Our Design DNA

At The Bartlett School of Architecture, we have been publishing annual exhibition catalogues for each of our design-based programmes for more than a decade. These catalogues, amounting to thousands of pages, illustrate the best of our students’ extraordinary work. Our Design Anthology series brings together the annual catalogue pages for each of our renowned units, clusters, and labs, to give an overview of how their practice and research has evolved.

Throughout this time some teaching partnerships have remained constant, others have changed. Students have also progressed from one programme to another. Nevertheless, the way in which design is taught and explored at The Bartlett School of Architecture is in our DNA. Now with almost 50 units, clusters and labs in the school across our programmes, the Design Anthology series shows how we define, progress and reinvent our agendas and themes from year to year.

2022 A Festival of the Mundane

Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

2021 The Living Laboratory: Being radical

Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

2020 Re -ou tottíα / Re -utopia

Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

2019 Hidden Spectacles

Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

2018 Hinterlands

Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

2010 Tesla Laboratory

Roz Barr, Ivan Redi

A Festival of the Mundane Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

A Festival of the Mundane

Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

The Everyday 01

Most of us have been locked in the cycle of the everyday for the last two years of lockdowns and quarantines: stuck in the same space, the same rooms and the same routines. The monotony of the everyday has become a mental health issue, with little to no chance to break out of the vicious cycle.

Everyday life is an amorphous concept. We all seem to refer to it as a universal state, but on close inspection each of us occupies a very particular and very personal ‘solo-verse’. At the same time, the extraordinary situation that Covid-19 produced suddenly put the spotlight on the simple things that have become important to us. The pandemic forced us to reset our relationship with how, where and why we inhabit; challenging our habits has been an interesting experience.

The Everyday 02

During his lifetime, it is estimated the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) completed around 50 paintings, of which 35 clearly attributed works survive today. Most depict domestic scenes celebrating the lives of ordinary people. It is remarkable that of these 35 paintings at least 19 were painted in the same room, often using the same subjects. Vermeer was not very successful during his lifetime and after his death was largely forgotten. Painting the everyday did not bring him any fame.

The scenes he portrayed may seem mundane, yet each painting is constructed using a precise array of props – pieces of furniture, domestic items and garments. Each element has been carefully chosen, playing a predetermined part in an everyday story. The real subjects of Vermeer’s paintings are not the characters depicted; they are rather the everyday space, the light and the materiality of the objects painted.

This year PG13 explored the ‘everyday’. We looked in detail at how we live together, how we inhabit space and the routines that inform architectures. We investigated common materials and traditional fabrication methods to challenge ourselves. The everyday does not need to be boring; it is the responsibility of the individual to elevate it to greatness.

The everyday is the measure of all things. Guy Debord

Year 4

Patricia Bob, Ernest Chin, Dilshod Perkins, Malgorzata Rutkowska, Hester Tollit, Maya Whitfield

Year 5

Nikhil (Isaac) Cherian, Agata Malinowska, Thabiso Nyezi, Jolanta Piotrowska, Muyun Qiu, Callum Richardson, Thomas Smith, Chloe Woodhead, Chenwei Ye

Technical tutors and consultants: James Hampton, Chloe Hurley, James Nevin

Thank you to Jenna de Leon, Edoardo Tibuzzi (Structural Engineer, AKT II), Tom Greenhill (Environmental Engineer, Max Fordham)

Thesis supervisors: Paul Dobraszczyk, Jane Hall, Claire McAndrew, Guang Yu Ren, Oliver Wilton

Critics: Barbara-Ann Campbell-Lange, Doville Ciapaite, Luke Draper, Sahra Hersi, Marjut Lisco, Inigo Minns, Maxwell Mutanda, Zahira el Nazer, Paolo Zaide

13.1, 13.17 Callum Richardson, Y5 ‘Ministry of the Inevitable’. Our climates are fragile and ever-changing. Since the dawn of the Anthropocene, our effect on the landscape has increased exponentially, yet governments across the globe remain fractured and unwilling to form a unified response to the climate emergency. The project contributes to a collective urban memory of experience and knowledge. One of the barriers to change is the lack of willpower necessary from those in power; the ministry aims to challenge this.

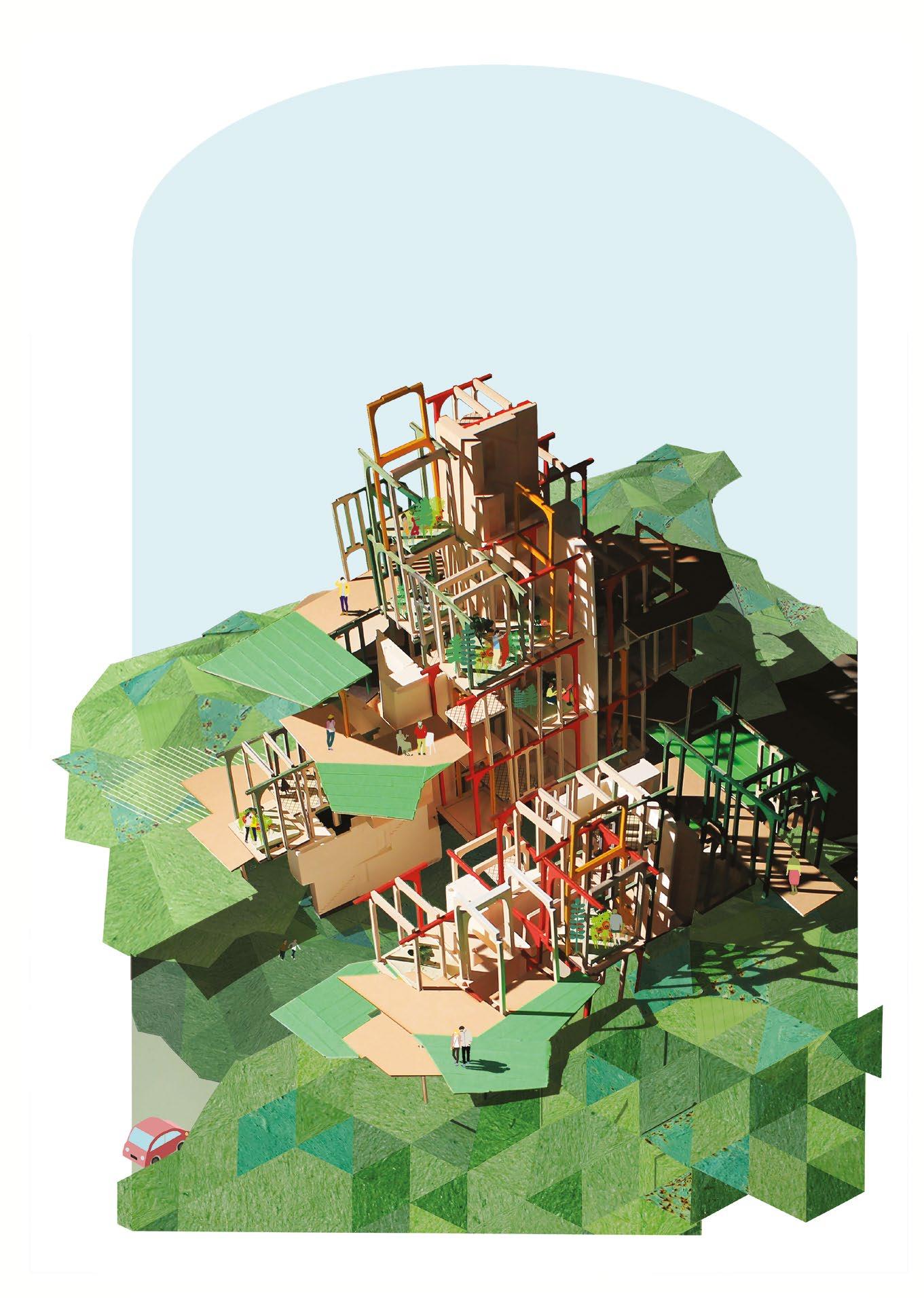

13.2–13.3 Chenwei Ye, Y5 ‘Tea Parliament’. The project questions current non-interventionist models of forest preservation triggered by the Chinese government’s propagandistic intentions in Longjing, Hangzhou. The architecture forms part of a new community forest, which aims to empower residents to participate in forest administration and ecological preservation. In centuries to come, the architecture and people will be gone, but the forest will remain and thrive.

