Our Design DNA

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our new Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across eight programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2022 Forms of Collision Where the Earth Meets the Sky

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

2021 A Stationary Body

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

2020 What Matters and the Capabilities to be Sensed

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

2019 Quasi-Agents and Explorations on the Edge of the World

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

2017 An Architecture of the Wild

Johan Berglund, Colin Herperger

2016 Supernatural

Johan Berglund, Dirk Krolikowski, Josep Miàs

2015 Bridges

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs, Dean Pike

2014 Adapt

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs

2013 Utopias

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs

2012 Islands

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs

2011 …This is Not a Gateway!

Simon Herron, Susanne Isa

2010 Common-Wealth

Simon Herron, Susanne Isa

2009 Experimental Station [T.O.A.D]

Simon Herron, Susanne Isa

2008 Real [ism] + e-state

Simon Herron, Susanne Isa

2007 Ancient + Modern

Simon

Herron, Susanne Isa

2006 Lost Curiosity

Simon Herron, Susanne Isa

2005 The Bureau of Land Management

Simon Herron, Susanne

Isa

2004 Weight and Measure

Simon Herron, Susanne Isa

Forms of Collision Where the Earth Meets the Sky

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

Forms of Collision Where the Earth Meets the Sky

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-CookPG16 is focused on the exploration of an architecture that reemphasises the need for us to have a physical engagement with, and a relationship to, the environments we choose to inhabit.

This year we focused our interest in explorations of particular environments, specifically by engaging with the ground (the Critical Zone) and architecture’s inherent relationship to it in three ways. Firstly as geology, to appreciate how deep time has formed the materials that give character to the places we live in, as well as providing evidence of the way in which ecologies are adjusting in the face of climate change; secondly, to understand architecture as primarily a material inference in the ground – and subsequently to seek to justify this inference as a means to reconnect us physically to the places we inhabit; and thirdly as tenure, to question how centuries-old forms of land ownership can inform contemporary sustainable forms of habitation.

The site of our enquiries and our field trip this year was the remote Highlands of Scotland. Here the relationship with the ground and the land has a rich, and at times fraught, history. We reflected on the matter beneath our feet by looking at the unique and historically unappreciated peatland that is intrinsic to the identity of this region. In focusing on this territory, we sought to engage recent international recognition of the environmental importance of this type of wetland as an extremely efficient carbon sink that can be found across the UK.1

Our research also focused on forms of land occupation and ownership, in particular the crofting model. This form of land tenure, unique to Scotland, has contributed to the retention of communities in the most remote parts of the United Kingdom. Through our study of the Scottish croft, we developed creative approaches to the diversification of rural activities as a way to support rural communities, biodiversity and the sustainable use of land.

Year 4

James Della Valle, Amy Kempa, Olga Korolkova, Kyle Mcguinness, Julia Remington, Alasdair Sheldon, Long (Ron) Tse

Year 5

Jack Barnett, Lauren Childs, Danny Dimbleby, Zachariah Harper-Le Petevin Dit Le Roux, Tudor Jitariu, Aleksandra Kugacka, Maria (Tea) Marta, Elliot Pick, Rupert Woods

Technical tutors and consultants: Will Jefferies, Ollie Wildman, Sal Wilson

Thesis supervisors: Alessandro Ayuso, Carolina Bartram, Stephen Gage, Polly Gould, Elise Hunchuck, Robin Wilson

Critics: Graham Burn, Tamsin Hanke, Johan Hybschman, Alex Kitching, Matthew Springett, Sabine Storp, Dimitar Stoynev, Patrick Weber

Partners: Emilia Leese (Natural Capital Laboratory), Richard Lindsay (UEL), Chris White (AECOM)

1. ‘Peatland Pavilion will feature at UN Climate Change Conference (COP26)’, IUCN: National Committee United Kingdom, 2021.

16.1, 16.22 Elliot Pick, Y5 ‘Tales of Isolation and Cultivation in Northern Scotland’. Set off the coast of Loch Hourn, Scotland, the project narrates the unique practices of three isolated cultivators. As atonement for past unsustainable practices, each cultivator wears a ritualised suit that causes discomfort to the body. The suits scale into tailored dwellings, navigating relationships between humans and nature.

16.2 Julia Remington, Y4 ‘Persistent Memories’. A new archive addresses the threatened cultural heritage of Pyramiden, an abandoned Soviet mining town in the High Arctic. Current conservation practices are challenged through the proposal of different strategies to archive, preserve and curate its forgotten paraphernalia. Developed strategies address conflicts between exploitative owners, dark tourism and a constantly changing environment.

16.3 Jack Barnett, Y5 ‘Peatland Proprioception: Vernaculars between People, Plants and Places’. The Ord Crofting Inn choreographs a series of environmental balancing acts on Skye and takes on the form of three dwellings. Each facilitates a unique experience of its surroundings and engages guests’ physicality and proprioceptive sense to build awareness and physical relationships between people, plants and places.

16.4–16.5 Olga Korolkova, Y4 ‘Reimagining Siberia: Byas Kuel Firefighters’ Village’. Dedicated to Siberia’s devastating wildfires, the scheme comprises a hybrid typology of fire station and biofuel production facility, which reuses wood from the burnt forests. Multiple fields and forest structures facilitate a new sustainable economy and celebrate Yakutian culture with architecture that rethinks centuries-old fireresilient construction and local spiritual rituals.

16.6 Kyle McGuinness, Y4 ‘A New Peatland Paradigm’. This project proposes the restoration of degraded Scottish peatland and its conversion to productive wetland to produce common reed. To reverse misconceptions about land use, the architecture embraces and celebrates the landscape’s deficiencies while actively restoring the ground’s water table to healthy conditions.

16.7 Alasdair Sheldon, Y4 ‘A Place between the Crofts’. The project proposes a new codependent crofting system on the island of Benbecula through two experimental houses and an intermediate building. The architecture attempts to mitigate the effects of coastal encroachment and increased flooding and in this way protects crofters from a threat to local land security.

16.8 Lauren Childs, Y5 ‘Caring for a Scarred Landscape’. The project is a response to the degraded state of the Scottish peatlands. It proposes a dam alongside workshops and bothies that will contribute to the remediation of the Strathy South Plantation, a landscape currently dominated by non-native Sitka spruce trees.

16.9 Aleksandra Kugacka, Y5 ‘Warp, Weft and the Wetlands’. The project examines the craft of willow weaving as a means of peatland rehabilitation in Scotland’s Flow Country. A proposal for a COP36 Convention Centre celebrates weaving and functions as a vessel for the Scottish crofting identity, engaging visitors with the condition of the unstable ground.

16.10–16.11 Tudor Jitariu, Y5 ‘The Space below Ground’. Located within the geological context of the Highland Boundary Fault, this project investigates structural, formal and spatial approaches to creating underground spaces to research the region’s geological diversity. A decentralised institution serves to question existing attitudes towards the image and the perception of the subterranean condition.

16.12–16.13 Zachariah Harper-Le Petevin Dit Le Roux, Y5 ‘Contested Ground’. Sited on the exposed coastal peat of Kentra, the project sets out a proposal for the conservation of the region’s eccentric bog system, looking to the antecedent practices of Highland Games to develop strategies that will defend their history and the landscapes on which they are performed. 16.14–16.15 Maria (Tea) Marta, Y5 ‘Acts of Resistance: Place and Policy in the Danube Delta, Romania’. Situated in the Danube Delta, Romania, the project investigates the possibility of using architecture as a catalyst for political and environmental debate. It is an architecture of protest that accompanies existing local resistance acts and hosts localised deliberation spaces, where international, national and local authorities engage with the context they affect. 16.16–16.17, 16.19 Amy Kempa, Y4 ‘Cultivating a Collective – Landscape as Timeshare’. Located within a degraded blanket bog, interventions of varying temperance serve both croft and crofter. The dwellings remediate the poor ground condition by proposing primitivist domestic spaces that value the cycle of nature.

16.18 Rupert Woods, Y5 ‘Erdkunde – Earth Tidings’. The literal translation of the German word erdkunde is ‘messages brought by the earth’. Two avatars have been developed on the Scottish peatlands that will listen to these messages by measuring environmental components. The avatars will then personify these results as emotions of celebration or distress. 16.20 James Della Valle, Y4 ‘The Mark of Man’. A collection of taigh (Gaelic for home) upholds the preservation of the crofting model through the construction of a contemporary crofting vernacular. An architectural proclamation declares the revival of centuries-old forms of Scottish craft while espousing novel forms of autonomous tooling.

16.21 Long (Ron) Tse, Y4 ‘Sheep Dyke Reimagined: Towards an Architecture of Wellbeing’. The project proposes living within a 13-mile-long dry-stone structure surrounding North Ronaldsay, Orkney Isles. The scheme explores a primitive relationship between domestic space and the island’s agricultural context.

A Stationary Body

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

A Stationary Body

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-CookPG16 is focussed on the exploration of an architecture that re-emphasises the need to have a physical engagement and relationship with the environments we choose to inhabit. This year we continued our explorations into the meaning of matter and sought to emphasise the human body as the primary site of architectural experience and enquiry. This investigation was framed by two distinct and emerging conditions. Firstly, the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on the way we experience the objects, materials and ecologies that frame and formulate our daily experiences. Central to this enquiry was the exploration of current circumstances that have forced us to gain a heightened awareness of how we physically interact with the world through our senses, in particular touch, and the way we manifest and develop social relationships through proximities in shared space. Secondly, our investigation was formulated by the desire to find architectures that negate a condition of reduced mobility within an increasingly globalised world.

Our investigations this year started with the human body as a site, looking at contemporary and historical ways to record and measure it, the relationship between our physicality and senses, and the way these affect our understanding of the world. These enquires sought to respond to the opinion that we have entered an era where existing building control and construction standards can be challenged, to consider the senses, character and our new emerging identities. The work then transitioned to proposing inventive and speculative approaches to the act of dwelling and new types of spaces that enhance our relationship with the environment.

Our design outcomes were varied, taking the form of speculative narratives, spatial transformations and material investigations. Students challenged the typology of the terraced house by experimenting with contemporary applications of clay and challenged conventional notions of ‘home’ through the practice of drag. Students also explored the preservation of environments through the study of existing ecologies, adapting these into building systems such as seed banks to narrate the history of a man-made forest, flood defence mechanisms that address balance in order to stimulate our proprioceptive senses and building structures warning of impending natural disasters, inspired by supernatural beliefs.

