch Speaker: David Cowhig

ASTROPHOTOGRAPHY IN KILBRITTAIN 9 Michael Prior

KILBRITTAIN POEM 10 Kathleen Coughlan

COOLMAIN CASTLE 15 Trióna O’Sullivan Enright

PHOTOGRAPHS 38

Annette Hickey

EVICTIONS AND AGRARIAN DISTURBANCES IN THE LOCAL AREA DURING THE 1880S 40 Jerome Lordan

PHOTOGRAPHS 46 Mike Brown

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY (1893-1921) PART 1 OF 3 47 Denis O’Brien

ACTION AT RATHCLAREN (REPRINT) Liam Deasy 72

THE KILLING OF CONSTABLE BOLGER, KILBRITTAIN, DECEMBER 1919 81 Fergal Browne

LOCAL LINKS WITH THE TUSKAR ROCK AIR TRAGEDY (1968) 96 Ann Marie Desmond

INTERVIEW WITH NORA COWHIG 109 Denis O’Brien

MARGARET COLLINS O’DRISCOLL ALONE AMONGST MEN 118 Con Mc Carthy

BALLYMORE BECKONS 45 YEARS OF THE O'CONNORS IN KILBRITTAIN 122

CONTENTS

MICHAEL MCCARTHY, CREAMERY MANAGER 127 Edward McCarthy

THE RARE STAINED GLASS OF ST. PATRICK’S CHURCH, KILBRITTAIN 132

By Fr. Jerry Cremin

THE WRITING OF THE ANCIENT IRISH LEGAL TRACTS 137 Ciarán O’Donovan

INTRODUCTION TO DOROTHY STOPFORD PRICE 150 Anne Mac Lellan

OF SEA PINKS, BLACK AND TANS, AND MEDICAL MATTERS: THE KILBRITTAIN YEARS (1921 1925) (PART 3 OF 3) 152 Anne Mac Lellan

SCHOOLS IN KILBRITTAIN, TEMPLETRINE AND KILMALODA IN 1824 Tony McCarthy 164

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY TRIPS 173

AMENDMENT 177

GIRLS FROM KILBRITTAIN NATIONAL SCHOOL 1926/1927 178

ASTROPHOTOGRAPHY IN KILBRITTAIN

9

A beautiful image of the coastguard station at Howe's Strand captured at night by Michael Prior.

KILBRITTAIN POEM

By Kathleen Coughlan, late of Clonbogue (originally Ballingeary)

I

We're here to entertain tonight, Correct me please, but I think I'm right. Kilbrittain's beauty we would extoll,

II

This old, old village within the Glen, The Castle poised upon the hill. The rustic bridge, the lazy stream, Where little brown trout from the bank is seen.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 10

Fig.1: Kilbrittain Castle with cargo ship sailing in the background (photo Brian Madden).

Fig. 2: Coolmain Estuary (photo Niall Hegarty, Pink Elephant)

III

Horse chestnuts guard our ancient church, The wood behind has larch and birch. The village hall is a place for fun, Here we foregather when day is done.

IV

Our shops have stocks of everything, From the football to the proverbial pin. The Garda Barrack is painted green, And Danny's roses are a dream.

V

The traveller here can shake his thirst, At Des's Bar or the 'Rovers Rest'. Industrious women will supply, Souvenirs to take the strangers eye.

VI

Famous people here reside, Statesmen, artists and more besides.

To equal one of radio fame.

11 KILBRITTAIN POEM

Fig.3: Coastguard Station at Howe’s Strand (photo Brian Madden)

VII

Now come with me to Coolmaine, Perchance you may remain. Do play upon the sandy beach, Or swim, Howe's Strand is on the east.

Fig.4: Sunset at Harbour View (photo Niall Hegarty, Pink Elephant)

VIII

At Rochestown, below the rocks, Carrigeen with minerals precious, IX

Kinsale's Old Head, that friendly light, Winks out a warning in darkest night. To ships that would approach too near, Majestic rocks of beauty sheer.

Fig.5: ‘Kinsale’s Old Head, that friendly light, Winks out a warning in darkest night’ (photo courtesy of Mike Brown)

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 12

X At Granfeen Bridge, you must pause a while, Here there’s much that would beguile. The eye, as far as one can see, Wild birds upon the estuary.

XI

The strand at Grán is long and wide, Here cars are driven at ebb of tide. For picnics, or to romp the dog, Until the tide steals back again.

XII

Of ships that called in days of sail. Stocks of salt were stored within, The walls of this now ruined kiln.

XIII

Now Harbour View, what can one say, There's a wooded peninsula beyond the bay. Children play on spits of sand, And sheltered rocks keep guard beyond.

13 KILBRITTAIN POEM

Fig.6: On the beach at Harbour View (photo Niall Hegarty, Pink Elephant)

XIV

Gayding ply the waterway,

To and fro across the bay.

If too put out to sea,

XV

Then on to Burren around the coast, Ah! Here is beauty one fain would boast.

Many scenes of splendour grand, Woodland, lake, and miles of sand.

XVI

One looks across at Courtmac Bay, And see men on boats put out to sea. Black divers undisturbed on Burren Rock, Shrouded and still like a covered clock.

XVII

Somehow her valleys and hills are more fair.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 14

Fig.7: ‘Somehow the elds of Kilbrittain are greener’ (photo Brian Madden)

COOLMAIN CASTLE

By Trióna O’Sullivan Enright

Fig. 1: Present day Coolmain Castle, 2018.

Thepresent day mansion known as Coolmain Castle, set overlooking the breathtaking Courtmacsherry Bay, is a famous Kilbrittain landmark for the many locals and visitors who drive the coast road along Harbour View or walk along the Strand Road at Coolmain.

What might not be as well known is that building seen today is not the original Coolmain Castle. This ancient castle was in fact situated about half a kilometre to the south of the present day mansion. 1

This original Coolmain Castle is thought to have been built as a small “look out” castle by the Lord of Kilbrittain Castle, either a McCarthy or a De Courcey.2 The date it was built is not recorded but would have been sometime after the 13th century when the de Courceys and McCarthys occupied Kilbrittain.

1. Journal of the Cork Historical & Archaeological Society, Kinsale in 1641 and 1642, Vol XIII; 1907.

2. Castles of County Cork, James N.Healy; 1988.

15 COOLMAIN CASTLE

The site of this original Coolmain Castle is situated on farmland currently belonged to a local McCarthy family, who it is thought are descendents of the McCarthy Reaghs who occupied it.3 Unfortunately, very little of this ancient Coolmain castle can be seen on its original site today. All that remains are the ivy covered stone walls that surrounded the site of the ancient castle.

Fig. 2: Coolmain, with tower of modern day mansion visible among the trees, overlooking Coolmain beach (Scott’s Strand). e site of the original castle lies half a kilometre to the south (right) of the current day mansion.

3: Site of the original ancient Coolmain Castle, which was situated directly to the north (le ) of the blue farmhouse on the McCarthy farm at Coolmain.

3. Conversation in 2018 with McCarthy sisters of Coolmain, Brigid and Maudie (Holland), who were told as children that they were descended from the McCarthy Reaghs by their school teacher, Ms.O’Sullivan, Ballymore.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 16

The location in which it was built was ideal to watch out to sea as a “look out point” for the main headquarters at Kilbrittain Castle. It would also have been a useful base to store any goods brought by sea for Kilbrittain by landing at Coolmain strand.4

17 COOLMAIN CASTLE

4. Castles of County Cork, James N. Healy; 1988.

Fig. 4: Remains of the ivy covered stone wall surrounding the site of the original Coolmain Castle.

Fig. 5: Remains of pillars across from the steps at Coolmain beach made from Castle stone. is was likely to have been an entrance connected to the site of the ancient Coolmain Castle.

original castle still existed. The Cork Historical and Archaeological Society recorded in 1907 that “a portion of its old square tower measuring 32 feet x 28 feet x 20 feet in height” was still standing. These dimensions were taken for the Society by a local farmer, Mr. Martin5, whose descendents, the O’Brien family, now reside in the Martin homestead which overlooks Coolmain Castle from the eastern side.