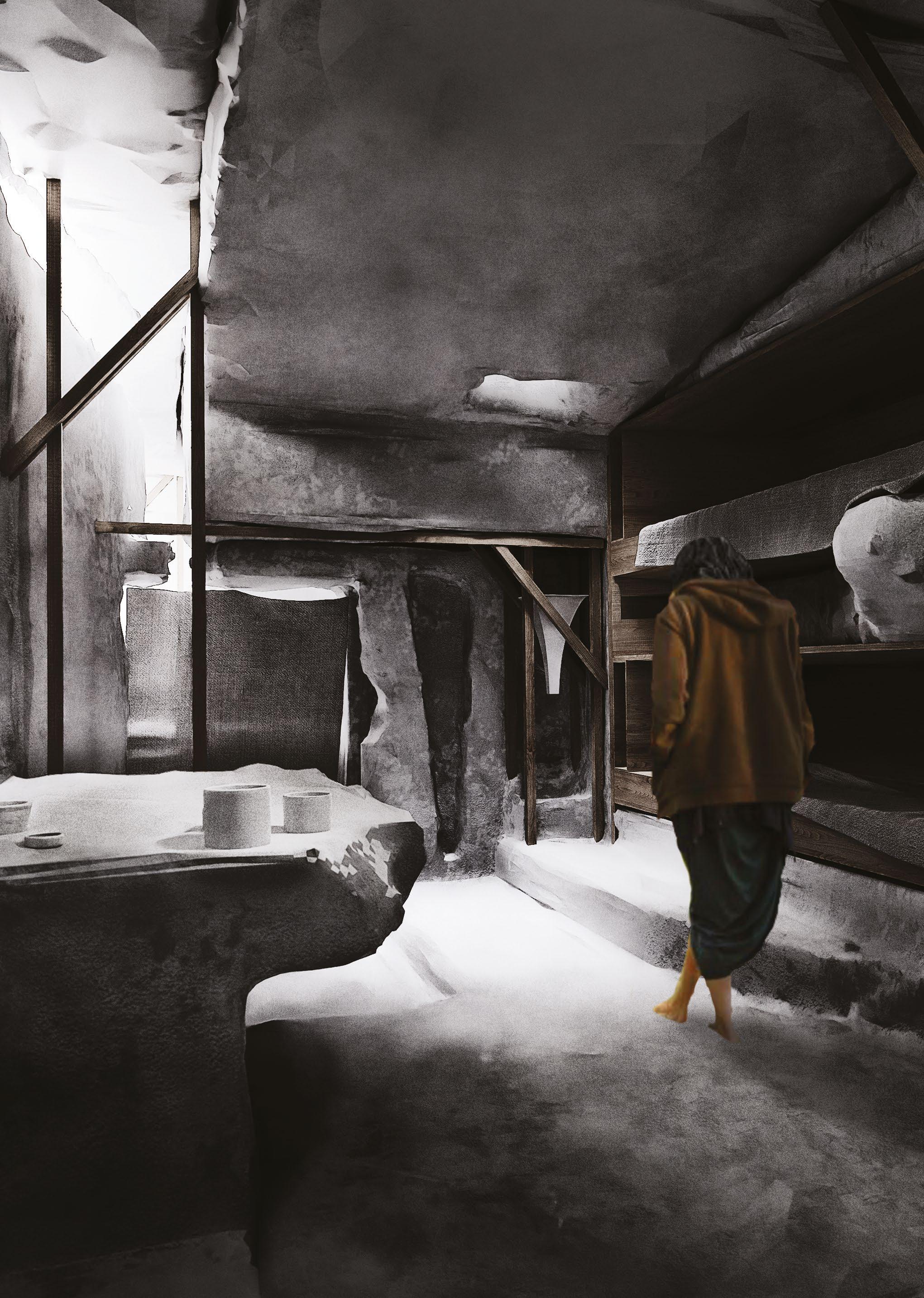

13.4 Nikhil (Isaac) Cherian, Y5 ‘Anthropomorphic Patina’. Care is essential not only in sustaining vulnerable members of society, but also in maintaining our everyday lives. How can this relationship exist as a two-way street? The project focuses on the now demolished Brook House in Hackney, initiating an exploration into the layered nature of memories and exploring the landscape of care as a sensory environment. It is a speculation on an alternative future for the existing Georgian health infrastructure that also examines the methods of care and the messy assemblages of memory.

13.5–13.6 Muyun Qiu, Y5 ‘(Don’t) Dwell on the Past: The Rebirth of Yuanming Yuan’. Sited in Yuanming Yuan, Beijing’s former Summer Palace destroyed in the Second Opium War, the project seeks to realise the potential of heritage through actively reusing the ruins instead of monumentalising them for nationalist propaganda. It proposes to return the ruins to the local population so that they can reconcile with a dark chapter of national history through the formation of a symbiotic relationship between the people themselves, their interventions and the ruins.

13.7 Chloe Woodhead, Y5 ‘Fabric Waste Depository’. Textile waste is a huge contributor to global environmental pollution. The Institute of Positive Fashion states that community, environment and craftsmanship are the key pillars in reducing the damage caused by textile waste. This project utilises these principles to create a space for waste that allows the community of Deptford to consider waste as part of their environmental experience. The dichotomy of material, movement and space is essential to the discussion of the waste experience.

13.8 Thomas Smith, Y5 ‘Water Descending’. Wild bathing is a necessity. It provides an escape from the city and water’s ephemeral properties awaken the senses as we purge ourselves of trivial woes, soothing a mind and body that yearns for untamed nature. With our tribal uniforms removed, we expose ourselves, releasing the barriers between us and nature. Only in this raw state can we truly tap into our primal and physiological needs. The project improves access to this cultural activity in London.