Year 4

Jack Barnett, Lauren Childs, Yang Di, Zachariah Harper-Le Petevin Dit Le Roux, Tudor Jitariu, Aleksandra Kugacka, Maria (Tea) Marta, Rupert Woods

Year 5

Ella Caldicott, Hoh Gun Choi, Christina Garbi, George Gil, Hannah Lewis, Przemyslaw Pastor, Daniel Pope, Andrew Riddell

Thank you to our design realisation practice tutor Will Jefferies, structural consultant Ollie Wildman and environmental consultant Sal Wilson

Thesis tutors: Brent Carnell, Stelios Giamarelos, Elise Hunchuck, Shaun Murray, Oliver Wilton, Simon Withers

Critics: Laura Allen, Ana Betancour, Tom Budd, Cristina Candito, Rhys Cannon, John Cruwys, Maria Fedorchenko, David Flook, Will Jefferies, Perry Kulper, Ness Lafoy, TJ Brook Lin, Jason O’Shaughnessy, Mark Smout, Neil Spiller, Dimitar Stoynev, Simon Withers, Carl-Johan Vesterlund

Guest speakers and masterclass hosts: Eddie Blake, Tom Budd, John Cruwys, Sam Davies, Marco Ferrari, Paloma Gormley, Niall Hobhouse, Elise Hunchuck, Summer Islam, Asif Khan, Holly Lewis, Geoff Manaugh, Niall Maxwell, Nicholas de Monchaux, Matthew Page, Nicola Twilley, Marie Walker-Smith, Michael Webb

16.1 Andrew Riddell, Y5 ‘Lipstick on a Pig’. The project proposes an architecture of a bespoke and new Queer domestic. Questioning traditional domestic spaces that fail to accommodate more fluid definitions of domesticity, it draws on the aesthetic and social attitudes of the drag community. Drag in this context acts as a visual sign of this deconstruction of the wider heteronormative model of living that is held today.

16.2–16.4 Hannah Lewis, Y5 ‘Four Cities, One Future.’ The project imagines a world where polar reversal becomes a reality. In response to this catastrophe, and derived from online user-generated content such as Reddit, a ‘cross’ of four imaginary cities is proposed at the edge of South Dakota. Each city captures an alternative response to survival and state of mind. Through online presence, the project provides an opportunity to picture a wildly different world with divergent imaginaries for alternate ways of living.

16.5, 16.21 Daniel Pope, Y5 ‘The Earthen Land Registry’. The project explores the use of clay in contemporary construction methods. Through augmenting extrusion techniques and adopting processes of additive manufacturing technology, the proposal heightens the sensuous relationship between the body and building materials. The project includes a house typology and a retrofit strategy for London’s current brick housing stock, supported by a new fabrication facility and a public monument in the heart of the city.

16.6–16.7 Ella Caldicott, Y5 ‘An Architecture Through an Orchid Sensibility’. The project explores how architecture can enhance a desire for ecological awareness in the limestone district of the Yorkshire Dales, home to one of the rarest orchids in the UK. Balancing the existing conflicts between tourism, the quarrying industry, farmers and locals, the project creates a new appreciation of the protected landscape at both the scale of the orchid as well as the wider ecosystem of the Dales.

16.8 Zachariah Harper-Le Petevin Dit Le Roux, Y4 ‘After the First Fire’. A proposal for a fire research settlement sited on London’s Building Research Establishment (BRE), dedicated to developing two experimental housing typologies. Throughout the two homes, the life of components after fire testing is accounted for; where sacrificial materials might combust to protect occupants. The project explores alternative strategies for risk in the home and suggests how architecture might play a more performative role in fire prevention and safety.

16.9 Przemyslaw Pastor, Y5 ‘A Society for Abandoned Landscapes’. An architectural intervention to address the negative ecological impact caused by abandoned farmland across the Palo Verde Valley, California. Taking inspiration from the Blythe Intaglios – a group of gigantic prehistoric figures etched on the ground in the Colorado Desert – the proposed structures are carved into the ground to form a satellite desert laboratory for new farming techniques and the creation of ‘A Society for Abandoned Landscapes’.

16.10 Aleksandra Kugacka, Y4 ‘Save the Date’. The project investigates what might constitute a postpandemic public space. Taking Willesden Junction as a test site, the project considers the railway station as a romantic space of encounter. Speculating on the use of the waiting room and platform as a way to find delight in the everyday commute, the project explores the influence public space has on our mental wellbeing.

16.11 Maria (Tea) Marta, Y4 ‘A School, a Barn and a House Can Start a Riot’. Situated in the Apuseni Mountains, Romania, the project interrogates the possibilities of ravaged landscapes and forgotten architecture as catalysts for political change. The region suffers from uncontrolled and reckless mining that has led to several major environmental disasters. Three traditional buildings, found in different states of decay,

act as a backdrop for annual activist gatherings, each receiving an architectural costume to protect and augment their presence in the extreme landscape.

16.12 Christina Garbi, Y5 ‘The Conifer Seed Sanctuary’. Located in Thetford Forest, Norfolk, the proposal speculates on ways to safeguard the future of softwood timber. It attempts to redesign ancestral timber plantation monocultures that show a sensitivity to the ecosystem by diversifying the forest stands. The architecture focusses on providing spaces for storing conifer seeds and preserving their diversity. The spaces, divided by columns of trees, become an extension of the architecture and are reminiscent of forests in the Neolithic period.

16.13 Lauren Childs, Y4 ‘The Island of Ladies’. The proposal located on Oliver’s Island, a narrow island in the River Thames, is a reaction to the self-contained suburban home. It is informed by Leslie Kanes Weisman’s research into women’s fantasies about the home. The communal dwelling for ten households, each consisting of women and children, proposes a new way of living that provides the conditions for radical kinship, in which everyone ‘mothers’ each other and domestic labour is shared and visible.

16.14 Tudor Jitariu, Y4 ‘Prophecy and Exodus’. The project speculates on the future of dwelling and investigates issues relating to ‘desertification’ in Southern Europe. Firstly, we must learn to accept or reject the relationship between an isolated way of living and increased water scarcity. Through testing the resilience of building materials in conditions of high humidity, moisture content and heat, the project suggests how architecture can act as a material register of this emerging type of environmental ecology.

16.15 Yang Di, Y4 ‘Non-Place ThinkTank’. Hangzhou, China, is going through an unprecedented process of urbanisation, including the mass development of suburban gated compounds, due to plans to build an international transportation hub in preparation for the 2022 Asian Games. As a response, THINKTANKTM is a replicable and mobile system that acts as an agent to activate communal life, utilising the potential of onsite farming to mobilise the community to participate in local entrepreneurship.

16.16–16.17 Jack Barnett, Y4 ‘Rewilding Balance’. The project reintroduces balance into our built environment at the scale of buildings and the landscape. Through designed curvatures and geometries, the manipulation of an object’s centre of mass informs an architecture no longer comprised of stationary bodies alone. Through rewilding the culverted Pymmes Brook in North London, a seasonal floodplain becomes the site of a lido that choreographs a series of balancing acts to re-engage an individual’s physicality and proprioceptive senses.

16.18–16.19 George Gil, Y5 ‘The Great Reset’. The proposal is a strategy for preparing the isolated, paranoid and mentally numbed architecture student for reintegration into the physical world. The project develops a process to explore and escape the fraught interaction between the body and the computer, which has come to define our consumption of information and the rhythm of existence during successive lockdowns as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Topographies of London are relearned to inform a desktop diorama and an inhabitable virtual landscape.

16.20 Hoh Gun Choi, Y5 ‘The Yokais of Disaster’. The residential project in the suburbs of Tokyo aims to stand as a prototype for rethinking our emotional and physical relationships with natural disaster, using Japanese supernatural beliefs. The introduction of yōkai (supernatural creatures) encourages the idea of catastrophe within a community’s imagination and nurtures acceptance for the unavoidable possibility of risk.

What Matters and the Capabilities to be Sensed

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

What Matters and the Capabilities to be Sensed

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-CookPG16 focuses on the exploration of an architecture that re-emphasises our physical engagement with, and relationship to, the environments we choose to inhabit. Specifically, this year we directed our interests in two key areas. Firstly, the experience and meaning of matter, manifest in the materials, objects and ecologies that frame and formulate our daily experiences; secondly, the exploration into the realm of the physical mediated by the realm of data. We investigated the ways in which both are sensed by us.

Our initial sites of enquiry were the vast automated agricultural landscapes of California and Arizona, increasingly being farmed and monitored by complex computational systems. We were interested in how farming – traditionally a mediation between humans, technology and nature – is being reinvented within the context of automation with the aim of achieving a more efficient, precise and responsive agriculture. We questioned how this reinvention might change our notions of space, distance, time, landscape and architecture. We explored how the shift to automated taskscapes acts as a model for the manifestation of a post-work economy; a particular economic condition that questions a radical change in our relationship with work.

We augmented our research into ways of living and working with an expansive fieldtrip through Southern California and Phoenix. This allowed us to contrast our observations of modernised, controlled and data-mediated worlds of farming with contemporary experimental ideas of collective living and working embodied in the desert town of Arcosanti, and in Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural community at Taliesin West. Both are examples of initiatives that look to reconcile the distance between architecture, building and the wider ecology, and both were initially conceived as self-sustained, isolated communities in desert conditions.

The outcomes this year are proposals that examine and address a possible future re-balance in the relationship of technology to our environment as well as our attitudes towards current forms of working, recreation and creative collaborative habitats. Our students’ work ranges from case studies for experimental living, questioning our relationship with the rituals and objects of the ordinary everyday, to designing for the collateral effects of decommissioning the last nuclear power plant in California, to researching provocative communes disengaged from societal norms.

The Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 challenged our working conditions and increased the intensity of our relationship with our immediate physical and material surroundings. Our ordinary habits and our state of mind have undergone a significant adjustment. The work presented here now resonates with us in different ways as we have been forced to reconsider the context and meaning of ‘what matters and the capabilities to be sensed’.

