A DECADE OF EXCELLENCE

A COMMEMORATIVE DOUBLE ISSUE

Evan

OFFICERS

Yionoulis PRESIDENT Michael John Garcés EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT Ruben Santiago-Hudson FIRST VICE PRESIDENTDan Knechtges

TREASURERMelia Bensussen

SECRETARYJoseph Haj

SECOND VICE PRESIDENTCasey Stangl THIRD

VICE PRESIDENTEXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Laura Penn

HONORARY ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Karen Azenberg Pamela Berlin Julianne Boyd Graciela Daniele Emily Mann Marshall W. Mason

Ted Pappas Susan H. Schulman Oz Scott Daniel Sullivan Victoria Traube

SDC EXECUTIVE BOARD

MEMBERS OF BOARD

Saheem Ali

Christopher Ashley Anne Bogart Jo Bonney Mark Brokaw Donald Byrd

Rachel Chavkin Desdemona Chiang Hope Clarke

Valerie Curtis-Newton Liz Diamond Lydia Fort Leah C. Gardiner Anne Kauffman

Pam MacKinnon Kathleen Marshall D. Lynn Meyers

Lisa Portes

Lonny Price John Rando Bartlett Sher Susan Stroman Seema Sueko

Eric Ting Maria Torres Michael Wilson Tamilla Woodard Annie Yee

SDC JOURNAL MANAGING EDITOR Kate Chisholm

FEATURES EDITOR Stephanie Coen GRAPHIC DESIGNER Adam Hitt

EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Melia Bensussen Joshua Bergasse Jo Bonney Noah Brody Desdemona Chiang Sheldon Epps Ann M. Shanahan

SDC JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWED SECTION EDITORIAL BOARD

SDCJ-PRS CO-EDITORS Emily A. Rollie Ann M. Shanahan

SDCJ-PRS BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Kathleen M. McGeever

SDCJ-PRS ASSOCIATE BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Ruth Pe Palileo

SDCJ-PRS SENIOR ADVISORY COMMITTEE Anne Bogart Joan Herrington James Peck

SDCJ-PRS PEER REVIEWERS Donald Byrd David Callaghan Jonathan Cole Thomas Costello Kathryn Ervin Liza Gennaro Baron Kelly Travis Malone Sam O’Connell Scot Reese Stephen A. Schrum

FALL 2022 CONTRIBUTORS

Lynn Ahrens Karen Azenberg

Andy Blankenbuehler

Father Gregory Boyle, S.J. Mark Brokaw

William Brown

Donald Byrd Desdemona Chiang Martha Clarke

Curt Columbus

Kristy Cummings

Graciela Daniele Zayd Dohrn

The Dramatist Brett Egan Sheldon Epps Charles Fee Stephen Flaherty

Richard Garner

Liza Gennaro Rebecca Gilman

Sam Gold Keith Huff

Thomas Kail Anne Kauffman

Jessica Kubzansky Nina Lannan

David Leong Gillian Lynne Taylor Mac

Davis McCallum

Jason Moore

Amy Morton Elizabeth Nelson James Nicola Sharon Ott Ron OJ Parson Laura Penn Nicole Hodges Persley Ben Pesner

Gina Pisasale

Lonny Price Harold Prince Robert Quinlan Mary B. Robinson Oz Scott

Niegel Smith Ted Sod Paul Tazewell Mei Ann Teo Tazewell Thompson Liesl Tommy Henry Wishcamper Evan Yionoulis

FALL 2022 SDCJ-PRS CONTRIBUTORS

Meredith Joelle Charlson

CHOREOGRAPHER, AMERICAN CONSERVATORY THEATER

Emily A. Rollie CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY

Ann M. Shanahan PURDUE UNIVERSITY

SDC JOURNAL is published by Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, located at 321 W. 44th Street, Suite 804, New York, NY 10036. ISSN 2576-6899 © 2022 Stage Directors and Choreographers Society. All rights reserved. SDC JOURNAL is a registered trademark of SDC.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Letters to the editor may be sent to SDCJournal@SDCweb.org

POSTMASTER Send address changes to SDC JOURNAL, SDC, 321 W. 44th Street, Suite 804, New York, NY 10036.

I hope this issue finds you, as I am, back in rehearsal, in a room with a great play whose investigation brings you rewarding artistic challenges and joy in collaboration.

Even in person, despite all our close work with actors and designers, directing and choreographing remain mostly solitary ventures. Although we enjoy seeing the fruits of each other’s labors, we rarely actually get to see each other work. SDC and the SDC Foundation aim to connect directors and choreographers with each other, through Union service and Foundation events, and also through the stimulation of reflection and conversation promoted by such ventures as this publication.

Celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, SDC Journal was created by the Union to further unite us by providing a glimpse into the work practices and artistic visions of our fellow directors and choreographers. It regularly features articles about the crafts of direction and choreography as well as interviews with Member practitioners from across the country who share their insights and artistry with its readers. Over the past few issues, I have dedicated a portion of my letters to the current moment and some to reflecting back—though, recently, mostly just back to March 12, 2020. This anniversary gives us an opportunity to consider a longer horizon.

The current issue brings together a collection of interviews and articles published since SDC Journal’s inaugural issue in 2012 and offers a sample of the kinds of inspiring pieces that have been the hallmark of the publication over the past decade, including interviews with the late Hal Prince and Dame Gillian Lynne and a feature which tackles the proverbial question: “What Does a Director Do?” There’s also Mary B. Robinson’s wonderful piece about the founding of SDC. The featured selections were chosen for their enduring resonance; some may also prompt you to consider how the context of our theatremaking has evolved since their first appearance.

SDC Journal was always intended to look ahead as well as to what came before. Then SDC President Karen Azenberg’s letter from September of 2012, published again in this issue, announced its purpose:

to give voice to an empowered collective of directors and choreographers working in all jurisdictions and venues across the country, encouraging Member advocacy and highlighting Member achievement. We hope you will find the new SDC Journal provocative and forward-thinking, as over time we will explore the full breadth of these two enigmatic crafts, examining various styles and approaches of creating theatre both in the past and present, and always with an eye to the future.

In looking ahead today, we find ourselves in a moment of cautious hope: that the recovery of our industry will proceed apace, and that the theatre will be able to help close the social distance of the past few years which has been so damaging to our nation’s psyche. It is a hope tempered by a recognition of the many challenges we face and the knowledge of the sustained effort that will be necessary on

multiple fronts to achieve the goals we have for ourselves and our communities.

Before the midterm elections, after surveying the Membership, SDC issued a voter’s guide with questions to consider in evaluating candidates. Arts and Culture was among the issues Members identified as most pressing in our current political moment, along with: Censorship, Climate Change, Gun Control Legislation, Health Care and Reproductive Rights, Human Rights, Organized Labor, and Racial Justice.

As you might recall, in July of 2020, following unanimous approval by the Executive Board and an overwhelmingly affirmative vote by Members Union-wide, for the first time in our 60-year history SDC endorsed a presidential candidate, Joe Biden. On September 30 of this year, President Biden issued an Executive Order on Promoting the Arts, the Humanities, and Museum and Library Service, setting forth initiatives to stimulate their advancement and deeming them

essential to the well-being, health, vitality, and democracy of our Nation. They are the soul of America, reflecting our multicultural and democratic experience. They further help us strive to be the more perfect Union to which generation after generation of Americans have aspired. They inspire us; provide livelihoods; sustain, anchor, and bring cohesion within diverse communities across our Nation; stimulate creativity and innovation; help us understand and communicate our values as a people; compel us to wrestle with our history and enable us to imagine our future; invigorate and strengthen our democracy; and point the way toward progress.

It is an honor to be a part of the community of workers in the art of theatre, seeking to have the impact President Biden so eloquently describes, and, with you all, to have the opportunity to practice the crafts of direction and choreography, which are so well celebrated in these pages.

