VOLUME 2, NO. 4 JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2023

C larksville-Montgomery County, Tennessee

931.552.0654 www.plantersbankonline.com Making Great Things Happen. Proudly serving Tennessee and Western Kentucky with 12 convenient locations. A 25 Year Tradition MEMBER FDIC

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Frank Lott

MANAGING EDITOR

Becky Wood

ART DIRECTION & DESIGN

Yvette Logmao Campagna

MARKETING DESIGN

April Papenfuss

MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS

Myranda Harrison

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

David Britton

Beau Duke Carroll

Adam Neblett

Larry R. Richardson

Jan F. Simek

Richard V. Stevens

Shana Thornton

The mission of this publication is to foster creativity and champion our area’s unique cultural diversity. SECOND & COMMERCE expands the Customs House Museum & Cultural Center’s purpose through supporting the arts community, exploring local history and telling stories about the past, present and future of Clarksville.

ARTS AND CULTURE INTERSECT AT THE CORNER OF SECOND & COMMERCE

This entire issue of Second & Commerce is dedicated to Dunbar Cave. The prehistoric cave system and its surrounding area became a Tennessee State Park fifty years ago in 1973. It is almost inconceivable that Dunbar Cave has been a geological marvel over eons of time, and yet many of us pass by the lovely site frequently without giving it a moment’s thought.

HOURS OF OPERATION

Tuesdays–Saturdays 10 am–5 pm

Sundays 1–5 pm

Closed Mondays

customshousemuseum.org

@customshousemuseum

#customshousemuseum

Frank Lott EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

For many longtime Clarksvillians, Dunbar Cave conjures vivid memories and sublime recollections. My parents often recounted their outings during the late 1940s as a young military couple enjoying big band music and the cave’s cool air refreshing the dance floor. My very first date with my wife Patti was to see Lee Castle & the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra playing for a big band dance at Dunbar Cave. It was one of the signature events during the 200th anniversary celebration of Clarksville’s founding. Check out page 28 for a picture of us on that cool night in June 1984.

Oh, the tales that cave could tell.

But wait… it does tell stories from its past. From its incredible geologic record, to its diverse and still evolving biological ecosystem, and now through a virtual reality tour available for those who cannot enter (or choose not to enter) the cave’s vast network of tunnels and passages.

Humans have an intrinsic fascination with the world “underground.” The cave has been used by untold generations of homo sapiens for many odd, sometimes clever and even sacred purposes. Dunbar Cave is the hallowed home to ancient cave drawings left by Indigenous peoples, candle smoke graffiti, gun powder storage—it even caught the eye of mushroom farmers. The cave served as a fallout shelter during the Cold War, and yes, was even abused in the name of science. The site is bordered by what was once known as Affricanna Town, and later by the Idaho Springs Resort. In its most recent heyday, it hosted countless dances, concerts and Roy Acuff performances.

So, what does the future hold for this alluring, mysterious labyrinth? Well, we must do our part to minimize the impact of our own intrusions if this geological marvel is to be appreciated by generations yet to come. My hope is that visitors long after us get to feel the cool breeze at the entrance of Dunbar Cave, just as we have felt it.

Enjoy this issue of Second & Commerce!

CUSTOMS HOUSE MUSEUM & CULTURAL CENTER BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Thomasa Ross, Chair

Larry Richardson, Vice Chair

Frazier Allen

Dan Black

Kell Black

Christina Clark*

Joe Creek*

Kyong Dawson

Jim Diehr

Jamie Durrett

Darwin Eldridge

Lawson Mabry

Deanna McLaughlin*

Linda Nichols

Brendalyn Player

Wes Sumner

Eleanor Williams*

*denotes ex-officio

SECOND & COMMERCE / 1

HISTORY,

2 / SECOND & COMMERCE 1 / Director’s Letter 12 / Art of Dunbar Cave 28 / Dunbar Cave Memories 30 / The Postscript 32 / Connect with Us TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTACT Advertising Inquiries Arts & Culture Events Article Submissions Please email Becky Wood at becky@customshousemuseum.org. customshousemuseum.org/second andcommerce The Clarksville Montgomery County Historical Museum (d.b.a. Customs House Museum & Cultural Center) is designated by the IRS as a 501 (c)(3) non-profit organization. © Customs House Museum & Cultural Center 2023-07/2023-4M

Cave State Park, 2013

Dunbar

ON THE COVER: we can help with that clarksville’s premier coworking space

Photo

by David Smith

4

Stewardship & Soul: The Ever-Evolving Significance of Dunbar Cave

In 1973, Dunbar Cave became a State Natural Area, designating it as a unique and treasured outdoor resource of Tennessee. This area has meant many different things to many different people for centuries—and its story is still being written.

6 / Night Flyers: The Bats of Dunbar Cave

Under Pressure: Unearthing Dunbar Cave’s Geological Wonder

Clarksville sits in the largest karst region of the United States, dotted with sinkholes, caves and underground streams. Millions of years of geologic processes have formed this local landmark, which stretches more than eight miles inward and features a variety of cave formations.

9 /

Many creatures call Dunbar Cave State Park home, but perhaps the most notable residents are the bats. Bats are essential to ecosystems across the globe, but the destruction of their habitats and diseases like whitenose syndrome continue to threaten their populations worldwide.

16 /

Ancient Art & Sacred Space: Tennessee’s First Peoples in Dunbar Cave

For the Mississippian people that lived along the Red River in the 14th century, Dunbar Cave was a sacred place. The symbols and art found within the cave continue to hold sacred meanings for modern Indigenous peoples of the southeastern United States.

21 /

A Summer Vacation at Idaho Springs: The Storied History of Dunbar Cave’s Resort Hotel

The rich mineral springs surrounding Dunbar Cave attracted commercial developers to the area in the 1850s, eventually leading to the construction of the Idaho Springs Hotel. Take a look back at the chronicles of Clarksville’s “lost valley.”

26 /

Classics at the Cave: The Big Band and Acuff Eras

As Clarksville entered the 1930s, Dunbar Cave continued to be a recreational hub. This era invited some of music’s biggest stars to the cave, from big band leaders to “King of Country Music” Roy Acuff, who bought the property himself in 1948.

SECOND & COMMERCE / 3

ISSUE /

IN THIS

FEATURES

/

Stewardship & Soul

THE EVER-EVOLVING SIGNIFICANCE OF DUNBAR CAVE

BY DAVID BRITTON, DUNBAR CAVE STATE PARK MANAGER

“We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related; the eternal ONE. And this deep power in which we exist, and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, aseen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject, and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are the shining parts, is the soul.”

The Over-Soul

Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1841

Why do we consider a place to be important? More specifically, what makes Dunbar Cave so significant? I regularly ask myself this question, and the answer is never straightforward or precise. Significance is often subjective and made narrow by the parameters of time. By the very nature of the average span of human life, we tend to be myopic in how we perceive significance.

In the short time over the last century, economics, preservation initiatives and discoveries have radically shifted Dunbar Cave’s significance. By the late 1960s, Dunbar Cave was a failed private resort. Despite the community’s fond memories of the place, it was no longer profitable. At the urging of Montgomery County leadership,

Dunbar Cave underwent a significant transformation to a State Natural Area in 1973, managed by Tennessee State Parks. This new identity placed a completely different set of values and significance upon Dunbar Cave, aimed at recreation through a lens of preservation, protection and interpretation of the cultural and natural resources of the site.

In 2005, discoveries again shifted the significance of Dunbar Cave. When Park rangers and scientists found cave art that was over 700 years old, it became clear that Dunbar Cave was significant to more than just EuroAmerican people. It now included the voices of descendant groups, like the Cherokees, whose role as stakeholders increased even more after Cherokee syllabary was found in the cave in

2019. Indigenous input into which stories we tell, how we tell them and how we steward this sacred space has become critical to Dunbar Cave State Park’s mission.