Year 4 Ella Caldicott, Hoh Gun Choi, Christina Garbi, George Gil, Kaizer Hud, Hannah Lewis, Daniel Pope, Andrew Riddell

Year 5 Jun Chan, Samuel Davies, Magdalena Filipek, Long Kwan, Ching (Albert) Leung, Achilleas Papakyriakou, Wing (Michelle) Yiu

Many thanks to our Technical Tutor Will Jefferies, Structural Consultant Ollie Wildman and Environmental Consultant, Sal Wilson

Thanks to our thesis tutors Polly Gould, Gary Grant, Anne Hultzsch, Zoe Laughlin, Luke Lowings, Oliver Wilton, Stamatis Zografos

Thank you to our critics Ana Betancour, BarbaraAnn Campbell-Lange, Nat Chard, Alex Cotrill, Sam Gray Coulton, Kate Davies, David Flook, Pedro Gil, Agnieszka Glowacka, Andrew Kovacs, Jimenez Lai, Ifigeneia Liangi, Doug Miller, Shaun Murray, Ralph Parker, Stephen Phillips, Nina Shen Poblete, Emily Priest, Rahesh Ram, Bob Sheil, Matt Turner, Carl-Johan Vesterlund, Gabriel Warshafsky, Dan Wilkinson

16.1, 16.19–16.20 Samuel Davies, Y5 ‘Sweat, Pant, Blush: Three Houses of Three Tomorrows’. The project examines the social and architectural stigmas that surround the notion of ‘comfort’. A cul-de-sac of three experimental houses is proposed in Palm Springs, on the edge of the desert. Within each house, everyday domestic conventions are dismantled to suit a different attitude to comfort. The project holds the architect responsible, not for the development of new technologies, but new ideas of what it means to be ‘at home.’

16.2, 16.6 Daniel Pope, Y4 ‘Foundation House: An Experimental Housing Typology for California City’. This experimental housing masterplan is sited in California City, a half-built complex of roads and infrastructure located in Southern California. The project proposes an experimental housing typology to restart the economy of California City. Using boron as a building material and the exploration of experimental ways of construction influenced by processes of mining, the typology seeks to become a new house-building mechanism, where the construction and firing of materials for one home generates the materials to begin constructing the next.

16.3 Long Kwan, Y5 ‘Southern California Water Chapels’. Excessive water consumption in the agricultural industry has brought serious environmental damage to this landscape. To limit the damage the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) has been signed. The building and landscape provide spaces to experience the rise and fall of water in the region and a space for local political discussion on the use and abuse of water resources in California.

16.4 Hoh Gun Choi, Y4 ‘The Trail Repair Outpost: Two Rocks Do Not Make a Duck’. This project challenges the ethics related to wilderness management, exploring the ramifications of building and the marks that humans leave on the wilderness. The project aims to touch the ground lightly. Six buildings each perform structural gymnastics in order to find a careful connection with the mountain.

16.5 Ella Caldicott, Y5 ‘Dirty Dozen: Strawberry Farm as an Urban Typology’. This project is an ethical approach to the future for strawberry farming innovation, infrastructure and architecture. Specifically, it addresses the efficiency of land use to optimise crops while also creating safe living conditions for the necessary workers. This is achieved through a plan for strategic land division and the introduction of ‘architectural buffers‘, creating an environment where farm, town and the natural environment can coexist.

16.7–16.8 Jun Chan, Y5 ‘The Predators and Preys for a Decommissioned Nuclear Power Plant’. Located in Diablo Canyon, California, this project investigates the collateral ecological effects that will be caused by the decommissioning process of the last nuclear power plant in the state. The proposed architecture becomes both a predator and a prey, feeding off and into the shifting ecological chain of the decommissioning process. Specifically, it looks to provide a framework to experience these disturbances in the landscape, while acknowledging its role as part of a wider ecology.

16.9 Kaizer Hud, Y4 ‘Into Dust: Politics and Dust Mitigation at the Salton Sea’. Originating from the deceivingly pristine Salton Sea, tiny invisible polluted sand particles, picked up by winds as the lake dries up cause severe breathing issues. The recent re-instigation of dust mitigation measures calls for an operational facility that not only acts as the implementation office for these projects, but as a provocation to raise awareness about the problem. The building within this capacity sees the constructive (rather than destructive) potentials of dust.

16.10 (Ching) Albert Leung, Y5 ‘The Obsolescence of Highway Stops in the Era of Autonomous Driving’. The premise for this project assumes that we will increasingly utilise, for the transport of goods and people, self-driving

vehicles. A future 24-hour, non-stop world will emerge where there is no longer a difference between conditions of night and day. The proposal presents a new model town with a series of performative architectures to help heal those experiencing distorted effects of living and working in such an environment.

16.11 George Gil, Y4 ‘The Golden Datum’. This project proposes a gold prospectors’ outpost and campsite, seeking to rebrand the preconception of gold prospecting to appeal to all. With this wider client base, the greater revenue from visitors will ensure its economic viability and pay for the upkeep of National Forest Land.

16.12 Magdalena Filipek, Y5 ‘The State of Change: LA Aqueduct Water Purification and Re-use’. This project for a purification plant and spa located in proximity to central California’s Lake Tulare has direct access to the LA Aqueduct. The proposal incorporates water purification processes into an architecture as a way of addressing toxicity with the aid of a ‘hydrogel’ purification coagulant. A chemically engineered hydrogel facade erodes over a period of 10 years, changing its presence in the landscape. 16.13 Hannah Lewis, Y4 ‘California City (Re)imagined: New Fossil Infrastructures’. California City was a failed Utopian vision of 1958. Following the lawsuit seeking a declaration that the fossils are part of one’s surface estate, the Mayor of California City turned to rare fossils to rejuvenate the economy. A ‘Prospecting House’ and other infrastructures sit above the landscape, as interventions designed to create a new culture, invigorated by architectural innovation and political manipulation. 16.14–16.15 Andrew Riddell, Y4 ‘Lakewood in Drag: Challenging the Heteronormative Ideal’. This project investigates the artform of drag and how its characterbased performance and radical self-expression could be used as a tool to challenge and subvert the heteronormative American ‘tract housing’ that was widely celebrated and mass-produced in a postwar California. Iconic ‘house mother’ Crystal LeBeija acts as a pioneering client. 16.16–16.17 Achilleas Papakyriakou, Y5 ‘Drop Out and Go Extinct’. Moros is a fictional anti-natalist commune, named after the Greek primordial deity, who is the embodiment of impending doom, isolated in the depths of the Mojave Desert. The proposed skeletal architecture acts as a memento mori and exposes its inhabitants to the visceral conditions of the Californian desert. Members of Moros engage in rituals and pageantry, while wearing elaborate uniforms and costumes that immerse the wearers and observers in unusual practices and interactions with the architecture. 16.18. Christina Garbi, Y4 ‘The Lake Powell Assembly: A Sediment-Trapping Instrument’. The Lake Powell Assembly provides a means to gather and collect sediment data through a series of seasonally flooded camping spaces for travelling explorers. The Assembly has been set up to investigate the excessive saturation of the lake with sediment, a condition caused by the construction and operation of the Glen Canyon Dam in the region.

16.21–16.22 Michelle Yiu, Y5 ‘East of Eden’. Set in California’s Salinas Valley, an agricultural school and museum interprets, and then manifests, the narrative of John Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden (1952). Presented as a series of spatial journeys, the architecture helps visitors understand the ideas and meaning embedded in the novel’s historical storyline. Specifically, the building seeks to reinterpret and then illustrate the novel’s criticism around the over-industrialisation of farming of the 1950s.

Quasi-Agents and Explorations

on the Edge of the World

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-Cook

Quasi-Agents and Explorations on the Edge of the World

Matthew Butcher, Ana Monrabal-CookPG16 is interested in the exploration of architecture that emphasises our physical engagement with the environments we choose to inhabit. This year, we investigated the experience and meaning of matter, as well as the materials which frame and formulate our daily architectural experiences. Through research and experimentation, we revised our comprehension of materials and of matter more generally. We looked at the capacity of materials to act as ‘quasi-agents’ 1 and be a creative tool to reconsider the nature of the architectures we conceive.

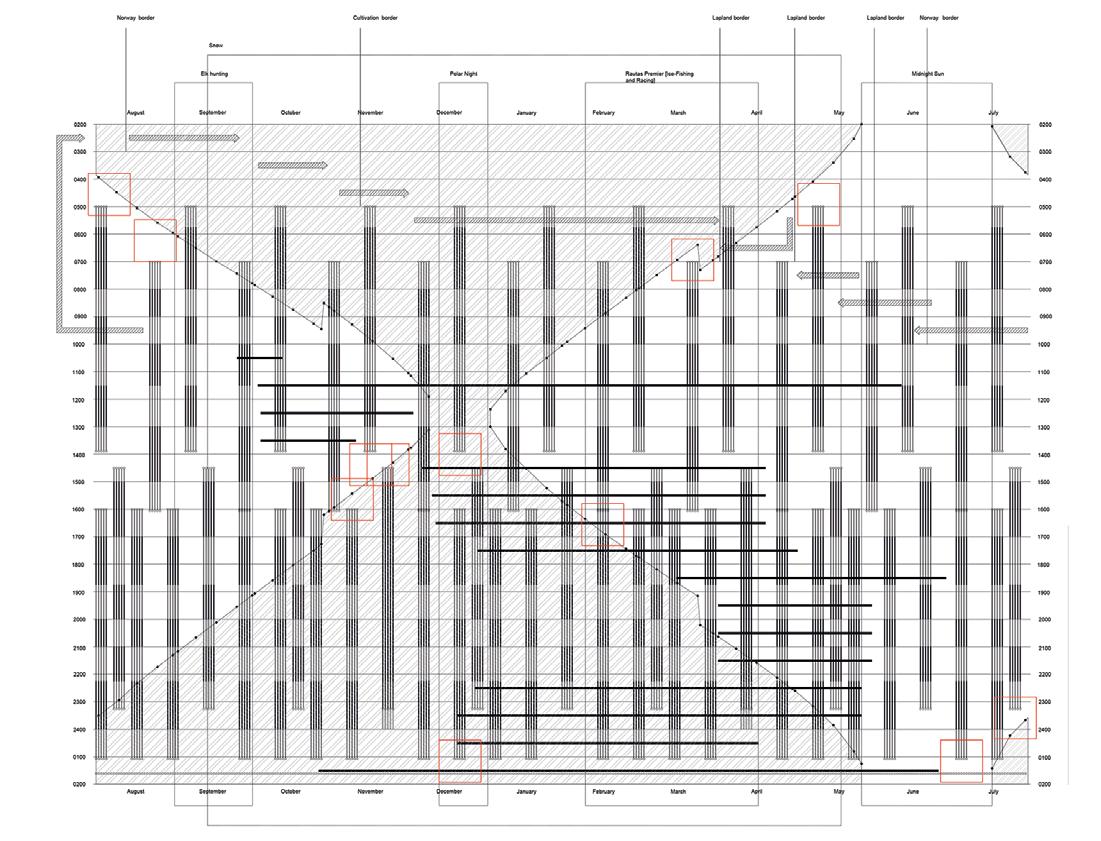

Our site of enquiry was the region of Norrland in northern Sweden, largely defined by raw materials and natural resources, as well as vast areas of cultivated forest, iron ore mines and large developments for farming hydro energy; in the early 1900s, Norrland provided 25% of the world’s timber. Although remote, the region’s material resources link it to global networks of commerce and geopolitics through trade, defining both how it has been inhabited, and its identity, for hundreds of years.