McCarthy sisters Brigid and Maudie (Holland) can still recall playing “shop”, as little children in the 1930s, in the remnants of these tower walls which then stood on their family farm.6

The stones of the original castle were thought to have been incorporated into a dwelling house occupied by the Scott family who lived in Coolmain until about 1870.7 Local farmers in the Coolmain/ Granasig area can also claim to have outbuildings made from this “recycled” ancient Coolmain Castle stone.

5. Irish Tourist Association Files, Kilbrittain, 1942.

6. Conversation with McCarthy sisters of Coolmain, Brigid and Maudie (Holland); 2018.

7. JCHAS, Vol XIII; 1907.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 18

“A short distance inland from the strand is situated in an old garden near strongly built wall which was once portion a proud castle.” Kilbrittain Irish Tourist Association Files, 1942.

Fig. 6: Remains of wall around site of original Coolmain Castle on McCarthy’s farm at Coolmain.

SECRET TUNNEL

A favourite local legend says that Coolmain Castle is connected to Kilbrittain Castle by a secret underground tunnel9 unlikely as they are almost three miles apart.

A variation of this legend was passed down to the current Coolmain McCarthy family who can recall as children searching for a secret tunnel between the original castle site on their farm and the newer mansion.10

1642 CASTLE LOST TO CROWN

At the end of May 1642, Coolmain was taken from the McCarthys by Crown

19 COOLMAIN CASTLE Fig. 7:

Gable end of “ e Old Stall” built in 1928 by the O’Sullivans, Granasig, with stone from the ancient Coolmain Castle.8

8. Information from John Madden,Glanavaud, Kilbrittain. 9. JCHAS, Vol XIII; 1907. 10. Conversation with Jim McCarthy, Coolmain; 2018

forces during the Confederate War. The force was led by Lord Kinealmeaky, a son of Richard Boyle. Coolmain was taken easily and without a struggle by a Captain Hooper who left eighteen men at Coolmain and proceeded on to take Kilbrittain Castle. 11

“ Captain Hooper went directly to Colemaine,and approaching something neer, espied aboundance of people upon the top of it; but presently vanished away left the Castle and betook themselves to Boats which lay neer them for the purpose, they rowed up the River of Tymeleague, and it is supposed they sheltered themselves, for the present in Tymeleague Castle.”

Letter from Tristram Whetcombe, Mayor of Kinsale to his brother, Benjamine, 1st June 1642.12

The McCarthy Reaghs who were only gone as far as Killavarrig Woods beyond Timoleague were unaware of the drama unfolding at home and been lost.

“A ward of 32 musketeers was left until the booty of both castles (Coolmain and Kilbrittain) valued at £1,000 could be brought away.” 13

Once Coolmain was seized, it was granted by Cromwell to Colonel John Jephson. After the Restoration, it was the Duke of York (afterwards James II) who returned it to the Earl of Clancarthy who later forfeited it. After remaining the property of the Crown for some years, it was sold at the great auctions of forfeited estates to the Hollow Sword Blade Company, a sword making company who used the corporate identity of the company to operate as a bank.14

STAWELLS (de STOWELLS)

The Hollow Sword Blade Company soon sold Coolmain Castle on in 1703 to the Stawell family, who had come to Cork from Devonshire in the previous century. 15

Jonas Stawell was the purchaser, but as he died that same year, it was unlikely that it was used as a residence.16 Jonas passed Coolmain to his son

11. JCHAS, Vol XIII; 1907

12. Ibid.

13. Irish Tourist Association Files, Kilbrittain; 1942.

14. The First Stock Market Crash: The South Sea Company; 2013.

15. The Harbour View Hotels and Coolmain Castle, Noel Coghlan, Christmas Bandon Opinion, 2003.

16. Castles of County Cork, James N. Healy; 1988.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 20

21 COOLMAIN CASTLE 17. Stawell St. Ledger Heard Vol I and II, Irish life and Lore Oral History Recordings. 18. Stawell Family Tree – www.wainwrightfamily.org. 19. Fair Strands of South Cork, J.M Semple, Cork Examiner, Nov 1934. Eustace, who married his cousin Elizabeth Stawell from Kilbrittain Castle in 1717.17 The Coolmain Estate passed to their grandson, also Eustace who married 18 Fig. 8:

Painting of Coolmain Castle by Patrick Henessy (d.1980)

Fig 9: e archway at the end of the avenue leading into the courtyard at Coolmain shown in the early 20th century (L) and present day(R), with the eagle from the crest of the Stawell family19.

SCOTT FAMILY

20 and then by the Scott family at the end of the 18th century, when Benjamin Scott leased it from Eustace Stawell around 1784.

Scott household in Coolmain at that time, paying his tithe (tax) on over 90 acres of agricultural land to the Church of Ireland.21 Valuation also records Hibernicus Scott as leasing the original Coolmain Castle site and lands (99 acres) however this time from a different owner, a Thomas Wyse, with the Stawells having moved on to the newer Coolmain mansion.22

The Scotts are the family after whom Coolmain Beach was called23 and it was only ever referred to by its original title of “Scott’s Strand” by Coolmain stalwarts such as Michael O’Donovan (RIP 2013).

BUILDING OF NEW MANSION: TWO COOLMAIN CASTLES

Fig. 10: 1848 map from Gri th’s Valuation showing the site of the ancient Coolmain Castle to the south of the current day Coolmain mansion. Note how the present day mansion was only then called “Coolmain”.

20. Castles of County Cork, James N. Healy; 1988. 21. 22. 23.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 22

During the late 1700s/early 1800s, it was probably the Stawells who built the mansion which is the building we see standing today.

This new dwelling was occupied by the Stawells until the mid 1800s while the Scott family occupied the original ancient Coolmain Castle and lands.24

Records are complicated during this period due to the fact that there were two Coolmain “castles” in existence for a time, the original older Coolmain Castle slowly going into decline after the newer mansion, known simply as Coolmain House, was built. It was only after the new mansion had been renovated into a castellated house and the ancient Castle no longer existed, that the newer building adopted the title of “Coolmain Castle”.25

Eustace Stawell, whose seat was at the new mansion at Coolmain was a First Lieutenant in the Kilbrittain troop of Cavalry and was said to have lived a very extravagant lifestyle. He was often present at the Court of France where he was known as the “The Handsome Irishman”. He died at Coolmain sometime daughters at the time of his death.26

The last generation of Stawells to occupy Coolmain was a grandson of Eustace Stawell, son of his daughter Esther Stawell who had married Alexander William Heard in 1832. 27

Fig. 11: Eustace Stawell “ e Handsome Irishman.”

BOYLE BERNARD

Soon after the death of Eustace Stawell, Colonel Henry Boyle Bernard arrived in Coolmain leasing the mansion along with forty eight acres from the Stawell family. 28

The Bernard family were responsible for adding the tower to the mansion and renovating the mansion into a castellated house, which was the fashion of the time.29

Stawell Family Tree – www.wainwrightfamily.org

Stawell St. Ledger Heard Vol I and II, Irish life and Lore Oral History Recordings, 2013.

Stawell St. Ledger Heard Vol I and II, Irish Life and Lore Oral History Recordings, 2013

23 COOLMAIN CASTLE 24. 25. 26.

27.

28. 29.

Fig. 12: Print of Colonel Henry Boyle Bernard 1867 reviewing the 87th South Cork Light Infantry. He is depicted on his Arab charger while the lines of soldiers march past. eir German bugle band play near the trees beneath the castle tower and on the right in the distance is Coolmain strand (Scott’s Strand).30

Colonel Henry was prominent in both political and social circles in Cork and London. Educated at Eton, he commanded the 87th South Cork Light Infantry for a number of years and was a magistrate for the county.31 After each summer drill in Bandon, Colonel Bernard created quite a lively scene in Coolmain when he would bring the regiment out for a day before it was disbanded for the harvest.

“

scarlet white and blue would march past him while the German bugle band played the quickstep. Casks of beer and porter were enjoyed by the soldiers and their friends until the early hours.”

“Fair Strands of South Cork”, J.M Semple, Southern Star November 10, 1934.

from Coolmain across the bay to Courtmacsherry village.

30. Fair Strands of South Cork, J.M Semple, Cork Examiner, Nov 1934. 31. Death of the Hon. Col. Bernard, Coolmain, Southern Star, March 1895.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 24

Bernard, reclined on an imposing lounge in the stern , the “castle boat” created lively interest in Courtmacsherry visitors as it swept across the water ."

