EffectActivity

12- 13

CLINIC POSTERS

4- 11

14-21 CANCER PREVENTION IN MOTION Reducing Cancer Risk 10% B 13% B E 13% R 15% HEA E 16% C N 20%MYEOD EUK 21% EN O T I 22% S R CAR 26% 27%

28-34 22-27

JOURNAL WATCH

PAINFUL SHOULDER: DON'T LABEL ME (INCORRECTLY)

Publisher/Founder TOR DAVIES tor@co-kinetic.com

Business Support

SHEENA MOUNTFORD sheena@co-kinetic.com

Technical Editor

KATHRYN THOMAS BSC MPhil

Art Editor DEBBIE ASHER

Sub-Editor ALISON SLEIGH PHD

Journal Watch Editor

BOB BRAMAH MCSP

Subscriptions & Advertising info@co-kinetic.com

DISCLAIMER

OCTOBER 2023 ISSUE 98 ISSN 2397-138X is published by Centor Publishing Ltd 88 Nelson Road Wimbledon, SW19 1HX, UK https://Co-Kinetic.com

Facebook www.facebook.com/CoKinetic

Instagram www.instagram.com/co_kinetic/

YouTube www.co-kinetic.com/youtube

Twitter https://twitter.com/co_kinetic

LinkedIn https://www.linkedin.com/company/co-kinetic/

Our Green Credentials

Paper:100% FSC Recycled Offset Paper Our paper is now offset through the World Land Trust

Naked Mailing No polybag used

Plant-Based Ink Used in Printing Process

More details

https://bit.ly/3dAwGwd

CBP006075

While every effort has been made to ensure that all information and data in this magazine is correct and compatible with national standards generally accepted at the time of publication, this magazine and any articles published in it are intended as general guidance and information for use by healthcare professionals only, and should not be relied upon as a basis for planning individual medical care or as a substitute for specialist medical advice in each individual case. To the extent permissible by law, the publisher, editors and contributors to this magazine accept no liability to any person for any loss, injury or damage howsoever incurred (including by negligence) as a consequence, whether directly or indirectly, of the use by any person of any of the contents of the magazine.

Copyright subsists in all material in the publication. Centor Publishing Limited consents to certain features contained in this magazine marked (*) being copied for personal use or information only (including distribution to appropriate patients) provided a full reference to the source is shown. No other unauthorised reproduction, transmission or storage in any electronic retrieval system is permitted of any material contained in this publication in any form.

The publishers give no endorsement for and accept no liability (howsoever arising) in connection with the supply or use of any goods or services purchased as a result of any advertisement appearing in this magazine.

A 34-year-old man was referred to physical therapy with a 16-year history of recurrent left ankle sprains and a diagnosis of chronic ankle instability (CAI). He had decreased ankle dorsiflexion ROM, lower quarter weakness, balance limitations and pain. In 6 sessions distributed over 8 weeks, he demonstrated clinically important improvements in ankle dorsiflexion, balance and lower quarter weakness without an appreciable change in ligamentous laxity and self-reported CAI. He returned to desired activities without

APPLICATION OF CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATIONS IN THE CLINICAL MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC ANKLE INSTABILITY: A CASE REPORT. Gallagher T, Gladwin A, Davenport TE. Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Practice 2023;35(1):22–27

recurrent sprains. The rehabilitation programme was informed by the recommendations of the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy’s Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments: Lateral Ankle Ligament Sprains (LAS) Revision 2021 CPG.8 (https://bit.ly/44HhKo0). This emphasised a home exercise programme to address proprioceptive, strength and mobility deficits.

MUSCLE INTERCONNECTIONS IN THE ANTERIOR AND POSTERIOR ARM COMPARTMENT: A CADAVERIC CASE SERIES WITH POSSIBLE CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS. Natsis K, Tsakotos G, Triantafyllou G et al. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 2023 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-023-03209-5

The information in this report came from the dissection of four formalin-embalmed donated male cadavers. It describes four cases of accessory bundles (ABs) or fibres connecting the muscles of the anterior with the posterior arm compartment. The AB morphology (pure muscular or musculofascial or musculoaponeurotic) is described, emphasising their attachment points, characterised as muscles’ interconnections.

In brief, in the first case, the two ABs originated from the coracobrachialis muscle (CB) and received fibres from the biceps brachii (BB), and were inserted into the triceps brachii (TB) medial head. The ABs created an arch over the

brachial vessels and the median nerve (MN). In the second case, an accessory musculoaponeurotic structure was identified between CB and TB medial head and extended over the brachial vessels. In the third case, the myofascial ABs between the BB short head and the upper arm fascia coursed anterior to the MN, the brachial artery and the ulnar nerve, with direction to the TB medial head. In the fourth case, the three muscular ABs originating from the CB superficial and deep heads, in common with the BB short head, joined the upper arm fascia and the TB medial head and possibly entrapped the musculocutaneous nerve, the MN and the brachial artery.

Don’t believe what you read in the standard anatomy texts. There are anomalies in people. The clinical implications of this are that anatomical variations such as these could predispose people to complications due to the potential compression on nerves and vessels. If anatomy is your thing there are some great pictures in the report.

Co-Kinetic comment

We could do with some more papers like this one. Take central guidance and see if it works in the real word. We refer you to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. They have nine musculoskeletal topics for you to choose from:

https://bit.ly/3R6JX4A.

MUSCULOSKELETAL AND NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION FINDINGS IN POSTCOVID-19: COVID-19 AND PAIN. Denli A, Turğut S, Dursun AD et al. Journal of European Internal Medicine Professionals 2023;1(3) DOI:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8159134

This study investigated the musculoskeletal and neurological examination findings in symptomatic patients who had previously experienced COVID-19. A prospective cohort of 101 patients who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 between January and April 2021 were included in the study. All received medication treatment and were followed up but did not require intensive care unit admission. The patients’ symptoms, dysfunctional segments identified through cervical and thoracic examinations, and VAS scores were analysed. The results showed that myalgia (63%) was the most commonly reported post-COVID symptom. The T5 segment (23%) was the most frequently observed dysfunctional area. Older individuals had a higher VAS score and a statistically significant correlation was found between age and VAS scores.

The pandemic never ends. This is one of a large number of papers examining the after-effects of the acute stage of the disease. The clinical dilemma is working out if your patient has an underlying musculoskeletal issue or a symptom of long COVID and then work out if the culprit is the virus or the inactivity that occurred either with illness and/or the long periods of lockdown.

This paper reviews the literature over the past 10 years regarding MCL diagnosis, management, and RTP.. It starts with an incidence report which is a bit USA-biased, which is unsurprising given that the authors are both from there. Sports commonly cited in the literature as having a high rate of MCL injuries include wrestling, hockey, judo, rugby, football, skiing and soccer (real football). In American high school athletes, MCL injuries account for 36% of knee injuries, with the highest rate of MCL injuries occurring in football (the American version). The sex prevalence in MCL injuries remains unclear as the male/female ratio differs from sport to sport and with age groups. Ultimately, there were no significant differences between sexes when comparing across multiple sports. About 70% of the time, the mechanism of MCL injury occurs via contact, either with another player or an object. Look out for contact to the lateral knee causing a valgus load on the knee joint or planting the leg with rotation at the knee with no contact. Patients may describe a pop of the knee when this occurs, or they may feel their knee give out. MCL tears can

This study was a blinded, retrospective analysis of 138 runners: 49.3% male; average age of both sexes, 36.2 years; with an average of 11.2 years of running history and weekly mileage of 19.2 miles. Halfmarathon runners made up 68.8% of the group and full-marathon runners 31.2%.

Pre-race ultrasound scans were performed on 138 asymptomatic half- and full-marathon runners (276 tendons in total) who were followed for 12 months after their races.

Specific patterns of morphologic abnormality were identified (location, size and appearance of ultrasound abnormality within the tendon). Sonographic findings

CLINICAL

COLLATERAL LIGAMENT INJURIES. Brown EE, Rho M. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports 2023 DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s40141-023-00415-5

occur in isolation or as part of a multiligamentous injury. The incidence of combined ACL and MCL injuries can be as high as 38%.

Diagnosis comes from the history, special tests (which apply a valgus stress to the knee at varying angles of flexion looking for laxity) and imaging. The latter modality is the subject of the latest findings, which show that point-of-care ultrasound in the hands of an experienced individual is easy to use, safe and accurate, and is therefore a reasonable alternative to magnetic resonance imaging.