As the global demand for iron ore has increased, over-mining threatens the stability of the ground in the northerly town of Kiruna, and the collapse of the mines there is now imminent. In response, the mining company plans to move the entire town two miles east, relocating 21 buildings, painstakingly, over 20 years. Vast infrastructural projects have also been instigated to connect the region with the rest of Europe, including railway networks for the transportation of resources. On our field trip, we collaborated with the architecture school based in Umea, and received invaluable input from local artists, activists and journalists. This exchange helped us draw on their knowledge of infrastructure, urban development and indigenous culture, as well as their global outlook.

In developing our investigations, PG16 questioned the impact, at various levels, of the use and abuse of natural resources as a catalyst for environmental strategies, structural deployments and new social models. Our students responded with projects that questioned the role of the architect in local policies, and the relationship between domesticity, forests and fire. Projects addressed the development of new vernaculars dealing with the loss of tradition and identity. We wondered at materials on a molecular level, exploring their response to the body and landscape. We engaged with a part of the world so defined by its infrastructure that is in danger of losing its identity to save itself. These are our explorations on the edge of the world.

Year 4

Jun Chan, Samuel Davies, Danny Dimbleby, Long Kwan, Ching Leung, Achilleas Papakyriakou, Przemyslaw Pastor, Wing (Michelle) Yiu

Year 5

Alessandro ConningRowland, Alex Kitching, Kin (Gigi) Kwong, Cameron Overy, Dimitar Stoynev

Many thanks to our technical tutor Will Jefferies for his dedication and insight. Thanks to all our critics for their invaluable feedback across the year: Andrew Belfield, Eva Branscome, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, Christina Candito, Ian Chalk, Tom Coward, Tom Dobson, Nick Elias, Stylianos Giamarelos, Pedro Gill, Agnieszka Glowacka, Tamsin Hanke, Colin Herperger, Ifigeneia Liangi, Shaun Murray, Duncan McLeod, Robert Mull, Renee Searle, Matthew Springett, Ellie Ward, Owain Williams, Max Wisotsky

1. Phrase derived from: Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), pviii

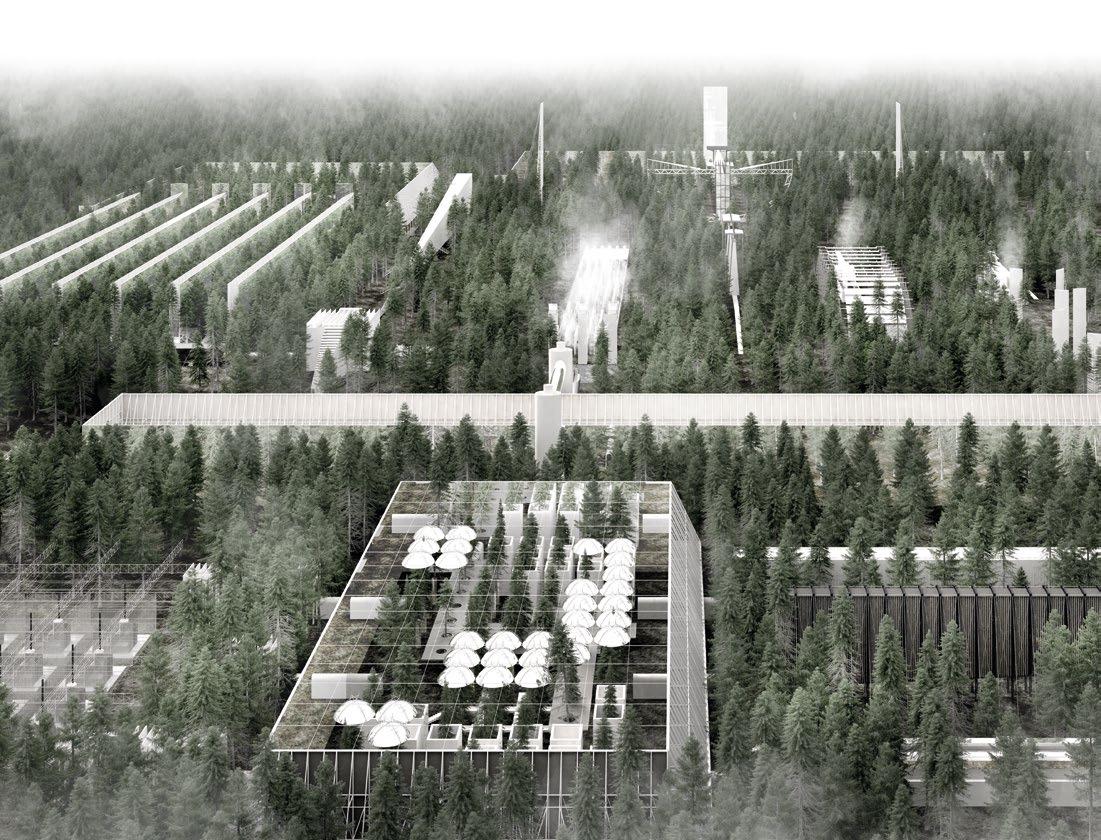

16.1, 16.23–16.24 Cameron Overy, Y5 ‘The Policy of Place’. This project questions the relationship between place and environmental policy-making, specifically laws that govern forest cultivation in Sweden. Whilst the vast majority of Sweden’s natural resources are located in the northerly region of Norrland, the governmental bodies making decisions on these resources reside in the southern city of Stockholm. This has, historically, resulted in the idea that there exists a colonisation of the north by the south. This project is a proposal for a remote (or proximal) deliberation space for the Swedish parliament in order to reconfigure decision-making on the consumption of Norrland’s natural resource of wood.

16.2 Kin Kwong , Y5 ‘Colourfield: Constructing Pigments on a Post-Industrial Landscape’. Raising awareness of the scarred landscapes created by the Anthropocene, this project proposes an architecture formed from chemical decay. Sited in the northern Swedish city of Kiruna, buildings purify waste from the adjacent mine, turning it into different-coloured pigments using a process of patination. Over time, the architecture slowly marks the ground with the pigments, transforming the deformed mining town with the colours created, and gradually replacing the vernacular Falu red as the main colour used to paint houses in Sweden.

16.3 Long Kwan, Y4 ‘White-Out Kiruna’. Celebrating the many visual and physical properties of snow in Kiruna, this proposal aims to reinforce the identity of the community at a time when it is being threatened by the relocation of the town due to over-mining. Positioned on a remote site to the east of the Kirunavaara Mine, the ‘White-Out Centre’ is a community and art centre, which facilitates a multitude of existing cultural activities that utilise snow and ice. The building seeks to bring these activities into one location, where certain climatic conditions needed to preserve and change the qualities of snow can be controlled and made manifest.

16.4–16.5 Jun Chan, Y4 ‘Inhabiting the Ecology: The Living Birchwood’. This project questions how we can challenge our perspectives on the ecological systems present in landscape through architecture, its materials and the environment it resides in? Situated in Sarek National Park – the most mountainous region in northern Sweden –the project functions as an outpost for the research and educational organisation, The International Bateson Institute, and focuses on the utilisation of birch wood, viewing the material as a body that is in constant negotiation with the environment.

16.6–16.8 Alex Kitching , Y5 ‘A Retreat for the Protagonists of the Swedish Forest Taskscape’. Focusing on the creation of a field condition in which the three protagonists of the Swedish forest ‘taskscape’ – logger, tourist and reindeer – are brought together, this project proposes a series of enclosures and viewing devices that generate subtle visual games and distortions in the forests of northern Sweden. Located in Dikanäs, the ‘retreat’ creates a choreographed orchestration of experience, highlighting the various ways that different individuals and groups inhabit and experience the landscape, simultaneously and in seclusion.

16.9–16.11 Samuel Davies, Y4 ‘Cookery and Apocalypse’. Responding to the prescribed burning of Swedish forests, this project proposes a series of houses as a meditative infrastructure that exists between the city of Umea and the forest that surrounds it. It explores the practical inhabitation of a place that is routinely burnt down and architecture that is emblematic of our conflicting attitudes and emotions towards domestic and landscape fires. It adapts fire control conventions and local policies to suit the conditions of forest fire and questions the way we manage building legislation.

16.12–16.14 Achilleas Papakyriakou, Y4 ‘Malmberget Centre for Relocation’. Due to extreme underground mining, a huge crater has split the Swedish town of Malmberget in two making it dangerous to live there. As a result, the community is undertaking a move to nearby towns in an evacuation effort set to last at least another decade. This project proposes three red pavilions that provide a warm and opulent sanctuary for the residents of the ailing Arctic town during the move.

16.15 Wing (Michelle) Yiu, Y4 ‘The Memory Kit’. The expansion of the mining activity in Kiruna has resulted in the city’s church being demolished. This project examines how memory can alter and distort over time, changing the way we inhabit and remember buildings, using ‘Memory Kits’ that test against the reality and observe how physical and cultural memory is recorded and preserved.