“Gossip from Mayfair,” Belfast Newsletter, June 22, 1928.

Colonel Bernard represented Bandon as an MP in the British Parliament winning a seat in 1863. Hot on his tails for his parliamentary seat was Mr. William Shaw, a man ironically soon also to have a Coolmain address. Bernard retained his seat after two hotly contested elections against Mr. Shaw, eventually losing out to him by only three votes in 1868.32 Not only was Mr Shaw successful in winning the seat, it was also around this period that he built a large house high above Coolmain beach.33

Fig. 13: Colonel Henry Boyle Bernard son of James the second Earl of Bandon.

Fig. 14: Spectacular views of Coolmain (Scott’s Strand) and Courtmacsherry . e manicured lawns were once the site of “ e Great Field” where Colonel Bernard paraded soldiers from the 87th South Cork Light Infantry every summer. Note also the pathway which leads down to what was once the Castle’s “private beach”.

32. Death of the Hon. Col. Bernard, Coolmain, Southern Star, March 1895. 33. Vectis Brand Concrete, Shaw’s Cottage, Cork Examiner, Sep. 1873.

25 COOLMAIN CASTLE

Would this election rivalry perhaps explain the local theory that this building, also known locally as the “Spite house,” was built as an eyesore to interrupt the panoramic views from Coolmain Castle?

and he was declared bankrupt before he passed away in 1895 at Coolmain, aged 83 years.34

McCarthy sisters, Brigid and Maudie (Holland), can recall Shaw’s cottage when it was used as a holiday home in the 1930s as having very modern the rooms.35

It was later referred to as “the Nun’s House”, when it was used by the Presentation Sisters who spent glorious summers overlooking Coolmain and the “Nun’s Cove”.

In the 1990s Shaw’s cottage was purchased and demolished by the Disneys, who had recently acquired Coolmain Castle.

Fig. 15: Photograph of a painting of Courtyard at Coolmain Castle in later half of the 19th century. It is thought to feature Coolmain local Denis Cronin, dancing a jig with his neighbour to the music of the band of the 87th Cork South Light Infantry rehearsing, while a group of neighbours look on.36 e original painting is today in the possession of the family of Stawell St.Ledger Heard (died 2015) in May eld, UK.37 Denis Cronin (born 1832), is a great grandfather to Dan, Mary, Humphrey, Redmond and Carmel Cronin, Coolmain.

34. Bankruptcy of Colonel, the Hon B Boyle Bernard, Kerry Sentinel, Jan 1885.

35. Conversation with McCarthy sisters of Coolmain, Brigid and Maudie (Holland), 2018.

36. Information from Mary Hall (Cronin), Coolmain, August 2018.

37. Stawell St. Ledger Heard Vol I and II, Irish Life and Lore Oral History Recordings; 2013.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 26

NO “TROUBLES” FOR COOLMAIN – THE STAWELL HEARD FAMILY, EARLY 1900s:

By the turn of the 20th century the original Coolmain Castle was fully abandoned and the site no longer inhabited. After the death of Colonel Bernard, the Stawell family returned to Coolmain when Alexander E. Stawell Heard, a grandson of Eustace Stawell, took up residence in the Castle with his wife Dorothia.38

Coolmain was one of the only great houses in the area that escaped burning during the years of the Troubles around 1920. Mr. Heard was a judge or magistrate in Clonakilty and deemed to be very fair and popular with the locals, which is probably why it was spared.39 The Castle was in fact searched for arms in 1918 and Mr Heard subsequently claimed £150 compensation for damage to his property.40

Alexander Stawell Heard died in May 1925 and the Castle was sold the same year to Mr Lionel Baldwin, bringing to an end the long reign of the Stawells at Coolmain.41

Fig. 16: e famous head of Brian Ború situated in courtyard of Coolmain Castle. A daughter of King Brian, Sive, married Cian, a son of the chief of Uí Eachach clan who controlled Kilbrittain. e e gy of King Brian was removed from Kilbrittain to Coolmain sometime during the 1920s/1930s a er Kilbrittain Castle was burnt by local Volunteers during the Troubles of 1920.42

National Archives – Census of Ireland 1901/1911 accessed at

Correspondence from Bob Willoughby to Sinclair family, 1976/1977.

Rural Councils, Kinsale; Cork Examiner, May 1918.

Sale of Historic Castle, Cork Examiner, July 1925.

“How Are the Mighty Fallen”, Richard Henchion, Bandon Historical Society, Vol.No.20; 2004.

27 COOLMAIN CASTLE 38.

www.census.nationalarchives.ie 39.

40.

41.

42.

Fig. 17: Steps and archway leading to the magni cent gardens o the courtyard in Coolmain, Castle. ese steps are said to have come from Kilbrittain Castle a er it was burnt during e Troubles of 1920.43

DONN BYRNE

Although he only lived there for a very brief period, one of Coolmain’s most famous residents was the world renowned novelist Donn Byrne who purchased the castle in the late 1920s. to Irish parents. The family returned home soon after and Donn spent his and literature at universities in Ireland and abroad. He became a world renowned author writing eleven novels, three collections of short stories and one Irish travel book.44

Donn Byrne came to Coolmain in 1926 after he caught sight of Coolmain Castle while travelling to Queenstown (Cobh) on a liner. He leased Coolmain for six months in 1926 and 1927, all the while enjoying racing and gambling on the French Riviera.

One lucky night at the Casino in Cannes gave him the £2,000 funds he

43. “How Are the Mighty Fallen”, Richard Henchion, Bandon Historical Society, Vol.No.20; 2004. 44. Recalling Donn Byrne on Visiting Coolmain, D.J. Murphy; Cork Holly Bough; Dec 1976.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 28

needed to buy the castle outright in 1928. 45

Unfortunately Donn’s lucky streak was not to last. In June of the same year, while driving home along the coast road from the Esplanade hotel in Courtmacsherry, his car went into the sea at Burren pier during high tide where he drowned. 46

His secretary, Miss Kathleen Britter who had been travelling with him, witnessed the accident and tragically minutes before had pleaded with him not to drive any further as the car’s steering was faulty and she was too afraid to travel any further. 47

Another theory is that Don might have been trying to turn the car around on the narrow road to go back for Miss Britter and toppled over the low roadside edge. 48

Don Byrne is buried at Rathclaren Graveyard with the famous inscription on his tombstone: “Tá me mo chodladh Is ná duisigh mé.

In 1930 Don Byrne’s widow, Dorothea, remarried an agent of her late 1933, when they left for England.

Fig. 18: Gravestone of Donn Byrne at Rathclaren cemetery, Kilbrittain: “Tá mé mo chodladh Is ná duisigh mé. DONN BYRNE Born 29th May 1889 Died 28th June 1928 I am in my sleeping And don’t waken me”

A Don Byrne Conspectus, J.J. O’Keeffe, Bandon Historical Journal No.13, 1997.

The Donn Byrne Story, Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vol 24, 2012.

Inquest of Death of Donn Byrne, Southern Star, June 1928.

The Donn Byrne Story, Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vol 24, 2012.

29 COOLMAIN CASTLE

45.

46.

47.

48.

Fig. 19: Mary “Molly” Murphy, Coolmain with Donn Byrne’s widow, Dorothea at Coolmain. Mary spent her lifetime looking a er Coolmain Castle from the time of the Stawell Heards (early 1900s). Two more generations of the Murphy family have looked a er the Castle to the present day. Reproduced with kind permission of the Murphy family, Coolmain.

AN ICA CONNECTION

In 1936 the Irish Country Women’s Association saw the potential of using Gahan from Dublin.50

Thirty two girls from all over the country camped in the grounds of Coolmain Castle for a fortnight, with numbers increasing up to one hundred as girls from local guilds attended daily.

Although the Castle was unfurnished, the innovative association borrowed utensils and arranged an impressive programme of classes and activities that would easily outshine any summer camps available today.

The ladies skills in “making do” were really put to the test when an

49. The Donn Byrne Story, Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vol 24, 2012. 50. Irish Countrywomen’s Summer School, Irish Press, August 1936.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 30 eye of Coolmain’s loyal caretaker, Mary Murphy. 49

Fig. 20: Tower at Coolmain Castle which was added on to the mansion by the Bernard family when they renovated Coolmain into a castellated house during the mid 19th century.