A grade 3 injury is likely to require surgery but grade 1 and 2 MCL injuries are generally managed conservatively. A progressive rehabilitation programme can start 1 to 2 days after injury with ROM exercises and very simple isometric contractions of the quadriceps muscle. Later add lower limb strength work, then aqua therapy, treadmill running or training on the field to start

the return-to-running process. There is no strong evidence about the use of a knee brace post-injury. The final phase is characterised by sport-specific training with the incorporation of sprinting, proprioception exercises, agility exercises and performance testing. Once the patient is pain-free with sprinting and changing direction and is performing the skills needed for their sport, a RTP will be implemented.

The timing of RTP varies from sport to sport and between individuals but an average figure for an isolated grade 1 MCL injury is 1 to 2 weeks and for grade 2 is 3 to 4 weeks.

If your organisation demands to know that what you are doing for an MCL injury is evidence-based and up to date, then this is the paper for you. Well done the authors. It has wriggle room in it for therapist choice of treatment depending on the circumstances. Can someone do similar papers on the other major joints please?

IDENTIFICATION OF PRE-RACE ULTRASONOGRAPHIC ABNORMALITIES OF THE ACHILLES TENDON AND ASSOCIATION WITH FUTURE INJURIES IN RUNNERS.

Nowak AS, Miro EW, Eby SF et al. The Physician and Sportsmedicine 2023 DOI:10.1080/00913847.2023.2246179

were blindly assessed by a medical student, a resident and a physician who has significant sonographic imaging experience. These specific abnormalities were then compared to those who later did or did not develop tendon pain.

The results showed that three findings had significant odds of association with the development of pain:

1. focal deep midsubstance intratendinous hypoechogenicity;

2. focal superficial midsubstance

intratendinous hypoechogenicity; and

3. linear hyperechogenicity extending into middle of tendon from calcaneus.

Unless you are up to speed in sonography these terms may not mean a lot but what they are telling us is that ultrasound can be a signpost to potential injury and that gives you something to work with. For the record, ‘hypoechogenicity’ literally means not many echoes, or, to be a tad more scientific, a decreased response (echo) during the ultrasound examination. The area shows up darker than the rest. ‘Hyperchogenicity’ means the opposite and tissues usually show up lighter.

Commonly used nuclear medicine techniques include bone scintigraphy (BS), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) combined with computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography (PET) combined with CT.

In BS, the patient is intravenously administered a radioisotope combined with an appropriate ligand (chemical binder) that integrates into the bones. It is used for the diagnosis of bone cancer, inflammation, infection and fractures that may not be visible by traditional X-radiography. It is particularly good at spotting stress fractures.

Hybrid SPECT/CT devices allow for

increased sensitivity of nuclear imaging by overlaying an anatomical image created by CT onto the functional image created by SPECT. The fusion method enables obtaining images in different anatomical planes, which allows for a better assessment of bones and their pathologies. An example is given of radiological assessment of the ankle joint, which is relatively difficult to scan using plain X-rays and MRI owing to its complex anatomy. The use of hybrid SPECT/CT imaging improves diagnosis and modifies the management of patients in approximately 48–62% of cases where other imaging methods are inconclusive or treatment does not improve the condition. It is particularly good at visualising increased osteoblastic activity resulting from ligament injuries that again may not have been picked up via other

modalities.

OPEN The purpose of this paper is to briefly introduce nuclear medicine in the diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal disorders developed among athletes. The data are based on a literature search of PubMed and Google Scholar for full text articles in English between 2015 and 2023.

The fundamental principle of PET imaging is the detection of high-energy photons produced in the annihilation process of positrons. It is particularly useful in oncology for detecting tumours and evaluating disease progression. It also allows the evaluation of the musculoskeletal system.

These are all excellent diagnostic tools but how easy is it for the average therapist to get access to them?

At the time of this study there were 9 teams in the Irish Women’s National League (WNL) with 25 players in each squad. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 17 players, 8 medical personnel, and 7 head coaches. The data were analysed using thematic analysis and showed the following results.

Elite-level women’s football players have a poor understanding of the most common injuries sustained during training and match-play.

Players, head coaches, and medical personnel have beliefs about injury risk factors that are not evidence-based. Unqualified and inexperienced medical and S&C personnel, who do not have the skill set to create a collaborative, highperformance environment in unison with the coaching staff, are commonly used by clubs in the Irish WNL.

The following are a selection of findings from the injury management section.

2 coaches, 1 medical personnel and 5 players believed that financial constraints at WNL clubs, leading to the use of

student medical personnel instead of qualified practitioners, was putting players’ health at risk.

l 1 coach, 4 medical personnel and 6 players thought that the lack of medical staff availability at all weekly training sessions had a negative impact on the management of injuries, with four of them highlighting the importance of medical staff being available to assess injuries on the day of their occurrence.

l 1 medical personnel and 4 players reported that some clubs shared medical personnel at matches leading to frustration among players and lack of confidence in the decision-making of the medical personnel.

l 1 medical personnel and 1 player mentioned that concussion management was an important area of competence for medical personnel despite suggesting that some medical personnel were not competent in this area.

l 1 coach, 1 medical personnel and 2 players thought that the medical

personnel had a duty of care to make decisions that are in the best interests of players, although some players expressed a feeling that this was not always the case.

l Coaches described weighing up the information they received from medical personnel and players, as well as their own judgement on injury risk and game importance when considering how to manage injured players.

Oh dear! A lack of injury knowledge may not be a surprise among the players and coaches but the medical staff! Hopefully this is a wake-up call for the Irish FA, but everyone involved in sport – not just football – in any country and at any level should read this paper and start asking themselves serious questions. If they don’t, lawyers soon will. Only 1 coach and 1 of the medical personnel thought there was a duty of care to the players. Where there is blame there is a claim.

YouTube was searched between 11 June and 13 June 2022 using the terms ‘ulnar collateral ligament’, ‘Tommy John surgery’, and ‘UCL surgery’. The first 100 results for each of the three terms were screened for inclusion. Each included video was graded based on its diagnostic and treatment content and assigned a quality assessment rating. Video characteristics such as duration, views and ‘likes’ were recorded and compared between video sources and quality assessment ratings.

A total of 120 videos were included in the final analysis. Only 17.5% provided very useful to excellent quality content. Only three videos (2.5%) provided excellent quality content; these were all physiciansponsored videos. These three videos only achieved an excellent score for diagnostic content; no video achieved an excellent score for treatment content. Most videos were scored as somewhat useful for both diagnostic (40%) and treatment (56.7%) content. Videos classified as somewhat useful had the highest number of average

THE QUALITY OF YOUTUBE CONTENT ON ULNAR COLLATERAL LIGAMENT INJURIES IS LOW: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF VIDEO CONTENT. Czerwonka N, Reynolds AW, Saltzman BM et al. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation 2023 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmr.2023.100769

views (27,197), with a mean duration of 7 minutes 40 seconds. The most common video source was physician sponsored (32%), followed by educational (26%). Physician videos had the lowest number of views (5,842 views).

What a great idea. Patients search for information online regarding their diagnoses and treatments but, sadly, much of the content they access is misinformation rather than useful information. Here the videos are marked so that you can pick the good ones and recommended them to your patients. The marking schemes come from similar earlier work on femoroacetabular impingement, here are links to them:

l MacLeod MG, Hoppe DJ, Simunovic N et al. YouTube as an information source for femoroacetabular

of video content. The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2015;31(1):136–142 (https://bit. ly/3P0JheB)

l Crutchfield CR, Frank JS, Anderson MJ et al. A systematic assessment of YouTube content on femoroacetabular impingement: an updated review. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;9(6) doi:10.1177/23259671211016340 (https://bit.ly/3Es6Qbo).

Return to play is the desired outcome following ACL reconstruction (ACLR). However, a quoted meta-analysis in 2014 demonstrated that only 65% of people who opt for surgery return to their preinjury level of sport. This study sought to understand factors that influence this from the athlete’s perspective. The subjects were 29 patients recruited as a convenience sample from 4 surgeons who underwent unilateral primary ACLR between 2 and 10 years before the study and engaged in sports prior to injury.

Data was collected via a semistructured interview with questions on factors that influenced the decision to return to sport or not after ACLR. Standardised instruments were also applied to evaluate psychological readiness to return to sport, via the Anterior Cruciate Ligament – Return to Sport after Injury Scale (ACL-RSI); self-perceived knee function using the International Knee Documentation

RETURN TO PLAY AFTER ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT RECONSTRUCTION WITH EXTRA-ARTICULAR AUGMENTATION: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW. Hurley ET, Manjunath AK, Strauss EJ et al. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2021;37(1):381–387

Committee (IKDC) subjective questionnaire; and the frequency of participation in sports with the Marx scale.