In 2020, Park staff determined much of the little-known story behind Affricanna Town—a freedman’s village where newly emancipated African Americans exercised their new citizenship for the first time in the aftermath of the American Civil War. Before this village, Dunbar Cave was a site of enslavement; over 100 people were enslaved there from 1784 until 1864. These stories make it abundantly clear that Dunbar Cave was also overwhelmingly a Black space. The 1879 creation of the Dunbar Cave resort subverted this community. Until 1973, with the

4 / SECOND & COMMERCE

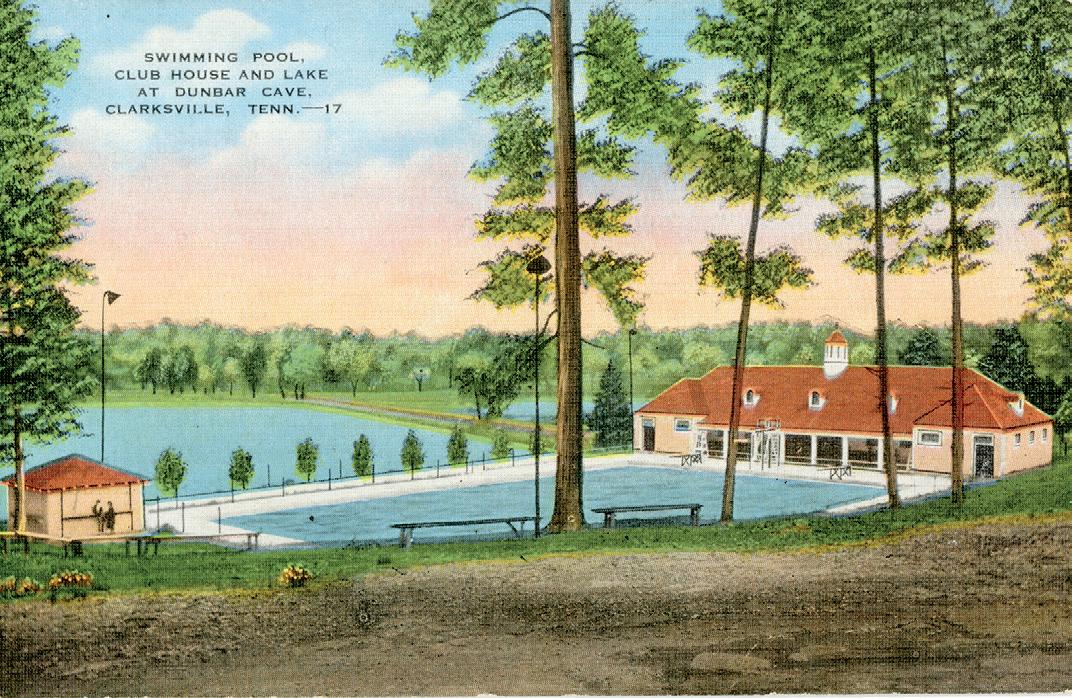

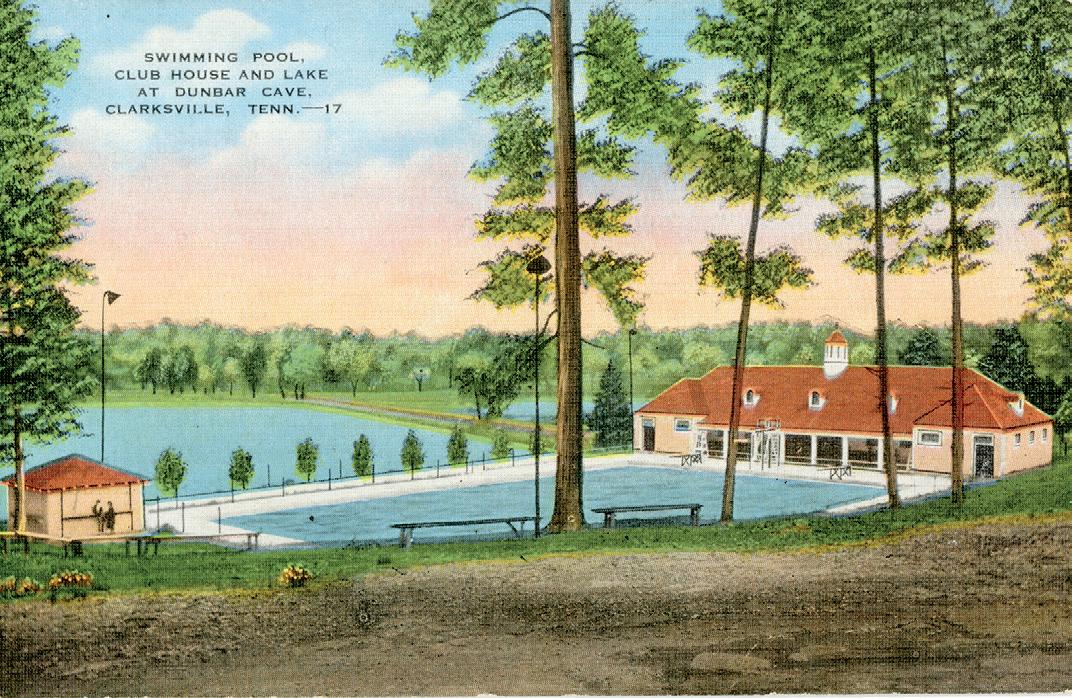

Distributed by Anderson's News Agency, Clarksville, Tenn. Genuine Curteich-Chicago "C.T. Art-Colortone" Postcard Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

Park’s creation, African Americans were only allowed back into this sacred space as employees. Once again, Dunbar Cave’s significance expanded.

Clearly, Dunbar Cave defies our tendencies toward a narrow significance. Places like this remind us that we are connected to everyone who has come before us and will come after. The stories of humankind are embedded in the ground at Dunbar Cave, and they challenge us to broaden

our worldview. If nurtured, this fosters empathy for the natural and human world. These stories are why Dunbar Cave is important, and this is why we should value the protection and preservation of such places around the world.

I invite you to stand in front of Dunbar Cave where countless others, of disparate cultures and times and for purposes both sacred and profane, have stood exactly where you stand, and connect with their stories. It’s a humbling thought.

tnstateparks.com/parks/dunbar-cave

SECOND & COMMERCE / 5

Check out Volume 1, Issue 1 of Second & Commerce to learn more about Affricanna Town and Clarksville’s Civil War contraband camp.

Places like this remind us that we are connected to everyone who has come before us and will come after.

PRESSURE

Unearthing

Dunbar Cave’s Geological Wonder

BY ADAM NEBLETT, DUNBAR CAVE STATE PARK RANGER

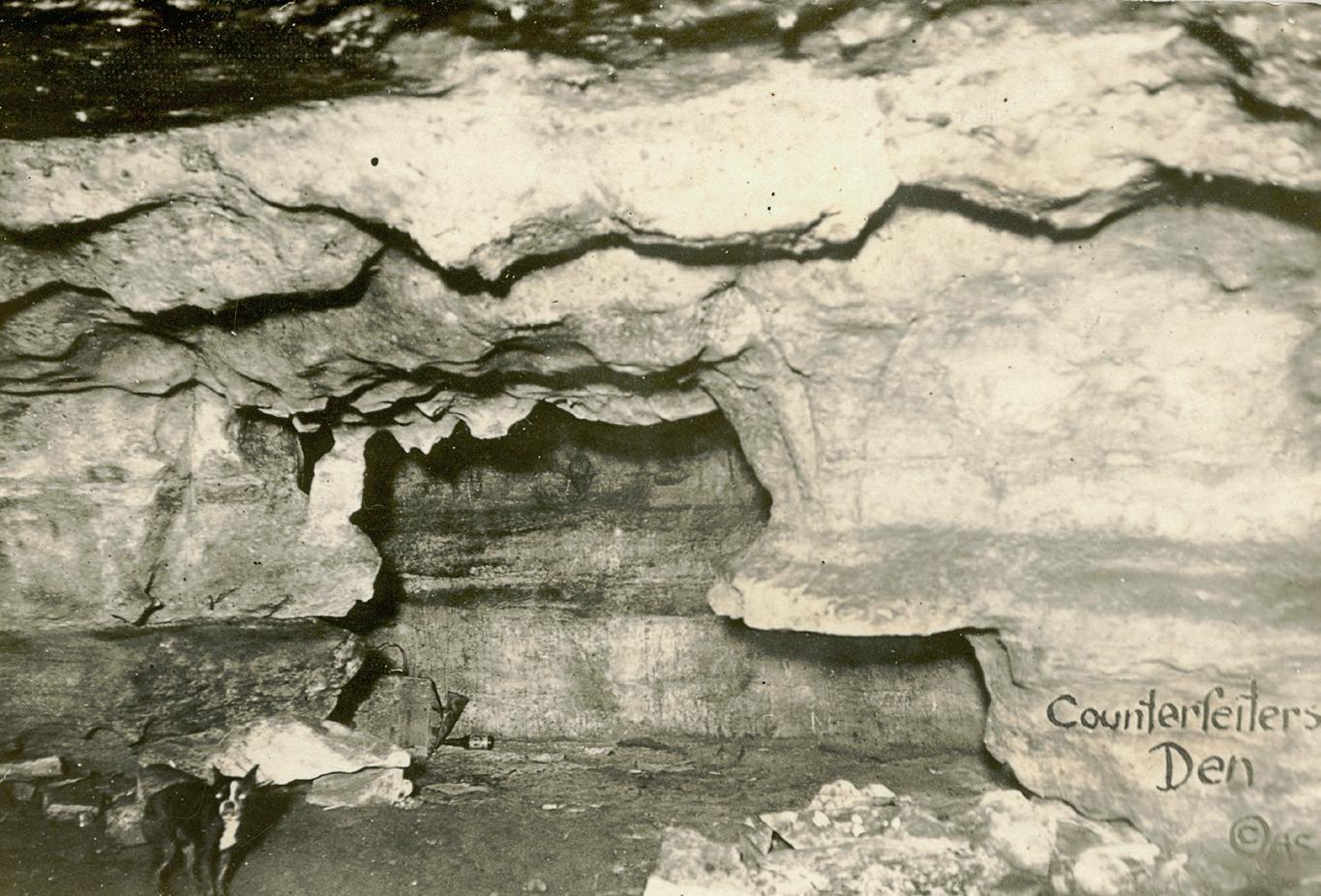

Dunbar Cave is a special place. Thousands of locals and tourists descend upon the Park every summer for a guided cave tour experience, where they can encounter everything from the remnants of a 1930s dance hall to centuries-old Indigenous artwork. Some of the most asked questions on tour revolve around the age of the cave. To answer these questions, we must look back to a previous geological era.