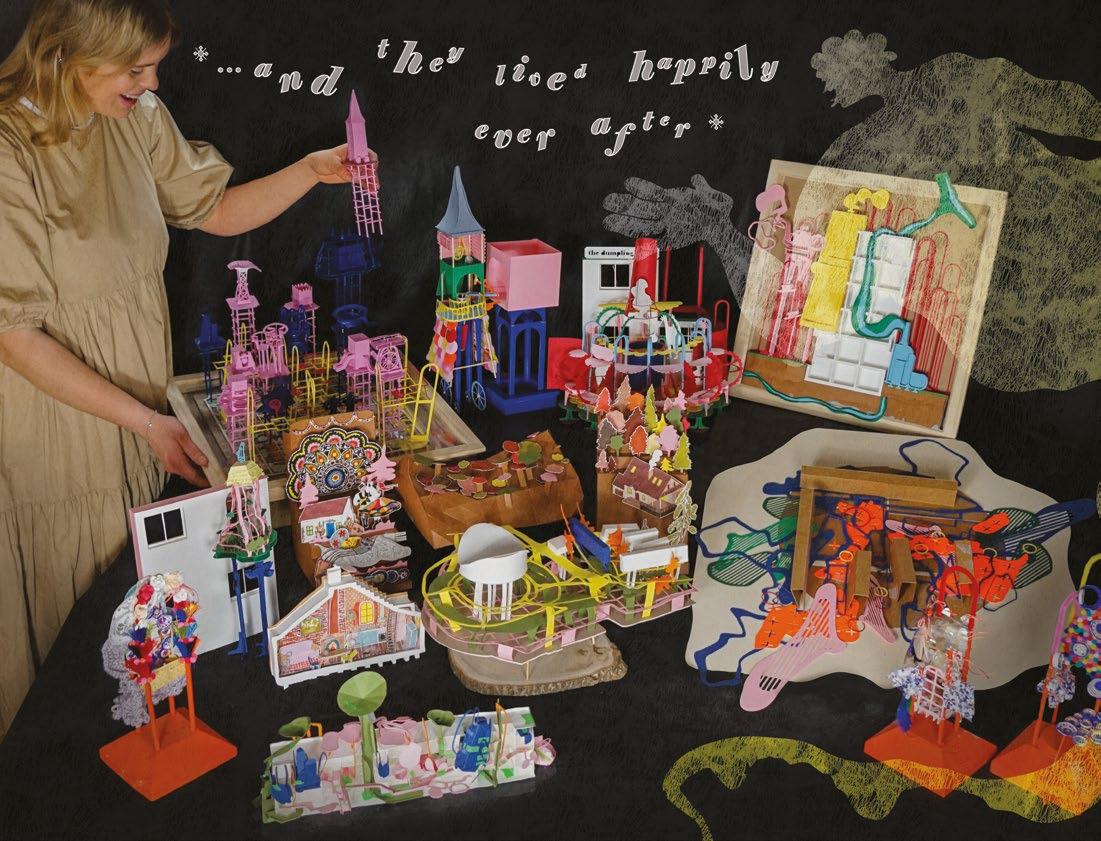

13.9 Agata Malinowska, Y5 ‘Polish Wonderland’. Our lives need some escapism. We often go about our everyday mundane tasks seeking something that will give us relief. This project explores escapism through Polish forests, envisioning them as enchanted places where anything can happen. Through storytelling, fairy tales and imagination, the project examines the way that narrative can help us interact with space.

13.10 Jolanta Piotrowska, Y5 ‘Reinventing the Longhouse’. Everyday life would look very different if it weren’t for the invisible work carried out by women. This ‘reproductive labour’, as Silvia Federici describes it, is ‘work we do that is sustaining, work that you have to do over and over again, work that seems to erase itself’. This project brings about change and highlights the wealth and wisdom of invisible labour by focusing on developing the cultural identity of Wolin, an island off the coast of Poland. The design adapts the invisible labour principles of care, value and community in order to form a relationship between the people and the land and create a building suited to their needs.

13.11–13.12 Ernest Chin, Y4 ‘Margate Placeholder’. The project asks: ‘What if regeneration strategies prioritised locals?’ The scheme, a self-build community centre, utilises the abundant chalk beneath Margate as a catalyst to suggest an alternative approach. The process of neighbourhood involvement, material use and collective building provides the platform for a bottom-up, intrinsically local regeneration strategy that empowers the community to reclaim Margate and improve it on their terms.

13.13 Maya Whitfield, Y4 ‘Constructing Play Store’. The project examines increasing child poverty, homelessness and inequality within Margate and Cliftonville. It challenges the existing environment, while facilitating a new procurement route for delivery and completion of a self-build scheme organised by the community. By allowing participation within the design process, the act of collective building as a pedagogical tool encourages community members to explore their everyday, while improving independence and common understanding.

13.14 Hester Tollit, Y4 ‘Curtain Call’. The project questions how under-represented voices can gain confidence to speak out and be heard. By exploring the characteristics and opportunities within degrees of transparency, the proposal investigates the relationship between internal and external activity, creating an open and creative dialogue in and around a community theatre. The dynamics of perspective and light interact to enable layered and evolving relationships between wider socio-economic communities and provide a beacon with which to ‘re-light’ Margate.

13.15–13.16 Thabiso Nyezi, Y5 ‘The Promised Land’. The project examines the different vernaculars that redefine relationships with community, landscape and living in the city of Milton Keynes. By reimagining the 1970s vision of a ‘City in the Forest’ in rural Buckinghamshire, the project explores how different cultures could be celebrated by the built environment while addressing the town’s urban ambitions. The result is a town that celebrates rather than resists transcultural exchanges and sees them as vital to its own evolution.

The Living Laboratory: Being radical Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

The Living Laboratory: Being radical

Sabine Storp, Patrick WeberThe most powerful architectures have been created out of crises, rebellions or clear breaks with the past. In times of great uncertainty radical ideas emerge – a pattern seen throughout architectural history.

The last year has challenged our students and staff. The Covid-19 pandemic is not an isolated event; it sits connected to other crises – most of them manmade and many existential threats to mankind. What is needed is a shift in how we operate and a reconsideration of the basic principles of how we live and treat each other and our planet; it is down to us to be radical.

This year PG13 – the Bartlett Living Laboratory – has been continuing to explore how we live and inhabit our spaces and cities. Our students have been empowering communities and inventing new typologies of living through their work.

The Bata – a Czech footwear manufacturer – company town in East Tilbury, Essex, was our focus site. Our Year 4 students envisaged new radical concepts for how this site could be unlocked and how the vulnerable landscape in the Thames Estuary provided potential rather than risk.

Our Year 5 students developed their own agenda, continuing with the themes of the unit but responding with a range of architectures in a personal way. Projects included an augmented town hall in Somers Town, London; a new aquatic way of living for Hong Kong, guided by the lunar calendar; an architecture fabricated out of universal elements that revives the village of Silver End in Essex; a new vernacular architecture on the Baltic coast of Lithuania that responds to local myths about forests; and a seedbank embedded in a glacier on the Nordic island of Svalbard that pushes the boundaries of architecture into the realm of fragile melting speculation.