Analysis of the interviews produced three main themes related to postACLR return to sport: self-discipline, fear of reinjury and social support. In qualitative analysis, the average scores obtained were 59.17 (±23.22) on the ACL-RSI scale; 78.16 (±19.03) for the IKDC questionnaire; and 9.62 (±4.73) and 7.86 (±5.44) for the Marx scale before and after surgery, respectively. The conclusion reached from this was that psychological factors influence the decision to return to sport post-ACLR. Physiotherapists should, therefore, be aware of the psychological aspects and

expectations of patients, and that other health professionals may be needed to help prepare these individuals to return to their preinjury sports level and achieve more satisfactory outcomes after ACLR.

Not much new here but it does highlight the massive psychological factors involved in return to play. This is for an ACL injury, but it applies to all serious injury. The paper raises the question of whether this can be left to physical therapists. Good question: do we need to bring in other health professional or do we need to improve the training of the physical therapists, or both?

THE EFFECTS OF END-RANGE INTERVENTIONS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF PRIMARY ADHESIVE CAPSULITIS OF THE SHOULDER: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW AND META-ANALYSIS. Kubuk BS, CarrascoUribarren A, Cabanillas-Barea S et al. Disability and Rehabilitation

The data for this study came from a search of the ‘usual suspect’ databases from inception to December 2022. Clinical trials investigating the effects of end-range mobilisation techniques on pain, ROM, and physical function in patients with adhesive capsulitis (AC) were included. Methodological quality was evaluated using the PEDro scale, and bias risk was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) was used to assess the

certainty of the evidence. Data were presented using forest plots, and the random effects models were applied according to the Cochrane handbook. The results showed that 10 randomised controlled trials were reviewed, involving 424 AC patients aged 20–70 years. Methodological quality of studies ranged from high to low. The end-range mobilisation showed improvements in pain intensity, shoulder abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation, and physical function compared to other

conservative interventions in the short-and medium-terms. Certainty of the evidence was downgraded too very low. The Kaltenborn, Maitland, and Mulligan concepts were the most commonly used manual therapy approaches [Are there others?].

Co-Kinetic comment

Low certainty is better than no certainty, so a plus for manual therapy. Most authorities say that the age group for a frozen shoulder is 40–60 years so there are some outliers here.

A total of 21 participants experienced two massage interventions targeting back soft tissues. During a first condition, the intervention was performed by a physical therapist (MM) whereas during a second condition the intervention was performed by a robot (RM).

The MM intervention lasted 20 minutes, used a massage lotion and involved traditional bilateral effleurage (1 minute) with the palmar aspect of the hands over the entire back and paravertebral muscles, followed by deep bilateral sliding pressures (1.5 minutes), and unilateral pressure (4.5 minutes) of the paravertebral, trapezius and rhomboid muscles. The protocol continued with deep kneading, unilateral sinusoids (4.5 minutes), and bilateral rotational friction of the paravertebral muscles (7 minutes). Finally, the physical therapist again applied unilateral (1.5 minutes) and bilateral (1.5 minutes) deep sliding pressure on the paravertebral, trapezius, and rhomboid muscles before targeting

COMPARATIVE EFFICACY OF ROBOTIC AND MANUAL MASSAGE INTERVENTIONS ON PERFORMANCE AND WELLBEING: A RANDOMIZED CROSSOVER TRIAL. Kerautret Y, Di Rienzo F, Eyssautier C et al. Sports Health 2023 DOI:10.1177/19417381231190869

the entire back with a simple light touch. For the RM, participants underwent a massage performed by a robotic device (iYU, Capsix). The robotic device consisted of a collaborative robot (LBR Med R820, Kuka Robotics), a homemade remote control, a 3D vision camera (Azure Kinect DK, Microsoft), and a motorised massage table (electric massage table 003815, Medeo Kosmetic GmbH). The RM protocol, defined by a physical therapist, accounted for the morphology of each participant through a preliminary scanning procedure using the 3D vision camera. Without leaving complete autonomy to users, the device exploited the potential of interaction offered by collaborative robots via a remote control available to users to increase or decrease the pressure at any time according to their needs. Participants were lying in a prone position on the massage table. The RM routine matched the criteria of MM routine (manoeuvre order and target areas,

treatment time per muscle, and total duration of routine). Unlike the MM condition, however, participants could adjust the pressure applied by the robot using the remote control. An operator provided assistance to calibrate and initiate the RM routine and guaranteed the safety of the participants.

Skin conductance decreased from pre-test to post-test in both conditions although the decrease was more pronounced after MM. Whereas both interventions were associated with improved subjective sensations (eg. pain, warmth, wellbeing), MM yielded additional benefits compared with RM. The physical therapist reported greater fatigue and tension and reduced perceived massage efficiency along with repeated massage interventions. MM outperformed RM to elicit a psychophysiological state of relaxation.

Another set of jobs that AI is going to take. Strike action anybody?

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF MUSCLE ENERGY TECHNIQUES IN RELIEVING LOW BACK PAIN OF QUADRATUS LUMBORUM MYOFASCIAL ORIGIN.

Kashyap R, Bhagat A, Naqvi SA et al. European Chemical Bulletin 2023;12(10):5021–5035

A total of 30 patients with low back pain of quadratus lumborum (QL) myofascial origin were randomly assigned to either a muscle energy technique (MET) group or a control group. The MET group received 10 sessions of METs, involving the patient contracting the QL against resistance in a specific direction while the therapist applied a counterforce. This technique was performed 3 times a week for 1 week. The control group did not receive any active treatment during the study period but continued with their regular daily activities. The results showed that the MET group had a significant reduction in pain

intensity, compared to the control group. The MET group also had a significant improvement in ROM for side-flexion and a significant decrease in tenderness. The Oswestry Disability Index did not change significantly in either group.

OPEN

Two thoughts. The first is that if you do a comparison between an intervention group with a control group that just carries on regardless and does all the things that probably cause the back pain, there is a good chance that the results will be better in the intervention group than the control whatever the intervention. Secondly, why is an article about a manual therapy published in a journal whose aims are to “publish original research papers, short communications, and review articles in all areas of chemistry”?

UNDER THE GUN: THE EFFECT OF PERCUSSIVE MASSAGE THERAPY ON PHYSICAL AND PERCEPTUAL RECOVERY IN ACTIVE ADULTS. Leabeater A, Clarke A, James L et al. Journal of Athletic Training 2023 DOI:https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-0041.23

The subjects for this study, 65 active young adults (34 female, 31 male), were recruited through a university sport science under-graduate program. All participated in regular physical exercise sessions (~3 times per week) and were free from lower limb injuries. They were allocated to experimental and control legs in a randomised, counterbalanced trial. Before the testing session, participants were asked to rate their perception on whether massage guns will improve recovery following exercise. The weight-bearing lunge test was performed as a measure of dorsiflexion ROM on each ankle at baseline and following recovery. In addition, calf circumference and isometric calf strength was measured, and single-leg calf raises performed to exhaustion. Participants were required to give ratings of their perceived lowerlimb muscle soreness for each leg on a scale of 1 (no soreness) to 10 (maximal

soreness). Ratings were provided while participants performed the single-leg calf raise on each side and at the 4-, 24- and 48-hours postrecovery time points.

Immediately following the post-exercise testing time point, participants in the intervention group (GUN) performed a recovery intervention on one of their legs using a massage gun (Hydragun), with a soft attachment head at a speed of 53hz or approximately 3,200rpm. The focus for the first 2.5 minutes of the massage treatment was the medial gastrocnemius, whereas the second 2.5 minutes focused on the lateral gastrocnemius. The control group (CON) received no massage. There was no statistically significant interaction between group and time on perceived muscle soreness. However, there was a main effect of time on perceived muscle

OPEN

soreness, which significantly increased at each respective time point as compared to baseline. There was a small difference in perceived muscle soreness in GUN compared to CON at two time points: perceived muscle soreness was higher in GUN immediately post-recovery and 4 hours post-recovery.

Why would you think that battering a muscle with heavy duty percussion is a post-exercise recovery strategy? In case you think this is a good idea, this study shows that it is not.

This study sets out with the excellent aim of finding how joint mobilisation helps to manage pain and it points out that previous research in both humans and animals says it does. The experiment was designed to test if joint mobilisation affected Cav3.2 T-type calcium channels which are inhibited by endocannabinoid signalling (basically neurotransmitters). They induced neurogenic pain in mice using the chronic constriction injury model which involves tying a ligature around the sciatic nerve. They had a sham treatment group in which the nerve was exposed but not tied off. Some of them were ‘knockout mice’. These have been genetically engineered so that their DNA does not express particular proteins with the intention of them mimicking the function of human genes to study human diseases. In this case Cav3.2-null mice, which are known to have compensatory mechanisms that allow them to develop some types of chronic pain. Others were described as ‘wild type mice’ or other words, in their natural state and not genetically messed

ANTIHYPERALGESIC EFFECT OF JOINT MOBILIZATION REQUIRES CAV3.2 CALCIUM CHANNELS. Martins DF, Sorrentino V, Mazzardo-Martins L et al. Molecular Brain 2023;16:60

with.