In Solidarity, Evan Yionoulis Executive Board PresidentFROM

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

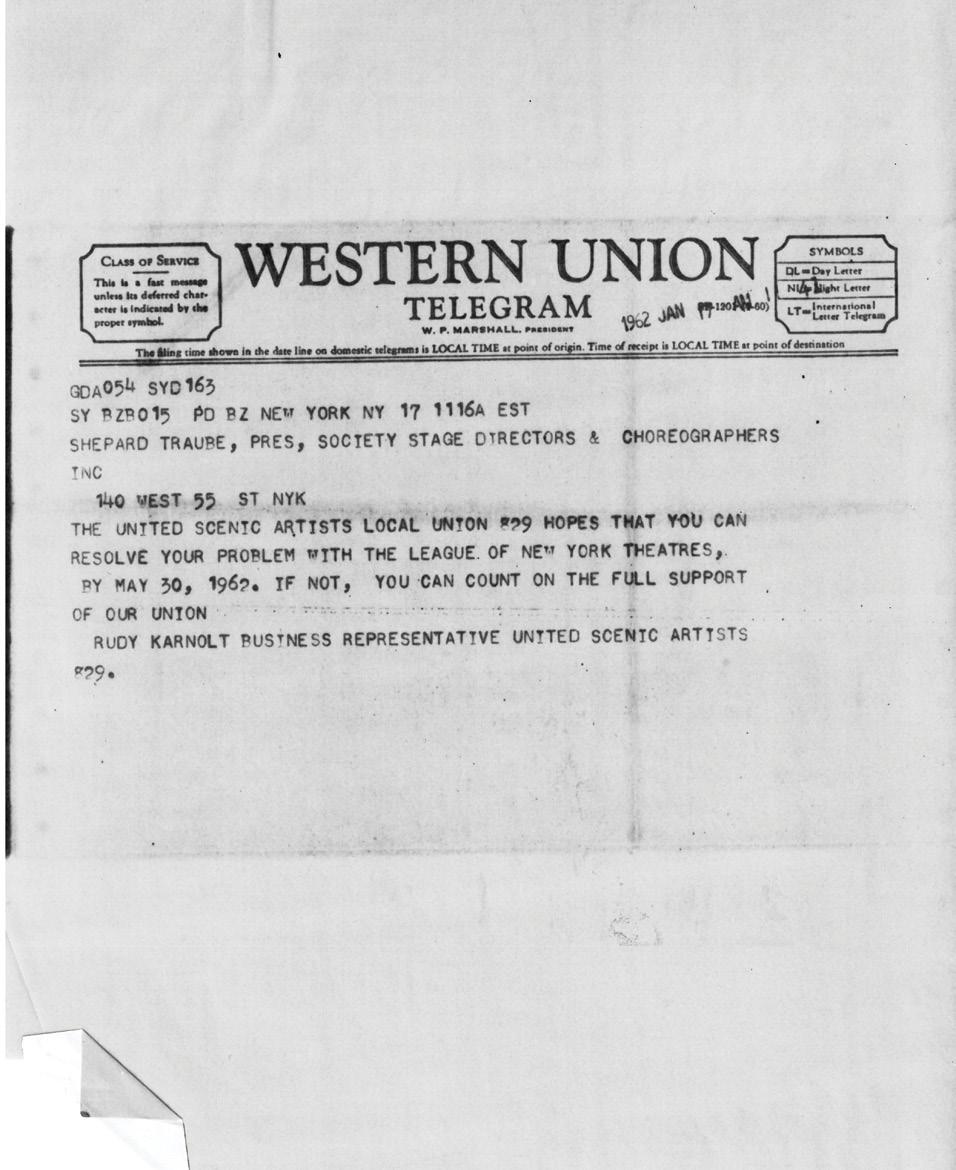

Anniversaries provide opportunities for celebration. We pause to partake of the ritual of well-deserved congratulations, parties, toasts. Anniversaries can also provide opportunities for reflection, assessment, and consideration of the future. Ten years ago, the Executive Board determined to take the opportunity of the 50th anniversary of the founding of SDC to do some of this important work. In partnership with the Membership, we would consider where the Union had been and what had been achieved from the beginnings of this now-formidable Union that took shape over late nights at Sardi’s on West 44th Street in NYC. We would also take a hard look at where we had fallen short and consider how the Union might respond to the changes in crafts and community that were beginning to reveal themselves in the early years of the 21st century, if not before. We challenged ourselves by saying, “If the only thing we can look back on is a great party or two, we will have failed.”

One early, central decision the Board made was to fully embrace the national nature of SDC. Though founded by a tight group of Broadway directors and choreographers, where and how our Members made their work had changed, and as such, the Union needed to embed new practices into its short- and long-term planning. Threaded through all our conversations was the belief that too many of your collaborators, employers, and peers did not understand what you do, and our ability to fight for protections was directly connected to bargaining partners understanding the undisputable value of your work.

And because you should be known for what you do, we needed to find ways to share your stories, and weren’t we best positioned to capture those, the essence of your work, who you are, what drives you? We envisioned SDC Journal. A magazine about craft; Union business would be shared through other communications. This would be a place to honor you, to preserve your history, to introduce you to one another. Modeled on the DGA Quarterly and other leading industry publications, it would be substantial. Rigorous, well written, well produced, surprising. With guidance from the Board, at-large Members, and an Editorial Advisory Committee, we looked at design concepts, brainstormed names, tested willingness to participate, interviewed editors.

Editors. What is a magazine without editors? Editors who push and pull. Who are passionate and stubborn. Who fit this freelance gig into their busy, demanding professional lives. This issue of SDC Journal was curated by a small group of Feature Editors and Managing Editors who represent the span of work of the past decade.

Elizabeth Nelson was our first Art Director and Managing Editor. The magazine was her vision as much as anyone’s—she understood the need and the potential, and she was relentless in her belief that this could be a publication to rival magazines in our field. Features Editor Shelley Butler could distill the essence of a conversation like no one else. Her insight as an SDC Member, a director of skill and ambition, raised the bar. She was tenacious in her pursuit of excellence, her collaboration with the Advisory Committee, and her unwillingness to accept anything less than representation from

across the field. Features Editor Elizabeth Bennett is known by many across the country as one of the foremost dramaturgs; I am not sure there are many out there who love directors and choreographers the way Elizabeth does. Her passion and devotion to the story, her knowledge of the field, gave depth and breadth to our magazine; she took care with every interview, initial edit, and collaboration with guest contributors. And the delight, I would say, was constant—but from time to time the laughter turned to panic as Kate Chisholm, our Managing Editor, reminded us of deadlines. SDC first met Kate when she was with the Kurt Weill Foundation supporting SDCF programs. Some years later she applied to join us as Managing Editor and it’s a life sentence as far as I’m concerned. With love and uncompromising professionalism, without question she makes the Journal happen.

I think time has lost its meaning, or we have lost our ability to measure time given the madness of the past two-and-a-half years, but I can’t believe it’s been 10 years. I appreciate the passing of time a little differently now, reading the content between these covers. This double issue contains the past and the present and the future, all in one place. We build on the past, standing on the shoulders of giants even as we learn to do better, see our shortcomings, and experience the transformation that comes from inspiration. And through the past and present we see glimpses of the future. More than just glimpses.

COVID interrupted our rhythm, professional as well as personal. We managed to get a few issues out during the pandemic. The good news is we have figured out how to publish online and will continue to do so even as we prepare to publish more issues next year, as we incrementally build back. Easy for me to say but I feel SDC Journal should be required reading for students of theatre, regardless of their course of study or aspirations. (I have loved those moments when graduate students confess to kidnapping their professor’s issues, hoping to return them before they go missing.) Perhaps I’ll take that on as we move into the next decade, with hope and continued dedication to telling your stories.

In Solidarity,

Laura Penn Executive Director

Welcome

SUMMER 2012 VOL. 1, NO. 1

Karen Azenberg was the SDC Executive Board President from 2007–2013. This was her letter for the first issue of SDC Journal

It is with great pleasure that I welcome you to our inaugural issue of SDC Journal. In these pages we seek to share with our Membership and the wider theatrical community the art and craft of professional directors and choreographers.

Some of you may remember The Journal, published semi-annually by the SDC Foundation; it was a beloved publication that had at its center transcriptions of Foundation programs such as one-on-one conversations and panel discussions.

In 2009 we began a relationship with the American Theatre Wing and created Masters of the Stage, an online podcast series featuring more than three decades of exceptional conversations with many of theatre’s most seminal directors and choreographers. This online library has allowed us to distribute these invaluable programs more broadly and widely. As such, The Journal in its old form was less current, less in keeping with today’s trends and needs.