Long geologic processes created the limestone bedrock where Dunbar Cave exists. During the Carboniferous Period, 350 million years ago, much of North America was covered by a warm, shallow ocean. Abundant sea life in the form of crinoids, mollusks, brachiopods and corals flourished. As these creatures, whose bodies were mainly composed of calcium carbonate, died, their remains accumulated on the seafloor,

creating layers of sediment. These layers, over time, continue to be compacted by accumulating material on top. Under pressure, chemical changes and cementation occur, creating limestone. Eventually, geologic uplift caused by plate tectonics raised the ocean floor. The sea drained, and the landscape we know today started to take shape.

Limestone is especially susceptible to chemical weathering. As rain falls through the atmosphere and passes through the soil, it collects carbon dioxide, forming a weak acid. This acid dissolves the rock at its weak points, creating channels that can eventually form sinkholes, caves and underground streams. Limestone regions with these features are called “karst” topography. The largest karst region in the United States includes Central Kentucky and the

UNDER

Calcite, the crystalline form of calcium carbonate, is the primary mineral component found in cave formations. One can also find round chert rocks inside the cave and on the surface above, commonly called flint. Chert forms from silica contained in microalgae living in that ancient ocean long ago. Fossilized coral heads and brachiopods (clam-like invertebrates) can be found in the walls and ceiling of Dunbar Cave. Photo by Micah Matthewson

Western Highland Rim of Tennessee, where Clarksville sits.

Located in the St. Bethlehem area, a sinkhole plain drains rainwater into Dunbar Cave, feeding an underground stream that emerges at a large spring below the cave's main entrance. This subterranean river flows the length of the cave and divides it into two sections via a flooded passage. The historical section is accessible from the main entrance and is where almost all human activity has occurred over the last 10,000 years. The Woodard extension is larger and can only be accessed by those with specialized skills and equipment. Spelunkers surveyed and mapped the cave decades ago and were the first humans to set foot into the Woodard extension. This survey found two additional entrances: Woodard and Double Dead Dog Drop (D4 for short). D4 gets its name from two dog skeletons found at the pit's bottom. Property owners sealed this entrance to prevent future canine misadventures.

Geologists think that Dunbar Cave began forming between two and ten million years ago. As the flowing groundwater continues to carve out new passages, the upper areas of the cave drain and fill with air. This process enables the creation of cave formations, or speleothems. As acidic rainwater drains through the limestone, it strips minerals like calcite, the crystalline form of calcium carbonate, from the rock. The calcite is held in the solution until the water drips from the cave ceiling. When exposed to air, calcite separates from the drops of water and remains behind in a ring. Water dripping at the same pace over time leaves behind layer upon layer of calcite, forming hollow tubes we call “soda straws,” the most common speleothem in Dunbar Cave. If the hollow center of a soda straw becomes clogged, water begins dripping from the outside of the tube, taking on an inverted cone shape and becoming a stalactite. As the water drips onto the floor, it retains some calcite. These drips can also accumulate into a cone shape called a stalagmite. As stalactites and stalagmites

SECOND & COMMERCE / 7

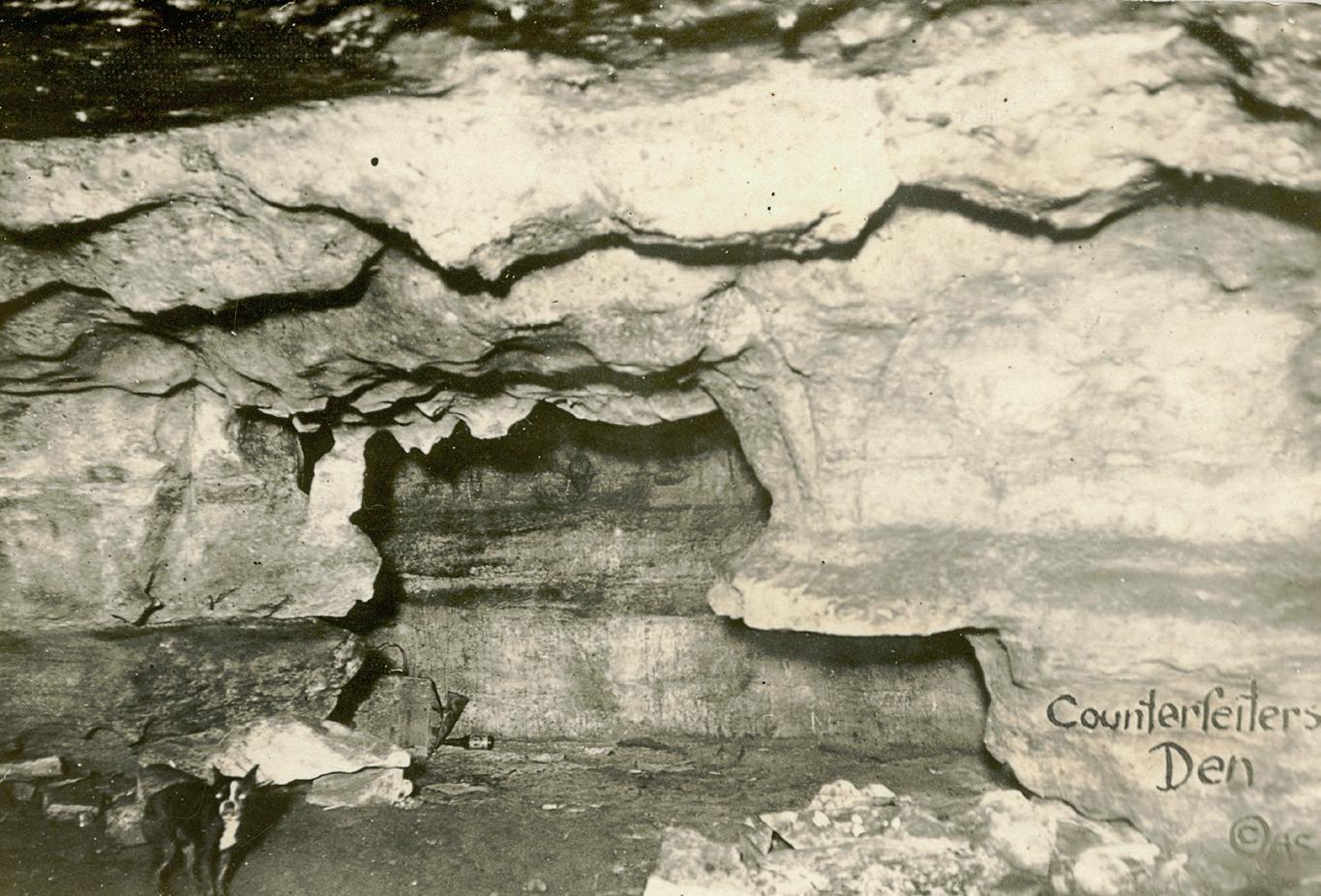

Dunbar Cave stretches more than eight miles inward, complete with different “rooms” that contain numerous examples of cave formations that have formed over thousands of years. Postcards, ca. 1925 | Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

grow and meet in the middle, they merge into a column.

Water flowing down vertical walls lays down sheets of calcite accumulating into flowstone, which looks like halfmelted ice cream. Speleothems can also form out of standing water on the floor. Calcite moves to the edges of the puddles and builds up into ridges that can grow several feet high and create deep pools of water called rimstone pools. The ridges that enclose them are called rimstone dams.

All these processes take time. The average rate of speleothem growth is one inch per hundred years. For this reason alone, vandalism in the cave is a serious issue. It only takes an instant to destroy features that took thousands of years to form.