16.16 Przemyslaw Pastor, Y4 ‘The Siedi Centre –An Observant Port Terminal’. Learning from specific perspectives on the environment from the Sami – the indigenous inhabitants of Sweden – this project animates a piece of the landscape and a building, utilising the changing states of certain materials, such as birch wood. Connecting the industrial and natural in the most northerly region of the country, the project proposes a port terminal and an observatory overlooking an 80-kilometre lake, located between the deepest mine in Europe and the tallest mountain in southern Sweden.

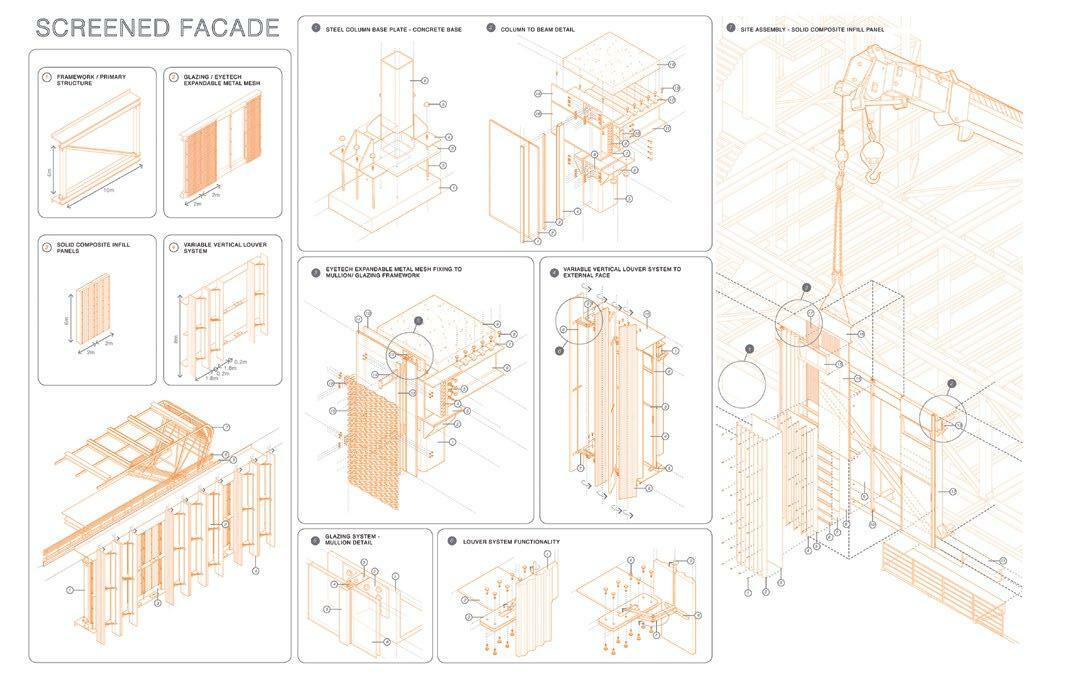

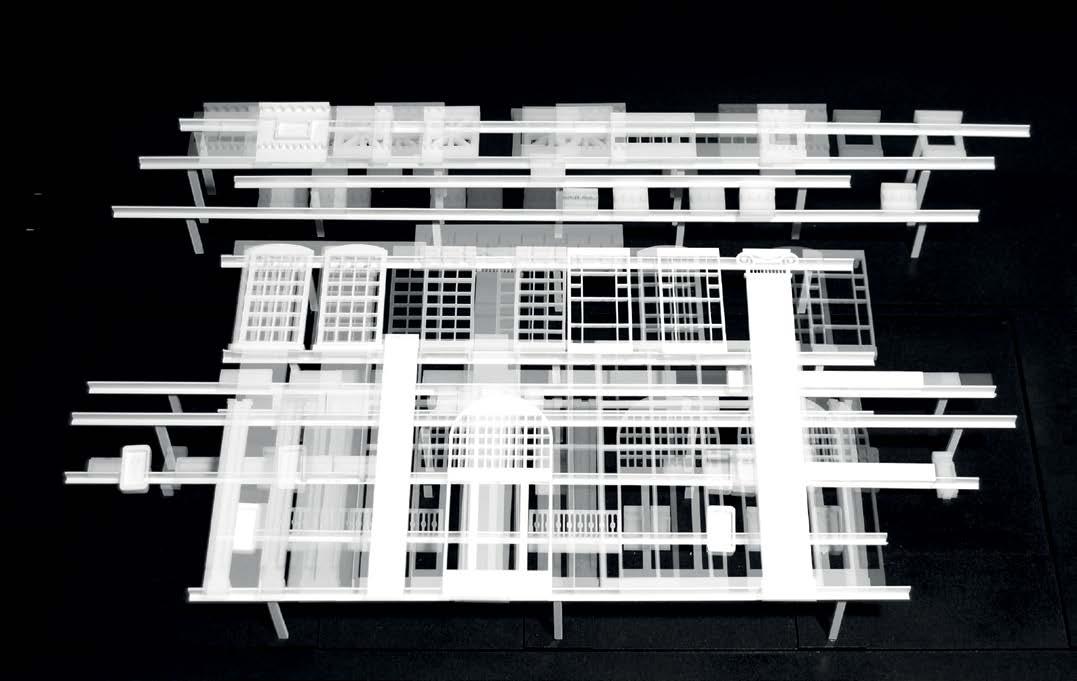

16.17, 16.19–16.20 Dimitar Stoynev, Y5 ‘Swedish Antiphony’. Set in the context of the proposed mass expansion of the mining industry in Norrland, this project explores the creation of a new northern Swedish vernacular, which seeks to preserve and expand upon traditional building typologies and practices. Through the use of ‘architecture of collision’, the new language seeks to disrupt the ongoing use of prefabricated and mass-produced structures as the default building typology in Sweden. To help develop this new architectural language, the project proposes techniques of building with rammed earth to create a tapestry of disjunction, material texture, memory and culture. 16.18 Ching (Albert) Leung, Y4 ‘Temporal Bathhouse, Kiruna, Sweden’. Exploring how architecture can frame and enhance the experience and understanding of multiple timescales – hourly, weekly, annually, etc. –this project aims to facilitate recovery from irregular working shifts and isolation from the outdoors that disrupts the Kiruna miners’ circadian rhythms. It looks at how ephemeral events that occur repetitively, in different moments of time, gradually feel more permanent, whilst continuous events gradually fade away. 16.21–16.22 Alessandro Conning-Rowland, Y5 ‘New Nomads: Inhabiting the Moving City of Kiruna’. This project proposes an infrastructural framework for a moving city, designed to cater for the population of Kiruna, who have been forced to relocate due to the over-mining of Iron Ore. The proposal aims to address residents’ fear of being forgotten through this forced move, as well as providing an alternative solution to the ‘blanket housing typologies’ of prefabricated construction and placeless masterplanning that is currently being imposed.

An Architecture

of

the Wild Johan Berglund, Colin Herperger

Year 4

Tom Budd, Charlotte Carless, Jarrell Goh, Karen Ko, Sonia Magdziarz, Rebecca Sturgess, Sarah Stone

Year 5

Jaspal Channa, Dean Hedman, Ian Ng, Amani Radeef, Simran Sidhu, Joshua Toh, Ozan ToksozBlauel, Richard Tsang

Thank you to Ralph Parker for teaching the DR module, Andrew Best and Nikul Vadgama from BuroHappold for technical input, all thesis tutors who have given valuable input to the Y5 projects, and all our critics for their immensely valuable input throughout the year

An Architecture of the Wild

Johan Berglund, Colin HerpergerUnit 16 enjoys the challenge of making difficult things. We seek to generate work and ideas that have the confidence to find their own language of expression and invention. There is a strong emphasis on exploration through a range of made and drawn physical production. We are not afraid to go rogue with an idea and encourage work that has the tenacity to take risks, or to rigorously chase a hunch into the unknown. Ultimately, we are interested in creating a learning environment where a variety of approaches to creative production help each student to work in a manner that both draws out and challenges their personal character and preferred approach.

This year, we took an interest in finite and infinite processes, and the exploration of the edge of the remote. To find this edge we ventured deep into the Icelandic wilderness to explore and work inventively over immense scales of time, in places that were very much alive. We considered how one might activate remote territories rich with aggressive natural phenomena, bursting bellies of thermal heat, and a stretching of time from the appearance of the midnight sun to full days of darkness.

The focus of the unit has been to notice the strange, often harder to find nuances of a place, and to react with inventive curiosity. How is architecture able to work with the environment and draw from its immense scale, strangeness and power? Lead by discovery but tested through invention, our design projects have sought to imagine new and unapologetic architectures that engage directly within the natural forces at the perceived edge of the civilized world.

When thinking about and working with landscapes, we need to be aware of the shift in timescale from the fast and relentless pace of 21st century life to a slower, deeper timescale. What if your architecture needs to last for centuries, or millennia?

We also wanted to understand how a sense of curiosity is developed within remote territories over longer periods, even decades, or perhaps a lifetime. How does one develop a self-sufficiency to excite one's own imagination? Living in a place that is on the edge of the remote, one can kindle curiosity in a range of ways. Both remoteness and emptiness signify a place of potential – and most importantly, an adventure that has to be made rather than given.

16.2

16.3 16.4

Figs. 16.1 – 16.4 Amani Radeef Y5, ‘An Architecture of Darkness – Lighting Lake Myvatn’. An architecture of darkness reveals the heterotopic nature of spatial constructs relative to our vision activated by light, or by the lack of it. This heightens our sensations and makes us more sensitive to our environments. The project re-imagines a Viking longhouse as a Town Hall and archives centre for Lake Myvatn, where, through materiality and formal language, the manipulation of light would also occur. Fig. 16.5 Joshua Toh Y5, ‘A Strange Thing in the Sky’. How would one create an architectural dress for the wilderness of Iceland? The Nostromo is an attempt to answer this question, a tailored airship for the skies, a piece of couture defining the sensory experience of its occupants as it floats above the Icelandic landscape.