The new Journal—now called SDC Journal is designed to give voice to an empowered collective of directors and choreographers working in all jurisdictions and venues across the country, encouraging Member advocacy and highlighting Member achievement. We hope you will find the new SDC Journal provocative and forward-thinking, as over time we will explore the full breadth of these two enigmatic crafts, examining various styles and approaches of creating theatre both in the past and present, and always with an eye to the future.

In this issue you have the opportunity to eavesdrop on a conversation between Tony Award winner Dan Sullivan and Clybourne Park’s Tony-nominated (at press time) Pam MacKinnon. Director/Choreographer Susan Stroman shares with director Timothy Douglas the origins of her remarkable, and at times controversial, Scottsboro Boys Executive Board Member Larry Carpenter meets up with DGA director Gary Halverson and the immeasurably talented Bart Sher to talk about their collaboration at the Metropolitan Opera in that company’s wildly successful broadcast series. In addition you will hear from the exceptionally talented Rob Marshall about his career arc, while Sheldon Epps speaks with Phylicia Rashad about her new venture into directing. Additionally, each issue will feature an In Your Words section where we hope you will participate in the conversations and questions posed there.

I am thrilled that you are now reading our first issue, and I hope you will keep reading—whether you are an SDC Member, a member of a peer union or guild, or working in our industry or the entertainment industry at large. We welcome you to be a part of this ongoing and necessary conversation about our craft. Thanks for reading, and enjoy!

Azenberg Executive Board President (2007–2013) KarenBLANKENBUEHLER

IN A SECOND

FALL 2012 VOL. 1, NO.

2

There is no single path to becoming a choreographer for the Broadway stage. Many have started as performers; others have assisted, learning on the job. Andy Blankenbuehler arrived in New York in 1990, and successfully worked as a dancer/singer/actor, a teacher, a choreographer and, most recently, a director. His work ethic, skill, and versatility—and his understanding of what makes popular entertainment—are evident in all his shows. At the time of this interview, he had completely immersed himself in hip-hop, competitive cheerleading, and the Great Depression for shows as diverse as In the Heights, Bring It On, and Annie. In this interview, Andy recounts his early influences, sheds light on his process, and talks about the delicate balance of career and family life.

TED SOD | I’d like to start with your background. I read you’re from Ohio.

ANDY BLANKENBUEHLER | I grew up in Cincinnati.

TED | Can you tell us about your trajectory to New York, how you got involved in dance?

ANDY | I went to a little studio in Cincinnati, and my mom sat outside and sewed while I danced. I had a very mathematical mind, and I could remember the steps, and I was very good at tap dancing, but I didn’t necessarily love it. I was the only boy and it wasn’t something I could really brag about or talk about. And then I started doing musicals in high school, and I just absolutely fell in love with what I was doing.

TED | I read you went to St. Xavier.

ANDY | I went to St. Xavier High School, a college prep school, and it was there that I started doing musicals. I did three musicals my sophomore, junior, and senior years. Junior year I actually choreographed the musical, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. I always grew up with the mentality that I was going to go into an academic field. I didn’t know anybody, men especially, in the business. I just assumed I was going to be an architect. I started applying to colleges. I got into some good schools for architecture and for visual arts. By that point in time, I was dancing constantly. I idolized Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines. We converted a room in the house into a dance studio, and I would just practice. I would practice one step over and over and over again for hours. I changed my plans and reapplied to schools with dance. I’d gotten scholarships to NYU, as well as Point Park, but I wasn’t ready to move to New York City as an 18-year-old; I was daunted by the city. But somebody at NYU told me about SMU in Dallas, and said there was a really great jazz teacher named Max Stone there. So I flew down on a Tuesday to Dallas and was enrolled on a Thursday. Earlier that summer I had done my first professional job at Kings Island,

a theme park in Cincinnati. I was over the moon. I couldn’t believe somebody was paying me—I think it was like $149 a week for five shows a day.

TED | Just like Disney!

ANDY | That was my second job, the summer after my freshman year. I had a total ball dancing in front of the castle. My time spent at Disney was great, because I got to see how many thousands of people that kind of big entertainment affects. Those bold brushstrokes were really important for me to learn, in terms of what I would do in the future as a choreographer. I like commercial entertainment that has really strong brushstrokes; but at the same time, the more subtle, artistic side is very important to me, too. At the end of that summer gig, they offered me a job at Tokyo Disneyland for the coming year. I told my professors that I wanted to pursue this, and they actually said, “So you’re going to leave school just so you can go to New York and dance in some, like, touring chorus of Oklahoma!?” And I replied, “YES! That’s exactly what I want to do. I just want to dance.”

TED | Which year was that?

ANDY | I moved here in 1990 when I was 20 years old.

TED | And you immediately got work?

ANDY | Yes and no. I started taking three classes a day. I thought that I could continue my education here, while trying to be a professional dancer. What I believe now is that you can always keep improving, but as soon as you enter the work force, only some things continue to improve. Technique doesn’t necessarily improve unless you’re studying constantly. Your work savvy improves, your performance ability, the nuances of learning the business improves, but once you get busy auditioning, learning how to be good on stage, you slow down other parts of your learning. I auditioned for everything—my audition technique got better—and then a couple of months after I moved here I got offered an international

company of Cats, and the same week I got offered a dinner theatre production of A Chorus Line. Rob Marshall was directing and choreographing it. So I passed on my dream show, Cats, to do A Chorus Line.

TED | Did you play Mike?

ANDY | I played Mark. [Laughs.] I know. I remember so specifically what Robbie did the first day of A Chorus Line rehearsals. He met with every person in the company individually to talk about how they felt about the show. As a director, now, it’s a reminder to me that it’s all about that relationship, it’s all about an open dialogue with your cast. A Chorus Line really set me up in a lot of ways, because I continued to work with Robbie and Kathleen [Marshall], his sister, who was his assistant. Through Kathleen I met Scott Ellis. Scott Ellis is how I met Susan Stroman.

TED | It sounds as if you were already thinking about becoming a choreographer.

ANDY | Even when I was 12 years old I was choreographing my own solos at dance school. For me, the battle has always been scale. I don’t remember the exact words, but the first chapter in Twyla Tharp’s most recent book talks about how different artists create on different scales—some people make really big pictures, and other people create tiny pictures. So for me, even from a very young age, I was always about trying to figure out how big of a story I wanted to tell, and most of the time, I bit off more than I could chew.

TED | It seems as if the jobs you got as a performer helped build your vocabulary as a choreographer/director.

ANDY | I loved the score of A Chorus Line because the trumpets, the percussion spoke to me as a dancer and as a choreographer. I feel accents and I feel rhythm. After I worked with Robbie on A Chorus Line, I spent a summer with him at the Pittsburgh Civic Light Opera. And after that I did West Side Story at Paper Mill Playhouse, which was a dream. I freaking love that show more than anything.

TED | And who was the choreographer on that West Side Story?

ANDY | Alan Johnson, whom I’ve become good friends with. But I got hurt in that show; I hurt my knee, and at that same time, I got my first offer for a Broadway show, the revival of The Most Happy Fella, and I had to turn it down.

TED | Was that The Most Happy Fella directed by Gerald Gutierrez?

ANDY | Yes. It came in from Goodspeed. I had this dark cloud over me, thinking, “This was supposed to be my avenue; why aren’t I dancing on Broadway?” But in retrospect it was actually good for me. You know in the movie The Matrix—how when he sees the numbers he understands how it works? During that time, I started listening to Ella Fitzgerald and Sammy Davis, Jr., music where the brass arrangements and percussion arrangements are so bold and so dynamic and intense, and I would listen to that stuff over and over on the exercise machines, and all of a sudden I felt like I was floating in that music. I felt like I understood it a lot more. From that point on, there was no looking back in terms of where I wanted to go stylistically with my movement. A couple of months later, I bounced back. I did a production of 42nd Street out on the road and then I booked my first teaching job at age 22. It was really good for me to use that as an opportunity to articulate my artistic impulses. Through teaching I learned to analyze what I wanted to do artistically. When I start to choreograph something, I sit down and write a document. My brain locks into, “Yes, I agree with that,” or, “No, I don’t agree with that.” I’m not this crazy talent who can just go into a studio and wing it. I have to think about what makes a person’s body language say that they’re shy or that they’re hurting inside. I have to think about that for a long time until I can roll the shoulders to the right place. I can’t just walk in the room and make a shy person.