The first mentions of the cave being vandalized date back to the 1880s. During this time, the first commercial operation was established at Dunbar Cave, and the entrance was gated to control access. The cave suffered greatly as the cave property changed

hands, and gates were broken into over the years. The worst period of vandalism occurred in the early 1970s when the property was abandoned, and the cave gate destroyed. During this time, the cave suffered from many instances of graffiti, smashed speleothems and lit fires. That all began to change in 1973 when Dunbar

Cave State Park was established. This year, we celebrate a half-century of protecting the natural and cultural resources of the cave and surrounding landscape.

tnstateparks.com/parks/dunbar-cave

8 / SECOND & COMMERCE

One of the highlights of the cave tour is Independence Hall, one of the only remaining rooms containing intact cave formations like stalactites, columns and more. Postcard, ca. 1925 | Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

Night Flyers

THE BATS OF DUNBAR CAVE

BY LARRY R. RICHARDSON

Our region is dotted with caves. This is limestone country, and water cuts through it to form openings in the subsurface. These karst formations are characterized by underground drainage systems of sinkholes and caves. Austin Peay State University sits on several sinkholes (or bowls, as we called them when I was a student there). The most famous cave in the area is at Mammoth Cave National Park, located just north of Bowling Green, the world’s longest cave system.

Our locally famous Dunbar Cave is the 280th largest cave in the world and 75th in the United States, stretching just over eight miles. It is estimated that there are about 10,000 caves in Tennessee due to the limestone and dolomite below the surface.

Life exists in caves, and Dunbar Cave is no exception.

The most noteworthy residents of the cave are the bats. They are nocturnal, so we do not always notice them flying about in seemingly erratic maneuvers, chasing flying insects. As their food foray comes to a close at dawn, they nestle in secluded places and rest.

“Bats that historically inhabited the cave were Big Brown, Little Brown, Tricolored and Northern LongEared,” explained Dunbar Cave State Park Ranger Adam Neblett. “However, the most recent survey in February 2023 found only 12 bats, a mix of Big Browns and Tricolored. In addition to bats, the cave has cave crickets, cave salamanders, blind fish and crayfish as well as various small spiders, millipedes and beetles.” Other bat species are present outside the cave and usually have summer evening roosts on trees or outcroppings.

Bats are mammals like you and me. Unlike people, they have a special ability to “go cold” to save energy when there isn’t anything to eat. This is called “torpor.” Scientists count bats in the winter to make sure their populations are sustaining and thriving. They look in caves and abandoned mines where bats hibernate when it is too cold to forage for insects. The average temperature of caves in Tennessee is 58°F. As you travel northward, the average is somewhat lower. For example, Kentucky caves have an average temperature of about 54°F.

A few years ago, during their annual winter bat counts, scientists noticed that bats in caves in New York State were dying. The bats that were still alive had a white fuzzy growth on their muzzles and wings, which scientists named white-nose syndrome (WNS). According to the National Park

SECOND & COMMERCE / 9

Photo by Micah Matthewson

Service, which manages several large caves across the country, WNS is a fungal disease killing bats across North America. Research indicates the fungus that causes WNS is likely exotic, introduced from Europe. What started in New York in 2006 had spread to more than half of the United States and five Canadian provinces by August 2016, leaving millions of dead bats in its path. WNS causes high death rates and fast population declines in the species affected by it, and scientists predict some regional extinction of bat species.

WNS causes bats to awaken prematurely and begin to burn stored-up fat. They die of starvation because cold temperatures outside mean a reduced number of insects to eat. WNS has been detected on bats in Dunbar Cave, and biologists with Austin Peay State University, State Parks and the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency continue to monitor this debilitating disease. Current evidence indicates that WNS is not transmissible from bats to humans, although humans could be a vector for the fungus when traveling from one cave to another.

U.S. Forest Service notes that our bat population nationwide is on a decline, mainly due to loss of habitat and whitenose syndrome. They suggest that the erection of “bat houses,” similar to bird houses, can help reverse this trend. Bats are pollinators and an essential part of our ecosystem—plus, they are far more effective at insect control than electric bug zappers. Bats eat more mosquitoes than any other creature, which is just one of many reasons we want to keep bats around.

While researching for this article, I interviewed Allen Coggins, former State

10 / SECOND & COMMERCE

TOP: A Little Brown bat with white-nose syndrome, evident through the white fuzz on bat’s face. WNS causes changes in bats that make them burn up fat they need to survive the winter.

Photo by Marvin Moriarty/ USFWS | Courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

BOTTOM: An Arnold Air Force Base team member swabs the muzzle of a Tricolored bat in a cave near Arnold AFB, Tennessee, to contribute to a study by Virginia Tech concerning the species and white-nose syndrome.

Photo by Jill Pickett | Courtesy of the U.S. Air Force

Parks Chief Naturalist and spelunking enthusiast. “Dunbar Cave served as a nuclear fallout shelter during the Cold War,” Coggins recalled. “One night in the 1970s, vandals trashed the supplies and set fire to Civil Defense boxes stored inside. When the flames were finally extinguished, investigators found thousands of tiny bat skeletons littering the cave floor.” Other bats later re-established a viable colony, but this tale is a stark reminder of the human impact on this living local treasure. We can all benefit from gaining a better understanding of the environment within Dunbar Cave and these often-misunderstood creatures that call it home.

Larry Richardson is an artist, naturalist and writer. Graduating from Austin Peay State University with a master's degree in biology, his professional environmental career included positions as Tennessee Parks Chief Naturalist and Chief of Information-Education for the Tennessee Wildlife Agency, where he also served as the editor of the agency magazine, and Ducks Unlimited as National Director of Field Fundraising Initiatives.

batcon.org

Make an Appointment

to face the future with confidence

.

Look forward to a healthy future by taking care of yourself now. At Tennova Medical Group, our healthcare providers take the time to identify your health risks and can help you prioritize good health. With same-day appointments and online scheduling, we make it easy to make an appointment right now. You can even see us from the comfort of home via telehealth. Make a strong choice for a healthy future. Make the most important appointment today. Visit PCPTennovaClarksville.com.

SECOND & COMMERCE / 11

A trio of Tricolored bats in Asheville, North Carolina. Each winter, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission checks caves to monitor bat populations, giving the biologists a clearer picture of bat numbers, diversity of bat species and the impacts of white-nose syndrome. The Tricolored bat is an at-risk species, currently being considered for inclusion on the federal threatened and endangered species list.

Photo by Gary Peeples/USFWS | Courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