Under light anaesthesia, the knee joint was stabilised, and the ankle joint was rhythmically flexed and extended to the end of the range of movement (animals that did not receive joint mobilisation were subjected to the same anaesthesia). The treatment group received three applications of mobilisation which each lasted 3min and which were separated by 30s of rest. Then, to test pain sensitivity they applied a stimulus to the hind foot and timed the flexion response.

The results showed that the joint mobilisation group wild type animals exhibited robust joint-manipulatedinduced relief from mechanical hypersensitivity, whereas Cav3.2-null mice did not. The conclusion drawn from this was that joint mobilisation triggers increased production of

THE EFFECT OF SLOW STROKE BACK MASSAGE ON BLOOD PRESSURE IN ELDERLY PATIENTS WITH HYPERTENSION.

Meidayanti GAMDD, Candrawati SAK, Lestari NKY. Holistic Nursing and Health Science 2023;6(1):30–37

Inclusion criteria in this study were hypertension sufferers aged 45–74 years, both male and female, and patients taking hypertension medication. A total of 44 patients received massage for 10 minutes, 3 times per week for 4 weeks. The

results showed a mean decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in the intervention group of 21.04mmHg and 11.68mmHg, respectively. The reduction in the control group was 3.00mmHg and 2.04mmHg.

Not our usual subject population but if massage reduces high blood pressure in the elderly it is reasonable to think it will do so with everyone. However, we include this study not just because it appears to show that massage reduces high blood pressure – we knew that from other studies – but as an example of frustrating practice on the part of researchers and their publishers. Presumably you want people to read your research and hopefully your work will help others with clinical decisions. The thing that pulls the reader into your work is the abstract. There are literally thousands of papers published every month and no one can read all of them, so we rely on the abstract to let us know if your work is worth seeking out.

In this study, at the time of writing the full text is listed as ‘not available’, and although the abstract suggests that there was an intervention and a control group there is no methodology, so we don’t know what has been done to either group. We don’t even know when the data was obtained. It makes your work worthless. Come on people, you can do better.

endocannabinoids which then blocks Cav3.2 channels in spinal and peripheral nerve and thus acts as an analgesic.

The poor mice cop for it again. The authors point out that all animal care and experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the USA’s National Institutes of Health’s Animal Care Guidelines (NIH publications No. 80-23) and conducted following approval of animal protocols by the Ethics and Institutional Animal Care and Use committees. If you want more information on this go to Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, 8th edn (https://bit.ly/44DF4Dk). There is also a UK version Code of practice for the housing and care of animals bred, supplied or used for scientific purposes (https://bit.ly/3Z38FES).

EFFECTIVENESS OF EXERCISE THERAPY, MANUAL THERAPY, MANIPULATION, AND DRY NEEDLING ON PAIN INTENSITY AND FUNCTIONAL DISABILITY IN PATIENTS WITH MIGRAINE HEADACHE: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS. Rezaeian T, Mosallanezhad Z, Saadat Z et al. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 2023;35(4) DOI:10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.2023047727

Six databases were searched from 1994 to January 2022. Primary outcome measures were pain intensity and functional disability, and the secondary outcomes were headache parameters, cervical range of motion, pressure pain threshold, quality of life, and psychological parameters. From a total of 663 relevant articles, 172 duplicate articles were removed. Of the remaining 491 articles, 452 articles were excluded based on the titles and abstracts for eligibility criteria. Finally, 24 studies were included for full review. Nine studies were of moderate quality, and 15 studies were good quality. The results verified that patients with migraine headache receiving exercise, manual therapy, manipulation, and dry needling showed better progress than those receiving conventional treatment or placebo.

Sadly we can’t tell you exactly what exercise was prescribed, nor the manual therapy done because we couldn’t get access to the full paper without paying $110. No thanks, we will settle for the knowledge that throwing the kitchen sink at the problem solves it.

EFFECT OF MANUAL THERAPY ON MUSCULOSKELETAL

REHABILITATION: PAIN MODULATION AND RANGE OF MOTION RESTORATION. Wei Y. Academic Journal of Medicine & Health Sciences 2023;4(7):96–101

This is basically manual therapy’s greatest hits. The paper lists a number of therapies and quotes a couple of papers for each to demonstrate their efficacy.

l Massage is good for reducing pain and increasing ROM.

l Graston technique uses instruments to address soft tissue restrictions that cause discomfort and pain. It breaks down scar tissue and reduces adhesions. It can effectively relieve tension and pressure on sensitive structures, such as nerves, leading to pain relief and an increase in ROM.

l Cupping therapy is a traditional Chinese medicine technique that involves applying cups on the skin and creating suction via a vacuum effect. This suction promotes blood flow and lifts fluids that are stagnant to the surface. Increased blood flow enhances the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the muscles, aiding in tissue repair and lessening pain.

l Soft tissue mobilisation and joint mobilisation are paired in the paper.

Both have been shown to be effective in pain modulation and ROM restoration.

l Stretching techniques are used throughout athletic training. They can be used to increase muscle length and flexibility, plus there are numerous studies looking into the effects on pain management and ROM. PNF stretches in particular show sustained increases in range of motion. Studies show that the amount of time spent stretching per week is more crucial than the duration of stretching within a single session. In comparison to stretching on a single day, stretching a joint for longer than 5 minutes per week led to greater ROM improvements.

If you work in an environment where the naysayers refrain is, “What about the evidence?”, this paper is for you. Either quote it directly or pick out the citations for each section.

N, Sharma D, Kumar C et al. Rivista Italiana di Filosofia Analitica Junior 2023;14(1):333–341

This paper is a report of a randomised control trial conducted with the aim of discovering which treatment regimen, Cyriax or Mulligan, worked best on lateral epicondylitis.

A group of 60 subjects were divided into two groups. One received Mulligan mobilisation with movement and the other a combination of Cyriax deep transverse frictions and Mills manipulation over a 15-day period. Both groups showed significant improvement in pain and functional ability throughout the treatment duration. When comparing both groups regarding pain, Cyriax’s approach showed significant improvement over Mulligan’s approach.

Manual Therapy rules whichever guru you follow.

THE OBJECTIVE AND SUBJECTIVE IMPACT OF A DAILY SELF-MASSAGE ON VISIBLE SIGNS OF STRESS ON THE SKIN AND EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING. Flament F, Maudet A, Bayer-Vanmoen M. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 2023 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/ics.12884

This study set out to discover if daily self-massage can improve skin quality and therefore wellbeing. Fifty women aged between 40–60 years completed the study. They all had Fitzpatrick skin type 2 or 3. This is a classification based on the amount of melanin pigment present and therefore the skin’s reaction to sunlight. They had self-reported dry skin and ptosis (upper eyelid droop), facial wrinkles and fine lines, lack of radiance, plumpness and firmness as measured between 3 and 6 on a 10-point visual scale. They also had to be “of non-childbearing potential or using appropriate contraception”. Why was not explained although it could be because pregnancy hormones lead to increased pigmentation and sensitivity to the sun.

All the subjects followed a facial self-massage protocol that is well described in the text. It basically involved stretching the skin and a type of tapotement applied by flicking the fingers on the skin’s surface. They did this every morning and evening for 14 days using a perfumed massage lotion. Clinical assessments on the first and last day were performed by a dermatologist and there was a self-administered questionnaire.

The results showed that of six clinical signs of stress visible on the skin, four significantly improved: ptosis, fine lines, radiance and visible wrinkles. On the questionnaire, all participants reported an increase in their feeling of wellbeing.

The paper starts by quoting the UnitedNations-initiated World Happiness Report 2022 which is an annual publication you can download at https://bit.ly/485nQSo. It’s been going for 10 years and it optimistically tells us that over that time “there has been a transformation of public interest in happiness. Policymakers worldwide increasingly see it as an important and overarching objective of public policy”. Errr … did a few governments miss the memo because it also states that “levels of stress, worry and sadness have been steadily increasing worldwide”. Which means that there is plenty of work for therapists. Either perform the massage or teach people to do it. You win either way and your patient feels better. Look Good, Feel Good.

Simply add your branding and order your printed copy through Canva

Better Sleep: Helps you sleep better and wake up feeling refreshed.

Weight Management: Helps control (and reduce) body weight by burning calories and maintaining a healthy metabolism.

Mental Health: Lifts your mood, reduces stress and anxiety, and improves brain function, making you feel happier.

Strong Muscles: Builds and keeps muscles strong for everyday tasks and prevents injuries - crucial for functional independence as you get older.

Healthy Bones: Weight-bearing activities like walking and strength exercises keep your bones strong and reduce the risk of fractures.