TED | Which jobs or experiences most influenced your identity as an artist?

ANDY | I desperately wanted to do the Jerry Zaks revival of Guys and Dolls, and I took dance classes with Chris Chadman, who scared the hell out of me. I loved his stuff, the staccato nature of it all was exhilarating to me. It was like a more fuel-injected version of that Fosse-era 1950s stuff that was so isolation based, and I just instantly loved it. He was really rough in the studio; he just knew what he wanted to see, and he put blinders on to get what he wanted from the dancers. But that didn’t put me off at all. I didn’t get the Broadway revival of Guys and Dolls. I got the national tour and toured

with it for a year and a half, and then I went into the Broadway cast. That national tour was filled with an unbelievable group of male dancers—Sergio Trujillo, Chris Gattelli, Darren Lee, Jerome Vivona—all of whom went on to have careers as choreographers. Then while in Guys and Dolls on Broadway, I herniated two discs in my back and I was out for 18 months. That was a really hard time for me, because I was getting offers for new Broadway shows, and I couldn’t accept them.

and create a world that would do justice to Lin’s wonderful score. I learned more in the process of working on Heights than in any other time in my career. I studied Lin’s music and learned to relish the many influences that had made him the songwriter that he was. His music had so much authenticity to it, but more importantly, it had a driving personality that was unique to Lin. His music began teaching me how to approach my movement with humanity first rather than vocabulary. And his lyrics were the greatest teacher to me. The ingenuity of the lyrics and their glorious musicality inspired me beyond belief. My work changed. My way of working changed. My life changed because of the collaboration with Lin, Tommy, and [musical director] Alex Lacamoire.

TED | Do you have to create a specific vocabulary for every show and dance?

ANDY BLANKENBUEHLERANDY | Correct. I toured with The Music of the Night, working with Kathleen Marshall, Scott Ellis, and John DeLuca. I got into Steel Pier with Stroman and Scott Ellis. I did Big for Stroman and On the Town in the park with Eliot Feld; I did the workshop of Parade with Hal Prince and Danny Ezralow; I did the workshop of Fosse. West Side Story and Fosse are the two biggest college courses you can take. My time with Fosse was great. One of the things Chris Chadman would do that Fosse did is he would hit a move fast enough so that there was a pause before and a pause after, and if the definition of the move was telling enough in that split second of a pause, the audience would take in what was meant. The audience could perceive character or a mood through what they were seeing physically. The pause before and the pause after was what made it happen for me. So more and more, as a performer and as a choreographer, I was moving ahead of the beat. So even if I was moving on the downbeat, I would attack the front of it with such energy that there would be a pause at the end of it, so the audience could take it in. Chris did that so well.

TED | In 2006, things really started picking up for you as a choreographer, correct?

ANDY | In 2006, my agent, John Buzzetti, set me up on an interview for In the Heights It was with Thomas Kail, the director, and Jeffrey Seller and Kevin McCollum, the producers. I knew that stylistically the show was way outside of my box, because I had very little experience with hip-hop or Latin styles, but I had confidence in my storytelling abilities. I believed that I could help develop these characters physically

ANDY | What I do when I first hear the music is dance like myself. And it’s usually not right. But it helps to figure out where I want to go. I start to learn how my body reacts to the score, and I start to learn what nuances connect the world I’m envisioning. But then the parameters of the show really present the rules. If a scene is set in a swing club for example, I know the movement needs to be based in that style. So slowly the vocabulary starts to name itself. And it becomes clearer to me that this is how the character would need to move in this location, in this particular situation. Those rules exist within each particular show. And once I find those rules, then I’m in a safe place. But I don’t want those rules of authenticity to stifle my process, so I’m of the mindset, especially in contemporary theatre, that you can just throw all the paint against the wall to learn what the show needs. It doesn’t matter if it’s modern dance, contemporary dance, or the Charleston. I’ll explore those styles if it’s helping me to express something. If the show is set in 1920, I’m not going to do hip-hop, because it’s not correct (unless the show is completely anachronistic). But I might actually start by doing hip-hop steps until I say, “Oh, I love that rhythm! Now let me find out how I can incorporate that syncopation into stylings that are more period authentic.” So I kind of crosspollinate the dances. I started doing hip-hop steps to the Annie music. They’re no longer hip-hop steps, but the rhythms from those early hip-hop steps helped me find the energy I wanted to use in the other physical styles.

TED | Tell us about the genesis of Bring It On and how that came together. Who approached you to direct and choreograph, and why?

TED | You continued to perform after you recovered from your injury, correct?

I’m notthis crazytalent who can just go into a studio andwing it.

ANDY | I was approached because there was so much movement in In the Heights, and the producers wanted Bring It On to move. I’d never seen any of the Bring It On movies, and I knew nothing about cheerleading. I had a relationship with these producers and they said, “Would you be interested in directing and choreographing it?” I’d never been offered anything as a director. And I was like, “Sure!” I was nervous about taking on a movie as a musical—I hadn’t done 9 to 5 yet. I was a little tentative. I knew, since I had no idea what I was doing as a director, that I had to be surrounded by people whom I could trust. Jeff Whitty, Alex Lacamoire, Tom Kitt and Amanda Green, Lin, the designer David Korins—I’ve worked with all of them before, so I felt safe with them. I said to the producers, “If you’re hiring me to direct this, you’re basically going to get a full-length ballet. I know how to choreograph, so I’m going to direct my choreography. I’m going to make a big dance show.”

TED | What was the preparation like? Are we talking six to eight months? More?

ANDY | Oh, we’ve been working on it for about three years now.

TED | I was impressed that there was not only dance and movement that was related to character, but there were full-on acrobatics. How did you enter that world?

ANDY | When I attended my first cheerleading competition, I’d never heard any place as loud as that arena. The volume was UNBELIEVABLE. I watched what the competitors were doing. They were on the edge of their lives. They were happier than any teenager has ever been and if they fell or if they lost, they were destroyed. But what I noticed in the physicality was that they were doing really intense stuff. I instantly knew that I wasn’t going to be able to teach Broadway performers to do this stuff. I wasn’t even going to try. I made the

decision that if we’re going to go the route of competitive cheerleading, we’re going to have to devise a show where half the cast can be professional cheerleaders.

TED | And they have to know how to sing!

ANDY | Yes. In a normal show, say you have ten ensemble members, five of those ensemble members are covering the principals, so they’re exceptional at those skills, but all ten of them are all musical theatre triple-threats. But in our show, five of those ten have never done a musical before, not even a first-grade play, so those other five have a whole other set of responsibilities. It’s kind of crazy. We decided in the development process to separate every element of the show. We worked on staging with just the actors to see if we liked the book; we worked on cheerleading just with the cheerleaders to figure out how that worked. We devised these systems whereby a person who’s

Lin-Manuel Miranda and company in the Broadway production of In the Heights, choreographed by Andy Blankenbuehlerdone five Broadway shows can step in and learn the part. And the girl who’s been flying through the air for 15 years, is flying through the air; it’s not new to her. The only exception is our two principal women who also have to go up in the air.

TED | You’re about to work with James Lapine on Annie. How did that job come to be?

ANDY | A couple of years ago I said to my representation, “Here’s a short list of directors that I want to work with, because I know I have a lot to learn, so let’s pursue those people.” And James was on the list. I also wanted to do a period piece. And so when Annie came around, we started pushing for the job, and James was very open to me. You know what I love about

him? James sat down and quizzed me and was very frank. He liked some of my work, but he had real problems with other parts of my work. And he wasn’t afraid to tell me that. We had four interviews.

TED | What was your initial reaction to Annie as a choreographer? And how deeply are you into the process?