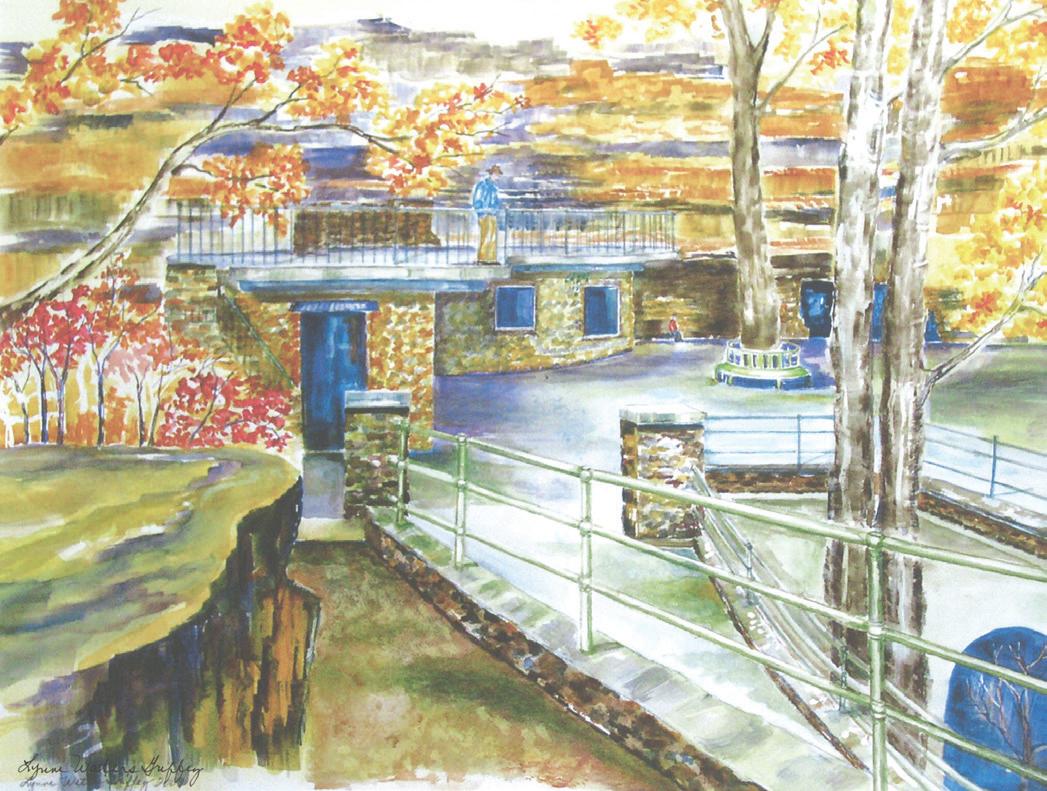

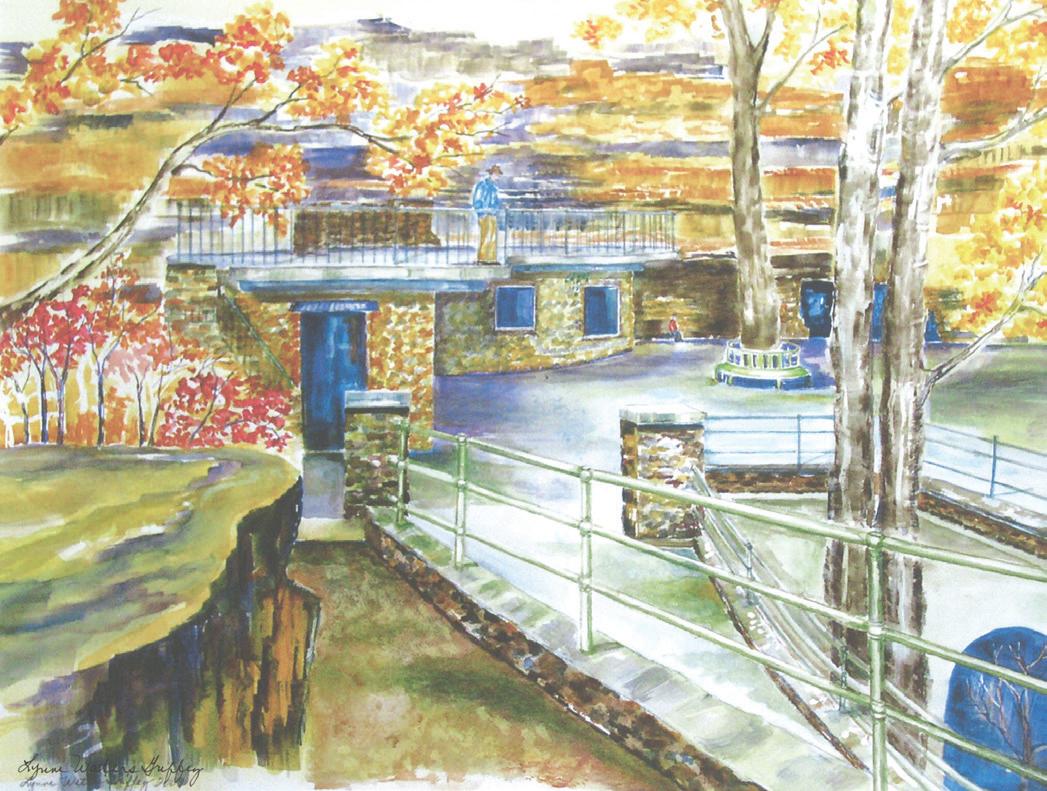

Art of Dunbar Cave

From the Mississippian art found deep inside the cave to the plein air paintings found in regional galleries today, Dunbar Cave has been inspiring artists for centuries. This selection of work from local artists showcases a variety of unique creative outlooks into this iconic natural gem.

Terri Jordan

David Smith

Larry Richardson

Lynne Waters Griffey

Rosemarie Rogoish

Terri Jordan

David Smith

Larry Richardson

Lynne Waters Griffey

Rosemarie Rogoish

Kitty Harvill

Peg Harvill

Frank Lott

Kitty Harvill

Peg Harvill

Frank Lott

DC Thomas

Lynne Waters Griffey

14 / SECOND & COMMERCE

Terri Jordan

David Smith

Peg Harvill

Lynne Waters Griffey

Beverly Parker

DC Thomas

SECOND & COMMERCE / 15 Pottery Studio | Art Gallery 115 Franklin St. Clarksville, TN Rivercityclay@gmail com 931-542-6615 B R I N G I N G T H E A R T O F H A N D M A D E P O T T E R Y T O D O W N T O W N C L A R K S V I L L E Rivercityclay.com LET YOUR CLAY JOURNEY SHOP BOOK A CLASS. BEGIN.

Kitty Harvill

DC Thomas

Patsy Sharpe

Ancient Art & Sacred

TENNESSEE’S FIRST PEOPLES IN DUNBAR CAVE

Human history in Dunbar Cave begins more than 10,000 years ago, when America’s original people occupied the cave near the end of the last ice age.

Excavations under the platform in front of the cave in the 1970s showed a deeply stratified sequence of Native American occupations. The earliest visit to the cave was by people using stone Beaver Lake spear points, a very early type.

On top of this Paleoindian level were more than 13 feet of successive occupation layers, spanning the entire precontact sequence in eastern North America: Paleoindian (14,00010,000 years ago), Archaic Period (10,000-3,500 years ago), Woodland Period (3,500-1,000 years ago) and Mississippian Period (1,100-400 years ago). These stratified occupations represent every period of Native American history in Tennessee, making Dunbar Cave one of the longest and most complete sequences known anywhere east of the Mississippi River.

BY BEAU DUKE CARROLL,

BAND

The ancient use of Dunbar Cave became even more unique when cave art was found deep in the dark zone of the cave, beyond the reach of external light. In January 2004, a caving group including Joseph Douglas (Professor of History at Volunteer Community College in Gallatin, Tennessee) and cave author Larry Matthews visited Dunbar Cave in the company of Amy Wallace, then Interpretive Specialist at the Park. In an area of the cave known as “the Ballroom,” several hundred meters into the dark zone, Douglas noticed two charcoal drawings on the wall overlaid by 19th-century graffiti (Figure 1).

16 / SECOND & COMMERCE

EASTERN

OF CHEROKEE INDIANS TENNESSEE, KNOXVILLE AND JAN F. SIMEK, UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE,

Space

& UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, KNOXVILLE

In February of 2005, Dr. Jan Simek joined Douglas, Wallace and photographer Alan Cressler at the site. On that visit, a significant number of new pictographs and petroglyphs were identified in the same Ballroom area of the cave and in other passages. Today, nearly 40 individual glyphs have been recorded, almost all concentrated in four panels along a west-side wall segment in the Ballroom. There are glyphs scattered elsewhere in the cave, including some inscriptions written by Cherokee visitors.

The most common figure involves the use of circles (Figure 2). Three

glyphs, two in the main room and one on the ceiling at its entrance, are simple single circles. Nineteen individual glyphs are sets of concentric circles.

There is a great deal of variability in the number of circles involved in these images. Some have only two rings, some have three nested together; one complex glyph has four concentric rings. These images were produced using two techniques. Some were painted with black pigment (pictographs); others were engraved directly into the limestone of the cave wall (petroglyphs). In one composition, 17 of the circle glyphs are disposed

in a single array of four vertical lines of images (Figure 3).

These lines include from two to six glyphs each, spaced about 25 centimeters apart. An arc was drawn passing over all the concentric circles in this panel, collecting them into a single composition. Stars made of crossing lines are positioned above the arc (Figure 4).

We do not know exactly what this complex composition might mean. In any case, circles like these are one of the most common design elements in prehistoric art in the southeastern United States. There are some circles in Dunbar

SECOND & COMMERCE / 17 Sacred

Figure

1

Figure 2

Cave that do have chronological context, including the first glyphs identified. Both are concentric circles with exterior rays and interior crosses inside their inner rings. This rayed cross-in-circle motif is found frequently in late precontact Mississippian period archaeological contexts.

Circles are not the only motifs in Dunbar Cave. There are also more complex and representational images, including two anthropomorphic figures that also implicate Mississippian artists in the production of Dunbar Cave’s artwork. One image is the profile of a human face with fine features and long hair (Figure 5). The second anthropomorph has a reclining human form with well-defined arms and legs (Figure 6).

Three fingers appear on the lower arm. The lower appendages (legs) thicken towards the feet, and those feet have claws, suggesting an animal element to the character’s form. The stippled head of this image is quite unusual. There is an axe or calumet above the head and a curving line extending out from the upper part of the head. There are circles at each side of the head, suggesting ear spools. The trunk below the arms is well defined and filled with pigment. The waist and upper legs are covered with an hour-glass shaped garment, a kilt perhaps, which has several lines suggesting folds or decoration. All of these elements are in keeping with precontact Mississippian iconography.

3

Figure

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Mythical warriors were common and important characters in their religious narratives. They frequently combined human and animal characteristics and are often shown with elaborate head decoration, including weapons in the hair, ear spools and curling hair locks. Kilts are also common aspects of the warrior’s regalia. The Dunbar Cave anthropomorph is readily interpreted as depicting a Mississippian cosmic warrior, which fits quite well chronologically with the denticulate circles discussed earlier.

All of the pictographs in Dunbar Cave are black, and chemical analysis shows that wood charcoal mixed with water was used to produce them. This is a simple paint recipe, but we know from other sites that this simple formula produces a paint that is vibrant and enduring.

The parietal art in Dunbar Cave was produced during the Mississippian period, but Native American people visited the cave both long before and after that period to conduct other activities. Almost 4,000 years ago, during the Archaic Period, large, finely-made tool stone artifacts were placed onto a hard travertine surface that once covered the floor of the Ballroom (Figure 7).