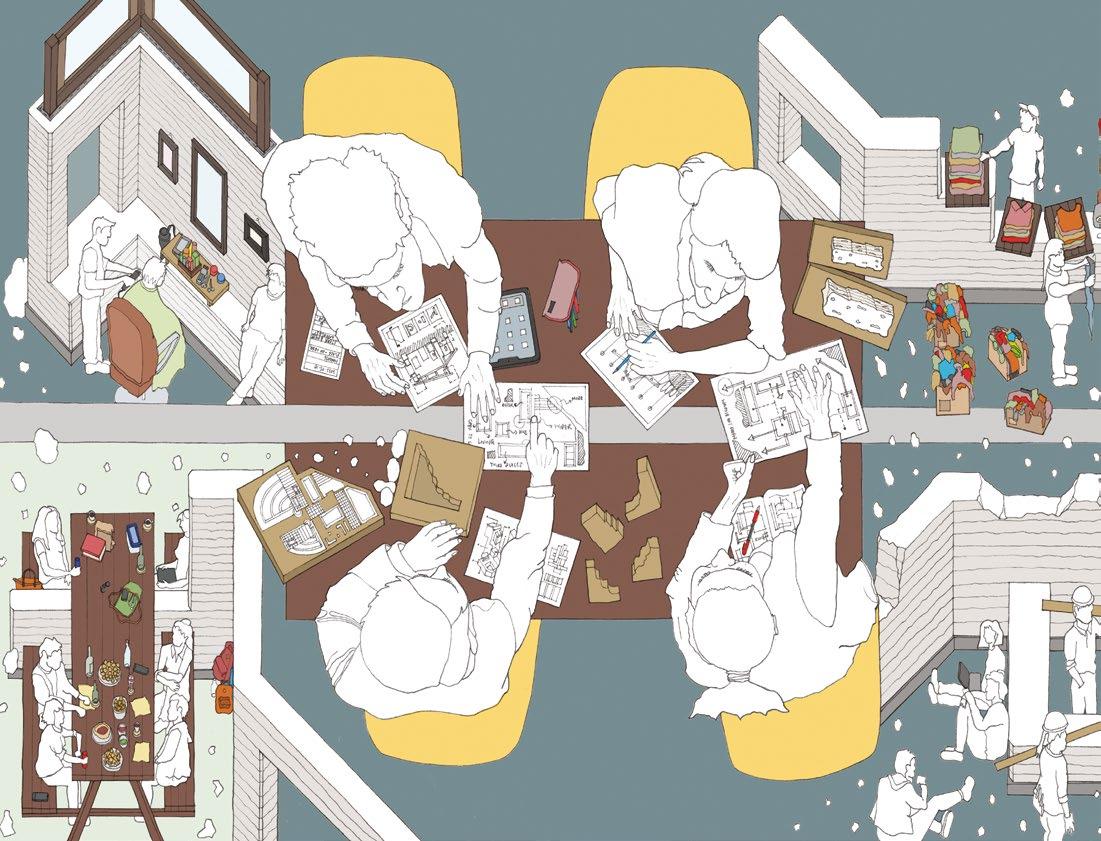

Over the last two years we have been participating in a collaborative workshop with students and teachers from Hanyang University, South Korea. Both universities have been radical in questioning the concept of ‘refuge’, exploring ideas of a resilient city fighting urgent urban issues, climate change and migration. The work of our students will be presented at the Seoul Biennale 2021.

Year 4

Nikhil Isaac Cherian, Agata Malinowska, Jolanta Piotrowska, Muyun Qiu, Callum Richardson, Thomas Smith, Chloe Woodhead

Year 5

Jonas Andresen, Dovile Ciapaite, Luke Draper, Victor Leung, Marjut Lisco, Jarron Tham

Thank you to our technical tutors and consultants: Toby Ronalds and Nick Wood

Thank you to our critics: Rita Adamo, David Bickle, Marc Brossa, Carlos Jiménez Cenamor, Paul Galindo, Alice Hardy, Ophélie Herranz, So Young Kim, Alicia Lazzaroni, Maxwell Mutanda, Inigo Minns, Robert Newcombe, Caspar Rodgers, Marianne Sætre, Antje Steinmuller, Serhan Ahmet Tekbas, Jonas Žukauskas

Partners: Samson Adjei, Tom Budd, Naomi De Barr, Jarrell Goh, Gintare Kapociute, So Young Kim, Emily Priest, Adrian Siu, Yip Siu

13.1 Luke Draper, Y5 ‘The New Rural: A guide to realising Arcadia’. Radical change is needed to evolve the way in which we inhabit our natural world. ‘The New Rural’ is a manifesto, guide and proposition for the necessary realisation of Arcadia in Britain. The culmination of ‘The New Rural’ has been an effort to ‘undesign’ Essex by providing a guide to a settlement typology that questions the existing separation of dwelling and nature.

13.2 Marjut Lisco, Y5 ‘Collegio Reborn’. The project looks at a new way of using collectives of materials that, through up-cycling systems, can mirror the interaction of different ethnicities living together in the former ruin site of the Collegio Tommaseo in Brindisi, Italy. The project investigates the new role of the architect as mediator, through three phases: ‘Collection’, ‘Interpretation’ and ‘Participation’. The city of Brindisi becomes the new European Bauhaus capital, as its scheme best represents the key points of the movement.

13.3 Callum Richardson, Y4 ‘Emergent Heartland’. A self-build masterplan to facilitate bottom-up, self-directed urbanism. Each building is made from a kit-of-parts constructed in a central workshop and communal space. Over time each cluster grows and adapts to the needs of its inhabitants. Modification, addition and eventual disassembly are central to the approach. The masterplan is a framework to allow the residents maximum flexibility in designing spaces for their own needs and to learn new skills in the process.

13.4 Dovile Ciapaite, Y5 ‘Crafting a Lithuanian Forest’. Carefully crafted building details highlight industrial forestry practices in the Lithuanian territory of Curonian Spit. The project introduces hand-carved structures that enable people to experience the forest and remind us of our caring responsibilities: to maintain, restore and sustain. Storytelling becomes a form of sharing this craft-based knowledge through intergenerational interactions that create a future for an old growth forest.

13.5 Chloe Woodhead, Y4 ‘DO (NOT) ERASE: A radical recording and register of intangible heritage’. The project redefines the traditional model of a museum for heritage, which is not physical but intangible. Methods of preserving the intangible involve erosion and mark-making via community interaction with material architecture, specifically chalk – a local building material. Through erosion over time, spaces of rest and pause are revealed that encourage the community to converse and interact and, in doing so, social heritage is recorded and preserved.

13.6 Jolanta Piotrowska, Y4 ‘Making Bata’. A project based in East Tilbury, Essex, that gives the community the power to create their own future through decisionmaking for the town. It focusses on providing people with the tools and skills needed to self-build and govern the new community facilities: a ceramics workshop, a wood workshop and a community space. The project explores how governmental streams of funding can focus the build on up-skilling and learning.

13.7 Muyun Qiu, Y4 ‘Yong’an Fang 2.0’. The project rejects Tabula Rasa planning and proposes an economically viable and socially sustainable alternative to the renewal of Shanghai’s lilong neighbourhoods, where domestic lives are highly socialised and exteriorised. By moving the residents into a superstructure designed to recreate the same social experience as the original lilong complex, and freeing up the existing buildings for commercial development, this proposal preserves the social network, lifestyle and collective memories of these communities and allows for land to adapt to changing market dynamics.

13.8 Nikhil Isaac Cherian, Y4 ‘Nine Meals from Anarchy’. This project redefines the public house as a community infrastructure. Taking cues from the masonry stove and

the centrality of the chimney, the scheme examines the hearth as a potential space for cohesive social praxis. The chimney was explored as both a structural and social component within the scheme.

13.9 Agata Malinowska, Y4 ‘Stacey’s KITSCHen & The Grand BATA Hostel’. The project researches alternative methods of living and building construction. It investigates how emphasising the absurdity and questioning the everyday can evolve into playfulness. The project is inspired by Wes Anderson’s film The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). It takes the form of an unconventional megastructure, where the residents benefit from a new approach of bringing back community spaces and helping young homeless adults seek a better future.

13.10 Thomas Smith, Y4 ‘Bata’s Wild Regeneration’. The project questions our contract with nature, within the context of our relationship with the once natural landscape of East Tilbury, Essex. Through the industrialisation of the past 200 years, we have severed our connection with nature, ignored its cyclical processes and, as an act of self-sabotage, abused the environments that benefit our health and wellbeing most. To reverse this damage, we must recognise the rights of nature, adhering to principles of permaculture to change the way we live, design and build.

13.11 Jonas Andresen, Y5 ‘Embassy of No-land’. Exploring the notion of time and transition, this project speculates an alternative future for the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. Through six narratives from different scales and perspectives, the project speculates how a stronger symbiosis with the natural environment can be created. It creates an infrastructure built on natural transitions and an architecture that grows and erodes with seasonal and social changes. 13.12–13.13 Victor Leung , Y5 ‘Isle of Lunar-Sea’. Amidst proposals for construction of a 1,700 ha artificial island within Hong Kong’s archipelago, ‘Isle of Lunar-Sea’ proposes an alternative floating city, establishing connections with the marine surroundings and offering safety to its boat people. The lunisolar calendar, tidal change and maritime geography form the basis of a model masterplan and its comprising modules, which ever-change to suit both seasonal and future climates.

13.14 Jarron Tham, Y5 ‘Virtually_Public’. The project speculates a public realm with a virtual townhall for the future expiration of Story Garden’s tenure. Although the garden physically appears as a public retreat, it is transformed through an augmented reality to become a townhall, taking an integrated form of two parts where one reality suggests the existence of the other. It speculates on how the civic, social and virtual constructs of future ‘publicness’ alter the nature of who we are, how we interact in public space and how we gather local information and meanings of civic symbolism.