Balanced Metabolism: Improves how your body handles sugar, lowering the risk of diabetes.

Flexible Joints: Keeps your joints flexible, reduces stiffness, and prevents joint issues like osteoarthritis.

Cancer Protection: Lowers the risk of 13+ cancers, including breast, colon, and prostate cancer.

Sharper Mind: Boosts memory and thinking skills, keeping your brain active as you age.

Strong Immunity: Strengthens your immune system to help you fight off illnesses.

Digestive Health: Supports a healthy digestive system, reducing issues like constipation.

Healthy Breathing: Enhances lung function, improving your respiratory health.

Pain Relief: Can reduce chronic pain like lower back pain and arthritis pain.

Social Fun: Enjoy social activities during group exercises for better mental and emotional wwell-being.

Longer Life: Regular activity is linked to a longer and healthier life.”

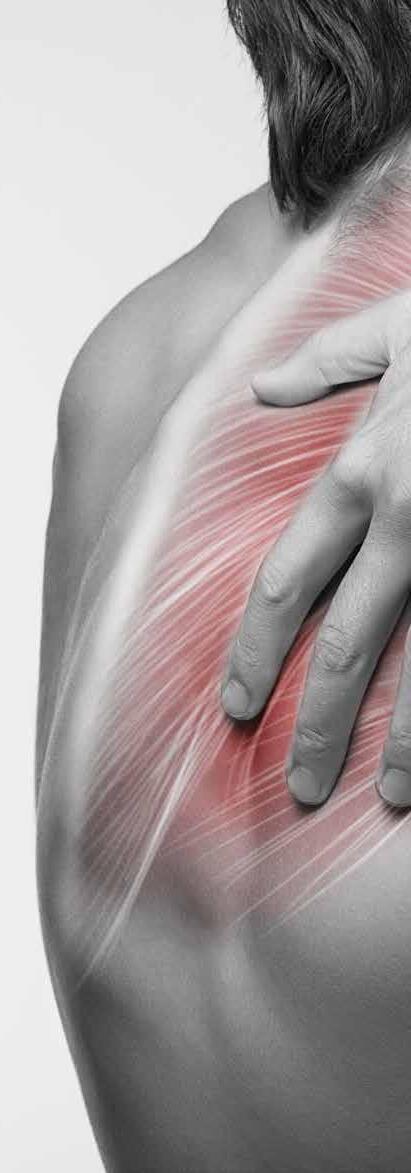

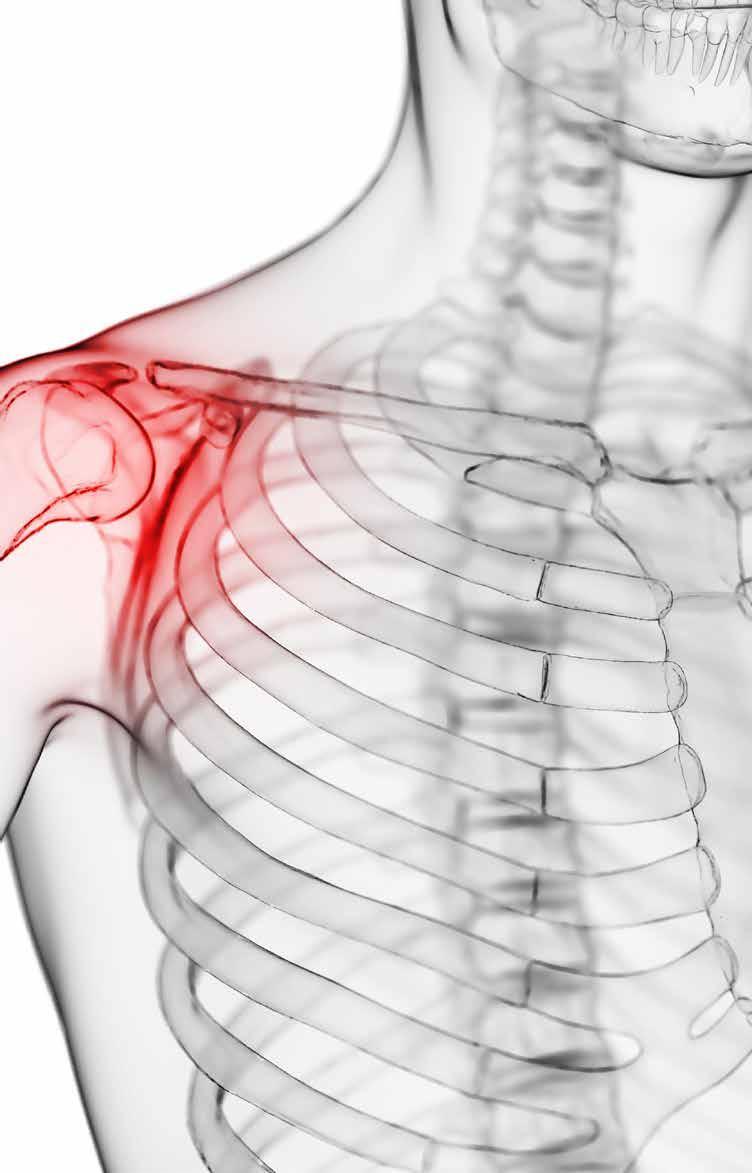

The cause of shoulder pain is often difficult to identify and diagnose precisely. There are a number of names for shoulderrelated pain and a fair few tests for its diagnosis. This article discusses the current thinking on the new term ‘subacromial pain syndrome’ for any pathology within the subacromial space and how best to use the variety of tests to diagnose it. The importance of using the correct terminology, is, of course, that it will enable the best treatment and management decisions for your shoulder pain patients. Read this article online https://bit.ly/45XSz1W

By Kathryn Thomas BSc MPhil

By Kathryn Thomas BSc MPhil

There has been huge debate and subsequently a confusing array of diagnostic labels used for pathology affecting the rotator cuff, subacromial space and related structures. For patients presenting with non-traumatic shoulder pain, this may include diagnostic labels of subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS or SAIS), subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS), rotator-cuffrelated disorders or disease and/or biomechanical impingement of the shoulder (1,2).

A recent Cochrane review suggested that an umbrella term of ‘rotator cuff disease’ may be a simple categorisation that encompasses all symptomatic disorders of the rotator cuff, regardless of mechanism (inflammatory, degenerative, or acute injury), or precise anatomical location (eg. supraspinatus tendon versus subacromial bursa) (3*). Under this umbrella term diagnoses may include rotator cuff tendinopathy or tendinitis, the impingement syndrome, partial and complete rotator cuff tears, calcific tendinitis, and subacromial bursitis (3*).

A patient with symptomatic rotator cuff disease may present with shoulder pain, often described as pain in the upper outer arm. Pain may be

aggravated by overhead activities and is often worse at night when lying on the affected side, leading to disrupted sleep. Significant disability with loss of function due to pain may be reported. A painful arc is nearly always present (3*). Does this sound familiar to other conditions labelled with other names?

Impingement was first introduced in 1972 by Dr Charles Neer, based on the mechanism of impingement of structures in the subacromial space (4). The term ‘subacromial impingement syndrome’ (SIS) as a diagnostic label was later coined for patients presenting with anterograde-lateral shoulder pain when the arm is elevated. SIS was viewed as symptomatic irritation of the subacromial structures between the coracoacromial arch and the humeral head during elevation of the arm above the shoulder/head. It can cover a spectrum of subacromial space pathologies which include rotator cuff tears, calcific tendinitis, biceps tendinopathy, rotator cuff tendinosis and subacromial bursitis. The aetiology of SIS remains a mystery (2,5*).

Two mechanisms, the extrinsic and intrinsic, have been proposed

for the genesis of the impingement syndrome. The intrinsic mechanism describes damage to the rotator cuff tendon which leads to impingement, whereas the extrinsic mechanism suggests impingement causes damage to the tendons (5). This is a bit like the chicken or the egg – which came first? Neither mechanism has been proven to be the cause; however, the intrinsic mechanism theory has gained popularity in recent years (3*).

Patients with SIS complain of antero-lateral shoulder pain which usually develops insidiously over a period of weeks to months. Night pain is common and is exacerbated by lying on the painful side and sleeping with the arm overhead. Overhead activities produce or exacerbate pain, and weakness and stiffness due to pain may also be present. Clinical tests used to diagnose SIS include the Neer test, Hawkins–Kennedy test, impingement test, drop arm test, and empty can (Jobe’s) test. The specificity for these tests is poor, however, and therefore it has been suggested these tests should not be used for diagnostic purposes (6*).