The travertine (a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs) was laid down by water, and this room, dry today, was likely covered by pools into which the artifacts were placed. This kind of offering is a common ceremonial activity known to have occurred in caves around the world. Referred to as “votives,” artifacts with symbolic iconographic meaning are often put into caves and springs as gifts to the spirits that reside there. The fact that two ceremonial practices, cave art and votive offerings, occurred in the same room at Dunbar Cave may or may not be coincidental, but they did occur thousands of years

apart in time. If our interpretation is correct, then this is the first example of votive offerings we know of in southeastern caves.

Cherokee people visited the cave much more recently than in the Mississippian Period. We know that an important Trail of Tears route passed close to Clarksville in the late 1830s, when groups of Cherokees, along with other eastern Native American peoples, were forced to leave their ancestral homelands in the Appalachian Mountains and move west to current-day Oklahoma. Thousands of Cherokees stopped and rested at Port Royal before moving on to the Mississippi Valley, and members of these groups certainly stopped at Dunbar Cave as they passed. Today, the Cherokee descendants of these removed people also stop in Clarksville as they undertake a bicycle trip from North Carolina to Oklahoma to commemorate the removal and those that suffered and died along the way.

At several points inside the dark zone of Dunbar Cave, but away

from the area with Mississippian art, inscriptions appear written with elements that are clearly not English letters (Figure 8). Cherokee language experts think these writings to be Cherokee syllabary, a writing system invented in the mid-19th century by the Cherokee scholar Sequoyah. There are several interesting aspects to these characters. First, several syllabary elements are found next to English letters in the same hand and painted with the same paint. Both syllabary and English inscriptions appear to be names or initials, presumably of the people making them. A date associated with one of these is 1855, years after the Cherokee Removal was complete. Thus, we believe that the syllabary elements were placed in the cave by Cherokees coming back to visit their homelands from the new lands in the west. Native Americans could and did move around after removal, and Dunbar Cave may contain evidence of such movement. The paint used to make these inscriptions is cadmium yellow, a commercial product available only for a short time in the mid-1850s due to its toxic ingredients; this date matches the

SECOND & COMMERCE / 19

7

Figure

date written on the wall. Thus, the Cherokee writers were memorializing their visit to a place that had significance to Cherokees because of its role in the Trail of Tears itself.

The interior of Dunbar Cave, then, was used by Tennessee’s first peoples for thousands of years. Votive offerings were made four thousand years ago into the dark waters of the cave interior; religious art was made on the cave walls one thousand years ago; and Cherokee people entered the cave as they were forced west, then returned to it after their removal from the lands of their ancestors. All of this reflects the continuing importance of Dunbar Cave to the original inhabitants of the region. That importance is not diminished. Native people today hold the cave and its contents as sacred space. We should all honor and respect that sacredness as we use and learn from the dark reaches of Dunbar Cave.

tnstateparks.com/parks/dunbar-cave

20 / SECOND & COMMERCE

All photos by Alan Cressler

Figure 8

A Summer Vacation at

Idaho Springs

THE STORIED HISTORY OF DUNBAR CAVE’S RESORT HOTEL

BY RICHARD V. STEVENS

A quarter-mile south of the gaping mouth of Dunbar Cave, in a sunken grove of maples and poplars, the earth opens in a more subtle way. In the marshy floodplain of the creek that connects the waters of the cave with the Red River some 500 yards away, three ancient springs seep, offering a slow trickle of groundwater that flows quietly toward the creek in shallow trenches.

The three springs, which came to be known as the Idaho Springs, are renowned for each having distinct mineral properties—and as an integral feature of the cave area’s natural wonders. The springs attracted Native Americans to the site at least 12,000 years ago. Centuries later, they lured generations of settlers, speculators and resort developers, who endeavored to exploit the waters’ reputed healing powers.

Today, the Idaho Springs are on private property and run in a “lost valley” along a creek among the residential neighborhoods known as Wingate East, Wingate West and Idaho Springs. Three moss-covered concrete structures, each six feet square and about three feet high, encase the springs. Their humble appearance stands in contrast to the days when the site attracted visitors who bottled the mineral water for transport, and to later days, when a paddle wheel pushed the water uphill to the grand Idaho Springs Hotel, where quests were promised the benefits of “running water in every room.”

WRITTEN HISTORY OF THE development of the area can be traced to 1858, when advertisements in the Clarksville Chronicle promoted the “Sulphur Springs Tract, containing 100 acres, with a new and commodious house, with 11 rooms, besides 2 good cellars and good outbuildings, well adapted for the accommodation of persons visiting the Springs, the waters of which enjoy a high reputation for their curative qualities.” Later that year, an advertisement offered investment opportunities in “twenty–four acres of Land near Peterson’s Sulfur Springs, about three miles from town, on which is a fine Spring.”

Other accounts note that around 1858 a number of cabins were built near the Idaho Springs with plans to erect a large hotel later.

By 1860, some enterprising landowner must have decided “sulphur springs” wasn’t enticing enough, and subsequent reports started calling the area Idaho Springs. Who bestowed the name, and why, is a mystery. One legend suggests an “Indian chief passing

SECOND & COMMERCE / 21

ABOVE: Postcard, ca. 1940s Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

through stopped to drink at the springs. Finding the water pleasant he named it Idaho, which meant ‘Gem of the Mountain.’”

A more plausible explanation, found in archives maintained by Dunbar Cave State Park, states that in 1860 when Colorado was about to become a U.S. territory, congressional delegate William Willing suggested the name Idaho, which he claimed was an Indian word for “Gem of the Mountain.” Later it was discovered that Idaho was not a word in any known Indigenous language, and the people of the territory requested the name Colorado, which is Spanish for “red.” But “Idaho” seemed to stick in the popular imagination of the time, and it got attached to the local sulfur springs—and also to the Idaho territory in 1863, after a steamboat of that name carried gold miners westward to seek fortune.

The renaming of Clarksville’s Idaho Springs is consistent with the desire of the city’s 19th century movers and shakers to capitalize on the natural wonders of Dunbar Cave and the springs. An 1860 article in the Clarksville Chronicle made this case: “With all the natural advantages possessed by these Springs, together with the close vicinity of Dunbar’s Cave, a small outlay, judiciously made in buildings, walk, and drives ought to make them a most popular place of resort.” The same article notes that the owner apparently had transformed the 11-room house into a boarding house with some nearby cabins, which in later accounts is referred to as a hotel operation.

THE IDAHO SPRINGS CONSISTED OF three mineral springs, which ran with red, white and black sulfur, alum and chalybeate. The red spring contained pyrite, a combination of iron ore and sulfur. The black spring primarily contained sulfur, which gave off a foul odor. These waters were thought to cure many types of skin and blood disorders.

The Civil War derailed hopes of more resort development for the area through the 1860s, beginning a cycle of boom and bust for the neighborhood’s tourism fortunes that would last for the next century. By 1871, the drumbeat on behalf of the cave and springs’ future had returned: “Idaho Springs is to be made a public resort,” the Chronicle trumpeted on June 17. But by August 1877, the doldrums had returned, with an article asking why someone doesn’t purchase the springs and provide better accommodations. “The few cabins that are there are filled every summer…”

TOP: Dunbar’s Cabins, ca. 1930s Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

BOTTOM: Idaho Springs Hotel brochure, 1915 Courtesy of Ed Tate

By 1879, things were looking up under a new proprietor, J.A. Tate, who employed workmen to expand hotel facilities and cabins for guests to enjoy the mineral waters and healthful air. Tate also bottled and marketed the mineral water. Families built summer homes around the resort grounds, and local residents would ride the St. Bethlehem train to and from Clarksville.

In June 1879, the Chronicle wrote that “Idaho Springs Will Open For The Season On June 15th. Special inducements offered those who spend the entire season. Those wishing accommodations must apply early, as most of the rooms are engaged. Parties and picnic excursions to the Cave can be accommodated on short notice.”

In 1884, the properties were purchased by Col. A.G. Goodlett and H.C. Merritt, who expanded the hotel. The hotel advertised that livery and feed stables were furnished, telephone services were available and that no mosquitoes were present.

AFTER A FIRE IN 1893, THE hotel was rebuilt, but scant details of its offerings remain. One account

concludes that in the late 1890s, spas and mineral springs declined and were no longer fashionable, and the hotel closed. A Leaf-Chronicle report in 1896 complains that “Dunbar Cave and Idaho Springs are in a state of chaotic neglect.”

In April 1912, the promise of another boom era for Idaho Springs emerged with a headline in The Leaf-Chronicle announcing, “Work Starting on New Hotel. Commodious new structure will be rushed to completion at Idaho Springs.” New owners W.W. and J.H. Tate tell the newspaper that each room in the hotel’s main building will have “two outside exposures, affording every opportunity for the occupant to drink in the all the cool clean air for which the place is famous.”