Re -outottíα / Re -utopia Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

Re -outottíα / Re -utopia

Sabine Storp, Patrick WeberIn PG13, we are interested in how we inhabit our cities. The places we live in, socialise, engage with others, building a community are immensely important for the functioning of our post-Covid-19 world.

At times of great uncertainty, we strive to find a way forward by projecting our dreams onto a better place – our own personal utopia. Architecture students dream, they speculate on what ‘could be’ real, they dream of spatial manifestations of real-life problems. Work produced is often speculative, and although some is rooted in reallife situations it is not real, it doesn’t have a client, it will not be built. Yet these speculations, these speculative architectures are incredibly important to bring about change, and to test out new innovative ideas.

As architects we (usually) strive to build a better world. This spirit created some of the most iconic housing developments of the 20th century in London: Alexandra Road and the Dunboyne Estate by Neave Brown, Robin Hood Gardens by the Alison and Peter Smithson, Trellick Tower by Erno Goldfinger to name a few. Sadly, other attempts to solve problems with buildings have failed and have created far bigger problems than the issues they were attempting to address. Modernism was seen as a brave new world for a modern forwardlooking society. For many, the utopian ideas expressed in inner-city housing estates have turned into dystopian nightmares. But some examples have stood the test of time, and developed into living, even thriving, communities.

This year, the unit has been revisiting a range of urban and rural living concepts. We started the year with a real competition to ‘re-stock’ depleted London housing stock. Students were asked to analyse and decode an existing example and develop a new model paradigm, echoing the shifts in society, culture, community and environment. The ideas identified in the competition formed a seed to explore inhabitation in London further. The new/old paradigms were used to invent a substantial spatial construct, set within a real social, urban or rural context. Students tackled inhabitation in London on various scales. The projects proposed included extending the Alexandra Road estate; completing Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower ensemble with a self-built high rise; translating the ideas of the Bata Estate in Tilbury into a 21st-century independent community in the flood plains; rethinking Kilburn High Street into a ‘slow street’; and a post EU-topia proposal for the borderlands of Luxembourg.

PG13 students have embarked on a journey of speculation. They have dreamt up their own utopias, harnessing the optimism embedded in the ideas and turning them into inhabitable spaces.

Year 4

Jonas Andresen, Nikhil (Isaac) Cherian, Dovile Ciapaite, Luke Draper, Victor Leung, Marjut Lisco, Issui Shihora, Jarron Tham

Year 5

Alex Haines, Ka Chi Law, Shi Yin Ling, Mabel Parsons, Maïté Seimetz, Yip Wing Siu, Ryan Tung

Thanks to our consultants Rae Whittow-Williams and Toby Ronalds

Thank you to our critics Samson Adjei, BarbaraAnn Campbell Lange, Alice Hardy, Sara Martinez, Rae Whittow-Williams, Paolo Zaide

Many thanks to our partners, Beebreeders

13.1, 13.3 Yip Wing Siu, Y5 ‘New Doggerland: A Dynamic Masterplan for Enabling the East Tilbury Commons’. Instead of working against the forces of nature, the ’commonity’ of East Tilbury has long sought to return to a nomadic way of life, forgoing the rampant pressures and excess of the neoliberal city for something more attuned; living with (and not against) the land. Returning to principles of the historic commons, their settlement has been designed with the foresight of adapting to change in both land and waterscapes, where the dynamic (master) plan is built across time, seasons and tides to speculate with new forms of living.

13.2 Ryan Tung , Y5 ‘Hacking RHG/Phygital Habitat’. Hacking RHG is a testbed showing how gaming can be used as a methodology to explore a different way for residents to engage with architecture. By playing against the rules, the algorithm of the game is turned into a planning system, capable of evaluating the best strategy of the collective bottom-up approach.

13.4 Dovile Ciapaite, Y4 ‘Self-Built Assembly of Rammed Earth’. The Self-Built Assembly of Rammed Earth is a project based around the community initiative to encourage a change in estate management and empower residents to reclaim land through urban commons. The project focuses on the idea of self-buildability and the nature of handmade urbanism. This has been explored through model-making and researching alternative methods of construction that embrace a handmade quality.

13.5-13.6 Jonas Andresen, Y4 ‘Responsive City’. Responsive City proposes a new way to inhabit our cities, where the boundaries between social distancing and daily inhabitation start to overlap and interact with each other. The project is particularly focused on the notion of overlooking. The ‘structure’ of overlooking, that is both how overlooking can mean to provide a view of and to oversee (as in not seeing), are translated into social interactions and architecture.

13.7 Ka Chi Law, Y5 ‘Therapeutic Landscape, Forest Gate’. This project continues the legacy of Forest Gate as a therapeutic location. Currently considered to be one of the most deprived and overpopulated areas in the UK, the project learns from the Queen’s Market at Newham and the Hong Kong back-lane typology, functioning to accommodate local micro-business as well as serving as a vibrant social arena.

13.8 Maïté Seimetz, Y5 ‘EUtopian Visions: Luxembourg’s Post-Territorial Borderlands’. The ‘EUtopian Visions’ critically engage with the EU’s current territorial cohesion strategy by reimagining the inhabitation of its open inner borderlands. Set in the Luxembourgish periphery, the project proposes post-territorial borderlands, which, in a time of Brexit and the rise of nationalist secession, choose neither Leave nor Remain and exist (in)dependent from inter-country differences. In this context, the borderlands are programmatically reinvented and hybridised, creating an eco-commercial, culturalindustrial and econo-domestic inhabitation network, with the first post-territorial community of its kind.

13.9 Mabel Parsons, Y5 ‘Lessons from the Peckham Experiment’. Drawing from the 1926 'Peckham Experiment' which endeavoured to challenge health and wellbeing to be considered a holistic practice, rather than pure treatment of ailments, this project aims to reinterpret the key values surrounding social, communal and physical activity as integral to the thriving individual. The project aims to create a phased, collective living scheme for single parents within the Peckham area which is becoming increasingly less accessible and affordable for diverse, marginalised communities.

13.10 Marjut Lisco, Y4 ‘(Re)Trellick 2.0’. This project features the endless assembly of the new self-built tower, which externally imitates the existing Trellick

tower. The community of residents is directly working and living inside the scheme, which appears always under construction.

13.11 Alex Haines, Y5 ‘A Quilt of Adaptive and Unbounded Care’. Initially comprised of a series of strategic architectural interventions, through the patching together of these smaller elements the quilt grows incrementally, adapted and repaired by multiple contributors over time.

13.12 Nikhil (Isaac) Cherian, Y4 ‘Ampthill Vivarium’. Set within the contexts of the climate and cladding crises, this project seeks to retrofit three existing tower buildings in Camden to provide an alternative vertical living scheme. By using an inhabitable cladding catalogue, 240 households will reconfigure their towers to provide family living units, courtyard gardens, workspaces and vertical villages within the tower, thus enriching domestic and community life.

13.13 Issui Shioura, Y4 ‘Minimum Meanwhile Maximum – Movable Module Housing’. This project speculates an active and flexible way of living with the movable spaces as an utopian urban planning vision. The design challenges to make a moduler housing kit for the temporary living where all the components of the building being able to move away as meanwhile use and rebuild in a different lands. The project suggests a catalogue of inhabitation: comic strips show specific moments for different users, and the different types of panels and combinations of the housing kit.

13.14 Luke Draper, Y4 ‘Stocking Up’. This project explores whether a new London Stock Brick could once again provide housing stock for London. Can the housing crisis be brought to an end by using the very clay found beneath the buildings of London? Clay bricks excavated, formed and fired on site could be used to construct new dwellings and fill the spare rooms of London.