31 COOLMAIN CASTLE

intruding foxhound helped himself to the cooked ham intended for the never knew their loss!51

Mornings were spent by girls attending lectures on a wide range embroidery stitches, gloves, using beach stones to make jewellery, interior design, wallpapering and painting rooms.

Daily cookery demonstrations were followed by physical exercise and drama in the afternoons. Evenings were spent Irish dancing and singing.

Swimming in Coolmain and a boat trip around the Bay was organised by a Mr Ruddock. On the 29th July, the group were also hosted by Mrs Healy who invited the girls to tea at Harbour View.52

At night, stretcher beds were pulled outside and the girls enjoyed sleeping under the stars overlooking the moonlit waters of Coolmain.

The summer school climaxed with a festival of three plays, ballet and mimes.

21: Church Cottage was built during the 1800s and served as a private chapel for the residents of Coolmain Castle.53 It also served food to the poor, and school classes were held here54

Irish Country Women Association Archives, Summer School, Coolmaine Castle, Cerise M.Parker.

Irish Countrywomen’s Association, Southern Star, August 1936.

Unchanged by Hands of Time, Philomena (Mary) Hall, Cork Holly Bough; Dec 2006.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 32

51.

52.

53. 54.

Fig.

Fig. Fig. 22: e Courtyard on the Northern side of Coolmain Castle.

COOLMAIN 1940s TO 1970s

Although Coolmain had fallen into a state of disrepair, it was purchased by the Shaw Steele family who took over the castle in the late 1940s and established a country house hotel attracting visitors who enjoyed beach

The O’Sullivans, Granasig can recall attending a Christmas Eve children’s tea party in 1949 with games and festivities for all.

Fig. 23: Innovative Coolmain Castle advert from 1948.55

It was about this time that Coolmain Castle was advertised as an innovative “holiday and Rest Camp for greyhounds”. The advert published in 1948 caused a London newspaper columnist familiar with the beautiful environs at Coolmain to quip:

“A London owner I know whose dogs have been in the class recently says. ‘They are staying in their kennels; I am going to the holiday camp myself.’”

33 COOLMAIN CASTLE 55. Advertisement, Southern Star; May 1948.

Farmer Victor Ruskell bought Coolmain in the 1950s and farmed the lands surrounding the castle growing crops of oats and barley. Mr Ruskell decided to leave Ireland in 1957 and emigrate down under, auctioning off much of the castle contents before he left.

“COOLMAINE” WITH A RUSSIAN CONNECTION

Millionaire, William Patrick Barbour, synonymous with the reels of linen thread produced in Belfast, bought Coolmain in 1957. Mr. Barbour is remembered for travelling around the local area in style, in a large chauffeur driven car and it was he who was responsible for temporarily adding the “e” to the name Coolmain. He spent a lot of money renovating Coolmain which had fallen into disrepair while it had been empty over the previous decades.56

In the 1970s, it emerged that Soviet spy Anthony Blunt, part of a Russian spy ring that had penetrated Britain’s secret service, was a regular visitor to Coolmain Castle as a guest of Mr. Barbour during these years. 57

Barbour left Ireland for Spain and by 1963 Coolmain was back on the market, along with forty acres.

Fig. 24: Gates to present day Coolmain Castle. Note how the “E” was removed during the ownership of Bob Willoughby, reverting to the original spelling of Coolmain. e avenue into this mansion in the mid 1800s was on the eastern side of this entrance above Croisín na Faillimhe.58 Up until the 1930s, there was also a gated entrance on the corner down below Cronins, above Poll na Deora (Hole of Tears).59

56. Irish Country Women Association Archives, Summer School, Coolmaine Castle, Cerise M.Parker. 57. Cork Examiner, Nov 1979. 58. Coolmain Ordnance Survey Map, Ref 124; 1847. 59. Information from Mary Hall (Cronin), Coolmain.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 34

GERMAN INDUSTRY 1966

In the current age of environmental awareness and “going green” it is hard to believe that the idyllic location of Coolmain Castle nearly became a German factory in 1966, with plans to manufacture chromium sand paper, sand bills and equipment.

A Frankfurt industrialist, Klingspur, bought Coolmain and had even gone so far as to move expensive equipment into the Castle. Several local men, including David Madden, Paddy Burke and Denny Murphy (son of Mary “Molly” Murphy), had been brought to Germany for a number of weeks for training.60 which led to the project being scrapped.61

35 COOLMAIN CASTLE 60. The Changing Faces at Coolmain Castle, Seán Quinlan, The Courcey Chronicle, 2014. 61. Kilbrittain Project Folds Up, Southern Star, July 1966.

Fig. 25: Magni cent gardens at Coolmain today.

Donn Byrne has certainly not been the only world famous owner of Coolmain Castle in this past century. 1973 saw international Hollywood photographer Bob Willoughby moving to Coolmain Castle with his wife

Bob had photographed many of Hollywood’s biggest stars including Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, John Wayne and Audrey Hepburn.

The Willoughbys did a superb job in renovating Coolmain as a family home and immersed themselves into the local community even taking their turn to host the Catholic “station” mass for all the neighbours. After 16 years and with their young family reared, the property became too large for Bob

Fig. 26: Present Day Coolmain Castle.

DISNEYS

Roy E. Disney, nephew of Walt Disney and vice chairman of the Walt Disney Company, purchased Coolmain Castle in 1989. A keen sailor, Roy was a regular visitor to the Cork Race week for the next 20 years before he passed away in December 2009. His wife Patricia died in Feb 2012.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 36

refurbishments on the house and surrounding gardens, under the careful supervision of their loyal staff, Coolmain local, Adrian Murphy and USA native Tim Herron and his Irish wife, Margaret, who sadly passed away in recent years. Today Coolmain remains the private residence of the Disney family.

With special thanks to Noel Coghlan (RIP Nov 2018), Brigid McCarthy and Maudie Holland (née McCarthy), Tim and Jim McCarthy, Barry O’Sullivan, Tim Herron, Mary Hall (Cronin), Dan and Helen Cronin, the Murphy family, Anne Madden and John Madden for their help and information in writing this article.

37 COOLMAIN CASTLE

Fig. 27: View of the Castle from the Strand Road- a familiar sight for those who frequent Coolmain beach.

ANNETTE HICKEY PHOTOGRAPHS

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 38

e entrance to Kilbrittain Village during the heavy Spring snowfall, taken on the 1st March 2018 (Annette Hickey)

In the centenary year of the armistice that ended WW1, we remember local man Michael Burke of the Royal Garrison Artillery, son of John and Catherine Burke, Ballycatten. Michael died in action aged 38 on June 9th 1918 (courtesy of Annette Hickey, grand-niece).

39 ANNETTE HICKEY PHOTOGRAPHS

EVICTIONS AND AGRARIAN DISTURBANCES IN THE LOCAL AREA DURING THE 1880S.

By Jerome Lordan

BACKGROUND:

Atthe end of the 1870s the relationship between landlords and tenants was stable. Good harvests and good markets contributed to the calm that existed. Within a couple of years poor harvests, adverse weather conditions and deteriorating markets changed things radically. In 1877 the oat and barley crops as well as the potato were particularly poor due to a cold and wet summer. This was followed by three successive years of similar weather conditions. In 1879 the winter was the coldest in living memory,

cattle fell dramatically with stock down 25% at Kinsale Fair compared to six months previously. Pasture and livestock deteriorated due to the excessive rainfall and very cold weather. Demands for reductions in rent in 1879 were not received too kindly by landlords and land agents. By enforcing the payment of the customary rents in spite of the depressed state of agriculture, they unwittingly assisted the start of agrarian upheaval in 1879. This led to the foundation of the Irish National Land League in October of

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 40

Fig.1: An eviction scene from 19th century Ireland. Battering rams such as the one shown were o en used to evict tenants.

EVICTIONS AND AGRARIAN DISTURBANCES IN THE LOCAL AREA DURING THE 1880S.

defence of those threatened with eviction for refusing to pay unjust rent, and the ownership of the land by the occupiers. In the initial period of evictions as a consequence of the aforementioned problems, landlords were sure that the lands would not be left unoccupied. This, however, was counteracted by boycotting the new tenants who moved in, the ‘land grabbers’ as they were known, were ostracised by members of the community and were often subjected to various forms of intimidation. Gangs of ‘moonlighters’ regularly dished out violent treatment to the land grabbers.