16.9 16.10 16.11

Fig. 16.6 Ian Ng Y5, ‘Invisible Infrastructure: An Ice Lens for Skutustadir’. Harnessing the natural climatology of Lake Myvatn, an ice lens 60m in diameter is formed annually within the negative space of a pseudocrater – both of which are geological formations unique to the area. The ice lens forms with different aberrations as an indicator of the year’s conditions, and the space within it changes and adapts according to the shrinking mass of the ice through a system of counterweights. Fig. 16.7 Ozan Toksoz-Blauel Y5, ‘The School of Land Restoration in Alftaver’. Situated between shrinking farmland and an expanding black sand desert, this project proposes to preserve a remnant of the man-made farmland landscape within a school campus. Figs. 16.9 – 16.11 Rebecca Sturgess Y4, ‘Vik Cultural Hub’. Situated in a country defined by

its strange and dramatic landscapes, the focus on mass and void creates a strangeness of the ‘in-between’. This encourages random interactions and meetings between refugees and tourists, as they transition into the peculiarity of life in Icelandic society.

16.12

16.13

Fig. 16.12 Jarrell Goh Y4, ‘The Nordur Saltworks’. The project imagines the expansion of a sea salt factory in the shallow shoals of the Icelandic Westfjords. The design was led by material tests that discovered the architectural potential of the crystals - creating a building which was making, and was made of, salt. Fig. 16.13 Jaspal Channa Y5, ‘The Wayward Observatory’. This project negotiates the anticipated realm of the mountain ridge, moving between clarity and discovery whilst investigating the spatial potential of waywardness. The employment of spontaneity in the design method encouraged this condition to emerge. Fig. 16.14 Charlotte Carless Y4, ‘Jarðskjálfti Seismic Station: Earth Moves’. The project explores a supernature – an ancient volcanic, seismic site – and proposes an architecture carved into the rock face it inhabits.

This has a closeness with the earth around it, in particular, with the ancient lava fields at the foothills of two sub-glacial volcanoes. Fig. 16.15 Sonia Magdziarz Y4, ‘Hús Is’. Hús Is explores what happens when you fuse a building with its landscape, creating a co-existence in which neither is sacrificed at the expense of the other. The house, carved into basalt rock, tries to domesticate the scale of the landscape. It is a poetic search for ways of engraving the memory of the changing climate into the fabric of the building. Fig. 16.16

Richard Tsang Y5, ‘Reykjavik Film School’. The project sets out to embody the feelings of nostalgia and desolation, which are often hallmarks of Icelandic cinema. Played out in a carved-out basalt quarry, the spaces unfold into a rich and atmospheric space for study and contemplation.

Fig. 16.17 Sonia Magdziarz Y4, ‘Hús Is’. Fig. 16.18 Karen Ko Y4, ‘Earth and Fire’. By digging into and shaping the ground, investigating clay and geological expressions inherent to their location, an outcome becomes synonymous with the setting in which it is made. Figs. 16.19 - 16.20 Tom Budd Y4, ‘Creating Intimacy within the Inhospitable’. This project focuses on the design of a space for social interaction within the remote landscape of Iceland. Through the study of swimming pool culture in the country, the project seeks to explore and draw out these distinctly Icelandic experiences whilst designing a new swimming pool and assembly halls in Reykjahlíð, a small town in the north of the country. Fig. 16.21 Simran Sidhu Y5, ‘StitchScape’. Examining the body as landscape, and the landscape as a body to be dressed, the work attempts to find

Supernatural Johan Berglund, Dirk Krolikowski, Josep Miàs

Year 4

Supichaya Chaisiriroj, Eleanor Figuiredo, Joshua Honeysett, Amani Radeef, Cassidy Reid, Simran Sidhu, Alexia Souvaliotis, Ozan Tokzas Blauel, Yin To Tsang, Anthony Williams

Year 5

Robin Ashurst, Richard Breen, Ashley Fridd, Chelsea Hodkinson, Elzbieta Kaleta, Janice Lau, Katherine Prudence, Louise Schmidt, Amy Wong

Many thanks to Mario Pirwitz, Falko Schmitt, Will Jefferies, Jan Guell, Francis Roper, Tosan Popo, Marc Subirana, Carles Sala, Tupac Martir, Chiara Montgomerie, Xavier Ferres, Damjan Iliev, Julia Backhaus

Supernatural

Johan Berglund, Dirk Krolikowski, Josep MiàsIn Unit 16, we have developed a close symbiosis between academic research and architectural practice. Our way of working is close to how projects are developed in our practices, with constant testing and “reflecting through action” in order to challenge the limits of architecture. Our work is centered around the production of buildings, landscapes and spaces, with a clear understanding of and interest in their relationships with the city. We see architecture as an act of realisation; of making real that which was only previously a brief thought, a vague concept or a utopian dream. Through this act we have the power to transform the world around us, and with that, the responsibility to make sure we leave something positive behind. This year, the unit went to Panama City, a complex city in rapid transformation. Our proposals are situated in and around the city and the Panama Canal Zone.

In Panama, nature is always present. The cities and man-made environments constantly battle the invasive force of nature. Over millennia, man has sought to tame nature, harness and control it. This has caused a long-standing conflict between the natural and the urban, where the search for everything bigger, faster and better has led to the precarious situation we find ourselves in today.

Panama epitomises this extremely fragile equilibrium between nature and architecture; one which can unravel in specific geographic scenarios. The two forces, one ancient and unexpected and the other based in knowledge and strategy, set up a dialogue from two radical positions. As a result, life in Panama is expressed in extreme form, where the physical world emerges as a stage for confrontation. The power of nature imposes rhythms and effects on our environment, while architecture too often reacts in a violent way. Panama today is a clear example of this: a place defined by beautiful woods, rainforests and the ocean, in amidst commercial skyscrapers that jut out from the earth’s surface and the (in)famous canal, which appears as a scar on the skin of the planet.

At the same time, man’s search for development and evolution has given rise to incredible inventions, events and places. The unit strongly believes in progress and a constant search for the new and unseen. We therefore set out to find a balance between both forces, a middle way that allows for the possibility of a compatible, complementary co-existence between both realities.

16.2 16.3

Fig. 16.1 Ashley Fridd Y5, ‘The Last Biotic Frontier - Exploration Vessels for the Rainforest Canopy’. Walkway Approach to Vessel Type A, providing canopy-level research facilities for the Smithsonian Foundation. Fig. 16.2 Louise Schmidt Y5, ‘Frame of Mind’, overview of Educational Visitors’ Centre.

Fig. 16.3 Chelsea Hodkinson Y5, ‘Inhabited Community Dam’, overview render. Fig. 16.4 Joshua Honeysett Y4, ‘Ship Dis-assembly Facility’. Sectional isometric, cutting through the facility, housed in the locks at Miraflores.

Fig. 16.5 Ashley Fridd Y5, ‘The Last Biotic FrontierExploration Vessels for the Rainforest Canopy’. Collection of ultra-lightweight structural components for the research vessels.

16.6

16.7 16.8

Figs. 16.6 – 16.8 Amani Radeef, Y4, ‘Balboa Public Dry Docks’. Detailed façade connections study, sectional perspective through exhibition tower, façade study. Fig. 16.9 Richard Breen Y5, ‘Biorock Growth Facility’, Central Laboratory and Fabrication Shed.

16.11

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2016

16.10 16.12

Fig. 16.10 Cassidy Reid Y4, ‘Mixed Use Development’. Final 1:20 Section through floating residential element. Fig. 16.11 Supichaya Chaisiriroj Y4, ‘Chagres Basecamp’. Detailed structural elements. Fig. 16.12 Anthony Williams Y4, ‘Naval Architecture School Panama’. Detailed isometric view.

16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16

Fig. 16.13 Eleanor Figueiredo Y4, ‘Hydro-Remediation Platform’. Final Models. Fig. 16.14 Yin To Tsang Y4, ‘Floating Pharmaceutical Centre and Gardens’. Elevation. Fig. 16.15 Elsbieta Kaleta Y5, ‘tropoFABric ARCHITECTURE - Iglesia del Carmen Train Station & Public Square, Panama City’. Short section. Fig. 16.16 Ozan Toksoz Blauel Y4, ‘Museum of Excavated Earth’. Geocell retention installation.

The Bartlett School of Architecture 2016 16.18

16.17 Fig. 16.17 Robin Ashurst Y5, ‘Gatun Lake Community Lighthouse’. Static and floating elements. Fig. 16.18 Simran Sidhu Y4, ‘Submerged Smithsonian’. Perspective collage view. A diver’s view of looking up towards the surface of the sea and the submerged marine research facility in Panama Bay, a facility adopting weighting and buoyancy strategies to inhabit the underwater environment.

16.21

Fig. 16.19 Alexia

Y4, ‘Off-Shore Casino’. Sectional model. Fig. 16.20 Katherine Prudence Y5, ‘Botanical Gardens of Cerro Ancon’. Responsive roof strategy and sectional diagram. Fig. 16.21 Janice Lau Y5, ‘Regenerating Boca La Caja’. Overview render of the fisherman’s wharf.

Bridges Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs, Dean Pike

Bridges

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs, Dean PikeYear 4

Robin Ashurst, Richard Breen, Ashley Fridd, Chelsea Hodkinson, Elzbieta Kaleta, Janice Tsz Lau, Catherine Prudence, Amy Wong

Year 5

Negin Amuridahaj, Leif Buchmann, Jack Morton-Gransmore, Matthew Hudspith, Rebecca Muirhead, Rachel Pickford, Michael Pugh, Alexander Sutton, Jonas Weiss

The unit would like to thank the following people for their support: Andrew Best and his team at Buro Happold, Dan Neal from Double Negative, all the thesis tutors who have enriched the projects through their input, Joachim Granit and Karin Englund at Färgfabriken Art Space, Niklas Svensson at Stockholms Stad, and all our critics and fellow tutors for their invaluable input throughout the year

Unit 16 aims to exist in a close symbiosis between academic research and architectural practice. Our way of working is close to how projects exists in a practice, with constant testing and reflecting through action, in order to challenge the limits of architecture. Our work is centered around the production of buildings, landscapes and spaces, with a clear understanding and interest in their relationships with the city. We see architecture as an act of realisation; of making something real which was only previously a brief thought, a vague concept, a utopian dream. We believe that actions speak louder than words, and we seek to educate architects who will use their proposals to challenge the lives, habits and actions of the world’s inhabitants.