The ever-evolving understanding of the shoulder complex has led in recent years to question impingement as a cause of rotator cuff disease. Rotator cuff disease is now believed to be a form of tendinopathy (like tendinopathies in other parts of the body), and hence viewed as an overuse injury rather than an inflammatory tendinitis. Histological studies have shown evidence of a failed healing response with little or no sign of inflammation. In addition to this, tendons show abnormalities of tenocyte proliferation, intracellular abnormalities in the tenocytes, collagen fibre disruption and an increase in the non-collagenous matrix. Ageing may bring about some of these characteristics as can physical loading, infection, smoking, vibration, injury, genetic factors and use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (7*).

Mechanoreceptors and free nerve endings are found in the glenohumeral, coracoclavicular, and coracoacromial ligaments as well as the glenoid labrum and subacromial bursa. The rotator cuff tendons themselves have few

Co-Kinetic.com

nerve fibres. The rotator cuff tendons must play a role in generating pain through some indirect mechanism, where peptides or neurotransmitters produced by the degenerated tendon initiate a pain response from the pain fibres in surrounding structures (7*).

Studies have shown that there is no direct relationship between the presence of a rotator cuff tear and the presence of pain. Some patients with small tears can have severe pain, whereas patients with large rotator cuff tears can have no pain. Likewise, patients with failed surgical rotator cuff repair can still experience pain relief following the surgery. This implies that some other mechanism is responsible for the pain (7*).

Randomised controlled trials have shown no supremacy of surgery over conservative treatment, thus supporting the concept refuting the existence of impingement (3*,7*,8*,9*,10*). One such study included a randomised, placebocontrolled, three-group trial at 32 hospitals (10*). The study included over 300 patients with subacromial pain of three months’ duration who had completed conservative treatment and had had at least one steroid injection and were eligible for arthroscopic surgery. Patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears were excluded. Patients in group 1 received decompression surgery, group 2 arthroscopy only, and group 3 had no treatment. At the six-month follow-up,

the Oxford shoulder score showed no difference between the decompression and arthroscopy groups. Although both surgical groups showed a small benefit over no treatment, these differences were not clinically significant. The authors concluded that the small difference between the surgical groups and no treatment group may be the result of a placebo effect or the post-operative physiotherapy which the surgical group had. The authors questioned the value of subacromial decompression for shoulder pain (10*).

The authors of a recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that the evidence available does not support the use of subacromial decompression in the treatment of rotator cuff disease in patients with painful shoulder impingement (3*), as it showed no clinically significant benefit compared to placebo in pain, function and health-related quality of life. Arguably, surgical treatment in the management of shoulder pain should have no role as the impingement theory has become outdated. Some authors have proposed that the syndrome be renamed as anterolateral shoulder pain syndrome or simply shoulder pain syndrome (3*,8*). As decompression with surgery does not provide additional benefits compared to conservative treatment for patients with SIS, the impingement theory has become antiquated.

The following points highlight the flaws and summarise why

A NEW TERM ‘SUBACROMIAL PAIN SYNDROME’ (SAPS) HAS BEEN SUGGESTED TO BEST DESCRIBE THE PAIN THOUGHT TO ORIGINATE FROM STRUCTURES LYING BETWEEN THE ACROMION AND THE HUMERAL HEAD

‘IMPINGEMENT’ SHOULD BE CONSIDERED A MECHANISM CONTRIBUTING TO THE PATIENT’S SYMPTOMS RATHER THAN A DIAGNOSIS OF PATHOLOGY

clinicians should abandon the use of impingement as a diagnosis.

1.

If rotator cuff failure was caused by mechanical irritation by the under-surface of the acromion and coracoacromial ligament, then this should result in abrasion to the superior bursal side surface of the rotator cuff, especially in the supraspinatus. Studies have shown that in as many as 91% of cases partial-thickness tears were found on the inferior articular side of the supraspinatus with only 4% on a superior side (11). Other studies have reported similar findings, resulting in the question: Why do tendons usually show tears on the underside? Jill Cook, a renowned shoulder physiotherapist, reasons that compressive load of the rotator cuff tendons on the humeral head might be an important factor for the development of tendinopathy (12).

2.

If the impingement theory was true, then one would expect people with a type 3, hooked, acromion to experience more shoulder problems due to impingement compared to people with other acromion shapes. However, Gill et al. found no significant association between acromion morphology and rotator cuff pathology in patients who were over the age of 50 in their study of 523 patients who underwent arthroscopic or open surgery of the shoulder (13).

3.

If the acromion was the underlying cause of the impingement syndrome, then resection of the acromion should lead to better outcomes than placebo surgery or no treatment. However, as highlighted earlier, surgical decompression and/ or arthroscopy was not superior to placebo, no treatment and conservative treatment (3*,9*,10*).

As seen in other parts of the body, overuse tendinopathies involving the lateral epicondyle, patella tendon, adductor and Achilles tendons may occur without impingement from external structures such as adjacent bony surfaces. This may also be the case for the rotator cuff. It is possible that the external irritation accentuates the tendon failure, but it is unlikely that it is the primary cause. The compressive load that a tendon must undergo when it wraps around its bony attachment might play an important role. When combined with possible mechanical factors including relative overload, genetics, nutrition and lifestyle variables, rotator cuff tendon failure may be seen as a continuum of pathology. For this reason, authors have come up with a new more appropriate term of ‘subacromial pain syndrome’, which includes rotator cuff tendinopathy. Some pain scientists suggest calling it simply ‘shoulder pain’ as the exact aetiology and structural culprits are not fully understood.

What is critical to understand is that ‘impingement’ on its own is not a diagnosis, but simply describes the mechanism. Impingement should be considered a cluster of symptoms rather than a pathology itself (1,2).

While controversy surrounding diagnostic labelling continues to exist, a new term ‘subacromial pain syndrome’ (SAPS) has been suggested to best describe the pain thought to originate from structures lying between the acromion and the humeral head. These are most often associated with some degree of shoulder dysfunction but does not reflect many other causes of shoulder pain located outside the subacromial space (1,14*).

SAPS is defined as all non-traumatic, usually unilateral, shoulder problems that cause pain, localised around the acromion, often worsening during or after lifting the arm (14*). Like a murder mystery, the historic way in which clinicians tried to pin-point the who, what, when and where of the shoulder pain led to much confusion and frustration. Basically, this generic term

now encompasses pain associated with any lesion within a structure or structures within the subacromial space. As such, SAPS incorporates all conditions such as subacromial bursitis, calcific tendinitis, rotator cuff tendinopathy, rotator cuff tears, biceps tendinopathy, or tendon cuff degeneration (8*).

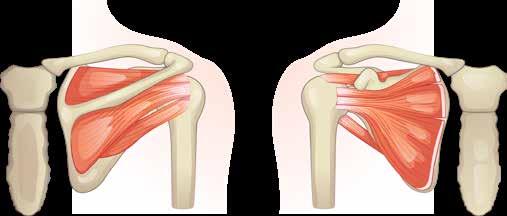

The subacromial space is the space beneath the acromion and the top surface of the humeral head and measures between 2 and 17mm depending on arm position. This space is outlined by the acromion and the coracoid process (which are parts of the scapula), and the coracoacromial ligament which connects the two. The space contains these anatomical structures (see also Fig. 1):

l coracoacromial arch, composed of the acromion, coracoid process and coracoacromial ligaments;

l humeral head;

l subacromial bursa;

l tendons of the rotator cuff; supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis;

l tendon of the long head of biceps brachii;

l coracoacromial ligament; and

l glenohumeral joint capsule.

Shoulder movements do not occur in isolation at the glenohumeral joint. During arm elevation, the following combinations of articulation and movements occur within the shoulder complex.

l Posterior roll and inferior glide of the humeral head.

l Posterior rotation of the clavicle allows for raising of the acromion and maintaining subacromial space.

l External rotation of the scapular, which involves the medial border of the scapula moving towards the thoracic spine and chest wall. As the humerus laterally rotates, the scapular follows with lateral rotation.

l Towards the end of elevation, the scapular tilts posteriorly; that is, the inferior angle of the scapula will move towards the chest wall.

l Upward rotation of the scapular may occur which involves movement

Co-Kinetic.com

of the inferior angle of the scapula from the thoracic spine. The upward rotation of the scapula keeps the acromion high, maintaining that acromiohumeral distance and reducing the possibility of compressing structures within the subacromial space. This movement is generally carried out with the recruitment of the different sections of the trapezius muscle (upper/ middle/lower). This upward rotation of the scapular also allows the glenoid fossa to follow the humeral head, maintaining congruency during arm elevation.

As with any discussion about biomechanics of the shoulder, scapulohumeral rhythm comes into play. The ratio of the glenohumeral movement to the scapulothoracic movement during arm elevation is not consistent across the entire arc. A general rule of 2:1; meaning for every 2° of humeral elevation there is 1° of scapular rotation.