The markets stabilised and conditions improved in the early 1880s. However, by 1884 conditions, both climatic and economic, again took a turn for the worse. A drought in the early summer of 1884 resulted in high feeding costs and decline in milk and butter production. This was repeated in 1887, the driest year of that century. Market prices fell sharply, and butter the mainstay of agricultural produce in Cork reached a new price low. New competition from continental Europe was one of the main reasons for this price decline. All this time the tenant and landlord were at odds over rental prices. Some tenants had judicial

Fig.2: e Land League issued a ‘No Rent Manifesto’ in 1881 while Parnell and the leadership were incarcerated in Kilmainham Gaol on false charges. Such actions emboldened tenants to resist evictions all over the country.

League was quick to see the possible danger in this distinction, as it created the possibility of dividing their organisation and jeopardising their stand. They fought strenuously to ensure this distinction did not gain currency. The Kinsale branch of the Land League (800 branches nationwide) passed a resolution in 1886 prohibiting those members who owned threshing machines from hiring them to farmers who had not joined the league.

41

These sanctions took their toll on the Landlord Class, the Earl of Bandon had no takers for the homes that the previously evicted tenant farmers

the harvest could not be gathered in by the continual wet weather of that year. Practically all landlords in County Cork offered to make at least some reduction in their rents in 1886 and early 1887. These reductions amounted to about 25%; although some, like the Earl of Bandon, refused to alter rents

agricultural production and markets. Things looked better than they had for suffered greatly during 1890.

Overall economic improvement, the decline in agrarian warfare, the 1887 Land Act all contributed to a return of normal conditions between both parties. Judicial leases became more commonplace and overall there was a reduction in rents by an average of 22% in Cork County. The landlord class had lost much of their former power, with representatives of the people taking up roles in all walks of life. The Local Government Act of 1898 further consolidated the role of the working class nationalist population with their appointments to local government, boards and urban district councils.

KNONCKNACURRA 1885.

An eviction took place in Knocknacurra in early August 1885. The person

was stated had nothing to do with the events that followed at his homestead. He occupied about 140 acres of land under the Court of Chancery on the usual lease of seven years, with his brother Denis being the nominal tenant. The yearly rent was £91.10s. The lease expired the previous September

Michael was left as caretaker as it was expected he would become tenant for a further term under the court. The land was valued by Mr. E.A. Appelbe, S.N. Hutchins of Ardnagashel, near Bantry. He was the Receiver under the

named Downey killed in an agrarian dispute. He valued the land at £75. Michael Flynn tendered at Appelbe’s valuation and his offer was refused by the court and a decree to possession was obtained against him at Innishannon petty sessions, which Hutchins proceeded on the following

42

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY

AND AGRARIAN DISTURBANCES IN THE LOCAL AREA DURING THE 1880S.

Monday to carry out. On his arrival in Bandon he sought to hire a car. There were plenty of available cars, however, none of them could be induced to drive him to Knocknacurra to carry out the eviction. Hutchins along with the sheriff’s bailiff, John Hosford and another man walked to the eviction scene. Meanwhile, the church bell rang in Ballinadee, horns were sounded and three or four hundred men proceeded to Knocknacurra before Hutchin’s

rest of the furniture having been removed days before. Michael Flynn, had no thought of resistance, passive or otherwise. This, however, did not suit the gathering crowd and after a discussion as to the best means of obstruction, a large Scotch cart was put in one of the rooms upstairs. This was easily done as the stairs was large (once the house of a country gentleman). The wheels were placed on after it was put in the upstairs room. The linchpins were riveted and battered down, the wheels secured by chains

taken upstairs and secured to the cart. The windows were closed, doors barricaded and several of the men remained inside. The crowd got bigger and bigger and were joined by twenty men on horses from Newcestown, who had been drawing coal from Colliers’ Quay (a short distance upriver from Kilmacsimon) and hearing about what was taking place they left their carts at the roadside. Eventually Hutchins and his party arrived and soon

arrived from Innishannon. While waiting for the RIC to arrive, a stone was thrown at Hutchins, but it failed to hit him. Whilst waiting, Hutchins was threatened by waving sticks. He then proceeded to the house surrounded by the RIC men and with a large stone started battering the door, no other appliance being at hand. Great excitement prevailed while this was being done. A man stuck his head out one of the top windows over Hutchins head, brandishing an iron bar and it was fully expected he was about to strike him with it. Shouts of encouragement to hit him were raised. One of the constables pointed up his gun at the man and cautioned him against doing so. A whisper went around from the back of the crowd to throw stones from

door was eventually broken in and the hall found to have a group of men ready to resist the entering party. They were, however, cautioned by the

trap had been set on the stairs by tearing up some of the boards and laying them across again. So that anyone stepping on them would fall through and risk injury. After two hours the only thing that had been removed was the donkey. It was found necessary to send to Bandon for reinforcements.

43 EVICTIONS

Mr. Hutchins sat outside under a tree while waiting, and another stone was thrown at him which missed the target. The crowd continued to jeer and goad him, with the chant “who shot Downey?” being repeatedly cried out. The wildest rumours prevailed in Bandon and all available policemen, with District Inspector Hayes and Head Constable Coughlan were dispatched to the scene. Cars were refused to the police and it took quite a while for them to arrive. When they got to the scene the greater part of the crowd had scattered. Those who remained were again cautioned by Mr. Hayes, and late in the evening the cart, after a most tremendous hammering was

property and land was taken soon after.

FURTHER EVICTIONS FROM THIS PERIOD:

Old Head 1884: The Hannon family of Dooneen were evicted from their land and neighbours helped fund the family on the voyage to America. The family worked hard and saved with the intention of returning home. They did so in 1904 and repurchased the land they were evicted from twenty years previously.

Ballinscarthy 1887: Tim Hurley was evicted from his home, known as

including the county inspector named Curling of Bandon.

Kilbeg 1887: Maurice Hickey was evicted from his farm. His landlord was Denis Wade and the rent on the land was £2 per acre, double the government valuation. The eviction was carried out under John Savage of Kinsale and eight policemen. There were approximately two hundred people present, including the Rev. Canon McSweeney and C. Crowley. Wade was a middleman and his agent was G.T. Appleby, Deputy County Surveyor of North Main Street, Bandon.

In 1888 up to sixty tenants had been served with eviction notices on the Bandon Estate.

Lauragh 1888: Denis Sullivan had always paid his rent and ‘noticed’ under the eviction made easy clause. The eviction was unexpected and ruthless. Ardcrow 1880s: John O’Neill refused to pay rent to Baldwin Sealy his

44

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY

EVICTIONS AND AGRARIAN DISTURBANCES IN THE LOCAL AREA DURING THE 1880S.

stones for throwing at the eviction party who came to evict O’Neill. They put a bull in the back kitchen and on opening the door the bull charged on the attacking party. Outside the front door they put a goat with a notice on her horns “Sealy keep clear”. Eventually the troops took over the house and the tenant paid the rent rather than be evicted.

Cloundreen 1880s: A man named Cullinane was also evicted by Sealy, because he could not pay the rent. He was afterwards allowed to live in the house as a labourer, and through the Land League, got back the land again.

Farranagark 1880s: Patrick Keohane was evicted by the father of Percy Scott and given a smaller holding in Ardcrow, from which he was later evicted for the second time.

Borleigh 1890: The following people were evicted from their holdings, Ellen Ring, Thomas Cotter, Daniel Crowley and a Driscoll man. The land they were evicted from was poor

good times. The Bandon Union refused them outdoor relief after the events.

Bibliography

Fig.3: e Royal Irish Constabulary were utilised by the agents to e ect evictions. is did not bode well for their popularity in subsequent decades.

The Cork Examiner, October 1904. Cork Constitution, 5th August 1885. Bandon Genealogies

Burren N S, Folklore School’s Collection 1939.

45

MIKE BROWN PHOTOGRAPHS

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 46

Two wonderful images of the wave breakers at Harbour View, by renowned local nature photographer, Mike Brown

CHARLIE HURLEY

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

1

By Denis O’Brien

3

but none of you will be with me”.