ANDY | Annie really is a classic score. You hear the music and the emotion just rides straightforward. James and I started by having design meetings. By doing homework even before I came up with the dance steps, I started to know how I wanted the orphanage to move, how I wanted the kids to move, how I thought it could help with the storytelling. It’s still going to be a classic revival of Annie, but it’s going to

move in a much different way. It’s going to move more fluidly from scene to scene. As far as process goes, it’s just like any other show. I put on the music. And then I create playlists. I listen at the gym; I listen to it on the subway. I improvise to it. I’ll go to the dance studio and warm up, and then I’ll improvise in the correct shoes. I have to be in shoes that feel like the show, I have to feel like I’m in the world. I can’t choreograph Annie barefoot. I usually see staging first. If there’s a great orchestration moment, I see vocabulary first, and I’ll find some cool ideas, like a recurring thumping stomp, and I’ll say, “Oh, I love this stomp. Let’s make this a motif in a section!” What I do is I chart the number. I follow where Annie goes. One thing that I realized recently was that I way over-choreographed a moment and the little James Lapine on my

ANDY BLANKENBUEHLERshoulder was saying, “Why the hell are they dancing?” I realized that they didn’t really need to dance. What was needed was the absence of movement.

TED | Do you work with an assistant to find the steps before rehearsals?

ANDY | I work by myself, trying to figure out how the staging works, starting to come up with steps. I videotape everything. I’ll improvise take after take after take, and then I’ll realize, “This is all bullshit! They’re just dancing people. But I love how my shoulders were there.” So it’s like adding little layers of paint. And then I’ll make what I call the “core step,” and then when I get far enough along, I’ll bring my assistant in. And then, when we get a little further along, I’ll go in a room with six people and I’ll start

working on a more realized version of it. I’ll bring people into the room to say, “Okay, I want the step to turn like this and stomp on count four.”

TED | How much time does that usually require?

ANDY | I do 75 percent of the work by myself, and another 10 percent with my assistant, and then I do the rest with a core group.

TED | Talk to me about dance arrangements. Are there going to be new arrangements for this?

ANDY | Yes. Dance arrangement is where it’s at. What I’ve found in the past few years is that if I don’t have the musical voice, I actually get paralyzed. And it got to the point last year where I was like, “I can’t work without Alex Lacamoire.” He’s such a musical mastermind that he can take the melodic structure that the composer has written, and if I say, “Now she runs up the steps,” he can change it so it sounds like she’s running up the steps. He’s a true dance arranger in that way. The thing about Annie, though, is that it hardly ever breaks open. I’m not much into dance breaks; I want the dance to be on the lyric. You know what I’m saying? Like in Oklahoma!: it’s scene, song, ballet. But in today’s theatre, people don’t really have the patience for that, they want more concentrated storytelling. So I like to try to develop the number on the lyric instead of adding additional time to bring the dance out. That also comes as a result of the fact that most shows economically don’t have a dance ensemble anymore; everybody does everything. If you think about it, In the Heights only had three male dancers and three female dancers; those were the three same people who were singing in all the big numbers.

TED | How do you juggle your family obligations and your career?

ANDY | You know, it’s intense. My family gets home today. They’ve been gone for almost a month. My mother-in-law lives in Italy and so we usually go to Italy for the month of July.

TED | Which part?

ANDY | In a little beach town called Fano on the Adriatic. My son is almost six, and my daughter is three. I couldn’t go with them this year because of Bring It On’s schedule. Years ago I decided, “I’m going to have everything. I’m going to have it all.” I’ll admit, there are times when I think, “I’m an idiot! You can’t have it all.” Or at least you can’t have it all all of the time. But I know

I’m going to keep trying to have it all. I do go home and have dinner with my family.

TED | They say that’s what Obama does.

ANDY | It’s really important. I have this breakdown with my wife Elly every couple of months because I think maybe I’m taking on too much work or because I missed my kid’s first bike ride. People say to me all the time, “Is this business what you thought it would be?” And I say all the time, “I am very lucky, I have a really amazing life. I’ve gotten to know a lot of great people, family, friends, and all of those things are so important. The thrill of my work is only surpassed by my home life.”

TED | Do you have advice for young people who want to do the kind of work you are doing?

ANDY | Your discipline and your energy have to match your passion. And it’s really about versatility. I dance, sing. I act. I tap. I can do hip-hop now. And you have to be able to do all those things, because if you put all your eggs in one tiny little basket, then you’re going to have very few opportunities. And I’m about a career; I’m not about a job. I’m about how can this translate into something that can sustain me and my family. If the dreams aren’t big, then you’re never going to sustain anything. I mean, the dreams have to be really, really big, and you have to be willing to go there, because it’s a lot of work.

TED | And it doesn’t get easier.

ANDY | It doesn’t get easier. In fact, it gets remarkably harder, which was surprising to me. I have friends who have nine-tofive jobs or whatever. I get so resentful of them and the time that they get to spend with their families on the weekends. I get envious that they leave work on Friday— they’re not trying to figure out eight counts or why the audience doesn’t laugh at a particular bit. They leave work behind. But the peaks and valleys that I have—I mean, the peaks! Most people don’t get the peaks that I get to have. The valleys can get really, really low, and I think that’s what people need to prepare themselves for. The highs are higher than you can imagine, but the lows can get brutally low. And I have no desire to be in the middle. And so sometimes I’m going to crash, sometimes I’m going to fly, but that’s the way it has to be. That’s what makes really stunning art.

ISSUES

SDCF SPEAKS WITH ANNE KAUFFMAN + JAMES NICOLA

FALL 2012 VOL. 1, NO. 2

SDC Foundation celebrates, develops, and supports professional stage directors and choreographers throughout every phase of their careers. By continually investigating how best to support directors and choreographers throughout their creative lives, the Foundation strengthens their influence and creativity; in doing so, it also enriches the field. In the Fall 2012 issue of SDC Journal, director Anne Kauffman and producer James Nicola spoke in separate conversations hosted by the Foundation about creating opportunities for renewal for freelance directors. (This year, Jim ended his tenure as Artistic Director of New York Theatre Workshop after 34 years at the helm.) Excerpts from those conversations follow.

QThere are many professional training programs of great stature in the U.S. Many have emerged in the past decades and many of our leading talents have passed through these programs, and yet the path to creating and developing a director is very complicated, time consuming, and resource demanding. What does it take to make a director?

ANNE KAUFFMAN

I think stamina and the fight to become a director is really important. I went to graduate school and I am happy that I did, but mostly because I was exposed to ideas and literature and politics outside of what was, back then, my very narrow focus and my very limited interests. If we’re to be relevant as theatre makers, we have to be engaged in the world and graduate school needs to open up that world.

I do think the model of an “associate artistic director” is a way of training on the job. It is one of the very few designated paths

for an aspiring director. The position of an associate provides the crucial action of being thrown into the deep end while offering young directors a stable home.

On the flip side, institutions come with aesthetics, and so young directors who become associates usually have to pay attention to the specific aesthetic of that theatre. I am not sure one can truly experiment and find one’s own voice in the setting of associate artistic director.

I’m a big fan of young directors creating their own companies. They are created and disbanded at the speed of light and most probably should be, but they’re useful because they demand that young directors articulate what they care about and how they want to express what they care about. To build a company requires the scrappiness I espouse, the will to forge a path that defines who one is as an artist.

JAMES NICOLA

The primary resource needed is time. You must begin by becoming masterful at writing, acting, and design. The real art of directing is in the way those things are fit together by one

aesthetic mind. It is the way a medical doctor has to learn chemistry, biology, and anatomy. It all has to be put into the brain and become rote, second nature. Once you have full faculty over it, you can begin to focus on what it is to direct a play. You understand what it is to act in one, write one, design one, and maybe even produce one. Next you have to have opportunities to utilize the resources of time, money, and space to make productions. You must receive response to your work and candid assessments of where you are along the way. You need to have time with masterful directors to observe their work in an old-fashioned, journeyman kind of way. A certain degree of constancy. It takes a long time and a lot of input from a lot of people to make a really good director.

I experienced this during my time at Arena Stage as a young director. It was a wonderful environment in which to learn and grow, making my own work, participating in the making of other directors’ work, observing, and discussing with other directors at work. There was an overarching aesthetic with Doug Wager and Zelda Fichandler. Zelda and Doug put forward a kind of guidepost, a center point from which I could wander away or into which I could collide; I could reject it or accept it. It was a key part of my growth.

QOur culture lacks fluency in talking about or evaluating directing.

Critics don’t know how to write about what a director does. We don’t know how to talk about it ourselves. Why is that?