13.15 Jarron Tham, Y4 ‘Extending Alexandra Estate’. What is the role of the architect in ‘homemaking‘? The State of Alextendra discovers ways to extend Neave Brown’s iconic Alexandra Estate into the 21st century by redefining homemaking and proposes a form of affordable housing that reacts to changing tenants‘ needs and identities; creating a utopian vision of a form of housing that allows tenants to continually modify their environments using local, recycled materials.

13.16–13.17 Victor Leung , Y4 ‘Nueva Costa del Alexandra 2050: An Active Ageing Utopia Amidst Continued Carbon Offsets’. Costa del Alexandra 2050 builds upon the original council-led model to create intergenerational retirement co-housing directly across the railway (West Coast Main Line), north of the Alexandra Estate. The scheme redevelops the undesirable site into a carbonoffset building for High Speed Two (HS2) powered by waste railway heat. Here, active ageing extends from basement coppice-wood workshops to rooftop greenhouses, contributing to the prolonging of lives of mutual support and care and continued carbon offsetting.

13.18 Shi Yin Ling, Y5 ‘Kilburn Slow Street’. A two-part investigation into the overarching question: ‘What makes a street?’ Term 1’s investigation into reimagining Alexandra Road Estate resulted in the development of a playable toolkit looking at the physical elements of the street. Term 2’s project, Kilburn Slow Street, is a spatial exploration of an alternative narrative for the future high street, focusing on the ‘non-physical’ aspects of the street, and exploring the ideas of deceleration and slowness.

Hidden Spectacles Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

Hidden Spectacles

Sabine Storp, Patrick WeberIn PG13, students propose creative new ways to inhabit the city by developing diverse spatial scenarios. This year, we looked at the embedded industrial urban fabrics of London and Seoul, and envisaged a new culture of sharing within urban communities, vital to the future of the sustainable city. We explored the inner working of a place and questioned what happens when ‘back of house’ becomes ‘front of house’ – is this the place where new models are tested and innovation happens? Some of the key terms we used as departure points were: ‘sharing city’, ‘urban hacking’, ‘re-acting’, ‘collective’, ‘community’, ‘trans-ient’ and ‘trans-loci’.

Presenting an alternative concept of living and working on the fringes of a city, students’ projects were a testing ground for interdisciplinary cooperation and the methodologies used to make a city more liveable. Inventing new models for future inhabitation, we carefully observed fringe communities and challenged regulatory frameworks, setting ourselves a personal design research question and speculating on an imagined part of the city set within a real context.

Our Year 4 students worked on the Park Royal industrial estate in northwest London. They collaborated with the Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation on ideas for the future of the area, to be exhibited in London in autumn 2019.

Year 5 students challenged concepts of inhabitation for the city of Seoul in South Korea. We developed a close relationship with Seoul University and Hanyang University, and collaborated on a series of workshops in Seoul and London, which explored the idea of the ‘sharing city’ from two different cultural viewpoints. The ideas were expressed in collective drawings and models, which are to be presented at the Seoul Architecture Biennale in September 2019.

Year 4

Ka Chi Law, Shi Yin Ling, Mabel Parsons, Maïte Seimetz, Yip Wing Siu

Year 5

Daniel Avilan Medina, Nicola Chan, Thomas Cubitt, Naomi De Barr, Emily Martin, Giles Nartey, Robert Newcombe, Hoi Lai (Kerry) Ngan, Rebecca Outterside, Allegra Willder

Thanks to our partners: Hanyang University, Seoul; University of Seoul; Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation, London

Thanks to our critics and consultants: Jan Ackenhausen, Samson Adjei, Chris Bryant, Barbara-Ann CampbellLange, James Christian, Soyoung Kim, Fiona MacDonald, Guan-Yu Ren, Caspar Rodgers, Toby Ronalds, Henry Thorold, Ray Whittow-Williams, Paolo Zaide

13.1 Yip Wing Siu, Y4 ‘Minerva Community Academy’. With the arrival of Crossrail and HS2 in Park Royal, the traditional industrial fabric of food production and light manufacturing in the area is under threat; the socioeconomic landscape is shifting, it is at an urban and theoretical juncture. Situated in one of London’s most deprived neighbourhoods, the ‘Minerva Community Academy’ seeks to renegotiate the boundary between industry and living by introducing a vocational academy, transforming the site into a pedagogical and social catalyst.

13.2 Naomi De Barr, Y5 ‘Ceramic House in Pieces’. This project proposes a crafted installation for environmental diversity in homes in Seoul. The heated and ventilated floor of the traditional urban Hanok house encourages a sedentary living condition, harnessing thermal properties in the floor. This project examines craft on the scale of furniture and its influence on inhabitation.

13.3–13.4 Giles Nartey, Y5 ‘Finding Artefacts’. A new digital territory in Euljiro in South Korea is proposed for the relocation of the printing community, in reaction to proposed redevelopment. Critiquing the forced redevelopment of industrial areas and satirically playing with the limits of preservation, this project asks the question: ‘How will we experience lost architectures and communities when they are gone?’ It investigates whether the memory of what is lost can become architecture.

13.5 Allegra Willder, Y5 ‘The Cheonggye Baths’. Sited along the recently ‘restored’ Cheonggyecheon River in Seoul, this project looks to exhibit and utilise the phenomenal amount of artificial stream produced by the river through a series of interventions built along its course. Varying in scale, due to the fluctuating amounts of water available from site to site, the public buildings and spaces use water to describe and express the immediate surroundings.

13.6–13.8 Hoi Lai (Kerry) Ngan, Y5 ‘Bukchon Slow Town’. This project realises a piece of ageing landscape, romantically reimagined as a safe vessel for the elderly in a mythic, prelapsarian time. In response to the ageing crisis in South Korea, it unveils a sustainable ageing process for both the landscape and man. The exploration subtly critiques the unstoppable urbanisation in Seoul, which has resulted in a loss of diversity in ways of living.

13.9 Shi Yin Ling, Y4 ‘The Park Royal Partnership’. This co-living and working development is based on the concept of the ‘circular economy’. From a social point of view, value is maintained through the act of sharing, learning and communication, prompted by the various spaces within the development. The building is raised on four cores, with an open internal courtyard and live-work spaces arranged around it. Reinventing the model of communal living, a flexible living typology is introduced, facilitating the growth and change of the building and occupants over time.

13.10 Mabel Parsons, Y4 ‘Minerva Multiplicities’. Situated above existing warehouses in Minerva Road in Park Royal, this project proposes affordable parasitic dwellings for a growing artists’ community, consisting of co-living houses of various tenure, as a platform to grow connections. The proposal seeks to improve the image of the industrial estate, and values its existing character and communities by merging industrial and residential environments.

13.11 Ka Chi Law, Y4 ‘Safeguarding London’. Sited above the Grand Union Canal at Park Royal, the keyworker housing scheme is a response to London’s land value and suggests an alternative of building on the free airspace above the canal. The building shelters a ‘closed-loop’ living system that not only harvests from the canal but also reactivates it through inhabitation. Its prefabricated design allows the scheme to expand along the London canal and provides homes close to work locations across the city.

13.12 Maïté Seimetz, Y4 ‘The Surplus City’. A prototype for temporary accommodation for women, combining experimental materiality, self-built construction and community participation to de-stigmatise homelessness and the treatment of surplus material. Set in the industrial zone of Park Royal, the scheme uses local industrial by-products as raw material for self-built components. Maker spaces become the catalysts for social reconnection and integration into the local community.

13.13 Robert Newcombe, Y5 ‘A Toolkit for an Architecture of Participation’. Collaborating with three real communities in the UK, South Korea and Chile, this project uses a set of experimental participatory tools to provide a common spatial language for architects and stakeholders. By engaging in a meaningful, collective architectural dialogue that informs design decisions, the architecture embeds the collective briefing and is informed by users’ living patterns, desired spatial qualities and relationships.