These prophetic words of Brigadier Commandant Charles Hurley, Brigade, came true on the 19th March 1921. Outside of Cork his name today is virtually unknown. Yet there are few soldiers of the War of Independence who have a stronger claim to remembrance or

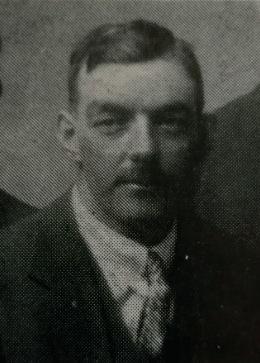

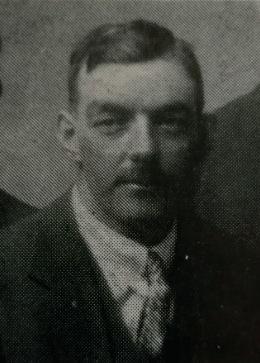

Fig. 1 – Portrait of Charles Hurley, Baurleigh (Photo courtesy of Michael Coleman, grand-nephew).

47

(1893-1921) PART

OF

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER:

Volunteer Organiser of the Cork Third (West Cork) Brigade, was born in 1893 in Baurleigh, Kilbrittain. Parish birth records from the time show that he was born on the 21st March 1893 and baptised by then Curate of Kilbrittain, Timothy McCarthy C.C., on the 22nd March 1893. Son of John Hurley, a farmer and Mary Hurley nee Fleming from Barryroe, his godparents were John McCarthy and Ellen Buckley.1 The tradition of the time was to have the child christened the day following the birth as infant mortality was usually high. However the birth record from the Birth Registrar in the District of Kilbrittain, Co. Cork showed Charlie’s date of birth as the 29th March 1893. The birth record was registered on the 4th May 1893.2 The question could be asked: did Timothy McCarthy C.C., enter the incorrect date on the baptism record or

brothers, James and William, and four sisters, Catherine ‘Katie’ (eldest), Mary, Ellie ‘Nellie’ and Margaret ‘Maggie’ (youngest).3 He came from that farming stock which has given Ireland so many of its great men.

By coincidence, also raised in Baurleigh at the time, was Charlie Hurley’s neighbour, friend and second cousin, Diarmuid 'Gaffer' O'Hurley (often called ‘Hurley’), who would become Midleton Company Commander and O.C. Cork No. 1 Brigade I.R.A. during the War of Independence.

EARLY YEARS

Charlie Hurley was educated at Baurleigh National School. In his early teenage years, Charlie had an interest in local Gaelic games and was a noted hurler for his local club, Kilbrittain. In 1910, Charlie lined out at right

Shanballymore at the Cork Athletic Grounds.4

After leaving national school he worked in a store in Bandon. While employed there he studied for, sat and passed the Boy Clerks’ Civil Service Examination and was appointed to a post at Haulbowline Dockyard, Queenstown (now Cobh), Co. Cork. He served at Haulbowline from 1911 to 1915, when he was ordered to transfer to a Liverpool depot for promotion.5 He refused to accept the transfer as it entailed conscription in the British

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 48

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

years old, that he joined the Irish Volunteers. He was already in the national tradition, for he was a hurler and a lover of Irish customs and the Irish language.6 He resigned from his job in Haulbowline and returned to his native West Cork to organise the Irish Volunteers.7

Fig. 2 – An American warship moored in Haulbowline in 1918.8

The following letter was sent by Charlie Hurley to Seamus Fitzgerald, fellow volunteer and later Fianna Fail T.D. and industrialist, then residing at 3 East Beach, Cobh on 1st August 1916:

1. Kilbrittain Parish Birth Records.

278 (Registered by Superintendent James Shorten, Registrar, District of Bandon, 4th May 1893) source, John Desmond.

1901 Census, Hurley family, Baurleigh, accessed from www.census.nationalarchives.ie

Southern Star 17 August 1963, p.7 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

Southern Star 24 March 1951, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

Southern Star 25 March 1961, p.12 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

Photo sourced from Ireland’s Naval Base & Navy booklet.

49

2.

3.

4. 5.

6.

7.

8.

Dear Jim,

Having learned from various sources that you are once again approachable and breathing the free air which many a patriot is denied, I write you that you may share your joy with an old friend with whom you once shared the labour which the good old cause demanded of you.

There is no need to dwell, I’m sure, on how proud I feel when my old chums in Cove [Cobh] were pronounced “disloyal”, a good old word which means loyal to Ireland – and also there is no need to congratulate you on being crowned with the “Felon’s Cap” because I know as regards this you feel as only having done your duty, for which no congratulations are necessary.

Speaking to Pat O’Dwyer, one of your fellow-prisoners, on the day following his arrival in Bandon, he told me you and Mick Leahy were

term and I hope he will pass from the “hand so vile who dare not hold hearts so brave”.

I need not refer now to the sudden shattering of our most cherished hopes, to that glorious, though bloody chapter recently added to our fair island’s story. Let us never forget the men who died and pray that their equals in other times may be blessed with better results attending their efforts.

Prior to the outbreak, Jim, I was sorry I was compelled to knock off our correspondence with you through illness, am yet pretty bad and have would never rise. But I am well again thank God and never in my life so anxious to be up and doing. I would dearly like to see you all in Cove now and perhaps in the near future I will turn my steps to that dear place. I would have written sooner but have been enjoying solitude on the seashore for the last six weeks.

I wrote to Maurice Mac some time ago, but as I never got an answer I take it he never received the letter. This is not at all unlikely as the matter it contained was deemed seditious by the Prison Authorities, I’m sure.

I trust you and the boys in Cove are well and would you please remember me to any with whom you may come in contact – more especially your fellow comrade, Mick Leahy. I shall anxiously look forward to a letter from you and believe me still a member of the Cove Special Scouting Section.

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 50

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

I remain, Yours sincerely, (Signed) C. Hurley

After recovering from the long illness described in the preceding letter, Charlie Hurley went to work at McSwiney’s corn merchants in Bandon, where he befriended Liam Deasy. There he became associated with Sinn Fein and the Gaelic League. Liam Deasy would later recall that “as an enthusiastic young Gael he was prominent in hurling. He was an ardent member of the Gaelic League and a popular member in the dramatic class.”10

CASTLETOWNBERE AND THE BEARA PENINSULA

In early autumn of 1917, Charlie Hurley left Bandon to work in Castletownbere. He was employed as a managing clerk for Denis F. McCarthy, who was also a Naval contractor. Also working at McCarthy’s General Supply/Naval Stores were the sisters Maggie and Nora O’Neill from nearby Church Gate. They

During the years between 1917 and 1918 the harbour at Berehaven was full American, were anchored there on and off for fresh stores and water.

Charlie Hurley was in receipt of a wage of £3 per week. Of this sum he contributed £1 per week to the support of his father.12 Had he remained in civilian life, Charlie Hurley may have developed into a prosperous merchant but instead chose to become involved in organising and training the local branch of Volunteers, the Castletown Company IV which had only just started. In the more responsible clerk jobs he was a success, but they were no longer his main work. That was soldiering. He practised sections and platoons and soon, as was inevitable to one with such energy, imagination

esteem in which he was held in the town was found in his immediate

9. Southern Star 29 May 1971, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

10. Southern Star 24 August 1963, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

11. Charlie Hurley Visit to the Beara Peninsula, Southern Star 05 June 1971, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

12.

PDF_Pensions/R5/1D189%20Charles%20Hurley/1D189%20%20Charles%20Hurley.pdf

51

9

11

brother of Maggie and Nora, was elected Second Captain and John Cronin was elected Third Captain. Charlie Hurley would rapidly rise (in days when command.13

A SURPRISE NATIONAL PARADE

hold a parade on St. Patricks Day, 17th March 1918. They marched from Company and also the Beara Battalion Engineer recalled:

“It was decided to carry out a St. Patricks Day Parade as a diversion and

The column of men on the parade carried hurleys and ash plants, pick handles, etc. It was a properly disciplined march and there were several military orders given. The townspeople were nervous as they didn’t know what was on.”14

It was arranged that Charlie Hurley would meet the Eyeries men (about one hundred volunteers led by John Driscoll, O.C. Eyries) there with his Company,

men of the Eyeries Company would unobtrusively drop out of the ranks on the way to the assembly, slip back to the village, and approach as closely as possible to the R.I.C. barracks without being seen. There they would lie in wait till the door of the barracks was opened, and then rush it. The

later of Crossbarry fame) who held up the barrack orderly (Constable 15 The

against an R.I.C. Barracks after the 1916 Rising.