ANNE | People often don’t think of directors as artists unless someone is an auteur director. They think of us as facilitators or craftspeople, so there isn’t always that much interest in what we do. When you go see a show, it’s easy to point to what the writer, designers, and actors have done. It’s identifiable. But it’s more difficult to identify how the director has brought all of the elements together, and it is such a subjective process. How I bring things together is going to be altogether different from how another director pulls them together. You can’t touch directing, or see it. It’s an extremely individual process. As a culture, we’re pretty literal-minded. The scope of what we do as directors is not easily articulated, which does not mean that we as a community shouldn’t attempt articulation.

I believe that if people had a clearer understanding of what a director does, that criticism would be different. The funding world might also change. In response to those two channels shifting, the art form itself could potentially grow and change. It’s all about transparency, right? I really love having non-theatre people attend my rehearsals, because they get to see what it is that a director does. They get to see how something is actually made, which in turn empowers them as audience members and impacts the way they watch and engage. I think there is a kind of secrecy in the theatre; we’re so protective of our precious process. Why? It isn’t necessarily to our

I’mabigfanofyoung directors creatingtheirown companies.Theyare created and disbanded atthe speed oflightandmostprobably should be, butthey’re useful becausetheydemandthat young directors articulate whattheycare about.

ANNE KAUFFMANadvantage. I think a little transparency allows for the ability to demonstrate what it is that we do, as well as a much richer experience on an audience’s part.

JAMES | This reflects the lack of value of the role of the director and the art and craft of directing in our culture. It is not deemed worthy of being considered. The role of a director is not seen as being in need of discussion and evaluation. It goes back to the very notion of the art form as practiced and understood in our culture, which is primarily that it is a literary form as opposed to a performative form. The pride of place goes to the literary representative in the process of making a performance. I think we all participate in this. I hear directors talk about how their job is to serve a playwright. I don’t see how a creative artist—and I certainly include directors in that category— can be in the position of being both subservient and creative. You can’t tell your creative imagination to serve someone else’s agenda. I don’t understand this construct. Wouldn’t an artist, like a playwright, want a partner who doesn’t feel boxed in or submissive? Doesn’t everyone want an artist who is playing the same full-throated game? The director has to have a place and respect in order for the culture to develop any fluency around what he or she does.

QWhat about renewal and lifelong learning? There seems to be no place, literally or figuratively, for ongoing development or artistic renewal.

ANNE | We are a company country, or we used to be. There’s this myth that you reach a certain level within a company where you know what you’re doing, and you maintain that level or position in that company until you retire. That structure doesn’t actually exist anymore, but we still adhere to it; we still pretend it exists, or our expectations and desires are driven by it. And I think the financial necessity of having to take on a certain number of projects a year forces directors into this company-like mentality even though it was never their reality to begin with. Once directors get to a certain level, there’s a sense, I think, whether it’s conscious or not, that we need to keep doing the same thing in order to maintain whatever traction we’ve gained. We, as artists, become predictable and therefore the work becomes predictable.

There are places and monies and residencies for almost all types of artists except for directors (perhaps the all-toocommon perspective that directors aren’t

JAMES NICOLAartists contributes to this dearth). We need to invest in supporting directors’ continued development, and we, as directors, need to take responsibility for our own renewal. We have to shake ourselves out of the company mentality. I think there should be a place where mid-career and established directors can go to experiment, to get paid to exercise and expand their chops, because I do know that if it is satisfying creatively, it is rejuvenating as well.

JAMES | The idea that someone must maintain and tend and nurture a creative imagination over a long period of time is foreign to us. I believe the lack of renewal and ongoing development is endemic in the American theatre, not just for directors. It is partly to do with the overall impoverishment of how we practice here. There simply isn’t enough financial support for artists. There is not enough room for everyone to try a new idea or a new way of doing something. Directors keep being asked to direct the same play, set in a living room, with five to seven actors, one set, nice language, good ideas, interesting characters, but that is it. I am not picking on that particular kind of play but it is the accepted format. Certainly if there was some kind of center or entity that could be created—that was about the director and the art and craft of directing—that would be a big part of the task. I have had the great fortune to be around people like Joe Papp and Zelda Fichandler, but those opportunities for the next generation aren’t as plentiful as they used to be. And even if they were, we have a lot to overcome because of America’s obsession with youth, the young, and the new.

You must begin bybecoming masterfulatwriting,acting, anddesign.Therealartof directing is inthewaythose thingsarefittogetherbyone aesthetic mind. It is the waya medical doctor hasto learn chemistry, biology, and anatomy.

TELEVISION THEATRE

ROUNDTABLE WITH SHELDON EPPS, THOMAS KAIL + JASON MOORE

SPRING 2013 VOL. 1, NO. 4

In 2013, director Thomas Kail spoke with two colleagues, Sheldon Epps and Jason Moore, about their experiences directing for television and their aspirations to build a career that included both the live stage and the sound stage. Today, happily, all three directors move comfortably between theatre, film, and television. In this conversation, they discuss how the craft of directing for theatre provided them many of the essential tools necessary to tackle the challenges of what was then dominant in the medium—broadcast television.

THOMAS KAIL | Everyone has their own way of going from theatre to television. I want to ask how that came about for each of you.

SHELDON EPPS | It actually was through my work in the theatre, which is kind of wonderful and I hope inspiring to others who are interested in doing this. I was fortunate enough to have and still have a

relationship with the Pasadena Playhouse, and the television career started as a direct result of my doing a production at the Playhouse when Paul Lazarus was the artistic director. He quite generously said to me, “Have you ever been interested in directing for television?” And I said sure, knowing almost nothing about it, and I said if I could direct shows like Frasier I’d love to direct television, and eventually I did get to direct Frasier for a long time. Paul said, “Well if that’s something that interests you, I’ll get my television agents to come and see the play.” So they came, and those same people became my agents and have been my agents ever since—since 1991.

THOMAS | How about you, Jason? What

was the bridge for you?

JASON MOORE | I had always wanted to do both film and theatre, so when I finished college, where I had studied theatre, I came to Los Angeles to figure out what the film and television world was all about. I spent about five years working for a features director and trying to understand how things worked and how to get behind the camera. I realized that I really had no entry point and wondered if I had made the wrong choice and should have gone to New York instead. So I took a job in theatre on the musical Ragtime, which took me

back to New York. While I was developing new plays and musicals I was still always trying to figure out ways to get behind a camera. I tried to pursue soaps, late night television—all the things that were available in New York at the time. I got an opportunity through a playwright friend of mine who had gone out to LA and quickly moved into TV. I went down to North Carolina and observed on a full episode of their TV show, Dawson’s Creek, from top to bottom and wound up spending five weeks there to learn all the things I felt I didn’t know. As it happened, a director fell out, which gave me the opportunity to direct my first episode. From there I directed multiple episodes of that show and many other shows for WB Network.

SHELDON | And you, Tommy?

THOMAS | You know, it’s one of the sort of strange and wonderful things about the business, which is sometimes the telephone rings, and your life can change a little bit. A gentleman by the name of Michael Patrick King, who is a showrunner, created a show called 2 Broke Girls. Michael was an actor who wrote and performed and loves musical theatre. He had seen some of my work. He knew that In the Heights, which he had seen, was very specifically about a neighborhood and a place—as was 2 Broke

A INTERVIEW BY THOMAS KAIL ABOVE Sheldon Epps + Thomas Kail speaking with Jason Moore via Skype at the offices of SDCGirls, which takes place in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. He asked me to come out and spend as much time as I could around the show. I was in the writers’ room and on set, and I had this incredible access with no guarantee of anything other than I knew it was an exceptionally worthwhile experience for me just to be absorbing. It ended up that the show did well and was picked up, and I was able to direct the first episode of the back nine. While I was out there, I had the good fortune to meet James Burrows, who had directed the pilot of 2 Broke Girls, and was over on Mike and Molly—he invited me to come over and watch. His father, Abe Burrows, had certainly worked in the theatre, and James himself had come from being a stage manager. One thing I asked him was, “Do you see it or do you hear it?” I can usually read a script and have an idea of what the rhythms are supposed to be in for performance, but I didn’t instinctively visualize camera positions for multi-camera. He said something very important to me; he said, “If you stage it right, the cameras work.” So I focused on staging, since that certainly translates cleanly from theatre.