External rotation of the humerus during elevation is critical as it permits the avoidance of compression of the greater tuberosity against the subacromial structures. If the timing is incorrect (due to poor neuromuscular recruitment, internal rotation of the humerus or dysfunctional biomechanics of the shoulder complex), the necessary external rotation will not occur and the greater tuberosity will

internally compromise the structures and cause an irritation of the tissues.

The debate continues and is at present unclear regarding the aetiology of subacromial pain. It has been proposed that there are intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms as well as a combination of influencing factors including muscle imbalance and anatomical structure that may affect the subacromial space. It is generally accepted that multiple factors are involved in the pathology. Some issues remain unresolved: for example, which structure initiated the pathology and what the paingenerating mechanisms are (14*).

As mentioned, both intrinsic and extrinsic factors could predispose a person to developing SAPS (Table 1).

Different types of impingement can still present in SAPS. Remember, impingement should be considered a mechanism contributing to the patient’s symptoms rather than a diagnosis of pathology. Types of impingement are described as follows.

1. Subacromial extra-articular impingement (bursal)

A decreased subacromial space results in compression. During shoulder elevation, pain is experienced on the anterior aspect.

2. Internal impingement (articular) Patients complain of pain posteriorly or deep ‘inside’ the Table

USING A COMBINATION OF SPECIFIC TESTS INCREASES THE POST-TEST PROBABILITY OF THE DIAGNOSIS OF SAPS

https://youtu.be/UErH4NUsDWQ

joint often in a throwing position of abduction and external rotation. This may be caused by contact between the articular side of the supra/infraspinatus and the posterosuperior rim of the glenoid.

3. Subcoracoid impingement

Pain is elicited or exacerbated by the shoulder in forward flexion, adduction and internal (medial) rotation (such as the motion of hitting the ball with a racket). This may be a dull pain in the anterior aspect of the shoulder.

accurately diagnose SAPS. A combination of symptoms, positive signs from tests and a detailed history are necessary for diagnosis or to sufficiently differentiate between various shoulder disorders. Using a combination of specific tests increases the post-test probability of the diagnosis of SAPS (14*,15).

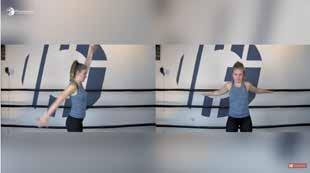

Research suggests that a combination of the following pain provocation tests should be performed for diagnosis of subacromial pain syndrome (15) (Video 1):

l Hawkins–Kennedy test (Video 2);

https://youtu.be/X9YiuvQJVJc

There are three main mechanisms that can affect the distance within the subacromial space. They include (i) loss of control of the humeral head or an unstable glenohumeral joint; (ii) poor scapular control; and (iii) a change in the size of structures within the space. Excessive loading of a tendon due to repetitive forces can result in thickening of the tendon and a reactive tendinopathy, thus reducing the space by ‘enlarging’ the tendon. Bear in mind that changes to the tendons may be normal depending on activity levels and age, and their thickness may not be an indication of pathology.

It’s not surprising that you may have heard this clinical presentation before. It generally presents in patients over the age of 40, with no history of trauma. Patients may have persistent pain or pain on elevation of the arm (affecting sports activities, household chores and work). They may complain of night pain or pain when sleeping on the affected side. The symptoms may be acute or chronic and of insidious onset. Most often it is a gradual, degenerative condition that results in impingement.

l painful arc test (Video 3);

l infraspinatus external rotation resistance test;

l empty can test (Video 4); and

l Neer test (Video 5).

A higher predictive value for SAPS is evident with the combination of all five tests. The cut-off point of three or more positive results out of five tests can confirm the diagnosis of SAPS, whereas less than three positive out of five rules out SAPS (15,16).

https://youtu.be/DeO50UTxwoo

There is no single test that can

A different interpretation of the value of clinical tests suggests that the Hawkins–Kennedy test (Video 2), Neer’s sign (Video 5), and empty can test (Video 4) are more useful for ruling out rather than ruling in impingement, with greater pooled sensitivity estimates (range, 0.69–0.78) than specificity (range, 0.57–0.62). The probability of impingement is reduced from 45% to 14% with a negative Neer’s sign. The drop arm test (Video 6) and lift-off test (Video 7) have the highest pooled specificities (range, 0.92–0.97) indicating that they are more useful for ruling in impingement if positive (17). Although it is recommended that one no longer diagnoses impingement as a condition, impingement may still be identified as part of a cluster of symptoms within SAPS. Therefore, the algorithm shown in Figure 2 may still

Co-Kinetic Journal 2023;98(October):14-21

THERE IS A GOOD CLINICAL–RADIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION BETWEEN SAPS AND FINDINGS ON ULTRASOUND

be of assistance (18).

Considerations for poor neuromuscular control of the scapula (and the shoulder girdle in general) should be assessed during the physical examination. One might be looking at loss of dynamic stability of the scapula as well as scapular muscle performance and endurance. The serratus anterior muscle facilitates movement of the scapula in upward rotation, posterior tilt, external rotation, and protraction of the scapula during arm elevation. Weakness of the serratus anterior muscle may impact scapular movement and thus contribute to SAPS. Tests including the scapular assistance test (SAT) (Video 8) and scapular retraction test (SRT) (Video 9) may be helpful.

Posture-related issues – for example the length and flexibility of pectoralis minor and thoracic spine function and mobility – may all affect the shoulder girdle. Range of motion of the glenohumeral joint, especially restricted internal rotation, may indicate a tight posterior capsule, whereas any instability may also lead to SAPS. Rotator cuff muscle balance, performance and endurance should also be considered while assessing the patient (1).

Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD), which can be understood as a loss of internal rotation range of motion in the presence of a loss of total rotational motion compared with the uninjured side. GIRD may be present in patients suspected of SAPS who are involved in sports or activities that use an overhead arm action. It has been theorised that GIRD is due to the thickening of the posterior glenohumeral capsule, limiting the overall range of internal rotation at the joint. It may be a contributing factor in patients presenting with SAPS. Evaluation should not only look at reduced internal rotation on the affected side but also total range of motion compared on both shoulders: GIRD = [side-to-side difference in ER] + [side-to-side difference in IR] (Video 10) (18).

Certain anatomical factors may influence the narrowing of the subacromial space, and thus the

Co-Kinetic.com

Impingement symptoms

Jobe – Neer + post Hawkins –apprehension + (pain) ant

External subacromial impingement

Jobe – Neer + post Hawkins –apprehension + (pain) post

Internal posteriosuperior glenoid impingement

Relocation + release + (pain) Relocation –

Primary impingement

Full can +

Relocation + release + (pain)

Secondary impingement

SAT + SRT +

Rotator cuff pathology Scapular dyskineis

Laxity tests + apprehension + (appr) relocation + (appr)

O’Brien + Speed’s + biceps load II + IR ROM +

Biceps-SLAP pathology Instability GIRD

−, negative; +, positive; , decreased; ant, anterior; appr, apprehension (feeling of instability); GIRD, glenohumeral internal rotation deficit; IR, internal rotation; post, posterior; ROM, range of motion; SAT, scapular assistance test; SLAP, superior labral anterior to posterior; SRT, scapular retraction test.

Figure 2: Algorithm for clinical reasoning for assessing shoulder impingement Cools AM, Cambier D, Witvrouw EE. Screening the athlete’s shoulder for impingement symptoms: a clinical reasoning algorithm for early detection of shoulder pathology. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2008;42(8):628–635 (18). Reproduced with permission.

development of SAPS. Radiographs may be used to detect anatomical variants, calcific deposits, or acromioclavicular joint arthritis.

There is a good clinical–radiological association between subacromial pain syndrome and findings on ultrasound. The diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound is considered good and comparable to that of conventional MRI for identification and quantification of complete (full-thickness) or partial rotator cuff tears (19). It is suggested that ultrasound, rather than MRI, be considered as a valuable and costeffective diagnostic tool.

The Dutch Orthopaedic Association Guidelines suggest imaging may be considered if the first period of conservative treatment fails (14*). Combined radiography and ultrasound of the shoulder may determine osteoarthritis, osseous abnormalities, and presence/absence of calcium deposits. Where reliable ultrasound is not available or inconclusive, then MRI of the shoulder may be indicated. One should always consider how useful the

imaging results may be in guiding management. The interpretation of ‘poor’ imaging results may unduly and negatively impact a patient’s psychology and attitude towards their pain and rehabilitation process. It may result in catastrophising with unnecessary overprotection of the joint. Unless the imaging is going to change treatment protocol, for example lead to surgical intervention, then one should consider its value. As mentioned earlier, the relationship of pain to the degree of injury severity is not always linear. Likewise, the degree of ‘damage’ seen on an X-radiograph or scan is not necessarily proportional to a patient’s symptoms or their prognosis.