13. Southern Star 24 March 1951, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

14. irishnewsarchive.com

15. Deasy, Liam, ‘Towards Ireland Free’, Mercier Press (1973, Rept. Cork, 2015) p.29.

16.

17. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1567. James McCarthy, Lieut. IRA, Cork 1921.

52

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY

No arrests were ever made in connection with this raid. On the night following the raid on the barrack, Constable Cahill met Peter Neill one of the raiders in a public house in the village. He referred to the raid saying that he had been in Drimoleague when a bomb had been thrown into the

were dismissed from the R.I.C. following the raid.17

Fig.4 – Some 1918 newspaper accounts of the Eyeries RIC Barrack raid. 18/19

The R.I.C. were very active following the parade and the raid at Eyeries. James O’Sullivan, member of Castletownbere Company, recalled the situation:

“Our Company O.C. (Con Lowney) was arrested. I think that he was charged with illegal drilling. He was brought before the Petty Sessions Court. He recognised the court and, for so doing, was removed from the post of Company O.C. by the Battalion O.C. (Charlie Hurley). It was an

53

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

Fig.3 – Le : Eyeries R.I.C. Barracks, (blue building) and right: Christy O’Connell, Eyeries (Photo courtesy of Diarmuid Begley).

order at this time that Volunteers, if arrested and charged in connection with their activities, should refuse to recognise the authority of the enemy

About this time the R.I.C. raided for John Driscoll and Charlie Hurley in connection with the parade in Castletownbere on St. Patrick's Day. It was proposed to arrest them on a charge of illegal drilling. They were not at home when the raids took place and both now went “on the run". Charlie Hurley, who was now Battalion O.C, spent most of his time in the Eyeries district at this period.21

RAIDERS OF THE FLYING FOX

Engineer recalled: “Charlie Hurley was determined that we should raid the Naval Stores and also raid the ‘Flying Fox’, a British Naval patrol boat.22 A few weeks after the raid on Eyeries Barracks, Charlie Hurley, Captain of the Castletownbere Company, assisted by Billy O’Neill, carried out a daring raid on the British patrol boat, HMS Flying Fox, which was stationed at Castletownbere Pier. Armed with revolvers, the two Volunteers boarded the

However, some of the crew of the HMS Flying Fox were local men whose

and the Volunteers reluctantly agreed to do so.23 The courage of the duo’s raid was all the more remarkable as there were two hundred or more crew on board.24 The raid was successful with the arms and ammunition secured

18. Skibbereen Eagle, 18 May 1918, p.3 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

19. Irish Examiner, 16 May 1918, p.2 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

20. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1528. James O’Sullivan, Castletownbere, Member, IRA, Cork 1921.

21. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1567. James McCarthy, Lieut. IRA, Cork 1921.

22. Southern Star 05 June 1971, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

23. Deasy, Liam, ‘Towards Ireland Free’, Mercier Press (1973, Rept. Cork, 2015) p.31.

24. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1474. Eamon O’Dwyer, Member IRB,

25. Based at Queenstown (modern Cobh) in the south of Ireland, this type of patrol boat escorted incoming ships from the North Atlantic and hunted German submarines. HMS Flying Fox was built on the Tyne in the Neptune Yard of Swan, Hunter & Wigham

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 54

20

Fig.5 – e dazzle camou aged painted '24' class Naval Sloop HMS Flying Fox on her sea trials.25

About the same time, a small group of unarmed Volunteers of the same Castletownbere Company under their intrepid Captain, Charlie Hurley, carried out an ambush on a party of armed military. Jeremiah McCarthy, a local Volunteer, observed three soldiers leaving the town and going in the direction of Furious Pier. He immediately alerted Charlie Hurley and Billy O’Neill. The three Volunteers hastened to Rodeen Cross where they took up a concealed position in the narrow laneway near the main road, and waited for the soldiers to come along. It was still daylight and local people were passing by, but the Volunteers could not be seen from the main road. The military appeared, and each Volunteer was assigned a soldier to overpower and disarm. The soldier assigned to Charlie was nearest in line as the trio approached the crossroads. Ironically enough, the song he was singing as Charlie jumped on him and brought him crashing to the ground was ‘Johnny, Get your Gun!” But this soldier was merely carrying a parcel and

swiftly snatched from them by the Volunteers. Bearing their precious prize they ran, Charlie Hurley remarked, ‘There is no Canon with us today!’26

FORMATION OF BEARA BATTALION

To meet the conscription threat of late spring of 1918, Charlie Hurley

26. Deasy, Liam, ‘Towards Ireland Free’, Mercier Press (1973, Rept. Cork, 2015) p.32.

55

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY without loss.

organised a very primitive munition factory in a vacant farm house at Eyeries. There he manufactured crude, but effective, canister bombs and mines for future activities.27

Commander.28 The Castletownbere area was organised on a battalion basis. There were now units at Bere Island, Castletownbere, Eyeries, Ardgroom, Urhan, Ballycrovane, Ardrigole and Inches. These companies formed Castletownbere (Beara) Battalion. On the 1st

O.C. Charlie Hurley; Vice O.C. Sean Driscoll; Adjutant, Mick Crowley; Q.M. Dan Sullivan.30 The only type of training carried on was ordinary close order foot drill, with occasional public parades and route marches. Training was carried out under our own military training manuals obtained from members of the British garrison on Bere Island. The strength of the Battalion was about 700.31

Vol. James O’Sullivan recalled:

“Early in June, 1918, the members of Beara Battalion seized a large quantity of gun-cotton, primers; and detonators from the military stores on Bere Island. The whereabouts of this material was discovered by Eugene Dunne (I/O Adrigole Company) who was employed by Bantry Bay Steamship Company as a clerk. He reported the position to me and to his own Company (Adrigole) O.C. It was decided to raid the store and remove the explosives. The raid was carried out on the morning of 5th June 1918. Operations began at about 1 a.m. Nearly every member of Bere Island Company was engaged, acting either as scouts, outposts or in the actual removal of the explosives from the store to a boat at the pier. When the store had been cleared of explosives we rowed across the harbour from Bere Island Pier to Bunow where the men from Adrigole were waiting to unload the boat. When the boat had been unloaded we returned to Bere Island some time about 5 a.m. This guncotton was dumped in Adrigole area, from where it was removed in small Quantities as required.”33

Engineer recalled the arms dumps:

“Charlie Hurley was the only man authorised to take stuff out of the arms dumps. Charlie stayed at my father's place and also at Timmy Kelly's of

56

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

Pullincha. He was on the run at that time. The British were trying to trace a box of ammunition (500 rounds of shotgun ammo consigned to D.F. McCarthy, Berehaven) taken out of the Bantry Bay Steamship

pointed at Charlie. That man was the only man authorised to take stuff. An arrangement was made with Hurley to take stuff out of the dumps and let a little note as proof. The great danger was if many people were allowed to go near the dumps it would show a trail. If arms were wanted they were taken out and put in a different place for distribution.”34

The Battalion O.C. (Charlie Hurley) was arrested on 26th July, 1918, in the street in Castletownbere by four R.I.C. men. The arrest however was in connection with the illegal drilling on St. Patrick's Day, 1918. He was replaced as Battalion O.C. by Adjutant, Michael Crowley.35

Fig.6 – Beara Battalion Monument in the square, Castletownbere Town. e inscription reads: ‘In memory of the men and women of the Berehaven Battalion who fought for the Irish Republic from 1916 to 1923.32

27. Southern Star 24 August 1963, p.4 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

28. Deasy, Liam, ‘Towards Ireland Free’, Mercier Press (1973, Rept. Cork, 2015) p.29.

29. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1536. William O’Neill, Captain IRA, Cork 1921.

30. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1528. James O’Sullivan, Castletownbere, Member, IRA, Cork 1921.

31. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1527. Liam O’Dwyer, Commandant, IRA, Cork 1921.

32. Photo accessed from – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baile_Chaisle%C3%A1in_

33. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1528. James O’Sullivan, Castletownbere, Member, IRA, Cork 1921.

34. Southern Star 27 February 1971, p.11 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com

35. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1567. James McCarthy, Lieutenant IRA, Cork 1921.