Stockholm, September 2014

Stockholm is a disconnected city, not only physically but also socially, financially, legally and mentally. Although it is known for its beautiful archipelago location, the centre is a land-locked, autonomous, highly gentrified urban island, disconnected from the larger metropolitan region. To make matters worse, the city is struggling to cope with the pressures of 50,000 new residents a year, most of whom aspire to live in the inner city. Stockholm needs to grow, and grow fast. Yet, the inner city cannot expand, due to both its geographic position and also the legal framework that protects a green belt that cuts off the inner city from the rest of the metropolitan region.

At the same time, Stockholm is very well connected to Europe and the rest of the world. It is highly influential in contemporary culture, with strong music and fashion scenes. The region has also for a long time been at the forefront of the digital revolution. Early on, companies like Ericsson paved the way for a normalisation of technology, which created new generations of early adopters, and soon the country had one of the highest number of mobile phones per resident in the whole world. We find the contradiction between these dual conditions for connectivity interesting, and we explored concepts for both the physical and ephemeral city during the year.

Stockholm, 2050 and beyond

We encouraged students to venture deep into the future in order to predict and imagine new and imaginative ways for us to live. Taking inspiration from science, philosophy, technology and progressive environmental thinking, we sought to bridge the physical and technological idea of the city and create holistic, forward-looking, hyper-modern, self-sufficient, constructible, and beautiful architecture and urban space. We imagined and created possibilities of a new, upgraded Stockholm, for a connected yet unstable future.

16.2 16.3

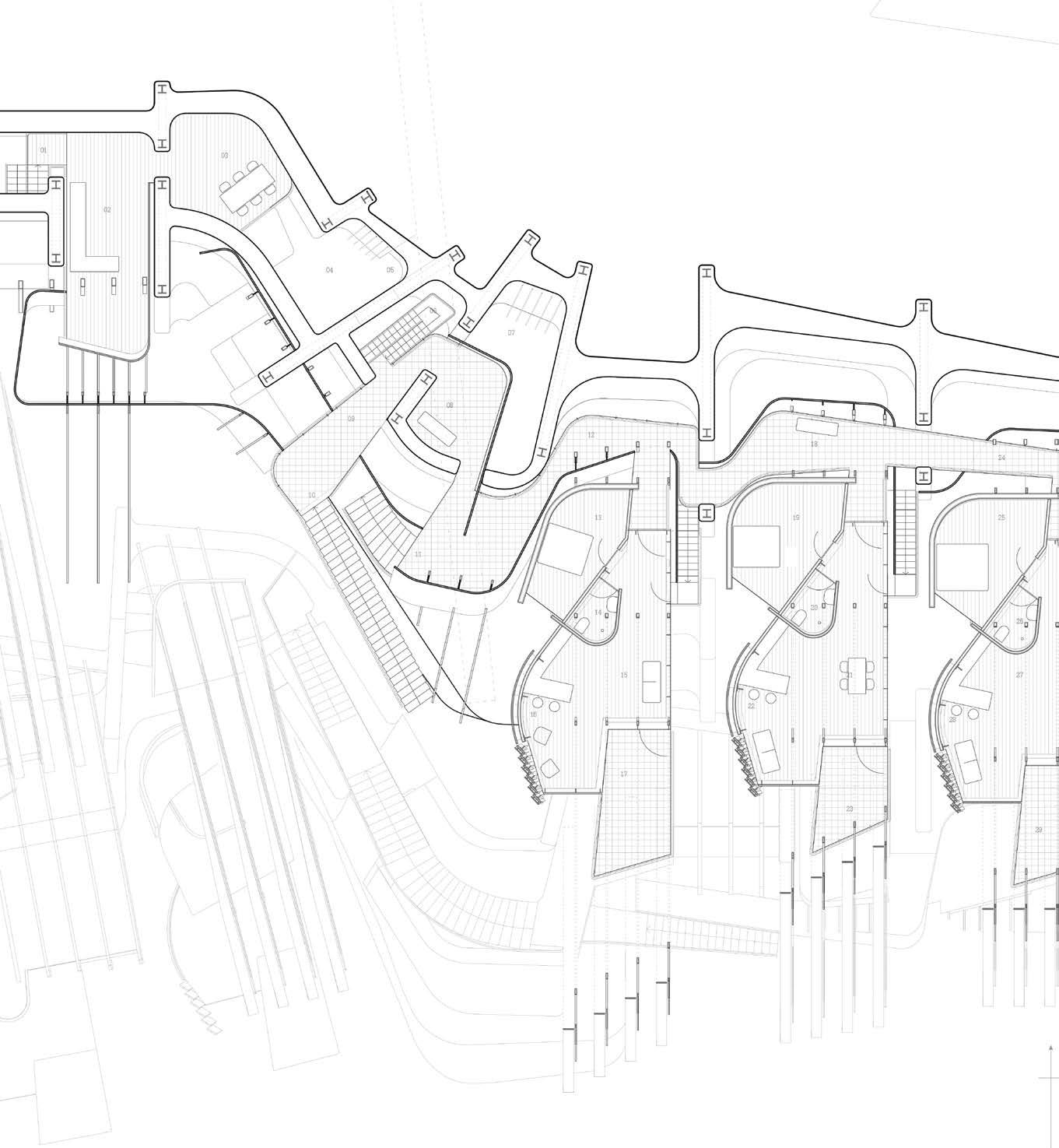

Fig. 16.1 Rebecca Muirhead Y5, ‘Bridging Cultures with the Kulu Women of Fittja’. The domestic kitchens of the Krögarvägen housing of Fittja are reimagined to act as ‘cultural mediums’, where the architecture can communicate the cultural practices of the Kulu migrant residents. New opportunities for positive social exchanges will mean that Kulu and Swedish cultures can truly bridge, and that this easily forgotten migrant settled suburb could be positively integrated with the city of Stockholm. Figs. 16.2 – 16.3 Jack Morton-Gransmore Y5, ‘Slussen Plan C’. Slussen is an existing monolithic transport interchange located at the very heart of Stockholm, positioned between the water and the city it connects the islands of Gamla Stan to Södermalm. The site has fallen into disrepair in recent years, demanding a new design. Slussen Plan C is a ‘Middle Ground’ in

all senses of the word. It creates an architecture between the existing structure and a new proposal, selectively adapting and interpreting the existing site to reveal a new architectural language. This creates an apex of a waterfront environment, developing an inhabitable topography and a public landscape between the city and the water. Most notably the private motor vehicle is eliminated from the site, enabling a programme that combines new and existing transport facilities and interchanges with a premises for the Ports Authority administration, as well as public outlets and services. This establishes Slussen as a starting point to a wider discussion concerning Stockholm’s urban waterfront and its future role within the city.

16.4

16.5

Figs. 16.4 – 16.5 Alexander Sutton Y5, ‘Stockholm City Airport’. Travel demand in the aviation industry is set to double by 2030 and continue increasing into the future. Stockholm is used as a testing ground to develop an airport as part of a new city district. Design solutions, generated in response to aviation research, suggest how a new design approach to airport design can be achieved. This creates a fully integrated urban airport, with airport systems joining city systems as part of the city’s infrastructure, including micro-termini and shorter runways to slot into the urban context. Through such mechanisms it is possible that airports may operate within a city on a more environmentally friendly level. The wonder of flight is immersed within the heart of the city.

Fig. 16.6 Negin Amiridahaj Y5, ‘Invisible Voids’. This project investigates a proposal between submerged architectures and mega floats, creating new hollow islands; voids in the water for public use. It uses the water surface and its depth as a space to inhabit while remaining connected to the city fabric. At the same time, it respects the horizontality of the water surface and the beautiful horizon seen from the city. The voids aim to create a seemingly invisible and continuous space, starting from the city edges and descending into the water to provide a new possible space for the growth of central Stockholm.

Fig. 16.7 Rachel Pickford Y5, ‘Stockholm Stadmission Headquarters and Education Centre’. The design helps to integrate the increasing number of EU homeless migrants within the city of Stockholm. Furthermore the project aims

to create a ‘pocket utopia’ under the Skanstullbron bridge creating a place for the migrants and the Stockholm citizens. The architecture of the buildings plays on the idea of nomadic infrastructure using a fabric core to investigate warm and tactile environments. Fig. 16.8 Kate Prudence Y4, ‘Stockholm Mixed-use Housing Scheme’. A mixed-use scheme links the districts of Norrmalm and Kungsholmen in central Stockholm consists of layered public and private spaces that aim to reconnect the city to the water. Using the space above Stockholm’s water and existing infrastructure, the scheme tackles the city’s housing shortage by providing accommodation in the heart of the city centre.

16.9 16.10

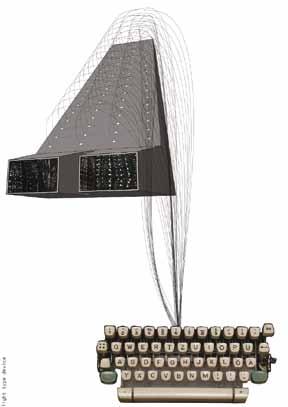

Fig. 16.9 Leif Buchmann Y5, ‘String Theatre’. The design’s central premise introduces an empirical investigation on the effectiveness and qualities of architectural space particular to the architecture of ‘veiling’ for an open air theatre in Stockholm. The focus is on the physical implications of veils consisting of lines, planes and surfaces. Veils – consisting of strings, rods, threads and traces – are interwoven to form a filigree lattice of tectonic material that is further enriched through the play and layering of light and shadow. Fig. 16.10 Matthew Hudspith Y5, ‘Alterity’. The project speculates over the devolvement of Rinkeby, a suburb on the edge of the city of Stockholm and proposes a new council and assembly hall to be located in the centre of Rinkeby. The architecture rejects the monumentality commonly found in political buildings,

and proposes a scene for political debate on a more domestic and human scale, attempting to bring the decisions surrounding the future of Rinkeby into the public domain.