13.14 Nicola Chan, Y5 ‘The Slow Sewing Symposium’. This project explores the garment-making process as a new architectural typology for Seoul. The unique processes of pattern-making, cutting and toile-making are used as a methodology to manipulate and challenge space. The symposium becomes a living reminder of the craftspeople and craftsmanship of Changsin-dong in Seoul.

13.15 Rebecca Outterside, Y5 ‘A Circular Seoul’. This project introduces the idea of self-sufficient highrise towers in Seoul. Tackling issues relating to food and construction waste, the project combines Korean food markets and kitchens with a new living typology. Spaces are designed for the inhabitants to grow and consume their own food, with any waste being regenerated into biomaterials for construction.

13.16–13.17 Emily Martin, Y5 ‘Community Catalyst’. This project negotiates the future of architectural practice by re-working the design process into an opportunity for community-driven development. By developing a new participatory method as a manual of engagement –through direct involvement and collective action within local communities – contemporary living opportunities are transformed and re-appropriated.

13.18 Daniel Avilan Medina, Y5 ‘Sewoon Archipelago’. An existing kilometre-long building in Seoul – currently the heart of the city’s industrial complex – is reestablished as a pig farm for the city’s inhabitants. Through a series of tectonic interventions, the farm becomes a new narrative for the people of South Korea, who have seen the city transform with the vanishing of its manufacturing heart. This new archipelago integrates Korean food culture and industrial growth into a rich environment for urban production.

13.19–13.21 Thomas Cubitt, Y5 ‘(Re) Placing the Urban Hanok’. This project questions the position of historic housing within the city. It proposes a higher-density evolution of Seoul’s 1930s-urban Hanok houses and introduces a new construction method, re-configuring domestic spaces, whilst retaining a layout influenced by the courtyard typology. The project focuses on preserving the social characteristics of a neighbourhood, whilst allowing it to adapt and change.

Hinterlands Sabine Storp, Patrick Weber

Hinterlands

Sabine Storp, Patrick WeberYear 4

Nicola Chan, Tasnim Eshraqi Najafabadi, Rui Ma, Emily Martin, Giles Nartey, Allegra Willder

Year 5

Ye Lone (Jarrell) Goh, Gintare Kapociute, Kannawat Limratepong, Sara Martinez Zamora, Katriona Pillay, Yan Kee (Adrian) Siu, Mai Que Ta, Yui Sze Wong, Alexander Wood

Thanks to Toby Ronalds, Design Realisation Structural Tutor, and Rae WhittowWilliams, Design Realisation Practice Tutor

Thank you to our critics: Samson Adjei, Barbara-Anne Campbell-Lange, Edward Denison, Edward Farndale, Andrew Friend, Christine Hawley, Simon Herron, Inigo Minns, Matt Lucraft, Thomas Parker, Guan Yu Ren, Nikolas Travasaros, Paolo Zaide

In the previous two years, we explored the ‘Hinterlands’ of the Bata Estate in East Tilbury. This year we explored Essex further – as both a site for projects and as inspiration for a broader investigation into how we inhabit spaces.

The way we live in and inhabit spaces is not fixed, it is in constant flux: changing not only with fashion but alongside subtler shifts in culture, economics, the social fabric and, ever more importantly, questions of sustainability. Surprisingly, the dream of the single-family detached dwelling is still very much alive – set in a perfect arcadian rural or suburban landscape.

Cities used to be heavily dependent on their surrounding land for the supply of food. Slowly the structures within our society are shifting, the work environment is changing, the way we supply ourselves with the necessary provisions can be challenged. ‘Off-grid’ is suddenly aspirational, rather than being perceived to be at odds with our modern way of life.

Over the last hundred years, Essex has been a testing ground for a variety of new models of alternative inhabitations and communities. From the Plotlanders leaving the city behind, occupying and dwelling in simple sheds, to the company towns and villages built by Bata Shoes in East Tilbury and the Crittall Window Factory in Silver End; the Hadley Colony for the poor; the Osea Island community for living without alcohol or drugs; Purleigh Colony – a Tolstoy-inspired colony living by anarchist principles; and the famous Permaculture Anarchist workshops at Dial House, a community set up by the anarcho-punk band Crass; the list seems to be endless.

Nowadays, Essex has a very different reputation: known for the television series TOWIE and its star Joey Essex, bottle-blondes with white stilettos, boy racers, and Saturdays spent in the Lakeside Shopping Centre or the Festival Leisure Centre in Basildon, affectionately called ‘Bas Vegas’.

Instead of repairing this ‘broken suburbia’, Unit 13 is interested in ways the abandoned industrial landscapes of Essex can be used to create different ways of living. Each approach is different, all our readings are personal, and every solution is driven by innovation. We are interested in how we inhabit spaces and cities, what forms new communities can take on, how technology and production can drive this progress, and where different methods of procurement can lead us.

Figs. 13.1 – 13.2 Yan Kee (Adrian) Siu Y5, ‘The Diggers Festival of Peace.’ A speculative settlement is proposed to relocate an evicted squatting community called ‘The Diggers’. Formerly inhabited in Runnymede, the squatters craft an off-grid woodland village to provoke a land reform. By highlighting disused lands in London, they advocate an ecologically sustainable living model with cultivation and dwellings built with local materials, establishing their own Arcadia within nature. The speculated settlement encapsulates collective visions that various squatting communities attempt to realise, creating an alternative ecosystem. The annual pilgrimage of nature, the Festival of Peace celebrates the reform of squatting communities, promoting social autonomy and equality. Fig. 13.3 Gintare Kapociute Y5, ‘The Southall Oasis:

The New Arrival City.’ The urban regeneration of Southall imagines an alternative future for high-density multigenerational living for culturally diverse communities. Through the lens of Hindu notions of spacemaking and community engagement studies, the Southall Oasis investigates how the use of wasteland can provide selfsustaining areas for habitation and stimulate alternative planning approaches though the cultivation of health and wellbeing. The project seeks to provide for integration and cohesion between the existing and future communities by encouraging participation in the design and construction of habitats, which are able to adapt and transform to the changing needs of a multigenerational family.

13.4

13.5

Fig. 13.4 Ye Lone (Jarrell) Goh Y5, ‘The Ganesh Chaturthi Festival Grounds’. The project proposes a new Hindu festival site in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex, for the annual celebration of Lord Ganesh’s birthday. The architecture embodies the fleeting nature of the ten-day festival with temporary buildings that fully exist only during the celebrations. The traditional ritual of dissolving clay idols in the River Thames is reflected in an impermanent, dissolving architecture created by the draping of clay-dipped fabric. The Festival Grounds consist of a temple, feasting halls, and visitor accommodation within a productive landscape that harvests the materials that support the event. Fig. 13.5 Katriona Pillay Y5, ‘Performance Accelerator of Pushkar Lake’. Pushkar in India is transformed into a host city for a one-day festival in celebration of the New Year.

The project aims to critique the intrinsic institutional division set between attributes classified under ‘tangible’ and ‘intangible’ cultural heritage, as inscribed by UNESCO. The mandala symbol is reflected upon as a spatial archetype, unintentionally maturing into an artform of scattered festival follies, expressing a symbiotic unity of the intangible conscious mind and imagination with the meticulous tangibility of its construction. Thus, an intangible process generates a tangible product.