The grand new Idaho Springs Hotel opened in June 1915, on the hillside above the Idaho Springs, touted in an attractive brochure as an “Up-to-date Summer Resort.” The new hotel enjoyed a strong run for the next decade, with its combination of a good restaurant, solid accommodations, a ballroom for special events and access to open spaces, the springs and the cave.

After several ownership changes, from the Tates to George Fort to J.H. Unseld, by 1925 “improvements to the cave and springs” were again being proposed.

According to research compiled by Eleanor Williams, Montgomery County historian, those plans unfolded through 1932, when a group of Clarksville businessmen formed the Dunbar Cave and Idaho Springs Corporation to develop the cave into a resort they claimed would be “The Show Place of the South.” An earthen dam was built near the cave entrance to form a lake fed by a stream from the cave. A bridge was constructed across the lake near the cave entrance. A modern concrete swimming pool with diving boards and a bathhouse was built, and tennis courts and other recreational facilities and restrooms were constructed. At the cave entrance, the dance floor was enlarged and the concession stand extended along the cliff wall with a railed, concrete-floored terrace overlooking the dance floor.

In April 1933, The Leaf-Chronicle reported, “the Lake is completed and filling with water. Idaho Springs Hotel is being renovated with running water in each

SECOND & COMMERCE / 23

ABOVE: Postcard, 1936

LEFT: Idaho Springs Hotel matchbook Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

room. The concrete swimming pool is under construction. The stone concession stand is being built at the cave to replace the wooden soft drink stand.”

In 1934, the corporation hired W.W. "Papa" Dunn as manager of the cave and the concessions. Electrical lighting was installed in the cave, and tours were conducted regularly. The Idaho Springs Hotel again was updated and remodeled. The mineral waters of the Idaho Springs were available for guests, along with food and recreation such as bowling. Each mineral spring had a roof with lattice walls and a concrete floor. A pump was installed on each spring to send the water bubbling to the top.

About this time, the cabins around the hotel began to be acquired and expanded into family homes. The original plat of cabin sites, drawn in the 1880s, which envisioned dozens of 50-by-100 lots designed as cabin and camp sites, gave way to consolidation into fewer tracts to accommodate larger homes. In the 1930s, another plat, named Dunbar Dell, was registered and part of it was developed.

THESE EXPANDED CABINS AND LOTS COMPRISE what is today the Idaho Springs neighborhood, which consists of homes on Dunbar Dell, Idaho Springs Road, Front Street and Woodstock Lane. For example, Jerry Clark’s parents bought and expanded the cabin at 519 Woodstock Lane in 1946, and Jerry lived there for 18 years, spending his boyhood roaming the hills and attractions around Idaho Springs and Dunbar Cave. Today, Jerry, a Clarksville architect, lives nearby, and his family still owns the Idaho Springs tract and much of the land along the creek that flows from Swan Lake to the Red River. His boyhood best friend, Ronnie Hunter, lived with his family in an expanded cabin on Front Street, which stands proudly today. Jack and Harriett Tate raised four daughters a block away in an improved resort cabin on Idaho Springs Road. Harriett lived in the house well beyond her 100th birthday, and one of her daughters, Peggy Clouser, still lives on Front Street.

BY ALL ACCOUNTS, THE CAVE AND THE HOTEL flourished during the 1930s and early 1940s. The pool was a popular gathering spot for teens and families, and the cave hosted dances and musical shows. The hotel was busy, and was a local gathering spot, hosting many civic club meetings and receptions.

In 1945, William Kleeman, mayor of Clarksville, purchased the 400-acre resort, and Dunn continued as manager.

In 1948, Kleeman sold the cave to Grand Ole Opry star Roy Acuff, who built an 18-hole golf course to the east of the lake, which stands today as the city-owned Swan Lake Golf Course. Roy Acuff’s Dunbar Cave was managed by members of Acuff’s family. The cave regularly hosted square dancing and round dancing nights, country music shows and a country music radio show.

24 / SECOND & COMMERCE

TOP: Hotel guests gathered in a pavilion over the springs, 1902 BOTTOM: Cotillion Party invitation, ca. 1860s Courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park OPPOSITE PAGE: Jerry Clark, pictured here with one of the moss-covered structures that now encase the mineral springs, spent his childhood exploring the "lost valley" of Idaho Springs and Dunbar Cave. Courtesy of Richard V. Stevens

IN THE 1950S, THE IDAHO SPRINGS HOTEL WAS destroyed by fire and never rebuilt. As historian Williams recounts, “The cave began to decline in popularity, as area residents no longer needed the cave for its cool breeze. Manmade air conditioning was available, and entertainment was provided by television.”

In 1963, Roy Acuff sold the property. The swimming pool closed in 1967 when several municipal pools opened. In 1971, owners closed the cave, and in 1973 it was acquired by the State of Tennessee and reopened as a state park and natural area. As you read this, the 50th anniversary celebration of the transition of the cave to state ownership is under way.

So, while the cave is protected as a state park and enjoys broad support from a long-standing and active Friends of Dunbar Cave organization, what will the future hold for the Idaho Springs and the magic “lost valley” in the middle of Clarksville?

The simple, and hopeful, answer is: probably not much.

The bulk of the valley is held by Jerry Clark and a few other private landowners, who have been good stewards. Much of it is designated as a floodplain, which restricts development. Clark says that some of the higher ground could become custom homesites, but market conditions have not been favorable.

For now, and for the foreseeable future, the springs and valley floor, once mythologized as the “Gem of the Mountain,” should remain a quiet, beautiful and peaceful place.

SECOND & COMMERCE / 25

Richard V. Stevens was Executive Editor of The Leaf-Chronicle from 1999-2015, and communications director of the City of Clarksville from 2016-2021. He lives with his family in a renovated 1936 home in the Idaho Springs neighborhood.

The Big Band & Acuff Eras

CLASSICS AT THE CAVE

Dancey Photographic Arts Inc., ca. 1950 |

Courtesy

of Dunbar Cave State Park Performances at Dunbar Cave’s amphitheater could draw over 1,000 guests. Dancey Studio Photography, ca. 1950 | Courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park

Courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park

Troyce Hutchinson Orchestra ticket, 1961 Courtesy of Billyfrank Morrison

“Roy Acuff: The Smoky Mountain Boy” by Elizabeth Schlappi Courtesy of Thomas Murff

Courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park

While dances on the wooden floor at Dunbar Cave’s entrance had been held since the late 1800s, the 1930s ushered in a whole new era of music and recreation. A new swimming pool, tennis courts and a new large dance floor had Clarksvillians and tourists flocking to the cave to enjoy the

cool temperatures and great acoustics. Whites-only dances, concerts and other gatherings were held at the mouth of the cave, with many notable big bands coming to Clarksville to perform, including those led by Glen Miller, Guy Lombardo, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman and more.

When Roy Acuff, “King of Country Music,” bought the property in 1948, he built an 18-hole golf course and installed benches for a 1,300seat amphitheater. Grand Ole Opry stars came through town to perform each Sunday afternoon. Square dances were held on Tuesday and Friday

nights with popular music dances on Saturdays, and a radio show was broadcast directly from the cave. Popularity declined through the 1950s with the rise of television (and air conditioning), and Acuff sold Dunbar Cave in 1963.

Roy Acuff’s Dunbar Cave sign Customs House Museum & Cultural Center Collection Studio Photography, ca. 1950 | Courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park

Correspondence from Peter Kyriakos, Dunbar Cave Manager, June 1963 Courtesy of Jimmy Dunn

Receipt from Thompson’s Community Service for miscellaneous Dunbar Cave souvenirs Courtesy of Jimmy Dunn

Roy Acuff's Dunbar Cave metal cuff Courtesy of Thomas Murff

Maidean & Harold Seals with Lillian Hoy at Dunbar Cave, 1949

Courtesy of Bill Hoy

Jim Long -

I grew up not far from Dunbar Cave, and on summer days when we would need some “cooling at the cave,” we would walk down through the woods and the golf course. Along the way, we would pick up lost golf balls. We would see how high we could bounce the golf balls up around the bluff surrounding the entrance. It was great fun.

Frank Lott -

Cassie Coughlin -

My dad would take us out to walk the trails and let us run and be kids. My brother and I would run ahead and pretend we were monster trucks driving on those trails… full on, with engine and shifting gear sounds! One of my favorite memories.

On a pleasantly cool evening in June of 1984, I spent my first date with my now-wife Patti Marquess dancing to the music of Lee Castle and the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra. Dunbar Cave was the site of a big band dance, one of the signature events during the City’s 200th Anniversary celebration.

Tim McCollum -

My mother, Jean Edwards McCollum, told me about the dances at the cave, and the big bands with Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller. I’ve seen a picture of her and her sister Madeleine standing in Swan Lake—can you believe it? It must have been in the 1930s, when you could actually swim in the lake.