16.11 16.12

16.13

Fig. 16.11 Richard Breen Y4, ‘Slakthusområdet’. The project embraces the rich site history of food and butchery, creating a vibrant self-sufficient mixed-use scheme, to transform the industrial area into an attractive, adaptable and hyper-dense residential area. This new living system is achieved through modularisation, vertical living and an innovative and flexible structural and service system. Fig. 16.12 Robin Ashurst Y4, ‘Final Short Detail Section’. The project is an attempt to reimagine the city as a growing, three-dimensional structure as opposed to the plan-driven design of cities that currently dominates the profession and therefore also urban evolution. Through excavation into the bedrock, a new public domain is exposed below the current ground datum, allowing more public space to be created without reducing the available space for

above. Fig. 16.13

Fig. 16.14 Amy Wong Y4, ‘Cliff Hotel (Söder Mälarstrand Waterfront Redevelopment)’. The hotel rooms overlook central Stockholm, with a spa that extends out onto the water. The building is a journey through the granite rock, with pocket views in the corridors and rock gardens, with a warm timber enclosure inspired by traditional Swedish vernacular.

Fig. 16.15 Chelsea Hodkinson Y4, ‘Renal Rehabilitation Centre’. Hagastaden is located in the North of Stockholm and acts as a transportation gateway to the city, set among intersecting roads, railways and pedestrian bridges. Technologies within the building’s fabric reduce the harmful toxins and gases emitted from vehicular engine combustion providing better air quality for Hagastaden. Fig. 16.16 Elzbieta Kaleta Y4, ‘Hammarby Lock Interchange Centre’. The masterplan introduces a new

public area, connecting to the existing leisure and sport facilities to reinforce the relationship between the waterbody and the built environment. As an integral part to the masterplan, a public, water-based transportation route is introduced that aims to overcome Stockholm’s disconnectivity through the myriad of waterways. Fig. 16.17 Ashley Fridd Y4, ‘Kolsyrefabriken Studio’. Stockholm’s rapid expansion is resulting in an incongruous design and building language further dividing an already fractured city. The studio sits at the public interface on the edge of a masterplan development prototyping building techniques and technologies to create a new language akin to the populous’ psychological idea of their city.

16.18 16.19

Fig. 16.18 Janice Lau Y4, ‘Urban Farming - Potato Garden’. The project introduces urban farming to Stockholm using a series of elevated walkways (food corridors) above an existing railway line. This combines public landscape, a growing environment and the existing transportation network to activate the existing site and its surrounding landscape to consider wider issues of sustainability across the city. Fig. 16.19 Ashley Fridd Y4, ‘Kolsyrefabriken Studio’.

Adapt Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs

Year 4

Leif Nader Buchmann, Jack Morton Gransmore, Rebecca Muirhead, Rachel Pickford, Michael Pugh, Alex Sutton

Year 5

Benjamin Murray Allan, Nathan Joseph Breeze, James Alexander Bruce, Robert Peter Burrows, Natalia Eddy, Francis Roper, Louise Sorensen, Richard Winter

Thanks to Andrew Best, Dean Pike and Happold Consulting, and all of our critics, supporters and friends

Adapt

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs

Being a shrinking city and a quintessential modern site in flux, Detroit is a testing ground for experimentation and rethinking. 1

Detroit is largely composed, today, of seemingly endless square miles of low-density failure. 2

Unit 16 aims to exist in a close symbiosis between academic research and architectural practice, with constant testing and ‘reflecting through action’ to challenge the limits of architecture. We see architecture as an act of realisation, with both the power to transform and the responsibility to make sure we leave something positive behind.

Re-boot

On 18 July 2013, the city of Detroit filed for bankruptcy after a long history of economic struggle. The city, known for its booming car production during the twentieth century, has been falling into an extreme state of disrepair, and now must reinvent itself in order to survive. In order to generate personal positions in relation to this problem, the Unit explored the questions: How do you save a city? How do you decide what your legacy is when new developments move in? Is nostalgic preservation valuable in the evolution of cities?

The City of the Future

Parallel to our study of Detroit, we began to investigate ideas for future cities. As the world’s population has increased in mobility, people migrate into cities in large quantities. Architects and urbanists will need to develop solutions for rapidly growing mega-cities, as well as sudden changes in growth or decline in other areas. We looked at current studies developed by planners, architects, sociologists, urbanists and economists, as well as fictional representations of the future city.

Cycles

We continued to develop ideas about the duration of our architecture, and encouraged students to look at extremes in order to find inventive architectural solutions. Our projects span from short-term interventions to aid mobilisation and relocation, to medium-term proposals dealing with the reconstruction of new Detroit, and long-term proposals that draw up future scenarios for the greater metropolitan area of Detroit. We visited the USA, traveling from Chicago, the city that gave birth to the skyscraper, to Detroit, the city that has become a symbol for its decline. We looked for utopian architectural proposals that question permanence, duration, and temporality; architectures that respond to and suggest contemporary and future modes of urban living; spaces that can evolve and change rather than being demolished or left to ruin as they become outdated.

1. Luis A. Croquer, www.mutualart.com

2. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (NY: Vintage, 1993)

16.2

16.3 16.4

Fig. 16.1 – 16.5 Francis Roper Y5, ‘Neo-Detroit’. A bold proposal that erases the current city structure to make way for a new flexible and re-configuable city structure. Through a collection of clever prefabricated elements, the city is easily built and unbuilt, and offers full flexibility to expand and contract with the changing needs of the city and its residents.

16.6 16.8 16.7

Fig. 16.6 Nathan Breeze Y5, ‘Detroit Film District’. After an initial study of the ways the City of Detroit are dealing with issues of conservation and preservation, Nathan explores an alternative conservation strategy which is occupied with the preservation of culture and events rather than the physical, static buildings that make up the city fabric. As part of the scheme, he proposes a small film district for on location shooting, where façade of the existing buildings can be manipulated and re-configured to allow for various styles and appearances as backdrops for future movies shot in Detroit.

Fig. 16.7 – 16.9 Benjamin Murray Allan Y5, ‘Greening Detroit’. By introducing a systematic and controlled system for forestry in Detroit, the project suggests a new future for the city in which timber becomes the main economic output. At the

same time, the city shrinks to make way for large planted areas, turning Detroit into a city of forests. A focal point for this new development is the Timber Institute, a building nestled within the first forest plantation, from which the new financial initiative can be promoted and controlled.

16.12

16.10 16.11 16.13

Fig. 16.10 Rebecca Muirhead Y4, ‘Community Salt Mine’. A study in how the residents of Detroit’s suburban neighbourhoods can utilise the loop holes in US legislation to set up and operate their own small-scale mining cooperative. Salt is an abundant resource in the Detroit area and a viable business model for community growth and prosperity.

Fig. 16.11 Michael Pugh Y4, ‘Eastern Market Artist Community’. The project suggests an extension of the popular Eastern Market, in order to accommodate facilities for a growing art scene. It includes artist studios, a small gallery space, and a public market area for selling and displaying artworks.

Fig. 16.12 Rachel Pickford Y4, ‘A Living and Learning Community’. An industrial, but inspired piece of architecture that cleverly mixes residential units with spaces

for learning, both in the traditional sense but also for use in home schooling groups, which is becoming more and more common in the U.S. Fig. 16.13 Alex Sutton Y4, ‘Detroit Hub’. The project proposes the re-use of an existing underground car park in downtown Detroit. Building on the growing trend of shared workspace facilities and business incubators, Alex carves out and reconfigures the car park into a great subterranean office complex. Fig. 16.14 Louise Sorensen Y5, ‘A Space for Sound and Performance’. A proposal for a new masterplan for Corktown, where the re-introduction of the historical creeks paves way for a regeneration of the area into an engaging landscape design. By cutting into the building and allowing it to be open to the elements, it seamlessly blends into the watery landscape that surrounds it.

16.15 16.16

16.17 16.18

Fig. 16.15 Richard Winter Y5, ‘Rouge River Car Recycling Plant’. Building on Detroit’s automotive history and its need to regenerate its economy as well as its urban spaces, the project introduces a new car recycling plant along the river, where the public can interact and engage with the recycling processes.

Fig. 16.16 Robert Peter Burrows Y5, ‘Belle Isle Farm’. The project proposes the reinvigoration of what used to be Detroit’s main park and recreation area. As the urban agriculture trend is growing in the city, the project sees the opportunity to expand this into a larger scale farmland complex, while education communities on farming techniques. Fig. 16.17 Leif Nader Buchmann Y4, ‘New Centre Train Station’. A project for a new Amtrak station that connects to the US governments plans for extending the current rail network into a high speed

rail system. The project builds on historical train station typologies while upgrading it to the twenty-first century in a playful manner. Fig. 16.18 Jack Morton Gransmore Y4, ‘Stormwater Facility and Water Park’. A strategy for handling the storm water run off in Detroit, while at the same time creating new public spaces along the riverfront. A visitor centre lies within a concrete trench landscape, shifting up and down depending on the amount of water flowing through the artificial river.

16.19

16.20

Fig. 16.19 Natalia Eddy Y5, ‘Steam Power Facility’. A proposal for a retrofit and upgrade of an exisiting steam power plant, which in the new iteration would be able to power a large part of central Detroit. Derelict skyscrapers become heat stores, large underground areas are utilised for heated public spaces, and the excavated rock from below ground is used to create new sculptural and imaginative public spaces above ground.

Fig. 16.20 James Alexander Bruce Y5 ‘Woodward Avenue Masterplan’. Following the City of Detroit’s new initiative to create a new tram link along Woodward Avenue, the project proposes a masterplan along the avenue with new public spaces, mobile kiosks, pavilions, and temporary markets used to activate the area surrounding the Avenue, and to open up possibilities for future expansion of the neighbouring areas.

Utopias

Johan Berglund, Josep Miàs

Unit

Utopias

Josep Miàs, Johan Berglund‘An

, September 2012

‘I do not want to talk to you about architecture. I detest talk about architecture.’ Le Corbusier, AA after-dinner speech, 1 April 1953

Unit 16 exists in a close symbiosis between academic research and architectural practice. We prefer to make architecture rather than just talking about it. Our way of working is close to how projects are executed in our practices, with constant testing and ‘reflecting through action’, in order to challenge the limits of architecture. Our work is centered on the production of buildings, landscapes and spaces. We see architecture as an act of realisation; of making something real, which was only previously a brief thought, a vague concept, a utopian dream. Through this act we have the power to transform the world around us, and with that, the responsibility to make sure we leave something positive behind.

Legacy