Fig. 13.6 Alexander Wood Y5, ‘Dirty Money.’ The project speculates on the relocation of the London Stock Exchange to the mudflats of Foulness Island off the Essex coast. Occupying this remote landscape, high-frequency trading takes place using servers powered by the tide and housed within concrete bastions. A lone maintenance person is the sole inhabitant of this remote landscape. Fig. 13.7 Yui Sze Wong Y5, ‘An Essex Love Story.’ A new typology in wedding architecture which provides an affordable and more convenient version of ‘lavish’ weddings. A series of stage sets are designed to compose perfect moments within a camera’s lens. The contrast between the ‘stage’ and the ‘back of house’ is a critique on how contemporary nuptials have evolved into superficial performances, utilised by individuals to display their social

status and identity. Fig. 13.8 Sara Martinez Zamora Y5, ‘Hacking the Green Belt: A Proposal for a Common Ground.’ In the context of the current housing crisis in London, the project studies the issue of land and its lack of availability. Attempting to unlock new land, the project takes the form of a manifesto advocating for the release and development of the green belt for a new type of housing. Through the reinterpretation of the current legislation, the ‘good design’ guide utilises the loopholes that allow for the proposal of a new village typology. These settlements promote new types of land ownership.

Fig. 13.9 Mai Que Ta Y5, ‘Dichotic Territories.’ The project seeks to address the phenomenon that without ever leaving home, we exist in two places simultaneously. It is designed as an urban site strategy for housing along the railway’s ecological corridor in Harringay. The proposal seeks to understand the dichotomies of space through the negotiation between the interior and the culturally fluid boundary of the exterior, where the common has the same cultural significance as the home itself. Explored through textile manipulations, the tactile tectonic structuring of the landscape forms a relationship with a plan which is able to shift, move and adapt – exploring the fragility and impermanence of both the home and the shelter. Figs. 13.10 – 13.11 Kannawat Limratepong Y5, ‘Paradise on Archipelago.’ Reimagining Wallasea Island in

as new British seaside retirement resorts. The project aims to reclaim the lost seaside heritage and highlights the growth of the third-age population. The design suggests a new model of retirement inhabitation as festive ground by utilising and revitalising the attributes and landscape of seaside towns.

13.12

13.13

Fig. 13.12 Nicola Chan Y4, ‘The Dagenhamlandia Showhome’. The rise of electric vehicles and the UK’s pledge to ban the sale of all diesel and petrol cars by the year 2040 provides the starting point for a conceptual rebranding of the major car company, Ford, in a strategic venture into the housemaking industry. The brand’s history as a pioneer of Fordist methodologies of mass-production and the assembly line have inspired an alternative form of highly customisable housing, consisting of pre-cast concrete platforms and prefabricated living components. Ford Homes aims to reform the pre-existing disciplines of home acquisition and ownership in light of changing social dynamics within suburbia. Fig. 13.13 Emily Martin Y4, ‘Essex Caravanserai’. In response to the failing and tragic conception of the

‘New Town Utopia’ Basildon, Essex Caravanserai aims to offer a new radical strategy for living in Essex by advertising a solution to the throwaway attitude of society endorsed by the council through providing a highly sustainable and self-sufficient living scheme which uses and promotes earth as a means of construction. The project proposes providing new qualifications in new building techniques to under-qualified people in Essex. Residents will use the newly developed excavation-extruder device to build their own homes made of earth and recycled concrete to form their own Essex Caravanserai.

13.15

Fig. 13.14 Rui Ma Y4, ‘Tollesbury Living Observatory.’ Facing climate change and ecological degradation, wetlands are lost. This is having negative effects on the natural landscape and dependent human life. The project gives a positive response to such changes on the tidal marshland. It focuses on finding new ways to explore the changes, proposing a new living model in these areas. Fig. 13.15 Allegra Willder Y4, ‘Jaywick Lagoon.’ The project proposes an alternative and radical way of living for the coastal community of Jaywick in Essex. Set within a reconstructed landscape, the design proposal is to build a land pier with community spaces. The project dicusses how to reinvent Jaywick’s holidaying community (and rebuild its associated tourist-driven economy) in a way that keeps the residents of Jaywick afloat, physically and economically.

Fig. 13.16 Giles Nartey Y4, ‘The Workers’ Club.’ An exploration of materiality through the proposition of a community-focused intervention within the industrial landscape of Dagenham. Using the surrounding industries as a ‘quarry’ for raw materials, the project explores a ‘hyper-recycling’ ethos, from materials to skillsets, with an aim to splice and collage a new formal expression. Fig. 13.17 Tasnim Eshraqi Najafabadi Y4, ‘Radical Regionalism: A New Inter-Tidal Habitat.’ In reaction to the degradation of saltmarshes along the Essex coast, the project envisages an off-grid habitat for volunteer conservationists interested in dwelling in and protecting these invaluable landscapes. Hybridising boats and barns, the design explores an alternative vernacular which responds to the fragility, ambiguity and dynamism of the site.

Tesla Laboratory Roz Barr, Ivan Redi

Dip/MArch Unit 13

Yr 4: Paul Broadbent, Sam Clark, Thomas Impiglia, Xin Yu Xie, Seng Chun Tan

Yr 5: Geraldine Holland, Morounkeji Majekodunmi

Tesla Laboratory

‘The scientific man does not aim at an immediate result. He does not expect that his advanced ideas will be readily taken up. His work is like that of a planter – for the future. His duty is to lay foundation of those who are to come and point the way.’ Nikola Tesla in a Wired interview 142 years after his birth.

Who was Tesla? A genius scientist, engineer, inventor and discoverer of the principles and laws of nature, claiming over 130 original patents. Tesla invented some of the most substantial contributions to the world’s scientific and technological advances. His biggest invention, however, was the worldwide wireless electrical transmission. He claimed that there was more than sufficient energy from natural sources on earth and that therefore everyone should have free access to it. Nevertheless, we do not associate his name with any of these inventions. Tesla had powerful enemies, and died alone and bankrupt.

The key question for Unit 13 was: what would the Tesla Laboratory and the Wardenclyffe Tower – which Tesla had not been able to finish because of financial issues – look like in the era of Ubiquitous- and Grid-Computing, and the technological advances of today? The task was to re-design those from a 21st-century point of view, bearing in mind important criteria such as new energy sources, resource-regenerative technologies, lifecycle intelligence, augmented realities, virtual world making, cutting edge computer technology, performative design strategies, on-demand and sensitive spaces, simulation platforms, architecture of the networks, connected intelligence and innovative materials.

Tutors: ORTLOS - Ivan Redi & Andrea Redi with Roz Barr

Ivan Redi & Roz Barr

Thomas Impiglia Belgrade, Belgrade: Memory Lab. Above: Memory lab in context, real and virtual, media art, architecture and ruin. Birthed from the urban fabric. Opposite page: Belgrade: Overlooking the Bridge, Building as a regenerative force for the rehabilitation of Belgrade.

Tutors: ORTLOS - Ivan Redi & Andrea Redi with Roz Barr

Ivan Redi & Roz Barr

Thomas Impiglia Belgrade, Belgrade: Memory Lab. Above: Memory lab in context, real and virtual, media art, architecture and ruin. Birthed from the urban fabric. Opposite page: Belgrade: Overlooking the Bridge, Building as a regenerative force for the rehabilitation of Belgrade.

Opposite page: Xinyu Xie, Design Process on Merging Vertical Farming Tower and Creative Tower. Above: Xinyu Xie, A New System/Economy Emerged out of the Old Collapsed System

Opposite page: Xinyu Xie, Design Process on Merging Vertical Farming Tower and Creative Tower. Above: Xinyu Xie, A New System/Economy Emerged out of the Old Collapsed System

Sam Clark, Solar Plant, Alice Springs, Australia.

Sam Clark, Solar Plant, Alice Springs, Australia.

Paul Broadbent, Click-to-Play, The Gratão Favela, São Paulo, rapid context model.

Paul Broadbent, Click-to-Play, The Gratão Favela, São Paulo, rapid context model.