Until recently, there has been no recognised terminology, nor diagnostic criteria, for patients with SAPS. This could result in misconceptions and misinterpretations of scientific results, clinical diagnosis, and management, as well as confusion amongst patients (2). Twenty-seven unique terms have been identified over the past decades relating to shoulder impingement and subacromial-pain-related syndromes (1). More recently, mechanistic terms and diagnoses containing ‘impingement’ have been used less than before, whereas the term SAPS is used increasingly. Diagnosis of SAPS should involve using a cluster of tests; the most useful are combinations of Hawkins–Kennedy, Neer’s, empty can, painful arc, and isometric shoulder external rotation strength tests. Imaging may primarily be used to exclude other pathologies (1).

So, one may ask: What’s in a label? The correct terminology may influence clinical trials and inclusion criteria resulting in homogenous patient populations within studies. This can lead to more accurate results for guiding management and so improve clinical outcomes. The correct or incorrect label can result in invasive procedures with potential adverse risks. A label can dictate a patient’s attitude towards their condition and thus impact their recovery.

1. Witten A, Mikkelsen K, Wagenblast Mayntzhusen T et al. Terminology and diagnostic criteria used in studies investigating patients with subacromial pain syndrome from 1972 to 2019: a scoping review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023;57(13):864–871

2. Cools AM, Michener LA. Shoulder pain: can one label satisfy everyone and everything? British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017;51(5):416–417

3. Karjalainen T V, Jain NB, Page CM et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019;1:CD005619 Open access https://bit.ly/3qx0OCZ

4. Neer C. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American Volume) 1972;54:41–50

5. Singh H, Thind A, Mohamed NS. Subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review of existing treatment modalities to newer proprioceptive-based strategies. Cureus 2022;14(8):e28405 Open access https://bit.ly/47GdKqz

6. Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S et al. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2007;42:80–92 Open access https://bit.ly/3snoUk3

7. McFarland EG, Maffulli N, Del Buono A et al. Impingement is not impingement: the case for calling it “Rotator Cuff Disease”. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 2013;3(3):196–200 Open access https://bit.ly/47AnuD3

8. Dhillon K. Subacromial impingement syndrome of the shoulder: a musculoskeletal disorder or a medical myth? Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal 2019;13(3):1–7

Open access https://bit.ly/3OHI5g4

9. Lähdeoja T, Karjalainen T, Jokihaara J et al. Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54(11):665–673

Open access https://bit.ly/3KQmK2D

10. Beard DJ, Rees JL, Cook JA et al. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, threegroup, randomised surgical trial. Lancet 2018;391(10118):329–338

Open access https://bit.ly/47Jqkpl

11. Payne LZ, Altchek DW, Craig EV et al. Arthroscopic treatment of partial rotator cuff tears in young athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine 1997;25(3):299–305

12. Cardoso TB, Pizzari T, Kinsella R et al. Current trends in tendinopathy management. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology 2019;33(1):122–140

13. Gill TJ, McIrvin E, Kocher MS et al. The relative importance of acromial morphology and age with respect to rotator cuff

pathology. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2002;11(4):327–330

14. Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O et al. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome: a multidisciplinary review by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association. Acta Orthopaedica 2014;85(3):314–322 Open access https://bit.ly/3QNy57v

15. Michener LA, Walsworth MK, Doukas WC et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of 5 physical examination tests and combination of tests for subacromial impingement. Archives of

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2009;90(11):1898–1903

16. Park HB, Yokota A, Gill HS et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American volume) 2005;87(7):1446–1455

17. Alqunaee M, Galvin R, Fahey T. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2012;93(2):229–236

l There has been huge debate about – and subsequently a confusing array of diagnostic labels used for – pathology affecting the rotator cuff, subacromial space and related structures.

l Rotator cuff disease is now believed to be a form of tendinopathy, like tendinopathies in other parts of the body; as such, it is an overuse injury rather than an inflammatory tendinitis.

l Randomised controlled trials have shown no supremacy of surgery over conservative treatment, thus supporting the concept refuting the existence of impingement and the need for decompression surgery.

l Impingement on its own is not a diagnosis but, rather, simply describes the mechanism; therefore impingement should be considered as a cluster of symptoms rather than a pathology.

l Currently, subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS) is believed to best describe the pain that is thought to originate from structures lying between the acromion and the humeral head, including subacromial bursitis, calcific tendinitis, rotator cuff tendinopathy, rotator cuff tears, biceps tendinopathy, or tendon cuff degeneration.

l SAPS presents as non-traumatic shoulder pain, persistent or aggravated by arm elevation and/ or overhead activities. This may include night pain or pain when sleeping on the affected side and may present as an acute or chronic condition.

l A combination of five tests, with a cut-off of at least three positive test results, gives the best predictive value for SAPS.

l Evaluation includes the Hawkins–Kennedy, empty can, painful arc, Neer, and infraspinatus external rotation resistance tests.

l Assessment should include evaluation of shoulder biomechanics, neuromuscular control, posture and ergonomics.

l Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) may be a contributing factor.

18. Cools AM, Cambier D, Witvrouw EE. Screening the athlete’s shoulder for impingement symptoms: a clinical reasoning algorithm for early detection of shoulder pathology. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2008;42(8):628–635

19. Rodríguez-Piñero Durán M, Vidal Vargas V, Castro Agudo M. Hallazgos ecográficos en el síndrome de dolor subacromial crónico [Ultrasound findings in chronic subacromal pain syndrome]. Rehabilitacion 2019;53(4):240–246 (in Spanish).

l Frozen Shoulder: Stuck and Stubborn [Article] https://bit.ly/3YGztuE

l Managing the Pinch: A Review of Shoulder Impingement Care [Article] https://bit.ly/44ktk8H

l Manual Therapy Student Handbook: Assessment and Treatment of the Shoulder - Part 8 [Article] https://bit.ly/3QIdBNu

l Clustering signs and symptoms to diagnose rotator cuff pathology [Group of Articles] https://bit.ly/3QNXUVc

l How much emphasis do you place on diagnosis and ‘labelling’ the patient’s condition? Or do you manage the patient according to their signs and symptoms without being driven by the label and its associated management protocols?

l What clinical tests or assessment tools do you find the most useful when evaluating a patient with subacromial shoulder pain?

Kathryn Thomas BSc Physio, MPhil Sports Physiotherapy is a physiotherapist with a Master’s degree in Sports Physiotherapy from the Institute of Sports Science and University of Cape Town, South Africa. She graduated both her honours and Master’s degrees Cum Laude, and with Deans awards. After graduating in 2000 Kathryn worked in sports practices focusing on musculoskeletal injuries and rehabilitation. She was contracted to work with the Dolphins Cricket team (county/provincial team) and The Sharks rugby teams (Super rugby). Kathryn has also worked and supervised physios at the annual Comrades Marathon and Amashova cycle races for many years. She has worked with elite athletes from different sporting disciplines such as hockey, athletics, swimming and tennis. She was a competitive athlete holding national and provincial colours for swimming, biathlon, athletics, and surf lifesaving, and has a passion for sports and exercise physiology. She has presented research at the annual American College of Sports Medicine congress in Baltimore, and at South African Sports Medicine Association in 2000 and 2011. She is Co-Kinetic’s technical editor and has taken on responsibility for writing our new clinical review updates for practitioners.

Email: kittyjoythomas@gmail.com

This article reviews the available evidence for exercise therapy in managing patients with shoulder pain to help you to guide your decision-making when creating a personalised treatment plan for your SAPS patients. Read this article online https://bit.ly/3PgoaFj

By Kathryn Thomas BSc MPhilOwing to current classification systems and multiple labels for shoulder pain, diagnostic consistency has been shown to be unreliable. This, in turn, leads to misguided treatment plans often resulting in disappointing outcomes (1,2*). Subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS) is the most common diagnosis for patients presenting with shoulder pain and includes rotator cuff syndrome (including rotator cuff tears), tendinitis, tendinopathy, impingement, and bursitis. This is a painful, disabling condition often taking weeks or months to resolve or consequently leading to surgery that may or may not have been necessary. The uncertainty about the pathogenesis of this syndrome is partly reflected in the diversity and confusion of its treatment (3,4).

and long-term clinical outcomes PT has shown results that are as positive as subacromial decompression/ acromioplasty and acromioplasty plus rotator cuff repair in patients with subacromial pain (2). There is a growing body of evidence that treating shoulder pain with PT greatly reduces the number of surgeries required for patients with subacromial pain syndrome or rotator cuff tear (5*). See also the article ‘Painful Shoulder: Don’t Label Me (Incorrectly!)’ https://bit.ly/45XSz1W which goes into more detail about surgical intervention.