SHELDON | That’s true. That’s the biggest lesson I learned, and that’s particularly true in multi-cam: if you stage the actors well, then everybody should understand what their assignments are before you even talk to them. You may have to talk to them if you want something quite particular, but in the broad general scheme of things, they should know where the focus should be. And the cameras are there to shift the focus, the cameras just become the audience’s eyes, and so you want to tell the camera where you want the audience’s eyes to be.

THOMAS | Can you talk more about the skills that were most useful when you first went on set?

SHELDON | I think it’s primarily a strong background with directing actors. All of us find when you go on the sets to do these things that there are a whole lot of people who know a whole lot of things that you don’t know, particularly when you start learning about cameras, and sound, and about editing, and all of those things which you come to learn. But in truth, you are often the only person who knows how to talk to an actor.

JASON | Yes. Having the language to talk to actors amidst all of the sometimes frantic energy is essential. There are so many time constraint considerations with writers and camera; I think that actors still always want interaction. So to be able to talk about character amidst all of the technical aspects is a skill that can single you out.

THOMAS | In terms of communicating with actors on a TV show, these actors have been living with their characters for a long time. You get there on day one with however much pre-production you’ve done, and the cast has shot possibly dozens of episodes. You inevitably have to play catch up, because they have been walking around in these characters for a couple years. How did you deal with this?

JASON | I’ve found that doing my research about where the character has been is the most helpful. If I could reference a couple significant moments of a character’s journey from an earlier season, that made the actor feel comfortable and confident that I understood their history. I think part of being a new director on a set is engendering that trust; that’s why I think they want directors to return, because you’ve created that trust with the actor and a knowledge of the show and its tone.

to me. I’ve found that the trickiest part for me in single camera was the idea that you could move the camera in 360 degrees in any direction. The change in perspective was the thing that I had to learn and catch up with the most in terms of blocking the actors in a realistic way that felt true to the scene and true to the rhythm of the scene. But also being mindful of how the blocking affected the camera positions and the lighting positions related to how much time we had to shoot it in. I couldn’t shoot the camera in four directions and light it in all those directions; so trying to find ways of using the staging techniques of theatre in terms of impulse and timing and comedy, but doing it in a way that didn’t feel like it was directed for proscenium, that made the world feel whole around them.

SHELDON | I think that Jason is absolutely right that the challenge of single camera is that it’s so non-rehearsal dependent. It’s about instincts and honing the actor’s instinct quickly, making adjustments quickly, and then praying that everything is going right technically so that when people nail it you also nail it; that you’re not having a sound problem or a truck doesn’t go by outside and ruin the take.

JASON MOORETHOMAS | Another thing that became very clear for me is that if something doesn’t work, that studio audience will tell you so fast—and there is nothing like the feeling in your stomach when you know you have to fix it right now. There’s no “we’ll get it tomorrow;” it has to happen now. In multi-cam you have 300 new friends in that audience to let you know immediately what is or isn’t working.

SHELDON | You’re right; the tape night on a multi-camera show is a singular experience, because you’re filming in front of an audience. You are improvising the changes from rehearsal that are being made on the floor—first by the writers, then giving it quickly to the actors, and sometimes then having to restage the cameras as it’s necessitated by the change in the material as those 300 people are screaming in the stands. Never is equilibrium and cool more called for from a director than on multicamera tape night. There is an enormous and thrilling juggling exercise that’s going on.

JASON | I’m dying to do multi-cam, because I hear you guys talk about the experience of getting it right in front of an audience and merging the idea of being able to focus where people look, and to do it in front of a live audience is really exciting

THOMAS | If there are 24 episodes, you’re going in to make that one bead on the necklace. It needs to look like the other 23 beads, and if you inspect closely it might have its own particular detail, but the style and rhythm of the show have been set, and you’re trying to serve that. You’re serving the showrunner’s vision. In multi-cam, you do a table read on day one, and the next day you take six hours to stage the entire thing, script in hand, so you can run it for the showrunner and other producers at the end of the day. I think it’s very much the feeling I imagine a choreographer has on a musical, where they’ve been working in the room on a number, and the director comes in to say yes, that works, or, no, let’s re-examine that moment, or that character wouldn’t do that.

SHELDON | Right. That’s not telling the story at all, or why are you doing that?

JASON | I love the idea that directing television is like being a choreographer for a musical. I think that’s really true and is somewhat eye-opening—something to consider in how you think of your choreographer as a collaborator. I’ll keep that in mind the next time I do it. Right now I’m having the experience of working on a pilot. It’s more like working with the playwright in that you are so closely bound in making all of those early decisions together in terms of realizing the vision of

I love the idea that directing television is like being a choreographerfor a musical.

the writer for the first time. The experience of going through the pilot reminded me of doing a new play. You have someone to ask when you feel stuck and they feel they can ask you the same kinds of questions. I found it very satisfying.

SHELDON | Another big thing is you go and do a play, and you know that you’re going to be with those people for a number of weeks. If I use Jason’s comparison about a new play, if it’s a new play or a musical in New York, you have a long rehearsal period and then you have a long preview period before you open with that same group of people. If you’re not the lead director on a TV show, you could be with a whole different community every other week and every show, and like every theatre production, it has its own distinct personality. So not only do you have to absorb the new materials because it’s a new script every time, you also have to absorb the sense of that particular community and how that community operates. Some communities are very loud and party animals and touchy-feely and some are quite cold.

THOMAS | Whereas in theatre you’re the person—as the director—that determines the community to some extent. Because you’ve hired the designers, you’ve hired these actors. So much of it is about what energy you’re bringing into the room. So, Jason, in helping create the world of the pilot, did assembling that team also feel like putting together a play or a musical?

JASON | Yes, it did. We were collaborative in making all of the key hires for the pilot and part of that was, like you say, sort of defining the atmosphere. I was also aware that the single camera work I had done previously was all drama, and this

is a comedy, so I was thinking about how to construct a set that was conducive to people being loose to try things—to try to create the energy of making something fun. I think when picking your key hires you’re trying to define a set and set a tone for the kind of work that’s gonna be done.

SHELDON | I think in television, as in theatre, you don’t have to have every single answer about how to accomplish something, but you do have to be able to articulate the vision of what you want. After all these years in the theatre, I don’t know a Leko from a Fresnel, or whether we even use those anymore, but I know how to talk to a lighting designer about what I want to see. If you can be clear and articulate about your vision on a television set, there are people who will help you to get that vision on camera. I have seen and heard of stage directors go on television sets pretending that they know things that they don’t know, and starting to shout orders and scream at people and all of that, and in many cases that has been their first and last episode, because they haven’t allowed themselves to be helped. The healthy egos that we develop with success in the theatre you sometimes have to put to the side.

THOMAS | Right. How do I communicate this one thing to ten actors and five writers and the show runner, as well as a 50-person crew?

SHELDON | And also how to say, “How can I help you?” to the sound guy or to the camera guy. “Will it be better if I pull this down a foot? Will your shot be improved if I do that?” So it really is, again, the communication skills that hopefully we develop from working in the theatre that can serve us well in this other medium.

THOMAS | If you were able to go back to that early bright-eyed, bushy-tailed you when you were starting out, what lessons would you share that you’ve cultivated over these last few years?

JASON | I would tell myself to trust the basics of what we were talking about: character, storytelling, staging, acting. Because those values get transferred into every form, and then if you want to pursue different forms, just keep your eyes and ears open for every opportunity. One of my biggest theatre opportunities came when I was in Los Angeles, and then one of my biggest film opportunities came when I was in New York. So you know, it was being aware and sending as many messages as I could that I wanted to do both.

SHELDON | It can be enormously satisfying in a number of ways to do both, but it is really hard to balance. For those who are doing it, including you two gentlemen and others who will pursue it, I hope people will keep their passion for working in the theatre as well. In Los Angeles there are a lot of theatre people I know who have made very successful careers working in television. Some of them have not gone back to working in the theatre. As an artistic director who is trying to hire directors, I frequently approach some of those people, and they’ve lost their desire to work in the theatre. We’re good at working in television, because we’re good theatre artists. So I hope that people will keep that alive in their souls and in their hearts and minds, no matter how successful they become in other mediums.