57

LIEUTENANT WILLIAM HURLEY

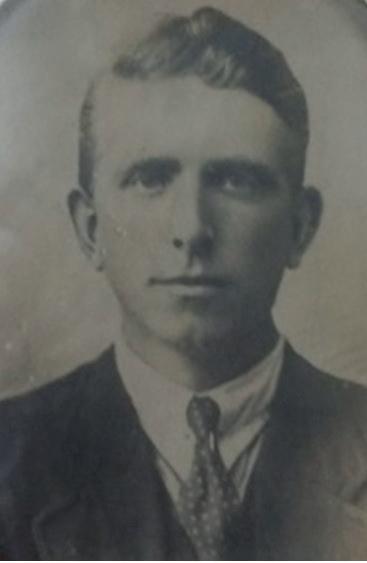

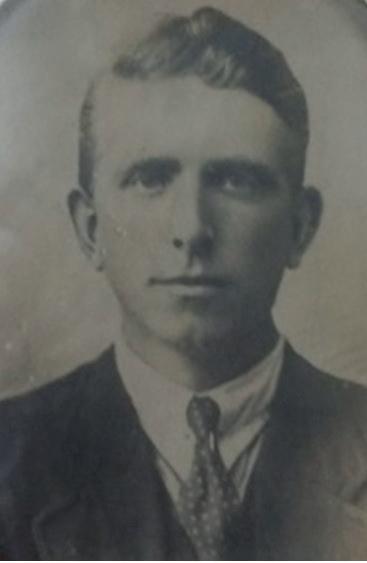

Charlie’s younger brother by three years, William, was also a volunteer with Kilbrittain Company, Third Cork Brigade. William (Liam) was born on 25th of January 1896.37 Similarly to his brother Charlie, William was also a noted scholar:

58

Fig. 7 – e building formerly known as Castletownbere R.I.C. Barracks.36

Fig.8

– Newspaper account of William Hurley’s entrance examination to Haulbowline.38

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

James Hurley recalled of his brothers, Charlie and Willie: “There was seven of us born & reared in a farm of 35 acres. Those two boys got education. They were both employed as clerks in Haulbowline Dockyards up to 1915 when they gave up their jobs to join the nation's call. They helped their father and mother out of their earnings up to then.”39

movement and was involved in a number of activities between January to 31st March 1918. He took part in an armed training camp held at the Lake House, Maryboro for the purpose of manufacture of buckshot, shrapnel, bombs and equipment for Kilbrittain Company. All the men engaged were trained in the use, cleaning and repairing of all arms. In February 1918, he took part in collecting all arms, principally shotguns and ammunition from sympathizers to be stored in local arm dumps. The houses of ten loyalists' families in the company area were raided for arms during March 1918, with all raids being carried out in one night.

As the company was engaged in resistance to conscription, William Hurley and the local parish priest addressed an organised public

fund, after which all men of military age were immediately enrolled as Volunteers and put through a course of instruction in drill and manoeuvres in view of the local R.I.C. Barracks. These recruits were mobilised twice weekly for drill and other activities until all danger of conscription passed off. In May 1918, he

Fig. 9 – Lieutenant William Hurley, Baurleigh (Photo courtesy of Michael Coleman, grand-nephew).

59

distant and took part in the proceedings for the reinstatement of an evicted 36. 37. record?id=ire%2fc1901%2f9073941 38. Southern Star 29 March 1913, p.6 – accessed from www.irishnewsarchive.com 39. PDF_Pensions/R5/1D189%20Charles%20Hurley/1D189%20%20Charles%20Hurley.pdf

in order to avoid arrest by military patrols who attempted to encircle the district. The same month he was engaged in raiding for arms at Ahiohill.40

During the months following the passing of the Conscription Act in April 1918, wholesale arrests of leaders of the Volunteers, Sinn Fein, and other nationalist movements were attempted by the British Government. To avoid arrest it became customary for a number of the more prominent Volunteers in adjoining Company areas to meet together at night and sleep in unoccupied labourers cottages and farmyard outhouses, and to post armed sentries for protection. The hardships incurred by this necessity were very great, and some Volunteers succumbed to the rigours of exposure. Among them was Charlie’s brother, Lieutenant William Hurley of Kilbrittain Company.41

On 2nd August, 1918, Lieut. Willie Hurley, age 22, "B" Company, 4th Battalion, Cork Brigade, I.R.A. died at his home in Baurleigh from typhoid

His brother James Hurley recalled of William’s death: “They came home, went organising and drilling the volunteers. They used to be away for weeks at a time. On the last occasion, William came home sick with typhoid fever. He had the care of two doctors but it killed him.”44

Michael J. Crowley, brother of Denis, Con and Paddy and Brigade Engineer with Kilbrittain Company, Cork Third Brigade later recalled of this tragic event in his witness statement:

“Charlie's younger brother, Liam, while 'on the run' had contracted typhoid and, after a brief illness, died. Charlie and I were present and, a few minutes after closing Liam's eyes, he and I walked out from the death chamber. I was surprised at his lack of emotion on the death of Liam whom, I knew, he idolised but when we had got clear from the house and friends, suddenly grasped me and moaned: "Oh, hillside". I mention this in an attempt to describe this man whose love of country

Fig.10 – Memorial Card of William Hurley, Baurleigh.43

KILBRITTAIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY 60

42

its sake transcended all mortal things. Hence, I know that he himself died as he would have wished.”45

On the 4th August, 1918, there was a full muster of the members of Kilbrittain Company together with the other Companies in the Battalion at the funeral of Lieutenant William Hurley (Kilbrittain Company) in Clogagh old cemetery.46

The parade marched from Baurleigh to Clogagh and was watched by British forces.47 He was given a military funeral, including a area was under martial law. All Companies of the Bandon Battalion were mobilised and paraded at the funeral. There was no interference by the British authorities.48

Fig. 11 – Michael J. Crowley, Kilbrittain Village (Photo courtesy of Diarmuid Begley).

AN UNFORTUNATE RETURN TO CASTLETOWNBERE

After the funeral of his brother Willie in August 1918, Charlie Hurley was

40. Cork 1921.

41. Deasy, Liam, ‘Towards Ireland Free’, Mercier Press (Cork, 2015) p.22.

PDF_Pensions/R5/1D189%20Charles%20Hurley/1D189%20%20Charles%20Hurley.pdf

43. Accessed from Fonsie Mealy Centenary Sale Archive, p. 21 https://fonsiemealy.ie/auction/ life for the world, receive in a loving embrace the soul of our gallant comrade Liam, who gave his young life for Ireland. Queen of Martyrs pray for him.

PDF_Pensions/R5/1D189%20Charles%20Hurley/1D189%20%20Charles%20Hurley.pdf

45. Cork 1921.

46. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1290. Laurence Sexton, Member IV,

47. Bureau of Military History – Witness Statement No. 1254. Michael Coleman, Captain IRA, Cork 1921.

48. Deasy, Liam, ‘Towards Ireland Free’, Mercier Press (1973, Rept. Cork, 2015) p.22.

61

KILBRITTAIN’S BELOVED BRIGADIER: CHARLIE HURLEY

42.

44.

captured upon leaving Baurleigh and was brought back to Castletownbere to stand his trial on the charge of illegal drilling on the previous St. Patrick’s Day, he was under such a heavy military guard that it prevented any possible hope of the rescue planned by the local battalion. On this occasion he received a sentence of two months, for the offence of unlawful assembly (drilling).49

ENTRY INTO CORK MALE PRISON

After receipt of sentence, Charlie Hurley was sent to Cork Male Prison (Cork Gaol). Some of the details from his record there showed the following: Age: 25 years old, Birth Year: 1893, Height: 5 feet 9 inches, Eyes: Brown, Hair: Brown, Complexion: Fair, Marks on Person: Fresh bruise on left arm. Mark on left hand. Weight on Admission: 148, Weight on discharge: 154, Trade or Occupation: Clerk. Date of Committal: 24th of August. Under Sentence: 31st of August. Offence: Unlawful Assembly. Court from which committed: Castletownbere, Expiration of Sentence: 30th October, 1918.

A letter from Cork Male Prison to his then sweetheart, Nora O’Neill, showed the indomitable spirit of the man which guided him all through his life: “Let England do her worst, our bodies she can have for the taking, but our spirit never.”

Male Prison

Hurley, Baurleigh.50

letter

Male Prison,