In the 1960s, my grandmother May Edwards would take me to the cave. There were checkered tables with folding chairs for picnicking. The concession stand and souvenir shop were still open, too. There were paddle boats and ACTUAL mute swans on the lake! Kids fed the fish and swans. My grandmother was afraid of falling in the cave, so I didn’t go in until lit tours were over. Blessed memories.

Images courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park, Bill Hoy, Frank Lott, Billyfrank Morrison and Thomas Murff

Images courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park, Bill Hoy, Frank Lott, Billyfrank Morrison and Thomas Murff

Kitty Hale

-

My mom told me about dancing to the bands. We would visit the cave during the summer with my grandmother and cousins. There was a swimming pool then. I've taken the tour several times, but the last time I did was with the man who became my husband six months later. Married 58 years.

Dunbar Cave Memories

Dunbar Cave has served this community in a multitude of ways for centuries. State park, sacred space, summer resort... This local landmark holds distinct and valued significance for everyone. Whether your favorite Dunbar Cave memory is from 70 years ago or last week, each experience is part of the story of this area that is still being written.

Amberly Corker -

Dunbar Cave has been a special place since I was a little kid, but it wasn’t until 2020 that I fell in love with it, and myself all over again. Its trails and beauty inspired my photography walks, which inspired me to start hiking the trails—always wanting to capture more beauty of the park. Whether it’s the plants, the blue heron named Ransom, taking my photography class out there, family photos... Dunbar will forever be one of the biggest stepping stones of my journey. I’ve already lost 103 pounds, and I’m sure I’ll lose many more walking these trails.

Bill Hoy -

In 1979, I was offered a job to come to Clarksville and work at First Trust and Savings Bank. I went back home to Gallatin and told my mom... first words out of her mouth, “You have to go to Dunbar Cave! Daddy and I used to go there.” She brought out

the family photo album and showed me these pictures.

In 2010, I was Chairman of the Museum Board of Trustees, and a Peg Harvill painting of Dunbar Cave came up for sale at Flying High. I said, "This is for my mama."

Honoring Balance in Nature and Community

BY SHANA THORNTON

BY SHANA THORNTON

I am close to the Indigenous artwork inside the cave, and I instinctively reach out my hand to touch it. Quickly, I pull back, remembering that the artwork cannot be touched—and that I’m not actually in the cave. The virtual reality (VR) film continues, revealing details about the pictographs and petroglyphs, the ringed spheres on part of the cave wall. I feel cold and buoyant, even though I’m not actually in the cave.

When entering the cave in person, people experience a variety of sensations and feelings. Some are similar to mine in the VR simulation, and others say they feel cramped and nervous. Some people choose not to physically enter the cave, due to physical and mental disabilities, the terrain or the dark. The Park rangers and the Friends of Dunbar Cave, Inc. (FODC) wanted as many people as possible to learn about the artwork and the history of the cave, whether they could or wanted to physically enter it.

Thanks to a grant from Humanities Tennessee and the National Endowment for the Humanities, there is now a high-definition cave tour film that can be viewed online, as well as a virtual reality cave tour that you will be able to experience from the Dunbar Cave State Park Visitor Center. To document the cave’s interior and history on film was a goal realized for the Friends group, and the VR version catapulted us into our wildest dreams. Now, the story of Dunbar Cave can reach people all over the world.

The Friends of Dunbar Cave formed 25 years ago out of a group of local volunteers who wanted to share their appreciation for the Park. Since then, FODC has evolved into a fundraising and support group dedicated to helping the Park—overseeing the expansion by purchasing the Grassland Meadow and a connected portion of wooded trail, planting the Three Sisters Garden and providing funds and support for the ADA walking trail around the lake. Additionally, the FODC helped to expand the cave tour season by providing partial funding for two seasonal AmeriCorp employees, allowing hundreds of additional people to

THE POSTSCRIPT

experience the cave each year. Grant writing and project development have become a vital part of FODC, helping to fund even more ways to provide accessibility and education. Members of FODC work together with Park rangers, staff and managers to provide support for the whole Park and help on the trails.

On any given day of the week, while out on the trails or sitting in the mouth of the cave, I will see a member of FODC. We are out walking, hiking with friends and clearing our heads. Some can tell you where they spied a fox, or where the muskrats live, or who was the last person to see the otters. More than a few Friends can identify the plants and tell you some history, who planted what in the butterfly garden and what that area used to be (a swimming pool, and perhaps they swam in it as a child), which big trees fell in the last wind storm and when the next Cooling at the Cave concert will take place.

Two nights a year, FODC hosts a special evening of music at the mouth of the cave. These Cooling at the Cave concerts are our biggest fundraisers and take place on the dance floor where the big bands used to play in the 1930s. These magical shows allow patrons to share an evening at the Park with the moonlight above, the lights reflecting on the lake and music swirling among families and friends, lovers and listeners.

Dunbar Cave is a place of solace and solitude, of community with nature and one another. The Friends of Dunbar Cave honor the balances in nature, the stories of the cave, the Indigenous artwork inside it, the people who have lived here, as well as the nature that continues to live here and provide us with environmental health and beauty. We are committed to sharing our mission with Clarksville and beyond. All are welcome and encouraged to join us.

Tour Dunbar Cave on YouTube today!

SECOND & COMMERCE / 31

Clarksville THE ONLY CICCHETTI BAR IN TN CRAFT COCKTAIL BAR FULL SERVICE COFFEE BAR CLARKSVILLE’S ONLY TRUE WOOD FIRED PIZZA OVEN 111 Franklin Street BREAKFAST LUNCH DINNER

Historic Downtown

friendsofdunbarcave.com

Shana Thornton is the Vice President of the Friends of Dunbar Cave. She served as President from 2020-2022. FODC meet at 6pm on the second Thursday of every month at the Park Office.

The Dunbar Cave Tour Film is brought to you by Friends of Dunbar Cave, Inc. in partnership with Dunbar Cave State Park and One Day Entertainment, Humanities Tennessee and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

CONNECT WITH US

customshousemuseum.org @customshousemuseum #customshousemuseum

There’s always something going on at the Museum. Share your visit with us! Tag us for a chance to be featured on our social media, in the Museum or right here in Second & Commerce.

32 / SECOND & COMMERCE

@kat_cansing

Anne Goetze

Autumn Simmons

USO Fort Campbell

Lesley Milliken

UPCOMING EXHIBITIONS

Mapping Wars

THROUGH JULY 6

Jammie Williams: Stories, Dreams and Visions

THROUGH JULY 6

Pearl of the Orient: Celebrating the Early Cultures of the Philippines THROUGH JULY 23

Between Tone & Texture: The Art of Edie Maney THROUGH AUGUST 21

Kitty Harvill: New to the Collection THROUGH AUGUST 27

David Smith: Tennessee Waterfalls THROUGH AUGUST 29

Women. Artists. Masters. The Big & the Small of It

JULY 8 – SEPTEMBER 24

Red Grooms: Selected Works from the Caldwell Collection

JULY 19 – JANUARY 7

Annual Staff Art Show

JULY 26 – OCTOBER 22

Tennessee Craft: A Statewide Member Exhibition

SEPTEMBER 1 – OCTOBER 26

Todd Saal: Telling Stories

SEPTEMBER 5 – OCTOBER 29

Monique Carr: Ethereal Abstractions

SEPTEMBER 5 – NOVEMBER 8

The Art of Mike Lugger

SEPTEMBER 8 – OCTOBER 29

Learn

At Rest: A Still Life Invitational THROUGH AUGUST 30

Tickets are on sale now for the Museum’s largest annual fundraising event!

Bid on exceptional works of art and unique experiences, enjoy a divine dinner and dance the night away at the grooviest party in town.

Time for Tea by Aida Garrity

Time for Tea by Aida Garrity

and

at customshousemuseum.org.

about Museum exhibits, programs

more

here for tickets or visit customshousemuseum.org. AT OAK GROVE RACING GAMING & HOTEL

Scan

YOU CAN DANCE • YOU CAN JIVE HAVING THE TIME OF YOUR LIFE AT A FUNDRAISER BENEFITING THE

PRESENTED BY THE MUSEUM GUILD

Clarksville Montgomery County Historical Museum d.b.a. P.O. Box 383 Clarksville, TN 37041 customshousemuseum.org NONPROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID CLARKSVILLE, TN PERMIT NO. 530

Terri Jordan

David Smith

Larry Richardson

Lynne Waters Griffey

Rosemarie Rogoish

Terri Jordan

David Smith

Larry Richardson

Lynne Waters Griffey

Rosemarie Rogoish

Kitty Harvill

Peg Harvill

Frank Lott

Kitty Harvill

Peg Harvill

Frank Lott

Images courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park, Bill Hoy, Frank Lott, Billyfrank Morrison and Thomas Murff

Images courtesy of Dunbar Cave State Park, Bill Hoy, Frank Lott, Billyfrank Morrison and Thomas Murff

BY SHANA THORNTON

BY SHANA THORNTON

Time for Tea by Aida Garrity

Time for Tea by Aida Garrity