THOMAS | Absolutely. There is a chance to do good work in TV and then bring that information with you when you go back home. One feeds the other in so many ways—and there was a pride in being someone who tries to make his living as a stage director being given a chance in TV. I felt like I was, in some way, representing something much larger than myself. We can all do this if somebody gives us a shot.

SHELDON | I think those of us who have worked in the theatre before we approach working in television or film hopefully have the benefit of the skills that theatre gives you. Obviously talking to actors, but the ability to communicate a vision, as I said before, and the knowledge of what it means to collaborate. Rather than having a new medium shut you down, you make sure that you take those skills into this great new adventure if you have the chance to do it. Those skills will serve you enormously well.

IN RESIDENCE

DONALD BYRD / NEPAL An Agent of Transformation

BY DONALD BYRDSUMMER 2013 VOL. 2, NO. 1

In this essay from 2013, Donald Byrd writes about traveling to South Asia for an arts residency—an experience that showed him how dance can bridge worlds and bring us closer in our shared humanity.

From February 21 through March 24 of this year, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to travel in South Asia to three countries I had never been to before— Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. This was made possible by a unique public/private partnership between the United States Department of State and the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). DanceMotion/ USA, as the program is called, states as its goal: “sharing American dance with international audiences to increase crosscultural understanding.” Since its pilot launching in 2010, it has sent 11 American dance companies along with technical staff and company managers to approximately 33 countries across the globe. Represented in this group have been SDC Members Ronald K. Brown, Doug Varone, Seán Curran,

as well as myself. Because my experiences in each country were so rich, it is impossible to include thoughts on each of them here, so I will focus on my first stop, Nepal.

My journey began when I, along with eight dancers, a technical director, and the company manager from my Seattlebased company Spectrum Dance Theater, landed at the airport in Kathmandu.

It is a boisterous, crowded, dusty, and exhilarating place, with an “aroma” unlike anything I have ever experienced. It felt as if we had been suddenly thrust smack-dab into the middle of an Indiana Jones movie. To mix movie references, we were clearly no longer in Kansas.

It is said that the first impression creates the lens through which all the following experiences are seen—and what a remarkable perspective was created with our first stop in Nepal. After 30 hours of travel and a few hours of sleep, early the next morning we had the first activity of our residency, or what the State Department refers to as “a program.” It was at a school in Lalitpur, one of the three municipalities that make up metropolitan Kathmandu (all in the Kathmandu Valley). We arrived at the school and were taken to a courtyard, where

large, tarp-like cloth mats had been laid on top of the dusty earth on which chairs had been placed, facing a small stage. There were children dressed in school uniforms, already seated and awaiting our arrival. Children dressed in various traditional costumes greeted us with flower garlands that they placed around our necks. We were then led down front and seated in places of honor. After a welcoming address by the principal of the school, a group of children, all dressed in traditional garb, came onto the stage and danced traditional Nepali dances for us. How beautiful they were with their smiles, eagerness, and enthusiasm. When they finished dancing, with a huge smile of my own and tears streaming down my cheeks, I applauded long and vigorously. It was a moving and exhilarating experience.

There was silence, and I realized that it was time for us to dance for them. Though exhausted from travel, without a warmup, and confronted with a small dusty concrete platform of a stage, the Spectrum dancers threw off their shoes and without prompting performed some of the most difficult excerpts from our repertory.

Inspired, I suspect, by the children’s spirit, they danced with such zest and zeal

Donald Byrd (top row at far right) with members of Spectrum Dance Theater in Nepal PHOTO DanceMotion USA/BAMthat I was surprised. The children oohed, aahed, and gasped with delight. When our presentation was over, they wildly applauded. Then I invited the children to come on stage to experience some of the movement they had just seen. They rushed the stage like it was a rock concert (surprising, because we had been told that in school settings Nepali children are often reticent when asked to participate). Together, we created a dazzling mix of colors, with the traditional costumes and the school uniforms swirling around the American dancers on the small stage.

What happened on that first day informed much of how we structured the remainder of our residency activities in Nepal. Working mostly with youth and young adults, our model became one of sharing and not just presenting, of exchanging perspectives, as opposed to “here is my American point of view, and you should pay attention.” We were simply trying to connect human being to human being.

What was most striking to me about Nepal was how important it was for the Nepali young people to share, not only their traditional culture and history with us, but also who they are becoming. The past was shared through the traditional dances, and the aspirational future was apparent from what they had assimilated from watching American movies, music videos, and especially clips on YouTube. There was wild enthusiasm over our hip-hop classes. Hip-hop has captured the imagination of and been embraced by youth all over the world (along with social media and Beyoncé), and Nepal is no different. It appears to be a mechanism through which they are able to express their sense of aliveness in the 21st century, as opposed to their traditional culture, where they often lack the voice or the means of expressing their individuality. But they were eager also to receive the new kind of dance we brought with us, contemporary modern dance. It was important for me to reveal through our contemporary classes and workshops that there are other ways to move, along with what they see on YouTube.

In fact, there are many ways to express oneself with movement. During the master classes and workshops that we presented over our 10-day residency, the experience was for them, it seemed, often new and startling. And the culminating performance of excerpts from my choreographies was exhilarating, challenging, and sometimes baffling—a good thing, I was told. My sense was they were excited by it all and eager to

do and to experience. There was such hunger and desires, to not only have these uniquely American experiences through the kind of dance we do, but also to have authentic and honest interactions and connections with Americans in general. To that point, with the older youth (late teens and early twenties), many would follow us to the different venues where we were teaching in order to have more encounters with us and experience what we were doing more deeply.

In many ways, the interactions before and after every event were just as meaningful and important as the event itself, and these were just the “formal” encounters. There were many informal interactions that also yielded meaningful connections. An example that stands out is the “omelet man” in the hotel restaurant. We saw him every morning at breakfast. He was so curious about who we were and what we did that the dancers gave him a ticket to

to listen. I now have lots of new Facebook friends and lots of email addresses.

The experience in Nepal was a complex, contradictory, moving, and deeply affecting one. From the lung-choking dust and horn honking of Kathmandu to the quiet magnificence of a sunrise high in the foothills of the Himalayas in Pokhara (second largest city of Nepal, situated about 200 km west of Kathmandu); to the beautiful, lively, alert, and attentive children in the schools we visited; to observing the cremation of the dead at the Hindu holy site Pashupatinath; from watching the throngs circle and circle the Buddhist stupa Boudhanath to observing the young Nepali dancers repeating over and over again the movement combinations that the Spectrum dancers had taught them; and to the audience’s screams of excitement and approval at our culminating performance when, as our encore, the Spectrum dancers performed a traditional Nepali dance they had learned from Nepali dancers.

the performance, and he rushed over to see it when he got off from work. The next morning he greeted each of us with an even bigger smile than usual, presented his program that he had brought to work that morning, and had each of us autograph it next to our names and bios.

Jokingly, I have said that as someone older, I felt obsolete in Nepal, because much of the meaningful communication seemed to happen dancer to dancer, young person to young person (the entire country seemed to be under 30 years of age). But there were many opportunities for me to share not only American values of individualism and self-expression but also the diversity of America—sometimes they would ask me, “Are you really an American?”—and to just share myself. This happened with not only the dancers that I met but also with others (again, the young staff in the hotel restaurant is a good example) who seemed so eager to share their aspirations with me. I was glad

I am still processing my experiences in South Asia, and they continue to resonate. But what I have taken away from the experience is a new commitment to three things that I had forgotten from years of being an “art-making machine,” churning out dance pieces and jumping from one theatrical project to the next. This was triggered when I was asked, “What is your dream?” My first response was the usual and very glib “I am living my dream; this is my dream.” But as I thought about it I realized the question required a much more thoughtful response. Today, as a result of my residency in South Asia, I know what my dream is.

I want my work to make a difference in the world—not just to a production that I am working on, but also to the regular Joes that encounter it. It is important to me that the kinds of productions and pieces I work on and create make people think—that they are encouraged by dance to consider their lives and who they are and how their actions affect the world in ways that perhaps they had not considered before. I want to be, through the work that I do, an agent of transformation, to affect people’s emotional, spiritual, and intellectual “DNA” and plant the seeds of transformation.

Big and very idealistic dreams, I know, but isn’t that what the theatre should do?

WITH COSTUME DESIGNER

WINTER 2014 VOL. 2, NO. 3